1. Overview

The Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) is a partially recognized state that claims sovereignty over the entire territory of Western Sahara, a former Spanish colony. Proclaimed by the Polisario Front on 27 February 1976, the SADR currently controls approximately 20-25% of the territory it claims, primarily an eastern strip often referred to as the "Free Zone" or "Liberated Territories." The majority of Western Sahara, including its major cities and natural resources, is administered by Morocco, which considers the territory its "Southern Provinces." This ongoing territorial dispute, known as the Western Sahara conflict, has its roots in decolonization and has involved decades of military conflict, diplomatic efforts, and significant human rights concerns, particularly regarding the Sahrawi people's right to self-determination. This article explores the history, political structure, international legal status, socio-economic conditions, and cultural aspects of the SADR and the Western Sahara conflict, emphasizing the Sahrawi perspective, the human rights dimensions of the protracted displacement of Sahrawi refugees, and the challenges to achieving a just and lasting resolution. The SADR is a full member of the African Union, a point of significant diplomatic contention with Morocco.

2. Etymology

The name Sahrawi (صحراويṢaḥrāwīArabic) is an Arabic term meaning 'Inhabitant of the Desert' or 'Desert Dweller,' derived from the Arabic word صحراءṢaḥrāʼArabic, meaning 'desert'. This term refers to the indigenous people of Western Sahara.

The Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) translates to الجمهورية العربية الصحراوية الديمقراطيةal-Jumhūriyyah al-ʿArabiyyah aṣ-Ṣaḥrāwiyyah ad-DīmuqrāṭiyyahArabic in Arabic and República Árabe Saharaui DemocráticaRASDSpanish in Spanish. The name signifies its Arab identity, its geographical origin in the Sahara, and its aspiration for a democratic republican system.

Western Sahara is the geographical term for the territory, a legacy of its colonial designation as Spanish Sahara. The Polisario Front and the SADR often refer to the territory as the Sahrawi Republic.

3. History

The history of Western Sahara is marked by its indigenous populations, European colonization, and a prolonged struggle for self-determination that continues to this day.

This section details the region's evolution from its pre-colonial societies through Spanish rule to the ongoing Western Sahara conflict and the emergence of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic.

3.1. Pre-Colonial Era and Early Contacts

The earliest inhabitants of Western Sahara were Berber populations, primarily nomadic Sanhadja tribes. From the 8th century onwards, Islam spread to the region, and Arab Bedouin tribes, notably the Beni Hassan, migrated southwards, gradually Arabizing the local Berber population and leading to the development of the Hassaniya Arabic dialect and a unique Sahrawi culture. Society was traditionally organized along tribal lines, with a pastoral nomadic lifestyle adapted to the arid desert environment.

Early contacts with Europeans were limited. In 1476, Spanish traders established a post named Santa Cruz de la Mar Pequeña opposite the Canary Islands, but it was abandoned in 1524. Portuguese navigators reached Cape Bojador in 1434. In 1878, the British established a trading post at Cape Juby, but it was ceded to Morocco in 1895 after an attack.

3.2. Spanish Colonization

Spanish colonial interest in the Western Sahara region solidified in the late 19th century. In 1884, at the Berlin Conference, Spain was granted a coastal protectorate stretching from Cape Bojador to Cape Blanc (present-day Nouadhibou). The boundaries of Spanish Sahara were further defined through treaties with France in 1900 and 1904, which established the modern borders with Mauritania and the northern frontier. These agreements often resulted in straight-line borders drawn across the desert.

Spanish control was initially limited to coastal enclaves. By 1916, Spain had secured Cape Juby, and in 1920, La Güera was founded at Cape Blanc. It wasn't until 1934 that Spain extended its control into the interior of Western Sahara. The territory was administered as part of Spanish West Africa, and later, in 1958, it became a Spanish province.

The discovery of large phosphate deposits at Bou Craa in 1964 significantly increased the territory's economic importance and strategic value to Spain.

During the Spanish colonial period, administration was largely focused on resource exploitation, particularly phosphates and fisheries. Sahrawi society underwent changes with increased urbanization, although many maintained nomadic traditions. Early stirrings of Sahrawi nationalism began to emerge in response to colonial rule. In 1956, Morocco gained independence from France and, in 1957, asserted its claim to Western Sahara at the United Nations, arguing it was historically part of Greater Morocco. This led to the Ifni War (1957-1958) between the Moroccan Army of Liberation and Spanish forces. Spain, with French assistance, repelled the Moroccan incursions but ceded the southern part of its protectorate (Cape Juby strip) to Morocco in the Treaty of Angra de Cintra in 1958. Ifni itself was ceded to Morocco in 1969.

From the 1960s, Mauritania also laid claim to the territory, arguing for a Greater Mauritania. The UN began to address the issue of Western Sahara's decolonization. In December 1966, UN General Assembly Resolution 2229 (XXI) reaffirmed the right of the people of Spanish Sahara to self-determination and called on Spain to organize a referendum in consultation with Morocco, Mauritania, and other interested parties.

In June 1970, an anti-colonial demonstration in El-Aaiun organized by Harakat Tahrir (Movement for the Liberation of Saguia el Hamra and Wadi el Dhahab) was violently suppressed by Spanish forces in what became known as the Zemla Intifada. This event is considered a turning point, pushing the Sahrawi nationalist movement towards armed struggle.

3.3. Western Sahara Conflict

The Western Sahara conflict is an ongoing dispute over the control and sovereignty of Western Sahara, primarily between the Kingdom of Morocco and the Polisario Front, the Sahrawi national liberation movement. The conflict has profound implications for the Sahrawi people's right to self-determination and has led to decades of displacement and human rights concerns.

It encompasses the period from the Spanish withdrawal, the proclamation of the SADR, the ensuing war, ceasefire efforts, and the recent resumption of hostilities, highlighting the struggle for independence and the complex geopolitical dynamics involved.

3.3.1. Declaration of Independence and Early Conflict (1975-1991)

As Spain prepared to withdraw from Western Sahara, the Polisario Front (Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguia el-Hamra and Río de Oro), formed in May 1973 by El-Ouali Mustapha Sayed, Brahim Ghali, and Mohamed Abdelaziz, among others, emerged as the leading Sahrawi nationalist movement, advocating for full independence. The Polisario Front launched an armed struggle against Spanish colonial rule, gaining control over parts of the territory.

In October 1975, a UN visiting mission reported that the majority of Sahrawis desired independence. On October 16, 1975, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued an advisory opinion stating that while there were historical legal ties between Western Sahara and both Morocco and Mauritania, these ties did not establish sovereignty over the territory and did not negate the Sahrawi people's right to self-determination.

Despite the ICJ's opinion, King Hassan II launched the "Green March" on November 6, 1975, a mass demonstration of some 350,000 unarmed Moroccans who crossed into Western Sahara to assert Moroccan claims. Facing internal political instability and pressure from Morocco and Mauritania, Spain signed the Madrid Accords on November 14, 1975, agreeing to a tripartite interim administration with Morocco and Mauritania and to withdraw by February 28, 1976. The Accords effectively partitioned Western Sahara, with Morocco taking control of the northern two-thirds (including the phosphate mines at Bou Craa) and Mauritania the southern third. The Polisario Front and Algeria, which supported Sahrawi independence, rejected the Madrid Accords.

As Spanish forces completed their withdrawal on February 26, 1976, the Polisario Front proclaimed the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) on February 27, 1976, in Bir Lehlou. El-Ouali Mustapha Sayed became its first president. A government was organized on March 5, 1976. This declaration was followed by the immediate entry of Moroccan and Mauritanian forces into the territories assigned to them, leading to a full-scale war with the Polisario Front. Thousands of Sahrawi civilians fled the advancing armies, primarily to refugee camps in the Tindouf Province of southwestern Algeria.

The Sahrawi People's Liberation Army (SPLA), the armed wing of the Polisario Front, waged a guerrilla war against both Morocco and Mauritania. The SPLA, receiving support from Algeria and Libya, proved effective against the Mauritanian army. In June 1976, El-Ouali Mustapha Sayed was killed during an SPLA raid on the Mauritanian capital, Nouakchott. Mohamed Abdelaziz succeeded him as president of the SADR and secretary-general of the Polisario Front.

The war placed a severe strain on Mauritania's economy and military. Following a military coup in July 1978, Mauritania signed a peace treaty with the Polisario Front in Algiers on August 5, 1979, renouncing all claims to Western Sahara and withdrawing its forces. Morocco immediately responded by annexing the southern portion of Western Sahara previously controlled by Mauritania, thereby controlling most of the territory.

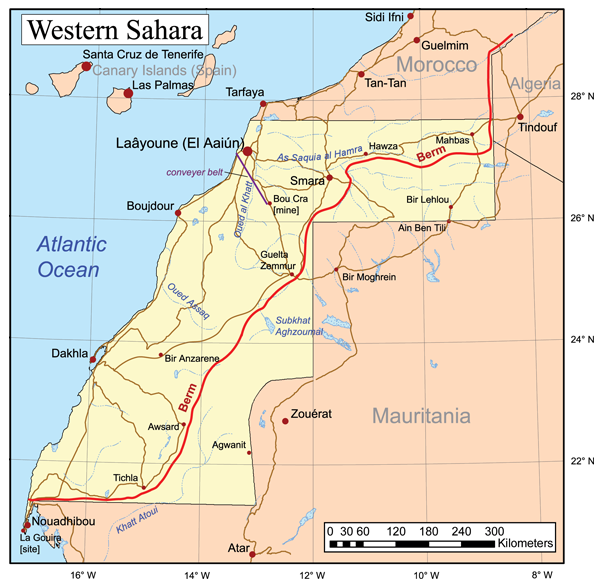

From the early 1980s, Morocco began constructing a series of defensive sand berms, known as the Moroccan Wall (or Berm). This heavily fortified barrier, eventually stretching over 1.7 K mile (2.70 K km), separated the Moroccan-controlled western parts of Western Sahara from the less populated eastern areas controlled by the Polisario Front (the "Free Zone"). The wall, surrounded by extensive minefields, significantly altered the military dynamics of the conflict and had severe humanitarian and environmental consequences.

3.3.2. 1991 Ceasefire and Peace Process Efforts

After years of conflict, diplomatic efforts led by the United Nations and the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), which the SADR joined as a full member in 1982 (leading to Morocco's withdrawal from the OAU in 1984), aimed to find a peaceful solution. In 1988, Morocco and the Polisario Front agreed in principle to a UN peace plan, known as the Settlement Plan.

This plan, endorsed by United Nations Security Council Resolution 690 in April 1991, called for a ceasefire and a referendum on self-determination that would allow the Sahrawi people to choose between independence or integration with Morocco. The United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) was established to monitor the ceasefire and organize the referendum.

A UN-brokered ceasefire came into effect on September 6, 1991, largely holding for nearly three decades. However, the referendum, initially scheduled for 1992, was repeatedly postponed due to disagreements between Morocco and the Polisario Front over voter eligibility. Morocco sought to include Moroccan settlers who had moved to the territory after 1975 and individuals it claimed had Sahrawi tribal links in Morocco, while the Polisario Front insisted on a voter roll based primarily on the 1974 Spanish census and their descendants, a position generally supported by the UN.

Several subsequent peace initiatives were attempted. The Houston Agreement (1997), negotiated under the auspices of former US Secretary of State James Baker III, aimed to resolve voter identification issues but ultimately failed. Baker later proposed two further plans. The "Framework Agreement" or Baker Plan I (2001) suggested autonomy for Western Sahara within Morocco for five years, followed by a referendum, but was rejected by the Polisario Front and Algeria as it did not offer independence as an option from the outset.

The Baker Plan II (2003), officially the "Peace Plan for Self-Determination of the People of Western Sahara," proposed a five-year period of Sahrawi autonomy under a Western Sahara Authority, followed by a referendum offering independence, autonomy within Morocco, or full integration. This plan was endorsed by the UN Security Council (Resolution 1495) and accepted by the Polisario Front and Algeria. However, Morocco rejected it, stating it would no longer consider any referendum that included independence as an option. James Baker resigned as UN Special Envoy in 2004, citing the lack of progress.

Subsequent UN-led negotiations, known as the Manhasset negotiations (2007-2008), also failed to break the deadlock. Morocco presented an Autonomy Proposal in 2007, offering self-government under Moroccan sovereignty, while the Polisario Front maintained its demand for a referendum that included independence. The peace process remained stalled, with MINURSO's mandate primarily focused on monitoring the ceasefire.

3.3.3. Conflict Resumption (2020-present)

The nearly 30-year ceasefire broke down in November 2020. Tensions had been rising, particularly around the Guerguerat buffer strip near the Mauritanian border, a demilitarized zone under the ceasefire agreement. Sahrawi civilian protesters had been blocking a road through Guerguerat, which Morocco and the Polisario Front both considered vital. The Polisario Front argued the road was illegal under the ceasefire terms and facilitated Moroccan resource exploitation.

On November 13, 2020, Morocco launched a military operation in Guerguerat to clear the road and secure the area, stating it was responding to "provocations" and ensuring free movement of goods and people. The Polisario Front declared this a violation of the ceasefire and announced an end to its commitment to the 1991 agreement, declaring a resumption of armed struggle.

Since then, the SPLA has reported regular attacks against Moroccan positions along the Berm, primarily using artillery and rockets. Morocco has largely downplayed the extent of the renewed hostilities, often referring to them as minor skirmishes or "harassment fire." Independent verification of battlefield claims has been difficult due to restricted access to the conflict zones.

International reactions to the renewed conflict have been generally muted, with most countries calling for restraint and a return to the ceasefire and the UN-led political process. The United Nations Secretary-General and various UN envoys have expressed concern and urged a de-escalation of tensions. The African Union has also called for dialogue.

The conflict was further complicated in December 2020 when the United States, under the Trump administration, recognized Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara in exchange for Morocco normalizing relations with Israel. This move broke with longstanding US and international policy and was criticized by the Polisario Front, Algeria, and several other countries and international organizations as undermining the UN peace process and the Sahrawi right to self-determination. While the Biden administration has not reversed the recognition, it has expressed support for the UN-led diplomatic efforts.

The current state of the conflict is one of low-intensity warfare, primarily along the Moroccan Wall. The Polisario Front continues to assert its commitment to armed struggle until a referendum on self-determination is held, while Morocco maintains its position that autonomy under its sovereignty is the only viable solution. The humanitarian situation for Sahrawi refugees in the Tindouf camps remains precarious, exacerbated by the renewed conflict and the ongoing political impasse.

4. Geography

The Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic claims the entirety of Western Sahara, a territory located in the Maghreb region of North Africa. This section details the physical characteristics of the land and the political divisions resulting from the ongoing conflict.

The description includes its topography, arid climate, the division of control marked by the Moroccan Wall, and key settlements including the claimed capital and provisional administrative centers.

4.1. Topography and Climate

Western Sahara covers an area of approximately 103 K mile2 (266.00 K km2). The territory is predominantly desert, forming part of the Sahara. The landscape consists largely of arid, rocky plains and hamada (stony desert), with some areas of sand dunes (erg). The terrain is generally flat or gently undulating, with some low mountain ranges and plateaus, particularly in the northeast (Zemmur region) and south, where elevations can reach up to 2297 ft (700 m). The average elevation is around 840 ft (256 m). The coastline along the Atlantic Ocean stretches for about 0.7 K mile (1.11 K km) and is characterized by cliffs in some areas and sandy beaches in others. There are no permanent rivers, though wadis (dry riverbeds) can fill with water after rare rainfall.

The climate of Western Sahara is a hot desert climate (Köppen climate classification BWh). Rainfall is scarce and erratic, generally averaging less than 2.0 in (50 mm) per year, and in some areas much less. Temperatures are high, especially in the interior. Summer daytime temperatures frequently exceed 104 °F (40 °C), and can reach over 122 °F (50 °C) in some inland areas. Winter temperatures are milder, typically ranging from 50 °F (10 °C) to 77 °F (25 °C), though night temperatures in the interior can drop significantly. Coastal areas experience more moderate temperatures due to the cooling influence of the Canary Current, with frequent fog and dew, particularly in the mornings. Sirocco winds, hot and dust-laden, can occur, blowing from the Sahara.

4.2. Areas of Control and the Moroccan Wall

The territory of Western Sahara is effectively divided by the Moroccan Wall (also known as the Berm), a series of defensive fortifications approximately 1.7 K mile (2.70 K km) long, built by Morocco between 1980 and 1987.

- Moroccan-controlled territory:** Morocco controls and administers about 80% of Western Sahara, located west of the Wall. This area includes the major cities (Laayoune, Dakhla, Smara), the phosphate mines at Bou Craa, and the entire Atlantic coastline with its rich fishing grounds. Morocco refers to this region as its "Southern Provinces."

- SADR-controlled territory (Free Zone):** The Polisario Front, representing the SADR, controls the remaining 20-25% of the territory, located east of the Wall. This area is often referred to as the "Free Zone" (المنطقة الحرةal-Mintaqa al-HurraArabic) or the "Liberated Territories" (الأراضي المحررةal-Aradi al-MuharraraArabic) by the SADR. It is sparsely populated, consisting mainly of desert terrain. Key settlements in this zone include Tifariti and Bir Lehlou.

The Moroccan Wall is a significant physical and political barrier. It consists of sand and stone walls, berms, trenches, and barbed wire, fortified with bunkers, artillery positions, and radar systems. The area immediately surrounding the Wall, particularly on its eastern side, is heavily contaminated with landmines and unexploded ordnance, posing a severe threat to the local population, livestock, and hindering movement and economic activity. The Wall has had a profound social impact, separating Sahrawi families and communities and restricting access to traditional grazing lands and water sources for nomadic populations. Environmentally, it has disrupted wildlife migration patterns and contributed to desertification in certain areas.

4.3. Provisional Capitals and Key Settlements

- Claimed Capital (Laayoune):** The SADR constitution designates Laayoune (العيونAl-ʿUyūnArabic; also spelled El Aaiún) as its capital city. However, Laayoune is located in the Moroccan-controlled part of Western Sahara and serves as the largest city and administrative center of that region.

- Provisional Capitals:**

- Bir Lehlou**: Located in the Free Zone, Bir Lehlou served as the symbolic provisional capital of the SADR from its proclamation in 1976 until 2008. It was here that the SADR was declared.

- Tifariti**: In 2008, Tifariti, also in the Free Zone, was formally declared the temporary capital or administrative center of the SADR. It hosts some government buildings, a hospital, a school, and a museum, and has been the site for SADR national celebrations and Polisario Front congresses.

- Sahrawi Refugee Camps (Tindouf, Algeria):** While not within Western Sahara, the Sahrawi refugee camps located near Tindouf in southwestern Algeria are crucial to the SADR's administration and the life of a significant portion of the Sahrawi population. These camps, including Rabouni (the administrative headquarters of the Polisario Front and SADR government-in-exile), Awserd, Smara, Laayoune, and Dakhla (named after cities in Western Sahara), have housed tens of thousands of Sahrawi refugees since 1975-1976. Much of the day-to-day administration of the SADR, including ministries and representative offices, operates from these camps.

Other settlements in the Free Zone include Mehaires, Agounit, and Dougaj. In the Moroccan-controlled zone, besides Laayoune, major towns include Dakhla (formerly Villa Cisneros), Smara, Bojador, and the phosphate mining town of Bou Craa.

5. Politics and Government

The Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) operates primarily as a government-in-exile, with its main administrative structures located in the Sahrawi refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria, and exercising de facto control over the "Free Zone" east of the Moroccan Wall. Its political system is closely intertwined with the Polisario Front, which is constitutionally recognized as the leading political force until full independence is achieved.

This section outlines the SADR's governmental framework, its constitution, and the pivotal role of the Polisario Front in its political life.

5.1. Government Structure in Exile

The SADR's government structure is based on a separation of powers model, though its functions are adapted to the context of exile and partial territorial control.

- Executive Branch:**

- The President is the head of state. Constitutionally, this position is held by the Secretary-General of the Polisario Front. The President is elected by the Polisario Front's General Popular Congress. Currently, the President is Brahim Ghali, who assumed office in 2016 following the death of Mohamed Abdelaziz. The President appoints the Prime Minister, presides over the Council of Ministers, is the commander-in-chief of the Sahrawi People's Liberation Army (SPLA), and represents the SADR internationally.

- The Prime Minister is the head of government, appointed by the President. The Prime Minister leads the Council of Ministers (cabinet) and is responsible for implementing government policies. The current Prime Minister is Bouchraya Hammoudi Bayoun, appointed in 2020.

- The Council of Ministers comprises various ministries responsible for sectors such as foreign affairs, interior, defense, education, health, economic development, culture, and information. These ministries operate primarily within the refugee camps and the Free Zone.

- Legislative Branch:**

- The Sahrawi National Council (SNC) is the unicameral parliament of the SADR. Its members are elected by the Polisario Front's General Popular Congress and represent different constituencies, including the refugee camps, the occupied territories, the diaspora, and the military. The SNC's functions include legislating, approving the budget, overseeing the government, and ratifying treaties. Its speaker is currently Hamma Salama. While its legislative role was initially consultative, constitutional revisions have aimed to strengthen its powers.

- Judicial Branch:**

- The judicial system includes trial courts, appeals courts, and a Supreme Court. Judges are appointed by the President. The legal system draws upon principles of Islamic law and secular law, influenced by Spanish legal traditions. A Sahrawi Bar Association exists. The practical application of the judicial system is largely confined to the refugee camps and areas under SADR control.

Many branches of the government do not fully function as they would in a sovereign state with full territorial control, due to the exile status. There is also a significant overlap between the structures of the SADR state and the Polisario Front.

5.2. Constitution

The SADR Constitution has undergone several revisions since its first adoption, with the most recent significant version adopted by the 14th Congress of the Polisario Front in 2015. It lays out the framework for governance, the rights and duties of citizens, and the national identity and aspirations of the Sahrawi people.

Key provisions of the constitution include:

- Sovereignty and Identity:** It declares the SADR as a "free, independent, and sovereign state" and defines the Sahrawi people as Arab, African, and Muslim. Islam is recognized as the state religion and a source of law. Hassaniya Arabic is the national language, and Modern Standard Arabic is the official language.

- System of Government:** It establishes a republican system based on democratic principles, with a multi-party system envisioned after the achievement of full independence. During the "pre-independence phase," the Polisario Front is designated as the leading political organization.

- Rights and Freedoms:** The constitution guarantees fundamental human rights and freedoms, including equality before the law, freedom of expression, assembly, and association, and the right to education and healthcare. It also enshrines the right to resist occupation and the commitment to self-determination.

- Territorial Claim:** It asserts sovereignty over the entire territory of Western Sahara as defined by its colonial borders.

- Foreign Policy:** It affirms commitment to the United Nations Charter, the African Union Constitutive Act, international law, human rights, peaceful resolution of conflicts, and good neighborliness. It also expresses a commitment to Maghreb unity and Pan-Arabism.

- Transitional Provisions:** Some articles are suspended or modified until "full independence" or "recovery of full sovereignty," acknowledging the current political situation. It outlines a transitory phase where the SADR government acts as the government of Western Sahara, leading to constitutional reforms upon full independence.

The constitution has evolved to reflect changing circumstances and to strengthen democratic institutions and human rights protections, at least in principle, within the SADR's structures.

5.3. Polisario Front

The Polisario Front (Frente Popular de Liberación de Saguía el Hamra y Río de OroPopular Front for the Liberation of Saguia el-Hamra and Río de OroSpanish) is the national liberation movement of the Sahrawi people and plays a central and constitutionally recognized role in the political life of the SADR.

- History and Ideology:** Founded on May 10, 1973, the Polisario Front initially aimed to achieve independence for Western Sahara from Spanish colonial rule through armed struggle. After Spain's withdrawal and the subsequent Moroccan and Mauritanian occupation in 1975, the Polisario Front continued its fight against these new occupying powers. Its ideology is primarily nationalist, focused on Sahrawi self-determination and independence. While it initially had socialist leanings, its current platform emphasizes democracy, social justice, and a market economy within an independent Sahrawi state.

- Organizational Structure:** The Polisario Front has a hierarchical structure:

- The General Popular Congress is the supreme body, convening every few years to elect the Secretary-General and the National Secretariat, and to define general policies.

- The Secretary-General is the leader of the Polisario Front and, by extension, the President of the SADR.

- The National Secretariat is the executive body responsible for implementing the decisions of the Congress and managing the day-to-day affairs of the Front.

- The Polisario Front has various branches and popular organizations, including those for youth (UJSARIO), women (National Union of Sahrawi Women - UNMS), workers, and students, which mobilize support and participate in the liberation struggle and state-building efforts.

- Role:** The Polisario Front is recognized by the United Nations as the representative of the people of Western Sahara in the peace process. It was responsible for proclaiming the SADR in 1976 and has since formed its government. The Polisario Front leads diplomatic efforts to gain international recognition for the SADR and to advocate for a referendum on self-determination. Its armed wing, the Sahrawi People's Liberation Army (SPLA), has conducted military operations against occupying forces.

The relationship between the Polisario Front and the SADR state apparatus is deeply intertwined. During the "pre-independence phase," the SADR's institutions are largely directed by the Polisario Front. The constitution envisages a separation or dismantling of the Polisario Front from the state structure upon the achievement of full independence, paving the way for a multi-party democracy. However, in the current context of ongoing conflict and exile, the Polisario Front remains the dominant political and military force guiding the Sahrawi struggle.

6. Legal Status and International Relations

The legal status of Western Sahara is a complex and contentious issue in international law, with the territory recognized by the United Nations as a Non-Self-Governing Territory. The Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) has garnered partial international recognition as the sovereign state of Western Sahara, but its claim is heavily contested by Morocco.

This section explores the international legal framework concerning Western Sahara, the SADR's diplomatic recognition, its membership in international organizations, and the ongoing impasse in the UN-led peace process.

6.1. Legal Status of Western Sahara

Western Sahara's status as a Non-Self-Governing Territory means that its people have not yet attained a full measure of self-government, and the administering power has an obligation to promote their well-being and lead them towards self-determination. Spain, the former colonial power, officially informed the UN in 1976 that it had terminated its presence and responsibilities, leaving the territory without a UN-recognized administering power. Morocco claims sovereignty based on historical ties, while the Polisario Front, representing the SADR, asserts the Sahrawi people's right to independence.

Key international legal milestones include:

- International Court of Justice (ICJ) Advisory Opinion (1975):** The ICJ found that while there were historical legal ties of allegiance between some Sahrawi tribes and the Sultan of Morocco, as well as ties with the Mauritanian entity, these did not amount to territorial sovereignty. Crucially, the Court affirmed that these ties did not override the applicability of UN General Assembly Resolution 1514 (XV) on decolonization and the principle of self-determination through the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of the Territory.

- UN Resolutions:** Numerous UN General Assembly and Security Council resolutions have reaffirmed the Sahrawi people's right to self-determination and called for a referendum to allow them to choose between independence and integration with Morocco.

The UN considers the Polisario Front as the legitimate representative of the Sahrawi people. The ongoing occupation and administration of the majority of Western Sahara by Morocco is viewed by many international legal scholars and the SADR as a violation of international law, particularly the prohibition on acquiring territory by force and the denial of the right to self-determination.

6.2. International Recognition of SADR

The SADR has been recognized by a varying number of UN member states since its proclamation in 1976. The dynamics of recognition are often influenced by geopolitical alliances, regional politics (particularly in Africa and Latin America), and economic or diplomatic pressure. As of late 2023/early 2024, around 40-45 UN member states maintain diplomatic relations with or recognize the SADR. A significant number of countries, particularly in Africa, have historically supported the SADR, viewing its struggle as one of national liberation.

The SADR maintains diplomatic missions (embassies or representative offices) in several countries that recognize it.

6.2.1. States Currently Recognizing SADR

As of early 2024, countries that recognize or maintain diplomatic relations with the SADR include a significant number of African and Latin American nations, among others. This list is subject to change due to the fluid nature of diplomatic recognitions. Some prominent or longstanding recognizers include:

- African Union members:** Algeria (a key supporter), South Africa, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Angola, Mozambique, Tanzania, Uganda, Kenya, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Botswana, Lesotho, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ghana, Mali, Mauritania (though Mauritania signed a peace treaty with Polisario, it does not host an SADR embassy and its position can be nuanced).

- Latin American and Caribbean states:** Cuba, Venezuela, Mexico, Nicaragua, Ecuador, Bolivia, Uruguay, Panama, Peru (recognition has been suspended and restored multiple times), Honduras (recognition has fluctuated), Belize, Guyana (status has fluctuated).

- Other states:** East Timor, Vietnam (maintains diplomatic relations, SADR has an ambassador accredited), North Korea, Syria, Yemen, Iran (recognition status can be complex). South Ossetia (a state with limited recognition itself) also recognizes the SADR.

It is important to note that the exact number and list can fluctuate. For example, Colombia re-established relations in 2022.

6.2.2. States that have Withdrawn or Frozen Recognition

A significant number of countries (around 35-40) that had previously recognized the SADR have since withdrawn, suspended, or "frozen" their recognition. Reasons for these changes vary and can include:

- Changes in government in the recognizing state.

- Diplomatic or economic pressure from Morocco or its allies.

- A desire to adopt a "neutral" stance in the conflict and support UN-led efforts without recognizing either party's claims exclusively.

- Shifting regional alliances.

Some countries that have historically withdrawn or frozen recognition include: India, Colombia (before recent re-recognition), Peru (multiple times), Paraguay, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Dominican Republic, numerous African states at different times (e.g., Chad, Madagascar, Burundi, Zambia, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Sao Tome and Principe, Seychelles, Eswatini, Malawi - some of these have fluctuated back and forth).

The United States, in December 2020, recognized Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara, a significant departure from previous US and international policy, although this move has not been widely followed by other major powers.

6.3. Membership in International Organizations

- African Union (AU):** The SADR became a full member of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), the AU's predecessor, in 1982. This led to Morocco's withdrawal from the OAU in 1984 in protest. The SADR remains a full and active member of the AU. Morocco rejoined the AU in 2017, and now both Morocco and the SADR are members, leading to sometimes tense interactions within the organization. The SADR is a signatory to the African Continental Free Trade Area.

- Other Organizations:** The SADR is not a member of the United Nations, the Arab League (of which Morocco is a member), or the Arab Maghreb Union. It has participated as a guest or observer in meetings of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), the New Asian-African Strategic Partnership (NAASP), and the Permanent Conference of Political Parties of Latin America and the Caribbean (COPPPAL), often despite Moroccan objections.

6.4. United Nations Role and Referendum Impasse

The United Nations has been centrally involved in efforts to resolve the Western Sahara conflict since Spain's decolonization process began. Its primary goals have been to facilitate a referendum on self-determination for the Sahrawi people and to maintain peace in the region.

- United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO):** Established in 1991, MINURSO's mandate includes:

1. Monitoring the ceasefire between Morocco and the Polisario Front.

2. Organizing and conducting a free and fair referendum to enable the people of Western Sahara to choose between independence or integration with Morocco.

While MINURSO has largely succeeded in monitoring the ceasefire (until its breakdown in 2020), the referendum component has been stalled for decades. The main obstacle has been the disagreement over voter eligibility. Morocco has advocated for the inclusion of Moroccan settlers and individuals with claimed Sahrawi tribal links residing in Morocco, while the Polisario Front insists on a voter roll primarily based on the 1974 Spanish census. The UN Identification Commission completed a provisional list of voters in 1999, but disagreements persisted.

- Peace Initiatives:** The UN has sponsored numerous peace plans and negotiations:

- The Settlement Plan (1988/1991): The original plan for the ceasefire and referendum.

- The Houston Agreement (1997): Attempted to resolve voter identification issues.

- The Baker Plan I (2001) and Baker Plan II (2003): Proposed periods of autonomy followed by a referendum. Baker Plan II, which included independence as an option, was accepted by the Polisario Front but rejected by Morocco.

- Manhasset negotiations (2007-2008): Direct talks between Morocco and the Polisario Front, facilitated by the UN, but failed to achieve a breakthrough.

- Current Impasse:** The UN-led political process remains deadlocked. Morocco's 2007 autonomy proposal (self-rule under Moroccan sovereignty) is its current official position, rejecting any referendum with independence as an option. The Polisario Front insists on the full implementation of the right to self-determination, including the option of independence. The resumption of hostilities in 2020 further complicated UN efforts.

UN Special Envoys for Western Sahara (such as James Baker, Christopher Ross, Horst Köhler, and currently Staffan de Mistura) have struggled to find common ground between the parties.

Human rights implications are a significant concern. The lack of a resolution perpetuates the displacement of Sahrawi refugees in Algeria, living in harsh conditions for nearly five decades. There are also ongoing reports of human rights violations in the Moroccan-controlled parts of Western Sahara against Sahrawi activists advocating for independence or self-determination. Some critics argue that MINURSO's mandate should be expanded to include human rights monitoring, a proposal consistently opposed by Morocco. The UN's inability to resolve the referendum impasse highlights the challenges of decolonization conflicts where geopolitical interests and competing national claims intersect.

7. Military

The defense forces of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic are primarily embodied by the Sahrawi People's Liberation Army (SPLA), which also serves as the armed wing of the Polisario Front.

This section details the history, structure, equipment, and operations of the SPLA, emphasizing its role in the Sahrawi struggle for independence and the challenges it faces.

7.1. Sahrawi People's Liberation Army (SPLA)

The Sahrawi People's Liberation Army (جيش التحرير الشعبي الصحراويJayš al-Taḥrīr al-Šaʿbī al-ṢaḥrāwīArabic; Ejército de Liberación Popular SaharauiSahrawi People's Liberation ArmySpanish) was founded in 1973 as the military arm of the Polisario Front to fight against Spanish colonial rule. Following Spain's withdrawal in 1975 and the subsequent Moroccan and Mauritanian occupation, the SPLA continued its armed struggle against these two nations.

- History and Operations:**

- War against Spain (1973-1975):** Engaged in guerrilla attacks against Spanish outposts.

- War against Morocco and Mauritania (1975-1991):** After Mauritania's withdrawal in 1979, the SPLA focused its efforts against Moroccan forces. It conducted highly mobile guerrilla warfare, often launching raids deep into Moroccan-controlled territory and even into southern Morocco. The construction of the Moroccan Wall (Berm) in the 1980s significantly changed the nature of the conflict, limiting SPLA incursions and leading to more static warfare along the fortifications. The SPLA proved adept at desert warfare, utilizing hit-and-run tactics.

- Ceasefire Period (1991-2020):** The SPLA largely observed the UN-brokered ceasefire, maintaining its positions in the Free Zone east of the Berm. During this time, it focused on training and maintaining readiness.

- Resumption of Conflict (2020-present):** Following the breakdown of the ceasefire in November 2020, the SPLA declared a return to armed struggle. It has since reported regular shelling and attacks against Moroccan military positions along the Berm.

- Structure and Organization:** The SPLA is commanded by the President of the SADR (who is also the Secretary-General of the Polisario Front). It is organized into military regions and various units, including infantry, mechanized infantry, artillery, and air defense. Its forces are primarily composed of Sahrawi volunteers, many drawn from the refugee camps. Estimates of its troop strength have varied over time, ranging from several thousand to potentially over 10,000 active personnel and reservists. Women have also served in the SPLA.

- Equipment:** The SPLA's arsenal historically consisted mainly of Soviet-era weaponry supplied by Algeria and, in earlier periods, Libya. This includes:

- Armored vehicles:** T-55 and T-62 main battle tanks; BMP-1 infantry fighting vehicles; BRDM-2 amphibious armored scout cars; BTR-60 armored personnel carriers; EE-9 Cascavel armored cars. Some equipment, such as Panhard AML, Eland Mk7, Ratel IFV, AMX-13, and SK-105 Kürassier tanks, was captured from Moroccan or Mauritanian forces.

- Artillery:** BM-21 Grad multiple rocket launchers; various towed artillery pieces and mortars. Reports have also mentioned BM-30 Smerch rocket launchers.

- Anti-tank weapons:** Anti-tank guided missiles and rocket-propelled grenades.

- Air defense:** Man-portable air-defense systems (MANPADS) like the SA-7 Strela and SA-9 Gaskin; mobile surface-to-air missile systems like the SA-6 Gainful and SA-8 Gecko. These systems were credited with downing several Moroccan F-5 Freedom Fighter jets during the 1975-1991 war.

The SPLA faces significant technological and numerical disadvantages compared to the Royal Moroccan Army. Much of its equipment is aging, though efforts are made to maintain and upgrade it where possible.

- Landmines:** Both sides used landmines extensively during the conflict. The Polisario Front signed the Geneva Call's "Deed of Commitment" banning anti-personnel mines in 2005 and has undertaken some mine destruction activities. Morocco has not signed the Ottawa Treaty (Mine Ban Treaty). The areas along the Berm remain heavily contaminated.

The SPLA remains a symbol of Sahrawi resistance and its stated goal is the liberation of all of Western Sahara. Its ability to sustain a long-term, effective military campaign against a much larger and better-equipped Moroccan army is a subject of ongoing analysis.

8. Economy

The economy of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) and the broader Western Sahara region is characterized by significant disparities between the Moroccan-controlled areas and the SADR-administered "Free Zone" and Sahrawi refugee camps. The ongoing conflict and unresolved political status severely hinder economic development and create widespread challenges, particularly for the Sahrawi population advocating for independence. This section discusses the resources, key sectors, economic challenges, currencies in use, and primary livelihoods, with a focus on social equity and the impacts of resource exploitation.

8.1. Resources, Key Sectors, and Economic Challenges

Western Sahara possesses notable natural resources, the control and exploitation of which are central to the conflict.

- Natural Resources:**

- Phosphates:** The territory holds some of the world's largest phosphate rock reserves, primarily at the Bou Craa mine in the Moroccan-controlled zone. Phosphate mining has been a major economic activity since the Spanish colonial era, and Morocco is a leading global exporter. The SADR and international solidarity groups have long protested what they consider the illegal exploitation of these resources by Morocco, arguing it violates international law concerning non-self-governing territories.

- Fisheries:** The Atlantic waters off the coast of Western Sahara are rich in fish stocks. Fishing agreements, particularly those between Morocco and the European Union, have been highly controversial and subject to legal challenges at the European Court of Justice, which has ruled that such agreements cannot legally apply to Western Sahara without the consent of its people. The SADR views these agreements as further exploitation of Sahrawi resources.

- Potential Oil and Gas:** There is speculation about offshore oil and gas reserves. The SADR has issued exploration licenses for blocks in its claimed maritime zone, while Morocco has also conducted exploration activities. However, no significant commercial production has occurred, partly due to the political risks.

- Other Minerals:** Limited deposits of iron ore and other minerals exist but are not extensively exploited.

- Key Sectors:**

- Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara:** The economy is dominated by phosphate mining, fisheries, and agriculture (where irrigation is possible, such as tomato production for export). Morocco has invested heavily in infrastructure (ports, roads, airports) to integrate the territory into its own economy and to support Moroccan settlers. Tourism is also being developed, particularly in coastal areas like Dakhla.

- SADR-controlled Free Zone:** Economic activity is minimal due to the arid environment, sparse population (mainly nomadic pastoralists), and lack of infrastructure. Pastoralism (camels, goats, sheep) is the traditional mainstay. Limited agriculture exists in oases. The ongoing conflict and landmine contamination further restrict development. The Polisario Front has signed some agreements for oil exploration in this zone, but no actual drilling has taken place.

- Sahrawi Refugee Camps (Tindouf):** The economy in the camps is almost entirely dependent on international humanitarian aid provided by organizations like the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the World Food Programme (WFP), and numerous NGOs. Livelihoods are precarious, with limited opportunities for employment. Small-scale commerce, handicrafts, and some public sector employment within the SADR administration provide some income.

- Economic Challenges:**

- Political Instability:** The unresolved conflict is the primary barrier to sustainable economic development for the entire territory.

- Resource Exploitation:** The SADR and many international observers argue that Morocco's exploitation of Western Sahara's natural resources without the consent of the Sahrawi people is illegal and detrimental to their right to self-determination and future economic prospects. Social equity concerns arise as benefits from these resources often do not primarily accrue to the indigenous Sahrawi population, especially those who advocate for independence or live in refugee camps.

- Dependence on Aid (Refugee Camps):** The Sahrawi refugee population is highly vulnerable and reliant on diminishing international aid, leading to food insecurity and limited access to essential services.

- Lack of Infrastructure (Free Zone):** The SADR-controlled areas suffer from a near-total absence of economic infrastructure.

- Unemployment and Limited Opportunities:** High unemployment rates persist, particularly among Sahrawi youth in the camps and in Moroccan-controlled areas for those perceived as pro-Polisario.

- Environmental Challenges:** Desertification, water scarcity, and the impact of the Moroccan Wall and landmines pose significant environmental and economic challenges.

8.2. Currency and Livelihoods

- Currencies in Use:**

- Moroccan dirham (MAD):** The primary currency used in the Moroccan-controlled parts of Western Sahara.

- Sahrawi peseta (EHP):** The official currency of the SADR, proclaimed but not widely circulated as a physical currency due to the economic situation. It is used for some official commemorative purposes and reflects a symbolic monetary sovereignty. Its value was notionally pegged to the Spanish peseta before the euro.

- Algerian dinar (DZD):** Commonly used in the Sahrawi refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria, and in parts of the Free Zone due to proximity and economic ties with Algeria.

- Mauritanian ouguiya (MRU):** May be used in areas of the Free Zone bordering Mauritania.

- Livelihoods:**

- Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara:** Employment is found in the phosphate industry, fishing, agriculture, public administration (largely staffed by Moroccans), and small businesses.

- SADR-controlled Free Zone:** Nomadic and semi-nomadic pastoralism (camels, goats, sheep) is the primary livelihood for the small population.

- Sahrawi Refugee Camps:** Livelihoods are extremely limited. Some Sahrawis are employed by the SADR administration, schools, and healthcare facilities within the camps. Others engage in small-scale trade, handicrafts, or seek remittances from relatives abroad. The majority depend on humanitarian aid for basic necessities like food, water, and shelter. The prolonged refugee situation has created a cycle of dependency and limited prospects for economic self-sufficiency.

The economic situation underscores the deep divisions and injustices stemming from the unresolved conflict, with the Sahrawi people, particularly refugees and those in the Free Zone, facing severe economic hardship and a lack of control over their territory's resources.

9. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Western Sahara has been a subject of significant concern for decades, documented by international human rights organizations, UN bodies, and local activists. Violations are reported in both the Moroccan-administered parts of the territory and, to a lesser extent, in the Sahrawi refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria, controlled by the Polisario Front. The protracted conflict and lack of a political solution exacerbate these issues, deeply affecting the lives of the Sahrawi people, especially vulnerable groups such as political dissidents, women, and children.

This section addresses concerns in Moroccan-administered areas, conditions in the refugee camps, and the findings of international monitors, reflecting the impact on vulnerable populations.

9.1. Human Rights Situation in Moroccan-administered Western Sahara

In the larger, resource-rich part of Western Sahara controlled by Morocco, numerous human rights violations have been reported, particularly against Sahrawis advocating for self-determination, independence, or expressing support for the Polisario Front. These include:

- Freedom of Expression, Assembly, and Association:** Moroccan authorities severely restrict these freedoms for Sahrawis perceived as challenging Moroccan sovereignty. Peaceful demonstrations are often violently dispersed, and Sahrawi human rights defenders, journalists, and activists face harassment, intimidation, arbitrary arrest, and surveillance. Forming or joining pro-independence organizations is effectively banned.

- Excessive Use of Force:** Security forces have been accused of using excessive force against protesters, leading to injuries and sometimes deaths.

- Arbitrary Arrest and Detention:** Sahrawi activists are frequently arrested and detained on politically motivated charges, often related to national security or undermining territorial integrity. Trials often fall short of international fair trial standards, with convictions based on confessions allegedly obtained under duress or torture.

- Torture and Ill-Treatment:** There are persistent reports of torture and other forms of ill-treatment of Sahrawi detainees by Moroccan security forces, particularly during interrogation, to extract confessions or punish them for their political views. Impunity for such acts is a major concern.

- Discrimination:** Sahrawis often report discrimination in employment, education, and access to public services, especially if they or their families are known for pro-independence sentiments.

- Suppression of Cultural Identity:** Efforts to promote Sahrawi cultural identity distinct from Moroccan culture are sometimes suppressed.

The Gdeim Izik protest camp in 2010, where thousands of Sahrawis peacefully protested for social and economic rights and self-determination, was forcibly dismantled by Moroccan authorities, leading to clashes, arrests, and trials widely criticized for lacking due process.

9.2. Conditions and Rights in Sahrawi Refugee Camps

The Sahrawi refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria, have hosted tens of thousands of Sahrawis since 1975-1976. While the Polisario Front administers the camps, Algeria has overall sovereignty over the territory. Human rights concerns in the camps include:

- Living Conditions and Basic Services:** Refugees live in harsh desert conditions with limited access to adequate food, clean water, sanitation, healthcare, and housing. They are heavily reliant on international humanitarian aid, which has been declining, leading to malnutrition and health problems. The long-term displacement has created a situation of protracted dependency and vulnerability.

- Freedom of Movement:** While refugees can move within the camps and to some extent in Algeria (with Algerian permission), their ability to leave the camps permanently or resettle elsewhere is restricted. Some critics, particularly Morocco, have alleged that the Polisario Front restricts freedom of movement out of the camps, though the Polisario and refugee representatives deny this, citing the desire to return to an independent Western Sahara.

- Freedom of Expression and Association:** While political activity supporting the Polisario Front and Sahrawi independence is prevalent, space for dissenting opinions or criticism of the Polisario leadership within the camps has been reported as limited by some external observers and former camp residents. However, an active civil society exists within the camps.

- Accountability and Justice:** There have been past allegations of human rights abuses by Polisario Front officials within the camps, including during the war years. While the SADR has a judicial system, ensuring full accountability and access to justice for all residents can be challenging in the camp context.

- Vulnerable Groups:** Women in the camps have played a significant role in camp administration and social organization but may still face challenges related to gender equality. Children face limited educational and future prospects due to the protracted displacement.

It's important to note that access to the camps for independent human rights monitors can sometimes be subject to permissions from both Algerian authorities and the Polisario Front.

9.3. International Monitoring and Reports

Numerous international human rights organizations and UN bodies have reported on the human rights situation in Western Sahara:

- Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch (HRW):** Both organizations have extensively documented violations by Moroccan authorities in the occupied territories, including restrictions on freedoms, torture, unfair trials, and impunity. They have also reported on conditions in the refugee camps, highlighting the humanitarian crisis and calling for increased aid and respect for refugee rights. They have consistently called for independent, impartial, and regular human rights monitoring in Western Sahara, including by expanding MINURSO's mandate.

- UN Human Rights Council and Special Procedures:** UN Special Rapporteurs (e.g., on torture, freedom of expression) have sought access to Western Sahara and the camps. Reports from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) have also highlighted concerns. The UN Secretary-General's reports on Western Sahara often include sections on human rights.

- European Parliament:** The European Parliament has passed resolutions expressing concern about human rights in Western Sahara and has called for monitoring mechanisms.

A key demand from many human rights groups and the Polisario Front has been the inclusion of a human rights monitoring component in the mandate of the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO). However, this has been consistently opposed by Morocco and has not been implemented by the UN Security Council, making Western Sahara one of the few UN peacekeeping missions without a dedicated human rights monitoring capacity. This lack of independent and permanent international monitoring on the ground remains a critical gap.

10. Society

The Sahrawi people possess a distinct social fabric, shaped by their nomadic heritage, Islamic faith, the legacy of Spanish colonialism, and nearly five decades of conflict and displacement. This section explores the demographics, languages, religion, and the profound impact of life in refugee camps and exile on Sahrawi society.

It details population distribution, linguistic landscape, religious practices, and the specific challenges and adaptations of Sahrawi society, particularly in the refugee camps.

10.1. Demographics: Population, Displacement, and Composition

Accurate demographic data for Western Sahara is difficult to obtain due to the political conflict and displacement. Estimates vary, but the total Sahrawi population is generally thought to be between 500,000 and 600,000 people.

- Population Distribution:**

- Moroccan-administered Western Sahara:** This area holds the majority of the current inhabitants of the territory. Estimates suggest a population of around 500,000. However, a significant portion of this population consists of Moroccan settlers who have moved to the territory since 1975, a policy encouraged by the Moroccan government. The indigenous Sahrawi population in these areas is estimated by some sources to be a minority.

- Sahrawi refugee camps (Tindouf, Algeria):** These camps host a large Sahrawi refugee population. The Algerian government and the Polisario Front estimate the number of refugees to be around 165,000 to 173,000 (as per UNHCR planning figures, though UNHCR itself does not conduct registration and relies on figures provided by hosts). Morocco disputes these figures, suggesting a lower number. These refugees have been living in the camps since 1975-1976.

- SADR-controlled Free Zone:** This area is very sparsely populated, primarily by nomadic Sahrawis, with estimates ranging from a few thousand to around 30,000.

- Sahrawi Diaspora:** Significant Sahrawi communities live abroad, particularly in Spain (the former colonial power), Mauritania, France, and Cuba.

- Displacement:** The 1975 Moroccan and Mauritanian takeover led to a mass exodus of Sahrawis, who fled the conflict and sought refuge in Algeria. This displacement has resulted in families being separated for decades by the Moroccan Wall and political boundaries.

- Impact of Moroccan Settlement Policies:** Morocco has actively encouraged its citizens to settle in Western Sahara through economic incentives and infrastructure development. This policy has significantly altered the demographic composition of the Moroccan-controlled areas and is seen by the Polisario Front and many Sahrawis as an attempt to dilute their demographic majority and undermine their claim to self-determination. This demographic engineering is a major point of contention in any discussion about a potential referendum.

10.2. Languages

The linguistic landscape of the Sahrawi people reflects their Arab-Berber heritage and colonial history.

- Hassaniya Arabic (حسانيةḤassānīyaArabic):** This is the vernacular dialect of Arabic spoken by the Sahrawi people. It is also spoken in Mauritania and parts of Mali, Niger, and Senegal. Hassaniya has Berber substratum influences and is a key component of Sahrawi cultural identity.

- Modern Standard Arabic (MSA):** MSA is the official language of the SADR, as per its constitution. It is used in formal education, government administration, and media.

- Spanish:** Due to the long period of Spanish colonization (1884-1975), Spanish is widely spoken and understood as a second language, particularly among older generations and those educated during or shortly after the colonial era. It continues to hold a significant cultural and practical role, especially within the SADR administration and in the refugee camps, where it is often taught in schools. The SADR has sometimes been described as the only Arab country where Spanish has a de facto official or working language status. The Instituto Cervantes estimates that around 20,000 Sahrawis have some competency in Spanish.

- Berber (Tamazight):** While Hassaniya Arabic is the dominant vernacular, Berber languages were historically spoken in the region, and some Berber linguistic influences remain.

- French:** French is also used to some extent, particularly in diplomatic contexts and due to regional influences, but it is less prevalent than Spanish.

10.3. Religion

The predominant religion among the Sahrawi people is Islam.

- Sunni Islam:** Virtually all Sahrawis are Sunni Muslims, adhering to the Maliki school of Islamic jurisprudence, which is common throughout North Africa. Islam is a central aspect of Sahrawi identity and daily life, influencing social customs, law, and culture. The SADR constitution recognizes Islam as the state religion and a source of law.

- Catholicism:** During Spanish colonial rule, there was a significant Spanish Catholic population (around 20,000 people, or 30% of the population at the time). Today, a small Catholic community of a few hundred individuals, mostly of Spanish origin or expatriates, resides in the Moroccan-controlled areas. There is a St. Francis of Assisi Cathedral in Laayoune and the Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church in Dakhla.

Sahrawi society is generally characterized by moderate Islamic practices. Traditional Sahrawi culture incorporates Islamic values with pre-Islamic Berber customs and a strong sense of tribal and family solidarity.

10.4. Life in Sahrawi Refugee Camps

Life in the Sahrawi refugee camps near Tindouf, Algeria, has defined the existence of a large segment of the Sahrawi population for nearly half a century. Established in 1975-1976, these camps (named Awserd, Boujdour, Dakhla, Laayoune, and Smara, after cities in Western Sahara, plus the administrative camp Rabouni) represent a unique society built in exile.

- Daily Life and Social Organization:** Daily life is challenging, marked by the harsh desert environment (extreme temperatures, sandstorms, scarce water) and dependence on international humanitarian aid for basic necessities like food, water, shelter (tents and mud-brick houses), and medicine. Despite these difficulties, Sahrawis have established a highly organized social structure. The camps are administered by the Polisario Front and the SADR government-in-exile, with committees responsible for various sectors like education, health, food distribution, and security. Women play a prominent role in the day-to-day administration and social cohesion of the camps. Traditional Sahrawi values of hospitality, community solidarity, and oral traditions (poetry, music) remain strong.

- Challenges:**

- Protracted Displacement:** Decades of displacement have led to frustration, hopelessness, and a sense of limbo, particularly among the youth who have never seen their homeland.

- Dependence on Aid:** Declining international aid has resulted in food shortages, malnutrition, and inadequate healthcare.

- Limited Opportunities:** Educational and employment prospects are severely limited, contributing to youth disillusionment.

- Harsh Environment:** The climate and lack of resources make self-sufficiency nearly impossible.

- Psychological Impact:** The trauma of war, displacement, and separation from family members in the occupied territories takes a heavy toll.

- Resilience:** Despite the adversities, the Sahrawi refugees have demonstrated remarkable resilience. They have developed a functioning society with schools, hospitals, and cultural institutions. Literacy rates are relatively high. There is a strong emphasis on preserving Sahrawi culture and identity and a steadfast commitment to the cause of self-determination and return to their homeland. The camps have become a symbol of the Sahrawi struggle.

10.5. Education and Health in Exile

The SADR government-in-exile, with support from Algeria, international NGOs, and countries like Cuba and Spain, has prioritized education and healthcare in the refugee camps and, to a lesser extent, in the Free Zone.

- Education:**

- A comprehensive school system has been established in the camps, offering primary and secondary education. Efforts have been made to ensure high enrollment rates for both boys and girls. The curriculum includes standard subjects along with Sahrawi history and culture. Spanish is often taught as a second language.

- Boarding schools exist for older students. Many Sahrawis have pursued higher education abroad through scholarships, particularly in Algeria, Cuba, Spain, and other sympathetic countries.

- Challenges include overcrowded classrooms, lack of materials, and the difficulty of providing quality education in a refugee context. Vocational training programs aim to provide practical skills.

- Healthcare:**

- A network of clinics and small hospitals operates in the camps, providing basic healthcare services. The SADR Ministry of Health oversees these facilities.

- Medical personnel include Sahrawi doctors and nurses, some trained abroad, as well as international medical volunteers.

- Common health issues include malnutrition-related illnesses, respiratory problems due to the desert climate, and diseases linked to poor sanitation and water scarcity.

- Specialized medical care often requires referral to hospitals in Tindouf or further afield in Algeria, which can be difficult to access. Medical supplies and equipment are often in short supply.

Despite the challenging conditions, the SADR has made significant efforts to provide basic education and healthcare to its population in exile, viewing these as essential for maintaining national cohesion and preparing for future independence.

11. Culture

Sahrawi culture is a rich tapestry woven from Arab and Berber traditions, nomadic desert life, Islamic values, and the influences of Spanish colonialism. It has been further shaped by decades of conflict, displacement, and the struggle for self-determination, which has imbued it with strong themes of resilience, identity, and hope.

This section highlights national commemorations, media, arts, film, festivals, and sports that are expressive of Sahrawi cultural heritage.

11.1. National Holidays and Commemorations

The SADR and the Sahrawi people observe several national holidays and commemorative dates that mark significant events in their history and struggle:

| Date | English Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 27 February | National Day (Independence Day) | Commemorates the proclamation of the SADR in Bir Lehlou in 1976. |

| 8 March | First Martyr's Day | Commemorates the first Sahrawi martyr in the struggle for independence in 1974. (Note: Some sources list this as "First Martyr" while others specify an event related to the general struggle, or link it to International Women's Day as a day of Sahrawi women's struggle). |

| 10 May | Foundation of the Polisario Front | Anniversary of the establishment of the Polisario Front in 1973. |

| 20 May | 20 May Revolution / Day of the Outbreak of Armed Struggle | Marks the beginning of the armed struggle against Spanish colonialism in 1973, with the first Polisario attack on El-Khanga. |

| 9 June | Day of the Martyrs | Commemorates the death of El-Ouali Mustapha Sayed, the first President of the SADR and co-founder of the Polisario Front, in 1976 during a military operation. |

| 17 June | Zemla Intifada Day | Commemorates the 1970 uprising in El-Aaiun against Spanish colonial rule, led by Harakat Tahrir. |

| 12 October | Day of National Unity | Celebrates the anniversary of the Ain Ben Tili Conference in 1975, where Sahrawi notables affirmed their unity and support for the Polisario Front as the sole legitimate representative of the Sahrawi people. |

In addition to these national holidays, Islamic holidays are observed according to the lunar Islamic calendar:

| Islamic Calendar Date | English Name | Observance |

|---|---|---|

| Muharram 1 | Islamic New Year | Marks the beginning of the Islamic lunar year. |

| Dhul Hijja 10 | Eid al-Adha | Festival of Sacrifice, commemorating Prophet Ibrahim's willingness to sacrifice his son. |

| Shawwal 1 | Eid al-Fitr | Festival of Breaking the Fast, marking the end of Ramadan. |

| Rabi' al-awwal 12 | Mawlid (Mawlid an-Nabi) | Commemorates the birth of Prophet Muhammad. |

These commemorations play a vital role in reinforcing Sahrawi national identity, collective memory, and the ongoing struggle for self-determination.

11.2. Media and Communications

The media landscape for the SADR and the Sahrawi people reflects their political situation, with outlets primarily serving the government-in-exile, the refugee camps, and the diaspora, as well as aiming to disseminate information about the Sahrawi cause internationally.

- SADR-Affiliated Media:**

- Sahara Press Service (SPS):** The official state news agency of the SADR, established in 1999. It provides news and information in several languages (Arabic, Spanish, French, English) about political developments, diplomatic efforts, human rights, and life in the camps and Liberated Territories.

- RASD TV**: The official television channel of the SADR. It broadcasts news, cultural programs, and political commentary.

- Radio Nacional de la R.A.S.D. (National Radio of the SADR):** The official state radio station, broadcasting in Hassaniya Arabic and Spanish. It plays a crucial role in disseminating information and cultural content to the Sahrawi population, particularly in the camps.

- Esahra Elhora:** A national newspaper that has been in circulation since 1975.

- Other Media and Access:**

- Independent Media:** There are some independent Sahrawi news websites, blogs, and social media activists who report on the situation, often from within the occupied territories (facing significant risks) or from the diaspora.

- Access to International Media:** In the refugee camps and the diaspora, Sahrawis have access to international satellite television, radio, and the internet, which provides diverse sources of information. Access in the Moroccan-controlled areas is similar to that in Morocco, though internet and social media use by activists is often monitored.

- Union of Sahrawi Journalists and Writers (UPES):** An organization that brings together Sahrawi media professionals.

Communications infrastructure in the Free Zone is extremely limited. In the refugee camps, mobile phone and internet access, while available, can be expensive or unreliable. The media plays a critical role in maintaining national cohesion, raising awareness about the Sahrawi cause, and countering narratives from opposing sides.

11.3. Arts, Film, and Festivals

Sahrawi culture is rich in artistic expression, deeply rooted in its nomadic heritage and oral traditions. Contemporary arts also reflect the experiences of conflict and exile.

- Traditional Arts:**

- Music:** Traditional Sahrawi music, known as Haul, is characterized by its poetic lyrics, distinctive rhythms, and use of instruments like the tidinit (a four-stringed lute played by men) and the ardin (a harp-like instrument played by women), along with percussion instruments like the t'bal (drum). Music is a vital part of social gatherings, celebrations, and storytelling.

- Poetry:** Poetry is highly valued in Sahrawi culture and is a powerful medium for expressing emotions, historical narratives, social commentary, and political aspirations. Hassaniya Arabic lends itself to rich poetic forms.

- Crafts:** Traditional crafts include leatherwork (saddles, bags, cushions), metalwork (jewelry), and weaving of textiles for tents (khaimas) and clothing. These crafts often feature intricate geometric patterns.

- Contemporary Cultural Expressions:**

- Modern Sahrawi music and poetry continue to thrive, often incorporating themes of resistance, longing for the homeland, and hope for the future. Many Sahrawi musicians and poets are active in the camps and in the diaspora.

- Film and Festivals:**

- FiSahara International Film Festival (Festival Internacional de Cine del Sáhara):** This unique annual film festival is held in the Sahrawi refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria. Founded in 2003, FiSahara aims to bring cinema to the refugees, raise international awareness about the Western Sahara conflict and human rights issues, and provide a platform for cultural exchange and entertainment. It screens a variety of international films and often focuses on themes of human rights, social justice, and resistance. The festival attracts international filmmakers, actors, activists, and journalists.

- ARTifariti (International Art and Human Rights Meeting of Western Sahara):** An annual art event held in Tifariti in the Liberated Territories. It brings together artists from around the world to create art installations and workshops focused on human rights and the Sahrawi cause.

These artistic and cultural expressions are crucial for preserving Sahrawi heritage, fostering identity, and communicating the Sahrawi experience to a wider global audience.

11.4. Sports

Sports play a role in Sahrawi society, both for recreation and as a means of national expression, though opportunities are often limited by the political situation and conditions in exile.

- Football (Soccer):** Football is the most popular sport among Sahrawis.

- The Sahrawi Football Federation (FSF) is the governing body for football in the SADR. However, it is not a member of FIFA or the Confederation of African Football (CAF), which prevents the Sahrawi national team from participating in official international tournaments recognized by these bodies.

- The Sahrawi national team has played friendly matches against other non-FIFA teams and club sides. There are also local football leagues and competitions within the refugee camps.

- The SADR is a member of CONIFA (Confederation of Independent Football Associations) and the World Unity Football Alliance (WUFA).

- Other Sports:** Other sports practiced include athletics (running), volleyball, and traditional games.

- International Participation:**

- The SADR was invited to participate in the 2015 African Games in Brazzaville, Congo, which would have been its debut at a major international multi-sport event. However, its thirteen athletes were reportedly not allowed to compete by the Congolese organizing committee due to political pressures.

Participation in international sporting events is often politically sensitive due to the SADR's disputed status. Despite these challenges, sports provide an important outlet for Sahrawi youth and contribute to a sense of community and national pride.

A mosque in Dakhla, a city under Moroccan control.