1. Overview

The Republic of Senegal, located on the westernmost point of mainland Africa, is a nation characterized by a diverse geography ranging from Sahelian plains to tropical rainforests. Its history encompasses ancient kingdoms, centuries of French colonial rule culminating in independence in 1960, and a subsequent path of democratic development, albeit with challenges. Senegal's political system is a presidential republic with a multi-party tradition, generally marked by peaceful transitions of power, though recent years have seen periods of social unrest and political tension. The economy relies on agriculture, fishing, mining, and a growing services sector, including tourism, but faces persistent issues of poverty, unemployment, and the need for equitable development. Senegalese society is a vibrant tapestry of numerous ethnic groups, with Wolof, Fula, and Serer being among the largest, and is predominantly Muslim, with a notable tradition of religious tolerance. Culturally, Senegal is renowned for its rich musical heritage, storytelling traditions embodied by griots, and the societal importance of "Teranga" (hospitality).

2. Etymology

The name "Senegal" is derived from the Senegal River, which forms its northern and eastern borders. There are several theories regarding the origin of the river's name. One prominent theory suggests it comes from the Wolof language phrase "sunuu gaal," meaning "our canoe." Another theory posits that the name is a Portuguese transliteration of the name of the Zenaga people (also known as Sanhaja), who lived north of the river. A third theory suggests a Serer origin, possibly a combination of "Rog Sene" (the supreme deity in Serer religion) and "o gal" (meaning "body of water" in the Serer language).

3. History

Senegal's history is rich and complex, stretching from ancient kingdoms and pre-colonial societies through the era of European colonialism and the slave trade, to its independence and subsequent development as a modern nation-state, marked by both democratic progress and socio-political challenges.

3.1. Early and Pre-colonial Eras

Archaeological findings across Senegal indicate inhabitation since prehistoric times, with continuous occupation by various ethnic groups. Around the seventh century, kingdoms began to emerge. Takrur, established in the sixth century in the Senegal River valley, was one of the earliest organized states in the region and among the first to embrace Islam in West Africa, influenced by contact with the Almoravid dynasty of the Maghreb through Toucouleur and Soninke traders. Eastern Senegal was also once part of the influential Ghana Empire.

By the 13th and 14th centuries, the region came under the influence of larger empires to the east, such as the Mali Empire. During this period, the Jolof Empire (also known as the Wolof Empire) was founded, initially as a vassal state of Mali. The Jolof Empire eventually grew powerful, uniting Cayor and the kingdoms of Baol, Siné, Saloum, Waalo, Futa Tooro, and Bambouk, encompassing much of present-day West Africa. It was structured as a voluntary confederacy of various states rather than an empire built on military conquest. The empire was founded by Ndiadiane Ndiaye, who was of part Serer and part Toucouleur heritage and successfully formed a coalition among diverse ethnic groups.

Islam continued to spread, primarily through Toucouleur and Soninke interactions with North African Muslims. The Almoravids and their Toucouleur allies played a role in propagating the faith. However, this movement faced resistance from ethnic groups adhering to traditional religions, notably the Serer people.

The trans-Saharan slave trade and internal systems of servitude existed in the region. In the Senegambia region, between 1300 and 1900, it is estimated that close to one-third of the population was enslaved, often as a result of capture in warfare. The Jolof Empire collapsed around 1549 when Lele Fouli Fak was defeated and killed by Amari Ngone Sobel Fall, leading to the fragmentation of the empire and the rise of successor states like the Cayor Kingdom.

3.2. Colonial Era

European contact with Senegal began in the mid-15th century. The Portuguese, led by explorers like Dinis Dias who reached the Cap-Vert peninsula and Gorée Island in 1444, were the first Europeans to establish a presence. They were followed by traders representing other European powers, including the Dutch and the British, who competed for trade in commodities such as gum arabic, gold, and enslaved people.

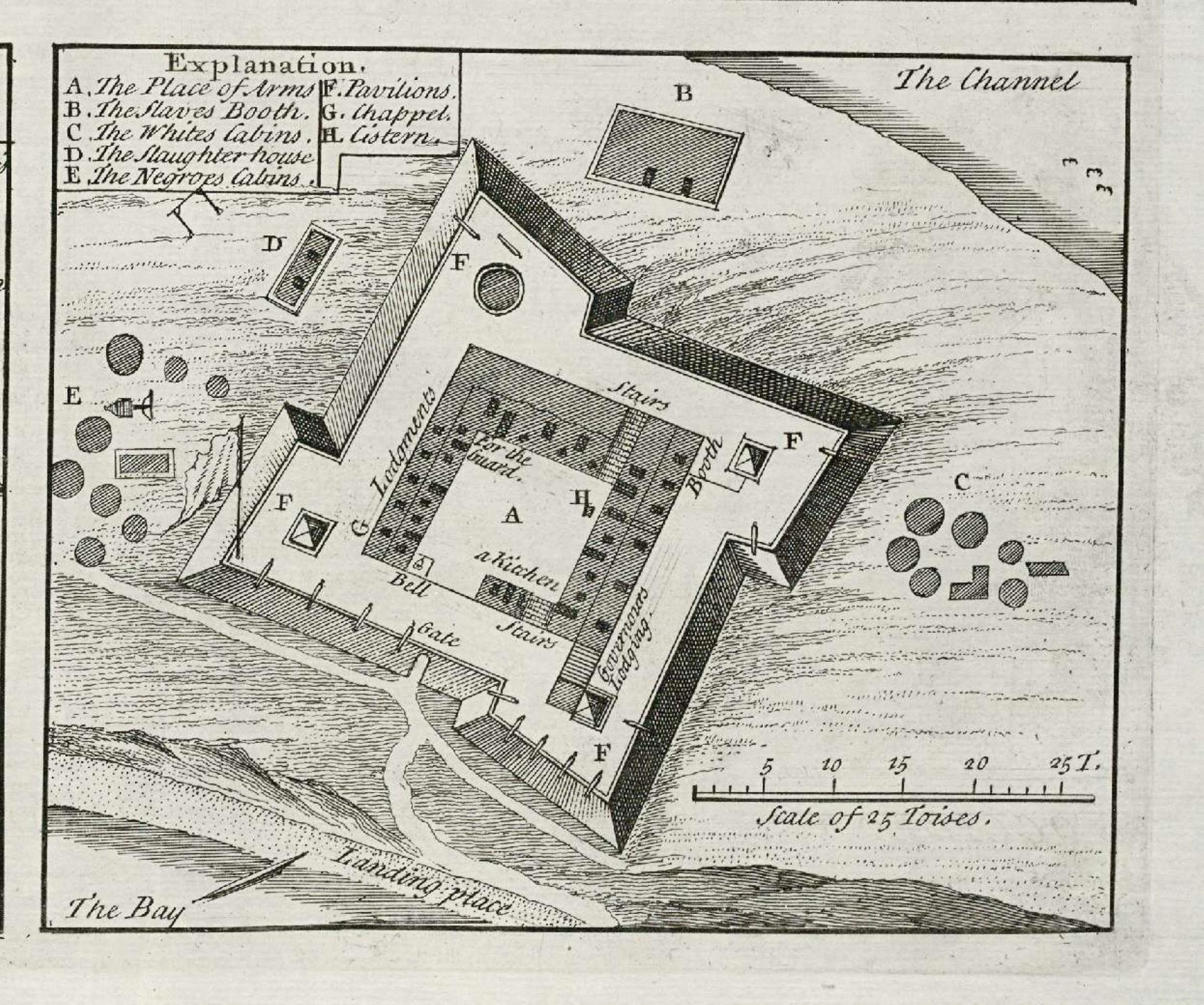

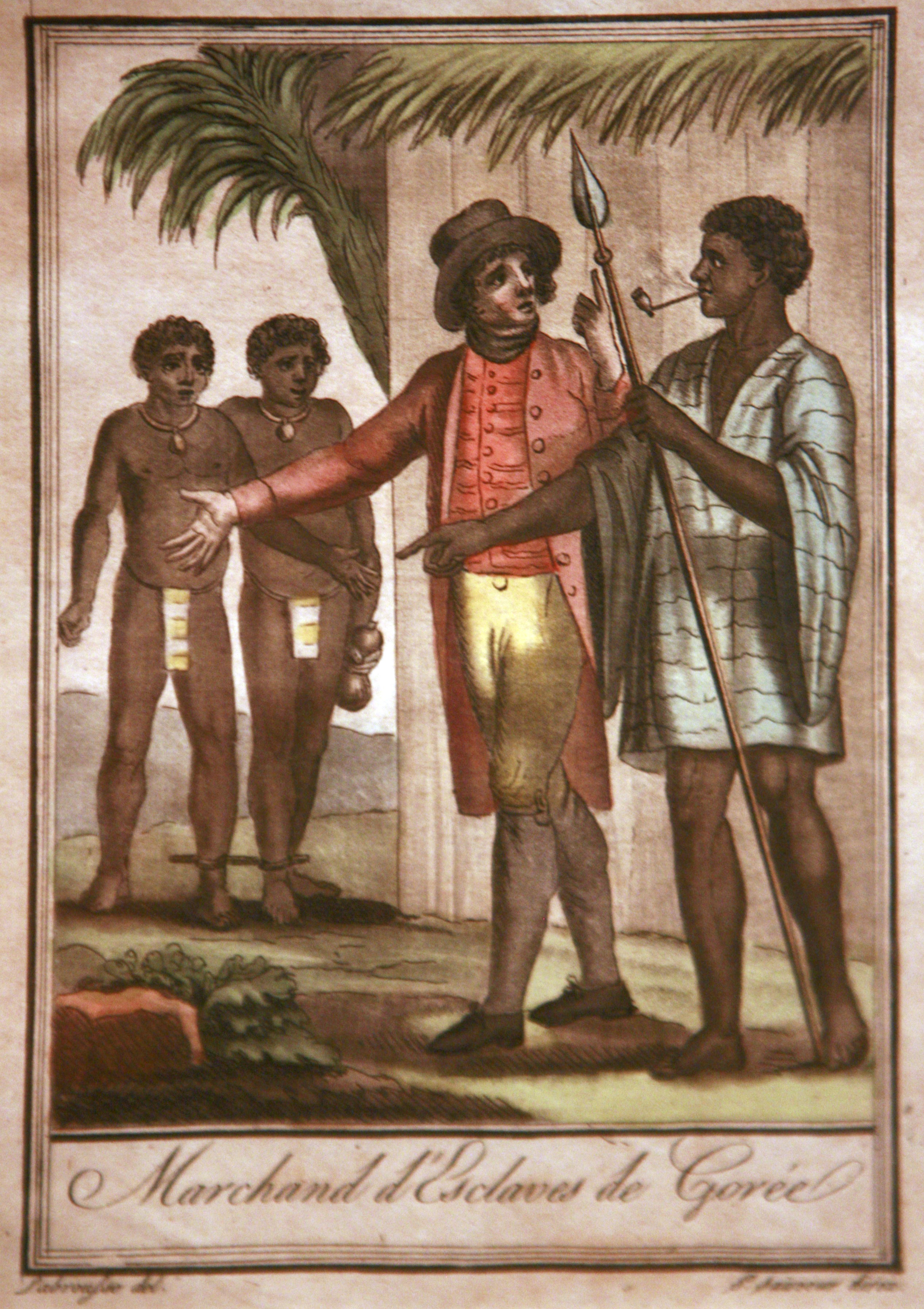

France's involvement began in the 17th century. In 1659, the French established a trading post at Saint-Louis on an island in the mouth of the Senegal River. In 1677, France gained control of Gorée Island, which became a major center for the Atlantic slave trade, serving as a base for purchasing enslaved individuals from warring chiefdoms on the mainland. The island's role in this tragic commerce has made it a symbolic site of remembrance. European missionaries also introduced Christianity to Senegal and the Casamance region during the 19th century.

It was not until the mid-19th century, particularly under Governor Louis Faidherbe (appointed in 1854), that the French began a systematic military expansion onto the Senegalese mainland. This period coincided with France's abolition of slavery in its colonies (1848) and the promotion of an abolitionist doctrine, though the economic exploitation of the region continued through other means. Faidherbe's campaigns led to the conquest and subjugation of many local kingdoms, including Waalo, Cayor, Baol, and the remnants of the Jolof Empire. Notable resistance to French expansion was led by figures such as Lat-Dior, the Damel (king) of Cayor, and Maad a Sinig Kumba Ndoffene Famak Joof, the king of the Serer Sine. The Battle of Logandème in 1859, where the Serer kingdom of Sine fiercely resisted French forces, was a significant event, marking one of the first instances the French employed cannonballs on Senegambian soil. Despite such resistance, most kingdoms were eventually overcome. Yoro Dyao, a local chief, collaborated with Faidherbe and was placed in command of the canton of Foss-Galodjina and Wâlo, serving from 1861 to 1914.

By the late 19th century, most of present-day Senegal was under French control. In 1895, Senegal became part of French West Africa (Afrique Occidentale Française, AOF), and Dakar was made its capital in 1902, serving as an important administrative and commercial hub for France's West African territories. French colonial rule brought significant social and economic changes, including the development of infrastructure like railways (e.g., the Dakar-Saint-Louis line) and ports, primarily to facilitate the export of cash crops such as groundnuts. A system of administration was established that often relied on co-opting local chiefs and creating a distinction between "citizens" (citoyens) in the Four Communes (Dakar, Gorée, Rufisque, Saint-Louis), who had limited political rights, and "subjects" (sujets) in the rest of the territory.

Senegalese men, known as Tirailleurs Sénégalais (Senegalese Riflemen), were conscripted into the French army and participated in various French colonial wars and both World Wars, serving in Europe, Africa, and Asia. During World War II, after the fall of France in 1940, Senegal initially came under the control of the pro-German Vichy regime. The Battle of Dakar in September 1940 was an unsuccessful attempt by the Allies to capture the strategic port. Later, Senegal rallied to Free France. On November 25, 1958, following the reforms of the French Community, Senegal became an autonomous republic within the Community, a step towards full independence.

3.3. Independence

The path to Senegal's independence accelerated in the late 1950s. In January 1959, Senegal and the neighboring French Sudan (present-day Mali) merged to form the Mali Federation. This federation achieved full independence from France on June 20, 1960, following a transfer of power agreement signed on April 4, 1960. However, due to internal political difficulties and differing visions for the federation's future, the union was short-lived. On August 20, 1960, Senegal seceded from the federation, and French Sudan, which retained the name Mali, also declared its full independence.

Léopold Sédar Senghor, a renowned poet, intellectual, and leader of the Senegalese Progressive Union (UPS), was elected as Senegal's first president in August 1960. Senghor was a key figure in the Négritude literary and ideological movement, which sought to promote and celebrate African cultural values. As president, he advocated for a brand of African socialism, emphasizing national unity and development while maintaining close ties with France.

Initially, Senegal operated under a parliamentary system, with Senghor as president and Mamadou Dia as prime minister. However, political rivalry between the two leaders culminated in an attempted coup by Dia in December 1962. The coup was suppressed without bloodshed, and Dia was arrested and imprisoned. Following this event, Senegal adopted a new constitution that significantly consolidated presidential power.

During the 1960s, Senghor's government focused on nation-building, establishing national institutions, and developing the economy, particularly the groundnut sector. While Senghor was generally more tolerant of opposition than many other African leaders of the era, political activity was somewhat restricted. From 1965 until 1975, Senghor's UPS (later renamed the Socialist Party of Senegal) was the only legally permitted political party. In 1975, Senghor allowed the formation of two opposition parties: a Marxist party (the African Independence Party) and a liberal party (the Senegalese Democratic Party).

Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, Senegal experienced border tensions and violations by the Portuguese military operating from Portuguese Guinea (now Guinea-Bissau), where an anti-colonial war was ongoing. Senegal brought these incidents to the attention of the United Nations Security Council on several occasions, including in 1963, 1965, 1969 (in response to shelling by Portuguese artillery), 1971, and 1972, highlighting the regional impact of colonial conflicts.

3.4. 1980s to Present

In 1980, President Léopold Sédar Senghor voluntarily retired from politics, a rare move for an African leader at the time. He handed over power to his chosen successor, Prime Minister Abdou Diouf, who became president in January 1981. Diouf continued Senghor's pro-Western policies and introduced further political liberalization, including a full multi-party system. Former prime minister Mamadou Dia, Senghor's earlier rival, ran against Diouf in the 1983 election but was unsuccessful. Senghor moved to France, where he passed away in 2001 at the age of 95.

On February 1, 1982, Senegal and The Gambia formed the Senegambia Confederation, aimed at promoting cooperation between the two countries. However, the confederation faced challenges, including disagreements over sovereignty and economic integration, and was dissolved in 1989.

A significant challenge during Diouf's presidency was the outbreak of the Casamance conflict in December 1982. The Movement of Democratic Forces of Casamance (MFDC), a separatist group in the southern Casamance region, began an armed struggle for independence, citing economic neglect and cultural differences. This low-intensity conflict has continued sporadically for decades, despite several peace agreements.

In the 1980s, Senegalese historian Boubacar Lam brought attention to Senegalese oral histories, initially compiled by the Toucouleur noble Yoro Dyâo after World War I. These histories documented migrations into West Africa from the Nile Valley, suggesting ancient eastern origins for several ethnic groups from the Senegal River to the Niger Delta.

Diouf was re-elected in 1983, 1988, and 1993. His tenure saw increased political participation and efforts to reduce government involvement in the economy. Senegal also widened its diplomatic engagements. However, domestic politics sometimes led to street violence and border tensions. Notably, the late 1980s saw the Mauritania-Senegal Border War, a conflict that led to the expulsion of tens of thousands of people from both countries. Despite these challenges, Senegal's commitment to democratic processes and human rights generally strengthened. During the Gulf War (1990-1991), Senegal contributed over 500 troops to the U.S.-led coalition, participating in the Battle of Khafji and the liberation of Kuwait.

In the presidential election of March 2000, opposition leader Abdoulaye Wade of the Senegalese Democratic Party (PDS) defeated Abdou Diouf. This marked Senegal's second peaceful transition of power and its first from one political party to another, a significant milestone for democracy in Africa. Wade's presidency focused on infrastructure projects and further economic liberalization. On December 30, 2004, President Wade announced a peace treaty with the MFDC in Casamance, but it failed to bring a definitive end to the conflict, with sporadic violence continuing.

Macky Sall won the presidential election in March 2012, defeating Wade, whose bid for a controversial third term had sparked protests. This transition was widely praised as a demonstration of Senegal's democratic maturity. Sall was re-elected in the 2019 election. During his presidency, the presidential term was reduced from seven years to five. However, Sall's tenure also faced periods of unrest. Mass protests, known as the 2021 Senegalese protests and 2023-2024 protests, erupted following the arrest of opposition figure Ousmane Sonko on various charges, and were also fueled by concerns about the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic and perceived democratic backsliding. These protests sometimes turned violent, with reports of fatalities and concerns raised by human rights organizations about the use of force by security services.

In the presidential election of March 2024, which was held after a controversial delay, opposition candidate Bassirou Diomaye Faye, backed by Ousmane Sonko, won a decisive victory. Faye became the youngest president in Senegal's history, promising reforms and a break with past policies. In November 2024, President Faye announced that French troops stationed in Senegal would withdraw by the end of 2025, signaling a potential shift in the country's long-standing security relationship with France.

4. Government and Politics

Senegal is a republic with a presidential system of government. The country has a strong tradition of democracy in Africa, characterized by a multi-party system and regular elections. However, its democratic journey has also faced challenges, including periods of political tension and concerns about the concentration of power.

4.1. Government Structure

The Constitution provides for a separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches.

The executive branch is headed by the President, who is the head of state and head of government. The president is elected by universal adult suffrage for a five-year term, a change instituted in 2016 from a previous seven-year term (which itself had varied over time). The president appoints the Prime Minister (a position that has been abolished and reinstated multiple times) and members of the cabinet. Notable presidents include Léopold Sédar Senghor (1960-1980), Abdou Diouf (1981-2000), Abdoulaye Wade (2000-2012), Macky Sall (2012-2024), and the current president, Bassirou Diomaye Faye (since 2024).

The legislative branch is a unicameral National Assembly (Assemblée Nationale). It currently consists of 165 members elected for five-year terms through a mixed system of direct universal suffrage and proportional representation. Senegal previously had a bicameral system with a Senate from 1999 to 2001 and again from 2007 to 2012, but it was abolished, partly due to cost-saving measures.

The judicial branch is independent. The highest courts include the Constitutional Council, which rules on the constitutionality of laws and election disputes, and the Court of Cassation for civil and criminal matters, and the Council of State for administrative cases. Judges for these high courts are appointed by the president.

Senegal has more than 80 registered political parties, reflecting a vibrant political landscape. Key political parties include the Patriots of Senegal for Work, Ethics and Fraternity (PASTEF, party of current president Faye and influential figure Ousmane Sonko), the Alliance for the Republic (APR, party of former president Macky Sall), the Senegalese Democratic Party (PDS, party of former president Abdoulaye Wade), and the Socialist Party of Senegal (PS, former ruling party of Senghor and Diouf).

4.2. Political Culture and Trends

Senegal is often cited as one of Africa's most stable democracies and has a history of peaceful transitions of power, including its first transfer from one political party to another in 2000. Civil society organizations and the media play active roles in political discourse. Marabouts, influential religious leaders of Senegal's Sufi brotherhoods, also exert significant, though often informal, political influence, particularly during election periods.

Despite its democratic credentials, Senegal has faced challenges. During Abdoulaye Wade's presidency, there were concerns about increased centralization of power in the executive, leading Freedom House to downgrade Senegal's status from "Free" to "Partially Free" in 2009, though it later regained "Free" status. The Ibrahim Index of African Governance has generally ranked Senegal favorably, though its position has fluctuated.

The lead-up to the 2012 presidential election was marked by controversy over President Wade's bid for a third term, which opponents argued was unconstitutional. This led to the emergence of youth opposition movements like M23 and Y'en a Marre (We're Fed Up). Macky Sall ultimately won the election, and Wade conceded, reinforcing Senegal's democratic process.

More recently, the period under President Macky Sall saw significant protests in 2021 and 2023-2024 linked to the arrest and prosecution of opposition leader Ousmane Sonko, as well as anxieties about a potential third-term bid by Sall (which he eventually disavowed). These protests, at times, resulted in violent clashes and fatalities, raising concerns about human rights and democratic freedoms. The controversial postponement of the 2024 presidential election by President Sall also led to a political crisis, which was resolved after intervention by the Constitutional Council, leading to the eventual victory of Bassirou Diomaye Faye. This peaceful handover of power, despite the preceding tensions, was seen as a reaffirmation of Senegal's democratic resilience.

4.3. Administrative Divisions

Senegal is a unitary state and is subdivided into 14 regions. Each region is administered by a Conseil Régional (Regional Council) whose members are elected. The regions are further subdivided into 45 departments, then into 113 arrondissements (which primarily serve as electoral and census units rather than having strong administrative functions), and finally into Collectivités Locales (local authorities), which include communes (urban and rural). These local authorities have elected officials and are responsible for local governance and development.

The 14 regions of Senegal are:

- Dakar

- Diourbel

- Fatick

- Kaffrine

- Kaolack

- Kédougou

- Kolda

- Louga

- Matam

- Saint-Louis

- Sédhiou

- Tambacounda

- Thiès

- Ziguinchor

The regional capitals share the same name as their respective regions.

4.4. Foreign Relations

Senegal maintains an active role in international affairs and is a member of numerous international organizations, including the United Nations (UN), the African Union (AU), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, and the Community of Sahel-Saharan States. It has served as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council (e.g., 1988-89, 2015-2016) and was elected to the UN Commission on Human Rights in 1997. Senegal has historically maintained close ties with Western nations, particularly France, its former colonial power, and the United States. The country has often advocated for increased assistance from developed countries to the developing world. The current Minister of Foreign Affairs is Yassine Fall, who assumed office in April 2024 under President Faye.

Relations with France, while historically strong, experienced some tension under former President Macky Sall, with public concerns about French companies receiving preferential contracts and alleged French influence in domestic politics. President Bassirou Diomaye Faye's government has signaled a desire for a revised partnership with France, including the announced withdrawal of French troops by the end of 2025.

Senegal generally enjoys cordial relations with its neighbors. However, challenges persist, such as the presence of an estimated 35,000 Mauritanian refugees who were expelled from their country in 1989 and remain in Senegal. Relations with Morocco are strong, highlighted by the King of Morocco's attendance at President Faye's inauguration. The country plays a significant role in regional stability and peacekeeping efforts.

Senegal has also been involved in global governance initiatives. It was one of the signatories of the agreement to convene a convention for drafting a world constitution. This led to the 1968 World Constituent Assembly which drafted the Constitution for the Federation of Earth, an initiative signed by then-President Léopold Sédar Senghor.

According to the 2024 Global Peace Index, Senegal is ranked as the 84th most peaceful country in the world.

4.5. Military

The Armed Forces of Senegal (Forces Armées du Sénégal) comprise an army, a navy, an air force, and a gendarmerie, with a total active personnel of approximately 17,000 to 19,000. The Senegalese military receives training, equipment, and support primarily from France and the United States, and to a lesser extent, Germany.

A notable characteristic of Senegal's political history is the military's consistent non-interference in political affairs, which has significantly contributed to the country's stability since independence. Senegal has a long record of participation in international and regional peacekeeping missions. It has contributed troops to UN missions in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUC) and Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL), among others. In 2015, Senegal participated in the Saudi Arabian-led military intervention in Yemen against Houthi forces. The gendarmerie plays a significant role in internal security and law enforcement, particularly in rural areas.

4.6. Law and Human Rights

Senegal is a secular state as defined by its Constitution. The legal system is based on French civil law.

The government has established bodies to combat corruption, such as the National Anti-Corruption Office (OFNAC), which replaced the earlier National Commission against Non-Transparency, Corruption and Misappropriation (CNLCC). OFNAC has the power to initiate its own investigations into corruption, embezzlement of public funds, and fraud. Despite these efforts, corruption remains a challenge.

The human rights situation in Senegal is generally considered better than in many other African nations, but concerns remain. Freedom of expression and freedom of the press are constitutionally guaranteed, though journalists and activists have sometimes faced pressure or arrest, particularly during periods of political tension. The response to protests, such as those in 2021 and 2023-2024, drew criticism from human rights organizations for excessive use of force by security forces and restrictions on assembly.

Homosexual acts are illegal in Senegal and are punishable by imprisonment and fines. Societal attitudes towards homosexuality are predominantly negative, with a 2013 Pew Research Center survey indicating that 96% of Senegalese believe homosexuality should not be accepted by society. LGBTQ+ individuals often face discrimination, social stigmatization, and harassment, and report feeling unsafe. This legal and social environment presents a significant human rights concern, contrasting with the country's broader democratic reputation. Other social justice issues include gender inequality, child labor (particularly in the context of some Koranic schools known as daaras), and the need for prison reform.

4.7. Casamance Conflict

The Casamance conflict is a long-running, low-intensity separatist insurgency in the southern Casamance region of Senegal, geographically separated from the north by The Gambia. The conflict began in December 1982, led by the Movement of Democratic Forces of Casamance (MFDC).

The roots of the conflict are complex, involving historical grievances, feelings of economic and political marginalization by the dominant Jola ethnic group in Casamance, land disputes, and cultural distinctiveness. The MFDC has sought greater autonomy or outright independence for Casamance.

Over the decades, the conflict has been characterized by sporadic clashes between the MFDC and the Senegalese military, ambushes, banditry, and the widespread use of land mines, which have had a severe humanitarian impact on civilians, causing deaths, injuries, and displacement. Several ceasefires and peace agreements have been signed, including a notable one in 2004, but a comprehensive and lasting resolution has remained elusive due to fragmentation within the MFDC and the complexity of the issues.

President Macky Sall initiated peace talks with rebel factions, including discussions held in Rome in December 2012. While violence has generally subsided compared to earlier periods, the conflict has continued to simmer, with occasional flare-ups. The government of President Bassirou Diomaye Faye has also expressed commitment to finding a peaceful resolution. The ongoing instability has affected the region's development and security.

5. Geography

Senegal is situated on the westernmost part of the African continent, characterized by varied landscapes ranging from Sahelian semi-desert in the north to tropical savanna and forests in the south.

5.1. Topography and Location

Senegal lies between latitudes 12° and 17° North, and longitudes 11° and 18° West. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the west (with a coastline of approximately 330 mile (531 km)), Mauritania to the north and east, Mali to the east, and Guinea and Guinea-Bissau to the south. Senegal almost entirely surrounds The Gambia, a narrow country that follows the course of the Gambia River, except for Gambia's short Atlantic coastline. This geographical configuration effectively separates Senegal's southern Casamance region from the rest of the country. Senegal also shares a maritime border with Cape Verde.

The Senegalese landscape consists mainly of rolling sandy plains of the western Sahel. These plains rise to foothills in the southeast, part of the Fouta Djallon highlands. Senegal's highest point is an unnamed feature near Nepen Diakha, sometimes referred to as the Baunez ridge, at 2126 ft (648 m) above sea level.

The northern border is largely defined by the Senegal River. Other important rivers include the Gambia River and the Casamance River. The capital city, Dakar, is located on the Cap-Vert (Cape Green) peninsula, which is the westernmost point of mainland Africa. This peninsula features "Les Mammelles," twin hills, one of which is topped by a lighthouse, and the "Pointe des Almadies," the absolute westernmost tip. The Cape Verde Islands lie approximately 348 mile (560 km) off the Senegalese coast.

5.2. Climate

Senegal has a tropical climate characterized by distinct wet and dry seasons, influenced by northeast winter winds and southwest summer winds. The dry season, typically from December to April, is dominated by the hot, dry Harmattan wind blowing from the Sahara. The wet season generally lasts from June to October.

Dakar, on the coast, receives annual rainfall of about 24 in (600 mm), mostly between June and October. During this period, maximum temperatures average 86 °F (30 °C) and minimums 75.56 °F (24.2 °C). From December to February, Dakar's maximum temperatures average 78.25999999999999 °F (25.7 °C), with minimums around 64.4 °F (18 °C).

Interior temperatures are generally higher than along the coast. For example, average daily temperatures in Kaolack and Tambacounda for May are 86 °F (30 °C) and 90.86 °F (32.7 °C) respectively, compared to Dakar's 73.75999999999999 °F (23.2 °C). Rainfall increases substantially farther south, exceeding 0.1 K in (1.50 K mm) annually in some areas of Casamance. In Tambacounda, in the far interior near the Malian border where desert conditions begin, temperatures can reach as high as 129.2 °F (54 °C).

Climatically, the country can be divided into zones: the northernmost part, including the Lompoul desert, has a near hot desert climate; the central part has a hot semi-arid climate; and the southernmost part, especially Casamance, has a tropical savanna climate (tropical wet and dry). Senegal is generally a sunny and dry country. Climate change in Senegal is a growing concern, with potential impacts on rainfall patterns, agriculture, and coastal erosion.

5.3. Wildlife and Ecosystems

Senegal possesses a variety of ecosystems and rich biodiversity. The country contains four main terrestrial ecoregions: the Guinean forest-savanna mosaic in the south, the Sahelian Acacia savanna in the north, the West Sudanian savanna in the central and eastern parts, and Guinean mangroves along the coast and river estuaries. Senegal had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.11/10, ranking it 56th globally out of 172 countries, indicating relatively good forest ecosystem integrity in certain areas.

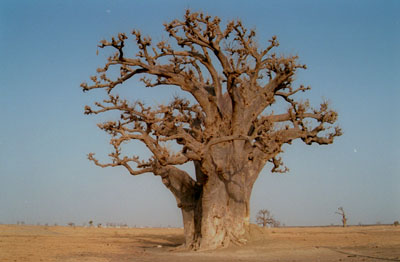

The flora includes iconic baobab trees (the national symbol), acacias, palms, and various savanna grasses. In the more humid Casamance region, denser forests with species like mahogany and teak can be found. Mangrove ecosystems, particularly in the Saloum Delta and Casamance River estuaries, are vital for coastal protection and as breeding grounds for fish and birds.

Senegal's fauna is diverse, though some larger mammal populations have declined due to habitat loss and poaching. Wildlife includes various species of monkeys, antelopes, warthogs, hyenas, and numerous bird species. Reptiles such as crocodiles and snakes are also present.

The country has several protected areas aimed at conserving its biodiversity. The Niokolo-Koba National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site located in southeastern Senegal, is one of the most important, harboring species like lions, leopards, elephants (though rare), African wild dogs, and a variety of ungulates and primates. The Djoudj National Bird Sanctuary, another UNESCO World Heritage Site situated in the Senegal River delta, is a crucial stopover and wintering site for millions of migratory birds, including pelicans, flamingos, and warblers. Other protected areas include the Saloum Delta National Park (also a UNESCO site, recognized for its mangroves and marine biodiversity) and various reserves and community-managed forests. Conservation efforts focus on anti-poaching, habitat restoration, and promoting sustainable resource use, often in collaboration with local communities and international organizations.

6. Economy

Senegal's economy is characterized by a mix of traditional subsistence agriculture, a growing services sector, and some industrial activity, primarily focused on resource processing. While it has made progress in economic reforms, it remains classified as a heavily indebted poor country and faces significant challenges related to poverty, unemployment, and equitable development.

6.1. Economic Overview

Senegal's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has experienced periods of growth, often driven by agriculture, mining, construction, and services, particularly telecommunications and finance. However, this growth has not always translated into widespread poverty reduction. The country ranks relatively low on the Human Development Index (HDI), at 169th out of 193 countries as of recent estimates.

Most of the population lives on the coast and is involved in agriculture or fishing. Key economic drivers include agriculture (especially groundnuts), fishing, phosphate mining, tourism, and services. Remittances from Senegalese working abroad also contribute significantly to the economy.

Major economic challenges include high rates of poverty (around 46.7% in 2011), substantial national debt, high unemployment (particularly among youth), and structural inequalities. The informal sector is large and provides livelihoods for many but often lacks social protection and formal support. The government has pursued various economic development plans, often with support from international institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, focusing on infrastructure development, diversification, and improving the business climate. Senegal has benefited from debt relief initiatives.

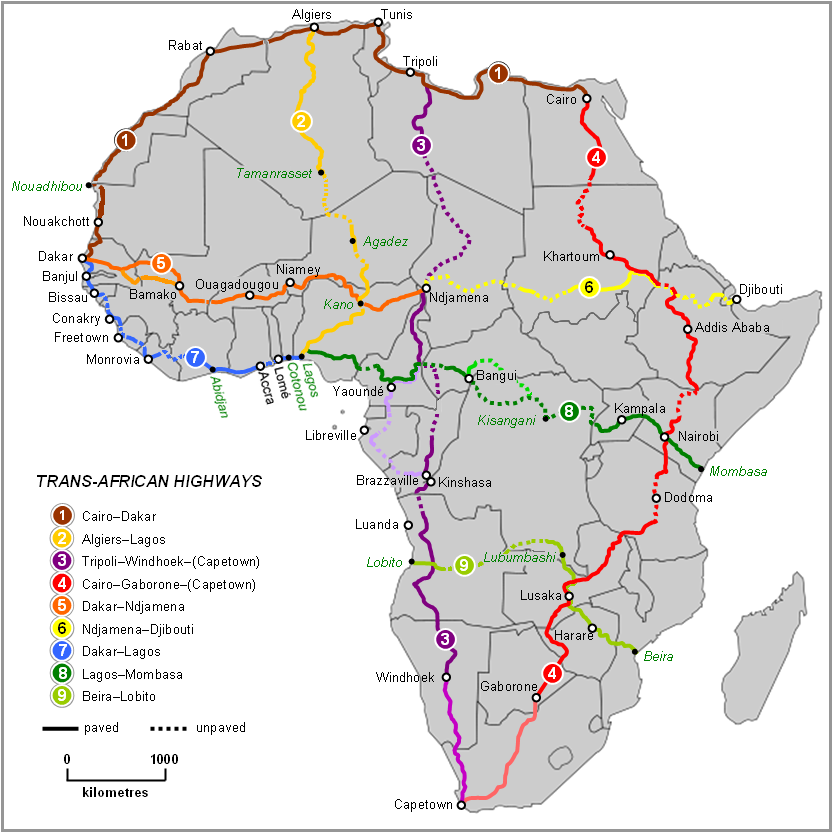

The country has historically invested a significant portion of its budget in education, recognizing it as a basis for development. Three trans-African automobile routes pass through Senegal: the Cairo-Dakar Highway, the Dakar-Ndjamena Highway, and the Dakar-Lagos Highway, highlighting its potential as a regional transport hub.

6.2. Main Industries

Senegal's industrial sector includes food processing (fish, groundnuts, sugar), mining, cement production, artificial fertilizer manufacturing, chemicals, textiles, and the refining of imported petroleum.

Mining is a significant contributor, particularly the extraction of phosphates (used in fertilizers) and, more recently, gold and heavy mineral sands (ilmenite, zircon). Calcium phosphate is also an important export.

Tourism is a major source of foreign exchange, attracting visitors to its coastal resorts, national parks, and cultural sites like Gorée Island. The services sector, encompassing telecommunications, financial services, and trade, has been a key driver of economic growth.

Senegal's main exports include fish and seafood products, phosphates, gold, groundnuts, cotton, and chemicals. As of 2020, its largest export markets were Mali (20.4%), Switzerland (12.2%), and India (8.3%).

As a member of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU), Senegal works towards greater regional integration with a unified external tariff. It is also a member of the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa, which aims to standardize business laws across member states. Senegal achieved full Internet connectivity in 1996, fostering a small boom in information technology-based services. Private activity accounts for a large share of its GDP (around 82%).

6.3. Agriculture

Agriculture remains a vital sector, employing a large portion of the workforce, especially in rural areas, although its contribution to GDP has declined relative to services. The primary cash crop is groundnuts (peanuts), which have historically dominated the agricultural economy, though efforts are underway to diversify. Other important crops include millet, sorghum, maize, rice, cotton, and various fruits and vegetables like mangoes, melons, and tomatoes.

Farming practices are often traditional and rain-fed, making the sector vulnerable to drought and climate variability. Food security is a persistent concern, with Senegal being a net importer of rice, its main staple food. Government policies have aimed to boost local rice production and improve irrigation.

The socio-economic conditions of agricultural workers are often precarious, with many smallholder farmers facing challenges such as limited access to credit, modern inputs, and markets. Land tenure systems can also be complex. The environmental impact of agriculture, including soil degradation and water management, is also a concern.

6.4. Fishing

The fishing sector is critically important to Senegal's economy, providing significant export revenue, employment for hundreds of thousands of people (directly and indirectly), and a key source of protein for the population. Senegal's waters are rich in diverse fish species, including tuna, sardines, mackerel, shrimp, and various demersal fish.

Artisanal fishing, carried out by small-scale fishers in traditional pirogues, dominates the sector and supplies both domestic and export markets. Industrial fishing, involving larger trawlers, also operates.

However, the sector faces severe challenges. Illegal fishing by foreign industrial trawlers (some registered in countries like Russia, Mauritania, Belize, and Ukraine) is a major problem, leading to estimated losses of hundreds of thousands of tonnes of fish annually and depleting fish stocks. The Senegalese government has made efforts to combat illegal fishing, including a notable seizure of the Russian trawler Oleg Naydenov in 2014. Overfishing by both legal and illegal fleets further threatens the sustainability of marine resources and the livelihoods of local fishing communities. This has led to declining catches for artisanal fishers and concerns about the long-term health of marine ecosystems. The social and environmental impacts of these pressures are significant, requiring robust management and conservation measures.

6.5. Energy

Senegal's energy sector faces challenges in meeting growing demand and ensuring reliable and affordable access to electricity. The country relies heavily on imported fossil fuels (primarily oil) for electricity generation, making it vulnerable to global price fluctuations. Electricity access is not universal, particularly in rural areas.

The state-owned utility Senelec is the main power producer and distributor. Efforts are underway to diversify the energy mix and increase the share of renewable energy sources, including solar, wind, and biomass. Senegal has significant solar potential, and several large-scale solar power plants have been commissioned. The development of recently discovered offshore oil and gas reserves is expected to transform the energy sector in the coming years, potentially making Senegal an energy exporter, though this also brings environmental and governance considerations. Challenges include aging infrastructure, transmission losses, and the need for substantial investment to modernize and expand the grid.

6.6. Transport

Senegal's transport infrastructure plays a crucial role in its national development and its position as a trade and transit hub in West Africa.

The road network is the primary mode of transport, connecting major cities and rural areas. Significant investments have been made in road construction and rehabilitation, including highways like the Dakar-Diamniadio toll highway.

The railway system includes the historic Dakar-Niger Railway, which once connected Dakar to Bamako in Mali. While parts of this line have fallen into disrepair or are underutilized, there are efforts to revitalize rail transport, including the new Train Express Regional (TER) connecting Dakar with the Blaise Diagne International Airport and Diamniadio.

The Port of Dakar is one of the largest and busiest deepwater seaports in West Africa, serving as a major transshipment hub and a vital gateway for Senegal's international trade.

Air transport is centered around the Blaise Diagne International Airport, which replaced the older Léopold Sédar Senghor International Airport as the main international gateway in 2017. Several domestic airports also serve regional connections.

Improving and expanding transport infrastructure remains a government priority to support economic growth, facilitate trade, and improve connectivity both domestically and regionally.

7. Demographics

Senegal's population is youthful and growing, characterized by a diversity of ethnic groups, languages, and religious traditions.

7.1. Population

Senegal has an estimated population of around 18 million people. The population growth rate is relatively high. The age structure is predominantly young, with a large proportion of the population under the age of 25. Population density varies significantly, from about 77 persons per square kilometer in the west-central region, which includes Dakar and its surroundings, to as low as 2 persons per square kilometer in the arid eastern section of the country. Approximately 42-48% of the population lives in rural areas, though urbanization is increasing, with Dakar being the main urban agglomeration.

7.2. Ethnic Groups

Senegal is home to a wide variety of ethnic groups, each with its own distinct cultural traditions and languages. Inter-ethnic relations are generally harmonious. The largest ethnic groups include:

- The Wolof, who make up about 39-43% of the population and are prominent in urban areas, commerce, and politics. Their language, Wolof, serves as a lingua franca.

- The Fula (also known as Fulani or Peul) and the closely related Toucouleur (who identify as Halpulaar, or Pulaar-speakers) together constitute about 24-27.5% of the population. They are traditionally pastoralists but are also found in various other occupations.

- The Serer are the third-largest group, comprising about 15-16% of the population. They are concentrated in the west-central part of the country and have a rich agricultural and historical heritage.

- The Jola (or Diola) primarily inhabit the Casamance region and make up about 4-5% of the population.

- The Mandinka (or Malinké) are found in various parts of the country and represent about 3-5% of the population.

- Other groups include the Soninke (around 1-2.4%), Lebou (concentrated in the Cap-Vert peninsula), Bassari, Bedick, Maures (Naarkajors), and smaller communities.

There are also small but significant populations of Europeans (mainly French) and people of Lebanese descent, primarily involved in commerce and residing in urban areas. Additionally, there are communities of Mauritanian refugees, particularly in the north, and smaller immigrant communities from other African nations, Vietnam, and China.

7.3. Languages

The linguistic landscape of Senegal is diverse, with around 39 distinct languages spoken. French is the official language, a legacy of the colonial era. It is used in government, formal education, media, and business. However, estimates suggest that only about 26-27% of the population are fluent French speakers, primarily those who have gone through the formal education system.

Wolof is the most widely spoken language, understood by an estimated 80% of the population either as a first or second language, and serves as the primary lingua franca across the country, especially in urban centers like Dakar.

Pulaar (the language of the Fula and Toucouleur) and Serer are also widely spoken by their respective communities and beyond; President Macky Sall, for instance, is a Pulaar speaker whose wife is Serer. Jola languages are prominent in the Casamance region.

Several indigenous languages have been accorded the status of "national languages," indicating official recognition and potential use in education and media. These include Balanta-Ganja, Arabic (specifically Hassaniya Arabic), Jola-Fonyi, Mandinka, Mandjak, Mankanya, Noon (a Cangin language spoken by ethnically Serer people), Pulaar, Serer, and Soninke, in addition to Wolof.

English is taught as a foreign language in secondary schools and some higher education programs, with dedicated bilingual schools in Dakar. It is increasingly used in scientific and business communities. Portuguese Creole, locally known as Portuguese, is spoken in Ziguinchor and other parts of Casamance, reflecting historical ties and proximity to Guinea-Bissau. Standard Portuguese is also taught in some schools. Immigrant languages like Bambara, Mooré, and Kabuverdiano are spoken by respective communities. There is a growing linguistic nationalist movement supporting the greater integration of Wolof into official domains, potentially alongside French.

7.4. Religion

Senegal is a constitutionally secular state, and religious freedom is generally respected, contributing to a climate of religious tolerance.

Islam is the predominant religion, practiced by approximately 97.2% of the population. The vast majority of Senegalese Muslims are Sunnis adhering to the Maliki school of jurisprudence, with a strong influence of Sufism. Islamic communities are largely organized around various Sufi orders (tariqas), each headed by a spiritual leader known as a khalif (xaliifa in Wolof). The two largest and most influential Sufi orders are:

- The Tijaniyya, with major centers in cities like Tivaouane and Kaolack, and a broad following across West Africa.

- The Mouride (Murīdiyya), centered in the holy city of Touba. The Mourides are known for their strong work ethic and have a significant economic and social influence primarily within Senegal.

Other Sufi orders include the older Qadiriyya and the Layene order, prominent among the coastal Lebu people. Formal Quranic schools, known as daara, play an important role in religious education, though some have faced criticism regarding child welfare issues.

Christianity is practiced by about 2.7% of the population. The majority of Christians are Roman Catholic, but there are also various Protestant denominations, including evangelicals. Christian communities are mainly found among coastal Serer, Jola, Mankanya, and Balant populations, and in eastern Senegal among the Bassari and Coniagui. Senegal's first president, Léopold Sédar Senghor, was a Catholic Serer.

Adherents of traditional indigenous beliefs (often referred to as Animism) constitute approximately 0.1% of the population, particularly in the southeastern region. Some Serer follow the traditional Serer religion, which includes belief in a supreme deity called Roog (or Koox among Cangin speakers), a distinct cosmogony, and divination ceremonies like the annual Xooy festival. It is noted by some scholars that many Senegambian Muslim festivals have names borrowed from ancient Serer religious festivals. Similarly, the Jola people have their own traditional religious ceremonies, such as the Boukout. Syncretism, where elements of traditional beliefs are blended with Islam or Christianity, is also common.

Small communities of other faiths exist, including a tiny group in the Senegalese bush claiming Jewish ancestry (Bani Israel), though this is disputed. Mahayana Buddhism is practiced by some members of the expatriate Vietnamese community. The Bahá'í Faith was established in Senegal in 1953 and has a community estimated at around 22,000.

7.5. Largest Cities

Senegal is experiencing ongoing urbanization, with Dakar being the dominant urban center.

Dakar, the capital, is by far the largest city, with a metropolitan population exceeding two million residents. It serves as the political, economic, and cultural heart of the country.

Touba, the holy city of the Mouride Brotherhood, is the second most populous urban area, with a population of over half a million. It is a major religious and pilgrimage center.

Other significant urban centers include:

- Pikine, a large commune within the Dakar metropolitan area.

- Thiès, an important industrial and transport hub.

- Kaolack, a regional capital and commercial center.

- M'Bour, a coastal city known for tourism and fishing.

- Rufisque, another city within the Dakar metropolitan area with historical significance.

- Ziguinchor, the main city in the Casamance region.

- Diourbel, a regional capital.

- Tambacounda, the largest city in eastern Senegal.

- Louga, a regional capital in the north.

| Rank | City | Region | Population (2013 Census) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dakar | Dakar | 2,646,503 |

| 2 | Touba | Diourbel | 753,315 |

| 3 | Pikine | Dakar | 317,763 (Pikine Ville, part of greater Dakar agglomeration) |

| 4 | Kaolack | Kaolack | 233,708 |

| 5 | M'Bour | Thiès | 232,777 |

| 6 | Rufisque | Dakar | 221,066 |

| 7 | Ziguinchor | Ziguinchor | 205,294 |

| 8 | Diourbel | Diourbel | 133,705 |

| 9 | Tambacounda | Tambacounda | 107,293 |

| 10 | Louga | Louga | 104,349 |

7.6. Women

The social, economic, and political status of women in Senegal reflects a complex interplay of traditional norms, religious influences, and modern legal frameworks. Senegal has ratified international conventions aimed at protecting women's rights, such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and the Maputo Protocol (Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa).

Legally, women have equal rights in many areas, including property ownership and political participation. Senegal has implemented a gender parity law for electoral lists, which has significantly increased female representation in the National Assembly and local councils. However, challenges to gender equality persist.

In education, while enrollment rates for girls have improved, disparities remain, particularly at higher education levels and in rural areas. Women's participation in the formal workforce is lower than men's, with many women engaged in the informal sector, agriculture, and small-scale trade. Access to economic resources, credit, and land can be limited for women.

Harmful traditional practices such as female genital mutilation (FGM) and child marriage continue to occur, despite legal prohibitions and awareness campaigns. According to a 2013 UNICEF report, 26% of women in Senegal have undergone FGM. Gender-based violence, including domestic violence, is also a concern.

Efforts to promote women's empowerment are ongoing, driven by government initiatives, civil society organizations, and women's groups. These efforts focus on improving access to education and healthcare, enhancing economic opportunities, increasing political participation, and combating harmful practices. Despite progress, achieving full gender equality and empowering women across all sectors of Senegalese society remains a critical goal for democratic development and social equity.

7.7. Health

Senegal has made notable progress in improving health outcomes, though significant challenges remain in ensuring equitable access to quality healthcare.

Key health indicators show improvements over time. Life expectancy at birth was estimated to be around 66.8 years in 2016 (64.7 for males, 68.7 for females). The infant mortality rate has seen a substantial decline, from 157 per 1,000 live births in 1950 to 32 per 1,000 in 2018. Efforts to combat malaria, a major cause of child mortality, have also shown success, with a drop in malaria-related infant deaths.

The healthcare system includes public and private facilities, with a hierarchical structure from health posts at the community level to regional and national hospitals. Public expenditure on health was around 2.4% of GDP in 2004, with private expenditure at 3.5%. Per capita health expenditure was US$72 (PPP) in 2004. The number of physicians remains low, at around six per 100,000 persons in the early 2000s.

Prevalent health issues include infectious diseases like malaria, respiratory infections, and diarrheal diseases, particularly among children. Non-communicable diseases are also on the rise. HIV/AIDS prevalence is relatively low compared to other sub-Saharan African countries. Senegal faced the COVID-19 pandemic starting in March 2020, leading to public health measures including curfews and experiencing a significant surge in cases in July 2021.

Access to medical services can be challenging, especially in rural and remote areas, due to geographical distance, cost, and shortages of healthcare professionals and supplies. The fertility rate remains high, averaging around 4-5 children per woman, with higher rates in rural areas. Female genital mutilation is practiced on about 26% of women, posing serious health risks.

Public health policies focus on strengthening primary healthcare, improving maternal and child health, combating infectious diseases, and expanding health insurance coverage. In June 2021, Senegal's Agency for Universal Health launched sunucmu.com, a digital platform aimed at streamlining healthcare access and achieving 75% health coverage within two years.

7.8. Education

Senegal's education system is structured on the French model, with primary, middle, secondary, and higher education levels. Articles 21 and 22 of the 2001 Constitution guarantee access to education for all children. Education is compulsory and, in principle, free up to the age of 16. The academic structure generally follows a 6-year primary, 4-year middle school, and 3-year high school system. French is the primary language of instruction in public schools. Portuguese is also taught in some secondary schools.

Despite constitutional guarantees, the public school system faces challenges in coping with the number of children who must enroll each year, leading to issues of overcrowding and resource shortages. Literacy rates remain a concern, particularly among women and in rural areas. The overall adult literacy rate was estimated at around 39.3% in 2002 (51.1% for men, 29.2% for women), though more recent figures likely show improvement. The net primary enrollment rate was 69% in 2005. Public expenditure on education constituted 5.4% of GDP between 2002 and 2005. Senegal was ranked 92nd in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.

Alongside the formal public education system, Koranic schools, known as daaras, are widespread and play a significant role in providing religious education. Many children attend daaras, often in parallel with or instead of public schools. While daaras are important cultural institutions, some have faced criticism for issues related to child welfare, forced begging (talibés), and lack of oversight.

Higher education institutions include the Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar (founded in 1957 as Dakar University), Gaston Berger University in Saint-Louis (founded in 1990), and Ziguinchor University (founded in 2007). Many Senegalese students also pursue higher education abroad, with France being a traditional destination.

Reforms in the education sector aim to improve access, quality, and relevance, including efforts to integrate national languages into early education and strengthen vocational training.

7.9. Public Order and Safety

The general security situation in Senegal is relatively stable compared to some other countries in the region, but it faces challenges related to crime and, more recently, concerns about terrorism and political unrest. Common types of crime in urban areas include petty theft, pickpocketing, and occasional burglaries. Violent crime is less common but does occur.

Law enforcement is primarily the responsibility of the National Police in urban areas and the Gendarmerie in rural areas. Efforts are made to maintain public order, but resources can be limited.

In recent years, particularly following periods of political tension and protests (such as those in 2021 and 2023-2024), there have been concerns about clashes between protesters and security forces, leading to injuries and fatalities. Human rights organizations have called for accountability and respect for freedom of assembly.

The threat of terrorism, linked to instability in the wider Sahel region, is a concern for Senegalese authorities. The government has increased security measures, particularly in border areas with Mali and in public places, to prevent potential attacks. Travelers are often advised to exercise caution, especially in crowded areas and during demonstrations. The Casamance region, due to the ongoing low-level conflict, has specific security considerations, including the risk of landmines in some rural areas.

8. Culture

Senegalese culture is a rich blend of diverse ethnic traditions, Islamic influences, and a French colonial legacy, expressed through vibrant arts, music, cuisine, and deeply ingrained social values.

8.1. Traditions and Arts

A cornerstone of West African tradition, particularly in Senegal, is the role of griots (géwël in Wolof). These hereditary storytellers, musicians, and oral historians have preserved the histories, genealogies, and cultural narratives of their communities for centuries through spoken word and music, often accompanied by instruments like the kora or xalam.

Notable modern landmarks include the African Renaissance Monument, a colossal bronze statue unveiled in Dakar in 2010 to commemorate Senegal's 50th anniversary of independence. It is the tallest statue in Africa.

Senegal is also a hub for contemporary African art, with the Dakar Biennale (Dak'Art) being one of the continent's most significant international art exhibitions, showcasing works from African and diaspora artists. The country also hosts film festivals such as Recidak.

Islamic festivals like Eid al-Adha (known locally as Tabaski) and Eid al-Fitr (Korité) are major national celebrations. Despite being predominantly Muslim, Christian holidays like Christmas are also observed, especially in urban areas, with festive decorations often seen in Dakar, reflecting the country's religious tolerance.

8.2. Cuisine

Senegalese cuisine is renowned throughout Africa for its flavorful and diverse dishes. Bordering the Atlantic, fish is a staple ingredient. Chicken, lamb, beef, peas, and eggs are also commonly used. Pork is generally not consumed due to the largely Muslim population. Key ingredients include groundnuts (peanuts), couscous, white rice, sweet potatoes, lentils, black-eyed peas, and a variety of vegetables. Meats and vegetables are typically stewed or marinated in herbs and spices and then served over rice or couscous, or eaten with bread.

Popular national dishes include:

- Thieboudienne (or ceebu jën): Considered the national dish, it consists of fish (often thiof, or white grouper) cooked with rice and vegetables in a tomato-based sauce.

- Yassa: A popular dish made with chicken or fish marinated in lemon juice, onions, and spices, then grilled or simmered.

- Maafe (or mafé): A rich stew made with meat (beef, lamb, or chicken) cooked in a peanut butter and tomato sauce.

- Soupou Kandja: A gumbo-like stew made with okra and palm oil, often with fish or meat.

Fresh juices are widely consumed, made from hibiscus flowers (bissap), ginger, bouye (fruit of the baobab tree), mango, or other fruits like soursop (corossol). Desserts are often rich and sweet, reflecting a blend of local ingredients and French culinary influence, frequently served with fresh fruit, followed by coffee or tea.

8.3. Music

Senegalese music is internationally acclaimed for its vibrant rhythms and diverse genres. Mbalax is the most popular modern genre, originating from the traditional percussive music of the Serer people, particularly the Njuup rhythm, and popularized by artists like Youssou N'Dour and Omar Pene. Sabar drumming, with its complex polyrhythms, is a key element of Mbalax and is integral to social celebrations like weddings and baptisms. The tama (talking drum) is another important traditional instrument used across various ethnic groups.

Internationally renowned Senegalese musicians, in addition to Youssou N'Dour, include Ismael Lô, Cheikh Lô, Orchestra Baobab, Baaba Maal, Akon (US-born of Senegalese descent), Thione Seck, Viviane, Fallou Dieng, Titi, Seckou Keita (kora player based in the UK), and Pape Diouf. Traditional instruments like the kora (a 21-string harp-lute), xalam (a five-string lute), and various percussion instruments remain central to Senegalese musical expression. Wolof hip hop (rap) is also a very popular genre among the youth.

8.4. Cinema

Senegalese cinema has a distinguished history and is considered one ofthe most important national cinemas in Africa. Ousmane Sembène (1923-2007) is widely regarded as the "father of African cinema." His films, often based on his novels, explored themes of colonialism, post-colonial disillusionment, social critique, and the role of women in African society. Notable works include Black Girl (La Noire de...), Xala, and Moolaadé.

Djibril Diop Mambéty (1945-1998) was another highly influential filmmaker, known for his unique visual style and allegorical storytelling. His films like Touki Bouki and Hyènes (Hyenas) are celebrated for their artistic innovation and critical commentary on Senegalese society. Common themes in Senegalese cinema include social justice, cultural identity, the clash between tradition and modernity, and political corruption.

8.5. Media

The media landscape in Senegal includes a mix of state-owned and private outlets. Newspapers, radio, and television are the primary forms of mass media. Several daily and weekly newspapers are published in French, with some content in national languages. Radio is the most widespread medium, with numerous public, private, and community radio stations broadcasting in French and various national languages, providing news, music, and cultural programming.

State broadcaster Radiodiffusion Télévision Sénégalaise (RTS) operates national television and radio channels. Private television channels have also emerged, increasing media diversity. Internet access and social media usage are growing, particularly in urban areas, providing alternative platforms for information and expression.

Freedom of the press is constitutionally guaranteed, and Senegal generally has a more open media environment than many African countries. However, journalists and media outlets have at times faced political pressure, legal challenges, and occasional restrictions, particularly when covering sensitive political issues or criticizing the government. Access to information remains a key aspect of democratic discourse.

8.6. Hospitality (Teranga)

Teranga is a core Senegalese cultural value that is deeply ingrained in the national identity. The Wolof word teranga translates roughly to hospitality, but encompasses broader meanings of generosity, warmth, respect, and welcoming acceptance of guests and strangers. It is considered a matter of national pride and is practiced widely across all ethnic groups and social strata.

The concept of teranga dictates that hosts should go out of their way to make guests feel comfortable and valued, often sharing meals, offering lodging, and engaging in friendly conversation. This spirit of openness and generosity is extended not only to acquaintances but also to unfamiliar visitors. The importance of teranga is such that the Senegal national football team is nicknamed "Les Lions de la Téranga" (The Lions of Teranga). Some scholars note that similar concepts of honor and hospitality, such as jom, are also rooted in Serer values and language.

8.7. Sport

Sports play a significant role in Senegalese culture, with several disciplines enjoying widespread popularity.

Senegalese wrestling (Laamb in Wolof) is arguably the country's most popular sport and a national obsession. It is a traditional form of wrestling with deep cultural roots, often accompanied by drumming, rituals, and fervent crowd support. For many young men, Laamb offers a path to fame and fortune, and it is distinct in being recognized as a sport developed independently of Western cultural influence. Champions like Balla Gaye 2, Bombardier, and Yékini are national heroes.

Football (soccer) is also immensely popular. The Senegal national football team, known as Les Lions de la Téranga, achieved its greatest success by winning the 2021 Africa Cup of Nations. They were runners-up in 2002 and 2019. The team made a memorable debut at the 2002 FIFA World Cup, reaching the quarter-finals and defeating reigning champions France in the opening match. They also qualified for the 2018 FIFA World Cup and the 2022 FIFA World Cup. Prominent Senegalese footballers like Sadio Mané, Kalidou Koulibaly, and Édouard Mendy have achieved international stardom.

Basketball is another popular sport. Senegal has traditionally been one of Africa's dominant basketball nations. The men's national team performed impressively at the 2014 FIBA Basketball World Cup, reaching the playoffs for the first time. The women's national team is highly successful, having won 19 medals at 20 African Championships, more than any other competitor. In 2019, when Senegal hosted the FIBA Women's AfroBasket, the Dakar Arena saw a record attendance of 15,000 fans. The National Basketball Association (NBA) launched an elite academy in Senegal in 2016.

Senegal hosted the Paris-Dakar Rally from its inception in 1979 until 2007. The rally was an off-road endurance race that traditionally finished in Dakar. The event was moved from Africa after 2007 due to security concerns in Mauritania. More recently, Senegal hosted the Ocean X-Prix, part of the Extreme E electric off-road racing championship.

Senegal is set to host the 2026 Summer Youth Olympics in Dakar, making it the first African country to host an Olympic event, a significant milestone for the nation and the continent.