1. Overview

Libya is a country located in the Maghreb region of North Africa, bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad and Niger to the south, and Algeria and Tunisia to the west. The nation's history is marked by ancient civilizations, Ottoman and Italian colonial rule, a monarchy, the long and authoritarian rule of Muammar Gaddafi, and significant political upheaval following the 2011 Arab Spring. This article explores Libya's journey, emphasizing its struggles for democratic development, the protection of human rights, and the pursuit of social equity, particularly in the context of its post-Gaddafi transition and ongoing challenges. Libya's economy is heavily reliant on its vast oil reserves, which have shaped its socio-economic landscape but also presented challenges related to governance and equitable wealth distribution. The country possesses a rich cultural heritage, blending Arab, Berber (Amazigh), and Mediterranean influences, reflected in its traditions, cuisine, and historical sites. Despite its potential, Libya continues to face significant hurdles in achieving political stability, national unity, and sustainable development, with ongoing efforts to address these complex issues.

2. Etymology

The origin of the name "Libya" can be traced back to ancient Egyptian inscriptions, where it appeared as rbw (rbwRebuEgyptian (Ancient)) in hieroglyphics. This name was a generalized identity given to a large confederacy of ancient east "Libyan" Berbers, North African peoples and tribes who inhabited the regions around Cyrenaica and Marmarica. An army of 40,000 men and a confederacy of tribes known as the "Great Chiefs of the Libu" were led by King Meryey, who fought a war against Pharaoh Merneptah in the fifth year of his reign (1208 BCE). This conflict, mentioned in the Great Karnak Inscription, occurred in the western delta and resulted in a defeat for Meryey. According to the inscription, the military alliance included the Meshwesh, the Lukka, and "Sea Peoples" known as the Ekwesh, Teresh, Shekelesh, and Sherden. The Great Karnak Inscription reads:

"... the third season, saying: 'The wretched, fallen chief of Libya, Meryey, son of Ded, has fallen upon the country of Tehenu with his bowmen - Sherden, Shekelesh, Ekwesh, Lukka, Teresh. Taking the best of every warrior and every man of war of his country. He has brought his wife and his children - leaders of the camp, and he has reached the western boundary in the fields of Perire.'"

The name "Libya" was revived in 1903 by Italian geographer Federico Minutilli. It was intended to supplant terms applied to Ottoman Tripolitania, the coastal region of what is today Libya, which had been ruled by the Ottoman Empire from 1551 to 1911 as the Eyalet of Tripolitania.

Libya gained independence in 1951 as the United Libyan Kingdom (المملكة الليبية المتحدةal-Mamlakah al-Lībiyyah al-MuttaḥidahArabic), changing its name to the Kingdom of Libya (المملكة الليبيةal-Mamlakah al-LībiyyahArabic, literally "Libyan Kingdom") in 1963. Following a coup d'état led by Muammar Gaddafi in 1969, the name of the state was changed to the Libyan Arab Republic (الجمهورية العربية الليبيةal-Jumhūriyyah al-'Arabiyyah al-LībiyyahArabic). The official name was "Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya" from 1977 to 1986 (الجماهيرية العربية الليبية الشعبية الاشتراكيةal-Jamāhīriyyah al-'Arabiyyah al-Lībiyyah ash-Sha'biyyah al-IshtirākiyyahArabic), and "Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya" (الجماهيرية العربية الليبية الشعبية الاشتراكية العظمىal-Jamāhīriyyah al-'Arabiyyah al-Lībiyyah ash-Sha'biyyah al-Ishtirākiyyah al-'UẓmáArabic) from 1986 to 2011.

The National Transitional Council, established in 2011, referred to the state as simply "Libya." The United Nations formally recognized the country as "Libya" in September 2011, based on a request from the Permanent Mission of Libya citing the Libyan interim Constitutional Declaration of 3 August 2011. In November 2011, the ISO 3166-1 standard was altered to reflect the new country name "Libya" in English and Libye (la)Libya (the)French in French.

In December 2017, the Permanent Mission of Libya to the United Nations informed the UN that the country's official name was henceforth the "State of Libya"; "Libya" remained the official short form, and the country continued to be listed under "L" in alphabetical lists.

3. History

Libya's history spans millennia, from ancient Berber settlements through colonization by Phoenicians, Greeks, and Romans, followed by Arab Islamic conquests, Ottoman rule, Italian colonization, a monarchy, the lengthy Gaddafi era, and recent periods of civil war and political transition. The nation's path has been shaped by its strategic location in North Africa and its rich natural resources, particularly oil. This historical overview covers the major periods including ancient and medieval times, the Ottoman era, Italian colonization which brought significant human cost, the Kingdom period with its socio-economic shifts, the long and oppressive Gaddafi era marked by human rights abuses, the tumultuous First Libyan Civil War, the difficult post-Gaddafi transition leading to a second civil war, and recent developments including ongoing efforts for stability and democratic governance.

3.1. Ancient and Medieval Periods

This period covers Libya's earliest inhabitants, the influence of major ancient Mediterranean civilizations, the spread of Christianity, the Arab Islamic conquest, and the subsequent rule by various medieval dynasties, significantly shaping the region's cultural and religious landscape.

The coastal plain of Libya was inhabited by Neolithic peoples from as early as 8000 BC. The Afroasiatic ancestors of the Berber people are assumed to have spread into the area by the Late Bronze Age. The earliest known name of such a tribe was the Garamantes, based in Germa. The Phoenicians were the first to establish trading posts in Libya, founding cities like Oea (modern Tripoli), Labdah (later Leptis Magna), and Sabratha, which collectively became known as Tripolis. By the 5th century BC, the greatest of the Phoenician colonies, Carthage, had extended its hegemony across much of North Africa, where a distinctive civilization, known as Punic, came into being.

In 630 BC, the ancient Greeks colonized Eastern Libya, founding the city of Cyrene. Within 200 years, four more important Greek cities were established in the area that became known as Cyrenaica: Barca, Euhesperides (later Berenice, modern Benghazi), Teuchira (later Arsinoe, modern Tukrah), and Apollonia (modern Susah), the port of Cyrene. Together, these formed the Pentapolis (Five Cities). The area was also home to the renowned philosophy school of the Cyrenaics. In 525 BC, the Persian army of Cambyses II overran Cyrenaica, which for the next two centuries remained under Persian or Egyptian rule. Alexander the Great ended Persian rule in 331 BC and received tribute from Cyrenaica. Eastern Libya again fell under the control of the Greeks, this time as part of the Ptolemaic Kingdom.

After the fall of Carthage, the Romans did not immediately occupy Tripolitania (the region around Tripoli), leaving it instead under the control of the kings of Numidia, until the coastal cities requested and obtained Roman protection. Ptolemy Apion, the last Greek ruler, bequeathed Cyrenaica to Rome, which formally annexed the region in 74 BC and joined it to Crete as the province of Creta et Cyrenaica. As part of the Africa Nova province, Tripolitania was prosperous and reached a golden age in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, when Leptis Magna, home to the Severan dynasty, was at its height.

On the eastern side, Cyrenaica's first Christian communities were established by the time of Emperor Claudius. The region was heavily devastated during the Kitos War and almost depopulated of Greeks and Jews alike. Although repopulated by Trajan with military colonies, its decline began thereafter. Libya was an early convert to Nicene Christianity and was the home of Pope Victor I; however, it was also home to many non-Nicene varieties of early Christianity, such as Arianism and Donatism. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the area of Libya was mostly occupied by the Vandals until the Byzantine reconquest in the 6th century.

Under the command of Amr ibn al-As, the Rashidun army conquered Cyrenaica in the 7th century. In 647, an army led by Abdullah ibn Saad definitively took Tripoli from the Byzantines. The Fezzan was conquered by Uqba ibn Nafi in 663. The Berber tribes of the hinterland accepted Islam, but they resisted Arab political rule. For the next several decades, Libya was under the purview of the Umayyad Caliphate of Damascus. The Abbasids overthrew the Umayyads in 750, and Libya came under the rule of Baghdad. When Caliph Harun al-Rashid appointed Ibrahim ibn al-Aghlab as his governor of Ifriqiya in 800, Libya enjoyed considerable local autonomy under the Aghlabid dynasty. By the 10th century, the Shiite Fatimids controlled Western Libya, ruling the entire region by 972 and appointing Bologhine ibn Ziri as governor.

Ibn Ziri's Berber Zirid dynasty ultimately broke away from the Shiite Fatimids and recognized the Sunni Abbasids of Baghdad as rightful Caliphs. In retaliation, the Fatimids brought about the migration of thousands from mainly two Arab Qaisi tribes, the Banu Sulaym and Banu Hilal, to North Africa. This act drastically altered the fabric of the Libyan countryside and cemented the cultural and linguistic Arabisation of the region. Zirid rule in Tripolitania was short-lived, and by 1001 the Berbers of the Banu Khazrun broke away. Tripolitania remained under their control until 1146, when the region was overtaken by the Normans of Sicily. For the next 50 years, Tripolitania was the scene of numerous battles among Ayyubids, the Almohad rulers, and insurgents of the Banu Ghaniya. Later, a general of the Almohads, Muhammad ibn Abu Hafs, ruled Libya from 1207 to 1221 before the later establishment of the Tunisian Hafsid dynasty independent from the Almohads. In the 14th century, the Banu Thabit dynasty ruled Tripolitania before it reverted to direct Hafsid control. By the 16th century, the Hafsids became increasingly caught up in the power struggle between Spain and the Ottoman Empire. After Abbasid control weakened, Cyrenaica was under Egypt-based states such as the Tulunids, Ikhshidids, Ayyubids, and Mamluks before the Ottoman conquest in 1517. Fezzan acquired independence under the Awlad Muhammad dynasty after Kanem rule. The Ottomans finally conquered Fezzan between 1556 and 1577.

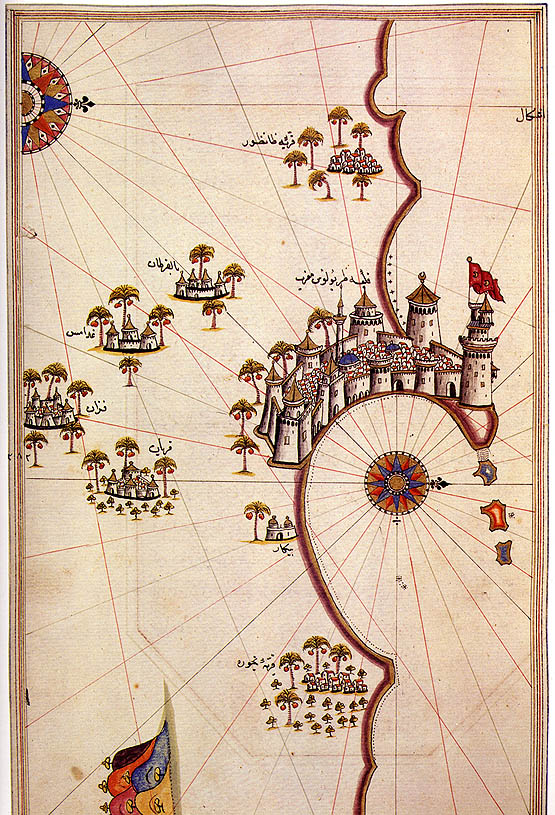

3.2. Ottoman Era

This section details Libya's period under the Ottoman Empire, including autonomous rule by the Karamanli dynasty and the Barbary Wars, leading to the reassertion of direct Ottoman control.

After a successful invasion of Tripoli by Habsburg Spain in 1510 and its handover to the Knights of St. John, the Ottoman admiral Sinan Pasha took control of Libya in 1551. His successor Turgut Reis was named the Bey of Tripoli and later Pasha of Tripoli in 1556. By 1565, administrative authority as regent in Tripoli was vested in a pasha appointed directly by the sultan in Constantinople/Istanbul. In the 1580s, the rulers of Fezzan gave their allegiance to the sultan, and although Ottoman authority was absent in Cyrenaica, a bey was stationed in Benghazi late in the next century to act as an agent of the government in Tripoli. European slaves and large numbers of enslaved Black Africans transported from Sudan were also a feature of everyday life in Tripoli. In 1551, Turgut Reis enslaved almost the entire population of the Maltese island of Gozo, some 5,000 people, sending them to Libya.

In time, real power came to rest with the pasha's corps of janissaries. In 1611, the deys staged a coup against the pasha, and Dey Sulayman Safar was appointed as head of government. For the next hundred years, a series of deys effectively ruled Tripolitania. The two most important Deys were Mehmed Saqizli (r. 1631-49) and Osman Saqizli (r. 1649-72), both also Pasha, who ruled effectively the region. The latter also conquered Cyrenaica.

Lacking direction from the Ottoman government, Tripoli lapsed into a period of military anarchy during which coup followed coup, and few deys survived in office more than a year. One such coup was led by Turkish officer Ahmed Karamanli. The Karamanli dynasty ruled from 1711 until 1835, mainly in Tripolitania, and had influence in Cyrenaica and Fezzan as well by the mid-18th century. Ahmed's successors proved to be less capable than himself; however, the region's delicate balance of power allowed the Karamanli to continue. The 1793-95 Tripolitanian civil war occurred in those years. In 1793, Turkish officer Ali Pasha Burghul deposed Hamet Karamanli and briefly restored Tripolitania to Ottoman rule. Hamet's brother Yusuf Karamanli (r. 1795-1832) re-established Tripolitania's independence.

In the early 19th century, war broke out between the United States and Tripolitania, and a series of battles ensued in what came to be known as the First Barbary War and the Second Barbary War. By 1819, the various treaties of the Napoleonic Wars had forced the Barbary states to give up piracy almost entirely, and Tripolitania's economy began to crumble. As Yusuf weakened, factions sprung up around his three sons, and civil war soon resulted. Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II sent in troops ostensibly to restore order, marking the end of both the Karamanli dynasty and an independent Tripolitania. Order was not recovered easily, and the revolt of the Libyans under Abd-El-Gelil and Gûma ben Khalifa lasted until the death of the latter in 1858. The second period of direct Ottoman rule saw administrative changes and greater order in the governance of the three provinces of Libya. Ottoman rule finally reasserted itself in Fezzan between 1850 and 1875 for earning income from Saharan commerce.

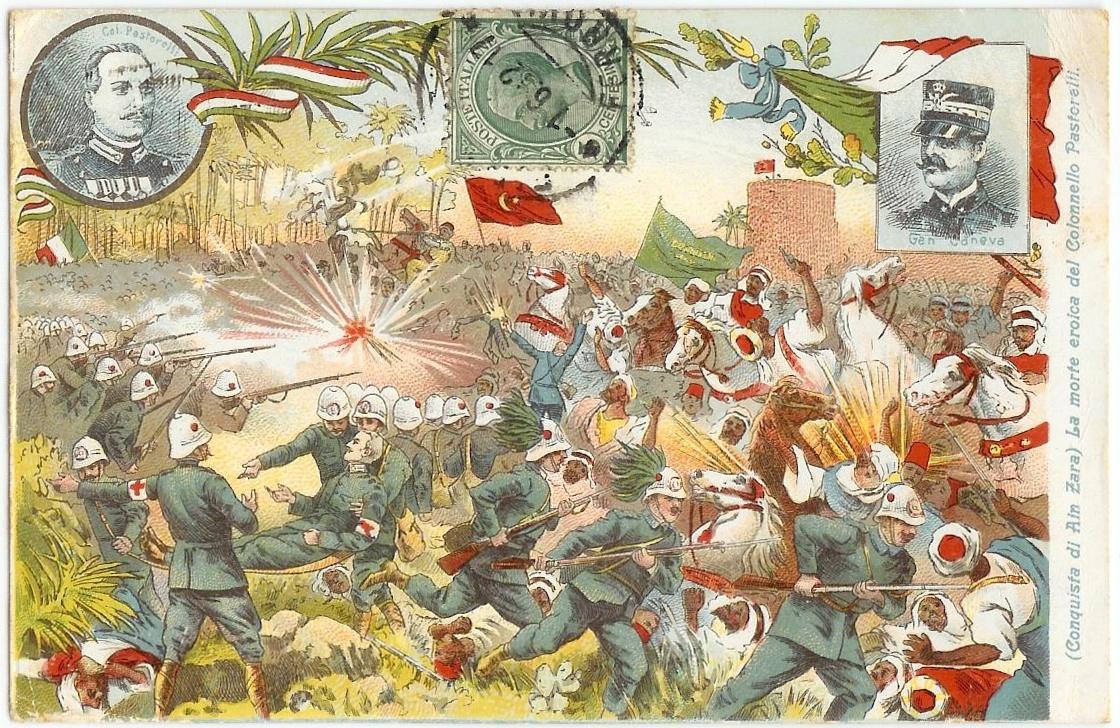

3.3. Italian Colonization and Allied Occupation

This section describes the Italian conquest of Libya, the significant Libyan resistance, the socio-economic impacts of colonization, Libya's role in World War II, and the subsequent Allied occupation, highlighting the human cost involved.

After the Italo-Turkish War (1911-1912), Italy simultaneously turned the three regions of Tripolitania, Cyrenaica, and Fezzan into colonies. From 1912 to 1927, the territory of Libya was known as Italian North Africa. From 1927 to 1934, the territory was split into two colonies, Italian Cyrenaica and Italian Tripolitania, run by Italian governors. Approximately 150,000 Italians settled in Libya, constituting about 20% of the total population.

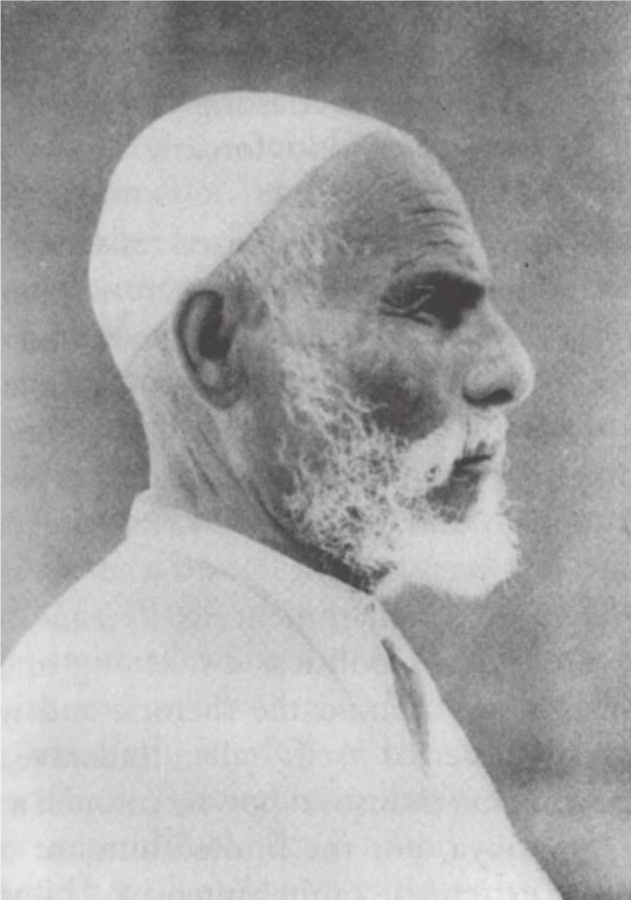

Omar Mukhtar rose to prominence as a leader of the Libyan resistance movement against Italian colonization and became a national hero despite his capture and execution on 16 September 1931. His face is currently printed on the Libyan ten dinar note in memory and recognition of his patriotism. Another prominent resistance leader, Idris al-Mahdi as-Senussi (later King Idris I), Emir of Cyrenaica, continued to lead the Libyan resistance until the outbreak of the Second World War.

The so-called "pacification of Libya" by the Italians resulted in mass deaths of the indigenous people in Cyrenaica, killing approximately one-quarter of Cyrenaica's population of 225,000 people. The human cost of this period was immense, with Ilan Pappé estimating that between 1928 and 1932, the Italian military "killed half the Bedouin population (directly or through disease and starvation in Italian concentration camps)." This brutal suppression aimed to quell resistance and solidify Italian control.

In 1934, Italy combined Cyrenaica, Tripolitania, and Fezzan and adopted the name "Libya" (a name used by the Ancient Greeks for all of North Africa except Egypt) for the unified colony, with Tripoli as its capital. The Italians emphasized infrastructure improvements and public works. In particular, they greatly expanded Libyan railway and road networks from 1934 to 1940, building hundreds of kilometres of new roads and railways and encouraging the establishment of new industries and dozens of new agricultural villages.

In June 1940, Italy entered World War II. Libya became the setting for the hard-fought North African campaign that ultimately ended in defeat for Italy and its German ally in 1943. During this period, the Italian population in Libya began to decline.

From 1943 to 1951, Libya was under Allied occupation. The British military administered the two former Italian Libyan provinces of Tripolitania and Cyrenaïca, while the French administered the province of Fezzan. In 1944, Idris returned from exile in Cairo but declined to resume permanent residence in Cyrenaica until the removal of some aspects of foreign control in 1947. Under the terms of the 1947 peace treaty with the Allies, Italy relinquished all claims to Libya.

3.4. Kingdom of Libya (1951-1969)

This section outlines Libya's independence as a monarchy under King Idris I, the discovery of oil, and the subsequent socio-economic and political developments that characterized this era, laying groundwork for future discontent due to inequitable wealth distribution and rising Arab nationalism.

On November 21, 1949, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution stating that Libya should become independent before January 1, 1952. Sayyid Idris, the Emir of Cyrenaica and leader of the influential Senussi religious brotherhood, represented Libya in the subsequent UN negotiations. A national assembly crafted a constitution that established a monarchy and extended an offer for the throne to Sayyid Idris. His devout Islamic movement had garnered significant support from the Bedouin population and had effectively governed the Libyan interior during the declining years of the Ottoman Empire. Born in an oasis in Cyrenaica in 1890, Sayyid Idris assumed leadership of the Senussi at a young age, spent considerable time in exile in Egypt under Italian rule, and returned to Libya after the Axis powers were ousted in 1943.

On December 24, 1951, as King Idris I, he addressed the nation via radio from Benghazi, declaring Libya's independence as the United Kingdom of Libya, a constitutional and hereditary monarchy. The new kingdom faced challenging prospects, lacking significant industry and agricultural resources. Its primary exports consisted of hides, wool, horses, and ostrich feathers. Despite having one of the lowest income per capita figures globally, it also suffered from one of the highest illiteracy rates. King Idris I, already in his sixties, had no direct heir; his son born in 1953 tragically died shortly after birth. Crown Prince Rida, Idris's brother, was the designated heir, but the royal family was riddled with incessant disputes. King Idris's devout Muslim piety, which solidified his support among the Bedouin, clashed with the modernizing and urban intellectual currents in Libya. To address the rivalry between Cyrenaica and Tripolitania, Benghazi and Tripoli alternated as the capital every two years. The swift emergence of a large number of bureaucrats resulted in a costly royal government.

The discovery of significant oil reserves in 1959 and the subsequent income from petroleum sales transformed one of the world's poorest nations into an extremely wealthy state. Although oil drastically improved the Libyan government's finances, popular resentment began to build over the increased concentration of the nation's wealth in the hands of King Idris and the national elite. This growing inequality fueled discontent, which continued to mount with the rise of Nasserism and Arab nationalism throughout North Africa and the Middle East.

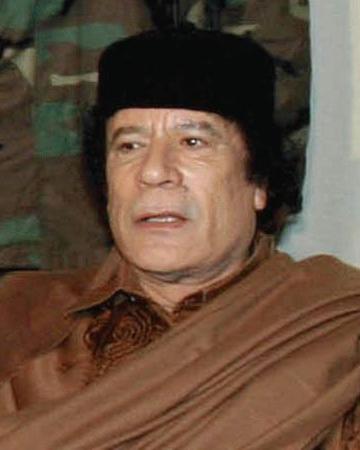

3.5. Gaddafi Era (1969-2011)

This era details the 1969 coup led by Muammar Gaddafi, the establishment of the Libyan Arab Republic and later the Jamahiriya, Gaddafi's unique political ideology, his regime's foreign policy and international isolation, and significant socio-economic developments alongside severe human rights abuses. The subsections cover his governance and ideology, foreign relations marked by anti-Western stances and support for militant groups leading to isolation, and socio-economic impacts including oil-funded welfare alongside corruption and inequality.

On September 1, 1969, a group of rebel military officers led by Muammar Gaddafi launched a coup d'état against King Idris, which became known as the Al Fateh Revolution. Gaddafi, referred to as the "Brotherly Leader and Guide of the Revolution" in government statements and the official Libyan press, dominated Libya's history and politics for the next four decades. Moving to reduce Italian influence, in October 1970, all Italian-owned assets were expropriated, and the 12,000-strong Italian community was expelled from Libya alongside the smaller community of Italian Libyan Jews. The day became a national holiday known as "Day of Revenge"; it was later renamed the "Day of Friendship" due to improvements in Italy-Libya relations.

3.5.1. Governance and Ideology

Gaddafi's rule was characterized by his distinct political philosophy, the "Third Universal Theory," outlined in The Green Book published in 1975. This ideology, a blend of utopian socialism, Arab nationalism, and elements of Bedouin tradition, aimed to be an alternative to both capitalism and communism. In March 1977, Libya officially became the "Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya." The new jamahiriya (جماهيريةstate of the massesArabic) governance structure was officially referred to as a form of "direct democracy". Power was ostensibly vested in the people through a system of People's Congresses and People's Committees. Gaddafi officially passed power to the General People's Committees and henceforth claimed to be no more than a symbolic figurehead.

However, in reality, power remained highly centralized under Gaddafi and his inner circle. The Revolutionary Committees played a pervasive role, carrying out widespread surveillance of the population and enforcing adherence to Gaddafi's ideology. Political dissent was made illegal under Law 75 of 1973 and was brutally suppressed, leading to numerous human rights abuses. An attempted coup on October 25, 1975, by a group of 20 military officers, mostly from Misrata, resulted in the arrest and execution of the plotters. While Gaddafi's regime was authoritarian, it also introduced some social reforms. He sought to ease strict social restrictions imposed on women by the previous regime, establishing the Revolutionary Women's Formation to encourage reform. In 1970, a law was introduced affirming equality of the sexes and wage parity. In 1971, Gaddafi sponsored the creation of a Libyan General Women's Federation. In 1972, a law was passed criminalizing the marriage of any girl under the age of sixteen and making a woman's consent a necessary prerequisite for marriage.

3.5.2. Foreign Relations and International Isolation

Libya's foreign policy under Gaddafi was marked by a strong anti-Western stance, support for various international movements and militant groups, and involvement in regional conflicts. Gaddafi financed a wide array of groups, from anti-nuclear movements to Australian trade unions, and supported leaders like Idi Amin of Uganda, Jean-Bédel Bokassa of the Central African Empire, Mengistu Haile Mariam of Ethiopia, Charles Taylor of Liberia, and Slobodan Milošević of Yugoslavia. In February 1977, Libya began delivering military supplies to Goukouni Oueddei and the People's Armed Forces in Chad, escalating into the Chadian-Libyan War. Later that year, Libya and Egypt fought a four-day border war known as the Libyan-Egyptian War, which ended with a ceasefire mediated by Algerian President Houari Boumédiène. Hundreds of Libyans lost their lives supporting Idi Amin's Uganda in its war against Tanzania.

Libya's regime was accused of state-sponsored terrorism, most notably the 1988 Lockerbie bombing, which killed 270 people. This event, along with others like the 1986 Berlin discotheque bombing, led to United Nations sanctions and significant international isolation. An American airstrike in 1986, ordered by U.S. President Ronald Reagan, aimed to kill Gaddafi but failed. The 1990s saw the regime threatened by militant Islamism and an unsuccessful assassination attempt on Gaddafi, which was met with repressive measures. Cyrenaica was particularly unstable between 1995 and 1998 due to tribal allegiances of local troops.

In 2003, Gaddafi announced that Libya would dismantle all its weapons of mass destruction programs and transition toward nuclear power. This decision, coming after the Iraq War and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, led to a complex process of rapprochement with Western nations and the lifting of sanctions. The humanitarian impact of the long period of international isolation on the Libyan population was significant, affecting access to goods and services. On November 19, 1977, Libya adopted its plain green national flag, which remained the only plain-colored national flag in the world until it was replaced in 2011.

3.5.3. Socio-economic Developments and Impacts

Libya's substantial oil revenues, which soared in the 1970s, were utilized for extensive social welfare programs and significant infrastructure projects. Per capita income rose to over 11.00 K USD, making it the fifth-highest in Africa, and its Human Development Index became the highest on the continent, surpassing even Saudi Arabia. These achievements were made without borrowing foreign loans, keeping Libya debt-free. A landmark project was the Great Man-Made River, designed to provide free access to fresh water across large parts of the country by tapping into the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System. Financial support was also provided for university scholarships and employment programs.

However, these developments were accompanied by critical issues. Much of Libya's oil income was also spent on arms purchases and sponsoring dozens of paramilitary and terrorist groups around the world. There were allegations of widespread corruption and significant limitations on economic freedom. Despite the social programs, economic inequality persisted, and the benefits of oil wealth were not always evenly distributed among the Libyan citizenry. Gaddafi's policies, while providing certain benefits, also created a society heavily dependent on state largesse and limited individual economic initiative, impacting the broader societal development of Libyan citizens.

3.6. First Libyan Civil War and Fall of Gaddafi (2011)

This section covers the 2011 uprising, its escalation into civil war, the role of the National Transitional Council, the controversial NATO intervention, Gaddafi's death, and the collapse of his regime, focusing on the human cost and the quest for democratic change.

The first Libyan Civil War erupted in the context of the Arab Spring movements that had overturned rulers in Tunisia and Egypt. Protests against Gaddafi's regime began on February 15, 2011, with a full-scale revolt commencing on February 17, Revolution Day. Gaddafi's authoritarian regime offered much more resistance than those in Egypt and Tunisia. The first announcement of a competing political authority, the National Transitional Council (NTC), appeared online, declaring itself an alternative government. One of Gaddafi's senior advisors resigned, defected, and advised Gaddafi to flee. By February 20, the unrest had spread to Tripoli. On February 27, 2011, the NTC was formally established to administer areas under rebel control. By March 10, 2011, the United States and many other nations recognized the council, headed by Mahmoud Jibril as acting prime minister, as the legitimate representative of the Libyan people, withdrawing recognition of Gaddafi's regime.

Pro-Gaddafi forces responded militarily to rebel pushes in Western Libya and launched a counterattack along the coast toward Benghazi, the de facto center of the uprising. The town of Zawiya, 30 mile (48 km) from Tripoli, was bombarded by air force planes and army tanks and seized by Jamahiriya troops, "exercising a level of brutality not yet seen in the conflict." United Nations organizations, including Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and the United Nations Human Rights Council, condemned the crackdown as violating international law, with the latter body expelling Libya in an unprecedented action.

On March 17, 2011, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1973 with a 10-0 vote and five abstentions (Russia, China, India, Brazil, and Germany). The resolution sanctioned the establishment of a no-fly zone and the use of "all means necessary" to protect civilians within Libya. This NATO-led military intervention was controversial, with debates surrounding its mandate and impact. On March 19, NATO allies began operations, with French military jets entering Libyan airspace. American forces were at the forefront of these operations, deploying over 8,000 U.S. personnel. At least 3,000 targets were struck in 14,202 strike sorties, including flights of B-2 Stealth bombers. The support from NATO air forces contributed significantly to the eventual success of the revolution.

By August 22, 2011, rebel fighters had entered Tripoli and occupied Green Square, which they renamed Martyrs' Square in honor of those killed since February 17. On October 20, 2011, the last heavy fighting of the uprising ended in the city of Sirte, Gaddafi's birthplace and last stronghold. Muammar Gaddafi was captured and killed by NATO-backed forces on this day, marking the collapse of his 42-year regime. The defeat of loyalist forces was celebrated on October 23, 2011. The civil war exacted a heavy human toll, with at least 30,000 Libyans dying and an estimated 50,000 wounded, underscoring the profound cost of the conflict and the struggle for democratic change.

3.7. Post-Gaddafi Transition and Second Libyan Civil War (2011-2020)

This period covers the challenging aftermath of Gaddafi's overthrow, marked by state-building difficulties, militia proliferation, political fragmentation into rival governments, the rise of extremist groups, and the devastating Second Libyan Civil War. It is further divided into subsections on Political Fragmentation and Power Struggles, and International Intervention and Peace Efforts.

Following the defeat of loyalist forces, Libya was torn among numerous rival, armed militias affiliated with distinct regions, cities, and tribes, while the central government remained weak and unable to effectively exert its authority. Competing militias pitted themselves against each other in a political struggle between Islamist politicians and their opponents.

3.7.1. Political Fragmentation and Power Struggles

The post-Gaddafi power vacuum led to a complex and shifting landscape of political factions, regional militias, tribal forces, and external actors vying for power and influence. On July 7, 2012, Libyans held their first parliamentary elections since the end of the former regime. On August 8, the National Transitional Council officially handed power over to the wholly-elected General National Congress (GNC), which was then tasked with forming an interim government and drafting a new constitution. However, stability remained elusive. On August 25, 2012, in what Reuters reported as "the most blatant sectarian attack" since the end of the civil war, unnamed organized assailants bulldozed a Sufi mosque with graves in Tripoli. Numerous acts of vandalism and destruction of heritage sites were carried out by suspected Islamist militias, including the removal of the Nude Gazelle Statue and the desecration of World War II-era British grave sites near Benghazi.

On September 11, 2012, Islamist militants mounted an attack on the American diplomatic compound in Benghazi, killing U.S. Ambassador to Libya, J. Christopher Stevens, and three others, generating outrage in both the United States and Libya. Political instability continued with Prime Minister-elect Mustafa A. G. Abushagur being ousted in October 2012 after failing to win parliamentary approval for a new cabinet. His successor, Ali Zeidan, was elected on October 14, 2012, but was himself ousted on March 11, 2014, and replaced by Prime Minister Abdullah al-Thani.

The Second Libyan Civil War began in May 2014. Elections to the House of Representatives (HoR), a new legislative body intended to replace the GNC, were held in June 2014. These elections were marred by violence and low turnout. Secularists and liberals performed well, to the consternation of Islamist lawmakers in the GNC, who reconvened and declared a continuing mandate for the GNC, refusing to recognize the new HoR. Armed supporters of the GNC occupied Tripoli, forcing the newly elected parliament to flee to Tobruk. This split led to two rival governments. Radical Islamist fighters seized Derna in 2014 and Sirte in 2015 in the name of the Islamic State (ISIL). In February 2015, neighboring Egypt launched airstrikes against ISIL in support of the Tobruk government. The power struggles profoundly impacted national unity, governance, and the civilian population.

3.7.2. International Intervention and Peace Efforts

The United Nations and various international actors attempted to mediate the conflict, facilitate peace negotiations, and enforce arms embargoes. In January 2015, meetings known as the Geneva-Ghadames talks aimed to find a peaceful agreement, but the GNC did not participate. The UN, through Special Representative of the Secretary-General (SRSG) Bernardino León and the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL), supported dialogue processes throughout 2015. In July 2015, a political agreement outlining a framework for transition was achieved, but implementation proved difficult. The UN Human Rights Council also requested a report on the Libyan situation and established an investigative body to report on human rights and the justice system.

Chaos-ridden Libya emerged as a major transit point for people trying to reach Europe. Between 2013 and 2018, nearly 700,000 migrants reached Italy by boat, many from Libya. In May 2018, rival Libyan leaders agreed in Paris to hold parliamentary and presidential elections, but these were repeatedly postponed.

In April 2019, Khalifa Haftar, leading the Libyan National Army (LNA), launched Operation Flood of Dignity, an offensive to seize Western territories from the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord (GNA). In June 2019, GNA forces captured Gharyan, a strategic town used by Haftar. In March 2020, the UN-backed GNA, led by Fayez al-Sarraj, commenced Operation Peace Storm in response to LNA assaults. External actors played significant roles: on August 28, 2020, BBC investigations revealed that a drone operated by the United Arab Emirates from Al-Khadim airbase had killed 26 unarmed cadets in Tripoli on January 4, 2020, using a Chinese-made Wing Loong II drone armed with a Blue Arrow 7 missile. The Guardian reported on October 7, 2020, that both the UAE and Turkey were blatantly violating the UN arms embargo by sending large-scale military cargo planes to support their respective proxies. These interventions highlighted the complexities of foreign involvement and its impact on humanitarian efforts. Finally, on October 23, 2020, the two main warring sides signed a permanent ceasefire agreement.

3.8. Recent Developments (2020-Present)

This section outlines post-ceasefire efforts towards stable governance, persistent instability, election postponements, and recent major events like the Derna floods, underscoring ongoing challenges to democratic consolidation and human security.

Following the 2020 ceasefire, efforts focused on establishing a stable, unified national government and preparing for democratic elections. However, Libya's first presidential election, initially scheduled for December 2021, was repeatedly delayed due to political rivalries and disagreements over electoral laws, and has yet to take place.

In February 2022, the eastern-based House of Representatives appointed Fathi Bashagha as prime minister to lead a transitional administration, the Government of National Stability (GNS). However, the incumbent interim prime minister of the Government of National Unity (GNU), Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh, based in Tripoli and recognized by the international community, refused to hand over power. This led to a renewed period of dual power, with both governments functioning simultaneously. Political instability persisted, with tribal leaders from Ubari shutting down the El Sharara oil field, Libya's largest, on April 18, 2022, in protest against the Dbeibah government. On July 2, 2022, the House of Representatives building in Tobruk was stormed and set on fire by protesters angered by deteriorating living conditions and political deadlock.

On September 10, 2023, Storm Daniel caused catastrophic floods due to dam failures in the port city of Derna. The floods resulted in the deaths of more than 5,900 people, with some estimates suggesting as many as 24,000 fatalities, making it the worst natural disaster in Libya's modern history. The disaster highlighted the vulnerability of the population and infrastructure, exacerbated by years of conflict and neglect.

In November 2024, the Tripoli-based Government of National Unity reportedly instated a morality police force to crack down on "weird haircuts," enforce "modest" clothing, and require male guardians for women, raising concerns about human rights and personal freedoms. These developments underscore the persistent political instability and significant challenges to democratic consolidation and the establishment of rule of law in Libya.

4. Geography

Libya is a vast North African country with diverse terrain, dominated by the Sahara Desert but also featuring a Mediterranean coastline and some mountainous regions. Its climate ranges from Mediterranean in the north to extremely arid desert conditions inland. Key geographical features include the coastal plain, the vast Sahara Desert, the Nafusa and Jebel Akhdar mountains, and the Libyan Desert. The country faces significant ecological issues including desertification and water scarcity.

Libya extends over 0.7 M mile2 (1.76 M km2), making it the 16th-largest nation in the world by size. Libya is bounded to the north by the Mediterranean Sea, the west by Tunisia and Algeria, the southwest by Niger, the south by Chad, the southeast by Sudan, and the east by Egypt. Libya lies between latitudes 19° and 34°N, and longitudes 9° and 26°E. At 1.1 K mile (1.77 K km), Libya's coastline is the longest of any African country bordering the Mediterranean. The portion of the Mediterranean Sea north of Libya is often called the Libyan Sea.

Six ecoregions lie within Libya's borders: Saharan halophytics, Mediterranean dry woodlands and steppe, Mediterranean woodlands and forests, North Saharan steppe and woodlands, Tibesti-Jebel Uweinat montane xeric woodlands, and West Saharan montane xeric woodlands. Natural hazards come in the form of hot, dry, dust-laden sirocco (known in Libya as the gibli). This is a southern wind blowing from one to four days in spring and autumn. There are also dust storms and sandstorms. Oases can also be found scattered throughout Libya, the most important of which are Ghadames and Kufra. Libya is one of the sunniest and driest countries in the world due to the prevailing presence of a desert environment.

4.1. Topography and Climate

The main geographical regions of Libya include the Mediterranean coastal plain, which hosts most of the population and agricultural activity. The vast Sahara Desert interior dominates the country, characterized by extensive sand seas, rocky plateaus, and arid plains. Notable mountainous areas include the Nafusa Mountains in the northwest and the Jebel Akhdar (Green Mountain) in the east, which receives higher rainfall and supports more vegetation.

The climate is mostly extremely dry and desertlike in nature. However, the northern coastal regions enjoy a milder Mediterranean climate, with warm, dry summers and mild, wetter winters. Further inland, an arid desert climate prevails, with extreme temperature fluctuations between day and night and very sparse rainfall.

4.2. Libyan Desert

The Libyan Desert, which covers most of Libya, is one of the most arid and sun-baked places on earth. In places, decades may pass without seeing any rainfall at all, and even in the highlands rainfall seldom happens, once every 5-10 years. At Jebel Uweinat, as of 2006, the last recorded rainfall was in September 1998.

Likewise, the temperature in the Libyan Desert can be extreme; on 13 September 1922, the town of 'Aziziya, located southwest of Tripoli, recorded an air temperature of 136.4 °F (58 °C), which was long considered to be a world record. However, in September 2012, the World Meteorological Organization determined this figure to be invalid.

There are a few scattered uninhabited small oases, usually linked to the major depressions, where water can be found by digging a few feet in depth. In the west, there is a widely dispersed group of oases in unconnected shallow depressions, the Kufra group, consisting of Tazerbo, Rebianae, and Kufra. Aside from the scarps, the general flatness is only interrupted by a series of plateaus and massifs near the centre of the Libyan Desert, around the convergence of the Egyptian-Sudanese-Libyan borders.

Slightly further to the south are the massifs of Arkenu, Uweinat, and Kissu. These granite mountains are ancient, having formed long before the sandstones surrounding them. Arkenu and Western Uweinat are ring complexes very similar to those in the Aïr Mountains. Eastern Uweinat (the highest point in the Libyan Desert) is a raised sandstone plateau adjacent to the granite part further west. The plain to the north of Uweinat is dotted with eroded volcanic features. With the discovery of oil in the 1950s also came the discovery of a massive aquifer underneath much of Libya. The water in the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System pre-dates the last Ice ages and the Sahara Desert itself. This area also contains the Arkenu structures, which were once thought to be two impact craters.

4.3. Ecology and Environmental Issues

Libya's biodiversity is adapted to its arid and semi-arid conditions, with ecosystems ranging from coastal Mediterranean habitats with maquis shrubland and some woodlands, to vast desert ecosystems with sparse vegetation, and unique mountain habitats in the Jebel Akhdar and Nafusa Mountains, as well as the southern Tibesti fringes. Wildlife includes desert-adapted species such as gazelles, fennec foxes, and various reptiles and rodents. Coastal areas and wetlands, though limited, serve as important stopover points for migratory birds.

Libya was a pioneer state in North Africa in species protection, with the creation in 1975 of the El Kouf protected area. However, significant environmental challenges persist. Desertification is a major concern, exacerbated by overgrazing and unsustainable agricultural practices. Water scarcity is a critical issue, with the country heavily reliant on the Great Man-Made River project, which extracts fossil water from the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System, a non-renewable resource. The impact of prolonged conflict has led to further degradation of natural resources and weakened environmental governance. Environmental degradation is also linked to oil exploitation, including pollution from spills and industrial activities, and unregulated development along the coast. The fall of Muammar Gaddafi's regime favored intense poaching: "Before the fall of Gaddafi even hunting rifles were forbidden. But since 2011, poaching has been carried out with weapons of war and sophisticated vehicles in which one can find up to 200 gazelle heads killed by militiamen who hunt to pass the time. We are also witnessing the emergence of hunters with no connection to the tribes that traditionally practice hunting. They shoot everything they find, even during the breeding season. More than 500,000 birds are killed in this way each year, when protected areas have been seized by tribal chiefs who have appropriated them. The animals that used to live there have all disappeared, hunted when they are edible or released when they are not," explains zoologist Khaled Ettaieb. There is a pressing need for sustainable practices, effective environmental protection measures, and conservation efforts to preserve Libya's unique ecosystems.

4.4. Major Cities

Libya's population is predominantly urban, with a few major cities housing a significant portion of its inhabitants.

- Tripoli: The capital and largest city, located in northwestern Libya on the Mediterranean coast. It is the country's primary political, economic, and cultural center, with a rich history dating back to Phoenician times.

- Benghazi: The second-largest city, situated in eastern Libya (Cyrenaica) on the Gulf of Sidra. Benghazi is a major economic hub and port, and has historically played a crucial role in Libyan politics and commerce.

- Misrata: A coastal city in northwestern Libya, east of Tripoli. It is a significant commercial and industrial center, known for its port and free trade zone, and played a prominent role during the 2011 revolution.

- Sirte: Located on the Gulf of Sidra, roughly midway between Tripoli and Benghazi. It was Muammar Gaddafi's birthplace and became an important administrative center during his rule. It suffered extensive damage during the civil wars.

- Sabha: The largest city in the southern Fezzan region and a historical crossroads for trans-Saharan trade. It serves as an administrative and commercial center for the sparsely populated south.

These cities are vital to Libya's demographic profile, economic activity, and cultural identity, each possessing unique historical importance within the nation.

5. Politics

Libya's political landscape has been characterized by profound instability and fragmentation since the 2011 revolution that overthrew Muammar Gaddafi. The country is currently grappling with establishing a unified and stable government amidst competing factions, regional power brokers, and the lingering effects of two civil wars. The sections below detail its complex government structure, the influential political factions and militias, administrative divisions, fluctuating foreign relations, fragmented military, and severe human rights challenges.

The politics of Libya has been in a tumultuous state since the start of the Arab Spring and the NATO intervention related to the Libyan Crisis in 2011. This crisis resulted in the collapse of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya and the killing of Muammar Gaddafi, amidst the First Libyan Civil War and the foreign military intervention. The crisis was deepened by factional violence in the aftermath of the First Civil War, resulting in the outbreak of the Second Civil War in 2014. Control over the country is currently split between the House of Representatives (HoR) in Tobruk and the Government of National Unity (GNU) in Tripoli and their respective supporters, as well as various jihadist groups and tribal elements controlling different parts of the country.

The former legislature was the General National Congress (GNC), which had 200 seats. The General National Congress (2014), a largely unrecognized rival parliament based in the de jure capital of Tripoli, claimed to be a legal continuation of the GNC. On July 7, 2012, Libyans voted in parliamentary elections, the first free elections in almost 40 years. Around thirty women were elected as members of parliament. Early results of the vote showed the National Forces Alliance, led by former interim Prime Minister Mahmoud Jibril, as the front runner. The Justice and Construction Party, affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood, performed less well than similar parties in Egypt and Tunisia, winning 17 out of 80 seats contested by parties, though about 60 independents later joined its caucus.

As of January 2013, there was mounting public pressure on the National Congress to set up a drafting body to create a new constitution. Congress had not yet decided whether the members of the body would be elected or appointed. On March 30, 2014, the General National Congress voted to replace itself with a new House of Representatives. The new legislature allocated 30 seats for women, would have 200 seats overall (with individuals able to run as members of political parties), and allowed Libyans of foreign nationalities to run for office.

Following the 2012 elections, Freedom House improved Libya's rating from Not Free to Partly Free and considered the country an electoral democracy. Gaddafi had merged civil and sharia courts in 1973. Civil courts now employ sharia judges who sit in regular courts of appeal and specialize in sharia appellate cases. Laws regarding personal status are derived from Islamic law.

At a meeting of the European Parliament Committee on Foreign Affairs on December 2, 2014, UN Special Representative Bernardino León described Libya as a non-state. An agreement to form a national unity government (GNA) was signed on December 17, 2015. Under the terms of the agreement, a nine-member Presidency Council and a seventeen-member interim GNA would be formed, with a view to holding new elections within two years. The House of Representatives would continue to exist as a legislature, and an advisory body, to be known as the State Council, would be formed with members nominated by the General National Congress (2014).

The formation of an interim unity government, the Government of National Unity (GNU), was announced on February 5, 2021, after its members were elected by the Libyan Political Dialogue Forum (LPDF). Mohamed al-Menfi, a former ambassador to Greece, became head of the Presidential Council. Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh, a businessman, became the transitional Prime Minister. All candidates who ran in this election, including members of the winning slate, promised to appoint women to 30% of all senior government positions. The politicians elected to lead the interim government initially agreed not to stand in the national elections scheduled for December 24, 2021. However, Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh announced his candidature for president in November 2021 despite the ban. The Appeals Court in Tripoli rejected appeals for his disqualification and allowed Dbeibeh back on the candidates' list, along with a number of other disqualified candidates. Even more controversially, the court also reinstated Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, a son of the former dictator, as a presidential candidate. On December 22, 2021, Libya's Election Commission called for the postponement of the election until January 24, 2022. Earlier, a parliamentary commission said it would be "impossible" to hold the election on December 24, 2021. The UN called on Libya's interim leaders to "expeditiously address all legal and political obstacles to hold elections, including finalising the list of presidential candidates." However, at the last minute, the election was postponed indefinitely, and the international community agreed to continue its support and recognition of the interim government headed by Mr. Dbeibeh.

5.1. Government Structure

Libya's current governmental framework is complex and contested, reflecting the deep political divisions that persist. The internationally recognized Government of National Unity (GNU), headed by Prime Minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh, is based in Tripoli and was formed through a UN-led process in early 2021. It is theoretically supported by the Presidential Council, currently chaired by Mohamed al-Menfi, which acts as the collective head of state.

However, the eastern-based House of Representatives (HoR), located in Tobruk and led by Speaker Aguila Saleh Issa, challenges the GNU's authority. In February 2022, the HoR appointed a rival prime minister, Fathi Bashagha, to head an alternative administration called the Government of National Stability (GNS), though Bashagha later stepped down and was replaced by Osama Hamada. The HoR considers the GNU's mandate to have expired.

The High Council of State, an advisory body based in Tripoli and largely composed of members from the former General National Congress, also plays a role in the political process, often acting as a counterweight to the HoR.

Ongoing efforts for political stabilization, constitutional reform, and the organization of long-delayed national elections are hampered by these divisions and the influence of various armed groups. The lack of a unified national vision and persistent power struggles pose significant challenges to democratic consolidation and the establishment of the rule of law across the country.

5.2. Major Political Factions and Militias

Libya's political and security landscape is characterized by a multitude of influential actors beyond formal government institutions. While formal political parties exist, their influence is often overshadowed by regional power brokers, prominent tribal leadership structures, and numerous armed groups or militias. These militias, which emerged or gained prominence after the 2011 revolution, often have local allegiances and varying ideologies, ranging from Islamist to secularist, and federalist to nationalist.

Key armed factions include forces aligned with the Tripoli-based GNU, and the Libyan National Army (LNA) under the command of Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, which is allied with the HoR in the east. Various other militias control specific territories or cities, such as in Misrata, Zintan, and Zawiya, and their loyalties can be fluid. These groups exert significant influence on governance, often controlling critical infrastructure like oil facilities or border crossings, and their actions heavily impact national cohesion and the safety of civilians. The proliferation of these groups and their competition for resources and power are major obstacles to forming a unified national security apparatus and achieving lasting stability.

5.3. Administrative Divisions

Historically, the area of Libya was considered three provinces (or states): Tripolitania in the northwest, Cyrenaica (also Barka) in the east, and Fezzan in the southwest. The conquest by Italy in the Italo-Turkish War united them into a single political unit.

Since 2007, Libya has been divided into 22 districts (singular: shabiyah, plural: shabiyat):

- 1. Nuqat al Khams

- 2. Zawiya

- 3. Jafara

- 4. Tripoli

- 5. Murqub

- 6. Misrata

- 7. Sirte

- 8. Benghazi

- 9. Marj

- 10. Jabal al Akhdar

- 11. Derna

- 12. Tobruk (Butnan)

- 13. Nalut

- 14. Jabal al Gharbi

- 15. Wadi al Shatii

- 16. Jufra

- 17. Al Wahat

- 18. Ghat

- 19. Wadi al Hayaa

- 20. Sabha

- 21. Murzuq

- 22. Kufra

In 2022, the Government of National Unity announced a plan to reorganize the country into 18 provinces, potentially superseding the 2007 district structure. These proposed provinces are: the Eastern Coast, Jabal Al-Akhdar, Al-Hizam, Benghazi, Al-Wahat, Al-Kufra, Al-Khaleej, Al-Margab, Tripoli, Al-Jafara, Al-Zawiya, West Coast, Gheryan, Zintan, Nalut, Sabha, Al-Wadi, and Murzuq Basin. The implementation and practical effect of this new provincial system remain subject to the evolving political situation.

5.4. Foreign Relations

Libya's foreign policies have fluctuated significantly since its independence in 1951. As a Kingdom, Libya maintained a definitively pro-Western stance and was recognized as belonging to the conservative traditionalist bloc in the Arab League, which it joined in 1953. The government was friendly towards Western countries such as the United Kingdom, United States, France, Italy, and Greece, and established full diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union in 1955. Although the government supported Arab causes, including the Moroccan and Algerian independence movements, it took little active part in the Arab-Israeli conflict or the tumultuous inter-Arab politics of the 1950s and early 1960s.

After the 1969 coup, Muammar Gaddafi closed American and British bases and partly nationalized foreign oil and commercial interests. Gaddafi was known for backing a number of leaders viewed as anathema to Westernization and political liberalism, including Ugandan President Idi Amin, Central African Emperor Jean-Bédel Bokassa, Ethiopian strongman Haile Mariam Mengistu, Liberian President Charles Taylor, and Yugoslav President Slobodan Milošević.

Relations with the West were strained by a series of incidents for most of Gaddafi's rule, including the killing of London policewoman Yvonne Fletcher, the bombing of a West Berlin nightclub frequented by US servicemen, and the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103, which led to UN sanctions in the 1990s. By the late 2000s, the United States and other Western powers had normalized relations with Libya. Gaddafi's decision to abandon the pursuit of weapons of mass destruction after the Iraq War saw Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein overthrown and put on trial, leading to Libya being hailed as a success for Western soft power initiatives in the War on Terror. In October 2010, Gaddafi apologized to African leaders on behalf of Arab nations for their involvement in the trans-Saharan slave trade.

Since the 2011 revolution, Libya's foreign policy has been shaped by its internal fragmentation and the competing interests of its rival factions. Relationships with neighboring countries (Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, Sudan, Chad, Niger), European powers (notably Italy and France), Turkey, Qatar, the UAE, and global organizations like the UN, EU, and African Union are critical. Libya's involvement in international bodies continues, but its representation has often been contested. The country plays a crucial role in regional security, counter-terrorism efforts, and migration issues affecting the Mediterranean. The humanitarian dimensions of its international engagements, particularly concerning migrants and refugees, are a significant concern for the international community. Differing perspectives among Libyan factions often lead to conflicting foreign policy approaches, complicating diplomatic efforts.

Libya is included in the European Union's European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), which aims at bringing the EU and its neighbors closer. However, Libyan authorities have rejected EU plans aimed at stopping migration from Libya by establishing processing centers on its territory. In 2017, Libya signed the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

5.5. Military

Libya's national military structure has been deeply fragmented since the 2011 revolution and the subsequent civil wars. The previous national army under Muammar Gaddafi was defeated and largely disbanded during the First Libyan Civil War.

In the ensuing period, various armed groups emerged. The Tobruk-based House of Representatives (HoR) attempted to re-establish a formal military known as the Libyan National Army (LNA), led by Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar. The LNA exerts control over much of eastern and parts of southern Libya. As of May 2012, an estimated 35,000 personnel had reportedly joined its ranks, though its composition includes regular soldiers as well as allied militias.

The internationally recognized Government of National Accord (GNA), established in 2015 and succeeded by the Government of National Unity (GNU) in 2021, also commands forces, often comprising various militia groups from western Libya aligned with the Tripoli-based authorities. These forces are often referred to collectively as the Libyan Army, though a truly unified command structure remains elusive.

A major challenge for Libya is the establishment of a unified national military under civilian control. Efforts towards Demobilization, Disarmament, and Reintegration (DDR) of the numerous militias and broader Security Sector Reform (SSR) are critical for long-term stability but have been hampered by ongoing political divisions and the power of these armed groups. Many militias remain disciplined primarily to their local or regional leadership rather than a central state authority. The "Libya Shield Force" was an example of a parallel national force operating at the request of, rather than under the direct order of, the Ministry of Defence. President Mohammed Magariaf in 2012 had promised that empowering the army and police force was the government's biggest priority and ordered that all militias must come under government authority or disband, but this has largely not been achieved.

5.6. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Libya has been a matter of grave concern, particularly since the 2011 uprising and the subsequent conflicts. Under the Gaddafi regime, systematic human rights abuses were common, including suppression of freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and the freedom of the press, arbitrary detention, torture, and extrajudicial killings. Political dissent was not tolerated.

In the post-Gaddafi era, the situation remains dire, exacerbated by political instability, the proliferation of militias, and a weak justice system. Human Rights Watch's 2016 annual report noted that journalists continued to be targeted by armed groups, and Libya ranked very low in the Press Freedom Index (154th out of 180 countries in 2015, worsening to 165th in 2021).

Key human rights issues include:

- Freedoms of Expression, Assembly, and Press: These remain severely restricted, with journalists, activists, and ordinary citizens facing threats, intimidation, and violence from various armed groups and state-affiliated actors.

- Rights of Women: While women played a role in the 2011 revolution, their participation in public life is challenged by insecurity and conservative interpretations of social norms. Issues include gender-based violence and discrimination. In November 2024, the GNU's re-establishment of a morality police with powers to enforce "modest" clothing and require male guardians for women raised further concerns.

- Ethnic and Religious Minorities: Berbers (Amazigh), Toubou, and other ethnic minorities face discrimination and challenges in asserting their cultural and linguistic rights. Religious minorities, including small Christian communities (primarily Coptic Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and some Protestant denominations, largely among expatriates), face risks, and proselytizing is illegal. Homosexuality is illegal and punishable by severe penalties.

- Due Process and Detention Conditions: Arbitrary detention is widespread, with thousands held in official and unofficial detention centers run by militias, often without charge or trial. Conditions in these facilities are frequently inhumane, with reports of torture, overcrowding, and lack of medical care.

- Migrants, Refugees, and Asylum Seekers: Libya is a major transit country for migrants and refugees attempting to reach Europe. They face extreme human rights abuses, including human trafficking, forced labor, torture, sexual violence, arbitrary detention in horrific conditions, and killings, at the hands of smugglers, traffickers, militias, and sometimes state-affiliated entities.

- Accountability and Transitional Justice: There is a profound lack of accountability for past and ongoing abuses. Efforts towards transitional justice and holding perpetrators accountable are severely hampered by the weak rule of law and the power of armed groups. The impact of ongoing conflict and political instability continues to devastate civilian populations.

6. Economy

Libya's economy is overwhelmingly dependent on its oil and gas sector, which constitutes the backbone of its revenue and exports. However, this reliance has also made the economy vulnerable to political instability and global oil price fluctuations. Challenges include diversifying the economy, addressing unemployment, and rebuilding infrastructure damaged by conflict. The following subsections explore the dominant oil and gas sector, the smaller but vital agriculture and water resources, the overall economic structure and its persistent challenges, and the potential of its tourism sector.

The Libyan economy depends primarily upon revenues from the oil sector, which account for over half of GDP and 97% of exports. Libya holds the largest proven oil reserves in Africa and is an important contributor to the global supply of light, sweet crude. During 2010, when oil averaged at 80 USD a barrel, oil production accounted for 54% of GDP. Apart from petroleum, the other natural resources are natural gas and gypsum. The International Monetary Fund estimated Libya's real GDP growth at 122% in 2012 and 16.7% in 2013, after a 60% plunge in 2011 due to the civil war.

The World Bank defines Libya as an 'Upper Middle Income Economy'. Substantial revenues from the energy sector, coupled with a small population, give Libya one of the highest per capita GDPs in Africa. This allowed the Jamahiriya state under Gaddafi to provide an extensive level of social security, particularly in housing and education. In the early 1980s, Libya was one of the wealthiest countries in the world; its GDP per capita was higher than some developed countries.

However, Libya faces many structural problems, including a lack of robust institutions, weak governance, and chronic structural unemployment. The economy displays a lack of economic diversification and significant reliance on immigrant labour. Libya has traditionally relied on unsustainably high levels of public sector hiring to create employment; in the mid-2000s, the government employed about 70% of all national employees. Unemployment rose from 8% in 2008 to 21% in 2009. According to an Arab League report based on data from 2010, unemployment for women stood at 18% while for men it was 21%, making Libya the only Arab country at the time where there were more unemployed men than women. Libya also has high levels of social inequality, high rates of youth unemployment, and regional economic disparities. Water supply is a problem, with some 28% of the

population not having access to safe drinking water in 2000.

The country joined OPEC in 1962. Libya is not a WTO member, but negotiations for its accession started in 2004. In the early 2000s, Jamahiriya-era officials carried out economic reforms to reintegrate Libya into the global economy. UN sanctions were lifted in September 2003, and Libya announced in December 2003 that it would abandon programs to build weapons of mass destruction. Other steps included applying for WTO membership, reducing subsidies, and announcing plans for privatization. Authorities privatized more than 100 government-owned companies after 2003 in industries including oil refining, tourism, and real estate, of which 29 were 100% foreign-owned. Many international oil companies returned to the country, including giants like Shell and ExxonMobil.

After sanctions were lifted, there was a gradual increase in air traffic, and by 2005 there were 1.5 million yearly air travellers. Libya had long been a notoriously difficult country for Western tourists to visit due to stringent visa requirements. In 2007, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi was involved in a green development project called the Green Mountain Sustainable Development Area, which sought to bring tourism to Cyrene and to preserve Greek ruins in the area.

In August 2011, it was estimated that it would take at least 10 years to rebuild Libya's infrastructure, which even before the 2011 war was in a poor state due to "utter neglect" by Gaddafi's administration. By October 2012, the economy had recovered somewhat from the 2011 conflict, with oil production returning to near normal levels (around 1.4 million barrels per day (bpd) compared to over 1.6 million bpd pre-war), thanks to the quick return of major Western companies like TotalEnergies, Eni, Repsol, Wintershall, and Occidental Petroleum. However, subsequent conflicts and blockades have caused production to fluctuate wildly. In 2016, aims were to reach 900,000 bpd, down significantly from pre-war levels.

Two trans-African automobile routes pass through Libya: the Cairo-Dakar Highway and the Tripoli-Cape Town Highway, which have historically contributed to economic activity.

In March 2024, reports indicated that Libya was actively promoting business development and encouraging both domestic and foreign investment, aiming for long-term economic stability and prosperity by diversifying its economic foundation. Embracing green industries like renewable energy, energy efficiency, sustainable agriculture, and eco-tourism was highlighted as holding potential for new employment prospects.

6.1. Oil and Gas Sector

The oil and gas sector is the cornerstone of Libya's economy, accounting for the vast majority of its export earnings and a significant portion of its GDP. Libya boasts the largest proven crude oil reserves in Africa, estimated at around 43.6 billion barrels, and substantial natural gas reserves. Its oil is predominantly light and sweet, making it desirable on the international market. The National Oil Corporation (NOC) is the state-owned entity responsible for overseeing oil and gas exploration, production, and export. Production capacity has historically been high, with major export infrastructure including numerous oil fields, pipelines, and coastal terminals such as Es Sider, Ras Lanuf, and Brega. Libya is a member of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and has historically played an influential role within the organization.

However, the sector has been severely impacted by political instability, conflict, and blockades since 2011. Damage to infrastructure, disputes over revenue distribution, and shutdowns of oil fields and ports by various armed groups or political factions have led to highly volatile production levels and significant losses in national revenue, undermining economic stability and development efforts.

6.2. Agriculture and Water Resources

Libya's agricultural sector plays a relatively small role in its GDP but is important for employment in certain regions. Main crops include dates, olives, grains (wheat and barley), citrus fruits, and vegetables. Livestock rearing, primarily sheep and goats, is also practiced. Before the discovery of oil in 1958, agriculture was the country's main source of revenue, making up about 30% of GDP. By 2005, its contribution had declined to less than 5% of GDP. Libya imports up to 90% of its cereal consumption requirements; in 2012/13, wheat imports were estimated at 1 million tonnes, while domestic wheat production was around 200,000 tonnes. The government had hoped to increase cereal production to 800,000 tonnes by 2020, but natural and environmental conditions, particularly water scarcity and limited arable land (about 1.2% of the total land area), severely restrict agricultural potential.

Water resources are critically important in this predominantly arid country. The Great Man-Made River project is the world's largest irrigation project, designed to transport vast quantities of fossil water from the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System in the southern desert to coastal cities and agricultural areas in the north. It is estimated to provide 70% of all freshwater used in Libya. However, the sustainability of relying on non-renewable fossil water is a long-term concern. The water infrastructure suffered neglect and occasional breakdowns during the second Libyan civil war (2014-2020). Challenges of food security and sustainable water management remain paramount for Libya's future.

6.3. Economic Structure and Challenges

The overall structure of the Libyan economy is characterized by its acute dependence on oil revenue, making it highly vulnerable to fluctuations in global oil prices and internal political instability that affects production. This "rentier state" model has historically led to a large public sector, high levels of state subsidies, and limited development of a diversified private sector.

Key challenges include:

- Diversification: Efforts to diversify the economy away from hydrocarbons have faced significant obstacles due to a lack of investment, institutional capacity, and a challenging business environment.

- Unemployment: High rates of unemployment, especially among the youth, persist despite oil wealth. The public sector has traditionally been the largest employer, but this is not sustainable.

- Inflation: Political instability and disruptions to supply chains have contributed to inflationary pressures.

- Infrastructure: Prolonged conflict has devastated national infrastructure, including transportation, power, and water systems, requiring massive investment for reconstruction.

- Governance and Corruption: Weak governance, corruption, and lack of transparency in managing national resources, particularly oil revenues, hinder economic development and fuel public discontent.

- Wealth Distribution and Social Equity: Despite high per capita GDP figures historically, issues of wealth distribution and social equity remain contentious, with regional disparities and perceptions of unequal access to resources and opportunities.

- Security Situation: The ongoing fragile security environment deters foreign investment and impedes normal economic activity.

By 2017, reports indicated that 60% of the Libyan population were malnourished, and 1.3 million people (out of a total population of about 6.3 million at the time) were in need of emergency humanitarian aid, reflecting the severe impact of conflict and economic collapse.

6.4. Tourism

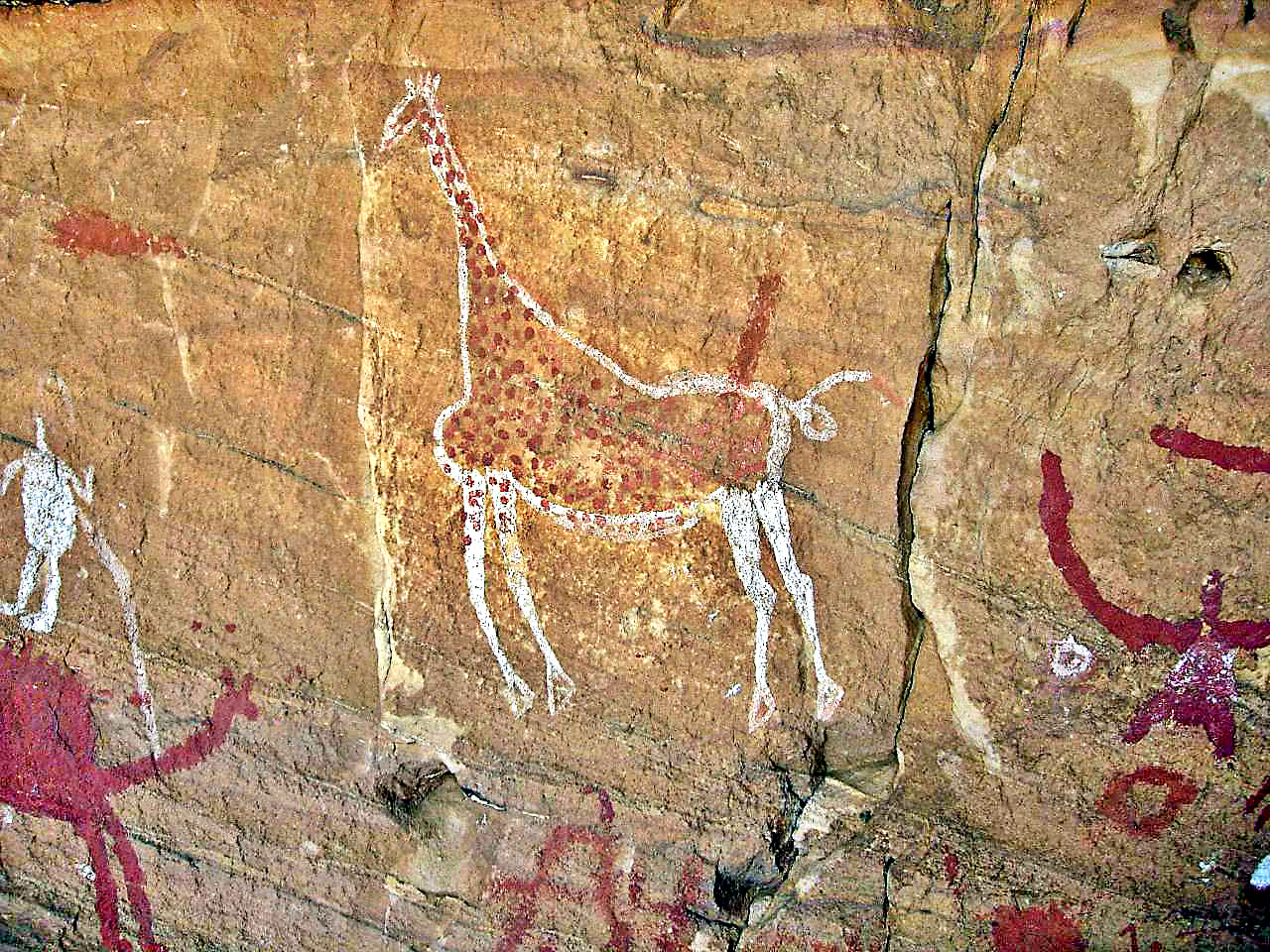

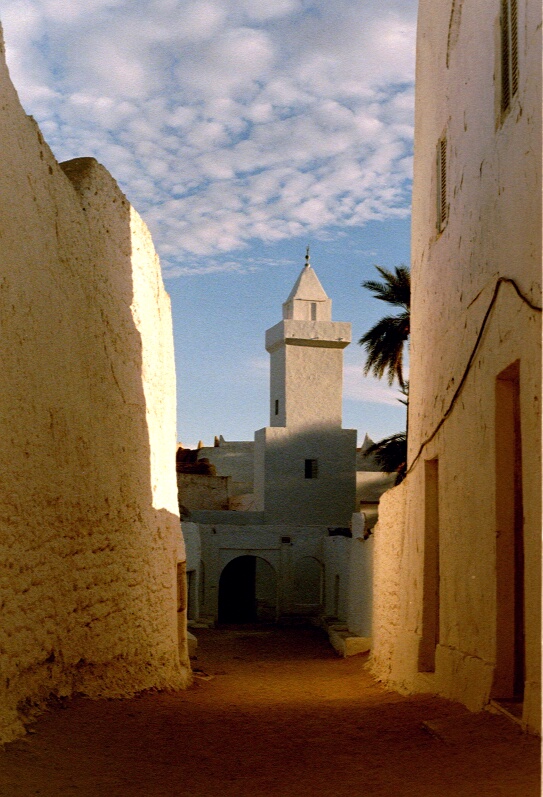

Libya possesses considerable potential for tourism, owing to its rich historical and archaeological sites, diverse desert landscapes, and Mediterranean coastline. The country is home to five UNESCO World Heritage Sites: the Archaeological Site of Leptis Magna, the Archaeological Site of Sabratha, the Archaeological Site of Cyrene, the Rock-Art Sites of Tadrart Acacus, and the Old Town of Ghadames. These sites represent immense historical, archaeological, and cultural significance, drawing from Phoenician, Greek, Roman, and indigenous Berber civilizations. The vast Sahara Desert offers unique opportunities for adventure tourism and exploring diverse geological formations and oases.

However, the tourism sector currently faces severe constraints due to persistent political instability, widespread security concerns, and underdeveloped infrastructure. Before the 2011 revolution, there were efforts to develop the tourism industry, including the Green Mountain Sustainable Development Area project involving Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, which aimed to promote tourism in Cyrene while preserving its antiquities. The ongoing conflicts and lack of a stable security environment have made international tourism virtually non-existent, and domestic tourism is also severely limited. Significant investment in security, infrastructure (hotels, transport, services), and marketing would be required for Libya to realize its tourism potential once stability is achieved.

7. Demographics

Libya is a large country with a relatively small population, primarily concentrated along the Mediterranean coast. The demographic landscape is predominantly Arab, with significant Berber and other minority groups, and has been shaped by historical migrations and, more recently, by conflict and displacement. The following subsections detail the population overview, ethnic composition, languages spoken, religious landscape, education system, health status, and the situation of migrants and refugees.

Libya is a large country with a relatively small population, which is concentrated very narrowly along the coast. Its population density is about 50 pd/sqkm in the two northern regions of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, but falls to less than 1 pd/sqkm elsewhere. Ninety percent of the people live along the coast in less than 10% of the country's area. About 88% of the population is urban, mostly concentrated in the three largest cities: Tripoli, Benghazi, and Misrata. Libya has a population of about 7 million, with 27.7% of whom are under the age of 15. In 1984, the population was 3.6 million, an increase from the 1.54 million reported in 1964.

Family life is important for Libyan families, the majority of whom live in apartment blocks and other independent housing units, with modes of housing depending on their income and wealth. Although Arab Libyans traditionally lived nomadic Bedouin lifestyles in tents, they have predominantly settled in towns and cities. Because of this, their old ways of life are gradually fading out. An unknown small number of Libyans still live in the desert as their families have done for centuries. Most of the population has occupations in industry and the services, and a small percentage is in agriculture.

According to the UNHCR, there were around 8,000 registered refugees, 5,500 unregistered refugees, and 7,000 asylum seekers of various origins in Libya in January 2013. Additionally, 47,000 Libyan nationals were internally displaced, and 46,570 were internally displaced returnees.

7.1. Population Overview

Libya's total population is estimated to be around 7 million people. The population density is low overall, approximately 3 people per square kilometer, but this figure is misleading as most Libyans live in coastal urban areas, particularly in and around Tripoli, Benghazi, and Misrata, where densities are much higher. The urbanization rate is high, with about 88% of the population residing in urban centers. Libya has a youthful population, with a significant "youth bulge" - approximately 27.7% of the population is under the age of 15. The population growth rate has historically been relatively high for the region, though recent conflicts may have impacted these trends.

7.2. Ethnic Groups

The population of Libya is primarily of Arab ancestry, with many tracing their lineage to Bedouin Arab tribes like the Banu Sulaym and Banu Hilal. Arabs and Arabized Berbers constitute the vast majority, estimated at around 92%.

Significant minority groups include the indigenous Berbers (Amazigh), who make up an estimated 5% to 10% of the population (approximately 600,000 people). They have a distinct cultural and linguistic heritage and are concentrated mainly in the Nafusa Mountains of the northwest, the coastal town of Zuwarah, and some oases like Ghadames.

Other ethnic minorities include the Tuareg, semi-nomadic Berber-speaking people found primarily in the southwestern desert regions around Ghat, and the Toubou, a Nilo-Saharan speaking group inhabiting the Tibesti Mountains region in the south, near the Chadian border. There is also a small Turkish minority, often called "Kouloughlis" (descendants of Ottoman Turkish men and local women), concentrated in and around some coastal towns and villages.