1. Overview

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (ኢትዮጵያĪtyōṗṗyāAmharic, ItiyoophiyaaItiyoophiyaaOromo, ItoobiyaItoobiyaSomali, ኢትዮጵያÍtiyop'iyaTigrinya, ItiyoppiyaItiyoppiyaAfar), is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east and southeast, Kenya to the south, South Sudan to the west, and Sudan to the northwest. Covering a land area of 0.4 M mile2 (1.10 M km2), Ethiopia is home to a diverse population of around 132 million inhabitants as of 2024, making it the world's 10th-most populous country, the second-most populous in Africa (after Nigeria), and the most populous landlocked country on Earth. The national capital and largest city, Addis Ababa, lies several kilometers west of the East African Rift, which splits the country into the African and Somali tectonic plates.

The nation's history is one of the oldest in the world, with its origins tracing back to ancient kingdoms like Dʿmt (around 980 BC) and the Kingdom of Aksum (from 100 AD). Aksum adopted Christianity in the 4th century, a faith that continues to be a significant part of Ethiopian identity. Unlike most African nations, Ethiopia largely avoided European colonialism during the Scramble for Africa, notably defeating Italian forces at the Battle of Adwa in 1896, although it experienced a period of Italian occupation from 1936 to 1941. The 20th century saw the long reign of Emperor Haile Selassie I, followed by the Derg military junta and its socialist regime (1974-1991), which was marked by significant social upheaval, the Red Terror, and devastating famines. The fall of the Derg led to the establishment of the Federal Democratic Republic in 1995, characterized by an ethnic federalism system. Recent history has been shaped by rapid economic development, but also by persistent challenges including ethnic conflicts, human rights concerns, and democratic backsliding, notably the Tigray War.

Ethiopia's geography is diverse, featuring the vast Ethiopian Highlands, the Great Rift Valley, deserts, and tropical forests, contributing to rich biodiversity with many endemic species. The country is a federal parliamentary republic. The economy is primarily based on agriculture, which employs a large portion of the population, with coffee being a major export. While Ethiopia has achieved significant economic growth in recent decades, it remains one of the least developed countries, grappling with issues like poverty, food insecurity, and the need for improvements in education and healthcare. Ethiopian culture is rich and varied, with unique traditions in music, cuisine (famously injera and wat), literature, and its own ancient script and calendar system. The country is a founding member of the United Nations and the African Union, with Addis Ababa hosting the AU headquarters, underscoring its significant role in African politics.

2. Etymology

The name "Ethiopia" (ኢትዮጵያĪtyōṗṗyāAmharic) has ancient origins. Ethiopian tradition holds that the name comes from "Ethiopis," believed to be an early king and the seventh in the ancestral lines of Ethiopia. The Metshafe AksumBook of AksumGeez, a 15th-century Ge'ez text, identifies Itiopis as the twelfth king of Ethiopia and the father of Aksumawi, the legendary founder of Axum. According to this tradition, Ethiopis was the twelfth direct descendant of Adam, with his father identified as Cush and his grandfather as Ham.

The term "Ethiopia" is also linked to Greek sources. The Greek name ΑἰθιοπίαAithiopíaGreek, Ancient, derived from ΑἰθίοψAithíops, "an Ethiopian"Greek, Ancient, is a compound word. It was later explained as being derived from the Greek words αἴθωaíthō, "I burn"Greek, Ancient and ὤψṓps, "face"Greek, Ancient, leading to the interpretation "burnt-face." The historian Herodotus used this term to refer to parts of Africa south of the Sahara known to the ancient Greeks. The earliest known mentions of the term appear in the works of Homer, where it is used to refer to two distinct groups of people, one in Africa and another in the East, ranging from eastern Turkey to India. This Greek name was borrowed into Amharic as ኢትዮጵያʾĪtyōṗṗyāAmharic.

In Greco-Roman epigraphs, "Aethiopia" was a specific toponym for ancient Nubia. By at least c. 850, the name Aethiopia also appeared in many translations of the Old Testament in reference to Nubia, which ancient Hebrew texts identified as Kush. In the New Testament, the Greek term Aithiops is used to describe a servant of Kandake, the queen of Kush.

Following Hellenic and biblical traditions, the Monumentum Adulitanum, a 3rd-century inscription from the Kingdom of Aksum, indicates that Aksum's ruler governed an area flanked to the west by the territory of Ethiopia and Sasu. King Ezana of Axum of Aksum conquered Nubia in the following century, and the Aksumites subsequently adopted the designation "Ethiopians" for their own kingdom. In the Ge'ez version of the Ezana inscription, Aἰθίοπες is equated with the unvocalized Ḥbšt and Ḥbśt (Ḥabashat), denoting for the first time the highland inhabitants of Aksum. This new demonym was later rendered as ḥbs ('AḥbāshAhbashUncoded languages) in the Sabaean language and as Ḥabasha in Arabic.

Historically, outside of Ethiopia, the country was often known as Abyssinia. This name was derived from the Latinized form of the ancient Habash. Derivatives of this term are used in some languages that borrow from Arabic, such as Habsyah in Malay.

3. History

Ethiopia's history is long and complex, stretching from human prehistory to its current status as a federal republic. The country is considered one of the cradles of humankind and has seen the rise and fall of powerful indigenous kingdoms, interactions with major world religions, periods of imperial expansion and fragmentation, resistance against foreign powers, and significant political transformations in the modern era.

This section chronicles the major historical events and developmental stages of Ethiopia from prehistoric times to the present day, including the early human presence, the rise of ancient kingdoms like D'mt and Aksum, the medieval Zagwe and Solomonic dynasties, early modern developments, imperial reunification, the Haile Selassie era, the Derg regime, and the current Federal Democratic Republic.

3.1. Prehistory

Ethiopia and the surrounding region are at the forefront of palaeontology due to several significant hominid discoveries. The oldest hominid found in Ethiopia to date is the 4.2 million-year-old Ardipithecus ramidus (nicknamed "Ardi"), discovered by Tim D. White in 1994. Perhaps the most famous hominid discovery is Australopithecus afarensis, widely known as "Lucy" (or Dinkinesh in Amharic). This specimen, found in the Awash Valley of Ethiopia's Afar Region in 1974 by Donald Johanson, is one of the most complete and best-preserved adult Australopithecine fossils ever uncovered. Lucy is estimated to have lived 3.2 million years ago.

Ethiopia is also considered one of the earliest sites for the emergence of anatomically modern humans, Homo sapiens. The oldest of these local fossil finds, the Omo remains, were excavated in the southwestern Omo Kibish Formation and date to the Middle Paleolithic, around 200,000 years ago. Skeletons of Homo sapiens idaltu (Herto Man) were found in the Middle Awash valley, dated to approximately 160,000 years ago. These may represent an extinct subspecies of Homo sapiens or direct ancestors of anatomically modern humans. While archaic Homo sapiens fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, have been dated earlier (around 300,000 years ago), the Omo-Kibish I (Omo I) skeleton from southern Ethiopia remains the oldest known anatomically modern Homo sapiens skeleton, dated to 196 ± 5 kya (thousand years ago).

According to some anthropologists, the first Afroasiatic-speaking populations arrived in the region during the Neolithic era, possibly from the Nile Valley or the Near East. However, most scholars today propose that the Afroasiatic language family developed in northeast Africa due to the higher diversity of its lineages in that region, a common indicator of linguistic origin.

In 2019, archaeologists discovered a 30,000-year-old Middle Stone Age rock shelter at the Fincha Habera site in the Bale Mountains, at an elevation of 11 K ft (3.47 K m) above sea level. This high-altitude dwelling provides evidence of the earliest known permanent human occupation at such elevations, where humans face challenges like hypoxia and extreme weather. The site yielded thousands of animal bones, hundreds of stone tools, and ancient fireplaces, indicating a diet that included giant mole rats.

Evidence of early stone-tipped projectile weapons, characteristic of Homo sapiens, was found at the Ethiopian site of Gademotta, dating to around 279,000 years ago. Additional Middle Stone Age projectile points, likely belonging to darts delivered by spear throwers, were found at Aduma, dated to 100,000-80,000 years ago.

3.2. Antiquity (Dʿmt and Kingdom of Aksum)

Around 980 BC, the kingdom of Dʿmt was established in present-day Eritrea and the northern Tigray Region of Ethiopia. It is widely believed to be a successor state to the Land of Punt. Dʿmt's capital was located at Yeha. While earlier theories suggested significant Sabaean influence from Southern Arabia due to Sabaean hegemony over the Red Sea, most modern historians consider Dʿmt to be an indigenous Ethiopian civilization. Some scholars view Dʿmt as a result of a union of Afroasiatic-speaking cultures, including local Agaw peoples and Sabaeans. However, Geʽez, the ancient Semitic language of Ethiopia, is thought to have developed independently from the Sabaean language, with Semitic speakers inhabiting Ethiopia and Eritrea where Ge'ez evolved as early as 2000 BC. Sabaean influence is now considered to have been minor and localized.

After the fall of Dʿmt in the 4th century BC, the Ethiopian plateau was dominated by smaller successor kingdoms. In the 1st century AD, the Kingdom of Aksum emerged in what is now the Tigray Region and Eritrea. According to the medieval Book of Axum, the kingdom's first capital, Mazaber, was built by Itiyopis, son of Cush. At its peak, Aksum extended its rule into Yemen across the Red Sea. The Persian prophet Mani, in the 3rd century, listed Aksum alongside Rome, Persia, and China as one of the four great powers of his era.

Around 316 AD, Frumentius and his brother Edesius from Tyre were taken to the Aksumite court as slaves after their ship was attacked. They gained positions of trust and converted members of the royal court to Christianity. Frumentius became the first bishop of Aksum. A coin dated to 324 indicates that Ethiopia was the second country (after Armenia in 301) to officially adopt Christianity, although the religion may have initially been confined to court circles. Aksum was a major trading power, connected to the Indian subcontinent and the Roman Empire via the Silk Road, primarily exporting ivory, tortoise shells, gold, and emeralds, while importing silk and spices.

3.3. Middle Ages (Zagwe Dynasty and Early Solomonic Period)

The Kingdom of Aksum adopted the name "Ethiopia" during the reign of King Ezana in the 4th century. After conquering the Kingdom of Kush around 330 AD, Aksumite territory reached its zenith between the 5th and 6th centuries. This period was marked by interactions with powers in South Arabia, including incursions by Dhu Nuwas of the Himyarite Kingdom and the Aksumite-Persian wars. In 575, Aksumites retook Sana'a after the assassination of its governor. However, by the 8th century, the rise of the Rashidun Caliphate led to the decline of Aksum's maritime power, with the port city of Adulis being plundered by Arab Muslims. Factors like land degradation, alleged climate change, and sporadic rainfall between 730 and 760 AD likely contributed to Aksum's decline as a major trade hub.

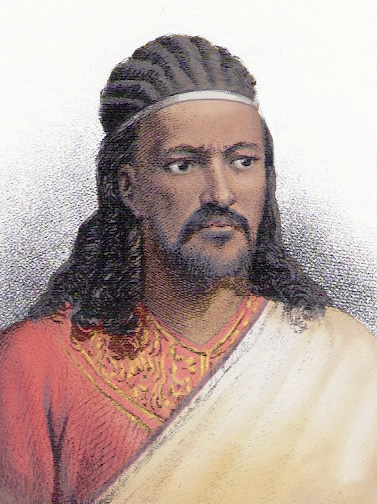

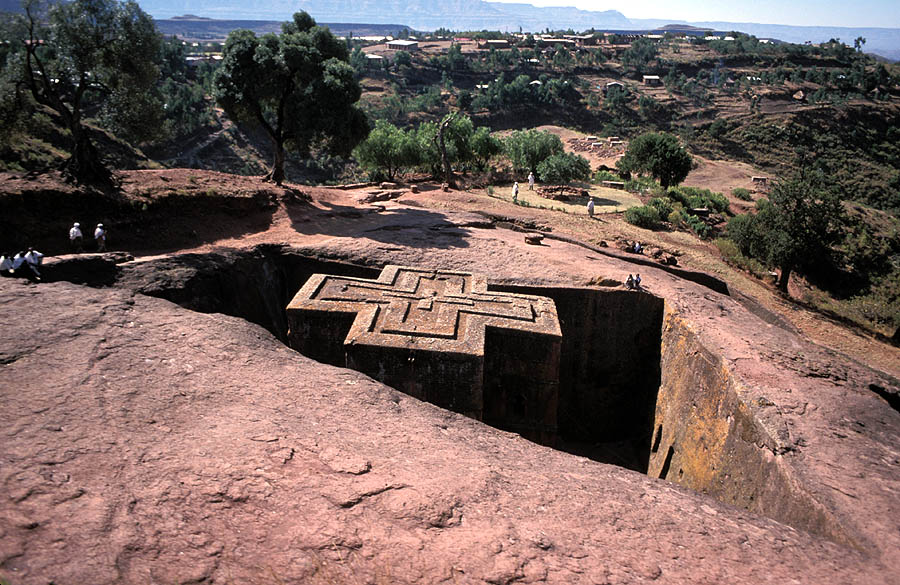

The Aksumite kingdom is believed to have ended around 960 AD when Queen Gudit (or Yodit) reportedly defeated the last Aksumite king. This event led the remnants of the Aksumite population to shift southwards, establishing the Zagwe dynasty with its capital at Lalibela (then known as Roha). The Zagwe dynasty, of Agaw origin, is most famous for the construction of the magnificent rock-hewn churches of Lalibela.

Zagwe rule ended in 1270 when Yekuno Amlak, an Amhara nobleman claiming descent from the biblical King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba through their son Menelik I, overthrew the last Zagwe king, Yetbarak. This event marked the restoration of the Solomonic dynasty and the establishment of the Ethiopian Empire (also known by the exonym "Abyssinia"). The Ethiopian Empire initiated territorial expansion under rulers like Amda Seyon I, who launched successful campaigns against Muslim principalities to the east, such as the Sultanate of Ifat. This shifted the balance of power in the Horn of Africa in favor of the Christian empire for nearly two centuries, with Ethiopian suzerainty extending from Gojjam to the Somali coast at Zeila.

During the reign of Emperor Zara Yaqob in the 15th century, the Ethiopian Empire reached a peak. His rule was characterized by the consolidation of territorial gains, the construction of numerous churches and monasteries, the promotion of literature and art, and the strengthening of central imperial authority. However, Ifat's successor, the Adal Sultanate, under the leadership of Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (Ahmad Gurey or Gragn), launched a major invasion of Ethiopia in 1529. The Ethiopian-Adal War (1529-1543) devastated much of Christian Ethiopia. With Ottoman support and firearms, Adal forces conquered large parts of the empire. Ethiopia, with the aid of Portuguese musketeers, eventually defeated Adal at the Battle of Wayna Daga in 1543, where Ahmad Gurey was killed.

By the 16th century, migrations of the ethnic Oromo people from the south into the northern parts of the region began to alter the political and demographic landscape, contributing to the fragmentation of the empire's power. These migrations, driven by various socio-political factors within Oromo society, continued for centuries.

Ethiopia saw significant diplomatic contact with Portugal from the 17th century, primarily related to religious matters. Starting in 1555, Portuguese Jesuit missionaries attempted to convert Ethiopia to Roman Catholicism. Under Emperor Susenyos I, Roman Catholicism briefly became the state religion in 1622. This decision, however, provoked a widespread revolt among the Orthodox populace and nobility.

3.4. Early Modern Period (Gondarine Period and Zemene Mesafint)

In 1632, Emperor Fasilides, son of Susenyos I, restored Orthodox Tewahedo Christianity as the state religion, expelling the Jesuits and curtailing foreign influence. Fasilides moved the imperial capital to Gondar in 1636, marking the beginning of the "Gondarine period." This era was characterized by relative stability, architectural achievements, and a flourishing of arts and culture. Fasilides and his successors built the iconic royal enclosure of Fasil Ghebbi in Gondar, along with numerous churches and bridges.

However, Gondar's power began to decline after the death of Emperor Iyasu I in 1706. Internal power struggles and the rise of regional lords gradually weakened the central authority of the emperors. Following the death of Emperor Iyasu II in 1755, Empress Mentewab brought her brother, Ras Wolde Leul, to Gondar, making him Ras Bitwaded (chief noble), leading to conflicts between different noble factions.

In 1769, Ras Mikael Sehul, a powerful regent from Tigray Province, seized Gondar, killed the child Emperor Iyoas I, and installed the elderly Yohannes II as a puppet emperor. This event is often considered the start of the Zemene Mesafint (ዘመነ መሳፍንትAge of PrincesGeez or Era of Judges), a period of profound political fragmentation and decentralization that lasted from roughly 1769 to 1855. During the Zemene Mesafint, emperors became mere figureheads, controlled by powerful regional warlords and nobles, such as Ras Mikael Sehul, Ras Wolde Selassie of Tigray, and later, the Yejju Oromo dynasty of Wara Sheh, including figures like Ras Gugsa of Yejju. These regional rulers vied for power, leading to frequent warfare and social instability. Before the Zemene Mesafint, Emperor Iyoas I had introduced the Oromo language (Afaan Oromo) at court, temporarily replacing Amharic, reflecting the growing influence of Oromo nobles. This era saw a decline in imperial authority and a shift in societal structures, with regional lords effectively ruling their own territories.

3.5. Imperial Reunification and Modernization (Mid-19th to Early 20th Century)

The period of Ethiopian isolationism and fragmentation known as the Zemene Mesafint began to end with the rise of Kassa Hailu, who was crowned Emperor Tewodros II in 1855. Tewodros II is credited with initiating the process of reunifying the Ethiopian Empire, centralizing power, and attempting early modernization. He sought to end the dominance of regional lords, restructure the empire's administration, and create a professional national army. His efforts laid the groundwork for establishing the effective sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Ethiopian state. However, his ambitious reforms and often harsh methods led to widespread opposition. His reign ended tragically after a conflict with the British Empire, which culminated in the 1868 Expedition to Abyssinia and Tewodros's suicide at Magdala.

Following Tewodros II, Yohannes IV (formerly Kassa Mercha of Tigray) became emperor in 1872. He continued the process of consolidation and successfully defended Ethiopia against external threats, notably from Egypt in the Ethiopian-Egyptian War (e.g., Battles of Gundet and Gura in 1875-1876) and from Mahdist Sudan. Yohannes IV was killed in battle against the Mahdists at the Battle of Gallabat (Metemma) in 1889.

Menelik II, who had been King of Shewa, succeeded Yohannes IV as emperor in 1889 and reigned until his death in 1913. Menelik II is a pivotal figure in modern Ethiopian history. He significantly expanded the empire's territory to roughly its current borders through a series of military campaigns, known as Menelik's Expansions, incorporating southern, eastern, and western regions inhabited by various peoples including the Oromo, Sidama, Gurage, and Welayta. He achieved this with the help of figures like Ras Gobana Dacche, a Shewan Oromo general.

Menelik II is also renowned for successfully defending Ethiopia's sovereignty against European colonial ambitions during the Scramble for Africa. He decisively defeated an invading Italian army at the Battle of Adwa on March 1, 1896, during the First Italo-Ethiopian War. This victory was a landmark event, as it ensured Ethiopia's independence and became a symbol of African resistance to colonialism. Menelik II also initiated significant modernization efforts, including the founding of Addis Ababa as the new capital, the introduction of a national currency, the establishment of the first modern schools and hospitals, and the construction of the Djibouti-Addis Ababa railway. Despite his achievements, his reign also saw hardship, including the devastating Great Ethiopian Famine (1888-1892) and a rinderpest epizootic that decimated livestock. On October 11, 1897, Ethiopia adopted a flag with green, yellow, and red stripes, colors that would later become influential in Pan-Africanism.

3.6. Haile Selassie Era (1916-1974)

The early 20th century was dominated by the figure of Haile Selassie I (born Tafari Makonnen). He came to prominence in 1916 when he was made Ras and Regent (Inderase) for Empress Zewditu, effectively becoming the de facto ruler of the Ethiopian Empire after the deposition of Lij Iyasu. Following Zewditu's death, Tafari was crowned Emperor Haile Selassie I on November 2, 1930.

Haile Selassie embarked on a nationwide modernization campaign, building upon the efforts of Menelik II. In 1931, he promulgated Ethiopia's first written constitution, modeled in part on Japan's Meiji Constitution. His reign aimed to centralize the state, improve education, and enhance Ethiopia's international standing. Ethiopia became a member of the League of Nations in 1923.

Ethiopia's independence was interrupted by the Second Italo-Ethiopian War (1935-1936). Fascist Italy, under Benito Mussolini, invaded Ethiopia in October 1935 and, despite Ethiopian resistance, occupied the country by May 1936. Haile Selassie went into exile in England, appealing to the League of Nations for assistance. Italy proclaimed Italian East Africa, incorporating Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Italian Somaliland. Italian rule (1936-1941) was met with ongoing resistance from Ethiopian patriots (Arbegnoch).

During World War II, British Empire forces, alongside the Arbegnoch, liberated Ethiopia in the course of the East African Campaign in 1941. Haile Selassie returned to Addis Ababa on May 5, 1941. The country was initially placed under British military administration, but its full sovereignty was restored with the signing of the Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement in December 1944.

Post-war, Haile Selassie continued his modernization policies. Ethiopia became a founding member of the United Nations in 1945. In 1952, following a UN resolution, Eritrea was federated with Ethiopia. However, in 1962, Haile Selassie's government annexed Eritrea, dissolving the federation and incorporating it as a province. This act sparked the long and devastating Eritrean War of Independence. Haile Selassie played a leading role in the formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 1963, with Addis Ababa becoming its headquarters, cementing Ethiopia's image as a symbol of African independence and unity.

Despite these international achievements, internal contradictions grew. The imperial government was seen as autocratic and slow to address issues of land tenure, poverty, and ethnic inequality. The social impact of his policies was mixed; while education and infrastructure saw some development, much of the rural population remained impoverished, and political dissent was suppressed. The human rights situation was characterized by a lack of political freedoms and harsh responses to opposition. The worldwide 1973 oil crisis exacerbated economic problems, leading to a sharp increase in gasoline prices and widespread discontent. Student and worker protests erupted in early 1974, leading to the toppling of the cabinet of Prime Minister Aklilu Habte-Wold and the appointment of Endelkachew Makonnen as his successor, but unrest continued.

3.7. Derg Regime (1974-1991)

Haile Selassie's long reign came to an end on September 12, 1974, when he was deposed by a coordinating committee of military officers known as the Derg (Amharic for "committee"). The coup followed months of escalating civil unrest, strikes, and military mutinies. The Derg, formally the Provisional Military Administrative Council (PMAC), initially declared its loyalty to the crown prince but soon moved to dismantle the imperial system entirely.

In March 1975, the Derg officially abolished the monarchy and declared Ethiopia a socialist state. It embarked on a radical program of social and economic reforms, including the nationalization of rural land, urban property, and major industries. Land reform, while aiming to abolish feudal land tenure, was implemented in a way that often led to state control rather than peasant ownership, and programs like resettlement and villagization were highly disruptive and often coercive.

A power struggle within the Derg culminated in Lieutenant Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam emerging as the undisputed leader in February 1977. Under Mengistu, the regime became increasingly authoritarian and brutal. From 1976 to 1978, the Derg launched the Qey Shibir (Red Terror), a violent campaign of political repression against rival Marxist factions, primarily the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Party (EPRP), and other perceived enemies of the revolution. Tens of thousands, possibly hundreds of thousands, of Ethiopians were killed, tortured, or imprisoned during the Red Terror, marking a period of severe human rights abuses.

In 1977, Somalia, under Siad Barre, invaded Ethiopia in an attempt to annex the Somali-inhabited Ogaden region, leading to the Ogaden War. Ethiopia, with massive military aid from the Soviet Union and Cuba, eventually repelled the Somali invasion in 1978. The Derg regime maintained a large military, becoming one of the most formidable in sub-Saharan Africa.

Despite its socialist rhetoric, the Derg's policies failed to alleviate poverty and often exacerbated existing problems. A devastating famine in 1983-1985, worsened by drought, government policies, and ongoing civil war, led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Ethiopians and attracted international condemnation.

Throughout its rule, the Derg faced numerous armed insurrections from various ethnic-based and political opposition groups. The Ethiopian Civil War intensified, particularly in Eritrea (led by the Eritrean People's Liberation Front, EPLF) and Tigray (led by the Tigray People's Liberation Front, TPLF). In 1987, the Derg dissolved itself and proclaimed the People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (PDRE) under a new constitution, with Mengistu as president, but this was largely a cosmetic change, and the Ethiopian Workers' Party remained the sole legal party.

The collapse of communism in Eastern Europe in 1989 and the subsequent withdrawal of Soviet support critically weakened the Mengistu regime. In 1989, the TPLF merged with other ethnically based opposition movements to form the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). By May 1991, EPRDF forces advanced on Addis Ababa. Mengistu Haile Mariam fled the country and was granted asylum in Zimbabwe. The Derg regime collapsed, ending 17 years of military rule and civil war.

3.8. Federal Democratic Republic Era (1991-Present)

Following the collapse of the Derg regime in May 1991, the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), a coalition of ethnically based rebel groups dominated by the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), took control of Addis Ababa. In July 1991, the EPRDF convened a National Conference to establish the Transitional Government of Ethiopia. This government, led by EPRDF chairman Meles Zenawi, adopted a transitional charter that functioned as an interim constitution. One of the first significant acts was to recognize the right of Eritrea to self-determination, leading to Eritrean independence in April 1993 after a UN-supervised referendum.

In 1994, a new constitution was drafted and adopted, establishing Ethiopia as a federal parliamentary republic based on ethnic federalism. This system divided the country into ethnically defined regional states. The first multiparty elections under the new constitution were held in May 1995, which the EPRDF won decisively. Meles Zenawi became the first Prime Minister of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. The EPRDF remained in power for nearly three decades, with Meles Zenawi serving as prime minister until his death in 2012, followed by Hailemariam Desalegn. While this period saw significant economic growth and development in infrastructure, it was also characterized by political repression, limited democratic space, and concerns about human rights. Opposition parties often alleged electoral irregularities and faced harassment.

In May 1998, a border dispute with Eritrea escalated into the bloody Eritrean-Ethiopian War, which lasted until June 2000. The war resulted in tens of thousands of casualties on both sides and had a severe negative impact on Ethiopia's economy. Although a peace agreement was signed, tensions and a border dispute remained unresolved for nearly two decades.

The EPRDF government faced increasing internal dissent and protests, particularly from the Oromo and Amhara ethnic groups, starting in the mid-2010s. These protests were driven by grievances over political marginalization, land issues, and human rights abuses. In response to years of unrest and a state of emergency, Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn resigned in February 2018.

In April 2018, Abiy Ahmed, an Oromo member of the EPRDF coalition, became prime minister. He initiated a series of sweeping political and economic reforms, including releasing thousands of political prisoners, unbanning opposition groups, and promising greater democratic freedoms. A landmark achievement was the peace agreement with Eritrea in July 2018, formally ending the long-standing border conflict, for which Abiy Ahmed was awarded the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize.

However, the reform process also coincided with a rise in ethnic tensions and violence across the country. Inter-ethnic clashes and conflicts led to the displacement of millions of Ethiopians. The EPRDF coalition was dissolved in 2019 and replaced by the Prosperity Party, which aimed to move away from ethnic federalism towards a more unified national identity, a move opposed by some, notably the TPLF.

The federal government's decision to postpone the 2020 general elections due to the COVID-19 pandemic was opposed by the TPLF, which governed the Tigray Region. The TPLF proceeded to hold its own regional elections in September 2020, which the federal government deemed illegal. Relations deteriorated rapidly, and in November 2020, the federal government launched a military offensive in Tigray in response to alleged attacks by TPLF forces on federal army bases, marking the beginning of the devastating Tigray War. The war involved federal forces, Amhara regional forces, and Eritrean troops against the TPLF. It resulted in a severe humanitarian crisis, widespread human rights abuses including mass killings and sexual violence, and famine conditions, with hundreds of thousands of deaths reported. After numerous mediation efforts, a cessation of hostilities agreement was signed in Pretoria, South Africa, on November 2, 2022, between the Ethiopian government and the TPLF.

Despite the peace agreement in Tigray, Ethiopia continues to face significant challenges. Ongoing ethnic conflicts persist in other regions, such as the OLA insurgency in Oromia and the conflict in the Amhara Region involving Fano militias that had previously allied with the government during the Tigray War. Reports by the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC) and international organizations have documented mass human rights violations, including extrajudicial killings and mass detentions. The impact of these conflicts on human rights, democratic progress, and the welfare of minorities and vulnerable groups remains a critical concern. The country continues to navigate a complex path toward stability, national reconciliation, and sustainable democratic development.

4. Geography

Ethiopia is a landlocked country situated in the Horn of Africa, with a diverse and striking landscape. Its geography significantly influences its climate, biodiversity, and human settlement patterns.

This section provides a general description of Ethiopia's location, area, borders, topography, climate, major rivers, and lakes.

4.1. Topography and Geology

Ethiopia's topography is characterized by immense diversity, dominated by the vast Ethiopian Highlands, a rugged mass of mountains and dissected plateaus. This highland complex is split by the Great Rift Valley, which runs generally from southwest to northeast through the country. The Highlands are the largest continuous area of their altitude in Africa, with many peaks exceeding 13 K ft (4.00 K m). The highest point is Ras Dashen in the Simien Mountains, reaching 15 K ft (4.55 K m).

The Great Rift Valley itself is a remarkable geological feature, part of the larger East African Rift system. Within Ethiopia, it contains numerous lakes, hot springs, and volcanic formations. To the east of the highlands lie extensive lowlands, steppes, and semi-desert areas.

One of the most extreme environments on Earth, the Danakil Depression (also known as the Afar Depression), is located in northeastern Ethiopia. It is a geological depression resulting from the divergence of three tectonic plates in the Horn of Africa. Parts of the Danakil Depression are more than 328 ft (100 m) below sea level, and it is renowned for its active volcanoes, salt flats, and extreme heat, with Dallol often cited as one of the hottest inhabited places on Earth.

Geologically, Ethiopia is largely composed of ancient Precambrian rocks forming the basement complex, overlain by Mesozoic sedimentary rocks and extensive Cenozoic volcanic rocks, particularly the Trap Series basalts which form the bulk of the Ethiopian Highlands. The rifting process that formed the Great Rift Valley is still active, leading to volcanic and seismic activity in the region.

4.2. Climate

Ethiopia's climate is highly varied due to its diverse topography and wide range of altitudes. The predominant climate type is tropical monsoon, but this is significantly modified by elevation.

The Ethiopian Highlands, where most of the population and major cities (including Addis Ababa, Gondar, and Axum) are located, generally experience a temperate or Weyna Dega climate. Altitudes in these areas typically range from 4.9 K ft (1.50 K m) to 9.8 K ft (3.00 K m). Addis Ababa, at an elevation of around 7.9 K ft (2.40 K m), has a mild climate year-round, with average annual temperatures around 60.8 °F (16 °C). Here, seasons are largely defined by rainfall: a dry season (Bega) from October to February, a light rainy season (Belg) from March to May, and a heavy rainy season (Kiremt) from June to September. The average annual rainfall in Addis Ababa is approximately 0.0 K in (1.20 K mm).

Areas above 9.8 K ft (3.00 K m) have a cool, alpine climate known as Dega. Conversely, low-lying regions, such as the Danakil Depression, the Ogaden, and areas along the western border, experience hot, arid (Bereha) or semi-arid (Kolla) climates. Dallol, in the Danakil Depression, holds the record for the highest average annual temperature for an inhabited location on Earth, around 93.2 °F (34 °C).

Rainfall patterns are generally monsoonal, influenced by the seasonal migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). The main rainy season (Kiremt) typically occurs from June to September in most parts of the country, crucial for agriculture. Some southern and southeastern regions experience two distinct rainy seasons.

Climate change is an increasing concern for Ethiopia, with observed trends including rising temperatures and more erratic rainfall patterns. These changes pose significant threats to agriculture, water resources, food security, and overall livelihoods, particularly for vulnerable rural populations. The country is also susceptible to recurring droughts and floods.

4.3. Water Resources

Ethiopia is often referred to as the "water tower of Africa" due to its numerous rivers originating in the highlands. The country has 14 major river basins. The most significant river is the Blue Nile (አባይAbayAmharic), which originates from Lake Tana, Ethiopia's largest lake, located in the northwestern highlands. The Blue Nile contributes a substantial portion (over 80% during the flood season) of the main Nile's water volume.

Other major rivers include the Awash River, which flows eastward and terminates in the Danakil Depression; the Omo River, which flows south into Lake Turkana; the Shebelle River and Juba River (Genale River in Ethiopia), which flow southeast towards Somalia; and the Tekezé River (Setit) in the north, a tributary of the Atbarah River, which itself is a tributary of the Nile.

Ethiopia also possesses several significant lakes, mostly located within the Great Rift Valley. These include Lake Tana, Lake Abaya, Lake Chamo, Lake Shala, Lake Langano, Lake Ziway, and Lake Awasa. These lakes vary in size, depth, and water chemistry.

Water resource management is a critical issue for Ethiopia. The country has immense potential for hydropower generation, and several large dams have been constructed or are under construction, most notably the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile. While these projects aim to boost energy production and economic development, they also have significant socio-economic and environmental impacts and have led to diplomatic tensions with downstream Nile countries, particularly Egypt and Sudan. Irrigation potential is also substantial but underdeveloped. Access to clean drinking water and sanitation remains a challenge, especially in rural areas. The sustainable management and equitable distribution of water resources are crucial for Ethiopia's development and regional stability.

4.4. Biodiversity

Ethiopia boasts a rich and unique biodiversity, owing to its diverse topography, varied climates, and geographical isolation of certain areas. It is recognized as a global centre of avian diversity and one of the eight Vavilov centers of origin for cultivated plants. The country is home to a wide array of flora and fauna, including numerous endemic species.

Notable endemic mammals include the Ethiopian wolf (the rarest canid in the world), the Walia ibex (a wild goat found in the Simien Mountains), the gelada (a species of baboon, sometimes called the "bleeding-heart monkey"), the mountain nyala, and the Swayne's hartebeest. Ethiopia has recorded over 856 bird species, with around 20 endemic to the country.

The flora is equally diverse, ranging from Afroalpine vegetation in the highest mountains (with species like giant lobelias and Erica arborea) to tropical forests in the south and southwest, and acacia-commiphora woodlands and grasslands in the lowlands. Ethiopia is the center of origin for important crops such as coffee (Coffea arabica), teff, ensete (false banana), and certain varieties of wheat and barley.

Major national parks and protected areas have been established to conserve this rich biodiversity, including Simien Mountains National Park (a UNESCO World Heritage Site), Bale Mountains National Park, Awash National Park, Nechisar National Park, and Omo National Park.

However, Ethiopia's biodiversity faces significant threats. Deforestation is a major concern, driven by agricultural expansion, firewood collection, and overgrazing. This has led to soil erosion, loss of habitat, and a decline in forest cover. Historically, around 35-40% of Ethiopia's land was covered by forests, but recent estimates suggest this has dwindled to around 11-15%. The country loses a significant area of natural forest annually.

Other challenges include land degradation, desertification in arid and semi-arid areas, poaching, human-wildlife conflict, and the impacts of climate change. Conservation efforts are underway, involving government programs, NGOs like SOS and Farm Africa, and community-based initiatives focusing on reforestation, sustainable land management, and the protection of endangered species. Despite these efforts, the pressures on Ethiopia's ecosystems and biodiversity remain intense.

5. Government and Politics

Ethiopia is a federal parliamentary republic. The governmental structure, major political parties, electoral system, and recent political trends are shaped by its 1995 constitution, which established a system of ethnic federalism.

This section explains Ethiopia's federal parliamentary republic system, governmental structure (President, Prime Minister, Council of Ministers, Federal Parliamentary Assembly), major political parties, electoral system, and recent political trends, including the challenges related to democratic development and human rights.

5.1. Government Structure

Ethiopia operates under a federal parliamentary republic system as defined by the 1995 constitution.

The President is the head of state. The role is largely ceremonial, with powers including promulgating laws approved by the legislature, granting pardons, and appointing ambassadors upon the Prime Minister's nomination. The President is elected by the House of Peoples' Representatives for a six-year term and can serve a maximum of two terms. The current President is Taye Atske Selassie.

The Prime Minister is the head of government and holds the executive power. The Prime Minister is chosen from among the members of the House of Peoples' Representatives and is typically the leader of the party or coalition that holds a majority in the House. The Prime Minister is responsible for the overall administration of the country, chairs the Council of Ministers, commands the armed forces, and implements laws. The current Prime Minister is Abiy Ahmed. The Deputy Prime Minister, currently Temesgen Tiruneh, assists the Prime Minister.

The Council of Ministers is the cabinet and the country's highest executive body. It is composed of the Prime Minister, the Deputy Prime Minister, and various ministers appointed by the Prime Minister and approved by the House of Peoples' Representatives. The Council is responsible for formulating and implementing government policies, preparing the budget, and managing government affairs.

The Federal Parliamentary Assembly is the bicameral federal legislature. It consists of two chambers:

- The House of Federation (የፌዴሬሽን ምክር ቤትYefedereshn Mekir BetAmharic) is the upper house. It has 108 members who are chosen by the regional state councils. Each "Nation, Nationality and People" recognized by the constitution is represented by at least one member, with an additional representative for each one million of its population. The House of Federation has powers related to interpreting the constitution, resolving disputes between states, and determining the division of federal and regional revenues.

- The House of Peoples' Representatives (የሕዝብ ተወካዮች ምክር ቤትYehizbtewekayoch Mekir BetAmharic) is the lower house and the primary law-making body. It has a maximum of 547 members, elected by direct universal suffrage for a five-year term from single-member constituencies. This house enacts laws, approves the national budget, ratifies international agreements, and oversees the executive branch.

The government structure reflects the principle of ethnic federalism, where regional states, largely defined along ethnic lines, have considerable autonomy.

5.2. Political Parties and Elections

Ethiopia has a multi-party system, although the political landscape has historically been dominated by a single coalition. Following the overthrow of the Derg regime in 1991, the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) - a coalition of four ethnically based parties (TPLF, ANDM, OPDO, SEPDM) - governed the country until 2019.

In December 2019, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed spearheaded the dissolution of the EPRDF and the formation of the Prosperity Party (PP). The PP aimed to move beyond ethnic-based federalism towards a more unified national party, incorporating three of the former EPRDF member parties and several allied regional parties. The Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) opted out of joining the Prosperity Party, a decision that significantly contributed to the political tensions leading to the Tigray War.

General elections are held every five years to elect members of the House of Peoples' Representatives and regional state councils. The most recent general election was held in June and September 2021. The Prosperity Party, led by Abiy Ahmed, won a large majority of seats. However, the election was marred by boycotts from some opposition parties, logistical challenges, and ongoing conflict in several regions, including Tigray, where elections were not held at the time.

Major opposition parties have included the National Movement of Amhara (NaMA), Ethiopian Citizens for Social Justice (Ezema), and various regional and ethnic-based parties like the Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC) and the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF). The participation and influence of opposition groups have often been constrained by legal restrictions, harassment, and an uneven playing field.

The fairness and freeness of past elections have been a subject of controversy. While some elections saw increased opposition participation, others, like the 2015 election where the EPRDF and its allies won all parliamentary seats, were criticized by international observers and opposition groups for lacking genuine competition and credibility. The political terrain remains dynamic, with ongoing debates about the nature of federalism, democratic consolidation, and the role of ethnicity in politics. Challenges include ensuring free and fair electoral processes, protecting political freedoms, and fostering inclusive political dialogue.

5.3. Judicial System

The Ethiopian judicial system is structured at both federal and regional state levels, reflecting the country's federal system of government. The 1995 Constitution of Ethiopia provides for an independent judiciary.

At the federal level, the highest court is the Federal Supreme Court, located in Addis Ababa. It has ultimate jurisdiction over federal matters and can hear appeals from the Federal High Court. The President and Vice-President of the Federal Supreme Court are nominated by the Prime Minister and appointed by the House of Peoples' Representatives. Other federal judges are appointed by the House of Peoples' Representatives based on recommendations from the Federal Judicial Administration Council. The current Chief Justice of the Federal Supreme Court is Tewodros Mihret.

Below the Federal Supreme Court are the Federal High Courts and Federal First Instance Courts. These courts handle cases involving federal law, constitutional issues, and matters where federal jurisdiction is specified.

Each regional state has its own independent judicial system, mirroring the federal structure, with a State Supreme Court at its apex, followed by State High Courts and State First Instance Courts (often called Woreda courts). These courts have jurisdiction over cases arising under state laws.

The constitution also provides for the establishment of religious and customary courts. Sharia courts can adjudicate personal and family law matters for Muslims if the parties consent. Similarly, customary courts can handle local disputes based on traditional practices, provided they do not contradict the constitution or federal laws.

The Judicial Administration Council at both federal and state levels is responsible for the administration of the judiciary, including the selection, promotion, and discipline of judges.

Despite constitutional guarantees of independence, the judiciary has faced challenges, including political interference, lack of resources, corruption, and a shortage of well-trained legal professionals. Efforts have been made to reform the judicial system to enhance its independence, efficiency, and accessibility. Ensuring the rule of law and providing equal access to justice for all citizens, particularly in rural and marginalized communities, remains a significant ongoing task. There are concerns regarding the capacity of the judicial system to effectively address human rights violations and hold perpetrators accountable, especially in contexts of political instability and conflict.

5.4. Administrative Divisions

Ethiopia is a federation divided into ethnically based Regional States (ክልሎችkililochAmharic; singular: ክልልkililAmharic) and two federally administered Chartered Cities. As of recent administrative changes, there are 12 regional states and two chartered cities. The regional states have their own constitutions, governments, and legislative councils.

The Regional States are:

1. Afar

2. Amhara

3. Benishangul-Gumuz

4. Central Ethiopia (formed in August 2023)

5. Gambela

6. Harari

7. Oromia

8. Sidama (became a region in June 2020, formerly part of SNNPR)

9. Somali

10. South Ethiopia (formed in August 2023)

11. South West Ethiopia Peoples' Region (formed in November 2021, formerly part of SNNPR)

12. Tigray

The two Chartered Cities are:

1. Addis Ababa (the national capital)

2. Dire Dawa

The now-dissolved Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region (SNNPR) was a highly diverse region that has been progressively divided into smaller, more ethnically homogenous regions (Sidama, South West Ethiopia Peoples', Central Ethiopia, and South Ethiopia).

Each regional state is further subdivided into Zones, which are in turn divided into Woredas (districts). Woredas are the basic administrative units and are further broken down into Kebeles (wards or neighborhood associations), which are the smallest administrative units, particularly in urban areas and for local governance in rural settings.

The population and major urban centers vary significantly across these administrative divisions. For example:

- Addis Ababa, the capital and a chartered city, is the largest urban center with a population exceeding 5 million.

- Oromia Region is the largest regional state by area and population (over 34.5% of the national population according to the 2007 census, primarily Oromo), with major cities like Adama (Nazret), Jimma, and Bishoftu.

- Amhara Region is the second-most populous (around 27% of national population, primarily Amhara), with cities like Bahir Dar (its capital), Gondar, and Dessie.

- Somali Region is predominantly inhabited by ethnic Somalis, with Jijiga as its capital.

- Tigray Region, home to the Tigrayan people (around 6.1% of national population), has Mekelle as its capital. It has been significantly affected by recent conflict.

- The newly formed regions (Sidama, South West, Central Ethiopia, South Ethiopia) reflect the ongoing process of administrative restructuring based on ethnic identity and self-determination demands. For instance, Hawassa is the capital of the Sidama Region.

This system of ethnic federalism is intended to grant self-rule to Ethiopia's diverse ethnic groups. However, it has also been a source of contention and conflict, with issues related to border demarcation between regions, representation of minorities within regions, resource sharing, and the balance of power between the federal government and regional states. Governance issues, including inter-ethnic conflict and disputes over administrative boundaries, are prevalent in several parts of the country.

5.5. Human Rights and Public Order

The human rights situation in Ethiopia has been a subject of significant concern for domestic and international observers for many years, with conditions fluctuating based on the political climate. While the constitution provides for fundamental human rights and freedoms, their practical implementation has often been lacking, particularly during periods of political instability and conflict.

Democratic Development and Freedoms: Ethiopia's journey towards democratic development has been challenging. After the overthrow of the Derg regime, there were hopes for a more open political system. However, the political space often remained restricted, with limitations on freedom of expression, assembly, and association. The initial reforms under Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed in 2018 brought a period of increased openness, with the release of political prisoners and the return of exiled opposition groups. However, this period was followed by a backsliding of some democratic gains, especially in the context of widespread ethnic conflict and the Tigray War. Freedom of the press has seen periods of improvement followed by crackdowns. Journalists and media outlets critical of the government have faced harassment, intimidation, and arrest. Internet shutdowns and restrictions on social media have also been employed by the government during times of unrest.

Human Rights Abuses: Reports by organizations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC) have documented various human rights abuses. These include:

- Extrajudicial killings: Security forces have been implicated in unlawful killings of civilians, particularly in conflict-affected regions like Tigray, Oromia, and Amhara.

- Arbitrary arrests and detentions: Thousands of individuals, including political opponents, activists, journalists, and ordinary citizens, have been arbitrarily arrested and detained, often without due process.

- Torture and ill-treatment: Detainees have reportedly been subjected to torture and other forms of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment in police stations, prisons, and unofficial detention centers.

- Restrictions on civil liberties: Freedoms of expression, assembly, and association have been frequently curtailed, with protests often met with excessive force by security forces.

- Conflict-related abuses: The Tigray War and other internal conflicts have been accompanied by widespread atrocities, including mass killings of civilians, ethnic cleansing, systematic sexual and gender-based violence, and deliberate starvation tactics. All parties to these conflicts have been accused of serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law.

Impact on Minorities and Vulnerable Groups: Ethnic minorities and vulnerable groups, including women, children, and internally displaced persons (IDPs), have often borne the brunt of human rights violations and conflict. Ethnic profiling and violence have been significant issues, leading to mass displacement and humanitarian crises. Access to justice and accountability for abuses remains a major challenge.

Public Order: Maintaining domestic public order has been a persistent challenge due to ethnic tensions, political instability, and armed conflicts. The proliferation of regional militias and armed groups has contributed to insecurity in various parts of the country. While the government has taken measures to address these issues, including peace agreements and security operations, the underlying causes of instability often remain unresolved.

Progress in democratic development and human rights is often intertwined with efforts to achieve national reconciliation, address historical grievances, strengthen independent institutions (like the judiciary and human rights commissions), and ensure accountability for past and ongoing abuses. The international community has frequently called on the Ethiopian government to uphold its human rights obligations and to ensure that those responsible for violations are brought to justice.

6. Foreign Relations

Ethiopia has a long and complex history of foreign relations, reflecting its strategic location in the Horn of Africa, its status as an ancient independent nation, and its role in regional and international affairs. Key foreign policy principles have traditionally revolved around safeguarding its sovereignty and territorial integrity, promoting regional stability, and fostering economic development through international partnerships.

This section summarizes Ethiopia's main foreign policy principles, its relationships with neighboring countries and major global powers, and its participation in international organizations.

6.1. Relations with Neighboring Countries

Ethiopia's relations with its neighbors have been a mix of cooperation and conflict, shaped by historical ties, border issues, resource competition (especially water), and regional power dynamics.

- Eritrea: Relations with Eritrea have been particularly volatile. After a long war of independence, Eritrea seceded from Ethiopia in 1993. A border dispute led to the devastating Eritrean-Ethiopian War (1998-2000). Tensions remained high for nearly two decades until a surprise peace agreement was reached in 2018 under Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki. Eritrean forces later controversially allied with Ethiopian federal forces during the Tigray War. The relationship remains complex and subject to shifts. Humanitarian concerns have been significant, especially regarding refugees and the impact of conflicts on civilian populations in border areas.

- Somalia: Relations with Somalia have historically been strained, largely due to territorial disputes, particularly over the Somali-inhabited Ogaden region of Ethiopia. This led to the Ogaden War in 1977-1978. Ethiopia has played a significant role in regional efforts to stabilize Somalia, including military interventions against Islamist militant groups like Al-Shabaab. Ethiopia also hosts a large number of Somali refugees.

- Sudan: Relations with Sudan have fluctuated. The two countries share a long border, and there have been historical ties as well as periods of tension, including disputes over the fertile al-Fashaga border region. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile has become a major point of contention, as Sudan is a downstream riparian state. Both countries also host refugees from each other and from regional conflicts.

- South Sudan: Ethiopia played a key role in mediating the conflict that led to South Sudan's independence in 2011 and has continued to be involved in peace efforts in South Sudan. The two countries share a border and have common interests in regional stability, though border demarcation remains an issue. Ethiopia hosts many South Sudanese refugees.

- Kenya: Relations with Kenya are generally stable and cooperative, focusing on trade, security cooperation (particularly against regional threats like Al-Shabaab), and infrastructure development, such as the LAPSSET corridor project. Border communities share cultural and economic ties.

- Djibouti: Djibouti is a crucial strategic partner for landlocked Ethiopia, as the Port of Djibouti serves as Ethiopia's primary access to the sea and handles the vast majority of its international trade. The Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway is a key infrastructure link. Relations are generally strong and economically interdependent.

Humanitarian concerns, including refugee flows and the impact of cross-border conflicts, are significant factors in Ethiopia's relations with all its neighbors.

6.2. Relations with Major Powers and Blocs

Ethiopia maintains diplomatic and economic ties with major global powers and international blocs, often balancing these relationships to serve its national interests.

- United States: The U.S. has historically been a significant partner, particularly in areas of development aid, food security, health programs, and counter-terrorism cooperation in the Horn of Africa. However, relations have been strained at times due to concerns over human rights and democratic governance in Ethiopia, especially during the Tigray War, leading to some sanctions and restrictions on aid.

- China: China has emerged as a major economic and political partner for Ethiopia. Chinese investment has been crucial in developing Ethiopia's infrastructure, including roads, railways (like the Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway), telecommunications, and industrial parks. Ethiopia is a key participant in China's Belt and Road Initiative. This relationship is primarily driven by economic interests, though political ties have also strengthened. Concerns exist regarding debt sustainability related to Chinese loans.

- European Union (EU): The EU and its member states are significant development and trade partners for Ethiopia. The EU provides substantial development assistance and humanitarian aid. Similar to the U.S., relations have faced challenges due to concerns about human rights, governance, and the humanitarian situation during recent conflicts.

- Russia: Ethiopia has historical ties with Russia, dating back to the Soviet era when the Derg regime received significant support. In recent years, relations have seen renewed engagement, particularly in areas like military cooperation and political alignment on some international issues.

- Middle Eastern Nations: Ethiopia has important historical, cultural, and economic ties with countries in the Middle East, including Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, and Israel. These relationships involve trade, investment, and sometimes geopolitical considerations. The Gulf states are major destinations for Ethiopian migrant workers. Religious ties (Christianity and Islam) also play a role.

- BRICS: Ethiopia became a full member of the BRICS group of emerging economies (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, and new members) in January 2024. This membership is seen as an opportunity to enhance economic cooperation, attract investment, and increase its influence on the global stage.

Ethiopia's foreign policy often seeks to maintain a degree of non-alignment while engaging with diverse partners to support its development agenda and regional influence.

6.3. Role in International Organizations

Ethiopia plays a prominent role in various international and regional organizations, reflecting its historical significance and strategic position in Africa.

- African Union (AU): Addis Ababa is the headquarters of the African Union, making Ethiopia a central hub for pan-African diplomacy and activities. Ethiopia was a founding member of the OAU (Organisation of African Unity), the AU's predecessor, in 1963. It actively participates in AU summits, peace and security initiatives, and socio-economic development programs. Ethiopian leaders have often held key positions within the AU.

- United Nations (UN): Ethiopia is a founding member of the United Nations (1945). It has contributed troops to UN peacekeeping missions and actively participates in various UN agencies and programs. The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) is headquartered in Addis Ababa. Ethiopia has also served as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council.

- Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD): Ethiopia is a key member of IGAD, a regional organization in the Horn of Africa focused on peace, security, and development. Ethiopia has played a significant role in IGAD-led mediation efforts for conflicts in neighboring countries, such as Sudan and South Sudan.

- Other International Bodies: Ethiopia is a member of numerous other international organizations, including the Non-Aligned Movement, the Group of 77 (G77), the World Trade Organization (WTO, as an observer actively pursuing full membership), and international financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. It became a full member of BRICS in 2024.

Ethiopia's participation in these organizations allows it to voice its interests on the global stage, contribute to multilateral solutions for regional and international challenges, and access development assistance and technical cooperation. Its role as a host to major international organizations like the AU and UNECA further enhances its diplomatic influence in Africa.

7. Military

The Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) is the military of Ethiopia. It is constitutionally mandated to protect the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the country and to defend the constitution. The ENDF's origins and military traditions date back to ancient Ethiopian kingdoms, and it has a long history of defending the nation against foreign invasions and participating in internal conflicts.

Organization: The ENDF primarily consists of two main branches:

- The Army: This is the largest branch and is responsible for land-based military operations. It is organized into various commands and divisions.

- The Air Force: Responsible for air defense, reconnaissance, and support for ground operations. It operates a range of aircraft, including fighter jets, transport planes, and helicopters.

Historically, Ethiopia also had a Navy, but it was disbanded after Eritrea (where Ethiopia's naval bases were located) gained independence in 1993, leaving Ethiopia landlocked. There have been recent discussions about re-establishing a naval capacity, potentially by securing access to ports in neighboring countries.

Personnel Strength and Budget: The ENDF is one of the largest and most experienced military forces in Africa. Prior to the Tigray War, its active personnel strength was estimated to be around 140,000-160,000. During and after the conflict, recruitment drives significantly increased its numbers, though precise current figures are difficult to ascertain. The defense budget has fluctuated, increasing significantly during periods of conflict. For example, in 2022, military spending reportedly increased substantially due to the Tigray War, reaching over 1.00 B USD.

Major Equipment: The ENDF's equipment is sourced from various countries. Historically, during the Derg era, much of its arsenal was Soviet-supplied. In recent decades, Ethiopia has diversified its suppliers, acquiring equipment from Russia, China, Ukraine, Israel, and other nations. Equipment includes tanks, armored personnel carriers, artillery, fighter jets (such as Sukhoi Su-27s), transport aircraft, and attack helicopters. Ethiopia also has a domestic arms industry capable of producing small arms and some types of armored vehicles.

Key Military Activities and Security Environment:

- Internal Security: The ENDF has been heavily involved in addressing internal conflicts and insurgencies in various regions, including Tigray, Oromia, Amhara, and Somali regions. These operations have often been complex and have raised concerns about human rights.

- Border Security: Securing Ethiopia's long and often porous borders with six neighboring countries is a major task. Border disputes, such as with Eritrea (now formally resolved but with lingering complexities) and Sudan (over the al-Fashaga triangle), have required significant military attention.

- Regional Peacekeeping and Counter-terrorism: Ethiopia has been a significant contributor to regional peace and security efforts, including peacekeeping missions under the African Union (e.g., AMISOM/ATMIS in Somalia) and the UN. It has also been a key partner in counter-terrorism operations in the Horn of Africa, particularly against groups like Al-Shabaab.

- Defense of Strategic Interests: The military is tasked with protecting national strategic interests, which can include major infrastructure projects like the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

Law Enforcement Agencies:

Beyond the ENDF, Ethiopia has several law enforcement agencies responsible for internal security and public order.

- The Ethiopian Federal Police (EFP) is the main federal law enforcement agency, responsible for enforcing federal laws, maintaining public order, preventing and investigating crimes, and protecting civil and political rights.

- Regional Police Forces: Each regional state has its own police force responsible for law enforcement within its jurisdiction.

- The National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) is the primary intelligence agency, responsible for national security, counter-terrorism, and counter-espionage. It also has some law enforcement powers related to national security threats and international economic crimes.

- Regional Special Forces: Many regional states have established their own "Special Forces," which are heavily armed paramilitary units. These forces have often operated alongside the ENDF in conflicts but have also been a source of tension and instability, sometimes acting outside clear legal frameworks. In 2023, the federal government announced a plan to integrate these regional special forces into the federal security structure (ENDF or federal/regional police), a move that met with resistance in some regions, notably Amhara.

The security environment in Ethiopia remains complex, shaped by internal ethnic and political tensions, regional instability, and geopolitical dynamics in the Horn of Africa.

8. Economy

Ethiopia's economy has undergone significant transformation in recent decades, shifting from a centrally planned system under the Derg regime to a more market-oriented approach. It is characterized by a large agricultural sector, a growing services sector, and an emerging industrial base. The country has experienced rapid economic growth for much of the 21st century, though it continues to face challenges related to poverty, income inequality, and structural vulnerabilities. The social and environmental impacts of economic development are also important considerations.

Ethiopia's GDP (PPP) was estimated at around 434.44 B USD in 2024, with a nominal GDP of approximately 145.03 B USD. Despite high growth rates, GDP per capita remains low (around 1.35 K USD nominal and 4.05 K USD PPP in 2024), placing Ethiopia among the least developed countries. The Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality, was 35.0 in 2015. The Human Development Index (HDI) was 0.492 in 2022, ranking 176th globally. The national currency is the Ethiopian birr (ETB).

Historically, Ethiopia registered over 10% annual economic growth between 2004 and 2009, and again averaged high single-digit or double-digit growth in the following decade, making it one of the fastest-growing economies in Africa. This growth was driven by public investment in infrastructure (roads, railways, dams), agriculture, and services. However, high inflation, foreign exchange shortages, and a difficult balance of payments situation have been recurrent challenges.

The Ethiopian constitution states that land is owned by "the state and the people," meaning citizens can lease land (up to 99 years) but cannot own it outright, mortgage, or sell it. This system has implications for agricultural investment and productivity.

The government has focused on developing industrial parks to attract foreign direct investment and transform Ethiopia into a light manufacturing hub, particularly in textiles and garments. In 2019, a law was passed allowing expatriate Ethiopians to invest in the financial service industry. The private sector is growing, but state-owned enterprises still play a significant role in key sectors. Poverty remains a major challenge, with a significant portion of the population affected by multidimensional poverty, although there has been a reduction in poverty rates since 2000.

8.1. Agriculture

Agriculture is the backbone of the Ethiopian economy, accounting for about 32-37% of GDP (as of 2022), over 80% of employment, and the majority of export earnings. Production is predominantly rain-fed and carried out by small-scale farmers.

Major Crops:

- Coffee: Ethiopia is the birthplace of Coffea arabica, and coffee remains its single largest export earner. Ethiopian coffee is renowned for its quality and diverse flavor profiles. The sector provides a livelihood for millions of Ethiopians.

- Teff: A fine grain endemic to Ethiopia, teff is the staple food crop used to make injera, the traditional flatbread.

- Cereals: Other important cereals include maize (corn), wheat, barley, and sorghum. Ethiopia is Africa's second-biggest maize producer.

- Pulses and Oilseeds: Beans, lentils, chickpeas, and various oilseeds (like sesame and niger seeds) are widely cultivated for domestic consumption and export.

- Floriculture: The flower industry has grown rapidly, making Ethiopia one of the world's leading exporters of cut flowers, particularly roses.

- Other Crops: Sugarcane, fruits, vegetables, and khat (a stimulant plant, primarily exported to neighboring countries) are also important.

Ethiopia is a Vavilov center of crop diversity, holding rich genetic resources for crops like enset (false banana), coffee, and teff.

Challenges: The agricultural sector faces numerous challenges:

- Dependence on Rainfall: Susceptibility to drought and erratic rainfall patterns due to climate change.

- Land Degradation: Soil erosion, deforestation, and loss of soil fertility.

- Small Landholdings and Low Productivity: Limited access to modern inputs (fertilizers, improved seeds), technology, and credit for smallholders.

- Land Tenure System: State ownership of land can create insecurity and disincentivize long-term investment.

- Market Access and Infrastructure: Poor rural roads and limited market linkages.

- Pests and Diseases: Crop losses due to pests and diseases.

Development Strategies: The government has implemented various strategies to boost agricultural productivity and ensure food security, such as the Agricultural Development Led Industrialization (ADLI) policy, and subsequent Growth and Transformation Plans (GTPs). These strategies focus on improving extension services, access to inputs, irrigation development, and promoting commercial agriculture, with an increasing emphasis on sustainability and benefiting smallholder farmers. Addressing land rights and the impact of climate change are crucial for the sector's long-term development.

8.2. Industry and Services

The industrial sector in Ethiopia, while still relatively small, has been a focus of government development efforts aimed at economic transformation and job creation. It contributes around 25-30% of GDP. Key manufacturing sub-sectors include:

- Textiles and Garments: This has been a priority area, with the development of industrial parks to attract foreign investment. Ethiopia aims to leverage its large, low-cost labor force.

- Leather and Leather Products: Utilizing the country's large livestock population, the leather industry produces shoes, bags, and other goods for domestic and export markets.

- Food and Beverages: Processing of agricultural products for local consumption and export.

- Cement and Construction Materials: Driven by large-scale infrastructure projects and urbanization.

- Agro-processing: Adding value to agricultural commodities.

Challenges in the industrial sector include shortages of foreign exchange for importing raw materials and machinery, power supply issues, bureaucratic hurdles, and the need for skilled labor. Labor conditions and environmental standards in some industrial parks have also been subjects of concern, and ensuring decent work and sustainable practices is an ongoing issue.

The services sector is the largest contributor to Ethiopia's GDP, accounting for around 37-40%. Key components include:

- Tourism: Ethiopia has significant tourism potential due to its rich history, cultural heritage (including UNESCO World Heritage Sites like Lalibela and Aksum), diverse landscapes, and unique wildlife. However, the sector has been affected by political instability and conflict, as well as infrastructure limitations.

- Transport and Logistics: Dominated by the state-owned Ethiopian Airlines, one of Africa's largest and most profitable carriers. Road and rail transport are also expanding.

- Telecommunications: Historically a state monopoly under Ethio telecom, the sector has recently opened up to private competition, with new licenses being issued.

- Finance: The banking and insurance industries are predominantly locally owned, with state-owned banks playing a major role. The sector is gradually liberalizing.

- Information Technology (IT): The IT sector is nascent but has growth potential, particularly in software development and business process outsourcing.

- Wholesale and Retail Trade.

- Public Administration and Defense.

The services sector has been a significant driver of economic growth and employment. Improving the quality and accessibility of services, particularly in finance and telecommunications, is crucial for overall economic development.

8.3. Energy and Mineral Resources

Ethiopia's energy policy heavily emphasizes the development of its abundant renewable energy resources, particularly hydropower. The country has the largest water reserves in Africa and is often referred to as the "water tower of Africa."

- Hydropower: As of 2012, hydroelectric plants represented around 88.2% of the total installed electricity generating capacity. This share remains very high. Major hydropower projects include:

- The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile River, with a planned capacity of 6,450 MW, is the largest hydroelectric power station in Africa. It began partial power generation in 2022 and was largely completed in 2023. The GERD is a flagship project intended to meet domestic energy needs and export electricity, but it has also been a source of diplomatic tension with downstream Nile countries, Egypt and Sudan, over water rights and dam operation.

- The Gilgel Gibe III Dam (1,870 MW) was previously the largest dam.

- Other dams like Gibe I, Gibe II, Tekeze, and Beles also contribute significantly.

- Other Renewable Sources: Ethiopia also has potential for geothermal, wind, and solar energy. Several wind farms are operational, and geothermal exploration is ongoing in the Rift Valley. These sources represent a smaller but growing portion of the energy mix (around 3.6% from various renewables excluding large hydro in 2012).

- Fossil Fuels: A small percentage of electricity (around 8.3% in 2012) was generated from fossil fuels, primarily for backup and off-grid applications. Ethiopia imports petroleum products for transport and other needs.

Electrification rates have been increasing but remain relatively low, especially in rural areas. In 2016, the overall electrification rate was 42% (85% in urban areas, 26% in rural areas). Total electricity production was 11.15 TWh, with consumption at 9.062 TWh. Ethiopia aims to achieve universal electricity access and become a regional power exporter.

Mineral Resources:

Ethiopia has various mineral resources, though the mining sector is relatively underdeveloped compared to agriculture.

- Gold: Gold is the most significant mineral export. It is mined both by large-scale companies and artisanal miners. The Lega Dembi mine is a major gold producer.

- Platinum: Deposits of platinum are also found.

- Tantalum: Ethiopia is a producer of tantalum, used in electronics. The Kenticha mine is a notable source.

- Potash: Significant potash reserves exist in the Danakil Depression, with projects underway for extraction.

- Opal: Ethiopia is known for its precious opals, particularly Welo opals.

- Other Minerals: Deposits of iron ore, coal, gemstones, and industrial minerals like limestone, clay, and gypsum also exist. Natural gas reserves have been identified in the Ogaden Basin, but commercial production has been limited.