1. Overview

The Republic of Kenya, a nation situated in East Africa on the Indian Ocean coast, is characterized by its diverse geography, rich tapestry of ethnic groups and languages, and a complex history marked by early human presence, vibrant coastal civilizations, colonial rule, and a dynamic post-independence journey towards democratic development. Geographically, Kenya encompasses snow-capped mountains like Mount Kenya, vast savanna grasslands teeming with wildlife, fertile agricultural highlands, and arid and semi-arid lands. Historically, the region is a cradle of humankind, later hosting Swahili city-states active in Indian Ocean trade, followed by Portuguese and Omani influence, and ultimately British colonization. The struggle for independence, notably the Mau Mau Uprising, paved the way for sovereignty in 1963. This article provides a comprehensive understanding of Kenya, covering its etymology, detailed history from prehistory to the contemporary William Ruto era, its physical and human geography, political system and governance structures, foreign relations, military, administrative divisions, and multifaceted economy including key sectors like agriculture, tourism, and emerging industries. It also delves into Kenyan society, examining its demographics, ethnic composition, languages, religions, health and education systems, and the specific concerns of women and youth. The cultural landscape, encompassing literature, music, sports, cuisine, and heritage sites, is also explored.

Reflecting a center-left/social liberalism perspective, this document gives due attention to the social impact of historical and ongoing developments, human rights issues, the evolution of democratic institutions, and the concerns of minorities and vulnerable groups. It aims to critically analyze the effects of colonial policies, the challenges of nation-building, the impacts of various political eras on citizens' rights and welfare, and the social and environmental consequences of economic development strategies, fostering a nuanced understanding of Kenya's past, present, and future trajectory.

2. Etymology

The name "Kenya" is derived from Mount Kenya, the highest mountain in the country and the second highest in Africa. The earliest recorded version of the modern name is attributed to the German explorer Johann Ludwig Krapf in the 19th century. During his travels with a Kamba caravan led by the trader Chief Kivoi, Krapf sighted the mountain and inquired about its name. Chief Kivoi reportedly referred to it as Kĩ-NyaaKĩ-NyaaKamba or Kĩlĩma-KĩinyaaKĩlĩma-KĩinyaaKamba in the Kamba language. This name is thought to have been inspired by the pattern of black rock and white snow on its peaks, which resembled the feathers of a male ostrich.

In the Kikuyu language, spoken by the Agikuyu who inhabit the slopes of Mount Kenya, the mountain is called Kĩrĩma Kĩrĩnyagathe mountain with brightnesskik, which literally translates to "the mountain with brightness" or "the shining mountain," likely referring to its snow-capped peaks. The Embu, who also live near the mountain, call it KirinyaaKirinyaaebu. These names all share a similar meaning related to brightness or whiteness.

Ludwig Krapf recorded the name as both Kenia and Kegnia. Some scholars suggest that this was a precise phonetic notation of the African pronunciation, approximating /ˈkɛnjə/. An 1882 map drawn by Joseph Thomson, a Scottish geologist and naturalist, also labeled the mountain as Mt. Kenia.

The name of the mountain was eventually adopted, pars pro toto, as the name for the entire country. However, it did not come into widespread official use during the early colonial period when the territory was known as the East Africa Protectorate. The official name was formally changed to the Colony of Kenya in 1920, solidifying "Kenya" as the designation for the nation.

3. History

Kenya's history spans from the dawn of humankind, through early migrations and the rise of coastal civilizations, to periods of foreign domination and a determined struggle for independence, followed by the challenges and achievements of a modern nation-state. The nation's past includes significant prehistoric findings, the development of Swahili city-states, European colonial rule, and a vibrant post-independence political evolution.

3.1. Human prehistory

The Kenyan region is one of the earliest known areas of human habitation and is considered a cradle of humankind. Hominid species such as Homo habilis, who lived approximately 1.8 to 2.5 million years ago, and Homo erectus, dating from 1.9 million to 350,000 years ago, resided in Kenya during the Pleistocene epoch. These species are considered possible direct ancestors of modern Homo sapiens.

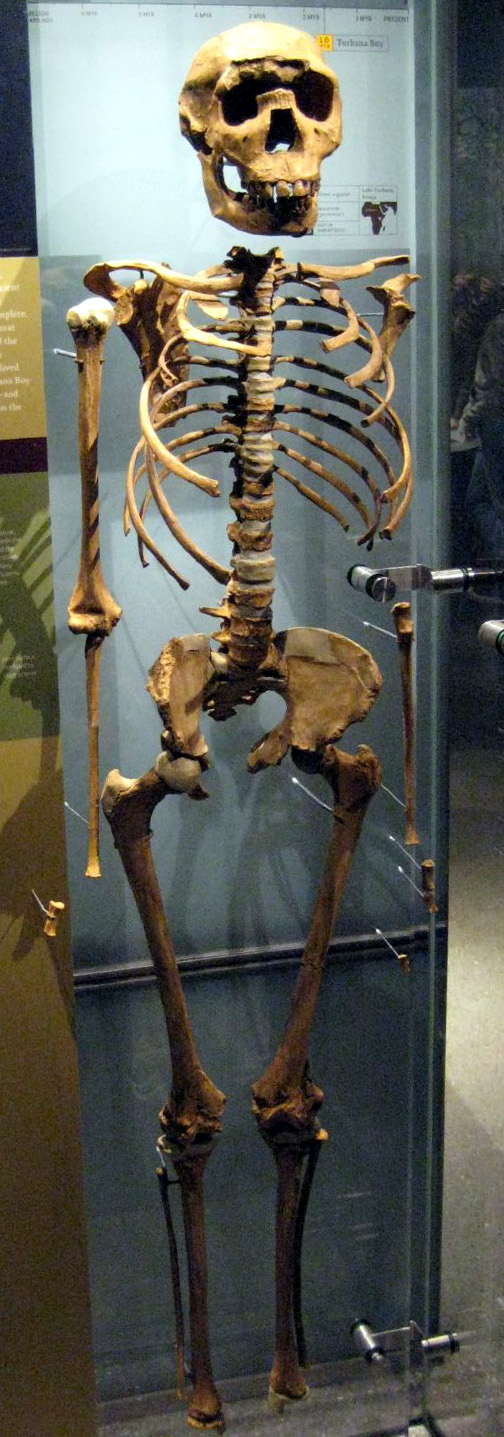

Archaeological discoveries in Kenya have provided significant insights into human evolution. In 1984, palaeoanthropologist Richard Leakey, assisted by Kamoya Kimeu, discovered the Turkana Boy near Lake Turkana. This remarkably complete fossil of a Homo erectus youth is dated to be 1.6 million years old.

East Africa, including Kenya, is also recognized as one of the earliest regions where modern humans, Homo sapiens, are believed to have emerged. Evidence found in 2018, dating to about 320,000 years ago, indicates the early emergence of modern human behaviors. These include the establishment of long-distance trade networks, involving goods such as obsidian, the use of pigments for symbolic purposes, and potentially the creation of projectile points. Researchers suggest that these findings point to complex and modern behaviors having already begun in Africa around the time Homo sapiens first appeared. Discoveries of dinosaur fossils, including those of giant crocodiles from the Mesozoic Era (around 200 million years ago), have also been made, particularly near Lake Turkana, indicating a long and diverse paleontological history in the region.

3.2. Neolithic period and early migrations

The earliest inhabitants of present-day Kenya were hunter-gatherer groups, similar in lifestyle to modern Khoisan-speaking peoples. During the early Holocene epoch, the regional climate shifted from dry to wetter conditions, creating a more favorable environment for the development of new cultural traditions, including the beginnings of agriculture and pastoralism.

Between 3,200 and 1,300 BC, Cushitic-speaking peoples from the Horn of Africa began to settle in Kenya's lowlands. This period, known as the Lowland Savanna Pastoral Neolithic, saw these groups largely replace the earlier hunter-gatherer populations. They introduced pastoral practices to the region.

Around 500 BC, Nilotic-speaking pastoralists, ancestors of Kenya's contemporary Nilotic speakers such as the Kalenjin, Samburu, Luo, Turkana, and Maasai, began migrating into Kenya from areas in present-day South Sudan. These migrations brought new pastoral traditions and social structures.

By the first millennium AD, Bantu-speaking farmers, originating from West Africa along the Benue River in what is now eastern Nigeria and western Cameroon, had moved into the region. They initially settled along the coast and later in the interior. The Bantu migration introduced new developments in agriculture, including the cultivation of new crops, and ironworking technology. Bantu groups in Kenya include the Kikuyu, Luhya, Kamba, Kisii (Gusii), Meru, Kuria, Embu, Mbeere, Wadawida (Taita)-Watuweta, Wapokomo, and Mijikenda, among others.

Notable prehistoric sites from this period in Kenya's interior include Namoratunga, an archeoastronomical site on the west side of Lake Turkana, and the walled settlement of Thimlich Ohinga in Migori County, a UNESCO World Heritage Site that exemplifies early fortified settlements. These migrations and settlements laid the foundation for the complex ethnic and linguistic diversity found in Kenya today.

3.3. Swahili coastal civilization and trade

The Kenyan coast was home to communities of ironworkers and Bantu subsistence farmers, hunters, and fishers who supported their economy through agriculture, fishing, metal production, and trade with foreign lands. These communities formed the earliest city-states in the region, collectively known in ancient texts as Azania.

By the 1st century CE, many of these city-states, including Mombasa, Malindi, and Zanzibar (though Zanzibar is part of modern Tanzania, its history is intertwined with the Kenyan coast), began to establish trading relations with Arabs from the Arabian Peninsula and later with Persians. This interaction led to significant economic growth for the Swahili states. It also facilitated the introduction of Islam and Arabic linguistic influences on the local Bantu languages, leading to the development of the Swahili language. This cultural diffusion was a hallmark of the Swahili civilization, and the city-states became integral parts of a vast Indian Ocean trade network.

While early historians often attributed the establishment of these city-states to Arab or Persian traders, archaeological evidence now supports the view that they were primarily an indigenous development. These states, while significantly influenced by foreign trade and cultural exchange, retained a Bantu cultural core. DNA evidence from medieval Swahili coast sites has confirmed that the Swahili people had mixed African and Asian (particularly Persian) ancestry.

The Kilwa Sultanate, centered in present-day Tanzania, was a powerful medieval sultanate whose authority, at its zenith, extended over the entire length of the Swahili Coast, including parts of Kenya. From the 10th century, rulers of Kilwa constructed elaborate coral mosques and introduced copper coinage, signifying a sophisticated urban culture.

Swahili, a Bantu language enriched with loanwords from Arabic, Persian, and other Middle Eastern and South Asian languages, evolved as a lingua franca for trade among the diverse peoples of the coast and the interior. Over time, particularly since the turn of the 20th century and during British colonial rule, Swahili has also adopted numerous loanwords and calques from English. The intricate carved wooden doors, such as those found in Lamu, are iconic representations of Swahili architectural and artistic traditions.

3.4. Portuguese arrival and Omani rule

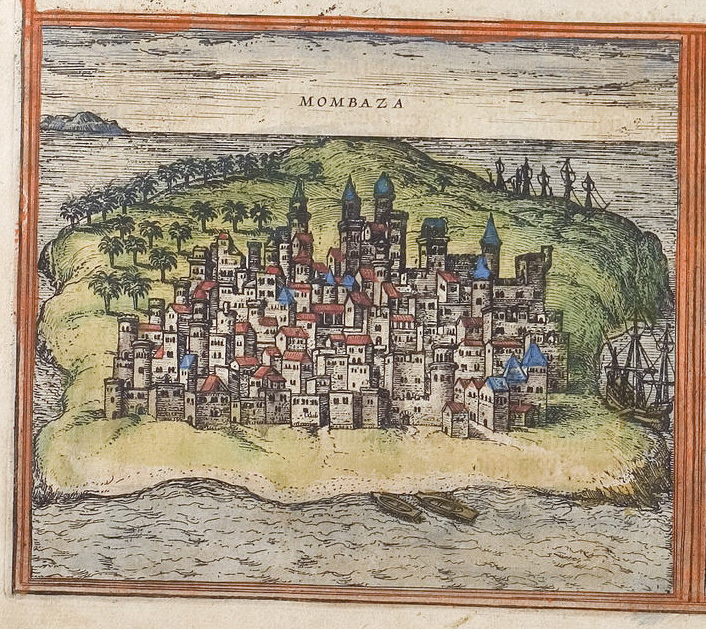

The Swahili city-states, particularly Mombasa, developed into major port cities, establishing robust trade links with other nearby coastal centers like Malindi, as well as commercial hubs in Persia, Arabia, and India. By the 15th century, Portuguese voyager Duarte Barbosa noted Mombasa as a place of significant traffic with a good harbor frequented by various small craft and large ships engaged in trade with Sofala, Cambay, Malindi, and Zanzibar.

The arrival of the Portuguese on the East African coast began in 1498 when Vasco da Gama reached Mombasa. The Portuguese aimed to control the lucrative Indian Ocean trade routes. Their presence in Kenya lasted intermittently from 1498 until 1730. Mombasa itself was under direct Portuguese rule from 1593 to 1698 and briefly again from 1728 to 1729, during which they constructed Fort Jesus to solidify their control. Malindi, another important Swahili settlement since the 14th century, often rivaled Mombasa for dominance. Malindi maintained traditionally friendly relations with foreign powers; in 1414, it was visited by the Chinese admiral Zheng He during one of his treasure voyages, and in 1498, Malindi authorities welcomed Vasco da Gama.

By the 17th century, the Swahili coast was largely conquered by and came under the direct rule of the Omani Arabs. The Omani Sultanate expanded the slave trade to meet the labor demands of plantations in Oman and Zanzibar. Initially, these traders were mainly from Oman, but later, many, like the infamous Tippu Tip, operated from Zanzibar. The Portuguese also became involved in purchasing enslaved people from Omani and Zanzibari traders, particularly as the transatlantic slave trade faced increasing disruption from British abolitionist efforts. The Omani period brought significant socio-economic changes to the coastal region, further shaping its cultural and demographic landscape.

3.5. 19th-century inland exploration and early European influence

During the 18th and 19th centuries, the Maasai migrated into the central and southern Rift Valley plains of Kenya from a region north of Lake Turkana (then Lake Rudolf). Though not numerous, they managed to conquer extensive territories in the plains, often facing little resistance from existing populations. However, the Nandi successfully opposed Maasai expansion, while groups like the Taveta sought refuge in forests on the eastern edge of Mount Kilimanjaro, though they were later impacted by smallpox. A significant outbreak of either rinderpest or pleuropneumonia devastated Maasai cattle, and smallpox epidemics affected the Maasai population itself. Following the death of Mbatian, their chief laibon (spiritual leader), the Maasai split into warring factions. Despite the strife caused by Maasai expansion, evidence of cooperation between groups like the Luo, Luhya, and Gusii exists, indicated by shared vocabulary for modern tools and similar economic practices. Arab traders remained in the area, but trade routes, particularly for ivory, were often disrupted by the Maasai, though some trade in ivory occurred even between these factions.

European inland exploration of Kenya began in earnest in the 19th century. German missionaries Johann Ludwig Krapf and Johannes Rebmann were among the first Europeans to successfully venture past the Maasai-controlled territories. In the 1840s, they established a mission in Rabai, near Mombasa. Krapf and Rebmann are credited with being the first Europeans to sight Mount Kenya (Krapf in 1849) and Mount Kilimanjaro (Rebmann in 1848), respectively. Their reports, initially met with skepticism in Europe, spurred further interest in the region.

These explorations, coupled with early missionary activities, gradually increased European awareness of and influence in the East African interior, paving the way for the subsequent Scramble for Africa and the establishment of colonial rule. The growing interest of European powers in the region's resources and strategic location marked the beginning of a new era for Kenya.

3.6. German Protectorate (1885-1890)

The colonial history of Kenya includes a brief period of German influence. In 1885, the German Empire established a protectorate over the coastal possessions of the Sultan of Zanzibar. This move was part of Germany's broader ambitions in East Africa and brought them into direct competition with British interests in the region, which were being advanced by entities like the Imperial British East Africa Company, chartered in 1888.

The potential for imperial rivalry between Germany and Britain over these coastal territories was largely averted by the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty of 1890. Under the terms of this treaty, Germany ceded its coastal holdings in East Africa, including its protectorate over parts of the Kenyan coast, to Britain in exchange for control of the island of Heligoland in the North Sea and other territorial considerations. This treaty effectively consolidated British influence over what would become modern-day Kenya and marked the end of the short-lived German protectorate on the Kenyan coast.

3.7. British East Africa and Kenya Colony (1888-1962)

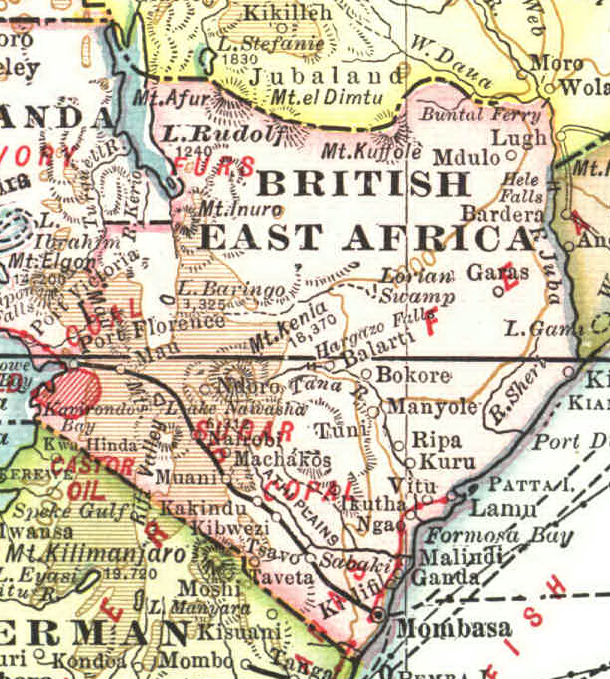

Following the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty of 1890 where Germany transferred its coastal holdings to Britain, British influence in the region solidified. The Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC) had been chartered in 1888 to administer territories stretching from the coast into the interior. The construction of the Uganda Railway from Mombasa to Lake Victoria, starting in 1895 and passing through the Kenyan highlands, was a pivotal project aimed at securing British strategic and economic interests, particularly access to Uganda. The building of the railway was met with resistance from some local ethnic groups, notably the Nandi, led by their Orkoiyot (spiritual leader) Koitalel Arap Samoei, who resisted from 1890 until his assassination by the British in 1900. The Nandi were subsequently among the first ethnic groups to be confined to "native reserves" to prevent disruption to the railway's construction.

During the railway construction, a significant number of Indian workers were brought in to provide skilled labor. Many of them and their descendants remained in Kenya, forming distinct Indian communities, such as the Ismaili Muslim and Sikh communities. The infamous Tsavo Man-Eaters, two lions that preyed on railway workers, became a legendary part of this era.

In 1895, the British government declared a formal protectorate, the East Africa Protectorate. Mombasa served as its capital from 1889 to 1907. In 1920, the status of the territory was changed, and it became the Kenya Colony and Protectorate (the coastal strip remained a protectorate under an agreement with the Sultan of Zanzibar, while the interior became a colony). This period saw the systematic implementation of colonial administration policies, significant socio-economic changes, and the rise of African resistance movements against British rule.

3.7.2. Impact of World War I and World War II

The two World Wars had significant political, economic, and social impacts on Kenya and its people.

During World War I, British East Africa (as Kenya was then known) became a theater of conflict in the East African Campaign against German East Africa (present-day Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi). The governors of British and German East Africa initially agreed to a truce to keep the colonies out of the war, but this was overruled by military commanders like Germany's Lieutenant Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck. Von Lettow-Vorbeck conducted an effective guerrilla campaign, tying down substantial British resources. To counter him, the British deployed British Indian Army troops and conscripted large numbers of Africans as soldiers and, more extensively, as porters in the Carrier Corps. Over 400,000 Africans were mobilized for the Carrier Corps, facing harsh conditions, disease, and high mortality rates. Their experiences in the war, exposure to different peoples, and the realization of their role in defending the Empire contributed to a growing political consciousness and long-term politicization, which later fed into anti-colonial sentiments. The war disrupted local economies and agricultural production.

In World War II, Kenya served as an important base for British operations in Africa and was a significant source of manpower and agricultural produce for the Allies. Kenyan soldiers, as part of the King's African Rifles, fought in various campaigns, including the East African Campaign against Italian forces in Somaliland and Ethiopia, as well as in Burma and the Middle East. Italian forces invaded Kenya in 1940-41, and towns like Wajir and Malindi were bombed.

The economic impact included increased demand for Kenyan agricultural products, but also shortages and inflation. Politically, the war further heightened African awareness of global events and the hypocrisy of fighting for freedom against fascism while being subjected to colonial rule. Returning soldiers, having fought alongside Europeans and witnessed different societies, became more assertive in demanding their rights and an end to colonialism. The wars, therefore, inadvertently accelerated the nationalist movements that would eventually lead to Kenya's independence.

3.8. Mau Mau Uprising (1952-1959)

The Mau Mau Uprising, also known as the Mau Mau Rebellion or the Kenya Emergency, was a significant military conflict that took place in British Kenya between 1952 and 1959. It was a key event in Kenya's path to independence.

Background: The uprising was rooted in grievances of the Kikuyu and other groups like the Embu and Meru against British colonial rule, primarily concerning land alienation (especially the fertile "White Highlands" reserved for European settlers), economic disparities, lack of political representation, and racial discrimination. The Kenya Land and Freedom Army (KLFA), the main fighting force of the Mau Mau, sought to reclaim lost lands and achieve political independence.

Progression and Major Events: The conflict officially began in October 1952 when the colonial government declared a state of emergency. The Mau Mau employed guerrilla warfare tactics, targeting colonial installations, European settlers, and African loyalists (those perceived as collaborators with the British). The British responded with a large-scale counter-insurgency operation, deploying British troops, African colonial troops (including the King's African Rifles), and forming a "Home Guard" of loyalist Africans.

Key figures in the Mau Mau movement included Dedan Kimathi and Waruhiu Itote (General China). The British military effort was led by General Sir George Erskine, appointed in May 1953. A major British tactic was Operation Anvil in April 1954, which involved a massive sweep of Nairobi to round up suspected Mau Mau members and supporters. This led to the detention of tens of thousands of Kikuyu.

Human Rights Abuses: The conflict was characterized by brutality and human rights abuses on all sides. Mau Mau fighters committed atrocities, including the Lari massacre where Kikuyu loyalists were killed. The British colonial forces and their allies also engaged in widespread human rights violations, including torture, summary executions, and inhumane conditions in detention camps where over 80,000 Kikuyu were held without trial. The Hola massacre in 1959, where 11 detainees were beaten to death by camp guards, drew international condemnation and highlighted the severity of abuses in the camps.

Outcomes and Historical Significance: The military offensive of the Mau Mau was largely suppressed by 1956, particularly after the capture of Dedan Kimathi in October of that year. The state of emergency was lifted in December 1959, though isolated incidents continued. Estimates of casualties vary, but it is believed that over 11,000 Mau Mau fighters were killed, along with around 100 British troops and approximately 2,000 Kenyan loyalist soldiers and civilians.

The Mau Mau Uprising, despite its military defeat, played a crucial role in accelerating Kenya's independence. It demonstrated the depth of African opposition to colonial rule and forced the British government to reconsider its policies in Kenya and other colonies. The uprising led to political reforms, including increased African participation in government, and ultimately contributed to the decision to grant Kenya independence in 1963. The Swynnerton Plan (1954), a land reform program, was introduced partly to address land grievances and reward loyalists, but it also created a class of landless Kikuyu. The legacy of the Mau Mau Uprising remains a complex and sometimes contentious part of Kenyan national identity, with ongoing debates about its nature, leadership, and the role of various communities. In recent years, there has been greater acknowledgement of the suffering endured by Kenyans during the Emergency, including a formal apology and compensation from the British government to some victims of colonial-era abuses.

3.9. Northern Frontier District Somali referendum (1962)

On the eve of Kenyan independence, a significant political issue arose concerning the Northern Frontier District (NFD). This vast, arid, and semi-arid region, bordering Somalia, was predominantly inhabited by ethnic Somalis and related Cushitic-speaking groups such as the Oromo and Rendille. Many Somalis in the NFD desired to secede from Kenya and unite with the newly independent Somali Republic (Somalia), which had been formed in 1960 from the union of former British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland, and which espoused a policy of "Greater Somalia" (Soomaaliweyn).

In response to these secessionist demands and to ascertain the wishes of the inhabitants, the British colonial administration, in conjunction with an independent commission, conducted a referendum in the NFD in 1962. The referendum asked the predominantly Somali population whether they wished to become part of Somalia, remain with Kenya, or have some other status.

The results of the referendum showed that an overwhelming majority of the Somalis in the NFD, reportedly around 86%, voted in favor of secession from Kenya and unification with Somalia.

Despite this clear expression of popular will by the Somali inhabitants, the British government, influenced by pressure from the emerging Kenyan nationalist leadership (who were strongly opposed to any territorial dismemberment) and Cold War geopolitical considerations, decided to disregard the referendum results. The NFD was subsequently incorporated into an independent Kenya in 1963.

This decision led to profound discontent among the Somali population of the NFD and was a direct cause of the Shifta War (1963-1967), a secessionist conflict between Somali guerrillas (referred to as "shifta" or bandits by the Kenyan government) and the Kenyan government. The conflict caused considerable instability and loss of life in the region. The legacy of the 1962 referendum and the subsequent Shifta War continued to affect relations between Kenya and Somalia, as well as the socio-political integration of the Somali community within Kenya for decades.

3.10. Independence (1963)

Kenya achieved independence from Britain on 12 December 1963, marking the end of nearly seven decades of colonial rule. The path to independence was shaped by decades of African political activism, trade union movements, and the armed struggle of the Mau Mau Uprising, which, despite its military suppression, significantly hastened political reforms.

The first direct elections for native Kenyans to the Legislative Council took place in 1957. Constitutional conferences, known as the Lancaster House Conferences, were held in London between 1960 and 1963 to negotiate the terms of Kenya's independence and draft a new constitution. Key Kenyan political figures involved in these negotiations included Jomo Kenyatta of the Kenya African National Union (KANU) and Ronald Ngala of the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU). KANU generally favored a unitary state, while KADU advocated for a federal system (Majimbo) to protect the interests of smaller ethnic groups.

In the general elections held in May 1963, KANU, led by Jomo Kenyatta (who had been released from detention in 1961), won a decisive victory. Despite British hopes of handing power to more "moderate" local rivals, KANU formed the government, and Kenyatta became Prime Minister under a system of internal self-government.

On 12 December 1963, the Colony of Kenya and the Protectorate of Kenya (the coastal strip leased from the Sultan of Zanzibar) officially came to an end. The United Kingdom ceded sovereignty over the Colony of Kenya. Simultaneously, the Sultan of Zanzibar agreed to cease his sovereignty over the Protectorate of Kenya, allowing all of Kenya to become one sovereign state under the Kenya Independence Act 1963 of the United Kingdom. Queen Elizabeth II remained head of state as Queen of Kenya, represented by a Governor-General.

The political climate at the time was one of optimism and anticipation, but also of underlying ethnic tensions and economic challenges. The new government faced the tasks of nation-building, addressing historical injustices related to land, and fostering economic development.

One year later, on 12 December 1964, Kenya became a republic, with Jomo Kenyatta as its first president, and remained a member of the Commonwealth of Nations.

3.11. Jomo Kenyatta era (1963-1978)

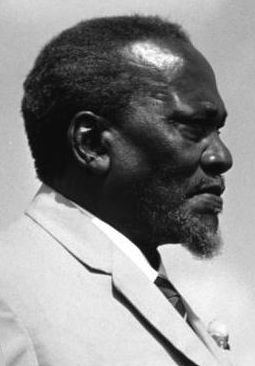

Following Kenya's transition to a republic on 12 December 1964, Jomo Kenyatta, who had been Prime Minister since independence, became the country's first President. His tenure, lasting until his death in August 1978, was a formative period for Kenya, characterized by efforts at nation-building, economic development, but also significant challenges including emerging corruption and concerns over human rights and democratic consolidation.

Under Kenyatta, Kenya adopted a capitalist economic model, encouraging foreign investment and promoting African entrepreneurship through policies like Africanization of the economy. The early years saw notable economic growth, often referred to as the "Kenyan miracle," driven by agriculture (particularly tea and coffee exports) and a nascent tourism industry. The government invested in infrastructure, education, and healthcare, aiming to improve living standards. Kenyatta pursued a policy of "Harambee" (meaning "all pull together" in Swahili), emphasizing self-help community projects for development.

In terms of political system, Kenya initially had a multi-party system, but by 1964, the main opposition party, the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU), voluntarily dissolved and merged with the ruling Kenya African National Union (KANU), effectively making Kenya a de facto one-party state. Kenyatta's government aimed to foster national unity among Kenya's diverse ethnic groups, but his administration was often perceived as favoring his own Kikuyu ethnic group, leading to ethnic tensions and accusations of tribalism.

Challenges during the Kenyatta era included widespread corruption that became entrenched in government, civil service, and business. Kenyatta and his family were themselves implicated in amassing considerable wealth and property, particularly land, which caused anger among landless Kenyans and raised ethical concerns. His family's business interests, including in the coastal hotel industry, were seen as benefiting from his presidential position.

On the human rights front, while Kenya was relatively stable compared to some of its neighbors, Kenyatta's government was not without its critics. Opposition figures like Oginga Odinga, who formed the Kenya People's Union (KPU) in 1966, faced suppression. The KPU was banned in 1969 following the Kisumu Massacre, where government forces clashed with Odinga's supporters, and KPU leaders were detained without trial. This crackdown on dissent and the consolidation of power within KANU raised concerns about the state of democracy and human rights. Amnesty International highlighted these issues, noting that stability often came at the cost of human rights abuses, including the outlawing of opposition parties and groups like the Kenya Students Union and Jehovah's Witnesses.

Despite these challenges, Kenyatta is often remembered as the "Founding Father" of Kenya (Mzee), credited with laying the foundations for a modern state and maintaining relative stability during a turbulent period in African history. However, his legacy is also viewed critically, particularly regarding issues of corruption, ethnic favoritism, and the suppression of political opposition, which had lasting impacts on Kenya's socio-political landscape.

3.12. Daniel arap Moi era (1978-2002)

Following Jomo Kenyatta's death in August 1978, Vice-President Daniel arap Moi ascended to the presidency, initially in an acting capacity and then formally. His presidency, which spanned 24 years until 2002, was a period of significant political and social change, marked by the consolidation of a one-party state, increasing authoritarianism, economic challenges, and eventually, growing demands for democratic reform. Moi's rule had a profound impact on Kenya's democratic institutions and human rights.

Moi initially enjoyed popular support, promising to follow Kenyatta's path (Nyayo philosophy, meaning "footsteps"). He retained the presidency in unopposed elections in 1979 and 1983. In June 1982, the constitution was amended to make Kenya a de jure one-party state under KANU. This move was partly a response to growing political dissent.

A critical event during Moi's early rule was the failed military coup on 1 August 1982, staged mainly by enlisted men of the Kenya Air Force and masterminded by Senior Private Hezekiah Ochuka. The coup was quickly suppressed by loyalist forces, including the General Service Unit (GSU) and regular police, commanded by Chief of General Staff Mahamoud Mohamed. The aftermath saw a crackdown on perceived dissidents, purges within the military and civil service, and further consolidation of Moi's power.

Throughout the 1980s, Moi's government became increasingly authoritarian. Political opposition was suppressed, freedom of expression and assembly were curtailed, and human rights abuses, including detention without trial, torture of political prisoners, and restrictions on the media, became more prevalent. Ethnic tensions were often exploited for political gain. Events like the Garissa Massacre of 1980 and the Wagalla massacre in 1984, where Kenyan troops committed atrocities against civilians primarily of Somali ethnicity in Wajir County and Garissa, highlighted severe state-sponsored violence and human rights violations. An official probe into the Wagalla massacre was ordered much later, in 2011.

The 1988 general election, which utilized the controversial mlolongo (queuing) system where voters lined up behind their favored candidates instead of using a secret ballot, was widely seen as undemocratic and further fueled discontent.

Economic performance during the Moi era was mixed. While there were periods of growth, issues like corruption, mismanagement of state resources, and declining international aid (often tied to governance concerns) hampered development. The Goldenberg scandal, a massive export compensation fraud scheme in the early 1990s, cost the country hundreds of millions of dollars and epitomized the scale of corruption.

3.12.1. Introduction of multi-party system and attempts at political reform

By the late 1980s and early 1990s, internal pressure from civil society, religious leaders, and pro-democracy activists, combined with external pressure from Western donor nations following the end of the Cold War, led to growing demands for political reform and a return to multi-party democracy.

In December 1991, under significant pressure, President Moi's government repealed Section 2A of the constitution, thereby ending KANU's legal monopoly on power and re-introducing a multi-party system after 26 years of single-party rule (de facto since 1964, de jure since 1982). This opened the way for the formation of opposition political parties.

The first multi-party elections were held in December 1992. Several opposition parties emerged, including the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD), which later split into FORD-Kenya (led by Jaramogi Oginga Odinga) and FORD-Asili (led by Kenneth Matiba). Mwai Kibaki also left KANU to form the Democratic Party (DP). The elections were marred by allegations of state-sponsored ethnic violence, intimidation of opponents, harassment of election officials, and rigging. Moi won the presidency, largely due to a divided opposition, and KANU retained control of Parliament, though opposition parties secured a significant number of seats (88 out of 188 elected). The aftermath of the 1992 elections saw ethnic clashes, particularly in the Rift Valley Province, leading to thousands of deaths and widespread displacement, which critics alleged were orchestrated to punish opposition supporters.

Despite the return to multi-partyism, genuine democratic reform was slow and often resisted by the Moi regime. Opposition parties faced harassment, and the state machinery was often used to favor KANU. In 1994, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga passed away. Richard Leakey formed the Safina party in 1995, but it faced difficulties in getting registered until November 1997.

In 1996, KANU revised the constitution to allow Moi to remain president for another term. Moi stood for re-election in the December 1997 general election and won a fifth term, again amid a divided opposition and claims of fraud by opponents like Mwai Kibaki and Raila Odinga. The period leading up to and following the 1997 elections also saw instances of ethnic violence.

Although Moi was constitutionally barred from seeking another presidential term after 1997, he attempted to influence succession politics by backing Uhuru Kenyatta as KANU's presidential candidate for the 2002 elections. The re-introduction of the multi-party system marked a significant shift, but the path to full democratic consolidation remained challenging, with ongoing struggles for greater political freedoms, institutional reforms, and an end to impunity.

3.13. Mwai Kibaki era (2002-2013)

The presidency of Mwai Kibaki, from December 2002 to April 2013, marked a significant period of transition for Kenya, characterized by initial optimism for democratic and economic reform, followed by major political crises and culminating in the promulgation of a new constitution.

In the December 2002 general election, Mwai Kibaki, leading the opposition coalition National Rainbow Coalition (NARC), decisively defeated KANU's candidate, Uhuru Kenyatta (who was endorsed by the outgoing President Moi). This election was widely hailed by local and international observers as free and fair, signifying a peaceful transfer of power and a turning point in Kenya's democratic evolution.

Kibaki's NARC government came to power with a strong mandate for change, promising to fight corruption, revive the economy, improve education, and deliver a new constitution. Early successes included the introduction of free primary education, which saw a massive increase in school enrollment. The economy experienced a period of recovery and robust growth for several years.

However, the NARC coalition was fraught with internal tensions, particularly over a pre-election Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) regarding power-sharing and the constitutional review process. In 2005, a government-backed draft constitution was put to a referendum. This draft was opposed by a faction within NARC led by Raila Odinga (the "Orange" camp, who argued it did not sufficiently reduce presidential powers) and supported by Kibaki (the "Banana" camp). The draft constitution was rejected by voters, leading to a political realignment and Kibaki dismissing his entire cabinet and forming a new one.

3.13.1. 2007 presidential election and Kenya crisis

The December 2007 presidential election pitted incumbent Mwai Kibaki, running under the newly formed Party of National Unity (PNU), against Raila Odinga of the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM). The election was highly contested. Initial results showed Odinga in the lead, but the final tally announced by the Electoral Commission of Kenya declared Kibaki the winner. Odinga and ODM immediately alleged widespread rigging and electoral fraud.

The announcement of Kibaki's victory triggered widespread protests and violence across the country, quickly taking on ethnic dimensions. Supporters of both PNU and ODM clashed, and police were accused of using excessive force. The violence was particularly severe in the Rift Valley Province, Nyanza Province, and urban slums like Kibera in Nairobi. An estimated 1,500 people were killed, and over 600,000 were internally displaced, making it the worst political crisis in Kenya's independent history. The violence had a devastating humanitarian impact and severely damaged Kenya's economy and international reputation.

International mediation efforts, led by former United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan and a panel of eminent African personalities, were launched to resolve the crisis. After weeks of negotiations, Kibaki and Odinga signed a National Accord and Reconciliation Act in February 2008. This agreement led to the formation of a Grand Coalition Government, with Kibaki remaining as President and Odinga becoming the newly created post of Prime Minister, effectively sharing executive power. The coalition government also included members from both PNU and ODM, aiming to restore stability and address the underlying causes of the conflict.

3.13.2. Promulgation of the new Constitution (2010)

One of the key mandates of the Grand Coalition Government was to deliver a new constitution, a demand that had been central to Kenyan politics for over two decades. The post-election violence of 2007-2008 underscored the urgent need for fundamental constitutional and institutional reforms to address issues of governance, power-sharing, ethnic grievances, land injustice, and impunity.

A Committee of Experts on Constitutional Review was established to draft a new constitution, incorporating views from various stakeholders and past review processes. After extensive public participation and debate, a proposed new constitution was put to a referendum on 4 August 2010.

The proposed constitution received overwhelming support, with 67% of voters approving it. It was officially promulgated on 27 August 2010, replacing the 1963 independence constitution.

The 2010 Constitution introduced significant changes aimed at strengthening democratic principles, human rights, and accountability. Key features included:

- A comprehensive Bill of Rights, protecting a wide range of civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights.

- Devolution of power and resources to 47 newly created counties, each with its own elected governor and assembly, aimed at promoting equitable development and local participation.

- Separation of powers among the executive, legislature, and judiciary, with checks and balances. The presidency's powers were reduced.

- An independent judiciary, with reforms to the appointment and oversight of judges.

- Reforms to land ownership and management.

- Provisions for gender equality, including requirements for female representation in elected bodies.

- Establishment of independent commissions to oversee various aspects of governance, such as elections, human rights, and land.

The promulgation of the new constitution was a landmark achievement and was seen as a critical step in Kenya's journey towards a more democratic, equitable, and just society. It provided a framework for addressing many of the historical grievances that had fueled political instability. During this period, in July 2010, Kenya, along with other East African countries, launched the East African Community Common Market. In 2011, Kenya also faced a severe drought, particularly in the Turkana region, and launched Operation Linda Nchi, a military intervention in southern Somalia to combat the Al-Shabaab militant group.

3.14. Uhuru Kenyatta era (2013-2022)

Uhuru Kenyatta, son of Kenya's first president Jomo Kenyatta, served as the fourth President of Kenya from April 2013 to September 2022. His tenure was marked by significant infrastructure development projects under the Vision 2030 blueprint, continued economic growth, but also persistent challenges including corruption, national debt, security threats, and political tensions surrounding elections.

Uhuru Kenyatta first won the presidency in the March 2013 general election, running on a ticket with William Ruto as his deputy. This was the first election held under the new 2010 Constitution. His main opponent, Raila Odinga, challenged the results in the Supreme Court, but the court upheld Kenyatta's victory. Both Kenyatta and Ruto faced charges at the International Criminal Court (ICC) related to the 2007-2008 post-election violence, though the charges against Kenyatta were later dropped in December 2014, and those against Ruto were vacated in April 2016 due to insufficient evidence, with the case marked by allegations of witness interference.

3.14.1. Key policies and socio-economic changes

President Kenyatta's government prioritized large-scale infrastructure projects, including the Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway (SGR), expansion of roads, ports, and energy generation (particularly geothermal power). These projects aimed to boost economic growth and regional connectivity. The Vision 2030 national development plan continued to guide policy, focusing on economic, social, and political pillars.

In social sectors, initiatives included efforts to improve healthcare, such as the Managed Equipment Services (MES) project to equip hospitals, and reforms in education. The digital literacy program, aimed at providing laptops to primary school children, was launched but faced implementation challenges.

Economically, Kenya saw continued GDP growth during much of his tenure, driven by services, construction, and agriculture. However, this growth was accompanied by a significant increase in public debt, raising concerns about sustainability. Corruption remained a major challenge, despite government pledges to combat it. Several high-profile corruption scandals emerged during this period.

Socially, issues of youth unemployment, income inequality, and land tenure remained pertinent. The government also faced security challenges, including attacks by the Al-Shabaab militant group, notably the Westgate Mall attack in 2013 and the Garissa University College attack in 2015.

The social and environmental impacts of large development projects, such as displacement of communities for infrastructure and concerns about environmental degradation, were subjects of public debate and activism. The government implemented a ban on single-use plastic bags in 2017, a significant environmental policy.

3.14.2. 2017 presidential election controversy

The August 2017 presidential election saw Uhuru Kenyatta seek a second term against Raila Odinga. The Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) declared Kenyatta the winner. However, Odinga's National Super Alliance (NASA) coalition challenged the result in the Supreme Court, alleging irregularities and illegalities in the electoral process.

In a landmark ruling on 1 September 2017, the Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice David Maraga, annulled the presidential election result, citing irregularities in the transmission of results and a failure by the IEBC to conduct the election in accordance with the Constitution and electoral laws. This was the first time in Africa that a presidential election result was overturned by a court.

A fresh presidential election was ordered to be held within 60 days. The repeat election took place on 26 October 2017. However, Raila Odinga and NASA boycotted the re-run, arguing that the IEBC had not implemented sufficient reforms to ensure a fair election. Uhuru Kenyatta won the repeat election with a large majority, though voter turnout was significantly lower. His victory was subsequently upheld by the Supreme Court after further legal challenges.

The 2017 election period was marked by heightened political tensions, protests, and accusations of police brutality.

In March 2018, President Kenyatta and Raila Odinga engaged in a widely publicized "handshake," a gesture of reconciliation aimed at ending political animosity and fostering national unity. This led to the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI), a process ostensibly aimed at constitutional reforms to address issues like divisive elections, ethnic antagonism, and inclusivity. The BBI proposed significant changes, including the creation of a Prime Minister post and an official Leader of the Opposition. However, critics, including Deputy President William Ruto, viewed it as an attempt by political dynasties to consolidate power and unnecessarily expand the government. The BBI process faced legal challenges, and in May 2021, the Kenyan High Court ruled that the BBI constitutional reform effort was unconstitutional. This ruling was upheld by the Court of Appeal in August 2021, effectively stopping the proposed amendments.

3.15. William Ruto era (2022-present)

Following the end of Uhuru Kenyatta's two terms, Kenya held its general election on 9 August 2022. William Ruto, who had served as Deputy President under Kenyatta, ran for the presidency under the Kenya Kwanza (Kenya First) coalition. His main opponent was Raila Odinga, representing the Azimio La Umoja (Resolution for Unity) coalition and backed by the outgoing President Kenyatta.

The election campaign was closely contested, focusing on economic issues, particularly the high cost of living, youth unemployment, and national debt. Ruto campaigned on a "bottom-up" economic model, promising to support small businesses and farmers.

On 15 August 2022, the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) chairman, Wafula Chebukati, declared William Ruto the winner of the presidential election, having garnered 50.49% of the vote against Odinga's 48.85%. However, four out of the seven IEBC commissioners disowned the results shortly before the announcement, citing opacity in the final tallying process, which led to controversy and uncertainty.

Raila Odinga and the Azimio La Umoja coalition challenged the presidential election results at the Supreme Court. On 5 September 2022, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld William Ruto's victory, dismissing the petitions challenging the result.

William Ruto was sworn in as Kenya's fifth president on 13 September 2022. Upon taking office, President Ruto outlined his administration's priorities, focusing on economic recovery, lowering the cost of living, creating employment, and implementing agricultural reforms. His government has initiated policies aimed at fiscal consolidation, reducing reliance on borrowing, and supporting sectors like agriculture through subsidies and other interventions.

Current challenges facing the Ruto administration include managing the high national debt, addressing persistent inflation and cost of living pressures, tackling youth unemployment, and navigating a complex regional security environment. Initial policies have included the removal of some subsidies on fuel and maize flour, which were controversial, and efforts to increase tax revenue.

In 2024, Ruto's government and the Kenya Kwanza coalition faced significant popular protests across the country in response to the proposed Kenya Finance Bill 2024, which included several tax hikes. The protests, largely led by youth, highlighted public discontent over the economic policies and the perceived burden on ordinary citizens.

4. Geography

Kenya is located in East Africa, straddling the equator. It is bordered by South Sudan to the northwest, Ethiopia to the north, Somalia to the east, Uganda to the west, and Tanzania to the south. To the southeast, it has a coastline on the Indian Ocean. With a total area of approximately 224 K mile2 (580.37 K km2) (or 225 K mile2 (582.65 K km2) according to some sources), Kenya is the world's 47th or 48th largest country.

The country's topography is remarkably diverse. Along the Indian Ocean coast lies a narrow, low-lying plain characterized by sandy beaches, coral reefs, and mangrove swamps. Inland, the plains rise to the Kenyan Highlands, a region of fertile plateaus and mountain ranges that forms the agricultural heartland of the country. The highlands are bisected by the Great Rift Valley, a prominent geological feature that stretches from north to south. This valley contains several lakes, including Lake Turkana, Lake Baringo, Lake Bogoria, Lake Nakuru, Lake Naivasha, and Lake Magadi.

The highest point in Kenya is Mount Kenya, an extinct volcano with a peak elevation of 17 K ft (5.20 K m), making it the second-highest mountain in Africa after Mount Kilimanjaro. Mount Kenya features several glaciers and diverse ecological zones on its slopes. Mount Kilimanjaro, though located in Tanzania, is visible from parts of southern Kenya.

West of the Rift Valley, the land slopes down towards Lake Victoria, Africa's largest lake, of which Kenya controls a northeastern portion. This region is also characterized by fertile plateaus.

Northern and northeastern Kenya are predominantly arid and semi-arid lands, including the Chalbi Desert and the Nyiri Desert (also known as the Taru Desert). These areas are characterized by sparse vegetation, low rainfall, and pastoralist communities.

Major rivers in Kenya include the Tana River, which is the longest, and the Athi-Galana-Sabaki River, both of which flow into the Indian Ocean. Other rivers, such as the Turkwel and Kerio, drain into Lake Turkana.

The geography of Kenya supports a wide variety of ecosystems, from tropical rainforests and montane forests to savanna grasslands, wetlands, and coastal marine environments. This diversity contributes to Kenya's rich biodiversity.

4.1. Climate

Kenya's climate is as diverse as its topography, ranging from tropical along the coast to temperate inland and arid in the northern and northeastern regions.

The coastal region experiences a tropical climate, characterized by high temperatures and humidity throughout the year. Rainfall is abundant, particularly during the "long rains" season.

The Kenyan Highlands, including areas around Nairobi, have a temperate or montane climate. Temperatures here are cooler due to the high altitude, and it is generally pleasant year-round. This region also receives significant rainfall, making it suitable for agriculture. It is usually cool at night and in the early morning at these higher elevations.

The western parts of Kenya, near Lake Victoria, have a more equatorial climate with rainfall distributed throughout the year.

Northern and northeastern Kenya are predominantly arid and semi-arid. These regions experience very high temperatures during the day, low and erratic rainfall, and vast desert or semi-desert landscapes.

Kenya generally experiences two rainy seasons:

- The "long rains" occur from March/April to May/June.

- The "short rains" occur from October to November/December.

Rainfall can be heavy during these periods, often occurring in the afternoons and evenings. The period between the rainy seasons is generally dry. The hottest period is typically February and March, leading into the long rains, while the coldest period is usually July and August.

Climate change is increasingly impacting Kenya's climate patterns. This includes alterations to the timing and intensity of rainfall, leading to more frequent and severe droughts (such as the 2008-2009 Kenya Drought and the 2011 East Africa drought) as well as episodes of flooding. The drought cycle has reportedly been reducing from every ten years to more frequent, almost annual events in some areas. These changes pose significant challenges to agriculture, water resources, and livelihoods, particularly for vulnerable communities. The country receives a great deal of sunshine every month.

4.2. Wildlife

Kenya is renowned for its rich and diverse wildlife, making it one of Africa's premier safari destinations. The country has dedicated a considerable land area to wildlife conservation through a network of national parks, national reserves, and private conservancies.

Iconic species include the "Big Five": the lion, leopard, elephant, rhinoceros (both black and white species), and Cape buffalo. These animals can be found in many of Kenya's protected areas, particularly in the Maasai Mara National Reserve.

The Maasai Mara is famous for the Great Migration, an annual event where over a million wildebeest, along with hundreds of thousands of zebras and gazelles, migrate from Tanzania's Serengeti into the Mara in search of fresh grazing, typically between June/July and September/October. This spectacle involves dramatic river crossings, particularly of the Mara River. This Serengeti Migration of the wildebeest is listed among the Seven Natural Wonders of Africa. Approximately two million wildebeest migrate a distance of around 1.8 K mile (2.90 K km) in a constant clockwise fashion.

Other notable wildlife includes giraffes (Masai, reticulated, and Rothschild's subspecies), cheetahs, hippos, crocodiles, various antelope species (such as impala, eland, oryx, kudu), hyenas, wild dogs, and a vast array of birdlife, with over 1,000 bird species recorded.

Major national parks and reserves include:

- Maasai Mara National Reserve: Famous for the Great Migration and high concentrations of predators.

- Amboseli National Park: Known for its large elephant herds and stunning views of Mount Kilimanjaro.

- Tsavo East and Tsavo West National Parks: Together forming one of the largest protected areas in Kenya, home to diverse wildlife and landscapes.

- Lake Nakuru National Park: Famous for its flamingo populations (though numbers can fluctuate) and as a sanctuary for rhinoceros.

- Samburu National Reserve: Located in the arid north, known for unique species like the Grevy's zebra, reticulated giraffe, Beisa oryx, gerenuk, and Somali ostrich.

- Mount Kenya National Park: Protecting the diverse ecosystems of Mount Kenya.

Kenya's flora is also diverse, ranging from coastal forests and mangroves to montane forests, grasslands, and desert vegetation.

The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 4.2/10, ranking it 133rd globally out of 172 countries, indicating challenges in maintaining forest ecosystem integrity.

4.3. Environmental issues and conservation

Kenya faces a range of significant environmental challenges that threaten its rich biodiversity, natural resources, and the livelihoods of its people. These issues are often interconnected and exacerbated by factors such as population growth, poverty, and climate change.

Major environmental issues include:

- Deforestation: Clearing of forests for agriculture, settlement, charcoal production, and illegal logging has led to significant loss of forest cover. This impacts biodiversity, water catchments, soil stability, and contributes to climate change.

- Soil erosion: Caused by deforestation, overgrazing, and unsustainable agricultural practices, soil erosion leads to loss of fertile topsoil, reduced agricultural productivity, and siltation of rivers and lakes.

- Water scarcity: Many parts of Kenya, particularly arid and semi-arid lands (ASALs), face chronic water shortages. Increasing population, demand from agriculture and industry, and the impacts of climate change (e.g., recurrent droughts) are putting immense pressure on water resources. Pollution of water sources is also a concern.

- Wildlife poaching and Human-Wildlife Conflict: Poaching, especially for ivory (elephants) and rhino horn (rhinoceroses), remains a threat despite concerted anti-poaching efforts. Human-wildlife conflict arises as human populations expand into wildlife habitats, leading to crop damage, livestock predation, and sometimes human casualties, often resulting in retaliatory killings of wildlife.

- Climate Change Impacts: Kenya is highly vulnerable to climate change. This manifests as increased frequency and intensity of droughts and floods, rising temperatures, and changes in rainfall patterns, affecting agriculture, water availability, ecosystems, and human health. Coastal areas are also threatened by sea level rise.

- Pollution: Water pollution from industrial effluents, agricultural runoff (pesticides and fertilizers), and untreated sewage, as well as air pollution in urban centers and plastic pollution, are growing concerns.

- Desertification: Particularly in ASAL regions, land degradation due to unsustainable land use practices and climate change is leading to desertification.

Conservation efforts in Kenya are undertaken by governmental bodies like the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) and the Kenya Forest Service (KFS), as well as numerous national and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs), community-based organizations (CBOs), and private conservancies.

Key conservation strategies include:

- Establishment and management of national parks and reserves.

- Anti-poaching patrols and law enforcement.

- Reforestation and afforestation programs.

- Promotion of sustainable land management and agricultural practices.

- Community-based conservation initiatives, which aim to involve local communities in wildlife management and share benefits from tourism and conservation. This is crucial for addressing human-wildlife conflict and ensuring that local communities, including indigenous groups, see value in conservation.

- Development of renewable energy sources to reduce reliance on wood fuel.

- Implementation of environmental policies and regulations, such as the ban on single-use plastic bags (2017) and the extension of this ban to protected areas (2020). A 2023 law mandates companies to actively reduce pollution from their products through extended producer responsibility schemes.

Despite these efforts, challenges remain, including inadequate funding, governance issues, corruption, and the need to balance conservation goals with development pressures and the rights and needs of local communities, particularly indigenous peoples who have historically been marginalized by some conservation approaches. There is a growing emphasis on ensuring that conservation is inclusive and respects human rights.

5. Government and politics

Kenya's government and political landscape have undergone significant transformations since independence, particularly with the promulgation of the 2010 Constitution. This section outlines the country's political system, key institutions, and political processes, acknowledging the ongoing efforts towards democratization and good governance, while also highlighting challenges such as corruption and the need to uphold human rights.

5.1. Political system

Kenya is a presidential representative democratic republic with a multi-party system. The President of Kenya is both the head of state and head of government. The political system is structured around the principle of separation of powers among the three branches of government: the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary.

The Executive: Executive power is exercised by the executive branch, headed by the President. The President is directly elected by popular vote for a five-year term and is limited to two terms. To win, a presidential candidate must receive over 50% of the total votes cast and at least 25% of the votes in at least half of Kenya's 47 counties. The President is assisted by a Deputy President and a Cabinet composed of Cabinet Secretaries appointed by the President with the approval of the National Assembly. Cabinet Secretaries are not members of Parliament.

The Legislature: Legislative power is vested in the Parliament, which is bicameral, consisting of the National Assembly (the lower house) and the Senate (the upper house).

- The National Assembly has 349 members: 290 elected from constituencies, 47 women elected from each county, 12 members nominated by parliamentary political parties according to their proportion of members elected, and the Speaker, who is an ex officio member.

- The Senate has 67 members: 47 elected from each county, 16 women nominated by political parties, 2 members (one man and one woman) representing the youth, 2 members (one man and one woman) representing persons with disabilities, and the Speaker, who is an ex officio member. The Senate's primary role is to represent the interests of the counties and their governments.

The Judiciary: The Judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature. It is headed by the Chief Justice. The Supreme Court is the highest court in the land, followed by the Court of Appeal, the High Court, and various subordinate courts (Magistrates' courts, Kadhis' courts for Islamic law matters, and tribunals). The 2010 Constitution significantly reformed the judiciary to enhance its independence and efficiency, including changes to the appointment process for judges.

Fundamental constitutional principles enshrined in the 2010 Constitution include national values and principles of governance such as patriotism, national unity, rule of law, democracy and participation of the people, human dignity, equity, social justice, inclusiveness, equality, human rights, non-discrimination, and protection of the marginalized. The constitution also provides for robust mechanisms for democratic participation and accountability, including provisions for referendums, right to recall elected officials, and public participation in governance processes.

Despite these constitutional safeguards, Kenya faces ongoing challenges related to governance, including high levels of corruption. Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index has consistently ranked Kenya poorly, though there have been efforts to combat corruption, such as the establishment of the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC). There have also been historical concerns about executive interference in the judiciary, particularly during the Moi era, but the 2010 Constitution has sought to strengthen judicial independence.

5.2. Major political parties and elections

Kenya operates under a multi-party system, which was formally re-introduced in 1991 after a period of de facto and de jure one-party rule by the Kenya African National Union (KANU). The political landscape is characterized by a multitude of political parties, though these often coalesce into larger alliances, especially during election periods. Party ideologies can be fluid, and support bases are frequently, though not exclusively, drawn along ethnic lines.

Major political parties and coalitions that have been prominent in recent years include:

- The Jubilee Party: Formed by the merger of several parties, including The National Alliance (TNA) of Uhuru Kenyatta and the United Republican Party (URP) of William Ruto. It was the ruling party from 2013 to 2022.

- The Orange Democratic Movement (ODM): Led by Raila Odinga, it has been a major opposition party and a key partner in coalition governments.

- The Wiper Democratic Movement: Led by Kalonzo Musyoka.

- Kenya Kwanza: A coalition that brought William Ruto to power in the 2022 elections, with key parties including the United Democratic Alliance (UDA).

- Azimio La Umoja: The coalition that supported Raila Odinga in the 2022 elections.

Political parties in Kenya often reflect regional and ethnic allegiances, which can contribute to political polarization and, at times, conflict, particularly around elections. Efforts to promote issue-based politics and national unity over ethnic loyalties are ongoing.

Elections: Kenya holds general elections every five years to elect the President, members of the National Assembly and Senate, County Governors, and members of County Assemblies. Presidential elections require a candidate to win over 50% of the national vote and at least 25% of the vote in at least half of the 47 counties. If no candidate achieves this, a run-off election is held.

Major elections since the re-introduction of multi-partyism include:

- 1992 and 1997:** Won by Daniel arap Moi (KANU) amid a divided opposition and allegations of irregularities and ethnic violence.

- 2002:** Won by Mwai Kibaki (NARC), marking a peaceful transfer of power from KANU. Generally considered free and fair.

- 2007:** Highly disputed results led to the post-election violence. Kibaki (PNU) was declared winner over Odinga (ODM).

- 2013:** Won by Uhuru Kenyatta (Jubilee Coalition) against Raila Odinga. Results were challenged but upheld by the Supreme Court.

- 2017:** Initial results declaring Kenyatta winner were annulled by the Supreme Court due to irregularities. Kenyatta won the re-run election, which was boycotted by Odinga.

- 2022:** Won by William Ruto (Kenya Kwanza) against Raila Odinga (Azimio La Umoja). Results were challenged but upheld by the Supreme Court.

Issues of fairness, transparency, and the potential for violence have often surrounded Kenyan elections. The Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) is responsible for managing elections, but its performance has faced scrutiny. The judiciary, particularly the Supreme Court, has played an increasingly assertive role in adjudicating electoral disputes, as seen in the 2017 annulment. Efforts to reform electoral laws and processes are ongoing to build public trust and ensure peaceful and credible elections. Voter education and peace initiatives by civil society organizations are also crucial components of the electoral process.

5.3. Human rights

The 2010 Constitution of Kenya includes a comprehensive Bill of Rights that guarantees a wide range of fundamental rights and freedoms. However, the human rights situation in Kenya, while having seen improvements in some areas, continues to face significant challenges.

Major human rights issues in Kenya include:

- Freedom of Expression and Assembly: While generally respected, there have been instances of restrictions on media freedom, harassment of journalists and activists, and the use of excessive force by police during protests.

- LGBTQ+ Rights: Homosexual acts between consenting adults remain criminalized under colonial-era provisions of the Penal Code, punishable by imprisonment. Societal discrimination and stigmatization against LGBTQ+ individuals are widespread. A 2020 Pew Research Center survey indicated that 83% of Kenyans believe homosexuality should not be accepted by society. Legal challenges to decriminalize same-sex relations have so far been unsuccessful.

- Judicial Justice and Rule of Law: While the judiciary has shown increased independence, challenges such as case backlogs, corruption within the justice system, and limited access to justice for many Kenyans persist.

- Police Brutality and Extrajudicial Killings: Security forces, particularly the police, have frequently been implicated in excessive use of force, extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, and torture, especially during law enforcement operations, counter-terrorism efforts, and the policing of protests. The Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR) and other human rights organizations have documented such abuses. The 2008 "Cry of Blood" report by KNCHR detailed extrajudicial killings by police. Impunity for these violations remains a serious concern.

- Minority Rights and Ethnic Discrimination: Despite constitutional protections, ethnic discrimination and marginalization persist in various forms, affecting access to resources, political representation, and employment. Inter-ethnic tensions sometimes flare up, particularly around elections or resource disputes.

- Women's Rights: Gender inequality and violence against women, including domestic violence, sexual assault, and female genital mutilation (FGM, though illegal since 2011), remain prevalent. Access to justice for survivors of gender-based violence can be limited. Women's political participation has increased but still falls short of constitutional targets for gender representation.

- Refugee Rights: Kenya hosts a large refugee population, primarily from neighboring countries like Somalia and South Sudan. While providing asylum, refugees often face restrictions on movement, employment, and access to services.

- Land Rights and Forced Evictions: Disputes over land ownership are common, and forced evictions, sometimes violent, affect vulnerable communities, particularly in informal settlements and areas slated for development projects.

The legal framework for human rights includes the Constitution, various statutes, and international human rights treaties to which Kenya is a party. Independent institutions like the KNCHR and the Commission on Administrative Justice (Ombudsman) are mandated to promote and protect human rights. Civil society organizations play a crucial role in advocating for human rights, providing legal aid, monitoring violations, and pushing for accountability and reform. Despite these efforts, full realization of human rights for all Kenyans remains an ongoing struggle requiring sustained commitment to institutional reform, accountability, and addressing systemic inequalities.

6. Foreign relations

Kenya maintains an active foreign policy focused on regional stability, economic cooperation, and multilateralism. It generally pursues a stance of non-alignment but has historically maintained strong ties with Western nations while increasingly engaging with emerging global powers. Kenya is a significant player in East African and African continental affairs.

Kenya is a member of numerous international organizations, including the United Nations (UN) - hosting the UN Office at Nairobi (UNON), which is the UN headquarters in Africa, as well as the headquarters for the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and UN-Habitat - the Commonwealth of Nations, the African Union (AU), the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA). It is also a major non-NATO ally of the United States.

6.1. Relations with neighboring countries

Kenya places a high priority on its relations with neighboring countries, particularly within the framework of the East African Community (EAC), which also includes Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The EAC aims for deeper economic integration, including a customs union, common market, monetary union, and ultimately, a political federation. Relations with Uganda and Tanzania are generally strong, with significant trade and social ties.

Relations with Somalia have historically been complex, marked by border disputes and security concerns related to the Shifta War in the 1960s and, more recently, the threat from the Al-Shabaab militant group. Kenya has undertaken military interventions in Somalia as part of regional and international efforts to stabilize the country and combat terrorism, notably Operation Linda Nchi launched in 2011, and subsequently as part of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM/ATMIS). Kenya also hosts a large number of Somali refugees.

Relations with Ethiopia are generally cordial, with cooperation on security matters and infrastructure projects, including a defense pact signed in 1969 which is still in effect. Kenya also engages with South Sudan on issues of peace, security, and regional development, having played a role in mediating peace talks for South Sudan.

Kenya's foreign policy in the region focuses on promoting peace and security, mediating conflicts, fostering economic integration, and addressing trans-boundary challenges such as terrorism, piracy, and illicit trade.

6.2. Relations with major powers

Kenya has maintained historically strong ties with the United Kingdom, its former colonial ruler. The UK is a significant trading partner, source of investment, and provider of development assistance. The British Army Training Unit Kenya (BATUK) conducts training exercises in Kenya.

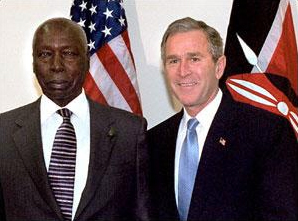

The United States is another key partner for Kenya, particularly in areas of security cooperation (especially counter-terrorism), trade, and health. The US provides substantial development and military aid. Kenya is considered one of the most pro-American nations in Africa. Former US President Barack Obama, whose father was Kenyan, visited Kenya in 2015, the first sitting American president to do so.

Relations with China have expanded significantly in recent decades. China has become a major economic partner, involved in large-scale infrastructure projects (such as the Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway), trade, and investment. This growing relationship has brought economic benefits but also concerns about debt sustainability and the social and environmental impacts of Chinese-funded projects. President Uhuru Kenyatta visited China in 2013, highlighting the growing ties.

Kenya also engages with other major powers, including Germany and France, and seeks to diversify its international partnerships. The social and economic implications of these relationships are subjects of ongoing national discussion, particularly regarding trade balances, debt, and the influence of foreign powers on domestic policy.

6.3. Relations with South Korea

Kenya and the Republic of Korea (South Korea) established diplomatic relations in February 1964, shortly after Kenya gained independence. Since then, the two countries have maintained generally cordial relations, with cooperation expanding in various sectors.

Political Exchange: There have been high-level visits and engagements between officials from both countries. Kenya maintains an embassy in Seoul, and South Korea has an embassy in Nairobi. Both nations cooperate within international forums like the United Nations.

Economic Cooperation: Trade between Kenya and South Korea has been growing, though it remains relatively modest. Kenya primarily exports agricultural products like coffee and tea, and imports electronics, machinery, and vehicles from South Korea. There is interest in increasing South Korean investment in Kenya, particularly in sectors like manufacturing, technology, infrastructure, and energy. Development cooperation, through agencies like the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA), has supported projects in Kenya related to education, healthcare, agriculture, and vocational training.

Cultural Exchange: Cultural exchange programs, educational partnerships between universities, and the growing popularity of Korean pop culture (Hallyu) in Kenya have contributed to a better mutual understanding between the peoples of the two countries.

Future Prospects: There is potential for strengthening bilateral ties, particularly in trade and investment, technology transfer, and development cooperation. Areas such as renewable energy, information and communication technology (ICT), and manufacturing are seen as promising for future collaboration. Kenya views South Korea as a valuable partner for its economic development goals, drawing lessons from South Korea's own rapid industrialization. South Korea, in turn, sees Kenya as an important gateway to the East African market.

7. Military

The Kenya Defence Forces (KDF) are the armed forces of the Republic of Kenya. The KDF consists of three main branches: the Kenya Army, the Kenya Navy, and the Kenya Air Force. The KDF's establishment and composition are outlined in Article 241 of the 2010 Constitution of Kenya, and it is governed by the Kenya Defence Forces Act of 2012.

The primary mission of the KDF is to defend and protect the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Kenya, to assist and cooperate with other authorities in situations of emergency or disaster, and to contribute to regional and international peace and security. The President of Kenya is the Commander-in-chief of the KDF.