1. Overview

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, is a country of significant historical and cultural depth located in West Asia. It stands as a cradle of one of the world's oldest civilizations, with a legacy stretching back to ancient empires like the Achaemenids, Parthians, and Sasanians, which have profoundly shaped global history. The nation's cultural tapestry is rich and diverse, woven from the contributions of numerous ethnic groups, including Persians, Azerbaijanis, Kurds, and Lurs, each with unique linguistic and traditional heritages. Persian, the official language, is a cornerstone of a vast literary tradition that includes globally renowned poets such as Rumi, Hafez, and Saadi.

The political system of contemporary Iran is a complex Islamic republic, established following the 1979 Revolution which overthrew the Pahlavi monarchy. It is founded on the principle of Velayat-e Faqih (Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist), vesting ultimate authority in the Supreme Leader. While the system incorporates democratic elements such as a popularly elected president and parliament (Majlis), these are significantly constrained by unelected bodies like the Guardian Council, which vets candidates and legislation, and the overarching influence of the Supreme Leader. This structure has led to persistent concerns regarding human rights, civil liberties, and the scope of democratic participation. Issues such as freedom of expression, assembly, women's rights, and the treatment of ethnic and religious minorities remain critical points of contention both domestically and internationally.

Iran's socio-economic landscape is characterized by its substantial oil and natural gas reserves, making it a major player in global energy markets. However, the economy has faced significant challenges, including international sanctions, inflation, and the need for diversification beyond the hydrocarbon sector. Government policies have aimed at economic development and self-sufficiency, but social equity and environmental sustainability, particularly issues like water scarcity and pollution, pose ongoing concerns. Despite these challenges, Iran has made notable advancements in science and technology, particularly in fields like nanotechnology, biotechnology, and its space program. The nation continues to navigate a complex path, balancing its rich historical identity and cultural values with the pressures of modernization, international relations, and the aspirations of its diverse and youthful population for greater social justice and democratic freedoms.

2. Etymology

The term Iran derives from the Middle Persian Ērān, which is first attested in a 3rd-century Sasanian inscription at Naqsh-e Rostam. This inscription, featuring Ardashir I (ruling 224-242 AD), is inscribed "This is the figure of Mazdaworshipper, the lord Ardashir, King of Iran." The accompanying Parthian inscription uses the term Aryān. Both Ērān (Middle Persian) and Aryān (Parthian) are oblique plural forms of gentilic nouns ēr- (Middle Persian) and ary- (Parthian), which themselves derive from the Proto-Iranian *arya-, meaning 'Aryan' or 'of the Iranians'. This term is recognized as a derivative of the Proto-Indo-European *ar-yo-, meaning 'one who assembles (skillfully)'. According to Persian mythology, the name "Iran" is also linked to Iraj, a legendary king. Thus, "Iran" essentially means "Land of the Aryans".

For centuries, Iran was known in the Western world as Persia. This exonym originated from Greek historians who referred to the entire Iranian plateau as PersísPersísGreek, Ancient, meaning 'the land of the Persians'. Persís itself referred to the region of Fars (or Pars) in southwestern Iran, which was the heartland of the Achaemenid Empire, founded by Cyrus the Great around 550 BC. Due to the historical prominence of Fars, the Greeks and subsequently other Western peoples extended this regional name to encompass the whole country. The Persian name Fârs (فارسFârsPersian) is derived from the earlier form Pârs (پارسPârsPersian), which in turn comes from the Old Persian Pârsâ (𐎱𐎠𐎼𐎿PārsaPersian, Old).

Iranians themselves have referred to their country as Iran since at least the Sasanian period, and the term has been used continuously within the country. In 1935, Reza Shah requested that the international community adopt the native name Iran for official use, aiming to emphasize the nation's Aryan heritage. While Iran became the official name in international contexts, the term Persia remained in cultural and historical usage. Today, both Iran and Persia are used, though Iran is the official and more common term. "Persia" is often used to refer to the historical and cultural aspects of the region.

The Persian pronunciation of Iran is ایرانIrân, pronounced /ʔiːˈɾɒːn/Persian. Common English pronunciations include /ɪˈrɑːn/ (ih-RAHN), /ɪˈræn/ (ih-RAN), and /aɪˈræn/ (eye-RAN).

3. History

Iran is home to one of the world's oldest continuous major civilizations, with historical and urban settlements dating back to 4000 BC. The southwestern and western parts of the Iranian plateau participated in the traditional ancient Near East with Elam from 3200 BC, and later with other peoples such as the Kassites, Mannaeans, and Gutians. The German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel referred to the Persians as the "first Historical People". The Iranian peoples arrived on the Iranian plateau in the late second millennium BC. The large part of Iran was first unified as a political entity by the Medes under Cyaxares in the seventh century BC, who unified Iran as a nation and empire around 625 BC. The Medes laid the groundwork for subsequent Iranian empires.

3.1. Prehistory and Ancient Empires

This section covers early settlements, the Elamite civilization, the arrival of Iranian peoples, and the rise and fall of major ancient empires including the Medes, Achaemenids, Seleucids, Parthians, and Sasanians, focusing on their societal structures, achievements, and regional impact.

Early human presence in Iran dates back to the Lower Palaeolithic. The Elamite civilization, flourishing from around 3200 BC in southwestern Iran, with its capital at Susa, was one of the earliest urban societies, contemporaneous with Mesopotamia. They developed a unique writing system, known as Proto-Elamite, and later adopted cuneiform. The ziggurat at Chogha Zanbil stands as a testament to their architectural and religious sophistication.

Around the late 2nd millennium BC, various Iranian peoples, including the Medes and Persians, migrated onto the Iranian plateau from Central Asia or via the Caucasus. The Medes established the first major Iranian empire, centered in Ecbatana (modern Hamadan), around 678 BC. They played a crucial role in the downfall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

In 550 BC, Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenids, a Persian, overthrew the Median king Astyages and founded the Achaemenid Empire. This empire became the largest the world had yet seen, stretching from the Balkans and Egypt in the west to the Indus Valley in the east. The Achaemenids were known for their centralized administration, efficient bureaucracy (including the use of Aramaic as a lingua franca), the Royal Road, a standardized system of coinage, and a policy of religious and cultural tolerance, famously exemplified by Cyrus's Edict allowing the Jews to return to Jerusalem. Zoroastrianism became influential during this period. Major Achaemenid capitals included Pasargadae, Susa, Ecbatana, and the ceremonial capital of Persepolis. The empire fell to Alexander the Great of Macedon after a series of battles culminating in 330 BC.

Following Alexander's death, his empire was divided among his generals (the Diadochi), and Iran came under the rule of the Seleucid Empire (312 BC - 63 BC), founded by Seleucus I Nicator. Hellenistic culture was introduced, but Iranian traditions persisted, particularly in the eastern regions.

Around 247 BC, the Parthians (Arsacids), an Iranian people from northeastern Iran, successfully rebelled against Seleucid rule and gradually established their own empire. The Parthians were renowned for their heavy cavalry (cataphracts) and their ability to resist Roman expansion in the east, engaging in centuries of conflict with Rome. Their culture represented a revival of Iranian traditions blended with Hellenistic influences. Their capital was Ctesiphon on the Tigris River.

In 224 AD, Ardashir I, a local Persian ruler from Pars (Persis), overthrew the last Parthian king, Artabanus IV, and founded the Sasanian Empire (224 AD - 651 AD). The Sasanians, claiming descent from the Achaemenids, aimed to restore Iranian glory. Zoroastrianism was firmly established as the state religion, with a highly organized clergy. The Sasanian era is considered a golden age of Iranian civilization, marked by significant achievements in art, architecture (e.g., the palaces at Ctesiphon and Bishapur, and intricate stucco work), music, literature (including the codification of the Avesta), and science. They developed a complex social hierarchy and a powerful centralized state. The Sasanians were in constant conflict with the Roman Empire and its successor, the Byzantine Empire, for control of the Near East and Caucasus. These long wars, along with internal strife, eventually weakened the empire, paving the way for the Arab Islamic conquest.

3.2. Middle Ages

This section details the Arab Islamic conquest, the Islamization of Iran, the contributions to the Islamic Golden Age, the rule of various Iranian and Turkic dynasties, and the impact of the Mongol and Timurid invasions.

The weakened Sasanian Empire fell to the invading Arab Muslim armies of the Rashidun Caliphate following decisive battles such as the Battle of al-Qadisiyyah (636 AD) and the Battle of Nihavand (642 AD). The last Sasanian Shah, Yazdegerd III, was killed in 651 AD, marking the end of ancient Iranian imperial rule. The Islamic conquest led to a profound transformation of Iranian society. While the conquest itself was relatively swift, the Islamization of the population was a gradual process spanning several centuries. Many Iranians converted to Islam, initially predominantly Sunni, though Zoroastrianism and other pre-Islamic faiths persisted in pockets for a long time.

Despite the Arab conquest, Persian culture and language endured and significantly influenced the developing Islamic civilization. Iranians played a crucial role in the administration of the Umayyad Caliphate and, more prominently, the Abbasid Caliphate (750-1258 AD). During the Islamic Golden Age, Persian scholars, scientists, poets, and artists made immense contributions. Figures like Avicenna (Ibn Sina) in medicine and philosophy, Al-Khwarizmi in mathematics (whose name gave us "algorithm" and "algebra"), Omar Khayyam (poet and mathematician), and Ferdowsi (author of the epic Shahnameh) are testaments to this era. Persian re-emerged as a major literary and administrative language, written in a modified Arabic script.

By the 9th century, local Iranian dynasties began to assert autonomy in various parts of Iran, marking the "Iranian Intermezzo". These included the Tahirids in Khorasan, the Saffarids in Sistan, the Samanids centered in Bukhara and Samarkand (who greatly patronized Persian literature and culture), and the Buyids, a Shi'a dynasty from Daylam who conquered Baghdad in 945 and controlled the Abbasid Caliphs for over a century.

From the 11th century, Iran experienced invasions by Turkic groups from Central Asia. The Seljuks, a Sunni Turkic dynasty, conquered Iran, Mesopotamia, and much of Anatolia, establishing a vast empire. Under Seljuk rule, Persian culture and administration continued to flourish; figures like Nizam al-Mulk, the Seljuk vizier, were patrons of arts and sciences, and Sunni Islam was promoted. The Khwarzamians, another Turkic dynasty, succeeded the Seljuks in the east but were soon overwhelmed by the Mongol invasions.

In the early 13th century, Iran suffered devastating Mongol invasions led by Genghis Khan and his successors. Cities were razed, populations massacred, and agricultural infrastructure was severely damaged. Iran became part of the Ilkhanate, a Mongol successor state founded by Hulagu Khan. Despite the initial destruction, the Ilkhanid rulers eventually converted to Islam and patronized Persian culture. Figures like the historian Rashid-al-Din Hamadani flourished under their rule.

The decline of the Ilkhanate led to a period of fragmentation until the rise of Timur (Tamerlane) in the late 14th century. Timur, of Turco-Mongol descent, conquered Iran and established the Timurid Empire, with its capital at Samarkand. While Timur's conquests were also marked by brutality, the Timurid era saw a renaissance in arts, architecture, and science, particularly under rulers like Shah Rukh and Ulugh Beg. Herat became a major cultural center. The Timurid Empire eventually fragmented, paving the way for new powers to emerge.

3.3. Early Modern Period

This section focuses on the Safavid Empire's establishment of Shia Islam as the state religion and its cultural zenith, followed by the Afsharid, Zand, and Qajar dynasties, examining political changes, socio-economic conditions, and interactions with emerging European powers.

In 1501, Ismail I founded the Safavid Empire (1501-1736), marking a pivotal moment in Iranian history. The Safavids, of mixed Kurdish and Azeri origin with claims of Sayyid descent, established Twelver Shi'ism as the state religion of Iran. This decision had profound and lasting consequences, differentiating Iran from its Sunni Muslim neighbors (notably the Ottoman Empire and the Uzbek khanates) and contributing to a distinct Iranian national and religious identity. The forced conversion to Shi'ism was sometimes brutal, but it unified the country under a single religious banner.

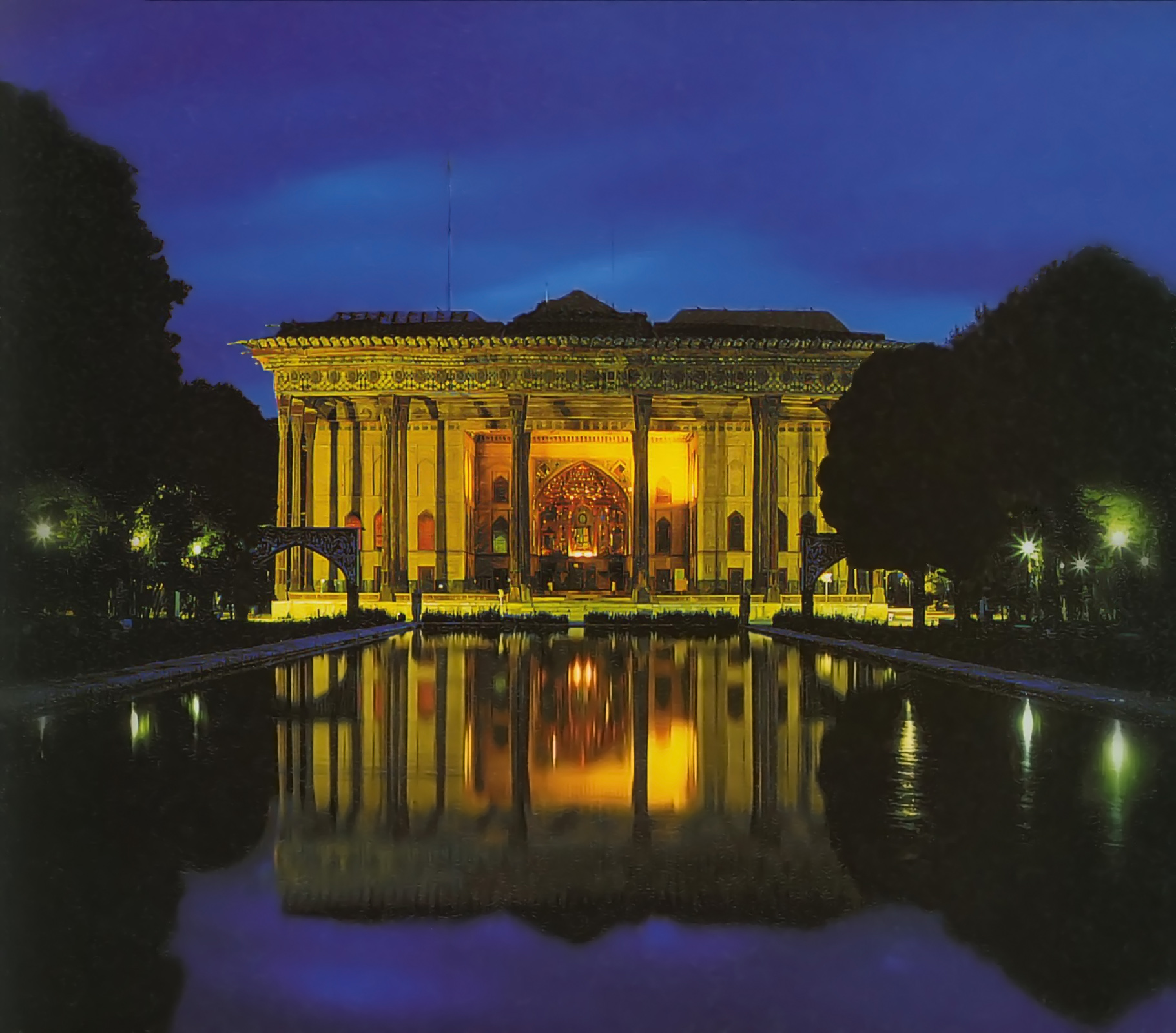

The Safavid era, particularly under Shah Abbas I (1588-1629), is considered a golden age of Iranian art, architecture, and culture. Shah Abbas moved the capital to Isfahan, which he transformed into one of the world's most beautiful cities with magnificent mosques (like the Imam Mosque), palaces (like Ali Qapu), and public squares (like Naqsh-e Jahan Square). Persian carpets, ceramics, miniature painting, and textiles reached new heights of artistic excellence. The Safavids also reformed the army, centralized administration, and engaged in extensive diplomatic and trade relations with European powers, including England and the Dutch Republic. However, conflicts with the Ottoman Empire to the west and the Uzbeks to the northeast were recurrent.

After the death of Shah Abbas I, the Safavid Empire gradually declined due to weak rulers, internal strife, and external pressures. In 1722, Afghan rebels of the Hotaki tribe captured Isfahan, effectively ending Safavid rule, though nominal Safavid shahs continued for a few more years.

The ensuing chaos was ended by Nader Shah, a brilliant military commander of Afsharid Turkic background, who expelled the Afghans and restored Iranian unity. He founded the Afsharid dynasty (1736-1796). Nader Shah was a formidable conqueror, launching successful campaigns into the Ottoman Empire, Russia, Central Asia, and famously, Mughal India, where he sacked Delhi in 1739. His military prowess briefly made Iran a dominant power. However, his rule became increasingly tyrannical, and his assassination in 1747 plunged the country into another period of civil war.

Out of this turmoil, Karim Khan Zand emerged as the ruler, founding the Zand dynasty (1751-1794). He did not take the title of Shah, preferring "Vakil ar-Ra'aya" (Regent of the People). Karim Khan ruled from Shiraz, which he beautified with many architectural projects. His reign is generally remembered as a period of relative peace, stability, and justice. However, after his death, infighting among Zand princes weakened the dynasty.

The Zands were eventually overthrown by Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, the founder of the Qajar dynasty (1785-1925). Agha Mohammad Khan brutally reunified Iran and established Tehran as the capital. The Qajar period was marked by increasing encroachment from European imperial powers, particularly Russia and Great Britain. Iran lost significant territories in the Caucasus (including modern-day Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan) to Russia through the Russo-Persian War (1804-1813) and (1826-1828), formalized in the Treaty of Gulistan (1813) and Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828). Britain expanded its influence in the Persian Gulf and Afghanistan. Internally, the Qajar shahs often faced challenges to their authority, and the country experienced socio-economic stagnation and corruption. Foreign powers gained significant economic concessions, such as the Reuter Concession and the tobacco concession, the latter sparking widespread protests. These interactions with Europe also introduced new ideas, leading to movements for reform and constitutionalism.

3.4. Modern and Contemporary Period

This section covers the Pahlavi dynasty, modernization efforts, the nationalization of the oil industry, the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the establishment of the Islamic Republic, the Iran-Iraq War, and subsequent political, social, and economic developments, including relations with the international community.

Growing discontent with Qajar rule and foreign interference culminated in the Persian Constitutional Revolution (1905-1911). This revolution led to the establishment of a constitution and a parliament (Majlis), limiting the Shah's absolute powers. However, the constitutional movement was fraught with internal divisions and faced opposition from conservative clergy and foreign powers, particularly Russia and Britain, who divided Iran into spheres of influence in the Anglo-Russian Entente of 1907.

World War I further destabilized Iran, with Ottoman, Russian, and British forces operating on its territory despite Iran's declared neutrality. In 1921, Reza Khan, a military officer, staged a coup d'état and became the dominant political figure. In 1925, he deposed the last Qajar Shah, Ahmad Shah Qajar, and was proclaimed Shah, founding the Pahlavi dynasty (1925-1979). Reza Shah embarked on an ambitious program of modernization, secularization, and nation-building. His reforms included centralizing the state, building a modern army and bureaucracy, developing infrastructure (such as the Trans-Iranian Railway), expanding education, and promoting Western dress and customs (including banning the veil for women). However, his rule was authoritarian, suppressing dissent and political freedoms. During World War II, Reza Shah's perceived pro-German sympathies led to the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran in 1941. He was forced to abdicate in favor of his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

After World War II, Iran became a key player in the Cold War. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's reign saw continued modernization and economic growth, particularly fueled by oil revenues. However, political tensions remained high. In the early 1950s, Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh gained immense popularity by nationalizing the British-owned Anglo-Persian Oil Company. This move was met with a Western boycott of Iranian oil and, in 1953, an Anglo-American-backed coup (Operation Ajax) that overthrew Mosaddegh and restored the Shah's full authority.

Following the coup, the Shah consolidated his power, becoming a staunch Western ally. He launched the White Revolution in 1963, a series of far-reaching social and economic reforms including land reform, women's suffrage, and literacy campaigns. While these reforms brought some progress, they also disrupted traditional social structures and were implemented in an autocratic manner. The Shah's regime became increasingly repressive, using the secret police, SAVAK, to crush opposition. Discontent grew among various segments of society, including secular intellectuals, students, and, crucially, the Shi'a clergy, led by the exiled Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

Years of mounting opposition, fueled by socio-economic grievances, political repression, and religious fervor, culminated in the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Mass protests and strikes paralyzed the country, forcing the Shah to flee Iran in January 1979. Ayatollah Khomeini returned from exile in February and became the leader of the revolution. On April 1, 1979, following a referendum, Iran was declared an Islamic Republic, and a new constitution based on Khomeini's principle of Velayat-e Faqih (Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist) was adopted. This established a theocracy with the Supreme Leader as the ultimate political and religious authority.

The early years of the Islamic Republic were marked by internal purges, the US embassy hostage crisis (1979-1981) which severely damaged relations with the United States, and the devastating Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988). Iraq, under Saddam Hussein, invaded Iran in September 1980, hoping to take advantage of post-revolutionary turmoil. The war, which ended in a stalemate with a UN-brokered ceasefire, resulted in hundreds of thousands of casualties on both sides and immense economic damage.

Following Khomeini's death in 1989, Ali Khamenei became the new Supreme Leader. The post-war period saw efforts at reconstruction and some economic liberalization. However, Iran faced international isolation, economic sanctions (particularly related to its nuclear program), and ongoing political tensions between reformist and conservative factions within the ruling establishment.

3.4.1. Since the 1990s

Details significant domestic political events, economic reforms, the impact of international sanctions, social issues and movements (including human rights concerns and protests), the nuclear program, and evolving foreign relations from the 1990s to the present day.

The 1990s began with the presidency of Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (1989-1997), who focused on post-war reconstruction and pragmatic economic policies, including some privatization and attempts to improve relations with the West. This period saw a degree of social and cultural loosening compared to the immediate post-revolutionary years.

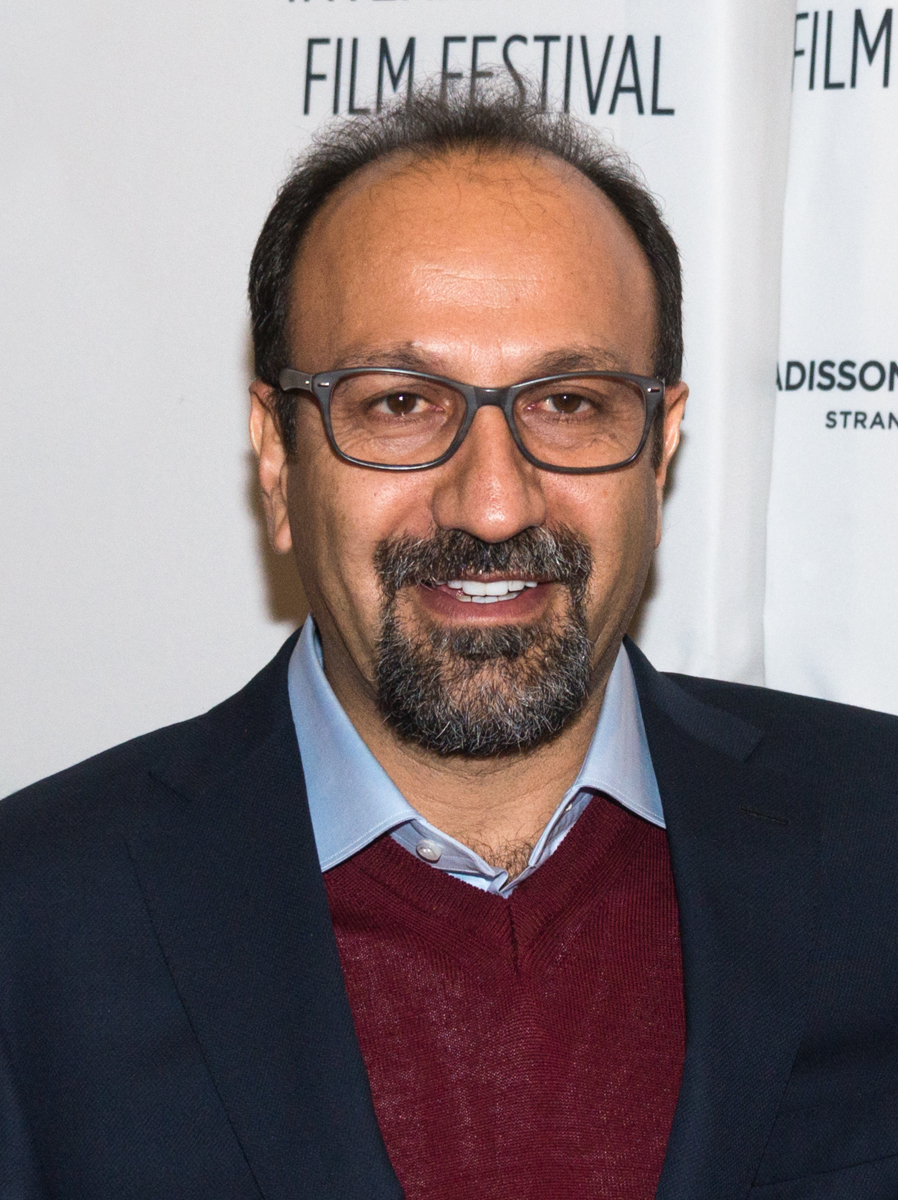

The election of the reformist Mohammad Khatami as president in 1997 ushered in an era of greater political and social openness, often referred to as the "Tehran Spring". Khatami advocated for a "dialogue among civilizations," civil society, and greater freedom of speech and press. However, his reform efforts faced strong opposition from conservative institutions, particularly the judiciary and the Guardian Council, which often blocked reformist legislation and suppressed student and pro-democracy movements. The period was marked by a vibrant cultural scene but also by significant human rights concerns, including crackdowns on dissidents and journalists.

The political pendulum swung back with the election of the conservative populist Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2005. His presidency (2005-2013) was characterized by a more confrontational foreign policy, particularly regarding Iran's nuclear program and relations with Israel and the United States. Domestically, there were increased restrictions on civil liberties and social freedoms. The 2009 presidential election, which saw Ahmadinejad re-elected amidst widespread allegations of fraud, led to massive protests known as the Green Movement. These protests were met with a harsh government crackdown, resulting in arrests, injuries, and deaths, and drawing international condemnation. During this time, international sanctions against Iran intensified due to concerns about its nuclear ambitions.

In 2013, Hassan Rouhani, a centrist cleric, was elected president on a platform of moderation and improved international relations. A major achievement of his first term was the negotiation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), or Iran nuclear deal, in 2015 with the P5+1 countries (China, France, Russia, UK, US, plus Germany) and the European Union. Under the JCPOA, Iran agreed to limit its nuclear activities in exchange for the lifting of international sanctions. This led to some economic relief and a period of cautious optimism. However, domestic challenges, including economic difficulties and continued human rights issues, persisted. Social movements, including those advocating for women's rights and environmental protection, continued to be active, often facing government resistance.

In 2018, the United States under the Trump administration unilaterally withdrew from the JCPOA and re-imposed stringent sanctions, severely impacting Iran's economy and escalating tensions. Iran responded by gradually reducing its compliance with the deal. The period since has been marked by increased economic hardship, social unrest (including major protests in 2017-2018 and 2019-2020 often linked to economic grievances and broader political demands), and heightened regional tensions. The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated economic and social challenges.

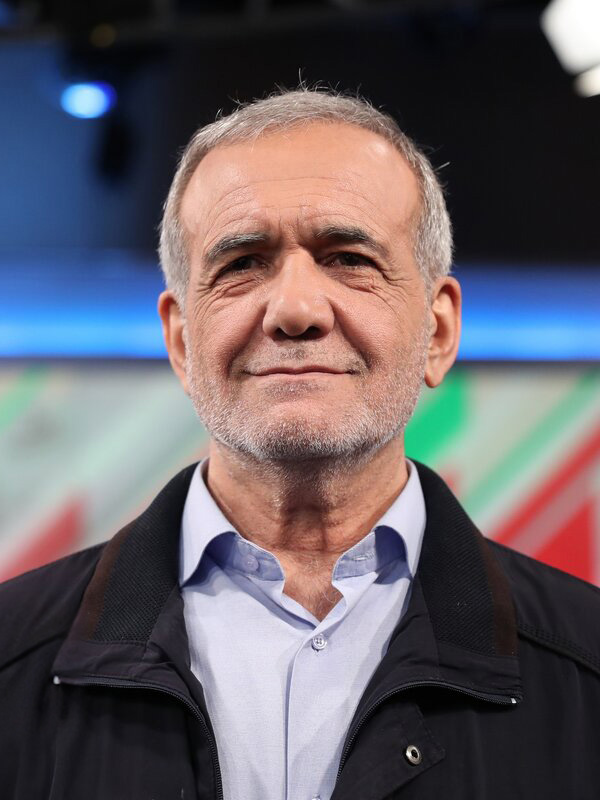

The election of hardliner Ebrahim Raisi as president in 2021, in an election with low turnout and disqualification of many reformist candidates, signaled a consolidation of conservative power. His presidency has seen continued economic struggles due to sanctions, stalled negotiations to revive the JCPOA, and significant social unrest, most notably the nationwide protests that erupted in late 2022 following the death of Mahsa Amini in the custody of the "morality police." These protests, often led by women and youth under the slogan "Woman, Life, Freedom," represented a major challenge to the Islamic Republic and were met with a severe state response, including widespread arrests and reported use of lethal force, drawing further international condemnation for human rights violations. Iran's foreign relations have also been marked by its support for Russia in the invasion of Ukraine, particularly through drone supplies, and its involvement in regional dynamics, including tensions with Israel, as seen in the 2024 drone and missile exchange. Following Raisi's death in a helicopter crash in May 2024, an early presidential election was held in June-July 2024, resulting in the election of reformist-backed Masoud Pezeshkian.

4. Geography

Iran's geographical location is in West Asia. It is bordered to the northwest by Armenia (22 mile (35 km)) and the Nakhchivan exclave of Azerbaijan (111 mile (179 km)), and the Republic of Azerbaijan (380 mile (611 km)); to the north by the Caspian Sea; to the northeast by Turkmenistan (616 mile (992 km)); to the east by Afghanistan (582 mile (936 km)) and Pakistan (565 mile (909 km)); to the south by the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman; and to the west by Iraq (0.9 K mile (1.46 K km)) and Turkey (310 mile (499 km)). Its diverse natural environment is marked by prominent mountain ranges, vast deserts, and fertile coastal plains, contributing to its strategic importance in the region.

Iran has a total area of 0.6 M mile2 (1.65 M km2). It is the sixth-largest country entirely in Asia and the second-largest in West Asia. It lies between latitudes 24° and 40° N, and longitudes 44° and 64° E.

Iran is situated in a seismically active area. On average, an earthquake of magnitude seven on the Richter scale occurs approximately once every ten years. Most earthquakes are shallow-focus and can be very devastating, such as the 2003 Bam earthquake.

4.1. Topography

Details the major landforms of Iran, including the Iranian Plateau, prominent mountain ranges such as the Alborz (including Mount Damavand) and Zagros, vast deserts like Dasht-e Kavir and Dasht-e Lut, and coastal plains.

Iran's topography is dominated by the vast central Iranian Plateau, which is ringed by several major mountain ranges. The country is one of the world's most mountainous. The most populous western part is the most mountainous, featuring the Zagros Mountains, a long and wide range stretching from the northwest to the southeast, forming a significant barrier. In the north, the Alborz mountain range runs along the southern coast of the Caspian Sea. The Alborz range includes Iran's highest peak, Mount Damavand, a dormant stratovolcano reaching an elevation of 18 K ft (5.61 K m), which is also the highest volcano in Asia and a significant symbol in Persian mythology. Other notable ranges include the Kopet Dag in the northeast.

These mountain ranges enclose several large basins or plateaus that form the Iranian Plateau. The eastern part of the country consists largely of desert basins. The Dasht-e Kavir (Great Salt Desert) is a vast desert located in the middle of the Iranian Plateau, characterized by salt marshes (kavirs). To its southeast lies the Dasht-e Lut (Emptiness Desert), one of the hottest and driest places on Earth, known for its dramatic yardang formations. The Lut Desert recorded one of the highest surface temperatures on Earth, reaching 159.26000000000002 °F (70.7 °C) in 2005.

The only extensive coastal plains are found along the southern shores of the Caspian Sea in the north and at the northern end of the Persian Gulf, where the country borders the mouth of the Shatt al-Arab (Arvand Rud) river. Smaller, discontinuous plains are also found along the remaining coast of the Persian Gulf, the Strait of Hormuz, and the Gulf of Oman. These mountains have significantly impacted Iran's political and economic history for centuries.

4.2. Climate

Explains the diverse climatic zones across Iran, from arid and semi-arid interiors to subtropical coastal regions, including regional variations in temperature, precipitation, and seasonal patterns, as well as the impacts of climate change.

Iran's climate is highly diverse, ranging from arid and semi-arid in the vast interior and eastern parts, to subtropical along the Caspian coast and the northern forests.

The northern edge of the country, along the Caspian coast, experiences a mild and humid subtropical climate. Temperatures here rarely fall below freezing in winter, and summer temperatures seldom exceed 84.2 °F (29 °C). This region receives the highest precipitation in Iran, with annual rainfall being 27 in (680 mm) in the eastern part of the plain and more than 0.1 K in (1.70 K mm) in the western part, particularly in Gilan Province.

To the west, settlements in the Zagros basin experience lower temperatures and severe winters with average daily temperatures often below freezing and heavy snowfall. Summers in these mountainous regions are typically mild.

The eastern and central basins, which form a large part of the country, have an arid or desert climate. These areas receive less than 7.9 in (200 mm) of rain annually and feature extensive deserts. Average summer temperatures in these regions frequently exceed 100.4 °F (38 °C). The Dasht-e Lut desert is particularly known for extreme heat.

The southern coastal plains along the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman have mild winters and very hot, humid summers. Annual precipitation in this region ranges from 5.3 in (135 mm) to 14 in (355 mm).

Climate change is an increasing concern for Iran, with projections indicating rising temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, and increased frequency of extreme weather events such as droughts and floods, which exacerbate existing challenges like water scarcity.

4.3. Biodiversity and Environment

Outlines Iran's flora and fauna, forest cover, national parks, protected areas, and significant environmental challenges such as water scarcity and pollution, as well as conservation efforts. This section will consider the social and economic impacts of environmental issues.

Iran possesses a rich biodiversity, reflecting its varied topography and climate. More than one-tenth of the country is forested. About 120 million hectares of forests and fields are government-owned for national exploitation. Iran's forests can be divided into five main vegetation regions:

- The Hyrcanian region forms a green belt along the northern slopes of the Alborz Mountains and the southern coast of the Caspian Sea. These lush, temperate deciduous forests are biologically diverse and include species like beech, oak, maple, and hornbeam.

- The Turanian region includes scattered woodlands and shrublands mainly in central and eastern Iran.

- The Zagros region in western Iran is characterized by oak forests and other deciduous trees adapted to a semi-arid mountainous environment.

- The Persian Gulf region in the south features subtropical and arid vegetation, including mangrove forests along the coast.

- The Arasbaran region in the northwest is known for its rare and unique species.

Iran is home to over 8,200 plant species. The land covered by natural flora is four times that of Europe.

The country's fauna is also diverse. Mammals include 34 species of bats, the Indian grey mongoose, small Indian mongoose, golden jackal, Indian wolf, various fox species, striped hyena, Persian leopard (a flagship species), Eurasian lynx, brown bear, and Asian black bear. Ungulate species include wild boar, urial, Armenian mouflon, red deer, and goitered gazelle. One of the most famous and critically endangered animals is the Asiatic cheetah, which now survives only in Iran. The Asiatic lion and the Caspian tiger became extinct in Iran by the early 20th century. Domestic ungulates are represented by sheep, goats, cattle, horses, water buffalo, donkeys, and camels. Bird species native to Iran include pheasants, partridges, storks, eagles, and falcons.

Iran has established over 200 protected areas, including more than 30 national parks, to preserve its biodiversity and wildlife.

However, Iran faces significant environmental challenges. Water scarcity is arguably the most severe, exacerbated by climate change, inefficient agricultural practices, and dam construction. This has led to the drying of lakes (like Lake Urmia) and rivers, desertification, and social tensions. Other challenges include air and water pollution (especially in large cities like Tehran), deforestation, soil erosion, and desertification. The social and economic impacts of these environmental issues are considerable, affecting agriculture, public health, and livelihoods. Conservation efforts are underway but face difficulties due to economic pressures and institutional limitations.

4.4. Major Islands

Describes key Iranian islands in the Persian Gulf and Caspian Sea, such as Kish, Qeshm, Abu Musa, and the Tunbs, noting their geographical, economic, strategic, and ecological significance, including any territorial disputes and their human impact.

Iran possesses several islands, primarily located in the Persian Gulf, with a few in the Caspian Sea and the Gulf of Oman. Some islands are also found within inland bodies of water like Lake Urmia (historically over 100, though many have been affected by the lake's desiccation) and the Aras River.

In the Persian Gulf, key Iranian islands include:

- Qeshm: The largest island in the Persian Gulf and in Iran. It is a UNESCO Global Geopark since 2016, recognized for its unique geological formations, including the Namakdan salt cave, one of the world's longest salt caves. Qeshm has significant ecological value, diverse wildlife, and a growing tourism industry. It is also a free-trade zone.

- Kish: Another major Iranian island in the Persian Gulf, known as a free-trade zone and a popular tourist destination. It features resorts, shopping malls, and recreational facilities, attracting around 12 million tourists annually before certain global disruptions.

- Hormuz Island: Located in the strategic Strait of Hormuz, known for its colorful, mineral-rich soil and unique landscapes. It has historical significance as a trading post.

- Abu Musa, Greater Tunb, and Lesser Tunb: These three islands are situated in the eastern Persian Gulf near the Strait of Hormuz. Iran took control of these islands in 1971. While small and with limited natural resources or population, their strategic location at the mouth of the Strait of Hormuz, a critical oil transit chokepoint, makes them highly valuable. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) also claims sovereignty over these islands, leading to an ongoing territorial dispute. Iran maintains full administrative control and has established military presence and civilian infrastructure on Abu Musa. The dispute occasionally surfaces in regional diplomatic discussions, with Iran consistently asserting its historical and legal rights to the islands. The local population on Abu Musa is affected by this geopolitical situation, living under Iranian administration amidst the unresolved claims.

In the Caspian Sea:

- Ashurada Island: Located off the eastern end of the Miankaleh Peninsula in the Caspian Sea, it is Iran's only island in this body of water. It has ecological importance, particularly for birdlife.

Many smaller islands are used for military purposes or wildlife protection, with restricted access. These islands contribute to Iran's strategic posture, economic activities (like fishing and tourism), and ecological diversity.

5. Politics and Government

The political system of the Islamic Republic of Iran is unique, combining elements of a modern republic with a theocracy based on the principle of Velayat-e Faqih (Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist), as conceptualized by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran, adopted in 1979 and revised in 1989, outlines this framework. While the system includes elected institutions like the presidency and the parliament (Majlis), ultimate authority rests with the Supreme Leader and unelected bodies that interpret Islamic law and vet candidates and legislation. This structure creates a complex interplay of democratic and authoritarian characteristics, with significant impacts on civil liberties and political freedoms, often drawing criticism from human rights organizations and international observers for its restrictions on expression, assembly, and due process, as well as discrimination against women and minorities.

The system is characterized by a division of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, but all are subordinate to the overriding authority of the Supreme Leader and the principles of Islamic governance. The government is officially a unitary Islamic republic with a presidential system. However, its authoritarian nature and the significant constraints on democratic processes and human rights are defining features of its political landscape. Iran ranked 154th in the 2022 Democracy Index by The Economist Intelligence Unit, categorized as an "authoritarian regime".

5.1. Supreme Leader

The Supreme Leader (رهبر انقلابRahbar-e EnqelābPersian, "Leader of the Revolution", or مقام رهبریMaqam-e RahbariPersian, "Supreme Leadership Authority") is the head of state and the highest-ranking political and religious authority in Iran. This position holds ultimate power and makes final decisions on all major state policies. The Supreme Leader is responsible for the supervision of the general policies of the Islamic Republic.

Powers and Responsibilities:

The Supreme Leader's powers are extensive and include:

- Delineating the general policies of the Islamic Republic.

- Supervising the proper execution of these policies.

- Commander-in-chief of the armed forces, controlling military intelligence and security operations.

- Sole power to declare war or peace.

- Appointing and dismissing the heads of the judiciary, the state radio and television network, the chief of staff of the armed forces, the commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), and commanders of the different branches of the armed forces.

- Appointing six of the twelve members of the Guardian Council.

- Appointing the members of the Expediency Discernment Council.

- Resolving disputes between the three branches of government when ordinary methods fail.

- Signing the decree formalizing the election of the President.

- Dismissing the President if deemed in the interest of the country by the Supreme Court or after a vote of no-confidence by the Majlis.

- Granting amnesty or reducing sentences of convicts, within the framework of Islamic criteria.

Key ministers, particularly for Defense, Intelligence, and Foreign Affairs, are selected with the Supreme Leader's implicit or explicit agreement. Regional policy is also heavily influenced, if not directly controlled, by the Supreme Leader's office, with the Quds Force (an IRGC branch responsible for extraterritorial operations) reporting directly to the Supreme Leader. The Supreme Leader can also order laws passed by the Majlis to be amended or overturned.

The office of the Supreme Leader controls significant economic assets, such as Setad Ejraiye Farmane Emam (Execution of Imam Khomeini's Order), an economic conglomerate whose holdings were estimated by Reuters in 2013 to be worth around 95.00 B USD. The accounts of such organizations are often opaque, even to the Iranian parliament.

Selection and Tenure:

The Supreme Leader is chosen by the Assembly of Experts, a body of 88 Islamic scholars elected by popular vote. The Assembly is also theoretically responsible for supervising the Supreme Leader and has the constitutional power to dismiss him if he is deemed incapable of fulfilling his duties or no longer meets the qualifications. However, in practice, the Assembly of Experts has not historically challenged the Supreme Leader's decisions or authority. Ruhollah Khomeini was the first Supreme Leader, serving from 1979 until his death in 1989. He was succeeded by Ali Khamenei, who has held the position since. The Supreme Leader holds the office for life.

The institution of the Supreme Leader, rooted in the concept of Velayat-e Faqih, ensures that an Islamic jurist oversees the state to prevent deviation from Islamic principles. This concentration of power has led to criticism regarding the democratic deficit and lack of accountability within the Iranian political system, impacting human rights and civil liberties.

5.2. President

The President is the head of government and the highest popularly elected official in Iran, second in authority only to the Supreme Leader. The President is elected by universal suffrage for a four-year term and can be re-elected for only one consecutive term.

Election Process:

Presidential candidates must be vetted and approved by the Guardian Council before they can run for office. This vetting process ensures that candidates are deemed sufficiently loyal to the principles of the Islamic Republic and Islamic law. The Supreme Leader also has the power to approve or disapprove candidates, effectively having the final say, and can dismiss an elected president.

Functions and Powers:

The President is responsible for:

- Implementing the Constitution and laws passed by the Majlis.

- Exercising executive powers, except for matters directly related to the Supreme Leader.

- Heading the executive branch of government.

- Appointing and dismissing cabinet ministers, subject to the approval of the Majlis.

- Signing treaties and agreements with foreign countries, after approval from relevant bodies.

- Administering national planning, budget, and state employment affairs.

- Chairing the Supreme National Security Council.

- Serving as the deputy commander-in-chief of the armed forces (though supreme command rests with the Supreme Leader).

- Appointing provincial governors and ambassadors, typically in consultation with other state bodies.

- Receiving credentials of foreign ambassadors.

The President supervises the Council of Ministers (Cabinet), coordinates government decisions, and selects government policies to be presented to the legislature. The President is assisted by several Vice Presidents, the most senior being the First Vice President, who may lead cabinet meetings in the President's absence. There are typically around eight Vice Presidents and a cabinet of approximately 22 ministers.

Relationship with the Supreme Leader:

While the President is the head of the executive branch, their power is significantly circumscribed by the Supreme Leader, who has the final say on all major state policies, including foreign affairs, defense, and key domestic issues. The President and cabinet ministers must operate within the guidelines set by the Supreme Leader. The Supreme Leader can also dismiss the President if deemed necessary, either through the Supreme Court or following a Majlis vote of no-confidence, effectively underlining the President's subordinate role in the power hierarchy. This dynamic often creates tension between the elected government, seeking to implement its mandate, and the unelected institutions loyal to the Supreme Leader, impacting governance and the potential for reform.

5.3. Legislature (Majlis)

The Islamic Consultative Assembly (مجلس شورای اسلامیMajles-e Showrā-ye EslāmiPersian), also known as the Majlis or Iranian Parliament, is the unicameral national legislature of Iran. It is composed of 290 members who are elected by direct popular vote for four-year terms.

Functions and Powers:

The Majlis is responsible for:

- Drafting and passing legislation in accordance with the Constitution and Islamic principles.

- Ratifying international treaties and agreements.

- Approving the national budget proposed by the government.

- Investigating and questioning government ministers and the President.

- Approving or rejecting cabinet ministers nominated by the President.

- Voting of no-confidence in individual ministers or the President (which can lead to their dismissal, though presidential dismissal also requires Supreme Leader's endorsement or Supreme Court action).

- Approving loans and grants from or to foreign entities.

Legislative Process and Oversight:

All legislation passed by the Majlis must be reviewed and approved by the Guardian Council to ensure its compatibility with the Constitution and Islamic law (Sharia). The Guardian Council has the power to veto any legislation it deems un-Islamic or unconstitutional. This oversight significantly influences the legislative output of the Majlis.

Parliamentary candidates must also be vetted and approved by the Guardian Council before they can run for election. This screening process has often been a point of contention, as it can lead to the disqualification of candidates, particularly those with reformist or dissenting views, thereby shaping the political composition of the Majlis. The Guardian Council also has the power to dismiss elected members of parliament under certain circumstances.

The Majlis has 207 constituencies. Of the 290 seats, five are reserved for representatives of recognized religious minorities: Zoroastrians, Jews, Assyrian and Chaldean Christians each have one seat, and Armenian Christians have two seats (one for Armenians of the north and one for Armenians of the south). The remaining 285 members represent territorial constituencies, each covering one or more of Iran's counties.

The Majlis plays a role in representing constituencies and shaping laws within the framework of the Islamic Republic. However, its power is significantly balanced and often overridden by unelected bodies like the Guardian Council and the ultimate authority of the Supreme Leader. If disputes arise between the Majlis and the Guardian Council over legislation, the Expediency Discernment Council can intervene to mediate and make a final decision.

Specialized commissions within the parliament, such as the National Security and Foreign Policy Commission or the Economic Affairs Commission, play a crucial role in scrutinizing legislation and government performance in their respective areas. The Supreme Audit Court of Iran and the Majlis Research Center provide research and auditing support to the legislature.

5.4. Judiciary

The judicial system of the Islamic Republic of Iran is based on Sharia (Islamic law) with elements of civil law. The system's structure and principles are outlined in the Constitution and are intended to uphold Islamic justice. However, the judiciary has been widely criticized by international human rights organizations for its lack of independence, due process violations, harsh punishments, and its role in suppressing dissent and political opposition, thereby having significant human rights implications.

Structure and Hierarchy:

- Chief Justice (Head of the Judiciary)**: Appointed by the Supreme Leader for a five-year term (renewable). The Chief Justice is the highest judicial authority and is responsible for establishing the organizational structure of the judiciary, drafting judicial bills for parliament, and appointing and dismissing judges.

- Supreme Court**: The highest court of appeal, responsible for ensuring the correct application of laws by lower courts and for standardizing judicial procedures. The head of the Supreme Court is appointed by the Chief Justice in consultation with the Supreme Court judges.

- Attorney-General (Public Prosecutor General)**: Also appointed by the Chief Justice.

The court system includes several types of courts:

- Public Courts (General Courts)**: Deal with most civil and criminal cases.

- Revolutionary Courts**: Established after the 1979 revolution, these courts handle cases deemed to be against national security, including political offenses, drug trafficking, and "corruption on earth." Their procedures often lack due process, and their rulings, which can include severe punishments like the death penalty, are often final or have limited avenues for appeal. Critics argue these courts are used to suppress political dissent and target human rights defenders.

- Special Clerical Court**: Tries cases involving members of the clergy for alleged offenses. It operates independently of the regular judicial framework and is directly accountable to the Supreme Leader. Its rulings are also typically final and cannot be appealed.

- Specialized Courts**: These include family courts, juvenile courts, administrative justice courts, and military courts.

Application of Islamic Law:

The judiciary applies Islamic legal principles derived primarily from Shi'a jurisprudence. Laws passed by the Majlis must conform to Sharia as interpreted by the Guardian Council. Penalties under Iranian law can include qisas (retribution in kind), hudud (fixed punishments for offenses against God, such as amputation or flogging), diyya (blood money or compensation), and ta'zir (discretionary punishments). The use of capital punishment is frequent, including for offenses not considered capital crimes under international law, and sometimes involves public executions. Stoning, although less common, remains a legal form of punishment for adultery.

Human rights concerns related to the judiciary include:

- Lack of judicial independence from political influence, particularly from security and intelligence agencies.

- Vague laws, especially concerning national security, that are used to criminalize peaceful expression and activism.

- Restrictions on access to legal counsel, particularly in politically sensitive cases.

- Use of confessions obtained under duress or torture.

- Discrimination against women and religious and ethnic minorities within the legal system.

- Harsh sentences, including long prison terms and the death penalty, for political prisoners, journalists, and human rights defenders.

The impact of the judiciary on the lives of Iranians is profound, shaping not only legal outcomes but also broader social and political norms, often in a manner that curtails individual freedoms and democratic aspirations.

5.5. Guardian Council

The Guardian Council (شورای نگهبان قانون اساسیShowrā-ye Negahbān-e Qānun-e AsāsiPersian) is one of the most powerful and influential bodies in the Iranian political system. Its primary functions are to ensure the compatibility of legislation with Islamic law (Sharia) and the Constitution, and to supervise elections.

Composition:

The Guardian Council consists of twelve members:

- Six Islamic jurists (faqihs): These members are specialists in Islamic law and are directly appointed by the Supreme Leader. They are chosen for their expertise in Shi'a jurisprudence.

- Six jurists (lawyers): These members are specialists in various branches of law. They are nominated by the Head of the Judiciary (who is himself appointed by the Supreme Leader) and must be approved by the Majlis (parliament).

Members serve six-year terms, with half of the members changing every three years to ensure continuity.

Functions and Powers:

1. **Vetting Legislation**: All bills passed by the Majlis must be submitted to the Guardian Council for review. The Council has the authority to veto any legislation it deems contrary to Islamic principles (Sharia) or the Constitution. If a bill is vetoed, it is sent back to the Majlis for amendment. This power allows the Guardian Council to significantly shape the legal landscape of Iran.

2. **Supervising Elections (Candidate Vetting)**: The Guardian Council is responsible for supervising all major elections in Iran, including presidential, parliamentary (Majlis), and Assembly of Experts elections. A crucial aspect of this supervision is the vetting (or screening) of all candidates. The Council determines the eligibility of individuals wishing to run for office based on criteria such as loyalty to the Islamic Republic, belief in Velayat-e Faqih, and adherence to Islamic principles. This vetting process has been a major source of political contention, as it has often resulted in the disqualification of reformist or moderate candidates, thereby influencing the outcome of elections and limiting the range of political choices available to voters. The Council's decisions on candidate eligibility are final.

3. **Interpreting the Constitution**: The Guardian Council has the authority to interpret the Constitution. This power, similar to that of a constitutional court in other countries, allows it to clarify constitutional ambiguities and ensure that all state actions align with constitutional provisions.

4. **Oversight of Referendums**: The Council also oversees national referendums.

Impact on Political Landscape and Democratic Processes:

The Guardian Council plays a critical role in maintaining the Islamic character of the state and acts as a check on the elected Majlis. Its power to vet candidates and legislation effectively makes it a gatekeeper of the political system. Critics argue that this concentration of power in an unelected body (half of whose members are directly appointed by the Supreme Leader and the other half indirectly influenced by him) undermines democratic processes by restricting political competition and limiting the scope of legislative action. The Council's decisions have often been seen as favoring conservative factions and hindering reforms aimed at greater political and social freedoms. The dynamic between the Majlis and the Guardian Council can lead to legislative deadlock, which is then typically resolved by the Expediency Discernment Council.

5.6. Expediency Discernment Council

The Expediency Discernment Council of the System (مجمع تشخیص مصلحت نظامMajma' Tashkhīs Maslahat NezāmPersian), often referred to as the Expediency Council, is an administrative assembly appointed by the Supreme Leader. It was originally established during the Iran-Iraq War to resolve legislative deadlocks between the Majlis (parliament) and the Guardian Council, and its role was formalized in the 1989 constitutional revision.

Composition:

The members of the Expediency Council are appointed by the Supreme Leader and typically include prominent political, religious, and military figures, often representing various factions within the establishment. The President, the Speaker of the Majlis, and the Head of the Judiciary are ex-officio members, as are the six clerical members of the Guardian Council relevant to the specific dispute being considered. The council has historically been chaired by influential figures like Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and later Sadeq Larijani.

Functions and Powers:

1. **Mediating Legislative Disputes**: The primary constitutional role of the Expediency Council is to arbitrate when the Majlis and the Guardian Council cannot agree on a piece of legislation. If the Majlis passes a bill that the Guardian Council rejects (either as un-Islamic or unconstitutional), and the Majlis is unable or unwilling to amend it to the Guardian Council's satisfaction, the bill can be referred to the Expediency Council. The Council then makes a final decision on whether the bill should become law, considering the "expediency" or "interest" of the system. This power allows the Council to override both the Majlis and, in effect, the Guardian Council's objections if it deems a law necessary for the state.

2. **Advisory Role to the Supreme Leader**: The Expediency Council serves as an advisory body to the Supreme Leader on matters of national policy. The Supreme Leader can refer major policy issues to the Council for deliberation and advice. This function makes it one of the most influential bodies in the country, shaping long-term strategies and policies.

3. **Formulating General Policies**: In some instances, the Council has been tasked with drafting or outlining general policies of the Islamic Republic, subject to the Supreme Leader's approval.

4. **Proposing Solutions for Systemic Problems**: The Supreme Leader may also delegate to the Council the responsibility of finding solutions to complex national problems or challenges facing the regime.

The Expediency Council's decisions in legislative disputes are final and cannot be appealed. Its role in balancing the interests of different state institutions and providing strategic advice to the Supreme Leader makes it a key player in Iran's complex political structure, often acting as a mechanism for maintaining regime stability and consensus among the ruling elite.

5.7. Supreme National Security Council

The Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) (شورای عالی امنیت ملیShowrā-ye Āli-ye Amniyat-e MellīPersian) is Iran's primary body for formulating defense and national security policies. It operates under the guidance of the Supreme Leader, who has the ultimate authority over all security matters. The council was formed during the 1989 constitutional revision.

Composition:

The SNSC is chaired by the President of Iran. Its members typically include:

- The President.

- The Speaker of the Majlis (Parliament).

- The Head of the Judiciary.

- The Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces.

- The Minister of Foreign Affairs.

- The Minister of Interior.

- The Minister of Intelligence.

- The head of the Plan and Budget Organization.

- Two representatives appointed by the Supreme Leader.

- The commanders-in-chief of the Army and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

- The minister relevant to the topic under discussion, if applicable.

The Secretary of the SNSC is a key position, appointed by the President in consultation with the Supreme Leader, and serves as the council's chief administrator and spokesperson. Historically, the Secretary has played a crucial role in sensitive negotiations, such as those concerning Iran's nuclear program.

Responsibilities and Functions:

According to Article 176 of the Constitution, the responsibilities of the SNSC include:

- Determining the defense and national security policies of the country within the framework of general policies set by the Supreme Leader.

- Coordinating political, intelligence, social, cultural, and economic activities related to defense and national security policies.

- Exploiting national material and intellectual resources for confronting internal and external threats.

The decisions of the SNSC become effective after confirmation by the Supreme Leader. The council plays a central role in managing crises, formulating responses to external threats, and coordinating the activities of various government agencies involved in national security. It has been particularly prominent in shaping Iran's nuclear policy and its regional foreign policy. While chaired by the President, the SNSC's policies and decisions must align with the directives of the Supreme Leader, who retains ultimate control over all strategic matters.

5.8. Administrative Divisions

Iran is a unitary state with a system of administrative divisions that organizes the country into several hierarchical levels for governance and public administration.

The primary administrative unit is the province (استانostānPersian). As of the early 2020s, Iran is subdivided into 31 provinces. Each province is governed from a local center, usually the largest local city, which is designated as the provincial capital (مرکزmarkazPersian). The provincial authority is headed by a Governor-General (استاندارostāndārPersian), who is appointed by the Minister of the Interior subject to the approval of the Cabinet. Governors-General are responsible for implementing national policies at the provincial level, coordinating local government activities, and overseeing security and development within their province.

The provinces are further subdivided into:

- Counties (شهرستانshahrestānPersian): Each province consists of several counties. A county is administered by a governor (فرماندارfarmāndārPersian).

- Districts (بخشbakhshPersian): Each county is typically divided into one or more districts. A district is headed by a bakhshdār.

- Rural Districts (دهستانdehestānPersian) and Cities (شهرshahrPersian): Districts are composed of rural districts (groupings of villages) and cities. Cities have municipalities headed by mayors, while villages have village councils.

Local Governance:

Since 1999, Iran has held elections for City and Village Councils (شوراهای اسلامی شهر و روستاShowrāhā-ye Eslāmī-ye Shahr va RūstāPersian). These councils are elected by local residents and are responsible for overseeing local affairs, electing mayors (in cities), and addressing local development and service provision issues. While these councils represent a degree of local participation, their powers are often limited by the authority of centrally appointed officials like governors and by budgetary constraints.

The administrative divisions are subject to change; new provinces have been created by splitting existing ones (e.g., Alborz province was separated from Tehran province in 2010). This system of administrative divisions facilitates the implementation of national policies and the management of public services across Iran's geographically diverse and populous territory.

The provinces of Iran are (in alphabetical order): Alborz, Ardabil, Azerbaijan, East, Azerbaijan, West, Bushehr, Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari, Fars, Gilan, Golestan, Hamadan, Hormozgan, Ilam, Isfahan, Kerman, Kermanshah, Khorasan, North, Khorasan, Razavi, Khorasan, South, Khuzestan, Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad, Kurdistan, Lorestan, Markazi, Mazandaran, Qazvin, Qom, Semnan, Sistan and Baluchestan, Tehran, Yazd, and Zanjan.

6. Foreign Relations

Iran's foreign policy is shaped by a complex interplay of revolutionary ideology, national interests, regional security concerns, and economic imperatives. Since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, its foreign relations have often been characterized by an assertion of independence from major world powers, a strong anti-imperialist stance (particularly directed against the United States), and a focus on its role as a leading Shi'a Muslim power in the Middle East. The principles of "Neither East, Nor West, but Islamic Republic" and the "export of the revolution" (though its interpretation has varied) were early ideological tenets. Key aspects influencing its foreign policy include its relationships with neighboring countries, major global powers, its involvement in regional conflicts, its nuclear program, and international sanctions. These factors are often viewed through the lens of their impact on regional stability, human rights, and geopolitical balances, with diverse perspectives existing both within and outside Iran regarding its international conduct.

6.1. Relations with Key Countries and Regions

Details Iran's bilateral relations with major global powers (e.g., United States, Russia, China, European Union), neighboring countries in the Middle East, and other significant nations, focusing on historical ties, current cooperation, areas of conflict, and diplomatic stances, including humanitarian impacts.

- United States**: Relations have been deeply adversarial since the 1979 Revolution and the Iran hostage crisis. Decades of mutual mistrust, US sanctions (particularly concerning Iran's nuclear program and alleged support for terrorism), and geopolitical rivalry in the Middle East define this relationship. The US derecognized Iran in 1979. There are no formal diplomatic ties; Switzerland acts as a protecting power. The US withdrawal from the JCPOA in 2018 and the assassination of Iranian General Qasem Soleimani in 2020 further heightened tensions. The humanitarian impact of US sanctions on the Iranian populace is a significant concern for human rights advocates.

- European Union (EU)**: Relations with EU countries have been mixed. European nations were key partners in the JCPOA and have generally sought diplomatic engagement with Iran. However, concerns over Iran's nuclear program, human rights record (including the use of capital punishment and suppression of dissent), and regional activities (such as missile development and support for proxies) have led to periodic EU sanctions and strained ties. Trade and cultural exchange exist but are often overshadowed by political disagreements.

- China**: Iran and China have cultivated a strategic partnership, strengthened by shared interests in countering US influence and economic cooperation. China is a major buyer of Iranian oil (often circumventing US sanctions) and a significant investor in Iranian infrastructure. In 2021, they signed a 25-year cooperation agreement encompassing political, strategic, and economic components, signaling deepening ties. This relationship dates back to ancient Silk Road connections.

- Russia**: Relations with Russia have become increasingly close, particularly in the military and strategic spheres. Both countries are subject to Western sanctions and share an interest in challenging the US-led global order. Russia has been a key partner in Iran's nuclear program (e.g., construction of the Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant) and has provided military hardware. Iran's support for Russia in its invasion of Ukraine, including drone supplies, has further solidified their alignment but also drawn international criticism. Iran has been invited to join the Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) as an observer.

- Saudi Arabia**: As the leading Shi'a and Sunni powers in the region, respectively, Iran and Saudi Arabia have a deeply adversarial relationship characterized by geopolitical rivalry, sectarian tensions, and proxy conflicts in countries like Yemen, Syria, and Lebanon. Diplomatic ties were severed in 2016 but restored in 2023 through Chinese mediation, though underlying tensions remain. The rivalry impacts regional stability and has had severe humanitarian consequences in conflict zones.

- Turkey**: Relations are complex, involving both cooperation and competition. They share economic ties and some common interests (e.g., concerns about Kurdish separatism), but have also backed opposing sides in regional conflicts like Syria and Libya, and compete for influence in the South Caucasus.

- Iraq**: Following the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in 2003, Iran has gained significant political, economic, and security influence in Iraq, particularly among Shi'a political groups and militias. This influence is a legacy of historical ties, shared religious heritage, and Iranian support against ISIS. Economic relations are strong, with Iran being a major trading partner.

- Syria**: Syria, under the Assad regime, has been Iran's closest Arab ally for decades. Iran has provided crucial military, economic, and political support to Bashar al-Assad during the Syrian civil war, helping to preserve his rule. This alliance provides Iran with a strategic foothold in the Levant and access to groups like Hezbollah. The fall of the Assad regime in December 2024 marked a significant setback for Iran's regional influence.

- Lebanon**: Iran wields significant influence in Lebanon primarily through its strong backing of Hezbollah, a powerful Shi'a political and militant organization. This support includes funding, training, and weaponry, enabling Hezbollah to be a major force in Lebanese politics and a key component of Iran's "axis of resistance" against Israel.

- Israel**: Iran does not recognize the state of Israel and considers it an illegitimate entity. Relations are openly hostile, marked by a shadow war involving covert operations, cyber-attacks, and support for anti-Israel militant groups like Hezbollah and Hamas. Israel views Iran's nuclear program and regional influence as existential threats. Iran's rhetoric often includes calls for Israel's destruction, which is widely condemned internationally. This conflict has significant humanitarian and security implications for the region.

- Afghanistan and Pakistan**: Relations with its eastern neighbors are complex, involving issues of border security, refugees (Iran hosts a large Afghan refugee population), water rights, and trade. Iran has sought to maintain influence with various factions in Afghanistan and has engaged with Pakistan on regional security and economic cooperation, though relations can be strained by cross-border militant activities.

- Tajikistan**: Iran shares close linguistic and cultural ties with Tajikistan and has fostered strong diplomatic and economic relations.

- North Korea and South Korea**: Iran maintains diplomatic relations with both Koreas. Its relationship with North Korea has included cooperation on missile technology, raising international concerns. Relations with South Korea have primarily focused on trade, though often complicated by international sanctions on Iran.

6.2. International Organizations and Alliances

Iran is a founding member of the United Nations (UN), the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), and the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO).

It is also a member of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM).

In recent years, Iran has sought to strengthen ties with non-Western blocs and organizations. It became a full member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in 2023 and joined the BRICS group of emerging economies in 2024.

Iran has observer status at the World Trade Organization (WTO) but its accession has been a lengthy process.

Iran participates in various UN agencies and international bodies, including the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), which plays a key role in monitoring its nuclear activities. Iran's engagement in multilateral diplomacy is often focused on issues such as nuclear non-proliferation (from its perspective), regional security, and challenging what it perceives as unilateralism by major powers. However, its human rights record and regional policies frequently lead to criticism and resolutions against it in international forums like the UN Human Rights Council.

7. Military

The armed forces of the Islamic Republic of Iran consist of two main branches: the regular military, known as the Artesh, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), also known as Sepah-e Pasdaran. Both operate under the command of the General Staff of the Armed Forces, with the Supreme Leader as the commander-in-chief. The military's posture is primarily defensive, but it also projects power regionally, often through asymmetric warfare and support for allied non-state actors. The ethical implications of its defense posture, regional activities, and human rights record of its security forces are subjects of ongoing international scrutiny. Conscription for males aged 18 has been mandatory since 1925, with service typically lasting around 14 to 24 months in either the Artesh or IRGC. Iran has over 610,000 active troops and around 350,000 reservists, totaling over 1 million military personnel, one of the world's highest percentages of citizens with military training. Excluding paramilitary forces like the Basij and the Law Enforcement Command (Faraja), Iran is identified as a major military power, possessing the 14th strongest military globally by some rankings. It has the largest armed forces in West Asia.

7.1. Structure and Organization

Details the composition of the regular military (Artesh: Ground Forces, Navy, Air Force, Air Defense) and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC: Ground Forces, Aerospace Force, Navy, Quds Force, Basij militia), including their respective roles and command structures.

- Artesh (Regular Military)**: The Artesh is responsible for conventional warfare and defending Iran's territorial integrity and borders. It comprises four main branches:

- Ground Forces: The largest branch, equipped with tanks, armored personnel carriers, and artillery.

- Navy: Operates primarily in the Persian Gulf, Gulf of Oman, and the Caspian Sea, with capabilities including frigates, submarines, and missile boats.

- Air Force (IRIAF): Operates a mix of aircraft, including older Western-supplied planes from before the revolution and more recent Russian and domestically produced aircraft.

- Air Defense Force: Responsible for protecting Iranian airspace, equipped with radar systems, surface-to-air missiles, and anti-aircraft artillery.

- Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC)**: Established after the 1979 Revolution, the IRGC is tasked with safeguarding the Islamic Republic system and its revolutionary values, both internally and externally. It has become a powerful military, political, and economic force. Its branches include:

- Ground Forces: Focuses on internal security, border control, and unconventional warfare.

- Aerospace Force: Controls Iran's ballistic missile program, drone fleet, and has some air combat capabilities. It also runs Iran's space program, including satellite launches.

- Navy: Operates a large number of fast attack craft and focuses on asymmetric naval warfare in the Persian Gulf, particularly in the Strait of Hormuz.

- Quds Force: An elite special forces unit responsible for extraterritorial operations, including intelligence gathering, supporting allied militias and governments (e.g., Hezbollah, Hamas, Iraqi Shi'a militias, Houthi rebels), and projecting Iranian influence abroad. It reports directly to the Supreme Leader.

- Basij: A large volunteer paramilitary militia, with millions of registered members (though active numbers are lower, estimated at around 600,000 available for immediate call-up and 300,000 reservists). The Basij is involved in internal security, law enforcement, social services, and moral policing. It can be mobilized in times of crisis or war.

- Law Enforcement Command (Faraja)**: Formerly known as NAJA, this is the uniformed police force of Iran, responsible for general law enforcement, traffic control, border protection (in some areas), and counter-narcotics operations. It has over 260,000 active personnel and functions analogously to a gendarmerie.

While the Artesh and IRGC have distinct roles, there is some overlap and occasional rivalry, but they also coordinate under the General Staff. The IRGC often has access to more advanced weaponry and greater political influence.

7.2. Defense Industry and Capabilities

Since the 1979 Revolution and facing international arms embargoes, Iran has significantly developed its domestic defense industry to achieve greater self-sufficiency. It is now capable of producing a wide range of armaments.

- Missile Program**: This is a cornerstone of Iran's defense capabilities. Iran possesses the largest and most diverse ballistic missile arsenal in the Middle East, including short-range, medium-range, and some longer-range missiles capable of reaching targets across the region. Examples include the Shahab, Sejjil, Ghadr, Emad, Khorramshahr, and Fattah (claimed to be a hypersonic missile). Iran is considered the world's 6th missile power by some assessments and one of only five countries with acknowledged hypersonic missile technology.

- Drone (UAV) Program**: Iran has become a major producer and exporter of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Its drone fleet includes surveillance, reconnaissance, and combat drones (UCAVs) like the Shahed, Mohajer, and Kaman series. Iranian drones have been used by its forces and supplied to allied groups and countries, notably Russia for use in the Ukraine conflict. Iran is considered a global leader in drone warfare and technology.

- Naval Capabilities**: Iran produces various naval vessels, including small submarines, frigates (like the Jamaran class), missile boats, and fast attack craft, suited for asymmetric warfare in the Persian Gulf.

- Armored Vehicles and Artillery**: The domestic industry manufactures tanks (e.g., Karrar, an upgraded T-72), armored personnel carriers, and various artillery systems.

- Aircraft**: While heavily reliant on pre-revolution Western aircraft and some Russian imports, Iran has made efforts to produce indigenous fighter aircraft (e.g., HESA Kowsar, HESA Saeqeh, based on older designs) and helicopters. It also overhauls and upgrades existing airframes. In November 2023, arrangements were reportedly finalized to acquire Russian Sukhoi Su-35 fighter jets and Mil Mi-28 attack helicopters.

- Air Defense Systems**: Iran has developed its own air defense systems, such as the Bavar-373 and Khordad series, alongside imported systems like the Russian S-300.

- Cyberwarfare Capabilities**: Iran is recognized as having significant cyberwarfare capabilities and is considered one of the most active players in the international cyber arena, engaging in both offensive and defensive cyber operations.

- Weapons of Mass Destruction**: Iran is a signatory to the Chemical Weapons Convention and the Biological Weapons Convention. While it maintains a civilian nuclear program, it denies aspirations for nuclear weapons. (See Nuclear Program section).