1. Overview

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, is a Southeast Asian country located at the eastern edge of the Indochinese Peninsula. It covers an area of approximately NaN Q mile2 (NaN Q km2) and has a population exceeding 100 million, making it the world's fifteenth-most populous country. Vietnam shares land borders with China to the north, and Laos and Cambodia to the west. It has maritime borders with Thailand through the Gulf of Thailand, and the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia through the South China Sea. The capital city is Hanoi, and the largest city is Ho Chi Minh City.

The history of Vietnam spans millennia, from Paleolithic human settlements and early states like Văn Lang and Âu Lạc, through over a thousand years of Chinese rule marked by resistance, to periods of independent dynasties characterized by cultural development and southward expansion. The 19th century saw French colonization, leading to economic exploitation and burgeoning nationalist movements. The 20th century was defined by prolonged conflicts, including the First Indochina War against France and the Vietnam War, which resulted in the country's division and eventual reunification under communist rule in 1976. Post-reunification, Vietnam underwent significant socio-economic reforms known as Đổi Mới in 1986, transitioning to a socialist-oriented market economy. These reforms have driven economic growth but also raised concerns about social inequalities and human rights.

Vietnam is a one-party socialist republic led by the Communist Party of Vietnam. The political system has faced international scrutiny regarding human rights, particularly concerning freedoms of expression, assembly, and the press. Economically, Vietnam has shifted from a centrally planned system to a market-oriented one, achieving notable progress in agriculture, industry, and services, and increasing its integration into the global economy. However, challenges related to social equity, labor rights, and environmental sustainability persist.

Demographically, Vietnam is a multi-ethnic nation, with the Kinh (Viet) people forming the majority. Rapid urbanization is transforming society, especially in major urban centers like Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City. Vietnamese culture is a rich blend of indigenous traditions, Chinese civilizational influences, French colonial legacies, and contemporary global trends. This article explores Vietnam's diverse facets, with an emphasis on social impacts, human rights, democratic development, and the welfare of minorities and vulnerable populations.

2. Etymology

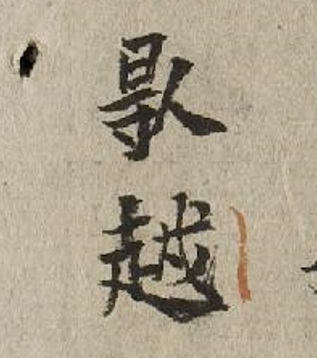

The name {{lang|vi|Việt Nam|Viet Nam|pronounced viətˀ nāːm}}, written in chữ Hán as 越南Việt NamVietnamese, literally translates to "Viet South." This can be interpreted as "Viet of the South" following Vietnamese word order, or "South of the Viet" according to Classical Chinese word order. A variation of the name, Nanyue (or Nam ViệtNam VietVietnamese, written in chữ Hán as 南越Nam ViệtVietnamese), was first documented in the 2nd century BC.

The term "Việt" (Yue) (Vietnamese: ViệtViệtVietnamese; Chinese: 越YuèChinese) in Early Middle Chinese was initially written using the logogram "戉" (戉yuèChinese, an axe, a homophone) in oracle bone and bronze inscriptions of the late Shang dynasty (c. 1200 BC), and later as "越" (越yuèChinese). At that time, it referred to a people or chieftain northwest of the Shang. In the early 8th century BC, a tribe on the middle Yangtze was called the Yangyue (揚越YángyuèChinese), a term later used for peoples further south.

Between the 7th and 4th centuries BC, 'Yue'/'Việt' referred to the State of Yue in the lower Yangtze basin and its people. From the 3rd century BC, the term was used for the non-Chinese populations of southern China and northern Vietnam, with particular ethnic groups called Minyue (閩越MǐnyuèChinese), Ouyue (甌越ŌuyuèChinese), Luoyue (Vietnamese: Lạc Việt, 駱越Lạc ViệtVietnamese), etc., collectively known as the Baiyue (Bách ViệtBách ViệtVietnamese; Chinese: 百越BǎiyuèChinese, "Hundred Yue/Viet"). The term 'Baiyue'/'Bách Việt' first appeared in the book Lüshi Chunqiu compiled around 239 BC. By the 17th and 18th centuries AD, educated Vietnamese apparently referred to themselves as người Việtngười ViệtVietnamese (Viet people) or người Namngười NamVietnamese (southern people).

The form Việt NamViet NamVietnamese (written in chữ Hán as 越南Việt NamVietnamese) is first recorded in the 16th-century oracular poem Sấm Trạng Trình. The name has also been found on 12 steles carved in the 16th and 17th centuries, including one at Bao Lam Pagoda in Hải Phòng that dates to 1558. In 1802, Nguyễn Phúc Ánh (later Emperor Gia Long) established the Nguyễn dynasty. In the second year of his rule, he asked the Jiaqing Emperor of the Qing dynasty to confer on him the title 'King of Nam Việt / Nanyue' (南越NányuèChinese) after seizing power in Annam. The Emperor refused because the name was related to Zhao Tuo's Nanyue, which included the regions of Guangxi and Guangdong in southern China. The Qing Emperor, therefore, decided to call the area "Việt Nam" instead. Between 1804 and 1813, the name Vietnam was used officially by Emperor Gia Long. It was revived in the early 20th century in Phan Bội Châu's History of the Loss of Vietnam, and later by the Vietnamese Nationalist Party (VNQDĐ). The country was usually called Annam until 1945, when the imperial government in Huế adopted Việt NamViệt NamVietnamese. The spelling "Viet Nam" or the full marked-Vietnamese form "Việt Nam" is sometimes used in English by local and government-operated media. "Viet Nam" is formally designated and recognized by the Government of Vietnam, the United Nations, and the International Organization for Standardization as the standardized country name.

3. History

The history of Vietnam spans millennia, from prehistoric settlements to its current status as a socialist republic. It encompasses periods of indigenous state formation, prolonged Chinese domination, the rise and fall of independent dynasties, colonial rule, devastating wars, and significant socio-economic transformations. This section details the major eras and events that have shaped modern Vietnam, with a focus on the social impacts of these developments, struggles for independence and self-determination, and issues related to human rights and democratic evolution.

3.1. Prehistory and early states

Archaeological excavations reveal human presence in what is now Vietnam dating back to the Paleolithic age. Stone artifacts found in Gia Lai province have been controversially dated to 780,000 years ago, based on associated tektite finds, though this dating is challenged due to the common occurrence of tektites in archaeological sites of various ages in Vietnam. Homo erectus fossils, dating to around 500,000 BC, have been discovered in caves in Lạng Sơn and Nghệ An provinces in northern Vietnam. The oldest Homo sapiens fossils from mainland Southeast Asia are of Middle Pleistocene origin, including isolated tooth fragments from Tham Om and Hang Hum. Teeth attributed to Homo sapiens from the Late Pleistocene have been found at Dong Can, and from the Early Holocene at Mai Da Dieu, Lang Gao, and Lang Cuom.

By about 1,000 BC, the development of wet-rice cultivation in the Ma River and Red River floodplains led to the flourishing of the Đông Sơn culture. This culture is notable for its sophisticated bronze casting techniques, used to create elaborate bronze Đông Sơn drums. The influence of the Đông Sơn culture spread to other parts of Southeast Asia, including Maritime Southeast Asia, throughout the first millennium BC. During this period, early Vietnamese kingdoms such as Văn Lang and Âu Lạc emerged. According to Vietnamese legends, the Hồng Bàng dynasty of the Hùng kings, believed to have been established in 2879 BC, is considered the first state in Vietnamese history, then known as Xích Quỷ and later Văn Lang. In 257 BC, the last Hùng king was defeated by Thục Phán. He consolidated the Lạc Việt and Âu Việt tribes to form Âu Lạc, proclaiming himself An Dương Vương. The region also participated in the Maritime Jade Road, connecting various Southeast Asian communities through trade and cultural exchange.

3.2. Chinese domination and independence

In 179 BC, a Chinese general named Zhao Tuo (Triệu ĐàTrieu DaVietnamese) defeated An Dương Vương and consolidated Âu Lạc into Nanyue. However, Nanyue itself was incorporated into the empire of the Chinese Han dynasty in 111 BC after the Han-Nanyue War. For the next thousand years, what is now northern Vietnam remained mostly under Chinese rule, a period known as Bắc thuộc. During this extensive period, Chinese administrative structures, language, and cultural norms, including Confucianism and Mahayana Buddhism, were introduced and gradually assimilated into Vietnamese society.

Despite the profound Chinese influence, the period was also marked by significant resistance movements. Early independence efforts, such as those led by the Trưng Sisters (Hai Bà TrưngHai Ba TrungVietnamese) in AD 40-43 and Lady Triệu (Bà TriệuBa TrieuVietnamese) in AD 248, were temporarily successful but ultimately suppressed. These uprisings, though defeated, became powerful symbols of Vietnamese resilience and desire for self-determination, significantly impacting the collective identity and fueling subsequent struggles for independence. Vietnam also experienced a longer period of independence as Vạn Xuân under the Anterior Lý dynasty between AD 544 and 602.

By the early 10th century, as the Tang dynasty in China weakened, Vietnam, then known as Annam, gained a degree of autonomy under the Khúc family. The culmination of centuries of resistance came in AD 938 when the Vietnamese lord Ngô Quyền decisively defeated the forces of the Chinese Southern Han state at the Bạch Đằng River. This victory marked the end of over a millennium of direct Chinese domination and established full independence for Vietnam in 939, paving the way for the formation of successive independent Vietnamese dynasties.

3.3. Dynastic Vietnam

Following the achievement of independence in 939 AD, Vietnam entered a long period of self-rule under a succession of native dynasties. These dynasties built upon the foundations of the past, further developing Vietnamese society, culture, and political institutions while continuously defending their sovereignty against external threats and expanding their territory southward. This era witnessed the consolidation of a distinct Vietnamese identity, blending indigenous traditions with adopted Chinese influences.

3.3.1. Early dynasties (Lý, Trần, Hồ)

After Ngô Quyền's victory, the Đinh dynasty (968-980) unified the country, followed by the Early Lê dynasty (980-1009). A more stable and prosperous era began with the Lý dynasty (1009-1225), which moved the capital to Thăng Long (modern Hanoi). The Lý dynasty promoted Buddhism, reformed administration, and initiated southward expansion.

The Trần dynasty (1225-1400) succeeded the Lý and is renowned for its military prowess, particularly its successful repulsion of three major Mongol invasions in the 13th century (1258, 1285, and 1288). These victories, achieved through strategic brilliance and popular resistance, are pivotal moments in Vietnamese history, reinforcing national pride and independence. Generals like Trần Hưng Đạo became national heroes. During this period, Mahayana Buddhism continued to flourish, often enjoying state patronage, and Confucianism played an increasingly important role in governance and education. The Trần dynasty also saw advancements in arts, literature, and technology, including the development of Chữ Nôm, a script based on Chinese characters used to write the Vietnamese language.

The Hồ dynasty (1400-1407), founded by Hồ Quý Ly, was short-lived. Despite implementing significant reforms in land ownership, currency, and education, aimed at strengthening the state, the Hồ dynasty faced internal opposition and external threats. In 1406, the Chinese Ming dynasty invaded, leading to the Ming-Hồ War and a brief period of Chinese rule known as the Fourth Northern Domination (1407-1427).

3.3.2. Later Lê, Mạc, and Restored Lê period (North-South division)

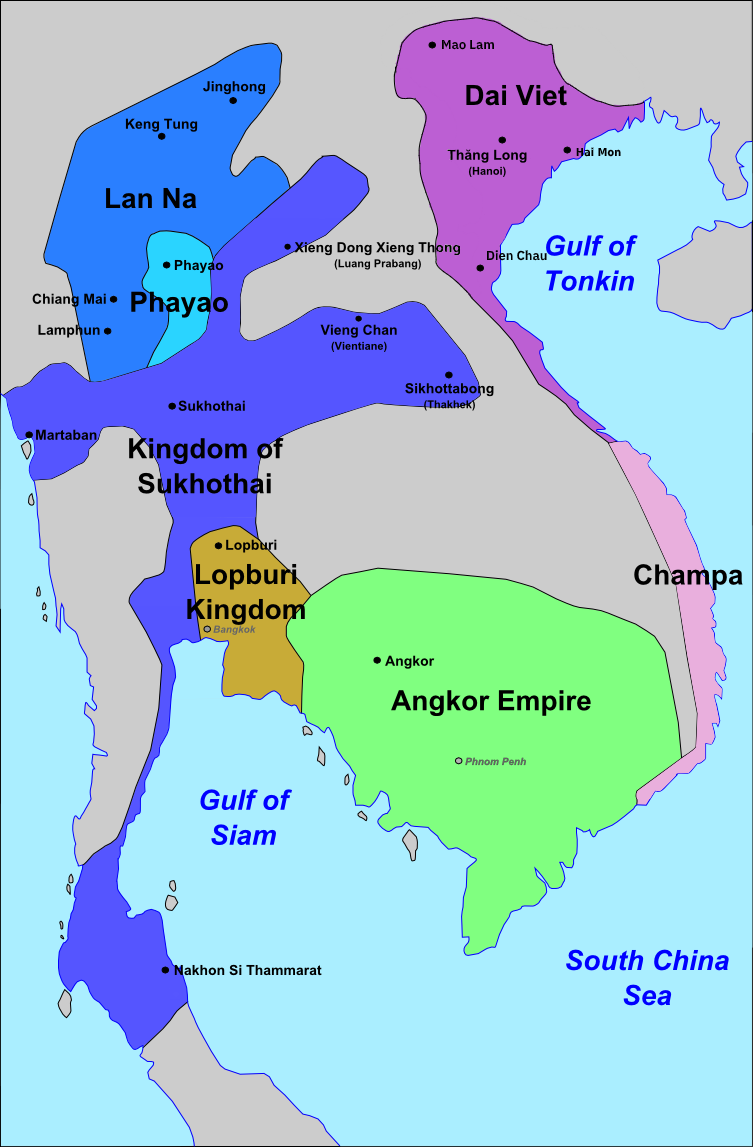

The Ming domination was ended by Lê Lợi, who, after a ten-year insurgency (the Lam Sơn uprising), established the Later Lê dynasty (1428-1789). The reign of Emperor Lê Thánh Tông (1460-1497) is considered a golden age, marked by administrative reforms, legal codification (the Hồng Đức Code), cultural achievements, and military strength. The Later Lê dynasty significantly expanded Vietnamese territory southward through the Nam tiến ("Southward March"), gradually conquering the Champa kingdom.

In 1527, a powerful general named Mạc Đăng Dung usurped the throne, establishing the Mạc dynasty (1527-1592). Supporters of the Lê loyalists retreated to the south and, with the help of the Nguyễn and Trịnh families, fought to restore the Lê. This led to a period of division known as the Southern and Northern Dynasties. Although the Lê dynasty was nominally restored in 1592, real power fell into the hands of two rival feudal families: the Trịnh lords in the north (Tonkin or Đàng Ngoài) and the Nguyễn lords in the south (Cochinchina or Đàng Trong).

This division persisted for nearly two centuries, marked by the Trịnh-Nguyễn conflict (1627-1672) and subsequent uneasy truces. During this time, the Nguyễn lords continued the southward expansion, extending Vietnamese control into the Mekong Delta, which was then part of the Khmer Empire. This expansion had profound demographic and cultural consequences, integrating new lands and populations into the Vietnamese sphere. The rivalry between the Trịnh and Nguyễn lords created a de facto partitioned state, each developing distinct administrative and economic characteristics, while the Lê emperors remained largely figureheads.

3.3.3. Tây Sơn and Nguyễn dynasties

In 1771, the Tây Sơn rebellion erupted, led by three brothers - Nguyễn Nhạc, Nguyễn Huệ (later Emperor Quang Trung), and Nguyễn Lữ. This peasant uprising rapidly gained momentum, overthrowing the Nguyễn lords in the south by 1777 and the Trịnh lords in the north by 1786, effectively unifying much of the country under Tây Sơn rule. In 1788, Nguyễn Huệ proclaimed himself Emperor Quang Trung and decisively defeated a Qing Chinese invasion force at the Battle of Ngọc Hồi-Đống Đa in 1789, which had sought to restore the Lê dynasty. The Tây Sơn dynasty implemented various reforms and sought to consolidate its power.

However, their rule was challenged by Nguyễn Phúc Ánh, a survivor of the Nguyễn lords, who, with significant foreign assistance including French military advisors and equipment provided through figures like Pigneau de Behaine, gradually reconquered lost territories. After years of warfare, Nguyễn Ánh defeated the Tây Sơn and established the Nguyễn dynasty in 1802, proclaiming himself Emperor Gia Long. He moved the capital to Huế.

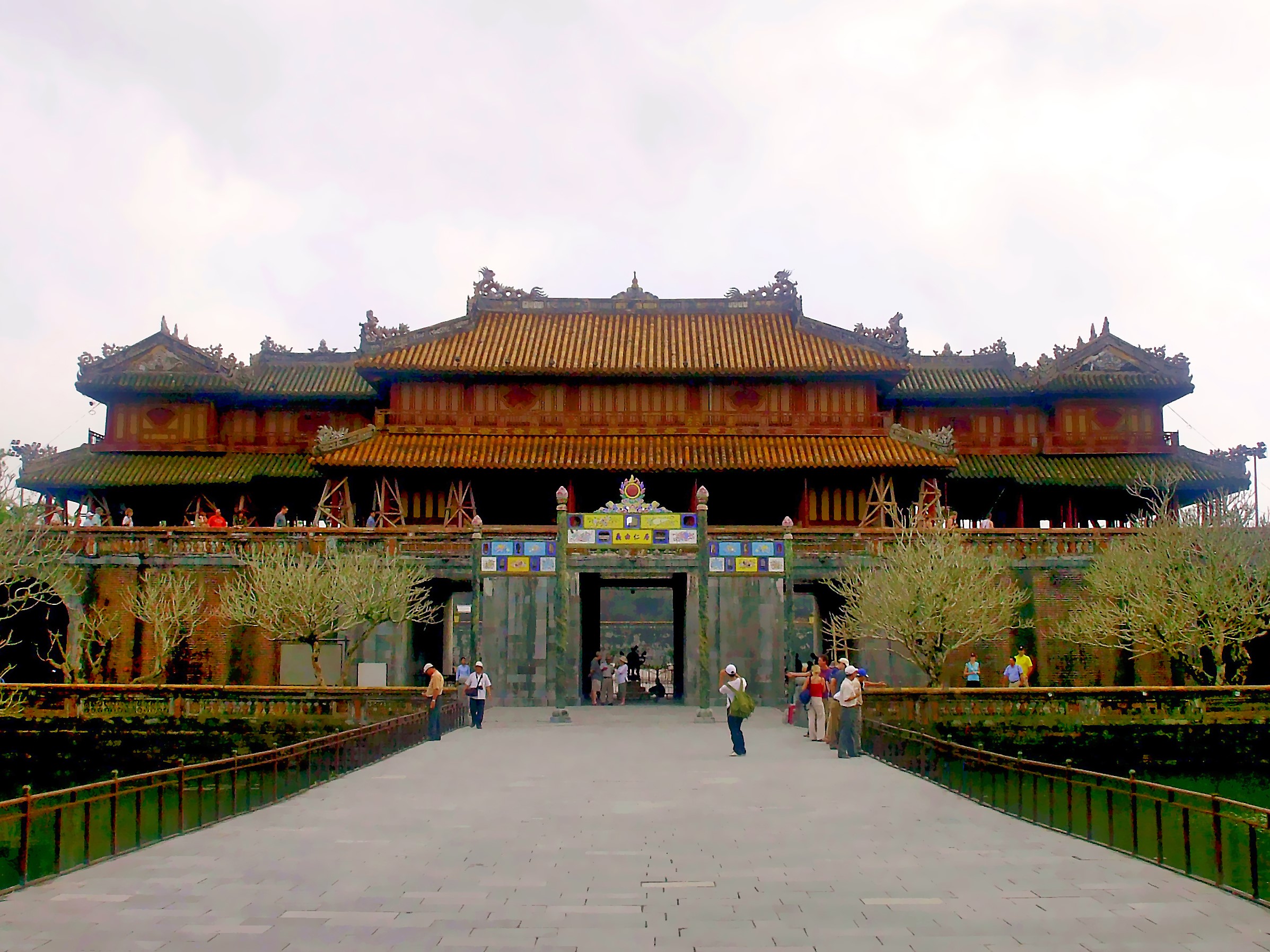

The Nguyễn dynasty, the last imperial dynasty of Vietnam, initially focused on administrative consolidation, adopting Confucian principles for governance, and attempting to restore order after decades of conflict. They standardized the administration, promoted education, and undertook public works. However, the dynasty also adopted conservative policies, including restrictions on foreign trade and persecution of Christians, which created internal dissent and provided pretexts for Western intervention. As European colonial ambitions in Asia grew in the 19th century, Vietnam increasingly faced pressure from Western powers, particularly France. This period saw societal changes and the beginnings of significant engagement with the West, which would ultimately lead to colonization.

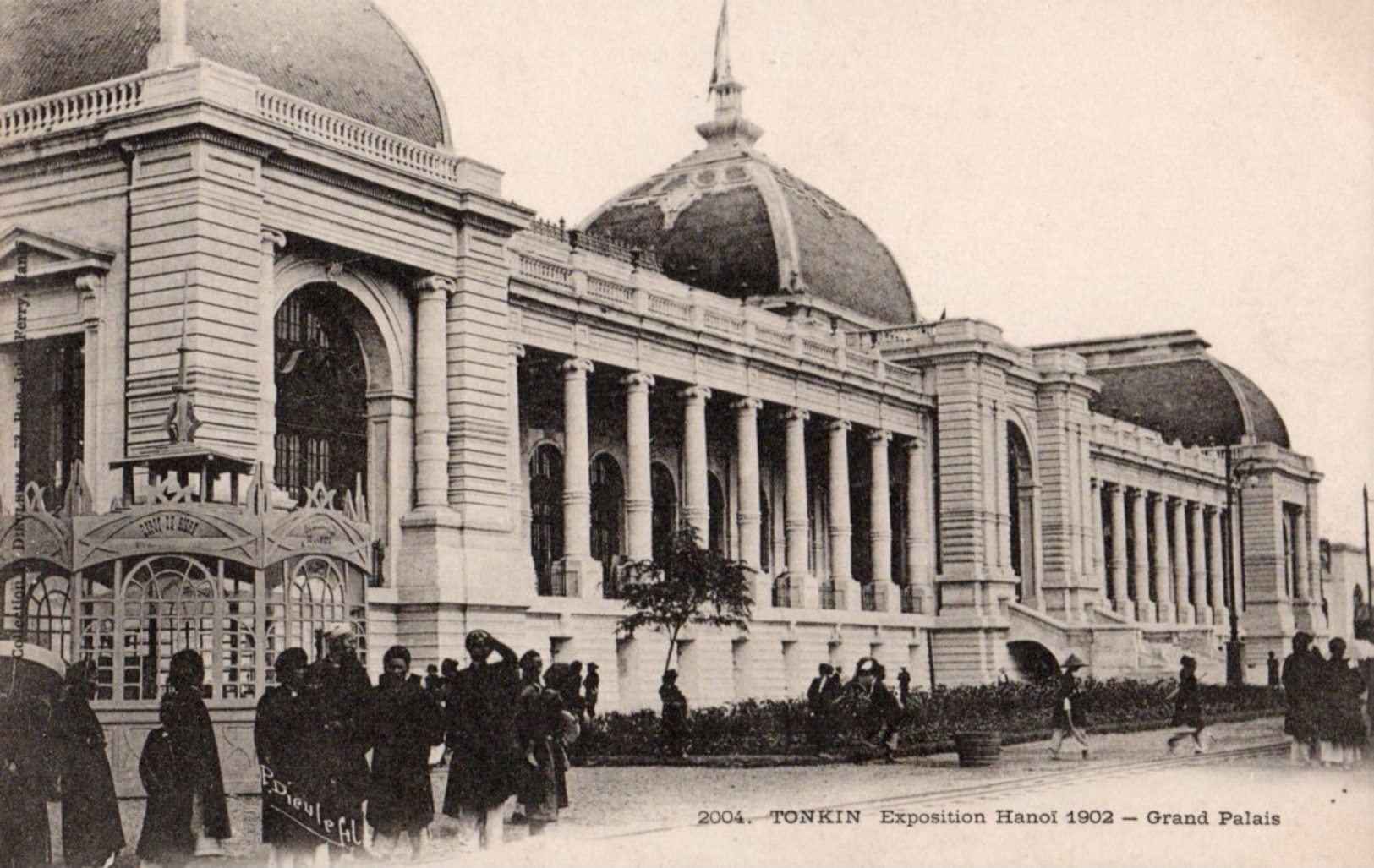

3.4. French Indochina

The French colonization of Vietnam began in the mid-19th century. In 1533, Portuguese explorers had landed in the Vietnamese delta but were forced to leave. Portuguese traders and Jesuit missionaries were active in both Đàng TrongDang TrongVietnamese (Cochinchina) and Đàng NgoàiDang NgoaiVietnamese (Tonkin) in the 17th century. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) established official relations with Tonkin in 1637. The English East India Company established relations with Tonkin by 1672. French traders were also active between 1615 and 1753. French missionaries arrived in 1658, and the Paris Foreign Missions Society actively sent missionaries.

Growing missionary activity and the Nguyễn dynasty's persecution of Christians provided a pretext for French intervention. Starting in 1858 with an attack on Da Nang (Tourane), France, aided by Spain, launched a series of military campaigns. The siege of Tourane was aided by Spanish forces from the Philippines. The 1862 Treaty of Saigon forced Emperor Tự Đức to cede three southern provinces, which became the French colony of Cochinchina. By 1867, France had seized all of Cochinchina. Subsequent military actions and treaties, often imposed under duress, extended French control. The 1883 Treaty of Huế and the 1884 (Patenôtre) Treaty established French protectorates over Annam (central Vietnam) and Tonkin (northern Vietnam). In 1887, Cochinchina, Annam, Tonkin, and Cambodia were formally integrated into the union of French Indochina, with Laos added in 1893.

French colonial rule brought significant political, economic, and social changes. The administration was centralized under French officials, with the Vietnamese monarchy in Huế reduced to a symbolic role. The colonial economy was geared towards exploiting Vietnam's natural resources (rubber, coal, rice, minerals) and labor for the benefit of France. A plantation economy was developed for exports like tobacco, indigo, tea, and coffee. This often involved land alienation and harsh labor conditions, leading to widespread peasant impoverishment and resentment. Infrastructure projects like railways and roads were built, primarily to facilitate resource extraction and military control. A Western-style education system was introduced but was limited in scope and aimed at creating a small class of collaborators.

Vietnamese resistance to French rule was persistent, though often fragmented. The royalist Cần Vương movement (Aid the King) in the late 19th century fought to restore imperial authority but was eventually suppressed. This movement involved guerrilla warfare and led to massacres of Christians, who were sometimes seen as collaborators. In the early 20th century, new nationalist movements emerged, inspired by both traditional ideals and modern ideologies. Figures like Phan Bội Châu advocated for independence through modernization and external support, while Phan Châu Trinh emphasized reform and education. The Yên Bái mutiny in 1930, led by the Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng (Vietnamese Nationalist Party), was a significant uprising but was brutally crushed. Communist groups, influenced by Ho Chi Minh, also began to organize, focusing on both national liberation and social revolution.

French colonial policies exacerbated social inequalities and suppressed basic human rights. Freedom of speech, press, and assembly were severely restricted. The economic exploitation led to social dislocation, and while some Vietnamese benefited from colonial rule, the majority experienced hardship. These conditions fueled the growth of various nationalist and revolutionary movements that would eventually challenge and overthrow French colonial power.

3.5. First Indochina War

During World War II, French Indochina was occupied by Japan. In September 1940, after France fell to Germany, Japan invaded and occupied French Indochina, though they allowed the pro-Vichy French colonial administration to continue functioning. Japan exploited Vietnam's resources for its war effort, which, combined with Allied bombing and French neglect, led to the devastating Vietnamese Famine of 1945, killing up to two million people. This period weakened French authority and fueled Vietnamese nationalism.

In 1941, Ho Chi Minh returned to Vietnam and founded the Việt Minh (League for the Independence of Vietnam), a broad nationalist front dominated by communists. The Việt Minh aimed to achieve independence from both French and Japanese rule. Following Japan's surrender in August 1945, the Việt Minh launched the August Revolution, seizing control of Hanoi and other key areas. On September 2, 1945, Ho Chi Minh proclaimed the independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) in Hanoi.

However, France was determined to re-establish its colonial rule. The Allies had decided at the Potsdam Conference to divide Indochina at the 16th parallel north, with Chinese Nationalist forces to disarm the Japanese in the north and British forces in the south. Both facilitated the return of French authority. Negotiations between Ho Chi Minh and the French failed to secure independence, and by late 1946, full-scale conflict erupted, marking the beginning of the First Indochina War (1946-1954).

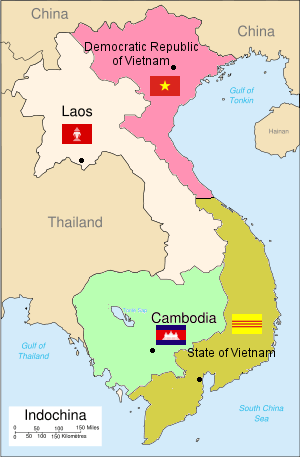

The war was a brutal guerrilla conflict. The Việt Minh, led by General Võ Nguyên Giáp, employed effective tactics against the technologically superior French forces. The DRV received support from the newly established People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union, while France received aid from the United States, which feared the spread of communism in Southeast Asia. The French established the State of Vietnam in 1949 under former emperor Bảo Đại as a rival Vietnamese government, but it lacked popular legitimacy.

The war culminated in the decisive Battle of Điện Biên Phủ in 1954. The Việt Minh besieged and overran the heavily fortified French garrison, a stunning victory that shattered French morale and political will to continue the war. The defeat at Điện Biên Phủ led to the 1954 Geneva Accords. The accords resulted in a ceasefire, the temporary partition of Vietnam at the 17th parallel north, with the DRV controlling the North and the State of Vietnam controlling the South. National elections were scheduled for 1956 to reunify the country. The accords also granted independence to Laos and Cambodia. A 300-day period of free movement was permitted, during which nearly a million northerners, mainly Catholics fearing communist persecution, moved south in Operation Passage to Freedom, often aided by the U.S. military. The First Indochina War ended French colonial rule but set the stage for further conflict and division in Vietnam.

3.6. Partition and Vietnam War

The 1954 Geneva Accords temporarily divided Vietnam at the 17th parallel, with elections planned for 1956 to reunify the country. However, these elections never took place. In South Vietnam, Ngô Đình Diệm, backed by the United States, ousted Bảo Đại in a fraudulent 1955 referendum and declared himself President of the newly formed Republic of Vietnam (RVN). Diệm, a staunch anti-communist, refused to participate in the nationwide elections, fearing a victory for Ho Chi Minh and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) in the North. The US supported Diệm's decision, viewing a unified communist Vietnam as a threat under the Domino theory.

The DRV in the North, under Ho Chi Minh and the Lao Dong (Workers') Party, implemented socialist reforms, including land redistribution which involved political repression and executions. In the South, Diệm's government became increasingly authoritarian and nepotistic, suppressing political opposition and alienating various groups, particularly the Buddhist majority, through pro-Catholic policies. This led to growing discontent and insurgency. In 1960, the National Liberation Front (NLF), often referred to as the Việt Cộng, was formed in the South, with backing from North Vietnam, to overthrow Diệm's regime and reunify the country.

The conflict escalated as the NLF intensified its guerrilla activities and the DRV increased its support. The United States, under Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson, progressively deepened its involvement, sending military advisors and financial aid to South Vietnam. The Buddhist crisis of 1963, marked by protests and self-immolations by monks, highlighted the instability of Diệm's regime, leading to a US-backed coup in November 1963 in which Diệm and his brother Ngô Đình Nhu were assassinated. A series of unstable military governments followed in South Vietnam.

The Gulf of Tonkin incident in August 1964 provided the pretext for direct US military intervention. The US Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, granting President Johnson broad authority to escalate the war. US combat troops began arriving in 1965, and Operation Rolling Thunder, a sustained bombing campaign against North Vietnam, commenced. The war became a major Cold War proxy conflict, with North Vietnam receiving significant military and economic aid from the Soviet Union and China, while South Vietnam was heavily supported by the United States and its allies, including South Korea, Australia, and Thailand.

The war was characterized by brutal fighting, including large-scale conventional battles, extensive guerrilla warfare, and devastating aerial bombardment. The US employed advanced weaponry, including napalm and Agent Orange, the latter causing long-term environmental damage and health problems. Both sides committed atrocities; the Việt Cộng conducted targeted assassinations and terror campaigns, while US and South Vietnamese forces were responsible for events like the My Lai Massacre. The Tết Offensive in January 1968, a massive coordinated attack by North Vietnamese and NLF forces on cities and towns across South Vietnam, was a military defeat for the communists but a significant political and psychological blow to the US. It shattered American public confidence in the war and intensified anti-war protests in the US and internationally.

President Richard Nixon, elected in 1968, pursued a policy of "Vietnamization", aiming to build up South Vietnamese forces to fight the war while gradually withdrawing US troops. Peace talks in Paris, which had begun in 1968, continued intermittently. In 1973, the Paris Peace Accords were signed, leading to a ceasefire and the complete withdrawal of US combat forces. However, the accords did not end the conflict between North and South Vietnam. Fighting resumed, and in the spring of 1975, North Vietnam launched a final major offensive. The South Vietnamese army (ARVN) collapsed rapidly, and on April 30, 1975, North Vietnamese tanks entered Saigon, leading to the surrender of South Vietnam.

The Vietnam War had devastating consequences. Millions of Vietnamese, both soldiers and civilians, were killed or wounded. The country's infrastructure and economy were shattered, and the social fabric was deeply torn. The extensive use of chemical defoliants like Agent Orange left a legacy of birth defects and environmental contamination. The war also had a profound impact on the United States, causing deep social and political divisions and shaping its foreign policy for decades. Internationally, the war fueled anti-colonial movements and became a symbol of resistance against superpower intervention.

3.7. Reunification and Đổi Mới reforms

Following the Fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, South Vietnam came under the control of the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam, which was heavily influenced by North Vietnam. On July 2, 1976, North and South Vietnam were formally reunified as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, with Hanoi as its capital. The Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV), formerly the Lao Dong Party, became the sole ruling party.

The immediate post-war period was marked by significant socio-economic challenges. The war had devastated the country, with estimates of Vietnamese deaths ranging from 966,000 to 3.8 million. The new government faced the task of rebuilding a shattered infrastructure, integrating the South's capitalist economy into the North's socialist system, and addressing deep social divisions. Under Lê Duẩn's administration, while mass executions of former South Vietnamese officials and collaborators were largely avoided, up to 300,000 individuals were sent to "re-education camps" for political indoctrination and forced labor, where many endured harsh conditions, torture, and starvation. The government implemented policies of collectivization of agriculture and nationalization of industries, which proved largely ineffective and led to economic stagnation.

Internationally, Vietnam faced isolation. A trade embargo imposed by the United States and other Western countries crippled its economy. Relations with neighboring countries were also strained. In 1978, Vietnam invaded Cambodia (Cambodian-Vietnamese War) to overthrow the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime, which had been launching cross-border attacks. While this intervention ended the Khmer Rouge's rule and installed a pro-Vietnamese government (the People's Republic of Kampuchea), it led to a protracted guerrilla war and further international condemnation. In response to the Cambodian invasion, China, which had supported the Khmer Rouge, launched a brief but bloody invasion of northern Vietnam in 1979. These conflicts placed enormous strain on Vietnam's already fragile economy and led to increased reliance on Soviet aid. The economic hardships and political repression also led to a large exodus of refugees, often referred to as "boat people."

By the mid-1980s, Vietnam was facing a severe socio-economic crisis. In response, at the Sixth National Congress of the CPV in December 1986, reformist leaders initiated a comprehensive program of economic and political reforms known as Đổi Mới ("Renovation"). Led by General Secretary Nguyễn Văn Linh, Đổi Mới marked a significant shift from a centrally planned economy towards a "socialist-oriented market economy." The reforms included de-collectivization of agriculture, encouragement of private enterprise, deregulation, and opening the country to foreign investment. While the CPV maintained its political monopoly, the economic reforms aimed to revitalize the economy by introducing market mechanisms.

Đổi Mới led to a period of rapid economic growth. Agricultural and industrial production increased, exports grew, and foreign investment flowed into the country. Vietnam gradually reintegrated into the global economy and politics, normalizing relations with China in 1991 and the United States in 1995, and joining ASEAN in 1995 and the WTO in 2007. However, the reforms also brought new challenges, including rising income inequality, social disparities, corruption, and environmental degradation. The transition to a market economy also impacted social welfare systems and labor rights. Despite these challenges, Đổi Mới transformed Vietnam from one of the world's poorest countries into a lower-middle-income economy, though the path towards further development continues to involve navigating the complexities of balancing economic growth with social equity and political stability under the CPV's leadership. In 2021, Nguyễn Phú Trọng was re-elected for his third term as General Secretary, making him Vietnam's most powerful leader in decades. He passed away on July 19, 2024, and was succeeded by Tô Lâm.

4. Geography

Vietnam is situated on the eastern Indochinese Peninsula, characterized by a long, narrow S-shape. It shares land borders with China to the north, Laos to the northwest, and Cambodia to the southwest. Its extensive coastline stretches along the Gulf of Tonkin, the South China Sea, and the Gulf of Thailand. This section explores Vietnam's key physical features, topography, climate, rich biodiversity, and pressing environmental concerns.

4.1. Topography

Vietnam's territory covers a total area of approximately NaN Q mile2 (NaN Q km2). The country's land boundaries have a combined length of NaN Q mile (NaN Q km), and its coastline spans NaN Q mile (NaN Q km), not including numerous islands. At its narrowest point in the central Quảng Bình province, Vietnam is only about 31 mile (50 km) wide, while it broadens to around 373 mile (600 km) in the north.

The topography is predominantly hilly and densely forested, with level land constituting no more than 20% of the total area. Mountains account for 40% of the country's land. The northern part of the country consists mainly of highlands and the fertile Red River Delta. This delta, a flat, roughly triangular region covering NaN Q mile2 (NaN Q km2), was formed by alluvial deposits from the Red River over millennia and is intensely cultivated and densely populated. Fansipan, located in Lào Cai province in the Hoàng Liên Sơn mountain range, is Vietnam's highest peak, standing at NaN Q ft (NaN Q m).

Central Vietnam is characterized by the Annamite Range (Dãy Trường SơnDay Truong SonVietnamese), which runs parallel to the coast, creating a narrow coastal plain. This region often experiences harsh weather conditions. Southern Vietnam features coastal lowlands, the foothills of the Annamite Range, and the vast, fertile Mekong Delta. The Mekong Delta, covering about NaN Q mile2 (NaN Q km2), is a low-lying plain, generally no more than 9.8 ft (3 m) above sea level. It is a complex network of rivers and canals, and its rich sediment deposits cause the delta to advance 197 ft (60 m) into the sea annually. The Central Highlands (Tây NguyênTay NguyenVietnamese) consist of five relatively flat plateaus of basalt soil, contributing significantly to agricultural land (16%) and forested land (22%).

Vietnam possesses numerous islands and archipelagos. Phú Quốc is the largest island. Vietnam also claims sovereignty over the Paracel Islands (Quần đảo Hoàng SaQuan dao Hoang SaVietnamese) and the Spratly Islands (Quần đảo Trường SaQuan dao Truong SaVietnamese) in the South China Sea, which are subjects of complex territorial disputes with other regional nations. Notable natural features include Hang Sơn Đoòng cave, considered the world's largest known cave passage, and Ba Bể Lake, the largest natural freshwater lake. The exclusive economic zone of Vietnam covers NaN Q mile2 (NaN Q km2) in the South China Sea.

4.2. Climate

Vietnam's climate is predominantly tropical and monsoonal, but it varies considerably from north to south due to differences in latitude and topography. The country generally experiences high rates of precipitation, with average annual rainfall ranging from NaN Q in (NaN Q mm), primarily during the monsoon seasons, which often leads to flooding.

The northern region has a subtropical climate with distinct seasons. Winters (November to April) are influenced by the northeast monsoon, bringing cool and sometimes damp weather. Summers (May to October) are hot and humid with heavy rainfall. Hanoi, the capital, experiences average temperatures ranging from around 59 °F (15 °C) in winter to 91.4 °F (33 °C) in summer. The mountainous areas in the far north can experience colder temperatures, with occasional snowfall on the highest peaks.

Central Vietnam has a transitional climate. The coastal areas often face typhoons and tropical storms, particularly from August to November. The Annamite Range creates diverse microclimates, with some areas experiencing heavy rainfall while others are in rain shadows.

Southern Vietnam has a more consistently tropical climate, characterized by high temperatures and humidity throughout the year. There are two main seasons: a dry season (November to April) and a rainy season (May to October). Ho Chi Minh City and the Mekong Delta experience temperatures generally ranging between 69.8 °F (21 °C) and 95 °F (35 °C).

Vietnam is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, including rising sea levels, increased frequency of extreme weather events like typhoons and droughts, and saltwater intrusion in coastal deltas. These changes pose significant threats to agriculture, infrastructure, and the livelihoods of its population, particularly those in low-lying coastal areas.

4.3. Biodiversity and environment

Vietnam is located within the Indomalayan realm and is recognized as one of the world's twenty-five countries with exceptionally high biodiversity. It ranks 16th globally in biological diversity, hosting approximately 16% of the world's species. The country's flora includes around 15,986 identified species, with 10% being endemic. Its fauna is equally rich, featuring 307 nematode species, 200 oligochaeta, 145 acarina, 113 springtails, 7,750 insects, 260 reptiles, 120 amphibians, 840 bird species (100 endemic), and 310 mammal species (78 endemic). Notable endemic or newly discovered species include the saola, giant muntjac, Tonkin snub-nosed monkey, and the endangered Edwards's pheasant. Vietnam is also home to 1,438 species of freshwater microalgae and 2,458 species of sea fish.

Vietnam has two World Natural Heritage Sites: Hạ Long Bay and Phong Nha-Kẻ Bàng National Park. Additionally, there are nine biosphere reserves, including Cần Giờ Mangrove Forest, Cát Tiên National Park, Cát Bà National Park, and U Minh Thượng National Park. The government has established 126 conservation areas, including 30 national parks, and spent approximately 49.07 M USD on biodiversity preservation in 2004 alone. Vietnam is also one of the world's twelve original cultivar centers, with its National Cultivar Gene Bank preserving 12,300 cultivars of 115 species.

Despite these conservation efforts, Vietnam faces significant environmental challenges. Wildlife poaching remains a major concern, driven by demand for traditional medicine and status symbols, as seen with the illegal trade in rhinoceros horns. Organizations like Education for Nature - Vietnam (ENV) and GreenViet work to combat poaching and promote wildlife conservation.

A critical and lasting environmental issue is the legacy of Agent Orange and other herbicides used during the Vietnam War. Nearly 4.8 million Vietnamese people were exposed, suffering from health problems and birth defects. The US has been involved in joint clean-up projects at former chemical storage sites like Đà Nẵng and Biên Hòa. The Vietnamese government allocates significant funds for victim support and rehabilitation. Reforestation efforts, particularly of mangrove forests in the Mekong Delta, aim to restore damaged ecosystems. However, Vietnam's Forest Landscape Integrity Index score in 2019 was 5.35/10, ranking it 104th globally.

Other environmental problems include arsenic contamination of groundwater in the Mekong and Red River Deltas, and the danger posed by unexploded ordnance (UXO) from past wars. Industrialization and urbanization have also led to increased pollution. For example, the 2016 Vietnam marine life disaster, caused by industrial discharge, highlighted the environmental risks of rapid development. Deforestation, driven by agriculture, logging, and infrastructure projects, also remains a serious concern, impacting biodiversity and ecosystem services.

5. Politics and government

The Socialist Republic of Vietnam is a unitary Marxist-Leninist one-party socialist state. Its political system is defined by the Constitution, which asserts the leading role of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) in all aspects of society. This section details Vietnam's governance structure, the dominance of the CPV, administrative divisions, foreign policy, military, and the human rights situation, particularly concerning democratic development and civil liberties.

5.1. Governance and the Communist Party

The Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) plays a central role in Vietnam's one-party system, as enshrined in the constitution, which designates it the "leading force of the state and society." State institutions operate under the party's guidance. The General Secretary of the CPV holds the highest and most influential position, overseeing the party's national organization and shaping state policy.

The President acts as the head of state and commander-in-chief of the armed forces, chairing the Council for National Defense and Security and handling executive duties such as state appointments. The Prime Minister is the head of government, leading the Council of Ministers (cabinet), which includes deputy prime ministers and heads of various ministries.

The National Assembly of Vietnam, a unicameral legislature with 500 members elected for five-year terms, is constitutionally the supreme organ of state power, superior to both the executive and judicial branches. All government ministers are appointed from its members. However, the National Assembly's functions are significantly influenced by the CPV. Electoral participation is limited to political organizations affiliated with or endorsed by the CPV, primarily through the Vietnamese Fatherland Front.

The Supreme People's Court of Vietnam, led by a Chief Justice, is the highest court of appeal. Military courts handle matters of national security. The judiciary, like other state organs, is accountable to the National Assembly and operates within the CPV's framework.

The top leadership, often called the "four pillars," includes the General Secretary of the CPV, the President, the Prime Minister, and the Chairperson of the National Assembly. As of late 2024, these roles are filled by Tô Lâm (General Secretary), Lương Cường (President), Phạm Minh Chính (Prime Minister), and Trần Thanh Mẫn (Chairperson of the National Assembly). Vietnam retains the death penalty for numerous offenses.

5.2. Administrative divisions

Vietnam is divided into 57 provinces (tỉnhtinhVietnamese; chữ Hán: 省) and 6 centrally-governed municipalities (thành phố trực thuộc trung ươngthanh pho truc thuoc trung uongVietnamese) which are administratively on the same level as provinces. The six municipalities are Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, Da Nang, Haiphong, Cần Thơ, and Huế.

Provinces are further subdivided into provincial municipalities (thành phố trực thuộc tỉnhthanh pho truc thuoc tinhVietnamese, 'city under province'), townships (thị xãthi xaVietnamese), and rural districts (huyệnhuyenVietnamese). These are then subdivided into commune-level towns (thị trấnthi tranVietnamese) or communes (xãxaVietnamese).

Centrally-governed municipalities are subdivided into urban districts (quậnquanVietnamese) and rural districts (huyệnhuyenVietnamese), which are further subdivided into wards (phườngphuongVietnamese).

Vietnam is often conceptually divided into eight regions: Northwest (Tây Bắc BộTay Bac BoVietnamese), Northeast (Đông Bắc BộDong Bac BoVietnamese), Red River Delta (Đồng bằng sông HồngDong bang song HongVietnamese), North Central Coast (Bắc Trung BộBac Trung BoVietnamese), South Central Coast (Duyên hải Nam Trung BộDuyen hai Nam Trung BoVietnamese), Central Highlands (Tây NguyênTay NguyenVietnamese), Southeast (Đông Nam BộDong Nam BoVietnamese), and Mekong Delta (Đồng bằng sông Cửu LongDong bang song Cuu LongVietnamese).

| Northwest (Tây Bắc BộTay Bac BoVietnamese) | Northeast (Đông Bắc BộDong Bac BoVietnamese) | Red River Delta (Đồng bằng sông HồngDong bang song HongVietnamese) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| style="vertical-align:top;" |

| style="vertical-align:top;" |

|- | North Central Coast (Bắc Trung BộBac Trung BoVietnamese) | Central Highlands (Tây NguyênTay NguyenVietnamese) | South Central Coast (Duyên hải Nam Trung BộDuyen hai Nam Trung BoVietnamese) |

| style="vertical-align:top;" |

| style="vertical-align:top;" |

|- | Southeast (Đông Nam BộDong Nam BoVietnamese) | Mekong Delta (Đồng bằng sông Cửu LongDong bang song Cuu LongVietnamese) | |

| style="vertical-align:top;" |

| |

5.3. Foreign relations

Vietnam's foreign policy emphasizes independence, self-reliance, peace, cooperation, and development. It officially pursues a policy of openness, diversification, and multilateralization in international relations, declaring itself a friend and reliable partner to all countries. Vietnam is a member of 63 international organizations, including the United Nations (UN), Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (OIF), and the World Trade Organization (WTO). As of 2010, Vietnam had established diplomatic relations with 178 countries and maintains relations with over 650 non-governmental organizations.

Throughout its history, Vietnam's most significant foreign relationship has been with various Chinese dynasties. While formal peace exists, significant territorial tensions, particularly over the South China Sea, persist between Vietnam and China. This dispute influences Vietnam's strategic calculus and its relationships with other major powers.

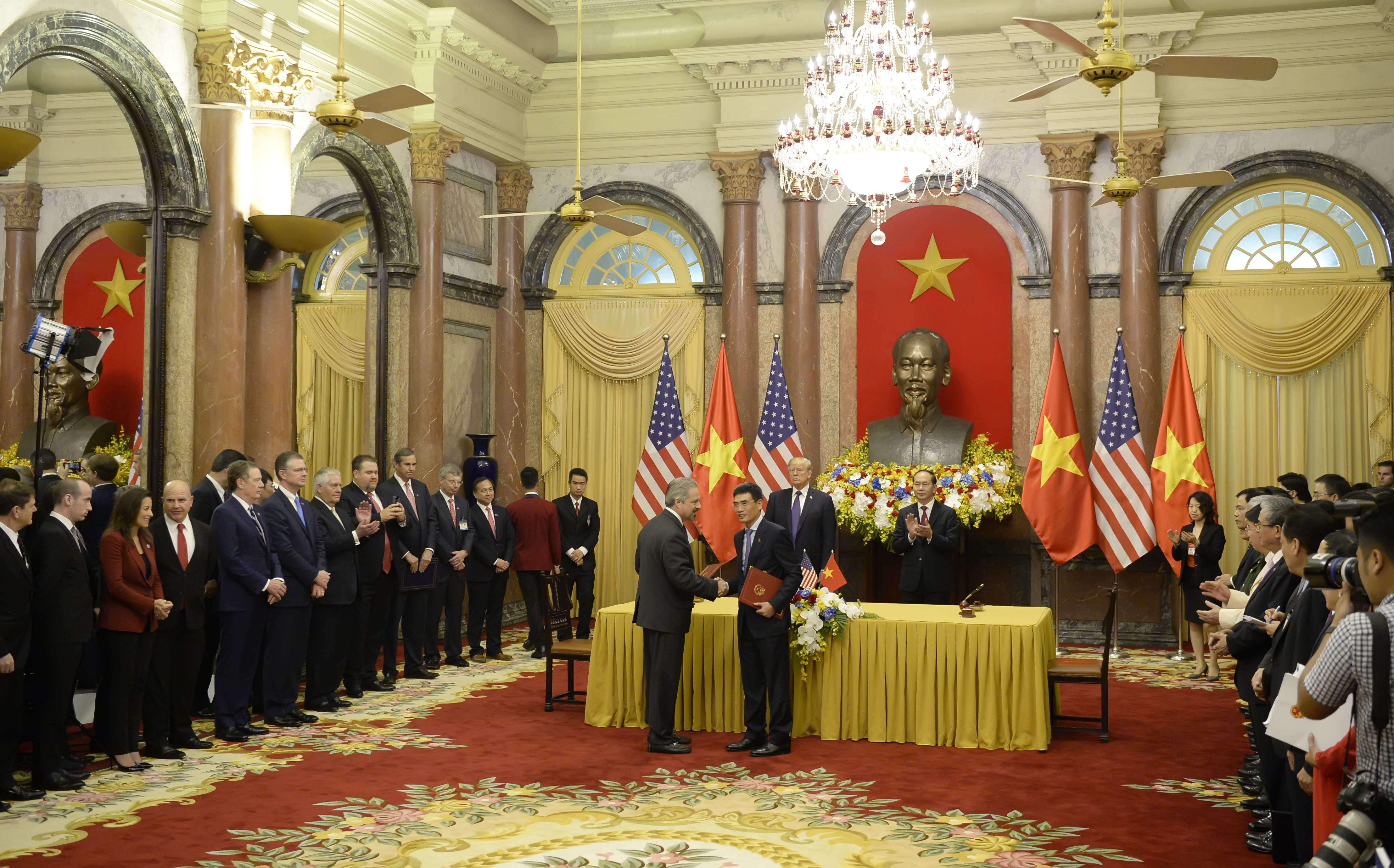

Since the 1990s, Vietnam has made substantial efforts to normalize and strengthen relations with Western countries. Relations with the United States were normalized in 1995, and have since developed into a "Comprehensive Strategic Partnership" as of 2023, reflecting growing cooperation in economic, security, and political spheres. This closer relationship is partly driven by shared concerns about China's increasing assertiveness in the region. In May 2016, US President Barack Obama announced the lifting of the arms embargo on Vietnam, further normalizing ties. President Bill Clinton was the first U.S. leader to officially visit Hanoi in November 2000 since the end of the Vietnam War.

Vietnam also maintains important relationships with other major powers, neighboring countries, and key partners.

5.3.1. Relations with major powers

Beyond China and the United States, Vietnam has significant ties with Russia. Historically, the Soviet Union was a crucial ally, providing substantial military and economic aid, especially during and after the Vietnam War. While the relationship has evolved since the Soviet Union's collapse, Russia remains an important partner, particularly in defense cooperation and energy.

5.3.2. Relations with neighboring countries and ASEAN

Vietnam plays an active role in ASEAN, which it joined in 1995. Membership in ASEAN is a cornerstone of its foreign policy, promoting regional stability and economic integration. Vietnam has complex but generally cooperative relationships with its Indochinese neighbors, Laos and Cambodia. Historical ties, border issues, and economic cooperation define these relationships. The intervention in Cambodia in 1978 to remove the Khmer Rouge, while controversial internationally, is viewed by Vietnam as necessary for its security and regional stability. It also maintains diverse relationships with other Southeast Asian nations.

5.3.3. Relations with South Korea

The relationship between Vietnam and South Korea has developed rapidly since the establishment of diplomatic ties in 1992. Economic cooperation is a key pillar, with South Korea being one of Vietnam's largest foreign investors and trading partners. Cultural exchange is also significant, with a large Vietnamese community in South Korea and growing popularity of Korean culture in Vietnam. Historical issues related to South Korea's participation in the Vietnam War on the side of South Vietnam are generally managed to allow for pragmatic cooperation, though calls for acknowledgment and reconciliation from victim groups persist.

5.3.4. Relations with Japan

Japan is another crucial economic partner for Vietnam, being a major source of official development assistance (ODA), foreign direct investment, and a significant trading partner. Cooperation extends to infrastructure development, technology transfer, and cultural exchange. Both countries share concerns about regional maritime security and have strengthened ties in recent years, including in defense cooperation.

5.4. Military

The Vietnam People's Armed Forces (VPAF) consist of the Vietnam People's Army (VPA), the Vietnam People's Public Security, and the Vietnam Self-Defence Militia. The VPA is the official name for the active military services and is subdivided into the Vietnam People's Ground Forces (Army), the Vietnam People's Navy, the Vietnam People's Air Force, the Vietnam Border Guard, and the Vietnam Coast Guard.

The VPA has an active manpower of around 450,000 personnel, but its total strength, including paramilitary forces and reserves, can be as high as 5,000,000. In 2015, Vietnam's military expenditure was approximately 4.40 B USD, equivalent to about 8% of its total government spending. Vietnam has been modernizing its military capabilities, particularly its navy and air force, in response to evolving regional security dynamics, including maritime disputes in the South China Sea.

Vietnam engages in joint military exercises and war games with various countries, including Brunei, India, Japan, Laos, Russia, Singapore, and the United States. This reflects its policy of diversifying defense partnerships. In 2017, Vietnam signed the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. The country's defense policy is officially based on principles of self-defense, non-alignment (no military alliances, no foreign military bases on its territory, not siding with one country against another), and maintaining peace and stability.

5.5. Human rights

The human rights situation in Vietnam is a subject of significant concern for international organizations and activists. The Government of Vietnam, while having moved from a totalitarian to a more authoritarian system, maintains tight control over fundamental freedoms. Issues frequently raised include restrictions on freedom of expression, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, association, and freedom of religion.

The Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) is the only legally permitted political party, and any organized political opposition is suppressed. Individuals who advocate for multi-party democracy, human rights, or criticize government policies often face harassment, intimidation, surveillance, and imprisonment. Activists, bloggers, and human rights defenders are particularly vulnerable. Charges such as "conducting propaganda against the state" or "abusing democratic freedoms" are often used to silence dissent. For example, in 2009, lawyer Lê Công Định and several associates were arrested and charged with subversion, and Amnesty International described them as prisoners of conscience.

Censorship of the media is pervasive, with all media outlets state-controlled or heavily influenced by the CPV. Internet censorship is also extensive, with authorities blocking access to websites deemed politically sensitive and monitoring online activities. The "Bamboo Firewall" is a term used to describe these measures.

While the constitution guarantees freedom of religion, in practice, religious activities are closely monitored and regulated by the government. Only government-approved religious organizations are allowed to operate freely. Unregistered groups, particularly certain Protestant denominations among ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands and Hmong communities, often face harassment and restrictions.

The government's official stance is that it respects human rights and that any restrictions are necessary for national security and social stability. It highlights its achievements in poverty reduction and improving living standards as evidence of its commitment to citizens' well-being. However, international human rights groups and some Western governments continue to call for greater respect for civil and political liberties, democratic reforms, and the release of political prisoners. Efforts by domestic activists to promote human rights and democratic development often occur under difficult and repressive conditions. Vietnam has also faced issues related to human trafficking.

6. Economy

Vietnam's economy has undergone a remarkable transformation from a centrally planned system to a socialist-oriented market economy. This transition, initiated by the Đổi Mới reforms in 1986, has led to significant economic growth and poverty reduction, but also presents challenges related to social equity, labor rights, and sustainable development.

6.1. Economic development and Đổi Mới

| Share of world GDP (PPP) | |

|---|---|

| Year | Share |

| 1980 | 0.21% |

| 1990 | 0.28% |

| 2000 | 0.39% |

| 2010 | 0.52% |

| 2020 | 0.80% |

After reunification in 1975, Vietnam adopted a centrally planned economy. The collectivization of farms and nationalization of industries, coupled with the devastation of war, US-led trade embargoes, and conflicts with Cambodia and China, led to severe economic inefficiency, underproduction, and hardship. By the mid-1980s, the country faced a profound socio-economic crisis, with high inflation and widespread poverty.

In response, the Sixth National Congress of the CPV in December 1986 launched the Đổi Mới ("Renovation") reforms. This marked a pivotal shift towards a "socialist-oriented market economy". While the CPV maintained its political dominance, Đổi Mới introduced market-oriented mechanisms, encouraged private ownership in agriculture, industry, and commerce, and sought to attract foreign investment. Key components included de-collectivizing agriculture, allowing farmers long-term land use rights, liberalizing prices, reforming state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and opening the economy to international trade and investment.

The impact of Đổi Mới was significant. Vietnam experienced high annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth, averaging around 8% between 1990 and 1997, and around 7% from 2000 to 2005, making it one of the fastest-growing economies in the world. Poverty rates declined dramatically. The country successfully reintegrated into the global economy, joining ASEAN in 1995 and the WTO in 2007. The United States ended its economic embargo in 1994.

However, the transition also brought challenges. Income inequality and gender disparities widened. Corruption remains a significant issue, particularly concerning SOEs and land management. The rapid industrialization and urbanization have led to environmental degradation. Ensuring equitable distribution of the benefits of growth and protecting labor rights in a more market-driven economy are ongoing concerns. The "socialist-oriented" aspect implies a continued role for the state in guiding economic development and addressing social welfare, though the balance between state control and market forces remains a subject of debate and policy adjustment. Despite a slowdown during the late-2000s global recession, growth remained relatively strong. Vietnam is currently classified as a developing country with a lower-middle-income economy.

6.2. Major industries

Vietnam's economy has diversified significantly under Đổi Mới, moving from a primarily agrarian base to one with growing industrial and service sectors.

6.2.1. Agriculture, forestry, and fishing

Agriculture remains a vital sector, though its share of GDP has declined. Vietnam is a major global exporter of several agricultural products. It is the world's largest producer of cashew nuts and black pepper, and consistently ranks as one of the top rice exporters (second or third globally). It is also the world's second-largest exporter of coffee, primarily Robusta. Other significant agricultural exports include tea and rubber. The land reform measures under Đổi Mới, which granted farmers more autonomy, were crucial to boosting agricultural output.

Aquaculture and fishing are also important. Vietnam is a major exporter of seafood, including shrimp and various types of fish. The fisheries sector has seen strong growth, largely driven by the expansion of aquaculture. Forestry contributes to the economy, but sustainable forest management and combating deforestation are ongoing challenges.

6.2.2. Industry and mining

The industrial sector has experienced rapid growth, fueled by foreign investment and an expanding manufacturing base. Key manufacturing industries include garments and textiles, footwear, and electronics. Vietnam has become an attractive destination for multinational corporations seeking to diversify their supply chains, partly due to its relatively low labor costs and strategic location. Industrial parks and export processing zones have been established across the country.

Mining also plays a role in the economy. Vietnam has significant reserves of bauxite (for aluminum production), coal, oil, and natural gas. It is the third-largest oil producer in Southeast Asia. The exploitation of these resources contributes to export earnings but also raises environmental concerns that require careful management.

6.2.3. Services

The services sector has become increasingly important, contributing a growing share to GDP and employment. Key sub-sectors include:

- Tourism**: This has been a rapidly expanding industry, with Vietnam attracting millions of international visitors annually to its diverse natural landscapes, cultural heritage sites, and beaches.

- Information Technology (IT) and Business Process Outsourcing (BPO)**: Vietnam has emerged as a significant player in IT services and software development, benefiting from a young, educated workforce.

- Retail and Wholesale Trade**: Modern retail formats like supermarkets and shopping malls are expanding, particularly in urban areas, alongside traditional markets.

- Finance and Banking**: The financial sector has been undergoing reforms to modernize and increase efficiency.

- Logistics and Transportation**: Essential for supporting the growing manufacturing and trade sectors.

The development of these service industries is crucial for Vietnam's continued economic diversification and job creation.

6.3. Science and technology

Vietnam has been making efforts to advance its science and technology (S&T) capabilities to support economic development and modernization. Government policies aim to foster research and development (R&D), improve S&T infrastructure, and enhance international cooperation. In 2010, total state spending on S&T was around 0.45% of GDP, and by 2011, UNESCO reported it at 0.19%. Despite a modest starting point, the number of Vietnamese scientific publications has increased significantly.

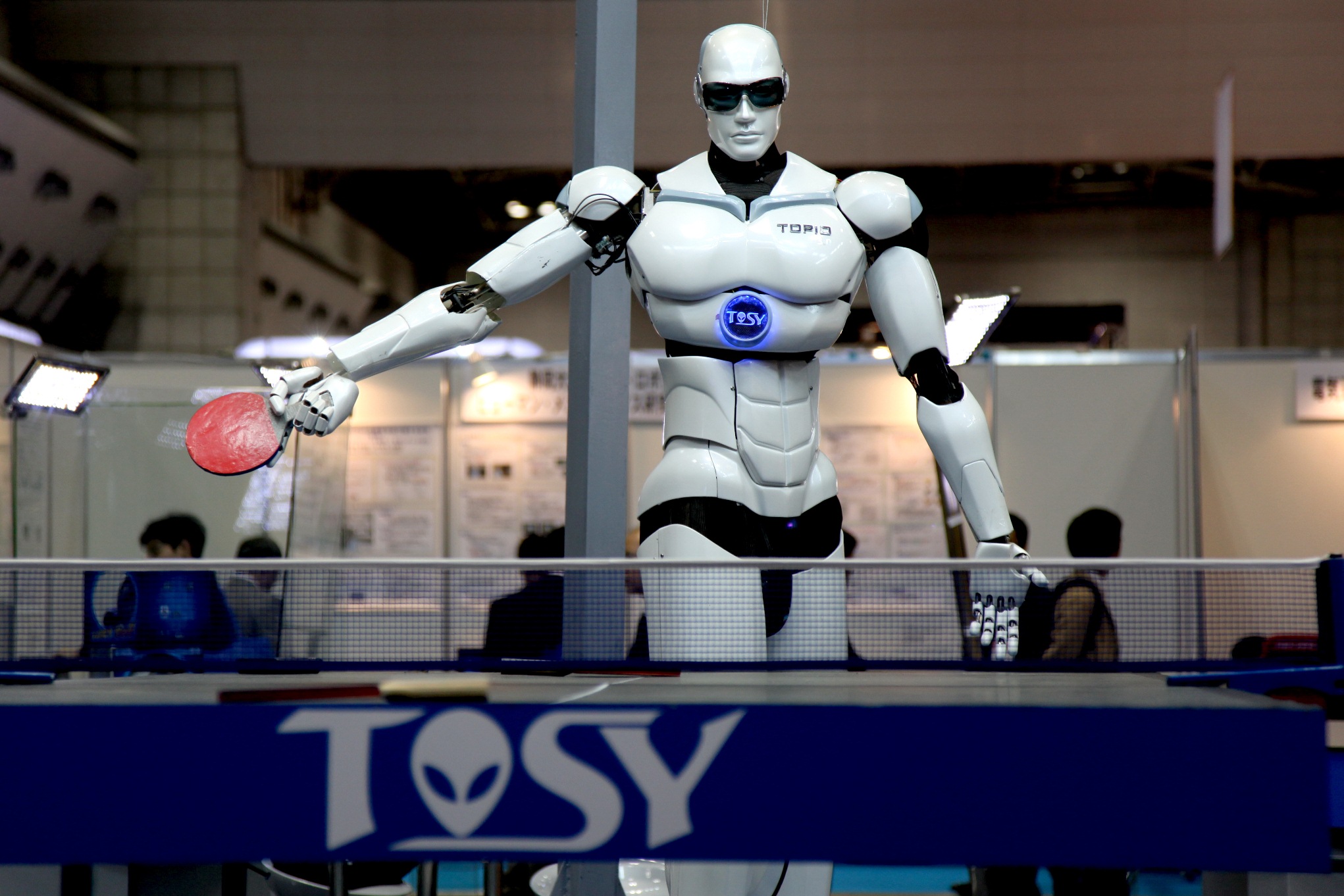

Key research areas include information technology, biotechnology, materials science, and agricultural technology. The government has established national S&T programs and high-tech parks to encourage innovation. The Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology (VAST), established in 1975, is a leading research institution. Vietnam is also working on developing its national space program, with the Vietnam Space Centre (VSC) becoming operational in 2018. Advances have been made in robotics, such as the TOPIO humanoid robot. The messaging app Zalo, developed by a Vietnamese team, is widely used.

Vietnamese scientists have made contributions in various fields, notably mathematics. Hoàng Tụy was a pioneer in global optimization, and Ngô Bảo Châu received the Fields Medal in 2010 for his proof of the fundamental lemma in automorphic forms.

Challenges in S&T development include limited funding for R&D compared to more developed nations, a shortage of highly skilled researchers and engineers, and the need for better linkages between research institutions and industry. International collaboration and attracting foreign investment in high-tech sectors are seen as crucial for further advancement. Vietnam was ranked 44th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024, a significant improvement from 76th in 2012.

6.4. Transport

Vietnam's transportation infrastructure has seen significant development and modernization, particularly since the Đổi Mới reforms, to support economic growth and connectivity. Much of the modern network traces its roots to the French colonial era.

- Roads**: The road system is the primary mode of transport and includes national highways, provincial roads, district roads, urban roads, and commune roads. In 2010, the total road length was about NaN Q mile (NaN Q km), with NaN Q mile (NaN Q km) being asphalted. The North-South Expressway is a major ongoing project to improve connectivity along the country's length. Bicycles, motorcycles, and motor scooters remain highly popular, especially in urban areas, though private car ownership is increasing. This has led to significant traffic congestion and air pollution in major cities like Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City. Traffic collisions are a major safety concern.

- Railways**: The main railway line is the Reunification Express, running nearly NaN Q mile (NaN Q km) from Ho Chi Minh City to Hanoi. Other lines branch out from Hanoi to the northeast, north, and west. Plans for a high-speed railway using Japanese technology have been discussed but postponed due to high costs, with priority given to developing urban metro systems and road networks.

- Aviation**: Vietnam has 20 major civil airports, including three main international gateways: Noi Bai (Hanoi), Da Nang, and Tan Son Nhat (Ho Chi Minh City), the last being the busiest. The government plans to expand the airport network, including the development of Long Thanh International Airport to serve the Ho Chi Minh City metropolitan area, with a projected capacity of 100 million passengers annually once fully operational. Vietnam Airlines is the state-owned national carrier, and several private airlines like VietJet Air and Bamboo Airways also operate.

- Ports and Waterways**: As a coastal nation with an extensive river network, Vietnam has numerous major seaports, including Haiphong, Da Nang, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon Port), Cai Mep-Thi Vai, and Vũng Tàu. These ports are crucial for international trade. Inland waterways, with over NaN Q mile (NaN Q km) of navigable routes, play a key role in rural transportation, supporting ferries, barges, and water taxis, especially in the Mekong Delta.

Challenges in the transport sector include managing urban traffic congestion, improving road safety, securing funding for large infrastructure projects, and ensuring sustainable development.

6.5. Energy

Vietnam's energy sector is largely dominated by state-controlled entities, primarily Vietnam Electricity (EVN), which accounted for about 61.4% of power generation capacity in 2017. Other significant state players include PetroVietnam (oil and gas) and Vinacomin (coal and minerals).

The primary energy sources are hydropower and fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas). Hydropower has been a significant contributor, with large dams like the Sơn La Dam, the largest in Southeast Asia. However, reliance on hydropower makes the country vulnerable to droughts. Coal-fired power plants are also a major part of the energy mix, but this raises environmental concerns due to emissions. Vietnam has proven crude oil reserves of approximately 4.4 billion barrels (ranking first in Southeast Asia as of 2015) and proven natural gas reserves of about 0.6 trillion cubic meters (ranking third in Southeast Asia).

There is a growing focus on developing renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, and biomass to diversify the energy mix, reduce reliance on fossil fuels, and mitigate climate change impacts. PetroVietnam operates several renewable energy plants. A plan to develop nuclear power was abandoned in late 2016 due to public concern over safety and cost.

Meeting the rapidly growing energy demand driven by economic development and industrialization is a key challenge. The government aims to ensure energy security while transitioning towards a more sustainable energy system. This involves attracting investment in new power generation capacity, upgrading the electricity grid, and promoting energy efficiency. The household gas sector is dominated by PetroVietnam, which controls nearly 70% of the domestic market for liquefied petroleum gas (LPG).

6.6. Telecommunications

Vietnam's telecommunications sector has undergone significant development and reform. Historically, services were monopolized by the state-owned Vietnam Post and Telecommunications Group (VNPT). Reforms began in the mid-1990s with the introduction of competition. The military-owned Viettel and the Saigon Post and Telecommunication Company (SPT or SaigonPostel, in which VNPT held a stake) were established. VNPT's monopoly officially ended in 2003.

By 2012, the top three telecom operators were Viettel, Vinaphone (a VNPT subsidiary), and MobiFone (formerly a VNPT subsidiary, now under the Ministry of Information and Communications). Other players include EVNTelecom, Vietnamobile, and S-Fone. The market is characterized by strong competition, particularly in mobile services.

Mobile phone penetration is high, and smartphone usage has grown rapidly. Internet penetration has also increased significantly, with widespread access in urban areas and growing access in rural regions. The government has invested in expanding fiber optic infrastructure.

The telecom market continues to be reformed to attract foreign investment and promote the development of new services and infrastructure, including 5G technology. However, the sector operates under government regulation and oversight, including issues related to internet censorship.

6.7. Foreign trade and investment

Vietnam's economy is highly open and dependent on foreign trade and investment. Since joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2007, Vietnam has further integrated into the global economy.

- Foreign Trade**: Key export products include electronics (especially mobile phones and components), garments and textiles, footwear, machinery, agricultural products (rice, coffee, seafood, cashews, pepper), and crude oil. Major import categories include machinery and equipment, raw materials for manufacturing (fabrics, plastics, iron and steel), petroleum products, and electronics components.

Vietnam's main trading partners include China, the United States, South Korea, Japan, and ASEAN countries. The US is a major export market, while China is a leading source of imports. Vietnam has actively pursued bilateral and multilateral trade agreements, such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement (EVFTA), to expand market access for its goods and services.

- Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)**: Attracting FDI has been a cornerstone of Vietnam's economic development strategy since Đổi Mới. Foreign investment has played a crucial role in developing export-oriented industries, creating jobs, and transferring technology and managerial expertise. Major sources of FDI include South Korea, Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. FDI is concentrated in manufacturing (particularly electronics and garments), real estate, and energy. The government offers various incentives to attract FDI, but challenges remain, including bureaucratic hurdles, infrastructure limitations, and the need for a more skilled workforce.

Economic liberalization, including reducing trade barriers and improving the business environment, continues to be a policy focus to enhance Vietnam's competitiveness and sustain economic growth.

7. Demographics

This section examines Vietnam's population composition, its multi-ethnic character, languages, religious landscape, education system, and health services, with attention to the socio-economic situation of ethnic minorities and the impact of government policies on freedoms and welfare.

7.1. Population and ethnic groups

According to the 2019 census, the Kinh (Viet) constitute about 85.32% of the population, making them the majority ethnic group. They are predominantly concentrated in the alluvial deltas and coastal plains and hold significant political and economic influence. The remaining 14.68% of the population comprises 53 other ethnic minority groups.

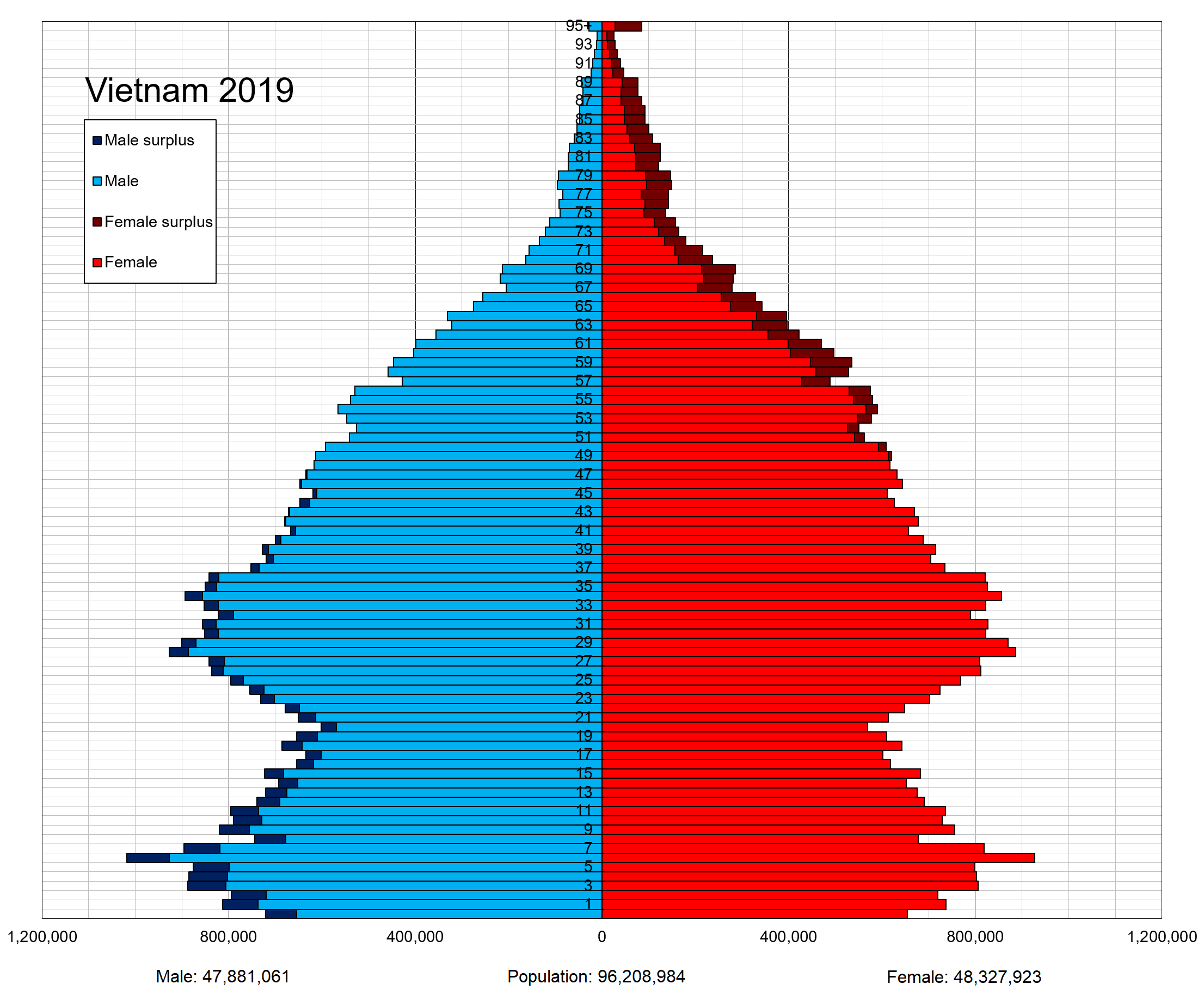

As of recent estimates, Vietnam's population exceeds 100 million people, making it the 15th most populous country in the world. The population has grown significantly from the 1979 census figure of 52.7 million. The 2019 census recorded a population of 96,208,984.

These minority groups vary greatly in size, language, culture, and socio-economic conditions. Major ethnic minorities include the Tày, Thái, Mường, Khmer, Hoa (ethnic Chinese), Nùng, and Hmong. Many ethnic minorities, such as the Mường (closely related to the Kinh), reside in the highlands, which cover two-thirds of Vietnam's territory. The Montagnards (Degar) of the Central Highlands encompass over 40 distinct tribal groups. The Hoa and Khmer Krom are mainly lowlanders. Historically, many Chinese migrated to Vietnam as administrators, merchants, and refugees. After reunification in 1976, increased communist policies, including nationalization of property, led many Hoa people to leave Vietnam.

The socio-economic situation of many ethnic minorities often lags behind that of the Kinh majority. They may face challenges in accessing education, healthcare, and economic opportunities. Government policies aim to promote development in ethnic minority areas, but issues of cultural preservation, land rights, and political representation remain. The resettlement of Kinh people into indigenous areas, particularly in the Central Highlands, has historically led to tensions and concerns about the displacement and assimilation of minority cultures.

7.2. Urbanization

Vietnam has been experiencing rapid urbanization, particularly since the Đổi Mới economic reforms initiated in 1986. According to the 2019 census, 34.4% of the population (33,122,548 people) lived in urban areas, a significant increase from previous decades. The government had forecast a 45% urbanization rate by 2020.

The primary drivers of urbanization are rural-to-urban migration, driven by the search for better economic opportunities and access to services, and the expansion of urban boundaries. Major cities like Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City have been the main recipients of migrants and have experienced substantial growth. Ho Chi Minh City, in particular, attracts a large number of migrants due to its dynamic economy and perceived better opportunities.

Urbanization is closely correlated with economic growth in Vietnam. As the country has urbanized, the economic structure has shifted from being predominantly agricultural to having larger industrial and service sectors. Access to basic services like electricity and fresh water has significantly improved in urban areas. For instance, household access to electricity grew from 14% in 1993 to over 96% in 2009, and access to piped water networks in areas covered by utility companies increased from 12% in 2002 to over 70% by 2007. Studies suggest that rural-to-urban migrants often achieve a higher standard of living than non-migrants in both rural and urban areas.

However, rapid urbanization also presents significant socio-economic and environmental challenges. These include:

- Infrastructure strain**: Growing urban populations place immense pressure on transportation, housing, water supply, sanitation, and energy infrastructure. Traffic congestion is a severe problem in major cities, exacerbated by the increasing number of motorcycles and cars.

- Housing**: Affordable housing for low-income migrants and residents is a major concern, leading to the growth of informal settlements in some areas.

- Environmental concerns**: Urban areas face increased air and water pollution from traffic, industrial activities, and inadequate waste management. The 2016 Vietnam marine life disaster highlighted the risks of industrial pollution. Solid waste generation in urban areas has increased dramatically.

- Social issues**: Urbanization can lead to social challenges such as crime, social disparities, and difficulties in integrating new migrants into urban life.

The Vietnamese government is implementing policies to manage urbanization, including developing urban master plans, investing in infrastructure, and attempting to promote more balanced regional development. Efforts are also being made to address environmental pollution, such as campaigns to encourage waste sorting and reduce reliance on motorcycles.

| Rank | City | Province/Municipality | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ho Chi Minh City | Ho Chi Minh City | 8,993,082 |

| 2 | Hanoi | Hanoi | 8,053,663 |

| 3 | Haiphong | Haiphong | 2,028,514 |

| 4 | Cần Thơ | Cần Thơ | 1,235,171 |

| 5 | Da Nang | Da Nang | 1,134,310 |

| 6 | Biên Hòa | Đồng Nai | 1,055,414 |

| 7 | Thủ Đức | Ho Chi Minh City | 1,013,795 |

| 8 | Thuận An | Bình Dương | 508,433 |

| 9 | Hải Dương | Hải Dương | 508,190 |

| 10 | Nha Trang | Khánh Hòa | 422,601 |

7.3. Languages and script

The official and national language of Vietnam is Vietnamese (Tiếng ViệtTieng VietVietnamese). It is an Austroasiatic language, part of the Mon-Khmer branch, and is spoken by the majority Kinh population. Vietnamese is a tonal language, with different tones conveying different meanings for the same syllable. It has several regional dialects, with the main variations being between the northern, central, and southern regions.

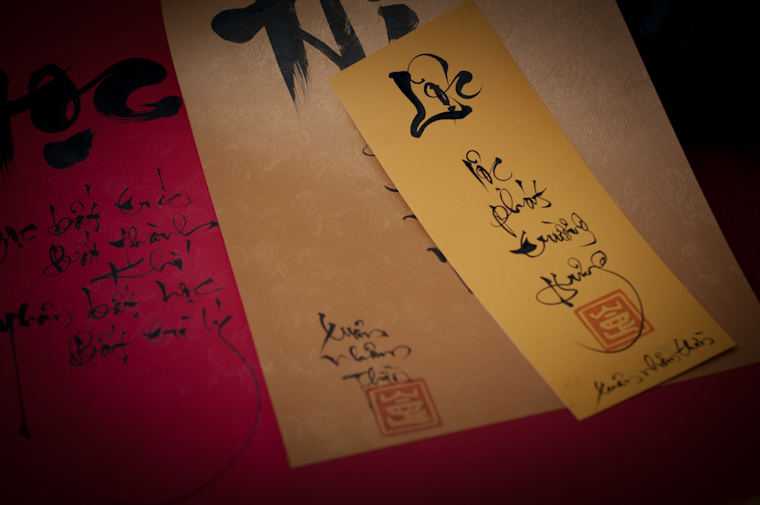

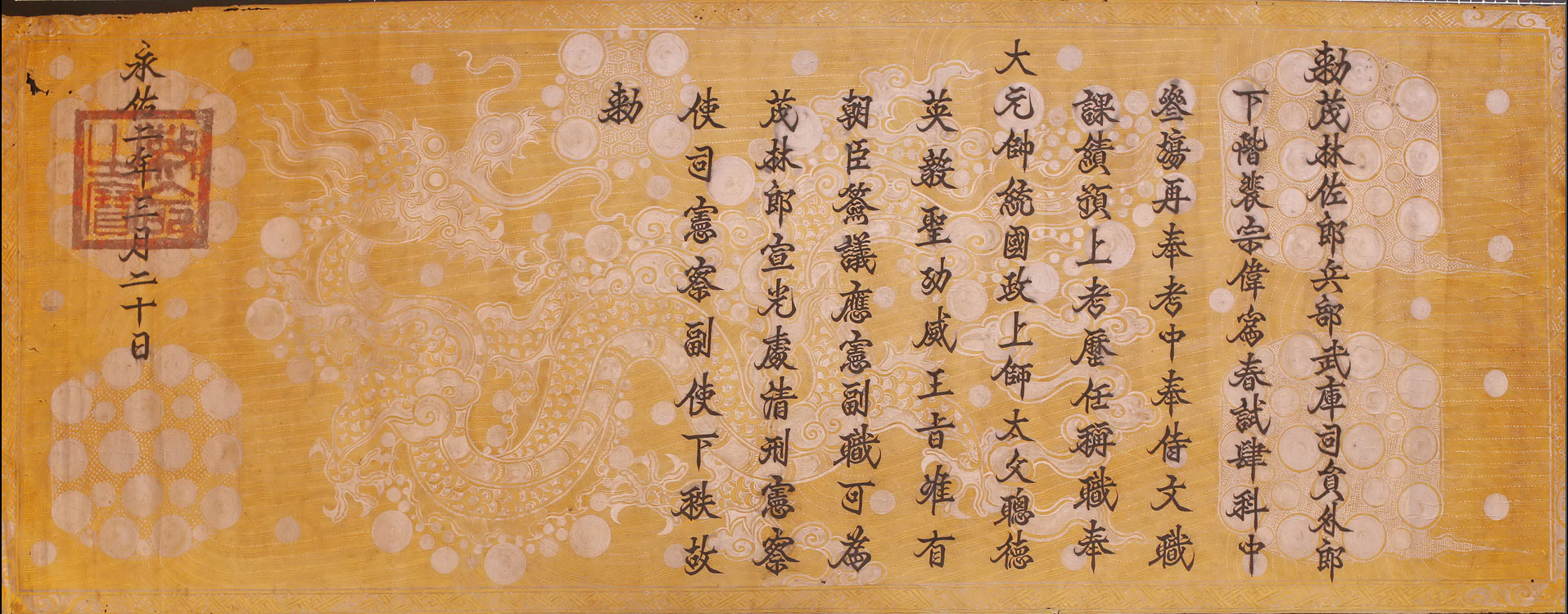

Historically, Vietnamese was written using Chữ Hán (Classical Chinese characters). From around the 13th century, Chữ Nôm, a script derived from Chinese characters but adapted to write vernacular Vietnamese, was developed and used alongside Chữ Hán, particularly for popular literature.

During the French colonial period, Chữ Quốc ngữ (national language script), a Latin-based script, was developed by European missionaries, notably the Jesuit Alexandre de Rhodes in the 17th century, based primarily on Portuguese orthography. Chữ Quốc ngữ gradually gained popularity, especially from the early 20th century, due to its relative simplicity and its promotion by both reformist intellectuals and the French colonial administration as a means to increase literacy. After independence in 1945, Chữ Quốc ngữ became the official writing system and is now used exclusively.

Vietnam's ethnic minority groups speak a variety of languages. Some of the major minority languages include Tày, Mường, Cham, Khmer, Chinese (various dialects), Nùng, and Hmong. The Montagnard peoples of the Central Highlands speak numerous distinct languages belonging to both the Austroasiatic and Malayo-Polynesian language families. The government officially recognizes these minority languages, and some education and media are available in certain minority languages, though Vietnamese remains the primary language of education and administration. In recent years, a number of sign languages have developed in major cities.

Regarding foreign languages, French, a legacy of colonial rule, is still spoken by some older and educated Vietnamese, particularly in the south where it was a principal language in administration and education. Vietnam is a member of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie. However, English has largely replaced French as the most popular and important foreign language, and it is now a compulsory subject in most schools. The popularity of Japanese, Korean, and Mandarin Chinese has also grown due to strengthening economic and cultural ties with East Asian nations. Russian and some Eastern European languages like Czech and Polish are known among some northern Vietnamese whose families had ties with the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War. Third-graders can choose one of seven languages (English, Russian, French, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, German) as their first foreign language.

7.4. Religion

The religious landscape of Vietnam is diverse, characterized by a mix of indigenous beliefs, major world religions, and syncretic local faiths. The 1992 Constitution (Article 70) officially guarantees freedom of belief and religion, stating that all religions are equal before the law and places of worship are protected. However, it also stipulates that religious beliefs cannot be misused to undermine state law and policies.

According to the 2019 census, 86.32% of the population identify as having no religion or practicing Vietnamese folk religion. This folk religion often involves ancestor veneration, worship of local deities, spirits, and heroes, and incorporates elements of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism. Confucian ethics continue to influence social and familial relationships.

Among organized religions:

- Buddhism**: Mahayana Buddhism is the dominant branch, historically playing a significant role in Vietnamese culture and society. The 2019 census reported 4.79% of the population as Buddhist. Theravada Buddhism is practiced mainly by the Khmer minority in the south.

- Catholicism**: Introduced by European missionaries in the 16th century, Catholicism became firmly established by the 17th century. It represents a significant religious minority, with 6.1% of the population according to the 2019 census.

- Protestantism**: Introduced more recently, primarily in the 20th century by American and Canadian missionaries, Protestantism accounts for 1.0% of the population (2019 census). It has seen rapid growth in recent decades, particularly among ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands (Montagnards) and Hmong communities. The largest denomination is the Evangelical Church of Vietnam.

- Caodaism**: An indigenous syncretic religion founded in southern Vietnam in 1926, Caodaism blends elements from Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, Christianity, and spiritualism. It had 0.58% adherents in the 2019 census.

- Hòa Hảo Buddhism**: A quasi-Buddhist socio-religious movement founded in 1939 in the Mekong Delta by Huỳnh Phú Sổ. It emphasizes lay practice, simplicity, and social welfare. The 2019 census reported 1.02% of the population as followers.

- Islam**: Practiced primarily by the Cham ethnic minority in central and southern Vietnam, comprising Sunni and Bani (a local Cham adaptation) branches. A small number of Kinh adherents also exist. Islam accounts for about 0.07% of the population.

- Hinduism**: A remnant of the ancient Champa Kingdom, Hinduism is practiced by a small segment of the Cham community.

- Other Religions**: The Baháʼí Faith and other minority faiths also exist, representing less than 0.2% of the population according to the 2019 census (0.12% "Others").