1. Overview

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America characterized by its rich tapestry of Mesoamerican cultures, most notably the Maya, and a history marked by Spanish colonization, subsequent independence, and persistent struggles for democratic development and social equity. Geographically diverse, it features mountainous interiors, extensive Caribbean and Pacific coastlines, and significant biodiversity, including the Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve. Historically, Honduras endured a long period of Spanish colonial rule that profoundly reshaped its society and economy, followed by independence in 1821. The 19th and 20th centuries were largely defined by political instability, foreign economic exploitation (particularly by U.S. fruit companies, leading to its "banana republic" status), military dictatorships, and social unrest, which severely hampered human rights and equitable development. The nation's economy, primarily agricultural, remains vulnerable, with high levels of poverty and inequality disproportionately affecting rural and indigenous populations. Significant challenges include widespread crime, gang violence, and corruption, which undermine public safety and governance. Culturally, Honduras reflects a blend of indigenous, Spanish, African, and Caribbean influences, expressed in its arts, music, and traditions.

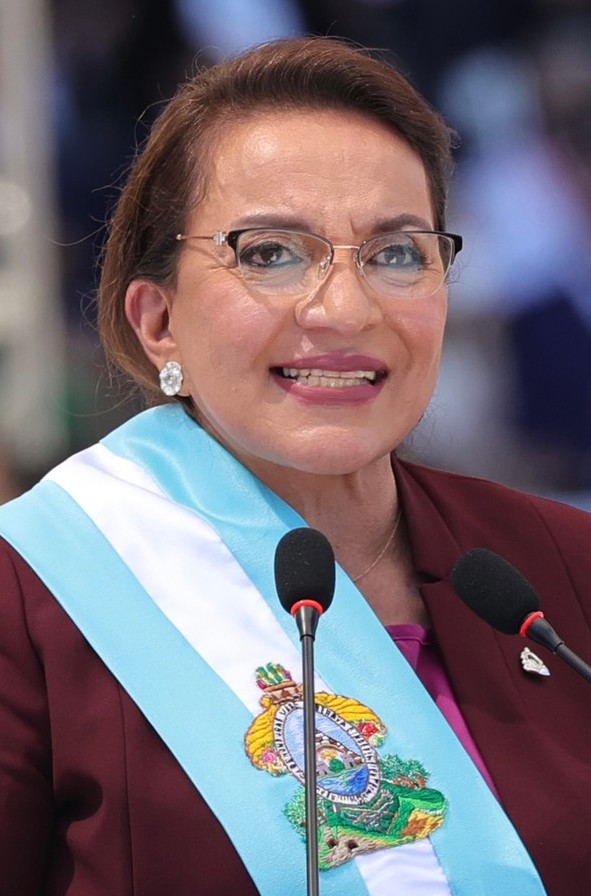

The 21st century has seen continued efforts towards democratic consolidation, punctuated by crises such as the 2009 coup d'état, which significantly impacted its democratic institutions and drew international condemnation. The election of Xiomara Castro in 2021 as the first female president marked a potential shift towards addressing deep-seated issues of social justice, human rights, and the needs of vulnerable populations. However, Honduras continues to grapple with the legacies of exploitation, internal conflict, and natural disasters, striving for a more equitable and democratic future amidst formidable socio-economic and political challenges.

2. Etymology

The name "Honduras" is Spanish for "depths." One common theory attributes the name to Christopher Columbus's purported exclamation during his final voyage in 1502, "Gracias a Dios que hemos salido de esas honduras" ("Thank God we have departed from those depths"), referring to the deep waters off the northern coast. Another possibility is that it refers to the bay of Trujillo as an anchorage, known as fondura in the Leonese dialect of Spain.

The name Honduras was not consistently applied to the entire province until the late 16th century. Before 1580, Honduras typically referred to the eastern part of the province, while Higueras designated the western part. Another early name for the region was Guaymuras, a term revived for the political dialogue in 2009. The country was officially named the Republic of Honduras in 1862.

Hondurans are often referred to by the demonyms Catracho (masculine) or Catracha (feminine) in Spanish. These terms are derived from the surname of the Honduran General Florencio Xatruch, who led Honduran forces against the invasion by American filibuster William Walker in 1857. The nickname, initially used by Nicaraguans, was adopted with pride by Hondurans.

3. History

The history of Honduras spans from ancient civilizations through Spanish colonization, independence, and a tumultuous modern era marked by political instability, foreign influence, and significant social and economic challenges, all of which have deeply impacted its societal development and the pursuit of democratic governance and human rights.

3.1. Pre-Columbian era

In the pre-Columbian era, the territory of modern Honduras was a crossroads of cultures, primarily divided between the Mesoamerican cultural region in the west and the Isthmo-Colombian area in the east. Archaeological evidence indicates human presence dating back to the Paleo-Indian period (10,000-3,000 BCE), though more definitive proof of settlement emerges with the establishment of villages. Puerto Escondido, near the mouth of the Ulúa River in the Sula Valley, dating to around 1600 BCE, is one of the oldest known settled sites.

The Maya civilization was the most prominent culture in western Honduras, with the city of Copán being a major center. Founded around 426 CE by K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo', possibly with influence from Teotihuacan, Copán flourished for centuries, particularly between the 7th and 8th centuries under rulers like "Smoke Imix" and "18 Rabbit" (Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil). During this period, significant structures such as temples and a new ball court were built. Copán's influence extended to Quiriguá in present-day Guatemala. However, after "18 Rabbit" was captured and killed by Quiriguá's ruler in 738 CE, Copán began a period of decline, though notable constructions like the Hieroglyphic Stairway (Temple 26) and Altar Q, which depicts sixteen rulers of the Copán dynasty, were completed later. By the end of the Classic Maya period (c. 900 CE), Copán, like other lowland Maya centers, was largely abandoned. The descendants of the Maya in this region are the Ch'orti' people.

Beyond Copán, other civilizations and settlements existed throughout Honduras. The Lenca people, inhabiting the interior highlands, are also considered culturally Mesoamerican. Important archaeological sites include Naco in the Naco Valley (a significant trading center for cacao, quetzal feathers, copper, and gold), Los Naranjos on Lake Yojoa (featuring a 62 ft (19 m) high pyramid and defensive works), and Yarumela in the Comayagua Valley (a large ceremonial center with a massive pyramid, Structure 101). Olmec influence is evident in sites like the Cuyamel caves in Colón Department, dating from 1200-400 BCE. In 2012, LiDAR scanning revealed previously unknown high-density settlements in the La Mosquitia region, possibly corresponding to the legendary "La Ciudad Blanca" (The White City), estimated to have peaked between 500 and 1000 CE.

3.2. Spanish conquest and colonial rule

European contact began in 1502 when Christopher Columbus, on his fourth voyage, reached the Bay Islands off the coast of Honduras and later landed near the modern town of Trujillo. Columbus's brother, Bartholomew, encountered a large Mayan trading canoe, seizing its cargo and kidnapping its captain to serve as an interpreter-the first recorded encounter between Spaniards and Maya.

The Spanish conquest of Honduras began in earnest in March 1524 with the arrival of Gil González Dávila. He was soon followed by forces loyal to Cristóbal de Olid (sent by Hernán Cortés from Mexico), Francisco de Montejo, and Pedro de Alvarado. The conquistadors relied not only on Spanish arms but also significantly on allied indigenous forces from Mexico, such as Tlaxcalans and Mexica warriors.

Indigenous resistance was fierce, notably led by the Lenca chieftain Lempira in 1537. Although Lempira's rebellion was ultimately suppressed, marking a significant step in Spanish consolidation of control, many regions, particularly in the north like the Miskito Kingdom, were never fully subdued by the Spanish. The Miskito, in fact, found allies in European privateers and, later, the British based in Jamaica.

After the conquest, Honduras was incorporated into the Captaincy General of Guatemala, a vast Spanish administrative region in the New World. Gracias and Trujillo served as early capitals, later shifting to Comayagua and eventually Tegucigalpa. For approximately three centuries, Spain ruled Honduras, profoundly transforming its socio-economic and cultural landscape. The Spanish introduced Catholicism and the Spanish language, which became dominant, blending with indigenous customs.

Silver mining was a key driver of Spanish colonization and settlement. Rich silver deposits, particularly around Tegucigalpa (discovered in the 1570s), were heavily exploited. Initially, indigenous populations were forced to work in the mines through the encomienda system. As disease, resistance, and population decline made this labor source insufficient, slaves were brought from other parts of Central America. When this trade ceased, African slaves, primarily from Angola, were imported, though in smaller numbers after 1650. This system of resource extraction and forced labor led to significant suffering and demographic collapse among indigenous communities, fundamentally altering the social structure and laying the groundwork for enduring inequalities.

3.3. Independence and 19th century

The early 19th century saw a rising tide of independence sentiment across Spanish America, fueled by events in Europe such as the Napoleonic Wars and the Spanish War of Independence. On September 15, 1821, Honduras, as part of the Captaincy General of Guatemala, declared independence from Spain. Shortly thereafter, it was briefly incorporated into the First Mexican Empire under Agustín de Iturbide. When the Mexican Empire collapsed in 1823, Honduras joined the newly formed Federal Republic of Central America, along with Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica.

Honduran General Francisco Morazán was a prominent liberal leader and a staunch advocate for the Central American federation, serving as its president. However, the federation was plagued by internal conflicts between liberals and conservatives, and regional rivalries. It ultimately disintegrated in 1838, and Honduras emerged as an independent republic. Despite the collapse, the ideal of Central American unity persisted, and Honduras participated in several failed attempts to revive it throughout the 19th century.

The remainder of the 19th century in Honduras was characterized by political instability, frequent internal rebellions (nearly 300 small rebellions and civil wars have been recorded since independence), and economic underdevelopment. Power often changed hands through force, and the country struggled to establish stable governing institutions. Caudillismo, or rule by strongmen, was common.

Beginning in the 1870s, under liberal presidents like Marco Aurelio Soto, policies were implemented to encourage foreign trade and investment. This led to the development of infrastructure, primarily railroads, by foreign companies, especially on the north coast for the burgeoning banana export industry. Comayagua served as the capital until 1880, when it was moved to Tegucigalpa. A projected railroad line from the Caribbean coast to Tegucigalpa ran out of money when it reached San Pedro Sula, inadvertently spurring that city's growth into the nation's primary industrial center and second-largest city. While these developments brought some economic activity, they also deepened foreign influence and often benefited a small elite, failing to address widespread poverty or foster equitable national development. The lack of a strong national workforce and internal capital also limited the growth of industries like coffee, which thrived in neighboring countries.

3.4. 20th century

The 20th century in Honduras was a period of profound transformation, marked by the deep entrenchment of foreign economic interests, persistent political instability including military rule, significant social unrest, and the devastating impact of external events like the Cold War and natural disasters. These factors critically shaped the nation's path towards democratic development and efforts to achieve social equity.

3.4.1. Rise of American companies and "Banana Republic" status

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Honduran government granted extensive land concessions and tax exemptions to U.S.-based fruit companies, notably the Cuyamel Fruit Company, United Fruit Company, and Standard Fruit Company, in exchange for developing the country's northern regions and infrastructure like railroads. This led to the rapid expansion of banana plantations, attracting thousands of workers, including immigrants from English-speaking Caribbean islands like Jamaica and Belize.

These powerful corporations established an enclave economy, particularly on the north coast. They controlled vast tracts of land, built their own infrastructure (ports, railways, communications), and operated largely as self-sufficient, tax-exempt entities, contributing relatively little to broader Honduran economic growth or social development. Their immense economic power translated into significant political influence, with U.S. companies often meddling in Honduran politics to protect their interests. This dominance led to the American writer O. Henry coining the term "banana republic" in his 1904 book Cabbages and Kings to describe Honduras, a term that came to symbolize countries whose economies and politics were subservient to foreign fruit companies. The U.S. military intervened in Honduras multiple times (1903, 1907, 1911, 1912, 1919, 1924, and 1925) to protect American interests.

This period entrenched a model of development heavily reliant on a single export crop, controlled by foreign entities, which exacerbated land tenure issues, often displaced peasant communities, and created exploitative labor conditions, hindering the development of a diversified and equitable national economy. Social stratification was reinforced, with wealth concentrated in the hands of a few and foreign corporations, while the majority of the population saw little benefit.

Tiburcio Carías Andino's long dictatorial rule (1933-1949) was characterized by strong ties to these U.S. banana companies and the suppression of labor movements, such as the strikes by banana workers in the late 1920s which were met with repression. The Great Depression further impacted the banana industry. Honduras joined the Allies of World War II on December 8, 1941.

3.4.3. Football War

In July 1969, Honduras and El Salvador fought a brief but brutal conflict known as the Football War (La Guerra del Fútbol) or the 100 Hours' War. While a series of hotly contested World Cup qualifying matches between the two nations served as an immediate trigger, the underlying causes were much deeper and more complex. These included unresolved border disputes, demographic pressures in El Salvador leading to significant undocumented Salvadoran migration into Honduras (estimated at around 300,000 people), and economic disparities.

Tensions escalated when the Honduran government under General Oswaldo López Arellano, facing economic difficulties, began to enforce land reform laws that led to the displacement of many Salvadoran peasant farmers living in Honduras. Nationalist sentiment flared in both countries, exacerbated by media coverage of the football matches. Following riots and violence associated with the games, diplomatic relations broke down.

On July 14, 1969, the Salvadoran army launched an invasion of Honduras. The Organization of American States (OAS) quickly intervened, negotiating a ceasefire that took effect on July 20. Salvadoran troops withdrew in early August. The war resulted in several thousand casualties, mostly civilians, and the displacement of tens of thousands. As many as 130,000 Salvadoran immigrants were expelled or fled Honduras, leading to a refugee crisis in El Salvador and long-lasting animosity between the two nations. The conflict also led to Honduras's withdrawal from the Central American Common Market in 1971, further impacting regional economic integration. The war highlighted the severe social and economic pressures within both countries and the fragility of regional stability.

3.4.4. Return to civilian rule and Cold War impact

Honduras began a transition back to civilian rule in the late 1970s and early 1980s. A constituent assembly was elected in April 1980 to draft a new constitution (approved in 1982), and general elections in November 1981 brought Roberto Suazo Córdova of the Liberal Party of Honduras (PLH) to the presidency.

However, this period coincided with the intensification of the Cold War in Central America. The United States, under the Reagan administration, viewed the region as a critical front against Soviet and Cuban influence, particularly after the Sandinista victory in Nicaragua in 1979 and the ongoing civil war in El Salvador. Honduras became a key U.S. ally and a linchpin of U.S. strategy.

The U.S. established a significant and continuous military presence in Honduras, using the country as a base to support the Contra rebels fighting the Sandinista government in Nicaragua and to aid the Salvadoran military. This involved building airstrips, expanding port facilities, and conducting large-scale military exercises. Honduras received substantial U.S. economic and military aid.

While spared the full-scale civil wars that ravaged its neighbors, Honduras experienced its own form of "dirty war." The Honduran military, often with U.S. support and training, quietly waged campaigns against perceived Marxist-Leninist militias like the Cinchoneros Popular Liberation Movement, as well as against students, labor organizers, human rights activists, and other suspected leftists. This campaign involved enforced disappearances, torture, and extrajudicial killings by government security forces. The most notorious unit responsible for these atrocities was Battalion 316, a military intelligence unit trained by the CIA. Honduras was later found internationally liable for a series of disappearances during this period by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in landmark cases such as Velásquez-Rodríguez v. Honduras. The U.S. role in supporting and collaborating with Honduran forces implicated in human rights abuses remains a contentious issue, highlighting the devastating human cost of Cold War policies in the region and their long-term impact on democratic institutions and the rule of law.

3.4.5. Late 20th-century challenges

Towards the end of the 20th century, Honduras faced significant challenges, notably the catastrophic impact of natural disasters which exacerbated existing socio-economic vulnerabilities. In September 1974, Hurricane Fifi skimmed the northern coast, causing severe damage and thousands of deaths, particularly in towns like Choloma where a dike broke.

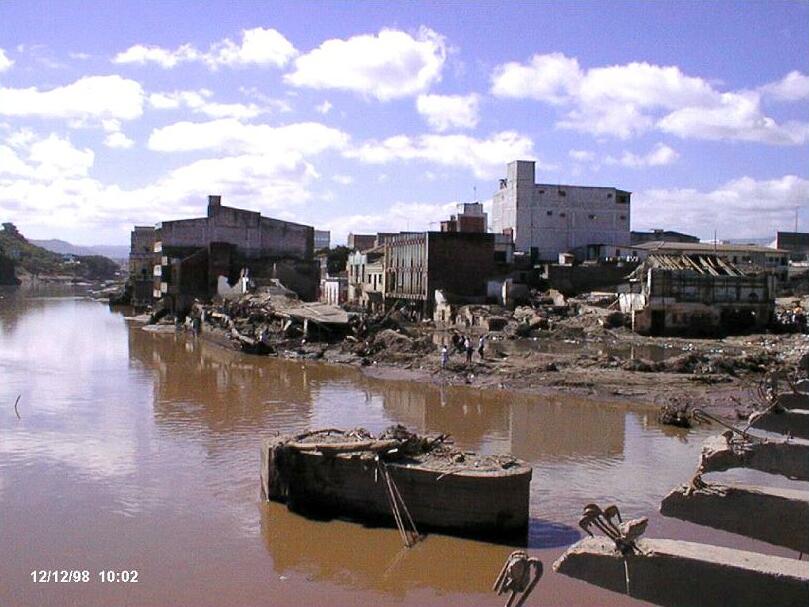

The most devastating natural disaster was Hurricane Mitch in October 1998. This Category 5 hurricane caused massive and widespread destruction across the country. President Carlos Roberto Flores stated that fifty years of national progress had been reversed. Mitch destroyed approximately 70% of the country's crops and an estimated 70-80% of its transportation infrastructure, including nearly all bridges and secondary roads. Across Honduras, 33,000 houses were destroyed, and an additional 50,000 were damaged. The storm resulted in an estimated 5,000 to 7,000 deaths, with thousands more injured or missing. Total economic losses were estimated at 3.00 B USD.

The impact of Hurricane Mitch was particularly severe for the most vulnerable populations, including small farmers, rural communities, and those living in precarious housing. The destruction of agriculture led to food shortages and increased poverty. The long-term consequences included setbacks in development, increased national debt due to reconstruction costs, and heightened social and economic hardship. These natural disasters underscored the country's vulnerability and the critical need for disaster preparedness and sustainable development strategies that address the underlying causes of poverty and inequality. Ongoing socio-economic issues, including poverty, limited access to education and healthcare, and land inequality, continued to plague the nation.

3.5. 21st century

The 21st century in Honduras has been characterized by continued efforts towards democratic consolidation, marred by significant political crises, persistent social and economic challenges, and ongoing struggles with governance, corruption, and human rights.

In 2007, President Manuel Zelaya initiated talks with U.S. President George W. Bush regarding U.S. assistance to combat drug cartels in eastern Honduras, marking a renewed U.S. military presence. Zelaya, a liberal, later shifted politically leftward, and in 2008, Honduras joined the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (ALBA), an alliance led by Venezuela.

The most significant political crisis of this period was the 2009 coup d'état. On June 28, 2009, President Zelaya was ousted by the military and exiled to Costa Rica just hours before a controversial non-binding referendum he had called on constitutional reform was scheduled to take place. Opponents, including the Supreme Court and Congress, argued the referendum was illegal and a step towards Zelaya unconstitutionally extending his term. The head of Congress, Roberto Micheletti, was installed as interim president.

The coup was widely condemned internationally by the United Nations, the Organization of American States (OAS, which suspended Honduras's membership), and many countries, who refused to recognize the de facto government. The U.S. response was initially mixed, with President Obama condemning the ouster as a coup, while Secretary of State Hillary Clinton's State Department was criticized by some for not taking a stronger stance and for its diplomatic approach that some perceived as legitimizing the post-coup elections. A subsequent Truth and Reconciliation Commission concluded that Zelaya's ousting was indeed an illegal coup. Honduras withdrew from ALBA in 2010 after the coup.

Presidential elections were held in November 2009 under the de facto government, which were won by Porfirio Lobo Sosa of the National Party. His successor, Juan Orlando Hernández (JOH), also of the National Party, took office in 2014. Hernández's presidency was controversial; he oversaw a constitutional court ruling that allowed for presidential re-election, previously banned, and won a disputed second term in the 2017 general election amidst widespread allegations of fraud and protests, leading to a violent crackdown and a declaration of a state of emergency. His administration was also plagued by accusations of corruption and links to drug trafficking. In April 2022, shortly after leaving office, Hernández was extradited to the United States to face charges of drug trafficking and firearms offenses, which he denied. This event highlighted the deep-seated problems of corruption and impunity within the Honduran state.

In the 2021 presidential election, Xiomara Castro of the left-wing Liberty and Refoundation (Libre) party, wife of Manuel Zelaya, won a landslide victory, becoming the first female president of Honduras. Her election on January 27, 2022, ended 12 years of National Party rule and was seen by many as an opportunity for democratic renewal and a greater focus on social justice and human rights. In March 2023, under Castro's administration, Honduras switched diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to the People's Republic of China.

Despite these political shifts, Honduras continues to face severe challenges, including high rates of poverty and inequality, pervasive crime and gang violence, weak institutions, and the ongoing impacts of climate change and natural disasters. The struggle for genuine democratic governance, rule of law, and respect for human rights remains central to Honduras's contemporary trajectory.

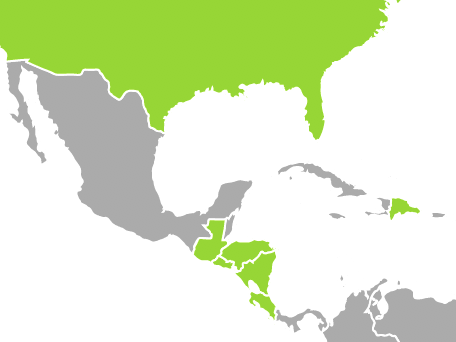

4. Geography

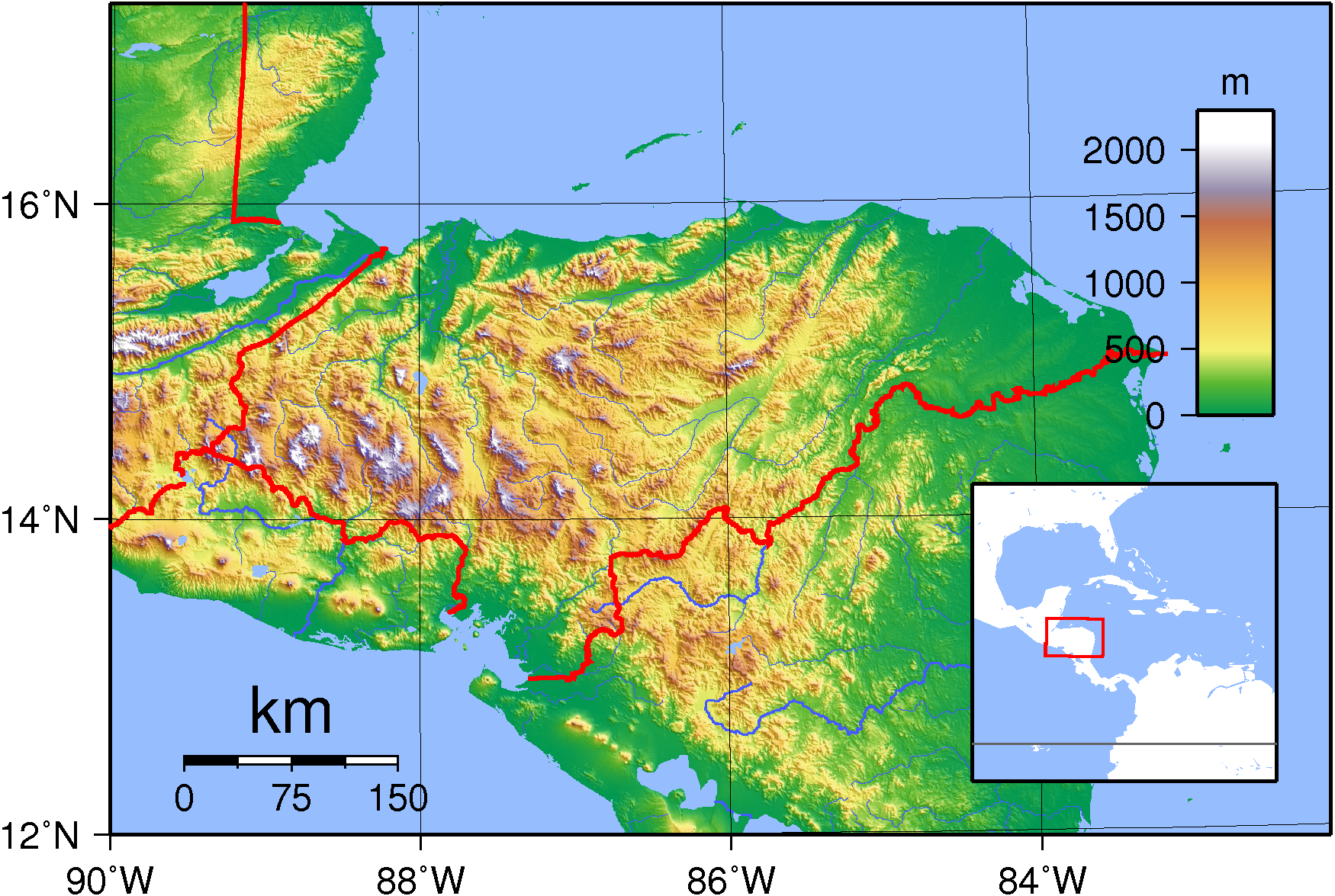

Honduras is located in Central America. It is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Ocean at the Gulf of Fonseca, and to the north by the Gulf of Honduras, a large inlet of the Caribbean Sea. The country has a total area of approximately 43 K mile2 (112.49 K km2).

The geography of Honduras is predominantly mountainous, with interior highlands constituting about 80% of its territory. Narrow coastal plains are found along both the Caribbean and Pacific coasts. The northern Caribbean coast is more extensive and features alluvial plains, particularly the heavily populated Sula Valley in the northwest. In the northeast lies La Mosquitia, a large, sparsely populated, and largely undeveloped lowland jungle and savanna region, which includes the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve. The Coco River (or Segovia River) forms a significant part of the border with Nicaragua and flows through La Mosquitia to the Caribbean. The Pacific coastal plain along the Gulf of Fonseca is smaller.

The interior highlands are a complex of mountain ranges, valleys, and plateaus. The highest peak in Honduras is Cerro Las Minas (also known as Celaque Peak), reaching an elevation of 9.4 K ft (2.87 K m).

Honduras possesses several groups of islands. In the Caribbean Sea, the Bay Islands (Islas de la Bahía), consisting of Roatán, Utila, and Guanaja, along with smaller cays, are a major tourist destination known for their coral reefs. The Swan Islands are also located in the Caribbean. Misteriosa Bank and Rosario Bank, submerged reef areas, lie north of the Swan Islands within Honduras's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

Natural resources of Honduras include timber, gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc, iron ore, antimony, coal, fish, shrimp, and hydropower potential. The country is susceptible to natural disasters, particularly hurricanes along the Caribbean coast, and to a lesser extent, earthquakes.

4.1. Climate

The climate of Honduras varies significantly by region and altitude. Generally, it is tropical in the lowlands and becomes more temperate in the mountainous interior.

- The Caribbean lowlands (northern coast and La Mosquitia) experience a hot and humid tropical rainforest climate. Temperatures are consistently high throughout the year, and rainfall is abundant, with no distinct dry season in some areas, though typically drier from March to May. This region is prone to hurricanes, especially from June to November.

- The Pacific lowlands (southern coast along the Gulf of Fonseca) also have a tropical climate but are generally drier than the Caribbean side, classified as a tropical savanna climate. There is a distinct dry season, usually from November to April, and a wet season from May to October. Temperatures are high.

- The interior highlands experience a more temperate climate, with temperatures decreasing with altitude. Days can be warm, but nights are often cool, especially at higher elevations. This region typically has a dry season (November to April) and a wet season (May to October). The capital, Tegucigalpa, located in a highland valley, has a pleasant, spring-like climate for much of the year.

Rainfall patterns vary considerably. The Caribbean coast receives the most precipitation, with some areas getting over 0.1 K in (2.50 K mm) annually. The Pacific coast and interior valleys are drier.

4.2. Biodiversity and environment

Honduras is part of the Mesoamerican biodiversity hotspot and possesses rich biological resources and diverse ecosystems. The country is home to more than 6,000 species of vascular plants, including around 630 orchid species. Its fauna includes approximately 250 reptile and amphibian species, over 700 bird species, and 110 mammalian species, about half of which are bats.

Key ecosystems include:

- Rainforests**: Particularly extensive in La Mosquitia, the Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve is a vast lowland rainforest and a UNESCO World Heritage Site (inscribed 1982), home to a great diversity of life, including jaguars, tapirs, and many bird species.

- Cloud forests**: Found at higher elevations (up to nearly 9.8 K ft (3.00 K m)), these forests are characterized by high humidity, frequent cloud cover, and unique flora and fauna, including many endemic species.

- Pine and Oak Forests**: Common in the mountainous interior.

- Mangroves**: Along both Caribbean and Pacific coasts, providing important habitat for marine life and coastal protection.

- Savannas**: Particularly in La Mosquitia.

- Coral Reefs**: Honduras is home to a significant portion of the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System, the second-largest barrier reef in the world. The Bay Islands are renowned for their vibrant reefs and marine life, including bottlenose dolphins, manta rays, parrotfish, schools of blue tang, and whale sharks.

Despite this rich biodiversity, Honduras faces significant environmental challenges that threaten its natural heritage and impact vulnerable communities:

- Deforestation**: This is a major issue, driven by logging (rampant in departments like Olancho), the expansion of agriculture and cattle ranching (especially in La Mosquitia), and fuelwood collection. Deforestation leads to habitat loss, soil erosion, and reduced water quality. Honduras had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 4.48/10, ranking it 126th globally out of 172 countries.

- Land Degradation and Soil Erosion**: These are consequences of deforestation and unsustainable agricultural practices.

- Water Pollution**: Lake Yojoa, Honduras's largest source of fresh water, suffers from pollution by heavy metals from nearby mining activities and nutrient runoff from agriculture. Many rivers and streams are also polluted by mining waste and agricultural chemicals.

- Impacts of Climate Change**: Honduras is highly vulnerable to climate change, including more frequent and intense hurricanes, droughts, and sea-level rise, which disproportionately affect poor rural and coastal communities.

These environmental problems pose serious threats to livelihoods, human health, and the long-term sustainable development of the country. Conservation efforts and sustainable resource management are critical but face challenges from economic pressures and weak governance.

5. Government and politics

Honduras is a presidential representative democratic republic. The Constitution, originally adopted in 1982 and subsequently amended, provides the framework for its government. It establishes a system of separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches.

The Honduran political system has historically been dominated by two major parties, the Liberal Party of Honduras (PLH) and the National Party of Honduras (PNH), though other parties have gained prominence in recent years. The country has faced significant challenges to its democratic stability, including military coups and periods of authoritarian rule, with ongoing concerns about corruption, human rights, and the rule of law.

5.1. Political system

The government of Honduras is structured into three main branches:

- Executive Branch**: The President of Honduras is both the head of state and head of government. The president is elected by popular vote for a single four-year term. Historically, re-election was prohibited, but a controversial 2015 Supreme Court ruling overturned this ban, allowing for re-election, which became a contentious issue in subsequent elections. The president appoints a cabinet of ministers to manage various government departments.

- Legislative Branch**: Legislative power is vested in the unicameral National Congress of Honduras (Congreso Nacional). It consists of 128 members (diputados) who are elected for four-year terms through a system of proportional representation based on departmental lists. The Congress is responsible for passing laws, approving the national budget, and ratifying treaties.

- Judicial Branch**: The judiciary is, in principle, independent of the executive and legislative branches. The highest court is the Supreme Court of Justice (Corte Suprema de Justicia), whose 15 magistrates are elected by the National Congress for seven-year terms. The judicial system also includes appellate courts and lower courts. However, the judiciary has faced challenges related to political influence, corruption, and inefficiency, which impact the rule of law and access to justice.

The electoral process is managed by the National Electoral Council (Consejo Nacional Electoral, CNE), which replaced the former Supreme Electoral Tribunal. General elections are held every four years to choose the president, members of Congress, and municipal officials.

5.2. Political culture and recent developments

Honduran political culture has been shaped by a history of instability, including numerous military coups and periods of authoritarian rule that have significantly impacted the development of democratic institutions. The 1963 military coup that removed democratically elected President Ramón Villeda Morales initiated a long period of military dominance that lasted until 1981.

Historically, the political landscape was dominated by two traditional parties: the center-right National Party of Honduras (Partido Nacional de Honduras, PNH) and the center-left Liberal Party of Honduras (Partido Liberal de Honduras, PLH). This two-party system persisted for much of the 20th and early 21st centuries. However, the 2009 coup d'état, which ousted President Manuel Zelaya (PLH), marked a turning point. The crisis fractured the traditional party system and led to the emergence of new political forces, including Zelaya's Liberty and Refoundation (Libre) party.

Public trust in political institutions, including the police and the judiciary, has often been low, with widespread perceptions of corruption and electoral irregularities. A 2012 survey, for instance, found that 60% of respondents believed the police were involved in crime, and 72% thought there was electoral fraud in the primary elections.

The presidency of Juan Orlando Hernández (PNH, 2014-2022) was marked by significant controversy. His re-election in the 2017 elections was highly disputed, with challenger Salvador Nasralla accusing the government of fraud. The ensuing protests were met with state repression and resulted in numerous deaths and human rights violations. Hernández's administration was also deeply implicated in corruption and drug trafficking scandals, culminating in his extradition to the U.S. shortly after leaving office.

The election of Xiomara Castro (Libre) as president in 2021, the country's first female head of state, represented a significant shift, ending 12 years of National Party rule. Her victory was seen as a mandate for change and an opportunity to address issues of social inequality, corruption, and human rights.

Ongoing social strife related to political governance, impunity, and economic hardship continues to challenge Honduras. The integrity of democratic processes, the independence of the judiciary, and the protection of human rights remain critical concerns for the consolidation of democracy in the country.

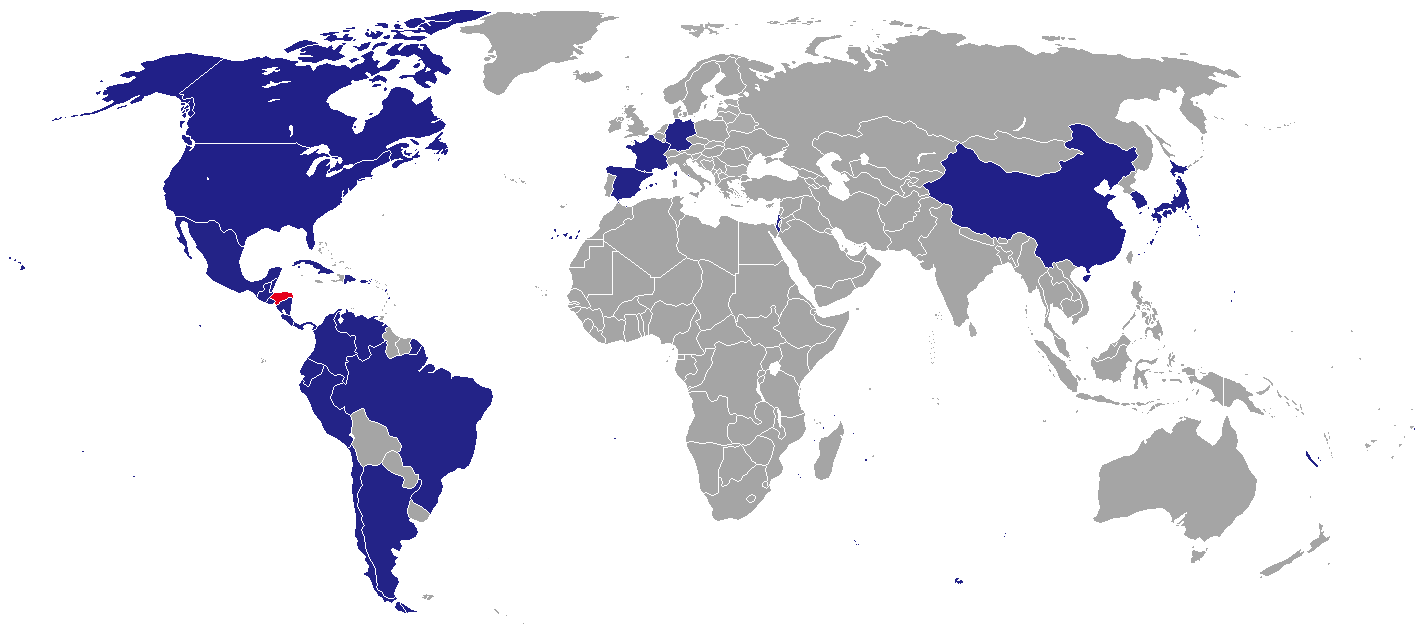

5.3. Foreign relations

Honduras pursues a foreign policy focused on maintaining positive relations with its Central American neighbors, the United States, and other nations, as well as participating in regional and international organizations. Historically, the United States has been Honduras's most significant foreign partner, exerting considerable economic and political influence. The U.S. is Honduras's chief trading partner and has maintained a military presence at Soto Cano Air Base (Palmerola). Joint military exercises focusing on peacekeeping, counter-narcotics, and disaster relief are common. However, this relationship has also been subject to criticism, particularly regarding U.S. involvement during the Cold War and its response to the 2009 coup.

Relations with neighboring countries have sometimes been strained. For example, Honduras and Nicaragua experienced tensions in 2000-2001 due to a maritime boundary dispute in the Caribbean Sea, which led to Nicaragua imposing a tariff on Honduran goods. The dispute was later resolved by the International Court of Justice. Relations with El Salvador were severely damaged by the Football War in 1969, though they have since normalized.

The 2009 coup that ousted President Manuel Zelaya had significant diplomatic repercussions. The Organization of American States (OAS) suspended Honduras's membership, and many Latin American nations temporarily severed diplomatic ties. Zelaya's prior decision to join the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (ALBA) in 2008 was reversed by the post-coup government in 2010.

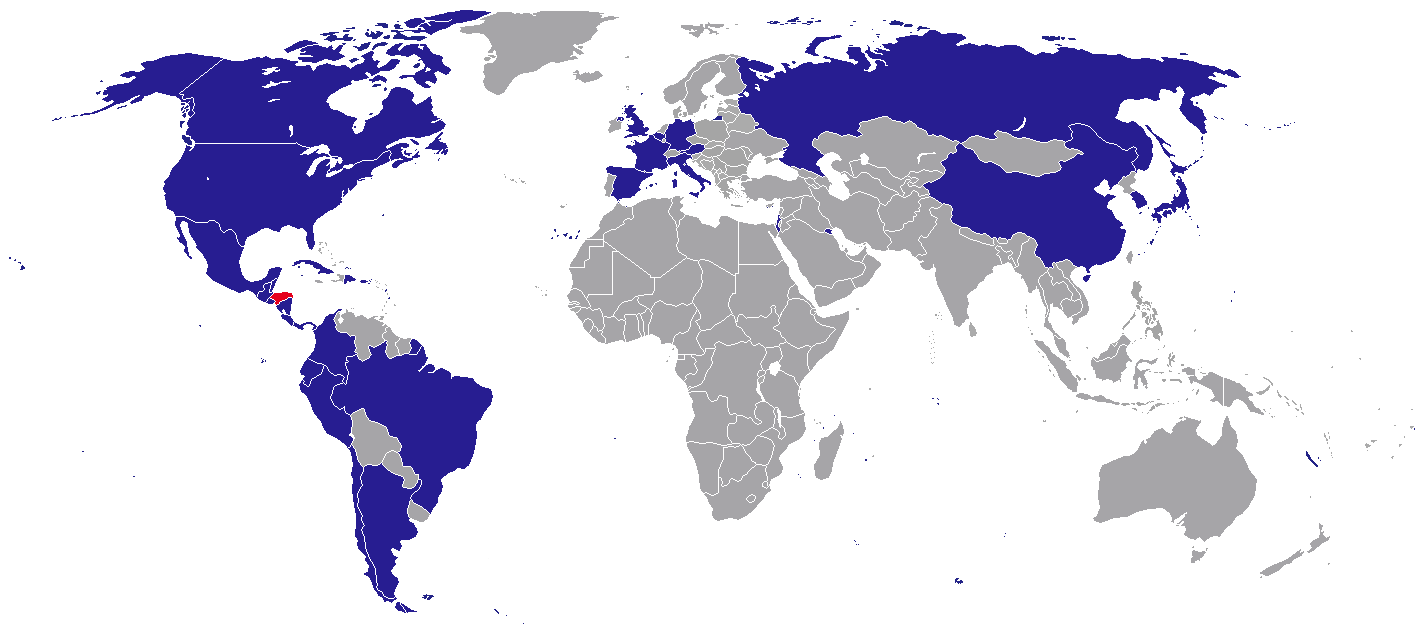

In March 2023, under President Xiomara Castro, Honduras established diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China, consequently severing its long-standing official ties with Taiwan (Republic of China). This move aligned Honduras with a growing number of Central American nations recognizing Beijing.

Honduras is a member of the United Nations, the World Trade Organization (WTO), the Central American Parliament (PARLACEN), the Central American Integration System (SICA), and was a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council for 1995-1996. It is also a member of the International Criminal Court, though it has a Bilateral Immunity Agreement with the U.S. regarding American military personnel. Honduras has been a member of The Forum of Small States (FOSS) since its founding in 1992.

5.4. Military

The Armed Forces of Honduras (Fuerzas Armadas de Honduras) consist of an Army, Navy, and Air Force. Conscription was abolished in 1995, and the military has since transitioned to an all-volunteer force. Estimates of total active personnel vary, with some sources suggesting around 12,000 to 15,000, though figures can differ based on whether paramilitary forces or reserves are included.

The military has historically played a significant role in Honduran politics, including periods of direct military rule and involvement in internal security matters. Following the 2009 coup, military and other security forces were implicated in numerous human rights abuses, including arbitrary detentions, enforced disappearances, and extrajudicial killings of opponents of the de facto government. These actions drew condemnation from international human rights organizations.

The military's budget has, at times, been among the highest in Central America relative to its economy. The U.S. has historically provided training and assistance to the Honduran military. In recent years, the military has been deployed to address public security challenges, including combating organized crime and gang violence, a role that has raised concerns among human rights groups about the militarization of law enforcement and potential for abuses.

In 2017, Honduras signed the United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

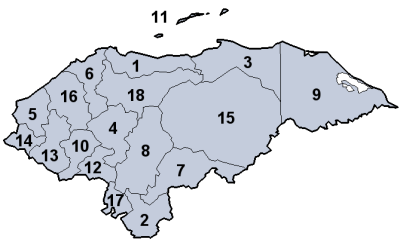

5.5. Administrative divisions

Honduras is divided into 18 departments (departamentos) for administrative purposes. Each department is further subdivided into municipalities (municipios), of which there are 298 in total. The capital city, Tegucigalpa, is located in the Central District within the department of Francisco Morazán.

The 18 departments are:

# Atlántida

# Choluteca

# Colón

# Comayagua

# Copán

# Cortés

# El Paraíso

# Francisco Morazán

# Gracias a Dios

# Intibucá

# Bay Islands (Islas de la Bahía)

# La Paz

# Lempira

# Ocotepeque

# Olancho

# Santa Bárbara

# Valle

# Yoro

Honduran geographer Noé Pineda Portillo has proposed a division of these departments into six regions based on natural geographic conditions and human elements:

- Central-East Region**: El Paraíso, Francisco Morazán, Olancho. Characterized by central mountains, intermontane basins, and includes the capital. Historically developed for mining and livestock; today, agriculture, livestock, and forestry are prominent.

- Southern Region**: Choluteca, Valle. Plains at the southern foot of the central mountains. Colonial mining and livestock; now agro-industry and export melon production. Traversed by the Pan-American Highway, with the Pacific port of San Lorenzo.

- Central-West Region**: Comayagua, Intibucá, La Paz. Comayagua plains and mountainous areas. Cement and food industries in plains; coffee, highland vegetables, and fruit in mountains.

- Western Region**: Copán, Lempira, Ocotepeque. Predominantly mountainous. Corn, coffee, tobacco production; livestock and agro-industry in valley floors.

- Northwestern Region**: Cortés, Santa Bárbara, Yoro. Mountains and alluvial plains extending to the Caribbean. Diverse agriculture (bananas, citrus, sugarcane, livestock) and industries (metals, chemicals, cement). San Pedro Sula is a transport hub, and Puerto Cortés is a major Atlantic port.

- Northeastern Region**: Atlántida, Colón, Gracias a Dios, Islas de la Bahía. Caribbean coastal plains and islands. Low population density; plantation agriculture (bananas, oil palm) and tourism development are significant.

In 2013, a new type of administrative division called ZEDE (Zonas de empleo y desarrollo económico) was created. These zones are designed with a high level of autonomy, including their own political, judicial, economic, and administrative systems, based on free market capitalism. ZEDEs have been highly controversial, with critics raising concerns about national sovereignty, labor rights, land displacement, environmental protection, and the potential for them to become enclaves that do not benefit the broader Honduran population equitably. The government under Xiomara Castro has moved to repeal the ZEDE law.

6. Economy

The Honduran economy is primarily based on agriculture and is one of the least developed in Central America, facing significant challenges related to poverty, inequality, and vulnerability to external shocks such as natural disasters and fluctuations in global commodity prices. The World Bank classifies Honduras as a lower-middle-income country. In 2022, according to the National Institute of Statistics of Honduras (INE), 73% of the population lived in poverty, with 53% in extreme poverty, making it one of the poorest countries in the Western Hemisphere. Economic inequality is also extremely high, among the highest in Latin America. Wealth tends to be concentrated in urban centers, while the lower class is predominantly based in agriculture. Honduras has a Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.624 (2021), ranking 137th in the world.

Historically, the economy was dominated by the export of a few agricultural commodities, particularly bananas and coffee, often under the control of foreign companies, which contributed to its "banana republic" status and limited broad-based development. While the economy has diversified to some extent, agriculture still accounted for about 14% of GDP in 2013. The maquiladora (assembly plant) sector, primarily in San Pedro Sula and Puerto Cortés, has become an important source of employment and export earnings, particularly in textiles. Other sectors include mining, tourism, and a growing service industry. Remittances from Hondurans living abroad, mainly in the United States, are a crucial component of the national economy, significantly contributing to household incomes and foreign exchange reserves.

Economic growth has been inconsistent. While there were periods of higher growth (e.g., averaging around 7% annually in the late 2000s before the global financial crisis and the 2009 coup), overall development has lagged. The 2009 coup had a negative impact, reversing trends in poverty reduction and increasing unemployment. Natural disasters, such as Hurricane Mitch in 1998, have had devastating effects, destroying infrastructure and agricultural production, and setting back development by years. The national currency is the Honduran lempira (HNL).

6.1. Key sectors

The Honduran economy relies on several key sectors, each with its own contributions, labor conditions, and environmental or social impacts:

- Agriculture**: Historically the backbone of the economy, agriculture remains significant.

- Coffee**: A major export crop, coffee production is vital for many smallholder farmers. It is susceptible to price volatility and climate change. Labor conditions can be precarious, especially for seasonal workers.

- Bananas**: Once the dominant export, bananas are still important, though production has faced challenges from diseases and hurricanes. Large plantations, often historically foreign-owned, have a legacy of difficult labor relations and significant environmental impact through monoculture and pesticide use.

- Other crops**: Sugarcane, palm oil (increasingly controversial due to deforestation and land conflicts), tropical fruits (melons, pineapples), and basic grains for domestic consumption are also cultivated.

The agricultural sector often faces issues of land tenure insecurity, limited access to credit and technology for small farmers, and vulnerability to natural disasters.

- Maquiladora (Assembly Plant) Industry**: Located primarily in industrial parks in cities like San Pedro Sula and Choloma, the maquiladora sector assembles imported components (mainly textiles and apparel) for re-export, largely to the U.S. market. It is a major source of formal employment, particularly for women. However, the sector has faced criticism regarding low wages, challenging working conditions, and limited opportunities for skill development or advancement. Its contribution to the local economy beyond wages can be limited due to tax incentives and reliance on imported inputs.

- Mining**: Honduras has resources of gold, silver, lead, zinc, and antimony. Mining, often conducted by foreign companies, contributes to export revenues but is highly controversial due to its severe environmental impacts, including water pollution from heavy metals (e.g., Lake Yojoa) and deforestation. Social impacts include land conflicts with local and indigenous communities, displacement, and concerns over the equitable distribution of benefits. The lack of stringent environmental regulation and enforcement is a major concern.

- Tourism**: Tourism is a growing sector, particularly focused on the Bay Islands (Roatán, Utila, Guanaja) for diving and beach holidays, the Maya ruins of Copán, and ecotourism in national parks. While it generates foreign exchange and employment, there are concerns about the environmental impact of coastal development, the sustainability of tourism practices, and ensuring that benefits reach local communities. Labor conditions in the tourism sector can also be precarious.

- Textiles**: Largely synonymous with the maquiladora industry, textile and apparel production is a key manufacturing activity.

The development of these sectors often highlights tensions between economic growth, social equity, labor rights, and environmental sustainability, which are critical concerns from a center-left/social liberalism perspective.

6.2. Poverty and economic inequality

Honduras suffers from exceptionally high levels of poverty and economic inequality, which are among the most severe in Latin America and the Caribbean. These issues are deeply entrenched and have profound impacts on the well-being of its population, particularly vulnerable groups, and hinder national development.

In 2022, the National Institute of Statistics of Honduras (INE) reported that 73% of the population lived below the poverty line, with a staggering 53% living in extreme poverty. The World Bank noted in 2016 that over 66% of the population lived in poverty. This widespread poverty means a large portion of Hondurans struggle to meet basic needs for food, housing, healthcare, and education.

Economic inequality is stark. Wealth and opportunities are highly concentrated in urban centers and among a small elite, while rural areas, where much of the agricultural lower class and indigenous populations reside, experience disproportionately high rates of poverty. The Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality, consistently places Honduras among the most unequal countries in the region. When Honduras's Human Development Index (HDI) is adjusted for inequality (IHDI), its value drops significantly, reflecting major disparities in access to health, education, and income. In 2015, for example, the inequality in income was reported at 41.5%.

- Causes of poverty and inequality include:**

- Historical factors**: A legacy of colonial exploitation, unequal land distribution (latifundio-minifundio system), and political systems that favored elites.

- Economic structure**: Reliance on low-wage agriculture and maquiladora industries with limited value addition, and vulnerability to global commodity price shocks.

- Weak governance and corruption**: Mismanagement of public resources, corruption, and impunity divert funds that could be used for social programs and development.

- Lack of access to quality services**: Unequal access to education, healthcare, and basic infrastructure (water, sanitation, electricity) perpetuates poverty cycles.

- Natural disasters**: Events like Hurricane Mitch have disproportionately affected the poor, destroying livelihoods and assets, particularly in rural areas and for subsistence farmers and indigenous communities like those along the Patuca River. Single-women headed households are often the most impacted.

- Political instability**: The 2009 coup, for example, reversed progress in poverty reduction and led to increased unemployment and extreme poverty.

The lower class predominantly consists of rural subsistence farmers, landless peasants, and a growing urban poor population who migrate to cities seeking work in informal sectors, manufacturing, or construction. Underemployment is a significant issue. Middle class in Honduras is relatively small. The upper class controls a vastly disproportionate share of national wealth. These deep-seated inequalities fuel social unrest, crime, and emigration, posing fundamental challenges to democratic stability and human rights.

6.3. Poverty reduction strategies

Various national and international efforts have been made to alleviate poverty and reduce inequality in Honduras, though their effectiveness and impact on social equity have been mixed and often undermined by political instability and structural challenges.

Since the 1970s, when Honduras was designated a "food priority country" by the UN, organizations like the World Food Programme (WFP) have worked to decrease malnutrition and food insecurity. The WFP has been involved in school feeding programs, reaching millions of children, and provides disaster relief to aid recovery from natural disasters that devastate agricultural production.

In 1999, Honduras implemented a Poverty Reduction Strategy (PRS), supported by international financial institutions like the World Bank and IMF, with the aim of halving extreme poverty by 2015. This strategy led to increased public spending, particularly in education and health sectors, and the implementation of programs like conditional cash transfers through the Family Assistance Program, targeting families in extreme poverty. Social spending as a percentage of GDP did increase in the early 2000s (from 44% in 2000 to 51% in 2004 for poverty-focused programs).

However, the results of these strategies have been limited. While extreme poverty saw an initial dip after the PRS implementation (to 36.2%), it later rose significantly, reaching 66.5% by 2012. GDP growth during the early PRS period (1999-2002) was modest at 2.5%. Critics, including some academics and civil society organizations, argued that PRSs often led to little substantive change in underlying economic policies, lacked clear priorities and strong commitment, and failed to address structural issues like unequal land distribution or promote effective macro-level economic reforms necessary for sustainable poverty reduction. The World Bank itself acknowledged inefficiencies, partly due to a lack of focus on infrastructure and rural development.

The period before the 2009 coup under President Manuel Zelaya saw an expansion of social spending and a significant increase in the minimum wage, which had begun to show some positive impact on reducing inequality. However, these efforts were largely reversed following the coup, with social spending as a percentage of GDP decreasing from 13.3% in 2009 to 10.9% in 2012. This decline exacerbated the effects of the global recession and further entrenched poverty and inequality.

The challenge for Honduras remains to implement comprehensive and sustained strategies that address the root causes of poverty and inequality, ensure equitable distribution of resources and opportunities, and are resilient to political shocks and natural disasters. This requires strong political will, good governance, and active participation of civil society and vulnerable communities themselves.

6.4. Trade and investment

Honduras's international trade patterns reflect its status as a developing economy, heavily reliant on agricultural exports and the maquiladora sector. Its primary trading partner is the United States, followed by other Central American countries and the European Union. Key export goods include coffee, bananas, shrimp, apparel (from maquiladoras), palm oil, and gold. Imports consist mainly of manufactured goods, machinery, transportation equipment, chemicals, and fuels.

Honduras is a signatory to several trade agreements, the most significant being the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) with the United States, which came into effect for Honduras in 2006. CAFTA-DR aimed to liberalize trade and investment but has been met with mixed reactions. Proponents argue it has increased export opportunities, particularly for the maquiladora sector. Critics, however, raise concerns about its impact on small farmers unable to compete with subsidized U.S. agricultural imports, potential negative effects on labor rights and environmental standards due to pressures to attract investment, and limited benefits for the broader population.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) has been encouraged by the Honduran government, particularly in sectors like tourism, renewable energy, and maquiladoras. However, attracting and retaining sustainable investment has been challenged by political instability, corruption, weak rule of law, and security concerns.

A particularly controversial initiative has been the creation of Zones for Employment and Economic Development (ZEDEs). Authorized by a 2013 decree, ZEDEs are designed as highly autonomous areas with their own legal, tax, and administrative systems, intended to attract large-scale investment. The concept, based on charter city ideas, has drawn severe criticism from various sectors of Honduran society and international observers. Concerns include potential violations of national sovereignty, displacement of communities, lack of transparency, risks to labor rights and environmental protection, and the creation of enclaves that could exacerbate inequality rather than promote inclusive development. The administration of President Xiomara Castro has expressed opposition to ZEDEs and initiated steps to repeal the ZEDE law, though legal and political challenges remain.

The main seaport, Puerto Cortés, is crucial for international trade and was included in the U.S. Container Security Initiative in 2005 and the Secure Freight Initiative in 2006, aimed at enhancing cargo security for U.S.-bound containers.

The national currency is the Honduran lempira (HNL).

6.5. Energy

The energy sector in Honduras faces significant challenges related to supply, distribution, cost, and sustainability. Electricity generation relies on a mix of sources, primarily hydroelectric power and thermal power (mostly fossil fuels). Renewable energy sources, particularly solar and wind, are gaining traction but still represent a smaller portion of the energy matrix.

The state-owned Empresa Nacional de Energía Eléctrica (ENEE) has historically dominated the electricity sector, responsible for generation, transmission, and distribution. However, about half of the generation capacity is now privately owned. ENEE has faced chronic financial problems, including high debt, technical and non-technical losses (including electricity theft), and has often required government subsidies.

Key challenges in the energy sector include:

- Financing**: Securing investment for new generation capacity (especially renewable) and modernizing the transmission and distribution grid is difficult due to ENEE's financial situation and reliance on external donors or private investment with favorable terms.

- Tariffs and Losses**: Re-balancing electricity tariffs to reflect costs while ensuring affordability for low-income consumers, reducing arrears in payments, and tackling electricity theft are ongoing issues.

- Environmental Concerns**: Large hydroelectric projects, while providing renewable energy, can have significant environmental and social impacts, including displacement of communities and effects on ecosystems. Reconciling these concerns with energy development goals is crucial.

- Rural Access**: While electricity coverage has improved, ensuring reliable access in remote rural areas remains a challenge and is vital for poverty reduction and economic development.

- Sustainability**: Shifting towards a more sustainable and resilient energy matrix with a greater share of renewable sources is a key policy objective, driven by both environmental concerns and the volatility of fossil fuel prices.

Policies related to energy development aim to diversify the energy mix, promote energy efficiency, and improve the regulatory framework to attract investment and ensure a more stable and affordable electricity supply. The impact of energy policies on vulnerable communities and the environment are critical considerations for equitable and sustainable development.

6.6. Transportation

Honduras's transportation infrastructure is a critical component for its economic development and social integration, yet it faces considerable challenges in terms of quality, coverage, and maintenance. The Ministry of Public Works, Transport and Housing (SOPRTRAVI, Secretaría de Obras Públicas, Transporte y Vivienda) is the government body responsible for policy in this sector.

- Road Network**: Roadways are the primary mode of transportation. Honduras has a network of paved and unpaved roads, totaling approximately 8.5 K mile (13.60 K km). Main highways connect major cities and ports, but many secondary and rural roads are in poor condition, particularly affected by heavy rains and lack of maintenance. This limits access to markets, education, and healthcare for many communities, especially in remote areas, hindering their economic opportunities and reinforcing regional disparities.

- Seaports**: Honduras has coastlines on both the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean. The most important seaport is Puerto Cortés on the Caribbean coast, which handles the majority of the country's international maritime trade and is one of the largest and most modern ports in Central America. Other Caribbean ports include La Ceiba, Tela, and Puerto Castilla. On the Pacific side, the main port is San Lorenzo in the Gulf of Fonseca.

- Airports**: Honduras has several international airports, with Toncontín International Airport in Tegucigalpa (notorious for its challenging approach), Ramón Villeda Morales International Airport in San Pedro Sula (the country's busiest), Golosón International Airport in La Ceiba, and Juan Manuel Gálvez International Airport in Roatán being the most significant. There are also numerous smaller airports and airstrips, many of which are unpaved, serving domestic routes and remote areas.

- Railways**: Rail transport is very limited in Honduras, with only about 434 mile (699 km) of track, primarily narrow-gauge lines built by fruit companies in the early 20th century on the north coast for transporting bananas. Most of this network is now in disrepair or abandoned, and rail plays a negligible role in national transportation.

Challenges in the transportation sector include insufficient investment in infrastructure development and maintenance, vulnerability to natural disasters (which frequently damage roads and bridges), difficult mountainous terrain, and security concerns on some routes. Improving connectivity, particularly for rural and impoverished regions, is crucial for promoting equitable economic growth, access to essential services, and overall national development.

7. Demographics

7.1. Population

As of 2023 estimates, Honduras has a population of over 10.5 million people. The population growth rate has historically been relatively high, though it has seen a decline in recent decades. In 2010, the age structure was youthful, with 36.8% of the population below the age of 15, 58.9% between 15 and 65 years old, and 4.3% aged 65 or older. This demographic profile presents both opportunities (a large potential workforce) and challenges (pressure on education, health services, and job creation).

Population density varies significantly, with higher concentrations in the Sula Valley (around San Pedro Sula), the central highlands (including Tegucigalpa), and parts of the Pacific coastal region. La Mosquitia in the northeast remains sparsely populated. Urbanization has been increasing, with a significant portion of the population now living in cities.

Migration has been a prominent demographic trend. Since the 1975, emigration from Honduras has accelerated, driven by economic hardship, lack of opportunities, political instability, high levels of crime and violence, and natural disasters. The majority of expatriate Hondurans reside in the United States, with estimates in 2012 suggesting between 800,000 and one million (nearly 15% of the Honduran population at the time), many of whom are undocumented. Significant Honduran communities also exist in Spain, Canada, Mexico, and neighboring Central American countries. Remittances sent by Hondurans living abroad are a vital source of income for many families and a significant contributor to the national economy. Internal migration, primarily from rural to urban areas, also continues.

7.2. Race and ethnicity

The ethnic composition of Honduras is diverse, with Mestizos (of mixed Amerindian and European ancestry) forming the predominant group, accounting for approximately 90% of the population. Indigenous peoples constitute around 7%, Afro-Hondurans (Black/Afro-descendant) make up about 2%, and White Hondurans (of European descent) represent about 1%.

- Indigenous Peoples**: Around 7% of the population identifies as indigenous. Honduras officially recognizes nine distinct indigenous and Afro-descendant groups. The largest indigenous group is the Lenca, primarily inhabiting the western and southwestern highlands. Other significant indigenous groups include the Miskito (mainly in La Mosquitia along the Caribbean coast, extending into Nicaragua), Ch'orti' (descendants of the Maya, in the west near the Guatemalan border), Tolupan (or Jicaque), Pech (or Paya), and Tawahka (or Sumo). These groups have rich cultural heritages but often face significant challenges, including poverty, discrimination, lack of access to land and resources, and threats to their cultural survival and languages. Their struggles for land rights and self-determination are ongoing.

- Afro-Hondurans**: Constituting about 2% of the population, Afro-Hondurans include several distinct communities.

- The Garifuna are descendants of mixed West African, Central African, Island Carib, and Arawak people, who were exiled from the island of St. Vincent in the late 18th century and settled along the Caribbean coast of Central America, including Honduras. They have a unique language, music (such as Punta), dance, and cultural traditions, recognized by UNESCO as part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

- English-speaking Afro-Caribbeans (often referred to as Creoles) are mainly found in the Bay Islands and parts of the Caribbean coast, descendants of enslaved Africans brought by the British and later West Indian laborers.

- Other Afro-descendants are integrated into the broader Ladino (culturally Hispanicized) population.

- People of European Descent (Whites)**: About 1% of the population is of predominantly European ancestry, mainly Spanish colonial descendants but also including smaller groups of other European origins.

- Other Groups**: Honduras also has small communities of people of Arab descent (primarily Palestinian and Lebanese, often called "turcos" due to their arrival during Ottoman rule), who are prominent in commerce, as well as people of East Asian descent (Chinese, Japanese).

Social stratification in Honduras has historically been influenced by ethnicity and race, stemming from the colonial era. While Mestizos form the majority, indigenous and Afro-Honduran populations have often faced systemic discrimination and marginalization, impacting their access to political power, economic opportunities, and social services. Recognizing and addressing these disparities is crucial for building a more equitable and inclusive Honduran society.

7.3. Languages

The official and most widely spoken language in Honduras is Spanish. It is the primary language of government, education, media, and daily life for the vast majority of the population. Honduran Spanish has its own regional variations and colloquialisms.

In addition to Spanish, a number of indigenous languages are still spoken, primarily within their respective communities, although many are endangered:

- Garifuna**: An Arawakan language spoken by the Garifuna people along the Caribbean coast. It has a significant number of speakers (estimated around 100,000 in Honduras, though not all are fluent).

- Miskito**: A Misumalpan language spoken by the Miskito people in the La Mosquitia region. It has around 29,000 speakers in Honduras.

- Mayangna (Tawahka/Sumo)**: Another Misumalpan language, spoken by a smaller number of people, mostly in La Mosquitia.

- Pech (Paya)**: A Chibchan language with very few remaining speakers.

- Tol (Jicaque/Tolupan)**: A Jicaquean language isolate, also with a small number of speakers.

- Ch'orti'**: A Mayan language spoken by a very small community in western Honduras, near the Guatemalan border.

The Lenca language, an isolate, lost all its fluent native speakers during the 20th century, but there are ongoing efforts among the Lenca ethnic population (around 100,000) to revive and reclaim their ancestral language as part of their cultural heritage.

Bay Islands Creole English is spoken in the Bay Islands. Honduran Sign Language is used by the deaf community.

Immigrant languages such as Arabic, Armenian, Turkish, and Yue Chinese are spoken within their respective communities.

The preservation and revitalization of indigenous languages are important for maintaining cultural diversity, but these languages face significant pressure from the dominance of Spanish. Bilingual education programs in some indigenous areas aim to support linguistic heritage.

7.4. Religion

The religious landscape of Honduras is predominantly Christian. Historically, Roman Catholicism has been the dominant religion, introduced during the Spanish colonial era. While a majority of Hondurans still identify as Catholic, its proportion has been declining in recent decades due to the significant growth of various Protestant denominations.

According to a 2008 CID Gallup poll, 51.4% of the population identified as Catholic, while 36.2% identified as evangelical Protestant. Another 1.3% reported affiliation with other religions (including Muslims, Buddhists, Jews, Rastafarians), and 11.1% stated they did not belong to any religion or were unresponsive. Approximately 8% identified as atheistic or agnostic. The Catholic Church's own tallies often report a higher percentage of adherence, around 81%. More recent surveys continue to show a strong Protestant presence, with some estimates placing Catholics and Protestants at roughly similar proportions or with Protestants forming a plurality.

Various Protestant churches, particularly Evangelical and Pentecostal groups, have experienced rapid growth. Other active denominations include Anglican, Presbyterian, Methodist, Seventh-day Adventist, Lutheran, and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons). There are Protestant seminaries in the country.

The Catholic Church remains an influential institution, operating numerous schools, hospitals, and pastoral institutions. Cardinal Óscar Rodríguez Maradiaga, former Archbishop of Tegucigalpa, has been a prominent figure both nationally and internationally.

Freedom of religion is constitutionally protected in Honduras. Small communities of Buddhists, Jews, Muslims (primarily from Arab immigrant communities), Baháʼís, and Rastafarians exist, as do practitioners of indigenous spiritual traditions, sometimes syncretized with Christian beliefs. Religion plays a significant role in the social and cultural life of many Hondurans.

7.5. Gender

Gender roles in Honduras are heavily influenced by traditional cultural norms, including concepts of machismo (exaggerated masculinity and male dominance) and marianismo (idealized femininity emphasizing purity and maternal roles), as well as familialism (prioritizing family interests). Historically, Honduras has functioned as a patriarchal society, with men often holding primary decision-making power in families and public life. However, these traditional roles are increasingly being challenged by feminist movements, increased access to education for women, urbanization, and global media influences.

Despite some progress, significant gender inequality persists in Honduras across political, economic, and social spheres:

- Political Participation**: Women's representation in political office remains limited, though it has increased. As of 2015, 25.8% of parliamentary seats were held by women. The election of Xiomara Castro as the first female president in 2021 was a landmark event.

- Economic Inequality**: Women face significant disadvantages in the labor market. While female educational attainment at the secondary level or higher (33.4% in 2015) slightly surpassed that of males (31.1%), women's labor force participation (47.2%) was much lower than men's (84.4%). Women are often concentrated in lower-paying jobs, the informal sector, or maquiladoras, and face a substantial gender pay gap. The GNI per capita for males in 2015 was 6.25 K USD, while for females it was only 2.68 K USD.

- Reproductive Health**: The maternal mortality ratio was 129 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2015, and the adolescent birth rate was 65.0 per 1,000 women aged 15-19. Access to comprehensive reproductive health services, including contraception, can be limited, particularly in rural areas. Total fertility rates have declined from 7.4 births per woman in 1971 to 4.4 in 2001, partly due to increased contraceptive use (62% of women in 2001).

- Gender-Based Violence**: This is a severe and pervasive problem in Honduras, which has one of the highest rates of femicide (the killing of women because of their gender) in the world. Domestic violence, sexual assault, and sexual harassment are widespread. Gang violence often includes sexual violence against women and girls as a tool of control. Impunity for these crimes is rampant, with official statistics in 2014 showing a 95% impunity rate for sexual violence and femicide. This extreme violence is a major factor driving migration, particularly for women and children. Child sexual abuse is also a serious concern.

Domestic violence was recognized as a public health issue and a punishable offense in the mid-1990s. However, implementation of laws and provision of support services for victims remain inadequate. Feminist organizations and civil society groups are actively working to advocate for women's rights, combat gender-based violence, promote legal reforms, and provide support to survivors. Educational programs like Sistema de Aprendizaje Tutorial (SAT) have attempted to promote gender equality by integrating gender consciousness into curricula.

The Gender Inequality Index (GII) for Honduras was 0.461 in 2015 (ranking 101 out of 159 countries), indicating significant disparities. Addressing these deep-rooted gender inequalities is crucial for Honduras's social development, human rights record, and democratic progress.

7.6. Largest cities

Honduras has several major urban centers that serve as hubs for population, commerce, and industry. The most populous cities, according to the 2013 census, include:

| City | Department | Population (2013 Census) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tegucigalpa (Central District) | Francisco Morazán | 996,658 | Capital city, political and administrative center. |

| San Pedro Sula | Cortés | 598,519 | Main industrial city, commercial hub, major transportation center. |

| La Ceiba | Atlántida | 176,212 | Important port city on the Caribbean coast, tourism gateway. |

| Choloma | Cortés | 163,818 | Industrial city, part of the Sula Valley metropolitan area. |

| El Progreso | Yoro | 114,934 | Agricultural and commercial center in the Sula Valley. |

| Comayagua | Comayagua | 92,883 | Historic former capital, colonial architecture. |

| Choluteca | Choluteca | 86,179 | Major city in southern Honduras, agricultural region. |

| Danlí | El Paraíso | 64,976 | Agricultural center in eastern Honduras. |

| La Lima | Cortés | 62,903 | Known for banana plantations, part of Sula Valley. |

| Villanueva | Cortés | 62,711 | Industrial town near San Pedro Sula. |

These cities face challenges common to urban areas in developing countries, including rapid urbanization, informal settlements (slums), inadequate infrastructure, traffic congestion, pollution, and crime. However, they also represent centers of economic opportunity and cultural activity.

8. Social issues

Honduras confronts a range of pressing social issues that significantly affect the well-being of its population and hinder national development. These include deficiencies in the education system, inadequate access to healthcare, and extremely high levels of crime and public insecurity. These challenges disproportionately impact vulnerable populations and are often intertwined with poverty, inequality, and weak governance.

8.1. Education

The education system in Honduras faces significant challenges in terms of access, quality, and equity, despite efforts to improve literacy rates and enrollment rates. The net primary enrollment rate was reported at 94% in 2004, and the primary school completion rate was 90.7% in 2014. The literacy rate for the population aged 15 and over is approximately 83.6%.

The education system is structured into preschool, primary (grades 1-6), lower secondary (grades 7-9), and upper secondary (grades 10-11/12) levels, followed by higher education. The National Autonomous University of Honduras (UNAH), founded in 1847, is the primary public institution of higher learning, with campuses in major cities. There are also private universities and bilingual (Spanish-English) or even trilingual schools.

Despite these structures, significant challenges persist:

- Quality of Education**: The quality of schooling is often low, particularly in public schools, due to under-resourced facilities, outdated curricula, lack of teaching materials, and insufficient teacher training and support.

- Access and Equity**: Disparities in access to education are stark, especially between urban and rural areas. Children in rural communities, indigenous populations, and impoverished families often have limited access to schools, particularly at the secondary and higher education levels. Dropout rates can be high, driven by economic pressures that force children into labor.

- Resources**: Public spending on education may be insufficient to meet the needs of a growing youth population and address quality gaps. Schools often lack basic infrastructure, including adequate classrooms, sanitation, and technology.

- Impact of Violence and Insecurity**: In some areas, school attendance and teacher retention are affected by high levels of crime and gang violence, creating unsafe environments for learning.

Addressing these educational challenges is critical for human capital development, reducing poverty, and fostering social mobility in Honduras. Efforts to improve teacher training, curriculum relevance, school infrastructure, and equitable access for all children, particularly those from vulnerable groups, are essential. Honduras was ranked 114th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.

8.2. Health

The public health situation in Honduras is characterized by significant challenges, including limited access to quality healthcare services for a large portion of the population, particularly in rural and impoverished areas. Major public health indicators often reflect these deficiencies.

The healthcare system comprises both public and private sectors. The Ministry of Health oversees public health services, but the system is often underfunded, understaffed, and lacks adequate medical supplies and infrastructure. Access to specialized medical care is largely concentrated in urban centers.

Key health issues and challenges include:

- Prevalent Diseases**: Honduras faces a burden of both communicable and non-communicable diseases. Vector-borne diseases like dengue fever, chikungunya, Zika virus, and malaria are concerns, especially in tropical areas. Respiratory infections and diarrheal diseases are common, particularly among children, often linked to inadequate sanitation and hygiene. Non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and cancer are also on the rise.

- Maternal and Child Health**: Maternal mortality and infant mortality rates remain relatively high compared to other countries in the region, although progress has been made. Malnutrition, especially chronic malnutrition among children (around one-quarter of children according to some reports), is a significant problem affecting child development. Access to prenatal care, skilled birth attendance, and postnatal care is often limited for women in remote areas.

- Access to Healthcare**: Many Hondurans, especially the poor and those in rural or indigenous communities, face barriers to accessing healthcare due to cost, distance to facilities, and lack of transportation. Out-of-pocket expenses can be prohibitive for many families.

- Healthcare Infrastructure and Resources**: There is a shortage of healthcare professionals, particularly specialists, in many parts of the country. Public hospitals and clinics often lack essential medicines, equipment, and supplies.

- Impact of Violence**: High levels of violence and crime also contribute to public health burdens, including trauma care needs and mental health issues.