1. Overview

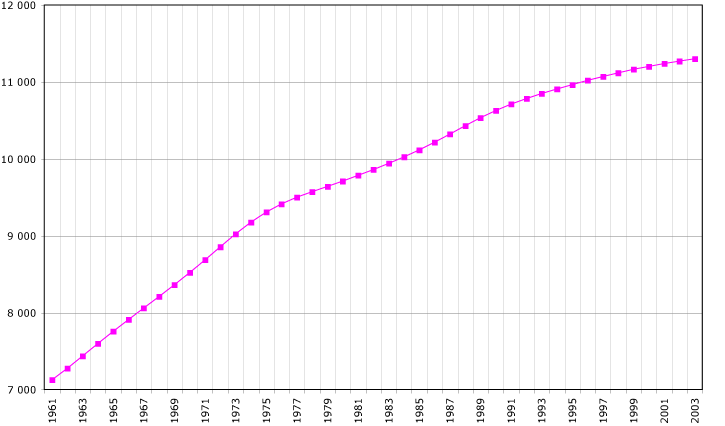

Cuba (pronounced KEW-bə; CubaSpanish: [ˈkuβa]Spanish), officially the Republic of Cuba (República de CubaSpanish: [reˈpuβlika ðe ˈkuβa]Spanish), is an island nation located at the confluence of the northern Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Atlantic Ocean. The republic comprises the main island of Cuba, the Isla de la Juventud, and numerous smaller archipelagos. Havana is its capital and largest city. With a population of approximately 11 million, Cuba is the most populous island nation in the Caribbean and is noted for its significant biodiversity, including many endemic species, and a tropical climate moderated by trade winds, though it is susceptible to hurricanes.

The island's history is marked by early indigenous habitation by peoples such as the Taíno and Guanahatabey, followed by nearly four centuries of Spanish colonization starting with Christopher Columbus's arrival in 1492. This period established a plantation economy reliant on sugar and enslaved African labor. Independence movements in the 19th century led to formal independence in 1902, albeit with considerable U.S. influence under the Platt Amendment. The early to mid-20th century was characterized by political instability, economic ties to U.S. interests, and social unrest, culminating in the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. The Cuban Revolution in 1959, led by Fidel Castro, overthrew Batista and established a socialist state under the Communist Party of Cuba.

The revolutionary government implemented widespread nationalizations and social reforms, particularly in education and healthcare, transforming Cuban society. However, these changes were accompanied by concerns over human rights and democratic freedoms, including the suppression of political opposition and state control over media. Cuba became a significant player in the Cold War, aligning with the Soviet Union, which led to events like the Cuban Missile Crisis and a long-standing U.S. embargo that continues to severely impact its economy. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 triggered a severe economic crisis known as the Special Period, prompting limited market-oriented reforms. Leadership has since transitioned from Fidel Castro to Raúl Castro and then to Miguel Díaz-Canel.

Cuba's economy remains centrally planned, with tourism, nickel mining, tobacco, sugar, and the export of skilled labor (notably medical professionals) as key sectors. While recent reforms have introduced more market mechanisms, the nation faces ongoing economic challenges, including resource shortages that affect living standards and nutrition. The Cuban population is ethnically diverse, with Spanish as the official language. Roman Catholicism and Afro-Cuban religions like Santería are prominent. Cuban culture is a vibrant synthesis of Spanish, African, and indigenous influences, expressed in its music, dance, literature, and sports, particularly baseball and boxing. This article examines Cuba's history, geography, political system, economy, demographics, and culture, with an emphasis on social impacts, human rights, and democratic development.

2. Etymology

The name Cuba is believed to originate from the Taíno language spoken by the indigenous inhabitants of the island prior to European arrival. However, its precise derivation and meaning are not definitively known. One prominent theory suggests it comes from the Taíno word cubao, which is interpreted as "where fertile land is abundant." Another possible origin is the Taíno word coabana, which is thought to mean "great place." These interpretations reflect the island's natural richness and significance to its original inhabitants. Christopher Columbus initially named the island Isla Juana ("John's Island") after John, Prince of Asturias, but the indigenous name 'Cuba' ultimately prevailed.

3. History

The history of Cuba spans from its earliest human settlements through indigenous societies, Spanish colonization, struggles for independence, a period as a republic with significant U.S. influence, the Cuban Revolution and the subsequent establishment of a socialist state, and its development into the present day. This history is marked by profound social, economic, and political transformations, deeply impacting its people and its role in international affairs, particularly concerning issues of democracy and human rights.

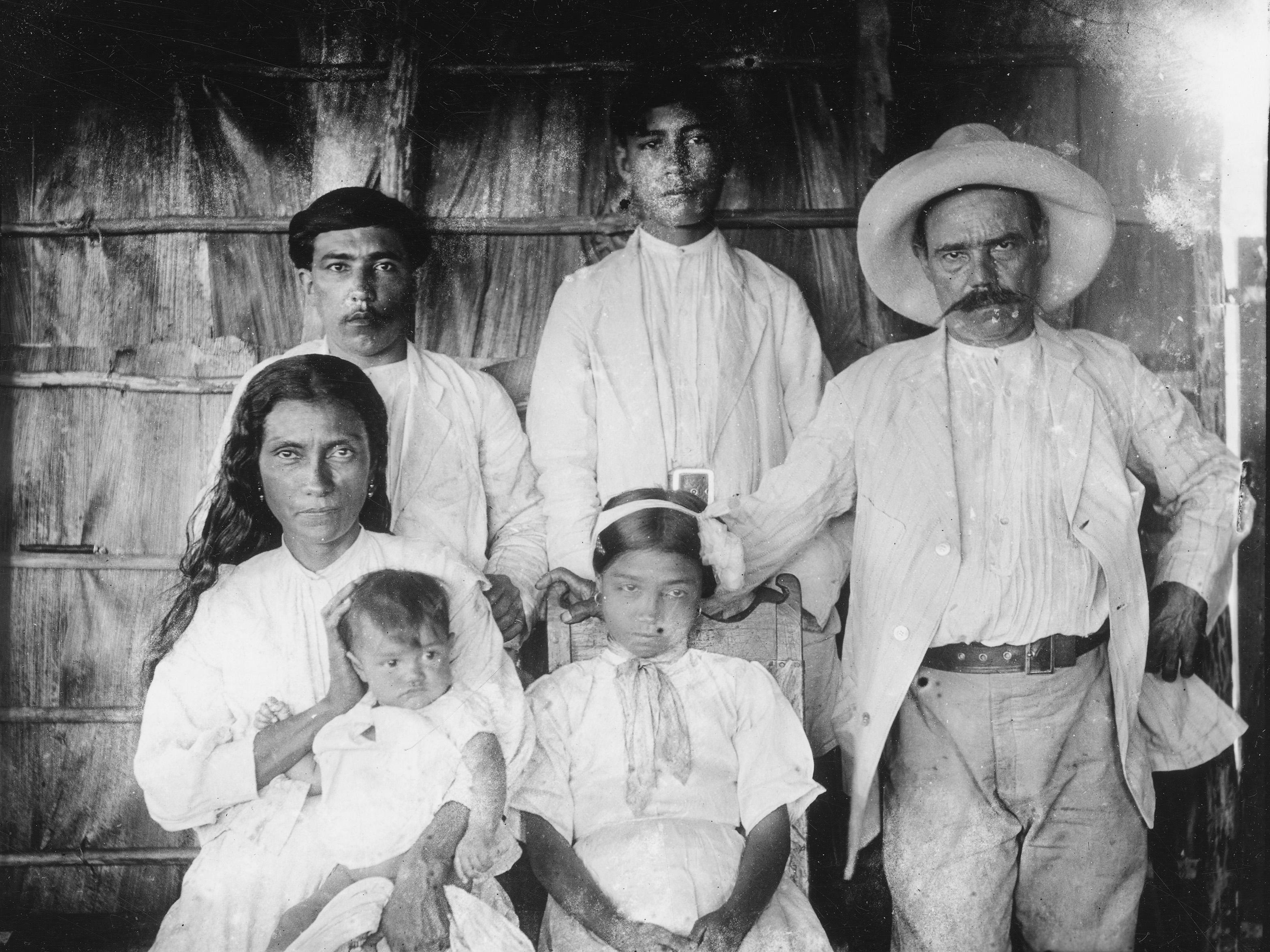

3.1. Pre-Columbian era

Humans first settled the island of Cuba around the 4th millennium BC, with migrations originating from northern South America or Central America. These early inhabitants included the Guanahatabey people, who primarily lived a hunter-gatherer lifestyle in the western part of the island and persisted until the arrival of Europeans. The arrival of humans on Cuba is associated with the extinction of some of the island's native fauna, notably its endemic sloths.

A later migration wave, around 1,700 years ago, brought the Arawakan-speaking ancestors of the Taíno people from South America. Unlike the earlier settlers, the Taíno developed more complex societies characterized by extensive pottery production and intensive agriculture. The earliest archaeological evidence of Taíno presence on Cuba dates to the 9th century AD. By the time Christopher Columbus arrived in 1492, the Taíno were the dominant group on the island, having established numerous villages and a sophisticated agricultural system based on crops like cassava, sweet potatoes, and maize. Their social structure was organized into cacicazgos (chiefdoms), and they possessed a rich cultural and spiritual life.

3.2. Spanish colonization and rule (1492-1898)

Christopher Columbus first landed on an island he called Guanahani (likely in the Bahamas) on October 12, 1492. He then reached Cuba on October 27, 1492, making landfall on the northeastern coast on October 28. Columbus claimed the island for the Kingdom of Spain and named it Isla Juana after John, Prince of Asturias, the heir to the Spanish throne.

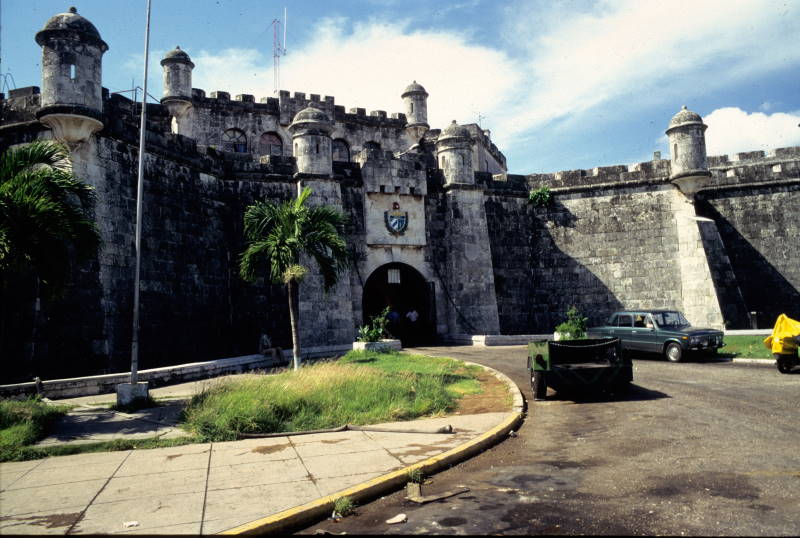

The Spanish conquest and colonization of Cuba began in earnest in 1511 when Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar founded the first Spanish settlement at Baracoa. Other settlements, including Havana (founded initially on the southern coast in 1514 and moved to its current location in 1519), soon followed. Havana eventually became the capital in 1607. The indigenous Taíno population was subjected to the brutal encomienda system, a form of forced labor akin to feudalism. Within a century, the indigenous population was decimated due to a combination of factors, primarily Old World diseases like smallpox and measles (to which they had no immunity), and the harsh conditions of colonial exploitation and violence. A measles outbreak in 1529, for instance, killed a significant portion of the remaining Taíno who had survived earlier smallpox epidemics.

In 1539, conquistador Hernando de Soto departed from Havana with around 600 men on an expedition to the southeastern United States in search of gold and glory. Gonzalo Perez de Angulo, appointed governor in 1548, declared the liberty of all remaining indigenous people upon his arrival in 1549 and was the first governor to reside permanently in Havana.

Cuba developed slowly as a settler colony compared to other Spanish territories in the Americas that were rich in silver or gold. Its strategic location, however, made Havana a key port for the Spanish treasure fleet. The island's economy initially diversified in agriculture, but the 18th century saw a dramatic shift towards a plantation economy centered on sugarcane cultivation. This transformation was fueled by the increasing demand for sugar in Europe and the massive importation of enslaved Africans. Between 1790 and 1820, approximately 325,000 Africans were forcibly brought to Cuba as slaves, a number four times greater than those imported in the preceding three decades. By the mid-18th century, there were around 50,000 enslaved people on the island; this number swelled significantly as the sugar industry boomed.

The Aponte Slave Rebellion of 1812, a major uprising of enslaved and free people of color, was brutally suppressed. Despite such resistance, the institution of slavery and the plantation system continued to expand. By 1817, Cuba's population was 630,980, of whom 291,021 were white, 115,691 were free people of color (often of mixed-race), and 224,268 were enslaved blacks.

A distinctive feature in Cuban slavery was the practice of coartacióncoartación (a system allowing slaves to purchase freedom)Spanish, which allowed enslaved individuals to negotiate a price for their freedom and pay it off in installments, eventually purchasing their liberty. This system, relatively unique in the Americas, contributed to a significant population of free people of color, particularly in urban areas where enslaved individuals often had more opportunities to earn money. By 1860, Cuba had 213,167 free people of color, constituting 39% of its non-white population. Due to a shortage of white labor, Black Cubans, both enslaved and free, dominated many urban industries.

While most of Spain's American empire gained independence in the early 19th century, Cuba remained a loyal Spanish colony, often referred to as "La Siempre Fiel Isla" (The Ever Faithful Isle). Its economy, deeply tied to Spain and increasingly to the United States through sugar exports, and a planter class wary of social upheaval, contributed to this continued allegiance. However, the desire for greater autonomy and eventual independence grew throughout the 19th century.

3.3. Independence movements

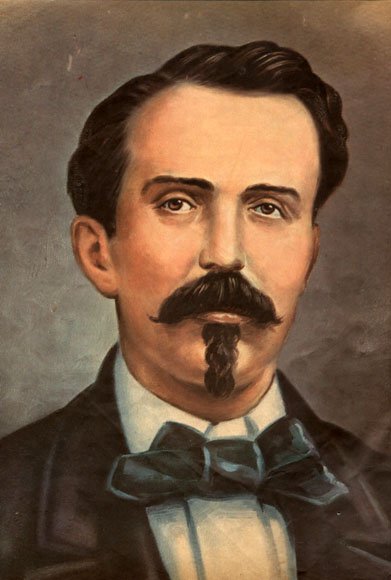

The struggle for Cuban independence from Spanish colonial rule intensified in the latter half of the 19th century, marked by several major uprisings and wars. The first significant push for independence was the Ten Years' War (1868-1878), initiated by sugar planter Carlos Manuel de Céspedes. On October 10, 1868, Céspedes issued the "Grito de Yara" (Cry of Yara), proclaiming Cuban independence and freeing his own slaves to join the rebellion. While his decree condemned slavery in theory, it accepted it in practice, freeing only those slaves whose masters presented them for military service. The war was a prolonged and brutal conflict, fought primarily in eastern Cuba. The rebel forces, lacking military experience, were joined by some Dominican refugees and mercenaries from various countries. However, internal strife, including racial tensions and divisions among the leadership, weakened the revolutionary movement. General Máximo Gómez, a key military leader, faced challenges due to his Dominican origin, and Antonio Maceo, a prominent mulatto general, encountered resistance from white factions. The United States declined to recognize the new Cuban government, though some European and Latin American nations did. The war ended with the Pact of Zanjón in 1878, which promised greater autonomy for Cuba but did not grant independence. This outcome was unsatisfactory to many patriots.

Dissatisfaction with the Pact of Zanjón led to the Little War (1879-1880), led by Calixto García, but it failed to gain sufficient support and was quickly suppressed. Despite these setbacks, the desire for independence remained strong. Slavery in Cuba was formally abolished in stages, with the process completed in 1886, a significant social change that also impacted the dynamics of the independence movement.

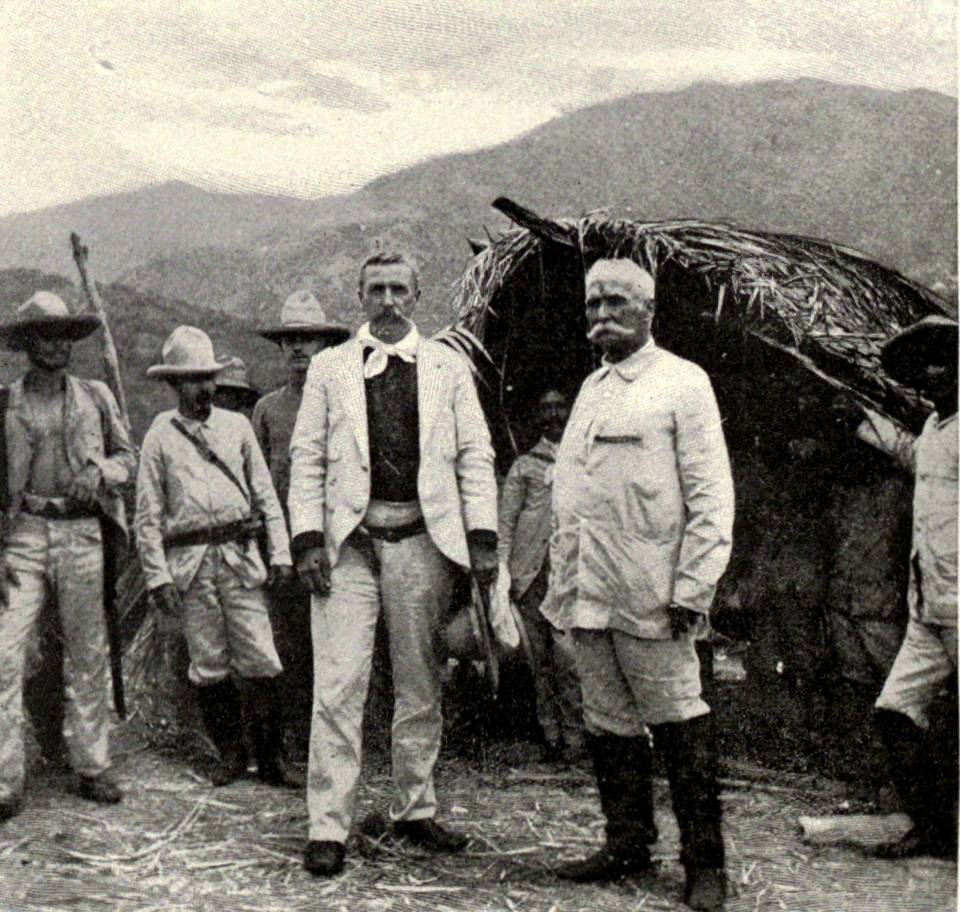

The definitive push for independence came with the Cuban War of Independence (1895-1898), orchestrated by José Martí. Martí, a poet, writer, and fervent nationalist, founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party in New York City in 1892 with the explicit aim of achieving Cuban independence. He united various exile factions and secured the support of veteran military leaders like Máximo Gómez and Antonio Maceo. In January 1895, Martí issued the Manifesto of Montecristi, outlining the political ideals of the revolution. Fighting began on February 24, 1895. Martí landed in Cuba on April 11, 1895, but was killed in the Battle of Dos Rios on May 19, 1895. His martyrdom transformed him into Cuba's foremost national hero and a symbol of the struggle for freedom.

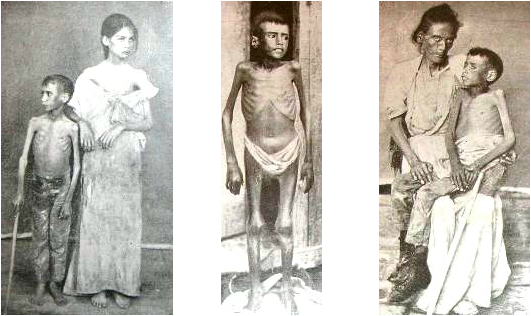

The war was characterized by brutal guerrilla warfare and harsh Spanish countermeasures. General Valeriano Weyler, the Spanish military governor, implemented the infamous reconcentration policy, forcing rural populations into fortified towns to deny support to the rebels. These reconcentradosreconcentrados (reconcentrated people)Spanish suffered from severe overcrowding, starvation, and disease, leading to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Cuban civilians-estimates range from 200,000 to 400,000. These atrocities were widely reported in the American press, fueling sensationalist journalism and increasing public sympathy in the United States for the Cuban cause.

The sinking of the U.S. battleship USS Maine in Havana harbor on February 15, 1898, became a critical turning point. Though the cause of the explosion was unclear (and later investigations suggest an internal accident), popular opinion in the U.S., inflamed by the press, blamed Spain. Cries of "Remember the Maine!" led to the Spanish-American War when the U.S. declared war on Spain in April 1898. U.S. forces intervened in Cuba, quickly defeating the Spanish. The war concluded with the Treaty of Paris (1898), in which Spain relinquished Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Guam to the United States, and sold the Philippines to the U.S. for 20.00 M USD. Cuba was occupied by the United States, setting the stage for its formal independence but under significant U.S. influence.

3.4. Republic (1902-1959)

The period from 1902 to 1959 marks the era of the first Republic of Cuba, a time characterized by formal independence but significant U.S. political and economic influence, internal political instability, economic development largely tied to sugar and American investment, and growing social unrest that ultimately led to the Cuban Revolution.

3.4.1. Early years (1902-1925)

Cuba gained formal independence from the United States on May 20, 1902, with Tomás Estrada Palma becoming its first president. However, independence came with significant stipulations imposed by the U.S. through the Platt Amendment, which was incorporated into the Cuban Constitution. This amendment granted the U.S. the right to intervene in Cuban affairs to preserve Cuban independence and maintain a government adequate for the protection of life, property, and individual liberty. It also stipulated the lease of naval stations to the U.S., leading to the establishment of the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base. This effectively made Cuba a U.S. protectorate.

The early years of the republic were marked by political instability and U.S. intervention. Following disputed elections in 1906, President Estrada Palma faced an armed revolt by independence war veterans. The U.S. intervened, occupying Cuba from 1906 to 1909 and appointing Charles Edward Magoon as governor. Magoon's governorship is often criticized by Cuban historians for fostering political and social corruption. Self-government was restored in 1908 with the election of José Miguel Gómez, but U.S. intervention continued. In 1912, an attempt by the Partido Independiente de Color (Independent Party of Color) to establish a separate black republic in Oriente Province was brutally suppressed by the Cuban army, resulting in considerable bloodshed.

Economically, Cuba continued to be heavily reliant on sugar exports, primarily to the U.S. market, and American capital dominated key sectors of the economy. While this brought some economic growth, it also perpetuated dependency and social inequalities. Tourism began to grow, particularly during the U.S. Prohibition era, with American-owned hotels and restaurants catering to an influx of visitors, which also led to an increase in gambling and prostitution.

Gerardo Machado was elected president in 1924. Initially popular, his administration oversaw increased tourism and some public works. However, his rule became increasingly authoritarian, and he extended his term unconstitutionally. The Wall Street Crash of 1929 severely impacted the Cuban economy by causing a collapse in sugar prices, leading to widespread unemployment, political unrest, and repression under Machado. Student protests by the "Generation of 1930" and labor strikes intensified opposition to his regime.

3.4.2. Revolution of 1933 and Constitution of 1940

The growing unpopularity of Gerardo Machado, exacerbated by economic hardship and political repression, culminated in a general strike and an army revolt that forced him into exile in August 1933. He was briefly replaced by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes y Quesada. However, this government was short-lived.

In September 1933, the Sergeants' Revolt, led by Sergeant Fulgencio Batista, overthrew Céspedes. A five-member executive committee, known as the Pentarchy of 1933, was initially chosen to head a provisional government. Soon after, Ramón Grau San Martín was appointed provisional president. Grau's government implemented several progressive reforms but faced opposition from the U.S. (which refused to recognize it) and from Batista, who effectively controlled the military. Grau resigned in January 1934.

For the next several years, Batista dominated Cuban politics from behind the scenes, ruling through a series of puppet presidents. This period (1933-1937) was characterized by "virtually unremitting social and political warfare," with significant instability and repression.

A significant development during this era was the drafting and adoption of the 1940 Constitution of Cuba. This constitution was remarkably progressive for its time, incorporating provisions for universal suffrage, land reform, a minimum wage, the right to labor, social security, and other social welfare measures. It also limited presidential terms and enshrined various civil liberties.

In 1940, Fulgencio Batista was elected president under the new constitution, serving until 1944. He remains the only non-white Cuban to have won the nation's highest political office. His administration implemented some social reforms and, interestingly, included members of the Communist Party (then known as the Popular Socialist Party) in his government. Cuba officially joined the Allies in World War II, though its direct military involvement was minimal. Cuban merchant ships suffered losses, and the Cuban Navy was credited with sinking a German U-boat.

Batista adhered to the 1940 constitution's prohibition against re-election and did not run in 1944. Ramón Grau San Martín won the 1944 presidential election, followed by Carlos Prío Socarrás in 1948. These two terms under the Auténtico Party saw an influx of investment, an economic boom fueled by post-war demand for sugar, rising living standards for some segments of society, and the growth of a middle class, particularly in urban areas. However, this period was also marred by increasing political corruption and violence, undermining the legitimacy of the democratic system.

3.4.3. Batista regime and Cuban Revolution

After his presidential term ended in 1944, Fulgencio Batista lived in Florida for several years. He returned to Cuba to run for president in the 1952 elections. Facing a likely electoral defeat, Batista staged a military coup on March 10, 1952, preempting the elections and overthrowing President Carlos Prío Socarrás. Batista suspended the 1940 Constitution, dissolved Congress, and established a de facto dictatorship. His regime received financial, military, and logistical support from the United States government.

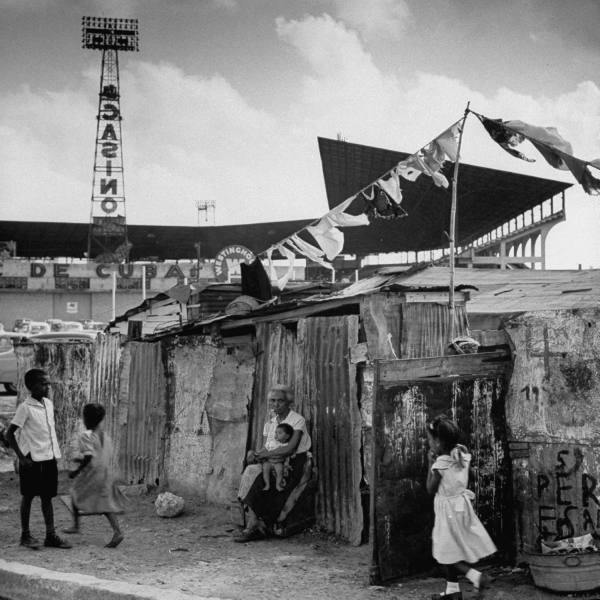

Batista's second period in power was characterized by authoritarian rule, repression of political dissent, and widespread corruption. He aligned himself with wealthy landowners and American corporate interests, particularly in the sugar industry and the burgeoning tourism and gambling sectors, which were heavily influenced by American organized crime. While Cuba in the 1950s had relatively high per capita consumption rates for some goods compared to other Latin American countries, and a significant middle class, the economic benefits were unevenly distributed. A large portion of the population, especially in rural areas, lived in poverty, and social inequalities widened. Batista outlawed the Cuban Communist Party in 1952.

Dissatisfaction with Batista's dictatorship grew. On July 26, 1953, a young lawyer named Fidel Castro led a group of armed rebels in an unsuccessful attack on the Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba. Castro was captured, tried, and imprisoned. During his trial, he delivered his famous "History Will Absolve Me" speech, outlining his revolutionary program, which included calls for land reform, industrialization, housing, employment, education, and healthcare improvements. Castro was released in an amnesty in 1955 and went into exile in Mexico, where he organized the 26th of July Movement (M-26-7).

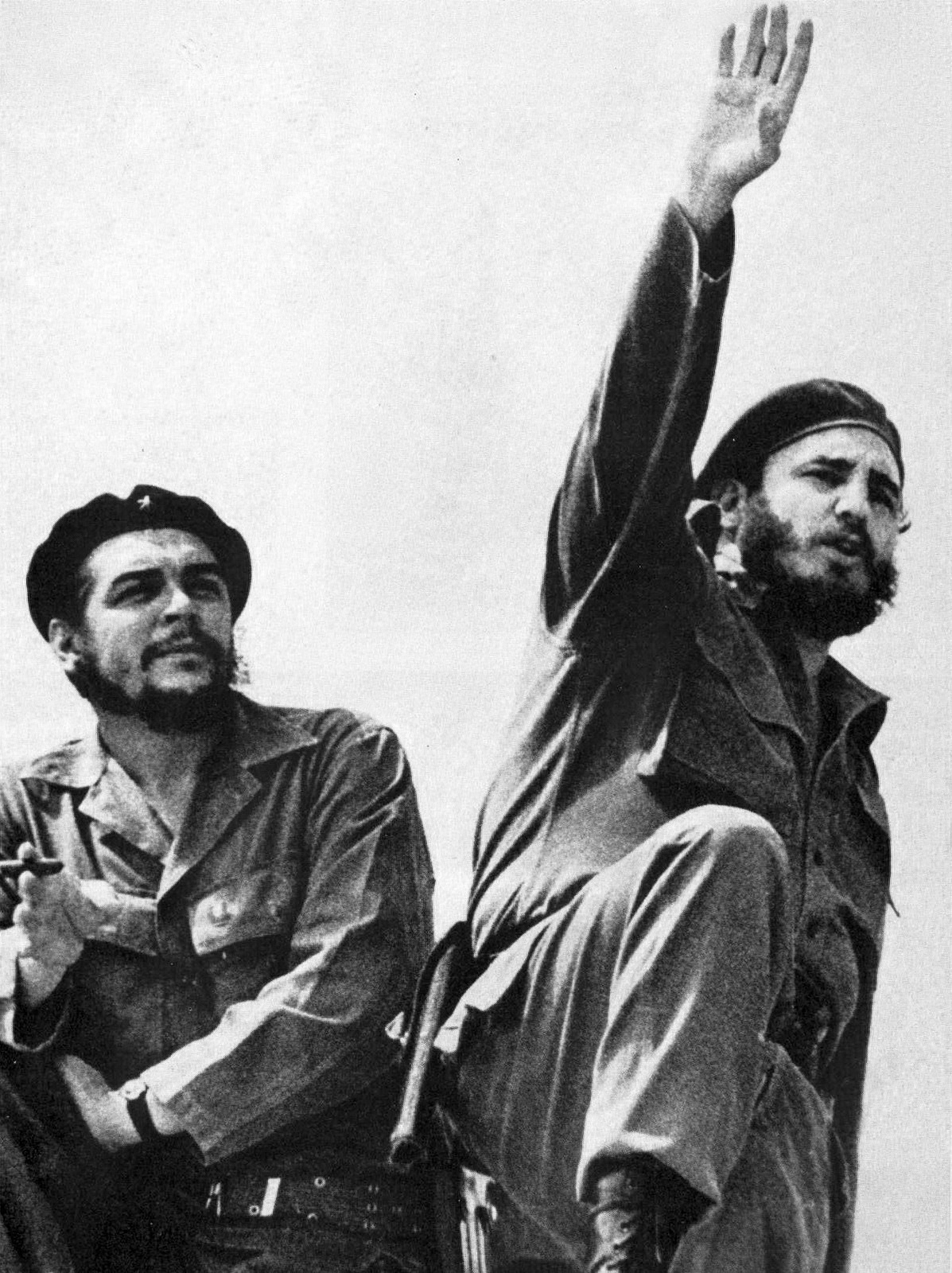

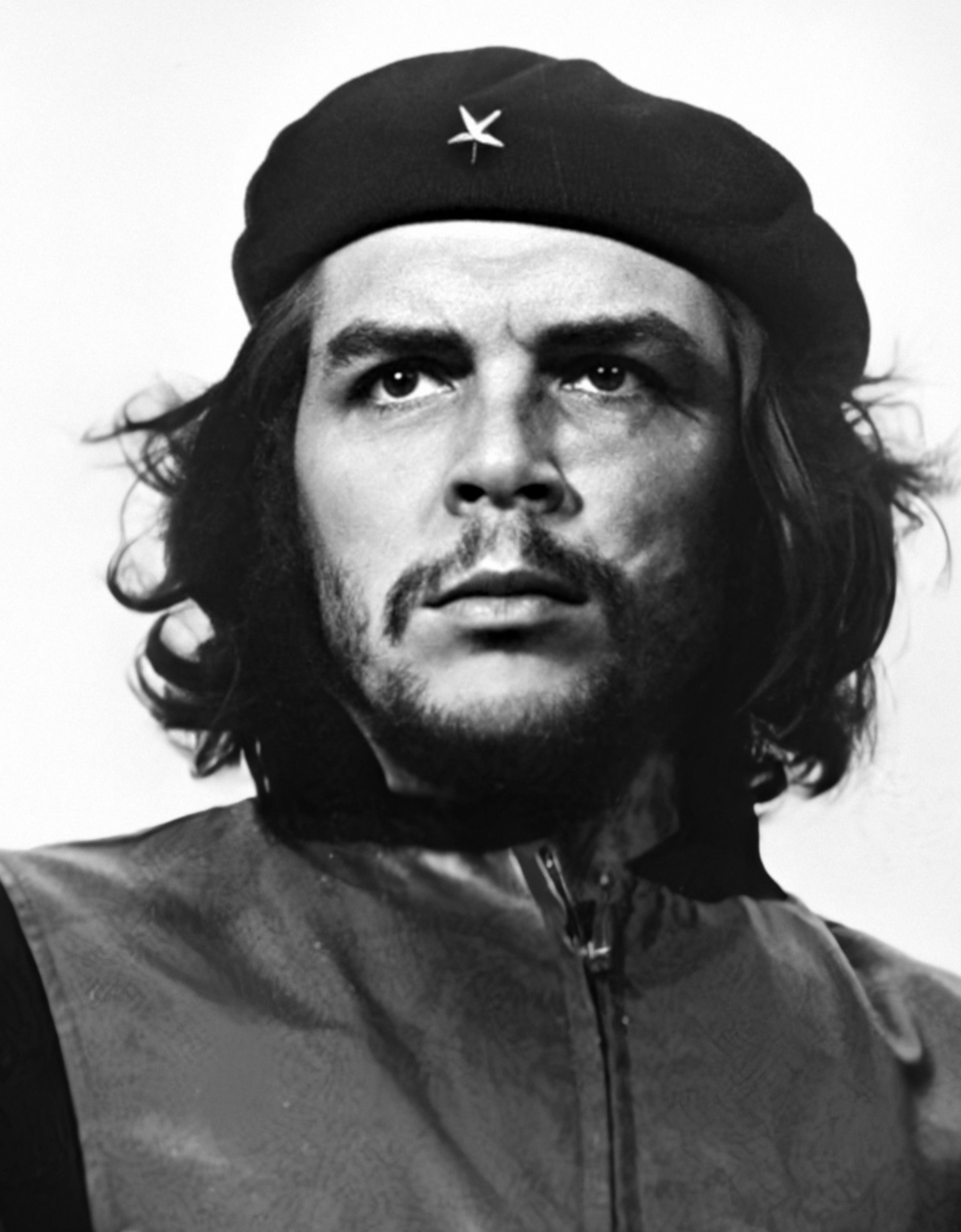

In December 1956, Castro, along with Che Guevara, Raúl Castro, Camilo Cienfuegos, and 78 other rebels, returned to Cuba aboard the yacht Granma. After a disastrous landing and initial encounters with Batista's army, the surviving rebels regrouped in the Sierra Maestra mountains and began a guerrilla war. Castro's M-26-7 gained increasing popular support, particularly from peasants and students, as Batista's regime responded with brutal counter-insurgency measures. Other opposition groups, both armed and non-violent, also challenged Batista's rule.

The Cuban Revolution gained momentum throughout 1957 and 1958. The U.S. government, initially supportive of Batista, grew wary of his regime's corruption and human rights abuses and imposed an arms embargo in March 1958, weakening Batista's military capabilities. Rebel forces expanded their operations, and by late 1958, they launched a final offensive. After key victories by rebel columns led by Che Guevara (capture of Santa Clara) and Camilo Cienfuegos, Batista's government collapsed. On January 1, 1959, Batista fled Cuba. Fidel Castro's forces entered Havana on January 8, 1959, to widespread popular acclaim.

The immediate aftermath of the revolution saw the establishment of a provisional government with Manuel Urrutia Lleó as president and Castro as commander-in-chief of the armed forces (he would become prime minister in February). The revolution's victory had a profound impact on Cuban society and its international relations, ushering in an era of radical social and economic change, but also raising serious concerns about the future of democracy and human rights on the island. The revolutionary government initiated trials and executions of former Batista officials accused of human rights abuses, a move that, while popular among many Cubans, drew international criticism. The revolution's commitment to social justice and national sovereignty would soon lead to direct confrontation with the United States and a fundamental reshaping of Cuba's political and economic system.

3.5. Revolutionary government (1959-present)

The victory of the Cuban Revolution in January 1959 marked the beginning of a new era in Cuban history, characterized by the establishment of a socialist state under the leadership of Fidel Castro. This period saw profound socio-economic transformations, Cuba's central role in the Cold War, the impacts of the Soviet Union's collapse, and ongoing political and economic developments under new leadership.

3.5.1. Consolidation and nationalization (1959-1970)

Following the overthrow of Batista, Fidel Castro consolidated power. Manuel Urrutia Lleó initially served as president, but resigned in July 1959, and Osvaldo Dorticós Torrado became president, with Castro as Prime Minister holding the real authority. The new government swiftly moved to implement its revolutionary program. The Agrarian Reform Law of May 1959 expropriated large landholdings, including those owned by U.S. corporations, and redistributed land to peasants and cooperatives. This was a cornerstone of the revolution's social justice agenda but a major point of contention with the United States.

Throughout 1959 and 1960, the Cuban government nationalized key sectors of the economy, including banks, utilities, oil refineries, and sugar mills, many of which were U.S.-owned. These nationalizations, often without compensation deemed adequate by the U.S., led to a rapid deterioration in U.S.-Cuba relations. The U.S. government responded by progressively imposing economic sanctions, culminating in a full trade embargo by 1962.

Internally, the revolutionary government undertook significant social programs. A nationwide literacy campaign in 1961 dramatically reduced illiteracy. Healthcare and education were made free and accessible to all citizens. However, political opposition was suppressed. Trials and executions of former Batista officials continued, and those deemed counter-revolutionaries faced imprisonment or exile. Independent media outlets were brought under state control. The revolutionary government's actions raised concerns among human rights organizations regarding due process and political freedoms.

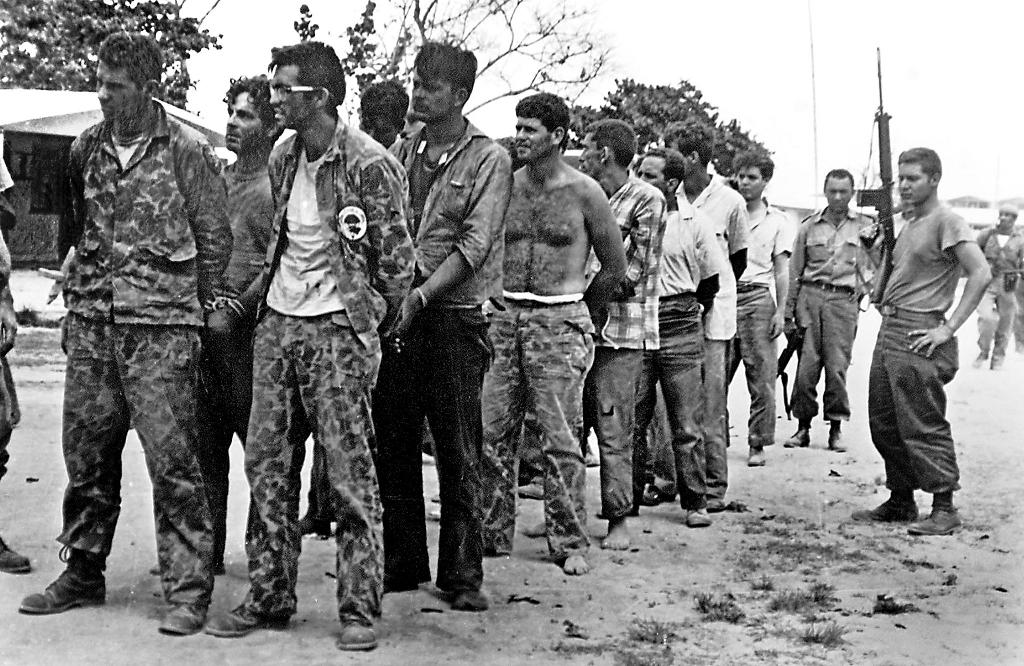

The escalating conflict with the U.S. and the latter's support for anti-Castro exiles pushed Cuba closer to the Soviet Union. In April 1961, a CIA-backed invasion by Cuban exiles at the Bay of Pigs (Playa Girón) was decisively defeated by Cuban forces. This victory solidified Castro's popular support and further radicalized the revolution. Shortly thereafter, Castro officially declared the Cuban Revolution a socialist one. Cuba formally aligned itself with the Soviet bloc, receiving economic and military aid. The Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962, when the Soviet Union placed nuclear missiles in Cuba, brought the world to the brink of nuclear war. The crisis was resolved when the Soviets agreed to remove the missiles in exchange for a U.S. pledge not to invade Cuba and a secret agreement to remove U.S. missiles from Turkey.

The 1960s saw the institutionalization of the socialist state. The Communist Party of Cuba (PCC), formed in 1965 by merging various revolutionary organizations, became the sole legal political party. The state expanded its control over all aspects of life. Efforts were made to diversify the economy away from sugar, but these met with limited success. A major push for a ten-million-ton sugar harvest in 1970 (the Zafra Diez Millones) fell short, highlighting the challenges of centralized economic planning. Dissident groups, often supported by the CIA and Cuban exiles, engaged in armed attacks and guerrilla activities, particularly in the Escambray Mountains, which lasted until the mid-1960s but was ultimately suppressed. The socio-economic transformations, while providing benefits in health and education, came at the cost of individual liberties and democratic processes.

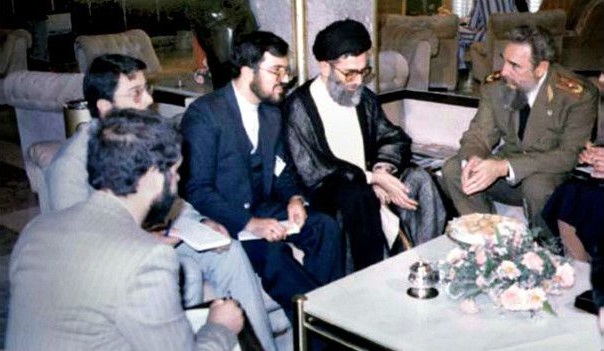

3.5.2. Foreign interventions (1971-1991)

During the Cold War, Cuba, with significant Soviet backing, played a prominent role in supporting revolutionary movements and allied governments, particularly in Africa and Latin America. This policy of "proletarian internationalism" involved deploying Cuban military forces, medical personnel, and technical advisors to various countries. Soviet aid, estimated at $33 billion by 1984, was crucial in enabling these interventions and maintaining the Cuban economy.

Cuba's most significant military engagement was in Angola. Starting in 1975, Cuba sent tens of thousands of troops (peaking at over 50,000) to support the MPLA government against rival factions backed by apartheid South Africa and the United States during the Angolan Civil War. Cuban forces were instrumental in repelling South African incursions and played a key role in battles such as Cuito Cuanavale (1987-1988), which is considered a turning point leading to Namibian independence and weakening the apartheid regime in South Africa. The presence of Cuban troops in Angola was a major factor leading South Africa to develop nuclear weapons.

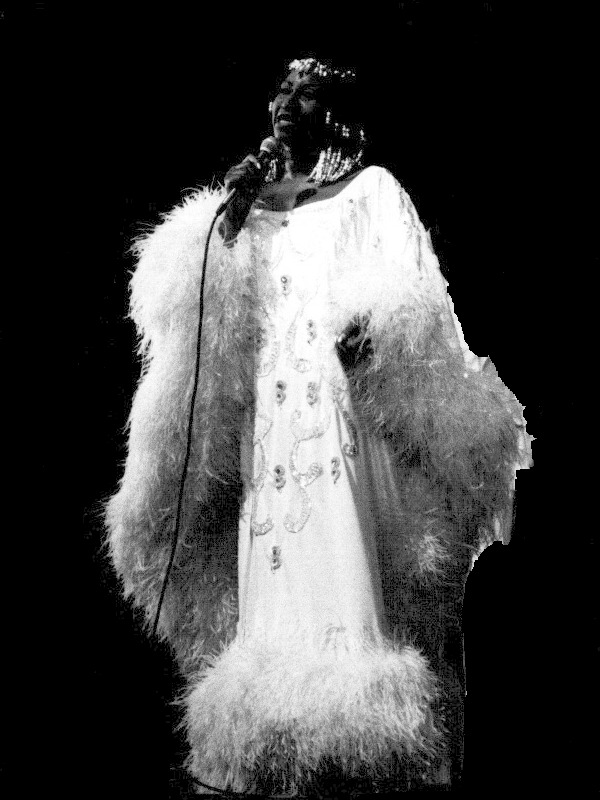

Relevant text is inserted between the second and third images.

In Ethiopia, Cuban troops (around 16,000) were dispatched in 1977-1978 to help the Derg regime repel a Somali invasion during the Ogaden War. Cuban military advisors and personnel were also present in other African nations, including Guinea-Bissau (supporting its war of independence), Mozambique, and the Congo-Brazzaville. Cuba also supported Eritrean independence fighters early on.

In the Middle East, Cuba sent a military mission to South Yemen in 1972 and provided advisors to Iraq until the Iran-Iraq War began in 1980. Cuban tank brigades reportedly participated alongside Syrian forces in the Golan Heights during the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War (1973-1974).

In Latin America, Cuba provided support, including weapons and training, to various left-wing insurgencies and movements in countries like Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua (particularly the Sandinistas), and Colombia.

The U.S. invasion of Grenada in 1983 overthrew a pro-Castro government. Cuban construction workers (many with military training) and advisors resisted the invasion, resulting in casualties on both sides.

These foreign interventions significantly raised Cuba's international profile but also strained its resources and led to considerable loss of life among Cuban personnel. The gradual withdrawal of Cuban troops from Angola began in 1989 and was completed by 1991, coinciding with the winding down of the Cold War and the impending collapse of the Soviet Union. The interventions had a complex impact, seen by some as acts of solidarity against colonialism and apartheid, and by others as extensions of Soviet foreign policy that contributed to regional conflicts.

3.5.3. Political readjustments and Special Period (1991-present)

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991 marked a devastating blow to Cuba. The withdrawal of Soviet subsidies, which had amounted to $4-6 billion annually, plunged the Cuban economy into a severe crisis known as the Special Period in Time of Peace. This era was characterized by acute shortages of food, fuel, medicine, and other essential goods. Cuba's GDP shrank by an estimated 35% between the start of the crisis and 1995. The government implemented austerity measures, including rationing, and sought new economic strategies. It reluctantly opened the country to international tourism and limited foreign investment, and legalized the use of the U.S. dollar. These measures helped to slowly stabilize the economy but also introduced new social inequalities.

During the Special Period, there were instances of social unrest, most notably the Maleconazo protest in Havana on August 5, 1994, which was dispersed by state security. The economic hardship also led to an increase in Cubans attempting to emigrate, often on makeshift rafts.

Politically, the Cuban government maintained its one-party system under the Communist Party of Cuba. Limited economic reforms were introduced, such as allowing some forms of self-employment (cuentapropistas). Cuba found new allies in China and later in left-leaning governments in Latin America, such as Hugo Chávez's Venezuela, which provided crucial oil supplies through the Petrocaribe agreement.

In 2003, the government launched a crackdown on dissidents and independent journalists, known as the Black Spring, arresting and imprisoning dozens of individuals. This action drew international condemnation and strained relations with the European Union.

Due to declining health, Fidel Castro provisionally transferred presidential duties to his brother, Raúl Castro, in July 2006. Fidel Castro formally resigned as President of the Council of State in February 2008, and Raúl Castro was elected as his successor by the National Assembly. Raúl Castro's presidency saw a cautious expansion of economic reforms, including decentralizing some state enterprises, expanding the private sector, and allowing Cubans to buy and sell homes and cars. In 2013, travel restrictions for Cuban citizens were significantly eased, ending the long-standing requirement for an exit permit.

A major development was the rapprochement with the United States under President Barack Obama, announced in December 2014. This led to the restoration of diplomatic relations in July 2015, the reopening of embassies, and an easing of some U.S. travel and trade restrictions. However, the U.S. embargo remained largely in place, requiring congressional action to lift. The Trump administration later reversed many of these normalization policies.

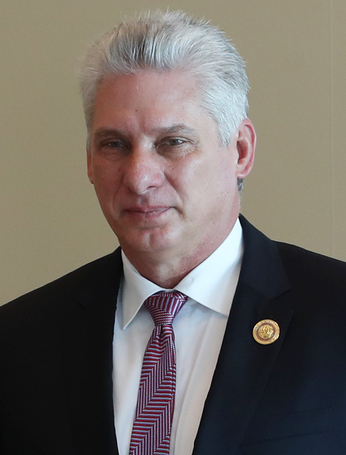

Raúl Castro stepped down as president in April 2018 and was succeeded by Miguel Díaz-Canel. Raúl Castro remained First Secretary of the Communist Party until April 2021, when Díaz-Canel also assumed that role, marking the first time since the revolution that a Castro did not hold the top party position.

A new constitution was approved in a referendum in 2019. It reaffirmed the "irrevocable" nature of socialism and the Communist Party's leading role but also recognized private property, foreign investment, and imposed presidential term limits. It also included provisions against discrimination. In September 2022, a referendum approved a new Family Code legalizing same-sex marriage and same-sex adoption.

Cuba continues to face significant economic challenges, exacerbated by the ongoing U.S. embargo, the economic crisis in Venezuela, and the COVID-19 pandemic, which severely impacted tourism. In July 2021, widespread protests erupted across the island, fueled by economic hardship, shortages, and demands for political freedom. These were the largest anti-government demonstrations since the Maleconazo. The government responded with arrests and trials, drawing further international criticism over the human rights situation. The social impacts of economic difficulties and restrictions on civil liberties remain pressing issues.

4. Geography

Cuba is an archipelago consisting of the main island of Cuba, Isla de la Juventud (Isle of Youth), and approximately 4,195 smaller islands, cays, and islets. It is situated in the northern Caribbean Sea, at the confluence of the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean. Geographically, Cuba lies between latitudes 19° and 24°N, and longitudes 74° and 85°W.

The main island, also named Cuba, is the largest island in the Caribbean and the 17th-largest island in the world. It is approximately 0.8 K mile (1.25 K km) long and constitutes the majority of the nation's land area, at 40 K mile2 (104.34 K km2). The island's terrain is mostly flat to rolling plains, with more rugged and mountainous areas primarily in the southeast. The Sierra Maestra mountain range, located in the southeast, contains Cuba's highest point, Pico Turquino, at 6.5 K ft (1.97 K m). Other notable mountain ranges include the Sierra Cristal in the southeast, the Escambray Mountains in the central region, and the Sierra del Rosario in the northwest.

Cuba is strategically positioned. To the north lie the United States (specifically Key West, Florida, about 93 mile (150 km) across the Straits of Florida) and The Bahamas (Cay Lobos is about 14 mile (22.5 km) to the north). To the west, across the Yucatán Channel, is Mexico (the closest point being Cabo Catoche in Quintana Roo, about 130 mile (210 km) away). To the east, across the Windward Passage, is Hispaniola, shared by Haiti (48 mile (77 km) away) and the Dominican Republic. To the south are Jamaica (87 mile (140 km) away) and the Cayman Islands.

Surrounding the main island are four primary smaller groups of islands:

- The Colorados Archipelago on the northwestern coast.

- The Sabana-Camagüey Archipelago on the north-central Atlantic coast.

- The Jardines de la Reina (Gardens of the Queen) on the south-central coast.

- The Canarreos Archipelago on the southwestern coast, which includes the Isla de la Juventud.

Isla de la Juventud is the second-largest Cuban island, with an area of 0.8 K mile2 (2.20 K km2). Cuba's total official land area is 42 K mile2 (109.88 K km2). Including coastal and territorial waters, its area is 43 K mile2 (110.86 K km2). The country has an extensive coastline, dotted with numerous bays and natural harbors, the most significant being the Bay of Havana.

4.1. Climate

Cuba has a tropical climate, specifically a tropical savanna climate (Aw) according to the Köppen climate classification. Its climate is significantly moderated by the surrounding waters and the northeasterly trade winds that blow year-round. The warm Caribbean Current, bringing waters from the equator, also contributes to the island's generally warm temperatures, making Cuba's climate warmer than that of Hong Kong, which is at a similar latitude but experiences a subtropical climate.

The year is generally divided into two seasons: a drier season from November to April, and a rainier season from May to October. Local variations exist, but this pattern is broadly consistent across the island. The average temperature is around 69.8 °F (21 °C) in January (the coolest month) and 80.6 °F (27 °C) in July (the warmest month).

Due to its location in the Caribbean Sea and at the entrance to the Gulf of Mexico, Cuba is prone to frequent hurricanes. The official hurricane season runs from June to November, with the peak activity typically occurring in September and October. These storms can bring strong winds, heavy rainfall, and significant storm surge, causing considerable damage to infrastructure and agriculture.

Hurricane Irma, a powerful Category 5 hurricane, made landfall on the Camagüey Archipelago on September 8, 2017, with winds of 162 mph (260 km/h). The storm caused extensive damage, particularly in the northern keys and coastal areas, leading to power outages, destruction of buildings, and necessitating the evacuation of nearly a million people, including tourists. Ten fatalities were reported in Cuba as a result of the hurricane.

4.2. Biodiversity

Cuba possesses a rich and diverse array of flora and fauna, with a high degree of endemism, making its ecosystems particularly unique. The island's varied geography, including mountains, wetlands, forests, and coastal areas, supports this biodiversity. Cuba signed the Convention on Biological Diversity on June 12, 1992, and became a party to it on March 8, 1994. The country has since developed a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan to guide its conservation efforts.

According to Cuba's fourth national report to the Convention on Biological Diversity, the country is home to a vast number of species. The breakdown includes:

- Animals: 17,801 species

- Bacteria: 270 species

- Chromista: 707 species

- Fungi (including lichen-forming species): 5,844 species

- Plants: 9,107 species

- Protozoa: 1,440 species

Among its most notable endemic species is the bee hummingbird (Mellisuga helenae), known locally as the zunzuncito, which is the world's smallest bird, measuring only about 2.2 in (55 mm) in length. The Cuban trogon (Priotelus temnurus), or tocororo, is the national bird, admired for its colorful plumage that mirrors the Cuban flag. Other significant endemic fauna include the Cuban crocodile (Crocodylus rhombifer), a critically endangered species found in the Zapata Swamp; the Cuban hutia (Capromys pilorides), a large rodent; the Cuban solenodon (Atopogale cubana), a rare, venomous insectivore; the Cuban gar (Atractosteus tristoechus), an ancient fish species; the Cuban boa (Chilabothrus angulifer); and the brightly colored land snail Polymita picta. The white mariposa (Hedychium coronarium), a type of ginger lily, is the national flower.

Cuba hosts six distinct terrestrial ecoregions: Cuban moist forests, Cuban dry forests, Cuban pine forests, Cuban wetlands (including the vast Zapata Swamp, one of the largest wetlands in the Caribbean), Cuban cactus scrub, and Greater Antilles mangroves. These ecoregions support a wide variety of habitats. In 2019, Cuba had a Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 5.4/10, ranking it 102nd globally out of 172 countries, indicating moderate integrity of its forest landscapes.

Environmental conservation efforts in Cuba include the establishment of numerous protected areas, such as national parks and biosphere reserves. Some of these, like the Alejandro de Humboldt National Park, are recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites for their exceptional biodiversity. Despite economic challenges, Cuba has made notable strides in sustainable development. A 2012 study suggested that Cuba was the only country at the time to meet the conditions of sustainable development as defined by the WWF, balancing human development with a relatively low ecological footprint. However, threats to biodiversity persist, including habitat loss, pollution, invasive species, and the impacts of climate change. Social and economic factors, such as the need for agricultural land and resources, sometimes create conflicts with conservation goals, requiring ongoing efforts to integrate environmental protection with sustainable livelihoods.

5. Government and politics

Cuba is a socialist state adhering to Marxist-Leninist ideology, as defined by its constitution. The Constitution of Cuba, most recently revised and approved by referendum in 2019, enshrines the Communist Party of Cuba (Partido Comunista de Cuba - PCC) as the "leading force of society and of the state." The political system operates on the principle of democratic centralism. While the constitution outlines rights and governmental structures, independent observers and human rights organizations characterize Cuba as an authoritarian regime where political opposition is not permitted and civil liberties are restricted. The impact of this system on democratic practices and citizen participation is a key area of concern from a social liberal perspective, which emphasizes pluralism, freedom of expression, and robust civic engagement.

The First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba is the most powerful political position in the country. This role is currently held by Miguel Díaz-Canel, who also serves as the President of Cuba. The President is the head of state and head of government (following the 2019 constitutional reform which re-established the post of Prime Minister but vested executive authority primarily in the President). The President is elected by the National Assembly of People's Power for a five-year term, with a limit of two consecutive terms.

The National Assembly of People's Power (Asamblea Nacional del Poder Popular) is the unicameral legislature and the supreme organ of state power. Its 474 members (as of the last election) are elected for five-year terms. Candidates for the Assembly are nominated by candidacy commissions, which are supervised by the PCC, and then "elected" by citizens in a process where voters can approve the entire slate or select individual candidates, but there is typically only one candidate per seat. While voting is described as free, equal, and secret, the lack of multi-party competition and the PCC's control over the nomination process mean that elections are not considered democratic by international standards. The Assembly meets twice a year; between sessions, the Council of State, headed by the President of the National Assembly, exercises legislative power.

The Prime Minister of Cuba (currently Manuel Marrero Cruz) is appointed by the President and approved by the National Assembly. The Prime Minister heads the Council of Ministers, which is the main administrative body.

The People's Supreme Court is the highest judicial body. The judiciary is not independent and is subordinate to the National Assembly and the Council of State, and ultimately influenced by the Communist Party.

While the constitution allows for citizen participation through local assemblies and organizations like the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs), these are largely seen as instruments of state control and mobilization rather than avenues for independent political expression or democratic accountability. Political dissent is actively suppressed, and independent civil society organizations face significant restrictions. The Democracy Index and Freedom in the World reports consistently rank Cuba as an authoritarian state with low scores for political rights and civil liberties.

5.1. Administrative divisions

Cuba is divided into 15 provinces and one special municipality, the Isla de la Juventud (Isle of Youth). This administrative structure was largely established in 1976, replacing an older system of six larger historical provinces: Pinar del Río, Habana, Matanzas, Las Villas, Camagüey, and Oriente. The current provincial boundaries somewhat resemble those of the Spanish military provinces during the Cuban Wars of Independence. Each province is further subdivided into municipalities, which are the basic units of local government.

The provinces of Cuba are:

- Pinar del Río

- Artemisa

- Havana (La Habana, the capital city, administered as a province)

- Mayabeque

- Matanzas

- Cienfuegos

- Villa Clara

- Sancti Spíritus

- Ciego de Ávila

- Camagüey

- Las Tunas

- Granma

- Holguín

- Santiago de Cuba

- Guantánamo

The special municipality is:

- Isla de la Juventud

Provinces are governed by Provincial Assemblies of People's Power, and municipalities by Municipal Assemblies of People's Power. These bodies are, in theory, responsible for local administration and services. However, the highly centralized nature of the Cuban state means that significant decision-making power and resource allocation remain with the national government and the Communist Party. The 2019 Constitution aimed to grant more autonomy to municipalities, but the extent of this decentralization in practice is still developing. Artemisa and Mayabeque provinces were created in 2011 from the former La Habana Province, with the city of Havana itself becoming a separate city-province.

5.2. Foreign relations

Cuba's foreign policy has historically been assertive for a small developing nation, particularly under the leadership of Fidel Castro. A central tenet has been anti-imperialism, opposition to U.S. influence, and solidarity with revolutionary movements and developing countries worldwide. Cuba was a prominent member of the Non-Aligned Movement and played a significant role in Cold War geopolitics.

Key aspects of Cuba's foreign relations include:

- Relationship with the United States:** This has been the defining feature of Cuban foreign policy since the 1959 revolution. Following the nationalization of U.S. properties, the U.S. severed diplomatic ties in 1961 and imposed a comprehensive economic embargo that continues to this day. The relationship has been marked by hostility, including the Bay of Pigs Invasion and the Cuban Missile Crisis. There was a period of rapprochement, known as the Cuban Thaw, under President Barack Obama, which saw the restoration of diplomatic relations in 2015. However, many of these policies were reversed by the subsequent Trump administration, and relations remain strained. The embargo significantly impacts Cuba's economy and social conditions.

- Relationship with the Soviet Union/Russia:** During the Cold War, Cuba was a close ally of the Soviet Union, receiving substantial economic and military aid. This alliance was crucial for Cuba's survival in the face of U.S. hostility. After the Soviet collapse in 1991, relations with Russia cooled but have seen a resurgence in recent years, with increased political and economic cooperation.

- Internationalism and Interventions:** Cuba engaged in numerous foreign interventions, particularly in Africa, supporting independence movements and allied governments. This included sending troops to Angola to support the MPLA government against South African-backed forces and to Ethiopia during the Ogaden War. Cuban medical missions have also been a significant aspect of its foreign policy, with tens of thousands of doctors and healthcare workers serving in developing countries, generating goodwill and foreign currency. These missions, while praised for their humanitarian impact, have also faced criticism regarding the working conditions and pay of the medical personnel involved.

- Latin America:** Cuba has historically supported leftist movements and governments in Latin America. It was a founding member of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (ALBA) and has maintained close ties with countries like Venezuela (especially under Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro, from whom Cuba received vital oil supplies) and Bolivia (under Evo Morales).

- European Union:** Relations with the EU have fluctuated. The EU has often criticized Cuba's human rights record but has also opposed the U.S. embargo and engaged in dialogue and cooperation. A Political Dialogue and Cooperation Agreement was signed in 2016.

- China:** China has become an increasingly important economic and political partner for Cuba, particularly after the collapse of the Soviet Union, providing trade, investment, and diplomatic support.

- International Organizations:** Cuba is a founding member of the United Nations, the Group of 77, and the Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States. It was suspended from the Organization of American States (OAS) in 1962; the suspension was lifted in 2009, but Cuba has not rejoined, criticizing the OAS as U.S.-dominated.

Cuba's foreign policy continues to prioritize national sovereignty and seeks to build alliances to counter the effects of the U.S. embargo. The social and economic conditions within Cuba are heavily influenced by its international relations, particularly the embargo and its access to trade and aid from allies.

5.2.1. Embargo by the United States

The United States embargo against Cuba (referred to in Cuba as el bloqueothe blockadeSpanish) is a comprehensive set of economic sanctions imposed by the United States on Cuba. It began on October 19, 1960, when the U.S. placed an embargo on exports to Cuba except for food and medicine, in response to the Cuban government's nationalization of U.S.-owned properties without compensation deemed adequate by the U.S. On February 7, 1962, the embargo was extended to include almost all imports. It stands as one of the longest-enduring trade embargoes in modern history.

- History and Rationale:**

The initial rationale for the embargo was a direct response to Fidel Castro's revolutionary government nationalizing American assets, valued at over 1.00 B USD at the time. President Dwight D. Eisenhower instituted the initial measures, which were significantly expanded under President John F. Kennedy. A declassified U.S. State Department memorandum from Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Lester D. Mallory dated April 6, 1960, argued for sanctions, stating, "The only foreseeable means of alienating internal support is through disenchantment and disaffection based on economic dissatisfaction and hardship... to decrease monetary and real wages, to bring about hunger, desperation and overthrow of government." This indicates a broader political aim of regime change from early on.

The embargo was further codified and strengthened over the years through various pieces of legislation, including:

- The Cuban Democracy Act of 1992 (Torricelli Act): This act prohibited foreign-based subsidiaries of U.S. companies from trading with Cuba, travel to Cuba by U.S. citizens, and sending family remittances to Cuba. It also stated that sanctions would continue "so long as it continues to refuse to move toward democratization and greater respect for human rights."

- The Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act of 1996 (Helms-Burton Act): This act further tightened the embargo, allowed U.S. nationals to sue foreign companies that use property confiscated by the Cuban government, and codified the embargo into law, meaning it can only be lifted by an act of Congress.

- Socio-Economic Impact on Cuba:**

The socio-economic impact of the embargo on the Cuban population is a subject of intense debate and a central point of concern.

- Cuban Government Perspective:** The Cuban government attributes most of its economic hardships directly to the embargo, estimating cumulative damages in the hundreds of billions of dollars. It argues that the embargo hinders access to essential goods, medicines, technologies, and financial markets, severely impacting living standards, healthcare, food security, and overall development.

- Impact on Daily Life:** Shortages of basic goods, medicines, and equipment are common in Cuba. While internal economic mismanagement is also a factor, the embargo undeniably restricts Cuba's ability to trade and access international financial systems, exacerbating these shortages. This affects everything from public transportation and infrastructure to the availability of food and medical supplies, directly impacting the well-being of ordinary Cubans.

- Humanitarian Concerns:** Critics of the embargo, including numerous international organizations and humanitarian groups, argue that it constitutes a violation of human rights by inflicting hardship on the civilian population. Access to life-saving medicines and medical equipment is often complicated or made more expensive due to the embargo's restrictions, impacting the otherwise lauded Cuban healthcare system.

- International Reactions:**

The U.S. embargo against Cuba has been overwhelmingly condemned by the international community. Since 1992, the United Nations General Assembly has annually passed a resolution calling for an end to the embargo, with near-unanimous support. The U.S. and Israel have consistently been the only countries to vote against these resolutions. Many countries and international bodies, including the European Union, maintain that the embargo is counterproductive, harms the Cuban people, and violates principles of international law and free trade.

- Evolution and Recent Developments:**

The embargo remains a highly contentious issue. Supporters argue it is a necessary tool to pressure the Cuban government towards democratic reforms and respect for human rights. Opponents, including many Cubans, international observers, and some U.S. policymakers, argue it is an outdated and failed policy that disproportionately harms the Cuban people, stifles economic opportunity, and hinders rather than promotes democratic change. The social impact on the Cuban population, particularly in terms of access to essential goods and overall quality of life, remains a significant concern from a humanitarian and social justice perspective. Despite the embargo, Cuba maintains trade relations with other countries, with China, Spain, and other EU nations being key partners.

5.3. Military

The Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias - FAR) are the military forces of Cuba. They consist of the Ground Forces (Army), Revolutionary Navy (Marina de Guerra Revolucionaria - MGR), Revolutionary Air and Air Defense Force (Defensa Anti-Aérea Y Fuerza Aérea Revolucionaria - DAAFAR), and paramilitary bodies including the Territorial Troops Militia (Milicias de Tropas Territoriales - MTT), the Youth Labor Army (Ejército Juvenil del Trabajo - EJT), and the Civil Defense Force (Defensa Civil - DC).

Historically, particularly during the Cold War, Cuba built up one of the largest and most capable armed forces in Latin America, second only to Brazil at its peak. This was largely due to substantial military assistance from the Soviet Union. The FAR played a crucial role in Cuba's foreign interventions, notably in Angola and Ethiopia. Soviet pilots and technicians sometimes assumed defense duties in Cuba, freeing Cuban personnel for overseas deployment.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the loss of Soviet subsidies, Cuba's military capabilities and personnel numbers were significantly scaled down. Military expenditures, which had been over 10% of GDP in 1985, were drastically reduced. In 2018, Cuba's military spending was estimated at around 91.80 M USD, or 2.9% of its GDP, though accurate figures are difficult to obtain. The number of active military personnel decreased from around 235,000 in 1994 to approximately 49,000 in 2021.

The current mission of the FAR is primarily focused on national defense and internal security. It also plays a role in economic activities and emergency response. Military service is compulsory for males, typically for two years. The armed forces have long been a powerful institution in Cuba, with many high-ranking government officials having military backgrounds. This has led some observers to describe Cuba as a militarized society.

Cuba is a signatory to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, having signed it in 2017. According to the 2024 Global Peace Index, Cuba is ranked as the 98th most peaceful country in the world. The FAR continues to maintain its equipment, much of which is Soviet-era, and focuses on a doctrine of "War of All the People" (Guerra de Todo el Pueblo), which emphasizes popular defense and guerrilla warfare in the event of an invasion.

5.4. Law enforcement and crime

Law enforcement in Cuba is primarily the responsibility of agencies under the Ministry of the Interior (Ministerio del Interior - MININT), which is supervised by the Revolutionary Armed Forces. The main police force is the National Revolutionary Police (Policía Nacional Revolucionaria - PNR), responsible for maintaining public order, preventing and investigating crime, and traffic control. Citizens can contact the police by dialing "106".

Cuba also has a powerful state security apparatus, the Intelligence Directorate (Dirección de Inteligencia - DI), also known_as G2, which conducts intelligence and counterintelligence operations. It has historically maintained close ties with Soviet/Russian intelligence services and is considered a significant counterintelligence threat by some nations, including the United States.

The Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (Comités de Defensa de la Revolución - CDRs) are neighborhood-based organizations that play a role in community vigilance. Established after the revolution, CDRs officially function as a neighborhood watch, monitoring for criminal activity and "counter-revolutionary" behavior. While membership is widespread, leading members are approved by the Communist Party, and CDRs have been criticized as instruments of social control and surveillance, impacting civil liberties and due process.

Cuba's legal system is based on civil law, with influences from Spanish and, post-revolution, socialist legal theory. The judiciary is not independent and is subordinate to the political structure. Crime rates in Cuba are generally reported to be relatively low compared to other countries in the region, particularly for violent crimes. Petty theft, scams (especially targeting tourists), and pickpocketing can be issues in tourist areas. However, obtaining accurate and independent crime statistics is challenging due to government control over information.

Concerns regarding due process and civil liberties in the context of law enforcement and the legal system are frequently raised by human rights organizations. These include issues such as arbitrary detention, lack of independent legal counsel, and restrictions on freedom of expression and assembly that can lead to arrests. Public safety is generally considered good for tourists, but underlying economic hardships can contribute to opportunistic crime.

5.5. Human rights

The human rights situation in Cuba is a subject of ongoing concern and criticism from international human rights organizations, foreign governments, and Cuban dissident groups. The Cuban government, however, maintains that its system prioritizes social rights like education and healthcare, and views critiques of its civil and political rights record as biased or politically motivated interference.

- Civil and Political Rights:**

- Freedom of Expression, Assembly, and Association:** These rights are severely restricted. The Cuban constitution subordinates these freedoms to the objectives of the socialist state. Criticism of the government or the Communist Party is not tolerated. Independent journalism is repressed, and all media outlets are state-controlled. Public demonstrations not sanctioned by the state are typically dispersed, and participants may face arrest. Independent civil society organizations, including political opposition groups and human rights organizations, operate under restrictive conditions and often face harassment, surveillance, and detention.

- Political Opposition and Prisoners:** The Communist Party is the only legal political party. Political opposition is not permitted, and individuals advocating for multi-party democracy or significant political change are often labeled as "counter-revolutionaries" and may be subjected to arbitrary detention, short-term arrests, or long prison sentences. Human rights groups report the existence of numerous political prisoners. In July 2010, the unofficial Cuban Human Rights Commission reported 167 political prisoners, a decrease from earlier years, noting a shift from long sentences to increased harassment and intimidation.

- Due Process and Fair Trial:** The judiciary lacks independence. Detainees often face prolonged pre-trial detention, limited access to legal counsel of their choice, and trials that do not meet international standards of fairness.

- Internet Access and Censorship:** While internet access has expanded in recent years, it remains controlled and expensive for many Cubans. The government monitors online activity and blocks access to websites deemed critical or "counter-revolutionary."

- Reports from Human Rights Organizations:**

Organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch consistently document restrictions on fundamental freedoms in Cuba. They report on arbitrary detentions of dissidents, harassment of human rights defenders, and lack of political pluralism. The European Union has frequently called for reforms and the unconditional release of political prisoners. The Committee to Protect Journalists and Reporters Without Borders rank Cuba among the worst countries for press freedom, citing imprisonment of journalists and extensive censorship.

- Government Perspective:**

The Cuban government rejects these criticisms, often framing them as part of a U.S.-led campaign to destabilize the country. It emphasizes its achievements in social rights, such as universal access to education and healthcare, which it argues are fundamental human rights. The government also highlights its sovereignty and the right to its own political system.

- Impact on Democratic Development and Vulnerable Groups:**

The lack of political freedoms and the suppression of dissent significantly hinder democratic development. Citizen participation is channeled through state-controlled organizations, limiting genuine political debate and accountability. While the 2019 constitution introduced provisions against discrimination and the 2022 Family Code legalized same-sex marriage, reflecting some progress for LGBT rights, other vulnerable groups and individuals who challenge the state continue to face repression. The overall human rights environment remains restrictive, posing significant challenges for those advocating for greater civil and political liberties.

6. Economy

Cuba's economy is predominantly a state-controlled, centrally planned economy based on socialist principles. The state owns and operates most means of production, and the majority of the labor force is employed by the state. However, since the economic crisis of the "Special Period" in the 1990s following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba has introduced limited market-oriented reforms, leading to a growing private sector. The impact of these reforms on social equity and the long-term economic model remains a subject of ongoing development and debate. The U.S. embargo significantly constrains Cuba's economic potential.

The main sectors of the Cuban economy include tourism, nickel and cobalt mining, agriculture (particularly sugar, tobacco, and citrus fruits), pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, and the export of skilled labor (notably medical professionals).

Government spending constitutes a large portion of the GDP, around 78.1%. Until 2021, Cuba operated a dual-currency system with the Cuban Peso (CUP) and the Convertible Peso (CUC). This system was unified into the CUP, but the transition has created economic challenges, including high inflation. As of July 2013, the average monthly wage was 466 CUP (about 19 USD). However, following a 2021 reform, the minimum wage is about 2.10 K CUP (18 USD) and the median wage is about 4.00 K CUP (33 USD). Ration books (libreta) still provide a monthly supply of subsidized basic staples for households, though the quantities often fall short of needs. Remittances from Cubans abroad, primarily from the United States, are a significant source of income for many families and the economy as a whole, though these have fluctuated due to U.S. policy changes and the pandemic.

Historically, Cuba's economy was heavily reliant on sugar exports and Soviet subsidies. The loss of these subsidies in 1991 led to a severe economic downturn. Since then, tourism has become a primary engine of growth and foreign currency earner. The country has also invested in biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries, achieving some notable successes, such as the development of certain vaccines.

Recent reforms under Raúl Castro and Miguel Díaz-Canel have aimed to modernize the economy and increase efficiency. These include expanding the list of activities permitted for self-employment (cuentapropistas), allowing the creation of small and medium-sized private enterprises, decentralizing some state-owned enterprises, and seeking more foreign investment. Agricultural reforms have focused on leasing idle state land to private farmers to boost food production, as Cuba imports a large percentage of its food.

Despite these reforms, the Cuban economy faces significant challenges:

- The U.S. Embargo:** This comprehensive set of sanctions restricts trade, investment, and financial transactions, making it difficult for Cuba to access international markets, credit, and essential goods.

- Dual Economy and Inequality:** While the formal currency unification aimed to address this, disparities persist between those with access to foreign currency (through tourism, remittances, or private enterprise) and those reliant solely on state salaries and rations. This impacts social equity.

- Bureaucracy and Inefficiency:** Centralized planning can lead to inefficiencies and slow adaptation to changing economic conditions.

- External Shocks:** The economy is vulnerable to external factors such as fluctuations in commodity prices (e.g., nickel), natural disasters (hurricanes), and global economic downturns (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic's impact on tourism). The economic crisis in Venezuela, a key political and economic ally that supplied subsidized oil, has also negatively affected Cuba.

- Debt:** Cuba carries significant foreign debt.

- Infrastructure:** Aging infrastructure requires substantial investment.

A 2023 report by the Cuban Observatory of Human Rights (OCDH), a non-governmental organization, controversially estimated that 88% of Cubans live in extreme poverty, highlighting concerns about food security and access to basic goods. The Cuban government typically disputes such figures from dissident-linked organizations. Living standards are a major concern, with shortages of food, medicine, and other essentials impacting daily life for many Cubans. The government implemented rationing for staples in May 2019 due to a worsening economic crisis.

The economic situation has contributed to significant emigration, particularly among younger, working-age Cubans, posing a demographic challenge. The government continues to balance its socialist principles with the need for economic pragmatism to address these pressing issues and improve the living standards of its population while navigating a complex international environment.

6.1. Resources

Cuba possesses a variety of natural resources that contribute to its economy, though their exploitation and development are influenced by the centrally planned economic system and the U.S. embargo.

Key natural resources include:

- Minerals:** Cuba is rich in mineral deposits.

- Nickel:** This is Cuba's most important mineral resource and a major export earner. The country holds some of the world's largest nickel reserves, primarily found in the eastern part of the island. In 2011, nickel accounted for 21% of total exports. The output of Cuban nickel mines in that year was 71,000 tons, representing a significant portion of world production. As of 2013, reserves were estimated at 5.5 million tons. Sherritt International, a Canadian company, operates a large nickel mining facility in Moa.

- Cobalt:** Cuba is also a major producer of refined cobalt, which is typically extracted as a by-product of nickel mining.

- Other Minerals:** Other mineral resources include iron ore, chromium, copper, manganese, salt, timber, and silica. There are also deposits of gypsum, asbestos, and pyrites.

- Oil and Natural Gas:** Cuba has domestic oil and natural gas production, primarily heavy crude, which is used largely for power generation. Exploration efforts have indicated potentially significant offshore reserves in the North Cuba Basin. A 2005 U.S. Geological Survey study estimated that this basin could produce about 4.6 to 9.3 billion barrels of oil. Cuba has engaged in test drilling and has sought foreign investment for further exploration and exploitation, though U.S. sanctions complicate these efforts.

- Arable Land:** Agriculture is a significant sector, supported by fertile land suitable for various crops.

- Sugarcane:** Historically the backbone of the Cuban economy, sugarcane remains an important crop, though its dominance has declined.

- Tobacco:** Cuba is world-renowned for its high-quality tobacco, used to produce premium cigars, a key export.

- Coffee and Citrus Fruits:** These are also important agricultural exports.

- Other Crops:** Beans, rice, potatoes, and various tropical fruits are grown for domestic consumption and export.

- Fisheries:** The waters surrounding Cuba support a fishing industry, providing seafood for domestic consumption and export.

- Forests:** Timber is another natural resource, though sustainable forestry practices are crucial.

The exploitation of these resources is largely managed by state-owned enterprises. Foreign investment is permitted in some sectors, particularly mining and oil exploration, often through joint ventures with the Cuban state. The U.S. embargo restricts Cuba's access to technology, financing, and markets for its resources, impacting the efficiency and scale of their development. The social and environmental impacts of resource extraction are also considerations in Cuba's development policies.

6.2. Tourism

Tourism is a vital sector of the Cuban economy, representing one of its largest sources of foreign currency. Since the "Special Period" in the 1990s following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Cuban government has actively promoted tourism to offset the loss of Soviet subsidies.

- Development and Characteristics:**

Initially, tourism development in Cuba was heavily focused on enclave resorts, where international tourists were largely segregated from the general Cuban population. This model, sometimes referred to as "enclave tourism" or "tourism apartheid," aimed to maximize foreign currency earnings while minimizing social interaction that could be deemed disruptive by the state. Between 1992 and 1997, direct contact between foreign visitors and ordinary Cubans was often de facto restricted.

The rapid growth of tourism has had widespread social and economic repercussions. It contributed to the emergence of a two-tier economy, with those working in the tourism sector having greater access to hard currency (formerly the Cuban Convertible Peso, CUC, and U.S. dollars) and a higher standard of living compared to those reliant on state salaries paid in the national peso (CUP).

- Visitor Statistics and Origins:**

Cuba attracted 1.9 million tourists in 2003, primarily from Canada and the European Union, generating revenues of 2.10 B USD. By 2011, this number grew to 2.688 million international tourists, making Cuba the third-most visited destination in the Caribbean at the time, after the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico. Canada has consistently been the largest source market for tourists to Cuba. European countries, particularly Spain, Germany, France, and Italy, also contribute significantly. Tourism from the United States was severely restricted for decades due to the embargo, but an easing of travel restrictions under the Obama administration (part of the "Cuban Thaw") led to a surge in American visitors, though many of these relaxations were later reversed.

- Major Tourist Destinations:**

- Varadero**: Cuba's premier beach resort, known for its long stretches of white sand beaches.

- Havana**: The capital city, offering rich history, colonial architecture (Old Havana is a UNESCO World Heritage Site), vibrant culture, music, and nightlife.

- Trinidad**: A UNESCO World Heritage Site, a well-preserved colonial town with cobblestone streets and colorful buildings.

- Viñales Valley**: Another UNESCO site, famous for its stunning karst landscape, tobacco plantations, and traditional farming methods.

- Cayo Coco and Cayo Guillermo**: Islands in the Jardines del Rey archipelago, popular for all-inclusive resorts and beaches.

- Santiago de Cuba**: Cuba's second-largest city, known for its Afro-Cuban culture, music, and historical significance.

- Medical Tourism:**

Cuba has also developed a medical tourism sector, attracting thousands of patients from Europe, Latin America, Canada, and even the U.S. (when travel is permissible) for various medical treatments, often at lower costs than in their home countries.

- Social and Environmental Impacts:**

The growth of tourism has brought economic benefits but also social and environmental challenges.

- Social Impacts:** Tourism has created employment but also exacerbated social inequalities due to differential access to hard currency. It has been linked to an increase in prostitution and other social issues in tourist areas. The Cuban Justice Minister has downplayed allegations of widespread sex tourism, and the government actively works to prevent child sex tourism, with severe penalties for offenders.

- Environmental Impacts:** The development of coastal resorts and increased visitor numbers put pressure on fragile ecosystems, including coral reefs and mangrove forests. The Cuban government has implemented some environmental regulations and sustainable tourism initiatives, but balancing economic development with environmental protection remains a challenge. A 2018 study highlighted the potential for mountaineering and other nature-based tourism activities to contribute to regional development outside traditional enclaves.

Natural disasters like hurricanes also pose a threat to the tourism infrastructure. Hurricane Irma in 2017 caused extensive damage to some tourist facilities, particularly in the northern keys, requiring significant repair efforts. The COVID-19 pandemic also severely impacted the tourism industry, leading to a drastic drop in visitor arrivals and revenue.

6.3. Transport

Cuba's transportation infrastructure includes a network of roads, railways, airports, and seaports, though much of it requires modernization and investment. The state of transportation has been significantly affected by the U.S. embargo, which limits access to new vehicles, spare parts, and technology, as well as by the country's economic challenges.

- Roads:** Cuba has an extensive road network, with the Autopista Nacional (National Highway) being the main arterial route running east-west across much of the island. However, many roads, especially secondary ones, are in poor condition. Classic American cars from the 1950s, kept running through ingenuity and makeshift repairs, are an iconic feature of Cuban roads, alongside older Soviet-era vehicles and more modern cars, often used in the tourism sector. Buses are the primary mode of public transport for Cubans, but services can be overcrowded and unreliable. Viazul is a state-run bus company primarily for tourists, offering more comfortable and direct routes between major cities. Collective taxis (almendrones or máquinas) are also common.

- Railways:** Cuba has the most extensive railway system in the Caribbean, historically developed for the sugar industry. The main railway line connects Havana with Santiago de Cuba. While passenger and freight services operate, the railway infrastructure and rolling stock are generally outdated and in need of significant upgrades. Efforts have been made, sometimes with foreign assistance (e.g., from Russia and China), to modernize parts of the network.

- Airports:** José Martí International Airport (HAV) in Havana is the main international gateway. Other international airports serve key tourist destinations like Varadero (VRA), Holguín (HOG), and Santa Clara (SNU). Cubana de Aviación is the national airline, operating domestic and international flights. Numerous international airlines also serve Cuba. Domestic air travel is available but can be limited.

- Seaports:** Cuba has several important seaports. The Port of Havana is the largest and historically most significant. Other major ports include Mariel (which has seen significant development as a special economic zone with a modern container terminal), Santiago de Cuba, Cienfuegos, and Matanzas. These ports handle cargo and, increasingly, cruise ships (though U.S.-based cruise operations have been subject to policy changes).

- Urban Transport:** In cities like Havana, public transport relies heavily on buses (often referred to as guaguas), collective taxis, and, more recently, some newer bus fleets. Bicycles and horse-drawn carriages are also used, particularly in smaller towns and rural areas.