1. Overview

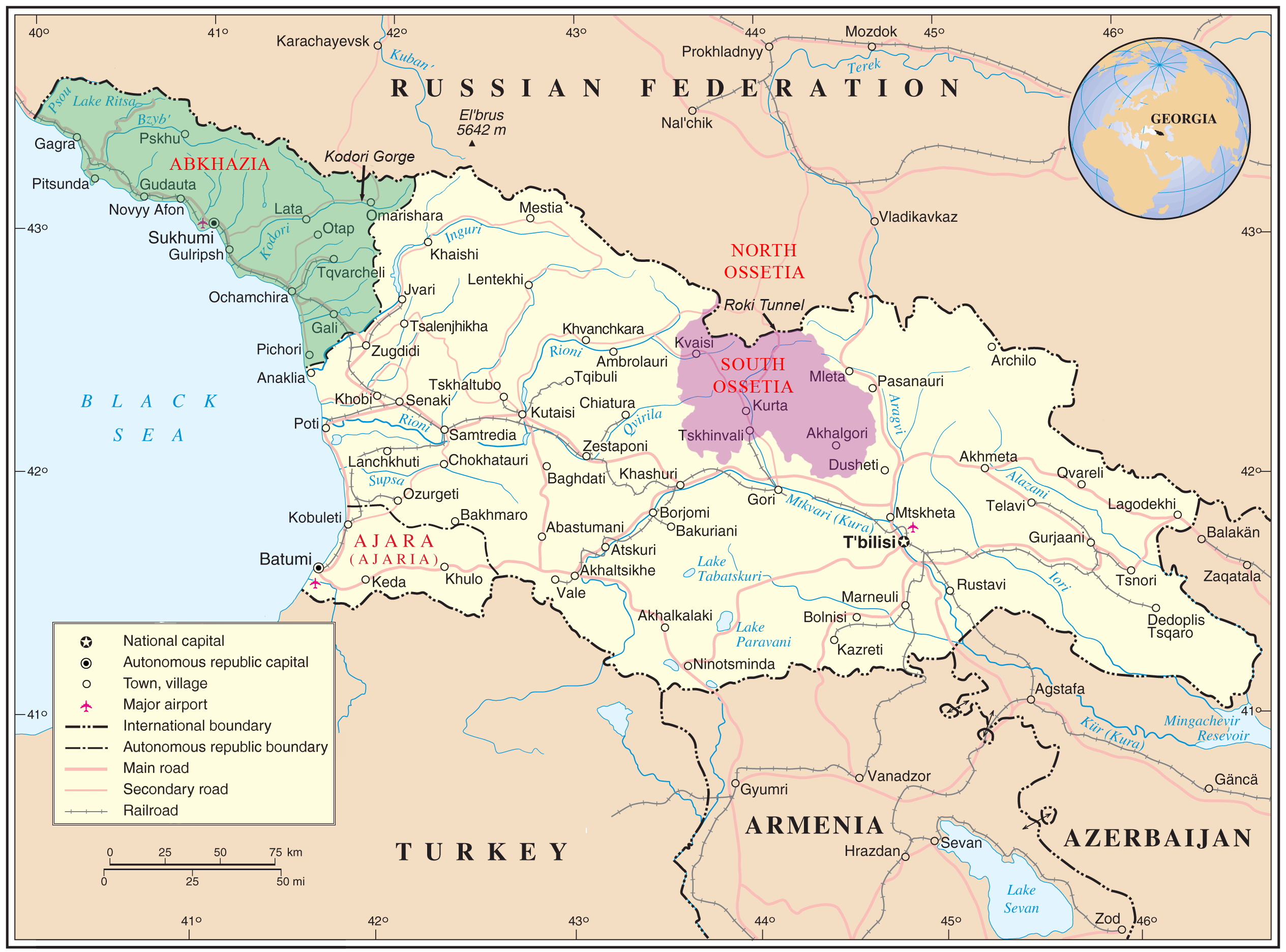

South Ossetia, officially the Republic of South Ossetia - State of Alania (Республикӕ Хуссар Ирыстон - Паддзахад АланиRespublikӕ Xussar Iryston - Paddzaxad AlaniOssetian; Республика Южная Осетия - Государство АланияRespublika Yuzhnaya Osetiya - Gosudarstvo AlaniyaRussian), is a de facto state in the South Caucasus. Located on the southern slopes of the Greater Caucasus mountain range, it covers an area of approximately 1.5 K mile2 (3.89 K km2) and has an officially stated population of 56,520 people (2022), with about 33,000 residing in its capital, Tskhinvali. The region is predominantly mountainous, with its economy largely based on agriculture, though heavily reliant on financial assistance from Russia. The official languages are Ossetian and Russian, and its time zone is Moscow Time (UTC+03:00).

Historically, the Ossetians, believed to be descendants of the Alans, migrated to this region of the Caucasus over centuries. The area was incorporated into the Russian Empire in the early 19th century along with Georgia. Following the Russian Revolution, it became the South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast within the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1922. Tensions rose with the decline of the Soviet Union, leading South Ossetia to declare independence from Georgia in 1990. This resulted in the 1991-1992 South Ossetia War. The conflict remained largely frozen, with sporadic escalations, until the 2008 Russo-Georgian War. After this war, Russia recognized South Ossetia's independence, a move followed by a few other UN member states (Venezuela, Nicaragua, Nauru, and Syria). However, Georgia and the vast majority of the international community consider South Ossetia to be an integral part of Georgia, often referring to it as the Tskhinvali Region (ცხინვალის რეგიონიTskhinvalis RegioniGeorgian).

The political status of South Ossetia remains highly disputed. It operates as a semi-presidential republic but faces significant challenges due to its limited international recognition and economic dependence on Russia. Discussions regarding potential annexation by Russia have occurred periodically. The region's demographics have been significantly affected by conflicts, particularly the displacement of ethnic Georgians. The human rights situation, especially concerning internally displaced persons (IDPs), refugees, and property rights, continues to be a major concern, reflecting the social impacts of the unresolved conflict and the need for democratic development and accountability.

2. History

The history of South Ossetia spans from ancient migrations and settlements through periods under larger empires, Soviet administration, and recent conflicts leading to its current disputed status. This section chronicles the key historical events and transformations of the region, covering its medieval origins, incorporation into the Russian Empire, the Soviet era including the establishment and existence of the South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast, and the complex Georgian-Ossetian conflict leading to post-2008 developments.

2.1. Medieval and early modern period

The Ossetians are believed to originate from the Alans, a nomadic Iranian tribe. In the 8th century, a consolidated Alan kingdom, referred to in sources of the period as Alania, emerged in the northern Caucasus Mountains. Around 1239-1277, Alania fell to the Mongol and later to Timur's armies, which massacred much of the Alanian population. The survivors among the Alans retreated into the mountains of the central Caucasus and gradually started migrating to the south, across the Caucasus Mountains into the Kingdom of Georgia. In the village of Zakagori, an inscription was found on a tombstone in the Ossetian language written in Syriac-Nestorian script, which dates back to 1326.

In the 17th century, under pressure from Kabardian princes, Ossetians began a second wave of migration from the North Caucasus to the Kingdom of Kartli. Ossetian peasants, migrating to the mountainous areas of the South Caucasus, often settled on the lands of Georgian feudal lords. The Georgian King of the Kingdom of Kartli permitted Ossetians to immigrate. According to Mikhail Tatishchev, the Russian ambassador to Georgia, at the beginning of the 17th century, a small group of Ossetians was already living near the headwaters of the Great Liakhvi. In the 1770s, there were more Ossetians living in Kartli than ever before.

This period was documented in the travel diaries of Johann Anton Güldenstädt, who visited Georgia in 1772. The Baltic German explorer called modern North Ossetia-Alania simply Ossetia, while he wrote that Kartli (the areas of modern-day South Ossetia) was populated by Georgians, and the mountainous areas were populated by both Georgians and Ossetians. Güldenstädt also wrote that the northernmost border of Kartli is the Major Caucasus Ridge. By the end of the 18th century, the primary sites of Ossetian settlement on the territory of modern South Ossetia were in Kudaro (კუდაროKudaroGeorgian) near the Jejora river estuary, the Greater Liakhvi gorge, the gorge of the Little Liakhvi, the Ksani River gorge, Guda (Tetri Aragvi estuary), and Truso (near the Terek estuary).

2.2. South Ossetia under Russian Imperial rule

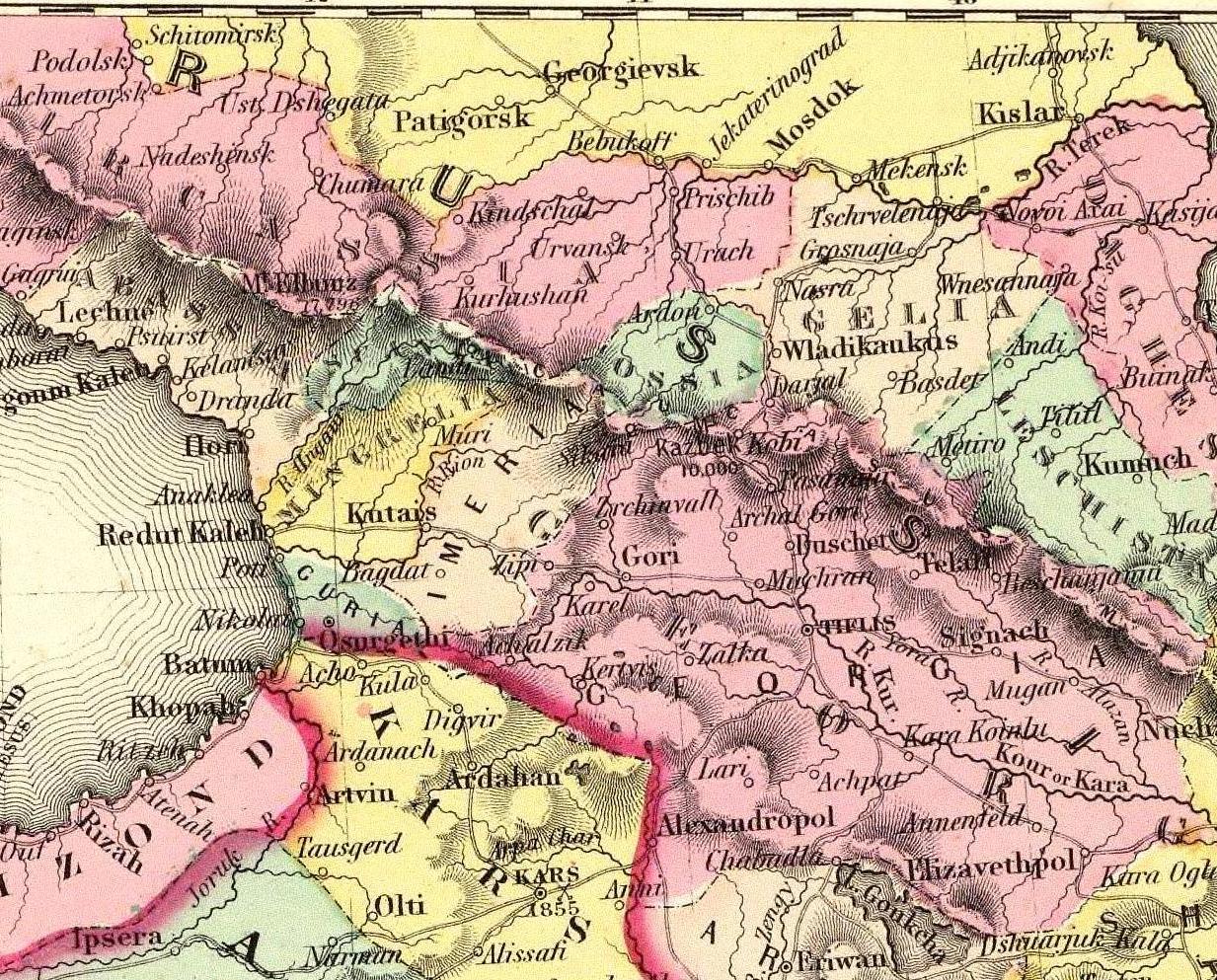

The Georgian Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti, including the territory of modern South Ossetia, was annexed by the Russian Empire in 1801. However, the Ossetians initially refused to submit to the new administration, considering themselves independent. The stage of annexation of South Ossetia by Russia began between 1821 and 1830, culminating in the conquest of South Ossetia by General Paul Rennenkampff in 1830. By this time, Ossetia was completely under Russian control. Ossetian migration to Georgian areas continued throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, during which Georgia was part of the Russian Empire. Ossetian settlements emerged in Trialeti, Borjomi, Bakuriani, and Kakheti as well. The 1856 map by J. H. Colton shows "Ossia" corresponding roughly to modern North Ossetia, with the area of modern South Ossetia depicted south of it.

2.3. Soviet era

The Soviet era brought significant political and social transformations to South Ossetia, including its establishment as an autonomous region within the Georgian SSR and its subsequent development under Soviet rule. This period saw the formalization of South Ossetia's administrative boundaries and cultural autonomy, alongside underlying tensions that would later contribute to conflict.

2.3.1. Establishment of the South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast

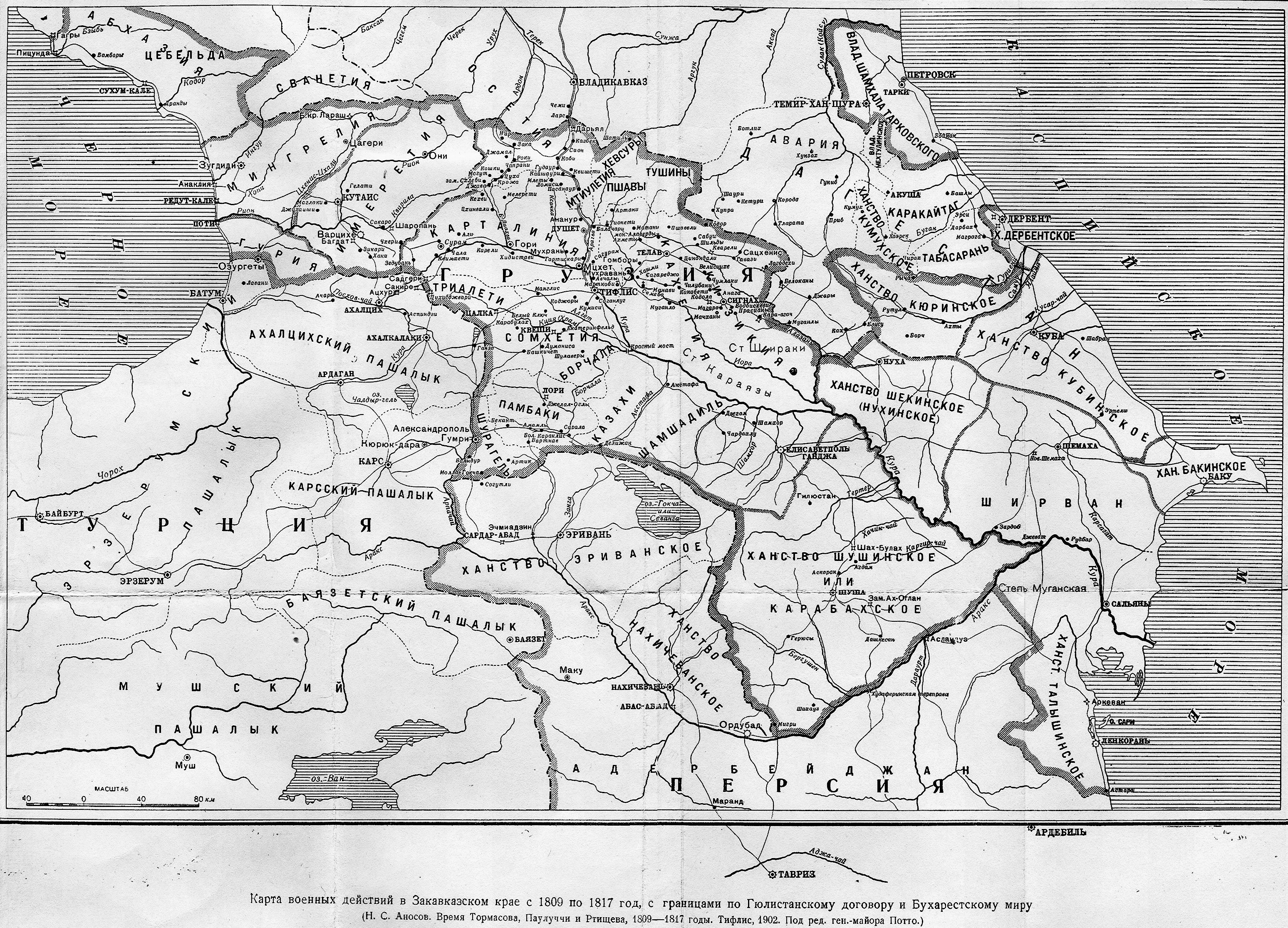

Following the Russian Revolution, the area of modern South Ossetia became part of the Democratic Republic of Georgia. In 1918, conflict began between landless Ossetian peasants living in Shida Kartli (Interior Georgia), who were influenced by Bolshevism and demanded ownership of the lands they worked, and the Menshevik government-backed ethnic Georgian aristocrats, who were the legal owners. Although the Ossetians were initially discontented with the economic policies of the central government, the tension soon transformed into an ethnic conflict. The first Ossetian rebellion began in February 1918, when three Georgian princes were killed and their land was seized by the Ossetians. The central government of Tiflis retaliated by sending the National Guard to the area. However, the Georgian unit retreated after engaging the Ossetians. Ossetian rebels then proceeded to occupy the town of Tskhinvali and began attacking the ethnic Georgian civilian population. During uprisings in 1919 and 1920, the Ossetians were covertly supported by Soviet Russia but were ultimately defeated. According to allegations made by Ossetian sources, the crushing of the 1920 uprising caused the death of 5,000 Ossetians, while ensuing hunger and epidemics led to the deaths of more than 13,000 people.

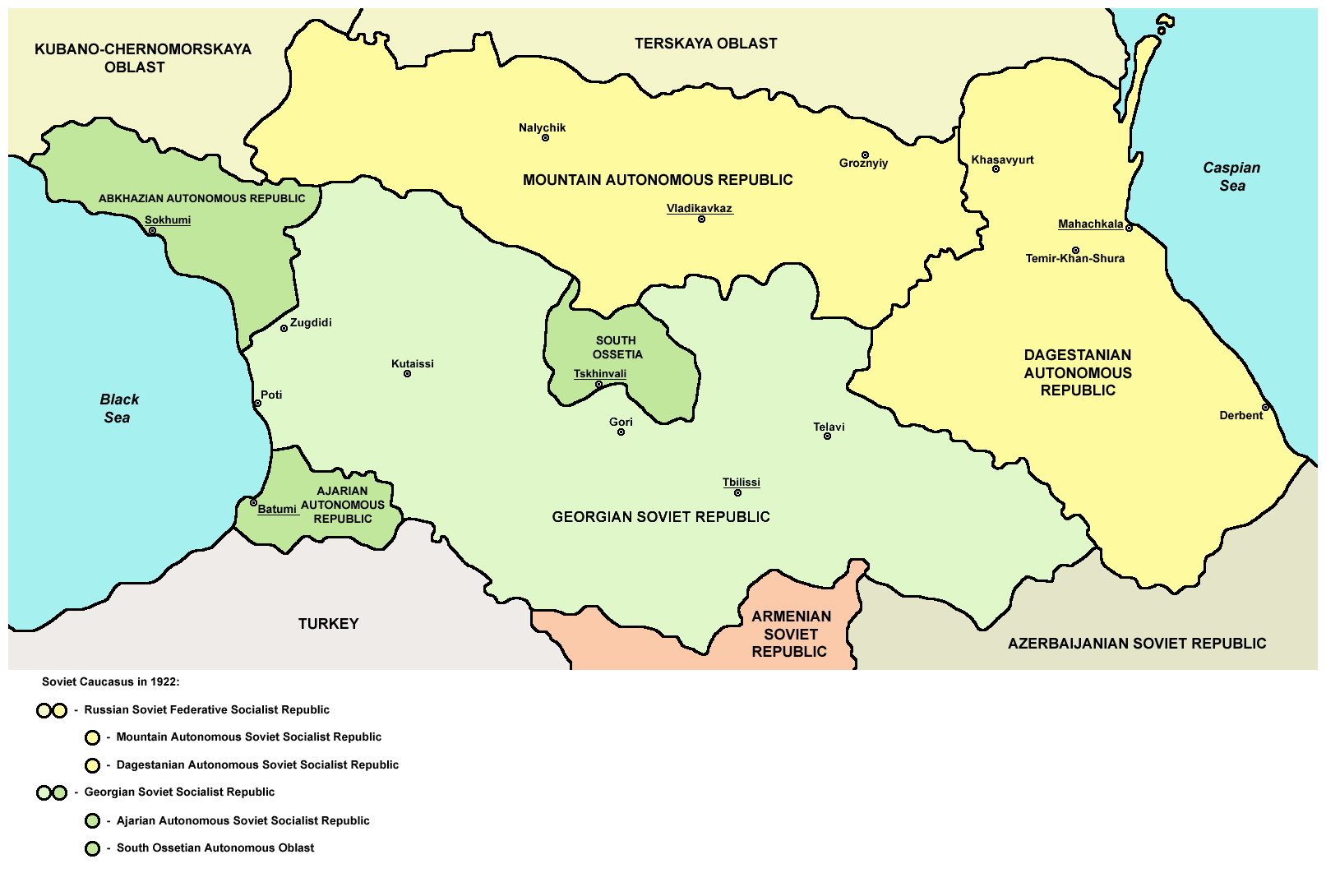

The Soviet Georgian government, established after the Red Army invasion of Georgia in 1921, created an autonomous administrative unit for Transcaucasian Ossetians in April 1922 under pressure from Kavbiuro (the Caucasian Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party), called the South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast (AO). Some believe that the Bolsheviks granted this autonomy to the Ossetians in exchange for their loyalty in fighting the Democratic Republic of Georgia and favoring local separatists, as this area had never been a separate entity prior to the Russian invasion. The drawing of administrative boundaries for the South Ossetian AO was a complicated process. Many Georgian villages were included within the South Ossetian AO despite numerous protests by the Georgian population. While the city of Tskhinvali did not have a majority Ossetian population at the time, it was made the capital of the South Ossetian AO. In addition to parts of Gori uezd and Dusheti uezd of the Tiflis Governorate, parts of Racha uezd of the Kutaisi Governorate (western Georgia) were also included within the South Ossetian AO. All these territories had historically been indigenous Georgian lands. Historical Ossetia in the North Caucasus did not have its own political entity before 1924, when the North Ossetian Autonomous Oblast was created.

2.3.2. South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast (1922-1990)

During its existence as an autonomous oblast within the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic, South Ossetia experienced various political, socio-economic, and cultural developments. Although the Ossetians had their own language (Ossetian), Russian and Georgian were the administrative/state languages. Under Soviet rule, Ossetians in Georgia enjoyed minority cultural autonomy, including speaking the Ossetian language and teaching it in schools. Inter-ethnic relations between Ossetians and Georgians within the oblast were generally peaceful for much of this period, with a high degree of interaction and intermarriage. However, underlying tensions related to land and national identity persisted. Economically, the region remained largely agrarian, with some industrial development centered around Tskhinvali. The Soviet nationality policies, while granting a degree of cultural autonomy, also sowed seeds for future conflict by creating administrative borders that did not always align with ethnic distributions or historical ties, leading to dissatisfaction among some Georgians who viewed the oblast's creation as artificial. In 1989, two-thirds of Ossetians in the Georgian SSR lived outside the South Ossetian AO. The period leading up to 1990 saw rising nationalist sentiments among both Georgians and Ossetians, setting the stage for the dissolution of the autonomous oblast and the subsequent conflicts.

2.4. Georgian-Ossetian conflict

The Georgian-Ossetian conflict stems from South Ossetia's desire for greater autonomy or independence from Georgia, a sentiment that intensified with the rise of nationalism in the late Soviet period. This section traces the conflict through its various stages, highlighting the causes, key events, and consequences, including the significant human rights and social impacts. The conflict evolved from initial clashes in the late 1980s and early 1990s, through a period of frozen conflict, to the 2008 Russo-Georgian War which dramatically altered the region's status.

2.4.1. Initial conflict (1989-1992)

Tensions in the region began to escalate amid rising nationalism among both Georgians and Ossetians in 1989. Before this, the two communities of the South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast of the Georgian SSR had largely coexisted peacefully, with significant interaction and intermarriage, except for the events of 1918-1920. The dispute over the historical presence of Ossetians in the South Caucasus contributed to the conflict. While Georgian historiography suggests mass Ossetian migration to Georgia began in the 17th century, Ossetians claim ancient residency, a view not widely supported by available sources. Some Ossetian historians accept migration after the 13th-century Mongol invasions, while a former South Ossetian de facto foreign minister acknowledged their appearance in the area in the early 17th century. Georgians generally viewed the Soviet-era creation of South Ossetia as artificial.

The South Ossetian Popular Front (Адæмон НыхасAdæmon NykhasOssetian) was formed in 1988. On November 10, 1989, the South Ossetian regional council requested the Georgian Supreme Council to upgrade the region to an "autonomous republic". This decision escalated the conflict. On November 11, the Georgian parliament, the Supreme Soviet, revoked this decision and removed the First Party Secretary of the oblast.

In the summer of 1990, the Georgian Supreme Council adopted a law barring regional parties, which the South Ossetian regional council interpreted as a move against Ademon Nykhas. Consequently, on September 20, 1990, South Ossetia passed a "declaration of national sovereignty," proclaiming the South Ossetian Soviet Democratic Republic within the Soviet Union. Ossetians boycotted the subsequent Georgian parliamentary elections and held their own in December. In October 1990, Zviad Gamsakhurdia's "Round Table" bloc won the Georgian parliamentary election. On December 11, 1990, Gamsakhurdia's government declared the Ossetian election illegitimate and abolished South Ossetia's autonomous status altogether, stating, "They [Ossetians] have no right to a state here in Georgia. They are a national minority. Their homeland is North Ossetia... Here they are newcomers."

When the Georgian parliament declared a state of emergency in South Ossetia on December 12, 1990, troops from both Georgian and Soviet interior ministries were sent to the region. After the Georgian National Guard was formed in early 1991, Georgian troops entered Tskhinvali on January 5, 1991. The ensuing 1991-1992 South Ossetia War was characterized by a general disregard for international humanitarian law by uncontrollable militias, with both sides reporting atrocities. The Soviet military facilitated a ceasefire in January 1991. In March and April 1991, Soviet interior troops reportedly disarmed militias and deterred inter-ethnic violence. Gamsakhurdia asserted that Soviet leadership was encouraging South Ossetian separatism to prevent Georgia from leaving the Soviet Union. Georgia declared its independence in April 1991.

The war resulted in significant displacement: about 100,000 ethnic Ossetians fled South Ossetia and Georgia proper, mostly to North Ossetia. A further 23,000 ethnic Georgians fled South Ossetia to other parts of Georgia. Many refugees went to North Ossetia's Prigorodnyi District, areas where South Ossetians had been resettled in 1944 after the Ingush were expelled by Stalin. This new wave of migration fueled conflict between Ossetians and Ingush. On April 29, 1991, an earthquake struck western South Ossetia, killing over 200 and leaving tens of thousands homeless, exacerbating the humanitarian crisis.

In late 1991, dissent against Gamsakhurdia grew in Georgia. A coup d'état on December 22, 1991, led to heavy fighting in Tbilisi. Gamsakhurdia fled in January 1992, and an interim Georgian military council invited Eduard Shevardnadze to assume control in March 1992.

An independence referendum was held in South Ossetia on January 19, 1992, asking voters if they agreed to independence and reunion with Russia. Both proposals were approved but not internationally recognized. On May 29, 1992, the South Ossetian regional council declared the independence of the Republic of South Ossetia.

2.4.2. Frozen conflict period (1992-early 2008)

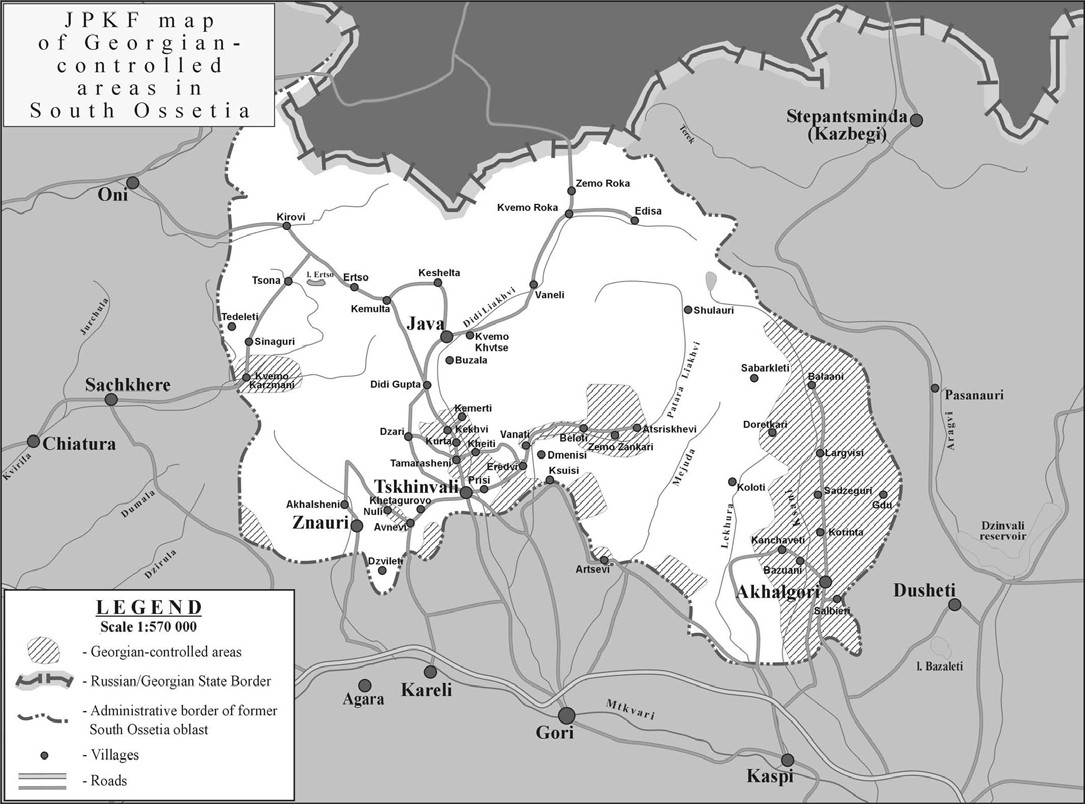

On June 24, 1992, Eduard Shevardnadze and the South Ossetian government signed the Sochi ceasefire agreement, brokered by Russia. The agreement included obligations to avoid the use of force, and Georgia pledged not to impose sanctions against South Ossetia. The Georgian government retained control over substantial portions of South Ossetia, including the town of Akhalgori. A Joint Peacekeeping Force of Ossetians, Russians, and Georgians was established. On November 6, 1992, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) set up a mission in Georgia to monitor the peacekeeping operation. From then until mid-2004, South Ossetia was generally peaceful, although the political status remained unresolved.

Following the 2003 Rose Revolution, Mikheil Saakashvili became President of Georgia in 2004, promising to restore Georgia's territorial integrity. In one of his early speeches, Saakashvili addressed the separatist regions, offering immediate negotiations and readiness to discuss models of statehood.

Since 2004, tensions began to rise as Georgian authorities strengthened efforts to regain control, particularly after succeeding in Adjara. Georgia sent police to close down the Ergneti black market, a chief source of revenue for the region, which sold foodstuffs and fuel smuggled from Russia. Georgian authorities claimed massive smuggling through the Roki Tunnel (not under Georgian control) cost the country significant customs revenues and proposed joint control, which was refused by South Ossetia. This anti-smuggling operation led to a breakdown of trust. A wave of violence erupted between Georgian peacekeepers and South Ossetian militiamen, including hostage-taking of Georgian peacekeepers, shootouts, and shelling of Georgian-controlled villages, leaving dozens dead and wounded. A ceasefire deal was reached on August 13, 2004, but was repeatedly violated.

The Georgian government protested increasing Russian economic and political presence and the uncontrolled military of the South Ossetian side. Georgian officials stated key South Ossetian security positions were occupied by (former) Russian security officials. Georgia also considered the peacekeeping force (comprising South Ossetians, North Ossetians, Russians, and Georgians) non-neutral and demanded its replacement with an internationalized force. The U.S. supported Georgia's call in 2006 for the withdrawal of Russian "peacekeepers." EU South Caucasus envoy Peter Semneby later stated that Russia's actions in the 2006 Georgia spy row damaged its credibility as a neutral peacekeeper. U.S. Senators Joe Biden, Richard Lugar, and Mel Martínez sponsored a resolution in June 2008 accusing Russia of attempting to undermine Georgia's territorial integrity.

2.4.3. 2008 Russo-Georgian War

Tensions between Georgia and Russia began escalating in April 2008. A bomb explosion on August 1, 2008, targeted a car transporting Georgian peacekeepers. South Ossetians were reportedly responsible for instigating this incident, which injured five Georgian servicemen and marked an opening of hostilities. In response, several South Ossetian militiamen were hit. South Ossetian separatists began shelling Georgian villages on August 1, prompting Georgian servicemen to return fire periodically.

At around 19:00 on August 7, 2008, Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili announced a unilateral ceasefire and called for peace talks. However, escalating assaults against Georgian villages in the South Ossetian conflict zone were soon matched with gunfire from Georgian troops. Georgian forces then moved towards Tskhinvali, the capital of the self-proclaimed Republic of South Ossetia, on the night of August 7-8, reaching its center on the morning of August 8. A Georgian diplomat stated that by taking control of Tskhinvali, Tbilisi aimed to demonstrate that Georgia would not tolerate the killing of Georgian citizens. According to Russian military expert Pavel Felgenhauer, the Ossetian provocation was aimed at triggering a Georgian response, which was needed as a pretext for a premeditated Russian military invasion. Georgian intelligence and some Russian media reports indicated that parts of the regular (non-peacekeeping) Russian Army had already moved into South Ossetian territory through the Roki Tunnel before the Georgian military action.

Russia accused Georgia of "aggression against South Ossetia" and launched a large-scale land, air, and sea invasion of Georgia on August 8, 2008, under the pretext of a "peace enforcement operation." Russian airstrikes targeted locations within Georgia. Abkhaz forces opened a second front on August 9 by attacking the Kodori Gorge, held by Georgia. Tskhinvali was seized by the Russian military by August 10. Russian forces occupied the Georgian cities of Zugdidi, Senaki, Poti, and Gori (the last after the ceasefire agreement was negotiated). The Russian Black Sea Fleet blockaded the Georgian coast.

A campaign of ethnic cleansing against Georgians in South Ossetia was conducted by South Ossetian forces, with Georgian villages around Tskhinvali being destroyed after the war had ended. The war displaced 192,000 people. While many returned to their homes, a year later, around 30,000 ethnic Georgians remained displaced. South Ossetian leader Eduard Kokoity stated he would not allow Georgians to return. The humanitarian impact was significant, with widespread damage to infrastructure and civilian casualties.

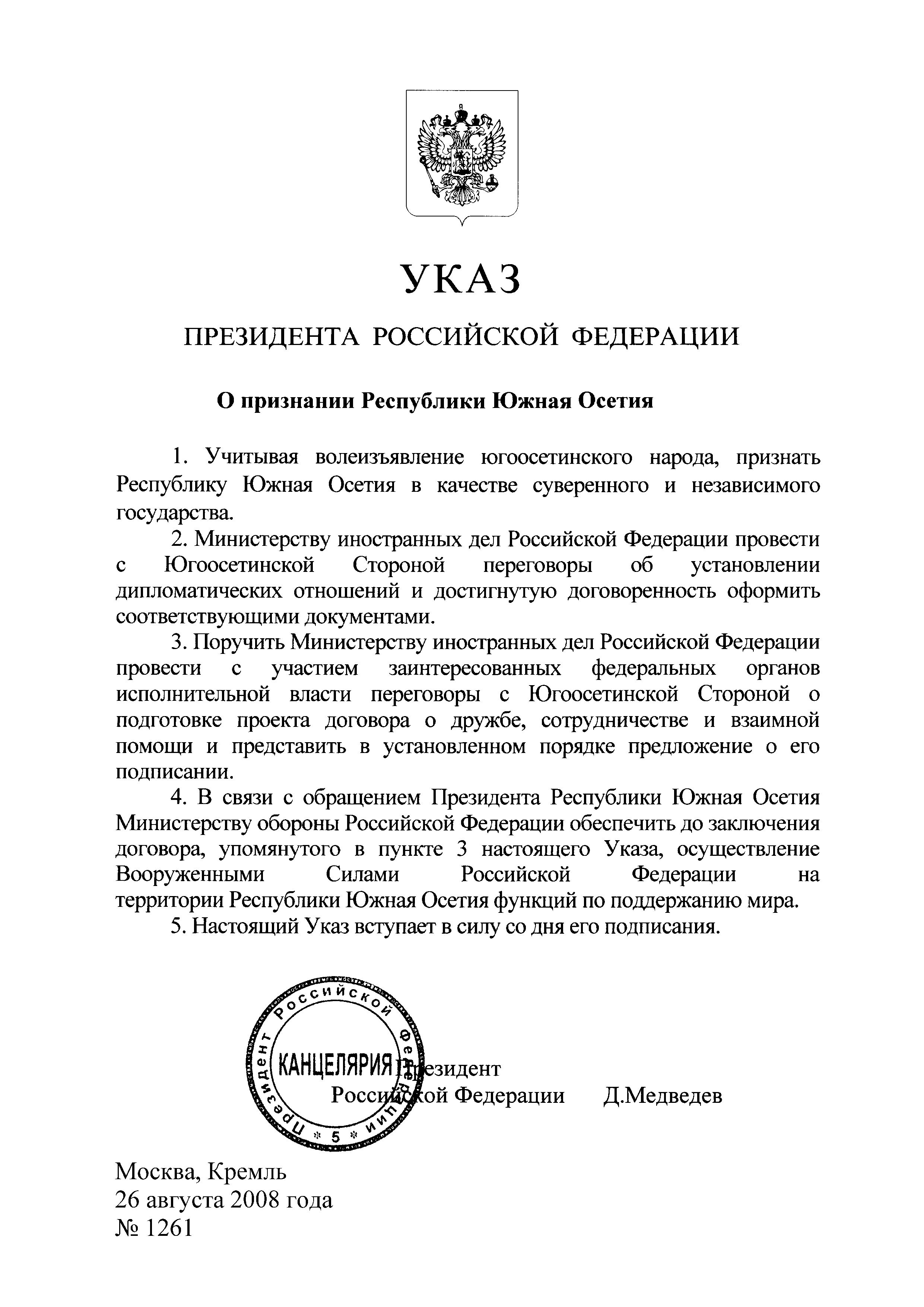

French President Nicolas Sarkozy negotiated a ceasefire agreement on August 12, 2008. On August 17, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev announced that Russian forces would begin to pull out of Georgia the following day. Russia recognized Abkhazia and South Ossetia as separate republics on August 26. In response, the Georgian government severed diplomatic relations with Russia. Russian forces left the buffer areas bordering Abkhazia and South Ossetia on October 8, and the European Union Monitoring Mission in Georgia assumed authority over these areas. Since the war, Georgia has maintained that Abkhazia and South Ossetia are Russian-occupied Georgian territories.

On September 30, 2009, the European Union-sponsored Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on the Conflict in Georgia stated that, while preceded by months of mutual provocations, "open hostilities began with a large-scale Georgian military operation against the town of Tskhinvali and the surrounding areas, launched in the night of 7 to 8 August 2008." The report also noted that Russia's subsequent military response was initially legal but later violated international law as it extended beyond South Ossetia and became an occupation. Both sides were criticized for actions violating international humanitarian law, highlighting serious human rights concerns.

2.5. Post-2008 war developments

Following the 2008 war and Russia's recognition of South Ossetia's independence, Russian influence in the region significantly increased. Russia provides substantial military, political, and financial aid, leading to South Ossetia's heavy dependence. In 2016, a referendum on integration with Russia was proposed but was put on hold indefinitely. A referendum on South Ossetia's official name was held on April 9, 2017; over three-quarters of voters supported amending the South Ossetian constitution to give the names "Republic of South Ossetia" and "State of Alania" equal status.

From 2020 to 2021, South Ossetia experienced significant protests following the death of Inal Djabiev, an opposition member, allegedly due to torture by police. These protests led to the sacking of several government ministers and highlighted ongoing issues with human rights and rule of law.

On March 26, 2022, then-President Anatoly Bibilov announced that South Ossetian troops had been sent to assist Russia in its invasion of Ukraine. On March 30, 2022, Bibilov announced that South Ossetia would initiate the legal process to become part of Russia. Russian politicians reacted positively, stating Russian law would permit parts of foreign nations to join the federation, emphasizing the need for a referendum to "express the will of the Ossetian people." Bibilov planned two referendums: one on annexation by Russia, and a second on joining North Ossetia. On May 13, the annexation referendum was scheduled for July 17. However, following Bibilov's defeat in the 2022 presidential election, the new president, Alan Gagloev, suspended the referendum on May 30, 2022. In August 2022, Gagloev announced that border crossings with Georgia would be open ten days a month, a slight easing of restrictions that had severely impacted freedom of movement and local livelihoods.

3. Geography

South Ossetia is a mountainous region located in the Caucasus at the juncture of Asia and Europe. It primarily occupies the southern slopes of the Greater Caucasus mountain range and its foothills, which are part of the Iberia Plain. The Likhi Range forms the western geographic boundary of South Ossetia, although the northwestern corner of the territory extends west of this range.

This section provides details on the topography and climate of the region.

3.1. Topography

South Ossetia covers an area of about 1.5 K mile2 (3.89 K km2). More than 89% of South Ossetia lies over 3.3 K ft (1.00 K m) above sea level. The Greater Caucasus Mountain Range forms its northern border with Russia. The highest point in South Ossetia is Mount Khalatsa, at 13 K ft (3.94 K m) above sea level. The only main road through the mountain range from South Ossetia to Russia is the TransKAM highway, which passes through the Roki Tunnel into North Ossetia-Alania. This tunnel, completed in 1986, was vital for the Russian military during the 2008 war as it is the only direct route connecting Russia and South Ossetia through the Caucasus Mountains. The section of the TransKAM highway located in South Ossetia is nominally part of the Georgian S10 highway, although Tbilisi effectively does not control it.

Out of the roughly 2,000 glaciers in the Greater Caucasus, approximately 30% are located within Georgia. About 10 glaciers of the Liakhvi River basin and a few from the Rioni River basin are situated in South Ossetia.

Most of South Ossetia is in the Kura Basin, with its northwestern part in the Black Sea basin. The Likhi and Racha ridges act as divides separating these two basins. Major rivers in South Ossetia include the Greater Liakhvi and Little Liakhvi, Ksani, Medzhuda, Tlidon, Canal Saltanis, and Ptsa River, along with numerous other tributaries. Russian troops patrolling the administrative boundary line have reportedly been involved in "borderization" activities, incrementally moving fences and markers into Georgian-controlled territory, a practice Georgia and international observers condemn as an "encroaching occupation."

3.2. Climate

South Ossetia's climate is influenced by subtropical patterns from the East and Mediterranean influences from the West. The Greater Caucasus range moderates the local climate by serving as a barrier against cold air from the north, resulting in warmer conditions at similar altitudes compared to the Northern Caucasus. Climatic zones in South Ossetia are determined by distance from the Black Sea and by altitude. The plains of eastern Georgia (part of which South Ossetia occupies) are shielded from the influence of the Black Sea by mountains, leading to a more continental climate.

The foothills and mountainous areas, including the Greater Caucasus Mountains, experience cool, wet summers and snowy winters, with snow cover often exceeding 6.6 ft (2 m) in many regions. The penetration of humid air masses from the Black Sea to the west of South Ossetia is often blocked by the Likhi Range. The wettest periods generally occur during spring and autumn, while winter and summer months tend to be the driest. Elevation plays a significant role, with climatic conditions above 4.9 K ft (1.50 K m) being considerably colder than in lower-lying areas. Regions above 6.6 K ft (2.00 K m) frequently experience frost even during summer months.

The average temperature in South Ossetia in January is around 39.2 °F (4 °C), and the average temperature in July is around 68.54 °F (20.3 °C). The average yearly liquid precipitation is around 24 in (598 mm). In general, summer temperatures average 68 °F (20 °C) to 75.2 °F (24 °C) across much of South Ossetia, and winter temperatures average 35.6 °F (2 °C) to 39.2 °F (4 °C). Humidity is relatively low, and rainfall averages 20 in (500 mm) to 31 in (800 mm) per year, though Alpine and highland regions have distinct microclimates. At higher elevations, precipitation can be twice as heavy as in the eastern plains. Alpine conditions begin at about 6.9 K ft (2.10 K m), and above 12 K ft (3.60 K m), snow and ice are present year-round.

4. Political Status and International Relations

South Ossetia's political status is highly contentious. It declared independence from Georgia in 1990 and, after the 2008 war, Russia recognized its independence. This recognition is shared by only a few other UN member states. Georgia and the vast majority of the international community consider South Ossetia an integral part of Georgia, occupied by Russia. This section provides an overview of its de facto independence, disputed international legal status, and relationships with key international actors, including Georgia, Russia, and other states and international organizations.

4.1. Declaration of Independence and International Recognition

The South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast declared independence from the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic in September 1990, and then as the Republic of South Ossetia on May 29, 1992, following a referendum. These declarations were not recognized by Georgia or the international community at the time. After the 2008 war, Russia officially recognized South Ossetia's independence on August 26, 2008. This unilateral recognition by Russia was met with condemnation from Western blocs, such as NATO, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), and the European Council, due to the violation of Georgia's territorial integrity. The EU's diplomatic response was delayed by disagreements among member states regarding the harshness of the response towards Russia.

As of 2024, only five United Nations member states recognize South Ossetia as a sovereign state:

- Russia (recognized August 26, 2008)

- Nicaragua (recognized September 5, 2008)

- Venezuela (recognized September 10, 2009)

- Nauru (recognized December 16, 2009)

- Syria (recognized May 29, 2018)

Tuvalu recognized South Ossetia in September 2011 but withdrew its recognition in March 2014.

South Ossetia is also recognized by other partially recognized states such as Abkhazia, Transnistria, and the now-defunct Artsakh Republic. It has also been recognized by the self-proclaimed Luhansk People's Republic and Donetsk People's Republic. The Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic has also indicated recognition.

The European Union, Council of Europe, NATO, and most UN member countries do not recognize South Ossetia as an independent state. The de facto republic held a second independence referendum on November 12, 2006, after its first referendum in 1992 was not recognized as valid. According to Tskhinvali election authorities, 99% of voters supported independence with a 95% turnout. This referendum was monitored by 34 international observers from various countries but was not recognized internationally due to the lack of ethnic Georgian participation and the illegality of such a referendum without recognition from the Georgian government.

4.2. Relations with Georgia

Relations between South Ossetia and Georgia are defined by the unresolved territorial dispute and ongoing conflict. Georgia considers South Ossetia an integral part of its sovereign territory and does not recognize its declared independence. South Ossetia, on the other hand, views itself as an independent state. There are no formal diplomatic relations between the two. This subsection details Georgia's perspective and its "Law on Occupied Territories."

4.2.1. Georgian perspective and Law on Occupied Territories

Georgia's official stance is that South Ossetia is an integral part of its sovereign territory, currently under Russian occupation. The Georgian constitution designates the area as "the former autonomous district of South Ossetia," referring to the South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast disbanded in 1990. The Georgian government informally refers to the area as the Tskhinvali region and considers it part of Georgia's Shida Kartli region. Lacking effective control over the territory, Georgia maintains an administrative body called the Provisional Administration of South Ossetia.

In late October 2008, then-President Mikheil Saakashvili signed into law the "Law on Occupied Territories" passed by the Georgian Parliament. This law covers the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali region (territories of the former South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast). The law spells out restrictions on free movement to, economic activity in, and real estate transactions in these territories. According to the law, foreign citizens should enter the two breakaway regions only through Georgia: Abkhazia from Zugdidi Municipality and South Ossetia from Gori Municipality. The main road leading to South Ossetia from the rest of Georgia passes through Gori Municipality but has been closed at Ergneti since 2008. The main crossing point to the Akhalgori district has been closed by South Ossetian authorities since 2019. South Ossetian authorities only allow entry for foreigners "through the territory of the Russian Federation."

The Georgian law lists "special" cases where entry into the breakaway regions is not illegal, such as if the trip "serves Georgia's state interests; peaceful resolution of the conflict; de-occupation or humanitarian purposes." The law also bans economic activities requiring Georgian permits, air, sea, and railway communications, international transit via the regions, mineral exploration, and money transfers. This provision is retroactive to 1990. The law states that Russia, as the occupying state, is fully responsible for human rights violations and for compensation of damages inflicted on Georgian citizens and others. De facto state agencies and officials operating in the occupied territories are regarded by Georgia as illegal. The law remains in force until "the full restoration of Georgian jurisdiction" over the regions.

In April 2007, Georgia created the Provisional Administrative Entity of South Ossetia, staffed by ethnic Ossetian members of the separatist movement, with Dmitry Sanakoyev appointed as its head. This body was intended to negotiate with central Georgian authorities regarding its final status and conflict resolution. In July 2007, Georgia set up a state commission to develop South Ossetia's autonomous status within the Georgian state.

4.3. Relations with Russia

The relationship between South Ossetia and the Russian Federation is exceptionally close, characterized by extensive military, political, and economic ties, and South Ossetia's significant dependence on Russia. This relationship includes direct Russian support and influence, as well as discussions about potential annexation by Russia.

4.3.1. Russian support and influence

South Ossetia relies heavily on military, political, and financial aid from Russia. This support has been crucial for the de facto authorities in Tskhinvali to maintain control and operate.

- Military Support: Russia maintains a significant military presence in South Ossetia, including the 4th Guards Military Base in Tskhinvali and Java, and numerous "militarized border guard bases" operated by the FSB along the administrative boundary line with Georgian-controlled territory. An estimated 3,000-3,500 Russian servicemen and 1,500 FSB personnel are deployed. In 2017, parts of South Ossetia's armed forces were incorporated into the Russian Armed Forces.

- Political Support: Russia was the first UN member state to recognize South Ossetia's independence in 2008 and has since been its primary diplomatic advocate on the international stage. Russia has signed numerous bilateral agreements with South Ossetia, including an "alliance and integration" treaty in 2015, which further deepened ties by integrating military and customs services and committing Russia to subsidize state worker salaries.

- Financial Assistance: South Ossetia's budget is overwhelmingly dependent on Russian financial aid. By 2010, Russian donations reportedly made up nearly 99% of its budget, and by 2021, this figure was still around 83%. Russia finances socio-economic development programs aimed at aligning South Ossetia's indicators with those of Russia's North Caucasus Federal District. Infrastructure projects, like a backup power transmission line completed in 2021, are also funded by Russia.

This extensive support has resulted in significant Russian influence over South Ossetia's internal and external affairs, leading many observers to describe it as a Russian protectorate or a heavily dependent client state.

4.3.2. Proposed annexation by Russia

Since 2008, the South Ossetian government has repeatedly expressed its intention to join the Russian Federation, which, if successful, would end its proclaimed independence and potentially lead to unification with North Ossetia-Alania within Russia.

On August 30, 2008, shortly after Russian recognition, Tarzan Kokoity, then Deputy Speaker of South Ossetia's parliament, announced that the region would soon be absorbed into Russia. Then-president Eduard Kokoity later stated that South Ossetia would not give up its independence by joining Russia, though this contradicted his earlier remarks.

The prospect of a referendum on this matter has been raised multiple times in domestic politics. In 2015, President Leonid Tibilov proposed a name change to "South Ossetia-Alania" (in analogy with North Ossetia-Alania) and suggested a referendum on joining Russia before April 2017. This referendum was postponed.

In March 2022, then-President Anatoly Bibilov announced that South Ossetia would initiate legal proceedings for integration with Russia, setting a referendum for July 17, 2022. However, after Bibilov lost the presidential election in May 2022, the new president, Alan Gagloev, suspended the referendum, stating the need for consultations with Moscow and citing the "inopportuneness" of such a move while Russia was engaged in the conflict in Ukraine. The feasibility of such an annexation is complex, involving geopolitical considerations, Russian strategic interests, and the potential reaction from Georgia and the international community.

4.4. Relations with other states and international organizations

South Ossetia's interactions with countries other than Russia and Georgia are extremely limited due to its disputed status. Only Nicaragua, Venezuela, Nauru, and Syria recognize its independence among UN member states, and diplomatic and economic ties with these nations are modest. South Ossetia also has relations with other partially recognized states like Abkhazia and Transnistria, forming part of the Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations.

Major international organizations such as the United Nations (UN), the European Union (EU), and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) do not recognize South Ossetia's independence and consider it part of Georgia.

- The UN has passed resolutions affirming Georgia's territorial integrity and calling for the safe and dignified return of internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees.

- The EU plays a role through the EU Monitoring Mission (EUMM), deployed after the 2008 war to monitor the ceasefire and normalize the situation along the administrative boundary lines with South Ossetia and Abkhazia. The EU also supports conflict resolution efforts and provides humanitarian aid.

- The OSCE was involved in peacekeeping monitoring before the 2008 war and continues to engage in discussions related to the conflict through mechanisms like the Geneva International Discussions.

These organizations generally advocate for a peaceful resolution of the conflict based on international law and respect for Georgia's sovereignty and territorial integrity.

5. Politics and Government

South Ossetia operates as a de facto independent state with its own governmental structure and political landscape, although it is not recognized by most of the international community. Its political system is heavily influenced by its relationship with Russia. This section discusses its governmental system, including the executive, legislative, and judicial branches; its political landscape and parties; and its administrative divisions.

5.1. Government structure

According to Article 47 of the Constitution of South Ossetia, the President is the head of state and head of the executive branch of government. The president is elected for a five-year term by direct popular vote, with a maximum of two consecutive terms for the same person. The current president is Alan Gagloev, who assumed office on May 24, 2022. The Prime Minister, currently Konstantin Dzhussoev, is appointed by the President and heads the government (cabinet of ministers).

The legislative body is the unicameral Parliament (НыхасNykhasOssetian), which consists of 34 members. They are elected for five-year terms through a mixed system: 17 members are elected from single-member constituencies, and 17 members are elected through proportional representation (Article 57 of the Constitution). The Chairman of the Parliament is Alan Tadtaev.

The judicial system is nominally independent, but its effectiveness and impartiality are often questioned due to the political context and limited resources.

5.2. Political landscape and parties

The political landscape in South Ossetia is characterized by a few dominant political parties and a strong alignment with Russia. Major political parties include:

- Nykhas: Led by President Alan Gagloev, it is currently the ruling party.

- United Ossetia: The former ruling party, previously led by Anatoly Bibilov. It generally advocates for closer ties with Russia, including potential unification.

- People's Party of South Ossetia

- Communist Party of South Ossetia

Elections, such as the 2022 presidential election won by Alan Gagloev against incumbent Anatoly Bibilov, often revolve around issues of socio-economic development, relations with Russia, and the unresolved conflict with Georgia. The political situation, while internally managed, is heavily influenced by Russian financial and political support. Protests, such as those following the death of Inal Djabiev in 2020-2021, indicate underlying social tensions and concerns about governance and human rights. Overall stability is largely maintained through Russian backing.

5.3. Administrative divisions

South Ossetia is divided into four districts (raions) and one city of republican significance (the capital):

- Dzau district (Дзауы районDzauy raionOssetian; also known as Java district) - in the north

- Znaur district (Знауыры районZnauyry raionOssetian) - in the west

- Leningor district (Ленингоры районLeningory raionOssetian; also known as Akhalgori district) - in the east

- Tskhinval district (Цхинвалы районTskhinvaly raionOssetian) - in the center/south

- Tskhinvali (ЦхинвалTskhinvalOssetian; also ცხინვალიTskhinvaliGeorgian) - the capital city

The Leningor (Akhalgori) district was predominantly Georgian-populated and largely under Georgian control before the 2008 war. After the war, South Ossetian and Russian forces took full control of the district.

6. Military

South Ossetia maintains its own armed forces, known as the Armed Forces of South Ossetia. In 2017, these forces were partially incorporated into the Russian Armed Forces. The exact size and equipment of South Ossetia's independent military units are modest, estimated to consist of around 2,500-3,000 active personnel and reservists. Their equipment is largely of Soviet and Russian origin.

A far more significant military factor in the region is the presence of Russian military forces. Russia has established the 4th Guards Military Base in South Ossetia, headquartered in Tskhinvali, with additional training sites and facilities, including one near Java for the Russian Airborne Troops. Estimates suggest that Russia deploys around 3,000-3,500 regular military personnel in South Ossetia.

In addition to regular military forces, Russia's Federal Security Service (FSB) Border Guard Service maintains approximately 20 "militarized border guard bases" along the administrative boundary line (ABL) with Georgian-controlled territory. An estimated 1,500 FSB personnel are deployed at these bases, tasked with enforcing what Russia and South Ossetia consider a "state border."

Military cooperation between South Ossetia and Russia is extensive, formalized through various treaties, including the 2015 "alliance and integration" treaty. This treaty includes provisions for the integration of South Ossetian military units with Russian forces, joint defense planning, and Russian assistance in equipping and training South Ossetian forces. According to South Ossetian de facto authorities, about 450 South Ossetian citizens were employed at the 4th Russian Military Base as of 2020.

In March 2022, then-President Anatoly Bibilov announced that South Ossetian troops had been sent to assist Russia in its invasion of Ukraine. Reports later emerged that some of these troops had deserted and returned home.

7. Economy

South Ossetia's economy is small, largely agrarian, and heavily dependent on financial assistance from Russia. The unresolved political status and the consequences of multiple conflicts have severely hampered its economic development, leading to significant challenges and limited opportunities for its population.

This section describes the main sectors, economic conditions, financial reliance on Russia, and the currency used.

7.1. Overview of industries and economic conditions

The economy of South Ossetia is primarily based on agriculture, although less than 10% of its land area is cultivated. Major agricultural products include cereals, fruits, and vines. Forestry and cattle industries also contribute to the local economy. Industrial activity is limited, with a few facilities, particularly around the capital, Tskhinvali. Before the 2008 war, South Ossetia's industry consisted of 22 small factories, but many were reported to be idle or in need of repair by 2009. One of the larger local enterprises is the Emalprovod factory.

The region faces significant economic challenges. Its GDP was estimated at US$15 million (US$250 per capita) in 2002. By 2017, the South Ossetian administration estimated its GDP to be nearly US$100 million, and in 2021, it was reported as $52 million ($1,000 per capita). The poverty threshold in late 2007 was 3,062 rubles a month, 23.5% below Russia's average at the time, with South Ossetians having significantly smaller incomes. The majority of the population has historically relied on subsistence farming.

Following the 2008 war, Georgia cut off electricity supplies to the Akhalgori region, which was previously supplied from adjacent Georgian-controlled areas. Electricity is now supplied from Tskhinvali, largely dependent on Russian sources. A new backup power transmission line from Russia was completed in November 2021, costing over 1.30 B RUB (approx. 17.00 M USD).

Unemployment is a significant issue. By the end of 2021, out of a working-age population of 34,308, 20,734 were employed, and 2,449 were registered as unemployed.

Socially, the economic conditions contribute to limited opportunities for youth and a reliance on public sector jobs funded by Russian aid. Environmentally, unregulated resource use and the impact of conflict on infrastructure pose potential risks, though detailed assessments are scarce.

7.2. Economic dependence on Russia

South Ossetia's economy is critically dependent on financial assistance from the Russian Federation. This dependence has been a defining feature, especially since the 2008 war. Russian donations reportedly constituted nearly 99% of South Ossetia's budget by 2010. By 2021, this figure was still approximately 83% (7.30 B RUB out of a total budget of 8.80 B RUB).

Russia finances a socio-economic development program for South Ossetia for the 2022-2025 period, aiming to bring its socio-economic indicators to the level of Russia's North Caucasus Federal District by 2025.

Historically, a significant economic asset for South Ossetia was the control of the Roki Tunnel, which links Russia and Georgia. Before the 2008 war, the South Ossetian government reportedly obtained a large part of its budget by levying customs duties on freight traffic through the tunnel. However, since the war and the effective closure of transit with Georgian-controlled territory, its role as a transit hub for Georgia has ceased, and its primary function is to connect South Ossetia with Russia.

The deep economic reliance on Russia creates structural dependency, limiting South Ossetia's autonomy and integrating its economy closely with Russia's.

7.3. Currency

The de facto currency in South Ossetia is the Russian ruble (RUB). It is used for all transactions, and salaries and pensions are paid in rubles. This reflects the region's close economic integration with Russia.

South Ossetia has also issued its own commemorative coins called the Zarin (ЗӕринZærinOssetian). These coins, minted in denominations such as 20, 25, and 50 Zarin, are typically made of precious metals like silver or gold and feature designs related to South Ossetian history and culture. However, the Zarin is not in general circulation and serves primarily as a collector's item or for ceremonial purposes rather than as a day-to-day medium of exchange. There is also mention of a "South Ossetian ruble," modeled on the Russian ruble with the same denominations, but this too appears to be largely ceremonial and not in widespread practical use compared to the Russian ruble.

8. Demographics

The demographic landscape of South Ossetia has been significantly shaped by historical migrations and, more recently, by the conflicts in the region, which have led to substantial population displacement and changes in ethnic composition.

This section details the ethnic makeup, population trends, languages spoken, and religious affiliations in South Ossetia.

8.1. Ethnic composition and population trends

Before the Georgian-Ossetian conflict in the early 1990s, roughly two-thirds of the population of South Ossetia was Ossetian, and 25-30% was Georgian. The eastern quarter of South Ossetia, around the town and district of Akhalgori, was predominantly Georgian, while the center and west were predominantly Ossetian.

The conflicts, particularly the 1991-1992 war and the 2008 war, led to significant demographic shifts. Many ethnic Georgians were displaced from South Ossetia, and some Ossetians were displaced from Georgian-controlled areas. According to Georgian officials, 15,000 Georgians moved to Georgia proper during the 2008 war. South Ossetian officials indicated that 30,000 Ossetians fled to North Ossetia during that war. The ethnic cleansing of Georgians during and after the 2008 war, particularly from areas around Tskhinvali and Akhalgori, has been reported by international organizations and Georgia, drastically reducing the Georgian population in the territory.

According to the 2015 census conducted by the South Ossetian authorities, the total population was 53,532. The ethnic composition was reported as:

- Ossetians: 48,146 (89.9%)

- Georgians: 3,966 (7.4%)

- Russians: 610 (1.1%)

- Armenians: 378 (0.7%)

- Others: 431 (0.8%)

Georgian authorities and some independent analysts have questioned the accuracy of these census data, suggesting the actual population might be lower. Estimates from 2009 put the population possibly as low as 26,000, while other estimates based on birth rates and school attendance suggested around 39,000. The South Ossetian Statistical agency estimated the population at 56,520 as of January 1, 2022, with 33,054 living in Tskhinvali. The social impact of these demographic changes includes the loss of multicultural communities, unresolved property issues for displaced persons, and significant challenges to social cohesion and reconciliation.

| Census year | Ossetians | Georgians | Russians | Armenians | Jews | Others | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | ||

| 1926 | 60,351 | 69.1% | 23,538 | 26.9% | 157 | 0.2% | 1,374 | 1.6% | 1,739 | 2.0% | 216 | 0.2% | 87,375 |

| 1939 | 72,266 | 68.1% | 27,525 | 25.9% | 2,111 | 2.0% | 1,537 | 1.4% | 1,979 | 1.9% | 700 | 0.7% | 106,118 |

| 1959 | 63,698 | 65.8% | 26,584 | 27.5% | 2,380 | 2.5% | 1,555 | 1.6% | 1,723 | 1.8% | 867 | 0.9% | 96,807 |

| 1970 | 66,073 | 66.5% | 28,125 | 28.3% | 1,574 | 1.6% | 1,254 | 1.3% | 1,485 | 1.5% | 910 | 0.9% | 99,421 |

| 1979 | 65,077 | 66.4% | 28,187 | 28.8% | 2,046 | 2.1% | 953 | 1.0% | 654 | 0.7% | 1,071 | 1.1% | 97,988 |

| 1989 | 65,232 | 66.2% | 28,544 | 29.0% | 2,128 | 2.2% | 984 | 1.0% | 397 | 0.4% | 1,242 | 1.3% | 98,527 |

| 2015 | 48,146 | 89.9% | 3,966 | 7.4% | 610 | 1.1% | 378 | 0.7% | 1 | <0.1% | 431 | 0.8% | 53,532 |

8.2. Languages

The official languages of South Ossetia are Ossetian and Russian. Ossetian, an Iranian language, is the language of the majority ethnic group and is used in daily life, media, and education. Russian is widely spoken and understood, serving as a language of inter-ethnic communication, administration, higher education, and as a link to the Russian Federation.

The Georgian language was historically spoken by a significant minority, particularly in areas like the Akhalgori district. However, its usage has declined considerably due to the displacement of ethnic Georgians and political tensions. The status and use of Georgian in education and public life within South Ossetia are now minimal. Other minority languages, such as Armenian, are spoken within smaller communities.

8.3. Religion

The predominant religion in South Ossetia is Eastern Orthodox Christianity. This is the faith of the majority of Ossetians, as well as ethnic Russians and Georgians who historically resided or still reside in the region. Religious life for Orthodox Christians in South Ossetia is largely aligned with the Russian Orthodox Church. While nominally under the jurisdiction of the Georgian Orthodox Church, the de facto authorities support clergy often linked to Russian Orthodox structures or non-canonical Ossetian Orthodox groups.

There are also small communities of other faiths, including Islam, primarily among some Ossetians whose ancestors adopted it (particularly those with links to Digor Ossetians in North Ossetia), though Islam is not widespread in South Ossetia itself. Assianism (УацдинUatsdinOssetian), a revival of Ossetian traditional folk religion, also has some followers, often syncretized with Christian practices.

9. Culture

South Ossetian culture is rooted in the traditions of the Ossetian people, with influences from the broader Caucasus region and historical ties with Georgia and Russia. This section introduces aspects of education, sports, and public holidays in South Ossetia.

9.1. Education

The education system in South Ossetia includes primary, secondary, and higher education. Instruction is primarily in Ossetian and Russian. The main institution of higher learning is the South Ossetian State University in Tskhinvali, which offers programs in various fields. After the 2008 Russo-Georgian War, there were efforts by education officials to facilitate the enrollment of university-bound students from South Ossetia into Russian post-secondary institutions, reflecting the region's close ties with Russia. The curriculum and educational standards are often aligned with those of the Russian Federation. Access to education for the remaining Georgian-speaking population in their native language has been severely restricted.

9.2. Sport

Football is a popular sport in South Ossetia. The South Ossetia national football team is not a member of FIFA or UEFA due to the region's disputed political status. However, it participates in tournaments organized by the Confederation of Independent Football Associations (CONIFA), an organization for football associations not affiliated with FIFA. The team notably won the 2019 CONIFA European Football Cup. Other popular sports include wrestling, which has a strong tradition in the Caucasus region, and various martial arts.

9.3. Public holidays

South Ossetia observes a number of public holidays that reflect its historical, cultural, and political identity. Some of the main public holidays include:

- New Year's Day** (January 1-2)

- Defender of the Fatherland Day** (February 23) - A holiday also celebrated in Russia.

- International Women's Day** (March 8)

- Day of the Republic** (September 20) - Commemorates the declaration of the South Ossetian Soviet Democratic Republic in 1990.

- Day of Courage and National Unity** (May 23)

- Day of State Independence of the Republic of South Ossetia** (May 29) - Marks the adoption of the Act of State Independence in 1992.

- Day of Recognition of Independence by Russia** (August 26) - Commemorates Russia's recognition of South Ossetia's independence in 2008.

- Constitution Day** (November 2) - Marks the adoption of the first constitution in 1993.

Religious holidays, particularly Orthodox Christian celebrations like Easter and Christmas, are also widely observed.

10. Human Rights Situation and Controversies

The human rights situation in South Ossetia has been a subject of significant concern, particularly following the armed conflicts and due to its unresolved political status. International human rights organizations and observers have reported numerous issues, many of which disproportionately affect ethnic Georgians and other minorities.

Allegations of ethnic cleansing of Georgians have been prominent, especially in the aftermath of the 2008 war. Reports from organizations like Human Rights Watch and findings from the EU-sponsored fact-finding mission indicated systematic destruction of ethnic Georgian villages and actions aimed at preventing the return of displaced Georgians. South Ossetian authorities at the time, including then-president Eduard Kokoity, made statements confirming an unwillingness to allow ethnic Georgians to return to certain areas.

The plight of internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees remains a critical issue. Tens of thousands of ethnic Georgians were displaced from South Ossetia, and a significant number of Ossetians were displaced from other parts of Georgia. While some Ossetian IDPs returned to South Ossetia, the vast majority of Georgian IDPs have been unable to return to their homes, facing loss of property and livelihoods. Their property rights are largely unprotected within South Ossetia.

Freedom of movement is severely restricted. The administrative boundary line (ABL) with Georgian-controlled territory is heavily controlled by Russian and South Ossetian forces, with frequent detentions of individuals for "illegal border crossings." The closure of crossing points, particularly those serving the Akhalgori (Leningor) district which had a significant ethnic Georgian population, has had severe humanitarian consequences, limiting access to healthcare, education, pensions, and family connections for the local population.

Access to justice for victims of the conflicts and human rights abuses is limited. Impunity for past atrocities and ongoing violations remains a problem. The de facto authorities' justice system is not recognized internationally, and its capacity to provide fair trials and redress is questioned. Ethnic Georgians remaining in South Ossetia, particularly in the Akhalgori district, have reported discrimination and pressure regarding language, education, and documentation.

Reports from international bodies like the OHCHR, the Council of Europe, and the OSCE have consistently highlighted these concerns. The Georgian government views these issues as direct consequences of Russian occupation and the actions of the de facto authorities. Russian and South Ossetian authorities generally deny allegations of systematic human rights abuses, often attributing problems to the consequences of Georgian aggression or legitimate security measures. The lack of access for international human rights monitoring mechanisms to South Ossetia further complicates independent verification and accountability efforts. The overall human rights situation underscores the profound social impact of the conflict and the challenges to democratic development and the rule of law in the region. The death of Inal Djabiev in custody in 2020 and the subsequent protests highlighted serious issues within the local law enforcement and justice system, leading to some governmental changes but persistent concerns about accountability.