1. Overview

Bolivia, officially the Plurinational State of Bolivia, is a landlocked country situated in central South America. It is bordered by Brazil to the north and east, Paraguay to the southeast, Argentina to the south, Chile to the southwest, and Peru to the west. Bolivia's geography is diverse, ranging from the snow-capped peaks of the Andes in the west to the eastern lowlands of the Amazon basin and the Gran Chaco. Sucre is the constitutional capital, housing the judiciary, while La Paz serves as the seat of government, accommodating the executive and legislative branches. The largest city and principal economic hub is Santa Cruz de la Sierra.

Historically, the region that is now Bolivia was part of the Inca Empire before Spanish colonization in the 16th century. During this period, it was known as Upper Peru and administered under the Viceroyalty of Peru. The exploitation of silver mines, particularly in Potosí, was central to the colonial economy and often relied on the forced labor of indigenous populations. Bolivia achieved independence in 1825, named in honor of Simón Bolívar, a key figure in the Spanish American wars of independence. The nation's history has been marked by political instability, significant territorial losses to neighboring countries, including its Pacific coastline in the War of the Pacific, and persistent social and economic challenges. The 20th century saw periods of military rule, including the repressive dictatorship of Hugo Banzer, intertwined with efforts towards democratic governance and social reform, such as the transformative 1952 Bolivian National Revolution.

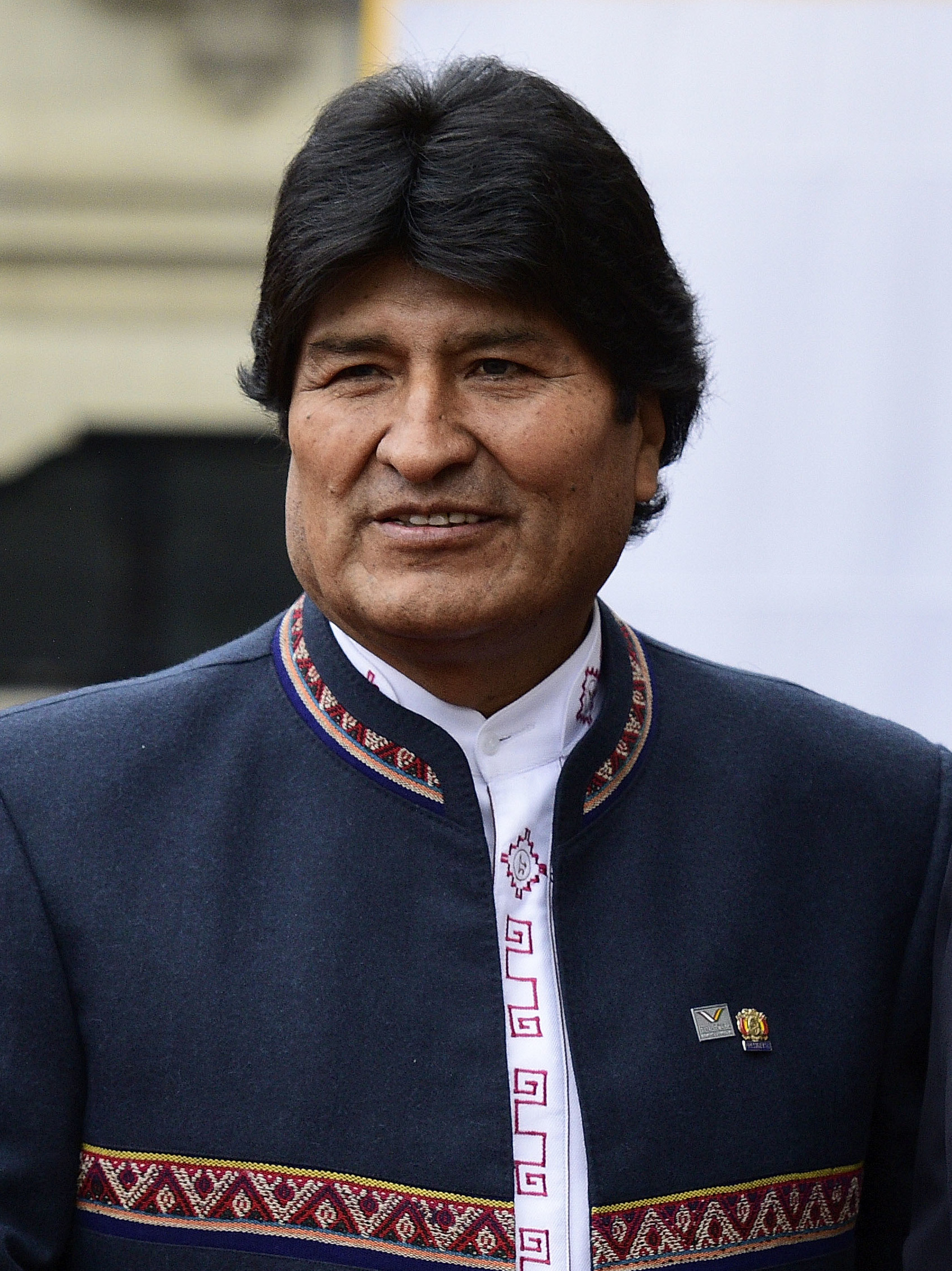

In the 21st century, Bolivia has undergone profound transformations, notably under the presidency of Evo Morales, its first indigenous head of state. His administration implemented socialist policies, nationalized key industries, enacted a new constitution establishing a plurinational state, and achieved significant reductions in poverty alongside economic growth. However, his tenure was also marked by controversies regarding extended presidential terms and democratic norms, culminating in a political crisis in 2019. Following an interim government, the Movement for Socialism (MAS) party returned to power with the election of Luis Arce in 2020. Bolivia continues to navigate challenges related to social equity, indigenous rights, democratic development, and sustainable progress, including an attempted coup d'état in 2024.

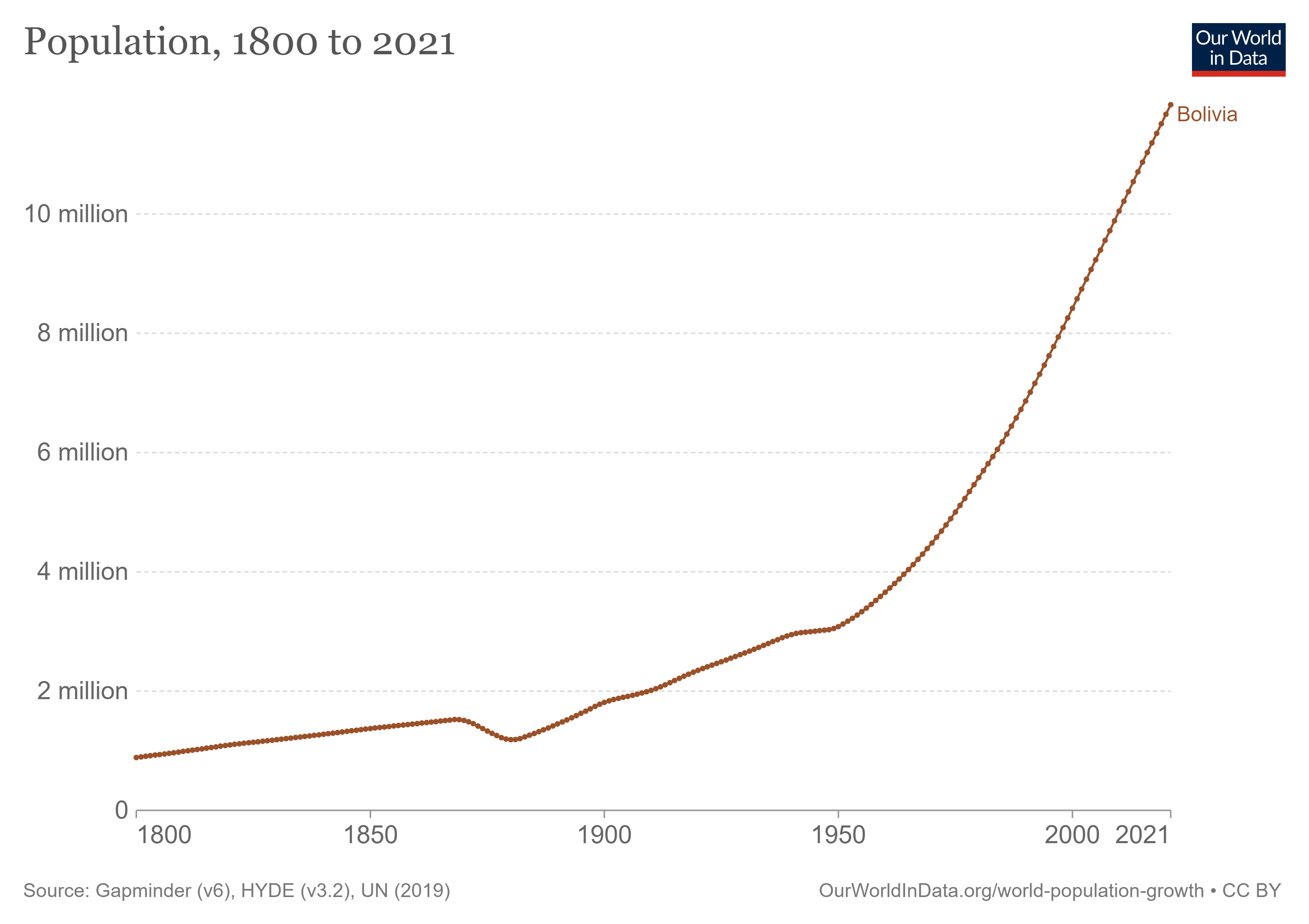

Bolivia is a developing country rich in natural resources, including vast deposits of lithium, natural gas, tin, and silver. Its economy relies on agriculture, mining, and manufacturing. The population of approximately 12 million is multiethnic, comprising indigenous peoples (such as Quechuas and Aymaras), Mestizos, Europeans, Asians, and Afro-Bolivians. This diversity is reflected in its culture, languages, and traditions, with Spanish and 36 indigenous languages holding official status. Bolivia is recognized for its exceptional biodiversity, making it one of the world's megadiverse countries, and its commitment to environmental protection, including unique legal frameworks like the Law of the Rights of Mother Earth.

2. Etymology

Bolivia is named after Simón Bolívar, a Venezuelan military and political leader who played a crucial role in the independence movements of several South American countries from Spanish rule. The territory, formerly known as Upper Peru or Charcas during the colonial period, was liberated by forces led by Bolívar and Antonio José de Sucre. Upon achieving independence on August 6, 1825, the newly formed republic was initially named the Republic of Bolívar (República de BolívarRepublic of BolívarSpanish).

A few days after the declaration of independence, a congressman named Manuel Martín Cruz proposed a change to the name. He famously argued, "If from Romulus comes Rome, then from Bolívar comes Bolivia" (Si de Rómulo, Roma; de Bolívar, BoliviaIf from Romulus, Rome; from Bolívar, BoliviaSpanish). This suggestion was formally approved, and the country officially adopted the name Bolivia on October 3, 1825.

In 2009, a new constitution was enacted, which changed the country's official name to the Plurinational State of Bolivia (Estado Plurinacional de BoliviaPlurinational State of BoliviaSpanish). This change was intended to officially recognize and reflect the multi-ethnic and multicultural nature of the country, particularly the significant presence and rights of its diverse indigenous populations. The term "plurinational" emphasizes the existence of multiple "nations" or indigenous groups within a single state, promoting their self-determination and cultural preservation. The official names in some of the prominent indigenous languages include Puliwya Achka Aylluska MamallaqtaPuliwya Achka Aylluska MamallaqtaQuechua in Quechua, Wuliwya Walja Ayllunakana MarkaWuliwya Walja Ayllunakana MarkaAymara in Aymara, and Tetã Hetate'ýigua VolíviaTetã Hetate'ýigua VolíviaGuarani in Guarani.

3. History

The history of Bolivia spans from ancient indigenous civilizations through Spanish colonization, the struggle for independence, periods of political instability and military rule, and recent efforts towards social and democratic reform. Key themes include the exploitation of natural resources, the enduring presence and resilience of indigenous cultures, territorial losses, and the ongoing pursuit of national identity and social equity. These periods collectively shape the nation's complex past and inform its present challenges and aspirations for a more equitable and democratic future.

3.1. Pre-Columbian Era

The region now known as Bolivia was inhabited for over 2,500 years before the arrival of the Spanish. One of the most significant early civilizations was the Tiwanaku culture (also spelled Tiahuanaco), which centered around the city of Tiwanaku, located near the southern shores of Lake Titicaca in western Bolivia. The capital city of Tiwanaku dates back as early as 1500 BC, when it was a small, agriculturally-based village. The community grew to urban proportions between 600 AD and 800 AD, becoming an important regional power in the southern Andes. At its peak, Tiwanaku covered approximately 2.5 mile2 (6.5 km2) and had a population estimated between 15,000 and 30,000 inhabitants, though some satellite imagery analyses of agricultural systems suggest a much larger carrying capacity.

Around 400 AD, Tiwanaku expanded its influence, reaching into the Yungas valleys and extending its culture and trade networks into present-day Peru, Bolivia, and Chile. Tiwanaku's expansion was characterized more by political astuteness, the establishment of colonies, trade agreements, and the spread of its religious cults rather than by military conquest. The Tiwanaku civilization developed advanced agricultural techniques, such as raised fields (suka qullu), and was known for its monumental architecture, intricate pottery, and sophisticated understanding of astronomy. Iconic structures like the Gate of the Sun stand as testaments to their achievements. The empire began to decline around 1000 AD, possibly due to climate change and drought, which impacted its agricultural base and led to the dispersal of its population.

Following the decline of Tiwanaku, various Aymara kingdoms, also known as the "Aymara seigneuries" or señoríos, emerged and flourished in the Altiplano region, particularly around Lake Titicaca. These kingdoms, such as the Colla, Lupaka, and Pacajes, maintained distinct cultural identities and often engaged in conflicts and alliances with each other.

Between 1438 and 1527, the Inca Empire, expanding from its capital at Cusco (in modern-day Peru), gradually conquered the Aymara kingdoms and incorporated the Bolivian highlands into its vast domain, known as Tawantinsuyu. The region became part of the Inca administrative division of Qullasuyu. The Incas imposed their political and economic systems, built roads, and established administrative centers, but also allowed local Aymara lords to retain some degree of autonomy. Inca influence was primarily concentrated in the Andean highlands, while the eastern and northern lowlands of Bolivia remained inhabited by independent Amazonian and Guaraní tribes.

3.2. Spanish Colonial Period

The Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire began in 1524 and was largely completed by 1533 with the capture and execution of the Inca emperor Atahualpa. The territory now known as Bolivia, then referred to as Upper Peru (Alto PerúHigh PeruSpanish) or Charcas, was brought under Spanish control by conquistadors arriving from Cusco. In 1538, Gonzalo Pizarro led an expedition that subdued local indigenous resistance.

Spanish colonial administration was established through the Viceroyalty of Peru, with Lima as its capital. Local governance for Upper Peru was centered in the Real Audiencia of Charcas, established in 1559 and based in the city of La Plata (also known as Chuquisaca, and later Sucre).

The discovery of immense silver deposits at Cerro Rico ("Rich Hill") in Potosí in 1545 dramatically transformed the region and the Spanish Empire. Potosí quickly became one of the largest and wealthiest cities in the New World, with a population exceeding 150,000 at its peak. Bolivian silver became a crucial source of revenue for Spain, funding its European wars and global empire. The extraction of silver relied heavily on a system of forced indigenous labor known as the mita. This system, adapted from an Inca precedent, compelled indigenous communities to send laborers to work in the mines and refineries under brutal and often deadly conditions. The immense wealth generated by Potosí came at a tremendous human cost, with countless indigenous lives lost due to overwork, accidents, and disease. This exploitation was a hallmark of the colonial system, prioritizing resource extraction over the well-being of the native population, an approach that deeply impacted the social fabric and fueled future resentments.

The colonial social structure was rigidly hierarchical, with Spanish-born peninsulares at the top, followed by American-born Spaniards (Creoles), Mestizos (people of mixed European and indigenous ancestry), indigenous peoples, and enslaved Africans. Indigenous communities were subjected to tribute payments and forced labor, and their lands were often expropriated.

Despite Spanish control, resistance to colonial rule occurred throughout the period. One of the most significant uprisings was led by Túpac Katari, an Aymara leader, who, in conjunction with the rebellion of Túpac Amaru II in Peru, laid siege to La Paz in 1781. The siege lasted for months and resulted in the deaths of thousands, but was ultimately suppressed by Spanish forces. These early resistance movements, though unsuccessful, laid the groundwork for future independence struggles and demonstrated the deep-seated desire for self-determination among indigenous populations.

In 1776, Upper Peru was transferred from the Viceroyalty of Peru to the newly created Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, with its capital in Buenos Aires. This administrative change shifted economic and political ties, contributing to growing regional identities and discontent among the Creole elite, who resented Spanish trade monopolies and political exclusion. As Spanish royal authority weakened during the Napoleonic Wars at the beginning of the 19th century, the sentiment against colonial rule intensified, paving the way for the wars of independence.

3.3. Independence and Early Republic

The struggle for Bolivian independence began in the early 19th century, fueled by the Enlightenment ideals, the weakening of Spanish authority due to the Napoleonic Wars in Europe, and growing Creole resentment towards colonial rule. The first calls for self-government emerged in 1809 with uprisings in Chuquisaca (present-day Sucre) on May 25 (the Chuquisaca Revolution) and in La Paz on July 16 (the La Paz revolution). While the Chuquisaca Revolution established a local junta in the name of the deposed Spanish King Ferdinand VII, the La Paz revolution marked a more radical break with Spanish authority. Both these early movements were suppressed by royalist forces, but they ignited a prolonged period of conflict.

For sixteen years, Upper Peru became a battleground between patriot forces, often supported by armies from the newly independent United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (Argentina), and royalist troops loyal to the Spanish Crown. The region was captured and recaptured multiple times. The decisive phase of the independence war came with the intervention of external liberation armies. Simón Bolívar, leading forces from the north (Gran Colombia), and his lieutenant, Antonio José de Sucre, played pivotal roles. After Bolívar's victory at the Battle of Junín (1824) and Sucre's decisive triumph at the Battle of Ayacucho (December 9, 1824) in Peru, which effectively ended Spanish power in South America, Sucre led his troops into Upper Peru.

On April 1, 1825, Sucre defeated the last significant royalist forces at the Battle of Tumusla. Following this, a general assembly was convened in Chuquisaca. On August 6, 1825, the assembly declared the independence of Upper Peru, establishing a new republic. The new nation was named "República Bolívar" in honor of Simón Bolívar, who drafted its first constitution. This was later changed to "Bolivia." Sucre became the first president of Bolivia (though Bolívar briefly held the title before him).

The early years of the republic were fraught with challenges. Bolivia faced political instability, economic hardship due to the long wars, regional caudillismo (rule by strongmen), and undefined borders. The nation struggled to establish a stable government and a cohesive national identity. The exploitation of silver, which had been the backbone of the colonial economy, had declined, and the new republic needed to find new economic foundations. Social divisions between Creoles, Mestizos, and the indigenous majority persisted. Building a functional state and integrating its diverse population proved to be a formidable task for the nascent republic.

3.3.1. Peru-Bolivian Confederation (1836-1839)

The Peru-Bolivian Confederation was a short-lived state that existed from 1836 to 1839, uniting Peru and Bolivia under the leadership of Bolivian President Andrés de Santa Cruz. Santa Cruz, an ambitious and capable leader of mixed Aymara and Spanish heritage, aimed to recreate a powerful political entity in the Andes, reminiscent of the former Inca Empire and the Viceroyalty of Peru.

The formation of the Confederation was facilitated by political instability in Peru. Santa Cruz intervened in a Peruvian civil war, supporting one faction and ultimately dividing Peru into two republics: North Peru and South Peru. These two entities, along with Bolivia, formed the Confederation. Santa Cruz assumed the title of "Supreme Protector" of the Confederation, effectively its head of state. The Confederation implemented various administrative, economic, and military reforms, seeking to centralize power and promote development.

However, the Confederation faced significant internal and external opposition. Within Peru, many resented Bolivian dominance and Santa Cruz's authoritarian style. Externally, neighboring countries, particularly Chile and Argentina, viewed the powerful Confederation as a threat to the regional balance of power and their own geopolitical interests. Chile, under the influence of minister Diego Portales, was especially hostile, fearing the rise of a dominant Andean power.

These tensions led to the War of the Confederation (1836-1839). Chile, allied with Peruvian dissidents opposed to Santa Cruz, launched military expeditions against the Confederation. Argentina also declared war but played a less significant role. Initially, Santa Cruz's forces achieved some victories, notably defeating a Chilean expedition at Paucarpata in 1837. However, a second, larger Chilean expedition proved decisive. On January 20, 1839, the Confederate army was decisively defeated by Chilean and Peruvian dissident forces at the Battle of Yungay.

The defeat at Yungay led to the collapse of the Peru-Bolivian Confederation. Andrés de Santa Cruz resigned and went into exile. Peru and Bolivia reverted to being separate, independent states. The dissolution of the Confederation had a lasting impact on Bolivia, marking the end of its most ambitious attempt to project regional power. It also exacerbated existing political divisions and contributed to a period of instability within Bolivia. For Peru, it reinforced its national identity separate from Bolivia. The war also established Chile as a significant military power in the Pacific region.

3.3.2. War of the Pacific (1879-1883) and Territorial Losses

The War of the Pacific (Guerra del PacíficoWar of the PacificSpanish) was a major conflict fought between Chile and an alliance of Bolivia and Peru from 1879 to 1884. The primary causes of the war were economic, centered on the control of valuable nitrate (saltpeter) deposits in the Atacama Desert, a region where the borders of the three countries were poorly defined. Bolivia's Litoral Department, its only coastal territory, was rich in these nitrate resources, as well as guano and copper.

Tensions escalated in the late 1870s due to disputes over taxation. In 1878, Bolivia imposed a new tax on a Chilean nitrate mining company, the Compañía de Salitres y Ferrocarril de Antofagasta (CSFA), operating in Bolivian territory. Chile argued this violated an 1874 treaty that prohibited new taxes on Chilean enterprises for 25 years. When Bolivia insisted on the tax and subsequently moved to confiscate the company's assets, Chile responded by occupying the Bolivian port city of Antofagasta on February 14, 1879.

Bolivia declared war on Chile on March 1, 1879. Peru, bound by a secret treaty of alliance with Bolivia signed in 1873, was drawn into the conflict after Chile demanded its neutrality and Peru refused. Chile then declared war on both Bolivia and Peru on April 5, 1879.

The war was fought on land and at sea. Chile's superior naval power proved decisive early on, allowing it to control sea lanes and project its forces along the coast. Bolivian and Peruvian forces, despite some notable instances of bravery and resistance (like the Battle of Topáter where Bolivian hero Eduardo Abaroa died), were generally outmatched in terms of military organization, training, and equipment. Key battles included the naval Battle of Angamos (1879), where the Peruvian ironclad Huáscar was captured, and land battles such as Tacna (1880) and Arica (1880).

Bolivia effectively withdrew from active combat after the defeat at Tacna in 1880, leaving Peru to face Chile alone. Chilean forces went on to occupy Lima in 1881. The war officially ended with the Treaty of Ancón between Chile and Peru in 1883, and a truce between Chile and Bolivia in 1884 (the Pact of Valparaíso).

The consequences for Bolivia were severe and long-lasting. It lost its entire Litoral Department, including the port of Antofagasta, to Chile, thus becoming a landlocked nation. This loss of sovereign access to the Pacific Ocean has had profound socio-economic and diplomatic repercussions for Bolivia, hindering its trade and economic development. The desire to regain access to the sea has remained a central and deeply emotional issue in Bolivian foreign policy and national identity, representing a significant point of national grievance and impacting regional relations. The war also exacerbated political instability within Bolivia and left a legacy of resentment towards Chile. For Chile, the victory resulted in the acquisition of resource-rich territories that fueled its economic growth for decades.

3.4. Early 20th Century

The early 20th century in Bolivia was characterized by the rise of the tin mining industry, which replaced silver as the country's primary source of wealth, persistent political instability, further territorial losses, and challenging socio-economic conditions for the majority of its population.

The demand for tin, driven by industrialization in Europe and North America, led to a boom in Bolivian tin mining. Figures like Simón Iturri Patiño, Carlos Víctor Aramayo, and Mauricio Hochschild became immensely wealthy "tin barons," controlling a significant portion of the national economy and wielding considerable political influence. While the tin industry generated substantial export revenues, much of the wealth was concentrated in the hands of these few magnates and foreign investors, with little benefit accruing to the broader population or national development. Working conditions in the mines remained harsh and dangerous for indigenous and mestizo laborers, highlighting the exploitative nature of the industry for many.

Politically, the period was marked by the dominance of an oligarchy, often referred to as "la Rosca," comprising mine owners, landowners, and their political allies. Governments, frequently led by figures from the Liberal and Republican parties, generally pursued laissez-faire capitalist policies that favored the interests of the economic elite. Political power was often contested, leading to frequent changes in government, coups, and a general climate of instability.

Territorial disputes continued to plague Bolivia. The most significant of these was the Acre dispute with Brazil. The Acre region, rich in rubber, was located in the Amazonian lowlands. Attracted by the rubber boom, Brazilian settlers and rubber tappers had moved into the territory. Tensions escalated, leading to armed conflict between 1899 and 1903. Ultimately, Bolivia was forced to cede the Acre territory (about 74 K mile2 (191.00 K km2)) to Brazil under the Treaty of Petrópolis in 1903, in exchange for a monetary payment and promises of railway construction, which were only partially fulfilled. This loss further reduced Bolivia's vast original territory. Through diplomatic channels in 1909, it also lost the basin of the Madre de Dios River and the territory of the Purus in the Amazon, yielding 97 K mile2 (250.00 K km2) to Peru.

Socio-economically, the indigenous majority continued to face marginalization and exploitation. Land ownership remained highly concentrated, with many indigenous peasants working as serfs or debt peons on large haciendas. Access to education, healthcare, and political participation was extremely limited for most Bolivians. The stark inequalities and lack of social mobility fueled growing discontent, though organized labor and peasant movements were still in their nascent stages. The early 20th century laid the groundwork for more profound social and political upheavals that would occur later in the century.

3.4.1. Chaco War (1932-1935) and its Impact

The Chaco War was a devastating conflict fought between Bolivia and Paraguay from September 9, 1932, to June 12, 1935, over control of the northern part of the Gran Chaco region, a sparsely populated and arid territory thought to be rich in oil. Both landlocked nations sought to gain access to the Paraguay River, which would provide a route to the Atlantic Ocean, and believed oil reserves lay beneath the Chaco.

The causes of the war were complex, involving long-standing border disputes, nationalistic fervor in both countries, the influence of oil companies (Standard Oil supporting Bolivia and Royal Dutch Shell allegedly backing Paraguay, though this is debated), and the desire of both governments to distract from internal economic and political problems, exacerbated by the Great Depression. Border skirmishes had been occurring for years, but escalated into full-scale war in 1932.

The war was fought under extremely harsh conditions in the hot, arid, and disease-ridden Chaco. Both armies were composed largely of conscripted indigenous soldiers who were often ill-equipped, poorly supplied, and unaccustomed to the terrain. Paraguay, though smaller and poorer, proved to be more effectively led and its soldiers demonstrated greater motivation and knowledge of the terrain. Bolivian forces, despite initial numerical and material advantages, suffered from logistical difficulties due to the long supply lines from the Andean highlands, poor leadership, and low morale among its highland indigenous troops who struggled in the lowland climate.

Major battles, such as Boquerón, Nanawa, and Villamontes, resulted in heavy casualties on both sides from combat, disease (especially malaria and dysentery), and thirst. Paraguay generally had the upper hand militarily, pushing Bolivian forces back and occupying most ofthe disputed territory.

By 1935, both nations were exhausted economically and humanly. A ceasefire was brokered on June 12, 1935, and a final peace treaty, the Chaco Treaty, was signed in 1938 in Buenos Aires. Under the terms of the treaty, Paraguay was awarded about three-quarters of the disputed Chaco Boreal territory, while Bolivia retained a small portion, including some access to the Paraguay River via Puerto Busch. The suspected oil reserves in the awarded Paraguayan territory later proved to be minimal.

The Chaco War had a profound and lasting impact on Bolivia. It resulted in further territorial losses (approximately 89 K mile2 (230.00 K km2)), an estimated 50,000 to 65,000 Bolivian deaths, and immense economic costs. More significantly, the defeat led to a deep national crisis of identity and confidence. It exposed the incompetence and corruption of the traditional ruling elite and the military leadership, and highlighted the stark social inequalities within the country, particularly the suffering and sacrifice of indigenous soldiers. The war fueled a sense of national humiliation and a desire for radical change, contributing to the rise of new political movements, including nationalist and socialist ideologies. It played a crucial role in awakening political consciousness among veterans and intellectuals, paving the way for the Bolivian National Revolution of 1952. The devastating human cost and perceived injustice fueled popular demands for social reform and greater accountability from the government.

3.5. Bolivian National Revolution and Military Rule

The Bolivian National Revolution of 1952, led by the Revolutionary Nationalist Movement (MNR), marked a pivotal turning point in Bolivian history, bringing about significant social, economic, and political reforms aimed at empowering the historically marginalized indigenous majority and restructuring the state. The revolution was the culmination of decades of social unrest, indigenous marginalization, and frustration following the Chaco War.

The MNR, a party with a broad base including intellectuals, middle-class reformers, and mine workers, had won the 1951 presidential elections with Víctor Paz Estenssoro as its candidate, but a military junta prevented him from taking office. This denial of the popular vote triggered a popular uprising in April 1952, supported by armed mine workers and segments of the police and military. After three days of fighting, the military junta was overthrown, and Paz Estenssoro assumed the presidency.

The revolutionary government implemented a series of sweeping reforms:

1. Nationalization of Mines: The government nationalized the country's three largest tin mining companies (Patiño, Hochschild, and Aramayo), which had long dominated the economy, creating the state-owned mining corporation, COMIBOL. This was a highly popular move aimed at reclaiming national wealth for public benefit.

2. Agrarian Reform: A comprehensive land reform program was enacted in 1953, breaking up large haciendas (estates) and redistributing land to indigenous peasants, who had previously worked under near-feudal conditions. While the implementation was complex and had mixed long-term results, it fundamentally altered rural social structures and empowered indigenous communities by granting them land tenure.

3. Universal Suffrage: The right to vote was extended to all adult citizens, including indigenous people and women, who had previously been excluded. This dramatically expanded political participation and democratic representation.

4. Educational Reform: Efforts were made to expand access to education, particularly in rural areas, and to promote literacy, aiming to integrate indigenous populations more fully into national life.

5. Military Reorganization: The traditional army, seen as an instrument of the oligarchy, was initially dismantled and later reorganized. Workers' and peasants' militias were formed, though their influence waned over time.

While the revolution brought about profound changes and improved the status of the indigenous majority, it also faced significant challenges. Economic difficulties, internal divisions within the MNR, and pressure from the United States (which initially viewed the revolution with suspicion but later provided aid) led to a moderation of some of its more radical policies.

The period following the initial revolutionary fervor was marked by increasing political instability. After twelve years of MNR rule (Paz Estenssoro 1952-1956, Hernán Siles Zuazo 1956-1960, Paz Estenssoro 1960-1964), Paz Estenssoro was overthrown in a military coup in November 1964, led by his own Vice President, General René Barrientos, and General Alfredo Ovando Candía.

This coup ushered in a long period of military dictatorships and weak civilian governments that often suppressed democratic movements and labor unions, rolling back some of the revolution's progressive gains. Barrientos himself ruled until his death in a helicopter crash in 1969, followed by a succession of short-lived governments. Military figures like Ovando Candía and Juan José Torres (who pursued a more leftist, nationalist agenda prioritizing popular interests) held power briefly before being overthrown by further coups. This era was characterized by authoritarianism, human rights abuses, and the frequent intervention of the military in politics, often with the backing or acquiescence of external powers concerned about leftist influences during the Cold War. The democratic aspirations awakened by the 1952 revolution were largely stifled during these years of military dominance, highlighting the fragility of democratic institutions in the face of entrenched interests and geopolitical pressures.

3.5.1. Che Guevara's Guerrilla Campaign (1966-1967)

In the mid-1960s, the iconic Argentine-Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara chose Bolivia as the staging ground for his ambitious plan to ignite a continent-wide revolution in South America, a concept known as the "foco" theory of guerrilla warfare. Guevara believed that a small, well-organized guerrilla force could inspire widespread peasant uprisings and topple existing governments, creating "one, two, three, many Vietnams."

Guevara arrived secretly in Bolivia in November 1966, using a false identity. He established a guerrilla group called the Ejército de Liberación Nacional de Bolivia (ELN - National Liberation Army of Bolivia) in the remote, rugged, and sparsely populated Ñancahuazú region in southeastern Bolivia. His force was small, consisting of a few dozen Cuban veterans and a mix of Bolivian recruits and international volunteers.

From the outset, Guevara's campaign faced numerous and ultimately insurmountable challenges:

1. Lack of Peasant Support: Contrary to Guevara's expectations, the local indigenous peasantry did not rally to his cause. They were largely suspicious of the foreign guerrillas, did not understand their communist ideology, and often collaborated with the Bolivian army, providing intelligence. The region chosen was not one of high peasant discontent, and land reforms from the 1952 revolution had, to some extent, addressed rural grievances in other areas. This lack of popular mobilization was a critical failure.

2. Isolation and Hostile Terrain: The Ñancahuazú region was geographically isolated, making supply and communication extremely difficult. The terrain was harsh, and the guerrillas were unfamiliar with it.

3. Internal Divisions: The ELN suffered from internal dissent and a lack of cohesion. The Bolivian Communist Party, led by Mario Monje, refused to fully support Guevara's efforts after disagreements over leadership and strategy, depriving the guerrillas of crucial urban support networks and recruits.

4. Effective Counter-Insurgency: The Bolivian military, under President René Barrientos, received significant counter-insurgency training, intelligence, and logistical support from the United States, including CIA operatives and U.S. Army Special Forces. Bolivian ranger battalions were specifically trained to combat the guerrillas.

The ELN engaged in several skirmishes with the Bolivian army throughout 1967, initially achieving some minor successes. However, as the army's operations intensified and the guerrillas' situation became more desperate due to lack of food, supplies, and local support, their numbers dwindled.

On October 8, 1967, after a fierce firefight in the Yuro Ravine (Quebrada del Yuro), a wounded Guevara was captured by Bolivian rangers. He was taken to the nearby village of La Higuera. The following day, October 9, 1967, on orders from the Bolivian high command (reportedly with approval from President Barrientos and alleged CIA involvement in the decision-making process), Che Guevara was executed by Bolivian soldier Mario Terán. His body was later publicly displayed in Vallegrande to prove his death and then secretly buried.

The failure of Che Guevara's guerrilla campaign in Bolivia was a major setback for revolutionary movements in Latin America. It demonstrated the limitations of the "foco" theory when applied without sufficient local support and understanding of specific national conditions. While Guevara's death transformed him into a global icon of revolution and martyrdom, his Bolivian venture itself was a military and political disaster, highlighting the difficulties of exporting revolutionary models without grassroots backing. For Bolivia, it reinforced the government's anti-communist stance and demonstrated its capacity, with U.S. assistance, to suppress armed insurgency.

3.5.2. Hugo Banzer Dictatorship (1971-1978)

The dictatorship of General Hugo Banzer Suárez from 1971 to 1978 was one of the longest and most repressive periods of military rule in Bolivia's history. Banzer, an army colonel, came to power through a bloody coup d'état on August 21, 1971, overthrowing the leftist government of General Juan José Torres. Banzer's coup received support from conservative political factions, including a segment of the Revolutionary Nationalist Movement (MNR), and crucially, from the United States, which was wary of Torres's nationalist policies and perceived alignment with socialist ideologies during the Cold War. Banzer's rule represented a sharp turn towards right-wing authoritarianism.

Banzer's regime was characterized by:

1. Authoritarian Rule and Suppression of Dissent: Upon taking power, Banzer suspended constitutional guarantees, banned leftist political parties, dissolved labor unions (particularly the powerful Central Obrera Boliviana - COB), and closed universities. Political opposition was met with severe repression. This crackdown on democratic freedoms created a climate of fear and silenced critical voices.

2. Human Rights Violations: The dictatorship was responsible for widespread human rights abuses, including arbitrary arrests, imprisonment, torture, forced disappearances, and extrajudicial killings of political opponents, students, labor leaders, and suspected leftists. Estimates of those killed, tortured, or exiled vary, but the number is significant. Banzer's government participated in Operation Condor, a U.S.-backed campaign of political repression and state terror involving intelligence sharing and assassination of political opponents coordinated by right-wing dictatorships in South America. The systematic nature of these abuses left deep scars on Bolivian society.

3. Economic Policies and Foreign Investment: Initially, Banzer's government benefited from high international commodity prices (particularly for tin and oil), which led to a period of economic growth. The regime encouraged foreign investment and adopted policies favorable to private enterprise and agribusiness in the eastern lowlands. However, this growth was often accompanied by increased foreign debt and did not translate into widespread improvements in living standards for the majority of Bolivians, exacerbating existing inequalities.

4. U.S. Support: The United States government under President Richard Nixon provided significant political, economic, and military support to the Banzer regime, viewing it as a bulwark against communism in the region. This support was instrumental in consolidating Banzer's power.

By the mid-1970s, Banzer's regime faced growing internal and international pressure. Economic problems began to surface as commodity prices fell. Dissent, though repressed, continued to simmer. International condemnation of human rights abuses, particularly from organizations and the Carter administration in the U.S. (which emphasized human rights in its foreign policy), increased pressure for a return to democracy.

In response to these pressures, Banzer announced a plan for a gradual transition to democracy. However, his attempts to manipulate the process and extend his rule led to further instability. He was eventually forced to resign in July 1978 after an election widely considered fraudulent was annulled, and a series of short-lived military governments followed.

The Hugo Banzer dictatorship left a legacy of deep social and political divisions, a culture of impunity for human rights violators, and a weakened democratic tradition. Despite his authoritarian past, Banzer later returned to Bolivian politics as a democratically elected president from 1997 to 2001, a controversial comeback that highlighted the complex and often cyclical nature of Bolivian political history and the challenges of achieving lasting democratic consolidation and accountability for past atrocities.

3.6. Transition to Democracy and Neoliberal Era

The late 1970s and 1980s marked Bolivia's difficult transition from military dictatorship back to democratic rule, a period characterized by severe economic crises, including hyperinflation, and the subsequent implementation of neoliberal economic policies which had profound social consequences.

Following the ousting of Hugo Banzer in 1978, Bolivia experienced a tumultuous period with several short-lived military governments, fraudulent elections, and attempted coups. The 1980 election was won by Hernán Siles Zuazo of the leftist Democratic and Popular Unity (UDP) coalition, but General Luis García Meza staged a brutal coup (the "Cocaine Coup," so-named due to its alleged links with drug traffickers) before Siles Zuazo could take office. García Meza's regime (1980-1981) was exceptionally repressive and corrupt, leading to international isolation and widespread internal opposition. After García Meza was forced out in 1981, three more military governments followed in quick succession.

By 1982, with the country facing economic collapse and intense popular pressure, the military finally agreed to reconvene the Congress elected in 1980. In October 1982, Hernán Siles Zuazo was allowed to assume the presidency, marking the formal restoration of democratic rule. Siles Zuazo's government inherited a catastrophic economic situation, characterized by soaring foreign debt, plummeting commodity prices (especially for tin), and rampant inflation. His administration struggled to manage the economy, facing constant strikes, social unrest, and political opposition. By 1985, Bolivia was experiencing one of the worst hyperinflation episodes in world history, with annual inflation rates reaching over 20,000%.

In the 1985 elections, no candidate won an outright majority, and Congress chose Víctor Paz Estenssoro (of the MNR, serving his fourth and final term as president). Faced with economic chaos, Paz Estenssoro, historically a populist leader of the 1952 Revolution, implemented a radical economic stabilization program known as the New Economic Policy (NEP), through Supreme Decree 21060. This program, designed with advice from economist Jeffrey Sachs, represented a sharp turn towards neoliberalism. Key elements of the NEP included:

1. Fiscal Austerity: Drastic cuts in public spending.

2. Liberalization: Freezing wages, lifting price controls, liberalizing trade, and unifying the exchange rate.

3. Privatization: Opening state-owned enterprises to private investment (though large-scale privatization came later).

4. Debt Restructuring: Renegotiating foreign debt.

The NEP succeeded in quickly curbing hyperinflation and stabilizing the economy, but it came at a high social cost. Mass layoffs in state-owned industries (especially mining, as tin mines were closed or downsized), increased unemployment, and cuts in social services led to widespread hardship and popular protests. The powerful Central Obrera Boliviana (COB) labor federation fiercely opposed these policies, arguing they disproportionately harmed workers and the poor.

Subsequent governments in the late 1980s and 1990s, including those of Jaime Paz Zamora (1989-1993) and Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada (1993-1997, 2002-2003), largely continued and deepened these neoliberal reforms. This period, often termed the "neoliberal era," saw further privatization of state assets (including oil and gas, telecommunications, and airlines under Sánchez de Lozada's "capitalization" program), promotion of foreign investment, and adherence to IMF and World Bank prescriptions.

While these policies achieved macroeconomic stability and attracted some foreign investment, they also led to increased social inequality, unemployment, and popular discontent. The benefits of economic growth were not evenly distributed, and many Bolivians, particularly indigenous communities and the urban poor, felt marginalized and excluded. The dismantling of state enterprises weakened the organized labor movement, but new social movements, often based on indigenous identity and grassroots mobilization, began to emerge, challenging the neoliberal model and demanding greater social justice, popular participation, and respect for human rights. This growing discontent set the stage for the political upheavals of the early 21st century.

3.6.1. Governments of Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada (1993-1997, 2002-2003)

Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada, often known as "Goni," was a prominent Bolivian politician and businessman who served two non-consecutive terms as President of Bolivia. His presidencies were marked by ambitious neoliberal reforms, particularly the "capitalization" program, and significant social conflicts arising from these policies and broader economic issues, which ultimately led to popular uprisings and concerns over human rights.

First Presidency (1993-1997)

Sánchez de Lozada, leader of the Revolutionary Nationalist Movement (MNR), won the 1993 presidential election. His running mate, Víctor Hugo Cárdenas, an Aymara intellectual, became Bolivia's first indigenous Vice President, a move seen as an attempt to promote multicultural inclusion.

During his first term, Sánchez de Lozada implemented a comprehensive package of structural reforms, building on the New Economic Policy initiated by Paz Estenssoro. The centerpiece was the "capitalization" program. Unlike traditional privatization where state assets are sold outright, capitalization involved transferring 50% ownership and management control of major state-owned enterprises (in sectors like oil and gas (YPFB), telecommunications (ENTEL), electricity (ENDE), airlines (Lloyd Aéreo Boliviano), and railways (ENFE)) to private, often foreign, investors. In return, these investors committed to making significant capital investments in the enterprises. The remaining shares were to be distributed to Bolivian citizens over 18 through private pension funds (AFPs), theoretically making them co-owners.

Other significant reforms included:

- Popular Participation Law (1994)**: This law decentralized administrative and fiscal responsibilities to municipalities, granting them a share of national tax revenues and promoting local governance and citizen participation.

- Educational Reform Law (1994)**: Aimed to modernize the education system, introducing intercultural and bilingual education.

- Agrarian Reform Law (INRA Law, 1996)**: Sought to clarify land tenure and address land conflicts.

While these reforms were praised by international financial institutions for modernizing the state and attracting investment, they were highly controversial within Bolivia. Critics argued that capitalization led to the loss of national control over strategic resources, resulted in job losses, and did not significantly improve services or reduce poverty for the majority. The social impact of these neoliberal policies fueled protests and opposition from labor unions, peasant organizations, and indigenous groups who felt their livelihoods and rights were threatened.

Second Presidency (2002-2003)

Sánchez de Lozada returned to power after winning the 2002 presidential election, a period of economic difficulty and growing social unrest. His second term was short-lived and tumultuous. He faced a deepening economic crisis, and his government's proposals to address fiscal deficits, such as an income tax increase, were met with fierce public opposition, including a police mutiny in February 2003.

The defining crisis of his second presidency was the Gas War in September-October 2003. The government's plan to export Bolivian natural gas through Chile to markets in North America ignited massive protests, particularly in El Alto and La Paz. Protesters, led by indigenous movements, labor unions, and coca growers, opposed the export plan on several grounds: they demanded nationalization of gas resources, greater state revenue from gas exports, domestic industrialization of gas, and vehemently opposed routing the pipeline through Chile, Bolivia's historic adversary from the War of the Pacific.

The government responded to the protests with force, leading to violent clashes and dozens of deaths, primarily of protesters. The crackdown, seen as a severe human rights violation by many, further inflamed public anger. Faced with escalating unrest, loss of political support, and international condemnation of the violence, Sánchez de Lozada was forced to resign on October 17, 2003, and fled the country to the United States.

His vice president, Carlos Mesa, assumed the presidency. The fall of Sánchez de Lozada marked a significant turning point, signaling widespread rejection of the neoliberal model and paving the way for the rise of new political forces, including the Movement for Socialism (MAS) led by Evo Morales. Sánchez de Lozada has since faced legal charges in Bolivia related to the deaths during the Gas War, though extradition requests have been unsuccessful. His legacy remains highly divisive, seen by some as a modernizing reformer and by others as a symbol of unpopular neoliberal policies and state repression that undermined social progress and democratic accountability.

3.7. 21st Century: Socialist Movement and Political Turmoil

The 21st century in Bolivia has been characterized by profound political and social transformations, driven by the rise of powerful social movements, the ascent of its first indigenous president, attempts to implement socialist policies, and periods of intense political turmoil and polarization. This era reflects a broader shift in Latin American politics, with increased demands for social inclusion, indigenous rights, and national control over natural resources, alongside ongoing struggles over democratic governance and economic models, significantly impacting human rights and social progress.

3.7.1. Gas War and Carlos Mesa's Presidency (2003-2005)

The Gas War of October 2003 was a pivotal event stemming from widespread public opposition to the government's plan to export Bolivia's vast natural gas reserves, primarily to the United States and Mexico, via a pipeline through Chile. This plan, under President Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada, ignited massive protests, particularly in La Paz and El Alto. Indigenous groups, labor unions, coca growers, and students demanded the nationalization of hydrocarbons, greater state revenue from gas, domestic industrialization, and vehemently opposed any pipeline through Chile, due to historical animosity following the War of the Pacific. The government's violent repression of these protests, resulting in dozens of deaths, was widely condemned as a human rights crisis and led to Sánchez de Lozada's resignation and exile. This event underscored the deep public desire for resource sovereignty and social justice.

His vice president, Carlos Mesa, a historian and journalist without a strong party affiliation, assumed the presidency on October 17, 2003. Mesa's presidency was marked by an attempt to navigate the intense social pressures and political fragmentation. He called a binding referendum in July 2004 on the future of Bolivia's gas policy, which approved repealing the existing Hydrocarbons Law, granting the state greater control over gas resources, and supporting the state oil company YPFB. Mesa also initiated a new Hydrocarbons Law aimed at increasing state royalties and taxes on foreign energy companies.

However, Mesa struggled to maintain stability. He faced continued pressure from social movements demanding full nationalization and a constituent assembly to rewrite the constitution. Simultaneously, he faced opposition from business elites, particularly in the eastern lowlands (the "Media Luna" region), who sought greater regional autonomy and resisted increased state intervention in the economy. Protests, road blockades, and regional strikes became frequent. Unable to reconcile these conflicting demands and facing a loss of support from key political actors, Carlos Mesa offered his resignation multiple times. After prolonged unrest and an escalating crisis, his resignation was finally accepted by Congress on June 9, 2005. The head of the Supreme Court, Eduardo Rodríguez Veltzé, took over as an interim president, tasked with organizing new general elections. Mesa's presidency highlighted the deep divisions within Bolivian society and the immense challenge of governing in a context of popular mobilization and demands for radical change, setting the stage for a new political era focused on indigenous rights and social equity.

3.7.2. Evo Morales Presidency (2006-2019)

The presidency of Evo Morales Ayma, Bolivia's first indigenous head of state, from January 2006 to November 2019, represented a historic shift in the country's political landscape. Morales, leader of the Movement for Socialism (MAS) party and a former coca growers' union leader, came to power on a wave of popular discontent with neoliberal policies and a demand for greater indigenous inclusion, national sovereignty, and social progress.

Key Policies and Achievements:

- Nationalization of Industries**: Fulfilling a key campaign promise, Morales's government decreed the "nationalization" of the hydrocarbons sector in May 2006. This involved renegotiating contracts with foreign energy companies to significantly increase state control and revenue (royalties and taxes) from oil and gas production, with the state company YPFB taking a more dominant role. Similar measures were taken in other sectors like telecommunications and mining, aiming to redirect resource wealth towards public benefit.

- New Plurinational Constitution**: A constituent assembly was convened, and a new constitution was approved by referendum in 2009. This constitution officially established Bolivia as a "Plurinational State," recognizing the rights of its 36 indigenous nations, promoting indigenous autonomy, and enshrining principles of social justice, state control over natural resources, and expanded state intervention in the economy. It also allowed for presidential re-election (initially one consecutive term). This was a landmark achievement for indigenous rights.

- Poverty Reduction and Social Programs**: Benefiting from high commodity prices (especially for gas) and increased state revenues, the Morales administration significantly expanded social programs. These included conditional cash transfers (like the Juancito Pinto bonus for school attendance and the Renta Dignidad universal old-age pension), investments in health and education, and infrastructure projects. These policies led to a notable reduction in poverty and extreme poverty, and improvements in some social indicators, contributing positively to social equity.

- Economic Growth and Stability**: During much of Morales's tenure, Bolivia experienced sustained economic growth, relatively low inflation, and an accumulation of international reserves, partly due to favorable commodity markets and prudent macroeconomic management initially.

- Indigenous Empowerment and Symbolism**: Morales's presidency was highly symbolic for Bolivia's indigenous majority, who had historically been marginalized. His government prioritized indigenous rights, cultural recognition, and political participation, fostering a sense of empowerment and inclusion.

Controversies and Criticisms:

- Extended Tenure and Democratic Backsliding**: Morales sought to extend his time in office beyond the constitutional limits. After winning re-election in 2009 under the new constitution, he successfully petitioned the Plurinational Constitutional Tribunal in 2013 to allow him to run for a third term in 2014 (arguing his first term under the old constitution didn't count towards the new limit), which he won. In 2016, he held a referendum to amend the constitution to allow for further re-election, which he narrowly lost. However, in 2017, the Constitutional Tribunal, stacked with pro-government judges, controversially ruled that term limits violated human rights (citing the American Convention on Human Rights), effectively allowing indefinite re-election. This move was widely criticized by the opposition, civil society groups, and some international observers as undermining democratic institutions and the rule of law, leading to accusations of democratic backsliding and a shift towards competitive authoritarianism. This raised concerns about the long-term health of Bolivian democracy.

- Human Rights Concerns**: While promoting indigenous rights, the Morales government also faced criticism for its handling of dissent, attacks on the independence of the judiciary and media, and harassment of political opponents and human rights defenders. These actions were seen by critics as detrimental to democratic freedoms.

- Environmental Policies**: Despite a discourse centered on "Pachamama" (Mother Earth) and indigenous cosmovision, Morales's government pursued extractivist policies (promoting mining and hydrocarbon exploitation) and infrastructure projects (like the TIPNIS highway) that sparked protests from environmental groups and some indigenous communities concerned about their impact on protected areas and traditional territories. This highlighted a tension between development goals and environmental/indigenous rights.

- Polarization**: Morales's transformative agenda and confrontational style led to significant political polarization between his supporters (primarily indigenous groups, peasant organizations, and urban working classes) and the opposition (centered in the eastern lowlands, traditional political parties, and parts of the urban middle class).

The controversies surrounding his bid for a fourth term in the 2019 general election ultimately led to a major political crisis and his resignation. Evo Morales's presidency left a complex legacy of significant social progress and indigenous empowerment alongside serious concerns about the erosion of democratic checks and balances and its impact on human rights.

3.7.3. 2019 Political Crisis and Interim Government

The 2019 Bolivian political crisis was a period of intense social unrest and political upheaval triggered by the disputed results of the presidential election held on October 20, 2019. Incumbent President Evo Morales of the Movement for Socialism (MAS) party was seeking a controversial fourth consecutive term, a move that had already fueled concerns about democratic norms.

Disputed Election and Protests:

The initial vote count, known as the TREP (Transmission of Preliminary Electoral Results), was abruptly halted for nearly 24 hours. When it resumed, Morales's lead over his main rival, former president Carlos Mesa, had widened, putting him just over the 10-percentage-point threshold needed to avoid a runoff election. This sudden shift sparked widespread allegations of electoral fraud from opposition parties, civil society groups, and international observers. Massive protests erupted across Bolivia, demanding a runoff or Morales's resignation. Clashes between protesters and security forces, as well as between rival groups, became increasingly violent, leading to concerns about human rights and democratic process.

OAS Audit and Morales's Resignation:

Amidst the growing crisis, the Morales government invited the Organization of American States (OAS) to conduct an audit of the election results. On November 10, 2019, the OAS released a preliminary report citing "serious irregularities" and recommending new elections. The findings of the OAS audit were later disputed by some independent researchers who argued that the statistical analysis used by the OAS was flawed, though the OAS maintained its conclusions.

Following the OAS report, calls for Morales's resignation intensified. Crucially, the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, General Williams Kaliman, and the police chief "suggested" that Morales step down to restore peace and stability. Facing mounting pressure, loss of support from the security forces, and escalating protests, Evo Morales announced his resignation on November 10, 2019. He, along with his vice president Álvaro García Linera and other key officials, subsequently fled the country, eventually finding asylum in Mexico and later Argentina. Morales and his supporters termed his ousting a "coup d'état," a claim contested by those who viewed it as a popular uprising against perceived authoritarian tendencies and electoral manipulation.

Interim Government of Jeanine Áñez:

Morales's resignation created a power vacuum. According to the constitutional line of succession, the presidency would have passed to the vice president, then the president of the Senate, and then the president of the Chamber of Deputies. However, all these officials, who were MAS party members, had also resigned. In this context, Jeanine Áñez, an opposition senator and second vice-president of the Senate, declared herself interim president on November 12, 2019, arguing it was her constitutional duty to fill the void and call new elections. Her assumption of power was endorsed by the Plurinational Constitutional Tribunal.

The Áñez interim government was highly controversial. Supporters viewed it as a necessary step to restore democracy after alleged electoral fraud and Morales's unconstitutional bid for a fourth term. Critics, including MAS and its allies, condemned it as an illegitimate coup government and raised concerns about its conservative shift and handling of human rights.

Social Polarization and Human Rights Issues:

The period following Morales's resignation saw continued social polarization and violence. Pro-Morales protests, particularly in indigenous areas like Sacaba (Cochabamba) and Senkata (El Alto), were met with deadly force by security forces under the Áñez government, resulting in numerous deaths and injuries. The interim government issued a decree (later repealed) that granted immunity to military personnel involved in restoring order, which was widely condemned by human rights organizations as enabling impunity for abuses against civilians. The Áñez administration also initiated legal proceedings against Morales and many MAS officials, accusing them of sedition and terrorism, actions criticized as politically motivated and a setback for democratic reconciliation.

The interim government's primary mandate was to organize new elections. After several postponements due to the COVID-19 pandemic and political tensions, new general elections were held in October 2020. The crisis of 2019 left deep scars on Bolivian society, exacerbating political divisions and raising serious concerns about democratic stability, the protection of human rights, and the need for accountability for violence committed during the unrest.

3.7.4. Luis Arce Presidency (2020-Present)

Following the tumultuous political crisis of 2019, Bolivia held new general elections on October 18, 2020. Luis Arce Catacora, the candidate for the Movement for Socialism (MAS) party and former Minister of Economy under Evo Morales, won a decisive victory in the first round with over 55% of the vote, defeating former president Carlos Mesa and other contenders. Arce was inaugurated as President of Bolivia on November 8, 2020, marking the return of MAS to power after a year-long interim government led by Jeanine Áñez. His running mate, David Choquehuanca, a prominent Aymara leader and former foreign minister, became Vice President. This election was seen as a crucial step in restoring democratic order.

Policy Directions:

President Arce's administration has largely signaled a continuation of the social and economic policies pursued during the Evo Morales era, albeit with an emphasis on economic reactivation and national reconciliation. Key policy directions include:

- Economic Stability and Reconstruction**: Arce, an economist by training, has focused on stabilizing the Bolivian economy, which was affected by the political crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and a decline in commodity prices. His government has prioritized public investment, social programs, and strengthening state-owned enterprises. In February 2021, the Arce government returned a loan of approximately 351.00 M USD to the IMF, which had been taken out by the Áñez interim government, citing unacceptable conditions and a desire to protect Bolivia's economic sovereignty.

- Social Programs**: The government has pledged to maintain and expand social welfare programs aimed at poverty reduction and supporting vulnerable populations, such as cash transfers and subsidies, continuing the focus on social equity.

- Industrialization and Resource Management**: A continued emphasis on state control over natural resources, particularly hydrocarbons and lithium, and efforts to promote industrialization, including the development of Bolivia's vast lithium reserves.

- Health and Education**: Strengthening public health and education systems, including the response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Justice and Accountability**: The Arce government has pursued legal action against officials of the Áñez interim government, accusing them of orchestrating a coup and committing human rights abuses during the 2019 crisis. Jeanine Áñez and several former ministers and military leaders were arrested and faced charges. These actions have been praised by MAS supporters as seeking justice but criticized by the opposition and some international observers as politically motivated persecution, potentially hindering national reconciliation and raising concerns about due process and human rights.

Ongoing Challenges:

The Arce administration faces numerous ongoing challenges:

- Political Polarization**: Deep political divisions persist between MAS supporters and the opposition. Efforts towards national reconciliation have been hampered by the contentious issue of accountability for the 2019 crisis.

- Economic Vulnerability**: While Bolivia experienced significant economic growth in previous years, it remains vulnerable to fluctuations in commodity prices and global economic conditions. Managing public finances, attracting investment, and diversifying the economy are key challenges.

- Judicial Reform**: The Bolivian justice system continues to face criticism for a lack of independence, corruption, and inefficiency. Meaningful judicial reform remains a pressing need to ensure rule of law and protect human rights.

- Social Demands**: Various social sectors continue to press demands for improved services, land rights, and greater inclusion.

- Democratic Governance**: Ensuring the independence of state institutions, protecting human rights, fostering a climate of democratic dialogue, and addressing concerns about potential authoritarian tendencies are crucial for long-term stability and social progress.

- Internal MAS Divisions**: Reports have emerged of growing tensions and divisions within the MAS party, particularly between factions loyal to President Arce and those aligned with former President Evo Morales, who remains an influential figure. These internal dynamics could impact governance and policy direction.

President Arce's term is focused on navigating these complex issues while seeking to consolidate the socio-economic model advanced by MAS and address the lingering effects of the 2019 political crisis, with an emphasis on restoring stability and continuing the path of social development.

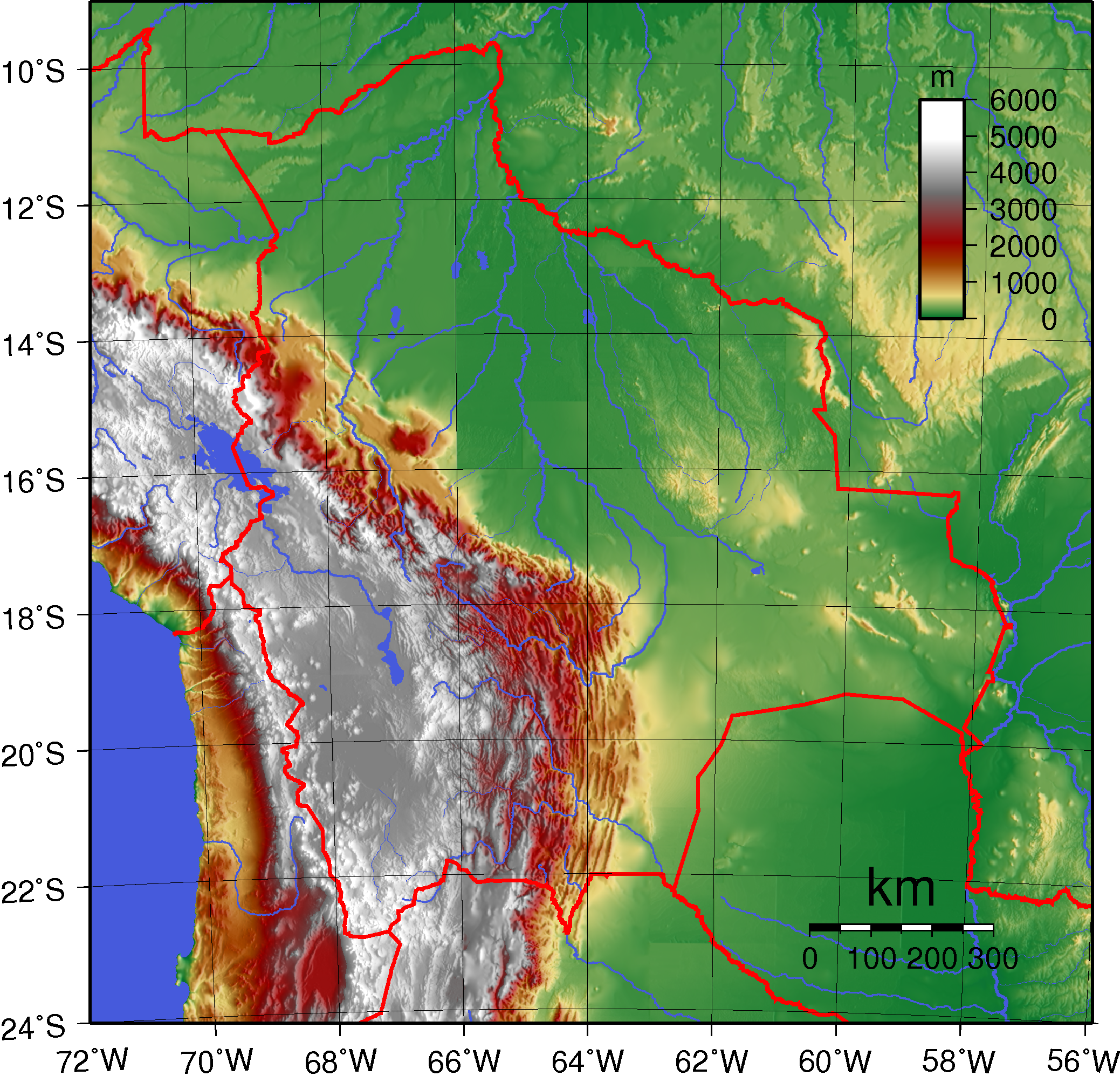

4. Geography

Bolivia is located in the central zone of South America, situated between 57°26'-69°38' West longitude and 9°38'-22°53' South latitude. It is a landlocked country, having lost its coastal territory to Chile in the War of the Pacific (1879-1883). Bolivia is bordered by Brazil to the north and east (a border of 2.1 K mile (3.42 K km)), Paraguay to the southeast (460 mile (741 km)), Argentina to the south (480 mile (773 km)), Chile to the southwest (528 mile (850 km)), and Peru to the west (0.7 K mile (1.05 K km)). The total length of its borders is 6,834 km. This section describes Bolivia's diverse physical regions, major drainage basins, and overall geographical features.

With a total area of 0.4 M mile2 (1.10 M km2) (424.16 K mile2), Bolivia is the 27th largest country in the world and the fifth largest in South America, after Brazil, Argentina, Peru, and Colombia. It is the largest landlocked country in the Southern Hemisphere and the seventh largest landlocked country globally. The geographic center of the country is referred to as Puerto Estrella ("Star Port") on the Río Grande, in Ñuflo de Chávez Province, Santa Cruz Department.

Bolivia's geography is characterized by great diversity in terrain and climates, ranging from the high Andes mountains to the Amazonian rainforests. One-third of the country lies within the Andean mountain range. The country has a high level of biodiversity and includes several ecoregions with distinct ecological sub-units. Forest cover in Bolivia is around 47% of the total land area, equivalent to 50,833,760 hectares in 2020.

The country can be broadly divided into three main physiographic regions:

1. The Andean Region (Altiplano)

2. The Sub-Andean Region (Valleys and Yungas)

3. The Llanos Region (Eastern Lowlands)

Bolivia has three major drainage basins:

- Amazon Basin: Also known as the North Basin, it covers approximately 66% of Bolivia's territory (280 K mile2 (724.00 K km2)). Its rivers, such as the Mamoré (Bolivia's longest river at 1.2 K mile (2.00 K km)), Beni, Madre de Dios, and Guaporé (or Iténez), generally flow north and northeast, eventually forming part of the Amazon River system. This region contains significant lakes like Rogaguado and Rogagua.

- Río de la Plata Basin: Also known as the South Basin, it covers about 21% of the territory (89 K mile2 (229.50 K km2)). Its main rivers are the Paraguay, Pilcomayo, and Bermejo, which flow generally southward. Lakes Uberaba and Mandioré are located in the Bolivian Pantanal within this basin.

- Central Basin (Endorheic Basin): Covering about 13% of the territory (56 K mile2 (145.08 K km2)), this is an internal drainage basin within the Altiplano. Rivers and lakes in this region do not flow to the sea. The most important river is the Desaguadero, which flows from Lake Titicaca (the world's highest commercially navigable lake and South America's largest by volume of water, shared with Peru) to Lake Poopó. This basin also includes the vast Salar de Uyuni (the world's largest salt flat) and the Salar de Coipasa.

4.1. Topography

Bolivia's topography is exceptionally diverse, encompassing some of the most dramatic landscapes in South America. It can be broadly divided into three major regions: the Andean Highlands, the Sub-Andean Region of valleys and yungas, and the Eastern Lowlands. Each region possesses unique geographical and climatic characteristics.

1. The Andean Region (Highlands): Located in the southwest, this region covers approximately 28% of Bolivia's national territory (about 119 K mile2 (307.60 K km2)) and is characterized by high altitudes, generally above 9.8 K ft (3.00 K m). It is dominated by two great parallel mountain ranges of the Andes:

- The Cordillera Occidental (Western Range): This range forms the border with Chile and Peru and is characterized by volcanic peaks, arid conditions, and numerous active and extinct volcanoes. Bolivia's highest peak, Nevado Sajama (a dormant volcano), is located here, reaching an altitude of 21 K ft (6.54 K m).

- The Cordillera Oriental (Eastern Range, also including the Cordillera Real and Cordillera Central): This range runs roughly north to south through central Bolivia. It is generally more rugged and wetter than the Occidental range and contains many towering, snow-capped peaks, including Illimani (21 K ft (6.46 K m)) and Illampu (21 K ft (6.49 K m)), which overlook La Paz. This range is rich in mineral deposits, particularly tin.

- The Altiplano (High Plateau): Situated between the Cordillera Occidental and Cordillera Oriental, the Altiplano is an extensive high plateau, one of the largest in the world after the Tibetan Plateau. It has an average altitude of about 12 K ft (3.75 K m). This cold, semi-arid region is home to major cities like La Paz, El Alto, and Oruro. It also contains Lake Titicaca, shared with Peru, and Lake Poopó (which has significantly diminished in size), as well as vast salt flats, most notably the Salar de Uyuni.

2. The Sub-Andean Region (Valleys and Yungas): This intermediate region lies to the east of the Andean highlands, forming a transition zone between the mountains and the eastern lowlands. It covers about 13% of Bolivia's territory (55 K mile2 (142.81 K km2)).

- The Valleys (Valles): These are fertile intermontane valleys, primarily in departments like Cochabamba, Chuquisaca, and Tarija. They generally have a temperate climate and are important agricultural areas, producing fruits, vegetables, and grains. Cities like Cochabamba and Sucre are located in this region.

- The Yungas: These are steep, forested, and humid valleys on the eastern slopes of the Cordillera Oriental, descending towards the Amazon basin. The Yungas are characterized by dramatic changes in altitude, lush vegetation, and a semi-tropical climate. This region is known for coffee, citrus fruit, and coca cultivation. The infamous Yungas Road (Death Road) is located here.

3. The Eastern Lowlands (Llanos Orientales or Oriente): This vast region in the northeast and east covers about 59% of Bolivia's territory (250 K mile2 (648.16 K km2)) and is generally below 1312 ft (400 m) in altitude. It extends from the Andean foothills to the borders with Brazil and Paraguay.

- Amazonian Lowlands**: The northern part of the Llanos is part of the Amazon basin, characterized by tropical rainforests, extensive river systems (like the Mamoré, Beni, and Madre de Dios rivers), high biodiversity, and a hot, humid climate. This region includes parts of the departments of Beni, Pando, and northern Santa Cruz.

- Chiquitania**: Located in the department of Santa Cruz, this area features tropical savannas, dry forests, and unique rock formations like the Serranías Chiquitanas.

- Gran Chaco**: The southeastern part of the Llanos extends into the Gran Chaco, a hot, semi-arid region of scrub forest and savanna shared with Paraguay, Argentina, and Brazil.

- Pantanal**: A small portion of Bolivia along its eastern border with Brazil includes part of the Pantanal, the world's largest tropical wetland.

This diverse topography results in a wide array of climates, ecosystems, and natural resources across the country.

4.2. Geology

The geology of Bolivia is complex and varied, reflecting its position at the convergence of major tectonic plates and its diverse topographical regions. The country can be broadly divided into two main geological provinces: the mountainous western region, part of the Andean orogenic belt, and the eastern lowlands, which form part of the stable Brazilian Shield and Chaco-Parnaíba Basin. These geological formations define the distribution of mineral and hydrocarbon resources crucial to the Bolivian economy.

1. Andean Orogenic Belt (Western Bolivia):

- Tectonic Setting**: This region is dominated by the Andes mountains, formed by the ongoing subduction of the Nazca Plate beneath the South American Plate. This process has led to intense crustal shortening, uplift, volcanism, and seismic activity.

- Cordillera Occidental**: Composed primarily of Cenozoic volcanic and volcaniclastic rocks, including large stratovolcanoes like Nevado Sajama. It hosts significant porphyry copper deposits and other metallic minerals. The underlying basement includes Paleozoic and Mesozoic sedimentary and igneous rocks.

- Altiplano**: This high plateau is a Cenozoic intermontane basin filled with thick sequences of continental sediments (clastic rocks, evaporites like halite and gypsum forming the salt flats such as Salar de Uyuni). The Salar de Uyuni is particularly notable for its vast lithium-rich brines. Volcanic activity has also influenced the Altiplano's geology.

- Cordillera Oriental**: This range consists of a thick sequence of Paleozoic sedimentary rocks (sandstones, shales, quartzites) that have been folded and faulted during the Andean orogeny. It is intruded by Mesozoic and Cenozoic granitic batholiths, which are associated with world-class tin, silver, tungsten, antimony, zinc, and lead deposits (e.g., the tin belt of Bolivia, including the historic Potosí silver mines).

- Sub-Andean Zone**: Located to the east of the Cordillera Oriental, this is a fold-and-thrust belt characterized by Mesozoic and Cenozoic sedimentary rocks, forming important hydrocarbon basins where oil and natural gas are trapped in anticlinal structures.

2. Eastern Lowlands (Eastern Bolivia):

- Brazilian Shield (Precambrian Shield)**: The northeastern part of Bolivia exposes Precambrian crystalline basement rocks of the Brazilian (or Guaporé) Shield. These include ancient gneisses, granites, and greenstone belts, which can host gold, iron ore (like the El Mutún deposit), and other mineral resources.

- Chaco-Parnaíba Basin (Beni Plain, Chiquitania, Chaco Plain)**: This vast area is a sedimentary basin overlying the Precambrian shield. It contains Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic sedimentary sequences. The region has potential for hydrocarbons and also hosts sedimentary mineral deposits. The Chiquitania region features unique Precambrian and Paleozoic rock formations.

Mineral and Hydrocarbon Deposits:

Bolivia is renowned for its rich mineral wealth. Historically, silver from Potosí was crucial. In the 20th century, tin became dominant. Today, Bolivia has significant reserves of:

- Metallic Minerals**: Tin, silver, gold, zinc, lead, antimony, tungsten, copper, and iron ore.

- Non-Metallic Minerals**: Lithium (in Salar de Uyuni, among the world's largest reserves), potassium, boron, gypsum, salt.

- Hydrocarbons**: Large reserves of natural gas and petroleum, primarily located in the Sub-Andean zone and the eastern lowlands.

The country's geological diversity and tectonic history have endowed it with these substantial resources, which play a critical role in its economy. However, geological exploration, particularly in the eastern regions, is still considered to be relatively incomplete.

4.3. Climate

Bolivia's climate is highly varied due to its diverse topography, which includes vast differences in altitude, and its location within the tropics. Generally, temperatures and rainfall patterns are determined by elevation and latitude, leading to distinct climatic zones across the country, from tropical heat to alpine cold.

- Eastern Lowlands (Llanos): This region, encompassing the Amazon basin, Chiquitania, and parts of the Gran Chaco, generally experiences a tropical climate.

- Northern Lowlands (Pando, Beni, northern Santa Cruz)**: Hot and humid year-round, with high rainfall, especially during the wet season (typically November to March). Average temperatures are around 77 °F (25 °C) to 86 °F (30 °C). This is a tropical rainforest and tropical savanna climate.

- Southeastern Lowlands (Gran Chaco)**: Subtropical semi-arid climate with very hot summers and mild, dry winters. Rainfall is less than in the northern lowlands and more seasonal. This region can experience "surazos," which are cold southerly winds that can cause sudden temperature drops, especially during winter (May to August).

- Sub-Andean Region (Valleys and Yungas): This transitional zone has a generally temperate climate.

- Valleys (Valles)** (e.g., Cochabamba, Sucre, Tarija): Pleasant, spring-like temperatures for much of the year. Days are warm, and nights are cool. Rainfall is moderate and concentrated in the summer months. Altitudes typically range from 4.9 K ft (1.50 K m) to 9.8 K ft (3.00 K m).

- Yungas**: Located on the steep eastern slopes of the Andes, this region has a humid subtropical to tropical rainforest climate due to moisture-laden winds from the Amazon. Rainfall is high, and temperatures vary with altitude, becoming cooler at higher elevations. Snow can occur at altitudes above 6.6 K ft (2.00 K m).

- Andean Region (Altiplano): The Altiplano experiences a cold, semi-arid to arid highland climate (often classified as a cool Tundra or Alpine climate due to altitude).

- Characterized by strong, cold winds, high solar radiation during the day, and significant diurnal temperature variation (large difference between day and night temperatures).