1. Overview

Belize is a small nation located on the northeastern coast of Central America, bordered by Mexico to the north, Guatemala to the west and south, and the Caribbean Sea to the east. It is the only country in Central America where English is the official language, a legacy of its history as a British colony known as British Honduras until 1973. Belize achieved full independence in 1981 and is a parliamentary constitutional monarchy within the Commonwealth realm, with King Charles III as its head of state, represented by a Governor-General. The capital city is Belmopan, though the largest city and former capital is Belize City.

The country possesses a rich and diverse natural heritage, including the extensive Belize Barrier Reef, the second-largest barrier reef system in the world and a UNESCO World Heritage site. This natural wealth supports a significant tourism industry, a cornerstone of the Belizean economy, alongside agriculture, particularly sugar and bananas. Belizean society is characterized by its multiculturalism, a blend of influences from Maya, Creole, Garifuna, Mestizo, Mennonite, and other ethnic groups, each contributing to a unique national identity.

This article explores Belize's history, from the ancient Maya civilization through European colonization and the struggle for independence, to its contemporary political, social, and economic landscape. It examines the nation's efforts towards democratic development, the promotion of human rights, and the challenges of ensuring social equity and environmental sustainability. Particular attention is given to the impact of historical and current events on various social groups, the welfare of minorities and vulnerable populations, ongoing territorial issues, and the pursuit of sustainable development that benefits all Belizeans while preserving the nation's rich biodiversity and cultural heritage for future generations.

2. Etymology

The origin of the name "Belize" is subject to some debate among scholars. The earliest known record of the name appears in the journal of the Dominican priest Fray José Delgado, dating to 1677. Delgado recorded the names of three major rivers he crossed while travelling north along the Caribbean coast: Rio Soyte (Sittee River), Rio Kibum (Sibun River), and Rio Balis (Belize River). It has been proposed that "Balis" was a Mayan word, possibly belix or beliz, meaning "muddy water." However, linguists like Matthew Restall have pointed out that no such Mayan word actually exists with that meaning; "mud" is rendered as lukʼ in Yucatecan languages, while "water" is jaʼ, ja, or ha.

Another theory, advanced by Restall, suggests that "Belize" derives from the Yucatec Maya phrase "bel Itza", meaning "the road to Itza" or "the way to Itza," referring to the Itza Maya kingdom centered around Lake Petén Itzá in present-day Guatemala. Given the difficulty Spanish speakers had with pronouncing "Itz" or "tz," the phrase might have evolved into "Beliz" or "Belize" and subsequently been adopted by English speakers.

Barbara and Victor Bulmer-Thomas, along with Mavis Campbell, also researched the name's origins and concluded that it likely came from 'Balis' or 'Baliz', reinforcing the "muddy water" theory from Mayan languages, specifically Yucatec Maya. Campbell noted this was plausible given the Belize River's tendency to flood and become turbid during the rainy season.

A widely circulated but now largely discredited theory, invented by the Creole elite in the 1820s and popularized by Spanish and British accounts, suggested that the name "Belize" was a Spanish mispronunciation of "Wallace," after a Scottish buccaneer named Peter Wallace, who supposedly established a settlement at the mouth of the Belize River in 1638. However, there is no historical proof of buccaneers settling in this specific area at that time, and the very existence of Peter Wallace is considered mythical by many historians. Other less substantiated theories have proposed French or African origins for the name.

3. History

Belize's history is a rich tapestry woven from ancient Maya civilizations, European colonial encounters, the brutal realities of slavery and resource exploitation, a long journey towards self-governance and independence, and ongoing challenges in nation-building and social development. This section details the historical development of Belize, emphasizing the impact on its diverse social groups, the evolution of its democratic institutions, and its struggles for sovereignty and social justice.

3.1. Early history and Maya civilization

The Maya civilization emerged in the lowland area of the Yucatán Peninsula and the highlands to the south, encompassing present-day southeastern Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, and western Honduras, at least three millennia ago. Many aspects of this ancient culture persist in the region despite nearly 500 years of European domination. Prior to about 2500 BC, some hunter-gatherer bands began to settle in small farming villages, domesticating crops such as corn, beans, squash, and chili peppers.

Over time, a profusion of languages and subcultures developed within the Maya core culture. Between approximately 2500 BC and 250 AD, the basic institutions of Maya civilization emerged. The civilization spread across the territory of present-day Belize around 1500 BC and flourished there until about 900-1200 AD. During the Classic Era of Maya Civilization (roughly 250 AD to 900 AD), it is estimated that between 400,000 and 1,000,000 people inhabited the area that is now Belize.

Several major Maya archaeological sites in Belize attest to the civilization's sophistication and scale. Caracol, located in the Cayo District, was a major urban political center that may have supported over 140,000 people at its peak. It was a significant regional power, known for its extensive causeway system, monumental architecture, and military victories over other Maya city-states like Tikal. North of the Maya Mountains, Lamanai, situated on the New River Lagoon, was another important political and ceremonial center, notable for its exceptionally long and continuous occupation, from the Preclassic period through the colonial era. Other significant sites include Xunantunich, known for its impressive "El Castillo" pyramid, Altun Ha, an important trading and ceremonial center, and Lubaantun in the south.

Maya society was hierarchical, with rulers (kings or ajaws), nobles, priests, warriors, artisans, traders, and farmers. They developed sophisticated systems of writing, mathematics (including the concept of zero), astronomy, and calendrics. Their art and architecture, characterized by pyramids, palaces, stelae, and intricate carvings, remain a testament to their ingenuity. The decline of the Classic Maya civilization in the southern lowlands around the 9th and 10th centuries AD was a complex process, likely involving factors such as environmental degradation, overpopulation, warfare, drought, and internal social unrest, leading to the abandonment of many major cities. However, Maya communities continued to exist in Belize, adapting to changing circumstances even as European colonizers arrived.

When Spanish explorers arrived in the 16th century, the area of present-day Belize included at least three distinct Maya territories:

- Chetumal Province, which encompassed the area around Corozal Bay.

- Dzuluinicob province, which encompassed the area between the lower New River and the Sibun River, west to Tipu. This area saw significant Maya resistance to Spanish rule.

- A southern territory controlled by the Manche Ch'ol Maya, encompassing the area between the Monkey River and the Sarstoon River.

3.2. European contact and early colonial period

European contact with the land now known as Belize began between 1502 and 1504 when Christopher Columbus sailed along the Gulf of Honduras during his fourth voyage. Spanish conquistadors subsequently explored the region and declared it part of the Spanish Empire. However, they largely failed to establish permanent settlements or effective control over the territory due to its perceived lack of easily exploitable resources like gold and silver, and the fierce resistance from the indigenous Maya tribes of the Yucatán who defended their lands.

Beginning in the early 17th century, English and Scottish pirates, known as Baymen, sporadically visited the coast of Belize. They sought sheltered regions from which they could attack Spanish ships and also began to cut logwood (Haematoxylum campechianum). Logwood was a valuable commodity in Europe, producing a prized dye used for textiles, particularly for achieving a fast black. The first permanent British settlement is believed to have been founded around 1638 or possibly later, around 1716, in what became the Belize District.

Throughout the 18th century, the Baymen established a system that heavily relied on the enslavement of Africans to cut logwood and later mahogany. These enslaved individuals were subjected to brutal conditions and forced labor in the difficult swampy and forested terrain. The Spanish Empire, while claiming sovereignty over the region, periodically attempted to dislodge the British settlers. These attempts often coincided with wars between Spain and Great Britain. The British government, for a long time, did not officially recognize the settlement as a colony, fearing it would provoke a stronger Spanish military response. This lack of direct government oversight allowed the settlers to establish their own rudimentary laws and forms of government, such as the Public Meeting, which was largely controlled by a small, wealthy elite who also owned most of the land and timber resources. The first British superintendent for the Belize area was not appointed until 1786.

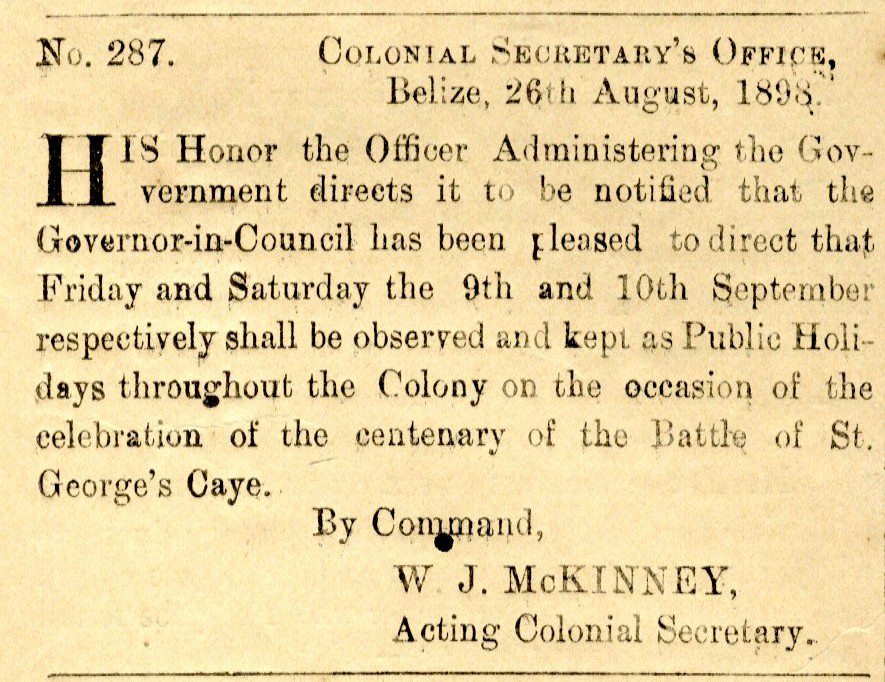

The Battle of St. George's Caye in September 1798 was the last major military engagement between the Spanish and the British settlers. From September 3rd to 5th, a Spanish fleet attempted to force its way through Montego Caye shoal but was blocked by the defenders, a mixed force of Baymen, British troops, and enslaved Africans who were compelled to fight. Spain's final assault occurred on September 10th, when the Baymen repelled the Spanish fleet in a short engagement. The anniversary of this battle is now a national holiday in Belize, commemorated as St. George's Caye Day, celebrating the defense of the settlement. However, from a human rights perspective, it's crucial to acknowledge the forced participation of enslaved people in these conflicts, whose own freedom and well-being were not the primary concern of the colonial powers. The exploitation of logwood and mahogany continued to define the economy and social structure, built upon the foundation of enslaved African labor.

3.3. British Honduras

In the early 19th century, the British government began to exert more direct control over the settlement, partly driven by the broader movement to abolish slavery. The abolition of slavery throughout the British Empire in 1833 had a profound impact. Slave owners in British Honduras were compensated by the British government for the loss of their "property" - the enslaved Africans - at an average of 53.69 GBP per person, the highest amount paid in any British territory. This compensation went to the enslavers, not to the formerly enslaved individuals who had endured generations of forced labor and abuse, highlighting the deep injustices of the system.

The end of slavery, however, did little to fundamentally alter the working conditions or economic prospects for many formerly enslaved Africans. A series of restrictive laws and practices, including limitations on land ownership and the implementation of debt-peonage systems, effectively forced many to continue working in the timber industry under exploitative conditions. A small elite, largely of European descent, continued to control the land and commerce, perpetuating a social hierarchy rooted in the colonial past. The capacities and limitations of people of African descent were often narrowly defined by the colonial elite, based on their roles in the mahogany and logwood extraction industries.

In 1836, following the emancipation of Central America from Spanish rule, the British formally claimed the right to administer the region. In 1862, the United Kingdom declared it a British Crown Colony, subordinate to Jamaica, and officially named it British Honduras. From 1854, the wealthiest inhabitants had elected an assembly of notables by censal vote, but this was replaced by a legislative council appointed by the British monarch.

As a colony, British Honduras began to attract British investors. Firms like the Belize Estate and Produce Company came to dominate the economy, eventually acquiring vast tracts of land - by some estimates, half of all privately held land - and further entrenching the colony's reliance on the mahogany trade through the late 19th and first half of the 20th century. This economic structure offered limited opportunities for the majority of the population and exacerbated social inequalities.

The Great Depression of the 1930s severely impacted the colony's economy as British demand for timber plummeted, leading to widespread unemployment. The hardship was compounded by a devastating hurricane in 1931 that struck Belize City. The government's relief efforts were widely perceived as inadequate, and its refusal to legalize labor unions or introduce a minimum wage fueled popular discontent. World War II brought some economic improvement as many Belizean men joined the armed forces or contributed to the war effort.

After the war, the economy stagnated again. Britain's decision to devalue the British Honduras dollar in 1949 worsened economic conditions and became a catalyst for the rise of the nationalist movement. The People's Committee was formed, demanding independence. Its successor, the People's United Party (PUP), led by figures like George Cadle Price, advocated for constitutional reforms, including the expansion of voting rights to all adults (universal suffrage). The first election under universal suffrage was held in 1954 and was decisively won by the PUP, marking the beginning of their political dominance for several decades. George Price became PUP's leader in 1956 and the head of government in 1961, a position he held under various titles until 1984.

Hurricane Hattie in 1961 caused catastrophic damage to Belize City, which led to the decision to build a new capital, Belmopan, further inland.

Progress towards independence was complicated by Guatemala's persistent territorial claim over Belize. In 1964, Britain granted British Honduras self-government under a new constitution. On June 1, 1973, the colony's name was officially changed from British Honduras to Belize, a significant step in asserting its distinct identity on the path to full sovereignty. Throughout this period, the independence movement also focused on issues of social justice and economic development for the Belizean people.

3.4. Independent Belize

Belize achieved full independence from the United Kingdom on September 21, 1981. However, Guatemala refused to recognize the new nation due to its long-standing territorial claim, asserting that Belize was part of Guatemalan territory. This unresolved dispute cast a shadow over Belize's early years of independence. To deter potential Guatemalan incursions, approximately 1,500 British troops remained stationed in Belize.

George Cadle Price, leader of the People's United Party (PUP), became the first Prime Minister of independent Belize. The PUP had been the dominant political force leading up to independence and won all national elections until 1984. In the 1984 general election, the PUP was defeated by the United Democratic Party (UDP), and UDP leader Manuel Esquivel became Prime Minister. Price himself unexpectedly lost his House seat. The PUP, under Price, returned to power in the 1989 election.

In 1990, the United Kingdom announced it would end its military involvement in Belize, and the RAF Harrier detachment was withdrawn. British soldiers were largely withdrawn by 1994, though the UK left behind a military training unit, the British Army Training and Support Unit Belize (BATSUB), to assist with the newly created Belize Defence Force. Guatemala formally recognized Belize's independence in 1991, which eased tensions, but the underlying territorial dispute remained.

The UDP regained power in the 1993 election, and Esquivel became Prime Minister for a second time. His government suspended a pact reached with Guatemala during Price's tenure, arguing that too many concessions had been made. Border tensions continued sporadically, although the two countries cooperated in other areas.

In 1996, the Belize Barrier Reef, a vital ecosystem and economic resource, was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, highlighting the country's natural wealth but also the need for its protection.

The PUP won a landslide victory in the 1998 national elections, and Said Musa became Prime Minister. The PUP maintained its majority in the 2003 elections, and Musa continued in office, pledging to improve conditions in the underdeveloped southern part of Belize. However, his government faced significant unrest in 2005 due to discontent over tax increases and perceived corruption, reflecting ongoing socio-economic challenges and demands for greater accountability.

On February 8, 2008, Dean Barrow was sworn in as Prime Minister after his UDP won a landslide victory. Barrow and the UDP were re-elected in 2012, albeit with a smaller majority, and won a third consecutive term in November 2015.

The territorial dispute with Guatemala continued to be a major foreign policy issue. Both countries eventually agreed to take the dispute to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for resolution, following referendums in both nations (Guatemala in 2018, Belize in 2019). The ICJ process is ongoing.

On November 11, 2020, the People's United Party (PUP), led by Johnny Briceño, defeated the UDP, winning 26 out of 31 seats. Briceño took office as Prime Minister on November 12, 2020. His administration faces challenges including economic recovery, addressing crime, promoting sustainable development, and managing the ongoing implications of the Guatemalan territorial claim, particularly for communities in border areas. Efforts towards democratic consolidation, strengthening human rights protections, addressing social inequalities, and pursuing environmental justice remain critical for Belize's future. In 2023, Belize was recognized by the World Health Organization for eliminating malaria, a significant public health achievement.

4. Geography

Belize is situated on the Caribbean coast of northern Central America. It is bordered by Mexico (specifically the state of Quintana Roo) to the north, Guatemala (the departments of Petén to the west and Izabal to the south) to the west and south, and the Caribbean Sea to the east. The country also shares a maritime boundary with Honduras to the southeast, across the Gulf of Honduras.

Belize's mainland is roughly rectangular, extending about 180 mile (290 km) from north to south and about 68 mile (110 km) from east to west at its widest point. Its total area is approximately 8.9 K mile2 (22.97 K km2), slightly larger than El Salvador or Wales. The actual land area is reduced to about 8.3 K mile2 (21.40 K km2) due to numerous lagoons along the coast and in the northern interior. Belize is the only Central American country with no coastline on the Pacific Ocean.

The northern part of Belize consists mostly of flat, swampy coastal plains, heavily forested in places. The south features the low Maya Mountains, a range of hills and rugged terrain. The highest point in Belize is Doyle's Delight, at 3.7 K ft (1.12 K m) above sea level, located in the Maya Mountains. Major rivers include the Belize River (which flows through the center of the country), the Rio Hondo (forming part of the northern border with Mexico), the New River, the Sibun River, the Sittee River, the Monkey River, and the Sarstoon River (forming the southern border with Guatemala).

The coastline of Belize spans approximately 240 mile (386 km) and is characterized by extensive mangrove swamps, estuaries, and sandy beaches. Offshore, Belize boasts a vast network of cayes (small islands) and the Belize Barrier Reef, the second-longest barrier reef system in the world.

4.1. Climate

Belize has a tropical climate characterized by pronounced wet and dry seasons, though there are significant variations in weather patterns by region. Temperatures are generally warm and humid throughout the year, moderated somewhat by the northeast trade winds blowing off the Caribbean Sea.

Average temperatures in the coastal regions range from about 75.2 °F (24 °C) in January to 80.6 °F (27 °C) in July. Inland areas tend to be slightly hotter, except for the southern highland plateaus like the Mountain Pine Ridge, where temperatures are noticeably cooler year-round. The seasons are distinguished more by differences in humidity and rainfall than by significant temperature fluctuations.

Rainfall varies considerably across the country. The northern and western regions receive an average of 0.1 K in (1.35 K mm) of rain annually, while the extreme south can receive over 0.2 K in (4.50 K mm). The dry season typically runs from February to May, with April being the driest month. During this period, particularly in the north and central regions, monthly rainfall can be less than 3.9 in (100 mm). The rainy season generally extends from June to November, with the heaviest rains often occurring in June/July and September/October. A brief, less rainy period, known locally as the "little dry," often occurs in late July or August.

Belize lies within the Atlantic hurricane belt, and tropical cyclones (hurricanes) are a significant threat, particularly from June to November. Historically, hurricanes have caused extensive damage and loss of life. Notable storms include an unnamed hurricane in 1931 that devastated Belize City, Hurricane Janet (1955) which leveled Corozal Town, Hurricane Hattie (1961) which prompted the relocation of the capital to Belmopan, Hurricane Greta (1978), Hurricane Keith (2000), Hurricane Iris (2001), Hurricane Dean (2007), Hurricane Richard (2010), and Hurricane Lisa (2022). These events underscore Belize's vulnerability to extreme weather, a concern amplified by climate change.

4.2. Environment preservation and biodiversity

Belize is renowned for its exceptional biodiversity and has made significant strides in environmental preservation. Its geographical position as part of the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor, a land bridge between North and South America, coupled with a wide range of climates and habitats, contributes to a rich variety of plant and animal life. The country's relatively low human population density and large areas of undistributed land have helped maintain these ecosystems.

Belize is home to over 5,000 species of plants and hundreds of species of animals, including iconic Neotropical fauna such as jaguars, ocelots, pumas, Baird's tapir (the national animal), manatees, howler monkeys, spider monkeys, armadillos, numerous snake species, and a vast array of resident and migratory birds, including the keel-billed toucan (the national bird). Its marine biodiversity is equally impressive, centered around the Belize Barrier Reef.

A significant portion of Belize's land and marine territory is under some form of protection. According to the World Database on Protected Areas, about 37% of Belize's land territory is protected, one of the most extensive systems in the Americas. This network includes national parks, wildlife sanctuaries, forest reserves, marine reserves, and private protected areas. The Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary, established in 1990, is particularly famous as the world's first jaguar preserve. It covers approximately 154 mile2 (400 km2) of tropical forest on the eastern slopes of the Maya Mountains and is crucial for the protection of jaguars and other wildlife, as well as important watersheds. Other notable protected areas include the Mountain Pine Ridge Forest Reserve, the Bladen Nature Reserve, the Crooked Tree Wildlife Sanctuary (a vital bird habitat), and numerous marine protected areas associated with the Barrier Reef.

In 2020, forest cover in Belize was around 56% of the total land area, equivalent to 1,277,050 hectares. This was a decrease from 1,600,030 hectares in 1990. Most of this is naturally regenerating forest, with a small percentage of planted forest. About 59% of the forest area was found within protected areas in 2020. While Belize has a relatively high forest cover, deforestation remains a concern, driven by agricultural expansion, logging, and infrastructure development. Studies have indicated an average annual loss of forest cover, although protected areas have been shown to be effective in slowing this trend. Belize had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.15/10, ranking it 85th globally out of 172 countries.

Belize's ecosystems include Petén-Veracruz moist forests, Belizian pine forests, Belizean Coast mangroves, and Belizean Reef mangroves. Mangrove ecosystems are particularly important for coastal protection, fisheries, and biodiversity. Conservation efforts are supported by government agencies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and international partners. These efforts focus on sustainable resource management, anti-poaching initiatives, research, and community involvement in conservation. The social and economic importance of biodiversity is increasingly recognized, with ecotourism being a significant contributor to the national economy. However, challenges remain, including balancing development needs with conservation goals, addressing the impacts of climate change, and ensuring equitable benefit-sharing from natural resources for local and indigenous communities.

4.3. Belize Barrier Reef

The Belize Barrier Reef is a globally significant and ecologically diverse marine ecosystem, forming a major part of the larger Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System, which stretches over 559 mile (900 km) from the Yucatán Peninsula to Honduras. The Belizean section itself is approximately 186 mile (300 km) long, running parallel to the country's coastline, from 984 ft (300 m) offshore in the north to about 25 mile (40 km) offshore in the south. It is the largest barrier reef in the Northern Hemisphere and the second largest in the world, after Australia's Great Barrier Reef.

In 1996, the Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in recognition of its outstanding universal value, its intricate network of reef types (fringing, barrier, and atoll), offshore atolls (including Lighthouse Reef, Glover's Reef, and Turneffe Atoll), hundreds of sand cayes, mangrove forests, coastal lagoons, and estuaries. This complex system supports an extraordinary level of biodiversity. It is home to:

- Over 70 hard coral species

- Around 36 soft coral species (Alcyonacea)

- Approximately 500 species of fish

- Hundreds of invertebrate species, including mollusks, crustaceans, and sponges.

It is estimated that much of the reef system (perhaps up to 90%) is still to be researched, suggesting that many more species may yet be discovered. The reef provides critical habitat for numerous threatened or endangered species, including West Indian manatees, green turtles, hawksbill turtles, loggerhead turtles, and the American crocodile. The Great Blue Hole, a giant marine sinkhole near the center of Lighthouse Reef, is one of its most famous and iconic features, popular with divers.

The Belize Barrier Reef is vital to the country's economy, particularly through tourism (scuba diving, snorkeling, sport fishing) and fisheries. It also provides important coastal protection services. However, the reef faces numerous threats. Climate change is a major concern, leading to rising sea temperatures that cause coral bleaching and ocean acidification which hinders coral growth. Pollution from land-based sources, including agricultural runoff (pesticides, fertilizers, sediment) and sewage, degrades water quality. Overfishing and unsustainable fishing practices can damage reef habitats and deplete fish stocks. Coastal development and increased shipping traffic also pose risks. Scientists have estimated that a significant portion (over 40% since 1998 by some accounts) of Belize's coral reef has suffered damage.

Conservation efforts are underway, involving government agencies, NGOs, and local communities. Belize has taken steps to protect the reef, such as banning bottom trawling in 2010 and later implementing a moratorium on offshore oil exploration and drilling in its waters. Marine protected areas have been established, but effective management and enforcement remain challenges. The social and economic well-being of many Belizean communities, especially coastal ones, is intrinsically linked to the health of the reef, making its conservation an issue of national importance and environmental justice.

4.4. Natural resources and energy

Belize possesses a range of natural resources, though large-scale commercial exploitation has been limited for some. Historically, timber (logwood and mahogany) was the primary resource extracted. Today, agricultural land remains a key resource.

In terms of minerals, Belize is known to have deposits of dolomite, barite, bauxite (the ore of aluminum), cassiterite (tin ore), and gold, but generally not in quantities that have warranted extensive mining operations. Limestone is quarried and used primarily for road construction and other domestic purposes.

A significant development in Belize's natural resource sector was the discovery of petroleum in 2006 in the Spanish Lookout area of the Cayo District. This discovery led to the country becoming a modest oil producer. As of 2017, oil production was around 2,000 barrels per day. While this provided a new source of revenue, it also brought challenges related to environmental management, ensuring equitable benefit distribution to local communities, and managing the economic impacts of a new resource sector. The environmental regulations and social considerations surrounding oil extraction are crucial, particularly given Belize's rich biodiversity and reliance on ecotourism.

Belize's energy sector relies on a mix of sources. The country has hydroelectric potential, with several hydroelectric generating facilities operating on rivers like the Macal River. However, Belize also imports a significant portion of its electricity, primarily from Mexico. There is ongoing interest in developing renewable energy sources, such as solar and biomass, to reduce reliance on imported fossil fuels and enhance energy security. Access to biocapacity in Belize is considerably higher than the world average. In 2016, Belize had 3.8 global hectares of biocapacity per person within its territory, much more than the world average of 1.6 global hectares per person. However, in the same year, Belize used 5.4 global hectares of biocapacity per person (its ecological footprint of consumption), indicating that it was running a biocapacity deficit, meaning it consumed more resources than its ecosystems could regenerate. This highlights the importance of sustainable resource management.

The exploitation of natural resources, including potential offshore oil reserves near sensitive marine areas like the Barrier Reef, has been a subject of public debate and environmental advocacy, emphasizing the need for careful consideration of environmental impacts and the long-term well-being of affected communities.

4.5. Climate change

Belize is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change due to its extensive low-lying coastal areas, its reliance on climate-sensitive sectors like agriculture and tourism, and the ecological fragility of its key ecosystems, particularly the Belize Barrier Reef.

Observed and projected impacts of climate change in Belize include:

- Sea-level rise:** This poses a significant threat to coastal communities, infrastructure, and ecosystems like mangroves and beaches. It can lead to increased coastal erosion, saltwater intrusion into freshwater aquifers, and inundation of low-lying lands.

- Increased intensity of extreme weather events:** Belize is already susceptible to hurricanes. Climate change is expected to increase the intensity of these storms, leading to more severe wind damage, heavier rainfall, and larger storm surges, exacerbating flooding and destruction. Droughts may also become more frequent or severe in certain areas.

- Impacts on the Belize Barrier Reef:** Rising sea surface temperatures are a primary driver of coral bleaching events, which can lead to widespread coral mortality. Ocean acidification, caused by the absorption of atmospheric CO2 by seawater, hinders the ability of corals and other marine organisms to build their skeletons and shells.

- Impacts on agriculture:** Changes in rainfall patterns, increased temperatures, and more frequent extreme weather events can negatively affect crop yields, disrupt planting and harvesting seasons, and increase the prevalence of pests and diseases, threatening food security and livelihoods in agricultural communities.

- Impacts on water resources:** Altered rainfall patterns can lead to both water scarcity during droughts and increased flooding, affecting freshwater availability for human consumption, agriculture, and ecosystems.

- Impacts on biodiversity and ecosystems:** Changes in temperature and precipitation can alter habitats, affecting the distribution and survival of plant and animal species, both terrestrial and marine. Mangroves and coastal wetlands, crucial for coastal protection and as nurseries for fish, are particularly at risk from sea-level rise and storm surges.

Belize has relatively low national greenhouse gas emissions in absolute terms (around 7.46 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent in 2023). However, on a per capita basis, its emissions (18.13 tonnes per person) are comparatively high, ranking 13th globally. Land use change and forestry (LULUCF) constitute the largest source of emissions in Belize, primarily due to deforestation and forest degradation.

The Government of Belize has acknowledged the threat of climate change and has developed national strategies for both mitigation (reducing greenhouse gas emissions) and adaptation (adjusting to the impacts). The country has committed to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. Adaptation measures include strengthening coastal defenses, promoting climate-resilient agriculture, improving water resource management, protecting and restoring ecosystems like mangroves and coral reefs, and enhancing early warning systems for extreme weather. These efforts often consider the disproportionate impact of climate change on vulnerable populations, including low-income communities, indigenous groups, and those reliant on natural resources for their livelihoods, aiming for climate justice. International support and finance are crucial for Belize to effectively implement its climate action plans.

5. Government and politics

Belize operates as a parliamentary constitutional monarchy and is a Commonwealth realm. The structure of its government is based on the British Westminster system, and its legal system is modeled on the common law of England. This framework emphasizes democratic processes, the rule of law, and the protection of human rights, although challenges in implementation and enforcement exist.

5.1. Government structure

The Monarch of Belize, currently Charles III, is the head of state. The King resides in the United Kingdom and is represented in Belize by a Governor-General, who performs ceremonial functions and assents to legislation.

Executive authority is exercised by the Cabinet, which is led by the Prime Minister, the head of government. The Prime Minister is typically the leader of the political party that commands a majority in the House of Representatives. Cabinet ministers are appointed by the Governor-General on the advice of the Prime Minister and are usually members of the National Assembly. The Cabinet is responsible for the day-to-day administration of the country and for formulating and implementing government policy. Checks and balances are intended through the separation of powers, though the executive often holds significant influence. Accountability mechanisms include parliamentary oversight, an independent judiciary, and a free press.

The National Assembly is the bicameral legislature of Belize. It consists of:

- The House of Representatives: This is the lower house, currently composed of 31 members who are directly elected by popular vote in single-member constituencies for a maximum term of five years. The House is responsible for introducing and passing legislation, particularly concerning financial matters.

- The Senate: This is the upper house, currently composed of 13 members (previously 12) who are appointed by the Governor-General. Six senators are appointed on the advice of the Prime Minister, three on the advice of the Leader of the Opposition, one on the advice of the Belize Council of Churches and the Evangelical Association of Churches, one on the advice of the Belize Chamber of Commerce and Industry and the Belize Business Bureau, one on the advice of the National Trade Union Congress of Belize and the Civil Society Steering Committee, and one on the advice of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in good standing. The Senate reviews and debates bills passed by the House of Representatives and can initiate non-money bills. Its role is primarily as a house of review, intended to provide a check on the power of the House.

Legislative power is vested in both the government (through the introduction of bills) and the Parliament of Belize. Constitutional safeguards protect fundamental rights and freedoms, including freedom of speech, press, worship, movement, and association.

The judiciary is constitutionally independent of the executive and legislative branches. It is responsible for interpreting and applying the laws of Belize. The judicial system includes:

- Magistrates' Courts, which hear less serious criminal and civil cases.

- The Supreme Court, which has original jurisdiction in more serious criminal (like murder) and civil cases, and also hears appeals from Magistrates' Courts. The Chief Justice heads the Supreme Court.

- The Court of Appeal, which hears appeals from the Supreme Court.

- The Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ), based in Trinidad and Tobago, is Belize's final court of appeal, having replaced the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the United Kingdom for this role. This move aimed to strengthen regional judicial independence.

Judges are appointed through a process designed to ensure their independence and competence.

5.2. Political culture and parties

Belizean political culture has been shaped by its colonial past, its journey to independence, and its multi-ethnic society. Since 1935, elections were reinstated, though initially with a very limited franchise (only 1.8% of the population eligible to vote). Women gained the right to vote in 1954, a significant step in democratic development.

Since the 1970s, the party system in Belize has been dominated by two major political parties:

- The People's United Party (PUP): Generally considered a centre-left party, the PUP was instrumental in leading Belize to independence under figures like George Cadle Price. It has historically drawn support from a broad base, including rural and urban populations.

- The United Democratic Party (UDP): Generally considered a centre-right party, the UDP has served as the main opposition and has also formed governments at various times.

These two parties have alternated in power, creating a competitive two-party system. While other smaller political parties have participated in elections at all levels, none have historically won a significant number of seats or offices, though their presence and challenge have grown over the years. Elections are generally considered free and fair, with citizen participation being a key feature of the democratic process. Political discourse can be robust, and issues such as economic development, social welfare, crime, and the Guatemalan territorial dispute often dominate campaigns.

Civil society organizations play an important role in Belizean political life, advocating for a range of issues including human rights, environmental protection, good governance, and social justice. These organizations contribute to public debate, policy formulation, and holding the government accountable. Promoting democratic values, transparency, and citizen engagement remains an ongoing effort.

5.3. Foreign relations

Belize pursues an independent foreign policy aimed at safeguarding its sovereignty and territorial integrity, promoting economic development, and fostering international cooperation. It is a full participating member of numerous international and regional organizations, including:

- The United Nations (UN)

- The Commonwealth of Nations

- The Organization of American States (OAS)

- The Central American Integration System (SICA)

- The Caribbean Community (CARICOM), including the CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME)

- The Association of Caribbean States (ACS)

- The Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ), which serves as its final court of appeal.

- The World Trade Organization (WTO), of which it is an original member (1995).

Belize actively participates in the work of these organizations and is involved in regional trade agreements, such as the pact between the Caribbean Forum (CARIFORUM) subgroup of the Group of African, Caribbean, and Pacific States (ACP) and the European Union.

A key aspect of Belize's foreign policy is the management of its longstanding territorial dispute with Guatemala. This issue significantly influences its relations with Guatemala and its engagement with international bodies like the OAS and the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

Belize maintains diplomatic relations with many countries worldwide. It is a party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. The country strives for balanced discussions on international issues, often emphasizing the perspectives of small states and vulnerable nations, particularly concerning climate change and sustainable development. The protection of human rights and democratic principles are also important considerations in its foreign policy.

5.3.1. Guatemalan territorial dispute

The Belizean-Guatemalan territorial dispute is a long-standing and complex issue that has significantly shaped Belize's history, foreign policy, and national identity. Guatemala has historically claimed sovereignty over a substantial portion, or at times all, of Belizean territory. This claim is occasionally reflected in maps produced by the Guatemalan government, depicting Belize as Guatemala's twenty-third department. The area claimed by Guatemala involves approximately 53% of Belize's mainland, encompassing significant parts of four districts: Belize, Cayo, Stann Creek, and Toledo. Roughly 43% of Belize's population (approximately 154,949 Belizeans based on older estimates) reside in this claimed region.

The historical origins of the dispute trace back to colonial-era treaties, particularly the Anglo-Guatemalan Treaty of 1859. Guatemala contends that Britain failed to fulfill certain obligations under this treaty (specifically, Clause VII, which involved the construction of a road between Belize City and Guatemala), thereby rendering the treaty void and Guatemala's claim to the territory (which it asserts it inherited from Spain) still valid. Belize, and formerly the United Kingdom, maintain that the treaty established the boundaries and that Belize's sovereignty is legitimate under international law, including the principle of self-determination.

Throughout Belize's history, the dispute has led to periods of tension and has required mediation efforts by various international actors, including the United Kingdom, CARICOM heads of government, the Organization of American States (OAS), Mexico, and the United States. The OAS has played a significant role in facilitating dialogue and confidence-building measures between the two countries, particularly along the undefined border area known as the Adjacency Zone.

In recent years, both Belize and Guatemala agreed to submit the territorial, insular, and maritime dispute to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for a final and binding resolution. This decision followed successful referendums in both countries:

- Guatemala held its referendum on April 15, 2018, with over 95% of voters approving taking the claim to the ICJ.

- Belize held its referendum on May 8, 2019 (postponed from an earlier date), with 55.4% of voters opting to send the matter to the ICJ.

Both countries subsequently submitted their requests to the ICJ. Guatemala filed its initial memorial (brief) in December 2020, and Belize submitted its counter-memorial by June 2022. Guatemala then submitted its reply in December 2022, and Belize submitted its rejoinder (final written pleading) by June 2023. The stage of written submissions concluded on June 7, 2023. The next step in the ICJ process involves oral arguments from each country's legal teams.

The dispute has a direct impact on bilateral relations between Belize and Guatemala and affects the lives of people living in border areas. Incidents have occurred in the Adjacency Zone, sometimes involving confrontations between security forces or civilians. Human rights concerns have been raised regarding the treatment of individuals, including indigenous Maya communities whose ancestral lands often straddle the disputed border region or lie within the claimed territory. The resolution of the dispute is seen as crucial for regional stability and for allowing both nations to move forward with greater certainty and cooperation. The perspectives of all involved parties, including the indigenous communities whose lives and lands are directly affected, are important considerations in seeking a just and lasting solution.

5.3.2. Relations with major countries

Belize maintains significant diplomatic, economic, and security relationships with several major countries.

United Kingdom: As a former colonial power and fellow Commonwealth realm member, Belize has strong historical and ongoing ties with the United Kingdom. The UK was instrumental in guaranteeing Belize's security in the early years of independence due to the Guatemalan territorial claim. While direct British military presence has been reduced, the British Army Training and Support Unit Belize (BATSUB) continues to operate, providing jungle warfare training for British troops and contributing to Belizean security. The UK also provides development assistance and supports Belize in various international forums.

United States: The United States is a major diplomatic and economic partner for Belize. Cooperation spans areas such as counter-narcotics efforts, security, trade, and development assistance. The U.S. is a significant market for Belizean exports and a source of tourism and investment. The U.S. has provided financial support, including through agencies like the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), focusing on areas like education and the energy sector to reduce poverty through economic growth. The U.S. Peace Corps has also had a long-standing presence in Belize, working on public health, education, and community development. The shared commitment to democratic governance and disaster relief efforts further strengthen bilateral relations. However, U.S. foreign policy in the region, particularly concerning drug trafficking and migration, can also have implications for Belize.

Caribbean Nations (CARICOM): Belize is an active member of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) and considers itself part of the Caribbean region. It participates in CARICOM initiatives related to economic integration (like the CSME), regional security, and coordinated foreign policy. CARICOM has been a consistent supporter of Belize's sovereignty and territorial integrity in the context of the Guatemalan dispute.

Mexico: As a neighboring country to the north, Mexico is an important partner for Belize. Relations involve trade, cultural exchange, and cooperation on border security and transnational issues. The border region sees significant cross-border movement and economic activity.

Central American Nations (SICA): Belize is also a member of the Central American Integration System (SICA), though its engagement with Central America has historically been more complex due to the Guatemalan dispute and its stronger ties to the Caribbean. However, cooperation on regional issues is increasing.

Republic of China (Taiwan): Belize is one of a relatively small number of countries that maintain full diplomatic relations with the Republic of China (Taiwan) rather than the People's Republic of China. Taiwan provides significant development assistance to Belize in areas such as agriculture, education, healthcare, and infrastructure.

These relationships impact Belize's social and economic policies through trade agreements, development aid, security cooperation, and foreign investment, all of which contribute to the nation's development trajectory.

5.4. Armed forces

The Belize Defence Force (BDF) is the primary military organization responsible for the defense of Belize's sovereignty and territorial integrity. The BDF, along with the Belize National Coast Guard and the Immigration Department, falls under the Ministry of Defence and Immigration (or similar ministerial portfolios depending on governmental structure at the time).

The BDF comprises:

- Army/Land Element:** The main component, responsible for land-based defense, border security, internal security assistance, and disaster relief.

- Air Wing:** Provides air support, reconnaissance, troop transport, and medical evacuation capabilities.

- Maritime Wing/Coast Guard:** The Belize National Coast Guard became a distinct entity from the BDF's maritime wing in 2005, though they work in close cooperation. It is responsible for maritime law enforcement, search and rescue, fisheries protection, and preventing illicit activities in Belize's territorial waters and Exclusive Economic Zone.

In 1997, the regular army numbered over 900 personnel, with a reserve force of 381, an air wing of 45, and a maritime wing of 36, totaling approximately 1,400. More recent figures would vary. In 2012, the Belizean government's military expenditure was about 17.00 M USD, representing approximately 1.08% of the country's Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Historically, after Belize achieved independence in 1981, the United Kingdom maintained a significant deterrent force (British Forces Belize) in the country to protect it from potential invasion by Guatemala due to the ongoing territorial dispute. During the 1980s, this force included an infantry battalion and No. 1417 Flight of Harriers. The main British combat force left in 1994, three years after Guatemala recognized Belizean independence. However, the United Kingdom maintained a training presence through the British Army Training and Support Unit Belize (BATSUB) and 25 Flight Army Air Corps. Most British forces, including BATSUB's permanent staff, were withdrawn in 2011, though some seconded advisers may remain, and British troops continue to use Belize for jungle warfare training on a rotational basis. BATSUB's presence provides economic benefits and security cooperation.

The BDF also engages in international peacekeeping operations and cooperates with regional and international partners on security matters, including counter-narcotics and counter-trafficking efforts.

5.5. Administrative divisions

Belize is divided into six districts for administrative purposes. These districts are:

1. Belize District (Capital: Belize City)

2. Cayo District (Capital: San Ignacio/Santa Elena)

3. Corozal District (Capital: Corozal Town)

4. Orange Walk District (Capital: Orange Walk Town)

5. Stann Creek District (Capital: Dangriga)

6. Toledo District (Capital: Punta Gorda)

These districts are further subdivided into 31 constituencies for electoral purposes, which are used for electing members to the House of Representatives.

Local government is established to manage affairs at the municipal and community levels. There are four types of local authorities:

- City councils:** Govern the two designated cities, Belize City and the capital, Belmopan.

- Town councils:** Govern the seven designated towns (Corozal Town, Dangriga, Orange Walk Town, Punta Gorda, San Ignacio/Santa Elena, San Pedro Town, and Benque Viejo del Carmen).

- Village councils:** Serve rural communities.

- Community councils:** Also serve rural communities, often smaller settlements.

City and town councils cover the urban population, while village and community councils cater to the rural population, providing local services and facilitating community development. The structure and functions of local government aim to promote local democracy and participation in governance.

5.6. Indigenous land claims

The issue of indigenous land claims is a significant and ongoing concern in Belize, primarily involving the Maya people (including the Yucatec, Mopan, and Q'eqchi' groups) and, to a lesser extent, the Garinagu (Garifuna). These claims are rooted in historical occupation and customary land tenure systems that predate European colonization and the formation of the modern Belizean state.

Historically, Maya communities have asserted their rights to ancestral lands and resources, which are crucial for their livelihoods, cultural practices, and collective identity. The expansion of logging, agriculture, and other development activities often encroached upon these lands without adequate consultation or consent from the indigenous communities.

Belize took a positive step by backing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in 2007, which affirms the rights of indigenous peoples to their traditional lands, territories, and resources, and to self-determination.

A series of landmark legal battles have been fought by Maya communities, particularly in the Toledo District, to have their customary land rights recognized by the Belizean legal system. Key court decisions include:

- A 2007 Supreme Court ruling that affirmed the customary land rights of the Maya villages of Conejo and Santa Cruz.

- A 2010 Supreme Court ruling that expanded this recognition to all Maya villages in the Toledo District, affirming that Maya customary land title constitutes property within the meaning of the Belize Constitution.

- A 2013 Supreme Court decision upheld the 2010 ruling.

- In 2015, the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ), Belize's highest appellate court, issued a consent order based on an agreement between the Maya leaders and the Government of Belize. This order affirmed the Maya land rights and obligated the government to take concrete steps to identify and demarcate these lands, protect them from incursions, and develop a legislative or administrative framework for their registration and governance, in consultation with the Maya people.

Despite these legal victories and international commitments, the implementation of these rulings has been slow and challenging. The government has faced difficulties in fully demarcating and registering Maya communal lands, and concerns persist among Maya communities about continued incursions by loggers, settlers, and resource extraction companies. For instance, years after the CCJ's decision, progress on creating a Mayan land registry was limited, prompting some indigenous groups to undertake their own land mapping initiatives.

The struggle for indigenous land rights has significant social, economic, and cultural implications. For Maya communities, secure land tenure is essential for maintaining their traditional ways of life, agricultural practices, spiritual connections to the land, and cultural heritage. It is also central to their efforts towards self-determination and having greater control over the resources within their territories. The ongoing dialogue and negotiations between indigenous representatives and the government are critical for achieving a just and sustainable resolution that respects indigenous rights and promotes inclusive development. As of 2017, reports indicated that indigenous groups were not adequately factored into some national development indicators, highlighting a continued need for greater recognition and inclusion.

6. Economy

Belize has a small, developing, private enterprise economy. Its primary sectors include agriculture, agro-based industry, merchandising, and increasingly, tourism and construction. The country is also a modest producer of crude oil. The economic policies aim for growth while addressing challenges like poverty, unemployment, and environmental sustainability, with a focus on equitable development and labor rights.

6.1. Main industries

- Agriculture:** This sector has traditionally been a mainstay of the Belizean economy.

- Sugar: Remains a chief crop, accounting for a significant portion of exports, particularly from the northern districts. Working conditions in the sugar industry have historically been a concern.

- Bananas: A major export crop, especially in the southern Stann Creek District, and a large employer. The industry is susceptible to weather events and plant diseases.

- Citrus: Oranges and grapefruits are important agricultural products, primarily grown for processing into concentrate for export.

- Other crops include rice, corn, beans, cacao, and various fruits and vegetables for domestic consumption and some export.

- The environmental impact of agriculture, through deforestation for land conversion and the use of agrochemicals, is a concern.

- Fisheries and Aquaculture:** The extensive coastline and barrier reef support commercial fishing, primarily for lobster, conch, and finfish. Aquaculture, particularly shrimp farming, has also become an important export industry. Sustainable fishing practices are crucial to protect marine resources.

- Manufacturing:** The manufacturing sector is relatively small, focusing on agro-processing (e.g., sugar refining, citrus concentrate, beverages), garment production, and light manufacturing for the domestic market.

- Petroleum:** Since the discovery of oil in 2006, crude oil has become an export commodity. Production levels are modest. The environmental impact of oil exploration and extraction, especially near sensitive ecological areas, is a subject of public and environmental scrutiny.

- Tourism:** (See separate section below, as it's a major pillar).

The contribution of these industries to GDP and employment varies. For example, in 2007, Belize became the world's third-largest exporter of papaya. The government faces challenges in promoting economic stability, improving tax collection, and managing public spending. Infrastructure development, while improving, remains a challenge. Major trading partners include the United States, the United Kingdom, the European Union, Mexico, and CARICOM nations. Belize has several commercial banks and a robust credit union movement. Due to its financial system and location, Belize has faced scrutiny regarding money laundering, prompting efforts to strengthen financial regulations.

6.2. Industrial infrastructure

Belize's industrial and economic development is significantly influenced by the state of its essential infrastructure. Key areas include energy, telecommunications, and transportation.

- Energy (Electricity):** Access to reliable and affordable electricity is a critical factor for economic development and social equity. Belize Electricity Limited (BEL) is the primary integrated electric utility and distributor. The country's electricity supply comes from a mix of sources:

- Domestic hydroelectric generation: Several hydroelectric plants, primarily on the Macal River (operated by Belize Electric Company Limited - BECOL), contribute to the power supply.

- Imported power: Belize imports a significant amount of electricity, mainly from Mexico's Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE).

- Other sources: There is some generation from biomass (e.g., bagasse from sugar production) and diesel generators. Efforts are underway to increase the share of renewable energy, such as solar.

Electricity costs in Belize have historically been among the highest in the region, posing a challenge for businesses and consumers. The ownership and regulation of the electricity sector have seen changes, including periods of nationalization and private investment. Improving energy efficiency and expanding access to underserved rural areas are ongoing goals.

- Telecommunications:** A modern telecommunications network is vital for business, education, and social connectivity. Belize Telemedia Limited (BTL) was historically the dominant provider. The sector has seen liberalization with the entry of competitors like Speednet (Smart). Services include fixed-line and mobile telephony, internet access (including fiber-to-the-home in some areas), and data networks. Expanding broadband internet access and affordability, especially in rural areas, is crucial for digital inclusion and economic growth. The nationalization of BTL in the past has also influenced the sector's dynamics and investment climate.

- Transportation:**

- Roads:** The road network is the primary mode of internal transportation. Major highways connect the main towns and districts, such as the Philip Goldson Highway (formerly Northern Highway), George Price Highway (formerly Western Highway), Hummingbird Highway, and Southern Highway. While main highways are generally paved, many secondary and rural roads are unpaved and can be challenging, especially during the rainy season. Ongoing investment is needed for road maintenance and upgrades to support agriculture, tourism, and general commerce.

- Ports:** Belize has several ports, with the main deep-water port located in Belize City, handling most of the country's cargo. Other ports include Big Creek (for bananas and other agricultural exports) and Commerce Bight. Port infrastructure is important for international trade.

- Airports:** The Philip S. W. Goldson International Airport (PGIA) near Belize City is the main international gateway. There are also numerous smaller airstrips throughout the country serving domestic flights and connecting to tourist destinations, particularly the cayes.

- Waterways:** Rivers are used for local transportation in some areas, and maritime transport is essential for connecting the mainland to the cayes.

Developing and maintaining this infrastructure requires significant investment and planning to support sustainable economic growth and ensure that benefits, such as access to electricity and telecommunications, are equitably distributed across the population, including remote and vulnerable communities.

6.3. Tourism

Tourism is a cornerstone of Belize's economy, making a significant contribution to its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and employment. The country's diverse natural and cultural attractions draw visitors from around the world.

- Major Attractions:**

- Belize Barrier Reef:** This UNESCO World Heritage site is the premier tourist attraction, offering world-class scuba diving, snorkelling, fishing, and boating opportunities. The Great Blue Hole, numerous cayes (islands) like Ambergris Caye (with San Pedro Town) and Caye Caulker, and atolls like Lighthouse Reef and Glover's Reef are major draws.

- Maya Archaeological Sites:** Belize is rich in Maya history, with impressive sites such as Caracol, Xunantunich, Lamanai, Altun Ha, and Lubaantun offering insights into this ancient civilization.

- Ecotourism and Nature:** The country's lush rainforests, extensive cave systems (like Actun Tunichil Muknal), diverse wildlife, and numerous national parks and reserves (Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary for jaguars, Mountain Pine Ridge for waterfalls and pine forests) support a thriving ecotourism sector. Activities include hiking, birdwatching, caving, zip-lining, and river kayaking/rafting.

- Cultural Tourism:** The diverse cultures of Belize, including Garifuna, Maya, Creole, and Mennonite communities, offer unique cultural experiences, from music and dance to cuisine and traditional crafts.

- Visitor Statistics and Economic Contributions:**

Tourist arrivals, including both overnight visitors and cruise ship passengers, have generally shown growth over the years, though the sector is susceptible to global economic conditions, natural disasters (hurricanes), and events like pandemics. In 2012, tourist arrivals totaled 917,869 (with about 584,683 from the United States), and tourist receipts amounted to over 1.30 B USD. After the COVID-19 pandemic impacted global travel, Belize was among the first Caribbean countries to implement measures to safely welcome vaccinated travelers. The tourism sector provides direct and indirect employment in accommodation, transportation, food services, tours, and retail.

- Sustainable Tourism Development:**

Recognizing the importance of its natural and cultural heritage, Belize has placed an emphasis on sustainable tourism development. Policies aim to:

- Minimize environmental impact: Promoting eco-friendly practices, managing visitor numbers at sensitive sites, and supporting conservation efforts.

- Benefit local communities: Ensuring that local people, including indigenous communities, share in the economic benefits of tourism through employment, entrepreneurship, and community-based tourism initiatives. This includes addressing potential negative impacts like displacement or cultural commodification.

- Preserve cultural heritage: Supporting the authentic representation and preservation of Belize's diverse cultures.

- Protect natural resources: Integrating tourism planning with environmental management to safeguard the ecosystems that attract visitors.

Challenges include balancing development pressures with conservation needs, ensuring adequate infrastructure, managing the environmental footprint of tourism (waste, water, energy), and distributing tourism benefits more equitably across different regions and communities. The impact of cruise tourism, in particular, requires careful management to avoid overwhelming local infrastructure and sensitive environments. The long-term viability of Belize's tourism industry is intrinsically linked to the health of its ecosystems, especially the Barrier Reef, making sustainable practices and climate resilience critical.

7. Society

Belizean society is a vibrant mosaic of diverse ethnic groups, languages, and cultural traditions, shaped by its unique history and geographical location. This section provides an overview of its demographic profile, ethnic composition, linguistic landscape, religious affiliations, education and healthcare systems, social structure, and contemporary social issues, with an emphasis on equity, human rights, and the well-being of all its communities.

7.1. Demographics

According to the 2022 census conducted by the Statistical Institute of Belize, the population of Belize was 397,483. The country has one of the lowest population densities in Central America and the Western Hemisphere.

Key demographic indicators include:

- Population Growth Rate:** Historically, Belize has had a relatively high population growth rate, around 1.87% per year in 2018, making it one of the highest in the region. This growth is influenced by birth rates and migration.

- Birth and Death Rates:** In 2022, the birth rate was 17.8 births per 1,000 population, and the death rate was 6.3 deaths per 1,000 population.

- Total Fertility Rate:** In 2023, the total fertility rate was estimated at 2.01 children per woman.

- Life Expectancy:** Life expectancy varies, but generally aligns with regional averages.

- Age/Gender Distribution:** Belize has a relatively young population, with a significant proportion under the age of 30.

- Urbanization:** A significant portion of the population lives in urban areas, with Belize City being the largest urban center, followed by towns like San Ignacio, Orange Walk Town, and the capital, Belmopan.

Migration has played a significant role in Belize's demographics. There has been emigration of Belizeans (particularly Creoles and Garinagu) to countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, seeking educational and economic opportunities. Concurrently, Belize has received immigrants and refugees, especially from neighboring Central American countries (El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua) during periods of conflict and economic hardship, contributing to the growth of the Hispanic/Mestizo population. This dynamic has led to shifts in the ethnic composition over recent decades. For example, the Creole/Hispanic ratio shifted from approximately 58/38 in 1980 to 26/53 by 1991, largely due to Creole emigration and increased Mestizo birth rates and immigration. As of 2018, migrants made up about 15% of Belize's population. The U.S. State Department estimates upwards of 100,000 Belizeans reside in the U.S., representing the largest Belizean diaspora.

7.2. Ethnic groups

Belize is renowned for its rich ethnic diversity, a "melting pot" of cultures. While colonial policies sometimes encouraged segregation, the small, interconnected population has fostered a relatively harmonious coexistence, though traces of racism exist. The national motto, "Sub Umbra Floreo" (Under the Shade I Flourish), reflects this unity in diversity. Major ethnic groups include:

- Hispanic/Mestizo:** The largest ethnic group, comprising around 51.7% of the population (2022 SIB estimate). This group includes descendants of Yucatec Maya and Spanish settlers who migrated from Mexico during the Caste War of Yucatán in the mid-19th century, as well as more recent immigrants and refugees from other Central American countries. They are predominant in the northern and western districts and have significantly influenced Belizean culture and language.

- Belizean Creoles:** Making up about 25.2% of the population, Creoles are primarily descendants of enslaved West and Central Africans and European (mainly English and Scottish) log cutters known as Baymen. Over time, they have intermarried with other groups. Historically the largest group, their proportion has decreased due to emigration. Belize City is a major Creole center.

- Maya:** Constituting about 9.8% of the population, the Maya are the original inhabitants. Three main Maya groups reside in Belize: the Yucatec (many fled the Caste War), the Mopan (indigenous to Belize, some returned from Guatemala), and the Q'eqchi' (fled enslavement in Guatemala in the 19th century). They are concentrated mainly in the Toledo, Stann Creek, and Cayo districts.

- Garinagu (Garifuna):** Around 4% of the population, the Garifuna are descendants of West/Central Africans and indigenous Carib and Arawak peoples from the island of St. Vincent. They arrived in Belize in the early 19th century via Roatán, Honduras, after being exiled by the British. They have a unique language, music, dance, and spiritual traditions, recognized by UNESCO. They primarily reside in southern coastal towns like Dangriga, Hopkins, and Punta Gorda.

- White Belizeans (including Mennonites):** Approximately 4.8% of the population. This group includes descendants of British settlers, more recent immigrants from North America and Europe, and distinct Mennonite communities. Plautdietsch-speaking Mennonites, primarily of German descent who came from Mexico and Canada starting in the late 1950s, live in agricultural settlements like Spanish Lookout and Shipyard. There are also smaller groups of Old Order Mennonites.

- East Indian:** About 1.5% of the population, descendants of indentured laborers brought from India in the 19th century after the abolition of slavery, mainly to work on sugar plantations. They are found primarily in the Corozal and Toledo districts.

- East Asian and Arab:** Around 1% of the population, including Chinese, Syrian, and Lebanese immigrants and their descendants, who have contributed to commerce and politics.

- Other Ethnic Groups/Not Stated:** Smaller groups and those who did not state an ethnicity make up the remainder.

Inter-ethnic relations are generally peaceful, with considerable cultural exchange and intermarriage. Each group has contributed to the national identity through cuisine, music, language, folklore, and traditions.

7.2.1. The Maya

The Maya are the indigenous peoples of Belize, with a presence dating back millennia. Today, they constitute a significant and culturally rich component of Belizean society, comprising approximately 9.8% of the total population. Three main Maya groups are recognized in Belize:

- Yucatec Maya:** Many Yucatec Maya migrated to northern Belize from the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico, particularly during the Caste War of Yucatán (1847-1901), fleeing the violence. They primarily settled in the Corozal and Orange Walk districts. They traditionally speak the Yucatec Maya language.

- Mopan Maya:** The Mopan are indigenous to parts of central and western Belize. Some were displaced to Guatemala during the colonial era by the British but later returned to Belize, particularly to the southern Toledo District and parts of Cayo and Stann Creek districts, to escape forced labor in Guatemala in the 19th century. They speak the Mopan Maya language.

- Q'eqchi' Maya:** The Q'eqchi' (Kekchi) migrated to southern Belize, mainly the Toledo District, from the Verapaz region of Guatemala in the late 19th century, also fleeing enslavement and land dispossession. They speak the Q'eqchi' language.

Maya communities in Belize maintain many of their traditional cultural practices, including languages, farming techniques (such as milpa agriculture), traditional medicine, spiritual beliefs, and forms of community governance. They have a deep connection to the land, which is central to their identity and livelihood.

Socio-economically, Maya communities, particularly in the Toledo District, are often among the most marginalized in Belize. They face challenges related to poverty, access to education and healthcare, infrastructure, and land security. The struggle for recognition of their customary land rights has been a prominent issue, leading to landmark legal victories that affirmed these rights, although implementation remains an ongoing process (see Indigenous land claims section).

Efforts to preserve Maya heritage and rights are active, with various Maya organizations working to promote cultural revitalization, bilingual education, sustainable development, and political representation. Maya culture is an integral part of Belize's national identity, contributing significantly to its diversity through traditions, crafts, cuisine, and historical legacy. Many Maya are also fluent in English, Belizean Creole, and sometimes Spanish, reflecting the multilingual nature of Belize.

7.2.2. Belizean Creoles

Belizean Creoles, also known as Kriols, are a significant ethnic group in Belize, constituting about 25.2% of the population. Their origins are primarily rooted in the historical intermixture of enslaved West and Central Africans and European settlers, predominantly English and Scottish Baymen (logwood and mahogany cutters), during the colonial period of British Honduras. Over generations, Creoles have also intermarried with other ethnic groups present in Belize, including Miskito from Nicaragua, Jamaicans and other Caribbean people, Mestizos, Europeans, Garinagu, and Maya.

The ancestors of many Belizean Creoles were brought to British Honduras (now Belize) primarily for forced labor in the logging industry. Many were transported from other British colonies in the Caribbean, such as Jamaica, which served as a hub for the slave trade. The conditions for enslaved people in the logging camps were harsh and brutal. However, the nature of the work, which sometimes required movement within the colony, may have led to a different dynamic of social interaction and cultural fusion compared to plantation-based slavery elsewhere.

Belize Town (now Belize City) became the epicenter of the colony and a major center for the Creole population. Lighter-skinned Creole communities also developed in the Belize River Valley, in villages like Crooked Tree, Isabella Bank, Bermudian Landing, and Lemonal, some of whom had more visible European ancestry.

The Belizean Creole language (Kriol), an English-lexified creole with African and other linguistic influences, developed during this period and became a lingua franca and a vital part of Belizean identity (see Languages section).

Belizean Creoles have played a pivotal role in the history and political development of Belize. They were involved in events such as the Battle of St. George's Caye, participated in the British West Indies Regiment during World War I and World War II, and were at the forefront of movements for workers' rights and racial equality. Educated Creoles, often returning from studies in Jamaica or the UK, were instrumental in the nationalist movement that advocated for adult suffrage, self-government, and ultimately, independence. Prominent Creole Belizeans who have shaped the nation include figures like Samuel Haynes (composer of the lyrics for the national anthem), Philip Goldson (national hero), George Cadle Price (often considered of Creole heritage and a key independence leader), Dean Barrow (former Prime Minister), Dame Minita Gordon (first Governor-General), Cleopatra White (pioneering nurse and community leader), Cordel Hyde (politician), and Patrick Faber (politician).