1. Overview

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola, is a country located on the west-central coast of Southern Africa. It is bordered by Namibia to the south, the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the north, Zambia to the east, and the Atlantic Ocean to the west. The nation also includes the exclave province of Cabinda, which has borders with the Republic of the Congo and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Luanda is its capital and largest city. Angola is rich in natural resources, particularly oil and diamonds, which have significantly shaped its economic trajectory, especially following the end of a long and devastating civil war in 2002.

This article examines Angola's history from its early kingdoms through Portuguese colonization, a protracted war for independence, and a subsequent lengthy civil war. It delves into the country's geography, diverse ecosystems, and climate. The political landscape, including its governmental structure, constitution, and administrative divisions, is explored, with a particular focus on human rights issues and the challenges of corruption and equitable development. Angola's foreign relations, particularly with major global partners like China, and its complex economy, heavily reliant on natural resources, are analyzed, emphasizing wealth distribution and social impacts. The article also covers Angolan society, including its diverse demographics, ethnic groups, languages, religions, education, and public health systems, highlighting social disparities. Finally, it explores Angola's rich culture, a blend of indigenous Bantu traditions and Portuguese influences, manifest in its arts, music, literature, and daily life. Throughout, the article adopts a perspective centered on social impact, human rights, and the pursuit of equitable and sustainable development for all Angolans.

2. Etymology

The name Angola is derived from the Portuguese colonial name Reino de AngolaKingdom of AngolaPortuguese, which appeared as early as Paulo Dias de Novais's charter in 1571. The Portuguese, in turn, derived this toponym from the title ngola, held by the kings of the Kingdom of Ndongo and the Kingdom of Matamba. The Ndongo kingdom was situated in the highlands between the Kwanza and Lucala rivers and was nominally a possession of the Kingdom of Kongo. However, during the 16th century, Ndongo sought greater independence from Kongo, and its rulers, bearing the title ngola, became significant figures in the region's interaction with the Portuguese.

3. History

Angola's history spans from prehistoric inhabitation through the rise and fall of indigenous kingdoms, centuries of Portuguese colonization, a protracted struggle for independence, and a devastating civil war, leading to its current phase of post-conflict reconstruction and development.

3.1. Early Migrations and Political Units

The area of modern Angola was originally inhabited by Khoisan-speaking peoples, who were predominantly nomadic hunter-gatherers. Around the first millennium BC, these groups were largely displaced or absorbed by Bantu peoples migrating from the north, likely originating from what is now northwestern Nigeria and southern Niger. These Bantu-speaking migrants introduced agriculture, including the cultivation of bananas and taro, as well as the herding of large cattle, particularly in Angola's central highlands and the Luanda plain. Geographic factors, such as difficult terrain, a hot and humid climate, and various diseases, limited intermingling between different tribal groups in the pre-colonial era.

Following these migrations, several political entities emerged. The most prominent was the Kingdom of Kongo, established in the 14th century, with its capital, Mbanza Kongo, located in what is now northwestern Angola. The kingdom extended its influence northward into the present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, and Gabon. The Kongo established extensive trade routes with other city-states and civilizations along the coast of southwestern and western Africa, trading in goods like copper, ivory, salt, and hides. Their trade networks even reached as far as Great Zimbabwe and the Mutapa Empire, although trans-oceanic trade was minimal before European contact.

To the south of the Kongo lay the Kingdom of Ndongo, whose rulers held the title ngola, and further south was the Kingdom of Matamba. The Ovimbundu kingdoms were established further south, while the Mbunda Kingdom was located in the east. The smaller Kingdom of Kakongo, to the north, later became a vassal of the Kingdom of Kongo. The peoples in these states often spoke dialects of the Kikongo language.

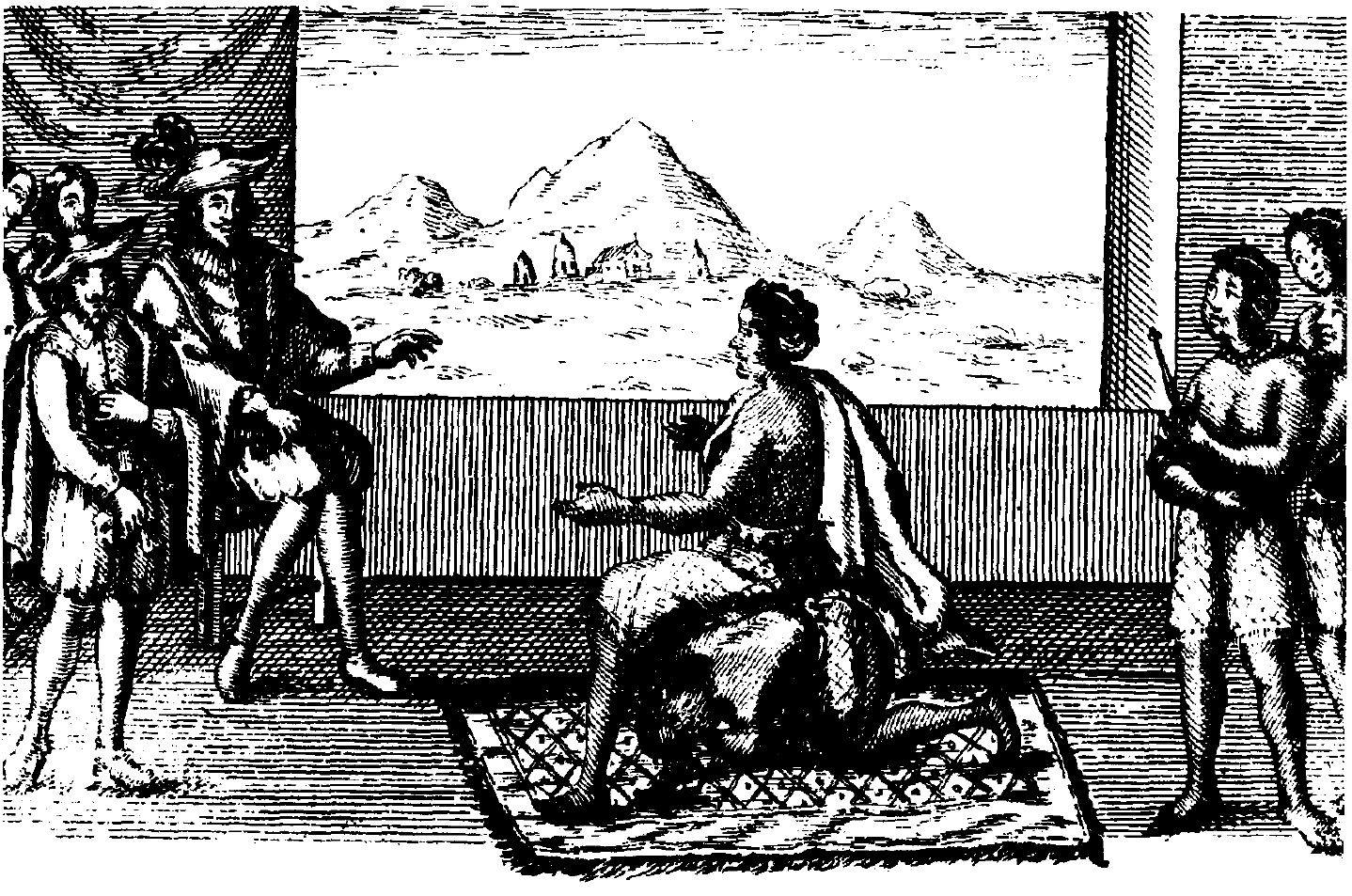

3.2. Portuguese Colonization

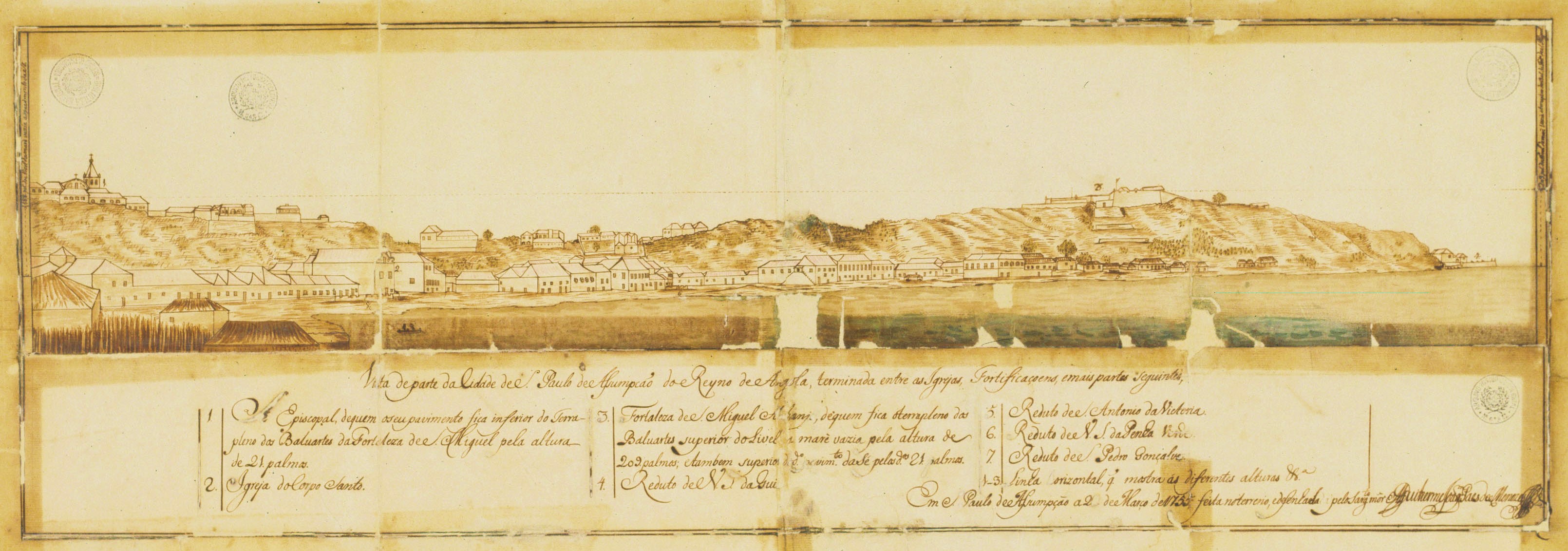

Portuguese explorer Diogo Cão reached the Angolan coast in 1484. A year earlier, in 1483, the Portuguese had established relations with the Kingdom of Kongo. Their primary early trading post was established at Soyo, near the mouth of the Congo River. In 1575, Paulo Dias de Novais founded São Paulo de Loanda (now Luanda) with a hundred settler families and four hundred soldiers. Benguela, further south, was fortified in 1587 and became a township in 1617.

The Kingdom of Kongo was a centralized state with a strong economy based on industries like copper, ivory, salt, hides, and, to a lesser extent, slaves. The arrival of the Portuguese and the ensuing trade relationship drastically altered Kongo's socio-economic fabric. Initially, trade focused on palm cloth, copper, and ivory. However, with the Portuguese development of sugar plantations on São Tomé, Kongo became a significant source of enslaved people for the island. King Afonso I's correspondence documents the internal slave trade and the sale of war captives to Portuguese merchants. Afonso expanded the kingdom and centralized power, establishing a royal monopoly on some trade, including a joint monopoly with Portuguese kings on the external slave trade.

The slave trade increasingly dominated Kongo's economy. Slaves became the primary commodity Europeans were willing to trade for, as Kongo lacked an effective international currency. Nzimbu shells served as a local currency for acquiring slaves, who could then be sold for international currency. This focus on the slave trade hindered economic diversification and industrialization, except in sectors related to slavery like the arms industry. The constant demand for slaves to trade for foreign goods, necessary for maintaining influence with European powers like Portugal and later the Dutch Republic, fueled internal conflict and violence.

By the early 17th century, as the external supply of captives dwindled, the Kongo government began enslaving its own citizens for minor infractions, sometimes enslaving entire villages. This led to chaos and internal conflict. Garcia II sought Dutch military aid to expel the Portuguese from Luanda, despite Portugal being a key slave trading partner. His successor, António I of Kongo, was killed by the Portuguese at the Battle of Mbwila in 1665, along with much of the aristocracy, as Portuguese colonial power expanded. The kingdom descended into wider war, disrupting the arms industry and placing almost every Kongolese citizen at risk of enslavement. Many skilled Kongolese gunsmiths were enslaved and transported to the Americas to work as blacksmiths and ironworkers.

The Portuguese established numerous settlements, forts, and trading posts along the Angolan coast, primarily for the trade in Angolan slaves destined for plantations, usually in exchange for European manufactured goods. This trade continued until after Brazilian independence in the 1820s.

Despite Portugal's territorial claims, its control over much of Angola's vast interior remained minimal for centuries. Life for European colonists was harsh, marked by frequent famines and epidemics that could decimate the population. During the Portuguese Restoration War, the Dutch West India Company occupied Luanda from 1641 to 1648, allying with local peoples against Portuguese holdings. A fleet under Salvador de Sá retook Luanda in 1648. The conquest of Pungo Andongo in 1671 was the last major Portuguese expansion from Luanda for some time, as attempts to invade Kongo (1670) and Matamba (1681) failed. Colonial outposts also expanded inward from Benguela, but significant inroads from both Luanda and Benguela were limited until the late 19th century.

The slave trade was officially abolished in Angola in 1836, and in 1854, the colonial government freed all its existing slaves. Slavery was completely abolished four years later, though these decrees were difficult to enforce, requiring assistance from the British Royal Navy's Blockade of Africa. This period coincided with renewed Portuguese military expeditions into the interior. By the mid-19th century, Portugal had established its dominion from the Congo River in the north to Moçâmedes in the south. Proposals to link Angola with Mozambique were blocked by British and Belgian opposition. Throughout this period, the Portuguese faced armed resistance from various Angolan peoples.

The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 delineated the boundaries of Portuguese claims in Angola, though many details were not resolved until the 1920s. Protective tariffs increased trade between Portugal and its African territories, leading to further development and a new wave of Portuguese immigrants.

In an expedition in 1925, American naturalist explorer Arthur Stannard Vernay visited Angola. Between 1939 and 1943, Portuguese army operations against the Mucubal people, accused of rebellion and cattle-thieving, resulted in hundreds of deaths. During this campaign, 3,529 Mucubal were taken prisoner, 20% of whom were women and children, and imprisoned in concentration camps. Many died from malnourishment, violence, and forced labor. Around 600 were sent to São Tomé and Príncipe, and hundreds more to a camp in Damba, where 26% perished.

3.3. Angolan War of Independence

Under Portuguese colonial law, black Angolans were forbidden from forming political parties or labour unions. Nationalist movements began to emerge after World War II, spearheaded by a largely Westernized, Portuguese-speaking urban class that included many mestiços (people of mixed European and African descent). In the early 1960s, these movements were joined by other associations arising from ad hoc labour activism in rural areas. Portugal's refusal to address Angolan demands for self-determination led to an armed conflict, which began in 1961 with the Baixa de Cassanje revolt. This gradually evolved into the Angolan War of Independence, a protracted struggle that lasted for twelve years (1961-1974).

Throughout the conflict, three main militant nationalist movements, each with its own guerrilla wing, emerged:

- The Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) was formed in the late 1950s as a coalition resistance movement by the Angolan Communist Party. Its leadership was predominantly Ambundu and it garnered support from public sector workers in Luanda and the Dembos hills. The MPLA held strong anti-imperialist views, was critical of the United States for its support of Portugal, and received material assistance from the Soviet Union and other nonaligned governments.

- The National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) recruited primarily from Bakongo refugees in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). Benefiting from a common border and shared cultural ties with the historical Kingdom of Kongo, the FNLA established a power base among Angolan exiles in Zaire.

- The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) was spearheaded by Jonas Savimbi from 1966. It was largely an Ovimbundu guerrilla initiative in central Angola, but was hampered by its geographic remoteness from friendly borders and the ethnic fragmentation of the Ovimbundu.

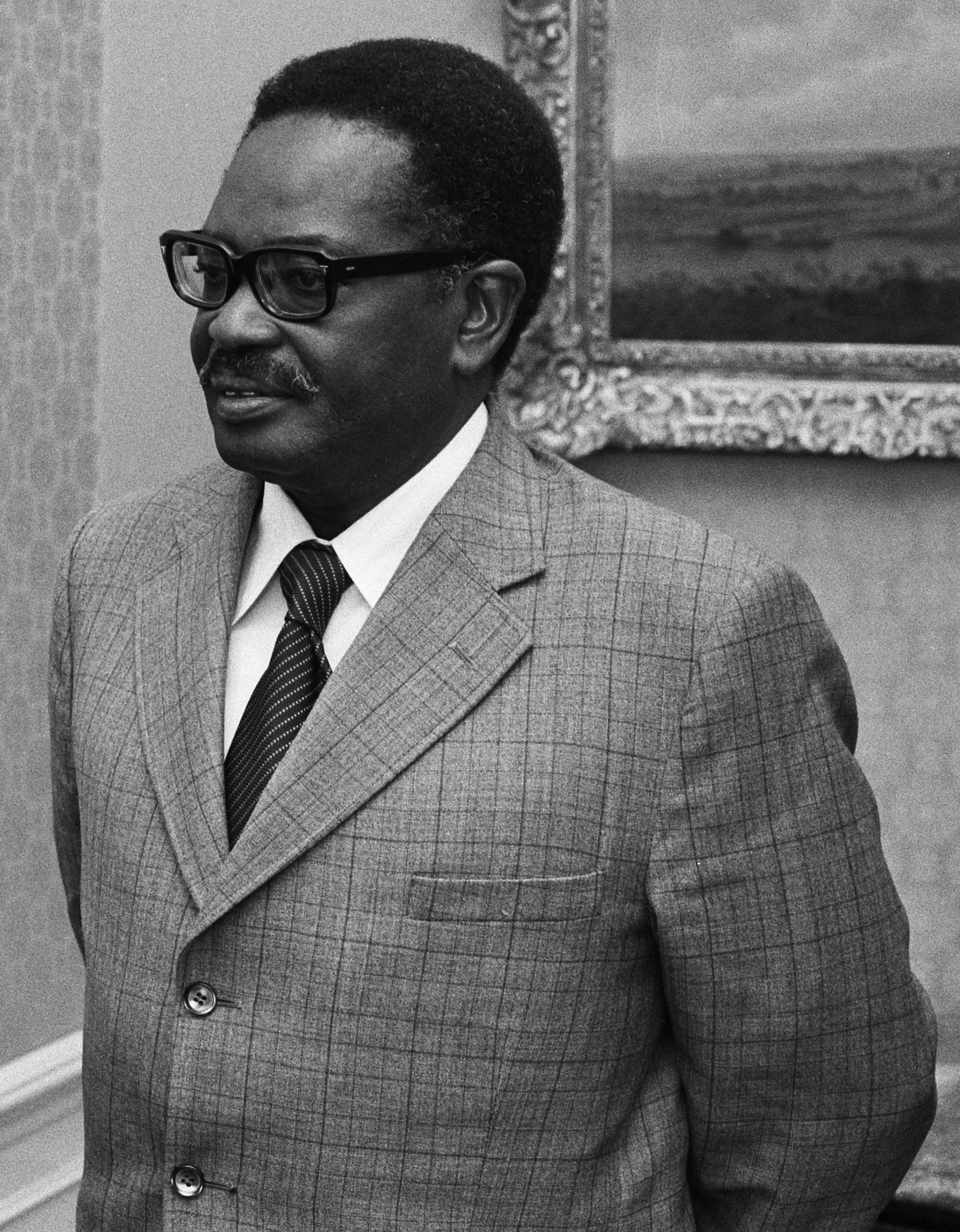

These rival movements were often hampered by political and military factionalism and their inability to unite efforts against the Portuguese. The MPLA, under Agostinho Neto, attempted to form a common front with the FNLA (then UPA) under Holden Roberto in 1961, but Roberto declined. Early attempts by the MPLA to insert insurgents into Angola were met with ambushes by UPA partisans, setting a precedent for the bitter factional strife that would later lead to the Angolan Civil War.

The Carnation Revolution in Portugal in 1974 overthrew the Estado Novo regime, leading to the suspension of Portuguese military activity in Africa and the brokering of a ceasefire pending negotiations for Angolan independence.

3.4. Angolan Civil War

Following the Carnation Revolution, the three main nationalist groups-MPLA, UNITA, and FNLA-competed for influence. Encouraged by the Organisation of African Unity, Holden Roberto (FNLA), Jonas Savimbi (UNITA), and MPLA chairman Agostinho Neto met in Mombasa in January 1975 and agreed to form a coalition government. This was ratified by the Alvor Agreement, which called for general elections and set Angola's independence date for November 11, 1975. However, all three factions used the gradual Portuguese withdrawal to seize strategic positions, acquire more arms, and enlarge their forces.

The rapid influx of weapons from external sources, particularly the Soviet Union (to MPLA) and the United States (to FNLA and UNITA), escalated tensions. The Soviet Union and Cuba became strong supporters of the MPLA, supplying arms, ammunition, funding, and training. With tacit American and Zairean support, the FNLA massed troops in northern Angola. The MPLA began securing control of Luanda. Sporadic violence broke out in March 1975, intensifying into street clashes by April and May. UNITA became involved after many of its members were massacred by an MPLA contingent in June. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) provided substantial covert aid to the FNLA and UNITA.

In August 1975, the MPLA requested direct Soviet military assistance. While the Soviets declined to send troops, offering advisers instead, Cuba was more forthcoming, dispatching combat personnel, weaponry, and supplies. By independence, over a thousand Cuban soldiers were in Angola, supplied by a massive Soviet-assisted airbridge. This support allowed the MPLA to drive its opponents from Luanda and repel interventions by Zairean and South African troops who attempted to assist the FNLA and UNITA. The FNLA was largely defeated after the Battle of Quifangondo, while UNITA withdrew to the southern provinces, from where Savimbi continued an insurgent campaign.

On November 11, 1975, Angola achieved independence with the MPLA declaring the People's Republic of Angola in Luanda, and Agostinho Neto as its first president. The FNLA and UNITA proclaimed a rival government in Huambo. The Angolan Civil War (1975-2002) ensued, becoming one of Africa's longest and most devastating conflicts.

Between 1975 and 1991, the MPLA implemented a Marxist-Leninist one-party state with a centrally planned economy. It nationalized private enterprises into state-owned entities (Unidades Economicas Estatais). While some industrialization occurred, corruption and embezzlement became rampant. The MPLA survived an attempted coup in 1977 by the Maoist-oriented Communist Organisation of Angola (OCA), which was suppressed through bloody political purges.

The war had a devastating impact on the civilian population, leading to widespread displacement, famine, and human rights abuses by all sides. Millions of landmines were laid, making vast areas of the country uninhabitable and agriculture perilous.

The MPLA abandoned its Marxist ideology in 1990, declaring social democracy as its new platform. Angola joined the International Monetary Fund, and market economy restrictions were eased. In May 1991, the Bicesse Accords were signed between the MPLA government and UNITA, scheduling general elections for September 1992. When the MPLA won a major electoral victory, UNITA rejected the results and returned to war. The Halloween massacre followed in October-November 1992, where MPLA forces killed thousands of UNITA supporters.

The war continued throughout the 1990s, with devastating consequences for the Angolan people and economy.

3.5. 21st Century

The Angolan Civil War finally came to an end on February 22, 2002, when UNITA leader Jonas Savimbi was killed in action by government troops in Moxico province. In April 2002, UNITA and the MPLA signed the Luena Memorandum of Understanding, with UNITA agreeing to demobilize its armed wing. This marked the end of 27 years of civil war.

Since 2002, Angola has emerged as a relatively stable constitutional republic. Parliamentary elections were held in 2008 and general elections in 2012, establishing an MPLA-ruled dominant-party system, with UNITA and FNLA as opposition parties. However, the country faces a serious humanitarian crisis resulting from the prolonged war, the abundance of minefields, and ongoing political agitation in the Cabinda exclave. The Cabinda conflict, waged by the Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda (FLEC), continues to be a source of instability. While many internally displaced persons have settled in musseques (shanty towns) around the capital, the general situation for many Angolans remains desperate.

A severe drought in 2016 caused a major food crisis in Southern Africa, affecting 1.4 million people across seven of Angola's eighteen provinces. Food prices rose, and acute malnutrition rates doubled, impacting over 95,000 children.

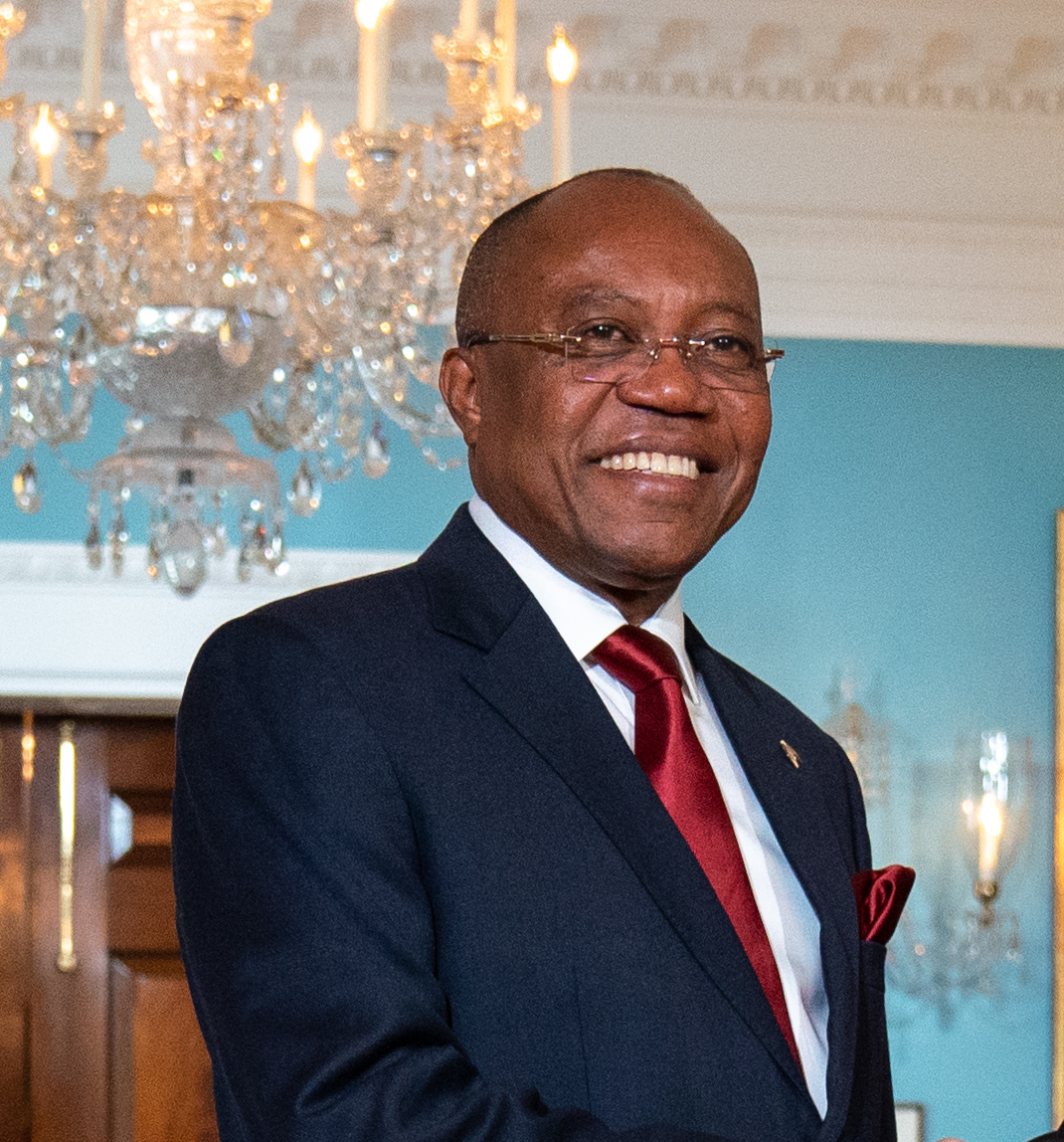

In 2017, José Eduardo dos Santos stepped down as President of Angola after 38 years in power. He was peacefully succeeded by João Lourenço, Santos's chosen successor from the MPLA. Lourenço initiated an anti-corruption drive, which has seen some members of the dos Santos family and former officials prosecuted. Critics, however, have questioned whether these actions are politically motivated. Former president José Eduardo dos Santos died in Spain in July 2022.

In the August 2022 general election, the ruling MPLA won another majority, and President Lourenço secured a second five-year term. However, this election was the tightest in Angola's history, indicating a shifting political landscape. Post-civil war Angola has focused on political stabilization and economic reconstruction, largely funded by its oil and diamond revenues. However, challenges such as poverty, inequality, and human rights concerns persist.

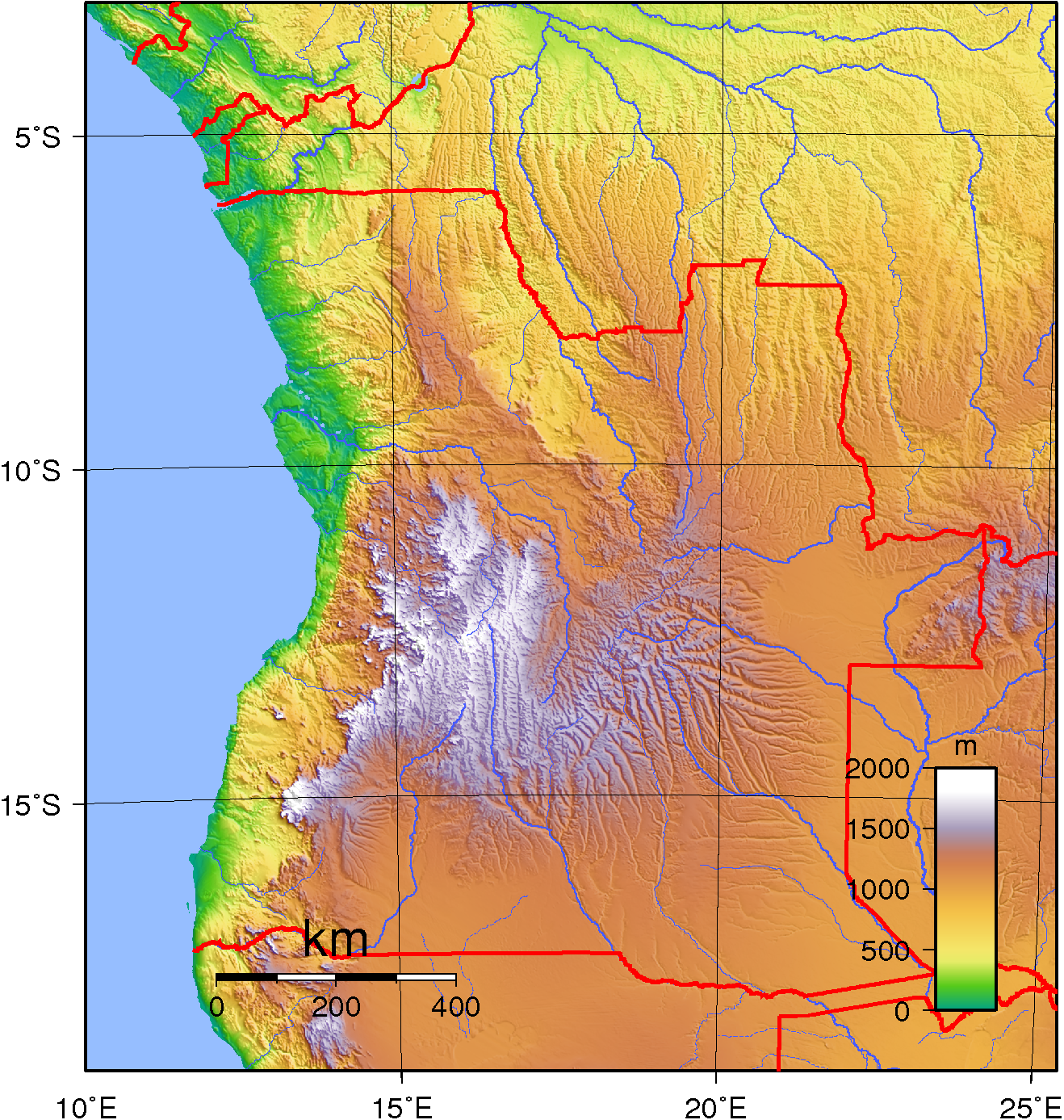

4. Geography

Angola is located on the western coast of Southern Africa, mostly between latitudes 4° and 18° South, and longitudes 12° and 24° East. With an area of 0.5 M mile2 (1.25 M km2), it is the world's twenty-second largest country, comparable in size to Mali. This section details Angola's physical geography, including its diverse climate zones influenced by latitude and the Benguela Current, and its rich but threatened wildlife and varied ecosystems.

The country is bordered by Namibia to the south, Zambia to the east, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the north and northeast. The Atlantic Ocean lies to its west, providing a coastline favorable for maritime trade with four natural harbors: Luanda, Lobito, Moçâmedes (now Namibe), and Porto Alexandre. The capital and largest city, Luanda, is situated on the Atlantic coast in the northwest.

Angola also includes the exclave of Cabinda, located to the north of the main territory, separated by a narrow strip of the Democratic Republic of the Congo along the lower Congo River. Cabinda borders the Republic of the Congo to the north and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the south and east.

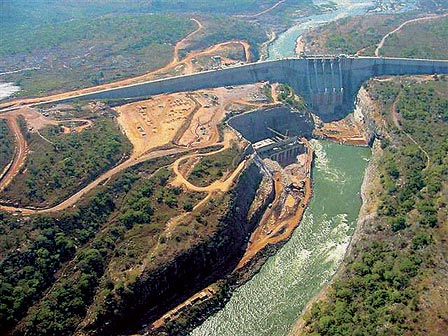

Angola's topography is varied. A narrow coastal plain, ranging in width from 16 mile (25 km) to 99 mile (160 km), rises to a vast interior plateau that covers most of the country. This central plateau, the Planalto, has an average elevation of 3.9 K ft (1.20 K m) to 5.9 K ft (1.80 K m). The highest point in Angola is Mount Moco (Morro de Moco) at 8.6 K ft (2.62 K m). The country's major rivers include the Cuanza, Cunene, and Zambezi (whose headwaters are in Angola).

Angola had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 8.35/10, ranking it 23rd globally out of 172 countries. In 2020, forest cover was around 53% of the total land area, equivalent to 66,607,380 hectares (ha), down from 79,262,780 ha in 1990. Naturally regenerating forest covered 65,800,190 ha, and planted forest covered 807,200 ha in 2020. Of the naturally regenerating forest, 40% was reported to be primary forest. Approximately 3% of the forest area was within protected areas. In 2015, 100% of the forest area was reported to be under public ownership.

4.1. Climate

Like much of tropical Africa, Angola experiences distinct, alternating rainy and dry seasons. The climate varies significantly across the country due to latitude, altitude, and proximity to the Atlantic Ocean with its cool Benguela Current.

In the north, the rainy season typically lasts from September to April, sometimes with a brief lull in January or February. In the south, the rainy season is shorter, usually beginning in November and lasting until about February. The dry season, known as cacimbo, is often characterized by heavy morning mist, especially along the coast.

Precipitation is generally higher in the north and decreases southward. At any given latitude, rainfall is greater in the interior highlands than along the semi-arid coastal strip. For example, Luanda on the coast receives an average annual rainfall of about 13 in (330 mm), while Huambo on the central plateau receives over 0.1 K in (1.40 K mm).

Temperatures generally fall with distance from the equator and with increasing altitude, and tend to rise closer to the Atlantic Ocean, although the Benguela Current has a cooling effect on coastal temperatures. At Soyo, at the mouth of the Congo River, the average annual temperature is about 78.8 °F (26 °C). In contrast, Huambo on the temperate central plateau experiences average annual temperatures under 60.8 °F (16 °C). The coolest months are July and August (during the dry season), when frost may occasionally form at higher altitudes.

Due to climate change, Angola's annual average temperature has increased by 2.5 °F (1.4 °C) since 1951 and is expected to continue rising. Rainfall patterns are becoming more variable. Angola is highly vulnerable to climate change impacts. Natural hazards such as floods, erosion, droughts, and epidemics (e.g., malaria, cholera, typhoid fever) are expected to worsen. Rising sea levels also pose a significant risk to Angola's coastal areas, where around 50% of the population lives.

In 2023, Angola emitted 174.71 million tonnes of greenhouse gases, approximately 0.32% of the world's total emissions, ranking it the 46th highest emitting country. In its Nationally Determined Contribution, Angola has pledged a 14% reduction in its greenhouse gas emissions by 2025 and an additional 10% reduction conditional on international support. Achieving climate resilience in Angola, according to the World Bank, requires diversifying the country's economy away from its dependence on oil.

4.2. Wildlife and Ecosystems

Angola possesses a rich biodiversity, a consequence of its varied climates, topography, and ecosystems. These range from tropical rainforests in the north and Cabinda, to savannas across much of the central plateau, miombo woodlands in the east, and arid and semi-arid environments in the southwest, including a portion of the Namib Desert. Major rivers like the Cuanza, Cunene, and Okavango support extensive wetland ecosystems.

The country's flora is diverse, with numerous endemic species, particularly in the highlands and escarpment areas. Notable plants include the iconic Welwitschia, a unique desert plant found in the Namib. Forests, particularly miombo woodlands, cover a significant portion of the country, though they face threats from deforestation.

Angola's fauna includes a wide array of mammals, birds, reptiles, and insects. Iconic African wildlife such as elephants, lions, leopards, giraffes, hippos, and various antelope species, including the rare giant sable antelope (Palanca Negra Gigante), which is a national symbol, inhabit the country. However, wildlife populations were severely impacted by the long civil war due to poaching and habitat disruption.

Several national parks and protected areas have been established to conserve Angola's biodiversity, including Quiçama National Park, Cangandala National Park (home to the giant sable antelope), and Iona National Park. Conservation efforts are ongoing but face challenges such as inadequate funding, limited enforcement capacity, human-wildlife conflict, and the lingering effects of landmines in some areas. Post-war, there have been initiatives to rehabilitate protected areas and reintroduce wildlife, aiming to restore ecological balance and potentially develop ecotourism.

5. Government and Politics

Angola is a unitary presidential republic. The government is composed of three branches: the executive, the legislative, and the judicial. For decades, political power has been concentrated in the presidency. The Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) has been the ruling party since independence in 1975. This section examines its constitutional framework, administrative structure, justice and security apparatus, and persistent human rights challenges.

The executive branch is led by the President, who is both the head of state and head of government. The president is typically the leader of the party that wins the most seats in parliamentary elections. The Council of Ministers (cabinet) is appointed by the president. João Lourenço became president in 2017, succeeding José Eduardo dos Santos, who had ruled for 38 years. Lourenço has initiated anti-corruption campaigns, sometimes described as political purges, which have targeted influential figures from the previous administration, including members of the dos Santos family. For instance, Isabel dos Santos, daughter of the former president, was removed as head of the state oil company Sonangol, and José Filomeno dos Santos, son of the former president, was sentenced for fraud and corruption.

The legislative branch is the unicameral National Assembly (Assembleia Nacional). It comprises 220 members elected for five-year terms through a system of party-list proportional representation. Some members are elected from multi-member province-wide constituencies, and others from a nationwide constituency.

Major political parties include the MPLA, the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), which is the main opposition party, and the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA). Following the end of the civil war in 2002, Angola has held parliamentary elections in 2008 and general elections in 2012, 2017, and 2022. While the MPLA has consistently won these elections, the opposition, particularly UNITA, has maintained a significant presence. The 2022 election was notably the tightest in Angola's history.

5.1. Constitution

The current Constitution of Angola was adopted in 2010. It establishes the framework for state governance and delineates the rights and duties of citizens. A key feature of the 2010 constitution is that it eliminated direct presidential elections; instead, the head of the list of the political party that wins the most votes in the parliamentary elections automatically becomes president, and the second on the list becomes vice-president.

The constitution outlines a system with separation of powers, but in practice, the president exercises significant control over all other organs of the state. Critics argue that this concentration of power has led to an authoritarian regime, despite the formal democratic structures. The legal system is based on Portuguese law and customary law. While the constitution provides for fundamental rights and freedoms, their full implementation and protection remain significant challenges.

5.2. Administrative Divisions

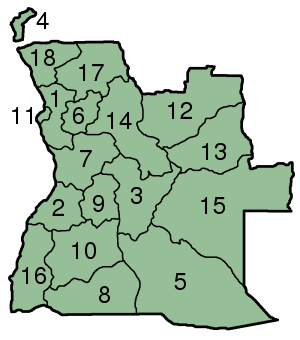

As of September 2024, Angola is divided into twenty-one provinces (províncias). These provinces are further subdivided into 162 municipalities, and the municipalities are divided into 559 communes (townships). Provincial governors are appointed by the president.

The provinces of Angola are:

| Number | Province | Capital | Area (km2) | Population (2014 Census) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bengo | Caxito | 31,371 | 356,641 |

| 2 | Benguela | Benguela | 39,826 | 2,231,385 |

| 3 | Bié | Cuíto | 70,314 | 1,455,255 |

| 4 | Cabinda | Cabinda | 7,270 | 716,076 |

| 5 | Cuando Province | Mavinga | ? | ? |

| 6 | Cuanza Norte | N'dalatando | 24,110 | 443,386 |

| 7 | Cuanza Sul | Sumbe | 55,600 | 1,881,873 |

| 8 | Cubango Province | Menongue | ? | ? |

| 9 | Cunene | Ondjiva | 87,342 | 990,087 |

| 10 | Huambo | Huambo | 34,270 | 2,019,555 |

| 11 | Huíla | Lubango | 79,023 | 2,497,422 |

| 12 | Icolo e Bengo | Catete | ? | ? |

| 13 | Luanda | Luanda | 2,417 | 6,945,386 |

| 14 | Lunda Norte | Dundo | 103,760 | 862,566 |

| 15 | Lunda Sul | Saurimo | 77,637 | 537,587 |

| 16 | Malanje | Malanje | 97,602 | 986,363 |

| 17 | Moxico Leste Province | Cazombo | ? | ? |

| 18 | Moxico | Luena | 223,023 | 758,568 |

| 19 | Namibe | Moçâmedes | 57,091 | 495,326 |

| 20 | Uíge | Uíge | 58,698 | 1,483,118 |

| 21 | Zaire | M'banza-Kongo | 40,130 | 594,428 |

5.2.1. Exclave of Cabinda

The northern Angolan province of Cabinda is an exclave, separated from the rest of the country by a strip of territory belonging to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, approximately 37 mile (60 km) wide, along the lower Congo River. Cabinda borders the Republic of the Congo to the north and north-northeast and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the east and south. The city of Cabinda is its chief population center.

With an area of approximately 2.8 K mile2 (7.28 K km2), Cabinda consists largely of tropical forest and produces hardwoods, coffee, cocoa, crude rubber, and palm oil. However, its most significant economic contribution is its vast offshore oil reserves, discovered by the Cabinda Gulf Oil Company (CABGOC) from 1968 onwards. Petroleum production from Cabinda accounts for more than half of Angola's total oil output, earning it the nickname "the Kuwait of Africa."

Since Portugal transferred sovereignty of Angola to local independence groups, Cabinda has been the focus of a separatist conflict. The Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda (FLEC) and its armed wing, the Forças Armadas de Cabinda (FAC), have waged a guerrilla war against the Angolan government, seeking independence for the territory. The Angolan government has employed its armed forces (FAA) to counter the insurgency. The conflict stems from Cabinda's distinct historical and cultural identity and its desire for greater control over its significant oil wealth. Population estimates for Cabinda are unreliable; a 1995 census estimated around 600,000 inhabitants, with a significant portion being citizens of neighboring countries.

5.3. Justice

Angola's judicial system is headed by a Supreme Court, which serves as the court of appeal. A Constitutional Court was established through Law no. 2/08 of June 17 and Law no. 3/08 of June 17, making it the supreme body of constitutional jurisdiction. Its first task was the validation of political party candidacies for the legislative elections of September 5, 2008. The Constitutional Court was institutionalized on June 25, 2008, when its Judicial Counselors assumed their positions. It currently comprises seven advisory judges (four men and three women). However, the Constitutional Court does not hold powers of full judicial review in the way some other countries' constitutional courts do.

The legal system is based on Portuguese law and customary law but is described as weak and fragmented. Courts operate in only a small fraction of the country's municipalities (reportedly 12 out of more than 140). This limited reach of the formal justice system means that many disputes, particularly in rural areas, are resolved through traditional mechanisms.

In 2014, a new penal code took effect in Angola. One of the notable changes in this new legislation was the classification of money laundering as a crime, reflecting efforts to combat financial crime and corruption. The state of the rule of law remains a challenge, with concerns about judicial independence, access to justice for ordinary citizens, and the effective enforcement of laws.

5.4. Military

The Angolan Armed Forces (Forças Armadas Angolanas, FAA) are responsible for the national defense of Angola. They are headed by a Chief of Staff who reports to the Minister of Defence. The FAA consists of three main branches:

- Army (Exército)

- Navy (Marinha de Guerra Angolana, MGA)

- National Air Force (Força Aérea Nacional, FAN)

As of 2015, the total active manpower was estimated at 107,000 personnel, with an additional 10,000 paramilitary forces. The FAA's equipment is diverse, reflecting its history and international relations. It includes Russian-manufactured fighters, bombers, and transport planes. For training and light attack roles, the air force operates Brazilian-made EMB-312 Tucano aircraft and Czech-made Aero L-39 Albatros jets. A variety of Western-made aircraft, such as the C-212 Aviocar and Sud Aviation Alouette III, are also in service.

The FAA has been involved in regional security operations. A small number of FAA personnel have been stationed in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Kinshasa). In March 2023, an additional 500 troops were deployed to the DRC due to the resurgence of the M23 rebellion. The FAA has also participated in the Southern African Development Community (SADC)'s mission for peace in Cabo Delgado, Mozambique, aimed at countering insurgency in the region. Angola's defense policy focuses on maintaining territorial integrity, contributing to regional stability, and modernizing its armed forces.

5.5. Police and Public Order

The Angolan National Police (Polícia Nacional de Angola) is the primary law enforcement agency responsible for maintaining public order, preventing and combating crime, and ensuring the safety of citizens and property. The National Police operates under the Ministry of Interior.

Its main departments include:

- Public Order Police

- Criminal Investigation Police

- Traffic and Transport Police

- Investigation and Inspection of Economic Activities Police

- Taxation and Frontier Supervision Police

- Riot Police

- Rapid Intervention Police

The National Police force has an estimated 6,000 patrol officers, 2,500 taxation and frontier supervision officers, 182 criminal investigators, 100 financial crimes detectives, and approximately 90 economic activity inspectors. The force has been undergoing a modernization and development plan aimed at increasing its capabilities and efficiency. This includes administrative reorganization, procurement of new vehicles, aircraft (including the development of an air wing for helicopter support), and equipment. Construction of new police stations and forensic laboratories, as well as restructured training programs, are also part of this effort. For officers in urban areas, there has been a move to replace AKM rifles with 9mm Uzi submachine guns.

Current law enforcement challenges in Angola include combating organized crime, drug trafficking, managing urban crime rates, and addressing issues related to corruption within the force. Ensuring human rights compliance in policing operations and building public trust are also ongoing priorities.

5.6. Human Rights

The state of human rights in Angola has been a subject of concern for both domestic and international observers. While the country has made some progress since the end of the civil war in 2002, significant challenges remain.

Freedom House classified Angola as 'not free' in its Freedom in the World reports for 2014 and 2024, although the 2024 report noted some increases in freedoms under President João Lourenço. The 2014 report highlighted serious flaws in the August 2012 parliamentary elections, including outdated and inaccurate voter rolls, and a drop in voter turnout.

A 2012 report by the U.S. Department of State identified key human rights abuses including official corruption and impunity; limits on freedoms of assembly, association, speech, and press; and cruel and excessive punishment, including reported cases of torture, beatings, and unlawful killings by police and other security personnel. These issues, to varying degrees, continue to be reported.

Angola has historically scored poorly on governance indices. For example, it ranked forty-two of forty-eight sub-Saharan African states on the 2007 Index of African Governance and also performed poorly on the 2013 Ibrahim Index of African Governance, particularly in areas of participation, human rights, sustainable economic opportunity, and human development.

Corruption has a significant impact on human rights by diverting public funds that could be used for essential services like healthcare, education, and infrastructure, thereby affecting the economic and social rights of citizens. The rights of vulnerable groups, including women, children, and ethnic minorities, also require attention.

On a positive note, in 2019, Angola decriminalized homosexuality and enacted legislation prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation, a move that was widely praised by human rights organizations. However, challenges persist in ensuring full LGBT equality in practice. International organizations continue to monitor issues such as restrictions on freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, police brutality, and impunity for human rights violators.

6. Foreign Relations

Angola's foreign policy objectives primarily focus on promoting peace and stability in the region, fostering economic development through international partnerships, and asserting its influence as a significant player in Southern and Central Africa. Angola is a founding member of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP), an international organization of Lusophone nations. It is also a member of the United Nations (UN), the African Union (AU), and the Southern African Development Community (SADC). The human rights implications of its foreign policy, especially in relation to its partnerships and regional interventions, are an area of focus for international observers. Key bilateral relationships, such as with China, are also explored.

Angola has played an active role in regional diplomacy. It chaired the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) starting in January 2014. In 2015, the ICGLR Executive Secretary highlighted Angola's progress in socio-economic stability and political-military terms since the end of its civil war as an example for other member states. Angola was elected as a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council for a term that began on January 1, 2015, and expired on December 31, 2016, its second time serving in this capacity.

Angola maintains diplomatic relations with numerous countries worldwide. Its relationships with neighboring countries, such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Namibia, and Zambia, are crucial for regional security and economic cooperation. Relations with major global actors like the United States, the European Union, and China are also significant, particularly concerning trade, investment, and development aid.

6.1. Relations with China

The relationship between Angola and the People's Republic of China has grown significantly since the early 2000s, particularly in the economic sphere. China has become one of Angola's most important international partners.

Economic ties are central to the relationship. China is Angola's largest trade partner and a primary destination for Angolan exports, mainly crude oil and diamonds. Bilateral trade reached 27.67 B USD in 2011. China's imports from Angola, predominantly oil, were valued at 24.89 B USD that year. Conversely, Angola is a significant market for Chinese goods, including mechanical and electrical products, machinery parts, and construction materials, with Chinese exports to Angola surging by 38.8% in 2011.

Investment and infrastructure development are also key components. China has provided substantial lines of credit to Angola, often in exchange for oil (oil-backed loans). For instance, in 2004, the Export-Import Bank of China approved a 2.00 B USD line of credit for rebuilding Angola's infrastructure, which had been devastated by the civil war. This was followed by other large loans, including one for 2.90 B USD from the China International Fund Ltd in 2005. These funds have been used for major infrastructure projects, such as roads, railways (like the reconstruction of the Benguela Railway), hospitals, and housing complexes, often built by Chinese construction companies employing Chinese labor. One such project was the Kilamba New Urbanisation (Nova Cidade de Kilamba), a large housing development near Luanda.

The impact of this relationship on Angola's development is complex. While Chinese investment has undeniably contributed to rapid infrastructure development and economic growth post-war, concerns have been raised about debt sustainability, the transparency of loan agreements, the environmental and social impacts of some projects, and the limited benefits for local employment and businesses. There have also been criticisms regarding the quality of some Chinese-built infrastructure and the influx of Chinese migrants. Despite these challenges, the Angolan government views China as a crucial partner in its national development strategy. The political relationship is generally cordial, with both countries often aligning on international issues based on principles of non-interference and South-South cooperation.

7. Economy

Angola's economy has undergone significant transformation since the end of the civil war in 2002, moving from a state of disarray to becoming one of Africa's fastest-growing economies for a period, largely driven by its vast oil and diamond resources. However, this growth has been characterized by heavy reliance on these commodities, leading to volatility and challenges related to equitable wealth distribution, economic inequality, and corruption. The social and environmental impacts of development, alongside labor rights, remain critical issues. This section details its reliance on natural resources like oil and diamonds, the state of its agricultural sector, developments in transport and telecommunications infrastructure, and ongoing issues of inequality and corruption.

Between 2001 and 2010, Angola recorded the world's highest annual average GDP growth at 11.1%. For instance, the economy grew by 18% in 2005, 26% in 2006, and 17.6% in 2007. However, it contracted by an estimated -0.3% in 2009 due to the global recession. The security established post-2002 allowed for the resettlement of 4 million displaced persons and a subsequent increase in agricultural production.

China has become Angola's largest trade partner and export destination. In 2004, the Export-Import Bank of China approved a 2.00 B USD line of credit to Angola for infrastructure rebuilding. This was followed by further significant loans. Bilateral trade reached 27.67 B USD in 2011. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has also played a role in Angola's economic policies.

The National Bank of Angola (Banco Nacional de Angola, BNA) manages the country's monetary policy. Efforts to control inflation have seen some success, with the rate decreasing to 7.96% in December 2013. The Angolan financial market has grown, becoming the third-largest in sub-Saharan Africa by 2014, with assets corresponding to 70 billion Kz (approximately 6.80 B USD at the time). The Angola Stock Exchange and Derivatives (BODIVA) was launched in December 2014.

Despite significant economic growth, Angola faces immense social and economic problems, partly due to the prolonged armed conflict but also stemming from persistent authoritarianism, "neo-patrimonial" practices, and pervasive corruption. Wealth is highly concentrated, with a small segment of the population benefiting disproportionately, while a large portion lives in poverty. A 2008 study by Angola's National Institute of Statistics found that 58% of the rural population and 19% of the urban population were classified as poor, with an overall rate of 37%. Social inequality is particularly extreme in Luanda. Angola consistently ranks low on the Human Development Index. Leaks such as the "Luanda Leaks" in 2020 and the Pandora Papers have exposed alleged corruption involving high-level officials and the family of former President dos Santos, implicating international consulting firms in facilitating the exploitation of state assets.

Regional economic disparities are stark, with most economic activity concentrated in Luanda and Bengo province, while interior regions suffer stagnation. This has led to a sharp increase in Angolan private investments abroad, particularly in Portugal.

Angola was ranked 133rd in the Global Innovation Index in 2024. The government has focused on upgrading critical infrastructure, financed by oil revenues. While standards of living have improved for some (life expectancy rose from 46 years in 2002 to 51 in 2011, and child mortality rates fell), deep-seated social and economic inequality persists.

7.1. Natural Resources

Angola is richly endowed with natural resources, with oil and diamonds forming the backbone of its economy, accounting for approximately 60% of GDP and nearly all of the country's revenue and dominant exports. Other resources include gold, copper, rich wildlife, forests, and fossil fuels.

Oil: Angola is one of Africa's largest oil producers. Production surpassed 1.4 million barrels of oil per day (Moilbbl/d) in late 2005 and was projected to reach 2 million barrels of oil per day by 2007. In 2022, average daily production was 1.165 million barrels. The state-owned company, Sonangol, plays a dominant role in the oil industry, often acting as concessionaire, regulator, and investor, which has raised concerns about conflicts of interest and transparency. Angola became a member of OPEC in December 2006 but announced its departure in December 2023, citing that membership was not serving its interests. China has been a major recipient of Angolan oil, often through oil-backed loan agreements. Significant oil revenues have also created opportunities for corruption; a Human Rights Watch report alleged that 32.00 B USD disappeared from government accounts between 2007 and 2010. In 2002, Angola fined Chevron Corporation for oil spills, marking a notable instance of holding a multinational accountable.

Diamonds: Angola is also a major diamond producer. The state-run company Endiama oversees diamond mining operations, often in partnership with international mining companies like ALROSA. The industry has been historically linked to conflict (so-called "blood diamonds"), but efforts have been made to improve regulation and transparency under the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme.

Other Resources: Angola also has deposits of gold, copper, iron ore, phosphates, and bauxite, though these have been less exploited compared to oil and diamonds. The country's forests and fisheries also represent significant natural wealth.

Biocapacity: Access to biocapacity in Angola is higher than the world average. In 2016, Angola had 1.9 global hectares of biocapacity per person within its territory, compared to the world average of 1.6 global hectares per person. In the same year, Angola used 1.01 global hectares of biocapacity per person (its ecological footprint of consumption). This indicates that Angola was running a biocapacity reserve, meaning its ecological footprint was smaller than its available biocapacity. However, sustainable management of these resources is crucial to avoid depletion and environmental degradation.

Challenges related to natural resource management include ensuring revenue transparency, combating corruption, diversifying the economy to reduce dependence on oil and diamonds, and mitigating the environmental impact of extraction activities.

7.2. Agriculture

Agriculture and forestry present significant potential opportunities for the country's economic diversification and food security. Before independence in 1975, Angola was a major exporter of agricultural products such as bananas, coffee, and sisal, and was considered a breadbasket in southern Africa. However, three decades of civil war devastated the fertile countryside, left vast areas littered with landmines, and drove millions of people from rural areas into cities.

Currently, Angola depends heavily on expensive food imports, mainly from South Africa and Portugal. More than 90% of farming is done at the family and subsistence level, with many small-scale farmers trapped in poverty. According to the African Economic Outlook, Angola requires 4.5 million tonnes of grain annually but grows only about 55% of the maize it needs, 20% of the rice, and just 5% of its required wheat.

The World Bank estimates that less than 3% of Angola's abundant fertile land is cultivated, and the economic potential of the forestry sector remains largely unexploited. Since the end of the civil war in 2002, there has been a large-scale increase in agricultural production due to the resettlement of displaced persons and government initiatives. However, challenges remain, including lack of infrastructure (roads, irrigation), limited access to credit and modern farming inputs, and the lingering threat of landmines in some rural areas. Addressing these issues is crucial for improving food security, reducing poverty, and promoting sustainable rural development.

7.3. Transport

Transport in Angola has been significantly impacted by decades of conflict but has seen substantial investment and improvement since the end of the civil war in 2002, largely funded by oil revenues. The country's transport infrastructure consists of road, rail, port, and aviation systems.

- Roads: Angola has approximately 48 K mile (76.63 K km) of highways, of which about 12 K mile (19.16 K km) are paved. While major efforts have been made to restore and expand the road network, many roads, especially outside urban centers, remain in poor condition due to war damage and lack of maintenance. Travel in rural areas often requires four-by-four vehicles. The government has contracted numerous projects to rehabilitate key road arteries. For example, the road between Lubango and Namibe was completed with funding from the European Union. Two trans-African automobile routes pass through Angola: the Tripoli-Cape Town Highway and the Beira-Lobito Highway.

- Railways: Angola has three separate railway systems totaling 1.7 K mile (2.76 K km). These are primarily east-west lines historically built to transport minerals and agricultural products from the interior to coastal ports:

- The Luanda Railway (CFL)

- The Benguela Railway (CFB) - This historically significant line connects the port of Lobito to the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia, and has been rehabilitated with Chinese assistance.

- The Moçâmedes Railway (CFM)

- Ports: Angola has five major seaports: Namibe, Lobito, Soyo, Cabinda, and Luanda. The Port of Luanda is the largest and one of the busiest on the African continent. These ports are crucial for Angola's international trade, particularly oil exports.

- Airports: There are 243 airports in Angola, of which 32 are paved. The main international airport is Quatro de Fevereiro Airport in Luanda. A new international airport, the Dr. Antonio Agostinho Neto International Airport, has been constructed to replace it and expand capacity. TAAG Angola Airlines is the state-owned national carrier.

- Inland Waterways: Angola has 1,295 km of navigable inland waterways, primarily on its larger rivers, though their use for transport is less developed compared to other modes.

The development of transport infrastructure remains a priority for the Angolan government to support economic growth, improve internal connectivity, and facilitate regional trade. Challenges include the high cost of construction and maintenance, the vastness of the territory, and the need to clear remaining landmines in some areas.

7.4. Telecommunications

The telecommunications industry in Angola is considered a strategic sector and has seen significant development, particularly in mobile services and internet connectivity, following the end of the civil war.

In 2015, it was reported that Angola had approximately 14 million mobile phone network users, with mobile penetration around 75%. The country was also noted as having the first telecommunications operator in Africa to test LTE technology, with speeds up to 400 Mbit/s. There were about 3.5 million smartphones in the Angolan market at that time, and approximately 16 K mile (25.00 K km) of optical fibre had been installed across the country.

To improve international connectivity and establish Angola as a continental hub, the construction of an optic fiber underwater cable was announced in October 2014. This project aimed to enhance internet connections both nationally and internationally.

Angola has also ventured into satellite technology. The first Angolan satellite, Angosat-1, was built by Russia's RSC Energia with a payload supplied by Airbus Defence and Space. It was launched on December 26, 2017, from the Baikonur Cosmodrome. However, communications contact was lost shortly after launch due to an on-board power failure during solar panel deployment. Although contact was briefly restored, AngoSat-1 was ultimately declared inoperable. The satellite was intended to provide telecommunications services, TV, internet, and e-government across the country for up to 18 years. A replacement satellite, AngoSat-2, was pursued and successfully launched on October 12, 2022.

The management of the .ao top-level domain was transferred from Portugal to Angola in 2015, following new legislation aimed at promoting the Angolan domain.

The First Angolan Forum of Telecommunications and Information Technology was held in Luanda in March 2015, focusing on the challenges and advancements in the sector. The government has also initiated projects like the Angolan Media Libraries Network, distributing facilities with bibliographic archives, multimedia resources, and internet access across provinces to improve access to information and knowledge.

8. Demographics and Society

Angola's society is characterized by its diverse ethnic composition, a young and rapidly growing population, increasing urbanization, and the lasting impacts of a long history of conflict and colonialism. Significant disparities in wealth, access to education, and healthcare persist.

8.1. Population and Urbanization

Angola conducted its first post-independence census in 2014, which recorded a population of 25,789,024 inhabitants. Preliminary results had indicated 24,383,301. The population is estimated to have reached 32.87 million by 2021 and 36.1 million by 2023. The country has a high population growth rate, estimated at 3.30% annually between 2010 and 2015, and is projected to exceed 60 million people by 2050. The population density is relatively low at around 20.7 people per km2 (as of 2015), but distribution is uneven, with higher concentrations in urban areas and along the coast.

Urbanization is a significant trend, with 44.1% of the population living in urban areas in 2015, a figure that has likely increased. Luanda, the capital, is by far the largest city and the country's economic and political hub, with a metropolitan population exceeding 6.7 million according to the 2014 census. Other major cities include Lubango, Huambo, Benguela, Cabinda, Malanje, Saurimo, Lobito, Cuíto, and Uíge. Rapid urbanization has placed strains on infrastructure and services in cities, leading to the growth of large informal settlements or musseques. Angola has a very young population, with a median age of 16.1 years in 2015. The total fertility rate is high, estimated at 5.54 children per woman in 2012.

Angola has also hosted refugee populations, primarily from the Democratic Republic of Congo. There is a notable expatriate community, including Portuguese, Chinese (estimated at around 259,000 in 2012), and Vietnamese (around 40,000) residents. Historically, a large Portuguese community existed before independence; while many left, there has been a resurgence in recent years. Approximately 1 million Angolans are of mixed race (Mestiço).

8.2. Ethnic Groups

Angola is a multiethnic country, predominantly composed of various Bantu peoples. The three largest ethnic groups are:

- The Ovimbundu, who speak Umbundu, constitute about 37% of the population. They are primarily located in the central highlands of Angola, with Huambo and Bié being major centers.

- The Ambundu (also known as Kimbundu-speakers), make up around 23-25% of the population. They are concentrated in the north-central part of the country, including the capital, Luanda, and the Kwanza River valley.

- The Bakongo, who speak Kikongo, represent about 13% of the. They mainly inhabit the northwest, including Uíge, Zaire, and parts of Cabinda, and share cultural ties with Bakongo populations in the neighboring Congos.

Together, the Ovimbundu and Ambundu form a majority of the population. Other significant ethnic groups include the Chokwe, Ovambo, Ganguela (Ngangela), Nyaneka-Khumbi, Herero, and Xindonga. There are also smaller groups of Khoisan-speaking peoples, who are considered the earliest inhabitants of the region.

In addition to indigenous African groups, about 2% of the population is Mestiço (of mixed European and African ancestry). There is also a European population, primarily of Portuguese descent (estimated around 200,000-220,000 in the early 2010s), and a growing Chinese community (estimated around 259,000 in 2012). A small Brazilian community of about 5,000 people and around 40,000 Vietnamese also reside in Angola. Romani people were historically deported to Angola from Portugal.

Ethnic identity plays a role in Angolan society and politics, though the government officially promotes national unity.

8.3. Languages

The official language of Angola is Portuguese. Due to centuries of colonial rule, Portuguese serves as the language of government, administration, education, media, and business. According to the 2014 census, Portuguese is spoken by 71.1% of Angolans, either as a first or second language. A 2012 study indicated that Portuguese was the first language for 39% of the population. Its use is more prevalent in urban areas.

In addition to Portuguese, Angola is home to a multitude of indigenous Bantu languages. The most widely spoken indigenous languages, according to the 2014 census, are:

- Umbundu: spoken by 23.0% of the population.

- Kikongo (Fiote is often considered a dialect of Kikongo): spoken by 8.2% (Kikongo) and 2.4% (Fiote).

- Kimbundu: spoken by 7.8%.

- Chokwe: spoken by 6.5%.

- Nyaneka: spoken by 3.4%.

- Ngangela (often a group of related languages): spoken by 3.1%.

- Kwanyama (a dialect of Oshiwambo): spoken by 2.3%.

- Muhumbi: spoken by 2.1%.

- Luvale: spoken by 1.0%.

Other indigenous languages are spoken by smaller percentages of the population (4.1% collectively). Many Angolans are bilingual or multilingual, speaking Portuguese alongside one or more indigenous languages. While Portuguese dominates public life, indigenous languages remain vital in local communities and for cultural identity. There have been efforts to promote and preserve national languages in education and media. Some Angolans, particularly in border regions or due to historical ties, may also have some knowledge of French or English.

8.4. Religion

Religion in Angola is predominantly Christian. Estimates from 2015 suggest that around 56.4% of the population identifies as Roman Catholic, a legacy of Portuguese colonization. Protestantism accounts for about 23.4%, with various denominations present. These include historical Protestant churches introduced during the colonial period, such as Congregationalists (mainly among the Ovimbundu), Methodists (concentrated among Kimbundu speakers), and Baptists (almost exclusively among the Bakongo). Other Protestant groups include Adventists, Reformed, and Lutherans.

Another 13.6% adhere to other Christian denominations. Since independence, hundreds of Pentecostal and Evangelical communities have emerged, particularly in urban areas, with some having origins in Brazil. There is also a presence of African-initiated churches, such as Tocoists (a syncretic Christian movement) in Luanda and its surroundings, and Kimbanguism in the northwest, spreading from the Congo region.

Traditional indigenous beliefs are practiced by about 4.5% of the population, although elements of these beliefs often coexist or are syncretized with Christianity for many Angolans. Approximately 1% of the population is classified as having no religion or adhering to other faiths.

Islam is a minority religion, practiced by less than 1% of the population. Estimates from the U.S. Department of State in 2008 suggested 80,000-90,000 Muslims, while the Islamic Community of Angola puts the figure closer to 500,000. Muslims in Angola consist largely of migrants from West Africa and the Middle East (especially Lebanon), though some are local converts. The Angolan government does not legally recognize all Muslim organizations and has, at times, shut down mosques or prevented their construction.

Foreign missionaries were active before independence but faced restrictions during the anti-colonial struggle. They have been able to return since the early 1990s. The Catholic Church and major Protestant denominations often provide social services, such as aid to the poor, education, and healthcare.

8.5. Education

Education in Angola is, by law, compulsory and free for eight years. However, the system faces significant challenges, and universal access and quality remain elusive goals. The government reports that a percentage of pupils do not attend school due to a lack of school buildings and teachers. Pupils are often responsible for additional school-related expenses, including fees for books and supplies.

In 1999, the gross primary enrollment rate was 74%, and in 1998, the net primary enrollment rate was 61%. These figures may not reflect actual attendance. Significant disparities in enrollment persist between rural and urban areas, and generally, more boys attend school than girls. The long Angolan Civil War (1975-2002) had a devastating impact on the education infrastructure, with nearly half of all schools reportedly looted or destroyed, leading to current problems with overcrowding.

The Ministry of Education has made efforts to recruit and train new teachers. In 2005, 20,000 new teachers were recruited. However, teachers often face issues such as low pay, inadequate training, and overwork, sometimes teaching multiple shifts a day. Other factors hindering school attendance include the presence of landmines in some areas, lack of resources, lack of identity papers, and poor health. Although budgetary allocations for education increased in 2004, the system continues to be under-funded.

The adult literacy rate has seen improvement. According to UNESCO Institute for Statistics estimates, it was 70.4% in 2011 and increased to 71.1% by 2015. There is a gender gap in literacy, with 82.9% of men and 54.2% of women being literate as of 2001.

Higher education institutions in Angola include the public Agostinho Neto University (founded in 1962) and the Catholic University of Angola (founded in 1999). Since independence, Angolan students, often from elite backgrounds, have also pursued higher education in Portugal, Brazil, and Cuba through bilateral agreements.

In September 2014, the Angolan Ministry of Education announced an investment of 16 million Euros in the computerization of over 300 classrooms across the country, including teacher training in new information technologies. In 2010, the government initiated the Angolan Media Libraries Network (Rede de Mediatecas de Angola, ReMA), aiming to establish media libraries with bibliographic archives, multimedia resources, and internet access in each province by 2017 to facilitate public access to information and knowledge. Mobile media libraries were also planned to reach isolated populations.

8.6. Health

Health in Angola faces significant challenges, many of which are legacies of the prolonged civil war, ongoing poverty, and inadequate infrastructure. The country has some of the poorest health indicators in the world.

Major public health issues include high rates of infectious diseases. Epidemics of cholera, malaria, rabies, and African hemorrhagic fevers like Marburg hemorrhagic fever are common in several parts of the country. Angola also has high incidence rates of tuberculosis and a significant HIV prevalence. Vector-borne diseases such as dengue, filariasis, leishmaniasis, and onchocerciasis (river blindness) also occur.

Angola has one of the highest infant mortality rates globally and one of the world's lowest life expectancies. A 2007 survey indicated that low and deficient niacin status was common. Malnutrition remains a serious problem, particularly among children. According to the 2024 Global Hunger Index (GHI), Angola has a serious level of hunger, ranking 103rd out of 127 countries with a GHI score of 26.6.

The healthcare system is often under-resourced, with shortages of medical personnel, medicines, and equipment, especially in rural areas. Access to quality healthcare is limited for much of the population. Disparities in health outcomes are significant between urban and rural areas, and between different socioeconomic groups.

The Angolan government has taken steps to address these issues. In September 2014, the Angolan Institute for Cancer Control (IACC) was created to integrate into the National Health Service, aiming to provide specialized oncology care and implement prevention programs. National vaccination campaigns, such as one against measles in 2014 (which also included polio vaccination and vitamin A supplementation), have been launched. A severe yellow fever outbreak began in December 2015, becoming the worst in three decades, with nearly 4,000 suspected infections and up to 369 deaths by August 2016. Demographic and Health Surveys have been conducted in Angola focusing on malaria, domestic violence, and other health topics to gather data for policy-making.

9. Culture

Angolan culture is a rich tapestry woven from the diverse traditions of its indigenous ethnic groups, predominantly of Bantu origin, and centuries of Portuguese influence. This blend is evident in language, religion, arts, music, and daily life. The following subsections explore specific cultural expressions, including its media landscape, literary and cinematic achievements, musical heritage, popular sports, distinctive cuisine, and national holidays.

The various ethnic communities, including the Ovimbundu, Ambundu, Bakongo, Chokwe, and Mbunda, maintain their distinct cultural traits, traditions, and languages to varying degrees, especially in rural areas. However, in urban centers, particularly Luanda (founded in the 16th century), where more than half the population now resides, a more mixed or creolized culture has been emerging since colonial times.

Portuguese heritage is prominent, most notably in the predominance of the Portuguese language as the official language and lingua franca, and the widespread adherence to the Catholic Church. African roots are strongly evident in music and dance, and these traditions have also influenced the way Portuguese is spoken in Angola, contributing to a unique Angolan Portuguese dialect. This cultural synthesis is well reflected in contemporary Angolan literature, arts, and popular culture.

In 2014, Angola resumed the National Festival of Angolan Culture after a 25-year break. The festival, held in all provincial capitals over 20 days, aimed to promote "Culture as a Factor of Peace and Development," showcasing the nation's cultural diversity and fostering national unity.

9.1. Mass Media

The mass media landscape in Angola includes newspapers, broadcasting (radio and television), and a growing internet media sector. However, the media environment has historically been characterized by significant government influence and restrictions on media freedom.

State-owned media outlets have a dominant presence. Televisão Pública de Angola (TPA) is the state-owned television broadcaster, and Rádio Nacional de Angola (RNA) is the state-owned national radio station. The Jornal de Angola is a major state-controlled daily newspaper. These outlets generally reflect government perspectives.

Private media exists but often faces challenges, including economic pressures and political influence. While some independent newspapers and radio stations operate, critical reporting can lead to repercussions. Journalists have reported instances of harassment, intimidation, and legal action. Access to diverse sources of information can be limited, particularly outside of urban centers.

Internet penetration has been increasing, leading to the growth of online news portals and social media as alternative sources of information and platforms for public discourse. However, internet access is not yet universal, and concerns about potential government surveillance and censorship of online content exist.

International organizations that monitor press freedom generally rank Angola poorly, citing issues such as lack of media pluralism, self-censorship due to fear of reprisal, and legal frameworks that can be used to restrict free expression. Efforts to improve media freedom and ensure a more diverse and independent media landscape are ongoing challenges for the country.

9.2. Literature

Angolan literature has a rich history, deeply intertwined with the country's colonial past, struggle for independence, and post-colonial experiences. It is primarily written in Portuguese, but often incorporates elements from indigenous oral traditions and languages.

The emergence of a distinct Angolan literary voice can be traced back to the 19th century, but it gained significant momentum in the mid-20th century with the rise of nationalist sentiments. Early writers often explored themes of cultural identity, colonial oppression, and the call for liberation. Key figures from this period include Agostinho Neto (who later became Angola's first president), whose poetry is celebrated for its powerful articulation of Angolan aspirations, and Mário Pinto de Andrade, another important political and literary figure. António Jacinto is also a notable poet of this era.

Post-independence literature continued to grapple with themes of nation-building, the trauma of the civil war, social critique, and the complexities of Angolan identity. José Luandino Vieira is a highly influential writer whose works, often set in the musseques (shantytowns) of Luanda, are known for their innovative use of language, blending Portuguese with Kimbundu and capturing the vernacular of urban life. His novel Luuanda (1963) is a seminal work.

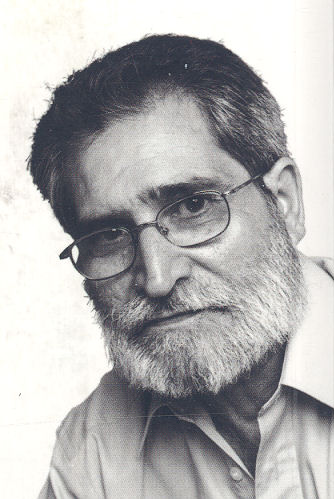

Pepetela (Artur Carlos Maurício Pestana dos Santos) is one of Angola's most renowned contemporary authors. His novels, such as Mayombe (1980), which offers a critical look at the liberation struggle, and Yaka (1984), explore Angola's historical and social landscape with depth and nuance. He was awarded the Camões Prize, the most prestigious award for Portuguese-language literature, in 1997.

José Eduardo Agualusa is another prominent contemporary Angolan writer whose works have gained international recognition. His novels, often characterized by a blend of history, fiction, and magical realism, include Creole (Nação Crioula, 1997) and The Book of Chameleons (O Vendedor de Passados, 2004), which won the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize in 2007.

Angolan literature continues to evolve, with new generations of writers exploring diverse themes and styles, reflecting the country's ongoing social and cultural transformations. Oral traditions, including storytelling, proverbs, and songs, also remain an important part of Angola's literary heritage.

9.3. Music

Angolan music is diverse and vibrant, reflecting the country's rich cultural heritage and historical influences. It encompasses a wide range of traditional and contemporary genres.

Traditional Music: Indigenous ethnic groups each have their own distinct musical traditions, often linked to rituals, ceremonies, storytelling, and social events. These traditions typically feature a variety of percussion instruments (drums, xylophones, rattles), stringed instruments (like the kissange or thumb piano), and call-and-response vocal styles.

Semba: Perhaps the most iconic Angolan music genre, Semba originated in the early 20th century in Luanda. It is characterized by its upbeat tempo, complex rhythms, and often melancholic or satirical lyrics. Semba is considered a precursor to Brazilian Samba. Notable Semba artists include Bonga Kuenda, Elias diá Kimuezo, Paulo Flores, and Waldemar Bastos. The band N'gola Ritmos, formed in 1947 with Liceu Vieira Dias, played a crucial role in popularizing and modernizing Semba.

Kizomba: Kizomba emerged in the late 1970s and 1980s, blending Semba with influences from French Caribbean Zouk and other genres. It is known for its romantic and sensual melodies and dance style. Kizomba has gained international popularity. Artists like Eduardo Paim are considered pioneers of the genre.

Kuduro: A more recent genre, Kuduro (meaning "hard ass" or "stiff bottom") originated in Luanda in the late 1980s and 1990s. It is an energetic, electronic dance music genre characterized by fast tempos, repetitive beats, and often humorous or socially conscious lyrics. It has also gained international attention, partly through artists like Buraka Som Sistema (a Portuguese-Angolan group).

Other genres popular in Angola include Afro-jazz, R&B, hip-hop, and gospel music, often with distinct Angolan flavors. Music plays a vital social role in Angola, serving as a form of entertainment, cultural expression, social commentary, and a means of preserving history and identity. Musicians often enjoy significant cultural influence.

9.4. Cinema

The history of Angolan cinema is relatively young but has produced notable works that reflect the country's social, political, and historical experiences. Like many African film industries, it has faced challenges related to funding, infrastructure, and distribution.

During the colonial period, film production was limited, often consisting of propaganda or ethnographic films made by the Portuguese. The struggle for independence and the subsequent civil war significantly impacted the development of a national cinema.

One of the earliest and most internationally acclaimed films associated with Angola is Sambizanga (1972), directed by Sarah Maldoror. Although an international co-production, it is set in Angola and depicts the beginning of the armed struggle against colonial rule. The film won the Tanit d'Or at the Carthage Film Festival.

After independence, some filmmakers emerged, often focusing on themes of liberation, war, and national identity. However, the ongoing civil war hampered consistent production. In the post-war era, there has been a gradual revival of filmmaking efforts. Angolan directors and producers have sought to tell their own stories, addressing contemporary issues as well as historical narratives.

Notable contemporary Angolan filmmakers include Zézé Gamboa, whose films like The Hero (O Herói, 2004) have received international awards. The Hero tells the story of a war veteran struggling to adapt to post-war Luanda and won the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival. Maria João Ganga directed Hollow City (Na Cidade Vazia, 2004), which also explores the impact of war on children.

Angolan films have been featured in various international film festivals, helping to bring Angolan stories and perspectives to a wider audience. The development of the Angolan film industry continues, with efforts to build capacity, secure funding, and create a sustainable environment for filmmakers.

9.5. Sports

Sports play an important role in Angolan society, with football (soccer) and basketball being particularly popular.

Football (Soccer): Football is the most popular sport in Angola. The national league, Girabola, was founded in 1979. The Angola national football team, nicknamed Palancas Negras (Sable Antelopes), achieved its most significant international success by qualifying for the 2006 FIFA World Cup in Germany, their first and only appearance to date. In the tournament, they drew with Mexico and Iran and lost to Portugal. Angola hosted the 2010 Africa Cup of Nations, reaching the quarter-finals. They have won the COSAFA Cup (a regional tournament for Southern African nations) three times and finished as runners-up in the 2011 African Nations Championship.

Basketball: Basketball is the second most popular sport. The men's national team is one of the most successful in Africa, having won the AfroBasket (African Basketball Championship) a record 11 times. Their dominance in Africa has made them regular competitors at the Summer Olympic Games and the FIBA World Cup. Angola is home to one of Africa's first competitive basketball leagues. Bruno Fernando, who plays in the NBA, is a prominent Angolan player.

Other Sports: Angola has also participated in the World Women's Handball Championship for several years. The country has competed in the Summer Olympics in various sports. Angola has also participated in and once hosted the FIRS Roller Hockey World Cup, with their best finish being sixth.

Angola is also believed to have historic roots in the martial art Capoeira Angola and the dance/martial art Batuque, which were practiced by enslaved Angolans transported to Brazil during the Atlantic slave trade.

9.6. Cuisine

Angolan cuisine is a flavorful blend of indigenous African ingredients and cooking techniques with strong influences from Portuguese cuisine, a legacy of centuries of colonization. Brazilian culinary traditions have also had some impact.