1. Overview

France, officially the French Republic, is a country primarily located in Western Europe, with several overseas regions and territories. Metropolitan France extends from the Mediterranean Sea to the English Channel and the North Sea, and from the Rhine to the Atlantic Ocean. It is a unitary semi-presidential republic with its capital in Paris, the nation's largest city and main cultural and commercial hub. France's history is marked by its Celtic origins, Roman conquest, Frankish kingdoms, a powerful medieval monarchy, the transformative French Revolution which established foundational democratic ideals and human rights, the Napoleonic Empire, extensive colonial endeavors, and significant roles in both World Wars. In the contemporary era, France is a major global power with a strong cultural, economic, political, and military influence, being a permanent member of the UN Security Council, a nuclear state, and a key member of the European Union.

The nation's geography is diverse, featuring coastal plains, ancient massifs like the Massif Central, and younger mountain ranges including the Alps and Pyrenees, alongside extensive river systems such as the Loire and Seine. This diversity contributes to varied climates, from oceanic in the northwest to Mediterranean in the south. Environmental policies address challenges like pollution and climate change, with a significant reliance on nuclear power for energy. France's political system is defined by the Fifth Republic, with a dual executive (President and Prime Minister), a bicameral Parliament, and a complex system of administrative divisions including overseas territories with varying statuses. Its foreign policy emphasizes European integration, international cooperation, and human rights, supported by a capable military.

The French economy is advanced and diversified, with strong service and industrial sectors, particularly in aerospace, luxury goods, and pharmaceuticals, alongside a leading agricultural sector and the world's most visited tourism industry. Demographically, France has experienced significant immigration, shaping a multi-ethnic society. The French language is official, though regional languages exist. The principle of laïcité (secularism) defines the state's relationship with religion in a landscape of religious diversity. The country has comprehensive healthcare and education systems. French culture is globally influential, renowned for its art, architecture, literature, philosophy, music, cinema, fashion, and cuisine, with numerous national symbols and public holidays reflecting its rich heritage and democratic values.

2. Etymology

The name "France" originates from the Latin word FranciaFRAN-kih-ahLatin, which translates to "land of the Franks" or "Frankland". This term was initially applied to the entire Frankish Empire. The name of the Franks itself is linked to the English word "frank," meaning 'free'. This connection stems from the Old French word francfrank (Old French)French, Old, which meant 'free, noble, sincere', and ultimately derives from the Medieval Latin word francusFRANG-kuhs (Medieval Latin)Latin, meaning 'free, exempt from service; freeman, Frank'. This Latin term was a generalization of the tribal name, which emerged as a Late Latin borrowing of the reconstructed Frankish endonym *FrankFrank (Frankish)frk.

One theory suggests that the meaning 'free' was adopted because, after the conquest of Gaul, only Franks were exempt from taxation. Another perspective is that they held the status of freemen, contrasting with servants or slaves.

The etymology of *Frank (*FrankFrank (Frankish)frk) itself is uncertain. Traditionally, it is derived from the Proto-Germanic word frankōnfrang-kon (Proto-Germanic)Germanic languages, which means 'javelin' or 'lance'. The throwing axe of the Franks was known as the francisca. However, it's also possible that these weapons were named after their use by the Franks, rather than the Franks being named after the weapons.

In English, 'France' is pronounced /fræns/ in American English and /frɑːns/ or /fræns/ in British English. The pronunciation with /ɑː/ is mostly confined to accents with the trap-bath split, such as Received Pronunciation, though it can also be heard in some other dialects such as Cardiff English.

In German, France is still called FrankreichFrank-rykh (German 'Realm of the Franks')German. To distinguish it from Charlemagne's Frankish Empire, modern France is referred to as FrankreichFrank-rykh (German 'Realm of the Franks')German, while the Frankish Realm is called FrankenreichFrank-en-rykh (German 'Frankish Realm')German.

The name France for the kingdom can be traced back to the 11th-century epic poem The Song of Roland, where it referred to the Frankish kingdom. The Capetian kings, descendants of the Robertines who held the title "Duke of the Franks" (dux Francorumdooks Fran-KOH-rum (Latin 'Duke of the Franks')Latin), began to be referred to as "Kings of France" (Roi de FranceRwa de France (French 'King of France')French) from around 1190, rather than "Kings of the Franks" (Rex FrancorumReks Fran-KOH-rum (Latin 'King of the Franks')Latin). Initially, the term "Francia" referred to the royal demesne around Paris and Orléans. As royal power consolidated and expanded, the name "France" eventually applied to the entire kingdom.

3. History

The history of France is marked by significant events from prehistory to the modern era, deeply influencing its societal structure, cultural landscape, and the evolution of democratic principles and human rights. Key periods include the Roman conquest of Gaul, the rise of Frankish kingdoms, the consolidation of royal power during the Middle Ages, the transformative French Revolution, the Napoleonic era, colonial expansion, two World Wars, and France's role in contemporary European and global affairs.

3.1. Prehistory and Antiquity

The earliest traces of archaic humans in the territory of present-day France date back approximately 1.8 million years. Neanderthals inhabited the region until the Upper Paleolithic era, around 35,000 BC, when they were gradually replaced by Homo sapiens. This period is notable for the emergence of cave painting in areas like the Dordogne and the Pyrenees, with the famous Lascaux cave paintings dated to circa 18,000 BC.

Around 10,000 BC, at the end of the Last Glacial Period, the climate in Western Europe became milder. From approximately 7,000 BC, the region entered the Neolithic era, leading to the development of sedentism and agriculture. Between the 4th and 3rd millennia BC, demographic and agricultural advancements paved the way for the appearance of metalworking, initially with gold, copper, and bronze, followed by iron during the Iron Age. France is home to numerous megalithic sites from the Neolithic period, including the extensive Carnac stones site, dating to around 3,300 BC.

In 600 BC, Ionian Greeks from Phocaea founded the colony of Massalia (present-day Marseille) on the Mediterranean coast. Celtic tribes, known as Gauls, began to penetrate eastern and northern France, eventually spreading throughout the country between the 5th and 3rd centuries BC. Around 390 BC, the Gallic chieftain Brennus led his troops into Roman Italy, defeated the Romans at the Battle of the Allia, and subsequently besieged and ransomed Rome. This event weakened Rome, and Gallic tribes continued to harass the region until 345 BC when a peace treaty was established. However, the Romans and Gauls remained adversaries for centuries.

Around 125 BC, the southern part of Gaul was conquered by the Romans, who named this region Gallia NarbonensisProvincia Nostra ('Our Province')Latin. This name later evolved into Provence. Julius Caesar completed the conquest of the remainder of Gaul, overcoming a major revolt led by the Gallic chieftain Vercingetorix in 52 BC at the Battle of Alesia. Under Roman rule, Gaul was divided into provinces by Emperor Augustus. Many cities were founded during the Gallo-Roman period, including Lugdunum (present-day Lyon), which served as the capital of the Gauls. The Gallo-Roman culture that emerged was a fusion of Roman and Celtic traditions.

In the period of 250-290 AD, Roman Gaul faced a crisis as its fortified borders (limes) were attacked by barbarian tribes. The situation improved in the first half of the 4th century, which was a period of revival and prosperity. In 312 AD, Emperor Constantine the Great converted to Christianity, and the religion, previously persecuted, began to spread rapidly. However, from the 5th century onwards, the Migration Period (Barbarian Invasions) resumed. Teutonic tribes, including the Visigoths (who settled in the southwest), the Burgundians (along the Rhine River Valley), and the Franks (in the north), invaded and established kingdoms within the former Roman territory. Celtic Britons, fleeing Anglo-Saxon invasions of Britain, settled in western Armorica, renaming the peninsula Brittany and reviving Celtic culture in the region.

3.2. Early Middle Ages (5th-10th century)

In Late Antiquity, ancient Gaul was divided into several Germanic kingdoms and a remaining Gallo-Roman territory. The first Germanic leader to unite most of the Franks was Clovis I, who began his reign as king of the Salian Franks in 481. He defeated the last Roman governor in Gaul in 486. According to tradition, Clovis pledged to be baptized a Christian if he won a crucial battle against the Visigothic Kingdom. After his victory, he regained the southwest from the Visigoths and was baptized, likely around 508 AD. Clovis I was the first Germanic conqueror after the fall of the Western Roman Empire to convert to Catholic Christianity rather than Arianism. This conversion was a pivotal moment, leading to France being called the "Eldest daughter of the Church" by the papacy, and French kings subsequently being known as "the Most Christian Kings of France."

The Franks embraced the Christian Gallo-Roman culture, and ancient Gaul was gradually renamed Francia ("Land of the Franks"). The Germanic Franks adopted Romanic languages, which evolved into French. Clovis established Paris as his capital and founded the Merovingian dynasty. However, his kingdom was divided among his heirs upon his death, as was the Frankish custom of treating land as private possession. This led to the emergence of four kingdoms: Paris, Orléans, Soissons, and Reims. Over time, the later Merovingian kings, known as the rois fainéants (do-nothing kings), lost power to their Mayors of the Palace (majordomos).

One such Mayor of the Palace, Charles Martel, famously defeated an Umayyad invasion of Gaul at the Battle of Tours in 732, halting Muslim expansion into Western Europe. His son, Pepin the Short, seized the crown from the weakened Merovingians in 751 and founded the Carolingian dynasty. Pepin's son, Charlemagne, reunited the Frankish kingdoms and built a vast empire across Western and Central Europe.

Charlemagne was proclaimed Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Leo III in 800 AD, further solidifying the Frankish government's historical association with the Catholic Church. He sought to revive the Western Roman Empire and its cultural grandeur, fostering a period known as the Carolingian Renaissance. Charlemagne's son, Louis the Pious, maintained the empire's unity. However, after Louis's death, the Treaty of Verdun in 843 partitioned the empire among his three sons: East Francia, Middle Francia, and West Francia. West Francia, roughly corresponding to the area of modern France, became the precursor to the Kingdom of France.

During the 9th and 10th centuries, West Francia faced repeated Viking invasions, contributing to the decentralization of the state. The nobility's titles and lands became hereditary, and the king's authority became more religious than secular, often challenged by powerful nobles. This period saw the firm establishment of feudalism in France. Some of the king's vassals grew so powerful that they rivaled the king himself. A notable example is the Duke of Normandy, who, after the Norman Conquest in 1066, became William the Conqueror, King of England, while still being a vassal to the French king. This created a complex and often tense relationship between the two kingdoms.

3.3. High and Late Middle Ages (10th-15th century)

The Carolingian dynasty ruled France until 987, when Hugh Capet, Duke of France and Count of Paris, was crowned King of the Franks, establishing the Capetian dynasty. His descendants, through strategic marriages, inheritance, and wars, gradually consolidated royal power and unified the country. From 1190, under Philip II Augustus, the Capetian rulers began to be referred to as "Kings of France" (Roi de FranceKing of France (French)French) rather than "Kings of the Franks" (Rex FrancorumKing of the Franks (Latin)Latin). By the 15th century, the royal demesne (domaine royal) had expanded to cover over half of modern continental France. Royal authority became more assertive, centered on a hierarchically structured society distinguishing between the nobility, clergy, and commoners. This period saw efforts to centralize power, though feudal structures remained significant.

The French nobility played a prominent role in the Crusades, launched to restore Christian access to the Holy Land. French knights constituted a large portion of the crusading forces over the two centuries of the Crusades, leading Arabs to refer to crusaders generally as Franj. French Crusaders also introduced the French language to the Levant, making Old French the basis of the lingua franca (Frankish language) in the Crusader states. Domestically, the Albigensian Crusade was launched in 1209 to eliminate the Cathars, a Christian sect deemed heretical, in the Languedoc region (southwest France). This crusade, while brutal, led to the increased influence of the French crown in the south.

From the 11th century, the House of Plantagenet, rulers of the County of Anjou, established control over neighboring provinces like Maine and Touraine. They eventually built an "empire" stretching from England to the Pyrenees, covering about half of modern France. Tensions between the Kingdom of France and the Plantagenet's Angevin Empire persisted for a century until King Philip II of France conquered most of the Plantagenet's continental possessions between 1202 and 1214, leaving only Aquitaine and England to them.

Charles IV, the Fair, the last direct Capetian king, died without a male heir in 1328. Under Salic Law, which barred female succession, the French crown passed to his cousin, Philip of Valois, founding the Valois dynasty, rather than to Edward III of England, who claimed the throne through his mother, Isabella, Charles IV's sister. During Philip VI's reign, the French monarchy reached a peak of medieval power. However, Edward III contested Philip's claim, leading to the outbreak of the Hundred Years' War in 1337. This dynastic conflict, marked by shifting boundaries and extensive English holdings in France, lasted for over a century. The war was devastating, compounded by the Black Death which struck France in the mid-14th century, killing an estimated half of its 17 million population. Despite initial English successes, charismatic leaders like Joan of Arc inspired French counterattacks, ultimately leading to the recovery of most English continental territories by 1453. The war significantly impacted French society, fostering a sense of national identity and strengthening the monarchy.

3.4. Early Modern Period (15th century-1789)

The French Renaissance marked a period of significant cultural development. The French language was standardized, becoming the official language of France by the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts in 1539, and also the language of Europe's aristocracy. France continued its rivalry with the House of Habsburg through the Italian Wars, which largely dictated French foreign policy until the mid-18th century. French explorers, such as Jacques Cartier and Giovanni da Verrazzano, claimed lands in the Americas, laying the groundwork for the expansion of the first French colonial empire.

The rise of Protestantism in Europe led to the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598), a devastating civil war between Catholics and Huguenots (French Protestants). The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in 1572 was a particularly horrific event, forcing many Huguenots to flee to Protestant regions like the British Isles and Switzerland. The wars were eventually ended by Henry IV's Edict of Nantes in 1598, which granted substantial rights and some freedom of religion to the Huguenots. During this period, Spanish troops assisted the Catholic League and even invaded France in 1597. The Franco-Spanish War (1635-1659) followed, costing France an estimated 300,000 casualties.

Under Louis XIII, Cardinal Richelieu vigorously promoted the centralization of the state and reinforced royal power. He suppressed defiant lords, destroyed their castles, and denounced the use of private armies. By the end of the 1620s, Richelieu had established "the royal monopoly of force." France also participated in the Thirty Years' War, supporting the Protestant side against the Habsburgs to counter their influence. From the 16th to the 19th century, France was involved in the Atlantic slave trade, responsible for about 10% of the total trade.

During the minority of Louis XIV, a period of unrest known as The Fronde (1648-1653) occurred. This rebellion, driven by feudal lords and sovereign courts, was a reaction against the increasing royal absolute power. The monarchy reached its zenith during the 17th century under the personal rule of Louis XIV, the "Sun King." By transforming powerful nobles into courtiers at the Palace of Versailles, his control over the military became unchallenged. France became the leading European power, the most populous European country, and exerted tremendous influence over European politics, economy, and culture. French became the lingua franca of diplomacy, science, and literature until the 20th century. France expanded its colonial empire, taking control of territories in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. However, in 1685, Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, forcing hundreds of thousands of Huguenots into exile, which was a significant loss of skilled artisans and intellectuals. He also published the Code Noir, providing the legal framework for slavery and expelling Jews from French colonies, highlighting the human rights abuses of the era.

Under Louis XV (reigned 1715-1774), France lost New France and most of its Indian possessions after its defeat in the Seven Years' War (1756-1763). Its European territory, however, continued to grow with acquisitions such as Lorraine (1766) and Corsica (1769). Louis XV's perceived weak rule and the decadence of his court discredited the monarchy, contributing to the social and political unrest that paved the way for the French Revolution.

Louis XVI (reigned 1774-1793) supported the American colonies with money, fleets, and armies in their war for independence from Great Britain. While this avenged France's earlier losses to Britain, the enormous cost pushed the French state to the brink of bankruptcy, a critical factor leading to the Revolution. The Age of Enlightenment flourished in French intellectual circles, with scientific breakthroughs such as the naming of oxygen by Antoine Lavoisier (1778) and the first hot air balloon flight carrying passengers by the Montgolfier brothers (1783). French explorers participated in voyages of scientific exploration. Enlightenment philosophy, advocating reason as the primary source of legitimacy, undermined the monarchy's authority and was a key ideological driver of the Revolution.

3.5. French Revolution (1789-1799)

The French Revolution was a period of profound political and societal upheaval in late 18th-century France that had a lasting impact on French history and more broadly on the world. It began with the convocation of the Estates General in May 1789 and culminated in the coup of 18 Brumaire in November 1799, which brought Napoleon Bonaparte to power and led to the formation of the French Consulate. The Revolution's causes were a complex interplay of social inequalities, political discontent with the Ancien RégimeOld RegimeFrench, and severe economic hardship, particularly a financial crisis exacerbated by costly wars and an inequitable taxation system.

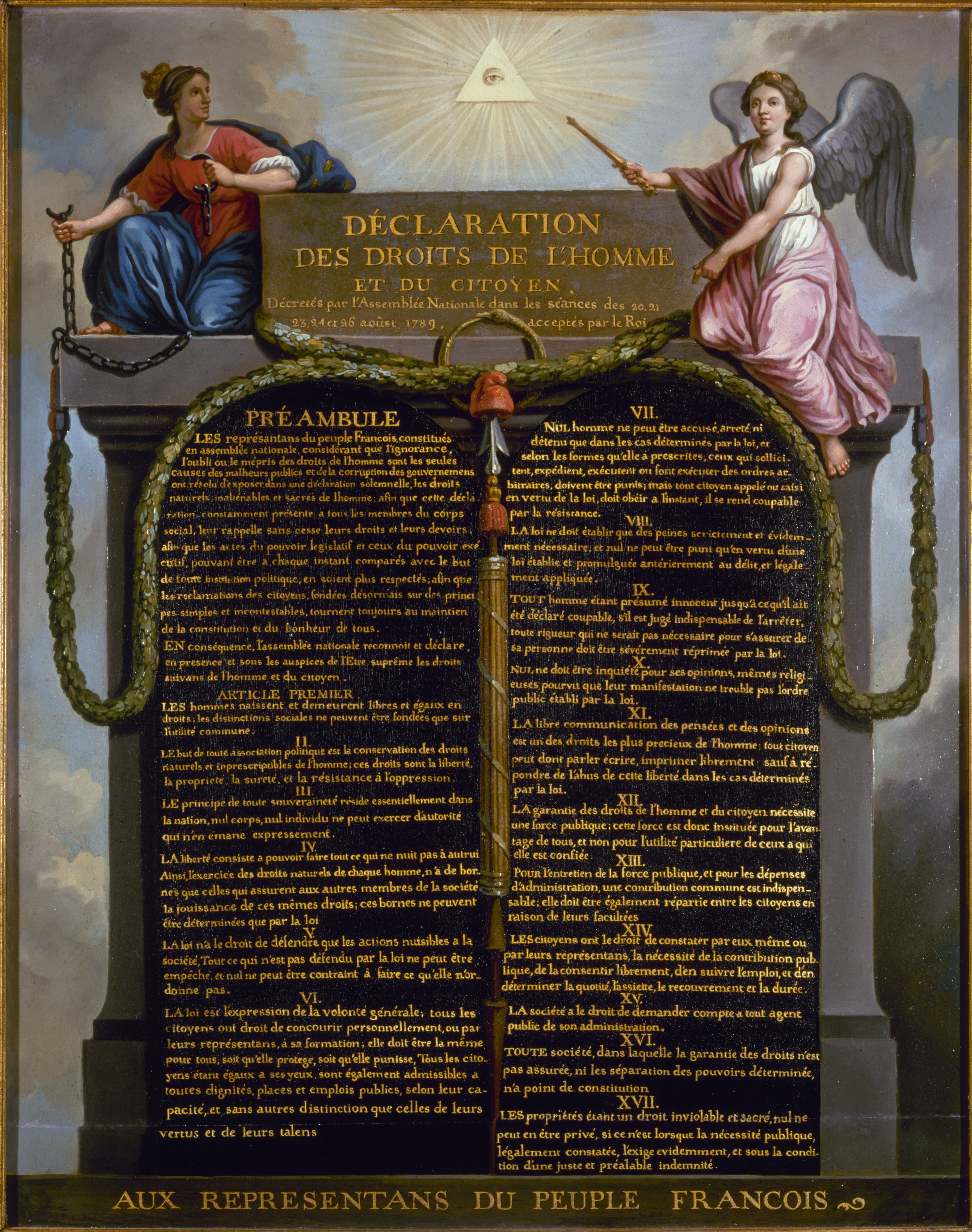

In June 1789, frustrated by the voting structure of the Estates General, the representatives of the Third Estate (commoners) declared themselves the National Assembly, asserting their right to represent the nation. The Storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, a royal fortress and prison in Paris, became a symbolic act of popular rebellion against royal authority. This event spurred a series of radical measures by the Assembly, including the abolition of feudalism in August 1789, the seizure of church property, and the promulgation of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. This declaration proclaimed fundamental rights such as liberty, equality, property, security, and resistance to oppression, and became a cornerstone of modern democratic thought and human rights.

The subsequent three years were marked by intense political struggle, further aggravated by economic depression and social unrest. The outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars in April 1792, as France faced threats from monarchist European powers, radicalized the Revolution. Military setbacks and popular pressure led to the insurrection of 10 August 1792, which overthrew the monarchy. In September 1792, the French First Republic was proclaimed, and King Louis XVI was tried for treason and executed by guillotine in January 1793.

Following another popular revolt, the Insurrection of 31 May - 2 June 1793, which saw the radical Montagnards oust the more moderate Girondins, the Constitution was suspended. Power effectively passed from the National Convention to the Committee of Public Safety, dominated by figures like Maximilien Robespierre. This period initiated the Reign of Terror (1793-1794), during which perceived enemies of the Revolution were systematically persecuted and executed. Approximately 16,000 people were officially executed, and many more died in prison or during uprisings. The Reign of Terror, while intended to consolidate revolutionary gains and defend against internal and external threats, resulted in widespread human rights violations. It ended with the Thermidorian Reaction in July 1794, which saw Robespierre and his allies overthrown and executed.

Weakened by internal opposition and external threats, the Republic struggled for stability. In 1795, the Directory, a five-man executive body, replaced the National Convention. However, the Directory was plagued by corruption, political instability, and ongoing wars. Four years later, in 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte seized power in the coup d'état of 18 Brumaire, effectively ending the revolutionary period and ushering in the Napoleonic era. Despite its violent excesses, the French Revolution profoundly reshaped French society, abolished aristocratic privileges, promoted ideals of nationalism and popular sovereignty, and left an enduring legacy for democratic movements and human rights discourse worldwide.

3.6. Napoleonic Era and 19th Century (1799-1914)

Napoleon Bonaparte rose to power as First Consul in 1799 and later proclaimed himself Emperor of the French in 1804, establishing the First French Empire (1804-1814; 1815). A series of shifting European coalitions declared wars on Napoleon's empire. His armies conquered much of continental Europe through decisive victories like the battles of Jena-Auerstadt and Austerlitz. Members of the Bonaparte family were installed as monarchs in several newly established kingdoms. These victories led to the widespread expansion of French revolutionary ideals and reforms, such as the metric system, the Napoleonic Code (which influenced legal systems worldwide), and the principles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man. However, Napoleonic rule also involved military occupation and the suppression of national aspirations in conquered territories.

In 1812, Napoleon's invasion of Russia proved disastrous. His Grande Armée reached Moscow but was decimated by supply problems, disease, Russian attacks, and the harsh winter during the retreat. This catastrophic campaign, followed by the uprising of European monarchies against his rule, led to Napoleon's defeat and abdication in 1814. Approximately one million Frenchmen died during the Napoleonic Wars. After a brief return from exile known as the Hundred Days, Napoleon was finally defeated at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

The Bourbon monarchy was restored under Louis XVIII and Charles X, with new constitutional limitations. However, the discredited Bourbon dynasty was overthrown by the July Revolution of 1830, which established the constitutional July Monarchy under Louis Philippe I. During this period, French troops began the conquest of Algeria. Growing unrest and economic hardship led to the February Revolution of 1848, ending the July Monarchy. The Second Republic was proclaimed, re-enacting the abolition of slavery (which had been reinstated by Napoleon) and introducing male universal suffrage.

In 1852, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, Napoleon I's nephew and president of the Republic, staged a coup d'état and was proclaimed Emperor Napoleon III of the Second Empire. He pursued an active foreign policy, engaging France in the Crimean War, the intervention in Mexico, and the war in Italy. Domestically, his reign saw significant industrialization and modernization, including Haussmann's renovation of Paris. Napoleon III was overthrown following France's defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, a conflict that led to the loss of Alsace-Lorraine to the newly unified German Empire. His regime was replaced by the Third Republic. By 1875, the French conquest of Algeria was largely complete, at the cost of approximately 825,000 Algerian lives due to famine, disease, and violence, reflecting the brutal realities of colonial expansion.

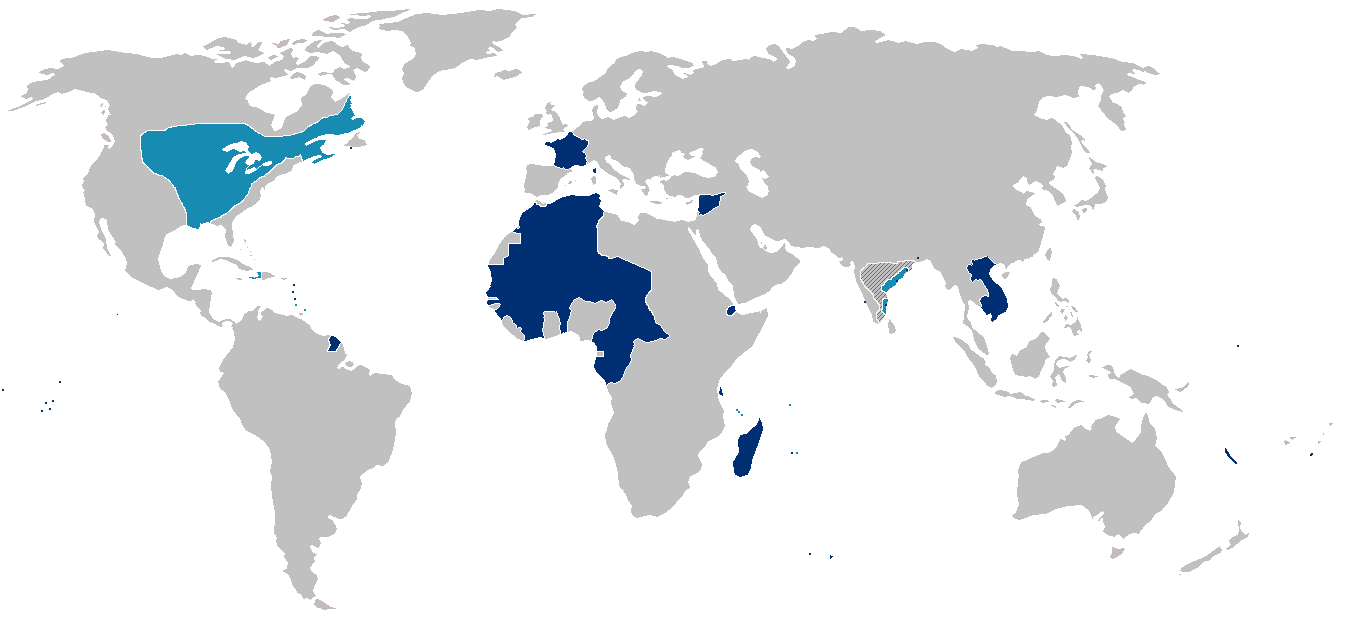

France had colonial possessions since the early 17th century, but its empire expanded greatly in the 19th and 20th centuries, becoming the second-largest in the world after the British Empire. By the 1920s and 1930s, including metropolitan France, its territories covered almost 13 million square kilometers, about 9% of the world's land area. The late 19th and early 20th centuries, known as the ''Belle Époque'' (Beautiful Era), were characterized by optimism, regional peace, economic prosperity, and significant technological, scientific, and cultural innovations. In 1905, state secularism (laïcitésecularismFrench'') was officially established, marking a significant shift in the relationship between the state and religious institutions. This era also saw ongoing social transformations and the consolidation of democratic institutions, though challenges related to workers' rights and social inequality persisted.

3.7. Early to Mid-20th Century (1914-1946)

France was invaded by Germany at the outset of World War I in August 1914, triggering its entry into the conflict alongside Great Britain and Russia as part of the Triple Entente. A significant industrial area in northeastern France was occupied by German forces. The war on the Western Front was largely fought on French soil and became a brutal war of attrition, characterized by trench warfare and immense casualties. France and the Allies emerged victorious against the Central Powers in 1918, but at a tremendous human and economic cost. The war left 1.4 million French soldiers dead, approximately 4% of its population, and millions more wounded or disabled. The devastation of its land and infrastructure was immense.

The interwar period (1919-1939) was marked by efforts to rebuild, intense international tensions, and significant political and social dynamics. France sought security through alliances and the League of Nations, but faced economic difficulties, including the Great Depression. Social reforms were introduced by the Popular Front government in the 1930s, such as annual leave, the eight-hour workday, and increased participation of women in government. However, political instability and ideological divisions persisted.

In 1939, World War II began. In 1940, France was invaded and rapidly defeated by Nazi Germany. The country was divided: northern and western France, including Paris, fell under German occupation; a zone in the southeast was under Italian occupation; and the remaining southern territory was governed by the authoritarian and collaborationist Vichy regime, led by Marshal Philippe Pétain. Free France, the government-in-exile led by General Charles de Gaulle, was established in London and continued the fight against the Axis powers, coordinating the French Resistance movement within occupied France.

From 1942 to 1944, approximately 160,000 French citizens, including around 75,000 Jews, were deported to Nazi concentration and extermination camps. The Vichy regime actively participated in these deportations, a dark chapter in French history involving human rights atrocities. On June 6, 1944 (D-Day), the Allies invaded Normandy. In August 1944, they launched Operation Dragoon, invading Provence in the south. The combined efforts of the Allied forces and the French Resistance led to the Liberation of Paris in August 1944 and the eventual restoration of French sovereignty with the establishment of the Provisional Government of the French Republic (GPRF). This interim government, established by de Gaulle, continued to wage war against Germany and initiated the purge of collaborators. It also implemented important social reforms, including extending suffrage to women and creating a comprehensive social security system. The war resulted in further significant human losses and societal shifts, leaving France to face the immense task of post-war reconstruction and redefining its place in the world.

3.8. Contemporary Era (1946-Present)

Following World War II, a new constitution led to the establishment of the French Fourth Republic (1946-1958). This period saw strong economic growth, known as les Trente Glorieuses (the Glorious Thirty), and France became a founding member of NATO. However, the Fourth Republic was plagued by political instability and the challenges of decolonization. France attempted to regain control of French Indochina but was defeated by the Viet Minh in 1954 at the Battle of Điện Biên Phủ. This defeat marked a significant blow to French colonial power.

Subsequently, France faced another major anti-colonialist conflict, the Algerian War (1954-1962). Algeria was then considered an integral part of France and was home to over one million European settlers (Pied-Noirs). The French military systematically used torture and repression, including extrajudicial killings, in its efforts to maintain control, leading to severe human rights violations. The conflict deeply divided French society and nearly led to a coup d'état and civil war in France.

The May 1958 crisis, stemming from the Algerian War and governmental instability, led to the collapse of the weak Fourth Republic and the establishment of the Fifth Republic, which featured a significantly strengthened presidency under Charles de Gaulle. The Algerian War concluded with the Évian Accords in 1962, leading to Algerian independence. The war came at a high human cost, with estimates of half a million to one million deaths and over two million internally displaced Algerians. Around one million Pied-Noirs and Harkis (Algerian Muslims who fought for France) fled from Algeria to France, creating significant social and economic challenges. The legacy of colonialism continued through French overseas departments and territories.

During the Cold War, de Gaulle pursued a policy of "national independence" (politique de grandeur) towards both the Western and Eastern blocs. He withdrew France from NATO's integrated military command (while remaining in the alliance), launched a nuclear development programme, making France the world's fourth nuclear power. He restored cordial Franco-German relations to create a European counterweight to American and Soviet influence. However, he opposed supranational European integration, favoring a "Europe of States."

The student and worker protests of May 1968 had an enormous social impact, marking a watershed moment when conservative moral ideals (religion, patriotism, respect for authority) shifted towards more liberal values (secularism, individualism, sexual revolution). Although the revolt was a political failure in the short term (the Gaullist party emerged stronger), it signaled a growing disconnect between the French people and de Gaulle, who resigned in 1969.

In the post-Gaullist era, France remained one of the world's most developed economies but faced crises resulting in high unemployment rates and increasing public debt. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, France has been at the forefront of developing a supranational European Union, notably by signing the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, establishing the Eurozone in 1999, and signing the Treaty of Lisbon in 2007. France fully reintegrated into NATO's military command in 2009 and has since participated in most NATO-sponsored operations.

Since the 19th century, France has received many immigrants. Initially, these were often male foreign workers from European Catholic countries who generally returned home. During the 1970s economic crisis, France allowed new immigrants, mostly from the Maghreb (Northwest Africa), to settle permanently with their families and acquire citizenship. This led to large Muslim communities, often living in subsidized public housing and facing high unemployment rates and discrimination. The government's initial policy of assimilation has faced challenges, leading to ongoing debates about multiculturalism, integration, Islam in French society, and racism.

Since the 1995 public transport bombings, France has been targeted by Islamist organizations. Notable attacks include the Charlie Hebdo attack in January 2015, which provoked the largest public rallies in French history, gathering 4.4 million people. The November 2015 Paris attacks resulted in 130 deaths, the deadliest attack on French soil since World War II. Opération Chammal, France's military efforts against ISIS, killed over 1,000 ISIS militants between 2014 and 2015. Contemporary France continues to grapple with these security challenges, alongside issues of social equity, economic reform, and its role in an evolving Europe and world.

4. Geography

France's geography is characterized by its diverse landscapes, extensive borders, and significant overseas territories, contributing to its varied climate and rich natural environment.

4.1. Location and Borders

Metropolitan France, the main territory of France in Western Europe, is situated mostly between latitudes 41° and 51° N, and longitudes 6° W and 10° E. It lies on the western edge of the European continent, placing it within the northern temperate zone. Its continental part covers approximately 0.6 K mile (1.00 K km) from north to south and from east to west.

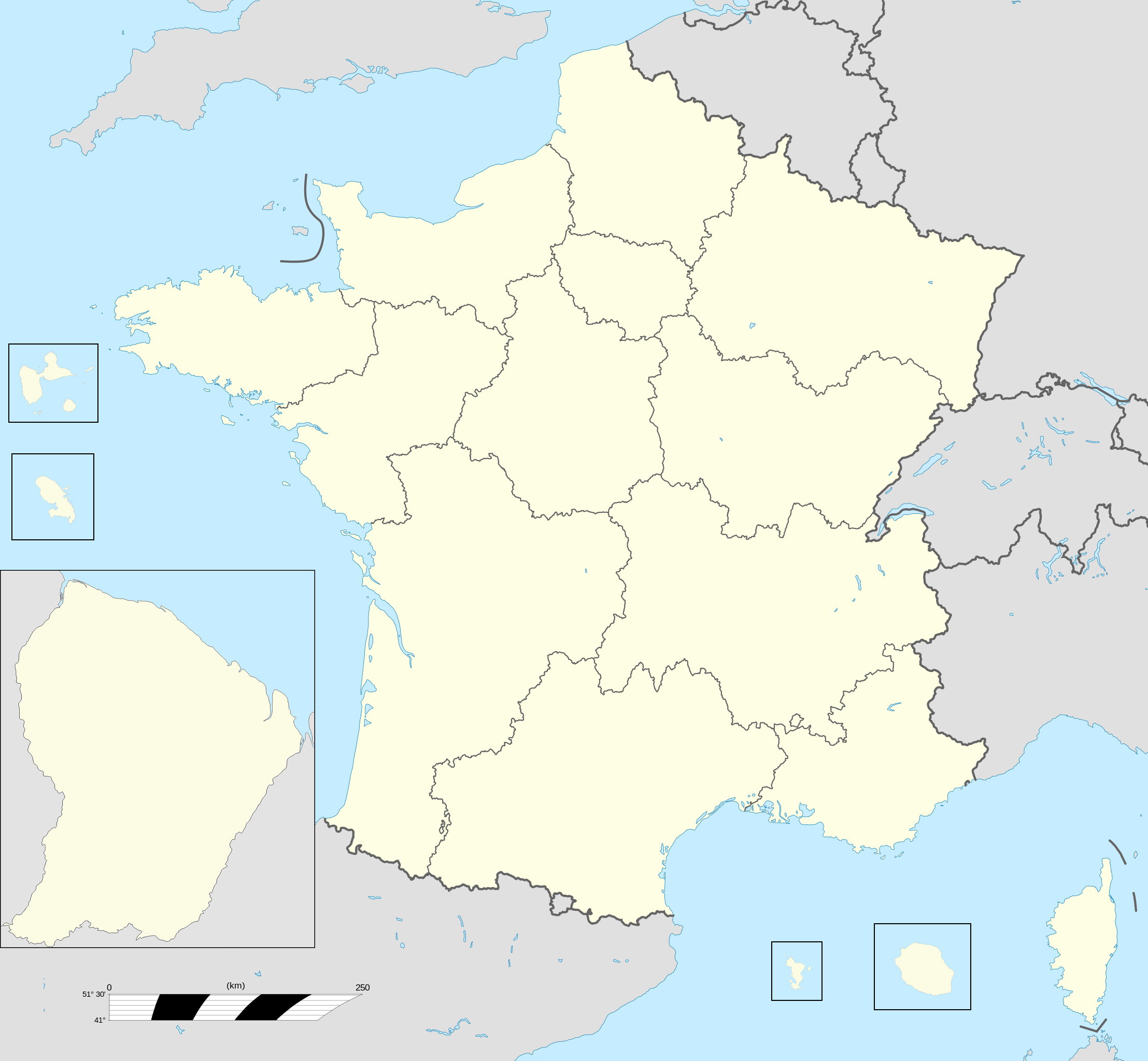

Metropolitan France covers an area of 551.50 K 0, making it the largest country by area among European Union members. France's total land area, including its overseas departments and territories (excluding Adélie Land in Antarctica, which is a French claim not universally recognized), is 643.80 K 0, representing 0.45% of the total land area on Earth.

Metropolitan France is bordered by the North Sea to the north, the English Channel to the northwest, the Atlantic Ocean (specifically the Bay of Biscay) to the west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the southeast. Its land borders are shared with Belgium and Luxembourg to the northeast; Germany, Switzerland, and Italy to the east; Monaco to the southeast; and Andorra and Spain to the south and southwest. With the exception of its northeastern frontier, most of France's land borders are delineated by natural boundaries: the Pyrenees mountains to the south, the Alps and Jura mountains to the southeast and east, and the Rhine river to the east.

France also has numerous overseas departments and territories scattered across the globe. These give France the second-largest exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the world, covering 11.04 M -3. This EEZ represents approximately 8% of the total surface of all EEZs worldwide. Due to these territories, France shares land borders with Brazil and Suriname (via French Guiana), and with the Netherlands (via Saint Martin on the island of Saint Martin). It also maintains a maritime border with the United Kingdom through the English Channel.

4.2. Topography and Hydrography

Metropolitan France possesses a wide variety of topographical features and natural landscapes. Significant portions of France's landforms were shaped during the Hercynian uplift in the Paleozoic Era, which formed ancient massifs such as the Armorican Massif in the northwest, the Massif Central in the south-central region, the Morvan in Burgundy, and the Vosges and Ardennes ranges in the east. The island of Corsica in the Mediterranean also has geological origins from this period. These older, eroded massifs delineate several major sedimentary basins, including the vast Aquitaine Basin in the southwest and the Paris Basin in the north, the latter being a particularly fertile agricultural region.

The Alps, Pyrenees, and Jura are much younger mountain ranges, formed during the Alpine orogeny, and consequently have more rugged and less eroded forms. Mont Blanc, located in the Alps on the border between France and Italy, stands at 4.81 K 0 above sea level, making it the highest point in Western Europe. While 60% of French municipalities are classified as having seismic risks, these risks are generally moderate.

France's coastlines offer diverse landscapes. The French Riviera (Côte d'AzurAzure CoastFrench) on the Mediterranean features mountainous terrain descending to the sea. The Côte d'Albâtre in Normandy is known for its dramatic coastal cliffs, while regions like the Languedoc boast wide, sandy plains. Corsica lies off the Mediterranean coast.

France has an extensive river system. The four major rivers are the Seine (flowing through Paris into the English Channel), the Loire (France's longest river, flowing into the Atlantic), the Garonne (flowing from the Pyrenees to the Atlantic), and the Rhône (originating in Switzerland, dividing the Massif Central from the Alps, and flowing into the Mediterranean Sea at the Camargue delta). The combined catchment area of these rivers and their tributaries covers over 62% of the metropolitan territory. The Garonne meets the Dordogne River near Bordeaux to form the Gironde estuary, the largest estuary in Western Europe, which empties into the Atlantic Ocean after approximately 100 0. Other significant watercourses, such as the Meuse and parts of the Rhine's watershed, drain towards the northeastern borders. France has approximately 11.00 M 0 of marine waters under its jurisdiction across three oceans, with 97% of this area being overseas.

4.3. Climate

Metropolitan France experiences a variety of climates due to its diverse geography and latitudinal extent. The northern and northwestern parts, including Paris, generally have a temperate oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfb), characterized by mild winters, warm summers, and rainfall distributed throughout the year. Coastal Brittany, for example, has very mild winters but cool summers.

The southern coastal regions, along the Mediterranean Sea (e.g., the French Riviera, Provence, Corsica), enjoy a Mediterranean climate (Csa, Csb), with hot, dry summers and mild, wetter winters. This region benefits from abundant sunshine.

Moving inland, particularly in eastern France (e.g., Alsace, Lorraine), the climate becomes more continental (Dfb in mountainous areas, Cfb in lower areas), with colder winters, often with snow, and warmer summers. The mountainous regions, such as the Alps, Pyrenees, and Massif Central, have an alpine climate (ET, Dfc, Dfb), where temperatures decrease and precipitation (often as snow) increases with altitude. These areas experience significant winter snowfall, supporting a major ski industry.

Overseas France exhibits a wider range of climates:

- French Guiana has a hot and humid equatorial climate.

- Islands in the Caribbean (Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Barthélemy, Saint Martin) and the Indian Ocean (Réunion, Mayotte) generally have tropical climates, with warm temperatures year-round and distinct wet and dry seasons.

- Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the North Atlantic has a cold, humid continental climate, influenced by Arctic air masses.

- French Polynesia in the Pacific has a tropical climate, varying from humid equatorial to tropical savanna depending on the island group.

- New Caledonia in the Pacific has a tropical savanna climate, with warm to hot temperatures.

- The French Southern and Antarctic Lands have climates ranging from oceanic to tundra and ice cap climates, depending on their latitude.

4.4. Environment

France has a rich biodiversity and varied ecosystems, reflecting its diverse geography and climates. Forests cover approximately 31% of France's land area, the fourth-highest proportion in Europe, and this area has increased by 7% since 1990. French forests are among the most diverse in Europe, with over 140 species of trees.

The country was one of the first to establish an environment ministry in 1971. France is ranked 19th globally for carbon dioxide emissions, a relatively low ranking for an industrialized nation, largely due to its significant investment in nuclear power. Following the 1973 oil crisis, France prioritized energy independence, and nuclear power now accounts for about 75% of its electricity production. This reliance on nuclear energy results in lower greenhouse gas emissions compared to countries heavily reliant on fossil fuels. According to the 2020 Environmental Performance Index by Yale and Columbia Universities, France was the fifth most environmentally conscious country in the world.

As a member of the European Union, France has committed to cutting carbon emissions by at least 20% of 1990 levels by 2020, and participates in subsequent EU climate targets. French per capita carbon dioxide emissions are lower than those of China. An attempt to impose a carbon tax in 2009 was abandoned due to concerns about its impact on French businesses.

France has established nine national parks and 46 regional natural parks (parcs naturels régionaux or PNRs) as of 2019. These PNRs are public establishments created between local authorities and the national government to protect scenic and heritage-rich inhabited rural areas while promoting sustainable economic development. They aim to balance conservation with human activities, fostering environmental education and research.

Significant environmental issues in France include air pollution, particularly in urban areas, primarily from vehicle emissions (diesel and petrol cars) and industry. Water pollution from agricultural runoff and industrial discharge is another concern. Climate change impacts, such as increased frequency of heatwaves, droughts, and changes in precipitation patterns, pose challenges to agriculture, water resources, and ecosystems. The government has implemented various environmental policies and conservation efforts, including promoting renewable energy, improving energy efficiency, and protecting biodiversity. Considerations of environmental justice, ensuring that environmental burdens and benefits are distributed equitably across society, are increasingly part of policy discussions.

5. Politics

France's political landscape is defined by its semi-presidential republican system, a robust democratic tradition, and a multi-party system. The structure of its government, administrative divisions, foreign policy, military, and legal framework reflect its history and commitment to democratic values and civil liberties.

5.1. Government Structure

France is a representative democracy organized as a unitary semi-presidential republic. The Constitution of the Fifth Republic, approved by referendum on September 28, 1958, establishes the framework for its government, dividing powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. This constitution significantly strengthened the authority of the executive branch relative to the legislature, aiming to address the instability of the Third and Fourth Republics by combining elements of both parliamentary and presidential systems. Democratic traditions and values are deeply embedded in French culture, identity, and politics.

The executive branch is led by two figures:

1. The President of the Republic, currently Emmanuel Macron, is the head of state. The president is elected directly by universal adult suffrage for a five-year term. The president's powers include appointing the Prime Minister, dissolving Parliament, submitting bills to referendums, appointing judges and civil servants, negotiating and ratifying international treaties, and serving as commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces.

2. The Prime Minister, currently François Bayrou (appointed in December 2024), is the head of government. The Prime Minister is appointed by the President to lead the government and is responsible for determining public policy, overseeing the civil service, and managing domestic affairs. The Prime Minister and the cabinet are responsible to the Parliament.

The legislature is bicameral, consisting of:

1. The National Assembly (Assemblée Nationale), the lower house. Its members, known as députés, represent local constituencies and are directly elected for five-year terms. The National Assembly has the power to dismiss the government through a vote of no confidence.

2. The Senate (Sénat), the upper house. Senators are chosen by an electoral college for six-year terms, with half the seats subject to election every three years. The Senate's legislative powers are more limited than those of the National Assembly; in the event of disagreement between the two chambers on legislation, the National Assembly generally has the final say.

The Parliament is responsible for determining rules and principles concerning most areas of law, political amnesty, and fiscal policy. However, the government can draft specific details for most laws.

French politics from World War II until 2017 was largely dominated by two main political groupings: a left-wing bloc, historically represented by the French Section of the Workers' International and later the Socialist Party (founded in 1969), and a right-wing bloc, historically represented by the Gaullist party, which evolved through various names such as the Rally of the French People, Union of Democrats for the Republic, Rally for the Republic, Union for a Popular Movement, and currently The Republicans (since 2015).

The 2017 presidential and legislative elections marked a significant shift with the rise of La République En Marche! (LREM), a centrist party led by Emmanuel Macron, which became the dominant force, overtaking both the Socialists and Republicans. The far-right National Rally (RN, formerly National Front) has also grown in influence, being the main opponent in the second round of the 2017 and 2022 presidential elections. Since 2020, Europe Ecology - The Greens (EELV) have performed well in local elections in major cities, while on a national level, an alliance of left-wing parties (the NUPES) became the second-largest voting bloc in the National Assembly in 2022. The right-wing populist RN became the largest single opposition party in the National Assembly in the same year. In the 2022 presidential election, Macron was re-elected. However, in the subsequent June 2022 legislative elections, Macron's coalition lost its parliamentary majority, leading to the formation of a minority government.

The electorate can vote on constitutional amendments passed by Parliament and on bills submitted by the president via referendums. Referendums have played a key role in French politics, deciding matters such as Algerian independence, the direct election of the president, EU treaty ratifications, and presidential term limits.

5.2. Administrative Divisions

France has a complex system of administrative divisions that includes regions, departments, and various overseas territories, reflecting its history and global presence. These divisions play crucial roles in local governance and representation.

5.2.1. Regions and Departments

Since 2016, Metropolitan France (mainland France plus Corsica) is divided into 13 administrative regions. These regions are the primary units for regional planning and economic development, possessing elected regional councils with significant budgetary autonomy. The regions are further subdivided into 96 departments. Departments are a traditional administrative unit, historically more powerful than regions, and are responsible for a wide range of local services, including social welfare, local roads, and secondary education infrastructure. Each department is administered by a departmental council and headed by a prefect appointed by the central government, representing the state at the local level. Departments are numbered, mainly alphabetically, and this number is used in postal codes and was formerly used on vehicle registration plates.

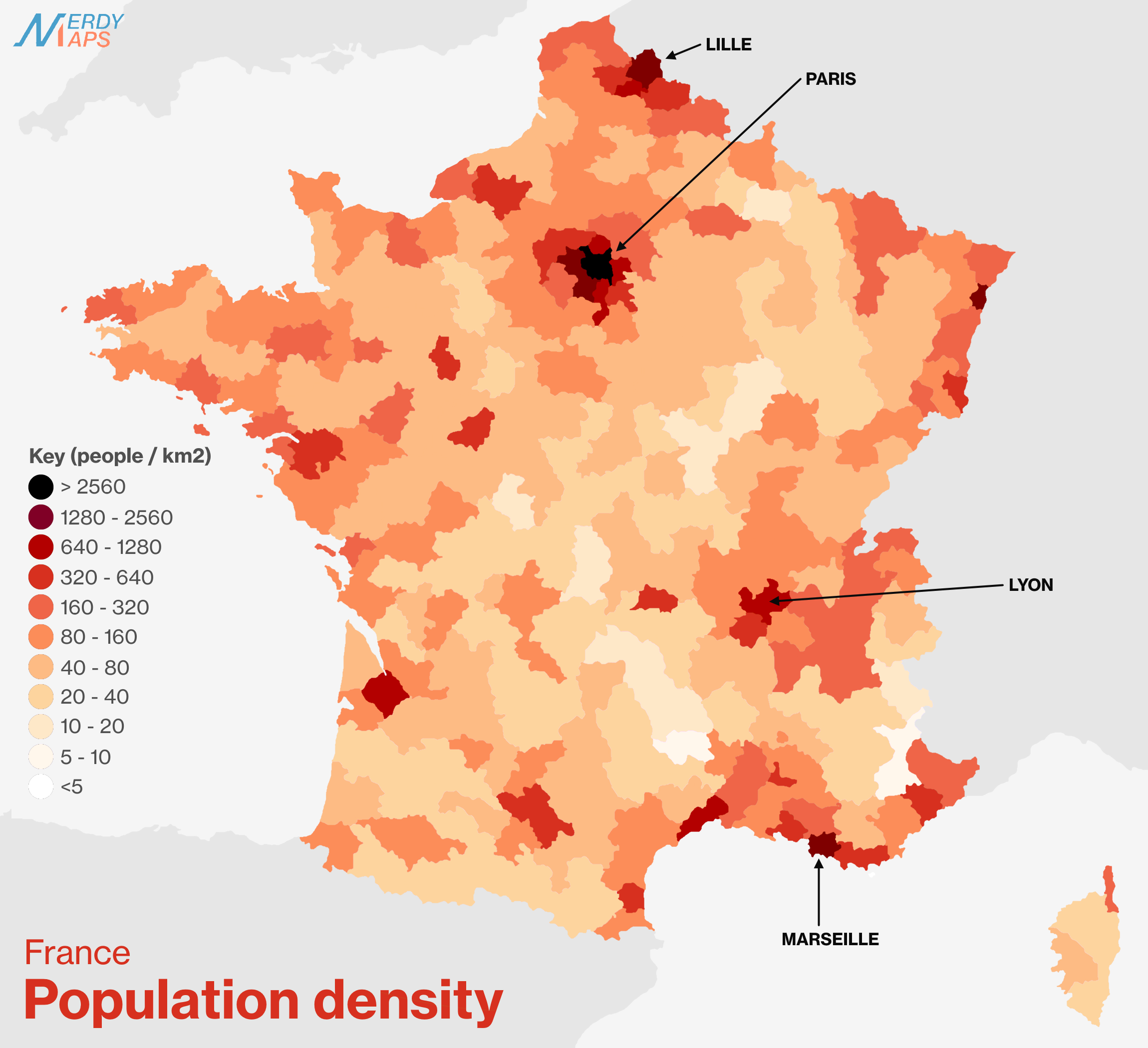

The departmental structure extends to the lowest levels of administration. Departments are subdivided into arrondissements (which primarily serve as administrative subdivisions of the prefect), which are in turn divided into cantons (mainly electoral districts). The most fundamental unit of local government is the commune (municipality). There are over 36,000 communes in France, each with an elected mayor and municipal council responsible for local matters such as urban planning, primary schools, and local policing. Three of the largest communes-Paris, Lyon, and Marseille-are further subdivided into municipal arrondissements.

5.2.2. Overseas France

In addition to its metropolitan territory, France includes a diverse array of overseas territories with varying statuses, reflecting its colonial history. These territories are integral parts of the French Republic but have different administrative arrangements and relationships with the European Union.

There are five overseas departments and regions (DROMs): French Guiana in South America, Guadeloupe and Martinique in the Caribbean, and Mayotte and Réunion in the Indian Ocean. These DROMs have the same political status as metropolitan departments and regions and are part of the European Union. They are represented in the French Parliament and participate in EU elections.

France also has five overseas collectivities (COMs):

- French Polynesia in the Pacific Ocean, which has a large degree of autonomy.

- Saint Barthélemy and Saint Martin in the Caribbean (Saint Martin shares an island with Sint Maarten, a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands). Saint Barthélemy is part of the EU's fiscal area, while Saint Martin is not fully.

- Saint Pierre and Miquelon off the coast of Newfoundland, Canada.

- Wallis and Futuna in the Pacific Ocean.

These COMs have specific statutes and varying degrees of autonomy, generally greater than DROMs.

New Caledonia, located in the Pacific, has a unique sui generis status, granting it a very high degree of self-governance following the Nouméa Accord. It has its own citizenship and has held referendums on independence.

The French Southern and Antarctic Lands (TAAF) constitute an overseas territory with no permanent population, administered directly from Réunion. This includes Adélie Land, France's Antarctic claim (not universally recognized). Clipperton Island is an uninhabited atoll in the Pacific Ocean, directly under the authority of the Minister of Overseas France.

The governance of these overseas territories presents ongoing challenges related to self-determination, socio-economic development, and representation within the French Republic. While some territories seek greater autonomy or independence, others maintain strong ties with metropolitan France. The economic situation in many overseas territories often lags behind the mainland, with higher unemployment and greater dependence on French state subsidies, highlighting issues of social equity and development.

5.3. Foreign Relations

France is a founding member of the United Nations and holds a permanent seat on the UN Security Council, granting it veto power. Described in 2015 as "the best networked state in the world" due to its extensive membership in international organizations, France is a member of the G7, World Trade Organization (WTO), the Pacific Community (SPC), and the Indian Ocean Commission (COI). It is an associate member of the Association of Caribbean States (ACS) and a leading member of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (Organisation internationale de la FrancophonieInternational Organization of La FrancophonieFrench; OIF), an organization of 84 French-speaking countries that promotes democratic values, multilingualism, and cultural diversity.

As a major hub for international relations, France hosts the third-largest number of diplomatic missions globally, after China and the United States. It is also home to the headquarters of several international organizations, including the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), UNESCO, Interpol, the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, and the OIF.

French foreign policy since World War II has been significantly shaped by its membership in the European Union (EU), of which it was a founding member. Since the Élysée Treaty in 1963, France has developed a close partnership with Germany, forming the most influential driving force within the EU. This Franco-German axis has been central to European integration efforts. France has also maintained an "Entente Cordiale" with the United Kingdom since 1904, with strengthening ties, particularly in military cooperation through agreements like the Defence and Security Co-operation Treaty.

France is a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). However, under President Charles de Gaulle, it withdrew from NATO's integrated military command in 1966 to preserve the independence of its foreign and security policies, protesting the "Special Relationship" between the United States and Britain. France fully rejoined NATO's joint military command under President Nicolas Sarkozy on April 4, 2009.

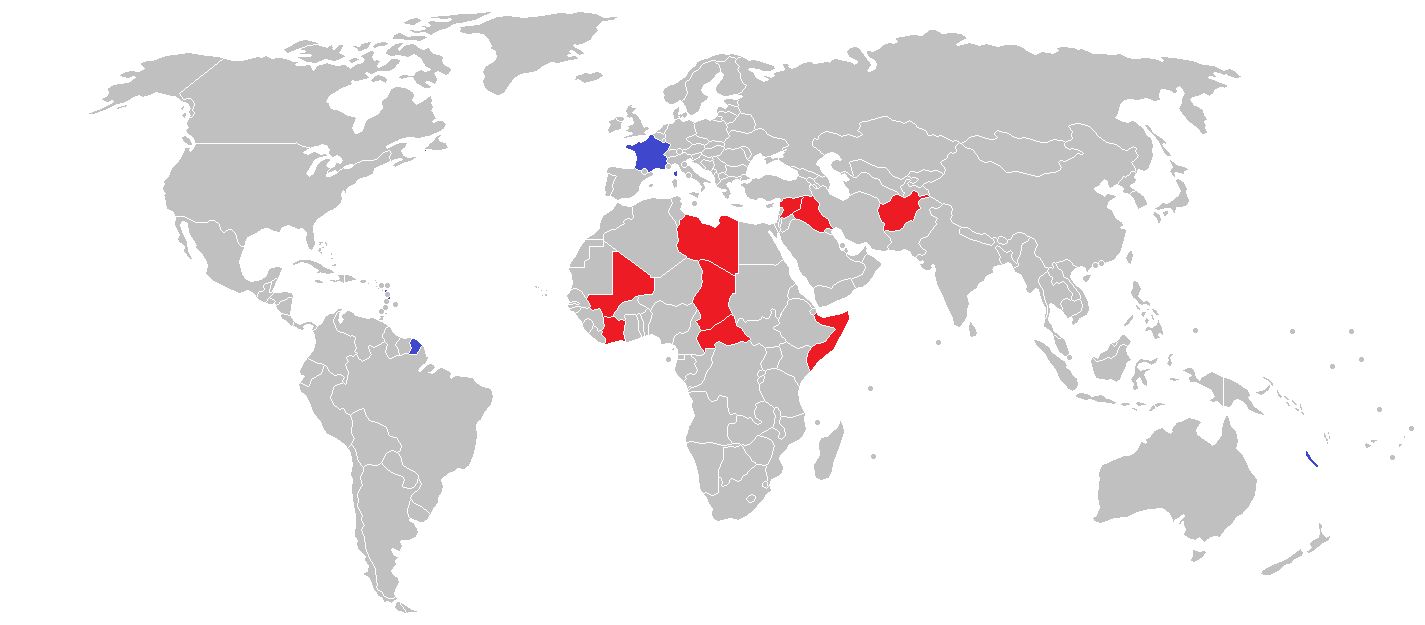

France maintains strong political and economic influence in its former African colonies (often referred to as Françafrique FrançafriqueFrance-AfricaFrench), though this relationship is complex and often criticized. It has supplied economic aid and troops for peacekeeping missions in countries like Ivory Coast and Chad. From 2012 to 2021, France, along with other African states, intervened in support of the Malian government in the Malian conflict against Islamist insurgents. French foreign policy emphasizes the importance of considering the perspectives of affected parties and addressing human rights issues in its international engagements.

In 2017, France was the world's fourth-largest donor of development aid in absolute terms, representing 0.43% of its Gross National Product (GNP), the 12th highest among OECD countries. Aid is primarily channeled through the governmental French Development Agency (AFD), which finances humanitarian projects, with a strong focus on sub-Saharan Africa. These projects emphasize developing infrastructure, improving access to healthcare and education, implementing appropriate economic policies, and consolidating the rule of law and democracy. France's engagement in development aid and human rights advocacy reflects its commitment to these values on the international stage.

5.4. Military

The French Armed Forces (Forces armées françaisesFrench Armed ForcesFrench) comprise the French Army (Armée de TerreArmyFrench), the French Navy (Marine NationaleNational NavyFrench), the French Air and Space Force (Armée de l'Air et de l'EspaceAir and Space ForceFrench), and the National Gendarmerie (Gendarmerie nationaleNational GendarmerieFrench). The President of the Republic is the supreme commander. The National Gendarmerie, while part of the armed forces, primarily serves as military police and as a civil police force in rural areas. Collectively, the French Armed Forces are among the largest in the world and the largest in the European Union. A 2015 study by Crédit Suisse ranked them as the world's sixth-most powerful military and the second most powerful in Europe.

France's annual military expenditure in 2023 was 61.30 B USD, or 2.1% of its GDP, making it the eighth-biggest military spender globally. Conscription was abolished in 1997, and the military has since transitioned to an all-professional force.

France has been a recognized nuclear state since 1960 and is a party to both the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). The French nuclear deterrent, known as the Force de Frappe, consists primarily of four Triomphant-class submarines equipped with submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). In addition, France is estimated to possess about 60 ASMP medium-range air-to-ground missiles with nuclear warheads. Around 50 of these are deployed by the Air and Space Force using Mirage 2000N long-range nuclear strike aircraft, while about 10 are deployed by the French Navy's Super Étendard Modernisé (SEM) attack aircraft, operating from the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle (R91).

France has major military industries and one of the largest aerospace sectors in the world. It produces advanced military equipment such as the Rafale fighter jet, the Charles de Gaulle aircraft carrier, the Exocet missile, and the Leclerc main battle tank. France is a major arms seller, with most of its arsenal designs available for the export market, excluding nuclear-powered devices. Among the largest French defence companies are Dassault, Thales, and Safran. In 2022, French weapons exports totaled 27.00 B EUR.

French intelligence services include the Directorate-General for External Security (DGSE), under the Ministry of Defense, and the General Directorate for Internal Security (DGSI), under the Ministry of the Interior. France's cybersecurity capabilities are regularly ranked among the most robust globally.

Major overseas deployments have included operations in Afghanistan, Ivory Coast, Chad, Libya, Somalia, Mali, the Central African Republic, Syria, and Iraq, reflecting France's global security interests and commitments, often in post-colonial spheres or as part of international coalitions. These interventions, while aimed at stabilization or counter-terrorism, also raise complex questions regarding their effectiveness, human rights implications, and long-term impact on regional stability and local populations.

5.5. Law

France employs a civil legal system, where law primarily originates from written statutes. Judges are tasked with interpreting the law rather than making it, although extensive judicial interpretation in certain areas can resemble case law in common law systems. The foundational principles of the rule of law were laid out in the Napoleonic Code (largely based on royal law codified under Louis XIV). In line with the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789), the law should only prohibit actions detrimental to society.

French law is broadly divided into private law (including civil law and criminal law) and public law (including administrative law and constitutional law). In practice, it comprises three main areas: civil law, criminal law, and administrative law. A key principle is that criminal laws cannot be applied retrospectively (ex post facto laws are prohibited). For a law to be applicable, it must be officially published in the Journal officiel de la République française.

France does not recognize religious law as a basis for enacting prohibitions; it abolished blasphemy laws and sodomy laws long ago (the latter in 1791). However, concepts like "offences against public decency" (contraires aux bonnes mœurscontrary to good moralsFrench) or "disturbing public order" (trouble à l'ordre publicdisturbance of public orderFrench) have occasionally been invoked in ways that have impacted minority expression or practices.

LGBTQ+ rights in France are generally considered progressive. Civil unions (PACS) for same-sex couples have been permitted since 1999, and same-sex marriage and LGBT adoption were legalized in 2013. Laws prohibiting discriminatory speech in the press date back to 1881. While hate speech laws in France exist to combat racism and antisemitism, some argue they can be overly broad, potentially undermining freedom of speech. The 1990 Gayssot Act prohibits Holocaust denial. In 2024, France became the first nation to explicitly enshrine the right to abortion in its Constitution, a significant step for reproductive rights.

Freedom of religion is constitutionally guaranteed. The 1905 law on the Separation of the Churches and the State established the principle of laïcité (laïcitésecularismFrench). Under laïcité, the state does not formally recognize any religion (except in Alsace-Moselle, where legacy statutes provide for state funding of Catholicism, Lutheranism, Calvinism, and Judaism). However, the state does recognize religious associations.

The French Parliament has classified some religious movements as "dangerous cults" (sectessectsFrench) since 1995. In 2004, a law banning the wearing of conspicuous religious symbols in public schools was passed. In 2010, a ban on wearing face-covering Islamic veils (like the niqab or burqa) in public spaces was enacted. These laws have sparked considerable debate. Supporters argue they uphold laïcité, promote equality (especially gender equality), and ensure public order. Critics, including human rights organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, argue these laws can be discriminatory, particularly towards Muslim women, and may infringe upon freedom of religion and expression for minorities. Despite these criticisms, such measures have generally received support from a majority of the French population. The application and interpretation of laïcité continue to be central to discussions about civil liberties, human rights, and the rights of minorities in France.

6. Economy

France possesses a developed, diversified social market economy with significant government involvement in certain sectors, alongside a robust private sector. The nation consistently ranks among the world's largest economies and plays a key role in European and global trade, with an emphasis on high-value industries, tourism, and energy. Considerations of social equity and environmental sustainability are increasingly influencing its economic policies.

6.1. Economic Structure and Major Industries

France has a social market economy characterized by a history of significant government involvement (dirigisme) and diverse industrial sectors. For approximately two centuries, the French economy has consistently ranked among the ten largest globally. It is currently the world's ninth-largest by purchasing power parity (PPP) and the seventh-largest by nominal GDP, making it the second-largest economy in the European Union by both metrics. France is a member of the Group of Seven (G7) leading industrialized countries, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the G20 major economies.

France's economy is highly diversified. The service sector dominates, representing about two-thirds of both the workforce and GDP. Key service industries include finance, insurance, retail, and business services. The industrial sector accounts for approximately one-fifth of GDP and a similar proportion of employment. France is the third-largest manufacturing country in Europe (behind Germany and Italy) and ranks eighth globally by manufacturing output (1.9% of the world total). Key industrial sectors include:

- Aerospace: France is a global leader, with companies like Airbus (a European consortium with a strong French component) and Dassault Aviation.

- Automotive: Home to major manufacturers such as Renault, Stellantis (owner of Peugeot and Citroën).

- Luxury Goods: World-renowned for brands in fashion, cosmetics, and perfumes, with Paris as a global center. Companies like LVMH, Kering, and L'Oréal are dominant.

- Pharmaceuticals: A significant research and production base with companies like Sanofi.

- Technology: Growing strengths in software, digital services, and high-tech manufacturing.

The primary sector (agriculture) generates less than 2% of GDP, yet France's agricultural sector is among the largest in value globally and leads the EU in overall production. It is often nicknamed "the granary of the old continent." Over half of its total land area is farmland.

Labor rights are strongly protected, and social partnership models, involving dialogue between government, employers, and trade unions, are a feature of its economic governance, though reforms to increase labor market flexibility have been a subject of ongoing debate and social protest.

In 2018, France was the fifth-largest trading nation globally and the second-largest in Europe, with exports representing over a fifth of its GDP. Its membership in the Eurozone and the broader European single market facilitates access to capital, goods, services, and skilled labor. Despite historical protectionist tendencies in certain sectors, particularly agriculture, France has generally supported free trade and commercial integration within Europe. In 2019, it ranked first in Europe and 13th worldwide for Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), with European countries and the United States as leading sources. Key sectors for FDI include manufacturing, real estate, finance, and insurance. The Île-de-France (Paris Region) has the highest concentration of multinational firms in mainland Europe.

Historically, under the doctrine of Dirigisme, the French government played a major role in the economy through indicative planning and nationalization, which contributed to the Trente Glorieuses (Thirty Glorious Years) of post-war economic growth. At its peak in 1982, the public sector accounted for a fifth of industrial employment. Since the late 20th century, France has significantly loosened regulations and state involvement, privatizing most leading companies. State ownership now primarily dominates transportation (e.g., SNCF), defense, and broadcasting. Policies promoting economic dynamism and privatization have improved France's global economic standing. It ranked among the world's 10 most innovative countries in the 2020 Bloomberg Innovation Index and 15th most competitive in the 2019 Global Competitiveness Report.

The Paris stock exchange (La Bourse de ParisThe Paris Stock ExchangeFrench), established in 1724, merged with counterparts in Amsterdam and Brussels in 2000 to form Euronext, which later merged with the New York Stock Exchange to form NYSE Euronext (now part of Intercontinental Exchange). Euronext Paris remains Europe's second-largest stock exchange market.

6.2. Tourism

France is consistently the world's leading tourist destination, having received 100 million foreign visitors in 2023. This figure typically includes business travelers but excludes people staying for less than 24 hours. While it leads in arrivals, France ranks third globally in tourism-derived income, partly due to shorter average visit durations compared to some other top destinations. Tourism is a vital sector of the French economy, contributing significantly to GDP and employment, and has a profound social impact, fostering cultural exchange.

Major attractions draw millions of visitors annually. Some of the most popular sites include:

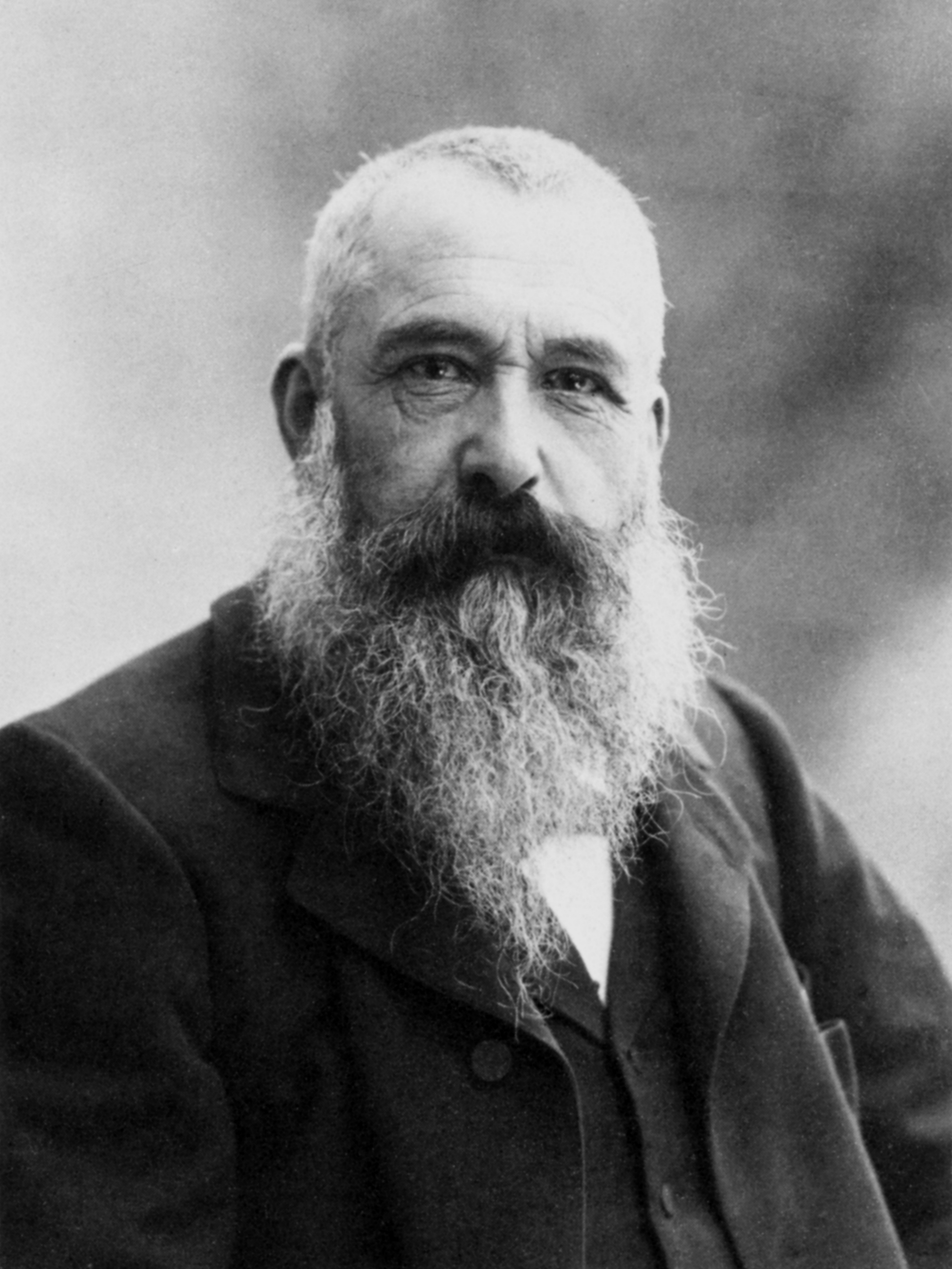

- In Paris: The Eiffel Tower (6.2 million visitors), the Louvre (the world's most visited art museum, 7.7 million in 2022), the Musée d'Orsay (3.3 million, focusing on Impressionism), the Musée de l'Orangerie (1.02 million, home to Monet's Water Lilies), the Centre Pompidou (3 million, dedicated to contemporary art), the Arc de Triomphe (1.2 million), and Sainte-Chapelle (683,000).

- Disneyland Paris is Europe's most popular theme park, with 15 million combined visitors to its Disneyland Park and Walt Disney Studios Park in 2009.

- Outside Paris: The Palace of Versailles (2.8 million visitors), Mont Saint-Michel in Normandy (1 million visitors), the Pont du Gard (Roman aqueduct, 1.5 million), the historic fortified city of Carcassonne (362,000), Château du Haut-Kœnigsbourg in Alsace (549,000), and the volcanic peak of Puy de Dôme (500,000).

- The French Riviera (Côte d'AzurAzure CoastFrench) in southeastern France is the second leading tourist destination after the Paris region, attracting over 10 million tourists annually with its beaches, resorts, and cities like Nice and Cannes.

- The castles of the Loire Valley (châteaux de la Loirecastles of the LoireFrench) and the Loire Valley itself are the third leading tourist destination, drawing 6 million visitors a year to iconic sites like Château de Chambord and Château de Chenonceau.

France has 52 sites inscribed on UNESCO's World Heritage List. Beyond major landmarks, France offers cities of high cultural interest, beaches and seaside resorts, ski resorts in the Alps and Pyrenees, and rural regions renowned for their beauty and tranquility, popular for ecotourism (green tourism). Picturesque French villages are promoted through associations like Les Plus Beaux Villages de France (The Most Beautiful Villages of France). The "Remarkable Gardens" label lists over 200 gardens classified by the Ministry of Culture. France also attracts many religious pilgrims, particularly to Lourdes in the Hautes-Pyrénées, which hosts several million visitors each year, and those following the Way of St. James (Camino de Santiago). The economic benefits of tourism are widespread, but managing its environmental and social impacts, such as overcrowding and strain on local resources, remains an ongoing challenge.

6.3. Energy

France is the world's tenth-largest producer of electricity. Électricité de France (EDF), majority-owned by the French government, is the country's main electricity producer and distributor and one of the world's largest electric utility companies. In 2018, EDF produced approximately one-fifth of the European Union's electricity, primarily from nuclear power.

Since the 1973 oil crisis, France has pursued a strong policy of energy security, heavily investing in nuclear energy. It is one of 32 countries with nuclear power plants and ranks second globally by the number of operational nuclear reactors (56 reactors). Consequently, about 70% of France's electricity is generated by nuclear power, the highest proportion in the world by a significant margin. Only Slovakia and Ukraine also derive a majority of their electricity from nuclear power (around 53% and 51%, respectively). France is considered a world leader in nuclear technology, with reactors and fuel products being major exports. This reliance on nuclear power significantly reduces France's carbon emissions from electricity generation compared to countries dependent on fossil fuels. However, it also raises environmental and safety concerns regarding nuclear waste disposal and the aging of its reactor fleet.

France's significant reliance on nuclear power has led to a comparatively slower adoption of renewable energy sources relative to other Western nations. Nevertheless, between 2008 and 2019, France's renewable energy production capacity rose consistently, nearly doubling. Hydropower is the leading renewable source, accounting for over half of the country's renewable energy and contributing 13% of its total electricity production, the highest proportion in Europe after Norway and Turkey. Most hydroelectric plants, such as Eguzon dam, Étang de Soulcem, and Lac de Vouglans, are managed by EDF. France aims to further expand hydropower capacity into 2040. Other renewable sources like wind and solar power are also being developed, though their contribution to the overall energy mix is still smaller. Energy policy in France continues to balance energy security, economic competitiveness, and environmental commitments, including meeting EU targets for renewable energy and emissions reductions.

6.4. Transport

France boasts a well-developed and extensive transport infrastructure, crucial for its economy and European connectivity. This includes high-speed rail, dense road networks, major airports, and significant maritime and inland waterways. Policies are increasingly focused on promoting sustainable transport.

The French railway network, stretching 29.47 K 0 as of 2008, is the second most extensive in Western Europe, after Germany's. It is primarily operated by the state-owned SNCF (Société Nationale des Chemins de fer Français). France is renowned for its high-speed rail service, the TGV (Train à Grande Vitesse), which travels at speeds up to 320 0 in commercial service. The TGV network connects major French cities and extends to neighboring countries. International high-speed services include the Thalys (to Belgium, Netherlands, Germany) and the Eurostar, which connects France with the United Kingdom via the Channel Tunnel. The Eurotunnel Shuttle also provides vehicle transport through the tunnel. Rail connections exist to all other neighboring European countries except Andorra. Intra-urban rail transport is also well-developed, with most major cities having underground metro systems (e.g., Paris, Lyon, Lille, Marseille) or tramway services, complementing extensive bus networks.

France has approximately 1.03 M 0 of serviceable roadway, making it the most extensive road network on the European continent. The Paris region is enveloped by the densest network of roads and highways (autoroutes), connecting it with virtually all parts of the country. French roads also handle substantial international traffic. There is no annual registration fee or road tax for vehicles; however, usage of the largely privately-owned motorways is typically through tolls, except in the vicinity of large urban areas. The new car market is dominated by domestic brands such as Renault, Peugeot, and Citroën. France is home to engineering marvels like the Millau Viaduct, the world's tallest bridge, and other important structures like the Pont de Normandie. Air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from diesel and petrol-driven vehicles remain significant environmental concerns, prompting efforts towards more sustainable road transport.

There are 464 airports in France. Charles de Gaulle Airport (CDG) near Paris is the largest and busiest airport in the country, handling the vast majority of passenger and commercial air traffic and connecting Paris with major cities worldwide. Air France is the national carrier, though numerous private airline companies also provide domestic and international services.

France has ten major ports. The largest is the Port of Marseille on the Mediterranean, which is also the largest port bordering the Mediterranean Sea. Other significant ports include Le Havre, Dunkirk, and Nantes-Saint Nazaire. Approximately 12.26 K 0 of inland waterways traverse France, including historic canals like the Canal du Midi, which connects the Mediterranean Sea to the Atlantic Ocean via the Garonne River. These waterways are used for both commercial freight and leisure boating.

6.5. Science and Technology

France has a long and distinguished history of contributions to scientific and technological advancement, dating back to the Middle Ages. In the early 11th century, the French-born Pope Sylvester II reintroduced the abacus and armillary sphere and introduced Arabic numerals and clocks to much of Europe. The University of Paris, founded in the mid-12th century, remains one of the most important academic institutions in the Western world.

In the 17th century, mathematician and philosopher René Descartes pioneered rationalism as a method for acquiring scientific knowledge, while Blaise Pascal made significant contributions to probability and fluid mechanics. Both were key figures in the Scientific Revolution. The French Academy of Sciences, founded in the mid-17th century by Louis XIV, was one of the earliest national scientific institutions, established to encourage and protect French scientific research.

The Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century saw groundbreaking work by French scientists. Biologist Buffon was one of the first naturalists to recognize ecological succession, and chemist Antoine Lavoisier discovered the role of oxygen in combustion. Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert published the Encyclopédie, a monumental work aiming to disseminate "useful knowledge" to the public.

The Industrial Revolution of the 19th century spurred further scientific developments in France. Augustin Fresnel founded modern optics, Sadi Carnot laid the foundations of thermodynamics, and Louis Pasteur pioneered microbiology and developed pasteurization and vaccines. Other eminent French scientists of this period have their names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

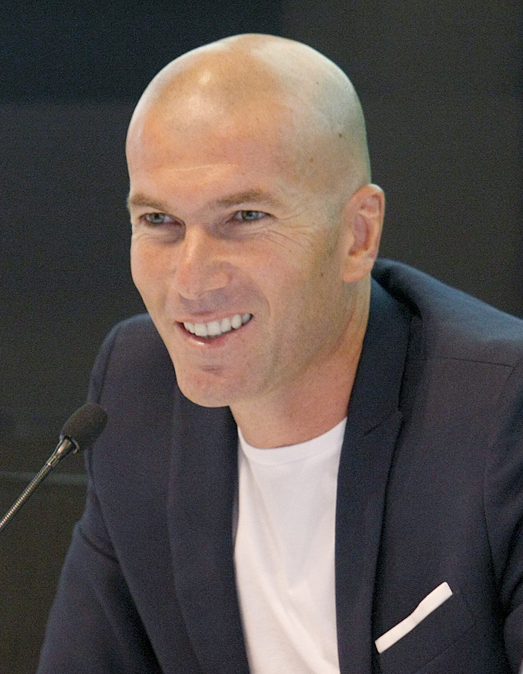

Famous French scientists of the 20th century include mathematician and physicist Henri Poincaré; physicists Henri Becquerel, Pierre Curie, and Marie Curie (renowned for their work on radioactivity); physicist Paul Langevin; and virologist Luc Montagnier, co-discoverer of HIV. France has also been at the forefront of medical innovations. The first hand transplantation was developed in Lyon in 1998 by an international team including Jean-Michel Dubernard, who later performed the first successful double hand transplant. Telesurgery (the Lindbergh operation) was first performed by French surgeons led by Jacques Marescaux in 2001, operating across the Atlantic Ocean. The first face transplant was performed on November 27, 2005, by Bernard Devauchelle.