1. Overview

Lesotho, formally the Kingdom of Lesotho, is a landlocked country and enclave entirely surrounded by South Africa. It is situated in the Maloti Mountains and is the only independent state in the world that lies entirely above 3.3 K ft (1.00 K m) in elevation, earning it the nickname "The Mountain Kingdom" or "The Kingdom in the Sky". Its capital and largest city is Maseru. The country's geography is characterized by mountainous terrain, a temperate climate influenced by altitude, and significant water resources, notably the Orange River. Historically, the Basotho nation was formed under King Moshoeshoe I in the early 19th century, navigating conflicts and eventually becoming the British protectorate of Basutoland before gaining independence in 1966. Lesotho's political system is a parliamentary constitutional monarchy, with a history marked by periods of political instability and military intervention, though it has made strides towards democratic consolidation. The economy relies on agriculture, livestock, manufacturing (particularly textiles), mining (diamonds), and remittances from migrant workers in South Africa, as well as revenue from the Lesotho Highlands Water Project. Socially, Lesotho faces challenges including high rates of HIV/AIDS and poverty, yet it boasts one of the highest literacy rates in Africa, with notable achievements in primary education. The population is predominantly ethnically Basotho, with Sesotho and English as official languages. Culturally, Lesotho is known for its traditional attire like the Basotho blanket and Mokorotlo hat, unique cuisine, and vibrant music and dance traditions. This article explores these facets of Lesotho, emphasizing social justice, human rights, democratic development, and the well-being of vulnerable groups, reflecting a center-left/social liberalism perspective.

2. History

The history of Lesotho spans from the early settlements of San and Sotho-Tswana peoples to the formation of the Basotho nation under King Moshoeshoe I, colonial rule as Basutoland, and its journey to independence and subsequent development as a modern nation-state, marked by both progress and periods of political challenge.

2.1. Early History and Formation of Basotho Nation

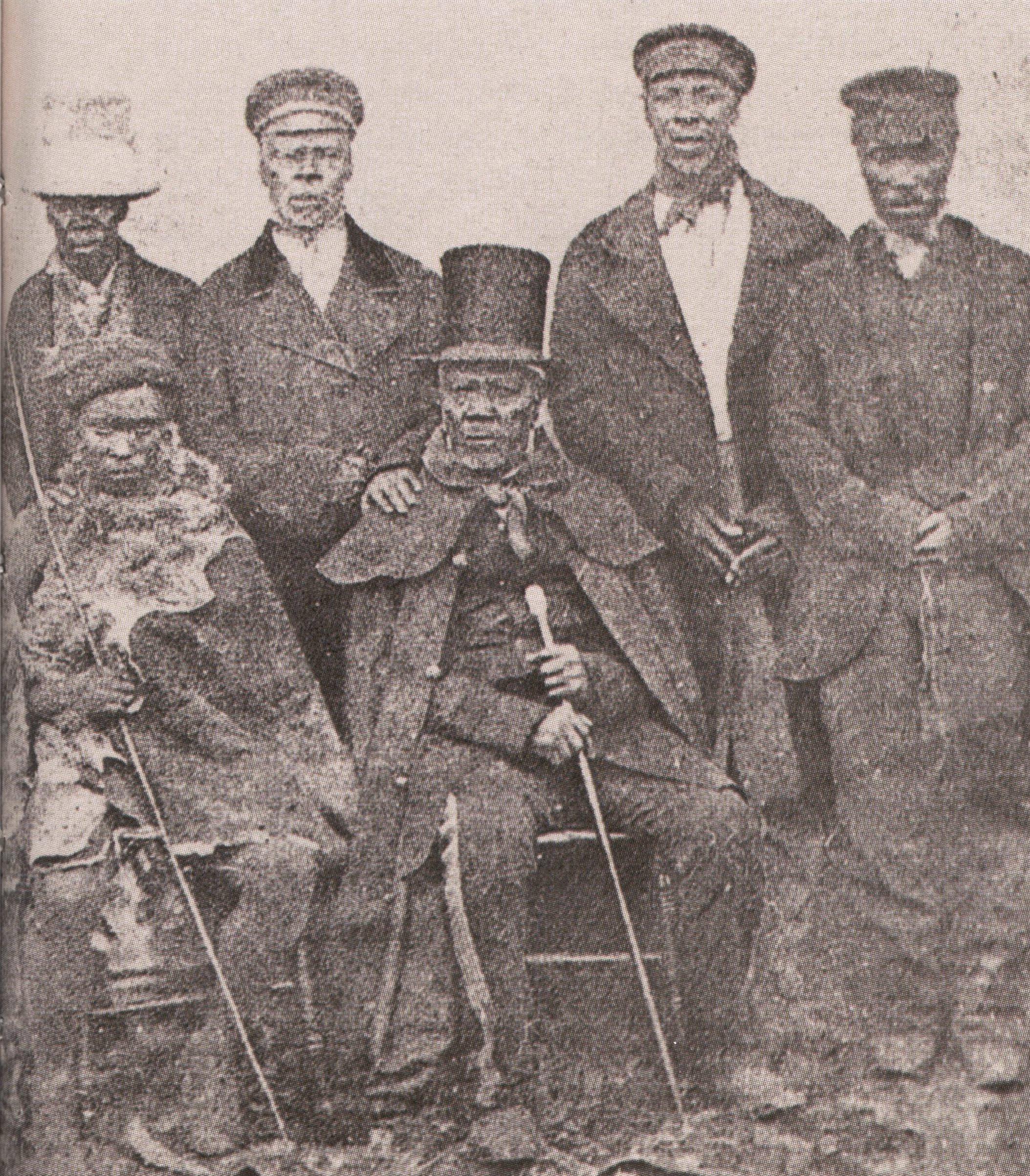

The earliest inhabitants of the area now known as Lesotho were the San people (Bushmen). In the 16th century, Bantu-speaking Sotho people migrated from the north, displacing the San and establishing dominance in the region. The modern Basotho nation emerged in the early 19th century under the leadership of King Moshoeshoe I. Born around 1786, Moshoeshoe, a son of Mokhachane, a minor chief of the Bakoteli lineage, formed his own clan and became a chief around 1804. The period between 1820 and 1823 was marked by the Mfecane (Difaqane or "great scattering"), a time of widespread warfare and disruption in Southern Africa, largely associated with the expansion of the Zulu Kingdom under Shaka Zulu (reigned 1818-1828). During this tumultuous period, Moshoeshoe I demonstrated remarkable diplomatic and military skill. He and his followers initially settled at Butha-Buthe Mountain. He successfully unified various Basotho clans and other refugee groups fleeing the Mfecane, offering them protection and incorporating them into his growing kingdom. He strategically fortified the Thaba Bosiu mountain stronghold, which proved impregnable to his enemies, including the Ngwane and Ndebele people.

As Boer Voortrekkers began to move into the interior from the Cape Colony in the 1830s, conflicts over land arose. Jan de Winnaar was the first Boer to settle in the Matlakeng area in 1838. Incoming Boers attempted to colonise the land between the Orange River and the Caledon River, and north of the Caledon, claiming it had been abandoned by the Sotho people. To counter the Boer encroachment and maintain the integrity of his kingdom, Moshoeshoe I sought alliances and engaged with European missionaries. In 1833, he invited missionaries from the Paris Evangelical Missionary Society, including Thomas Arbousset, Eugène Casalis, and Constant Gosselin. They established a mission at Morija, developing a Sesotho orthography and publishing works in the Sesotho language between 1837 and 1855. Casalis served as Moshoeshoe's translator and advisor on foreign affairs, helping to establish diplomatic channels and acquire firearms. Moshoeshoe signed a treaty with the British Governor of the Cape Colony, Sir George Thomas Napier, which annexed the Orange River Sovereignty where Boers had settled. Outraged Boers were suppressed in a skirmish in 1848. In 1851, a British force was defeated by the Basotho army at Kolonyama. After repelling another British attack in 1852, Moshoeshoe sent an appeal to the British commander that settled the dispute diplomatically. He then defeated the Batlokoa in 1853.

2.2. Basutoland Protectorate and Colonial Rule

In 1854, the British withdrew from the Orange River Sovereignty, which then became the Orange Free State, an independent Boer republic. This led to increased pressure on Basotho lands. From 1858, Moshoeshoe I fought a series of wars with the Boers of the Orange Free State, known as the Free State-Basotho Wars. These wars resulted in significant territorial losses for the Basotho, particularly in the fertile western lowlands. Facing overwhelming Boer military power, Moshoeshoe I appealed to Queen Victoria for protection. In 1868, Basutoland, as it came to be known, was declared a British protectorate. The following year, in 1869, the British signed the Treaty of Aliwal North with the Boers, which formally defined the boundaries of Basutoland. This treaty significantly reduced Moshoeshoe's kingdom to about half its previous size, ceding much of the western arable land to the Orange Free State, leaving the Basotho with predominantly mountainous territory.

King Moshoeshoe I died on 11 March 1870, marking the end of an era and the beginning of direct colonial administration. In 1871, the administration of Basutoland was transferred from Moshoeshoe's capital at Thaba Bosiu to a police camp on the northwest border, Maseru, and then annexed to the Cape Colony. This annexation was met with resistance from the Basotho, who felt humiliated as they were treated similarly to other forcibly annexed territories. The Cape Colony government's attempt to disarm the Basotho led to the Basuto Gun War (1880-1881). The Basotho successfully resisted disarmament, leading the British government to separate Basutoland from the Cape Colony in 1884. The territory then became a Crown colony, with Maseru as its capital. It remained under direct rule by a British governor, although effective internal power was often wielded by traditional chiefs. In 1903, a National Council was established. In 1905, a railway line was built connecting Maseru to the South African railway network, facilitating labor migration and trade. During the colonial period, nationalist movements began to emerge, advocating for greater self-governance and eventual independence. Political parties such as the Basutoland National Party (BNP) and the Basutoland Congress Party (BCP) were formed, playing crucial roles in the path towards independence. In 1960, Basutoland was granted self-government.

2.3. Path to Independence and Post-Colonial Era

Basutoland gained its independence from the United Kingdom on 4 October 1966, and was renamed the Kingdom of Lesotho. King Moshoeshoe II became the head of state under a constitutional monarchy, and Chief Leabua Jonathan of the Basotho National Party (BNP) became the first Prime Minister, following the BNP's victory in the 1965 pre-independence elections.

The early post-colonial era was marked by political instability. In January 1970, the ruling BNP lost the first post-independence general elections to the Basutoland Congress Party (BCP). However, Prime Minister Jonathan refused to cede power, suspended the constitution, declared a state of emergency, and imprisoned the BCP leadership, establishing a de facto one-party state. This led to a period of authoritarian rule and suppression of dissent. The BCP launched an insurgency, with its armed wing, the Lesotho Liberation Army (LLA), receiving training in Libya. The LLA launched sporadic guerrilla attacks throughout the 1970s and early 1980s. Jonathan's government, initially pro-South Africa, shifted towards a more critical stance against apartheid, leading to strained relations with its powerful neighbor and economic sanctions. Some Basotho who sympathised with the exiled BCP were threatened with death and attacked by Jonathan's government. On 4 September 1981, the family of Benjamin Masilo was attacked, resulting in the death of his 3-year-old grandson. Four days later, Edgar Mahlomola Motuba, editor of the newspaper Leselinyana la Lesotho, was abducted and murdered along with two friends.

In January 1986, Jonathan's government was overthrown in a military coup led by Major General Justin Metsing Lekhanya. The Transitional Military Council granted executive powers to King Moshoeshoe II, who had previously been a ceremonial monarch. However, disagreements arose between Lekhanya and the King. In 1987, King Moshoeshoe II was forced into exile after proposing constitutional changes that would have given him more executive power. His son, Letsie III, was installed as King in his place. In 1990, King Moshoeshoe II was again exiled.

In 1991, Lekhanya himself was ousted in another military coup led by Major General Elias Phisoana Ramaema. Ramaema's government facilitated a return to democratic rule. Multi-party elections were held in 1993, which the BCP won by a landslide, and Ntsu Mokhehle became Prime Minister. King Moshoeshoe II returned from exile in 1992 as an ordinary citizen. King Letsie III attempted to persuade the BCP government to reinstate his father as head of state. In August 1994, frustrated by the government's refusal, Letsie III staged a military-backed coup, deposing the BCP government. Negotiations led by member states of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) resulted in the BCP government's reinstatement. One condition for this was the re-installation of Moshoeshoe II as head of state. Letsie III abdicated in favor of his father in 1995. Tragically, King Moshoeshoe II died in a car accident on 15 January 1996. Letsie III re-ascended to the throne in February 1997.

In 1997, Prime Minister Ntsu Mokhehle, facing leadership disputes within the BCP, formed a new party, the Lesotho Congress for Democracy (LCD), taking a majority of parliamentarians with him and forming a new government. Pakalitha Mosisili succeeded Mokhehle as party leader and LCD won the 1998 general elections. However, opposition parties disputed the results, leading to widespread protests and civil unrest. The situation escalated, and a demonstration outside the royal palace in August 1998 turned violent. In September 1998, at the request of Prime Minister Mosisili, SADC forces, primarily from South Africa and Botswana, intervened to restore order. While Botswana Defence Force troops were welcomed, tensions with South African National Defence Force troops resulted in fighting. Incidences of rioting intensified when South African troops hoisted a South African flag over the Royal Palace. By the time SADC forces withdrew in May 1999, parts of Maseru and other towns like Mafeteng and Mohale's Hoek had suffered significant damage.

An Interim Political Authority (IPA) was established in December 1998 to review the electoral system. It devised a mixed-member proportional representation system, retaining 80 constituency seats and adding 40 seats to be filled on a proportional basis. Elections under this new system were held in May 2002, and the LCD won again, gaining 54% of the vote and 79 of the 80 constituency seats. Nine opposition parties shared the 40 proportional seats, with the BNP taking the largest share (21).

Political tensions continued. In 2012, Thomas Thabane of the All Basotho Convention (ABC) became Prime Minister, leading a coalition government. On 30 August 2014, an alleged military coup attempt forced Prime Minister Thabane to flee to South Africa for three days. SADC mediation helped to resolve the crisis. Following elections in 2015, Pakalitha Mosisili returned as Prime Minister. In 2017, Thabane again became Prime Minister. On 19 May 2020, Thomas Thabane formally stepped down as prime minister following months of pressure after he was named as a suspect in the 2017 murder of his estranged ex-wife. Moeketsi Majoro, an economist and former Minister of Development Planning, was elected as Thabane's successor. On 28 October 2022, Sam Matekane was sworn in as Lesotho's new Prime Minister after his Revolution for Prosperity (RFP) party, formed earlier that year, won the general elections on 7 October 2022, forming a new coalition government. The ongoing process of democratic consolidation continues to face challenges, including the need for constitutional and security sector reforms to ensure long-term stability and good governance, addressing issues of poverty, inequality, and human rights.

3. Geography

Lesotho is a landlocked country located in Southern Africa, entirely surrounded by the Republic of South Africa. It is notable for its high altitude and mountainous terrain.

3.1. Topography and Landforms

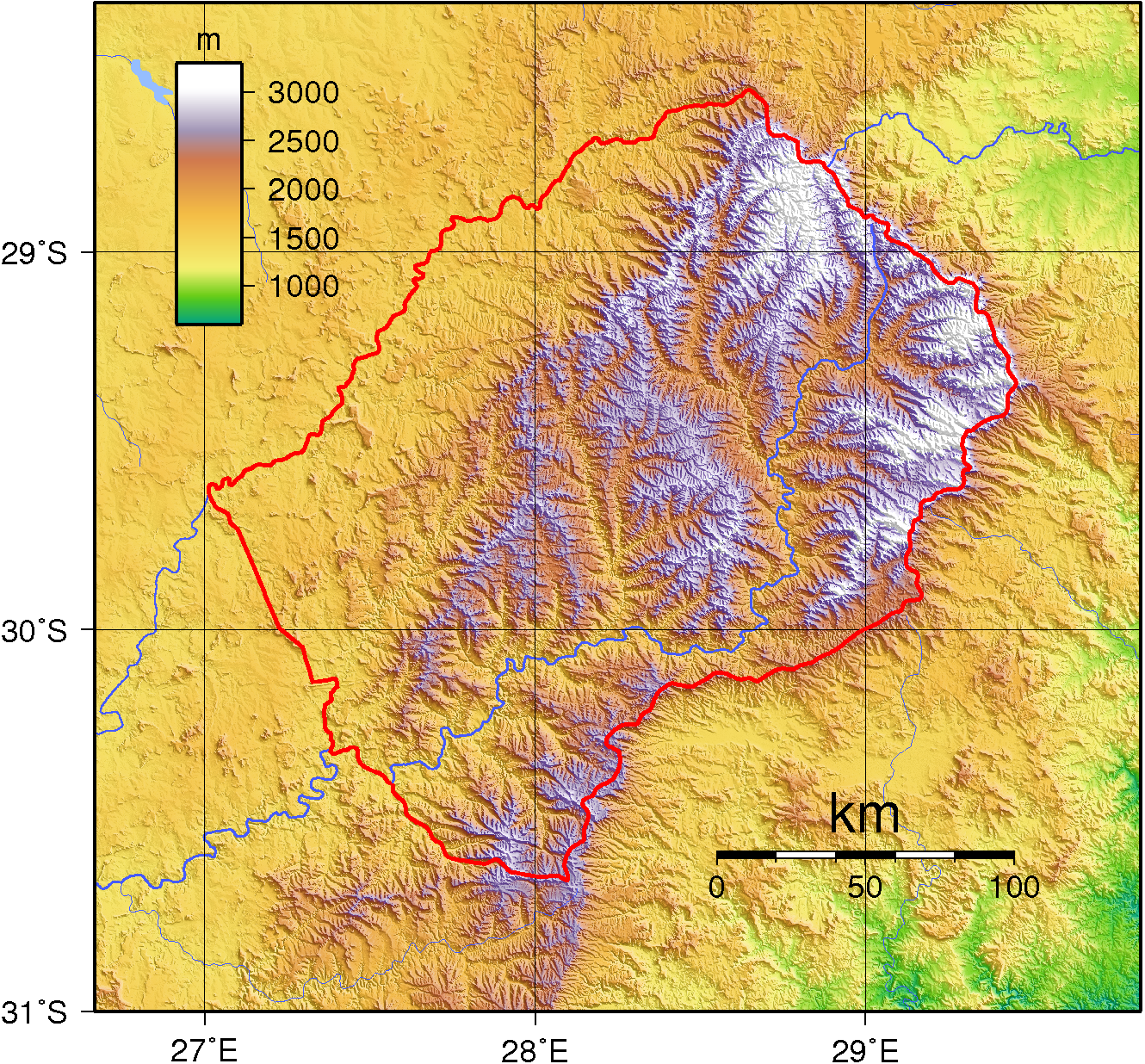

Lesotho covers an area of 12 K mile2 (30.36 K km2). It is the only independent state in the world that lies entirely above 3.3 K ft (1.00 K m) in elevation. Its lowest point, at 4.6 K ft (1.40 K m), is the highest lowest point of any country in the world. Over 80% of the country lies above 5.9 K ft (1.80 K m). Lesotho is characterized by its rugged, mountainous terrain, primarily consisting of the Maloti Mountains, which are part of the greater Drakensberg Range. The highest peak in Southern Africa, Thabana Ntlenyana, at 11 K ft (3.48 K m), is located in eastern Lesotho. The landscape features dramatic escarpments, deep river valleys, and rolling highlands. Major river systems originate in these mountains, including the Orange River (known as Senqu in Lesotho), which flows westward across Southern Africa to the Atlantic Ocean, and its main tributary, the Caledon River (Mohokare), which forms much of Lesotho's western border with South Africa. The western lowlands, along the Caledon River, are the most densely populated and agriculturally productive region, though still relatively high in elevation. About 12% of Lesotho is arable land, which is vulnerable to soil erosion; it is estimated that 40 million tons of soil are lost each year due to erosion.

3.2. Climate

Lesotho has a temperate climate, significantly influenced by its high altitude. The country experiences distinct seasons. Summers (October to April) are warm to hot, with most rainfall occurring during this period in the form of thunderstorms. Maseru and the surrounding lowlands can reach temperatures of 86 °F (30 °C) in summer. Winters (May to September) are cool to cold, particularly in the highlands where temperatures can drop significantly. The lowlands can experience temperatures as low as 19.4 °F (-7 °C), while the highlands can reach -0.3999999999999986 °F (-18 °C) at times. Snowfall is common in the highlands between May and September, and the highest peaks may experience snow year-round. Rainfall is variable, both in terms of timing and location. Annual precipitation can range from approximately 20 in (500 mm) in some areas to 0.0 K in (1.20 K mm) in others, largely due to elevation differences. The majority of the country receives over 3.9 in (100 mm) of rain per month from December to February, while June typically sees the least rainfall, with most regions receiving less than 0.6 in (15 mm).

3.3. Natural Hazards

The most significant natural hazard affecting Lesotho is periodic drought. These droughts have a severe impact on the country's predominantly rural population, many of whom rely on subsistence agriculture or small-scale farming for their livelihood. Droughts affect agricultural output, leading to food insecurity, and strain water resources. These conditions are often exacerbated by certain agricultural practices and the effects of climate change. In 2007, Lesotho experienced a severe drought, prompting the United Nations to advise the government to declare a state of emergency to facilitate international aid. The rainy season of 2018/2019 started late and recorded below-average rainfall, with precipitation between October 2018 and February 2019 ranging from 55% to 80% below normal rates. This led to predictions that hundreds of thousands of people would require humanitarian assistance due to food insecurity. Droughts also contribute to issues such as lack of clean water, leading to hygiene-related diseases like typhoid fever and diarrhea. Women and girls, often responsible for water collection, face increased risks as they travel longer distances. Drought conditions can also lead to migration to urban areas and emigration to South Africa.

3.4. Wildlife and Biodiversity

Lesotho's flora is predominantly alpine, a consequence of its mountainous terrain. The country is home to several endemic plant species, including the iconic spiral aloe (Aloe polyphylla). The Katse Botanical Gardens houses a collection of medicinal plants and maintains a seed bank of plants from the Malibamat'so River area. Three terrestrial ecoregions lie within Lesotho's boundaries: Drakensberg alti-montane grasslands and woodlands, Drakensberg montane grasslands, and Highveld grasslands. Most of the country is covered by grasslands, with limited forest cover.

In terms of fauna, Lesotho is known to have 339 bird species, including 10 globally threatened species and two introduced species. There are 17 reptile species, including geckos, snakes, and lizards. Some 60 mammal species are endemic to Lesotho, including the endangered white-tailed rat. Conservation efforts are underway to protect this biodiversity. Sehlabathebe National Park, located in the southeastern part of the country, is Lesotho's first national park and forms part of the Maloti-Drakensberg Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site recognized for its exceptional natural beauty and rich biodiversity, including unique alpine and sub-alpine ecosystems, and important San rock art sites.

4. Politics and Government

Lesotho operates as a parliamentary constitutional monarchy, with a political system that has evolved through periods of transition and reform. The government structure is based on a separation of powers, though the monarchy's role is largely ceremonial.

4.1. Government Structure

The King of Lesotho, currently Letsie III, is the head of state. The King's functions are primarily ceremonial, and he does not possess executive authority nor is he permitted to actively participate in political initiatives. Executive power is vested in the Prime Minister, who is the head of government, and the Cabinet. The Prime Minister is appointed by the King and is typically the leader of the political party or coalition of parties that commands a majority in the National Assembly. The current Prime Minister is Sam Matekane.

4.2. Legislature

The Parliament of Lesotho is bicameral, consisting of the Senate (Upper House) and the National Assembly (Lower House).

The Senate is composed of 33 members. Twenty-two of these are Principal Chiefs, whose membership is hereditary, reflecting the traditional leadership structure. The remaining 11 Senators are nominated by the King on the advice of the Prime Minister. The Senate's primary role is to review legislation passed by the National Assembly.

The National Assembly is the main legislative body. It currently has 120 members. Eighty members are elected from single-member constituencies using the first-past-the-post system. The remaining 40 seats are allocated on a proportional representation basis to ensure broader representation of political parties that contested the election. Members of the National Assembly serve a five-year term, unless Parliament is dissolved earlier. The National Assembly is responsible for passing laws, approving the national budget, and holding the government accountable.

4.3. Judiciary and Legal System

The Constitution of Lesotho provides for an independent judicial system. The judiciary is structured with several tiers. The highest courts are the Court of Appeal and the High Court. The Court of Appeal is the final appellate court on all matters and has supervisory and review jurisdiction over all other courts. Most of the Justices on the Court of Appeal are South African jurists. The High Court has unlimited original jurisdiction to hear and determine any civil or criminal proceedings under any law. Below these are Magistrate's Courts, which handle a majority of civil and criminal cases at a local level. Additionally, traditional courts (Local Courts) exist, predominantly in rural areas, and primarily apply customary law in resolving disputes.

Lesotho has a dual legal system, combining Roman-Dutch common law, inherited from the Cape Colony and influenced by English law, with customary law. Customary law, primarily the Laws of Lerotholi, governs personal matters and traditional issues. Roman-Dutch law, as modified by Lesotho statutes and judicial precedent, forms the general law of the land. Decisions from South African courts are persuasive but not binding. There is no trial by jury; judges make rulings alone, or in criminal trials, with two other judges as assessors.

4.4. Political Parties and Elections

Lesotho has a multi-party democratic system, though it has experienced periods of political instability and coalition governments. Major political parties include the Revolution for Prosperity (RFP), which currently leads the coalition government, the Democratic Congress (DC), the All Basotho Convention (ABC), the Basotho National Party (BNP), and the Lesotho Congress for Democracy (LCD), among others. These parties represent a range of ideologies and contest seats in the National Assembly during general elections, typically held every five years. The Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) is responsible for organizing and overseeing elections. Coalition governments have become common due to the proportional representation component of the electoral system, which often prevents a single party from winning an outright majority. This has sometimes led to challenges in maintaining stable governments.

4.5. Human Rights

The Constitution of Lesotho guarantees fundamental human rights and civil liberties, including freedom of speech, freedom of association, freedom of the press, freedom of peaceful assembly, and freedom of religion. Lesotho was ranked 12th out of 48 sub-Saharan African countries in the 2008 Ibrahim Index of African Governance. However, the practical enjoyment of these rights has faced challenges, particularly during periods of political tension. Key human rights concerns include police brutality, conditions in detention centers, and issues related to the functioning of the justice system. There are ongoing efforts to strengthen democratic institutions and improve human rights protections. The country has also faced calls for reforms to address corruption and ensure greater accountability.

In 2010, the People's Charter Movement called for the practical annexation of the country by South Africa due to the HIV epidemic. Nearly a quarter of the population tests positive for HIV. The country faced economic collapse, a weaker currency, and travel documents restricting movement. An African Union report called for economic integration of Lesotho with South Africa but stopped short of suggesting annexation. In May 2010, the Charter Movement delivered a petition to the South African High Commission requesting integration. South Africa's home affairs spokesman Ronnie Mamoepa rejected the idea that Lesotho should be treated as a special case. At the peak of the AIDS epidemic, over 30,000 Lesotho residents signed a petition for the country to be annexed to prevent life expectancy from falling to 34 years old.

Scholars like Jeffrey Herbst argue that the lack of border disputes for countries like Lesotho has kept them politically weak, a weakness stemming from colonial remnants in the government, influenced by English and Roman-Dutch common law. This system was not designed to serve the Basotho people but rather to be exploitative. After Prime Minister Tom Thabane resigned in 2020 amid impeachment threats and an arrest warrant related to his wife's murder, the South African finance minister suggested a confederation between Lesotho, Eswatini, and South Africa. His successor, Moeketsi Majoro, resigned in 2022 after a vote of "no-confidence" for misconduct with the military and improper handling of COVID-19. While current Prime Minister Sam Matekane is working with SADC towards legal reform, his administration has faced accusations of corruption, highlighted when 40,000 garment workers protesting for better conditions faced excessive force, resulting in two deaths.

4.5.1. Violence Against Women

Violence against women remains a significant human rights challenge in Lesotho. This includes domestic violence, sexual assault, and other forms of gender-based violence. According to a UN report, Lesotho had the highest reported rape rate of any country in 2008 (91.6 per 100,000 people). A study in Lesotho found that 61% of women reported having experienced sexual violence at some point in their lives, with 22% reporting being physically forced to have sexual intercourse. The 2009 Demographic and Health Survey indicated that 15.7% of men believed a husband is justified in hitting his wife if she refuses sex, and 16% believed a husband is justified in using force for sex. Societal norms, economic disparities, and weaknesses in the justice system contribute to the prevalence of such violence. The high prevalence of HIV/AIDS further exacerbates the vulnerability of women and girls. While legal frameworks like the Married Persons Equality Act 2006 (which abolished the husband's marital power) exist to protect women, implementation and enforcement remain key challenges. The World Economic Forum's 2020 Gender Gap Report ranked Lesotho 88th worldwide for gender parity. Efforts by government and civil society organizations are ongoing to combat violence against women, provide support to victims, raise awareness, and promote gender equality. These initiatives focus on legal reforms, strengthening law enforcement and judicial responses, providing psycho-social support, and challenging harmful cultural practices.

5. Administrative Divisions

Lesotho's administrative structure is organized into districts, which serve as the primary units for local governance and administration. These districts are further subdivided for more localized management.

5.1. Districts

For administrative purposes, Lesotho is divided into ten districts. Each district is headed by a District Administrator and has a capital town, known as a camptown. The ten districts are:

- Berea

- Butha-Buthe

- Leribe

- Mafeteng

- Maseru

- Mohale's Hoek

- Mokhotlong

- Qacha's Nek

- Quthing

- Thaba-Tseka

These districts are responsible for implementing government policies at the local level, coordinating development projects, and delivering various public services. The districts are further subdivided into 80 constituencies for electoral purposes, which in turn consist of 129 local community councils. These councils play a role in local development planning and governance.

5.2. Major Cities and Urban Centers

The capital city of Lesotho is Maseru, located in the Maseru District on the Caledon River, which forms the border with South Africa. Maseru is the largest urban center in the country and serves as its political, economic, and cultural hub. It is home to government ministries, the royal palace, parliamentary buildings, major businesses, and the National University of Lesotho's main campus is nearby in Roma. According to 2022 estimates, the population of Maseru District, which includes the city and surrounding areas, is approximately 519,186.

Other significant urban centers, though considerably smaller than Maseru, include:

- Teyateyaneng (often abbreviated as TY) in the Berea District, known for its crafts and as an administrative center. Population estimate: 75,115.

- Mafeteng in the Mafeteng District, an important commercial and administrative town in the southwest. Population estimate: 57,059.

- Hlotse (also known as Leribe) in the Leribe District, a key town in the north, historically significant and an administrative center. Population estimate: 47,675.

- Maputsoe, also in the Leribe District, is a major industrial and commercial border town adjacent to Ficksburg, South Africa. It plays a vital role in the country's textile industry. Population estimate: 32,117.

- Mohale's Hoek in the Mohale's Hoek District, serving as an administrative and commercial center in the south. Population estimate: 24,992.

- Mazenod in Maseru District, notable for being the location of Moshoeshoe I International Airport. Population estimate: 27,553.

These urban centers function as focal points for trade, administration, and service delivery within their respective regions.

6. Foreign Relations

Lesotho's foreign policy is shaped by its unique geographical position as an enclave within South Africa, its status as a small developing nation, and its commitment to regional and international cooperation.

6.1. Overview of Foreign Policy

Lesotho generally pursues a foreign policy of non-alignment and maintains diplomatic relations with a wide range of countries. Key foreign policy priorities include promoting peace and security, fostering economic development through international partnerships, and advocating for the interests of small and developing states. Lesotho has historically maintained strong ties with the United Kingdom (particularly Wales, with which it has cultural links), Germany, the United States, and other Western nations. It has also cultivated relationships with countries in Asia and other parts of Africa.

Lesotho has, at different times, managed its relations with China and Taiwan. It broke relations with China and established relations with Taiwan in 1990, but later restored ties with mainland China. Lesotho recognizes the State of Palestine. From 2014 to 2018, it recognized the Republic of Kosovo but has since withdrawn this recognition.

Historically, Lesotho was a vocal opponent of apartheid in South Africa and granted political asylum to a number of South African refugees during that era. In 2019, Lesotho signed the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

6.2. Relations with South Africa

Lesotho's relationship with South Africa is of paramount importance due to its complete encirclement by its larger neighbor. This geographical reality dictates a high degree of economic interdependence. Many Basotho work in South Africa, particularly in mines and farms, and their remittances are a significant source of income for Lesotho. The two countries share deep historical, cultural, and linguistic ties.

Economic cooperation is formalized through the Southern African Customs Union (SACU), from which Lesotho derives a substantial portion of its government revenue. The Lesotho loti is pegged at par to the South African rand, and both currencies are legal tender in Lesotho, reflecting the close monetary ties within the Common Monetary Area (CMA).

A critical area of cooperation is water resources. The Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) is a bi-national project that involves transferring water from Lesotho's highlands to the industrial heartland of South Africa (Gauteng province) and generating hydroelectricity for Lesotho. This project is a major source of revenue for Lesotho.

Despite the close ties, the relationship is complex and sometimes involves sensitivities related to sovereignty, border security, and the movement of people.

6.3. Membership in International Organizations

Lesotho is an active member of numerous international and regional organizations, which serve as platforms for diplomatic engagement, economic cooperation, and addressing global challenges. Key memberships include:

- The United Nations (UN) and its specialized agencies.

- The African Union (AU), where it participates in efforts to promote peace, security, and development on the continent.

- The Southern African Development Community (SADC), a regional bloc focused on economic integration and cooperation among Southern African states. Lesotho has benefited from SADC's mediation efforts during times of political instability.

- The Commonwealth of Nations, maintaining historical ties with the United Kingdom and other member states.

- The Southern African Customs Union (SACU), one of the world's oldest customs unions, providing for a common external tariff and revenue sharing.

- The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM).

Lesotho's participation in these organizations allows it to engage on issues of global and regional importance, access development assistance, and contribute to collective problem-solving efforts.

7. Military and Security

Lesotho maintains a small defense force and police service responsible for national security and law enforcement. These institutions have, at times, been involved in the country's political dynamics.

7.1. Lesotho Defence Force (LDF)

The Lesotho Defence Force (LDF) is the country's military. Its primary mandate is to defend the territorial integrity and sovereignty of Lesotho, maintain internal security in support of the police when required, and participate in disaster relief and development activities. The LDF is a relatively small force, consisting mainly of an army and an air wing. The chief officer of the LDF is designated as the Commander. The LDF has been involved in several instances of political instability in Lesotho's history, including military coups and interventions. Efforts have been made, often with support from SADC, to reform the security sector and ensure its subordination to civilian democratic control.

7.2. Police Services

The Lesotho Mounted Police Service (LMPS) is the national police force responsible for maintaining law and order, preventing and detecting crime, traffic control, and providing community policing services. Its chief officer is designated as the Commissioner. The LMPS has a long history, dating back to 1872, and has evolved over time. It includes uniformed police, criminal investigation units, and specialized units dealing with issues such as high-tech crime, immigration, wildlife protection, and counter-terrorism. Like the LDF, the LMPS has also faced challenges related to professionalism, resource constraints, and occasional accusations of human rights abuses, prompting calls for reform and improved accountability.

7.3. National Security Service (LNSS)

The Lesotho National Security Service (LNSS) is Lesotho's primary intelligence agency. Established in its modern form by the National Security Services Act of 1998, its main role is the protection of national security through the collection, analysis, and dissemination of intelligence. The chief officer of the LNSS is designated as the Director General, who is appointed and can be dismissed by the Prime Minister. The LNSS operates under the Ministry of Defence and National Security and reports directly to the Government. Its functions are critical for informing government decision-making on matters of national security and potential threats.

8. Economy

Lesotho's economy is classified as lower-middle income and is closely intertwined with that of South Africa. It faces challenges related to poverty, unemployment, and reliance on a few key sectors, but has also seen development in areas like manufacturing and water exports. A focus on social equity in development is crucial given the existing disparities.

8.1. Overview of Economic Conditions

Lesotho's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is modest, with income levels reflecting its status as a developing country. A significant portion of the population, almost half, lives below the poverty line. Unemployment is high, particularly among youth. Inflation rates can be influenced by trends in South Africa due to the pegged currency. The economy heavily relies on remittances from Basotho workers in South Africa and revenue from the Southern African Customs Union (SACU). The country has also benefited from initiatives like the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) for its textile exports. However, economic growth has sometimes been hampered by political instability and global economic fluctuations. Addressing social equity in economic development is a key challenge, ensuring that the benefits of growth reach the most vulnerable segments of the population. Life expectancy is low, partly due to the high prevalence of HIV/AIDS. The country is among the "Low Human Development" countries, ranking 160 out of 187 on the Human Development Index as of 2009. Adult literacy is high at 82% (2009), but 20% of children under five were underweight.

8.2. Major Sectors

Lesotho's economy is based on several key sectors, including agriculture, mining, manufacturing, and increasingly, services like tourism and water exports.

8.2.1. Agriculture and Livestock

Agriculture is a mainstay for a large portion of the population, though much of it is subsistence farming. The main crops grown include maize, sorghum, wheat, and beans. Livestock rearing, particularly of cattle, sheep, and goats, is also important, providing food, income, and traditional wealth. Wool and mohair are significant agricultural exports. However, the agricultural sector faces numerous challenges, including soil erosion on the mountainous terrain, limited arable land (only about 9-12% of the land is suitable for cultivation), dependence on rain-fed farming, and the impacts of climate change, especially recurrent droughts. These factors contribute to chronic food insecurity for many households.

8.2.2. Mining and Manufacturing

The mining sector in Lesotho is dominated by diamond mining. The Letšeng diamond mine is famous for producing large, high-value diamonds, making it one of the richest mines in the world on an average price per carat basis. Other mines include Mothae, Liqhobong, and Kao. Diamond exports contribute significantly to the country's foreign exchange earnings. In 1967, a 601-carat diamond (the Lesotho Brown) was discovered by a Mosotho woman. In August 2006, the 603-carat Lesotho Promise diamond was found at Letšeng, and another 478-carat diamond was discovered there in 2008. In 2018, a 910-carat diamond, one of the largest ever found, was unearthed at Letšeng.

The manufacturing sector, particularly textiles and garments, grew substantially under the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which provided preferential access to the US market. Lesotho became one of the largest exporters of garments to the US from sub-Saharan Africa. US brands sourcing from Lesotho have included Foot Locker, Gap, JCPenney, Levi Strauss, and Wal-Mart. This sector has been a major source of formal employment, especially for women, reaching over 50,000 workers at its peak in mid-2004. However, it has faced challenges from international competition and changes in trade policies, leading to some decline in employment, which stood at about 45,000 in mid-2011. The sector initiated the Apparel Lesotho Alliance to fight AIDS (ALAFA) program to provide disease prevention and treatment for workers.

8.2.3. Tourism

Tourism is a developing sector with considerable potential, given Lesotho's stunning natural landscapes, unique cultural heritage, and opportunities for adventure tourism. Attractions include the Maloti Mountains and Drakensberg range, offering hiking, pony trekking, and bird watching. Sehlabathebe National Park and the Maloti-Drakensberg Park (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) are key natural attractions. Cultural experiences include visiting traditional Basotho villages and learning about local crafts and customs. Adventure tourism is also growing, with facilities like the Afriski Mountain Resort, one of only two ski resorts in Southern Africa, offering skiing and snowboarding in winter, and other activities like mountain biking and abseiling in summer. The Sani Pass, a spectacular mountain pass connecting Lesotho to South Africa, is also a major tourist draw. The Katse and Mohale dams, part of the LHWP, have also become tourist attractions.

8.3. Water Resources and Energy

Water is one of Lesotho's most valuable natural resources. The Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) is a massive, multi-phase engineering project undertaken jointly with South Africa. Initiated in 1986, the LHWP is designed to capture, store, and transfer water from the Orange River system in Lesotho's highlands to South Africa's water-scarce Gauteng province, which is its industrial and economic heartland. The project involves the construction of several large dams (like Katse and Mohale), tunnels, and hydropower stations.

The LHWP is a major source of revenue for Lesotho through the sale of water to South Africa. It also generates hydroelectricity, making Lesotho almost self-sufficient in electricity production and even allowing for some export. In 2010, it generated approximately 70.00 M USD from water and electricity sales. However, the project has also had significant social and environmental impacts. These include the displacement of communities, loss of grazing land, and alterations to river ecosystems. Addressing these impacts through compensation, resettlement programs, and environmental management plans has been an ongoing aspect of the project.

8.4. Labor, Remittances, and Social Equity

A significant feature of Lesotho's economy is the migration of Basotho labor, primarily men, to work in South Africa, especially in the mining and agricultural sectors. This tradition dates back to the late 19th century. Remittances sent home by these migrant workers are a crucial source of income for many households in Lesotho and contribute substantially to the national economy.

However, migrant labor also presents challenges. Workers often face difficult and dangerous working conditions, and the cyclical nature of migration can disrupt family life. The decline in employment in the South African mining sector in recent decades has also affected remittance flows.

Issues of labor rights for both migrant workers and those employed within Lesotho, particularly in the textile sector, are important. Ensuring fair wages, safe working conditions, and the right to organize are key aspects of promoting social equity. The equitable distribution of economic benefits from national projects like the LHWP and from sectors like diamond mining is also a critical concern for addressing poverty and inequality in the country.

8.5. Currency and Finance

The official currency of Lesotho is the loti (LSL), plural maloti. The loti is pegged at a 1:1 ratio to the South African rand (ZAR). The rand is also accepted as legal tender throughout Lesotho. This peg and dual currency system reflects the close economic integration with South Africa.

Lesotho is a member of the Common Monetary Area (CMA), along with South Africa, Namibia, and Eswatini. The CMA allows for the free flow of capital between member states and provides a framework for monetary policy coordination, although Lesotho's monetary policy is largely influenced by that of South Africa due to the currency peg.

The Central Bank of Lesotho is responsible for issuing the loti, managing foreign exchange reserves, overseeing the financial system, and advising the government on monetary policy. The financial sector in Lesotho includes commercial banks, insurance companies, and other financial institutions.

9. Society

Lesotho's society is characterized by a largely homogeneous ethnic makeup, a strong Christian presence, and significant social challenges including poverty and a high HIV/AIDS prevalence, alongside notable achievements in education.

9.1. Demographics

Lesotho has a population of approximately 2.2 million people. The population distribution is about 25% urban and 75% rural, with an estimated annual increase in urban population of 3.5%. Population density is relatively low, but concentrated in the western lowlands due to the mountainous terrain elsewhere. Key demographic indicators include a youthful population, with about 60.2% of the population between 15 and 64 years of age. Life expectancy is low, around 51 years for men and 55 for women (2016), largely due to the impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Infant mortality is approximately 8.3%. Urbanization is occurring, with people moving from rural areas to towns, especially Maseru, in search of employment and better services.

9.2. Ethnic Groups and Languages

Lesotho is remarkable for its ethnic homogeneity. An estimated 99.7% of the population identify as Basotho (Sotho people), a Bantu-speaking people. This makes Lesotho one of the few nation states in Africa with a single dominant cultural ethnic group and language, as most African nations' borders were drawn by colonial powers without regard to ethnic boundaries. Basotho subgroups include the Bafokeng, Batloung, Baphuthi, Bakuena, Bataung, and Batšoeneng. There are very small minorities of Europeans, Asians, and Xhosa people (about 1%).

The official languages are Sesotho (Southern Sotho) and English. Sesotho is the national language and is spoken by the vast majority of the population. English is widely used in government, business, and education. Other minority languages spoken include Zulu and Xhosa.

9.3. Religion

Christianity is the dominant religion in Lesotho, with over 95% of the population identifying as Christian as of December 2011. Roman Catholics constitute the largest single denomination, representing approximately 49.4% of the population. The Catholic Church is served by the Metropolitan Archdiocese of Maseru and its three suffragan dioceses (Leribe, Mohale's Hoek, and Qacha's Nek).

Protestants account for a significant portion of the Christian population, with various denominations present. This includes evangelicals (part of the 18.2% Protestant figure), Pentecostals (15.4%), Anglicans (5.3%), and other Christian groups (1.8%). Traditional African beliefs often coexist with Christian practices for some individuals. Non-Christian religions represent about 9.6% of the population, and a very small percentage (0.2%) report no religion.

9.4. Education

Lesotho has made significant strides in education and boasts one of the highest literacy rates in Africa. According to estimates, 85% of women and 68% of men over the age of 15 are literate. The overall adult literacy rate was reported as 82% in 2009 and 79.4% in 2015 (female literacy 88.3%, male literacy 70.1%). This higher literacy rate for women compared to men is unusual in the region and is partly attributed to the traditional role of boys in herding livestock, which sometimes keeps them out of school.

The government invests a significant portion of its GDP in education (over 12%). While education is not compulsory, the government has been incrementally implementing a program for free primary education. According to a 2000 study by the Southern and Eastern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality, 37% of grade 6 pupils in Lesotho (average age 14) were at or above reading level 4 ("Reading for Meaning").

Higher education is provided by the National University of Lesotho (NUL), located in Roma, as well as several other public and private institutions. The African Library Project works to establish school and village libraries in partnership with US Peace Corps Lesotho and local education authorities. Access to the internet was reported at 3.4% of the population by the International Telecommunication Union, with services like Econet Telecom Lesotho expanding access to email and educational information via mobile phones.

9.5. Health

The public health situation in Lesotho is challenging, with several major health issues affecting the population. Life expectancy at birth was estimated at 52 years in 2009.

Lesotho has the second-highest HIV/AIDS adult prevalence rate in the world, after Eswatini. As of 2018, the rate was 23.6%, and in 2021, it was 22.8% among people aged 15-49. The epidemic has had a devastating impact on individuals, families, and the healthcare system, contributing to high mortality rates and a large number of orphans.

Tuberculosis (TB) is another major public health concern, with Lesotho having the highest incidence of TB in the world. The co-infection of HIV and TB is common and complicates treatment.

The healthcare system comprises government hospitals, clinics, and health centers, as well as facilities run by church organizations and private practitioners. Access to medical services, particularly in remote rural areas, can be limited. The government, with support from international partners, is working to strengthen the healthcare system, improve access to HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment (including antiretroviral therapy), and combat TB and other diseases.

According to the 2006 census, around 4% of the population had some form of disability, though the actual figure is thought to be closer to the global estimate of 15%. People with disabilities in Lesotho face social and cultural barriers preventing access to education, healthcare, and employment. Lesotho signed the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2008. WHO data since 2008 indicates Lesotho has had the world's highest suicide rate per capita.

9.6. Poverty, Inequality, and Social Welfare

Poverty and income inequality are widespread in Lesotho. Almost half of the population lives below the national poverty line. Rural areas are particularly affected by poverty, where many households depend on subsistence agriculture, which is vulnerable to drought and climate change. High unemployment rates, especially among young people, contribute to poverty.

Income inequality is also a significant issue, with a large gap between the rich and the poor. The impacts of poverty and inequality are particularly severe for vulnerable populations, including women-headed households, orphans and vulnerable children (often due to HIV/AIDS), the elderly, and people with disabilities.

The government of Lesotho, along with non-governmental organizations and international partners, implements various social welfare programs aimed at providing support to vulnerable groups and reducing disparities. These include cash transfer programs, food assistance, support for orphans and vulnerable children, and old-age pensions. However, the scale of need often outstrips available resources. Addressing the root causes of poverty and inequality, through pro-poor economic growth, job creation, improved access to education and healthcare, and strengthened social protection systems, remains a key priority for the country's development and the well-being of its citizens.

10. Culture

Lesotho possesses a rich and distinctive culture, deeply rooted in the traditions of the Basotho people, while also showing influences from its historical interactions.

10.1. Traditional Attire and Crafts

Two of the most iconic symbols of Basotho culture are the Basotho blanket and the Mokorotlo (conical grass hat). The Basotho blanket, traditionally made of wool but now often of acrylic fibers, is a distinctive and colorful covering worn by people of all ages, especially in the colder highland regions. The designs on the blankets often have specific meanings and significance. The main manufacturer of the Basotho blanket is Aranda, which has a factory in South Africa. The Mokorotlo, a hat woven from local grasses, is shaped to resemble Mount Qiloane and is a national symbol, even appearing on the country's flag.

Traditional crafts are an important part of Basotho culture. These include pottery, intricate basketry using local grasses, and beadwork. These crafts are not only functional but also serve as artistic expressions. British influence is visible in the remnants of trading posts from the 18th to 20th centuries in villages like Roma, Ramabantana, Ha Matala, Malealea, and Semonkong, which historically sold fuel, grains, and animals. Examples of San rock art can be found in the mountains, such as in the village of Ha Matela.

10.2. Cuisine

The cuisine of Lesotho combines traditional African culinary practices with some British influences. Staple foods include pap (also known as 'mealies'), a stiff porridge made from maize meal, which is often served with a vegetable sauce or relish, such as moroho (cooked leafy greens). Another traditional porridge is motoho, a fermented sorghum porridge, which is the national dish. Meat, particularly beef, mutton, and chicken, is also consumed, often stewed or grilled (braai). Locally brewed beer, made from sorghum, and tea are common beverages. Lesotho is also famed for its fermented ginger beer, available in varieties with and without raisins, often sold by roadside vendors. Sishenyama (grilled meat) is regularly sold throughout Lesotho with side dishes such as cabbage, pap, and baked bean salad.

10.3. Music, Dance, and Festivals

Traditional Basotho music features strong vocal harmonies, often accompanied by traditional instruments such as the lekolulo (a type of flute played by herding boys), the setolo-tolo (a stringed mouth-bow played by men), and the thomo (a stringed instrument played by women). Folk dances are an integral part of cultural expression, performed at social gatherings, ceremonies, and festivals.

The Morija Arts & Cultural Festival is a prominent annual event held in the historic town of Morija, where the first missionaries arrived in 1833. The festival showcases traditional and contemporary Basotho music, dance, theatre, poetry, crafts, and art, attracting local and international participants and visitors.

10.4. Sports

Soccer (football) is the most popular sport in Lesotho. The country has a national football league, the Lesotho Premier League, and the national team, nicknamed "Likuena" (Crocodiles), competes in regional and international competitions. Other sports practiced in Lesotho include athletics, boxing, netball, and volleyball. Lesotho also participates in the Olympic Games and the Commonwealth Games. The mountainous terrain lends itself to endurance sports like long-distance running. The Basotho pony, historically used in battle, is now utilized for transport and agriculture, and pony trekking is a popular tourist activity.

10.5. Media and Film

The media landscape in Lesotho includes print newspapers, radio stations (which are the most widespread medium), and television. Lesotho Television is the state broadcaster.

The film industry in Lesotho is small but developing. Ryan Coogler, director of the 2018 film Black Panther, stated that his depiction of Wakanda was inspired by Lesotho, and Basotho blankets gained more international recognition as a result of the film. In November 2020, the film This Is Not a Burial, It's a Resurrection became the first Lesotho film to be submitted for the Academy Award for Best International Feature Film.

10.6. World Heritage Sites

Lesotho is home to part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Maloti-Drakensberg Park is a transboundary site shared with South Africa. In Lesotho, this includes the Sehlabathebe National Park. The site is recognized for its "outstanding natural beauty," its unique biodiversity including high levels of endemic and globally threatened species, and its rich concentration of San rock art, which provides a glimpse into the beliefs and way of life of the San people who inhabited the region for millennia. This makes it a site of both natural and cultural significance.

11. Transport

Lesotho's transport infrastructure is shaped by its mountainous terrain and its status as a landlocked country. Connectivity relies primarily on roads, with limited air and rail options.

11.1. Road Network

The road network is the primary mode of transportation within Lesotho. The network includes paved highways connecting major towns and border crossings, as well as a significant number of gravel and dirt roads, particularly in rural and mountainous areas. Major routes include those connecting Maseru to other district capitals and to the South African road system.

Public transportation is largely provided by privately-owned buses and minibus taxis, which operate on fixed routes and are the main means of travel for most Basotho.

The mountainous terrain poses significant challenges to road construction and maintenance, making travel to remote highland areas difficult, especially during adverse weather conditions. Investment in road infrastructure is ongoing to improve accessibility and support economic development. Driving is on the left.

11.2. Air Transport

Moshoeshoe I International Airport (IATA: MSU, ICAO: FXMM), located near Mazenod, southeast of Maseru, is Lesotho's main international airport. It offers flights connecting Lesotho to Johannesburg, South Africa, which serves as a regional hub for further international travel.

There are also several smaller domestic airstrips scattered throughout the country, primarily serving remote highland communities, missions, and tourist lodges. These airstrips are often unpaved and are accessible mainly by small aircraft. Air travel plays a role in providing access to isolated areas that are difficult to reach by road.

11.3. Rail Transport

Lesotho has very limited railway infrastructure. It consists of a short railway line, approximately 1.0 mile (1.6 km) or 1 mile in length, that connects Maseru's industrial area to the South African rail network at Marseilles on the Bloemfontein-Bethlehem line. This line is primarily used for freight transport, facilitating the movement of goods to and from South Africa. There are no passenger rail services operating within Lesotho.