1. Overview

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country located in West Asia, at the southeastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea and the northern shore of the Red Sea. It is geographically situated in the Southern Levant region of the Middle East. Israel shares land borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the northeast, Jordan and the West Bank to the east, and Egypt and the Gaza Strip to the southwest. Tel Aviv is the country's economic and technological center, while its proclaimed capital and seat of government is Jerusalem, although Israeli sovereignty over East Jerusalem is not recognized internationally.

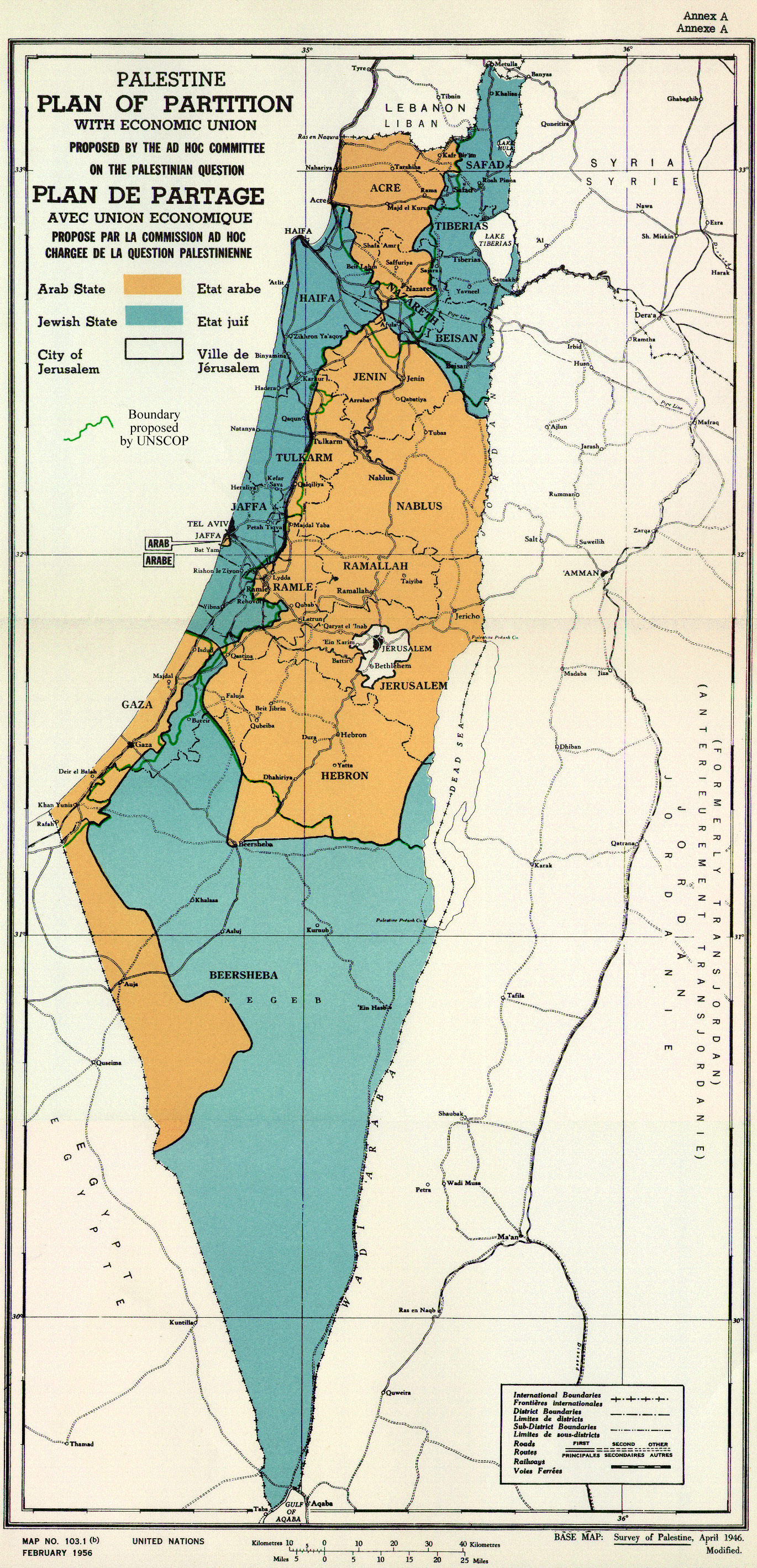

The region known as the Land of Israel has been central to Jewish identity for millennia. Historically, it was home to ancient Canaanite civilizations and later the Israelite kingdoms of Israel and Judah. Over centuries, the land was ruled by various empires, including the Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, and Ottomans. The late 19th century saw the rise of Zionism, a movement advocating for the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, which gained support from Great Britain particularly through the Balfour Declaration of 1917. Following World War I, Britain administered the region under the Mandate for Palestine. Increased Jewish immigration, especially as a consequence of the Holocaust, coupled with British colonial policies, led to escalating conflict between Jews and Arabs. In 1947, the United Nations approved a partition plan for Palestine, recommending the creation of separate Arab and Jewish states and an internationalized Jerusalem. This plan was accepted by the Jewish leadership but rejected by Arab leaders, leading to the 1947-1948 civil war in Mandatory Palestine.

Israel declared its independence on May 14, 1948. The ensuing war with neighboring Arab states resulted in Israeli control over a larger territory than envisaged by the UN plan. This period also saw the displacement of a majority of Palestinian Arabs, an event known as the Nakba (catastrophe), while those who remained became Israeli citizens. Israel subsequently absorbed large numbers of Jewish immigrants and refugees from around the world. The Arab-Israeli conflict has continued through several major wars and ongoing confrontations, with significant humanitarian consequences, particularly for Palestinians. Israel has occupied the West Bank, East Jerusalem, the Gaza Strip, and the Golan Heights since the Six-Day War of 1967. Israeli settlements in these occupied territories are considered illegal under international law and have been a major obstacle to peace. Despite peace treaties with Egypt and Jordan, and normalization agreements with several other Arab nations (the Abraham Accords), a comprehensive resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict remains elusive. Israel's actions in the occupied territories have drawn international criticism, including accusations of war crimes and apartheid.

Israel is a parliamentary democracy with a proportional representation electoral system. The President is the head of state, while the Prime Minister is the head of government. The Knesset is the unicameral legislature. Israel's Basic Laws function as an uncodified constitution. The country has a technologically advanced, market economy with a strong high-tech sector. Its society is diverse, reflecting waves of immigration from various parts of the world. Hebrew is the official language, and Arabic has a special status. Culturally, Israel blends Jewish traditions with influences from the Jewish diaspora and the broader Middle Eastern and Mediterranean regions. The nation faces ongoing challenges related to social equity, the peace process, human rights, and the integration of its diverse population groups.

2. Etymology

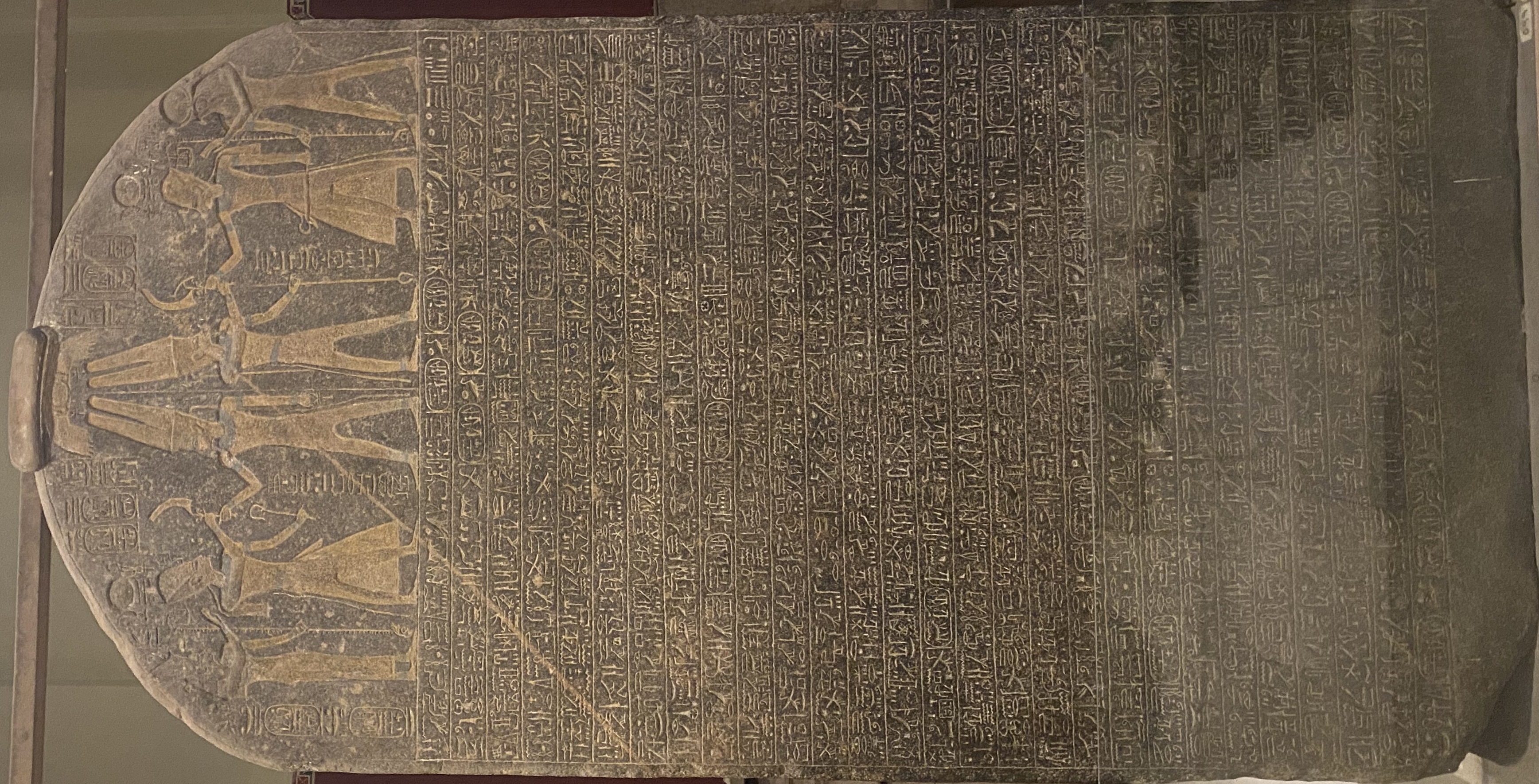

The name "Israel," adopted by the modern state in 1948, has ancient origins rooted in the Hebrew Bible, where it was given to the patriarch Jacob. Its earliest archaeological mention as a people is on the Egyptian Merneptah Stele from the 13th century BCE.

2.1. Origins of the name

During the British Mandate (1920-1948), the region was officially known as Palestine. Upon its establishment on May 14, 1948, the country formally adopted the name State of Israel (מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵלMedīnat Yisrā'el (IPA: mediˈnat jisʁaˈʔel)Hebrew; دَوْلَة إِسْرَائِيلDawlat Isrāʼīl (IPA: dawlat ʔisraːˈʔiːl)Arabic). Other names considered at the time included Land of Israel (אֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵלEretz YisraelHebrew), Ever (from the biblical ancestor Eber), Zion, and Judea, but these were ultimately rejected. The name Israel was proposed by David Ben-Gurion, the first Prime Minister of Israel, and was approved by a vote of 6-3. In the initial weeks following the establishment of the state, the government chose the term Israeli to denote a citizen of the State of Israel.

The names Land of Israel and Children of Israel have historically been used to refer to the biblical Kingdom of Israel and the entire Jewish people respectively. The name Israel (יִשְׂרָאֵלYīsrāʾēlHebrew), derived from the Hebrew Bible, is traditionally understood to mean "El (God) persists/rules" or "He Who Struggles with God". It was given to the patriarch Jacob after he successfully wrestled with an angel of God, as recounted in the Book of Genesis (Genesis 32:28).

The earliest known archaeological artifact to mention the word "Israel" as a collective entity or people is the Merneptah Stele, an ancient Egyptian inscription dated to the late 13th century BCE (circa 1208 BCE). The stele, erected by Pharaoh Merneptah, son of Ramesses II, recounts his military victories in Canaan. A specific line on the stele reads, "Israel is laid waste and his seed is not," which most scholars interpret as a reference to a people named Israel existing in Canaan at that time. This is considered the earliest extrabiblical reference to Israel. The personal name "Israel" itself appears even earlier in texts from Ebla (modern Syria), dating back to the 3rd millennium BCE, but the Merneptah Stele is significant for its use of "Israel" to denote a people or tribal group.

3. History

The history of the land of Israel spans from early hominin presence and ancient civilizations like the Canaanites, through the Israelite kingdoms, classical antiquity under Persian, Greek, and Roman rule, medieval periods under Islamic and Crusader control, to Ottoman rule and the rise of Zionism. The 20th century saw the British Mandate, the Holocaust, the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, and the ensuing Arab-Israeli conflict which continues to shape the region.

3.1. Prehistory

The Levant, where Israel is located, has a rich prehistoric past. Evidence of early hominin presence dates back at least 1.5 million years, as indicated by finds at the Ubeidiya prehistoric site in the Jordan Rift Valley. This site has yielded Oldowan-type stone tools, making it one of the oldest hominin sites outside of Africa.

Later, anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) appeared in the region. Fossils discovered in the Skhul Cave on Mount Carmel and Qafzeh Cave in Galilee date back approximately 80,000 to 120,000 years. These remains are among the earliest evidence of modern humans outside of Africa, suggesting that the Levant was a crucial corridor for early human migrations. For a period, modern humans and Neanderthals, whose remains have also been found in the region (e.g., Kebara Cave, Amud Cave), likely coexisted or alternated presence in the Levant.

The Epipalaeolithic period saw the emergence of the Natufian culture (circa 12,500 to 9,500 BCE). The Natufians were hunter-gatherers who established some of the earliest known permanent or semi-permanent settlements. They are notable for their intensive harvesting of wild cereals and for early signs of social complexity, including elaborate burials. The Natufian culture is considered a precursor to the Neolithic period, which marked the beginning of agriculture. Some scholars link the Natufians to the speakers of Proto-Afroasiatic languages.

The Neolithic period in the Levant (beginning around 9,500 BCE) witnessed the transition to farming and animal domestication. Sites like Jericho show evidence of early agricultural communities and fortified settlements. This era was followed by the Chalcolithic period (Copper Age), during which the Ghassulian culture (circa 4500 to 3500 BCE) flourished, particularly in the southern Levant. The Ghassulians are known for their copper metallurgy, distinctive pottery, and complex village life.

3.2. Bronze and Iron Ages

The Bronze Age (circa 3500-1200 BCE) in the region, then known as Canaan, was characterized by the development of city-states, many of which were influenced or controlled by larger empires such as Egypt and later the Hittites. Canaanite civilization thrived, engaging in extensive trade and developing a unique material culture. Key Canaanite cities included Hazor, Megiddo, and Lachish. During the Late Bronze Age (1550-1200 BCE), much of Canaan was under Egyptian suzerainty. The period ended with the Late Bronze Age collapse, a time of widespread societal upheaval, migration, and destruction across the Near East and Eastern Mediterranean.

The Iron Age (circa 1200-586 BCE) saw the emergence of new political entities in the Levant. According to biblical tradition and supported by some archaeological evidence, this is the period when the ancient Kingdoms of Israel and Judah arose. The Merneptah Stele (late 13th century BCE) contains the earliest extrabiblical reference to a people called "Israel" in Canaan.

Modern archaeological accounts suggest that the Israelites emerged from indigenous Canaanite populations. Their culture gradually differentiated, particularly through the development of a distinct monolatristic-and later monotheistic-religion centered on the worship of Yahweh. They spoke an archaic form of the Hebrew language, known as Biblical Hebrew. Around the same time, the Philistines, one of the Sea Peoples, settled in the southern coastal plain of Canaan, establishing cities like Ashdod, Ashkelon, Ekron, Gath, and Gaza.

The existence and extent of a United Monarchy under kings Saul, David, and Solomon (traditionally dated to the 10th century BCE) are subjects of ongoing scholarly debate. However, by the 9th century BCE, the northern Kingdom of Israel (also known as Samaria or Ephraim) and the southern Kingdom of Judah were established entities. The Kingdom of Israel, with its capital eventually at Samaria, was generally larger and more prosperous. The Omride dynasty in Israel (9th century BCE) is well-attested in both biblical and extrabiblical sources, such as the Mesha Stele.

In 722/720 BCE, the Neo-Assyrian Empire conquered the Kingdom of Israel, deporting a significant portion of its population (the "Ten Lost Tribes"). The Kingdom of Judah, with its capital in Jerusalem, survived as an Assyrian vassal state and later a Babylonian one. Judah experienced periods of religious reform and consolidation under kings like Hezekiah and Josiah. In 587/586 BCE, following a revolt, the Neo-Babylonian Empire under Nebuchadnezzar II conquered Judah, destroyed Jerusalem and Solomon's Temple, and exiled much of the Judean elite to Babylon. This event marked a critical turning point in Jewish history, leading to the development of new forms of religious expression and communal identity in exile.

3.3. Classical antiquity

The classical period for the Land of Israel spans from the Persian restoration to the end of Roman rule and the Jewish-Roman wars.

In 539 BCE, Cyrus the Great of Persia conquered the Neo-Babylonian Empire. The following year, he issued the Edict of Cyrus, allowing exiled peoples, including the Judeans, to return to their homelands and rebuild their temples. This marked the beginning of the Second Temple period. Many Judeans returned to Yehud (Judah), which became a Persian province, and the Second Temple in Jerusalem was completed around 516 BCE. During Persian rule, figures like Ezra and Nehemiah played key roles in reorganizing the Jewish community and codifying religious law.

In 332 BCE, Alexander the Great conquered the region from the Persians. After his death, the Land of Israel became a contested territory between the Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt and the Seleucid dynasty of Syria, part of the larger territory known as Coele-Syria. Hellenistic culture spread, leading to tensions within Jewish society. These tensions culminated in the Maccabean Revolt (167-160 BCE) against the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes, who attempted to suppress Jewish religious practices.

The successful Maccabean Revolt led to the establishment of the Hasmonean Kingdom, which gradually achieved full independence and expanded its territory. The Hasmoneans ruled as high priests and later as kings, but internal strife and Roman expansionism eventually undermined their rule.

In 63 BCE, the Roman general Pompey conquered Jerusalem, and Judea became a Roman client state. Herod the Great was appointed king by the Romans in 37 BCE and undertook extensive building projects, including a major renovation of the Second Temple. After Herod's death, Judea was increasingly brought under direct Roman rule, becoming the Roman province of Judaea in 6 CE.

Roman rule was often met with resistance from various Jewish groups. The First Jewish-Roman War (66-73 CE) resulted in the destruction of Jerusalem and the Second Temple in 70 CE by the Roman general Titus. This event was a profound catastrophe for the Jewish people, leading to significant loss of life, displacement, and the end of the sacrificial cult centered at the Temple. The fortress of Masada was the last Jewish stronghold to fall in 73/74 CE.

Despite the devastation, Jewish life continued in the region, particularly in Galilee, which became a new center of Jewish learning. However, further tensions led to the Bar Kokhba revolt (132-136 CE), led by Simon bar Kokhba. This revolt was brutally suppressed by the Romans under Emperor Hadrian. The aftermath was even more severe: Judea was devastated, many Jews were killed or enslaved, and Jews were banned from Jerusalem. Hadrian renamed the province Syria Palaestina in an attempt to erase Jewish connections to the land, and rebuilt Jerusalem as a Roman colony named Aelia Capitolina. These events significantly intensified the Jewish diaspora, with Jewish communities becoming more dispersed throughout the Roman Empire and beyond, though a Jewish presence remained in the Land of Israel, especially in Galilee.

3.4. Late antiquity and the medieval period

This era covers the transition from Roman to Byzantine rule, the early Islamic conquests, the Crusader period, and subsequent rule by various Islamic dynasties.

After the Bar Kokhba revolt, Galilee became the primary center of Jewish life in Palestine. The Sanhedrin, the supreme Jewish religious and judicial body, was re-established in cities like Usha and Tiberias. It was during this period (2nd to 4th centuries CE) that the Mishnah (codification of Jewish oral law) and the Jerusalem Talmud were compiled.

In the 4th century CE, Emperor Constantine I legalized Christianity throughout the Roman Empire, and it eventually became the state religion under Theodosius I. Palestine, as the Holy Land, became a major center of Christian pilgrimage and monasticism. Churches were built on sites associated with the life of Jesus, and the Christian population grew, partly through immigration and conversion. Byzantine rule brought periods of both tolerance and persecution for the Jewish community. A series of laws were passed that discriminated against Jews and Judaism. Samaritan revolts in the 5th and 6th centuries were harshly suppressed, leading to a significant decline in the Samaritan population.

In 614 CE, the Sasanian Persians, with Jewish support during the Jewish revolt against Heraclius, conquered Jerusalem and much of Palestine from the Byzantines. This period of Sasanian control was short-lived; the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius recaptured the region in 628 CE.

A few years later, the Islamic conquests swept through the Middle East. In 636-638 CE, Arab Muslim armies under the Rashidun Caliphate conquered Palestine from the Byzantines. Under early Islamic rule, Jews and Christians were generally considered "People of the Book" (Ahl al-Kitab) and granted dhimmi status, allowing them to practice their religion in exchange for paying a poll tax (jizya). Jerusalem became a holy city for Muslims, recognized as the site of Muhammad's Night Journey (Isra and Mi'raj) and the first qibla (direction of prayer).

Control of Palestine passed through several Islamic dynasties:

- Umayyads** (661-750 CE): Damascus was their capital, and they built iconic structures in Jerusalem, such as the Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount (Haram al-Sharif).

- Abbasids** (750-969 CE): Their capital was Baghdad. Palestine became a more peripheral province.

- Fatimids** (969-1099 CE): A Shi'a dynasty ruling from Egypt, their control over Palestine was often contested by groups like the Seljuks.

In 1099, the First Crusade culminated in the capture of Jerusalem by European Crusaders. They established the Kingdom of Jerusalem and other Crusader states in the Levant. The Crusader period was marked by conflict between Christians and Muslims, and also brought significant changes to the demographic and religious landscape. Many Muslims and Jews were massacred during the initial conquest of Jerusalem.

In 1187, Saladin, the Ayyubid sultan, decisively defeated the Crusaders at the Battle of Hattin and recaptured Jerusalem. The Ayyubids restored Muslim control over much of Palestine. Subsequent Crusades attempted to regain Christian control but were largely unsuccessful in the long term.

In 1260, the Mamluks of Egypt defeated the Mongols at the Battle of Ain Jalut in Palestine, halting Mongol westward expansion. The Mamluks then consolidated their rule over Palestine, which lasted until 1516. Under Mamluk rule, Palestine was generally a period of economic decline and relative obscurity, though it remained religiously significant.

Throughout the medieval period, despite conquests and demographic shifts, Jewish communities persisted in cities like Jerusalem, Tiberias, Safed, and Hebron, often engaging in scholarship and maintaining religious traditions.

3.5. Modern period and the emergence of Zionism

The modern period in the history of the Land of Israel is marked by Ottoman rule, the rise of European influence, the emergence of the Zionist movement, and the beginnings of significant Jewish immigration.

In 1516, the Ottoman Empire conquered Palestine from the Mamluks, and the region became part of Ottoman Syria for the next four centuries. Under Ottoman rule, the land was divided into various administrative districts (sanjaks). While Jerusalem retained its religious significance, the region was generally a relatively impoverished and sparsely populated part of the empire. Local Arab notables and Bedouin tribes often held considerable influence. Incidents of violence against Jews, such as the 1517 Safed attacks and 1517 Hebron attacks, occurred after the Ottoman conquest.

The Ottoman millet system allowed religious communities, including Jews and Christians (as dhimmi), a degree of autonomy in their internal affairs in exchange for loyalty and payment of the jizya tax. Jewish communities, known as the Old Yishuv (Old Settlement), continued to exist, particularly in the Four Holy Cities: Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, and Tiberias. Safed became a major center of Kabbalah (Jewish mysticism) in the 16th century. There were small waves of Jewish immigration, often for religious reasons, such as Sephardi Jews fleeing the Spanish Inquisition who were invited by Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent to settle in Tiberias. In 1697, Rabbi Yehuda Hachasid led a group of 1,500 Jews to Jerusalem. A Druze revolt in 1660 led to the destruction of Safed and Tiberias. In the 18th century, Perushim (opponents of Hasidic Judaism) from Eastern Europe also settled in Palestine.

In the late 18th century, a local Arab sheikh, Zahir al-Umar, created a de facto independent emirate in the Galilee. After his death, Ottoman control was reasserted. In 1799, Jazzar Pasha, the Ottoman governor of Acre, successfully repelled Napoleon Bonaparte's siege, forcing the French to abandon their Syrian campaign. In the 19th century, Egyptian rule under Muhammad Ali of Egypt briefly extended over Palestine (1831-1840), followed by the restoration of Ottoman control with British support after a Palestinian Arab peasants' revolt in 1834. The Tanzimat reforms implemented by the Ottoman Empire aimed to modernize the state but had limited impact in Palestine.

The 19th century witnessed increasing European interest and intervention in the Ottoman Empire, including Palestine. Consulates were established, and Christian missionary activity grew. This period also saw growing antisemitism in Europe, particularly in Tsarist Russia with widespread pogroms (anti-Jewish riots). These persecutions, along with the rise of modern nationalism and the ideas of the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment), fueled the development of Zionism. Zionism, as a modern political movement, advocated for the establishment of a Jewish national home in Palestine to solve the "Jewish question" and provide a refuge for persecuted Jews.

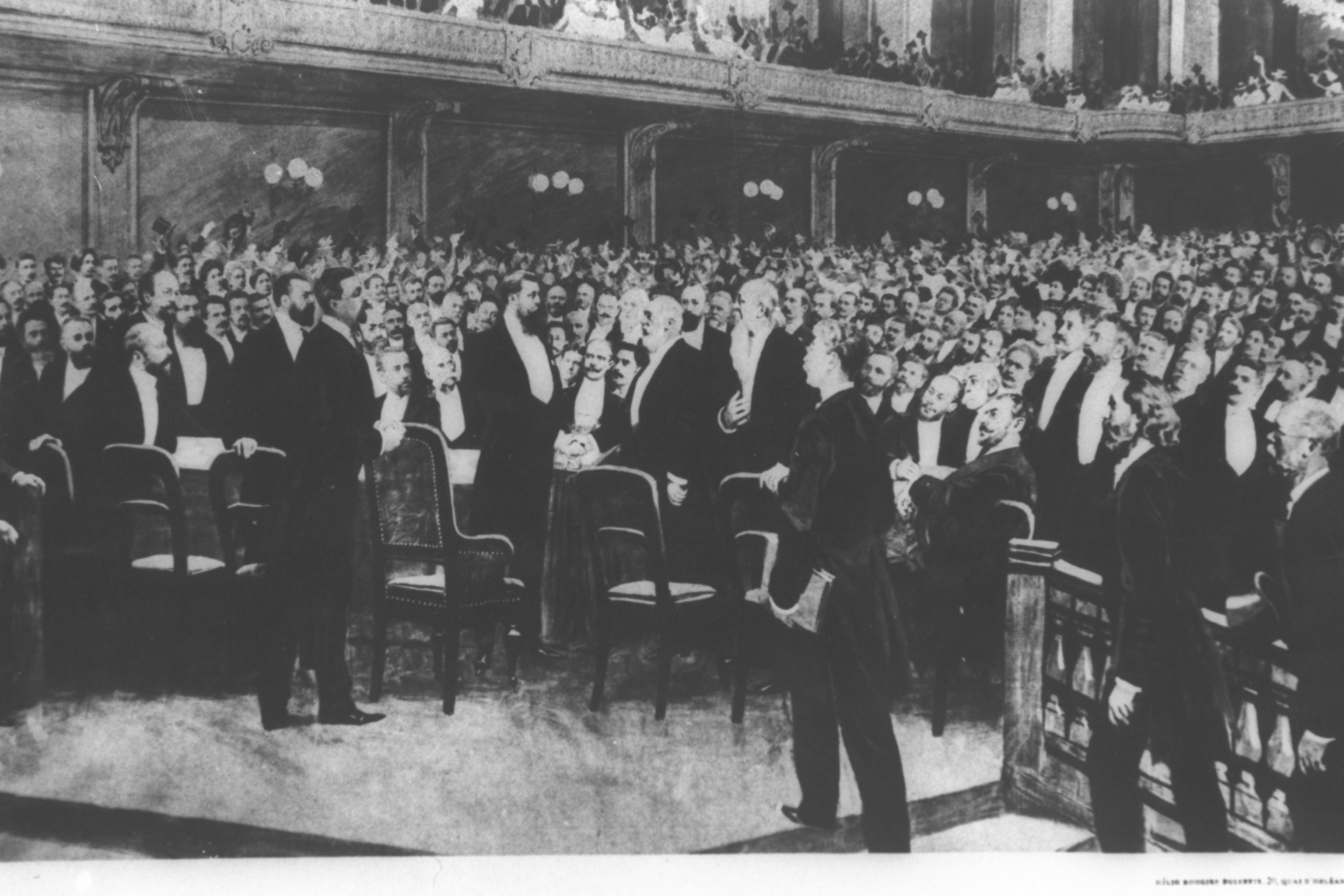

Key figures in early Zionism included Moses Hess, Leon Pinsker, and most prominently, Theodor Herzl. Herzl's pamphlet Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State, 1896) and his organization of the First Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland, in 1897, were pivotal in transforming Zionism into an organized international movement. The Congress adopted the Basel Program, which stated, "Zionism seeks to establish a home for the Jewish people in Palestine secured under public law."

The Zionist movement spurred Jewish immigration to Palestine, known as Aliyahs (ascents).

- The First Aliyah (1882-1903) brought around 25,000-35,000 Jews, mostly from Eastern Europe, who established agricultural settlements. This was motivated by pogroms and the May Laws in Russia.

- The Second Aliyah (1904-1914), following the Kishinev pogrom, brought another 35,000-40,000 immigrants. Many of these immigrants were imbued with socialist ideals and played a key role in developing the kibbutz (collective farm) movement and laying the foundations for future Jewish self-governance, including the establishment of Tel Aviv in 1909 and armed self-defense groups like Hashomer.

These early waves of Jewish immigration and land purchases, often from absentee Arab landlords, led to increasing friction with the local Arab population, who began to fear displacement and demographic change. This laid the groundwork for the escalating Arab-Israeli conflict in the 20th century.

3.6. British Mandate for Palestine

Following World War I and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the League of Nations established the British Mandate for Palestine in 1922. The Mandate instrument incorporated the Balfour Declaration of 1917, in which the British government had expressed support for "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people," while also stipulating that "nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine."

During the Mandate period, Jewish immigration (Aliyah) continued, significantly increasing the Jewish population (the Yishuv).

- The Third Aliyah (1919-1923) brought around 40,000 Jews, mainly from Eastern Europe, motivated by Zionist ideals and post-war instability.

- The Fourth Aliyah (1924-1929) saw about 82,000 immigrants, many from Poland and Hungary, including middle-class families who contributed to urban development.

- The Fifth Aliyah (1929-1939) was driven by the rise of Nazism in Germany and growing antisemitism in Europe, bringing approximately 250,000 Jews to Palestine.

Jewish institutions were developed, including the Histadrut (labor federation), the Haganah (defense organization), and the Jewish Agency, which acted as a quasi-government for the Yishuv. Land was purchased, often from absentee Arab landlords, and new agricultural settlements (kibbutzim and moshavim) and urban centers like Tel Aviv expanded.

The increasing Jewish presence and land acquisitions led to growing Arab resentment and fear of dispossession. This resulted in several outbreaks of violence:

- The 1920 Nebi Musa riots and the 1921 Jaffa riots.

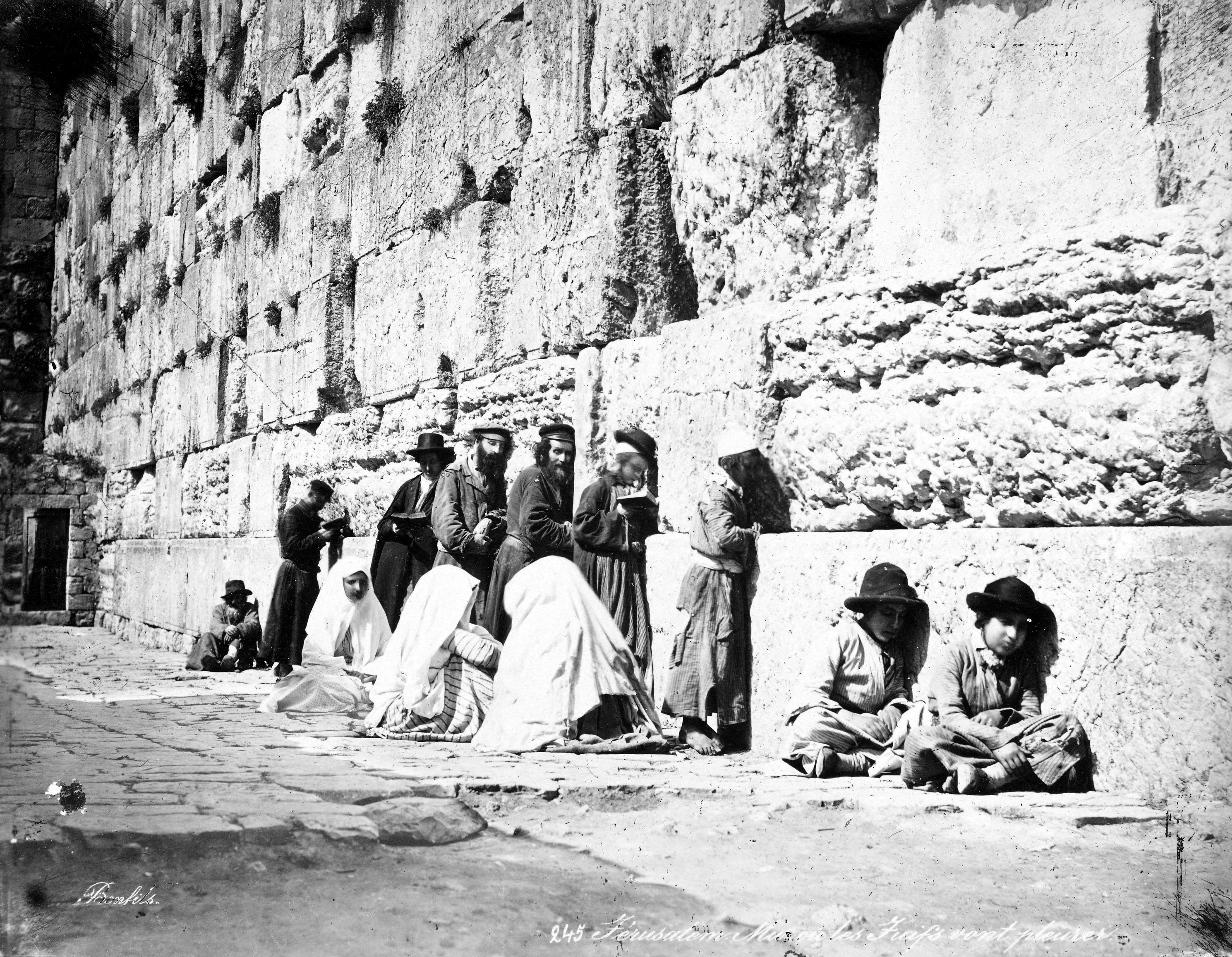

- The 1929 Palestine riots, sparked by disputes over the Western Wall, which led to the Hebron massacre of Jews and attacks in other cities.

- The 1936-1939 Arab revolt, a major nationalist uprising against British rule and Jewish immigration. The British suppressed the revolt harshly, with significant casualties on both sides and a lasting impact on Arab political organization.

In response to the Arab revolt, the British Peel Commission (1937) proposed the partition of Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states, with an international corridor for Jerusalem. This was rejected by the Arabs and met with mixed reactions from the Jews. Subsequently, the White Paper of 1939 severely restricted Jewish immigration and land purchases, a policy seen by Zionists as a betrayal, especially with the Holocaust unfolding in Europe during World War II.

During World War II, many Palestinian Jews fought with the British Allies, and the Jewish Brigade was formed within the British Army. The Holocaust galvanized international sympathy for the Zionist cause and intensified Jewish determination to establish a state. After the war, the British maintained immigration restrictions, leading to clandestine immigration efforts (Aliyah Bet) and a growing Jewish armed resistance against British rule by groups like the Haganah, Irgun, and Lehi. Notable incidents included the King David Hotel bombing in 1946 by the Irgun.

Unable to resolve the escalating conflict, Britain referred the Palestine question to the newly formed United Nations in 1947. The UN Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) recommended partition. On November 29, 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 181(II), which proposed the division of Palestine into an Arab state, a Jewish state, and an internationally administered corpus separatum for Jerusalem. The Jewish Agency accepted the plan, but the Arab Higher Committee and Arab states rejected it.

The UN vote was immediately followed by the outbreak of the 1947-1948 civil war in Mandatory Palestine between Jewish and Arab militias. As British forces began to withdraw, the fighting intensified. This period saw significant military operations by both sides and the beginning of the Palestinian exodus (Nakba), as hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs fled or were expelled from their homes in areas that would become part of Israel.

3.7. State of Israel

The establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 marked a pivotal moment, leading to immediate conflict and shaping the nation's subsequent political, social, and military trajectory. This section covers the key developments from Israel's founding to the present day.

3.7.1. Establishment and early years

On May 14, 1948, the day before the British Mandate for Palestine was due to expire, David Ben-Gurion, head of the Jewish Agency, proclaimed the establishment of the State of Israel. The United States and the Soviet Union were among the first countries to recognize the new state.

The declaration was immediately followed by the invasion of the former Mandate territory by the armies of five Arab states: Egypt, Transjordan (later Jordan), Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, joined by contingents from other Arab countries. The newly formed Israel Defense Forces (IDF), consolidating various Jewish paramilitary groups, fought against the invading Arab armies and local Palestinian Arab militias. The war, known in Israel as the War of Independence and by Palestinians as the Nakba ("catastrophe"), lasted for over a year.

The 1949 Armistice Agreements were signed between Israel and its neighboring states (Egypt, Lebanon, Transjordan, and Syria), establishing temporary borders known as the Green Line. Israel controlled about 78% of the former Mandate territory, a larger area than allocated under the UN Partition Plan. Jordan annexed the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), and Egypt took control of the Gaza Strip. No Palestinian Arab state was established.

The war had profound demographic consequences. Approximately 700,000 to 750,000 Palestinian Arabs fled or were expelled from the territories that became Israel. Their property was largely confiscated by the new Israeli state. The reasons for the exodus are debated, including Israeli military actions, fear of violence, calls from Arab leaders (a disputed claim), and the collapse of Palestinian Arab society. The Palestinian refugees and their descendants remain a central issue in the ongoing conflict. About 160,000 Palestinian Arabs remained within Israel's borders and became Israeli citizens.

The early years of Israel were characterized by nation-building efforts under a predominantly Labor Zionist government led by David Ben-Gurion. Key developments included:

- Mass Immigration (Aliyah)**: Israel absorbed a massive wave of immigrants, including Holocaust survivors from Europe and over 600,000 Jewish refugees who fled or were expelled from Arab and Muslim countries following the 1948 war. This influx doubled Israel's Jewish population within a few years and placed enormous strain on the new state's resources. Immigrants were often housed in temporary camps called ma'abarot. This mass immigration significantly shaped Israel's diverse society but also led to social and economic challenges, including austerity measures and tensions between different Jewish ethnic groups (Ashkenazi, Mizrahi, Sephardi).

- Establishment of State Institutions**: Israel developed its democratic institutions, including the Knesset (parliament), a judicial system, and a civil service. The Law of Return (1950) granted Jews the right to immigrate to Israel and gain citizenship.

- Economic Development**: The economy was initially fragile, relying on agriculture, reparations from West Germany, and aid from diaspora Jewry.

- Security Challenges**: Ongoing border skirmishes and infiltrations by Palestinian fedayeen were common.

3.7.2. Arab-Israeli conflict

The Arab-Israeli conflict continued to dominate Israel's existence, marked by several major wars and protracted lower-intensity conflicts. The core issues included territorial disputes, the status of Jerusalem, the plight of Palestinian refugees, Israeli security concerns, and Arab states' initial refusal to recognize Israel's legitimacy.

- Suez Crisis (1956)**: Israel, in alliance with Britain and France, invaded Egypt's Sinai Peninsula. The motivations included ending Palestinian fedayeen attacks from Gaza (then Egyptian-controlled) and reopening the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping, which Egypt had blockaded. Under international pressure, particularly from the US and USSR, Israel withdrew from Sinai in 1957, but a UN peacekeeping force (UNEF) was stationed in Sinai and the Straits of Tiran were reopened.

- Six-Day War (1967)**: Following a period of heightened tension, including Egypt's remilitarization of Sinai, expulsion of UNEF, and closure of the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping, along with threatening rhetoric from Arab leaders, Israel launched a preemptive strike against Egypt, Syria, and Jordan. In a swift victory, Israel captured the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip from Egypt, the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) from Jordan, and the Golan Heights from Syria. This war dramatically altered the geopolitical map of the region, placing a large Palestinian population under Israeli military occupation. The UN Security Council passed Resolution 242, calling for Israeli withdrawal from occupied territories in exchange for peace and secure borders.

- War of Attrition (1967-1970)**: A prolonged period of shelling, air battles, and commando raids primarily between Israel and Egypt along the Suez Canal.

- Yom Kippur War (1973)**: Egypt and Syria launched a surprise coordinated attack on Israel on Yom Kippur, the holiest day in Judaism. After initial setbacks, Israel managed to repel the Arab forces and push into their territories. The war had a profound psychological impact on Israel, shattering the sense of invincibility following the 1967 victory. It also paved the way for future peace negotiations, particularly with Egypt.

- Ongoing Conflict with Palestinian Groups**: The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), established in 1964, became the main umbrella organization for Palestinian nationalist groups. From bases in neighboring countries (Jordan, then Lebanon), the PLO and other factions launched attacks against Israeli targets. Notable events include the 1972 Munich Olympics massacre of Israeli athletes by Black September. Israel responded with counter-terrorism operations, including Operation Wrath of God. The conflict with Palestinian groups, including Hamas (founded in 1987) and Islamic Jihad, has continued, marked by uprisings (First and Second Intifadas), rocket attacks from Gaza, and Israeli military operations in the West Bank and Gaza. The humanitarian consequences, particularly for Palestinians living under occupation or blockade, have been severe, including restrictions on movement, economic hardship, and loss of life and property. The plight of Palestinian refugees from 1948 and subsequent conflicts remains a core unresolved issue.

3.7.3. Peace process

Despite the ongoing conflict, various efforts have been made to achieve peace between Israel and its Arab neighbors, as well as with the Palestinians.

- Peace with Egypt (1979)**: Following the Camp David Accords (1978) brokered by U.S. President Jimmy Carter, Israel and Egypt signed a historic peace treaty. This was the first peace treaty between Israel and an Arab state. Israel withdrew from the Sinai Peninsula, which was returned to Egypt. Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

- Peace with Jordan (1994)**: Israel and Jordan signed a peace treaty, normalizing relations and resolving border and water issues.

- Oslo Accords (1993-1995)**: A series of agreements between Israel and the PLO, initiated by secret talks in Oslo, Norway. The Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements (Oslo I, 1993) established mutual recognition between Israel and the PLO and created the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) with limited self-rule in parts of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. This was followed by the Interim Agreement (Oslo II, 1995), which further detailed the arrangements for Palestinian autonomy. Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, Foreign Minister Shimon Peres, and PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The Oslo process generated hope but faced significant challenges, including opposition from extremists on both sides, continued Israeli settlement construction, and Palestinian attacks. The assassination of Rabin in November 1995 by a Jewish extremist was a major blow to the peace process.

- Subsequent Negotiations**: Numerous attempts at further negotiations, such as the 2000 Camp David Summit and the Taba talks (2001), failed to achieve a final status agreement. Issues like borders, Jerusalem, settlements, security, and Palestinian refugees proved intractable. The Arab Peace Initiative (2002), proposed by Saudi Arabia and endorsed by the Arab League, offered Israel full normalization in exchange for withdrawal from occupied territories and a just solution for Palestinian refugees, but it did not lead to a breakthrough.

The peace process has been largely stalled for many years, with periods of intense conflict and violence. The impact on all populations involved has been significant, with cycles of hope and despair. Critics argue that the expansion of Israeli settlements has undermined the viability of a two-state solution.

3.7.4. 21st century

The 21st century has been marked by continued conflict, political shifts within Israel and the Palestinian territories, and evolving regional dynamics.

- Second Intifada (Al-Aqsa Intifada, 2000-2005)**: A major Palestinian uprising that began in September 2000, following a visit by then-opposition leader Ariel Sharon to the Temple Mount. It was characterized by widespread protests, clashes, Israeli military operations, and a significant increase in Palestinian suicide bombings and other attacks against Israelis. Israel responded with military incursions, targeted killings, and the construction of the Israeli West Bank barrier. Thousands were killed on both sides, mostly Palestinians. The Intifada severely damaged the peace process and mutual trust.

- Gaza Disengagement (2005)**: Under Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, Israel unilaterally withdrew its settlements and military forces from the Gaza Strip. This move was controversial within Israel.

- 2006 Lebanon War**: A conflict triggered by a Hezbollah cross-border raid. The war involved intense fighting between Israel and Hezbollah in southern Lebanon and northern Israel, resulting in significant casualties and infrastructure damage on both sides.

- Conflicts in the Gaza Strip**: Following Hamas's takeover of the Gaza Strip in 2007, Israel and Egypt imposed a blockade on the territory. Several major military escalations have occurred:

- Gaza War (2008-2009) (Operation Cast Lead)**

- Operation Pillar of Defense (2012)**

- 2014 Gaza War (Operation Protective Edge)**

- 2021 Israel-Palestine crisis**

These conflicts have caused thousands of deaths, predominantly among Palestinians in Gaza, and widespread destruction. They have also drawn international scrutiny regarding Israeli military conduct and the humanitarian situation in Gaza. Accusations of war crimes have been leveled against both Israel and Hamas.

- Abraham Accords (2020)**: A series of US-brokered agreements leading to the normalization of relations between Israel and several Arab nations: the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Sudan, and Morocco. These accords marked a significant shift in regional diplomacy, though they did not directly address the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

- 2023 Israel-Hamas war**: On October 7, 2023, Hamas launched an unprecedented large-scale surprise attack on southern Israel from the Gaza Strip, involving rocket barrages and infiltrations by militants. Over 1,200 Israelis, mostly civilians, were killed, and around 240 people were taken hostage into Gaza. Israel declared war on Hamas and launched an extensive military campaign in Gaza, involving intense airstrikes and a ground invasion. The war has resulted in tens of thousands of Palestinian deaths, widespread destruction in Gaza, a severe humanitarian crisis, and accusations of genocide against Palestinians being brought against Israel at the International Court of Justice. The conflict also led to escalations on other fronts, including clashes with Hezbollah on the Lebanon border and attacks by Houthi rebels in Yemen on shipping in the Red Sea, as well as an Israeli invasion of Syria.

Throughout the 21st century, social and human rights implications of the ongoing conflict and occupation have remained a critical concern. International human rights organizations and UN bodies have repeatedly criticized Israeli policies, including settlement expansion, the blockade of Gaza, demolitions of Palestinian homes, and the treatment of Palestinians in the occupied territories, sometimes labeling these practices as constituting apartheid.

4. Geography

Israel's diverse geography features a Mediterranean coastal plain, central highlands including Galilee and the Judean Hills, the Jordan Rift Valley with the Dead Sea, and the Negev Desert. The country's location on the Dead Sea Transform fault system results in seismic activity. Climates range from Mediterranean to desert, presenting challenges like water scarcity, which Israel addresses with advanced technology.

4.1. Topography

Israel is situated at the eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea, in the Levant region of the Middle East. It is bordered by Lebanon to the north, Syria to the northeast, Jordan and the West Bank to the east, and Egypt and the Gaza Strip to the southwest. The country also has a short coastline on the Gulf of Aqaba (Gulf of Eilat) at the Red Sea in the south.

Israel's topography can be divided into four main geographical regions:

1. **The Coastal Plain**: This is a fertile, relatively flat strip of land running along the Mediterranean coast from the Lebanese border in the north to the Gaza Strip in the south. It is the most densely populated region of Israel and includes major cities like Tel Aviv, Haifa, and Ashdod. The plain varies in width, being narrower in the north (around Mount Carmel) and widening towards the south. It includes areas like the Sharon Plain and the Jezreel Valley (Emek Yizra'el), which is a large, fertile inland valley extending southeast from Haifa.

2. **The Central Highlands (or Hills and Mountains)**: East of the coastal plain, a range of hills and mountains runs north to south. This region includes:

- Galilee** in the north, divided into Upper Galilee (mountainous, with peaks like Mount Meron, Israel's highest point within its internationally recognized borders) and Lower Galilee (hilly).

- Samarian Hills** (largely corresponding to the northern West Bank).

- Judean Hills** (including Jerusalem) and the Hebron Hills (largely corresponding to the southern West Bank). These highlands are characterized by rocky terrain and terraced agriculture.

3. **The Jordan Rift Valley**: This is a deep depression forming part of the larger Great Rift Valley (Syrian-African Rift). It runs along Israel's eastern border and includes:

- The Hula Valley in the north.

- The Sea of Galilee (Lake Kinneret or Lake Tiberias), Israel's largest freshwater lake and an important water source.

- The Jordan River, which flows south from the Sea of Galilee.

- The Dead Sea, a hypersaline lake that is the lowest point on Earth's land surface (approximately -1412.4 ft (-430.5 m) below sea level). It is shared with Jordan.

- The Arabah valley, extending south from the Dead Sea to the Gulf of Eilat.

4. **The Negev Desert**: This desert region occupies the southern half of Israel, constituting about 60% of the country's land area (within the Green Line). It is characterized by arid and semi-arid conditions, rocky mountains, and erosion craters known as makhteshim (singular: makhtesh), such as Makhtesh Ramon. The northern Negev is more fertile and supports some agriculture, while the southern Negev is extremely arid.

The Golan Heights, occupied by Israel since 1967 and effectively annexed in 1981 (a move not recognized internationally), is a plateau east of the Sea of Galilee, characterized by volcanic soil and higher elevations, including parts of Mount Hermon.

4.2. Geology and seismicity

Israel's geology is largely shaped by its location at the boundary of the African Plate and the Arabian Plate. The most significant geological feature is the Dead Sea Transform (DST) fault system, which is a major transform fault extending from the Red Sea in the south to the Taurus Mountains in Turkey. The Jordan Rift Valley is a direct result of the tectonic movements along this fault. The DST is a left-lateral strike-slip fault, meaning the Arabian Plate is moving northwards relative to the African Plate. This movement has created the deep depression of the Dead Sea and the surrounding rift valley features.

The region experiences significant seismic activity due to the DST. Historically, Palestine has been affected by numerous earthquakes, some of which have been highly destructive. Major historical earthquakes include:

- The earthquake of 749 CE, which caused widespread destruction in Galilee, the Jordan Valley, and beyond, devastating cities like Tiberias, Beit She'an, and Pella.

- The earthquake of 1033 CE, which also caused major damage in the region, including to Jerusalem and Ramla.

- The Galilee earthquake of 1837, which severely damaged Safed and Tiberias.

- The Jericho earthquake of 1927, which caused considerable damage in Jerusalem, Jericho, Nablus, and Tiberias.

Seismic risk remains a concern in modern Israel. The country is located in an active seismic zone, and there is a recognized potential for future damaging earthquakes. Israeli building codes include seismic-resistant design standards, particularly for new constructions. However, many older buildings, especially those constructed before modern codes were implemented, are more vulnerable. Government and research institutions monitor seismic activity and work on preparedness measures, including public awareness campaigns and retrofitting of critical infrastructure. The Geological Survey of Israel plays a key role in seismic research and hazard assessment. The concentration of population and infrastructure along the coastal plain and within the rift valley system increases the potential impact of a major seismic event.

4.3. Climate

Israel has a diverse climate, largely influenced by its location between the temperate Mediterranean zone and arid desert regions. The climate varies significantly from north to south and from the coastal areas to the inland and desert regions. Generally, the country experiences long, hot, dry summers and short, cool, rainy winters.

The main climate zones are:

1. **Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csa)**: This climate characterizes the coastal plain, the northern and central highlands (including Galilee, Samaria, and Judea), and the northern Negev.

- Summers** (April/May to September/October) are hot and dry with abundant sunshine. Coastal areas like Tel Aviv and Haifa experience high humidity, while inland areas like Jerusalem, being at a higher altitude, have warm to hot summers but lower humidity and cooler evenings.

- Winters** (November to March) are mild to cool and rainy. Most of Israel's annual precipitation occurs during this period, typically brought by low-pressure systems moving across the Mediterranean. Snowfall is rare in coastal areas but can occur in higher elevation areas like Jerusalem and the Golan Heights. The highest temperature recorded in Israel was 129.2 °F (54 °C) at Tirat Zvi in the Jordan Valley in 1942.

2. **Semi-arid climate (Köppen BSh)**: This transitional zone is found in areas like the northern Negev (e.g., Beersheba) and parts of the Jordan Valley. It experiences hotter summers and less rainfall than the Mediterranean zone.

3. **Desert climate (Köppen BWh)**: This climate prevails in the southern Negev, the Arava Valley, and the Dead Sea area. Summers are extremely hot and dry, and winters are mild with very little rainfall.

- Precipitation**:

Rainfall is highly seasonal, concentrated in the winter months. Annual precipitation varies greatly by region:

- Northern Galilee and the Golan Heights can receive over 0.0 K in (1.00 K mm) annually.

- The coastal plain and central hills typically receive 20 in (500 mm) to 28 in (700 mm).

- The northern Negev receives around 7.9 in (200 mm) to 12 in (300 mm).

- The southern Negev and Eilat receive very little rainfall, often less than 2.0 in (50 mm) annually.

Droughts are a recurring problem.

- Temperature**:

Temperatures also vary significantly.

- Coastal areas: Summer average highs are around 86 °F (30 °C), winter average highs around 62.6 °F (17 °C).

- Jerusalem (highlands): Summer average highs are around 84.2 °F (29 °C), winter average highs around 53.6 °F (12 °C), with occasional frost and snow.

- Eilat (southern desert): Summer average highs can exceed 104 °F (40 °C), winter average highs around 69.8 °F (21 °C).

- Environmental Challenges**:

- Water Scarcity**: Israel has historically faced water scarcity. It has developed advanced water management technologies, including drip irrigation, water recycling, and large-scale desalination of seawater, which now provides a significant portion of its fresh water.

- Climate Change**: Israel is vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, including rising temperatures, decreased precipitation, increased frequency of extreme weather events (droughts, heatwaves, floods), and sea-level rise affecting coastal areas. These changes pose risks to water resources, agriculture, biodiversity, and public health. The Israeli government acknowledges these threats and has developed national adaptation plans.

- Desertification**: Parts of the semi-arid northern Negev are at risk of desertification.

- Air and Water Pollution**: Urbanization and industrial activity contribute to air and water pollution, though efforts are made to mitigate these issues.

5. Government and politics

Israel is a parliamentary democracy with a President as head of state and a Prime Minister as head of government, leading a multi-party Knesset. Administratively, it is divided into six districts, plus the Israeli-administered Judea and Samaria Area. Citizenship is largely defined by the Law of Return for Jews. The Israeli-occupied territories, including the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Golan Heights, are a major international concern, with settlements widely deemed illegal and leading to accusations of apartheid. Israel maintains complex foreign relations, notably with the United States, and has a technologically advanced military (IDF) and a mixed legal system based on common law, civil law, and Jewish religious law.

5.1. System of government

Israel is a parliamentary democracy. The system is based on the separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches.

- The President (President of the State of Israel)**: The President is the head of state. The role is largely ceremonial and apolitical. The President is elected by the Knesset for a single seven-year term. Duties include signing laws (except those pertaining to presidential powers), appointing judges, the governor of the Bank of Israel, and other officials based on recommendations, granting pardons, and formally assigning the task of forming a government to a Knesset member after elections. The current president is Isaac Herzog.

- The Executive Branch (Government)**: The government is headed by the Prime Minister, who is the head of government. The Prime Minister is typically the leader of the party or coalition that can command a majority in the Knesset. After elections, the President consults with party leaders and tasks a Knesset member (usually the leader of the largest party) with forming a government. The government, once formed, must win a vote of confidence in the Knesset. The Prime Minister and cabinet ministers are responsible to the Knesset and can be removed by a constructive vote of no confidence. The current prime minister is Benjamin Netanyahu.

- The Legislative Branch (Knesset)**: The Knesset is Israel's unicameral parliament. It has 120 members, elected for a four-year term through a system of nationwide proportional representation using party lists. The entire country is a single electoral district. Parties must pass an electoral threshold (currently 3.25% of the total votes) to gain representation. This system often leads to coalition governments, as it is rare for a single party to win an outright majority. The Knesset's functions include legislating, overseeing the government, electing the President and State Comptroller, and can dissolve itself to call early elections.

- Electoral System**: Elections are based on universal suffrage for citizens aged 18 and older. The proportional representation system means that the number of seats a party receives in the Knesset is directly proportional to the percentage of votes it receives nationally (provided it passes the threshold). This system encourages a multi-party landscape.

- Coalition Politics**: Due to the electoral system, Israeli governments are almost always coalitions of several parties. The process of forming a coalition can be complex and involve extensive negotiations over policy agreements and ministerial portfolios. Coalition governments can sometimes be unstable, leading to frequent early elections.

Israel's political culture is characterized by a wide spectrum of political parties, representing diverse ideologies from religious Zionism and secular nationalism to left-wing social democratic and Arab political parties.

5.2. Administrative divisions

Israel is divided into six main administrative districts (מְחוֹזוֹתmeḥozotHebrew; singular: מָחוֹזmaḥozHebrew). These districts are further subdivided into sub-districts (נָפוֹתnafotHebrew; singular: נָפָהnafaHebrew) and natural regions. The districts serve as the primary administrative units for various government services.

The six main districts are:

1. **Northern District**: Capital - Nof HaGalil. Largest city - Nazareth. Includes much of the Galilee region and the Golan Heights (the latter's annexation by Israel is not internationally recognized).

2. **Haifa District**: Capital and largest city - Haifa. Surrounds the major port city of Haifa and includes parts of Mount Carmel.

3. **Central District**: Capital - Ramla. Largest city - Rishon LeZion. Located in the densely populated coastal plain, including the Sharon plain.

4. **Tel Aviv District**: Capital and largest city - Tel Aviv-Yafo. The smallest district by area but the most densely populated, encompassing the Tel Aviv metropolitan area (Gush Dan).

5. **Jerusalem District**: Capital and largest city - Jerusalem. Includes Israel's proclaimed capital, encompassing both West Jerusalem and East Jerusalem (the latter's annexation is not internationally recognized).

6. **Southern District**: Capital - Beersheba. Largest city - Ashdod. The largest district by area, covering the Negev desert and the Arabah valley.

In addition to these six districts, Israel administers the Judea and Samaria Area, which largely corresponds to the West Bank, excluding East Jerusalem. This area is under military administration, and Israeli settlements within it are governed by Israeli civilian law. However, this administration is not recognized internationally as part of Israel's sovereign territory; these are considered occupied territories.

| District | Capital | Largest city | Population (2021 Estimate) | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jews | Arabs | Total | ||||

| Jerusalem | Jerusalem | 802,400 | 389,000 | 1,209,700 | Includes East Jerusalem. As of 2020, this included 361,700 Arabs and 233,900 Jews in East Jerusalem. | |

| North | Nof HaGalil | Nazareth | 641,500 | 811,700 | 1,513,600 | Includes Golan Heights. |

| Haifa | Haifa | 735,200 | 277,600 | 1,092,700 | ||

| Center | Ramla | Rishon LeZion | 2,002,100 | 190,300 | 2,304,300 | |

| Tel Aviv | Tel Aviv | 1,362,900 | 25,200 | 1,481,400 | ||

| South | Beersheba | Ashdod | 982,800 | 303,100 | 1,386,000 | |

| Judea and Samaria Area | Ariel | Modi'in Illit | 455,700 | 900 | 465,400 | Israeli citizens in West Bank settlements; Palestinians under Palestinian National Authority or Israeli military rule are not included in this Israeli citizen count. |

5.3. Israeli citizenship law

Israeli citizenship law is primarily based on two main pieces of legislation: the Law of Return (1950) and the Citizenship Law (1952). These laws reflect Israel's identity as a Jewish state and its historical context of providing a homeland for Jews from around the world.

- Law of Return (חוק השבותHok HashvutHebrew)**: This law grants every Jew the right to immigrate to Israel (make Aliyah) and gain Israeli citizenship. The law defines a Jew as someone born to a Jewish mother or who has converted to Judaism and is not a member of another religion. The right of return also extends to the children, grandchildren, and spouses of Jews, even if they are not themselves Jewish by halakhic (Jewish religious law) standards. This provision was intended to allow families to immigrate together and to provide refuge for those persecuted due to their Jewish ancestry.

- Citizenship Law (1952)**: This law details the various ways Israeli citizenship can be acquired:

- By Return**: Under the Law of Return, as described above. This is the primary means of citizenship for Jewish immigrants.

- By Residence**: This applied to non-Jewish inhabitants, mainly Palestinian Arabs, who were residents of Mandatory Palestine before the establishment of Israel in 1948 and remained within its borders after the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. They had to meet certain criteria, including registration and continuous presence.

- By Birth (Jus sanguinis)**: A person born in Israel to at least one Israeli citizen parent is an Israeli citizen by birth. A person born outside Israel to an Israeli citizen parent also generally acquires citizenship, although there are some limitations regarding transmission through generations born abroad.

- By Naturalization**: Non-Jews can apply for Israeli citizenship through naturalization. Requirements typically include a period of residence in Israel (usually three out of five years), some knowledge of the Hebrew language, renunciation of prior citizenship (unless Israeli law or the other country's law permits dual citizenship), and an oath of allegiance to the State of Israel. Naturalization is granted at the discretion of the Minister of the Interior.

- By Grant**: Citizenship can be granted by the Minister of the Interior in special cases, such as to non-Jewish spouses of Israeli citizens or for individuals who have made a special contribution to the state.

- Implications for Different Population Groups**:

- Jewish Citizens**: The Law of Return provides a privileged path to citizenship for Jews worldwide, reflecting Israel's role as a homeland for the Jewish people.

- Arab Citizens**: Most Arab citizens of Israel acquired citizenship by residence (if they were present in 1948-1952 and met criteria) or by birth. They have full civil and political rights, including the right to vote and be elected to the Knesset. However, they face various forms of discrimination and socio-economic disparities compared to Jewish citizens. The 2018 Nation-State Law, which defines Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people, has been criticized by Arab citizens and others for potentially undermining their status and rights.

- Palestinians in the Occupied Territories**: Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip (occupied since 1967) are generally not Israeli citizens and do not have the right to vote in Israeli national elections, though they are subject to Israeli military rule or significant Israeli control (in the case of Gaza's borders). Residents of East Jerusalem, which Israel annexed (a move not recognized internationally), hold Israeli permanent residency and can apply for Israeli citizenship, though many have not done so for political reasons or due to complexities in the application process.

- Druze and Circassian Citizens**: These minority groups generally serve in the IDF, unlike most Arab citizens who are exempt (though some volunteer).

Dual citizenship is generally permitted in Israel. The citizenship law has been a subject of ongoing political and social debate, particularly concerning issues of national identity, the rights of minorities, and the relationship between Israel's Jewish and democratic character.

5.4. Israeli-occupied territories

Since the Six-Day War in June 1967, Israel has occupied several territories: the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), the Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights (captured from Syria), and formerly the Sinai Peninsula (captured from Egypt, but returned between 1979 and 1982 as part of the Egypt-Israel peace treaty). The status and administration of these territories are highly contentious and central to the Arab-Israeli conflict, particularly the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

- The West Bank**: This territory, located west of the Jordan River, was captured from Jordan in 1967. It is home to a large Palestinian population (around 3 million) and also to over 450,000 Israeli settlers living in numerous settlements and outposts established since 1967. Israel refers to the West Bank as Judea and Samaria, reflecting historical and religious Jewish connections to the land.

- Administration**: Following the Oslo Accords in the 1990s, the West Bank was divided into three areas:

- Area A**: Full civil and security control by the Palestinian National Authority (PNA). Includes major Palestinian cities.

- Area B**: Palestinian civil control and joint Israeli-Palestinian security control. Includes Palestinian villages and rural areas.

- Area C**: Full Israeli civil and security control. Comprises about 60% of the West Bank and includes most Israeli settlements, military areas, and sparsely populated Palestinian land.

- Legal Status**: The international community considers the West Bank to be occupied territory under international law (Fourth Geneva Convention). Israeli settlements are widely regarded as illegal under international law. Israel disputes this legal interpretation, often citing historical claims and security needs. Palestinians in the West Bank are not Israeli citizens and are subject to Israeli military law in Area C and for security matters, while civil matters for Palestinians in Areas A and B are handled by the PNA.

- Administration**: Following the Oslo Accords in the 1990s, the West Bank was divided into three areas:

- East Jerusalem**: Captured from Jordan in 1967, Israel effectively annexed East Jerusalem shortly thereafter, extending its law, jurisdiction, and administration over the area and incorporating it into a unified Jerusalem, which Israel declared its capital. This annexation is not recognized by the international community, which considers East Jerusalem to be occupied territory. Around 230,000 Israeli settlers live in East Jerusalem alongside over 350,000 Palestinians. Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem generally hold Israeli permanent residency status, which allows them to live and work in Israel and access social services, but most are not Israeli citizens.

- The Gaza Strip**: Captured from Egypt in 1967. In 2005, Israel unilaterally disengaged from Gaza, withdrawing its military forces and dismantling its settlements. However, Israel continues to control Gaza's airspace, maritime access, and most of its land borders (along with Egypt controlling the Rafah crossing). Since Hamas took control of Gaza in 2007, Israel has imposed a strict blockade on the territory, severely restricting the movement of people and goods. The international community, including the UN, generally still considers Gaza to be occupied territory due to the extent of Israeli control over its external access and lifelines, despite the absence of a permanent Israeli military presence within the Strip itself. The blockade and repeated military conflicts have led to a severe humanitarian crisis in Gaza, which is home to over 2 million Palestinians.

- The Golan Heights**: Captured from Syria in 1967. In 1981, Israel passed the Golan Heights Law, effectively annexing the territory by applying Israeli law and administration. This annexation is not recognized internationally, and the UN considers the Golan Heights to be Syrian territory occupied by Israel. Approximately 27,000 Israeli settlers live in the Golan Heights, alongside around 24,000 Syrian Druze residents, most of whom have retained Syrian citizenship but hold Israeli permanent residency.

- Israeli Settlements**: The establishment and expansion of Israeli settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem (and formerly in Gaza and Sinai) are a major point of contention. Palestinians view settlements as a violation of international law, an impediment to a future Palestinian state, and a cause of dispossession and fragmentation of their land. The international community, including the United Nations, the European Union, and most countries, generally considers settlements illegal under international law, specifically Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which prohibits an occupying power from transferring parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies. Israel disputes this, arguing that the territories are "disputed" rather than "occupied" in a legal sense that would preclude settlement, or citing historical and security justifications.

The presence of these territories under Israeli control and the ongoing conflict have significant human rights implications for the Palestinian population living there, including restrictions on movement, access to resources, economic development, and exposure to violence.

5.4.1. International opinion

International opinion regarding Israel's policies in the occupied territories, particularly concerning Israeli settlements and the overall occupation, is largely critical. Key aspects include:

- Legality of Settlements**: The overwhelming international consensus, including the United Nations, the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the European Union, and most individual countries, is that Israeli settlements in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Golan Heights are illegal under international law. This position is primarily based on Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which states that "The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies."

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 2334**: Adopted in December 2016, this resolution explicitly states that Israeli settlement activity "constitutes a flagrant violation under international law and a major obstacle to the achievement of the two-State solution and a just, lasting and comprehensive peace." It called on Israel to cease all settlement activities. The resolution passed with 14 votes in favor and one abstention (the United States, then under the Obama administration).

- International Court of Justice (ICJ)**: In its 2004 advisory opinion on the legality of the construction of the Israeli West Bank barrier, the ICJ concluded that settlements established in occupied Palestinian territory were illegal. In its 2024 advisory opinion, the ICJ reaffirmed the illegality of the settlements and stated that Israel's prolonged occupation itself violates international law.

- Status of Occupied Territories**: Most of the international community considers the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip (despite the 2005 disengagement, due to ongoing control over borders, airspace, and maritime access) to be occupied Palestinian territories. The Golan Heights are considered occupied Syrian territory. Consequently, international humanitarian law, particularly the Fourth Geneva Convention, is deemed applicable to Israel's actions in these territories. Israel disputes the de jure applicability of the Fourth Geneva Convention to the West Bank and Gaza, often referring to them as "disputed territories" rather than "occupied," though it states it voluntarily applies the humanitarian provisions of the convention.

- Two-State Solution**: Many countries and international bodies support a two-state solution as the basis for resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which would involve the establishment of an independent, viable Palestinian state alongside Israel, generally based on the 1967 borders with mutually agreed land swaps. Settlement expansion is widely seen as undermining the feasibility of such a solution.

- Stances of Major Countries**:

- United States**: Traditionally a strong ally of Israel, the U.S. has historically considered settlements an obstacle to peace. However, its policy has varied. The Trump administration shifted U.S. policy, stating that settlements were not per se inconsistent with international law and recognized Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights and Jerusalem as Israel's capital. The Biden administration has reverted to a more traditional U.S. stance, criticizing settlement expansion.

- European Union**: The EU consistently states that settlements are illegal under international law and an obstacle to peace, advocating for a two-state solution based on 1967 lines.

- United Nations**: Various UN bodies, including the General Assembly, Security Council, and Human Rights Council, have repeatedly condemned settlement activity and called for Israel's compliance with international law. UNSC Resolution 446 (1979) determined that Israeli settlements have "no legal validity."

- Human Rights Concerns**: International human rights organizations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the Israeli organization B'Tselem frequently report on human rights violations in the occupied territories linked to settlement policies and the occupation, including land confiscation, restrictions on Palestinian movement and development, settler violence, and a discriminatory legal and administrative system.

Israel generally rejects these international legal interpretations regarding settlements and the status of the territories, citing historical Jewish ties to the land, security needs, and its own legal arguments. The discrepancy between Israeli positions and international consensus remains a significant source of diplomatic tension and a major challenge to resolving the conflict.

5.4.2. Apartheid accusations

In recent years, Israel has faced increasing accusations that its policies and practices, particularly in the occupied Palestinian territories but also to some extent towards its Arab minority within Israel, constitute the crime of apartheid under international law. These allegations have been made by prominent international human rights organizations, Israeli human rights groups, United Nations experts, and scholars.

- Key Arguments for Apartheid Accusations**:

Proponents of the apartheid label argue that Israeli policies create a system of domination and oppression by one racial group (Israeli Jews) over another (Palestinians). They point to:

1. **Fragmented Legal and Administrative Regimes**: Different sets of laws and administrative practices apply to Jews and Palestinians living in the same territory (especially in the West Bank), leading to unequal rights and treatment concerning land ownership, building permits, freedom of movement, access to resources, and political participation.

2. **Israeli Settlements**: The establishment and expansion of settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, which are exclusively for Israeli Jews and receive preferential treatment and resources, are seen as a core component of a system designed to entrench Jewish control over land and dispossess Palestinians.

3. **Restrictions on Movement**: The Israeli West Bank barrier, checkpoints, permit systems, and road restrictions severely limit Palestinian freedom of movement, fragmenting Palestinian communities and hindering access to work, education, healthcare, and family.

4. **Gaza Blockade**: The long-standing blockade of the Gaza Strip, which has devastated its economy and created a humanitarian crisis, is cited as an extreme form of control and collective punishment.

5. **Discriminatory Laws and Policies within Israel**: While Arab citizens of Israel have formal citizenship and voting rights, critics point to dozens of laws and policies that directly or indirectly discriminate against them in areas such as land allocation, housing, employment, and political expression. The 2018 Nation-State Law, which enshrines Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people and prioritizes Jewish settlement, has been highlighted as further institutionalizing inequality.

6. **Denial of the Right of Return for Palestinian Refugees**: The continued denial of the right of Palestinian refugees from 1948 and their descendants to return to their homes is contrasted with Israel's Law of Return, which grants Jews worldwide the right to immigrate to Israel.

- Major Reports and Statements**:

- B'Tselem (Israeli human rights organization)**: In January 2021, B'Tselem published a report concluding that Israel maintains "a regime of Jewish supremacy from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea," which it characterized as apartheid.

- Human Rights Watch (HRW)**: In April 2021, HRW released a comprehensive report asserting that Israeli authorities are committing the crimes against humanity of apartheid and persecution against Palestinians.

- Amnesty International**: In February 2022, Amnesty International published a report accusing Israel of imposing a system of apartheid against Palestinians across all areas under its control.

- United Nations Special Rapporteurs**: Several UN Special Rapporteurs on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967 (such as Michael Lynk and Francesca Albanese) have concluded that the situation amounts to apartheid.

- International Court of Justice (ICJ)**: In its 2024 advisory opinion, the ICJ found that Israeli policies in the occupied Palestinian territories, including prolonged occupation and settlement activities, violate international law and involve systematic discrimination against Palestinians, breaching Article 3 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination which pertains to racial segregation and apartheid.

- Israel's Response and Counterarguments**:

The Israeli government and its supporters vehemently reject the apartheid label, arguing that:

- The term is a misapplication of the concept, which originated in the specific context of South Africa.

- Israel is a vibrant democracy that grants equal rights to all its citizens, including its Arab minority, who participate fully in political life.

- Security measures in the occupied territories are necessary responses to terrorism and violence, not instruments of racial domination.

- The situation in the West Bank and Gaza is a complex political conflict, not a racial one, and should be resolved through negotiations.

- Accusations of apartheid are often politically motivated, aimed at delegitimizing Israel and are sometimes seen as antisemitic.

The debate over whether Israel's policies constitute apartheid is highly polarized and has significant political and legal implications. It remains a central and contentious issue in discussions about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and human rights in the region.

5.5. Foreign relations

Israel maintains diplomatic relations with 165 out of 193 UN member states, as well as with the Holy See, Kosovo, the Cook Islands, and Niue. It has 107 diplomatic missions around the world. Countries with which it has no diplomatic relations include most Muslim-majority countries, a legacy of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

- Key Allies and Partners**:

- United States**: The U.S. is Israel's closest and most important ally. The relationship is based on shared democratic values, strategic interests, and strong cultural ties. The U.S. has provided Israel with significant military and economic aid for decades and often plays a key role in diplomatic efforts in the region.

- European Countries**: Israel has strong ties with many European nations, including Germany, France, and the United Kingdom. Relations with the European Union are extensive, governed by an Association Agreement, though often complicated by EU criticism of Israeli policies in the occupied territories. Israel is part of the EU's European Neighbourhood Policy.

- Other Western Nations**: Countries like Australia and Canada also maintain close and friendly relations with Israel.

- Relations with Neighboring Countries and the Arab World**:

- Egypt**: Signed a peace treaty in 1979, the first Arab country to do so. Relations are often described as a "cold peace" but involve security cooperation, particularly concerning Sinai and Gaza.

- Jordan**: Signed a peace treaty in 1994. Cooperation exists on security, water, and other issues, though popular sentiment in Jordan is often critical of Israel.

- Lebanon and Syria**: Israel remains formally in a state of war with both Lebanon and Syria. Borders are tense, with significant conflicts having occurred, particularly the ongoing low-intensity conflict with Hezbollah in Lebanon and issues related to the Golan Heights with Syria.

- Arab-Israeli Normalization (Abraham Accords)**: Beginning in 2020, Israel normalized relations with the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Sudan, and Morocco, brokered by the U.S. These agreements marked a significant shift in regional diplomacy, driven partly by shared concerns about Iran.

- Iran**: Following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Iran became one of Israel's staunchest adversaries. The two countries are engaged in an ongoing proxy conflict across the region, with Iran supporting groups like Hezbollah and Hamas. Israel views Iran's nuclear program as an existential threat.

- Turkey**: Historically, Turkey was one of the first Muslim-majority countries to recognize Israel (1949) and maintained strong ties. However, relations significantly deteriorated in the 21st century, particularly under the AKP government, over issues related to the Palestinians and Israeli policies, though some efforts at rapprochement have occurred.

- Relations with Other Key Countries**:

- Russia**: Relations are complex, balancing cooperation on some issues with disagreements, particularly concerning Syria and Iran. Russia has a large Russian-speaking diaspora in Israel.

- China and India**: Israel has developed increasingly important economic, technological, and, in the case of India, defense ties with both Asian giants.

- African Nations**: Israel has sought to strengthen ties with African countries, focusing on development aid, technology transfer (especially in agriculture and water), and security cooperation.

- International Organizations**:

Israel is a member of the United Nations (since 1949) but often faces criticism and numerous condemnatory resolutions in UN bodies, particularly concerning the Palestinian issue. It joined the OECD in 2010.