1. Overview

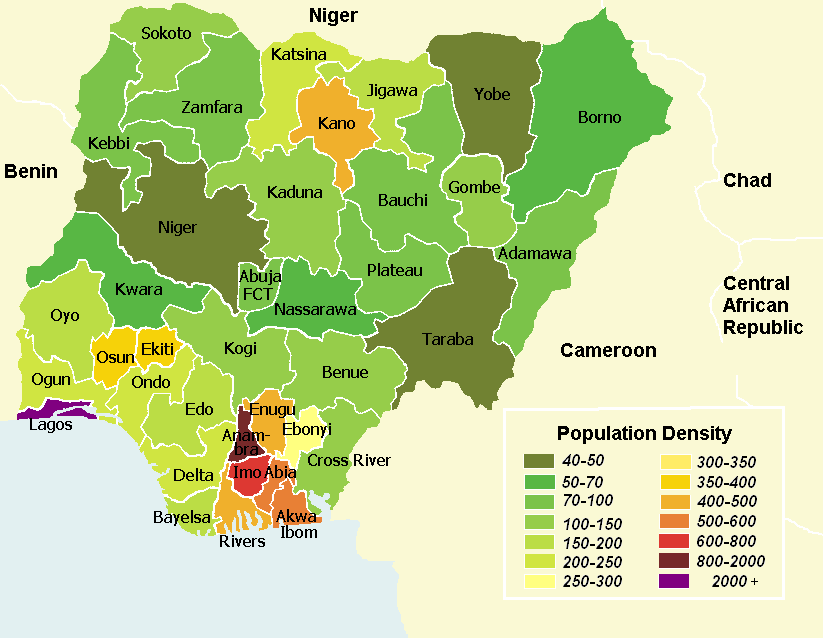

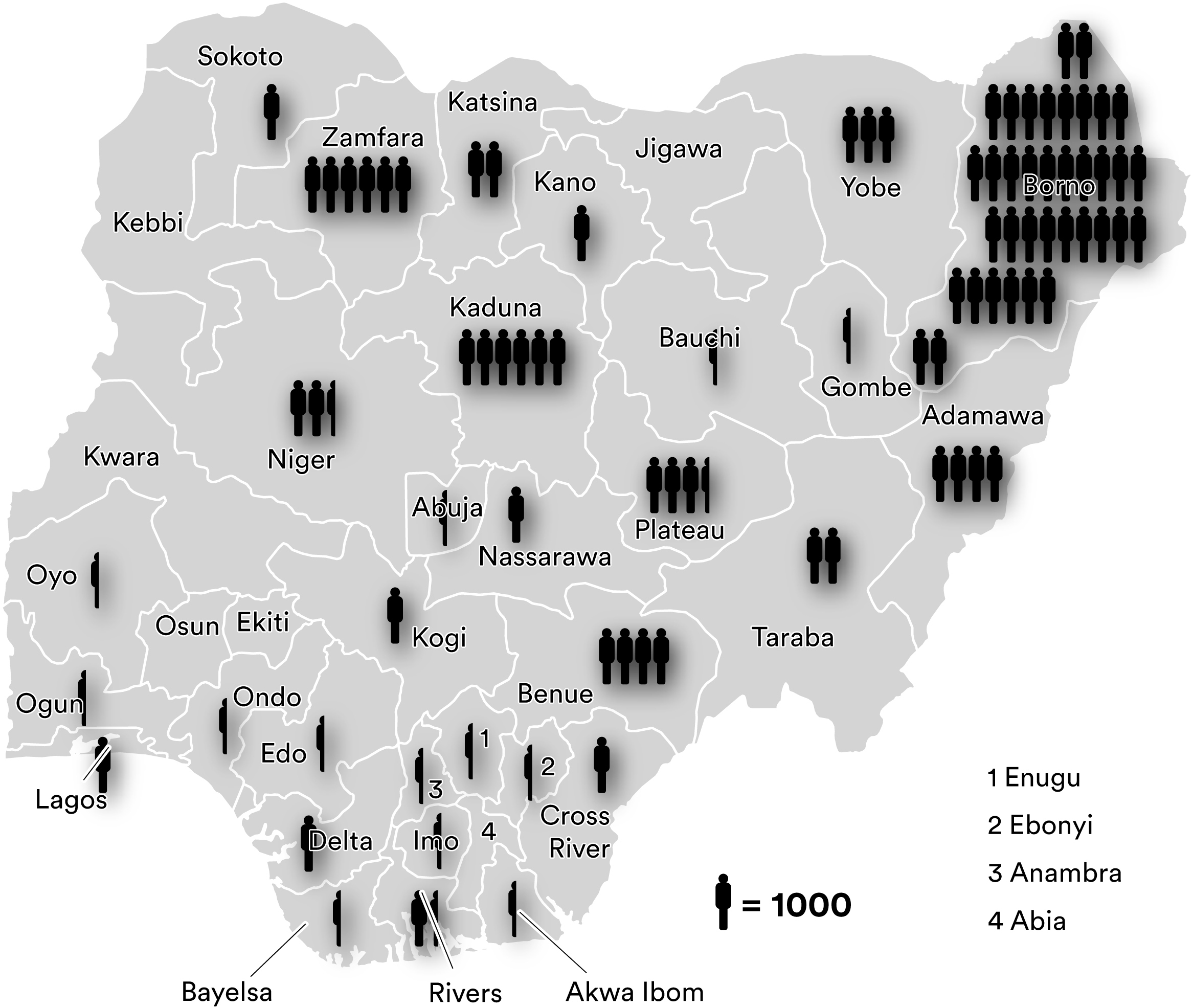

Nigeria (NajeriyaNah-JEH-ree-yahHausa; NaìjíríyàNah-ee-JEE-ree-yahIgbo; NàìjíríàNah-ee-JEE-ree-ahYoruba; NaijáNYE-jahpcm; NaajeeriyaNaa-jeh-ree-yahFulah; NaijeriyaNai-jeh-ree-yahkcg), officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a large and diverse country located in West Africa, bordering Niger to the north, Chad to the northeast, Cameroon to the east, and Benin to the west. Its southern coast lies on the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean. With a population exceeding 230 million, Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa and the world's sixth-most populous. It is a federal republic comprising 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory, where its capital, Abuja, is situated. Lagos, its largest city, is one of the biggest metropolitan areas globally and the largest in Africa.

The nation's geography is varied, featuring tropical rainforests in the south, transitioning to savanna plains in the central regions, and sahelian conditions in the far north. The Niger and Benue Rivers are its most significant waterways, converging to form the vast Niger Delta. Nigeria's history is rich, having been home to numerous indigenous kingdoms and empires like the Nok, Hausa Kingdoms, Kanem-Bornu, Nri, Ife, and Oyo, long before British colonization in the 19th century. The modern state was formed in 1914 with the amalgamation of the Northern and Southern Nigeria Protectorates. Nigeria gained independence in 1960, but its post-colonial history has been marked by periods of military rule, a devastating civil war (the Biafran War, 1967-1970), and persistent struggles for democratic consolidation and good governance. The country returned to democratic rule in 1999, ushering in the Fourth Republic, which continues to face challenges including corruption, electoral integrity, and internal security threats from groups like Boko Haram and herder-farmer conflicts.

Nigeria's economy is the largest in Africa, driven significantly by its vast oil and natural gas reserves, making it a key member of OPEC. However, the economy is diversifying, with growing sectors in agriculture, manufacturing, technology (Nollywood, its film industry, is globally recognized), and services. Despite its economic potential, Nigeria grapples with significant social issues, including widespread poverty, high inequality, and substantial infrastructural deficits. The society is characterized by immense ethnic and linguistic diversity, with over 250 ethnic groups and more than 500 languages. The three largest ethnic groups are the Hausa-Fulani, Yoruba, and Igbo. Religiously, the population is roughly split between Muslims, predominantly in the north, and Christians, mainly in the south, with traditional beliefs also practiced. This vibrant nation continues to strive for unity and progress amidst its complexities, asserting its role as a significant player on the African continent and globally.

2. Etymology

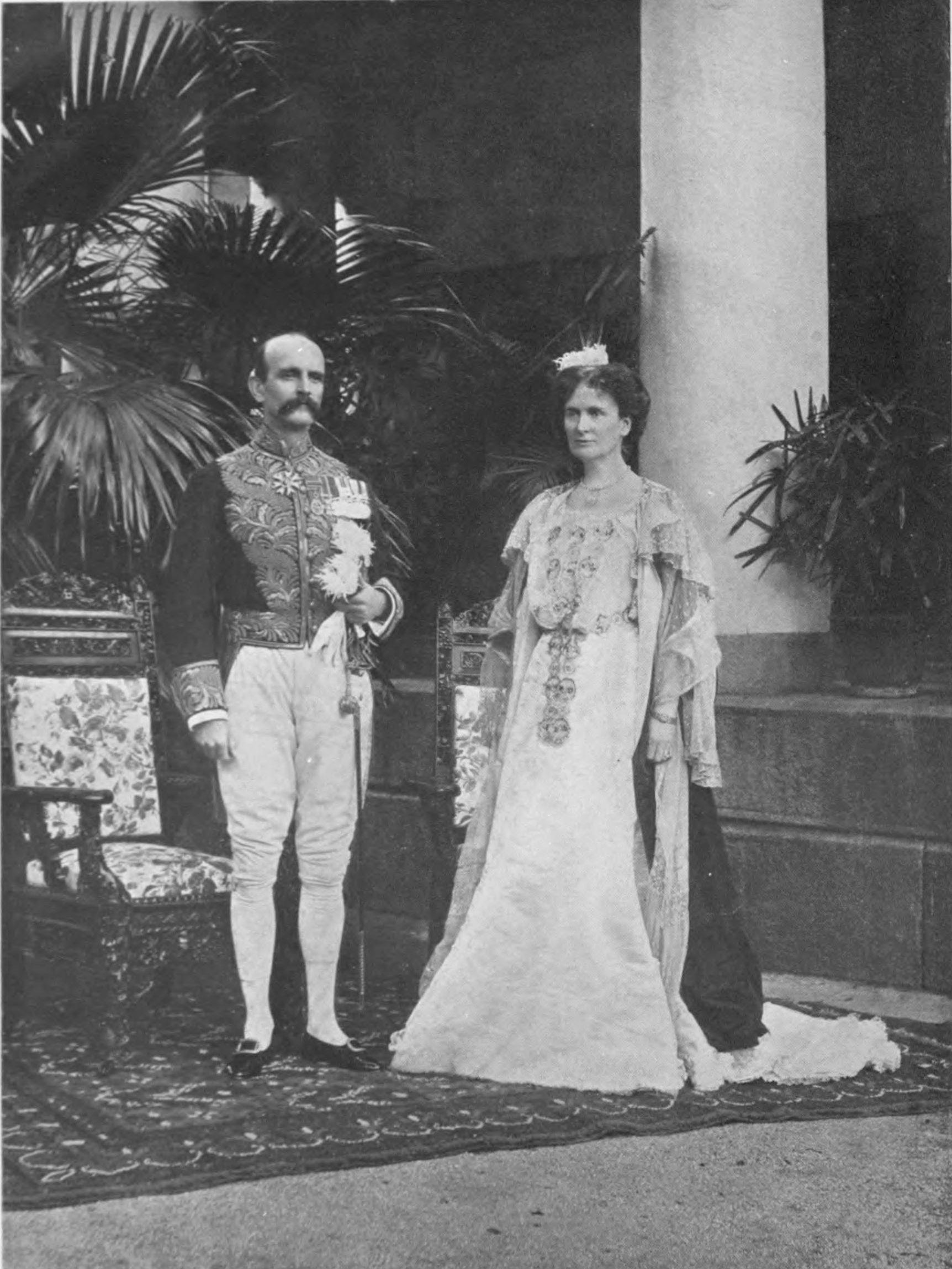

The name Nigeria is derived from the Niger River, which flows through the country. This name was reportedly coined on January 8, 1897, by Flora Shaw, a British journalist who later married Lord Frederick Lugard, a colonial administrator. The neighboring Republic of Niger also takes its name from the same river.

The origin of the name Niger itself, which originally applied only to the middle reaches of the Niger River, is uncertain. It is likely an alteration of the Tuareg name egerew n-igerewen, meaning "river of rivers" or "great river," used by inhabitants along the middle reaches of the river around Timbuktu before 19th-century European colonialism. The Arabic name for the river, nahr al-anhur, is a direct translation of the Tuareg term. While sometimes linked by folk etymology to the Latin word niger (meaning "black"), this connection is not considered accurate, though the spelling might have been influenced by it.

Before Flora Shaw suggested the name Nigeria, other proposed names for the territory included Royal Niger Company Territories, Central Sudan, Niger Empire, Niger Sudan, and Hausa Territories.

3. History

Nigeria's history encompasses ancient civilizations like the Nok, early kingdoms such as Ife and Benin, the era of the trans-Atlantic slave trade significantly impacting its societies, and subsequent British colonization leading to the amalgamation of diverse regions in 1914. Independence in 1960 was followed by periods of military rule, a civil war, and a challenging transition to the current democratic Fourth Republic.

3.1. Prehistory

Early human settlements in Nigeria date back thousands of years. Archaeological evidence from various sites across the country indicates long-standing human presence and cultural development. Excavations at Kainji Dam revealed evidence of ironworking by the 2nd century BC. The transition from the Neolithic period (New Stone Age) to the Iron Age in this region appears to have occurred without an intermediate Bronze Age. Some earlier theories suggested that iron technology moved west from the Nile Valley. However, more recent research indicates that the Iron Age in the Niger River valley and the forest region may predate the introduction of metallurgy in the upper savanna by more than 800 years and possibly also predates it in the Nile Valley. Some scholars now propose that iron metallurgy was developed independently in sub-Saharan Africa.

The Nok culture is one of the most significant prehistoric civilizations in Nigeria, flourishing between approximately 1500 BC and AD 200 in the area of modern-day central Nigeria. The Nok civilization is renowned for its life-sized terracotta figures, which are among the earliest known sculptures in sub-Saharan Africa. These sophisticated artworks display a high level of artistic skill and often depict human heads, figures, and animals with distinctive stylistic features, such as triangular or semi-circular eyes and elaborate hairstyles or headdresses.

Beyond their artistic achievements, the Nok people were also early practitioners of iron smelting. Evidence of iron smelting has been found at Nok sites dating to around 550 BC, and possibly even a few centuries earlier. This makes the Nok culture one of the earliest Iron Age societies in West Africa. Archaeological findings in the Nsukka region of southeastern Nigeria, specifically at the site of Lejja, suggest even earlier iron smelting, possibly dating back to 2000 BC, and at the site of Opi, to around 750 BC. The societal structures of these early cultures are inferred from archaeological findings, suggesting settled agricultural communities with complex social organization and artistic traditions.

3.2. Early Kingdoms and Empires

Prior to European colonization, the territory of modern-day Nigeria was home to a diverse array of sophisticated kingdoms, empires, and city-states, each with unique political, social, and cultural characteristics.

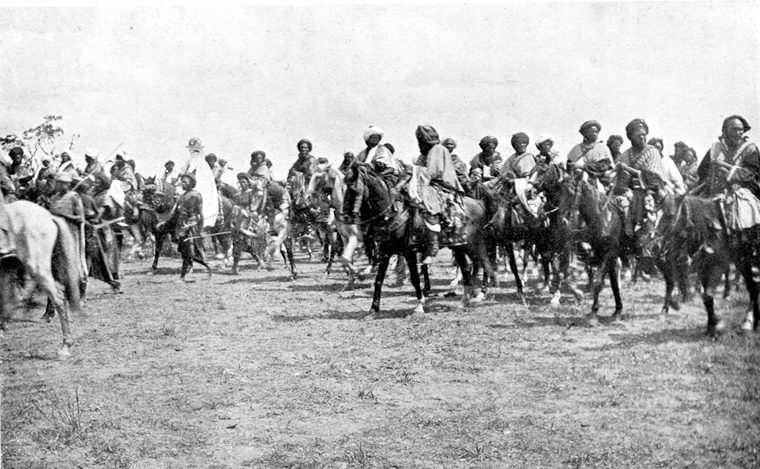

In the north, the Hausa Kingdoms (Hausa Bakwai) emerged as prominent centers of trade and Islamic learning. Cities like Kano, Katsina, Zazzau (Zaria), Daura, Hadeija, Rano, and Gobir had recorded histories dating back to the 10th century. The Kano Chronicle details an ancient history for Kano dating to around 999 AD. With the spread of Islam from the 7th century AD, the region became known as Sudan or Bilad Al Sudan (Land of the Blacks). These kingdoms participated extensively in the trans-Saharan trade, connecting West Africa with North Africa, the Middle East, and Europe.

The Kanem-Bornu Empire, centered around Lake Chad, was another major power in the region, flourishing for centuries as a center for Islamic civilization and trade. Its influence extended over a vast area, including parts of modern-day Nigeria, Niger, Chad, and Cameroon.

In southeastern Nigeria, the Kingdom of Nri, an Igbo state, consolidated in the 10th century and continued until its sovereignty was lost to the British in 1911. Nri was ruled by the Eze Nri, and the city of Nri is considered the foundation of Igbo culture. Nri and Aguleri, where the Igbo creation myth originates, are in the territory of the Umeuri clan, who trace their lineage to the patriarchal king-figure Eri. The oldest bronzes in West Africa made using the lost-wax process were found at Igbo-Ukwu, a city under Nri influence, dating to the 9th century AD. These artifacts demonstrate a highly developed artistic and metallurgical tradition.

In southwestern Nigeria, the Yoruba established powerful city-states and kingdoms. Ife became prominent in the 12th century and is traditionally regarded as the cradle of Yoruba civilization. It is renowned for its naturalistic terracotta and bronze sculptures, considered masterpieces of African art. The oldest signs of human settlement at Ife's current site date back to the 9th century. The Oyo Empire emerged in the 14th century and, by the 17th and 18th centuries, grew to become one of the largest and most powerful states in West Africa, extending its influence from western Nigeria to modern-day Togo.

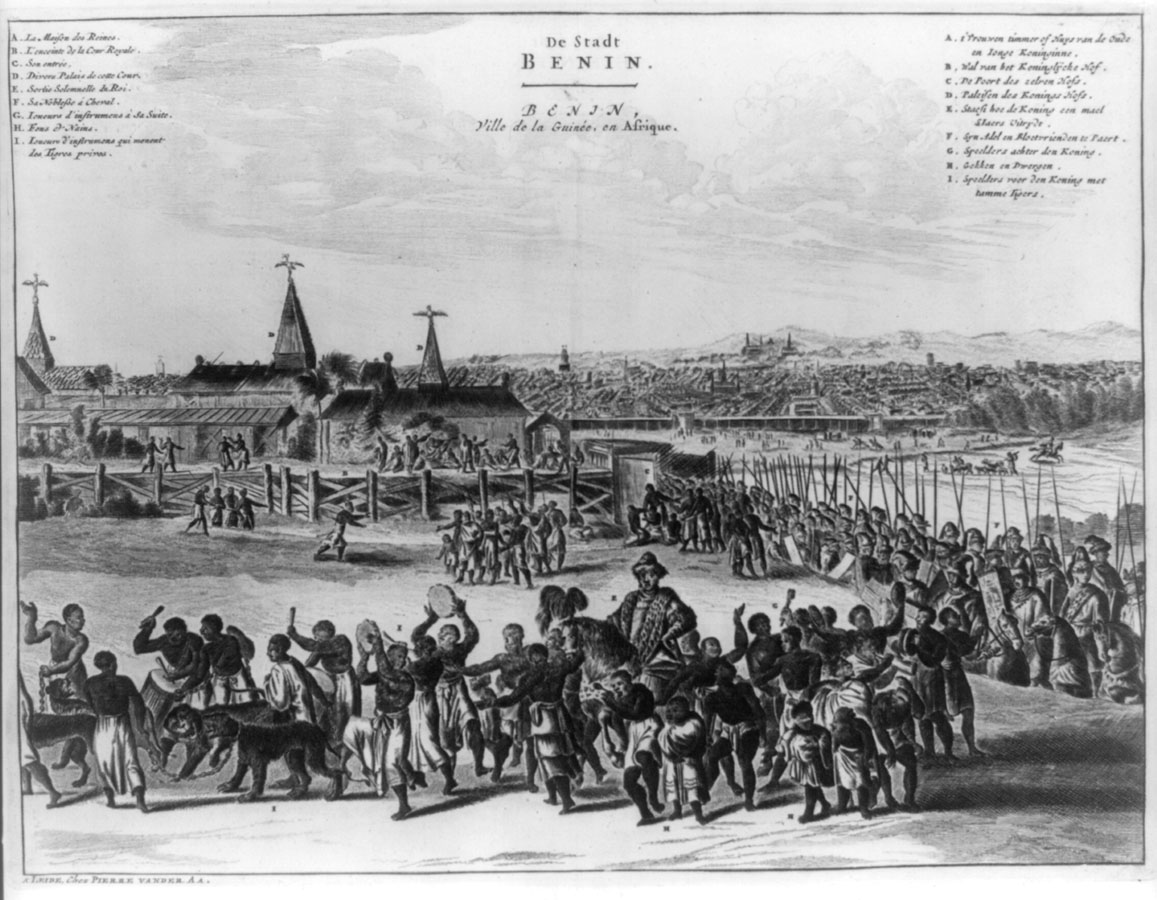

In the south, the Edo Kingdom of Benin (not to be confused with the modern Republic of Benin) became a significant power from the 15th century. Known for its intricate bronze plaques, ivory carvings, and well-organized political structure centered on the Oba (king), Benin City was a major center of trade and culture.

These early kingdoms and empires developed complex systems of governance, trade networks, artistic traditions, and societal norms, laying the foundations for the rich cultural tapestry of modern Nigeria. Their interactions, rivalries, and periods of dominance shaped the historical landscape of the region long before European contact.

3.3. Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and European Contact

European contact with the peoples of what is now Nigeria began in the late 15th century. Portuguese explorers were the first Europeans to establish significant, direct trade with the coastal communities, particularly at the port they named Lagos (originally Eko) and in Calabar, along the region that became known as the Slave Coast. Initially, trade focused on goods like pepper, ivory, and gold, but it soon became dominated by the Atlantic slave trade.

The development of the trans-Atlantic slave trade had a devastating and transformative impact on local societies. European traders, including the Portuguese, British, Dutch, and French, established trading posts along the coast and relied on local African intermediaries and rulers to supply enslaved people. Many of these individuals were captured in wars, raids, or through kidnapping. Powerful coastal and hinterland kingdoms and states, such as the Oyo Empire, the Benin Empire, and the Aro Confederacy in the southeast, became deeply involved in the slave trade, which brought them wealth and European goods, including firearms, in exchange for human lives. The port of Calabar on the historical Bight of Biafra (now Bight of Bonny), Badagry, Lagos, and Bonny Island became major slave-trading posts.

The slave trade led to widespread depopulation in some areas, increased warfare and instability among African states, and profound social disruption. It reoriented local economies towards slaving and fundamentally altered social structures. While some African elites profited, the overall impact on the societies involved was largely negative, fostering an environment of violence and mistrust. Millions of Africans were forcibly removed from their homes and transported across the Atlantic under brutal conditions.

The legal imperative to abolish the slave trade began in the early 19th century, with Britain outlawing the Atlantic slave trade in 1807. The West Africa Squadron of the British Royal Navy was established to patrol the coast and intercept slave ships. Rescued slaves were often taken to Freetown in Sierra Leone, a colony established for resettling freed slaves. Despite the ban, illegal slave trading continued for several decades, perpetrated by smugglers and some local slavers who resisted the change.

As the slave trade declined, European interest shifted towards "legitimate" trade in agricultural products like palm oil, which was in demand for European industries. This shift also marked a new phase in European engagement with the region, eventually leading to increased political intervention and colonization in the latter half of the 19th century. Early European interactions were largely confined to coastal areas, but missionaries, traders, and explorers gradually began to penetrate the interior, setting the stage for colonial conquest.

3.4. British Colonization

The process of British colonization in Nigeria unfolded throughout the 19th century and into the early 20th century, transforming diverse kingdoms and societies into a single colonial entity.

British intervention intensified in the mid-19th century. In 1851, Britain bombarded Lagos, deposing the slave-trade-friendly Oba Kosoko and installing the more amenable Oba Akitoye. This was followed by the Treaty between Great Britain and Lagos in 1852, which aimed to suppress the slave trade. In August 1861, Britain annexed Lagos as a Crown Colony through the Lagos Treaty of Cession. British missionaries expanded their operations inland, and in 1864, Samuel Ajayi Crowther became the first African bishop of the Anglican Church.

The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, where European powers partitioned Africa, recognized British claims to a sphere of influence in the Niger area. In 1886, the British government chartered the Royal Niger Company, led by Sir George Taubman Goldie. The company was granted political and economic control over vast territories along the Niger River, effectively acting as an agent of British imperialism. It used its private army to subjugate independent southern kingdoms and consolidate British commercial interests. Notable conquests included the defeat of the Benin Empire in 1897 (the Benin Expedition of 1897) and the defeat of the Aro Confederacy in the Anglo-Aro War (1901-1902).

In 1900, the Royal Niger Company's territory came under the direct control of the British government. The Southern Nigeria Protectorate was established, incorporating the former Niger Coast Protectorate and territories previously administered by the company.

Simultaneously, the British pushed northwards into the Sokoto Caliphate. Lord Frederick Lugard, a key figure in British colonial expansion, led this effort. By exploiting rivalries among emirs and the central Sokoto administration, Lugard's forces gradually advanced. After the Battle of Kano in 1903, the British gained a logistical advantage. On March 13, 1903, the vizier of the Caliphate officially conceded to British rule in Sokoto. The British appointed Muhammadu Attahiru II as the new Caliph, abolishing the Caliphate but retaining the title of Sultan as a symbolic position within the newly organized Northern Nigeria Protectorate. Remnants of this structure became the Sokoto Sultanate Council. By 1906, most organized resistance to British rule had ended.

3.4.1. Amalgamation of 1914

On January 1, 1914, Lord Lugard, then Governor of both protectorates, formally united the Southern Nigeria Protectorate and the Northern Nigeria Protectorate into the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria. This amalgamation was primarily for administrative convenience and economic efficiency from the British perspective, merging the disparate regions into a single political entity. However, it brought together diverse ethnic groups with different histories, cultures, political systems, and levels of exposure to Western influence, without significant consultation with the local populations.

Administratively, Nigeria remained divided into the Northern and Southern Provinces (the former protectorates) and Lagos Colony. The British implemented a system of indirect rule, particularly in the North, governing through existing traditional rulers and institutions. This system preserved the authority of emirs and chiefs, who collected taxes and maintained order on behalf of the colonial administration. In the South, where centralized traditional authorities were less common or weaker (especially in Igboland), indirect rule was often more challenging to implement and sometimes involved the creation of "warrant chiefs."

The amalgamation had profound long-term implications for Nigeria's national unity and governance. It created a large, complex country with significant internal divisions. The differing administrative approaches in the North and South (e.g., the encouragement of Christian missions and Western education in the South versus their restriction in parts of the North to preserve Islamic traditions) exacerbated regional disparities. These historical divisions and the structure of the amalgamated state have continued to influence Nigerian politics and society, contributing to challenges in forging a unified national identity and equitable power-sharing. The socio-economic consequences of colonial rule included the development of infrastructure geared towards resource extraction (e.g., railways for transporting cash crops), the introduction of a cash economy, and changes in land tenure and labor systems.

3.4.2. Path to Independence

The early 20th century saw the rise of Nigerian nationalism, fueled by several factors: the spread of Western education, exposure to democratic ideals, dissatisfaction with colonial rule, the experiences of Nigerian soldiers in World Wars I and II, and global anti-colonial sentiments. Early nationalist movements were often led by educated elites who sought greater participation in governance and, eventually, self-rule.

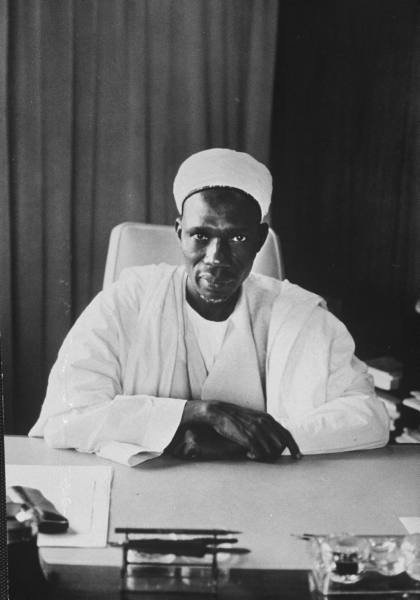

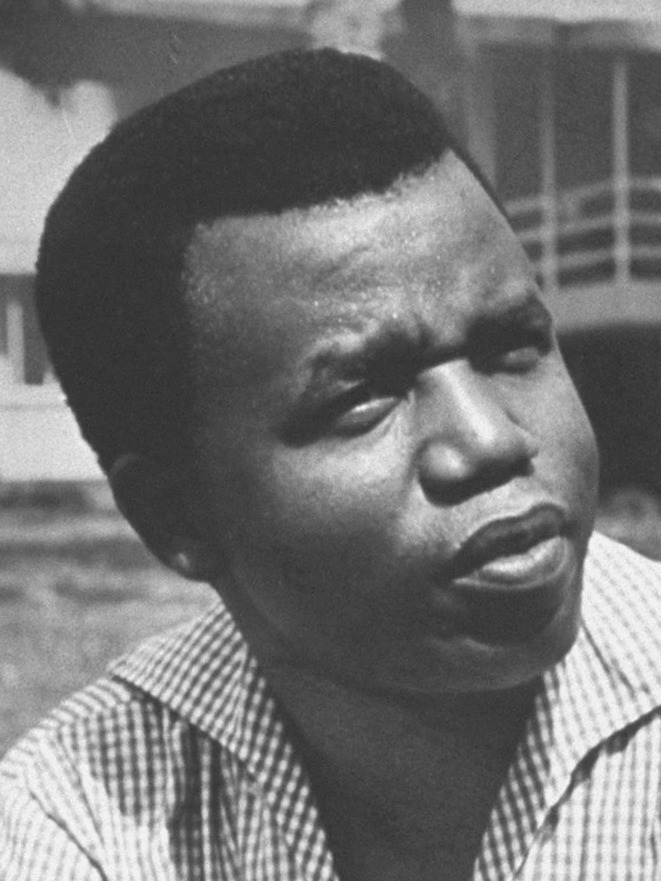

Pioneering figures like Herbert Macaulay founded the Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP) in 1923, which dominated Lagos politics. The Nigerian Youth Movement (NYM), formed in the 1930s, had a broader national outlook. The post-World War II era witnessed a surge in nationalist activities. New political parties emerged, often with strong regional and ethnic bases. Key among these were the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC), led by Nnamdi Azikiwe (popular in the East); the Action Group (AG), led by Obafemi Awolowo (dominant in the West); and the Northern People's Congress (NPC), led by Sir Ahmadu Bello (representing Northern interests).

These parties and nationalist leaders used newspapers, political rallies, and constitutional negotiations to press for reforms and independence. A series of constitutions introduced by the British government (e.g., the Richards Constitution of 1946, the Macpherson Constitution of 1951, and the Lyttelton Constitution of 1954) progressively granted more autonomy and moved Nigeria towards a federal system of government. These constitutional developments involved complex negotiations over regional representation, revenue allocation, and the timeline for independence.

Regional differences in educational access, economic development, and political outlook posed challenges to unified nationalist efforts. However, the common goal of ending colonial rule eventually brought diverse groups together. By the late 1950s, the momentum for independence was unstoppable. Nigeria achieved a degree of self-rule in 1954 and full independence from the United Kingdom on October 1, 1960.

3.5. Independence and First Republic

Nigeria gained full independence from the United Kingdom on October 1, 1960, as the Federation of Nigeria. It initially retained the British monarch, Elizabeth II, as nominal head of state and Queen of Nigeria, represented by a Governor-General. Nnamdi Azikiwe became the first indigenous Governor-General in November 1960. Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa of the Northern People's Congress (NPC) became the first Prime Minister.

The government of the First Republic (1960-1963 as a monarchy, 1963-1966 as a republic) was a parliamentary democracy based on the Westminster system. In 1963, Nigeria adopted a republican constitution, and Nnamdi Azikiwe became the country's first President, a largely ceremonial role, while Balewa continued as Prime Minister with executive power.

The founding government was a coalition primarily between the conservative NPC, dominated by Northern Muslims, and the NCNC, largely supported by Igbos and Christians from the Eastern Region. The opposition was formed by the comparatively liberal Action Group (AG), led by Obafemi Awolowo, which was largely dominated by the Yoruba of the Western Region.

Early challenges of nation-building and governance were immense. Cultural and political differences among Nigeria's dominant ethnic groups - the Hausa-Fulani in the North, Igbo in the East, and Yoruba in the West - were sharp and often led to political tensions. Issues of regionalism, revenue allocation from resources, and census controversies (which determined parliamentary representation and resource distribution) plagued the First Republic. A 1961 plebiscite resulted in Southern Cameroons opting to join the Republic of Cameroon, while Northern Cameroons chose to remain part of Nigeria. This further altered the regional balance, making the Northern Region geographically larger than the Southern regions combined.

Political crises, including a contentious census in 1962-63, a controversial federal election in 1964, and widespread violence and electoral malpractice in the Western Region election of 1965 (the "Wild, Wild West" crisis), eroded public trust in the political system. Perceptions of corruption, ethnic favoritism, and political instability grew. These challenges, coupled with the disequilibrium in the polity, ultimately led to the collapse of the First Republic through a military coup in January 1966, setting the stage for a long period of military rule and civil war. The period highlighted the difficulties of forging national unity and democratic institutions in a diverse and newly independent nation.

3.6. Civil War and Military Rule

The period following the collapse of the First Republic was characterized by profound political instability, military coups, the devastating Nigerian Civil War (also known as the Biafran War), and subsequent prolonged military dictatorships. This era had a deep and lasting impact on Nigeria's democratic development, human rights, and national psyche.

The first military coup occurred in January 1966, led primarily by young, mostly Igbo officers under Majors Emmanuel Ifeajuna, Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu, and Adewale Ademoyega. The coup plotters assassinated key political leaders, including Prime Minister Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, Northern Premier Sir Ahmadu Bello, and Western Premier Samuel Akintola. The coup was justified by its leaders as a move against corruption and political mismanagement, but its ethnically skewed nature (most victims were Northern or Western leaders, while key Igbo leaders were spared) led to accusations of an Igbo-led plot. The coup plotters failed to consolidate power, and Senate President Nwafor Orizu handed over government control to the Army Commander, Major General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi, an Igbo officer.

Aguiyi-Ironsi's regime attempted to unify the country by abolishing the federal system in favor of a unitary state (Decree No. 34), a move that was deeply unpopular, especially in the North, as it was perceived as a consolidation of Igbo power. In July 1966, a counter-coup, largely orchestrated by Northern military officers, overthrew Aguiyi-Ironsi (who was assassinated). Lieutenant Colonel (later General) Yakubu Gowon, a Northerner from a minority ethnic group, became the head of state. The counter-coup was followed by widespread pogroms against Igbos living in Northern cities, leading to the deaths of thousands and the flight of many more Igbos back to the Eastern Region, their homeland. This significantly heightened ethnic tensions and set the stage for secession.

3.6.1. Nigerian Civil War (Biafran War)

In response to the massacres and the perceived inability of the federal government to protect them, the Military Governor of the Eastern Region, Lieutenant Colonel Emeka Ojukwu, declared the independence of the Eastern Region as the Republic of Biafra on May 30, 1967. The federal government rejected the secession, and the Nigerian Civil War began on July 6, 1967, when federal forces attacked Biafra.

The war lasted for 30 grueling months, until January 1970. It was characterized by intense fighting and a federal blockade of Biafra, which led to widespread starvation and a humanitarian crisis, particularly affecting children. Images of starving Biafran children garnered international attention and sympathy. Estimates of the death toll, mostly civilians from famine and disease, range from one to three million people.

The war had significant international dimensions. Britain and the Soviet Union were the main military backers of the Nigerian federal government, with Egypt providing air support. France, Israel, Portugal, South Africa, and Rhodesia provided varying degrees of support to Biafra. The Congolese government under Mobutu Sese Seko strongly supported the Nigerian federal government and deployed troops against the secessionists. African nations were divided, though the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) largely supported Nigerian territorial integrity.

Biafra surrendered on January 15, 1970. Gowon's government declared a policy of "no victor, no vanquished" and focused on reconciliation, rehabilitation, and reconstruction. While this policy helped to reintegrate the Igbo people into Nigeria, the war left deep scars on national cohesion and trust. The conflict highlighted the fragility of the Nigerian state and the severe consequences of unresolved ethnic and political grievances. The humanitarian impact was immense, and the memory of the war continues to influence Nigerian politics and identity.

3.6.2. Successive Military Regimes

Following the civil war, Nigeria experienced an oil boom in the 1970s, which brought substantial revenue but also exacerbated corruption and economic mismanagement. Despite the wealth, improvements in living standards for the majority of Nigerians were limited, and investment in critical infrastructure was often inadequate.

General Gowon's regime was overthrown in a bloodless coup in July 1975, led by Generals Shehu Musa Yar'Adua and Joseph Nanven Garba. General Murtala Muhammed became the head of state, with General Olusegun Obasanjo as his second-in-command. Murtala's government initiated popular anti-corruption campaigns and plans for a return to civilian rule. However, Murtala Muhammed was assassinated in a failed coup attempt in February 1976 led by Colonel Buka Suka Dimka. General Olusegun Obasanjo then became head of state and continued the program for transition to democracy.

Obasanjo peacefully transferred power to a civilian government under President Shehu Shagari in 1979, marking the beginning of the Second Nigerian Republic. However, this civilian rule was short-lived. The Shagari government was widely viewed as corrupt and ineffective, and was overthrown in a military coup on December 31, 1983, which brought Major General Muhammadu Buhari to power.

Buhari's regime, known for its "War Against Indiscipline," was itself overthrown in a coup in August 1985 by General Ibrahim Babangida. Babangida's regime (1985-1993) was marked by complex political maneuvering, promises of a return to democracy that were repeatedly postponed, and significant economic liberalization programs under the Structural Adjustment Program (SAP), which had harsh social consequences. His annulment of the June 12, 1993 presidential election, widely believed to have been won by Chief Moshood Abiola, plunged the country into a deep political crisis. Babangida "stepped aside" in August 1993, appointing an Interim National Government (ING) headed by Ernest Shonekan.

The ING was overthrown in November 1993 by General Sani Abacha, whose regime (1993-1998) became one of the most brutal and corrupt in Nigeria's history. Abacha suppressed all opposition, detained political activists (including Abiola, who died in detention in 1998), and oversaw widespread human rights abuses. The execution of environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight other Ogoni leaders in 1995 led to Nigeria's suspension from the Commonwealth. Abacha died suddenly in June 1998.

His successor, General Abdulsalami Abubakar, initiated a swift transition to civilian rule. A new constitution was adopted, and elections were held. These prolonged periods of military dictatorship severely undermined democratic institutions, fostered a culture of impunity and corruption, and led to significant human rights violations, stunting Nigeria's political and social development.

3.7. Fourth Republic (Return to Democracy)

The death of General Sani Abacha in June 1998 paved the way for a transition back to democratic rule. His successor, General Abdulsalami Abubakar, initiated a rapid program for the return to civilian government. A new constitution was promulgated in May 1999, and multi-party elections were organized.

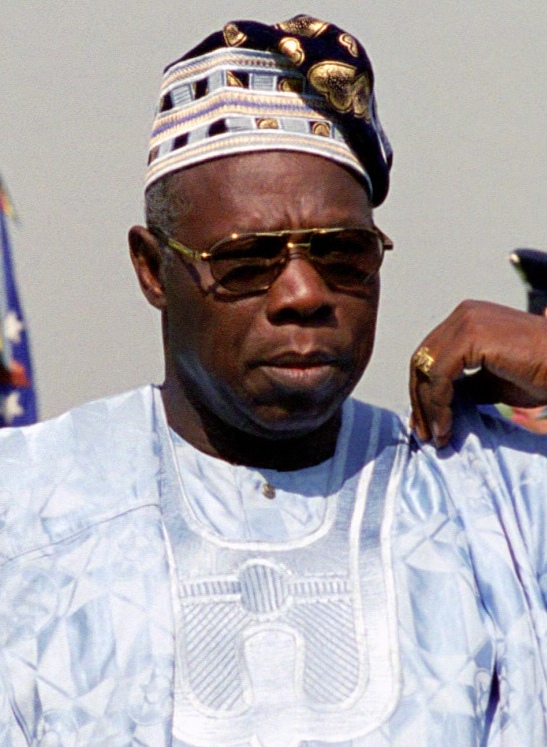

On May 29, 1999, Olusegun Obasanjo, a former military head of state who had been imprisoned under Abacha, was sworn in as President, heralding the beginning of the Fourth Nigerian Republic. This marked an end to 16 years of continuous military rule and was met with optimism both domestically and internationally. Obasanjo, representing the People's Democratic Party (PDP), served two terms, winning re-election in the 2003 elections. While these elections, and subsequent ones, faced criticism regarding fairness and irregularities, Nigeria made strides in democratic consolidation under Obasanjo. His administration focused on economic reforms, anti-corruption efforts (though with mixed success), and restoring Nigeria's international standing.

In the 2007 general elections, Umaru Musa Yar'Adua, also of the PDP, succeeded Obasanjo. These elections were widely condemned by international observers as seriously flawed. Yar'Adua's presidency was marked by his "seven-point agenda" focusing on power and energy, food security, wealth creation, transport, land reforms, security, and education. He also initiated an amnesty program for militants in the Niger Delta. However, Yar'Adua suffered from ill health for much of his term and died on May 5, 2010.

Vice President Goodluck Jonathan had been sworn in as Acting President three months prior and formally succeeded Yar'Adua. Jonathan won the 2011 presidential election, which was generally considered an improvement in electoral integrity compared to previous polls. His administration oversaw significant economic growth, with Nigeria rebasing its GDP to become Africa's largest economy. However, his tenure was also plagued by accusations of widespread corruption, particularly in the oil sector, and a significant escalation of the Boko Haram insurgency in the northeast, including the infamous Chibok schoolgirls kidnapping in 2014.

Ahead of the 2015 general election, a coalition of major opposition parties formed the All Progressives Congress (APC). The APC's candidate, Muhammadu Buhari, a former military head of state, defeated the incumbent Jonathan. This election was historic as it marked the first time an incumbent president had lost re-election in Nigeria. The transition was peaceful, with Jonathan conceding defeat, a move widely praised for strengthening democratic norms.

Buhari was re-elected in the 2019 presidential election. His presidency focused on combating corruption, improving security, and diversifying the economy. However, Nigeria continued to face significant challenges, including ongoing insecurity from Boko Haram and banditry, economic difficulties, and social tensions.

The 2023 presidential election saw Bola Tinubu of the APC emerge as the winner, succeeding Buhari. The election was notable for the strong showing of a third-party candidate, Peter Obi of the Labour Party, particularly among young and urban voters, indicating a shifting political landscape. The results were contested by opposition candidates, but Tinubu's victory was upheld by the courts. His inauguration took place on May 29, 2023.

The Fourth Republic, while representing a sustained period of civilian rule, continues to grapple with issues of consolidating democratic institutions, ensuring electoral integrity, combating corruption, addressing insecurity, and promoting equitable economic development for its large and diverse population. The journey towards stable and effective democratic governance remains an ongoing process, marked by both progress and persistent challenges.

4. Geography

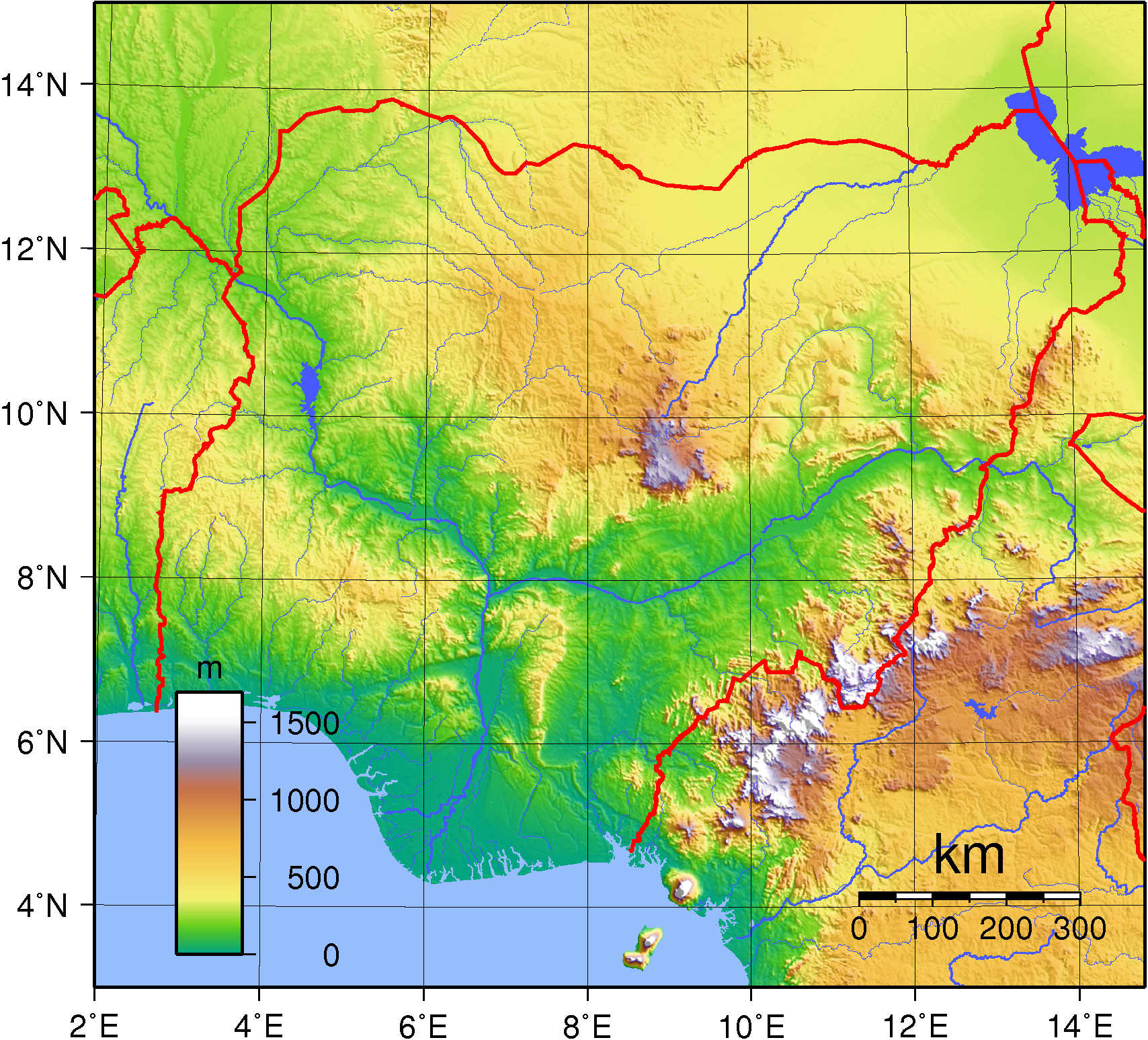

Nigeria is situated in West Africa, sharing land borders with Benin, Niger, Chad, and Cameroon, and has a southern coastline on the Gulf of Guinea. Its varied topography ranges from southern coastal plains and the vast Niger Delta to central highlands like the Jos Plateau and the Mambilla Plateau in the east, which includes Nigeria's highest point.

4.1. Topography and Climate

Nigeria's topography is diverse, featuring several distinct physical regions. The most expansive topographical region consists of the valleys of the Niger and Benue rivers, which converge in the center of the country (near Lokoja) and form a "Y" shape before flowing south to the Niger Delta.

To the southwest of the Niger River lies a rugged highland area. To the southeast of the Benue River, hills and mountains form the Mambilla Plateau, which is the highest plateau in Nigeria and includes the country's highest point, Chappal Waddi, at 7.9 K ft (2.42 K m). This plateau extends across the border into Cameroon, where the montane land is part of the Bamenda Highlands. The Jos Plateau, located in the north-central part of the country, is another significant highland area, rising sharply above the surrounding plains.

Coastal plains are found in both the southwest and the southeast. The far south of Nigeria, particularly around the Niger Delta and along the coast, is characterized by low-lying swamps and mangrove forests.

Nigeria's climate is varied and corresponds to its different topographical zones:

- Tropical Rainforest Climate**: The far south, especially the coastal and Niger Delta regions, experiences a tropical rainforest climate (Köppen classification Af). This zone receives high annual rainfall, typically between 0.1 K in (1.50 K mm) and 0.1 K in (2.00 K mm), and in some areas, like the Niger Delta, it can exceed 0.2 K in (4.00 K mm). Temperatures are consistently high, and humidity is also high throughout the year.

- Tropical Savanna Climate**: Moving northwards, the climate transitions to a tropical savanna climate (Köppen Aw). This zone covers the majority of central Nigeria. It is characterized by distinct wet and dry seasons. Annual rainfall is more limited, ranging from 20 in (500 mm) to 0.1 K in (1.50 K mm). The length of the dry season increases further north.

- Sahel Climate (Hot Semi-Arid)**: In the far north and northeast, Nigeria experiences a Sahelian or hot semi-arid climate (Köppen BSh). This region receives low annual rainfall, typically less than 20 in (500 mm). It has a long, intense dry season and a short, often unreliable wet season. Desertification is a significant concern in this zone as the Sahara Desert encroaches from the north.

The Obudu Plateau in the southeast has a more temperate climate due to its altitude.

4.2. Hydrology

Nigeria's hydrology is dominated by two major river systems and the Lake Chad basin.

The Niger River is the country's principal river and the third-longest river in Africa. It enters Nigeria from the northwest, flows southeastward, and is joined by its main tributary, the Benue River, at Lokoja in central Nigeria. The Benue River originates in Cameroon and flows westward into Nigeria. After their confluence, the combined Niger River flows southwards and empties into the Gulf of Guinea through the extensive Niger Delta. The Niger Delta is one of the largest river deltas in the world, characterized by a complex network of creeks, distributaries, and swamps. The Niger catchment area covers about 63% of the country.

The Lake Chad Basin is another significant hydrological feature, located in the far northeast of Nigeria. Nigeria shares Lake Chad with Niger, Chad, and Cameroon. The lake's size has fluctuated dramatically over millennia and has shrunk considerably in recent decades due to factors including climate change, reduced rainfall, and increased water extraction for irrigation from rivers that feed it, such as the Komadugu Yobe River system. The Komadugu Yobe river system gives rise to the internationally important Hadejia-Nguru wetlands and oxbow lakes around Lake Nguru during the rainy season. The Chad Basin National Park is located in this region. Other rivers in the northeast, such as the Ngadda and Yedseram, flow through the Sambisa swamps and contribute to this river system. The El Beid River forms part of the border with Cameroon, flowing from the Mandara Mountains into Lake Chad.

In addition to these major systems, Nigeria has numerous smaller coastal rivers that flow directly into the Atlantic Ocean. The country's water resources are crucial for agriculture, domestic use, industry, and hydroelectric power generation (e.g., Kainji Dam on the Niger River). However, these resources face challenges from pollution, mismanagement, and the impacts of climate change.

4.3. Vegetation and Biodiversity

Nigeria's vegetation is diverse, reflecting its varied climatic zones and topography. The country can be broadly divided into three main vegetation types: forests, savannas, and montane land.

1. **Forest Zone**: Located primarily in the southern part of the country, this zone is characterized by high rainfall and humidity.

- Mangrove Swamps**: Along the coast, especially in the Niger Delta and around the estuaries of the Niger and Cross rivers, are extensive mangrove swamps. This vegetation is adapted to brackish water conditions.

- Freshwater Swamps**: Inland from the mangrove swamps, freshwater swamp forests are found. The vegetation here differs from the saltwater mangroves.

- Tropical Rainforest**: Further inland, where conditions are less waterlogged but still humid, is the tropical rainforest zone. This area once supported dense forests with a rich diversity of tree species, but much of it has been cleared for agriculture and human settlement. The area near the border with Cameroon, close to the coast, is part of the Cross-Sanaga-Bioko coastal forests ecoregion, an important center for biodiversity. It is a habitat for the drill primate, found in the wild only in this area and across the border in Cameroon. The areas surrounding Calabar, Cross River State, also in this forest, are believed to contain the world's largest diversity of butterflies. The area of southern Nigeria between the Niger and Cross Rivers has lost most of its forest due to development and harvesting, and has been replaced by grassland in many parts (forming the Cross-Niger transition forests ecoregion).

2. **Savanna Zone**: This is the most extensive vegetation zone in Nigeria, covering the central and northern parts of the country. It is characterized by grasslands with scattered trees. The savanna zone is further divided into three sub-types:

- Guinean Forest-Savanna Mosaic**: This transitional zone lies north of the rainforest belt. It consists of plains of tall grass interspersed with trees and patches of forest, particularly along river courses. It is the most common vegetation type across the country.

- Sudan Savanna**: North of the Guinean savanna, the Sudan savanna is characterized by shorter grasses and more scattered, shorter trees. The dry season is longer and more pronounced here.

- Sahel Savanna**: Found in the extreme northeast, this zone is the driest, with sparse vegetation consisting of patches of short grass, thorny shrubs, and sand. It is prone to desertification.

3. **Montane Vegetation**: This is the least common vegetation type, found in highland areas, primarily in the mountains near the Cameroon border, such as the Mambilla Plateau and the Obudu Plateau. The vegetation here is adapted to cooler temperatures and higher altitudes and includes montane forests and grasslands.

Nigeria's biodiversity is rich, reflecting its diverse ecosystems. The country is home to numerous species of plants, mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and insects. Important ecoregions include the aforementioned coastal forests, mangrove swamps, and various savanna types. However, this biodiversity is under threat from habitat loss due to deforestation, agricultural expansion, urbanization, and other human activities, as well as poaching and climate change. Several national parks and forest reserves have been established to protect Nigeria's wildlife and natural habitats, but enforcement and management challenges persist.

4.4. Environmental Issues

Nigeria faces a multitude of significant environmental challenges that impact its ecosystems, public health, and socio-economic development. These issues are often exacerbated by population growth, poverty, inadequate regulation and enforcement, and unsustainable practices.

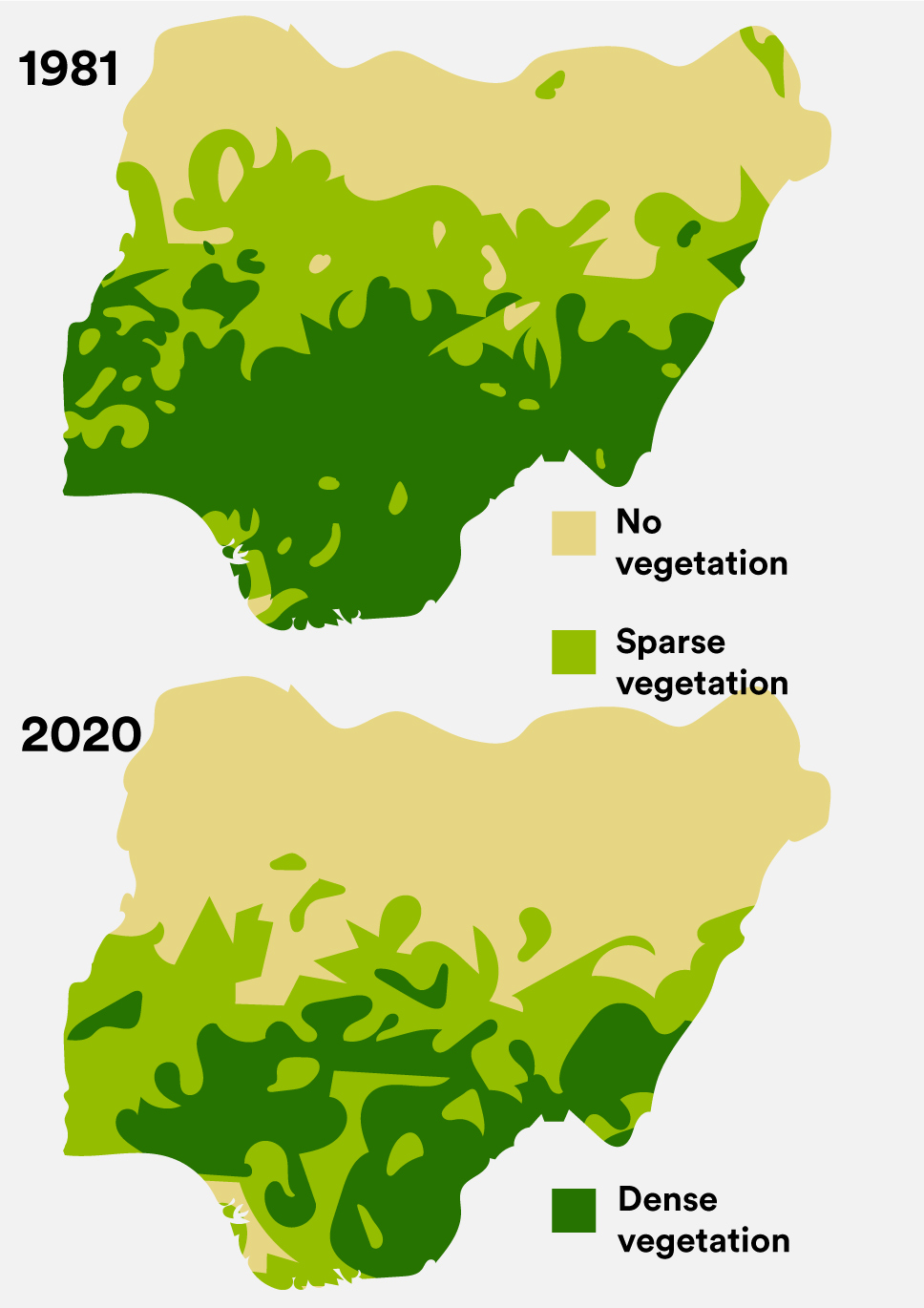

1. **Deforestation**: Nigeria has one of the highest rates of deforestation globally. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), in 2005, Nigeria had the highest rate of deforestation in the world. Between 1990 and 2005, the country lost approximately 35.7% of its forest cover, equivalent to around 6,145,000 hectares. The primary drivers include logging (both legal and illegal), expansion of agricultural land, fuelwood collection, and urbanization. Deforestation leads to loss of biodiversity, soil erosion, and contributes to climate change. Nigeria had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.2/10, ranking it 82nd globally out of 172 countries.

2. **Oil Pollution in the Niger Delta**: The Niger Delta region, the heart of Nigeria's oil industry, is one of the most polluted areas in the world due to frequent and extensive oil spills from pipelines and facilities, gas flaring, and improper disposal of drilling waste. This pollution has devastated local ecosystems, contaminated water sources and agricultural land, and severely impacted the livelihoods and health of communities, predominantly ethnic minorities like the Ogoni and Ijaw. The environmental degradation has also fueled social unrest and conflict in the region. Illegal oil refineries, where stolen crude oil is crudely processed, are particularly "dirty, dangerous and lucrative," causing severe localized pollution and frequent deadly explosions. The situation is often cited as an example of ecocide.

3. **Waste Management**: Inadequate waste management is a major problem in urban areas, especially in megacities like Lagos. Rapid urbanization, population growth, and the inability of municipal authorities to cope with the increasing volume of domestic and industrial waste contribute to this issue. Indiscriminate dumping of waste, including hazardous materials, in open spaces, waterways, and along roads is common, leading to pollution of air, water, and soil, and posing public health risks.

4. **Soil Degradation and Erosion**: Unsustainable agricultural practices, deforestation, and overgrazing contribute to widespread soil degradation and erosion across the country. This reduces agricultural productivity, threatens food security, and can lead to desertification, particularly in the northern regions.

5. **Water Pollution**: Besides oil pollution, waterways are contaminated by untreated sewage, industrial effluents, agricultural runoff (pesticides and fertilizers), and solid waste. This affects drinking water quality, aquatic life, and public health. Access to safe drinking water remains a challenge for a significant portion of the population.

6. **Air Pollution**: Air pollution is a serious issue in urban centers due to vehicle emissions, industrial activities, burning of waste, and use of generators because of unreliable electricity supply. Gas flaring in the Niger Delta also contributes significantly to air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.

7. **Climate Change**: Nigeria is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. These include rising temperatures, changes in rainfall patterns, increased frequency of extreme weather events (floods and droughts), sea-level rise affecting coastal areas, and exacerbation of desertification in the north. These impacts threaten agriculture, water resources, infrastructure, and livelihoods.

8. **Loss of Biodiversity**: Habitat destruction, pollution, and poaching are leading to a significant loss of Nigeria's rich biodiversity. Many plant and animal species are threatened or endangered.

9. **Lead Poisoning**: In 2010, a major lead poisoning outbreak occurred in Zamfara State due to informal gold mining, where lead-containing soil was processed. Hundreds of children died, making it one of the worst such incidents globally.

Addressing these environmental issues requires concerted efforts in policy-making, regulation, enforcement, public awareness, investment in sustainable technologies, and international cooperation. The social justice implications are profound, as vulnerable communities often bear the brunt of environmental degradation and lack the resources to adapt.

5. Politics

Nigeria operates as a federal presidential republic with a multi-party system. Its government is divided into executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The country is administratively structured into 36 states and a Federal Capital Territory. Key political dynamics involve managing ethnic and religious diversity, combating corruption, and ensuring electoral integrity. Nigeria maintains an active role in regional and international affairs and possesses one of Africa's largest militaries.

5.1. Government

Nigeria is a federal republic with a political system modelled after that of the United States. It operates a presidential system with a clear separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The Constitution of Nigeria is the supreme law of the land and has been revised several times, with the current version adopted in 1999, marking the beginning of the Fourth Republic.

The executive power is vested in the President, who is both the head of state and the head of the federal government. The President is elected by popular vote for a four-year term and is limited to a maximum of two terms. To be elected, a candidate must receive a relative majority of the national vote and at least 25% of the votes in a minimum of 24 of the 36 states, a provision designed to ensure broad national support. The President appoints a cabinet of ministers, who must be confirmed by the Senate. By convention, presidential candidates select a running mate (for the vice presidency) who often represents a different ethnic or religious background to promote national balance, though this was notably deviated from in the 2023 election where both the presidential and vice-presidential candidates of the ruling party were Muslims.

The legislative branch is a bicameral National Assembly, consisting of:

- The Senate: The upper house, with 109 members. Each of the 36 states elects three senators, and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) elects one. Senators are elected by popular vote for four-year terms.

- The House of Representatives: The lower house, with 360 members. Seats are allocated to states based on population, and members are also elected by popular vote for four-year terms.

The National Assembly is responsible for making laws, approving the national budget, and exercising oversight functions over the executive branch.

The judicial branch is responsible for interpreting laws and administering justice. The highest court is the Supreme Court of Nigeria. The judiciary also includes the Court of Appeal, Federal High Courts, State High Courts, Sharia Courts of Appeal, and Customary Courts of Appeal at the state level, reflecting Nigeria's mixed legal system. While constitutionally independent, the judiciary has faced challenges regarding executive influence and corruption, impacting the consistent application of the rule of law and protection of human rights.

Nigeria's political system is characterized by a multi-party system, though a few dominant parties have historically controlled the political landscape since the return to democracy in 1999. Elections have often been contentious, marked by allegations of irregularities and violence, posing ongoing challenges to democratic consolidation and public trust in electoral processes. Issues of ethnicity, religion, and regionalism (often referred to as "zoning" for power-sharing) play significant roles in Nigerian politics. Corruption remains a pervasive challenge, undermining governance, economic development, and social justice. Efforts to strengthen democratic institutions, improve electoral integrity, combat corruption, and ensure accountability are central to Nigeria's political discourse and development.

5.2. Administrative Divisions

Nigeria is a federation divided into 36 states and one Federal Capital Territory (FCT), where the capital city, Abuja, is located. Each state has its own executive (Governor), legislature (State House of Assembly), and judiciary. State governors are elected for four-year terms and can serve a maximum of two terms.

The states are further subdivided into 774 Local Government Areas (LGAs). LGAs are the third tier of government and are responsible for local administration and development. The effectiveness and autonomy of LGAs have been subjects of ongoing debate and reform efforts.

In some socio-political contexts, the 36 states are unofficially grouped into six geopolitical zones. These zones were ostensibly created for equitable power-sharing and resource distribution among the country's diverse ethnic and regional groups, although they do not have constitutional status. The zones are:

- North West**: Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Sokoto, Zamfara

- North East**: Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Taraba, Yobe

- North Central** (also known as the Middle Belt): Benue, Kogi, Kwara, Nasarawa, Niger, Plateau, Federal Capital Territory

- South West**: Ekiti, Lagos, Ogun, Ondo, Osun, Oyo

- South East**: Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu, Imo

- South South** (also known as the Niger Delta region): Akwa Ibom, Bayelsa, Cross River, Delta, Edo, Rivers

This administrative structure reflects Nigeria's complex federal character and the challenges of managing diversity within a unified state. The distribution of powers and resources among federal, state, and local governments is a recurring theme in Nigerian politics and constitutional discourse, often linked to issues of social justice, regional equity, and democratic accountability.

5.2.1. States and Federal Capital Territory

Nigeria is composed of 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Abuja. Each state is a semi-autonomous political unit with its own governor, legislature, and judiciary, responsible for various administrative and developmental functions within its jurisdiction. The FCT, Abuja, serves as the nation's capital and is administered by a Minister appointed by the President.

The 36 states are:

1. Abia

2. Adamawa

3. Akwa Ibom

4. Anambra

5. Bauchi

6. Bayelsa

7. Benue

8. Borno

9. Cross River

10. Delta

11. Ebonyi

12. Edo

13. Ekiti

14. Enugu

15. Gombe

16. Imo

17. Jigawa

18. Kaduna

19. Kano

20. Katsina

21. Kebbi

22. Kogi

23. Kwara

24. Lagos

25. Nasarawa

26. Niger

27. Ogun

28. Ondo

29. Osun

30. Oyo

31. Plateau

32. Rivers

33. Sokoto

34. Taraba

35. Yobe

36. Zamfara

And the Federal Capital Territory (Abuja).

The creation of states has been a dynamic process in Nigeria's history, often aimed at addressing ethnic minority demands, promoting development, and balancing regional power. The administrative roles of state governments include providing public services like education, healthcare, infrastructure, and maintaining law and order, often in conjunction with or supplementary to federal efforts.

5.2.2. Major Cities

Nigeria is home to several large and economically vibrant urban centers. These cities serve as hubs for commerce, politics, culture, and population.

- Lagos**: Located in the South West, Lagos is Nigeria's largest city and former capital. It is one of the largest metropolitan areas in the world and the most populous city in Africa. Lagos is the economic and commercial heart of Nigeria, a major port city, and a significant cultural center, known for its vibrant arts, music (Afrobeats), and film (Nollywood) industries. Despite its dynamism, Lagos faces significant challenges related to overpopulation, traffic congestion, and inadequate infrastructure.

q=Lagos, Nigeria|position=left

- Abuja**: Situated in the Federal Capital Territory in the North Central region, Abuja officially became Nigeria's capital in 1991, replacing Lagos. It is a planned city, chosen for its central location, perceived neutrality among ethnic groups, and to ease congestion in Lagos. Abuja is the seat of the federal government, hosting the Presidential Villa (Aso Villa), the National Assembly, the Supreme Court, and most federal ministries and foreign embassies. It has experienced rapid growth and development.

q=Abuja, Nigeria|position=right

- Kano**: Located in Kano State in the North West, Kano is one of the oldest cities in West Africa and a historic center of trans-Saharan trade and Islamic culture. It remains a major commercial and industrial hub in northern Nigeria, known for its traditional markets, leather goods, textiles, and agricultural products.

q=Kano, Nigeria|position=left

- Ibadan**: Situated in Oyo State in the South West, Ibadan is one of the largest cities by land area in Africa and historically a significant Yoruba city. It is home to the University of Ibadan, Nigeria's oldest university, and has a rich intellectual and cultural heritage. Ibadan is an important commercial and agricultural center.

q=Ibadan, Nigeria|position=right

- Port Harcourt**: Located in Rivers State in the South South (Niger Delta region), Port Harcourt is the heart of Nigeria's oil industry. It is a major industrial and commercial city, with significant port facilities. Its economy is heavily reliant on petroleum and related activities.

q=Port Harcourt, Nigeria|position=left

- Benin City**: The capital of Edo State in the South South, Benin City is the historic capital of the Benin Empire, renowned for its rich artistic heritage, particularly its bronze sculptures and plaques. It remains an important cultural and commercial center.

q=Benin City, Nigeria|position=right

- Kaduna**: Located in Kaduna State in the North West (though often considered part of the North Central/Middle Belt region contextually), Kaduna is a significant political, commercial, and transportation hub. It was the former capital of the Northern Region during the colonial era.

These cities, among others, reflect Nigeria's urbanization trend and play crucial roles in its national life, each with its unique character and contributions to the country's economy, political landscape, and cultural diversity. They also face common urban challenges such as infrastructure deficits, housing shortages, and environmental pressures.

5.3. Law and Judiciary

Nigeria's legal system is multifaceted, reflecting its colonial history and diverse cultural and religious landscape. It incorporates English common law, customary law, and, in some northern states, Sharia law.

- English Common Law**: This forms the bedrock of the Nigerian legal system, a legacy of British colonial rule. It comprises statutes received from England, Nigerian statutes, and case law developed by Nigerian courts. It applies primarily to criminal law and civil matters not covered by customary or Sharia law.

- Customary Law**: Derived from indigenous traditional norms and practices of Nigeria's various ethnic groups, customary law governs personal matters such as marriage, divorce, inheritance, and land tenure, particularly in rural areas. It includes dispute resolution mechanisms like the meetings of pre-colonial Yoruba secret societies and the Èkpè and Okónkò societies of Igboland and Ibibioland. The application and recognition of customary law vary, and it is generally not applicable if it is repugnant to natural justice, equity, and good conscience, or incompatible with any written law.

- Sharia Law**: Used primarily in twelve northern states where Islam is the predominant religion, Sharia law has been expanded in these states since 1999 to cover not only personal status matters (as it had historically) but also criminal matters for Muslims. This expansion has been controversial, raising concerns about human rights, religious freedom for minorities, and its compatibility with Nigeria's secular constitution. Sharia law is also used in Lagos State, Oyo State, Kwara State, Ogun State, and Osun State by Muslims for personal status matters. Muslim penal codes and their punishments can differ between states. For example, alcohol consumption and distribution are offenses under Sharia, often with different penalties depending on religious affiliation.

The Constitution of Nigeria is the supreme law of the country, and all other laws must conform to its provisions, including those related to fundamental human rights.

The Judiciary is the third branch of government, tasked with interpreting the laws and administering justice. The judicial structure is hierarchical:

- Supreme Court**: This is the highest court in Nigeria, located in Abuja. Its decisions are final and binding.

- Court of Appeal**: Hears appeals from Federal and State High Courts and other specialized courts.

- Federal High Court**: Has jurisdiction over matters related to federal revenue, admiralty, copyright, banking, etc.

- State High Courts**: Have broad jurisdiction over civil and criminal matters within their respective states.

- Sharia Courts of Appeal and Customary Courts of Appeal**: Exist in states that apply Sharia or customary law, respectively, and hear appeals from lower Sharia or customary courts on matters within their specific jurisdictions.

Challenges facing the Nigerian judiciary include underfunding, corruption, executive interference, delays in the administration of justice, and ensuring access to justice for all citizens, particularly the poor and vulnerable. Efforts to reform the judiciary and strengthen the rule of law are ongoing, crucial for democratic consolidation and the protection of human rights.

5.4. Foreign Relations

Upon gaining independence in 1960, Nigeria made African unity and the liberation of African countries from colonial rule the centerpiece of its foreign policy. It played a prominent role in anti-apartheid movements and supported struggles against white minority governments in Southern Africa, notably backing the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa.

Nigeria was a founding member of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), now the African Union (AU), and has consistently been an influential voice in continental affairs. In West Africa, Nigeria is a leading member of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and has been instrumental in its peacekeeping initiatives, notably through ECOMOG (ECOWAS Cease-fire Monitoring Group) during the civil wars in Liberia and Sierra Leone. Nigeria has also contributed troops to numerous United Nations peacekeeping missions, beginning with the Congo mission shortly after its independence.

The country actively supported various Pan-African and pro-self-government causes in the 1970s, including backing Angola's MPLA, SWAPO in Namibia, and aiding opposition to minority governments in Portuguese Mozambique and Rhodesia. Nigeria is a member of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). In 2006, it hosted an Africa-South America Summit in Abuja to promote "South-South" cooperation.

Nigeria has been a key player in the international petroleum industry since the 1970s and is a long-standing member of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which it joined in July 1971. Its status as a major oil producer significantly shapes its international relations with both developed and developing countries, including the United States and, increasingly, China.

Chinese-Nigerian trade relations have grown exponentially since 2000, with total trade increasing significantly. However, this relationship is characterized by a substantial trade imbalance, with Nigeria importing far more from China than it exports. This over-reliance on Chinese imports has raised concerns about its impact on Nigerian domestic industries and economic sovereignty.

Nigeria is also a member of the Commonwealth of Nations, though it was temporarily suspended in 1995 during the repressive regime of General Sani Abacha due to human rights abuses. It rejoined after the return to civilian rule. Nigeria is a state party to the International Criminal Court.

In its diplomatic efforts, Nigeria has often projected itself as a champion of democracy and human rights in Africa, although its own domestic record on these issues has sometimes been criticized. The country's foreign policy objectives generally include promoting peace and security in Africa, fostering economic cooperation, and enhancing Nigeria's influence on the global stage. It continues to navigate complex relationships with global powers and regional neighbors, balancing its economic interests with its commitment to African solidarity and development. Nigeria introduced the idea of a single currency for West Africa, the Eco, though its implementation has faced delays and challenges.

5.5. Military

The Nigerian Armed Forces (NAF) are the combined military forces of Nigeria, consisting of three main service branches: the Nigerian Army, the Nigerian Navy, and the Nigerian Air Force. The President of Nigeria is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, exercising constitutional authority through the Ministry of Defence, which is responsible for managing the military and its personnel. The operational head of the NAF is the Chief of the Defence Staff, who is subordinate to the Minister of Defence.

With a force of more than 223,000 active personnel, the Nigerian military is one of the largest uniformed combat services in Africa. According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies (2020), Nigeria had 143,000 troops in the armed forces (Army: 100,000; Navy: 25,000; Air Force: 18,000), with an additional 80,000 personnel in gendarmerie and paramilitary forces. Nigeria's defense budget in 2022 was approximately 2.26 B USD.

The roles of the Nigerian Armed Forces include:

1. Defending Nigeria from external aggression.

2. Maintaining its territorial integrity and securing its borders.

3. Suppressing insurrection and acting in aid of civil authorities to restore order when called upon to do so by the President (subject to conditions prescribed by an Act of the National Assembly).

4. Performing other such functions as may be prescribed by an Act of the National Assembly.

Historically, the Nigerian military has played a significant role in the country's politics, with several periods of military rule since independence. Since the return to democracy in 1999, efforts have been made to professionalize the military and ensure its subordination to civilian authority.

Internationally, Nigeria has a long history of participation in peacekeeping operations. It has contributed troops to United Nations and African Union missions in various conflict zones, including the Congo, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Sudan (Darfur), and Mali. Nigeria was a key contributor to ECOMOG, the peacekeeping force of ECOWAS.

Domestically, the military has been heavily involved in internal security operations, particularly in combating the Boko Haram insurgency in the northeast, addressing militancy in the Niger Delta, and tackling widespread banditry and communal conflicts in various parts of the country. These internal operations have sometimes raised concerns about human rights abuses and the conduct of military personnel, prompting calls for greater accountability and adherence to international humanitarian law. The military also faces challenges related to equipment, funding, and adapting to asymmetric warfare.

6. Economy

Nigeria possesses a mixed emerging economy, noted for its significant natural resources, particularly oil and natural gas, which form the backbone of its exports and government revenue. The country is actively working to diversify beyond petroleum, with growth in agriculture, manufacturing, technology (including the prominent Nollywood film industry), and services. However, it contends with challenges such as infrastructural deficits, corruption, high inflation, unemployment, and social inequality, which impact labor rights and equitable development.

6.1. Overview and Structure

Nigeria's economy is classified as a lower-middle-income, mixed, and emerging market. As of recent estimates, it ranks as the fourth-largest economy in Africa by nominal GDP and around the 30th-largest globally by PPP. In 2022, its GDP (PPP) per capita was approximately 9.15 K USD.

Historically, the Nigerian economy was primarily agricultural. However, the discovery and exploitation of crude oil in the late 1950s and 1960s transformed its structure, making petroleum the dominant sector for revenue and exports. While oil wealth fueled periods of growth, it also led to dependency, vulnerability to global oil price fluctuations, and issues like the "Dutch disease," where other sectors like agriculture and manufacturing were neglected.

Since the return to democracy in 1999, Nigeria has undertaken various economic reforms aimed at diversification, privatization, and improving the business environment. The banking sector has been significantly reformed, and there has been growth in telecommunications, entertainment (Nollywood), and services.

Despite its size and potential, Nigeria's economy faces persistent challenges, including:

- Inflation**: High inflation rates have been a recurrent problem, eroding purchasing power.

- Unemployment and Underemployment**: These remain high, particularly among the youth, contributing to social pressures.

- Infrastructure Deficit**: Inadequate power supply, poor transportation networks (roads, rail), and limited access to clean water and sanitation hinder economic development and quality of life.

- Corruption**: Widespread corruption diverts public funds, increases the cost of doing business, and undermines development efforts.

- Over-reliance on Oil**: Although efforts are being made to diversify, oil still accounts for a significant portion of government revenue and export earnings, making the economy susceptible to oil price shocks.

- Inequality**: Wealth is unevenly distributed, with high levels of poverty despite overall economic growth. This raises critical questions about social equity.

- Security Challenges**: Insurgency, banditry, and communal conflicts in various parts of the country disrupt economic activities and deter investment.

The informal sector plays a substantial role in the Nigerian economy, providing employment for a large segment of the population, though often characterized by low wages and lack of labor protections. Labor rights and social equity are key concerns, with ongoing debates about minimum wage, working conditions, and the need for inclusive growth that benefits all segments of society. Environmental sustainability is another critical aspect, particularly concerning the impact of oil extraction and the broader challenges of climate change and resource management.

6.2. Major Sectors

Nigeria's economy is composed of several key sectors, each contributing to its overall GDP and employment. The government has been making efforts to diversify the economy away from over-reliance on oil.

6.2.1. Agriculture

Agriculture was the mainstay of Nigeria's economy before the oil boom and remains a significant sector, employing a large percentage of the population (around 35% in 2019, though this figure varies). In 2021, agriculture, forestry, and fishing contributed about 23.4% to Nigeria's GDP.

Key agricultural products include:

- Staple Crops**: Cassava (Nigeria is the world's largest producer), yams, maize (corn), millet, sorghum, and rice. These are crucial for domestic food consumption.

- Cash Crops**: Cocoa (a major export earner), palm oil and palm kernel, rubber, cotton, groundnuts (peanuts), and sesame seeds.

Despite its potential, the agricultural sector faces challenges such as reliance on traditional farming methods, poor infrastructure (storage, transportation, irrigation), limited access to credit and modern inputs, land tenure issues, and post-harvest losses. These factors impact productivity and food security. Nigeria, once self-sufficient in food, now imports significant quantities of certain food items like rice and wheat. Government initiatives have aimed to boost local production, reduce import dependency, and promote agribusiness. Ensuring fair prices for farmers, improving rural livelihoods, and adopting sustainable agricultural practices are crucial for social equity and development in this sector.

6.2.2. Petroleum and Natural Gas

Nigeria possesses vast reserves of crude petroleum and natural gas, making it one of Africa's largest producers and a member of OPEC. This sector has historically been the primary driver of government revenue and foreign exchange earnings, accounting for about 80% of government earnings and around 70% of export earnings (in 2019). Nigeria is the 15th largest oil producer globally and the 9th largest in terms of proven reserves. It also has the 9th largest proven natural gas reserves.

The petroleum industry is concentrated in the Niger Delta region. Operations involve multinational oil companies in joint ventures with the state-owned Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC).

However, the sector is fraught with significant social and environmental problems:

- Environmental Degradation**: Frequent oil spills from aging pipelines and sabotage, along with gas flaring, have caused severe pollution in the Niger Delta, devastating farmlands, fishing grounds, and mangrove ecosystems. This has had a dire impact on the livelihoods and health of local communities.

- Social Unrest and Conflict**: The perceived inequitable distribution of oil wealth, environmental damage, and lack of development in oil-producing communities have fueled militancy, sabotage of oil facilities, and conflict in the Niger Delta.

- Oil Theft and Illegal Refining**: Large-scale theft of crude oil ("bunkering") and subsequent illegal refining cause significant revenue losses and further environmental damage.

- Corruption**: The oil sector has been susceptible to high levels of corruption, hindering the translation of oil wealth into broad-based development.

- Labor Issues**: Workers in the oil and gas sector have periodically engaged in industrial actions over pay and working conditions.

Efforts to reform the sector, such as the Petroleum Industry Act, aim to improve transparency, governance, and benefits for host communities. The development of natural gas resources, including liquefied natural gas (LNG) for export and domestic use (e.g., for power generation and industry), is seen as a key area for future growth and economic diversification. However, addressing the deep-seated social and environmental injustices associated with resource extraction remains a critical challenge for sustainable and equitable development.

6.2.3. Manufacturing and Technology

The manufacturing sector in Nigeria has seen periods of growth and decline, historically focused on import substitution industries. Key sub-sectors include:

- Food Processing**: Beverages, flour milling, sugar refining, and processing of agricultural products.

- Textiles and Leather Goods**: Once a major employer, the textile industry (centered in Kano, Abeokuta, Onitsha, and Lagos) has faced challenges from cheap imports but still holds potential. Leather production, particularly from Kano, is significant. The city of Aba is known for handicrafts and shoes ("Aba made").

- Cement**: Nigeria is a leading cement producer in sub-Saharan Africa, with major players like Dangote Cement.

- Automotive Assembly**: There are efforts to revive and expand local vehicle assembly. Nigeria has a market for about 720,000 cars per year, but less than 20% are produced domestically.

- Plastics, Pharmaceuticals, and Chemicals**: These industries cater to both domestic and regional markets. Nigeria hosts about 60% of Africa's pharmaceutical production capacity, with larger companies in Lagos.

- Steel**: The Ajaokuta Steel Mill, though historically plagued by mismanagement and underutilization, and other smaller steel plants represent efforts in this capital-intensive sector.

Challenges for the manufacturing sector include inadequate infrastructure (especially power supply and transport), high operating costs, limited access to finance, competition from imports, and policy inconsistencies. Promoting local content, improving the business environment, and investing in skills development are seen as crucial for its growth. This growth needs to be managed with consideration for labor rights, ensuring fair wages, safe working conditions, and opportunities for skill development.

The Technology and ICT sector has been a bright spot in Nigeria's economy, experiencing rapid growth. This includes:

- Telecommunications**: A liberalized telecom market has led to a massive increase in mobile phone penetration and data usage, driven by major operators.

- Fintech**: Nigeria has a burgeoning financial technology (fintech) ecosystem, with innovative solutions for payments, lending, and other financial services. Lagos is regarded as a major technology hub in Africa.

- Software Development and E-commerce**: There is a growing community of software developers and an expanding e-commerce market.

- Space Technology**: Nigeria has a space program, with satellites like Nigeria EduSat-1 (the first built in Nigeria) launched for various purposes.

The tech sector offers significant opportunities for job creation, innovation, and economic diversification. However, it also requires continued investment in digital infrastructure, education, and a supportive regulatory environment. Equitable access to technology and digital literacy are important considerations to prevent a widening digital divide. Nigeria hosts several "unicorn" companies (startups valued at over 1.00 B USD).

6.2.4. Services

The services sector is the largest contributor to Nigeria's GDP and encompasses a wide range of activities, including wholesale/retail trade, financial services, real estate, and the globally recognized Nollywood entertainment industry. This sector is crucial for job creation and economic diversification.

6.3. Energy

Nigeria's energy sector is critical to its economy but is characterized by a paradox of abundant resources and inadequate supply, particularly in electricity. The country relies heavily on fossil fuels while also possessing significant renewable energy potential. Environmental and social equity concerns are prominent in discussions about energy policy.

- Energy Resources and Production:**

- Fossil Fuels**:

- Oil**: Nigeria is a major oil producer, and crude oil is its primary export. Oil is also used domestically for refining into petroleum products, though Nigeria has historically relied on imported refined products due to insufficient domestic refining capacity.

- Natural Gas**: Nigeria has vast proven natural gas reserves, among the largest in the world (9th largest). A significant portion is exported as Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG), while some is used for domestic power generation and industry. However, gas flaring (burning off associated gas during oil production) has been a persistent problem, wasting resources and causing environmental pollution. The government values its gas reserves at potentially 803.40 T USD.

- Hydropower**: Hydropower is a significant source of electricity, with major dams like Kainji, Jebba, and Shiroro on the Niger River and its tributaries. There is potential for further hydropower development. In 2019, fossil fuels accounted for 73% of total primary energy production, with hydropower making up the remaining 27%.

- Renewable Energy (other than hydro)**: Nigeria has substantial potential for solar energy (due to its location in the tropics), wind energy (particularly in the north), and biomass. However, the development of these resources is still in its early stages.

- Nuclear Energy**: Nigeria has explored the development of nuclear power for electricity generation. In 2004, it opened a Chinese-origin research reactor at Ahmadu Bello University. It has sought support from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) with plans to develop up to 4,000 MWe of nuclear capacity by 2027. In 2015, Nigeria began talks with Russia's Rosatom for the design, construction, and operation of four nuclear power plants by 2035, with sites selected in Akwa Ibom and Kogi States. Agreements for the Itu nuclear power plant were signed in 2017. Nigeria signed the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in 2017.

- Energy Consumption and Challenges:**

Nigeria's energy consumption significantly exceeds its reliable generation capacity, especially for electricity. This leads to:

- Chronic Electricity Shortages**: Discussed in more detail in the next subsection.

- High Reliance on Generators**: Businesses and households widely use expensive and polluting diesel or petrol generators.

- Energy Access**: Many rural and some urban areas lack access to the national grid.

- Policies for Energy Access and Sustainability:**

The Nigerian government has various policies aimed at:

- Increasing electricity generation capacity from diverse sources.

- Improving transmission and distribution infrastructure.

- Promoting renewable energy development.

- Reducing gas flaring and increasing domestic gas utilization.

- Reforming the power sector to attract private investment.