1. Overview

The Republic of Namibia is a country located on the west coast of Southern Africa. It shares land borders with Angola and Zambia to the north, Botswana to the east, and South Africa to the south and east. To the west lies the Atlantic Ocean. Windhoek is its capital and largest city.

Namibia gained independence from South Africa on 21 March 1990, following the Namibian War of Independence. The country's name is derived from the Namib Desert, considered the oldest desert in the world.

Namibia's political structure is a unitary dominant-party semi-presidential republic, operating as a stable parliamentary democracy since independence. The government is divided into executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The current president is Nangolo Mbumba. The nation's motto is "Unity, Liberty, Justice," and its national anthem is "Namibia, Land of the Brave".

Geographically, Namibia is the driest country in sub-Saharan Africa, characterized by vast deserts like the Namib and the Kalahari, a central plateau, and the Great Escarpment. Its area is approximately 319 K mile2 (825.62 K km2). With a population of about 3.1 million people (2023-2025 estimates), Namibia is one of the world's most sparsely populated countries, with an average population density of around 3.7 people per km2.

The Namibian economy relies heavily on mining (diamonds, uranium, gold, silver, base metals), agriculture, tourism, and a comparatively small manufacturing sector. Despite significant GDP growth since independence, poverty and wealth inequality remain major challenges. In 2015, Namibia's Gini coefficient was 59.1, one of the highest globally. The Namibian dollar (NAD) and the South African rand (ZAR) are its official currencies.

Namibian society is ethnically diverse, with the Ovambo being the largest group. English is the official language, while Afrikaans, German, and various indigenous languages such as Oshiwambo, Khoekhoegowab, and Otjiherero are also spoken. Christianity, particularly Lutheranism, is the predominant religion.

2. History

Namibia's history spans from its early indigenous inhabitants, through periods of German and South African colonial rule marked by significant conflicts such as the Herero and Namaqua genocide and the imposition of apartheid, to a protracted liberation struggle led by SWAPO. The nation achieved independence in 1990, embarking on a path of national reconciliation, democratic development, and addressing socio-economic legacies of its past.

2.1. Etymology

The name "Namibia" is derived from the Namib Desert, which is considered the oldest desert in the world. The word Namib itself originates from the Nama language (also known as Khoekhoegowab) and means "vast place" or "enclosure." This name was chosen by Mburumba Kerina, a prominent nationalist figure, who initially proposed the "Republic of Namib." Before independence in 1990, the territory was known as German South West Africa (Deutsch-SüdwestafrikaGerman South West AfricaGerman) during German colonial rule, and subsequently as South West Africa under South African administration, reflecting its colonial past.

2.2. Pre-colonial Period

The arid lands of Namibia have been inhabited since prehistoric times. The earliest inhabitants were the San people (also known as Bushmen), Damara people, and Nama people (collectively part of the Khoisan peoples). For thousands of years, these groups maintained distinct lifestyles: the San were primarily hunter-gatherers, while the Khoikhoi (including the Nama) were pastoralists.

Around the 14th century, Bantu-speaking groups began migrating into the region from Central Africa as part of the larger Bantu expansion. These groups included the ancestors of the Ovambo, Kavango, and Herero, among others, who gradually settled in different parts of the territory. From 1600, the Ovambo established kingdoms, such as Ondonga and Oukwanyama, in the northern regions.

From the late 18th century, the Oorlam people, a group of mixed Khoikhoi and European ancestry from the Cape Colony, crossed the Orange River and moved into what is now southern Namibia. Their interactions with the nomadic Nama tribes were largely peaceful, and they were generally receptive to missionaries who accompanied them. However, as the Oorlam moved further north, they encountered Herero clans in areas like Windhoek, Gobabis, and Okahandja, leading to conflicts over resources and territory. The Nama-Herero War broke out in 1880, with hostilities continuing until the German Empire intervened.

The first Europeans to explore the Namibian coast were Portuguese navigators: Diogo Cão in 1485 and Bartolomeu Dias in 1486. However, the Portuguese did not attempt to claim the area. European exploration of the interior remained limited until the 19th century, when traders, settlers (primarily from Germany and Sweden), and missionaries arrived. Finnish missionaries, for example, began work in northern Namibia in 1870, spreading Lutheranism among the Ovambo and Kavango peoples. In the late 19th century, Dorsland Trekkers (Afrikaner voortrekkers) also crossed the region.

In 1878, the Cape of Good Hope, then a British colony, annexed the port of Walvis Bay and the offshore Penguin Islands. These territories later became an integral part of the Union of South Africa upon its formation in 1910.

2.3. German Colonial Rule

Namibia became a German colony in 1884 under Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, primarily to preempt perceived British encroachment. The territory was named German South West Africa (Deutsch-SüdwestafrikaGerman South West AfricaGerman). This colonization began when German merchant Adolf Lüderitz, through his agent Heinrich Vogelsang, purchased land at Angra Pequena from a local Nama chief, Joseph Fredericks, in 1883. The British Palgrave Commission had earlier determined that only the natural deep-water harbor of Walvis Bay was worth occupying, leading to its annexation by the Cape Colony.

German colonial administration, led by figures like Commissioner Paul Rohrbach and Governor Theodor Leutwein, aimed to establish settler agriculture and exploit local resources. This often involved dispossessing indigenous communities of their land and cattle. In 1897, a devastating rinderpest epidemic killed an estimated 95% of cattle in southern and central Namibia, severely impacting indigenous livelihoods and creating opportunities for German settlers to acquire more land. In response, German colonizers established a veterinary cordon fence known as the Red Line, which later defined the boundaries of the Police Zone, concentrating colonial control and development in the southern and central parts of the territory while largely excluding the northern Ovamboland.

The harsh colonial policies, land expropriation, and forced labor led to increasing resentment among the indigenous populations, culminating in widespread resistance.

2.3.1. Herero and Namaqua Genocide

Between 1904 and 1908, the Herero and Nama peoples rose up against German colonial rule in what became known as the Herero Wars. The Herero, led by Chief Samuel Maharero, initiated the revolt in January 1904 due to ongoing land confiscation and ill-treatment by German settlers. Later that year, the Nama, under leaders like Hendrik Witbooi and Jakob Marengo, also joined the uprising.

The German military response was brutal, particularly under the command of General Lothar von Trotha. After the Battle of Waterberg in August 1904, where Herero forces were defeated, von Trotha issued an extermination order (Vernichtungsbefehl) against the Herero people on October 2, 1904, declaring that any Herero found within German territory would be shot. Thousands of Herero were driven into the Omaheke Desert (part of the Kalahari), where many perished from thirst and starvation. A similar order was issued against the Nama in April 1905.

Those who survived or were captured were interned in concentration camps, such as the one on Shark Island off Lüderitz, where they endured horrific conditions, forced labor, medical experiments, and high mortality rates from disease and malnutrition. It is estimated that approximately 65,000 Herero (about 80% of their population) and 10,000 Nama (about 50% of their population) were killed. This event is widely recognized by scholars as the first genocide of the 20th century and has had a profound and lasting impact on Namibian society and its relations with Germany.

Survivors of the genocide were subjected to policies of dispossession, forced labor, racial segregation, and discrimination, which laid the groundwork for the later apartheid system imposed by South Africa. The memory of the genocide remains a significant part of Namibian national identity. In 2004, a German minister offered an apology for the genocide, but it was not until May 2021 that the German government officially acknowledged the atrocities as genocide and agreed to pay 1.10 B EUR in development aid over 30 years to benefit the descendants of the affected communities. This agreement, however, has faced criticism from some Herero and Nama groups for not being direct reparations and for a perceived lack of adequate consultation.

German rule ended during World War I when South African forces, allied with the British, defeated the German troops in the South West Africa campaign in 1915.

2.4. South African Mandate and Occupation

Following Germany's defeat in World War I, the League of Nations formally granted South Africa a Class C mandate to administer South West Africa in 1920. Walvis Bay, which had been part of the Cape Colony and thus South Africa since 1910, was administratively reintegrated into South West Africa. South Africa was tasked with promoting the material and moral well-being and social progress of the inhabitants. However, the South African government increasingly treated the territory as a fifth province, rather than a separate entity with a path to self-determination.

Resistance to South African rule continued, exemplified by events such as the Bondelswarts Rebellion in 1922, which was suppressed by South African forces. White settlement, primarily by Afrikaners, was encouraged, further dispossessing indigenous Africans of their land.

After World War II and the dissolution of the League of Nations in 1946, South Africa refused to place South West Africa under the new UN Trusteeship System, which was designed to guide former mandates towards independence. Instead, South Africa sought to formally annex the territory. The United Nations General Assembly rejected this proposal and, in a series of advisory opinions, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) affirmed that South Africa's mandate continued but that it was obliged to submit to UN supervision.

From 1948, with the National Party's rise to power in South Africa, the system of apartheid - codified racial segregation and discrimination - was systematically extended and rigorously enforced in South West Africa. This involved classifying the population by race, implementing pass laws restricting movement, creating racially segregated residential areas, and establishing "native reserves" or "homelands" (Bantustans) for different ethnic groups. These homelands were typically located on marginal land, while fertile areas were reserved for white farmers. Development was concentrated in the "Police Zone," the southern and central parts of the territory primarily inhabited by white settlers. Black South West Africans faced severe restrictions on their political, economic, and social rights. This period was marked by entrenched discrimination and the exploitation of African labor, particularly in mines and on white-owned farms.

International opposition to South African rule grew throughout the 1950s and 1960s, fueled by the broader decolonization movement in Africa and the increasing global condemnation of apartheid.

2.5. Struggle for Independence

The imposition of apartheid and the denial of self-determination fueled the rise of Namibian nationalism. In the late 1950s, several political organizations emerged, including the Ovamboland People's Congress (OPC), which was later reconstituted as the South West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO) in 1960, with Sam Nujoma as one of its key leaders. SWAPO, initially focused on labor issues, evolved into the leading liberation movement, advocating for Namibia's full independence. Other nationalist parties, such as the South West African National Union (SWANU), also played a role.

The 1959 Windhoek Massacre, where police fired on protestors demonstrating against forced removals, killing 11 people, further galvanized the independence movement. In 1966, after the International Court of Justice controversially ruled that Ethiopia and Liberia (who had brought the case against South Africa) lacked legal standing to challenge South African rule, the United Nations General Assembly voted to terminate South Africa's mandate over South West Africa (Resolution 2145) and declared that the territory was under the direct responsibility of the UN. In 1968, the UN General Assembly renamed the territory "Namibia" (Resolution 2372).

Frustrated by the lack of peaceful progress, SWAPO launched an armed struggle, the Namibian War of Independence (also known as the South African Border War), in August 1966. The military wing of SWAPO, the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN), conducted guerrilla warfare, primarily from bases in newly independent neighboring countries like Zambia and, after 1975, Angola. The war was protracted and brutal, involving South African Defence Force (SADF) incursions into neighboring states and significant human rights abuses.

In 1971, contract workers in Namibia led a general strike against the exploitative contract labor system, which significantly disrupted the economy and demonstrated widespread opposition to South African rule. Many striking workers later joined PLAN.

In 1973, the UN General Assembly recognized SWAPO as the "sole and authentic representative of the Namibian people." International pressure on South Africa intensified, including arms embargoes and calls for economic sanctions. The UN Security Council Resolution 435, adopted in 1978, provided a detailed plan for UN-supervised elections and a transition to independence. However, South Africa resisted its implementation for over a decade, linking Namibian independence to the withdrawal of Cuban troops from Angola, who were supporting the MPLA government against South African-backed UNITA rebels.

The conflict became enmeshed in the Cold War, with the Soviet Union and Cuba supporting SWAPO and the MPLA, while the United States and other Western powers engaged in complex diplomacy, often seen as tacitly supporting South Africa's regional agenda due to anti-communist concerns.

The Tripartite Accord (also known as the New York Accords), signed in December 1988 by Angola, Cuba, and South Africa, and mediated by the United States, finally paved the way for the implementation of Resolution 435. The agreement linked the withdrawal of Cuban troops from Angola to the withdrawal of South African forces from Namibia and the territory's independence.

The United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG), a UN peacekeeping force and civilian mission, was deployed in April 1989 to oversee the transition, monitor the ceasefire, ensure the withdrawal of South African troops, supervise the return of refugees, and conduct free and fair elections for a constituent assembly. Despite initial clashes when PLAN forces crossed into Namibia, the transition process largely proceeded.

In November 1989, Namibians participated in UN-supervised elections for the Constituent Assembly. SWAPO won 57% of the vote, securing 41 of the 72 seats, short of the two-thirds majority needed to unilaterally draft the constitution. The Democratic Turnhalle Alliance (DTA) became the main opposition. The Constituent Assembly drafted and adopted a democratic constitution in February 1990, which included a bill of rights and established a multi-party system.

Namibia officially achieved independence on 21 March 1990. Sam Nujoma was sworn in as the first President of Namibia at a ceremony attended by international dignitaries, including Nelson Mandela, who had been released from prison just a month earlier. Walvis Bay and the Penguin Islands, which South Africa had retained, were eventually transferred to Namibia on 1 March 1994, following the end of apartheid in South Africa.

2.6. Post-Independence Era

Since achieving independence on 21 March 1990, Namibia has made significant strides in establishing a stable, multi-party parliamentary democracy. The SWAPO party, which led the liberation struggle, has remained the dominant political force, winning every national election. Sam Nujoma served as the first president for three terms (after a constitutional amendment allowed him a third term) until 2005. He was succeeded by Hifikepunye Pohamba (2005-2015), who also served two terms. Hage Geingob became president in 2015 and was re-elected in 2019. Following President Geingob's death in February 2024, Vice President Nangolo Mbumba assumed the presidency. Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah, SWAPO's candidate, was declared the winner of the 2024 Namibian general election, becoming the country's first female president-elect.

A key policy in the post-independence era has been national reconciliation, aiming to heal the divisions of the colonial past and the liberation war. An amnesty was granted to those who fought on both sides. The government has focused on nation-building, socioeconomic development, and addressing the legacies of apartheid, including severe inequalities in land distribution, education, and healthcare.

Namibia has faced several challenges. The spillover from the Angolan Civil War affected the northern regions in the early years of independence. In 1998, Namibian Defence Force (NDF) troops were deployed to the Democratic Republic of the Congo as part of a Southern African Development Community (SADC) contingent. In 1999, the government suppressed a secessionist attempt in the northeastern Caprivi Strip (now Zambezi Region), known as the Caprivi conflict, led by the Caprivi Liberation Army (CLA) under Mishake Muyongo.

Economically, Namibia has focused on diversifying its economy beyond mining, with efforts to develop tourism, fisheries, and manufacturing. However, challenges such as high unemployment (particularly among youth), poverty, and extreme income inequality persist. Land reform has been a contentious and slow process, aiming to redress historical imbalances in land ownership where a small minority of predominantly white commercial farmers own a disproportionate amount of arable land.

In terms of human rights, Namibia generally has a good record compared to many other African nations, with a free press and an independent judiciary. However, issues such as police brutality, conditions in detention centers, discrimination against minority groups (including San communities and LGBT individuals), and corruption remain concerns.

Namibia has actively participated in regional and international affairs, being a member of the United Nations, the African Union, the Southern African Development Community, and the Commonwealth of Nations.

Culturally, Namibia has seen a resurgence of indigenous cultures and traditions, alongside the development of contemporary arts. In 2007, Twyfelfontein, with its extensive rock engravings, became Namibia's first UNESCO World Heritage Site.

3. Geography

Namibia's geography is dominated by arid and semi-arid landscapes, including the Namib and Kalahari Deserts, a Central Plateau, and the Great Escarpment. Its climate is largely dry with scarce water resources, yet it supports diverse wildlife, with conservation being a key national policy.

3.1. Topography

The Namibian landscape is diverse and can be broadly divided into five major geographical regions:

1. **The Central Plateau**: Running from north to south, this is the largest geographical region and home to the majority of Namibia's population and economic activity, including the capital, Windhoek. It features rugged mountains, rocky outcrops, and broad valleys. The highest point in Namibia, Königstein peak in the Brandberg Massif, with an elevation of 8.6 K ft (2.61 K m), is located here. This region generally has higher rainfall than the coastal desert.

2. **The Namib Desert**: This is a long, narrow coastal desert stretching along the entire Atlantic coastline. It is one of the oldest and driest deserts in the world, characterized by vast sand seas with some of the world's highest dunes (such as those at Sossusvlei), gravel plains, and rugged mountains. Specific areas within the Namib include the Skeleton Coast in the north, known for its shipwrecks and stark beauty, and the Kaokoveld desert.

3. **The Great Escarpment**: This is a prominent and often steep topographical feature that separates the coastal Namib Desert from the inland Central Plateau. It rises sharply, in places to over 6.6 K ft (2.00 K m). The escarpment influences local climate patterns, and while rocky with poorly developed soils, it is generally more productive than the Namib Desert.

4. **The Bushveld**: Found in northeastern Namibia, particularly in the Kavango East and West regions and the Zambezi Region (formerly Caprivi Strip), along the Angolan border. This region receives significantly more rainfall (around 16 in (400 mm) annually) than the rest of the country, supporting denser woodland and savanna vegetation. The soils are generally flat and sandy.

5. **The Kalahari Desert**: Covering much of eastern and southern Namibia, the Kalahari extends into Botswana and South Africa. While known as a desert, it includes a variety of localized environments, from arid sandy areas to some more vegetated and technically non-desert regions. Part of the Kalahari in Namibia includes the Succulent Karoo biome, which is a biodiversity hotspot with over 5,000 plant species, many of them endemic.

The Caprivi Strip, a narrow panhandle extending eastwards from northeastern Namibia, provides the country with access to the Zambezi River and borders Zambia, Angola, Botswana, and Zimbabwe (at a near quadripoint).

3.2. Climate

Namibia's climate is predominantly arid to semi-arid, heavily influenced by the sub-Tropical High-Pressure Belt, which results in generally clear skies and over 300 days of sunshine per year. The country lies at the southern edge of the tropics, with the Tropic of Capricorn bisecting it.

Rainfall is scarce and erratic, varying from almost zero in the coastal Namib Desert to over 24 in (600 mm) annually in the Caprivi Strip in the northeast. The majority of the country receives less than 20 in (500 mm) of rain per year, making droughts a common occurrence. The main rainy season occurs during the summer months, with a smaller rainy season typically between September and November, and a more significant one between February and April. Humidity is generally low. In May 2019, Namibia declared a national state of emergency due to severe drought.

The coastal climate is significantly moderated by the cold, north-flowing Benguela Current in the Atlantic Ocean. This current causes very low precipitation (2.0 in (50 mm) per year or less), frequent dense fog along the coast (especially in the mornings), and cooler temperatures compared to the interior. Inland, temperatures can be extreme. Summer (November to March) temperatures can exceed 104 °F (40 °C) in the interior, while winter (June to August) days are usually mild and sunny, but nights can be very cold, often dropping below freezing in the inland plateau and desert areas. The Central Plateau and Kalahari regions experience wide diurnal temperature variation, sometimes up to 54 °F (30 °C).

Occasionally, particularly during winter, a hot, dry wind known as Bergwindmountain windGerman or Oosweereast weatherAfrikaans blows from the interior towards the coast. These winds can cause rapid temperature increases and may lead to sandstorms, carrying desert sand out into the Atlantic Ocean.

The northern regions experience seasonal flooding known as efundja, particularly in the Cuvelai-Etosha Basin, when heavy rains in Angola cause rivers to overflow into Namibian floodplains (oshanas). These floods can cause significant damage to infrastructure and displace communities, but also replenish water sources and support local ecosystems.

3.3. Water Resources

Namibia is the driest country in Sub-Saharan Africa and relies heavily on limited water resources. Surface water is scarce and largely ephemeral, with perennial rivers found only on its national borders: the Orange River in the south (border with South Africa), the Kunene River and Okavango River in the north (border with Angola), and the Zambezi River and Cuando/Linyanti/Chobe River system in the northeast (borders with Zambia, Angola, and Botswana).

In the interior, rivers are seasonal and typically flow only during the rainy season after heavy rainfall. Surface water availability is supplemented by a few large storage dams. Consequently, groundwater is the primary source of water for about 80% of the country, supplying domestic, agricultural, and industrial needs. Over 100,000 boreholes have been drilled, though a significant portion of these are dry or have low yields.

In 2012, a large aquifer, named Ohangwena II, was discovered underlying northern Namibia and southern Angola. It is estimated to hold enough water to supply the northern population for hundreds of years at current consumption rates, offering a significant potential resource, though sustainable management is crucial.

Water scarcity is a major challenge, exacerbated by erratic rainfall, high evaporation rates, and increasing demand. Water management strategies include water harvesting, desalination (on the coast), water recycling (such as Windhoek's pioneering wastewater reclamation plant), and transboundary water cooperation with neighboring countries for shared river basins. On 8 June 2023, Namibia acceded to the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes (UN Water Convention), becoming the first Southern African country to do so, underscoring its commitment to cooperative water resource management.

3.4. Wildlife and Conservation

Namibia boasts rich biodiversity despite its arid environment. The country is home to a diverse array of flora and fauna, including numerous endemic species adapted to desert conditions. Notable wildlife includes large populations of elephants, rhinos (both black and white), lions, leopards, cheetahs, giraffes, zebras, and a wide variety of antelope species, such as gemsbok (Namibia's national animal), springbok, and kudu. The country has approximately 200 terrestrial mammal species, 645 bird species, and 115 fish species.

Conservation is a cornerstone of Namibian policy and is enshrined in its constitution (Article 95), which mandates the state to actively promote and maintain ecosystems, ecological processes, and biological diversity, and to ensure the sustainable utilization of living natural resources.

Namibia is internationally recognized for its innovative conservation efforts, particularly its Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) program. Launched in the 1990s, this program empowers local communities by granting them rights to manage and benefit from wildlife and tourism on their communal lands. This approach has led to significant recoveries in wildlife populations, including endangered species, and has provided economic benefits (such as employment, income from tourism ventures, and game meat) to rural communities, thereby creating incentives for conservation. The success of CBNRMs has contributed to Namibia being a prime destination for ecotourism and wildlife tourism.

The country has an extensive network of protected areas, including national parks, game reserves, and conservancies. Etosha National Park is one of Africa's premier wildlife viewing destinations, centered around a large salt pan. Other significant protected areas include the Namib-Naukluft National Park (one of the largest in Africa, encompassing Sossusvlei and the Namib Sand Sea), the Skeleton Coast National Park, and the Waterberg Plateau Park. Twyfelfontein, a site with one of the largest concentrations of prehistoric rock engravings in Africa, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Despite these successes, challenges remain, including poaching (especially of rhinos and elephants), human-wildlife conflict, habitat degradation, and the impacts of climate change on fragile ecosystems and water resources.

4. Government and Politics

Namibia operates as a unitary semi-presidential representative democratic republic, with a government structured around executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The country is divided into 14 administrative regions. While its constitution upholds human rights, challenges related to social justice and accountability persist.

4.1. Government Structure

The framework of Namibia's government is established by its Constitution, which was adopted on 9 February 1990 and came into effect on 21 March 1990. It provides for a separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches.

- Executive Branch**: The President of Namibia is the head of state and head of government. The President is elected by popular vote for a five-year term and is limited to two terms (though founding President Sam Nujoma served three terms following a constitutional amendment). As of February 2024, the President is Nangolo Mbumba, who assumed office after the death of President Hage Geingob. The Vice President is Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah. The President appoints the Prime Minister, who is the head of government administration, and other ministers who form the Cabinet. The current Prime Minister is Saara Kuugongelwa. The Cabinet is responsible to the National Assembly.

- Legislative Branch**: The Parliament is bicameral, consisting of:

- The **National Assembly** (lower house): It has 104 members, of whom 96 are elected by popular vote through a proportional representation system for a five-year term. The remaining 8 members are appointed by the President and are non-voting. The National Assembly is the primary law-making body.

- The **National Council** (upper house): It has 42 members, with three members elected from each of the 14 regional councils for a six-year term. The National Council reviews legislation passed by the National Assembly and can make recommendations.

- Judicial Branch**: The judiciary is independent. The court system consists of the Supreme Court (the highest court of appeal and constitutional review), the High Court, and lower courts (Magistrate's Courts). The Chief Justice (currently Peter Shivute) is the head of the judiciary. Judges are appointed by the President on the recommendation of the Judicial Service Commission.

Elections are held regularly for presidential, National Assembly, and regional council positions. The Electoral Commission of Namibia (ECN) is responsible for organizing and supervising elections. While Namibia is a multi-party system, SWAPO has consistently won a majority in parliamentary elections since independence. Opposition parties include the Popular Democratic Movement (PDM, formerly Democratic Turnhalle Alliance - DTA), the Landless People's Movement (LPM), and others.

4.2. Administrative Divisions

Namibia is divided into 14 regions, which are the primary administrative subdivisions. Each region is governed by a Regional Council, whose members are directly elected by the inhabitants of their respective constituencies. The regions are further subdivided into 121 constituencies. This administrative structure was established by Delimitation Commissions, with the most recent delimitation occurring in 2013, which included the division of the former Kavango Region into Kavango East and Kavango West.

The 14 regions of Namibia are:

1. Kunene

2. Omusati

3. Oshana

4. Ohangwena

5. Oshikoto

6. Kavango West

7. Kavango East

8. Zambezi (formerly Caprivi Region)

9. Erongo

10. Otjozondjupa

11. Omaheke

12. Khomas

13. Hardap

14. ǁKaras (the "ǁK" represents a lateral click consonant)

Local authorities in Namibia consist of municipalities, town councils, and village councils, which manage local governance and service delivery within their jurisdictions. The most urbanized and economically active regions are Khomas (home to the capital, Windhoek) and Erongo (home to major coastal towns like Walvis Bay and Swakopmund).

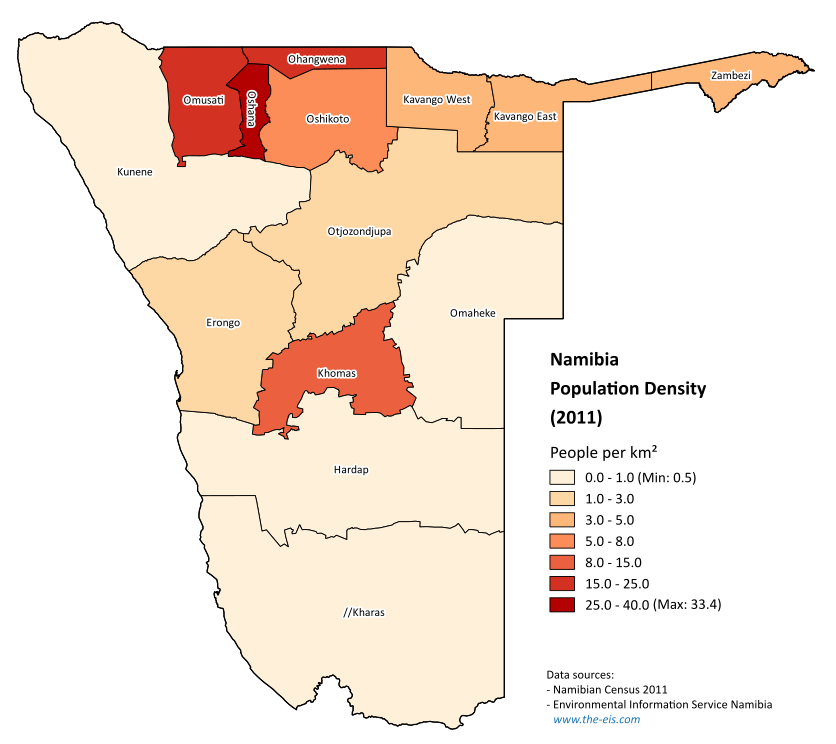

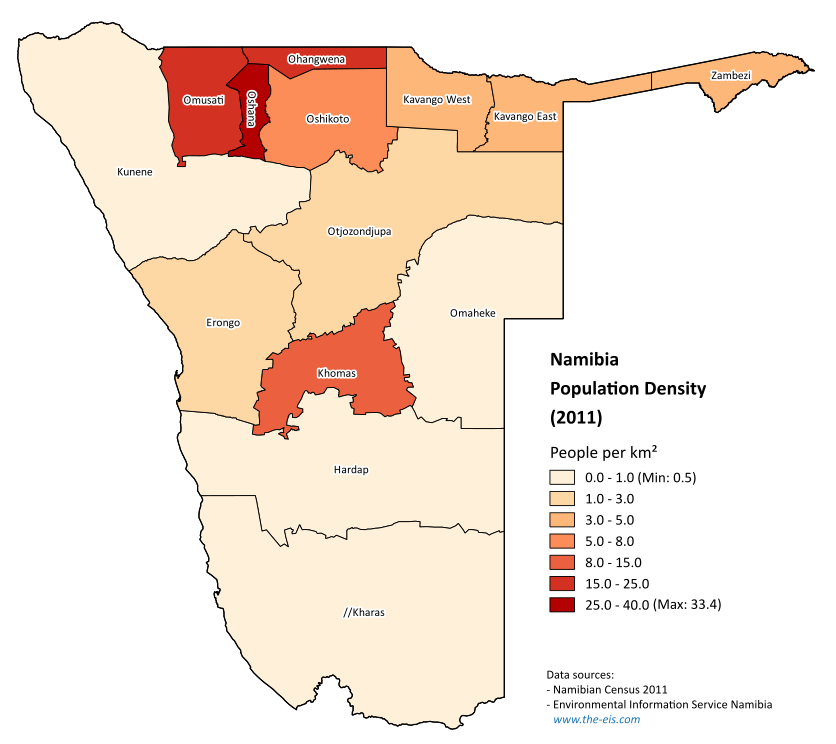

The following table shows regional population statistics from the 2023 Namibia Population and Housing Census:

| Region | Population (2023) | People per km2 | Average household size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Khomas | 494,605 | 13.4 | 3.3 |

| Ohangwena | 337,729 | 31.5 | 4.8 |

| Omusati | 316,671 | 11.9 | 4.2 |

| Oshikoto | 257,302 | 6.7 | 4.1 |

| Erongo | 240,206 | 3.8 | 3.1 |

| Oshana | 230,801 | 26.7 | 3.7 |

| Otjozondjupa | 220,811 | 2.1 | 3.6 |

| Kavango East | 218,421 | 9.1 | 5.3 |

| Zambezi | 142,373 | 9.7 | 3.7 |

| Kavango West | 123,266 | 5.0 | 5.5 |

| Kunene | 120,762 | 1.0 | 3.8 |

| Hardap | 106,680 | 1.0 | 3.6 |

| ǁKaras | 109,893 | 0.7 | 3.1 |

| Omaheke | 102,881 | 1.2 | 3.3 |

4.3. Human Rights

Namibia's constitution provides a strong framework for the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms. The country is generally considered to have a positive human rights record compared to many others in Africa, with an independent judiciary, a free press, and active civil society organizations. However, several human rights challenges persist.

- Civil Liberties and Political Rights**: Namibians generally enjoy freedom of speech, assembly, and association. Elections have been regularly held and deemed largely free and fair, though the dominance of the SWAPO party has led to some concerns about the vibrancy of multi-party competition. Media freedom is constitutionally guaranteed and largely respected, with Namibia often ranking highly in Africa on press freedom indices.

- Social Justice Issues**:

- Rights of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples**: The San people, in particular, continue to face marginalization, poverty, and discrimination, with limited access to land, education, healthcare, and political representation. Efforts to address their situation have been slow. Other minority ethnic groups also experience varying degrees of social and economic exclusion.

- Women's Rights**: While the constitution guarantees gender equality, women in Namibia still face significant challenges, including gender-based violence (GBV), which is widespread. Domestic abuse and sexual violence are serious concerns. Despite a "zebra system" policy within SWAPO aimed at ensuring gender balance in political representation, women remain underrepresented in leadership positions in both the public and private sectors.

- LGBT Rights**: Same-sex sexual activity between men was criminalized under a sodomy law inherited from the colonial era, though it was rarely enforced. In June 2024, the Windhoek High Court ruled this ban unconstitutional. Societal discrimination and intolerance against LGBT individuals remain prevalent, particularly in rural areas, although urban areas have seen increased visibility and some support. In May 2023, the Supreme Court ruled that same-sex marriages legally performed abroad must be recognized for residency purposes, a decision that sparked political backlash and attempts by parliament to overturn it via legislation.

- Vulnerable Groups**: Children, particularly orphans and vulnerable children (many affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic), persons with disabilities, and refugees face various challenges in accessing rights and services. Refugees, for instance, are often restricted in their freedom of movement.

- Corruption and Accountability**: Corruption remains a significant problem in Namibia, affecting public service delivery and undermining public trust. Despite the existence of anti-corruption bodies and laws, enforcement has been inconsistent, and high-level corruption cases often proceed slowly. There are ongoing efforts to improve transparency and accountability.

- Justice System**: Issues within the justice system include prison overcrowding, lengthy pre-trial detentions, and limited access to legal aid for the poor. Reports of police brutality and misconduct also occur.

Overall, while Namibia has a robust constitutional and legal framework for human rights, the effective implementation and enjoyment of these rights, particularly for marginalized and vulnerable groups, continue to be areas requiring sustained attention and improvement from a social justice perspective.

5. Military

The Namibian Defence Force (NDF) is the military organization responsible for the defense of Namibia's territory and national interests. It was established upon independence in 1990, integrating former combatants from the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN), the armed wing of SWAPO, and the South West African Territorial Force (SWATF), which had fought on behalf of South Africa. The British government played a role in the initial training and integration plan for the NDF.

The NDF's mandate, as defined by the Namibian Constitution, is to defend the territory, protect national interests, and contribute to international peace and security. It consists of an Army, an Air Wing, and a small Maritime Wing (Navy). The President of Namibia is the Commander-in-Chief of the NDF. The Chief of the Defence Force is Air Vice Marshal Martin Pinehas (as of April 2020).

The NDF is a volunteer force. Its total active personnel strength is relatively small, estimated to be around 9,000 to 15,000, though precise figures vary. The military budget in recent years has been a subject of public discussion, with some critics arguing it is disproportionately high relative to other national priorities. For the 2019/2020 financial year, the Ministry of Defence budget was approximately 5.88 B NAD. While some global indices have ranked Namibia's military strength as relatively low in global and African comparisons, the NDF is primarily structured for territorial defense and participation in regional security initiatives.

Namibia has participated in international peacekeeping operations, including UN missions in various African countries. The NDF was involved in the Second Congo War as part of a SADC contingent and also dealt with the Caprivi conflict in the late 1990s.

Namibia does not face immediate external military threats from its neighbors. It signed the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in 2017, affirming its commitment to nuclear disarmament.

6. Foreign Relations

Namibia pursues a largely independent foreign policy centered on non-alignment and regional cooperation, particularly within SADC. It maintains relationships with key international partners including South Africa, Angola, Germany, and China, balancing historical ties with economic development goals.

Namibia is an active member of several international and regional organizations, including:

- The United Nations (UN) (joined on 23 April 1990)

- The African Union (AU)

- The Southern African Development Community (SADC)

- The Commonwealth of Nations (joined on independence in 1990)

- The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM)

A cornerstone of Namibia's foreign policy is its commitment to the SADC, where it advocates for greater regional economic integration and cooperation on political and security matters. The country has historically maintained strong ties with nations that supported its struggle for independence, such as Cuba, Angola, and other African "frontline states."

6.1. Relations with Key International Partners

Namibia has cultivated diverse diplomatic and economic relationships with various global and regional actors.

- South Africa**: Due to historical ties and geographical proximity, South Africa remains one of Namibia's most significant partners, particularly in trade and investment. The two countries share a common currency area (the Common Monetary Area) and are members of the Southern African Customs Union (SACU). While relations are generally strong, issues such as historical debt and economic imbalances are sometimes points of discussion.

- Angola**: Angola, sharing a long northern border, is another key partner. Cooperation exists in areas such as border security, trade, and shared water resources (Kunene River). The historical support Angola provided to SWAPO during the independence struggle underpins strong political ties.

- Botswana**: Botswana and Namibia share common interests in regional stability, environmental conservation (particularly in transboundary parks like the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area), and economic cooperation within SADC. Past border disputes, such as over Kasikili/Sedudu Island in the Chobe River, were resolved peacefully through the International Court of Justice.

- Germany**: As the former colonial power, Germany maintains a significant relationship with Namibia. This includes substantial development aid, cultural exchange, and economic ties. A critical aspect of this relationship revolves around addressing the legacy of the Herero and Namaqua genocide. In May 2021, Germany officially recognized the atrocities as genocide and pledged 1.10 B EUR financial support for reconciliation and reconstruction projects, though the terms of this agreement have been a subject of debate within Namibia, particularly concerning the adequacy and nature of the reparations from a human rights perspective.

- China**: China has become an increasingly important economic partner for Namibia, with investments in infrastructure, mining, and other sectors. This relationship is part of China's broader engagement with Africa. Concerns have been raised by some civil society groups regarding labor practices in Chinese-owned enterprises and the environmental impact of some projects.

- United States and European Union**: Namibia also maintains relations with the United States and EU member states, which are significant development partners and markets for Namibian exports. These relationships often involve dialogues on governance, human rights, and sustainable development.

Namibia's foreign policy generally seeks to balance its historical alliances with pragmatic engagement to foster economic development and maintain regional stability. It often aligns with broader African positions on international issues, advocating for multilateralism and a more equitable global order.

7. Economy

Namibia's economy, classified as upper-middle-income, relies on mining, agriculture, tourism, and fisheries, but faces challenges of high unemployment and extreme income inequality. The nation possesses well-developed infrastructure in transport and telecommunications, though water supply and sanitation remain critical development areas.

7.1. Overview of Economic Structure

Namibia is classified as an upper-middle-income country by the World Bank. Its economy is closely linked to South Africa's due to historical connections and membership in the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) and the Common Monetary Area (CMA), which pegs the Namibian dollar (NAD) to the South African rand (ZAR) at a one-to-one ratio.

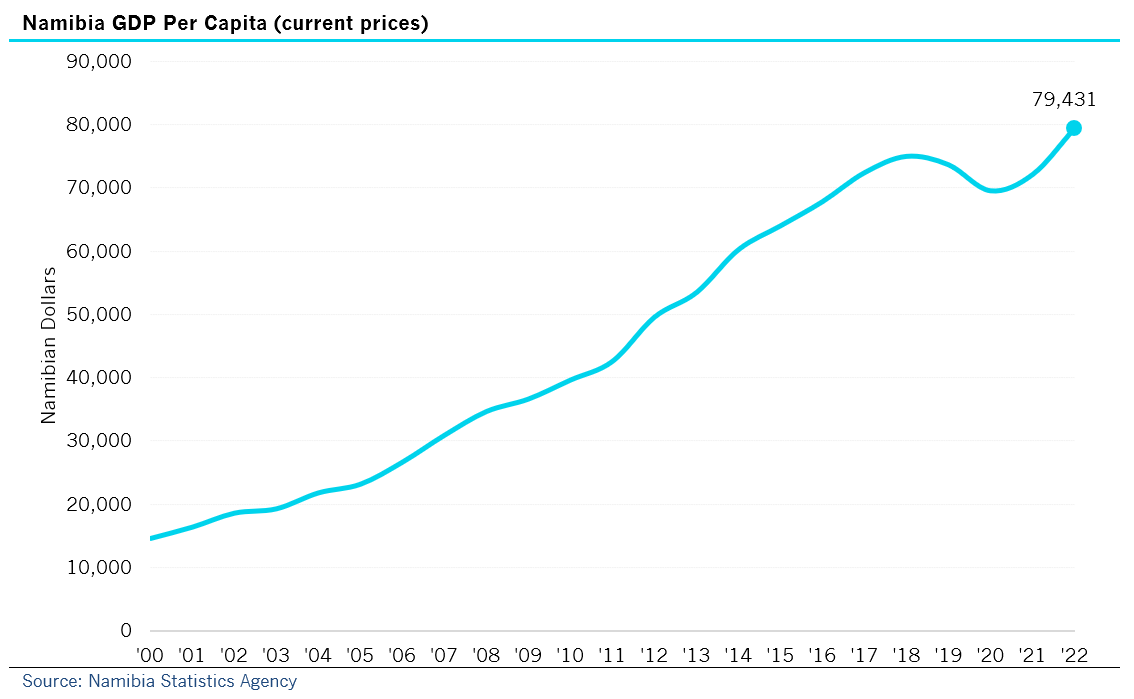

In Q3 2023, the largest contributors to Namibia's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) were mining (18.0%), public administration (12.9%), manufacturing (10.1%), and education (9.2%). Other important sectors include agriculture, fisheries, and tourism. The country has a relatively well-developed financial services sector, with the Bank of Namibia serving as the central bank.

Despite its relative wealth in terms of per capita GDP (PPP of around 11.60 K USD in 2023, nominal per capita GDP around 4.79 K USD), Namibia suffers from extreme income inequality. The Gini coefficient was 59.1 in 2015, among the highest in the world. This reflects deep-seated structural inequalities inherited from the apartheid era. Poverty remains a significant issue, with 40.9% of the population affected by multidimensional poverty in 2023. Unemployment is also a major challenge, with the overall rate at 33.4% in 2018 and youth unemployment particularly high at 38.4% in 2023.

The economy is dualistic, with a modern, formal sector concentrated in urban areas and a large informal sector, particularly in rural areas and townships, where many rely on subsistence agriculture or informal trade.

7.2. Main Sectors

The Namibian economy is driven by several key sectors, each with its own set of social, economic, and environmental implications.

7.2.1. Mining and Energy

Mining is a cornerstone of the Namibian economy, contributing significantly to GDP and export earnings (around 25% of revenue). Namibia is a major global producer of diamonds (mostly gem-quality) and uranium. Other important minerals include gold, copper, zinc, lead, and salt. The Rössing Uranium Mine is one of the world's largest open-pit uranium mines, and the Husab Mine is another major uranium producer. Diamond mining is dominated by Namdeb, a joint venture between the Namibian government and De Beers.

The mining sector provides relatively few direct jobs but generates substantial government revenue. There are ongoing concerns regarding the environmental impact of mining activities, such as water usage in an arid country and the management of mining waste. Labor rights and conditions in the mining sector are also subject to scrutiny. Efforts are made to ensure that benefits from mining accrue to local communities and the national economy through royalties, taxes, and local content policies, but the distribution of these benefits remains a challenge.

Recent offshore oil and gas discoveries, particularly in the Orange Basin, hold significant potential for transforming Namibia's economy, with estimates suggesting billions of barrels of oil. However, careful management will be required to avoid the "resource curse" and ensure sustainable and equitable development.

The energy sector relies on a mix of hydroelectric power (from the Kunene River), thermal power plants, and electricity imports, mainly from South Africa. Namibia has considerable potential for renewable energy, particularly solar power, due to its high solar irradiation levels.

7.2.2. Agriculture, Livestock, and Fisheries

Agriculture, though contributing a smaller percentage to GDP (around 5-7%), supports about half of the Namibian population, largely through subsistence farming in communal areas, particularly in the northern regions. Main subsistence crops include millet, sorghum, maize, and groundnuts.

Commercial agriculture is dominated by extensive livestock ranching (cattle and sheep, including Karakul sheep for pelts) on large, privately-owned farms, predominantly in the central and southern parts of the country. Land ownership remains highly unequal, a legacy of colonial dispossession. Land reform has been a slow and contentious process, aimed at resettling landless Namibians and promoting more equitable access to agricultural land. The social consequences of past land policies and the pace of reform are ongoing issues.

The fisheries sector is economically important, based on the rich fishing grounds of the Benguela Current. Hake, horse mackerel, and monkfish are key commercial species. The government manages fisheries through quotas to ensure sustainability. This sector provides significant export revenue and employment, though concerns about equitable benefit-sharing for local coastal communities and the rights of fishery workers are sometimes raised.

7.2.3. Tourism

Tourism is a major and growing contributor to Namibia's GDP (around 14.5%) and employment (around 18.2%). The country is renowned for its spectacular landscapes, abundant wildlife, and commitment to ecotourism. Key attractions include Etosha National Park, the Namib-Naukluft National Park (featuring Sossusvlei and Deadvlei), the Fish River Canyon, the Skeleton Coast, and cultural heritage sites like Twyfelfontein.

Wildlife tourism, including photographic safaris and regulated trophy hunting, is a significant component. Namibia's Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) program has been instrumental in linking tourism to conservation and local community development. These conservancies allow local communities to manage and benefit from wildlife on their lands, creating incentives for conservation and providing income and employment opportunities. The social and economic impact of tourism on local communities is a key consideration for sustainable development, ensuring that benefits are equitably distributed and that cultural integrity is respected.

7.3. Infrastructure

Namibia has relatively well-developed physical infrastructure compared to many other Sub-Saharan African countries, though challenges remain, particularly in extending services to remote rural areas and informal settlements.

7.3.1. Transport and Telecommunications

Namibia has an extensive network of roads, totaling over 26 K mile (41.81 K km) (though only a smaller portion, around 2.8 K mile (4.57 K km), is paved). Major highways, like the Trans-Kalahari Corridor and the Trans-Caprivi Highway, connect Namibia to neighboring countries and facilitate regional trade. The road network is generally well-maintained. Driving is on the left.

The railway system, operated by TransNamib, consists of narrow-gauge lines connecting major towns and extending to the South African border. It is primarily used for freight transport, including minerals and agricultural products.

The main port is Walvis Bay, a deep-water harbor that serves as a key gateway for Namibian trade and a transit hub for landlocked neighboring countries like Botswana, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. The smaller port of Lüderitz also plays a role.

Hosea Kutako International Airport, near Windhoek, is the main international airport. There are numerous smaller airports and airstrips throughout the country, supporting domestic travel and the tourism industry. Air Namibia, the former national airline, ceased operations in February 2021.

Telecommunication services have expanded significantly. Mobile phone penetration is high, and internet access is growing, though connectivity in rural areas can be limited and expensive. Fiber optic networks are being extended.

7.3.2. Water Supply and Sanitation

Water supply and sanitation in Namibia face significant challenges due to the country's aridity and vast, sparsely populated areas. NamWater, a state-owned enterprise, is the bulk water supplier, selling water to municipalities and other distributors. In rural areas, the Directorate of Rural Water Supply is responsible for water provision.

Access to improved water sources has increased significantly since independence, but disparities remain between urban and rural areas, and between affluent and low-income communities. High consumption costs and long distances to water points can be barriers for many, especially in rural regions.

Sanitation coverage lags behind water supply. While urban areas generally have better access to flush toilets and sewerage systems, many informal settlements and rural communities lack adequate sanitation facilities. Open defecation is still practiced in some areas, posing public health risks. Lack of proper sanitation and hygiene contributes to waterborne diseases and child mortality. Efforts are ongoing to improve sanitation infrastructure and promote hygiene practices, but this remains a critical development challenge impacting public health and quality of life. Windhoek's Goreangab Water Reclamation Plant is a pioneering facility that recycles wastewater into potable water.

7.4. Economic Challenges and Development

Despite its natural resource wealth and upper-middle-income status, Namibia faces significant economic challenges that impact social equity and sustainable development.

- High Unemployment**: Unemployment, particularly among youth (38.4% in 2023) and in rural areas, is a persistent problem. The formal sector has limited absorptive capacity, and many rely on the informal economy or subsistence agriculture. The government has implemented initiatives like the Internship Tax Incentive Programme to encourage youth employment.

- Poverty and Inequality**: Namibia has one of the highest levels of income inequality in the world, with a Gini coefficient of 59.1 (2015). Wealth and land ownership remain highly concentrated, a legacy of apartheid. While poverty rates have declined since independence, a significant portion of the population still lives in poverty. In 2023, 40.9% of the population experienced multidimensional poverty. More than 400,000 people live in informal housing (shacks).

- Dependence on Primary Commodities**: The economy's heavy reliance on mining (especially diamonds and uranium) and other primary commodities makes it vulnerable to global price fluctuations and resource depletion. Diversification efforts are ongoing but face challenges.

- Land Reform**: Addressing historical imbalances in land ownership through land reform remains a politically sensitive and slow process. The "willing buyer, willing seller" policy has had limited success in redistributing land to landless Namibians.

- Skills Gaps**: While Namibia has a relatively high literacy rate, there are skills gaps in certain sectors, hindering economic diversification and productivity growth.

- HIV/AIDS Impact**: The HIV/AIDS epidemic, though being managed with expanded treatment, has had a significant socio-economic impact, affecting the labor force and increasing the number of orphans and vulnerable children.

- Government Policies and Initiatives**: The Namibian government has implemented various national development plans (NDPs) and long-term visions (e.g., Vision 2030) aimed at addressing these challenges. Key policy objectives include poverty reduction, employment creation, economic diversification, improved education and healthcare, and empowerment of previously disadvantaged groups. Policies like Affirmative Action aim to correct historical imbalances in employment. The Harambee Prosperity Plan, launched by President Geingob, focused on poverty eradication, economic growth, and infrastructure development. There is an ongoing focus on attracting foreign investment, reducing bureaucratic red tape (Namibia ranks relatively well in ease of doing business regionally), and promoting local entrepreneurship. Taxation policies, including personal income tax and VAT, are used to fund public services and development initiatives, with recent adjustments aimed at providing relief to lower-income earners (e.g. raising tax threshold from 50.00 K NAD to 100.00 K NAD). The Internship Tax Incentive Programme provides corporate tax deductions for employers enrolling interns, with an estimated cost to the government of 126.00 M NAD.

Achieving more equitable and sustainable development requires addressing structural inequalities, investing in human capital, fostering inclusive growth, and ensuring good governance and effective resource management.

8. Society

Namibia's society is characterized by its sparse population, significant ethnic and linguistic diversity, and the widespread influence of Christianity. Access to education has improved, but challenges in healthcare, particularly HIV/AIDS, persist alongside efforts to enhance public services and address social disparities.

8.1. Demographics

Namibia has a population of approximately 3.1 million people (2023-2025 estimates). It is one of the most sparsely populated countries in the world, with an average population density of around 3.08 people per square kilometer in 2017, and 3.7 people per square kilometer according to the 2023 census. The population growth rate between the 2001 and 2011 censuses was 1.4% annually, a decrease from 2.6% in the preceding decade. The 2023 census counted 3,022,401 inhabitants.

Population distribution is uneven, with higher concentrations in the northern regions (such as Ohangwena, Omusati, Oshana, and Oshikoto, which are traditionally home to the Ovambo people) and in urban centers, particularly the capital, Windhoek, located in the Khomas Region. Urbanization is increasing, though a significant portion of the population still resides in rural areas.

Life expectancy at birth was estimated at 64 years in 2017. The total fertility rate was 3.47 children per woman in 2015, which is lower than the sub-Saharan African average. Since the end of the Cold War, Namibia has attracted some immigration from Germany, Angola, and Zimbabwe.

Namibia conducts a national census every ten years, with the most recent ones in 2011 and 2023 (delayed from 2021). These censuses provide crucial data on population size, distribution, ethnic composition, and socio-economic indicators.

8.2. Ethnic Groups

Namibia is a multi-ethnic nation with a rich diversity of cultures and traditions. The population comprises various groups, primarily of Bantu and Khoisan origin.

- Bantu-speaking groups** form the majority:

- Ovambo**: The largest ethnic group, constituting about 49-50% of the population (2014-2023 estimates). They predominantly inhabit the northern regions.

- Kavango**: Comprising about 9-10% of the population, living mainly along the Okavango River in the northeast.

- Herero**: Making up about 7-9% of the population, traditionally pastoralists, found in central and eastern Namibia. The Himba, a distinct sub-group known for their traditional lifestyle, are closely related to the Herero and live in the remote Kunene Region.

- Damara**: Accounting for about 7% of the population. They speak a Khoisan language (Khoekhoegowab) similar to the Nama, but are considered to be of Bantu origin by some anthropologists, or a distinct group.

- Lozi**: Around 3.5-5% of the population, primarily in the Zambezi Region.

- Tswana**: A smaller group, about 0.3-0.6%, mainly in the eastern parts.

- Khoisan-speaking groups**: Descendants of the earliest inhabitants of Southern Africa.

- Nama** (also known as Khoekhoe): About 4.7-5% of the population, mainly in southern and central Namibia.

- San** (Bushmen): Comprising about 0.7-3% of the population. They are one of the most marginalized groups, facing challenges related to land rights, poverty, and social exclusion.

- Mixed-ancestry groups**:

- Coloureds**: About 2.1-8% of the population (estimates vary), primarily Afrikaans-speaking and of mixed European and African/Khoisan descent.

- Basters**: Around 1.5-2.5%, concentrated in the town of Rehoboth and surrounding areas. They are descendants of Khoikhoi women and Dutch/Afrikaner men from the Cape Colony.

- White Namibians**: Constituting about 1.8-7% of the population (estimates vary, with recent census data suggesting the lower end). They are mainly of Afrikaner (Dutch descent), German, British, and Portuguese origin. Many speak Afrikaans or German as their first language. The German-speaking community maintains distinct cultural and educational institutions.

- Other groups**: There is also a small Chinese minority, estimated at around 40,000 in 2006, and other smaller immigrant communities.

Inter-ethnic relations are generally peaceful, although historical grievances and socio-economic disparities between groups persist. The government promotes a policy of national unity, but ensuring equitable development and representation for all ethnic groups, particularly minorities and vulnerable communities like the San, remains a critical social justice challenge.

8.3. Languages

Namibia has a diverse linguistic landscape, reflecting its multi-ethnic composition.

- Official Language**: English is the sole official language since independence in 1990. It is used in government, formal education (especially secondary and tertiary levels), and the media. However, only about 2.3-3.4% of the population speaks English as a home language. While proficiency is growing, particularly among the youth and in urban areas, its widespread use as a daily communication tool is limited for a large part of the population.

- National and Regional Languages**: Several indigenous languages and Afrikaans hold recognized status as national languages and can be used as mediums of instruction in primary schools.

- Oshiwambo** (a cluster of related dialects like Kwanyama and Ndonga) is the most widely spoken home language, used by about 49-50% of households.

- Khoekhoegowab** (Nama/Damara) is spoken by about 11% of households.

- Afrikaans** serves as a lingua franca for a significant portion of the population across different ethnic groups and is the home language for about 9-10% of households, including most Coloureds, Basters, and a majority of White Namibians.

- Otjiherero** is spoken by about 9% of households.

- Kavango languages** (including RuKwangali, Gciriku, Mbukushu) are spoken by about 8.5-10% of households.

- SiLozi** is spoken by about 4.8-4.9% of households, mainly in the Zambezi Region.

- German** is spoken by about 0.6-0.9% of households, primarily within the German-Namibian community, and retains some commercial importance.

- San languages** (various distinct languages like !Kung) are spoken by about 0.7-0.8% of households.

- Setswana** is spoken by about 0.3% of households.

- Other African and European languages are spoken by smaller percentages. Portuguese has gained some presence due to proximity and historical ties with Angola, with an estimated 100,000 speakers in 2011.

The government's policy of promoting English as the sole official language aimed to foster national unity and avoid the ethnic fragmentation associated with the apartheid-era promotion of separate languages. However, critics argue that this has sometimes led to challenges in education, particularly for students whose first language is not English, potentially impacting learning outcomes and contributing to school drop-out rates. Multilingualism is a practical reality in Namibian society.

The distribution of home languages in Namibia (based on 2011/2016 data) is approximately:

- Oshiwambo languages: 49.7%

- Khoekhoegowab: 11.0%

- Afrikaans: 9.4% (though often cited as 10.4%)

- Otjiherero languages: 9.2%

- Kavango languages: 10.4% (though often cited as 8.5-9%)

- SiLozi languages: 4.9%

- English: 2.3% (though often cited as 3.4%)

- German: 0.6% (though often cited as 0.9%)

- San languages: 0.7% (though often cited as 0.8%)

- Setswana: 0.3%

- Other African Languages: 0.5% - 1.2%

- Other European Languages: 0.1% - 0.7%

- Asian Languages: 0.1%

(Note: Percentages can vary slightly between different census reports and surveys.)

8.4. Religion

Christianity is the dominant religion in Namibia, adhered to by 80% to 90% of the population. This is largely a result of missionary activities that began in the 19th century.

- Protestantism**: Protestants constitute the majority of Christians, with estimates around 75%.

- Lutheranism**: This is the largest single Christian denomination, accounting for at least 50% of the population. The Evangelical Lutheran Church in Namibia (ELCIN), the Evangelical Lutheran Church in the Republic of Namibia (ELCRN), and the German-speaking Evangelical Lutheran Church in Namibia (GELC/DELK) are the main Lutheran bodies. This strong Lutheran presence is a legacy of German and Finnish missionary work during the colonial era.

- Other Protestant denominations include Anglicanism (Diocese of Namibia, about 17%), Methodist, Dutch Reformed, African Methodist Episcopal, and various Pentecostal and evangelical groups.

- Catholicism**: Roman Catholics make up a significant minority, around 22.8% of Christians.

- Traditional Indigenous Beliefs**: Approximately 10% to 20% of the population adhere to traditional indigenous beliefs, although many Christians may also incorporate some traditional practices into their faith.

- Other Faiths**:

- Islam is practiced by a small minority, estimated at around 9,000 people, many of whom are from the Nama ethnic group.

- Judaism is present with a very small community of about 100 people.

- Other religious groups such as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and Jehovah's Witnesses also have a presence.

- A small percentage of the population (around 1.6%) identifies as having no religion.

Freedom of religion is constitutionally guaranteed and generally respected in Namibia. Religious institutions often play an important role in social welfare and community life.

8.5. Education

Education in Namibia is compulsory for 10 years between the ages of 6 and 16. The government provides free education at both primary and secondary levels. The education system is structured into:

- Grades 1-7: Primary level

- Grades 8-12: Secondary level (Grades 8-9 Junior Secondary, Grades 10-12 Senior Secondary)

Since independence, Namibia has made significant strides in expanding access to education. However, challenges remain in terms of quality, equity (especially for children in remote rural areas, San communities, and those with disabilities), and resource allocation. In 1999, education expenditure was about 8% of GDP; in 2014, it was 3.1% (though this figure can vary and sometimes is reported higher, indicating substantial government investment). The pupil-teacher ratio was estimated at 32:1 in 1999.

The National Institute for Educational Development (NIED) in Okahandja is responsible for curriculum development, educational research, and teacher professional development. English is the official medium of instruction from Grade 4 upwards, although mother-tongue instruction is encouraged in the early primary grades (Grades 1-3). The transition to English can be challenging for many students whose first language is not English.

Namibia has one of the highest literacy rates in sub-Saharan Africa. As of 2018, the literacy rate for the population aged 15 and over was estimated at 91.5% (91.6% for males and 91.4% for females).

Higher education institutions include:

- The University of Namibia (UNAM)

- The Namibia University of Science and Technology (NUST), formerly the Polytechnic of Namibia

- The International University of Management (IUM)

There are also four teacher training colleges and three agricultural colleges.

According to the 2018 Namibia Labour Force Survey, 6.6% of the working-age population had tertiary education of any level, and 1.5% had postgraduate education. Employment rates generally increase with higher levels of education.

Despite progress, issues such as school infrastructure deficits (especially in rural areas), teacher shortages in certain subjects, high repetition and dropout rates, and the relevance of the curriculum to labor market needs are ongoing concerns. Efforts are focused on improving the quality of education, enhancing vocational training, and ensuring that education contributes to equitable socio-economic development.

8.6. Health

Namibia has made progress in improving public health since independence, but faces significant challenges, including a high burden of both communicable and non-communicable diseases, and disparities in health outcomes and access to services, particularly between urban and rural areas and among different socio-economic groups. Life expectancy at birth was estimated at 64 years in 2017.

- Major Health Concerns**:

- HIV/AIDS**: Namibia has one of the highest HIV prevalence rates in the world. In 2015, UNAIDS projected HIV prevalence among 15-49-year-olds at 13.3%, with an estimated 210,000 people living with HIV. The epidemic has had a profound impact, reducing the working-age population and increasing the number of orphans. However, Namibia has made significant strides in expanding access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and prevention programs (like prevention of mother-to-child transmission). HIV prevalence among men aged 15-49 is lower among circumcised men (8.0%) than uncircumcised men (11.9%) according to the 2013 DHS. Prevalence peaks in the 35-39 age group for both women (30.9%) and men (22.6%).

- Tuberculosis (TB)**: TB is a major public health problem, often co-occurring with HIV.

- Malaria**: Malaria is endemic in the northern regions of the country, particularly during the rainy season. Concurrent HIV infection increases the risk of contracting malaria and the risk of death from it.

- Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs)**: NCDs such as hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancers are an increasing concern. The 2013 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) found that among adults aged 35-64, 44% of women and 45% of men had elevated blood pressure or were on medication for it. About 6-7% of adults were diabetic.

- Maternal and Child Health**: While progress has been made, maternal and child mortality rates still require improvement. Malnutrition and diarrheal diseases (often linked to poor sanitation and hygiene) contribute to child morbidity and mortality.

- Healthcare Infrastructure and Access**:

Healthcare services are provided by both the public and private sectors. The Ministry of Health and Social Services oversees the public healthcare system, which includes hospitals, health centers, and clinics. Private healthcare facilities are concentrated in urban areas and cater to a smaller segment of the population, typically those with medical aid.

Access to healthcare services can be challenging for people in remote rural areas due to long distances, transportation difficulties, and staff shortages. There was a reported 598 physicians in the country in 2002. In 2012, Namibia launched a National Health Extension Programme, training health extension workers to provide basic health services and health promotion in communities.- Social Determinants of Health**:

Poverty, malnutrition, inadequate water and sanitation, limited educational attainment, and gender inequality are significant social determinants that affect health outcomes in Namibia. Addressing these underlying factors is crucial for improving the overall health status of the population. Government health policies focus on primary healthcare, disease prevention, and strengthening the health system to provide equitable access to quality care.

9. Culture

Namibian culture is a rich tapestry woven from the traditions of its diverse ethnic groups, influences from its colonial past (German and South African), and contemporary global trends. Due to its shared history and close ties, Namibian culture shares some similarities with South African culture. Namibians generally express a strong national identity and preference for their homeland.

9.1. Media

Namibia enjoys a significant degree of media freedom compared to many neighboring countries and often ranks well in international press freedom indices (e.g., 21st on Reporters Without Borders index in 2010, 23rd in 2019, making it one of the highest-ranked African countries). The constitution guarantees freedom of speech and the press.

The media landscape is diverse for a country with a relatively small population:

- Print Media**: There are several daily newspapers, including the private publications The Namibian (primarily English, with some content in Oshiwambo and other local languages), Die Republikein (Afrikaans), Allgemeine Zeitung (German, the oldest daily newspaper, founded 1898 as Windhoeker Anzeiger), and Namibian Sun (English). The state-owned New Era is also a daily (predominantly English). Weekly newspapers like the Windhoek Observer and Namibia Economist, as well as various magazines and special publications, also exist.

- Broadcast Media**: The state-run Namibian Broadcasting Corporation (NBC) operates television and radio services, including a national radio service in English and services in various indigenous languages. There are also private radio stations (mostly English-language, with some like Radio Omulunga in Oshiwambo and Kosmos 94.1 in Afrikaans) and a private television station, One Africa Television.

- Online Media**: Most print publications have an online presence. The Namibia Press Agency (NAMPA) is the state-owned news agency.

While generally free, the media can experience some influence from state and economic actors. Media representative bodies include the Namibian chapter of the Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA) and the Editors' Forum of Namibia. An independent media ombudsman was appointed in 2009.

9.2. Sport

Sport in Namibia plays an important role in national life.

- Football (Soccer)**: This is the most popular sport. The Namibia national football team (the "Brave Warriors") has qualified for the Africa Cup of Nations multiple times (1998, 2008, 2019, 2023) but has not yet qualified for the FIFA World Cup. Notable players include Ryan Nyambe, Peter Shalulile, and retired footballer Collin Benjamin. A professional league, the Namibia Premier Football League, operates domestically.

- Rugby Union**: The Namibia national rugby union team (the "Welwitschias") is the most successful national team in terms of international tournament participation, having competed in seven consecutive Rugby World Cups (1999, 2003, 2007, 2011, 2015, 2019, 2023). While they have yet to win a match at the World Cup, their consistent qualification is a significant achievement. Former professional player Jacques Burger is a well-known Namibian rugby figure.

- Cricket**: Cricket is also popular. The Namibia national cricket team qualified for the 2003 Cricket World Cup and more recently for the 2021 ICC Men's T20 World Cup (reaching the Super 12s stage) and the 2022 ICC Men's T20 World Cup. Namibia is set to co-host the 2027 Cricket World Cup with South Africa and Zimbabwe.

- Athletics**: Frankie Fredericks is Namibia's most famous athlete, a sprinter who won four Olympic silver medals in the 100m and 200m events at the 1992 and 1996 Olympics, as well as World Championship medals.

- Other Sports**: Boxing (e.g., Julius Indongo, former unified world champion), golf (e.g., Trevor Dodds), and cycling (e.g., Dan Craven) also have a following.

Namibians are also known for high rates of alcohol consumption, particularly beer, ranking among the highest in Africa per capita.

9.3. Arts and Traditions

Namibia's arts and traditions reflect its cultural diversity.

- Visual Arts**: Traditional crafts include basketry, pottery, woodcarving, and beadwork, often specific to particular ethnic groups. Rock art, such as the engravings at Twyfelfontein, provides a link to ancient artistic traditions. Contemporary Namibian art is a growing field, with artists exploring themes of identity, history, and social issues. The National Art Gallery of Namibia in Windhoek showcases Namibian, African, and European art. Namibia participated in the Venice Biennale for the first time in 2022 with the exhibition "A Bridge to the Desert," featuring the "Lone Stone Men" project by artist Renn.

- Music and Dance**: Traditional music and dance vary widely among ethnic groups, often playing a significant role in ceremonies, storytelling, and social gatherings. Contemporary music genres, including Kwaito, Afro-pop, reggae, and hip-hop, are popular, particularly among the youth.

- Literature**: Namibian literature includes works in English, Afrikaans, German, and indigenous languages. Themes often explore colonial history, the struggle for independence, post-colonial identity, and social realities.

- Cultural Heritage**: Efforts are made to preserve and promote cultural heritage sites and practices. Traditional leadership structures still play a role in many communities, alongside modern governmental systems. Oral traditions, folklore, and traditional medicine are important aspects of cultural heritage for many groups. The distinctive red ochre body paint and hairstyles of the Himba people are internationally recognized cultural markers.

9.4. Public Holidays

Namibia observes several public holidays, which include:

- New Year's Day (January 1)

- Independence Day (March 21)

- Good Friday (movable feast, March/April)

- Easter Monday (movable feast, March/April)

- Workers' Day (May Day) (May 1)

- Cassinga Day (May 4) - Commemorates the 1978 Cassinga massacre.

- Ascension Day (movable feast, 40 days after Easter)

- Africa Day (May 25)

- Heroes' Day (August 26) - Commemorates the start of the Namibian War of Independence.

- Human Rights Day (December 10)

- Christmas Day (December 25)

- Family Day (Boxing Day) (December 26)

When a public holiday falls on a Sunday, the following Monday is observed as a public holiday. These holidays reflect Namibia's history, cultural values, and religious observances.