1. Overview

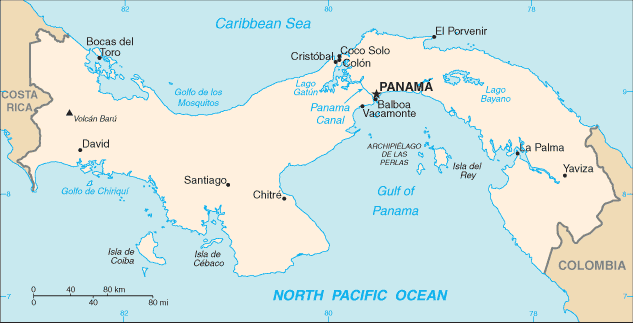

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a transcontinental country situated at the southern end of Central America, bridging North America and South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and the Pacific Ocean to the south. The capital and largest city is Panama City, whose metropolitan area is home to nearly half of the country's approximately 4.4 million inhabitants. Panama's geography is characterized by a central spine of mountains, extensive coastlines, and numerous rivers, with a tropical climate supporting rich biodiversity.

Historically, Panama was inhabited by various indigenous peoples before Spanish colonization in the 16th century. It gained independence from Spain in 1821, subsequently joining the Republic of Gran Colombia. After Gran Colombia's dissolution, Panama remained part of Colombia until 1903, when it seceded with United States backing, a move intrinsically linked to the construction of the Panama Canal. The canal, completed in 1914, has been a central element of Panama's history and economy. The Torrijos-Carter Treaties led to the full transfer of the canal to Panamanian control on December 31, 1999. The 20th century saw periods of political instability, including military rule under figures like Omar Torrijos and Manuel Noriega, and a U.S. invasion in 1989 that ousted Noriega. Subsequent decades have focused on democratic consolidation, economic development centered on the canal and services, and addressing social challenges such as inequality and governance.

Panama's government is a presidential representative democratic republic with a multi-party system. The economy is heavily reliant on its well-developed service sector, including the Panama Canal, logistics, international banking, and tourism. While considered a high-income economy, Panama faces challenges of social equity and income distribution.

Panamanian society is a melting pot of cultures, with a population primarily composed of Mestizo people, alongside significant indigenous, Afro-Panamanian, and European-descended groups. Spanish is the official language. The nation's culture reflects this diversity in its music, dance, cuisine, and traditional arts. This article explores these facets from a perspective that emphasizes social equity, human rights, and democratic development, providing a comprehensive overview of Panama.

2. Etymology

The precise origin of the name "Panama" (Panamápa-na-MASpanish) is not definitively known, and several theories exist. One widely accepted theory suggests that the country was named after a commonly found species of tree, the Panama tree (Sterculia apetala).

Another popular theory, often relayed in Panamanian folklore, posits that the first Spanish settlers arrived in August, a time when butterflies are abundant, and that the name "Panamá" means "many butterflies" in one or more of the indigenous languages spoken in the territory prior to Spanish colonization.

A further theory suggests that the word is a Castilianization of the Kuna language word "bannaba", meaning "distant" or "far away."

A commonly recounted legend in Panama states that there was a fishing village named "Panamá," which purportedly meant "an abundance of fish," when Spanish colonists first landed in the area. This legend is often corroborated by diary entries of Captain Antonio Tello de Guzmán, who reported landing at an unnamed village while exploring the Pacific coast in 1515, describing it only as a "small indigenous fishing town." In 1517, Don Gaspar de Espinosa, a Spanish lieutenant, decided to establish a trading post in the same location. Later, in 1519, Pedro Arias Dávila chose this site to establish the Spanish Empire's Pacific port, which became Panama City.

The official definition and origin of the name, as promoted by Panama's Ministry of Education and commonly found in social studies textbooks, is the "abundance of fish, trees, and butterflies," effectively combining some of the prevailing theories.

3. History

Panama's history spans from its early indigenous inhabitants through Spanish colonial rule, its union with and eventual separation from Colombia, and its development as an independent nation significantly shaped by the Panama Canal and its relationship with the United States. The nation's journey includes struggles for sovereignty, periods of political upheaval, and ongoing efforts towards democratic and social progress.

3.1. Pre-Columbian Period

The Isthmus of Panama formed approximately three million years ago, creating a land bridge between North and South America that allowed for the gradual crossing of plants, animals, and eventually, human populations. This geological event significantly influenced the dispersal of people, agriculture, and technology throughout the American continent, from the era of the first hunters and collectors to the development of villages and cities.

The earliest discovered artifacts of indigenous peoples in Panama include Paleo-Indian projectile points. Later, central Panama became home to some of the earliest pottery-making cultures in the Americas, such as those at the Monagrillo site, dating back to 2500-1700 BC. These early societies evolved into significant populations, best known through their spectacular burials (dating to c. 500-900 AD) at Monagrillo and their distinctive Gran Coclé style polychrome pottery. The monumental monolithic sculptures at the Barriles site in Chiriquí are also important traces of these ancient isthmian cultures.

Before the arrival of Europeans in the early 16th century, Panama was widely settled by Chibchan, Chocoan, and Cueva peoples. The largest group was the Cueva, whose specific linguistic affiliation is not well-documented. The exact size of the indigenous population at the time of European colonization is uncertain, with estimates ranging from as high as two million people to more recent studies suggesting a figure closer to 200,000. Archaeological finds and accounts from early European explorers describe diverse native groups exhibiting cultural variety and suggest that these peoples developed through regular regional routes of commerce. There is also evidence of Austronesians having a trade network extending to Panama, as indicated by the presence of coconuts from the Philippines on Panama's Pacific coast in pre-Columbian times.

When Panama was colonized, the indigenous populations largely fled into the forests and onto nearby islands. Scholars believe that infectious diseases, to which the indigenous peoples had no acquired immunity, were the primary cause of their population decline. Diseases such as smallpox, which had been chronic in Eurasian populations for centuries, had a devastating impact.

3.2. Spanish Colonial Era

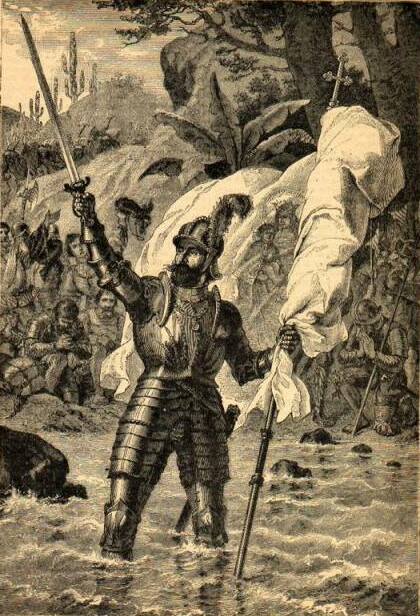

Rodrigo de Bastidas, sailing westward from Venezuela in 1501 in search of gold, became the first European to explore the Isthmus of Panama. A year later, in 1502, Christopher Columbus visited the isthmus and established a short-lived settlement in the Darien region. Vasco Núñez de Balboa's arduous trek from the Atlantic to the Pacific in 1513 definitively demonstrated that the isthmus was the path between the seas. This discovery quickly positioned Panama as a crucial crossroads and marketplace for Spain's empire in the New World. King Ferdinand II of Aragon appointed Pedro Arias Dávila (also known as Pedrarias) as Royal Governor, who arrived in June 1514 with 19 vessels and 1,500 men. In 1519, Dávila founded Panama City on the Pacific coast.

Panama became a vital transit point for the Spanish Empire. Gold and silver extracted from South America, particularly from the mines of Peru, were shipped to Panama City, transported overland across the isthmus, and then loaded onto ships at Caribbean ports like Portobelo or Nombre de Dios for the journey to Spain. This trans-isthmian route became known as the Camino Real (Royal Road), though it was often grimly referred to as the Camino de Cruces (Road of Crosses) due to the many gravesites along its path.

By 1520, Genoese merchants controlled the port of Panama, having obtained a concession from the Spanish Crown primarily for the slave trade, a role they maintained until the original city was destroyed in 1671. Panamanian resources and manpower were also drawn into broader imperial endeavors; for instance, in 1635, Governor Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera recruited Genoese, Peruvians, and Panamanians as soldiers to fight in the Philippines and found the city of Zamboanga City.

Panama remained under Spanish rule for nearly 300 years, from 1538 to 1821. Initially, it was part of the Viceroyalty of Peru, which encompassed all Spanish possessions in South America. From the outset, Panamanian identity was shaped by a sense of "geographic destiny," with the region's fortunes fluctuating with the geopolitical importance of the isthmus. The colonial experience fostered a nascent Panamanian nationalism alongside a racially complex and highly stratified society, which became a source of internal conflicts.

In 1538, the Real Audiencia of Panama was established, a judicial district that functioned as an appeals court, initially with jurisdiction from Nicaragua to Cape Horn. Spanish authorities, however, had limited control over much of Panama's territory. Large sections resisted conquest and missionization until late in the colonial era, and indigenous peoples in these areas were often referred to as "indios de guerra" (war Indians). Despite this, Panama's strategic importance for transporting Peruvian silver to Europe remained paramount. Beyond the European route, an Asian-American trade route also developed, with traders carrying silver from Peru, overland through Panama to Acapulco, Mexico, and then sailing to Manila, Philippines, via the Manila galleons. In 1579, Panama was granted permission to trade directly with Asia, breaking Acapulco's previous monopoly.

The incompletely controlled Panama route was vulnerable to attacks from pirates, mainly Dutch and English, and from cimarrons-Africans who had freed themselves from enslavement and established communities (palenques) near the Camino Real and on coastal islands. One notable cimarron community, led by Bayano, effectively formed a small kingdom between 1552 and 1558. Francis Drake's raids in 1572-73 were aided by Panamanian cimarrons, and Spanish authorities eventually made an alliance with them in 1582, granting freedom in exchange for military support.

Several factors contributed to a distinct sense of autonomy and regional identity in Panama: the prosperity during the first two centuries (1540-1740), the extensive regional judicial authority of the Real Audiencia, and its pivotal role in the Spanish Empire. The abolition of the encomienda system in the Azuero Peninsula in 1558, following protests against the mistreatment of indigenous populations, led to a system of medium and smaller-sized landownership, shifting power away from large landowners. This, in turn, sparked the conquest of Veraguas in the same year, where the encomienda system was imposed.

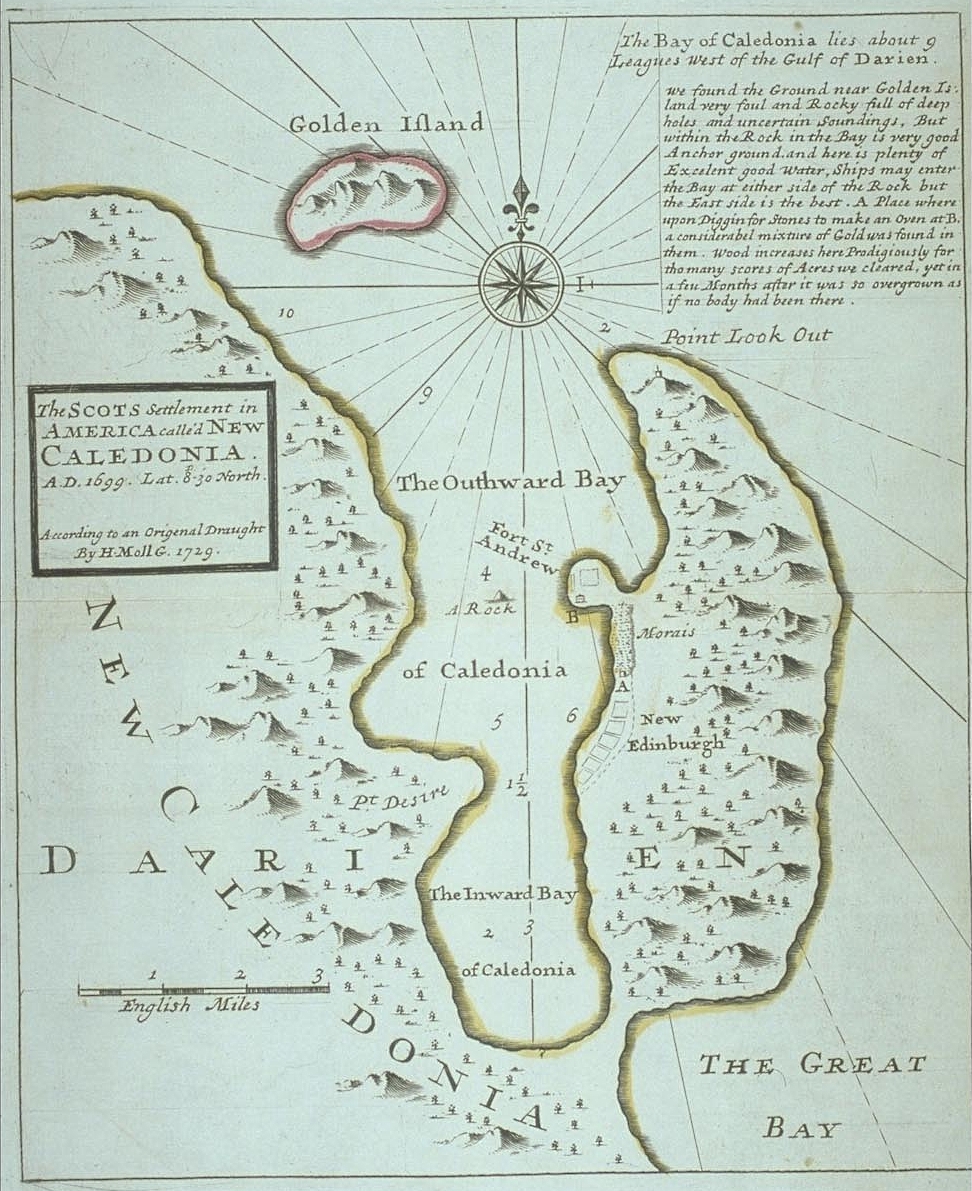

In the late 17th century, Panama was the site of the ill-fated Darien scheme, a Scottish attempt to establish a colony in 1698. The colony failed due to various factors, and the resulting debt significantly contributed to the union of England and Scotland.

In 1671, the privateer Henry Morgan, licensed by the English government, sacked and burned the original city of Panama, then the second most important city in the Spanish New World. In 1717, the Viceroyalty of New Granada was created, and the Isthmus of Panama was placed under its jurisdiction. However, the remoteness of New Granada's capital, Santa Fe de Bogotá (modern Bogotá), proved an obstacle, and Panama's ties to the Viceroyalty of Peru and its own initiatives often contested Bogotá's authority. This uneasy relationship would persist for centuries.

By the mid-18th century, Panama's importance declined as Spain's power waned and advances in navigation allowed ships to round Cape Horn to reach the Pacific, bypassing the laborious and expensive overland Isthmian route. In 1744, Bishop Francisco Javier de Luna Victoria DeCastro established the College of San Ignacio de Loyola, and in 1749, founded La Real y Pontificia Universidad de San Javier.

3.3. Path to Independence from Colombia

As the Spanish American wars of independence gained momentum across Latin America, Panama City was also preparing for independence. These plans were accelerated by the unilateral Grito de La Villa de Los Santos (Cry from the Town of Saints), issued on November 10, 1821, by residents of the Azuero Peninsula without direct backing from the capital. This declaration of separation from the Spanish Empire was met with disdain in both Veraguas (where it was seen as treason) and Panama City (where it was viewed as inefficient and irregular, forcing an acceleration of their own plans). The Grito from Azuero signified antagonism towards the capital's independence movement, with fears that Azuero sought self-rule separate from Panama City post-independence.

The move was risky, as Colonel José de Fábrega, a staunch loyalist with control over the isthmus's military supplies, was initially feared to retaliate. However, separatists in the capital had been working since October 1821 (when Governor General Juan de la Cruz Mourgeón left for Quito) to sway Fábrega. By November 10, Fábrega supported independence. Soon after the Los Santos declaration, Fábrega convened organizations in the capital with separatist interests and formally declared the city's support for independence. Military repercussions were avoided through skillful bribing of royalist troops.

Following its independence from Spain in 1821, Panama voluntarily joined the Republic of Gran Colombia, a union formed by Simón Bolívar that included Nueva Granada (present-day Colombia and Panama), Ecuador, and Venezuela. After Gran Colombia dissolved in 1831, Panama became part of the Republic of New Granada. This entity later transformed, and Panama was designated as the State of Panama in 1855, an autonomous entity within subsequent Colombian federations like the Granadine Confederation (1858-1863) and the United States of Colombia (1863-1886). The Colombian Constitution of 1886 then re-centralized power, creating the Department of Panama.

Throughout the 19th century, the people of the isthmus made over 80 attempts to secede from Colombia. They came close to success in 1831 and again during the Thousand Days' War (1899-1902). This war was understood by many indigenous Panamanians, under leaders like Victoriano Lorenzo, as a struggle for land rights.

The United States' intent to construct and control a trans-isthmian canal heavily influenced Panamanian separatism. When the Senate of Colombia rejected the Hay-Herrán Treaty on January 22, 1903, which would have granted the U.S. rights to build the canal, the U.S. decided to support the Panamanian secessionist movement.

In November 1903, Panama, with tacit U.S. support including the presence of U.S. warships to prevent Colombian military intervention, proclaimed its independence. The new republic immediately concluded the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty with the United States. This treaty was controversially negotiated by Philippe Bunau-Varilla, a French engineer and lobbyist with interests in a French company that held the previous canal rights, without the presence of any Panamanian representatives, who arrived in New York too late. The treaty granted the United States rights "as if it were sovereign" in a zone roughly 10 mile wide and 50 mile long, where the U.S. would build, administer, fortify, and defend a canal "in perpetuity." This treaty became a long-standing source of contention and fueled Panamanian nationalism until its abrogation by the Torrijos-Carter Treaties in 1977.

3.4. 20th Century and Beyond

Panama's 20th and early 21st-century history is largely defined by the Panama Canal, significant U.S. influence, periods of political instability and military rule, and eventual transitions towards a more consolidated democracy. Key themes include the struggle for full sovereignty over the Canal Zone, addressing human rights issues during authoritarian periods, and navigating economic development alongside social challenges.

3.4.1. Early 20th Century and Canal Construction

Following Panama's U.S.-backed independence in 1903, the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty immediately granted the United States control over the Panama Canal Zone and the right to construct the canal. The United States Army Corps of Engineers undertook the monumental task, completing the canal, approximately 52 mile (83 km) long, between 1904 and 1914. The canal's construction was a feat of engineering but came at a high human cost, with many workers, largely from the Caribbean, perishing due to disease and harsh conditions.

The opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 transformed global maritime trade and cemented Panama's strategic importance. However, the U.S. presence in the Canal Zone, an area effectively under American sovereignty, created a state-within-a-state and became a persistent source of tension and nationalist sentiment among Panamanians. The U.S. extensively fortified the canal, especially during World War II, reflecting its strategic military value.

From 1903 to 1968, Panama was a constitutional democracy nominally, but political power was largely dominated by a commercially oriented oligarchy. This period saw the beginning of sustained pressure for the renegotiation of the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty. During the 1950s, the Panamanian military (then the National Guard) began to challenge the oligarchy's political hegemony. Tensions over U.S. control of the Canal Zone and Panamanian sovereignty culminated in riots in early 1964, sparked by a dispute over flying the Panamanian flag in the Zone. These riots resulted in widespread looting, dozens of deaths, and a temporary severance of diplomatic relations with the U.S., highlighting the depth of national feeling and the need for a new treaty arrangement.

3.4.2. Military Rule and U.S. Intervention

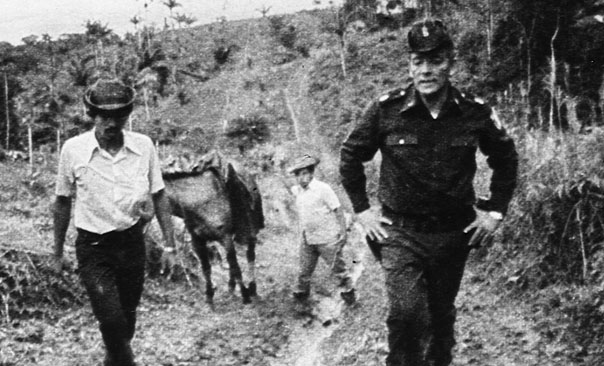

The period from the late 1960s into the 1980s was marked by military dominance in Panamanian politics. In 1968, after Arnulfo Arias Madrid was elected president and attempted to assert control over the National Guard, he was overthrown in a coup led by Lieutenant Colonel Omar Torrijos Herrera and Major Boris Martínez. Torrijos consolidated power, proclaiming himself the "Maximum Leader of the Panamanian Revolution."

Under Torrijos, the military government implemented populist measures, including land redistribution, expansion of social security, and increased public education. However, this era was also characterized by the suppression of political opposition and limitations on civil liberties. Torrijos's key foreign policy achievement was the negotiation of the Torrijos-Carter Treaties with U.S. President Jimmy Carter in 1977. These treaties mandated the eventual transfer of the Panama Canal and the Canal Zone to Panamanian control by December 31, 1999, and the immediate restoration of Panamanian jurisdiction over the Zone in 1979. This was a significant victory for Panamanian sovereignty, though it also allowed for a continued U.S. role in defending the canal's neutrality.

Omar Torrijos died in a plane crash in 1981. His death altered Panama's political evolution, and despite constitutional amendments in 1983 intended to limit the military's political role, the Panama Defense Forces (PDF), as the National Guard was renamed, continued to dominate. General Manuel Noriega, who had been a close associate of Torrijos and head of intelligence, gradually consolidated power, becoming the de facto ruler of Panama.

Noriega's regime became increasingly authoritarian and corrupt. He was implicated in drug trafficking, money laundering, and severe human rights abuses, including the assassination and torture of political opponents. Initially, Noriega maintained a complex relationship with the United States, providing intelligence and support for U.S. operations in Central America, such as assisting the Nicaraguan Contras. However, as evidence of his criminal activities and human rights violations mounted, and his regime became more repressive, relations with the U.S. deteriorated.

In 1987, denunciations by retired Colonel Roberto Díaz Herrera, accusing Noriega of electoral fraud and involvement in Torrijos's death and the murder of opposition leader Dr. Hugo Spadafora, sparked widespread protests led by the Civic Crusade. The regime responded with violent repression. The U.S. imposed economic sanctions, which severely damaged Panama's economy but failed to oust Noriega. In 1988, Noriega was indicted by U.S. federal juries for drug trafficking. The May 1989 Panamanian general election, which opposition candidates appeared to win overwhelmingly, was annulled by Noriega, leading to further repression and international condemnation.

On December 20, 1989, the United States launched a military invasion of Panama, codenamed Operation Just Cause. The stated U.S. objectives were to safeguard American lives, defend democracy and human rights, combat drug trafficking, and secure the neutrality of the Panama Canal. The invasion involved a large U.S. military force and resulted in the overthrow of Noriega, who eventually surrendered and was taken to the U.S. for trial. The invasion led to significant Panamanian casualties, with estimates of civilian deaths ranging from around 200 (U.S. figure) to several hundred or even thousands according to other sources, and widespread destruction, particularly in the El Chorrillo district of Panama City, displacing thousands. The United Nations General Assembly condemned the invasion as a "flagrant violation of international law." While many Panamanians reportedly supported the intervention to remove Noriega, the invasion remains a controversial event due to its impact on civilian lives and Panamanian sovereignty.

3.4.3. Canal Handover and Contemporary Era

Following the U.S. invasion, civilian constitutional government was restored. The results of the May 1989 election were reinstated, and Guillermo Endara became president. A key task was to rebuild the country, dismantle Noriega's Panama Defense Forces (which was abolished by constitutional amendment in 1994), and establish new public security forces. The early post-invasion years were challenging, with high public expectations for economic recovery and democratic consolidation.

Panama successfully managed the full handover of the Panama Canal and all associated territories on December 31, 1999, as stipulated by the Torrijos-Carter Treaties. This marked a historic moment of achieving full sovereignty. Mireya Moscoso, widow of former president Arnulfo Arias Madrid, was president at the time of the handover.

The 21st century has seen a series of democratically elected governments. Martín Torrijos, son of Omar Torrijos, served as president from 2004 to 2009, focusing on anti-corruption measures and social programs. He was succeeded by conservative supermarket magnate Ricardo Martinelli (2009-2014), whose administration oversaw significant infrastructure projects, including the Panama Canal expansion project (completed in 2016) and the construction of Panama City's first metro line. However, Martinelli's term was also plagued by corruption scandals.

Juan Carlos Varela (2014-2019) followed, campaigning on an anti-corruption platform. His presidency saw the fallout from the Panama Papers scandal in 2016, which exposed Panama's role as an offshore financial center and a hub for tax evasion, prompting international pressure for greater financial transparency.

Laurentino Cortizo of the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD) assumed the presidency in 2019. His term has been marked by the COVID-19 pandemic and its severe economic impact, as well as significant social unrest. Large-scale protests occurred in 2022 and 2023, fueled by rising living costs, corruption concerns, and opposition to a controversial mining contract with a Canadian company, First Quantum Minerals. The Supreme Court ultimately declared the mining contract unconstitutional in late 2023. These protests highlighted ongoing challenges related to social inequality, governance, and environmental concerns.

In May 2024, José Raúl Mulino, a close ally of former President Ricardo Martinelli, won the presidential election and was sworn in on July 1, 2024. Contemporary Panama continues to navigate its role as a global logistics hub while striving for sustainable economic growth, improved social equity, and strengthened democratic institutions.

4. Geography

Panama is a country of varied landscapes, dominated by its strategic location on the isthmus connecting two continents. Its geography is characterized by mountains, extensive coastlines on two oceans, numerous rivers vital for the Panama Canal, and a tropical climate that supports rich biodiversity.

4.1. Topography and Water Systems

Panama is located in Central America, forming an S-shaped isthmus that borders both the Caribbean Sea to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the south. It lies between Colombia to the southeast and Costa Rica to the west. Most of the country is situated between latitudes 7° and 10°N, and longitudes 77° and 83°W. Its strategic location has been pivotal throughout its history, particularly due to the Panama Canal which bisects the country, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Panama's total area is approximately 29 K mile2 (74.18 K km2).

The dominant feature of Panama's landform is a central spine of mountains and hills that forms the continental divide. This divide is not part of the major mountain chains of North America; only near the Colombian border are there highlands related to the Andes system of South America. The mountainous spine is a highly eroded arch, uplifted from the sea bottom, with peaks formed by volcanic intrusions.

In the west, near the Costa Rican border, this mountain range is known as the Cordillera de Talamanca. Further east, it becomes the Serranía de Tabasará. The portion closer to the lower saddle of the isthmus, where the Panama Canal is located, is often called the Sierra de Veraguas. Geographers generally refer to the entire range between Costa Rica and the canal as the Cordillera Central.

The highest point in Panama is the Volcán Barú, an active stratovolcano, which rises to 11 K ft (3.48 K m). The eastern part of the country, particularly the Darién Province, features the Darién Gap, a nearly impenetrable jungle and swamp region that forms a natural barrier between Panama and Colombia. This area is the only break in the Pan-American Highway, which otherwise connects Alaska to Patagonia.

Panama's rugged landscape is laced with nearly 500 rivers. Most originate as swift highland streams, meander through valleys, and form coastal deltas. While many are unnavigable for large vessels, they are crucial for local ecosystems and water supply. The Chagres River (Río Chagres), located in central Panama, is one of the few wide rivers and a significant source of hydroelectric power. The central part of the Chagres is dammed by the Gatun Dam, forming Gatun Lake, a large artificial lake that constitutes a major part of the Panama Canal. Gatun Lake, created between 1907 and 1913, was once the largest man-made lake in the world. The Chagres River drains northwest into the Caribbean. The Kampia and Madden Lakes (Alajuela Lake), also fed by the Chagres, provide hydroelectricity and water for the canal system.

Rivers on the Pacific side are generally longer and slower-running than those on the Caribbean side, and their basins are more extensive. One of the longest is the Tuira River (Río Tuira), which flows into the Gulf of San Miguel and is the nation's only river navigable by larger vessels.

4.2. Climate

Panama has a tropical climate, specifically a tropical maritime climate. Temperatures are uniformly high throughout the year, as is relative humidity, with little seasonal variation. Diurnal ranges (the difference between daytime high and nighttime low) are also generally low. In Panama City, a typical dry-season day might see an early morning minimum of 75.2 °F (24 °C) and an afternoon maximum of 86 °F (30 °C). Temperatures seldom exceed 89.6 °F (32 °C) for extended periods.

Temperatures on the Pacific side of the isthmus tend to be somewhat lower than on the Caribbean side. Breezes often rise after dusk in most parts of the country. In the higher elevations of the mountain ranges, particularly in the Cordillera de Talamanca in western Panama, temperatures are markedly cooler, and frosts can occur.

Climatic regions in Panama are determined more by rainfall patterns than by temperature. Rainfall varies regionally, ranging from less than 0.1 K in (1.30 K mm) per year in some areas to more than 0.1 K in (3.00 K mm) per year in others. Almost all rain falls during the rainy season, which typically lasts from April or May to December, varying in length from seven to nine months. The dry season generally extends from January to April.

In general, rainfall is significantly heavier on the Caribbean coast than on the Pacific side of the continental divide. This is partly due to the influence of prevailing winds and occasional proximity to tropical cyclone activity, although Panama itself lies outside the main hurricane development region. For example, the annual average rainfall in Panama City on the Pacific coast is little more than half of that in Colón on the Caribbean coast.

Panama is one of the few countries recognized as carbon-negative, meaning its forests absorb more carbon dioxide than the country emits into the atmosphere.

4.3. Biodiversity

Panama's position as a land bridge between North and South America has resulted in extraordinary biodiversity. Its tropical environment supports an abundance of plant and animal species, including many found nowhere else on Earth. Forests are the dominant ecosystem, interspersed with grasslands, scrub, and agricultural areas.

The country's rainforests are home to a vast array of wildlife. Soberanía National Park, near the Panama Canal, is renowned for its bird diversity, with over 525 species recorded, making it a prime location for birdwatching. It also hosts a variety of mammals such as capybaras and coyotes, reptiles like the green iguana, and amphibians such as the cane toad. Panama's wildlife includes many South American species as well as North American fauna.

Despite its rich natural heritage, Panama faces significant environmental challenges. Deforestation is a continuing threat to its rain-drenched woodlands. Since the 1940s, tree cover has been reduced by more than 50 percent, largely due to subsistence farming (which often involves clearing land for corn, bean, and tuber plots), cattle ranching, and infrastructure development. Mangrove swamps occur along parts of both coasts and are also under pressure. In many areas, a multi-canopied rainforest abuts coastal swamps on one side of the country and extends to the lower mountain slopes on the other.

Conservation efforts include the establishment of numerous national parks and protected areas, which cover approximately 23% of the country's land area. Panama had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.37/10, ranking it 78th globally out of 172 countries. The government has also engaged in initiatives aimed at sustainable development, such as plans announced in May 2022 to develop a major biorefinery for lower-carbon aviation fuel.

4.4. Major Harbors

Panama's strategic maritime location is supported by several important harbors on both its Caribbean and Pacific coasts. The Caribbean coastline features several natural harbors. However, Cristóbal, at the Caribbean terminus of the Panama Canal, has historically been the most significant port facility on this side. The numerous islands of the Bocas del Toro Archipelago, near the Costa Rican border, provide an extensive natural roadstead and shield the banana port of Almirante. The more than 350 San Blas Islands (Guna Yala archipelago), near Colombia, are strung out over more than 99 mile (160 km) along the sheltered Caribbean coastline.

The terminal ports located at each end of the Panama Canal are critical for international trade. These are the Port of Cristóbal in Colón on the Caribbean side, and the Port of Balboa near Panama City on the Pacific side. These ports consistently rank among the busiest in Latin America in terms of container units (TEU) handled.

The Port of Balboa covers 182 hectares and features multiple berths for containers and multi-purpose cargo. Its berths are over 7.9 K ft (2.40 K m) long with an alongside depth of about 49 ft (15 m). The port is equipped with numerous super post-Panamax and Panamax quay cranes and gantry cranes, along with extensive warehouse space.

The Ports of Cristobal, which include the container terminals of Panama Ports Cristobal, Manzanillo International Terminal (MIT), and Colon Container Terminal (CCT), collectively handle a massive volume of container traffic, making it one of the largest port complexes in the region.

In addition to the canal-adjacent ports, excellent deep-water ports capable of accommodating Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCCs) are located at Charco Azul in Chiriquí Province (Pacific coast) and Chiriquí Grande in Bocas del Toro Province (Atlantic coast), near Panama's western border with Costa Rica. The Trans-Panama pipeline, running 81 mile (131 km) across the isthmus between Charco Azul and Chiriquí Grande, has been operational since 1979, facilitating the transport of crude oil. These port facilities underscore Panama's role as a major logistics and transshipment hub in the Americas.

5. Politics

Panama's political system operates within the framework of a presidential representative democratic republic. The President of Panama serves as both head of state and head of government. The country has a multi-party system, and national elections are held every five years for the executive and legislative branches. Power is constitutionally divided among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, though the strength and independence of these branches have varied throughout Panama's history.

5.1. Government Structure

Panama is a presidential representative democratic republic. The Constitution of Panama, originally adopted in 1972 and significantly amended in 1983 and subsequently, outlines the structure of the state.

The Executive Branch is headed by the President of Panama, who is elected by popular vote for a single five-year term and cannot serve consecutive terms. The President is assisted by one or two Vice Presidents (the number has varied) and a Cabinet of ministers appointed by the President. The President is responsible for administering the government, executing laws, and conducting foreign policy.

The Legislative Branch is vested in the unicameral National Assembly (Asamblea Nacional). Its members, currently 71 diputados (deputies), are elected by popular vote from multi-member and single-member constituencies for five-year terms, using a system of proportional representation in many districts. The National Assembly is responsible for debating and passing laws, approving the national budget, and exercising oversight over the executive branch.

The Judicial Branch is headed by the Supreme Court of Justice (Corte Suprema de Justicia), which consists of nine magistrates appointed by the President with the approval of the National Assembly for staggered 10-year terms. The judiciary is constitutionally independent, tasked with interpreting and applying the law, though its independence and efficiency have faced challenges. Below the Supreme Court are superior tribunals, circuit courts, and municipal courts.

National elections are universal for all citizens 18 years and older. Presidential elections are decided by a plurality of votes.

5.2. Political Culture and Major Parties

Panama's political culture has been shaped by its history of U.S. influence, periods of military rule, and a transition to democracy since 1989. The country has successfully completed several peaceful transfers of power between opposing political factions. However, issues such as corruption, clientelism, and a degree of political polarization persist. Voter turnout in elections is generally high.

The political landscape is characterized by a multi-party system, though it has often been dominated by a few major parties and alliances. Many political parties tend to be driven by individual leaders and personalities rather than distinct, deeply rooted ideologies.

Major political parties include:

- The Democratic Revolutionary Party (Partido Revolucionario Democrático, PRD): Founded by Omar Torrijos, it has historically been a major force in Panamanian politics, often described as center-left or populist.

- The Panameñista Party (Partido Panameñista): One of Panama's oldest parties, historically associated with the Arias family (particularly Arnulfo Arias Madrid). It is generally considered nationalist and center-right.

- Democratic Change (Cambio Democrático, CD): Founded by former President Ricardo Martinelli, this party emerged as a significant force in the early 21st century, typically described as center-right or populist-conservative.

- Realizing Goals (Realizando Metas, RM): A newer party, also associated with Ricardo Martinelli, which became prominent in the lead-up to the 2024 elections.

Other smaller parties also participate in the political process, often forming alliances for electoral purposes. Civil society organizations, labor unions, and student groups have played important roles in political discourse and advocating for social and democratic reforms, particularly during periods of authoritarian rule and in response to controversial government policies, as seen in the large-scale protests of 2022 and 2023.

Campaigns often focus on issues like economic management, social programs, infrastructure development, and, increasingly, anti-corruption efforts. The influence of money in politics and allegations of corruption remain significant concerns affecting public trust and political stability. USAID has noted Panama's efforts in democratic processes while highlighting ongoing challenges with political corruption. Reports in 2020 suggested that Panama lost approximately 1% of its GDP annually due to corruption, including government corruption.

5.3. Foreign Relations

Panama's foreign policy is largely shaped by its strategic geographic location, the Panama Canal, and its historical relationship with the United States. The country maintains diplomatic relations with 167 nations and is a member of the United Nations, the Organization of American States (OAS), the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), the Latin American Integration Association (LAIA), the Group of 77, the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Non-Aligned Movement.

The United States remains a key partner. Cooperation spans economic, political, security (especially counter-narcotics and canal security), and social development initiatives. Cultural ties are strong, with many Panamanians pursuing higher education in the U.S. The Torrijos-Carter Treaties defined the terms for the handover of the Panama Canal and continue to underpin aspects of the relationship, including the U.S. right to defend the canal's neutrality. However, the history of U.S. intervention, particularly the 1989 invasion, remains a sensitive issue for Panamanian sovereignty.

Panama has increasingly sought to diversify its foreign relations. It established diplomatic ties with the People's Republic of China in 2017, severing longstanding relations with the Republic of China (Taiwan). This move was driven by economic considerations, with China being a major user of the Panama Canal and a significant global economic power. Chinese companies have invested in Panamanian infrastructure, including ports. This shift has been watched closely by the U.S. due to strategic implications concerning the canal.

With its Latin American neighbors, Panama generally maintains close ties. It shares a border with Colombia, which has sometimes been a source of security concerns due to drug trafficking and guerrilla activity in the Darién region. Relations with Costa Rica are generally stable. Panama participates in regional integration efforts.

Panama has also engaged with countries beyond the Americas. It was the first Central American country where India established a resident embassy (1973), viewing Panama as a gateway to Latin America. Relations with Indonesia were established in 1979. Panama was also the first Latin American country to recognize the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (1978), though relations were suspended between 2013 and 2016. It recognized Kosovo in 2009.

The country's foreign policy often emphasizes its neutrality, its role as a facilitator of international trade and dialogue, and the importance of multilateralism. However, issues related to its status as an international financial center and concerns about money laundering and tax evasion (highlighted by the Panama Papers) have sometimes complicated its international image, prompting efforts towards greater financial transparency. Panama was ranked the 96th most peaceful country in the world according to the 2024 Global Peace Index.

5.4. Military

Panama officially abolished its standing army through a constitutional amendment in 1994, a decision heavily influenced by the country's experience with military dictatorships and the 1989 U.S. invasion which dismantled the Panama Defense Forces (PDF) led by Manuel Noriega. This makes Panama one of the few countries in Latin America (along with Costa Rica) without a permanent military.

The security and defense responsibilities are handled by the Panamanian Public Forces (Fuerza Pública de Panamá). These are civilian-led security forces tasked primarily with law enforcement, border security, maritime and aerial surveillance, and public order. While they can perform limited actions that might be considered military in nature (such as counter-narcotics operations or border defense), they are not structured as a traditional army.

The Panamanian Public Forces consist of several distinct branches:

- The National Police (Policía Nacional): The primary law enforcement agency responsible for maintaining public order and safety throughout the country.

- The National Aeronaval Service (Servicio Nacional Aeronaval, SENAN): Responsible for maritime security, search and rescue operations, and aerial surveillance. It operates a small fleet of patrol boats and aircraft.

- The National Border Service (Servicio Nacional de Fronteras, SENAFRONT): Tasked with securing Panama's land borders, particularly the challenging Darién region bordering Colombia, and combating transnational crime like drug trafficking and illegal immigration.

- The Institutional Protection Service (Servicio de Protección Institucional, SPI): Primarily responsible for the security of the President, government officials, and state buildings.

The decision to abolish the army was a significant step towards demilitarization and democratic consolidation. Early in its history, shortly after independence from Colombia in 1903, Panama had also abolished its initial army, maintaining police operations. However, over time, particularly from the 1940s, the police force (later National Guard, then the PDF) became increasingly militarized and politically powerful, culminating in the military dictatorships of the latter 20th century. The current structure aims to prevent a recurrence of such military dominance in politics.

Panama cooperates with other countries, particularly the United States, on security matters, including counter-narcotics efforts and canal security. In 2017, Panama signed the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

6. Administrative Divisions

Panama is divided into ten provinces (provincias) and six indigenous territories known as comarcas indígenas. The provinces are the primary administrative subdivisions, each headed by a governor appointed by the President. Provinces are further subdivided into districts (distritos), and districts into corregimientos (townships). The comarcas have varying degrees of administrative autonomy, reflecting the rights and self-governance of indigenous groups.

6.1. Provinces

The ten provinces of Panama are:

- Bocas del Toro

- Chiriquí

- Coclé

- Colón

- Darién

- Herrera

- Los Santos

- Panamá

- Panamá Oeste (West Panama, created in 2014 from part of Panamá Province)

- Veraguas

Each province has its unique characteristics in terms of geography, economy, and culture. For example, Chiriquí is known for its agriculture and highlands, while Colón is a major port city at the Caribbean entrance of the Canal. Panamá Province, which includes the capital, Panama City, is the most populous and economically dominant.

6.2. Comarcas (Indigenous Territories)

Panama officially recognizes six indigenous territories, or comarcas, which have a special administrative status and a degree of autonomy. These territories are established to protect the lands, cultures, and traditional governance systems of various indigenous groups. The socio-economic conditions within the comarcas often present distinct challenges compared to the rest of the country, including higher poverty rates and limited access to services, but they also represent important spaces for cultural preservation and indigenous self-determination.

The six comarcas are:

- Emberá-Wounaan: Primarily inhabited by the Emberá and Wounaan peoples. It has the status of a province and is divided into two districts.

- Guna Yala: Inhabited by the Guna (formerly Kuna). It is known for its archipelago of islands (San Blas Islands) and strong traditions of self-governance. It has provincial status.

- Naso Tjër Di: The newest comarca, formally established in 2020 for the Naso (Teribe) people. It is located in Bocas del Toro Province. It has provincial status.

- Ngäbe-Buglé: The largest comarca by area and population, primarily inhabited by the Ngäbe and Buglé peoples. It has provincial status.

There are also two comarcas that are considered sub-provincial level, meaning they are subordinate to a province but have their own defined territory and some autonomy:

- Kuna de Madugandí: Located within Panamá Province.

- Kuna de Wargandí: Located within Darién Province.

The establishment and administration of comarcas are crucial for addressing the rights and needs of Panama's indigenous minority groups, who constitute a significant portion of the national population and have unique cultural heritages. Issues related to land rights, resource management, and political representation remain important for these communities.

6.3. Major Cities

Panama's urban population is concentrated primarily in a few key cities, with Panama City being the dominant metropolitan area. These urban centers are hubs of economic activity, governance, and culture.

- Panama City (Ciudad de Panamá): The capital and largest city of Panama, located at the Pacific entrance of the Panama Canal. It is the country's political, administrative, economic, and cultural center. Panama City is known for its modern skyline of skyscrapers, its historic Casco Viejo district (a UNESCO World Heritage site), and its role as an international banking and commercial hub. The Panama City metropolitan area is home to nearly half of the country's population.

- San Miguelito: Located adjacent to Panama City, San Miguelito is one of the most populous districts in the country and effectively forms part of the greater Panama City metropolitan area. It is primarily a residential area with significant commercial activity.

- Colón: Situated on the Caribbean coast at the Atlantic entrance of the Panama Canal, Colón is Panama's second-largest city. It is a major port city and home to the Colón Free Trade Zone (Zona Libre de Colón), one of the largest duty-free zones in the world. Despite its economic importance, Colón has faced significant social and economic challenges, including high unemployment and urban decay in some areas.

- David (officially San José de David): The capital of Chiriquí Province in western Panama. David is the third-largest city and serves as an important commercial, agricultural, and transportation hub for the western region of the country. It is a gateway to the Chiriquí highlands, known for coffee production and tourism.

- La Chorrera: The capital of the Panamá Oeste Province, located west of Panama City. It has experienced significant growth due to its proximity to the capital and is an important residential and commercial center.

- Arraiján: Also located in Panamá Oeste Province, Arraiján is another rapidly growing district and city near Panama City, serving as a major suburban area.

Other notable urban areas include Santiago de Veraguas (capital of Veraguas Province), Penonomé (capital of Coclé Province), and Chitré (capital of Herrera Province). The development of these cities reflects Panama's ongoing urbanization and economic diversification efforts.

7. Economy

Panama's economy is primarily service-based, leveraging its strategic geographic location and the Panama Canal. It is considered a high-income economy by the World Bank, though it faces significant challenges related to income inequality and ensuring that economic benefits are broadly shared. The nation's economic policies have generally favored trade and foreign investment, but issues of labor rights, environmental sustainability, and financial transparency remain pertinent.

7.1. Economic Structure and Sectors

Panama's economy is heavily dominated by its service sector, which accounts for nearly 80% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and a majority of its foreign income. Key service industries include:

- Logistics and transportation, centered around the Panama Canal and its associated ports (like the Colón Free Trade Zone, the largest in the Americas).

- International banking and financial services, making Panama a significant regional financial center.

- Tourism, which has grown considerably, attracting visitors with its natural beauty, historic sites, and commercial offerings.

- Insurance and ship registration (Panama has one of the world's largest maritime fleets registered under its flag, a practice known as flags of convenience).

The industrial sector is relatively small and includes activities such as the manufacturing of aircraft parts, cement, beverages, adhesives, and textiles. There is also a growing mining sector, particularly for copper.

The agricultural sector contributes a smaller portion to the GDP but remains important for employment in rural areas. Key agricultural exports include bananas, shrimp, sugar, coffee, and some livestock products.

Panama has experienced periods of strong economic growth, particularly in the 2000s and early 2010s, driven by canal expansion, large infrastructure projects, and a booming construction sector. Between 2014 and 2019, Panama's GDP grew at an average of 4.7%, well above the Latin American regional average. However, the COVID-19 pandemic caused a severe economic contraction in 2020, though the economy rebounded in subsequent years, supported by high vaccination rates, investment, and increased exports from a new copper mine.

Challenges to Panama's economic structure include the need for greater economic diversification, addressing educational disparities that perpetuate income inequality, and strengthening institutions to combat corruption and improve governance. Between 2015 and 2017, poverty (at less than US$5.5 a day) fell from 15.4% to an estimated 14.1%, but significant pockets of poverty persist, especially in rural and indigenous areas.

7.2. Panama Canal and its Economic Impact

The Panama Canal is the cornerstone of Panama's economy and its most significant international asset. Since its transfer to full Panamanian control on December 31, 1999, the Panama Canal Authority (ACP), an autonomous government agency, has managed its operations.

The canal's economic impact is multifaceted:

- Revenue Generation: Tolls collected from ships transiting the canal represent a substantial portion of Panama's national revenue and GDP.

- Employment: The canal and related industries (ports, logistics, maritime services) are major sources of employment for Panamanians.

- Global Trade Facilitation: The canal is a critical artery for global maritime trade, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and significantly reducing travel times and costs for shipping.

The Panama Canal expansion project, completed in 2016, involved the construction of a third set of locks (Neopanamax locks) to accommodate larger ships. This project, with an official estimated cost of 5.25 B USD, has significantly increased the canal's capacity and revenue-generating potential. It has also boosted related economic activities and reinforced Panama's position as a global logistics hub.

While the canal is a major economic driver, its operations and expansion also raise considerations regarding:

- Labor Conditions: Ensuring fair labor practices and worker safety for those employed in canal operations and associated industries.

- Environmental Impact: The canal's operation depends on vast amounts of fresh water, primarily from Gatun Lake, which is fed by the Chagres River. Managing water resources sustainably, especially in the face of climate change and potential droughts, is crucial. The expansion project also involved significant environmental considerations, including reforestation efforts and water-saving basins in the new locks. Deforestation in the canal's watershed can affect water levels and increase sedimentation, posing a long-term challenge.

The efficient and sustainable management of the Panama Canal is vital not only for Panama's economy but also for international commerce.

7.3. Role as an International Financial Center

Since the early 20th century, Panama has leveraged revenues from the canal and favorable legislation to develop into the largest Regional Financial Center (IFC) in Central America. Its consolidated banking assets are several times larger than Panama's GDP, and the banking sector directly employs over 24,000 people. Financial intermediation contributes significantly to the national GDP (around 9.3%).

The services offered by Panama's IFC include:

- Offshore banking and corporate services.

- Wealth management and private banking.

- Formation of international business companies (IBCs) and foundations.

Stability has historically been a key strength of Panama's financial sector, benefiting from the country's dollarized economy and business climate. The banking supervisory regime is largely compliant with international standards like the Basel Core Principles for Effective Banking Supervision.

However, Panama has also gained a worldwide reputation as a tax haven and a center for money laundering and tax evasion. This reputation was starkly highlighted by the 2016 Panama Papers scandal, a massive leak of documents from the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca, which revealed how wealthy individuals and public officials worldwide used offshore shell corporations to evade taxes and hide assets.

In response to international pressure, particularly from organizations like the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and the OECD, Panama has made efforts to enhance financial transparency and strengthen its anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing (CFT) frameworks. These efforts have included legislative reforms and increased cooperation with international bodies. Panama was removed from the FATF's "gray list" in February 2016, and the European Union also removed Panama from its tax haven blacklist in 2018. However, challenges remain, and international bodies like the IMF have repeatedly emphasized the need for further strengthening of financial transparency and fiscal structures.

The social impact of this economic model on national development and equity is a subject of ongoing debate. While the financial sector contributes to GDP and employment, concerns exist about whether the benefits are broadly distributed and whether the emphasis on offshore services has diverted resources from other productive sectors or contributed to socio-economic inequalities. Ensuring that the financial center operates with high standards of integrity and transparency is crucial for Panama's long-term economic sustainability and international reputation.

7.4. Transportation and Logistics

Panama's strategic location and the Panama Canal have made it a critical hub for transportation and logistics in the Americas. The country has developed significant infrastructure to support this role.

Maritime Transportation: The Panama Canal is the centerpiece of its maritime infrastructure. Major ports like Balboa (Pacific) and Cristóbal (Caribbean), along with others like Manzanillo International Terminal and Colon Container Terminal, handle vast amounts of cargo. The Colón Free Trade Zone further enhances its role as a transshipment and distribution center. Panama also operates the Trans-Panama pipeline for oil transport across the isthmus.

Air Transportation: Tocumen International Airport (PTY) in Panama City is the largest airport in Central America and a major regional hub for passengers and cargo. It is the home base for Copa Airlines, Panama's flag carrier, which connects to numerous destinations throughout the Americas and beyond. There are also over 20 smaller airfields across the country serving domestic and limited international flights.

Road Transportation: The Pan-American Highway is the main artery for road transport, traversing Panama from its border with Costa Rica to the Darién Gap near Colombia. The Darién Gap remains the only uncompleted section of the highway in the Americas. Panama's road network has seen improvements, but driving conditions can be challenging, especially in urban areas due to traffic congestion and in rural areas where road maintenance may be lacking. Traffic in Panama moves on the right, and seat belt use is mandatory.

Public Transportation: In Panama City, public transportation includes the MiBus system, a network of publicly operated bus routes, and the Panama Metro, Central America's first subway system, which has expanded with multiple lines. Prior to MiBus, privately operated, colorfully painted retired school buses known as "diablos rojos" (red devils) were common; they are now mostly used in rural areas.

Rail Transportation: The Panama Canal Railway operates between Panama City (Pacific) and Colón (Caribbean), primarily for container transport and some passenger (tourist) services, paralleling the canal. This railway has historical significance, predating the canal.

Panama's logistics network, combining maritime, air, road, and rail transport, supports its role as a vital link in global supply chains and a center for international trade.

7.5. Tourism Industry

Tourism is a significant and growing sector of Panama's economy, contributing substantially to its GDP and employment. The country attracts visitors with a diverse range of attractions, including its natural beauty, rich history, vibrant culture, and modern amenities.

Main Attractions:

- Natural Attractions:** Panama's biodiversity is a major draw. Rainforests, national parks (like Soberanía, Darién, Coiba), cloud forests in the highlands (e.g., Boquete), and numerous islands with pristine beaches (e.g., Bocas del Toro, San Blas/Guna Yala, Pearl Islands) offer opportunities for ecotourism, birdwatching, hiking, snorkeling, diving, and surfing.

- Cultural Attractions:** Indigenous communities, particularly the Guna people of Guna Yala with their unique mola art, offer cultural tourism experiences. Festivals, traditional music and dance, and local handicrafts are also part of the cultural appeal.

- Historical Attractions:** The Panama Canal itself is a major tourist attraction, with visitor centers at the Miraflores and Agua Clara locks. Panamá Viejo (the ruins of the original Panama City) and Casco Viejo (the historic colonial quarter of Panama City), both UNESCO World Heritage sites, are popular. The fortifications at Portobelo and San Lorenzo on the Caribbean coast, also UNESCO sites, reflect the country's colonial past.

- Urban Attractions:** Panama City offers a modern skyline, shopping malls, a vibrant nightlife, and a cosmopolitan dining scene.

The Panamanian government has actively promoted tourism through tax incentives and price discounts for foreign guests and retirees, which has led to Panama being regarded as an attractive retirement destination. Real estate development, particularly in coastal and highland areas, has increased the number of tourism destinations and accommodations.

In 2012, tourism reportedly contributed over 4.50 B USD to the Panamanian economy, accounting for a significant percentage of the GNP, with over 2.2 million tourist arrivals. European tourists, particularly from Spain, Italy, France, and the UK, have become an important market segment.

Social, Economic, and Environmental Impacts:

The growth of tourism has brought economic benefits, including job creation and foreign exchange earnings. However, it also presents challenges:

- Social Impact:** Ensuring that local communities, especially indigenous groups and those in rural areas, benefit equitably from tourism development and that their cultures and lifestyles are respected is crucial.

- Economic Impact:** Over-reliance on tourism can make the economy vulnerable to external shocks. The distribution of tourism revenue and its impact on local labor conditions are also important considerations.

- Environmental Impact:** Uncontrolled tourism development can lead to environmental degradation, habitat loss, and strain on natural resources in ecologically sensitive areas. Sustainable tourism practices are essential to preserve Panama's natural assets for the future.

Panama enacted Law No. 80 in 2012 to promote foreign investment in tourism, offering exemptions from income tax, real estate taxes, and import duties for construction materials and equipment for qualifying tourism projects.

7.6. Currency

The official currency of Panama is the balboa (PAB). However, Panama has a unique monetary system as it is officially dollarized. Since its independence in 1903, the balboa has been pegged to the United States dollar (USD) at a fixed exchange rate of 1:1.

In practice:

- The U.S. dollar is legal tender in Panama and is used for all paper currency. There are no Panamanian balboa banknotes; U.S. dollar bills are the circulating paper money.

- Panama mints its own coins, which are equivalent in size and value to their U.S. counterparts (e.g., 1, 5, 10, 25, 50 centésimos, and 1 balboa coins correspond to U.S. pennies, nickels, dimes, quarters, half-dollars, and dollar coins respectively). U.S. coins also circulate freely and are used interchangeably with Panamanian coins.

This dollarized system means that Panama does not have an independent monetary policy; its monetary conditions are largely influenced by the monetary policy of the United States and the U.S. Federal Reserve.

Implications of Dollarization:

- Low Inflation:** Historically, Panama has experienced low and stable inflation rates, similar to those in the U.S., due to the currency peg.

- Price Stability:** The use of the U.S. dollar provides a stable an_anchor for prices and facilitates international trade and investment by eliminating exchange rate risk with its largest trading partner.

- No Exchange Rate Risk with USD:** Businesses and individuals do not face risks associated with fluctuations in the exchange rate against the U.S. dollar.

- Limited Monetary Policy Tools:** Panama's central bank (the National Bank of Panama acts as a government bank but not a typical central bank with monetary policy functions) cannot devalue its currency or use traditional monetary policy tools like adjusting interest rates to manage economic cycles. The economy adjusts to shocks primarily through fiscal policy and changes in prices and wages.

The balboa replaced the Colombian peso in 1904 following Panama's independence. Balboa banknotes were briefly printed in 1941 under President Arnulfo Arias but were recalled within days (earning them the nickname "The Seven Day Dollars") and subsequently burned by the new government. These were the only banknotes ever issued by Panama.

In April 2022, Panamanian lawmakers approved a bill to legalize and regulate the use of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, covering their use, trading, tokenization of precious metals, and issuance of digital securities, including for tax payments. However, in July 2023, the Supreme Court of Justice declared this bill unenforceable.

7.7. International Trade

International trade is a cornerstone of Panama's economy, largely driven by its strategic location, the Panama Canal, and the Colón Free Trade Zone (Zona Libre de Colón, ZLC).

The Colón Free Trade Zone is the largest free trade zone in the Western Hemisphere and a major global hub for import, export, and re-export activities. It serves as a critical distribution center for goods destined for Latin American and Caribbean markets. In some years, the ZLC has accounted for a vast majority of Panama's exports (primarily re-exports) and a significant portion of its imports.

Major Exports and Imports:

- Exports:** Panama's main domestic exports include bananas, shrimp, sugar, coffee, fish, and, more recently, copper from the Cobre Panama mine. However, a large share of its "exports" as recorded in trade statistics are actually re-exports from the Colón Free Trade Zone, encompassing a wide variety of manufactured goods.

- Imports:** Panama imports a wide range of goods, including machinery, transportation equipment, fuels, chemicals, food products, and consumer goods, both for domestic consumption and for re-export through the ZLC.

Key Trading Partners: Panama's key trading partners include the United States, China, countries in the European Union, and various Latin American nations. The U.S. has historically been its most important trading partner. China has become increasingly significant, especially as a major user of the Panama Canal and an investor.

Trade Agreements: Panama has pursued various trade agreements to enhance its commercial ties.

- The Panama-United States Trade Promotion Agreement (TPA), signed in 2007 and entered into force in 2012, eliminated tariffs on most U.S. industrial and consumer goods and services, and aimed to promote bilateral trade and investment.

- Panama also has trade agreements with other countries and blocs in Latin America and Asia.

A Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) between the United States and Panama was signed in 1982 to protect U.S. investment and assist Panama in developing its economy. It was the first such treaty signed by the U.S. in the Western Hemisphere.

The country's logistics infrastructure, including the canal, ports, and airports, underpins its role in international trade, facilitating the movement of goods globally.

7.8. Mining

Panama's mining sector, while historically smaller compared to its service-based economy, has seen significant developments, particularly in copper extraction. The country possesses deposits of various minerals, including copper, gold, silver, manganese, and iron.

Key Resources and Projects:

- Copper:** The most significant recent development has been the Cobre Panama mine, one of the largest new copper mines globally. Located in Colón Province, this large open-pit mine started commercial production in 2019 and is operated by First Quantum Minerals, a Canadian company. The mine represents a substantial investment and has become a major contributor to Panama's exports and GDP. However, the project has also been a source of significant environmental and social controversy.

- Gold:** Gold mining, including artisanal and small-scale operations, has a longer history in Panama. Deposits are found in regions like Darién (known for alluvial gold or 砂金placer goldJapanese), Veraguas, and the Azuero Peninsula.

- Salt:** Salt is produced, primarily through solar evaporation in salt pans (salinas), notably in the Aguadulce area.

Economic Benefits and Concerns:

The development of large-scale mining projects like Cobre Panama offers potential economic benefits, including export revenues, job creation, and contributions to government income. However, the mining sector also raises significant environmental and social concerns:

- Environmental Impact:** Large-scale mining can lead to deforestation, habitat destruction, soil erosion, water pollution (from tailings and chemical use), and biodiversity loss. Many mining concessions are located in or near environmentally sensitive areas, including protected zones.

- Social Concerns and Land Rights:** Mining projects can impact local communities, including indigenous populations, leading to disputes over land rights, displacement, loss of traditional livelihoods, and concerns about the distribution of economic benefits. The consultation process with affected communities and the protection of their rights are critical issues.

- Governance and Transparency:** Ensuring transparency in mining contracts, revenue management, and environmental oversight is crucial to prevent corruption and ensure that mining contributes to sustainable development.

The Cobre Panama mine, for example, faced widespread public protests in 2023 over the terms of its renewed contract, leading to a Supreme Court ruling that declared the contract unconstitutional. This highlighted the public's deep concerns about environmental sustainability, national sovereignty over resources, and the socio-economic impacts of large-scale mining. The future of the mining sector in Panama will likely involve navigating these complex economic, environmental, and social considerations.

8. Society

Panamanian society is characterized by its diverse ethnic makeup, a significant urban-rural divide, and ongoing challenges related to social equity, access to services, and human development. While the country has made progress in several areas, disparities persist, particularly affecting indigenous populations, Afro-Panamanians, and those living in poverty.

8.1. Demographics

Panama had an estimated population of approximately 4.47 million in 2023. The population growth rate has been moderate.

Key demographic indicators include:

- Age Structure:** In 2010, about 29% of the population was under 15 years old, 64.5% was between 15 and 65, and 6.6% was 65 years or older. Like many countries, Panama is experiencing a gradual aging of its population.

- Population Density:** Population density varies significantly across the country, with the highest concentrations in the Panama City-Colón metropolitan corridor.

- Urbanization:** Over 75% of Panama's population lives in urban areas, making it one of the most urbanized countries in Central America. The capital, Panama City, and its surrounding areas account for nearly half of the total population.

- Life Expectancy:** Life expectancy at birth is relatively high for the region.

- Fertility Rate:** The fertility rate has been declining, contributing to slower population growth.

The country has seen various waves of immigration throughout its history, linked to the construction of the railroad, the Panama Canal, and its role as an international trade and financial hub, contributing to its diverse demographic profile.

8.2. Ethnic Groups

Panama is a multi-ethnic nation, a result of its history as a crossroads and a recipient of various migration waves. The main ethnic groups include:

- Mestizos:** This is the largest group, comprising an estimated 60-70% of the population. Mestizos are people of mixed European (primarily Spanish) and indigenous Amerindian ancestry.

- Indigenous Peoples:** Indigenous groups make up about 10-12.3% of the population. There are seven officially recognized major indigenous ethnic groups:

- Ngäbe (the largest group)

- Guna (Kuna)

- Emberá

- Buglé

- Wounaan

- Naso Tjerdi (Teribe)

- Bribri

- Minor groups like the Bokota.

These groups largely reside in designated autonomous territories (comarcas) and maintain distinct languages, cultures, and traditions. They have made significant cultural contributions but often face socio-economic marginalization, higher poverty rates, and challenges in accessing education, healthcare, and land rights.

- Afro-Panamanians:** People of African descent constitute a significant portion of the population, estimated around 9-15%. This group is diverse and includes:

- Afro-colonials: Descendants of Africans enslaved during the Spanish colonial period.

- Afro-Antilleans (Afroantillanos): Descendants of laborers, primarily from English-speaking Caribbean islands (like Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad, and Martinique), who came to Panama in the 19th and early 20th centuries to work on the construction of the Panama Railroad and the Panama Canal. Most Afro-Panamanians live in the Panama City-Colón metropolitan area, Darién Province, La Palma, and Bocas del Toro Province. Areas in Panama City with significant Afro-Panamanian influence include Rio Abajo and Casco Viejo.

- Whites (European Panamanians):** This group makes up about 7-10% of the population and primarily consists of descendants of Spanish colonists. There are also smaller communities of descendants from other European countries (e.g., Italy, UK, Germany) who immigrated during the canal construction era or later.

- Other Groups:** Panama has a notable Chinese population, largely descendants of laborers who arrived for railroad and canal construction, with most residing in Chiriquí Province. There are also communities of Indians (South Asians), Arabs (many of whom are Christian Levantines, though there is also a Muslim Arab community), and Jews.

Issues of racial discrimination and social inclusion remain relevant for several ethnic minority groups. Efforts to promote multiculturalism and address disparities are ongoing.

8.3. Languages

The official and dominant language of Panama is Spanish. Approximately 93% of the population speaks Spanish as their first language. The Spanish spoken in Panama has its own regional characteristics and vocabulary.

English is also widely spoken and understood, particularly in business circles, the tourism industry, and in areas with historical U.S. influence, such as the former Canal Zone. About 14% of Panamanians speak English. The government has made efforts to promote English language education in public schools, recognizing its importance for international commerce and opportunities.

Indigenous Languages: A significant number of Panamanians (over 400,000) speak indigenous languages, which are primarily used within their respective native territories (comarcas). Major indigenous languages include Ngäbere (spoken by the Ngäbe people), Guna (Dulegaya), Emberá, Buglere, Wounaan Meu, and Naso (Teribe). There are ongoing efforts to preserve and promote these languages, though some are endangered.

Other Languages: Due to immigration, various other languages are spoken by smaller communities, including Chinese (various dialects), Arabic, French (spoken by about 4% of the population, often as a second language), and Hindi. Some Afro-Antillean communities, particularly older generations, may also speak Caribbean English creoles.

The linguistic diversity reflects Panama's multicultural heritage.

8.4. Religion

Christianity is the predominant religion in Panama.

- Roman Catholicism: An official government survey in 2015 estimated that 63.2% of the population (approximately 2.55 million people) identifies as Roman Catholic. The Catholic Church has historically played a significant role in Panamanian society and culture since the Spanish colonial era.

- Protestantism: Evangelical Protestants constitute the second-largest religious group, accounting for about 25% of the population (approximately 1 million people) according to the 2015 survey. Various Protestant denominations are present, including Pentecostal, Baptist, Methodist, and Adventist churches. Seventh-day Adventists and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) each comprise a smaller percentage (1.3% and 0.6% respectively in the 2015 survey). Anglicans (Episcopalians) also have a presence, with around 7,000 to 10,000 members.

- Jehovah's Witnesses: This group comprises about 1.4% of the population.

- Baháʼí Faith: Panama has a notable Baháʼí community, estimated at around 2% of the national population (about 60,000 people), which includes a significant proportion (around 10%) of the Ngäbe (Guaymí) indigenous population. Panama City is home to one of the eight continental Baháʼí Houses of Worship in the world.

- Indigenous Religions: Traditional indigenous beliefs and spiritual practices, such as Ibeorgun (among the Guna) and Mamatata (among the Ngäbe), are maintained by some indigenous communities, often alongside or syncretized with Christianity.

- Other Religions: Smaller religious communities in Panama include:

- Buddhism: Practiced mainly by the Chinese and other East Asian communities (around 0.4% or 18,560 people).

- Judaism: Panama has a well-established Jewish community of about 5,000-10,000 people, mainly residing in Panama City. It is one of the largest Jewish communities in Central America.

- Islam: The Muslim community also numbers around 10,000, consisting of Arabs, South Asians, and local converts.

- Hinduism: Practiced by the Indian (South Asian) community.

- There is also a small number of Rastafarians.

- No Religion: About 7.6% of the population identified as having no religion in the 2015 survey.

The Panamanian Constitution provides for freedom of religion, and the government generally respects this right.

8.5. Education