1. Overview

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is the largest country in Africa and the Arab world, located in the Maghreb region of North Africa. Its geography is diverse, dominated by the vast Sahara Desert in the south, while the northern coastal region, characterized by the Tell and Saharan Atlas Mountains, is more fertile and home to the majority of its population of over 44 million. Algiers is the capital and largest city.

Algeria's history is rich and complex, marked by ancient Berber civilizations like Numidia, periods of Carthaginian and Roman rule, and the transformative arrival of Islam and Arab influence in the Middle Ages, leading to the rise of various Berber Islamic dynasties. The early modern era saw Ottoman suzerainty through the Regency of Algiers, a significant Mediterranean power. French colonization from 1830 brought profound societal changes, widespread European settlement, and protracted resistance, culminating in a devastating War of Independence (1954-1962). Post-independence Algeria adopted socialist policies and a single-party system under the National Liberation Front (FLN), later experiencing economic challenges and political turmoil, including a brutal civil war in the 1990s following the annulment of elections an Islamist party was poised to win. Subsequent efforts have focused on national reconciliation and political reforms, though democratic development and human rights remain significant concerns. The Hirak protests starting in 2019 led to major political shifts, including the resignation of long-time president Abdelaziz Bouteflika.

The country operates under a semi-presidential republic. Its economy is heavily reliant on hydrocarbon exports (oil and natural gas), which form the backbone of state revenue. Efforts to diversify the economy face challenges, including social equity and labor rights issues. Algerian society is predominantly Arab-Berber, with Islam as the state religion. The cultural landscape includes a vibrant literary tradition, diverse musical forms like Raï, and a rich culinary heritage. The government plays a significant role in the health and education sectors, though challenges in accessibility and quality persist, particularly affecting vulnerable groups. The nation's foreign policy emphasizes non-alignment and regional cooperation, though relations with some neighbors, particularly Morocco over the Western Sahara issue, remain tense. Algeria's journey reflects an ongoing struggle to balance economic development with social justice, enhance democratic institutions, and ensure the rights and well-being of all its citizens, including minorities.

2. Name

The official name of the country is the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria. In Arabic, this is الجمهورية الجزائرية الديمقراطية الشعبيةal-Jumhūriyyah al-Jazāʾiriyyah ad-Dīmuqrāṭiyyah ash-ShaʿbiyyahArabic. In French, it is République algérienne démocratique et populaireFrench. In Berber, using the Tifinagh script, it is ⵜⴰⴳⴷⵓⴷⴰ ⵜⴰⵣⵣⴰⵢⵔⵉⵜ ⵜⴰⵎⴰⴳⴷⴰⵢⵜ ⵜⴰⵖⴻⵔⴼⴰⵏⵜBerber languages, and in the Berber Latin alphabet, it is Tagduda tazzayrit tamagdayt taɣerfantBerber languages. The common name is Algeria (ælˈdʒɪəriəEnglish, الجزائرal-JazāʾirArabic, ⴷⵣⴰⵢⴻⵔDzayerBerber languages). The inclusion of "People's Democratic Republic" in the official title reflects the country's socialist orientation in the early post-independence period, although Algeria has since moved away from a strictly socialist economic model. Historically, the country was also rendered in English as the "Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria," as seen on the 1981 Algiers Accords.

2.1. Etymology

The name "Algeria" is derived from the city of Algiers. The name "Algiers" itself comes from the Arabic word الجزائرal-JazāʾirArabic, meaning "The Islands." This refers to the four small islands that were formerly situated off the coast of the city of Algiers, which have since become part of the mainland. "Al-Jazāʾir" is a truncated form of an older name, جزائر بني مزغنةJazāʾir Banī MazghannaArabic, meaning "Islands of the Sons of Mazghanna" or "Islands of the Mazghanna tribe."

This name was reportedly given by Buluggin ibn Ziri, the founder of the Zirid dynasty, when he established the city in 950 AD on the ruins of the ancient Phoenician city of Icosium. Medieval geographers such as Muhammad al-Idrisi and Yaqut al-Hamawi also used this name.

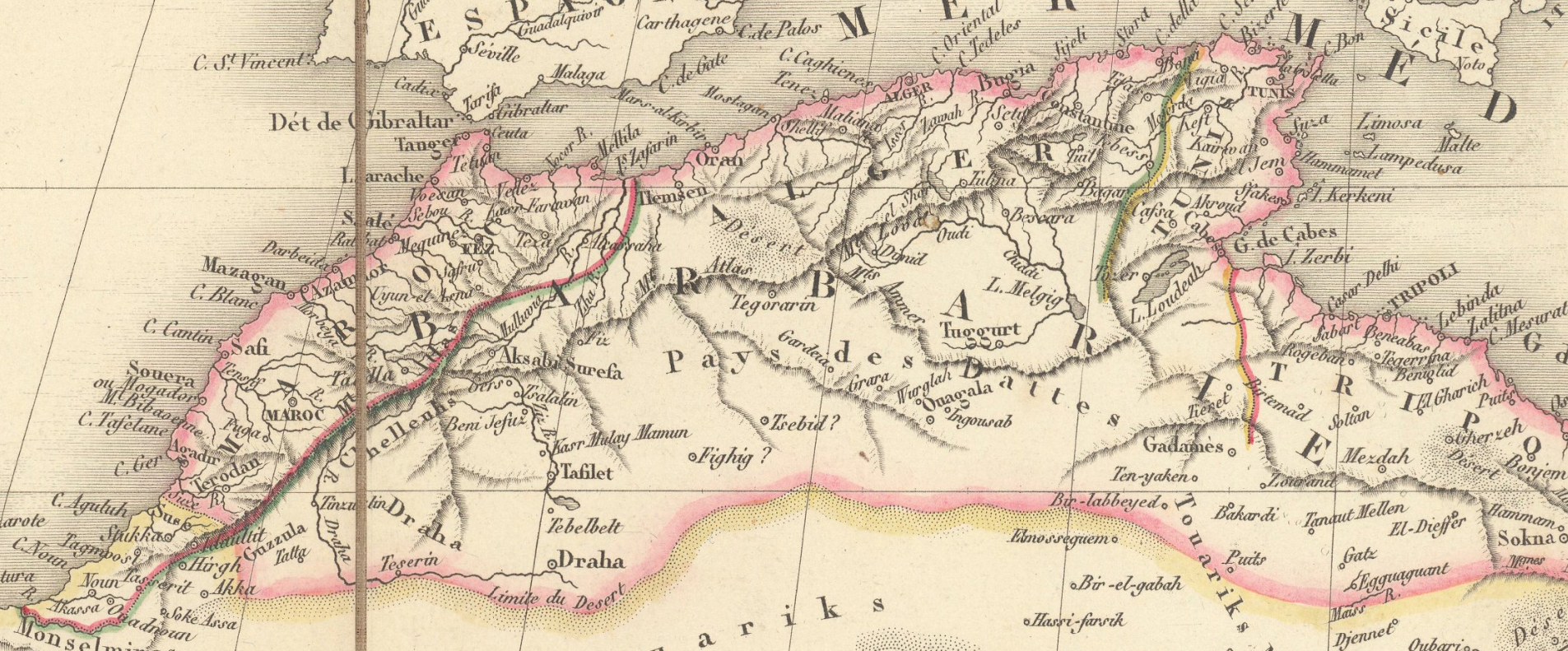

The country of Algeria took its name from the Regency of Algiers (وطن الجزائرWatan el djazâïrArabic, meaning "Country of Algiers"), the political entity established under Ottoman rule in the early 16th century. This period was crucial in defining Algeria's territorial borders with its neighbors and shaping its modern political identity as a largely independent state, though nominally subject to the Ottoman Sultan. Algerian nationalist historian Ahmed Tewfik El Madani regarded the Regency as the "first Algerian state." The French name "Algérie" was formally adopted in 1837 by Jean-de-Dieu Soult, then French Minister of War, to refer to the French possessions in North Africa.

3. History

Algeria's history spans millennia, from ancient human settlements and powerful Berber kingdoms to Roman and Byzantine rule, followed by Arab conquests that brought Islam and Arabization. Ottoman suzerainty preceded French colonization, which led to a protracted and bloody war for independence. Post-independence Algeria has navigated nation-building, socialist policies, political upheavals including a civil war, and ongoing efforts towards reform and stability.

3.1. Prehistory and Ancient History

The earliest traces of hominid occupation in Algeria are found at Ain Hanech, where stone artifacts dating back to approximately 1.8 million years ago have been discovered. Even older artifacts, estimated to be around 2.4 million years old, were found at Ain Boucherit, suggesting that ancestral hominins inhabited the Mediterranean fringe of North Africa much earlier than previously thought. This evidence points to an early dispersal of stone tool manufacture from East Africa or a possible multiple-origin scenario for stone technology.

Neanderthal tool makers produced hand axes using Levalloisian and Mousterian techniques (around 43,000 BC), similar to those found in the Levant. Algeria was a site of significant development for Middle Paleolithic flake tool techniques. Tools from this era, starting about 30,000 BC, are known as Aterian (named after the archaeological site of Bir el Ater). The earliest blade industries in North Africa are termed Iberomaurusian, primarily found in the Oran region, and appear to have spread across the coastal Maghreb between 15,000 and 10,000 BC.

The Neolithic civilization, characterized by animal domestication and agriculture, developed in the Saharan and Mediterranean Maghreb possibly as early as 11,000 BC, or later between 6000 and 2000 BC. This way of life is richly depicted in the rock paintings of Tassili n'Ajjer, which flourished until the classical period. The diverse peoples of North Africa eventually coalesced into a distinct indigenous population known as the Berbers (Imazighen).

Phoenician traders and settlers arrived around 1000 BC, establishing coastal colonies like Tipasa, Hippo Regius (modern Annaba), and Rusicade (modern Skikda). Their principal center of power, Carthage (in modern Tunisia), greatly influenced the Berber populations through trade, military recruitment, and territorial expansion. By the 4th century BC, Berbers formed the largest contingent of the Carthaginian army and participated in the Mercenary War (241-238 BC) against Carthage.

As Carthaginian power waned due to defeats in the Punic Wars against Rome, Berber kingdoms rose to prominence. Numidia, located inland from Carthaginian coastal territories, became a significant power, especially under King Masinissa in the 2nd century BC, who unified the Numidian tribes and allied with Rome. After Masinissa's death in 148 BC, Numidia was gradually absorbed by the Roman Republic, and by 24 AD, all remaining Berber territory was annexed into the Roman Empire.

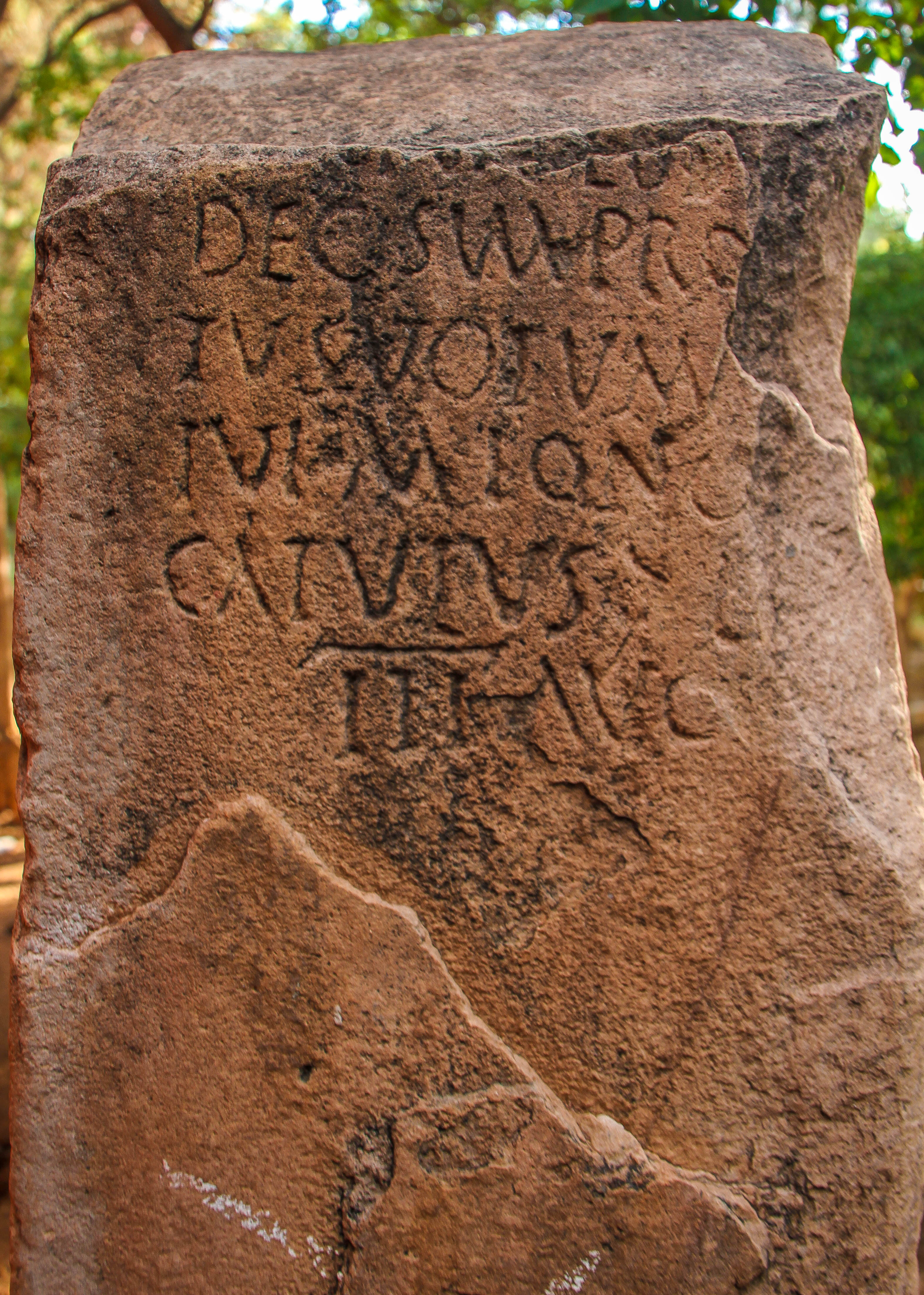

Roman rule in Algeria lasted for several centuries. The Romans founded numerous colonies and cities, such as Timgad and Djémila, and the region became a major supplier of grain and agricultural products to the empire. Saint Augustine, one of Christianity's most influential theologians, was bishop of Hippo Regius.

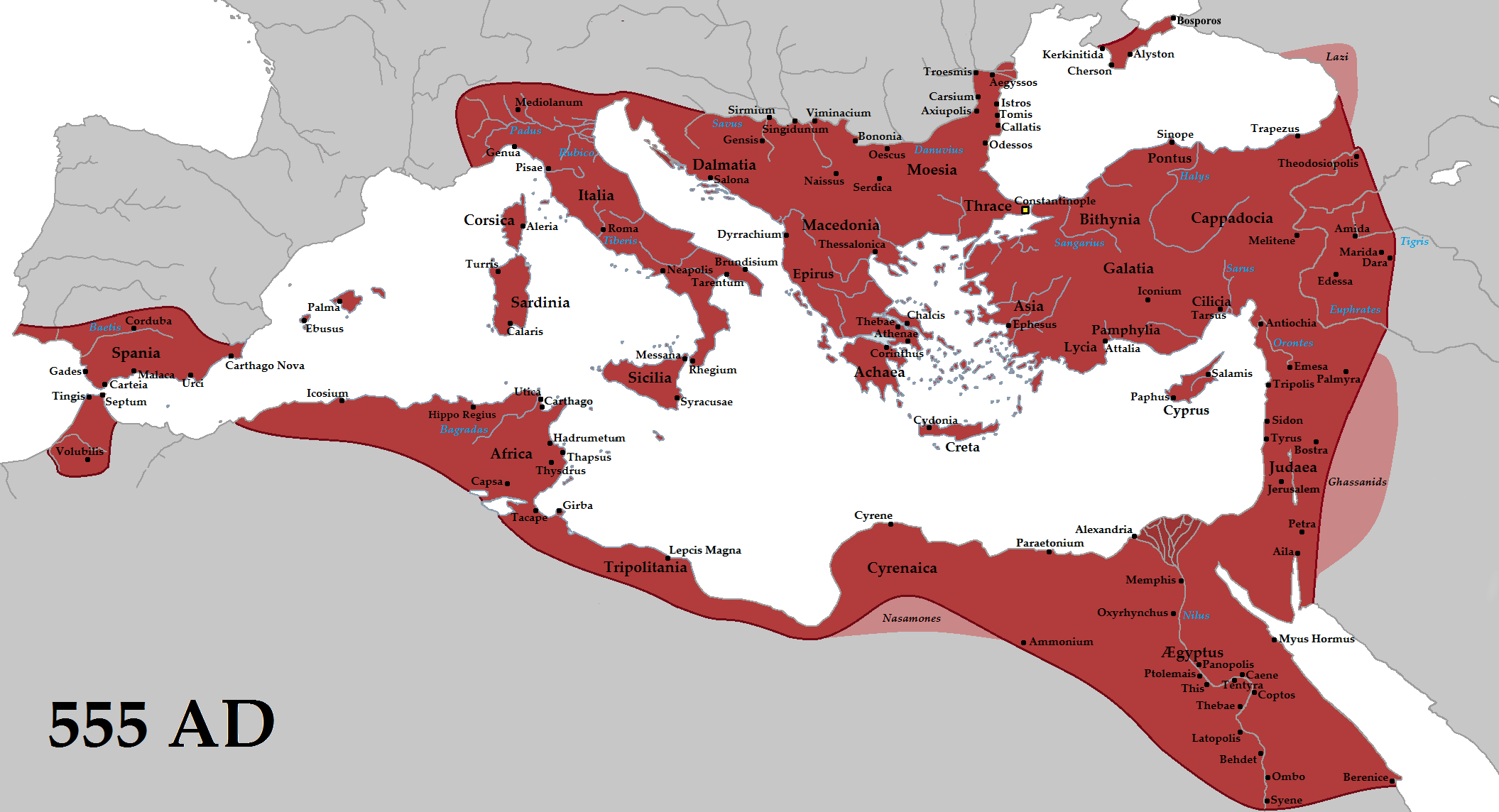

In 429 AD, the Germanic Vandals under Geiseric invaded North Africa, establishing a kingdom that controlled coastal Numidia by 435 AD. Vandal rule was relatively short-lived and marked by conflict with local Berber tribes, who often maintained their independence in mountainous regions. The Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire) under Emperor Justinian I reconquered North Africa from the Vandals in 533 AD, establishing the Praetorian prefecture of Africa. However, Byzantine control was often tenuous, particularly in the interior. Native Berber kingdoms, such as the Mauro-Roman Kingdom and later the Kingdom of Altava under leaders like Kusaila, continued to exist and resist external rule, asserting Berber political and cultural identity.

3.2. Middle Ages

The Muslim conquest of the Maghreb began in the 7th century. After initial resistance, notably led by figures like the Berber queen Dihya (also known as Kahina), Arab forces under the Umayyad Caliphate conquered the region by the early 8th century. Large numbers of Berbers converted to Islam, and Arabic gradually became a prominent language, although Berber languages and cultural identities persisted. Christian and Latin-speaking communities continued to exist for several centuries, diminishing significantly by the 10th-11th centuries.

Following the collapse of direct Umayyad rule, several local Islamic dynasties, often of Berber origin, emerged. These included:

- The Rustamids (777-909): An Ibadi Kharijite imamate centered at Tahert (near modern Tiaret), founded by Abd al-Rahman ibn Rustam. Their realm stretched across much of central Maghreb.

- The Aghlabids (800-909): An Arab dynasty, nominally vassals of the Abbasids, ruling Ifriqiya (modern Tunisia and eastern Algeria).

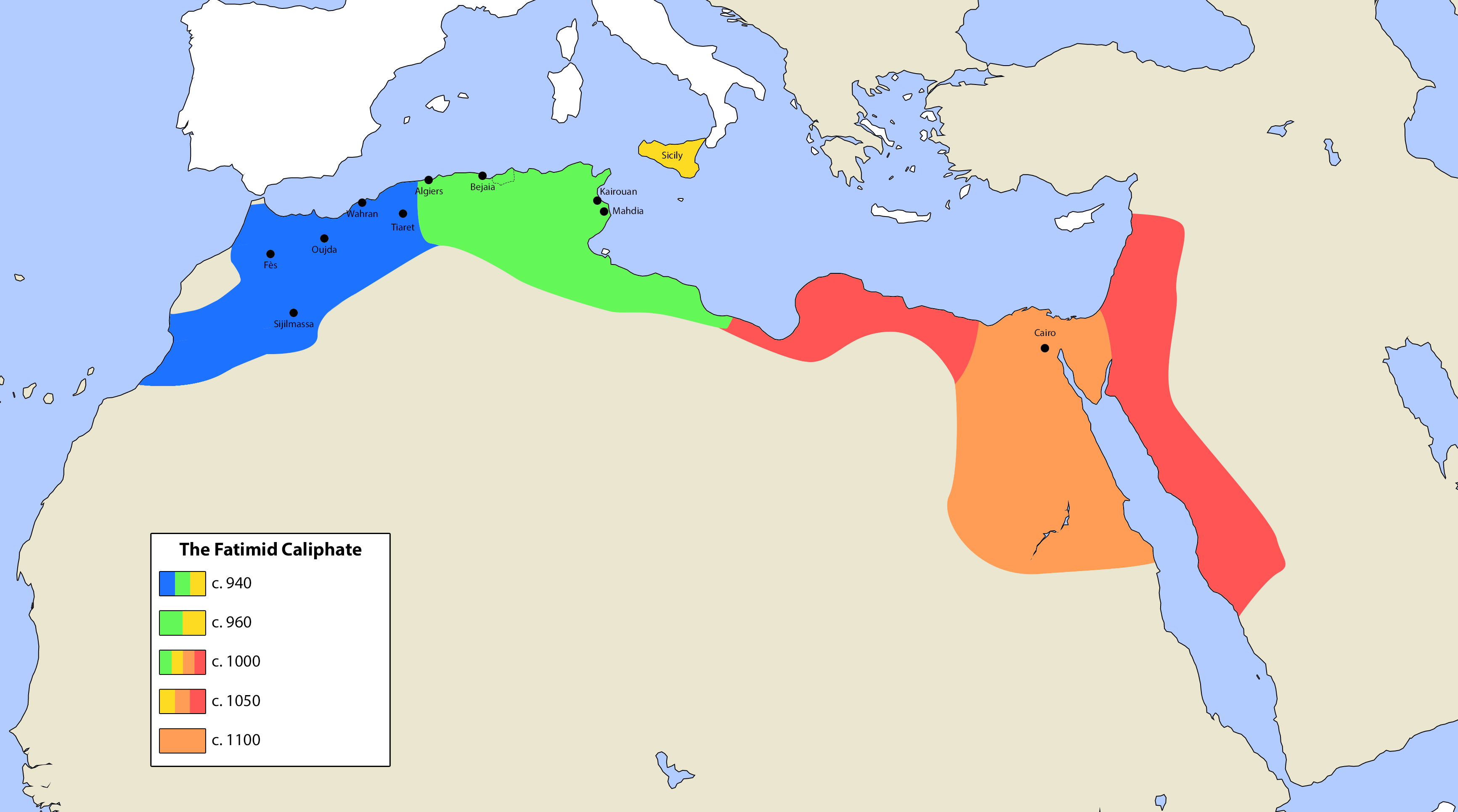

- The Fatimids (909-1171): A Shia Ismaili dynasty that originated among the Kutama Berbers of eastern Algeria. They overthrew the Rustamids and Aghlabids, conquered Egypt, and established a vast empire.

- The Zirids (972-1148) and Hammadids (1014-1152): Berber dynasties that initially served as Fatimid governors but later declared independence, ruling significant parts of Algeria. The Zirids were based in Ifriqiya, while the Hammadids, a branch of the Zirids, established their capital at Qal'at Bani Hammad and later Béjaïa.

In the mid-11th century, the Fatimids, to punish the Zirids for breaking away, encouraged the migration of Arab Bedouin tribes, the Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym, into North Africa. This migration had a profound impact, accelerating the Arabization of the countryside and contributing to the decline of some Berber groups and agricultural areas.

Two major Berber empires subsequently dominated the Maghreb:

- The Almoravids (c. 1040-1147): Originating from Sanhaja Berber tribes in the Sahara, they established an empire stretching from Al-Andalus (Muslim Spain) to parts of West Africa, including western Algeria.

- The Almohads (c. 1121-1269): A Berber religious movement founded by Ibn Tumart among the Masmuda Berbers of the Atlas Mountains. Led by Abd al-Mu'min (who was from the Koumïa tribe of Algeria), they overthrew the Almoravids and created an even larger empire encompassing all of the Maghreb and Al-Andalus.

After the decline of the Almohads in the 13th century, Algeria was primarily dominated by the Zayyanid dynasty (also known as Abdalwadids) (1235-1556), centered in Tlemcen. The Zayyanids, a Zenata Berber dynasty founded by Yaghmurasen Ibn Zyan, maintained control over much of western and central Algeria. Eastern Algeria often fell under the influence of the Hafsid dynasty of Tunis. The Zayyanid kingdom engaged in trade and intermittent warfare with its neighbors, the Marinids of Morocco and the Hafsids.

Starting in the early 16th century, the Spanish Empire launched incursions along the Algerian coast, capturing key ports such as Mers El Kébir (1505), Oran (1509), and Béjaïa (1510), seeking to counter Barbary piracy and expand their influence.

3.3. Early Modern Era (Ottoman Rule)

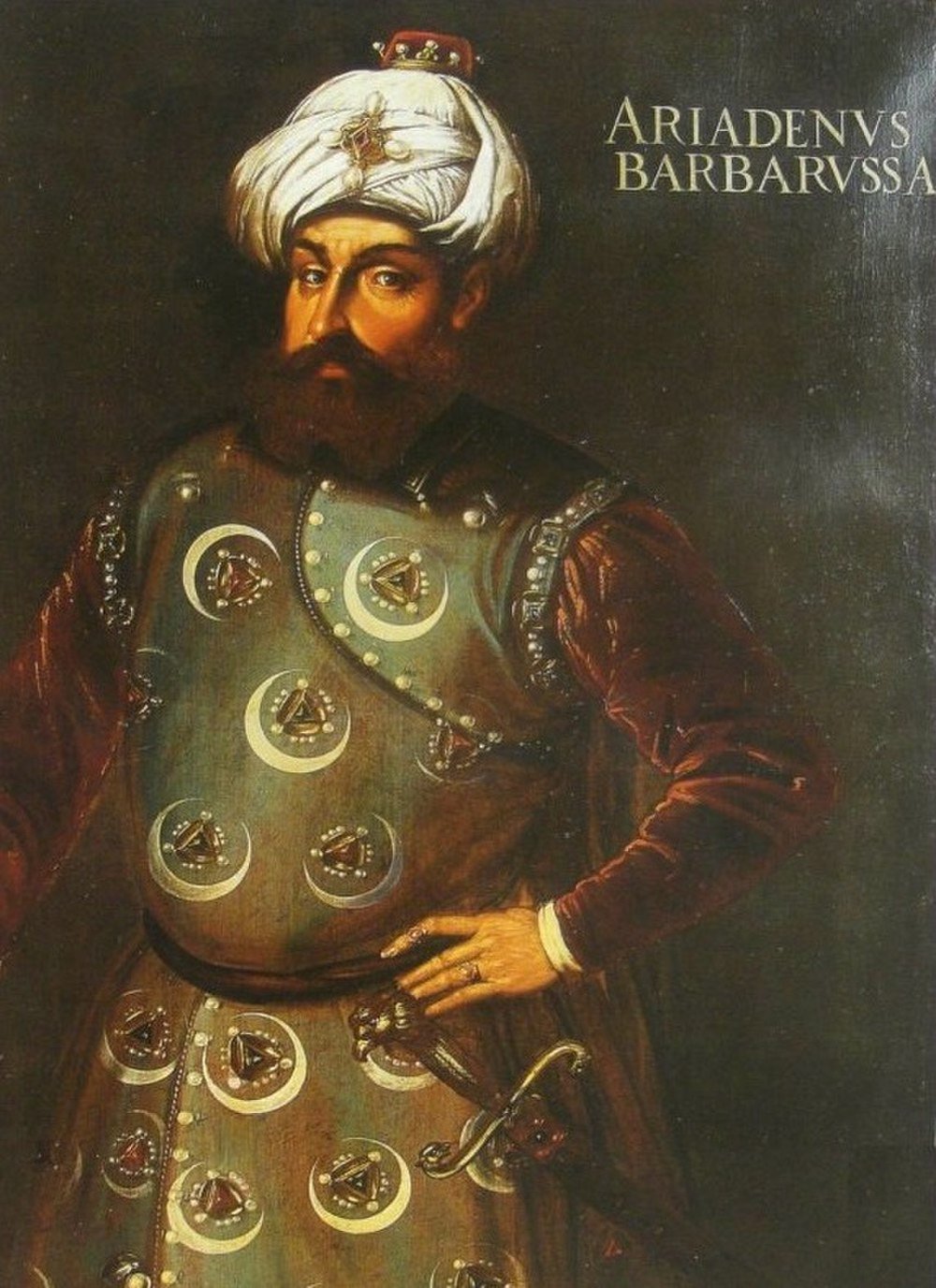

In response to Spanish expansion and local appeals, the Ottoman privateer brothers Aruj and Hayreddin Barbarossa intervened in Algeria. In 1516, they captured Algiers, establishing what became known as the Regency of Algiers. After Aruj's death in 1518, Hayreddin sought Ottoman protection, and Algeria became a province of the Ottoman Empire, though it enjoyed considerable autonomy. Hayreddin was appointed Beylerbey (governor-general) by the Ottoman Sultan.

The Regency of Algiers became a major power in the Mediterranean, largely due to the activities of the Barbary corsairs. These corsairs, operating from Algiers and other North African ports, preyed on Christian and other non-Islamic shipping, capturing goods and enslaving crews and passengers. This activity provided significant revenue for the Regency but led to frequent conflicts with European maritime nations. Millions of Europeans were estimated to have been captured and sold into slavery over several centuries. Raids extended as far as Iceland and the Faroe Islands.

The political structure of the Regency evolved over time. Initially ruled by Beylerbeys appointed by the Sultan, power later shifted to Pashas serving three-year terms. By the mid-17th century, discontent among the Janissaries (the Ottoman military corps stationed in Algiers, known locally as the Ojaq) led to them seizing power. In 1659, the Agha of the Janissaries became the de facto ruler, and from 1671, the head of state was an elected Dey. The Dey, chosen for life by a council of military officers (the Divan), ruled as a constitutional autocrat. Although nominally part of the Ottoman Empire, the Regency of Algiers operated with a high degree of independence, conducting its own foreign policy and even engaging in wars with other Ottoman territories like the Beylik of Tunis. The authority of the Deys was often strongest in coastal cities and less effective in the interior, particularly in the Kabylie region, where Berber tribes maintained significant autonomy.

European powers launched numerous expeditions against Algiers to suppress piracy, including Spanish attacks in 1775, 1783, and 1784. The newly independent United States fought the First Barbary War (1801-1805) and Second Barbary War (1815) against Algiers and other Barbary states to end attacks on American shipping. In 1816, an Anglo-Dutch fleet under Lord Exmouth bombarded Algiers, forcing the Dey to release Christian slaves and agree to curb piracy. Despite these efforts, corsair activity continued, albeit on a reduced scale, until the French conquest. In 1792, Algiers successfully recaptured Oran and Mers El Kébir from Spain, ending Spanish presence on the Algerian mainland. The Regency also experienced recurrent outbreaks of plague, which significantly impacted its population, with Algiers losing tens of thousands of inhabitants in major epidemics.

3.4. French Colonial Era (1830-1962)

In 1830, under the pretext of an insult to their consul (the Fan Affair), France invaded Algiers. The conquest of Algeria was a long and brutal process, marked by widespread violence, massacres, and scorched-earth policies. Resistance was fierce, led by figures such as Emir Abdelkader in the west, Ahmed Bey in Constantine, and later popular uprisings like the Mokrani Revolt in Kabylie (1871). French methods to establish control have been described by some historians as genocidal, with the indigenous population declining by up to one-third between 1830 and 1872 due to warfare, disease, and starvation. Historian Ben Kiernan wrote that the war had killed approximately 825,000 indigenous Algerians by 1875. French policy aimed at "civilizing" the country, which often meant suppressing local culture and institutions. The slave trade and piracy were ended with the French conquest.

From 1848, northern Algeria was formally annexed and administered as an integral part of France, divided into départements. This status, however, largely benefited European settlers, known as colons or Pied-Noirs, who immigrated in large numbers from France, Spain, Italy, and Malta. Between 1825 and 1847, 50,000 French people emigrated to Algeria. These settlers acquired vast tracts of fertile land, often confiscated from Algerian communities, and dominated the political and economic life of the colony. By the early 20th century, Europeans formed a majority in cities like Oran and Algiers.

While European settlers and Algerian Jews (granted French citizenship by the Crémieux Decree of 1870) enjoyed the rights of French citizens, the Muslim Algerian majority faced discrimination, political disenfranchisement, and economic hardship. French rule disrupted traditional social structures and land ownership patterns, leading to widespread impoverishment and resentment.

The growth of Algerian nationalism was fueled by these inequalities and the desire for self-determination. The Sétif and Guelma massacre in May 1945, where French forces suppressed nationalist demonstrations with extreme brutality, killing thousands of Algerians, became a turning point, galvanizing the independence movement.

During World War II, Algeria played a significant role after the Allied Operation Torch in 1942, becoming a base for Free French Forces. French promises of political reform after the war were largely unfulfilled, further fueling nationalist aspirations.

The Algerian War of Independence began on November 1, 1954, launched by the National Liberation Front (FLN). The war was characterized by intense guerrilla warfare, FLN attacks on both military and civilian targets, and brutal French counter-insurgency tactics, including widespread torture, collective punishment, forced relocations of populations into concentration camps, and the destruction of over 8,000 villages. The conflict resulted in hundreds of thousands of Algerian deaths (estimates range from 300,000 to over a million, with Alistair Horne estimating around 700,000 Algerian casualties) and displaced over two million people. French casualties were also significant. During this period, France also conducted its first nuclear tests in the Algerian Sahara.

The war deeply divided French society and led to the collapse of the French Fourth Republic. After Charles de Gaulle returned to power, negotiations began, leading to the Évian Accords in March 1962. A referendum on independence in July 1962 resulted in an overwhelming vote for sovereignty, and Algeria officially gained independence on July 5, 1962. The independence was followed by the Oran massacre of 1962 and a mass exodus of over 900,000 Pied-Noirs and tens of thousands of Harkis (Muslim Algerians who served with the French army) to France.

3.5. Post-Independence

The decades following Algeria's independence were marked by efforts at nation-building under a socialist, single-party state, followed by economic challenges, political unrest, a devastating civil war, and subsequent attempts at reconciliation and reform.

3.5.1. Early Independence (1962-1991)

Algeria's independence in 1962 was followed by the mass exodus of European settlers (Pied-Noirs) and many Harkis. The FLN became the sole legal political party. Ahmed Ben Bella became the first President. His government pursued socialist policies, including land reform and nationalization of key industries. In 1963, a border dispute with Morocco led to the brief Sand War.

In 1965, Ben Bella was overthrown in a bloodless coup by his Minister of Defence, Colonel Houari Boumédiène. Boumédiène continued and intensified socialist policies, with a focus on state-led industrialization, collectivization of agriculture, and nationalization of the crucial oil and gas sector (completed in 1971). The army's influence in politics became more pronounced. Algeria played a prominent role in the Non-Aligned Movement and supported various national liberation movements, including the Polisario Front in Western Sahara. The oil price boom of the 1970s provided significant revenue for development projects but also increased the economy's dependence on hydrocarbons.

After Boumédiène's death in 1978, Colonel Chadli Bendjedid became president. His tenure saw some economic liberalization and a policy of Arabization in education and public life, which aimed to promote Arabic language and culture but also led to discontent among the Berber-speaking minority, particularly in the Kabylie region, sparking the Berber Spring protests in 1980. The Algerian economy suffered significantly from the 1980s oil glut and falling oil prices, leading to increased social unrest and austerity measures. The 1988 October Riots, triggered by economic hardship and frustration with the FLN's rule, forced Bendjedid to introduce political reforms. A new constitution in 1989 ended the FLN's monopoly on power and allowed for a multi-party system. This opening led to the rapid rise of Islamist parties, most notably the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS).

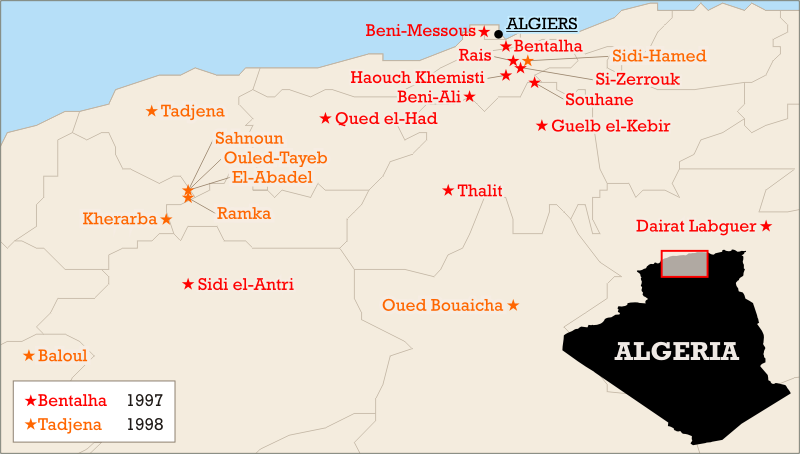

3.5.2. Civil War (1991-2002) and Aftermath

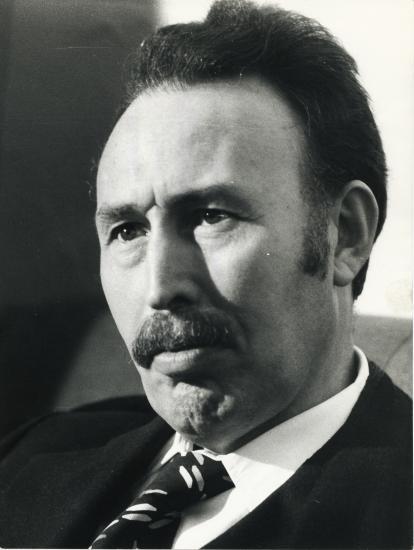

In December 1991, the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) won a landslide victory in the first round of parliamentary elections. Fearing the establishment of an Islamist state, the Algerian military intervened in January 1992, cancelling the second round of elections, forcing President Bendjedid to resign, and installing a High Council of State to govern. The FIS was banned, and its leaders arrested.

This triggered the Algerian Civil War, a brutal conflict between the government's security forces and various Islamist armed groups, primarily the Armed Islamic Group (GIA) and the Islamic Salvation Army (AIS), the armed wing of the FIS. The war was characterized by extreme violence, including widespread massacres of civilians, bombings, and assassinations. Estimates of the death toll range from 100,000 to 200,000. The conflict had a devastating impact on Algerian society, economy, and human rights. International concern grew, notably during crises like the 1994 hijacking of Air France Flight 8969 by the GIA. The GIA declared a ceasefire in October 1997, and the AIS largely disbanded following an amnesty.

Abdelaziz Bouteflika was elected president in 1999 in an election contested by opposition groups. He launched a "Civil Concord" initiative, approved by referendum, which offered amnesty to many who had participated in the insurgency. This led to a significant reduction in violence, although a splinter group, the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC), which later affiliated with Al-Qaeda to become Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), continued sporadic attacks.

Bouteflika was re-elected in 2004 and pushed for a Charter for Peace and National Reconciliation, approved by referendum in 2005, offering further amnesty to both former militants and state security forces. This was aimed at promoting national healing but was criticized by human rights groups for precluding accountability for past abuses. In 2008, a constitutional amendment removed presidential term limits, allowing Bouteflika to win re-election in 2009 and 2014.

Inspired by the Arab Spring, protests erupted in Algeria in early 2011. In response, the government lifted the 19-year-old state of emergency and introduced some political reforms, though significant systemic change was limited. In January 2013, an AQIM-linked group attacked the In Amenas gas plant, leading to a hostage crisis with numerous casualties.

In February 2019, massive, peaceful protests, known as the Hirak Movement, began across Algeria after Bouteflika announced his intention to seek a fifth presidential term despite his failing health. The sustained protests forced Bouteflika to resign in April 2019. Abdelmadjid Tebboune was elected president in December 2019, though the election saw low turnout and was boycotted by the Hirak movement, which demanded more fundamental reforms. Protests continued, albeit with interruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Tebboune won a second term in the 2024 presidential election, with opponents alleging fraud. The aftermath of the civil war continues to shape Algeria's political and social landscape, with ongoing debates about democracy, human rights, and accountability.

4. Geography

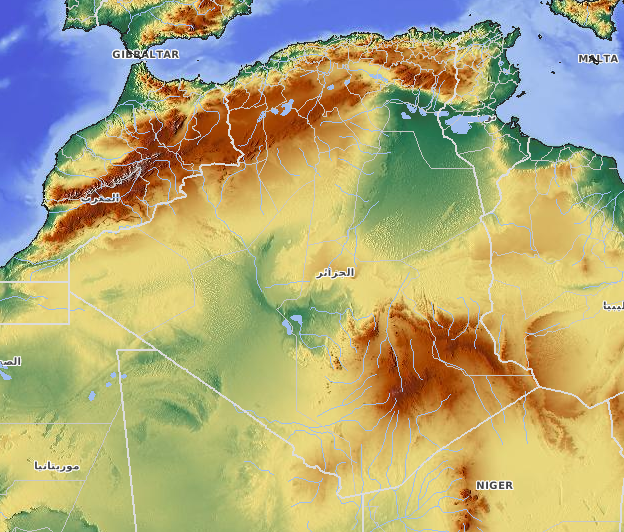

Algeria, the largest country in Africa and the Mediterranean Basin, is characterized by diverse geographical features. The vast Sahara Desert dominates its southern territory, while the northern coastal region is marked by mountain ranges and fertile plains where most of the population resides.

Algeria is located in North Africa, bordered by Tunisia to the northeast, Libya to the east, Niger to the southeast, Mali, Mauritania, and Western Sahara to the southwest, Morocco to the west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north. It spans an area of 0.9 M mile2 (2.38 M km2). The country lies mostly between latitudes 19° and 37°N, and longitudes 9°W and 12°E.

The northern part of Algeria features two parallel mountain ranges of the Atlas Mountains system: the Tell Atlas, which runs close to the coast, and the Saharan Atlas, further inland. Between these ranges lie fertile plains and high plateaus (Hauts Plateaux). The Tell Atlas region is relatively narrow but contains most of Algeria's arable land and major cities, including Algiers, Oran, and Constantine. Eastward, the Aures and Nememcha mountains occupy northeastern Algeria, bordering Tunisia.

South of the Saharan Atlas, the landscape transitions into a steppe region before giving way to the immense Sahara Desert, which constitutes more than 80% of Algeria's total land area. The Algerian Sahara includes vast expanses of sand seas (ergs) such as the Grand Erg Oriental and Grand Erg Occidental, as well as rocky plateaus (hamadas) and gravel plains (regs). In the southeastern Sahara lies the Hoggar Mountains (Ahaggar), a rugged highland region of volcanic origin. Algeria's highest point, Mount Tahat, at 9.5 K ft (2.91 K m) (some sources cite 9.8 K ft (3.00 K m)), is located in the Hoggar range.

The coastal area is often hilly and mountainous, with few natural harbors. The main cities are concentrated in the north.

4.1. Climate and Hydrology

Algeria exhibits diverse climate zones. The northern coastal region, part of the Tell Atlas, experiences a Mediterranean climate, characterized by warm, dry summers and mild, wet winters. Annual rainfall in this area ranges from 16 in (400 mm) to 26 in (670 mm), with some parts of northeastern Algeria receiving up to 0.0 K in (1.00 K mm) annually. Precipitation generally increases from west to east along the coast.

South of the Tell Atlas, in the High Plateaus and Saharan Atlas, a semi-arid climate (steppe climate) prevails, with lower rainfall and greater temperature extremes.

The vast Sahara Desert region has an arid desert climate. Daytime temperatures can be extremely hot year-round, often exceeding 104 °F (40 °C) in summer. After sunset, the clear, dry air allows for rapid heat loss, leading to cool or even chilly nights and significant diurnal temperature ranges. Rainfall is scarce and erratic in the Sahara. The Sirocco, a hot, dust-laden wind originating from the Sahara, can affect northern Algeria, especially during the spring and summer.

Hydrologically, Algeria has limited permanent water resources. Most rivers, known as wadis, are seasonal, flowing only after rainfall. The longest river is the Chelif River, which rises in the Saharan Atlas and flows into the Mediterranean Sea. There are several endorheic basins containing salt lakes or playas (chotts), particularly in the High Plateaus region, such as Chott Melrhir and Chott Ech Chergui. Groundwater resources, particularly in the Saharan aquifers, are important but face challenges of over-extraction and sustainability. Algeria is also experiencing the impacts of climate change, including rising temperatures and potentially altered rainfall patterns, which could further strain its water resources.

4.2. Fauna and Flora

Algeria's diverse geography supports a varied range of wildlife and vegetation. The country's ecosystems include coastal regions, mountainous areas, steppes, and vast desert landscapes. Forest cover is limited, estimated at around 1% of the total land area, primarily found in the northern mountainous regions.

Flora:

The northern coastal and Tell Atlas regions feature Mediterranean vegetation, including maquis shrubland, olive trees, oaks (such as cork oak), Aleppo pines, and cedars (notably the Atlas cedar). The mountain regions contain forests of evergreen and some deciduous trees. Grape vines are indigenous to the coast. Warmer areas support fig trees, eucalyptus, agave, and various palm tree species. The steppe regions are characterized by grasses like esparto grass and drought-resistant shrubs.

The Saharan flora is adapted to arid conditions. Oases support date palm cultivation. Other desert plants include acacias, tamarisks, and various hardy grasses and shrubs.

Fauna:

Commonly seen animals include wild boar, jackals, and various species of gazelles. The fennec fox, known for its large ears and adaptation to desert life, is the national animal of Algeria. The Barbary macaque, the only native monkey species north of the Sahara, inhabits forested areas in the north. The Barbary stag, a subspecies of red deer, is found in the dense, humid forests of northeastern Algeria.

Less common but present are small populations of the African leopard and the critically endangered Saharan cheetah. Various rodents, such as jerboas, are adapted to arid environments.

Reptiles are abundant, including snakes (both venomous and non-venomous), monitor lizards, and other lizards. Scorpions and numerous insect species are also prevalent, especially in the desert.

Birdlife is diverse, with Algeria being a route for migratory birds. Forested areas are home to various resident and migratory bird species.

Several species have become extinct in Algeria, including the Barbary lion, the Atlas bear, and the West African crocodile (though a small, isolated population may persist in the Tassili n'Ajjer).

Camels (dromedaries) are extensively used by nomadic populations in the Sahara.

Conservation efforts include the establishment of national parks, such as Tassili n'Ajjer National Park (also a UNESCO World Heritage site), Djurdjura National Park, and El Kala National Park, aimed at protecting biodiversity and unique ecosystems. Algeria's Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score in 2018 was 5.22/10, ranking it 106th globally out of 172 countries.

5. Politics and Government

Algeria is a semi-presidential republic. The political system has historically been dominated by a powerful elite, often referred to as "le pouvoir" (the power), comprising senior military officials and civilian figures, which has significantly influenced political decision-making. While formally a multi-party system, the political landscape has been characterized by the long-standing influence of the National Liberation Front (FLN) and the military. The Hirak protests starting in 2019 challenged this established order, demanding fundamental political reforms and greater democratic accountability.

5.1. Government Structure

The government of Algeria operates under a framework defined by its constitution. The main branches of government are the executive, legislative, and judicial.

Executive Branch:

The President is the head of state, commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and holds significant executive powers. The president is elected by universal suffrage for a five-year term. Constitutional amendments in the past altered term limits; the 2016 constitution reinstated a two-term limit, which was then removed and later re-discussed. Abdelmadjid Tebboune is the current president, first elected in December 2019 and re-elected in 2024. The President appoints the Prime Minister, who is the head of government. The Prime Minister, along with the cabinet (Council of Ministers) appointed by the President on the Prime Minister's recommendation, is responsible for implementing laws and managing the day-to-day affairs of the state. The President also presides over the Council of Ministers and the High Security Council.

Legislative Branch:

The Parliament of Algeria is bicameral, consisting of:

- The People's National Assembly (Al-Majlis al-Sha'abi al-Watani): This is the lower house, composed of 407 members (previously 462) who are directly elected for a five-year term through proportional representation.

- The Council of the Nation (Majlis al-Umma): This is the upper house, with 174 members (previously 144) serving six-year terms. Two-thirds of its members are indirectly elected by local and provincial assemblies, and one-third are appointed by the President. Half of the elected and appointed members are renewed every three years.

Parliament's functions include debating and passing legislation, approving the national budget, and overseeing the government's actions. The constitution places some restrictions on the formation of political parties, for example, prohibiting those based on religion, language, race, gender, or region. The last parliamentary elections were held in June 2021. Major political parties include the FLN, the Democratic National Rally (RND), and various Islamist and secular opposition parties.

Judicial Branch:

The judiciary is, in principle, independent. The highest court is the Supreme Court. There is also a Constitutional Council (or Constitutional Court, depending on constitutional revisions) responsible for ensuring the constitutionality of laws and overseeing elections. The judicial system is based on French civil law and Islamic law (Sharia), particularly in matters of personal status. The effectiveness and independence of the judiciary have been subjects of public and international scrutiny, particularly concerning human rights cases and political freedoms.

Universal suffrage is granted at 18 years of age.

5.2. Foreign Relations

Algeria's foreign policy has traditionally been guided by principles of non-alignment, support for national liberation movements, and Arab and African solidarity. It is a prominent member of the African Union, the Arab League, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), OPEC, and the United Nations. Algeria is also a founding member of the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU), although the organization has been largely inactive due to regional tensions.

Key aspects of Algeria's foreign relations include:

- Maghreb Relations**: Relations with its Maghreb neighbors are crucial. However, the relationship with Morocco has been persistently strained, primarily due to the unresolved Western Sahara conflict. Algeria provides significant support to the Polisario Front and hosts Sahrawi refugee camps in Tindouf. This dispute has been a major obstacle to regional integration. In August 2021, Algeria severed diplomatic relations with Morocco, citing hostile actions.

- Relations with France**: As the former colonial power, relations with France are complex and multifaceted, encompassing strong economic, cultural, and human ties (due to a large Algerian diaspora in France) alongside historical grievances. Issues such as colonial archives, nuclear test compensations, and memory of the Algerian War continue to be sensitive.

- Relations with Russia**: Algeria maintains close ties with Russia, particularly in military and defense cooperation. Russia is a major supplier of arms to Algeria.

- Relations with Europe**: Algeria is a key energy supplier (particularly natural gas) to Europe and is part of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) of the European Union. It has an Association Agreement with the EU, aiming to foster closer economic and political ties. Countries like Italy and Spain are significant importers of Algerian gas.

- Counter-terrorism**: Algeria has been an active partner in international counter-terrorism efforts, particularly in the Sahel region, given its own experience with Islamist extremism.

- Palestine**: Algeria is a strong supporter of the Palestinian cause and does not recognize Israel.

- African Affairs**: Algeria plays an influential role in the African Union, contributing to peacekeeping efforts and advocating for African development and sovereignty.

The government has sought to improve its international image and attract foreign investment, though domestic political developments and human rights concerns sometimes affect these efforts. From a social liberal perspective, Algeria's foreign policy is often viewed through its stance on self-determination, its role in regional stability, and its engagement with international human rights norms.

5.3. Military

The Algerian People's National Armed Forces (Armée Nationale Populaire, ANP) is the military of Algeria. It consists of the Army (Land Forces), Navy, Air Force, and the Territorial Air Defence Forces. The ANP is a direct successor to the National Liberation Army (ALN), the armed wing of the FLN during the Algerian War of Independence.

The military has historically played a significant role in Algerian politics. It is one of the largest and best-equipped armed forces in Africa, with the highest defense budget on the continent. In 2024, Algeria's defense budget ranked among the highest globally. Personnel strength includes approximately 147,000 active-duty personnel, 150,000 reservists, and around 187,000 paramilitary staff (estimates vary by year).

Military service is compulsory for men aged 19-30, typically for 12 months, though this has been subject to changes and exemptions. Algeria's military expenditure has been a significant portion of its GDP.

Major equipment is primarily sourced from Russia, with whom Algeria maintains a close defense relationship. Recent acquisitions have included advanced fighter jets (like MiG-29s and Su-30s), air defense systems, naval vessels (including Kilo-class submarines), and armored vehicles. China and some Western countries also supply military hardware.

Algeria's national security policy focuses on border security (given its long land borders in often unstable regions like the Sahel), counter-terrorism (particularly against groups like AQIM), and maintaining regional influence. The military has been heavily involved in combating Islamist insurgencies since the 1990s. Algeria has also participated in some international peacekeeping efforts. The country has a domestic arms industry and has pursued self-sufficiency in some areas of military production. According to the 2024 Global Peace Index, Algeria was ranked 90th most peaceful country in the world.

From a human rights perspective, the military's role in governance and its conduct during internal conflicts, particularly the civil war of the 1990s, have faced scrutiny. The emphasis on military strength also raises questions about resource allocation in a country with significant social and economic development needs.

5.4. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Algeria has been a subject of concern for domestic and international organizations. While the constitution guarantees certain rights, their practical application often falls short, particularly in areas of political freedom, freedom of expression, and assembly.

- Key Human Rights Issues**:

- Freedom of Expression, Assembly, and Association**: Restrictions on these freedoms have been significant. Journalists, activists, and human rights defenders often face harassment, intimidation, and legal prosecution for criticizing the government or reporting on sensitive issues. Media censorship, both direct and indirect (e.g., through control of advertising revenue), is a concern. While large-scale protests like the Hirak movement were initially tolerated to a degree, authorities later increased restrictions, and many activists were arrested. Laws on public gatherings are restrictive, and forming independent associations, particularly those critical of the government, can be difficult.

- Political Freedoms**: While Algeria has a multi-party system, the political space for genuine opposition has been limited. Elections have faced criticism regarding fairness and transparency.

- Due Process and Fair Trial**: Concerns persist about the independence of the judiciary, prolonged pre-trial detention, and allegations of unfair trials, especially in politically sensitive cases.

- Torture and Ill-Treatment**: Although prohibited by law, there have been credible reports of torture and ill-treatment of detainees by security forces, particularly in the context of counter-terrorism operations and during the civil war. Accountability for such abuses remains limited due to amnesty laws and a reluctance to investigate past violations.

- Minority Rights**: The rights of the Berber (Amazigh) minority have seen some improvements, such as the recognition of Tamazight as an official language. However, concerns remain regarding cultural expression and full political participation.

- Religious Freedom**: Islam is the state religion. While the constitution provides for freedom of worship, non-Muslim religious groups, particularly Protestant Christians, have faced restrictions and harassment, including the closure of churches and difficulties in registering. Proselytizing by non-Muslims to Muslims is illegal.

- LGBT Rights**: Homosexuality is criminalized in Algeria, and individuals face social stigmatization and legal penalties. Public homosexual behavior can lead to imprisonment. However, some surveys suggest a slowly growing, albeit still low, level of societal acceptance compared to other Arab nations.

- Women's Rights**: While women have made gains in education and public life, discrimination persists in law and practice. The Family Code, based on Islamic law, contains provisions that are discriminatory against women in matters of marriage, divorce, inheritance, and child custody. Domestic violence remains a significant issue.

- Refugees and Migrants**: Algeria hosts a large population of Sahrawi refugees in camps near Tindouf. Conditions in these camps are often difficult. Migrants from sub-Saharan Africa face discrimination and risk of arbitrary detention and expulsion.

The Algerian government has often rejected criticisms of its human rights record, citing national security concerns and its efforts to combat terrorism. Civil society organizations and human rights defenders continue to advocate for greater freedoms and accountability. The aftermath of the civil war and the "national reconciliation" process have left many victims' demands for justice unaddressed. From a social liberal perspective, strengthening human rights protections, ensuring accountability for abuses, and expanding civil liberties are crucial for Algeria's democratic development and social progress.

6. Administrative Divisions

Algeria is divided into 58 provinces, known as wilayas (singular: wilaya). Each wilaya is further subdivided into daïras (districts or sub-prefectures), and the daïras are then divided into baladiyahs (municipalities). As of recent administrative changes, there are 553 daïras and 1,541 baladiyahs.

Each wilaya, daïra, and baladiyah is named after its administrative seat or capital city, which is usually the largest urban center within that unit. The wilayas are headed by a wali (governor) appointed by the President. Elected assemblies exist at the wilaya (APW - Assemblée Populaire de Wilaya) and baladiyah (APC - Assemblée Populaire Communale) levels, responsible for local governance.

The administrative divisions have been reorganized several times since Algeria's independence to better manage the country's vast territory and growing population. The most recent major reorganization increased the number of wilayas from 48 to 58 in 2019, by creating 10 new wilayas primarily in the southern Saharan region. When new provinces are created, the numbering of older provinces is generally kept, which can result in a non-alphabetical or non-sequential order of province numbers.

The 58 wilayas of Algeria are (province number, name, area, and population figures vary by source and year of data; the table below is illustrative based on typical English Wikipedia presentations):

| # | Wilaya | Area (km2) | Population (approx.) |  | # | Wilaya | Area (km2) | Population (approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adrar | 402,197 | 439,700 | 30 | Ouargla | 211,980 | 552,539 | |

| 2 | Chlef | 4,975 | 1,013,718 | 31 | Oran | 2,114 | 1,584,607 | |

| 3 | Laghouat | 25,057 | 477,328 | 32 | El Bayadh | 78,870 | 262,187 | |

| 4 | Oum El Bouaghi | 6,768 | 644,364 | 33 | Illizi | 285,000 | 54,490 | |

| 5 | Batna | 12,192 | 1,128,030 | 34 | Bordj Bou Arréridj | 4,115 | 634,396 | |

| 6 | Béjaïa | 3,268 | 915,835 | 35 | Boumerdès | 1,591 | 795,019 | |

| 7 | Biskra | 20,986 | 730,262 | 36 | El Taref | 3,339 | 411,783 | |

| 8 | Béchar | 161,400 | 274,866 | 37 | Tindouf | 159,000 | 58,193 | |

| 9 | Blida | 1,696 | 1,009,892 | 38 | Tissemsilt | 3,152 | 296,366 | |

| 10 | Bouïra | 4,439 | 694,750 | 39 | El Oued | 54,573 | 673,934 | |

| 11 | Tamanrasset | 335,602 | 198,691 | 40 | Khenchela | 9,811 | 384,268 | |

| 12 | Tébessa | 14,227 | 657,227 | 41 | Souk Ahras | 4,541 | 440,299 | |

| 13 | Tlemcen | 9,061 | 945,525 | 42 | Tipaza | 2,166 | 617,661 | |

| 14 | Tiaret | 20,673 | 842,060 | 43 | Mila | 3,407 | 768,419 | |

| 15 | Tizi Ouzou | 2,956 | 1,119,646 | 44 | Aïn Defla | 4,897 | 771,890 | |

| 16 | Algiers | 1,190 | 2,947,461 | 45 | Naâma | 29,950 | 209,470 | |

| 17 | Djelfa | 66,415 | 1,223,223 | 46 | Aïn Témouchent | 2,376 | 384,565 | |

| 18 | Jijel | 2,577 | 634,412 | 47 | Ghardaïa | 23,890 | 375,988 | |

| 19 | Sétif | 6,504 | 1,496,150 | 48 | Relizane | 4,870 | 733,060 | |

| 20 | Saïda | 6,764 | 328,685 | 49 | Timimoun | 65,203 | 122,019 | |

| 21 | Skikda | 4,026 | 904,195 | 50 | Bordj Badji Mokhtar | 120,026 | 16,437 | |

| 22 | Sidi Bel Abbès | 9,150 | 603,369 | 51 | Ouled Djellal | 11,410 | 174,219 | |

| 23 | Annaba | 1,439 | 640,050 | 52 | Béni Abbès | 101,350 | 50,163 | |

| 24 | Guelma | 4,101 | 482,261 | 53 | In Salah | 131,220 | 50,392 | |

| 25 | Constantine | 2,187 | 943,112 | 54 | In Guezzam | 88,126 | 11,202 | |

| 26 | Médéa | 8,866 | 830,943 | 55 | Touggourt | 17,428 | 247,221 | |

| 27 | Mostaganem | 2,269 | 746,947 | 56 | Djanet | 86,185 | 17,618 | |

| 28 | M'Sila | 18,718 | 991,846 | 57 | El M'Ghair | 8,835 | 162,267 | |

| 29 | Mascara | 5,941 | 780,959 | 58 | El Meniaa | 62,215 | 57,276 |

Note: Population and area data for the 10 new provinces created in 2019 (numbers 49-58) might be estimates derived from previous larger provinces and are subject to revision. The map shows the 48 provinces prior to the 2019 division for provinces 11, 33, 37, 39, 47. The additional 10 provinces were carved out of these larger Saharan provinces.

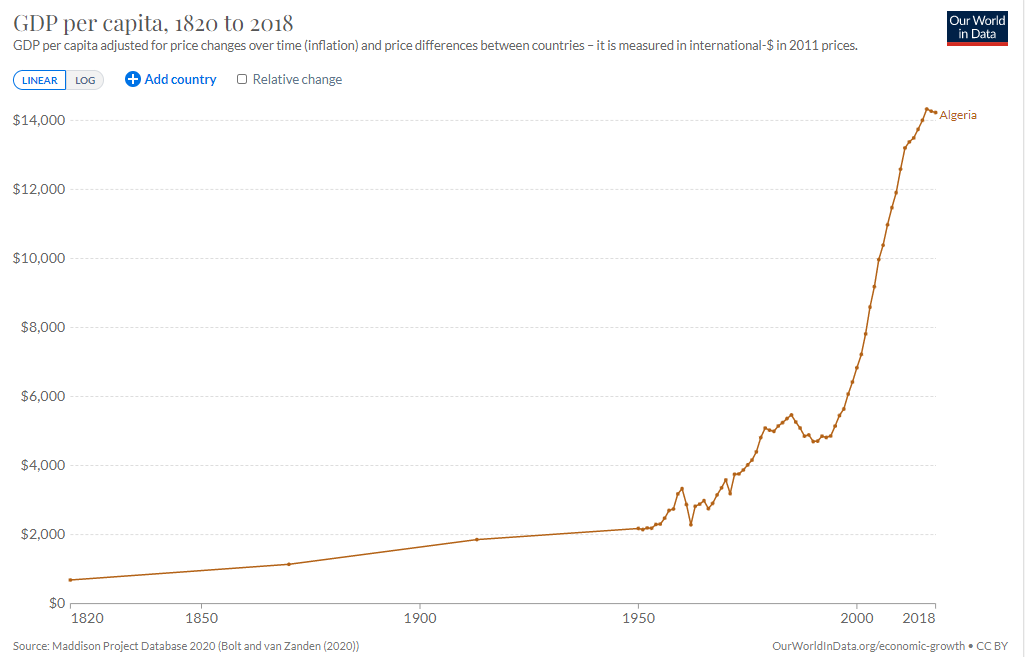

7. Economy

Algeria's economy is largely dominated by the state, a legacy of its post-independence socialist development model. Hydrocarbons, particularly oil and natural gas, have long been the backbone of the economy, accounting for roughly 60% of budget revenues, 30% of GDP, and the vast majority (around 90%) of export earnings. The currency is the Algerian dinar (DZD). In June 2024, the World Bank reclassified Algeria as an upper-middle-income country.

Despite strong revenues from hydrocarbons, which have provided Algeria with substantial foreign currency reserves (historically over 170.00 B USD) and a hydrocarbon stabilization fund, the economy faces challenges. These include a high dependence on volatile global energy prices, the need for diversification, high youth unemployment, and regional inequalities. Efforts to attract foreign and domestic investment outside the energy sector and to develop industries like manufacturing and agriculture have had limited success, partly due to bureaucratic hurdles, high costs, and an often restrictive business climate. The government has historically maintained significant control over industries, and privatization efforts have been slow or reversed at times.

In recent years, there has been a renewed push for economic reforms aimed at improving the business environment, encouraging private sector growth, and reducing reliance on imports. Algeria has not joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) despite years of negotiations but is a member of the Greater Arab Free Trade Area (GAFTA) and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), and has an association agreement with the European Union. Foreign direct investment has seen some increase, with Turkish companies, for example, becoming more active.

Economic policies often involve significant public spending on social programs, infrastructure development, and job creation schemes, particularly in response to social demands and protests. However, the sustainability of this spending is linked to hydrocarbon revenues. Inflation can be a concern, especially related to food prices.

Social aspects such as labor rights, environmental protection in resource extraction, and equitable wealth distribution are important considerations from a social liberal perspective. The transition to a more diversified and sustainable economy that benefits all segments of the population remains a key challenge.

7.1. Oil and Natural Resources

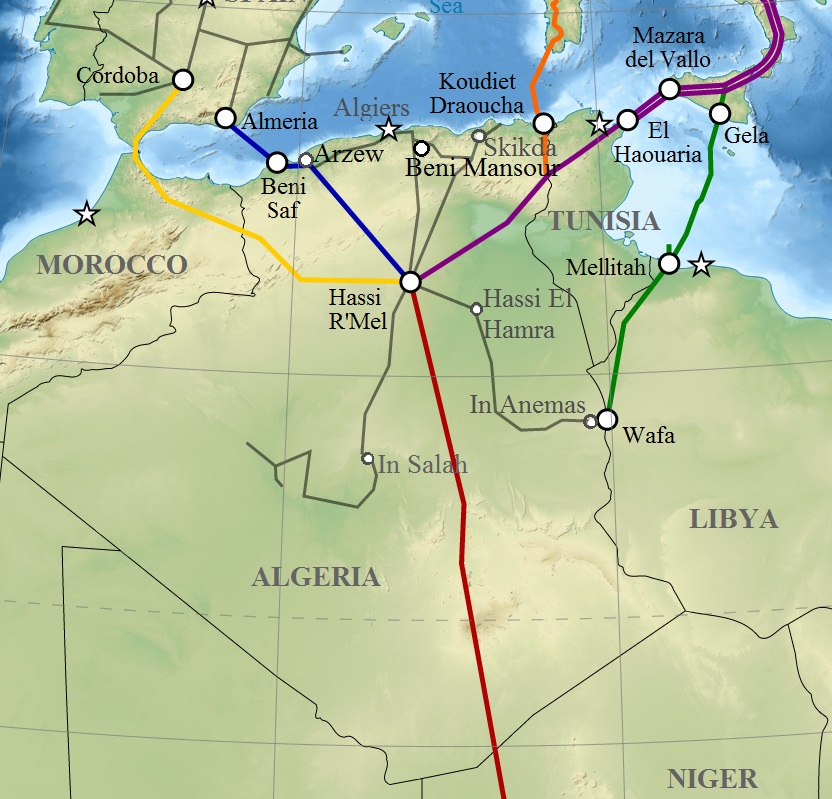

Algeria is a major player in the global energy market and has been a member of OPEC since 1969. Its economy is heavily reliant on its vast hydrocarbon resources.

- Oil: Algeria has significant proven oil reserves, ranking among the top 20 countries globally and second in Africa. Its crude oil production is substantial, typically around 1.1 million barrels per day. Algerian crude oil is known for being light and sweet, making it desirable on international markets.

- Natural Gas: The country holds the 10th-largest natural gas reserves in the world and is the sixth-largest gas exporter. In 2005, proven natural gas reserves were estimated at 160 Tcuft. Algeria is a key supplier of natural gas to Europe, primarily via pipelines such as the Trans-Mediterranean Pipeline to Italy and the Medgaz Pipeline to Spain. It also exports Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG).

- Sonatrach: The state-owned oil and gas company, Sonatrach, dominates the hydrocarbon sector. It is involved in all aspects of the industry, from exploration and production to refining, transportation, and marketing. Foreign oil companies operate in Algeria typically through partnerships or production-sharing agreements with Sonatrach, where Sonatrach usually holds a majority stake. Sonatrach is the largest company in Africa.

Hydrocarbons account for about 60% of budget revenues, 30% of GDP, and approximately 87.7% of export earnings. This heavy dependence makes the Algerian economy vulnerable to fluctuations in global oil and gas prices. While high prices in the past allowed Algeria to build substantial foreign currency reserves and a hydrocarbon stabilization fund, and maintain low external debt (around 2% of GDP), periods of low prices have strained the budget and highlighted the need for economic diversification.

Other mineral resources include iron ore, phosphates, uranium, zinc, and lead. Algeria also has notable deposits of mercury. The mining industry for non-hydrocarbon resources is less developed but holds potential.

From a social and environmental perspective, the extraction of oil and natural resources raises concerns about environmental degradation, the equitable distribution of wealth generated, and the impact on local communities. The sustainability of resource exploitation and the transition towards a less carbon-intensive economy are significant long-term challenges. Algeria has a high biocapacity deficit, meaning its ecological footprint of consumption significantly exceeds the biocapacity available within its territory.

7.2. Research and Alternative Energy

Algeria has recognized the importance of diversifying its energy sources and investing in scientific research and technological development. The government has allocated significant funds, estimated at around 100.00 B DZD, towards developing research facilities and supporting researchers.

A key focus of this effort is the development of renewable energy sources, particularly solar energy and wind power. Algeria possesses immense solar energy potential, especially in the Sahara Desert, considered among the largest in the Mediterranean region. To harness this, the government has supported initiatives such as the creation of a solar science park in Hassi R'Mel. The country has ambitious targets for renewable energy generation, aiming to reduce its dependence on fossil fuels for domestic consumption and potentially export green energy in the future.

Beyond renewable energy, research in Algeria also encompasses areas such as:

- Space technology and satellite telecommunications: Algeria has its own space agency and has launched several satellites for observation and communication purposes.

- Nuclear energy: Algeria has a peaceful nuclear program focused on research and potential energy generation, with research reactors in operation.

- Medical research: Efforts are made to advance local capabilities in health sciences and pharmaceutical production.

Algeria has numerous universities and research laboratories. As of 2008, there were an estimated 20,000 research professors and over 780 research labs, with goals to expand these numbers. The development of a robust research and innovation ecosystem is seen as crucial for long-term economic diversification and sustainable development. However, challenges remain in translating research into commercial applications and fostering a dynamic innovation culture. In the Global Innovation Index of 2024, Algeria was ranked 115th.

7.3. Labour Market

Algeria's labor market is characterized by a relatively young population and challenges related to unemployment, particularly among youth and women. The overall unemployment rate was 11.8% in 2023, though figures vary by source and year. Youth unemployment (ages 15-24) has consistently been much higher, often exceeding 20%.

The public sector has traditionally been a major employer, a legacy of the country's socialist past. However, efforts to diversify the economy and promote private sector growth are aimed at creating more sustainable employment opportunities. The government has implemented various job creation programs and support schemes for job seekers, such as the Dispositif d'Aide à l'Insertion Professionnelle (DAIP), which aims to help young graduates gain professional experience.

Key aspects of the Algerian labor market include:

- High Youth Unemployment**: This remains a significant socio-economic challenge, contributing to social unrest at times. Mismatches between education/skills and market demands are often cited as a contributing factor.

- Female Labor Force Participation**: While women's educational attainment has increased, their participation in the formal labor market remains relatively low compared to men, though it has been gradually increasing.

- Informal Sector**: A significant portion of employment is in the informal sector, which often lacks social protections and job security.

- Labor Policies and Trade Unions**: Algeria has a framework for labor rights, and trade unions exist. However, independent and autonomous trade unions have reported facing harassment from the government, with some leaders imprisoned and protests suppressed. Several unions involved in past protests have reportedly been deregistered. This impacts the ability of workers to advocate for better conditions and rights, a concern from a social liberal perspective.

- Skills Mismatch**: There are concerns about the alignment of the education system's output with the needs of the evolving economy. Vocational training and skills development are areas of focus for reform.

The government's economic policies, including public investment programs and efforts to improve the business climate, aim to address unemployment. However, structural reforms are needed to create a more dynamic and inclusive labor market that can absorb the growing number of young entrants and provide decent work for all.

7.4. Tourism

Algeria possesses significant tourism potential, with diverse attractions ranging from historical sites and vibrant cities to stunning natural landscapes in the Sahara Desert and along the Mediterranean coast. However, the development of the tourism sector has historically been hampered by factors such as political instability (particularly the civil war in the 1990s), lack of adequate infrastructure, and complex visa procedures.

Since the early 2000s, especially after the reduction in internal conflict, the Algerian government has implemented strategies to promote tourism. This has involved investments in hotel construction, infrastructure development, and efforts to improve the country's international image.

- Main Tourist Attractions**:

- Historical and Archaeological Sites**: Algeria is rich in ancient ruins. Several UNESCO World Heritage Sites are major draws:

- Al Qal'a of Beni Hammad: The first capital of the Hammadid emirs.

- Tipasa: A Phoenician and later Roman port city.

- Djémila and Timgad: Well-preserved Roman colonial towns.

- M'Zab Valley: A traditional limestone valley oasis with unique urban architecture of the Mozabite Berbers.

- Casbah of Algiers: The historic citadel and old city of Algiers.

- Saharan Tourism**: The Algerian Sahara offers dramatic landscapes, including vast sand dunes (ergs), rock formations, and ancient rock art. The Tassili n'Ajjer National Park (also a UNESCO World Heritage site) is renowned for its prehistoric cave paintings and stunning natural scenery. Towns like Djanet, Tamanrasset, and Ghardaïa (gateway to the M'Zab Valley) are key Saharan destinations.

- Coastal and Mountain Tourism**: The Mediterranean coast offers beaches and coves, while the northern Atlas Mountains provide opportunities for hiking and exploring traditional Berber villages.

- Cultural Tourism**: Cities like Algiers, Oran, and Constantine offer a blend of Ottoman, French colonial, and modern Algerian architecture, vibrant markets (souks), and museums.

- Challenges and Prospects**:

Despite its potential, the tourism industry's contribution to the Algerian economy remains relatively modest compared to other North African countries. Challenges include:

- Security Perceptions**: Lingering concerns about security, particularly in remote Saharan regions, can deter some international tourists.

- Infrastructure**: While improving, there is still a need for more high-quality accommodation, transportation links, and tourist services.

- Visa Policies**: Visa requirements can be cumbersome for visitors from some countries.

- Marketing and Promotion**: Algeria has been less prominent in international tourism marketing compared to its neighbors.

The government continues to view tourism as a potential sector for economic diversification and job creation. Future prospects depend on continued stability, investment in infrastructure and services, streamlined visa processes, and effective international promotion. From a social liberal perspective, sustainable tourism development that benefits local communities, respects cultural heritage, and minimizes environmental impact would be ideal.

- Historical and Archaeological Sites**: Algeria is rich in ancient ruins. Several UNESCO World Heritage Sites are major draws:

8. Transport

Algeria has developed a relatively extensive transportation infrastructure, particularly in the more densely populated northern regions. The government has invested significantly in modernizing and expanding its road, rail, air, and maritime transport networks.

- Road Network**: Algeria has one of the densest road networks in Africa, estimated at around 112 K mile (180.00 K km) of highways and roads, with a high paving rate (around 85%). A major project is the East-West Highway, a 0.8 K mile (1.22 K km) motorway linking Annaba in the east to Tlemcen in the west, near the Moroccan border. This highway is a crucial artery for domestic transport and trade.

Two trans-African automobile routes pass through Algeria:

- Cairo-Dakar Highway (Trans-African Highway 1)

- Trans-Sahara Highway (Algiers-Lagos Highway, TAH 2), which is now largely paved, connecting Algeria with Niger and Mali to the south, facilitating trade with sub-Saharan Africa.

Development plans continue to focus on expanding and upgrading all modes of transport to support economic growth, improve internal connectivity (especially between the north and the vast southern regions), and enhance Algeria's role as a regional trade hub.

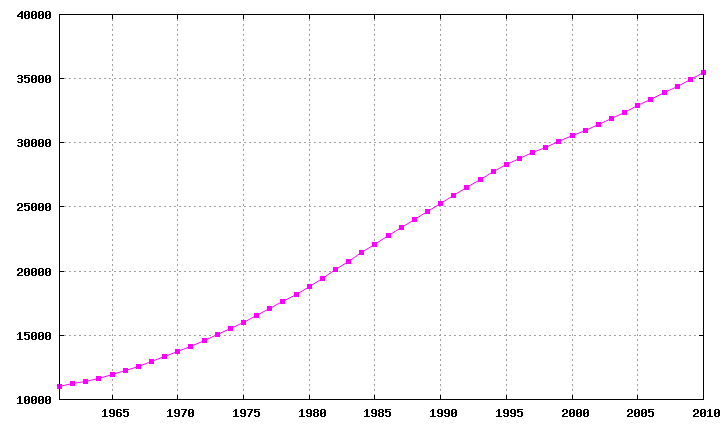

9. Demographics

Algeria has a substantial and youthful population, largely concentrated in its northern coastal regions. The country has experienced significant demographic shifts since its independence, including rapid population growth and urbanization.

As of 2023-2024 estimates, Algeria's population is around 45 to 46 million people, making it the tenth-most populous country in Africa and the 32nd to 33rd most populous in the world. The population growth rate has slowed from its very high levels in the post-independence decades but remains significant. Life expectancy has improved considerably due to better healthcare and living standards.

Approximately 90% of Algerians live in the northern coastal area, which accounts for only about 12% of the country's total land area. The inhabitants of the Sahara Desert are mainly concentrated in oases, although some 1.5 million people remain nomadic or partly nomadic. The urbanization rate is high, with around 75% of the population living in urban areas.

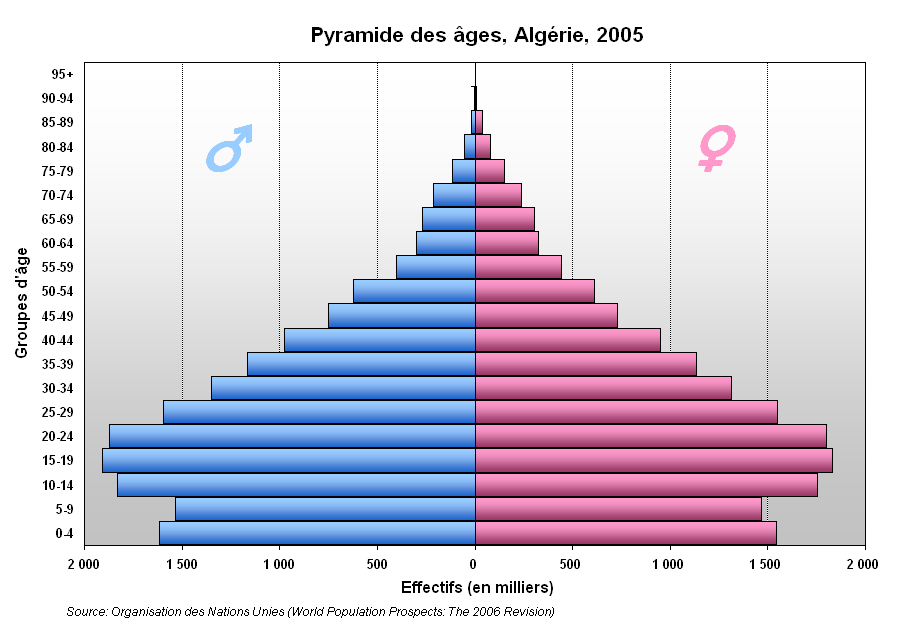

The age structure is relatively young, with about 28.1% of Algerians under the age of 15 (though this percentage is decreasing). This youth bulge presents both opportunities and challenges for education, employment, and social services.

Algeria hosts a significant number of refugees, primarily Sahrawis from Western Sahara, who live in refugee camps near Tindouf in southwestern Algeria. Estimates of their numbers range from 90,000 to 165,000. There are also smaller numbers of Palestinian refugees and, more recently, migrants and asylum seekers from sub-Saharan African countries. A notable Algerian diaspora exists, with the largest community residing in France (reportedly over 1.7 million people of Algerian origin up to the second generation). There were also around 35,000 Chinese migrant workers in Algeria as of 2009.

The five largest cities, according to the 2008 census, are:

# Algiers (Algiers Province): 2,364,230 inhabitants (urban area significantly larger)

# Oran (Oran Province): 803,329 inhabitants

# Constantine (Constantine Province): 448,028 inhabitants

# Annaba (Annaba Province): 342,703 inhabitants

# Blida (Blida Province): 331,779 inhabitants

Other major cities include Batna, Djelfa, Sétif, Sidi Bel Abbès, and Biskra.

9.1. Ethnic Groups

The population of Algeria is predominantly of Arab-Berber origin. Centuries of interaction, intermarriage, and cultural assimilation have resulted in a largely homogenous population where clear ethnic distinctions are often blurred. Historically, various peoples including Phoenicians, Romans, Vandals, Byzantines, Arabs, Turks, and French have contributed to the genetic and cultural makeup of Algeria. Descendants of Andalusi refugees (Muslims and Jews expelled from Spain) are also present, particularly in coastal cities.

- Arabs**: The majority of Algerians identify as Arab or Arabized Berber. The arrival of Arab tribes from the 7th century onwards led to the gradual Arabization and Islamization of the indigenous Berber population. Arab identity in Algeria is often closely linked with the Arabic language and Islamic culture. Estimates suggest that those identifying primarily as Arab constitute between 75% and 85% of the population.

- Berbers (Imazighen)**: Berbers are the indigenous peoples of North Africa. While many Berbers have been Arabized over centuries, a significant portion, estimated between 15% and 25% of the population, maintain a distinct Berber identity and speak Berber languages. The main Berber groups in Algeria include:

- The Kabyles: Residing primarily in the mountainous Kabylie region east of Algiers. They are the largest Berber-speaking group.

- The Chaouis: Inhabiting the Aurès Mountains in northeastern Algeria.

- The Mozabites: Living in the M'Zab Valley in the northern Sahara, known for their distinct Ibadi Islamic faith and traditional architecture.

- The Tuaregs: A nomadic or semi-nomadic Berber people inhabiting the vast Saharan regions of southern Algeria.

- The Chenouas: A smaller group living in the coastal mountainous region west of Algiers.

The Algerian constitution recognizes Tamazight (Berber language) as an official language alongside Arabic. The promotion of Berber culture and language has been a key demand of Berber identity movements, particularly since the "Berber Spring" of 1980. From a social liberal perspective, ensuring the cultural and linguistic rights of the Berber minority and fostering an inclusive national identity that respects Algeria's diverse heritage are important.

During the colonial period, a significant European population (Pied-Noirs), primarily of French, Spanish, and Italian origin, lived in Algeria, constituting about 10% of the population in 1960. Almost all of this group left Algeria during or immediately after the War of Independence.

9.2. Languages

Algeria has a complex linguistic landscape shaped by its history.

- Arabic**: Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) is an official language and the primary language of government, education, and media. Algerian Arabic (known as Darja) is the vernacular spoken by the majority of the population (around 83%) in daily life. Darja incorporates loanwords from Berber, French, and Spanish, and varies regionally.

- Berber (Tamazight)**: Berber, in its various regional dialects, is spoken by a significant minority (estimated around 27% of the population, though many are bilingual in Arabic). The main Berber languages/dialects include Kabyle, Chaouïa, Tumzabt (Mozabite), and Tamahaq (Tuareg). Following decades of activism by Berber cultural movements, Tamazight was recognized as a "national language" in 2002 and then upgraded to an "official language" in the 2016 constitutional revision. This has led to its increasing introduction in education and public life, particularly in Berber-speaking regions. The Kabyle dialect has a significant substratum from Arabic, French, Latin, Greek, Phoenician, and Punic, with Arabic loanwords representing about 35% of its vocabulary.

- French**: Although it has no official status, French is widely used and understood in Algeria, a legacy of over 130 years of French colonial rule. It functions as a lingua franca in many contexts, particularly in business, higher education (especially in science and technology fields), media, and among the elite. In 2008, an estimated 11.2 million Algerians could read and write in French. By some estimates in 2013, up to 60% of the population could speak or understand French, and in 2022, about 33% were considered Francophone. However, there have been government efforts to promote Arabic and, more recently, English in certain domains, sometimes at the expense of French.

- English**: The use of English has been increasing, particularly among younger generations and in scientific and international business contexts, driven by globalization. In 2022, it was announced that English would be introduced as a language of instruction in elementary schools, reflecting a policy shift to diversify foreign language education.

Language policy in Algeria has often been a sensitive issue, reflecting debates about national identity, decolonization, and cultural heritage. The promotion of Arabic and Tamazight while acknowledging the practical role of French and the growing importance of English represents an ongoing balancing act.

9.3. Religion

Islam is the predominant religion in Algeria and is designated as the state religion in the constitution.

- Islam**: Approximately 99% of the Algerian population are Muslims, according to CIA World Factbook estimates (2021), and 97.9% according to Pew Research (2020). The vast majority of Algerian Muslims are Sunnis following the Maliki school of Islamic jurisprudence. There is also a small but historically significant community of Ibadi Muslims, estimated at around 290,000, concentrated in the M'Zab Valley in the Ghardaïa region.

- Christianity**: The Christian population is small, with estimates ranging from 100,000 to 200,000 adherents. Prior to independence, Algeria was home to over 1.3 million Christians, mostly of European (Pied-Noir) ancestry, who largely left after 1962. Today, Algerian Christians are predominantly Protestants, including Evangelicals, Methodists, and Reformed Church members. There is also a small Roman Catholic community. Christian groups, particularly Protestants, have reported facing increasing pressure from the government in recent years, including difficulties with registration and forced closures of places of worship. Proselytizing by non-Muslims to Muslims is illegal and can lead to penalties.

- Judaism**: Historically, Algeria had a significant Jewish community. However, after independence, the vast majority of Algerian Jews, who had been granted French citizenship under the Crémieux Decree, emigrated, mostly to France and Israel. Today, the Jewish community is very small, estimated at fewer than 200 individuals.

- Other Religions and Irreligion**: A small number of Algerians may adhere to other faiths, or identify as non-religious. Surveys by Arab Barometer have indicated a growing percentage of Algerians, particularly among the youth, identifying as non-religious (around 15% in a 2018 report), though a later 2021 report showed a decrease in this figure (to 2.6%), with the majority identifying as religious or somewhat religious.

The Algerian government regulates religious practice. While the constitution guarantees freedom of belief, laws and policies can restrict religious freedom for non-Muslim minorities. Public expression of non-Islamic faiths can be limited.

Algeria has contributed notable Islamic thinkers to the Muslim world, including Emir Abdelkader, Abdelhamid Ben Badis, Mouloud Kacem Naît Belkacem, Malek Bennabi, and Mohamed Arkoun.

10. Society

Algerian society is a blend of Arab, Berber, Mediterranean, and Islamic influences, shaped by its long history and post-independence development. Key societal features include strong family ties, a youthful demographic, and ongoing social and economic transformations. This section examines societal aspects with an emphasis on social impact, the well-being of vulnerable groups, and challenges related to health and education systems.

10.1. Health

Algeria has made significant progress in improving health indicators since independence, though challenges remain in ensuring equitable access and quality of care for all citizens. The government officially provides universal healthcare, but the public system often faces issues of under-resourcing and regional disparities.

- Healthcare System**: The system comprises public hospitals and clinics, as well as a growing private sector. The government favors preventive healthcare and clinic-based services. Healthcare is generally free of charge for the poor in public facilities. In 2018, Algeria had a relatively high number of physicians (1.72 per 1,000 people), nurses (2.23 per 1,000), and dentists (0.31 per 1,000) compared to other Maghreb countries.

- Health Indicators**: Life expectancy has significantly increased, standing at around 77 years (estimates vary). Infant and maternal mortality rates have declined considerably. However, disparities exist between urban and rural areas, and among different socio-economic groups.

- Major Health Issues**: While communicable diseases like tuberculosis, hepatitis, measles, and typhoid fever persist, particularly in areas with poor sanitation, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and cancer are increasingly prevalent, reflecting lifestyle changes.

- Access to Services**: Access to improved water sources is high (around 97.4% in urban areas, 98.7% in rural areas in 2018). Access to improved sanitation was around 99% in urban areas and 93.4% in rural areas. Despite these figures, challenges in water quality and sanitation can contribute to health problems.

- Government Policies**: The government maintains an immunization program and has focused on expanding healthcare infrastructure. However, issues like drug shortages, quality of care in public facilities, and brain drain of medical professionals are concerns.

- Vulnerable Groups**: Access to quality healthcare can be more challenging for people in remote Saharan regions, the urban poor, and other vulnerable populations. Mental health services are also an area needing further development.

Health records have been maintained in Algeria since 1882, with inclusion of Muslims in southern regions from 1905.

10.2. Education

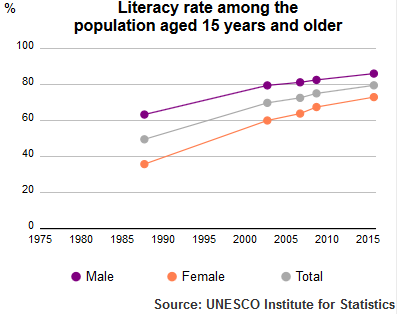

Education in Algeria is officially compulsory and free for children between the ages of six and 15 (recently extended to age 16 or starting from age 5, according to some sources). The government has made significant investments in education since independence, leading to a dramatic increase in literacy rates and school enrollment. The literacy rate was around 92.6% in 2021, a substantial improvement from less than 10% at independence.

- Structure**: The education system generally consists of:

- Primary Education (École fondamentale): 9 years (sometimes cited as starting from age 5 or 6).

- Secondary Education (Lycée): 3 years, leading to the baccalaureate examination, which is required for university entrance. Secondary education offers general and technical streams.

- Language of Instruction**: Arabic is the primary language of instruction, particularly in the early years, a result of the post-independence Arabization policy. French is typically introduced as a second language from the third year of primary school and is often used as the language of instruction for science and technical subjects at the secondary and higher education levels. English is also taught as a foreign language, and its importance is growing. Berber (Tamazight) has been gradually introduced into the education system, especially in Berber-speaking regions.

- Higher Education**: Algeria has numerous universities (around 26) and other higher education institutions (around 67), accommodating a large student population, including foreign students. The University of Algiers, founded in 1879, is the oldest. Many universities were established after independence. While some disciplines like law and economics are taught in Arabic, science, medicine, and technology often continue to use French. Notable institutions include the University of Sciences and Technology Houari Boumediene and universities in Oran, Constantine, Tlemcen, and Batna.

- Challenges**: Despite progress, the education system faces challenges:

- Quality and Relevance**: Concerns exist about the quality of education, overcrowded classrooms, and the relevance of curricula to labor market needs, contributing to youth unemployment.

- Regional Disparities**: Access to quality education can vary between urban and rural areas, and between northern and southern regions.

- Resources**: Ensuring adequate funding, qualified teachers, and modern educational materials remains an ongoing task.

- Language Policy**: Debates around language of instruction and the balance between Arabic, French, Tamazight, and English continue.

From a social liberal perspective, ensuring equitable access to high-quality education for all, promoting critical thinking, and adapting the education system to meet the needs of a modern economy and diverse society are crucial goals. The illiteracy rate for people over 10 was 22.3% in 2008 (15.6% for men, 29.0% for women), indicating that while progress has been made, disparities persist.

11. Culture

Algerian culture is a rich tapestry woven from Berber, Arab, Andalusian, Ottoman, and French influences, with Islam playing a central role in shaping societal values and traditions. The country boasts a vibrant heritage in arts, literature, music, cuisine, and sports.

11.1. Arts

Algerian art encompasses a diverse range of traditional and contemporary expressions.

- Traditional Arts**:

- Islamic Art**: Characterized by intricate geometric patterns, calligraphy, and arabesques, evident in mosque architecture, textiles, and ceramics.

- Berber Art**: Includes distinctive pottery, jewelry (especially silverwork from Kabylie and the Aurès), carpet weaving with symbolic motifs, and traditional tattoos. Each Berber region has its unique artistic styles.

- Crafts**: Algeria has a strong tradition of handicrafts, including leatherwork, metalwork (copper and brass), and woodworking.

- Painting**: In the 20th century, painters like Mohammed Racim and his brother Omar were pioneers in reviving traditional Algerian miniature painting. Baya gained international recognition for her vibrant, surreal works rooted in Algerian folklore. Post-independence, artists like M'hamed Issiakhem and Mohammed Khadda moved away from figurative painting, exploring abstract and modern styles that reflected Algeria's new realities and struggles.