1. Overview

Mali, officially the Republic of Mali, is a large landlocked country in West Africa, notable for its rich history, diverse cultures, and significant contemporary challenges including political instability and conflict. Geographically, it spans from the Sahara Desert in the north to the Sudanian savanna in the south, with the Niger and Senegal rivers being vital lifelines. Historically, the territory of modern Mali was the heart of several powerful West African empires-the Ghana, Mali, and Songhai Empires-which were centers of trans-Saharan trade, Islamic learning, and immense wealth. Timbuktu, a historic city in Mali, was a renowned center of scholarship and commerce.

Following French colonial rule as French Sudan, Mali gained independence in 1960, initially as part of a short-lived federation with Senegal. The early post-independence era saw socialist policies under Modibo Keïta, followed by a long period of military rule under Moussa Traoré. A transition to democracy occurred in the early 1990s, but the 21st century has been marked by significant political upheavals, including Tuareg rebellions, the rise of Islamist extremist groups in the north, and multiple military coups in the 2020s, leading to ongoing instability and a complex humanitarian situation.

The Malian economy is predominantly based on agriculture, particularly cotton and livestock, and mining, especially gold. However, it remains one of the poorest countries in the world, facing challenges such as poverty, food insecurity, and the impacts of climate change and conflict on its development. Malian society is ethnically diverse, with numerous groups including the Bambara, Fula, Soninke, and Tuareg, each contributing to a vibrant cultural mosaic. Islam is the predominant religion.

2. Etymology

The name Mali is derived from the Mali Empire. The word "mali" in the Bambara language means "hippopotamus" but it has also come to mean "the place where the king lives" or "strength". The 14th-century Maghrebi traveller Ibn Battuta reported that the capital of the Mali Empire was called Mali.

According to one Mandinka tradition, the legendary first emperor Sundiata Keita transformed himself into a hippopotamus upon his death in the Sankarani River. It is said that villages in the area of this river are referred to as "old Mali," and one village in this region, Malikoma, means "New Mali." This suggests that "Mali" could have originally been the name of a city.

Another theory posits that "Mali" is a Fulani pronunciation of the name of the Mande peoples. It is suggested that a sound shift occurred where the alveolar segment /nd/ in Mande shifted to /l/ in Fulani, and the terminal vowel denasalized and raised, leading "Manden" to become /mali/.

The country was formerly known as French Sudan during its colonial period. Upon achieving independence in 1960, initially as part of the Mali Federation with Senegal, it adopted the name Mali, drawing on the legacy of the historic empire to forge its new national identity.

3. History

Mali's history is characterized by the rise and fall of great empires, the impact of trans-Saharan trade, the period of French colonization, and a post-independence journey marked by political shifts, democratic experiments, and significant recent conflicts. The nation's development has been shaped by these profound transformations, influencing its socio-political landscape and its people's lives.

3.1. Pre-colonial Period

Rock art found in the Sahara suggests that northern Mali has been inhabited since 10,000 BC, when the region was more fertile and supported abundant wildlife. Archaeological evidence, including early ceramics discovered at Ounjougou in central Mali dating to around 9,400 BC, indicates an independent invention of pottery in the area. Agriculture began by 5000 BC, and iron use was established by around 500 BC.

During the first millennium BC, Mande peoples, related to the Soninke people, established early cities and towns along the middle Niger River. These included Dia, which emerged around 900 BC and peaked around 600 BC, and Djenné-Djenno, which flourished from approximately 300 BC to 900 AD. By the 6th century AD, the lucrative trans-Saharan trade in gold, salt, and slaves had commenced, fostering the rise of major West African empires.

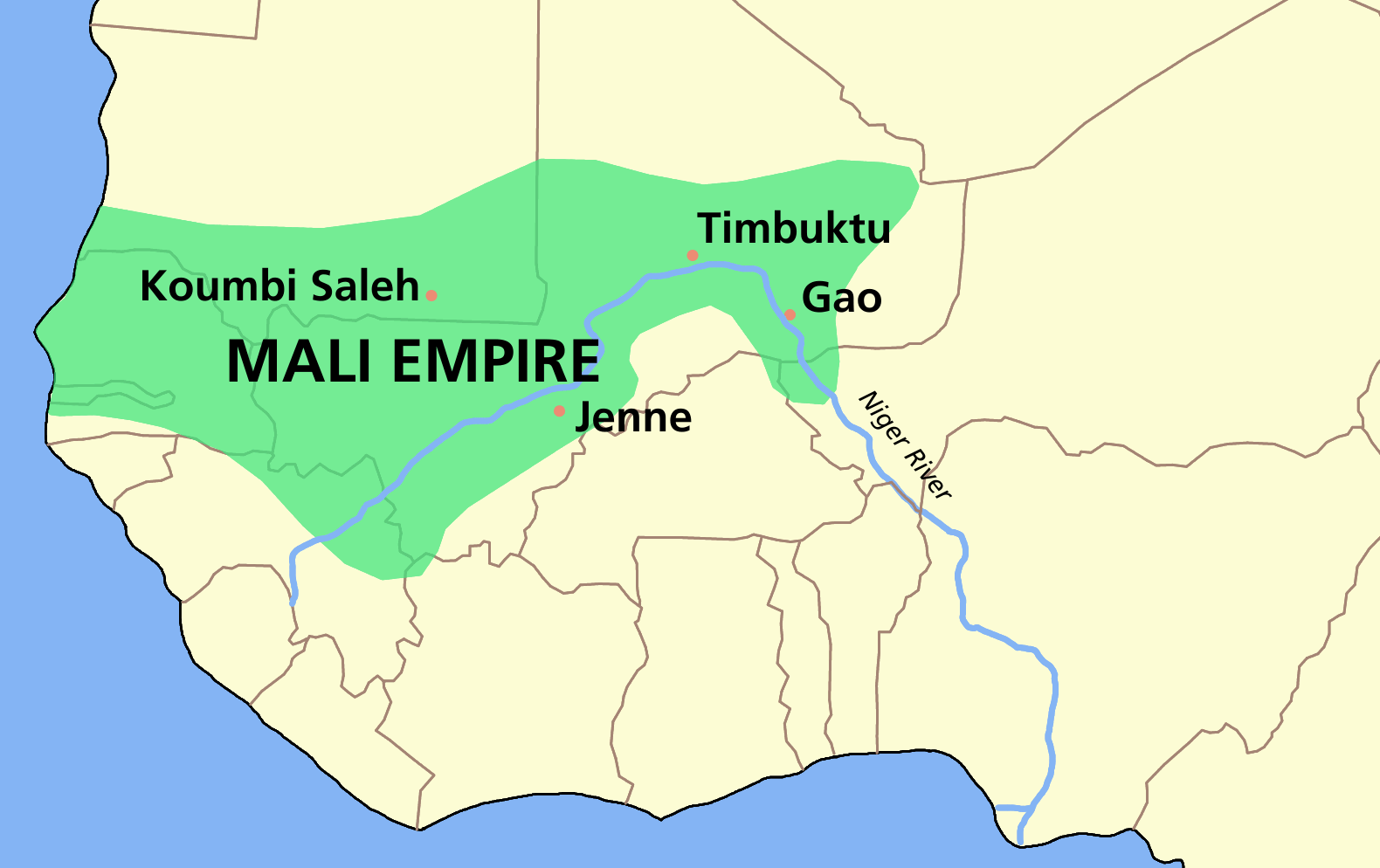

The first of these prominent empires was the Ghana Empire, dominated by the Soninke people. It expanded throughout West Africa from the 8th century until 1078, when it was weakened by the Almoravids. Following Ghana's decline, the Sosso Empire briefly rose to prominence.

In 1235, the Battle of Kirina saw the Mandinka, led by the exiled prince Sundiata Keita, defeat the Sosso Empire, leading to the establishment of the Mali Empire. The Mali Empire, centered on the upper Niger River, reached its zenith in the 14th century under emperors like Mansa Musa. During his reign (c. 1312 - c. 1337), the empire became renowned for its wealth, particularly in gold, and Mansa Musa's lavish pilgrimage to Mecca became legendary. Cities like Djenné and Timbuktu became significant centers of trade and Islamic learning, with the University of Timbuktu being one of the oldest in the world.

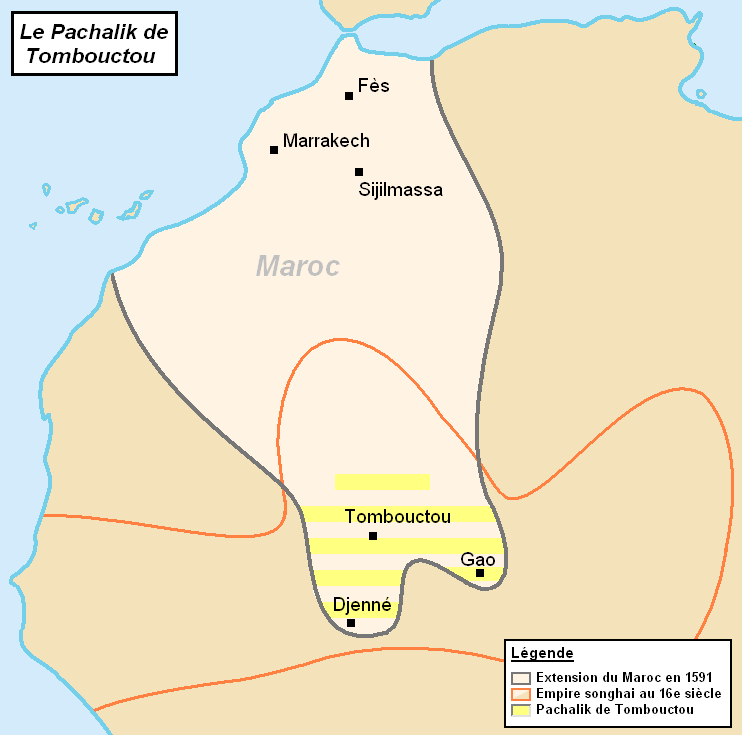

By the late 14th century, the Songhai Empire, initially a vassal state of Mali centered around Gao, began to assert its independence and expand. Under rulers like Sonni Ali and Askia Muhammad I, the Songhai Empire eventually supplanted Mali, controlling a vast territory along the Niger River. However, internal strife and a Moroccan invasion in 1591, led by Judar Pasha of the Saadian dynasty, resulted in the Battle of Tondibi and the subsequent collapse of the Songhai Empire. This event marked a decline in the region's role as a major trading crossroads, as European powers began establishing sea routes that bypassed the trans-Saharan network.

The period following the Songhai Empire's fall saw the fragmentation of power. The Saadian Moroccans struggled to maintain control over the vast territory, and their rule eventually weakened, leading to the emergence of smaller kingdoms and political entities. Among these were the Bamana Empire (or Ségou Empire), which rose in the 17th century and controlled a significant portion of the middle Niger. The 19th century was marked by Fulani jihads, which led to the establishment of Islamic states such as the Massina Empire in the Inner Niger Delta and the Toucouleur Empire led by El Hadj Umar Tall, which conquered both the Bamana and Massina states. In the upper Niger region, Samori Ture established the Wassoulou Empire. However, these states faced increasing pressure from European colonial expansion. A severe famine, one of

the worst in the region's recorded history, occurred in the 18th century, particularly between 1738-1756, due to drought and locusts, reportedly killing half the population of Timbuktu.

3.2. French Colonial Rule

In the late 19th century, during the Scramble for Africa, France began its conquest of the region. Starting from their base in Senegal, French forces moved eastward along the Senegal River. By 1880, they established the Upper Senegal colony, which was renamed French Sudan in 1890. The capital was initially at Kayes but was moved to Bamako in 1904. French control was consolidated by 1905, and the territory became part of the larger federation of French West Africa.

French colonial rule brought significant social, economic, and political changes. The French administration focused on resource extraction, particularly promoting cotton cultivation and developing irrigation schemes in the Inner Niger Delta for rice production through the Office du Niger. The Dakar-Niger Railway was constructed, linking the region to the port of Dakar in Senegal, facilitating trade and military control. However, colonial policies often led to forced labor, heavy taxation, and the disruption of traditional socio-economic structures. Resistance to French rule occurred, notably the Volta-Bani War (1915-1916), a major anti-French uprising in the regions of present-day Mali and Burkina Faso, which was suppressed by French colonial troops, resulting in the destruction of over 100 villages.

During the colonial period, traditional power structures were often undermined or co-opted by the French administration. Education was limited and primarily aimed at training a small elite to serve in the colonial bureaucracy. The imposition of French language and culture also had a lasting impact. The economic focus on export crops sometimes led to food insecurity in certain areas. Despite these changes, many traditional social and cultural practices persisted. The colonial experience profoundly shaped Mali's future trajectory, laying the groundwork for some of the challenges the nation would face post-independence.

3.3. Independence

The movement towards independence in Mali gained momentum after World War II, in line with broader decolonization efforts across Africa. On November 24, 1958, French Sudan, which then changed its name to the Sudanese Republic, became an autonomous republic within the French Community.

In January 1959, the Sudanese Republic and Senegal united to form the Mali Federation. This federation formally gained independence from France on June 20, 1960. However, political differences and internal tensions quickly led to the dissolution of the Mali Federation. Senegal withdrew from the federation in August 1960.

Following Senegal's withdrawal, the Sudanese Republic declared itself the independent Republic of Mali on September 22, 1960. This date is now celebrated as Mali's Independence Day.

3.4. Modibo Keïta Regime and Socialist Path

Modibo Keïta became the first president of the newly independent Republic of Mali. His government quickly established a one-party state under the Sudanese Union - African Democratic Rally (US-RDA) party and adopted an independent African and socialist orientation. This involved forging close ties with Eastern Bloc countries and pursuing policies aimed at reducing French influence and achieving economic self-sufficiency.

Keïta's regime implemented extensive nationalization of economic resources, including key industries and agricultural enterprises. The government launched ambitious development plans focused on industrialization and agricultural collectivization. In 1962, Mali withdrew from the CFA franc zone and created its own currency, the Malian franc, in an effort to assert monetary sovereignty.

While these policies were aimed at fostering national development and independence, they faced significant challenges. Economic difficulties arose due to a lack of capital, skilled labor, and managerial expertise. Nationalization efforts sometimes led to inefficiency, and the new currency struggled with convertibility and inflation. The regime's socialist policies also led to a degree of political centralization and suppression of dissent. Despite these challenges, Keïta was a prominent figure in the Pan-African movement and played a role in the formation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU).

By 1960, the population of Mali was approximately 4.1 million. The progressive economic decline and growing dissatisfaction with some of the regime's policies culminated in a bloodless military coup on November 19, 1968, led by Lieutenant Moussa Traoré. This event marked the end of Mali's first post-independence era and its initial socialist path. The day of the coup is now commemorated as Liberation Day.

3.5. Moussa Traoré Military Regime

Following the 1968 coup, Lieutenant (later General) Moussa Traoré became the head of state, initially leading the Military Committee for National Liberation (CMLN). His regime would rule Mali for over two decades. Traoré's government initially attempted to address the economic problems inherited from the Keïta era, but these efforts were severely hampered by political turmoil and a devastating Sahel drought that afflicted the region from 1968 to 1974. The drought led to widespread famine, killing thousands of people and severely impacting agriculture and livestock, the mainstays of the Malian economy.

The Traoré regime faced recurrent student unrest, particularly in the late 1970s, driven by economic grievances and demands for political reform. There were also several coup attempts against his rule. The government responded by repressing dissent, and political freedoms were curtailed. In 1974, a new constitution was adopted which nominally provided for a return to civilian rule, but in practice, Traoré maintained control. In 1979, the Democratic Union of the Malian People (UDPM) was established as the sole legal political party, and Traoré was elected president under this one-party system.

Economically, Mali continued to struggle. The country remained heavily reliant on foreign aid, and structural adjustment programs imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank in the 1980s brought increased hardship to the population, while elites close to the government were perceived to be accumulating wealth. Corruption became a significant issue.

Internationally, the Traoré regime faced border disputes with neighboring Burkina Faso over the Agacher Strip, a resource-rich area. These tensions led to brief military conflicts in 1974 and again in December 1985 (the Christmas War). The dispute was eventually settled by the International Court of Justice in 1986.

By the late 1980s, opposition to the long-standing military rule and one-party state grew, fueled by economic hardship and a desire for greater political freedom.

3.6. Democratic Transition

Growing opposition to the corrupt and dictatorial regime of General Moussa Traoré intensified during the 1980s. Strict economic programs imposed to satisfy demands of the International Monetary Fund brought increased hardship, while elites close to the government were perceived to live in growing wealth. In response to increasing demands for multi-party democracy, the Traoré regime allowed some limited political liberalization in the late 1980s but refused to usher in a full-fledged democratic system.

In 1990, cohesive opposition movements began to emerge, including student groups and pro-democracy associations. This period was also complicated by ethnic tensions in the north, particularly with the return of many Tuareg people who had migrated to Algeria and Libya during earlier droughts.

Peaceful student protests in January 1991 were met with brutal suppression, including mass arrests and torture of leaders and participants. Scattered acts of rioting and vandalism of public buildings followed, but most actions by dissidents remained nonviolent. From March 22 to March 26, 1991, mass pro-democracy rallies and a nationwide strike occurred in both urban and rural communities. These events became known as les événements ("the events") or the March Revolution. In Bamako, soldiers opened fire indiscriminately on nonviolent demonstrators, leading to riots. Despite an estimated loss of 300 lives, protesters continued to demand Traoré's resignation and democratic reforms. March 26, the day of a major clash and massacre, is now a national holiday in Mali.

The growing refusal of soldiers to fire on protesters turned into a full-scale tumult. On March 26, 1991, Lieutenant Colonel Amadou Toumani Touré announced on the radio that he had arrested President Moussa Traoré. This coup d'état marked the end of Traoré's 23-year rule.

Following the coup, Touré led a transitional government, the Transitional Committee for the Salvation of the People (CTSP). Opposition parties were legalized, and a national conference of civil and political groups was convened to draft a new democratic constitution. This constitution, which established a multi-party system and guaranteed fundamental freedoms, was approved by a national referendum in January 1992.

In 1992, Mali held its first democratic, multi-party presidential and legislative elections. Alpha Oumar Konaré, leader of the Alliance for Democracy in Mali (ADEMA-PASJ) party, won the presidential election. His presidency (1992-2002) marked a period of democratic consolidation. Konaré was re-elected in 1997 for a second term, the last allowed under the constitution. During this democratic period, Mali was regarded as one of the most politically and socially stable countries in Africa, and significant progress was made in areas such as freedom of the press and civil society development. In 2002, Amadou Toumani Touré, who had retired from the military and led the 1991 democratic uprising, was elected president as an independent candidate.

3.7. 21st Century: Conflict and Political Instability

The 21st century in Mali has been characterized by a resurgence of conflict, particularly in the northern regions, and significant political instability, including multiple coups d'état. These events have severely impacted the country's development, security, and humanitarian situation, undermining the democratic gains of the 1990s.

3.7.1. Northern Mali Conflict (2012-present)

In January 2012, a major Tuareg rebellion erupted in northern Mali, led by the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA). The rebellion was fueled by long-standing grievances over political marginalization and economic neglect, and was strengthened by an influx of arms and experienced fighters returning from the Libyan civil war. The Malian military, ill-equipped and demoralized, struggled to contain the insurgency.

The government's handling of the rebellion led to widespread discontent within the military, culminating in a military coup on March 22, 2012, which overthrew President Amadou Toumani Touré. Captain Amadou Sanogo emerged as the leader of the junta, known as the National Committee for the Restoration of Democracy and State (CNRDR). The coup created a power vacuum that was swiftly exploited by the rebels.

On April 6, 2012, the MNLA declared the independence of Azawad, a territory covering the northern three regions of Mali: Timbuktu, Gao, and Kidal. However, the MNLA's secular nationalist agenda was soon overshadowed by Islamist extremist groups, including Ansar Dine, Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), and the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO). These groups, initially allied with the MNLA, turned against them and imposed a strict interpretation of Sharia law in the areas under their control, leading to widespread human rights abuses, including public floggings, amputations, and the destruction of historic shrines and manuscripts in Timbuktu.

The deteriorating security situation and the threat of northern Mali becoming a safe haven for terrorists prompted international concern. In January 2013, as Islamist forces began advancing southwards towards the capital, Bamako, the interim Malian government requested French military assistance. France launched Operation Serval, a military intervention that quickly pushed back the Islamist militants and helped Malian forces recapture major northern towns, including Gao, Timbuktu, and Kidal, by February 2013.

Following the French intervention, the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) was deployed in July 2013 to support the political process, protect civilians, and help stabilize the country. Presidential elections were held in July and August 2013, resulting in the victory of Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta. A peace agreement, known as the Algiers Accords, was signed in 2015 between the Malian government and a coalition of Tuareg and Arab armed groups, but its implementation has been slow and fraught with challenges.

Despite these efforts, insecurity has persisted and even spread to central Mali. Jihadist groups have regrouped and continue to launch attacks against Malian and international forces, as well as civilians. The conflict has caused a severe humanitarian crisis, with hundreds of thousands of people displaced and widespread food insecurity. The ongoing instability has also exacerbated inter-communal tensions and undermined state authority in many parts of the country.

3.7.2. Conflict in Central Mali

Since around 2015, the central regions of Mali, particularly Mopti and parts of Ségou, have experienced a dramatic escalation of violence. This conflict is multifaceted, involving inter-communal tensions, the expansion of jihadist groups, and struggles over resources.

Historically, there have been conflicts between agriculturalist communities, such as the Dogon and Bambara, and semi-nomadic pastoralist Fula (or Fulani) people over access to land and water. These tensions have been exacerbated by climate change, demographic pressures, and the weakening of traditional conflict resolution mechanisms.

Jihadist groups, including those affiliated with Al-Qaeda (such as Jama'at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin, JNIM) and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (IS-GS), have exploited these local grievances to expand their influence. They have recruited from various communities, often by offering protection or preying on existing frustrations with the state.

The violence in central Mali has involved attacks on villages, killings of civilians, cattle rustling, and the displacement of populations. Both agriculturalist and pastoralist communities have formed "self-defense groups" or militias. Some Dogon militias, such as Dan Na Ambassagou, have been accused of large-scale massacres of Fula civilians, whom they often accuse of colluding with jihadists. Conversely, Fula communities have also been targeted by state security forces and militias, leading to a cycle of reprisal and escalating violence. While some Fula individuals have joined jihadist groups, human rights organizations have noted that the association of the entire Fula community with these groups is an oversimplification often instrumentalized for political ends.

The Malian government, along with international forces, has struggled to contain the violence in the central regions. The state's presence is often weak, and security forces have themselves been implicated in human rights abuses. The conflict has had a devastating humanitarian impact, closing schools, disrupting livelihoods, and exacerbating food insecurity. The ethnicization of the conflict poses a significant threat to social cohesion in Mali. Efforts to address the crisis require a comprehensive approach that includes security measures, dialogue, reconciliation, and addressing the root causes of the conflict, such as poverty, governance deficits, and competition for resources.

3.7.3. 2020s Coups and Military Junta

The early 2020s in Mali were marked by two military coups that further destabilized the country and led to the establishment of a military junta.

The first coup occurred on August 18, 2020, when elements of the Malian Armed Forces mutinied and arrested President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta and Prime Minister Boubou Cissé. This followed months of popular protests against Keïta's government, fueled by discontent over corruption, the handling of the ongoing insurgency, and disputed legislative elections. Keïta resigned shortly after his arrest. The coup leaders formed the National Committee for the Salvation of the People (CNSP), led by Colonel Assimi Goïta. ECOWAS condemned the coup and imposed sanctions, demanding a swift return to civilian rule.

In September 2020, a transitional government was established, with Bah Ndaw, a retired colonel and former defense minister, appointed as interim president, and Assimi Goïta as interim vice president. A civilian, Moctar Ouane, was named prime minister. The transitional charter stipulated an 18-month transition period leading to new elections.

However, tensions persisted between the military and civilian elements of the transitional government. On May 24, 2021, President Ndaw and Prime Minister Ouane were arrested by the military following a cabinet reshuffle in which two key military figures from the 2020 coup were removed from their posts. This event was effectively a second coup. Colonel Assimi Goïta subsequently declared himself interim president. This move was widely condemned internationally, leading to Mali's suspension from ECOWAS and the African Union.

The military junta, led by Goïta, has since consolidated its power. The promised transition to civilian rule has faced repeated delays. Initially, elections were planned for February 2022, but the junta proposed a much longer transition period, leading to further sanctions from ECOWAS. A revised timeline eventually scheduled presidential elections for February 2024, but these were also postponed indefinitely in September 2023, citing technical reasons.

The junta's rule has been characterized by a shift in Mali's international relations. Relations with France, the country's traditional key military partner, deteriorated significantly, leading to the withdrawal of French forces (Operation Barkhane and Task Force Takuba) by August 2022. Mali also ordered the departure of the UN peacekeeping mission, MINUSMA, which concluded its withdrawal in December 2023. Concurrently, Mali has strengthened its ties with Russia, reportedly engaging the services of the Wagner Group, a Russian private military company, to combat insurgents. This move has been criticized by Western countries and human rights organizations, who have accused Wagner operatives and Malian forces of committing human rights abuses, including the Moura massacre in March 2022 where hundreds of civilians were reportedly executed.

The junta has pushed for constitutional changes, with a new constitution approved in a referendum in June 2023. This new constitution grants more powers to the president and notably removed French as an official language, making it a working language instead, while elevating 13 national languages to official status.

The human rights situation and democratic governance have suffered under the junta. Freedom of expression and the media have been curtailed, and there are concerns about the rule of law and due process. The security situation remains precarious, with jihadist groups continuing their activities and, in some areas, expanding their control, particularly the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara in southeastern Mali. In September 2023, JNIM militants attacked a vessel on the Niger River, killing many civilians. In July 2024, rebels from the CSP-DPA and JNIM militants reportedly killed dozens of Russian mercenaries and Malian government forces during the Battle of Tinzaouaten (2024). In response to alleged Ukrainian involvement in providing intelligence for this attack, Mali severed diplomatic relations with Ukraine in August 2024. In September 2024, JNIM launched a series of attacks in Bamako, killing dozens. The junta also announced Mali's withdrawal from ECOWAS in January 2024, alongside Niger and Burkina Faso.

4. Geography

Mali is a landlocked country in West Africa, located southwest of Algeria. It lies between latitudes 10° and 25°N, and longitudes 13°W and 5°E. Mali is bordered by Algeria to the north-northeast, Niger to the east, Burkina Faso to the southeast, Ivory Coast to the south, Guinea to the southwest, and Senegal and Mauritania to the west and northwest, respectively.

With an area of 0.5 M mile2 (1.24 M km2), Mali is the world's 24th-largest country and the eighth-largest in Africa, comparable in size to South Africa or Angola. The country's northern borders extend deep into the Sahara Desert, while its southern part, where the majority of the population resides, features the Niger and Senegal rivers and is part of the Sudanian savanna zone.

4.1. Topography and Climate

Mali's topography is predominantly flat, rising to rolling northern plains largely covered by sand. The Adrar des Ifoghas massif, an upland plateau, is situated in the northeast. The highest point in Mali is Mount Hombori (Hombori Tondo) at 3.8 K ft (1.16 K m), located in the central part of the country near the border with Burkina Faso.

The country can be broadly divided into three main geographical zones:

1. The Sahara Desert in the north: This region constitutes about two-thirds of Mali's land area. It is characterized by vast expanses of sand dunes (ergs) and gravel plains (regs). It has a hot desert climate (Köppen BWh) with extremely hot summers, scarce rainfall (decreasing northwards), and significant diurnal temperature variations.

2. The Sahel in the central part: This is a semi-arid transitional zone between the Sahara and the Sudanian savanna. It features a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen BSh) with very high temperatures year-round, a long, intense dry season, and a brief, irregular rainy season. Vegetation consists mainly of grasses and thorny shrubs.

3. The Sudanian savanna in the south: This region receives more rainfall and supports denser vegetation, including woodlands and agricultural lands. It has a tropical wet and dry climate (Köppen Aw). The rainy season generally lasts from June to October, with the heaviest rainfall occurring in the southernmost areas.

The Niger River is the most important river in Mali, flowing through the country from southwest to east before turning southeast towards Niger. It creates the vast Inner Niger Delta, a large area of lakes, marshes, and channels that is crucial for agriculture, fishing, and biodiversity. The Senegal River also originates in southwestern Mali.

Mali lies in the torrid zone and is among the hottest countries in the world. The thermal equator, which marks the hottest spots year-round based on mean daily annual temperature, crosses the country. Droughts are a recurrent problem, particularly in the Sahelian and Saharan zones.

4.2. Natural Resources

Mali possesses considerable natural resources. The most significant and widely exploited include:

- Gold: Mali is one of Africa's largest gold producers. Gold mining is a major contributor to the country's economy and export earnings. Deposits are primarily found in the southern and western regions. Both industrial-scale mining by international companies and artisanal mining by local populations occur.

- Uranium: Significant uranium deposits exist, particularly in the Falea area in the Kayes Region and in the Kidal Region. Mali is estimated to have over 17.40 K t of uranium. Exploration and development have been undertaken, though large-scale exploitation faces challenges.

- Phosphates: Phosphate rock, used in fertilizers, is mined, notably in the Tilemsi Valley near Gao.

- Salt: Salt has historically been a crucial commodity in trans-Saharan trade. Traditional salt mining continues in areas like Taoudenni in the far north, where salt slabs are extracted from ancient lake beds.

- Limestone: Limestone deposits are exploited for cement production and construction.

- Kaolinite: Kaolin, a type of clay, is also found and utilized.

Other potential mineral resources include iron ore, bauxite, manganese, tin, and copper, though many of these are not yet commercially exploited on a large scale. The country also has potential for petroleum exploration, particularly in the northern basins.

Beyond minerals, the Niger and Senegal rivers are vital water resources for agriculture, hydroelectric power, and transportation. Arable land, though limited by arid conditions in much of the country, is a key resource for the predominantly agricultural population.

4.3. Environment and Biodiversity

Mali faces significant environmental challenges, largely driven by its arid and semi-arid climate, coupled with human activities. Key issues include:

- Desertification: This is a major problem, particularly in the Sahelian zone, where the Sahara Desert is advancing southwards. Overgrazing, deforestation for fuelwood, and unsustainable agricultural practices contribute to land degradation and loss of fertile soil.

- Deforestation: The demand for fuelwood, charcoal, and agricultural land has led to significant loss of forest and woodland cover, especially in the southern and central regions. This exacerbates soil erosion and loss of biodiversity.

- Soil erosion: Wind and water erosion are prevalent, reducing soil fertility and agricultural productivity.

- Water Scarcity and Pollution: Access to clean water supplies is a challenge for much of the population. Rivers and water sources can be affected by pollution from agriculture, mining, and urban areas. The Inner Niger Delta is a critical wetland ecosystem facing pressures from changing water flows and human activities.

- Climate Change: Mali is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, including rising temperatures, more erratic rainfall patterns, and increased frequency of droughts and floods. These changes threaten agriculture, water resources, and livelihoods.

Mali's biodiversity is adapted to its various climatic zones. Five terrestrial ecoregions are found within its borders: Sahelian Acacia savanna, West Sudanian savanna, Inner Niger Delta flooded savanna, South Saharan steppe and woodlands, and West Saharan montane xeric woodlands.

Wildlife includes various species of mammals, birds, reptiles, and fish, although populations of many larger animals have declined due to habitat loss and hunting. Notable wildlife areas include the Boucle du Baoulé National Park and several Ramsar sites (wetlands of international importance), such as the Inner Niger Delta. Birdlife is particularly rich in the delta, which serves as a crucial stopover for migratory birds.

Efforts towards biodiversity conservation and sustainable environmental management are underway, often supported by international partners. These include projects focused on reforestation, sustainable land management, protecting national parks and reserves, and promoting community-based natural resource management. However, these efforts are often hampered by limited resources, insecurity, and the scale of the environmental challenges. The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.16/10, ranking it 51st globally out of 172 countries.

5. Politics and Government

Mali is currently a unitary republic under a military junta, following coups in 2020 and 2021. The political system, nominally based on a semi-presidential republic framework, has been significantly impacted by these events, with democratic institutions suspended or operating under military oversight. The country's political dynamics are heavily influenced by ongoing security challenges, particularly the conflict in the northern and central regions, and the complex process of transitioning back to civilian rule.

5.1. Government Structure

Prior to the 2012 coup, Mali was a constitutional democracy governed by the Constitution of 12 January 1992 (amended in 1999), which provided for a separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. A new constitution was approved by referendum in June 2023 under the military junta, which strengthens presidential powers.

- Executive Branch:

- The President is the head of state. Under the 1992 constitution, the president was elected by universal suffrage for a five-year term, limited to two terms. Currently, Colonel Assimi Goïta holds the position of interim President following the 2021 coup. The 2023 constitution maintains a presidential system.

- The Prime Minister is the head of government, appointed by the President. The Prime Minister, in turn, appoints the Council of Ministers. The current interim Prime Minister is Abdoulaye Maïga.

- The Council of Ministers is responsible for implementing government policy.

- Legislative Branch:

- The unicameral National Assembly (Assemblée Nationale) was Mali's sole legislative body, with deputies elected for five-year terms. Its functions included debating and voting on legislation. Following the 2020 coup, the National Assembly was dissolved. A transitional legislative body, the National Transitional Council (CNT), was established to act as a parliament during the transition period.

- Judicial Branch:

- The constitution provides for an independent judiciary. The highest courts include the Supreme Court (with judicial and administrative powers) and a Constitutional Court (which reviews the constitutionality of laws and serves as an election arbiter). Various lower courts also exist. However, the judiciary has historically faced challenges regarding its independence and resources, and its functioning has been further complicated by the recent political instability. Village chiefs and elders often resolve local disputes in rural areas.

The current government structure is largely transitional and operates under the authority of the military junta, the National Committee for the Salvation of the People (CNSP), although the CNSP was officially declared disbanded in January 2021, military influence remains paramount.

5.2. Recent Political Developments

Mali's political landscape since the 2020s has been dominated by the military junta led by Colonel Assimi Goïta. Following the August 2020 coup that ousted President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, and a subsequent coup in May 2021 that consolidated Goïta's power as interim president, the country has been navigating a challenging transition period.

The junta initially committed to an 18-month transition back to civilian rule, but this timeline has faced significant delays. Elections originally scheduled for February 2022 were postponed, leading to sanctions from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). A new electoral law was adopted, and a revised timetable set presidential elections for February 2024. However, in September 2023, these elections were postponed indefinitely, with the junta citing technical reasons related to the adoption of a new constitution and a review of electoral lists. The new constitution, approved via a referendum in June 2023, significantly expands presidential powers and changed the status of the French language.

The junta's governance has been marked by a more assertive nationalist stance and a shift in foreign policy. Relations with traditional partners like France have deteriorated, leading to the withdrawal of French military forces. Conversely, Mali has strengthened ties with Russia, including the reported deployment of Wagner Group mercenaries to assist Malian forces in combating insurgents. This has drawn criticism from Western nations and human rights organizations.

Domestically, the junta has faced ongoing security challenges from jihadist insurgencies and inter-communal violence, particularly in the northern and central regions. There are concerns about the shrinking civic space, with restrictions on freedom of expression and the media. Many political actors and civil society groups have called for a clear and credible timeline for the restoration of constitutional order and democratic elections. The activities of major political parties have been constrained under the current political climate. The long-term stability and democratic future of Mali remain uncertain, contingent on the junta's willingness to cede power and the ability to address the deep-rooted security and governance issues.

5.3. Foreign Relations

Mali's foreign relations have undergone a significant transformation following the military coups of 2020 and 2021. Historically, Mali pursued a pragmatic, pro-Western foreign policy, maintaining close ties with France, its former colonial ruler, and other Western partners, particularly in security and development cooperation. However, the military junta has steered the country towards new alliances, leading to strained relations with traditional allies and regional bodies.

- France and European Partners**: Relations with France have deteriorated sharply. The junta accused France of interference and neo-colonialism, leading to the termination of defense accords and the withdrawal of French troops involved in counter-terrorism operations (Operation Barkhane and Task Force Takuba) by August 2022. Similar tensions have affected relations with other European countries.

- Russia**: Mali has significantly deepened its ties with Russia, particularly in the security sector. This includes the reported engagement of the Wagner Group, a Russian private military company, to support Malian armed forces against insurgents. This closer relationship has been a source of concern for Western countries. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov visited Bamako in February 2023, signaling strengthening ties.

- Neighboring States and ECOWAS**: The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) condemned the coups and imposed sanctions on Mali due to delays in the transition to civilian rule. Mali, along with military-led Burkina Faso and Niger, announced its withdrawal from ECOWAS in January 2024, further isolating it within the region. Relations with some neighboring countries remain complex due to shared security challenges and border issues.

- United Nations**: The UN peacekeeping mission, MINUSMA, which had been present in Mali since 2013, was asked to leave by the junta and completed its withdrawal in December 2023. This decision has raised concerns about civilian protection and monitoring of the human rights situation.

- African Union**: The African Union also suspended Mali following the coups, urging a swift return to constitutional order.

- Other International Relations**: Mali severed diplomatic relations with Ukraine in August 2024, accusing it of involvement in an attack on Malian forces and their Russian allies. The country continues to be a member of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and other international bodies.

Mali's foreign policy objectives under the junta emphasize sovereignty, national interests, and diversified partnerships. However, its diplomatic shifts have created new challenges related to international aid, regional security cooperation, and its overall standing in the international community. The country's ability to address its internal conflicts and development needs is increasingly intertwined with these evolving foreign relations.

5.4. Military

The Malian Armed Forces (Forces Armées Maliennes, FAMA) are responsible for the territorial defense of Mali and for participating in internal security operations. The military consists of the Army (Armée de Terre), the Air Force (Force Aérienne de la République du Mali), and the National Gendarmerie (Gendarmerie Nationale), which functions as a paramilitary police force with responsibilities in both rural security and military policing. The Republican Guard (Garde Républicaine) is another component, primarily responsible for state ceremonial duties and protecting government officials and institutions.

The President of Mali is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. The military is under the control of the Ministry of Defense and Veterans. In recent years, particularly since the 2020 and 2021 coups, military figures have held key government positions, including the presidency.

The Malian military has faced significant challenges, including under-equipment, inadequate training, and low morale, particularly highlighted during the 2012 Northern Mali conflict. Efforts have been made to reform and strengthen the armed forces, often with international assistance, though this assistance has been affected by recent political developments.

The primary roles of the Malian military include:

- Defending the country's sovereignty and territorial integrity.

- Combating armed insurgent groups, including jihadist organizations and separatist movements, particularly in the northern and central regions.

- Maintaining internal security and public order, often in conjunction with other security forces.

- Participating in regional and international peacekeeping operations (historically, though less so recently).

The size of the Malian Armed Forces is estimated to be around 15,000-20,000 active personnel, though precise figures can vary. The defense budget has seen increases in response to ongoing security threats, but resource constraints remain. Equipment is sourced from various countries, with recent acquisitions reportedly including materiel from Russia.

The military's involvement in politics has been a recurring feature of Malian history, with multiple coups d'état since independence. The current military junta's control over the state apparatus underscores the significant political influence of the armed forces. Their performance in addressing the complex security situation, particularly concerning civilian protection and human rights, remains a critical issue for the country's stability.

6. Administrative Divisions

Mali's administrative structure has undergone reforms aimed at decentralization and bringing governance closer to local populations. The country is divided into regions, which are further subdivided into cercles, communes, and villages or quarters.

6.1. Regions and Cercles

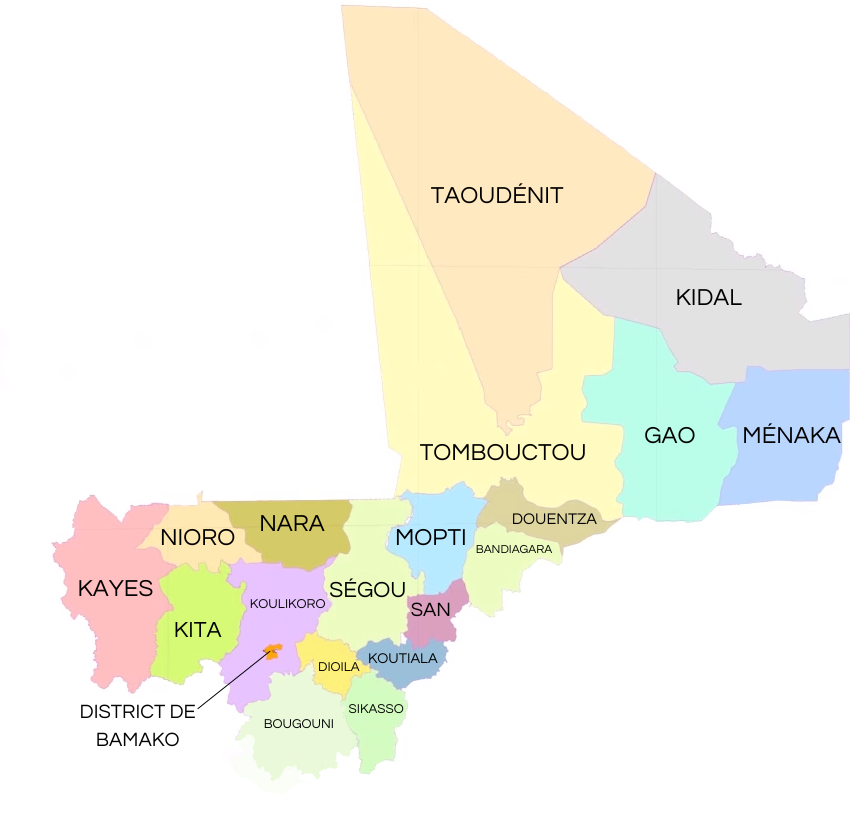

As of a major administrative reorganization finalized in 2023, Mali is divided into 19 regions (régions) and the Bamako Capital District. This is an increase from the previous structure of 8 regions and the capital district. The creation of new regions, such as Taoudénit and Ménaka (established in 2016 and fully operationalized later), and others formalized in the 2023 reforms, aimed to improve administrative efficiency and address regional specificities.

Each region is headed by a Governor, appointed by the central government.

The 19 regions and the Bamako Capital District are:

- Bamako Capital District

- Kayes

- Koulikoro

- Sikasso

- Ségou

- Mopti

- Tombouctou

- Gao

- Kidal

- Taoudénit

- Ménaka

- Bougouni

- Dioïla

- Nioro du Sahel

- Koutiala

- Kita

- Nara

- Bandiagara

- San

- Douentza

The regions are further subdivided into administrative units called cercles. There are 159 cercles in Mali. Each cercle is administered by a prefect (préfet). The cercles are themselves divided into communes, which are the basic local government units. There are 815 communes, which can be urban or rural. Communes are governed by elected mayors and municipal councils, although the functioning of these elected bodies has been affected by the ongoing political and security crises.

This multi-tiered administrative structure is intended to facilitate decentralization, a process that has been ongoing for several decades, though its effective implementation faces challenges related to resource allocation, capacity building, and the security situation in many parts of the country.

6.2. Major Cities

Mali's urban centers are crucial for its economy, administration, and cultural life. Most major cities are located in the southern part of thecountry or along the Niger River.

- Bamako: The capital and largest city of Mali, Bamako is situated on the Niger River in the southwestern part of the country. It is the administrative, economic, and cultural heart of Mali. With a rapidly growing population exceeding 4 million in the metropolitan area, Bamako faces challenges related to urbanization, infrastructure, and employment. It hosts key government institutions, international organizations, and major markets.

q=Bamako|position=right

- Sikasso: Located in the southern agricultural heartland, Sikasso is the second-largest city. It is a major center for trade in agricultural products like cotton, fruits, and vegetables. Its strategic location near the borders with Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast also makes it an important commercial hub.

- Ségou: Situated on the Niger River, northeast of Bamako, Ségou is a historic city, once the capital of the Bamana Empire. It is an important regional administrative and commercial center, known for its pottery, textiles, and the Ségou'Art festival. The Office du Niger irrigation scheme nearby supports extensive agriculture.

- Mopti: Often called the "Venice of Mali," Mopti is located at the confluence of the Niger and Bani rivers, at the edge of the Inner Niger Delta. It is a vital port and trading center, particularly for fish, livestock, and salt. Mopti is also a gateway to the Dogon Country and Timbuktu, though tourism has been severely affected by insecurity.

- Timbuktu (Tombouctou): A legendary historical city in northern Mali, near the Niger River, Timbuktu was a major center of trans-Saharan trade and Islamic scholarship during the Mali and Songhai Empires. It is home to famous mosques (Djingareyber, Sankoré, Sidi Yahya) and ancient manuscripts. While its economic importance has diminished, it retains immense cultural and historical significance. It has been heavily impacted by the Northern Mali conflict.

q=Timbuktu|position=left

- Gao: Located on the Niger River in eastern Mali, Gao was the capital of the Songhai Empire. It remains an important regional capital and trading post for the Sahel region. Like Timbuktu, Gao has been significantly affected by the ongoing conflict and the presence of armed groups.

- Koutiala: Another important city in the southern cotton-producing region, Koutiala is a significant industrial and agricultural center.

- Kayes: Situated in western Mali on the Senegal River, Kayes is a regional capital and was historically an important point on the Dakar-Niger Railway. It is known for its hot climate.

- Kati: A town near Bamako, Kati is a major military center and has been prominent in recent political events, including coups d'état.

These cities, while diverse, share common challenges related to rapid urbanization, infrastructure deficits, and, in some regions, the impacts of conflict and climate change. They also serve as critical nodes for governance, commerce, and social services for their respective regions.

7. Economy

Mali's economy is predominantly based on agriculture and natural resource extraction, but it faces significant challenges including poverty, climate vulnerability, and the impact of political instability and conflict. The country is classified as one of the least developed countries in the world, with a high dependence on foreign aid.

7.1. Economic Overview

Key economic indicators for Mali often reflect its developmental challenges:

- GDP and Per Capita Income: Mali has a low Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and GDP per capita. In 2023, the nominal GDP was estimated around 21.30 B USD, with a GDP per capita of approximately 912 USD. This places Mali among the poorest nations.

- Poverty: A significant portion of the population lives below the international poverty line. Poverty is more acute in rural areas and has been exacerbated by conflict and climate shocks, disproportionately affecting vulnerable groups such as women and children. The Gini index was 33.0 in 2010, indicating a degree of income inequality.

- Inflation and Unemployment: Inflation rates can be volatile, influenced by food prices and external factors. Unemployment and underemployment are high, particularly among youth.

- Human Development Index (HDI): Mali consistently ranks very low on the HDI, reflecting challenges in health, education, and living standards. In 2022, its HDI was 0.410, ranking 188th globally.

- Economic Growth: Economic growth has been impacted by political instability, security issues, climate variability (affecting agriculture), and fluctuations in global commodity prices (especially gold and cotton).

- Debt and Aid Dependence: Mali is heavily reliant on foreign aid and has benefited from debt relief initiatives in the past. However, recent political developments have affected aid flows from some traditional partners.

The Malian economy underwent reforms starting in the late 1980s, with programs supported by the World Bank and IMF aimed at liberalizing the economy and privatizing state-owned enterprises. However, progress has been uneven, and structural challenges persist. The country is a member of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA), which uses the West African CFA franc as a common currency, pegged to the Euro. This provides monetary stability but limits independent monetary policy. It is also a member of the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA).

The impact of political instability and conflict on economic development has been severe, disrupting trade, agriculture, and investment, and leading to increased humanitarian needs. Ensuring that economic development benefits all segments of society and addresses social inequities remains a critical challenge.

7.2. Key Sectors

Mali's economy is primarily driven by agriculture and mining, with services also playing a growing role.

7.2.1. Agriculture and Livestock

Agriculture is the backbone of the Malian economy, employing the majority of the workforce (around 80%) and contributing significantly to GDP.

- Major Crops:

- Cotton: Mali is one of Africa's largest cotton producers, and it is a key export commodity, providing income for millions of farmers. The sector is largely managed by the state-owned Compagnie malienne pour le développement du textile (CMDT).

- Cereals: Millet, sorghum, rice, and maize are the main staple food crops. Rice cultivation is concentrated in irrigated areas, particularly the Inner Niger Delta managed by the Office du Niger.

- Other crops include peanuts, fruits (mangoes are a notable export), and vegetables.

- Livestock: Livestock rearing (cattle, sheep, goats, camels) is a vital activity, especially in the Sahelian and northern regions. It contributes significantly to livelihoods, food supply, and export earnings (live animals, hides, and skins).

- Challenges:

- Food Security: Despite agricultural potential, Mali faces recurrent food insecurity due to climate variability (droughts, floods), land degradation, limited access to inputs (fertilizers, improved seeds), and underdeveloped infrastructure. Conflict has further disrupted agricultural production and access to food in affected areas.

- Impact of Climate Change: Agriculture is highly vulnerable to climate change, with rising temperatures and erratic rainfall patterns threatening yields and pastoralist livelihoods.

- Labor Conditions: Smallholder farmers often face precarious conditions, low prices for their products, and limited access to credit and markets. Issues of child labor in agriculture also exist.

- Land Tenure: Secure land rights are a concern, particularly for women and pastoralist communities, and can be a source of conflict.

Policies aimed at improving agricultural productivity, resilience to climate change, and market access are crucial for poverty reduction and economic development, with a focus on ensuring benefits reach small-scale producers and vulnerable households.

7.2.2. Mining

[[File:Kalabougou potters (6392346).jpg|thumb|upright|Kalabougou potters, an example of artisanal industry often linked to local resources. While not large-scale mining, it shows resource utilization.]

Mining, particularly gold, is a cornerstone of the Malian economy and a major source of export revenue.

- Gold: Mali is one of the largest gold producers in Africa. Large-scale industrial gold mines are operated by international companies, primarily in the western and southern regions. Gold has been the leading export product since 1999. Artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) is also widespread, providing livelihoods for many but often associated with significant social and environmental problems, including hazardous working conditions, child labor, and mercury pollution.

- Uranium: Mali has known uranium deposits, particularly in the Falea area and the Kidal region. While there has been exploration, large-scale commercial exploitation has not yet fully materialized due to various factors, including security and investment climate.

- Other Minerals: Mali also has deposits of phosphates (used in fertilizers, mined in the Tilemsi Valley), limestone (for cement), salt (traditionally extracted in the Sahara), kaolin, iron ore, bauxite, and manganese, though most are exploited on a smaller scale compared to gold.

- Economic Contribution: The mining sector contributes significantly to government revenue through taxes and royalties, and to foreign exchange earnings.

- Social and Environmental Impacts:

- Large-scale mining can lead to displacement of communities, loss of agricultural land, and environmental degradation if not properly managed.

- Concerns exist regarding the distribution of mining revenues and ensuring that benefits reach local communities and contribute to sustainable development.

- The ASGM sector, while economically important for many, often operates outside formal regulation, leading to severe health and safety risks for miners and environmental damage. Conflicts can also arise over control of artisanal mining sites.

- The security situation in some mining areas, particularly in the north and central regions, poses challenges for the sector.

Ensuring transparency in the mining sector, equitable benefit-sharing, and strong environmental and social safeguards are critical for maximizing the positive development impact of Mali's mineral wealth while mitigating negative consequences.

7.2.3. Fishing

Fishing is a vital economic activity in Mali, particularly in the Inner Niger Delta formed by the Niger River and its tributaries, as well as along the Senegal River. It provides a crucial source of protein, income, and livelihoods for a significant portion of the population.

- Key Areas: The Inner Niger Delta is one of the most productive inland fisheries in Africa. Other important fishing grounds include the Senegal River basin and various lakes and seasonal water bodies.

- Species: A variety of freshwater fish species are caught, including Nile perch, tilapia, and catfish.

- Methods: Traditional fishing methods are widely used, including nets, lines, and traps. Collective fishing practices are common in many communities, often regulated by traditional rules.

- Economic and Social Importance:

- Fish is a staple food for many Malians and contributes significantly to food security and nutrition.

- The sector supports a large number of fishers, fish processors (often women involved in smoking, drying, and selling fish), boat builders, and traders.

- Dried and smoked fish are important commodities traded both domestically and regionally.

- Challenges:

- Overfishing: In some areas, fish stocks are under pressure due to overfishing and the use of unsustainable fishing practices.

- Environmental Degradation: Changes in water flow due to dams (both within Mali and upstream in neighboring countries), climate variability (droughts), pollution, and habitat degradation (e.g., loss of floodplain vegetation) can negatively impact fish populations and the livelihoods of fishing communities.

- Infrastructure and Market Access: Limited infrastructure for fish preservation, processing, and transportation can lead to post-harvest losses and hinder access to wider markets.

- Conflict: Insecurity in some regions can disrupt fishing activities and access to fishing grounds.

- Governance: Effective management of fisheries resources, including regulation, monitoring, and enforcement, is essential but can be challenging.

Efforts to promote sustainable fishing practices, manage fisheries resources effectively, support fishing communities, and address the impacts of environmental change are important for the long-term viability of this crucial sector. The traditional ecological knowledge of fishing communities, like the Bozo people, plays a significant role in resource management.

7.3. Energy

Mali's energy sector is characterized by low overall energy consumption, limited access to electricity, particularly in rural areas, and a heavy reliance on traditional biomass (firewood and charcoal) for household energy needs.

- Electricity Supply:

- The national electricity utility is Énergie du Mali (EDM-SA).

- Electricity generation is primarily from two sources:

- Hydroelectric Power: Mali has significant hydroelectric potential, mainly from the Niger and Senegal Rivers. Major hydroelectric dams include Manantali (shared with Senegal and Mauritania on the Senegal River) and Sélingué Dam on the Sankarani River (a tributary of the Niger). Hydropower constitutes a significant portion of Mali's electricity generation, but its output can be affected by seasonal water availability and droughts.

- Thermal Power: Diesel-fired thermal power plants supplement hydropower, especially during periods of low water or to meet peak demand. These are often more expensive to operate due to reliance on imported fuel.

- Access to Electricity: Access to electricity is limited, with significant disparities between urban and rural areas. While cities like Bamako have relatively higher connection rates, a large majority of the rural population lacks access. In 2002, it was estimated that 700 GWh of hydroelectric power were produced. Only 55% of the population in cities had access to EDM.

- Traditional Biomass: Firewood and charcoal are the primary sources of energy for cooking and heating for most households, especially in rural areas. This reliance contributes to deforestation and indoor air pollution, which has health implications.

- Renewable Energy Potential: Mali has considerable potential for other renewable energy sources, particularly solar energy, given its high levels of solar irradiation. There is growing interest in developing solar power projects, both large-scale and decentralized (e.g., solar home systems, mini-grids) to improve energy access. Wind energy potential also exists in some regions.

- Challenges and Development:

- Expanding electricity access to underserved populations.

- Improving the reliability and efficiency of the power grid.

- Diversifying the energy mix to reduce reliance on hydropower (vulnerable to climate change) and expensive thermal generation.

- Attracting investment for energy infrastructure development.

- Promoting sustainable use of biomass and transitioning to cleaner cooking fuels.

- Addressing the financial viability of the energy sector.

The development of the energy sector is critical for Mali's economic growth, poverty reduction, and improvement of living standards. Expanding access to modern, reliable, and affordable energy services, particularly through renewable sources, is a key policy objective.

7.4. Transport and Infrastructure

Mali's transport network and infrastructure face significant challenges due to the country's vast size, landlocked status, and limited financial resources. These challenges impact trade, economic development, and access to services.

- Roads:

- The road network is the primary mode of transport for goods and passengers.

- Paved roads connect major cities and provide links to neighboring countries, but a large portion of the network consists of unpaved rural roads, many ofwhich are in poor condition and may become impassable during the rainy season.

- Key international road corridors link Mali to ports in neighboring coastal countries (e.g., Senegal, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo).

- Maintenance and expansion of the road network are ongoing priorities but are constrained by funding and security issues in some regions.

- Dakar-Niger Railway:

- This historic railway line connects Bamako (and Koulikoro, a river port near Bamako) to the port of Dakar in Senegal.

- It has historically been a crucial route for Mali's external trade. However, the railway has suffered from underinvestment, operational difficulties, and periodic disruptions. Efforts have been made to revitalize the railway, but challenges remain.

- Airports:

- Bamako-Sénou International Airport is the main international gateway.

- There are several other airports and airstrips in regional capitals and other towns, some with paved runways, facilitating domestic and limited regional air travel. Mali has approximately 29 airports, of which 8 have paved runways.

- Niger River Navigation:

- The Niger River is an important inland waterway, particularly between Koulikoro (near Bamako) and Gao. It is used for transporting goods (such as agricultural products, livestock, and fuel) and passengers, especially in areas where road infrastructure is limited.

- Navigation is seasonal, dependent on water levels, which can be low during the dry season.

- River ports like Mopti, Timbuktu, and Gao are important hubs.

- Telecommunications:

- Mobile phone penetration has grown significantly, providing voice and increasingly data services across much of the country.

- Fixed-line telephone infrastructure is less developed.

- Internet access is expanding, primarily through mobile networks, but affordability and quality of service can be issues, especially in rural areas. Mali had 869,600 mobile phones, 45,000 televisions, and 414,985 Internet users as of earlier estimates.

- Other Infrastructure:

- Access to basic infrastructure like sanitation and clean water remains a challenge, particularly in rural areas.

- Urban infrastructure in cities like Bamako is often strained by rapid population growth.

The development of transport and other essential infrastructure is critical for Mali's economic integration, reducing transport costs, improving access to markets and social services, and fostering overall development. Security challenges in certain regions can also hinder infrastructure development and maintenance.

8. Demographics and Society

Mali's population is characterized by its youthfulness, ethnic diversity, and predominantly rural nature, though urbanization is increasing. The society is shaped by a rich tapestry of languages, cultures, and religious traditions, primarily Islam. Access to education and healthcare remains a significant challenge, impacting overall human development.

8.1. Population

[[File:19553f0a239_c1e0f3d8.png|width=3400px|height=2400px|thumb|Population trend of Mali (1961-2003)]]

Mali's demographic profile presents several key characteristics:

- Total Population**: As of 2024, the population of Mali is estimated to be around 23.29 million people. The country has experienced rapid population growth over the past decades.

- Growth Rate**: The population growth rate is high, estimated at around 2.7% to 3% annually. This is driven by a high total fertility rate.

- Age Distribution**: Mali has a very young population. In 2024, approximately 47.19% of the population was estimated to be under the age of 15. About 50% were between 15-64 years old, and only around 3% were 65 and older. The median age was around 16.4 years.

- Population Density**: Given its large land area, Mali's overall population density is relatively low, at about 11.7 people per square kilometer. However, population distribution is uneven, with the majority concentrated in the southern and central regions, particularly along the Niger River. The northern desert regions are sparsely populated.

- Urbanization Trends**: While predominantly rural (about 68% in 2002), Mali is experiencing increasing urbanization. The capital, Bamako, is the largest urban center and has grown rapidly, with a population exceeding 2 million (over 4 million in the metropolitan area according to recent estimates). Other major towns are also expanding. About 5-10% of Malians are nomadic.

- Fertility and Mortality Rates**: The birth rate is high (around 40 births per 1,000 in 2024), and the total fertility rate is also high (around 5.35 children per woman in 2024). The death rate was around 8.1 deaths per 1,000 in 2024. Infant mortality and child mortality rates, though declining, remain among the highest in the world. Life expectancy at birth was approximately 63.2 years in 2024.

- Migration**: Mali has a history of both internal and international migration. Internal migration often involves movement from rural areas to urban centers or seasonal migration for work. International migration includes movement to neighboring West African countries and to Europe, particularly France. Conflict and insecurity have also led to significant internal displacement and refugee flows.

These demographic trends pose challenges for development, including providing education, healthcare, and employment opportunities for a rapidly growing young population, and managing the pressures of urbanization.

8.2. Ethnic Groups

Mali is a multi-ethnic country with a rich diversity of cultures and traditions. While inter-ethnic relations have historically been largely peaceful, based on long coexistence and intermarriage, recent conflicts have sometimes exacerbated ethnic tensions, particularly in the north and central regions. The rights and representation of minority groups are important considerations for social cohesion.

[[File:194e5663a77_597f5ebb.tiff|width=4209px|height=2215px|thumb|left|A Bambara wedding in Mali, observed by a tourist.]]

[[File:194e56644ee_b30df972.jpg|width=3504px|height=2336px|thumb|right|Fulani children in Mali.]]

Major ethnic groups include:

- Bambara**: The largest ethnic group, making up approximately 33.3% of the population. They are primarily agriculturalists and are concentrated in the southern and central regions, including the capital, Bamako. The Bambara language is widely spoken.

- Fula** (also known as Fulani or Peul): Constituting about 13.3% of the population, the Fula are traditionally pastoralists, though many are also settled agriculturalists or engaged in urban professions. They are widely dispersed across the Sahel region, including central Mali where they have been significantly affected by recent conflicts.

- Soninke** (also Sarakole or Marka): Comprising around 9.6%, the Soninke are historically known as traders and were founders of the ancient Ghana Empire. They are mainly found in western Mali.

- Senufo** and **Bwa**: Together making up about 9.6%, these groups are primarily agriculturalists residing in southern Mali, particularly in the Sikasso region. They are known for their distinct artistic traditions.

- Malinke** (or Mandinka): Accounting for about 8.8%, the Malinke are closely related to the Bambara and were key figures in the Mali Empire. They are found mainly in western and southern Mali.

- Dogon**: Representing about 8.7% of the population, the Dogon are renowned for their unique cosmology, art, and cliff-dwelling villages in the Bandiagara Escarpment region (a UNESCO World Heritage site). They are primarily agriculturalists and have also been heavily impacted by the conflict in central Mali.

- Songhai**: Making up about 5.9%, the Songhai are historically associated with the Songhai Empire. They are concentrated along the Niger River in eastern Mali, particularly around Gao and Timbuktu.

- Tuareg**: Constituting about 3.5%, the Tuareg are a traditionally nomadic Berber-speaking people inhabiting the Saharan regions of northern Mali. They have a distinct culture and social structure. Tuareg grievances have fueled several rebellions, and they are a key group in the ongoing Northern Mali conflict. Within Tuareg society, there are distinctions between noble, vassal, and formerly enslaved (Bella/Ikelan) groups, which can impact social relations and rights.

[[File:194c77dfe3e_cf2d0b79.jpg|width=3982px|height=2668px|thumb|left|The Tuareg people are nomadic inhabitants of northern Mali.]]

- Bobo**: About 2.1% of the population, the Bobo are agriculturalists found in southeastern Mali and neighboring Burkina Faso, known for their mask traditions.

- Other groups**: This category (around 4.5%) includes smaller ethnic groups such as the Bozo (traditionally fishers on the Niger River), Kassonke, Samogo, and Maure (Moors, or Azawagh Arabs, primarily in the north).

Hereditary servitude, a form of slavery, has historically existed in Mali and persists in some communities, affecting an estimated 800,000 people descended from slaves. This is particularly notable among some Tuareg, Soninke, and Fulani communities, where individuals of slave descent (often referred to as Bella, Ikelan, or Rimaïbé) face discrimination and limited rights. The ongoing conflicts have sometimes led to the re-assertion of such relationships or increased vulnerability for these groups. Addressing these historical injustices and ensuring the rights of all ethnic groups, including minorities and those affected by descent-based discrimination, is crucial for national reconciliation and social justice.

8.3. Languages

{{bar box

|title=Spoken Languages in Mali (2009 Census)

|titlebar=#ddd

|left1=Spoken Languages

|right1=percent

|float=right

|bars=

{{bar percent|Bambara|darkgreen|51.82}}

{{bar percent|Fula|purple|8.29}}

{{bar percent|Dogon|red|6.48}}

{{bar percent|Maraka / Soninké|black|5.69}}

{{bar percent|Songhai / Zarma|orange|5.27}}

{{bar percent|Mandinka|green|5.12}}

{{bar percent|Minyanka|darkblue|3.77}}

{{bar percent|Tamasheq|pink|3.18}}

{{bar percent|Senufo|darkred|2.03}}

{{bar percent|Bobo|gray|1.89}}

{{bar percent|Bozo|red|1.58}}

{{bar percent|Kassonké|lime|1.07}}

{{bar percent|Maure|violet|1}}

{{bar percent|Samogo|purple|0.43}}

{{bar percent|Dafing|yellow|0.41}}

{{bar percent|Arabic|brown|0.33}}

{{bar percent|Hausa|black|0.03}}

{{bar percent|Other Malian|green|0.49}}

{{bar percent|Other African|orange|0.18}}

{{bar percent|Other foreign|red|0.18}}

{{bar percent|Not Stated|pink|0.75}}

}}

{{bar box

|title=Mother Tongues in Mali (2009 Census)

|titlebar=#ddd

|left1=Mother Tongues

|right1=percent

|float=right

|bars=

{{bar percent|Bambara|darkgreen|46.5}}

{{bar percent|Fula|purple|9.39}}

{{bar percent|Dogon|red|7.12}}

{{bar percent|Maraka / Soninké|black|6.33}}

{{bar percent|Mandinka|green|5.6}}

{{bar percent|Songhai / Zarma|orange|5.58}}

{{bar percent|Minianka|darkblue|4.29}}

{{bar percent|Tamasheq|pink|3.4}}

{{bar percent|Senufo|darkred|2.56}}

{{bar percent|Bobo|gray|2.15}}

{{bar percent|Bozo|red|1.85}}

{{bar percent|Kassonké|lime|1.17}}

{{bar percent|Maure|violet|1.1}}

{{bar percent|Samogo|yellow|0.5}}

{{bar percent|Dafing|purple|0.46}}

{{bar percent|Arabic|brown|0.34}}

{{bar percent|Hausa|black|0.04}}

{{bar percent|Other Malian|green|0.55}}

{{bar percent|Other African|orange|0.31}}

{{bar percent|Other Foreign|red|0.08}}

{{bar percent|Not Stated|pink|0.69}}

}}

Mali has a rich linguistic diversity, with numerous languages spoken across the country, reflecting its multi-ethnic composition.

Under the 2023 constitution, 13 national languages were designated as official languages. These are:

- Bambara

- Bobo

- Bozo

- Dogon (specifically Toro So Dogon)

- Fula (also Fulfulde or Pular)

- Hassaniya Arabic (Maure)

- Kassonke (Xaasongaxango)

- Maninka (Malinke)

- Minyanka (Mamara)

- Senufo (specifically Senara Senufo)

- Songhay (specifically Koyraboro Senni Songhay)

- Soninke (Sarakolé)

- Tamasheq (Tuareg language)

French, which was previously the sole official language, was relegated to the status of a working language by the 2023 constitution. It continues to be used in administration, formal education, and media, though efforts are being made to promote the use of national languages in these domains.

Bambara serves as the most widely spoken language and acts as a lingua franca across much of the country, particularly in the south and central regions, including the capital, Bamako. It is estimated that around 80% of the population can communicate in Bambara. Many other African languages are spoken by various ethnic groups. The promotion of national languages in education and public life is an ongoing objective.

According to the 2009 census data on spoken languages:

- Bambara was spoken by 51.82% of the population.

- Fula was spoken by 8.29%.

- Dogon by 6.48%.

- Soninké (Maraka) by 5.69%.

- Songhai/Zarma by 5.27%.

- Mandinka by 5.12%.

- Minyanka by 3.77%.

- Tamasheq by 3.18%.

Other languages like Senufo, Bobo, Bozo, Kassonké, and Maure (Hassaniya Arabic) are also spoken by significant portions of the population. Arabic is also used, particularly for religious purposes and among Arab communities.

8.4. Religion

[[File:194e5664e69_1af94289.jpg|width=1813px|height=2812px|thumb|upright|An entrance to the Djinguereber Mosque in Timbuktu, a historic center of Islamic learning.]]

{{bar box

|title=Religion in Mali

|titlebar=#ddd

|left1=Religion

|right1=Percent

|float=right

|bars=

{{bar percent|Islam|green|95}}

{{bar percent|Christianity|blue|~2-3}}

{{bar percent|Traditional African beliefs & Other|red|~2-3}}

}}

Islam is the predominant religion in Mali, with an estimated 90-95% of the population identifying as Muslim. The vast majority of Malian Muslims are Sunni, generally following the Maliki school of jurisprudence, often with Sufi influences. Islam was introduced to West Africa as early as the 9th century through trans-Saharan trade routes and has a long and influential history in the region, with cities like Timbuktu becoming major centers of Islamic learning. Historically, Islam in Mali has been characterized by its syncretic nature, often incorporating local customs and traditions, and has generally been tolerant and moderate.

A small percentage of the population, around 2-5%, adheres to Christianity. This includes Roman Catholics and various Protestant denominations. Christian communities are more prevalent in some southern urban areas.

Another small percentage, also around 2-5%, follows traditional African beliefs or animist practices. These belief systems vary among different ethnic groups and often involve reverence for ancestors, nature spirits, and a supreme being. The Dogon religion, with its complex cosmology, is a well-known example. It's common for elements of traditional beliefs to coexist or be integrated with Islamic or Christian practices for some individuals. Atheism and agnosticism are rare.