1. Overview

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a nation situated in Southeast Africa. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Africa to the southwest. The country's capital and largest city is Maputo, located in the southern region. Mozambique's geography is characterized by a long coastline, coastal plains, inland plateaus, and highlands, with major rivers like the Zambezi River traversing its territory. The population is predominantly composed of Bantu peoples, with Portuguese as the official language, alongside numerous indigenous Bantu languages.

The history of Mozambique spans from early Bantu migrations and the development of Swahili coastal trading towns to over four centuries of Portuguese colonial rule, which began in the late 15th century. The struggle for self-determination culminated in the Mozambican War of Independence (1964-1975), leading to independence in 1975 and the establishment of the People's Republic of Mozambique. This was soon followed by a devastating Mozambican Civil War (1977-1992). Since the end of the civil war, Mozambique has transitioned into a multi-party democratic system, though it continues to face challenges, including an ongoing insurgency in Cabo Delgado province.

Mozambique's government operates as a presidential republic with a multi-party system. The economy relies heavily on agriculture and increasingly on its rich natural resources, particularly natural gas and coal. However, despite significant economic growth in recent decades, Mozambique remains one of the world's poorest and least developed countries, grappling with issues of poverty, inequality, and social development. This article explores Mozambique's multifaceted aspects, examining its path towards social development, respect for human rights, and equitable progress while providing factual descriptions of its history, governance, economy, and diverse culture. Key challenges include improving education, healthcare, and access to clean water and sanitation for all its citizens. The nation's rich cultural heritage is expressed through various art forms, music, literature, and cuisine, reflecting both indigenous traditions and historical influences.

2. Etymology

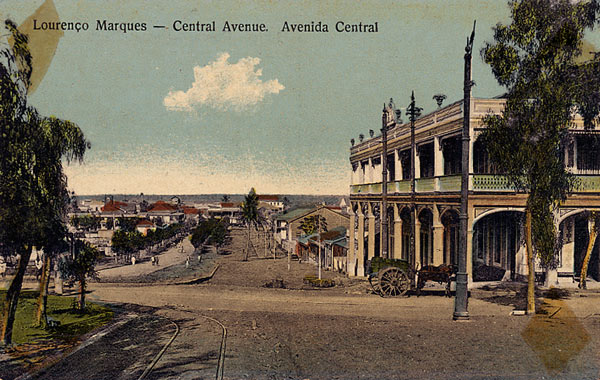

The country was named Moçambique by the Portuguese after the Island of Mozambique, a small coral island at the mouth of Mossuril Bay on the Nacala coast of northern Mozambique. The name of the island is derived from either Mussa Bin Bique (also spelled Musa Al Big, Mossa Al Bique, Mussa Ben Mbiki or Mussa Ibn Malik), an Arab trader who first visited the island and later lived there. He was reportedly still alive when the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama reached the island in 1498. The island-town of Mozambique served as the capital of the Portuguese colony until 1898, when the administration was moved south to Lourenço Marques (now Maputo).

3. History

Mozambique's history is marked by early migrations, the rise of coastal trading states, a long period of Portuguese colonization, a hard-fought war for independence, a devastating civil war, and subsequent efforts towards democratic governance and development.

3.1. Early History

Human habitation in the region of present-day Mozambique dates back approximately 3 million years, with evidence of early hominids. By the Christian era, the San people (also known as Bushmen) were inhabitants of the area. Starting as early as the 4th century BC, and continuing in waves between the 1st and 5th centuries AD, Bantu-speaking peoples migrated into Mozambique from the west and north. These groups moved through the Zambezi River valley and gradually settled into the plateau and coastal areas of Southern Africa. They established agricultural communities, with some societies also based on herding cattle. These Bantu-speaking migrants brought with them advanced technology for the time, including the skills for smelting and smithing iron.

Early records suggest that by the 1st century BC, Greek and Roman traders engaged in commerce with the coastal populations. Indonesian and Indian traders also frequented the Mozambican coast.

3.2. Swahili Coast

From the late first millennium AD, vast Indian Ocean trade networks extended as far south into Mozambique as evidenced by the ancient port town of Chibuene. Beginning in the 9th century, a growing involvement in this trade led to the development of numerous port towns along the entire East African coast, including in modern-day Mozambique. These towns, largely autonomous, broadly participated in the incipient Swahili culture and contributed to the development of a distinct Swahili dialect. Islam was often adopted by urban elites, which facilitated trade with Arab, Persian, and Indian traders. In Mozambique, key Swahili trading centers such as Sofala, Angoche, and Mozambique Island had become regional powers by the 15th century. These towns traded with merchants from both the African interior and the broader Indian Ocean world. Particularly important were the gold and ivory caravan routes. Inland states like the Kingdom of Zimbabwe and Kingdom of Mutapa provided coveted gold and ivory, which were then exchanged up the coast to larger port cities like Kilwa and Mombasa.

3.3. Portuguese Colonization (1498-1975)

The arrival of Europeans marked a significant turning point. In 1498, the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama, on his voyage around the Cape of Good Hope, reached the Mozambican coast. This initiated Portuguese entry into the region's trade, politics, and society. By the early 16th century, around 1505, the Portuguese began a gradual process of colonization and settlement. They gained control of the Island of Mozambique and the port city of Sofala, displacing the existing Arabic commercial and military hegemony. These locations became regular ports of call on the new European sea route to the East.

By the 1530s, small groups of Portuguese traders and prospectors seeking gold penetrated the interior regions. They established garrisons and trading posts at Sena and Tete on the Zambezi River, attempting to gain exclusive control over the gold trade.

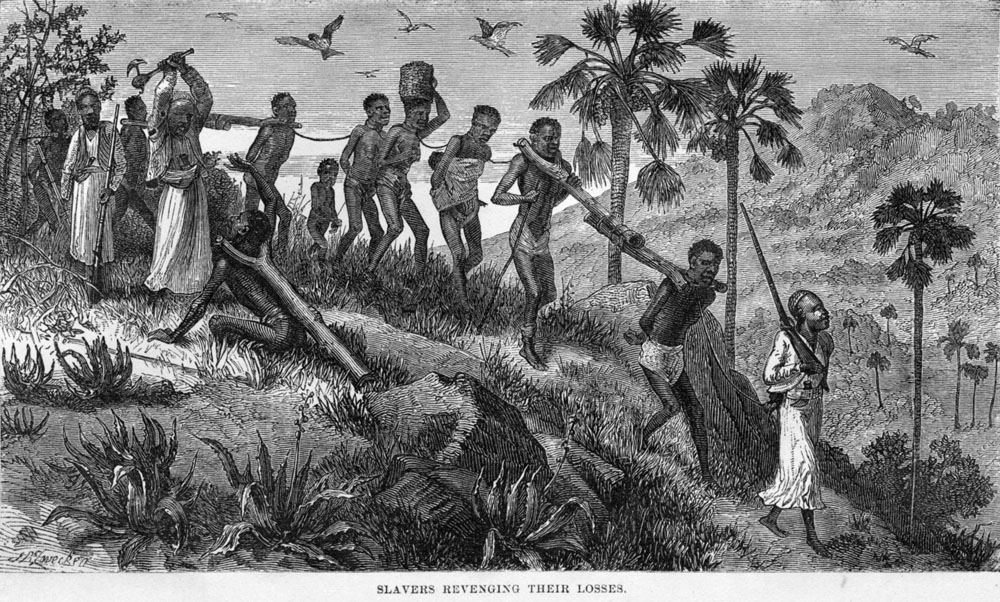

In the central part of the Mozambique territory, the Portuguese attempted to legitimize and consolidate their trade and settlement positions through the creation of prazos. These were land grants intended to tie emigrants to their settlements. Inland Mozambique was largely left to be administered by prazeiros, the grant holders, while central authorities in Portugal concentrated on what they considered more important possessions in Asia and the Americas. Slavery in Mozambique pre-dated European contact. African rulers and chiefs dealt in enslaved people, first with Arab Muslim traders, who sent them to Middle Eastern cities and plantations, and later with Portuguese and other European traders. Enslaved people were supplied by warring local African rulers who raided enemy tribes and sold their captives to the prazeiros. The authority of the prazeiros was maintained among the local population by armies of these enslaved men, known as the Chikunda. Mozambique also became a source of enslaved people transported to Brazil.

While prazos were originally intended for Portuguese colonists, through intermarriage and the relative isolation from ongoing Portuguese influences, they often became African-Portuguese or African-Indian entities. Continuing emigration from Portugal occurred at comparatively low levels until the late nineteenth century, promoting a degree of "Africanisation." Although Portuguese influence gradually expanded, its power was often limited and exercised through individual settlers and officials granted extensive autonomy. Between 1500 and 1700, the Portuguese managed to wrest much of the coastal trade from Arab Muslims. However, with the Arab Muslim seizure of Portugal's key foothold at Fort Jesus on Mombasa Island (now in Kenya) in 1698, the balance of power began to shift. Investment in Mozambique lagged as Lisbon focused on more lucrative trade with India and the Far East, and the colonization of Brazil. The Mazrui and Omani Arabs reclaimed much of the Indian Ocean trade, forcing the Portuguese to retreat south. Many prazos had declined by the mid-19th century, but several survived.

In 1782, the settlement of Lourenço Marques (now Maputo) was established. After the British abolished the slave trade in 1807, making slave exports from West Africa difficult, Portugal turned to Mozambique as a new supply source for Brazil. This, combined with the slave trade from Zanzibar under Sayyid Said, made inland East Africa a major source of enslaved people in the first half of the 19th century. Slavery was legally abolished in Portuguese territories in 1858, but exploitative contract labor systems, effectively continuing slave-like conditions, persisted.

During the 19th century, other European powers, particularly the British (British South Africa Company) and the French (from Madagascar), became increasingly involved in the trade and politics of the region around Portuguese East African territories. Portugal's "Pink Map" plan to connect Angola and Mozambique overland was thwarted by British pressure. The current borders of Mozambique were largely established by treaties with Britain (1891) and Germany. In 1891, the Portuguese administration granted development rights and significant autonomy (excluding judicial power) to large private chartered companies, such as the Mozambique Company, the Zambezia Company, and the Niassa Company. These were often controlled and financed by British financiers like Solomon Joel. These companies established railroad lines to neighboring colonies (South Africa and Rhodesia) and implemented forced labor policies, supplying cheap African labor to mines and plantations. The Zambezia Company was particularly profitable.

Indigenous resistance to Portuguese rule was frequent, such as the 1894 attack on Lourenço Marques, but these uprisings were suppressed by Portuguese military force. In 1898, the colonial capital was moved from Island of Mozambique to Lourenço Marques.

By the early 20th century, due to unsatisfactory performance and a shift under Salazar's Estado Novo regime towards stronger Portuguese control over the empire's economy, the chartered companies' concessions were not renewed when they expired (e.g., Niassa Company in 1929, Mozambique Company in 1942). In 1951, the Portuguese overseas colonies in Africa, including Mozambique, were rebranded as Overseas Provinces of Portugal, formally making them part of Portugal, though colonial exploitation continued. The Mueda massacre on June 16, 1960, where Portuguese forces killed Makonde protestors, became a pivotal event provoking the armed struggle for independence.

3.4. Mozambican War of Independence (1964-1975)

As communist and anti-colonial ideologies spread across Africa, many clandestine political movements emerged in support of Mozambican independence. These movements argued that colonial policies and development plans primarily benefited the Portuguese population, with little attention paid to the integration and development of native Mozambican communities. This resulted in state-sponsored discrimination and social pressure on the indigenous majority.

In response to the growing guerrilla movement, the Portuguese government, particularly from the 1960s and early 1970s, initiated gradual changes with new socioeconomic developments and some egalitarian policies, but these were insufficient to quell the desire for independence.

The Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (FRELIMO), established in 1962 with Eduardo Mondlane as its first president, initiated a guerrilla campaign against Portuguese rule from bases in Tanzania in September 1964. This conflict, along with those in Angola and Portuguese Guinea, became part of the Portuguese Colonial War (1961-1974). FRELIMO, espousing Marxism and receiving aid from the Soviet Union and China, aimed to undermine Portuguese control in rural and tribal areas, primarily in the north and west, while the Portuguese regular army maintained control of population centers.

Eduardo Mondlane was assassinated in 1969 by a parcel bomb, but Samora Machel and others continued the struggle.

3.5. Independence and People's Republic (1975-1990)

FRELIMO took control of the territory after ten years of sporadic warfare. The Carnation Revolution in Portugal in April 1974, which overthrew the authoritarian Estado Novo regime, was a crucial catalyst. The new democratic government in Lisbon was unwilling to sustain the costly colonial wars. Mozambique gained independence on June 25, 1975, becoming the People's Republic of Mozambique. Samora Machel became the first president.

Within a year, most of the approximately 250,000 Portuguese settlers in Mozambique had left. Some were expelled by the new government, while others fled fearing reprisals. A law, reportedly initiated by Armando Guebuza of FRELIMO, ordered Portuguese nationals to leave within 24 hours with only 44 lb (20 kg) of luggage, leading many to return to Portugal penniless.

The new FRELIMO government established a one-party state based on Marxist principles. It received diplomatic and military support from Cuba and the Soviet Union and proceeded to suppress opposition. In 1976, in compliance with United Nations sanctions, Mozambique closed its border with Rhodesia (then under white minority rule), a move that significantly impacted Rhodesia's economy but also harmed Mozambique's revenue from transit trade.

3.6. Mozambican Civil War (1977-1992)

Shortly after independence, Mozambique descended into a long and violent civil war (1977-1992). The conflict pitted the FRELIMO government against the Mozambican National Resistance (RENAMO), an anti-communist rebel militia. RENAMO was initially created by the Rhodesian intelligence service and later heavily supported by apartheid South Africa and other Western interests.

The civil war, combined with sabotage from Rhodesia and South Africa, ineffective FRELIMO policies, failed central planning, and the resulting economic collapse, characterized the first decades of Mozambican independence. This period was also marked by the exodus of Portuguese nationals and Mozambicans of Portuguese heritage, a collapsed infrastructure, lack of investment in productive assets, and government nationalization of privately owned industries, leading to widespread famine.

During most of the civil war, the FRELIMO government struggled to exercise effective control outside urban areas. RENAMO controlled up to 50% of rural areas in several provinces, isolating them from health services. The war was marked by mass human rights violations from both sides, with terror tactics and indiscriminate targeting of civilians. The government executed tens of thousands and sent many to "re-education camps" where thousands died. RENAMO, lacking a strong ideological base, initially relied on forced recruitment and employed violence against civilian infrastructure like schools and hospitals.

An estimated one million Mozambicans perished during the civil war, 1.7 million sought refuge in neighboring states, and several million more were internally displaced. Between 300,000 and 600,000 people died of famine during the war.

On October 19, 1986, President Samora Machel died in a plane crash in the Lebombo Mountains near Mbuzini, South Africa, under controversial circumstances. Allegations of South African involvement, possibly through a false navigational beacon, have persisted.

Machel's successor, Joaquim Chissano, implemented sweeping changes, moving away from Marxism towards capitalism and initiating peace talks with RENAMO. A new constitution in 1990 provided for a multi-party political system, a market-based economy, and free elections. The country's official name was changed from the People's Republic of Mozambique to the Republic of Mozambique.

The civil war ended in October 1992 with the Rome General Peace Accords, brokered initially by the Christian Council of Mozambique and then by the Community of Sant'Egidio. Peacekeeping forces from the United Nations Operation in Mozambique (ONUMOZ) supervised the transition.

3.7. Democratic Era (1993-present)

Mozambique held its first multi-party elections in 1994, which were largely accepted as free and fair, although contested by some. FRELIMO, under Joaquim Chissano, won, while RENAMO, led by Afonso Dhlakama, became the official opposition. In 1995, Mozambique joined the Commonwealth of Nations, notable as it was the only member at the time that had never been part of the British Empire. This decision aimed to strengthen economic ties with its Anglophone neighbors. In 1996, it also became a founding member of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP).

By mid-1995, over 1.7 million refugees had returned, part of the largest repatriation in sub-Saharan Africa. An additional four million internally displaced persons returned to their homes.

Elections were held again in December 1999, with FRELIMO winning once more. RENAMO alleged fraud and threatened to resume conflict but ultimately pursued legal channels, losing their case in the Supreme Court.

In early 2000, Cyclone Eline caused widespread flooding, killing hundreds and devastating infrastructure. Suspicions arose that foreign aid was diverted by FRELIMO leaders. Carlos Cardoso, a journalist investigating these allegations, was murdered, and his death remains a point of contention regarding press freedom and corruption.

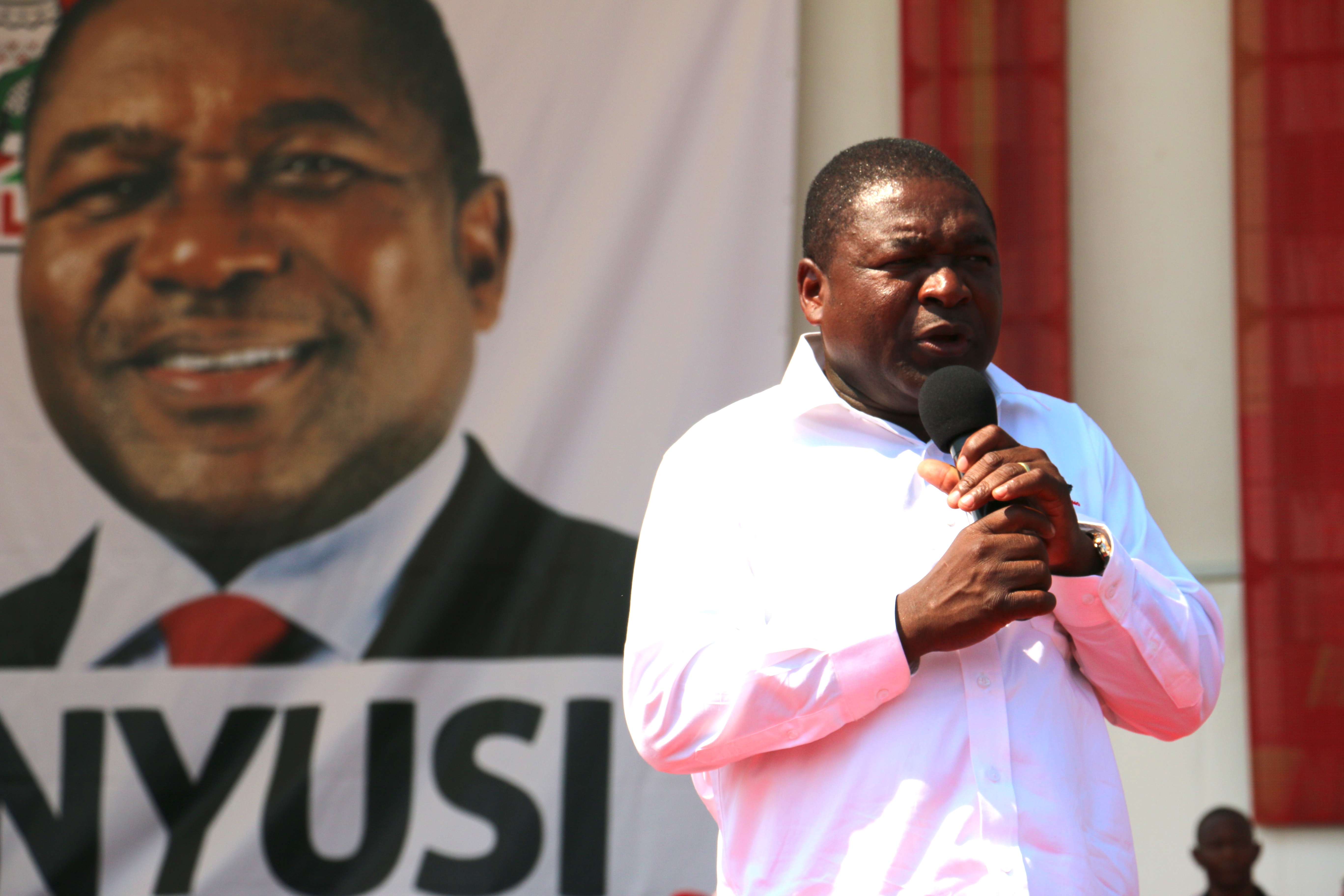

Chissano announced in 2001 he would not seek a third term, a move seen as a subtle critique of other African leaders who extended their rule. Presidential and National Assembly elections in December 2004 saw FRELIMO candidate Armando Guebuza win with 64% of the vote. Guebuza was inaugurated in February 2005 and served two terms. His successor, Filipe Nyusi, became president on January 15, 2015.

From 2013 to 2019, a low-intensity insurgency by RENAMO re-emerged, mainly in central and northern regions. An Accord on Cessation of Hostilities was signed in September 2014, but political crisis followed the October 2014 elections, with RENAMO disputing results and demanding control of six provinces where they claimed majorities. This led to thousands fleeing to Malawi and reports of human rights abuses by government forces. A definitive peace agreement was signed between the government and RENAMO on August 1, 2019, aiming to end the prolonged military tension and disarm RENAMO's military wing.

In October 2019, President Filipe Nyusi was re-elected in a landslide victory, with FRELIMO securing a two-thirds majority in parliament, allowing constitutional changes without opposition agreement. Opposition parties alleged fraud and irregularities.

3.7.1. Insurgency in Cabo Delgado

Since 2017, Mozambique has faced an ongoing insurgency by Islamist militants in the northern Cabo Delgado Province. This region is rich in natural gas reserves, and the conflict has severe humanitarian consequences and threatens economic development. Groups affiliated with the Islamic State (ISIL) have been involved. In September 2020, ISIL insurgents briefly captured Vamizi Island. In March 2021, a major attack on the town of Palma resulted in dozens of civilian deaths and displaced tens of thousands. The insurgency has also spread to the neighboring Niassa Province, with thousands fleeing jihadist attacks in December 2021. The conflict has drawn international military support to aid Mozambican forces.

4. Geography

Mozambique is located on the southeast coast of Africa. It is bordered by Eswatini to the south, South Africa to the southwest, Zimbabwe to the west, Zambia and Malawi to the northwest, Tanzania to the north, and the Indian Ocean to the east. The country lies between latitudes 10° and 27°S, and longitudes 30° and 41°E. With an area of 309 K mile2 (801.54 K km2) (or 309.48 K mile2), Mozambique is the world's 35th-largest country. It is separated from the Comoros, Mayotte, and Madagascar by the Mozambique Channel to the east.

The country is divided into two main topographical regions by the Zambezi River. North of the Zambezi, a narrow coastal strip gives way to inland hills and low plateaus. Further west are rugged highlands, including the Niassa highlands, Namuli (or Shire) highlands, Angonia highlands, Tete highlands, and the Makonde plateau, largely covered with miombo woodlands. South of the Zambezi River, the lowlands are broader, with the Mashonaland plateau and the Lebombo Mountains located in the far south.

Mozambique is drained by five principal rivers and several smaller ones, with the Zambezi being the largest and most important. The country has four notable lakes: Lake Niassa (also known as Lake Malawi, of which Mozambique shares a part), Lake Chiuta, Lake Cahora Bassa (a large artificial lake), and Lake Shirwa, all located in the north.

The coastline stretches for over 1.6 K mile (2.50 K km) and features tropical beaches and coral reefs.

Major cities include Maputo (the capital), Matola, Beira, Nampula, Tete, Quelimane, Chimoio, Pemba, Inhambane, Xai-Xai, and Lichinga.

4.1. Climate

Mozambique has a tropical climate with two distinct seasons: a wet season from October to March and a dry season from April to September. Climatic conditions, however, vary depending on altitude. Rainfall is generally heavy along the coast and decreases in the north and south. Annual precipitation varies from 20 in (500 mm) to 35 in (900 mm) depending on the region, with an average of 23 in (590 mm).

Tropical cyclones are common during the wet season and can cause severe flooding and destruction, particularly in coastal areas. Average temperature ranges in Maputo are from 55.4 °F (13 °C) to 75.2 °F (24 °C) in July and from 71.6 °F (22 °C) to 87.8 °F (31 °C) in February.

In 2019, Mozambique was struck by two devastating cyclones, Idai and Kenneth, marking the first time two major cyclones had hit the nation in a single season. These events caused extensive flooding, destroyed thousands of crops, and affected over 10 million people throughout the region, including in neighboring Malawi and Madagascar, highlighting the country's vulnerability to climate-related disasters. The FAO launched urgent campaigns to address the impact on farming, fisheries, and food security.

4.2. Wildlife and Protected Areas

Mozambique boasts a rich biodiversity. There are known to be 740 bird species in the country, including 20 globally threatened species and two introduced species. Over 200 mammal species are endemic to Mozambique, including the critically endangered Selous' zebra (a subspecies of plains zebra), Vincent's bush squirrel, and 13 other endangered or vulnerable species. The country's marine life is also diverse, with extensive coral reefs and populations of dugongs, sea turtles, and various cetaceans, including whale sharks and manta rays, particularly in areas like the Bazaruto Archipelago.

To conserve its natural heritage, Mozambique has established a network of protected areas. These include thirteen forest reserves, seven national parks (such as Gorongosa National Park, Banhine National Park, and Quirimbas National Park), six nature reserves, three frontier conservation areas (transboundary parks shared with neighboring countries), and three wildlife or game reserves. These areas are crucial for protecting endemic and endangered species and for promoting ecotourism. The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.93/10, ranking it 62nd globally out of 172 countries.

5. Government and Politics

Mozambique is a presidential republic with a multi-party system. The Constitution of Mozambique, adopted in 1990 and revised since, provides the framework for the country's governance.

The President of the Republic is the head of state, head of government, and commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and serves as a symbol of national unity. The president is directly elected by popular vote for a five-year term and is eligible for a second term. Runoff voting is used if no candidate receives an absolute majority in the first round.

The Prime Minister is appointed by the President. The Prime Minister's functions include convening and chairing the Council of Ministers (cabinet), advising the President, assisting the President in governing the country, and coordinating the functions of other ministers.

The legislative branch is the Assembly of the Republic (Assembleia da RepúblicaAssembly of the RepublicPortuguese), a unicameral body with 250 members. Members are elected for a five-year term by proportional representation from multi-member constituencies corresponding to the country's provinces.

The judiciary is headed by the Supreme Court. There are also provincial, district, and municipal courts. The legal system is based on civil law, influenced by Portuguese law, and customary law in some local matters.

The Economist Intelligence Unit rated Mozambique as an "authoritarian regime" in its 2022 Democracy Index.

5.1. Administrative Divisions

Mozambique is divided into ten provinces (provínciasprovincesPortuguese) and one capital city (cidade capitalcapital cityPortuguese) with provincial status. The provinces are:

# Niassa

# Cabo Delgado

# Nampula

# Tete

# Zambezia

# Manica

# Sofala

# Gaza

# Inhambane

# Maputo (city)

# Maputo Province

The provinces are further subdivided into 129 districts (distritosdistrictsPortuguese). The districts are then divided into 405 "postos administrativosadministrative postsPortuguese" (administrative posts), which are headed by secretáriossecretaries (administrative post heads)Portuguese. The lowest geographical level of central state administration is the localidadeslocalitiesPortuguese (localities). There are also 53 "municípiosmunicipalitiesPortuguese" (municipalities) with elected local governments.

5.2. Foreign Relations

Mozambique's foreign policy has become increasingly pragmatic, though allegiances dating back to the liberation struggle remain relevant. The core pillars of its foreign policy are maintaining good relations with its neighbors and sustaining and expanding ties with development partners.

During the 1970s and early 1980s, Mozambique's foreign policy was deeply intertwined with the struggles for majority rule in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and South Africa, as well as superpower competition during the Cold War. Mozambique's decision to enforce UN sanctions against Rhodesia and deny it access to the sea led Ian Smith's Rhodesian government to undertake actions against Mozambique. Even after Zimbabwe's independence in 1980 removed this threat, the apartheid government of South Africa continued to destabilize Mozambique by supporting RENAMO. Mozambique was a member of the Frontline States. The 1984 Nkomati Accord with South Africa, aimed at ending South African support for RENAMO in exchange for Mozambique limiting African National Congress (ANC) activities, failed to achieve its primary goal but opened initial diplomatic contacts. Relations with South Africa improved significantly after the end of apartheid, leading to full diplomatic relations in October 1993. While relations with neighboring Zimbabwe, Malawi, Zambia, and Tanzania sometimes experience strains, ties generally remain strong.

Immediately after independence, Mozambique received considerable assistance from some Western countries, notably the Scandinavian nations. The Soviet Union and its allies became Mozambique's primary economic, military, and political supporters. This began to shift in 1983; in 1984, Mozambique joined the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Western aid, particularly from Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Iceland, quickly replaced Soviet support. Finland and the Netherlands are also important sources of development assistance. Italy played a key role during the peace process and maintains a significant profile. Relations with Portugal, the former colonial power, remain important, with Portuguese investors playing a visible role in Mozambique's economy.

Mozambique is a member of the Non-Aligned Movement and is generally considered a moderate member of the African bloc in the United Nations and other international organizations. It is also a member of the African Union (AU) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC). In 1994, Mozambique became a full member of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), partly to broaden international support and to engage its sizable Muslim population. In 1995, Mozambique joined the Commonwealth of Nations, becoming the only member at the time that had never been part of the British Empire. In the same year, it became a founding member and the first president of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP), maintaining close ties with other Portuguese-speaking countries.

5.3. Military

The Mozambique Defence Armed Forces (Forças Armadas de Defesa de MoçambiqueArmed Forces for the Defence of MozambiquePortuguese, FADM) are responsible for national defense. The FADM was formed in 1976 from three conventional battalions. It includes the General Staff of the Armed Forces and three branches: the Army, Navy, and Air Force.

During the Cold War, the FADM received training and support from Soviet and Chinese military instructors. Following a treaty with the Soviet Union in 1977, officer candidates were trained in various Warsaw Pact countries. The Soviet military mission helped expand the FADM to include infantry and armored brigades. By the peak of the civil war, this had grown to eight infantry brigades, an armored brigade, and a counter-insurgency brigade.

After the civil war, the FADM was restructured under the Joint Commission for the Formation of the Mozambican Defence Force (CCFADM), with advisors from Portugal, France, and the United Kingdom. The aim was to integrate former government soldiers and RENAMO rebels into a unified force of about 30,000, but logistical and budgetary constraints resulted in a smaller force of around 12,195 by 1995.

As of 2016, the Mozambican Army consisted of approximately 10,000 troops, organized into special forces battalions, light infantry battalions, engineering battalions, artillery battalions, and a logistics battalion.

Mozambique has participated in international peacekeeping operations in Burundi, the Comoros, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, East Timor, and Sudan. It has also taken part in joint military exercises like Blue Hungwe in Zimbabwe (1997) and Blue Crane in South Africa (1999). The military is currently heavily involved in combating the insurgency in Cabo Delgado, receiving support from SADC forces and other international partners.

5.4. Human Rights

The state of human rights in Mozambique presents a mixed picture, with progress in some areas and persistent challenges in others. The constitution provides for various civil liberties and political freedoms, but their practical application can be inconsistent.

Same-sex sexual activity has been legal since 2015, following the adoption of a new penal code that decriminalized consensual homosexual acts. However, discrimination against LGBT people remains widespread in society, affecting access to services and social acceptance.

Human trafficking is a significant concern, with Mozambique being a source, transit, and destination country for men, women, and children subjected to forced labor and sex trafficking.

Issues within the justice system include lengthy pre-trial detention, corruption, and limited access to legal aid, particularly in rural areas. Prison conditions are often poor, characterized by overcrowding and inadequate sanitation and healthcare.

Freedom of speech and the press are constitutionally guaranteed, but journalists sometimes face harassment, intimidation, or violence, particularly when reporting on sensitive issues like corruption or the insurgency in Cabo Delgado. The murder of journalist Carlos Cardoso in 2000, while investigating corruption, remains a stark reminder of the risks faced by the media.

Efforts by governmental bodies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are ongoing to address human rights abuses and promote awareness. However, challenges such as limited resources, weak institutional capacity, and the ongoing conflict in Cabo Delgado, which has led to significant human rights violations by both insurgents and, at times, security forces, continue to impact the human rights situation. The rights of minorities and vulnerable groups, including women, children, and internally displaced persons, require continued attention and protection.

6. Economy

Mozambique's economy has experienced periods of strong growth, particularly after the end of the civil war, but it remains one of the poorest and most underdeveloped countries globally. Challenges include widespread poverty, inequality, corruption, and a heavy reliance on agriculture and foreign aid, though the development of its vast natural resource wealth, especially natural gas, holds potential for future transformation.

6.1. Economic Overview

Mozambique's economy is characterized by a low GDP per capita and high levels of poverty and income inequality. Between 1994 and 2006, the country experienced an average annual GDP growth of approximately 8%. However, since 2014/2015, household real consumption has decreased significantly, and economic inequality has risen sharply. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) classifies Mozambique as a Heavily Indebted Poor Country (HIPC). Despite improvements in some macroeconomic indicators, a large portion of the population has not proportionally benefited from economic growth, indicating a need for more inclusive development strategies. The official currency is the Mozambican metical (MZN). As of October 2023, US$1 was roughly equivalent to 64 meticais. The United States dollar, South African rand, and euro are also widely accepted in business transactions. The minimum legal salary is around 60 USD per month.

6.2. Key Sectors

Agriculture is the backbone of the Mozambican economy, employing about 80% of the population, primarily in small-scale subsistence farming. Major crops include cassava, maize, cashews, cotton, sugar, citrus fruits, copra, coconuts, and timber. However, the sector suffers from inadequate infrastructure, limited access to markets and credit, and vulnerability to climate change.

Fisheries are also important, with shrimp being a significant export.

Manufacturing includes food and beverages, chemical products, aluminium (with the Mozal smelter being a major industrial enterprise using imported alumina and cheap electricity), and petroleum products.

The services sector is growing, contributing significantly to GDP, with areas like telecommunications and finance showing development.

6.3. Natural Resources and Energy

Mozambique is endowed with significant natural resources. Large reserves of natural gas were discovered offshore in the Rovuma Basin (Mamba South gas field) around 2010-2011, with recoverable reserves estimated at 4,200 billion cubic metres (150 trillion cubic feet). This discovery has the potential to make Mozambique one of the world's largest producers of liquefied natural gas (LNG). Major international energy companies are involved in developing these resources, with LNG exports scheduled to increase significantly from 2024. In 2019, the Mozambique LNG Project, led by TotalEnergies, secured $19 billion in investment.

The country also has substantial coal deposits, particularly in Tete province, as well as titanium (heavy sands), tantalum, graphite, and gemstones like ruby and garnet. The development of these resources presents opportunities for economic growth but also poses challenges related to governance, environmental protection, and ensuring that benefits are shared equitably to avoid exacerbating social tensions (the "resource curse").

Energy production relies heavily on hydropower, with the Cahora Bassa Dam on the Zambezi River being a major producer, exporting electricity to neighboring countries, including South Africa. GL Africa Energy (UK) was awarded a tender in 2017 to build and operate a 250 MW gas-powered plant.

6.4. Tourism

Mozambique's tourism sector has significant potential, owing to its extensive coastline with pristine beaches, coral reefs, and diverse marine life, as well as its wildlife parks and cultural heritage. Key attractions include the Bazaruto Archipelago and Quirimbas Islands for beach and diving tourism, renowned for clear waters and biodiversity, including whale sharks and manta rays in areas like Inhambane. National parks such as Gorongosa National Park offer wildlife viewing opportunities. The historic Island of Mozambique, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is another important destination.

However, the sector's growth has been hampered by infrastructure limitations, security concerns (particularly the insurgency in Cabo Delgado), and occasional natural disasters.

6.5. Transport and Infrastructure

Mozambique's transport infrastructure is crucial for its economic development and for serving its landlocked neighbors.

There are over 19 K mile (30.00 K km) of roads, but a significant portion is unpaved, making travel difficult, especially during the rainy season. Efforts are ongoing to upgrade and expand the road network. Traffic circulates on the left.

The railway system comprises three main corridors originating from the ports of Maputo, Beira, and Nacala, connecting to Zimbabwe, Malawi, Zambia, and South Africa. These lines are vital for freight, particularly for mineral exports. As of 2005, there were 1.9 K mile (3.12 K km) of railway track, mostly 1,067 mm gauge, with a 87 mile (140 km) line of 762 mm gauge (Gaza Railway). The state-owned Mozambique Ports and Railways (CFM) oversees the system, with some operations outsourced. A new route for coal haulage between Tete and Beira was planned, and a memorandum of understanding was signed with Botswana in 2010 to develop a railway to carry coal to a deepwater port at Techobanine Point.

Major ports include Maputo, Beira, and Nacala, which are key transit hubs for the region.

There is an international airport in Maputo (Maputo International Airport), along with 21 other paved airports and over 100 unpaved airstrips. LAM Mozambique Airlines is the national carrier.

Navigable inland waterways cover approximately 2.3 K mile (3.75 K km).

Infrastructure for energy and communications is still developing.

6.6. Economic Reforms and Challenges

Since the end of the civil war, Mozambique has undertaken significant economic reforms, including the privatization of over 1,200 mostly small state-owned enterprises. Sector liberalization has been pursued in telecommunications, energy, ports, and railways. Customs duties have been reduced, and customs management streamlined. A value-added tax (VAT) was introduced in 1999.

Despite these reforms and periods of high growth, Mozambique faces persistent challenges. Corruption is a major issue, with numerous scandals shaking the economy. In 2011, new anti-corruption laws were proposed, and some high-profile convictions have occurred. Mozambique often ranks poorly on international corruption indices.

Other challenges include high levels of external debt (the "hidden debts" scandal in the mid-2010s severely impacted the economy and donor relations), high unemployment and underemployment (especially among youth), and vulnerability to external shocks like commodity price fluctuations and natural disasters.

A critical challenge is ensuring that economic growth is sustainable and inclusive, leading to tangible reductions in poverty and inequality. The development of natural resources needs careful management to avoid negative social and environmental consequences and to ensure benefits reach the broader population. The ProSAVANA agricultural development project, a triangular cooperation between Japan, Brazil, and Mozambique, faced criticism and was eventually halted in 2020 due to concerns about its impact on small-scale farmers.

7. Demographics

Mozambique's population is diverse, young, and rapidly growing, with significant regional variations in density and ethnic composition.

7.1. Population

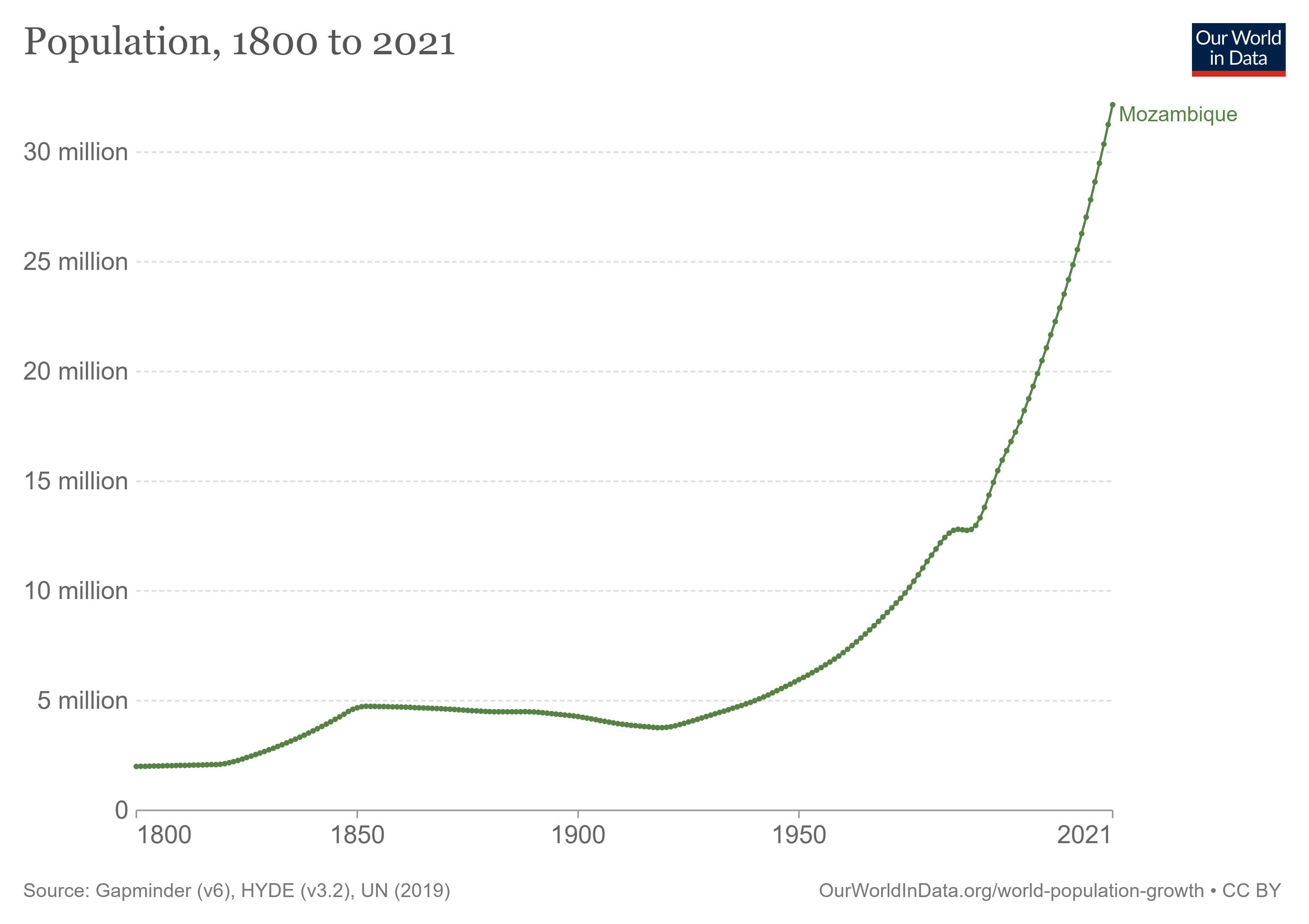

As of 2024 estimates, the population of Mozambique is around 34,777,605, representing a 2.96% increase from 2023. The country has a high total fertility rate, which was 5.9 children per woman according to a 2011 survey (6.6 in rural areas and 4.5 in urban areas). Population density varies, with the north-central provinces of Zambezia and Nampula being the most populous, accounting for about 45% of the total population. The population is predominantly rural, though urbanization is increasing. The age structure is youthful, characteristic of many developing countries.

| Population Estimates | |

|---|---|

| Year | Population (thousands) |

| 1950 | 5,959 |

| 1960 | 7,185 |

| 1970 | 9,023 |

| 1980 | 11,630 |

| 1990 | 12,987 |

| 2000 | 17,712 |

| 2010 | 23,532 |

| 2020 | 31,255 |

| 2023 | 32,514 |

7.2. Ethnic Groups

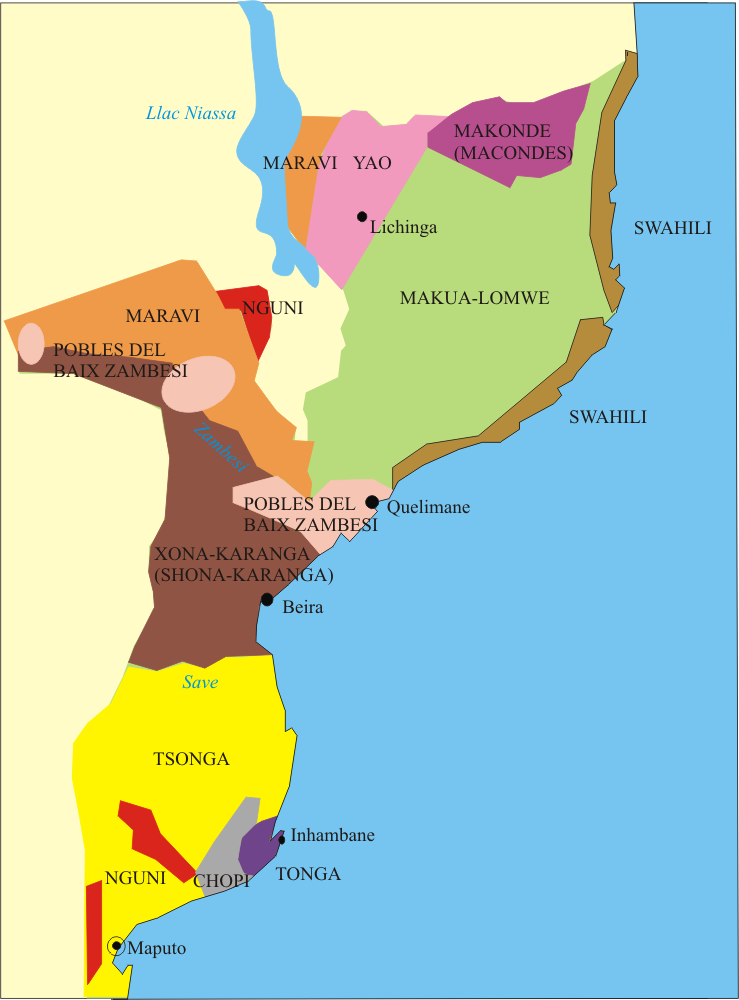

Mozambique is home to approximately 40 distinct ethnic groups, almost entirely of Bantu origin, who comprise about 97.8% of the population. The largest group is the Makua (or Emakhuwa), dominant in the northern part of the country, who along with the related Lomwe constitute about 40% of the population. In the Zambezi valley, the Sena and Shona (mostly Ndau and Manyika) are prominent. The Tsonga (including Shangaan) dominate in southern Mozambique.

Other significant groups include the Makonde, Yao, Swahili, Tonga, Chopi, and Nguni (including Zulu).

The remainder of the population consists of people of Portuguese ancestry (0.06%), Euro-Africans (Mestiço people of mixed Bantu and Portuguese ancestry, 0.2%), and people of Indian descent (0.08%, roughly 45,000). During colonial rule, about 360,000 people of Portuguese heritage lived in Mozambique, many of whom left after independence. In recent years, due to economic conditions, some Portuguese professionals have moved to Mozambique, with an estimated 20,000 in Maputo in the early 2010s. A Chinese community of 7,000 to 12,000 was estimated in 2007.

The historical figure Yasuke, who served Oda Nobunaga in 16th century Japan, is believed to have originated from Portuguese East Africa, possibly Mozambique.

7.3. Languages

Portuguese is the official language of Mozambique and is widely spoken, particularly in urban areas and as a lingua franca among younger, educated Mozambicans. According to the 2017 census, Portuguese is spoken at home by 16.58% of the population and known by 50.3% of the population over 5 years old. In Maputo, around 50% speak Portuguese as a native language.

Besides Portuguese, numerous Bantu languages are spoken throughout the country. Glottolog lists 46 languages spoken in Mozambique, including one sign language (Mozambican Sign Language/Língua de Sinais de MoçambiqueMozambican Sign LanguagePortuguese). The most widely spoken indigenous languages, based on the 2017 census figures for language most frequently spoken at home, include:

- Emakhuwa: 26.13% (5,813,083 speakers)

- Xichangana (Tsonga): 8.63% (1,919,217 speakers)

- Cinyanja (Chewa): 8.05% (1,790,831 speakers)

- Cisena (Sena): 7.09% (1,578,164 speakers)

- Elomwe (Lomwe): 7.08% (1,574,237 speakers)

- Echuwabo: 4.72% (1,050,696 speakers)

- Xitswa (Tswa): 3.76% (836,644 speakers)

- Cindau (Ndau, a Shona dialect): 3.76% (836,038 speakers)

Other significant Bantu languages include Makonde, ChiYao, Cinyungwe, Xironga, and Cicopi.

Swahili is spoken in a small coastal area near the Tanzanian border, and Kimwani (considered a Swahili dialect) is used south of this, towards Mozambique Island.

7.4. Religion

Mozambique has a diverse religious landscape.

The 2007 census indicated that Christians made up 59.2% of the population, Muslims comprised 18.9%, people holding other beliefs (mainly animism or traditional African religions) accounted for 7.3%, and 13.9% had no religious beliefs.

A 2015 Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) program survey showed Roman Catholicism at 30.5%, Muslims at 19.3%, and various Protestant denominations totaling 44%.

Estimates from the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom in 2018 suggested that 28% of the population is Catholic, 18% Muslim (mostly Sunni), 15% Zionist Christians, 12% Protestant, 7% members of other religious groups, and 18% have no religion.

The Catholic Church has twelve dioceses, including the archdioceses of Beira, Maputo, and Nampula. Major Protestant denominations include the United Baptist Church of Mozambique, the Assemblies of God, the Seventh-day Adventist Church, the Anglican Church of Southern Africa, the Church of the Full Gospel of God, the United Methodist Church, the Presbyterian Church of Mozambique, the Churches of Christ, and the Evangelical Assembly of God. Methodism in Mozambique dates back to 1890.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a growing presence, with over 7,943 members as of April 2015. The Baháʼí Faith has been present since the early 1950s, with about 3,000 adherents as of 2010.

Muslims are particularly concentrated in the northern part of the country and are organized into several "tariqa" (brotherhoods). National Islamic organizations include the Conselho Islâmico de Moçambique and the Congresso Islâmico de Moçambique. There are also significant Pakistani and Indian Muslim associations, as well as some Shia communities.

A very small but thriving Jewish community exists in Maputo.

7.5. Largest Cities

Mozambique has several major urban centers, with Maputo being the largest city and the political and economic hub.

The following table lists the largest cities according to the 2017 Census:

| Rank | City | Province | Population (2017) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maputo | Maputo City | 1,080,277 |

| 2 | Matola | Maputo Province | 1,032,197 |

| 3 | Nampula | Nampula Province | 663,212 |

| 4 | Beira | Sofala Province | 592,090 |

| 5 | Chimoio | Manica Province | 363,336 |

| 6 | Tete | Tete Province | 307,338 |

| 7 | Quelimane | Zambezia Province | 246,915 |

| 8 | Lichinga | Niassa Province | 242,204 |

| 9 | Mocuba | Zambezia Province | 240,000 (estimate) |

| 10 | Nacala | Nampula Province | 225,034 |

| 11 | Gurúè | Zambezia Province | 210,000 (estimate) |

| 12 | Pemba | Cabo Delgado Province | 201,846 |

| 13 | Xai-Xai | Gaza Province | 132,884 |

| 14 | Maxixe | Inhambane Province | 123,868 |

| 15 | Angoche | Nampula Province | 89,998 |

| 16 | Inhambane | Inhambane Province | 82,119 |

| 17 | Cuamba | Niassa Province | 79,013 |

| 18 | Montepuez | Cabo Delgado Province | 76,139 |

| 19 | Dondo | Sofala Province | 70,817 |

| 20 | Moçambique (city) | Nampula Province | 65,712 |

Note: Populations for Mocuba and Gurúè are often cited as estimates around the 2017 census period.

8. Education

The education system in Mozambique has faced significant challenges due to historical underinvestment, a long civil war, and rapid population growth, but efforts are ongoing to improve access and quality. Portuguese is the primary language of instruction in all Mozambican schools.

Primary education is compulsory by law, but in practice, many children, especially in poor rural areas, do not attend school regularly as they may need to contribute to family subsistence farming. In 2007, an estimated one million children were out of school.

The structure of the education system typically includes:

- Primary Education: Divided into two levels.

- Secondary Education: Requires passing national standardized exams after grade 7. Secondary school runs from 8th to 10th grade.

- Higher Education: Access to universities is extremely limited. Many students who complete pre-university schooling do not immediately proceed to university studies, often working as teachers or facing unemployment. Vocational training institutes specializing in agricultural, technical, or pedagogical studies are alternatives after grade 10.

A significant challenge has been the qualification of teachers; in 2007, almost half of all teachers were reportedly unqualified. However, there has been progress in enrollment. Girls' enrollment increased from 3 million in 2002 to 4.1 million in 2006, though completion rates remained low.

The literacy rate has seen improvement. In 1950, during the colonial era, the illiteracy rate was 97.8%. By 2010, estimates put the literacy rate at 56.1% (70.8% male and 42.8% female). By 2017, it had risen to 60.7% (72.6% male and 50.3% female), and further to 58.8% (73.3% male and 45.4% female) by 2015 according to other UNESCO estimates, showing some fluctuation in data but an overall upward trend.

Major higher education institutions include Eduardo Mondlane University (founded in 1962) in Maputo and the Pedagogical University of Mozambique. After independence, bilateral agreements allowed Mozambican students to study at Portuguese high schools, polytechnics, and universities.

9. Health

Mozambique faces significant public health challenges, characteristic of many low-income countries, although progress has been made in some areas.

The country has a high fertility rate, around 5.5 births per woman. Public expenditure on health was 2.7% of GDP in 2004, with private expenditure at 1.3%. Per capita health expenditure was 42 USD (PPP) in 2004. Access to healthcare professionals is limited; in the early 21st century, there were only 3 physicians per 100,000 people.

Major health issues include:

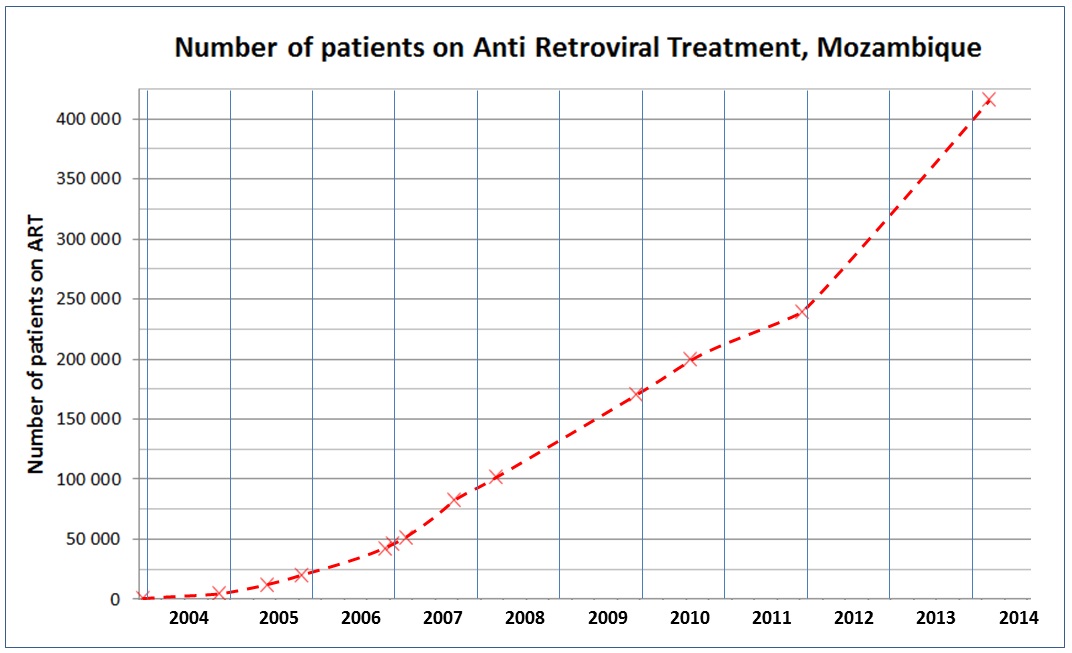

- HIV/AIDS: Mozambique has a high prevalence rate. In 2011, official HIV prevalence was 11.5% for the population aged 15-49 years, with significantly higher rates in southern provinces like Maputo and Gaza. In 2019, an estimated 2.2 million Mozambicans were living with HIV. Access to antiretroviral treatment (ART) has been expanding; by March 2014, 416,000 people were receiving ART, up from 240,000 in December 2011.

- Malaria: Malaria is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, especially among children. In 2017, a severe malaria epidemic saw 1.48 million diagnosed cases and 288 deaths between January and March alone.

- Tuberculosis: TB remains a significant public health problem, often co-occurring with HIV.

- Maternal and Child Mortality: Rates are high. The infant mortality rate was 100 per 1,000 births in 2005. The under-5 mortality rate was 147 per 1,000 births, with neonatal mortality accounting for 29% of these. The maternal mortality rate was 550 per 100,000 births in 2010. Access to skilled birth attendants is limited, with only 3 midwives per 1,000 live births, and a lifetime risk of maternal death for pregnant women of 1 in 37.

- Cholera: Outbreaks are recurrent, especially following floods or disruptions to water and sanitation systems. A cholera epidemic in 2017 infected 1,222 people, resulting in 2 deaths.

- Malnutrition and Food Insecurity: Mozambique has experienced high levels of acute food insecurity for years, contributing to malnutrition, especially in children.

Life expectancy remains low compared to global averages, though it has been gradually increasing.

10. Water Supply and Sanitation

Access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation remains a major challenge in Mozambique, significantly impacting public health and socio-economic development. There are considerable disparities between urban and rural areas.

In 2011, access to an improved water source was estimated at 51%, while access to adequate sanitation was only 25%. Service quality is often poor.

The government defined a strategy for water supply and sanitation in rural areas, where 62% of the population lives, in 2007. In urban areas, water is supplied by a mix of informal small-scale providers and formal providers.

Starting in 1998, Mozambique reformed the formal urban water supply sector by creating an independent regulatory agency (CRA), an asset-holding company (FIPAG), and engaging in a public-private partnership (PPP) with a company called Aguas de Moçambique. This PPP covered parts of the capital and four other cities with formal water systems. However, the PPP faced challenges; management contracts for four cities expired in 2008, and the foreign partner for the capital's lease contract withdrew in 2010, citing heavy losses.

While urban water supply has received considerable policy attention, a comprehensive strategy for urban sanitation has been slower to develop. External donors finance a large proportion (around 87.4%) of all public investments in the water and sanitation sector. The lack of access to clean water and proper sanitation contributes to high rates of waterborne diseases like cholera and diarrhea, particularly affecting children.

11. Culture

Mozambican culture is a rich tapestry woven from indigenous Bantu traditions and influences from centuries of interaction with Arab traders and Portuguese colonizers. Despite the long period of Portuguese rule, which left a legacy in language (Portuguese) and religion (Roman Catholicism), the majority Bantu population has largely preserved its native cultural expressions, especially in rural areas. Urban culture often shows a stronger blend of African and Portuguese influences. Mozambican culture has also, in turn, influenced Portuguese culture.

11.1. Arts and Crafts

Mozambican art is diverse and vibrant. The Makonde, from northern Mozambique, are particularly renowned for their intricate wood carvings and elaborate masks. Their wood carvings often fall into two types: shetani (spirit figures), which are typically carved from heavy ebony, are often tall, elegantly curved, and feature symbolic or non-representational faces; and ujamaa (unity or family) carvings, which are totem-like sculptures depicting lifelike faces of people and various figures, often telling stories of multiple generations and referred to as "family trees."

During the later colonial period, Mozambican art often reflected the oppression by colonial powers and became a symbol of resistance. After independence in 1975, modern art entered a new phase. Two of the most influential contemporary Mozambican artists are the painter Malangatana Ngwenya and the sculptor Alberto Chissano. Much post-independence art from the 1980s and 1990s reflects the political struggle, civil war, suffering, and aspirations for peace. Other crafts include pottery, basket weaving, and textile production.

11.2. Music

The music of Mozambique is rich and serves many purposes, from religious expression to traditional ceremonies and social commentary. Musical instruments are often handmade.

Some traditional instruments include:

- Drums: Made of wood and animal skin, central to many musical forms.

- Lupembe: A woodwind instrument made from animal horns or wood.

- Marimba: A type of xylophone native to Mozambique and other parts of Africa. The marimba is particularly popular among the Chopi of the south-central coast, who are famous for their complex musical skill and dance performances, including the timbila orchestras, recognized by UNESCO as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

Popular music genres include Marrabenta, a lively urban dance music style that originated in southern Mozambique, blending local rhythms with Western influences. Contemporary Mozambican music incorporates various local and international styles.

Traditional dances are usually intricate and highly developed. Many different kinds of dances exist from tribe to tribe, often ritualistic in nature. For example, the Chopi act out battles dressed in animal skins. The men of Makua dress in colorful outfits and masks while dancing on stilts around the village for hours. Groups of women in the northern part of the country perform a traditional dance called tufo, often to celebrate Islamic holidays.

11.3. Literature

Mozambican literature is primarily expressed in Portuguese, though oral traditions in indigenous languages form a vital cultural underpinning. Written literature began to emerge in the early 20th century with poets like Rui de Noronha.

Key figures who emerged, particularly during the anti-colonial struggle and post-independence periods, include:

- Noémia de Sousa: A pioneering female poet whose work criticized colonialism.

- José Craveirinha: A highly acclaimed poet, considered one of the greatest in the Portuguese language, who received the Camões Prize in 1991.

- Luís Bernardo Honwana: Known for his collection of short stories, Nós Matámos o Cão-Tinhoso (We Killed Mangy-Dog), published in 1964, which gained international recognition.

- Mia Couto: A prominent contemporary novelist and short story writer, known for his innovative use of language, blending Portuguese with local expressions and magical realism. His works, such as Terra Sonâmbula (Sleepwalking Land), have been widely translated.

- Ungulani Ba Ka Khosa: A novelist who debuted with Ualalapi in 1987, exploring historical and cultural themes.

- Luís Carlos Patraquim: A notable post-independence poet.

Themes common in Mozambican literature include the colonial experience, the war of independence, the civil war, national identity, social critique, and the interplay between tradition and modernity.

11.4. Cuisine

Mozambican cuisine is a flavorful blend of indigenous African ingredients and cooking techniques with significant influences from Portuguese, Arab, and Indian culinary traditions, reflecting its history as a trading hub.

The Portuguese introduced staples and crops such as cassava (a starchy root of Brazilian origin), cashew nuts (also of Brazilian origin; Mozambique was once the largest producer), and pãozinho (Portuguese-style bread rolls). They also brought spices and seasonings like bay leaves, chili peppers (including the famous piri-piri), fresh coriander, garlic, onions, paprika, red sweet peppers, and wine, as well as maize, potatoes, rice, and sugarcane.

Signature dishes and common foods include:

- Matapa: A dish made from cassava leaves, ground peanuts, coconut milk, and often seafood like crab or shrimp.

- Piri-piri chicken (Frango com piri-piriChicken with piri-piriPortuguese): Grilled chicken marinated in spicy piri-piri sauce.

- Seafood: Fresh fish, prawns, lobster, and crab are abundant along the coast and feature prominently in the cuisine.

- Espetada: Grilled meat skewers.

- Prego: A steak roll.

- Pudim: Pudding, a Portuguese dessert.

- Rissol: Battered shrimp or meat turnovers.

Staple carbohydrates include xima (a maize porridge, similar to ugali or sadza) and rice. Coconut milk, peanuts, and cashews are frequently used in sauces.

11.5. Media

The media landscape in Mozambique is heavily influenced by the government.

Newspapers have relatively low circulation rates due to high prices and low literacy levels. State-controlled dailies such as Notícias and Diário de Moçambique, and the weekly Domingo, are among the most circulated, primarily in Maputo. Most funding and advertising revenue tend to go to pro-government newspapers.

Radio programs are the most influential form of media due to ease of access and wider reach, especially in rural areas. Rádio Moçambique, the state-owned radio station established shortly after independence, is the most popular station in the country.

Television stations include the state broadcaster Televisão de Moçambique (TVM), and private channels like STV (Soico Televisão) and TIM (Televisão Independente de Moçambique). Cable and satellite television provide access to numerous other African, Asian, Brazilian, and European channels.

Internet penetration is growing but remains relatively low, particularly outside urban centers. Freedom of the press is constitutionally guaranteed, but journalists can face challenges, as noted in the Human Rights section.

11.6. Sports

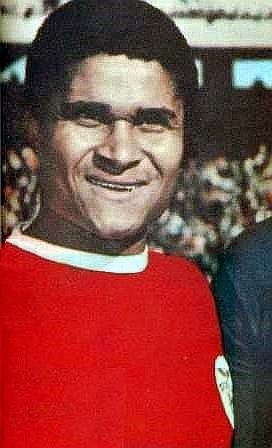

Football (soccer) is the most popular sport in Mozambique. The Mozambique national football team (the Mambas) competes internationally, though it has not yet qualified for the FIFA World Cup. It has participated in the Africa Cup of Nations on several occasions. During the colonial era, Mozambican-born players like Eusébio became legendary figures playing for the Portuguese national team. Carlos Queiroz, a renowned football manager, is also of Mozambican heritage.

Track and field and basketball are also keenly followed. Mozambique has achieved international success in athletics, most notably through Maria Mutola, an 800-metres runner who won a gold medal at the 2000 Sydney Olympics and multiple World Championships.

Roller hockey is popular, and the national team achieved its best result by finishing fourth at the 2011 FIRS Roller Hockey World Cup.

The women's beach volleyball team finished second at the 2018-2020 CAVB Beach Volleyball Continental Cup. The Mozambique national cricket team represents the nation in international cricket. Chess is also played, with the Mozambican Chess Federation being a member of FIDE.

11.7. Public Holidays

Mozambique observes several national holidays that reflect its history, culture, and significant national events.

| Date | English Name | Local Name (Portuguese) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| January 1 | New Year's Day | Dia da Fraternidade Universal | Universal Fraternity Day |

| February 3 | Mozambican Heroes' Day | Dia dos Heróis Moçambicanos | Commemorates the death of Eduardo Mondlane |

| April 7 | Mozambican Women's Day | Dia da Mulher Moçambicana | In tribute to Josina Machel |

| May 1 | International Workers' Day | Dia Internacional dos Trabalhadores | Workers' Day |

| June 25 | Independence Day | Dia da Independência Nacional | Proclamation of independence from Portugal in 1975 |

| September 7 | Victory Day | Dia da Vitória | Commemorates the Lusaka Accord signed in 1974 |

| September 25 | Armed Forces Day / Revolution Day | Dia das Forças Armadas de Libertação Nacional (Dia da Revolução) | Marks the start of the armed struggle for national liberation |

| October 4 | Peace and Reconciliation Day | Dia da Paz e Reconciliação | Commemorates the General Peace Agreement signed in Rome in 1992 |

| October 19 | Samora Machel's Birthday | (Aniversário de Samora Machel) | (Sometimes observed, significance for the first president) |

| November 10 | Maputo City Day | Dia da Cidade de Maputo | Observed in Maputo only |

| December 25 | Family Day / Christmas Day | Dia da Família / Dia de Natal | Christians also celebrate Christmas |