1. Overview

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the largest country in the Central American isthmus, bordered by Honduras to the northwest, the Caribbean Sea to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest. Geographically, it is a land of lakes and volcanoes, featuring diverse ecosystems ranging from fertile Pacific lowlands and volcanic highlands to extensive Caribbean coastal plains and the second-largest rainforest in the Americas, the Bosawás Biosphere Reserve. Managua is the country's capital and largest city.

Historically, Nicaragua was inhabited by various indigenous cultures before being colonized by Spain in the 16th century. It gained independence in 1821, subsequently experiencing periods of political unrest, foreign intervention, and dictatorship, notably the long rule of the Somoza family. The Nicaraguan Revolution in 1979, led by the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN), overthrew the Somoza regime, ushering in an era of significant social reforms but also the devastating Contra War, fueled by Cold War dynamics.

Since the end of the Contra War and the 1990 elections, Nicaragua has navigated a complex path toward multi-party democracy. However, the return of Daniel Ortega to the presidency in 2007 has been marked by increasing concerns over democratic backsliding, the concentration of power, erosion of civil liberties, and human rights violations. This trend culminated in widespread anti-government protests in 2018, which were met with a severe government crackdown, leading to a protracted political and social crisis. Subsequent constitutional and political changes have further consolidated executive power, raising alarms about the state of democracy and human rights in the country.

Economically, Nicaragua is one of the poorest countries in the Americas, heavily reliant on agriculture, remittances, and, increasingly, tourism. The nation faces significant challenges related to poverty, unemployment, and social inequality, with the social impacts of economic policies and political instability being a key concern, particularly for vulnerable populations and minority groups. Nicaraguan society is multiethnic, with a majority Mestizo population, and significant White, Afro-Nicaraguan, and indigenous communities, each with distinct cultural contributions.

Culturally, Nicaragua boasts a rich heritage blending indigenous, European (primarily Spanish), and African influences, evident in its music, dance, literature, and cuisine. The country is renowned for literary figures like Rubén Darío. Despite its challenges, Nicaragua's natural beauty and cultural richness continue to define its national identity. This article explores Nicaragua's geography, history, political system, economy, demographics, and culture, with a particular focus on social impacts, human rights, democratic development, and the situation of its diverse population groups, reflecting a center-left/social liberalism perspective.

2. Etymology

The name Nicaragua NicaraguanikaˈɾaɣwaSpanish is generally thought to have originated from Nicarao, the name of a powerful indigenous cacique (chief) who ruled a Nahua-speaking tribe encountered by the Spanish conquistador Gil González Dávila in southwestern Nicaragua in 1522. According to one long-held theory, the name was a portmanteau of "Nicarao" and the Spanish word aguawaterSpanish, agua, purportedly referring to the country's two large freshwater lakes, Lake Nicaragua and Lake Managua, and other bodies of water.

However, this traditional etymology has been challenged. Historical research, particularly findings in 2002, suggests that the cacique's actual name may have been Macuilmiquiztli, not Nicarao. An alternative and increasingly accepted theory posits that the name "Nicaragua" derives from the Nahuatl term Nicānāhuac. This term is interpreted as "here lies Anahuac" or "here by the water," combining "nicān" (here) with "Ānāhuac" (a term itself meaning "near the water" or "surrounded by water," from "ātl" for water and "nāhuac" for surrounded). This etymology aligns well with Nicaragua's geography, characterized by its extensive lakes, rivers, and coastlines on both the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. Other related Nahuatl words proposed as origins include nican-nahuahere are the Nahuasnci and nic-atl-nahuachere by the waternci. Despite the ongoing scholarly discussion, both theories highlight the significance of indigenous heritage and the country's prominent water features in its nomenclature.

3. History

Nicaragua's history is a complex tapestry woven from its pre-Columbian indigenous roots, the profound impact of Spanish colonization, struggles for independence, internal political conflicts, foreign interventions, revolutionary movements, and ongoing challenges in democratic and social development. This section chronicles these major periods, emphasizing the social impact of events, the pursuit of human rights and democracy, and the conditions of various groups within Nicaraguan society.

3.1. Pre-Columbian history

The land now known as Nicaragua was inhabited by Paleo-Indians as early as 12,000 BCE. In later pre-Columbian times, its indigenous peoples were part of the Intermediate Area, situated between the major cultural spheres of Mesoamerica to the north and the Andean civilizations to the south, and also fell within the influence of the Isthmo-Colombian Area.

The central region and the Caribbean coast were home to various Macro-Chibchan language ethnic groups, including the ancestors of the contemporary Miskito, Rama, Mayangna, and Matagalpas. These groups had coalesced in Central America and had migratory links with present-day northern Colombia and adjacent areas. Their subsistence was based primarily on hunting and gathering, fishing, and slash-and-burn agriculture.

By the late 15th century, western Nicaragua was inhabited by several indigenous peoples culturally and linguistically related to Mesoamerican civilizations like the Aztec and Maya. The Chorotegas, a Mangue-speaking group, arrived from what is now the Mexican state of Chiapas around 800 CE. The Nicarao people, a branch of the Nahuas who spoke the Nawat dialect, also migrated from Chiapas around 1200 CE, having previously been associated with the Toltec civilization. Both the Chorotegas and Nicaraos are believed to have originated in Mexico's Cholula valley. A third group, the Subtiabas, an Oto-Manguean people, migrated from the Mexican state of Guerrero around 1200 CE. Additionally, Aztec trading colonies were established in Nicaragua from the 14th century. These groups developed sophisticated societies with structured agriculture, complex social hierarchies, and distinct artistic traditions, including elaborate pottery and stone carvings, particularly evident on islands like Ometepe.

3.2. Spanish colonial era (1523-1821)

European contact with Nicaragua began in 1502 when Christopher Columbus, on his fourth voyage, reached its Caribbean coast. However, permanent Spanish presence and conquest started two decades later. In 1522, Gil González Dávila led an expedition into southwestern Nicaragua, encountering indigenous groups, including the Nahua tribe led by a chief whose name is often cited as Nicarao (though modern scholarship suggests Macuilmiquiztli). While González Dávila initially engaged in some peaceful interactions and collected gold, his forces were later attacked and driven off by the Chorotega, led by chief Diriangén, who fiercely resisted Spanish attempts at conversion and subjugation.

The systematic conquest and colonization began in 1524 with Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, who founded two of Nicaragua's principal colonial cities: Granada on Lake Nicaragua and León, west of Lake Managua. These cities became centers of Spanish power and intense rivals. Córdoba himself was later executed for defying his superior, Pedro Arias Dávila, who became the first governor of the colony, establishing León as its capital in 1527.

The Spanish colonial period had a devastating impact on the indigenous populations. They suffered massive depopulation due to infectious diseases introduced by the Europeans, to which they had no immunity. Furthermore, they were subjected to forced labor in mines and on plantations, brutal violence, and the transatlantic slave trade, with many being shipped to Panama and Peru. The Spanish imposed their political, economic, and religious systems, leading to the destruction of indigenous social structures and cultural practices. The intermingling of Spanish settlers with indigenous women (often through force or coercion) led to the emergence of the Mestizo population, which became the demographic majority in western Nicaragua.

Economically, the colony focused on agriculture, including cacao and indigo, and cattle ranching, primarily for export. Western Nicaragua also served as a port and shipbuilding facility for galleons in the trans-Pacific trade. However, Nicaragua remained a relatively peripheral part of the Spanish Empire compared to richer colonies like Mexico or Peru. In 1610, the Momotombo volcano erupted, destroying the original site of León, which was subsequently rebuilt nearby (the ruins are now known as León Viejo).

The eastern Mosquito Coast followed a different trajectory. It was largely beyond Spanish control and became a refuge for indigenous groups and, later, a sphere of British influence. English privateers and settlers established presence there from the 17th century, allying with the Miskito people. During the American Revolutionary War, Central America saw conflict between Britain and Spain, with British admiral Horatio Nelson leading expeditions, including one on the San Juan River in 1780.

Colonial society was rigidly hierarchical, with Spanish-born peninsulares at the top, followed by American-born Spaniards (criollos), mestizos, indigenous peoples, and enslaved Africans. This structure bred resentment among the criollos, who, despite their wealth and land ownership, were excluded from the highest positions of power, contributing to the growing desire for independence in the early 19th century.

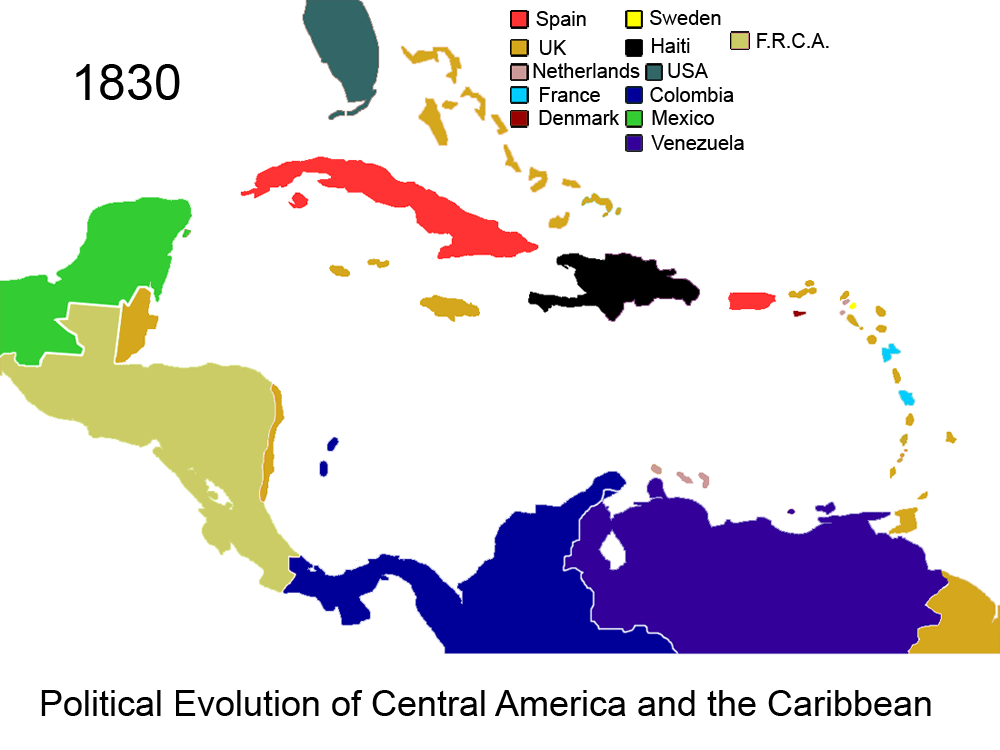

3.3. Independent Nicaragua from 1821 to 1909

Nicaragua gained independence from Spain in September 1821 as part of the broader Act of Independence of Central America, which dissolved the Captaincy General of Guatemala. Shortly thereafter, it was briefly incorporated into the First Mexican Empire under Agustín de Iturbide. Following the collapse of the Mexican Empire in March 1823, Nicaragua joined the newly formed United Provinces of Central America (later the Federal Republic of Central America). However, this federation was plagued by internal divisions and conflicts between Liberal and Conservative factions. Nicaragua formally declared itself an independent republic in 1838 after the federation's dissolution.

The early years of independent Nicaragua were marked by intense rivalry between the Liberal elite based in León and the Conservative elite based in Granada. This rivalry frequently erupted into civil war, particularly during the 1840s and 1850s, hindering national development and stability. To mitigate this conflict, Managua was chosen as the nation's capital in 1852, located geographically between the two feuding cities.

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 brought Nicaragua into prominence as a transit route for travelers from the eastern United States heading to California. They utilized the San Juan River and Lake Nicaragua as part of this interoceanic passage. This strategic importance attracted foreign interests and intervention.

A defining and tumultuous episode of this period was the National War (1856-1857). In 1855, invited by the Liberals to aid in their struggle against the Conservatives, the American filibuster William Walker arrived with a band of mercenaries. He quickly seized power, had himself "elected" president in a farcical election in 1856, and instituted policies such as re-establishing slavery (which had been abolished) and making English an official language, with ambitions of creating a slaveholding empire in Central America. His actions provoked a united military response from Costa Rica, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaraguan patriots from both Liberal and Conservative factions. Walker was defeated and expelled in 1857. This conflict had a profound impact, fostering a sense of Central American unity against foreign intervention and leaving a legacy of suspicion towards U.S. intentions in the region. The war also severely weakened the Liberal party for inviting Walker, leading to three decades of Conservative rule.

The Mosquito Coast on the Caribbean side, which Britain had claimed as a protectorate since 1655, was gradually integrated into Nicaragua. Britain delegated the area to Honduras in 1859 before transferring it to Nicaragua in 1860. It remained an autonomous territory until 1894 when President José Santos Zelaya, a Liberal who came to power in 1893, formally incorporated it into Nicaragua, naming the region Zelaya Department in his honor. Zelaya's presidency (1893-1909) was characterized by modernization efforts, such as railway construction, and attempts to assert Nicaraguan sovereignty and reduce foreign influence. However, his nationalistic policies and efforts to control foreign access to Nicaraguan natural resources, along with his attempts to exert influence over neighboring countries, eventually brought him into conflict with the United States, leading to his ousting in 1909 with U.S. backing. Throughout the late 19th century, the idea of a Nicaragua Canal linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans remained a significant international interest, with both the United States and European powers considering various schemes.

3.4. United States occupation (1909-1933)

Following the ousting of President José Santos Zelaya in 1909, which the United States supported due to concerns over his nationalist policies, regional influence, and disputes regarding a potential Nicaragua Canal, Nicaragua entered a period of intense political instability and direct U.S. military and political intervention. The U.S. motives included protecting its economic interests, ensuring regional stability conducive to these interests (particularly concerning the future Panama Canal), and preventing other foreign powers from gaining influence.

U.S. Marines occupied Nicaragua for most of the period between 1912 and 1933. The initial intervention in 1912 was at the request of President Adolfo Díaz, who faced a rebellion led by General Luis Mena. Díaz claimed he could not protect U.S. lives and property, prompting the U.S. to land Marines. This occupation aimed to stabilize the country, protect U.S. assets, and ensure pro-U.S. governments remained in power.

In 1914, the Bryan-Chamorro Treaty was signed between Nicaragua and the United States. This controversial treaty granted the U.S. exclusive rights in perpetuity to build an interoceanic canal across Nicaragua, the right to lease the Corn Islands, and the right to establish a naval base in the Gulf of Fonseca. While the U.S. paid Nicaragua 3.00 M USD, the treaty was widely seen as a violation of Nicaraguan sovereignty and an instrument of U.S. imperial control, and it caused resentment among many Nicaraguans and concern among neighboring Central American countries whose own rights were affected.

The U.S. Marines briefly withdrew in 1925, but returned in 1926 after another civil war erupted between Liberals and Conservatives. It was during this second phase of occupation that a significant resistance movement emerged, led by General Augusto César Sandino. Sandino, a Liberal nationalist, refused to accept the U.S.-brokered peace settlement (the Pact of Espino Negro) and waged a guerrilla war against the U.S. Marines and the Nicaraguan government forces from 1927 to 1933. Sandino's struggle, framed as a defense of national sovereignty against foreign domination, gained him popular support within Nicaragua and sympathy across Latin America, making him an iconic figure of anti-imperialist resistance.

Before withdrawing its forces in 1933, the United States oversaw the creation and training of the Guardia Nacional (National Guard). This new military force was intended to maintain order and protect U.S. interests after the Marines' departure. However, it became a highly politicized institution. After the U.S. withdrawal, Sandino negotiated a peace agreement with President Juan Bautista Sacasa. But in February 1934, Sandino was assassinated on the orders of the National Guard's ambitious director, Anastasio Somoza García. This act paved the way for the Somoza family's rise to power, marking the beginning of a long and oppressive dictatorship that would profoundly shape Nicaragua's 20th-century history. The U.S. occupation, while ostensibly aimed at promoting stability, ultimately fostered deep-seated anti-American sentiment and contributed to the conditions that allowed the Somoza dictatorship to take root.

3.5. Somoza dynasty (1936-1979)

The Somoza dynasty established a repressive and corrupt dictatorship that dominated Nicaragua for 43 years, from 1936 to 1979. The dynasty was founded by Anastasio Somoza García ("Tacho"), who rose to power through his leadership of the U.S.-trained National Guard. After orchestrating the assassination of the nationalist hero Augusto César Sandino in 1934, Somoza García consolidated his control, forced President Juan Bautista Sacasa out of office, and officially became president in 1937 through a rigged election.

The Somoza family's rule was characterized by:

1. Political Control and Repression: The Somozas maintained power through the manipulation of elections, suppression of political opposition, censorship of the press, and the brutal force of the National Guard, which acted as their personal army. Democratic institutions were hollowed out, and civil liberties were severely curtailed. Opponents faced imprisonment, torture, exile, or death.

2. Economic Exploitation and Corruption: The family amassed a vast personal fortune by treating Nicaragua as their private estate. They controlled large segments of the economy, including agriculture (coffee, sugar, cattle), industry, and finance, often through monopolies, expropriation of land, and corrupt dealings. By the time the dynasty fell, their wealth was estimated to be between 500.00 M USD and 1.50 B USD. While the country experienced some economic growth during certain periods, the benefits were largely concentrated in the hands of the Somoza family and their cronies, exacerbating social inequality and poverty for the majority of the population.

3. U.S. Support: The Somoza regime largely enjoyed the support of the United States, which viewed them as a bulwark against communism in Central America during the Cold War. This support, including military and economic aid, was crucial for the dynasty's longevity, despite their undemocratic nature and human rights abuses. Anastasio Somoza García famously remarked, "He's a son of a bitch, but he's our son of a bitch," a quote often attributed to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt referring to him or similar dictators.

Anastasio Somoza García ruled until his assassination in 1956 by the poet Rigoberto López Pérez. His eldest son, Luis Somoza Debayle, succeeded him. Luis adopted a somewhat more moderate façade, allowing limited political activity, but the family's grip on power remained firm. After Luis's death from a heart attack in 1967, his brother, Anastasio Somoza Debayle ("Tachito"), who had been head of the National Guard, became president. Tachito's rule was even more overtly repressive and corrupt than his predecessors'.

A turning point was the devastating Managua earthquake in 1972, which destroyed much of the capital city. The Somoza regime's blatant misappropriation of international relief funds, siphoning them off for personal enrichment while neglecting the suffering population, fueled widespread outrage and significantly eroded what little legitimacy the regime had left, even among some segments of the elite. The mishandling of aid also famously prompted baseball star Roberto Clemente to personally attempt to deliver supplies, leading to his tragic death in a plane crash.

This growing discontent, coupled with worsening social and economic conditions for the majority, created fertile ground for armed opposition. The Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN), a Marxist-inspired guerrilla group founded in 1961 and named after Augusto César Sandino, gained increasing popular support throughout the 1970s, eventually leading the revolution that would topple the dynasty. The Somoza regime's impact on Nicaragua was profoundly negative, characterized by decades of stunted democratic development, systematic human rights violations, entrenched corruption, and deep social divides, which ultimately culminated in a bloody civil war.

3.6. Nicaraguan Revolution (1960s-1990)

The Nicaraguan Revolution refers to the period of opposition and insurgency against the Somoza dictatorship, primarily led by the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN), and the subsequent period of Sandinista rule. Founded in 1961 by figures like Carlos Fonseca Amador, who drew inspiration from Augusto César Sandino, the FSLN initially engaged in small-scale guerrilla activities.

The movement gained significant momentum in the 1970s, fueled by widespread popular discontent with the Somoza regime's corruption, repression, and extreme social inequality. The regime's mishandling of the aftermath of the 1972 Managua earthquake and the assassination in January 1978 of Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal, a prominent opposition newspaper editor, galvanized broad opposition, uniting students, peasants, workers, business sectors, and even factions of the Catholic Church against the dictatorship.

After years of escalating armed conflict, the FSLN, leading a popular insurrection, triumphed on July 19, 1979, forcing Anastasio Somoza Debayle to flee the country. This victory marked the end of the 43-year Somoza dynasty and ushered in a period of profound transformation in Nicaragua. The revolution initially enjoyed widespread popular support and international sympathy due to its success in overthrowing a brutal and long-standing dictatorship. The Carter administration in the U.S. initially provided some aid to the new government.

3.6.1. Sandinista government and Contra War

Following their victory in 1979, the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) established a revolutionary government, the Junta of National Reconstruction, with Daniel Ortega emerging as a key leader. The Sandinista government implemented ambitious social and economic programs aimed at addressing historical inequalities and fostering national development. Key initiatives included:

- National Literacy Crusade (Cruzada Nacional de Alfabetización):** Launched in 1980, this campaign significantly reduced illiteracy rates, particularly in rural areas, by mobilizing tens of thousands of volunteer teachers (students and educators). It received international recognition, including a UNESCO award.

- Land Reform (Reforma Agraria):** The government expropriated lands owned by the Somoza family and their associates, as well as other large unproductive estates, and redistributed them to landless peasants and agricultural cooperatives. This aimed to democratize land ownership and boost food production.

- Healthcare and Education Expansion:** Efforts were made to expand access to healthcare and education, particularly for the poor and in previously neglected regions. Public health campaigns focused on vaccination and primary care.

- Nationalization:** Some key sectors of the economy were nationalized, although a mixed economy with a private sector was officially maintained.

However, the Sandinista period was also marked by intense internal and external conflict. The government's increasingly Marxist orientation, close ties with Cuba and the Soviet Union, and perceived authoritarian tendencies alienated some domestic groups and alarmed the United States, particularly under the Reagan administration.

The Contra War (1981-1990) became the dominant feature of this era. The Contras were a collection of counter-revolutionary armed groups, including former members of Somoza's National Guard, disaffected peasants, indigenous Miskito people (who resisted Sandinista policies in their autonomous regions), and former Sandinista allies who opposed the FSLN's direction. The U.S. government, viewing the Sandinistas as a Soviet-Cuban proxy, provided extensive financial, military, and logistical support to the Contras through the CIA. This support included training, weapons, and funding, and operations were often launched from neighboring Honduras and Costa Rica.

The Contra War had devastating consequences for Nicaragua:

- Humanitarian Impact:** Tens of thousands of Nicaraguans were killed, wounded, or displaced. Civilian populations, particularly in rural areas, bore the brunt of the violence.

- Human Rights Violations:** Both the Sandinista government and the Contra forces were accused of significant human rights abuses. The Contras were widely documented as engaging in attacks on civilian targets, including health clinics, schools, and agricultural cooperatives, as well as kidnappings, torture, and summary executions, aiming to disrupt social programs and terrorize the population. The U.S. government's production and dissemination of the "Psychological Operations in Guerrilla Warfare" manual, which advised on tactics including the "neutralization" of civilian officials, was particularly condemned. The Sandinista government was also criticized for suppressing dissent, forced conscription, and abuses against perceived opponents, including the forced relocation of Miskito communities.

- Economic Devastation:** The war crippled Nicaragua's economy. Resources were diverted to military spending, infrastructure was destroyed, and U.S. economic sanctions, including a full trade embargo imposed in 1985, severely hampered economic activity. The U.S. also mined Nicaraguan harbors (such as Corinto), an action condemned as illegal by the International Court of Justice in the Nicaragua v. United States case.

- Political Polarization:** The war deeply polarized Nicaraguan society and had significant international repercussions, becoming a focal point of Cold War tensions in Central America. The Iran-Contra affair in the U.S., where funds from covert arms sales to Iran were illegally diverted to the Contras, became a major political scandal for the Reagan administration.

Despite the ongoing war, general elections were held in 1984, in which Daniel Ortega was elected president and the FSLN won a majority in the National Assembly. While some international observers deemed the elections generally fair, the U.S. government dismissed them as a "sham," partly because some opposition groups, encouraged by the U.S., boycotted the vote.

The war eventually led to peace negotiations, spurred by the Arias Peace Plan involving Central American presidents. The FSLN government, facing a crippled economy and war-weariness, agreed to new elections in 1990, which marked the end of their initial period in power and the transition to a post-war era. The legacy of this period includes both advancements in social equity and literacy, and the deep scars of a brutal civil war and foreign intervention that profoundly impacted Nicaragua's development.

3.7. Post-war era (1990-present)

The 1990 general election marked a significant turning point for Nicaragua, signaling the end of the Contra War and the FSLN's first period in power. Violeta Chamorro, widow of the assassinated newspaper editor Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal and leader of a broad 14-party coalition called the National Opposition Union (UNO), defeated Daniel Ortega and the FSLN. Chamorro's victory, with a 55% majority, surprised many, including the Sandinistas. Her presidency (1990-1997) focused on national reconciliation, demobilizing the Contras and significantly reducing the size of the Sandinista-controlled army (renamed the Nicaraguan Army). Her government implemented neoliberal economic reforms, including privatization and austerity measures, aimed at stabilizing the war-torn economy and securing international aid. These policies, while achieving some macroeconomic stability, also led to increased unemployment and social hardship for many.

In the 1996 general election, Arnoldo Alemán of the Constitutionalist Liberal Party (PLC) defeated Daniel Ortega. Alemán's presidency (1997-2002) was marred by widespread corruption. He was later convicted and sentenced to 20 years in prison for embezzlement, money laundering, and other charges. This period saw the consolidation of a political pact (El Pacto) between Alemán's PLC and Ortega's FSLN, which critics argued was designed to divide power and exclude smaller parties, undermining democratic institutions.

Enrique Bolaños, Alemán's vice president, won the 2001 presidential election for the PLC. Bolaños (2002-2007) made anti-corruption a central theme of his presidency, pursuing charges against his predecessor Alemán. However, his efforts were often stymied by the PLC-FSLN alliance in the National Assembly, which sought to curtail his powers. Nicaragua briefly participated in the Iraq War in 2004 as part of the Plus Ultra Brigade. Before the 2006 general elections, the National Assembly passed a highly restrictive law banning all abortions, even in cases of rape or to save the mother's life, making Nicaragua one of the few countries in the world with such a total ban.

3.7.1. Return of Daniel Ortega and democratic backsliding

Daniel Ortega of the FSLN returned to the presidency after winning the 2006 election with 37.99% of the vote. This victory was facilitated by a change in electoral law (lowering the threshold to win without a runoff) and divisions within the liberal and conservative opposition. His return marked the beginning of a period characterized by a gradual but significant erosion of democratic institutions and civil liberties, a process often described as democratic backsliding.

Ortega's subsequent terms in office (re-elected in 2011, 2016, and 2021) have been characterized by:

- Concentration of Power:** Ortega and the FSLN systematically gained control over all branches of government, including the legislature, judiciary, electoral council, and security forces. Constitutional changes were pushed through, notably in 2014, to remove presidential term limits, allowing Ortega to run for office indefinitely. His wife, Rosario Murillo, became Vice President in 2017, further cementing family control over the state.

- Electoral Irregularities:** Elections have been increasingly criticized by domestic and international observers for lacking transparency and fairness. Opposition candidates have faced harassment, disqualification, and imprisonment. International monitoring has often been restricted or barred. The 2021 election, in particular, was widely condemned as a "sham" by the OAS, the United States, and the European Union, following the arrest of numerous opposition presidential candidates.

- Erosion of Civil Liberties:** Freedom of speech, press, and assembly has been progressively curtailed. Independent media outlets have faced harassment, closure, and seizure of assets. Journalists and activists critical of the government have been subjected to intimidation, arbitrary detention, and criminal charges.

- Repression of Opposition and Civil Society:** The government has increasingly repressed political opposition and independent civil society organizations. NGOs have been stripped of their legal status, their assets confiscated, and their members persecuted.

- Human Rights Concerns:** Human rights organizations have documented a pattern of abuses, including arbitrary arrests, torture, politically motivated prosecutions, and restrictions on fundamental freedoms.

While the Ortega government initially implemented some social programs, often funded by aid from Venezuela under the ALBA alliance, and maintained a degree of economic stability, the political trajectory has been one of increasing authoritarianism. This trend has led to a significant decline in Nicaragua's democratic standing and growing international isolation.

3.7.2. 2018 protests and political crisis

In April 2018, Nicaragua was convulsed by widespread anti-government protests, marking the most significant political crisis in the country since the end of the Contra War. The immediate trigger for the demonstrations was a government decree announcing reforms to the social security system, which included increasing taxes and reducing pension benefits. These reforms, implemented without broad consultation, sparked initial protests led by students and retirees.

The government's response to these early demonstrations was swift and brutal, involving the National Police and pro-government paramilitary groups (often referred to as turbas or parapoliciales). The violent repression of protesters, resulting in deaths and injuries, quickly inflamed public anger and transformed the protests from a specific grievance over social security into a broader movement demanding President Daniel Ortega's resignation, an end to repression, justice for victims, and democratic reforms.

Key aspects of the 2018 protests and ensuing crisis include:

- Widespread Mobilization:** Protests spread rapidly across the country, involving diverse sectors of society, including students, peasants, business groups, and ordinary citizens. Roadblocks (tranques) were erected in many areas, paralyzing the country for weeks.

- Government Repression:** The government's response was characterized by excessive use of force. Human rights organizations, including the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), documented hundreds of deaths (mostly protesters), thousands of injuries, arbitrary detentions, torture, enforced disappearances, and attacks on universities, churches, and media outlets. Medical personnel who treated injured protesters faced reprisals.

- Human Rights Violations:** Reports from human rights groups detailed systematic violations, including extrajudicial killings, the use of live ammunition against unarmed protesters, and the denial of due process for detainees. The IACHR identified a pattern of state-sponsored violence and impunity.

- Impact on Victims and Civil Society:** The crisis had a devastating impact on victims and their families. Many were forced into exile to escape persecution. Civil society organizations and human rights defenders faced intense harassment and criminalization. Independent media played a crucial role in documenting abuses despite facing severe pressure.

- Failed Dialogue Attempts:** Attempts at a national dialogue, mediated by the Catholic Church, failed to resolve the crisis due to the government's unwillingness to address core demands for justice and democratic reform.

- Economic Consequences:** The political instability and repression led to a sharp economic downturn, with significant impacts on tourism, investment, and overall economic activity, exacerbating poverty and unemployment.

- International Condemnation:** The Nicaraguan government's actions drew widespread international condemnation from human rights organizations, foreign governments, and international bodies like the OAS and the UN, leading to sanctions against key officials and entities.

The 2018 protests and the government's violent response marked a turning point, deepening the country's authoritarian slide and resulting in a protracted political, social, and human rights crisis with long-lasting consequences for Nicaragua.

3.7.3. Recent constitutional and political changes

Since the 2018 protests, the Nicaraguan government under President Daniel Ortega has undertaken a series of constitutional and political changes that critics and international observers argue have further consolidated executive power, eroded democratic institutions, and severely curtailed human rights. These changes often occur with limited debate and through a legislature dominated by the FSLN.

Key developments include:

- Electoral System Reforms:** Changes to electoral laws have been criticized for further advantaging the ruling FSLN and making it more difficult for opposition parties to compete. These reforms have often been enacted close to elections, limiting the ability of opponents to adapt. The independence and impartiality of the Supreme Electoral Council (CSE) remain a major concern.

- Restrictions on Political Participation:** Laws have been passed that restrict the ability of opposition figures to participate in politics. For example, legislation has been used to disqualify candidates, strip political parties of their legal status, and criminalize dissent under vague pretexts such as "treason" or "undermining national sovereignty." Ahead of the 2021 general election, numerous opposition presidential candidates and political leaders were arrested and detained.

- Further Consolidation of Executive Power:** Constitutional amendments and new laws have continued to strengthen the presidency and weaken checks and balances. In November 2024, the government presented a significant partial constitutional reform, which was subsequently passed. This reform reportedly defined Nicaragua as a revolutionary socialist state, recognized the FSLN flag as a national symbol, increased presidential powers by establishing a co-presidency (allowing the vice president, Rosario Murillo, to share presidential functions), extended the presidential term from 5 to 6 years, and introduced provisions that could be used to further limit freedom of speech and assembly by disallowing actions deemed to transgress "principles of security, peace, and wellbeing." Opponents were declared "traitors to the homeland."

- Crackdown on Civil Society and Media:** The legal framework has been used to systematically dismantle independent civil society. Hundreds of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), including human rights groups, women's organizations, academic institutions, and charitable foundations, have been stripped of their legal status, their assets often confiscated. Independent media outlets continue to face immense pressure, including censorship, financial strangulation, and legal persecution of journalists.

- Erosion of Judicial Independence:** The judiciary is widely seen as lacking independence and being subservient to the executive branch, frequently used to legitimize repressive actions and prosecute political opponents.

- Implications for Democracy and Human Rights:** These changes have been widely condemned by international human rights organizations, the OAS, the United Nations, and various countries as representing a severe regression in democratic governance and a deepening of authoritarian rule. Concerns are consistently raised about the lack of due process, the suppression of fundamental freedoms, and the creation of a climate of fear and repression. The reforms are seen as institutionalizing a system that prioritizes the perpetuation of power for the ruling party and its leaders over democratic principles and the protection of human rights.

These developments have further isolated Nicaragua internationally and have had a profound impact on the political landscape and the daily lives of its citizens, particularly those who express dissent or advocate for democratic change.

4. Geography

Nicaragua, located in the Central American isthmus, covers a landmass of approximately 50 K mile2 (130.37 K km2), making it the largest country in the region. It is bordered by Honduras to the northwest, the Caribbean Sea to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest. The country's diverse geography is characterized by three distinct regions: the Pacific lowlands, the North-central highlands (Amerrisque Mountains), and the Caribbean lowlands (Mosquito Coast). Nicaragua is often called "the land of lakes and volcanoes" due to its numerous volcanic formations and large bodies of freshwater.

4.1. Pacific lowlands

The Pacific lowlands, situated in the western part of the country, consist of a broad, hot, and remarkably fertile plain. This region was the primary area of Spanish colonial settlement and remains the most densely populated and economically significant part of Nicaragua, housing over half the nation's population. The landscape is punctuated by a chain of volcanoes, many of which are active, belonging to the Cordillera Los Maribios mountain range. Notable volcanoes include Mombacho near Granada and Momotombo near León. The volcanic ash from past eruptions has greatly enriched the soil, making it highly suitable for agriculture.

This region is home to Central America's two largest freshwater lakes: Lake Managua (also known as Lake Xolotlán) to the north and the much larger Lake Nicaragua (also known as Cocibolca) to the south. Lake Nicaragua is the largest lake in Central America and is unique for being home to freshwater sharks (Nicaraguan shark) and sawfish, as well as numerous islands, including the twin-volcano island of Ometepe. The lowlands extend from the Gulf of Fonseca in the northwest, along a rift valley that encompasses the lakes, down to the border with Costa Rica.

The Pacific zone is classified as tierra caliente (hot land), with elevations generally under 2001 ft (610 m). Temperatures are consistently high throughout the year, typically ranging between 84.2 °F (29 °C) and 89.6 °F (32 °C). The region experiences a distinct dry season from November to April and a rainy season from May to October, receiving 0.0 K in (1.00 K mm) to 0.1 K in (1.50 K mm) of precipitation annually. The fertile soils and favorable climate make this area the demographic and economic heartland of Nicaragua, supporting extensive agriculture and major urban centers like Managua, León, and Granada. The region's geological activity also results in frequent tremors and occasional devastating earthquakes, which have historically impacted cities like Managua.

4.2. North central highlands

The North-central highlands, also known as the Amerrisque Mountains, form a triangular area in the interior of Nicaragua, extending from the northwest towards the southeast, separating the Pacific lowlands from the Caribbean lowlands. This region is characterized by rugged mountain ranges, plateaus, and valleys, with elevations generally ranging from 2001 ft (610 m) to 5.0 K ft (1.52 K m), creating a more temperate climate (tierra templada) than the coastal plains. Daily high temperatures are milder, typically between 75.2 °F (24 °C) and 80.6 °F (27 °C).

This mountainous interior is significantly less populated and economically developed than the Pacific region, though certain valleys are fertile and support agriculture. The highlands are crucial for coffee production, which is a major export crop for Nicaragua, typically grown on the higher slopes. Other agricultural products include grains, vegetables, and cattle.

The North-central highlands are rich in biodiversity, featuring various ecosystems, including cloud forests at higher elevations. These forests are home to a variety of plant species such as oaks, pines, mosses, ferns, and numerous orchids. The region also supports diverse wildlife, including birds like the resplendent quetzal, goldfinches, hummingbirds, jays, and toucanets. The rugged terrain and extensive forests make this area suitable for ecotourism. While some areas suffer from soil erosion on steep slopes due to a longer and wetter rainy season, the region also contains mineral resources, including gold. Major towns in this region include Estelí, Jinotega, and Matagalpa.

4.3. Caribbean lowlands

The Caribbean lowlands, also known as the Atlantic lowlands or Mosquito Coast (La Mosquitia), constitute the largest geographical region of Nicaragua, covering roughly 57% of the country's territory. This vast, sparsely populated area extends along the entire eastern coast, from the Honduran border in the north to the Costa Rican border in the south. The plains can be up to 60 mile (97 km) wide in some areas.

Characterized by extensive rainforests, large rivers, and a hot, humid tropical climate with high rainfall throughout most of the year, this region is distinct from the rest of the country both geographically and culturally. Major rivers, including the Río Coco (which forms part of the border with Honduras and is the longest river in Central America), Río Grande de Matagalpa, Escondido, and San Juan, flow through these lowlands, creating vast floodplains and deltas as they empty into the Caribbean Sea. The coastline is sinuous, featuring numerous lagoons, estuaries, and offshore cays, such as the Corn Islands (Islas del Maíz).

The Caribbean lowlands are home to significant natural resources, including timber and minerals (such as gold in the "Mining Triangle" municipalities of Siuna, Rosita, and Bonanza). The region also boasts immense biodiversity and contains the Bosawás Biosphere Reserve, the second-largest rainforest in the Americas, covering nearly 7% of Nicaragua's land area and protecting a vast expanse of La Mosquitia forest.

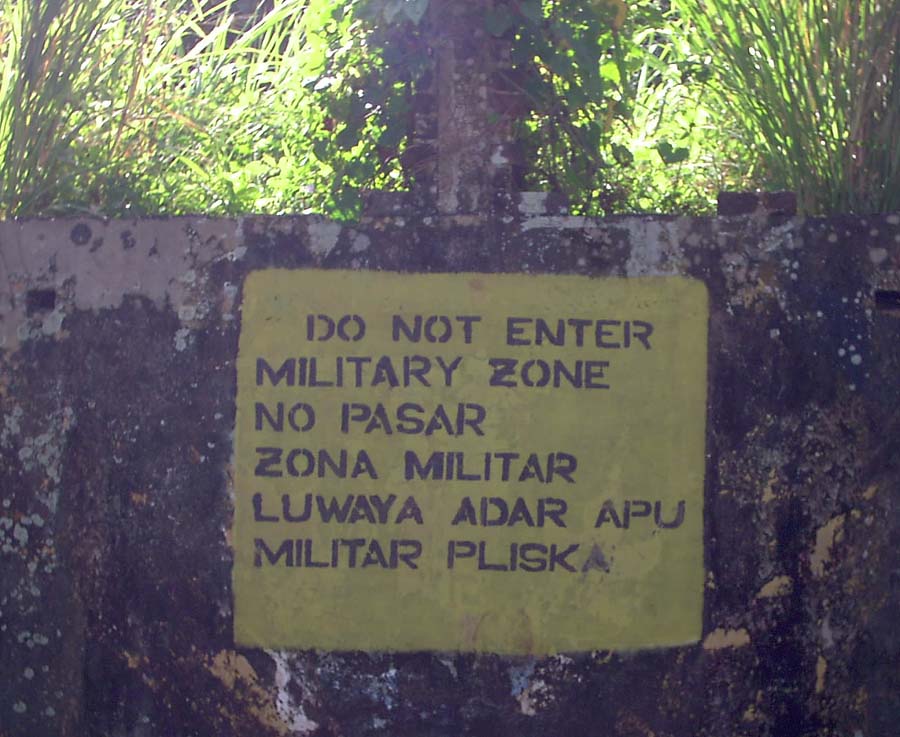

The population is sparse and culturally diverse, with a significant presence of indigenous groups like the Miskito, Mayangna (Sumo), and Rama, as well as Afro-Nicaraguan communities, including English-speaking Creoles and the Garifuna. Historically, this region had strong British influence, and English or English-based creoles are still widely spoken alongside Spanish and indigenous languages. The principal city is Bluefields. Access to this region has historically been challenging, though infrastructure is gradually improving. The area faces environmental pressures from deforestation, agricultural expansion, and resource extraction.

4.4. Climate

Nicaragua has a predominantly tropical climate, but it varies significantly by region and altitude. Generally, the country experiences two main seasons: a dry season (verano or summer) from approximately November to April, and a rainy season (invierno or winter) from May to October.

- Pacific Lowlands:** This region has a tropical savanna climate (Köppen Aw). It is characterized by consistently high temperatures, typically ranging from 71.6 °F (22 °C) at night to 89.6 °F (32 °C) during the day, with little seasonal variation in temperature. Humidity is high, especially during the rainy season. The dry season is marked by less rainfall and often strong offshore winds (Papagayo winds). Annual rainfall ranges from 0.0 K in (1.00 K mm) to 0.1 K in (1.50 K mm).

- North-Central Highlands:** This region experiences a more temperate climate (tierra templada) due to its higher altitudes (generally 1969 ft (600 m) to 4.9 K ft (1.50 K m)). Temperatures are cooler than in the lowlands, with average daily highs between 75.2 °F (24 °C) and 80.6 °F (27 °C). This area receives more rainfall than the Pacific lowlands, and the rainy season can be longer and more intense, contributing to lush vegetation but also to soil erosion on steep slopes. Higher elevations can experience cloud forests.

- Caribbean Lowlands:** This region has a tropical rainforest climate (Köppen Af) or a tropical monsoon climate (Köppen Am) in some parts. It is characterized by high temperatures and high humidity year-round. Rainfall is abundant and more evenly distributed throughout the year compared to the Pacific side, though there might be a slightly drier period from February to April. Annual rainfall can exceed 0.1 K in (2.50 K mm) and in some areas reach up to 0.2 K in (5.00 K mm) or more, making it one of the wettest regions in Central America. This region is also susceptible to hurricanes and tropical storms approaching from the Caribbean Sea, particularly from June to November.

Nicaragua's location makes it vulnerable to extreme weather events like hurricanes (such as Hurricane Felix in 2007 and Hurricanes Eta and Iota in 2020) and tropical storms, which can cause significant flooding and damage, especially in the Caribbean lowlands and along major rivers. The country is also affected by El Niño and La Niña phenomena, which can lead to droughts or excessive rainfall, respectively.

4.5. Flora and fauna

Nicaragua boasts remarkable biodiversity, a result of its geographical position as a land bridge between North and South America and its varied ecosystems, which range from tropical rainforests and cloud forests to tropical dry forests, mangroves, and freshwater and marine environments. The country is part of the Mesoamerican biodiversity hotspot, one of the most biologically rich yet threatened regions on Earth.

- Flora:**

Nicaragua is home to an estimated 12,000 species of plants, with many still unclassified. The Caribbean lowlands feature vast expanses of tropical rainforest, characterized by towering trees, lianas, epiphytes (like orchids and bromeliads), and a dense understory. The Bosawás Biosphere Reserve, the largest protected area in Nicaragua and Central America, is a critical reservoir of this biodiversity. The North-central highlands harbor cloud forests with oak, pine, and unique montane vegetation, as well as areas of pine-oak forest. The Pacific lowlands were once covered by tropical dry forests, though much of this has been converted to agriculture; remnants still exist, showcasing species adapted to seasonal drought, such as the Guanacaste tree (Nicaragua's national tree). Coastal areas feature mangrove forests, important for marine life and coastal protection.

- Fauna:**

Nicaragua's fauna is equally diverse. The country is home to approximately 183 species of mammals, 705 bird species, 248 species of amphibians and reptiles, and 640 fish species.

- Mammals:** Notable mammals include several species of monkeys (howler, spider, capuchin), jaguars, pumas, ocelots, tapirs (Baird's tapir), giant anteaters, sloths, and a variety of bats.

- Birds:** Avian diversity is spectacular, featuring the Guardabarranco (Turquoise-browed Motmot, the national bird), toucans, macaws (including the scarlet macaw), parrots, quetzals (in cloud forests), eagles, and numerous migratory species.

- Reptiles and Amphibians:** The country has a rich herpetofauna, including crocodiles, caimans, various snakes (boas, pit vipers), iguanas, and numerous frog species, some of which are endemic.

- Fish:** Lake Nicaragua is famous for its unique freshwater fauna, including the Nicaraguan shark (a population of bull sharks adapted to freshwater) and the sawfish, though populations of both have declined significantly. The lake and rivers also support numerous cichlid species and other freshwater fish. Marine biodiversity is rich on both the Pacific and Caribbean coasts, with coral reefs found around the Corn Islands.

- Protected Areas and Conservation:**

Nearly one-fifth of Nicaragua's territory is designated as protected areas, including national parks, biological reserves, and nature reserves. The Indio Maíz Biological Reserve in the southeast and the Bosawás Biosphere Reserve in the north are two of the largest and most important. Despite these efforts, Nicaragua faces significant environmental challenges, including:

- Deforestation:** This is a major issue, driven by agricultural expansion (especially cattle ranching and subsistence farming), logging (both legal and illegal), and settlement. The agricultural frontier is rapidly advancing into forested areas, particularly in the Caribbean lowlands and Bosawás.

- Soil Erosion and Water Pollution:** Unsustainable agricultural practices, deforestation, and mining activities contribute to soil erosion and contamination of water sources with pesticides and heavy metals.

- Threats to Wildlife:** Habitat loss, poaching, and the illegal wildlife trade threaten many species.

- Climate Change:** Nicaragua is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, including more intense storms, altered rainfall patterns, and sea-level rise.

Conservation efforts involve governmental agencies, NGOs, and local communities, focusing on sustainable resource management, reforestation, and the protection of endangered species and critical habitats. However, these efforts often face challenges due to limited resources, institutional weaknesses, and competing economic pressures.

5. Government and Politics

Nicaragua is a presidential representative democratic republic. However, in recent decades, particularly since the return of Daniel Ortega to power, the country has experienced significant democratic backsliding, with increasing concerns over authoritarian tendencies, the erosion of checks and balances, and human rights violations. This has led to widespread criticism from domestic opposition groups and the international community.

5.1. Government structure

The Constitution establishes three main branches of government:

- Executive Branch:** Headed by the President of Nicaragua, who is both the head of state and head of government. The President and Vice President are elected by popular vote for a five-year term (a 2024 constitutional reform extended this to six years and established a co-presidency where the Vice President can share presidential functions). The President appoints the Council of Ministers. Constitutional changes in 2014 removed presidential term limits, allowing for indefinite re-election.

- Legislative Branch:** Vested in the unicameral National Assembly (Asamblea Nacional). It consists of 92 members: 90 deputies elected through a system of proportional representation (20 national deputies and 70 departmental/regional deputies) for five-year terms, plus the outgoing President and the presidential candidate who finishes second with a significant vote share in the presidential election. The FSLN has maintained a strong majority in the Assembly, enabling it to pass legislation and constitutional reforms with little effective opposition.

- Judicial Branch:** Headed by the Supreme Court of Justice. The judiciary also includes appellate courts and lower courts. However, the independence of the judiciary has been severely compromised, with appointments and decisions widely seen as politically influenced by the executive branch.

The Supreme Electoral Council (Consejo Supremo Electoral - CSE) is responsible for organizing and overseeing elections, but its impartiality has also been a major point of contention, with accusations of manipulation in favor of the ruling party.

5.2. Political developments and human rights

Since Daniel Ortega's return to the presidency in 2007, Nicaragua has undergone a significant political transformation marked by the consolidation of power by Ortega, his wife Vice President Rosario Murillo, and the ruling Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN). This period has been characterized by:

- Democratic Backsliding:** There has been a systematic weakening of democratic institutions, including the legislature, judiciary, and electoral authorities. Checks and balances have been eroded, and power has become increasingly centralized in the executive.

- Restrictions on Political Opposition:** Opposition parties and leaders have faced increasing harassment, disqualification from elections, and persecution. Ahead of the 2021 general election, numerous presidential candidates and prominent opposition figures were arrested and detained on charges widely viewed as politically motivated, effectively eliminating meaningful competition.

- Suppression of Dissent and Media:** Freedom of expression, assembly, and the press have been severely curtailed. Independent media outlets have faced censorship, closure, seizure of assets, and attacks. Journalists, activists, and human rights defenders critical of the government have been subjected to intimidation, arbitrary detention, and criminalization. Numerous NGOs have been stripped of their legal status and forced to close.

- Human Rights Violations:** The government's response to the widespread anti-government protests in 2018 was particularly brutal, resulting in hundreds of deaths, thousands of injuries, and widespread arrests. Human rights organizations documented extrajudicial killings, torture, and other severe abuses by state forces and pro-government paramilitary groups. Impunity for these violations remains a significant concern.

- Constitutional Changes:** Constitutional reforms have been implemented to remove presidential term limits and further entrench the FSLN's power. A 2024 reform, among other changes, reportedly established a co-presidency, extended the presidential term, and introduced provisions that could further restrict fundamental freedoms under the guise of national security and stability.

These developments have led to Nicaragua being widely described as an authoritarian state by international observers and human rights organizations. The situation has resulted in international condemnation, sanctions from countries like the United States and the European Union, and a significant exodus of Nicaraguans seeking refuge abroad. The government typically denies these accusations, attributing criticism to foreign interference and attempts to destabilize the country. The human rights situation remains dire, with ongoing reports of repression against any form of dissent.

5.3. Foreign relations

Nicaragua's foreign policy under the Daniel Ortega administration has been characterized by a strong anti-imperialist rhetoric, particularly critical of the United States, and a deepening of alliances with countries that share similar ideological stances or offer alternative partnerships.

Key aspects of Nicaragua's foreign relations include:

- Relations with the United States:** Historically complex, relations with the U.S. have become increasingly strained due to concerns over democratic backsliding and human rights abuses in Nicaragua. The U.S. has imposed sanctions on Nicaraguan officials and entities and has been a vocal critic of the Ortega government.

- Relations with Russia:** Nicaragua has cultivated closer ties with Russia, including military cooperation, economic agreements, and diplomatic support. Russia has provided military equipment and training to Nicaragua and has supported the Ortega government in international forums. In 2022, Nicaragua authorized the temporary stationing of Russian troops, ships, and aircraft for training and humanitarian purposes, a move viewed with concern by some regional actors.

- Relations with China:** In December 2021, Nicaragua switched diplomatic recognition from Taiwan (Republic of China) to the People's Republic of China, aligning with Beijing's "One China" policy. This move was seen as an effort to secure new economic and political partnerships.

- ALBA Alliance:** Nicaragua is a member of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA), a leftist political and economic alliance founded by Venezuela and Cuba. Through ALBA, Nicaragua received significant economic assistance from Venezuela, particularly during the Chávez era, though this aid has diminished with Venezuela's own economic crisis.

- Relations with Cuba and Venezuela:** Nicaragua maintains close political and ideological ties with Cuba and Venezuela, forming part of a bloc critical of U.S. foreign policy in Latin America.

- Central American Relations:** Relations with neighboring Central American countries are generally functional, though occasional tensions arise, particularly with Costa Rica over border issues and migration. Nicaragua participates in regional integration efforts like the Central American Integration System (SICA).

- International Organizations:** Nicaragua is a member of the United Nations and other international bodies. However, its relationship with the Organization of American States (OAS) deteriorated significantly following the 2018 crisis. In November 2021, Nicaragua announced its withdrawal from the OAS, a process that formally concluded in November 2023, after the OAS repeatedly condemned human rights violations and the erosion of democracy in the country.

- Territorial Disputes:** Nicaragua has had historical territorial disputes with Colombia over maritime boundaries and islands in the Caribbean Sea (such as the San Andrés archipelago and Quita Sueño Bank). The International Court of Justice (ICJ) has issued rulings on these disputes, some of which have redefined maritime borders. There have also been disputes with Costa Rica concerning navigation rights on the San Juan River, which forms part of their border, and maritime delimitation in both the Pacific and Caribbean.

- International Stance on Global Issues:** Nicaragua has often aligned itself with countries critical of Western foreign policy. For instance, it voted against UN resolutions condemning Russia's invasion of Ukraine. It recognized the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia in 2008.

Nicaragua's foreign policy choices reflect a strategy of seeking diverse international partnerships while navigating criticism and pressure regarding its domestic political situation.

5.4. Military

The Nicaraguan Armed Forces (Fuerzas Armadas de Nicaragua) are responsible for the national defense of Nicaragua. The current military was established after the Nicaraguan Revolution in 1979, evolving from the Sandinista Popular Army (EPS).

The main branches of the Nicaraguan Armed Forces are:

- The Army (Ejército de Nicaragua):** This is the largest branch, responsible for land-based operations, border security, and internal defense.

- The Navy (Fuerza Naval):** Responsible for maritime security in Nicaragua's territorial waters in both the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, including combating drug trafficking and illegal fishing.

- The Air Force (Fuerza Aérea):** Provides air support, reconnaissance, and transport capabilities.

The President of Nicaragua is the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces. The military's role is defined by the constitution and national laws, primarily focusing on defending national sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity.

- Historical Context and Evolution:**

The Nicaraguan military has undergone significant transformations throughout its history. The U.S.-trained National Guard under the Somoza dynasty was dismantled after the 1979 revolution. The Sandinista Popular Army (EPS) was a large, conscript-based force heavily involved in the Contra War of the 1980s. Following the end of the war and the change of government in 1990, the military was significantly downsized, professionalized, and depoliticized, with conscription abolished. It was renamed the Nicaraguan Army and later the Nicaraguan Armed Forces.

- Current Size and Capabilities:**

Compared to the revolutionary era, the current Nicaraguan military is relatively small, with an active duty personnel estimated to be around 12,000 to 14,000. Its equipment is largely of Soviet-era origin, a legacy of support during the 1980s, though there have been some efforts to modernize and acquire new equipment, including from Russia in recent years. The defense budget is modest.

- Roles and Engagements:**

Beyond traditional defense roles, the Nicaraguan military is involved in:

- Combating drug trafficking and organized crime, often in coordination with other Central American nations and international partners.

- Disaster relief and humanitarian assistance operations.

- Environmental protection, including efforts against illegal logging and poaching in protected areas.

- Border security, particularly along the borders with Honduras and Costa Rica.

In recent years, there has been increased military cooperation with Russia, including training, technical assistance, and the acquisition of Russian military hardware. In 2017, Nicaragua signed the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. The role and influence of the military in domestic politics remain a subject of observation, particularly given the country's recent political developments.

5.5. Law enforcement

Law enforcement in Nicaragua is primarily the responsibility of the National Police of Nicaragua (Policía Nacional de Nicaragua). Established in its modern form after the 1979 Nicaraguan Revolution, it replaced the Somoza-era National Guard in civilian policing functions, with the National Guard's military functions transitioning to the new army.

- Structure and Functions:**

The National Police is a centralized force under the Ministry of Interior (Ministerio de Gobernación). Its responsibilities include:

- Maintaining public order and safety.

- Preventing and investigating crimes.

- Traffic control and enforcement.

- Border policing functions in some areas, often in coordination with the military.

- Combating organized crime, including drug trafficking and gang activity.

Historically, the Nicaraguan National Police had a reputation, particularly in the 1990s and early 2000s, for a community policing model that contributed to relatively low homicide rates compared to some neighboring Central American countries. For example, in 2021, the intentional homicide rate was reported at 11 per 100,000 inhabitants.

- Challenges and Concerns:**

However, in recent years, particularly since the 2018 anti-government protests, the National Police has faced severe criticism from national and international human rights organizations for:

- Excessive Use of Force:** Allegations of widespread and disproportionate use of force against protesters, including the use of live ammunition, resulting in numerous deaths and injuries.

- Arbitrary Arrests and Detentions:** Reports of mass arbitrary arrests of protesters, opposition figures, journalists, and human rights defenders.

- Torture and Ill-Treatment:** Numerous testimonies and reports of torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment of detainees in police custody.

- Politicization and Lack of Independence:** The police force is widely perceived as being heavily politicized and acting in the interests of the ruling FSLN party and the Ortega government, rather than as an impartial enforcer of the law. Its leadership is closely aligned with the executive.

- Impunity:** A lack of accountability for human rights violations committed by police officers. Investigations into abuses are rare, and prosecutions even rarer.

- Corruption:** Like many institutions in the region, the police force has faced issues of corruption, although this has been overshadowed by the more severe human rights concerns in recent years.

- Cooperation with Paramilitary Groups:** During the 2018 crackdown, the police were observed operating alongside and, in some cases, directing pro-government armed civilian groups (paramilitaries or turbas) in suppressing protests.

These issues have led to a significant loss of public trust in the National Police and have resulted in sanctions being imposed by countries like the United States and the European Union against high-ranking police officials. The transformation of the police from an institution once lauded for community engagement to one accused of systematic repression represents a major challenge for public security and the rule of law in Nicaragua. A 2024 constitutional reform also established a voluntary civilian police as "an auxiliary body in support of the National Police," raising further concerns about the militarization of public security and potential for abuse.

5.6. Administrative divisions

Nicaragua is a unitary republic, and for administrative purposes, it is divided into 15 departments (departamentosdepartmentsSpanish) and two autonomous regions (regiones autónomasautonomous regionsSpanish). This structure is based on the Spanish model. The departments are further subdivided into 153 municipalities (municipiosmunicipalitiesSpanish).

The two autonomous regions, located on the Caribbean coast, were established in 1987 to grant a degree of self-governance to the indigenous and Afro-descendant populations in that historically distinct part of the country. They are:

- North Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region (Región Autónoma de la Costa Caribe Norte - RACCN), formerly known as Región Autónoma del Atlántico Norte (RAAN). Its capital is Bilwi (Puerto Cabezas).

- South Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region (Región Autónoma de la Costa Caribe Sur - RACCS), formerly known as Región Autónoma del Atlántico Sur (RAAS). Its capital is Bluefields.

The 15 departments are:

| # | Department | Capital city |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Boaco | Boaco |

| 2 | Carazo | Jinotepe |

| 3 | Chinandega | Chinandega |

| 4 | Chontales | Juigalpa |

| 5 | Estelí | Estelí |

| 6 | Granada | Granada |

| 7 | Jinotega | Jinotega |

| 8 | León | León |

| 9 | Madriz | Somoto |

| 10 | Managua | Managua |

| 11 | Masaya | Masaya |

| 12 | Matagalpa | Matagalpa |

| 13 | Nueva Segovia | Ocotal |

| 14 | Rivas | Rivas |

| 15 | Río San Juan | San Carlos |

Each department and autonomous region has its own local government structure, though the degree of autonomy is most significant in the RACCN and RACCS, which have their own regional councils and coordinators with specific mandates related to cultural preservation, resource management, and local governance for their diverse ethnic populations.

6. Economy

Nicaragua's economy is primarily focused on the agricultural sector, and it is one of the poorest countries in the Americas, facing significant challenges related to poverty, unemployment, and underdevelopment. The social impacts of economic policies and political instability have been profound, often exacerbating inequality and hardship for vulnerable populations.

6.1. Economic overview and structure

Nicaragua has the second-lowest GDP per capita (nominal) and third-lowest GDP per capita (PPP) among Latin American and Caribbean countries. In 2008, its GDP (PPP) was estimated at 17.37 B USD. The economy is characterized by its reliance on a few key sectors:

- Agriculture:** This sector remains a cornerstone of the Nicaraguan economy, contributing significantly to GDP (around 15.5%, the highest in Central America) and employment. Key agricultural exports include coffee, beef, sugar, peanuts, and seafood.

- Services:** The services sector, including commerce, tourism, and finance, is the largest contributor to GDP.

- Industry:** Manufacturing, particularly in the maquila (assembly plant) sector producing textiles and apparel for export, plays an important role, though it faces competition from Asian markets. Mining (gold) also contributes to exports.

- Key Economic Indicators and Challenges:**

- Poverty and Inequality:** High levels of poverty and income inequality persist. According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), in the past, nearly half the population lived below the poverty line, with a significant portion living on less than $2 per day. Indigenous populations often face even more severe poverty.

- Unemployment and Underemployment:** Formal unemployment rates can be misleading, as underemployment and participation in the informal sector are widespread.

- Remittances:** Remittances from Nicaraguans living abroad (primarily in Costa Rica, the United States, and Spain) are a crucial source of income for many families and a significant contributor to the national economy, accounting for over 15% of GDP.

- Foreign Debt:** Historically, Nicaragua has struggled with high levels of foreign debt, though it has benefited from debt relief initiatives like the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) program.

- Political Instability:** Periods of political instability, such as the crisis following the 2018 protests, have had severe negative impacts on the economy, deterring investment, disrupting tourism, and leading to economic contraction. Restrictive tax measures and civil conflict further impacted public spending and investor confidence. The COVID-19 pandemic also negatively affected the economy.

- Inflation:** While hyperinflation was a major problem in the 1980s, it has generally been brought under control, though it can still be a concern.

- Corruption:** Nicaragua ranks poorly on international corruption indices. In 2024, it was ranked as the second most corrupt country in Latin America by the Corruption Perceptions Index.

- Dependence on International Aid and Commodity Prices:** The economy is vulnerable to fluctuations in international commodity prices and has historically relied on international aid and preferential trade agreements.

The government has pursued various economic strategies, including attracting foreign investment, promoting exports, and seeking alternative economic partnerships, such as through the ALBA alliance. However, structural challenges and the prevailing political climate continue to pose significant obstacles to sustainable and equitable economic development. Nicaragua was ranked 124th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.

6.2. Main sectors

Nicaragua's economy is primarily based on agriculture, with growing contributions from manufacturing, mining, and services, including tourism.

- Agriculture:** This sector is a mainstay of the Nicaraguan economy, employing a significant portion of the labor force and accounting for a large share of export earnings (around 60% historically).

- Coffee:** One of the most important export crops, primarily grown in the northern highlands (departments like Jinotega, Matagalpa, Nueva Segovia, Estelí). Nicaraguan coffee is recognized for its quality and is purchased by international companies like Nestlé and Starbucks.

- Beef:** Cattle ranching is a major activity, and beef is a significant export.

- Sugar:** Sugarcane cultivation is prominent, particularly in the western regions, for sugar production and export.

- Other Crops:** Other important agricultural products include beans, corn (staple food crops), rice, bananas, peanuts, sesame, melons, onions, and tobacco. Tobacco, especially for cigars, has become an increasingly valuable export.

- Fisheries and Aquaculture:** Shrimp and lobster from the Caribbean coast are important exports. Aquaculture, particularly shrimp farming, is also present.

- Challenges:** The agricultural sector faces challenges such as vulnerability to climate change (droughts, hurricanes), price volatility for export commodities, soil erosion, and pollution from pesticide use.

- Manufacturing (Maquila Sector):** The maquila or Free Trade Zone (FTZ) sector focuses on the assembly of goods for export, primarily textiles and apparel. This sector has been an important source of employment, particularly for women, but it faces competition from lower-cost manufacturing centers in Asia and is sensitive to international trade conditions and labor standards concerns.

- Mining:** Mining, particularly for gold, has become an increasingly significant industry, contributing to export revenues. The "Mining Triangle" (Siuna, Rosita, Bonanza) in the North Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region is a key gold-producing area. However, mining activities also raise environmental and social concerns regarding deforestation, water pollution, and impacts on indigenous communities.

- Services:** This is the largest sector of the economy.

- Commerce:** Wholesale and retail trade are vital.

- Tourism:** This sector grew significantly prior to the 2018 political crisis and remains a potential area for economic recovery (covered in a separate section).

- Finance:** Banking and financial services are established, though access to credit can be limited, especially for small businesses and rural populations.

The Nicaraguan economy's structure reflects its status as a developing country, with a heavy reliance on primary commodity exports and a need for diversification and value addition to achieve more resilient and equitable growth.

6.3. Tourism

Tourism grew to become a significant industry in Nicaragua, at one point becoming the second-largest source of foreign exchange, before being severely impacted by the political crisis that began in 2018. Prior to this, the sector had experienced substantial growth for over a decade, with annual growth rates often exceeding 10%. In 2010, Nicaragua welcomed over one million tourists for the first time. The government has historically viewed tourism as a key tool for economic development and poverty reduction.

- Major Attractions:**

Nicaragua offers a diverse range of attractions:

- Colonial Cities:** León and Granada are prime destinations, renowned for their well-preserved Spanish colonial architecture, historic churches, and vibrant cultural scenes. Granada, founded in 1524, is one of the oldest colonial cities in the Americas.

- Volcanoes:** Known as "the land of lakes and volcanoes," Nicaragua has numerous volcanoes, many of which are accessible for hiking, climbing, and even sandboarding (e.g., Cerro Negro near León). Popular volcanoes include Mombacho (with cloud forests and coffee plantations), Masaya Volcano (with an active lava lake), Momotombo, and the twin volcanoes Concepción and Maderas on Ometepe Island.

- Lakes and Islands:** Lake Nicaragua is a major attraction, offering boat tours, fishing, and visits to islands like Ometepe (known for its volcanoes, pre-Columbian petroglyphs, and diverse ecosystems) and the Solentiname Islands (famous for their primitivist art and birdlife). Apoyo Lagoon, a pristine crater lake, is popular for swimming, kayaking, and ecotourism.

- Beaches and Surfing:** The Pacific coast boasts numerous beaches, with San Juan del Sur being a well-known hub for surfing, nightlife, and tourism. Other surfing spots have also gained international recognition. The Corn Islands (Big Corn and Little Corn) in the Caribbean offer white-sand beaches, turquoise waters, snorkeling, and diving.

- Ecotourism and Nature Reserves:** Nicaragua's rich biodiversity and extensive protected areas, such as the Bosawás Biosphere Reserve and the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve, provide opportunities for ecotourism, birdwatching, wildlife viewing, and exploring rainforests. The Somoto Canyon is another popular natural attraction.