1. Overview

Western Sahara represents one of the world's most protracted and unresolved territorial disputes, situated in the Maghreb region of North-western Africa. Formerly a Spanish colony, its decolonization process was interrupted in 1975, leading to conflicting claims primarily between Morocco, which administers approximately 70-80% of the territory (including most of the coastline and natural resources), and the Polisario Front, which seeks full independence for the indigenous Sahrawi population under the banner of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). The SADR controls the remaining, largely uninhabited, eastern portion of the territory.

This article explores the complex history of Western Sahara, from its early inhabitants and colonial period through the ongoing conflict and peace efforts. It delves into the geography of the arid land, the political structures in both Moroccan-administered and SADR-administered areas, and the critical human rights situation affecting Sahrawis, including those in refugee camps. The dispute itself is examined in detail, including the role of the United Nations, various peace proposals, and the profound humanitarian consequences. The economic aspects, particularly the controversial exploitation of natural resources, the demographics, and the unique culture of the Sahrawi people are also covered. Finally, the article discusses the international dimensions of the conflict, including the foreign relations and diplomatic efforts of both Morocco and the SADR. Throughout, this document aims to reflect a perspective centered on the unresolved status of the territory, the fundamental right to self-determination for the Sahrawi people, and the pressing human rights concerns that have characterized this enduring issue.

2. History

The history of Western Sahara is marked by ancient indigenous populations, successive waves of migration and conquest, European colonialism, and a prolonged post-colonial conflict over its sovereignty and the right to self-determination for its native Sahrawi people. Key phases include early settlements, Spanish colonization, and the ongoing dispute following Spain's withdrawal, primarily between Morocco and the Polisario Front.

2.1. Early history

The earliest known inhabitants of Western Sahara were likely Berber populations, including the Gaetuli. Roman-era sources describe the area as inhabited by Gaetulian Autololes or Gaetulian Daradae tribes. Berber heritage is still evident in regional and place-name toponymy, as well as in tribal names. Other early inhabitants may include the Bafour and later the Serer people. The Bafour were eventually replaced or absorbed by Berber-speaking populations.

The arrival of Islam in the 8th century CE played a crucial role in the development of the Maghreb region. Trade routes, particularly caravan routes connecting Marrakesh with Timbuktu in Mali, likely traversed the territory. In the 11th century, Maqil Arab groups began migrating westward. Over several centuries, a complex process of acculturation and intermarriage occurred between the indigenous Berber tribes and Arab groups, notably the Beni Ḥassān tribe (a sub-tribe of the Maqil). This fusion led to the development of the Hassaniya Arabic dialect and the unique cultural identity of the Sahrawi people. The Sanhaja Berber confederation was also influential in the region.

2.2. Spanish colonial rule

Spain's colonial involvement in Western Sahara began in the late 19th century. At the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, European powers divided Africa into spheres of influence, and Spain was allocated the coastal region of Western Sahara. In 1884, Spain declared a protectorate over the coastal zone from Cape Bojador to Cap Blanc, establishing trading posts and military garrisons, with Villa Cisneros (present-day Dakhla) becoming a key administrative center. Initial Spanish interest focused on fishing and strategic coastal control, rather than extensive inland exploitation.

The territory, then known as Spanish Sahara, was formally divided into two districts: Río de Oro in the south and Saguia el-Hamra in the north. Penetration into the interior was slow and met with resistance from Sahrawi tribes. It was not until the 1930s, often in cooperation with French colonial forces in neighboring territories, that Spain managed to pacify the interior. During the colonial period, some infrastructure development occurred, particularly related to phosphate mining discovered at Bou Craa in 1947, which became a significant economic interest for Spain.

Following World War II, a global wave of decolonization began. In 1958, Spain merged Río de Oro and Saguia el-Hamra into a single overseas province called Spanish Sahara. Morocco, which gained independence in 1956, began to claim historical sovereignty over Spanish Sahara, as well as Ifni and other Spanish-held territories. Mauritania, upon its independence in 1960, also laid claim to parts of the territory.

In 1963, Western Sahara was included on the United Nations list of non-self-governing territories. The United Nations General Assembly passed its first resolution on the territory in 1965, asking Spain to decolonize and allow for self-determination. Subsequent resolutions reiterated this call for a referendum. By the early 1970s, Sahrawi nationalist sentiment grew, leading to the formation of movements like the Movement for the Liberation of Saguia el-Hamra and Wadi ed-Dahab (MLS), which organized the Zemla Intifada in Laayoune in 1970, an event met with Spanish repression. This was followed by the establishment of the Polisario Front (Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguia el-Hamra and Río de Oro) in 1973, which advocated for armed struggle to achieve independence. Spain, under the declining regime of Francisco Franco, eventually promised a referendum on self-determination in 1974-75.

2.3. Beginning of the territorial dispute and the Western Sahara War

The withdrawal of Spain in 1975 marked a critical turning point, leading directly to the Western Sahara conflict. As Spain prepared to decolonize, both Morocco and Mauritania intensified their claims to the territory. In October 1975, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued an advisory opinion acknowledging historical ties between Western Sahara and both Morocco and Mauritania, but crucially affirmed that these ties did not constitute a basis for sovereignty that would override the Sahrawi people's right to self-determination.

Ignoring the ICJ's emphasis on self-determination, King Hassan II of Morocco launched the Green March on November 6, 1975. This event saw approximately 350,000 unarmed Moroccan civilians cross into Western Sahara to assert Moroccan sovereignty. Simultaneously, Moroccan troops had already begun entering the territory from the north. Under immense pressure, Spain signed the Madrid Accords on November 14, 1975, with Morocco and Mauritania. This agreement effectively partitioned Spanish Sahara: Morocco was to administer the northern two-thirds, and Mauritania the southern third. Spain officially terminated its presence on February 26, 1976.

The Polisario Front, vehemently opposing the partition and backed by Algeria, declared the establishment of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) on February 27, 1976. This marked the beginning of the Western Sahara War, a protracted guerrilla conflict. The Polisario Front, utilizing its knowledge of the desert terrain and support from Algeria (including refugee camps in Tindouf), waged war against both Moroccan and Mauritanian forces. The Sahrawi population faced significant upheaval, with tens of thousands fleeing the conflict, many becoming refugees in the Tindouf camps. This period was characterized by intense fighting and displacement, underscoring the Sahrawi people's resistance against what they viewed as foreign occupation and a denial of their right to independence.

Mauritania, facing internal instability and military setbacks due to Polisario attacks (including raids on its capital, Nouakchott, and iron ore mines), found the war economically and militarily unsustainable. In 1979, Mauritania signed a peace treaty with the Polisario Front, renouncing all claims to Western Sahara and withdrawing its forces. Morocco promptly moved to occupy the southern portion previously held by Mauritania, further consolidating its control over most of the territory. The conflict then continued primarily between Morocco and the Polisario Front. Morocco constructed a series of defensive sand berms, known as the Moroccan Wall, heavily fortified with landmines and military outposts, to restrict Polisario incursions into the economically significant western parts of the territory.

2.4. Ceasefire and peace negotiation attempts

After years of conflict, a United Nations-brokered ceasefire came into effect on September 6, 1991. This was part of a larger peace initiative known as the Settlement Plan, which had been accepted by both Morocco and the Polisario Front in 1988. A key component of the Settlement Plan was the organization of a referendum that would allow the Sahrawi people to choose between independence or integration with Morocco. To oversee the ceasefire and organize this referendum, the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) was established.

However, the referendum process quickly stalled due to disagreements over voter eligibility. The Polisario Front insisted that the electorate should be based on the 1974 Spanish census of the territory, with updates for births and deaths. Morocco, on the other hand, argued for the inclusion of individuals it claimed were Sahrawis who had fled to Morocco in previous decades or had tribal links to the territory, as well as Moroccan citizens who had settled in Western Sahara after 1975. These disagreements proved insurmountable, and the referendum, initially scheduled for 1992, has never been held.

Several attempts were made to revive the peace process. The Houston Agreement of 1997, brokered by former U.S. Secretary of State James Baker III, who was appointed as the UN Secretary-General's Personal Envoy for Western Sahara, aimed to resolve the voter identification deadlock but ultimately failed. Baker later proposed two comprehensive peace plans. The first, known as the "Framework Agreement" or Baker Plan I (2001), suggested a period of autonomy for Western Sahara within Morocco, followed by a referendum on final status after five years, with all residents of the territory (including Moroccan settlers) eligible to vote. This plan was accepted by Morocco but rejected by the Polisario Front because it did not guarantee the option of independence and diluted the Sahrawi electorate.

The second plan, "Peace Plan for Self-Determination of the People of Western Sahara" or Baker Plan II (2003), proposed a similar five-year period of autonomy under a Western Sahara Authority, followed by a referendum offering three options: independence, integration with Morocco, or continuation of autonomy. Voter eligibility would be based on the 1974 census and UNHCR refugee lists. This plan was endorsed by the UN Security Council and accepted by the Polisario Front as a basis for negotiation, but Morocco rejected it, primarily because it included independence as an option. James Baker resigned as UN Envoy in 2004, frustrated by the lack of progress. Subsequent UN envoys have continued efforts to facilitate negotiations, but the political stalemate has persisted.

2.5. Recent developments (21st century)

The 21st century has seen continued political deadlock, intermittent tensions, and significant shifts in international dynamics concerning Western Sahara, profoundly impacting the Sahrawi people and the prospects for peace. Morocco has continued to propose an autonomy plan for the territory under Moroccan sovereignty as the only viable solution, a proposal first formally submitted to the UN in 2007. The Polisario Front, supported by Algeria, insists on the Sahrawi right to a referendum that includes independence as an option.

Periods of military tension have occurred despite the 1991 ceasefire. In November 2020, clashes erupted near Guerguerat, a buffer zone near the Mauritanian border, after Morocco launched a military operation to clear a road blockade by Sahrawi protesters. The Polisario Front declared the ceasefire over and announced a resumption of armed struggle, leading to sporadic reports of shelling along the Moroccan Wall. MINURSO's mandate has been consistently renewed by the UN Security Council, with its primary role being ceasefire monitoring.

The human rights situation, particularly in the Moroccan-controlled parts of Western Sahara, remains a significant concern. International human rights organizations and Sahrawi activists have reported restrictions on freedom of speech, assembly, and association for those advocating independence or Sahrawi self-determination. There have also been reports of arbitrary arrests, detentions, and alleged torture of Sahrawi activists. The conditions in the Tindouf refugee camps in Algeria, where tens of thousands of Sahrawis have lived for decades, also present humanitarian challenges, including dependence on international aid.

A major diplomatic shift occurred in December 2020 when the United States, under the Trump administration, recognized Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara as part of a deal in which Morocco agreed to normalize relations with Israel (the Israel-Morocco normalization agreement). This move broke with longstanding U.S. and international consensus that the territory's final status should be decided through a UN-led process. While the Biden administration has not reversed this recognition, it has expressed support for the UN peace process and the role of MINURSO. Spain, the former colonial power, shifted its stance in March 2022, publicly endorsing Morocco's autonomy plan as the "most serious, realistic, and credible basis" for resolving the dispute, a move that drew criticism from the Polisario Front and strained relations with Algeria. Israel officially recognized Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara in July 2023. In October 2024, French President Emmanuel Macron also backed Morocco's autonomy proposal.

These developments have further complicated the peace process, with the Sahrawi people's aspirations for self-determination remaining unfulfilled. The UN continues to call for a "just, lasting, and mutually acceptable political solution, which will provide for the self-determination of the people of Western Sahara."

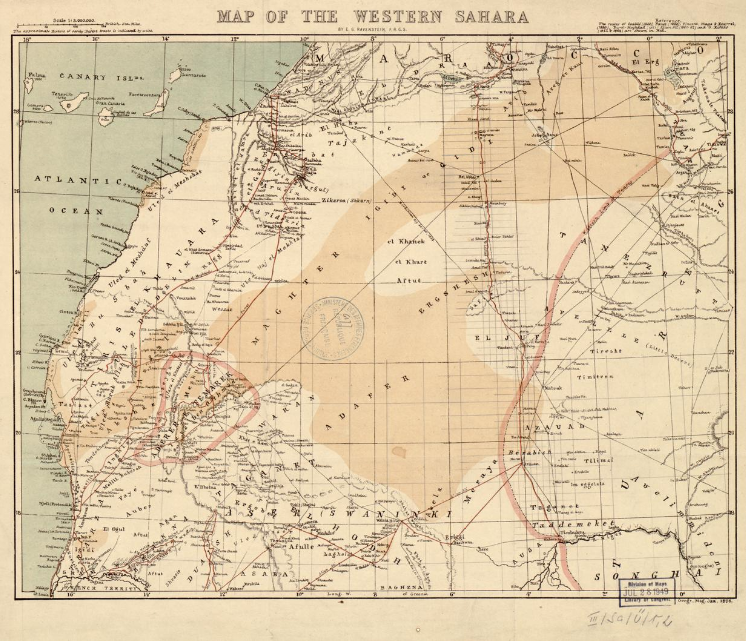

3. Geography

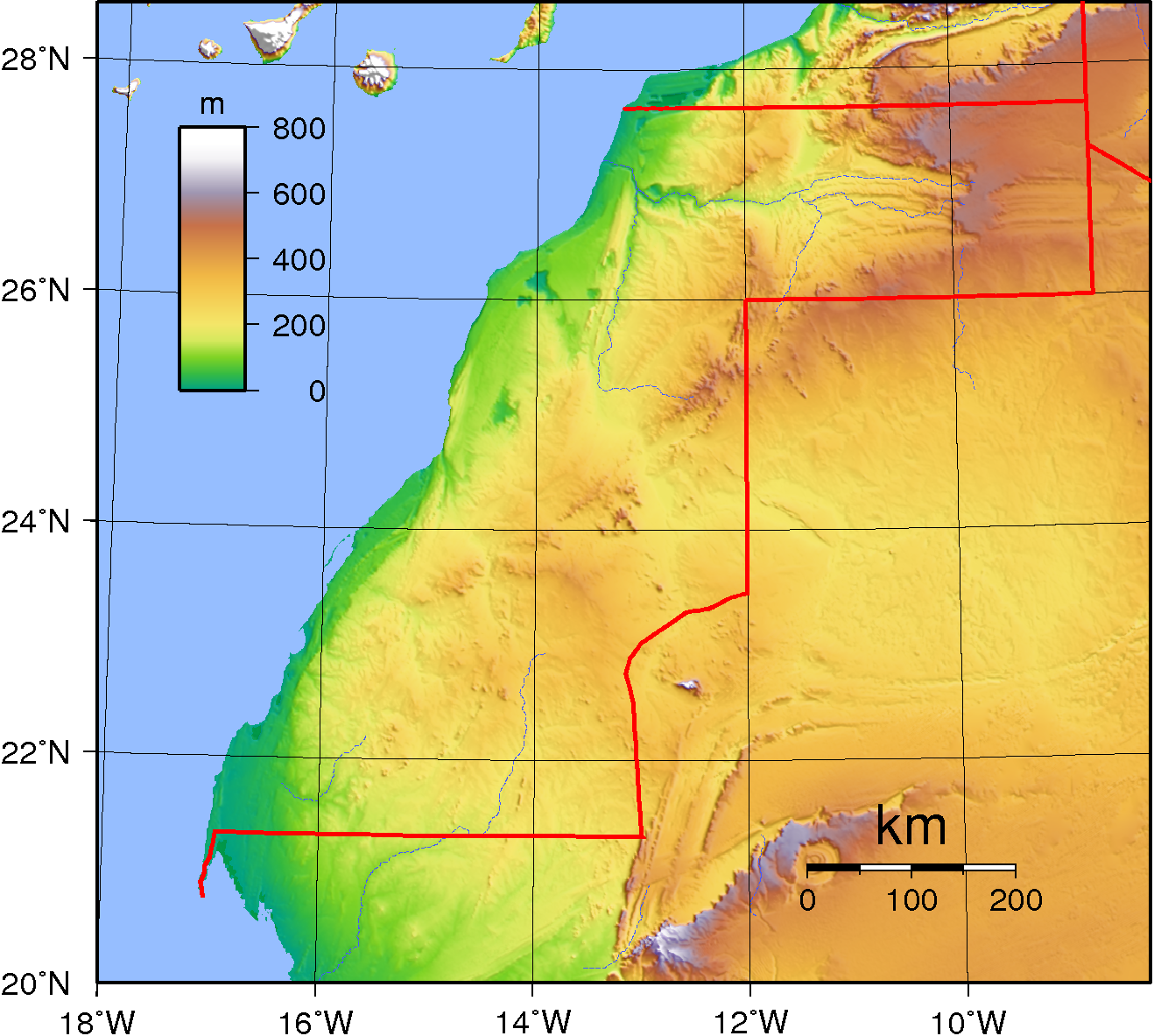

Western Sahara is located in North Africa, bordering the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Morocco to the north, Algeria to the east, and Mauritania to the east and south. It covers an area of approximately 103 K mile2 (266.00 K km2) (or 105 K mile2 (272.00 K km2) according to some sources), making it slightly larger than the United Kingdom. The territory is characterized by its arid desert landscape.

3.1. Topography and climate

The topography of Western Sahara is predominantly low-lying, flat desert plains and plateaus. The land generally rises from the Atlantic coast eastward. In the north and east, there are some areas of low mountains and rocky uplands, with elevations occasionally reaching up to 1969 ft (600 m). The coastal plain is relatively narrow. The territory is bisected by dry riverbeds, or wadis, the most prominent of which are the Saguia el-Hamra in the north and the Río de Oro (Oued Ed-Dahab) in the south. These wadis only carry water sporadically after infrequent rainfall.

Western Sahara has a hot desert climate (Köppen climate classification BWh). Rainfall is scarce and irregular, generally averaging less than 2.0 in (50 mm) per year in most areas, though some northern regions might receive slightly more. Temperatures are high throughout the year, particularly in the interior. Summer daytime temperatures can frequently exceed 104 °F (40 °C), with average highs in July and August reaching 109.4 °F (43 °C) to 113 °F (45 °C). Winter days are warm to hot, with average highs from 77 °F (25 °C) to 86 °F (30 °C); however, nights can be cool, especially in the interior, where temperatures can drop significantly, occasionally nearing freezing in December and January in the northern parts.

Coastal areas experience a slightly more moderated climate due to the influence of the cool Canary Current from the Atlantic Ocean. This current can lead to frequent fog and heavy dew along the coast, particularly in the mornings, which provides some moisture to the arid environment. Winds are common, often carrying sand and dust, leading to sandstorms. Vegetation is sparse, consisting mainly of drought-resistant shrubs and grasses adapted to the arid conditions. There are no permanent streams or rivers, and water resources are extremely limited, primarily relying on groundwater and occasional oases.

3.2. Major ecoregions

Western Sahara lies within the vast Sahara Desert and contains several distinct terrestrial ecoregions, reflecting variations in substrate, salinity, and proximity to the coast. The primary ecoregions found in the territory include:

- Saharan halophytics: This ecoregion is characterized by salt-tolerant vegetation and is found in areas with high soil salinity, such as inland depressions and coastal salt flats. Plant life typically includes species adapted to saline conditions, such as various Chenopodiaceae and other halophytic shrubs.

- North Saharan steppe and woodlands: Occupying parts of the northern and northeastern interior, this ecoregion represents a transition zone between the Mediterranean climates to the north and the hyper-arid core of the Sahara. It features sparse grasslands and shrublands, with vegetation consisting of drought-resistant grasses, small shrubs like Acacia and Ziziphus, and ephemeral plants that appear after rains.

- Atlantic coastal desert: This ecoregion extends along the Atlantic coast of Western Sahara. It is characterized by a relatively cool and humid microclimate due to the influence of the Canary Current, which often produces fog and dew. Vegetation includes succulent plants and shrubs adapted to aridity and saline spray from the ocean. This zone is ecologically important for migratory birds.

- Mediterranean acacia-argania dry woodlands and succulent thickets: While more characteristic of southwestern Morocco, fringes of this ecoregion may extend into the northernmost parts of Western Sahara. It is known for endemic species like the Argan tree, though its presence in Western Sahara proper is limited.

These ecoregions support a variety of wildlife adapted to desert conditions, including gazelles, foxes, rodents, reptiles, and numerous bird species, particularly along the coast.

4. Politics

The political situation in Western Sahara is highly complex and defined by its unresolved legal status and the ongoing sovereignty dispute. The territory is divided into areas administered by Morocco and areas controlled by the Polisario Front's Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), with distinct governance structures in each. Human rights issues are a persistent concern throughout the territory.

4.1. Legal status and sovereignty dispute

Western Sahara is classified by the United Nations as a non-self-governing territory. This status dates back to 1963 when it was under Spanish colonial rule. The core of the political dispute lies in the conflicting claims to sovereignty following Spain's withdrawal in 1975.

Morocco claims historical sovereignty over the territory, which it refers to as its "Southern Provinces." It bases its claim on historical allegiance ties between Sahrawi tribes and Moroccan sultans, as well as geographical contiguity. Morocco effectively controls and administers about 80% of Western Sahara, including all major towns and natural resources.

The Polisario Front, a Sahrawi nationalist movement, proclaimed the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) in 1976 and seeks full independence for Western Sahara. The SADR is recognized by a number of states, primarily in Africa and Latin America, and is a full member of the African Union. The Polisario Front controls the eastern, less populated part of the territory, often referred to as the "Free Zone" or "liberated territories."

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued an advisory opinion in 1975. It found that while historical legal ties of allegiance existed between the Sultan of Morocco and some tribes living in Western Sahara, and similar links existed with the Mauritanian entity, these ties did not establish territorial sovereignty over Western Sahara at the time of Spanish colonization. Crucially, the ICJ affirmed that its findings did not affect the application of UN General Assembly Resolution 1514 (XV) on decolonization, particularly the principle of self-determination through the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of the territory. This principle of self-determination for the Sahrawi people remains the cornerstone of the UN's approach to resolving the conflict, typically envisioned through a referendum. However, disagreements over who is eligible to vote have prevented such a referendum from taking place. No country other than the United States (since 2020) and Israel (since 2023) officially recognizes Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara, with most of the international community supporting a UN-led resolution process.

4.2. Moroccan-administered territory

The roughly 80% of Western Sahara controlled by Morocco, often referred to by Rabat as its "Southern Provinces", is administered as an integral part of the Kingdom of Morocco. This area includes all major cities such as Laayoune (the largest city), Dakhla, and Smara, as well as the territory's significant phosphate mines and rich coastal fishing waters.

Morocco has established an administrative system in these areas, dividing them into regions and provinces that mirror the structure in Morocco proper. These regions participate in Moroccan national and local elections, and their inhabitants are considered Moroccan citizens. The Moroccan government has invested heavily in infrastructure development, including roads, ports, airports, schools, and hospitals, aiming to integrate the territory and improve living standards. Subsidies on basic goods and fuel are also provided, which has encouraged Moroccan settlement in the territory. This policy of encouraging Moroccan citizens to move to Western Sahara has significantly altered the demographic composition of the area, a point of contention in discussions about a potential referendum.

Governance in the Moroccan-administered territory is characterized by a strong state presence, including a significant deployment of Moroccan military and security forces. While Morocco promotes its development efforts and its autonomy plan as a solution to the conflict, Sahrawi activists advocating for independence or challenging Moroccan policies often face restrictions on freedom of expression, assembly, and association. International human rights organizations have documented concerns regarding the treatment of these activists and the broader human rights climate. The social and economic impact on the local Sahrawi population is complex; while some have benefited from economic opportunities and development, others feel marginalized or discriminated against, and express concerns about the exploitation of natural resources without their consent.

4.3. Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR)-administered territory

The Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), proclaimed by the Polisario Front, administers the eastern part of Western Sahara, located east of the Moroccan Wall (Berm). This area, often referred to as the "Free Zone" or "liberated territories," constitutes about 20-25% of Western Sahara's total landmass. It is a sparsely populated, arid region consisting mainly of desert. The main settlements in this zone, such as Tifariti (which the SADR considers its temporary capital) and Bir Lehlou (former temporary capital), are small and serve primarily as military and administrative outposts.

The SADR's government structures are largely based in the Sahrawi refugee camps near Tindouf in southwestern Algeria, where a significant portion of the Sahrawi population has lived since 1975-76. These camps house the SADR's presidency, ministries, and the Sahrawi National Council (its parliament). The Polisario Front is the leading political and military force of the SADR. Within the Free Zone, the SADR maintains a military presence through its army, the Sahrawi People's Liberation Army (SPLA), which patrols the area and monitors the ceasefire with Moroccan forces along the Berm.

The administration in the Free Zone is limited due to the harsh environment, scarce resources, and the ongoing conflict. Basic services are minimal, and the population largely consists of nomadic communities and SPLA personnel. The SADR's activities in this area are often symbolic, such as holding political congresses or national celebrations, to assert its claim to the territory. The SADR's governance model is that of a single-party state led by the Polisario Front, though its constitution envisages a multi-party system upon achieving full independence and control over the entire territory. The SADR relies heavily on support from Algeria and international humanitarian aid for the refugee camps.

4.4. Human rights situation

The human rights situation in Western Sahara is a significant concern and a contentious aspect of the conflict, with reports of violations affecting individuals on both sides of the dispute, particularly the Sahrawi population. International human rights organizations, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, as well as UN bodies, have documented a range of issues.

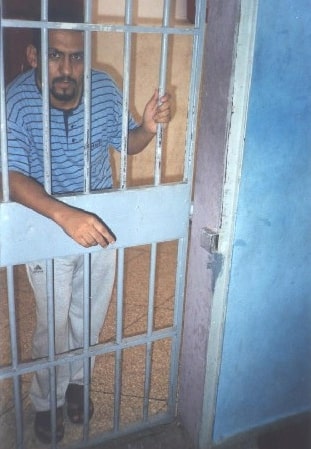

In the Moroccan-administered parts of Western Sahara, key concerns include:

- Restrictions on freedom of expression, assembly, and association: Sahrawis advocating for independence or greater self-determination, or those critical of Moroccan policies, often face harassment, intimidation, and legal repercussions. Peaceful demonstrations are sometimes met with excessive force by Moroccan security forces.

- Arbitrary detention and unfair trials: Numerous Sahrawi activists have been arrested and imprisoned, with some trials reportedly failing to meet international fair trial standards. Allegations of torture and ill-treatment in detention have also been persistent.

- Suppression of Sahrawi cultural identity: Some Sahrawis report difficulties in expressing their distinct cultural identity and language.

- Exploitation of natural resources: The exploitation of Western Sahara's resources (phosphates, fisheries) by Morocco without the explicit consent of the Sahrawi people is a major point of contention, often framed as a human rights issue related to the right to self-determination and control over natural wealth.

In the Sahrawi refugee camps near Tindouf, Algeria, administered by the Polisario Front, concerns have been raised regarding:

- Restrictions on freedom of movement: Some reports suggest limitations on the ability of refugees to leave the camps.

- Freedom of expression and dissent: While the Polisario Front maintains it upholds democratic principles, some critics and former members have alleged a lack of political pluralism and suppression of dissenting voices within the camps.

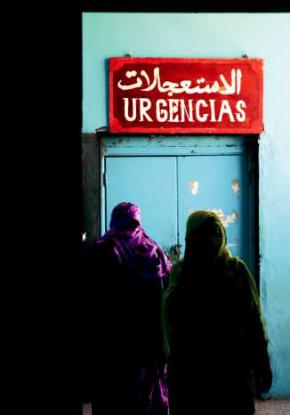

- Living conditions and dependency on aid: The prolonged refugee situation, with harsh desert conditions and dependence on international humanitarian aid, raises concerns about basic human rights, including access to adequate food, water, healthcare, and education.

- Accountability for past abuses: There have been calls for investigations into alleged human rights abuses committed by Polisario members during the war years and in the early period of camp administration.

The United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) has a mandate focused on monitoring the ceasefire and the referendum process, but it notably lacks a specific human rights monitoring component, a point frequently criticized by human rights groups who advocate for its inclusion. The lack of independent, consistent human rights monitoring across the entire territory remains a challenge. Vulnerable groups, including women, children, and political prisoners, face particular hardships in the context of this protracted conflict.

5. Administrative divisions

The administrative divisions of Western Sahara are complex due to the disputed status of the territory and its de facto partition. Both Morocco and the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) have established their own administrative structures for the areas they control or claim.

5.1. Moroccan administrative divisions

Morocco administers the western, more populated part of Western Sahara (approximately 80% of the territory) as its "Southern Provinces". These provinces are integrated into Morocco's national administrative framework. As of recent reforms, the Moroccan-administered parts of Western Sahara fall primarily within three regions of Morocco:

1. Laâyoune-Sakia El Hamra Region: This is the most populous region in the Moroccan-controlled part of Western Sahara.

- It includes the provinces of:

- Laâyoune Province (with Laayoune city as its capital and the largest city in Western Sahara)

- Boujdour Province (with Boujdour city)

- Tarfaya Province (partially in Western Sahara, partially in Morocco proper, with Tarfaya city)

- Es Semara Province (with Smara city)

2. Dakhla-Oued Ed-Dahab Region: This region covers the southern part of the Moroccan-controlled territory.

- It includes the provinces of:

- Oued Ed-Dahab Province (with Dakhla city)

- Aousserd Province (with Aousserd town)

3. Guelmim-Oued Noun Region: A smaller part of this region, specifically the southern portion of Assa-Zag Province, extends into the northernmost part of Western Sahara claimed by Morocco.

These regions and provinces have elected councils and governors appointed by the Moroccan central government, similar to other regions in Morocco.

5.2. Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic administrative divisions

The Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), proclaimed by the Polisario Front, claims sovereignty over the entire territory of Western Sahara. It effectively controls the eastern part of the territory, known as the "Free Zone" or "liberated territories," which is east of the Moroccan Wall. The SADR's administrative divisions are primarily notional for the Moroccan-controlled areas but are applied in the Free Zone and within the structure of the refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria, where much of its governmental apparatus is based.

The SADR's proclaimed administrative structure divides the territory into several wilayat (provinces or governorates) and further into dairas (districts or sub-prefectures), which are often named after towns in Western Sahara, some of which are under Moroccan control. The main wilayat are often cited as:

- El Aaiún Wilaya

- Smara Wilaya

- Dakhla Wilaya

- Auserd Wilaya

- Boujdour Wilaya (sometimes included)

The SADR considers Laayoune its de jure capital. However, due to the de facto situation, Tifariti in the Free Zone has served as a temporary or symbolic capital for events and some administrative functions on Sahrawi soil. Bir Lehlou, also in the Free Zone, previously served a similar role. The day-to-day administration and organization of the Sahrawi population under SADR control primarily occur within the refugee camps in Tindouf, which are themselves organized into wilayat-like structures mirroring those proclaimed for Western Sahara proper.

6. The Dispute

The Western Sahara dispute is one of Africa's longest-running territorial conflicts, stemming from the decolonization of the territory by Spain in 1975. It primarily involves Morocco, which claims sovereignty and administers most of the territory, and the Polisario Front, which seeks independence for the Sahrawi people. The United Nations has been involved for decades in efforts to find a peaceful resolution.

6.1. Background and development of the conflict

The conflict's roots lie in Spain's decision to withdraw from its colony, Spanish Sahara, in 1975. Instead of an orderly transfer of power to the indigenous population or a referendum on self-determination as advocated by the UN, Spain signed the Madrid Accords with Morocco and Mauritania. This agreement led to the partition of the territory: Morocco annexed the northern two-thirds, and Mauritania the southern third. The Polisario Front, which had been fighting for Sahrawi independence since 1973, rejected this partition and, backed by Algeria, proclaimed the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) in February 1976.

This triggered the Western Sahara War (1975-1991). The Polisario Front waged a guerrilla war against both Moroccan and Mauritanian forces. Mauritania, facing significant military pressure and internal instability, withdrew from the conflict in 1979 and renounced its claims. Morocco then occupied the southern part previously held by Mauritania, extending its control over most of the territory. To counter Polisario incursions, Morocco constructed the Moroccan Wall (Berm), a system of heavily fortified sand walls, minefields, and electronic surveillance stretching over 1.7 K mile (2.70 K km). This effectively divided the territory, with Morocco controlling the western, economically valuable areas (including phosphate mines and fishing grounds), and the Polisario Front controlling the sparsely populated eastern "Free Zone". The war resulted in significant casualties, displacement of Sahrawi civilians (many becoming refugees in Tindouf, Algeria), and a protracted stalemate.

6.2. UN role and peacekeeping operations

The United Nations has been central to efforts to resolve the Western Sahara conflict since its inception. Its involvement began with calls for decolonization and self-determination during Spanish rule. Following the outbreak of war, the UN Security Council and General Assembly repeatedly called for a ceasefire and a negotiated settlement.

The most significant UN intervention was the 1988 Settlement Plan, agreed upon by Morocco and the Polisario Front. This plan called for a ceasefire and a referendum to allow the people of Western Sahara to choose between independence or integration with Morocco. To implement this plan, the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) was established in 1991. MINURSO's mandate included:

- Monitoring the ceasefire, which came into effect on September 6, 1991.

- Verifying the reduction of Moroccan troops in the territory.

- Identifying and registering qualified voters for the referendum.

- Organizing and conducting the referendum.

While MINURSO has largely succeeded in maintaining the ceasefire (despite recent tensions), its core mandate of organizing a referendum has been stalled since the early 1990s due to irreconcilable differences between Morocco and the Polisario Front over voter eligibility. MINURSO continues to operate in Western Sahara, with military observers monitoring the ceasefire along the Berm and civilian staff working on political and logistical aspects. Its mandate is renewed periodically by the UN Security Council. Successive UN Secretary-Generals and their Personal Envoys have engaged in diplomatic efforts to find a political solution, but a breakthrough remains elusive. MINURSO's mandate does not include human rights monitoring, a point of criticism from many human rights organizations.

6.3. Peace negotiation process and major proposals

The peace negotiation process has been marked by periods of intense diplomatic activity followed by prolonged stalemates. Several major proposals and negotiation rounds have taken place:

- The Settlement Plan (1988/1991):** This UN plan, accepted by both parties, aimed for a referendum on self-determination. It failed primarily due to disputes over voter identification.

- The Houston Agreement (1997):** Brokered by UN Personal Envoy James Baker, this agreement sought to overcome obstacles to voter identification but ultimately did not break the deadlock.

- The Baker Plan I (Framework Agreement, 2001):** Proposed by James Baker, it suggested a five-year period of autonomy for Western Sahara within Morocco, followed by a referendum on final status where all residents (including Moroccan settlers) could vote. Morocco accepted it, but the Polisario Front rejected it.

- The Baker Plan II (Peace Plan for Self-Determination, 2003):** This revised plan also proposed a five-year interim autonomy period under a "Western Sahara Authority," followed by a referendum offering options of independence, integration, or autonomy. The electorate would be based on the 1974 Spanish census and UNHCR refugee lists. The Polisario Front accepted this as a basis for negotiation, and it was endorsed by the UN Security Council. However, Morocco rejected it, primarily because it included independence as an option. James Baker resigned in 2004.

- Moroccan Autonomy Proposal (2007):** Morocco formally submitted its "Initiative for Negotiating an Autonomy Statute for the Sahara Region" to the UN. This plan proposes significant autonomy for Western Sahara under Moroccan sovereignty, with Morocco retaining control over defense, foreign affairs, and constitutional/religious matters. The Polisario Front rejected this proposal, as it does not offer independence as an option.

- Manhasset negotiations (2007-2008, and subsequent informal talks):** Following Morocco's autonomy proposal and a counter-proposal from the Polisario Front reaffirming the right to self-determination, the UN facilitated several rounds of direct talks between the parties in Manhasset, New York, and elsewhere. These talks, overseen by UN envoys Peter van Walsum, Christopher Ross, and Horst Köhler, failed to produce a breakthrough, with both sides adhering to their fundamental positions. Staffan de Mistura is the current UN Personal Envoy.

The core obstacle remains the fundamental disagreement over the final status of the territory: Morocco insists on autonomy under its sovereignty, while the Polisario Front, backed by Algeria, demands a referendum that includes the option of independence, based on the principle of self-determination for the Sahrawi people. Regional stability is also a key concern, with tensions between Morocco and Algeria often linked to the Western Sahara issue.

6.4. Humanitarian issues

The Western Sahara conflict has generated a severe and protracted humanitarian crisis, profoundly affecting the Sahrawi population for decades.

- Sahrawi Refugees:** The most significant humanitarian consequence is the plight of tens of thousands of Sahrawi refugees living in camps near Tindouf, southwestern Algeria. These refugees fled the conflict in 1975-76 and have since lived in harsh desert conditions, heavily reliant on international humanitarian aid for basic necessities such as food, water, shelter, and healthcare. The main camps are named after towns in Western Sahara: Laayoune, Smara, Auserd, and Dakhla. Organizations like the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the World Food Programme (WFP), and various NGOs provide assistance. The exact number of refugees is disputed; the Polisario Front claims around 165,000-170,000, while other estimates, including those used by aid agencies for planning, are lower (e.g., around 90,000 "most vulnerable"). The refugees face limited opportunities for self-sufficiency, and generations have grown up in the camps.

- Hardships in the Territory:** Residents in both the Moroccan-controlled parts of Western Sahara and the Polisario-controlled "Free Zone" face challenges. In Moroccan-controlled areas, Sahrawis advocating for independence or human rights often report repression, restrictions on freedoms, and socio-economic marginalization. In the Free Zone, the population is small and predominantly nomadic, contending with an arid environment, limited infrastructure, and the proximity to the Moroccan Wall.

- Landmines and Unexploded Ordnance:** The territory, particularly along and near the Moroccan Wall and in the Free Zone, is heavily contaminated with land mines and unexploded ordnance (UXO) from the war. These pose a constant threat to civilians, especially nomads, herders, and children, and hinder development and freedom of movement. MINURSO and organizations like the UN Mine Action Service (UNMAS) have been involved in mine clearance and awareness activities, but the scale of contamination remains vast.

- Separation of Families:** The conflict and the division of the territory by the Berm have led to the separation of Sahrawi families for decades, with limited opportunities for contact or reunification.

- Health and Education:** Access to adequate healthcare and quality education is a challenge, both in the refugee camps and in parts of the territory. In the camps, malnutrition and waterborne diseases have been concerns.

- Psychological Impact:** The prolonged uncertainty, displacement, and unresolved conflict have had a significant psychological impact on the Sahrawi people, particularly refugees.

International relief efforts are crucial for alleviating the suffering, but a sustainable solution to the humanitarian crisis is intrinsically linked to a political resolution of the conflict that respects the rights and aspirations of the Sahrawi people. The plight of victims and affected communities, especially refugees who have endured decades of displacement, underscores the urgent need for a just and lasting peace.

7. Economy

The economy of Western Sahara is largely shaped by its arid environment, its disputed political status, and the de facto administration by Morocco over the resource-rich western part of the territory. Key economic activities include phosphate mining, fishing, and limited agriculture, with emerging potential in tourism and renewable energy. The exploitation of natural resources is a major point of international controversy.

7.1. Main industries and resources

- Phosphate Mining:** Western Sahara possesses significant phosphate rock reserves, primarily located at the Bou Craa mine in the Moroccan-controlled zone. Phosphate mining has historically been a major industry, with exports managed by Phosboucraa, a subsidiary of Morocco's state-owned OCP Group. The Bou Craa mine is connected to the port of Laayoune by a 62 mile (100 km) long conveyor belt, one of the longest in the world.

- Fishing:** The Atlantic waters off the coast of Western Sahara are rich in fish stocks, making fishing a vital economic activity. Moroccan and international fleets (often through agreements with Morocco) operate in these waters. This sector provides employment and is a significant source of revenue, primarily benefiting the Moroccan economy and settlers.

- Agriculture and Pastoralism:** Agriculture is limited due to the arid climate and scarce water resources, primarily concentrated in oases and areas where groundwater is accessible. Small-scale farming of vegetables, dates, and cereals occurs. Traditional pastoralism (herding of camels, goats, and sheep) remains a way of life for some Sahrawis, particularly in the interior and the Polisario-controlled Free Zone.

- Oil and Gas Potential:** There has been speculation about offshore oil and natural gas reserves. Morocco has issued exploration licenses to international companies for blocks off the coast of Western Sahara. However, no commercially viable discoveries have been confirmed to date, and exploration activities are highly controversial due to the territory's disputed status.

- Renewable Energy:** Morocco has invested in renewable energy projects in Western Sahara, particularly wind farms, capitalizing on the strong coastal winds. These projects are part of Morocco's broader national strategy for renewable energy but are also subject to controversy.

- Tourism:** Tourism is a developing sector, particularly in coastal cities like Dakhla, which is known for kitesurfing and other water sports. However, the unresolved political situation limits its full potential.

- Trade and Services:** Most food and consumer goods in the Moroccan-controlled urban areas are imported, largely from Morocco. Trade and service sectors are growing, supported by Moroccan government subsidies and investment aimed at integrating the territory.

The economy in the Polisario-controlled Free Zone is minimal, based on nomadic pastoralism and small-scale trade, with heavy reliance on aid for the refugee camps in Algeria, which are the SADR's main population base.

7.2. Controversies surrounding natural resource exploitation

The exploitation of Western Sahara's natural resources is a central point of contention in the conflict and a subject of international legal and ethical debate. The core issue revolves around the principle that the resources of a non-self-governing territory should not be exploited by an administering power (or occupying power, as the Polisario Front and its supporters characterize Morocco's presence) without the consent and for the benefit of the people of that territory.

- Legality and Consent:** The Polisario Front, the SADR, and numerous international organizations and legal scholars argue that Morocco's exploitation of Western Sahara's resources (phosphates, fish, potential hydrocarbons, agricultural products from irrigated farms) is illegal under international law because it lacks the consent of the Sahrawi people, the rightful owners of these resources. They cite UN resolutions and the ICJ's advisory opinion, which emphasize the Sahrawi right to self-determination.

- Benefit Distribution:** Critics argue that the primary beneficiaries of resource exploitation are the Moroccan state, Moroccan companies, and settlers, rather than the indigenous Sahrawi population. While Morocco claims that revenues are reinvested in the development of the "Southern Provinces" for the benefit of all inhabitants, Sahrawi pro-independence groups dispute this and assert that the Sahrawi people are systematically excluded from equitable benefit sharing.

- International Agreements:** Morocco has signed trade and fisheries agreements (e.g., with the European Union) that have included Western Sahara within their scope. These agreements have faced legal challenges, notably in European courts, which have in some instances ruled that such agreements cannot legally apply to Western Sahara without the consent of its people. This has led to revisions and ongoing debates about the territorial scope of these deals.

- Corporate Responsibility and Divestment:** Numerous international campaigns have targeted companies involved in resource extraction or trade originating from Western Sahara, urging them to cease operations or divest due to ethical and legal concerns. Some international investors and companies have withdrawn from activities in the territory following pressure from human rights groups and shareholders.

- Impact on Self-Determination:** The exploitation of resources is seen by the Polisario Front as entrenching Moroccan control and undermining the prospects for a genuine self-determination process, as it creates economic dependencies and alters the demographic and physical landscape of the territory.

- Environmental and Social Consequences:** Concerns have also been raised about the environmental impact of resource extraction (e.g., water usage for phosphate mining and agriculture in an arid region) and the social consequences for traditional Sahrawi livelihoods.

Morocco maintains that its activities are legal and beneficial for the population of the territory. The UN Secretary-General, in a 2002 legal opinion by Under-Secretary-General for Legal Affairs Hans Corell, stated that resource exploration and exploitation activities are permissible only if conducted for the benefit of and in accordance with the wishes of the people of Western Sahara. Whether current practices meet these criteria remains highly disputed. The issue highlights the tension between economic development under de facto administration and the international legal principles governing non-self-governing territories and the rights of indigenous peoples.

8. Demographics

The demographics of Western Sahara are complex and politically sensitive, particularly due to the ongoing conflict, displacement of populations, and Moroccan settlement policies. Accurate and universally accepted figures are difficult to obtain.

8.1. Ethnic composition and Sahrawis

The indigenous population of Western Sahara are the Sahrawis (صحراويونṣaḥrāwīyūnArabic, meaning "Saharans"). They are primarily of Arab-Berber descent, speaking the Hassaniya Arabic dialect. Sahrawi society is traditionally nomadic and organized along tribal lines, with a strong clan-based structure. Major tribal confederations include the Reguibat, Tekna, and Oulad Delim, among others. Their culture shares similarities with other Moorish and Bedouin groups in the Sahara region.

The original Sahrawi population has been significantly affected by the conflict:

- A large number of Sahrawis fled the territory in 1975-76 and became refugees, primarily settling in camps near Tindouf, Algeria. These camps, administered by the Polisario Front, are home to a substantial portion of the Sahrawi population (estimates vary widely, from around 90,000 to over 170,000).

- Sahrawis who remained in or returned to the Moroccan-controlled parts of Western Sahara live alongside Moroccan settlers.

- A Sahrawi diaspora also exists in Mauritania, Spain, and other countries.

Since 1975, Morocco has encouraged its citizens to move to Western Sahara through various incentives, including housing, employment opportunities, and subsidies. This has led to a significant influx of Moroccan settlers, and it is widely believed that they now outnumber the indigenous Sahrawi population in the Moroccan-controlled areas. This demographic shift is a major point of contention, particularly concerning voter eligibility for any potential referendum on self-determination. The Polisario Front views the Moroccan settlers as an obstacle to a fair referendum, while Morocco considers them legitimate residents.

The Spanish colonial census of 1974 recorded approximately 74,000 Sahrawis in the territory. This census, despite potential inaccuracies inherent in counting nomadic populations, became a baseline for UN efforts to identify eligible voters for the planned referendum. The process of identifying and verifying voters based on this census and subsequent tribal affiliations proved to be a major stumbling block in the peace process.

Other ethnic groups are present in smaller numbers, including Moroccans from various regions and some remaining individuals of Spanish descent.

8.2. Language

The primary languages spoken in Western Sahara are:

- Hassaniya Arabic**: This is the traditional language of the Sahrawi people and is a distinct dialect of Arabic with Berber influences. It is also spoken in Mauritania and parts of Morocco, Algeria, and Mali. It serves as a key element of Sahrawi cultural identity.

- Moroccan Arabic** (Darija): Widely spoken in the Moroccan-controlled areas, especially by Moroccan settlers and as a lingua franca.

- Berber languages** (Tamazight): Some Sahrawi tribes, particularly those with stronger Berber roots (e.g., certain Tekna groups), may speak or retain knowledge of Berber dialects. Berber languages are more prevalent in Morocco proper.

- Spanish**: Due to the long period of Spanish colonial rule (until 1976), Spanish was an official language and is still spoken by some older Sahrawis and used to some extent in the SADR administration and among the diaspora in Spain. It has a cultural and historical significance. Educational exchanges with Spain and Cuba for Sahrawi refugee children have also helped maintain its prevalence.

- French**: While not traditionally spoken, French is used in administration and commerce in Morocco and has some presence in the Moroccan-controlled parts of Western Sahara, particularly in education and business contexts.

Official language status varies. In Moroccan-controlled areas, Modern Standard Arabic and Berber (Tamazight) are official languages of Morocco, with Moroccan Darija being the common vernacular. For the SADR, Hassaniya Arabic and Spanish are often considered official or working languages.

8.3. Religion

The predominant religion in Western Sahara is Islam. The vast majority of the population, both Sahrawis and Moroccans, are Sunni Muslims, adhering to the Maliki school of Islamic jurisprudence, which is prevalent throughout North Africa.

Local Islamic practices among Sahrawis have traditionally been influenced by their nomadic lifestyle and pre-Islamic Berber customs. Sufism has also played a role in the region, with various Sufi orders and maraboutic (saintly) figures historically holding spiritual importance. While Islam is a central aspect of Sahrawi identity, their traditional practice, adapted to nomadic life, sometimes differed from urban Islamic practices, for example, functioning without formal mosque structures in some contexts. In contemporary times, especially in urban areas and the refugee camps, more conventional Islamic practices are common. Religious identity often intertwines with cultural and national identity for both Sahrawis and Moroccans in the territory.

9. Culture

The culture of Western Sahara is primarily that of the Sahrawi people, shaped by their nomadic heritage, the desert environment, Islamic traditions, and the profound impact of decades of political conflict and displacement. It encompasses a rich oral tradition, distinctive social structures, and resilient artistic expressions.

9.2. Arts and cultural expression

Sahrawi culture is rich in oral traditions, music, and poetry.

- Poetry:** Hassaniya poetry is a highly valued art form, serving as a means of storytelling, expressing emotions, preserving history, and conveying political messages. It is composed and recited by both men and women. Traditionally, poetry was transmitted orally, with younger poets often apprenticing with experienced ones. Notable poets include Al Khadra Mabrook, Hadjatu Aliat Swelm, and Beyibouh El Haj. The political nature of much contemporary Sahrawi poetry can make it difficult to publish, especially through Arab publishers.

- Music:** Traditional Sahrawi music often features instruments like the tidinit (a four-stringed lute played by men) and the tbal (a kettledrum). Music plays a significant role in social gatherings, celebrations, and expressing cultural identity. Modern Sahrawi music often incorporates themes of resistance and longing for their homeland.

- Oral Literature:** Storytelling, proverbs, and legends are important parts of Sahrawi cultural heritage.

- Festivals and Modern Arts:** The FiSahara International Film Festival is an annual event held in the Sahrawi refugee camps, showcasing international films and providing a platform for Sahrawi filmmakers. It aims to raise awareness about the Sahrawi cause and offer cultural enrichment. Visual arts, including painting and graffiti art, have also emerged as forms of expression, particularly among younger Sahrawis in the camps and the diaspora, often depicting themes of struggle, identity, and hope. ARTifariti, the International Art and Human Rights Meeting, is an annual workshop that brings international artists to the Free Zone and refugee camps.

9.3. Society and women

Women have traditionally held a relatively prominent and respected position in Sahrawi society compared to some other Arab and Islamic cultures. While society was patriarchal in formal leadership, women often enjoyed considerable autonomy within the family and community. They could inherit property and had significant influence in domestic and social matters. Monogamy was generally valued. During men's long absences for trade or warfare, women managed camp affairs.

The Western Sahara conflict and the subsequent establishment of refugee camps saw Sahrawi women take on even more significant roles. They were instrumental in organizing and managing the camps in the early years, establishing schools, health services, and administrative structures. Women have been highly active in the Sahrawi independence movement, participating in political, diplomatic, and social mobilization efforts. The National Union of Sahrawi Women (NUSW), established by the Polisario Front, has been a key organization advocating for women's rights and their participation in public life.

Despite these contributions, Sahrawi women, like women in many societies, face challenges related to gender equality, access to education and economic opportunities, and the impact of conflict and displacement. Their resilience and activism continue to be vital for the social fabric and the pursuit of Sahrawi self-determination, with many advocating for greater democratic participation and human rights within their own community and in the broader context of the conflict. The cross-cultural influence from Spanish colonialism also left a mark, with Spanish language and certain social norms being adopted or adapted. Programs like "Vacaciones en Paz" (Vacations in Peace), which send Sahrawi children to Spain for summer holidays, have also fostered cultural exchange and maintained linguistic ties.

10. Foreign relations

The foreign relations concerning Western Sahara are dominated by the efforts of Morocco and the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) to gain international support for their respective positions on the territory's status. The international community remains divided, with most countries officially supporting a UN-led resolution process.

10.1. International recognition and diplomacy of the SADR

The Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), proclaimed by the Polisario Front in 1976, has sought international recognition as the legitimate sovereign state of Western Sahara. Its diplomatic efforts focus on promoting the Sahrawi right to self-determination and independence.

- States Recognizing SADR:** The SADR has been recognized by a varying number of states over the years. As of the early 2020s, around 40-46 UN member states officially recognize the SADR, though this number fluctuates as some countries have withdrawn or suspended recognition, often due to diplomatic pressure or changing relations with Morocco. Most recognizing states are in Africa and Latin America, with some in Asia and Oceania. Key historical supporters include Algeria, South Africa, Nigeria, Cuba, Venezuela, and Mexico.

- African Union Membership:** The SADR is a full member of the African Union (AU) and its predecessor, the Organisation of African Unity (OAU). Its admission to the OAU in 1984 led to Morocco's withdrawal from the organization in protest, a situation that lasted until Morocco rejoined the AU in 2017. The SADR's continued membership in the AU provides it with a significant platform for multilateral diplomacy.

- Diplomatic Missions:** The SADR maintains diplomatic missions (embassies or representative offices) in countries that recognize it and in key international centers. These missions engage in lobbying, advocacy, and providing information about the Sahrawi cause.

- International Support Efforts:** The Polisario Front and SADR representatives actively participate in international forums, including the UN (as petitioners before the Fourth Committee), the AU, and various non-governmental conferences, to garner support for a referendum on self-determination that includes the option of independence. They highlight issues such as human rights violations, the illegal exploitation of natural resources, and the humanitarian plight of Sahrawi refugees.

The SADR's foreign policy heavily relies on the support of Algeria, which hosts the Sahrawi refugee camps and provides crucial political, financial, and military assistance.

10.2. Moroccan foreign policy and international support

Morocco's foreign policy regarding Western Sahara is centered on securing international endorsement for its sovereignty over the territory, which it refers to as its "Southern Provinces". Its primary diplomatic objective is to gain acceptance for its autonomy plan, first proposed in 2007, as the sole basis for resolving the conflict.

- Sovereignty Claims and Autonomy Plan:** Morocco actively promotes its historical and legal claims to the territory and presents its autonomy plan as a "serious and credible" compromise offering self-governance under Moroccan sovereignty. It emphasizes its investments in infrastructure and economic development in the region.

- International Backing:** Morocco has garnered support for its position or its autonomy plan from several influential countries, including France (historically a strong ally), and more recently, the United States (which recognized Moroccan sovereignty in 2020) and Spain (which endorsed the autonomy plan in 2022). Many Arab League and Organisation of Islamic Cooperation member states also support Morocco's territorial integrity.

- Diplomatic Lobbying:** Morocco engages in extensive lobbying efforts in international capitals and at the UN to counter the Polisario Front's narrative and to prevent wider recognition of the SADR. It highlights security concerns in the Sahel region and presents itself as a partner in counter-terrorism efforts.

- Position in International Organizations:** Morocco rejoined the African Union in 2017, partly to advocate for its position on Western Sahara from within the organization and to challenge the SADR's membership. It actively participates in other international and regional bodies to promote its interests.

- Economic Diplomacy:** Morocco uses economic ties, trade agreements, and development aid as tools of its diplomacy, including in relation to Western Sahara.

Morocco views the Polisario Front as an Algerian-backed separatist movement and often seeks to frame the conflict as a regional rivalry with Algeria rather than a decolonization issue.

10.3. Relations with key involved countries

Several countries play significant roles or have particular stakes in the Western Sahara conflict:

- Algeria**: Algeria is the primary supporter of the Polisario Front and the SADR, providing political, military, financial, and humanitarian assistance, including hosting the Sahrawi refugee camps in Tindouf. Algeria views the conflict through the lens of regional balance of power with Morocco and advocates for the Sahrawi right to self-determination. Relations between Morocco and Algeria have been historically tense, with the Western Sahara issue being a major point of contention, leading to the closure of their common border since 1994 and a severance of diplomatic ties by Algeria in 2021.

- Spain**: As the former colonial power, Spain has a historical responsibility and maintains significant cultural and economic ties with the region. Traditionally, Spain supported a UN-led solution and Sahrawi self-determination. However, in March 2022, the Spanish government shifted its stance to publicly support Morocco's autonomy plan as the "most serious, realistic and credible basis" for resolving the dispute. This marked a significant departure from its previous neutrality and drew criticism from the Polisario Front and within Spain itself.

- France**: France is a key political and economic partner of Morocco and has generally been supportive of Morocco's position on Western Sahara, often using its influence as a permanent member of the UN Security Council to temper resolutions critical of Morocco. While officially supporting a negotiated political solution, France is widely seen as favoring the Moroccan autonomy plan. In October 2024, French President Emmanuel Macron explicitly backed Morocco's autonomy proposal.

- United States**: The U.S. traditionally supported the UN peace process and a referendum. However, in December 2020, the Trump administration recognized Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara in exchange for Morocco normalizing relations with Israel. The Biden administration has not reversed this recognition but has reiterated support for the UN-led political process and the work of the UN Personal Envoy to find a "durable and dignified solution." The U.S. also supports MINURSO's mandate.

- Mauritania**: Mauritania shares a long border with Western Sahara and was initially a party to the conflict, annexing the southern third of the territory in 1975. It withdrew in 1979 after signing a peace treaty with the Polisario Front. Mauritania now maintains a position of neutrality, recognizing the SADR but also having important relations with Morocco. It is concerned about regional stability and the impact of the conflict on its own territory, including the presence of Sahrawi refugees and cross-border movements.

- African Union members**: AU member states are divided. While the SADR is a member, Morocco's re-entry and diplomatic efforts have led some African nations to support its autonomy plan or adopt a more neutral stance. Key AU powers like South Africa and Nigeria have historically been strong supporters of Sahrawi self-determination.

The positions of these and other international actors significantly influence the diplomatic landscape and the prospects for resolving the Western Sahara conflict.