1. Overview

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a federal republic located in the southern portion of North America. It is a nation characterized by a rich and complex history, a vibrant and diverse culture shaped by the confluence of Indigenous civilizations and Spanish colonial influence, and a dynamic, developing economy. Mexico's political journey has been marked by struggles for independence, democratic consolidation, and ongoing efforts to address social inequality and uphold human rights. The country possesses vast biodiversity, making it one of the world's megadiverse nations, and its varied geography encompasses deserts, mountains, and tropical rainforests. Contemporary Mexico faces challenges related to public security, corruption, and economic disparities, while also playing a significant role in regional and global affairs, particularly through its deep economic ties with the United States and its active participation in international organizations. This article examines Mexico from a perspective that emphasizes social equity, the protection and advancement of human rights, and the continuous development of its democratic institutions.

2. Etymology

The name "Mexico" originates from MēxihcoMe-SHI-koNahuatl languages, the Nahuatl term for the heartland of the Aztec Empire, specifically the Valley of Mexico and its surrounding territories. The people of this region were known as the Mexica. It is generally believed that the toponym for the valley was the origin of the primary ethnonym for the Aztec Triple Alliance, although it may have been the other way around. One interpretation suggests "Mēxihco" means "place of Mexi" or "Mexitli's land," where Mexitli was a secret or alternative name for Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec god of war and the sun, signifying "chosen by the gods." Another common interpretation breaks down "Mēxihco" into Nahuatl roots: mētztliMETS-tleeNahuatl languages (moon), xictliSHEEK-tleeNahuatl languages (navel, center, or son), and the locative suffix -co (place of), translating to "place at the center of the moon." This refers to Lake Texcoco, whose system of interconnected lakes resembled a rabbit, an image the Aztecs also associated with the moon, with their capital, Tenochtitlan, situated at its center.

During the Spanish colonial era (1519-1821), when Mexico was known as New Spain, this central region became the Intendency of Mexico. After achieving independence from the Spanish Empire in 1821, the new country was named after its capital, Mexico City, which itself was built on the ruins of Tenochtitlan. The spelling of "México" in Spanish, using an "x", reflects an older Spanish pronunciation where "x" represented a sound like English "sh". Over time, this sound evolved into the Spanish velar fricative sound (similar to the "ch" in German "Bach"), which is also represented by the letter "j". While the Royal Spanish Academy accepts both "México" and "Méjico" as correct, the spelling with "x" is standard in Mexico and recommended internationally.

The country's official name is the United Mexican States (Estados Unidos Mexicanoses-TA-dos oo-NEE-dos meh-hee-KA-nosSpanish). This name was first adopted in the Constitution of 1824, influenced by the United States of America. There has been some public discussion and occasional political proposals in Mexico to change the "United Mexican States" part of the official name, often to "Mexican Republic" (República MexicanaMexican RepublicSpanish), to distinguish the country more clearly from its northern neighbor and to reflect a unique national identity. However, such changes have not been implemented, with many valuing the historical continuity of the current official name.

3. History

Mexico's history is a long and multifaceted narrative, stretching from ancient Indigenous civilizations through Spanish colonization, a protracted struggle for independence, periods of political instability and foreign intervention, a transformative revolution, a long era of single-party rule, and its contemporary transition towards a more pluralistic democracy, all marked by ongoing efforts to achieve social justice and national development.

3.1. Pre-Columbian civilizations

Human presence in the region of present-day Mexico dates back at least 20,000 years, with the earliest stone tool artifacts found near campfire remains in the Valley of Mexico radiocarbon-dated to circa 10,000 years ago. The region is recognized as one of the world's six independent cradles of civilization. The domestication of maize (corn), tomato, and beans around 5000 BC led to an agricultural surplus, enabling the transition from Paleo-Indian hunter-gatherer societies to sedentary agricultural villages. This formative period in Mesoamerica saw the emergence of distinct cultural traits, including complex religious and symbolic traditions, advanced artistic and architectural styles, and a vigesimal (base-20) numeral system, which spread throughout the Mesoamerican cultural area. Villages grew denser and socially stratified, developing into chiefdoms where rulers held both religious and political power, often organizing the construction of large ceremonial centers.

The earliest complex civilization in Mexico was the Olmec culture, which flourished on the Gulf Coast from around 1500 BC. Known for their colossal stone heads, believed to depict rulers, the Olmecs exerted significant cultural influence that diffused to other formative-era cultures in Chiapas, Oaxaca, and the Valley of Mexico. During the subsequent pre-classical period, the Maya and Zapotec civilizations developed major centers at sites like Calakmul and Monte Albán, respectively. This era also saw the development of the first true Mesoamerican writing systems by the Epi-Olmec and Zapotec peoples. The Mesoamerican writing tradition reached its peak with the Classic Maya hieroglyphic script, which recorded the earliest written histories of the region.

In Central Mexico, the Classic period (c. 200-900 AD) was dominated by the city of Teotihuacan, which grew to be one of the largest cities in the world, with a population exceeding 150,000. Teotihuacan featured enormous pyramidal structures, such as the Pyramid of the Sun and the Pyramid of the Moon, and its influence extended through military and commercial networks. After Teotihuacan's decline around 600 AD, various political centers like Xochicalco and Cholula competed for dominance. During this Epi-Classic period, Nahua peoples began migrating south into Mesoamerica, eventually becoming culturally and politically dominant in central Mexico.

The Post-Classic period (c. 900-1519 AD) saw the rise of the Toltec culture in Central Mexico, the Mixtec in Oaxaca, and important Maya centers like Chichen Itza and Mayapan in the Yucatán lowlands. By the late 15th century, the Aztecs (or Mexica) established a powerful political and economic empire centered on their magnificent capital city of Tenochtitlan, built on an island in Lake Texcoco (the site of modern Mexico City). The Aztec Empire, a Triple Alliance of city-states, dominated much of central Mexico and extended its influence as far south as Guatemala through tribute and military might. Their society was highly stratified, with complex religious practices that included human sacrifice, and a sophisticated understanding of agriculture, engineering, and astronomy, as evidenced by the Templo Mayor, their great temple in Tenochtitlan.

3.2. Spanish colonial era (1519-1821)

Although the Spanish Empire had established colonies in the Caribbean starting in 1493, the Spanish first learned of Mexico during the Juan de Grijalva expedition of 1518. The Spanish conquest began in February 1519 when Hernán Cortés landed and founded the Spanish city of Veracruz. Leveraging internal dissent within the Aztec Empire, forming alliances with subjugated Indigenous groups like the Tlaxcalans, and benefiting from the devastating impact of European diseases (like smallpox) on Indigenous populations, Cortés's forces, after a brutal siege, captured Tenochtitlan in August 1521. The destruction of the Aztec capital and the subsequent founding of Mexico City on its ruins marked the beginning of a 300-year colonial era during which Mexico was known as the Viceroyalty of New Spain (Nueva EspañaNew SpainSpanish).

New Spain became a cornerstone of the Spanish Empire due to two primary factors: the existence of large, hierarchically organized Mesoamerican populations who could be compelled to provide tribute and labor, and the discovery of vast silver deposits, particularly in northern Mexico (e.g., Zacatecas, Guanajuato). The colonial economy was largely extractive, based on silver mining using forced Indigenous labor under systems like the encomienda and later the repartimiento, as well as the enslavement of Africans in some regions. This system created a rigidly stratified colonial society based on race and origin, with Peninsular Spaniards (born in Spain) at the top, followed by Creoles (Spaniards born in the Americas), Mestizos (of mixed Spanish and Indigenous ancestry), Indigenous peoples, and enslaved Africans.

The two pillars of Spanish rule were the State and the Roman Catholic Church, both under the authority of the Spanish crown. Under the Patronato Real, the Spanish monarchy was granted extensive powers over Church affairs in the Americas in exchange for promoting Christianity. The Council of the Indies, based in Spain, oversaw colonial administration, while in New Spain, the highest royal official was the Viceroy, supported by the Real AudienciaRoyal AudienceSpanish (high court) in Mexico City. The Catholic Church played a pervasive role in colonial life, not only in religious matters but also in education, social welfare, and as a major landowner and economic power. The Mexican Inquisition, established in 1571, aimed to enforce religious orthodoxy, primarily among non-Indigenous populations.

Indigenous populations suffered catastrophic demographic decline due to disease, warfare, and exploitation. While Spanish law theoretically offered some protections, in practice, Indigenous communities were largely dispossessed of their lands and subjected to forced labor and cultural suppression. Despite this, Indigenous cultures often survived by adapting and syncretizing with Spanish traditions. Resistance to colonial rule took various forms, including numerous Indigenous revolts such as the Chichimeca War (1576-1606), the Tepehuán Revolt (1616-1620), the Pueblo Revolt (1680) in the north, and the Tzeltal Rebellion of 1712 in Chiapas. These uprisings, though often brutally suppressed, demonstrated ongoing resistance to colonial oppression. Urban unrest also occurred, notably the 1692 riot in Mexico City, where the urban poor protested against maize prices and attacked symbols of colonial power.

To protect its lucrative colony and trade routes from rivals like England, France, and the Netherlands, Spain restricted trade to only two main ports: Veracruz on the Atlantic (connecting to Spain) and Acapulco on the Pacific (connecting to the Philippines via the Manila galleons). Coastal fortifications were built, and a standing military was eventually established, particularly in response to threats like the British capture of Havana and Manila during the Seven Years' War.

3.3. War of Independence and First Mexican Empire (1810-1823)

The Mexican War of Independence was ignited by a confluence of factors, including resentment among Creoles against Peninsular Spanish dominance, the influence of Enlightenment ideas, the examples of the American and French Revolutions, and the political crisis in Spain caused by Napoleon Bonaparte's invasion in 1808, which deposed King Ferdinand VII.

On September 16, 1810, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, a Creole priest in the small town of Dolores, Guanajuato, issued the "Cry of Dolores" (Grito de DoloresCry of DoloresSpanish), a call to arms against "bad government." This event is commemorated annually as Mexico's Independence Day. Hidalgo's initial uprising, largely composed of Indigenous and Mestizo peasants, was marked by early victories but also by widespread violence and a lack of clear political objectives beyond ending Peninsular rule. Hidalgo's forces were eventually defeated, and he was captured, defrocked, and executed by firing squad on July 31, 1811.

The leadership of the insurgency passed to another priest, José María Morelos, also of humble origins, who was a more skilled military strategist and had clearer political goals, including independence, an end to slavery, and social reforms. Morelos convened the Congress of Chilpancingo in 1813, which formally declared independence and drafted a constitution. However, Morelos too was eventually defeated and executed by royalist forces in 1815. After Morelos's death, the independence movement fragmented into guerrilla warfare led by figures like Vicente Guerrero and Guadalupe Victoria.

The character of the independence struggle shifted when, in 1820, a liberal revolt in Spain (the Trienio Liberal) forced Ferdinand VII to restore the liberal Spanish Constitution of 1812. This alarmed conservative elites in New Spain, including high-ranking clergy and military officers, who feared losing their traditional privileges. This led to an unlikely alliance between conservative Creoles and the remaining insurgents. Agustín de Iturbide, a royalist Creole officer who had previously fought against the insurgents, switched sides and negotiated the Plan of Iguala with Vicente Guerrero in 1821. This plan called for an independent Mexico as a constitutional monarchy, the equality of Peninsulares and Creoles, and the supremacy of the Roman Catholic Church.

With widespread support, Iturbide's Army of the Three Guarantees triumphantly entered Mexico City on September 27, 1821, effectively ending Spanish rule. The Treaty of Córdoba, signed by Iturbide and the last Spanish viceroy (though later repudiated by Spain), recognized Mexican independence.

Following independence, the First Mexican Empire was established. The Plan of Iguala had envisioned inviting a European monarch to rule, but when no suitable candidate was found, Iturbide himself was proclaimed Emperor Agustín I in May 1822. His reign was short-lived and fraught with problems, including economic instability, internal political divisions, and opposition from republicans. In December 1822, military commanders, including Antonio López de Santa Anna, revolted under the Plan of Casa Mata. Facing mounting opposition, Iturbide abdicated in March 1823 and went into exile (he was later executed upon returning to Mexico in 1824). The collapse of the empire led to the secession of the Central American provinces, which formed the Federal Republic of Central America, and paved the way for the establishment of a republic in Mexico.

3.4. Early Republic and territorial losses (1824-1855)

The period following the fall of the First Mexican Empire was marked by profound political instability, economic stagnation, and significant territorial losses, primarily to the United States. The First Mexican Republic was established under the Constitution of 1824, which created a federal system. Guadalupe Victoria, a former insurgent leader, became the first president. However, the early republic was plagued by struggles between Centralists (often Conservatives, favoring a strong central government and the privileges of the Church and military) and Federalists (often Liberals, advocating for states' rights and limitations on Church/military power). Military coups (pronunciamientospronouncements (military coups)Spanish) were frequent, and the presidency changed hands numerous times.

General Antonio López de Santa Anna emerged as a dominant and often controversial figure, holding the presidency on multiple occasions during this era, which is sometimes called the "Age of Santa Anna." His political opportunism and military actions significantly shaped Mexico's fortunes. In 1829, President Vicente Guerrero, an Afro-Mestizo hero of the independence war, formally abolished slavery, but he was soon overthrown and judicially murdered. Spain attempted to reconquer Mexico in 1829 but was repelled, with Santa Anna gaining national hero status. France also intervened briefly in the Pastry War (1838-1839) over financial claims, a conflict where Santa Anna again played a prominent military role.

A major challenge for the young republic was governing its vast northern territories, which were sparsely populated by Mexicans but inhabited by powerful Indigenous groups like the Comanche and Apache. To populate and develop Tejas (Texas), the Mexican government encouraged immigration from the United States. These Anglo-American settlers, primarily Protestant and many bringing enslaved people (despite Mexico's abolition of slavery), soon outnumbered Mexicans in the region and grew restive under Mexican rule.

In 1835, Santa Anna, then president, sought to centralize power by abrogating the 1824 Constitution and promulgating the Siete Leyes (Seven Laws), which established a centralist republic. This sparked widespread revolts, including the Texas Revolution. Texan forces, after initial setbacks like the Battle of the Alamo, defeated Santa Anna's army at the Battle of San Jacinto in 1836, securing de facto independence for the Republic of Texas. Other regions, like the Republic of the Rio Grande and the Republic of Yucatán, also declared independence, though they were eventually reincorporated into Mexico.

The annexation of Texas by the United States in 1845 led directly to the Mexican-American War (1846-1848). The U.S., driven by Manifest Destiny, invaded Mexico. Despite some resistance, Mexican forces were outmatched. U.S. troops occupied Mexico City, and the war concluded with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. Under this treaty, Mexico was forced to cede nearly half of its territory to the United States, including present-day California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, and parts of New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming, in exchange for 15.00 M USD. This devastating loss exacerbated Mexico's internal problems. Santa Anna returned to power again but was finally ousted and exiled in 1855 by the liberal Revolution of Ayutla, which ushered in a new era of reform.

3.5. Liberal Reform, French intervention, and Restored Republic (1855-1876)

The Revolution of Ayutla (1854-1855) successfully overthrew the dictatorship of Antonio López de Santa Anna and brought a new generation of Liberals to power. This marked the beginning of La Reforma (The Reform), a period aimed at modernizing Mexico's economy and institutions along liberal principles, reducing the power of the Roman Catholic Church and the military, and establishing a secular state with individual rights. Key figures of La Reforma included Benito Juárez, Melchor Ocampo, and Miguel Lerdo de Tejada.

The Liberals promulgated a new constitution, the Constitution of 1857, which enshrined principles such as freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and the separation of church and state. It also included controversial provisions like the Ley Juárez (abolishing special courts or fueros for clergy and military) and the Ley Lerdo (mandating the sale of Church-owned property and Indigenous communal lands, aiming to create a class of small landholders but often leading to land concentration in the hands of speculators). These reforms were met with fierce opposition from Conservatives, who saw them as an attack on tradition and religion.

The conflict between Liberals and Conservatives escalated into the Reform War (Guerra de ReformaWar of the ReformSpanish; 1858-1861), a brutal civil war. Benito Juárez, as president of the Supreme Court, became the constitutional president of the Liberal government, which was initially forced out of Mexico City. After three years of fighting, the Liberals emerged victorious, with Juárez re-establishing his government in the capital.

However, Mexico's financial troubles, exacerbated by the civil war, led Juárez's government to suspend payments on foreign debts in 1861. This provided a pretext for European powers - Britain, Spain, and France - to intervene. While Britain and Spain eventually withdrew after negotiations, Napoleon III of France had broader imperial ambitions. He sought to establish a European-backed monarchy in Mexico that would serve French interests and counter U.S. influence in the Americas (especially as the U.S. was preoccupied with its own Civil War, 1861-1865).

French forces invaded Mexico in 1862. Despite an initial Mexican victory at the Battle of Puebla on May 5, 1862 (now celebrated as Cinco de Mayo), the French army, reinforced, eventually occupied Mexico City in 1863. A French-backed Assembly of Notables declared the establishment of the Second Mexican Empire and offered the crown to Archduke Maximilian of Habsburg, a younger brother of the Austrian emperor. Maximilian and his wife, Carlota, arrived in Mexico in 1864.

Maximilian, though a well-intentioned liberal monarch, found himself dependent on French military support and alienated both Mexican Conservatives (who found him too liberal) and Liberals (who rejected foreign imposition). Benito Juárez and the Liberal government maintained a government-in-exile and continued armed resistance. With the end of the U.S. Civil War in 1865, the United States government exerted diplomatic pressure on France to withdraw and provided aid to Juárez's forces. Facing increasing Mexican resistance and pressure from the U.S. and Prussia, Napoleon III withdrew French troops in 1866-1867. Maximilian, refusing to abdicate, was captured by Republican forces, court-martialed, and executed by firing squad in Querétaro on June 19, 1867.

The collapse of the Second Mexican Empire led to the "Restored Republic" (1867-1876). Benito Juárez returned to the presidency, a symbol of national sovereignty and resistance. His government focused on reconstruction, secular education, and infrastructure development. The Conservatives were largely discredited by their collaboration with the French. Juárez was re-elected but died in office in July 1872. He was succeeded by Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada, president of the Supreme Court. Lerdo continued Juárez's liberal policies but faced challenges, including economic difficulties and political opposition. When Lerdo sought re-election, General Porfirio Díaz, a hero of the war against the French, rebelled under the Plan of Tuxtepec, accusing Lerdo of violating no-re-election principles. Díaz's rebellion gained support, and Lerdo was forced into exile in 1876, paving the way for Díaz's long rule.

3.6. Porfiriato and Mexican Revolution (1876-1920)

The period from 1876 to 1911, known as the Porfiriato, was dominated by General Porfirio Díaz, who ruled Mexico as a dictator. While his regime brought political stability (paz porfiriana) and significant economic modernization under the motto "Order and Progress," it came at a high cost of political repression, social inequality, and the concentration of land and wealth in the hands of a few, including foreign investors. Díaz encouraged foreign investment, particularly from the United States and Britain, which fueled the development of railroads, mining, oil, and export agriculture. A group of technocratic advisors known as the Científicos, influenced by Positivism, guided economic policy. However, the benefits of this modernization largely bypassed the rural peasantry and urban working class. Indigenous communities lost vast amounts of communal land (ejidos) to large estates (haciendas), leading to widespread rural poverty and discontent. Labor movements were suppressed, as seen in the violent repression of strikes like the Cananea strike (1906) and the Río Blanco strike (1907). The long-standing Yaqui Wars also continued, culminating in the forced relocation of thousands of Yaqui people.

As Díaz aged and the 1910 centennial of independence approached, political tensions grew. In a 1908 interview with American journalist James Creelman, Díaz stated he would not seek re-election in 1910, seemingly opening the door for political change. This sparked political activity, including the candidacy of Francisco I. Madero, a wealthy landowner from Coahuila, who advocated for democracy and effective suffrage. However, Díaz reneged on his statement, ran for re-election, and had Madero imprisoned. The fraudulent 1910 election, declaring Díaz the winner, became the catalyst for the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920).

Madero, having escaped from prison, issued the Plan of San Luis Potosí, calling for an armed uprising against Díaz. The revolution quickly spread, with diverse regional leaders and movements emerging. In the north, figures like Pancho Villa (Doroteo Arango) and Pascual Orozco led popular armies, while in the south, Emiliano Zapata championed the cause of land reform for peasants with the slogan "Land and Liberty" (Tierra y LibertadLand and LibertySpanish). Facing widespread rebellion, Díaz resigned in May 1911 and went into exile.

Madero was democratically elected president in late 1911. However, his moderate reformist government struggled to satisfy the diverse demands of the revolutionaries and faced opposition from both entrenched Porfirian interests and more radical revolutionary factions. In February 1913, during a period known as the Ten Tragic Days (Decena TrágicaTen Tragic DaysSpanish), a military coup led by General Victoriano Huerta, with the clandestine support of the U.S. ambassador Henry Lane Wilson, overthrew Madero's government. Madero and his vice president were subsequently murdered.

Huerta's counter-revolutionary regime was opposed by a broad coalition of revolutionary forces known as the Constitutionalists, led by Venustiano Carranza, governor of Coahuila, along with Álvaro Obregón and Pancho Villa in the north, and Zapata in the south. The U.S. administration under President Woodrow Wilson refused to recognize Huerta's government and allowed arms sales to the Constitutionalists, even briefly occupying the port of Veracruz in 1914. The Federal Army was defeated in mid-1914, and Huerta fled into exile.

The victorious revolutionary coalition soon fractured. At the Convention of Aguascalientes, disagreements over the future direction of the country led to a split between Carranza and the more radical Conventionists, Villa and Zapata. This plunged Mexico back into civil war. Obregón, Carranza's most capable general, decisively defeated Villa's forces in a series of battles, notably the Battle of Celaya in 1915. With Villa marginalized and Zapata confined to guerrilla warfare in Morelos, Carranza became the de facto leader of Mexico and gained U.S. recognition. In 1916, Villa's raid on Columbus, New Mexico, prompted the U.S. to send the Punitive Expedition under General John J. Pershing into northern Mexico to capture Villa, an unsuccessful endeavor that further strained U.S.-Mexican relations. During World War I, Germany attempted to draw Mexico into an alliance against the U.S. via the Zimmermann Telegram (1917), promising the return of lost territories, but Mexico remained neutral.

Carranza convened a constitutional convention in 1916, which drafted the Constitution of 1917. This document, still in effect today (though heavily amended), was progressive for its time. It included provisions for land reform (Article 27, empowering the state to expropriate land and subsoil resources), labor rights (Article 123, establishing an eight-hour workday, minimum wage, and the right to organize and strike), and strengthened anticlerical measures from the 1857 Constitution. The revolution resulted in an estimated 900,000 to 2 million deaths and profound social and economic upheaval.

Consolidating power, Carranza had Zapata assassinated in 1919. When Carranza attempted to impose a civilian successor, Obregón and other Sonoran generals issued the Plan of Agua Prieta in 1920, leading to Carranza's overthrow and death while fleeing Mexico City. Adolfo de la Huerta served as interim president before Obregón was elected, marking the end of the most violent phase of the revolution and the beginning of a period of political consolidation under Sonoran leadership.

3.7. Political consolidation and PRI rule (1920-2000)

The period from 1920 to 2000 was largely dominated by a single political party, which eventually became known as the Institutional Revolutionary Party (Partido Revolucionario InstitucionalInstitutional Revolutionary PartySpanish, PRI). The initial decades (1920-1940s) saw revolutionary generals, primarily from Sonora, serving as presidents, including Álvaro Obregón (1920-1924), Plutarco Elías Calles (1924-1928), and Lázaro Cárdenas (1934-1940). Their administrations focused on consolidating state power, implementing some revolutionary reforms, and managing relations with various social sectors and foreign powers.

Obregón initiated limited land reform and strengthened organized labor. He also secured U.S. recognition for his government. Calles, his successor, enforced anticlerical provisions of the 1917 Constitution more strictly, leading to the Cristero War (1926-1929), a violent conflict between the government and Catholic rebels. Although the constitution initially forbade presidential re-election, it was amended to allow Obregón to run again in 1928. He won but was assassinated by a Catholic militant before taking office, creating a political crisis.

Calles, unable to serve as president again, established the National Revolutionary Party (Partido Nacional RevolucionarioNational Revolutionary PartySpanish, PNR) in 1929. This party, later renamed the Party of the Mexican Revolution (Partido de la Revolución MexicanaParty of the Mexican RevolutionSpanish, PRM) in 1938 and finally the PRI in 1946, aimed to institutionalize political succession and incorporate various interest groups (workers, peasants, the popular sector, and initially, the military) under a single umbrella. Calles remained the de facto power behind the presidency during the Maximato (1929-1934), a period of puppet presidents.

Lázaro Cárdenas's presidency (1934-1940) marked a significant shift. He asserted his independence by exiling Calles, accelerated land reform (distributing more land than all his predecessors combined), strengthened labor unions, and, most notably, nationalized the foreign-owned oil industry in 1938, creating the state-owned company Pemex. This act was immensely popular and became a symbol of Mexican economic sovereignty. Cárdenas's successor, Manuel Ávila Camacho (1940-1946), adopted more moderate policies and aligned Mexico with the Allies during World War II, even sending the Escuadrón 201 to fight in the Pacific.

From 1946, with the election of Miguel Alemán Valdés, the first civilian president of the post-revolutionary era, Mexico embarked on a period of rapid industrialization and economic growth known as the Mexican Miracle (roughly 1940s-1970s). This era saw significant urbanization, infrastructure development, and improvements in education and healthcare. However, this growth was often accompanied by increasing social inequality, corruption, and authoritarian tendencies within the PRI-dominated state. The Green Revolution, which significantly increased agricultural productivity, also began in Mexico during this period.

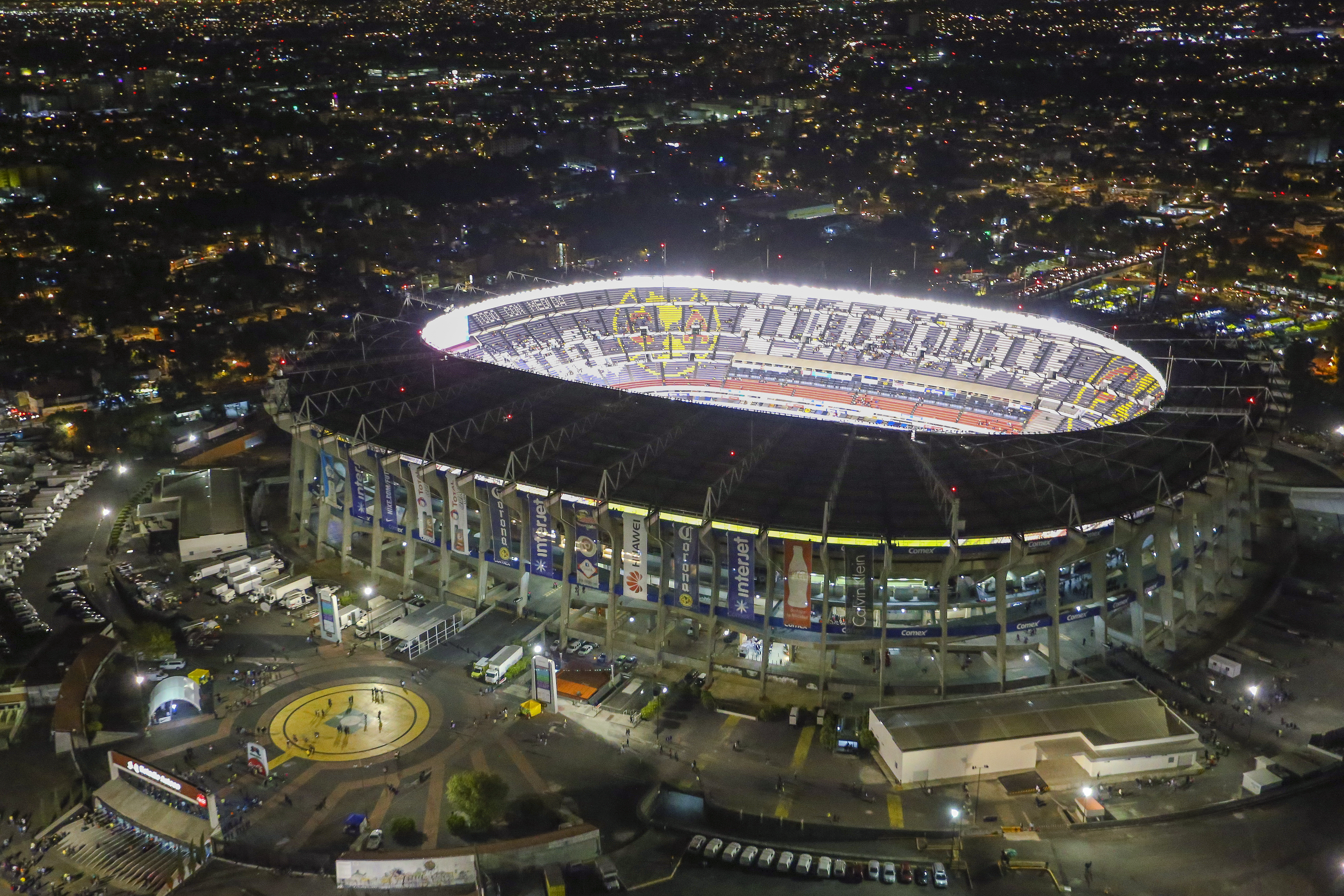

The PRI maintained its grip on power through a combination of co-optation, patronage, electoral manipulation, and, at times, repression. Dissent was often met with force. A key event exposing the regime's authoritarianism was the Tlatelolco massacre on October 2, 1968, just days before Mexico City hosted the 1968 Summer Olympics. Government forces opened fire on a student protest, killing hundreds. This event became a watershed moment, fueling further opposition and criticism of the PRI. The period from the late 1960s to the early 1980s also saw the "Dirty War" (Guerra SuciaDirty WarSpanish), a low-intensity conflict involving state repression of leftist student and guerrilla groups, resulting in forced disappearances and extrajudicial killings, further eroding faith in the democratic process and human rights protections.

Economic problems, including the 1982 debt crisis triggered by falling oil prices and rising interest rates, began to erode the PRI's legitimacy. The government's slow response to the devastating 1985 Mexico City earthquake further fueled public discontent. In the 1988 presidential election, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas (son of Lázaro Cárdenas), who had broken from the PRI to form a leftist coalition, mounted a strong challenge. The PRI's candidate, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, was declared the winner amidst widespread allegations of electoral fraud, further damaging the party's credibility.

Salinas (1988-1994) implemented sweeping neoliberal economic reforms, including privatization of state-owned enterprises, deregulation, and trade liberalization. The cornerstone of his economic policy was the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with the United States and Canada, which came into effect on January 1, 1994. On the same day, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), an Indigenous rebel group in the southern state of Chiapas, launched an uprising, protesting against NAFTA's perceived negative impacts on Indigenous communities and demanding greater autonomy and social justice. While the armed conflict was brief, the Zapatistas gained international attention and continued as a significant social and political movement.

The year 1994 was tumultuous: besides the Zapatista uprising, the PRI's presidential candidate, Luis Donaldo Colosio, was assassinated, as was another high-ranking PRI official. Salinas's successor, Ernesto Zedillo (1994-2000), inherited the "December Mistake" (peso crisis) shortly after taking office, requiring a 50.00 B USD IMF bailout. Zedillo implemented further macroeconomic reforms and, crucially, oversaw significant electoral reforms that paved the way for a more competitive political system. These reforms, coupled with growing public demand for change, set the stage for the end of the PRI's long dominance.

3.8. Contemporary Mexico (2000-present)

The presidential election of 2000 marked a historic turning point for Mexico. Vicente Fox of the conservative National Action Party (PAN) won, ending 71 years of uninterrupted rule by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). This peaceful transition to a multi-party democracy was widely hailed as a significant step in Mexico's political development. Fox's presidency (2000-2006) focused on maintaining macroeconomic stability and attempting further reforms, but he often faced a divided Congress that limited his legislative agenda.

The 2006 presidential election was highly contentious. Felipe Calderón of the PAN was declared the winner by a very narrow margin (0.58%) over Andrés Manuel López Obrador (often known as AMLO) of the leftist Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD). López Obrador alleged widespread fraud and organized massive protests, refusing to concede and even declaring himself the "legitimate president." Calderón's presidency (2006-2012) was largely defined by the escalation of the conflict with drug cartels. He deployed the military to combat organized crime, leading to a dramatic increase in violence and homicides across the country, raising significant human rights concerns.

In the 2012 presidential election, the PRI returned to power with the election of Enrique Peña Nieto. His administration (2012-2018) pushed through significant structural reforms in energy, education, telecommunications, and finance. The energy reform, in particular, ended Pemex's decades-long monopoly and opened the sector to private and foreign investment. However, Peña Nieto's term was also marred by corruption scandals, persistent violence, and human rights issues, such as the disappearance of 43 students in Iguala, which sparked national and international outrage and highlighted impunity and alleged state collusion with organized crime.

The 2018 presidential election saw a landslide victory for Andrés Manuel López Obrador, running under his newly formed MORENA party. Promising to combat corruption, reduce inequality, and pacify the country, AMLO's populist message resonated with voters disillusioned with the traditional parties. His coalition also won majorities in both houses of Congress. López Obrador's presidency (2018-2024) focused on social programs, austerity in government, and infrastructure projects like the Tren Maya. His approach to security continued to rely heavily on the military, formalizing its role in public security through the creation of the National Guard. His tenure also faced challenges including the COVID-19 pandemic, ongoing cartel violence, and economic pressures. The privatization of state-owned enterprises, a hallmark of previous neoliberal reforms, saw some reversal or slowdown, particularly concerning Pemex, though some exploration licenses continued to be issued. Efforts to combat corruption included the arrest of figures like Emilio Lozoya Austin, former CEO of Pemex, in 2020.

In the 2024 presidential election, Claudia Sheinbaum, López Obrador's chosen successor from MORENA, won a landslide victory, becoming Mexico's first female president. She took office on October 1, 2024, promising to continue many of AMLO's policies while addressing pressing issues such as security, water scarcity, and social equity. Contemporary Mexico continues to grapple with significant challenges, including high crime rates, the power of drug cartels, economic inequality, and ensuring the full protection of human rights, alongside navigating its complex relationship with the United States, particularly on issues of trade (under the USMCA, successor to NAFTA), immigration, and security cooperation.

4. Geography

Mexico is a country of diverse geography, characterized by extensive mountain ranges, high plateaus, coastal plains, and a varied climate. Its geographical features have significantly influenced its history, biodiversity, and human settlement patterns.

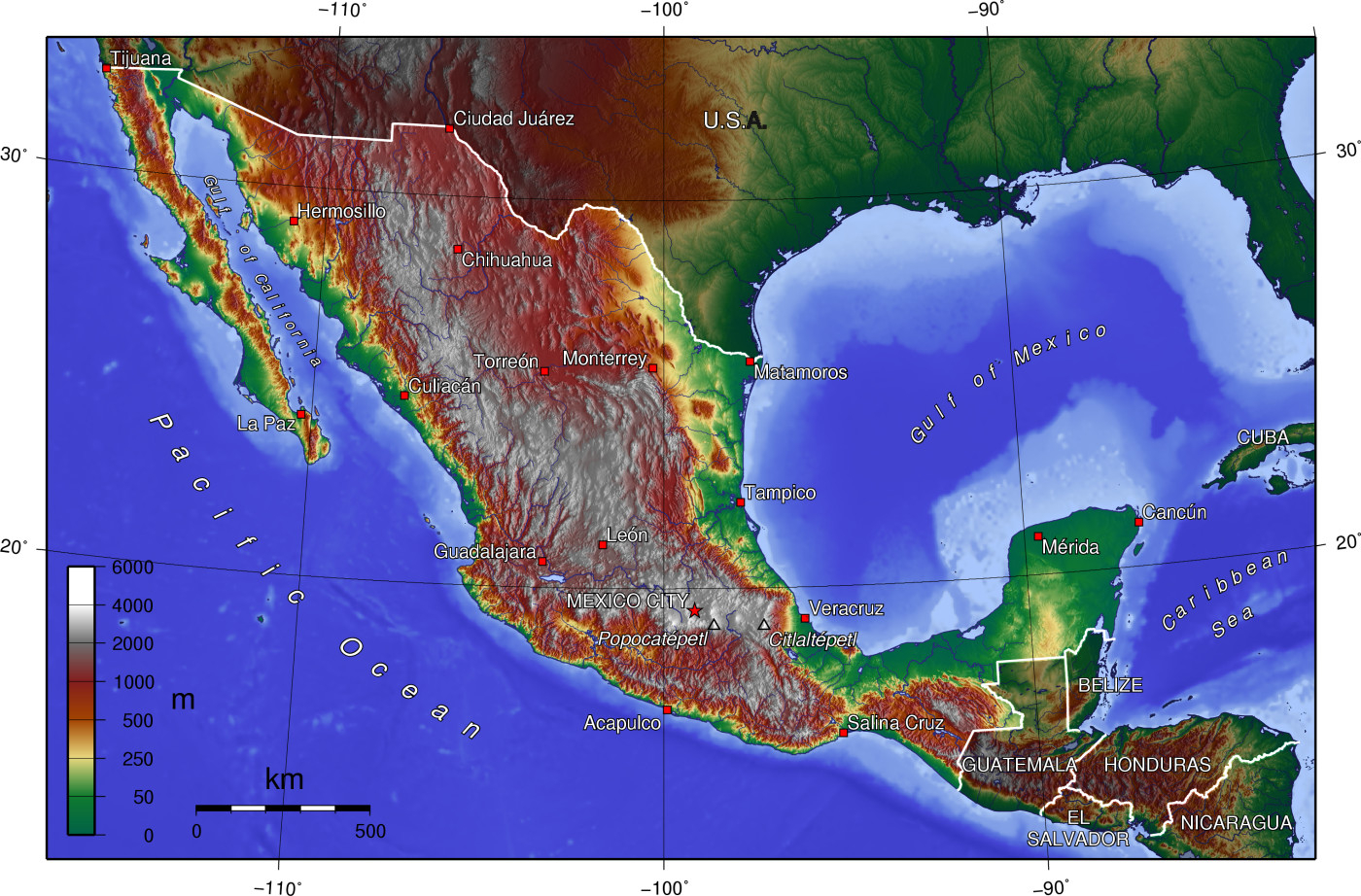

4.1. Topography and geology

Mexico is located in the southern portion of North America, bordered by the United States to the north, Belize and Guatemala to the southeast, the Pacific Ocean to the west and south, the Gulf of Mexico to the east, and the Caribbean Sea to the southeast. The country covers a total area of 0.8 M mile2 (1.97 M km2). Most of Mexico lies on the North American Plate, with parts of the Baja California peninsula on the Pacific Plate and the Cocos Plate. Geophysically, some geographers include the territory east of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec (about 12% of the total) within Central America, but geopolitically, Mexico is considered part of North America.

The country's topography is dominated by mountain ranges. The Sierra Madre Occidental runs along the western side, and the Sierra Madre Oriental along the eastern side; these are extensions of the Rocky Mountains. The Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt (Eje NeovolcánicoNeo-Volcanic AxisSpanish), also known as the Sierra Nevada, stretches east-west across central Mexico and contains the country's highest peaks, many of which are active or dormant volcanoes. These include Pico de Orizaba (Citlaltépetl), the highest point at 19 K ft (5.64 K m), Popocatépetl (18 K ft (5.43 K m)), Iztaccihuatl (17 K ft (5.23 K m)), and Nevado de Toluca (15 K ft (4.68 K m)). The Sierra Madre del Sur extends along the southern coast. Between these mountain ranges lies the vast Mexican Plateau (Altiplano MexicanoMexican PlateauSpanish), which itself is divided into a lower, arid northern section and a higher, more temperate southern section (the Mesa Central), where most of Mexico's population and major cities are located.

Coastal plains are found along the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean. The Yucatán Peninsula in the southeast is a large, low-lying limestone platform, known for its cenotes (natural sinkholes) and the Chicxulub crater, the impact site linked to the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event. Mexico is geologically active, situated in the Ring of Fire, leading to frequent earthquakes and volcanic activity. Major rivers include the Rio Grande (Río Bravo del NorteBrave River of the NorthSpanish), which forms a large part of the border with the United States, and the Usumacinta River, which forms part of the border with Guatemala. Lake Chapala is the largest freshwater lake in Mexico.

4.2. Climate

Mexico's climate is highly varied due to its large size, diverse topography, and the influence of the Pacific Ocean and Gulf of Mexico. The Tropic of Cancer effectively divides the country into temperate zones to the north and tropical zones to the south.

Land north of the Tropic of Cancer generally experiences cooler temperatures during the winter months and has predominantly arid (desert climate, BWk/BWh) or semi-arid (steppe climate, BSk/BSh) conditions. The Sonoran Desert and Chihuahuan Desert are major features of this region, with some areas experiencing summer temperatures exceeding 104 °F (40 °C).

South of the Tropic of Cancer, temperatures are generally constant year-round, varying primarily with elevation rather than season. Coastal plains and the Yucatán Peninsula have tropical climates, ranging from tropical savanna (Aw) with distinct wet and dry seasons to tropical monsoon (Am) and tropical rainforest (Af) in areas with higher rainfall, particularly in the south and southeast, where annual precipitation can exceed 0.1 K in (2.00 K mm).

The mountainous regions and the high Mexican Plateau experience temperate climates due to their altitude. Mexico City, at an elevation of about 7.3 K ft (2.24 K m), has a subtropical highland climate (Cwb) with mild temperatures year-round and a rainy season from May to October. Higher elevations in the mountain ranges can have alpine climates (ET) or even small glaciers on the highest volcanic peaks.

Mexico is affected by tropical cyclones (hurricanes) on both its Pacific and Atlantic/Caribbean coasts, typically between June and November. The northern part of the country can experience occasional cold fronts (nortesnorthers (cold fronts)Spanish) during winter, bringing cooler temperatures and sometimes precipitation.

4.3. Biodiversity and environment

Mexico is recognized as one of the world's 17 megadiverse countries, ranking among the top five globally for natural biodiversity. It is home to an estimated 10-12% of the world's species, with over 200,000 different species identified within its borders. The country ranks first in the world for reptile diversity (with over 707 known species), second for mammals (over 438 species), fourth for amphibians (over 290 species), and fourth for flora (with over 26,000 different species). This extraordinary biodiversity is a result of its complex topography, varied climates, and its position as a transition zone between Nearctic and Neotropical biogeographic realms.

Major ecosystems in Mexico include vast deserts in the north (Sonoran and Chihuahuan), temperate and tropical rainforests (such as the Lacandon Jungle), cloud forests, mangrove swamps, alpine tundra, and extensive coral reef systems, notably the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef along the Yucatán Peninsula. Many species are endemic to Mexico, meaning they are found nowhere else in the world. These include iconic animals like the axolotl, the vaquita (a critically endangered porpoise), and numerous species of cacti and agaves.

To protect its natural heritage, Mexico has established a significant network of "Protected Natural Areas," covering approximately 66 K mile2 (170.00 K km2). These include 34 biosphere reserves, 67 national parks, 4 natural monuments, 26 areas for protected flora and fauna, 4 areas for natural resource protection (focused on soil and water conservation), and 17 wildlife sanctuaries.

Despite these efforts, Mexico faces significant environmental challenges. Deforestation has been a major issue, driven by agricultural expansion, logging, and urbanization. In 2002, Mexico had one of the highest rates of deforestation globally. While the rate has since slowed, forest degradation and loss continue to threaten biodiversity. Soil erosion is another pressing problem, particularly in rural areas. Other environmental concerns include water scarcity and pollution in many regions, overfishing, and the impacts of climate change. Environmental protection laws have improved, especially in urban areas, but enforcement remains a challenge, particularly in remote and rural regions.

Mexico is the center of origin and diversification for many important domesticated plants, including maize (corn), beans, squash, chili peppers, tomatoes, avocados, and vanilla. These crops, originally cultivated by Indigenous peoples, are now staples in global cuisine. Tequila and mezcal, distilled alcoholic beverages made from native agave plants, are major industries and cultural exports. The country's rich biodiversity has also made it a site for bioprospecting, such as the discovery of Dioscorea composita (Barbasco), a yam species rich in diosgenin, which was crucial in the development of synthetic hormones and the first oral contraceptive pills in the mid-20th century. These activities raise important questions about benefit-sharing and the rights of local communities over their genetic resources, aligning with broader concerns for social equity and sustainable development.

5. Government and politics

The United Mexican States is a federal republic operating under a presidential system and a democratic framework established by the 1917 Constitution. The constitution outlines a separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, and defines the rights and responsibilities of citizens, emphasizing social justice and national sovereignty.

5.1. Government structure

The federal government of Mexico is structured into three branches:

1. Executive Branch: The President is the head of state and head of government, as well as the commander-in-chief of the Mexican Armed Forces. The president is elected by popular vote for a single six-year term (sexeniosix-year termSpanish) and cannot be re-elected. The president appoints the Cabinet (Secretaries of State) and other high-ranking officials, is responsible for executing and enforcing laws, and has the power to veto legislation passed by the Congress. There is no vice president; in the event of the president's death or removal, the Congress designates an interim president.

2. Legislative Branch: The federal legislature is the bicameral Congress of the Union (Congreso de la UniónCongress of the UnionSpanish), composed of:

- The Senate (Senado de la RepúblicaSenate of the RepublicSpanish): Comprises 128 senators. Ninety-six are elected from the 32 states (three per state: two by plurality for the winning party/coalition and one for the first minority party). The remaining 32 are elected by proportional representation from national party lists. Senators serve six-year terms.

- The Chamber of Deputies (Cámara de DiputadosChamber of DeputiesSpanish): Consists of 500 deputies. Three hundred are elected by plurality vote in single-member districts (federal electoral districts), and 200 are elected by proportional representation from closed party lists within five multi-state electoral constituencies. Deputies serve three-year terms.

The Congress is responsible for making federal laws, declaring war, imposing taxes, approving the national budget and international treaties, and ratifying certain presidential appointments.

3. Judicial Branch: The highest judicial body is the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation (Suprema Corte de Justicia de la NaciónSupreme Court of Justice of the NationSpanish), which consists of eleven justices (ministers) appointed by the President with the approval of the Senate. The Supreme Court interprets laws and judges cases of federal competency. Other federal courts include the Federal Electoral Tribunal, collegiate circuit courts, unitary circuit courts, and district courts. The Council of the Federal Judiciary oversees the administration of the federal court system.

The 1917 Constitution also establishes three levels of government: federal, state, and municipal. This federal structure grants significant autonomy to the 32 federal entities (31 states and Mexico City), whose political systems are also influenced by a blend of Indigenous traditions and European Enlightenment ideals, particularly concerning individual rights and democratic governance.

5.2. Political parties

Mexico has a multi-party system, a significant evolution from the 71-year period of single-party dominance by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) which ended in 2000. The current political landscape features several major parties with varying ideologies and support bases:

- MORENA (Movimiento Regeneración NacionalNational Regeneration MovementSpanish): Founded by current President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), MORENA is a left-wing party that emerged as a dominant force in the 2018 elections. It generally advocates for social justice, anti-corruption measures, and a stronger state role in the economy, often appealing to a broad base concerned with inequality and traditional political elites.

- PAN (Partido Acción NacionalNational Action PartySpanish): A conservative, center-right party founded in 1939. The PAN traditionally supports free-market economic policies, fiscal conservatism, and often aligns with socially conservative values. It was the party that broke the PRI's long hold on the presidency in 2000 with Vicente Fox and held it again with Felipe Calderón. Its support base is often found in the urban middle class and northern states.

- PRI (Partido Revolucionario InstitucionalInstitutional Revolutionary PartySpanish): For seven decades, the PRI was the hegemonic party in Mexico, originating from the factions of the Mexican Revolution. Historically a catch-all party with corporatist structures, its ideology has shifted over time, often described as centrist. While significantly weakened since 2000, it remains a relevant political force, particularly at state and local levels, and briefly regained the presidency with Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-2018).

Other notable parties include:

- PRD (Partido de la Revolución DemocráticaParty of the Democratic RevolutionSpanish): A center-left to left-wing party founded in 1989, originally as a major opposition force to the PRI. Its influence has waned in recent years with the rise of MORENA, from which many of its former members, including AMLO, originated.

- MC (Movimiento CiudadanoCitizens' MovementSpanish): A social democratic party that has positioned itself as an alternative to the larger blocs, often appealing to younger and urban voters.

- PVEM (Partido Verde Ecologista de MéxicoEcologist Green Party of MexicoSpanish): A party focused on environmental issues, though often criticized for opportunistically allying with larger parties.

- PT (Partido del TrabajoLabor PartySpanish): A left-wing party often in alliance with MORENA.

Mexico's electoral system and political finance laws have undergone significant reforms aimed at promoting fairer competition and transparency, contributing to a more dynamic, though sometimes fragmented, multi-party democracy. Coalitions between parties are common, especially in presidential and gubernatorial elections.

5.3. Administrative divisions

The United Mexican States is a federation composed of 32 federal entities: 31 free and sovereign states (estados libres y soberanosfree and sovereign statesSpanish) and Mexico City (Ciudad de MéxicoMexico CitySpanish, CDMX), which is the capital of the republic and a federal entity with a status comparable to that of the states.

Each of the 31 states has its own constitution, a unicameral state congress, and a judiciary. The citizens of each state elect a governor for a six-year term and representatives to their state congress for three-year terms. States have considerable autonomy in local affairs, including the power to levy certain taxes and manage local services, within the framework of the federal constitution.

Mexico City (CDMX) holds a unique status. Formerly known as the Federal District (Distrito FederalFederal DistrictSpanish, D.F.), it was directly administered by the federal government. However, a significant political reform in 2016 granted Mexico City greater autonomy, transforming it into a federal entity with its own constitution, local congress, and a Head of Government (Jefe de GobiernoHead of GovernmentSpanish) elected by popular vote, similar to state governors. It is the seat of the federal powers and the country's most populous city.

The states are further divided into municipalities (municipiosmunicipalitiesSpanish), which are the smallest administrative and political entities in the country. Each municipality is governed by a municipal president (presidente municipalmunicipal presidentSpanish) and a municipal council, elected by its residents. There are over 2,400 municipalities in Mexico, varying greatly in size and population. Municipal governments are responsible for local public services such as water, sanitation, local roads, public safety, and markets. The autonomy and capacity of municipal governments can vary significantly depending on their resources and political context.

6. Foreign relations

Mexican foreign policy is guided by principles enshrined in its Constitution, including respect for international law, the self-determination of peoples, peaceful resolution of conflicts, and non-intervention in the internal affairs of other states (historically known as the Estrada Doctrine). Mexico is an active participant in numerous international organizations and forums.

6.1. Relations with the United States

The relationship between Mexico and the United States is one of the most complex and consequential bilateral relationships in the world. It is characterized by deep historical ties, extensive economic interdependence, and shared challenges, as well as periods of tension and cooperation. The two countries share a 2.0 K mile (3.14 K km) border, one of the busiest in the world.

Historically, the relationship has been shaped by conflict, notably the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), which resulted in Mexico ceding nearly half its territory to the U.S. This legacy has, at times, fueled Mexican nationalism and a cautious approach to its powerful northern neighbor.

Economically, the U.S. is by far Mexico's largest trading partner. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), implemented in 1994, and its successor, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), effective in 2020, have profoundly integrated the two economies, particularly in manufacturing (especially automotive), agriculture, and energy. This interdependence brings significant economic benefits but also makes Mexico vulnerable to U.S. economic fluctuations and policy changes.

Security cooperation is a major aspect of the relationship, focused on combating transnational organized crime, particularly drug trafficking. The U.S. has provided Mexico with assistance through initiatives like the Mérida Initiative to bolster its law enforcement and judicial capacities. However, issues such as arms trafficking from the U.S. into Mexico and differing approaches to drug policy remain points of contention. The human rights implications of the "war on drugs" in Mexico are also a concern for bilateral relations.

Immigration is another critical and often sensitive dimension. Millions of Mexicans live in the U.S., and remittances sent home are a vital part of Mexico's economy. The U.S. relies on Mexican labor in various sectors. However, undocumented immigration, border security, and the treatment of migrants are persistent sources of political debate and tension. U.S. immigration policies and border enforcement measures directly impact Mexican communities on both sides of the border.

Cultural exchange between the two countries is extensive, influencing music, food, language, and popular culture in both nations. Despite historical grievances and ongoing challenges, the U.S.-Mexico relationship is managed through numerous bilateral mechanisms and dialogues, reflecting a shared understanding of their intertwined destinies and the need for cooperation on a wide range of issues affecting the well-being and security of their populations. Perspectives from affected communities, particularly border communities and migrant groups, often highlight the human cost of unresolved issues and advocate for more equitable and humane policies.

6.2. Relations with other countries and regions

While the relationship with the United States is paramount, Mexico also maintains significant diplomatic, economic, and cultural ties with other countries and regions, reflecting its status as a regional power and an emerging global player.

Canada: As the third partner in the USMCA (formerly NAFTA), Canada is an important economic ally. Bilateral trade and investment have grown, and cooperation extends to areas like temporary worker programs and multilateral forums.

Latin America: Mexico sees itself as a leading nation in Latin America and the Caribbean. It is a founding member of the Organization of American States (OAS) and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC). Mexico has historically played a role in regional diplomacy, sometimes acting as a mediator or advocating for principles like non-intervention. It has strong cultural and economic ties with many Latin American nations, though relationships can vary. Mexico has championed regional integration efforts and has provided development assistance to some Central American and Caribbean countries.

European Union and Spain: The European Union (EU) is Mexico's third-largest trading partner and a significant source of foreign direct investment. Mexico and the EU have a comprehensive Free Trade Agreement that has deepened economic ties. Within the EU, Spain, as the former colonial power, holds a special place. The relationship is characterized by strong historical, cultural, linguistic, and economic links, with significant Spanish investment in Mexico and a robust flow of tourism and migration in both directions.

Asia-Pacific: Mexico has increasingly sought to diversify its foreign relations and has strengthened ties with key Asia-Pacific countries. It is a member of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum and was a signatory to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Japan, China, and South Korea are important trading partners and sources of investment, particularly in the manufacturing sector. Cultural exchange with Asian nations has also grown.

Mexico actively participates in global governance forums such as the United Nations (where it has served multiple terms as a non-permanent member of the Security Council), the G20, and the OECD. Its foreign policy often emphasizes multilateralism, sustainable development, human rights, and disarmament. Areas of international cooperation include climate change, global health, and combating organized crime, though potential conflicts can arise over trade disputes, differing approaches to international crises, or human rights criticisms.

7. Military

The Mexican Armed Forces (Fuerzas Armadas de MéxicoMexican Armed ForcesSpanish) are administered by two secretariats: the Secretariat of National Defense (Secretaría de la Defensa NacionalSecretariat of National DefenseSpanish, SEDENA), which oversees the Mexican Army and the Mexican Air Force, and the Secretariat of the Navy (Secretaría de MarinaSecretariat of the NavySpanish, SEMAR), which oversees the Mexican Navy (Armada de México), including its naval infantry (marines) and coast guard. The President of Mexico is the commander-in-chief.

As of 2024, the active armed forces personnel are estimated to be around 220,000, with approximately 160,000 in the Army, 10,000 in the Air Force, and 50,000 in the Navy (including about 20,000 marines). In 2019, the National Guard (Guardia NacionalNational GuardSpanish) was formed, primarily from former Federal Police units and elements of the military police from the Army and Navy. It functions as a gendarmerie, responsible for public security and law enforcement, and although initially placed under civilian command, it has increasingly come under military control, with around 110,000 personnel. Military expenditure is relatively low as a percentage of GDP, around 0.6% as of 2023. Mexico employs a system of selective conscription for males reaching the age of 18, who are required to perform one year of national military service, though active duty is not always required.

The primary roles of the Mexican Armed Forces include national defense, safeguarding internal security, and providing disaster relief. In recent decades, the military has become heavily involved in the conflict against drug cartels and organized crime. This has led to an increased focus on acquiring airborne surveillance platforms, aircraft, helicopters, digital warfare technologies, urban warfare equipment, and capabilities for rapid troop transport. The military also maintains infrastructure for the design, research, testing, and manufacturing of some of its own weapons systems, vehicles, and naval vessels.

Historically, Mexico has maintained a policy of neutrality in international conflicts, with its most significant foreign military engagement being its participation on the Allied side in World War II (sending the 201st Fighter Squadron). While Mexico has the capability to manufacture nuclear weapons, it renounced this option under the Treaty of Tlatelolco (1968), which established Latin America as a nuclear-weapon-free zone, pledging to use its nuclear technology only for peaceful purposes. Mexico is also a signatory to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. In recent years, there have been discussions about potentially amending the Constitution to allow Mexican forces to participate in United Nations peacekeeping missions or provide military assistance to countries that request it.

The extensive involvement of the military in domestic law enforcement, particularly in the "war on drugs," has raised significant concerns about human rights violations, including extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, and torture. There is ongoing debate within Mexico about the appropriateness and effectiveness of militarizing public security and the need for greater accountability and civilian oversight of all security forces, including the National Guard.

8. Economy

Mexico possesses a developing, upper-middle-income market economy. It is the 12th largest in the world by nominal GDP and the 12th largest by purchasing power parity (PPP) as of April 2024, with a GDP (PPP) per capita of approximately 24.97 K USD. The Mexican economy is characterized by a strong manufacturing sector, significant foreign trade (especially with the United States), a growing services industry, and important contributions from oil exports and tourism. However, it also faces challenges such as income inequality, informal labor, and the economic impacts of crime and corruption. Economic policies have generally trended towards liberalization since the 1990s, with a focus on fiscal stability and integration into the global economy, though recent administrations have shown some preference for a stronger state role in strategic sectors.

Historically, Mexico transitioned from an agriculture-based economy to one focused on mining and then industrialization, particularly after World War II during the "Mexican Miracle" period of rapid growth (1940s-1970s). The economy experienced significant debt crises in the 1980s and a currency crisis in 1994, which led to structural reforms and greater openness. The signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994 (now the USMCA) deeply integrated Mexico's economy with those of the United States and Canada.

Remittances from Mexican citizens working abroad, primarily in the United States, are a significant source of foreign income, often rivaling or exceeding revenues from oil exports or tourism. While the country has seen a reduction in overall poverty rates in recent years, particularly between 2018 and 2022, extreme poverty saw a slight increase, and a significant portion of the population still lives below national poverty lines. Access to healthcare services remains a challenge for many. Mexico has one of the highest degrees of economic disparity between the rich and poor among OECD countries, though this gap has shown signs of narrowing. Social spending on poverty alleviation and development is lower than the OECD average. The daily minimum wage has seen rapid increases in recent years, particularly under the López Obrador administration, in an effort to improve living standards for low-income workers.

8.1. Major industries

Mexico's economy is diversified across several key sectors, with manufacturing playing a particularly prominent role, especially for export.

Manufacturing: This is a cornerstone of the Mexican economy, heavily integrated into North American supply chains.

- Automotive: Mexico is one of the world's largest auto producers and exporters, hosting assembly plants for many major global automakers (e.g., General Motors, Ford, Stellantis, Volkswagen, Nissan, Kia, Audi, BMW, Mercedes-Benz). The industry also includes a significant number of auto parts manufacturers. This sector is a major source of employment and foreign exchange but has faced scrutiny regarding labor conditions and wages, which, while rising, have historically been lower than in the U.S. or Canada.

- Electronics: Mexico has a large electronics industry, producing consumer electronics, telecommunications equipment, and components, much of which is exported to the United States. It is considered one of the top global players in this sector.

- Aerospace: This is a growing sector, with numerous international companies establishing manufacturing operations for aircraft components.

- Other manufacturing includes appliances, medical devices, and industrial machinery.

Oil and Gas: The petroleum industry, historically dominated by the state-owned company Pemex (Petróleos Mexicanos), has been a vital part of Mexico's economy for decades. Mexico is a significant global oil producer and exporter, although production has declined from its peak. Pemex is involved in exploration, extraction, refining, and distribution. Recent energy reforms (beginning around 2013-2014) aimed to open the sector to private and foreign investment to boost production and modernize infrastructure, though the current administration has shown a preference for strengthening Pemex's role. The environmental impact of oil and gas extraction and processing is an ongoing concern.

Agriculture: While its share of GDP has declined, agriculture remains important for employment, particularly in rural areas. Mexico is a major producer and exporter of various agricultural products, including avocados (world's largest producer), tomatoes, chili peppers, limes, mangoes, coffee, sugarcane, and corn (maize), which is a cultural and dietary staple. Challenges include water scarcity, land tenure issues, and competition from imports. Labor conditions for agricultural workers, particularly migrant laborers, are often precarious.

Mining: Mexico has a long history of mining and remains a leading global producer of silver. It also produces significant quantities of gold, copper, zinc, lead, and fluorite. The mining sector attracts foreign investment but also faces environmental and social scrutiny regarding land use, water consumption, pollution, and impacts on local communities.

Services Sector: This is the largest component of Mexico's GDP and includes a wide range of activities:

- Tourism: A major source of foreign exchange and employment (see separate section).

- Financial Services: Banking, insurance, and other financial activities are well-developed, particularly in major urban centers.

- Retail and Wholesale Trade: A large and dynamic sector catering to domestic consumption.

- Telecommunications: (see separate section).

- Transportation and Logistics: Essential for supporting manufacturing and trade.

Labor rights and environmental sustainability are increasingly important considerations across all industries. While labor laws exist, enforcement can be inconsistent, and challenges related to union freedom, fair wages, and safe working conditions persist, particularly in export-oriented manufacturing and agriculture. Environmental regulations are in place, but their effective implementation and the transition to more sustainable practices are ongoing processes.

8.2. Energy

Mexico's energy sector is predominantly managed by state-owned companies: Pemex (Petróleos Mexicanos) for oil and gas, and the Federal Commission of Electricity (CFE) for electricity generation, transmission, and distribution.

Oil and Gas: Pemex, one of the world's largest oil companies by revenue, has historically been the cornerstone of Mexico's energy production and a major source of government revenue. Mexico is a significant global oil producer, with major reserves in the Gulf of Mexico. However, production has declined from its peak in the early 2000s. The country has seven oil refineries on its territory and Pemex also co-owns the Deer Park refinery in the United States. Energy reforms initiated around 2013-2014 aimed to attract private and foreign investment to reverse production declines and modernize the sector, but the current administration has sought to reassert Pemex's dominance. Natural gas production is also significant, though Mexico is a net importer of natural gas.

Electricity: The CFE has traditionally held a monopoly over the electricity sector. Mexico's electricity generation mix includes thermal plants (natural gas, coal, oil), hydroelectricity, nuclear power, and increasingly, renewable energy.

- Hydroelectric Power: Mexico has around 60 hydroelectric plants, accounting for about 12% of its electricity. The largest is the 2.40 K MW Manuel Moreno Torres Dam on the Grijalva River in Chiapas, one of the world's most productive.

- Nuclear Power: Mexico operates one nuclear power plant, the Laguna Verde Nuclear Power Station in Veracruz, which has two reactors.

- Renewable Energy: Mexico has significant potential for renewable energy, particularly solar and wind.

- Solar Power: The country has the world's third-largest solar power potential. As of 2018, the Villanueva Solar Park in Coahuila (828 MW) was the largest in the Americas, and the SEGH-CFE 1 project in Sonora (46.8 MW) also contributes significantly. Over 11 M ft2 (1.00 M m2) of solar thermal panels are installed.

- Wind Power: Numerous wind farms have been developed, especially in regions with strong wind resources like Oaxaca, home to the Eurus Wind Farm, one of the largest in Latin America.

The energy sector is undergoing a period of transition, with debates over the role of state-owned enterprises versus private investment, the pace of transition to cleaner energy sources, and ensuring energy security and affordability. The government's policies aim to increase domestic refining capacity and strengthen Pemex and CFE, while also meeting renewable energy targets.

8.3. Tourism

Tourism is a vital industry for Mexico, contributing significantly to its economy, foreign exchange earnings, and employment. The country's rich cultural heritage, diverse natural landscapes, favorable climate, and extensive coastline make it a highly attractive destination for international and domestic travelers. As of 2017, Mexico was the 6th most-visited country globally and ranked 15th in tourism income worldwide, the highest in Latin America.

Major Tourist Attractions:

- Archaeological Sites: Mexico is home to impressive remnants of ancient civilizations. Iconic sites include Chichen Itza and Tulum (Maya) in the Yucatán Peninsula; Teotihuacan (with its Pyramids of the Sun and Moon) near Mexico City; Palenque (Maya) in Chiapas; and Monte Albán (Zapotec) in Oaxaca. These sites offer insights into the sophisticated cultures that flourished before European contact.

- Colonial Cities: Centuries of Spanish colonial rule left a legacy of beautiful historic cities with well-preserved architecture, churches, and plazas. Examples include Mexico City's historic center, Puebla, Guanajuato, San Miguel de Allende, Oaxaca, and Zacatecas. Many of these are UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

- Beaches and Coastal Resorts: Mexico's extensive coastlines boast numerous world-renowned beach destinations.

- Caribbean Coast: Cancún, Playa del Carmen, Cozumel, and the Riviera Maya in the state of Quintana Roo are famous for their white-sand beaches, turquoise waters, coral reefs (part of the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef), and vibrant nightlife. These areas are particularly popular with international tourists, including university students during spring break. Ecological parks like Xcaret and Xel-Há are also major attractions.

- Pacific Coast: Destinations include Acapulco, historically a glamorous resort; Puerto Vallarta; Mazatlán; and the Los Cabos corridor (Cabo San Lucas and San José del Cabo) at the southern tip of the Baja California Peninsula, known for luxury resorts, sport fishing (especially marlin), and whale watching. San Felipe is a popular weekend destination closer to the U.S. border.

Economic Significance: The tourism industry is a major driver of economic growth, job creation (directly and indirectly), and regional development. It attracts significant foreign investment in hotels, infrastructure, and services. The majority of international tourists come from the United States and Canada, followed by Europe and Asia, with a smaller number from other Latin American countries.

Social and Environmental Impact: While tourism brings economic benefits, it also presents social and environmental challenges. Rapid development in some coastal areas has led to concerns about environmental degradation, strain on water resources, and impacts on local ecosystems like mangroves and coral reefs. There are ongoing efforts to promote sustainable tourism practices. Socially, the industry can create opportunities but also lead to issues like displacement of local communities, cultural commodification, and dependence on a volatile global market. Medical tourism has also become significant in Mexican cities along the U.S. border, with visitors seeking more affordable healthcare services such as medication, dentistry, and elective surgeries. This creates economic activity but also raises questions about equitable access to healthcare for local populations.

8.4. Transportation

Mexico has an extensive and developing transportation infrastructure designed to connect its vast territory and support its large economy, though challenges remain due to difficult topography and regional disparities.

Road Network: The roadway network is the primary mode of transportation for passengers and freight. It has an extent of approximately 227 K mile (366.10 K km), of which about 73 K mile (116.80 K km) are paved. This includes federal highways, state roads, and rural roads. A significant portion, around 6.5 K mile (10.47 K km), consists of multi-lane expressways (toll roads or autopistas, and some free autovías), with the majority being four-lane highways. Major highway projects continue to improve connectivity, such as the Durango-Mazatlán highway featuring the Baluarte Bridge.

Railways: Mexico was one of the first Latin American countries to promote railway development in the late 19th century. The current network covers approximately 19 K mile (30.95 K km). Historically, passenger rail services declined significantly with the privatization of railways in the 1990s, which focused on freight. However, there has been a recent resurgence of interest in passenger rail.

- Tren Maya: A major ongoing intercity railway project aimed at connecting tourist destinations and communities in the Yucatán Peninsula, including cities like Cancún, Mérida, Chichen Itza, and Palenque.

- El Insurgente: An intercity train connecting Toluca with Mexico City, designed to alleviate road congestion.

- Tren Interoceánico: A project to restore and modernize the rail corridor across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, connecting Pacific and Atlantic ports to create a trade route.

- A high-speed rail link between Mexico City and Guadalajara has been proposed in the past, aiming to connect the country's two largest metropolitan areas.

Airports: Mexico has 233 airports with paved runways. Ten major airports handle about 72% of national cargo and 97% of international cargo.

- Mexico City International Airport (AICM) is the busiest airport in Latin America and a major international hub, transporting around 45 million passengers annually.

- To alleviate congestion at AICM, two additional airports serve the Mexico City metropolitan area: Toluca International Airport and the newer Felipe Ángeles International Airport (AIFA).

- Other major airports are located in Cancún, Guadalajara, Monterrey, and Tijuana.

Seaports: Mexico has numerous seaports on both the Pacific and Gulf/Caribbean coasts, crucial for international trade. Major ports include Manzanillo and Lázaro Cárdenas on the Pacific, and Veracruz, Altamira, and Coatzacoalcos on the Gulf of Mexico. These ports handle diverse cargo, including containerized goods, bulk commodities, and petroleum products. Many coastal cities are also important destinations for cruise ships.

Urban transportation in major cities like Mexico City, Guadalajara, and Monterrey includes extensive metro systems, bus rapid transit (BRT) lines (e.g., Metrobús in Mexico City), and traditional bus networks. Traffic congestion and air pollution remain significant challenges in these large urban centers.

8.5. Communications

Mexico's communications sector includes telecommunications (fixed-line, mobile, internet) and media broadcasting (television, radio). The industry has undergone significant changes due to technological advancements and regulatory reforms aimed at increasing competition and expanding access.

Telecommunications: