1. Overview

The Republic of the Niger is a landlocked country in West Africa, named after the Niger River. It is bordered by Libya to the northeast, Chad to the east, Nigeria to the south, Benin and Burkina Faso to the southwest, Mali to the west, and Algeria to the northwest. Covering a land area of almost 0.5 M mile2 (1.27 M km2), over 80% of which lies in the Sahara Desert, Niger is the largest landlocked country in West Africa. Its predominantly Muslim population of approximately 25 million lives mostly in clusters in the south and west of the country. The capital, Niamey, is located in Niger's southwest corner.

Niger's history includes the influence of major empires such as the Mali Empire and Songhai Empire, followed by French colonial rule from the early 20th century until independence in 1960. The post-colonial era has been marked by political instability, including multiple coups d'état and periods of military rule, interspersed with attempts at democratization. The most recent coup in 2023 has once again placed the country under military administration, significantly impacting its democratic development and human rights situation.

Geographically, Niger is characterized by vast desert plains, the Aïr Mountains, and the Sahelian zone. Its climate is predominantly hot and dry, facing severe environmental challenges such as desertification and drought. The nation's biodiversity is concentrated in areas like the W National Park and the Aïr and Ténéré National Nature Reserve.

Niger's society is ethnically diverse, with the Hausa being the largest group. French is the official language, alongside several national languages. Islam is the dominant religion. The country faces significant socio-economic challenges, including high poverty rates, one of the world's highest fertility rates leading to rapid population growth, low literacy rates, and poor health indicators. Its economy relies heavily on subsistence agriculture, livestock, and uranium mining, a key export. Ongoing security issues, including jihadist insurgencies, further compound the nation's developmental struggles.

2. Etymology

The name "Niger" originates from the Niger River, which flows through the western part of the country. The precise origin of the river's name remains uncertain. The Alexandrian geographer Ptolemy, in his writings, described a wadi named GirGirGreek, Ancient in what is now Algeria, and another called Ni-GirNi-GirGreek, Ancient (meaning Lower Gir) further south, which might refer to the Niger River.

The modern spelling "Niger" was first recorded in 1550 by the Berber scholar Leo Africanus. It is possibly derived from the Tuareg phrase (e)gărăw-n-gărăwăn(e)gărăw-n-gărăwănTamashek, meaning "river of rivers." There is a broad consensus among linguists that the name does not derive from the Latin word nigernigerLatin, meaning "black," as was once erroneously believed. The standard pronunciation in English is NigerNEE-zhairEnglish, while some Anglophone media also use NigerNYE-jerEnglish. The French pronunciation is approximately Nigernee-ZHERFrench. Other local names include النيجرAl-NayjarArabic, NiiserNiiserFulah, and NijarNijarHausa.

3. History

The history of Niger spans from early human habitation and ancient empires to French colonization and its subsequent, often turbulent, path as an independent nation.

3.1. Prehistory

The region of present-day Niger has been inhabited since prehistoric times. Stone tools, some dating as far back as 280,000 BC, have been discovered in Adrar Bous, Bilma, and Djado in the northern Agadez Region. These findings are linked to the Aterian and Mousterian tool cultures of the Middle Paleolithic period, which flourished in northern Africa from approximately 90,000 BC to 20,000 BC. The humans of this era are believed to have lived a hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

During the African humid period, the Sahara Desert experienced a wetter and more fertile climate, a phenomenon known as the "Green Sahara." This environment provided favorable conditions for hunting and, later, for the development of agriculture and livestock herding. The Neolithic era, beginning around 10,000 BC, brought significant changes, including the introduction of pottery, as evidenced at sites like Tagalagal, Temet, and Tin Ouffadene. The spread of cattle husbandry and the practice of burying the dead in stone tumuli also characterized this period.

As the climate changed between 4000 BC and 2800 BC, the Sahara gradually underwent desertification, forcing human populations to shift their settlement patterns southward and eastward. Agriculture expanded, with the cultivation of crops like millet and sorghum, alongside continued pottery production. Iron and copper items began to appear, with discoveries made at Azawagh, Takedda, Marendet, and the Termit Massif. The Kiffian culture (circa 8000-6000 BC) and the later Tenerian culture (circa 5000-2500 BC), centered around Adrar Bous and Gobero where skeletons have been uncovered, flourished during this era.

Societies continued to develop with regional variations in agricultural and funerary practices. The Bura culture (circa 200-1300 AD), named after the Bura archaeological site where burials containing iron and ceramic statuettes were found, is an example from this period. The Neolithic era also saw a flourishing of Saharan rock art, particularly in the Aïr Mountains, Termit Massif, Djado Plateau, Iwelene, Arakao, Tamakon, Tzerzait, Iferouane, Mammanet, and Dabous. This art, spanning from 10,000 BC to 100 AD, depicts a range of subjects from the diverse fauna of the landscape to figures carrying spears, often referred to as 'Libyan warriors.'

3.2. Empires and kingdoms in pre-colonial Niger

By at least the 5th century BC, the territory of what is now Niger had become an area of trans-Saharan trade. This trade was largely facilitated by Tuareg tribes from the north, who used camels for transportation across the increasingly arid desert. This mobility, which continued in waves for centuries, was accompanied by further migration to the south, intermixing between sub-Saharan African and North African populations, and the gradual spread of Islam. The Muslim conquest of the Maghreb in the 7th century, resulting from Arab invasions, further spurred population movements southward. Several empires and kingdoms rose and fell in the Sahel region during this era, influencing the territories that would later constitute Niger.

3.2.1. Mali Empire (1200s-1400s)

The Mali Empire, founded by Sundiata Keita (reigned 1230-1255) around 1230, was a Mandinka empire that emerged as a breakaway region of the Sosso Empire, which itself had split from the earlier Ghana Empire. After defeating the Sosso at the Battle of Kirina in 1235 and the Ghana Empire in 1240, Mali expanded significantly. From its heartland near the modern Guinea-Mali border, the empire grew under successive kings and came to dominate the Trans-Saharan trade routes. It reached its greatest extent during the rule of Mansa Musa (reigned 1312-1337). At this peak, parts of what is now Niger's Tillabéri Region fell under Malian rule. Mansa Musa, a devout Muslim, performed the hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca) in 1324-25 and encouraged the spread of Islam within the empire, although traditional animist beliefs often persisted alongside or instead of the new religion among the general populace. The empire began to decline in the 15th century due to internal strife over royal succession, weak rulers, the shift of European trade routes towards the coast, and rebellions by Mossi, Wolof, Tuareg, and Songhai peoples on its peripheries. A rump Mali kingdom continued to exist until the 1600s.

3.2.2. Songhai Empire (1000s-1591)

The Songhai Empire, named after its dominant ethnic group, the Songhai people, was centered on the bend of the Niger River in present-day Mali. The Songhai began settling this region between the 7th and 9th centuries. By the 11th century, Gao, the former capital of the Kingdom of Gao, had become the empire's capital. From 1000 to 1325, the Songhai Empire coexisted with the Mali Empire to its west. In 1325, Songhai was conquered by Mali but regained its independence in 1375.

Under King Sonni Ali (reigned 1464-1492), Songhai adopted an expansionist policy. This expansion reached its zenith during the reign of Askia Mohammad I (reigned 1493-1528). At this time, the empire stretched from its Niger-bend heartland eastward, encompassing most of what would become western Niger. The city of Agadez was conquered in 1496. However, the empire was unable to withstand repeated attacks from the Saadi dynasty of Morocco and was decisively defeated at the Battle of Tondibi in 1591. Following this defeat, the Songhai Empire collapsed and fragmented into several smaller kingdoms.

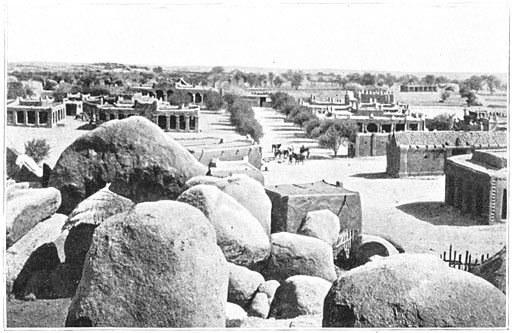

3.2.3. Sultanate of Aïr (1400s-1906)

Around 1449, in the north of what is now Niger, the Sultanate of Aïr was founded by Sultan Ilisawan, with its capital in Agadez. Originally a trading post inhabited by a mix of Hausa and Tuareg peoples, Agadez grew in strategic importance on the Trans-Saharan trade routes. In 1515, Aïr was conquered by the Songhai Empire and remained part of it until Songhai's collapse in 1591. In the subsequent centuries, the sultanate appears to have entered a period of decline, marked by internal wars and clan conflicts. When European explorers began to venture into the region in the 19th century, much of Agadez lay in ruins. The French eventually took control of the area as part of their colonial expansion.

3.2.4. Kanem-Bornu Empire (700s-1700s)

To the east, the Kanem-Bornu Empire dominated the region around Lake Chad for an extensive period. Founded by the Zaghawa people around the 8th century, its initial center was Njimi, northeast of the lake. The kingdom gradually expanded, particularly under the Sayfawa dynasty, which began around 1075 under Mai (king) Hummay. The kingdom reached its greatest extent in the 1200s, partly due to the efforts of Mai Dunama Dibbalemi (reigned 1210-1259). It grew wealthy from its control of some Trans-Saharan trade routes, and most of eastern and southeastern Niger, including Bilma and Kaouar, fell under Kanem's control during this period. Islam was introduced to the kingdom by Arab traders from the 11th century and gained more converts over the following centuries.

Attacks by the Bulala in the 14th century forced Kanem to shift its center westward of Lake Chad, where it became known as the Bornu Empire, ruled from its capital Ngazargamu, located on what is now the Niger-Nigeria border. Bornu prospered during the rule of Mai Idris Alooma (reigned circa 1575-1610), who reconquered most of Kanem's traditional lands, leading to the designation 'Kanem-Bornu' for the empire. By the 17th and into the 18th century, the Bornu kingdom entered a period of decline, shrinking back to its Lake Chad heartland.

Around 1730-40, a group of Kanuri settlers led by Mallam Yunus left Kanem and founded the Sultanate of Damagaram, centered on the town of Zinder. The sultanate remained nominally subject to the Borno Empire until the reign of Sultan Tanimoune Dan Souleymane in the 19th century, who declared independence and initiated a phase of expansion. The sultanate managed to resist the advance of the Sokoto Caliphate but was later captured by the French in 1899.

3.2.5. The Hausa states and other smaller kingdoms (1400s-1800s)

Between the Niger River and Lake Chad lay the Hausa Kingdoms, encompassing the cultural-linguistic area known as Hausaland, which straddles the modern Niger-Nigeria border. The Hausa people are thought to be a mixture of autochthonous populations and migrants from the north and east, emerging as a distinct group sometime between the 900s and 1400s when their kingdoms were founded. They gradually adopted Islam from the 14th century, though often syncretically alongside traditional beliefs; some Hausa groups, like the Azna (in areas such as Dogondoutchi, which remains an animist stronghold), resisted Islam altogether. The Hausa kingdoms were not a unified entity but rather several federations of kingdoms, largely independent of one another. Their organization was hierarchical yet somewhat democratic: Hausa kings were elected by notables and could be removed by them.

According to the Bayajidda legend, the Hausa Kingdoms began as seven states founded by the six sons of Bawo. Bawo was the son of Queen Daurama of Daura and Bayajidda (or Abu Yazid), an immigrant from Baghdad. The seven original Hausa states (the 'Hausa bakwai') were: Daura, Kano, Rano, Zaria, Gobir, Katsina, and Biram. An extension of the legend states that Bawo had seven more sons with a concubine, who founded the so-called 'Banza Bakwai' (illegitimate seven): Zamfara, Kebbi, Nupe, Gwari, Yauri, Ilorin, and Kwararafa. A smaller state not fitting this scheme was Konni, centered on Birni-N'Konni.

The Fulani (also Peul, Fulbe), a pastoral people found throughout the Sahel, began migrating to Hausaland between the 1200s and 1500s. By the late 18th century, some Fulani were discontented with the syncretic form of Islam practiced there and the corruption among the Hausa elite. The Fulani scholar Usman Dan Fodio, from Gobir, declared a jihad in 1804. After conquering most of Hausaland (though not the Bornu Kingdom, which remained independent), he proclaimed the Sokoto Caliphate in 1809. Some Hausa states survived by fleeing south, such as the Katsina who moved to Maradi in what later became southern Niger. These surviving states harassed the Caliphate, leading to a period of wars and skirmishes. Some states like Katsina and Gobir maintained independence, while newer ones like the Sultanate of Tessaoua were formed. The Caliphate survived until it was fatally weakened by the invasions of the Chad-based warlord Rabih az-Zubayr and finally fell to the British in 1903, its lands later partitioned between Britain and France.

Other smaller kingdoms of the period include the Dosso Kingdom, a Zarma polity founded in 1750, which resisted the rule of Hausa and Sokoto states.

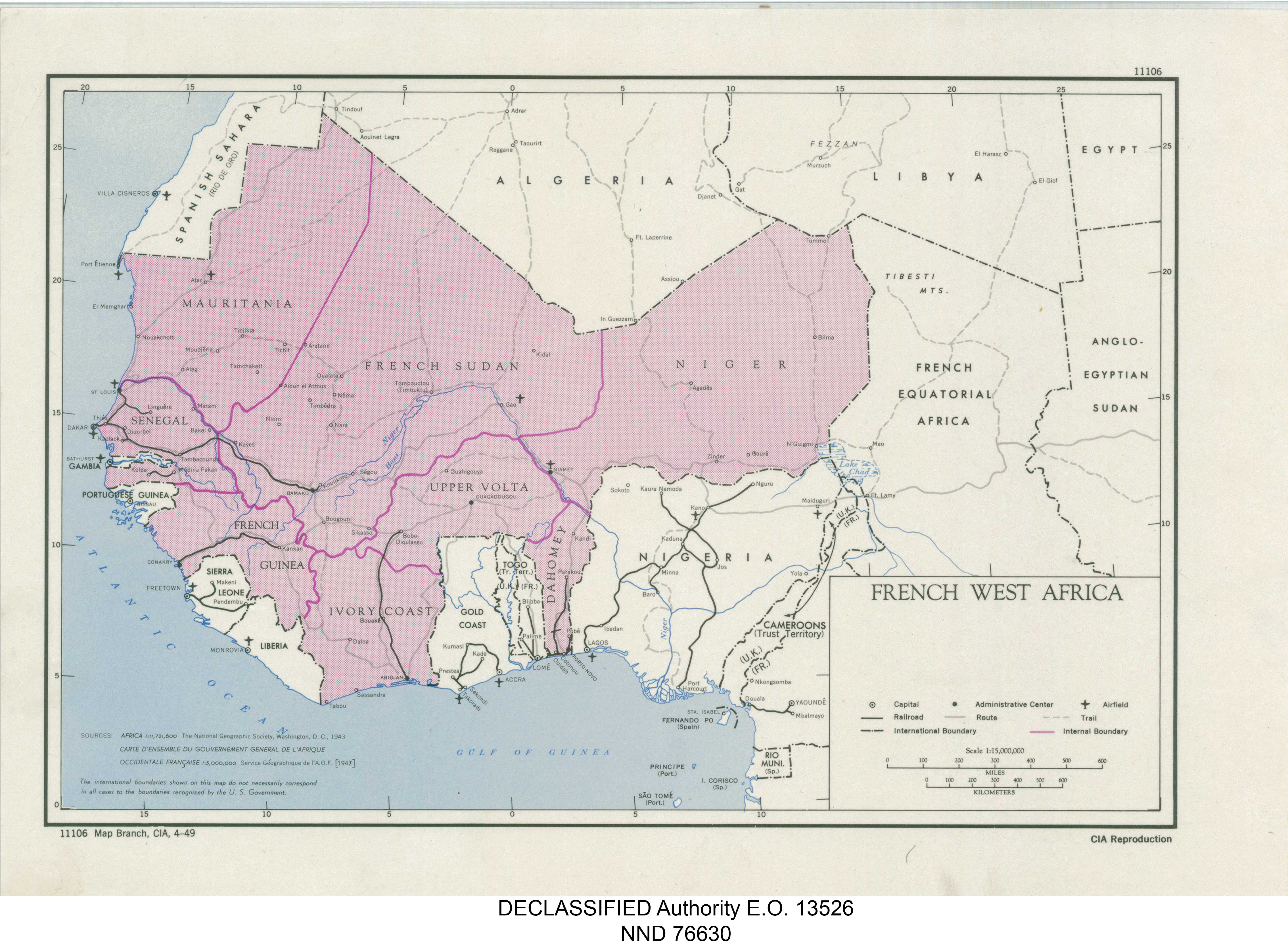

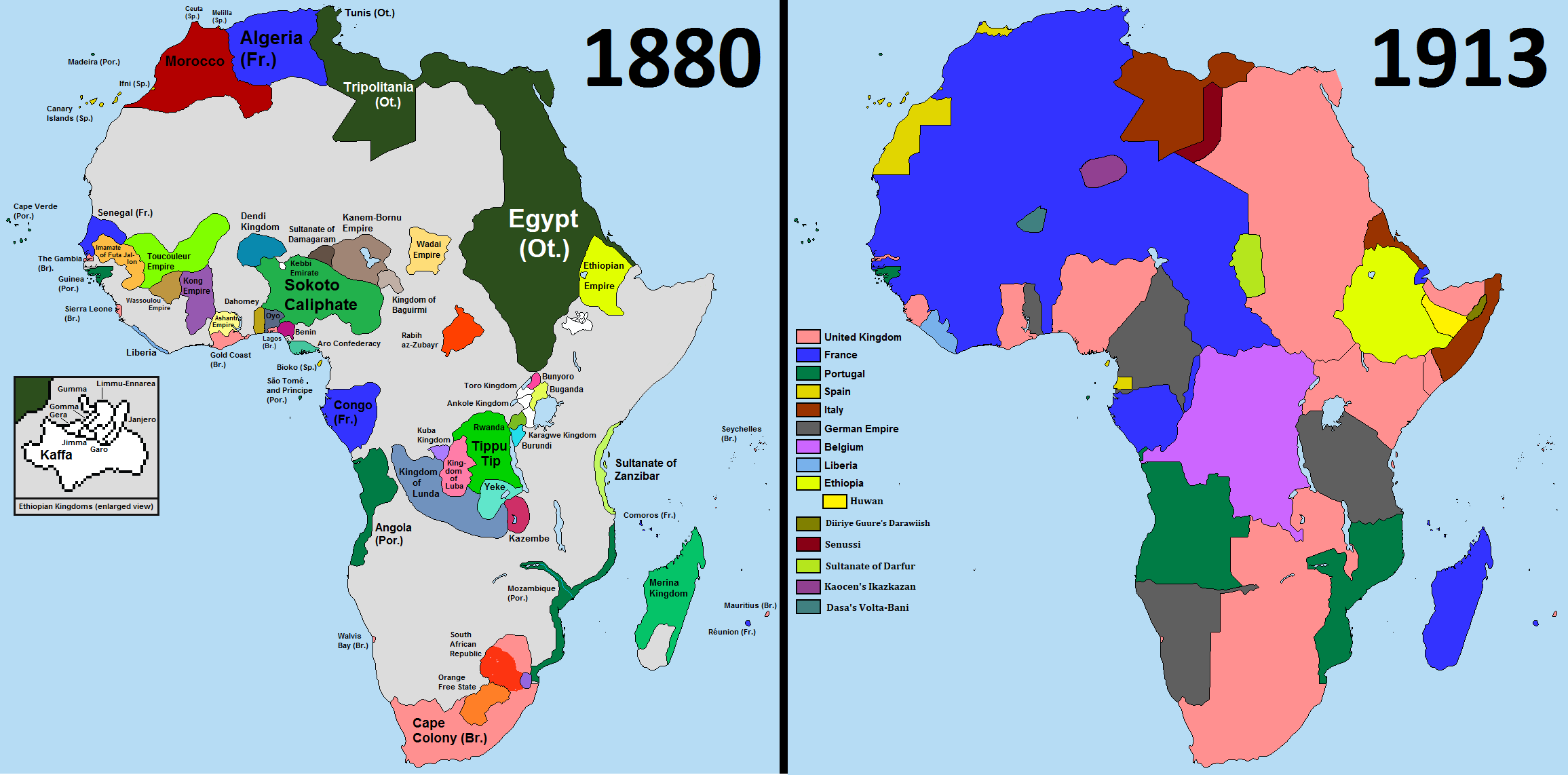

3.3. French Colonial Rule (1900-1960)

In the 19th century, European explorers such as Mungo Park (1805-1806), the Oudney-Denham-Clapperton expedition (1822-1825), Heinrich Barth (1850-1855, with James Richardson and Adolf Overweg), Friedrich Gerhard Rohlfs (1865-1867), Gustav Nachtigal (1869-1874), and Parfait-Louis Monteil (1890-1892) traveled through the area that would become Niger. As European powers expanded their colonial presence in Africa during the 'Scramble for Africa', the Berlin Conference of 1885 formalized the division of the continent into spheres of influence. France gained control of the upper valley of the Niger River, roughly corresponding to present-day Mali and Niger.

France then began to assert its rule on the ground. In 1897, French officer Marius Gabriel Cazemajou was sent to Niger, reaching the Sultanate of Damagaram in 1898 and staying in Zinder at the court of Sultan Amadou Kouran Daga. Cazemajou was later killed, as Daga feared he would ally with the Chad-based warlord Rabih az-Zubayr. In 1899-1900, France coordinated three expeditions-the Gentil Mission from French Congo, the Foureau-Lamy Mission from Algeria, and the Voulet-Chanoine Mission from Timbuktu-to link its African possessions. The three expeditions met at Kousséri (in northern Cameroon) and defeated Rabih az-Zubayr's forces at the Battle of Kousséri.

The Voulet-Chanoine Mission became notorious for its atrocities, including pillaging, looting, raping, and killing local civilians throughout southern Niger. On May 8, 1899, in retaliation for the resistance of Queen Sarraounia, Captain Voulet and his men murdered all the inhabitants of the village of Birni-N'Konni in what is considered one of the worst massacres in French colonial history. The brutal methods of Voulet and Chanoine caused a scandal, forcing Paris to intervene. Lieutenant-Colonel Jean-François Klobb, sent to relieve them of command, was killed near Tessaoua. Lieutenants Paul Joalland and Octave Meynier eventually took over the mission after a mutiny in which Voulet and Chanoine were killed.

The Military Territory of Niger was created within the Upper Senegal and Niger colony in December 1904, with its capital at Niamey. The border with Britain's colony of Nigeria was finalized in 1910. The capital of the territory was moved to Zinder in 1912 when the Niger Military Territory was split from Upper Senegal and Niger, before being moved back to Niamey in 1922 when Niger became a full-fledged colony within French West Africa. The borders of Niger were fixed by the 1930s after several territorial adjustments: areas west of the Niger River were attached to Niger in 1926-1927; during the dissolution of Upper Volta (modern Burkina Faso) from 1932-1947, most of eastern Upper Volta was added to Niger; and in the east, the Tibesti Mountains were transferred to Chad in 1931.

The French generally adopted a form of indirect rule, allowing existing native structures to continue within the colonial framework, provided they acknowledged French supremacy. The Zarma of the Dosso Kingdom proved particularly amenable to French rule, using the French as allies against Hausa and other neighboring states; consequently, the Zarma became one of the more educated and Westernized groups in Niger. However, perceived threats to French rule, such as the Kobkitanda rebellion in Dosso Region (1905-1906) led by Alfa Saibou, and the Karma revolt in the Niger valley (December 1905 - March 1906) led by Oumarou Karma, were suppressed with force, as were the later Hamallayya and Hauka religious movements. The French faced considerable difficulty subduing the Tuareg in the north, centered on the Sultanate of Aïr in Agadez, which France was unable to occupy until 1906. Tuareg resistance continued, culminating in the Kaocen revolt of 1916-1917, led by Ag Mohammed Wau Teguidda Kaocen with backing from the Senussi in Fezzan. The revolt was violently suppressed, and Kaocen fled to Fezzan, where he was later killed. A puppet sultan was installed by the French, and the north of the colony continued to decline and be marginalized, exacerbated by a series of droughts. Some limited economic development occurred, such as the introduction of groundnut cultivation, and measures were introduced to improve food security following devastating famines in 1913, 1920, and 1931.

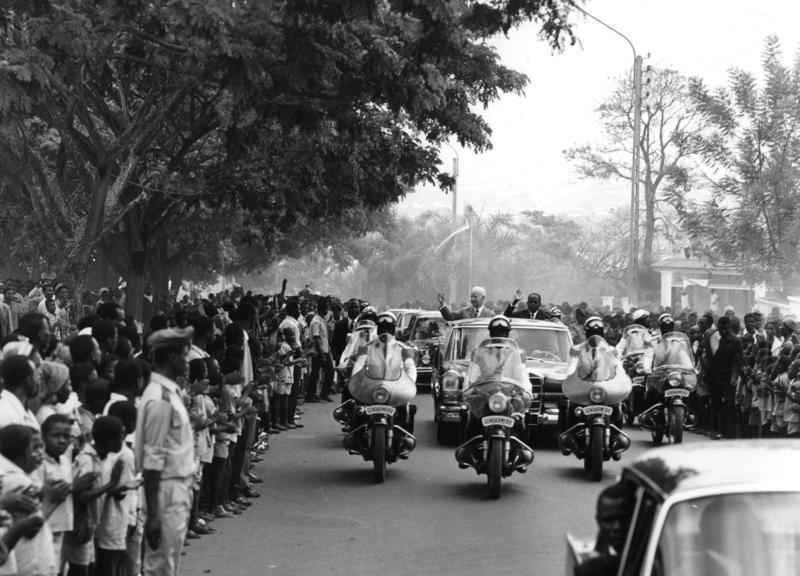

During World War II, Charles de Gaulle issued the Brazzaville Declaration, promising that the French colonial empire would be replaced post-war with a less centralized French Union. The French Union (1946-1958) conferred limited French citizenship on colonial inhabitants, with some decentralization of power and limited participation in local advisory assemblies. During this period, the Nigerien Progressive Party (PPN), led by Hamani Diori, and the left-wing Mouvement Socialiste Africain-Sawaba (MSA), led by Djibo Bakary, were formed. Following the Overseas Reform Act (Loi Cadre) of 1956 and the establishment of the Fifth French Republic in 1958, Niger became an autonomous state within the French Community. On December 18, 1958, an autonomous Republic of Niger was created under Diori's leadership. The MSA was banned in 1959 for its perceived anti-French stance. On July 11, 1960, Niger decided to leave the French Community and acquired full independence at midnight, local time, on August 3, 1960, with Diori becoming the country's first president.

3.4. Post-Colonial Era (1960-present)

Niger's post-colonial history has been characterized by significant political upheaval, economic challenges, and social unrest. The nation has struggled to establish stable democratic institutions, facing recurrent military interventions and persistent developmental issues, often exacerbated by regional instability and environmental pressures. The impact on human rights and social welfare has been a consistent concern throughout this period.

3.4.1. Diori presidency and first military regime (1960-1987)

For its first 14 years as an independent state, Niger was run by a single-party civilian regime under President Hamani Diori. The 1960s saw an expansion of the education system and some limited economic development and industrialization. Links with France remained strong, with Diori allowing French-led uranium mining in Arlit and supporting France in the Algerian War. Relations with other African states were mostly positive, with the exception of Dahomey (now Benin) due to a border dispute. Niger remained a one-party state, and Diori survived a planned coup in 1963 and an assassination attempt in 1965, largely masterminded by Djibo Bakary's MSA-Sawaba group, which had launched an abortive rebellion in 1964. In the 1970s, a combination of economic difficulties, severe droughts, and accusations of rampant corruption and mismanagement of food supplies resulted in the 1974 coup d'état that overthrew the Diori regime. The coup, led by Colonel Seyni Kountché, established a military government called the Conseil Militaire Supreme. Kountché ruled the country until his death in 1987.

The Kountché regime's first action was to address the food crisis. While political prisoners from Diori's era were released, political and individual freedoms generally deteriorated. Several attempted coups (in 1975, 1976, and 1984) were thwarted, and their instigators punished. Kountché aimed to create a 'development society', largely funded by uranium mines in the Agadez Region. Parastatal companies were created, and infrastructure projects (roads, schools, health centers) were undertaken, though corruption within government agencies persisted, which Kountché sometimes addressed. In the 1980s, Kountché cautiously began to loosen the military's grip, with some relaxation of state censorship and attempts to 'civilianize' the regime. However, the economic boom ended with the collapse of uranium prices, and IMF-led austerity and privatization measures provoked opposition. In 1985, a Tuareg revolt in Tchintabaraden was suppressed. Kountché died in November 1987 from a brain tumor.

3.4.2. Second Republic and Saibou's transition (1987-1991)

Colonel Ali Saibou, Kountché's chief of staff, succeeded him. Saibou curtailed some of the most repressive aspects of Kountché's rule, such as the secret police and media censorship, and initiated a process of political reform under the single-party Mouvement National pour la Société du Développement (MNSD). A Second Republic was declared, and a new constitution was adopted following a referendum in 1989. General Saibou became the first president of the Second Republic after winning the presidential election in December 1989.

However, President Saibou's efforts to control political reforms failed in the face of demands from trade unions and students for a multi-party democratic system. On February 9, 1990, a violently repressed student march in Niamey led to the death of three students, which increased national and international pressure for further democratic reform. The Saibou regime acquiesced to these demands by the end of 1990. Meanwhile, unrest re-emerged in the Agadez Region when a group of armed Tuaregs attacked Tchintabaraden, an event seen by some as the start of the first Tuareg Rebellion. This prompted a military crackdown that led to significant casualties (estimates range from 70 to 1,000).

3.4.3. Third Republic and political instability (1991-1996)

The National Sovereign Conference of 1991 brought about multi-party democracy. Held from July 29 to November 3, the conference gathered representatives from all segments of society to make recommendations for the country's future. Presided over by Professor André Salifou, it developed a plan for a transitional government, which was installed in November 1991 to manage state affairs until the institutions of the Third Republic were established in April 1993. The transitional government drafted a new constitution that eliminated the previous single-party system of the 1989 Constitution and guaranteed more freedoms. This new constitution was adopted by a referendum on December 26, 1992.

Following this, presidential and parliamentary elections were held. Mahamane Ousmane became the first president of the Third Republic on March 27, 1993. Ousmane's presidency was marked by coalition governments, significant political instability, four government changes, legislative elections in 1995, and an economic slump. Violence in the Agadez Region continued, prompting the government to sign an ineffective truce with Tuareg rebels in 1992 due to internal dissension within Tuareg ranks. Another rebellion, led by dissatisfied Toubou claiming neglect similar to the Tuareg, broke out in the east. In April 1995, a peace deal was signed with a Tuareg rebel group, with the government agreeing to absorb some former rebels into the military and, with French assistance, help others return to civilian life. However, the persistent governmental paralysis and instability ultimately led to military intervention.

3.4.4. Second and third military regimes (1996-1999)

On January 27, 1996, Colonel Ibrahim Baré Maïnassara led a coup that deposed President Ousmane and ended the Third Republic. Maïnassara headed a Conseil de Salut National (National Salvation Council) composed of military officials, which oversaw a six-month transition period. During this time, a new constitution was drafted and adopted on May 12, 1996.

Presidential campaigns were organized, and Maïnassara entered as an independent candidate, winning the election on July 8, 1996. However, these elections were widely viewed, both nationally and internationally, as irregular, particularly as the electoral commission was replaced during the campaign. Maïnassara's regime implemented an IMF and World Bank-approved privatization program, which reportedly enriched some of his supporters and was opposed by trade unions. Following fraudulent local elections in 1999, the opposition ceased all cooperation with the Maïnassara regime. On April 9, 1999, Maïnassara was assassinated at Niamey Airport under unclear circumstances, possibly while attempting to flee the country. This event plunged Niger back into a period of military rule and political transition.

Major Daouda Malam Wanké then took power, establishing a transitional National Reconciliation Council to oversee the drafting of a new constitution featuring a French-style semi-presidential system. This constitution was adopted on August 9, 1999, followed by presidential and legislative elections in October and November of the same year. The elections were generally deemed free and fair by international observers. Wanké subsequently withdrew from governmental affairs, paving the way for a return to civilian rule.

3.4.5. Fifth Republic (1999-2009)

After winning the election in November 1999, President Mamadou Tandja was sworn into office on December 22, 1999, as the first president of the Fifth Republic. Tandja initiated administrative and economic reforms that had been halted due to military coups since the Third Republic. He also helped peacefully resolve a decades-long boundary dispute with Benin. In August 2002, unrest occurred within military camps in Niamey, Diffa, and Nguigmi, but the government restored order within days. On July 24, 2004, municipal elections were held to elect local representatives, who had previously been appointed by the government. These were followed by presidential elections in which Tandja was re-elected for a second term, becoming the first president of the republic to win consecutive elections without being deposed by military coups. The legislative and executive configuration remained similar to his first term: Hama Amadou was reappointed as prime minister, and Mahamane Ousmane, head of the CDS party, was re-elected as president of the National Assembly.

By 2007, the relationship between President Tandja and his prime minister had deteriorated, leading to Amadou's replacement in June 2007 by Seyni Oumarou following a successful vote of no confidence. Subsequently, President Tandja sought to extend his presidency by modifying the constitution, which limited presidential terms. Proponents of this extension, rallying behind the 'Tazartche' (Hausa for 'overstay') movement, were countered by opponents ('anti-Tazartche'), composed of opposition party militants and civil society activists. This period also saw the outbreak of a Second Tuareg Rebellion in the north in 2007, led by the Mouvement des Nigériens pour la justice (MNJ). Despite a number of kidnappings, the rebellion had largely fizzled out inconclusively by 2009. The poor security situation in the region is believed to have allowed elements of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) to gain a foothold in the country.

3.4.6. Sixth Republic and fourth military regime (2009-2010)

In 2009, President Mamadou Tandja decided to organize a constitutional referendum aimed at extending his presidency. This move was opposed by other political parties and contradicted a decision by the Constitutional Court, which had ruled the referendum unconstitutional. Tandja then modified and adopted a new constitution by referendum, an act declared illegal by the Constitutional Court. This prompted Tandja to dissolve the Court and assume emergency powers. The opposition boycotted the referendum, and the new constitution was adopted with 92.5% of voters in favor and a 68% turnout, according to official results. The adoption of this constitution created a Sixth Republic with a presidential system, suspending the 1999 Constitution and establishing a three-year interim government with Tandja as president. These events generated significant political and social unrest, undermining democratic norms and institutions.

In a coup d'état in February 2010, a military junta led by Salou Djibo was established in response to Tandja's controversial attempt to extend his political term. The Supreme Council for the Restoration of Democracy, headed by Djibo, implemented a one-year transition plan, drafted a new constitution, and held elections in 2011, aiming to restore constitutional order and civilian rule. This period highlighted the fragility of democratic processes in Niger and the persistent influence of the military in its political landscape.

3.4.7. Seventh Republic (2010-2023)

Following the adoption of a new constitution in 2010 and presidential elections a year later, Mahamadou Issoufou was elected as the first president of the Seventh Republic. He was subsequently re-elected in 2016. The new constitution restored the semi-presidential system that had been abolished a year earlier. An attempted coup against Issoufou in 2011 was thwarted, and its ringleaders were arrested.

Issoufou's time in office was marked by significant threats to the country's security, stemming from the fallout of the Libyan Civil War and the Northern Mali conflict. Niger faced a jihadist insurgency in its western regions by groups affiliated with al-Qaeda and the Islamic State, the spillover of Nigeria's Boko Haram insurgency into southeastern Niger, and the use of Niger as a transit country for migrants, often organized by people-smuggling gangs. French and American forces assisted Niger in countering these threats.

On December 10, 2019, a large group of fighters belonging to the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (IS-GS) attacked a military post in Inates, killing over seventy soldiers and kidnapping others. This attack was the deadliest single incident Niger's military had ever experienced. On January 9, 2020, IS-GS militants assaulted a Nigerien military base at Chinagodrar, in Niger's Tillabéri Region, killing at least 89 Nigerien soldiers.

On December 27, 2020, Nigeriens participated in the general election after President Issoufou announced he would step down, paving the way for a peaceful transition of power. No candidate won an absolute majority in the first round; Mohamed Bazoum came closest with 39.33%. A run-off election was held on February 20, 2021, with Bazoum securing 55.75% of the vote against former president Mahamane Ousmane's 44.25%.

At the start of 2021, IS-GS began killing civilians en masse. On March 21, 2021, IS-GS militants attacked several villages around Tillia, killing 141 people, mostly civilians. On March 31, 2021, Niger's security forces thwarted an attempted coup by a military unit in Niamey, just two days before President-elect Bazoum was due to be sworn in. On April 2, 2021, Bazoum was sworn in as President of Niger, marking a significant moment for the country's democratic aspirations despite the ongoing security and political challenges.

3.4.8. 2023 Coup d'état and fifth military regime (2023-present)

Late on July 26, 2023, a military coup overthrew President Mohamed Bazoum, bringing an end to the Seventh Republic and the government of Prime Minister Ouhoumoudou Mahamadou. On July 28, General Abdourahamane Tchiani was proclaimed as the de facto head of state, leading the National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland. Former finance minister Ali Lamine Zeine was subsequently declared the new Prime Minister.

The coup was condemned by ECOWAS, which, during the 2023 Nigerien crisis, threatened military intervention to reinstate Bazoum's government if the coup leaders did not stand down by August 6. The deadline passed without military intervention, though ECOWAS imposed sanctions, including cuts to Nigerian energy exports, which had previously supplied 70-90% of Niger's power. In November 2023, the coup-led governments of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger formed the Alliance of Sahel States in opposition to potential military intervention. On February 24, 2024, several ECOWAS sanctions against Niger were dropped, reportedly for humanitarian and diplomatic reasons, and Nigeria agreed to resume electricity exports.

In the buildup to the August ECOWAS deadline, the junta requested assistance from the Russian Wagner Group, although Wagner mercenaries were not known to have entered the country as a result. In October 2023, the junta expelled French troops, presenting the move as a step towards sovereignty. In December, it suspended cooperation with the Francophonie, alleging its promotion of French interests. The UN resident coordinator, Louise Aubin, was also expelled in October after the junta alleged "underhanded maneuvers" by UN Secretary-General António Guterres. In October, the U.S. officially designated the takeover as a coup, suspending most Niger-US military cooperation and foreign assistance programs. In April 2024, Russian military trainers and equipment began to arrive in Niger under a new military agreement, and the US agreed to withdraw its troops following the termination of a Niger-US agreement that had allowed US personnel to be stationed in the country. This series of events has significantly altered Niger's international relations and internal political landscape, with profound implications for regional stability and human rights.

4. Geography

Niger is a landlocked nation in West Africa, situated along the border between the Sahara and Sub-Saharan regions. It shares borders with Nigeria and Benin to the south, Burkina Faso and Mali to the west, Algeria and Libya to the north, and Chad to the east.

Niger lies between latitudes 11° and 24°N, and longitudes 0° and 16°E. Its total area is 0.5 M mile2 (1.27 M km2), of which 116 mile2 (300 km2) is water. This makes it less than twice the size of France and the world's 21st largest country. Niger borders seven countries and has a total perimeter of 3.5 K mile (5.70 K km). The longest border is with Nigeria to the south (0.9 K mile (1.50 K km)). This is followed by Chad to the east (0.7 K mile (1.18 K km)), Algeria to the north-northwest (594 mile (956 km)), and Mali to the west (510 mile (821 km)). Niger also has shorter borders in its southwest with Burkina Faso (390 mile (628 km)) and Benin (165 mile (266 km)), and to the north-northeast with Libya (220 mile (354 km)).

The lowest point in Niger is the Niger River, with an elevation of 656 ft (200 m). The highest point is Mont Idoukal-n-Taghès in the Aïr Mountains at 6.6 K ft (2.02 K m). Niger's terrain is predominantly desert plains and sand dunes, with flat to rolling savanna in the south and hills in the north.

4.1. Climate

Niger has a predominantly hot and dry climate. The northern four-fifths of the country, largely within the Sahara Desert, experiences a desert climate (Köppen BWh), characterized by extreme temperatures and very low precipitation. The southern part of the country, particularly along the Niger River basin and the border with Nigeria, has a tropical Sahelian climate, which is a semi-arid steppe climate (Köppen BSh). This region experiences a short rainy season, typically from June to September, followed by a long, intense dry season.

Rainfall is scarce and highly variable, decreasing from south to north. The southern regions might receive 12 in (300 mm) to 24 in (600 mm) of rain annually, while the northern desert areas often receive less than 5.9 in (150 mm). Temperatures are generally high throughout the year. During the hottest months (March to May), temperatures can soar above 104 °F (40 °C) in many parts of the country. The harmattan, a dry, dusty trade wind from the Sahara, blows from November to March, bringing cooler temperatures but also significantly reducing visibility and air quality.

The country is highly vulnerable to climate change, with issues like recurrent droughts and increasing desertification posing significant threats to agriculture, water resources, and livelihoods. The hotter and drier conditions also contribute to more frequent bush fires in some regions.

4.2. Biodiversity and Wildlife

Niger's territory encompasses five terrestrial ecoregions: Sahelian Acacia savanna, West Sudanian savanna, Lake Chad flooded savanna, South Saharan steppe and woodlands, and West Saharan montane xeric woodlands. The northern part of the country is covered by deserts and semi-deserts. Typical mammal fauna in these arid regions includes addax antelopes, scimitar-horned oryx, gazelles, and, in mountainous areas, Barbary sheep. The Aïr and Ténéré National Nature Reserve was established in the northern parts of Niger to protect these and other desert-adapted species.

The southern parts of Niger are naturally dominated by savannas. The W National Park, situated in the bordering area with Burkina Faso and Benin, is one of the most important areas for wildlife in West Africa and forms part of the WAP (W-Arli-Pendjari) Complex. This park is home to a population of the West African lion and one of the last remaining populations of the Northwest African cheetah. Other wildlife found in Niger includes elephants, buffaloes, roan antelopes, kob antelopes, and warthogs. The critically endangered West African giraffe is found in a relict population in the southwestern part of the country, representing one of the last viable populations of this subspecies.

Conservation efforts are crucial for protecting Niger's unique biodiversity, which faces threats from habitat loss, climate change, and human activities.

4.3. Environmental Issues

Niger faces significant environmental challenges that impact its natural resources, agricultural productivity, and the well-being of its population. Desertification is a major concern, with the Sahara Desert expanding southward, degrading arable land and pastures. This process is exacerbated by factors such as deforestation for fuelwood and agriculture, overgrazing, and unsustainable land management practices.

Periodic droughts are a recurrent feature of Niger's climate, leading to water scarcity, crop failures, and food shortages. The country's reliance on rain-fed agriculture makes it particularly vulnerable to these climatic variations. Water scarcity is a chronic issue, especially in rural areas, affecting both human consumption and agricultural needs. The Niger River and Lake Chad are vital water sources, but their levels can fluctuate significantly, and they are also subject to pressures from dam construction in neighboring countries and overuse.

Human activities, including population growth and the expansion of agriculture into marginal lands, put additional pressure on natural resources. Illegal hunting (poaching) threatens wildlife populations, while bush fires, often started for land clearing or accidentally, further degrade vegetation and soil. Encroachment upon the floodplains of the Niger River for paddy cultivation also has environmental consequences.

National and international efforts are underway to address these issues. Farmer-managed natural regeneration (FMNR) has been practiced since 1983 to increase food and timber production and enhance resilience to climate extremes. Various conservation programs aim to protect biodiversity and promote sustainable land use. However, a lack of adequate staff and resources to guard wildlife in parks and reserves remains a challenge for effective environmental management.

5. Politics and Governance

Niger's political system was defined as a republic under a semi-presidential system by its 2010 constitution. However, following the July 2023 military coup, the country is currently under the control of a military junta, the National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland, led by General Abdourahamane Tchiani. This has significantly altered the governance structure and suspended constitutional norms. The country's political history has been marked by periods of democratic rule interspersed with military interventions, reflecting ongoing struggles for stable governance, democratic consolidation, and respect for human rights.

5.1. Constitution and Government Structure

Prior to the 2023 coup, Niger operated under the constitution approved on October 31, 2010. This constitution restored the semi-presidential system of government of the 1999 constitution (Fifth Republic). Under this system, the President, elected by universal suffrage for a five-year term, was the head of state. The Prime Minister, appointed by the President, was the head of government, and they shared executive power. The National Assembly served as the unicameral legislature, with its members also elected for five-year terms. The judiciary was designed to be independent.

The 2023 coup led to the suspension of the 2010 constitution and the dissolution of the elected government institutions, including the presidency and the National Assembly. The National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland assumed all state powers. General Abdourahamane Tchiani was declared head of state, and Ali Lamine Zeine was appointed as Prime Minister by the junta. The current governance structure operates outside the constitutional framework, with the military junta exercising supreme authority. This situation has raised concerns about the rule of law, democratic processes, and the protection of fundamental freedoms, often leading to repression of dissent and limitations on civil liberties.

5.2. Foreign Relations

Niger pursues a moderate foreign policy and has historically maintained relations with Western nations, the Islamic world, and non-aligned countries. It is a member of the United Nations (UN) and its main specialized agencies, having served on the UN Security Council in 1980-1981. Niger maintains a significant, though recently strained, relationship with its former colonial power, France, particularly concerning security cooperation and uranium mining. It also has close ties with its West African neighbors.

Niger is a charter member of the African Union (AU) and the West African Monetary Union (WAMU). It also belongs to the Niger Basin Authority (NBA), the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), and the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA). The westernmost regions of Niger are joined with contiguous regions of Mali and Burkina Faso under the Liptako-Gourma Authority.

A border dispute with Benin, inherited from colonial times and concerning, among other issues, Lété Island in the Niger River, was resolved by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 2005, largely in Niger's favor.

Following the 2023 coup, Niger's foreign relations have undergone significant shifts. ECOWAS condemned the coup and imposed sanctions, although these were later partially lifted. The junta has sought closer ties with other military-led governments in the Sahel, forming the Alliance of Sahel States with Mali and Burkina Faso. Relations with France and the United States deteriorated, leading to the expulsion of French troops and the termination of a military cooperation agreement with the US. Conversely, Niger has strengthened military ties with Russia. The coup also led to the suspension of Niger's cooperation with the Francophonie. These developments reflect a reorientation of Niger's foreign policy amidst domestic political upheaval.

5.3. Military

The Niger Armed Forces (Forces armées nigériennes or FAN) comprise the military and paramilitary forces of Niger, historically under the president as supreme commander, though currently under the authority of the military junta. The FAN consists of the Niger Army (Armée de Terre), the Niger Air Force (Armée de l'Air), and auxiliary paramilitary forces, including the National Gendarmerie (Gendarmerie Nationale) and the National Guard (Garde Nationale). Both paramilitary forces are trained in military fashion and have military responsibilities in wartime; in peacetime, their duties are primarily policing.

The armed forces are composed of approximately 12,900 active personnel, including 3,700 gendarmes, 3,200 national guards, 300 air force personnel, and 6,000 army personnel. The Nigerien military has been involved in several coups, with the most recent occurring in July 2023.

Historically, Niger's armed forces have had extensive military cooperation with France and the United States. From 2013, Niamey hosted a U.S. drone base. However, following the 2023 coup, these relationships significantly deteriorated. On March 16, 2024, Niger's junta announced it was terminating its military cooperation agreement with the United States, leading to a planned withdrawal of U.S. troops. French troops were also expelled. Conversely, Niger has since strengthened military ties with Russia, with Russian military trainers and equipment arriving in the country in April 2024.

The Niger Army includes units for logistics, motorized infantry, airborne infantry, artillery, and armored reconnaissance. It has several pure motorized infantry battalions, some of which are specialized for Saharan operations, and mixed-arms battalions. The Niger Air Force, originally formed as the Escadrille Nationale du Niger in 1961, was later restructured and renamed. The military has participated in international peacekeeping missions, including in Ivory Coast, Liberia, Guinea-Bissau, Burundi, and the Comoros, and contributed a contingent to the U.S.-led coalition during the Gulf War.

5.4. Judicial System and Law Enforcement

Niger's judicial system, prior to the 2023 coup, was established with the creation of the Fourth Republic in 1999 and further defined by the 2010 Constitution. It is based on the Code Napoleon (an inquisitorial system), established during French colonial rule and retained after independence. The system included the Supreme Court, which reviewed applications of the law and constitutional questions, and a Court of Appeals, which reviewed questions of fact and law. The High Court of Justice (HCJ) was designated to deal with cases involving senior government officials. The justice system also comprised civil criminal courts, customary courts (which do not provide the same rights as civil courts), traditional mediation, and a military court. The military court had jurisdiction over military personnel but could not try civilians. The suspension of the constitution following the 2023 coup has created uncertainty regarding the current functioning and independence of the judiciary.

Law enforcement in Niger is the responsibility of the Ministry of Defense through the National Gendarmerie and the Ministry of the Interior through the National Police and the National Guard. The National Police is primarily responsible for law enforcement in urban areas. Outside major cities and in rural areas, this responsibility largely falls to the National Gendarmerie and the National Guard. These forces play a crucial role in maintaining internal security, particularly in a context of political instability and armed insurgencies.

5.5. Government Finance and Foreign Aid

Government finance in Niger is derived from export revenues (primarily from mining, oil, and agricultural exports) as well as various forms of taxes collected by the government. Historically, foreign aid has constituted a significant portion of the national budget. In 2013, Niger's government adopted a zero-deficit budget of 1.28 T XOF (approximately 2.53 B USD), which aimed to balance revenues and expenditures through an 11% reduction from the previous year's budget. The 2014 budget was 1.87 T XOF, allocated across public debt, personnel expenditures, operating expenditures, subsidies and transfers, and investment.

The importance of external support for Niger's development is evident from the fact that about 45% of the government's fiscal year 2002 budget, including 80% of its capital budget, was derived from donor resources. Key donors have included France, the European Union, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and various United Nations agencies (such as UNDP, UNICEF, FAO, World Food Program, and UNFPA). Other principal donors have included the United States, Belgium, Germany, Switzerland, Canada, and Saudi Arabia. The USAID has been a major donor, contributing significantly to Niger's development, particularly in areas like food security and HIV/AIDS prevention. Following the 2023 coup, many international partners suspended or re-evaluated their aid programs, impacting the country's finances and development projects, and raising concerns about the humanitarian consequences for the population.

6. Administrative Divisions

Niger is divided into 7 Regions and one capital district (Niamey). These Regions are further subdivided into 36 Departments. The 36 Departments are currently broken down into Communes of varying types. As of 2006, there were 265 communes, including communes urbaines (Urban Communes, as subdivisions of major cities), communes rurales (Rural Communes) in sparsely populated areas, and postes administratifs (Administrative Posts) for largely uninhabited desert areas or military zones.

Rural communes may contain official villages and settlements, while Urban Communes are divided into quarters. Niger's subdivisions were renamed in 2002 as part of a decentralization project that began in 1998. Previously, Niger was divided into 7 Departments, 36 Arrondissements, and Communes. These subdivisions were administered by officials appointed by the national government. The decentralization plan aimed to replace these appointed officials with democratically elected councils at each level, although the implementation and effectiveness of this reform have faced challenges, particularly with ongoing political instability.

The regions (formerly departments pre-2002) and the capital district are:

- Agadez Region

- Diffa Region

- Dosso Region

- Maradi Region

- Tahoua Region

- Tillabéri Region

- Zinder Region

- Niamey (capital district)

| Region | Area (km2) | Population (2012 Census) | Population (2020 Estimate) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agadez | 258 K mile2 (667.80 K km2) | 487,620 | 687,540 |

| Diffa | 61 K mile2 (156.91 K km2) | 593,821 | 837,290 |

| Dosso | 13 K mile2 (33.85 K km2) | 2,037,713 | 2,873,180 |

| Maradi | 16 K mile2 (41.80 K km2) | 3,402,094 | 4,796,950 |

| Niamey (Capital District) | 155 mile2 (402 km2) | 1,026,848 | 1,447,860 |

| Tahoua | 44 K mile2 (113.37 K km2) | 3,328,365 | 4,692,990 |

| Tillabéri | 38 K mile2 (97.25 K km2) | 2,722,842 | 3,839,210 |

| Zinder | 60 K mile2 (155.78 K km2) | 3,539,764 | 4,991,070 |

6.1. Largest Cities and Towns

Niger's population is predominantly rural, but the country has several important urban centers. These cities serve as administrative, economic, and cultural hubs for their respective regions.

The largest cities and towns in Niger, based on the 2012 census, include:

- Niamey: The capital and largest city, located in the southwestern part of the country on the Niger River. It is the administrative, economic, and cultural center of Niger. Population (2012): 978,029.

- Maradi: The second-largest city, located in the south-central region near the Nigerian border. It is a major commercial center, particularly for agriculture and trade with Nigeria. Population (2012): 267,249.

- Zinder: The third-largest city and a historically significant Hausa city in southern Niger. It served as the capital of the French colony of Niger until 1926. Population (2012): 235,605.

- Tahoua: A major town in central Niger, serving as an important market and administrative center for the Tahoua Region. Population (2012): 117,826.

- Agadez: A historic Tuareg city in northern Niger, a traditional center for trans-Saharan trade and home to the famous Agadez Mosque. It is the capital of the Agadez Region. Population (2012): 110,497.

- Arlit: A town in the Agadez Region, primarily known for its uranium mining industry. Population (2012): 78,651.

- Birni-N'Konni: An important trading town in the Tahoua Region, near the Nigerian border. Population (2012): 63,169.

- Dosso: The capital of the Dosso Region in southwestern Niger, historically the center of the Dosso Kingdom. Population (2012): 58,671.

- Gaya: A town in the Dosso Region on the Niger River, at the border with Benin and Nigeria, making it a key point for cross-border trade. Population (2012): 45,465.

- Tessaoua: A town in the Maradi Region, historically a Hausa state. Population (2012): 43,409.

These urban centers play a vital role in Niger's socio-economic fabric, though they also face challenges related to rapid urbanization, infrastructure deficits, and poverty.

7. Economy

The economy of Niger is centered on subsistence crops, livestock, and some of the world's largest uranium deposits. In 2021, Niger was the main supplier of uranium to the European Union, followed by Kazakhstan and Russia. However, drought cycles, desertification, a high population growth rate (around 3.3% annually, with 7.1 children per mother), and fluctuations in world demand for uranium have significantly undercut the economy. Traditional subsistence farming, pastoralism, small-scale trade, and informal markets dominate an economy that generates few formal sector jobs. Between 1988 and 1995, an estimated 28% to 30% of Niger's total economy was in the unregulated informal sector, including small-scale rural and urban production, transport, and services.

Niger shares a common currency, the CFA franc, and a common central bank, the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO), with seven other members of the West African Monetary Union. Niger is also a member of the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA). Two trans-African automobile routes, the Algiers-Lagos Highway and the Dakar-Ndjamena Highway, pass through Niger.

According to official World Bank data, Niger's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was approximately 16.62 B USD in 2023. The economy is largely based on internal markets, subsistence agriculture, and the export of raw commodities: foodstuffs to neighboring countries and raw minerals to world markets.

In December 2000, Niger qualified for enhanced debt relief under the International Monetary Fund program for Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) and concluded an agreement with the Fund for a Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF). Debt relief provided under the enhanced HIPC initiative significantly reduced Niger's annual debt service obligations, freeing funds for expenditures on basic health care, primary education, HIV/AIDS prevention, rural infrastructure, and other programs geared at poverty reduction. In December 2005, it was announced that Niger had received 100% multilateral debt relief from the IMF, translating into the forgiveness of approximately 86.00 M USD in debts to the IMF, excluding remaining assistance under HIPC. Nearly half of the government's budget has historically been derived from foreign donor resources. Future growth prospects may be sustained by the exploitation of oil, gold, coal, and other mineral resources. Uranium prices have recovered somewhat in recent years. A drought and locust infestation in 2005 led to food shortages for as many as 2.5 million Nigeriens.

Niger was ranked 137th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.

7.1. Agriculture and Livestock

The agricultural sector, including livestock, is the backbone of Niger's economy, engaging the majority of the population. However, only about 15% of Niger's land is suitable for cultivation, primarily located along the southern border with Nigeria. Subsistence agriculture is dominant, with main crops including pearl millet, sorghum, and cassava, which are adapted to the semi-arid conditions and seasonal rainfall. Rice is also cultivated for domestic consumption in the Niger River valley in the west. The introduction of domestically sold rice at prices lower than imported rice, partly due to the devaluation of the CFA franc, has encouraged additional production.

Cash crops include cowpeas and onions, which are grown for commercial export, along with smaller quantities of garlic, bell peppers, potatoes, and wheat. Oases in the north also contribute to agricultural output, primarily through the cultivation of onions, dates, and some vegetables for export.

Livestock, including cattle, sheep, goats, and camels, is crucial to the economy and the livelihoods of many Nigeriens, particularly nomadic and semi-nomadic pastoralist communities like the Fulani (who primarily raise cattle in the south) and the Tuareg (who focus on camels and goats in the north). Livestock and their products are significant export items, often traded informally across the border with Nigeria.

The agricultural sector is highly vulnerable to climatic conditions, particularly variable rainfall and recurrent droughts, which can lead to crop failures and food insecurity. Traditional farming practices, coupled with population pressure and land degradation, pose ongoing challenges to increasing productivity. Deforestation for fuel and farming, and overgrazing contribute to desertification. Efforts to improve agricultural output include the development of irrigation, such as the Kandadji Dam project on the Niger River, which aims to provide water for thousands of hectares of farmland.

7.2. Mining

Niger possesses significant mineral resources, with uranium being its most prominent and historically most valuable export. The country has some of the world's largest uranium deposits, and for many years, uranium mining has been a cornerstone of the formal economy. Production began in the late 1960s and early 1970s from two major mines near the northern town of Arlit: the SOMAIR open-pit mine and the COMINAK underground mine. These operations have largely been joint ventures between the Nigerien government and foreign companies, primarily French interests (originally the French Atomic Energy Commission, later Areva, now Orano). Uranium revenue has historically accounted for a substantial portion of Niger's export earnings, although its contribution has fluctuated with global uranium prices. In 2007, new licenses were granted to Canadian and Australian companies to explore and develop new uranium deposits.

Gold is another mineral resource being exploited in Niger. The Samira Hill Gold Mine, located in the Liptako region near the border with Burkina Faso, began commercial production in 2004, marking Niger's first commercial gold output. It is operated as a joint venture between foreign companies and the Nigerien government. The region, known as the "Samira Horizon" gold belt, is believed to hold further significant gold deposits.

Coal is mined by the state-owned company SONICHAR (Societe Nigerienne de Charbon) in Tchirozerine, north of Agadez. This coal is primarily used to fuel a power plant that supplies electricity to the uranium mines. Other coal reserves of higher quality exist in the southern and western parts of the country.

Niger also has potential oil reserves. In 1992, Hunt Oil was granted exploration rights in the Djado Basin, and in 2003, the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) obtained rights in the Ténéré desert. The Agadem block, in the Diffa Region north of Lake Chad, was later awarded to CNPC in June 2008. Under the agreement, CNPC committed to developing oil wells and constructing a refinery near Zinder, with plans for an export pipeline. The government estimates the Agadem block's reserves at around 324 million barrels. Exploration for further oil resources continues.

The mining sector, while vital for export revenues, also presents social and environmental considerations, including impacts on local communities, water resources, and land use. The government has sought to attract foreign investment through revisions to its mining and petroleum laws.

7.3. Transport

Being a vast, landlocked country with widely dispersed population centers separated by desert and other natural obstacles, transportation infrastructure is crucial for Niger's economy and social cohesion. During the colonial period (1899-1960), transport development was limited, relying mainly on animal transport, foot travel, and restricted river navigation in the far southeast and southwest. No railways were built during this era, and most roads outside the capital remained unpaved. The Niger River, while a significant waterway, is not suitable for large-scale transport for much of the year due to insufficient depth and seasonal interruptions. Camel caravans historically served as vital transport links across the Sahara and in the northern Sahel regions.

Road transport, primarily by taxicabs, buses, and trucks, is the main mode of long-distance travel for most Nigeriens. As of 1996, Niger had a total of 6.3 K mile (10.10 K km) of roads, but only 496 mile (798 km) were paved. Most paved roads are in major cities or form part of two key highways. The first, known as the "Uranium Highway," was built in the 1970s and 1980s to transport uranium from the northern mines at Arlit to the Benin border, from where goods continue to ports like Cotonou, Lomé, and Port Harcourt. This highway, part of the Trans-Sahara Highway network, passes through Agadez, Tahoua, Birni-N'Konni, and Niamey. The second major paved highway, Route Nationale 1 (RN1), runs east-west across the southern part of the country, connecting Niamey, Dosso, Maradi, Zinder, and Diffa near Lake Chad, though the Zinder-Diffa section is only partially paved. Other roads are typically laterite, dirt, or sand tracks, particularly in the northern desert. The Kennedy Bridge in Niamey and a bridge at Gaya are important crossings over the Niger River.

Niger has several airports, with Diori Hamani International Airport in Niamey being the primary international gateway. Other notable airports include Mano Dayak International Airport in Agadez and Zinder Airport. However, since the 1980s, domestic air services beyond charter flights have been very limited, making air transport insignificant for internal freight or passenger movement.

There are no railways in Niger. Colonial-era plans for a railway linking Abidjan (Côte d'Ivoire) through Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso) to Niamey were halted at Ouagadougou in 1954. The Abidjan-Niger Railway name is a relic of this plan. An alternative plan for a railway via Dahomey (now Benin) led to the creation of the Benin-Niger Railway Transport Organisation (OCBN) in 1959, integrating Niger into Benin's rail system. Plans in the 1970s to extend the railway from Parakou (Benin) to Niamey were suspended due to lack of funds.

7.4. Poverty and Food Security

Niger consistently ranks among the poorest countries in the world and faces severe and persistent food security challenges. Widespread poverty affects a large majority of the population, particularly in rural areas where access to basic services, education, and economic opportunities is limited. According to the UN's Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) report of 2023, Niger is one of the world's poorest nations. The 2024 Global Hunger Index (GHI) ranked Niger 121st out of 127 countries with sufficient data, with a score of 34.1, indicating a serious level of hunger.

The causes of poverty and food insecurity are multifaceted and interconnected. Climate change contributes to recurrent droughts, desertification, and erratic rainfall patterns, severely impacting agricultural production, which is the mainstay of the economy and livelihoods for most Nigeriens. Rapid population growth, driven by one of the world's highest fertility rates, places increasing pressure on limited natural resources, including land and water. Political instability, including coups and ongoing conflicts with jihadist insurgencies, disrupts economic activities, displaces populations, and hinders development efforts.

The country frequently experiences food crises, often triggered by poor harvests. For example, a drought and locust infestation in 2005 led to severe food shortages affecting an estimated 2.5 million people. Malnutrition, especially among children, is a chronic problem.

Various national and international efforts are aimed at improving food availability and nutrition. These include programs to enhance agricultural productivity, promote sustainable land management, improve access to markets, provide social safety nets, and deliver humanitarian assistance during crises. Farmer-managed natural regeneration is one successful approach to combat desertification and improve land fertility. However, the scale of the challenges requires sustained and comprehensive interventions to achieve lasting improvements in poverty reduction and food security. The socio-economic well-being of the population remains a critical concern, heavily influenced by environmental vulnerability and political stability.

8. Society and Demographics

Nigerien society is characterized by its youthful population, high population growth, ethnic diversity, and the pervasive influence of Islam. Social and demographic factors significantly impact the country's development, human rights landscape, and cultural expression.

8.1. Demographics

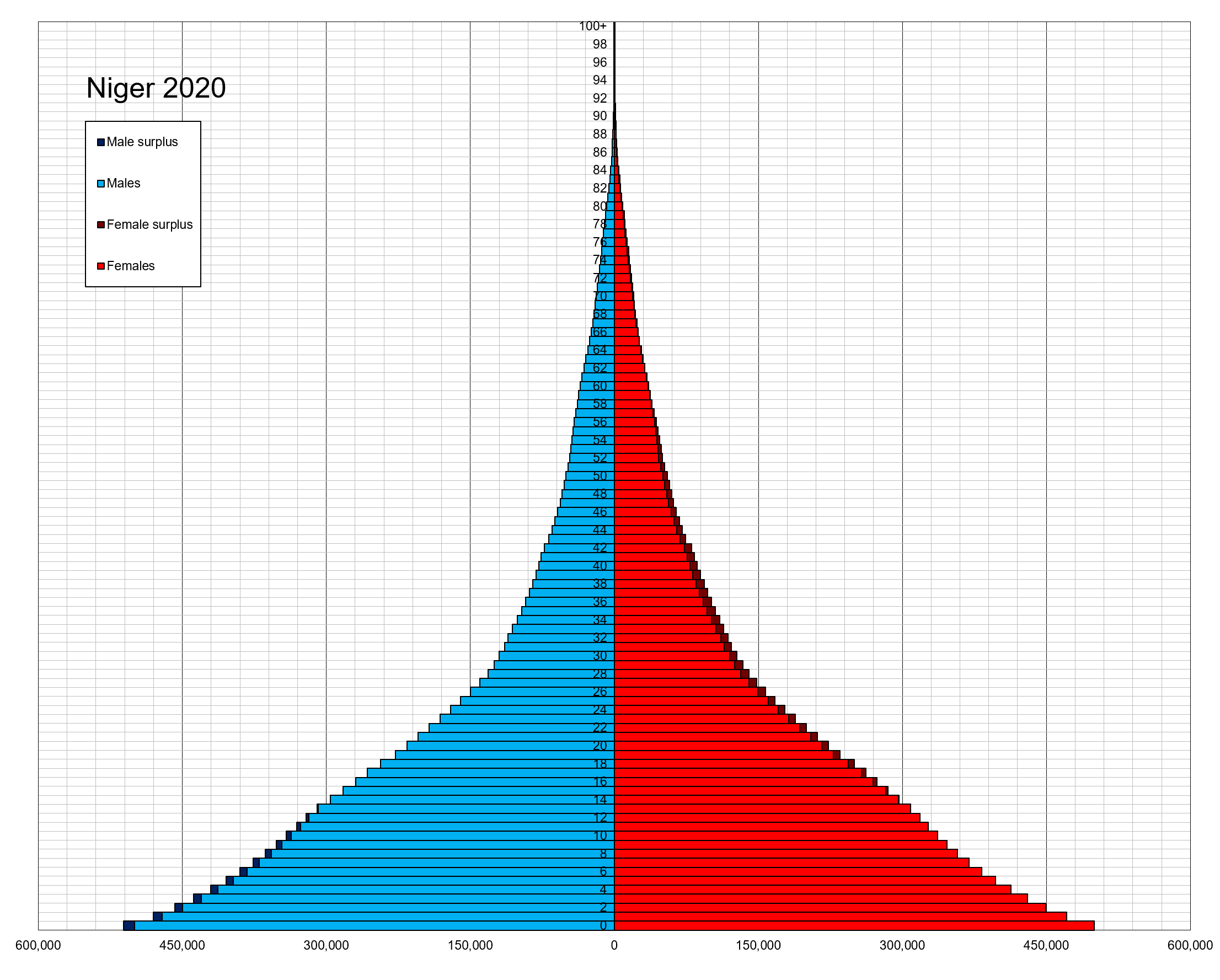

As of 2023, the population of Niger was estimated to be around 27.2 million by the UN. The population has increased dramatically from approximately 3.4 million in 1960. Niger has one of the highest population growth rates in the world, around 3.3% annually, and the world's highest total fertility rate, estimated at 6.5 to 7.1 children per woman in recent years. This rapid growth is a significant concern for the government and international agencies due to the strain it places on resources, infrastructure, and social services.

The population is predominantly young, with about 49.2% under the age of 15 and only 2.7% over 65 years old (as of 2020). This youthful age structure presents both opportunities and challenges for development. The population is also predominantly rural, with only about 21% living in urban areas, though urbanization is increasing. Long-term population projections indicate continued extreme growth, potentially reaching over 100 million by the latter half of the 21st century if current trends persist, posing immense challenges for poverty reduction, food security, education, and healthcare.

A 2005 study stated that over 800,000 people (nearly 8% of the population at the time) in Niger were enslaved, an issue with deep historical roots that continues to affect vulnerable communities despite legal prohibitions.

8.2. Ethnic Groups

Niger has a diverse array of ethnic groups, each with its own distinct cultural traditions. According to the 2001 census, the ethnic composition was as follows: Hausa (55.4%), Zarma & Songhai (21%), Tuareg (9.3%), Fulani (also known as Peul or Fulɓe) (8.5%), Kanuri Manga (4.7%), Toubou (0.4%), Arab (0.4%), Gourmantché (0.4%), and Other (0.1%).

These groups have historically coexisted, though competition for resources and political representation has sometimes led to tensions. Inter-ethnic relations are a significant aspect of Nigerien society and politics.

8.3. Languages

French, inherited from the colonial period, is the official language of Niger. It is primarily used in administration, formal education (often as a second language), and by a minority of the population. Niger has been a member of the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie since 1970, though its cooperation with the group was suspended following the 2023 coup.

Niger recognizes ten national languages, reflecting its ethnic diversity. These are:

- Arabic

- Buduma

- Fulfulde (language of the Fulani)

- Gourmanchéma (language of the Gourmantché)

- Hausa

- Kanuri

- Zarma and Songhay (often grouped together)

- Tamasheq (language of the Tuareg)

- Tassawaq

- Tebu

Each of these national languages is spoken as a first language primarily by the ethnic group with which it is associated. Hausa and Zarma-Songhai are the two most widely spoken languages and are often used as lingua francas in various parts of the country, either as a first or second language.

8.4. Religion

Niger is a secular state, and the separation of state and religion is guaranteed by Articles 3 and 175 of the 2010 Constitution, which also stipulate that future amendments may not modify the secular nature of the republic. Religious freedom is protected by Article 30 of the same constitution.

Islam is the dominant religion, practiced by an overwhelming majority of the population. According to the 2012 census, 99.3% of the population is Muslim. Islam, widespread in the region since the 10th century, has greatly shaped the culture and customs of the people of Niger. The majority of Muslims in Niger are Sunni, with smaller percentages of Shi'a (around 7%), Ahmadiyya (around 5%), and a significant portion (around 20%) identifying as non-denominational Muslims.

The other two main religions are Christianity, practiced by 0.3% of the population, and Animism (traditional indigenous religious beliefs), practiced by 0.2%. Christianity was established in the country primarily by missionaries during the French colonial years. Urban Christian expatriate communities from Europe and West Africa are also present. Religious persecution has reportedly increased in recent years; the Christian charity Open Doors listed Niger as the 37th most difficult country in which to be a Christian on their 2022 World Watch List, reflecting growing pressure on Christian communities. However, relations between Muslims and Christians have generally been reported as cordial by representatives of both groups.

The number of Animist practitioners is a point of contention. As recently as the late 19th century, much of the south-central part of the nation was unreached by Islam, and the conversion of some rural areas has been only partial. There are still areas where animist-based festivals and traditions (such as the Bori religion) are practiced by syncretic Muslim communities (in some Hausa areas as well as among some Toubou and Wodaabe pastoralists), as opposed to several small communities who maintain their pre-Islamic religion. These include the Hausa-speaking Maouri (or Azna, the Hausa word for "pagan") community in Dogondoutchi in the south-southwest and the Kanuri-speaking Manga near Zinder, both of whom practice variations of the pre-Islamic Hausa Maguzawa religion. There are also some tiny Boudouma and Songhay animist communities in the southwest. Over the past decade, syncretic practices have reportedly become less common among Muslim Nigerien communities.

8.4.1. Islam in Niger

Islam was introduced to the area that is now Niger beginning in the 15th century, through the expansion of the Songhai Empire in the west and the influence of Trans-Saharan trade originating from the Maghreb and Egypt. The expansion of Tuareg groups from the north, culminating in their seizure of far eastern oases from the Kanem-Bornu Empire in the 17th century, spread distinctively Berber Islamic practices.

Both the Zarma and Hausa areas were greatly influenced by the 18th- and 19th-century Fulani-led Sufi brotherhoods, most notably the Sokoto Caliphate (in present-day Nigeria). Modern Muslim practice in Niger is often tied to the Tijaniya Sufi brotherhoods, although there are small minority groups associated with Hammallism and Nyassist Sufi orders in the west, and the Sanusiya in the far northeast.

A small center of followers of the Salafi movement within Sunni Islam has appeared in the last thirty years, primarily in the capital, Niamey, and in Maradi. These small groups, linked to similar groups in Jos, Nigeria, came to public prominence in the 1990s during a series of religious riots.

Despite these developments, Niger maintains a tradition as a secular state, protected by law. Interfaith relations are generally considered good, and the forms of Islam traditionally practiced in most of the country are marked by tolerance of other faiths and a lack of restrictions on personal freedom. Alcohol, such as the locally produced Bière Niger, is sold openly in most parts of the country.

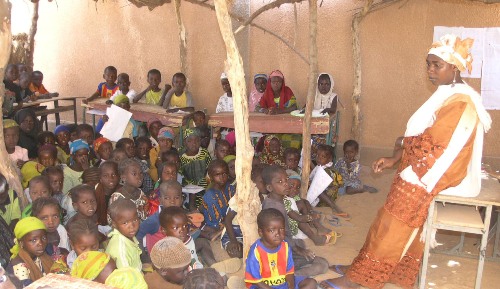

8.5. Education

The education system in Niger faces significant challenges, reflected in some of the lowest literacy and school enrollment rates in the world. In 2005, the literacy rate was estimated to be only 28.7% (42.9% for males and 15.1% for females); by 2015, it had fallen to 19.1%. Primary education in Niger is compulsory for six years. The educational structure generally follows a 6-4-3-3 system (6 years primary, 4 years middle school, 3 years high school, 3 years university), with the first 10 years (primary and middle school) being compulsory.

However, primary school enrollment and attendance rates are low, particularly for girls. In 1997, the gross primary enrollment rate was 29.3%, and in 1996, the net primary enrollment rate was 24.5%. About 60% of children who finish primary school are boys, as the majority of girls rarely attend school for more than a few years. Children are often forced to work rather than attend school, especially during planting or harvest periods, due to widespread poverty. Nomadic children in the northern part of the country often lack access to schools. Systems for grade repetition and skipping grades exist, but dropout rates are high.

Higher education institutions include the Abdou Moumouni University (formerly University of Niamey), established in 1971, and the Say Islamic University. Access to higher education is limited, and the quality of education at all levels is a persistent concern, impacted by insufficient funding, a lack of trained teachers, and inadequate infrastructure. Efforts to improve the education system are ongoing but are hampered by the country's socio-economic conditions and rapid population growth.

8.6. Health

The public health situation in Niger is among the most challenging in the world, characterized by high rates of mortality, prevalent diseases, and limited access to healthcare services. The child mortality rate (deaths among children between the ages of 1 and 4) is high (248 per 1,000) due to generally poor health conditions and inadequate nutrition for most of the country's children. According to the organization Save the Children, Niger has had the world's highest infant mortality rate.

Niger also has the highest fertility rate in the world (6.49 births per woman according to 2017 estimates), which has resulted in nearly half (49.7%) of the Nigerien population being under age 15 in 2020. This demographic structure places immense strain on maternal and child health services. Niger has the 11th highest maternal mortality rate in the world, at 820 deaths per 100,000 live births. In 2006, there were only 3 physicians and 22 nurses per 100,000 persons.

Access to clean drinking water is scarce by global standards, with significant differences between urban and rural areas. Roughly 92% of the population lives in rural areas, particularly in the Tillabéri region, where there is a chronic scarcity of clean water, especially during the hot season when temperatures regularly exceed 104 °F (40 °C). For instance, in Téra, a city northwest of Niamey, only about 40% of its 30,000 inhabitants had access to working public water infrastructure in the late 2010s. Initiatives by Niger's water authority, Société de Patrimoine des Eaux du Niger (SPEN), with support from international partners like the European Investment Bank and the Dutch government, aim to improve water supply and sanitation, including repairing infrastructure and exploring new water sources such as treating and transporting water from the Niger River. The World Bank has identified Niger as one of the 18 fragile regions of Sub-Saharan Africa requiring significant investment in basic services.

Common diseases include malaria, respiratory infections, and diarrheal diseases, often linked to poor sanitation and hygiene. Despite these immense challenges, Niger became the first African country and the fifth worldwide to eradicate onchocerciasis (river blindness) in 2025, according to the World Health Organization, a significant public health achievement. Niger consistently ranks near the bottom of the Human Development Index.

8.7. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Niger is a significant concern, influenced by political instability, poverty, armed conflict, and deeply entrenched social norms. While constitutional provisions for human rights exist, their enforcement is often weak, and abuses are reported across various sectors.

Civil liberties, including freedom of speech, assembly, and the press, have historically faced restrictions, particularly during periods of military rule and political crises. The 2023 coup and the subsequent actions of the military junta have further exacerbated these concerns, with reports of crackdowns on dissent, arrests of political opponents and activists, and limitations on media freedom.