1. Overview

Egypt, officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and the southwest corner of Asia by a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. A cradle of civilization, Egypt's extensive history, dating back to the 6th-4th millennia BCE, witnessed foundational developments in writing, agriculture, urbanisation, organised religion, and central government. Ancient Egypt's legacy includes monumental architecture such as the Giza pyramids and Sphinx, alongside significant cultural achievements that have shaped subsequent societies. Historically a vital center of Christianity, Egypt became predominantly Islamic following the Arab conquest in the 7th century.

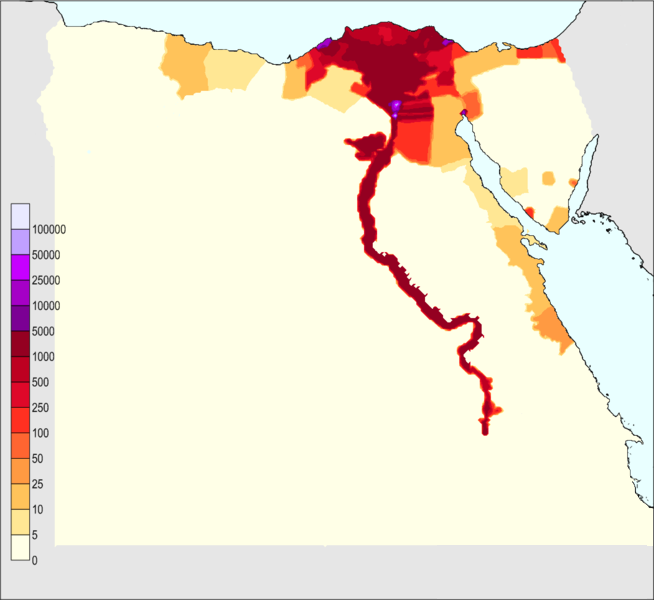

Geographically, the nation is largely defined by the Nile River, whose fertile valley and delta are flanked by vast expanses of desert. The majority of Egypt's over 100 million people reside in this narrow strip of arable land, making it one of the most densely populated agricultural regions in the world. Cairo serves as the capital and largest city, with Alexandria, the second-largest city, being a key industrial and tourist hub on the Mediterranean coast.

Egypt's modern era has been marked by profound transformations. After periods of Ottoman rule and the establishment of a de facto autonomous Khedivate by Muhammad Ali Pasha, who initiated significant modernization, the country experienced British occupation and protectorate status before gaining independence as a kingdom in 1922. The 1952 revolution established a republic. Under Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt pursued pan-Arabism and socialist-oriented reforms, which brought social development but also entrenched authoritarian rule and suppressed political dissent. Anwar Sadat shifted policies towards the West and controversially made peace with Israel; his economic liberalization, however, faced criticism for exacerbating social inequalities and failing to distribute benefits equitably. Hosni Mubarak's subsequent long rule, while maintaining stability, was characterized by continued authoritarianism, widespread corruption, and growing social discontent, culminating in the 2011 revolution. The post-revolution period has seen significant political transitions and social upheaval, including the brief Morsi government and the rise of Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. El-Sisi's government has overseen large infrastructure projects but has also faced extensive international scrutiny for its record on human rights, democratic development, and freedom of expression, with significant restrictions on political opposition and civil liberties.

Economically, Egypt relies on agriculture, tourism, petroleum and natural gas exports, and revenues from the Suez Canal. It is a developing country with one of the largest economies in Africa and is considered a regional power in North Africa, the Middle East, and the Muslim world. Egypt is a founding member of the United Nations, the Non-Aligned Movement, the Arab League, and the African Union. The nation's culture is a vibrant mix of ancient heritage and contemporary Arab influences in literature, music, film, and the arts, though artistic expression has also faced periods of constraint.

2. Names and Etymology

The English name "Egypt" is derived from the Ancient Greek Aígyptos (ΑἴγυπτοςAígyptosGreek, Ancient), via Middle French "Egypte" and Latin Aegyptus (AegyptusAegyptusLatin). The Greek term is reflected in early Greek Linear B tablets as "a-ku-pi-ti-yo". The adjective "aigýpti-"/"aigýptios" was borrowed into Coptic as "gyptios," and from there into Arabic as "qubṭī," which was then back-formed into قبطqubṭArabic, the origin of the English word "Copt". The ancient Greek historian Strabo provided a folk etymology suggesting that Aígyptos had evolved as a compound from Aegaeou huptiōs (Aἰγαίου ὑπτίωςAegaeou huptiōsGreek, Ancient), meaning "Below the Aegean," referring to the Aegean Sea.

The Arabic name for Egypt is Miṣr (مصرMiṣrArabic), pronounced Misr in Classical Arabic. In the local Egyptian Arabic dialect, it is pronounced Maṣr (مَصرMaṣrarz). This name originates from Semitic languages and is cognate with the Biblical Hebrew Miṣráyīm (מִצְרַיִם). The term Miṣr originally connoted "civilization" or "metropolis." The oldest attestation of this name for Egypt is the Akkadian "mi-iṣ-ru" (miṣru), related to miṣru/miṣirru/miṣaru, meaning "border" or "frontier". The Neo-Assyrian Empire used the derived term Mu-ṣur. In Japanese, Egypt is written in Kanji as 埃及AikyūJapanese and often abbreviated as 埃AiJapanese.

The ancient Egyptian name of the country was km.t, often vocalized as Kemet (km.tKemetEgyptian (Ancient)), which means "black land." This likely referred to the fertile black soils of the Nile flood plains, distinct from the dšṛt (dšṛtdeshretEgyptian (Ancient)), or "red land" of the desert. This name was probably pronounced approximately ku-mat in ancient Egyptian. In the Coptic stage of the Egyptian language, the name is realized as K(h)ēmə (ⲭⲏⲙⲓKhemiCoptic in Bohairic Coptic, ⲕⲏⲙⲉKēmeCoptic in Sahidic Coptic) and appeared in early Greek as Khēmía (ΧημίαKhēmíaGreek, Ancient). Another ancient name was tꜣ-mry (tꜣ-mryTa-meryEgyptian (Ancient)), meaning "land of the riverbank." The names for Upper and Lower Egypt were Ta-Sheme'aw (tꜣ-šmꜥwTa-Sheme'awEgyptian (Ancient), "sedgeland") and Ta-Mehew (tꜣ mḥwTa-MehewEgyptian (Ancient), "northland"), respectively.

3. History

The history of Egypt spans millennia, from the dawn of one of the world's earliest civilizations along the Nile River to its current status as a modern republic in a pivotal region. Key periods include the era of the pharaohs, characterized by monumental building and cultural achievements; conquest and rule by foreign powers like the Persians, Greeks (Ptolemies), and Romans; the Middle Ages, which saw the Arab-Islamic conquest and the rise of influential Islamic dynasties; Ottoman rule; the modernizing efforts of the Muhammad Ali Dynasty; British colonial influence and the subsequent struggle for independence; and the republican era marked by significant political figures like Nasser, Sadat, and Mubarak, leading to the 2011 revolution and its ongoing aftermath, a period characterized by both hopes for democratic progress and challenges to human rights.

3.1. Prehistory and Ancient Egypt

Evidence of rock carvings along the Nile terraces and in desert oases indicates early human presence in Egypt. Around the 10th millennium BCE, a culture of hunter-gatherers and fishers was gradually replaced by a grain-grinding culture. Climate changes or overgrazing around 8000 BCE began to desiccate the pastoral lands, contributing to the formation of the Sahara desert. Early tribal people migrated to the Nile River, where they developed a settled agricultural economy and a more centralised society. This agricultural society, dependent on the Nile's floods, laid the foundation for a complex civilization. Societal structures began to emerge, with increasing specialization of labor and the development of social hierarchies.

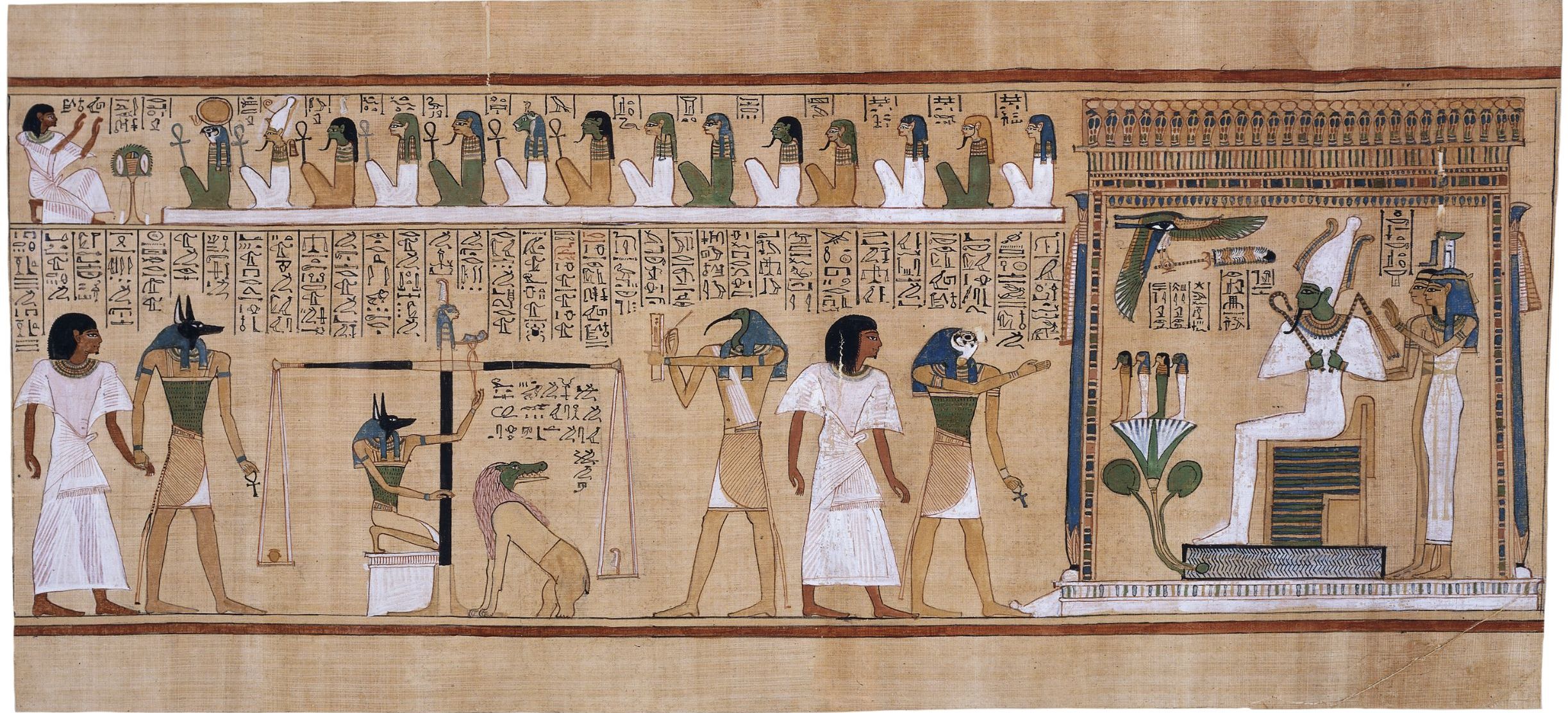

By about 6000 BCE, a Neolithic culture had taken root in the Nile Valley. During this era, several predynastic cultures developed independently in Upper and Lower Egypt. The Badarian culture and the succeeding Naqada series are generally regarded as precursors to dynastic Egypt. The earliest known Lower Egyptian site, Merimda, predates the Badarian by about seven hundred years. These Lower Egyptian communities coexisted with their southern counterparts for over two thousand years, remaining culturally distinct but maintaining frequent contact through trade. The earliest known evidence of Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions appeared during the predynastic period on Naqada III pottery vessels, dated to about 3200 BCE. These early writing systems were crucial for administration, religious rituals, and the recording of history.

A unified kingdom was founded around 3150 BCE by King Menes (possibly Narmer), leading to a series of dynasties that ruled Egypt for the next three millennia. Egyptian culture flourished during this long period and remained distinctively Egyptian in its religion, arts, language, and customs. The societal structure was highly stratified, with the pharaoh at the apex, considered a divine ruler. Below the pharaoh were priests, nobles, scribes, artisans, farmers, and laborers, each playing a role in the state's functioning. The first two ruling dynasties of a unified Egypt set the stage for the Old Kingdom period (circa 2700-2200 BCE). This era is renowned for the construction of many pyramids, most notably the Third Dynasty pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara, an early example of large-scale stone architecture, and the Fourth Dynasty Giza pyramids, including the Great Pyramid of Giza, a testament to the advanced engineering, organizational skills, and labor mobilization of the time. These monuments served as tombs for the pharaohs and were part of larger religious complexes.

The First Intermediate Period (circa 2181-2055 BCE) ushered in a time of political upheaval and decentralization lasting about 150 years. Provincial governors (nomarchs) gained more power, and central authority weakened. However, stronger Nile floods and the stabilization of government eventually brought renewed prosperity in the Middle Kingdom (circa 2055-1650 BCE). This period saw a resurgence in art, literature, and building projects, reaching a peak during the reign of Pharaoh Amenemhat III. Thebes rose to prominence as a religious and political center.

A second period of disunity heralded the arrival of the first foreign ruling dynasty in Egypt, that of the Semitic Hyksos. The Hyksos invaders, who introduced new military technologies like the horse-drawn chariot and composite bow, took over much of Lower Egypt around 1650 BCE and founded a new capital at Avaris. They were eventually driven out by an Upper Egyptian force led by Ahmose I, who founded the Eighteenth Dynasty and relocated the capital from Memphis back to Thebes. This event marked the beginning of the New Kingdom.

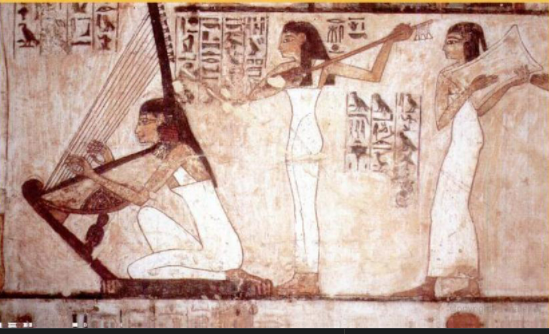

The New Kingdom (circa 1550-1070 BCE) began with the Eighteenth Dynasty, marking the rise of Egypt as an international power. Egypt expanded its empire to its greatest extent, reaching as far south as Tombos in Nubia and including parts of the Levant in the east. This period is noted for some of the most well-known Pharaohs, including Hatshepsut, a female pharaoh who undertook extensive building projects and trade expeditions; Thutmose III, a great military leader who expanded the empire; Akhenaten, who attempted a radical religious revolution by promoting the worship of a single deity, Aten, and his wife Nefertiti; Tutankhamun, whose largely intact tomb provided immense archaeological insight; and Ramesses II (the Great), known for his extensive building programs (like Abu Simbel) and military campaigns. The first historically attested expression of monotheism came during this period as Atenism. Frequent contacts with other nations brought new ideas and cultural influences to the New Kingdom. However, internal struggles and external pressures eventually led to its decline. The country was later invaded and conquered by Libyans, Nubians from Kush (who formed the 25th Dynasty), and Assyrians, but native Egyptians eventually drove them out and regained control of their country.

In 525 BCE, the powerful Achaemenid Empire, led by Cambyses II, began their conquest of Egypt, eventually capturing Pharaoh Psamtik III at the Battle of Pelusium. Cambyses II then assumed the formal title of pharaoh but ruled Egypt from his home in Susa in Persia (modern Iran), leaving Egypt under the control of a satrapy (province). The entire Twenty-seventh Dynasty of Egypt, from 525 to 402 BCE, save for the brief revolt of Petubastis III, was an Achaemenid-ruled period, with Achaemenid emperors granted the title of pharaoh. A few temporarily successful revolts against the Achaemenids marked the fifth century BCE, but Egypt was never able to permanently overthrow them during this first Persian period. This era saw cultural exchange but also resentment towards foreign rule.

The Thirtieth Dynasty was the last native ruling dynasty during the Pharaonic epoch. It fell to the Achaemenids again in 343 BCE after the last native Pharaoh, King Nectanebo II, was defeated in battle. This second Persian period (Thirty-first Dynasty), however, did not last long, as the Achaemenids were toppled several decades later by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE. The Macedonian Greek general of Alexander, Ptolemy I Soter, founded the Ptolemaic dynasty, ushering in the Hellenistic era in Egypt.

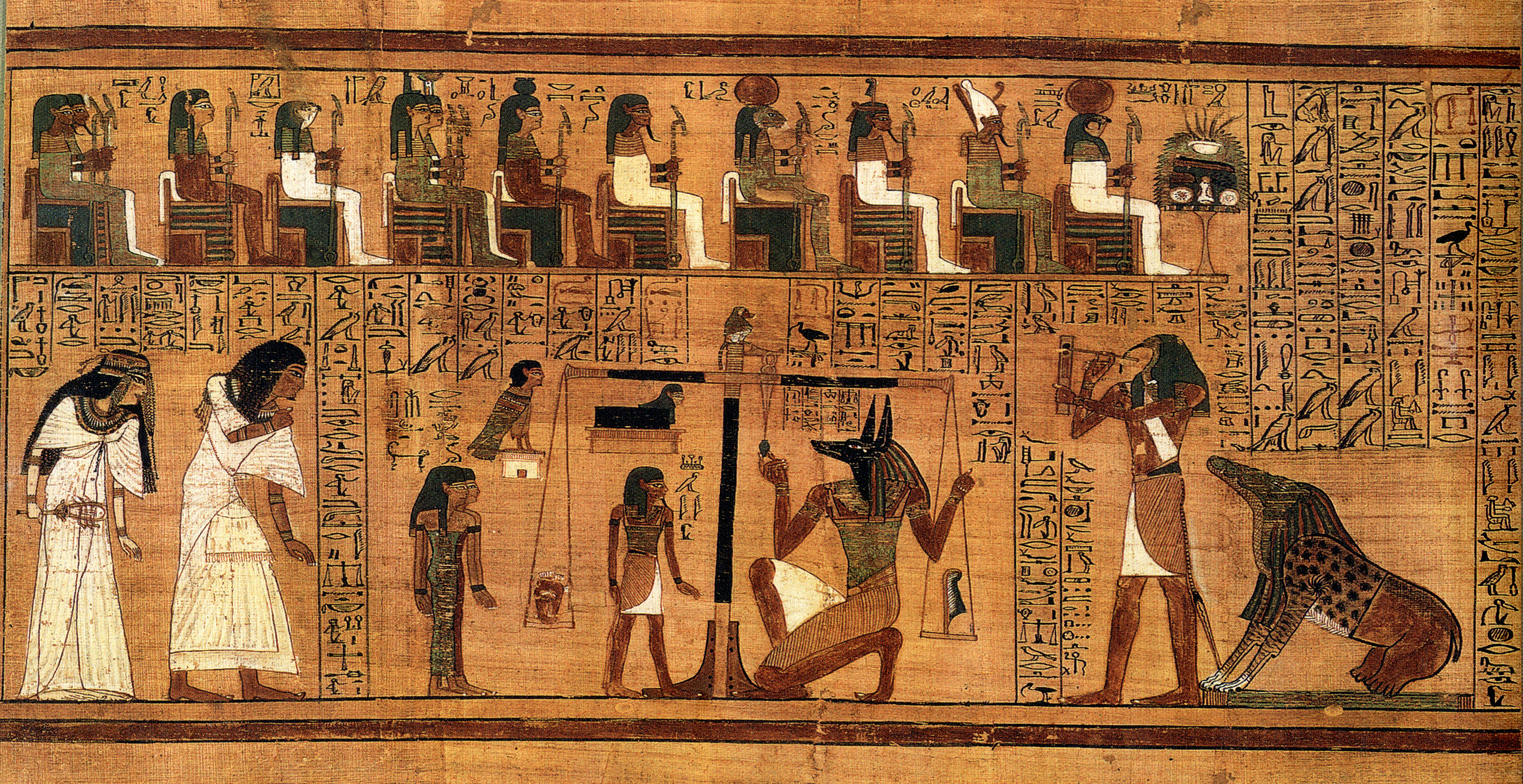

Significant archaeological sites from Ancient Egypt include the Giza Necropolis (Pyramids and Sphinx), Karnak and Luxor temple complexes in Thebes, the Valley of the Kings (royal tombs), Abu Simbel temples, Saqqara (Step Pyramid), and Dendera. Artifacts such as the Rosetta Stone, the treasures of Tutankhamun's tomb, numerous papyri (like the Book of the Dead), statues, and reliefs provide invaluable information about their society, beliefs, and daily life.

3.2. Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt

Following Alexander the Great's conquest of the Persian Empire in 332 BCE, Egypt came under Macedonian Greek rule. After Alexander's death, his general Ptolemy I Soter established himself as ruler of Egypt in 305 BCE, founding the Ptolemaic Kingdom. This kingdom became a powerful Hellenistic state, extending its influence from southern Syria in the east to Cyrene in the west, and south to the frontier with Nubia.

Alexandria, founded by Alexander, became the capital city and a renowned centre of Greek culture, learning, and trade. The Library of Alexandria and the Musaeum attracted scholars, scientists, and philosophers from across the Hellenistic world, making Alexandria a vibrant intellectual hub. Figures like Euclid (geometry), Eratosthenes (who calculated the Earth's circumference), and Hero of Alexandria (engineer and mathematician) worked there. Hellenistic culture flourished, coexisting and sometimes blending with ancient Egyptian traditions.

To gain recognition and legitimacy among the native Egyptian populace, the Ptolemaic rulers adopted the title of Pharaoh and were often depicted in traditional Egyptian style on public monuments and in temples. They participated in Egyptian religious life, patronized Egyptian temples, and sometimes adopted Egyptian deities into their own pantheon, or equated Greek gods with Egyptian ones (e.g., Zeus-Ammon). Despite these efforts, the Ptolemies faced rebellions from native Egyptians, often sparked by heavy taxation and resentment of foreign rule. They were also involved in numerous foreign wars, particularly against the Seleucid Empire for control of Coele-Syria, and internal civil wars, which gradually led to the decline of the kingdom.

The last ruler from the Ptolemaic line was the famous Cleopatra VII. She became entangled in Roman power politics, allying herself first with Julius Caesar (with whom she had a son, Caesarion) and later with Mark Antony. Her alliance with Antony brought her into conflict with Octavian (later Emperor Augustus). After their defeat at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE and Octavian's subsequent invasion of Egypt, Cleopatra committed suicide in 30 BCE, following Antony's death. Egypt was then annexed by Rome and became the Roman province of Aegyptus.

As a Roman province, Egypt was of immense importance to Rome, primarily as a major supplier of grain (the annona) for the city of Rome and the Roman army. It was governed directly by a prefect appointed by the emperor. Roman rule brought a degree of stability initially, but also heavy exploitation of Egypt's resources. Alexandria continued to be a major city and cultural center within the Roman Empire.

Christianity was brought to Egypt, according to tradition, by Saint Mark the Evangelist in the 1st century CE. Alexandria became a major center of Christian thought and theology, producing influential figures like Clement of Alexandria and Origen. Over time, a large portion of the Egyptian population converted to Christianity. The reign of Emperor Diocletian (284-305 CE) marked a period of intense persecution of Christians in Egypt (the "Era of Martyrs" in Coptic tradition). This period also marked the transition from the Roman Principate to the Dominate, and later the division of the Empire, with Egypt falling under the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire. The New Testament had by then been translated into the Egyptian language (Coptic). After the Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE, a doctrinal dispute led to a schism, and a distinct Egyptian Coptic Church was firmly established, differing from the Chalcedonian imperial church. This religious distinction would later play a role in Egypt's relationship with Byzantine rule.

3.3. Middle Ages (Arab Conquest to Mamluk Sultanate)

The Byzantine Empire regained control of Egypt after a brief Sasanian Persian invasion early in the 7th century during the Byzantine-Sasanian War of 602-628. The Persians established a new, short-lived province known as Sasanian Egypt for about ten years. However, Byzantine rule was short-lived as, between 639 and 642 CE, Egypt was invaded and conquered by the Islamic Caliphate under the Rashidun Caliph Umar, with the Arab Muslim armies led by General Amr ibn al-As. The Arab conquest marked a pivotal turning point in Egyptian history.

When the Arabs defeated the Byzantine armies in Egypt, they brought Sunni Islam to the country. The processes of Islamization (conversion of the population to Islam) and Arabization (adoption of the Arabic language and Arab culture) were gradual, occurring over several centuries. Initially, the Christian Coptic population was granted dhimmi status (protected non-Muslims) and allowed to practice their religion upon payment of the jizya (poll tax). Over time, various factors, including social and economic incentives, led to a majority of the population embracing Islam. Some Egyptians blended their new faith with indigenous beliefs and practices, leading to various Sufi orders that have flourished to this day. These earlier rites had survived the period of Coptic Christianity.

In 639, an army was sent to Egypt by Caliph Umar under Amr ibn al-As. They defeated a Roman (Byzantine) army at the Battle of Heliopolis. Amr then proceeded towards Alexandria, which surrendered to him by a treaty signed on November 8, 641. Alexandria was briefly regained for the Byzantine Empire in 645 but was retaken by Amr in 646. In 654, an invasion fleet sent by Emperor Constans II was repulsed. The Arabs founded a new capital for Egypt called Fustat, which was later burned down during the Crusades. Cairo was later built nearby in 968 CE.

Egypt was ruled as a province under the Umayyad (661-750) and then the Abbasid (750-1258) caliphs. The Abbasid period was marked by new taxation, and the Copts revolted again in the fourth year of Abbasid rule. In the early 9th century, the practice of ruling Egypt through a governor resumed under Abdallah ibn Tahir, who resided in Baghdad and sent a deputy to govern Egypt. In 828, another Egyptian revolt broke out, and in 831, Copts joined native Muslims against the government.

As Abbasid central power weakened, local governors and dynasties began to assert more autonomy. The Tulunids (868-905), founded by Ahmad ibn Tulun, a Turkic soldier, established the first de facto independent state in Egypt since pharaonic times, though nominally still under Abbasid suzerainty. They were followed by the Ikhshidids (935-969), another dynasty of Turkic origin.

In 969, the Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty originating from Ifriqiya (modern Tunisia), conquered Egypt and established Cairo (al-Qahira) as their new capital. Under the Fatimids (969-1171), Egypt became the center of a powerful empire that included North Africa, Sicily, Palestine, Syria, and the Hejaz. Cairo flourished as a major center of Islamic learning and culture, with the founding of Al-Azhar Mosque and University in 970 CE.

The Fatimid era ended with the rise of Saladin, a Kurdish general who overthrew the last Fatimid caliph in 1171 and established the Ayyubid Sultanate (1171-1250). Saladin, a Sunni Muslim, restored Egypt's allegiance to the Abbasid Caliphate (though he ruled independently) and became famous for his campaigns against the Crusader states in the Levant, notably recapturing Jerusalem in 1187. The Ayyubids continued to rule Egypt and Syria, strengthening Sunni Islam and building significant fortifications like the Citadel of Cairo.

With the decline of the Ayyubid dynasty, the Mamluks, a military caste composed primarily of Turkic and Circassian slave soldiers who had served the Ayyubids, seized control around 1250. The Mamluk Sultanate (1250-1517) was divided into two periods: the Bahri Mamluks (1250-1382) and the Burji Mamluks (1382-1517). The Mamluks successfully repelled the Mongol invasions (notably at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260) and expelled the last Crusaders from the Levant. Under Mamluk rule, Cairo became the largest and wealthiest city in the Islamic world, a major center of trade, art, and architecture. By the late 13th century, Egypt linked the Red Sea, India, Malaya, and the East Indies through trade. However, the Mamluk period was also marked by internal power struggles and economic challenges, including the devastating impact of the Black Death in the mid-14th century, which killed about 40% of the country's population. The Mamluk Sultanate eventually fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1517.

3.4. Ottoman Egypt (1517-1867)

Egypt was conquered by the Ottoman Turks under Sultan Selim I in 1517, following the defeat of the Mamluk Sultanate at the Battle of Ridaniya. After the conquest, Egypt became a province (eyalet) of the Ottoman Empire, known as the Egypt Eyalet. While politically subordinate to Istanbul, Egypt retained a significant degree of local autonomy, largely due to the continued influence of the Mamluks, who, despite their sultanate's overthrow, remained a powerful military and landowning class within the Ottoman administrative structure.

The Ottoman period in Egypt saw a complex interplay between the centrally appointed Ottoman governor (wali) and the powerful Mamluk beys. The defensive militarization that characterized this era had a detrimental impact on its civil society and economic institutions. The weakening of the economic system, combined with the effects of recurrent plagues, left Egypt vulnerable. Portuguese traders began to encroach upon Egypt's traditional trade routes, particularly in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean, diminishing Cairo's role as a major commercial hub.

Between 1687 and 1731, Egypt experienced six famines. The severe famine of 1784, exacerbated by the Laki volcanic eruption in Iceland which affected global climate, cost Egypt roughly one-sixth of its population. Throughout this period, Egypt proved to be a difficult province for the Ottoman Sultans to control effectively. Mamluk factions often vied for power, and Ottoman authority was sometimes nominal outside of Cairo.

A significant turning point came with the French invasion led by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798. Napoleon's expedition aimed to disrupt British trade routes to India and establish a French presence in the Middle East. The French forces defeated the Mamluk armies, notably at the Battle of the Pyramids. Although the French occupation was relatively short-lived (1798-1801), ending with their defeat by combined British and Ottoman forces, it had a profound impact. It exposed Egypt's military and technological weaknesses relative to European powers and shattered the existing Mamluk-Ottoman political order.

After the French withdrawal, a three-way power struggle ensued between the Ottoman Turks seeking to reassert direct control, the remnants of the Egyptian Mamluks attempting to regain their former dominance, and Albanian mercenaries who had been part of the Ottoman forces sent to expel the French. This period of instability paved the way for the rise of Muhammad Ali Pasha, an Albanian officer in the Ottoman army, who would fundamentally transform Egypt. By 1805, Muhammad Ali had consolidated power and was recognized by the Ottoman Sultan as the Wali (governor) of Egypt, though he would soon establish a de facto autonomous state that evolved into the Khedivate by 1867 under his successors, effectively ending direct Ottoman control in practice, though nominal suzerainty continued.

3.5. Muhammad Ali Dynasty and Khedivate (1805-1914)

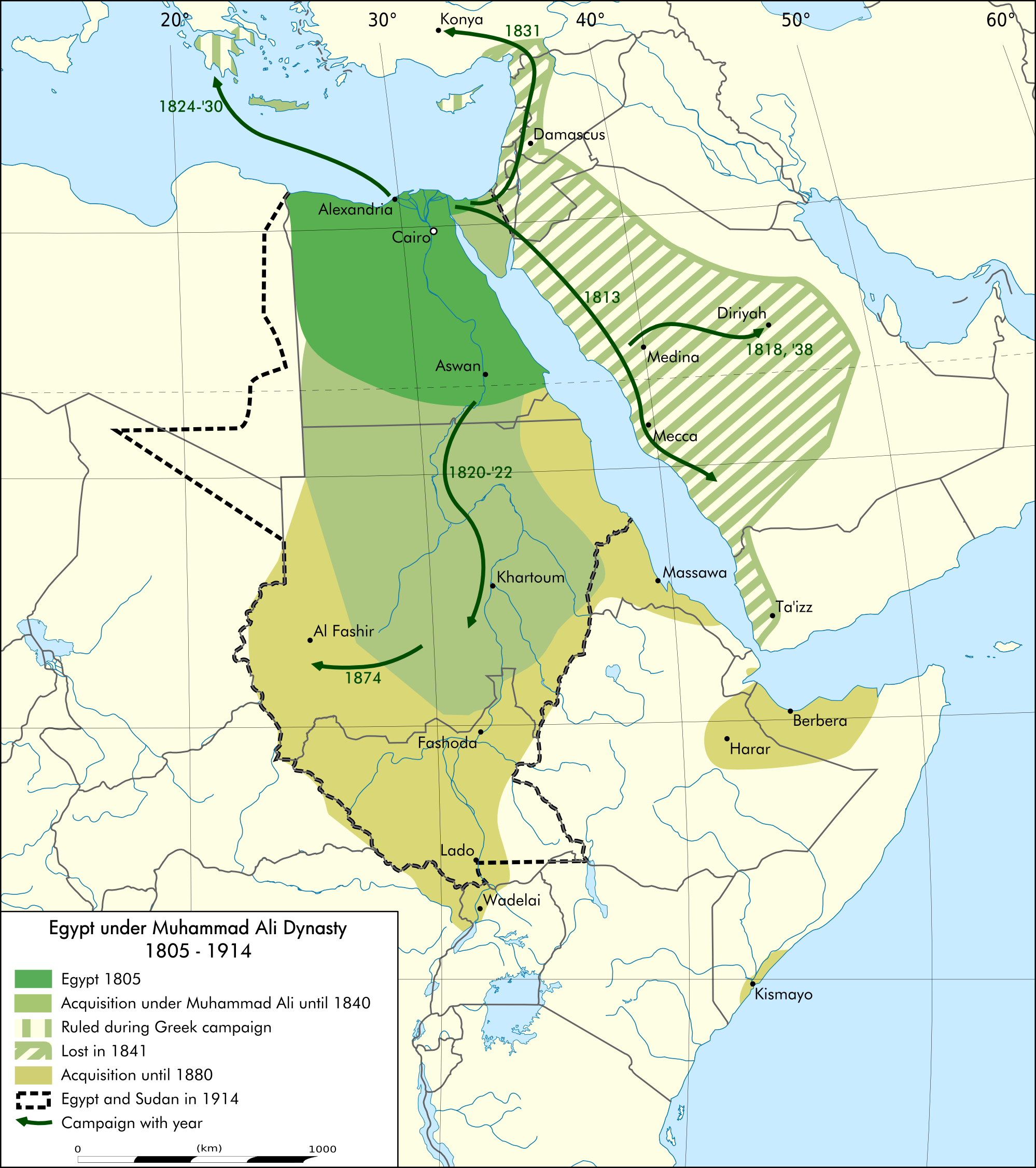

Following the expulsion of French forces in 1801, a power vacuum emerged in Egypt. Muhammad Ali Pasha, an ambitious Albanian commander in the Ottoman army, skillfully navigated the ensuing chaos. By 1805, he had outmaneuvered his rivals, including Ottoman officials and Mamluk factions, and was appointed Wali (governor) of Egypt by the Ottoman Sultan. He ruthlessly eliminated the Mamluk leadership in 1811, consolidating his control and establishing the Muhammad Ali dynasty that would rule Egypt until the 1952 revolution.

Muhammad Ali embarked on an ambitious program of modernization. He reformed the military along European lines, introducing conscription and modern training, transforming it from a traditional force into a formidable modern army. This military strength allowed him to expand Egyptian territory significantly. He annexed Northern Sudan (1820-1824), conquered Syria and parts of Arabia (1833), and even threatened Anatolia. However, European powers, fearing the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of a powerful Egyptian state, intervened in 1841 and forced him to return most of his conquests, though he retained hereditary rule over Egypt and Sudan.

His military ambitions required modernizing the country's infrastructure and economy. He introduced new industries, particularly in textiles and armaments, built a system of canals for irrigation and transport, and reformed the civil service and education. Long-staple cotton was introduced in the 1820s, transforming Egyptian agriculture into a cash-crop monoculture geared towards international markets, which had profound social consequences, including the concentration of land ownership. Muhammad Ali constructed a military state, with a significant portion of the populace serving in the army. While these reforms aimed to strengthen Egypt, the investment in education primarily benefited the military and industrial sectors, leading to limited improvement in general numeracy compared to other regions.

Muhammad Ali was succeeded by his son Ibrahim (briefly in 1848), then his grandson Abbas I (1848-1854), followed by Sa'id Pasha (1854-1863), and then Isma'il Pasha (1863-1879). Isma'il Pasha accelerated modernization efforts, investing heavily in infrastructure, education, and urban development, including the construction of the Suez Canal in partnership with the French, completed in 1869. He also encouraged science and agriculture and officially banned slavery.

Under Isma'il, Egypt under the Muhammad Ali dynasty remained nominally an Ottoman province but was granted the status of an autonomous vassal state or Khedivate in 1867, giving its rulers the title of Khedive. However, the ambitious development projects and Isma'il's lavish spending led to massive foreign debt. The Suez Canal's construction was financed by European banks, and Isma'il's attempts to avoid bankruptcy led him to sell Egypt's shares in the canal to the British government in 1875. This financial crisis resulted in the imposition of British and French financial controllers who effectively ran the Egyptian government, further increasing Egypt's dependency on foreign powers. Epidemic diseases, floods, and wars exacerbated the economic downturn.

Local dissatisfaction with Khedive Isma'il, his successor Khedive Tewfik, and growing European intrusion led to the formation of the first nationalist groupings in 1879, with Ahmed ʻUrabi emerging as a prominent figure. The 'Urabi Revolt (1879-1882), an uprising aimed at ending foreign influence and establishing constitutional rule, prompted British military intervention. The United Kingdom invaded Egypt in 1882, crushing the Egyptian army at the Battle of Tell El Kebir and militarily occupying the country. Following this, the Khedivate became a de facto British protectorate under nominal Ottoman sovereignty, a status that would last until the outbreak of World War I in 1914. In 1899, the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium Agreement was signed, establishing joint Anglo-Egyptian rule over Sudan, though in practice, Britain held effective control. The Denshawai incident in 1906, where British officers clashed violently with Egyptian villagers, further fueled nationalist sentiment and opposition to British rule.

3.6. British Protectorate and Kingdom of Egypt (1914-1952)

In 1914, with the outbreak of World War I and the Ottoman Empire joining the Central Powers against Britain, the British formalized their control over Egypt. They declared the abolition of Ottoman suzerainty and proclaimed Egypt a British protectorate. Khedive Abbas II, who had shown pro-Ottoman sympathies, was deposed and replaced by his uncle, Hussein Kamel, who assumed the title of Sultan of Egypt. This move severed Egypt's last formal ties to the Ottoman Empire.

The social impact of colonial rule was significant, fostering resentment and a burgeoning nationalist movement. After World War I, this movement, led by figures like Saad Zaghlul and the Wafd Party, gained widespread support. When the British exiled Zaghlul and his associates to Malta on March 8, 1919, it sparked the Egyptian Revolution of 1919, a nationwide uprising against British rule. The intensity of the revolt compelled the British government to issue a unilateral declaration of Egypt's independence on February 22, 1922.

Following this nominal independence, Sultan Fuad I assumed the title of King of Egypt. A constitution was drafted in 1923, establishing a parliamentary monarchy. The Wafd Party won a landslide victory in the 1923-1924 elections, and Saad Zaghloul became the new prime minister. However, despite formal independence, British influence remained pervasive. The Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 allowed for the withdrawal of most British troops from Egypt, except for those stationed in the Suez Canal Zone, which Britain retained control over. The treaty did not resolve the question of Sudan, which continued under the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, effectively meaning British control. The struggle for genuine independence and complete British withdrawal continued.

During World War II, Britain used Egypt as a crucial base for Allied operations, particularly in the North African Campaign. Egypt declared martial law and severed diplomatic relations with Germany, and later with Italy, but did not declare war, even when invaded by Italian forces. King Farouk I's government faced British pressure; in the Abdeen Palace incident of 1942, British forces surrounded the palace and forced Farouk to appoint a Wafd-led government more favorable to British war aims. This further undermined the monarchy's legitimacy and fueled anti-British sentiment.

After World War II, nationalist feelings intensified. The disastrous performance of the Egyptian army in the 1948 Arab-Israeli War further discredited the monarchy. In 1951, the Wafd government, led by Prime Minister Mostafa El-Nahas, unilaterally abrogated the 1936 treaty and ordered all remaining British troops to leave the Suez Canal. This led to increased conflict between Egyptian nationalists (including guerrillas) and British forces. A deadly clash in Ismailia on January 25, 1952, where Egyptian police fought British troops, resulted in the "Black Saturday" riots in Cairo the next day, targeting British and foreign-owned properties. King Farouk dismissed the Wafd government, but the monarchy's days were numbered. The period was marked by political instability, economic hardship for many, and a growing desire for complete sovereignty.

3.7. Republican Egypt

The period of Republican Egypt began with the 1952 revolution, which overthrew the monarchy and established a republic. This era saw transformative leadership under Gamal Abdel Nasser, who championed pan-Arabism and socialist reforms which brought social development but also severe authoritarian rule and widespread human rights abuses. Anwar Sadat shifted foreign policy towards the West and made peace with Israel, but his economic liberalization faced challenges in equitable distribution and increased corruption. Hosni Mubarak's long tenure was marked by political stability intertwined with deepening authoritarianism, suppression of dissent, and growing social discontent, ultimately leading to the 2011 revolution. The impacts of their major political, social, and economic policies shaped modern Egypt, often at great cost to democratic freedoms and human rights.

3.7.1. Nasser Era (1952-1970)

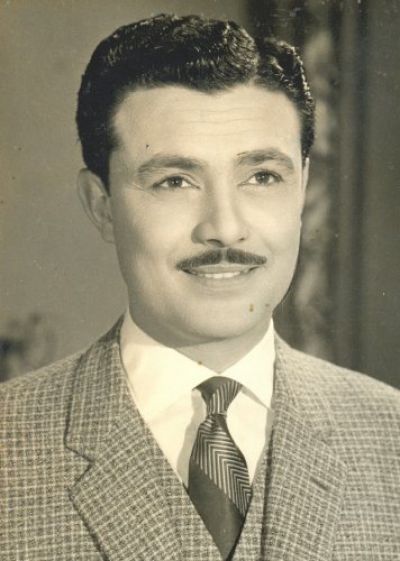

On July 22-23, 1952, the Free Officers Movement, a group of nationalist army officers led by Muhammad Naguib and Gamal Abdel Nasser, launched a coup d'état, known as the 1952 Revolution, against King Farouk. Farouk abdicated in favor of his infant son, Fuad II, and the royal family left Egypt. A Revolutionary Command Council (RCC) effectively took power. On June 18, 1953, the monarchy was officially abolished, and the Republic of Egypt was declared, with General Muhammad Naguib as its first President.

Nasser soon emerged as the dominant figure. In 1954, Naguib was forced to resign and placed under house arrest, and Nasser assumed full control, becoming President in 1956. Nasser's era was characterized by Pan-Arabism, a movement aiming for political unity among Arab states. His policies were also strongly anti-colonial and anti-imperialist. One of his most significant acts was the nationalization of the Suez Canal Company on July 26, 1956. This move aimed to use canal revenues to finance the Aswan High Dam project after Western powers withdrew funding. The nationalization triggered the Suez Crisis (also known as the Tripartite Aggression), where Israel, Britain, and France invaded Egypt. However, international pressure, particularly from the United States and the Soviet Union, forced the invaders to withdraw, resulting in a major political victory for Nasser, bolstering his image as a leader of the Arab world and the developing nations.

In 1958, Egypt and Syria merged to form the United Arab Republic (UAR), with Nasser as its president, as a step towards broader Arab unity. However, the union was short-lived and dissolved in 1961 when Syria seceded. Egypt continued to be known as the UAR until 1971.

Nasser pursued socialist-oriented reforms domestically. These included extensive land reform programs aimed at redistributing land from large landowners to peasants, the nationalization of major industries and financial institutions, and an expansion of public services such as education and healthcare. These policies led to significant social development, improved social mobility, and increased access to education for many Egyptians, contributing to the growth of a new middle class. However, the economy faced challenges, and these reforms were accompanied by the brutal suppression of political opposition, the banning of political parties (except the ruling Arab Socialist Union), and the establishment of an authoritarian state with an extensive security apparatus that systematically violated human rights. Emergency Law, enacted during the 1967 war, further curtailed civil liberties and was used to justify widespread arbitrary arrests and detentions.

Egypt became heavily involved in Middle Eastern conflicts under Nasser. He supported Palestinian aspirations and maintained a hostile stance towards Israel. Egypt occupied the Gaza Strip from 1949 to 1967. Tensions culminated in the Six-Day War of June 1967, where Israel launched a preemptive strike, defeating Egypt, Syria, and Jordan. Egypt lost the Sinai Peninsula and the Gaza Strip to Israeli occupation. The defeat was a severe blow to Nasser's prestige and to pan-Arabism, though he remained a popular figure. He died of a heart attack in September 1970. Nasser's legacy is complex: he is lauded for his contributions to social justice, national sovereignty, and Arab unity, but heavily criticized for his authoritarian rule, systemic human rights abuses, suppression of democratic development, and costly military ventures that ultimately harmed Egypt's progress.

3.7.2. Sadat Era (1970-1981)

Anwar Sadat succeeded Nasser as President in 1970. He initiated significant shifts in Egypt's domestic and foreign policies, moving away from Nasser's pan-Arab socialism and Soviet alignment. In 1971, Egypt officially changed its name to the Arab Republic of Egypt. One of Sadat's primary goals was to regain the Sinai Peninsula, lost in the 1967 war. To this end, Egypt, along with Syria, launched a surprise attack on Israeli forces in the Sinai and the Golan Heights on October 6, 1973, starting the Yom Kippur War (October War). The initial Egyptian crossing of the Suez Canal was a military success and restored Egyptian morale, though Israel eventually repulsed the Arab forces. The war paved the way for diplomatic negotiations.

Domestically, Sadat introduced the Infitah (Open Door) economic policy in 1974, aiming to liberalize the economy, attract foreign investment, and encourage private sector growth. This policy involved reducing state control over the economy, privatizing some state-owned enterprises, and offering incentives to investors. While Infitah led to some economic growth and the availability of more consumer goods, its benefits were unevenly distributed, fostering corruption and cronyism. It was widely criticized for increasing income inequality and negatively impacting social equity as subsidies on basic goods were reduced, leading to widespread suffering and the 1977 "Bread Riots". These policies often benefited a select elite connected to the regime, while failing to address the needs of the broader population.

In foreign policy, Sadat dramatically reoriented Egypt towards the West, particularly the United States, expelling Soviet military advisors in 1972. The most controversial and defining act of his presidency was his pursuit of peace with Israel. In a historic move, Sadat visited Jerusalem in November 1977, addressing the Israeli Knesset. This led to the Camp David Accords in 1978, brokered by U.S. President Jimmy Carter, and the signing of the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty in 1979. Under the treaty, Israel agreed to withdraw fully from the Sinai Peninsula (completed in 1982) in exchange for Egypt's recognition of Israel and the establishment of normal diplomatic relations.

Sadat's peace initiative with Israel was met with widespread condemnation from most of the Arab world, leading to Egypt's suspension from the Arab League and diplomatic isolation in the region. However, it was generally supported by many Egyptians who hoped for peace and economic prosperity. For his efforts, Sadat, along with Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1978.

Internally, Sadat's policies faced opposition from both the left (Nasserists and socialists) and increasingly from Islamist groups who opposed the peace treaty with Israel, Westernization, and secular policies. Sadat responded with an iron fist, clamping down on dissent and arresting thousands of critics, including intellectuals, journalists, and activists, in September 1981. This further eroded democratic freedoms and human rights. On October 6, 1981, during a military parade commemorating the October War, Anwar Sadat was assassinated by Islamist extremists within the army. His presidency marked a significant departure from the Nasser era, with lasting consequences for Egypt's economy, foreign relations, and a continued legacy of authoritarian practices and human rights concerns.

3.7.3. Mubarak Era (1981-2011)

Hosni Mubarak, who had been Vice President, came to power after Sadat's assassination in October 1981. He was confirmed as president in a referendum where he was the sole candidate, setting the stage for a long period of autocratic rule. Mubarak's presidency would last for nearly 30 years, characterized by a surface of political stability maintained through severe authoritarian means and systemic human rights abuses. He immediately reinstated the Emergency Law, which had been lifted shortly before Sadat's death, and it remained in effect throughout his rule, severely curtailing political freedoms, human rights, and due process.

In foreign policy, Mubarak largely continued Sadat's approach, maintaining the peace treaty with Israel and close ties with the United States, which provided Egypt with significant military and economic aid. He gradually repaired relations with other Arab nations that had been severed after the Camp David Accords, and Egypt was readmitted to the Arab League in 1989. Mubarak positioned Egypt as a key mediator in regional conflicts, particularly the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Domestically, Mubarak's government focused on economic liberalization, continuing aspects of Sadat's Infitah policy. This included privatization of state-owned enterprises and efforts to attract foreign investment. While the economy experienced periods of growth, the benefits were often concentrated among a business elite connected to the regime, fueling widespread corruption and cronyism. High unemployment, particularly among youth, rising income inequality, and lack of social justice fueled social discontent. Mass poverty persisted, and many rural families migrated to overcrowded urban slums, particularly in Cairo, which grew into a megacity of over 20 million people, straining resources and infrastructure.

The political system under Mubarak was dominated by the ruling National Democratic Party (NDP). While multi-party elections were held, they were widely seen as neither free nor fair, with the NDP consistently winning overwhelming majorities through manipulation and suppression of opposition. Opposition parties were weak, fragmented, and heavily restricted. Islamist groups, particularly the Muslim Brotherhood, though officially banned, operated within certain limits and represented the most significant, albeit repressed, political challenge. The government used the Emergency Law to brutally suppress dissent, arbitrarily detain activists, journalists, and any perceived opponents, and restrict freedom of expression, assembly, and the press. Human rights organizations frequently documented systematic torture, arbitrary detentions, enforced disappearances, and unfair trials before military and state security courts, highlighting a dire human rights situation.

During the 1990s, Egypt faced a significant challenge from Islamist militant groups, such as Al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya, which engaged in a campaign of violence, including attacks on tourists, Coptic Christians, and government officials. The Luxor massacre in 1997, where 62 people, mostly tourists, were killed, severely damaged Egypt's vital tourism industry. The government responded with a harsh crackdown on these groups, often leading to further human rights violations.

By the late 2000s, despite economic reforms and some growth, social discontent was widespread. Factors contributing to this included a profound lack of political freedom, pervasive police brutality, severe economic hardship for many, high youth unemployment, and deep-seated frustration over systemic corruption and cronyism. The aging Mubarak's apparent intention to groom his son, Gamal Mubarak, as his successor also fueled public anger and fears of a hereditary republic. These simmering tensions, rooted in decades of authoritarian rule and denial of basic rights, eventually erupted in the 2011 revolution, which brought an end to Hosni Mubarak's long and oppressive rule.

3.8. 2011 Revolution and Aftermath

The 2011 Egyptian revolution, a key event of the Arab Spring, was driven by a confluence of factors including decades of autocratic rule under Hosni Mubarak, pervasive police brutality, widespread corruption, severe economic hardship, high unemployment (especially among youth), and a profound desire for political freedoms, social justice, and democratic governance. Inspired by the Tunisian Revolution, protests began on January 25, 2011, centered in Cairo's Tahrir Square. Millions of Egyptians from diverse backgrounds participated in demonstrations, strikes, and acts of civil disobedience across the country, demanding an end to tyranny and a new era of rights and accountability. After 18 days of intense protests and violent clashes with security forces, which resulted in hundreds of deaths and thousands of injuries among protesters due to excessive force, Hosni Mubarak resigned on February 11, 2011. Power was transferred to the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), headed by Field Marshal Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, which promised a transition to civilian democratic rule.

The aftermath of the revolution was a period of significant political transition, social upheaval, and ongoing challenges in establishing a stable democratic system and ensuring respect for human rights. The impact on various social groups, including youth activists, women, workers, and religious minorities, was profound, with initial hope for transformative change often giving way to disillusionment as the transition process faced numerous obstacles, including resistance from entrenched interests and the military's continued influence. The victims of the revolution and their families sought justice and accountability for past abuses, which proved difficult to achieve, further highlighting the struggle for a truly democratic and just society.

3.8.1. Transition and Morsi Government (2011-2013)

Following Mubarak's ouster, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) governed Egypt during an interim period. This period was marked by continued protests, as many activists grew wary of the military's intentions, its handling of the transition, and its commitment to genuine democratic reform. SCAF oversaw a constitutional referendum in March 2011 that approved amendments paving the way for parliamentary and presidential elections. Parliamentary elections held from late 2011 to early 2012 saw Islamist parties, particularly the Muslim Brotherhood's Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) and the ultraconservative Salafist Al-Nour Party, win a majority of seats.

The first multi-candidate presidential elections were held in May-June 2012. Mohamed Morsi, the candidate of the FJP, narrowly defeated Ahmed Shafik, Mubarak's last prime minister, in a runoff. Morsi was sworn in as Egypt's first democratically elected civilian president on June 30, 2012.

Morsi's presidency was soon mired in controversy and intense political polarization. His government faced immense challenges, including a struggling economy, deep societal divisions, and a powerful, often obstructive, military establishment. Critics accused Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood of attempting to monopolize power, prioritizing their Islamist agenda over national unity and democratic principles, and failing to address the country's pressing economic and social problems. In November 2012, Morsi issued a constitutional declaration granting himself sweeping powers immune from judicial review, ostensibly to protect the Islamist-dominated constituent assembly drafting a new constitution. This move sparked massive protests from secular and liberal opposition groups, who accused him of betraying the revolution's democratic ideals and exhibiting authoritarian tendencies similar to the previous regime.

The new constitution, drafted by an assembly largely boycotted by non-Islamist members due to concerns over its inclusiveness and protection of rights, was approved in a referendum in December 2012 amid low turnout and allegations of irregularities. It further deepened political divisions and failed to unify the nation. Throughout early 2013, protests against Morsi's government intensified, fueled by economic grievances, concerns about restrictions on freedoms (including freedom of speech and assembly), and fears of an "Islamization" of the state that would undermine minority rights and secular values. Large-scale demonstrations demanding Morsi's resignation were planned for June 30, 2013, the first anniversary of his inauguration. Millions participated in these protests across the country. On July 3, 2013, following an ultimatum from the military, General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, then head of the armed forces, announced Morsi's removal from office in what is widely described as a coup d'état, which was condemned by many as a setback for Egypt's nascent democracy. The constitution was suspended, and Adly Mansour, head of the Supreme Constitutional Court, was appointed interim president.

3.8.2. Sisi Government (2013-present)

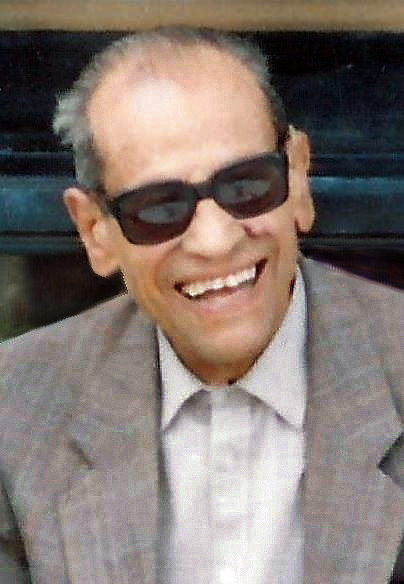

Following the military's removal of President Mohamed Morsi in July 2013, General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi emerged as the country's de facto leader, marking a significant shift in the post-revolutionary landscape. An interim government was installed, and a new constitution was drafted and approved in a referendum in January 2014, though concerns were raised about the process and its inclusiveness. El-Sisi, having retired from the military, ran for president and won the May 2014 presidential election by a landslide, with official results showing over 96% of the vote. However, turnout was relatively low, and the election was boycotted by Morsi's supporters and some secular groups critical of the military's role in politics and the restrictive electoral environment. He was sworn in as president on June 8, 2014.

El-Sisi's administration prioritized stability and security, often at the expense of democratic freedoms and human rights. The government launched a severe and widespread crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood, which was declared a terrorist organization, and its supporters. Thousands were arrested, many faced mass trials criticized for lacking due process, resulting in lengthy prison sentences or death penalties, drawing widespread international condemnation from human rights organizations and democratic governments. The crackdown extended to secular activists, journalists, human rights defenders, and any critics of the government, leading to a significant deterioration in freedom of expression, assembly, and the press. Many observers described the socio-political climate as increasingly authoritarian, with a shrinking space for dissent and a resurgence of practices reminiscent of the Mubarak era, if not more severe.

Economically, the Sisi government has pursued large-scale national infrastructure projects, including the expansion of the Suez Canal and the construction of a New Administrative Capital east of Cairo. It has also implemented economic reforms, often in coordination with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), including subsidy cuts and currency devaluation, aimed at tackling budget deficits and attracting investment. These measures have had mixed results, with some macroeconomic improvements but also increased hardship for many Egyptians due to rising inflation, austerity measures, and concerns about equitable distribution of benefits and social justice. The military's role in the economy significantly expanded under Sisi, raising concerns about fair competition and cronyism.

In foreign policy, Sisi has maintained close ties with Gulf Arab states like Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which provided significant financial support to Egypt after 2013. Relations with the United States, initially strained after Morsi's ouster due to human rights concerns, improved, particularly under the Trump administration, with continued military aid. Egypt has also strengthened ties with Russia and China. Regionally, Egypt has been involved in efforts to combat Islamist militancy in the Sinai Peninsula and Libya and has played a role in mediating the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

El-Sisi was re-elected in the March 2018 presidential election with a reported 97% of the vote, in an election where credible opposition candidates were largely absent or suppressed, leading to criticism about its fairness and legitimacy. In April 2019, constitutional amendments were approved in a referendum that extended presidential terms from four to six years and allowed Sisi to potentially run for a third term, potentially keeping him in power until 2030. These amendments also further strengthened the role of the military in politics and the president's control over the judiciary, raising further concerns about the separation of powers and democratic accountability.

Assessments of governance under Sisi have been highly critical, particularly from human rights groups and pro-democracy advocates. They point to the systematic suppression of political opposition, severe restrictions on civil liberties, widespread use of arbitrary detention, alleged torture and ill-treatment in detention, enforced disappearances, and a lack of accountability for security forces. The government maintains that its actions are necessary to ensure stability, combat terrorism, and implement economic development. However, the challenges of democratic development, upholding human rights, ensuring social justice, and improving living standards for the majority of Egyptians remain significant and pressing concerns.

4. Geography

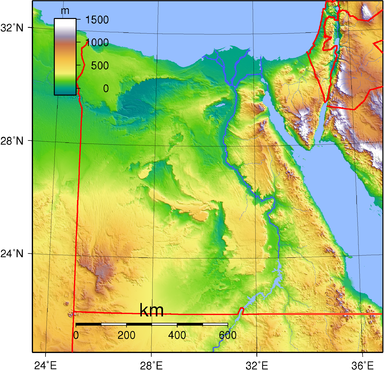

Egypt's geography is dominated by the Nile River, which has been the lifeline of its civilization for millennia. The country is situated in the northeast corner of Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge to Asia. Its diverse topography includes the fertile Nile Valley and Delta, vast deserts, and coastlines on the Mediterranean and Red Seas.

4.1. Topography and Borders

Egypt's land area is approximately 0.4 M mile2 (1.00 M km2). The country can be divided into four major geographical regions:

1. **The Nile Valley and Delta:** This is the most important region, forming a narrow strip of fertile land along the Nile River, which flows northwards from the Sudanese border to the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile Delta, north of Cairo, is a broad, fertile, fan-shaped area where the river branches out before emptying into the sea. This region, comprising only about 5.5% of Egypt's total land area, is home to approximately 99% of its population due to its arable land and water resources.

2. **The Western Desert (Libyan Desert):** Lying west of the Nile Valley, this region constitutes about two-thirds of Egypt's land area. It is an arid plateau, part of the Sahara Desert, characterized by vast sand dunes, rocky plains, and several oases, including Siwa, Bahariya, Farafra, Dakhla, and Kharga. The Qattara Depression, a large area below sea level, is also located here.

3. **The Eastern Desert (Arabian Desert):** Located east of the Nile Valley and extending to the Red Sea coast, this region is a rugged, mountainous plateau. It is rich in mineral resources and features prominent mountain ranges, including those along the Red Sea.

4. **The Sinai Peninsula:** A triangular peninsula situated in the northeast, forming a land bridge between Africa and Asia. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, the Gulf of Suez and the Red Sea to the west and south, and Israel and the Gaza Strip to the east. The southern part of Sinai is mountainous, containing Mount Catherine, Egypt's highest peak at 8.7 K ft (2.64 K m), and the historic Mount Sinai. The northern part is largely a flat, sandy plain.

Egypt is bordered by Libya to the west, Sudan to the south, the Gaza Strip and Israel to the northeast. Its northern coast faces the Mediterranean Sea, and its eastern coast faces the Red Sea. The Gulf of Aqaba in the northeast separates Egypt from Jordan and Saudi Arabia. A transcontinental nation, it possesses a land bridge (the Isthmus of Suez) between Africa and Asia, traversed by a navigable waterway (the Suez Canal) that connects the Mediterranean Sea with the Indian Ocean by way of the Red Sea.

4.2. Climate

Egypt has a predominantly desert climate (Köppen climate classification BWh), characterized by hot, dry summers and mild winters.

- Temperature:** Average high temperatures are high in the north but very to extremely high in the rest of the country during summer (May to September), often exceeding 104 °F (40 °C) in inland areas. Winters (November to March) are generally mild, with daytime temperatures ranging from 57.2 °F (14 °C) on the Mediterranean coast to 68 °F (20 °C) in Aswan in the south. Nighttime temperatures can drop significantly, especially in the desert.

- Precipitation:** Rainfall is scarce across most of Egypt. The Mediterranean coastal region receives the most rainfall, averaging 3.9 in (100 mm) to 7.9 in (200 mm) annually, mostly during the winter months. South of Cairo, rainfall is extremely rare, averaging only around 0.1 in (2 mm) to 0.2 in (5 mm) per year, often occurring at intervals of many years. Snowfall is rare but can occur on Sinai's mountains and occasionally in coastal cities like Alexandria. A very small amount of snow fell on Cairo on December 13, 2013, the first time in many decades.

- Winds:** The cooler Mediterranean winds consistently blow over the northern sea coast, which helps to moderate temperatures, especially during the summer. The Khamaseen (also spelled Khamsin) is a hot, dry, sand-laden wind that blows from the south or southwest in the spring (typically April to June). It can cause sudden sharp increases in temperature, often over 104 °F (40 °C) and sometimes over 122 °F (50 °C) in the interior, and drastically reduce visibility due to sand and dust storms. Relative humidity can drop to 5% or even less during these events.

- Sunshine:** Egypt enjoys a high amount of sunshine throughout the year.

Prior to the construction of the Aswan Dam, the Nile flooded annually, replenishing Egypt's soil. This gave Egypt a consistent harvest throughout the years. The dam has regulated these floods, providing benefits like year-round irrigation and hydroelectric power, but also leading to issues like soil salinity and loss of fertile silt deposition.

- Climate Change Impact:** Egypt is considered highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Rising sea levels threaten the densely populated Nile Delta. Increased temperatures could exacerbate water scarcity and affect agricultural productivity. Changes in Nile River flow due to climate change in upstream countries are also a major concern. These impacts pose significant challenges to Egypt's environment, economy, and population.

4.3. Biodiversity

Despite its predominantly desert environment, Egypt possesses a surprisingly diverse range of flora and fauna, adapted to its various ecosystems, including the Nile Valley and Delta, deserts, oases, coastal areas of the Mediterranean and Red Sea, and the Sinai Peninsula. Egypt signed the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity on June 9, 1992, and became a party to the convention on June 2, 1994. It subsequently produced a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan.

- Flora:** The Nile Valley and Delta support a variety of cultivated crops (cotton, cereals, fruits, vegetables) and natural vegetation like reeds and papyrus (historically important). Desert flora is sparse but adapted to arid conditions, including acacia trees, tamarisks, and various succulents and ephemeral plants that bloom after rare rainfalls. Oases support date palms and other vegetation. The coastal regions have salt-tolerant plants and mangroves in some Red Sea areas.

- Fauna:**

- Mammals:** Desert animals include the Dorcas gazelle, Nubian ibex, fennec fox, Rüppell's fox, various rodents like jerboas, and bats. The dugong can be found in Red Sea coastal waters. Larger mammals like the Barbary sheep are rare. Historically, animals like lions and giraffes were present but are now extinct in Egypt.

- Birds:** Egypt is an important migratory route for birds traveling between Eurasia and Africa. Over 480 bird species have been recorded. Wetlands along the Nile and coastal areas are crucial habitats for waterbirds like herons, egrets, pelicans, and flamingos. Birds of prey include eagles (like the Eastern Imperial Eagle), falcons, and vultures.

- Reptiles and Amphibians:** Reptiles include various lizards (e.g., geckos, agamas), snakes (including the Egyptian cobra), and tortoises. The Nile crocodile, once widespread, is now mainly found in Lake Nasser. Amphibians like the Nile Valley toad are present.

- Fish:** The Nile River and its associated lakes host numerous freshwater fish species, including Nile perch and tilapia.

- Marine Life:** The Red Sea is renowned for its rich coral reef ecosystems and diverse marine life, including over 1,000 fish species, numerous coral species, sharks, dolphins, and sea turtles. This makes it a major attraction for diving and snorkeling. The Mediterranean coast also supports marine biodiversity, though it has faced more environmental pressures.

- Insects and Fungi:** The National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan noted about 15,000 animal species, with over 10,000 being insects. Over 2,200 species of fungi (including lichen-forming species) have been recorded.

- Conservation Efforts:** Egypt has established several protected areas, including national parks like Ras Muhammad National Park (known for its coral reefs), Wadi El Gemal National Park, and Gebel Elba, as well as nature reserves and protectorates like Zaranik Protectorate and Siwa Oasis. These aim to conserve unique ecosystems and endangered species.

- Environmental Challenges:** Egypt faces significant environmental challenges, including water scarcity and pollution, desertification, habitat loss due to urbanization and agricultural expansion, and the impacts of climate change. Overfishing and damage to coral reefs from tourism and coastal development are also concerns. National efforts are underway to address these issues through conservation programs, sustainable resource management, and environmental legislation, though challenges remain.

5. Government and Politics

Egypt is a republic with a semi-presidential system of government. The political landscape has undergone significant transformations, particularly since the 2011 revolution, which initially promised democratic progress but has since seen a consolidation of authoritarian power. Contemporary political issues revolve around the severe lack of democratic development, widespread human rights violations, economic stability for the elite versus hardship for the masses, and regional security.

5.1. Political System and Constitution

Egypt's current political system is defined by the constitution approved in 2014 and controversially amended in 2019. It establishes a republican form of government with a separation of powers on paper, though in practice, the executive branch, particularly the President, holds significant and largely unchecked authority, undermining democratic institutions.

- The President:** The President is the head of state and wields substantial executive powers. The president is elected by direct popular vote, though the fairness and competitiveness of these elections have been widely questioned by international observers. Constitutional amendments in 2019 extended the presidential term from four to six years and allowed the incumbent, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, to potentially run for a third term, which could extend his rule until 2030, a move seen by critics as further entrenching authoritarianism. The president appoints the prime minister and cabinet, is the supreme commander of the armed forces, declares war (after nominal parliamentary approval), and can declare a state of emergency, often used to suppress dissent.

- The Parliament:** The legislature is currently unicameral, known as the House of Representatives (Majlis al-Nuwab). Its members are elected for five-year terms through a mix of individual candidacy and party-list systems. The 2019 constitutional amendments reintroduced an upper house, the Senate (Majlis al-Shuyukh), with one-third of its members appointed by the president and two-thirds elected; its powers are largely consultative. The House of Representatives is responsible for legislation, approving the state budget, and overseeing the government. However, its ability to act as a check on executive power is severely limited in practice, and it is largely dominated by pro-government figures.

- The Cabinet (Council of Ministers):** Headed by the Prime Minister, the cabinet is the chief executive body responsible for implementing state policies and managing government affairs. The Prime Minister and ministers are appointed by the President and must gain the confidence of the House of Representatives, a process largely controlled by the executive.

- Electoral System:** Elections are held for the presidency and the House of Representatives (and now the Senate). The fairness, transparency, and competitiveness of elections have been a subject of ongoing and severe criticism from domestic and international rights groups, particularly in the post-2013 period, with widespread reports of restrictions on opposition candidates, suppression of campaigning, and lack of independent oversight.

- Political Parties:** Egypt has a multi-party system in name, but the political landscape has been overwhelmingly dominated by pro-government parties and figures since 2013. The ruling Nation's Future Party (Mostaqbal Watan) holds a significant majority in parliament. Genuine opposition parties exist but face considerable restrictions, harassment, and limitations on their activities, rendering them largely ineffective. The Muslim Brotherhood, once a powerful political force, was outlawed and declared a terrorist organization after 2013, with its members and supporters facing severe persecution.

- Current Constitution:** The 2014 constitution (as amended in 2019) includes provisions for citizens' rights and freedoms, the separation of powers, and the rule of law. However, critics and human rights organizations argue that many of these provisions are not implemented or are actively undermined by law and practice, and that the amendments have dangerously consolidated presidential power and strengthened the already dominant role of the military in politics, further eroding democratic safeguards.

- State of Democratic Institutions and Political Freedoms:**

Since 2013, there has been a severe and systematic contraction of political space and a drastic decline in democratic freedoms and human rights. The government has prioritized state security and stability, often justifying repressive measures that have effectively dismantled many of the gains of the 2011 revolution. Severe restrictions on freedom of expression, assembly, and association are commonplace and ruthlessly enforced. Opposition voices, human rights defenders, independent journalists, lawyers, and academics face harassment, arbitrary arrest, politically motivated prosecution, and imprisonment. International organizations like Freedom House and The Economist Democracy Index have consistently rated Egypt as "Not Free" or an "authoritarian regime." The development of robust, independent democratic institutions and the protection of fundamental political and civil liberties remain major, unaddressed challenges, with the current trajectory indicating a deepening of authoritarian rule.

Egyptian nationalism predates its Arab counterpart by many decades, having roots in the 19th century and becoming the dominant mode of expression of Egyptian anti-colonial activists and intellectuals until the early 20th century. The ideology espoused by Islamists such as the Muslim Brotherhood has historically found support primarily among the lower-middle strata of Egyptian society, though it has been forcibly suppressed in recent years.

Egypt has the oldest continuous parliamentary tradition in the Arab world, with the first popular assembly established in 1866. It was disbanded as a result of the British occupation of 1882, and the British allowed only a consultative body to sit. In 1923, however, after the country's independence was declared, a new constitution provided for a parliamentary monarchy, though democratic development has been repeatedly interrupted by authoritarian rule.

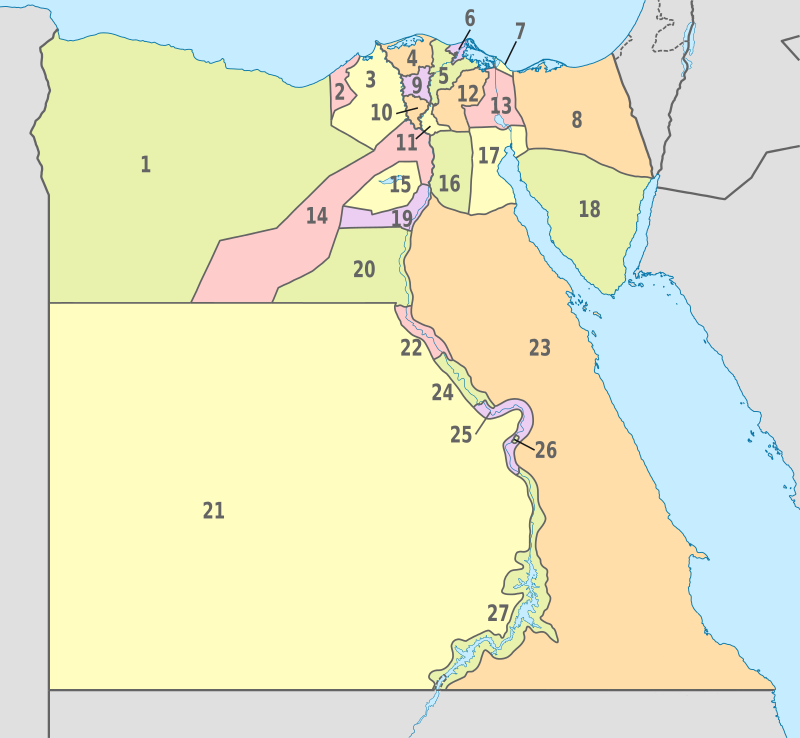

5.2. Administrative Divisions

Egypt is divided into 27 governorates (محافظاتmuḥāfaẓātArabic, singular محافظةmuḥāfaẓahArabic). These governorates are the highest tier of the country's administrative divisions. Each governorate is headed by a governor appointed by the President of Egypt. The governorates vary widely in terms of area and population density, with urban governorates like Cairo and Alexandria being densely populated, while vast desert governorates like New Valley are sparsely inhabited.

The governorates serve as the primary administrative units for implementing state policies, delivering public services, and managing local affairs. They are further subdivided into regions (marakiz or aqsam), which in turn contain towns (mudun) and villages (qura). Each governorate has a capital city, often carrying the same name as the governorate itself.

The 27 governorates are:

1. Alexandria

2. Aswan

3. Asyut

4. Beheira

5. Beni Suef

6. Cairo

7. Dakahlia

8. Damietta

9. Faiyum

10. Gharbia

11. Giza

12. Ismailia

13. Kafr El Sheikh

14. Luxor

15. Matrouh

16. Minya

17. Monufia

18. New Valley

19. North Sinai

20. Port Said

21. Qalyubia

22. Qena

23. Red Sea

24. Sharqia

25. Sohag

26. South Sinai

27. Suez

This system of administrative divisions aims to facilitate governance and development across Egypt's diverse regions.

5.3. Military

The Egyptian Armed Forces are the largest in Africa and the Middle East, and they play a highly influential, often decisive, role in the political and economic life of Egypt. The military establishment enjoys considerable power, prestige, and a significant degree of autonomy within the state, often being described as part of the Egyptian "deep state" that operates with limited civilian oversight. It is constitutionally mandated to protect the country, its security, and its territory, and also, controversially, to safeguard the constitution, democracy (though its actions have often undermined it), the fundamental components of the state, and the freedoms of citizens.

- Structure and Capabilities:** The Egyptian Armed Forces consist of the Egyptian Army, Egyptian Navy, Egyptian Air Force, and Egyptian Air Defense Forces. The total active personnel is estimated to be around 440,000 to 470,000, with a substantial reserve force of nearly 480,000.

- The Army is the largest branch, equipped with a mix of older Soviet-era and more modern Western (primarily U.S.) hardware, including main battle tanks, armored personnel carriers, and artillery.

- The Navy operates in the Mediterranean and Red Seas and is responsible for protecting Egypt's coastlines, maritime interests, and the Suez Canal. It has a diverse fleet including frigates, submarines, and amphibious assault ships.

- The Air Force is one of the largest in the region, with a variety of combat aircraft, including U.S.-made F-16s, French Rafales, and Russian MiG-29s and Su-35s.

- The Air Defense Forces are responsible for protecting Egyptian airspace and operate a range of surface-to-air missile systems.

- Political and Economic Influence:** Historically, all Egyptian presidents from 1952 until 2012, and again from 2014, have come from military backgrounds, underscoring the military's deep entrenchment in the political system. The military has significant and expanding economic interests, owning and operating a wide range of businesses in sectors such as construction, infrastructure, agriculture, consumer goods, and services. This economic role has expanded considerably since 2013, leading to serious concerns about fair competition, the crowding out of the private sector, lack of transparency, and the impact on democratic governance. The military is also exempt from many laws that apply to other sectors, and its budget is not subject to full parliamentary oversight, further cementing its autonomous and powerful position.

- Defense Policy and Operations:** Egypt's defense policy focuses on maintaining regional stability, countering terrorism (particularly in the Sinai Peninsula, where operations have raised human rights concerns), securing its borders, and protecting its national interests, including the Suez Canal and Nile water resources. Egypt has been involved in several regional conflicts, including the Arab-Israeli conflict and, more recently, operations against Islamist militants in Sinai and involvement in the Libyan conflict.

- Foreign Military Relations:** Egypt receives substantial annual military assistance from the United States, amounting to around 1.30 B USD. In 1989, Egypt was designated a major non-NATO ally of the United States. While ties with the U.S. remain crucial, particularly for military aid, Egypt has also diversified its arms suppliers, acquiring equipment from Russia, France, and other countries. It participates in joint military exercises with various nations. Egypt also has a space program and has launched reconnaissance satellites like EgyptSat 1 and EgyptSat 2.

The military's pervasive influence extends deeply into Egyptian society and governance, and it is often seen as a guarantor of national stability, though its role in perpetuating authoritarianism and hindering democratic development is a major concern for human rights and pro-democracy advocates.

5.4. Foreign Relations

Egypt's foreign policy is shaped by its strategic location at the crossroads of Africa, Asia, and Europe, its historical leadership role in the Arab world, its significant population, and its control over the Suez Canal. Key objectives include maintaining national security, promoting regional stability, protecting its interests in the Nile River, and fostering economic development through international partnerships. However, its human rights record and democratic backsliding often complicate relations with Western democracies.

- Relations with Major Powers:**

- United States:** Relations with the United States have been a cornerstone of Egyptian foreign policy since the 1970s. The U.S. is a major provider of military and economic aid. Ties were strained after the 2013 ouster of Mohamed Morsi, with the Obama administration expressing concerns over human rights and democratic backsliding, leading to a temporary suspension of some aid. However, strategic cooperation, particularly in counter-terrorism and regional security, has continued. Relations saw periods of closer engagement under the Trump administration, despite ongoing human rights concerns from the U.S. Congress.

- Russia:** Relations with Russia have significantly improved since 2013, with increased military, economic, and political cooperation. This includes arms deals, Russian involvement in building Egypt's first nuclear power plant, and coordinated stances on some regional issues, reflecting Egypt's efforts to diversify its foreign partnerships.

- China:** Relations with China have also strengthened, with Egypt joining China's Belt and Road Initiative and both countries establishing a "comprehensive strategic partnership" in 2014, focusing on economic and investment ties.

- European Union:** The EU is a major trading partner and source of development aid for Egypt. Relations focus on economic cooperation, migration, and security, though concerns over human rights, democratic deficits, and the rule of law in Egypt are often voiced by EU institutions and member states, sometimes leading to tensions.

- Regional Relations:**

- Arab World:** Cairo is the headquarters of the Arab League, and Egypt has traditionally played a leading role in Arab politics. Relations with Gulf monarchies, particularly Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, became very close after 2013, with these states providing substantial financial aid to Egypt. Egypt is a key player in efforts to resolve conflicts in Libya, Sudan, and Yemen, often aligning with these Gulf partners.

- Israel:** Egypt was the first Arab nation to establish diplomatic relations with Israel following the 1979 peace treaty. Despite a "cold peace" at the popular level due to ongoing Israeli-Palestinian issues, security and intelligence cooperation between the two governments is strong, particularly regarding the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza. Egypt has historically acted as a mediator in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, though its leverage has varied.

- African Union:** Egypt is a founding member of the African Union (and its predecessor, the Organization of African Unity) and plays an active role in African affairs, particularly concerning Nile Basin issues (especially the dispute with Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam) and regional security.

- Turkey and Iran:** Relations with Turkey have been severely strained, particularly since 2013, due to Turkey's support for the Muslim Brotherhood and differing regional policies. Relations with Iran have also been historically tense, stemming from geopolitical rivalries, sectarian differences, and Egypt's alliance with Gulf states opposed to Iran.

- International Organizations:** Egypt is a founding member of the United Nations and the Non-Aligned Movement. It has also been a member of the Organisation internationale de la FrancophonieOrganisation internationale de la FrancophonieFrench since 1983. Former Egyptian Deputy Prime Minister Boutros Boutros-Ghali served as Secretary-General of the United Nations from 1991 to 1996. Egypt recently joined the BRICS economic bloc.

- Humanitarian Concerns:** Egypt has hosted a significant number of refugees, primarily from Sudan, Syria, and other African and Middle Eastern countries. Its policies on border control and refugee management have sometimes drawn criticism from human rights organizations regarding protection and access to services. Humanitarian concerns, such as the situation in neighboring Gaza and Libya, also feature in its foreign policy considerations, often balanced with security interests.

Egypt's foreign policy seeks to balance its various alliances and interests, navigating a complex regional and international environment to protect its sovereignty and promote its strategic goals. This balancing act is often influenced by domestic political considerations and the need for external economic and military support, sometimes leading to compromises on its stated values regarding democracy and human rights.

5.5. Law and Judiciary