1. Overview

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is a vast country in Central Africa, rich in natural resources but plagued by a history of colonial exploitation, political instability, authoritarian rule, and devastating conflicts that have had a profound impact on its society, human rights, and democratic development. From its early kingdoms through the brutal era of the Congo Free State and Belgian colonial rule, the nation's path to independence was fraught with challenges, leading to crises, dictatorships, and wars that have deeply affected the Congolese people, particularly vulnerable groups and minorities. This article explores the DRC's complex history, its diverse geography and significant environmental challenges including climate change and threats to its rich biodiversity, its governmental structures and persistent issues of corruption and human rights violations, its resource-dependent economy, and the socio-cultural fabric of its diverse population. The narrative emphasizes the social impact of historical and ongoing events, the struggles for democratic progress, the protection of human rights, and the welfare of its citizens from a center-left/social liberalism perspective.

2. Etymology

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is named after the Congo River, which flows through the country. The Congo River is the world's deepest river and its third-largest by discharge. The name "Congo" originates from the Kingdom of Kongo, a significant pre-colonial state located near the mouth of the river. European sailors in the 16th century named the river after this kingdom and its Kongo people (Bakongo). The word Kongo itself is derived from the Kikongo language (KikongoKikongoKongo), and American writer Samuel Henry Nelson suggested it likely implies a public gathering, based on the root word konga, meaning "to gather". The modern term Bakongo for the Kongo people was introduced in the early 20th century.

Several early European-led organizations also derived their names from the river, including the Comité d'études du haut Congo (Committee for the Study of the Upper Congo), established by King Leopold II of Belgium in 1876, and the International Association of the Congo, established by him in 1879.

The country has been known by several names throughout its history:

- Congo Free State (1885-1908): King Leopold II's personal possession.

- Belgian Congo (1908-1960): A Belgian colony.

- Republic of the Congo-Léopoldville (1960-1964): Upon independence, to distinguish it from the neighboring former French colony, the Republic of the Congo (Congo-Brazzaville). The capital city was Léopoldville (now Kinshasa).

- Democratic Republic of the Congo (1964-1971): Adopted with the promulgation of the Luluabourg Constitution on August 1, 1964.

- Republic of Zaire (1971-1997): Renamed by President Mobutu Sese Seko on October 27, 1971, as part of his Authenticité (Authenticity) policy. The name "Zaire" is a Portuguese adaptation of the Kikongo word nzadi ("river"), a truncation of nzadi o nzere ("river swallowing rivers"). The Congo River itself was known as the Zaire River during the 16th and 17th centuries, though "Congo" gradually replaced it in English usage by the 18th century.

- Democratic Republic of the Congo (1997-present): The name was restored by President Laurent-Désiré Kabila after he overthrew Mobutu in 1997. A proposal to change the name to DRC by the Sovereign National Conference in 1992 was not implemented at the time.

To distinguish it from its neighbor, the Republic of the Congo, the country is often referred to as DR Congo, DRC, Congo-Kinshasa (after its capital), or occasionally Big Congo (due to its larger size). In French, it is commonly abbreviated as RDC.

3. History

This section details the history of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from its earliest inhabitants through major pre-colonial kingdoms, the brutal period of the Congo Free State under Leopold II, Belgian colonial rule, the turbulent path to independence and the subsequent Congo Crisis, the long dictatorship of Mobutu Sese Seko and the Zaire era, the devastating Congo Wars, and the political developments under Joseph Kabila and Félix Tshisekedi, analyzing their impact on the nation's society, political landscape, and human rights.

3.1. Early history

The geographical area now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo has been populated for at least 90,000 years. Archaeological evidence, such as the Semliki harpoon discovered in 1988 at Katanda, dates back to this period. This harpoon, one of the oldest barbed harpoons found, is believed to have been used for catching giant river catfish, indicating early sophisticated fishing practices.

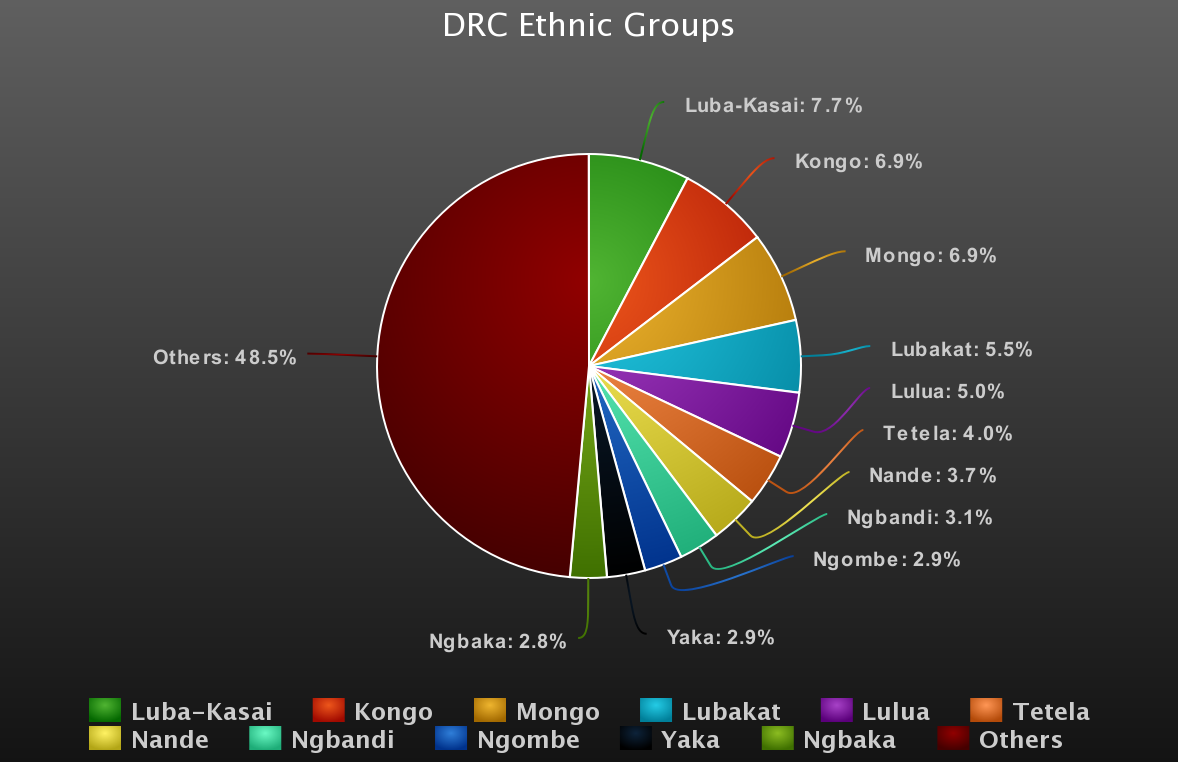

The first inhabitants were likely Central African foragers, often referred to as Pygmy peoples, whose hunter-gatherer cultures have persisted in some parts of the country. Around 2,000 to 3,000 years ago (during the first millennium BC), Bantu-speaking peoples began migrating into Central Africa from West Africa in what is known as the Bantu expansion. This expansion was accelerated by their adoption of pastoralism and Iron Age technologies, including iron tools which revolutionized agriculture. This led to the gradual displacement or assimilation of the indigenous Pygmy populations.

By circa 700 AD, processes of state and class formation began to emerge. Three main centers of development appeared: one in the west around Pool Malebo, another to the east around Lake Mai-Ndombe, and a third further east and south around the Upemba Depression.

By the 13th century, several confederations of states existed in the western Congo Basin. The Seven Kingdoms of Kongo dia Nlaza, considered the oldest and most powerful, likely included territories such as Nsundi, Mbata, and Mpangu. South of these was Mpemba, stretching from modern-day Angola to the Congo River. Further west, across the Congo River, was a confederation of three smaller states: Vungu, Kakongo, and Ngoyo.

Several significant pre-colonial kingdoms rose and fell in the region:

- The Kingdom of Kongo was founded in the 14th century and became a dominant force in the western part of the region, around the mouth of the Congo River. It developed a sophisticated political structure and engaged in trade with Europeans, particularly the Portuguese, from the late 15th century onwards. This interaction eventually led to its decline and fragmentation due to internal conflicts and the pressures of the Atlantic slave trade.

- The Luba Kingdom (or Luba Empire) emerged in the 15th century from the Upemba Depression in what is now the southeastern DRC (Katanga region). It was known for its centralized political system, spiritual leadership, and extensive trade networks dealing in salt, copper, and iron goods.

- The Lunda Kingdom (or Lunda Empire) developed in the 17th century, also originating from the Upemba Depression area and expanding its influence over a vast territory in the southern DRC, Angola, and Zambia. It had complex political and social structures and was a major trading power.

- The Kuba Kingdom flourished in the Kasai region from the 17th century, renowned for its artistic traditions, particularly raffia cloth, wooden sculptures, and intricate beadwork, as well as its hierarchical political system.

- The Mwene Muji empire was founded around Lake Mai-Ndombe.

- In the northeast, Azande kingdoms also existed, ruling from the 16th and 17th centuries into the 19th century.

These kingdoms had varied social structures, often hierarchical, with ruling elites, commoners, and, in some cases, enslaved people. They exerted regional influence through trade, diplomacy, and military power. Initial contact with Europeans, primarily Portuguese explorers and traders starting in the late 15th century, brought new goods, technologies, and religions (like Christianity to the Kongo Kingdom) but also sowed the seeds of future exploitation, particularly through the devastating East African slave trade conducted by Arab-Swahili traders like Tippu Tip in the eastern regions, and the transatlantic slave trade which impacted western regions.

3.2. Congo Free State (1885-1908)

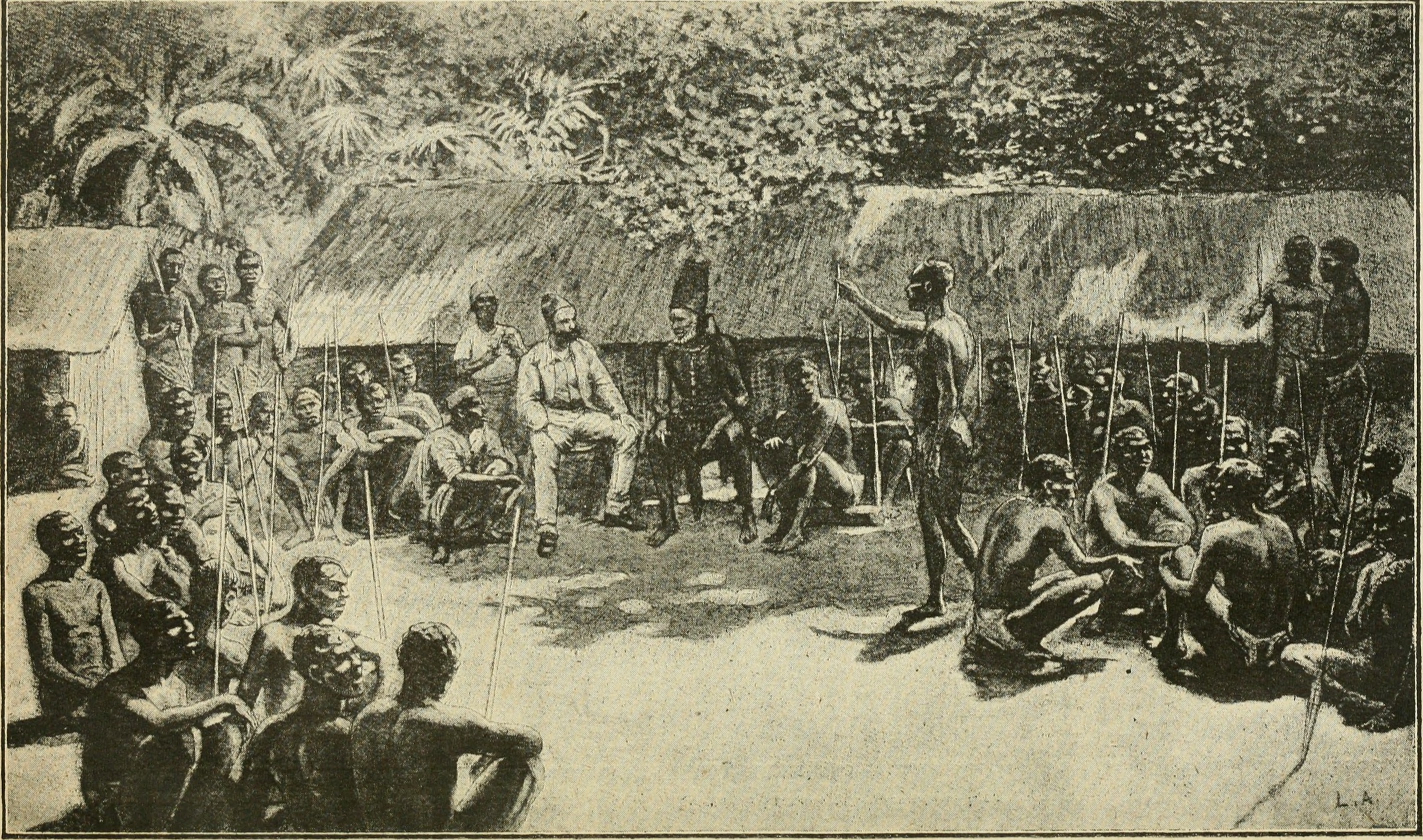

The period leading to the establishment of the Congo Free State was marked by European exploration and the assertion of colonial ambitions in Central Africa. King Leopold II of Belgium harbored personal designs on the Congo territory, driven by the potential for vast economic wealth. From the 1870s, exploration and administrative groundwork were laid, notably by Henry Morton Stanley, who undertook expeditions under Leopold's sponsorship. Leopold skillfully manipulated European rivalries, professing humanitarian objectives through front organizations like the International African Association (Association Internationale Africaine) to achieve his goals.

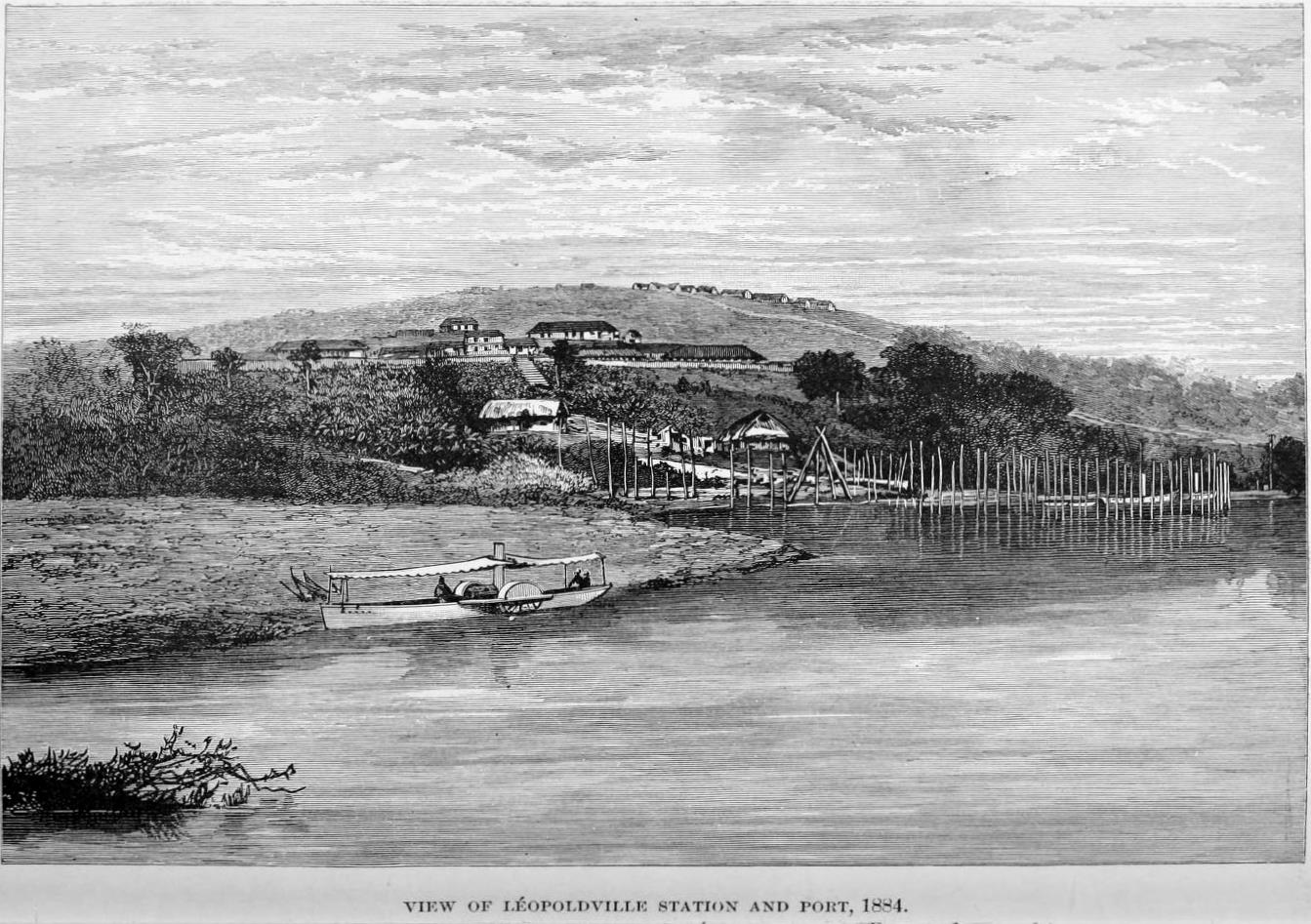

At the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, Leopold II formally acquired rights to the Congo territory, not as a Belgian colony, but as his personal private property. He named this vast territory the Congo Free State (État indépendant du Congo). This arrangement granted him absolute control over an area roughly 76 times the size of Belgium. Leopold's regime initiated some infrastructure projects, such as the railway from the coast to Léopoldville (now Kinshasa), which took eight years to complete and involved significant forced labor.

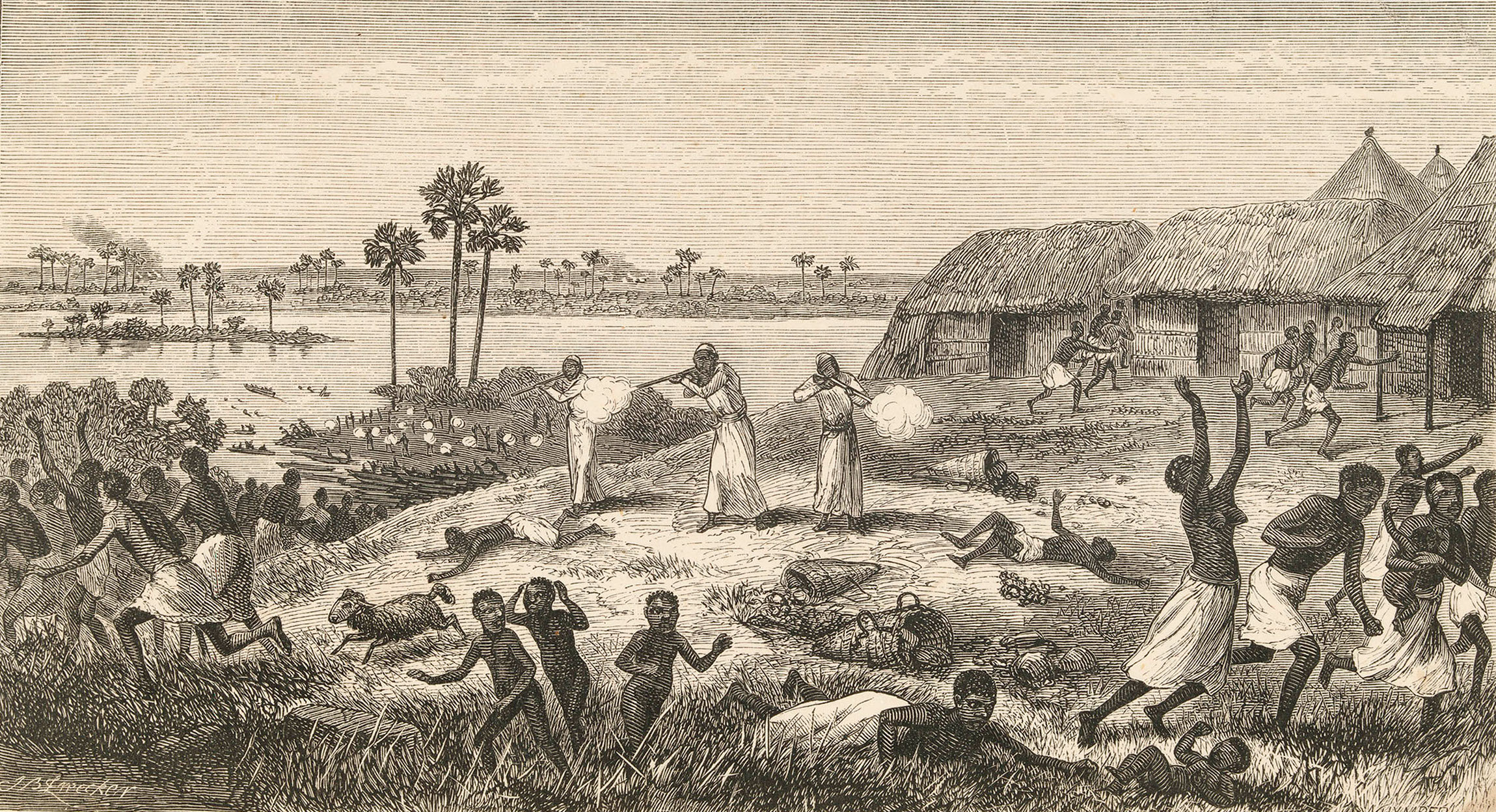

The primary economic driver of the Congo Free State was the extraction of rubber and ivory. The burgeoning automobile industry and the development of rubber tires created a massive international demand for rubber. To meet this demand, Leopold's administration imposed a brutal system of forced labor on the Congolese population. His colonial military, the Force Publique, was used to enforce rubber quotas. Failure to meet these quotas resulted in horrific atrocities, including murder, village destruction, and the infamous practice of cutting off the hands or feet of workers or their family members as punishment or to terrorize them into compliance. This system of terror was designed to maximize rubber collection at minimal cost.

The administration granted concessions to private companies, which were given monopolies over resource extraction and often employed their own militias or used the Force Publique to enforce their demands. The concession regions, particularly those focused on rubber plantations, became notorious for extreme violence. Local chiefs were often co-opted or coerced into enforcing quotas. Those who failed to comply faced severe repercussions, including the kidnapping of family members who were held ransom until quotas were met. "Village sentries," often non-local Africans armed by the Europeans, carried out much of the direct violence with impunity and were known for their extreme brutality.

The period from 1885 to 1908 was catastrophic for the Congolese people. Millions died as a direct consequence of murder, mutilation, starvation due to the disruption of agriculture, and disease. Sleeping sickness and smallpox epidemics, exacerbated by the horrific conditions and population movements, decimated communities. Some estimates suggest the population of the Congo may have been reduced by as much as half during this period, potentially amounting to 10 million deaths, though precise figures are impossible to ascertain due to a lack of accurate records.

News of the widespread atrocities gradually began to circulate internationally, largely thanks to the efforts of missionaries, journalists like E. D. Morel, and humanitarians. In 1904, the British consul at Boma, Roger Casement, was instructed by the British government to investigate. His detailed and damning Casement Report confirmed the scale of the abuses. The international outcry, fueled by figures like Morel who founded the Congo Reform Association, and authors like Mark Twain and Arthur Conan Doyle, put immense pressure on Leopold II and the Belgian government. In response, the Belgian Parliament forced Leopold II to establish an independent commission of inquiry. Its findings largely corroborated Casement's report, acknowledging the severe reduction in the Congolese population and the systemic nature of the abuses.

The mounting international pressure and the undeniable evidence of widespread human rights violations ultimately led to the dissolution of the Congo Free State. In 1908, Leopold II was forced to cede the territory to the Belgian state, which then became the Belgian Congo. This marked the end of his personal rule but transitioned the Congo into a new phase of colonial administration.

3.3. Belgian Congo (1908-1960)

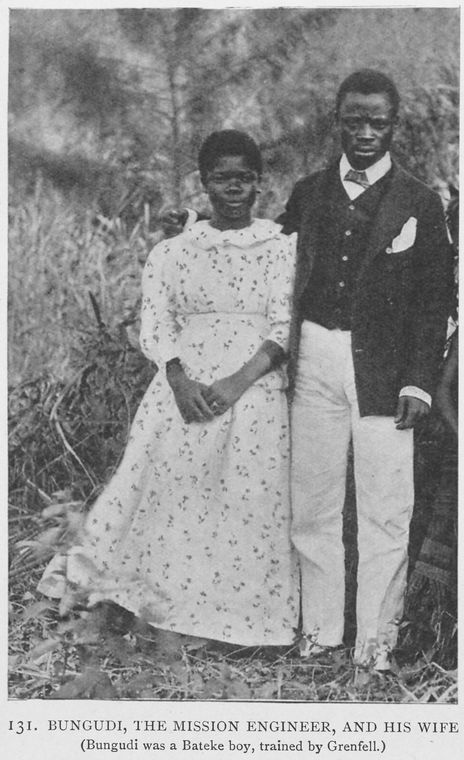

In 1908, facing intense international pressure, particularly from the United Kingdom, the Belgian parliament voted to annex the Congo Free State from King Leopold II. On October 18, 1908, the territory officially became the Belgian Congo (Congo BelgeBelgian CongoFrench). While this marked a shift from personal to state rule, there was significant continuity in administration. Baron Théophile Wahis, the last governor-general of the Congo Free State, remained in office, as did much of Leopold II's administrative staff. The primary motive for colonial expansion remained the exploitation of the Congo's vast natural and mineral resources for the benefit of the Belgian economy. However, over time, other priorities such as healthcare and basic education for the Congolese population began to gain some, albeit limited, importance. In 1923, the colonial capital was moved from Boma to Léopoldville (now Kinshasa), further inland.

Colonial administration was characterized by direct rule, with Belgian officials governing the territory. A dual legal system existed, with European courts for Europeans and tribunaux indigènes (indigenous courts) for the Congolese population. These indigenous courts had limited powers and remained under the strict control of the colonial administration. Belgian authorities permitted no political activity by the Congolese, and the Force Publique, the colonial army, was used to suppress any attempts at rebellion or dissent. Socially, a system of racial segregation was implemented, and Congolese people faced discrimination and limited opportunities for advancement.

Economically, the Belgian Congo was developed primarily for resource extraction. Mining (copper, gold, diamonds, tin, cobalt, uranium) became a cornerstone of the economy, largely controlled by powerful Belgian corporations like the Union Minière du Haut-Katanga. Plantation agriculture (rubber, palm oil, cotton, coffee) also expanded, often relying on systems of forced or low-wage labor. While infrastructure such as roads, railways, and ports were developed, these were primarily to facilitate the export of resources rather than for the benefit of the local population. Some improvements in healthcare and education were made, often through missionary efforts, but access remained limited, and the education provided was typically basic, aimed at creating a semi-skilled workforce rather than fostering indigenous leadership.

The Belgian Congo was directly involved in both World War I and World War II.

- During World War I (1914-1918), the Force Publique fought against German colonial forces in German East Africa as part of the East African campaign. Under General Charles Tombeur, they achieved a notable victory by capturing Tabora in September 1916. As a reward for its participation, Belgium received a League of Nations mandate over the former German colony of Ruanda-Urundi (present-day Rwanda and Burundi) after the war.

- During World War II (1939-1945), the Belgian Congo played a crucial role for the Allies. After Belgium was occupied by Germany, the colony provided vital resources (especially uranium, copper, and industrial diamonds) to the Belgian government-in-exile in London and the Allied war effort. The Force Publique again participated in Allied campaigns in Africa, notably in the East African campaign against the Italian colonial army in Ethiopia. Congolese troops under Belgian officers fought in battles such as Asosa, Bortaï, and the Saïo under Major-General Auguste-Eduard Gilliaert.

The post-World War II era saw the rise of nationalist sentiments across Africa, and the Congo was no exception. Congolese people, increasingly urbanized and educated (albeit to a limited extent), began to demand greater political rights and, eventually, independence. Early nationalist movements and cultural associations (évolués) emerged, challenging the colonial system. Belgian colonial policy initially resisted these demands but faced growing internal and international pressure. By the late 1950s, the movement for independence gained significant momentum, leading to political reforms and ultimately, the end of Belgian rule.

3.4. Independence and Congo Crisis (1960-1965)

The path to independence for the Belgian Congo was rapid and tumultuous, culminating in a period of profound crisis that shaped the nation's future and drew in significant international involvement, deeply impacting its democratic development and human rights.

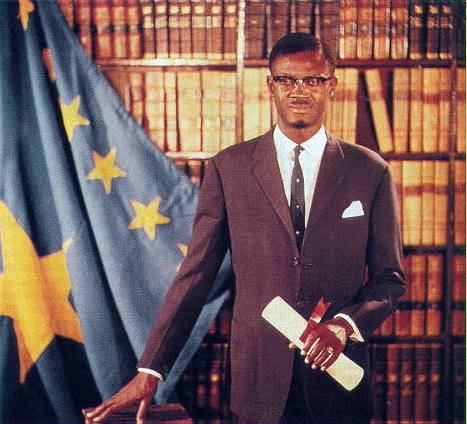

In May 1960, the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC), a growing nationalist movement led by the charismatic Patrice Lumumba, won the parliamentary elections. On June 24, 1960, Lumumba became the first Prime Minister of the newly independent nation. The parliament elected Joseph Kasa-Vubu, leader of the Alliance des Bakongo (ABAKO) party, as President. Other significant political parties included the Parti Solidaire Africain (PSA) led by Antoine Gizenga, and the Parti National du Peuple (PNP) led by Albert Delvaux and Laurent Mbariko.

The Belgian Congo achieved independence on June 30, 1960, under the name "République du Congo" (Republic of Congo). To distinguish it from the neighboring former French colony which also adopted the name Republic of the Congo (upon its independence on August 15, 1960), the former Belgian Congo became known as Congo-Léopoldville (after its capital) or later, the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Almost immediately after independence, the country plunged into the Congo Crisis (1960-1965), a complex series of conflicts characterized by:

- Army Mutiny:** The Force Publique, renamed the Armée Nationale Congolaise (ANC), mutinied against its Belgian officers just days after independence, leading to widespread disorder and the flight of many of the 100,000 Europeans who had remained.

- Secessionist Movements:** On July 11, 1960, the mineral-rich Katanga Province, led by Moïse Tshombe and backed by Belgian mining interests and mercenaries, declared independence as the State of Katanga. Shortly thereafter, the region of South Kasai, rich in diamonds and led by Albert Kalonji, also seceded. These secessions deprived the central government of crucial revenue and territory.

- Assassination of Patrice Lumumba:** Prime Minister Lumumba appealed to the United Nations for assistance to end the secessions. When UN intervention proved slow and ineffective in reunifying the country by force, Lumumba controversially sought and received military aid (supplies and advisers) from the Soviet Union. This move alarmed Western powers, particularly the United States and Belgium, during the height of the Cold War. On September 5, 1960, President Kasa-Vubu, citing Lumumba's perceived Soviet ties and alleging responsibility for massacres by the ANC in South Kasai during an attempt to quell the secession, unconstitutionally dismissed him. Lumumba contested this dismissal. On September 14, Colonel Joseph Mobutu (later Mobutu Sese Seko), the army chief of staff, launched a coup d'état backed by the US and Belgium, effectively removing Lumumba from power. Lumumba was placed under house arrest, later escaped, was recaptured, and on January 17, 1961, was handed over to Katangan authorities. He was brutally tortured and executed by Belgian-led Katangan troops. His assassination became a symbol of neo-colonial interference and martyrdom for African nationalists. A 2001 Belgian parliamentary inquiry found Belgium "morally responsible" for his murder, and the country later officially apologized.

- UN Intervention and Foreign Involvement:** The United Nations Operation in the Congo (ONUC) was deployed with a mandate to restore order and help maintain the territorial integrity of the Congo. However, its role was often hampered by Cold War politics and the conflicting interests of major powers. The UN Secretary-General, Dag Hammarskjöld, was killed in a plane crash near Ndola, Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), on September 18, 1961, while on a peace mission to negotiate a ceasefire with Tshombe. The Katangan secession was eventually crushed in January 1963 with the assistance of UN forces.

- Political Instability:** Following Lumumba's ousting and death, a series of short-lived and weak governments led by figures like Joseph Iléo, Cyrille Adoula, and eventually Moïse Tshombe (after the end of the Katanga secession) struggled to govern the fractured country.

- Rebellions:** In 1964, the Simba rebellion, a leftist, Lumumbist-inspired uprising supported by Soviet and Cuban elements, erupted in the eastern Congo. The Simbas captured significant territory and proclaimed a "People's Republic of the Congo" in Stanleyville (now Kisangani). They were eventually defeated by the central government forces, aided by Western mercenaries and a controversial US-Belgian military operation (Operation Dragon Rouge) in November 1964 to rescue hostages.

The Congo Crisis resulted in immense loss of life, widespread displacement, and severe damage to the country's nascent democratic institutions. It highlighted the devastating impact of Cold War rivalries on newly independent African nations and left a legacy of political fragility and unresolved grievances. The period culminated in a second coup by Joseph Mobutu on November 24, 1965, who, taking advantage of a leadership crisis between President Kasa-Vubu and Prime Minister Tshombe, seized power and began a long period of authoritarian rule. A constitutional referendum in 1964 had already changed the country's official name to the "Democratic Republic of the Congo."

3.5. Mobutu Sese Seko era and Zaire (1965-1997)

Following his coup d'état on November 24, 1965, General Mobutu Sese Seko consolidated power, ushering in over three decades of autocratic rule that profoundly shaped the nation's political, social, and economic landscape. His regime, while initially bringing a degree of stability after the tumultuous Congo Crisis, was characterized by severe political repression, egregious human rights violations, systemic corruption (kleptocracy), and a pervasive cult of personality.

Mobutu swiftly moved to centralize authority. He established a one-party state under his Popular Movement of the Revolution (MPR) party and declared himself Head of State. He periodically held elections in which he was the sole candidate, ensuring his continued grip on power. By late 1967, he had effectively neutralized political opponents, either by co-opting them, arresting them, or rendering them politically impotent. The death of former President Joseph Kasa-Vubu in April 1969 removed a significant figure from the First Republic era who could have challenged his rule.

A key aspect of Mobutu's rule was the policy of Authenticité (Authenticity), launched in the early 1970s. This ideology aimed to decolonize Congolese culture and promote a sense of national identity by rejecting Western influences. As part of this policy:

- On October 27, 1971, the country was renamed the Republic of Zaire (République du ZaïreRepublic of ZaireFrench).

- The Congo River was renamed the Zaire River.

- Cities were renamed: Léopoldville became Kinshasa, Stanleyville became Kisangani, Elisabethville became Lubumbashi, and Coquilhatville became Mbandaka.

- Congolese citizens were required to adopt African names, and Western-style attire (like the suit and tie, termed the "abacost") was discouraged in favor of traditional or Zairian-designed clothing. Mobutu himself adopted the name Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga.

During the Cold War, Mobutu's Zaire was a crucial Western ally in Africa due to his staunch anti-communism. The United States, in particular, provided significant financial and military support, viewing his regime as a bulwark against Soviet influence in the region. Mobutu skillfully leveraged this geopolitical position, meeting with several U.S. Presidents including Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and George H. W. Bush. Zaire also established relationships with other African states, sometimes playing a role as a regional power broker.

However, Mobutu's rule was disastrous for the country's economy and governance. He presided over a system of rampant corruption, which became so endemic that the term le mal Zaïrois ("the Zairian sickness") was coined to describe the gross mismanagement and theft of state resources. Mobutu and his associates amassed vast personal fortunes by embezzling government funds and international aid, much of which came in the form of loans that burdened the country with debt. This system of institutionalized looting is often described as a kleptocracy. While Mobutu enriched himself, the nation's infrastructure, including roads and public services, deteriorated significantly from what had existed at independence in 1960.

Human rights abuses were widespread under Mobutu. Political dissent was brutally suppressed, critics were imprisoned or exiled, and freedom of speech and assembly were severely curtailed. A pervasive security apparatus maintained tight control over the population.

With the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, Zaire's strategic importance to the West diminished, and international criticism of Mobutu's human rights record and corruption grew. Internally, demands for democratic reform intensified. In response to this pressure, Mobutu declared the "Third Republic" in 1990, ostensibly paving the way for a multi-party system and democratic reforms. However, these reforms proved largely cosmetic, and Mobutu maneuvered to retain power.

By the mid-1990s, Mobutu's regime was severely weakened by economic collapse, internal dissent, and failing health. The Rwandan genocide in 1994 and its aftermath, which saw a massive influx of Hutu refugees and militias into eastern Zaire, further destabilized the region and set the stage for Mobutu's downfall. The First Congo War (1996-1997), led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila with support from neighboring Rwanda and Uganda, ultimately forced Mobutu to flee the country in May 1997. He died in exile in Morocco in September 1997, ending his 32-year rule, which left a legacy of economic ruin, entrenched corruption, and a deeply fractured society, severely hampering social progress and democratic development.

3.6. Congo Wars (1996-2003)

The period from 1996 to 2003 was marked by two devastating conflicts, often referred to as the First and Second Congo Wars. These wars involved numerous domestic and foreign actors, led to immense human suffering, and had profound, lasting impacts on the stability and development of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Great Lakes region of Africa. The wars were characterized by widespread human rights abuses, the exploitation of natural resources to fund conflict, and a massive humanitarian crisis.

This period covers the intense conflicts of the First Congo War, which overthrew Mobutu, and the subsequent Second Congo War, often termed "Africa's World War." These sections will detail the causes, key belligerents, major events, resource exploitation, human rights abuses, the humanitarian crisis, and peace efforts.

3.6.1. First Congo War (1996-1997)

The First Congo War (October 1996 - May 1997) was triggered by a confluence of factors, primarily the spillover effects of the 1994 Rwandan genocide. Large numbers of Rwandan Hutu perpetrators of the genocide, including Interahamwe militias and former Rwandan army (ex-FAR) soldiers, fled to eastern Zaire (now DRC) and established refugee camps that also served as bases for cross-border attacks against the new Tutsi-led government in Rwanda. Mobutu Sese Seko's regime, already weakened and corrupt, supported these Hutu forces and also incited violence against Congolese ethnic Tutsis, particularly the Banyamulenge in South Kivu and other Tutsi communities in North Kivu.

In response, Rwanda and Uganda, citing security concerns and aiming to dismantle the Hutu extremist threat, provided crucial military support to an alliance of Zairian opposition groups. This coalition, known as the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (AFDL), was led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila. Angola and Burundi also supported the anti-Mobutu coalition for their own strategic reasons.

The AFDL, spearheaded by Rwandan and Ugandan troops, launched its offensive in October 1996. The Zairian Armed Forces (FAZ), demoralized and poorly equipped, offered little effective resistance. The rebel forces made rapid advances across eastern Zaire, capturing key towns and cities. As Mobutu's regime crumbled, he fled Kinshasa in May 1997. On May 17, 1997, Kabila's forces entered the capital, and he declared himself president, renaming the country the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The immediate aftermath of the First Congo War included significant humanitarian consequences. While it brought an end to Mobutu's long and repressive rule, the war itself involved atrocities and mass killings, particularly targeting Hutu refugees, some of whom were implicated in the Rwandan genocide while many others were civilians. The war further destabilized the region, setting the stage for new conflicts as alliances shifted and unresolved issues resurfaced. The extensive involvement of neighboring countries underscored the regional dimensions of Zaire/DRC's internal problems.

3.6.2. Second Congo War (1998-2003)

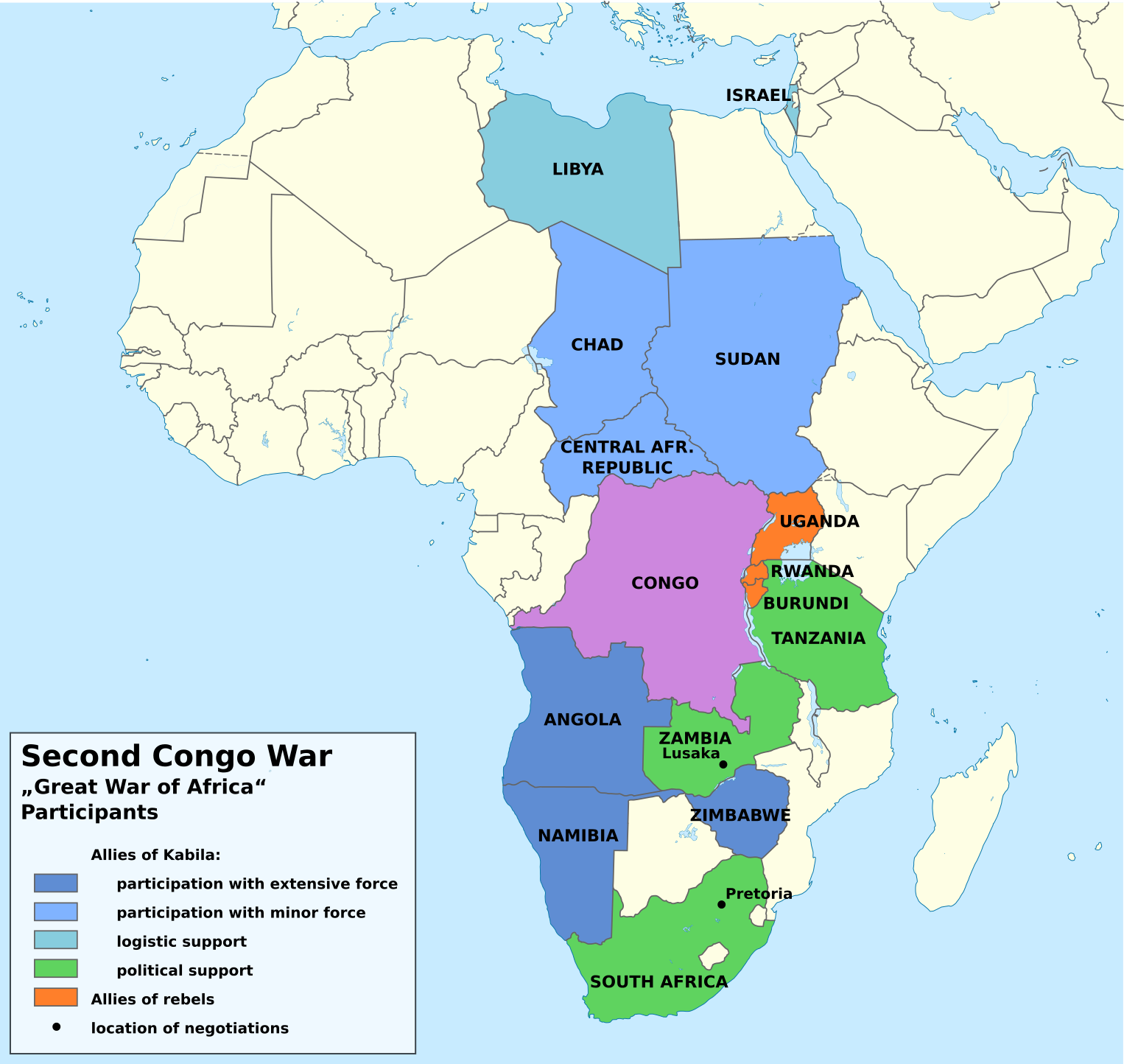

The Second Congo War, also known as the Great War of Africa, erupted in August 1998, little more than a year after Laurent-Désiré Kabila came to power. It was a far more complex and devastating conflict than the first, involving at least nine African nations and around twenty-five armed groups.

The origins of the war were rooted in Kabila's decision in July 1998 to expel his Rwandan and Ugandan military allies, who had been instrumental in his rise to power. This move was driven by Kabila's desire to assert Congolese sovereignty and fears of Rwandan and Ugandan influence, particularly over eastern DRC's rich mineral resources. Rwanda and Uganda, in turn, accused Kabila of failing to address the threat posed by Hutu extremist groups still operating from Congolese territory and of marginalizing Congolese Tutsis.

In August 1998, Rwandan and Ugandan forces, along with Congolese rebel groups they supported, launched a new offensive against Kabila's government. The main rebel group backed by Rwanda was the Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD), while Uganda supported the Movement for the Liberation of the Congo (MLC), led by Jean-Pierre Bemba. Kabila's government received military support from Angola, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Chad, and Sudan, each with its own strategic and economic interests in the DRC.

The war quickly escalated, engulfing vast swathes of the country. Key military campaigns and battles were fought across multiple fronts. The conflict was characterized by:

- Massive Human Rights Abuses:** All parties to the conflict committed widespread atrocities against civilians, including mass killings, torture, and mutilation. Rape and other forms of sexual violence were systematically used as weapons of war, causing immense physical and psychological trauma.

- Exploitation of Natural Resources:** The war was heavily fueled by the illegal exploitation of the DRC's vast mineral wealth (diamonds, gold, coltan, cobalt, copper, etc.) by all belligerents, both foreign armies and Congolese armed groups. This "conflict minerals" trade provided funding for military operations and enriched individuals and corporations involved.

- Humanitarian Crisis:** The conflict led to one of the deadliest humanitarian crises since World War II. An estimated 5.4 million people died between 1998 and 2003, primarily from war-related disease, starvation, and displacement, rather than direct combat. Millions more were internally displaced or became refugees in neighboring countries.

- Child Soldiers:** The recruitment and use of child soldiers was rampant among many armed groups.

Peace efforts were protracted and complex. The Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement, signed in July 1999 by the DRC, Angola, Namibia, Rwanda, Uganda, Zimbabwe, and key rebel groups (MLC and RCD), aimed to establish a ceasefire, deploy UN peacekeepers (MONUC, later MONUSCO), and initiate a national dialogue. However, implementation was fraught with difficulties, and fighting continued.

President Laurent-Désiré Kabila was assassinated by one of his bodyguards on January 16, 2001. His son, Joseph Kabila, succeeded him. Joseph Kabila proved more amenable to peace negotiations. Renewed diplomatic efforts, particularly under South African mediation, led to a series of agreements, including the Pretoria Agreement (2002) between DRC and Rwanda, and the Luanda Agreement (2002) between DRC and Uganda, which outlined troop withdrawals. The Inter-Congolese Dialogue brought together the government, rebel groups, political opposition, and civil society, culminating in the Global and All-Inclusive Agreement signed in Pretoria in December 2002. This agreement paved the way for a transitional government and aimed to reunify the country and lead to democratic elections.

Although the war officially ended in 2003 with the establishment of the transitional government, violence and instability persisted, particularly in the eastern provinces, where numerous armed groups continued to operate, fueled by ethnic tensions and the illicit trade in natural resources. The Second Congo War left a legacy of immense suffering, a shattered economy, and a deeply traumatized society, posing long-term challenges for peacebuilding, state reconstruction, and accountability for human rights violations.

3.7. Transitional government and Joseph Kabila presidency (2003-2019)

Following the official end of the Second Congo War, the Democratic Republic of the Congo entered a period of transition aimed at peace consolidation, state rebuilding, and the establishment of democratic institutions. This era was largely dominated by the presidency of Joseph Kabila.

The **Transitional Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo** was established in July 2003, based on the Global and All-Inclusive Agreement. Joseph Kabila remained as President, sharing power with four vice-presidents representing former belligerent factions and the political opposition. The transitional government's main tasks were to reunify the country, disarm militias, draft a new constitution, and organize democratic elections. The United Nations Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUC), later renamed MONUSCO, played a significant role in supporting these efforts, including peacekeeping and election logistics. A new constitution was approved by referendum in December 2005.

In July 2006, the DRC held its first multi-party democratic elections in over four decades. Joseph Kabila won the presidential election in a second-round run-off against former rebel leader Jean-Pierre Bemba. His inauguration in December 2006 marked the formal end of the transitional period. Kabila was re-elected in November 2011 in elections marred by allegations of irregularities and violence.

Despite the formal peace process and elections, Joseph Kabila's presidency (2006-2019) was characterized by:

- Ongoing Violence in Eastern DRC:** The eastern provinces of North Kivu, South Kivu, and Ituri remained highly unstable. Numerous local and foreign armed groups, including remnants of Rwandan Hutu militias (FDLR), various Mai-Mai militias, and new rebel movements, continued to operate. These conflicts were fueled by competition for land and resources, ethnic tensions, and weak state authority.

- The Kivu conflict saw several major flare-ups, including the rebellion led by Laurent Nkunda and his National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP) from 2006 to 2009.

- The M23 rebellion (2012-2013), largely composed of former CNDP soldiers, briefly captured Goma, the capital of North Kivu, highlighting ongoing regional interference, particularly from Rwanda, which was accused of supporting the rebels.

- The Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), originating from Uganda, also terrorized populations in northeastern DRC.

- Role of UN Peacekeeping:** MONUC/MONUSCO, one of the largest and most expensive UN peacekeeping missions, worked to protect civilians and support government efforts to stabilize the east. In 2013, a UN Force Intervention Brigade with a more offensive mandate was deployed to neutralize armed groups, contributing to the defeat of M23.

- Political Tensions and Electoral Processes:** Kabila's rule faced increasing political opposition. His second term was constitutionally mandated to end in December 2016, but elections were repeatedly delayed, leading to widespread protests and accusations that he sought to cling to power. This period was marked by crackdowns on dissent, restrictions on freedom of speech and assembly, and arrests of opposition figures and activists.

- Human Rights Concerns:** Human rights abuses remained a serious concern throughout Kabila's presidency. These included extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, torture, arbitrary arrests, and continued widespread sexual violence in conflict zones. Impunity for perpetrators was a major problem.

- State Rebuilding Efforts:** Efforts to rebuild state institutions, reform the security sector (army and police), and improve governance were slow and often undermined by corruption and lack of political will. The economy remained heavily reliant on mining, and issues of resource governance and transparency persisted.

The general election was finally held on December 30, 2018, to choose Kabila's successor. The election was highly contentious, with widespread allegations of irregularities and fraud. Opposition candidate Félix Tshisekedi was declared the winner, leading to the country's first (nominally) peaceful transfer of power since independence, though the Catholic Church's election observers stated their data showed a different winner. Joseph Kabila stepped down in January 2019, but his political coalition maintained significant influence in parliament, setting the stage for a complex power-sharing dynamic in the subsequent administration.

3.8. Félix Tshisekedi presidency (2019-present)

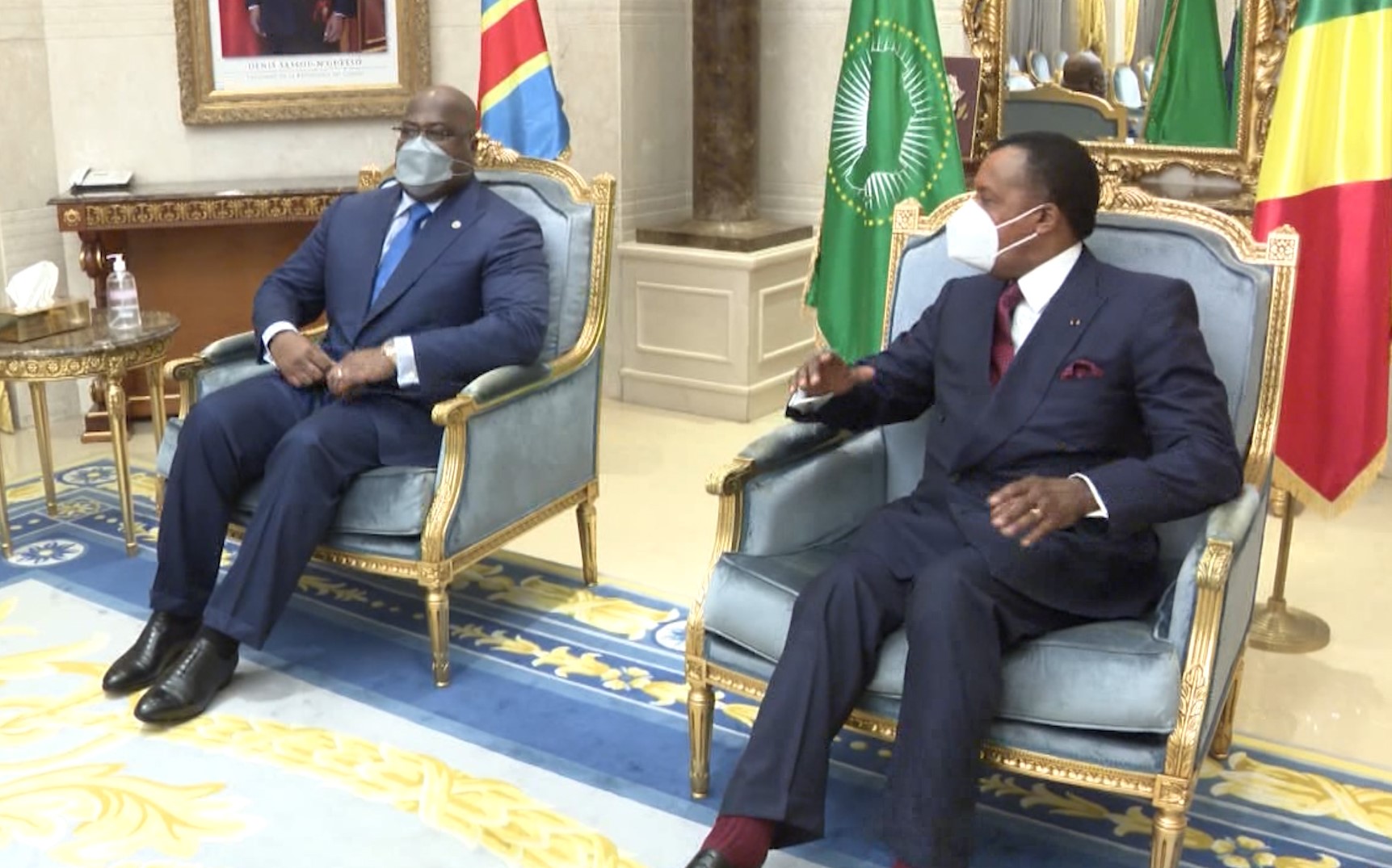

Félix Tshisekedi was declared the winner of the highly contentious December 2018 general election and was inaugurated as President on January 24, 2019. This marked the DRC's first nominally peaceful transfer of power since independence, although the election results were disputed by other opposition candidates and the influential Catholic Church, which reported that its own tally indicated a different winner.

Tshisekedi's early presidency was characterized by a delicate power-sharing arrangement with his predecessor, Joseph Kabila, whose "Common Front for Congo" (FCC) coalition held a strong majority in parliament and controlled key ministries. This led to political gridlock and limited Tshisekedi's ability to implement his agenda. However, by late 2020 and early 2021, Tshisekedi successfully maneuvered to break from Kabila's influence, forming a new parliamentary majority called the "Sacred Union of the Nation" and appointing his own government.

Key developments and challenges during Tshisekedi's presidency include:

- Persistent Security Challenges in Eastern DRC:** Despite initial hopes for peace, violence has continued and, in some areas, escalated in the eastern provinces of North Kivu, South Kivu, and Ituri.

- The Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), an Islamist extremist group with links to the Islamic State, has intensified its attacks on civilians, leading to numerous massacres.

- The M23 rebellion resurfaced in late 2021 and significantly escalated in 2022-2025, capturing territory in North Kivu and displacing hundreds of thousands. The DRC government, along with UN experts, has accused Rwanda of actively supporting M23, leading to a severe deterioration in relations between DRC and Rwanda, including border clashes and the DRC severing diplomatic ties in January 2025 after M23 rebels launched the Goma offensive. The offensive resulted in nearly 3,000 deaths and horrific atrocities, including reports of hundreds of female inmates being raped and burned alive during a mass jailbreak from Goma's prison. President Tshisekedi called for a national mobilization against what he termed "Rwanda's barbaric aggression."

- Numerous other Mai-Mai militias and armed groups continue to operate, exploiting local grievances and resources.

- Evolving Regional Dynamics:** Tensions with Rwanda have become a major focus. Uganda has also been involved in joint military operations with the FARDC against the ADF in eastern DRC. The DRC officially joined the East African Community (EAC) in 2022, a move aimed at fostering regional economic integration and cooperation on security, though regional military deployments have had mixed results.

- Political Developments:** Tshisekedi has focused on consolidating his political power. After the 2023 presidential election, he was declared re-elected with a large majority, though opposition candidates again alleged irregularities and called for a rerun. In May 2024, an attempted coup led by Christian Malanga, a US-based Congolese politician, was quickly repelled by security forces in Kinshasa.

- Human Rights and Governance:** Tshisekedi's administration has made some commitments to improving human rights and fighting corruption. Some political prisoners were released, and space for civil society and media saw some initial improvement. However, significant human rights violations by security forces and armed groups persist, particularly in conflict zones. Impunity remains a major challenge. Efforts to combat corruption have yielded limited results, though some high-profile figures have faced investigation.

- Social Welfare and Economic Issues:** The DRC continues to face immense socio-economic challenges, including high poverty rates, inadequate infrastructure, and limited access to basic services like healthcare and education. The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent global economic pressures further strained the economy. Tshisekedi has called for a review of mining contracts signed under previous administrations, particularly with Chinese companies, to ensure greater benefits for the Congolese people.

- Health Crises:** Beyond COVID-19, the DRC has faced outbreaks of Ebola (including the end of the 2018-2020 Kivu Ebola epidemic and smaller subsequent outbreaks) and a major measles outbreak in 2019.

- International Relations:** The DRC has sought to re-engage with international partners. The killing of the Italian ambassador, Luca Attanasio, in North Kivu in February 2021 highlighted the ongoing security risks. Tshisekedi's government has also engaged in diplomatic efforts with countries like Kenya to bolster trade and security cooperation.

The impact of Tshisekedi's policies on long-term democratic processes, sustainable peace, human rights, social welfare, and accountability for past and present abuses remains a critical area of observation and concern for both the Congolese people and the international community.

4. Geography

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is located in Central sub-Saharan Africa. It straddles the Equator, with approximately one-third of its territory to the north and two-thirds to the south. With a total area of 0.9 M mile2 (2.35 M km2), it is the second-largest country in Africa (after Algeria) and the 11th-largest in the world.

The country is bordered by nine nations:

- To the northwest: the Republic of the Congo

- To the north: the Central African Republic

- To the northeast: South Sudan

- To the east: Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and Tanzania (the border with Tanzania is across Lake Tanganyika)

- To the south and southeast: Zambia

- To the southwest: Angola (including a border with the Cabinda exclave of Angola)

- To the west: The DRC has a very short coastline on the South Atlantic Ocean, approximately 23 mile (37 km) wide, along the north bank of the Congo River estuary.

The DRC's topography is diverse. The vast, low-lying central area is the Congo Basin, the world's second-largest river basin, covered by dense Congolian rainforests. This basin slopes westward towards the Atlantic Ocean. The basin is surrounded by:

- Plateaus merging into savannas in the south and southwest.

- Mountainous terraces in the west.

- Dense grasslands extending beyond the Congo River in the north.

- The Albertine Rift mountains in the extreme eastern region, which is part of the East African Rift. This region includes high mountain ranges such as the Rwenzori Mountains (with glaciated peaks like Mount Stanley) and volcanic mountains like Mount Nyiragongo and Nyamuragira.

The Congo River is the dominant geographical feature. It is the world's deepest river and the second-largest by discharge (after the Amazon). Its sources are in the Albertine Rift mountains and lakes such as Lake Tanganyika and Lake Mweru. The river flows generally west from Kisangani, then bends southwest, passing Mbandaka, joining the Ubangi River, and running into Pool Malebo (Stanley Pool), where the capital Kinshasa and Brazzaville (capital of the Republic of the Congo) are located on opposite banks. Downstream from Pool Malebo, the river narrows and drops through a series of cataracts known as the Livingstone Falls before flowing past Boma into the Atlantic. Major tributaries include the Kasai, Sangha, Ubangi, Ruzizi, Aruwimi, and Lulonga. These rivers form an extensive network of navigable waterways, crucial for transportation and commerce.

The African Great Lakes form part of the DRC's eastern frontier: Lake Albert, Lake Edward, Lake Kivu, and Lake Tanganyika. The Albertine Rift region is geologically active, leading to volcanism and earthquakes. It is also exceptionally rich in mineral wealth, including cobalt, copper, diamonds, gold, tin, and coltan, particularly in the southeastern Katanga region.

On January 17, 2002, Mount Nyiragongo erupted, with lava flows reaching the city of Goma, causing significant destruction, loss of life, and displacing over 120,000 people. The lava also impacted Lake Kivu.

4.1. Climate

The Democratic Republic of the Congo has a predominantly tropical equatorial climate due to its location straddling the Equator. This results in high temperatures and humidity throughout much of the year.

- Equatorial Zone:** The vast central Congo Basin experiences a hot and humid equatorial climate with significant rainfall year-round. Average temperatures range from 68 °F (20 °C) to 80.6 °F (27 °C), and annual rainfall can exceed 0.1 K in (2.00 K mm) in some areas. This zone has the highest frequency of thunderstorms in the world. There are typically two rainy seasons and two relatively drier seasons, though rainfall occurs in all months.

- Tropical Zones (North and South of Equator):** Areas north and south of the equatorial belt experience a tropical climate with distinct wet and dry seasons.

- North of the Equator: The rainy season generally lasts from April to October, and the dry season from December to February.

- South of the Equator: The rainy season is typically from November to March, and the dry season from April to October.

- Highland/Mountain Zones:** The eastern highlands and mountainous regions (Albertine Rift, Rwenzori Mountains) have a more temperate or mountain climate, with cooler temperatures due to altitude. Higher elevations, like the Rwenzori Mountains, can experience frost and snow. Rainfall in these areas is also generally high.

- Coastal Strip:** The small Atlantic coastal region has a maritime-influenced tropical climate.

Overall, the DRC experiences high precipitation, sustaining the vast Congo rainforest. Regional variations exist primarily based on latitude and altitude.

4.2. Climate change

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, which exacerbate existing environmental and socio-economic challenges. Specific manifestations and impacts include:

- Temperature Rise:** Average temperatures are projected to increase, potentially leading to more frequent and intense heatwaves, affecting human health, agriculture, and ecosystems.

- Changes in Precipitation Patterns:** While overall rainfall is high, climate change is expected to alter rainfall patterns, leading to increased variability. Some regions may experience more intense rainfall and flooding, while others could face prolonged droughts. This variability impacts agriculture, water availability, and can trigger landslides.

- Extreme Weather Events:** The frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, such as heavy storms and floods, are likely to increase, causing damage to infrastructure, displacement of populations, and loss of livelihoods.

- Impacts on Ecosystems:** The Congo Rainforest, a critical global carbon sink and biodiversity hotspot, is under threat. Changes in temperature and rainfall can alter forest composition and health. Deforestation, driven by agriculture, logging, and fuel wood collection, is exacerbated by climate pressures.

- Agricultural Impacts:** Agriculture, a mainstay for a large portion of the population, is highly sensitive to climate change. Altered seasons, droughts, and floods can reduce crop yields, threatening food security and increasing poverty, particularly for smallholder farmers.

- Water Resources:** Changes in rainfall and increased evaporation can affect water availability for drinking, sanitation, agriculture, and hydropower generation (a key energy source).

- Health Impacts:** Climate change can worsen health outcomes by increasing the incidence of vector-borne diseases (like malaria, due to changing mosquito habitats), waterborne diseases (due to flooding and contamination), and heat stress.

- Vulnerable Communities:** Rural populations, indigenous communities (like the Pygmies), women, and children are often the most vulnerable to climate change impacts due to their reliance on natural resources and limited adaptive capacity. Conflict-affected populations in eastern DRC are also particularly exposed.

- National Adaptation and Mitigation Efforts:**

The DRC has developed national strategies and action plans to address climate change, such as its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) under the Paris Agreement. These plans focus on:

- Adaptation:** Measures include promoting climate-resilient agriculture, sustainable forest management, improving water resource management, disaster risk reduction, and enhancing early warning systems.

- Mitigation:** Efforts primarily center on reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+), promoting renewable energy (especially hydropower), and improving energy efficiency.

- International Cooperation:**

The DRC relies heavily on international support (financial and technical) to implement its climate change agenda. It participates in various international climate initiatives and partnerships. Challenges include limited institutional capacity, financial constraints, political instability, and the need to integrate climate action with broader development and poverty reduction goals. The protection of the Congo Basin rainforest is a key area of international concern and cooperation due to its global importance for climate regulation and biodiversity.

4.3. Biodiversity and conservation

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is one of the world's 17 megadiverse countries and is considered the most biodiverse country in Africa. Its vast territory, particularly the immense Congolian rainforests (the world's second-largest tropical rainforest after the Amazon), harbors an extraordinary array of flora and fauna.

- Rich Biodiversity:**

- Endemic and Notable Species:** The DRC is home to numerous rare and endemic species. Iconic wildlife includes:

- Primates:** Common chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes), bonobo (Pan paniscus, also known as the pygmy chimpanzee, found only in the DRC south of the Congo River), eastern gorilla (Gorilla beringei, including the mountain gorilla subspecies Gorilla beringei beringei and the eastern lowland gorilla or Grauer's gorilla subspecies Gorilla beringei graueri), and possibly a population of the western gorilla (Gorilla gorilla).

- Mammals:** Okapi (a forest giraffe relative endemic to the Ituri Forest), African forest elephant, forest buffalo, leopard, and, in the southern savannas, historically the southern white rhinoceros.

- Other Wildlife:** The country boasts a rich diversity of birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish (especially in the Congo River system), and insects.

- Protected Areas:**

The DRC has a network of protected areas designed to conserve its biodiversity, managed by the Institut Congolais pour la Conservation de la Nature (ICCN). Five of these are UNESCO World Heritage Sites:

- Garamba National Park

- Kahuzi-Biéga National Park

- Salonga National Park (Africa's largest tropical rainforest reserve)

- Virunga National Park (Africa's oldest national park, home to mountain gorillas and active volcanoes)

- Okapi Wildlife Reserve

- Conservation Challenges:**

Despite its biological richness, the DRC's biodiversity faces severe threats:

- Deforestation:** Large-scale deforestation occurs due to slash-and-burn agriculture, logging (both legal and illegal), fuelwood collection, charcoal production, and infrastructure development. The rate of deforestation has increased in recent years.

- Poaching:** Poaching for bushmeat, ivory (elephants), and traditional medicine (e.g., gorilla parts) poses a major threat to many species, including endangered ones. Organized crime syndicates are often involved in international wildlife trafficking.

- Habitat Loss and Degradation:** Expansion of agriculture, mining activities (often unregulated artisanal mining for minerals like coltan, gold, and diamonds), and human settlement encroachment into protected areas lead to significant habitat loss and fragmentation.

- Impact of Conflict:** Decades of armed conflict, particularly in the eastern DRC, have had devastating consequences for conservation. Conflicts lead to displacement of people into protected areas, increased poaching by armed groups and desperate populations, illegal resource extraction to fund militias, and insecurity that hampers conservation efforts and endangers park rangers.

- Weak Governance and Law Enforcement:** Limited resources, corruption, and inadequate law enforcement capacity hinder effective protection of national parks and wildlife reserves.

- Poverty and Lack of Alternatives:** High levels of poverty often drive local communities to rely on unsustainable exploitation of natural resources for their livelihoods.

Conservation efforts involve the ICCN, international NGOs, local communities, and international donors. These efforts focus on anti-poaching patrols, habitat restoration, community-based conservation initiatives, promoting sustainable livelihoods, and strengthening governance. However, the scale of the challenges, compounded by political instability and conflict, makes conservation in the DRC exceptionally difficult and critical for global biodiversity.

- Endemic and Notable Species:** The DRC is home to numerous rare and endemic species. Iconic wildlife includes:

5. Government and politics

This section outlines the DRC's semi-presidential republic system, the functions of its executive, legislative, and judicial branches, major political parties, the electoral process, and challenges to democratic governance.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo operates under a semi-presidential framework as defined by the constitution adopted in 2006 and revised in 2011. The political system is characterized by a separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches.

- Executive Branch:**

- President:** The President is the head of state, elected by universal suffrage for a five-year term, renewable once. The President is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, promulgates laws, appoints and dismisses the Prime Minister, and has significant powers in foreign policy and defense. Félix Tshisekedi is the current president.

- Prime Minister and Government:** The Prime Minister is the head of government, appointed by the President from the political party or coalition that holds the majority in the National Assembly. The Prime Minister, along with the Council of Ministers (Cabinet), is responsible for implementing laws and managing the day-to-day affairs of the state. The government is responsible to the National Assembly.

- Legislative Branch:**

The Parliament is bicameral, consisting of:

- National Assembly:** The lower house, composed of 500 members directly elected by universal suffrage for five-year terms through a system of proportional representation. The National Assembly legislates, controls the government, and approves the budget.

- Senate:** The upper house, composed of 108 members indirectly elected by the Provincial Assemblies, plus former presidents who are senators for life (though this provision has been contentious). Senators serve five-year terms. The Senate also legislates and has oversight functions.

- Judicial Branch:**

The judiciary is nominally independent. The 2006 constitution restructured the judicial system, which includes:

- Constitutional Court:** Rules on the constitutionality of laws and treaties, and adjudicates electoral disputes.

- Court of Cassation:** The highest court for civil and criminal matters.

- Council of State:** The highest court for administrative matters.

- High Military Court:** The highest court for military justice.

There are also lower courts, including courts of appeal, tribunals, and customary courts. The judiciary faces challenges related to underfunding, corruption, political interference, and a lack of capacity, which undermine the rule of law and access to justice.

- Political Parties and Electoral Process:**

The DRC has a multi-party system, though political parties are often based on regional or ethnic affiliations or centered around prominent individuals rather than distinct ideologies. Major political parties and coalitions have included the People's Party for Reconstruction and Democracy (PPRD) of former President Joseph Kabila, the Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDPS) of President Félix Tshisekedi, and various opposition groupings.

Elections (presidential, legislative, provincial, and local) are managed by the Independent National Electoral Commission (CENI). Electoral processes have often been marred by controversy, logistical challenges, allegations of irregularities, and violence, posing significant challenges to democratic consolidation.- Challenges to Democratic Governance:**

Democratic governance in the DRC faces numerous obstacles:

- Political Instability and Conflict:** Ongoing armed conflicts, particularly in the east, undermine state authority and democratic processes.

- Corruption:** Pervasive corruption weakens state institutions, diverts public resources, and erodes public trust.

- Weak Institutions:** State institutions, including the judiciary, security sector, and civil service, often lack capacity, resources, and independence.

- Human Rights:** Persistent human rights violations, including restrictions on fundamental freedoms, challenge democratic principles.

- Ethnic and Regional Tensions:** Political competition often exacerbates ethnic and regional divisions.

- Resource Governance:** The management of the DRC's vast natural resources is a critical governance challenge, often linked to conflict and corruption.

Despite these challenges, there is a vibrant civil society and a persistent popular demand for democracy, accountability, and improved governance.

5.1. Administrative divisions

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is divided into the city-province of Kinshasa and 25 other provinces. This administrative structure was implemented in 2015, replacing the previous 11 provinces, as mandated by the 2006 constitution. Each province is headed by a governor and has a provincial assembly. The provinces are further subdivided into 145 territories and 33 cities.

The 26 current provinces are:# Province Capital Former Province (pre-2015) 1 Bas-Uele Buta Orientale 2 Équateur Mbandaka Équateur 3 Haut-Katanga Lubumbashi Katanga 4 Haut-Lomami Kamina Katanga 5 Haut-Uele Isiro Orientale 6 Ituri Bunia Orientale 7 Kasaï Luebo (interim), Tshikapa (proposed) Kasaï-Occidental 8 Kasaï-Central Kananga Kasaï-Occidental 9 Kasaï-Oriental Mbuji-Mayi Kasaï-Oriental 10 Kinshasa Kinshasa (City-Province) Kinshasa 11 Kongo Central Matadi Bas-Congo 12 Kwango Kenge Bandundu 13 Kwilu Kikwit Bandundu 14 Lomami Kabinda Kasaï-Oriental 15 Lualaba Kolwezi Katanga 16 Mai-Ndombe Inongo Bandundu 17 Maniema Kindu Maniema 18 Mongala Lisala Équateur 19 North Kivu Goma North Kivu 20 Nord-Ubangi Gbadolite Équateur 21 Sankuru Lusambo Kasaï-Oriental 22 South Kivu Bukavu South Kivu 23 Sud-Ubangi Gemena Équateur 24 Tanganyika Kalemie Katanga 25 Tshopo Kisangani Orientale 26 Tshuapa Boende Équateur

The rationale behind the 2015 administrative reform (découpage) was to decentralize power, bring administration closer to the people, and promote more equitable development. However, the implementation has faced challenges, including a lack of resources for the new provincial administrations and, in some cases, the exacerbation of local political or ethnic tensions. The demographic characteristics of these provinces vary widely in terms of population size, density, ethnic composition, and economic activities.5.2. Foreign relations

Former President Joseph Kabila with then U.S. President Barack Obama in August 2014. The DRC's foreign relations are complex, involving engagement with global powers and neighboring African states, often influenced by its resource wealth and internal conflicts. The foreign relations of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) are complex and multifaceted, shaped by its colonial history, vast natural resources, strategic location in Central Africa, and persistent internal conflicts that often have regional dimensions. The country's foreign policy aims to promote national interests, regional stability, and economic development, though these goals are frequently challenged by domestic instability and external pressures.

- Relations with Neighboring African Countries:**

- Rwanda and Uganda:** Relations with Rwanda and Uganda have been historically fraught and central to the DRC's security challenges. Both countries played significant roles in the First and Second Congo Wars, initially supporting Laurent-Désiré Kabila's overthrow of Mobutu, and later backing rebel groups operating in eastern DRC. The DRC has repeatedly accused Rwanda and Uganda of meddling in its internal affairs, supporting proxy militias (like M23 by Rwanda), and exploiting its mineral resources. These accusations have led to severe diplomatic tensions, border clashes, and at times, severed ties (e.g., with Rwanda in 2025). Conversely, Rwanda and Uganda have cited security concerns related to armed groups operating from Congolese territory (like the FDLR and ADF, respectively). Efforts at dialogue and regional peace initiatives (e.g., through the ICGLR, SADC, EAC) have had mixed success.

- Angola:** Angola has been a key ally, providing military support to the DRC government during the Congo Wars and in subsequent periods of instability. Relations are generally cooperative, though issues related to border security and migration sometimes arise.

- Republic of the Congo:** Relations are generally peaceful, though sometimes strained by political differences or refugee flows. The Congo River forms a major part of their shared border, with Kinshasa and Brazzaville being the world's closest capital cities.

- Burundi, Tanzania, Zambia, South Sudan, Central African Republic:** The DRC shares long borders with these countries, leading to concerns about cross-border insecurity, refugee movements, and illicit trade. Cooperation on these issues is often sought through regional bodies.

- Relations with Major Global Powers:**

- United States:** The U.S. was a key supporter of Mobutu Sese Seko during the Cold War. Post-Mobutu, U.S. policy has focused on promoting democracy, human rights, stability, and humanitarian aid. The U.S. has also been involved in efforts to professionalize the Congolese armed forces (FARDC) and has expressed concerns about resource governance and corruption. The DRC's cobalt reserves, critical for electric vehicle batteries, have increased its strategic importance.

- China:** China's engagement with the DRC has grown significantly, particularly in the economic sphere. Chinese companies are heavily involved in mining and infrastructure projects, often through large-scale resource-for-infrastructure deals (e.g., the Sicomines deal). While this investment has contributed to some infrastructure development, concerns have been raised about transparency, labor conditions, environmental impact, and the terms of these deals, leading to calls for review by recent DRC administrations.

- France and Belgium:** As former colonial powers (Belgium directly, France regionally influential), both countries maintain significant diplomatic, cultural, and economic ties with the DRC. They often play a role in international discussions regarding the DRC's political situation, human rights, and development.

- Other European Nations and the European Union:** The EU is a major aid donor and has been involved in supporting electoral processes, security sector reform, and humanitarian efforts.

- Role in International and Regional Organizations:**

The DRC is a member of numerous international and regional organizations, including:

- United Nations (UN): The UN has a large and long-standing peacekeeping mission in the DRC (MONUC/MONUSCO).

- African Union (AU): Participates in AU peace and security initiatives and political processes.

- Southern African Development Community (SADC): A member since 1997, SADC has provided political and, at times, military support to the DRC.

- Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS).

- East African Community (EAC): Joined in 2022, aiming for greater economic integration and regional security cooperation.

- Organisation internationale de la Francophonie.

- Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA).

- Key Foreign Policy Considerations:**

- Domestic Stability and Security:** The primary driver of DRC's foreign policy is often the need to address internal conflicts and secure its borders, which frequently involves engaging with neighboring states.

- Resource Management:** The control and exploitation of its vast natural resources heavily influence its foreign relations, attracting investment but also creating vulnerabilities to external exploitation and interference.

- Human Rights and Governance:** International scrutiny of the DRC's human rights record and governance practices impacts its relationships with Western donors and international organizations.

- Regional Security Complex:** The DRC is central to the Great Lakes security complex, where internal conflicts in one country often spill over and affect neighbors, necessitating regional diplomatic and security cooperation.

The DRC's foreign relations are dynamic, reflecting its ongoing efforts to achieve stability, assert its sovereignty, and harness its potential for development amidst complex internal and regional challenges. The perspective taken often reflects a need to balance national sovereignty with the necessity of international cooperation to address its deep-seated problems, while being wary of foreign exploitation that has marked much of its history.

5.3. Military

Congolese soldiers of the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (FARDC) being trained by UN personnel. Military reform and professionalization are ongoing challenges for the DRC. The Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du CongoArmed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the CongoFrench, FARDC) are the state military organization responsible for defending the DRC. The FARDC was established in 2003 after the end of the Second Congo War, through a process that aimed to integrate various former rebel groups and militias along with remnants of the previous Zairian armed forces into a unified national army.

- Branches and Structure:**

The FARDC nominally consists of:

- Land Forces (Army):** The largest component, responsible for ground operations. It is organized into defense zones (Western, South-Central, Eastern) which are further divided into military regions, and comprises brigades and regiments.

- Air Force (Force Aérienne Congolaise):** Operates a limited number of aircraft, primarily for transport and reconnaissance, though its operational capacity is severely constrained by aging equipment and lack of maintenance.

- Navy (Marine Nationale):** A small force primarily responsible for patrolling the Congo River, its tributaries, and the country's short Atlantic coastline.

- Republican Guard:** A separate, better-equipped, and often better-trained force primarily responsible for presidential security and strategic installations. It nominally operates outside the direct FARDC command structure, reporting to the President.

- Strength and Equipment:**

Estimates of the FARDC's total active personnel vary, but in 2023, it was estimated to have around 134,250 personnel (Land Forces: 103,000; Navy: 6,700; Air Force: 2,550; Central Command: 14,000; Republican Guard: 8,000). Much of its equipment is Soviet-era or aging Western hardware, often in poor condition due to lack of maintenance and spare parts. Many units are reported to be at significantly less than their official strength due to combat losses, desertions, and "ghost soldier" payroll issues.

- Roles and Challenges:**

The FARDC's primary roles include:

- Defending national sovereignty and territorial integrity.

- Conducting counter-insurgency operations against numerous armed groups, particularly in eastern DRC (Kivu and Ituri provinces) and the Kasai region. These groups include local Mai-Mai militias, foreign-backed rebels like M23, and extremist groups like the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF).

- Participating in internal security operations, sometimes alongside the national police.

- Contributing to international peacekeeping efforts, though this is limited.

The FARDC faces enormous challenges:

- Reform and Professionalism:** Decades of conflict, political interference, and the difficult integration of former adversaries have hindered efforts to build a professional, disciplined, and effective national army. Low pay, poor living conditions, and inadequate training contribute to low morale and discipline issues.

- Civilian Oversight:** Establishing effective civilian oversight and accountability for the military remains a significant governance challenge.

- Human Rights Conduct:** FARDC units have frequently been implicated in serious human rights abuses against civilians, including unlawful killings, rape, looting, and forced recruitment, often with impunity.

- Corruption:** Corruption within the military is rampant, affecting procurement, payroll, and resource allocation, further weakening its operational capabilities.

- Logistics and Equipment:** Lack of vehicles, aircraft, and adequate equipment severely hampers mobility and operational effectiveness across the DRC's vast territory.

- Cohesion:** The integration of former rebel groups with differing loyalties has often led to a lack of cohesion and, at times, defections or collaboration with armed opponents.

President Félix Tshisekedi announced military reforms in 2022, including changes in high command and increased military spending, aimed at creating a more cohesive and effective force. International partners, including the UN (MONUSCO), have been involved in training and capacity-building efforts, but progress has been slow and difficult.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is a signatory to the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.5.4. Law enforcement and crime

Law enforcement in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is primarily the responsibility of the **Congolese National Police** (Police Nationale CongolaiseCongolese National PoliceFrench, PNC). The PNC operates under the Ministry of Interior and Security and is tasked with maintaining public order, preventing and detecting crime, and enforcing laws throughout the country.

- Structure and Functions of the PNC:**

The PNC is theoretically a unified national force, but its effectiveness and presence vary significantly across the vast territory of the DRC. It includes various specialized units, such as those for criminal investigation, public order maintenance, and border protection. However, the police force, much like the military, suffers from systemic issues that undermine its ability to function effectively and protect the population.

- Common Types of Crime:**

The DRC experiences high levels of crime, exacerbated by poverty, unemployment, political instability, ongoing conflicts, and the proliferation of weapons. Common types of crime include:

- Violent Crime:** Armed robbery, banditry (especially on roads and in rural areas), carjackings, and murder are prevalent.

- Organized Crime:** This includes illicit trafficking of minerals (conflict minerals), drugs, weapons, and human trafficking.

- Gender-Based Violence (GBV):** Rape and other forms of sexual violence are widespread, particularly but not exclusively in conflict-affected eastern regions. Domestic violence is also a serious issue.

- Property Crime:** Burglary, theft, and pickpocketing are common, especially in urban areas.

- Corruption within Law Enforcement:** Police officers are often poorly paid, leading to extortion, bribery, and arbitrary detention for financial gain.

- Challenges in Law Enforcement:**

- Under-resourcing and Lack of Training:** The PNC is chronically underfunded, lacks adequate equipment (vehicles, communication tools, forensic capabilities), and officers often receive insufficient training.

- Corruption and Impunity:** Corruption within the police force is pervasive, eroding public trust and hindering effective crime fighting. Impunity for crimes committed by police officers and other officials is common.

- Weak Judicial System:** The justice system itself is weak, under-resourced, and often subject to political interference and corruption. This means that even when arrests are made, successful prosecution and fair trials are not guaranteed.

- Access to Justice for Victims:** Victims of crime, particularly in remote areas or those from marginalized communities, face significant barriers in accessing justice. This is especially true for victims of sexual violence.

- Prison Conditions:** Prisons are severely overcrowded, with deplorable sanitary conditions, inadequate food and medical care, and high rates of disease and mortality. Pre-trial detention is often lengthy.

- Conflict and Insecurity:** In eastern DRC and other conflict-affected areas, the PNC often lacks the capacity to maintain law and order, with security frequently dominated by the military (FARDC) and various armed groups. State authority is weak or non-existent in many remote regions.

Efforts to reform the police and justice sectors have been ongoing, often with international support, but progress has been slow due to the scale of the challenges, political obstacles, and persistent insecurity. Improving law enforcement and the rule of law is critical for the DRC's stability and development, as well as for protecting the human rights of its citizens.

5.5. Corruption

Corruption has been a persistent issue under various administrations, including that of former President Joseph Kabila. Corruption is a deeply entrenched and pervasive issue in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), affecting all levels of government and public sector operations. It has historical roots stretching back to the colonial era and was institutionalized during the long dictatorship of Mobutu Sese Seko, whose regime is often cited as a prime example of kleptocracy. This legacy has continued to plague the country, severely hampering its economic development, social equity, resource governance, and public trust in state institutions.

- Historical Roots:**

- Colonial Era:** Exploitative colonial practices laid some groundwork for systems where resources were extracted for personal or external benefit rather than public good.

- Mobutu Era (Zaire):** Mobutu Sese Seko (1965-1997) perfected a system of state-sponsored corruption. He used patronage and the illicit diversion of state revenues and international aid to enrich himself, his family, and his allies, while simultaneously preventing political rivals from challenging his control. This led to the coining of the term "le mal Zaïrois" (the Zairian sickness) to describe the gross corruption, theft, and mismanagement. Mobutu allegedly amassed a personal fortune estimated to be in the billions of US dollars, while the country's infrastructure and public services crumbled.

- Common Forms of Corruption:**

Corruption in the DRC manifests in various forms, including:

- Bribery and Extortion:** Demands for bribes by public officials for services that should be free (e.g., obtaining official documents, passing checkpoints, accessing healthcare or education) are commonplace. Extortion by security forces is also widespread.

- Embezzlement of Public Funds:** Diversion of state revenues, particularly from the lucrative mining sector, and international aid for personal gain by officials.