1. Overview

The Republic of South Sudan is a landlocked country located in East Africa, bordered by Sudan to the north, Ethiopia to the east, Kenya, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the south, and the Central African Republic to the west. Its capital and largest city is Juba. The nation's geography is characterized by vast plains, plateaus, tropical savannas, inland floodplains, and forested mountains, with the Nile River system, particularly the White Nile and the expansive Sudd wetlands, being a defining feature. South Sudan gained independence from Sudan on July 9, 2011, following a referendum where nearly 99% of voters chose secession, making it the world's newest sovereign state with widespread recognition as of 2024.

The country's history is marked by prolonged conflict, including two major Sudanese civil wars, which significantly hindered its development and led to immense human suffering. Post-independence, South Sudan experienced its own devastating civil war from 2013 to 2020, characterized by widespread human rights abuses, ethnic violence, and a severe humanitarian crisis. While a peace deal was signed in 2020 leading to the formation of a transitional government, the nation continues to grapple with political instability, ongoing localized conflicts, profound economic challenges primarily due to its heavy reliance on oil revenues, and severe humanitarian needs affecting a large portion of its population of approximately 12.7 million. The population is predominantly composed of Nilotic peoples, with diverse ethnic, tribal, and linguistic groups, and is one of the youngest demographically in the world. Christianity and traditional indigenous faiths are the main religions. South Sudan is a member of the United Nations, the African Union, the East African Community, and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development.

2. Etymology

The name "Sudan" originates from the Arabic phrase بلاد السودانbilād as-sūdānArabic, meaning "Land of the Blacks." This term was historically used by Arab traders and travelers to refer to the geographical region south of the Sahara Desert, stretching from Western Africa to eastern Central Africa, and the various indigenous black African cultures and societies they encountered therein. When the southern part of Sudan prepared for independence, the name "South Sudan" was adopted for the new nation, primarily for familiarity and convenience. Other names considered included Azania, Nile Republic, Kush Republic (referencing the ancient Kingdom of Kush), and Juwama, a portmanteau of Juba, Wau, and Malakal, three major cities in the country. Ultimately, the Republic of South Sudan was chosen as the official name.

3. History

South Sudan's past includes early migrations and the establishment of various indigenous societies before experiencing colonial rule under Turco-Egyptian and Anglo-Egyptian administrations, which often exacerbated regional disparities. Decades of struggle for autonomy and self-determination culminated in two major civil wars against the Sudanese government, eventually leading to a peace agreement and an independence referendum. However, the post-independence era has been marked by further internal conflicts, severe humanitarian crises, and ongoing efforts toward peace and stable governance.

3.1. Pre-independence

The Nilotic peoples, including the Dinka, Nuer, Shilluk, Bari, Acholi, and Anyuak, are among the primary inhabitants of South Sudan, with their migrations into the region beginning before the tenth century, around the time of the decline of medieval Nubia. Between the 15th and 19th centuries, significant tribal migrations, largely from the Bahr el Ghazal area, brought these groups to their present locations in Bahr el Ghazal and the Upper Nile Region. The Azande, Mundu, Avukaya, and Baka peoples entered South Sudan in the 16th century and established the largest state in the Equatoria Region. The Dinka are the largest ethnic group, followed by the Nuer, then the Zande, and the Bari.

In the 19th century, Ottoman Egypt, under Khedive Ismail Pasha, attempted to control the region, establishing the province of Equatoria in the 1870s with governors like Samuel Baker, Charles George Gordon, and Emin Pasha. The Mahdist Revolt in the 1880s destabilized this Egyptian outpost. Subsequently, the region became part of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan following the Fashoda Incident in 1898, which nearly led to war between Britain and France. British colonial policy largely favored the development of the Arab north while neglecting the Black African south. The Closed District Ordinance of 1922, for instance, limited the spread of Islam to the south and favored Christian missionaries, allowing southern tribes to retain much of their cultural and political heritage. However, this also led to a lack of schools, hospitals, and basic infrastructure in the south.

In 1947, the Juba Conference reversed the policy of treating the South as distinct, moving towards unification with the North, without significant Southern consultation. After Sudan's independence in 1956, the continued neglect of the southern region by the Khartoum government led to uprisings and the First Sudanese Civil War (1955-1972). The government fought the Anyanya rebel army (a Madi term for "snake venom"). This war resulted in the Addis Ababa Agreement of 1972, which granted the South a degree of autonomy, forming the Southern Sudan Autonomous Region (1972-1983) and promising a future referendum on secession.

3.2. Autonomy and independence process

The autonomy granted in 1972 was short-lived. In 1983, President Gaafar Nimeiry, influenced by Islamist factions, abrogated the Addis Ababa Agreement, abolished the Southern Sudan Autonomous Region, divided the south into three smaller regions, and imposed Sharia law across Sudan. These actions, coupled with disputes over oil resources discovered in the south, triggered the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005). The Sudan People's Liberation Army/Movement (SPLA/M), led by John Garang, a Dinka, emerged as the main rebel force fighting against the Khartoum government. This conflict was one of Africa's longest and deadliest, resulting in an estimated 2.5 million deaths and millions more displaced.

International pressure and mediation efforts eventually led to the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) on January 9, 2005, in Naivasha, Kenya, between the SPLA/M and the Sudanese government under President Omar al-Bashir. The CPA restored southern autonomy through the establishment of the Autonomous Government of Southern Sudan (GOSS), with John Garang as its first president. It also stipulated that a referendum on independence for the south would be held after a six-year interim period. Tragically, Garang died in a helicopter crash just weeks after taking office, and Salva Kiir Mayardit, his deputy, succeeded him as President of Southern Sudan and First Vice President of Sudan.

The independence referendum was held from January 9 to 15, 2011. The results, announced in February, showed an overwhelming 98.83% of voters in favor of secession. On July 9, 2011, the Republic of South Sudan formally declared its independence, becoming Africa's 54th country and the world's newest sovereign state. The declaration was met with widespread international recognition and celebrations within South Sudan.

3.3. Post-independence conflicts

Independence did not bring lasting peace to South Sudan. The new nation quickly faced numerous challenges, including border disputes with Sudan, internal ethnic tensions, and political power struggles, which culminated in a devastating civil war. These conflicts have had a catastrophic humanitarian impact and have been marked by widespread human rights abuses.

3.3.1. Key events and phases

Shortly after independence in 2011, South Sudan was reportedly at war with at least seven armed groups in 9 of its 10 states, displacing tens of thousands. These groups accused the government of plotting to stay in power indefinitely, not fairly representing all tribal groups, and neglecting development in rural areas. The Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) also operated in areas including South Sudan. Inter-ethnic warfare, some predating independence, was widespread. In December 2011, tribal clashes intensified between the Nuer White Army of the Lou Nuer and the Murle people.

In March 2012, South Sudanese forces seized the Heglig oil fields, claimed by both Sudan and South Sudan, after conflict with Sudanese forces. South Sudan withdrew in April 2012. The Abyei Area remained a key point of contention, with its status unresolved and a planned referendum on whether to join Sudan or South Sudan not held. The South Kordofan conflict also broke out in June 2011 between the Sudanese army and the SPLA-North over the Nuba Mountains.

The most significant post-independence conflict, the South Sudanese Civil War, erupted in December 2013. It began as a political power struggle between President Salva Kiir Mayardit (a Dinka) and his former Vice President Riek Machar (a Nuer), whom Kiir accused of attempting a coup. The conflict quickly took on ethnic dimensions, with widespread violence between Dinka and Nuer communities, as well as other ethnic groups becoming involved.

Key phases of the civil war included:

- Initial Outbreak (December 2013 - August 2015): Fighting began in Juba and rapidly spread to Jonglei, Unity, and Upper Nile states. Ugandan troops intervened on the side of President Kiir's government. Atrocities were committed by both sides, including ethnic massacres like the 2014 Bentiu massacre.

- Compromise Peace Agreement and Renewed Conflict (August 2015 - July 2016): A peace agreement, the "Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan" (ARCSS), was signed in August 2015. Machar returned to Juba in April 2016 and was reinstated as First Vice President. However, the peace was fragile, and in July 2016, heavy fighting broke out again in Juba between forces loyal to Kiir and Machar. Machar fled the capital, and the conflict resumed with renewed intensity.

- Fragmented Conflict and Stalemate (July 2016 - September 2018): The war became more fragmented, with the emergence of new rebel groups and internal splits within existing factions. Violence continued, and the humanitarian situation worsened.

- Revitalised Peace Agreement and Transitional Period (September 2018 - February 2020): Renewed regional and international pressure led to the signing of the "Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan" (R-ARCSS) in September 2018. This agreement aimed to establish a new power-sharing government.

3.3.2. Humanitarian impact and displacement

The post-independence conflicts, particularly the 2013-2020 civil war, had a devastating humanitarian impact. An estimated 400,000 people were killed. The violence led to mass displacement, with over 4 million people forced to flee their homes. This included approximately 1.8 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) and about 2.5 million refugees who sought safety in neighboring countries, primarily Uganda, Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Food insecurity became rampant, with parts of the country, notably former Unity State, experiencing famine in 2017. Over 100,000 people were directly affected by the famine declaration, and the UN World Food Programme stated that 4.9 million people (about 40% of the population) urgently needed food. UNICEF warned that over a million children were subjected to malnutrition. Access to clean water, sanitation, and healthcare services was severely disrupted. Civilians, particularly women and children, bore the brunt of the conflict, facing violence, displacement, and loss of livelihoods. Humanitarian access was often restricted by fighting and deliberate obstruction, hampering relief efforts. The widespread violence included ethnic massacres, sexual violence used as a weapon of war, and the recruitment of child soldiers.

3.3.3. Peace efforts and agreements

Numerous peace efforts and ceasefire agreements were made throughout the post-independence conflicts, often mediated by the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) and supported by the African Union and the wider international community.

- Initial Ceasefires (2014-2015):** Several ceasefires were agreed upon during the early stages of the civil war but were frequently violated by both sides.

- Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (ARCSS, August 2015):** This was a comprehensive peace deal brokered by IGAD Plus (including representatives from the UN, AU, China, US, UK, Norway, and the EU Troika). It provided for a transitional government of national unity, security sector reforms, and accountability mechanisms. However, its implementation was flawed, and it collapsed in July 2016.

- Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS, September 2018):** After the failure of the 2015 agreement, further negotiations led to this revitalized peace deal. It largely mirrored the 2015 agreement but with some modifications and a renewed commitment from regional leaders. Key provisions included the formation of a Revitalised Transitional Government of National Unity (R-TGoNU), power-sharing arrangements (including the reinstatement of Riek Machar as First Vice President), unification of security forces, and establishment of a Hybrid Court for South Sudan to try war crimes.

The implementation of the R-ARCSS faced significant delays and challenges, including disagreements over the number of states, security arrangements, and funding for implementation. Despite these difficulties, it remained the main framework for peace.

3.4. Recent developments

Following the official end of the civil war with the formation of the Revitalised Transitional Government of National Unity (R-TGoNU) in February 2020, with Salva Kiir as President and Riek Machar as First Vice President, South Sudan has embarked on a challenging transitional period. The implementation of the R-ARCSS has been slow and fraught with difficulties. Key aspects, such as the unification of the armed forces (a critical component for long-term stability), constitutional reforms, and preparations for general elections, have faced significant delays. Trust issues between the former warring parties persist.

Despite the formal peace, localized violence, often inter-communal or involving non-signatories to the peace deal, has continued in various parts of the country, exacerbating the humanitarian situation. Accountability for past atrocities remains a major concern for victims and human rights organizations.

South Sudan became a full member of the East African Community (EAC) on August 15, 2016, aiming to foster economic integration and cooperation with its East African neighbors. The country had initially been scheduled to hold its first general elections since independence in 2023, as per the R-ARCSS. However, due to slow progress in implementing key electoral and constitutional reforms, the transitional government and opposition parties agreed in August 2022 to extend the transitional period by 24 months, postponing the elections to late 2024. In September 2024, President Kiir's office announced a further postponement of the elections by an additional two years, to December 2026, citing continued unpreparedness and the need for further implementation of the peace agreement's provisions. This delay has raised concerns among international partners and civil society about the commitment to democratic transition and the potential for prolonged instability.

4. Geography

South Sudan's geography is characterized by vast plains, the extensive Sudd wetlands formed by the White Nile, and mountainous regions like the Imatong Mountains. The country experiences a tropical climate with distinct rainy and dry seasons, influencing its rich biodiversity across various ecoregions, including significant wildlife populations and large-scale animal migrations. The country covers an area of approximately 249 K mile2 (644.33 K km2), situated between latitudes 3° and 13°N, and longitudes 24° and 36°E. It is bordered by Sudan to the north, Ethiopia to the east, Kenya, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the south, and the Central African Republic to the west.

4.1. Topography

South Sudan's topography is diverse, featuring vast plains, plateaus, and mountainous regions. The defining physical feature is the Nile River system, particularly the White Nile (known locally as Bahr al Jabal, meaning "Mountain River" or "Sea of the Mountain"), which flows from south to north through the center of the country.

A significant portion of central South Sudan is dominated by the Sudd, one of the world's largest swamps or inland floodplains. This vast wetland, formed by the Bahr al Jabal, covers an extensive area and is characterized by dense papyrus, reeds, and floating vegetation. The Sudd plays a crucial role in the regional hydrology and supports unique ecosystems.

To the south, near the border with Uganda, lie the Imatong Mountains, which include Mount Kinyeti, South Sudan's highest peak at 10 K ft (3.19 K m). Other highland areas include the Didinga Hills in the southeast and parts of the Ironstone Plateau in the southwest, which extends into the Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Much of the rest of the country consists of expansive plains and savanna grasslands, gently sloping towards the Sudd and the Nile.

4.2. Climate

South Sudan experiences a tropical climate, characterized by distinct rainy and dry seasons. The rainy season typically occurs from April/May to October/November, bringing high humidity and significant rainfall. The dry season generally lasts from November/December to March/April.

Average temperatures are consistently high throughout the year. July is often the coolest month, with average temperatures ranging from 68 °F (20 °C) to 86 °F (30 °C), while March is usually the warmest month, with average temperatures between 73.4 °F (23 °C) and 98.6 °F (37 °C).

Rainfall patterns vary across the country. The southern regions, particularly the Equatorias with their tropical forests, receive higher annual rainfall (often exceeding 0.0 K in (1.20 K mm)) compared to the northern and eastern savanna regions, which are drier. The amount and timing of rainfall are crucial for agriculture, which is the mainstay for much of the population. The annual shift of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) heavily influences the seasonal patterns, bringing moisture-laden southerly and southwesterly winds during the rainy season.

Climate change is a growing concern for South Sudan, with potential impacts including increased variability in rainfall, more frequent extreme weather events like floods and droughts, and rising temperatures. These changes could exacerbate existing vulnerabilities related to food security, water resources, and conflict over scarce resources. In recent years, severe flooding has affected large parts of the country, displacing hundreds of thousands of people.

4.3. Wildlife and ecoregions

South Sudan possesses a rich biodiversity, with diverse ecosystems that support a wide variety of wildlife. The country's habitats include tropical forests, wooded and grassy savannas, high-altitude plateaus and escarpments, vast floodplains, and extensive wetlands like the Sudd.

Several important ecoregions extend across South Sudan:

- East Sudanian Savanna**: Covers a large part of the country, characterized by grasslands interspersed with trees.

- Northern Congolian Forest-Savanna Mosaic**: Found in the southwest, a transition zone between forests and savannas.

- Saharan Flooded Grasslands (Sudd)**: The vast wetland ecosystem.

- Sahelian Acacia Savanna**: Extends into the northernmost parts.

- East African Montane Forests**: Occur in the Imatong Mountains and other highland areas.

- Northern Acacia-Commiphora Bushlands and Thickets**: Found in parts of the southeast.

South Sudan is renowned for its large-scale wildlife migrations. The Bandingilo National Park hosts the second-largest annual animal migration in Africa (after the Serengeti), involving vast numbers of white-eared kob, tiang (topi), and Mongalla gazelle. Boma National Park, located in the east near the Ethiopian border, along with the Sudd wetlands and Southern National Park near the Congolese border, are also critical habitats for large populations of hartebeest, kob, topi, African buffalo, elephants, giraffes, lions, African wild dogs, common eland, and giant eland. The country's forest reserves are home to species like bongo, giant forest hogs, red river hogs, forest elephants, chimpanzees, and various monkeys. The Nile Lechwe is an antelope species endemic to the Sudd and surrounding grasslands.

Conservation efforts in South Sudan face significant challenges due to decades of conflict, poaching, habitat degradation from human activities (such as agriculture, logging, and charcoal production), and weak institutional capacity. However, organizations like the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) have worked with the government to conduct surveys and support conservation initiatives. Protected areas include national parks like Bandingilo, Boma, Southern, Nimule, and Lantoto, as well as numerous game reserves such as Zeraf Wildlife Reserve within the Sudd. The country had a high 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 9.45/10, ranking it fourth globally out of 172 countries, indicating significant intact forest landscapes. However, the pressures of development and resource exploitation pose ongoing threats to these valuable ecosystems. Little is documented about the fungi of South Sudan, though many species were recorded when it was part of Sudan.

5. Government and politics

South Sudan operates as a federal presidential republic under a transitional constitution, with a government structure featuring a President, a bicameral National Legislature, and an independent judiciary, though democratic processes and institutions face significant challenges. The political landscape is dominated by the Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) and its factions, with elections repeatedly postponed. Administratively, the country is divided into ten states and three special administrative areas, and it has ongoing plans for a new national capital. The South Sudan People's Defence Forces (SSPDF) is the national military, currently undergoing a complex unification process mandated by peace agreements.

5.1. Government structure and constitution

The Transitional Constitution of the Republic of South Sudan, 2011 (as amended) serves as the supreme law of the land. It establishes a presidential system where the President is the head of state, head of government, and commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Salva Kiir Mayardit has been the President since independence. The R-ARCSS introduced a power-sharing arrangement, creating the post of First Vice President, currently held by Riek Machar, along with four other Vice Presidents representing different signatory parties to the peace agreement.

The National Legislature is bicameral, consisting of:

- The Reconstituted Transitional National Legislative Assembly (R-TNLA): This is the lower house, directly elected in principle, though its current membership is based on appointments according to the R-ARCSS power-sharing formula. It holds primary legislative authority. Jemma Nunu Kumba is the current Speaker. On May 8, 2021, President Kiir dissolved the previous parliament and later reconstituted it with an expanded membership of 550 lawmakers as stipulated in the 2018 peace deal.

- The Transitional Council of States: This is the upper house, representing the states and administrative areas.

The judiciary is constitutionally independent, with the Supreme Court as the highest judicial organ. Chan Reec Madut is the Chief Justice. However, the judicial system faces significant challenges, including lack of resources, capacity, and political interference, which undermine its effectiveness and independence.

According to the 2023 V-Dem Democracy indices, South Sudan ranks as one of the lowest electoral democracies in Africa. The transitional period established by the R-ARCSS is intended to lead to credible democratic elections, but these have been repeatedly postponed.

5.2. Political parties and elections

The dominant political party in South Sudan is the Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM), which led the struggle for independence and has largely controlled the government since. However, the SPLM itself has experienced internal divisions, notably the split that led to the civil war when factions loyal to President Kiir (SPLM-IG, or "In Government") clashed with those loyal to Riek Machar (SPLM-IO, or "In Opposition"). Other smaller political parties exist, but their influence has been limited in a political landscape dominated by the SPLM factions and shaped by armed conflict.

South Sudan has not held general elections since its independence in 2011. The 2010 general elections in Sudan included voting for Southern Sudanese positions, which formed the basis of the initial post-independence government. The R-ARCSS mandates the holding of general elections at the end of the transitional period to establish a democratically elected government. These elections were initially planned for 2023, then postponed to late 2024, and most recently further postponed to December 2026.

Challenges to democratic development are immense. They include ongoing insecurity, a deeply divided political elite, weak state institutions, lack of a permanent constitution (a new one is supposed to be drafted during the transition), issues with voter registration and census data (no reliable census has been conducted for decades), and the need for significant civic education and a conducive environment for free and fair campaigning. The continued delays in holding elections raise concerns about the commitment of the political leadership to a genuine democratic transition and the potential for a return to wider conflict.

5.3. Administrative divisions

The administrative structure of South Sudan has undergone several changes since independence.

2011-2015: Ten States

Upon independence, South Sudan was divided into ten states, which corresponded to the three historical provinces of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan:

- Bahr el Ghazal (region): Northern Bahr el Ghazal, Western Bahr el Ghazal, Lakes, and Warrap.

- Equatoria (region): Western Equatoria, Central Equatoria (containing the capital, Juba), and Eastern Equatoria.

- Greater Upper Nile (region): Jonglei, Unity, and Upper Nile.

The Abyei Area, a border region claimed by both Sudan and South Sudan, was granted special administrative status under the CPA, with its final status to be determined by a referendum that has yet to occur.

2015-2020: 28 then 32 States

In October 2015, President Kiir issued a decree replacing the ten states with twenty-eight states, largely along ethnic lines. This move was controversial and opposed by rebel groups and some international observers, who argued it could exacerbate ethnic tensions and violated the 2015 peace agreement. In January 2017, the number of states was further increased to 32.

2020-present: Ten States and Three Administrative Areas

As part of the R-ARCSS signed in 2018 and implemented with the formation of the transitional government in February 2020, South Sudan reverted to a system of ten states, largely based on the original ten. Additionally, three administrative areas were created:

- Abyei Special Administrative Area: Continues to have a special status due to its unresolved dispute with Sudan.

- Greater Pibor Administrative Area: Created in the eastern part of Jonglei State, primarily inhabited by the Murle people.

- Ruweng Administrative Area: Located in the oil-rich northern part of former Unity State, primarily inhabited by Dinka groups.

The creation and demarcation of these administrative areas, particularly Ruweng, have also been sources of contention. The Kafia Kingi area remains disputed with Sudan, and the Ilemi Triangle is disputed with Kenya and Ethiopia.

5.4. National capital project

The current national capital of South Sudan is Juba, which is also the capital of Central Equatoria state. However, Juba faces challenges related to its infrastructure, rapid and often unplanned urban growth, and its geographical location in the southern part of the country, which is not central to all regions.

In February 2011, shortly before independence, the then-Autonomous Government of Southern Sudan adopted a resolution to explore the possibility of establishing a new, planned capital city. The primary rationale was to find a more central location that could better serve the entire nation, promote national unity, and allow for more organized development. Ramciel, located in Lakes state near the borders of Central Equatoria and Jonglei, was identified as a potential site. Ramciel is considered to be near the geographical center of South Sudan, and the late SPLA leader John Garang had reportedly considered it for a future capital.

In September 2011, the government announced its intention to relocate the capital to Ramciel. The project was envisioned to be similar to other planned capital cities like Abuja in Nigeria or Brasília in Brazil. A master plan for Ramciel was developed with the support of international partners, including South Korea. However, the project has faced significant delays and has largely stalled due to the outbreak of the civil war in 2013, ongoing political instability, and severe economic constraints, particularly the lack of funding. While the ambition to move the capital to Ramciel remains, Juba continues to function as the de facto capital, and the timeline for any potential relocation is uncertain.

5.5. Military

The primary military force of South Sudan is the South Sudan People's Defence Forces (SSPDF). The SSPDF was officially formed from the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA), which was the armed wing of the SPLM during the wars of independence against the Sudanese government.

A Defence White Paper was initiated in 2007 by then Minister for SPLA Affairs Dominic Dim Deng, outlining plans for land, air, and riverine forces. Following independence, the SPLA officially became the national army. During the South Sudanese Civil War (2013-2020), the SPLA itself fractured, with significant portions joining rebel factions, most notably the SPLA-IO (In Opposition) led by Riek Machar. Other armed groups also emerged or realigned.

The R-ARCSS (2018 peace agreement) mandates the creation of a unified national army, police, and other security services by integrating forces from the government (SSPDF), SPLA-IO, and other signatory armed groups. This process, known as the Necessary Unified Forces (NUF), has been extremely slow and challenging, plagued by mistrust, logistical issues, lack of resources, and political disagreements. The successful formation and deployment of a truly national and professional NUF is considered crucial for long-term peace and stability.

The SSPDF's role is national security, border protection, and maintaining internal order, though it has been heavily involved in internal conflicts and has been implicated in numerous human rights abuses by various monitoring groups. South Sudan has historically had one of the highest military expenditures as a percentage of GDP globally, reflecting the protracted state of conflict. The military continues to grapple with issues of professionalism, discipline, ethnic divisions, and adequate resourcing.

6. Foreign relations

Since its independence in 2011, South Sudan's foreign policy has focused on managing its critical and often contentious relationship with Sudan, building ties with East African neighbors like Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda, and engaging with major international partners such as the United States, China, and European nations. The country has actively joined key international organizations including the United Nations, African Union, and the East African Community to foster cooperation and integration.

6.1. Relations with Sudan

The relationship with Sudan is arguably South Sudan's most critical and complex foreign policy challenge. Sudan's President Omar al-Bashir initially suggested dual citizenship would be allowed, but this offer was later retracted. Key issues of contention have included:

- Border Demarcation:** Several sections of the approximately 1.2 K mile (2.00 K km) border remain undemarcated and disputed, leading to tensions and occasional clashes.

- Oil Revenue Sharing:** South Sudan inherited about 75% of the former Sudan's oil reserves, but it is landlocked and relies on Sudan's pipelines and port facilities (Port Sudan) for export. Disputes over transit fees and revenue sharing led South Sudan to temporarily shut down oil production in 2012, severely impacting both economies. Agreements have been reached, but implementation remains a challenge.

- Status of Abyei:** The Abyei Area, rich in oil and culturally significant to both Dinka Ngok (aligned with South Sudan) and Misseriya Arabs (aligned with Sudan), remains a major flashpoint. A referendum to decide its fate, mandated by the CPA, has not been held due to disagreements over voter eligibility. The area is currently under a special administrative status, with UN peacekeeping forces present.

- Support for Rebel Groups:** Both countries have accused each other of supporting rebel groups operating in their respective territories.

Despite these disputes, there are also areas of cooperation, driven by mutual economic dependence, particularly on oil. The political transitions in Sudan, including the ousting of al-Bashir in 2019, have introduced new dynamics into the relationship.

6.2. Relations with neighboring and major countries

South Sudan has actively engaged with its East African neighbors:

- Ethiopia:** Has played a significant role as a mediator in South Sudanese peace processes, particularly through IGAD. It hosts a large number of South Sudanese refugees.

- Kenya:** A key economic partner, providing access to the port of Mombasa and a route for trade. Kenya has also been involved in peace initiatives and hosts many refugees.

- Uganda:** A close ally, particularly of President Kiir's government. Ugandan troops intervened in the South Sudanese Civil War on the government's side. Uganda also hosts the largest number of South Sudanese refugees and is a major trading partner.

- Democratic Republic of the Congo & Central African Republic:** Border security and cross-border movements are concerns.

Among major international partners:

- United States:** Played a crucial role in orchestrating the referendum leading to South Sudan's independence and has been a major provider of humanitarian aid and diplomatic support for peace processes. However, relations have been strained at times due to concerns over governance, human rights, and the slow pace of peace implementation. The U.S. has imposed sanctions on individuals deemed to be undermining peace.

- China:** A significant economic partner, primarily due to its investments in South Sudan's oil sector (China National Petroleum Corporation is a major player). China has also contributed to UN peacekeeping efforts and infrastructure development.

- United Arab Emirates:** In recent years, the UAE has emerged as a significant financial partner, reportedly providing substantial loans to South Sudan, though the terms and transparency of these arrangements have faced scrutiny.

- Troika (United States, United Kingdom, Norway):** This group has historically been deeply involved in peace negotiations and monitoring the implementation of peace agreements.

- European Union:** A major humanitarian and development aid donor, and a supporter of peace and governance reforms.

In July 2019, South Sudan, along with 36 other countries, signed a joint letter to the UNHRC defending China's treatment of Uyghurs in the Xinjiang region, reflecting its alignment with China on certain international issues.

6.3. Membership in international organizations

South Sudan became a member of the United Nations (UN) on July 14, 2011, as its 193rd member state. The UN has a large peacekeeping mission, the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS), focused on protecting civilians, monitoring human rights, and supporting the peace process.

It joined the African Union (AU) on July 27, 2011, as its 54th member. The AU has been actively involved in mediation and peace-building efforts.

South Sudan acceded to the treaty of the East African Community (EAC) in April 2016 and became a full member in August 2016. Membership aims to foster economic integration, trade, and free movement of people.

It is also a member of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), a regional bloc in the Horn of Africa that has been the primary mediator in South Sudan's peace negotiations.

South Sudan has applied to join the Commonwealth of Nations. It has also sought membership or cooperation with the Arab League (potentially as an observer, given its Arabic-speaking population and proximity), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Bank. It is also part of OPEC+, reflecting its status as an oil-producing nation.

7. Economy

South Sudan's economy is overwhelmingly dependent on oil, which constitutes the vast majority of its revenue, making it vulnerable to price fluctuations and disputes with Sudan over transit. Agriculture provides livelihoods for most of the population, though productivity is low. The nation's infrastructure, including transport and energy, is severely underdeveloped. Profound economic challenges include extreme poverty, high inflation, significant national debt, and widespread food insecurity, all exacerbated by prolonged conflict and governance issues.

7.1. Economic overview and major industries

The economy of South Sudan is overwhelmingly dependent on oil resources, which account for almost all of its export revenues and a vast majority of government income (over 90% in 2023). This extreme reliance makes the economy highly vulnerable to fluctuations in global oil prices and production disruptions due to conflict or disputes with Sudan over transit.

Agriculture is the primary livelihood for the majority of the population (around 80%), largely in the form of subsistence farming and livestock rearing. Key subsistence crops include sorghum, maize, millet, cassava, groundnuts, and sweet potatoes. Livestock, particularly cattle, are a significant cultural and economic asset. Despite fertile land and abundant water resources, agricultural productivity is low due to conflict, displacement, lack of modern farming techniques, poor infrastructure, and limited access to markets and credit. As a result, South Sudan is heavily reliant on food imports and humanitarian aid.

Other potential industries remain largely untapped or underdeveloped. These include:

- Forestry:** South Sudan has significant timber resources, including teak plantations, which are exported.

- Mining:** Besides oil, the country is believed to possess deposits of gold, iron ore, copper, chromium, zinc, tungsten, mica, and silver, but commercial exploitation is minimal.

- Fisheries:** The Nile River and its tributaries, along with the Sudd wetlands, offer considerable fishing potential.

- Tourism:** The country's wildlife and national parks have potential for tourism, but insecurity and lack of infrastructure have prevented its development.

Southern Sudan Beverages Limited, a subsidiary of SABMiller, was an example of foreign investment in the non-oil sector.

7.2. Oil resources

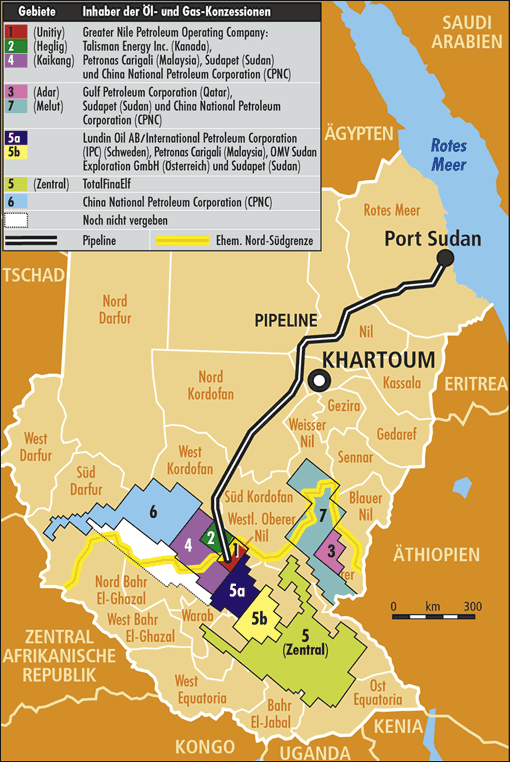

South Sudan possesses the third-largest oil reserves in Sub-Saharan Africa. Upon independence, it inherited about 75% of the former Sudan's oil production. Key oil-producing regions are located in Unity and Upper Nile states. Major international oil companies involved in South Sudan include China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), Petronas (Malaysia), and ONGC Videsh (India).

The oil sector faces numerous challenges:

- Dependence on Sudan:** South Sudan is landlocked and relies on pipelines passing through Sudan to reach the export terminal at Port Sudan on the Red Sea. This has led to frequent disputes with Sudan over transit fees. In 2012, South Sudan shut down its oil production for over a year due to such a dispute, severely damaging its economy.

- Conflict and Insecurity:** Oil fields and infrastructure have been targets during internal conflicts, leading to production disruptions and damage.

- Transparency and Governance:** Concerns persist about the management of oil revenues, with issues of corruption and lack of transparency hindering the use of these resources for broad-based development.

- Declining Reserves:** Without new discoveries or enhanced recovery techniques, existing oil fields are projected to decline in output.

In 2017, Nile Drilling & Services was established as South Sudan's first locally owned and run petroleum drilling company. The government has expressed intentions to diversify the economy away from its near-total dependence on oil, but progress has been limited.

7.3. Transport and infrastructure

South Sudan's infrastructure is severely underdeveloped, a legacy of prolonged conflict and neglect.

- Roads:** The road network is extremely limited and largely unpaved. Many roads become impassable during the rainy season, hindering trade, access to services, and humanitarian efforts. The USAID-funded Juba-Nimule Road (to the Ugandan border) is one of the few major paved highways.

- Railways:** South Sudan has a single-track, 154 mile (248 km) narrow-gauge railway line connecting Wau to Babanusa in Sudan. This line has often been in disrepair. There have been proposals to extend the railway from Wau to Juba and to connect Juba with the railway networks of Kenya and Uganda, but these remain largely aspirational.

- Air Transport:** Juba International Airport is the main international gateway, with connections to regional capitals. Other airports like Malakal, Wau, and Rumbek have limited services. Many airstrips exist across the country, often unpaved, primarily used for humanitarian flights and domestic travel. Plans to launch a national airline have been discussed.

- River Transport:** The White Nile and its tributaries are important for transport, especially for bulk goods and in areas inaccessible by road. However, navigability can be an issue, and port facilities are basic.

- Energy:** Access to electricity is extremely low, among the lowest in the world. Juba has some power generation, but most of the country relies on generators or lacks electricity altogether. Hydropower potential exists but is undeveloped.

- Communications:** Mobile phone penetration has grown, but coverage is mainly limited to urban areas. Internet access is also limited and expensive.

The lack of adequate infrastructure is a major impediment to economic development, service delivery, and national integration.

7.4. Economic challenges and poverty

South Sudan faces profound economic challenges and widespread poverty:

- Poverty:** An estimated 90% of the population lives on less than $1 a day. Poverty is pervasive and deeply entrenched, particularly in rural areas.

- Inflation:** The country has experienced periods of hyperinflation, eroding savings and purchasing power, largely driven by conflict, economic mismanagement, and dependence on oil revenues. The South Sudanese Pound has significantly devalued since its introduction.

- National Debt:** South Sudan has accumulated significant external debt. At independence, it shared a large debt burden with Sudan (approximately 38.00 B USD accumulated over decades). The specifics of how this debt was to be divided and managed have been complex.

- Underdevelopment:** Decades of conflict have resulted in a severe lack of human capital, weak institutions, and minimal economic diversification.

- Food Insecurity:** Despite agricultural potential, a large portion of the population faces chronic food insecurity and relies on humanitarian assistance, exacerbated by conflict, displacement, and climate shocks (floods and droughts). The 2017 famine in parts of Unity State highlighted this vulnerability.

- Corruption:** Corruption is a major issue, diverting scarce resources from development and public services.

- Impact of Conflict:** Prolonged conflict has destroyed infrastructure, displaced populations, disrupted economic activity, and deterred investment. Military spending has often consumed a large portion of the national budget.

Addressing these challenges requires sustained peace, improved governance, investment in infrastructure and human capital, economic diversification, and effective management of natural resources with a focus on social equity and sustainable development.

8. Society

The society of South Sudan is characterized by its rich ethnic diversity, complex linguistic landscape, varied religious practices, and significant social challenges, many of which are rooted in its history of conflict and underdevelopment.

8.1. Population and ethnic groups

South Sudan has an estimated population of around 11 to 12.7 million people (as of 2023-2024), though precise figures are difficult to obtain due to the lack of a recent census and significant population displacement. The population is predominantly rural and is one of the youngest in the world, with roughly half its people under 18 years old.

The country is home to over 60 indigenous ethnic groups, primarily of Nilotic origin. Major ethnic groups include:

- Dinka:** The largest ethnic group, estimated to be around 35-40% of the population. They are predominantly pastoralists and are found across many parts of the country, particularly in Bahr el Ghazal, Jonglei, and Upper Nile regions.

- Nuer:** The second-largest group, around 15-20%. Traditionally pastoralists, they primarily inhabit areas of Greater Upper Nile. Relations between Dinka and Nuer have often been marked by conflict, particularly during the civil war.

- Azande:** The third-largest group, found in Western Equatoria. They are primarily agriculturalists and belong to the Niger-Congo linguistic family, distinct from the Nilotic groups.

- Bari:** Concentrated around Juba in Central Equatoria.

- Shilluk (Chollo):** Historically influential, with a kingdom centered around Kodok (Fashoda) in Upper Nile State.

Other significant groups include the Anyuak, Murle, Toposa, Lotuka, Acholi, Mundari, Moru, Avukaya, Baka, Kaligi, Kuku, and Boya. Inter-ethnic relations are complex and have often been manipulated for political purposes, leading to localized conflicts over resources (like cattle and grazing land) and political power.

The South Sudanese diaspora is substantial, with many South Sudanese having fled abroad as refugees or migrants during the long years of war. Large communities exist in neighboring countries (Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia, Sudan), as well as in North America (USA, Canada), Europe (UK), and Australia.

8.2. Languages

English is the official language of South Sudan, used in government, education, and business. However, its everyday use as a first language is limited.

Juba Arabic, a pidgin or creole language based on Arabic, serves as a widely spoken lingua franca, particularly in urban areas and for inter-ethnic communication. It differs significantly from Sudanese Arabic and Modern Standard Arabic.

South Sudan is linguistically diverse, with over 60 indigenous languages spoken. These languages are constitutionally recognized as "national languages" that "shall be respected, developed and promoted." Most belong to the Nilo-Saharan language family (particularly Nilotic languages and Central Sudanic languages), with a smaller number from the Niger-Congo family (such as Azande).

Major indigenous languages include:

- Dinka (with its various dialects)

- Nuer

- Shilluk

- Bari

- Zande

- Luo languages (including Acholi, Anyuak, Jur-Luo, Pari)

- Murle

- Ma'di

- Otuho

Swahili has been proposed as a potential additional language for wider communication, particularly given South Sudan's membership in the East African Community, and its teaching has been introduced in some schools.

8.3. Religion

The primary religions in South Sudan are Christianity and traditional African religions. Islam is practiced by a minority.

- Christianity:** A majority of the population, estimated at around 60.5% (Pew Research Center 2020 estimate), identifies as Christian. The main denominations are Roman Catholicism and various Protestant churches, including the Episcopal Church of South Sudan (part of the Anglican Communion) and the Presbyterian Church of South Sudan. Christianity spread significantly during the colonial era and the subsequent civil wars, often seen as a differentiating factor from the predominantly Muslim north.

- Traditional African Religions:** A significant portion of the population, around 32.9%, adheres to traditional indigenous beliefs. These faiths are diverse and vary among ethnic groups but often involve a belief in a supreme being, ancestral spirits, and nature spirits. Many Christians and Muslims may also incorporate elements of traditional beliefs into their practices (syncretism).

- Islam:** A smaller minority, estimated at about 6.2%, practices Islam. Muslims are found throughout the country but are more concentrated in some urban areas and border regions.

The 2011 transitional constitution provides for freedom of religion and separation of church and state. Religious leaders and institutions, both Christian and Muslim, have often played important roles in peace-building, reconciliation, and humanitarian efforts. Interreligious relations are generally peaceful, though conflicts can sometimes take on religious dimensions when intertwined with ethnic or political disputes.

8.4. Education

South Sudan's education system faces immense challenges due to decades of conflict, underfunding, lack of infrastructure, and a shortage of qualified teachers. Literacy rates are among the lowest in the world, particularly for women.

The education system is structured on an 8+4+4 model: 8 years of primary education, 4 years of secondary education, and 4 years of university-level instruction. English is the official language of instruction at all levels, a shift from the Arabic-medium system used when South Sudan was part of Sudan. However, the transition to English has been hampered by a lack of English-proficient teachers and learning materials.

Key challenges in the education sector include:

- Low Enrollment and High Dropout Rates:** Particularly for girls and in rural areas.

- Lack of Infrastructure:** Many schools were destroyed or damaged during the wars. Existing schools often lack basic facilities like classrooms, desks, latrines, and clean water.

- Shortage of Qualified Teachers:** Many teachers are untrained or undertrained, and teacher salaries are often low and inconsistently paid.

- Curriculum and Materials:** Developing and distributing a standardized national curriculum and adequate learning materials in English has been a slow process.

- Impact of Conflict:** Ongoing insecurity and displacement continue to disrupt schooling for many children.

- Gender Disparities:** Girls face significant barriers to education, including early marriage, cultural norms, and lack of sanitation facilities in schools.

Despite these challenges, there have been efforts by the government and international partners to improve access to and quality of education. These include school construction programs, teacher training initiatives, and alternative learning programs for out-of-school children. Higher education institutions include the University of Juba, Rumbek University, and Upper Nile University, among others, but they also suffer from under-resourcing and disruptions. In 2019, the Juba Public Peace Library, the country's first public library, was opened by the South Sudan Library Foundation.

9. Humanitarian situation and human rights

South Sudan faces one of the world's most severe and complex humanitarian crises, deeply intertwined with its human rights situation. Decades of conflict, political instability, and underdevelopment have resulted in widespread suffering and systemic abuses.

9.1. Health and humanitarian crisis

The health and humanitarian indicators in South Sudan are among the worst globally.

- Health System:** The healthcare system is extremely weak, with a severe shortage of health facilities, qualified medical personnel (doctors, nurses, surgeons), and essential medicines. In 2004, there were reportedly only three surgeons in the entire southern region. Many health services are provided by international NGOs.

- Mortality Rates:** The country has exceptionally high infant and maternal mortality rates.

- Prevalent Diseases:** Malaria is a leading cause of illness and death. Other significant health threats include diarrheal diseases (due to poor sanitation and lack of clean water), respiratory infections, HIV/AIDS (prevalence estimated around 3.1% but poorly documented), and dracunculiasis (Guinea-worm disease), which South Sudan is one of the last countries to eradicate.

- Famine and Food Insecurity:** Recurrent famines and chronic food insecurity affect millions. In 2017, a famine was declared in parts of former Unity State, affecting over 100,000 people directly, with millions more needing urgent food aid. Factors contributing to food insecurity include conflict, displacement, disruption of agriculture, climate shocks (floods and droughts), and pest outbreaks like the fall armyworm.

- Water and Sanitation:** Access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation is extremely limited for a large portion of the population, contributing to waterborne diseases.

- Refugee and IDP Crisis:** The South Sudanese Civil War (2013-2020) and ongoing localized conflicts have displaced millions. As of recent estimates, over 2.3 million South Sudanese are refugees in neighboring countries (Uganda, Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya, DRC), and around 1.6-2 million are internally displaced persons (IDPs). Many IDPs live in Protection of Civilians (PoC) sites managed by UNMISS, while others are scattered in host communities or remote areas. South Sudan also hosts refugees from neighboring countries, primarily Sudan (due to conflicts in Darfur, South Kordofan, and Blue Nile).

- Humanitarian Aid:** A significant portion of the population (estimated at 8.3 million in need in 2021) relies on international humanitarian assistance for survival. Relief efforts by UN agencies (like UNHCR, WFP, UNICEF, OCHA) and numerous NGOs are critical but are often hampered by insecurity, access restrictions, and funding shortfalls.

The humanitarian crisis disproportionately affects vulnerable groups, including women, children, the elderly, and persons with disabilities.

9.2. Human rights

The human rights situation in South Sudan is dire, marked by widespread abuses committed by all parties to the various conflicts, both before and after independence.

- Violations During Conflict:**

- Unlawful Killings and Civilian Massacres: Numerous reports document targeted killings of civilians based on ethnicity or perceived political affiliation. The 2014 Bentiu massacre is a notable example.

- Forced Displacement: Deliberate displacement of civilian populations has been a common tactic.

- Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (SGBV): Rape and other forms of SGBV have been used systematically as weapons of war by various armed actors. The UN has reported that fighters were sometimes allowed to rape women as a form of payment.

- Use of Child Soldiers: Thousands of children have been recruited and used by armed forces and groups.

- Attacks on Humanitarian Workers and Infrastructure: Aid workers and facilities have been targeted, hindering relief efforts.

- Freedom of Expression and Media:**

- Media freedom is severely restricted. Journalists face intimidation, harassment, arbitrary arrest, detention, and violence. Several journalists have been killed. News websites and blogs critical of the government have been blocked. President Kiir has, in the past, threatened journalists reporting "against the country." This climate of fear has led to self-censorship and the exodus of many journalists.

- Arbitrary Arrest and Detention:** Security forces, particularly the National Security Service (NSS), have been implicated in arbitrary arrests, prolonged detention without trial, torture, and ill-treatment of perceived opponents, activists, and journalists.

- Child Marriage:** The rate of child marriage is very high (around 52%), with severe consequences for girls' health, education, and well-being.

- LGBT Rights:** Homosexual acts are illegal and punishable by imprisonment. Societal discrimination against LGBT individuals is prevalent.

- Accountability and Justice:** Impunity for human rights violations remains a major challenge. The R-ARCSS provides for the establishment of transitional justice mechanisms, including a Hybrid Court for South Sudan, a Commission for Truth, Reconciliation and Healing, and a Compensation and Reparation Authority. However, progress in establishing these bodies has been extremely slow, and there is a significant need for justice, institutional reforms, and accountability to protect human rights and foster democratic development.

The UN Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan has described the situation as "one of the most horrendous human rights situations in the world" and has repeatedly called for perpetrators of widespread violations to be brought to justice.

10. Culture

The culture of South Sudan is a rich tapestry woven from the traditions of its more than 60 distinct ethnic groups. Years of civil war and displacement have also led to significant cultural exchange with neighboring countries like Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda, where many South Sudanese sought refuge. Despite these influences and the adoption of English and Juba Arabic as common languages, most South Sudanese maintain strong connections to their tribal origins, traditional customs, and dialects.

10.1. Traditions and lifestyle

Traditional social structures vary among ethnic groups but often revolve around clans, lineages, and age-sets. Cattle play a central role in the lifestyle and economy of many Nilotic groups like the Dinka and Nuer, serving as a measure of wealth, a source of food (milk, blood, occasionally meat), and a key component of social transactions such as bride price. Oral traditions, including storytelling, proverbs, and historical narratives, are vital for transmitting cultural knowledge and values across generations.

Customs related to marriage, birth, death, and initiation ceremonies are diverse and deeply ingrained. For example, scarification has been a traditional practice among some groups, serving as a rite of passage or ethnic identifier. Traditional governance often involves councils of elders who resolve disputes and uphold community norms. Hospitality is generally highly valued. Daily life for many, especially in rural areas, is closely tied to agricultural cycles (for farming communities like the Azande) or pastoralism.

10.2. Arts and music

South Sudan's artistic expressions are diverse and vibrant.

- Music:** Traditional music is integral to ceremonies, storytelling, and daily life, often featuring drums, stringed instruments (like the thom or lyre), and call-and-response vocals. Contemporary South Sudanese music is a fusion of traditional rhythms with genres like Afro-beat, R&B, Zouk, reggae, and hip-hop. Many artists sing in English, Swahili, Juba Arabic, their native languages, or a mix. Popular artists include Barbz, Yaba Angelosi, De Peace Child, and Emmanuel Kembe. Emmanuel Jal, a former child soldier turned musician, has gained international recognition for his hip-hop music with positive messages. Other hip-hop artists include FTG Metro, Flizzame, and Dugga Mulla. Dynamq is known for reggae.

- Dance:** Traditional dances are numerous and vary by ethnic group, often performed during social gatherings, celebrations, and rituals. They are typically energetic and involve intricate footwork and body movements.

- Oral Literature:** Storytelling, poetry, and proverbs form a rich oral literary tradition.

Traditional crafts include pottery, basket weaving, beadwork, and wood carving, often with symbolic meanings.

10.3. Sports

Both traditional and modern sports are popular in South Sudan.

- Traditional Sports:** Wrestling is a particularly popular traditional sport, especially among Dinka and Nuer communities. Matches often take place after harvest seasons and attract large crowds, accompanied by singing, drumming, and dancing. Mock battles are also part of traditional festivities.

- Modern Sports:**

- Football (Soccer): Football is widely followed and played. The South Sudan national football team became a member of the Confederation of African Football (CAF) in February 2012 and FIFA in May 2012. The country has a national football championship. Notable footballers with South Sudanese heritage include Machop Chol, James Moga, and Richard Justin.

- Basketball: Basketball has gained significant popularity, partly due to the success of players of South Sudanese origin in international leagues, most notably Luol Deng (who represented Great Britain internationally and played in the NBA) and the late Manute Bol. Other prominent players include Wenyen Gabriel and Thon Maker. The South Sudan national basketball team has achieved remarkable success recently, qualifying for the FIBA Basketball World Cup in 2023 and AfroBasket 2021 (finishing 7th).

- Olympics:** South Sudan first competed in the Olympics as an independent nation at the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, sending athletes in track and field. Guor Marial, a marathon runner, competed as an Independent Olympic Athlete at the 2012 London Olympics before South Sudan had an official Olympic committee.

Initiatives like the South Sudan Youth Sports Association (SSYSA) work to promote sports among youth.

10.4. Media

The media landscape in South Sudan includes print, broadcast (radio and television), and online outlets. Radio is the most widespread medium, particularly in rural areas, with numerous local and international stations broadcasting. Television access is more limited, mainly in urban centers like Juba. Several newspapers operate, such as The Citizen, but face challenges with distribution and readership due to low literacy rates and infrastructure issues. Online news websites and blogs have emerged, including South Sudan Friendship Press (established 2020) and Nile citizens.

However, media freedom is severely curtailed. Journalists and media houses frequently face intimidation, harassment, censorship, arbitrary arrests, and violence from state security forces, particularly the National Security Service (NSS). Former Information Minister Barnaba Marial Benjamin had vowed respect for press freedom, but realities have often been different. The lack of a formal media law for a period and the government's sensitivity to criticism have created a difficult operating environment.

On November 1, 2011, the editor of the Juba-based daily Destiny was arrested and its activities suspended over an opinion article critical of the president. The Committee to Protect Journalists has repeatedly voiced concerns. In 2015, President Kiir controversially threatened to kill journalists who reported "against the country." This led to a 24-hour news blackout by South Sudanese journalists after the targeted killing of journalist Peter Moi, the seventh journalist killed that year. In August 2017, American freelance journalist Christopher Allen was killed in Kaya during fighting. The government has also blocked access to critical news websites and blogs like Sudan Tribune and Radio Tamazuj. This restrictive environment has led to widespread self-censorship and the exodus of many journalists.