1. Overview

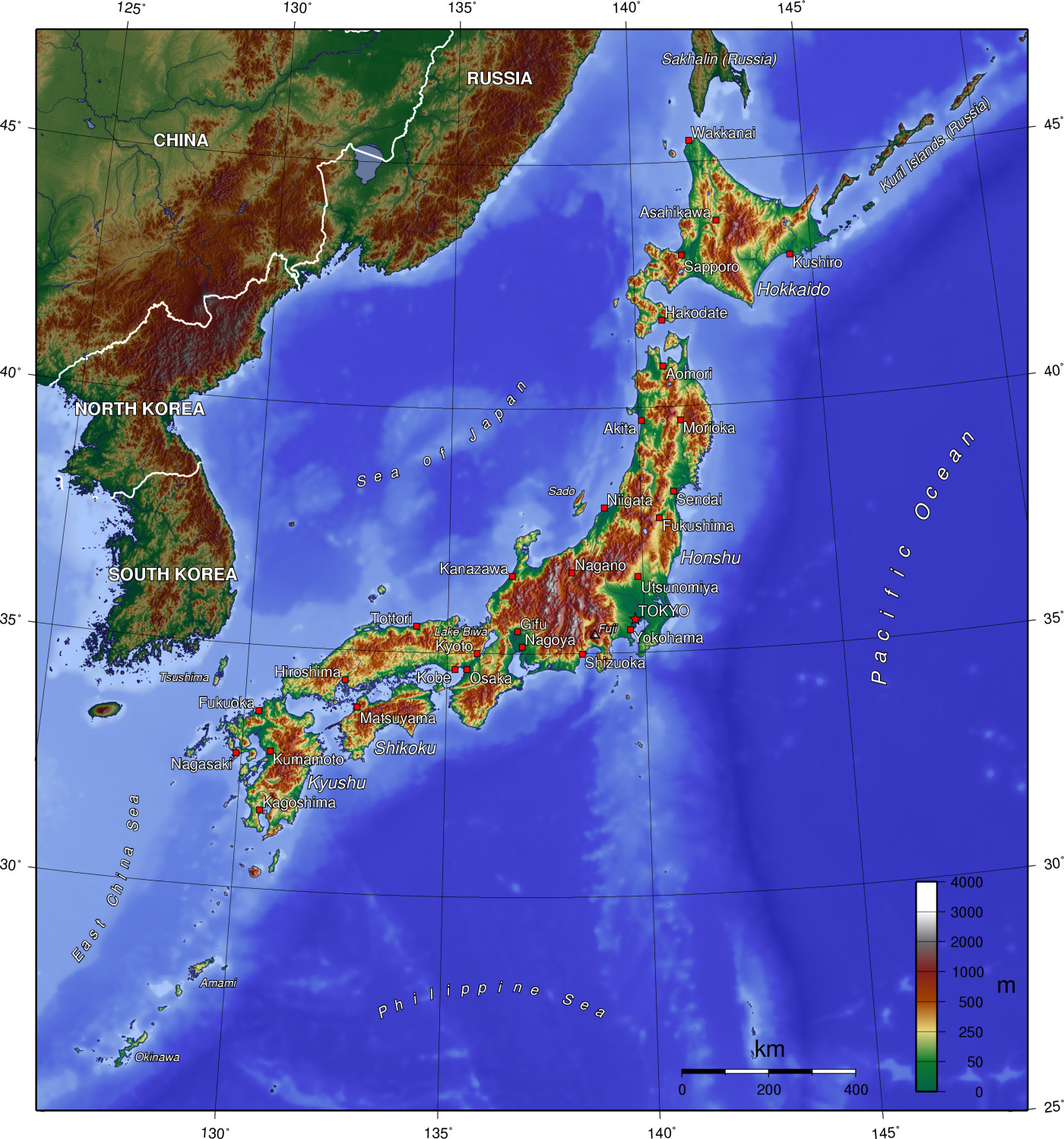

Japan, an island country in East Asia, is characterized by its unique blend of ancient traditions and cutting-edge modernity. Geographically, it is an archipelago comprising thousands of islands, with four main islands-Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu-forming the core of its landmass. The country's terrain is largely mountainous and forested, leading to a high concentration of its population in urban coastal plains, most notably the Greater Tokyo Area, the world's largest metropolitan area. Situated on the Pacific Ring of Fire, Japan is frequently subject to earthquakes and tsunamis.

Historically, Japan's development has seen periods of unification under an emperor, feudal rule by military dictators (shogun) and warrior nobility (samurai), and a period of isolation followed by rapid modernization during the Meiji Restoration. The 20th century witnessed Japan's rise as an imperial power, its involvement and defeat in World War II, and subsequent transformation into a pacifist democracy with a thriving economy.

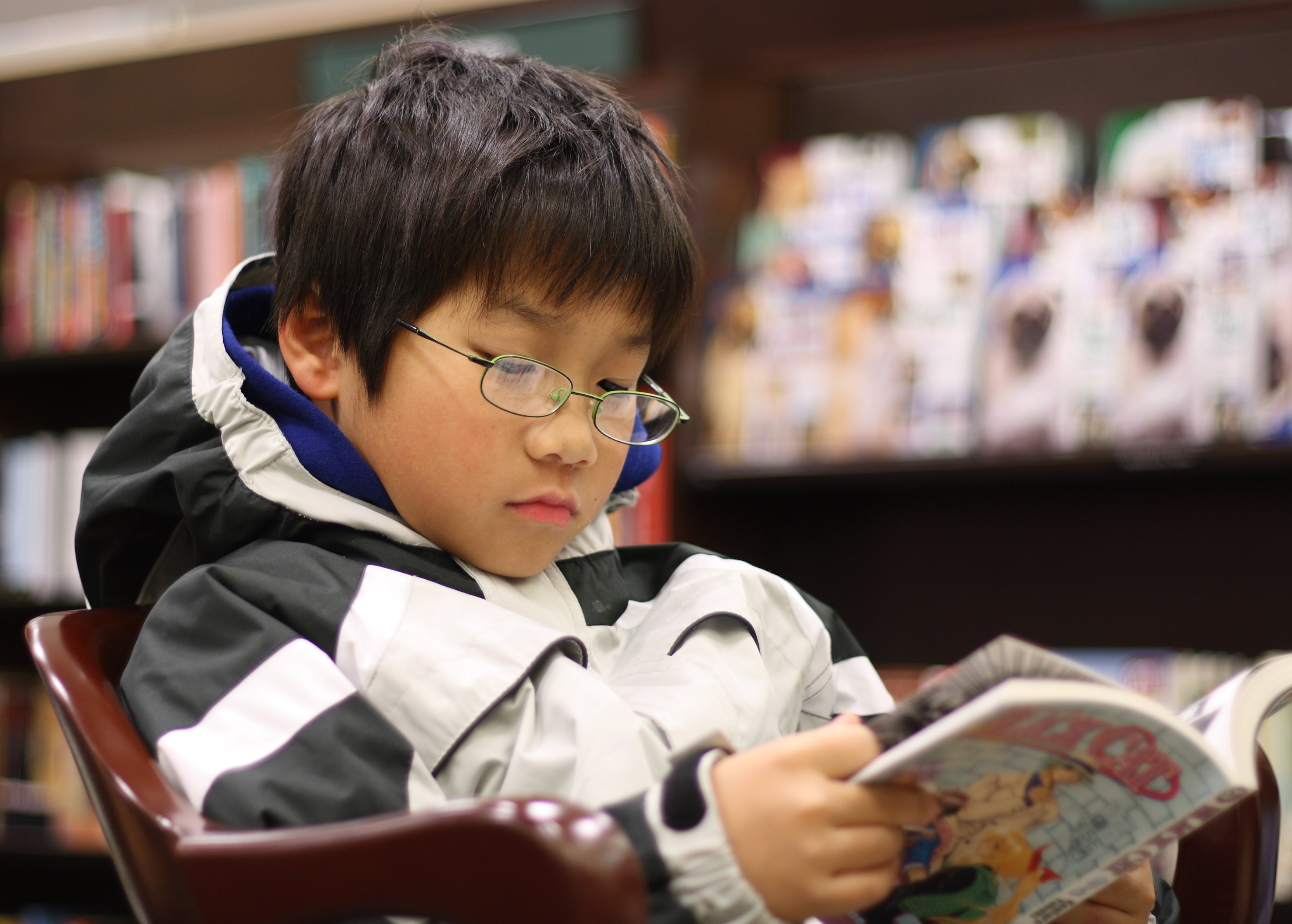

Culturally, Japan is renowned worldwide for its distinct art forms, cuisine, cinema, music, and popular culture, including anime, manga, and video games. Societally, Japan is grappling with challenges such as an aging population and low birthrate, which have significant implications for its workforce and social welfare systems. The country's political system is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary government.

This article analyzes Japan from a center-left/social liberalism perspective, emphasizing its societal dynamics, the evolution of its democratic institutions, and human rights aspects, alongside its significant economic and technological achievements. It aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of Japan's complex identity, from its historical roots to its contemporary societal fabric and its role in the global community, paying particular attention to issues of social equity, environmental sustainability, and the rights and inclusion of all its residents, including minorities and marginalized groups.

2. Etymology

The name for Japan in the Japanese is written using kanji as 日本Japanese and is pronounced 日本NihonJapanese or 日本NipponJapanese. Formally, it is 日本国Nihon-kokuJapanese or 日本国Nippon-kokuJapanese, meaning "State of Japan," as it appears on official documents including the country's constitution. The shorter name 日本Japanese is also often used officially.

Before 日本Japanese was adopted in the early 8th century, the country was known in China as 倭WaChinese (changed in Japan around 757 to 和WaJapanese) and in Japan by the endonym 大和YamatoJapanese. The pronunciation "Nippon" is the original Sino-Japanese reading of the characters and is favored for official uses, such as on Japanese banknotes and postage stamps. "Nihon" is typically used in everyday speech and reflects shifts in Japanese phonology during the Edo period. The characters 日本Japanese mean "sun origin," which is the source of the popular Western epithet "Land of the Rising Sun." This name is mentioned in correspondence between the Japanese Imperial court and the Sui dynasty of China and refers to Japan's location east of the Chinese mainland.

The English word "Japan" is based on Min or Wu Chinese pronunciations of 日本Japanese and was introduced to European languages through early trade. In the 13th century, Marco Polo recorded the Early Mandarin Chinese pronunciation of the characters 日本國Chinese as CipanguCipangucmn. The old Malay name for Japan, JapangMalay or JapunMalay, was borrowed from a southern coastal Chinese dialect and encountered by Portuguese traders in Southeast Asia. They brought the word to Europe in the early 16th century. The first version of the name in English appeared in a book published in 1577, which spelled the name as Giapan in a translation of a 1565 Portuguese letter.

3. History

Japanese history encompasses its prehistoric origins and classical development, followed by a long feudal era dominated by warrior rule, and a modern period of rapid transformation, imperial expansion, and post-war democratization, each with significant societal impacts.

3.1. Prehistory and classical antiquity

Modern humans are believed to have arrived in the Japanese archipelago around 38,000 years ago (circa 36,000 BCE), marking the beginning of the Japanese Paleolithic period. This era was followed by the Jōmon period, starting around 14,500 BCE, characterized by a Mesolithic to Neolithic semi-sedentary hunter-gatherer culture. The Jōmon people developed pit dwellings, rudimentary agriculture, and created some of the world's oldest known pottery.

Around 300 BCE, the Yayoi period began with the arrival of the Yayoi people, who are thought to have migrated from the Korean Peninsula. They introduced new technologies such as wet-rice farming, a new style of pottery, and metallurgy (iron and bronze working) from China and Korea, intermingling with the indigenous Jōmon population. This period saw the formation of numerous small states or "kuni."

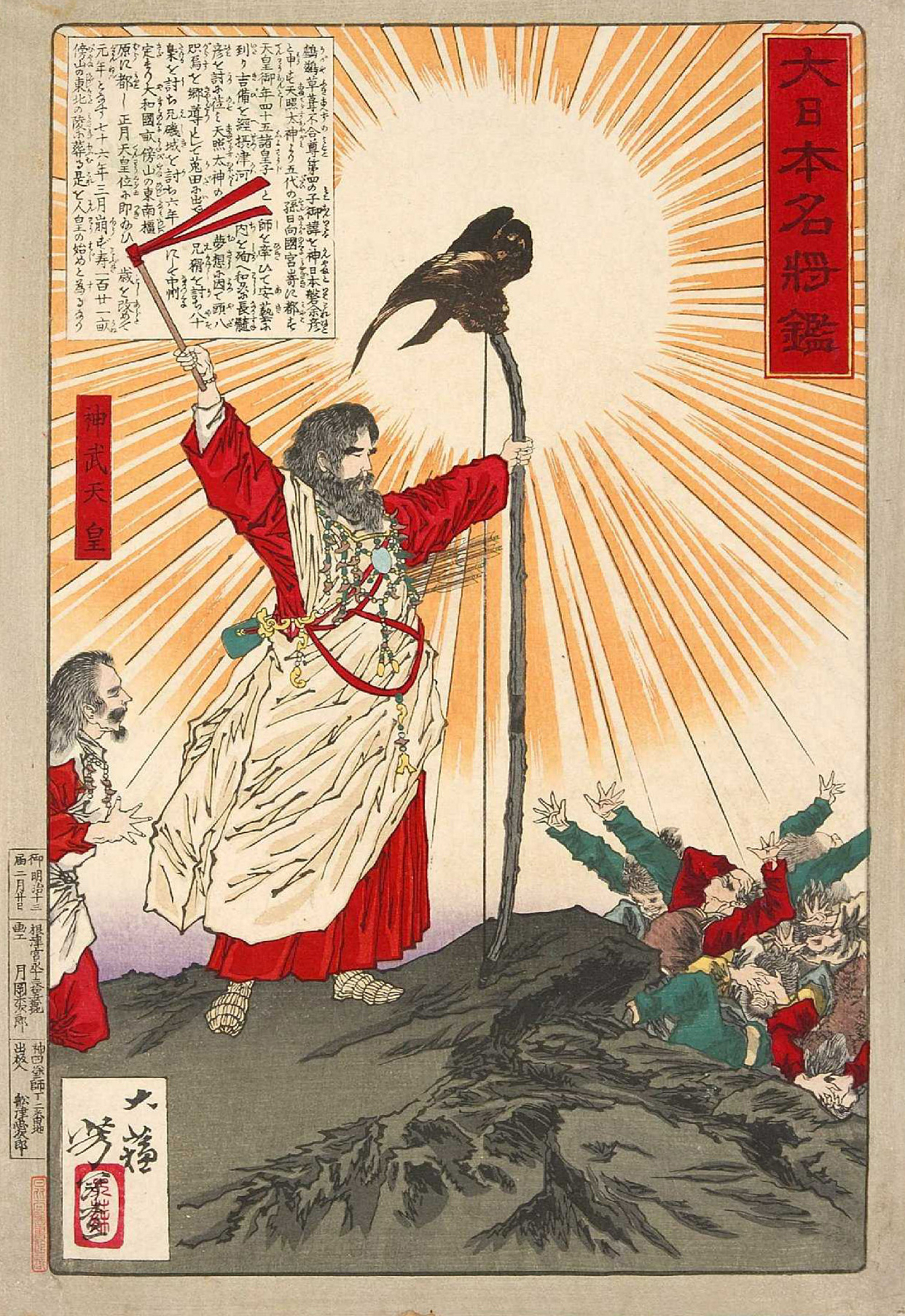

The Kofun period (circa 250 CE - 538 CE) is named after the large burial mounds (kofun) constructed for the ruling elite. During this time, the Yamato polity (also known as the Yamato kingdom) emerged in central Japan, gradually consolidating power and laying the foundations for an early Japanese state. According to legend, Emperor Jimmu, a descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu, founded this kingdom in 660 BCE, initiating the continuous imperial line. Japan first appears in written history in the Chinese Book of Han, completed in 111 CE. The Chinese Records of the Three Kingdoms mentions Yamatai, a powerful country in the archipelago during the 3rd century ruled by Queen Himiko.

From the 5th and 6th centuries, Buddhism was introduced to Japan from the Korean kingdom of Baekje, along with the Chinese writing system and other aspects of Chinese culture. Despite initial resistance from those adhering to native Shinto beliefs, Buddhism was promoted by the ruling class, including figures like Prince Shōtoku, and gained widespread acceptance starting in the Asuka period (592-710). This period also saw significant political and administrative reforms influenced by Chinese models. In 645 CE, the Taika Reforms, led by Prince Naka no Ōe and Fujiwara no Kamatari, aimed to centralize the state by nationalizing land and establishing a new taxation system based on household registries, inspired by Confucian ideas. These reforms culminated in the Taihō Code of 701 CE, which established a system of centralized government (the ritsuryō state) that would last for centuries. The Jinshin War of 672 was a critical conflict that further spurred these administrative reforms.

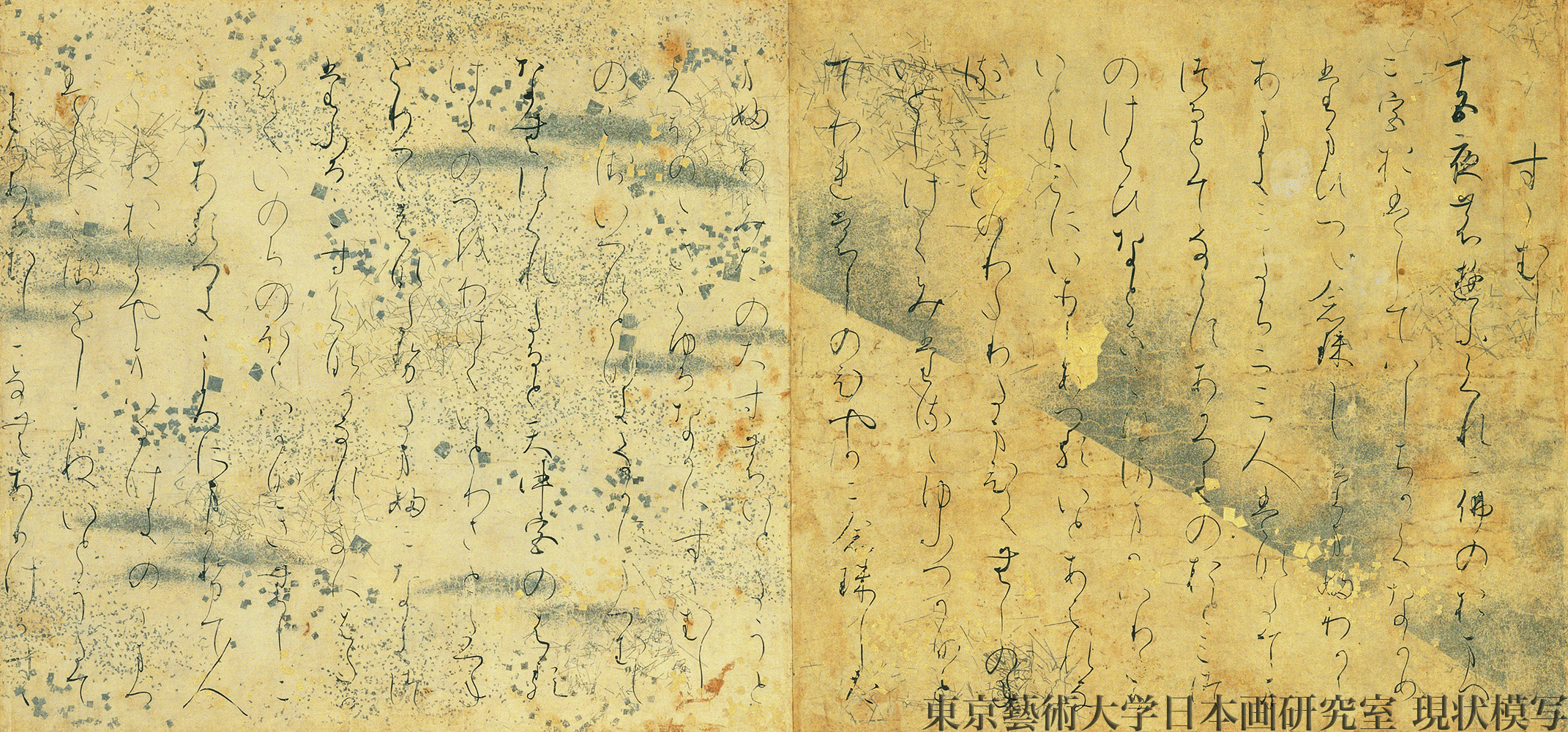

The Nara period (710-784) marked the emergence of a strong Japanese state centered on the Imperial Court in Heijō-kyō (modern Nara). This era is characterized by the flourishing of literary culture with the completion of the Kojiki (712) and Nihon Shoki (720), as well as the development of Buddhist-inspired artwork and architecture. A smallpox epidemic in 735-737 is believed to have killed as much as one-third of Japan's population. In 784, Emperor Kanmu moved the capital, eventually settling on Heian-kyō (modern-day Kyoto) in 794. This marked the beginning of the Heian period (794-1185), during which a distinctly indigenous Japanese culture emerged, particularly in literature, art, and poetry. Works such as Murasaki Shikibu's The Tale of Genji and the lyrics of Japan's national anthem, "Kimigayo," were written during this time. However, the centralized ritsuryō system gradually weakened as powerful aristocratic families, particularly the Fujiwara clan, gained influence and large, tax-exempt private estates (shōen) developed, undermining imperial authority.

3.2. Feudal era

Japan's feudal era, lasting from the late 12th century to the mid-19th century, was characterized by the dominance of a ruling class of warriors, the samurai, and the establishment of military governments known as shogunates. This system had a profound impact on social structures, with power largely decentralized among feudal lords.

The Kamakura period (1185-1333) began after Minamoto no Yoritomo defeated the Taira clan in the Genpei War (1180-1185). Yoritomo established a military government, the Kamakura shogunate, in Kamakura. While the Emperor remained the nominal ruler in Kyoto, actual political power was wielded by the shogun. After Yoritomo's death, the Hōjō clan effectively controlled the shogunate as regents (shikken). During this period, Zen Buddhism was introduced from China and became popular among the samurai. The Kamakura shogunate successfully repelled two Mongol invasions in 1274 and 1281, but the costs of defense weakened the shogunate, leading to its overthrow by Emperor Go-Daigo in the Kenmu Restoration (1333-1336).

Go-Daigo's attempt to restore direct imperial rule was short-lived. Ashikaga Takauji, a powerful samurai general, turned against Go-Daigo and established the Ashikaga shogunate (also known as the Muromachi shogunate) in Kyoto in 1336, which lasted until 1573. The early Muromachi period was marked by conflict between rival imperial courts (the Northern and Southern Courts), which ended in 1392. While the Ashikaga shoguns patronized arts and culture, including the development of Noh theater and the tea ceremony, their control over the regional feudal lords (daimyo) gradually weakened. The Ōnin War (1467-1477), a devastating civil war, marked the breakdown of central authority and ushered in the Sengoku period (c. 1467 - c. 1600), an era of intense internal warfare and social upheaval as daimyo vied for power. This period also saw the arrival of the first Europeans-Portuguese traders and Jesuit missionaries-in the mid-16th century, introducing firearms and Christianity.

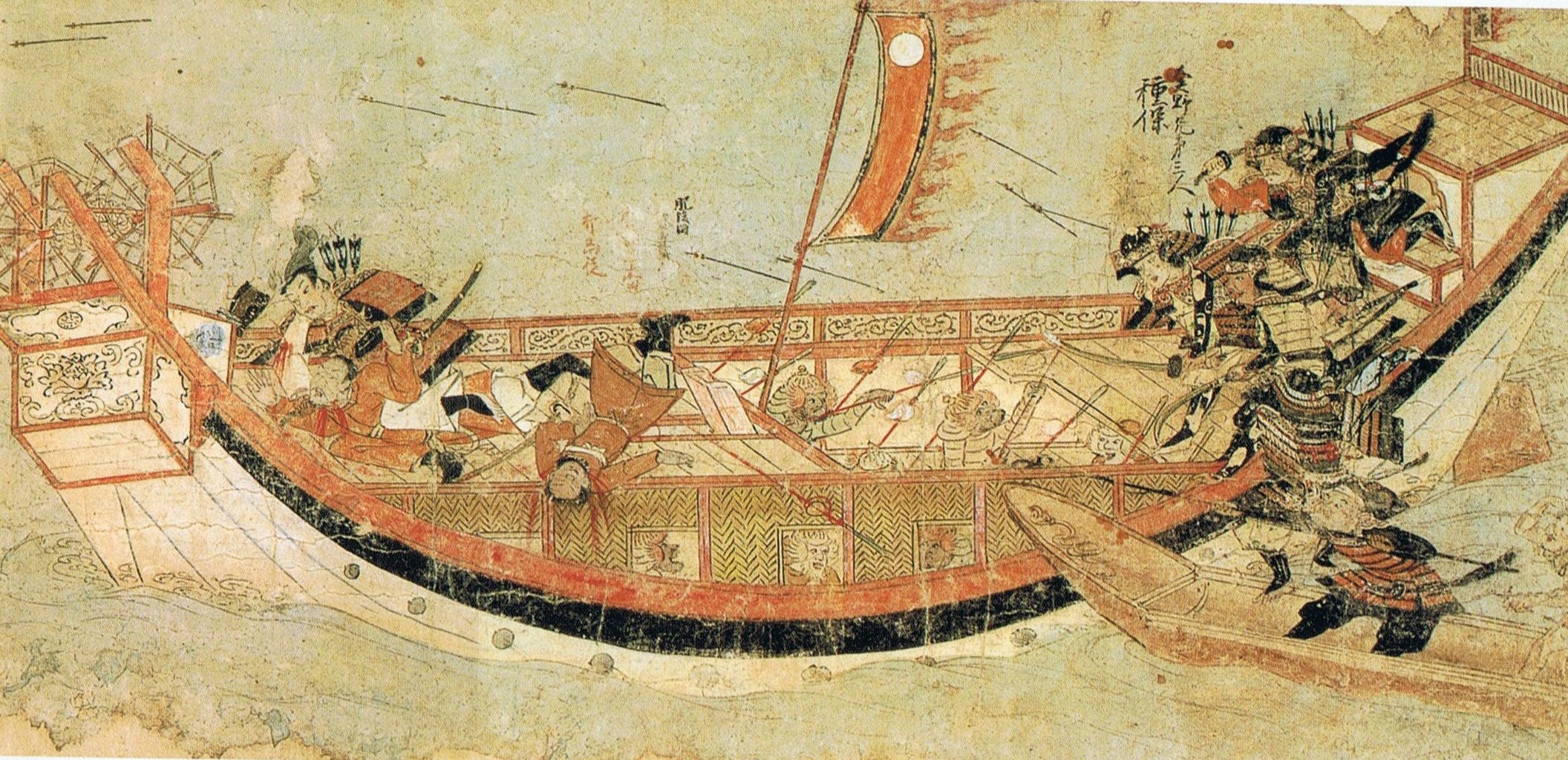

The late Sengoku period saw the emergence of powerful daimyo who sought to unify Japan. Oda Nobunaga made significant progress in conquering rival daimyo using European firearms and innovative tactics, beginning the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573-1603). After Nobunaga's assassination in 1582, his successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, completed the unification of Japan in the early 1590s. Hideyoshi implemented land surveys (kenchi) and disarmed the peasantry (katanagari), solidifying the feudal social order. He also launched two unsuccessful invasions of Korea in 1592 and 1597.

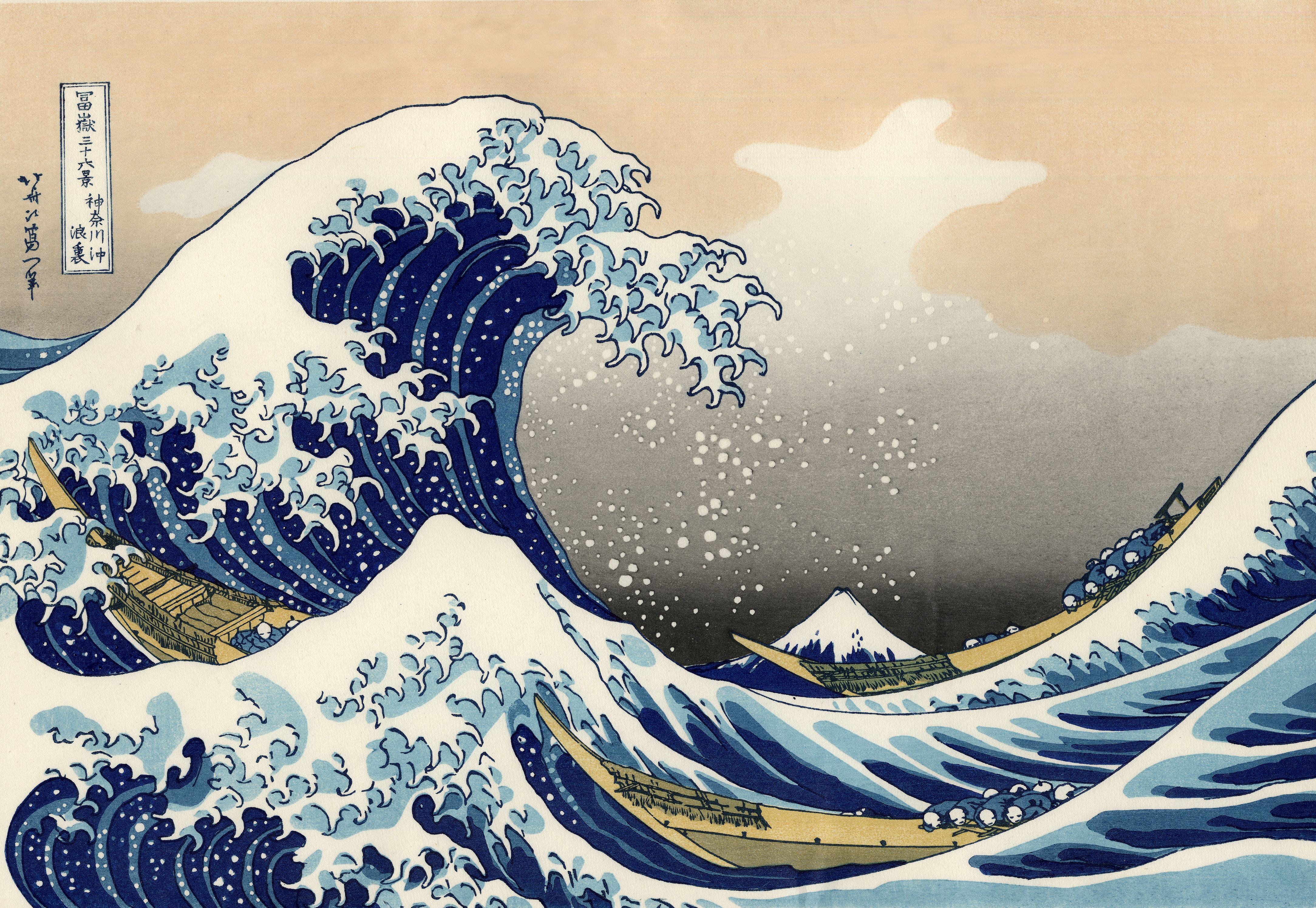

Following Hideyoshi's death in 1598, Tokugawa Ieyasu emerged victorious from the ensuing power struggle, notably at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600. In 1603, Ieyasu was appointed shogun by the emperor and established the Tokugawa shogunate in Edo (modern Tokyo). The Edo period (1603-1868) brought over two centuries of relative peace and stability. The Tokugawa shogunate implemented a strict social hierarchy and controlled the daimyo through policies like sankin-kōtai (alternate attendance). A key policy was sakoku ("closed country"), which severely restricted foreign relations and trade from the 1630s, primarily allowing contact only with the Dutch through the port of Dejima in Nagasaki and with China and Korea. This isolationist policy aimed to prevent foreign influence and maintain social order. Despite isolation, domestic trade, agriculture, and urban culture flourished. A vibrant merchant class emerged, and arts like ukiyo-e (woodblock prints) and kabuki theater became popular. The study of Western sciences (rangaku) continued through Dutch sources, and indigenous scholarship (kokugaku) also developed. However, the feudal system imposed rigid social structures that limited individual mobility and rights for much of the populace.

3.3. Modern era

Japan's modern era began in the mid-19th century with the forced end of its isolationist policy and the subsequent overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate, leading to the Meiji Restoration. This period was characterized by rapid modernization, industrialization, and the rise of Japan as an imperial power. However, it also involved significant social upheaval, the suppression of dissent, and eventually, devastating involvement in World War II. The post-war era saw Japan's transformation into a democratic nation and an economic powerhouse, alongside ongoing efforts to address its wartime past and promote human rights.

In 1853, Commodore Matthew C. Perry of the United States Navy arrived with a fleet of "Black Ships" and compelled Japan to open to foreign trade, leading to the Convention of Kanagawa in 1854. Subsequent treaties with other Western powers further exposed the shogunate's weakness and fueled anti-foreign sentiment and calls for political change. Dissatisfied samurai from domains like Chōshū and Satsuma led a movement to "revere the Emperor and expel the barbarians" (Sonnō jōi). This culminated in the Boshin War (1868-1869), the resignation of the last shogun, and the restoration of direct imperial rule under Emperor Meiji in 1868.

The Meiji period (1868-1912) was a time of transformative change. The new government embarked on a program of rapid modernization, adopting Western political, judicial, military, and industrial models. Feudal domains were abolished and replaced with prefectures (Abolition of the han system). A national army was created, and a modern education system was established. The Meiji Constitution was promulgated in 1889, establishing a constitutional monarchy with a bicameral legislature, the Imperial Diet. Industrialization progressed swiftly, with the development of railways, telegraph lines, and new industries. However, this rapid change also brought social tensions, harsh working conditions for many, and the suppression of early labor movements and political dissent. Japan also pursued imperial expansion, defeating China in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) and Russia in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), gaining control of Taiwan, Korea (annexed in 1910), and southern Sakhalin. This expansion was often achieved through military force and resulted in the colonization and oppression of local populations.

The Taishō period (1912-1926) saw a brief flourishing of democratic movements, known as "Taishō democracy." However, this period was also marked by economic instability, social unrest, and the rise of militarism and ultranationalism. Japan joined the Allies in World War I and expanded its influence in China and the Pacific. The Great Kantō earthquake of 1923 devastated Tokyo and led to massacres of Koreans and leftists amidst widespread panic. In the 1930s, during the early Shōwa period, military factions increasingly dominated the government. Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931, establishing the puppet state of Manchukuo, and withdrew from the League of Nations in 1933 following international condemnation. Political assassinations and attempted coups further destabilized civilian government.

In 1937, Japan launched a full-scale invasion of China, initiating the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945). This conflict was marked by widespread atrocities, including the Nanjing Massacre. Japan's expansionist ambitions led it to sign the Tripartite Pact with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy in 1940, forming the Axis powers. In 1941, after the U.S. imposed an oil embargo, Japan launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, bringing the United States into World War II. Japan achieved rapid military successes in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. However, the tide turned against Japan following the Battle of Midway in 1942. The war inflicted immense suffering on both Japanese civilians and the populations of occupied territories, where millions were subjected to forced labor, exploitation, and violence, including the systematic use of "comfort women" (sex slaves). After years of brutal fighting and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the U.S. in August 1945, coupled with the Soviet invasion of Manchuria, Japan surrendered unconditionally on August 15, 1945.

The Allied occupation, led by the United States under General Douglas MacArthur, lasted from 1945 to 1952. During this period, Japan underwent sweeping democratic reforms. A new constitution was enacted in 1947, establishing a parliamentary democracy, guaranteeing fundamental human rights, and renouncing war (Article 9). The Emperor was reduced to a symbolic role. Land reforms, the dissolution of zaibatsu (large industrial conglomerates), and the promotion of labor unions were also implemented. The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal) prosecuted Japanese leaders for war crimes, though Emperor Hirohito was not indicted, a decision that remains controversial. Millions of Japanese settlers and soldiers were repatriated from former colonies.

After the occupation ended with the Treaty of San Francisco in 1952, Japan focused on economic reconstruction. Aided by U.S. support and global economic expansion, Japan experienced a period of remarkable economic growth known as the Japanese economic miracle, becoming the world's second-largest economy by the late 1960s. This era saw significant improvements in living standards but also environmental pollution problems. Japan rejoined the international community, becoming a member of the United Nations in 1956. The 1964 Tokyo Olympics symbolized its post-war recovery.

The late 20th century saw Japan solidify its status as an economic superpower, though the bursting of an asset price bubble in the early 1990s led to a prolonged period of economic stagnation known as the "Lost Decade." Socially, Japan continued to grapple with issues of gender equality, the rights of minorities like the Ainu and Koreans in Japan, and the implications of its aging population. Politically, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) dominated for most of the post-war period. In 2011, Japan was struck by the devastating Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, which triggered the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, prompting a national debate on nuclear energy and disaster preparedness. On May 1, 2019, Emperor Akihito abdicated, and his son Naruhito ascended the Chrysanthemum Throne, beginning the Reiwa era. Japan continues to navigate complex domestic challenges and its role in an evolving East Asian and global landscape, with ongoing discussions about constitutional reform, historical memory, and the promotion of a more inclusive and rights-respecting society.

4. Geography

Japan is an island country situated in East Asia, in the Pacific Ocean. It lies off the northeast coast of the Asian mainland, bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan (also known as the East Sea) and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and the Philippine Sea in the south. The territory of Japan comprises approximately 14,125 islands, which stretch over 1.9 K mile (3.00 K km) from northeast to southwest. The five main islands, from north to south, are Hokkaido, Honshu (the largest island), Shikoku, Kyushu, and Okinawa. The Ryukyu Islands, including Okinawa, form a chain south of Kyushu, while the Nanpō Islands are located south and east of the main islands. Collectively, these islands form the Japanese archipelago.

Japan's total land area is approximately 377.98 K abbr=on. It has the sixth-longest coastline in the world, measuring about 29.75 K abbr=on. Due to its numerous outlying islands, Japan possesses the eighth-largest exclusive economic zone (EEZ) globally, covering around 4.47 M abbr=on.

The country is characterized by its rugged, mountainous terrain, with about 70-80% of the land consisting of mountains and forests. This topography limits the area suitable for agriculture, industry, and dense human settlement, concentrating the population largely in coastal plains. The habitable zones, therefore, have very high population densities. Japan is located on the Pacific Ring of Fire at the convergence of several tectonic plates, including the Pacific, Philippine Sea, Okhotsk, and Eurasian (Amurian) plates. This geological setting makes Japan highly prone to earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions. The country has 111 active volcanoes.

4.1. Topography

Japan's topography is predominantly mountainous, with mountains covering approximately 75% of its land area. These mountain ranges are typically steep and heavily forested. The most prominent mountain ranges are the Japanese Alps (Nihon Arupusu), located in central Honshu, which consist of the Hida Mountains (Northern Alps), Kiso Mountains (Central Alps), and Akaishi Mountains (Southern Alps). Many peaks in the Japanese Alps exceed 9.8 K ft (3.00 K m) in elevation. The highest peak in Japan is Mount Fuji, an active stratovolcano located on Honshu island, southwest of Tokyo, with an elevation of 12 K ft (3.78 K m). Mount Fuji is an iconic symbol of Japan and a major tourist attraction. Other significant volcanoes include Mount Ontake, Mount Aso, and Sakurajima.

Plains in Japan are relatively small and scattered, mostly found along the coastlines or in river valleys. The largest plain is the Kantō Plain on Honshu, where Tokyo is situated. Other notable plains include the Nōbi Plain (around Nagoya), the Osaka Plain, and the Ishikari Plain in Hokkaido. These plains are the primary areas for agriculture, industry, and urban development.

Japan's coastlines are long and varied. The Pacific coast is generally more indented, featuring numerous bays, inlets, and peninsulas, forming complex ria coastlines. The Sea of Japan coast tends to be straighter. The Seto Inland Sea, situated between Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu, is a shallow body of water dotted with many small islands.

The formation of the Japanese archipelago is a result of complex tectonic processes. The islands are part of several volcanic arcs formed by the subduction of the Pacific Plate and the Philippine Sea Plate beneath the Eurasian and North American (Okhotsk) plates. The Fossa Magna, a major geological rift valley, transects central Honshu, dividing Japan geologically into Northeast Japan and Southwest Japan. The Median Tectonic Line is another significant fault system running through southwestern Japan. These geological features contribute to the country's seismic activity and the abundance of onsen (hot springs). Lake Biwa, located in Shiga Prefecture, is Japan's largest freshwater lake and an ancient lake, formed by tectonic activity.

4.2. Climate

The climate of Japan is predominantly temperate but varies greatly from north to south due to its considerable latitudinal extent and diverse topography. The country experiences four distinct seasons: spring, summer, autumn, and winter.

- Hokkaido (Northern Region):** This region has a humid continental climate characterized by long, cold, and snowy winters, and warm to cool summers. Precipitation is not excessively heavy, but the island often sees deep snowbanks in winter.

- Sea of Japan Coast (Western Honshu):** Northwest winter winds crossing the Sea of Japan bring heavy snowfall to this region during winter. Summers can be hot, and the area sometimes experiences extremely high temperatures due to the Foehn effect.

- Central Highland (Inland Honshu):** This area has a typical inland humid continental climate with significant temperature differences between summer and winter, as well as between day and night.

- Seto Inland Sea Region (Chūgoku and Shikoku coasts):** The mountains of the Chūgoku and Shikoku regions shelter this area from seasonal winds, resulting in mild weather throughout the year with relatively low precipitation.

- Pacific Coast (Eastern and Southern Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu):** This region features a humid subtropical climate with milder winters (occasional snowfall) and hot, humid summers influenced by the southeast seasonal wind.

- Ryukyu and Nanpō Islands (Southwestern Islands):** These islands have a subtropical climate and tropical rainforest climate (in parts of the Ryukyus like Ishigaki Island), with warm winters and hot summers. Precipitation is very heavy, especially during the rainy season. Typhoons are common in this region.

The main rainy season (tsuyu or baiu) typically begins in early May in Okinawa and gradually moves north, reaching most of Honshu in June and lasting for about six weeks. It generally does not affect Hokkaido. Late summer and early autumn (August to October) are prone to typhoons, which often bring heavy rain and strong winds, particularly to the southern and western parts of the country.

Temperatures vary significantly. The highest temperature ever recorded in Japan was 105.98 °F (41.1 °C), observed in Kumagaya (Saitama Prefecture) on July 23, 2018, and later in Hamamatsu (Shizuoka Prefecture) on August 17, 2020. Winters can be very cold in the north and in mountainous areas, with temperatures dropping well below freezing. Climate change impacts, such as increased frequency of heavy rainfall and rising temperatures, are causing concerns for agriculture and other sectors in Japan.

4.3. Biodiversity

Japan boasts a rich and diverse range of flora and fauna, a result of its varied climate zones, complex topography, and island geography, which has led to a high degree of endemism. The country is recognized as one of the world's 36 biodiversity hotspots. As of 2019, over 90,000 species of wildlife have been recorded in Japan, with around 6,342 of these being endemic.

Japan has nine distinct forest ecoregions. These range from tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests in the Ryūkyū and Bonin Islands (Ogasawara Islands) to temperate broadleaf and mixed forests in the milder climate regions of the main islands, and temperate coniferous forests in the colder, northern parts of Hokkaido and mountainous areas of Honshu. Approximately 67% of Japan's land area is covered by forests.

Notable endemic or characteristic fauna include the brown bear (Ursus arctos yesoensis in Hokkaido, and the Asiatic black bear, Ursus thibetanus japonicus, in Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu), the Japanese macaque (Macaca fuscata, also known as the snow monkey), the Japanese raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides viverrinus or tanuki), the small Japanese field mouse (Apodemus argenteus), the Japanese serow (Capricornis crispus), and the Japanese giant salamander (Andrias japonicus), one of the largest amphibians in the world. Japan is also home to a variety of bird species, including the Blakiston's fish owl, copper pheasant, and the Japanese crane.

The flora is equally diverse, with approximately 5,560 species of vascular plants. Endemic plants include species like the Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica or sugi) and various types of cherry blossom (sakura) trees, which hold significant cultural importance.

To protect its biodiversity, Japan has established numerous protected areas, including national parks, quasi-national parks, and wildlife protection areas. There are 53 Ramsar wetland sites in Japan, recognized for their international importance for waterfowl and wetland ecosystems. Additionally, five sites have been inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List for their outstanding natural value: Yakushima, Shirakami-Sanchi, Shiretoko, the Ogasawara Islands, and Amami-Oshima Island, Tokunoshima Island, northern part of Okinawa Island, and Iriomote Island.

Despite these conservation efforts, Japan's biodiversity faces threats from habitat loss due to development, deforestation and afforestation with single species, the decline of traditional rural landscapes (satoyama), and the impact of invasive alien species. The importance of biodiversity for environmental and social well-being is increasingly recognized, with ongoing efforts to promote sustainable use of natural resources and conservation.

4.4. Environmental issues

Japan faces several significant environmental challenges, stemming from its high population density, industrial activities, and vulnerability to natural disasters, which are exacerbated by climate change. Historically, during the period of rapid economic growth after World War II (1950s-1960s), environmental protection was often secondary to industrial development, leading to severe pollution problems, famously exemplified by the Four Big Pollution Diseases (Minamata disease, Niigata Minamata disease, Itai-itai disease, and Yokkaichi asthma).

Public concern and activism led to the enactment of comprehensive environmental protection laws in 1970 and the establishment of the Environment Agency (now the Ministry of the Environment) in 1971. The oil crisis of 1973 also spurred efforts towards energy efficiency due to Japan's reliance on imported energy resources.

Current major environmental issues include:

- Air pollution:** Urban areas, particularly large metropolitan regions, still struggle with air pollution from vehicle emissions and industrial activities, including nitrogen oxides (NOx), particulate matter, and toxics.

- Waste management:** As a densely populated and highly consumerist society, Japan generates a large volume of waste. Efforts are focused on reducing waste, promoting recycling (3R initiative - Reduce, Reuse, Recycle), and developing advanced waste treatment technologies, including incineration with energy recovery. However, issues with plastic waste and illegal dumping persist.

- Water pollution and eutrophication:** While industrial water pollution has significantly decreased, eutrophication of enclosed water bodies like lakes and bays due to nutrient runoff from agriculture and domestic wastewater remains a concern.

- Climate change:** Japan is the world's fifth-largest emitter of carbon dioxide. It is a signatory to the Kyoto Protocol (hosting the 1997 conference) and the Paris Agreement. The government announced a target of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. Key challenges include transitioning to renewable energy sources, reducing reliance on fossil fuels (especially coal), and adapting to the impacts of climate change, such as increased frequency of extreme weather events. The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011 also significantly impacted its energy policy and public debate on nuclear power.

- Loss of biodiversity and nature conservation:** Habitat destruction, fragmentation due to development, and the impact of invasive alien species threaten Japan's rich biodiversity. Conservation of natural ecosystems, forests, and marine environments is ongoing.

- Chemical management:** Control and management of hazardous chemical substances from industrial processes and consumer products are important for public health and environmental safety.

- International cooperation:** Japan actively participates in international environmental cooperation, providing technical assistance and funding for environmental projects in developing countries.

Japan ranked 20th in the 2018 Environmental Performance Index. Environmental policies aim to balance economic development with environmental sustainability, with increasing emphasis on creating a circular economy and addressing global environmental problems. However, the social and equitable implications of these policies, such as the impact on local communities or the fair distribution of environmental burdens and benefits, are also important considerations from a social liberal perspective.

5. Politics and government

Japan is a unitary state and a constitutional monarchy where the Emperor serves as a ceremonial head of state, a "symbol of the State and of the unity of the people," whose powers are strictly limited by the constitution. Sovereignty is vested in the Japanese people. The political system is a parliamentary democracy based on the principle of separation of powers among the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. Japan's system encourages citizen participation through elections and various civic activities, although challenges remain in ensuring broad and equitable engagement across all segments of society.

5.1. Government structure

The government of Japan operates under the framework established by the 1947 Constitution. This structure comprises the Emperor as the symbolic head of state, and three distinct branches of government: the legislative (National Diet), the executive (Cabinet), and the judicial (Courts), ensuring a system of checks and balances.

5.1.1. Emperor

The Emperor of Japan (天皇TennōJapanese) is the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people, as defined in Article 1 of the Constitution. The Emperor performs ceremonial duties as stipulated by the Constitution, such as appointing the Prime Minister (as designated by the Diet) and the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court (as designated by the Cabinet), convoking the Diet, and promulgating laws and treaties. However, the Emperor does not possess any powers related to government; all acts of the Emperor in matters of state require the advice and approval of the Cabinet.

The current Emperor is Naruhito, who ascended to the Chrysanthemum Throne on May 1, 2019, following the abdication of his father, Emperor Akihito. Succession to the Chrysanthemum Throne is hereditary and currently limited to male descendants in the male line of the Imperial lineage, as stipulated by the Imperial Household Law. The role of the Emperor and the Imperial Family in modern Japan is primarily focused on public appearances, cultural preservation, and representing the nation in ceremonial contexts. The functioning and status of the Imperial system are sometimes subjects of public discussion, particularly regarding issues of succession and the role of women in the Imperial Family, reflecting broader societal debates about tradition and modernity.

5.1.2. National Diet

The National Diet (国会KokkaiJapanese) is Japan's bicameral parliament and serves as the sole law-making organ of the state. It consists of two houses: the lower House of Representatives (衆議院ShūgiinJapanese) and the upper House of Councillors (参議院SangiinJapanese).

The House of Representatives currently has 465 members who are elected for a four-year term, although the house can be dissolved earlier by the Prime Minister, leading to a general election. The House of Councillors has 245 members who serve six-year terms, with half of its members elected every three years. Universal suffrage is granted to all adult citizens aged 18 and over, and elections are conducted by secret ballot.

The Diet's primary powers include enacting laws, approving the national budget, ratifying treaties, and designating the Prime Minister. Both houses participate in the legislative process, but the House of Representatives holds precedence in several key areas. For example, if the two houses disagree on a bill, the House of Representatives can override the House of Councillors' decision with a two-thirds majority vote. Similarly, the budget and the designation of the Prime Minister are ultimately decided by the House of Representatives if there is a disagreement.

The Diet plays a crucial role in Japan's democratic governance, providing a forum for political debate, policy formation, and oversight of the executive branch. The effective functioning of the Diet, including issues of representation, transparency, and responsiveness to public concerns, is vital for maintaining a healthy democracy.

5.1.3. Cabinet

The Cabinet (内閣NaikakuJapanese) is the executive branch of the Japanese government. It is headed by the Prime Minister (内閣総理大臣Naikaku Sōri-DaijinJapanese), who is designated by the National Diet and formally appointed by the Emperor. The Prime Minister then appoints the other Ministers of State who form the Cabinet. The majority of Cabinet ministers, including the Prime Minister, must be members of the Diet.

The Cabinet is collectively responsible to the Diet. If the House of Representatives passes a no-confidence resolution or rejects a confidence resolution, the Cabinet must either resign en masse or the Prime Minister must dissolve the House of Representatives and call for a general election within ten days.

The Cabinet's main functions include:

- Administering the law faithfully; conducting affairs of state.

- Managing foreign affairs.

- Concluding treaties (with the approval of the Diet).

- Administering the civil service.

- Preparing the budget and presenting it to the Diet.

- Enacting cabinet orders (政令seireiJapanese) to execute the provisions of the Constitution and of the law.

- Deciding on general amnesties, special amnesties, commutation of punishment, reprieve, and restoration of rights.

The Cabinet, through various ministries and agencies, is responsible for the day-to-day administration of the country. The current Prime Minister of Japan is Shigeru Ishiba, who took office in October 2024. The effectiveness and accountability of the Cabinet are central to Japan's governance.

5.1.4. Judiciary

The judicial system of Japan is independent of the executive and legislative branches. It is headed by the Supreme Court (最高裁判所Saikō-SaibanshoJapanese), which has the ultimate authority in interpreting the Constitution and determining the constitutionality of any law, order, regulation, or official act.

The court system is organized into four basic tiers:

1. **Supreme Court:** The highest court in the land. It consists of a Chief Justice and 14 Associate Justices. The Chief Justice is appointed by the Emperor as designated by the Cabinet, and other justices are appointed by the Cabinet and attested by the Emperor. Appointments to the Supreme Court are reviewed by popular vote at the first general election following their appointment and then every ten years.

2. **High Courts (高等裁判所Kōtō-SaibanshoJapanese):** There are eight High Courts with territorial jurisdiction over specific regions. They primarily hear appeals from lower courts.

3. **District Courts (地方裁判所Chihō-SaibanshoJapanese):** These are the principal courts of first instance for most civil and criminal cases. There are 50 District Courts.

4. **Family Courts (家庭裁判所Katei-SaibanshoJapanese):** These courts handle domestic relations cases and juvenile delinquency cases. They are established at the same locations as District Courts.

5. **Summary Courts (簡易裁判所Kan'i-SaibanshoJapanese):** These courts handle minor civil and criminal cases. There are 438 Summary Courts.

Judges of lower courts are appointed by the Cabinet from a list of persons nominated by the Supreme Court and serve ten-year terms, with eligibility for reappointment. The judiciary plays a crucial role in upholding the rule of law, protecting human rights, and ensuring due process. Japan utilizes a lay judge system (saiban-in seido) for serious criminal trials, where citizens participate alongside professional judges in deciding verdicts and sentences. The independence and impartiality of the judiciary are fundamental to Japan's democratic system and the protection of civil liberties.

5.2. Administrative divisions

Japan is divided into 47 prefectures (都道府県to-dō-fu-kenJapanese), each overseen by an elected governor and legislature. These prefectures are the primary level of local government below the national level. The 47 prefectures consist of:

- One "metropolis" (都toJapanese): Tokyo

- One "circuit" or "territory" (道dōJapanese): Hokkaido

- Two "urban prefectures" (府fuJapanese): Osaka and Kyoto

- Forty-three "prefectures" (県kenJapanese): all others

Below the prefectural level, there are further administrative divisions into municipalities. These are primarily cities (市shiJapanese), towns (町chō or machiJapanese), and villages (村son or muraJapanese). Larger cities, known as designated cities (政令指定都市seirei shitei toshiJapanese), have greater administrative autonomy and are further subdivided into wards (区kuJapanese). Tokyo's 23 special wards (特別区tokubetsu-kuJapanese) function with a degree of autonomy similar to cities.

The local autonomy system grants prefectures and municipalities significant responsibilities in areas such as education, welfare, public works, and local policing (though the police are ultimately under national oversight). These local governments have their own elected assemblies and chief executives (governors and mayors). The system aims to promote decentralization and citizen participation in local governance, though debates continue regarding the balance of power between national and local authorities and the financial resources available to local governments.

The prefectures are often grouped into eight traditional regions, which do not have formal administrative status but are commonly used for geographical, cultural, and economic reference. These regions are:

| Region | Prefectures |

|---|---|

| Hokkaido | 1. Hokkaido |

| Tōhoku | 2. Aomori, 3. Iwate, 4. Miyagi, 5. Akita, 6. Yamagata, 7. Fukushima |

| Kantō | 8. Ibaraki, 9. Tochigi, 10. Gunma, 11. Saitama, 12. Chiba, 13. Tokyo, 14. Kanagawa |

| Chūbu | 15. Niigata, 16. Toyama, 17. Ishikawa, 18. Fukui, 19. Yamanashi, 20. Nagano, 21. Gifu, 22. Shizuoka, 23. Aichi |

| Kansai (or Kinki) | 24. Mie, 25. Shiga, 26. Kyoto, 27. Osaka, 28. Hyōgo, 29. Nara, 30. Wakayama |

| Chūgoku | 31. Tottori, 32. Shimane, 33. Okayama, 34. Hiroshima, 35. Yamaguchi |

| Shikoku | 36. Tokushima, 37. Kagawa, 38. Ehime, 39. Kōchi |

| Kyushu | 40. Fukuoka, 41. Saga, 42. Nagasaki, 43. Kumamoto, 44. Ōita, 45. Miyazaki, 46. Kagoshima, 47. Okinawa |

5.3. Foreign relations

Japan maintains an active role in the international community, with its foreign policy primarily based on multilateralism, economic diplomacy, and a strong security alliance with the United States. As a member state of the United Nations since 1956, Japan has served as a non-permanent member of the Security Council multiple times (11 times as of recent counts, the most of any UN member) and is one of the G4 nations advocating for Security Council reform, including a permanent seat for itself.

Japan is a key member of various international organizations and forums, including the G7 (Group of Seven) industrialized nations, the G20, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum, and the ASEAN Plus Three framework. It also participates in the East Asia Summit. In 2016, Japan announced its Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) vision, which frames its regional policies focusing on rule-based international order, freedom of navigation, and economic prosperity. Japan is also a member of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (the Quad), a strategic dialogue with the United States, Australia, and India, aimed at promoting a free, open, and inclusive Indo-Pacific region, often seen as a counter to China's growing influence.

A cornerstone of Japan's foreign policy is the security alliance with the United States, which has been in place since the post-World War II era. This alliance involves close economic and military cooperation, including the stationing of U.S. military forces in Japan.

Japan is also a significant contributor to international development. It was the world's fifth-largest donor of official development assistance (ODA) in 2014, and in 2023, it was the third-largest donor among Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members, providing substantial aid for humanitarian efforts, infrastructure development, and human resource capacity building globally. The humanitarian and human rights dimensions of its foreign policy are increasingly emphasized, reflecting a commitment to global peace, stability, and the well-being of individuals. Japan maintains one of the largest diplomatic networks in the world, with 251 overseas missions in 156 countries and regions as of 2024.

Despite its generally positive international engagement, Japan faces several complex bilateral relationships and territorial disputes with its neighbors, which are detailed in subsequent sections. Addressing historical issues related to its actions during World War II also remains a sensitive aspect of its foreign relations, particularly with China and South Korea.

5.3.1. Relations with major countries

Japan's relations with major countries are multifaceted, shaped by historical ties, economic interdependence, security alliances, and sometimes, ongoing points of contention.

- United States: The U.S. is Japan's most important ally. The relationship is anchored by the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security, which commits the U.S. to defend Japan and allows for the stationing of U.S. military forces in Japan. Economically, the U.S. is a major trading partner and investor. Both countries collaborate closely on regional and global security issues, including North Korea's nuclear program and stability in the Indo-Pacific. However, occasional trade friction and issues related to U.S. military bases, particularly in Okinawa, sometimes strain the relationship. From a social liberal perspective, the alliance's impact on local communities and Japan's autonomy in foreign policy are points of discussion.

- China: Relations with China are complex and often tense. Economically, China is Japan's largest trading partner, and the two economies are deeply intertwined. However, historical grievances stemming from Japan's wartime aggression, ongoing territorial disputes over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, and strategic competition in East Asia create significant friction. Japan is concerned about China's military modernization and assertiveness in the East China Sea and South China Sea. Efforts are made to maintain dialogue and manage disputes, but mutual distrust remains high. Human rights issues in China are also a concern for Japanese civil society and are sometimes raised by the government.

- South Korea: Relations with South Korea are characterized by close economic and cultural ties, but also by significant historical and political tensions. Disputes over historical interpretations of Japan's colonial rule of Korea (1910-1945), including the issue of "comfort women" and forced labor, periodically flare up. The territorial dispute over the Dokdo/Takeshima islands is another major point of contention. Despite these challenges, both countries share democratic values and common security concerns regarding North Korea. Efforts towards reconciliation and future-oriented cooperation are ongoing, often driven by civil society and economic interests, though progress can be slow and subject to domestic political pressures in both nations.

- Russia: Relations with Russia are primarily dominated by the unresolved territorial dispute over the Northern Territories (Southern Kuril Islands), which were occupied by the Soviet Union at the end of World War II and are still administered by Russia. This dispute has prevented the signing of a formal peace treaty between the two countries. Economic relations, particularly in energy, exist but are limited by the political impasse. Japan has aligned with Western sanctions against Russia following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, further complicating relations.

Japan also maintains important relationships with other countries in Asia (especially ASEAN nations), Europe, and Oceania, focusing on trade, investment, development aid, and cooperation on global issues like climate change and non-proliferation. The humanitarian and human rights dimensions of these relationships are increasingly important considerations in Japan's foreign policy.

5.3.2. Territorial disputes

Japan is involved in several ongoing territorial disputes with its neighboring countries. These disputes are sources of diplomatic tension and can impact regional stability and human security.

- Northern Territories (Southern Kuril Islands) - with Russia**: This is Japan's most significant territorial dispute with Russia. It concerns the four southernmost islands of the Kuril Islands chain: Iturup (択捉島Etorofu-tōJapanese), Kunashir (国後島Kunashiri-tōJapanese), Shikotan (色丹島Shikotan-tōJapanese), and the Habomai islands (歯舞群島Habomai-guntōJapanese). These islands were occupied by the Soviet Union at the end of World War II in 1945 and are currently administered by Russia. Japan claims these islands as an inherent part of its territory, arguing they were not part of the Kuril Islands chain that Japan renounced under the Treaty of San Francisco. Russia maintains that its sovereignty over the islands is a legitimate outcome of World War II. The dispute has prevented the signing of a formal peace treaty between Japan and Russia. Former Japanese residents of the islands were displaced, and their right to return or receive compensation remains an unresolved humanitarian issue.

- Takeshima (Dokdo) - with South Korea**: Japan claims sovereignty over a group of small islets known as Takeshima (竹島Japanese) in Japanese and Dokdo (독도Korean) in Korean. These islets are currently administered by South Korea, which maintains a small coast guard detachment there. Japan argues that Takeshima is historically and legally part of its territory. South Korea asserts its sovereignty based on historical records and effective control. The dispute is a significant source of friction in Japan-South Korea relations, often inflaming nationalist sentiments in both countries. The dispute also has implications for fishing rights and maritime boundaries in the surrounding waters.

- Senkaku Islands (Diaoyu Islands) - with China and Taiwan**: Japan administers the Senkaku Islands (尖閣諸島Senkaku-shotōJapanese) in the East China Sea, but both the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of China (Taiwan) claim sovereignty over them, calling them the Diaoyu Islands (釣魚臺DiàoyútáiChinese) in Chinese. Japan incorporated the islands in 1895. China and Taiwan argue that the islands have historically been part of Chinese territory. The dispute intensified after the discovery of potential undersea oil reserves in the area in the late 1960s and has led to increased maritime patrols and occasional confrontations between Japanese, Chinese, and Taiwanese vessels in the surrounding waters. The dispute affects not only diplomatic relations but also regional maritime security and resource management.

- Okinotorishima**: While not a territorial dispute in the sense of competing sovereignty claims over land, Japan's assertion that Okinotorishima-a remote coral atoll-is an island entitled to a 200 abbr=off Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and continental shelf is contested by China and South Korea. They argue that Okinotorishima consists only of rocks that cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own and therefore cannot generate an EEZ or continental shelf under UNCLOS. This dispute has implications for maritime boundaries and access to marine resources in the Philippine Sea.

These territorial disputes are complex, rooted in historical events, legal interpretations, and national identity. From a social liberal perspective, peaceful resolution through dialogue, international law, and a focus on shared interests and human security are paramount. The impact of these disputes on local communities, such as fishing access and cross-border interactions, also warrants consideration.

5.4. Military

Japan's military, known as the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) (自衛隊JieitaiJapanese), operates under unique constitutional constraints. Article 9 of the post-World War II constitution renounces war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. It also stipulates that "land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained." However, successive Japanese governments have interpreted this to mean that Japan can maintain forces for self-defense.

The JSDF was established in 1954 and is governed by the Ministry of Defense. It consists of three branches:

- The Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (JGSDF)

- The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF)

- The Japan Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF)

Despite the constitutional limitations, the JSDF is a modern and well-equipped military force. Japan's defense budget was the tenth largest in the world in 2022, though it typically remains around 1% of its GDP. In recent years, there has been a gradual increase in defense spending and a reinterpretation of Article 9 to allow for a more proactive role in international security and collective self-defense under specific conditions. In December 2022, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida instructed the government to increase defense spending significantly by 2027.

Japan's defense policy emphasizes an exclusively defense-oriented posture, the Three Non-Nuclear Principles (not possessing, not producing, and not permitting the introduction of nuclear weapons into Japan), and civilian control of the military. The cornerstone of Japan's security is the U.S.-Japan Security Alliance, which involves the stationing of U.S. forces in Japan and a commitment by the U.S. to defend Japan.

In recent decades, the JSDF has expanded its activities to include participation in UN peacekeeping operations, disaster relief missions, and international counter-piracy efforts. The deployment of troops to Iraq and Afghanistan for reconstruction and support missions marked the first overseas use of Japan's military in non-combat roles since World War II.

The security environment in East Asia, particularly concerns regarding North Korea's nuclear and missile programs and China's military modernization and regional assertiveness, has fueled ongoing debate in Japan about its defense posture and the interpretation of its constitution. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's government in May 2014 advocated for Japan to take more responsibility for regional security, leading to security legislation in 2015 that expanded the scope of JSDF activities. These developments reflect an evolving understanding of self-defense in a changing regional and global context, a topic of considerable public and political discussion regarding its implications for Japan's pacifist identity and democratic principles.

5.5. Law and law enforcement

Japan's legal system is primarily based on civil law, with significant influences from German and French law, particularly in the development of its Six Codes (六法RoppōJapanese). These codes form the core of Japanese statutory law and cover the Constitution, Civil Code, Commercial Code, Penal Code, Code of Civil Procedure, and Code of Criminal Procedure. After World War II, the legal system also incorporated elements of Anglo-American law, especially in areas like constitutional law and criminal procedure, reflecting the democratic reforms of the occupation period.

The Constitution of Japan, adopted in 1947, is the supreme law and emphasizes fundamental human rights, popular sovereignty, and pacifism. Statutory law originates in the National Diet. The Emperor promulgates laws passed by the Diet but has no power to oppose legislation.

Law enforcement in Japan is primarily the responsibility of prefectural police departments, which operate under the oversight of the National Police Agency (NPA). The NPA, an agency of the National Public Safety Commission (which is under the jurisdiction of the Cabinet Office), sets national standards and policies, coordinates between prefectural forces, and handles matters of national security. Each of the 47 prefectures has its own autonomous police force responsible for daily law enforcement activities within its jurisdiction.

Japan is known for its low crime rates and high level of public safety. Law enforcement agencies focus on community policing through a network of local police stations (kōban and chūzaisho). The Japan Coast Guard is responsible for maritime security, including patrolling territorial waters, search and rescue, and combating smuggling and piracy.

The public prosecutors (検察庁kensatsu-chōJapanese) have considerable authority in the criminal justice process, including the power to investigate crimes and decide whether to indict suspects. The conviction rate in Japanese criminal trials is very high, which has led to some scrutiny regarding pre-trial detention practices and the rights of suspects, particularly concerning lengthy interrogations and the reliance on confessions. Issues related to civil liberties and due process, such as access to legal counsel during interrogation and the transparency of investigations, are areas of ongoing discussion and reform efforts aimed at strengthening human rights protections within the justice system.

The Firearm and Sword Possession Control Law strictly regulates the civilian ownership of guns, swords, and other weaponry, contributing to Japan's low rates of gun violence. Overall, Japan's legal and law enforcement systems are designed to maintain social order and public safety, but, like any system, face continuous challenges in balancing these objectives with the protection of individual rights and civil liberties.

5.6. Human rights

The Constitution of Japan, enacted in 1947, guarantees a wide range of fundamental human rights. Chapter III is dedicated to "Rights and Duties of the People" and includes provisions for equality under the law, freedom of thought and conscience, freedom of religion, freedom of assembly and association, freedom of speech and the press, academic freedom, the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, the right to receive an equal education, the right to maintain the minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living, and the rights of workers. Japan is also a signatory to numerous international human rights treaties.

Despite these constitutional and international commitments, Japan faces various human rights challenges. The Japanese government has stated its commitment to promoting and protecting human rights, but various domestic and international organizations, including the United Nations Human Rights Committee, have pointed out areas needing improvement.

Major human rights issues in Japan include:

- Gender Equality**: Despite legal frameworks for equality, significant gender disparities persist in employment, political representation, and societal roles. Women face challenges in career advancement (the "glass ceiling"), wage gaps, and underrepresentation in leadership positions. Harassment in the workplace (pawahara and sekuhara) and societal pressures related to traditional gender roles remain prevalent.

- LGBTQ+ Rights**: While societal acceptance of LGBTQ+ individuals has been growing, Japan does not have national-level legal recognition of same-sex marriage or comprehensive anti-discrimination laws protecting LGBTQ+ people. Some municipalities have introduced partnership systems, but these do not confer the same legal rights as marriage. Transgender individuals face hurdles in legal gender recognition.

- Minority Rights**:

- Ainu**: The indigenous Ainu people of Hokkaido continue to face discrimination and work towards the preservation of their language and culture. While the government recognized the Ainu as an indigenous people in 2008 and enacted new legislation in 2019 to promote Ainu culture, challenges remain in addressing historical injustices and ensuring full rights.

- Ryukyuan/Okinawan People**: Some groups in Okinawa (Ryukyu Islands) assert a distinct ethnic and cultural identity and raise concerns about the disproportionate burden of U.S. military bases and related human rights impacts, as well as the preservation of Ryukyuan languages and culture.

- Burakumin**: Descendants of feudal outcast groups, Burakumin still face subtle discrimination in marriage and employment despite anti-discrimination efforts.

- Zainichi Koreans and other resident foreigners**: Long-term foreign residents, particularly Zainichi Koreans, have historically faced discrimination and challenges related to nationality, employment, and social integration. Racism and xenophobia against foreigners, though not widespread overt violence, manifest in microaggressions, housing and employment discrimination, and sometimes racial profiling by police.

- Death Penalty**: Japan is one ofthe few developed democracies that retains capital punishment. The system has been criticized by international human rights organizations for issues such as the lengthy periods inmates spend on death row, the psychological strain on condemned prisoners (who are often informed of their execution only hours before it occurs), and concerns about miscarriages of justice and access to retrials.

- Criminal Justice System**: Concerns have been raised about aspects of the criminal justice system, including lengthy pre-trial detention, interrogation practices that can lead to false confessions (the daiyo kangoku or "substitute prison" system), and the high conviction rate. Access to legal counsel during interrogation has improved but remains an area of focus.

- Refugees and Asylum Seekers**: Japan has a very low recognition rate for refugees and asylum seekers compared to other developed countries. The asylum application process has been criticized as overly restrictive and lengthy, and the treatment of detainees in immigration facilities has also drawn criticism.

- Freedom of the Press**: While generally free, concerns have been raised about government pressure on media organizations and the impact of the "state secrets" law on investigative journalism and whistleblowers. The unique kisha club system has also been cited as potentially limiting media access and diversity of reporting.

Civil society organizations in Japan are actively working to address these human rights concerns through advocacy, legal action, and public awareness campaigns. From a social liberal perspective, strengthening legal protections against discrimination, ensuring due process and fair treatment within the justice system, promoting diversity and inclusion, and fostering a culture of respect for human rights for all individuals are crucial for Japan's continued democratic development and social progress. Japan currently lacks a national human rights institution independent of the government, which is a recommendation often made by international bodies.

6. Economy

Japan possesses the world's fourth-largest economy by nominal GDP, following the United States, China, and Germany, and the fifth-largest by purchasing power parity (PPP) as of 2023. It is a highly developed, market-oriented economy characterized by advanced manufacturing, a strong service sector, and significant investment in science and technology. Key aspects include considerations of social equity, such as addressing income inequality and ensuring a robust social safety net, and promoting sustainable development to balance economic growth with environmental protection.

The post-World War II economic miracle saw Japan achieve rapid growth, becoming the second-largest global economy for several decades. However, the bursting of an asset price bubble in the early 1990s led to a prolonged period of economic stagnation known as the "Lost Decade." While the economy has seen periods of recovery, it continues to face challenges such as deflation, an aging population, and high levels of public debt (estimated at 248% relative to GDP in 2022, the highest among advanced economies).

Japan's labor force is the world's eighth-largest, comprising over 68.6 million workers (as of 2021). The unemployment rate is typically low, around 2.6% in 2022. However, issues such as the prevalence of non-regular employment, wage stagnation, and poverty (with a rate of 15.7%, the second highest among G7 nations) raise concerns about social equity. The Japanese yen is the world's third-largest reserve currency.

Japan is a major player in international trade, ranking as the fifth-largest exporter and fourth-largest importer in 2022. Its main export markets include China and the United States, with key exports being motor vehicles, iron and steel products, semiconductors, and auto parts. Imports primarily consist of machinery, fossil fuels, foodstuffs, and chemicals.

The Japanese variant of capitalism, often characterized by keiretsu (interlocking business groups), lifetime employment, and seniority-based career advancement, has been undergoing changes. The country has a significant cooperative sector. While Japan ranks highly for competitiveness, efforts continue to promote economic freedom and structural reforms. Tourism is a growing sector, with Japan attracting 31.9 million international tourists in 2019 and ranking first in the 2021 Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report. The pursuit of sustainable economic development includes investing in green technologies and addressing the social implications of economic policies to ensure inclusive growth.

6.1. Economic sectors

Japan's economy is characterized by a highly developed and diversified structure, with the tertiary (service) sector being the largest contributor to its GDP, followed by the secondary (manufacturing) sector, and a smaller primary (agriculture, forestry, fisheries) sector.

6.1.1. Agriculture, forestry, and fisheries

The Japanese agricultural, forestry, and fisheries sector accounted for about 1.2% of the country's total GDP in 2018. Only about 11.5% of Japan's land is suitable for cultivation due to its mountainous terrain. This scarcity of arable land has led to intensive farming practices, including the use of terraces in hilly areas. Japan achieves high crop yields per unit area but has an agricultural self-sufficiency rate of about 50% on a calorie basis (as of 2018), relying on imports for a significant portion of its food supply.

Rice is the staple crop and is heavily subsidized and protected under government policy. Other important agricultural products include vegetables, fruits, and livestock. The agricultural sector faces significant challenges, including an aging farming population, difficulty in finding successors for farms, and pressure from trade liberalization to open its markets. Government policies aim to support domestic agriculture, improve productivity, promote sustainable farming practices, and ensure food security. The livelihoods of farmers and the vitality of rural communities are key considerations in agricultural policy, alongside environmental sustainability concerns such as pesticide use and water management.

Forestry covers a large portion of Japan's land, but the domestic timber industry faces competition from cheaper imports. Sustainable forest management and the revitalization of the forestry sector are ongoing goals.

Japan has one of the world's largest fishing fleets and a long tradition of consuming seafood. It ranked seventh globally in tonnage of fish caught in 2016, capturing 3,167,610 metric tons. However, concerns about overfishing and the depletion of fish stocks, such as tuna, have led to increased international scrutiny and calls for more sustainable fishing practices. Japan's support for commercial whaling also remains a controversial international issue. Aquaculture is also an important part of the fisheries sector. Policies in this sector focus on resource management, promoting sustainable fisheries, and supporting fishing communities.

6.1.2. Manufacturing

Japan's manufacturing sector is a cornerstone of its economy, renowned for its technological advancement, high-quality products, and global competitiveness. It accounts for a significant portion of the country's GDP (approximately 27.5% for the broader industrial sector) and employment. Japan's manufacturing output was the fourth highest in the world as of 2023.

Key manufacturing fields include:

- Automobiles**: Japan is one of the world's top three producers and exporters of motor vehicles. Companies like Toyota, Honda, and Nissan are global leaders, known for their innovation in fuel efficiency, hybrid technology, and manufacturing processes (e.g., the Toyota Production System). The automotive industry has a vast supply chain and significantly impacts regional economies.

- Electronics**: Japan has historically been a leader in consumer electronics, components, and industrial electronics. While facing increased competition from South Korea and China in consumer electronics, Japanese companies remain strong in areas like high-precision components, factory automation equipment, and specialized electronic materials. The video game industry is also a major global force, with companies like Nintendo and Sony (PlayStation) having a significant market presence. In 2014, Japan's consumer video game market grossed $9.6 billion. By 2015, Japan was the world's fourth-largest PC game market by revenue.

- Robotics**: Japan is a world leader in the production and use of industrial robots, supplying around 45% of the world's total in 2020. It also invests heavily in service robots and advanced robotics research.

- Steel and Metals**: Japan has a highly advanced steel industry, producing high-quality steel for various applications. It is also prominent in nonferrous metals.

- Machine tools**: Japanese manufacturers are known for their precision machine tools, which are crucial for various manufacturing processes globally.

- Chemicals**: The chemical industry produces a wide range of products, from basic chemicals to highly specialized materials for electronics and pharmaceuticals.

- Shipbuilding**: While facing strong competition from South Korea and China, Japan maintains a significant shipbuilding industry, particularly for specialized and high-value vessels.

- Food Processing**: A large and sophisticated food processing industry caters to domestic demand and export markets.

The manufacturing sector is characterized by a strong emphasis on research and development, quality control (kaizen or continuous improvement), and efficient production systems. However, it also faces challenges such as an aging workforce, the need to adapt to decarbonization goals, and supply chain vulnerabilities. The social impact of manufacturing includes providing stable employment but also concerns about working conditions in some sub-sectors. Environmental impacts, such as resource consumption and emissions, are being addressed through stricter regulations and corporate sustainability initiatives.

6.1.3. Service industry

The service industry (tertiary sector) is the largest component of Japan's economy, accounting for approximately 69.5% of its total economic output as of 2021 and employing a majority of the workforce. It encompasses a wide range of activities, from retail and finance to healthcare and tourism.

Key areas within the service sector include:

- Retail and Wholesale Trade**: This is a massive sector, with a diverse range of businesses from large department stores and supermarket chains (like Aeon) to numerous small, family-owned shops and an expanding e-commerce market.

- Finance and Insurance**: Japan has a sophisticated financial system, including major banks like Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group and Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group, insurance companies, and securities firms. The Tokyo Stock Exchange is one of the world's largest.

- Telecommunications**: Companies like NTT and SoftBank provide extensive mobile and fixed-line communication services, with ongoing development in 5G and advanced network technologies.

- Tourism**: Tourism has become an increasingly important contributor to the economy, with a significant rise in international visitors prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The government has actively promoted tourism to stimulate regional economies.

- Transportation and Logistics**: This sector includes extensive railway networks (including the Shinkansen), road transport, aviation, and maritime shipping, supporting both passenger travel and freight movement.

- Healthcare and Social Welfare**: With an aging population, the demand for healthcare and elderly care services is substantial and growing, forming a large part of the service economy.

- Business Services**: This includes professional services such as consulting, IT services, advertising, and legal services, which support the activities of other industries.

- Real Estate**: The real estate sector is significant, particularly in urban areas, covering residential, commercial, and industrial property development and management.

- Restaurants and Food Services**: A vibrant and diverse food service industry is a major employer and cultural feature.

The service sector has been a key driver of employment growth. However, productivity in some service areas has lagged behind manufacturing, and there are ongoing efforts to improve efficiency and innovation. The rise of the digital economy is transforming many service industries, creating new opportunities and challenges. Companies like Hitachi (which has diversified into IT and social infrastructure services) and Itochu (a major trading company with extensive service operations) are among the largest in the world, reflecting the scale and scope of Japan's service economy. Social considerations include job quality, wage levels in different service sub-sectors, and ensuring access to essential services for all members of society.

6.2. Science and technology

Japan is a global leader in science and technology, with a strong tradition of innovation and significant investment in research and development (R&D). The country has produced numerous Nobel laureates in physics, chemistry, and medicine (22 as of recent counts), as well as three Fields Medalists in mathematics, reflecting its high level of basic research.

Japan's R&D expenditure relative to its gross domestic product (GDP) is among the highest in the world (sixth or seventh globally, with 3.43% of GDP in 2016, and around ¥19 trillion or USD equivalent, shared by approximately 867,000 researchers in 2017). The country also has one of the highest numbers of researchers per capita. Historically, Japan has excelled in patent applications, particularly in international patents (Patent Cooperation Treaty filings), ranking second globally in 2016, and has consistently been a top filer of patent families (patents filed in multiple countries). However, in recent years, while overall R&D spending remains high, there have been concerns about a relative decline in the global share of highly cited scientific papers and a need to further foster innovation and basic research to maintain competitiveness.

Key areas of scientific and technological strength include:

- Robotics**: Japan is a dominant force in both the production and use of industrial robots, supplying approximately 45% of the world's total in 2020. It is also at the forefront of developing advanced service robots, humanoid robots (like ASIMO), and AI-driven automation.

- Automotive Technology**: Japanese automotive companies are renowned for innovations in fuel efficiency, hybrid and electric vehicle technology, and advanced manufacturing processes.

- Electronics**: Japan is a major producer of electronic components, materials, and equipment, including semiconductors (though facing increased competition), optical devices, and precision instruments.

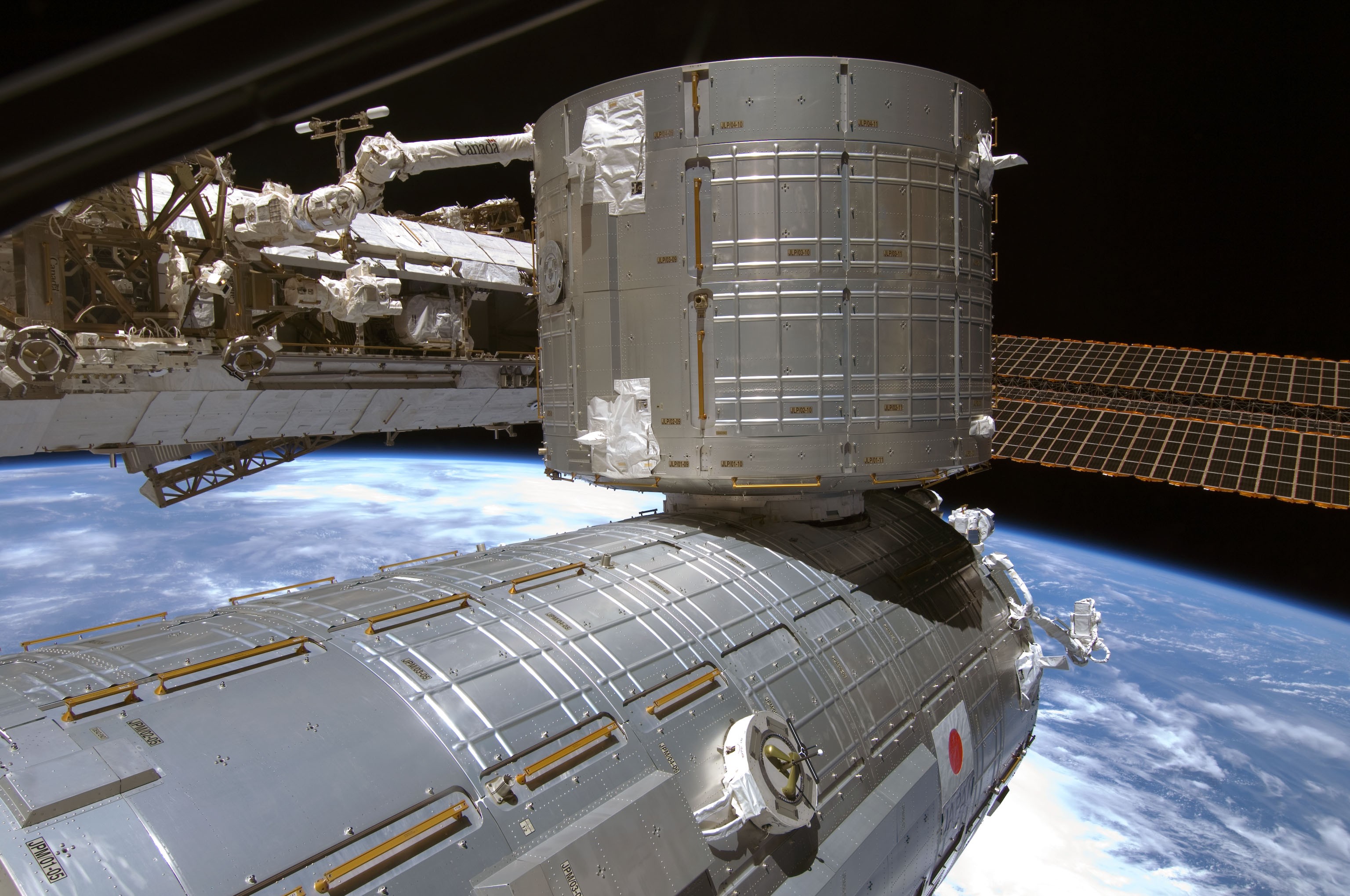

- Aerospace**: The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) is Japan's national space agency, conducting research in space, planetary science, and aviation. JAXA is a participant in the International Space Station (ISS), contributing the Kibō laboratory module. It has launched successful space probes like Hayabusa2 (asteroid sample return) and Akatsuki (Venus orbiter). Japan has ambitious space exploration plans, including lunar missions and aspirations for crewed missions. In 2007, it launched the lunar explorer SELENE (Kaguya) to gather data on the Moon's origin and evolution.

- Materials Science**: Japan is a leader in advanced materials, including carbon fiber, ceramics, and specialized alloys.

- Biotechnology and Pharmaceuticals**: While traditionally strong in fermentation technologies, Japan is also making strides in biotechnology, regenerative medicine, and pharmaceutical research.

- Optics and Imaging**: Japanese companies are world leaders in cameras, optical instruments, and medical imaging equipment.

The Japanese government promotes science and technology through various policies and funding initiatives, aiming to address societal challenges such as an aging population, energy security, and environmental sustainability. Ethical considerations and the societal implications of new technologies, such as AI and genetic engineering, are also subjects of public and academic discussion. Ensuring a pipeline of talent in STEM fields and fostering a dynamic research environment are ongoing priorities.

7. Infrastructure

Japan possesses a highly developed and modern social infrastructure, encompassing extensive transportation networks, a complex energy system, advanced telecommunications, and comprehensive water and sewerage systems. Significant investment, particularly since the 1990s, has gone into maintaining and upgrading these essential facilities.

7.1. Transportation

Japan's transportation system is renowned for its efficiency, punctuality, and technological sophistication, particularly its railway networks.

- Railways**: Railways are a dominant mode of passenger transport, especially for intercity travel and commuting in urban areas. The Shinkansen (bullet train) network connects major cities across Honshu, Kyushu, and Hokkaido with high-speed services known for their safety and reliability. Numerous private railway companies, along with the JR Group (formed after the privatization of Japanese National Railways in 1987), operate extensive networks of commuter, regional, and freight trains. Major companies include seven JR enterprises, Kintetsu, Seibu Railway, and Keio Corporation.

- Roads**: Japan has an extensive road network, totaling approximately 0.7 M mile (1.20 M km) as of 2017. This includes about 0.6 M mile (1.00 M km) of city, town, and village roads, 81 K mile (130.00 K km) of prefectural roads, 34 K mile (54.74 K km) of general national highways, and 4.7 K mile (7.64 K km) of national expressways. The expressway network is well-maintained and continues to expand, though tolls are common.

- Aviation**: There are 175 airports in Japan (as of 2021). Haneda Airport in Tokyo is one of the busiest airports in Asia and primarily handles domestic flights, while Narita International Airport serves as a major international hub for Tokyo. Other key international airports include Kansai International Airport (serving Osaka, Kyoto, and Kobe) and Chubu Centrair International Airport (near Nagoya). Japan Airlines (JAL) and All Nippon Airways (ANA) are the country's two largest airlines.

- Maritime Transport**: As an island nation, maritime transport is crucial for international trade. Major ports include Yokohama, Tokyo, Nagoya, Kobe, and Osaka. The Keihin (Tokyo Bay) and Hanshin (Osaka Bay) superport hubs are among the largest in the world in terms of container traffic. Coastal shipping also plays a role in domestic freight.