1. Overview

Burundi, officially the Republic of Burundi (Repuburika y'UburundiRepublika y'UburundiRundi; République du BurundiRepublik du BurundiFrench), is a landlocked country in the Great Rift Valley at the confluence of the African Great Lakes region and East Africa. It is bordered by Rwanda to the north, Tanzania to the east and southeast, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west; Lake Tanganyika lies along its southwestern border. With a population of over 12 million, Burundi is a densely populated nation, primarily rural, with its political capital in Gitega and its largest city and economic capital in Bujumbura.

The nation's history is marked by a transition from the pre-colonial Kingdom of Burundi, through periods of German and Belgian colonial rule, to independence in 1962. Post-independence Burundi has faced significant socio-political challenges, including recurrent ethnic conflict between the Hutu and Tutsi populations, several coups d'état, and devastating civil wars and genocides, notably in 1972 and 1993. These events have profoundly shaped Burundian society, leading to immense human suffering and hindering development.

The country has struggled with political instability, including the 2015 unrest triggered by then-President Pierre Nkurunziza's bid for a third term. Despite peace agreements, such as the Arusha Accords, and international interventions, including United Nations peacekeeping missions, achieving lasting stability, reconciliation, and respect for human rights remains a formidable challenge. Economically, Burundi is one of the poorest countries in the world, heavily reliant on subsistence agriculture, particularly coffee and tea exports, and foreign aid. High rates of poverty, malnutrition, and limited access to education and healthcare are persistent issues.

Culturally, Burundi has rich traditions, most famously its master drummers. The official languages are Kirundi, French, and English. From a center-left/social liberalism perspective, this article examines Burundi's journey through conflict, its socio-economic struggles, the human rights situation, and ongoing efforts towards development, democratization, and national reconciliation, emphasizing the need for inclusive governance and justice for past atrocities to build a more equitable and peaceful future.

2. Etymology

The name "Burundi" is derived from the country's core ethnic group and language. The prefix "Bu-" in Bantu languages like Kirundi often denotes "land of" or "country of." "Rundi" refers to the Rundi people, the primary inhabitants of the nation. Thus, "Burundi" essentially means "Land of the Rundi." The people are referred to as "Barundi" (plural) or "Umurundi" (singular), and the language is "Kirundi." During the colonial era, the territory was often referred to as "Urundi," which was later adapted with the "B-" prefix, possibly influenced by European administrative practices, to become Burundi.

3. History

The history of Burundi is characterized by the rise and fall of a kingdom, the impact of colonialism, and a post-independence period fraught with ethnic conflict, political instability, and efforts towards peace and reconciliation. These historical developments have deeply influenced the nation's socio-political fabric and its path towards development.

3.1. Kingdom of Burundi

The first evidence of a Burundian state dates to the late 16th century, emerging on the eastern foothills of the current country. According to some legends, Ntare Rushatsi, the founder of the first dynasty, came from Rwanda in the 17th century; other, more reliable sources suggest Ntare originated from Buha, in the southeast, and established his kingdom in the Nkoma region. Over the following centuries, it expanded, annexing smaller neighbors. The Kingdom of Burundi, or Urundi, was a hierarchical polity ruled by a traditional monarch, the mwami (translated as ruler), with several princes (batware) beneath him; succession struggles were common. The mwami headed a princely aristocracy, the ganwa, which owned most of the land and exacted tribute from local farmers (predominantly Hutu) and herders (predominantly Tutsi). The kingdom was characterized by a hierarchical political authority and tributary economic exchange.

In the mid-18th century, the Tutsi royalty consolidated authority over land, production, and distribution with the development of the ubugabire-a patron-client relationship in which the populace received royal protection in exchange for tribute and land tenure. By this time, the royal court was primarily composed of the Tutsi-Banyaruguru, who held higher social status than other pastoralist groups like the Tutsi-Hima. At lower levels of this society were generally Hutu people, and at the very bottom of the pyramid were the Twa. However, the system had some fluidity; some Hutu individuals belonged to the nobility and thus had a say in the state's functioning.

The classification of Hutu or Tutsi was not solely based on ethnic criteria. Hutu farmers who managed to acquire wealth and livestock were often granted the higher social status of Tutsi, with some even becoming close advisors to the Ganwa. Conversely, there are reports of Tutsi who lost all their cattle and subsequently lost their higher status, being referred to as Hutu. Thus, the distinction between Hutu and Tutsi was also a socio-cultural concept, not purely ethnic. Marriages between Hutu and Tutsi people were also reported. In general, regional ties and power struggles played a far more determining role in Burundi's politics than ethnicity during this period. Until the fall of the monarchy in 1966, it remained one of the last links to Burundi's pre-colonial past.

3.2. Colonial Rule

The period of European colonization significantly altered Burundi's political and social landscape, integrating it into global imperial systems and laying groundwork for future conflicts by hardening ethnic distinctions.

3.2.1. German East Africa

From 1884, the German East Africa Company was active in the African Great Lakes region. Following heightened tensions and border disputes with the British Empire and the Sultanate of Zanzibar, the German Empire intervened to suppress the Abushiri revolt and protect its interests. In 1891, the German East Africa Company transferred its rights to the German Empire, establishing the colony of German East Africa, which included Burundi (Urundi), Rwanda (Ruanda), and the mainland part of Tanzania (then Tanganyika). Germany stationed armed forces in Rwanda and Burundi in the late 1880s. The Germans, however, largely maintained the existing monarchical structure of the Kingdom of Burundi, practicing a form of indirect rule. The present-day city of Gitega served as an administrative center for the Ruanda-Urundi region under German authority. German colonial impact, while relatively short-lived, initiated Burundi's integration into a wider colonial economy and administration.

3.2.2. Belgian Mandate and Trust Territory (Ruanda-Urundi)

During World War I, the East African Campaign heavily impacted the region. Belgian and British colonial forces launched a coordinated attack on German East Africa. The German army in Burundi was forced to retreat, and by June 17, 1916, Burundi and Rwanda were occupied by Belgian forces. After the war, under the Treaty of Versailles, Germany ceded control of the western section of former German East Africa to Belgium.

On October 20, 1924, Ruanda-Urundi, consisting of modern-day Rwanda and Burundi, became a Belgian mandate territory, with Usumbura (now Bujumbura) as its capital. Though technically a mandate, it was administered as part of the Belgian colonial empire. The Belgian administration continued the policy of indirect rule, preserving many of the kingdom's institutions, including the Burundian monarchy. However, Belgian colonial policies had a profound and often detrimental impact. They formalized and rigidified ethnic identities (Hutu, Tutsi, Twa), often favoring the Tutsi minority for administrative roles based on racist theories like the Hamitic hypothesis. This exacerbated existing social distinctions and sowed seeds of future conflict. The Belgians also focused on economic exploitation, primarily through the cultivation of cash crops like coffee.

Following World War II, Ruanda-Urundi was reclassified as a United Nations Trust Territory under Belgian administrative authority in 1946. During the 1940s, a series of policies caused further divisions. On October 4, 1943, powers were split in the legislative division of Burundi's government between chiefdoms and lower chiefdoms, with chiefdoms in charge of land. In 1948, Belgium allowed the region to form political parties, which began to advocate for independence in the late 1950s. The colonial administration's preference for the Tutsi elite and its economic policies contributed to growing resentment and laid the groundwork for post-independence political instability.

3.3. Independence and Early Republic

On January 20, 1959, King Mwami Mwambutsa IV requested Burundi's independence from Belgium and the dissolution of the Ruanda-Urundi union. In the following months, Burundian political parties began to advocate for the end of Belgian colonial rule and the separation of Rwanda and Burundi. The first and largest of these political parties was the Union for National Progress (UPRONA). Burundi's push for independence was influenced by the Rwandan Revolution (1959-1961) and the accompanying instability and ethnic conflict there, which led many Rwandan Tutsi refugees to arrive in Burundi.

Burundi's first legislative elections took place on September 8, 1961. UPRONA, a multi-ethnic unity party led by Prince Louis Rwagasore, son of Mwami Mwambutsa IV, won over 80% of the vote. However, on October 13, 1961, just weeks before independence, the 29-year-old Prince Rwagasore was assassinated, robbing Burundi of its most popular nationalist leader. This event created a political vacuum and heightened existing tensions.

Burundi gained independence on July 1, 1962, as the Kingdom of Burundi, with Mwami Mwambutsa IV as head of state. It joined the United Nations on September 18, 1962. The early years of independence were marked by political instability and increasing ethnic polarization. In 1963, King Mwambutsa appointed a Hutu prime minister, Pierre Ngendandumwe, but he was assassinated on January 15, 1965, by a Rwandan Tutsi. Parliamentary elections in May 1965 brought a Hutu majority into parliament, but when the King appointed a Tutsi prime minister, Léopold Biha, many Hutus felt this was unjust. In October 1965, an attempted coup d'état led by Hutu-dominated police failed. The Tutsi-dominated army, led by Captain Michel Micombero, retaliated by purging Hutus from their ranks and carrying out reprisal attacks, killing up to 5,000 people. This event was a precursor to larger-scale violence.

King Mwambutsa, who had fled during the 1965 coup attempt, was deposed in a coup in July 1966 by his teenage son, Prince Ntare V, who claimed the throne. Just months later, in November 1966, Prime Minister Captain Michel Micombero carried out another coup, deposing Ntare V, abolishing the monarchy, and declaring Burundi a republic. Micombero became president, establishing a one-party state under UPRONA, which effectively became a military dictatorship dominated by Tutsis. This period set the stage for decades of authoritarian rule and ethnic conflict.

3.4. Civil War and Genocides

The post-independence period in Burundi was marred by recurrent cycles of ethnic violence, civil war, and mass killings, primarily between the Hutu majority and the Tutsi minority, which controlled the state and military apparatus for much of this time. These conflicts resulted in immense loss of life, widespread human rights abuses, and a legacy of impunity that continues to challenge the nation.

3.4.1. 1972 Genocide

In late April 1972, a Hutu rebellion broke out in the lakeside towns of Rumonge and Nyanza-Lac, with rebels attacking both Tutsis and Hutus who refused to join them, declaring the short-lived Martyazo Republic. Estimates of those killed in this initial Hutu outbreak range from 800 to 1,200. Simultaneously, the exiled King Ntare V returned to Burundi, heightening political tension. On April 29, 1972, Ntare V was murdered.

The Tutsi-dominated government of Michel Micombero responded to the Hutu rebellion with systematic and widespread killings targeting educated Hutus, Hutu civil servants, and other perceived Hutu leaders. This period, often referred to as the Ikiza or the "Burundian genocide of 1972," saw the army and Tutsi militias unleash brutal violence. Estimates of the Hutu death toll vary significantly, ranging from 80,000 to over 210,000. Additionally, hundreds of thousands of Hutus fled to neighboring countries as refugees. The international response was muted, and the events of 1972 entrenched deep-seated fear and resentment, contributing to a cycle of violence and a culture of impunity. No one was held accountable for these mass killings, which had a devastating and lasting impact on Burundian society.

Following the 1972 genocide, Micombero's regime continued until 1976, when Colonel Jean-Baptiste Bagaza, a Tutsi, led a bloodless coup. Bagaza's rule also suppressed Hutu political participation. In 1987, Major Pierre Buyoya, another Tutsi, overthrew Bagaza. In August 1988, anti-Tutsi ethnic propaganda led to killings of Tutsi peasants in Ntega and Marangara. The army's response resulted in the deaths of thousands of Hutus, with some estimates suggesting up to 20,000 casualties. Buyoya initiated some reforms, including appointing a Hutu prime minister and creating a commission for national unity, eventually leading to a new constitution in 1992 that allowed for a multi-party system.

3.4.2. 1993 Assassination, Genocide, and Intensification of Civil War

In June 1993, Burundi held its first multi-party democratic presidential election. Melchior Ndadaye, leader of the Hutu-dominated Front for Democracy in Burundi (FRODEBU), won, becoming Burundi's first Hutu president. His election was seen as a significant step towards ethnic reconciliation and democracy. However, on October 21, 1993, after only three months in office, President Ndadaye was assassinated by a group of Tutsi soldiers during a failed military coup.

Ndadaye's assassination triggered widespread ethnic violence. Hutu extremists retaliated by targeting and killing Tutsi civilians, leading to what is often described as the "1993 genocide of Tutsis." Estimates suggest tens of thousands of Tutsis were killed. In turn, the Tutsi-dominated army and Tutsi militias launched reprisal attacks against Hutu civilians. The ensuing Burundian Civil War lasted for over a decade (1993-2005), characterized by persistent violence between Hutu rebel groups (such as CNDD-FDD and Palipehutu-FNL) and the Tutsi-controlled army. The war resulted in an estimated 300,000 deaths, mostly civilians, and displaced hundreds of thousands more, both internally and as refugees in neighboring countries. The conflict had a devastating impact on all communities, shattering the fragile hopes for democracy and peaceful coexistence. The violence was marked by severe human rights abuses committed by all sides, including massacres, rape, and the use of child soldiers, further entrenching the culture of impunity.

In early 1994, parliament elected Cyprien Ntaryamira (Hutu) as president. However, on April 6, 1994, he and Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana were killed when their plane was shot down over Kigali, an event that triggered the Rwandan genocide. Speaker of Parliament, Sylvestre Ntibantunganya (Hutu), became president in October 1994. In 1996, Pierre Buyoya (Tutsi) retook power in a coup, suspending the constitution.

3.5. Peace Process and Transitional Government

Efforts to end the devastating Burundian Civil War involved complex negotiations and international mediation. Following years of intense conflict after the 1993 assassination of President Ndadaye, regional leaders, notably former Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere and later South African President Nelson Mandela, spearheaded peace talks. These efforts culminated in the signing of the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement in Arusha, Tanzania, on August 28, 2000. The agreement was signed by most, though not all, political factions and aimed to address the root causes of the conflict, including issues of power-sharing, security sector reform, justice, and reconciliation.

The Arusha Agreement laid the groundwork for a transitional government based on ethnic power-sharing principles, designed to ensure representation for both Hutu and Tutsi communities in state institutions. A complex formula was devised for the executive, legislative, and military branches. In 2001, a transitional government was established, with Pierre Buyoya (Tutsi) serving as president for the first 18 months, followed by Domitien Ndayizeye (Hutu), a leader from FRODEBU, for the subsequent 18 months.

However, major Hutu rebel groups, particularly the National Council for the Defense of Democracy - Forces for the Defense of Democracy (CNDD-FDD) and the Party for the Liberation of the Hutu People - National Forces of Liberation (Palipehutu-FNL), were not signatories to the initial Arusha Agreement and continued their armed struggle. Further negotiations led to ceasefire agreements with the CNDD-FDD in 2003. The integration of former rebels into the political and military structures was a key challenge. A new constitution, incorporating many provisions of the Arusha Agreement, was approved by referendum in February 2005, paving the way for general elections later that year. Pierre Nkurunziza of the CNDD-FDD won the presidential election. The peace process was arduous, marked by continued sporadic violence and mistrust, but the Arusha Agreement and the subsequent transitional period were crucial in halting large-scale conflict and establishing a framework for a more inclusive political system, though many underlying tensions and issues of justice remained unresolved.

3.6. United Nations Involvement

The United Nations played a significant role in Burundi's peace process and post-conflict reconstruction, primarily through peacekeeping operations, peacebuilding initiatives, humanitarian assistance, and support for democratic transitions. Between 1993 and 2003, as regional leaders mediated peace talks, the UN provided political support. After the Arusha Agreement and the establishment of a transitional government, the international community increased its engagement.

The most direct UN involvement came with the deployment of the United Nations Operation in Burundi (ONUB) in June 2004, taking over from an African Union peacekeeping mission (AMIB) that had been deployed earlier to protect Burundian leaders and support the transitional process. ONUB's mandate, under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, included:

- Monitoring the ceasefire.

- Assisting with the disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) of former combatants.

- Supporting humanitarian assistance and the return of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs).

- Assisting with the 2005 elections.

- Protecting international staff and Burundian civilians.

- Monitoring Burundi's borders and helping to halt illicit arms flows.

- Assisting in institutional reforms, including those of the constitution, judiciary, armed forces, and police.

ONUB comprised military personnel, civilian police, and international and local civilian staff. The mission was generally considered successful in helping to stabilize the country, facilitate the 2005 elections, and support the DDR process for many former combatants.

After the successful conclusion of the transitional period and the 2005 elections, ONUB's mandate ended in December 2006. It was succeeded by the United Nations Integrated Office in Burundi (BINUB), established on January 1, 2007. BINUB's focus shifted towards peacebuilding, including strengthening democratic institutions, promoting human rights, supporting reconciliation efforts (such as transitional justice mechanisms), and coordinating international aid for socio-economic recovery.

Subsequently, the United Nations Office in Burundi (BNUB) replaced BINUB in 2011, continuing peacebuilding efforts with a focus on consolidating governance and rule of law. BNUB's mandate concluded at the end of 2014, and it was replaced by the UN Electoral Observation Mission in Burundi (MENUB) for the 2015 elections.

Throughout these phases, various UN agencies (like UNHCR, WFP, UNICEF, UNDP) provided critical humanitarian aid and development support. However, the UN's efforts faced challenges, including ongoing political tensions, human rights abuses, and the slow pace of reconciliation and economic recovery. The 2015 political crisis saw renewed UN engagement focusing on mediation and human rights monitoring.

3.7. 21st Century Developments

Burundi in the 21st century has been characterized by attempts to consolidate peace after the civil war, navigate complex political transitions, and address deep-seated socio-economic challenges, though significant setbacks, particularly regarding human rights and democratic governance, have occurred.

Following the Arusha Peace Agreement and the 2005 elections, Pierre Nkurunziza of the CNDD-FDD became president. His initial years saw efforts to integrate former rebel groups, including the Palipehutu-FNL which signed a final peace deal in 2008 and transformed into a political party. Reconstruction efforts began, with the UN shifting from peacekeeping to peacebuilding. Burundi joined the East African Community (EAC) in 2007, aiming to boost regional trade and integration.

However, political tensions remained. The government faced criticism for corruption, restrictions on press freedom, and human rights abuses. The 2010 elections were marred by an opposition boycott and allegations of irregularities, consolidating CNDD-FDD's power.

In 2014, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established, initially for four years and extended in 2018, tasked with investigating past human rights violations, though its work has been controversial and seen by some as politically influenced.

3.7.1. 2015 Political Unrest

A major crisis erupted in April 2015 when the ruling CNDD-FDD party announced that President Pierre Nkurunziza would seek a third term in office. Opponents argued this violated the constitution and the spirit of the Arusha Accords, which limited presidential terms. Widespread protests, led by civil society and opposition parties, ensued, primarily in Bujumbura. The government responded with a crackdown, leading to clashes, arrests, and deaths.

On May 13, 2015, while Nkurunziza was attending an EAC summit in Tanzania, a coup d'état was attempted by a group of military officers led by Major General Godefroid Niyombare. However, the coup failed within days as loyalist forces regained control. Nkurunziza returned to Burundi and initiated a purge within the government and military.

The failed coup intensified the crisis. Protests continued, and the government's repression escalated. Over 100,000 people fled the country by late May 2015, creating a humanitarian emergency in neighboring countries. Reports of widespread human rights abuses, including unlawful killings, torture, enforced disappearances, and restrictions on freedom of expression, became common. Despite calls from the United Nations, African Union, and international partners to postpone, parliamentary and presidential elections were held in June and July 2015, respectively. These elections were boycotted by most opposition parties, and Nkurunziza was declared the winner.

The aftermath of the 2015 crisis saw a severe deterioration in human rights, a shrinking of democratic space, and increased authoritarianism. The United Nations Human Rights Council established a Commission of Inquiry on Burundi in September 2016, which documented serious human rights violations, including potential crimes against humanity. The Burundian government largely refused to cooperate with this commission. In October 2017, Burundi became the first country to officially withdraw from the International Criminal Court (ICC), following the ICC's decision to open an investigation into crimes committed since 2015.

3.7.2. 2018 Onwards

Following the 2015 crisis, President Nkurunziza's government further consolidated its power. In a constitutional referendum held in May 2018, Burundians voted to approve an amended constitution. Key changes included extending the presidential term from five to seven years, allowing a president to serve two consecutive seven-year terms. This change potentially allowed Nkurunziza to remain in power until 2034. The referendum was held in a climate of fear and repression, with reports of intimidation of opponents. In February 2019, the government officially moved the political capital from Bujumbura to Gitega, while Bujumbura remained the economic capital.

Surprisingly, Nkurunziza announced in late 2019 that he would not run for another term in the 2020 general election. The ruling CNDD-FDD party nominated Évariste Ndayishimiye as its presidential candidate. The elections, held on May 20, 2020, were conducted amidst the COVID-19 pandemic (which the government largely downplayed) and concerns about fairness and transparency. Ndayishimiye was declared the winner with 71.45% of the vote.

On June 8, 2020, just weeks before he was due to step down, President Pierre Nkurunziza died suddenly, reportedly of a cardiac arrest, at the age of 55. There was unconfirmed speculation that his death might have been related to COVID-19. Following a ruling by the Constitutional Court, President-elect Évariste Ndayishimiye's inauguration was brought forward, and he was sworn in on June 18, 2020.

President Ndayishimiye's tenure has seen some initial overtures towards improving international relations and addressing domestic issues, but significant human rights concerns and restrictions on political freedoms persist. In December 2021, a large fire at Gitega's central prison killed dozens of inmates, highlighting poor prison conditions. Economically, Burundi continues to face severe challenges, remaining one of the world's poorest nations, with issues exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and global economic shocks like the war in Ukraine. Tensions in the Kivu region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with the M23 rebel campaign, have also raised concerns about broader regional instability, particularly due to the presence of Burundian troops deployed to assist the Congolese army in South Kivu. These regional dynamics are complicated by Burundi's historical accusations against Rwanda of backing the 2015 coup attempt.

4. Geography

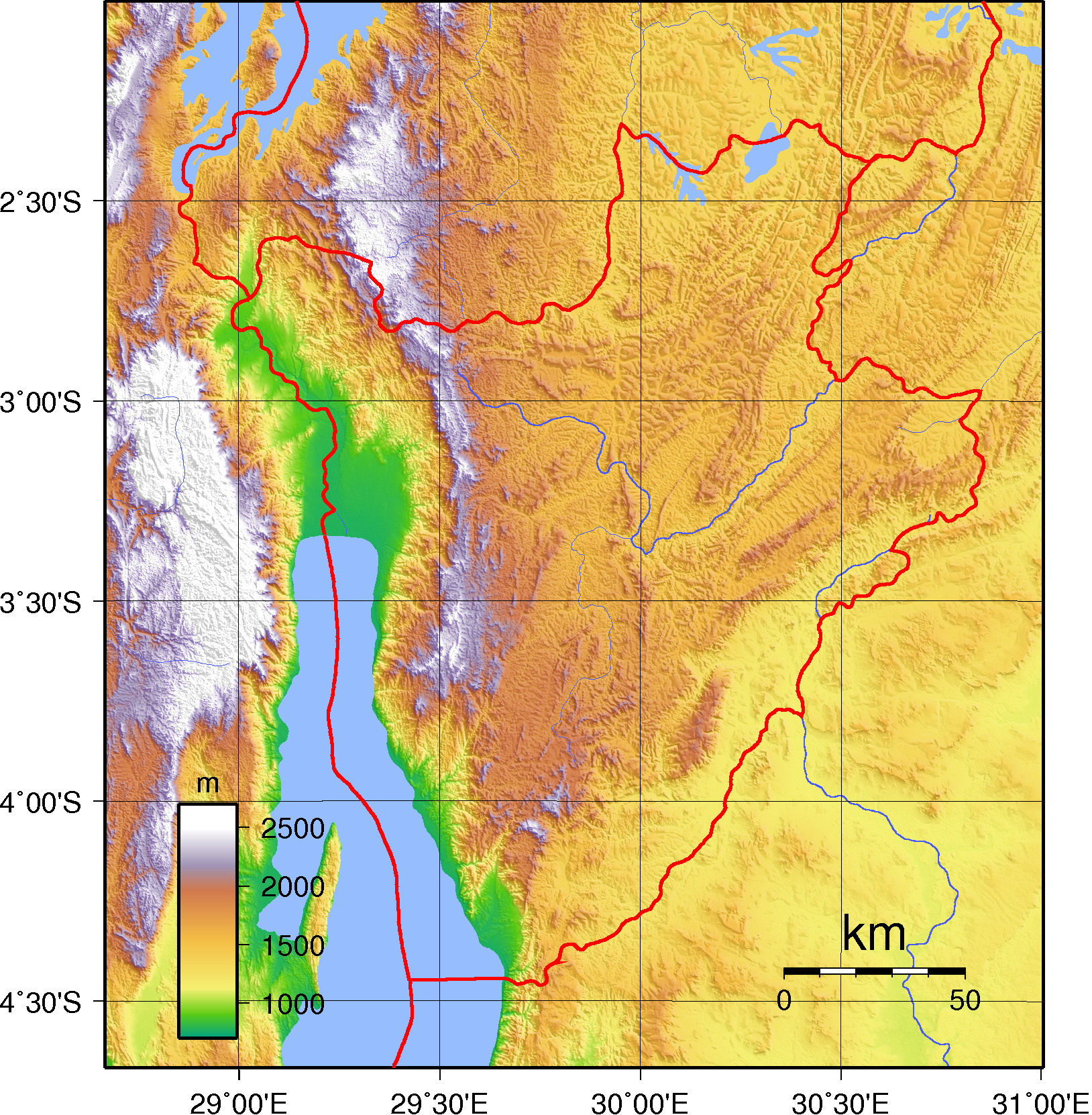

Burundi is a small, landlocked country located in East Africa, within the Albertine Rift, the western extension of the East African Rift. It occupies an area of 11 K mile2 (27.83 K km2). The country is bordered by Rwanda to the north, Tanzania to the east and southeast, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) to the west. Its southwestern border is largely defined by Lake Tanganyika, one of the African Great Lakes. The general landscape is hilly and mountainous, characterized by a rolling plateau in the center of Africa. Burundi lies within the Albertine Rift montane forests, Central Zambezian miombo woodlands, and Victoria Basin forest-savanna mosaic ecoregions.

4.1. Topography and Hydrography

Burundi's topography is diverse, largely consisting of a high plateau with an average elevation of around 5.6 K ft (1.70 K m). The terrain descends to a plain along the Ruzizi River valley in the west, which forms part of the border with the DRC and flows into Lake Tanganyika. The western part of the country is dominated by a mountain range that is part of the Albertine Rift mountains. The highest peak in Burundi is Mount Heha, located southeast of Bujumbura, reaching an elevation of 8.8 K ft (2.68 K m). To the east, the land slopes down towards the Tanzanian border, forming part of the central African plateau.

Lake Tanganyika, the world's second-deepest and second-largest freshwater lake by volume, is a dominant hydrographic feature, covering a significant portion of Burundi's southwestern border. The lake provides important fishing resources and a transport route. The country's major river systems include the Ruvubu River (also Rurubu or Ruvuvu) and the Kagera River, which is a major tributary of Lake Victoria. The southernmost source of the Nile River is located in Bururi province, originating from the Ruvyironza River, a tributary of the Ruvubu, which flows into the Kagera and then into Lake Victoria. This makes Burundi one of the countries where the Nile's headwaters can be found. Other significant rivers include the Malagarasi River, which flows into Lake Tanganyika.

4.2. Climate

Burundi has an equatorial climate, but its high altitude moderates temperatures, resulting in a pleasant, temperate climate in many parts of the country. Average daily temperatures vary with altitude, generally ranging from 62.6 °F (17 °C) to 73.4 °F (23 °C) on the central plateau. The western rift valley area around Lake Tanganyika and the Ruzizi River plain is warmer and more humid.

Rainfall is generally abundant but varies regionally and seasonally. The country experiences two main rainy seasons: a longer one from February to May and a shorter one from September to November. There are also two dry seasons: a long dry season from June to August and a shorter one from December to January. Average annual rainfall is around 0.1 K in (1.50 K mm) but can be higher in the mountainous regions and lower in the eastern plains. The climate supports agriculture, which is the mainstay of the economy, but also makes the country vulnerable to droughts and flooding, which can impact food security.

4.3. Wildlife and National Parks

Burundi's biodiversity includes a variety of flora and fauna typical of the Albertine Rift region, although habitat loss due to high population density and deforestation poses significant challenges to conservation. As of 2005, the country was almost completely deforested, with less than 6% of its land covered by trees, over half of that being commercial plantations. In 2020, forest cover was around 11% of the total land area, with naturally regenerating forest covering 166,670 hectares and planted forest covering 112,970 hectares.

Notable fauna includes primates such as chimpanzees, various monkey species, antelopes, hippopotamuses (especially in and around Lake Tanganyika and rivers), crocodiles, and numerous bird species, making it a point of interest for ornithologists.

Burundi has established several protected areas to conserve its natural heritage. The two main national parks are:

- Kibira National Park: Located in the northwest, adjacent to Nyungwe Forest National Park in Rwanda, Kibira is a montane rainforest covering about 154 mile2 (400 km2). It is home to chimpanzees, colobus monkeys, and a rich diversity of birdlife. The park plays a crucial role in watershed protection.

- Ruvubu National Park: Situated in the northeast along the Ruvubu River, this is Burundi's largest national park, covering approximately 196 mile2 (508 km2). It consists of savanna, gallery forests, and grasslands, providing habitat for hippos, crocodiles, buffalo, various antelope species, and numerous bird species.

Other protected areas include forest reserves and natural monuments.

Conservation efforts face significant challenges, including encroachment from agriculture and settlements due to land pressure, poaching, illegal logging, and insufficient resources for park management and enforcement. International and local NGOs are involved in supporting conservation initiatives.

5. Politics and Government

Burundi's political system is that of a presidential representative democratic republic based upon a multi-party state. The current constitution was adopted by referendum in 2018. The political landscape has been shaped by a history of ethnic conflict, authoritarian rule, and efforts towards democratic consolidation and national reconciliation, often with significant challenges and setbacks.

From a social liberal perspective, while Burundi has formal democratic institutions, the actual practice of democracy has been constrained by a dominant ruling party, restrictions on political freedoms, and a weak rule of law, hindering genuine political pluralism and accountability.

5.1. Government Structure

The Burundian state operates under a system of separation of powers, though in practice the executive branch holds significant influence. The government is structured into three main branches:

5.1.1. Executive Branch

The President is both the head of state and head of government. The president is elected by universal direct suffrage for a seven-year term, renewable once, according to the 2018 constitution. The president appoints the Vice-President and the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister and the Council of Ministers (Cabinet), who are appointed by the President in consultation with the Vice-President and Prime Minister, are responsible for implementing government policy. The executive branch wields considerable power over state administration and security forces. The ethnic balance stipulated by the Arusha Accords and subsequent constitutions (e.g., 60% Hutu, 40% Tutsi in government) remains a key feature, though its practical impact on equitable power-sharing is debated.

5.1.2. Legislative Branch

The Parliament is bicameral, consisting of the National Assembly (lower house) and the Senate (upper house).

- The National Assembly has at least 100 members, directly elected by proportional representation for five-year terms. The constitution mandates that 60% of members be Hutu and 40% Tutsi, with at least 30% being women. Three members representing the Twa minority are co-opted.

- The Senate is composed of members indirectly elected by electoral colleges in each province, ensuring representation from different ethnic groups (one Hutu and one Tutsi senator per province, plus three Twa co-opted members and former heads of state). Senators also serve five-year terms, with similar quotas for women.

The Parliament's functions include passing legislation, overseeing the executive, and approving the budget. However, its independence and effectiveness have often been challenged by executive dominance.

5.1.3. Judicial Branch

The judicial branch is headed by the Supreme Court (Cour Suprême). Below it are Courts of Appeal, Tribunals of First Instance in each province, and local tribunals (tribunaux de résidence). A Constitutional Court is responsible for interpreting the constitution and ruling on the constitutionality of laws.

The judiciary has faced persistent challenges regarding independence, corruption, lack of resources, and political interference. The rule of law is often weak, and access to justice for ordinary citizens, particularly victims of human rights abuses, is limited. Efforts to reform the justice sector have been slow and have yielded mixed results, which is a significant concern for democratic development and accountability.

5.2. Political Parties and Elections

Burundi has a multi-party system, with over twenty registered political parties. However, the political space has often been dominated by the ruling National Council for the Defense of Democracy - Forces for the Defense of Democracy (CNDD-FDD), which emerged from a Hutu rebel group and has been in power since 2005.

Other historically significant parties include:

- The Union for National Progress (UPRONA), traditionally Tutsi-led, which was the sole legal party for a period post-independence.

- The Front for Democracy in Burundi (FRODEBU), a Hutu-led party that won the 1993 elections.

Opposition parties have frequently faced harassment, intimidation, and restrictions on their activities, particularly during election periods.

Elections (presidential, legislative, and local) have been held periodically since the end of the civil war. The 2005 elections marked a key step in the peace process. However, subsequent elections, including those in 2010, 2015, and 2020, have been marred by controversy, opposition boycotts, allegations of irregularities, and violence, particularly the 2015 polls. The conduct of elections and the fairness of the electoral process remain critical issues for Burundi's democratic trajectory, with international observers often noting significant shortcomings.

5.3. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Burundi has long been a matter of serious concern, deeply impacted by decades of political instability, ethnic conflict, and authoritarian governance. From a social liberal perspective, the consistent failure to protect fundamental human rights and ensure accountability for past and present abuses is a major impediment to national reconciliation and sustainable development.

Key human rights issues include:

- Unlawful Killings and Enforced Disappearances: Security forces and allied militias have been implicated in extrajudicial killings, particularly of political opponents, perceived government critics, and during periods of unrest like the 2015 crisis. Enforced disappearances have also been a recurrent problem.

- Torture and Ill-Treatment: Torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment of detainees by security forces remain widespread, often used to extract confessions or punish dissidents. Prison conditions are dire, characterized by severe overcrowding, lack of food and medical care, contributing to high mortality rates.

- Freedoms of Expression, Association, and Assembly: These fundamental freedoms are severely restricted. Journalists, human rights defenders, and members of the political opposition often face harassment, intimidation, arrests, and violence for their work. Independent media outlets have been shut down or operate under duress.

- Political Freedoms: The space for political opposition is narrow. Opposition parties face obstacles in registering, holding meetings, and campaigning. Elections have often been marred by irregularities and an environment of fear.

- Impunity: A pervasive culture of impunity for human rights violations committed by state agents and others has been a hallmark of Burundi's history. Efforts to establish credible transitional justice mechanisms have been slow and often politicized, failing to deliver justice for victims of past atrocities, including genocides and crimes against humanity. Burundi withdrew from the International Criminal Court (ICC) in 2017 after the court opened an investigation into alleged crimes.

- Rights of Minorities and Vulnerable Groups: The Twa minority continues to face historical marginalization and discrimination. LGBT individuals face legal discrimination, as consensual same-sex relations were criminalized in 2009. Women face discrimination and high rates of sexual and gender-based violence, often exacerbated during conflicts.

International human rights organizations and UN bodies have consistently documented these abuses and called for reforms and accountability, but the government has often been resistant to scrutiny and cooperation.

5.4. Military

The National Defence Force of Burundi (Force de défense nationale du BurundiFDNFrench) is the state military organization responsible for defending the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Burundi. Its structure and role have been significantly shaped by the Arusha Peace Accords, which mandated its reform to ensure ethnic balance between Hutu and Tutsi personnel and to integrate former combatants from various armed groups.

The FDN consists of an army and a small air wing. Given Burundi's landlocked status, it does not have a navy, though it operates patrols on Lake Tanganyika. The military's primary roles include national defense, internal security support (though this is primarily the police's role), and participation in disaster relief.

A key aspect of the post-civil war military is its mandated ethnic composition, aimed at preventing the kind of ethnically-based dominance that characterized the army in the past and contributed to conflict. This integration process has been a complex but relatively successful component of the Arusha Accords compared to other reforms.

Burundi has also been an active contributor to international peacekeeping missions, notably the African Union Mission to Somalia (AMISOM), now African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS), where its troops have played a significant role. This participation has provided the FDN with experience and international support but has also involved casualties.

The military's budget and resources are constrained by Burundi's overall economic situation. Challenges include modernization, professionalization, and ensuring its apolitical stance and respect for human rights, particularly given the country's history of military involvement in politics and human rights abuses.

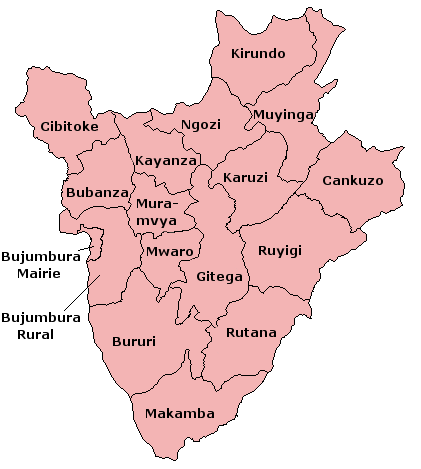

6. Administrative Divisions

Burundi is divided into a hierarchy of administrative units. The primary level of subdivision is the province. As of a 2015 reorganization, there are 18 provinces. These provinces are further divided into communes, of which there are currently 119. The communes are then subdivided into collines (hills), which are the smallest administrative units, numbering 2,639.

Provincial governments are structured upon these boundaries, with governors appointed to head each province. Provincial and communal councils are elected.

The provinces are:

| Province | Capital |

|---|---|

| Bubanza | Bubanza |

| Bujumbura Mairie | Bujumbura |

| Bujumbura Rural | Isale |

| Bururi | Bururi |

| Cankuzo | Cankuzo |

| Cibitoke | Cibitoke |

| Gitega | Gitega |

| Karuzi | Karuzi |

| Kayanza | Kayanza |

| Kirundo | Kirundo |

| Makamba | Makamba |

| Muramvya | Muramvya |

| Muyinga | Muyinga |

| Mwaro | Mwaro |

| Ngozi | Ngozi |

| Rumonge | Rumonge |

| Rutana | Rutana |

| Ruyigi | Ruyigi |

The province encompassing Bujumbura was separated into Bujumbura Rural and Bujumbura Mairie in 2000. The newest province, Rumonge, was created on March 26, 2015, from portions of Bujumbura Rural and Bururi provinces.

In July 2022, the Burundian government announced a proposal for a complete overhaul of the country's territorial subdivisions, which would reduce the number of provinces from 18 to 5, and communes from 119 to 42. This change requires parliamentary approval to take effect and aims to streamline administration and reduce costs.

7. Economy

Burundi's economy is predominantly agricultural and faces significant challenges, making it one of the poorest countries in the world. It is landlocked, resource-poor in terms of easily exploitable minerals for large-scale export, and has an underdeveloped manufacturing sector. Decades of political instability, civil war, and corruption have severely hampered economic growth and development. The country relies heavily on foreign aid. A social liberal perspective emphasizes the need for equitable resource distribution, poverty reduction programs, investment in human capital (health and education), and sustainable development practices to improve the well-being of its population.

7.1. Key Sectors

The Burundian economy is characterized by its dependence on a few key sectors.

7.1.1. Agriculture

Agriculture is the backbone of the Burundian economy, accounting for around 30-40% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (though figures vary, with some sources like the English one stating 50% in 2017) and employing the vast majority (over 90%) of the population. Subsistence agriculture is dominant, with most farmers cultivating small plots of land (average farm size was about one acre in 2014) to feed their families.

Key food crops include bananas, sweet potatoes, cassava, maize, beans, and sorghum.

The main cash crops and primary exports are coffee and tea, which traditionally account for the bulk (up to 90%) of foreign exchange earnings. The coffee sector, primarily Arabica, involves many smallholder farmers. The tea industry is also significant. Other agricultural products include cotton, hides, and skins.

Challenges in the agricultural sector are numerous:

- Land scarcity and degradation: High population density leads to very small farm sizes and cultivation on marginal lands, resulting in soil erosion and declining fertility.

- Low productivity: Use of traditional farming methods, limited access to modern inputs (fertilizers, improved seeds), and poor infrastructure contribute to low yields.

- Climate change vulnerability: Dependence on rain-fed agriculture makes the sector susceptible to droughts and irregular rainfall patterns.

- Price volatility: Reliance on coffee and tea makes export earnings vulnerable to fluctuations in international commodity prices.

- Food insecurity: Despite the agricultural focus, chronic food insecurity and malnutrition are widespread.

7.1.2. Mining and Resources

Mining is a small but potentially growing sector. Burundi has known deposits of several minerals, including:

- Nickel: Significant nickel deposits, among the largest in the world, exist, particularly at Musongati. Exploitation has been slow due to infrastructure challenges and the need for large investments.

- Gold: Artisanal gold mining occurs, often informally.

- Rare earth elements: Deposits have been identified.

- Other minerals include cobalt, copper, platinum, vanadium, tin, tungsten, and kaolin. Peat is also extracted for fuel.

The development of the mining sector is seen as a potential driver of economic diversification and growth. However, concerns exist regarding environmental impact, revenue transparency, and ensuring that benefits reach the local population. The lack of infrastructure (energy, transport) is a major impediment to large-scale mining.

Manufacturing is very limited, focusing on the processing of agricultural products (e.g., coffee, tea, sugar) and light consumer goods like blankets, shoes, and soap, primarily for the domestic market.

7.2. Economic Challenges and Development Efforts

Burundi faces profound macroeconomic and structural challenges:

- Poverty: Widespread and extreme poverty affects the majority of the population (approximately 80% live in poverty). Burundi consistently ranks among the world's poorest countries by GDP per capita (nominal GDP per capita was around 310 USD in 2019). The 2018 World Happiness Report ranked Burundians as the world's least happy.

- High Population Density and Growth: This puts immense pressure on land, resources, and social services.

- Dependence on Foreign Aid: Foreign aid constitutes a significant portion of the national income (42% according to one source, the second highest in Sub-Saharan Africa) and government budget.

- Debt: While Burundi received debt relief under initiatives for heavily indebted poor countries, managing public debt remains a challenge.

- Inflation: Price instability can erode purchasing power.

- Unemployment and Underemployment: Particularly high among youth.

- Corruption: Corruption is a major obstacle to development, diverting resources and undermining governance.

- Political Instability: Past and recurrent political crises have severely damaged the economy, deterred investment, and disrupted trade.

- Infrastructure Deficit: Poor road networks, limited energy supply, and inadequate communication technology hinder economic activity.

- Lack of Economic Diversification: Over-reliance on agriculture, especially coffee and tea, makes the economy vulnerable.

Development efforts, often supported by international partners like the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, African Development Bank, and bilateral donors, focus on:

- Poverty reduction strategies.

- Improving agricultural productivity and food security.

- Investing in infrastructure (energy, transport).

- Strengthening governance and combating corruption.

- Promoting private sector development.

- Investing in health and education.

- Regional integration, particularly through the East African Community.

However, the effectiveness of these efforts is often hampered by political instability, governance weaknesses, and limited institutional capacity. Social equity concerns, such as ensuring that the benefits of any growth are broadly shared and that vulnerable populations are protected, are critical from a social liberal viewpoint.

7.3. Currency

The official currency of Burundi is the Burundian franc (ISO 4217 code: BIF). It is nominally subdivided into 100 centimes, although centime coins have not been issued in independent Burundi and are not in circulation.

The Bank of the Republic of Burundi (Banque de la République du BurundiBRBFrench) is the central bank, responsible for issuing the currency and managing monetary policy. Monetary policy faces challenges in maintaining price stability and managing the exchange rate in a context of economic vulnerability and dependence on external flows.

7.4. Transport

Burundi's transportation infrastructure is limited and underdeveloped, posing a significant constraint on economic development, trade, and access to services. The country's landlocked status further complicates its transport logistics.

- Road Network: Roads are the primary mode of transport. However, the network is insufficient, and a large proportion of roads are unpaved and in poor condition, especially in rural areas. Paved roads connect major urban centers, but maintenance is a challenge. The road network comprised about 7.7 K mile (12.32 K km) in total, but as of 2005, less than 10% of this was paved.

- Air Transport: Bujumbura International Airport (Melchior Ndadaye International Airport) is the country's only international airport and the main gateway for air travel. It is serviced by a few regional and international airlines, connecting Burundi to other African capitals and Europe. There are a few smaller airfields for domestic use, but domestic air services are minimal.

- Water Transport: Lake Tanganyika provides an important waterway for domestic and international transport. The port of Bujumbura is the main port, handling cargo and passenger traffic with neighboring countries like Tanzania (port of Kigoma) and the DRC. The MV Mwongozo is a notable ferry operating on the lake.

- Rail Transport: Burundi currently has no railway system. There have been long-term plans for regional rail links, such as connecting Burundi to Tanzania's central line or as part of the East African Railway Master Plan to link with Rwanda, Uganda, and Kenya, but these projects face significant financial and logistical hurdles.

- Public Transport: Public transport in urban areas relies on minibuses, taxis, and motorcycle taxis. Intercity transport is primarily by bus and minibus. Bicycles are also a common means of transport, especially in rural areas, for both people and goods.

The poor state of transport infrastructure increases the cost of doing business, isolates rural communities, and hinders access to markets and social services. Improving transport infrastructure is a key priority for the government and development partners. According to a 2012 DHL Global Connectedness Index, Burundi was the least globalized of 140 surveyed countries, partly due to its transport limitations.

8. Demographics

Burundi is one of the most densely populated countries in Africa, with a young and rapidly growing population. Its demographic profile is significantly influenced by its history of conflict, poverty, and limited access to resources and services.

8.1. Population Statistics

As of recent estimates (e.g., UN estimate for October 2021 was 12,346,893; the English source mentions "over 14 million" in its overview with a 2024 citation), Burundi's population continues to grow rapidly. In 1950, the population was only around 2.45 million. The population growth rate is high, estimated at around 2.5% to 3% per year.

- Population Density: With a small land area, the population density is very high, exceeding 400 people per square kilometer, making it one of the highest in Sub-Saharan Africa. This puts immense pressure on land and resources.

- Urbanization: Burundi remains overwhelmingly rural, with only about 13-14% of the population living in urban areas (as of 2019-2020). Bujumbura is the largest urban center and economic capital, followed by Gitega, the political capital.

- Age Structure: The population is very young, with a large proportion of children and adolescents. This youthful demographic presents both opportunities (a potential demographic dividend) and challenges (pressure on education, health, and employment).

- Total Fertility Rate: The total fertility rate is very high, among the highest in the world, with women having an average of around 5 children (e.g., 5.10 children per woman cited from the English source for 2021).

- Life Expectancy: Life expectancy at birth is low, reflecting poor health conditions, poverty, and the impact of past conflicts. Recent estimates place it around 60-62 years.

- Migration: Burundi has experienced significant outflows of refugees due to conflict and political instability, particularly during the civil war and the 2015 crisis. There is also internal migration and emigration for economic opportunities.

The following table presents the largest cities in Burundi, based on available population estimates.

| Rank | City | Province | Population (Estimate) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bujumbura | Bujumbura Mairie | ~374,809 (city proper, older estimates vary; metropolitan area significantly larger) |

| 2 | Gitega | Gitega | ~135,467 |

| 3 | Ngozi | Ngozi | ~39,884 |

| 4 | Rumonge | Rumonge | ~35,931 |

| 5 | Cibitoke | Cibitoke | ~23,885 |

| 6 | Kayanza | Kayanza | ~21,767 |

| 7 | Bubanza | Bubanza | ~20,031 |

| 8 | Muyinga | Muyinga | ~9,609 (older estimates may be higher) |

| 9 | Karuzi | Karuzi | ~10,705 |

| 10 | Kirundo | Kirundo | ~10,024 |

Note: Population figures for Burundian cities can vary widely between sources and over time due to rapid urbanization and displacement. The figures above are indicative, drawn from various source inputs.

8.2. Ethnic Groups

Burundi's population is composed of three main indigenous ethnic groups:

- Hutu: Constituting the large majority, estimated at around 85% of the population. Traditionally, Hutus were primarily agriculturalists.

- Tutsi: Forming a significant minority, estimated at around 14-15% of the population. Traditionally, Tutsis were predominantly pastoralists and held a dominant position in the pre-colonial kingdom and for much of the post-independence period.

- Twa (or Batwa): A Pygmy group, they are the smallest minority, estimated at less than 1% of the population. Historically hunter-gatherers, the Twa have faced severe marginalization and discrimination.

It is crucial to note that these ethnic distinctions, while having historical roots, were significantly hardened and politicized during the colonial era and became a central axis of conflict in post-independence Burundi. The groups share the same language (Kirundi) and culture, and intermarriage has occurred. The relationship between Hutus and Tutsis has been characterized by periods of cooperation and intense conflict, including genocides and civil war. Reconciliation efforts aim to build a shared national identity that transcends these ethnic divisions, though the legacy of conflict continues to impact social relations. The perspective of social liberalism emphasizes equality, justice for past wrongs, and inclusive governance to prevent future ethnic-based violence.

8.3. Languages

The languages of Burundi reflect its indigenous roots and colonial history.

- Kirundi (or Rundi): A Bantu language, Kirundi is the national language and is spoken by virtually the entire population. It is a unifying factor, as it is shared across all ethnic groups (Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa). Kirundi is closely related to Kinyarwanda, the main language of Rwanda, and the two are mutually intelligible to a large extent.

- French: Introduced during the Belgian colonial period, French has long been an official language and is widely used in government administration, education (especially higher education), formal business, and the media. However, fluency is generally limited to the educated elite and urban populations.

- English: English was officially adopted as an official language in 2014, partly to facilitate Burundi's integration into the East African Community, where English is a key lingua franca. Its use is growing, particularly in business and among younger, educated Burundians.

- Swahili: A Bantu lingua franca widely spoken in East Africa, Swahili is also commonly spoken in Burundi, especially in urban areas and along trade routes, including Bujumbura and areas bordering Tanzania and the DRC. While not always listed as an official language in the same capacity as the others, its practical importance is significant for regional communication and trade.

The official recognition and promotion of Kirundi alongside French and English aim to balance national identity with international communication and regional integration.

8.4. Religion

The religious landscape of Burundi is predominantly Christian, with significant minorities practicing Islam and traditional indigenous beliefs.

- Christianity is the majority religion, adhered to by an estimated 80-90% of the population.

- Roman Catholicism is the largest Christian denomination, with estimates ranging from 60-65% of the population. The Catholic Church has a significant presence in education and social services.

- Protestantism (including Anglicanism) constitutes the remaining Christian population, around 15-25%. Various denominations are present, including Pentecostal and Evangelical churches which have seen growth.

- Islam is practiced by a minority, estimated at 2-5% of the population. Muslims are primarily Sunni and are concentrated mainly in urban areas, particularly Bujumbura, and in towns like Rumonge and Nyanza-Lac.

- Traditional Indigenous Beliefs: An estimated 5% (though some sources suggest a higher percentage of the population, or that many Christians and Muslims also incorporate traditional beliefs and practices) adhere primarily to traditional animist beliefs. These often involve reverence for ancestors and nature spirits.

Freedom of religion is generally respected, and religious institutions play an active role in public life, including education, healthcare, and sometimes in peace and reconciliation efforts. Religious holidays for both Christians and Muslims are officially recognized.

9. Education

The education system in Burundi faces significant challenges related to access, quality, and resources, despite government efforts to improve literacy and enrollment rates. The country's history of conflict and poverty has severely impacted its educational infrastructure and capacity.

9.1. System and Access

The education system generally follows a structure of primary, secondary, and higher education.

- Primary Education: Officially, primary education (typically starting around age 7) is compulsory and has been declared free since 2005, leading to a significant increase in enrollment. It usually lasts for 6 years.

- Secondary Education: Secondary education is divided into lower and upper cycles. Access to secondary education is more limited than primary, with lower enrollment rates, particularly for girls and in rural areas. Only a small percentage of Burundian children (e.g., an older estimate suggested 10% of boys) are allowed a secondary education, though this may have improved.

- Higher Education: The main public university is the University of Burundi in Bujumbura. There are also other public and private higher education institutions. Access to higher education is limited.

- Literacy Rates: Adult literacy rates have improved but remain a challenge. Estimates vary; a 2012 estimate indicated an adult literacy rate (ages 15-24) of 74.71% (men and women combined), with a youth literacy rate (15-24) of 92.58%. A 2021 estimate showed male literacy at 81.3% and female at 68.4%. Burundi's literacy rate is comparatively higher than some countries in the region.

Disparities in educational attainment exist based on gender, socio-economic status, and geographic location (urban vs. rural).

9.2. Challenges and Reforms

The education sector faces numerous challenges:

- Quality of Education: Overcrowded classrooms, a shortage of qualified teachers, and inadequate teaching materials affect the quality of education.

- Resource Constraints: Insufficient government funding, despite allocating a significant portion of its GDP to education (around 5% in 2022), limits the ability to build and maintain schools, pay teachers adequately, and provide necessary resources.

- Teacher Training and Motivation: Lack of sufficient training programs and low salaries for teachers contribute to challenges in maintaining a motivated and skilled teaching workforce.

- High Dropout Rates: Despite increased enrollment, dropout rates, especially at the primary level, are high due to poverty, child labor, early marriage (for girls), and the perceived low value or quality of education.

- Infrastructure: Many schools lack basic facilities such as clean water, sanitation, and electricity.

- Impact of Conflict: Past conflicts destroyed infrastructure, displaced teachers and students, and diverted resources from education.

Reforms and efforts to improve the educational system have focused on increasing access (e.g., free primary education), improving quality through curriculum development and teacher training, building more schools, and addressing gender disparities. International organizations and NGOs play a role in supporting these efforts. Investment in education is critical for Burundi's social development and long-term economic progress.

10. Health

The public health situation in Burundi is critical, characterized by a heavy burden of disease, limited access to healthcare services, and severe under-resourced health system. Decades of conflict, poverty, and political instability have profoundly undermined the health and well-being of the population.

10.1. Healthcare System and Access

The healthcare system in Burundi is organized into public, private, and faith-based facilities. It includes national and provincial hospitals, district health centers, and smaller clinics. However, the system suffers from:

- Shortage of Facilities and Personnel: There is a significant lack of hospitals, clinics, qualified doctors, nurses, and other health professionals, especially in rural areas where the majority of the population lives.

- Limited Access: Geographic and financial barriers limit access to healthcare for many Burundians. The cost of services and medicines can be prohibitive for impoverished families, even with some government subsidies for certain services (e.g., maternal and child health).

- Poor Infrastructure and Equipment: Many health facilities lack essential medicines, medical supplies, and equipment. Water and electricity supply can be unreliable.

- Dependence on International Aid: The health sector is heavily reliant on funding and support from international donors and NGOs.

Like other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, Burundi utilizes traditional/indigenous medicine alongside biomedicine. Efforts have been made to integrate traditional practitioners and research medicinal plants.

10.2. Major Health Issues

Burundi faces a high prevalence of communicable and non-communicable diseases, as well as conditions related to malnutrition and poor sanitation.

- Malaria: Malaria is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, particularly among children under five.

- HIV/AIDS: While prevalence rates are lower than in some southern African countries, HIV/AIDS remains a significant public health concern.

- Tuberculosis: TB is also a major health problem, often co-occurring with HIV infection.

- Malnutrition: Chronic malnutrition is widespread, especially among children. High rates of stunting (low height for age) and wasting (low weight for height) contribute to child mortality and long-term developmental problems. Burundi has one of the worst hunger and malnourishment rates globally.

- Maternal and Child Mortality: Maternal mortality rates and infant/child mortality rates are very high. Leading causes of child death include pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, and malnutrition - many of which are preventable or treatable.

- Waterborne Diseases: Lack of access to clean water and sanitation contributes to diseases like diarrhea, cholera, and typhoid fever.

- Respiratory Infections: Acute respiratory infections are a common cause of illness.

The political unrest since 2015 further strained the healthcare system, limiting access to medication and hospital equipment. Life expectancy was around 60.1 years as of 2015. In 2013, Burundi spent about 8% of its GDP on healthcare. Efforts to address these public health challenges include vaccination campaigns, disease prevention programs, maternal and child health initiatives, and efforts to improve nutrition and sanitation, often supported by international partners.

10.3. Poverty, Hunger, and Malnutrition

Poverty is deeply entrenched in Burundi and is a primary driver of hunger and malnutrition. An estimated 80% of the population lives below the poverty line. Food insecurity is chronic and widespread, affecting a large portion of households.

The causes are multifaceted:

- Reliance on subsistence agriculture with low productivity.

- Land scarcity and degradation due to high population density.

- Climate shocks such as droughts and floods.

- The legacy of conflict, which disrupted agricultural production and displaced populations.

- Limited economic opportunities outside of agriculture.

Malnutrition, particularly among children under five, is a severe public health crisis. According to the World Food Programme, 56.8% of children under five suffer from chronic malnutrition (stunting). This has long-term consequences for physical and cognitive development, educational attainment, and overall productivity. High rates of acute malnutrition (wasting) also occur, especially during lean seasons or crises.

Addressing poverty, hunger, and malnutrition requires integrated approaches, including improving agricultural productivity, promoting economic diversification, strengthening social safety nets, investing in health and nutrition services (especially for mothers and children), and ensuring peace and stability.

11. Culture

Burundi's culture is rich and diverse, primarily based on local traditions with influences from neighboring countries. Despite the disruptions caused by civil unrest and poverty, many cultural expressions remain vibrant. Farming is the main industry, shaping daily life and customs.

11.1. Traditions and Social Customs

Social life in Burundi often revolves around family and community. Respect for elders is a key value. Traditional ceremonies related to birth, marriage, and death are important social events. When several Burundians of close acquaintance meet for a gathering, they may drink impeke, a traditional sorghum beer, together from a large container to symbolize unity and fellowship. Oral tradition plays a vital role in transmitting history, values, and life lessons through storytelling, proverbs, poetry, and songs. Literary genres in Kirundi include imigani (tales/proverbs), indirimbo (songs/poems), amazina (praise poems for cattle or heroes), and ivyivugo (heroic or self-praise poetry).

11.2. Arts and Literature

- Drumming: Burundi is world-renowned for its traditional drumming. The Royal Drummers of Burundi (Abatimbo) represent a significant cultural heritage, performing intricate rhythms on large, sacred drums known as karyenda (the royal drum, a symbol of the monarchy and the nation), amashako (providing a continuous beat), ibishikiso (providing a varied rhythm), and ikiranya drums. Drumming performances, often accompanied by dance, are integral to celebrations, official ceremonies, and rituals.

- Dance: Dance is a common accompaniment to drumming. The abatimbo is performed at official ceremonies, while the fast-paced abanyagasimbo is another well-known dance.

- Music: Besides drumming, traditional musical instruments include the flute, zither, ikembe (a lamellophone), indonongo (a stringed instrument), umuduri (a musical bow), inanga (a trough zither), and inyagara (shakers). Contemporary Burundian music blends traditional sounds with modern influences. Singer Jean-Pierre Nimbona (Kidumu) is a notable Burundian musician with international recognition.

- Crafts: Crafts are an important art form. Basket weaving is a popular skill among local artisans, producing intricate and colorful items. Other crafts include pottery, masks, shields, and statues, often sold to tourists.

Literature in written form is less developed than oral traditions, partly due to historical factors and limited publishing opportunities.

11.3. Media

The media landscape in Burundi includes print, radio, television, and increasingly, the internet and social media. Radio is the most widespread and influential medium, particularly in rural areas.

- Radio: Several public and private radio stations operate, offering news, music, and educational programming in Kirundi, French, and sometimes Swahili. International broadcasters like BBC and RFI also have a presence.

- Television: Television access is more limited, mainly concentrated in urban areas. There is a national public broadcaster and a few private channels.

- Print Media: A small number of newspapers and magazines are published, primarily in French and Kirundi, but circulation is generally low.

- Internet: Internet penetration is growing but remains relatively low, concentrated in urban centers. Mobile internet access is increasing.

Issues related to press freedom are a significant concern. Journalists and media outlets often face restrictions, harassment, and intimidation, particularly when reporting on sensitive political issues or human rights. The 2015 political crisis saw a severe crackdown on independent media. Access to diverse and unbiased information is crucial for a healthy democracy.

11.4. Sports

Sports are popular, with association football (soccer) being the most widely followed and played sport throughout the country. The Burundi national football team, known as "The Swallows" (Intamba mu Rugamba), participates in regional and continental competitions. The Burundi Premier League is the top domestic football league.

Other popular sports include:

- Basketball: Gaining popularity, especially in urban areas.

- Athletics (Track and Field): Burundi has produced internationally successful long-distance runners. Vénuste Niyongabo won a gold medal in the 5,000 meters at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, and Francine Niyonsaba won a silver medal in the 800 meters at the 2016 Rio Olympics.

- Martial Arts: Judo is popular, with several clubs in operation.

Mancala board games are also a common pastime.

11.5. Cuisine

Burundian cuisine is based on staple foods grown locally. Due to the high cost of meat, it is eaten sparingly, perhaps only a few times a month in many households.

Common staple ingredients include:

- Plantains (cooking bananas)

- Sweet potatoes

- Cassava (manioc)

- Maize (corn)

- Beans

- Peas

- Rice

Dishes are often simple stews or porridges made from these staples, sometimes accompanied by vegetables or, less frequently, meat (goat, beef, chicken) or fish (especially from Lake Tanganyika, like ndagala - small dried fish).

Common dishes include:

- Ubugali (or ugali): A stiff porridge made from cassava or maize flour, similar to that found in other parts of East Africa.

- Beans and plantains are frequently cooked together.

- Grilled meat or fish, when available.

Fruits like bananas, mangoes, and pineapples are also consumed. Traditional drinks include sorghum beer (impeke) and banana beer.

11.6. Public Holidays

Public holidays in Burundi include a mix of national and religious observances.

Major national holidays include:

- January 1: New Year's Day

- February 5: Unity Day

- May 1: Labour Day

- July 1: Independence Day (from Belgium in 1962)

- August 15: Assumption Day

- October 13: Rwagasore Day (commemorating the assassination of Prince Louis Rwagasore)

- October 21: Ndadaye Day (commemorating the assassination of President Melchior Ndadaye)

- November 1: All Saints' Day

- December 25: Christmas Day

Christian holidays like Easter (Good Friday, Easter Monday) are also observed. The Burundian government also declared the Islamic holiday of Eid al-Fitr as a public holiday in 2005, reflecting the religious diversity of the nation.

12. Science and Technology

The state of science and technology in Burundi is nascent, facing significant challenges due to limited resources, inadequate infrastructure, a small pool of trained researchers, and the impact of past conflicts and ongoing economic hardship. However, there are efforts to develop this sector as a component of national development.

Burundi's Strategic Plan for Science, Technology, Research and Innovation (2013) identified several priority areas: food technology, medical sciences, energy, mining and transportation, water, desertification, environmental biotechnology and indigenous knowledge, materials science, engineering and industry, ICTs, space sciences, mathematical sciences, and social and human sciences.

- Research Institutions: The University of Burundi is the primary institution for higher education and research. There are also specialized research institutes, such as the National Institute of Public Health, which was designated an EAC Centre of Excellence in October 2014.

- Research Output: Scientific output is low compared to global standards but has shown some growth. Medical sciences tend to be a main focus of research publications. A significant proportion of Burundian scientific publications involve international co-authorship, indicating reliance on external collaboration. Between 2011 and 2019, medical researchers accounted for 4% of the country's scientists but 41% of scientific publications. Burundi's publication intensity in material sciences doubled from 0.6 to 1.2 articles per million inhabitants between 2012 and 2019. Overall, with six scientific publications per million inhabitants (as of data leading to 2021), Burundi still has one of the lowest publication rates in Central and East Africa.

- Researcher Density and Funding: Researcher density (headcounts per million inhabitants) grew from 40 to 55 between 2011 and 2018. Domestic research expenditure rose from 0.11% to 0.21% of GDP between 2012 and 2018.

- Challenges: Major challenges include insufficient funding for research and development (R&D), a "brain drain" of skilled personnel, limited access to scientific equipment and information, and weak linkages between research institutions and the productive sectors of the economy.

- ICT Development: Information and Communication Technology (ICT) infrastructure is underdeveloped. Access to computers and the internet is limited, especially outside urban areas, though mobile phone penetration has increased. Burundi has ranked very low in global network readiness indices.

Government policies aim to promote science and technology education, build research capacity, and foster innovation. However, the impact on societal progress is constrained by the broader socio-economic and political environment. Strengthening science and technology is crucial for addressing challenges in agriculture, health, environmental management, and for fostering economic diversification and sustainable development.

13. Foreign Relations

The foreign relations of Burundi are shaped by its history, geographical location in the volatile Great Lakes region, economic dependencies, and its efforts to maintain sovereignty while engaging with international partners. Key aspects include relations with neighboring countries, former colonial powers, major international actors, and its participation in international and regional organizations. The humanitarian aspects, including refugee flows and the impact of internal conflicts on regional stability, are also significant factors.

13.1. General Foreign Policy

Burundi's foreign policy generally aims to:

- Maintain national sovereignty and territorial integrity.

- Promote peace and security, both domestically and regionally.

- Foster economic development through international cooperation, trade, and investment.

- Participate actively in regional and international organizations.

Principles often invoked include non-interference in the internal affairs of other states, peaceful resolution of disputes, and adherence to international law. However, its foreign relations have often been strained by internal political crises and human rights concerns, leading to periods of isolation or criticism from international partners.

13.2. Relations with Neighboring Countries

Relations with its immediate neighbors-Rwanda, Tanzania, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)-are of paramount importance.

- Rwanda: Relations have historically been complex, marked by shared cultural and ethnic ties (Hutu, Tutsi, Twa) but also by periods of intense rivalry and mutual suspicion, often linked to internal political dynamics and refugee flows in both countries. Accusations of interference in each other's affairs have been common. For example, Burundi accused Rwanda of backing the 2015 coup attempt. Both countries are members of the EAC.