1. Overview

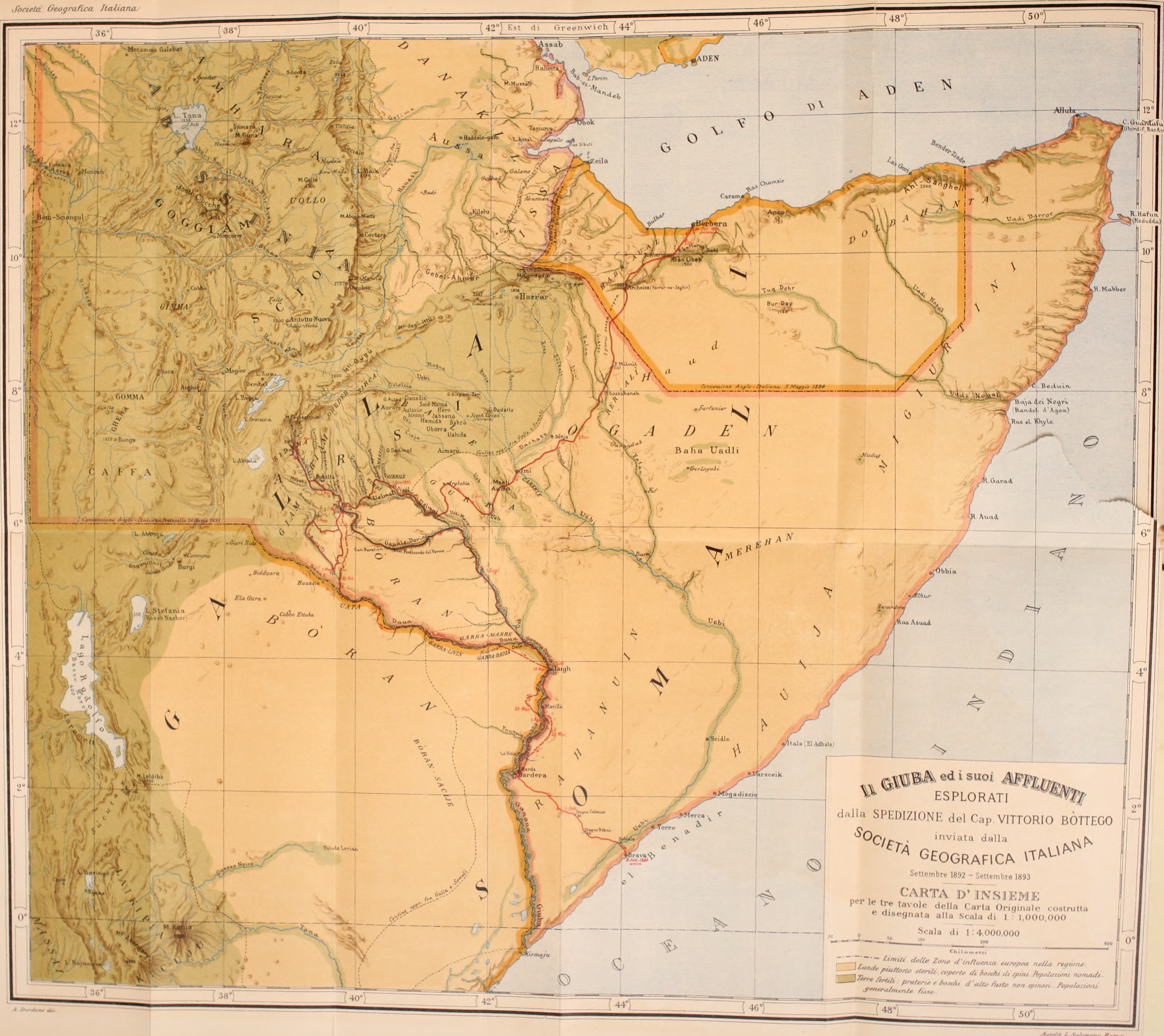

Somaliland, officially the Republic of Somaliland (Jamhuuriyadda SoomaalilandJamhuuriyadda SoomaalilandSomali; جمهورية صوماليلاندJumhūrīyat ṢūmālīlāndArabic), is a de facto sovereign state in the Horn of Africa, which is internationally considered to be part of Somalia. Somaliland is located on the southern coast of the Gulf of Aden and is bordered by Djibouti to the northwest, Ethiopia to the south and west, and the Puntland region of Somalia to the east. Its claimed territory has an area of 68 K mile2 (176.12 K km2), with approximately 6.2 million people as of 2024. The capital and largest city is Hargeisa.

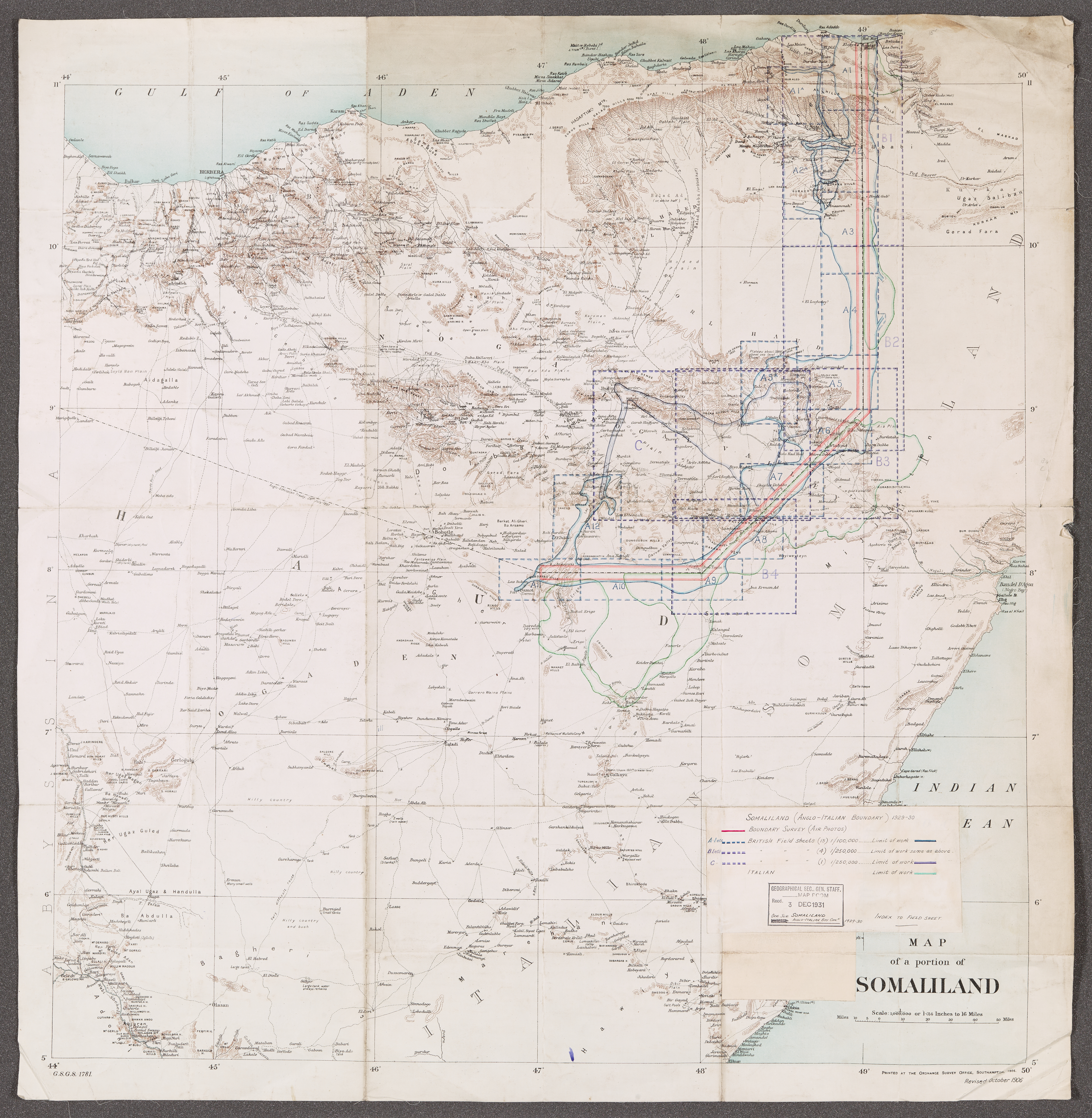

The region's modern history is marked by its experience as British Somaliland, established in the late 19th century. After a brief period of independence as the State of Somaliland in June 1960, it voluntarily united with the Trust Territory of Somaliland (formerly Italian Somaliland) to form the Somali Republic. However, this union was fraught with challenges, leading to political marginalization and economic disparity for the northern regions. The oppressive policies of Siad Barre's regime in Somalia, particularly against the Isaaq clan, culminated in the Somaliland War of Independence (1981-1991) and the Isaaq Genocide. Following the collapse of Barre's regime, Somaliland declared the restoration of its sovereignty on May 18, 1991.

Since its declaration of independence, Somaliland has embarked on a journey of democratic governance, establishing its own constitution, holding regular multi-party elections, and developing state institutions, including an executive, legislature, and judiciary. This process has largely been an indigenous effort, with limited external assistance due to its lack of international recognition. Despite maintaining relative peace and stability compared to much of Somalia, Somaliland faces significant socio-economic challenges, including high unemployment, poverty, and the constraints imposed by its unrecognized status, which limits access to international aid and investment. The nation continues its quest for international recognition, highlighting its democratic credentials, historical claim to sovereignty, and its role as a stabilizing force in a volatile region. Recent events, such as the 2023 Las Anod conflict, underscore ongoing territorial disputes and internal complexities. Somaliland's aspirations are deeply rooted in its distinct historical identity and its people's struggle for self-determination and a more equitable future.

2. Etymology

The name Somaliland is derived from two words: "Somali" and "land," signifying "Land of the Somalis." The area was named when the United Kingdom took control from the Egyptian administration in 1884, after signing successive treaties with the ruling Somali Sultans from the Isaaq, Issa, Gadabursi, and Warsangali clans. The British established a protectorate in the region referred to as British Somaliland. In 1960, when the protectorate became independent from Britain, it was called the State of Somaliland. Five days later, on July 1, 1960, the State of Somaliland united with the Trust Territory of Somaliland under Italian Administration (the former Italian Somaliland). The name "Republic of Somaliland" was adopted upon the declaration of independence following the Somali Civil War in 1991.

At the Grand Conference in Burao held in 1991, many names for the country were suggested. Among these were Puntland, in reference to Somaliland's location in the ancient Land of Punt (this name is now used by the Puntland state in neighboring Somalia), and Shankaroon, meaning "better than five" in the Somali, a reference to the five regions of Greater Somalia.

3. History

The history of the Somaliland region spans millennia, from early human settlements and ancient trade with civilizations like Egypt to the arrival of Islam, the rise and fall of sultanates, colonial rule under Britain, a brief period of independence, a troubled union with Somalia, a devastating war of independence that included genocide, and the subsequent restoration of sovereignty as an unrecognized republic striving for democratic governance and international acceptance. Key events have profoundly shaped its political identity and its people's resilience in the face of conflict and human rights abuses, leading to a strong desire for self-determination.

3.1. Prehistory

The area of Somaliland was inhabited around 10,000 years ago during the Neolithic age. The ancient shepherds raised cows and other livestock and created vibrant rock art paintings. During the Stone Age, the Doian and Hargeisan cultures flourished here. The oldest evidence of burial customs in the Horn of Africa comes from cemeteries in Somaliland dating back to the 4th millennium BCE. The stone implements from the Jalelo site in the north were also characterized in 1909 as important artifacts demonstrating the archaeological universality during the Paleolithic between the East and the West.

According to linguists, the first Afroasiatic-speaking populations arrived in the region during the ensuing Neolithic period from the family's proposed urheimat ("original homeland") in the Nile Valley, or the Near East.

The Laas Geel complex on the outskirts of Hargeisa dates back around 5,000 years and has rock art depicting both wild animals and decorated cows. Other cave paintings are found in the northern Dhambalin region, which feature one of the earliest known depictions of a hunter on horseback. The rock art is in the distinctive Ethiopian-Arabian style, dated to 1,000 to 3,000 BCE. Additionally, between the towns of Las Khorey and El Ayo in eastern Somaliland lies Karinhegane, the site of numerous cave paintings of real and mythical animals. Each painting has an inscription below it, which collectively have been estimated to be around 2,500 years old.

3.2. Antiquity and Classical Era

Ancient pyramidical structures, mausoleums, ruined cities and stone walls, such as the Wargaade Wall, are evidence of civilizations thriving in the Somali peninsula. Ancient Somaliland had a trading relationship with ancient Egypt and Mycenaean Greece dating back to at least the second millennium BCE, supporting the hypothesis that Somalia or adjacent regions were the location of the ancient Land of Punt. The Puntites traded myrrh, spices, gold, ebony, short-horned cattle, ivory and frankincense with the Egyptians, Phoenicians, Babylonians, Indians, Chinese and Romans through their commercial ports. An Egyptian expedition sent to Punt by the 18th dynasty Queen Hatshepsut is recorded on the temple reliefs at Deir el-Bahari, during the reign of the Puntite King Parahu and Queen Ati. In 2015, isotopic analysis of ancient baboon mummies from Punt that had been brought to Egypt as gifts indicated that the specimens likely originated from an area encompassing eastern Somalia and the Eritrea-Ethiopia corridor.

The camel is believed to have been domesticated in the Horn region sometime between the 2nd and 3rd millennium BCE. From there, it spread to Egypt and the Maghreb. During the classical period, the northern Barbara city-states of Mosylon, Opone, Mundus, Isis, Malao, Avalites, Essina, Nikon, and Sarapion developed a lucrative trade network, connecting with merchants from Ptolemaic Egypt, Ancient Greece, Phoenicia, Parthian Persia, Saba, the Nabataean Kingdom, and the Roman Empire. They used the ancient Somali maritime vessel known as the beden to transport their cargo.

After the Roman conquest of the Nabataean Empire and the establishment of a Roman naval presence at Aden to curb piracy, Arab and Somali merchants cooperated with the Romans to bar Indian ships from trading in the free port cities of the Arabian peninsula to protect the interests of Somali and Arab merchants in the lucrative commerce between the Red and Mediterranean Seas. However, Indian merchants continued to trade in the port cities of the Somali peninsula, which was free from Roman interference.

For centuries, Indian merchants brought large quantities of cinnamon to Somalia and Arabia from Ceylon and the Spice Islands. The source of the spices is said to have been the best-kept secret of Arab and Somali merchants in their trade with the Roman and Greek world; the Romans and Greeks believed the source to have been the Somali peninsula. The collaboration between Somali and Arab traders inflated the price of Indian and Chinese cinnamon in North Africa, the Near East, and Europe, and made the spice trade profitable, especially for the Somali merchants through whose hands large quantities were shipped across sea and land routes.

In 2007, more rock art sites with Sabaean and Himyarite writings in and around Hargeisa were found, but some were bulldozed by developers.

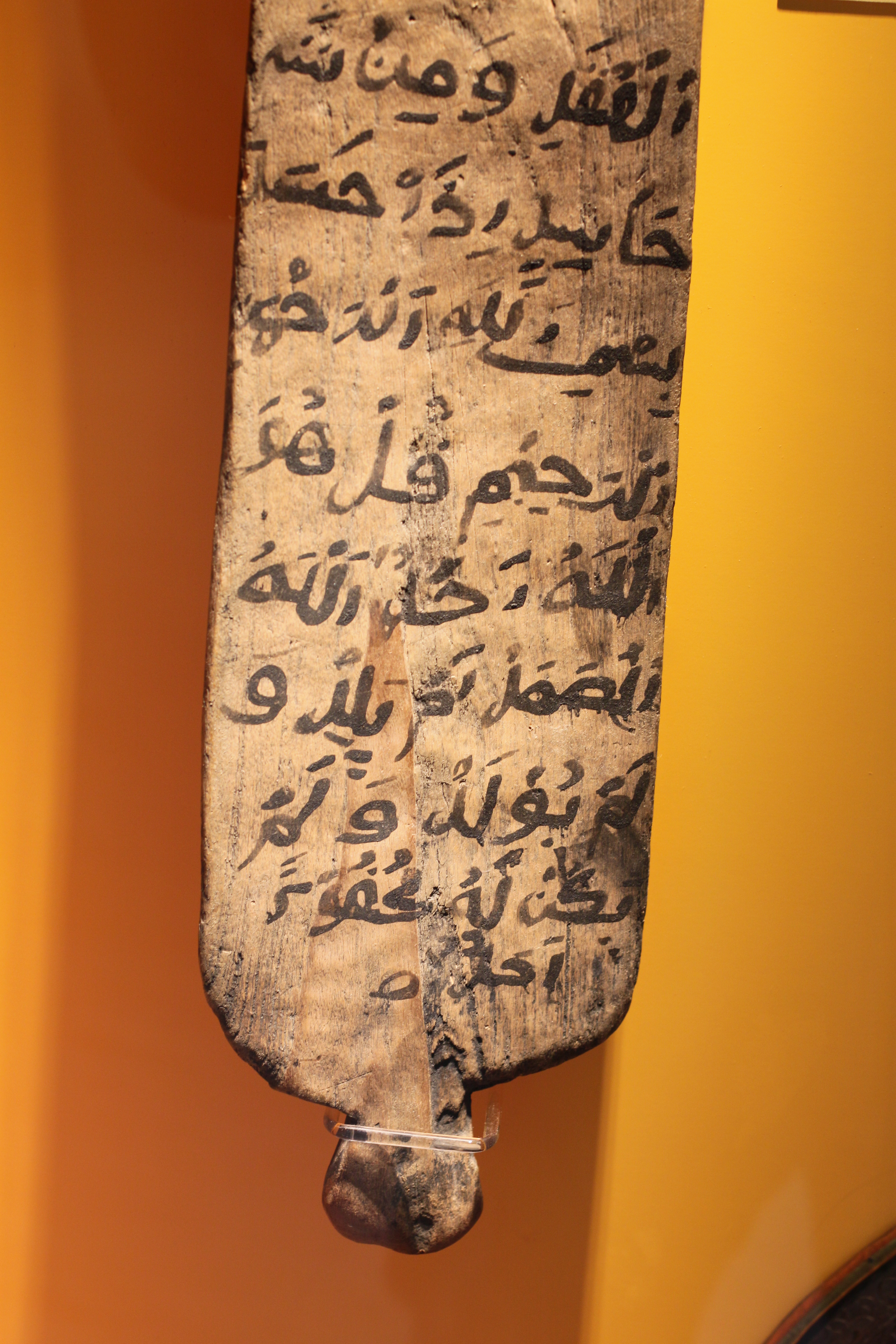

3.3. Spread of Islam and Medieval Period

The Isaaq people traditionally claim to have descended from Sheikh Ishaaq bin Ahmed, an Islamic scholar who purportedly traveled to Somaliland in the 12th or 13th century and married two women; one from the local Dir clan and the other from the neighboring Harari people. He is said to have sired eight sons who are the common ancestors of the clans of the Isaaq clan-family. He remained in Maydh until his death. As the Isaaq clan-family grew in size and numbers during the 12th century, they migrated and spread from their core area in Mait (Maydh) and the wider Sanaag region in a southwestward expansion over a wide portion of present-day Somaliland by the 15th and 16th centuries. In this expansion, earlier Dir communities were driven westwards and southwards. One fraction of the Habar Yunis clan, the Muse 'Arre, remains in Mait as the custodians of Sheikh Ishaaq's tomb. By the 1300s, the Isaaq clans united to defend their territories and resources during conflicts with migrating clans.

After a war, the Isaaq clans, along with other tribes like the Darod, grew in numbers and territory, pushing westwards into the plains of Jijiga and beyond, where they played an important role in the Adal Sultanate's campaigns against Christian Abyssinia. By the 16th to 17th century, these movements established the Isaaqs on coastal Somaliland.

Various Somali Muslim kingdoms were established in the area in the early Islamic period. In the 14th century, the Zeila-based Adal Sultanate battled the forces of the Ethiopian emperor Amda Seyon I. The Ottoman Empire later occupied Berbera and environs in the 1500s. Muhammad Ali, Pasha of Egypt, subsequently established a foothold in the area between 1821 and 1841.

The Sanaag region is home to the ruined Islamic city of Maduna near El Afweyn, considered the most substantial and accessible ruin of its type in Somaliland. The main feature is a large rectangular mosque with 3-metre high walls, a mihrab, and possibly smaller arched niches. Archaeologist Sada Mire dates the city to the 15th-17th centuries.

3.4. Early Modern Sultanates

In the early modern period, successor states to the Adal Sultanate began to flourish in Somaliland, including the Isaaq Sultanate and Habr Yunis Sultanate. These sultanates played a significant role in the region's socio-political landscape before the arrival of European colonial powers.

3.4.1. Isaaq Sultanate

The Isaaq Sultanate was a Somali kingdom that ruled parts of the Horn of Africa during the 18th and 19th centuries. It spanned the territories of the Isaaq clan, descendants of the Banu Hashim clan, in modern-day Somaliland and Ethiopia. The sultanate was governed by the Rer Guled branch established by the first sultan, Sultan Guled Abdi, of the Eidagale clan. The sultanate is the pre-colonial predecessor to the modern Republic of Somaliland. The Isaaq Sultanate had a robust economy with significant trade through its main port of Berbera and the smaller port town of Bulhar, as well as eastern ports like Heis, Karin, and El-Darad known for exporting frankincense.

According to oral tradition, prior to the Guled dynasty, the Isaaq clan-family were ruled by a dynasty of the Tolje'lo branch, descending from Ahmed nicknamed Tol Je'lo, the eldest son of Sheikh Ishaaq's Harari wife. There were eight Tolje'lo rulers in total, starting with Boqor Harun (Boqor HaaruunBoqor HaaruunSomali) who ruled the Isaaq Sultanate for centuries starting from the 13th century. The last Tolje'lo ruler, Garad Dhuh Barar (Dhuux BaraarDhuux BaraarSomali), was overthrown by a coalition of Isaaq clans. The once strong Tolje'lo clan were scattered and took refuge among the Habr Awal with whom they still mostly live.

The Sultan of Isaaq regularly convened shirs (meetings) where he would be informed and advised by leading elders or religious figures on decisions. For instance, Sultan Deria Hassan chose not to join the Dervish movement after counsel from Sheikh Madar. He also addressed early tensions between the Saad Musa and Eidagale upon the former's settlement into the growing town of Hargeisa in the late 19th century. The Sultan was responsible for organizing grazing rights and, in the late 19th century, new agricultural spaces. The allocation and sustainable use of resources were crucial in this arid region. In the 1870s, a famous meeting between Sheikh Madar and Sultan Deria proclaimed a ban on hunting and tree cutting near Hargeisa. It was also decided that holy relics from Aw Barkhadle would be brought, and oaths would be sworn on them by the Isaaqs in the presence of the Sultan whenever internal combat broke out.

Aside from the leading Sultan of Isaaq, numerous Akils, Garaads, and subordinate Sultans, alongside religious authorities, constituted the Sultanate. Occasionally, these would declare their independence or break from its authority.

The Isaaq Sultanate had 5 rulers prior to the creation of British Somaliland in 1884. Historically, Sultans would be chosen by a committee of several important members of the various Isaaq subclans. Sultans were usually buried at Toon, south of Hargeisa, which was a significant site and the capital of the Sultanate during Farah Guled's rule.

| Name | Reign Start | Reign End |

|---|---|---|

| Abdi Eisa (Traditional leader) | Mid-1700s | Mid-1700s |

| Guled Abdi (First Sultan) | Late 1700s | 1808 |

| Farah Guled | 1808 | 1845 |

| Hassan Farah | 1845 | 1870 |

| Deria Hassan | 1870 | 1939 (British Somaliland established 1884) |

3.4.2. Battle of Berbera (1827)

The first engagement between Somalis of the region and the British occurred in 1825, leading to hostilities that culminated in the Battle of Berbera in 1827. This was followed by a trade agreement between the Habr Awal clan and the United Kingdom. Subsequently, a British treaty was signed with the Governor of Zeila in 1840. Further engagements took place between the British and elders of the Habar Garhajis and Habar Toljaala clans of the Isaaq in 1855. A year later, the "Articles of Peace and Friendship" were concluded between the Habar Awal and the East India Company. These interactions paved the way for formal treaties signed between 1884 and 1886 with various clans including the Habar Awal, Gadabursi, Habar Toljaala, Habar Garhajis, Esa, and the Warsangali. These treaties were instrumental in the British establishment of a protectorate known as British Somaliland. The protectorate was initially administered from Aden as part of British India until 1898. It was then managed by the Foreign Office until 1905, and subsequently by the Colonial Office. These agreements significantly altered the political landscape of the region, marking the beginning of British colonial influence.

3.5. British Somaliland

British Somaliland was established as a protectorate in the late 19th century, primarily to secure a supply route for Aden and to counter other European colonial interests in the Horn of Africa. British administration was generally indirect, particularly in the interior, focusing on maintaining stability and trade. This period saw significant resistance movements, most notably the Dervish campaign, and later, the region became a minor theater in World War II. Colonial policies had lasting impacts on local governance structures, the economy, and societal organization, laying some of the groundwork for future political developments.

3.5.1. Dervish Period and Somaliland Campaign (1900-1920)

The Somaliland Campaign, also known as the Anglo-Somali War or the Dervish War, was a protracted series of military expeditions from 1900 to 1920. It pitted the Dervish forces, led by the charismatic religious and nationalist leader Mohammed Abdullah Hassan (often dubbed the "Mad Mullah" by the British), against the British. The British were aided by Ethiopian and Italian forces. During World War I, Hassan also received support from the Ottomans, Germans, and briefly from Emperor Iyasu V of Ethiopia. The Dervish movement represented a significant and sustained resistance against colonial rule, mobilizing various Somali clans. The conflict was marked by numerous battles and expeditions. The Fifth Expedition of the Somaliland campaign in 1920 was the final British offensive. Utilizing air power for one of the first times in African colonial warfare, the Royal Air Force bombed the Dervish capital of Taleh in February 1920. This effectively ended the Dervish resistance after two decades. The Somaliland Campaign was one of the longest and bloodiest anti-colonial struggles in sub-Saharan Africa, causing immense devastation. It is estimated that nearly a third of Somaliland's population perished during these two decades of conflict, and the local economy was severely ravaged, leaving a lasting impact on the region's people and infrastructure.

3.5.2. Italian Conquest of British Somaliland (1940-1941)

The Italian conquest of British Somaliland was a military campaign in East Africa that took place in August 1940, during World War II. It was part of the larger East African campaign. Forces of Italy, advancing from Italian East Africa, invaded and occupied British Somaliland. The British and Commonwealth forces, outnumbered and outgunned, conducted a fighting withdrawal and evacuated from Berbera to Aden. This occupation was relatively brief, as British forces, as part of their broader offensive in East Africa, recaptured the territory in March 1941. The campaign had significant implications, temporarily shifting colonial control and impacting the local population and administration, though British authority was soon restored.

3.6. Anti-Colonial Resistance

Beyond the major Dervish campaign, British colonial rule in Somaliland faced other significant local resistance movements. These uprisings, often sparked by specific grievances such as taxation or administrative policies, reflected the ongoing struggle for self-determination and opposition to foreign domination. Key figures emerged to lead these movements, employing various methods of resistance, which, though often suppressed, highlighted the deep-seated desire for autonomy among the Somali clans.

3.6.1. 1922 Burao Tax Revolt and RAF Bombing

In 1922, the people of Burao revolted against the British colonial administration in opposition to a newly imposed tax. The revolt involved rioting and attacks on British government officials. During the unrest, Captain Allan Gibb, a Dervish war veteran and the District Commissioner, was shot and killed. In response, the British authorities, with the approval of Sir Winston Churchill, then Secretary of State for the Colonies, dispatched Royal Air Force (RAF) bombers from Aden. The RAF planes arrived at Burao within two days and proceeded to bomb the town with incendiaries, effectively burning the entire settlement to the ground.

Governor of British Somaliland, Sir Geoffrey Archer, telegraphed Churchill stating: "I deeply regret to inform that during an affray at Burao yesterday... Captain Gibb was shot dead... Miscreants then disappeared under the cover of darkness. To meet the situation... we require two aeroplanes for about fourteen days... We propose to inflict fine of 2,500 camels on implicated sections... and aeroplanes to be used to bomb stock on grazing grounds."

Churchill reported to the House of Commons that Gibb's murder "does not appear to have been premeditated, but it inevitably had a disturbing effect upon the surrounding tribes, and immediate dispositions of troops became necessary to ensure the apprehension and punishment of those responsible."

James Lawrence, in Imperial Rearguard: Wars of Empire, wrote that after Gibb's murder, "Governor Archer immediately called for aircraft which were at Burao within two days. The inhabitants of the native township were turned out of their houses, and the entire area was razed by a combination of bombing, machine-gun fire and burning."

Following the aerial bombardment, the leaders of the rebellion acquiesced, agreeing to pay a fine for Gibb's death but refused to identify and apprehend the individuals accused of killing him. Most of those responsible evaded capture. The controversial and brutal use of air power to quell the revolt had a significant human impact and led to political repercussions, ultimately forcing the British to abandon the direct taxation policy in the protectorate due to the violent resistance it provoked.

3.6.2. 1945 Sheikh Bashir Rebellion

The 1945 Sheikh Bashir Rebellion was an uprising waged by tribesmen of the Habr Je'lo clan in the former British Somaliland protectorate against British authorities in July 1945, led by Sheikh Bashir, a Somali religious leader.

On July 2, Sheikh Bashir gathered 25 of his followers in the town of Wadamago and transported them to the vicinity of Burao, where he distributed arms. On the evening of July 3, the group entered Burao and attacked the police guard of the central prison, as well as the house of the district commissioner, Major Chambers, resulting in the death of Major Chamber's police guard. The rebels then escaped to Bur Dhab, a strategic mountain south-east of Burao, where Sheikh Bashir's small unit occupied a fort and took up a defensive position.

The initial British campaign against Sheikh Bashir's troops proved abortive as his forces kept moving. The war exposed the British administration to humiliation. The government concluded that another expedition would be useless without effectively occupying the whole protectorate, which led to a temporary withdrawal of advance posts, confining British administration to the coast town of Berbera in early 1945. During this period, Sheikh Bashir settled many disputes among local tribes using Islamic Sharia and gathered a strong following.

The British administration later recruited Indian and South African troops, led by police general James David, to fight against Sheikh Bashir. On July 7, British forces found Sheikh Bashir and his unit in defensive positions in the mountains of Bur Dhab. After clashes, Sheikh Bashir and his second-in-command, Alin Yusuf Ali (nicknamed Qaybdiid), were killed. A third rebel was wounded and captured along with two others; the rest fled. On the British side, the police general and a number of Indian and South African troops perished.

After his death, Sheikh Bashir was widely hailed by locals as a martyr and held in great reverence. His family quickly removed his body from the place of his death at Geela-eeg mountain. This rebellion further highlighted the ongoing resistance to colonial rule and the desire for self-governance among the local population.

3.7. State of Somaliland (1960)

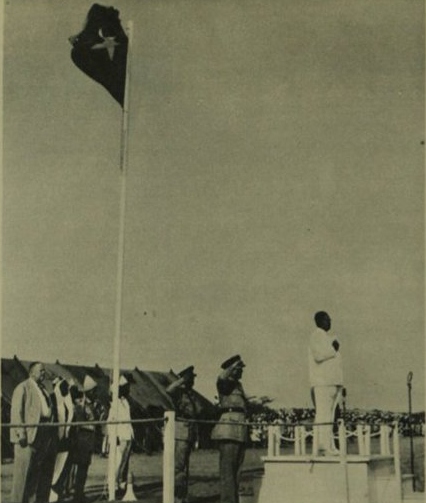

In the lead-up to 1960, the British government initially planned to delay the independence of the British Somaliland protectorate, favoring a gradual transfer of power to allow local politicians to gain more administrative experience. However, strong pan-Somali nationalism and a landslide victory for pro-unification parties in earlier elections spurred demands for immediate independence and unification with the Trust Territory of Somaliland under Italian Administration (the former Italian Somaliland), which was also scheduled for independence.

In May 1960, the British government announced its preparedness to grant independence to British Somaliland, with the intention that the territory would unite with the Italian-administered Trust Territory. The Legislative Council of British Somaliland passed a resolution in April 1960 requesting independence and union. This proposal was agreed upon by the legislative councils of both territories following a joint conference in Mogadishu.

On June 26, 1960, the former British Somaliland protectorate achieved independence as the State of Somaliland. During its brief five-day period of sovereignty, the State of Somaliland received international acknowledgements from thirty-five sovereign states, including Egypt, Ethiopia, and members of the Commonwealth of Nations. The United States, through Secretary of State Christian Herter, sent a congratulatory message to the Somaliland Council of Ministers on June 26, acknowledging its independence, though formal recognition was not extended.

The following day, on June 27, 1960, the newly convened Somaliland Legislative Assembly approved a bill that would formally allow for the union of the State of Somaliland with the Trust Territory of Somaliland, which gained its independence on July 1, 1960.

3.8. Somali Republic (Union with Somalia, 1960-1991)

On July 1, 1960, the State of Somaliland and the Trust Territory of Somaliland (the former Italian Somaliland) united as planned to form the Somali Republic. Inspired by Somali nationalism, the northerners (from the former State of Somaliland) were initially enthusiastic about the union. A government was formed by Abdullahi Issa, with Aden Abdullah Osman Daar as President and Abdirashid Ali Shermarke as Prime Minister (later President from 1967 to 1969).

On July 20, 1961, a new constitution, first drafted in 1960, was ratified through a popular referendum. However, the constitution received little support in the former Somaliland, where it was perceived to favor the south. Many northerners boycotted the referendum in protest, and over 60% of those who did vote in the north were against the new constitution. Despite this, the referendum passed, and the northern region quickly found itself politically marginalized and economically dominated by southerners. Dissatisfaction became widespread in the north, and popular support for the union plummeted. These emerging North-South tensions and disparities were significant. In December 1961, British-trained Somaliland officers attempted a revolt to end the union, but their uprising failed. The northern regions continued to experience marginalization over the subsequent decades.

In 1967, Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal, a northerner, became Prime Minister under President Shermarke. Shermarke was assassinated two years later by one of his own bodyguards. His murder was swiftly followed by a military coup d'état on October 21, 1969 (the day after his funeral), in which the Somali Army seized power without encountering armed opposition. The putsch was spearheaded by Major General Mohamed Siad Barre, who commanded the army at the time. The new regime under Barre would go on to rule Somalia for the next 22 years, a period marked by increasing authoritarianism and human rights abuses that disproportionately affected the northern population.

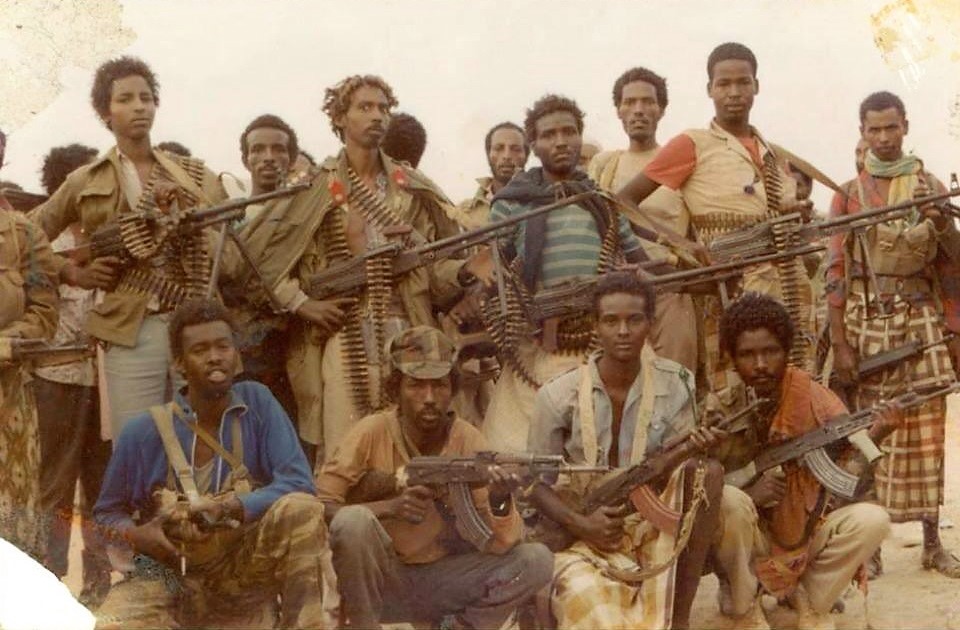

3.9. Somali National Movement and Barre Regime Persecution

The moral authority of Siad Barre's government gradually eroded as many Somalis became disillusioned with life under military rule. By the mid-1980s, resistance movements, supported by Ethiopia's communist Derg administration, had sprung up across the country. In the northern regions (now Somaliland), the Somali National Movement (SNM), largely composed of members from the Isaaq clan, emerged as a major force. This led to the Somaliland War of Independence. Barre responded by ordering punitive measures against those he perceived as locally supporting the guerrillas, especially in the northern regions. The clampdown included the indiscriminate bombing of cities. The northwestern administrative center of Hargeisa, an SNM stronghold, was among the targeted areas in 1988, along with Burao. The bombardment was led by General Mohammed Said Hersi Morgan, Barre's son-in-law.

In May 1988, the SNM launched a major offensive on Hargeisa and Burao. The SNM captured Burao on May 27 within two hours, and entered Hargeisa on May 29, overrunning most of the city apart from its airport by June 1.

The Barre regime's rule was marked by targeted, brutal persecution of the Isaaq clan. This campaign of state-sponsored violence is widely referred to as the Isaaq Genocide or the "Hargeisa Holocaust." A United Nations investigation concluded that the crime of genocide was "conceived, planned and perpetrated by the Somali Government against the Isaaq people." The number of civilian casualties is estimated to be between 50,000 and 100,000, with some reports estimating upwards of 200,000 Isaaq civilians killed. Along with the deaths, the Barre regime's forces bombarded and razed Hargeisa and Burao, the second and third largest cities in Somalia at the time. This systematic destruction and violence displaced an estimated 400,000 local residents to Hart Sheik in Ethiopia, and another 400,000 individuals were internally displaced. The counterinsurgency against the SNM targeted the rebel group's civilian base of support, escalating into a genocidal onslaught that had a lasting and traumatic impact on the population. The Barre regime's persecution was not limited to the Isaaq, as it also targeted other clans, such as the Hawiye.

The Barre regime collapsed in January 1991. Thereafter, as the political situation in Somaliland stabilized under the SNM, the displaced people began to return to their homes, militias were demobilized or incorporated into the new army, and tens of thousands of houses and businesses were reconstructed from rubble, marking the beginning of Somaliland's journey towards self-governance.

3.10. Restoration of Sovereignty (1991 Declaration of Independence)

Although the Somali National Movement (SNM) at its inception had a unionist constitution, it eventually began to pursue independence, looking to secede from the rest of Somalia amidst the escalating Somali Civil War and the brutal persecution under the Barre regime. Under the leadership of Abdirahman Ahmed Ali Tuur, the local administration, following extensive local peace-building processes and political deliberations, declared the northwestern Somali territories independent at a conference held in Burao between April 27, 1991, and May 15, 1991. On May 18, 1991, Somaliland unilaterally declared the restoration of its sovereignty, based on the borders of the former British Somaliland.

Abdirahman Ahmed Ali Tuur became the first President of the newly established Somaliland polity. However, he subsequently renounced the separatist platform in 1994 and began instead to publicly seek and advocate reconciliation with the rest of Somalia under a power-sharing federal system of governance. A brief armed conflict had begun in January 1992 against rebels opposing Tuur's administration, lasting until August 1992, when it was settled by a conference at the town of Sheikh.

Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal was appointed as Tuur's successor in 1993 by the Grand Conference of National Reconciliation in Borama. This conference, which met for four months, was a crucial local peace-building process that led to a gradual improvement in security and the consolidation of the new territory. However, another armed conflict erupted between the Somaliland government, now under Egal, and militias of the Eidagalley clan who occupied Hargeisa airport. Fighting re-erupted when government troops attacked the airport in October 1994, sparking a new war that spread out of Hargeisa and lasted until around April 1995, ending in a rebel defeat. Around the same time, Djiboutian-backed forces of the Issa-dominated United Somali Front attempted and failed to carve out Issa-inhabited areas of Somaliland.

Egal was reappointed in 1997 and remained in power until his death on May 3, 2002. The vice-president, Dahir Riyale Kahin, who was a high-ranking National Security Service (NSS) officer in Berbera during Siad Barre's government in the 1980s, was sworn in as president shortly afterward. In 2003, Kahin became the first elected president of Somaliland in a multi-party election.

The war in southern Somalia between Islamist insurgents on one hand, and the Federal Government of Somalia and its African Union allies on the other, has for the most part not directly affected Somaliland, which, like neighboring Puntland, has remained relatively stable through its own peace-building and governance efforts.

3.11. 2001 Constitutional Referendum

In August 2000, President Egal's government distributed thousands of copies of a proposed constitution throughout Somaliland for consideration and review by the people. A critical clause among the 130 individual articles of the constitution was the ratification of Somaliland's self-declared independence and its final separation from Somalia, thereby restoring the nation's independence which it had briefly held in 1960. In late March 2001, President Egal set the date for the referendum on the Constitution for May 31, 2001.

The referendum was held as scheduled, and according to official results, 99.9% of eligible voters participated. An overwhelming 97.1% of those voters cast their ballots in favor of the constitution. This referendum was a significant step in reaffirming Somaliland's declared independence and establishing the democratic framework of the state, although it did not lead to international recognition.

3.12. 2023 Las Anod Conflict

On February 6, 2023, a significant conflict erupted in Las Anod, the administrative capital of the Sool region. The Dhulbahante clan elders of Las Anod declared their intent to secede from Somaliland and form a new state government named "SSC-Khatumo" with the aim of rejoining the Federal Government of Somalia. This declaration triggered armed clashes between Somaliland government forces and local Dhulbahante militias.

The background to the conflict is rooted in long-standing territorial disputes over Sool, Sanaag, and Cayn (SSC) regions, which are claimed by both Somaliland (based on colonial-era British Somaliland borders) and Puntland (based on clan affiliations, as the Dhulbahante are part of the Harti-Darod clan dominant in Puntland). Tensions had been escalating in Las Anod due to political assassinations and local grievances against the Somaliland administration.

The conflict led to significant displacement of the civilian population and a severe humanitarian crisis. Fighting resulted in numerous casualties on both sides and widespread destruction in Las Anod. By August 2023, SSC-Khatumo forces had reportedly taken control of Las Anod and significant parts of the Sool region from Somaliland. The conflict has complex implications for regional stability, Somaliland's territorial integrity, and its ongoing quest for international recognition. As of late 2024, the situation remained tense, with SSC-Khatumo administering parts of the Sool region.

In November 2024, Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi 'Irro' won the Somaliland presidential election.

4. Government and Politics

Somaliland has developed a political system that combines traditional Somali governance structures with modern democratic institutions. The government is based on a constitution adopted by referendum and features a multi-party system, an elected president, a bicameral parliament, and an independent judiciary. Despite its lack of international recognition, Somaliland has conducted multiple presidential, parliamentary, and local elections, often praised by observers for their relative fairness, though challenges related to political freedoms and inclusion remain.

President

Vice President

4.1. Constitution

The Constitution of Somaliland, adopted by a popular referendum in 2001, serves as the supreme law of the land. It defines Somaliland as a unitary state and a Presidential Republic based on the principles of peace, co-operation, democracy, and a multi-party system. The constitution outlines the structure of the government, dividing powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. It enshrines fundamental rights and freedoms for its citizens, establishes Islam as the state religion, and stipulates that laws must be compliant with Sharia principles. The constitution also affirms Somaliland's sovereignty and independence based on the borders of the former British Somaliland.

4.2. Executive

The executive branch of the Somaliland government is led by an elected President, who is the head of state and head of government. The President is elected by popular vote for a five-year term and can serve a maximum of two terms. The President is assisted by a Vice President, who is elected on the same ticket. The Council of Ministers (Cabinet) is appointed by the President and must be approved by the House of Representatives. The Cabinet is responsible for the day-to-day administration of the country and implementing government policies. The President has the power to approve bills passed by Parliament before they become law. Presidential elections are overseen and confirmed by the National Electoral Commission of Somaliland. The official residence and administrative headquarters of the President is the Somaliland Presidential Palace in the capital city of Hargeisa.

4.3. Parliament

Legislative power in Somaliland is vested in a bicameral Parliament.

The upper house is the House of Elders (Guurti), currently chaired by Suleiman Mohamoud Adan. It consists of 82 members who are traditionally selected by local communities and clan elders for six-year terms, though elections for this house have been repeatedly postponed. The House of Elders plays a crucial role in conflict resolution, reviewing legislation passed by the lower house, and has the exclusive power to extend the terms of the President and representatives under extraordinary circumstances that make elections impossible.

The lower house is the House of Representatives, currently chaired by Abdirisak Khalif Ahmed. It also comprises 82 members who are directly elected by the people through a multi-party system for five-year terms. The House of Representatives is the primary legislative body, responsible for drafting and passing laws, approving the national budget, and confirming presidential appointments (except for the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court). It can pass a law rejected by the House of Elders if it votes for the law by a two-thirds majority.

4.4. Judiciary and Law

The judicial system of Somaliland is structured with several tiers of courts. At the base are district courts, which handle matters of family law, succession, civil lawsuits for amounts up to 3.00 M SLSH, criminal cases punishable by up to 3 years' imprisonment or 3.00 M SLSH fines, and crimes committed by juveniles. Above these are regional courts, which deal with lawsuits and criminal cases not within the jurisdiction of district courts, labor and employment claims, and local government election disputes. Regional appeals courts handle all appeals from the district and regional courts.

The highest court is the Supreme Court, which also functions as the Constitutional Court. It deals with disputes between courts, issues between different branches of government, and reviews its own decisions. Somaliland nationality law defines who is a Somaliland citizen and the procedures for naturalization or renunciation of citizenship. The Somaliland government continues to apply the 1962 penal code of the Somali Republic. Consequently, homosexual acts are illegal in the territory. The legal system incorporates elements of secular law (based on British common law and the Somali penal code) and Sharia law, particularly in personal status matters.

4.5. Political Parties and Elections

Somaliland operates a multi-party system, a transition that occurred in 2002 after an initial period of interim governance following the 1991 restoration of independence. The guurti (House of Elders) played a key role in working with rebel leaders to establish the new government and was incorporated into the governance structure. Initially, the government was a power-sharing coalition of Somaliland's main clans, with parliamentary seats allocated proportionally.

The shift to multi-party democracy aimed to create ideology-based elections rather than clan-based ones, though clan affiliations continue to influence politics. The Constitution of Somaliland restricts the number of national political parties to a maximum of three. As of recent elections, the main political parties include the Peace, Unity, and Development Party (Kulmiye), the Justice and Development Party (UCID), and Waddani. The minimum voting age is 15.

Somaliland has held multiple presidential, parliamentary, and local elections since 2001. Freedom House has often ranked Somaliland as partly free, noting its democratic progress but also challenges related to political freedoms and press restrictions. Analyst Seth Kaplan has argued that Somaliland has built a more democratic mode of governance from the bottom up, largely without foreign assistance, by integrating customary laws and traditional leadership with modern state structures. This, along with factors like a relatively homogeneous population (primarily Isaaq clan), comparatively equitable income distribution (though poverty is widespread), a common historical narrative of persecution under Somalia, and a degree of insulation from external interference, has been suggested as contributing to its relative stability and governmental legitimacy compared to other parts of the Horn of Africa.

4.6. Foreign Relations

Somaliland maintains political contacts and informal ties with several countries and international bodies, despite its lack of formal international recognition. It has particularly close relationships with its neighbors Ethiopia and Djibouti. Ethiopia maintains a trade office in Hargeisa and relies on the Port of Berbera for some of its trade. In January 2024, Somaliland and Ethiopia signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) which, if implemented, would grant Ethiopia access to the Red Sea via Berbera in exchange for a stake in Ethiopian Airlines and potential future recognition of Somaliland by Ethiopia.

Somaliland also has relations with Republic of China (Taiwan), with both establishing representative offices in each other's capitals in 2020. Other countries with which Somaliland has engaged include the United Kingdom (the former colonial power), Kenya, South Africa, Sweden, and the United Arab Emirates (which has invested in the Port of Berbera through DP World). The European Union and the African Union have sent delegations to Somaliland to discuss cooperation and the issue of recognition, but neither organization has formally recognized it. Somaliland has applied to join the Commonwealth under observer status, but its application is still pending. The United States has increased its engagement with Somaliland, providing aid and sending diplomats, but has stopped short of formal recognition. Various UK political figures and parties, such as UKIP, have expressed support for Somaliland's recognition.

4.6.1. International Recognition

Since its unilateral declaration of independence from Somalia in 1991, Somaliland has consistently sought international recognition as a sovereign state. However, as of late 2024, no United Nations member state has formally recognized it. The international community generally views Somaliland as an autonomous region within Somalia, adhering to the African Union's policy of upholding colonial-era borders to prevent widespread secessionist conflicts across the continent.

The primary legal argument for Somaliland's recognition centers on its status as the successor state to the State of Somaliland, which was briefly independent in June 1960 (gaining acknowledgements from 35 countries) before voluntarily uniting with the Trust Territory of Somaliland to form the Somali Republic. Somalilanders argue that this union was legally flawed and ultimately failed, justifying their decision to withdraw and restore their prior sovereignty.

Political reasons for the continued non-recognition include concerns that recognizing Somaliland could destabilize the Horn of Africa by encouraging other secessionist movements, and a desire by international actors to support the unity and territorial integrity of Somalia, particularly efforts to re-establish a functional federal government in Mogadishu. The stance of key international players, such as the United States, the European Union, and influential African nations, has been to engage with Somaliland on practical matters like development, security cooperation (especially against piracy and extremism), and democratization, while deferring the question of recognition. The 2024 MOU with Ethiopia, which includes a provision for eventual recognition in exchange for sea access, represents a potential shift, but its full implementation and broader international impact remain to be seen. Somaliland continues to argue that its track record of peace, stability, and democratic governance in a volatile region warrants its recognition as an independent state.

4.6.2. Border Disputes

Somaliland claims sovereignty over the entire territory of the former British Somaliland, based on the borders established during the colonial era and at its brief independence in 1960. However, it faces significant territorial disputes with the neighboring Puntland state of Somalia, particularly over the eastern regions of Sool and Sanaag, and parts of Togdheer (often collectively referred to as SSC).

Puntland's claim is primarily based on clan affiliations, as the Dhulbahante and Warsangali clans, who are part of the Harti confederation of the Darod clan family, are predominant in these disputed areas and also form a core constituency of Puntland. These clans largely participated in the establishment of Puntland in 1998 and many within these communities express a desire to remain part of a united Somalia.

Tensions between Somaliland and Puntland have frequently escalated into armed clashes, notably around Las Anod, the capital of the Sool region. Somaliland forces took control of Las Anod in October 2007. Over the years, various local unionist movements, such as the SSC Movement and later Khatumo State (established in 2012), have emerged in these regions, challenging Somaliland's administration and advocating for local autonomy or reunification with Somalia. An agreement was signed in Aynabo in October 2017 between the Somaliland government and leaders of Khatumo State, aiming to integrate Khatumo into Somaliland's governmental structures and amend Somaliland's constitution. This agreement, however, was unpopular among parts of the Dhulbahante community and did not fully resolve the underlying disputes.

The conflict over these territories reignited significantly with the 2023 Las Anod conflict, where Dhulbahante clan elders declared their intention to form SSC-Khatumo as a state within the Federal Government of Somalia, leading to Somaliland losing de facto control over significant portions of the Sool region. Somaliland maintains its claim based on historical colonial borders and the principle of uti possidetis juris, while Puntland and local SSC groups emphasize clan identity and self-determination within a federal Somalia.

4.7. Military

The Somaliland Armed Forces are the primary military command in Somaliland, responsible for national security and border control. They operate under the oversight of Somaliland's Ministry of Defence. The current Minister of Defence is Abdiqani Mohamoud Aateye.

Following the declaration of independence in 1991, various pre-existing militia affiliated with different clans, primarily those of the Somali National Movement (SNM), were absorbed into a centralized military structure. This integration was crucial in preventing inter-clan violence and establishing state authority. The resultant military is relatively large for the region and consumes a significant portion of the country's budget.

The Somaliland Army consists of several divisions equipped primarily with light weaponry, though it also possesses some howitzers and mobile rocket launchers. Its armored vehicles and tanks are mostly of Soviet design, with some ageing Western vehicles also in its arsenal. The Somaliland Navy (often referred to as a Coast Guard) operates with limited equipment and formal training but has reportedly achieved some success in curbing piracy and illegal fishing within Somaliland's waters. Internal security is primarily handled by the Somaliland Police.

4.8. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Somaliland presents a mixed picture. While the region has maintained relative peace and stability and has established democratic institutions, several human rights challenges persist. According to the 2023 Freedom House report, Somaliland has seen a consistent erosion of political rights and civic space. Authorities have been criticized for exerting pressure on public figures and journalists, including arrests and detentions that limit freedom of the press and freedom of expression.

Minority clans and marginalized groups often face economic and political marginalization. Violence against women, including female genital mutilation (FGM), remains a serious problem despite government fatwas condemning severe forms of FGM; legal frameworks to punish perpetrators are weak or unenforced. While the constitution guarantees certain political rights, their practical application can be inconsistent, particularly for opposition voices or those critical of the government. Issues related to due process and prison conditions have also been raised by human rights organizations. The ongoing conflict in areas like Las Anod has further exacerbated humanitarian concerns and raised questions about the conduct of security forces. From a social liberal perspective, while Somaliland has made strides in democratic development compared to Somalia, continued efforts are needed to strengthen protections for fundamental human rights, ensure press freedom, protect vulnerable groups, and address impunity.

5. Administrative Divisions

Somaliland's administrative structure is organized into regions and districts. This system has evolved since its 1991 declaration of independence, building upon previous administrative frameworks.

5.1. Regions and Districts

The Republic of Somaliland is divided into six administrative regions (gobollogobolladaSomali). These regions are Awdal, Sahil, Maroodi Jeex, Togdheer, Sanaag, and Sool. Each region is further subdivided into administrative districts. The 2019 local government law (Lr. 23/2019), which came into force on January 4, 2020, formally re-established these six regions. Under Article 11, Section 1 of this act, the regional boundaries are intended to correspond to the boundaries of the six districts that existed under the British Somaliland protectorate. However, in practice, the boundaries established during the Siad Barre era often subsist as the de facto administrative lines for some areas, and ongoing territorial disputes, particularly in Sool and Sanaag, affect Somaliland's administrative control over the entirety of these claimed regions.

The regions and their primary districts are as follows:

| Map | Region | Area (km2) | Capital | Districts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Awdal | 6.3 K mile2 (16.29 K km2) | Borama | Baki, Borama, Zeila, Lughaya | |

| Sahil | 5.4 K mile2 (13.93 K km2) | Berbera | Sheikh, Berbera | |

| Maroodi Jeex | 6.7 K mile2 (17.43 K km2) | Hargeisa | Gabiley, Hargeisa, Salahlay, Baligubadle | |

| Togdheer | 12 K mile2 (30.43 K km2) | Burao | Oodweyne, Buhoodle, Burao | |

| Sanaag | 21 K mile2 (54.23 K km2) | Erigavo | Garadag, El Afweyn, Erigavo, Lasqoray | |

| Sool | 15 K mile2 (39.24 K km2) | Las Anod | Aynabo, Las Anod, Taleh, Hudun |

6. Geography

Somaliland's geography is diverse, characterized by a long coastline on the Gulf of Aden, mountain ranges, plateaus, and arid to semi-arid plains, reflecting its location in the Horn of Africa.

6.1. Location and Topography

Somaliland is situated in the northwest of the internationally recognized territory of Somalia. It lies between latitudes 08°N and 11°30'N, and longitudes 42°30'E and 49°00'E. It is bordered by Djibouti to the west, Ethiopia to the south, and the Puntland region of Somalia to the east. Somaliland has an 528 mile (850 km) coastline along the Gulf of Aden. The total land area claimed by Somaliland is 68 K mile2 (176.12 K km2).

The northern part of the region is hilly, with altitudes in many places ranging between 2953 ft (900 m) to 6.9 K ft (2.10 K m) above sea level. The Awdal, Sahil, and Maroodi Jeex regions are generally fertile and mountainous. In contrast, the Togdheer region is mostly semi-desert with limited fertile greenery. The Awdal region is also known for its offshore islands, coral reefs, and mangroves.

Cal Madow is a mountain range in the eastern part of the country, extending from the northwest of Erigavo towards Bosaso in neighboring Puntland. It features Somaliland's highest peak, Shimbiris, which sits at an elevation of about 7.9 K ft (2.42 K m). The rugged east-west ranges of the Karkaar Mountains also lie to the interior of the Gulf of Aden littoral. In the central regions, the northern mountain ranges give way to shallow plateaus and typically dry watercourses, collectively referred to as the Ogo. The Ogo's western plateau gradually merges into the Haud, an important grazing area for livestock. In the east, the Haud is separated from the Ain and Nugal valleys by the Buur Dhaab mountain range.

A scrub-covered, semi-desert plain known as the Guban lies parallel to the Gulf of Aden littoral. Its width varies from 7.5 mile (12 km) in the west to as little as 1.2 mile (2 km) in the east. The plain is bisected by watercourses that are essentially dry sand beds except during rainy seasons, when they transform into lush vegetation. This coastal strip is part of the Ethiopian xeric grasslands and shrublands ecoregion.

6.2. Climate

Somaliland is located north of the equator and has a predominantly semi-arid to arid climate. Average daily temperatures generally range from 77 °F (25 °C) to 95 °F (35 °C). The sun passes vertically overhead twice a year, in April and in August or September.

Somaliland consists of three main topographic zones, each with distinct climatic characteristics:

- The coastal plain (Guban): This zone experiences high temperatures and low rainfall. Summer temperatures can easily average over 100 °F. However, temperatures decrease during the winter, leading to an increase in human and livestock populations in the area.

- The coastal range (Ogo): A high plateau immediately south of the Guban, with elevations ranging from 6.00 K ft above sea level in the west to 7.00 K ft in the east. Rainfall is heavier here than in the Guban, though it varies considerably within the zone.

- The plateau (Hawd): Located south of the Ogo range, this region is generally more heavily populated during the wet season when surface water is available. It is an important area for livestock grazing.

Somalilanders recognize four seasons:

- Gu: The first or major rainy season (late March, April, May, and early June). The Ogo range and Hawd experience the heaviest rainfall during this period, which is characterized by fresh grazing, abundant surface water, and the breeding season for livestock.

- Hagaa: (Late June through August) Usually dry, though scattered showers known as Karan rains can occur in the Ogo range. Hagaa tends to be hot and windy in most parts of the country.

- Dayr: (September, October, and early November) Roughly corresponding to autumn, this is the second or minor wet season. Precipitation is generally less than that of Gu.

- Jilaal: (Late November to early March) The coolest and driest months of the year, considered the season of thirst. The Hawd receives virtually no rainfall in winter. The Guban zone receives its "Hays" rains from December to February.

The average annual rainfall is around 18 in (446 mm) in some parts of the country, with most ofit occurring during Gu and Dayr. The country's humidity varies from 63% in the dry season to 82% in the wet season.

6.3. Wildlife

Somaliland is home to a variety of flora and fauna adapted to its predominantly arid and semi-arid ecosystems. The Cal Madow mountains in the east are a notable biodiversity hotspot, hosting numerous endemic species of plants and some animals due to their higher altitude and unique microclimates. These mountains contain remnants of ancient juniper forests and other unique vegetation.

Common fauna include various species of antelope such as Speke's gazelle, dibatag, and Beira antelope. Larger mammals like kudu, oryx, warthogs, and the Somali wild ass (a subspecies of the African wild ass) can be found, though their populations have been affected by habitat loss and hunting. Predators include jackals, hyenas, and occasionally leopards and cheetahs, though these are rare. The area around Burao is known as a significant habitat for the caracal. Birdlife is diverse, particularly in coastal areas and mountain ranges, with various resident and migratory species. Reptiles, including several snake and lizard species, are common.

The marine environment along the Gulf of Aden coast supports coral reefs and mangroves, particularly in areas like the Awdal region and the Zeila Archipelago, providing habitats for various fish species and marine life.

Conservation efforts in Somaliland are challenged by factors such as climate change, deforestation (primarily for charcoal production), overgrazing, and limited resources due to the country's unrecognized status. Poaching and illegal wildlife trade also pose threats. There is a growing awareness of environmental issues, but institutional capacity for effective conservation and enforcement of environmental regulations remains underdeveloped.

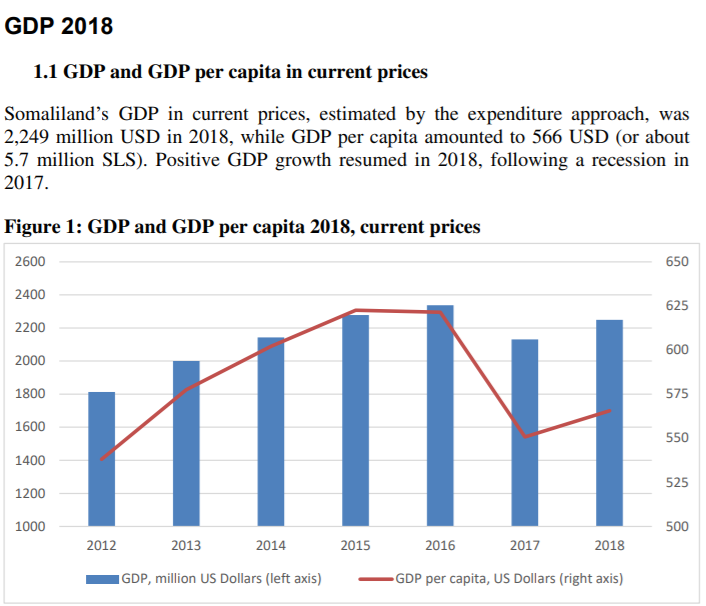

7. Economy

Somaliland's economy faces significant challenges, including high rates of unemployment and poverty, exacerbated by its lack of international recognition which limits access to foreign aid, loans, and investment. The World Bank has noted Somaliland as having one of the lowest GDP per capita figures globally. Youth unemployment is particularly severe, estimated to be between 60% and 70% or higher. Illiteracy rates are also high, especially among females and the elderly population in several areas. Despite these challenges, Somaliland has developed a functioning market economy, largely driven by the private sector and remittances from its diaspora. There is a focus on developing key sectors like livestock, trade, and potentially natural resources, with considerations for social equity and sustainable development.

Since Somaliland is unrecognized, international donors have found it difficult to provide direct aid to the government. As a result, the government relies mainly upon tax receipts from trade and businesses, and remittances from the large Somali diaspora. These remittances contribute significantly to the Somaliland economy, estimated by the World Bank to be around 1.00 B USD annually for Somalia as a whole, with a substantial portion reaching Somaliland. Dahabshiil is the largest of the money transfer companies handling these flows.

Service provisions have improved since the late 1990s through limited government efforts and contributions from non-governmental organisations, religious groups, the international community (especially the diaspora), and the growing private sector. Local and municipal governments have been developing key public services such as water in Hargeisa and education, electricity, and security in Berbera. In 2009, the Banque pour le Commerce et l'Industrie - Mer Rouge (BCIMR), based in Djibouti, opened a branch in Hargeisa, becoming the first commercial bank in the country since the 1990 collapse of the Commercial and Savings Bank of Somalia. In 2014, Dahabshil Bank International became the country's first locally-owned commercial bank. In 2017, Premier Bank from Mogadishu also opened a branch in Hargeisa.

7.1. Currency and Payment Systems

The official currency is the Somaliland shilling (SLSH). Due to Somaliland's lack of international recognition, the shilling is not easily exchangeable outside its borders and has no official international exchange rate. The Bank of Somaliland, the central bank established constitutionally in 1994, is responsible for regulating the currency and monetary policy.

Somaliland has a notably high adoption rate of mobile payment systems. The most popular and widely used service is ZAAD, a mobile money transfer service launched in 2009 by Telesom, the largest mobile operator. Mobile payments are used for a vast range of transactions, from everyday purchases to salary payments, contributing to a largely cashless economy in urban areas. This system has been crucial for financial inclusion in a country with limited traditional banking infrastructure.

7.2. Key Sectors

Somaliland's economy is primarily based on a few key sectors, with livestock being the most dominant. Efforts are underway to diversify and develop other areas such as telecommunications and tourism, though progress is hampered by lack of international recognition and investment.

7.2.1. Livestock and Agriculture

Livestock is the backbone of Somaliland's economy. Sheep, camels, and cattle are shipped from the Berbera port primarily to Gulf Arab countries, such as Saudi Arabia, especially for the Hajj pilgrimage season. The country is home to some of the largest livestock markets (known in Somali as seylad) in the Horn of Africa. Markets in Burao and Yirowe can see as many as 10,000 heads of sheep and goats sold daily, many of whom are destined for export. These markets handle livestock from all over the Horn of Africa.

Agriculture, while less dominant than livestock, is considered a potentially successful industry, especially for cereals and horticulture. The primary method of agricultural production is rain-fed farming. Sorghum is the main crop, occupying about 70% of rain-fed agricultural land, while maize accounts for another 25%. Other crops like barley, millet, groundnuts, beans, and cowpeas are grown on scattered marginal lands. Most farms are located near riverbanks, along the banks of seasonal streams (togs), and other water sources. Irrigation methods mainly involve flood diversion or crude earth canals channelling water from springs. Fruits and vegetables are grown for commercial use on the majority of irrigated farms.

7.2.2. Telecommunications

The telecommunications sector in Somaliland is relatively developed, with several private companies providing services. Major operators include Telesom, Somtel, Telcom, and NationLink. These companies offer mobile phone services, internet access, and are instrumental in the widely adopted mobile money systems. Mobile penetration is high, even in rural areas. The state-run Somaliland National TV is the main national public service television channel, launched in 2005, and its radio counterpart is Radio Hargeisa.

7.2.3. Tourism

Somaliland possesses several attractions with potential for tourism, though the industry is underdeveloped due to lack of recognition and infrastructure.

The rock art and caves at Laas Geel, located on the outskirts of Hargeisa, are a prominent archaeological site and popular local tourist attraction. Discovered by a French archaeological team in 2002, these ten caves contain exceptionally well-preserved paintings believed to date back around 5,000 years. Access is restricted to protect the site.

Other sights in Hargeisa include the Freedom Arch and the War Memorial. Natural attractions include the Naasa Hablood, twin hills near Hargeisa, considered a majestic natural landmark.

The Ministry of Tourism encourages visits to historic towns such as Sheekh, near Berbera, which has old British colonial buildings. Berbera itself houses historic Ottoman architectural buildings. Zeila, another historic city, was once part of the Ottoman Empire and a major trade hub in the 19th century, known for old colonial landmarks, offshore mangroves, coral reefs, and beaches. The nomadic culture of Somaliland also attracts some tourists interested in experiencing traditional pastoral life.

7.3. Transport

Transport infrastructure in Somaliland is developing, with roads being the primary mode of internal transport, complemented by air and sea links.

Bus services operate in major towns like Hargeisa, Burao, Gabiley, Berbera, and Borama. Road transportation services also connect major towns with adjacent villages, utilizing various vehicles including taxis, four-wheel drives, minibuses, and light goods vehicles (LGVs). The road network is gradually being improved, with key corridors like the Berbera Corridor to Ethiopia being upgraded.

The most prominent airlines serving Somaliland include Daallo Airlines, a Somali-owned private carrier offering regular international flights. African Express Airways and Ethiopian Airlines also operate flights from airports in Somaliland to destinations such as Djibouti City, Addis Ababa, Dubai, and Jeddah. These airlines also offer flights for the Hajj and Umrah pilgrimages. The main international airport is Egal International Airport in Hargeisa. Other major airports include the Berbera Airport, which has undergone significant upgrades.

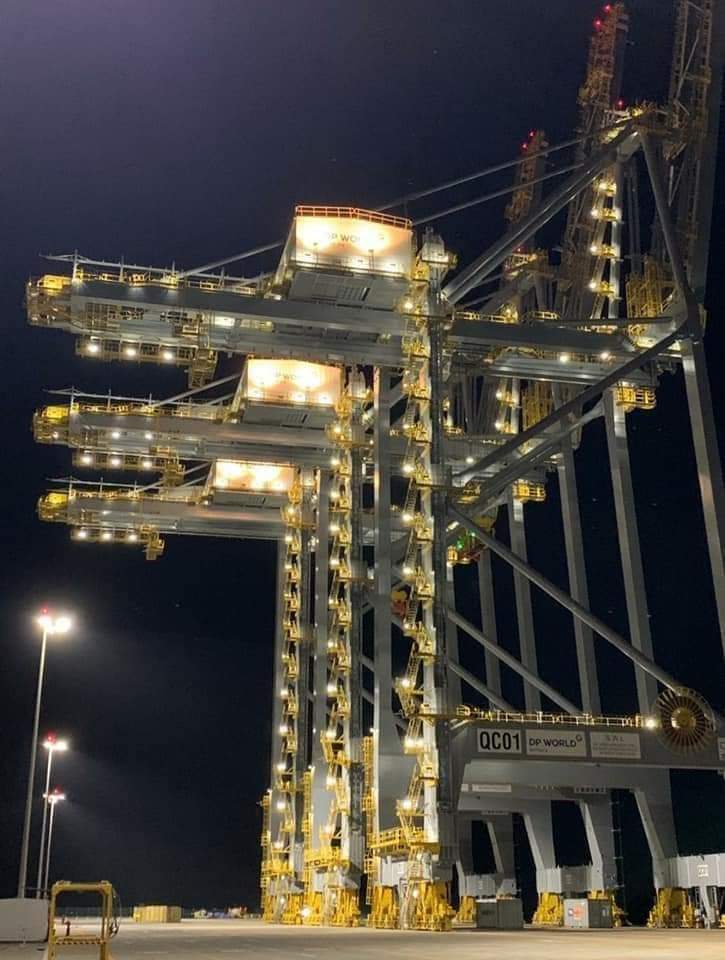

7.3.1. Ports

Maritime transport and logistics are strategically important for Somaliland's economy, centered on the Port of Berbera on the Gulf of Aden. In June 2016, the Somaliland government signed a significant agreement with DP World, a global port operator based in Dubai, to manage and develop the Port of Berbera. The project aims to enhance the port's productive capacity, improve its infrastructure, and establish it as a key trade gateway for the Horn of Africa, particularly as an alternative port for landlocked Ethiopia. The development has included the construction of a new container terminal and other facilities. The Berbera Corridor project, which involves upgrading the road connecting Berbera to the Ethiopian border, is integral to this strategy. The port's development is seen as crucial for Somaliland's economic growth and its geopolitical positioning.

7.4. Natural Resources and Energy

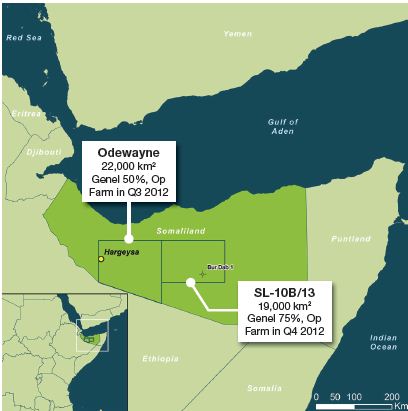

Somaliland is believed to possess various natural resources, with oil and natural gas exploration being a key area of interest, though development is hindered by the lack of international recognition and associated investment risks.

The first oil test well was dug in 1958 by Standard Vacuum (a joint venture of Exxon Mobil and Shell) in Dhagax Shabeel, Saaxil region. Three of the four test wells reportedly produced light crude oil, though these were drilled without extensive seismic data.

In August 2012, the Somaliland government awarded Genel Energy a license to explore for oil within its territory. Results of a surface seep study completed in early 2015 suggested significant potential in the SL-10B, SL-13, and Oodweyne blocks, with initial estimates of oil reserves around 1 billion barrels for each block. Genel Energy was set to drill an exploration well in the Buur-Dhaab area (near Aynabo) by late 2018, though timelines have shifted. In December 2021, Genel Energy signed a farm-out deal with OPIC Somaliland Corporation (backed by Taiwan's CPC Corporation) for the SL10B/13 block, which Genel stated could contain over 5 billion barrels of prospective resources. Drilling was subsequently scheduled for late 2023 or early 2024.

Besides oil and gas, there is potential for other mineral resources, but current operations are largely limited to simple quarrying for construction materials. Energy development is a major challenge, with heavy reliance on imported fossil fuels for electricity generation. There are efforts to explore renewable energy sources, but large-scale development requires significant investment and a stable regulatory environment, considering environmental and social impacts.

8. Society and Demographics

Somaliland's society is characterized by its largely homogenous Somali ethnic population, structured around a complex system of clan affiliations that play a significant role in social and political life. Islam is the predominant religion, deeply influencing cultural norms. The region faces demographic challenges common to developing countries, including rapid population growth and urbanization.

8.1. Demographics

There has not been an official census conducted in Somaliland since the Somalia census in 1975; results from a 1986 census were never publicly released. A population estimate was conducted by the UNFPA in 2014, primarily for aid distribution purposes, which put the combined population of the regions of Somaliland at approximately 3.5 million. The Somaliland government estimated the population at 5.7 million in 2021, and more recently at 6.2 million as of 2024.

Historical population estimates include:

- 1899: Approximately 246,000 (British estimate)

- 1960: Approximately 650,000 (At independence of British Somaliland)

- 1997: Approximately 2,000,000

- 2006: Approximately 3,500,000

- 2013: Approximately 4,500,000

- 2021: 5,700,000 (Somaliland government estimate)

- 2024: 6,200,000 (Somaliland government estimate)

The population is relatively young, with a high growth rate. Urbanization is increasing, with Hargeisa, Burao, and Berbera being the largest urban centers. Population density varies, being higher in urban areas and more fertile western regions compared to the arid eastern regions. Somaliland also has a significant diaspora, estimated to be between 600,000 and one million people, mainly residing in Western Europe, the Middle East, North America, and several other African countries. These diaspora communities play a crucial role in the economy through remittances.

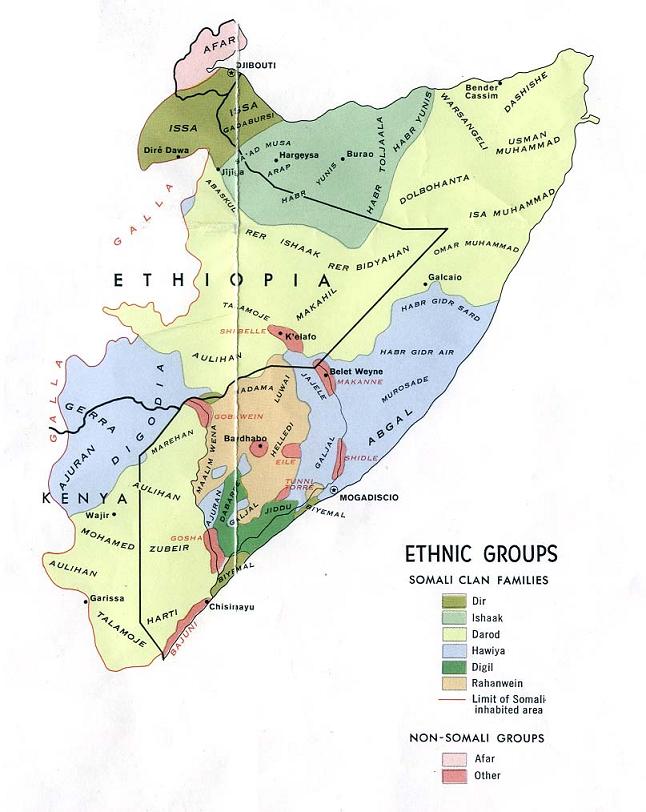

8.2. Clan Groups

Somali society is structured around clan families and sub-clans, which are patrilineal and play a central role in social, political, and economic life. The largest clan family in Somaliland is the Isaaq, who are estimated to constitute around 80% of the population and are predominant in most regions and major cities like Hargeisa, Burao, and Berbera. The Isaaq clan family is further divided into several major sub-clans, including the Habr Awal, Garhajis (which includes the Habr Yunis and Eidagale), Habr Je'lo, and Arap.

The second largest clan family is the Dir, represented primarily by the Gadabuursi (who are predominant in the Awdal region, including Borama) and the Issa (who mainly inhabit the Zeila District and areas bordering Djibouti and Ethiopia).

The Darod clan family is also present, mainly through the Harti confederation, which includes the Dhulbahante and Warsangeli sub-clans. The Dhulbahante are concentrated in the Sool region (including Las Anod), parts of eastern Sanaag, and the Buhoodle District of Togdheer. The Warsangeli primarily inhabit eastern Sanaag, particularly around Las Khorey. These Harti groups have complex political affiliations, with significant portions historically identifying with Puntland or advocating for autonomy within Somalia, leading to the Sool and Sanaag border disputes.

Smaller clans such as the Gabooye (a traditionally marginalized artisanal group), Gahayle, Jibrahil, Magaadle, Fiqishini, and Akisho also reside in Somaliland. Clan identity influences political representation, resource allocation, and social interactions. While the government aims for a national identity, clan loyalties remain a powerful factor in Somaliland's society.

8.3. Languages

The primary language spoken in Somaliland is Somali, which is the mother tongue of the vast majority of the population and one of the official languages. It is a member of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family. The main dialect spoken is Northern Somali, which is distinct from the Benadiri Somali dialect more common in southern Somalia. Somali has a rich oral tradition, especially in poetry. It was officially standardized with a Latin script in 1972.

Arabic is the second official language, as stipulated in the Constitution. It holds significant religious importance, being the language of the Quran, and is a mandatory subject in schools. It is widely used in mosques and for religious education.

English is also widely spoken and understood, particularly in urban areas, in government, business, and higher education. It was the administrative language during the British colonial period and continues to be an important language for international communication and in the education system. Many official documents and media outlets also use English. The rate of trilingualism (Somali, Arabic, English) is common among educated individuals, while bilingualism in Somali and Arabic is more widespread.

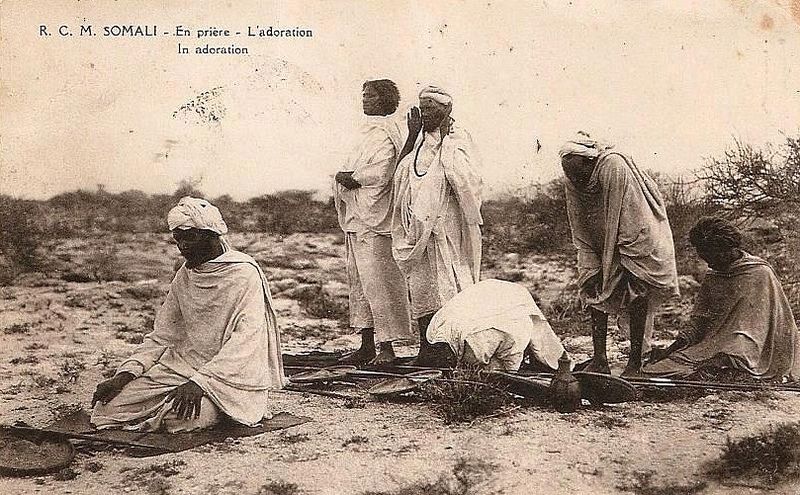

8.4. Religion

The population of Somaliland is overwhelmingly Muslim, with the vast majority belonging to the Sunni branch of Islam and adhering to the Shafi'i school of Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh). Islam is the state religion as per the Constitution of Somaliland, which also stipulates that no laws may violate the principles of Sharia. The state is mandated to promote Islamic tenets and discourage behavior contrary to "Islamic morals."

Islam plays a central role in Somali national identity and daily life. Many social norms are derived from religious teachings. For example, most Somali women wear a hijab in public. Religious Somalis abstain from pork and alcohol, and avoid riba (usury). Mosques are central to community life, and Friday afternoon prayers (Jumu'ah) are an important congregational activity.

There is also a presence of Sufism, with various tariqas (Sufi orders), such as the Arab Rifa'iya, having followers. In more recent times, influenced by the diaspora from Yemen and Gulf states, stricter interpretations of Islam, sometimes associated with Wahhabism or Salafism, have also gained a noticeable presence.

Traces of pre-Islamic traditional religious beliefs are minimal. The number of non-Muslims in Somaliland is very small. During the colonial era, a few Catholic missions operated schools and orphanages, leading to a small Christian community, primarily associated with institutions in Aden, Djibouti, and Berbera. Today, Somaliland falls within the Episcopal Area of the Horn of Africa (Anglican Communion), but there are no active congregations. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Mogadiscio is nominally responsible for the area, but has been vacant for decades, with the Bishop of Djibouti acting as Apostolic Administrator. Proselytizing any religion other than Islam is illegal.

8.5. Health

Somaliland faces significant public health challenges, characteristic of many developing regions, compounded by its lack of international recognition which limits access to direct bilateral aid and resources for the health sector. Key health indicators show room for considerable improvement.

Access to improved water sources is available to about 40.5% of households, but nearly a third of households are located at least an hour away from their primary source of drinking water. Sanitation facilities are also limited. Infant and child mortality rates are high: according to UNICEF data, 1 in 11 children die before their first birthday, and 1 in 9 die before their fifth birthday, primarily from preventable diseases like respiratory infections, diarrhea, and malaria, often exacerbated by malnutrition.

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is a deeply entrenched practice. A UNICEF multiple indicator cluster survey (MICS) in 2006 found that 94.8% of women in Somaliland had undergone some form of FGM. In 2018, the Somaliland government issued a fatwa condemning the two most severe forms of FGM (infibulation and clitoridectomy), but there are currently no comprehensive laws to punish those responsible for the practice, and less severe forms are often still considered culturally acceptable. This poses severe health risks for women and girls.

The healthcare system struggles with underfunding, a shortage of qualified health professionals, and inadequate infrastructure and medical supplies. Healthcare services are concentrated in urban areas, leaving rural and nomadic populations with limited access. The private sector plays a role in healthcare provision, but services can be expensive for much of the population. The Edna Adan Maternity Hospital in Hargeisa is a notable institution, particularly for maternal and child health, founded by Edna Adan Ismail. Common health issues include communicable diseases, maternal and child health problems, and nutritional deficiencies. There are ongoing efforts by the government, local NGOs, and international partners (where engagement is possible) to improve healthcare access and outcomes, but significant challenges remain, particularly concerning disparities in access for vulnerable groups.

8.6. Education

The education system in Somaliland has been rebuilt and expanded significantly since 1991, largely through community efforts, private initiatives, and some support from international organizations and the diaspora. The system comprises primary, secondary, technical/vocational, and tertiary (higher) education.

Literacy rates have seen improvement but remain a challenge. According to a 2015 World Bank assessment, the urban literacy rate was 59% and the rural literacy rate was 47%. Enrollment rates in primary education have increased, but access and quality vary, particularly between urban and rural areas, and for girls. Challenges include a shortage of qualified teachers, inadequate school facilities and learning materials, and high dropout rates, often linked to economic factors and cultural practices.