1. Overview

Somalia, officially the Federal Republic of Somalia (Jamhuuriyadda Federaalka SoomaaliyaJamhuuriyadda Federaalka SoomaaliyaSomali, جمهورية الصومال الفيدراليةJumhūriyyat aṣ-Ṣūmāl al-FiderāliyyaArabic), is a country located in the Horn of Africa in East Africa. It is bordered by Ethiopia to the west, Djibouti to the northwest, the Gulf of Aden to the north, the Indian Ocean to the east, and Kenya to the southwest. Somalia has the longest coastline on Africa's mainland. The country has an estimated population of approximately 18.1 million, with the capital and largest city being Mogadishu. The majority of residents are ethnic Somalis, and the official languages are Somali and Arabic. Most Somalis are Sunni Muslims.

Historically, the Somali peninsula was an important commercial center, potentially the location of the ancient Land of Punt. During the Middle Ages, several powerful Somali sultanates, such as the Ajuran Sultanate and the Adal Sultanate, dominated regional trade. In the late 19th century, European colonial powers, primarily Italy and the United Kingdom, partitioned the territory into Italian Somaliland and British Somaliland. In 1960, these two territories united to form the independent Somali Republic. A 1969 coup d'état led by Siad Barre established the Somali Democratic Republic, a socialist state. Barre's regime collapsed in 1991, plunging the country into a prolonged Somali Civil War marked by factional fighting, state fragmentation, and severe humanitarian crises. Various transitional governments attempted to restore stability, but faced challenges from ongoing conflict and the rise of militant groups like Al-Shabaab.

In 2012, a new provisional constitution was adopted, and the Federal Government of Somalia was established, marking a step towards reconstruction and state-building. However, Somalia continues to face significant challenges, including political instability, insecurity due to terrorism and clan conflicts, economic underdevelopment, and environmental issues like drought and desertification. The country's economy relies heavily on livestock, remittances from the diaspora, and a growing telecommunications sector. This article explores Somalia's history, geography, political system, economy, and culture, analyzing these aspects through a lens that emphasizes social justice, human rights, and the difficult path towards democratic development and stability in the aftermath of decades of conflict.

2. Etymology

The name "Somalia" is derived from the ethnonym "Somali," the dominant ethnic group in the country. The term "Somali" itself has several proposed origins. One widely accepted theory links it to Samaale, considered the oldest common ancestor of several major Somali clans. Another popular etymological theory suggests the name comes from the Somali words soo ("go") and maal ("milk"). This interpretation varies by region: northern Somalis often associate it with camel's milk, reflecting the pastoral lifestyle, while southern Somalis may use the transliteration "sa' maal" referring to cow's milk. This "go and milk" phrase is seen as a poetic reference to the ubiquitous pastoralism of the Somali people.

A further theory proposes that "Somali" derives from the Arabic word zāwamāl, meaning "wealthy," again alluding to the Somali people's traditional riches in livestock. An alternative, less common theory suggests the name is derived from the Automoli (Asmach), a group of warriors from ancient Egypt described by Herodotus. "Asmach" is thought to have been their Egyptian name, with "Automoli" being a Greek derivative of the Hebrew word S'mali, meaning "on the left hand side."

A Tang Chinese document from the 9th century CE referred to the northern Somali coast as Po-pa-li. This area was part of a broader region in Northeast Africa known as Barbaria, in reference to its Cushitic-speaking inhabitants. The first clear written reference to the term "Somali" dates to the early 15th century, in a hymn composed by an official of Ethiopian Emperor Yeshaq I celebrating a military victory over the Sultanate of Ifat. Simur was also an ancient Harari alias for the Somali people.

Somalis overwhelmingly prefer the demonym Somali over Somalian, as the former is an endonym, while the latter is an exonym with double suffixes. The hypernym for Somali in a geopolitical sense is Horner, and in an ethnic sense, it is Cushite. In Japanese, "Somalia" is understood as combining the ethnic name "Somali" with the Latin suffix "-ia," meaning country or land.

3. History

The history of Somalia spans millennia, from early human settlements in prehistory, through ancient trading civilizations and powerful medieval Islamic sultanates, to the colonial era, independence, a period of socialist rule, and a devastating civil war followed by ongoing efforts at state reconstruction. This section will chronicle these major periods and their impact on the Somali peninsula and its people.

3.1. Prehistory

Somalia was likely one of the first lands to be settled by early humans, possibly serving as a settlement area for hunter-gatherers before their migrations out of Africa. During the Stone Age, the Doian and Hargeisan cultures flourished in the region. Archaeological findings indicate the presence of these cultures through stone tools and other artifacts. The oldest evidence of burial customs in the Horn of Africa comes from cemeteries in Somalia dating back to the 4th millennium BCE. Stone implements from the Jalelo site in northern Somalia, characterized in 1909, are considered important artifacts demonstrating archaeological universality during the Paleolithic era between the East and the West.

According to linguists, the first Afroasiatic-speaking populations arrived in the region during the ensuing Neolithic period, possibly from the family's proposed urheimat ("original homeland") in the Nile Valley or the Near East.

The Laas Geel complex, located on the outskirts of Hargeisa in northwestern Somalia, dates back approximately 5,000 years. It features remarkable rock art depicting wild animals and decorated cows with long horns, providing insights into the ancient pastoralist cultures of the region. Other significant cave paintings are found in the northern Dhambalin region, which include one of the earliest known depictions of a hunter on horseback, dated between 1,000 and 3,000 BCE. Additionally, between the towns of Las Khorey and El Ayo in northern Somalia lies Karinhegane, a site with numerous cave paintings estimated to be around 2,500 years old. These prehistoric sites highlight a rich artistic and cultural heritage from ancient times.

3.2. Antiquity and Classical Era

Ancient pyramidical structures, known locally as taalo, along with mausoleums, ruined cities, and stone walls like the Wargaade Wall, serve as evidence of an old civilization that thrived in the Somali peninsula. This civilization engaged in trade with ancient Egypt and Mycenaean Greece since the second millennium BCE. This has led many scholars to hypothesize that Somalia or adjacent regions were the location of the ancient Land of Punt. The Puntites, native to this region, traded valuable commodities such as myrrh, spices, gold, ebony, short-horned cattle, ivory, and frankincense with the Egyptians, Phoenicians, Babylonians, Indians, Chinese, and Romans through their commercial ports. An Egyptian expedition to Punt, sent by Queen Hatshepsut of the 18th dynasty, is famously recorded on temple reliefs at Deir el-Bahari, depicting the Puntite King Parahu and Queen Ati.

In the classical era, the Macrobians, who may have been ancestral to Somalis, established a powerful kingdom that ruled large parts of modern Somalia. They were renowned for their longevity and wealth, described as the "tallest and handsomest of all men." According to Herodotus, when the Persian Emperor Cambyses II conquered Egypt in 525 BC, he sent ambassadors to Macrobia with gifts to entice the Macrobian king into submission. The Macrobian ruler, elected based on stature and beauty, responded with a challenge: an unstrung bow. If the Persians could draw it, they could invade his country; otherwise, they should thank the gods the Macrobians never decided to invade their empire. The Macrobians were a regional power, noted for advanced architecture and such plentiful gold that they shackled prisoners in golden chains.

The camel is believed to have been domesticated in the Horn region between the 2nd and 3rd millennium BCE, subsequently spreading to Egypt and the Maghreb.

During the classical period, several Barbara city-states, including Mosylon, Opone, Mundus, Isis, Malao, Avalites, Essina, Nikon, and Sarapion, developed a lucrative trade network. They connected with merchants from Ptolemaic Egypt, Ancient Greek city-states, Phoenicia, Parthian Persia, Saba, the Nabataean Kingdom, and the Roman Empire. These Somali city-states utilized an ancient Somali maritime vessel known as the beden to transport their cargo.

After the Roman conquest of the Nabataean Empire and the establishment of a Roman naval presence at Aden to curb piracy, Arab and Somali merchants made an agreement with the Romans to bar Indian ships from trading in the free port cities of the Arabian peninsula. This was intended to protect the interests of Somali and Arab merchants in the lucrative commerce between the Red and Mediterranean Seas. However, Indian merchants continued to trade in the port cities of the Somali peninsula, which remained free from Roman interference. For centuries, Indian merchants brought large quantities of cinnamon to Somalia and Arabia from Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka) and the Spice Islands. The source of cinnamon and other spices was said to be a well-kept secret of Arab and Somali merchants in their trade with the Roman and Greek world; the Romans and Greeks believed the source to have been the Somali peninsula. This collusive agreement among Somali and Arab traders inflated the price of Indian and Chinese cinnamon in North Africa, the Near East, and Europe, making the cinnamon trade a highly profitable venture, especially for Somali merchants.

3.3. Birth of Islam and the Middle Ages

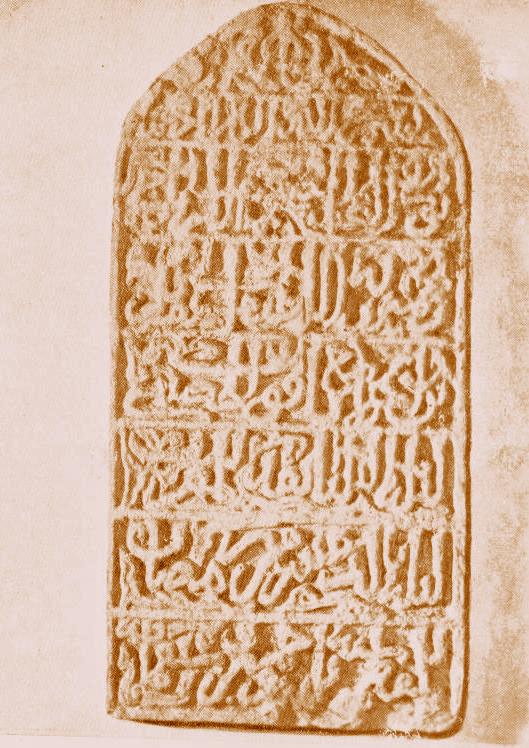

Islam was introduced to the Somali peninsula early on, as some of the first Muslims from Mecca fled persecution during the first Hijra (migration) and sought refuge in the region. The Masjid al-Qiblatayn in Zeila is said to have been built even before the Qibla (direction of prayer) was changed towards Mecca, making it one of the oldest mosques in Africa. By the late 9th century, the Arab historian Al-Yaqubi wrote that Muslims were living along the northern Somali seaboard. He also mentioned that the Adal Kingdom had its capital in Zeila.

Throughout the Middle Ages, Arab immigrants arrived in the Somali lands. This historical experience later contributed to legendary stories about Muslim sheikhs such as Daarood and Ishaaq bin Ahmed (the purported ancestors of the Darod and Isaaq clans, respectively) traveling from Arabia to Somalia and marrying into the local Dir clan.

In 1332, the Zeila-based King of Adal was killed in a military campaign aimed at halting the Abyssinian emperor Amda Seyon I's march toward the city. When the last Sultan of Ifat, Sa'ad ad-Din II, was also killed by Emperor Dawit I in Zeila in 1410, his children escaped to Yemen before returning in 1415. In the early 15th century, Adal's capital was moved further inland to the town of Dakkar, where Sabr ad-Din II, the eldest son of Sa'ad ad-Din II, established a new base after his return from Yemen.

Adal's headquarters were relocated again in the following century, this time southward to Harar. From this new capital, Adal organized an effective army led by Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (Ahmad "Gurey" or "Gran," both meaning "the left-handed") and his top general Garad Hirabu, "Emir of The Somalis," that invaded the Abyssinian empire. This 16th-century campaign is historically known as the Conquest of Abyssinia (Futuh al-Habash). During the war, Imam Ahmad pioneered the use of cannons supplied by the Ottoman Empire, which he imported through Zeila and deployed against Abyssinian forces and their Portuguese allies led by Cristóvão da Gama. Some scholars argue that this conflict was an early example of proxy war, as the Ottomans supported Adal and the Portuguese supported Abyssinia.

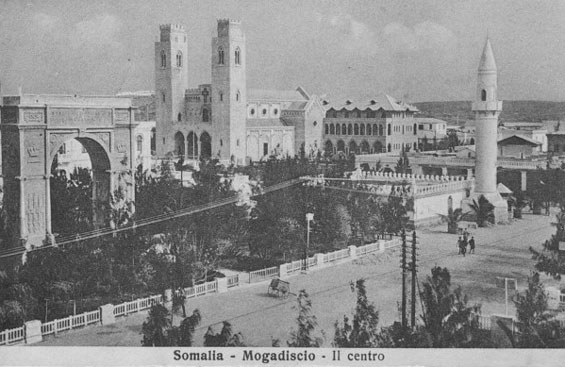

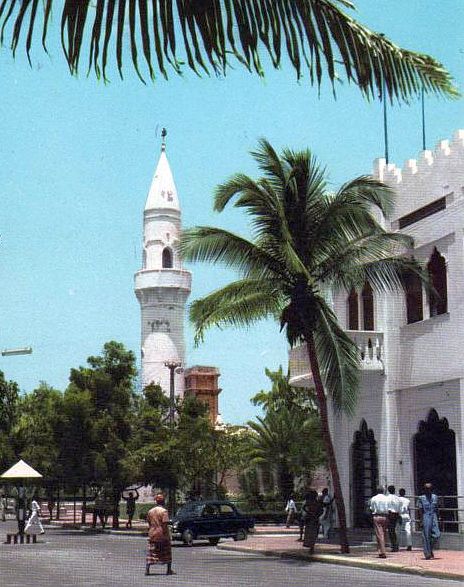

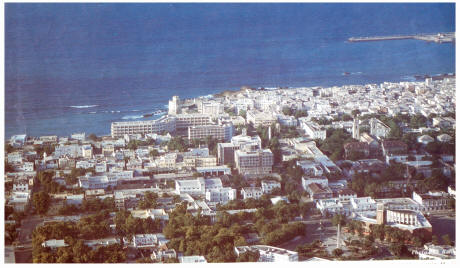

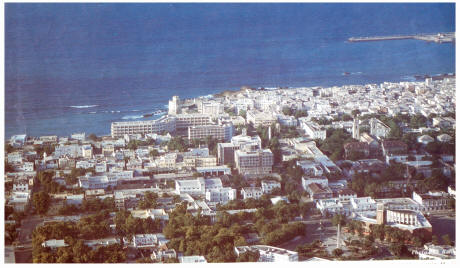

During the period of the Ajuran Sultanate, the city-states and republics of Merca, Mogadishu, Barawa, Hobyo, and their respective ports flourished. They maintained lucrative foreign commerce with ships sailing to and from Arabia, India, Venetia, Persia, Egypt, Portugal, and as far away as China. Vasco da Gama, who passed by Mogadishu in the 15th century, noted it was a large city with multi-story houses, grand palaces in its center, and many mosques with cylindrical minarets. The Harla, an early Hamitic group of tall stature who inhabited parts of Somalia, Tchertcher, and other areas in the Horn, also erected various tumuli. These masons are believed to have been ancestral to ethnic Somalis.

In the 16th century, Duarte Barbosa noted that many ships from the Kingdom of Cambaya in modern-day India sailed to Mogadishu with cloth and spices, for which they received gold, wax, and ivory in return. Barbosa also highlighted the abundance of meat, wheat, barley, horses, and fruit on the coastal markets, which generated enormous wealth for the merchants. Mogadishu, the center of a thriving textile industry known as toob benadir (specialized for markets in Egypt and elsewhere), along with Merca and Barawa, also served as a transit stop for Swahili merchants from Mombasa and Malindi and for the gold trade from Kilwa. Jewish merchants from the Hormuz brought their Indian textiles and fruit to the Somali coast in exchange for grain and wood.

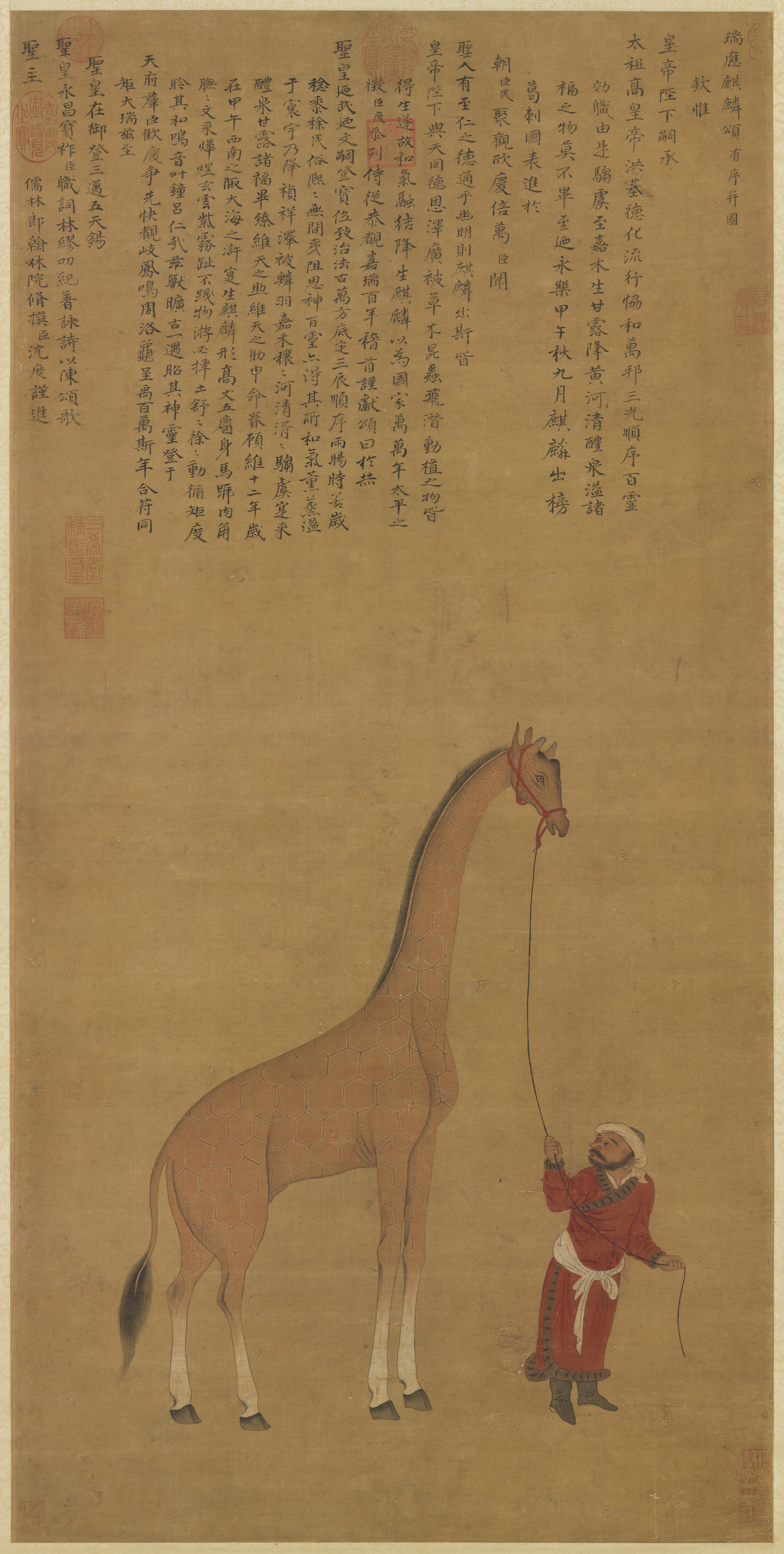

Trading relations were established with Malacca in the 15th century, with cloth, ambergris, and porcelain being the main commodities of the trade. Giraffes, zebras, and incense were exported to the Ming Empire of China, which established Somali merchants as leaders in the commerce between East Asia and the Horn of Africa. Hindu merchants from Surat and Southeast African merchants from Pate, seeking to bypass both the Portuguese India blockade and later Omani interference, used the Somali ports of Merca and Barawa (which were outside the direct jurisdiction of the two powers) to conduct their trade safely and without interference.

3.4. Early Modern Era and the Scramble for Africa

In the early modern period, successor states to the Adal Sultanate and Ajuran Sultanate began to flourish in Somalia. These included the Hiraab Imamate, the Isaaq Sultanate led by the Guled dynasty, the Habr Yunis Sultanate led by the Ainanshe dynasty, the Sultanate of the Geledi (Gobroon dynasty), the Majeerteen Sultanate (Migiurtinia), and the Sultanate of Hobyo (Obbia). They continued the tradition of castle-building and seaborne trade established by previous Somali empires.

Sultan Yusuf Mahamud Ibrahim, the third Sultan of the House of Gobroon, initiated the golden age of the Gobroon Dynasty. His army was victorious during the Bardheere Jihad, which restored stability in the region and revitalized the East African ivory trade. He also maintained cordial relations and received gifts from the rulers of neighboring and distant kingdoms such as the Omani, Witu, and Yemeni Sultans. Sultan Ibrahim's son, Ahmed Yusuf, succeeded him and became one of the most important figures in 19th-century East Africa, receiving tribute from Omani governors and creating alliances with important Muslim families on the East African coast.

In Somaliland, the Isaaq Sultanate was established around 1750. It was a Somali kingdom that ruled parts of the Horn of Africa during the 18th and 19th centuries, spanning the territories of the Isaaq clan, who are descendants of the Banu Hashim clan, in modern-day Somaliland and Ethiopia. The sultanate was governed by the Rer Guled branch, established by its first sultan, Sultan Guled Abdi of the Eidagale clan. According to oral tradition, prior to the Guled dynasty, the Isaaq clan-family was ruled by a dynasty of the Tolje'lo branch, descendants of Ahmed, nicknamed Tol Je'lo, the eldest son of Sheikh Ishaaq bin Ahmed's Harari wife. There were eight Tolje'lo rulers in total, starting with Boqor Harun (Boqor HaaruunSomali), who ruled the Isaaq Sultanate for centuries, beginning in the 13th century. The last Tolje'lo ruler, Garad Dhuh Barar (Dhuux BaraarSomali), was overthrown by a coalition of Isaaq clans. The once-strong Tolje'lo clan was scattered and took refuge amongst the Habr Awal, with whom they still mostly live.

In the late 19th century, following the Berlin Conference of 1884, European powers began the Scramble for Africa. Britain, Italy, and France established protectorates over various parts of the Somali coast. In 1884, a British protectorate was declared over part of Somalia, on the African coast opposite South Yemen. Initially, this region was under the control of the Indian Office and administered as part of the Indian Empire; in 1898, it was transferred to control by London. In 1889, the protectorate and later colony of Italian Somaliland was officially established by the Kingdom of Italy through various treaties signed with a number of chiefs and sultans. Sultan Yusuf Ali Kenadid of the Sultanate of Hobyo requested Italian protection in late December 1888 before signing a treaty in 1889.

The Dervish movement, led by the religious poet Mohammed Abdullah Hassan (often called the "Mad Mullah" by the British), emerged as a significant resistance against colonial rule. The Dervishes successfully repulsed the British Empire four times, forcing it to retreat to the coastal region. They defeated Italian, British, and Abyssinian colonial powers on numerous occasions, most notably in the 1903 victory at Cagaarweyne, commanded by Suleiman Aden Galaydh. The Dervishes aimed to unite Somalis and drive out all colonial powers. They were finally defeated in 1920 by British airpower, marking one of the first uses of aerial bombardment in colonial warfare in Africa.

The rise of fascism in Italy in the early 1920s brought a change in strategy. The north-eastern sultanates were forced within the boundaries of La Grande Somalia ("Greater Somalia") according to Fascist Italy's plans. With the arrival of Governor Cesare Maria De Vecchi on December 15, 1923, Italian Somaliland's administration became more direct and aggressive. The last piece of land acquired by Italy in Somalia was Oltre Giuba (present-day Jubaland region) in 1925. The Italians initiated local infrastructure projects, including hospitals, farms, and schools.

Under Benito Mussolini, Fascist Italy attacked Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1935 with the aim of colonizing it. The invasion was condemned by the League of Nations, but little was done to stop it or liberate occupied Ethiopia. In 1936, Italian Somaliland was integrated into Italian East Africa, alongside Eritrea and Ethiopia, as the Somalia Governorate. On August 3, 1940, Italian troops, including Somali colonial units, crossed from Ethiopia to invade British Somaliland, and by August 14, they succeeded in taking Berbera from the British.

A British force, including troops from several African countries, launched the East African Campaign in January 1941 from Kenya to liberate British Somaliland, Italian-occupied Ethiopia, and conquer Italian Somaliland. By February, most of Italian Somaliland was captured, and in March, British Somaliland was retaken from the sea. The British Empire forces operating in Somaliland comprised three divisions of South African, West African, and East African troops, assisted by Somali forces led by Abdulahi Hassan, with Somalis of the Isaaq, Dhulbahante, and Warsangali clans prominently participating. The number of Italian Somalis began to decline after World War II, with fewer than 10,000 remaining in 1960.

3.5. Independence and Somali Republic (1960-1969)

Following World War II, Britain retained control of both British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland as protectorates. In 1945, during the Potsdam Conference, the United Nations granted Italy trusteeship of Italian Somaliland as the Trust Territory of Somaliland. This was on the condition, first proposed by the Somali Youth League (SYL) and other nascent Somali political organizations like Hizbia Digil Mirifle Somali (HDMS) and the Somali National League (SNL), that Somalia achieve independence within ten years. British Somaliland remained a protectorate of Britain until 1960.

The trusteeship provisions gave Somalis in the Italian-administered territory opportunities to gain experience in Western political education and self-government. These were advantages that British Somaliland, which was to be incorporated into the new Somali state, did not have. Although British colonial officials in the 1950s attempted, through various administrative development efforts, to compensate for past neglect, the protectorate stagnated in political and administrative development. The disparity between the two territories in economic development and political experience would later cause serious difficulties in integrating the two parts.

Meanwhile, in 1948, under pressure from their World War II allies and to the dismay of Somalis, the British returned the Haud (an important Somali grazing area presumably protected by British treaties with Somalis in 1884 and 1886) and the Somali Region (Ogaden) to Ethiopia. This was based on an 1897 treaty in which the British ceded Somali territory to Ethiopian Emperor Menelik II in exchange for his help against possible advances by the French. Britain included a conditional provision that Somali residents would retain their autonomy, but Ethiopia immediately claimed sovereignty over the area. This prompted an unsuccessful bid by Britain in 1956 to buy back the Somali lands it had turned over. Britain also granted administration of the almost exclusively Somali-inhabited Northern Frontier District (NFD) to Kenyan nationalists, despite a plebiscite in which, according to a British colonial commission, almost all of the territory's ethnic Somalis favored joining the newly formed Somali Republic.

A referendum was held in neighboring Djibouti (then known as French Somaliland) in 1958, on the eve of Somalia's independence in 1960, to decide whether or not to join the Somali Republic or to remain with France. The referendum favored continued association with France, largely due to a combined "yes" vote by the sizable Afar ethnic group and resident Europeans. There was also widespread vote rigging, with the French expelling thousands of Somalis before the referendum. The majority of those who voted "no" were Somalis strongly in favor of joining a united Somalia, as proposed by Mahmoud Harbi, Vice President of the Government Council. Harbi was killed in a plane crash two years later. Djibouti finally gained independence from France in 1977, and Hassan Gouled Aptidon, a Somali who had campaigned for a "yes" vote in the 1958 referendum, eventually became Djibouti's first president (1977-1999).

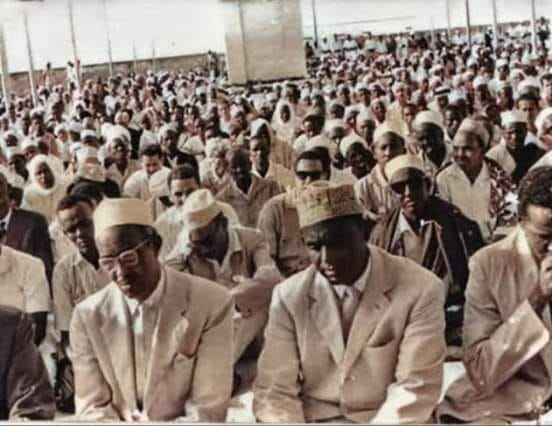

On June 26, 1960, the former British Somaliland protectorate obtained independence as the State of Somaliland. Five days later, on July 1, 1960, it united with the Trust Territory of Somaliland (the former Italian Somaliland) to form the Somali Republic, albeit within boundaries drawn up by Italy and Britain. A government was formed by Abdullahi Issa and Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal, with other members of the trusteeship and protectorate governments. Abdulcadir Muhammed Aden served as President of the Somali National Assembly, Aden Abdullah Osman Daar became the first President of the Somali Republic, and Abdirashid Ali Shermarke was appointed as Prime Minister (later becoming president from 1967 to 1969). On July 20, 1961, a popular referendum ratified a new constitution, first drafted in 1960. Most people from the former Italian Somaliland participated, while participation from the former British Somaliland was lower, with a small number of those who did participate voting against it, reflecting early discontent in the north. In 1967, Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal became Prime Minister, appointed by Shermarke. Egal would later become the President of the self-declared autonomous Somaliland region in northwestern Somalia.

The early years of the Somali Republic were characterized by a multi-party parliamentary democracy. However, issues of national integration, development, and the pursuit of "Greater Somalia" (the unification of all Somali-inhabited territories in the Horn of Africa) dominated the political landscape and often led to tensions with neighboring countries.

3.6. Somali Democratic Republic (1969-1991)

On October 15, 1969, while President Abdirashid Ali Shermarke was touring the drought-stricken town of Las Anod, he was shot and killed by one of his own bodyguards. Former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger concluded that the bodyguard acted of his own accord, though motives remain debated. The bodyguard, who hailed from the same clan as the president, was later tried, tortured, and executed by the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC).

Six days after Shermarke's assassination, on October 21, 1969, General Siad Barre led a bloodless military coup, overthrowing the civilian parliamentary government. Political analysts suggest the coup was motivated by widespread corruption within the parliamentary government and a desire for stronger leadership. The SRC, which assumed power, was initially led by Barre, Brigadier General Mohamed Ainanshe Guled, Lieutenant Colonel Salaad Gabeyre Kediye (who officially held the title "Father of the Revolution"), and Chief of Police Jama Korshel. Barre shortly afterwards became the undisputed head of the SRC.

The SRC renamed the country the Somali Democratic Republic, dissolved the parliament and the Supreme Court, and suspended the constitution. The revolutionary government embarked on large-scale public works programs and implemented an urban and rural literacy campaign, which significantly increased the literacy rate, reportedly reaching 70% at one point, one of the highest in Africa at the time. The regime also nationalized industry and land. Its foreign policy emphasized Somalia's traditional and religious links with the Arab world, leading to Somalia joining the Arab League in February 1974. That same year, Barre also served as chairman of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), the predecessor of the African Union (AU).

In July 1976, Barre's SRC disbanded itself and established the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (SRSP) in its place, creating a one-party state based on scientific socialism and Islamic tenets. The SRSP attempted to reconcile the official state ideology with the official state religion by adapting Marxist precepts to local circumstances. Emphasis was placed on Muslim principles of social progress, equality, and justice, which the government argued formed the core of scientific socialism and its own focus on self-sufficiency, public participation, popular control, and direct ownership of the means of production. While the SRSP encouraged private investment on a limited scale, the administration's overall direction was essentially communist.

In July 1977, the Ogaden War broke out after Barre's government, using a plea for national unity, launched an aggressive campaign to incorporate the predominantly Somali-inhabited Ogaden region of Ethiopia into a Pan-Somali Greater Somalia. This also included ambitions for rich agricultural lands in southeastern Ethiopia, infrastructure, and strategically important areas as far north as Djibouti. Initially, Somali armed forces achieved rapid success, taking southern and central Ogaden and controlling 90% of the region by September 1977. They captured strategic cities like Jijiga and put heavy pressure on Dire Dawa. However, following the siege of Harar, a massive Soviet intervention, including 20,000 Cuban forces and several thousand Soviet experts, came to the aid of Ethiopia's communist Derg regime. By 1978, Somali troops were pushed out of the Ogaden. This shift in Soviet support motivated the Barre government to seek new allies, eventually aligning with the United States, the Soviet Union's Cold War rival. This strategic realignment allowed Somalia to build one of the largest armies in Africa.

A new constitution was promulgated in 1979, under which elections for a People's Assembly were held. However, Barre's Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party politburo continued to rule. In October 1980, the SRSP was disbanded, and the Supreme Revolutionary Council was re-established. By this time, Barre's government had become increasingly unpopular, with many Somalis disillusioned by life under military dictatorship and its increasingly oppressive nature.

The regime was further weakened in the 1980s as the Cold War drew to a close and Somalia's strategic importance diminished. The government became increasingly authoritarian, and resistance movements, often encouraged by Ethiopia, sprang up across the country. These included the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF), United Somali Congress (USC), Somali National Movement (SNM), and the Somali Patriotic Movement (SPM), alongside non-violent political opposition groups. The government's response to dissent was often brutal, exemplified by the bombardment of Hargeisa in 1988 during the Somaliland War of Independence and repressive actions in other regions, such as Beledweyne and Baidoa, which contributed to widespread human rights abuses and loss of life. These actions severely eroded Barre's moral authority and fueled the growing insurgency that eventually led to the Somali Civil War.

3.7. Somali Civil War (1991-Present)

The collapse of Siad Barre's regime in January 1991 marked the beginning of the Somali Civil War, a devastating and prolonged conflict that led to state fragmentation, widespread humanitarian crises, and the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people. As Barre's government lost its grip on power, various clan-based opposition groups, backed by Ethiopia's Derg regime and Libya, vied for control. The moral authority of the Barre regime had been severely eroded by the mid-1980s due to its increasingly authoritarian and repressive policies. These included punitive measures against perceived supporters of guerrillas, especially in the northern regions, culminating in events like the bombing of Hargeisa, a Somali National Movement (SNM) stronghold, in 1988. This brutal clampdown extended to other parts of the country, such as the aerial assault on Beledweyne in southern Somalia in 1991 and actions in Baidoa, which earned the nickname 'the city of death' due to famine and conflict targeting the Rahanweyn community.

In May 1991, following a meeting of the SNM and northern clan elders, the former British Somaliland portion of the country declared its independence as the Republic of Somaliland. Although de facto independent and relatively stable compared to the tumultuous south, Somaliland has not been recognized by any foreign government.

In the south, the ousting of Barre led to a power vacuum where numerous opposition groups competed for influence. Armed factions led by United Somali Congress (USC) commanders General Mohamed Farah Aidid and Ali Mahdi Mohamed, in particular, clashed as each sought to exert authority over the capital, Mogadishu. In 1991, a multi-phased international conference on Somalia was held in neighboring Djibouti. Owing to the legitimacy bestowed on Muhammad by the Djibouti conference, he was subsequently recognized by the international community as the new President of Somalia. However, he was unable to exert authority beyond parts of the capital, with power contested by other faction leaders in the southern half of Somalia and by autonomous sub-national entities in the north. The Djibouti conference was followed by two abortive agreements for national reconciliation and disarmament.

The early 1990s saw Somalia characterized as a "failed state" due to the protracted lack of a permanent central authority, leading to widespread famine and lawlessness. The United Nations intervened with peacekeeping missions, UNOSOM I and later UNOSOM II, along with the US-led UNITAF (Operation Restore Hope), primarily to provide humanitarian aid and restore order. However, these interventions faced significant challenges, including the infamous Battle of Mogadishu in October 1993, which led to the withdrawal of US and later UN forces.

The civil war resulted in immense suffering for the civilian population. Factional fighting, widespread displacement, food insecurity, and the collapse of public services created a dire humanitarian situation. The conflict undermined any progress towards democratic development, as power became concentrated in the hands of warlords and militias, further entrenching clan divisions and violence. Human rights abuses were rampant, committed by various armed groups with impunity.

3.7.1. Transitional Institutions and Governments

Following the collapse of the Barre regime and the initial chaotic years of the civil war, numerous efforts were made by Somali leaders and the international community to establish a functioning central government. These attempts led to the formation of several transitional bodies. The Transitional National Government (TNG) was established in April-May 2000 at the Somalia National Peace Conference held in Arta, Djibouti. Abdiqasim Salad Hassan was selected as its President. The TNG was an interim administration intended to guide Somalia towards its third permanent republican government. However, the TNG faced significant internal problems, leading to the replacement of the Prime Minister four times in three years, and it reportedly went bankrupt in December 2003, with its mandate ending simultaneously.

On October 10, 2004, Somali legislators elected Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed as the first President of the Transitional Federal Government (TFG), the TNG's successor. The TFG was the second interim administration aiming to restore national institutions after the 1991 collapse. It was established as one of the Transitional Federal Institutions (TFIs) defined in the Transitional Federal Charter (TFC) adopted in November 2004 by the Transitional Federal Parliament (TFP). The TFG officially comprised the executive branch, with the TFP serving as the legislative branch. The government was headed by the President, to whom the cabinet reported through the Prime Minister. These transitional governments struggled to assert authority beyond limited areas, often confined to parts of Mogadishu or temporary capitals like Baidoa, and faced constant challenges from warlords, militias, and emerging Islamist groups. Their efforts were hampered by internal divisions, lack of resources, and the ongoing security vacuum.

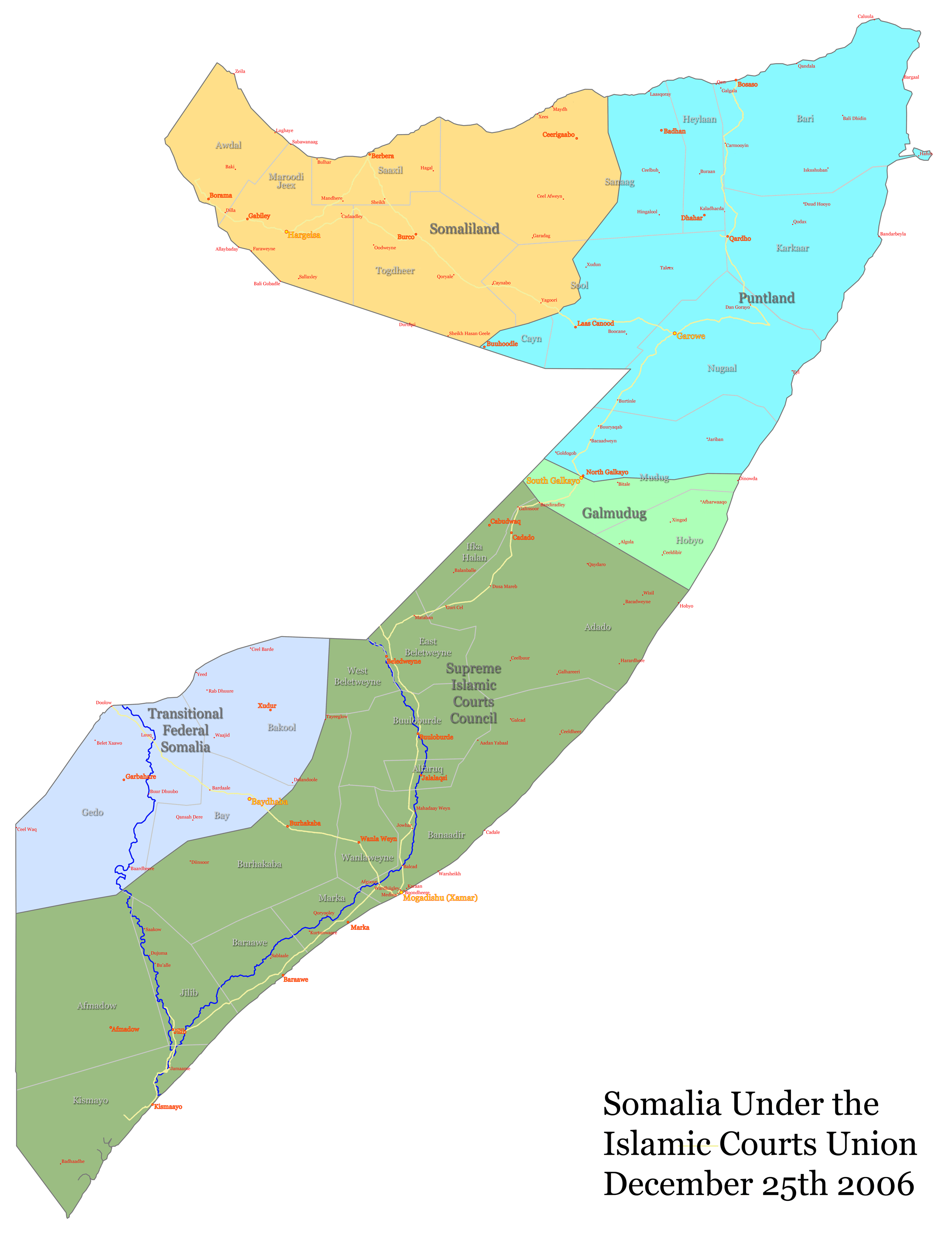

3.7.2. Islamic Courts Union and Ethiopian Intervention

In 2006, the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), an alliance of Sharia courts, rose to prominence and assumed control of Mogadishu and much of southern Somalia for approximately six months. The ICU managed to restore a degree of law and order in areas under its control, which was welcomed by some segments of the population weary of years of chaos and warlord rule. They imposed Sharia law, the interpretation and implementation of which varied across different courts and localities. Some top UN officials referred to this brief period of ICU rule as a "Golden era" in terms of relative peace in the capital. However, the ICU's rise also caused concern both domestically among secular Somalis and internationally, particularly for neighboring Ethiopia and the United States, who feared the establishment of a hardline Islamist state and potential links to extremist groups.

The Transitional Federal Government (TFG), which was based in Baidoa at the time, sought to re-establish its authority. In late 2006, with the direct military assistance of Ethiopian troops, air support from the United States, and the backing of African Union peacekeepers, the TFG launched an offensive against the ICU. The Ethiopian intervention was swift and decisive, ousting the ICU from Mogadishu and other key areas. On January 8, 2007, TFG President Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed entered Mogadishu with Ethiopian military support for the first time since being elected. The TFG then relocated its seat to Villa Somalia in the capital. This marked the first time since the fall of the Siad Barre regime in 1991 that a federally recognized government controlled most of the country, albeit heavily reliant on foreign military presence.

The Ethiopian intervention and the ousting of the ICU had varied impacts. While it enabled the TFG to expand its nominal control, it also fueled resentment among some Somalis who viewed it as a foreign occupation. The intervention contributed to the fragmentation of the ICU, with more hardline elements, notably Al-Shabaab, emerging to wage an insurgency against the TFG and Ethiopian forces.

3.7.3. Al-Shabaab Insurgency and Ongoing Conflict

Following the ousting of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) in late 2006 by Ethiopian forces and the Transitional Federal Government (TFG), the more radical youth wing of the ICU, Al-Shabaab (meaning "The Youth"), emerged as a powerful insurgent group. Al-Shabaab vehemently opposed the Ethiopian military presence in Somalia and the TFG, which it viewed as an illegitimate puppet government. It launched a protracted and brutal insurgency, initially targeting Ethiopian forces and later the TFG and African Union (AU) peacekeepers (AMISOM) deployed to support the government.

Throughout 2007 and 2008, Al-Shabaab scored significant military victories, seizing control of key towns and ports in central and southern Somalia. By January 2009, the insurgency, coupled with internal Somali political dynamics, had forced Ethiopian troops to withdraw. This left behind an under-equipped AMISOM force to assist the TFG's troops. Al-Shabaab exploited the power vacuum, expanding its territorial control and imposing a strict interpretation of Sharia law in areas it governed. This included harsh punishments such as public executions, amputations, and stoning, as well as bans on activities like watching football, listening to music, and smoking. The group also systematically destroyed Sufi shrines and targeted those who did not adhere to its extremist ideology.

Al-Shabaab's governance was characterized by a mix of service provision in some areas (like rudimentary justice systems) and extreme repression. The group engaged in widespread human rights abuses, including targeted killings, recruitment of child soldiers, and restrictions on basic freedoms. Its activities caused immense suffering for the civilian population, leading to mass displacement and exacerbating humanitarian crises. The insurgency also had a devastating impact on any prospects for democratic development, further destabilizing the country.

In February 2012, Al-Shabaab formally pledged allegiance to Al-Qaeda. While AMISOM and Somali government forces, sometimes with international support (including Kenyan forces who intervened in 2011 under Operation Linda Nchi), managed to push Al-Shabaab out of major urban centers like Mogadishu (2011) and Kismayo (2012), the group retreated to rural areas and continued to launch attacks, including large-scale bombings in Mogadishu and other cities, as well as cross-border attacks in Kenya and other neighboring countries. Al-Shabaab still controls significant territory in central and southern Somalia, particularly rural areas, and continues to wield influence through extortion, intimidation, and by providing alternative governance structures in some regions. The town of Jilib has often been cited as its de facto capital. The ongoing conflict with Al-Shabaab remains a primary security challenge for Somalia and the wider region, with a severe humanitarian toll on the civilian population.

3.7.4. Federal Government and Reconstruction Efforts

The Transitional Federal Government's (TFG) interim mandate officially ended on August 20, 2012, as part of the "Roadmap for the End of Transition," a political process designed to establish permanent democratic institutions. This led to the inauguration of the Federal Parliament of Somalia. In the same month, the Federal Government of Somalia was formed, becoming the first permanent central government in the country since the start of the civil war in 1991. A new provisional constitution was passed in August 2012, reforming Somalia as a federation.

Hassan Sheikh Mohamud was elected as the first president of the Federal Republic of Somalia in September 2012. His government, and subsequent administrations, embarked on a challenging period of reconstruction and state-building. Key priorities included strengthening national institutions, improving security, fostering political stabilization, promoting economic recovery, and addressing deep-seated social challenges.

Efforts have been made towards democratic consolidation, including attempts to hold regular elections, though these have often faced delays and security concerns. The development of Federal Member States has been a significant part of the federalization process, but has also led to political tensions between the central government and regional authorities. Reconciliation efforts aim to address historical grievances and clan-based conflicts that have fueled decades of instability.

Economically, the government has focused on rebuilding infrastructure, attracting investment, and improving public financial management. Somalia has made progress in areas like debt relief and re-engaging with international financial institutions. However, poverty, unemployment, and reliance on remittances and foreign aid remain significant issues. Social challenges include improving access to education and healthcare, addressing high rates of displacement, and tackling issues like female genital mutilation (FGM) and other human rights concerns.

Despite the formal end of the transition, reconstruction efforts in Mogadishu and other areas have been frequently hampered by Al-Shabaab attacks. The Federal Government, supported by the African Union Mission to Somalia (AMISOM) (now ATMIS) and other international partners, continues to battle the Al-Shabaab insurgency. In August 2014, the Somali government-led Operation Indian Ocean was launched against insurgent-held pockets in the countryside, part of ongoing efforts to degrade the militant group's capabilities and expand government control. The path to full stability, democratic governance, and socio-economic recovery remains long and arduous.

4. Geography

Somalia's geography is characterized by its strategic location in the Horn of Africa, its extensive coastline, diverse topography, and predominantly arid to semi-arid climate. This section will provide an overview of these physical features and the country's natural resources.

4.1. Location and Topography

Somalia is the easternmost country in continental Africa, situated in the Horn of Africa. It is bordered by Ethiopia to the west, Djibouti to the northwest, Kenya to the southwest, the Gulf of Aden to the north, and the Indian Ocean to the east (specifically the Somali Sea and the Guardafui Channel). With a land area of 246 K mile2 (637.66 K km2), Somalia has the longest coastline on mainland Africa, stretching over 2.1 K mile (3.33 K km). The country's shape has been described as roughly resembling a "tilted number seven."

Its strategic location is at the mouth of the Bab el Mandeb strait, a crucial chokepoint for maritime traffic transiting the Red Sea and the Suez Canal. Somalia lies between latitudes 2°S and 12°N, and longitudes 41°E and 52°E.

The terrain of Somalia consists mainly of plateaus, plains, and highlands. In the far north, the rugged east-west ranges of the Ogo Mountains (also known as the Galgala mountains) lie at varying distances from the Gulf of Aden coast. This region also includes the Cal Madow mountain range, which features Somalia's highest peak, Shimbiris, at an elevation of about 7.9 K ft (2.42 K m). These northern highlands give way to shallow plateaus in the central regions. The western plateau gradually merges into the Haud, an important grazing area for livestock. The southern part of the country features flatter plains, particularly along the river valleys.

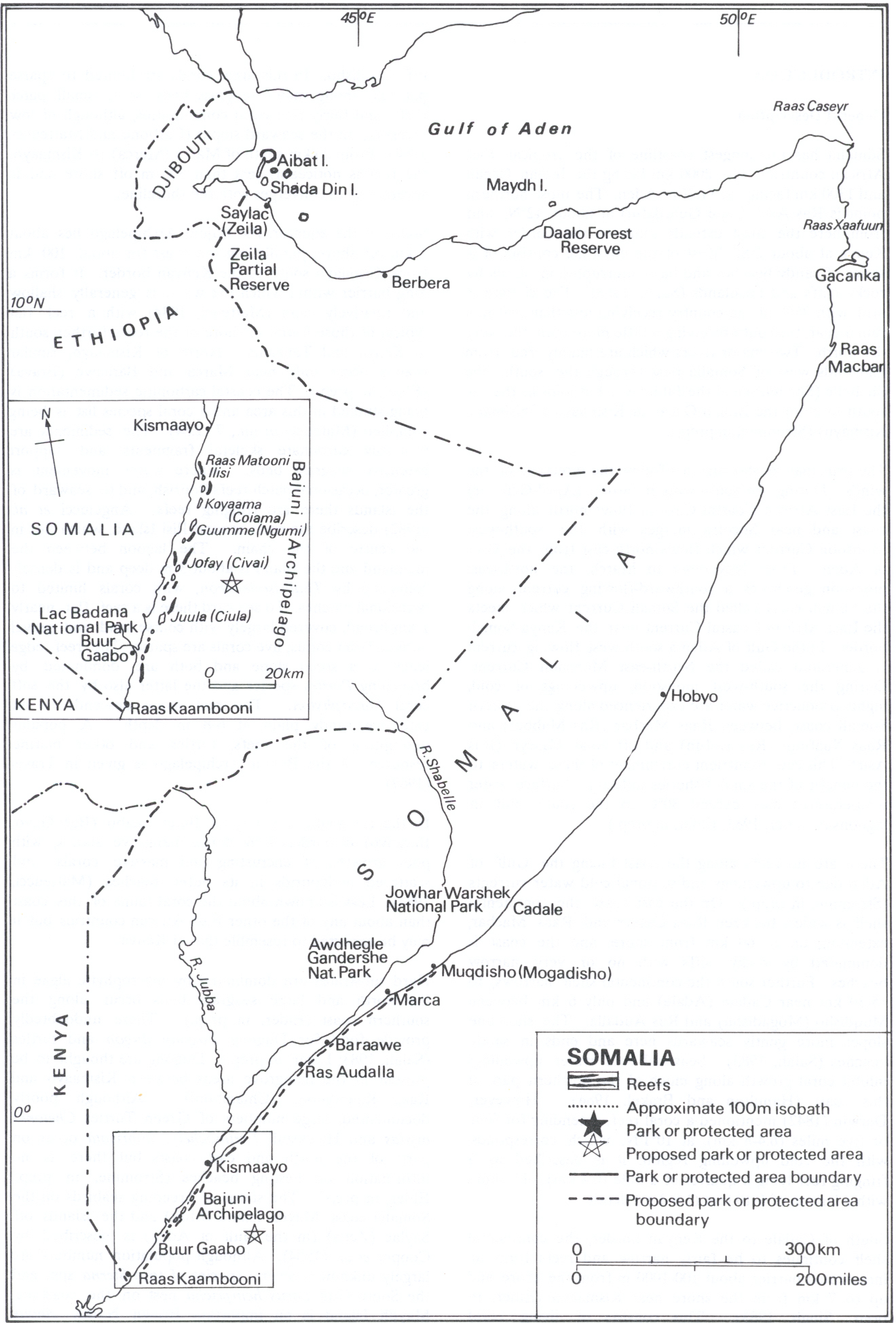

4.2. Waters

Somalia's most significant water features are its two permanent rivers, the Jubba River and the Shebelle River. Both originate in the Ethiopian Highlands and flow southwards towards the Indian Ocean. The Jubba River enters the Indian Ocean at Kismayo. The Shebelle River historically used to reach the sea near Merca, but now typically peters out in a series of swamps and dry reaches just southwest of Mogadishu, eventually disappearing in the desert terrain east of Jilib, near the Jubba River. These rivers are crucial for agriculture and human settlement, particularly in the southern regions, providing the primary source of freshwater for irrigation and domestic use in an otherwise arid country.

Somalia's extensive coastline borders the Indian Ocean to the east and south, and the Gulf of Aden to the north. The Guardafui Channel separates Somalia from the island of Socotra (Yemen). The Somali Sea is part of the western Indian Ocean. The coastline features diverse environments, including sandy beaches, rocky cliffs, and mangrove areas. Somalia also has several islands and archipelagos off its coast, including the Bajuni Islands and the Saad ad-Din Archipelago. The territorial waters claimed by Somalia extend 200 nmi.

4.3. Climate

Somalia's climate is predominantly hot and ranges from arid in the northeastern and central regions to semi-arid in the northwest and south. Owing to its proximity to the equator, there is not much seasonal variation in temperature. Hot conditions prevail year-round, along with periodic monsoon winds and irregular rainfall patterns, which often lead to droughts.

Mean daily maximum temperatures range from 86 °F (30 °C) to 104 °F (40 °C), except at higher elevations and along the eastern seaboard, where the effects of a cold offshore current can be felt. In Mogadishu, for instance, average afternoon highs range from 82.4 °F (28 °C) to 89.6 °F (32 °C) in April. Some of the highest mean annual temperatures in the world have been recorded in the country; Berbera on the northwestern coast has an afternoon high that averages more than 100.4 °F (38 °C) from June through September. Nationally, mean daily minimums usually vary from about 59 °F (15 °C) to 86 °F (30 °C). The greatest range in climate occurs in northern Somalia, where temperatures sometimes surpass 113 °F (45 °C) in July on the littoral plains and drop below freezing point during December in the highlands. Relative humidity in this region ranges from about 40% in the mid-afternoon to 85% at night, changing somewhat according to the season.

Rainfall is generally sparse and erratic. The northeastern regions receive less than 4 in of rain annually, while the central plateaus receive about 8 in to 12 in. The northwestern and southwestern parts of the nation, however, receive considerably more rain, with an average of 20 in to 24 in falling per year.

There are four main seasons dictated by shifts in wind patterns, around which pastoral and agricultural life revolve:

- Jilal: From December to March, this is the harshest dry season of the year.

- Gu: From April to June, this is the main rainy season, characterized by the southwest monsoons, which rejuvenate pastureland and briefly transform the desert into lush vegetation.

- Xagaa (pronounced "Hagaa"): From July to September, this is the second dry season.

- Dayr: From October to December, this is the shortest rainy season.

The tangambili periods that intervene between the two monsoons (October-November and March-May) are hot and humid.

4.4. Environment and Wildlife

Somalia possesses diverse ecoregions, including Ethiopian montane forests, Northern Zanzibar-Inhambane coastal forest mosaic, Somali Acacia-Commiphora bushlands and thickets, Ethiopian xeric grasslands and shrublands, Hobyo grasslands and shrublands, Somali montane xeric woodlands, and East African mangroves. These habitats support a variety of flora and fauna, including several endemic species. In the north, a scrub-covered, semi-desert plain known as the Guban lies parallel to the Gulf of Aden littoral. The rugged Cal Madow and Karkaar Mountains are also significant features.

Wildlife in Somalia includes mammals such as the cheetah, lion, reticulated giraffe, baboon, serval, elephant, bushpig, various gazelle species, ibex, kudu, dik-dik, oribi, Somali wild ass, reedbuck, and Grévy's zebra. The country also has a large population of dromedary camels. Somalia is home to around 727 species of birds, with eight being endemic. Reptile species number around 235, with almost half living in the northern areas; several are endemic. The territorial waters are prime fishing grounds for tuna and other marine species.

Environmental challenges are severe. Desertification and deforestation, partly due to unsustainable charcoal production for export, are major concerns. Somalia is highly vulnerable to climate change, experiencing recurrent droughts and, at times, floods. The long, unregulated coastline has allegedly been used for the dumping of toxic waste, particularly after the outbreak of the civil war. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami is believed to have stirred up some of these hazardous materials, leading to health problems in coastal communities. Reports by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) have highlighted the serious environmental and health risks posed by such waste.

Conservation efforts have been undertaken, though often hampered by instability. From 1971, the Siad Barre government initiated a massive tree-planting campaign to combat sand dune encroachment. Somali environmental activist Fatima Jibrell has led successful campaigns to conserve old-growth acacia forests and combat charcoal production, earning her the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2002. The importance of sustainable resource management is critical for Somalia, especially from a social equity perspective, to ensure that vulnerable communities are not disproportionately affected by environmental degradation and that natural resources are used for the benefit of all Somalis.

5. Politics and Government

Somalia's political system is structured as a federal parliamentary republic, though its stability and effectiveness have been profoundly impacted by decades of civil war and ongoing insurgency. This section details the governmental structure, legal framework, administrative organization, human rights situation, and security challenges.

5.1. Government Structure

The Federal Republic of Somalia is a parliamentary representative democratic republic. The President of Somalia is the head of state and commander-in-chief of the Somali Armed Forces. The President is elected by the members of the Federal Parliament. The President, in turn, appoints a Prime Minister, who serves as the head of government and leads the Council of Ministers (Cabinet).

The Federal Parliament of Somalia is the national legislature. It is bicameral, consisting of:

1. The House of the People (Lower House): Members are indirectly elected through a clan-based power-sharing formula, where clan elders and delegates select representatives.

2. The Senate (Upper House): Represents the Federal Member States. Its members are also elected by the legislatures of these states.

Members of both houses serve four-year terms. The Parliament elects the President, the Speaker of Parliament, and Deputy Speakers. It also has the authority to pass and veto laws. The provisional Constitution of Somalia, adopted in August 2012, provides the legal foundation for the Federal Republic. However, the country has faced significant challenges in implementing full democratic elections and ensuring the writ of the federal government throughout its territory. According to 2023 V-Dem Democracy indices, Somalia is the 5th least democratic country in Africa.

5.2. Judiciary

The Judiciary of Somalia is defined by the Provisional Constitution. The national court structure is organized into three tiers:

1. The Constitutional Court: Adjudicates issues pertaining to the constitution, as well as various Federal and sub-national matters. It consists of five members.

2. Federal Government level courts.

3. State level courts.

A nine-member Judicial Service Commission is responsible for appointing any Federal tier member of the judiciary. It also selects and presents potential Constitutional Court judges to the House of the People for approval. If endorsed, the President appoints the candidate as a judge of the Constitutional Court.

Somali law draws from a mixture of three different systems:

- Civil law: Influenced by the Italian colonial period.

- Islamic law (Shari'a): The constitution declares Islam as the state religion and Shari'a as a basic source for national legislation. No law inconsistent with Shari'a can be enacted.

- Customary law (Xeer): Traditional Somali clan-based customary law, which has historically played a significant role in dispute resolution and social regulation, especially in areas where formal state institutions are weak.

The judicial system faces enormous challenges, including lack of resources, insecurity, corruption, and the difficulty of enforcing judgments uniformly across the country.

5.3. Administrative Divisions

Somalia is officially divided into eighteen regions (gobollada, singular gobol), which are in turn subdivided into districts. The regions are:

| Region | Area (km2) | Population (2021/2023 est.) | Capital |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awdal | 8.3 K mile2 (21.37 K km2) | 1,010,566 | Borama |

| Bari | 27 K mile2 (70.09 K km2) | 949,693 | Bosaso |

| Nugal | 10 K mile2 (26.18 K km2) | 473,940 | Garowe |

| Mudug | 28 K mile2 (72.93 K km2) | 864,728 | Galkayo |

| Galguduud | 18 K mile2 (46.13 K km2) | 634,309 | Dusmareb |

| Hiran | 12 K mile2 (31.51 K km2) | 566,431 | Beledweyne |

| Middle Shabelle | 8.7 K mile2 (22.66 K km2) | 622,660 | Jowhar |

| Banaadir | 143 mile2 (370 km2) | 2,330,708 | Mogadishu |

| Lower Shabelle | 9.8 K mile2 (25.29 K km2) | 1,218,733 | Barawa |

| Togdheer | 15 K mile2 (38.66 K km2) | 962,439 | Burao |

| Bakool | 10 K mile2 (26.96 K km2) | 383,360 | Xuddur |

| Woqooyi Galbeed | 11 K mile2 (28.84 K km2) | 1,744,367 | Hargeisa |

| Bay | 14 K mile2 (35.16 K km2) | 1,035,904 | Baidoa |

| Gedo | 23 K mile2 (60.39 K km2) | 566,318 | Garbahaarreey |

| Middle Juba | 3.8 K mile2 (9.84 K km2) | 432,248 | Bu'aale |

| Lower Juba | 17 K mile2 (42.88 K km2) | 632,924 | Kismayo |

| Sanaag | 21 K mile2 (53.37 K km2) | 578,092 | Erigavo |

| Sool | 9.7 K mile2 (25.04 K km2) | 618,619 | Las Anod |

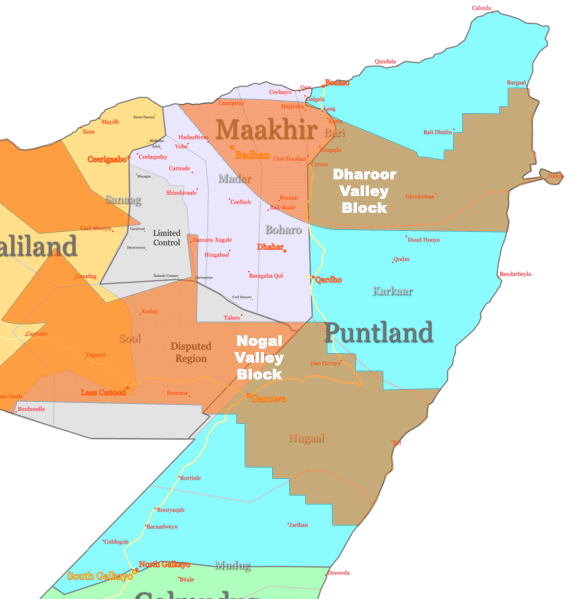

Under the federal system, Somalia is also composed of Federal Member States (FMS). These include Puntland, Jubaland, South West State, Galmudug, and Hirshabelle. The capital city, Mogadishu, is administered as the Banaadir Regional Administration. The Somaliland region in the northwest declared independence in 1991 but is not internationally recognized; it is considered part of Somalia by the federal government and the international community. Khatumo State in eastern Somaliland declared its intention to be a federal member state in 2023. The Federal Parliament is tasked with determining the ultimate number and boundaries of the FMS. The relationship between the federal government and the FMS has often been a source of political tension. After the collapse of Somalia in 1991, there were no relations or contact between the government of Somaliland and the government of Somalia.

5.4. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Somalia remains dire, severely impacted by decades of armed conflict, political instability, weak rule of law, and extreme poverty. From a social liberal perspective, which emphasizes individual freedoms, equality, and social justice, the challenges are immense.

Civilians continue to bear the brunt of the ongoing conflict, particularly with Al-Shabaab and other armed groups. Violations include unlawful killings, indiscriminate attacks, abductions, forced recruitment (including of children), and sexual violence. Freedom of expression and the press are heavily curtailed. Journalists face threats, intimidation, arrest, and violence from both state and non-state actors.

Women's rights are severely restricted. Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) is almost universal, despite laws against it in some regions. Women face discrimination in law and practice, limited political participation, and high rates of sexual and gender-based violence, often with impunity for perpetrators. Child marriage is also prevalent.

Children's rights are gravely violated, including recruitment as child soldiers, lack of access to education and healthcare, and vulnerability to violence and exploitation.

Minority groups and marginalized clans often face discrimination, displacement, and exclusion from resources and political representation. The Somali Bantu and other ethnic minorities are particularly vulnerable.

LGBT rights are non-existent. Same-sex sexual activity is criminalized and punishable by death under Sharia law implemented in areas controlled by Al-Shabaab and in some interpretations within the formal legal system. Societal stigma is extreme.

The justice system is weak, under-resourced, and often unable to provide fair trials or accountability for human rights abuses. Impunity for serious crimes is widespread. Access to justice for victims is severely limited. In October 2020, a UN human rights investigator raised concerns over the Somali government's backtracking on human rights commitments, highlighting the ongoing struggle to embed a culture of human rights respect and accountability.

5.5. Security and Piracy

Somalia faces persistent and complex security challenges that profoundly affect governance, civilian life, and regional stability. The primary threat stems from the Al-Shabaab insurgency, which continues to control significant territory, particularly in rural areas of southern and central Somalia. The group launches frequent attacks against government targets, security forces, and civilians, including bombings, assassinations, and assaults. Efforts to counter Al-Shabaab involve the Somali National Army, supported by the African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) and other international partners.

Beyond Al-Shabaab, clan-based conflicts over resources, land, and political power remain a significant source of instability. These conflicts often lead to localized violence and displacement, undermining state-building efforts and social cohesion. The proliferation of small arms and light weapons further exacerbates insecurity.

Somali piracy emerged as a major international concern in the mid-2000s, disrupting global shipping lanes in the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean. The root causes of piracy are complex, linked to the collapse of the Somali state and its inability to police its waters, leading to illegal foreign fishing and toxic waste dumping by foreign vessels, which devastated local fishing communities. Economic hardship, lack of alternative livelihoods, and the potential for lucrative ransoms fueled its growth. At its peak, pirates operated sophisticated networks, hijacking commercial vessels and holding crews hostage.

International counter-piracy efforts, including naval patrols by multinational task forces (e.g., CTF-150, CTF-151, Operation Atalanta), the adoption of best management practices by shipping companies (e.g., armed guards, secure vessel hardening), and onshore efforts to build Somali maritime security capacity, significantly reduced piracy incidents from their peak around 2011. While large-scale commercial vessel hijackings became rare for a period, underlying vulnerabilities remain, and there have been sporadic reports of resurgent piracy attempts, particularly linked to ongoing instability and economic pressures. Japan, among other nations, has actively participated in international anti-piracy patrols.

6. Foreign Relations

Somalia's foreign relations are managed by the President, the Prime Minister, and the federal Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The country's foreign policy focuses on seeking international support for peace-building, security, development, and humanitarian aid, as well as engaging in regional cooperation and re-establishing its position in the global community after decades of conflict. This section details Somalia's interactions with key countries and its participation in international organizations.

6.1. Relations with Key Countries and International Organizations

Somalia maintains bilateral relations with numerous countries. Key relationships include:

- Neighboring Countries:

- Ethiopia: Relations have been complex, marked by historical border disputes (Ogaden) and Ethiopian military interventions in Somalia. However, Ethiopia is also a key partner in security cooperation against Al-Shabaab and a member of AMISOM/ATMIS. The 2024 agreement between Ethiopia and Somaliland regarding port access caused significant tension with the Somali federal government, which viewed it as a violation of its sovereignty, though later diplomatic efforts, including Turkish mediation, sought to de-escalate the issue.

- Kenya: Kenya hosts a large Somali refugee population and has also intervened militarily in southern Somalia (Operation Linda Nchi) to counter Al-Shabaab. Maritime boundary disputes have also been a point of contention.

- Djibouti: Djibouti shares ethnic and cultural ties with Somalia and has played a significant role in peace and reconciliation processes, hosting several important conferences.

- Arab Nations: As a member of the Arab League, Somalia has close ties with Arab countries, which provide significant humanitarian aid, development assistance, and political support. Key partners include Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar.

- Turkey: Turkey has emerged as a major strategic partner for Somalia, providing substantial humanitarian aid, development assistance (including infrastructure projects like the airport and port in Mogadishu), military training, and political support since its engagement following the 2011 famine.

- Western Powers:

- United States: The US provides significant security assistance, counter-terrorism support, and humanitarian aid. It has conducted military operations against Al-Shabaab.

- United Kingdom: The UK is a key partner in development, security sector reform, and humanitarian efforts.

- European Union (EU): The EU is a major donor and supports AMISOM/ATMIS, security sector reform, and development initiatives. Several EU operations like EUTM Somalia, EU NAVFOR Operation Atalanta (counter-piracy), and EUCAP Somalia (maritime security capacity building) have been active.

- Italy: As a former colonial power, Italy maintains historical ties and provides development aid.

- China: China has growing economic interests in Somalia and the Horn of Africa, including investments under the Belt and Road Initiative which Somalia joined in 2018.

- Russia: Maintains diplomatic relations.

- South Korea: South Korea has participated in international counter-piracy efforts off the Somali coast and provides humanitarian assistance.

- North Korea: Diplomatic relations were established on April 13, 1967. North Korea opened an embassy in Mogadishu on November 23, 1967. During the 1970s, Kim Il-sung provided economic and military support to Siad Barre's Somalia, viewing it as a model for self-reliance in Africa. However, relations soured when North Korea shifted support to Ethiopia during the Ogaden War. The North Korean embassy in Somalia closed in January 1991.

Somalia is a member of numerous international organizations:

- United Nations (UN): A member since its independence. Various UN agencies are heavily involved in humanitarian aid, peacekeeping, and development.

- African Union (AU): A founding member of its predecessor, the OAU. The AU leads the ATMIS security mission.

- Arab League

- Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC): A founding member.

- Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD): A regional bloc in the Horn of Africa, playing a key role in peace and security initiatives.

- East African Community (EAC): Somalia officially joined the EAC in 2023, aiming to boost regional trade and integration.

- Non-Aligned Movement (NAM)

The Somali diaspora also plays a significant role in the country's foreign relations and development through remittances and advocacy.

7. Military

The Somali Armed Forces (SAF) are the military forces of the Federal Republic of Somalia. Headed by the President as Commander-in-Chief, they are constitutionally mandated to ensure the nation's sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity. The SAF historically consisted of the Army, Navy, Air Force, and the Police Force, as well as the National Security Service (NSS) for intelligence.

In the post-independence period, particularly during the Siad Barre era, the Somali military grew to become one of the larger and more capable forces on the African continent, largely due to support first from the Soviet Union and later from the United States during the Cold War. The military played a central role in Barre's regime and was heavily involved in the Ogaden War against Ethiopia in 1977-1978.

The outbreak of the Somali Civil War in 1991 led to the complete collapse and disbandment of the Somali National Army and other security institutions. For over a decade, Somalia had no formal national military; security was in the hands of various clan militias and warlord factions.

The gradual process of reconstituting the military began with the establishment of the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) in 2004. The Somali Armed Forces are now overseen by the Ministry of Defence of the Federal Government of Somalia, which was formed in mid-2012. Efforts to rebuild and professionalize the national security apparatus have been ongoing, heavily supported by international partners, including the African Union Mission to Somalia (AMISOM), now ATMIS, the United States, Turkey, the European Union, and others. These efforts focus on training, equipping, and integrating various militia groups into a unified national command structure.

The modern Somali National Army is composed of brigades, some of which have been formed along clan lines, reflecting the complex societal structure. Specialized units, such as the US-trained Danab Brigade (Lightning Brigade), an elite counter-terrorism force, and the Turkish-trained Gorgor (Eagle) commandos, form key components of the army's operational capabilities. As of 2022, the Danab Brigade reportedly consisted of 16 smaller brigade units totaling over 2,000 personnel, while the Gorgor brigade had two units.

The rebuilding process faces significant challenges, including:

- Resources:** Limited domestic funding for salaries, equipment, and logistics.

- Training:** Ensuring consistent and high-quality training across all units.

- Integration:** Overcoming clan loyalties and integrating former militias into a truly national force.

- Command and Control:** Establishing effective and unified command structures.

- Corruption:** Combating corruption within the security sector.

- Arms Embargo:** While partially lifted to allow for the equipping of government forces, an arms embargo remains in place, complicating rearmament efforts.

In January 2013, the Somali federal government also re-opened the national intelligence service, renaming it the National Intelligence and Security Agency (NISA). The Somaliland and Puntland regional governments maintain their own autonomous security and police forces, which operate independently of the federal military. The transition of security responsibilities from ATMIS to Somali forces is a key ongoing process, critical for the long-term stability of the country.

8. Economy

Somalia's economy has been severely impacted by decades of conflict and political instability, yet it demonstrates remarkable resilience, particularly in its informal sector. This section provides an overview of its current state, key sectors, challenges, and potential for development, viewed through a lens of poverty and social equity.

8.1. Overview

The Somali economy is characterized by a large informal economy, a strong reliance on livestock, substantial remittance inflows from the diaspora, and a surprisingly developed telecommunications sector. Decades of civil war have shattered formal government institutions and infrastructure, making it difficult to gauge the exact size or growth of the economy. For 1994, the CIA estimated the GDP at 3.30 B USD. By 2009, the CIA estimated GDP had grown to 5.73 B USD, with a projected real growth rate of 2.6%. In 2023, Somalia's GDP per capita was estimated at 683 USD, ranking it among the lowest in the world (183rd out of 195).

Despite the lack of a strong central government for many years, the private sector has shown significant dynamism, particularly in services like trade, money transfer, transport, and communications. This activity has been largely financed by the Somali diaspora. However, Somalia remains one of the least developed countries, facing immense challenges of poverty, unemployment, and food insecurity. Social equity is a major concern, with widespread disparities in wealth and access to resources, often exacerbated by clan affiliations and the ongoing conflict. Reconstruction and sustainable development efforts are hampered by insecurity, weak governance, corruption (Somalia consistently ranks at or near the bottom of global corruption indices), and environmental vulnerability. Remittances from Somalis working abroad are a crucial lifeline, constituting a significant portion of the national income (estimated at 15.82% of GDP in 2023 by the CIA).

8.2. Agriculture and Livestock

Agriculture, particularly livestock rearing, is the backbone of the Somali economy. It accounts for about 65% of the GDP and employs approximately 65-80% of the workforce. Livestock - primarily camels (Somalia has the largest camel population in the world), goats, and sheep, along with cattle - contributes about 40% to GDP and more than 50% of export earnings. Somali livestock is highly valued in Gulf Arab markets, and traders increasingly challenge Australia's traditional dominance in this sector. This has led to strategic investments from countries like Saudi Arabia (in export infrastructure) and the United Arab Emirates (in farmlands).

Major agricultural products for export include bananas (historically a key export), frankincense, and myrrh. Crops for domestic consumption include sorghum, corn, and sugar. Fisheries also offer significant potential along Somalia's long coastline, though the sector is underdeveloped and affected by illegal foreign fishing.

The agricultural sector faces severe challenges from recurrent droughts, land degradation, lack of infrastructure (irrigation, storage, transport), and insecurity. Supporting pastoral communities, promoting sustainable land and water management, and investing in climate-resilient agriculture are crucial for food security and economic development. In 1984, livestock was the largest export commodity, accounting for 59.6% of export value. Other exports then included bananas (7.9%), hides, and skins.

8.3. Industry and Manufacturing

Somalia's industrial sector is small-scale, largely based on the processing of agricultural products, and accounts for about 10% of GDP. Prior to the civil war in 1991, there were roughly 53 state-owned small, medium, and large manufacturing firms, many of which were already foundering. The conflict destroyed most of the remaining industries.

However, primarily due to substantial local investment by the Somali diaspora, some small-scale plants have re-opened, and new ones have been created. These include fish-canning and meat-processing plants, particularly in the northern regions. In the Mogadishu area, around 25 factories reportedly manufacture items such as pasta, mineral water, confectionery, plastic bags, textiles, hides and skins, detergent and soap, aluminium products, foam mattresses and pillows, fishing boats, and engage in packaging and stone processing. In 2004, an 8.30 M USD Coca-Cola bottling plant opened in Mogadishu, with investors from various Somali constituencies. Foreign investment in the past included companies like General Motors and Dole Fruit.

The revival of the industrial sector is crucial for job creation and economic diversification. Challenges include lack of reliable electricity, poor infrastructure, insecurity, and limited access to finance. Fostering local entrepreneurship and creating a conducive investment climate are key to industrial development.

8.4. Energy and Natural Resources

Somalia possesses reserves of several natural resources, including uranium, iron ore, tin, gypsum, bauxite, copper, salt, and potentially significant deposits of natural gas and oil. The CIA reports 7.4 B yd3 (5.66 B m3) of proven natural gas reserves.

The extent of proven oil reserves is uncertain. While the CIA asserted in 2011 that there were no proven oil reserves, UNCTAD suggested that most potential reserves lie off the northwestern coast (Somaliland region). Range Resources, an oil group listed in Sydney, estimated that the Puntland region could produce 5 oilbbl to 10 oilbbl of oil. The Somalia Petroleum Corporation was established by the federal government to oversee exploration and development. In the late 1960s, UN geologists discovered major uranium deposits, estimated to be over 25% of the world's then-known reserves. In 1984, Somalia was reported to have 5,000 tons of uranium reasonably assured resources (RAR) and 11,000 tons of estimated additional resources (EAR). American, UAE, Italian, and Brazilian mineral companies have shown interest in extraction rights.

The energy sector faces immense challenges. Electricity supply is largely provided by local private businesses, often at high cost and with limited reliability. The Somali Energy Company is one such firm involved in generation, transmission, and distribution. In 2010, the nation produced 310 million kWh and consumed 288.3 million kWh of electricity. The Trans-National Industrial Electricity and Gas Company, a conglomerate of five major Somali companies, was formed in 2010 with an initial investment budget of 1.00 B USD to provide electricity and gas infrastructure, launching the Somalia Peace Dividend Project aimed at facilitating local industrialization.

Sustainable energy development, including exploring renewable energy sources, and the transparent and equitable management of natural resources are critical for Somalia's future economic growth and social equity.

8.5. Monetary and Payment System

The Central Bank of Somalia is the official monetary authority, responsible for formulating and implementing monetary policy. The official currency is the Somali shilling (SOS). However, due to decades of conflict and instability, the Somali shilling suffered from hyperinflation, and a lack of confidence in the local currency led to widespread dollarization. The US dollar is widely accepted as a medium of exchange, particularly for larger transactions. Most government-issued banknotes in circulation predate the civil war, with a significant portion of shillings in use being counterfeit. Discussions about issuing new banknotes have occurred periodically.

Despite the absence of a functioning central monetary authority for many years (between 1991 and the re-establishment of the Central Bank in 2009), Somalia developed a surprisingly advanced informal payment system. Private money transfer operators (MTOs), known as hawalas, became crucial, acting as informal banking networks. These firms handle an estimated 1.60 B USD to 2.00 B USD in remittances annually from the Somali diaspora. Most are members of the Somali Money Transfer Association (SOMTA). The largest Somali MTO is Dahabshiil, a Somali-owned firm operating in numerous countries. With improved local security, some MTOs have sought to transition into formal banks.

Following the re-establishment of the central government, the Somali shilling has seen periods of appreciation. In March 2014, it appreciated by almost 60% against the US dollar over the previous 12 months, becoming the strongest performing currency globally during that period according to Bloomberg.

The Somalia Stock Exchange (SSE) was founded in 2012 by a Somali diplomat to attract investment from Somali-owned firms and global companies to accelerate post-conflict reconstruction.

Germany's Bavarian State Mint has been issuing Somalia-branded bullion coins (silver since 2004, gold since 2010), known as "Elephant coins," primarily for collectors and investors outside Somalia; they are not used as currency within Somalia.

Rebuilding a formal, stable, and trustworthy financial sector, including a fully functional central bank capable of managing monetary policy and regulating financial institutions, is a key priority for Somalia's economic recovery.

8.6. Transport

Somalia's transportation infrastructure has been severely degraded by decades of conflict and lack of maintenance, but efforts are underway for rehabilitation and expansion.

Roads: Somalia's road network is approximately 14 K mile (22.10 K km) long. As of 2000, only about 1.6 K mile (2.61 K km) were paved, with 12 K mile (19.49 K km) unpaved. A 466 mile (750 km) highway connects major cities in the northern part of the country, such as Bosaso, Galkayo, and Garowe, with towns in the south. Many roads are in poor condition, hindering trade and access to essential services.

Airports: The Somali Civil Aviation Authority (SOMCAA) is the national civil aviation body. After a long period of management by the Civil Aviation Caretaker Authority for Somalia (CACAS), SOMCAA has been working to re-assume full control of Somalia's airspace. There are 62 airports in Somalia, seven of which have paved runways. Major airports include Aden Adde International Airport in Mogadishu, Hargeisa International Airport in Hargeisa, Kismayo Airport in Kismayo, Baidoa Airport in Baidoa, and Bender Qassim International Airport (Bosaso Airport) in Bosaso.