1. Overview

Oman, officially the Sultanate of Oman (سلْطنة عُمانSalṭanat ʻUmānArabic), is a country located on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to the west, the United Arab Emirates to the northwest, and Yemen to the southwest. The country shares maritime borders with Iran and Pakistan. Muscat is the capital and largest city. Oman's territory also includes the exclaves of Madha and the Musandam Peninsula.

Historically a significant maritime power, the Omani Empire once extended its influence across the Strait of Hormuz to parts of modern-day Iran and Pakistan, and southwards to Zanzibar on the East African coast. During the 20th century, Oman came under significant British influence, though it was never formally a British colony or protectorate. The Al Said dynasty has ruled Oman since 1744.

Oman is an absolute monarchy led by the Sultan. Qaboos bin Said, who ascended to the throne in 1970 after deposing his father, initiated a period of extensive modernization and development known as the "Omani Renaissance." His reign saw significant improvements in living standards, healthcare, and education, alongside the abolition of slavery and the end of the Dhofar Rebellion. However, his rule was also characterized by limited political freedoms and human rights concerns. Upon Sultan Qaboos's death in January 2020, his cousin Haitham bin Tariq became the new Sultan, vowing to continue Qaboos's policies while also addressing contemporary economic and social challenges.

The Omani economy has traditionally relied on its oil reserves, though diversification efforts, particularly in tourism, logistics, and manufacturing, are underway as part of "Oman Vision 2040." The country is a member of the United Nations, the Arab League, the Gulf Cooperation Council, the Non-Aligned Movement, and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation.

2. Etymology

The origin of the name "Oman" is subject to several theories. The oldest known written mention of "Oman" is on a tomb in the Mleiha Archaeological Centre in the United Arab Emirates.

The name is thought to be older than Pliny the Elder's reference to "Omana" or Ptolemy's reference to "Omanon" (Ὄμανον ἐμπόριονOmanon emporionGreek, Ancient), both of which likely referred to the ancient port city of Sohar.

In Arabic, the name is typically etymologized as deriving from عامِنʿāminArabic or عَمونʿamūnArabic, meaning "settled" people, as opposed to the nomadic Bedouin. Another theory suggests it is named after Oman bin Ibrahim al-Khalil, Oman bin Siba' bin Yaghthan bin Ibrahim, or Oman bin Qahtan.

A further hypothesis links the name "Oman" to a valley in Yemen at Ma'rib, presumed to be the original homeland of the Azd tribe, one of the early Arab groups to migrate and settle in the region. The Azd are mentioned in pre-Islamic inscriptions, specifically Sabaic inscriptions from the reign of Sha'r Awtar (circa 210-230 CE).

3. History

Oman's history stretches from early human settlements in prehistory, through ancient civilizations like Magan, Arab settlement and Islamization, various Imamates and dynasties, Portuguese colonization, the rise and fall of the Omani Empire, increasing British influence, and its modern development under the Al Busaidi dynasty, particularly since 1970. Key periods include the conservative rule of Sultan Said bin Taimur, the transformative reign of Sultan Qaboos bin Said, and the contemporary leadership of Sultan Haitham bin Tariq.

3.1. Prehistory and ancient history

Evidence of early human habitation in Oman dates back over 100,000 years. In 2011, a site at Aybut Al Auwal in the Dhofar Governorate revealed more than 100 surface scatters of stone tools belonging to a regionally specific African lithic industry-the late Nubian Complex-previously known only from Northeast Africa and the Horn of Africa. Optically stimulated luminescence dating placed the Arabian Nubian Complex at 106,000 years old, supporting the theory that early human populations migrated from Africa into Arabia during the Late Pleistocene.

Surveys in recent years have uncovered Palaeolithic and Neolithic sites on the eastern coast, with Saiwan-Ghunaim in the Barr al-Hikman region being a main Palaeolithic site. Archaeological remains are particularly numerous for the Bronze Age Umm an-Nar and Wadi Suq periods. At sites like Bat, Al-Janah, and Al-Ayn, archaeologists have found wheel-turned pottery, hand-made stone vessels, metal industry artifacts, and monumental architecture. These findings indicate sophisticated early societies.

Ancient Sumerian tablets refer to Oman as "Magan", and in the Akkadian language as "Makan". These names are often linked to Oman's ancient copper resources, suggesting its importance in regional trade networks. Frankincense was a significant trade commodity from Oman by 1500 BCE, and the Land of Frankincense, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, testifies to the wealth and sophistication of South Arabian civilizations built on this trade.

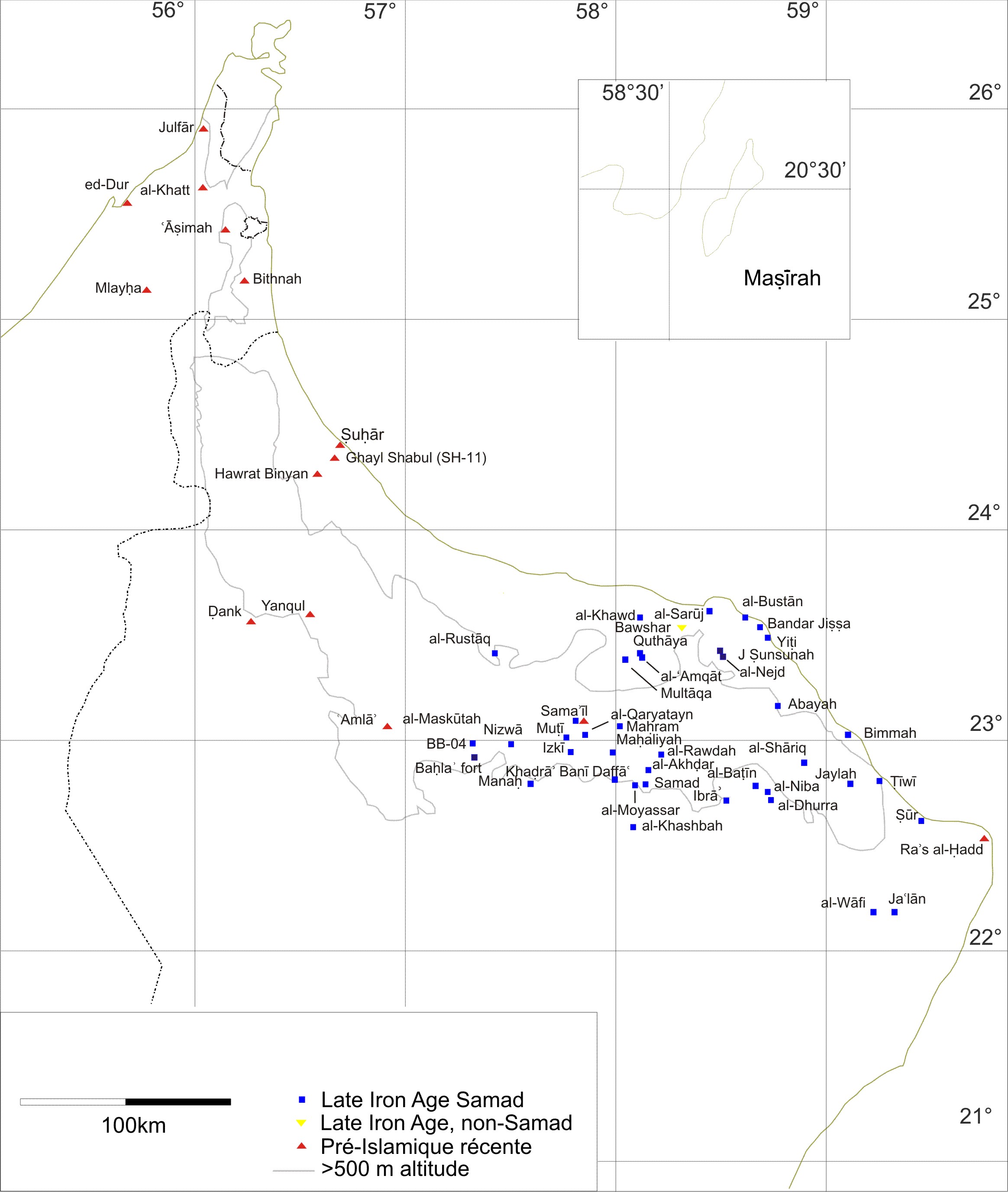

During the 8th century BCE, it is believed that the Yaarub, descendants of Qahtan, ruled the region of Yemen, including Oman. Wathil bin Himyar bin Abd-Shams (Saba) bin Yashjub (Yaman) bin Yarub bin Qahtan later ruled Oman, suggesting early Yemeni influence. Some scholars, like John C. Wilkinson, based on oral history, believed that in the 6th century BCE, the Achaemenid Empire exerted control over the Omani peninsula, likely ruling from a coastal center such as Sohar. Central Oman has its own indigenous Samad Late Iron Age cultural assemblage, named eponymously from Samad al-Shan. In the northern part of the Oman Peninsula, the Recent Pre-Islamic Period begins in the 3rd century BCE and extends into the 3rd century CE. However, the lack of Persian archaeological finds casts some doubt on the extent of Achaemenid control. Armand-Pierre Caussin de Perceval suggests that Shammir bin Wathil bin Himyar recognized the authority of Cyrus the Great over Oman in 536 BCE.

3.2. Arab settlement and Islamization

Over centuries, tribes from western Arabia settled in Oman, engaging in fishing, farming, herding, and stock breeding. Many present-day Omani families trace their ancestry to various parts of Arabia. Arab migration to Oman primarily originated from northwestern and southwestern Arabia. These settlers competed with the indigenous population for arable land.

Two distinct groups of Arab tribes migrated to Oman. One group, a segment of the Azd tribe, migrated from Yemen around 120/200 CE following the collapse of the Marib Dam. The other group, known as Nizari, migrated a few centuries before the advent of Islam from Nejd (present-day Saudi Arabia). Some historians believe the Yaarubah from Qahtan, an older branch, were the first settlers from Yemen, followed by the Azd.

The Azd settlers in Oman, descendants of Nasr bin Azd, became known as "the Al-Azd of Oman". About seventy years after the initial Azd migration, another branch of Alazdi, under Malik bin Fahm (founder of the Tanukhite kingdom west of the Euphrates), is believed to have settled in Oman. According to Al-Kalbi, Malik bin Fahm was the first settler of Alazd, establishing himself initially in Qalhat. With an armed force of over 6,000 men and horses, Malik reportedly fought and defeated Persian forces under a Marzban (governor) in the battle of Salut in Oman. However, this account is considered semi-legendary, likely condensing centuries of migration, conflict, and merging traditions from Arab tribes and the region's original inhabitants.

In the 7th century CE, Omanis came into contact with and accepted Islam. The conversion is largely attributed to Amr ibn al-As, who was sent by the Prophet Muhammad. Amr met with Jaifer and Abd, the sons of Julanda who ruled Oman at the time, and they readily embraced Islam, leading to the decline of Persian influence.

3.3. Imamate of Oman

Omani Azd tribesmen frequently traveled to Basra for trade during the Umayyad era. Basra was a significant center of Islamic learning and commerce, and the Omani Azd were granted a section of the city to settle and conduct their affairs. Many became wealthy merchants and, under their leader al-Muhallab ibn Abi Sufra, expanded their influence eastward towards Khorasan.

The Ibadi school of Islam originated in Basra with its founder, Abd Allah ibn Ibad, around 650 CE. The Omani Azd in Iraq subsequently adopted Ibadism as their predominant faith. Later, Al-Hajjaj, the governor of Iraq, came into conflict with the Ibadis, which compelled many of them to return to Oman. Among those who returned was the scholar Jaber bin Zaid. His return, along with that of other scholars, greatly strengthened the Ibadi movement in Oman.

Al-Hajjaj also attempted to subjugate Oman, then ruled by Suleiman and Said, sons of Abbad bin Julanda. Al-Hajjaj dispatched Mujjaah bin Shiwah, who was confronted by Said bin Abbad. Said's army was defeated, and he retreated to the Jebel Akhdar mountains. Mujjaah pursued and eventually dislodged them from Wadi Mastall. Mujjaah then moved towards the coast, where he confronted Suleiman bin Abbad. Suleiman's forces initially won, but Al-Hajjaj sent another force under Abdulrahman bin Suleiman, who eventually conquered Oman and took over its governance.

The first elective Imamate of Oman is believed to have been established shortly after the fall of the Umayyad Caliphate in 750/755 CE, when Janaħ bin ʕibadah Alħinnawi was elected. Other scholars claim that Janaħ bin Ibadah served as a Wāli (governor) under the Umayyads and later ratified the Imamate, and that Julanda bin Masud was the first elected Imam in 751 CE. This first Imamate reached its peak power in the ninth century CE. It established a maritime empire whose fleet controlled the Gulf, at a time when trade with the Abbasid Caliphate, the Far East, and Africa flourished. The authority of the Imams later declined due to internal power struggles, constant interventions by the Abbasids, and the rise of the Seljuk Empire.

3.4. Nabhani dynasty

During the 11th and 12th centuries, the Omani coast came under the sphere of influence of the Seljuk Empire. They were expelled in 1154 when the Nabhani dynasty (Banu Nabhan) came to power. The Nabhanis ruled as muluk (kings), while the Imams were reduced to largely symbolic significance. The capital of the dynasty was Bahla.

The Banu Nabhan controlled the trade in frankincense on the overland route via Sohar to the Yabrin oasis, and then north to Bahrain, Baghdad, and Damascus. The mango tree was introduced to Oman during the Nabhani dynasty's rule, by ElFellah bin Muhsin.

The Nabhani dynasty began to deteriorate in 1507 when Portuguese colonizers captured the coastal city of Muscat and gradually extended their control along the coast up to Sohar in the north and down to Sur in the southeast. Some historians argue that the Nabhani dynasty ended earlier, around 1435 CE, due to conflicts between the dynasty and the Alhinawis, which led to the restoration of the elective Imamate.

3.5. Portuguese era

A decade after Vasco da Gama's successful voyage around the Cape of Good Hope and to India in 1497-1498, the Portuguese arrived in Oman. They occupied Muscat in 1507 and controlled it for 143 years, until 1650. The Portuguese needed an outpost to protect their sea lanes, so they built up and fortified the city, where remnants of their architectural style still exist. Several other Omani cities were colonized in the early 16th century by the Portuguese to control the entrances of the Persian Gulf and trade in the region, as part of a network of fortresses extending from Basra to Hormuz Island.

However, in 1552, an Ottoman fleet briefly captured the fort in Muscat during their struggle for control of the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean. They soon departed after destroying the surroundings of the fortress.

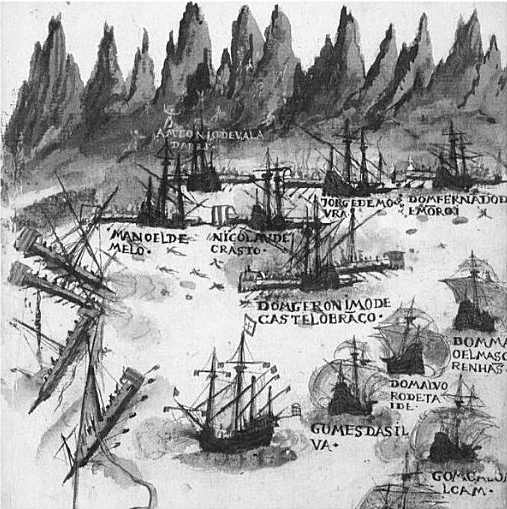

Later, in the 17th century, using its bases in Oman, Portugal engaged in the largest naval battle ever fought in the Persian Gulf. The Portuguese force fought against a combined armada of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the English East India Company, supported by the Safavid empire. The battle was a draw but resulted in the loss of Portuguese influence in the Gulf.

3.6. Yaruba dynasty (1624-1744)

The Ottoman Empire temporarily captured Muscat from the Portuguese again in 1581 and held it until 1588. During the 17th century, the Omanis were reunited by the Yaruba Imams. Nasir bin Murshid became the first Yaruba Imam in 1624, when he was elected in Rustaq. His energy and determination are believed to have led to his election.

Imam Nasir and his successors succeeded in the 1650s in expelling the Portuguese from their coastal domains in Oman and subsequently from their possessions in East Africa. The Omanis established a maritime empire that pursued the Portuguese, driving them from Zanzibar and Mombasa. To capture Zanzibar, Saif bin Sultan, the Imam of Oman, pressed down the Swahili Coast. A major obstacle was Fort Jesus at Mombasa, which fell to Imam Saif bin Sultan in 1698 after a two-year siege. Saif bin Sultan also occupied Bahrain in 1700.

The Yaruba dynasty weakened due to internal rivalries over power following the death of Imam Sultan in 1718. With their power dwindling, Imam Saif bin Sultan II eventually sought help against his rivals from Nader Shah of Persia. A Persian force arrived in March 1737 to aid Saif. From their base at Julfar, the Persian forces eventually turned against the Yaruba in 1743. The Persian empire then attempted to take possession of the coast of Oman until 1747.

3.7. 18th and 19th centuries

This period saw the rise of the Al Busaidi dynasty, the expansion of the Omani Empire, its subsequent division into the Sultanate of Muscat and Oman and the Sultanate of Zanzibar, and the increasing influence of European powers, particularly Great Britain.

After the Omanis expelled the Persians, Ahmed bin Said Al Busaidi became the elected Imam of Oman on November 20, 1744, with Rustaq serving as the capital. The Omanis continued with an elective system for the Imamate, but preference was given to members of the ruling family if deemed qualified.

Following Imam Ahmed's death in 1783, his son, Said bin Ahmed, became the elected Imam. However, Said bin Ahmed's son, Seyyid Hamed bin Said, overthrew his father's representative in Muscat and obtained possession of Muscat fortress, ruling as "Seyyid." Subsequently, Seyyid Sultan bin Ahmed, uncle of Seyyid Hamed, took power. Seyyid Said bin Sultan, son of Sultan bin Ahmed, succeeded him and became one of Oman's most notable rulers. Under Said bin Sultan, the Omani Empire reached its zenith, with its capital moved to Zanzibar in 1832 due to its importance in the slave, ivory, and spice trades.

Throughout the 19th century, apart from Imam Said bin Ahmed who retained the title until his death in 1803, Azzan bin Qais was the only other elected Imam of Oman, ruling from 1868. However, the British refused to accept Imam Azzan as a ruler, viewing him as detrimental to their interests. This played a role in supporting the deposition of Imam Azzan in 1871 by his cousin, Sayyid Turki, a son of the late Sayyid Said bin Sultan and brother of Sultan Barghash of Zanzibar, whom Britain deemed more acceptable.

Oman's Imam Sultan, the defeated ruler of Muscat, was granted sovereignty over Gwadar, an area in modern-day Pakistan, in 1783. Gwadar remained an Omani possession until 1958 when it was purchased by Pakistan.

After the death of Said bin Sultan in 1856, a dispute between his sons led to the division of the empire, arbitrated by the British. Majid bin Said inherited Zanzibar and its East African dominions, while Thuwaini bin Said inherited Muscat and Oman. This division significantly weakened both entities. Zanzibar became a British protectorate, and Oman's influence in East Africa diminished.

3.7.1. British influence and de facto protectorate

The British Empire was keen to dominate southeast Arabia to counter the growing power of other European states and to curb Omani maritime power, which had grown during the 17th century. Starting from the late 18th century, Britain began to establish a series of treaties with the Sultans of Muscat to advance British political and economic interests, while offering military protection.

In 1798, the first treaty between the British East India Company and the Al Busaidi dynasty was signed by Sayyid Sultan bin Ahmed. This treaty aimed to block French and Dutch commercial competition and to obtain a concession to build a British factory at Bandar Abbas. A second treaty in 1800 stipulated that a British representative would reside at the port of Muscat and manage all external affairs with other states.

As the Omani Empire weakened, British influence over Muscat grew throughout the 19th century. In 1854, a deed of cession of the Omani Kuria Muria Islands to Britain was signed by the Sultan of Muscat and the British government. The British government achieved predominating control over Muscat, largely impeding competition from other nations.

Between 1862 and 1892, British Political Residents like Lewis Pelly and Edward Ross were instrumental in securing British supremacy over the Persian Gulf and Muscat through a system of indirect governance. By the end of the 19th century, with the loss of its African dominions and revenues, British influence increased to the point that the Sultans became heavily dependent on British loans and signed declarations to consult the British government on all important matters. The Sultanate thus came under de facto British control, effectively becoming a British protectorate, although it was never formally declared as such.

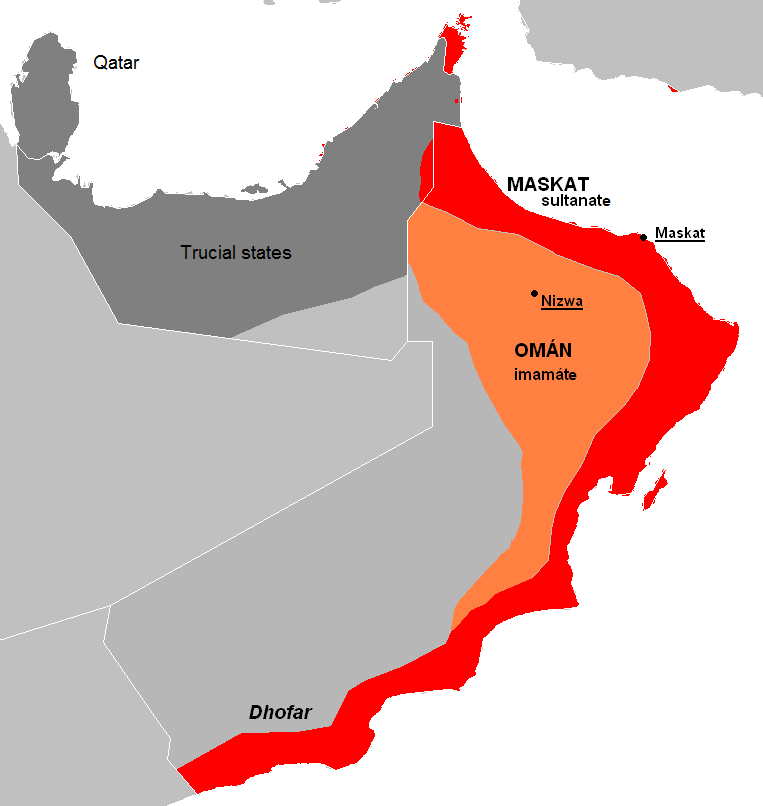

3.7.2. Treaty of Seeb (1920)

The Hajar Mountains, including the Jebel Akhdar range, separate Oman into two distinct regions: the interior and the coastal area dominated by the capital, Muscat. The British imperial development over Muscat and Oman during the 19th century led to a renewed revival of the Imamate in the interior of Oman, a cause that had appeared in cycles for over 1,200 years. The British Political Agent in Muscat attributed the alienation of the interior to the vast influence of the British government over Muscat, which was seen as self-interested and disregardful of local conditions.

In 1913, Imam Salim Alkharusi instigated an anti-Muscat rebellion by the interior tribes, which lasted until 1920. In that year, the Sultanate of Muscat established peace with the Imamate of Oman by signing the Treaty of Seeb. The treaty was brokered by Britain, which at that time had no significant economic interest in the interior of Oman. The treaty granted autonomous rule to the Imamate in the interior regions, while recognizing the sovereignty of the Sultanate of Muscat over the coastal areas. Imam Salim Alkharusi died in 1920, and Muhammad Alkhalili was elected as the new Imam. This treaty effectively created a bifurcated state, with the Sultan controlling Muscat and the coast, and the Imam controlling the interior.

3.8. Reign of Sultan Said bin Taimur (1932-1970)

Said bin Taimur became the Sultan of Muscat and Oman on February 10, 1932. His rule, backed by the British government, was characterized as feudal, reactionary, and isolationist. Oman under his reign remained largely undeveloped, with severe restrictions on personal freedoms and minimal spending on education, health, or infrastructure. The Sultan feared that modernization would lead to instability and undermine his authority. The British government maintained vast administrative control over the Sultanate, with British officials holding key advisory and ministerial positions, including defense secretary, chief of intelligence, and chief adviser to the Sultan.

In 1937, an agreement was signed between the Sultan and the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC), a consortium 23.75% British-owned, granting oil concessions. After failing to discover oil elsewhere in the Sultanate, IPC became interested in promising geological formations near Fahud, an area within the Imamate's territory. IPC offered financial support to the Sultan to raise an armed force against any potential resistance from the Imamate.

During World War II, Oman declared war on Germany on September 10, 1939. The country played a strategic role in defending British trade routes. The Royal Air Force (RAF) established stations on Masirah Island (RAF Masirah) and at Ras al Hadd. Air-sea rescue units were also stationed in Oman. No. 244 Squadron RAF flew Bristol Blenheim V light bombers and Vickers Wellington XIIIs out of RAF Masirah on anti-submarine duties. On October 16, 1943, the German U-boat U-533 was sunk in the Gulf of Oman by depth charges from a Blenheim of No. 244 Squadron.

The 1951 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation between Oman and the United Kingdom recognized the Sultanate of Muscat and Oman as a fully independent state. In 1955, the exclave coastal Makran strip acceded to Pakistan and was made a district of its Balochistan province, while Gwadar remained in Oman. On September 8, 1958, Pakistan purchased the Gwadar enclave from Oman for 3.00 M USD.

3.8.1. Jebel Akhdar War (1954-1959)

Sultan Said bin Taimur expressed interest in occupying the Imamate immediately after the death of Imam Alkhalili, aiming to exploit any potential instability during the Imamate's elections. The British political agent in Muscat believed that assisting the Sultan in taking over the Imamate was the only way to gain access to oil reserves in the interior. In 1946, the British government offered arms, ammunition, auxiliary supplies, and officers to prepare the Sultan for an attack on the interior.

In May 1954, Imam Muhammad Alkhalili died, and Ghalib Alhinai was elected as the new Imam. Relations between Sultan Said bin Taimur and Imam Ghalib Alhinai frayed over disputes concerning oil concessions and the Imamate's autonomy.

In December 1955, Sultan Said bin Taimur, with British backing and supplies, sent troops of the Muscat and Oman Field Force to occupy the main centers in Oman, including Nizwa, the capital of the Imamate of Oman, and Ibri. The interior Omanis, led by Imam Ghalib Alhinai, his brother Talib Alhinai (Wali of Rustaq), and Suleiman bin Hamyar (Wali of Jebel Akhdar), defended the Imamate in the Jebel Akhdar War against British-backed attacks by the Sultanate.

In July 1957, the Sultan's forces, facing strong resistance, were withdrawing but were repeatedly ambushed, sustaining heavy casualties. Sultan Said, however, with the direct intervention of British infantry (two companies of the Cameronians), armored car detachments from the British Army, and RAF aircraft, was able to suppress the rebellion. The Imamate's forces retreated to the inaccessible Jebel Akhdar mountains.

Colonel David Smiley, seconded to organize the Sultan's Armed Forces, managed to isolate the mountain in autumn 1958. On August 4, 1957, the British Foreign Secretary approved air strikes without prior warning to the local population. Between July and December 1958, the RAF conducted 1,635 raids, dropping 1,094 tons of bombs and firing 900 rockets at the interior, targeting insurgents, mountain-top villages, water channels, and crops. This campaign had a severe impact on local communities and resulted in civilian casualties, a human rights concern. On January 27, 1959, the Sultanate's forces occupied the mountain in a surprise operation. Imam Ghalib, his brother Talib, and Sulaiman managed to escape to Saudi Arabia, where the Imamate's cause was promoted until the 1970s. The exiled partisans presented Oman's case to the Arab League and the United Nations. The UN General Assembly adopted resolutions in 1965, 1966, and 1967 calling for an end to British control and affirming the Omani people's right to self-determination.

3.8.2. Dhofar Rebellion (1962-1976)

The Dhofar Rebellion (also known as the Dhofar War) began in 1962 in the southern province of Dhofar. It was initially a local tribal uprising against the conservative and oppressive rule of Sultan Said bin Taimur, fueled by economic hardship and lack of development. The rebellion later transformed into a more organized, Marxist-Leninist revolutionary movement, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Oman (PFLO), which received support from South Yemen, China, and the Soviet Union.

The rebels aimed to overthrow the Sultan and establish a socialist state. The conflict escalated throughout the 1960s, posing a significant threat to the Sultan's control over Dhofar and, potentially, the entire country, especially as oil revenues began to flow.

Sultan Said bin Taimur's mishandling of the rebellion and his general resistance to modernization led to his deposition in a bloodless coup d'état on July 23, 1970, orchestrated by his son Qaboos bin Said with British support. Sultan Qaboos immediately reversed his father's isolationist policies, initiated a program of modernization and social reform, and focused on defeating the rebellion.

He expanded and modernized the Sultan of Oman's Armed Forces (SAF), offered amnesty to surrendering rebels, and launched development projects in Dhofar to win the "hearts and minds" of the population. The war was fought with significant foreign assistance for the Sultan's government, including British military advisors and SAS troops, as well as forces from Jordan, Iran (under the Shah), and Pakistan.

The counter-insurgency campaign was brutal, with significant impact on the civilian population in Dhofar. There were reports of human rights abuses by both sides. The Sultan's forces, with their superior firepower and international support, gradually gained the upper hand. The rebellion was officially declared suppressed in 1976.

The consequences of the Dhofar Rebellion were profound. It led to the transformation of Oman under Sultan Qaboos, with oil revenues used for national development and integration. However, the conflict also left scars, particularly on the affected populations in Dhofar, and underscored the geopolitical sensitivities of the region. The successful suppression of the rebellion was seen as a victory against communist expansion in the Arabian Peninsula.

3.9. Modern history (1970-present)

Oman's modern history is largely defined by the reign of Sultan Qaboos bin Said, who transformed the country from an isolated and underdeveloped state into a modern nation, and the subsequent transition to Sultan Haitham bin Tariq. This period has seen significant political, economic, and social changes, as well as challenges.

3.9.1. Reign of Sultan Qaboos bin Said (1970-2020)

Sultan Qaboos bin Said ascended to the throne on July 23, 1970, after overthrowing his father, Said bin Taimur, in a British-supported palace coup. His long reign, which lasted nearly 50 years until his death on January 10, 2020, marked a period of profound transformation for Oman, often referred to as the "Omani Renaissance."

Upon taking power, Sultan Qaboos immediately ended his father's isolationist policies and initiated widespread modernization programs. He utilized the country's growing oil revenues to develop infrastructure, education, healthcare, and social services. Key achievements included the abolition of slavery in 1970, the successful conclusion of the Dhofar Rebellion in 1976, and the promulgation of Oman's first written "Basic Law" (constitution) in 1996. This Basic Law established the framework for governance, though it solidified the Sultan's absolute power.

Under Sultan Qaboos, Oman pursued a moderate and independent foreign policy, often acting as a mediator in regional conflicts. He maintained good relations with Western powers, particularly the United Kingdom and the United States, while also fostering ties with Iran, a unique position among GCC states.

Social reforms included expanding education and healthcare access to all citizens, including women. In 1997, a royal decree granted women the right to vote and stand for election to the Majlis al-Shura (Consultative Assembly). The first female minister was appointed in 2004.

Despite these modernizations, political power remained highly centralized in the hands of the Sultan. Political parties were banned, and freedom of expression, assembly, and press were significantly restricted. Criticism of the Sultan or the government was not tolerated. Human rights organizations frequently reported on the lack of political freedoms, arbitrary detentions, and restrictions on civil society.

The 2011 Omani protests, inspired by the Arab Spring, saw Omanis take to the streets demanding political reforms, more jobs, and better living conditions, though not the overthrow of the Sultan. Sultan Qaboos responded by dismissing unpopular ministers, promising more jobs, increasing benefits, and granting more legislative powers to the elected Majlis al-Shura. However, these reforms were seen by critics as insufficient to address underlying issues of democratic participation and accountability. A crackdown on internet criticism and activists followed in subsequent years.

Economically, while oil wealth fueled development, efforts were made towards diversification under plans like "Vision 2020." Tourism and logistics were identified as key growth sectors.

Sultan Qaboos's impact on Oman was transformative in terms of development and raising living standards. He unified the country and established its place on the international stage. However, his reign was also marked by a lack of significant democratic progress and persistent human rights concerns. While providing stability and material progress, his rule did not foster a culture of broad political participation or dissent. Criticisms often centered on the concentration of power and the slow pace of genuine political reform.

3.9.2. Reign of Sultan Haitham bin Tariq (2020-present)

Sultan Haitham bin Tariq succeeded his cousin, Sultan Qaboos bin Said, on January 11, 2020, following Qaboos's death. Sultan Qaboos, who died childless, had named Haitham as his successor in a sealed letter opened by the royal family council.

Upon assuming power, Sultan Haitham pledged to continue his predecessor's foreign policy of neutrality and non-interference, emphasizing Oman's role as a regional mediator. He also vowed to continue the path of development and modernization initiated by Sultan Qaboos.

One of Sultan Haitham's early significant moves was the amendment of the Basic Law in January 2021 to establish the position of Crown Prince, naming his eldest son, Theyazin bin Haitham, as the heir apparent. This move aimed to ensure a smooth succession process in the future, a matter of some speculation during Sultan Qaboos's later years.

Economically, Sultan Haitham inherited challenges including fluctuating oil prices, high government debt, and the need for continued economic diversification and job creation for a young population. His government has focused on fiscal consolidation, austerity measures, and accelerating the "Oman Vision 2040" plan, which aims to reduce reliance on oil, promote private sector growth, and attract foreign investment.

In terms of political and social landscape, there have been limited signs of significant shifts towards greater democratic development or expansion of civil liberties under Sultan Haitham thus far. The fundamental structure of absolute monarchy remains. Challenges to social equity, such as youth unemployment and the rights of migrant workers, continue to be pertinent issues. The government has faced some protests related to economic conditions, particularly unemployment, and has responded with promises of job creation and economic reforms.

The COVID-19 pandemic also presented significant public health and economic challenges early in his reign, impacting government revenues and development plans. Sultan Haitham's leadership is navigating Oman through a period of economic transition while trying to maintain the stability and unique foreign policy stance established by his predecessor. The extent to which his reign will address calls for deeper democratic reforms and enhance social equity remains a key question for Oman's future.

4. Geography

Oman is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, bordered by the United Arab Emirates to the northwest, Saudi Arabia to the west, and Yemen to the southwest. It has a coastline on the Arabian Sea to the southeast and the Gulf of Oman to the northeast. The country's diverse geography includes mountains, deserts, and extensive coastlines.

Oman lies between latitudes 16°N and 28°N, and longitudes 52°E and 60°E. A vast gravel desert plain covers most of central Oman. Mountain ranges are prominent along the north (the Al Hajar Mountains) and the southeast coast (the Dhofar Mountains). The country's main cities, including the capital Muscat, Sohar, and Sur, are located in the north, while Salalah is a major city in the south.

The Al Hajar Mountains, which run parallel to the Gulf of Oman coast, form the backbone of northern Oman. The highest peak in this range, and in Oman, is Jebel Shams at approximately 10 K ft (3.08 K m). The Dhofar Mountains in the south are notable for catching the summer monsoon, known as the Khareef.

Oman has two exclaves. The Musandam Peninsula, strategically located on the Strait of Hormuz, is separated from the rest of Oman by the UAE. The small exclave of Madha is entirely surrounded by UAE territory and is located halfway between the Musandam Peninsula and the main body of Oman. Within Madha, there is a UAE enclave called Nahwa, belonging to the Emirate of Sharjah.

The central desert of Oman is a significant source of meteorites. The country's total area is approximately 119 K mile2 (309.50 K km2).

4.1. Climate

Oman's climate varies significantly by region. Overall, it is hot and dry in the interior and humid along the coast. Like the rest of the Persian Gulf, Oman generally experiences some of the hottest temperatures in the world, particularly during the summer months.

In Muscat and northern Oman, summer temperatures average between 86 °F (30 °C) and 104 °F (40 °C). The region receives little rainfall, with Muscat's annual average around 3.9 in (100 mm), mostly occurring in January.

The southern region of Dhofar, near Salalah, has a tropical-like climate due to the Khareef (monsoon) from late June to late September. This phenomenon brings moisture from the Indian Ocean, resulting in cooler temperatures, typically ranging from 68 °F (20 °C) to 86 °F (30 °C) during the summer, along with drizzle and heavy fog, transforming the landscape into a lush green area. This makes Salalah a popular summer destination.

The mountainous areas, such as the Jebel Akhdar ("Green Mountain") in the Al Hajar range, receive more rainfall, with annual amounts possibly exceeding 16 in (400 mm). These higher elevations also experience cooler temperatures, and snow cover can occur once every few years.

Some coastal parts, particularly near Masirah Island, may receive no rain at all in a given year. The climate is generally very hot, with peak temperatures in the hot season (May to September) capable of reaching around 129.2 °F (54 °C). On June 26, 2018, the city of Qurayyat set a record for the highest minimum temperature in a 24-hour period, 108.68 °F (42.6 °C).

Climate change poses challenges for Oman, particularly concerning water resources. The country is ranked among the most water-stressed globally. The CO2 emissions from energy consumption are high, although imported CO2 emissions are relatively low.

4.2. Wadis

Oman is characterized by numerous wadis, which are dry riverbeds or valleys that temporarily fill with water after rainfall. These wadis are crucial geographical features and play a significant role in the country's hydrology, ecology, and human life.

They are distributed throughout the country, particularly in mountainous regions like the Al Hajar Mountains and the Dhofar Mountains. When rain occurs, often in intense, short bursts, these wadis can quickly transform into flowing rivers, sometimes leading to flash floods.

Wadis are vital water resources in an arid country like Oman. Historically, settlements and agriculture, especially date palm cultivation using the traditional aflaj (irrigation channels), developed along wadis where water was more accessible. Many aflaj systems draw water from wadis or their underground sources.

The ecosystems associated with wadis are unique. Even when dry, they often support more vegetation than the surrounding desert due to residual moisture. When water flows, they become hotspots for biodiversity, attracting various plants, insects, birds, and other animals. Some wadis, like Wadi Shab and Wadi Bani Khalid, retain water in pools year-round, creating oases with lush vegetation and are popular destinations for recreation and tourism. Human uses of wadis include agriculture, grazing, water collection, and increasingly, tourism and leisure activities such as hiking, swimming, and picnicking. However, wadis also pose risks due to flash floods, and sustainable management is crucial to protect their ecological and water resource values.

4.3. Biodiversity

Oman possesses a diverse range of flora and fauna, adapted to its varied environments, from arid deserts and mountains to coastal areas. Desert shrub and desert grass, common in southern Arabia, are found in Oman, but vegetation is sparse in the interior plateau, which is largely gravel desert.

The greater monsoon rainfall in Dhofar and the Al Hajar Mountains supports more luxuriant growth. In Dhofar, coconut palms grow plentifully on the coastal plains, and frankincense trees are native to the hills. Oleander and varieties of acacia are also common. The Al Hajar Mountains form a distinct ecoregion, hosting unique wildlife, including the Arabian tahr.

Indigenous mammals include the Arabian leopard (critically endangered), hyena, fox, wolf, hare, Arabian oryx, and ibex. Birdlife is also rich, with species such as the vulture, eagle, stork, bustard, Arabian partridge, bee-eater, falcon, and sunbird.

Oman has several endangered species. As of 2001, these included nine mammal species and five bird species. Nineteen plant species were also listed as threatened. The government has passed decrees to protect endangered species, including the Arabian leopard, Arabian oryx, mountain gazelle, goitered gazelle, Arabian tahr, green sea turtle, hawksbill turtle, and olive ridley turtle.

Despite conservation efforts, challenges remain. The Arabian Oryx Sanctuary was the first site ever to be deleted from UNESCO's World Heritage List in 2007, following the government's decision to reduce the site's area by 90% to clear the way for oil prospecting. This decision was criticized by conservationists as detrimental to the oryx population and broader biodiversity goals.

Nature reserves and protected areas have been established to safeguard critical habitats and species. These areas also support ecotourism, which is a growing sector in Oman. However, balancing development with environmental protection and sustainable resource use remains a significant challenge. The ethical treatment of animals, particularly stray dogs and cats, has also been noted as an area of concern by local and national entities, with calls for more humane population control methods like spay and neuter programs and the establishment of animal shelters.

Oman's coastal waters are rich in marine life. In recent years, Oman has become a notable destination for whale watching, featuring species such as the critically endangered Arabian humpback whale (a unique non-migratory population), sperm whales, and pygmy blue whales.

5. Politics

Oman's political system is an absolute monarchy, with the Sultan holding ultimate authority in legislative, executive, and judicial matters. While there are consultative bodies, political power is concentrated, and democratic processes and civil liberties are limited. The country's foreign policy emphasizes neutrality and mediation.

The following subsections delve into the political system, government structure, legal framework, foreign policy, military, human rights situation, and administrative divisions.

5.1. Political system

Oman is a unitary state and an absolute monarchy. The Sultan is the hereditary head of state and head of government, and holds ultimate authority. All legislative, executive, and judiciary power ultimately rests in the hands of the Sultan. Power is passed down through the male line of the Al Said dynasty.

The current Sultan is Haitham bin Tariq, who succeeded Sultan Qaboos bin Said in January 2020. In January 2021, Sultan Haitham amended the Basic Law to establish the position of Crown Prince, appointing his eldest son, Theyazin bin Haitham, as the heir apparent, formalizing the line of succession.

The Basic Statute of the State, issued in 1996 and amended in 2011 and 2021, functions as the country's constitution. It outlines the system of governance, the rights and duties of citizens, and the powers of the state. However, the Sultan's authority is paramount, and he issues laws by decree. Political parties are banned, and any affiliations based on religion are also prohibited. Consequently, Freedom House has routinely rated the country as "Not Free." While the system provides stability, it significantly curtails democratic participation and political dissent.

5.2. Government and Legislature

The government of Oman is led by the Sultan, who also serves as Prime Minister and holds key ministerial portfolios such as Defence, Foreign Affairs, and Finance (though he may delegate day-to-day responsibilities or appoint ministers to oversee these areas). The Council of Ministers is appointed by the Sultan and is responsible for implementing state policy. Ministers are accountable to the Sultan.

The legislature is the bicameral Council of Oman (Majlis Oman). It consists of:

1. The Council of State (Majlis al-Dawla): This is the upper chamber, with its members (currently 71) appointed by the Sultan from among prominent Omanis, including former senior government officials, academics, and business leaders. It has advisory powers and can propose legislation and review laws passed by the lower house before they are submitted to the Sultan.

2. The Consultative Assembly (Majlis al-Shura): This is the lower chamber, with its members (currently 85, with the number evolving over time) elected by universal suffrage for four-year terms. All citizens over the age of 21 have the right to vote. While the Majlis al-Shura can propose legislation, review and amend draft laws prepared by the government (except those related to defense, security, and foreign policy), and question ministers, its powers are largely consultative. The Sultan retains the final authority on all legislation.

Political parties are banned, so candidates run as individuals. The extent of democratic participation is limited by the overarching authority of the Sultan and the consultative nature of the Council of Oman. While elections are held for the Majlis al-Shura, the true locus of power remains with the monarch.

5.3. Legal system

Oman's legal system is based on a mixture of Sharia law (Islamic law) and English common law, with influences from Egyptian and French civil codes. The Sultan's decrees form the primary source of legislation. The Basic Statute of the State, issued in 1996, serves as the country's constitution and outlines the fundamental principles of the legal and judicial framework.

According to the Basic Statute, Sharia law is a source of legislation. Sharia court departments within the civil court system are primarily responsible for family law matters, such as marriage, divorce, inheritance, and child custody. Commercial and criminal law are largely based on codified statutes.

The judiciary is nominally independent, but it is subordinate to the Sultan, who appoints judges and can grant pardons and commute sentences. The highest court is the Supreme Court. There are also Courts of Appeal and Primary Courts. Specialized courts, such as commercial courts, also exist.

While the legal code theoretically protects civil liberties and personal freedoms, human rights organizations have noted that these protections are often limited in practice, especially in political and security-related cases. Due process protections can be insufficient, and fair trial standards are not always met. The administration of justice can be highly personalized.

Legal discrimination against women exists in areas such as personal status law (marriage, divorce, inheritance) and certain state benefits. Children also face some legal discrimination. The rule of law is developing, but significant challenges remain in ensuring full judicial independence, access to justice for all, and consistent application of due process.

5.4. Foreign policy

Since 1970, under Sultan Qaboos and continued by Sultan Haitham, Oman has pursued a pragmatic and moderate foreign policy characterized by neutrality, non-interference in the internal affairs of other countries, and a role as a regional mediator. This approach has allowed Oman to maintain generally good relations with a wide range of international actors, including those who are adversaries to each other.

Key tenets of Omani foreign policy include:

- Neutrality and Mediation: Oman often avoids taking sides in regional disputes and has frequently served as a go-between for conflicting parties. It played a role in facilitating talks between the United States and Iran, and has been involved in mediation efforts in Yemen and other regional conflicts.

- Relations with GCC Nations: Oman is a founding member of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). While it participates in GCC initiatives, it has sometimes charted an independent course, for example, by maintaining diplomatic relations with Iran when other GCC states have had strained ties, and by not participating in the blockade of Qatar.

- Relations with Iran: Uniquely among Arab Gulf states, Oman has historically maintained strong and stable diplomatic and economic ties with Iran. The two countries share control of the strategically important Strait of Hormuz.

- Relations with Western Powers: Oman has close political, economic, and military ties with Western countries, particularly the United Kingdom and the United States. These relationships include defense cooperation agreements and access to Omani military facilities. The port of Duqm is strategically important and has seen investment and use by international navies, including the UK and India.

- International Organizations: Oman is an active member of the United Nations, the Arab League, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, and the Non-Aligned Movement.

Oman's foreign policy is driven by a desire to maintain its own stability and security in a volatile region, promote peaceful conflict resolution, and foster economic development through international partnerships. This balanced approach has given Oman a distinct and often influential voice in regional and international affairs, though its success is also dependent on the broader geopolitical landscape. Diverse perspectives on its impact highlight both its stabilizing influence and the limitations of a small state in a complex region.

5.5. Military

The Sultan of Oman's Armed Forces (SAF) are responsible for the defense of Oman. They consist of the Royal Army of Oman (RAO), the Royal Navy of Oman (RNO), and the Royal Air Force of Oman (RAFO). The Sultan is the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. Additionally, the Royal Household maintains its own guard and special forces units.

Oman's military expenditure as a percentage of GDP has historically been high, often ranking among the highest in the world. For example, in 2020, SIPRI estimated it at 11% of GDP. This reflects the country's security concerns in a volatile region and its commitment to maintaining a well-equipped, albeit moderately sized, military.

The Royal Army of Oman is the largest branch, with approximately 25,000 active personnel. Its equipment includes main battle tanks such as M60A1/A3s and Challenger 2s, as well as armored personnel carriers and artillery.

The Royal Navy of Oman has around 4,200 personnel and operates from several bases, including Seeb, Wudam, Musandam, and Salalah. Its fleet includes corvettes, patrol boats, and landing craft. The navy's primary role is to protect Oman's long coastline and maritime interests, particularly in the strategically vital Strait of Hormuz and the Gulf of Oman.

The Royal Air Force of Oman comprises about 4,100 personnel. Its combat aircraft include F-16C/D Fighting Falcons, Eurofighter Typhoons, and Hawk advanced trainer/light attack aircraft. It also operates transport aircraft and helicopters.

Oman maintains close defense cooperation with several countries, most notably the United Kingdom, with which it has a long-standing military relationship that includes joint exercises, training, and procurement of British military equipment. The United States also has defense agreements with Oman and has access to Omani facilities. India has also increased its military cooperation with Oman, including access to the port of Duqm for its navy.

The national defense policy focuses on protecting the Sultanate's sovereignty and territorial integrity, securing its maritime trade routes, and contributing to regional stability. Despite its relatively small size, Oman's military is considered well-trained and equipped, benefiting from significant investment and international partnerships.

5.6. Human rights

The human rights situation in Oman has been a subject of concern for international human rights organizations. While Oman has made significant socio-economic progress, its record on political freedoms and civil liberties is poor, reflecting its status as an absolute monarchy.

Key human rights issues in Oman include:

- Freedom of Expression, Assembly, and Association: These freedoms are severely restricted. Criticism of the Sultan or the government is prohibited by law and can lead to arrest and imprisonment. Public meetings and demonstrations require government approval, and independent civil society organizations, including human rights groups, face significant obstacles to formation and operation. Journalists and online activists often practice self-censorship due to fear of reprisal. Several journalists and activists have been arrested, prosecuted, and imprisoned for expressing critical views or reporting on sensitive topics like corruption. Books and other media are subject to censorship.

- Torture and Ill-Treatment: There have been credible reports from human rights organizations detailing allegations of torture and other forms of ill-treatment of detainees by Omani security forces, particularly against protesters and those detained for political reasons. Reported methods include mock execution, beatings, hooding, solitary confinement, and subjection to extreme temperatures and constant noise.

- Due Process and Fair Trial: While the Basic Law provides for some legal protections, due process rights are often not respected in practice, especially in security-related cases. Search warrants are not always required for police to enter homes. Detainees may be held incommunicado without access to lawyers or family for extended periods.

- Women's Rights: While women in Oman have access to education and employment, and the right to vote and stand for election, they continue to face legal and societal discrimination. Personal status laws, based on Sharia, can disadvantage women in matters of marriage, divorce, inheritance, and child custody. Women may also face restrictions on their autonomy concerning health and reproductive rights and require government permission to marry foreigners (though this law was liberalized in 2023).

- Migrant Workers' Rights: Migrant workers constitute a significant portion of Oman's labor force. While some legal protections exist, they are often inadequately enforced. Migrant workers, particularly domestic workers, are vulnerable to exploitation, including unpaid wages, excessive working hours, confiscation of passports, and physical or sexual abuse. The kafala (sponsorship) system ties workers to their employers, limiting their ability to change jobs or leave the country.

- LGBTQ+ Rights: Homosexual acts are illegal in Oman and are punishable by imprisonment. Societal discrimination against LGBTQ+ individuals is prevalent.

The Omani government has established a National Human Rights Commission, but its independence and effectiveness have been questioned by international observers. While Oman presents an image of stability and moderation, the overarching authority of the Sultan and the state security apparatus significantly limits fundamental freedoms and democratic participation.

5.7. Administrative divisions

Oman is administratively divided into eleven governorates (محافظاتmuḥāfaẓātArabic, singular محافظةmuḥāfaẓahArabic). These governorates were established in October 2011, replacing the previous system of regions (mintaqah) and governorates. Each governorate is further subdivided into wilayats (ولاياتwilāyātArabic, singular ولايةwilāyahArabic). There are a total of 60 wilayats.

The eleven governorates are:

- Ad Dakhiliyah (The Interior)

- Ad Dhahirah (The Back)

- Al Batinah North

- Al Batinah South

- Al Buraimi

- Al Wusta (The Central)

- Ash Sharqiyah North (The Eastern North)

- Ash Sharqiyah South (The Eastern South)

- Dhofar

- Muscat (The Capital)

- Musandam

Each governorate is headed by a governor appointed by the Sultan. The wilayats are administered by Walis. This system of administrative divisions facilitates governance and the delivery of public services across the country. The governorates and wilayats vary significantly in terms of population, geographical area, and economic characteristics. For example, Muscat Governorate is the most populous and economically active, while Al Wusta Governorate is vast but sparsely populated. Dhofar Governorate in the south has unique climatic and cultural features. The Musandam Governorate is an exclave strategically located on the Strait of Hormuz.

5.7.1. Major cities

Oman has several major cities that serve as centers of population, administration, economy, and culture.

- Muscat: The capital and largest city of Oman, located in the Muscat Governorate on the Gulf of Oman coast. It is the political, economic, and administrative heart of the country. Muscat is a historic port city that has undergone significant modernization and urban development. It is known for its blend of traditional architecture, such as the Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque and the Al Alam Palace, with modern infrastructure. The wider Muscat metropolitan area includes several important towns like Seeb, Bawshar (Boshar), and Muttrah (home to a traditional souq and port). Its population, including the metropolitan area, is over 1.5 million.

- Salalah: The second-largest city and the capital of the Dhofar Governorate in southern Oman. Salalah is historically significant as a center for the frankincense trade. It is unique for its Khareef (monsoon) season, which attracts many tourists. It has a major port and an international airport, contributing to its economic importance. Population is around 400,000.

- Sohar: An ancient port city located in the Al Batinah North Governorate. Historically, it was a major trading hub. In modern times, Sohar has re-emerged as a significant industrial center, with a major port, an industrial estate, and a free zone, focusing on petrochemicals, metals, and logistics. Its population is over 200,000.

- Nizwa: Located in the Ad Dakhiliyah Governorate, Nizwa is a historic city that was once the capital of Oman and a center for the Ibadi Imamate. It is known for its well-preserved fort, traditional souq, and silver craftsmanship. It remains an important cultural and commercial center for the interior region. Population is around 100,000.

- Sur: A coastal city in the Ash Sharqiyah South Governorate, historically renowned for its shipbuilding traditions, particularly the construction of dhows. It remains an important fishing port and has a maritime museum. Population is around 100,000.

- Al Buraimi: An oasis town in the Al Buraimi Governorate, located on the border with the United Arab Emirates, adjacent to the UAE city of Al Ain. It is an important border crossing and commercial center.

- Ibri: The largest town in the Ad Dhahirah Governorate, serving as an administrative and commercial hub for the western interior region.

- Rustaq: Another historic town in the Al Batinah South Governorate, known for its fort and hot springs. It was once a capital of Oman.

Urban development in these cities has focused on improving infrastructure, housing, and public services, while also attempting to preserve cultural heritage. Social services and economic opportunities tend to be more concentrated in these urban centers.

6. Economy

Oman's economy, while traditionally reliant on oil and gas, is undergoing a process of diversification as outlined in its long-term development strategy, "Vision 2040." The government is focusing on developing sectors such as tourism, logistics, manufacturing, and fisheries to reduce dependence on hydrocarbons and create sustainable growth. These efforts have social and economic impacts, including effects on labor markets, social equity, and environmental sustainability.

The Omani national economy is officially based on principles of justice and a free economy, as stated in Article 11 of the Basic Statute of the State. By regional standards, Oman has a relatively diversified economy but remains significantly dependent on oil exports. In 2018, mineral fuels accounted for 82.2 percent of total product exports. Tourism is the fastest-growing industry. Other sources of income, such as agriculture and non-oil industry, are comparatively small, accounting for less than 1% of the country's exports, but diversification is a government priority. Agriculture, often subsistence in nature, produces dates, limes, grains, and vegetables. However, with less than 1% of the land under cultivation, Oman is likely to remain a net importer of food.

Oman's socio-economic structure is described as a hyper-centralized rentier welfare state. The largest 10 percent of corporations employ almost 80 percent of Omani nationals in the private sector. Half of the private sector jobs are classified as elementary. About one-third of employed Omanis are in the private sector, with the majority in the public sector. This structure can create a monopoly-like economy.

Since the oil price slump in 1998, Oman has actively planned to diversify its economy, emphasizing tourism and infrastructure. The "Vision 2020" plan, established in 1995, targeted a decrease in oil's share to less than 10 percent of GDP by 2020, but this was rendered obsolete. Oman then established "Vision 2040." A free-trade agreement with the United States took effect on January 1, 2009, eliminating tariff barriers and providing protections for foreign businesses.

Foreign workers in Oman send an estimated 10.00 B USD annually to their home states, with more than half earning a monthly wage of less than 400 USD. The largest foreign community is from India (Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Punjab), representing more than half of the entire workforce. Salaries for overseas workers are generally lower than for Omani nationals but still significantly higher than for equivalent jobs in India.

In terms of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), total investments in 2017 exceeded 24.00 B USD. The oil and gas sector received the highest share (13.00 B USD or 54.2%), followed by financial intermediation (3.66 B USD or 15.3%). The United Kingdom was the largest source of FDI (11.56 B USD or 48%), followed by the UAE (2.60 B USD or 10.8%), and Kuwait (1.10 B USD or 4.6%).

In 2018, Oman had a budget deficit of 32 percent of total revenue and a government debt-to-GDP ratio of 47.5 percent. Military spending averaged around 10% of GDP between 2016-2018, much higher than the world average of 2.2%. Health spending was 4.3% of GDP (2015-2016), compared to a world average of 10%. Research and development spending was low at 0.24% (2016-2017) versus the world average of 2.2%. Government spending on education was 6.11% of GDP in 2016, above the world average of 4.8% (2015). These figures highlight priorities and challenges in public spending and investment impacting long-term social equity and sustainable development.

6.1. Oil and gas

Oman's economy is heavily reliant on its oil and natural gas resources. The country's proved reserves of petroleum total about 5.5 billion barrels, ranking it 25th largest in the world. Oil is primarily extracted and processed by Petroleum Development Oman (PDO), a joint venture with the Omani government holding a majority stake. While proven oil reserves have remained relatively steady due to new discoveries and enhanced oil recovery techniques, overall oil production has faced challenges and has seen periods of decline, though efforts are made to sustain or increase output.

The Ministry of Energy and Minerals is responsible for all oil and gas infrastructure and projects in Oman. Following the 1970s energy crisis, Oman significantly increased its oil output between 1979 and 1985.

In 2018, oil and gas revenues accounted for 71 percent of the government's total revenues, a slight decrease from 72 percent in 2016, indicating slow progress in fiscal diversification. The oil and gas sector represented 30.1 percent of the nominal GDP in 2017.

Between 2000 and 2007, oil production fell by more than 26%, from 972,000 to 714,800 barrels per day. Production subsequently recovered, reaching 816,000 barrels per day in 2009 and 930,000 barrels per day in 2012.

Oman's natural gas reserves are estimated at 849.5 billion cubic metres, ranking 28th globally. In 2008, production was about 24 billion cubic metres per year. Natural gas is increasingly important for domestic power generation, industrial use (such as in petrochemicals and aluminum smelting), and as an export commodity in the form of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG). The Oman LNG project is a key part of this strategy.

The state heavily controls the oil and gas sector, and revenues from these resources are crucial for funding government expenditure, social programs, and development projects. However, the volatility of global oil prices poses a significant risk to Oman's economy and fiscal stability, underscoring the urgency of economic diversification efforts. Management of these revenues, including investments in sovereign wealth funds, is critical for long-term economic health.

In September 2019, Oman was confirmed as the first Middle Eastern country to host the International Gas Union Research Conference (IGRC 2020), highlighting its growing role in the global gas industry.

6.2. Industry, innovation, and infrastructure

Oman faces significant challenges in industry, innovation, and infrastructure development, according to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals index (2019). While the country scores well on internet use, mobile broadband subscriptions, logistics performance, and the average ranking of its top universities, it lags in scientific and technical publications and research & development (R&D) spending.

Oman's manufacturing value added to GDP was 8.4 percent in 2016, lower than the Arab world average (9.8 percent) and the world average (15.6 percent). R&D expenditure as a percentage of GDP averaged only 0.20 percent between 2011 and 2015 (0.24% between 2016-2017), significantly below the world average of 2.11 percent (2.2% for 2016-2017). The majority of firms in Oman operate in the oil and gas, construction, and trade sectors.

| Non-hydrocarbon GDP growth | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value (%) | 4.8 | 6.2 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

Oman is actively refurbishing and expanding its port infrastructure in Muscat, Duqm, Sohar, and Salalah to boost tourism, local production, and export shares. A major refinery and petrochemical plant in Duqm, with a projected capacity of 230,000 barrels per day, was planned for completion by 2021 to expand downstream operations. Most industrial activity is concentrated in eight industrial estates and four free zones, focusing on mining-and-services, petrochemicals, and construction materials.

The largest employers in the private sector are construction (nearly 48% of the total labor force), wholesale-and-retail (around 15%), and manufacturing (around 12%). However, the percentage of Omanis employed in the construction and manufacturing sectors remains low as of 2011 statistics, with heavy reliance on expatriate labor. This reliance on 'low-skilled' and 'low-wage' foreign labor for infrastructure expansion hinders innovation and technology-based growth.

The Dutch disease phenomenon, where oil and gas investments dominate and other sectors rely heavily on imports, impedes local business growth and global competitiveness, thus hampering economic diversification. This suggests a 'factor-driven economy' with inefficiencies and bottlenecks. Innovation is further hindered by an economic structure dominated by a few large firms, with limited opportunities for SMEs to enter the market and foster healthy competition. The ratio of patent applications per million people was 0.35 in 2016, far below the MENA average (1.50) and high-income countries' average (around 48.0). Oman was ranked 74th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024. These factors impact sustainable growth, employment for nationals, and the development of a knowledge-based economy.

6.3. Agriculture and fishing

Agriculture and fishing are traditional sectors of the Omani economy, contributing to food security and rural livelihoods, though their overall share of GDP is modest.

Agriculture: Less than 1% of Oman's land is under cultivation due to arid conditions and water scarcity. Dates are the most significant crop, representing 80 percent of all fruit crop production and occupying 50 percent of the total agricultural area. In 2016, Oman produced an estimated 350.00 K t of dates, making it the 9th largest producer globally. Date exports in 2016 amounted to 12.60 M USD, nearly equivalent to the value of imported dates (11.30 M USD). India is the main importer of Omani dates (around 60%). Other agricultural products include limes, bananas, coconuts (especially in Dhofar), wheat, and vegetables. The government supports agriculture through subsidies and research, and the traditional aflaj irrigation systems (a UNESCO World Heritage site) are crucial for water distribution in many farming areas. Challenges include water scarcity, soil salinity, and the need for modern farming techniques and better supply chain coordination. Oman also produces frankincense, historically a major export, primarily in the Dhofar region.

Fishing: Oman has a long coastline of about 2.0 K mile (3.17 K km) and rich fishing grounds in the Arabian Sea and Gulf of Oman. The fishing industry contributed 0.78 percent to GDP in 2016. Fish exports grew from 144.00 M USD in 2000 to 172.00 M USD in 2016, an increase of 19.4 percent. Vietnam was the main importer of Omani fish in 2016 (80.00 M USD, 46.5%), followed by the United Arab Emirates (26.00 M USD, 15%). Other importers include Saudi Arabia, Brazil, and China. Omani fish consumption per capita is almost twice the world average. The ratio of exported fish to total fish captured (by weight) fluctuated between 49 and 61 percent from 2006 to 2016.

Strengths in the fishing industry include a good market system and extensive water areas. However, weaknesses include insufficient modern infrastructure, limited research and development, and inconsistent quality and safety monitoring. The government aims to develop the fisheries sector further to enhance its contribution to GDP, create employment, and improve food security, including investments in modern fishing fleets, ports, and processing facilities. Sustainable fishing practices are also a growing concern to prevent overexploitation of fish stocks.

6.4. Tourism

Tourism is a rapidly growing sector in Oman's economy and is a key pillar of its diversification strategy under "Vision 2040." The World Travel & Tourism Council has identified Oman as one of the fastest-growing tourism destinations in the Middle East.

Tourism contributed 2.8 percent to Oman's GDP in 2016. The revenue from tourism grew from 505.00 M OMR in 2009 to 719.00 M OMR in 2017, a 42.3 percent increase.

Oman offers a diverse range of attractions, including:

- Natural landscapes: Deserts like Wahiba Sands, mountain ranges such as Jebel Akhdar and Jebel Shams, numerous wadis (riverbeds) with pools and greenery (e.g., Wadi Shab, Wadi Bani Khalid), and a long coastline with beaches and opportunities for diving and watersports. The Khareef (monsoon) season in Salalah transforms the southern region into a lush, green area, attracting many visitors.

- Cultural and historical sites: Oman has a rich history and culture, with numerous forts (e.g., Nizwa Fort, Bahla Fort - a UNESCO site), traditional souqs (markets), ancient irrigation systems (Aflaj - also a UNESCO site), and archaeological sites like Bat, Al-Khutm and Al-Ayn. Muscat, the capital, was named the second-best city to visit in the world in 2012 by Lonely Planet and was chosen as the Capital of Arab Tourism in 2012.

- Ecotourism and adventure tourism: Activities include whale watching (for species like the Arabian humpback whale), turtle watching (e.g., at Ras al-Jinz, a nesting site for green turtles), hiking, rock climbing, and desert safaris.

Citizens of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, including Omanis residing abroad, represent the largest group of tourists (estimated at 48 percent). Visitors from other Asian countries form the second-largest group (17 percent).

The Omani government actively promotes tourism through investments in infrastructure (airports, hotels, resorts), marketing campaigns, and visa facilitation. In November 2019, Oman largely shifted from visa-on-arrival to an e-visa system for tourists.

Challenges in the tourism sector include the heavy reliance on the government-owned firm Omran for development, which may create barriers for private sector participation. There is also a need for a deeper understanding and protection of ecosystems and biodiversity to ensure sustainable tourism. The socio-economic impact of tourism includes job creation and revenue generation, but careful planning is needed to manage environmental impacts and ensure benefits are distributed equitably.

7. Transport

Oman has made significant investments in developing its transportation infrastructure to support economic growth, diversification, and connectivity, both domestically and internationally.

Road Network: Oman has an extensive and well-maintained road network, particularly connecting major cities and towns. Highways like the Sultan Qaboos Highway in Muscat and the Batinah Expressway are major arteries. Efforts have been made to expand road access to more remote areas. Road transport is the primary mode for domestic passenger and freight movement.

Ports: Oman has several strategically important seaports.

- Port of Salalah: Located in southern Oman, it is a major transshipment hub on the Arabian Sea, handling significant container traffic and bulk cargo.

- Port Sultan Qaboos (Muscat): Historically Oman's main commercial port, it is now being redeveloped primarily as a tourism and cruise ship destination, with cargo operations shifted to Sohar.

- Port of Sohar: Located in northern Oman, it is a deep-water port and industrial hub, part of the Sohar Industrial Port Company (SIPC). It handles a wide range of cargo, including containers, dry bulk, liquid bulk, and is integrated with a free zone.

- Port of Duqm: A new, large-scale port and dry dock complex being developed on the central Omani coast as part of the Duqm Special Economic Zone (SEZAD). It aims to become a major regional logistics, industrial, and maritime hub.

These ports are crucial for Oman's trade, import/export activities, and its ambitions to become a regional logistics center.

Airports:

- Muscat International Airport (MCT): The main international gateway to Oman, located near the capital. It has undergone significant expansion and modernization.

- Salalah International Airport (SLL): Serves the southern Dhofar region and is important for tourism, especially during the Khareef season.

- Duqm International Airport (DQM): Supports the development of the Duqm Special Economic Zone.

- Sohar Airport and Khasab Airport (Musandam): Smaller airports serving regional needs.

Oman Air is the national airline, operating international and domestic flights. SalamAir is a low-cost carrier.

Railways: Currently, Oman does not have an operational railway network. However, plans for a national and GCC-wide railway network have been discussed as part of long-term infrastructure development, though progress has been slow due to financial and logistical challenges.

Public transport within cities is developing, with bus services operated by Mwasalat (Oman National Transport Company) in Muscat and other major urban areas. Taxis are also widely available. The development of an efficient and integrated transport system is a key component of Oman's economic development plans, aiming to enhance connectivity, facilitate trade, and support tourism growth.

8. Society

Oman's society is a blend of traditional Arab and Islamic values with influences from its maritime history and recent modernization. The demographic composition includes a majority Omani Arab population alongside significant expatriate communities. Islam, particularly the Ibadi school, shapes many aspects of life. The country has invested heavily in education and healthcare since 1970.

8.1. Population

As of 2020, Oman's population exceeded 4.5 million people, and by 2024, it was estimated to be around 5.28 million, reflecting a 4.60% increase from 2023. It is the 123rd most-populous country globally. The total fertility rate in 2020 was estimated to be 2.8 children born per woman, a rate that has been rapidly decreasing in recent years.

Approximately half of the population resides in Muscat and the Batinah coastal plain northwest of the capital. Omani citizens are predominantly of Arab, Baluchi, and African origins. Around 20 percent of Omanis are of Baloch descent, whose ancestors migrated to Oman centuries ago and are now considered native. Historical connections with Zanzibar also mean that many Omanis have East African ancestry. The population of Gwadar in Pakistan, a former Omani territory, also shares Omani heritage.

Omani society is largely tribal, and tribal structures and affiliations continue to play a role in social and political life, particularly in rural areas. There are three major cultural identities: that of the tribe, the Ibadi faith, and maritime trade. The first two are closely tied to tradition and are especially prevalent in the interior. The third identity pertains mostly to Muscat and coastal areas, reflected in business, trade, and the diverse origins of many Omanis.

A significant portion of Oman's resident population consists of foreign workers (expatriates), who play a crucial role in the economy, particularly in the construction, domestic service, and private sectors. In 2014, expatriates constituted about 44% of the total population (1.76 million out of over 4 million). The largest expatriate communities are from India (particularly Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Punjab), Bangladesh, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Indonesia. The status and conditions of these foreign workers, particularly issues related to wages, working conditions, and rights under the kafala (sponsorship) system, are ongoing social concerns.

8.2. Religion

Islam is the official state religion of Oman, and the vast majority of Omani citizens are Muslims. The Omani government does not keep official statistics on religious affiliation for its citizens. Statistics from the US Central Intelligence Agency estimate that 85.9% of the total population (including expatriates) are Muslims.

A distinctive feature of Islam in Oman is the predominance of the Ibadi school of Islam among Omani Muslims. Ibadism is a branch of Islam separate from Sunni and Shia Islam, though it shares some commonalities with Sunnism. It originated from the Kharijites but evolved into a more moderate form. The Sultan of Oman is traditionally an Ibadi Muslim. Estimates suggest that Ibadis constitute more than half of the Omani Muslim population.

There are also significant communities of Sunni Muslims in Oman, particularly those following the Shafi`i school of jurisprudence, and a smaller community of Shia Muslims (primarily Twelvers), concentrated in the Muscat area and along the Batinah coast.

Virtually all non-Muslims in Oman are foreign workers. These communities include:

- Christians (estimated at 6.4% of the total population): These communities are centered in major urban areas like Muscat, Sohar, and Salalah. They include Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, and various Protestant congregations, often organized along linguistic and ethnic lines. Over 50 different Christian groups and fellowships are active, primarily serving migrant workers from Southeast Asia and other regions.

- Hindus (estimated at 5.7%): Mostly comprising ethnic Indian expatriates. There are two long-standing Hindu temples in Muscat.

- Buddhists (estimated at 0.8%), Jains, Zoroastrians, and Sikhs also form smaller communities among expatriates.

The Basic Law of Oman states that Islam is the state religion and Sharia is a basis for legislation. However, it also provides for freedom of religion, and the government generally respects this right for non-Muslims to practice their faith in private and in designated places of worship. Proselytizing by non-Muslims is restricted. Interfaith relations are generally amicable, and Oman is known for its religious tolerance compared to some other countries in the region.

8.3. Languages