1. Overview

The People's Republic of China (PRC) (中华人民共和国Zhōnghuá Rénmín GònghéguóChinese), commonly known as China (中国ZhōngguóChinese), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's second-most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion people, and covers an area of approximately 3.7 M mile2 (9.60 M km2). Officially a socialist state under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), China's governance model, "Socialism with Chinese characteristics", combines a single-party political system with a socialist market economy. This article explores China's etymology, extensive history from prehistory through imperial dynasties to the modern republic and the PRC, its diverse geography and pressing environmental concerns, its complex political system and government structure, and its evolving foreign relations and military. It further delves into significant sociopolitical issues and the human rights situation, particularly concerning civil liberties, ethnic minorities, and social welfare, reflecting a center-left/social liberalism perspective that emphasizes social impact and democratic development. The document also examines China's multifaceted economy, its scientific and technological advancements, extensive infrastructure development, demographic trends and policies, and rich cultural heritage. The ranking of China's total area relative to other countries like the United States can vary depending on the measurement methods used and the inclusion or exclusion of coastal and territorial waters.

2. Etymology

The word "China" has been used in English since the 16th century. Its origin is traced through Portuguese, Malay, and Persian back to the Sanskrit word Cīna (चीनCīnaSanskrit), used in ancient India. "China" appears in Richard Eden's 1555 translation of the 1516 journal of the Portuguese explorer Duarte Barbosa. Barbosa's usage was derived from Persian Chīn (چینChīnPersian), which in turn derived from Sanskrit Cīna. The origin of the Sanskrit word is debated. Cīna was first used in early Hindu scripture, including the Mahabharata (5th century BCE) and the Laws of Manu (2nd century BCE). In 1655, Martino Martini suggested that the word China is derived ultimately from the name of the Qin dynasty (221-206 BCE). Although use in Indian sources precedes this dynasty, this derivation is still given in various sources. Alternative suggestions include the names for Yelang and the Jing or Chu state. In Japan, the term "Shina" (支那) was widely used from the Meiji era until World War II. While derived from the same Sanskrit root, "Shina" is now considered offensive by many Chinese people due to its association with Japanese imperialism. Similar terms like "Jina" (지나) in Korean also carry historical baggage.

The official name of the modern state is the "People's Republic of China" (中华人民共和国Zhōnghuá Rénmín GònghéguóChinese). The shorter form is "China" (中国ZhōngguóChinese), from 中zhōngChinese ('central') and 国guóChinese ('state'). This term developed under the Western Zhou dynasty in reference to its royal demesne. Its earliest extant use is on the ritual bronze vessel He zun, apparently referring to the Shang dynasty's immediate demesne conquered by the Zhou dynasty. Its meaning "Zhou's royal demesne" is attested from the 6th-century BCE Classic of History, which states "Huangtian bestowed the lands and the peoples of the central state to the ancestors" (皇天既付中國民越厥疆土于先王Huángtiān jì fù Zhōngguó mín yuè jué jiāngtǔ yú xiānwángChinese). It was used in official documents as a synonym for the state under the Qing dynasty. The name Zhongguo is also translated as "Middle Kingdom" in English. China is sometimes referred to as "mainland China" or "the Mainland" when distinguishing it from the Republic of China (Taiwan) or the PRC's Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau. In official contexts within the PRC, and sometimes internationally, "China" refers exclusively to the PRC. The term "Zhonggong" (中共), an abbreviation for the Chinese Communist Party, is sometimes used, particularly in Taiwan or by critics, to refer to the PRC government.

3. History

The history of China spans millennia, from early human settlements and legendary dynasties to the vast empires that shaped East Asian civilization, and culminating in the establishment of the People's Republic of China in the 20th century. This historical narrative encompasses profound social, political, and cultural transformations, the rise and fall of dynasties, and the ongoing evolution of Chinese society, with particular attention to the impact on various social groups and the development of concepts related to human rights and governance.

3.1. Prehistory

Archaeological evidence suggests that early hominids inhabited China between 2.25 million and 250,000 years ago. The hominid fossils of Peking Man, a Homo erectus who used fire, have been dated to between 680,000 and 780,000 years ago. The fossilized teeth of Homo sapiens (dated to 125,000-80,000 years ago) have been discovered in Fuyan Cave in Hunan.

The Neolithic period in China saw the development of agriculture. Evidence of rice cultivation dates back to 8,200-13,500 years ago in the Yangtze River valley, potentially making it one of the earliest centers of rice domestication. Millet cultivation in northern China has been dated to around 6000 BCE. Early agricultural societies gave rise to distinct cultural traditions. Chinese proto-writing existed in Jiahu around 6600 BCE, at Damaidi around 6000 BCE, in the Dadiwan from 5800 to 5400 BCE, and at Banpo dating from the 5th millennium BCE. Some scholars have suggested that the Jiahu symbols (7th millennium BCE) constituted the earliest Chinese writing system. Pottery production was also well-established, with some of the world's oldest pottery found at sites like Xianren Cave, dating back to 20,000-19,000 years ago. These early cultures laid the groundwork for the complex societies and states that would later emerge.

3.2. Early dynastic rule

According to traditional Chinese historiography, the Xia dynasty (c. 2070 - c. 1600 BCE) was the first dynastic state in China. While its existence was long considered legendary, archaeological discoveries at Erlitou in Henan in the early Bronze Age are now often identified by Chinese archaeologists as sites of the Xia dynasty. However, this identification remains a subject of debate among scholars, as contemporary written records from the Xia period are lacking.

The Shang dynasty (c. 1600 - c. 1046 BCE) is the earliest Chinese dynasty to be confirmed by contemporary archaeological and inscriptional evidence. The Shang ruled much of the Yellow River valley. They are known for their sophisticated bronze casting and the development of the oracle bone script, the earliest known form of written Chinese and the direct ancestor of modern Chinese characters. Shang society was highly stratified, with a king at the top who also served as a chief priest.

The Shang were overthrown by the Zhou dynasty (c. 1046 - 256 BCE), which initially established a centralized state but later saw its authority erode as feudal lords gained power. The Zhou dynasty is divided into the Western Zhou (c. 1046 - 771 BCE) and the Eastern Zhou (770 - 256 BCE). The Eastern Zhou is further subdivided into the Spring and Autumn period (771 - 476 BCE) and the Warring States period (475 - 221 BCE). During these periods, especially the Warring States period, China was characterized by intense warfare among competing states but also by significant philosophical, social, and technological advancements. This era saw the emergence of the "Hundred Schools of Thought", including Confucianism, Taoism, Legalism, and Mohism, which profoundly shaped Chinese civilization. Iron tools became widespread, agriculture advanced, and new military techniques were developed. These periods laid the groundwork for the imperial unification that followed.

3.3. Imperial China

Imperial China spans over two millennia, from the unification under the Qin dynasty in 221 BCE to the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912 CE. This era was characterized by the rule of successive dynasties that shaped China's governance, culture, societal structures, and territorial extent. Key developments included the establishment of a centralized bureaucratic state, the flourishing of arts and sciences, significant economic expansion, and complex interactions with neighboring peoples and empires. The societal structures were typically hierarchical, often based on Confucian principles, with an emperor at the apex.

3.3.1. Qin and Han dynasties

The Warring States period ended in 221 BCE when the state of Qin conquered the other six major states, unifying China under a single rule. King Zheng of Qin proclaimed himself Qin Shi Huang ("First Emperor of Qin") and established the Qin dynasty. He implemented sweeping reforms based on Legalist principles, creating a centralized, bureaucratic imperial system. These reforms included standardizing Chinese characters, weights and measures, currency, and even the width of cart axles. The Qin dynasty also undertook massive construction projects, including the precursor to the Great Wall of China, and expanded its territory, notably conquering the Yue tribes in Guangxi, Guangdong, and Northern Vietnam. However, the harshness of Qin rule and heavy taxation led to widespread discontent, and the dynasty collapsed shortly after Qin Shi Huang's death in 210 BCE, lasting only fifteen years. The imperial library at Xianyang was burned during the ensuing revolts, a significant loss of classical texts, compounded by the earlier "burning of books and burying of scholars". The destruction of these confiscated copies was a severe blow to historical records; texts that survived often had to be reconstructed from memory or, in some cases, were later found to be forgeries.

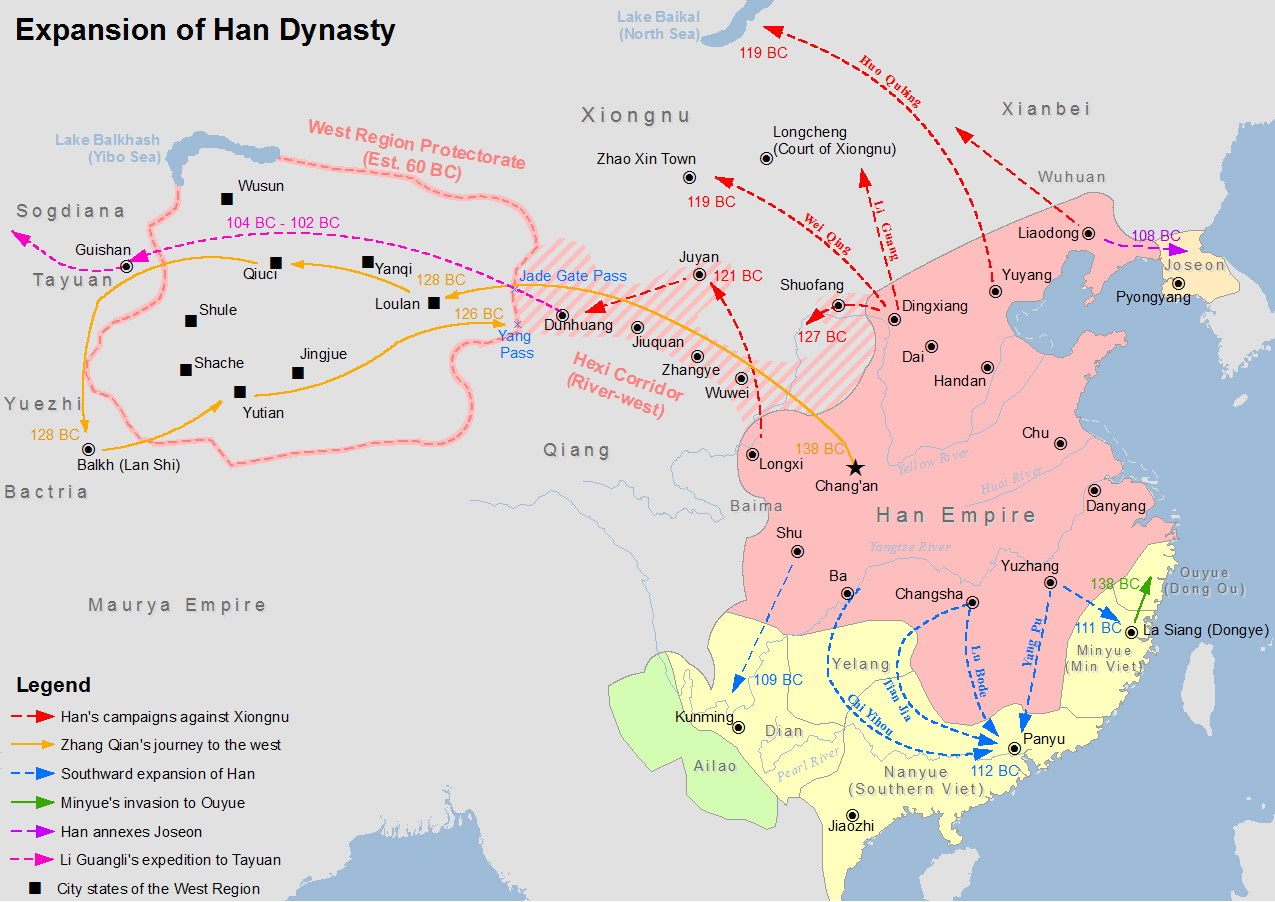

Following a period of civil war known as the Chu-Han Contention, Liu Bang (Emperor Gaozu) established the Han dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE). The Han dynasty consolidated and expanded upon the foundations laid by the Qin but adopted Confucianism as its official state ideology, though Legalist institutions largely remained. The Han era is considered a golden age in Chinese history, marked by significant cultural flourishing, technological innovation (such as papermaking), and territorial expansion. Military campaigns extended Chinese influence into Central Asia, Korea, and Yunnan. The Han dynasty formally established the Silk Road, a network of trade routes connecting China to the West, facilitating cultural and economic exchange. The Han period also saw the codification of the Han Chinese ethnic identity. Despite periods of instability, such as the Xin dynasty interregnum (9-23 CE), the Han dynasty's influence on Chinese civilization was profound and enduring. Its societal structure was based on Confucian hierarchies, with scholar-officials playing a key role in governance.

3.3.2. Three Kingdoms, Jin, and Northern and Southern dynasties

After the end of the Han dynasty in 220 CE, China entered a long period of disunity and warfare. This era began with the Three Kingdoms period (220-280 CE), where the states of Wei, Shu, and Wu vied for control. This was a time of famous heroes and epic battles, later romanticized in Chinese literature.

The Three Kingdoms period was followed by a brief reunification under the Western Jin dynasty (265-316 CE). However, internal strife, including the War of the Eight Princes, weakened the Jin, allowing various non-Han ("Five Barbarians") peoples to invade northern China and establish numerous short-lived states during the Sixteen Kingdoms period (304-439 CE). This Upheaval of the Five Barbarians led to significant social turmoil and population displacement.

The Jin court fled south, establishing the Eastern Jin dynasty (317-420 CE) with its capital at Jiankang. Meanwhile, northern China eventually saw the Northern Wei dynasty (386-534 CE), founded by the Xianbei people, unify the region. Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei implemented policies of Sinicization, promoting cultural assimilation. The period from 420 to 589 CE is known as the Northern and Southern dynasties, characterized by political division between the north and south, frequent warfare, but also significant cultural exchange and the further spread of Buddhism throughout China. Despite the political fragmentation and social upheaval, this era witnessed important artistic and intellectual developments.

3.3.3. Sui, Tang, and Song dynasties

China was reunified in 581 CE by the Sui dynasty (581-618 CE). The Sui emperors undertook major public works projects, most notably the construction of the Grand Canal, linking northern and southern China, which facilitated trade and communication. They also reformed the bureaucracy and promoted Buddhism. However, the Sui dynasty's massive conscription for these projects and costly, unsuccessful military campaigns, particularly the wars against Goguryeo in Korea, led to widespread unrest and its swift collapse.

The Sui was succeeded by the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE), often regarded as a high point of Chinese civilization and a golden age of cosmopolitan culture. The Tang capital, Chang'an (modern Xi'an), was one of the largest and most vibrant cities in the world. The Tang expanded its territory, re-established control over the Western Regions, and saw a flourishing of poetry, painting, and sculpture. Buddhism reached its apogee during this period. International trade along the Silk Road thrived, and Chinese culture significantly influenced neighboring countries like Japan and Korea. However, the An Lushan Rebellion (755-763 CE) severely weakened the Tang, leading to a gradual decline and eventual fragmentation.

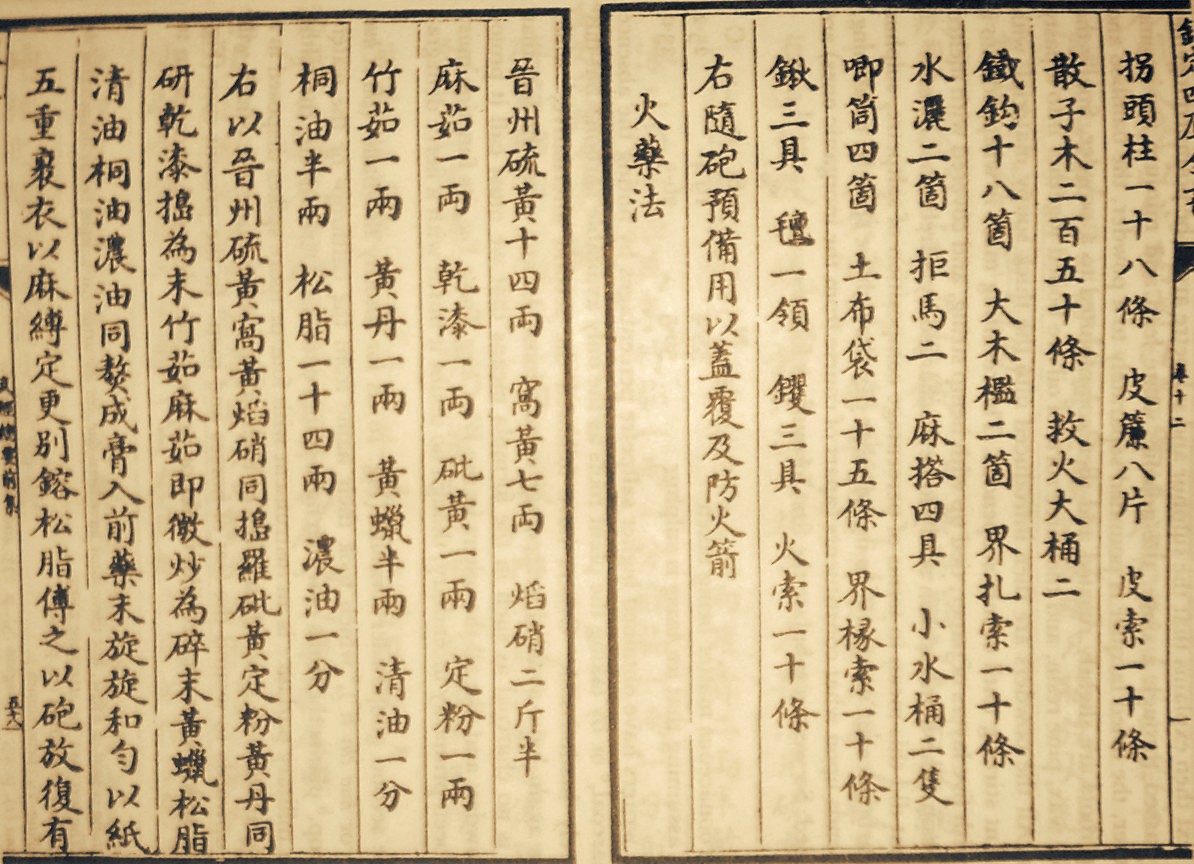

After the fall of the Tang, China experienced another period of division known as the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (907-960 CE). The Song dynasty (960-1279 CE) eventually reunified most of China. The Song era was marked by extraordinary economic prosperity, population growth, and significant technological innovation, including the invention of gunpowder, movable type printing, and the widespread use of paper money. Neo-Confucianism became the dominant philosophy. The Song dynasty faced constant military pressure from northern nomadic empires like the Liao dynasty (Khitan) and the Jin dynasty (Jurchen). In 1127, the Jin captured the Song capital Kaifeng, forcing the Song court to retreat south and establish the Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279 CE) with its capital at Lin'an (modern Hangzhou). Despite its military challenges, the Southern Song continued to be a period of economic and cultural achievement. Social developments included increased urbanization and a more complex social structure.

3.3.4. Yuan dynasty

The Mongol Empire, founded by Genghis Khan, began its conquest of China in the early 13th century, first targeting the Western Xia and then the Jin dynasty. In 1271, Kublai Khan, a grandson of Genghis Khan, officially proclaimed the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368 CE) and completed the conquest of the Southern Song dynasty in 1279. The Yuan dynasty marked the first time that all of China was ruled by a non-Han people.

The Yuan established a vast empire that stretched across much of Eurasia, facilitating trade and cultural exchange along the Silk Road, as exemplified by the travels of Marco Polo. The Mongols implemented a social hierarchy that placed Mongols and other non-Han allies at the top, with Southern Chinese (former Song subjects) at the bottom. This led to resentment among the Han Chinese population. The Yuan administration adopted many Chinese institutions and practices but also introduced Mongol customs and laws. The population of China, estimated at 120 million under the Song, was reduced to around 60 million by a census in 1300, partly due to warfare, famine, and plague.

Cultural interactions between Mongols and Han Chinese were complex. While some Mongols adopted Chinese culture, others maintained their distinct traditions. The Yuan dynasty saw developments in drama and vernacular literature. However, internal power struggles, corruption, natural disasters, and growing Han Chinese rebellions, such as the Red Turban Rebellion, led to the decline and eventual overthrow of the Yuan dynasty.

3.3.5. Ming dynasty

In 1368, Zhu Yuanzhang, a peasant leader of the Red Turban Rebellion, overthrew the Yuan dynasty and established the Ming dynasty (1368-1644 CE), becoming the Hongwu Emperor. This marked the restoration of Han Chinese rule. The Ming dynasty is known for its cultural achievements, economic developments, and ambitious construction projects.

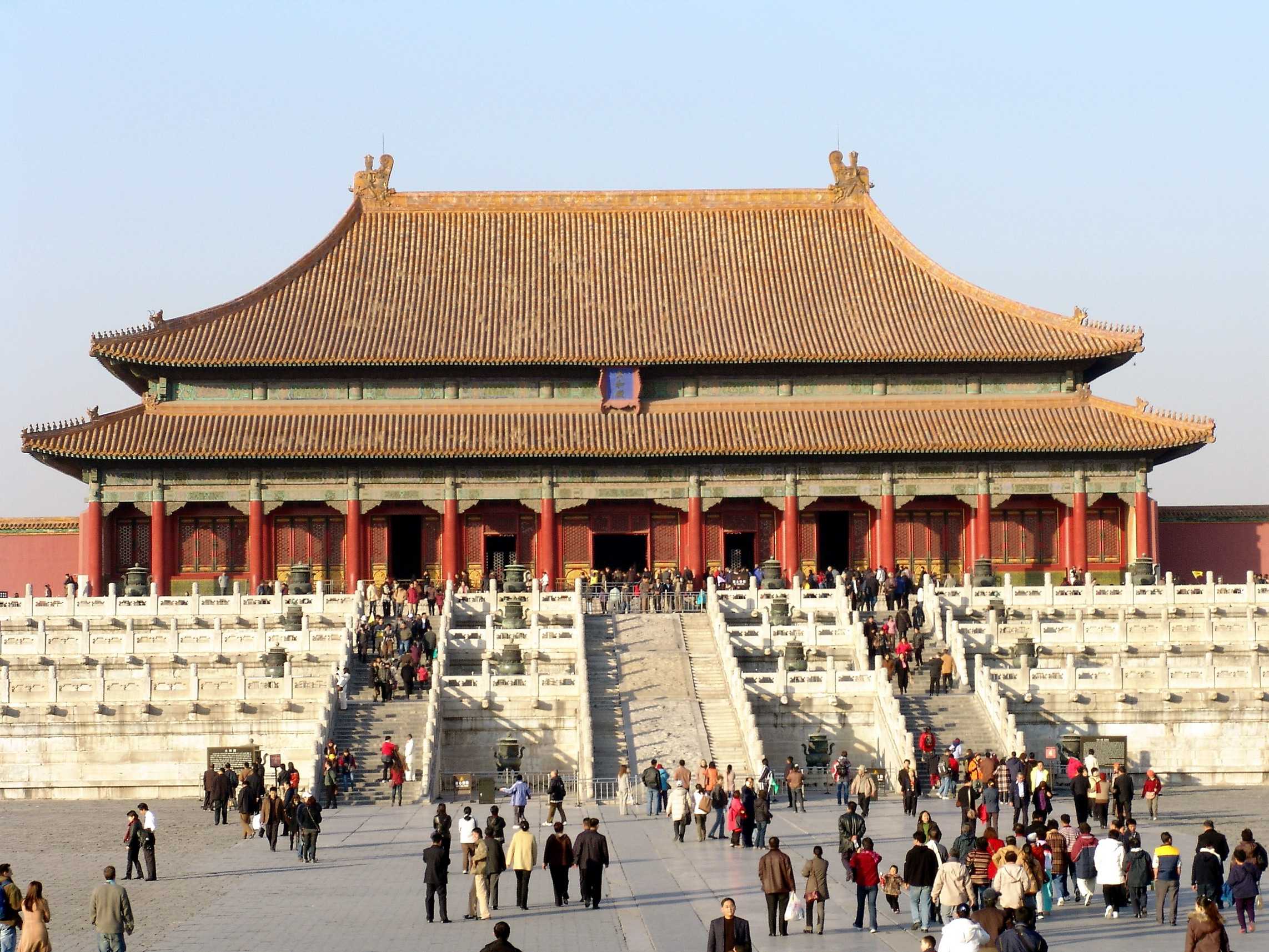

The early Ming emperors consolidated power, reformed the administration, and moved the capital from Nanjing to Beijing. The Ming dynasty sponsored immense maritime expeditions led by Admiral Zheng He in the early 15th century, which sailed throughout the Indian Ocean, reaching as far as East Africa. Domestically, the Ming undertook massive construction projects, including the reinforcement and expansion of the Great Wall of China to its present form and the building of the Forbidden City in Beijing.

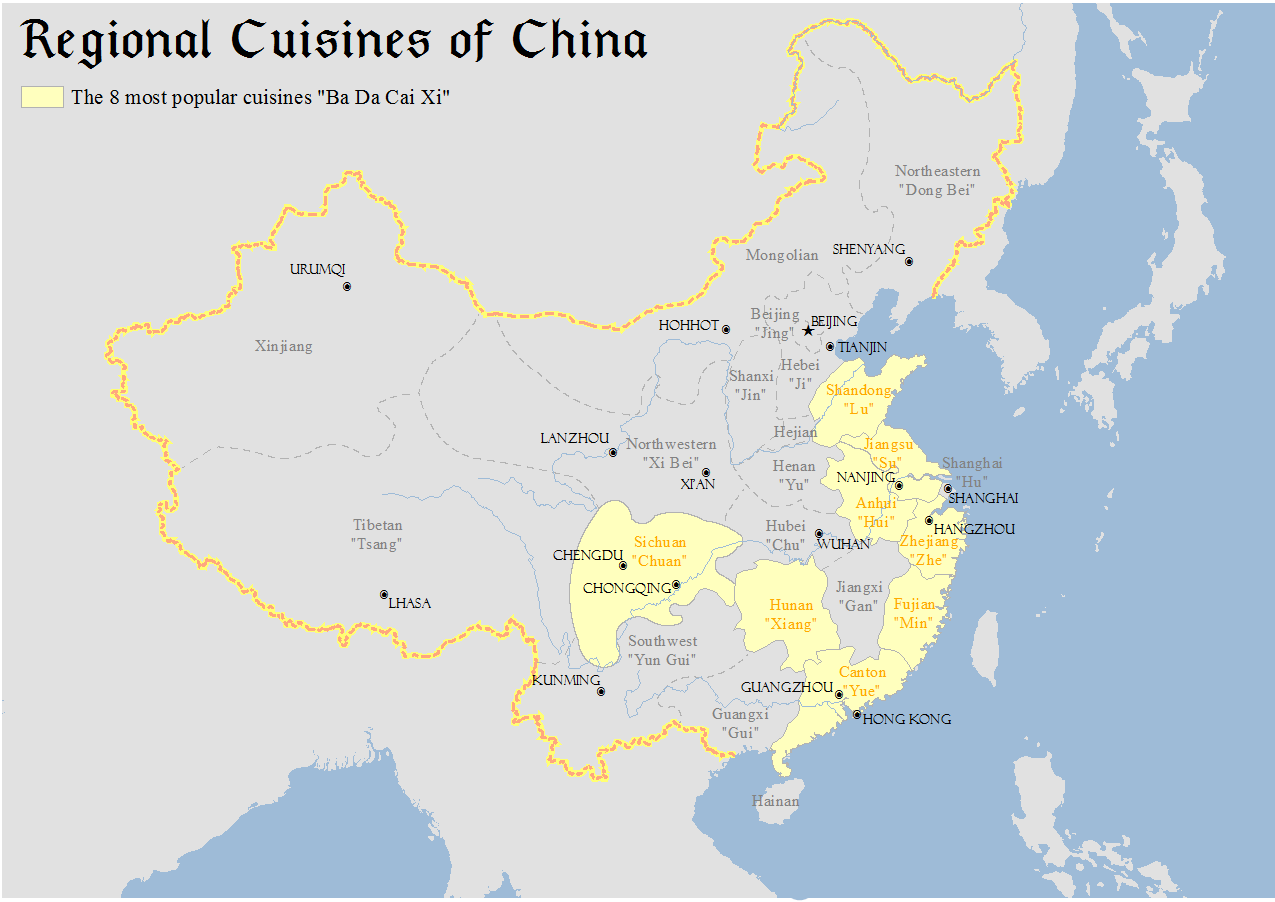

Economically, the Ming dynasty saw continued agricultural growth, commercialization, and urbanization. Porcelain production, particularly blue-and-white ware, reached new heights of artistry and became a major export. Philosophically, the Ming era saw debates within Neo-Confucianism, with thinkers like Wang Yangming emphasizing individualism and innate moral knowledge. Culturally, novels written in vernacular Chinese, such as Water Margin and Journey to the West, gained widespread popularity.

However, in its later period, the Ming dynasty faced challenges including fiscal problems, corruption, eunuch influence at court, peasant rebellions (such as those led by Li Zicheng), and external threats from the Manchus to the northeast and Japanese pirates (wokou) along the coast. These pressures, combined with famines, ultimately led to the dynasty's collapse. In 1644, Beijing was captured by Li Zicheng's rebel forces, and the Chongzhen Emperor committed suicide. The Manchu forces, invited by Ming general Wu Sangui to help suppress the rebels, subsequently seized power and established the Qing dynasty.

3.3.6. Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty (1644-1912 CE), founded by the Manchu people from Manchuria, was the last imperial dynasty of China. The transition from Ming to Qing (1618-1683) was a protracted and bloody period, costing an estimated 25 million lives. After consolidating control, the Qing adopted many Chinese institutions and Confucian principles of governance but maintained a distinct Manchu identity and imposed certain Manchu customs, such as the queue hairstyle, on the Han Chinese population.

The Qing dynasty expanded the empire to its largest territorial extent, incorporating Taiwan, Tibet, Xinjiang (Eastern Turkestan), and Mongolia into a vast multi-ethnic state. The High Qing era (roughly the 18th century), under emperors like Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong, was a period of stability, prosperity, and population growth. By the end of the 18th century, China was possibly the most commercialized country in the world.

However, from the late 18th century onwards, the Qing dynasty faced increasing internal and external pressures. Internally, corruption, population pressure, and social unrest, such as the White Lotus Rebellion, weakened the state. Externally, Western powers, driven by trade interests and imperial ambitions, began to exert pressure on China. The Opium Wars with Britain in the mid-19th century resulted in humiliating defeats for the Qing, the imposition of unequal treaties, the opening of treaty ports, and the cession of Hong Kong. These events marked the beginning of what is often called the "Century of Humiliation". The Qing dynasty attempted reforms, such as the Self-Strengthening Movement and later the Hundred Days' Reform, but these were often insufficient or thwarted by conservative elements within the court.

3.4. Fall of the Qing dynasty and establishment of the Republic

The 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed the decline of the Qing dynasty, driven by internal rebellions, foreign imperialism, and failed reform attempts, ultimately leading to the 1911 Revolution and the establishment of the Republic of China. This period brought significant social upheaval, impacting various segments of the population and fostering the rise of nationalist and revolutionary movements.

3.4.1. Century of Humiliation

The "Century of Humiliation" refers to the period from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century when China suffered repeated military defeats, territorial losses, and infringements on its sovereignty by foreign powers. Key events include the First Opium War (1839-1842) and Second Opium War (1856-1860), which resulted in the imposition of unequal treaties that granted extraterritoriality to foreigners, opened numerous treaty ports, and led to the cession of Hong Kong to Britain. The Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864), a massive civil war, further devastated the country, costing tens of millions of lives.

The First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) resulted in China's loss of influence in Korea and the cession of Taiwan to Japan. The Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901), an anti-foreign uprising, led to an invasion by the Eight-Nation Alliance and further weakened the Qing dynasty. These interventions profoundly impacted Chinese sovereignty, leading to a loss of national pride and a growing sense of crisis among the Chinese populace. Different social groups experienced these events differently; coastal populations in treaty ports faced direct foreign influence, while inland areas often suffered from the breakdown of central authority and economic hardship. The period fueled nationalist sentiments and a desire for modernization and strengthening the nation to resist foreign encroachment.

3.4.2. 1911 Revolution and Republic of China (1912-1949)

Growing discontent with Qing rule and the desire for a modern nation-state culminated in the 1911 Revolution (also known as the Xinhai Revolution). On January 1, 1912, the Republic of China (ROC) was established, with Sun Yat-sen of the Kuomintang (KMT, or Nationalist Party) as its provisional president. The last Qing emperor, Puyi, abdicated on February 12, 1912.

The nascent republic faced immense challenges. Sun Yat-sen soon ceded the presidency to Yuan Shikai, a powerful Qing general, who later attempted to establish himself as emperor in 1915 but was forced to abdicate due to widespread opposition. The early years of the Republic were marked by political instability, struggles for legitimacy, and a lack of national unity. Aspirations for democracy and modernization were strong among intellectuals and revolutionaries, who sought to build a new China free from foreign domination and internal decay. However, the transition from imperial rule to a stable republic proved difficult, leading to further fragmentation.

3.4.3. Warlord Era and Northern Expedition

After Yuan Shikai's death in 1916, China descended into the Warlord Era (1916-1928), a period of political fragmentation where regional military leaders (warlords) controlled their own territories and fought amongst themselves. The central government in Beijing was internationally recognized but virtually powerless. This era caused immense social turmoil and suffering for the civilian population, with frequent warfare, banditry, and economic disruption.

The Kuomintang, under the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek after Sun Yat-sen's death in 1925, sought to reunify the country. From 1926 to 1928, the KMT launched the Northern Expedition, a military campaign to defeat the warlords and establish a unified national government. The Northern Expedition was largely successful in form, leading to the nominal reunification of China under the KMT government, which established its capital in Nanjing. However, many warlords retained significant local power, and the KMT's control remained tenuous in many regions. The social cost of the Warlord Era was high, and while the Northern Expedition brought a semblance of unity, it did not fully resolve the underlying issues of regionalism and political instability.

3.4.4. Second Sino-Japanese War and Chinese Civil War

In 1931, Japan invaded and occupied Manchuria. Full-scale invasion of China proper by the Empire of Japan began in 1937, marking the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), which became a major theater of World War II. The war inflicted immense human suffering and social disruption. Japanese forces committed numerous atrocities, including the Nanjing Massacre, and as many as 20 million Chinese civilians died. China's resistance involved both the KMT government and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), who formed an uneasy Second United Front against the common enemy.

After Japan's surrender in 1945, the Chinese Civil War between the KMT and the CCP, which had begun in 1927 but was largely suspended during the war against Japan, resumed with greater intensity. The United States supported the KMT, while the Soviet Union provided some aid to the CCP. The KMT government was plagued by corruption and hyperinflation, losing popular support. The CCP, under Mao Zedong, gained peasant support through land reform policies and effective guerrilla warfare. The humanitarian consequences of the renewed civil war were severe. By 1949, the CCP had achieved a decisive victory, forcing the KMT government to retreat to the island of Taiwan.

3.5. People's Republic of China (1949-present)

The establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949 under the rule of the Chinese Communist Party initiated a period of profound political, social, and economic transformations. China's journey from a war-torn nation to a major global power has been marked by ambitious campaigns, ideological struggles, economic reforms, and significant societal shifts. These developments are explored here with critical attention to their effects on human rights, social equity, democratic aspirations, and the lives of ordinary citizens.

3.5.1. Maoist Era (1949-1976)

On October 1, 1949, CCP Chairman Mao Zedong formally proclaimed the establishment of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in Tiananmen Square, Beijing. The early years of the PRC were characterized by efforts to consolidate power, rebuild the war-torn country, and implement socialist transformation.

Key policies and campaigns during this era included:

- Land Reform Movement|Land Reform**: From the late 1940s to early 1950s, land was redistributed from landlords to peasants. While aimed at social equity, this process often involved violence and executions, with estimates of landlord deaths ranging from hundreds of thousands to millions.

- Political Campaigns**: A series of campaigns aimed to suppress perceived enemies of the revolution and consolidate CCP control. These included the Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries, the Three-anti and Five-anti Campaigns, and the Anti-Rightist Campaign (1957), which targeted intellectuals and critics, severely curtailing freedom of expression and dissent. The human cost of these campaigns included persecution, imprisonment, and loss of life.

- Great Leap Forward** (1958-1962): An ambitious campaign to rapidly industrialize and collectivize agriculture. It led to disastrous economic mismanagement and the Great Chinese Famine, resulting in tens of millions of deaths. This period highlighted the immense human cost of ideological fervor and flawed policy-making.

- Sino-Soviet split**: Ideological differences and national interests led to a deterioration of relations with the Soviet Union in the late 1950s and 1960s, impacting China's foreign policy and development path.

- Cultural Revolution** (1966-1976): Launched by Mao to reassert his authority and purge capitalist and traditional elements from society. It led to widespread social turmoil, factional violence, persecution of intellectuals and officials, destruction of cultural heritage, and severe economic disruption. The Cultural Revolution had a profound negative impact on individual freedoms, traditional Chinese culture, and the lives of millions of citizens. It ended with Mao's death in 1976.

The Maoist era brought significant changes to China, including increased literacy and basic healthcare for some, but at a tremendous social, economic, and human cost. Individual freedoms were severely restricted, and traditional culture suffered greatly under ideological campaigns.

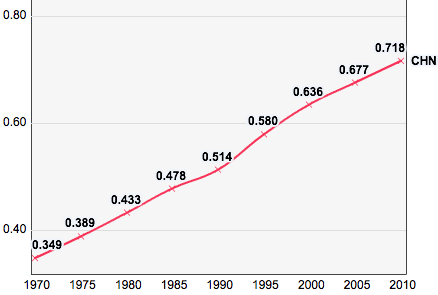

3.5.2. Reform and Opening Up (Deng Xiaoping era to early 2000s)

Following Mao Zedong's death in 1976 and a brief power struggle, Deng Xiaoping emerged as the paramount leader in 1978. He initiated a period of transformative economic reforms known as "Reform and Opening Up" (改革开放, Gǎigé Kāifàng). This era marked a shift away from Maoist ideology towards pragmatism and economic development, establishing a "Socialist market economy".

Key developments included:

- Economic Reforms**: De-collectivization of agriculture through the Household responsibility system, allowance for private enterprise, creation of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) to attract foreign investment, and gradual price liberalization. These reforms unleashed rapid economic growth and significantly improved living standards for many.

- Societal Changes**: Increased urbanization, greater personal mobility, and exposure to foreign ideas and culture. However, rapid development also led to social dislocations, including rising income inequality, particularly between coastal and inland regions, and urban and rural areas.

- Environmental Degradation**: Unchecked industrial growth resulted in severe environmental problems, including air and water pollution, and deforestation.

- Political Limitations**: While economic freedoms expanded, the CCP maintained its monopoly on political power. Aspirations for political reform and greater democracy grew, culminating in the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, which were violently suppressed by the military. This event led to international condemnation and a temporary halt to some reforms, but economic liberalization soon resumed. The aftermath saw a tightening of political control and a focus on maintaining "social stability".

- Leadership Transitions**: Jiang Zemin succeeded Deng as paramount leader in the 1990s, followed by Hu Jintao in the early 2000s. Both leaders continued the policy of economic reform while maintaining political stability. China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, further integrating its economy into the global system.

The Reform and Opening Up era brought unprecedented economic prosperity to China, lifting hundreds of millions out of poverty. However, it also created new social challenges, exacerbated environmental issues, and left democratic aspirations largely unfulfilled, with the CCP prioritizing economic development and political control over significant political liberalization.

3.5.3. Contemporary China (Early 2000s-present)

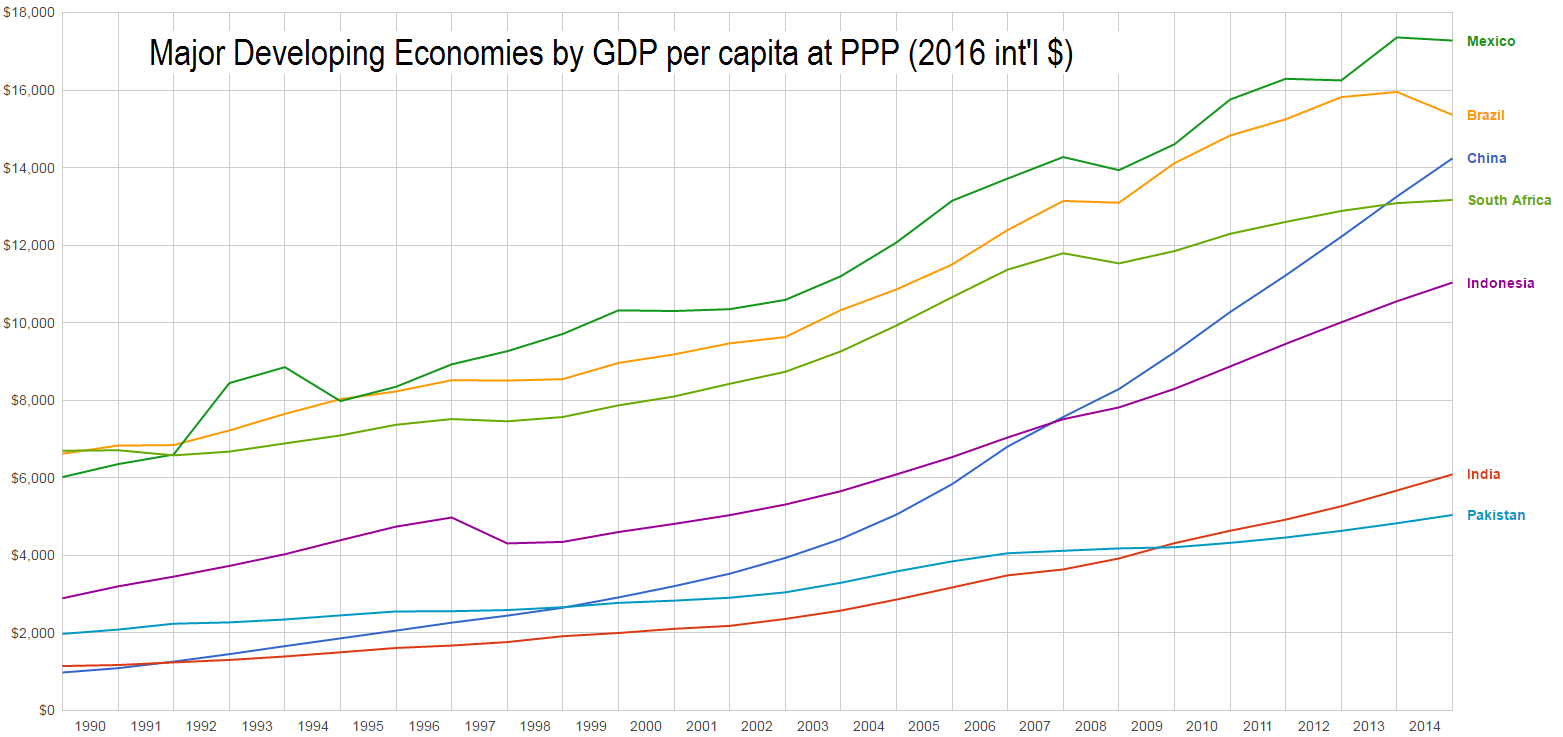

Contemporary China, from the early 2000s under leaders Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, and more prominently under Xi Jinping since 2012, has witnessed continued economic growth, an expanding global footprint, and significant political and social developments. This period is marked by China's rise as a major world power, alongside persistent and emerging domestic challenges, viewed through a center-left lens that emphasizes societal impacts and human rights.

Key aspects include:

- Continued Economic Growth and Global Influence**: China became the world's second-largest economy and a dominant force in global trade and manufacturing. Initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) expanded China's economic and geopolitical reach, though concerns about debt sustainability, labor practices, and environmental impacts in participating countries have been raised.

- Social Challenges**: Despite poverty reduction, income inequality remains a significant issue. Access to quality healthcare, education, and social welfare varies greatly between urban and rural areas and across different social groups. An aging population and shrinking workforce present demographic challenges.

- Human Rights Situation**: The human rights record continues to draw international criticism.

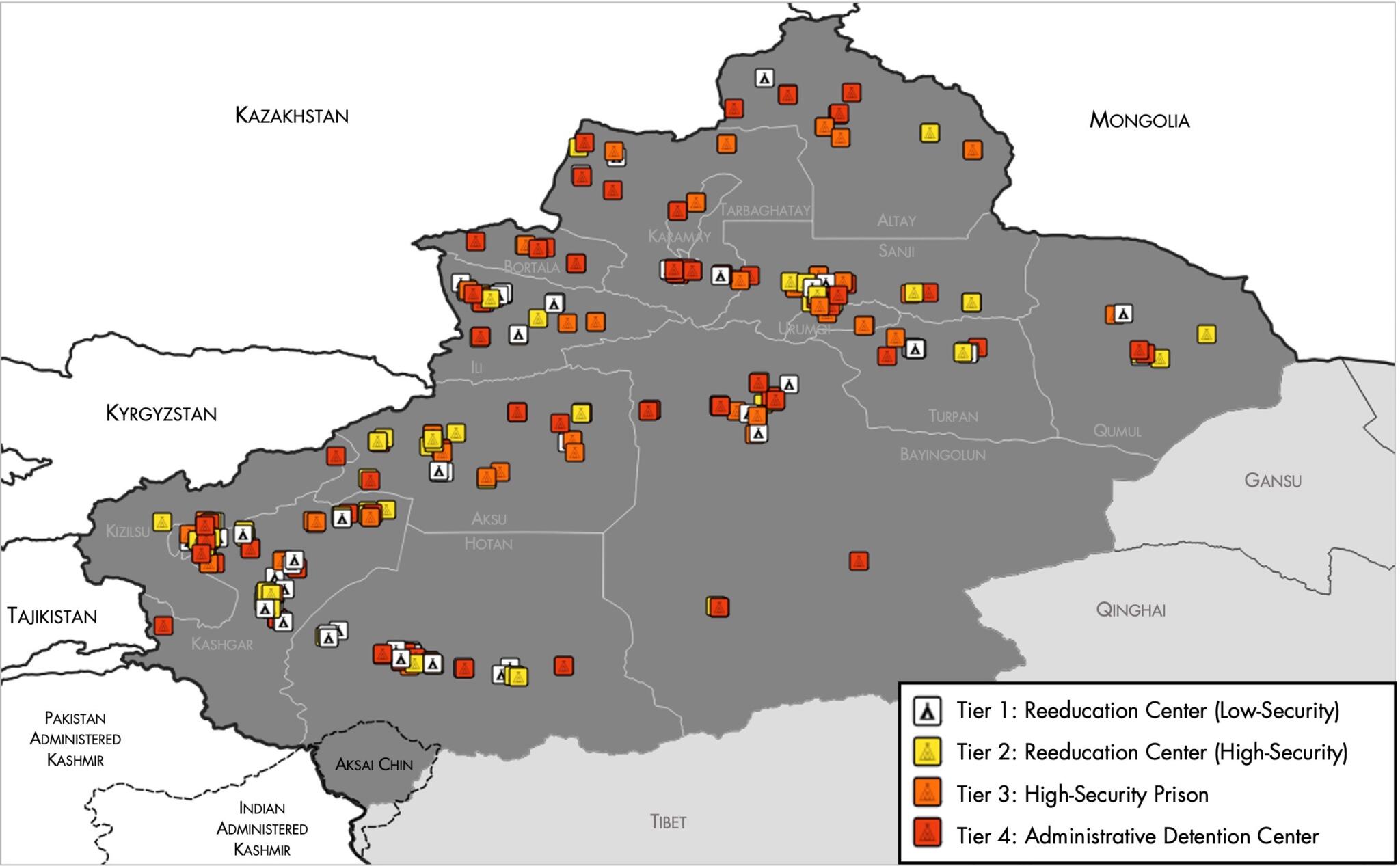

- Ethnic Minorities**: The situation in Xinjiang, involving the mass detention of Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims in "re-education camps," forced labor, pervasive surveillance, and restrictions on cultural and religious practices, has been labeled by some Western governments and human rights groups as crimes against humanity or genocide. In Tibet, concerns persist over cultural and religious repression and restrictions on autonomy.

- Hong Kong**: The implementation of the National Security Law in 2020 has severely curtailed civil liberties, freedom of the press, and judicial independence, eroding the "One country, two systems" framework and drawing international condemnation. Pro-democracy movements have faced significant suppression.

- Civil Liberties**: Censorship of media and the internet (the "Great Firewall") remains stringent, with limited freedom of expression, assembly, and religion. Human rights lawyers and activists face harassment, detention, and imprisonment.

- Environmental Issues**: Severe air, water, and soil pollution continue to affect public health and ecosystems. While the government has set ambitious goals for renewable energy and carbon neutrality, reliance on coal remains high, and the environmental impact of large-scale development projects is a concern.

- Technological Advancements and Surveillance**: China has made rapid strides in technology, particularly in areas like artificial intelligence, 5G, and e-commerce. However, this has been accompanied by the development of a pervasive surveillance state, utilizing facial recognition, big data, and the social credit system, raising concerns about privacy and social control.

- Consolidation of Power under Xi Jinping**: Xi Jinping has overseen a significant centralization of power, removing presidential term limits and launching a far-reaching anti-corruption campaign that has also served to eliminate political rivals. Ideological control has tightened, and Xi Jinping Thought has been enshrined in the CCP constitution. This consolidation has led to concerns about the direction of China's political development and the potential for increased authoritarianism.

From a center-left perspective, contemporary China presents a mixed picture: remarkable economic achievements and poverty reduction stand alongside significant challenges to human rights, democratic development, social equity, and environmental sustainability. The government's focus on stability and CCP dominance often comes at the expense of individual freedoms and the rights of marginalized groups.

4. Geography

China's vast territory encompasses a wide array of physical landscapes, diverse climates, rich biodiversity, and significant natural resources. However, it also faces pressing environmental challenges and is involved in several territorial disputes. The country's geography has profoundly influenced its history, culture, and development.

4.1. Physical geography

China's terrain is incredibly diverse, featuring some of the world's highest mountains and plateaus, expansive plains, and long coastlines.

- Mountain Ranges**: China is home to several major mountain ranges. The Himalayas form a natural barrier along its southwestern border, containing Mount Everest, the world's highest peak, which lies on the China-Nepal border. Other significant ranges include the Kunlun and Qilian Mountains in the west, the Tian Shan in the northwest, the Qinling dividing northern and southern China, and the Greater and Lesser Khingan Ranges in the northeast.

- Plateaus**: The Tibetan Plateau, often called the "Roof of the World," is the largest and highest plateau globally, dominating southwestern China. The Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau is in the south, and the Loess Plateau is in central China, known for its fine, wind-blown silt deposits.

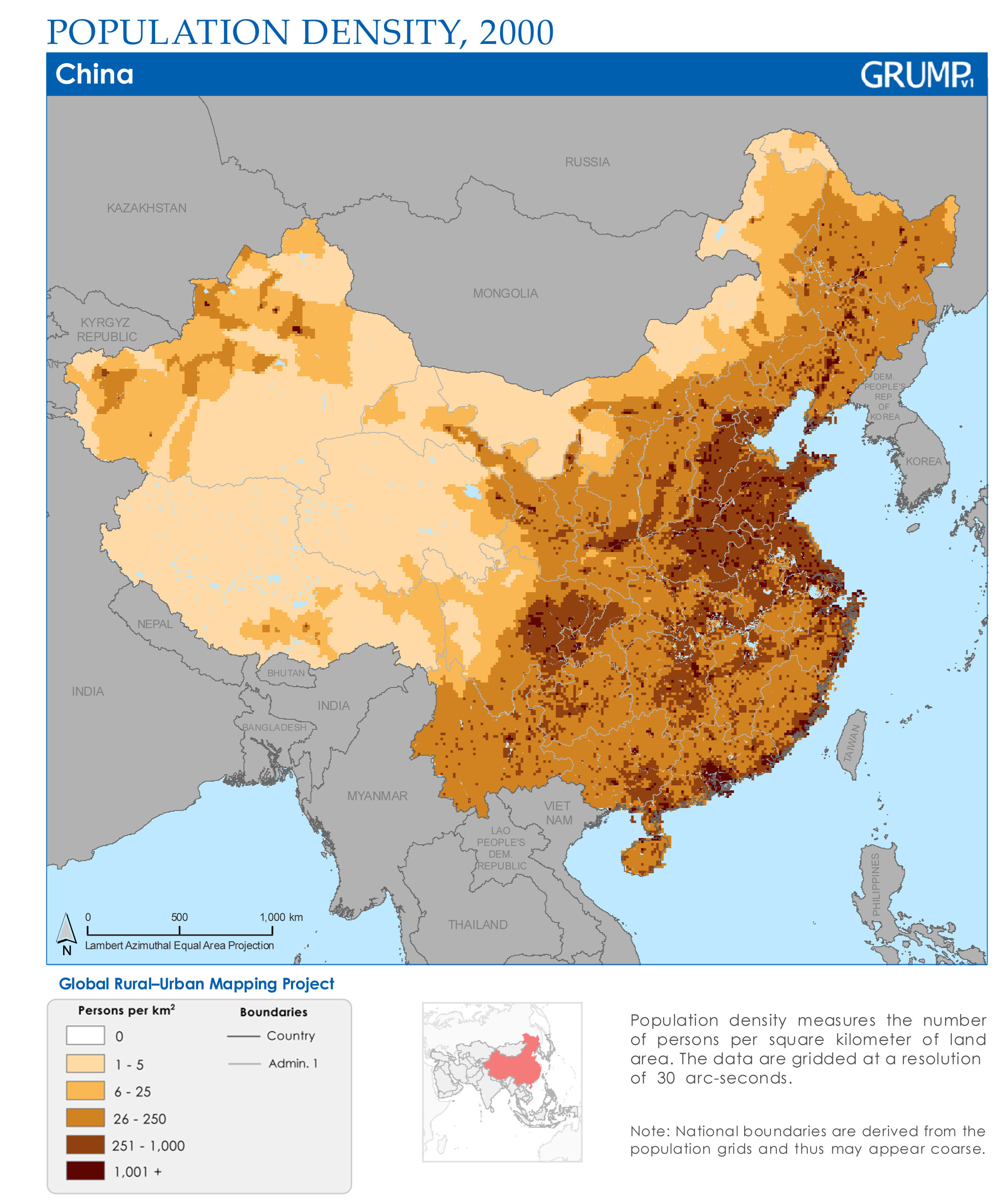

- Plains**: Vast alluvial plains are found in eastern China, which are densely populated and agriculturally productive. The North China Plain (or Yellow River Plain) and the Northeast China Plain (Manchurian Plain) are the largest. The Yangtze Plain is also a crucial agricultural region.

- Deserts**: Large deserts are located in northern and northwestern China. The Gobi Desert extends from Mongolia into Inner Mongolia, and the Taklamakan Desert is situated in the Tarim Basin of Xinjiang. These arid regions present challenges of desertification.

- Rivers**: China has numerous major rivers, many originating from the Tibetan Plateau. The Yangtze River (Chang Jiang) is the longest river in Asia and the third-longest in the world, flowing through central China to the East China Sea. The Yellow River (Huang He), often called the "cradle of Chinese civilization," flows through northern China. The Pearl River (Zhu Jiang) system is in the south. Other important rivers include the Heilongjiang (Amur), Lancang (Mekong), and Nu (Salween).

- Coastlines**: China has an extensive coastline of about 9.0 K mile (14.50 K km) along the Pacific Ocean, bordered by the Bohai, Yellow Sea, East China Sea, and South China Sea. This coastline has numerous ports and has been vital for trade and maritime activities.

The varied topography results in significant regional differences in climate, resources, and human settlement patterns.

4.2. Climate

China's vast size and complex topography result in a wide variety of climatic zones. The climate is predominantly influenced by the monsoon system.

- Southern China**: Experiences a humid subtropical to tropical climate. Summers are hot and humid with heavy rainfall, often brought by the summer monsoon from the South China Sea. Winters are generally mild and shorter. Regions like Hainan island have a fully tropical climate.

- Northern and Northeastern China**: Characterized by a temperate continental climate with hot, humid summers and long, cold, dry winters. The winter monsoon brings cold air from Siberia. Rainfall is concentrated in the summer months.

- Northwestern China**: This region, including Xinjiang and parts of Inner Mongolia, has an arid or semi-arid continental climate. It experiences large diurnal and seasonal temperature variations, with hot summers and very cold winters. Precipitation is scarce.

- Tibetan Plateau**: Features a highland or alpine climate due to its high altitude. Winters are extremely cold and long, while summers are short and cool. Strong winds and intense solar radiation are common.

- Regional Variations**: The Qinling Mountains act as a significant climatic divide between northern and southern China. Microclimates exist in many mountainous areas.

- Impacts of Climate Change**: China is vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, including rising temperatures, changes in precipitation patterns, increased frequency of extreme weather events (such as droughts and floods), melting glaciers in the Himalayas (affecting water resources), and sea-level rise in coastal areas. These changes pose significant risks to agriculture, water security, ecosystems, and human populations, particularly affecting vulnerable communities. Efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change are ongoing but face substantial challenges.

The diverse climates support a wide range of agricultural practices and ecosystems across the country.

4.3. Biodiversity

China is one of the 17 megadiverse countries in the world, possessing a remarkably rich array of flora and fauna due to its vast and varied territory, diverse climates, and complex topography. It lies within two major biogeographic realms: the Palearctic and the Indomalayan.

- Species Richness**: China is home to over 34,687 species of animals and vascular plants. It ranks third globally in mammal species (at least 551), eighth in bird species (1,221), seventh in reptile species (424), and seventh in amphibian species (333). The country also has over 32,000 species of vascular plants and over 10,000 recorded species of fungi.

- Endemic Species**: China boasts numerous endemic species, meaning they are found nowhere else in the world. Famous examples include the giant panda, Chinese alligator, South China tiger (critically endangered, possibly extinct in the wild), Golden snub-nosed monkey, and the Dawn redwood. The Yangtze River basin is home to unique aquatic species like the (now extinct) Baiji (Yangtze River dolphin) and the critically endangered Chinese sturgeon and Chinese giant salamander.

- Ecosystems**: China's diverse ecosystems range from cold coniferous forests in the north (supporting moose and Asian black bear) to tropical rainforests in Yunnan and Hainan (containing a quarter of all Chinese animal and plant species). Other ecosystems include temperate deciduous forests, grasslands, deserts, wetlands, and extensive montane ecosystems on its numerous mountain ranges, including the Himalayas and the Hengduan Mountains, which are biodiversity hotspots.

- Conservation Efforts**: The Chinese government has established over 2,349 nature reserves, covering about 15% of the country's total land area, to protect its biodiversity. There are laws to protect endangered wildlife. The country is a party to the Convention on Biological Diversity.

- Threats to Biodiversity**: Despite conservation efforts, China's biodiversity faces severe threats from human activities. Habitat loss and fragmentation due to urbanization, agricultural expansion, and infrastructure development are major concerns. Pollution of air, water, and soil also degrades habitats. Poaching and the illegal wildlife trade for food, fur, and traditional medicine ingredients continue to threaten many species. Invasive species also pose a risk to native ecosystems. The immense human population puts acute pressure on wildlife and their habitats. Many wild animals have been eliminated from eastern and central China's core agricultural regions, though they fare better in the more remote mountainous south and west.

The preservation of China's rich biodiversity is crucial not only for the country itself but also for global ecological balance.

4.4. Environmental issues and policies

China faces significant and complex environmental challenges stemming from its rapid industrialization, urbanization, large population, and historical development patterns. These issues have considerable social and public health impacts.

- Air Pollution**: Severe air pollution, particularly in major urban and industrial areas, is a major concern, caused by coal combustion, industrial emissions, and vehicle exhaust. High levels of particulate matter (PM2.5) contribute to respiratory illnesses, cardiovascular diseases, and premature deaths. While regulations have been tightened and some improvements seen, air quality remains a critical issue.

- Water Scarcity and Pollution**: Water scarcity affects many parts of China, especially the north. Water pollution from industrial discharge, agricultural runoff (pesticides and fertilizers), and untreated sewage contaminates rivers, lakes, and groundwater, impacting drinking water safety and aquatic ecosystems. Only a fraction of national surface water is graded suitable for human consumption.

- Soil Degradation and Contamination**: Soil degradation through erosion, salinization, and desertification affects large areas of agricultural land. Soil contamination with heavy metals and pollutants from industrial activities and waste disposal poses risks to food safety and human health.

- Desertification**: The expansion of deserts, especially the Gobi Desert, is a serious problem, driven by climate change, overgrazing, and unsustainable land use practices. This leads to loss of arable land and increased frequency of sandstorms.

- Deforestation and Loss of Arable Land**: While afforestation programs have been implemented, deforestation has historically been an issue. The conversion of agricultural land to urban and industrial use contributes to the loss of arable land.

- Impacts of Large-Scale Projects**: Projects like the Three Gorges Dam, while providing benefits such as flood control and hydroelectric power, have also had significant negative environmental and social consequences, including habitat destruction, alteration of river ecosystems, increased risk of landslides, and the displacement of millions of people. The social and health impacts on affected communities are often severe.

- Government Policies and Initiatives**: The Chinese government has acknowledged the severity of environmental problems and has implemented various policies and initiatives. These include strengthening environmental laws and enforcement, investing in renewable energy (China is a world leader in solar and wind power production), promoting energy efficiency, and setting targets for carbon neutrality (aiming for peak CO2 emissions before 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060). Afforestation projects like the "Great Green Wall" aim to combat desertification.

- Social and Health Impacts**: Environmental degradation has direct and severe social and health impacts. Air and water pollution contribute to a significant burden of disease and premature mortality. Cancer villages, areas with unusually high cancer rates linked to industrial pollution, have been acknowledged. Environmental issues can also lead to social unrest and protests.

Addressing China's environmental challenges requires sustained effort, significant investment, robust enforcement of regulations, and a transition towards a more sustainable development model, balancing economic growth with environmental protection and social well-being.

4.5. Political geography and territorial disputes

China's political geography is defined by its extensive land borders, diverse administrative divisions, and a number of significant territorial disputes with its neighbors. China's border with Pakistan is disputed by India, which claims the entire Kashmir region as its territory. China is tied with Russia as having the most land borders of any country.

- Borders**: China shares land borders with 14 countries: Afghanistan, Bhutan, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Mongolia, Myanmar (Burma), Nepal, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Vietnam. Its total land border length is approximately 14 K mile (22.12 K km). China has resolved its land borders with 12 of these 14 neighbors, often through substantial compromises.

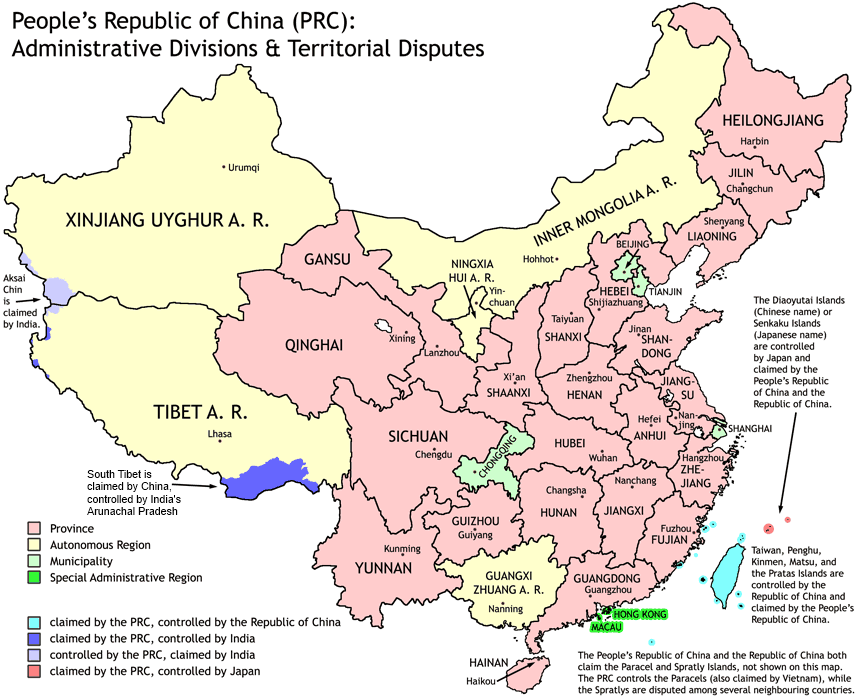

- Administrative Divisions**: The PRC is divided into 23 provinces (it claims Taiwan as its 23rd province), 5 autonomous regions (Guangxi, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Tibet, Xinjiang), 4 municipalities directly under the central government (Beijing, Chongqing, Shanghai, Tianjin), and 2 Special Administrative Regions (SARs) - Hong Kong and Macau. These divisions vary greatly in size, population, and economic development.

- Territorial Disputes**:

- South China Sea**: China claims almost the entire South China Sea through its "nine-dash line" (now often depicted as a ten-dash or eleven-dash line), overlapping with claims from Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and Taiwan (ROC). Disputes involve the Paracel Islands (controlled by China, claimed by Vietnam and Taiwan) and the Spratly Islands (claimed in whole or part by China, Taiwan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Philippines, and Brunei). China has engaged in extensive land reclamation and militarization of features it controls in the area, increasing regional tensions. An arbitral tribunal under UNCLOS in 2016 ruled against many of China's claims, but China rejected the ruling. These disputes impact freedom of navigation, access to resources (fishing, oil, gas), and regional stability. Local populations, particularly fishing communities, are directly affected.

- East China Sea**: China has a dispute with Japan over the Senkaku Islands (Diaoyu Islands in Chinese), which are controlled by Japan but claimed by both China and Taiwan. This dispute involves historical claims, potential oil and gas reserves, and strategic maritime positioning.

- India**: China and India have a long-standing border dispute primarily concerning two main areas: Aksai Chin in the west (administered by China, claimed by India) and Arunachal Pradesh in the east (administered by India, claimed by China as "South Tibet"). Tensions have occasionally flared into border skirmishes, most notably the 1962 war and more recent clashes. The dispute affects local populations and relations between the two regional powers.

- Bhutan**: China and Bhutan also have an unresolved border dispute, particularly concerning areas like the Doklam plateau, which is strategically important due to its proximity to India's Siliguri Corridor.

These disputes are often complex, involving historical claims, national pride, strategic interests, resource competition, and interpretations of international law. China's approach to these disputes is a key factor in its foreign relations and regional stability. A balanced presentation requires acknowledging the de facto control, the claims of other parties, the historical context, the principles of international law, and the impact on local communities and broader geopolitical dynamics.

5. Government and politics

The People's Republic of China operates under a political system dominated by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The structure of the national government and its administrative framework are designed to implement the CCP's policies and maintain its control. This section examines the interplay between state control, the limited avenues for citizen participation, and the overall governance model, with a critical perspective on its democratic features and human rights implications.

5.1. Political system

The People's Republic of China is constitutionally defined as a "socialist state under the people's democratic dictatorship led by the working class and based on an alliance of workers and peasants." In practice, it is a one-party state led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The official ideology is "Socialism with Chinese characteristics", which integrates Marxist-Leninist principles with Chinese realities and, more recently, Xi Jinping Thought.

The political system is based on the principle of democratic centralism, where the National People's Congress (NPC) is formally the highest organ of state power, but all state organs are effectively under the leadership of the CCP. The CCP's paramount role is enshrined in the constitution.

While the PRC officially describes its system as a form of democracy, such as "socialist consultative democracy" or "whole-process people's democracy", most external observers and international assessments characterize it as an authoritarian state. The Economist Intelligence Unit's Democracy Index consistently ranks China low, categorizing it as an "authoritarian regime." Governance in China is marked by a high degree of state control over political life, society, and information.

The implications for political freedoms and human rights are significant. There are severe restrictions on freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, and freedom of association. Dissent is not tolerated, and the legal system is often used to suppress critics of the government and the CCP. While the government emphasizes economic development and social stability as achievements, these often come at the cost of individual civil and political liberties. The comparison between official claims of democracy and the reality of authoritarian control reveals a substantial gap, with limited accountability and genuine citizen participation in the political decision-making process beyond CCP-controlled channels.

5.2. Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is the founding and sole ruling political party of the People's Republic of China, exercising comprehensive control over all aspects of the state and society.

- Organization and Leadership**: The CCP's highest body is the National Congress, convened every five years. It elects the Central Committee, which in turn elects the Politburo and its Politburo Standing Committee (PSC). The PSC is the apex of power, typically comprising 5 to 9 members. The General Secretary is the party leader and, in practice, the paramount leader of the country. This position is currently held by Xi Jinping. Other key leadership bodies include the Secretariat, responsible for daily administrative work, and the Central Military Commission (CMC), which controls the armed forces. The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection is responsible for combating corruption and enforcing party discipline.

- Ideology**: The CCP's guiding ideology is officially "Socialism with Chinese characteristics", which includes Marxism-Leninism, Mao Zedong Thought, Deng Xiaoping Theory, the "Three Represents", the "Scientific Outlook on Development", and most recently, "Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era". This ideology has evolved to incorporate market-based economic reforms while maintaining the CCP's political dominance.

- Dominant Role**: The CCP's leadership is enshrined in the state constitution. It controls the government, the military (People's Liberation Army), the legislature (National People's Congress), the judiciary, state-owned enterprises, and has significant influence over media, education, and social organizations. Party committees exist at all levels of government and in most institutions.

- Membership**: The CCP is one of the largest political parties in the world, with over 90 million members. Membership is often seen as a pathway to career advancement.

- Internal Discipline**: The party maintains strict internal discipline and conducts periodic rectification campaigns and anti-corruption drives, which can also serve to consolidate power and eliminate political rivals.

- Mechanisms of Control**: The CCP exercises control through various mechanisms, including:

- The nomenklatura system, which controls appointments to all key positions in the state and public institutions.

- Party cells and committees embedded within government agencies, state-owned enterprises, universities, and even some private companies.

- Control over the media and propaganda apparatus to shape public opinion.

- The United Front Work Department, which aims to co-opt and influence non-Party groups and individuals.

- A vast security and surveillance apparatus to monitor and suppress dissent.

The CCP's enduring grip on power is a defining feature of China's political system, shaping its domestic policies and international relations.

5.3. National government

The national government of the People's Republic of China is structured around several key state organs, all operating under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

- National People's Congress (NPC)**: Constitutionally, the NPC is the highest organ of state power and the national legislature. It has nearly 3,000 deputies elected for five-year terms from provinces, autonomous regions, municipalities, special administrative regions, and the armed forces. The NPC meets annually for about two weeks to review and approve major policies, laws, the budget, and key personnel appointments. When the NPC is not in session, its powers are exercised by the NPC Standing Committee, a smaller body of about 150 members. While formally powerful, the NPC is largely seen as a "rubber-stamp" body that ratifies decisions already made by the CCP leadership. The current Chairman of the NPC Standing Committee is Zhao Leji.

- Presidency**: The President is the head of state, a largely ceremonial role but one that has gained significance when held concurrently by the CCP General Secretary. The President is elected by the NPC for a five-year term. Xi Jinping is the current President. The President promulgates laws, appoints and removes the Premier and other State Council members (upon NPC approval), and represents China in state affairs.

- State Council**: This is the chief administrative body, effectively the cabinet of the PRC, headed by the Premier. The Premier is nominated by the President and approved by the NPC. The State Council is responsible for implementing laws and policies, managing the economy and social affairs, and overseeing ministries and commissions. The current Premier is Li Qiang. Vice Premiers and State Councillors assist the Premier.

- Central Military Commission (CMC)**: There are two CMCs: one belonging to the state and one to the CCP. In practice, their memberships are identical, and they function as one body controlling the People's Liberation Army (PLA). The Chairman of the CMC is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, a position also currently held by Xi Jinping.

- Supreme People's Court (SPC)**: The SPC is the highest judicial organ. It supervises the administration of justice by local people's courts and special people's courts. However, the judiciary is not independent and operates under the political leadership of the CCP.

- Supreme People's Procuratorate (SPP)**: The SPP is the highest organ for legal supervision and prosecution. It directs the work of local people's procuratorates.

- National Supervisory Commission**: Established in 2018, this body is responsible for overseeing all public officials exercising public power, including anti-corruption investigations. It operates in parallel with, and is closely linked to, the CCP's Central Commission for Discipline Inspection.

While these institutions have formal roles and responsibilities, the CCP's overarching leadership ensures that the Party's policies and priorities guide the functioning of the national government.

5.4. Administrative divisions

The People's Republic of China (PRC) is a unitary state constitutionally divided into several levels of administrative divisions. The top level consists of provinces, autonomous regions, municipalities directly under the central government, and special administrative regions. The PRC claims Taiwan as its 23rd province, though it is governed by the Republic of China (ROC).

- Provinces (省shěngChinese)**: There are 22 provinces administered by the PRC. Each province has its own CCP committee, people's government, and people's congress. The PRC considers Taiwan to be its 23rd province, but Taiwan is currently administered by the Republic of China.

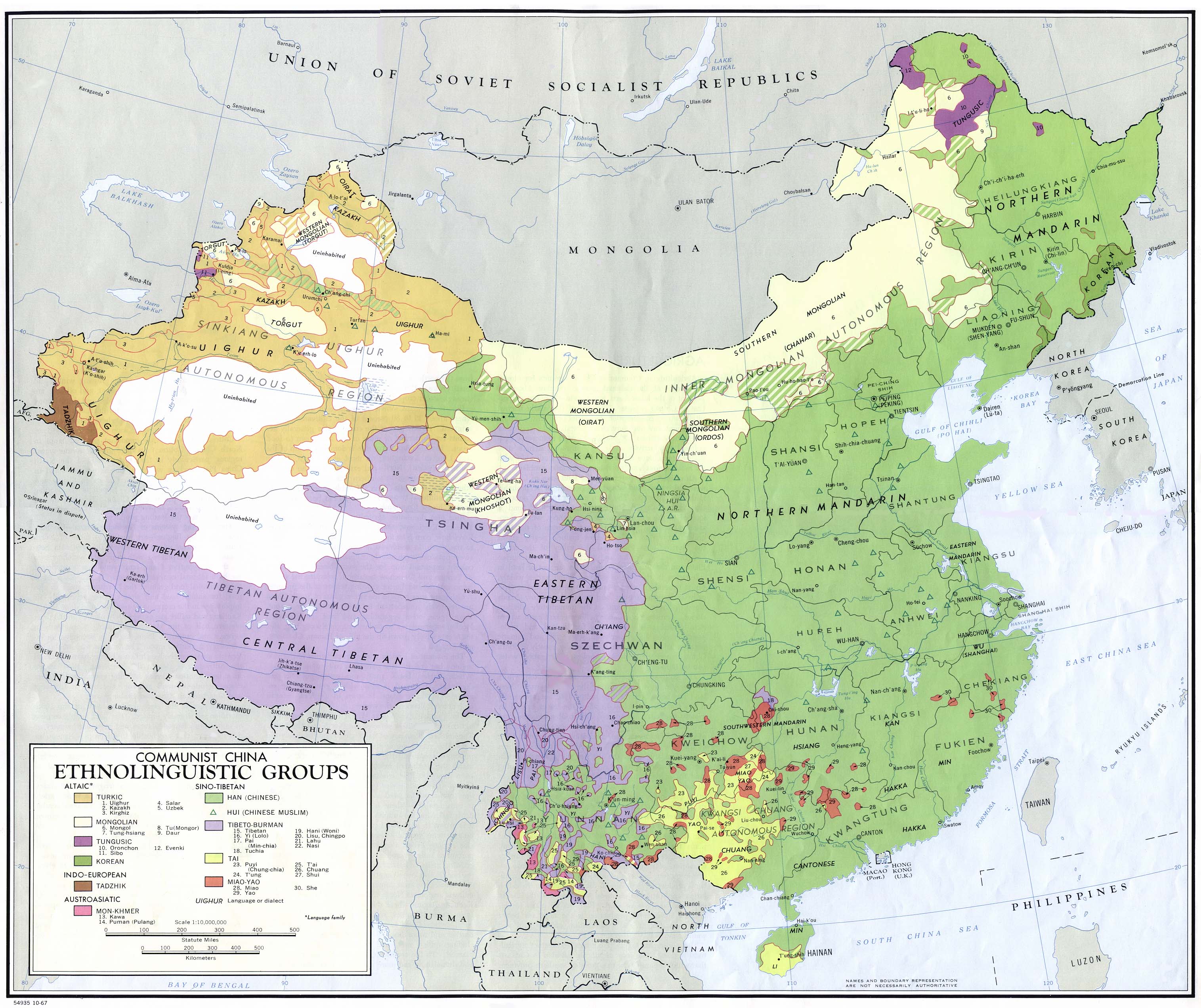

- Autonomous Regions (自治区zìzhìqūChinese)**: There are 5 autonomous regions, designated for specific large ethnic minority groups, granting them a degree of nominal autonomy in cultural and administrative affairs: Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (for the Zhuang), Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (Nei Mongol) (for the Mongols), Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (for the Hui), Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (for the Uyghurs), and Tibet Autonomous Region (Xizang) (for the Tibetans). Despite the "autonomous" designation, these regions are under tight central control, and concerns about the actual extent of autonomy and the rights of ethnic minorities are widespread, particularly in Xinjiang and Tibet where policies of assimilation and control are prominent.

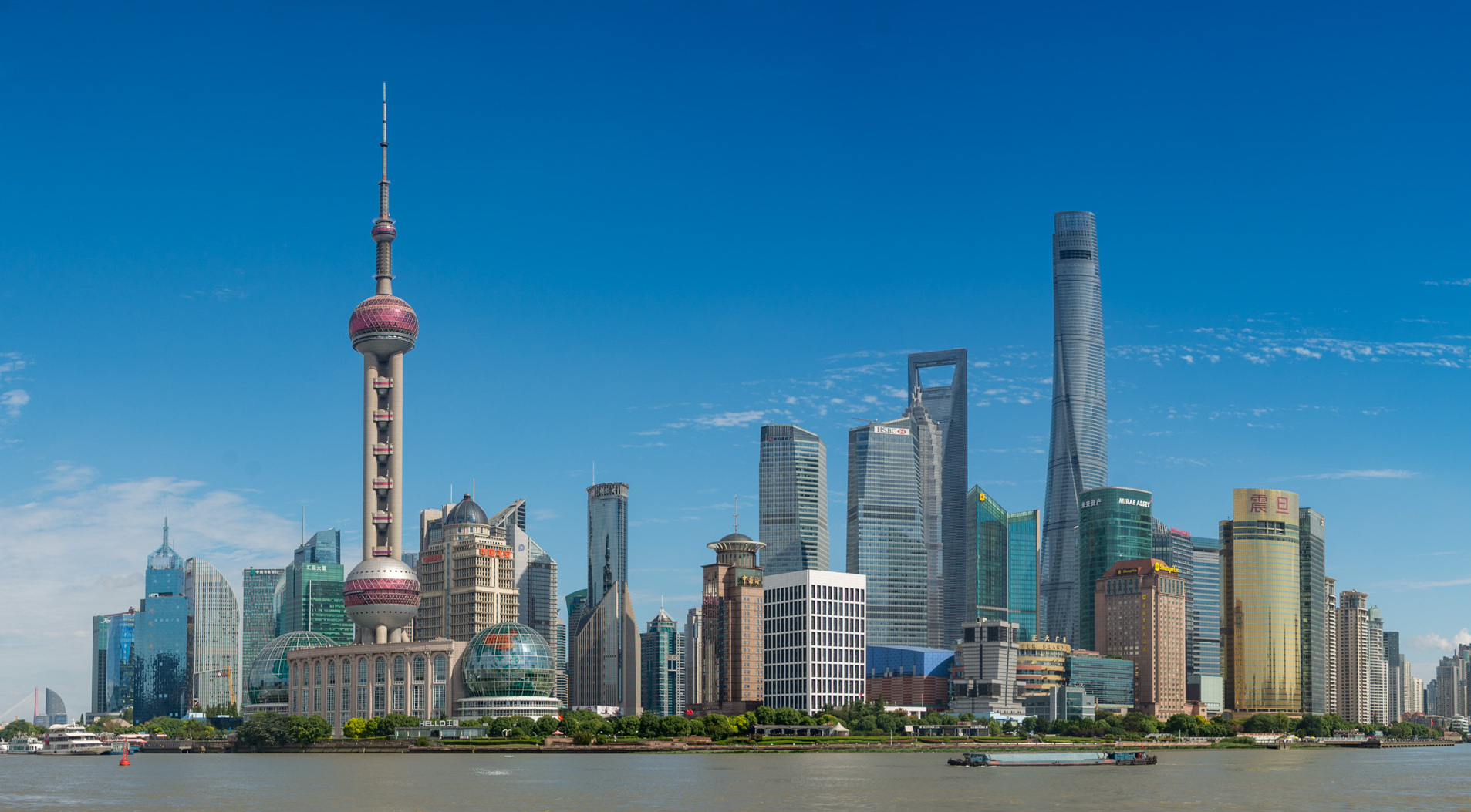

- Municipalities directly under the Central Government (直辖市zhíxiáshìChinese)**: There are 4 municipalities that have provincial-level status due to their size and importance: Beijing (the national capital), Chongqing, Shanghai (a major financial and commercial hub), and Tianjin.

- Special Administrative Regions (SARs) (特别行政区tèbié xíngzhèngqūChinese)**: There are 2 SARs, established under the "One country, two systems" principle: Hong Kong (Xianggang), formerly a British colony, returned to China in 1997, and Macau (Aomen), formerly a Portuguese colony, returned to China in 1999. SARs are promised a high degree of autonomy, except in defense and foreign affairs, and maintain their own currencies, customs territories, and legal systems. However, particularly in Hong Kong, there have been increasing concerns and international criticism regarding the erosion of autonomy, civil liberties, and judicial independence following the implementation of the National Security Law in 2020.

These top-level divisions are further subdivided into prefectures, counties, townships, and villages. The administrative structure is hierarchical, with each level responsible to the level above it and ultimately to the central government in Beijing.

| Provinces (省shěngChinese) |

>- | Claimed Province | Taiwan (台湾省Táiwān ShěngChinese), governed by the Republic of China | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous regions (自治区zìzhìqūChinese) |

>- | Municipalities (直辖市zhíxiáshìChinese) |

>- | Special administrative regions (特别行政区tèbié xíngzhèngqūChinese) |

>} |