1. Overview

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia, occupying the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula. It is the largest country in the Middle East by land area and the fifth-largest in Asia. The nation's geography is diverse, featuring vast deserts such as the Rub' al Khali, mountain ranges, and coastlines along the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf. Historically, the territory of modern-day Saudi Arabia was the cradle of Islam in the early 7th century, with Mecca and Medina becoming its holiest cities. The Al Saud dynasty unified the regions of Hejaz, Najd, Al-Ahsa, and Asir in 1932, establishing an absolute monarchy. The political system is based on Islamic law (Sharia), with the Quran and Sunnah serving as the constitution. The discovery of petroleum in 1938 transformed Saudi Arabia into a global energy superpower, leading to significant economic development but also a heavy reliance on oil revenues. Recent efforts, such as Saudi Vision 2030, aim to diversify the economy and implement social reforms. Saudi society is traditionally conservative, with Islamic values deeply influencing daily life, though recent years have seen some easing of social restrictions, particularly concerning women's rights. However, the country continues to face international scrutiny for its human rights record, including limitations on freedom of expression, the application of the death penalty, and the treatment of migrant workers. From a center-left/social liberalism perspective, this article examines Saudi Arabia's complex tapestry, emphasizing the social impacts of its policies, the ongoing human rights challenges, and the path towards potential democratic development, while acknowledging its significant role in global politics and the Islamic world.

2. Etymology

Following the amalgamation of the Kingdom of Hejaz and the Nejd, King Abdulaziz issued a royal decree on 23 September 1932, naming the new state ٱلْمَمْلَكَة ٱلْعَرَبِيَّة ٱلسُّعُودِيَّةal-Mamlaka al-ʿArabiyya as-SuʿūdiyyaArabic. This is commonly translated into English as "the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia", but literally means "the Saudi Arab Kingdom" or "the Saudi Kingdom of Arabia".

The word "Saudi" is derived from the element as-Suʿūdīyya in the Arabic name of the country. This is a type of adjective known as a nisba, formed from the dynastic name of the Saudi royal family, the Al Saud (آل سعودĀl SuʿūdArabic). The inclusion of the family name in the country's name expresses the view that the country is the personal possession of the royal family. Al Saud is an Arabic name formed by adding the word Āl, meaning "family of" or "House of", to the personal name of an ancestor. In the case of Al Saud, this ancestor is Saud ibn Muhammad ibn Muqrin, the father of the dynasty's 18th-century founder, Muhammad bin Saud.

3. History

The history of Saudi Arabia encompasses the early human presence on the Arabian Peninsula, the rise of Islam, centuries of shifting tribal and imperial control, and the eventual unification under the House of Saud leading to the modern nation-state. This section details the key periods and events that shaped the country, from ancient civilizations through the Ottoman era, the establishment of the Saudi state, and its development throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, with a focus on socio-political changes and their impact.

3.1. Prehistory and Ancient Civilizations

Evidence suggests human habitation in the Arabian Peninsula dates back approximately 125,000 years. A 2011 study indicated that the first modern humans to spread east across Asia left Africa about 75,000 years ago, crossing the Bab-el-Mandeb strait which connects the Horn of Africa and Arabia. The Arabian Peninsula is considered central to understanding human evolution and dispersal. The region experienced extreme environmental fluctuations during the Quaternary period, leading to profound evolutionary and demographic changes. Arabia has a rich Lower Paleolithic record, and the numerous Oldowan-like sites suggest a significant role for Arabia in the early hominin colonization of Eurasia.

In the Neolithic period, prominent cultures such as Al-Magar, centered in modern-day southwestern Najd, flourished. Al-Magar is considered a "Neolithic Revolution" in human knowledge and handicraft skills. This culture is noted as one of the world's first to involve the widespread domestication of animals, particularly the horse. Al-Magar statues, made from local stone, appear to have been fixed in a central building, possibly playing a significant role in the social and religious life of the inhabitants. In November 2017, hunting scenes depicting likely domesticated dogs (resembling the Canaan Dog) wearing leashes were discovered in Shuwaymis, a hilly region of northwestern Saudi Arabia. These rock engravings date back more than 8,000 years, making them the earliest known depictions of dogs.

By the end of the 4th millennium BC, Arabia entered the Bronze Age. Metals were widely used, and the period was characterized by 2-meter-high burials and numerous temples featuring free-standing sculptures originally painted with red colors. In May 2021, archaeologists announced that a 350,000-year-old Acheulean site named An Nasim in the Hail region could be the oldest human habitation site in northern Saudi Arabia. The 354 artifacts found, including hand axes and stone tools, provide information about the tool-making traditions of early humans in southwest Asia and are similar to materials from Acheulean sites in the Nefud Desert.

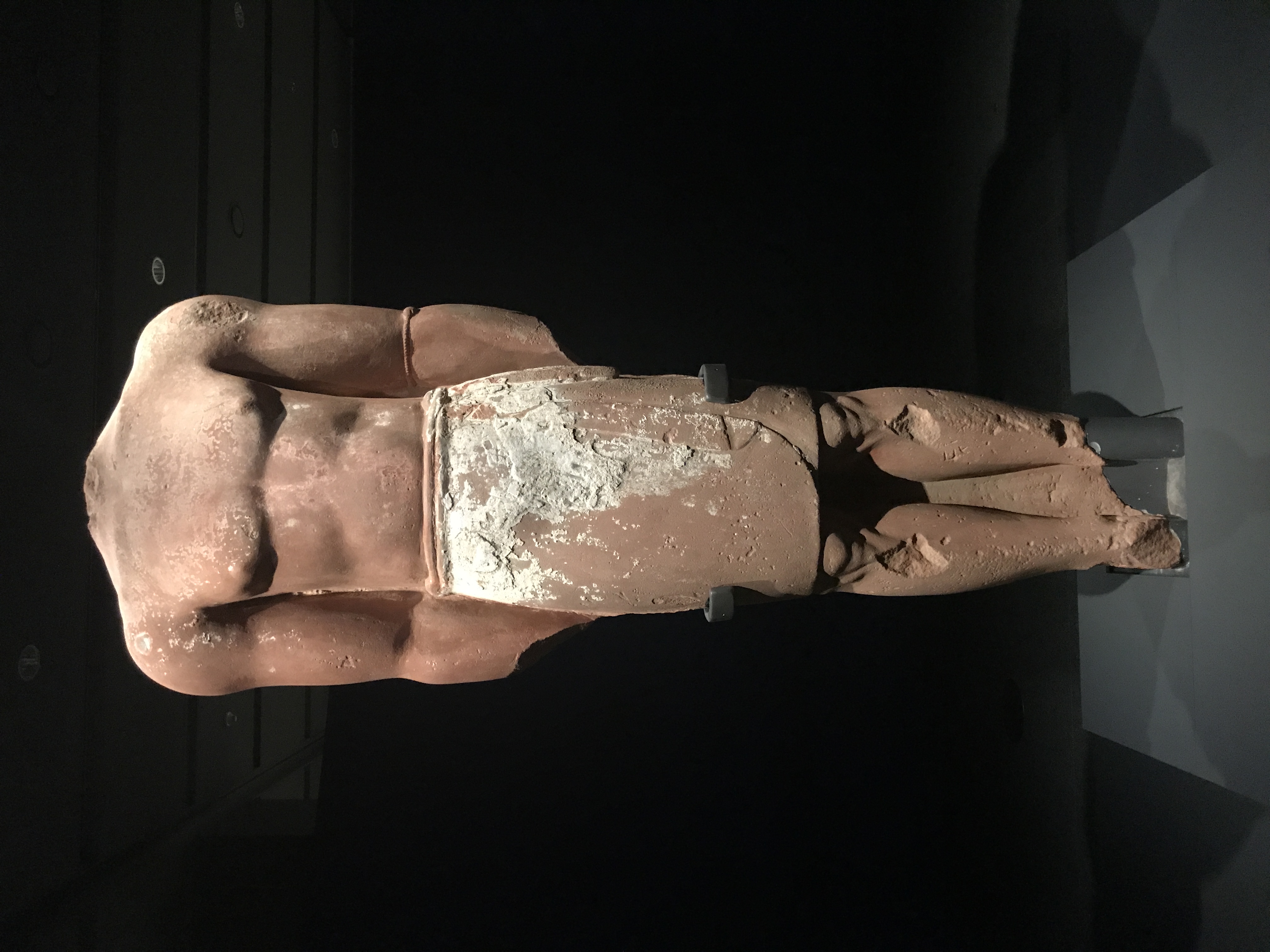

The earliest sedentary culture in Saudi Arabia dates back to the Ubaid period at Dosariyah. Climatic change and the onset of aridity may have ended this phase of settlement, as little archaeological evidence exists from the succeeding millennium. Settlement resumed in the period of Dilmun in the early 3rd millennium. Records from Uruk refer to Dilmun, associated with copper and later as a source of imported woods in southern Mesopotamia. Scholars suggest Dilmun originally designated the eastern province of Saudi Arabia, linked with major Dilmunite settlements like Umm an-Nussi, Umm ar-Ramadh, and Tarout Island on the coast, with Tarout likely being its main port and capital. Mesopotamian clay tablets suggest a hierarchical political structure existed in early Dilmun. In 1966, an ancient burial field in Tarout yielded a large statue from the Dilmunite period (mid-3rd millennium BC), locally made under strong Mesopotamian influence.

By 2200 BC, the center of Dilmun shifted from Tarout and the Saudi mainland to the island of Bahrain for unknown reasons, where a highly developed settlement with a temple complex and thousands of burial mounds emerged.

In the late Bronze Age, the land of Midian and its people, the Midianites, in northwestern Saudi Arabia are well-documented in the Bible. Centered in Tabuk, it stretched from Wadi Arabah in the north to al-Wejh in the south. The capital of Midian was Qurayyah, a large fortified citadel covering 35 hectares with a walled settlement of 15 hectares below it, hosting as many as 12,000 inhabitants. The Bible recounts Israel's wars with Midian in the early 11th century BC. Politically, Midianites had a decentralized structure headed by five kings, whose names appear to be toponyms of important settlements. Midian likely designated a confederation of tribes, with sedentary elements in Hijaz and nomadic affiliates who pastured and sometimes pillaged as far as Palestine. The nomadic Midianites were early exploiters of camel domestication.

At the end of the 7th century BC, a kingdom emerged in northwestern Arabia, starting as the sheikdom of Dedan and developing into the kingdom of Lihyan. Dedan transformed into a kingdom encompassing a much wider domain. By the early 3rd century BC, with bustling economic activity, Lihyan acquired significant influence due to its strategic position on the caravan road, ruling a large domain from Yathrib in the south to parts of the Levant in the north. The Gulf of Aqaba was anciently called the Gulf of Lihyan, testifying to Lihyan's extensive influence. The Lihyanites fell to the Nabataeans around 65 BC, who seized Hegra, then Tayma, and their capital Dedan in 9 BC. The Nabataeans ruled large portions of north Arabia until their domain was annexed by the Roman Empire, renamed Arabia Petraea, and remained under Roman rule until 630.

3.2. Rise of Islam and Medieval Period

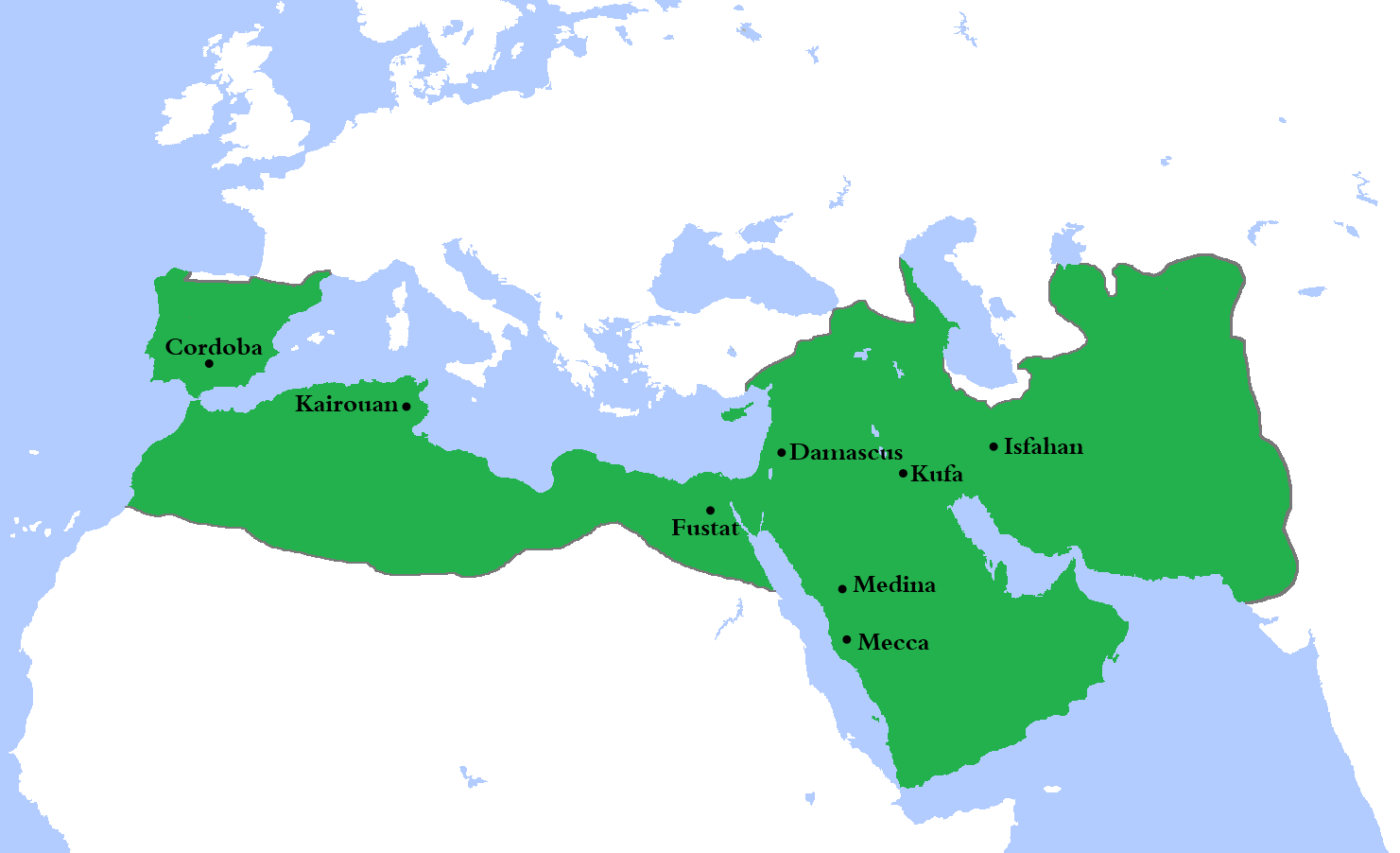

Shortly before the advent of Islam, apart from urban trading settlements such as Mecca and Medina, much of what was to become Saudi Arabia was populated by nomadic pastoral tribal societies. The Islamic prophet Muhammad was born in Mecca in about 570 CE. In the early 7th century, Muhammad united the various tribes of the peninsula and created a single Islamic religious polity. Following his death in 632, his followers rapidly expanded the territory under Muslim rule beyond Arabia, conquering vast territories from the Iberian Peninsula in the west to parts of Central and South Asia in the east within decades. Arabia then became a more politically peripheral region of the Muslim world as the focus shifted to the newly conquered lands.

Arabs originating from modern-day Saudi Arabia, particularly the Hejaz, founded the Rashidun (632-661), Umayyad (661-750), Abbasid (750-1517), and the Fatimid (909-1171) caliphates. From the 10th century to the early 20th century, Mecca and Medina were under the control of a local Arab ruler known as the Sharif of Mecca. However, at most times, the sharif owed allegiance to the ruler of one of the major Islamic empires based in Baghdad, Cairo, or Istanbul. Most of the remainder of what became Saudi Arabia reverted to traditional tribal rule.

For much of the 10th century, the Isma'ili-Shi'ite Qarmatians were the most powerful force in the Persian Gulf. In 930, the Qarmatians pillaged Mecca and stole the Black Stone, outraging the Muslim world. In 1077-1078, an Arab sheikh named Abdullah bin Ali Al Uyuni defeated the Qarmatians in Bahrain and al-Hasa with the help of the Seljuk Empire and founded the Uyunid dynasty. The Uyunid Emirate later expanded, with its territory stretching from Najd to the Syrian Desert. They were overthrown by the Usfurids in 1253. Usfurid rule was weakened after Persian rulers of Hormuz captured Bahrain and Qatif in 1320. The vassals of Ormuz, the Shia Jarwanid dynasty, came to rule eastern Arabia in the 14th century. The Jabrids took control of the region after overthrowing the Jarwanids in the 15th century and clashed with Hormuz for over two decades for its economic revenues, until finally agreeing to pay tribute in 1507. The Al-Muntafiq tribe later took over the region and came under Ottoman suzerainty. The Bani Khalid tribe later revolted against them in the 17th century and took control. Their rule extended from Iraq to Oman at its height, and they too came under Ottoman suzerainty.

3.3. Ottoman Era

In the 16th century, the Ottomans added the Red Sea and Persian Gulf coasts (the Hejaz, Asir, and Al-Ahsa) to their empire and claimed suzerainty over the interior. One reason was to thwart Portuguese attempts to attack the Red Sea (and thus the Hejaz) and the Indian Ocean. The Ottoman degree of control over these lands varied over the next four centuries, fluctuating with the strength or weakness of the empire's central authority. These changes contributed to later uncertainties, such as the dispute with Transjordan over the inclusion of the sanjak of Ma'an, which included the cities of Ma'an and Aqaba.

3.4. Emergence of the Saud Dynasty and Unification

The emergence of what was to become the Saudi royal family, known as the Al Saud, began in the town of Diriyah in Najd, central Arabia, with the accession of Muhammad bin Saud as emir on 22 February 1727. In 1744, he joined forces with the religious leader Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, founder of the Wahhabi movement, a strict puritanical form of Sunni Islam. This alliance provided the ideological impetus for Saudi expansion and remains the basis of Saudi Arabian dynastic rule today.

The Emirate of Diriyah, established in the area around Riyadh, rapidly expanded and briefly controlled most of the present-day territory of Saudi Arabia. It sacked Karbala in 1802 and captured Mecca in 1803, also undertaking the destruction of early Islamic heritage sites. In 1818, it was destroyed by the Ottoman viceroy of Egypt, Mohammed Ali Pasha. A much smaller Emirate of Nejd was established in 1824. Throughout the rest of the 19th century, the Al Saud contested control of the interior of what was to become Saudi Arabia with another Arabian ruling family, the Al Rashid, who ruled the Emirate of Jabal Shammar. By 1891, the Al Rashid were victorious, and the Al Saud were driven into exile in Kuwait.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Ottoman Empire continued to control or have suzerainty over most of the peninsula. Subject to this suzerainty, Arabia was ruled by a patchwork of tribal rulers, with the Sharif of Mecca having pre-eminence and ruling the Hejaz. In 1902, Abdul Rahman's son, Abdulaziz-later known as Ibn Saud-recaptured control of Riyadh, bringing the Al Saud back to Nejd and creating the third "Saudi state". Ibn Saud gained the support of the Ikhwan, a tribal army inspired by Wahhabism and led by Faisal Al-Dawish, which had grown quickly after its foundation in 1912. With the aid of the Ikhwan, Ibn Saud captured Al-Ahsa from the Ottomans in 1913.

In 1916, with the encouragement and support of the Britain (which was fighting the Ottomans in World War I), the Sharif of Mecca, Hussein bin Ali, led a pan-Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire to create a united Arab state. Although the revolt failed in its objective, the Allied victory in World War I resulted in the end of Ottoman suzerainty and control in Arabia, and Hussein bin Ali became King of Hejaz.

Ibn Saud avoided involvement in the Arab Revolt and instead continued his struggle with the Al Rashid. Following the latter's final defeat, he took the title Sultan of Nejd in 1921. With the help of the Ikhwan, the Kingdom of Hejaz was conquered in 1924-25, and on 10 January 1926, Ibn Saud declared himself King of Hejaz. For the next five years, he administered the two parts of his dual kingdom as separate units.

After the conquest of the Hejaz, the Ikhwan leadership's objective switched to the expansion of the Wahhabist realm into the British protectorates of Transjordan, Iraq, and Kuwait, and they began raiding those territories. This met with Ibn Saud's opposition, as he recognized the danger of a direct conflict with the British. At the same time, the Ikhwan became disenchanted with Ibn Saud's domestic policies, which appeared to favor modernization and the increase in the number of non-Muslim foreigners in the country. As a result, they turned against Ibn Saud and, after a two-year struggle, were defeated in 1929 at the Battle of Sabilla, where their leaders were massacred. On behalf of Ibn Saud, Prince Faisal declared the unification on 23 September 1932, and the two kingdoms of Hejaz and Nejd were unified as the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. That date is now a national holiday called Saudi National Day.

3.5. 20th Century

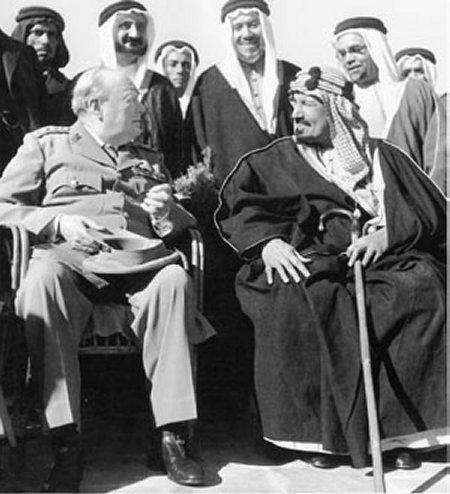

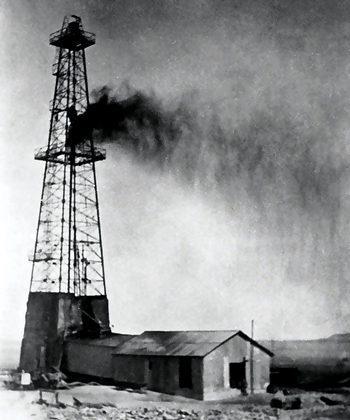

The new kingdom was reliant on limited agriculture and pilgrimage revenues. In 1938, vast reserves of oil were discovered in the Al-Ahsa region along the coast of the Persian Gulf, and full-scale development of the oil fields began in 1941 under the US-controlled Aramco (Arabian American Oil Company). Oil provided Saudi Arabia with economic prosperity and substantial political leverage internationally. Cultural life rapidly developed, primarily in the Hejaz, which was the center for newspapers and radio. However, the large influx of foreign workers in Saudi Arabia in the oil industry increased the pre-existing propensity for xenophobia. At the same time, the government became increasingly wasteful and extravagant. By the 1950s, this had led to large governmental deficits and excessive foreign borrowing.

In 1953, Saud of Saudi Arabia succeeded as the king of Saudi Arabia. In 1964, he was deposed in favor of his half-brother Faisal of Saudi Arabia, after an intense rivalry, fueled by doubts in the royal family over Saud's competence. In 1972, Saudi Arabia gained 20% control in Aramco, thereby decreasing US control over Saudi oil. In 1973, Saudi Arabia led an oil boycott against the Western countries that supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War against Egypt and Syria, leading to the quadrupling of oil prices. In 1975, Faisal was assassinated by his nephew, Prince Faisal bin Musaid, and was succeeded by his half-brother King Khalid.

By 1976, Saudi Arabia had become the largest oil producer in the world. Khalid's reign saw economic and social development progress at an extremely rapid rate, transforming the infrastructure and educational system of the country; in foreign policy, close ties with the US were developed. In 1979, two events occurred which greatly concerned the government and had a long-term influence on Saudi foreign and domestic policy. The first was the Iranian Revolution. It was feared that the country's Shi'ite minority in the Eastern Province (which is also the location of the oil fields) might rebel under the influence of their Iranian co-religionists. There were several anti-government uprisings in the region, such as the 1979 Qatif Uprising. The second event was the Grand Mosque Seizure in Mecca by Islamist extremists. The militants involved were in part angered by what they considered to be the corruption and un-Islamic nature of the Saudi government. The government regained control of the mosque after 10 days, and those captured were executed. Part of the response of the royal family was to enforce a much stricter observance of traditional religious and social norms in the country (for example, the closure of cinemas) and to give the ulema a greater role in government. Neither entirely succeeded as Islamism continued to grow in strength.

In 1980, Saudi Arabia bought out the American interests in Aramco. King Khalid died of a heart attack in June 1982. He was succeeded by his brother, King Fahd, who added the title "Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques" to his name in 1986 in response to considerable fundamentalist pressure to avoid the use of "majesty" in association with anything except God. Fahd continued to develop close relations with the United States and increased the purchase of American and British military equipment. The vast wealth generated by oil revenues was beginning to have an even greater impact on Saudi society. It led to rapid technological (but not cultural) modernization, urbanization, mass public education, and the creation of new media. This and the presence of increasingly large numbers of foreign workers greatly affected traditional Saudi norms and values. Although there was a dramatic change in the social and economic life of the country, political power continued to be monopolized by the royal family, leading to discontent among many Saudis who began to look for wider participation in government.

In the 1980s, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait spent $25 billion in support of Saddam Hussein in the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988); however, Saudi Arabia condemned the invasion of Kuwait in 1990 and asked the United States to intervene. King Fahd allowed American and coalition troops to be stationed in Saudi Arabia. He invited the Kuwaiti government and many of its citizens to stay in Saudi Arabia but expelled citizens of Yemen and Jordan because of their governments' support of Iraq. In 1991, Saudi Arabian forces were involved both in bombing raids on Iraq and in the land invasion that helped to liberate Kuwait, which became known as the Gulf War (1990-1991).

Saudi Arabia's relations with the West was one of the issues that led to an increase in Islamist terrorism in Saudi Arabia, as well as Islamist terrorist attacks in Western countries by Saudi nationals. Osama bin Laden was a Saudi citizen (until stripped of his citizenship in 1994) and was responsible for the 1998 United States embassy bombings in East Africa and the 2000 USS Cole bombing near the port of Aden, Yemen. Fifteen of the hijackers involved in the September 11 attacks were Saudi nationals. Many Saudis who did not support the Islamist terrorists were nevertheless deeply unhappy with the government's policies, viewing them as insufficiently Islamic or too closely aligned with Western interests, contributing to social and political tensions.

Islamism was not the only source of hostility to the government. Although extremely wealthy, Saudi Arabia's economy was near stagnant by the early 21st century. High taxes and a growth in unemployment contributed to discontent and were reflected in a rise in civil unrest and discontent with the royal family. In response, a number of limited reforms were initiated by King Fahd. In March 1992, he introduced the "Basic Law", which emphasized the duties and responsibilities of a ruler. In December 1993, the Consultative Council was inaugurated. It is composed of a chairman and 60 members-all chosen by the King. Fahd made it clear that he did not have democracy in mind, stating: "A system based on elections is not consistent with our Islamic creed, which [approves of] government by consultation [shūrā]." These reforms were seen by many as insufficient to address the growing calls for political participation and accountability.

In 1995, Fahd suffered a debilitating stroke, and the Crown Prince, Abdullah, assumed the role of de facto regent. However, his authority was hindered by conflict with Fahd's full brothers (known, with Fahd, as the "Sudairi Seven"), which created further complexities in governance during this period.

3.6. 21st Century

Signs of discontent continued into the 21st century, including a series of bombings and armed violence in Riyadh, Jeddah, Yanbu, and Khobar in 2003 and 2004. In February-April 2005, the first-ever nationwide municipal elections were held in Saudi Arabia. However, women were not allowed to take part, highlighting the ongoing limitations on political participation and gender equality.

In 2005, King Fahd died and was succeeded by Abdullah, who continued the policy of minimum reform and clamping down on protests. The king introduced economic reforms aimed at reducing the country's reliance on oil revenue: limited deregulation, encouragement of foreign investment, and privatization. In February 2009, Abdullah announced a series of governmental changes to the judiciary, armed forces, and various ministries to modernize these institutions. This included the replacement of senior appointees in the judiciary and the Mutaween (religious police) with more moderate individuals and the appointment of the country's first female deputy minister. These steps, while significant, were often criticized as being too slow or merely cosmetic by those advocating for deeper systemic change.

On 29 January 2011, hundreds of protesters gathered in Jeddah in a rare display of criticism against the city's poor infrastructure after flooding killed 11 people. Police stopped the demonstration after about 15 minutes and arrested 30 to 50 people. This event, though small, indicated simmering public frustration.

Since 2011, Saudi Arabia has been affected by its own Arab Spring protests. In response, King Abdullah announced on 22 February 2011 a series of benefits for citizens amounting to $36 billion, of which $10.7 billion was earmarked for housing. No political reforms were included, though some prisoners indicted for financial crimes were pardoned. Abdullah also announced a package of $93 billion, which included 500,000 new homes at a cost of $67 billion, in addition to creating 60,000 new security jobs. These measures were largely seen as attempts to quell dissent through economic appeasement rather than addressing underlying political grievances.

Although male-only municipal elections were held on 29 September 2011, King Abdullah later allowed women to vote and be elected in the 2015 municipal elections, and also to be nominated to the Shura Council. This was a landmark decision, though its practical impact on women's overall status and political influence remained a subject of debate.

The period also saw the rise of Mohammed bin Salman as a dominant figure, particularly after his father Salman became king in 2015. Mohammed bin Salman, as Crown Prince, launched Saudi Vision 2030, an ambitious plan to diversify the economy away from oil, modernize society, and implement various social reforms, including lifting the ban on women driving and curtailing the powers of the religious police. While these reforms were welcomed by some internationally and domestically, they were accompanied by a crackdown on dissent, including the arrest of activists, intellectuals, and members of the royal family.

Internationally, Saudi Arabia became more assertive, notably through its leading role in the intervention in the Yemeni Civil War starting in 2015, which led to a devastating humanitarian crisis. The assassination of Jamal Khashoggi in 2018 brought intense international condemnation and scrutiny upon the Saudi government and its leadership. The 21st century for Saudi Arabia has thus been characterized by attempts at socio-economic transformation amidst ongoing political authoritarianism, regional instability, and persistent human rights concerns. The impact of these changes on the Saudi population includes new opportunities for some, particularly women in certain sectors, but also heightened fear of repression for those critical of the government.

4. Geography

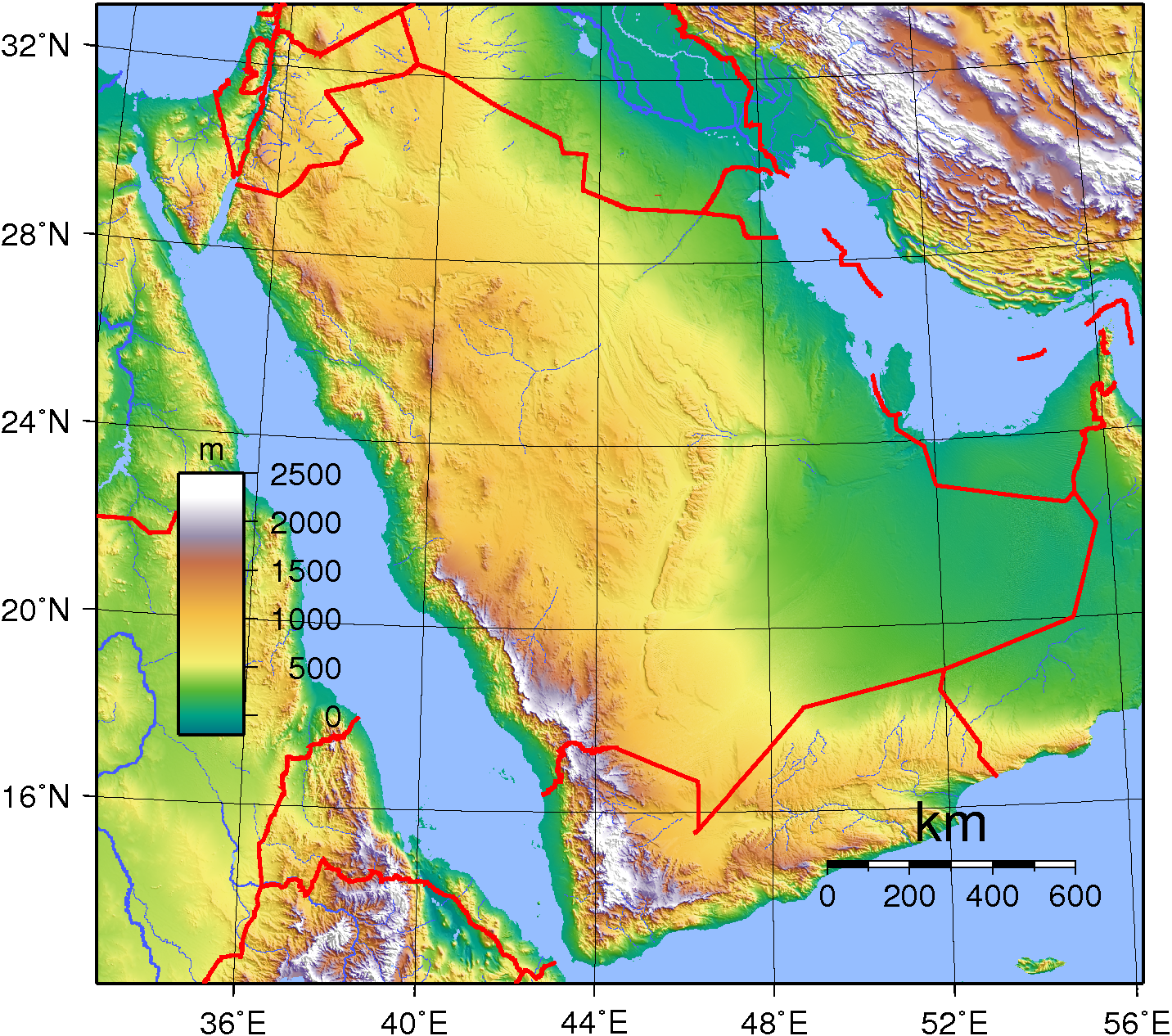

Saudi Arabia occupies approximately 80% of the Arabian Peninsula, the world's largest peninsula. It lies between latitudes 16° and 33° N, and longitudes 34° and 56° E. Because the country's southeastern and southern borders with the United Arab Emirates and Oman are not precisely demarcated, the exact size of the country remains undefined. The United Nations Statistics Division estimates its area at 2.15 M abbr=on. It is geographically the largest country in the Middle East and on the Arabian Plate. Saudi Arabia is bordered by the Red Sea to the west; Jordan, Iraq, and Kuwait to the north; the Persian Gulf, Bahrain, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates to the east; Oman to the southeast; and Yemen to the south. The Gulf of Aqaba in the northwest separates Saudi Arabia from Egypt and Israel. Saudi Arabia is unique in having coastlines along both the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf. There are approximately 1,300 islands in the Red Sea and Arabian Gulf under Saudi sovereignty.

4.1. Topography and Climate

Saudi Arabia's geography is dominated by the Arabian Desert, associated semi-desert, shrubland, steppes, several mountain ranges, volcanic lava fields (known as harrat), and highlands. The 647.50 K abbr=on Rub' al Khali ("Empty Quarter") in the southeastern part of the country is the world's largest contiguous sand desert. The main topographical feature is the central plateau which rises abruptly from the Red Sea and gradually descends into the Najd and toward the Arabian Gulf. On the Red Sea coast, there is a narrow coastal plain, known as the Tihamah, parallel to which runs an imposing escarpment. The southwest province of Asir is mountainous and contains the 3.00 K abbr=on Jabal Ferwa, which is the highest point in the country. Saudi Arabia is home to more than 2,000 dormant volcanoes. The lava fields in Hejaz, locally known as harrat (singular: harrah), form one of Earth's largest alkali basalt regions, covering some 180.00 K abbr=on.

Except for the southwestern regions such as Asir, Saudi Arabia has a desert climate with very high daytime temperatures during the summer and a sharp temperature drop at night. Average summer temperatures are around 113 °F (45 °C), but can be as high as 129.2 °F (54 °C). In the winter, the temperature rarely drops below 32 °F (0 °C), with the exception of the northern regions where annual snowfall, particularly in the mountainous areas of Tabuk Province, is not uncommon. The lowest recorded temperature, 10.399999999999999 °F (-12 °C), was measured in Turaif. Of the Gulf states, Saudi Arabia is likely to experience snowfalls most frequently. In the spring and autumn, the heat is temperate, with temperatures averaging around 84.2 °F (29 °C). Annual rainfall is very low. The southern regions differ in that they are influenced by the Indian Ocean monsoons, usually occurring between October and March. An average of 12 in (300 mm) of rainfall occurs during this period, which is about 60% of the annual precipitation.

4.2. Biodiversity

Saudi Arabia is home to five terrestrial ecoregions: Arabian Peninsula coastal fog desert, Southwestern Arabian foothills savanna, Southwestern Arabian montane woodlands, Arabian Desert, and Red Sea Nubo-Sindian tropical desert and semi-desert. Wildlife includes the Arabian leopard, Arabian wolf, striped hyena, mongoose, baboon, Cape hare, sand cat, and jerboa. Animals such as gazelles, oryx, leopards, and cheetahs were relatively numerous until the 19th century, when extensive hunting reduced these animals almost to extinction. The culturally important Asiatic lion occurred in Saudi Arabia until the late 19th century before it was hunted to extinction in the wild. Birds include falcons (which are caught and trained for hunting), eagles, hawks, vultures, sandgrouse, and bulbuls. There are several species of snakes, many of which are venomous. Domesticated animals include the legendary Arabian horse, Arabian camel, sheep, goats, cattle, donkeys, and chickens.

The Red Sea is a rich and diverse ecosystem with more than 1,200 species of fish, around 10% of which are endemic. This also includes 42 species of deep water fish. The rich diversity is partly due to the 2.00 K abbr=on of coral reef extending along the coastline; these fringing reefs are largely formed of stony acropora and porites corals. The reefs form platforms and sometimes lagoons along the coast and occasional other features such as cylinders (like the Blue Hole at Dahab). These coastal reefs are also visited by pelagic species, including some of the 44 species of shark. There are many offshore reefs including several atolls. Many of the unusual offshore reef formations defy classic (i.e., Darwinian) coral reef classification schemes and are generally attributed to the high levels of tectonic activity that characterize the area.

Reflecting the country's dominant desert conditions, plant life mostly consists of herbs, plants, and shrubs that require little water. The date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) is widespread. Environmental challenges include desertification, depletion of underground water resources, and pollution from oil spills. Conservation efforts are underway, including the establishment of protected areas and initiatives to promote sustainable practices.

4.3. Water Resources

Saudi Arabia faces critical water scarcity as it is the largest country in the world by area with no permanent rivers. Wadis, non-permanent rivers, however, are very numerous throughout the kingdom. Historically, oases and wells were the primary sources of water. Today, the country relies heavily on desalination of seawater, which provides about 50% of its drinking water. Another 40% comes from the mining of non-renewable groundwater, and the remaining 10% from surface water, mainly in the mountainous southwest.

The massive use of groundwater for agriculture, particularly for wheat cultivation in the past, led to significant depletion of aquifers. This unsustainable practice resulted in the loss of an estimated four-fifths of total groundwater reserves by 2012, prompting the government to phase out domestic wheat production to conserve water. Water management and conservation are critical policy areas, involving substantial investments in desalination technology, water distribution networks, wastewater treatment, and promoting water-efficient irrigation techniques. The social and environmental impacts of these water policies are significant, as ensuring a sustainable water supply is crucial for the country's population and future development, while the energy-intensive nature of desalination poses environmental challenges.

5. Government and Politics

Saudi Arabia is an absolute monarchy, and its political system is deeply intertwined with the House of Saud and the principles of Wahhabism, a conservative interpretation of Islam. The country lacks a democratically elected legislature and political parties are banned. This section outlines the governmental structure, the role of the royal family and religion in politics, the legal system based on Sharia law, and the human rights situation, reflecting a critical perspective on democratic development and social justice.

5.1. Governmental Structure

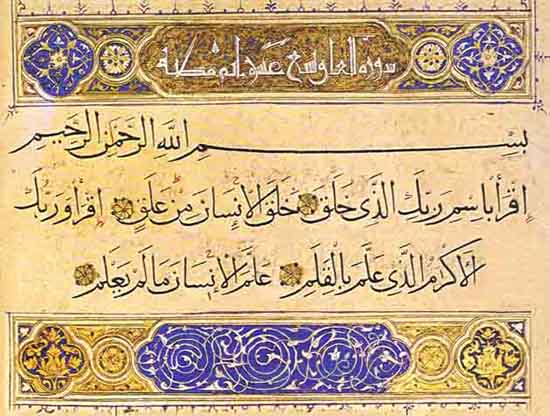

Saudi Arabia is an absolute monarchy. According to the Basic Law of Saudi Arabia, adopted by royal decree in 1992, the King must comply with Sharia (Islamic law) and the Quran. The Quran and the Sunnah (the traditions of Muhammad) are declared to be the country's constitution. No political parties or national elections are permitted. Critics often describe the regime as authoritarian, lacking public input in governance. The Economist ranked the Saudi government 150th out of 167 in its 2022 Democracy Index, and Freedom House consistently gives it a "Not Free" rating, highlighting severe restrictions on political and civil liberties.

The King combines legislative, executive, and judicial functions. Royal decrees form the basis of the country's legislation. The King is also the Prime Minister and presides over the Council of Ministers of Saudi Arabia, which functions as the cabinet. The Consultative Assembly (Majlis ash-Shura), an advisory body, consists of members appointed by the King. While it can propose legislation, it has no binding legislative power and its role is largely to provide recommendations to the King and the Council of Ministers. The judiciary operates under Sharia law, with judges appointed by the King. The separation of powers is nominal, as all branches ultimately answer to the monarch.

5.2. Royal Family

The House of Saud dominates the political system of Saudi Arabia. The family's vast numbers, estimated to be at least 7,000 princes, allow it to control most of the kingdom's important posts and maintain an involvement at all levels of government. Most power and influence are wielded by the approximately 200 male descendants of King Abdulaziz Ibn Saud, the founder of modern Saudi Arabia. Key ministries, such as Defense, Interior, and Foreign Affairs, are traditionally reserved for senior members of the royal family, as are the 13 regional governorships.

Succession to the throne was historically from brother to brother among the sons of King Abdulaziz. However, with the aging of this generation, the Allegiance Council was created in 2007 to regulate the succession process and select future kings and crown princes from among the grandsons of King Abdulaziz. Mohammed bin Salman's rise to Crown Prince in 2017, sidelining other senior princes, marked a significant shift in these traditional succession mechanisms.

The royal family's immense wealth, largely derived from oil revenues, and its pervasive political influence have led to accusations of corruption and nepotism. The lines between state assets and the personal wealth of senior princes are often blurred, which has been a source of public discontent and international criticism. The 2017 anti-corruption purge, which saw the arrest of hundreds of princes, ministers, and businessmen, was presented as an effort to combat corruption but was also seen by some as a move by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman to consolidate power and neutralize potential rivals within the family. Dynamics among major factions within the family, often based on lineage from different wives of King Abdulaziz (like the Sudairi Seven), continue to influence political decisions and power distribution.

5.3. Role of Religion in Politics

Wahhabism, a strict and puritanical interpretation of Sunni Islam, is the state-sponsored religious doctrine in Saudi Arabia and has a profound influence on its politics and society. The ulema (Islamic scholars), particularly those adhering to Wahhabi teachings and often led by the Al ash-Sheikh family (descendants of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab), have historically played a significant role in legitimizing the rule of the House of Saud and shaping public policy. This alliance dates back to the 18th century and forms the basis of the Saudi state's religious and political identity.

The ulema have traditionally held significant sway over the legal and education systems, and public morality. They interpret Sharia law, which forms the basis of the Saudi legal system, and their fatwas (religious edicts) can influence government decisions. The Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice (CPVPV), commonly known as the Mutaween or religious police, was historically empowered to enforce adherence to Wahhabi norms of behavior in public, such as dress codes, prayer times, and gender segregation.

However, in recent years, particularly under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, there has been a noticeable effort to curtail the influence of the more conservative elements of the ulema and the Mutaween. Reforms have included stripping the religious police of their power to arrest, allowing public entertainment like cinemas and concerts, and easing some restrictions on women. These changes reflect a top-down effort to modernize the country and reduce the dominance of the religious establishment in daily life and certain policy areas, aiming for a more "moderate Islam" as publicly stated by the Crown Prince. Despite these shifts, Islam, and specifically the Wahhabi interpretation, remains a cornerstone of the state's identity and legitimacy, and the role of religion in politics continues to be a defining feature of Saudi Arabia, albeit one that is evolving.

5.4. Legal System

The legal system of Saudi Arabia is based on Sharia (Islamic law) derived from the Quran and the Sunnah (the traditions of the Prophet Muhammad). It is unique among modern Muslim states in that Sharia is not codified in a comprehensive manner, and there is no formal system of judicial precedent. Judges, or qadis, exercise independent legal reasoning (ijtihad) to make decisions, primarily following the principles of the Hanbali school of jurisprudence, which is known for its literalist interpretation. This can lead to divergent judgments in similar cases, creating a lack of legal predictability.

Royal decrees, referred to as regulations rather than laws to signify their subordination to Sharia, supplement Islamic law in areas such as labor, commercial, and corporate law. Traditional tribal law and custom also retain significance in some contexts. Extra-Sharia government tribunals often handle disputes relating to specific royal decrees. The King serves as the final court of appeal and holds the power of pardon. All courts and tribunals are expected to follow Sharia rules of evidence and procedure.

The application of law in Saudi Arabia has drawn significant international criticism, particularly concerning human rights. Punishments can be severe and include capital punishment (often by public beheading) for a range of offenses including murder, rape, drug trafficking, apostasy, sorcery, and terrorism. Other forms of punishment include flogging (though officially abolished in 2020 for most offenses and replaced with fines or imprisonment), and amputation for theft. Retaliatory punishments, or Qisas, are practiced, where a victim or their family can demand equivalent harm (e.g., an eye for an eye) or opt for diyya (blood money).

In recent years, there have been announcements of judicial reforms, including efforts towards codifying laws to reduce judicial discretion and increase consistency. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman indicated in 2022 that capital punishments would be significantly reduced, except for those explicitly mentioned in the Quran for offenses like homicide under specific conditions. However, the extent and impact of these reforms on human rights and due process remain subjects of ongoing scrutiny by international observers. The legal system's impact on human rights, especially regarding fair trial standards, freedom of expression, and the rights of women and minorities, is a persistent concern.

5.5. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Saudi Arabia is a subject of significant international concern, with numerous organizations and governments criticizing the country for widespread violations. The authoritarian regime, operating under an absolute monarchy and a strict interpretation of Sharia law, imposes severe restrictions on fundamental freedoms.

Freedom of Expression, Assembly, and Association: Freedom of speech is heavily curtailed. Criticism of the government, the royal family, or Islamic principles can lead to severe punishment, including imprisonment and flogging. Independent media is non-existent, and the internet is heavily censored. Public protests and political parties are banned. Human rights defenders, activists, and journalists often face harassment, arbitrary detention, and prosecution under vaguely worded anti-terrorism laws or for "disrupting public order." The murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018 starkly highlighted the risks faced by critics.

Women's Rights: Despite some recent reforms, such as lifting the ban on women driving in 2018 and easing some aspects of the male guardianship system (e.g., women over 21 can obtain passports and travel abroad without a male guardian's permission), women continue to face significant discrimination. They require a male guardian's approval for critical life decisions like marriage or certain medical procedures, though the scope of guardianship has been somewhat reduced. Women face discrimination in employment, legal matters (a woman's testimony is often worth half that of a man's), and personal status laws related to marriage, divorce, and child custody. While more women are entering the workforce, they still face barriers to equality. Activists campaigning for women's rights have faced imprisonment.

Freedom of Religion: Islam (specifically the Sunni Wahhabi interpretation) is the state religion. The public practice of any religion other than Islam is prohibited. Non-Muslims are not allowed to build houses of worship. Conversion from Islam (apostasy) is punishable by death. Shi'a Muslims, who constitute a significant minority, face systematic discrimination in employment, education, and the justice system, and their religious practices are restricted. Atheists and agnostics are considered terrorists under the law.

Death Penalty and Judicial System: Saudi Arabia has one of the highest execution rates in the world. The death penalty is applied for a wide range of offenses, including non-violent crimes like drug trafficking, apostasy, and sorcery. Executions are often carried out by public beheading. Concerns persist about the fairness of trials, with reports of confessions obtained through torture or duress, lack of access to legal counsel, and lengthy pre-trial detentions. Mass executions have drawn international condemnation.

Migrant Workers: A large population of migrant workers faces exploitation under the Kafala (sponsorship) system, which ties workers' legal status to their employers. This system often leads to abuses such as wage withholding, passport confiscation, forced labor, and restrictions on movement. Domestic workers are particularly vulnerable to physical and sexual abuse. Human trafficking remains a serious issue.

LGBTQ+ Individuals: Homosexual acts are criminalized and can be punished by death, imprisonment, flogging, or deportation. There is no legal recognition or protection for LGBTQ+ individuals, and societal discrimination is rampant.

International human rights organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch consistently rank Saudi Arabia among the worst violators of human rights. While the government has established a Human Rights Commission, its independence and effectiveness are widely questioned. Governmental responses often dismiss criticisms as interference in internal affairs or assert that its laws are based on Islamic principles. The social justice and rights of vulnerable groups remain severely compromised.

6. Administrative Divisions

Saudi Arabia is divided into 13 provinces (مناطق إداريةmanātiq idāriyyaArabic; singular: منطقة إداريةmintaqah idāriyyaArabic). These provinces are the first-level administrative divisions of the Kingdom. Each province is governed by an Emir (governor), who is typically a member of the royal family and is appointed by the King.

The 13 provinces are:

- Al-Bahah

- Northern Borders (Al-Hudud ash Shamaliyah)

- Al-Jawf

- Al-Madinah (Medina)

- Al-Qassim

- Ar-Riyad (Riyadh)

- Ash-Sharqiyah (Eastern Province)

- 'Asir

- Ha'il

- Jazan

- Makkah (Mecca)

- Najran

- Tabuk

The provinces are further divided into 118 governorates (محافظاتmuhafazatArabic; singular: محافظةmuhafazahArabic). This number includes the 13 provincial capitals, which have a different status as municipalities (أمانةamanahArabic) headed by mayors (أمينaminArabic). The governorates are further subdivided into sub-governorates (مراكزmarakizArabic; singular: مركزmarkazArabic). This hierarchical structure allows for centralized control while managing local affairs.

6.1. Major Cities

Saudi Arabia has several major urban centers that are significant for their population, economic activity, and cultural or religious importance.

- Riyadh: The capital and largest city of Saudi Arabia, located in the Riyadh region in the heart of the country. It is the political and administrative center of the kingdom, with a rapidly growing population estimated at over 6.5 million. Riyadh is a major financial hub and has undergone significant modernization and development, featuring impressive skyscrapers, universities, and cultural institutions.

- Jeddah: A major port city on the Red Sea coast, located in the Makkah region. With a population of nearly 4 million, Jeddah is the second-largest city and serves as the principal gateway for pilgrims traveling to Mecca and Medina. It is a crucial commercial and economic center, known for its historic Al-Balad district and modern waterfront.

- Mecca (Makkah): The holiest city in Islam, located in the Makkah region. It is the birthplace of Prophet Muhammad and the site of the Kaaba in the Grand Mosque, toward which Muslims worldwide pray. Non-Muslims are prohibited from entering Mecca. Millions of Muslims visit Mecca annually for the Hajj and Umrah pilgrimages. Its resident population is nearly 2 million, which swells significantly during pilgrimage seasons.

- Medina (Al-Madinah): The second-holiest city in Islam, located in the Al-Madinah region. It is where Prophet Muhammad migrated from Mecca and established the first Islamic community. The Prophet's Mosque (Al-Masjid an-Nabawi), containing Muhammad's tomb, is a major pilgrimage site. Medina has a population of over 1.2 million and, like Mecca, is closed to non-Muslims in its sacred core.

Other significant cities include Dammam, Khobar, and Dhahran in the Eastern Province, which form a major industrial and oil-producing hub; Ta'if, a mountainous city near Mecca known for its cooler climate; and Tabuk in the northwest, a historical and agricultural center.

7. Foreign Relations

Saudi Arabia's foreign policy is shaped by its status as a major oil exporter, its role as the custodian of Islam's two holiest cities, and its geopolitical position in the Middle East. The kingdom maintains extensive diplomatic ties and plays a significant role in regional and international organizations. This section discusses its foreign policy principles, relations with key countries, its role in international bodies, and international controversies, with a focus on humanitarian impacts and diverse perspectives.

7.1. Foreign Policy Principles

Saudi Arabia's foreign policy is guided by several core principles. Firstly, its immense oil wealth underpins its oil-based diplomacy, using its position as a leading OPEC member to influence global energy markets and foreign policy. Secondly, its role as the custodian of Mecca and Medina gives it significant influence in the Islamic world, often positioning itself as a leader of Sunni Muslim countries and a key player in the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). Thirdly, its geopolitical stance in the Middle East is characterized by efforts to maintain regional stability (often defined by its own interests), counter perceived threats (historically from pan-Arab nationalism, communism, and more recently from Iran and Islamist extremist groups), and support allied regimes. The kingdom has traditionally relied on strong security alliances, particularly with the United States. Promoting a conservative vision of Islam globally has also been a component of its foreign policy, though this has faced increased scrutiny.

7.2. Relations with Key Countries

- United States: A cornerstone of Saudi foreign policy has been its strategic alliance with the U.S., based on oil-for-security. This relationship has involved close military cooperation and U.S. support for Saudi security, though it has faced strains, particularly after the September 11 attacks (as 15 of the 19 hijackers were Saudi nationals), over human rights issues, and regional policies like the Yemeni Civil War. Despite tensions, arms sales and counter-terrorism cooperation continue.

- China: Relations with China have grown significantly, driven by China's increasing energy demands and Saudi Arabia's desire to diversify its partnerships. Cooperation extends to trade, investment, and infrastructure projects under China's Belt and Road Initiative. Saudi Arabia has notably refrained from criticizing China's human rights record, including its treatment of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang.

- Iran: Relations with Iran have been characterized by deep rivalry, fueled by sectarian differences (Sunni Saudi Arabia vs. Shia Iran), competition for regional influence, and divergent geopolitical alignments. This has manifested in proxy conflicts in Yemen, Syria, and Lebanon. In 2016, diplomatic ties were severed after the Saudi embassy in Tehran was attacked following Saudi Arabia's execution of a prominent Shia cleric. However, in March 2023, the two countries agreed to restore diplomatic relations in a deal brokered by China.

- Neighboring Arab States: Saudi Arabia plays a leading role in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and seeks to maintain influence among Arab nations. It has complex relationships with its neighbors, supporting some monarchies while engaging in disputes with others, such as the diplomatic crisis with Qatar (2017-2021). Its interventions in Bahrain to suppress pro-democracy protests and its leadership in the Yemeni conflict highlight its assertive regional posture.

7.3. Role in International Organizations

Saudi Arabia is a founding member of the United Nations (UN), the Arab League, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), and the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). It is also a member of the G20 major economies and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC).

- Within OPEC, Saudi Arabia is the de facto leader, wielding significant influence over global oil production levels and prices.

- In the OIC and the Arab League, it often takes a leading role on issues concerning the Muslim and Arab worlds, respectively, though its positions are sometimes contested.

- As a GCC member, it works towards economic and security cooperation among Gulf monarchies.

- In the UN, it participates in various forums but has faced criticism for its human rights record and its actions in regional conflicts. It is also a dialogue partner of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation.

7.4. International Scrutiny and Controversies

Saudi Arabia has faced significant international criticism and controversy on several fronts:

- Allegations of Sponsoring Terrorism: The kingdom has been accused of directly or indirectly supporting extremist Islamist groups and promoting a Wahhabi ideology that has inspired terrorist organizations. While the Saudi government officially denounces terrorism and has been a partner in counter-terrorism efforts, its past funding of religious institutions and groups worldwide has been linked to the spread of radicalism. The Saudi government denies these allegations.

- Intervention in the Yemeni Civil War: Since 2015, Saudi Arabia has led a military coalition intervening in Yemen against Houthi rebels. This intervention has resulted in a severe humanitarian crisis, with widespread civilian casualties, famine, and displacement. The coalition's airstrikes have been criticized for hitting civilian targets, and the humanitarian impact has drawn condemnation from international organizations and activists. The Saudi government states its intervention is at the request of the internationally recognized Yemeni government and aims to restore stability.

- Human Rights Record: As detailed in the Human Rights section, issues such as the lack of political freedoms, severe restrictions on women's rights, use of the death penalty, suppression of dissent (including the assassination of Jamal Khashoggi), and treatment of minorities and migrant workers continuously place Saudi Arabia under international scrutiny.

These controversies have led to calls for arms embargoes, sanctions, and greater accountability from the international community, impacting Saudi Arabia's global standing despite its economic and political influence.

8. Military

The Saudi Arabian Armed Forces are responsible for the defense of Saudi Arabia. They fall under the Ministry of Defence and consist of several branches: the Royal Saudi Land Forces (which includes the Royal Guard Regiment), the Royal Saudi Air Force, the Royal Saudi Navy, the Royal Saudi Air Defense Forces, and the Royal Saudi Strategic Missile Force. Additionally, the Saudi Arabian National Guard (SANG), under the separate Ministry of National Guard, is a key component, historically composed of tribal forces loyal to the House of Saud and tasked with both internal security and national defense. Paramilitary forces, including the Border Guard and the Facilities Security Force, operate under the Ministry of Interior, while the Presidency of State Security includes the Special Security Force and the Emergency Force. As of 2023, there are approximately 127,000 active personnel in the Armed Forces, 130,000 in the National Guard, and 24,500 in paramilitary security forces.

Saudi Arabia maintains one of the highest military expenditures in the world, spending around 7% of its GDP on its military. According to the 2023 Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) estimate, it is the world's fifth-largest military spender and was the world's second-largest arms importer from 2019 to 2023, receiving 15% of all U.S. arms exports. Spending on defense and security has increased significantly since the mid-1990s, reaching about 78.40 B USD as of 2019. This modern, high-technology arsenal makes Saudi Arabia among the world's most densely armed nations.

The kingdom has significant security relationships with key allies, primarily the United States, the United Kingdom, and France, which provide advanced weaponry, training, and logistical support. There has also been a long-standing military relationship with Pakistan, leading to speculation about Saudi Arabia secretly funding Pakistan's nuclear program and potentially seeking to acquire atomic weapons from Pakistan in the future.

The Saudi military has been actively involved in regional conflicts, most notably leading a coalition in the Yemeni Civil War since March 2015. This intervention has involved deploying a large number of troops, fighter jets, an aerial bombing campaign, and a naval blockade aimed at Houthi forces. Despite capturing some territory, the conflict has been protracted and resulted in a severe humanitarian crisis, with Houthi forces launching cross-border attacks into Saudi Arabia. The military's performance and the conduct of the war have faced international scrutiny.

9. Economy

The Saudi Arabian economy is the largest in the Middle East and the 18th largest globally by nominal GDP. It is heavily reliant on its vast oil and natural gas resources, though significant efforts are underway for economic diversification. This section covers the dominant role of oil, the strategic economic development plans like Saudi Vision 2030, key non-oil sectors, and the critical area of water supply and sanitation, with consideration for social equity and labor implications.

9.1. Oil and Natural Resources

Saudi Arabia holds the world's second-largest proven oil reserves and is the third-largest oil producer and the leading oil exporter. The petroleum industry accounts for roughly 63% of budget revenue, 67% of export earnings, and about 45% of nominal GDP. The state-owned Saudi Aramco is the world's most valuable company by market capitalization and plays a central role in the national economy. The country also possesses the sixth-largest proven natural gas reserves. Saudi Arabia is considered an "energy superpower", with its total estimated value of natural resources valued at 34.40 T USD in 2016.

The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), of which Saudi Arabia is a founding and leading member, influences global oil production and prices. Saudi Arabia's oil policy has generally aimed to stabilize the world oil market, although it has also used oil as a political tool, such as during the 1973 oil crisis. Despite consistent production, concerns about peak oil and the long-term sustainability of its reserves have been raised. Besides oil and gas, Saudi Arabia has a significant gold mining sector in the Mahd adh Dhahab region and other mineral resources.

9.2. Economic Development and Diversification (Saudi Vision 2030)

Saudi Vision 2030 is a strategic framework launched in 2016 by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman to reduce Saudi Arabia's dependence on oil, diversify its economy, and develop public service sectors such as health, education, infrastructure, recreation, and tourism. Key goals include increasing non-oil government revenue, boosting private sector participation, and creating jobs for Saudi nationals under the "Saudization" program.

Major projects under Vision 2030 include the development of NEOM (a futuristic mega-city), the Red Sea Project (a luxury tourism destination), and Qiddiya (an entertainment city). The plan also involves privatizing state-owned assets, including a partial IPO of Saudi Aramco, and establishing large investment funds like the Public Investment Fund (PIF) to drive domestic and international investments.

Challenges to implementing Vision 2030 include attracting sufficient foreign investment, developing a skilled domestic workforce, overcoming bureaucratic hurdles, and managing the social impact of rapid changes. From a social equity perspective, concerns exist about whether the benefits of these developments will be broadly shared and whether labor rights, particularly for the large expatriate workforce, will be adequately protected during this transition. The plan's success is critical for Saudi Arabia's long-term economic stability and social progress. The COVID-19 pandemic and fluctuating oil prices have presented additional challenges to its implementation.

9.3. Key Sectors

Beyond the dominant oil and gas sector, Saudi Arabia is working to develop other key economic sectors:

- Agriculture: Despite its arid climate, Saudi Arabia has invested heavily in agriculture, particularly in the southwest. It is self-sufficient in several foodstuffs like meat, milk, and eggs, and exports dates, dairy products, and some fruits and vegetables. However, due to water scarcity concerns, domestic production of water-intensive crops like wheat has been phased out. The focus is shifting towards sustainable agricultural practices.

- Tourism: Historically, tourism was primarily religious, centered on the Hajj and Umrah pilgrimages to Mecca and Medina, which attract millions annually. Under Vision 2030, leisure tourism is being aggressively developed. This includes new resorts, entertainment venues, and easing visa restrictions for international tourists. The aim is to make tourism a significant contributor to GDP and job creation.

- Finance: The financial sector is well-established, with a robust banking system and a growing stock market (Tadawul). Efforts are underway to position Riyadh as a regional financial hub, attracting international financial institutions and investments.

- Manufacturing: The manufacturing sector, particularly petrochemicals, is a key area for diversification. Investments are being made in downstream industries, mining, and other manufacturing capabilities to reduce reliance on raw material exports and create value-added products.

- Renewable Energy: As part of its sustainability goals, Saudi Arabia is investing in renewable energy sources like solar and wind power, aiming to reduce domestic oil consumption for power generation and become a player in clean energy technologies.

Efforts towards sustainable development and environmental protection are increasingly being integrated into these sectors, though balancing rapid economic growth with environmental concerns remains a challenge.

9.4. Water Supply and Sanitation

Water supply and sanitation are critical infrastructure areas in Saudi Arabia due to extreme water scarcity. The country has made substantial investments in:

- Desalination: Saudi Arabia is the world's largest producer of desalinated water, which provides approximately 50% of its drinking water. Major desalination plants are located along the Red Sea and Persian Gulf coasts. The capital, Riyadh, receives desalinated water pumped over long distances.

- Groundwater: About 40% of drinking water comes from non-renewable groundwater sources. Over-extraction for agriculture in the past led to severe depletion of aquifers, prompting policy changes.

- Surface Water: Around 10% of water comes from surface sources, mainly in the mountainous southwest.

- Water Distribution and Wastewater Treatment: Significant investments have been made in water distribution networks to supply cities and industries. Wastewater treatment and reuse for non-potable purposes (like irrigation and industrial cooling) are also being expanded to conserve fresh water resources.

The economic aspects involve high capital and operational costs for desalination plants, which are energy-intensive. The government heavily subsidizes water for consumers, though there have been moves towards tariff reforms to encourage conservation. Ensuring a sustainable and secure water supply is a major economic and strategic priority for the kingdom.

10. Society

Saudi Arabian society is characterized by its deeply rooted Islamic traditions, a young and rapidly growing population, and significant social transformations underway, particularly under Saudi Vision 2030. This section explores its demographics, languages, the pervasive role of religion, education and healthcare systems, and critical social issues like the status of women and the conditions of foreign workers, reflecting a center-left/social liberalism perspective on social impacts and human rights.

10.1. Demographics

Saudi Arabia's reported population was 32,175,224 as of 2022, making it the fourth most populous country in the Arab world. A significant characteristic is its high proportion of young people, with approximately half the population being under 25 years old. This youth bulge presents both opportunities and challenges for employment and social services.

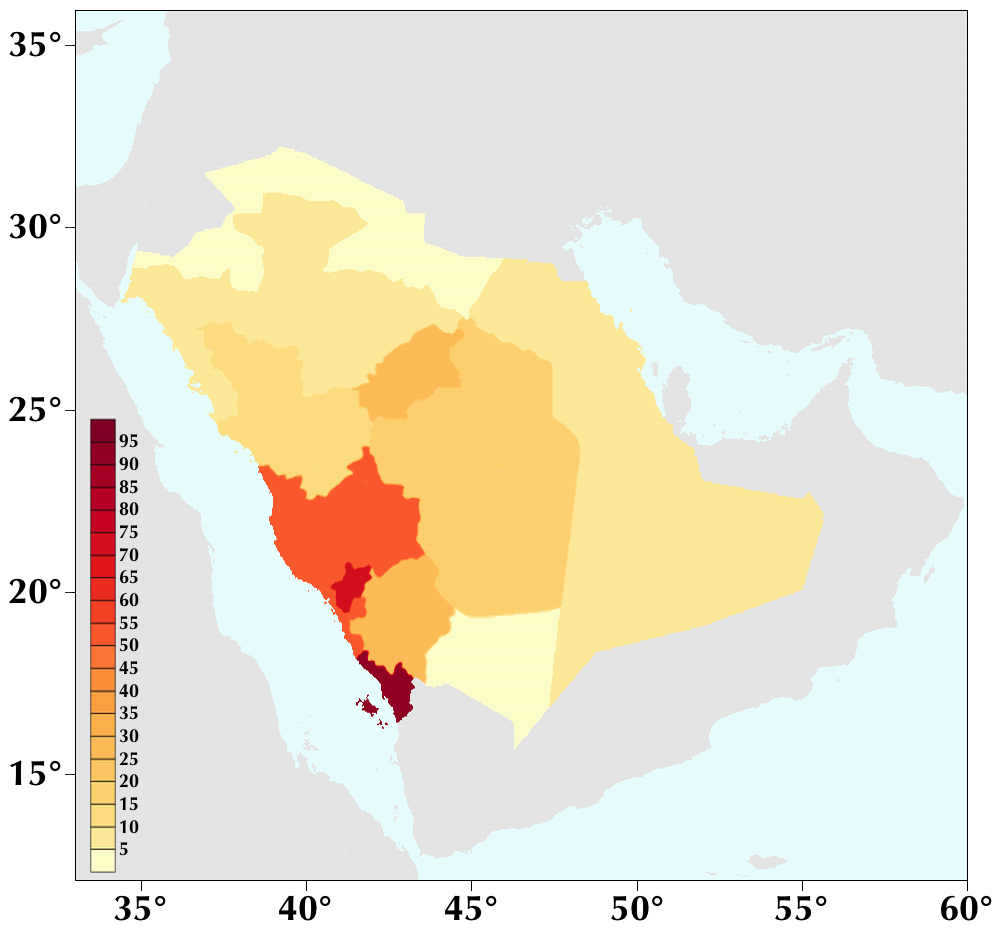

The population growth rate has been historically high, around 3% annually, though it has moderated to about 1.62% per year. The ethnic composition of Saudi citizens is predominantly Arab (90%), with a notable Afro-Arab population (10%). Most Saudis are concentrated in the southwest (Hejaz region, the most populated), Najd (central region), and the Eastern Province. Urbanization has been rapid, with about 85% of Saudis now living in urban metropolitan areas, primarily Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam.

A critical demographic feature is the large number of foreign workers, who constituted close to 42% of the total inhabitants in 2022. These expatriates, mostly from South Asia, Southeast Asia, other Middle Eastern countries, and Africa, are crucial to the economy but also raise complex social and labor issues.

10.2. Languages

The official language of Saudi Arabia is Arabic. The formal Modern Standard Arabic is used in government, education, and media. In daily life, Saudis speak various regional dialects of Arabic. The main dialect groups are:

- Najdi Arabic: Spoken in the central region, including Riyadh, by about 14.6 million speakers.

- Hejazi Arabic: Spoken in the western region (Hejaz), including Mecca, Medina, and Jeddah, by about 10.3 million speakers.

- Gulf Arabic: Spoken in the Eastern Province by about 0.96 million speakers, including Baharna dialects.

- Southern Hejaz and Tihama dialects.

Other indigenous languages include Faifi (spoken by about 50,000) and Mehri (spoken by around 20,000 Mehri citizens). Saudi Sign Language is used by the deaf community, estimated at around 100,000 speakers.

Due to the large expatriate population, numerous other languages are spoken, including Bengali (approx. 1.5 million), Tagalog (approx. 900,000), Punjabi (approx. 800,000), Urdu (approx. 740,000), Egyptian Arabic (approx. 600,000), Rohingya, North Levantine Arabic (both approx. 500,000), and Malayalam. English is widely understood and used in business and among educated Saudis.

10.3. Religion

Islam is the state religion of Saudi Arabia, and its laws and social customs are deeply rooted in Islamic teachings. Virtually all Saudi citizens are Muslim. Estimates suggest that 85-90% of the Saudi Muslim population are Sunni, while 10-15% are Shia. The official and dominant form of Sunni Islam is Salafism, commonly known in the West as Wahhabism, which was founded in the Arabian Peninsula by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab in the 18th century. This interpretation of Islam is characterized by its strict adherence to what it considers the original teachings of Islam and its rejection of practices it deems innovations or polytheistic.

The government actively promotes Wahhabism, and it influences all aspects of life, including the legal system, education, and public morality. The public practice of any religion other than Islam is prohibited. Non-Muslims, primarily foreign workers, are allowed to practice their religion in private, but they face severe restrictions and are vulnerable to discrimination and harassment. Building non-Muslim houses of worship (like churches or temples) is forbidden. Conversion from Islam (apostasy) is a crime punishable by death.

Shia Muslims, concentrated mainly in the Eastern Province (especially Qatif and Al-Ahsa) and in Najran (Ismailis), face systematic discrimination in employment, education, and the justice system. Their religious practices are often restricted, and they have been targets of sectarian rhetoric and violence.

There are an estimated 1.5 million Christians and about 390,000 Hindus in Saudi Arabia, almost all of whom are foreign workers. Atheists and agnostics exist but face severe repression, as atheism can be equated with terrorism under Saudi law. The U.S. State Department has designated Saudi Arabia as a "Country of Particular Concern" for systematic and egregious violations of religious freedom. Historically, the region of Najran was home to local Christian and Jewish communities, but these are no longer present.

10.4. Education

Education in Saudi Arabia is free at all levels for citizens, though higher education is generally restricted to them. The school system comprises elementary, intermediate, and secondary schools, with classes segregated by sex. At the secondary level, students can choose between general education, vocational/technical schools, or religious institutes. The literacy rate was 99% for males and 96% for females in 2020. Youth literacy (ages 15-24) is approximately 99.5% for both sexes.

Higher education has expanded rapidly, with numerous universities and colleges founded, particularly since 2000. Key institutions include King Saud University in Riyadh, the Islamic University in Medina, and King Abdulaziz University in Jeddah. Princess Nora bint Abdul Rahman University is the largest women's university in the world. A significant development was the founding of King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) in 2009, the first mixed-gender university campus in Saudi Arabia, focusing on graduate-level research. Curricula often emphasize sciences, technology, military studies, religion, and medicine, with Islamic studies institutes being particularly prominent.

Saudi universities have improved in international rankings. The Academic Ranking of World Universities (Shanghai Ranking) included five Saudi institutions in its 2022 top 500. The QS World University Rankings listed 14 Saudi universities among the world's top in 2022 and 23 among the top 100 in the Arab world. Saudi Arabia ranked 28th worldwide in high-quality research output in 2018 according to Nature. The country spends a significant portion of its GDP on education (8.8%, compared to a global average of 4.6%) and ranked 44th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.

The education system has faced criticism for encouraging religious extremism. Following 9/11, the government initiated the "Tatweer" reform program to modernize the system, moving away from rote memorization towards analytical and problem-solving skills, and aiming for more secular and vocational training. Recent efforts have included revising textbooks to remove antisemitic, sexist, and extremist content, a move welcomed by international observers.

10.5. Healthcare

Saudi Arabia has a national healthcare system where the government provides free healthcare services to its citizens through various agencies. The Ministry of Health, established in 1950 by merging regional health departments, is the primary provider of preventive, curative, and rehabilitative healthcare. The country has been ranked among the top 26 globally for high-quality healthcare. In 2016, the "Ada'a" project was launched as a nationwide performance indicator system for services and hospitals, leading to improvements in areas like waiting times.

To address lifestyle-related health issues, the Ministry developed the Diet and Physical Activity Strategy (DPAS), which included tax increases on unhealthy food, drinks, and cigarettes (implemented in 2017) and mandatory calorie labeling on some products from 2019. Women-only gyms were permitted to open in 2017 to encourage physical activity among women.

Smoking is widespread, with higher rates among males and elderly populations. Several Saudi cities (Unayzah, Riyadh Al Khabra, Ad Diriyah, Jalajil, Al-Jamoom, Al-Baha) have received "Healthy City" certificates from the World Health Organization (WHO) for their public health initiatives. In 2019, Saudi Arabia received a global award for its efforts in combating smoking, aiming to reduce tobacco use significantly by 2030.

Life expectancy in Saudi Arabia was 78 years (77 for males, 80 for females) in 2022. Infant mortality was 6 per 1,000 live births in 2022. Obesity is a major public health concern, with 71.8% of the adult population overweight and 40.6% obese in 2022.

10.6. Status and Rights of Women

The status and rights of women in Saudi Arabia have historically been severely restricted, based on a conservative interpretation of Islamic law and deeply entrenched patriarchal traditions. The male guardianship system (wali) has traditionally treated women as legal minors, requiring them to have a male guardian (typically a father, husband, brother, or uncle) for most significant life decisions.

In recent years, particularly under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, there have been notable reforms. Key changes include:

- Lifting the ban on women driving (June 2018).

- Amendments to the guardianship system (2019), allowing women over 21 to obtain passports, travel abroad, register marriages or divorces, and apply for official documents without a male guardian's permission. The new Personal Status Law (2022) also granted women more rights in divorce proceedings.

- Increased participation in the workforce: The female labor force participation rate has doubled, with women entering fields previously closed to them like law, engineering, and geology. There are now female newspaper editors, diplomats, TV anchors, and public prosecutors. A woman heads the Saudi stock exchange, and another sits on the board of Saudi Aramco.

- Easing of hijab (headscarf) and abaya (full-length robe) enforcement in public, with more women appearing without head coverings in major cities, though social pressure often remains.

Despite these reforms, significant limitations and challenges persist. Women still face discrimination in legal matters, particularly in family and inheritance law, where a woman's testimony may be valued less than a man's, and female heirs generally receive half the portion of male heirs. Polygyny is permitted for men. Domestic violence remains a concern, although an anti-domestic violence law was passed in 2014. Women activists who have campaigned for greater rights have faced arrest and imprisonment, indicating the limits of state-led reform and tolerance for independent activism.

The social impact of these changes is complex. While many women have welcomed new freedoms and opportunities, conservative segments of society may resist these shifts. The long-term effects on gender equality and women's full participation in society are yet to be fully realized, and international human rights organizations continue to call for deeper and more comprehensive reforms to dismantle systemic discrimination.

10.7. Foreign Workers

Saudi Arabia hosts a very large population of foreign workers, estimated to be around 33-42% of the total population. These migrants, predominantly from South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh), Southeast Asia (Philippines, Indonesia), other Middle Eastern countries (Egypt, Yemen), and Africa (Sudan, Ethiopia), are integral to the Saudi economy, filling roles in construction, domestic service, hospitality, retail, and other sectors.

A major concern is the Kafala (sponsorship) system, which legally binds migrant workers to their employers (kafeel). This system grants employers significant control over workers' legal status, ability to change jobs, or leave the country. It has been widely criticized by human rights organizations for facilitating exploitation and abuse, including:

- Labor Rights Issues: Common problems include wage withholding or non-payment, excessive working hours, confiscation of passports (though illegal, it still occurs), and poor living and working conditions.

- Human Trafficking: The Kafala system can create conditions conducive to forced labor and debt bondage. Workers, especially domestic helpers who are often isolated in private homes, are particularly vulnerable to physical, sexual, and psychological abuse with limited avenues for redress.

- Socio-economic Impact: While migrant labor is crucial for economic development, it also contributes to high unemployment rates among Saudi nationals in certain sectors. The government's "Saudization" policies aim to replace foreign workers with Saudi citizens, leading to periodic crackdowns on undocumented workers and mass expulsions. Since 2013, hundreds of thousands of undocumented migrants have been detained and deported, sometimes under harsh conditions.

In recent years, Saudi Arabia has introduced labor reforms aimed at improving conditions for migrant workers and modifying aspects of the Kafala system, such as allowing some workers to change employers or leave the country without their kafeel's permission under certain conditions. However, the effectiveness and full implementation of these reforms remain a subject of scrutiny. Saudi Arabia is not a signatory to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention. Foreigners generally cannot obtain permanent residency, though a specialized "Premium Residency" visa became available in 2019. Citizenship is typically granted only to Muslims, with Palestinians often excluded due to Arab League policies.

11. Culture

Saudi Arabian culture is deeply rooted in Islam and Arab traditions, shaped by its historical role as a trade center and the birthplace of Islam. The values of family, hospitality, and religious piety are central to Saudi life. However, the country is also undergoing significant social changes influenced by globalization, youth demographics, and government-led modernization efforts.

11.1. Lifestyle and Traditions

Daily life in Saudi Arabia is significantly influenced by Islamic law and practice. The five daily prayers (Salat) structure the day, with businesses often closing briefly during prayer times. Friday is the main day of congregational prayer and rest. Family is the cornerstone of Saudi society, with strong emphasis on kinship ties, respect for elders, and collective responsibility. Traditional gatherings and hospitality, often involving serving Arabic coffee and dates, are important customs.

Traditional clothing is common. Men typically wear an ankle-length white robe called a thawb and a head covering, either a ghutra (a white or checkered square cloth) held in place by an agal (a black cord). For formal occasions or in cooler weather, a bisht (a camel-hair cloak) may be worn over the thawb. Women traditionally wear a black, full-length cloak called an abaya in public and a hijab (headscarf). While enforcement of strict dress codes has eased in some urban areas recently, modesty remains a key societal expectation.

Saudi culinary culture features dishes like Kabsa (spiced rice with meat, often chicken or lamb), Mandi (meat and rice cooked in a tandoor-like pit), shawarma, and falafel. Dates, lamb, yogurt, and flatbreads are staples.

11.2. Arts and Entertainment