1. Overview

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately 249 mile (400 km) off the coast of East Africa across the Mozambique Channel. At 229 K mile2 (592.80 K km2), Madagascar is the world's second-largest island country (after Indonesia) and the fourth-largest island. The nation comprises the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Following the prehistoric breakup of the supercontinent Gondwana, Madagascar split from the Indian subcontinent around 88 million years ago, allowing native plants and animals to evolve in relative isolation. Consequently, Madagascar is a biodiversity hotspot; over 90% of its wildlife is found nowhere else on Earth.

The island was first settled by Austronesian peoples arriving on outrigger canoes from Borneo between 350 BC and 550 AD. They were joined around the 9th century AD by Bantu migrants crossing the Mozambique Channel from East Africa. Other groups continued to settle on Madagascar over time, each making lasting contributions to Malagasy cultural life. This diverse heritage has shaped a unique Malagasy identity, with a common Malagasy language of Malayo-Polynesian origin and shared traditional beliefs centered on a creator god and veneration of ancestors.

Madagascar's history includes a period of fragmented kingdoms before the rise of the Merina Kingdom in the 19th century, which unified much of the island. French colonization began in 1897, a period marked by economic exploitation and resistance, culminating in the Malagasy Uprising of 1947. Madagascar gained independence in 1960 and has since navigated four republics, characterized by political instability, popular protests, and challenges to democratic development and human rights. The capital and largest city is Antananarivo.

Despite rich natural resources and a burgeoning ecotourism sector, Madagascar remains one of the world's poorest countries, with a significant portion of its population living in poverty. The country faces ongoing struggles for democratic stability, social justice, and sustainable development, exacerbated by environmental degradation and vulnerability to climate change, including recent famines. This article explores Madagascar's multifaceted identity from a perspective that emphasizes its journey towards social justice, democratic progress, and the protection of human rights.

2. Etymology

In the Malagasy language, the island of Madagascar is called Madagasikara (MadagasikaramadaɡasʲˈkʲarəMalagasy) and its people are referred to as Malagasy. The origin of the name "Madagascar" is uncertain and is likely of foreign origin, having been popularized in the Middle Ages by Europeans. It is unknown when the name was adopted by the inhabitants of the island. No single Malagasy-language name predating Madagasikara appears to have been used by the local population to refer to the entire island, although some communities had their own names for parts or all of the lands they inhabited. The term TanindrazanaAncestral LandMalagasy is also a cherished epithet for the island.

One hypothesis suggests that "Madagascar" is a corrupted transliteration of Mogadishu (MuqdishoMakdishuSomali), the capital of Somalia and an important medieval Indian Ocean port. This theory posits that the 13th-century Venetian explorer Marco Polo confused the two locations in his memoirs, where he mentions a land called Madageiscar to the south of Socotra. This name would then have been popularized on Renaissance maps by Europeans. An early 17th-century book by Jerome Megiser (1609) offers a narrative where kings from Mogadishu and Adal invaded Madagascar. After a tempest threw them off course, they conquered the island and erected pillars engraved with "Magadoxo," which later corrupted into Madagascar. This account is supported by Dutch traveler Jan Huyghen van Linschoten, who noted that "Madagascar has its name from 'makdishu' (Mogadishu)" whose "shayk" (sheikh) invaded it.

Another hypothesis relates "Madagascar" to the word "Malay", referring to the Austronesian origin of the Malagasy people, who migrated from what is now Indonesia. A map by Muhammad al-Idrisi dating from 1154 names the island Gesira Malai, or "Malay island" in Arabic. The inversion of this name to Malai Gesira, as it was known by the Greeks, is thought to be a precursor to the modern name. This "Malay island" was later rendered in Latin as Malichu, an abbreviated form of Malai Insula, in the medieval Hereford Mappa Mundi. An 1882 edition of the British newspaper The Graphic also referred to "Malagascar" as being of Malay origin, possibly related to Malacca.

The name Malagasikara, or Malagasy, is also historically attested. A British state paper in 1699 records the arrival of passengers from "Malagaskar" to New York City. In 1891, Saleh bin Osman, a Zanzibari traveler, referred to the island as "Malagaskar". In 1905, Charles Basset wrote that Malagasikara was how the island was referred to by its natives, who emphasized they were Malagasy, not Madagasy.

3. History

Madagascar's history is characterized by waves of settlement from Southeast Asia and Africa, the rise and fall of indigenous kingdoms, French colonization, and a turbulent path to independence and democratic governance, all of which have profoundly shaped its society and the lives of its people.

3.1. Early Period and Settlement

Archaeologists traditionally estimate that the first Austronesian settlers arrived in successive waves in outrigger canoes, likely from South Borneo in present-day Indonesia, possibly between 350 BC and 550 AD. Other researchers are cautious about dates earlier than 250 AD. These dates make Madagascar one of the most recent major landmasses on Earth to be settled by humans, predating the settlement of Iceland and New Zealand. It is proposed that Ma'anyan people were brought as laborers and slaves by Javan and Sumatran Malay traders. While dates of settlement earlier than the mid-first millennium AD are not strongly supported, scattered evidence for much earlier human visits exists. Archaeological finds, such as cut marks on bones found in the northwest (dated to around 2000 BCE) and stone tools in the northeast, suggest foragers visited the island much earlier. The oldest known settlement, a cave near Antsiranana, yielded charcoal dated to around 420 AD, though it may have been a temporary shelter for castaways. More definitive evidence of long-term settlement comes from Nosy Mangabe island, with pottery and signs of slash-and-burn agriculture dating to the 8th-9th centuries AD.

Upon arrival, early settlers practiced slash-and-burn agriculture (known locally as tavyslash-and-burnMalagasy) to clear coastal rainforests for cultivation. They encountered Madagascar's abundant megafauna, including 17 species of giant lemurs, large flightless elephant birds (such as Aepyornis maximus, possibly the largest bird ever to exist), the giant fossa (Cryptoprocta spelea), and several species of Malagasy hippopotamus. These animals subsequently became extinct due to hunting and habitat destruction. By 600 AD, groups of early settlers had begun clearing the forests of the central highlands.

Around the 9th or 10th century AD, Bantu-speaking migrants from East Africa arrived, crossing the Mozambique Channel. They introduced zebu cattle, which intermingled with existing Sanga cattle. Irrigated paddy fields were first developed in the central highland Betsileo kingdoms by the 17th century and were extended with terraced paddies throughout the neighboring Kingdom of Imerina a century later. The rising intensity of land cultivation and the demand for zebu pasturage largely transformed the central highlands from a forest ecosystem to grassland by the 17th century.

The oral histories of the Merina people, who arrived in the central highlands between 600 and 1,000 years ago, describe encountering an established population they called the Vazimba. The Vazimba were likely descendants of an earlier, less technologically advanced Austronesian settlement wave. They were assimilated or expelled from the highlands by Merina kings Andriamanelo, Ralambo, and Andrianjaka in the 16th and early 17th centuries. Today, the spirits of the Vazimba are revered as tompontanyancestral masters of the landMalagasy by many traditional Malagasy communities, though their historical reality remains a subject of debate.

3.2. Arab and European Contacts

The written history of Madagascar began with Arab traders, who established trading posts along the northwest coast by at least the 7th-9th centuries (some sources say 10th century). They introduced Islam, the Arabic script (used to transcribe the Malagasy language in a form of writing known as sorabe), Arab astrology, and other cultural elements.

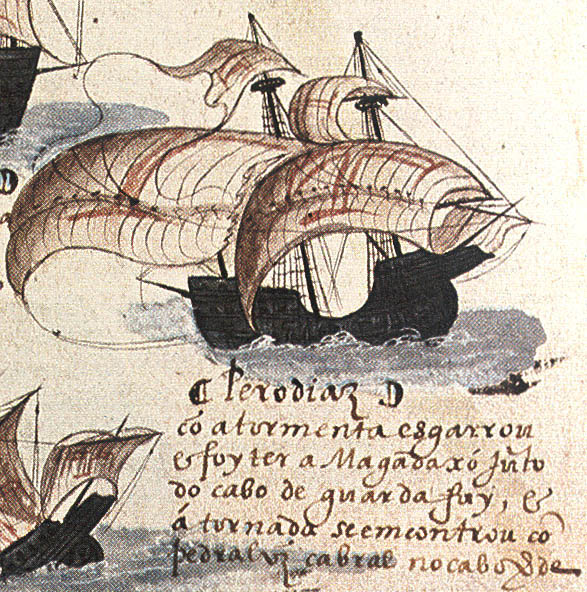

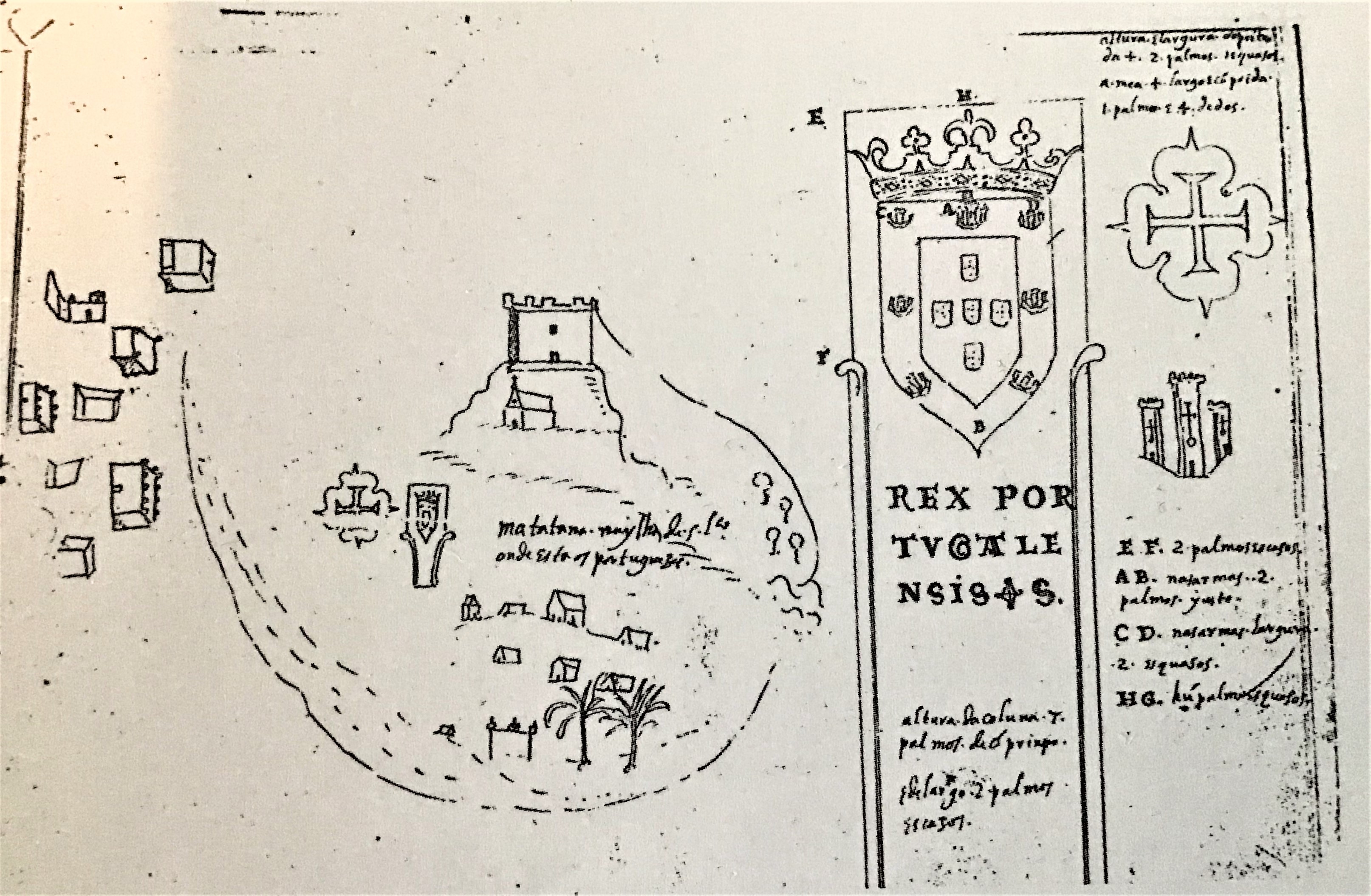

European contact began in 1500 when the Portuguese sea captain Diogo Dias sighted the island while participating in the 2nd Armada of the Portuguese India Armadas. Contacts with the Portuguese continued from the 1550s. Matatana was the first Portuguese settlement on the south coast, 6.2 mile (10 km) west of Fort Dauphin. In 1508, settlers there built a tower, a small village, and a stone column. This settlement was established in 1513 at the behest of Jerónimo de Azevedo, the viceroy of Portuguese India. Several colonization and conversion missions were ordered by King João III and the Viceroy of India, including one in 1553 by Baltazar Lobo de Sousa. Emissaries reportedly reached the inland via rivers, exchanged goods, and even converted a local king.

The French established trading posts along the east coast in the late 17th century. From about 1774 to 1824, Madagascar gained prominence among pirates and European traders, particularly those involved in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The small island of Nosy Boroha (Sainte Marie) off the northeastern coast of Madagascar has been proposed by some historians as the site of the legendary pirate utopia of Libertalia, possibly founded by Captain Misson or Henry Every. Many European sailors were shipwrecked on the coasts of the island; the journal of Robert Drury is one of the few written depictions of life in southern Madagascar during the 18th century. European accounts until the early 20th century sometimes identified Malagasy people as being of Jewish origin, a theory now largely dismissed.

The wealth generated by maritime trade spurred the rise of organized kingdoms on the island, some of which had grown quite powerful by the 17th century. Among these were the Betsimisaraka alliance of the eastern coast and the Sakalava chiefdoms of Menabe and Boina on the west coast. The Kingdom of Imerina, located in the central highlands with its capital at the royal palace of Antananarivo, emerged around the same time under King Andriamanelo.

3.3. Kingdom of Madagascar

Upon its emergence in the early 17th century, the highland kingdom of Imerina was initially a minor power relative to the larger coastal kingdoms like the Betsileo and Sakalava. It grew weaker in the early 18th century when King Andriamasinavalona divided it among his four sons. Following almost a century of internal conflict and famine, Imerina was reunited in 1793 by King Andrianampoinimerina (reigned 1787-1810). From his initial capital at Ambohimanga, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and later from the Rova in Antananarivo, Andrianampoinimerina rapidly expanded his rule over neighboring principalities.

His ambition to bring the entire island under his control was largely achieved by his son and successor, King Radama I (reigned 1810-1828). Radama I was recognized by the British government as "King of Madagascar." In 1817, he concluded a treaty with the British governor of Mauritius to abolish the lucrative slave trade in return for British military and financial assistance. This alliance was partly aimed at countering French influence. Artisan missionary envoys from the London Missionary Society (LMS) began arriving in 1818. Key figures like James Cameron, David Jones, and David Griffiths established schools, transcribed the Malagasy language using the Roman alphabet (replacing the earlier Sorabe script based on Arabic), translated the Bible, and introduced new technologies.

Radama I's successor, Queen Ranavalona I (reigned 1828-1861), responded to increasing political and cultural encroachment by Britain and France by issuing a royal edict prohibiting the practice of Christianity and pressuring most foreigners to leave. Her reign was marked by a strong assertion of Malagasy sovereignty and traditional values, but also by harsh measures. She utilized the traditional practice of fanompoana (forced labor as tax payment) for public works and to develop a standing army of 20,000-30,000 Merina soldiers, used to pacify outlying regions and expand the kingdom. The ordeal of tangena (a poison ordeal used in trials for crimes like witchcraft and Christianity) caused thousands of deaths annually; estimates suggest up to 100,000 deaths in Imerina alone by 1838, roughly 20% of its population. The combination of warfare, disease, forced labor, and harsh justice led to a high mortality rate, with the island's population estimated to have declined from around 5 million to 2.5 million between 1833 and 1839. Despite these internal pressures, some foreigners like Jean Laborde, an entrepreneur who developed munitions and industries, and Joseph-François Lambert, a French adventurer and slave trader, remained. Lambert controversially signed the Lambert Charter with the future Radama II.

Succeeding his mother, Radama II (reigned 1861-1863) attempted to relax the queen's stringent policies but was overthrown and assassinated two years later by Prime Minister Rainivoninahitriniony and an alliance of Andriana (noble) and Hova (commoner) courtiers, who sought to end the absolute power of the monarch. This coup marked a significant shift, establishing a constitutional monarchy where power was shared between the monarch and the Hova elite, particularly the Prime Minister.

Following the coup, the courtiers offered Radama's queen, Rasoherina (reigned 1863-1868), the opportunity to rule if she accepted a power-sharing arrangement with the Prime Minister, sealed by a political marriage. Queen Rasoherina accepted, first marrying Rainivoninahitriniony, then later deposing him and marrying his brother, Prime Minister Rainilaiarivony. Rainilaiarivony would remain Prime Minister for 31 years (1864-1895), successively marrying Queen Rasoherina, Queen Ranavalona II (reigned 1868-1883), and Queen Ranavalona III (reigned 1883-1897).

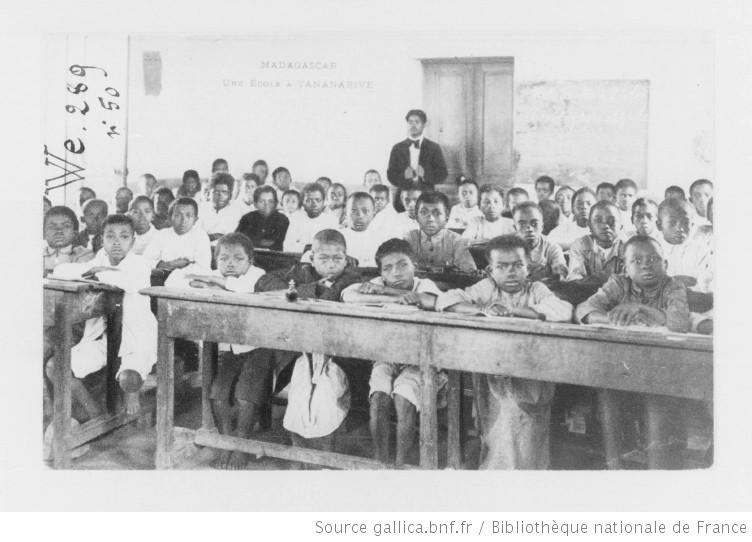

Under Rainilaiarivony, numerous policies were adopted to modernize and consolidate the power of the central government. Schools were constructed throughout the island, and attendance was made mandatory. The army was improved with British consultants. Polygamy was outlawed, and Christianity, declared the official religion of the court in 1869 (during Ranavalona II's reign), was adopted alongside traditional beliefs by a growing portion of the populace. Legal codes were reformed based on British common law, and three European-style courts were established in Antananarivo. Rainilaiarivony also successfully ensured the defense of Madagascar against several French colonial incursions.

3.4. French Colonization (1897-1960)

Primarily citing the non-respect of the Lambert Charter and seeking to expand its colonial empire, France invaded Madagascar in 1883, initiating the first Franco-Hova War (1883-1885). At the war's end, Madagascar ceded the northern port town of Antsiranana (Diego Suarez) to France and paid 560.00 K FRF to Lambert's heirs. In 1890, Britain, in exchange for recognition of its protectorate over Zanzibar, formally accepted the imposition of a French protectorate over Madagascar, but this was not acknowledged by the Malagasy government. To force capitulation, the French launched a second military expedition in 1895. They bombarded and occupied the harbor of Toamasina on the east coast and Mahajanga on the west coast in December 1894 and January 1895, respectively.

A French military flying column then marched towards Antananarivo, losing many men to malaria and other diseases rather than to Malagasy resistance. Reinforcements arrived from Algeria and Sub-Saharan Africa. Upon reaching the city in September 1895, the column bombarded the royal palace (Rova) with heavy artillery, causing heavy casualties and leading Queen Ranavalona III to surrender. France annexed Madagascar in 1896 and declared the island a colony the following year, dissolving the Merina monarchy and sending the royal family into exile, first to Réunion and then to Algeria.

Popular resistance to French rule, known as the Menalamba rebellion ("Red Shawls" rebellion), broke out in December 1895, primarily among rural populations and disaffected Merina officials. It was a widespread guerrilla war that was not fully suppressed until 1897, with some accounts suggesting pockets of resistance continued for over a decade. The French "pacification" campaign was brutal, resulting in tens of thousands of Malagasy deaths, significantly impacting the population and sowing deep resentment against colonial rule.

Under colonial rule, plantations were established for export crops like coffee, vanilla, and cloves, often using forced labor. Slavery was abolished in 1896, freeing approximately 500,000 slaves. However, many remained in subservient positions as servants or sharecroppers, and discriminatory views against slave descendants persist in some parts of the island today. Antananarivo was modernized with wide paved boulevards, and the Rova palace compound was turned into a museum. Schools were built, particularly in rural and coastal areas, with education focusing on the French language and practical skills, and attendance made mandatory for ages 6 to 13. This education system aimed to create a compliant workforce and assimilate the Malagasy into French culture, though access and quality remained uneven.

Large mining (especially graphite) and forestry concessions were granted to French companies, and loyal local chiefs were given land. Forced labor, under systems like SMOTIG (Service de la Main-d'Œuvre des Travaux d'Intérêt Général), was extensively used for public works, including constructing railways and roads linking key coastal cities to Antananarivo. Peasants were encouraged through taxation to work for wages in colonial concessions, often to the detriment of their own small farms.

Despite the oppressive colonial regime, nationalist movements continued. The early 20th century saw the Vy Vato Sakelika (VVS) secret society. In 1927, major demonstrations occurred in Antananarivo, partly led by communist activist François Vittori. The 1930s saw the Malagasy anti-colonial movement gain further momentum, with the emergence of trade unionism and the formation of the Communist Party of the Madagascar region. These organizations were dissolved by the Vichy-aligned colonial administration in 1939.

Malagasy troops fought for France in World War I. During the 1930s, Nazi political thinkers in Germany developed the Madagascar Plan, which considered the island a potential site for the deportation of Europe's Jews, though this plan was never implemented. During World War II, the island was the site of the Battle of Madagascar (1942) between the Vichy French administration and an Allied expeditionary force, primarily British, who sought to prevent Japan from using the island as a naval base.

The occupation of France during World War II tarnished the prestige of the colonial administration and galvanized the growing independence movement, leading to the Malagasy Uprising of 1947. This nationalist revolt, led mainly by the Mouvement démocratique de la rénovation malgache (MDRM), was brutally suppressed by the French military. Estimates of Malagasy deaths range from 11,000 to over 90,000, marking one of the darkest chapters of French colonial history and deeply impacting the Malagasy struggle for self-determination. The repression further fueled anti-colonial sentiment and demands for human rights.

The uprising led France to establish reformed institutions in 1956 under the Loi Cadre (Overseas Reform Act), and Madagascar moved peacefully towards independence. The Malagasy Republic was proclaimed on October 14, 1958, as an autonomous state within the French Community. A period of provisional government ended with the adoption of a constitution in 1959 and full independence on June 26, 1960.

3.5. Independent State (1960-present)

Madagascar's journey since independence has been marked by cyclical political crises, military interventions, and persistent economic challenges, hindering sustained democratic development and improvements in human rights.

3.5.1. First Republic (1960-1972)

The First Republic (1960-1972), under the leadership of French-appointed President Philibert Tsiranana, was characterized by a continuation of strong economic, political, and military ties to France. Many high-level technical positions remained filled by French expatriates, and French educational systems persisted. Tsiranana, a coastal Tsimihety, initially enjoyed broad support, but his administration faced growing criticism for its neo-colonial arrangements, perceived corruption, and increasingly authoritarian tendencies. Popular resentment, particularly from students and urban workers in Antananarivo (many of Merina ethnicity), culminated in a series of farmer and student protests (the "Malagasy May") in 1972. These protests, fueled by social inequalities and demands for greater national sovereignty and cultural authenticity (malgachization), led to Tsiranana handing over power to the military under General Gabriel Ramanantsoa.

3.5.2. Second Republic (1975-1992)

General Ramanantsoa was appointed interim president and prime minister in 1972. His military government attempted "malgachization" policies but struggled with low public approval and internal divisions, leading to his resignation in 1975. Colonel Richard Ratsimandrava, appointed to succeed him, was assassinated just six days into his tenure, plunging the country into further instability. General Gilles Andriamahazo ruled briefly before Vice Admiral Didier Ratsiraka seized power, ushering in the Marxist-Leninist Second Republic (1975-1992).

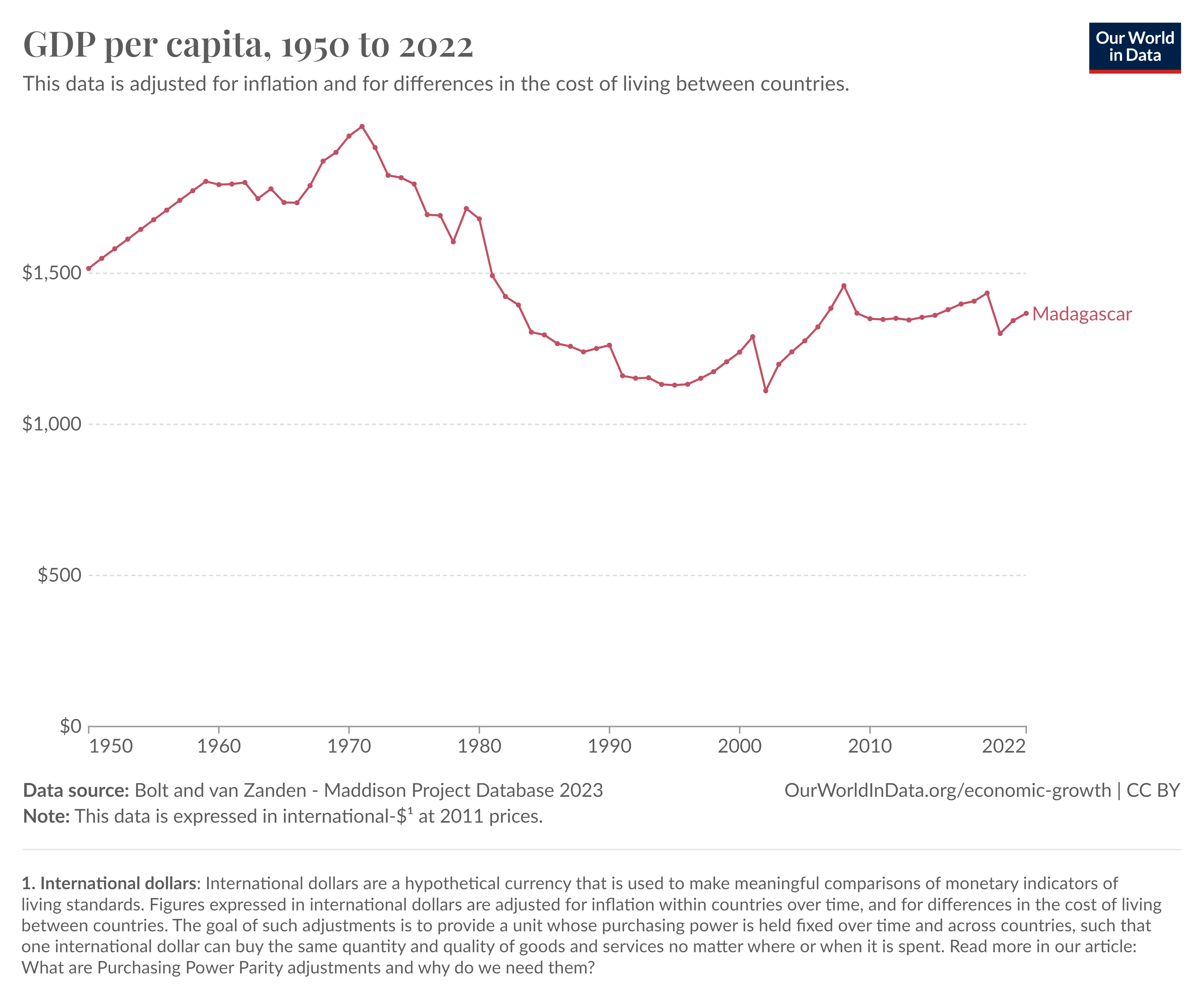

Ratsiraka's regime implemented widespread nationalization of industries and financial institutions, severed close ties with France, and aligned with the Eastern Bloc. This period saw economic insularity, with policies like withdrawing from the CFA Franc zone. These policies, coupled with economic pressures from the 1973 oil crisis and mismanagement, resulted in the rapid collapse of Madagascar's economy, a sharp decline in living standards, and widespread shortages. By 1979, the country was effectively bankrupt. Facing severe economic hardship and social unrest, the Ratsiraka administration was forced to accept structural adjustment programs imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, which included conditions of transparency, anti-corruption measures, and a shift towards free-market policies. These reforms, however, did little to alleviate poverty or restore democratic freedoms immediately.

3.5.3. Third Republic (1992-2010)

Ratsiraka's dwindling popularity in the late 1980s, fueled by economic hardship and lack of political freedom, reached a critical point in 1991 when presidential guards opened fire on unarmed protesters during a rally, killing several. This event, known as the "Iavoloha massacre," forced Ratsiraka to concede to a transitional government. This transition led to a new constitution and multi-party elections.

Albert Zafy won the 1992 presidential elections, inaugurating the Third Republic (1992-2010). The new constitution established a multi-party democracy and a separation of powers that placed significant control in the hands of the National Assembly, emphasizing human rights, social and political freedoms, and free trade. Zafy's term (1993-1996), however, was marred by economic decline, allegations of corruption, and his attempts to consolidate personal power. He was consequently impeached in 1996. Norbert Ratsirahonana served as interim president prior to the next election.

Surprisingly, Didier Ratsiraka was voted back into power in the 1996 elections on a platform of decentralization and economic reforms. His second term lasted from 1997 to 2001.

The 2001 presidential elections were highly contested. The then-mayor of Antananarivo, Marc Ravalomanana, claimed victory, but Ratsiraka refused to concede, leading to a seven-month standoff in 2002 that split the country, with rival governments and significant economic disruption. Ravalomanana eventually prevailed. His presidency (2002-2009) initially saw progressive economic and political policies, with investments in education and ecotourism, facilitation of foreign direct investment, and cultivation of trading partnerships. National GDP grew at an average rate of 7% per year. However, in the latter half of his second term, Ravalomanana faced criticism from domestic and international observers who accused him of increasing authoritarianism, corruption (including controversial land deals like the Daewoo project, which aimed to lease vast tracts of arable land for agribusiness, sparking public outcry over land rights and food security), and insensitivity to the needs of the population.

3.5.4. Fourth Republic and Contemporary Era (2010-present)

Opposition leader and then-mayor of Antananarivo, Andry Rajoelina, led a movement in early 2009 in which Ravalomanana was pushed from power in an unconstitutional process widely condemned as a coup d'état. In March 2009, Rajoelina was declared by the Supreme Court as the President of the High Transitional Authority (HAT), an interim governing body responsible for moving the country toward new elections. This period was marked by international condemnation, suspension from organizations like the African Union and SADC, and a significant decline in foreign aid and investment, worsening the already precarious socio-economic situation.

In 2010, a new constitution was adopted by referendum, establishing a Fourth Republic, which ostensibly sustained the democratic, multi-party structure. After a protracted transition, Hery Rajaonarimampianina was declared the winner of the 2013 presidential election, which the international community deemed relatively fair and transparent, leading to the restoration of constitutional governance in January 2014 and Madagascar's readmission to international bodies.

However, political stability remained elusive. The 2018 presidential election saw Andry Rajoelina return to power after a runoff against Marc Ravalomanana. Rajaonarimampianina was eliminated in the first round. Ravalomanana contested the results, alleging fraud. In June 2019, Rajoelina's party secured an absolute majority in parliamentary elections, consolidating his power.

The country has continued to face significant challenges. Mid-2021 marked the beginning of the 2021-2022 famine in the south, primarily attributed to severe drought exacerbated by climate change, though poverty and governance issues were also contributing factors. This humanitarian crisis saw hundreds of thousands facing acute food insecurity and over a million on the verge of famine, highlighting the extreme vulnerability of parts of the population and the urgent need for social safety nets and climate adaptation measures. The government's response was criticized for being slow and insufficient, relying heavily on international aid.

In November 2023, Rajoelina was re-elected in the first round of the presidential election amidst an opposition boycott and controversy surrounding his acquisition of French citizenship and eligibility. Turnout was the lowest in the country's history at 46.36%, reflecting widespread disillusionment and ongoing concerns about democratic processes, governance, and the persistent struggle for economic development and human rights.

4. Geography

Madagascar is an island nation located in the Indian Ocean, off the southeastern coast of Africa, separated from the continent by the Mozambique Channel. With an area of 229 K mile2 (592.80 K km2), it is the world's fourth-largest island and the second-largest island country. Its extensive landmass and long period of geological isolation have resulted in unique geographical features and a distinct ecological profile.

4.1. Topography and Geology

Madagascar's geological origins trace back to the breakup of the supercontinent Gondwana. It separated from Africa during the Early Jurassic period, around 180 million years ago, and from the Indian subcontinent approximately 84-92 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous period. This long isolation is key to its unique biodiversity. Geologically, Madagascar is an old landmass, similar to Australia, characterized by ancient crystalline basement rocks and, in some areas, rich mineral deposits due to the lack of recent large-scale volcanic activity, although some volcanic features like the Ankaratra Massif exist. Much of the soil, particularly in the highlands, is lateritic, giving it a characteristic red color.

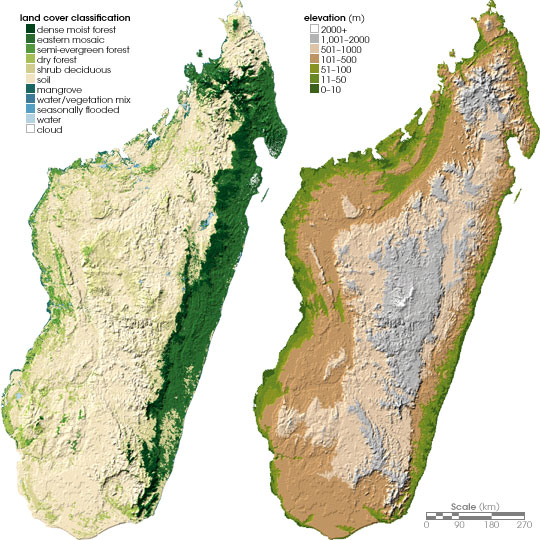

The island's topography is diverse. A central spine of highlands, known as the Central Highlands or Hauts Plateaux, runs north-south, with average altitudes between 2461 ft (750 m) and 4.9 K ft (1.50 K m). This region, traditionally the homeland of the Merina people and site of the capital, Antananarivo, is characterized by terraced rice paddies, rolling hills, and remnants of subhumid forests.

To the east of the highlands, a steep escarpment drops sharply to a narrow coastal plain, home to much of the island's remaining tropical rainforests. The western side of the highlands slopes more gently towards the Mozambique Channel, forming broader plains that become progressively drier towards the west and south. The coastline features numerous bays and natural harbors, though some, particularly on the west coast, are affected by silting from rivers carrying eroded sediment.

Major mountain massifs include:

- The Tsaratanana Massif in the north, containing Maromokotro, the island's highest peak at 9.4 K ft (2.88 K m).

- The Andringitra Massif in the south-central region, with Pic Boby at 8.7 K ft (2.66 K m).

- The Ankaratra Massif, a volcanic range in the central highlands near Antananarivo, with Tsiafajavona reaching 8.7 K ft (2.64 K m).

The Canal des Pangalanes, a series of natural and artificial waterways, runs parallel to the east coast for about 373 mile (600 km), historically used for transportation.

4.2. Climate

Madagascar's climate is highly varied due to its topography and latitudinal extent. Generally, there is a hot, rainy season from November to April, and a cooler, dry season from May to October.

- Eastern Coast**: Receives the highest rainfall due to the southeastern trade winds encountering the escarpment. This region is characterized by tropical rainforests and is frequently hit by destructive tropical cyclones during the rainy season.

- Central Highlands**: Experiences a more temperate climate, cooler and drier than the coasts. Frost can occur at higher altitudes during the dry season.

- Western Plains**: Lie in the rain shadow of the highlands, resulting in a drier climate with dry deciduous forests.

- Southern and Southwestern Regions**: These are the driest parts of the island, with semi-arid to arid conditions supporting spiny forests and succulent woodlands. The extreme south can experience prolonged droughts.

Northwestern monsoons also influence rainfall patterns, particularly in the north and northwest during the rainy season. Tropical cyclones, forming in the Indian Ocean, regularly impact the island, causing significant damage to infrastructure, agriculture, loss of life, and exacerbating food insecurity for vulnerable populations. For example, Cyclone Gafilo in 2004 was one of the most intense, and more recently, Cyclone Batsirai in 2022 caused widespread devastation. Climate change is projected to increase the intensity of these cyclones and prolong droughts, posing severe adaptation challenges.

4.3. Biodiversity and Conservation

Madagascar is recognized as one of the world's 17 megadiverse countries and a top global biodiversity hotspot due to its exceptionally high concentration of endemic species - approximately 90% of its wildlife is found nowhere else on Earth. This unique biodiversity evolved due to the island's long geological isolation. Some ecologists refer to Madagascar as the "eighth continent" because of its distinctive ecology. The country hosts seven terrestrial ecoregions: Madagascar lowland forests, Madagascar subhumid forests, Madagascar dry deciduous forests, Madagascar ericoid thickets, Madagascar spiny forests, Madagascar succulent woodlands, and Madagascar mangroves.

4.3.1. Flora

thumb

Madagascar's flora is exceptionally rich and unique, with over 80% of its 14,883 vascular plant species being endemic, including five endemic plant families.

Key examples of endemic flora include:

- The entire family Didiereaceae (octopus trees), comprising four genera and 11 species, is restricted to the spiny forests of southwestern Madagascar.

- Four-fifths of the world's Pachypodium species (elephant's foot plants) are endemic to the island.

- Six of the world's nine baobab species are native only to Madagascar, with Adansonia grandidieri (Grandidier's baobab) forming the iconic "Avenue of the Baobabs."

- The traveler's palm (ravinalatraveler's treeMalagasy), though not a true palm, is highly iconic and featured in the national emblem. It is endemic to the eastern rainforests.

- Madagascar is home to around 170 palm species, three times as many as on mainland Africa, with 165 of them being endemic.

- There are over 860 orchid species, with three-fourths being endemic, including the famous comet orchid (Angraecum sesquipedale).

- Many native plants have medicinal significance. The Madagascar periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus) is the source of vinca alkaloids like vinblastine and vincristine, used in cancer treatment (e.g., Hodgkin lymphoma, leukemia).

4.3.2. Fauna

Madagascar's fauna is equally remarkable for its diversity and high endemism.

- Lemurs**: These strepsirrhine primates are Madagascar's flagship mammal group. In the absence of monkeys and other direct competitors, they diversified into over 100 species and subspecies, adapting to a wide range of habitats. As of 2012, 103 species were officially recognized, many discovered recently. Almost all lemur species are classified as rare, vulnerable, or endangered. At least 17 species of giant lemurs became extinct after human arrival.

- Other Mammals**: Other endemic mammals include the fossa (Cryptoprocta ferox), a cat-like carnivore and Madagascar's largest predator, various Malagasy mongooses, and tenrecs.

- Birds**: Over 300 bird species have been recorded, with over 60% being endemic, including four endemic bird families (e.g., mesites, ground-rollers) and 42 endemic genera. The extinct elephant birds (Aepyornis and Mullerornis) were giant flightless ratites.

- Reptiles and Amphibians**: Madagascar is home to about two-thirds of the world's chameleon species, including the smallest known chameleon, Brookesia nana. Over 90% of its more than 260 reptile species are endemic, including one endemic family. The island also has a high diversity of endemic frogs, but no native toads (until the recent problematic introduction of the Asian common toad).

- Fish**: Endemic freshwater fish include two families, 15 genera, and over 100 species.

- Invertebrates**: Endemism is extremely high among invertebrates. All 651 species of terrestrial snails are endemic, as are a majority of the island's butterflies, scarab beetles, lacewings, spiders, and dragonflies.

4.3.3. Environmental Issues and Conservation Efforts

Madagascar's unique biodiversity is severely threatened by human activity. Since human arrival around 2,350 years ago, Madagascar has lost more than 90% of its original forest cover.

- Deforestation**: The primary driver is tavyslash-and-burnMalagasy, a traditional slash-and-burn agricultural practice. While culturally significant and providing short-term agricultural benefits, its widespread use has led to extensive habitat loss. Other contributors include charcoal production (a primary fuel source), illegal logging (especially of precious woods like rosewood and ebony), and land clearing for cattle grazing and cash crops like coffee. It is estimated that about 40% of the original forest cover was lost between the 1950s and 2000.

- Soil Erosion**: Deforestation, particularly on steep slopes, has led to massive soil erosion, creating distinctive gully formations known as lavaka. This results in loss of arable land, siltation of rivers and coastal areas, and damage to infrastructure.

- Habitat Loss and Fragmentation**: This directly impacts endemic species, pushing many towards extinction. A 2023 study indicated that 120 of the 219 endemic mammal species are threatened.

- Overexploitation and Hunting**: Bushmeat hunting, particularly of lemurs and other wildlife, continues to be a threat, exacerbated by poverty and political instability.

- Invasive Species**: The introduction of non-native species poses a significant threat. The Asian common toad, discovered in 2014, is a major concern due to its potential to decimate native fauna, similar to the cane toad's impact in Australia.

- Climate Change**: Madagascar is highly vulnerable to climate change, which is expected to increase the frequency and intensity of droughts, cyclones, and alter habitats, further stressing biodiversity and human populations.

Conservation efforts are underway but face enormous challenges in balancing environmental protection with the socio-economic needs of a largely impoverished population.

- Protected Areas**: The government, often with international support, has established a network of protected areas, including national parks, strict nature reserves, and special reserves. In 2003, then-President Ravalomanana announced the "Durban Vision," aiming to triple the protected area to over 23 K mile2 (60.00 K km2) (10% of the land surface). As of 2011, these included 5 Strict Nature Reserves, 21 Wildlife Reserves, and 21 National Parks.

- World Heritage Sites**: The Rainforests of the Atsinanana, a serial World Heritage Site comprising six national parks (Marojejy, Masoala, Ranomafana, Zahamena, Andohahela, and Andringitra), was inscribed in 2007 for its exceptional biodiversity. However, it was placed on the List of World Heritage in Danger in 2010 due to illegal logging and poaching. The Tsingy de Bemaraha Strict Nature Reserve is another World Heritage site, known for its unique limestone karst formations.

- International Collaboration and NGOs**: Numerous international and local NGOs are involved in conservation research, community-based conservation projects, and efforts to combat illegal wildlife trade and deforestation.

- Challenges**: Enforcement of environmental laws is often weak due to limited resources, corruption, and political instability. The illicit harvesting of protected forests, especially for precious woods like rosewood (often smuggled to Asia), remains a critical problem, sometimes occurring even within national parks. The 2009 political crisis, for example, saw a dramatic intensification of illegal logging as state revenues from donor support were cut.

The struggle to conserve Madagascar's irreplaceable biodiversity is ongoing and critical for both the island's ecological integrity and the well-being of its people, many of whom depend directly on natural resources for their livelihoods.

5. Politics

Madagascar's political landscape has been characterized by recurrent instability, transitions between republics, and an ongoing struggle to consolidate democratic institutions and uphold human rights. The governance structure aims for a balance of power, but historical tensions and socio-economic pressures often complicate political developments.

5.1. Government Structure

Madagascar is a semi-presidential republic with a multi-party system. The constitution (currently the Fourth Republic's, adopted in 2010) outlines the structure of government:

- Executive Branch**:

- The President is the head of state, popularly elected for a five-year term, renewable once (though historical practice has varied). The President has significant powers, including appointing the Prime Minister, commanding the armed forces, and dissolving the National Assembly under certain conditions.

- The Prime Minister is the head of government, recommended by the majority party or coalition in the National Assembly and appointed by the President. The Prime Minister and the Cabinet (Council of Ministers) are responsible for implementing laws and managing the day-to-day affairs of the state.

- Legislative Branch**: The Parliament is bicameral:

- The National Assembly (AntenimierampirenenaNational AssemblyMalagasy) is the lower house, with 151 members directly elected for five-year terms through a mixed electoral system. It has the primary legislative power.

- The Senate (AntenimierandoholonaSenateMalagasy) is the upper house. Two-thirds of its members are elected by an electoral college composed of regional and communal officials, and one-third are appointed by the President, all for five-year terms (previously six). The Senate reviews legislation and has an advisory role.

- Judicial Branch**: The judicial system is largely based on French civil law. It includes:

- The High Constitutional Court (Haute Cour ConstitutionnelleHigh Constitutional CourtFrench), which reviews the constitutionality of laws and treaties and rules on electoral disputes.

- The Supreme Court (Cour SuprêmeSupreme CourtFrench), which is the highest court of appeal for civil, commercial, social, and criminal matters.

- Courts of Appeal.

- Tribunals of first instance and criminal tribunals.

- A High Court of Justice (Haute Cour de JusticeHigh Court of JusticeFrench), competent to try the President and other high officials for serious offenses, though its effective functioning has been limited.

The judiciary often faces challenges related to independence, resources, corruption, and lengthy pre-trial detentions in overcrowded prisons.

5.2. Political Developments and Recent Trends

Since independence in 1960, Madagascar has experienced a pattern of political instability, including:

- Popular protests leading to regime changes (e.g., 1972, 1991, 2009).

- Disputed elections (e.g., 2001).

- Coups d'état or unconstitutional transfers of power (e.g., the 2009 crisis leading to Andry Rajoelina's rise via the High Transitional Authority).

- Impeachments (e.g., President Albert Zafy in 1996).

These events have frequently disrupted democratic development, undermined the rule of law, negatively impacted the economy, and strained social cohesion. Historical tensions between the highland Merina elite, who dominated the 19th-century kingdom and often held key positions in post-independence administrations, and coastal populations (côtierscoastal dwellersFrench) have also been a recurring factor in political dynamics.

Recent trends include efforts to strengthen democratic institutions, but challenges persist with governance, corruption (Madagascar consistently ranks poorly on international corruption indices), and ensuring free and fair elections. The international community often plays a significant role in mediating crises and providing aid, which can be suspended during periods of unconstitutional governance. The 2013 and 2018 elections were closely watched, with hopes for greater stability, though the 2023 election saw an opposition boycott and low turnout, raising concerns about political polarization and democratic health.

5.3. Military and Law Enforcement

The Malagasy Armed Forces consist of the Army, Navy, and Air Force. Since independence in 1960, the military has primarily focused on internal security, disaster relief, and development projects. It has never engaged in armed conflict with another state but has played a significant and sometimes decisive role in domestic politics, including intervening during political crises (e.g., 1972, 2009). While often professing neutrality, factions within the military have at times supported particular political actors. Mandatory national service (armed or civil) was in effect under Didier Ratsiraka's Second Republic but was later abolished.

Law enforcement is primarily the responsibility of:

- The National Police (Police NationaleNational PoliceFrench), under the Ministry of Public Security, operating mainly in urban areas.

- The National Gendarmerie (Gendarmerie NationaleNational GendarmerieFrench), a paramilitary force under the Ministry of National Defense, responsible for policing rural areas and maintaining public order.

Both forces face challenges with resources, training, corruption, and public trust. Public safety is a concern, with rising crime rates in some areas, particularly petty crime, but also more serious issues like cattle rustling (dahalocattle rustlersMalagasy) in the south, which has become increasingly violent and organized. Traditional community justice systems (dina) still play a role in resolving disputes in some rural areas where state presence is weak, though their compatibility with formal law and human rights standards can be problematic.

5.4. Foreign Relations

Madagascar is a member of the United Nations, the African Union (AU), the Southern African Development Community (SADC), and the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie. Its membership in the AU and SADC has been suspended at times due to unconstitutional changes of government (e.g., after the 2009 crisis), underscoring the importance of democratic legitimacy in its regional engagements.

Key aspects of its foreign policy include:

- France**: Historically, France has been Madagascar's most significant international partner due to colonial ties. Relations cover economic, cultural, military, and political spheres, though Madagascar has also sought to diversify its partnerships. France remains a major aid donor and trading partner.

- African Nations**: Madagascar actively participates in African regional affairs through the AU and SADC, focusing on peace, security, and economic integration.

- Other Global Powers**: The country maintains diplomatic relations with numerous countries, including the United States, China, India, Japan, and European nations. China has become an increasingly important economic partner in terms of trade and investment.

- International Organizations**: Madagascar collaborates with various international organizations on development, humanitarian aid, and environmental protection.

Territorial disputes exist with France over several small islands in the Mozambique Channel and Indian Ocean, such as the Glorioso Islands, Juan de Nova Island, Europa Island, and Bassas da India, which France administers as part of the Scattered Islands in the Indian Ocean. Madagascar claims sovereignty over these islands.

5.5. United Nations Involvement

Madagascar became a member state of the United Nations (UN) on September 20, 1960, shortly after gaining independence. The country participates in various UN agencies and programs focused on development, poverty reduction, health, education, environmental sustainability, and human rights.

Key areas of UN involvement include:

- Development and Humanitarian Aid**: UN agencies such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, and World Health Organization (WHO) are active in Madagascar, providing critical support, especially during times of crisis like famines, cyclones, and disease outbreaks (e.g., plague, measles, COVID-19). The WFP, for instance, has run significant programs to address food insecurity, particularly in the drought-prone southern regions.

- Peacekeeping**: Madagascar has contributed personnel, including police officers, to UN peacekeeping missions, such as the UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH).

- International Treaties and Conventions**: Madagascar is a signatory to numerous UN treaties and conventions concerning human rights, environmental protection, disarmament (e.g., the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons), and international law. Adherence to and implementation of these treaties are often supported by UN bodies.

- Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)**: The UN supports Madagascar in its efforts to achieve the SDGs, working with the government and civil society on strategies to address poverty, inequality, climate change, and other development challenges.

The UN's role is often crucial in coordinating international responses to humanitarian crises and in supporting long-term development efforts in Madagascar.

5.6. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Madagascar is complex, with constitutional protections often challenged by practical realities and governance issues. The constitution guarantees fundamental rights and freedoms, and Madagascar is a party to major international human rights conventions. However, reports by organizations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the U.S. State Department frequently highlight concerns.

Key human rights challenges include:

- Freedom of Expression and Assembly**: While legally protected, these freedoms have faced restrictions, particularly during periods of political tension. Journalists have reported harassment and intimidation, and authorities have sometimes denied permits for opposition rallies or protests. Media self-censorship can occur due to political pressure or ownership patterns.

- Judicial System and Rule of Law**: The judiciary suffers from under-resourcing, corruption, and a backlog of cases, leading to prolonged pre-trial detention in overcrowded and unsanitary prisons. Access to justice can be difficult, especially for marginalized populations. Mob justice (fitsaram-bahoaka) occurs in some areas due to lack of faith in the formal justice system.

- Prison Conditions**: Prisons are often severely overcrowded, with poor sanitation, inadequate food, and limited medical care, leading to conditions that can amount to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.

- Corruption**: Widespread corruption remains a significant impediment to development and the effective protection of human rights, diverting public resources and undermining public trust in institutions. Anti-corruption bodies exist but have struggled to prosecute high-level officials effectively.

- Rights of Minorities and Vulnerable Groups**:

- Ethnic Minorities**: While overt ethnic conflict is not constant, historical tensions (e.g., highland vs. coastal) can surface, and minority groups may face discrimination.

- Women's Rights**: Women face discrimination in law and practice, particularly concerning inheritance and property rights. Gender-based violence is a serious issue.

- Children's Rights**: Child labor, particularly in agriculture and mining, child trafficking, and child prostitution remain concerns despite legal prohibitions. Access to education and healthcare for children is often limited by poverty.

- LGBT Rights**: Same-sex sexual activity is legal, but LGBT individuals may face social stigma and discrimination. There are no specific legal protections against discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity.

- Poverty and Socio-economic Rights**: Extreme poverty affects a large portion of the population, impacting access to adequate food, clean water, healthcare, and education, which are fundamental human rights. Recurrent famines in the south, often linked to climate change, have highlighted severe vulnerabilities.

- Security Force Abuses**: There have been reports of excessive force and abuses by security forces, particularly in operations against cattle rustlers (dahalo) in the south.

Civil society organizations and human rights defenders play a role in advocating for improvements, but often operate in challenging environments.

6. Administrative Divisions

Madagascar's administrative structure is hierarchical. As of a reform in 2004, which became fully effective after a 2007 referendum abolished the six historical provinces, the country is divided into 22 regions (faritraregionMalagasy). These regions are the highest level of sub-national administration.

The 22 regions are:

| Region | Former Province | Area (km2) | Population (2018 Census) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diana | Antsiranana | 19,993 | 889,962 |

| Sava | 23,794 | 1,123,772 | |

| Itasy | Antananarivo | 6,579 | 898,549 |

| Analamanga | 17,346 | 3,623,925 | |

| Vakinankaratra | 17,884 | 2,079,659 | |

| Bongolava | 18,096 | 670,993 | |

| Sofia | Mahajanga | 50,973 | 1,507,591 |

| Boeny | 31,250 | 929,312 | |

| Betsiboka | 28,964 | 393,278 | |

| Melaky | 40,863 | 308,944 | |

| Alaotra-Mangoro | Toamasina | 27,846 | 1,249,931 |

| Atsinanana | 22,031 | 1,478,472 | |

| Analanjirofo | 21,666 | 1,150,089 | |

| Amoron'i Mania | Fianarantsoa | 16,480 | 837,116 |

| Haute Matsiatra | 20,820 | 1,444,587 | |

| Vatovavy-Fitovinany | 20,740 | 1,440,657 | |

| Atsimo-Atsinanana | 16,632 | 1,030,404 | |

| Ihorombe | 26,046 | 418,520 | |

| Menabe | Toliara | 48,814 | 692,463 |

| Atsimo-Andrefana | 66,627 | 1,797,894 | |

| Androy | 18,949 | 900,235 | |

| Anosy | 29,505 | 809,051 | |

| Totals | 591,896 | 25,674,196 |

The regions are further subdivided into:

- 119 districts (formerly sub-prefectures)

- 1,579 communes (urban or rural)

- 17,485 fokontanyvillage/neighborhoodMalagasy (villages or neighborhoods), which are the smallest administrative units.

Major cities include the capital, Antananarivo (located in the Analamanga region), Toamasina (the main seaport, in Atsinanana), Antsirabe (in Vakinankaratra), Fianarantsoa (in Haute Matsiatra), Mahajanga (in Boeny), and Toliara (in Atsimo-Andrefana). These cities serve as important economic, administrative, and cultural centers for their respective regions. The administrative divisions are intended to facilitate decentralization and local governance, though the effectiveness of this varies.

7. Economy

Madagascar's economy is predominantly agricultural, with significant potential in tourism and mining. However, it faces substantial challenges including widespread poverty, political instability, infrastructural deficits, and vulnerability to climate change, all of which impact social justice and human development.

7.1. Economic History and Current State

Since independence in 1960, Madagascar's economic trajectory has been volatile. The First Republic maintained close economic ties with France. The Second Republic (1975-1992) under Didier Ratsiraka saw a period of socialist experimentation with widespread nationalizations and economic insularity. This, combined with the 1973 oil crisis, led to severe economic decline and near-bankruptcy by 1979, forcing the country to adopt IMF and World Bank-led structural adjustment programs and market-oriented reforms in the 1980s.

The transition to the Third Republic in the early 1990s brought further market liberalization. Marc Ravalomanana's presidency (2002-2009) initially saw significant economic growth, averaging 7% annually, driven by foreign investment and pro-business policies. However, the 2009 political crisis led to a sharp economic contraction, suspension of international aid, and loss of preferential trade access (like the US AGOA), severely impacting industries like textiles.

As of 2015, Madagascar's GDP was estimated at 9.98 B USD, with a per capita GDP of around 411.82 USD, making it one of the poorest countries in the world. Approximately 69% of the population lived below the national poverty line of one dollar per day. The UNDP reported in 2021 that 68.4% of the population was multidimensionally poor. Economic growth has been inconsistent, with an average of 2.6% between 2011-2015, picking up to 4.1% in 2016, but frequently disrupted by political events and external shocks like cyclones and droughts. Inflation remains a concern. The COVID-19 pandemic further strained the economy. As of January 2025, the World Food Programme reported that 1.31 million citizens faced high levels of food insecurity, and over 90% of its 28 million people lived on less than $3.10 per day.

7.2. Natural Resources, Agriculture, and Trade

Madagascar's economy is heavily reliant on its natural resource base.

- Agriculture**: This sector employed around 80% of the workforce and constituted about 24-29% of GDP in the early 2010s.

- Key export crops include vanilla (Madagascar is the world's leading producer, supplying about 80% of natural vanilla), cloves, ylang-ylang (for essential oils), coffee, cocoa, and lychees. The vanilla and clove markets are subject to price volatility.

- Staple food crops for domestic consumption are primarily rice (the main staple, with extensive terraced paddies in the highlands), cassava, sweet potatoes, and maize. However, Madagascar is often not self-sufficient in rice and requires imports.

- Issues in agriculture include low productivity, reliance on rain-fed cultivation, limited access to modern inputs and credit, and vulnerability to cyclones and droughts. Land tenure insecurity also affects investment.

- Fisheries and Forestry**: Fisheries, including shrimp and tuna, are important for export. Forestry resources are significant, but illegal logging of precious woods like rosewood and ebony poses a major environmental and economic challenge, often linked to corruption and weak governance. Raffia palm products are also a source of income.

- Mineral Resources**: Madagascar possesses a variety of mineral resources:

- Gemstones: It is a major producer of sapphires (discovered near Ilakaka in the late 1990s), rubies, and other precious and semi-precious stones. The gemstone sector often involves informal and unregulated mining, with concerns about labor conditions and revenue leakage.

- Industrial Minerals: Large reserves of ilmenite (titanium ore), nickel, cobalt, chromite, graphite, bauxite, and coal exist. Major mining projects, such as the Ambatovy nickel and cobalt mine and QIT Madagascar Minerals' (QMM, majority-owned by Rio Tinto) ilmenite operations, represent significant foreign investments.

- Trade**:

- Major exports: Vanilla, nickel, cloves, textiles (though impacted by AGOA suspensions), coffee, lychees, shrimp, cobalt.

- Major imports: Foodstuffs (especially rice), fuel, capital goods, vehicles, consumer goods, electronics.

- Primary trading partners: France, United States, China (increasingly significant), Germany, Japan, India, and other European and Asian countries.

- Trade deficits are common, and the country relies on external financing.

The exploitation of natural resources, while crucial for the economy, often raises concerns about environmental sustainability, equitable benefit-sharing with local communities, transparency in revenue management, and labor rights, particularly in the mining and forestry sectors.

7.3. Tourism

Tourism, particularly ecotourism, is a key sector with significant growth potential, leveraging the island's unique biodiversity, stunning landscapes, national parks, and distinct culture. Attractions include lemur viewing, birdwatching, diving, trekking, and beaches.

- Trends**: Tourist arrivals have fluctuated, heavily influenced by political stability and global events. For example, arrivals reached around 365,000 in 2008 but dropped significantly after the 2009 crisis. The sector saw recovery, with 293,000 tourists in 2016 (a 20% increase from 2015), and government targets aimed for 500,000 by 2018. The COVID-19 pandemic severely impacted the industry.

- Economic Contribution**: Tourism generates foreign exchange, creates employment (directly and indirectly), and can support local communities if managed sustainably.

- Challenges**: The sector is vulnerable to political instability, which deters visitors. Infrastructure limitations (roads, domestic air travel), health concerns, and the need for improved marketing and service standards are also challenges. Environmental concerns, such as deforestation impacting national parks, can also affect its long-term viability. Sustainable tourism practices that benefit local communities and contribute to conservation are crucial for the sector's future.

7.4. Extractive Industries

The extractive industries, encompassing mining, oil, and gas, are seen as a potential engine for economic growth in Madagascar, attracting significant foreign investment.

- Mining**:

- Major Projects**:

- The Ambatovy project (near Moramanga for mining, Toamasina for processing) is one of the largest industrial projects in Sub-Saharan Africa, focusing on nickel and cobalt extraction. It is a joint venture involving international companies like Sherritt International and Sumitomo Corporation.

- QIT Madagascar Minerals (QMM), majority-owned by Rio Tinto, operates a large-scale ilmenite (titanium dioxide) and zircon mining operation from mineral sands near Tôlanaro (Fort Dauphin) at the Mandena mine.

- Artisanal and Small-scale Mining (ASM)**: Significant ASM activity exists, particularly for gold and gemstones (sapphires, rubies). This sector provides livelihoods for many but is often informal, poorly regulated, and associated with environmental damage, unsafe labor conditions, child labor, and smuggling.

- Major Projects**:

- Oil and Gas**:

- Exploration for oil and gas has occurred both onshore and offshore. Madagascar Oil has been developing heavy oil deposits at Tsimiroro and Bemolanga. While significant reserves have been identified, commercial production has faced technical and financial challenges. Offshore exploration has also attracted international oil companies.

- Economic Benefits and Concerns**:

- Anticipated Benefits**: These industries are expected to generate substantial export revenues, fiscal income for the government, employment, and infrastructure development (e.g., ports, railways linked to mining projects).

- Concerns**:

- Revenue Transparency and Governance**: Ensuring that revenues from extractive industries are managed transparently and benefit the broader population is a major challenge (e.g., through initiatives like the EITI, which Madagascar has joined).

- Environmental Protection**: Large-scale mining and oil/gas operations can have significant environmental impacts, including habitat destruction, water pollution, and carbon emissions. Strong environmental impact assessments and mitigation measures are crucial.

- Community Impact**: Issues include land acquisition and resettlement of communities, distribution of benefits, and ensuring that local populations are not negatively impacted by industrial activities. Social license to operate is a key consideration.

- Labor Conditions**: Ensuring fair wages, safe working conditions, and respect for labor rights in both large-scale projects and the ASM sector is vital.

- "Resource Curse"**: There are concerns about avoiding the "resource curse," where abundant natural resources lead to corruption, conflict, and a lack of diversified economic development.

The Malagasy government aims to develop these sectors to drive economic growth, but achieving this sustainably and equitably, while upholding human rights and environmental standards, remains a complex task requiring robust governance and international cooperation.

8. Infrastructure and Media

Madagascar's infrastructure faces significant challenges, particularly in transport and energy, which impede economic development and access to basic services, especially in rural areas. The media landscape is diverse but also subject to political influences and constraints on freedom.

8.1. Transport Network

Madagascar's transport network is underdeveloped, hindering connectivity and economic activity.

- Roads**: In 2010, Madagascar had approximately 4.7 K mile (7.62 K km) of paved roads out of a much larger network of unpaved roads. Many unpaved roads become impassable during the rainy season (November-April), isolating rural communities. Largely paved national routes connect the six largest regional towns to Antananarivo, but access to other population centers is often difficult. The World Bank estimated that 17 million people in rural areas live more than 1.2 mile (2 km) from an all-season road. Significant investment is needed for road construction and maintenance. Construction of the Antananarivo-Toamasina toll highway, the country's first toll highway (a 1.00 B USD project), began in December 2022, aiming to improve connection between the capital and the main seaport over four years. Other road improvement projects are underway with international support (e.g., EU, EIB).

- Railways**: The rail network is limited and largely dates from the colonial era. Key lines connect Antananarivo to Toamasina (the main freight line), Antsirabe, and Ambatondrazaka. Another line connects Fianarantsoa to Manakara on the southeast coast (FCE railway), which is a tourist attraction but also vital for local transport. Much of the network is in poor condition and requires rehabilitation.

- Seaports**: Toamasina is the country's most important seaport, handling the majority of international trade. Other ports include Mahajanga, Antsiranana, Toliara, and the newer port of Ehoala (near Tôlanaro), built primarily for Rio Tinto's ilmenite mining operations and set to come under state control around 2038. Silting is a problem for some ports on the west coast. The government aims to expand ports at Antsiranana and Taolagnaro.

- Air Transport**: Air Madagascar, the national airline, services domestic and international routes. There are numerous small regional airports, which are crucial for accessing remote areas, especially during the rainy season. Ivato International Airport (Antananarivo) and Fascene Airport (Nosy Be) are the main international gateways.

8.2. Energy and Communications

Access to modern energy and communication services is limited, particularly in rural areas, creating a significant urban-rural divide.

- Energy**:

- Electricity is supplied by the state-owned utility, Jirama. However, access is very low: as of 2009, only 9.5% of fokontanyvillage/neighborhoodMalagasy had access to Jirama's electricity. In 2019, it was estimated that only 15% of the population had access to electricity (11% in rural areas).

- Generation is primarily from hydroelectric power (around 56%) and diesel generators (around 44%), making it expensive and often unreliable. The reliance on imported fuel for diesel generators strains foreign exchange reserves. There is significant potential for renewable energy (solar, wind, hydro) development.

- Water and Sanitation**: Access to safe drinking water and improved sanitation is also limited. In 2009, only 6.8% of fokontanyvillage/neighborhoodMalagasy had access to piped water from Jirama. Millions lack access to clean water, relying on unimproved sources.

- Communications**:

- Mobile telephone coverage has grown significantly and is more widespread than fixed-line services, with several private operators. However, rural coverage can be patchy.

- Internet penetration is increasing but remains relatively low, concentrated in urban areas. As of January 2022, around 22.3% of the population (6.43 million people) had internet access, mostly via mobile phones. Internet cafés are common in towns. The digital divide between urban and rural areas is substantial.

Lack of reliable and affordable energy and transport significantly constrains economic growth and affects the quality of life, particularly for the poor and those in remote regions.

8.3. Media Landscape

The media landscape in Madagascar is diverse, featuring a mix of state-owned and private outlets.

- Radio**: Radio is the most important source of news and information for a large majority of the population, especially in rural areas. State radio broadcasts have national coverage, while hundreds of private and community radio stations operate locally or regionally.

- Television**: State television coexists with numerous private television stations, broadcasting local and international programs, primarily in urban areas.

- Print Media**: Several daily and weekly newspapers and magazines are published, mostly in Malagasy and French, with circulation concentrated in Antananarivo and other major towns.

- Online Media**: Online news portals and social media are increasingly used, particularly by the urban and younger population.

- Media Ownership and Freedom**:

- Many media outlets are owned by political partisans or politicians themselves (e.g., MBS owned by former President Ravalomanana, and Viva by President Rajoelina). This contributes to a polarized media environment, where reporting can be biased.

- Press freedom is guaranteed by the constitution but has faced challenges. Media outlets have historically come under varying degrees of pressure to censor criticism of the government. Journalists have occasionally faced threats, harassment, or arrest (e.g., for allegedly spreading "fake news" or incitement). Accusations of media censorship intensified after the 2009 political crisis.

- Access to information can be limited, and self-censorship is sometimes practiced by journalists.

The media plays a crucial role in political discourse and social development, but its ability to operate freely and independently is often tested, particularly during periods of political instability.

9. Demographics

Madagascar's population is a unique blend of Austronesian and African origins, resulting in a distinct Malagasy culture. The demographic profile is characterized by a young population, high growth rate, and uneven distribution, with significant implications for development, resource management, and social services.

9.1. Population and Distribution

As of 2024, the population of Madagascar was estimated at 32 million, a significant increase from 2.2 million in 1900. The annual population growth rate was approximately 2.4% in 2024. This rapid growth places considerable strain on resources and services.

The population is predominantly young:

- Approximately 39.3% are younger than 15 years old.

- 57.3% are between the ages of 15 and 64.

- 3.4% are aged 65 and older.

This age structure results in a high dependency ratio.

Life expectancy in 2009 was 63 years for men and 67 years for women.

Population density varies significantly across the island. The most densely populated regions are the eastern highlands (especially around Antananarivo and Fianarantsoa) and the eastern coast. The western plains and arid southern regions are sparsely populated. Urbanization is increasing, with people migrating from rural areas to cities in search of economic opportunities, though almost 60% of the population still lives in rural areas (as of 2024). Antananarivo is the largest urban center, followed by Toamasina, Antsirabe, Mahajanga, Fianarantsoa, and Toliara.

Only two general censuses have been conducted since independence, in 1975 and 1993. More recent population data relies on estimates and surveys.

9.2. Ethnic Groups

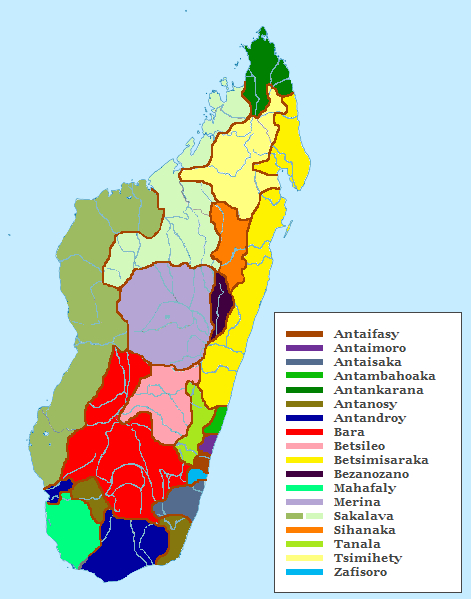

The Malagasy people form over 90% of Madagascar's population. They are not a homogenous group but are typically divided into 18 or more officially recognized ethnic subgroups (karazanaethnic subgroupMalagasy or fokoethnic subgroupMalagasy), each with distinct cultural nuances, dialects, and historical territories. Despite these subgroupings, there is a strong sense of a shared Malagasy identity, language, and core cultural values.

Recent DNA research indicates that the genetic makeup of the average Malagasy person is an approximately equal blend of Southeast Asian (primarily from Borneo) and East African genes. However, the genetic admixture varies regionally:

- Highland Groups**: Peoples of the Central Highlands, such as the Merina (the largest subgroup, approx. 26% of the population) and the Betsileo (approx. 12%), tend to exhibit more pronounced Southeast Asian genetic and physical features.

- Coastal Groups (Côtierscoastal dwellersFrench)**: Peoples along the coasts generally show a stronger East African genetic influence, though still with significant Austronesian heritage. The largest coastal subgroups include the Betsimisaraka (approx. 15%) on the east coast, and the Tsimihety (approx. 7%) and Sakalava (approx. 6% each) in the north and west. Other coastal groups include the Antankarana, Vezo (semi-nomadic fishers), Mahafaly, Antandroy, and Antanosy. Peoples along the east and southeastern coasts often have a more balanced blend of Austronesian and Bantu ancestry, and some also show minor genetic influence from Arab, Somali, Gujarati, and Tamil traders.

The main ethnic subgroups and their traditional regional concentrations are:

| Malagasy Ethnic Subgroups | Regional Concentration |

|---|---|

| Antankarana, Sakalava, Tsimihety | Northern and northwestern coasts (Former Antsiranana Province) |

| Sakalava, Vezo | Western coast (Former Mahajanga Province) |

| Betsimisaraka, Sihanaka, Bezanozano | Eastern coast (Former Toamasina Province) |

| Merina | Central highlands (Former Antananarivo Province) |

| Betsileo, Antaifasy, Antambahoaka, Antemoro, Antaisaka, Tanala | Southeastern highlands and coast (Former Fianarantsoa Province) |

| Mahafaly, Antandroy, Antanosy, Bara, Vezo | Southern inland regions and coast (Former Toliara Province) |

Minority communities of non-Malagasy origin include those of Chinese, Indian (often called Karanas), Comoran, and European (primarily French) descent. Emigration in the late 20th century, sometimes due to political unrest (e.g., an exodus of Comorans in 1976 following anti-Comoran riots in Mahajanga), has reduced some of these populations. There were an estimated 25,000 Comorans, 18,000 Indians, and 9,000 Chinese living in Madagascar in the mid-1980s.

9.3. Languages

The languages of Madagascar are primarily characterized by the dominance of the Malagasy language and the historical influence of French.

- Malagasy**: This is the national language and is spoken throughout the island. It is an Austronesian language, belonging to the Malayo-Polynesian branch, and its closest relative is the Ma'anyan language spoken in the Barito River region of Borneo, Indonesia. It also incorporates numerous loanwords from Malay, Javanese, Bantu languages, Arabic, Swahili, English, and French. The numerous dialects of Malagasy are generally mutually intelligible and can be broadly clustered into two groups:

- Eastern Malagasy: Spoken along the eastern forests and highlands, including the Merina dialect of Antananarivo, which forms the basis of Standard Malagasy.

- Western Malagasy: Spoken across the western coastal plains.

The language was first transcribed using the Arabic-based Sorabe script (mainly by the Antemoro people) and later standardized using the Latin alphabet by LMS missionaries in the 19th century.

- French**: French became an official language during the colonial period. It continues to be an official language alongside Malagasy and is widely used in government, business, education (especially higher education), and international communication. It is mostly spoken as a second language among the educated population, and for some upper-class urban dwellers, it may be a native or near-native language. Madagascar is a member of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie.

- English**: English was briefly an official language from 2007 to 2010, reflecting a desire to engage more with the Anglophone world. However, its official status was removed by referendum in 2010. It is taught in some schools and used in tourism and international business to a lesser extent than French.

- Minority Languages**: Other languages spoken by minority communities include Gujarati and Hindi (among Indo-Madagascans), Comorian, and Chinese dialects.

The linguistic situation often reflects a diglossia, where French is used in formal written contexts and Malagasy in everyday spoken communication. A mixed language form known as Vazaha miteny gasy or "Variaminanana" (French mixed with Malagasy) is also common in urban settings.

9.4. Religion

The religious landscape of Madagascar is diverse, with a complex interplay between traditional beliefs, Christianity, and Islam.

- Traditional Beliefs (Fomba Gasy)**: Approximately 50-58% of the population adheres to traditional indigenous beliefs, though many also practice Christianity or Islam concurrently. These beliefs are centered on veneration of ancestors (razanaancestorsMalagasy), who are considered intermediaries between the living and a creator god, known as Zanahary or Andriamanitra. Ancestors are believed to influence the daily lives of the living, and rituals like famadihana (the "turning of the bones" or reburial ceremony, mainly in the highlands) are performed to honor them and seek their blessings. Adherence to fady (ancestral prohibitions or taboos) is widespread and guides many aspects of social life. Traditional healers and diviners (ombiasyhealer/divinerMalagasy) also play important roles.

- Christianity**: Around 41-85% of the population identifies as Christian, depending on the survey (Pew Research Center in 2020 estimated 85%, while ARDA in 2020 estimated 58.1%). The Malagasy Council of Churches comprises the four oldest and most prominent denominations:

- Roman Catholicism

- Church of Jesus Christ in Madagascar (FJKM, a united Protestant church with Reformed and Congregationalist roots)

- Lutheran Church

- Anglican Church