1. Overview

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country located in Southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula, and is the westernmost country of continental Europe. It is bordered by Spain to the north and east and by the Atlantic Ocean to the west and south. Its territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of the Azores and Madeira, both autonomous regions with their own regional governments. Lisbon is the capital and largest city.

The nation's geography is characterized by the Tagus River dividing the mountainous north from the rolling plains of the south, with a predominantly Mediterranean climate. Portugal's history is marked by early Celtic and Iberian settlements, Roman rule, Germanic kingdoms, and centuries of Islamic influence, followed by the Christian Reconquista which shaped its formation as a kingdom in 1139. Portugal rose as a global maritime power during the Age of Discovery, establishing a vast colonial empire that had profound social and human rights impacts worldwide. Periods such as the Iberian Union, the Pombaline Enlightenment reforms, 19th-century liberal struggles, the authoritarian Estado Novo regime, and the 1974 Carnation Revolution have significantly shaped its path towards modern democracy and European integration. This democratic transition emphasized human rights, social progress, and the welfare of its citizens, including minorities and vulnerable groups.

Portugal's political system is a semi-presidential republic. It is a developed country with a high-income economy, primarily driven by services, industry, and tourism. Key social aspects include a complex history of emigration and recent immigration, a predominantly Catholic religious landscape though constitutionally secular, and a national health service. Culturally, Portugal is known for its unique Manueline and Pombaline architecture, rich literary traditions, Fado music, distinctive cuisine, and numerous UNESCO World Heritage sites. This article explores Portugal's multifaceted identity, focusing on its democratic development, social impacts, human rights considerations, and the well-being of its diverse population, reflecting a center-left, social liberal perspective.

2. Etymology

The word Portugal derives from the Roman-Celtic place name Portus Cale. Portus is the Latin word for "port" or "harbour." The origin and meaning of Cale are less clear, though it is likely an ethnonym. The mainstream explanation suggests it derives from the Callaeci, also known as the Gallaeci, a Celtic people who inhabited the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula. Some theories propose Cale is a Celtic word meaning "port" or "harbour," similar to the Irish caladh or Scottish Gaelic cala. Another theory suggests Cala was a Celtic goddess. Some French scholars have proposed it might originate from Portus Gallus, meaning "port of the Gauls" or Celts.

Around 200 BC, the Romans conquered the Iberian Peninsula from the Carthaginians during the Second Punic War. In this process, they captured Cale (modern-day Vila Nova de Gaia, located on the south bank of the Douro River) and renamed it Portus Cale. This combined name referred to the settlement at the mouth of the Douro River, which is today the conurbation of Porto (on the north bank) and Vila Nova de Gaia. The region around Portus Cale became known as the Condado Portucalense (County of Portucale) during the Middle Ages under the Suebi and Visigoths.

The name Portucale evolved into Portugale during the 7th and 8th centuries. By the 9th century, Portugale was used to refer to the region between the Douro and Minho rivers. By the 11th and 12th centuries, terms such as Portugale, Portugallia, Portvgallo, or Portvgalliae were already being used to refer to the nascent kingdom, which officially became the Kingdom of Portugal. The term Lusitania, the name of the ancient Roman province that covered much of modern-day central and southern Portugal, is often used as a poetic or literary alternative for Portugal, and its people are sometimes referred to as Lusitanians (Lusitanos).

3. History

3.1. Prehistory and Antiquity

The region now known as Portugal has been inhabited by humans since prehistoric times, approximately 400,000 years ago, when Homo heidelbergensis entered the area. The oldest human fossil found in Portugal is the 400,000-year-old Aroeira 3 skull, discovered in the Cave of Aroeira in 2014. Later, Neanderthals roamed the northern Iberian Peninsula; a Neanderthal tooth was found in the Nova da Columbeira cave in Estremadura. Homo sapiens arrived in Portugal around 35,000 years ago and spread rapidly.

Pre-Celtic tribes inhabited Portugal, including the Cynetes in the south, who developed a written language, leaving behind stelae. Early in the first millennium BC, several waves of Celts invaded from Central Europe and intermarried with local populations, forming various ethnic groups. Celtic presence is evident in archaeological finds and linguistic traces. They dominated most of northern and central Portugal. The south, however, retained much of its older, likely non-Indo-European character (possibly related to Basque) until the Roman conquest. Along the southern coast, small, semi-permanent commercial settlements were established by Phoenicians and Carthaginians.

The Romans first invaded the Iberian Peninsula in 219 BC, expelling the Carthaginians. During Julius Caesar's rule, almost the entire peninsula was annexed to Rome. This conquest took two hundred years, leading to many deaths and the enslavement of local populations who were forced to work in mines or sold elsewhere in the empire. Roman occupation faced a significant setback in 155 BC with the outbreak of the Lusitanian War. The Lusitanians and other native tribes, under the leadership of Viriathus, gained control of western Iberia. Rome sent numerous legions but failed to quell the rebellion until Roman leaders bribed Viriathus's allies to assassinate him in 139 BC. He was succeeded by Tautalus.

In 27 BC, Lusitania was established as a Roman province. Later, under Emperor Diocletian's reforms, a northern province, Gallaecia, was separated from Hispania Tarraconensis. Roman influence brought Latin, which evolved into Portuguese, as well as Roman law, infrastructure (roads, bridges, aqueducts), and urban centers like Conímbriga, Miróbriga, and Citânia de Briteiros. The Roman Temple of Évora stands as a significant, well-preserved landmark of this era. The social structure was transformed, with the introduction of Roman citizenship and administrative systems, though local traditions and resistance persisted in some areas.

With the decline of the Roman Empire in the 5th century AD, Germanic tribes invaded the Iberian Peninsula. In 409, the Suebi and Vandals settled in Gallaecia, with the Suebi establishing a kingdom centered in Braga. The Visigoths arrived later, initially as Roman foederati, and eventually conquered the Suebi kingdom in 585, unifying most of the peninsula under Visigothic rule with their capital in Toledo. The Germanic period saw a decline in urban life and the disappearance of many Roman institutions, except for ecclesiastical organizations, which were fostered by the Suebi and later adopted by the Visigoths. These tribes, initially Arian Christians, eventually converted to Catholicism, influenced by the local Hispano-Roman population. St. Martin of Braga was a key figure in this evangelization. The Visigoths introduced a new nobility, which played a significant social and political role, and the Church became increasingly influential in state affairs. However, Visigothic rule was often marked by internal strife and a failure to fully integrate with the local populace, setting the stage for the next major conquest.

3.2. Islamic Rule and Reconquista

In 711 AD, the Umayyad Caliphate launched an invasion of the Iberian Peninsula, swiftly defeating the Visigothic kingdom. By 726, most of what is now Portugal became part of the vast Umayyad Caliphate of Damascus. This Islamic rule, known as Al-Andalus, lasted for several centuries, particularly in the south. After the collapse of the Umayyad Caliphate in 750, the western part of the empire gained independence under Abd-ar-Rahman I, establishing the Emirate of Córdoba, which later became the Caliphate of Córdoba in 929. The Caliphate eventually dissolved in 1031 into numerous small kingdoms called Taifas.

Most of present-day Portugal fell under the Taifa of Badajoz and later the Taifa of Seville. The cultural landscape of Al-Andalus in Portugal was rich, with cities like Beja, Silves, Alcácer do Sal, Santarém, and Lisbon (al-ʾUšbūnahArabic: الأشبونةArabic) becoming important centers. The Muslim population consisted mainly of native Iberian converts to Islam (Muladis) and Berbers. Arabs, though a minority, formed the elite. Islamic rule brought advancements in agriculture, science, and art, leaving a lasting impact on Portuguese culture and language. However, society was stratified, and non-Muslims (Christians and Jews) lived as dhimmis, subject to special taxes and restrictions, although often allowed to practice their religions. Viking raids also occurred along the coast between the 9th and 11th centuries, including Lisbon, leading to small Norse settlements.

The Reconquista, the Christian reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula, began almost immediately after the Moorish invasion. In 718, the Visigothic noble Pelagius of Asturias was elected leader and, after the Battle of Covadonga in 722, founded the Christian Kingdom of Asturias in the northern highlands. This kingdom became the nucleus of Christian resistance.

Towards the end of the 9th century, Vímara Peres, a nobleman under King Alfonso III of Asturias, reconquered the region between the Minho and Douro rivers. In 868, he established the County of Portugal (Condado Portucalense), named after the port town of Portus Cale (modern Porto). He repopulated the area, founding Guimarães, which became known as the "birthplace of the Portuguese nation." The County of Portugal was initially a vassal state of the Kingdom of León.

In 1093, Alfonso VI of León granted the county to Henry of Burgundy and married him to his illegitimate daughter, Teresa of León. Henry and Teresa expanded the county's territory and influence. Their son, Afonso Henriques, became a pivotal figure in Portuguese independence. The Reconquista in Portugal was characterized by prolonged warfare, shifting alliances, and the establishment of military orders like the Knights Templar and the Order of Aviz, which played crucial roles in capturing and defending territories. The process involved not only military conquest but also the resettlement of Christian populations in reconquered lands, often leading to displacement and hardship for existing Muslim and Jewish communities.

3.3. Kingdom and Maritime Empire

Afonso Henriques continued his father's efforts in the Reconquista and sought to establish an independent kingdom. In 1128, at the Battle of São Mamede near Guimarães, Afonso Henriques defeated the forces of his mother, Countess Teresa, and her Galician allies, asserting his sole leadership over the County of Portugal. Following a significant victory against the Almoravids at the Battle of Ourique in 1139, Afonso Henriques was proclaimed King of Portugal by his troops. This event is traditionally considered the foundation of the Kingdom of Portugal.

Independence was formally recognized in 1143 by King Alfonso VII of León and Castile through the Treaty of Zamora, and in 1179, Pope Alexander III officially recognized Afonso I as King of Portugal with the papal bull Manifestis Probatum. The capital was moved from Guimarães to Coimbra. Afonso I and his successors, aided by military monastic orders such as the Knights Templar and the Order of Aviz, continued the southward expansion against the Moors. The Reconquista in Portugal concluded in 1249 with the capture of Faro in the Algarve under King Afonso III. This established Portugal's borders largely as they are today, making it one of Europe's oldest nation-states with defined frontiers. King Denis I (1279-1325) consolidated the kingdom, promoted agriculture, founded the University of Coimbra (initially in Lisbon in 1290), and fostered the Portuguese language. The Treaty of Alcañices (1297) with Castile definitively established the border. The crisis of 1383-1385 followed the death of King Ferdinand I without a male heir. John I of Castile, married to Ferdinand's daughter Beatrice, claimed the Portuguese throne. However, a popular uprising and a faction of nobles supported John, Master of Aviz (illegitimate son of Peter I). The Battle of Aljubarrota in 1385 saw John of Aviz, aided by English archers, decisively defeat the Castilians, securing Portuguese independence and establishing the House of Aviz as the new ruling dynasty. This victory cemented Portuguese national identity and fostered the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance, the world's oldest active military alliance.

Under the House of Aviz, Portugal embarked on the Age of Discovery. Prince Henry the Navigator, son of John I, was a key patron of exploration. In 1415, Portugal captured Ceuta in North Africa, marking the beginning of its overseas expansion. Throughout the 15th century, Portuguese explorers charted the African coast, establishing trading posts for gold, ivory, and enslaved Africans. They discovered and colonized the Madeira and Azores archipelagos. Key milestones included Bartolomeu Dias rounding the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 and Vasco da Gama reaching India by sea in 1498, opening a direct maritime route to Asia. In 1500, Pedro Álvares Cabral landed in Brazil and claimed it for Portugal. Afonso de Albuquerque secured Portuguese dominance in the Indian Ocean by conquering Goa (1510), Malacca (1511), and Hormuz (1515). The Portuguese established a vast maritime empire with trading posts and colonies in Africa (e.g., Angola, Mozambique), Asia (e.g., Goa, Malacca, Macau, Nagasaki), and South America (Brazil).

This expansion brought immense wealth to Portugal through trade in spices, gold, sugar, and, tragically, enslaved people. The Atlantic slave trade, in which Portugal played a major role, had devastating consequences for millions of Africans, forcibly removed from their homes and subjected to brutal conditions. The wealth from colonial ventures funded a cultural flourishing known as the Portuguese Renaissance. However, the social and human rights impacts of colonialism were profound and often brutal. Indigenous populations in colonized lands faced violence, displacement, disease, and the imposition of foreign rule and religion. The exploitation of resources and labor in the colonies enriched the metropole but often at a tremendous human cost, contributing to long-lasting inequalities and societal disruptions in the colonized territories. The governance of this empire also led to conflicts with other European powers like Spain, the Netherlands, and England, and eventually to its decline as global power dynamics shifted.

3.4. Iberian Union and Restoration

The death of King Sebastian I at the Battle of Alcácer Quibir in 1578, without an heir, and the subsequent death of his great-uncle and successor, Cardinal-King Henry, in 1580, led to the Portuguese succession crisis of 1580. Several claimants vied for the throne, but Philip II of Spain, a grandson of King Manuel I, ultimately prevailed, supported by a segment of the Portuguese nobility and through military intervention. In 1581, Philip II was recognized as King Philip I of Portugal by the Portuguese Cortes in Tomar, initiating the Iberian Union, a dynastic union where Portugal and Spain shared the same monarch but maintained separate administrations, laws, and currencies.

During the Iberian Union (1580-1640), Portugal's vast empire faced increasing challenges. The union dragged Portugal into Spain's conflicts, particularly the Eighty Years' War against the Dutch Republic. This led to Dutch attacks on Portuguese colonies and trading posts in Asia (e.g., Ceylon, Malacca, Indonesia), Africa (e.g., Elmina), and Brazil. The Dutch West India Company and Dutch East India Company systematically eroded Portugal's colonial holdings and trade monopolies. The Anglo-Portuguese Alliance also suffered, and strategic posts like Hormuz were lost. Portuguese resentment grew due to perceived Spanish neglect of Portuguese interests, increased taxation, and the appointment of Castilians to Portuguese offices.

Discontent culminated in the Portuguese Restoration War, which began on December 1, 1640, when a group of conspirators, known as the Forty Conspirators, acclaimed John, Duke of Braganza, as King John IV. This move was supported by disgruntled nobles, clergy, and the general populace. The war against Spain was long and arduous, lasting 28 years. Portugal received some support from France and England, who were rivals of Spain. Key battles included the Battle of Montijo (1644) and the Battle of the Lines of Elvas (1659).

The war ended with the Treaty of Lisbon in 1668, in which Spain formally recognized Portugal's independence and the legitimacy of the House of Braganza. The restoration re-established Portuguese sovereignty but found the empire significantly weakened. Portugal had lost many of its Asian possessions and faced ongoing Dutch competition. However, Brazil remained a cornerstone of the Portuguese economy, especially with the discovery of gold in the late 17th century, which would fuel a new era of prosperity for the restored monarchy. The struggle for independence and the subsequent efforts to rebuild and defend the empire had a lasting impact on Portuguese national identity and its foreign policy.

3.5. Pombaline Era and Enlightenment

The 18th century in Portugal was significantly shaped by the figure of Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, later known as the Marquis of Pombal. He rose to prominence during the reign of King Joseph I (1750-1777), effectively becoming the head of government. Pombal was a proponent of Enlightened absolutism, seeking to modernize Portugal, strengthen royal authority, and reduce the power of traditional institutions like the old nobility and the Jesuit Order.

His reforms were wide-ranging, covering economic, social, administrative, educational, and religious spheres. Economically, Pombal aimed to reduce Portugal's dependence on England, particularly after the restrictive Methuen Treaty. He established state-sponsored companies to promote Portuguese industries and trade, such as the Alto Douro Wine Company to regulate Port wine production (creating one of the world's first demarcated wine regions). He also reformed the tax system and sought to centralize economic control. Socially, Pombal's reforms included the abolition of slavery in mainland Portugal and Portuguese India in 1761 (though the transatlantic slave trade to Brazil continued and was even encouraged by companies he founded). He also ended legal discrimination against "New Christians" (descendants of converted Jews).

The defining event of this era was the devastating 1755 Lisbon earthquake on November 1st, which, along with subsequent tsunamis and fires, destroyed much of Lisbon and killed tens of thousands. Pombal's swift and pragmatic response to the disaster - famously summarized as "bury the dead and feed the living" - and his ambitious plan for the reconstruction of Lisbon's Baixa district with earthquake-resistant grid-patterned streets (the Pombaline Baixa) solidified his power and demonstrated his modernizing vision.

Pombal's methods were often autocratic and ruthless. He suppressed opposition with a heavy hand. The Távora affair in 1758, following an alleged assassination attempt on King Joseph I, resulted in the public and brutal execution of prominent members of the Távora and Aveiro families, effectively crushing a powerful segment of the old nobility. In 1759, he expelled the Jesuits from Portugal and its empire, confiscating their assets, arguing they were a state within a state and an obstacle to reform. This move had significant social impact, particularly on education, as Jesuits had controlled many schools; Pombal subsequently reformed the university system, emphasizing secular and scientific studies.

The Pombaline reforms aimed at creating a more efficient, centralized, and modern state. While they brought about significant changes and laid groundwork for a more modern Portugal, they were implemented through authoritarian means, often disregarding individual liberties and traditional rights. The social impact was mixed: some reforms, like the abolition of slavery in Portugal or the end of discrimination against New Christians, were progressive. However, the concentration of power and suppression of dissent were characteristic of enlightened despotism. After King Joseph I's death in 1777, Queen Maria I, who disliked Pombal's excesses, dismissed him. Many of his policies were reversed or modified in a period known as the Viradeira (turnaround), although his legacy on Portuguese administration and urban planning remained.

3.6. 19th-Century Crises and Constitutional Monarchy

The 19th century was a period of profound political, social, and economic turmoil for Portugal, marked by foreign invasions, the loss of its most valuable colony, civil war, and the difficult transition to a constitutional monarchy.

The Napoleonic Wars had a devastating impact. In 1807, Portugal refused Napoleon's demand to join the Continental System against the United Kingdom. French forces under General Junot subsequently invaded, capturing Lisbon. The Portuguese royal family, led by Prince Regent John (later John VI), fled to Brazil, transferring the seat of the monarchy to Rio de Janeiro in 1808. This transfer had significant consequences, elevating Brazil's status (it became a kingdom in 1815, co-equal with Portugal in the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves) and fostering sentiments for independence there. The Peninsular War (1807-1814) saw fierce fighting on Portuguese soil, with British forces under Wellington playing a crucial role in expelling the French by 1812. The war ravaged the country and left it under de facto British influence for a time.

The absence of the royal court led to the Liberal Revolution of 1820 in Porto, which demanded a constitution and the return of the king. John VI returned in 1821, accepting a liberal constitution in 1822. However, his son Pedro, who had remained in Brazil as regent, declared Brazilian independence in 1822 and became Emperor Pedro I of Brazil. This loss of Brazil, Portugal's economic powerhouse, was a severe blow.

The death of John VI in 1826 triggered a succession crisis and the Liberal Wars (also known as the War of the Two Brothers, 1828-1834). Pedro I of Brazil (Pedro IV of Portugal) abdicated the Portuguese throne in favor of his seven-year-old daughter, Maria II, on the condition she marry his brother, Miguel, who would act as regent and uphold the liberal Constitutional Charter of 1826. However, Miguel, supported by absolutists (nobility, clergy, and traditional landowners), usurped the throne in 1828, revoking the Charter and ruling as an absolutist monarch. Pedro then abdicated the Brazilian throne in 1831 and launched a military campaign from the Azores to restore Maria II and constitutionalism. The Liberal Wars were devastating, dividing the country and causing significant loss of life and property. Liberals, with British and French support, eventually triumphed. Miguel was defeated and exiled in 1834, and Maria II was restored to the throne under the Constitutional Charter.

The remainder of the 19th century was characterized by the instability of the constitutional monarchy. Frequent political conflicts between different liberal factions (Chartists, more conservative, and Septembrists, more radical), military uprisings (pronunciamentos), and economic difficulties plagued the nation. A period of relative stability and development, known as the Regeneração (Regeneration), began in the 1850s, focusing on infrastructure (railways, roads, telegraphs) and attempts at industrialization, largely funded by foreign loans. However, Portugal remained economically underdeveloped compared to other Western European nations.

Colonial ambitions in Africa ("Pink Map" project to link Angola and Mozambique) led to the 1890 British Ultimatum, forcing Portugal to cede territory and causing a national humiliation that fueled republican sentiment. Growing dissatisfaction with the monarchy, economic problems, and the influence of republican and socialist ideas set the stage for the end of the monarchy in the early 20th century. The social impact of these crises included increased poverty for many, emigration, and growing class tensions.

3.7. First Republic and Estado Novo

The 5 October 1910 revolution overthrew the nearly 800-year-old monarchy, and the First Portuguese Republic was proclaimed. King Manuel II went into exile. The First Republic (1910-1926) was a period of intense political instability, marked by frequent changes in government (45 governments in 16 years), social unrest, strikes, and economic difficulties. It introduced a liberal constitution, separated church and state, and expanded suffrage, but faced strong opposition from monarchists, the Catholic Church, and conservative elements. Portugal's participation in World War I on the Allied side (from 1916) further strained its weak economy and exacerbated social tensions. The war's impact, including casualties and economic hardship, contributed to the republic's instability.

This chronic instability led to the 28 May 1926 coup d'état, a military coup that ended the First Republic and established the Ditadura Nacional (National Dictatorship). This military regime paved the way for António de Oliveira Salazar, a finance professor, who was appointed Minister of Finance in 1928 with extraordinary powers to stabilize the dire financial situation. Salazar's success in balancing the budget and restoring financial stability earned him immense prestige and power.

In 1932, Salazar became Prime Minister, and in 1933, he institutionalized his rule through a new constitution, establishing the Estado Novo (New State). This was an authoritarian, corporatist, and nationalist regime that lasted until 1974. Salazar's Estado Novo was characterized by:

- Authoritarianism:** Political parties were banned (except for the official National Union), censorship was strict, and political dissent was suppressed by the secret police, the PIDE (Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado). Elections were heavily manipulated.

- Corporatism:** Society was organized into corporate bodies representing employers, workers, and various professions, theoretically to promote social harmony but in practice to control labor and social groups.

- Conservatism and Catholicism:** The regime emphasized traditional values, the authority of the Catholic Church (though formally separate from the state), and a conservative social order. Women's roles were largely confined to the domestic sphere.

- Nationalism and Colonialism:** A core tenet was the indivisibility of Portugal's multi-continental empire. The regime fiercely resisted decolonization movements in its African colonies (Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau).

Portugal remained neutral in World War II, a policy that allowed Salazar to maintain power and benefit economically from trade with both Allied and Axis powers. After the war, Portugal joined NATO (1949) and the United Nations (1955), but its colonial policies increasingly isolated it internationally.

From the early 1960s, nationalist guerrilla movements in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau launched armed struggles for independence, leading to the brutal and costly Portuguese Colonial War (1961-1974). The war drained Portugal's resources, caused significant casualties, and led to growing dissent within the military and society. The regime's insistence on maintaining the empire became its undoing.

In 1968, Salazar suffered a stroke and was replaced by Marcelo Caetano. Caetano initially signaled some liberalization (the "Marcelist Spring"), but these reforms were limited and failed to address the core issues of the colonial wars and lack of political freedom. The social impact of the Estado Novo was profound: it maintained stability and a degree of economic development (particularly in the 1960s), but at the cost of political repression, limited civil liberties, social conservatism, high emigration due to lack of opportunities, and the perpetuation of poverty and inequality for significant parts of the population. The regime's education policies also led to low literacy rates compared to other Western European nations for a long period.

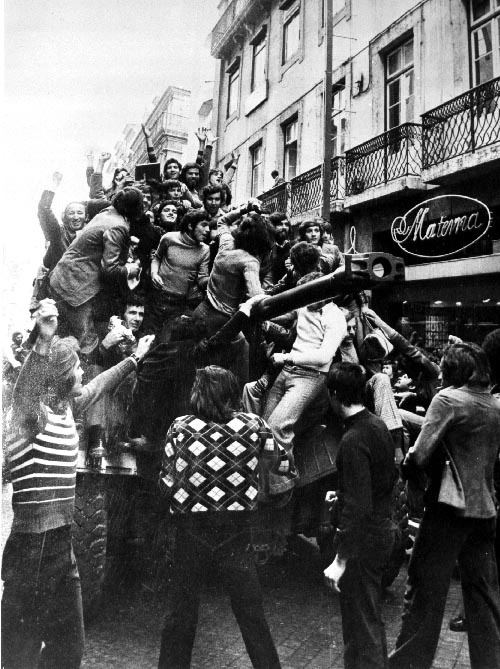

3.8. Carnation Revolution and Democratization

The Estado Novo dictatorship, weakened by decades of authoritarian rule and the increasingly unpopular and costly colonial wars in Africa, came to an end on April 25, 1974, with the Carnation Revolution. This was a largely bloodless military coup orchestrated by the Movimento das Forças Armadas (MFA - Armed Forces Movement), a group of left-leaning junior military officers. The revolution was met with widespread popular support, with civilians taking to the streets and placing carnations in soldiers' rifle barrels, giving the revolution its name.

The immediate aftermath of the revolution was a turbulent period known as the Processo Revolucionário Em Curso (PREC - Ongoing Revolutionary Process), lasting about two years. This period was characterized by intense political and social upheaval, with various factions (socialists, communists, centrists, and far-left groups) vying for control. Key developments included:

- Restoration of Democracy:** Political prisoners were freed, censorship was abolished, political parties were legalized, and exiles returned. A National Salvation Junta, initially led by General António de Spínola, took power.

- Decolonization:** One of the primary aims of the MFA was to end the colonial wars. Portugal rapidly granted independence to its African colonies: Guinea-Bissau (recognized in 1974, already self-proclaimed in 1973), Mozambique (1975), Cape Verde (1975), São Tomé and Príncipe (1975), and Angola (1975). East Timor also declared independence in 1975 but was soon invaded by Indonesia. Macau remained under Portuguese administration until 1999. The decolonization process was often chaotic, particularly in Angola and Mozambique where civil wars erupted. It led to a massive exodus of Portuguese settlers (Retornados) from the former colonies, creating significant social and economic challenges for Portugal.

- Social and Economic Reforms:** The PREC saw widespread nationalizations of key industries (banking, insurance, heavy industry), land reform (especially in the south, with expropriation of large estates), and measures to improve workers' rights and living conditions.

Political instability marked the PREC, including coup attempts from both the right and far-left. The "Hot Summer" of 1975 saw near-civil war conditions. However, moderate forces within the MFA and civilian political parties, notably the Socialist Party led by Mário Soares and the Social Democratic Party (then more centrist), gradually gained ascendancy over more radical elements.

In April 1975, free elections were held for a Constituent Assembly, which drafted a new democratic constitution, approved in April 1976. This constitution enshrined fundamental rights and freedoms, established a semi-presidential republic, and initially included strong socialist-inspired provisions (many of which were later revised). The first legislative elections under the new constitution were won by the Socialist Party, and Mário Soares became Prime Minister. António Ramalho Eanes was elected President.

The transition to democracy brought significant improvements in human rights and civil liberties. Portugal embarked on a path of modernization and European integration. It joined the Council of Europe in 1976 and formally applied to join the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1977, becoming a member state (along with Spain) in 1986. EEC/EU membership brought substantial development funds and accelerated Portugal's economic and social modernization.

Democratic Portugal has seen alternating governments of the Socialist Party and the Social Democratic Party. The country successfully hosted Expo '98 in Lisbon and was a founding member of the Euro in 1999. The early 21st century saw economic growth, but also challenges related to the global financial crisis of 2007-2008 and the subsequent European sovereign debt crisis, which led to an IMF-EU bailout package in 2011 and a period of austerity. Portugal exited the bailout in 2014 and has since experienced economic recovery. The country continues to consolidate its democratic institutions and address social challenges, with ongoing debates about social equity, the rights of minorities, and sustainable development, reflecting its commitment to the democratic values re-established by the Carnation Revolution.

4. Geography

4.1. Topography

Mainland Portugal is geographically diverse. The main river, the Tagus (Tejo), flows from Spain, bisecting the country. North of the Tagus, the landscape is generally mountainous, particularly in the interior. This region features several plateaus deeply indented by river valleys. Major mountain ranges include the Serra da Estrela, which contains the highest peak in mainland Portugal, Torre, at 6.5 K ft (1.99 K m). Other significant ranges are the Serra do Gerês, Serra do Marão, and Serra de Montesinho. The northern coastline is often rocky with interspersed beaches.

South of the Tagus, the terrain is characterized by rolling plains and hills, particularly in the Alentejo region, which is known for its vast agricultural lands and cork oak forests. The Algarve region in the far south is separated from the Alentejo by a series of low mountains like the Serra de Monchique (highest point: Fóia, 2959 ft (902 m)). The Algarve coast is famous for its sandy beaches, cliffs, and grottoes. Other important rivers in Portugal include the Douro, which flows through the Port wine region, the Minho forming part of the northern border with Spain, and the Guadiana, which also partly forms the eastern border with Spain.

The Azores archipelago is located on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a tectonically active area. These nine islands are of volcanic origin and display dramatic landscapes with calderas, crater lakes, hot springs, and volcanic cones. Mount Pico on Pico Island is an active stratovolcano and the highest point in Portugal, reaching 7.7 K ft (2.35 K m). The islands are characterized by lush vegetation due to their mild, humid climate.

The Madeira archipelago, also volcanic in origin, is situated on the African Plate. It consists of the main island of Madeira, Porto Santo Island, and the uninhabited Desertas and Savage Islands. Madeira is rugged and mountainous, with high cliffs, deep valleys (ribeiras), and laurel forests. Its highest peak is Pico Ruivo at 6.1 K ft (1.86 K m). The coastline is predominantly steep, with fewer sandy beaches compared to the mainland's Algarve.

4.2. Climate

Portugal predominantly features a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification: Csa in the south and inland, Csb in the north, central regions, and coastal Alentejo), characterized by mild, wet winters and hot, dry summers. However, its climate is strongly influenced by the Atlantic Ocean, which moderates temperatures, especially along the coast. Regional variations are significant.

In mainland Portugal, the north is generally cooler and wetter than the south. The northwestern region, particularly Minho, receives the highest rainfall due to Atlantic weather systems. Winters are mild, but inland mountainous areas like Serra da Estrela experience colder temperatures and regular snowfall, making it a popular skiing destination. Summers in the north are warm, but coastal areas benefit from sea breezes.

The central region, including Lisbon, has mild winters and hot, sunny summers. Lisbon's average annual temperature is around 62.6 °F (17 °C).

The south, particularly the Alentejo and Algarve, experiences very hot, dry summers with temperatures often exceeding 86 °F (30 °C) and sometimes reaching over 104 °F (40 °C) in the interior Alentejo. Winters are mild and relatively dry compared to the north. The Algarve coast enjoys over 3,000 hours of sunshine per year.

The Azores have a mild, oceanic climate or humid subtropical climate (Cfb/Cfa), with high humidity and rainfall throughout the year, though summers are drier. Temperatures are moderated by the Atlantic, with small annual variations. Snow is rare, occurring only at the highest elevations like Mount Pico.

Madeira has a subtropical or Mediterranean climate (Csb/Csa), often described as having an "eternal spring." Temperatures are mild year-round, with warm, dry summers and mild, wetter winters. The Savage Islands, part of the Madeira archipelago, have a hot desert climate (BWh) with very low rainfall.

Overall, Portugal is one of the warmest countries in Europe. The average annual temperature in mainland Portugal varies from 50 °F (10 °C) in the mountainous interior north to 62.6 °F (17 °C) in the south and on the Guadiana river basin. The record high of 117.32 °F (47.4 °C) was recorded in Amareleja. The country receives around 2,300 to 3,200 hours of sunshine annually. Sea surface temperatures on the west coast range from 57.2 °F (14 °C) in winter to 66.2 °F (19 °C) in summer, while the south coast sees summer sea temperatures of 71.6 °F (22 °C), occasionally reaching 78.8 °F (26 °C).

4.3. Biodiversity

Portugal is situated in the Mediterranean Basin, one of the world's biodiversity hotspots. Its varied geography and climate contribute to a rich diversity of flora, fauna, and ecosystems. The country is home to six terrestrial ecoregions: Azores temperate mixed forests, Cantabrian mixed forests, Madeira evergreen forests, Iberian sclerophyllous and semi-deciduous forests, Northwest Iberian montane forests, and Southwest Iberian Mediterranean sclerophyllous and mixed forests. Over 22% of Portugal's land area is included in the Natura 2000 network, reflecting a commitment to conservation.

The flora of mainland Portugal includes extensive forests of maritime pine, cork oak (Portugal is the world's leading cork producer), and holm oak. Eucalyptus plantations, introduced for the pulp industry, are also widespread but controversial due to their impact on water resources and biodiversity. Native deciduous forests, with species like Portuguese oak and Pyrenean oak, are found in more humid northern and mountainous areas. The Laurisilva forest of Madeira is a UNESCO World Heritage site, a relic of a type of laurel forest that once covered much of Southern Europe. The Azores also host unique laurel forest remnants and numerous endemic plant species.

Portugal's fauna includes mammals such as the Iberian wolf (endangered), Iberian lynx (critically endangered, but subject to successful reintroduction programs), wild boar, red deer, roe deer, Iberian ibex, European otter, and various bat species. The country is an important migratory route for birds, with numerous protected areas like the Tagus Estuary and Ria Formosa lagoons serving as vital stopover and wintering sites. Coastal and marine biodiversity is significant due to the long Atlantic coastline and the influence of upwelling systems that bring nutrient-rich waters. This supports diverse fish populations, including sardines (a staple of Portuguese cuisine), mackerel, and tuna, as well as marine mammals like dolphins and whales. The Azores are a prime location for whale watching. Freshwater fish in Iberian rivers include many endemic species, though some are threatened by habitat loss and pollution.

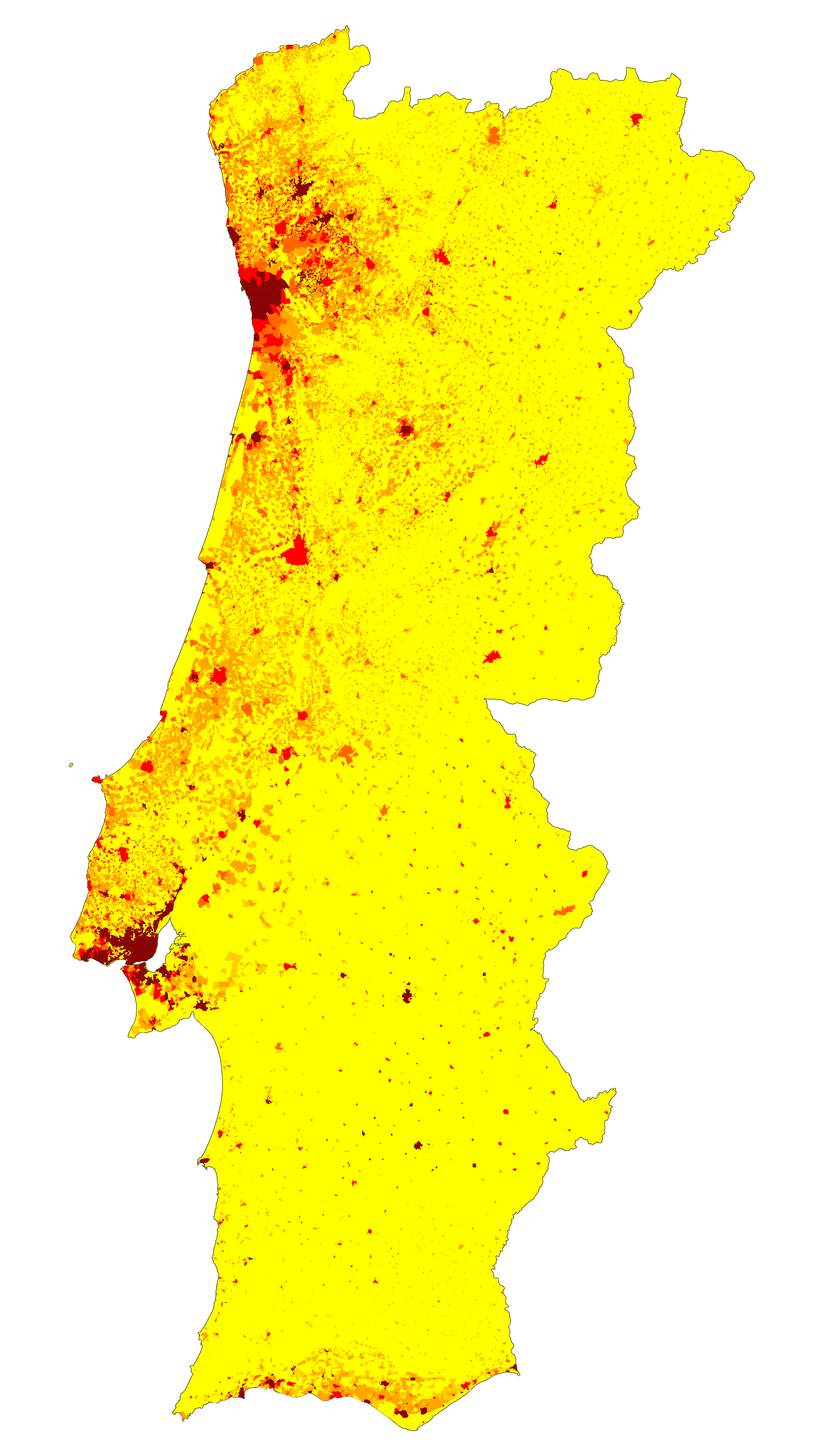

Environmental challenges include habitat loss due to urbanization and agriculture, forest fires (a recurrent summer problem, exacerbated by climate change and monoculture plantations), water scarcity in some regions, and coastal erosion. Conservation efforts are managed through national parks (such as the Peneda-Gerês National Park), natural parks, nature reserves, and protected landscapes. There's a growing societal awareness of environmental protection as a social value, leading to increased efforts in sustainable practices, renewable energy development, and biodiversity conservation. However, balancing economic development with environmental protection remains a significant challenge. Invasive alien species, such as the Argentine ant or certain exotic plants, also pose a threat to native ecosystems.

5. Politics

5.1. Government Structure

Portugal operates as a unitary semi-presidential republic. The four main organs of sovereignty are the President of the Republic, the Government (headed by the Prime Minister), the Assembly of the Republic (the unicameral parliament), and the Courts.

The President of the Republic is the head of state, elected by direct universal suffrage for a five-year term, renewable once. The current President is Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa. While the President's role is partly ceremonial, they hold significant powers, including appointing the Prime Minister (usually the leader of the party or coalition with the most seats in parliament), dismissing the Government, dissolving the Assembly of the Republic and calling new elections, vetoing legislation (which can be overridden by a parliamentary majority), and serving as Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. The President is also responsible for ensuring the regular functioning of democratic institutions and representing the Portuguese Republic internationally.

The Government is the executive branch, headed by the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister is appointed by the President after legislative elections and is responsible for forming the Council of Ministers (cabinet). The Government is politically responsible to both the President and the Assembly of the Republic. It defines and implements the country's general policies and directs public administration. The current Prime Minister is Luís Montenegro.

The Assembly of the Republic is the legislative branch. It is a unicameral parliament composed of a maximum of 230 deputies, elected for a four-year term through a system of proportional representation using the D'Hondt method in multi-member constituencies corresponding to the districts and autonomous regions. The Assembly's functions include passing laws, approving the state budget, overseeing government actions, and ratifying international treaties.

The Judiciary is independent and organized into several levels. The system is based on civil law. The highest courts are the Supreme Court of Justice (for common law matters) and the Constitutional Court, which reviews the constitutionality of laws. There are also administrative and fiscal courts, with the Supreme Administrative Court at their apex. The Public Ministry, headed by the Attorney General, represents the state in legal proceedings and defends democratic legality.

Portugal has a multi-party system. The main political parties that have historically dominated are the Socialist Party (PS, centre-left) and the Social Democratic Party (PSD, centre-right, despite its name). Other significant parties include Chega (far-right), Liberal Initiative (classical liberal), the Left Bloc (BE, left-wing), the Unitary Democratic Coalition (CDU, a coalition of the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP) and the Ecologist Party "The Greens"), LIVRE (eco-socialist), and the CDS - People's Party (CDS-PP, conservative).

The Autonomous Regions of the Azores and Madeira have their own regional governments and legislative assemblies with significant powers over local affairs.

5.2. Foreign Relations

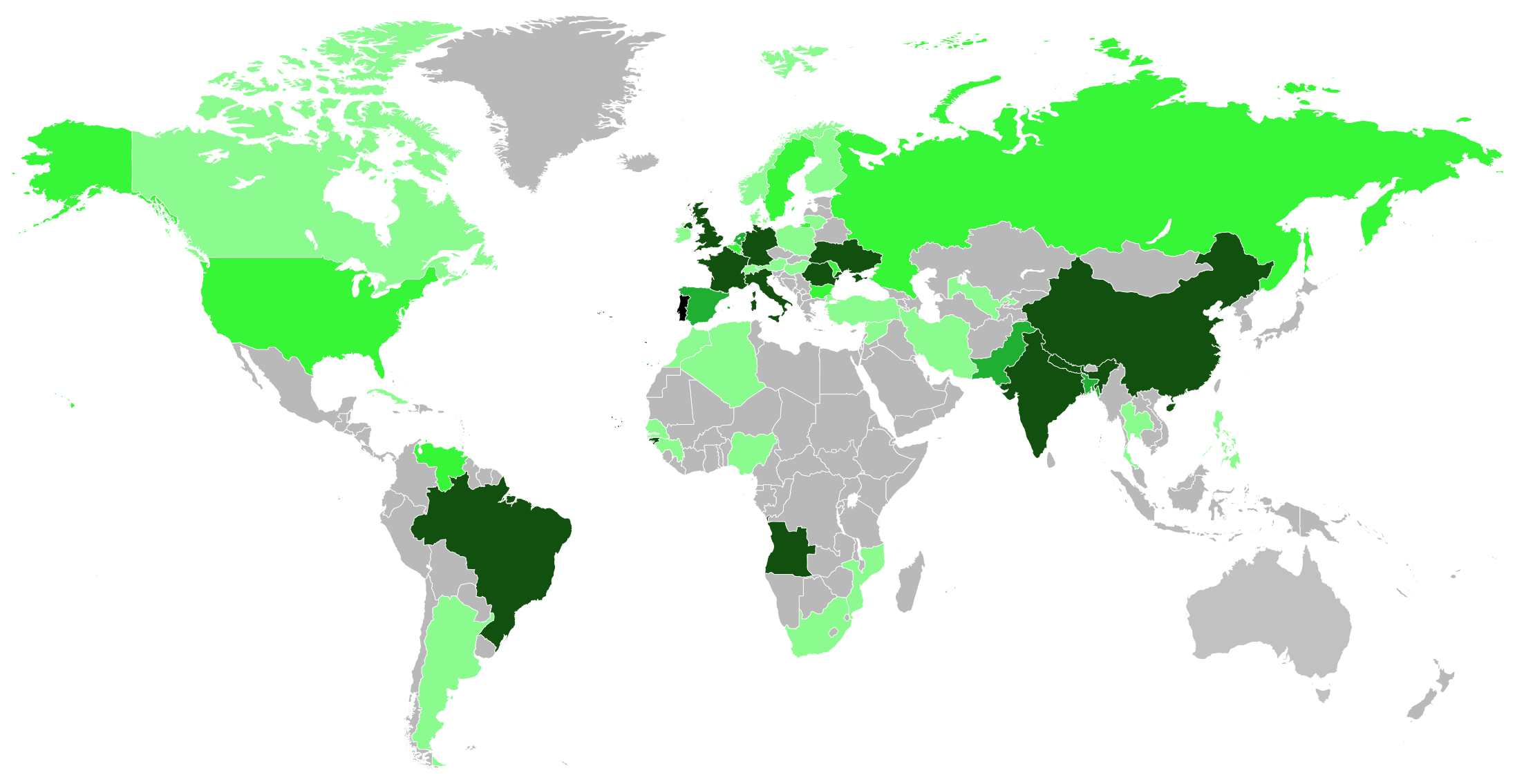

Portugal's foreign policy is deeply rooted in its history as a maritime nation and former colonial power, its geographical position at the crossroads of Europe, Africa, and the Atlantic, and its commitment to multilateralism and European integration. Key pillars of its foreign policy include its membership in the European Union (EU), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP).

As a member of the European Union since 1986, Portugal is a strong proponent of European integration. It actively participates in EU decision-making processes and has benefited from EU structural funds for its development. Portugal has held the rotating Presidency of the Council of the EU multiple times, notably overseeing the signing of the Treaty of Lisbon in 2007. Its EU policy often focuses on strengthening the Union's social dimension, cohesion policies, and its role as a global actor, including relations with Africa and Latin America.

Membership in NATO since its foundation in 1949 is a cornerstone of Portugal's defense and security policy. Portugal contributes to NATO missions and operations and hosts important NATO facilities, such as the Joint Force Command Lisbon.

The Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP), founded in 1996 and headquartered in Lisbon, is a key platform for Portugal's relations with other Lusophone nations (Angola, Brazil, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Equatorial Guinea, Mozambique, São Tomé and Príncipe, and Timor-Leste). The CPLP promotes cooperation in political, diplomatic, economic, social, and cultural spheres, as well as the diffusion of the Portuguese language. Portugal plays a leading role in fostering these ties.

Portugal maintains strong bilateral relations with numerous countries. Its relationship with Spain is particularly close, given their shared Iberian heritage and EU membership, though historical issues like the Olivenza dispute remain. Relations with Brazil are historically profound, based on shared language and culture, though they have evolved into a partnership of equals. Portugal also prioritizes relations with its former African colonies (PALOP countries), often focusing on development aid, education, and economic cooperation, reflecting a post-colonial approach that seeks to address historical legacies and support sustainable development and good governance. The relationship with the United States is significant, particularly in defense and security cooperation, including the U.S. presence at Lajes Air Base in the Azores.

Portugal is an active member of the United Nations and other international organizations like the OECD, the Council of Europe, and the World Trade Organization. It advocates for multilateral solutions to global problems, including climate change, human rights, and international security. A notable aspect of its foreign policy is its role as a bridge-builder, particularly between Europe and Africa, and Europe and Latin America. Portugal has consistently supported international development efforts, contributing to humanitarian aid and development assistance programs. Its foreign policy often reflects a commitment to human rights, democracy, and the rule of law internationally, aligning with the social liberal perspective that emphasizes these values. António Guterres, a former Portuguese Prime Minister, has served as the Secretary-General of the United Nations since 2017.

5.3. Territorial Disputes

Portugal has a long history of defined borders, especially its mainland frontier with Spain, which is one of the oldest in Europe. However, a few territorial issues persist, though they generally do not disrupt diplomatic relations significantly.

- Olivenza (OlivençaPortuguese): This is the most prominent territorial dispute. Olivenza is a town and municipality currently administered by Spain as part of the province of Badajoz, in Extremadura. Historically, Olivenza was Portuguese since the Treaty of Alcañices in 1297. During the War of the Oranges in 1801, Spain, allied with Napoleonic France, invaded Portugal, and Olivenza was occupied by Spanish forces. The subsequent Treaty of Badajoz ceded Olivenza to Spain. However, Portugal has never formally renounced its claim. The Congress of Vienna in 1815, in its Final Act, recognized Portugal's rights to Olivenza, but Spain did not return the territory. Portugal maintains a de jure claim, arguing that the Treaty of Badajoz was signed under duress and was abrogated by Spain's subsequent actions during the Peninsular War. Spain exercises de facto control and considers Olivenza an integral part of its territory. The issue is largely dormant in practical terms, but it remains an unresolved point in Portuguese national consciousness and occasionally surfaces in political discourse. The bridge connecting Olivenza to Portugal, the Ajuda Bridge, was destroyed during the War of the Oranges and was only partially rebuilt much later, symbolizing the unresolved status for some.

- Savage Islands (Ilhas SelvagensPortuguese): These are a small, uninhabited archipelago in the North Atlantic, situated between Madeira and the Canary Islands. They are administered by Portugal as part of the Autonomous Region of Madeira and constitute a nature reserve. Spain has occasionally questioned Portugal's sovereignty or, more significantly, the extent of Portugal's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) generated by the islands. While Spain formally recognized Portuguese sovereignty over the islands themselves in the past, disputes have arisen concerning maritime delimitation, particularly whether the Savage Islands can generate a full EEZ or only a territorial sea, which would impact fishing rights and resource exploitation in the surrounding waters. Portugal firmly maintains its claim to a full EEZ around the Savage Islands, in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Tensions have occasionally flared, such as incidents involving Spanish fishing vessels or military aircraft, but the issue is generally managed through diplomatic channels. Portugal has reinforced its presence and scientific research activities on the islands to underscore its sovereignty.

These disputes are approached from a perspective that upholds Portugal's historical and legal claims while seeking peaceful resolution and cooperation, particularly within the framework of European Union and international law. The de facto control exercised by Portugal over the Savage Islands and by Spain over Olivenza means that these issues, while historically significant, do not typically lead to major diplomatic crises in contemporary relations.

5.4. Military

The Portuguese Armed Forces (Forças Armadas PortuguesasPortuguese) are responsible for the national defense of Portugal. They consist of three branches: the Army (Exército), the Navy (Marinha), and the Air Force (Força Aérea). The President of the Republic is the constitutional Commander-in-Chief, but operational command is exercised through the Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces, under the authority of the Government and the Minister of National Defence.

The primary roles of the Armed Forces are to defend the country's independence, territorial integrity, and sovereignty, and to safeguard the freedom and security of its population. They also participate in international missions under the aegis of organizations like NATO, the European Union, and the United Nations, contributing to international peacekeeping, crisis management, and security operations.

Conscription was abolished in 2004, and the Portuguese Armed Forces are now an all-volunteer professional force. As of recent estimates, the active military personnel number around 24,000. Military expenditure in 2023 was approximately 1.48% of GDP.

- The Army comprises three main brigades: an Infantry Brigade (equipped with assets like Pandur II APCs), a Mechanized Brigade (with Leopard 2 A6 tanks and M113 APCs), and a Rapid Reaction Brigade (including paratroopers, commandos, and special operations forces). It is responsible for land-based defense and contributes to international missions.

- The Navy, one of the oldest continuously serving naval forces in the world, operates a fleet that includes frigates, corvettes, submarines, and oceanic patrol vessels. It is responsible for maritime defense, surveillance of Portugal's vast Exclusive Economic Zone (one of the largest in Europe), search and rescue operations, and participation in international maritime security efforts. The Navy also includes a marine corps (Fuzileiros).

- The Air Force operates aircraft for air defense, transport, reconnaissance, and maritime patrol. Its main combat aircraft include the F-16 Fighting Falcon. It also plays a crucial role in search and rescue and medical evacuation, particularly for the Azores and Madeira archipelagos.

In addition to the three main branches, Portugal has the National Republican Guard (Guarda Nacional Republicana - GNR). The GNR is a gendarmerie-type security force, with military status and organization, responsible for internal security, law enforcement in rural areas, border control, traffic enforcement, and environmental protection. It is under the dual authority of the Ministry of National Defence and the Ministry of Internal Administration and has also participated in international missions.

Portugal is a founding member of NATO and plays an active role in the alliance's collective defense and security initiatives. The Allied Joint Force Command Lisbon (JFC Lisbon), a major NATO command, was headquartered near Lisbon until its deactivation as part of NATO restructuring, though Portugal continues to host other NATO facilities. The United States also maintains a military presence at Lajes Air Base in the Azores, which has historically been a strategically important airbase for transatlantic operations. Portugal's defense policy emphasizes collective security through these alliances and contributions to international stability operations.

5.5. Law and Justice

The Portuguese legal system is based on civil law, influenced by Roman law and later by other European legal traditions, particularly French and German law. The cornerstone of the legal framework is the Constitution of 1976, which guarantees fundamental rights and freedoms and outlines the organization of the state.

Key legislation includes the Civil Code (1966), the Penal Code (1982), the Commercial Code (1888), and codes of civil and criminal procedure. These laws are regularly updated to reflect societal changes and EU directives.

The Judiciary is an independent branch of government. The court system is hierarchical:

- Courts of First Instance:** These are the general trial courts for civil and criminal matters.

- Courts of Appeal (Tribunais da Relação):** There are five of these, which hear appeals from the courts of first instance.

- Supreme Court of Justice (Supremo Tribunal de Justiça):** This is the highest court for common (civil and criminal) law matters, serving as the final court of appeal.

- Administrative and Fiscal Courts:** These deal with disputes involving public administration and tax matters, with the Supreme Administrative Court (Supremo Tribunal Administrativo) at their apex.

- Constitutional Court (Tribunal Constitucional):** This specialized court is responsible for reviewing the constitutionality of laws and decrees, ruling on electoral disputes, and overseeing referendums. It consists of thirteen judges.

The Public Ministry (Ministério Público), headed by the Attorney General of the Republic (Procurador-Geral da República), is an autonomous body responsible for representing the state in legal proceedings, conducting criminal prosecutions, and defending democratic legality and the rights of citizens.

Access to justice is a constitutional right, and legal aid is available for those who cannot afford legal representation. Portugal was a pioneer in abolishing life imprisonment (in 1884) and was one of the first countries to abolish the death penalty for common crimes (in 1867). The maximum prison sentence is generally 25 years.

Drug Decriminalization: A significant aspect of Portuguese law is its approach to drug policy. In 2001, Portugal decriminalized the personal use and possession of all illicit drugs. This means that possessing small quantities of drugs for personal consumption is treated as an administrative offense (punishable by fines or referral to a "Dissuasion Commission" for treatment or counseling) rather than a criminal offense leading to imprisonment. Drug trafficking remains a serious crime. This policy, which focuses on public health and harm reduction rather than criminalization of users, has been studied internationally. While outcomes are debated, data has shown decreases in problematic drug use, HIV infections among drug users, and drug-related deaths, without a significant long-term increase in overall drug consumption. This approach reflects a concern for human rights and the social well-being of vulnerable individuals.

Other notable legal developments include advancements in LGBT rights, such as the legalization of same-sex marriage in 2010 and adoption by same-sex couples in 2016. Euthanasia was legalized in 2023 for terminally ill adult residents under strict conditions.

5.5.1. Human Rights

The state of human rights in Portugal is generally considered good, with the country being a democratic republic that upholds fundamental freedoms. The 1976 Constitution, adopted after the Carnation Revolution, provides a strong framework for the protection of human rights and civil liberties. Portugal is a signatory to major international human rights treaties and is subject to the jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights.

Civil and Political Rights: Freedom of speech, assembly, association, and religion are guaranteed and generally respected. Elections are free and fair. The press is independent, though media concentration can be a concern. The right to privacy is protected. Arbitrary detention is prohibited, and legal safeguards exist for those accused of crimes, including the right to a fair trial and legal aid.

Social and Economic Rights: The constitution recognizes rights to work, housing, health, education, and social security. The National Health Service (SNS) aims to provide universal healthcare coverage, though challenges in access and quality persist, particularly due to resource constraints. Access to education is widespread. Social security provides pensions, unemployment benefits, and family allowances. However, poverty and social exclusion remain concerns, particularly for certain vulnerable groups. The economic crises of the early 21st century put pressure on these rights, leading to austerity measures that impacted social services.

Rights of Minorities and Vulnerable Groups:

- Immigrants and Ethnic Minorities:** While Portugal has become a country of immigration, challenges related to the integration of immigrants, discrimination (particularly against Roma and people of African descent), and occasional xenophobia exist. Efforts are made to combat discrimination through legislation and public policies, but societal prejudice can persist. The social liberal perspective emphasizes the need for effective integration policies and robust anti-discrimination measures.

- Roma Community:** The Roma population often faces significant social exclusion, discrimination in housing, employment, and access to education and healthcare.

- LGBT Rights:** Portugal has made significant progress in LGBT rights, including legalizing same-sex marriage (2010), adoption by same-sex couples (2016), and gender self-determination for transgender individuals (2018). Anti-discrimination laws cover sexual orientation and gender identity.

- Gender Equality:** While legal equality exists, gender disparities persist in areas like pay, representation in leadership positions, and domestic violence remains a serious concern.

- Persons with Disabilities:** Legislation aims to protect the rights of persons with disabilities, but challenges remain in ensuring full accessibility and inclusion in all areas of life.

Justice System and Detention Conditions: Concerns have been raised by human rights organizations regarding prison overcrowding, poor conditions in some detention facilities, and the length of pre-trial detention in some cases. Efforts are underway to reform the justice system and improve prison conditions.

Drug Policy and Human Rights: Portugal's drug decriminalization policy (2001) is often cited as a human rights-based approach, prioritizing public health and harm reduction over criminalization of users. This has led to positive outcomes in reducing drug-related deaths and HIV infections, aligning with a social liberal emphasis on rehabilitation and support for vulnerable individuals.

Democratic Strengthening: Portugal has robust democratic institutions. However, issues such as political corruption and the need for greater transparency and accountability in public life are subjects of ongoing public debate and reform efforts.

From a social liberal perspective, while Portugal has a strong legal framework for human rights, continuous efforts are needed to address existing inequalities, combat discrimination effectively, ensure equitable access to social services for all, and strengthen democratic accountability. The welfare of minorities and vulnerable groups remains a key area for policy focus and societal improvement.

6. Administrative Divisions

6.1. Main Administrative Units

Portugal is administratively divided into several levels. The primary and most stable units of local government are the municipalities (municípios or concelhos) and, below them, the civil parishes (freguesias).

- Municipalities (Municípios):** There are 308 municipalities in Portugal (278 on the mainland, 19 in the Azores, and 11 in Madeira). Each municipality is governed by a Municipal Assembly (Assembleia Municipal), which is the deliberative body, and a Municipal Chamber (Câmara Municipal), which is the executive body, headed by a Mayor (Presidente da Câmara Municipal). Municipalities are responsible for a wide range of local services, including urban planning, local infrastructure, cultural facilities, social services, and basic education facilities.

- Civil Parishes (Freguesias):** There are 3,092 civil parishes. Each parish is governed by a Parish Assembly (Assembleia de Freguesia) and a Parish Executive Board (Junta de Freguesia), headed by a President. Parishes are the smallest administrative units and deal with very local matters. A significant local government reform in 2013 led to the aggregation and reduction in the number of parishes.

For statistical and some administrative purposes, mainland Portugal is also divided into 18 Districts (Distritos). These were historically more significant administrative divisions but have lost many of their powers to municipalities and regional coordination bodies. However, they still serve as territorial units for state deconcentrated services (e.g., for electoral purposes, some police and civil protection organization). The districts are: Aveiro, Beja, Braga, Bragança, Castelo Branco, Coimbra, Évora, Faro, Guarda, Leiria, Lisbon, Portalegre, Porto, Santarém, Setúbal, Viana do Castelo, Vila Real, and Viseu. Each district is named after its capital city.

The Autonomous Regions of the Azores and Madeira have a distinct political-administrative status established by the Constitution. They possess their own regional governments (Governo Regional) and legislative assemblies (Assembleia Legislativa Regional) with significant legislative and executive powers over local affairs, reflecting their geographical and cultural distinctiveness. They are not subdivided into districts.

For EU statistical purposes (NUTS system), Portugal is divided into:

- NUTS I:** Mainland Portugal, Azores, Madeira.

- NUTS II (Regions):** Norte, Centro, Lisboa Metropolitan Area, Alentejo, Algarve, Azores, Madeira. (Note: The Lisboa Metropolitan Area is a NUTS II region, while the rest of the former Lisboa e Vale do Tejo region was split and reconfigured into Oeste e Vale do Tejo and Península de Setúbal, among others, in more recent NUTS revisions).

- NUTS III (Subregions):** These are 25 entities (23 on the mainland plus the two autonomous regions) that often correspond to intermunicipal communities (Comunidades Intermunicipais - CIMs) or metropolitan areas (Áreas Metropolitanas).

Intermunicipal Communities (CIMs) and Metropolitan Areas (AMs) are associations of municipalities aimed at joint planning and management of services and development projects. The two legally defined Metropolitan Areas are Lisbon and Porto.

Historically, Portugal was also divided into Provinces (e.g., Minho, Trás-os-Montes, Beira Litoral, Estremadura, Ribatejo, Alto Alentejo, Baixo Alentejo, Algarve). These historical provinces, though no longer official administrative units (except for a brief period in the 20th century), still hold strong cultural and regional identities for many Portuguese people and are often used in everyday language and tourism.

6.2. Major Cities

Portugal has several important urban centers that are significant for their demographic weight, economic activity, cultural heritage, and administrative roles.

- Lisbon (LisboaPortuguese): The capital and largest city of Portugal, Lisbon is the political, economic, and cultural heart of the country. Located on the estuary of the Tagus River, it is one of the oldest cities in Western Europe. Lisbon is a major global city, known for its historic neighborhoods like Alfama and Belém, its vibrant cultural scene, and its role as a key port and transportation hub. The Lisbon Metropolitan Area is the most populous urban agglomeration in the country.

- Porto (OportoPortuguese): The second-largest city, Porto is located in northern Portugal at the mouth of the Douro River. It is a major economic and industrial center, famous worldwide for Port wine. Its historic center, Ribeira, is a UNESCO World Heritage site. The Porto Metropolitan Area is the second most populous in Portugal.

- Vila Nova de Gaia: Located directly across the Douro River from Porto, Gaia is technically a separate city but forms a continuous urban area with Porto. It is renowned for its Port wine cellars.

- Braga: An ancient city in the Minho region of northern Portugal, Braga is one ofthe country's oldest cities and a significant religious center, often called the "Portuguese Rome" due to its numerous churches. It is also a dynamic economic and university city.

- Coimbra: Located in central Portugal, Coimbra was the medieval capital of Portugal and is home to the University of Coimbra, one of the oldest universities in continuous operation in the world. It is a major educational and cultural center.

- Faro: The capital of the Algarve region in southern Portugal, Faro is an important tourist gateway due to its international airport and proximity to popular coastal resorts. It has a charming old town and is a center for services and commerce in the region.

- Setúbal: A port city south of Lisbon, Setúbal is an important industrial and commercial center, known for its fishing industry and proximity to the Arrábida Natural Park and beautiful beaches.

- Aveiro: Often dubbed the "Portuguese Venice" due to its canals (rias) and colorful moliceiro boats, Aveiro is a city in central Portugal with a strong university presence and growing tourism.

Other notable cities include Guimarães (considered the "birthplace of Portugal"), Évora (a UNESCO World Heritage city in Alentejo known for its Roman temple and medieval walls), Funchal (the capital of Madeira), and Ponta Delgada (the administrative capital of the Azores). These cities, each with unique characteristics, contribute to Portugal's diverse urban landscape and national identity.

7. Economy

7.1. Overview and Main Sectors

Portugal's economy is characterized as a diversified and increasingly service-based economy. As a member of the Eurozone, its monetary policy is guided by the European Central Bank. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita (PPP) was $47,209 in 2023, according to the World Bank. The country's Human Development Index (HDI) was 0.874 in 2022, ranking 42nd globally.

Main Sectors:

- Services:** This is the largest sector, contributing the most to GDP and employment. It includes tourism (a vital component), retail, banking and finance, real estate, business services, healthcare, and education. Lisbon and Porto are major service hubs.

- Industry:** Manufacturing plays a significant role, with key industries including automotive (e.g., Volkswagen Autoeuropa plant in Palmela), machinery and equipment, electronics, textiles and clothing (though diminished from its past prominence), footwear, wood products (including paper pulp), and cork (Portugal is the world's largest producer). Other notable areas include food processing, ceramics, and renewable energy technology. The country has significant lithium reserves, which are becoming increasingly important for the battery industry.

- Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing:** While its share of GDP has declined, this sector remains important for rural employment and exports. Key agricultural products include wine (Port wine, Vinho Verde, etc.), olives and olive oil (Portugal is a major producer and exporter), fruits (citrus, pears, apples, berries), vegetables, and dairy. Forestry is crucial for cork and pulp production. The fishing industry, though smaller than in the past, remains culturally and economically significant, with a long tradition of cod fishing and a high per capita fish consumption.

Recent Economic Trends and Challenges: Portugal experienced robust growth after EU accession but was severely affected by the 2007-2008 global financial crisis and the subsequent European sovereign debt crisis. This led to a €78 billion bailout package from the EU and IMF in 2011, accompanied by austerity measures. The economy has since recovered, with periods of growth driven by exports and tourism.

Challenges include:

- Public Debt:** While decreasing, public debt remains relatively high.

- Unemployment:** Unemployment rates, particularly among youth, rose significantly during the crisis but have since fallen. Ensuring quality employment and fair labor rights remains a focus.

- Productivity and Competitiveness:** Improving productivity and fostering innovation are key to long-term competitiveness.

- Social Equity:** Despite progress, income inequality and poverty persist. Social policies aim to mitigate these issues and ensure a social safety net.

- Environmental Sustainability:** Balancing economic growth with environmental protection, particularly in tourism, agriculture, and energy, is crucial. This includes managing water resources, reducing carbon emissions, and protecting biodiversity.

National Economic Policies: Policies often focus on fiscal consolidation, structural reforms to enhance competitiveness, attracting foreign investment, promoting exports, and investing in education, research, and innovation. EU funds continue to play a vital role in infrastructure development and economic modernization. There is an increasing emphasis on sustainable development and the green transition. Labor rights are protected by law, and social dialogue between government, employers, and trade unions is an established part of the policy-making process, though sometimes contentious.

7.2. Tourism

Tourism is a cornerstone of the Portuguese economy, contributing significantly to GDP, employment, and foreign exchange earnings. In 2023, tourism accounted for 16.5% of Portugal's GDP. The country's appeal lies in its diverse offerings, including a rich cultural heritage, historic cities, varied landscapes, extensive coastline with popular beaches, favorable climate, and distinctive cuisine and wines.

Major Tourist Destinations:

- Lisbon**: The capital city attracts millions of visitors with its historic neighborhoods (Alfama, Baixa, Belém), monuments (e.g., Belém Tower, Jerónimos Monastery), Fado music, museums, and vibrant nightlife.

- Algarve**: Located in the south, the Algarve is renowned for its beaches, cliffs, golf courses, and resorts. It is a major destination for sun and sea tourism, particularly popular with British, German, and other European tourists.

- Porto**: Portugal's second city, famous for Port wine, its historic Ribeira district (a UNESCO World Heritage site), the Douro River, and contemporary architecture like the Casa da Música.

- Madeira**: This Atlantic archipelago is known for its dramatic volcanic landscapes, laurel forests (Laurisilva, a UNESCO site), mild climate (making it a year-round destination), hiking trails (levadas), and unique traditions.

- Azores**: Another Atlantic archipelago, the Azores offer stunning natural beauty, including volcanic craters, lakes, hot springs, and opportunities for whale watching, hiking, and eco-tourism.

- Other Destinations:** Historic cities like Sintra (with its fairytale palaces), Coimbra (home to one of the world's oldest universities), Évora (a UNESCO site in Alentejo), and Guimarães (the "birthplace of Portugal") are also popular. Religious tourism is significant, with Fátima being one of the most important Marian shrines in the world. Rural tourism, nature tourism (e.g., Peneda-Gerês National Park), and niche tourism like surfing (e.g., Nazaré, Peniche) are growing.

Types of Tourism: Portugal caters to a wide range of tourism types, including cultural tourism, beach tourism, city breaks, nature and eco-tourism, rural tourism, MICE (Meetings, Incentives, Conferences, and Exhibitions) tourism, health and wellness tourism, and wine tourism.

Recent Trends:

- Growth and Diversification:** The sector has seen significant growth in recent years, with efforts to diversify beyond traditional sun and sea markets and promote year-round tourism.

- Sustainability Concerns:** The rapid growth of tourism, particularly in cities like Lisbon and Porto, has raised concerns about overtourism, housing affordability for locals (due to short-term rentals like Airbnb), and environmental impacts. There is an increasing focus on promoting sustainable tourism practices.

- Impact of Global Events:** The COVID-19 pandemic severely impacted the tourism sector, highlighting its vulnerability to global crises. Recovery efforts have focused on adapting to new travel norms and ensuring safety.

The Portuguese government and tourism authorities actively promote the country internationally. Infrastructure, including airports and transportation networks, has been developed to support the sector. While tourism brings economic benefits, managing its social and environmental impacts to ensure sustainability and equitable distribution of benefits is an ongoing challenge and policy priority.

7.3. Science and Technology

Portugal has been making concerted efforts to develop its science and technology (S&T) sector, recognizing its importance for economic competitiveness, innovation, and societal progress. While historically lagging behind some other European nations, significant investments and policy initiatives have led to notable advancements.

Research and Development (R&D) Landscape:

- Institutions:** R&D activities are primarily conducted in public universities, state-managed autonomous research institutions (e.g., the former INETI and INRB, now often integrated into university structures or other bodies), and associated laboratories. A network of R&D units, often linked to universities, forms the backbone of the research system.

- Funding and Management:** The Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education (MCTES) is the main government body responsible for S&T policy. The Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT; Fundação para a Ciência e TecnologiaPortuguese) is the primary public funding agency for research, providing grants for projects, PhD scholarships, postdoctoral fellowships, and supporting research institutions. EU structural and research funds (like Horizon Europe) are also crucial sources of funding.

- Private Sector R&D:** While public sector R&D has grown, R&D expenditure by the private sector is comparatively lower than the EU average, though efforts are being made to stimulate business innovation and university-industry collaboration.

- Leading Research Centers:** Notable non-state research institutions include the Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência (IGC), a leading biomedical research institute, and the Champalimaud Foundation, which focuses on cutting-edge research in neuroscience and oncology.

Areas of Innovation and Strength: Portugal has developed strengths in several S&T areas, including:

- Information and Communication Technologies (ICT):** The ICT sector has seen growth, with a vibrant startup ecosystem, particularly in Lisbon and Porto.

- Biotechnology and Life Sciences:** This is a priority area, with significant research in genomics, molecular medicine, and marine biotechnology.

- Renewable Energy:** Portugal has been a pioneer in renewable energy, particularly wind, solar, and wave power, supported by R&D in these fields.

- Nanotechnology:** The International Iberian Nanotechnology Laboratory (INL) in Braga, a joint Portugal-Spain initiative, is a leading European research center in nanotechnology.

- Materials Science and Engineering.**

- Ocean Sciences:** Given its extensive maritime territory, research related to the ocean (marine biology, oceanography, sustainable exploitation of marine resources) is increasingly important.

Government Policies and Initiatives:

- Promoting Innovation:** Policies aim to increase overall R&D investment (both public and private), strengthen the link between academia and industry, support startups and entrepreneurship, and enhance the internationalization of Portuguese S&T.

- Human Capital Development:** Efforts focus on increasing the number of PhD holders and researchers, and retaining talent.

- International Collaboration:** Portugal actively participates in international S&T programs and organizations, including the European Space Agency (ESA), CERN, ITER, and the European Southern Observatory (ESO). Bilateral and multilateral research collaborations are encouraged.

- Science Communication:** Ciência Viva is a national agency dedicated to promoting scientific culture and literacy through a network of science centers, exhibitions, and educational programs.