1. Overview

The Republic of the Sudan is a country located in Northeast Africa. It is bordered by Egypt to the north, Libya to the northwest, Chad to the west, the Central African Republic to the southwest, South Sudan to the south, Ethiopia to the southeast, Eritrea to the east, and the Red Sea to the northeast. Sudan is Africa's third-largest country by area and the third-largest by area in the Arab League. Its capital and most populous city is Khartoum. The nation has a population of approximately 50 million people as of 2024 and covers an area of 0.7 M mile2 (1.89 M km2).

Sudan's history is marked by ancient civilizations, including the Kingdom of Kush, followed by periods of Egyptian rule, Christian kingdoms, and subsequent Islamization. The 19th century saw Turco-Egyptian conquest, followed by the Mahdist War and Anglo-Egyptian condominium rule. Independence in 1956 was followed by decades of political instability, military coups, and protracted civil wars, significantly between the North and South, and later in the Darfur region. These conflicts have had devastating humanitarian consequences, including widespread displacement and human rights abuses. The secession of South Sudan in 2011, following a referendum, reshaped the country's geography and economy, particularly impacting its oil revenues.

Recent Sudanese history has been characterized by popular uprisings and struggles for democratic governance. The 2019 Sudanese Revolution led to the ousting of long-time authoritarian president Omar al-Bashir, ushering in a transitional government aimed at democratic reforms and social justice. However, a military coup in October 2021 disrupted this transition, leading to further political turmoil and popular resistance. Since April 2023, Sudan has been embroiled in a devastating civil war between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), resulting in a severe humanitarian crisis, mass displacement, and widespread human rights violations.

This article explores Sudan's etymology, complex history, geography, political structures, economy, societal issues, and diverse culture, with a particular focus on its journey towards democratic development, the challenges to human rights, and the pursuit of social equity.

2. Etymology

The name "Sudan" originates from the Arabic phrase بلاد السودانbilād as-sūdānArabic, meaning "Land of the Blacks." This term was historically used by Arabs to refer to the vast Sahel region stretching across Africa, south of the Sahara Desert, from West Africa to Northeast Africa, including the area of the modern-day Republic of the Sudan. The name was given in reference to the dark skin of the indigenous inhabitants of this broader geographical region.

Before the Arab designation, the region of present-day Sudan, particularly Nubia, was known by various names in ancient times. Ancient Egyptians referred to it as Ta Nehesi or Ta Seti, terms associated with the Nubian and Medjay peoples, who were renowned as archers. The term "Nubia" itself has ancient roots and was a prominent historical designation for the area.

Since the secession of South Sudan in 2011, the Republic of the Sudan is sometimes informally referred to as "North Sudan" to distinguish it from the newly independent nation of South Sudan. However, "Sudan" remains its official and most common name.

3. History

The history of Sudan encompasses millennia of human development, from early prehistoric settlements through ancient kingdoms, periods of foreign rule, Islamization, colonial administration, and a tumultuous post-independence era marked by internal conflicts and struggles for governance. This section chronicles the major historical events and transformations in the region of Sudan from prehistoric times to the present day, examining the societal changes and political dynamics that have shaped the nation.

3.1. Prehistoric Sudan

Evidence of early human habitation in the Sudan region dates back tens of thousands of years. The Affad 23 archaeological site, located in the Affad region of southern Dongola Reach in northern Sudan, contains well-preserved remains of prehistoric camps, including relics of what are considered the oldest open-air huts in the world, and diverse hunting and gathering loci dating back some 50,000 years. The Khormusan industry flourished between 40,000 and 16,000 BC. The Halfan culture existed from around 20,500 to 17,000 BC, followed by the Sebilian culture (13,000-10,000 BC) and the Qadan culture (15,000-5,000 BC). The site of Jebel Sahaba is notable for evidence of the earliest known organized warfare in the world, dating to around 11,500 BC.

By the eighth millennium BC, people of a Neolithic culture had settled into a sedentary way of life in fortified mudbrick villages along the Nile. They supplemented hunting and fishing with grain gathering and cattle herding. Neolithic peoples created cemeteries such as R12. During the fifth millennium BC, migrations from the drying Sahara brought Neolithic people into the Nile Valley, along with agriculture. The A-Group culture (c. 3800-3100 BC) emerged during this period. The population resulting from this cultural and genetic mixing developed a social hierarchy over the next centuries, which eventually became the Kingdom of Kerma around 2500 BC. Anthropological and archaeological research indicates that during the predynastic period, Nubia and Nagadan Upper Egypt were ethnically and culturally nearly identical, and thus, simultaneously evolved systems of pharaonic kingship by 3300 BC.

3.2. Ancient Nubian Kingdoms

Ancient Nubia, located in present-day Sudan and southern Egypt, was home to a series of powerful indigenous kingdoms that flourished for millennia. These kingdoms, including Kerma, the various phases under Egyptian rule, and the influential Kingdom of Kush, developed sophisticated cultures, engaged in extensive trade, and had complex political and military interactions, particularly with their northern neighbor, Egypt.

3.2.1. Kerma culture

The Kerma culture, flourishing from approximately 2500 BC to 1500 BC, was an early civilization centered in Kerma, Sudan. It was based in the southern part of Nubia, or "Upper Nubia," in what is now northern and central Sudan, and later extended its reach northward into Lower Nubia and the Egyptian border. The polity appears to have been one of several Nile Valley states during the Middle Kingdom of Egypt.

Kerma was characterized by its urban centers, distinctive pottery (often highly polished black-topped red ware), and monumental mud-brick structures known as deffufas. The Western Deffufa, a massive temple-like structure, stands as a testament to Kerma's architectural and organizational capabilities. The society was hierarchical, with powerful rulers who controlled extensive trade networks, particularly in gold, ivory, cattle, and slaves, which were highly sought after by Egypt. Archaeological evidence, including rich burial sites with numerous sacrificial retainers and imported goods, indicates a wealthy and powerful elite. The Kerma culture maintained a distinct identity while also absorbing influences from Egypt and other African cultures. In its latest phase, from about 1700-1500 BC, it absorbed the Sudanese kingdom of Saï and became a sizable, populous empire that rivaled and often conflicted with Egypt.

3.2.2. Egyptian rule of Nubia

Ancient Egypt exerted significant influence and, at various times, direct control over Nubia, driven by the desire for Nubia's rich resources, including gold, ivory, ebony, incense, and manpower. Egyptian rule in Nubia was established through military campaigns and the construction of fortified settlements and temples.

Mentuhotep II, the 21st century BC founder of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt, is recorded to have undertaken campaigns against Kush in the 29th and 31st years of his reign. This is the earliest Egyptian reference to Kush; the Nubian region had gone by other names in the Old Kingdom. Under Thutmose I during the New Kingdom (circa 1504 BC), Egypt made several campaigns south, conquering Kush and destroying its capital, Kerma. This marked the beginning of a long period of Egyptian domination.

After the conquest, Kerma culture was increasingly Egyptianized, yet rebellions continued for centuries, lasting about 220 years until circa 1300 BC. Nubia became a key province of the New Kingdom, economically, politically, and spiritually. Major pharaonic ceremonies were held at Jebel Barkal near Napata. As an Egyptian colony from the 16th century BC, Nubia ("Kush") was governed by an Egyptian Viceroy of Kush. Egyptian administration brought Egyptian language, religion, and culture to Nubia, and many Nubians served in the Egyptian military or administration. Temples to Egyptian gods were built throughout Nubia, and Egyptian artistic styles influenced Nubian art.

Resistance to early Eighteenth Dynasty Egyptian rule by neighboring Kush is evidenced in the writings of Ahmose, son of Ebana, an Egyptian warrior. At the end of the Second Intermediate Period (mid-sixteenth century BC), Egypt faced threats from the Hyksos in the North and the Kushites in the South. The Egyptians undertook campaigns to defeat Kush and conquer Nubia under Amenhotep I (1514-1493 BC). In Ahmose's writings, the Kushites are described as archers. By 1200 BC, direct Egyptian involvement in the Dongola Reach was nonexistent. Egypt's international prestige declined considerably towards the end of the Third Intermediate Period, facilitating the later resurgence of an independent Kushite kingdom. According to Josephus Flavius, the biblical Moses led the Egyptian army in a siege of the Kushite city of Meroe. To end the siege, Princess Tharbis was reportedly given to Moses as a diplomatic bride, and the Egyptian army retreated.

3.2.3. Kingdom of Kush

The Kingdom of Kush was an ancient Nubian state centered on the confluences of the Blue Nile and White Nile, and the Atbarah River and the Nile River. It was established after the Bronze Age collapse and the disintegration of the New Kingdom of Egypt. The kingdom had two major phases: the Napatan period and the Meroitic period.

The Napatan period (c. 1070 BC - c. 350 BC, though often considered to begin with Kashta's reign around 760 BC for the dynasty that conquered Egypt) was initially centered at Napata, near Jebel Barkal. After King Kashta invaded Egypt in the eighth century BC, the Kushite kings, including notable figures like Piye and Taharqa, ruled as pharaohs of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt for nearly a century. They controlled an empire stretching from South Kordofan to the Sinai. Pharaoh Piye attempted to expand into the Near East but was thwarted by the Assyrian king Sargon II. The Kushite dynasty was eventually defeated and driven out of Egypt by the Assyrians under Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal. Ashurbanipal sacked Thebes, effectively ending Kushite rule in Egypt.

Following their expulsion from Egypt, the Kushite kingdom continued to thrive, with its capital eventually shifting south to Meroë (c. 300 BC - c. 350 AD). The Meroitic period is characterized by a stronger indigenous African influence. Meroë became a major center for iron production, agriculture (especially sorghum), and trade, connecting sub-Saharan Africa with the Mediterranean world, India, and China. The Meroites developed their own script, Meroitic, which remains largely undeciphered, and continued the tradition of pyramid building for royal burials, though distinct in style from Egyptian pyramids. Nubian pyramids were built in locations such as El-Kurru, Nuri, Jebel Barkal, and Meroë. The Kingdom of Kush is mentioned in the Bible, notably as having potentially aided the Israelites against the Assyrians. The decline of Meroë is attributed to various factors, including environmental degradation, loss of trade routes to the rising Aksumite Kingdom, and possible internal strife. It eventually collapsed around 350 AD, traditionally attributed to an invasion by King Ezana of Aksum.

3.3. Medieval Christian Nubian kingdoms

After the fall of Kush, Nubia saw the emergence of three Christian kingdoms: Nobatia, Makuria, and Alodia. These kingdoms flourished from approximately the 6th to the 15th centuries and played a significant role in the history of Northeast Africa.

Around the turn of the fifth century, the Blemmyes established a short-lived state in Upper Egypt and Lower Nubia, possibly centered around Talmis (Kalabsha). However, before 450 AD, they were driven out of the Nile Valley by the Nobatians, who subsequently founded the kingdom of Nobatia. By the sixth century, three distinct Nubian kingdoms had emerged:

- Nobatia in the north, with its capital at Pachoras (modern Faras).

- Makuria in the center, with its capital at Tungul (Old Dongola), about 8.1 mile (13 km) south of modern Dongola.

- Alodia in the south, in the heartland of the old Kushitic kingdom, with its capital at Soba (near modern-day Khartoum).

These kingdoms converted to Christianity in the sixth century, largely through the efforts of missionaries from the Byzantine Empire. Coptic Christianity became the dominant form. In the seventh century, probably between 628 and 642, Nobatia was incorporated into Makuria.

Between 639 and 641, Muslim Arabs conquered Byzantine Egypt. They subsequently invaded Nubia in 641 or 642 and again in 652 but were repelled by Makurian forces. This led to the Baqt treaty, a unique non-aggression pact between Makuria and Muslim Egypt that included an annual exchange of goods (including slaves from Nubia and grain from Egypt) and acknowledged Makuria's independence. This treaty largely stabilized relations for several centuries. While the Arabs failed to conquer Nubia militarily, some Arab traders and settlers began to live east of the Nile, intermarrying with the local Beja people.

From the mid-eighth to the mid-eleventh century, Christian Nubia experienced a golden age of political power and cultural development. Makuria invaded Egypt in 747 during the decline of the Umayyad Caliphate and again in the early 960s, pushing as far north as Akhmim. Makuria maintained close dynastic ties with Alodia, possibly resulting in a temporary unification of the two kingdoms. The culture of medieval Nubians has been described as "Afro-Byzantine," though it was also increasingly influenced by Arab culture. The state organization was highly centralized, based on Byzantine bureaucracy. Arts flourished, particularly pottery painting and vibrant wall paintings in churches. The Nubians developed an alphabet for their language, Old Nobiin, based on the Coptic alphabet, while also using Greek, Coptic, and Arabic. Women enjoyed a relatively high social status, with access to education, land ownership, and often endowed churches. Royal succession was often matrilineal.

From the late 11th/12th century, Makuria's capital Dongola began to decline, and Alodia's capital Soba also declined in the 12th century. In the 14th and 15th centuries, Bedouin Arab tribes overran most of Sudan, migrating to the Butana, Gezira, Kordofan, and Darfur. In 1365, a civil war forced the Makurian court to flee to Gebel Adda in Lower Nubia, while Dongola was destroyed and left to the Arabs. Makuria continued as a petty kingdom. After the reign of King Joel of Dotawo (c. 1463-1484), Makuria collapsed. Coastal areas from southern Sudan up to Suakin were succeeded by the Adal Sultanate in the fifteenth century. To the south, the kingdom of Alodia fell to either Arab tribal leader Abdallah Jamma or the Funj, an African people from the south, with dates ranging from the late 14th to early 16th century (often cited as 1504). An Alodian rump state might have survived as the kingdom of Fazughli until 1685.

3.4. Islamization and Islamic Sultanates

The gradual process of Islamization in Sudan began with increased Arab migration and trade following the decline of the Christian Nubian kingdoms. Sufi holy men played a crucial role in spreading Islam, particularly from the 15th and 16th centuries onwards.

In 1504, the Funj, an African people of uncertain origin, are recorded to have founded the Funj Sultanate of Sennar, which incorporated Abdallah Jamma's realm. By 1523, when Jewish traveler David Reubeni visited Sudan, the Funj state already extended as far north as Dongola. King Amara Dunqas, previously a Pagan or nominal Christian, was recorded to be Muslim by Reubeni's visit. However, the Funj retained un-Islamic customs like divine kingship and alcohol consumption until the 18th century. Sudanese folk Islam preserved many rituals stemming from Christian traditions.

The Funj soon came into conflict with the Ottoman Empire, which had occupied Suakin around 1526 and eventually pushed south along the Nile, reaching the third Nile cataract area by 1583/1584. An Ottoman attempt to capture Dongola was repelled by the Funj in 1585. Hannik, south of the third cataract, became the border. Following the Ottoman invasion, Ajib the Great, a minor king of northern Nubia, attempted usurpation. Though the Funj eventually killed him in 1611/1612, his successors, the Abdallab, were granted governance over the region north of the confluence of the Blue and White Niles with considerable autonomy.

During the 17th century, the Funj state reached its widest extent. However, it began to decline in the 18th century. A coup in 1718 brought a dynastic change, and another in 1761-1762 resulted in the Hamaj Regency, where the Hamaj (a people from the Ethiopian borderlands) effectively ruled while the Funj sultans were mere puppets. The sultanate then began to fragment, and by the early 19th century, it was essentially restricted to the Gezira region. The coup of 1718 initiated a policy of pursuing a more orthodox Islam, which promoted the Arabization of the state. To legitimize their rule over Arab subjects, the Funj began to propagate an Umayyad descent. North of the confluence of the Blue and White Niles, as far downstream as Al Dabbah, the Nubians adopted the tribal identity of the Arab Ja'alin. By the 19th century, Arabic had become the dominant language of central riverine Sudan and most of Kordofan.

West of the Nile, in Darfur, the Islamic period saw the rise of the Tunjur kingdom, which replaced the old Daju kingdom in the 15th century and extended as far west as Wadai. The Tunjur were likely Arabized Berbers, and their ruling elite were Muslims. In the 17th century, the Tunjur were driven from power by the Fur Keira Sultanate. The Keira state, nominally Muslim since the reign of Sulayman Solong (r. c. 1660-1680), was initially a small kingdom in northern Jebel Marra but expanded significantly in the early 18th century. Under Muhammad Tayrab (r. 1751-1786), it conquered Kordofan in 1785. The Keira Sultanate reached its peak, roughly the size of present-day Nigeria, and lasted until its conquest during the Turco-Egyptian period in 1874, though it was later briefly restored.

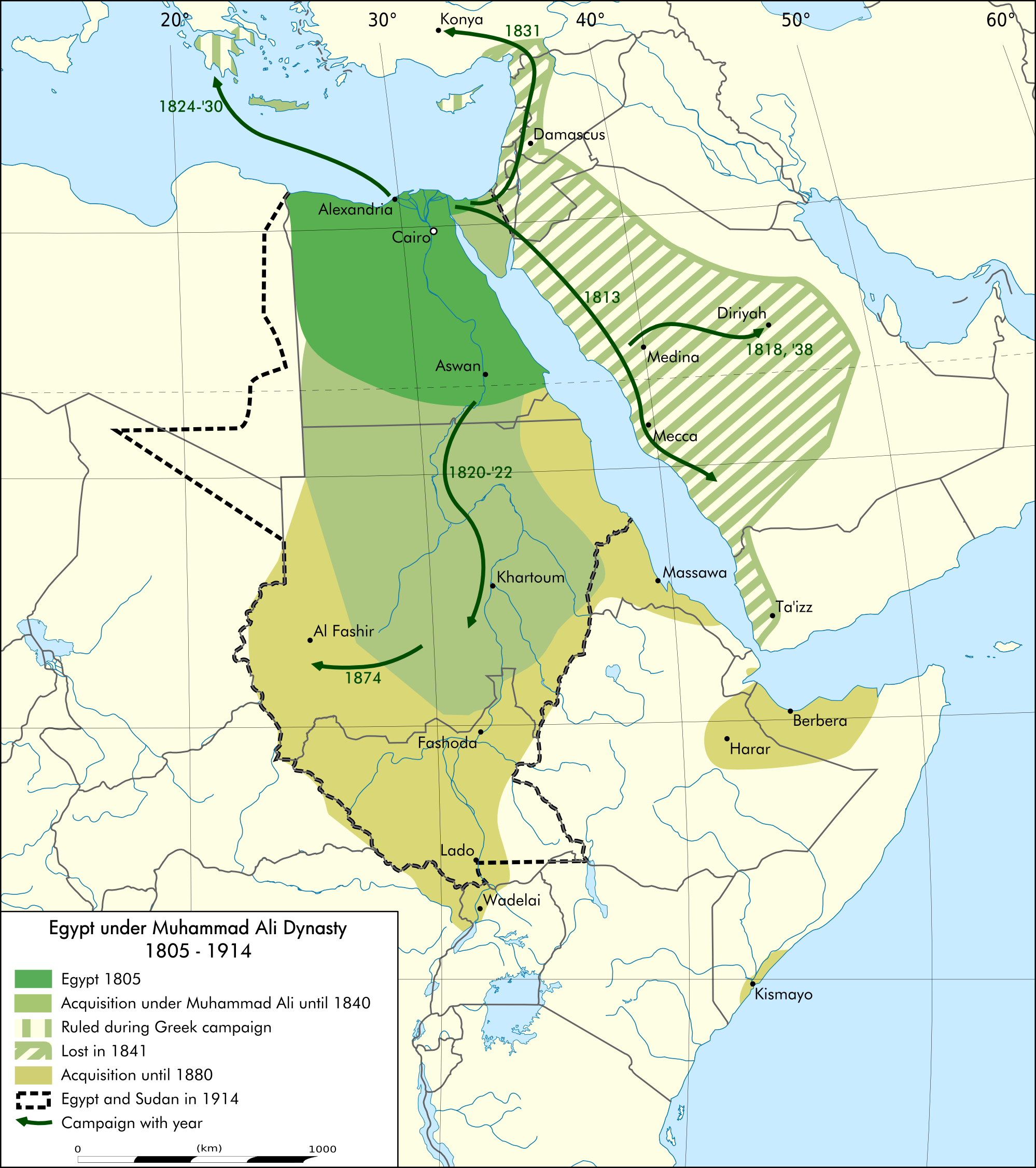

3.5. Turco-Egyptian Rule and the Mahdist War

This period covers the conquest of Sudan by Muhammad Ali of Egypt, the establishment of Turco-Egyptian administration (known as the Turkiyya), the subsequent Mahdist Uprising led by Muhammad Ahmad, the creation of the Mahdist State, and its eventual overthrow by Anglo-Egyptian forces. This era fundamentally reshaped Sudanese society, economy, and its relationship with external powers, laying some of the groundwork for modern Sudan.

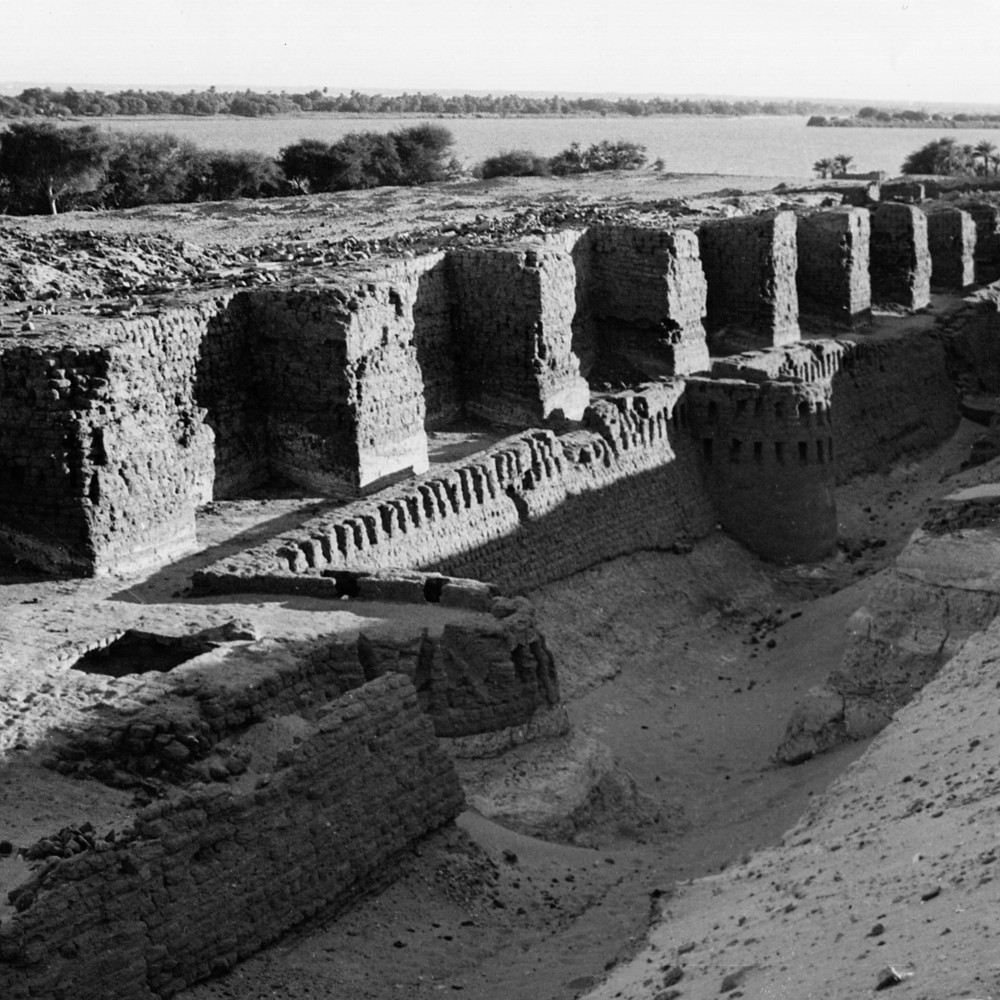

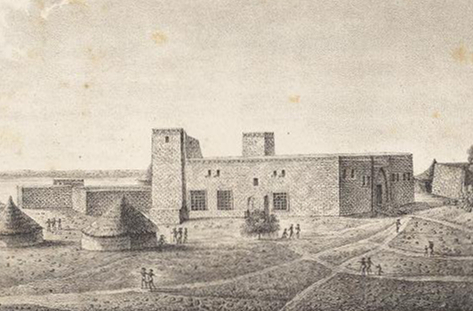

3.5.1. Turco-Egyptian Sudan (Turkiyya)

In 1821, Muhammad Ali Pasha, the Ottoman wali (governor) of Egypt who ruled as a virtually independent Khedive, initiated the conquest of Sudan. His primary motives were to secure access to gold, slaves, and to eliminate Mamluk remnants who had fled south. His third son, Ismail Kamil Pasha, led the invasion force, which conquered northern and central Sudan. With the exception of the Shaiqiya tribe and the Darfur Sultanate in Kordofan, he met little resistance. The Egyptian policy of conquest was expanded and intensified by Ibrahim Pasha's son, Isma'il Pasha (Khedive Isma'il), under whose reign (1863-1879) most of the remainder of modern-day Sudan was conquered, extending Egyptian control far south along the Nile and into Darfur (annexed in 1874).

The Turco-Egyptian administration, known as the Turkiyya, brought significant changes. It established a centralized government, introduced new administrative structures, and attempted to modernize aspects of the Sudanese economy, particularly focusing on agriculture (e.g., cotton) and trade. However, the rule was often harsh, characterized by heavy taxation, forced labor, and the brutal expansion of the slave trade, particularly from the southern regions. These policies generated widespread resentment among the Sudanese population. European powers increasingly pressured Egypt to suppress the slave trade, leading to the appointment of European governors like Charles George Gordon in Equatoria, but the trade persisted.

In 1879, the Great Powers forced the removal of Khedive Isma'il, replacing him with his son Tewfik Pasha. Tewfik's perceived weakness, corruption, and mismanagement within his administration, including in Sudan, contributed to the 'Urabi Revolt in Egypt. Tewfik appealed for British help, leading to the British occupation of Egypt in 1882. Sudan remained under nominal Khedivial control but was increasingly mismanaged. The harsh taxes and the adverse impact of European anti-slavery initiatives on the northern Sudanese economy, which relied on slave labor and trade, precipitated widespread discontent and paved the way for the Mahdist Uprising.

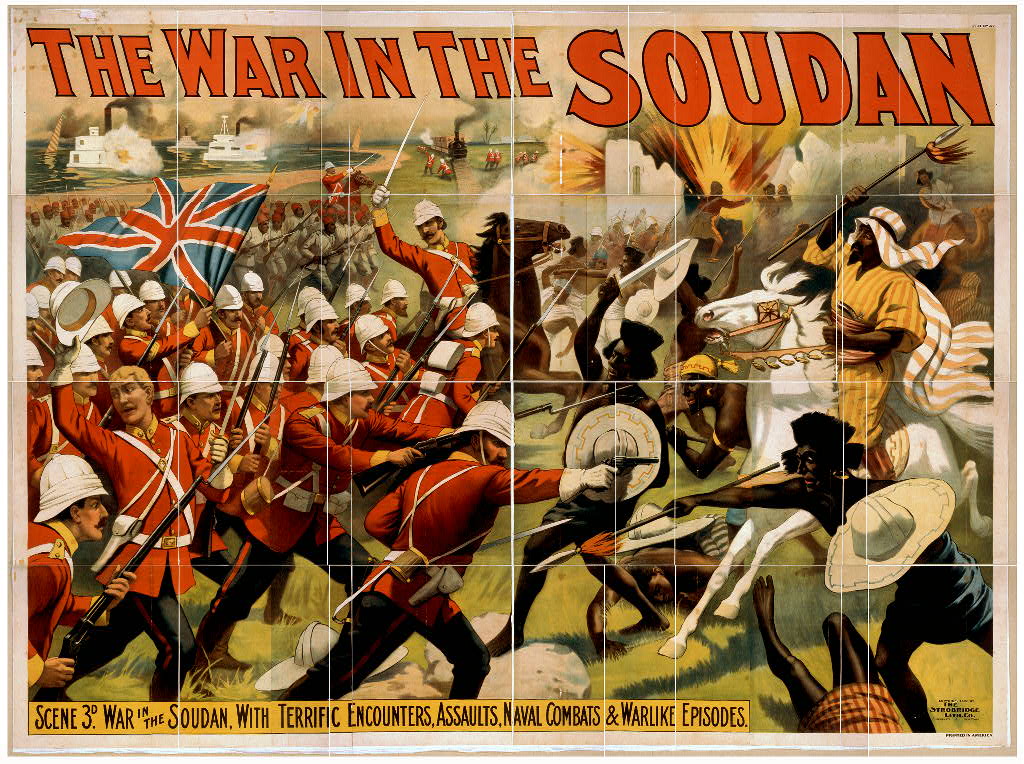

3.5.2. Mahdist State

In June 1881, Muhammad Ahmad ibn Abd Allah, a Sufi religious leader from Dongola, proclaimed himself the Mahdi (the "Guided One" expected in Islamic eschatology). He denounced the Turco-Egyptian rulers as corrupt and un-Islamic and called for a jihad to purify Islam and establish an Islamic state. His movement rapidly gained support from various Sudanese groups, including religious followers (Ansar), displaced pastoralists, and those resentful of Egyptian taxation and administration.

The Mahdist War (1881-1899) began with an incident at Aba Island. The Mahdist forces, despite being poorly equipped initially, won a series of stunning victories against Egyptian forces, culminating in the Siege of Khartoum. In January 1885, Khartoum fell, and the British-appointed Governor-General Charles George Gordon was killed. This victory effectively ended Turco-Egyptian rule and established the Mahdist State.

Muhammad Ahmad died in June 1885, just six months after capturing Khartoum. After a power struggle, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, known as the Khalifa, emerged as his successor. The Khalifa consolidated power, primarily with the support of the Baggara Arabs from western Sudan, and established a centralized administration. The Mahdist State enforced a strict interpretation of Sharia law. It faced internal rebellions and external threats. The Khalifa pursued an expansionist policy, launching campaigns against Ethiopia (capturing Gondar in 1887, though King Yohannes IV was killed in a counter-attack at Metemma in 1889), Egypt (defeated at Tushkah in 1889), and Italian Eritrea (repelled at Agordat in 1893). These campaigns, often brutal, strained the state's resources and alienated some populations. The failure of the Egyptian invasion, in particular, diminished the Ansar's reputation for invincibility.

By the 1890s, Britain, concerned about French and Belgian colonial ambitions in the Nile headwaters and seeking to secure the Nile for Egypt (and its planned Aswan Dam), decided to reconquer Sudan. General Herbert Kitchener led a well-equipped Anglo-Egyptian force. The reconquest campaign (1896-1898) utilized modern weaponry and infrastructure (like railways and gunboats). The decisive Battle of Omdurman on September 2, 1898, resulted in a catastrophic defeat for the Mahdist forces. The Khalifa Abdallahi was killed a year later at the Battle of Umm Diwaykarat on November 25, 1899, effectively ending the Mahdist State and the Mahdist War.

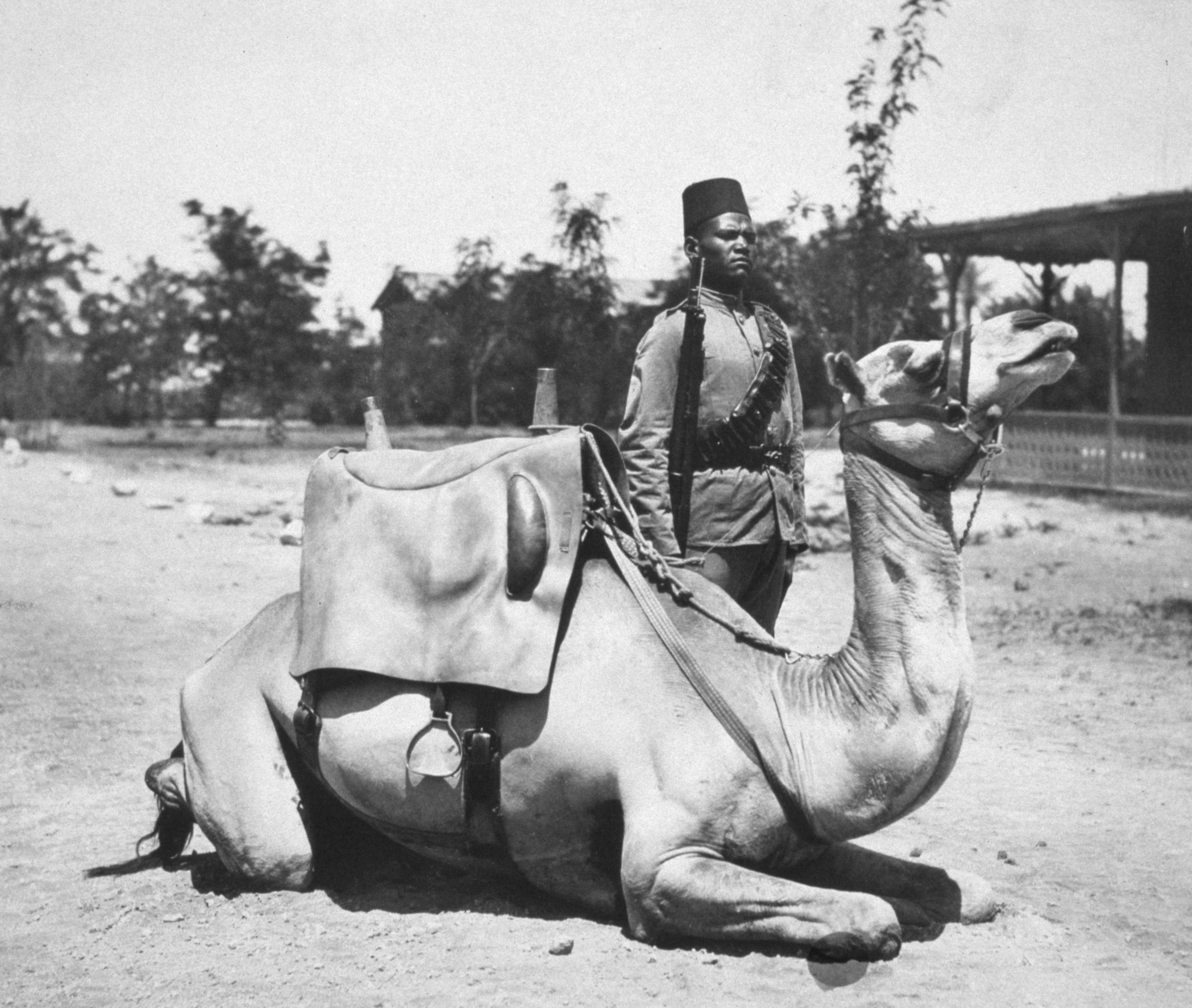

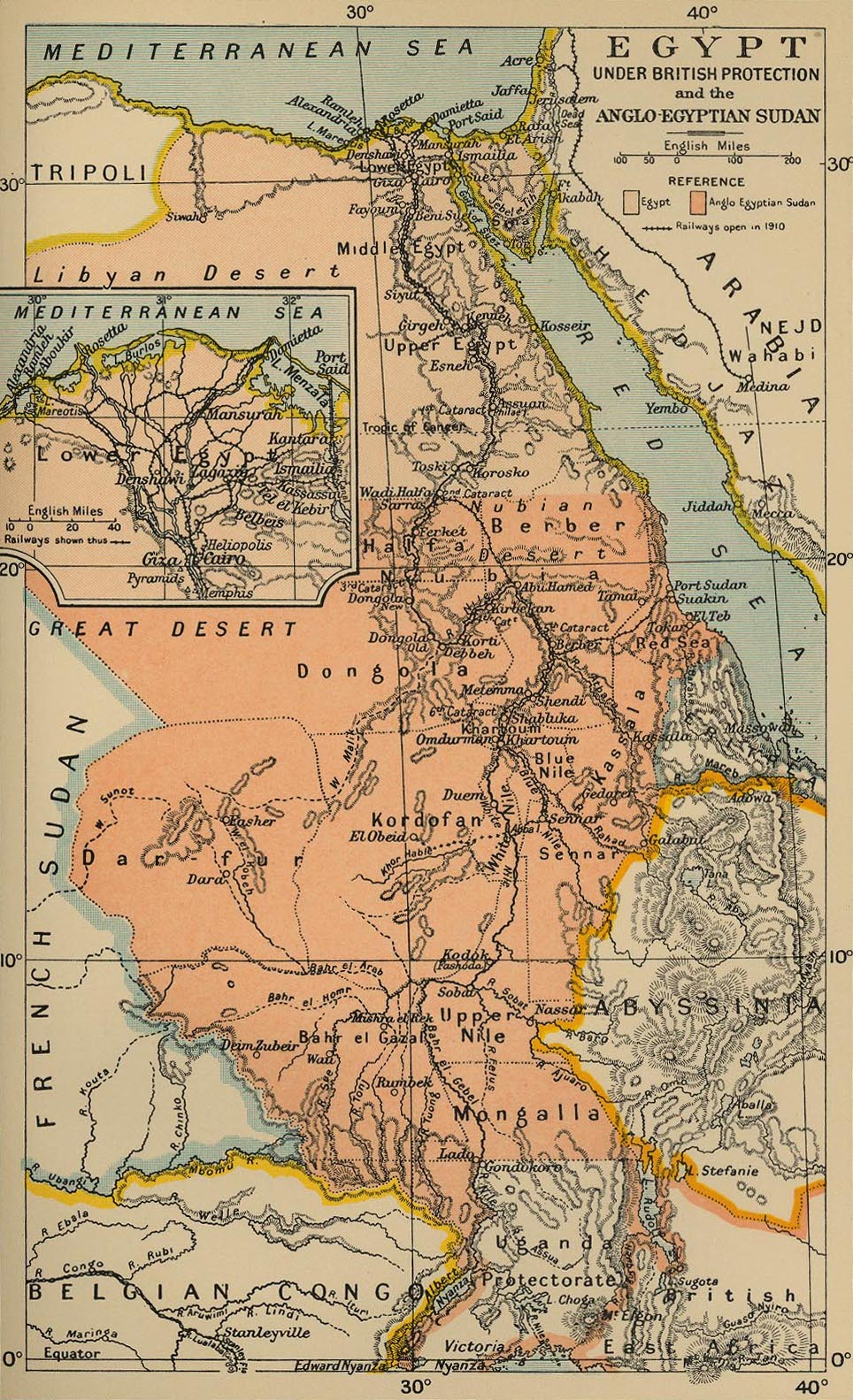

3.6. Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

Following the defeat of the Mahdist State, Sudan entered a period of joint Anglo-Egyptian rule, known as the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium (1899-1956). In 1899, Britain and Egypt signed an agreement establishing this shared sovereignty. However, in practice, Britain held the dominant administrative power, with the Governor-General of Sudan typically being British and appointed by Egypt with British consent. Sudan was effectively administered as a British colonial possession. The British were keen to reverse the process started under Muhammad Ali of uniting the Nile Valley under Egyptian leadership and sought to frustrate efforts aimed at further uniting the two countries.

British administration focused on establishing law and order, developing infrastructure (railways, telegraphs), and promoting export-oriented agriculture, notably the Gezira Scheme for cotton cultivation. A system of taxation was enacted. British policies often aimed to govern the North and South as separate entities. After the assassination of Sir Lee Stack, Governor-General of Sudan, in Cairo in 1924, this "Southern Policy" became more pronounced. It restricted movement and interaction between the predominantly Muslim, Arabic-speaking North and the largely animist or Christian, African South, aiming to prevent Northern cultural and political influence from spreading south and to allow Christian missionary activity in the South. This policy exacerbated existing divisions and contributed to future conflict.

Sudanese nationalism began to emerge during this period, fueled by opposition to colonial rule and inspired by Egyptian nationalism. Educated Sudanese formed political groups, advocating for greater self-governance and eventually independence. The Sudan Defence Force (SDF), formed in 1925, replaced the Egyptian army garrison and saw action during World War II, particularly in the East African Campaign against Italian forces in Abyssinia and Italian Somaliland.

The Egyptian revolution of 1952, which overthrew the monarchy, significantly impacted Sudan's path to independence. Egypt's new leaders, Muhammad Naguib (who was half-Sudanese) and later Gamal Abdel Nasser, demanded British withdrawal from both Egypt and Sudan and officially abandoned Egypt's claims of sovereignty over Sudan to expedite the end of British rule. Facing pressure from both Egyptian and Sudanese nationalists, Britain agreed to terminate the condominium and grant Sudan independence. The British had supported the Mahdist successor, Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi, hoping he would resist Egyptian pressure, but his regime suffered from political ineptitude. Both Britain and Egypt sensed growing instability and opted for self-determination.

3.7. Independence and Post-Colonial Era

Sudan was declared an independent state on January 1, 1956. The post-colonial era has been characterized by a series of unstable parliamentary governments, military coups, and devastating civil wars, primarily between the North and South, and later in Darfur. These conflicts have profoundly affected Sudan's political development, human rights record, and socio-economic progress.

Upon independence, Ismail al-Azhari became the first Prime Minister. However, political stability proved elusive. The legacy of colonial policies, particularly the North-South divide, ethnic and religious tensions, and competition for resources and power, quickly led to conflict.

3.7.1. First Sudanese Civil War (1955-1972)

The First Sudanese Civil War, also known as the Anyanya Rebellion, began in August 1955, even before formal independence, and lasted until 1972. The primary causes were the southern region's grievances against the northern-dominated government in Khartoum. Southerners, who were predominantly non-Arab, non-Muslim (animist or Christian), feared political and cultural marginalization, Arabization, and Islamization. They sought greater autonomy or secession.

The war was fought between the Sudanese government and southern rebel groups, collectively known as the Anyanya. It was a brutal conflict characterized by guerrilla warfare, widespread human rights abuses, and significant civilian displacement. The fighting primarily occurred in the southern provinces of Equatoria, Bahr el Ghazal, and Upper Nile. The war severely hampered development in the South and deepened the mistrust between the North and South.

The conflict eventually ended with the Addis Ababa Agreement in March 1972. This agreement granted significant autonomy to the southern region, establishing the Southern Sudan Autonomous Region with its own regional government and assembly. While the agreement brought a decade of relative peace, the underlying issues of power-sharing, resource distribution, and cultural identity remained largely unresolved, setting the stage for future conflict. The humanitarian impact was severe, with hundreds of thousands killed and many more displaced.

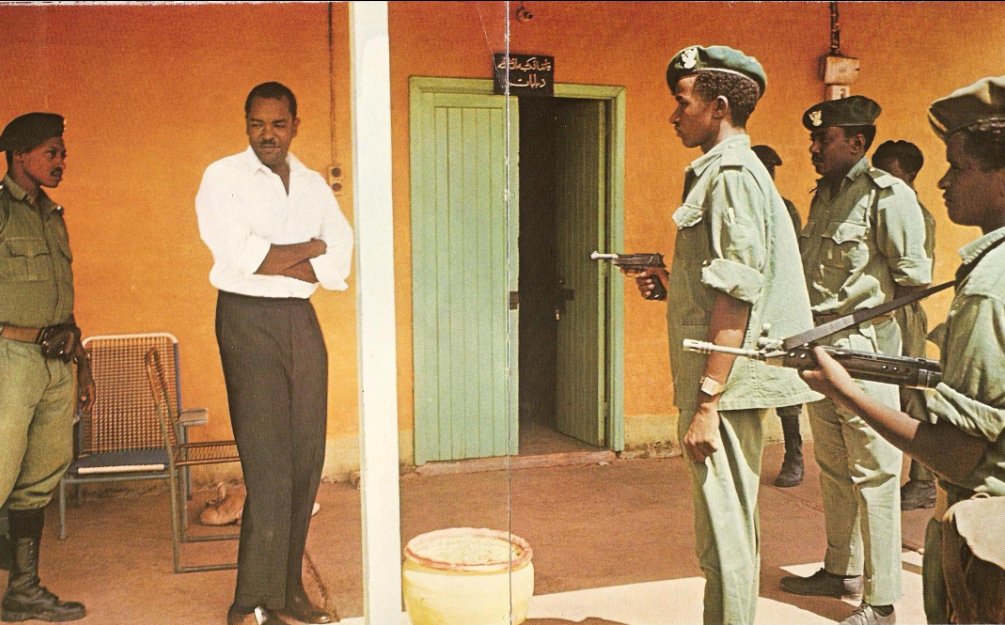

3.7.2. Gaafar Nimeiry Era (1969-1985)

Colonel Gaafar Nimeiry came to power in a military coup on May 25, 1969, overthrowing the existing parliamentary government. His rule, which lasted until 1985, was marked by shifting ideologies, authoritarian policies, and ultimately, the reignition of civil war. Initially, Nimeiry's regime adopted a socialist and pan-Arabist stance, nationalizing banks and industries. He abolished parliament and outlawed all political parties. In July 1971, a short-lived communist-backed coup briefly ousted him, but he was restored to power within days with the help of anti-communist military elements and external support.

A significant achievement of Nimeiry's early rule was the 1972 Addis Ababa Agreement, which ended the First Sudanese Civil War and granted autonomy to the South. This brought a period of peace but also saw American investment in projects like the Jonglei Canal, intended to irrigate the Upper Nile region, though its construction was later halted by renewed conflict and had negative environmental and social impacts on local tribes like the Dinka.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Nimeiry's regime shifted towards a more pro-Western and Islamist orientation. In 1976, the Ansars mounted an unsuccessful coup attempt. In July 1977, Nimeiry met with Ansar leader Sadiq al-Mahdi, leading to a brief reconciliation and the release of political prisoners. However, economic problems worsened, exacerbated by declining commodity prices, rising debt from agricultural mechanization projects, and an IMF-negotiated Structural Adjustment Program in 1978, which caused hardship for pastoralists.

A pivotal and highly controversial move was Nimeiry's decision in September 1983 to implement a strict form of Sharia law, known as the "September Laws," across the country, including the predominantly non-Muslim South. This involved public amputations for theft and the symbolic disposal of alcohol. He declared himself the imam of the Sudanese Umma in 1984. The imposition of Sharia law, along with other grievances such as the redrawing of regional boundaries to benefit the North (especially concerning oil-rich areas) and the abrogation of parts of the Addis Ababa Agreement, directly led to the outbreak of the Second Sudanese Civil War in 1983. Nimeiry was overthrown in a popular uprising and subsequent military coup in April 1985 while he was out of the country. His era left a legacy of political repression and deepened societal divisions.

3.7.3. Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005)

The Second Sudanese Civil War erupted in 1983 and lasted until the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in 2005. It was one of Africa's longest and deadliest conflicts, resulting in an estimated two million deaths and the displacement of over four million people.

The primary causes were the Nimeiry regime's imposition of Sharia law nationwide, the abrogation of the Addis Ababa Agreement which had granted autonomy to the South, and long-standing grievances related to political marginalization, economic exploitation (particularly of southern oil resources), and cultural and religious oppression of the non-Arab, non-Muslim southern population by the northern-dominated government.

The main belligerents were the Sudanese government, increasingly influenced by Islamist ideologies (especially under the National Islamic Front, NIF, after 1989), and the Sudan People's Liberation Army/Movement (SPLA/M), led by Dr. John Garang. The SPLA/M, initially seeking a reformed, secular, and united "New Sudan," eventually fought for southern self-determination. The war was characterized by extreme brutality, including widespread human rights abuses by all sides: mass killings of civilians, abductions, enslavement, use of child soldiers, rape, and the deliberate creation of famine conditions.

International involvement was varied. Neighboring countries often supported different factions, and major powers had strategic interests in the region, including oil. Numerous peace initiatives were attempted, but the conflict persisted due to the intractability of the core issues and the vested interests of the warring parties. The war devastated the infrastructure of Southern Sudan and had profound social and psychological impacts on its population. The conflict finally ended with the CPA, which granted Southern Sudan autonomy for a six-year interim period, followed by a referendum on independence.

3.7.4. Omar al-Bashir Era (1989-2019)

Colonel (later General) Omar al-Bashir seized power in a bloodless military coup on June 30, 1989, overthrowing the democratically elected government of Prime Minister Sadiq al-Mahdi. His rule, spanning three decades, was characterized by authoritarianism, the consolidation of an Islamist state, severe human rights abuses, internal conflicts, and international isolation.

Immediately after the coup, Bashir, in alliance with the National Islamic Front (NIF) led by Hassan al-Turabi, suspended the constitution, banned political parties and independent newspapers, and dissolved parliament. He carried out purges in the army and civil service, imprisoning political opponents and journalists. In 1993, Bashir appointed himself President and disbanded the Revolutionary Command Council. Sudan became a one-party state under the National Congress Party (NCP), the successor to the NIF.

During the 1990s, under al-Turabi's influence, Sudan pursued a radical Islamist agenda, hosting figures like Osama bin Laden. This led the United States to list Sudan as a state sponsor of terrorism. Following Al Qaeda's 1998 bombings of U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, the U.S. launched retaliatory missile strikes against targets in Sudan, including the Al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory, which the U.S. mistakenly believed was producing chemical weapons. Later, al-Bashir marginalized al-Turabi to consolidate his own power and sought to improve international relations by expelling bin Laden.

The most devastating event of the Bashir era was the War in Darfur, which began in February 2003. Rebel groups, the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), took up arms, accusing the government of oppressing non-Arab Darfuris in favor of Sudanese Arabs. The government responded with a brutal counter-insurgency campaign, heavily relying on Arab militias known as the Janjaweed. This conflict resulted in widespread atrocities, including mass killings, systematic rape, forced displacement, and the destruction of villages, leading to accusations of genocide and crimes against humanity. An estimated 300,000 to 400,000 people died, and millions were displaced. In 2009 and 2010, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued arrest warrants for al-Bashir for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide related to Darfur, making him the first sitting head of state to be indicted by the ICC. Bashir's government consistently denied the charges and refused to cooperate with the ICC.

The Second Sudanese Civil War with the South continued under Bashir until the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) was signed in 2005. This agreement led to the 2011 referendum and the secession of South Sudan. Despite the CPA, conflicts persisted in border regions like South Kordofan and Blue Nile.

Throughout his rule, Bashir's regime was marked by severe repression of political dissent, restrictions on freedom of speech and the press, and systematic human rights violations. International sanctions and isolation further crippled Sudan's economy. Protests against his rule, fueled by economic hardship and lack of political freedoms, grew in intensity, culminating in the Sudanese Revolution of 2018-2019. On April 11, 2019, following months of mass demonstrations, the military removed al-Bashir from power and placed him under arrest, ending his 30-year dictatorship.

3.7.5. Secession of South Sudan

The secession of South Sudan in 2011 was a landmark event in Sudanese history, resulting from the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) signed in 2005, which ended the Second Sudanese Civil War. A key provision of the CPA was the right of the people of Southern Sudan to hold a referendum on independence after a six-year interim period of autonomy.

The 2011 South Sudanese independence referendum was held from January 9 to 15, 2011. The result was an overwhelming vote in favor of secession, with nearly 99% of voters choosing independence. The Sudanese government under Omar al-Bashir, which had initially resisted southern autonomy, accepted the outcome. On July 9, 2011, the Republic of South Sudan was officially declared an independent nation, with its capital in Juba.

The secession had profound implications for both Sudan and South Sudan. Sudan lost approximately three-quarters of its oil reserves, which were located in the South, leading to severe economic challenges, including high inflation and a currency crisis. South Sudan, despite its oil wealth, faced immense challenges in nation-building, including establishing governance structures, addressing internal ethnic conflicts, and developing its infrastructure.

Several critical issues remained unresolved between the two countries post-secession. These included:

- Border Demarcation:** The precise border between Sudan and South Sudan, particularly in oil-rich and contested areas, remained a source of tension.

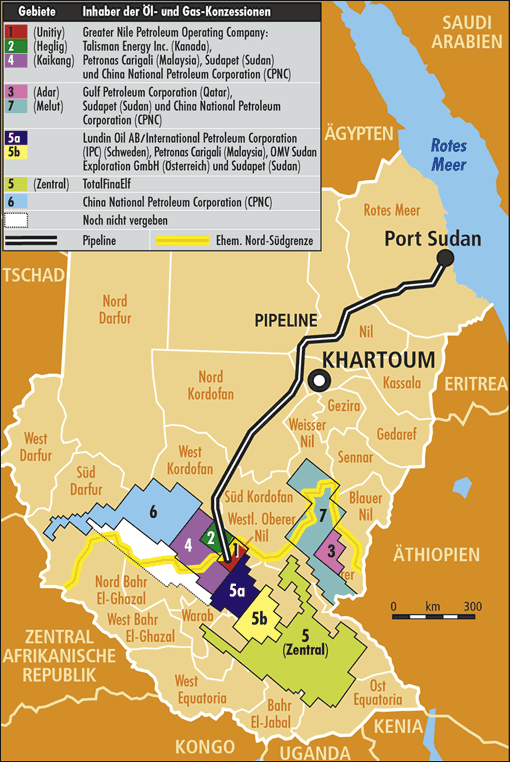

- Oil Revenue Sharing:** Agreements on transit fees for South Sudanese oil, which had to be transported through pipelines in Sudan to reach Port Sudan for export, were contentious and led to disputes, including a temporary shutdown of oil production by South Sudan.

- Status of Abyei:** The oil-rich Abyei region, claimed by both sides, was due to have its own referendum to decide whether to join Sudan or South Sudan. However, disagreements over voter eligibility and security arrangements prevented the referendum from taking place, leaving Abyei's status in limbo and a persistent flashpoint for conflict.

- Citizenship:** The status of southerners living in Sudan and northerners in South Sudan became a complex issue, with concerns about statelessness and discrimination.

- Debt:** The division of Sudan's substantial external debt was another point of negotiation.

Conflicts erupted in border regions like South Kordofan and Blue Nile, where populations with historical ties to the South resisted Khartoum's authority, leading to further displacement and humanitarian crises (e.g., Heglig Crisis in 2012). Relations between Sudan and South Sudan have remained fragile, oscillating between cooperation and conflict over these unresolved issues.

3.7.6. 2019 Revolution and Transitional Government

The Sudanese Revolution, which began in December 2018 and culminated in 2019, was a period of major political upheaval driven by widespread popular protests demanding an end to Omar al-Bashir's three-decade rule and a transition to democratic governance.

Background and Protests: The protests were initially triggered by a government decision to triple the price of bread and address fuel shortages, amid a severe economic crisis marked by high inflation (around 70%) and a scarcity of foreign currency. These economic grievances quickly transformed into broader demands for political change, an end to corruption, improved human rights, and the resignation of President al-Bashir. The Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA) played a key role in organizing and sustaining the protests, which spread across the country, involving diverse segments of society, particularly youth and women. The government responded with force, leading to arrests of activists and protesters, and dozens of deaths, though civilian reports indicated much higher casualty figures.

Overthrow of al-Bashir: After months of persistent demonstrations, including a massive sit-in outside the military headquarters in Khartoum, the Sudanese Armed Forces intervened. On April 11, 2019, the military announced the removal and arrest of President al-Bashir, declared a state of emergency, and established a Transitional Military Council (TMC) to govern the country.

Transitional Period and Challenges: The overthrow of Bashir did not immediately lead to civilian rule. Protesters, organized under the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) coalition, continued their sit-in, demanding a swift transfer of power to a civilian-led government. Negotiations between the TMC and FFC were fraught with tension. A major crisis occurred on June 3, 2019, when security forces, including the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), violently dispersed the Khartoum sit-in, resulting in the deaths of over 100 protesters (known as the Khartoum massacre). This event drew international condemnation and led to Sudan's suspension from the African Union.

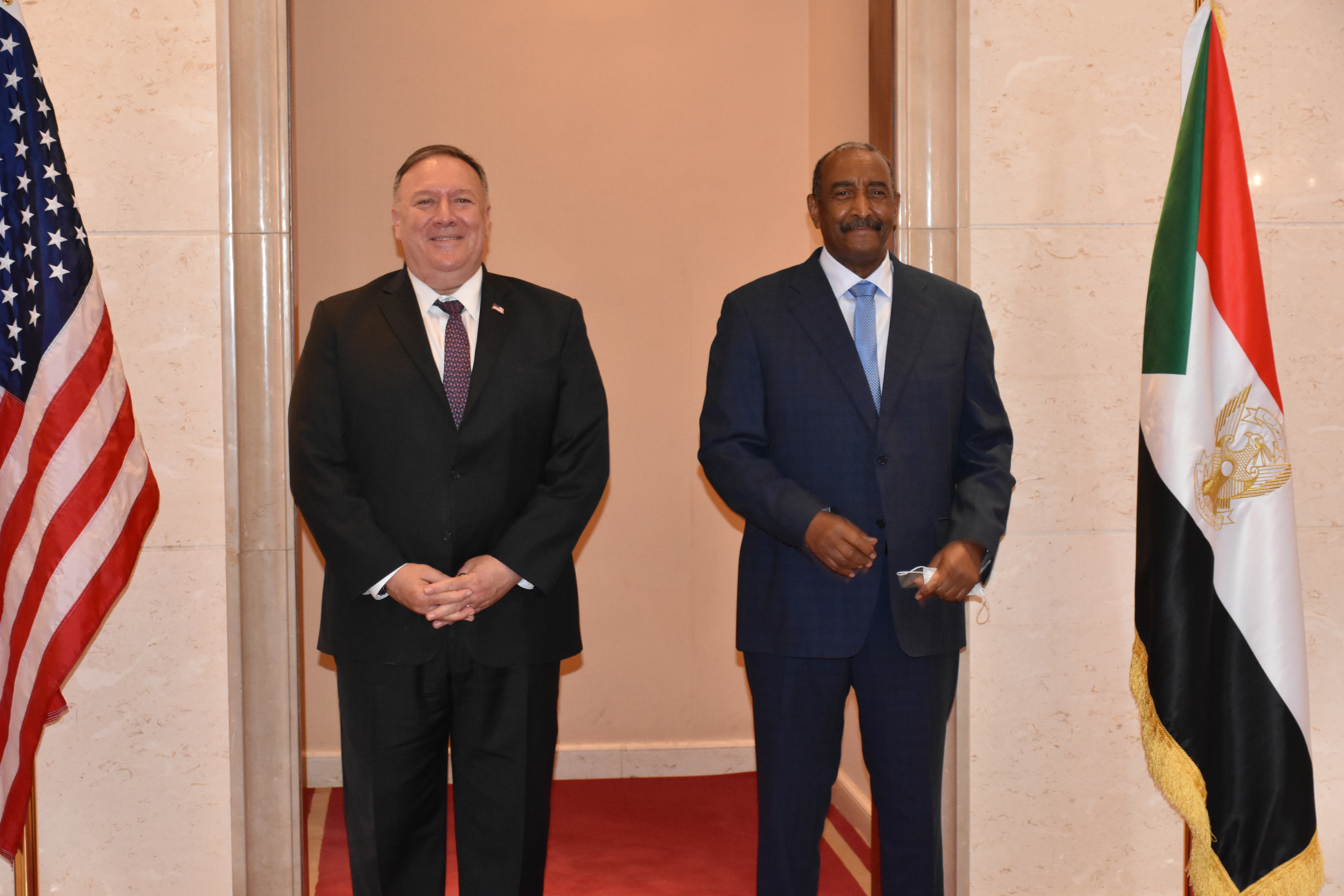

Despite the violence, negotiations resumed, mediated by the African Union and Ethiopia. In July 2019, the TMC and FFC signed a Political Agreement, followed by the August 2019 Draft Constitutional Declaration. These agreements outlined a 39-month transitional period leading to elections. A joint military-civilian Sovereignty Council of Sudan was established as the collective head of state, initially chaired by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan (from the military) to be followed by a civilian chair. Abdalla Hamdok, an economist with international experience, was appointed Prime Minister to lead a civilian cabinet.

The transitional government faced immense challenges, including a dire economic situation, the need for justice and accountability for past abuses, reforming the security sector, achieving peace with various rebel groups, and navigating the complex power-sharing arrangement between civilian and military components. The government initiated economic reforms, sought international financial assistance, and began peace talks with rebel groups. There was a focus on repealing repressive laws, improving human rights, and addressing issues of social justice. By August 2021, the country was jointly led by Chairman of the Transitional Sovereign Council, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok.

3.7.7. 2021 Coup and Military Rule

The democratic transition in Sudan faced a severe setback with the military coup of October 25, 2021. This event dissolved the civilian-led transitional government and returned the country to military rule, undermining the progress made since the 2019 revolution.

A month prior to the coup, on September 21, 2021, the Sudanese government had announced a failed coup attempt, leading to the arrest of several military officers. This indicated underlying tensions within the power-sharing arrangement.

On October 25, 2021, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, head of the Sovereignty Council and commander-in-chief of the armed forces, led a military takeover. Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and other civilian leaders were arrested, a state of emergency was declared, and the Sovereignty Council and cabinet were dissolved. Al-Burhan justified the coup by citing political infighting among civilian factions and the need to prevent civil war, but the move was widely seen as an attempt by the military to retain its grip on power and protect its interests.

The coup was met with widespread domestic and international condemnation. Sudanese citizens, who had been at the forefront of the 2019 revolution, launched mass protests and civil disobedience campaigns demanding the restoration of civilian rule. Security forces responded harshly, leading to numerous deaths and injuries among protesters. Human rights violations, including arbitrary detentions and restrictions on freedom of expression and assembly, escalated.

Under international pressure, a deal was announced on November 21, 2021, to reinstate Hamdok as Prime Minister. The agreement called for the release of political detainees and stated that the 2019 constitutional declaration would remain the basis for the transition. However, the military retained ultimate authority, with al-Burhan forming a new army-backed governing council on November 11, 2021, effectively making him the de facto head of state. Hamdok's reinstatement was viewed with skepticism by many pro-democracy groups, who saw it as legitimizing the coup. Hamdok subsequently dismissed some police chiefs.

Feeling unable to govern effectively amidst ongoing military dominance and popular protests, Hamdok resigned as Prime Minister on January 2, 2022. Osman Hussein later became acting Prime Minister. The coup and subsequent military rule led to increased political instability, a deteriorating economic situation (as international aid was suspended), and a deepening crisis of trust between the military and the civilian population. By March 2022, over 1,000 people, including children, had been detained for opposing the coup, with numerous allegations of rape and dozens killed in protests. The democratic transition envisioned in 2019 was largely derailed, raising serious concerns about Sudan's future.

3.7.8. Sudanese Civil War (2023-present)

In April 2023, Sudan plunged into a devastating civil war, primarily between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan (the de facto national leader), and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), led by his former deputy, General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, commonly known as Hemedti. The conflict erupted from a power struggle between the two generals as an internationally brokered plan for a transition to civilian rule was being discussed. Tensions had been building over the integration of the RSF into the regular army, a key component of the proposed transition.

Fighting broke out on April 15, 2023, with intense battles in the capital, Khartoum, and other parts of the country, particularly in the Darfur region. The conflict quickly escalated, involving heavy artillery, airstrikes, and street fighting, leading to a catastrophic humanitarian situation. By the third day, hundreds had been reported killed and thousands injured.

Consequences and Humanitarian Catastrophe:

The war has had devastating consequences for the civilian population. Millions have been displaced internally, and over 1.5 million have fled to neighboring countries as refugees. Access to food, water, healthcare, and other essential services has been severely disrupted. Widespread atrocities and human rights violations have been reported, including targeted attacks on civilians, sexual violence, looting, and the destruction of infrastructure. Both the SAF and RSF have been accused of committing war crimes.

The World Food Programme reported in February 2024 that over 95% of Sudan's population could not afford a meal a day. By April 2024, the UN reported over 8.6 million people displaced, 18 million facing severe hunger, and 5 million at emergency levels of food insecurity. Estimates of the death toll vary, with US government officials suggesting at least 150,000 deaths in the first year alone.

Darfur Crisis Renewed:

The conflict has led to a resurgence of ethnic violence in Darfur, with reports of mass killings, particularly of the Masalit people, by the RSF and allied Arab militias. The city of Geneina in West Darfur experienced particularly brutal attacks, with estimates of up to 15,000 people killed. International officials have warned of the risk of another genocide in Darfur, echoing the atrocities of the early 2000s.

International Response and Allegations:

The international response has included calls for ceasefires, humanitarian aid efforts, and mediation attempts, but these have largely failed to halt the fighting. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has been accused by Sudanese General Yasser al-Atta and others of providing supplies and arms to the RSF, allegedly fueling the conflict. In May 2024, a US congressional briefing focused on the UAE's involvement in Sudan, including allegations of war crimes and arms exports, with calls for an end to such support.

As of early 2025, the UN anticipates that 30.4 million people in Sudan will require humanitarian aid due to the ongoing military conflict, highlighting the deepening crisis and the immense suffering of the Sudanese people.

4. Geography

Sudan is situated in North Africa, sharing borders with seven countries and possessing a significant coastline on the Red Sea. This section provides an overview of its topography, climate, major river systems, environmental challenges, and biodiversity.

Sudan has a land area of 1.89 M abbr=on, making it the third-largest country in Africa after Algeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the fifteenth-largest in the world. It is located between latitudes 8° and 23°N. The country has an 853 abbr=on coastline bordering the Red Sea to the east. Its land borders are with Egypt to the north, Eritrea and Ethiopia to the southeast, South Sudan to the south, the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, and Libya to the northwest.

4.1. Topography

The terrain of Sudan is generally characterized by vast flat plains, punctuated by several mountain ranges. In the west, the Marrah Mountains are a prominent feature, with the Deriba Caldera (3.04 K abbr=on) being the highest point in Sudan. In the east, along the Red Sea coast, are the Red Sea Hills. The northern part of the country is dominated by the Nubian Desert to the northeast and the Bayuda Desert to the east, which are extensions of the Sahara Desert. Central and southern Sudan feature more extensive plains, including the fertile Gezira plain between the Blue and White Niles, and savanna grasslands further south. The Nuba Mountains are an isolated range in South Kordofan.

4.2. Climate

Sudan's climate varies significantly from north to south. The north is characterized by an arid desert climate with extremely hot summers and very little rainfall. The central regions have a semi-arid or steppe climate, with a rainy season that typically lasts from June to September in the north and up to six months (May to October) in the south. Rainfall increases towards the south, which experiences a tropical savanna climate with more abundant precipitation and lusher vegetation.

Temperatures are generally high throughout the country, especially during the summer months. In the desert regions, daytime temperatures can be extreme. Sandstorms, known locally as haboob, are common in the dry regions and can completely block out the sun, reducing visibility significantly. The sunshine duration is very high across the country, particularly in the deserts where it can exceed 4,000 hours per year.

4.3. Rivers and Lakes

The Nile River system is the dominant hydrological feature of Sudan. The two main tributaries, the White Nile and the Blue Nile, converge at the capital, Khartoum, to form the main Nile River, which then flows northwards through Egypt to the Mediterranean Sea.

The White Nile enters Sudan from South Sudan and flows north. Within Sudan, it has no significant tributaries. The Blue Nile originates from Lake Tana in Ethiopia and flows west and then northwest into Sudan. Its course through Sudan is nearly 800 abbr=on long, and it is joined by the Dinder River and Rahad Rivers between Sennar and Khartoum. The Blue Nile carries a larger volume of water and most of the sediment, especially during the rainy season in the Ethiopian Highlands.

Several dams have been constructed on the Blue and White Niles for irrigation and hydroelectric power generation. Notable dams include the Sennar Dam and Roseires Dam on the Blue Nile, and the Jebel Aulia Dam on the White Nile. Lake Nubia, the Sudanese part of Lake Nasser, created by the Aswan High Dam in Egypt, is located on the Sudanese-Egyptian border.

4.4. Environmental issues

Sudan faces significant environmental challenges that impact its natural resources and the livelihoods of its population.

Desertification is a major problem, particularly in the northern and central regions. Overgrazing, deforestation for fuelwood and agriculture, and unsustainable land management practices contribute to the expansion of desert areas and the degradation of arable land.

Soil erosion is another serious concern, exacerbated by deforestation and inappropriate agricultural techniques. This leads to loss of soil fertility and reduced agricultural productivity.

Deforestation is widespread, driven by demand for fuelwood (the primary energy source for many Sudanese), expansion of agriculture, and logging. This contributes to soil erosion, loss of biodiversity, and desertification.

Water scarcity and pollution are critical issues. While the Nile provides a major water source, access to clean water is limited for many. Water resources are under pressure from agriculture, population growth, and climate change. Pollution from agricultural runoff and industrial waste also affects water quality.

Agricultural expansion, both public and private, has often proceeded without adequate conservation measures, leading to land degradation and the lowering of the water table. Climate change is expected to exacerbate these environmental problems, potentially leading to more frequent droughts and increased variability in rainfall.

4.5. Wildlife and Conservation

Sudan possesses a diverse range of wildlife, reflecting its varied ecosystems from desert to savanna. Notable fauna includes elephants, giraffes, lions, leopards, cheetahs, various antelope species, and a rich birdlife. The Red Sea coast hosts important marine biodiversity, including coral reefs.

However, Sudan's wildlife is under significant threat from poaching, habitat loss due to agricultural expansion and deforestation, and the impacts of conflict. As of 2001, twenty-one mammal species and nine bird species were listed as endangered, along with two plant species. Critically endangered species include the waldrapp (northern bald ibis), northern white rhinoceros (though likely extirpated from Sudan), tora hartebeest, rhim gazelle (slender-horned gazelle), and hawksbill turtle. The Sahara oryx has become extinct in the wild in Sudan.

Conservation efforts in Sudan have been hampered by political instability, conflict, and lack of resources. There are several national parks and protected areas, such as Dinder National Park and Radom National Park, but enforcement of conservation laws is often weak. Poaching for ivory, bushmeat, and other wildlife products remains a serious challenge. International and local organizations are involved in conservation initiatives, but the scale of the threats requires greater commitment and resources.

5. Government and politics

Sudan's political system has been characterized by prolonged periods of authoritarian rule, military coups, and transitions towards, and away from, democratic governance. The country has faced significant challenges related to establishing stable institutions, upholding human rights, resolving internal conflicts, and achieving political consensus.

The politics of Sudan formally took place within the framework of a federal authoritarian Islamic republic until April 2019, when President Omar al-Bashir's regime was overthrown in a military coup led by Vice President Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf. Initially, the Transitional Military Council (TMC) was established. Ibn Auf resigned after one day, and leadership was handed to Abdel Fattah al-Burhan. On August 4, 2019, a new Constitutional Declaration was signed between the TMC and the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC). On August 21, 2019, the TMC was officially replaced by an 11-member Sovereignty Council as head of state, and a civilian Prime Minister. This transitional government aimed to guide Sudan towards democratic elections.

However, this transition was disrupted by a military coup on October 25, 2021, led by General al-Burhan, which dissolved the civilian government and the Sovereignty Council. Following the coup, al-Burhan declared a state of emergency. While Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok was briefly reinstated in November 2021 under a new power-sharing agreement, he resigned in January 2022, citing the military's continued dominance. Since then, Sudan has been under de facto military rule.

In April 2023, a devastating civil war erupted between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), loyal to al-Burhan, and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), led by General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo ("Hemedti"). This conflict has further destabilized the country and shattered the framework for governance. According to 2023 V-Dem Democracy indices, Sudan is the 6th least democratic country in Africa.

5.1. Government Structure

Prior to the 2021 coup and the 2023 civil war, the transitional government structure established in 2019 aimed for a balance between civilian and military components.

- Executive: The Sovereignty Council, composed of military and civilian members, served as the collective head of state. The Prime Minister, a civilian, headed the Council of Ministers (cabinet) and was responsible for the day-to-day administration of the government.

- Legislative: A Transitional Legislative Council was planned but had not been fully formed before the 2021 coup. Under Bashir, Sudan had a bicameral National Legislature, consisting of the National Assembly (lower chamber) and the Council of States (upper chamber), but this was dissolved in 2019.

- Judicial: The judiciary is intended to be independent. Key institutions include the Constitutional Court, the National Supreme Court, and other national courts. A National Judicial Service Commission is responsible for the overall management of the judiciary. The appointment of a new Chief Justice, Nemat Abdullah Khair (the first woman to hold the post in Sudan and the Arab world), was a significant step during the 2019-2021 transition.

The ongoing conflict since 2023 has effectively dismantled these transitional structures, with power concentrated in the hands of the warring military factions.

5.2. Sharia Law

The application of Sharia (Islamic law) has been a contentious and defining issue in Sudanese politics and law for decades, significantly impacting human rights and religious freedom.

5.2.1. Under Nimeiry

In September 1983, President Gaafar Nimeiry introduced a strict interpretation of Sharia law nationwide, known as the "September Laws." This included the implementation of hudud punishments such as public amputations for theft and flogging for alcohol consumption, even for non-Muslims. This move was supported by figures like Hassan al-Turabi but opposed by others, including Sadiq al-Mahdi. The imposition of Sharia was a major catalyst for the outbreak of the Second Sudanese Civil War, as it was deeply resented by the predominantly non-Muslim population of Southern Sudan and by secularists in the North. Nimeiry's regime also pushed for an Islamic economy, eliminating interest and instituting zakat, and in 1984, Nimeiry declared himself the imam of the Sudanese Umma.

5.2.2. Under al-Bashir

During the regime of Omar al-Bashir (1989-2019), the legal system in Sudan remained based on Sharia law, often applied rigorously. The 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), which ended the Second Sudanese Civil War, provided some protections for non-Muslims in Khartoum, stipulating that Sharia would not apply to them in the capital. However, its application remained geographically inconsistent and often harsh.

Stoning was a judicial punishment, and several women were sentenced to death by stoning for adultery between 2009 and 2012, though international outcry often prevented executions. Flogging was a common legal punishment for various offenses, including "indecent behavior" (often arbitrarily defined for women's dress or association with men), alcohol consumption, and apostasy. Many people, including Christians, were sentenced to lashes. Sudan's Public Order Laws allowed police to publicly whip women accused of public indecency. Crucifixion was also a legal, though rarely applied, punishment. Apostasy (conversion from Islam) was a capital offense.

5.2.3. After al-Bashir

Following the ousting of al-Bashir in 2019, the transitional government took steps to reform the legal system and move towards a secular state. The interim constitution signed in August 2019 made no mention of Sharia law as the primary source of legislation.

In July 2020, significant legal reforms were introduced:

- The apostasy law, which carried the death penalty, was abolished.

- Public flogging was largely ended.

- Non-Muslims were permitted to consume alcohol.

- Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) was criminalized, with a punishment of up to 3 years in jail.

In September 2020, an accord between the transitional government and rebel groups further solidified the separation of state and religion, officially ending three decades of rule under Islamic law and agreeing that no official state religion would be established. These reforms were widely hailed as progress towards greater religious freedom and human rights. However, the 2021 military coup and the subsequent 2023 civil war have created uncertainty regarding the long-term status and implementation of these reforms.

5.3. Administrative divisions

Sudan is divided into 18 states (wilayat, singular wilayah). These states are further subdivided into 133 districts. The states are:

- Gezira

- Al Qadarif

- Blue Nile

- Central Darfur

- East Darfur

- Kassala

- Khartoum

- North Darfur

- North Kordofan

- Northern

- Red Sea

- River Nile

- Sennar

- South Darfur

- South Kordofan

- West Darfur

- West Kordofan

- White Nile

5.4. Disputed Territories and Conflict Zones

Sudan has several disputed territories and regions affected by internal conflict, which significantly impact local populations and regional stability.

- Abyei: Located on the border between Sudan and South Sudan, Abyei is an oil-rich region claimed by both countries. The 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) granted Abyei special administrative status and stipulated a referendum for its residents to decide whether to join Sudan or South Sudan. However, disagreements over voter eligibility and security have prevented the referendum from taking place. The area has experienced sporadic violence and displacement, and its final status remains a major point of contention. It is currently under a complex administrative arrangement, often with UN peacekeeping presence.

- Hala'ib Triangle: This area on the Red Sea coast is disputed between Sudan and Egypt. Egypt has exercised de facto administrative control over the Hala'ib Triangle since the 1990s, but Sudan maintains its claim to the territory.

- South Kordofan and Blue Nile States: These two states, often referred to as the "Two Areas," are located in Sudan but have significant populations with historical ties to South Sudan and who fought alongside the SPLA during the civil wars. The CPA mandated "popular consultations" for these states to determine their future constitutional relationship with Khartoum. However, these consultations were not satisfactorily completed, and conflict between the Sudanese government and factions of the Sudan People's Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) erupted in 2011. These conflicts have caused widespread displacement and a severe humanitarian crisis. The fighting in these regions has often been linked to broader national power struggles.

- Darfur: While not a border dispute, the Darfur region has been a major conflict zone since 2003. The conflict involves government forces, allied militias (like the Janjaweed, predecessors to the RSF), and various rebel groups. The conflict has led to massive human rights violations, displacement, and a humanitarian crisis. The Darfur Regional Government, established by peace agreements, aims to coordinate the states within Darfur, but ongoing insecurity and the current civil war (2023-present) have severely hampered its effectiveness and exacerbated suffering.

- Heglig: An oil field near the Sudan-South Sudan border, Heglig was a flashpoint in April 2012 when South Sudanese forces briefly captured it from Sudan. Sudan later recaptured it. The area remains sensitive due to its oil resources.

- Kafia Kingi and Radom National Park: These areas, historically part of Bahr el Ghazal (now in South Sudan) in 1956, are claimed by South Sudan based on the 1 January 1956 border demarcation, but Sudan exercises control. This is part of the broader border demarcation disputes.

- Bir Tawil: An unusual case, Bir Tawil is an area of approximately 0.8 K mile2 (2.06 K km2) along the Egyptian-Sudanese border that is terra nullius, claimed by neither state due to discrepancies arising from different historical border definitions for the Hala'ib Triangle.

These disputed territories and conflict zones contribute significantly to regional instability, humanitarian crises, and strained relations between Sudan and its neighbors. The ongoing civil war since 2023 has further complicated the situation in these areas, often intensifying existing conflicts and creating new waves of displacement and suffering for civilian populations.

6. Foreign relations

Sudan's foreign policy and international relationships have been shaped by its internal conflicts, ideological shifts, economic needs, and regional dynamics. Historically, Sudan has navigated complex ties with its neighbors, major global powers, and international organizations, often marked by periods of tension and cooperation.

Sudan has had troubled relationships with many of its neighbors and much of the international community, partly due to its past radical Islamic stance. During the 1990s, Uganda, Kenya, and Ethiopia formed an ad hoc alliance called the "Front Line States," with support from the United States, to check the influence of the National Islamic Front government in Sudan. The Sudanese government, at the time, supported anti-Ugandan rebel groups like the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA). As the NIF regime emerged as a perceived threat, the U.S. listed Sudan as a state sponsor of terrorism. Consequently, Sudan developed relations with Iraq and later Iran.

From the mid-1990s, Sudan began to moderate its positions, partly due to U.S. pressure following the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania, and the development of oil fields. Sudan also has a territorial dispute with Egypt over the Hala'ib Triangle. Since 2003, foreign relations have largely centered on efforts to end the Second Sudanese Civil War and condemnation of government support for militias in the Darfur conflict.

The ongoing civil war since 2023 has further complicated Sudan's foreign relations, with various regional and international actors involved in mediation efforts and expressing concerns over the humanitarian crisis and regional stability. Accusations of external support for the warring factions have also surfaced, notably regarding the UAE's alleged backing of the RSF.

6.1. Bilateral relations

- Egypt: Relations with Egypt have historically been close yet complex, given shared Nile resources, cultural ties, and border disputes (Hala'ib Triangle). Both countries have influenced each other's internal politics.

- Ethiopia: Relations have been strained by border disputes (especially around the al-Fashaga triangle), issues related to the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) impacting Nile water flow, and refugee movements. The Tigray conflict in Ethiopia led to a significant influx of refugees into Sudan.

- South Sudan: Since South Sudan's independence in 2011, relations have been volatile, marked by disputes over oil transit fees, border demarcation (including Abyei), and mutual accusations of supporting rebel groups. However, there have also been periods of cooperation.

- Chad: Relations have been tense due to cross-border rebel activities and the Darfur conflict, which spilled over into Chad. Agreements have been signed to manage border security.

- Libya: The porous border has been a concern for arms trafficking and movement of militants, especially given Libya's instability.

- Eritrea: Relations have fluctuated, with periods of tension and cooperation, often linked to regional conflicts and alliances.

- China: China has been a major economic partner, particularly in the oil sector, and a significant arms supplier. China has generally maintained a policy of non-interference in Sudan's internal affairs while pursuing its economic interests.

- United States: Relations were highly strained during much of the Bashir era, with the U.S. imposing sanctions and listing Sudan as a state sponsor of terrorism. Following Bashir's overthrow, there was a rapprochement, and the U.S. removed Sudan from the terrorism list in December 2020 as part of a deal that included Sudan normalizing ties with Israel (Abraham Accords). However, the 2021 coup and 2023 civil war have led to renewed U.S. criticism and calls for a return to civilian rule.

- Russia: Russia has sought to expand its influence in Sudan, engaging in military cooperation and pursuing economic interests, including potential access to Red Sea ports.

- Middle Eastern Nations:

- Saudi Arabia and UAE: These Gulf states have been influential, providing financial support and engaging in diplomatic efforts. Sudan participated in the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen. However, the UAE has also faced accusations of supporting the RSF in the current civil war.

- Iran: Sudan had close ties with Iran in the 1990s but later distanced itself, aligning more with Saudi Arabia, including severing diplomatic ties with Iran in 2016.

- Turkey: Turkey has also sought to increase its influence in Sudan, particularly through economic and cultural ties, including development projects like the Suakin Island initiative.

- Israel: In October 2020, under U.S. brokerage, Sudan agreed to normalize ties with Israel. Envoys have exchanged visits, but the full implementation has been affected by Sudan's internal instability.

- Indonesia: Sudan and Indonesia established diplomatic relations in 1960 and have embassies in each other's capitals. They have agreed to enhance bilateral cooperation in various fields.

The international conference hosted by France in April 2024, marking one year of the current civil war, aimed to draw global attention to Sudan's humanitarian crisis, which has been overshadowed by other global conflicts.

6.2. Membership in international organizations

Sudan is a member of several international and regional organizations, reflecting its engagement with the global community, although its participation has sometimes been affected by internal conflicts and political sanctions. Key memberships include:

- United Nations (UN): Sudan has been a UN member since November 12, 1956. Various UN agencies (e.g., WFP, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNDP, WHO) operate in Sudan, providing humanitarian aid, development assistance, and peacekeeping support (e.g., UNMIS, UNAMID, UNITAMS).

- African Union (AU): Sudan is a founding member of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), the AU's predecessor. However, its membership has been suspended at times due to unconstitutional changes of government, such as after the 2019 Khartoum massacre and the 2021 military coup. The AU has been involved in mediation efforts in Sudan's conflicts.

- Arab League: Sudan is an active member of the Arab League, participating in its political, economic, and cultural initiatives.

- Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC): As a predominantly Muslim country, Sudan is a member of the OIC and participates in its activities.

- Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA): Sudan is a member of this regional economic bloc aimed at promoting trade and integration.

- Non-Aligned Movement (NAM): Sudan is a member of NAM, a forum of countries not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc.

- Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD): Sudan is a member of this East African regional organization, which has played a key role in peace negotiations concerning Sudan and South Sudan.

Sudan also engages with international financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank for economic assistance and reform programs. International Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and aid agencies play a crucial role in providing humanitarian relief and development support, especially in conflict-affected areas like Darfur, South Kordofan, Blue Nile, and regions impacted by the 2023 civil war.

7. Military

The Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) are the regular military forces of Sudan. Historically, it has been a significant institution in the country, often playing a central role in politics, including staging multiple coups. The SAF is divided into five branches: the Sudanese Army, the Sudanese Navy (including the Marine Corps), the Sudanese Air Force, the Border Patrol, and the Internal Affairs Defence Force. Estimates of total troop strength have varied, with figures around 109,300 (IISS, 2011) to 200,000 (CIA estimates).

The SAF's primary strategic principles include defending Sudan's external borders and preserving internal security. However, a significant portion of its history has involved internal conflicts, including the civil wars with the South, the Darfur conflict, and conflicts in South Kordofan and Blue Nile. Since the Darfur crisis in 2004, countering armed resistance from various rebel groups has been a major priority.

The military of Sudan has become a relatively well-equipped fighting force, partly due to increasing local production of arms and acquisitions from foreign suppliers, notably China and Russia. Equipment has historically included Soviet/Russian, Chinese, Ukrainian, and some Western-made weaponry. The Military Industry Corporation (MIC) in Sudan produces a range of armaments, from small arms (like the "Dinar," an H&K G3 variant) to armored vehicles and ammunition. Sudan has acquired tanks such as the T-54/55, Type 59, M-60, and the Chinese Type 96. It also developed a licensed version of the Type 85-IIM tank called "Al-Bashier." The Air Force operates aircraft like MiG-21 (and its Chinese version J-7), MiG-29, and Mi-24/35 and Mi-8/17 helicopters.

A critical aspect of Sudan's military landscape has been the role of paramilitary groups. The Janjaweed militias were extensively used by the government in the Darfur conflict and were accused of widespread atrocities. Many Janjaweed fighters were later incorporated into the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a powerful paramilitary group led by General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo ("Hemedti"). The RSF grew significantly in strength and influence, operating semi-autonomously and even participating in foreign conflicts like the Yemeni civil war (with around 40,000 members participating in 2016-2017).

The uneasy relationship and power struggle between the SAF and the RSF, particularly concerning the RSF's integration into the regular army, was a key factor leading to the devastating civil war that erupted in April 2023. This conflict has pitted the two strongest military entities in the country against each other, with profound consequences for Sudan's stability and civilian population. The violence has resulted in an estimated 200,000 to 400,000 deaths in earlier conflicts (like Darfur) and at least 150,000 in the current civil war's first year alone.

8. Economy

Sudan's economy has historically relied heavily on agriculture, but the discovery and exploitation of oil in the late 20th century brought a period of rapid growth, albeit unevenly distributed and impacted by political instability and conflict. The secession of South Sudan in 2011, which held about 75% of the former united Sudan's oil reserves, delivered a significant shock to Sudan's economy. The ongoing civil war since April 2023 has caused a catastrophic economic collapse. The perspective of social equity and the impact of economic policies on vulnerable populations are critical considerations.

8.1. Economic overview and structure

In 2010, before the secession of South Sudan, Sudan was considered the 17th-fastest-growing economy globally, largely due to oil profits. GDP growth was around 5.2% in 2010. However, after South Sudan's independence in July 2011, Sudan lost a significant portion of its oil revenue, leading to stagflation. GDP growth slowed (e.g., 3.1% in 2015), and inflation remained high (21.8% in 2015). Sudan's GDP fell sharply from US$123.053 billion in 2017 to US$40.852 billion in 2018.

Even with oil revenues, Sudan faced formidable economic problems, including a low level of per capita output, high external debt, and the impact of international sanctions related to terrorism sponsorship and human rights abuses. The economy was heavily reliant on oil exports, and production in Sudan (post-secession) fell from around 450,000 barrels per day to under 60,000 barrels per day, though it recovered somewhat to around 250,000 barrels per day by 2014-15. South Sudan relied on Sudanese pipelines and refineries to export its oil, leading to disputes over transit fees.

The economy has been plagued by high inflation, currency devaluation, and shortages of essential goods. International sanctions, though partially lifted in 2017 and with the removal from the U.S. list of state sponsors of terrorism in 2020, had a long-term negative impact. The transitional government (2019-2021) initiated reforms and sought assistance from the IMF and World Bank to stabilize the economy, but these efforts were derailed by the 2021 coup and subsequently the 2023 civil war.