1. Overview

Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east. To the south, it is separated from Estonia by the Gulf of Finland, while the Gulf of Bothnia lies to its west. With a population of approximately 5.6 million people, primarily concentrated in its southern regions, Finland is one of the most sparsely populated countries in Europe. Helsinki, the capital, is also the largest city.

The nation's geography is characterized by vast boreal forests and over 180,000 lakes, earning it the moniker "the land of a thousand lakes." Its climate ranges from humid continental in the south to boreal in the north.

Finland's history is marked by long periods under foreign rule. From the late 13th century until 1809, it was an integral part of Sweden. Subsequently, it became an autonomous Grand Duchy within the Russian Empire until it declared independence in 1917 following the Russian Revolution. The early years of independence were tumultuous, including a civil war. During World War II, Finland fought against the Soviet Union in the Winter War and the Continuation War, and later against Nazi Germany in the Lapland War, managing to preserve its independence despite territorial losses.

Post-World War II, Finland rapidly industrialized, transforming from a largely agrarian society into an advanced economy. It developed a comprehensive welfare state based on the Nordic model, ensuring a high quality of life, free education, and universal healthcare. Finland is a parliamentary republic and has consistently ranked high in international comparisons of national performance, including education, economic competitiveness, civil liberties, and human development. A member of the European Union since 1995 and the Eurozone since 1999, Finland officially joined NATO in 2023, marking a significant shift in its foreign policy which had traditionally emphasized neutrality during the Cold War. The official languages are Finnish and Swedish. Finnish culture is distinct, with unique traditions such as the sauna, a vibrant arts scene, and strong connections to nature.

2. Etymology and Symbols

This section explores the origins of Finland's names and its significant national symbols that represent its identity and heritage.

2.1. Etymology

The name "Finland" has origins that are not entirely clear, but it is similar to Scandinavian place names such as Finnmark and Finnveden. These names are likely derived from finnr, a Germanic word for a nomad or hunter-gatherer. It is uncertain how or when "Finnr" began to specifically refer to the people of Finland Proper, the coastal region around Turku, from where the name spread from the 15th century onwards to denote the inhabitants of the entire country. One of the earliest documented mentions of a "land of the Finns" appears on two runestones: one in Söderby, Sweden, with the inscription finlont (U 582), and another on Gotland with finlandi (G 319), both dating from the 11th century.

The native name for Finland is SuomiSOO-oh-meeFinnish. The etymology of "Suomi" is also uncertain. One theory suggests it is derived from the Proto-Baltic word *zeme, meaning "land". An earlier theory proposed origins from suomaa (fen land) or suoniemi (fen cape). Another common suggestion is a shared etymology with saame (the Sami), who are also Finno-Ugric. Historically, in the 12th and 13th centuries, the term "Finland" (and by extension Suomi) primarily referred to the coastal region around Turku. This area later became known as "Finland Proper" (Varsinais-SuomiVarsinais-Suomi (Finnish)Finnish) to distinguish it from the country name "Finland" as a whole.

The official long protocol name is the Republic of Finland (Suomen tasavaltaSuomen tasavalta (Finnish)Finnish; Republiken FinlandRepubliken Finland (Swedish)Swedish; Suoma dásseváldiSuoma dásseváldi (Sami)Northern Sami), although this is not defined by law; legislation recognizes only the short name "Finland."

2.2. National Symbols

Finland possesses several official and unofficial symbols that represent its national identity.

The Flag of Finland, also known as Siniristilippu ("Blue Cross Flag"), features a blue Nordic cross on a white background. The blue represents Finland's numerous lakes and the sky, while the white symbolizes the snow that covers the land in winter.

The Coat of arms of Finland depicts a crowned lion rampant on a red field, brandishing a sword and trampling a sabre. The lion is a traditional symbol of power and valor in Northern Europe.

The national anthem is "Maamme" (Our Land), with music composed by Fredrik Pacius and lyrics by J. L. Runeberg. Originally written in Swedish (Vårt land), it was later translated into Finnish.

The national animal of Finland is the brown bear (Ursus arctos). Bears feature prominently in Finnish folklore and mythology.

The national plant (or national flower) is the lily of the valley (Convallaria majalis). Its delicate white, bell-shaped flowers and sweet fragrance are cherished by Finns.

Other symbols include the whooper swan (national bird), perch (national fish), granite (national stone), and birch (specifically the silver birch, Betula pendula, as the national tree).

3. History

Finland's history stretches from prehistoric human settlements to its modern status as a European nation. This journey includes centuries under Swedish and Russian rule, a hard-won independence, and navigation through major 20th-century conflicts before emerging as a prosperous democratic republic.

3.1. Prehistory

The area now known as Finland was first settled around 8500 BC, during the Mesolithic Stone Age, following the retreat of the last ice age. The earliest inhabitants were hunter-gatherers, utilizing stone tools. Archaeological artifacts from these first settlers share characteristics with those found in Estonia, Russia, and Norway.

The first pottery appeared around 5200 BC with the introduction of the Comb Ceramic culture. This culture, named for its distinctive comb-like patterns on pottery, extended to the western limits of present-day Finland. The arrival of the Corded Ware culture on the southern coast between 3000 and 2500 BC is often associated with the beginnings of agriculture in the region. However, even with the introduction of farming, hunting and fishing remained crucial for sustenance.

The Bronze Age in Finland (circa 1500-500 BC) saw the spread of permanent, year-round cultivation and animal husbandry, although the cold climate slowed this transition. The Seima-Turbino phenomenon brought the first bronze artifacts to the region, possibly along with Finno-Ugric languages. Commercial contacts, previously mainly with Estonia, began to extend to Scandinavia. Domestic manufacturing of bronze artifacts started around 1300 BC.

During the Iron Age (circa 500 BC - 1200 AD), the population grew, with Finland Proper becoming the most densely populated area. Trade in the Baltic Sea region expanded, particularly during the 8th and 9th centuries. Finland exported furs, slaves, castoreum, and falcons, while importing silk, fabrics, jewelry, and Ulfberht swords. Iron production began around 500 BC. By the end of the 9th century, indigenous artifact culture, especially weapons and women's jewelry, showed more common local features, which has been interpreted as an expression of a developing common Finnish identity.

An early form of Finnic languages is thought to have spread to the Baltic Sea region around 1900 BC, with a common Finnic language spoken around the Gulf of Finland about 2000 years ago. The dialects that evolved into the modern Finnish language emerged during the Iron Age, influenced by contacts with ancient Baltic and eastern Germanic peoples. The Sami people, though distantly related linguistically, retained a hunter-gatherer lifestyle longer than the Finns and have maintained their cultural identity and language in Lapland, the northernmost region.

3.2. Swedish Era

The 12th and 13th centuries were a period of significant change and conflict in the northern Baltic Sea region. The Livonian Crusade was ongoing, and Finnish tribes, such as the Tavastians and Karelians, were frequently in conflict with Novgorod and with each other. During this time, several crusades were launched from the Catholic realms of the Baltic Sea area against Finnish tribes. Danes conducted at least three crusades to Finland: one around 1187 or slightly earlier, another in 1191, and one in 1202. Sweden also undertook crusades, notably the so-called Second Swedish Crusade around 1249 against the Tavastians and the Third Swedish Crusade in 1293 against the Karelians. The historicity of the First Swedish Crusade, supposedly in 1155, is debated by modern historians, with many suggesting it likely never occurred as a distinct military expedition.

As a result of these crusades, particularly the Second Swedish Crusade led by Birger Jarl, and the subsequent colonization of some Finnish coastal areas by Christian Swedish-speaking settlers during the Middle Ages, Finland gradually became an integral part of the Kingdom of Sweden and came under the influence of the Catholic Church. Sweden built fortresses in Häme and Turku. An administrative structure, fiscal apparatus, and codified laws were established during the reigns of Magnus Ladulås (1275-1290) and Magnus Eriksson (1319-1364), firmly integrating the Finnish lands into the Swedish realm and Western European cultural sphere.

Swedish became the dominant language of the nobility, administration, and education, while Finnish was primarily spoken by the peasantry, clergy, and in local courts in Finnish-speaking areas. During the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, Finns gradually converted to Lutheranism. Bishop Mikael Agricola, a key Lutheran Reformer, published the first written works in Finnish, laying the foundation for literary Finnish. In 1550, King Gustav Vasa founded Helsinki. The Royal Academy of Turku, Finland's first university, was established in 1640 by Queen Christina of Sweden at the suggestion of Count Per Brahe.

Finnish soldiers, particularly the Hakkapeliitta cavalry, gained a reputation for their prowess during the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648). However, Finland also suffered greatly during this period and later. The severe famine of 1695-1697 resulted in the deaths of about one-third of the Finnish population. This was followed by a devastating plague.

In the 18th century, wars between Sweden and Russia led to the Russian occupation of Finland twice. These periods are known to Finns as the Greater Wrath (1714-1721) and the Lesser Wrath (1742-1743, during the Russo-Swedish War). These occupations caused immense suffering, with widespread destruction of homes and farms, and the burning of Helsinki, leading to the loss of almost an entire generation of young men. The repeated use of Finland as a battlefield between Sweden and Russia began to foster a sense of distinct Finnish identity among some elites, who questioned the benefits of remaining under Swedish rule.

3.3. Grand Duchy of Finland

The Swedish era in Finland concluded with the Finnish War (1808-1809). On March 29, 1809, following its conquest by the armies of Alexander I of Russia, Finland became an autonomous Grand Duchy within the Russian Empire, a status recognized by the Diet of Porvoo. This arrangement lasted until the end of 1917. In 1812, Tsar Alexander I incorporated the Russian province of Vyborg (also known as Old Finland) into the Grand Duchy, reuniting it with the rest of Finland. Helsinki was made the capital of the Grand Duchy in 1812, replacing Turku.

During the Crimean War (1853-1856), Finland became indirectly involved when British and French navies bombarded the Finnish coast and the Åland Islands in what is known as the Åland War.

Under Russian rule, Finland enjoyed considerable autonomy, retaining its Swedish legal system, Lutheran religion, and eventually its own currency (the Finnish markka, introduced in 1860) and postal system. While Swedish initially remained the language of administration and higher education, the 19th century saw a powerful surge of Finnish nationalism, known as the Fennoman movement. Prominent figures like the philosopher and statesman J.V. Snellman championed the Finnish language and culture. Key milestones included the publication of the Kalevala, Finland's national epic compiled by Elias Lönnrot, in 1835, and the Finnish Language Decree of 1863, which gradually elevated Finnish to an official language alongside Swedish, achieving full legal equality in 1892. The sentiment "Swedes we are no longer, Russians we do not want to become, so let us be Finns," attributed to Adolf Ivar Arwidsson, encapsulated the burgeoning national identity.

Despite this cultural awakening, a significant independence movement did not emerge until the early 20th century. The Finnish famine of 1866-1868, a devastating event that killed around 15% of the population, was one of the worst famines in European history. This tragedy led the Russian Empire to relax financial regulations, and investment in Finland increased in subsequent decades, fostering rapid economic development, though GDP per capita remained significantly lower than in Western European powers like Britain or the United States.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw periods of intensified Russification efforts by the Russian imperial government, particularly from 1899 to 1905 (the "First Period of Oppression") and from 1908 to 1917 (the "Second Period of Oppression"). These policies aimed to limit Finnish autonomy and integrate Finland more closely with the Russian Empire. The February Manifesto of 1899, issued by Tsar Nicholas II, was a significant catalyst for Finnish resistance. Despite these pressures, Finland achieved a remarkable political milestone in 1906 when it became the first territory in Europe to grant universal suffrage (the right to vote for all adult citizens) and the first in the world to give all adult citizens the right to run for public office. However, the Tsar's power to dissolve the Finnish parliament (the Eduskunta) and reject its laws limited the practical impact of this suffrage. These periods of Russification fueled the desire for independence among Finns, particularly radical liberals and socialists.

3.4. Independence and Civil War

Following the February Revolution in Russia in 1917, the authority of the Tsar collapsed, creating a power vacuum in Finland. The Finnish Parliament (Eduskunta), where the Social Democrats held a majority, passed the "Power Act" (Valtalaki) in July 1917, declaring itself the supreme authority in Finland except in foreign policy and military matters. However, the Russian Provisional Government in Petrograd rejected this act and dissolved the Parliament. New elections were held in October 1917, resulting in a narrow majority for non-socialist, right-wing parties. Some Social Democrats refused to accept this outcome, arguing the dissolution and new elections were illegal. This deepened the already significant political divide.

The October Revolution in Russia in November 1917 (New Style), which brought the Bolsheviks to power, further altered the situation. The non-socialist Finnish government, led by Prime Minister P. E. Svinhufvud, saw an opportunity. On December 4, 1917, the government presented a Declaration of Independence, which the Parliament officially approved on December 6, 1917. This date is now celebrated as Finland's Independence Day. The Bolshevik government in Russia, led by Vladimir Lenin, recognized Finland's independence on January 4, 1918.

However, internal tensions in Finland escalated. On January 27, 1918, radical elements of the labor movement, known as the Reds, launched an offensive, seizing control of southern Finland, including Helsinki. The "White" government, representing the non-socialist forces, retreated to Vaasa in Ostrobothnia. This marked the beginning of the Finnish Civil War, a short but brutal conflict. The Whites, led by General C. G. E. Mannerheim and supported by Imperial Germany, fought against the Reds, who had ties to Soviet Russia and proclaimed a Finnish Socialist Workers' Republic.

The Whites ultimately prevailed in May 1918. The war was devastating, with significant casualties on both sides, not only in combat but also through executions and deaths in prison camps. Tens of thousands of Reds were interned after the war, and many died from malnutrition and disease. The Civil War left deep social and political scars, creating an enmity between the "Reds" and "Whites" that persisted for decades, influencing Finnish society and politics until the Winter War and beyond.

After a brief and failed attempt to establish a monarchy with a German prince, Prince Frederick Charles of Hesse, as king, Finland adopted a republican constitution in July 1919. K. J. Ståhlberg, a liberal nationalist, was elected as the first President. Ståhlberg's presidency focused on anchoring the new state in liberal democracy, promoting the rule of law, and initiating internal reforms. The Treaty of Tartu in 1920 formally defined the border with Soviet Russia, largely following the historical boundary but granting Finland the Petsamo region and its Barents Sea port. The interwar period saw Finnish democracy survive challenges from Soviet coup attempts and the right-wing anti-communist Lapua Movement. Social reforms continued, with Miina Sillanpää becoming Finland's first female government minister in 1926.

3.5. World War II

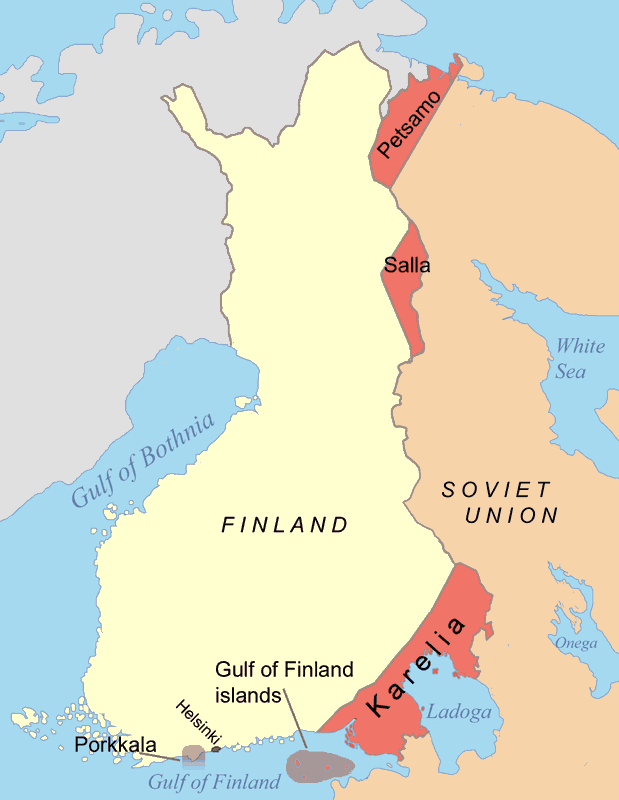

Finland's involvement in World War II was defined by three distinct conflicts. The first was the Winter War (November 30, 1939 - March 13, 1940). The Soviet Union, aiming to improve its strategic position in the Baltic Sea region and having secured a sphere of influence under the secret protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany, demanded territorial concessions from Finland. When Finland refused, the Soviet Union launched an invasion. The Finnish Democratic Republic, a Soviet puppet government led by Otto Wille Kuusinen, was established by Joseph Stalin at the war's outset, intended to govern Finland after a Soviet conquest. Despite being vastly outnumbered and outgunned, the Finnish forces mounted a determined and effective defense, inflicting heavy casualties on the Red Army, notably at the Battle of Suomussalmi. The unprovoked attack was widely condemned internationally, leading to the Soviet Union's expulsion from the League of Nations. However, after months of fierce fighting and significant Soviet advances in February 1940, Finland was forced to sue for peace. The Moscow Peace Treaty, signed on March 12, 1940, ended the war. Finland preserved its independence but ceded approximately 9% of its territory, including parts of Karelia with the city of Vyborg (ViipuriViipuri (Finnish for Vyborg)Finnish), Salla, and parts of the Rybachy Peninsula.

The second conflict was the Continuation War (June 25, 1941 - September 19, 1944). Seeking to reclaim lost territories and aligning with Germany following Operation Barbarossa (Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union), Finland joined the offensive against the Soviet Union. Finnish troops advanced into Soviet Karelia, occupying significant areas. However, the war turned against the Axis powers. The massive Soviet Vyborg-Petrozavodsk Offensive in the summer of 1944 pushed Finnish forces back, but the Finns managed to halt the advance at key battles like the Battle of Tali-Ihantala. This defensive success, though costly, prevented a full Soviet occupation and led to a stalemate, paving the way for an armistice. The Moscow Armistice was signed on September 19, 1944, ending hostilities with the Allies (primarily the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom).

The armistice terms required Finland to cede further territory (including Petsamo), pay substantial war reparations amounting to $300 million (a significant sum at the time, equivalent to billions in today's currency), and, crucially, to expel German forces from its territory. This led to the third conflict, the Lapland War (September 15, 1944 - April 27, 1945), where Finnish forces fought retreating German troops in northern Finland.

As a result of these wars, Finland lost approximately 12% of its land area and 20% of its industrial capacity, including its second-largest city, Vyborg, and its only ice-free Arctic port, Liinakhamari. Nearly 400,000 Finns from the ceded territories had to be resettled within Finland's new borders. Around 97,000 Finnish soldiers died. Despite these losses, Finland crucially avoided Soviet occupation, maintained its independence, and preserved its democratic institutions, a rare achievement among European countries bordering the Soviet Union that participated in the hostilities. Along with Great Britain, Finland was one of the few European countries involved in World War II that was never fully occupied.

In the immediate post-war years, the Communist Party gained considerable influence. Finland, under Soviet pressure, declined Marshall Plan aid. However, the United States provided covert development aid and supported the Social Democratic Party to help maintain Finland's independence and counter communist influence.

3.6. Cold War Era

During the Cold War, Finland's domestic and foreign policy was heavily influenced by its relationship with the Soviet Union. The cornerstone of this relationship was the Agreement of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance (YYA Treaty). This treaty obligated Finland to resist attacks by Germany or its allies against Finland or through Finland against the Soviet Union, and it allowed for Soviet military assistance if needed. While recognizing Finland's desire to remain outside great-power conflicts, the treaty effectively limited Finnish sovereignty in foreign policy. This policy of cautious neutrality, often involving deference to Soviet interests to maintain independence, became known in the West as "Finlandization."

Urho Kekkonen, who served as President from 1956 to 1982, dominated Finnish politics during much of this era. His skillful management of relations with the Soviet Union was crucial to his long tenure and to maintaining Finland's delicate balancing act. Domestically, there was a tendency to avoid any policy or public statement that could be interpreted as anti-Soviet.

Despite these constraints, Finland maintained a market economy and democratic institutions. The development of trade with Western powers, such as the United Kingdom, alongside the payment of war reparations and continued bilateral trade with the Soviet Union, transformed Finland from a primarily agrarian society into an industrialized one. Valmet, for example, originally involved in producing goods for war reparations, grew into a significant industrial company.

By the 1950s, although 46% of Finnish workers were still in agriculture, urbanization was accelerating as new jobs in manufacturing, services, and trade drew people to cities. The post-war baby boom (peaking at 3.5 births per woman in 1947) was followed by a sharp decline in fertility (to 1.5 by 1973). The economy struggled to create enough jobs for the baby boomers entering the workforce, leading to significant emigration, particularly to more industrialized Sweden, peaking in 1969-1970.

Economically, Finland integrated with Western institutions, participating in the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Economic growth was rapid, and by 1975, Finland's GDP per capita was the 15th highest in the world. During the 1970s and 1980s, Finland built one of the most extensive welfare states globally, based on the Nordic model, providing comprehensive social security, healthcare, and education. In 1973, Finland negotiated a treaty with the European Economic Community (EEC) that largely eliminated tariffs, further linking its economy to Western Europe from 1977 onwards.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 marked a turning point. The loss of its largest trading partner, coupled with miscalculated macroeconomic decisions and a banking crisis, plunged Finland into a deep recession in the early 1990s. The recession bottomed out in 1993, after which Finland experienced over a decade of steady economic growth, increasingly orienting itself towards the West.

3.7. 21st Century

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Finland significantly reoriented its foreign and economic policies. A key development was its accession to the European Union (EU) in 1995, and it joined the Eurozone at its inception in 1999. Much of Finland's economic growth in the late 1990s was driven by the success of the mobile phone manufacturer Nokia, which became a global leader in the industry.

In the 2000 presidential election, Tarja Halonen was elected, becoming Finland's first female president. Her predecessor, Martti Ahtisaari, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2008 for his work in international conflict resolution. The global financial crisis of 2007-2008 impacted Finland's export-reliant economy, leading to weaker economic growth throughout the following decade. Sauli Niinistö served as president from 2012 to 2024, succeeded by Alexander Stubb.

A pivotal moment in Finland's 21st-century foreign policy came with the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. This event dramatically shifted Finnish public opinion and political consensus regarding NATO membership. Prior to the invasion, polls consistently showed a majority against joining NATO. However, support for membership surged rapidly after February 2022, reaching a clear supermajority by April.

On May 11, 2022, Finland signed a mutual security pact with the United Kingdom. The following day, May 12, President Niinistö and then-Prime Minister Sanna Marin jointly called for Finland to apply for NATO membership "without delay." On May 17, 2022, the Finnish Parliament overwhelmingly voted 188-8 in favor of applying for NATO membership. Finland officially became the 31st member of NATO on April 4, 2023, ending decades of military non-alignment and marking a historic shift in its security policy. This move was seen as a direct response to increased security concerns following Russia's aggression in Ukraine.

4. Geography

Finland's geography is defined by its northern location, extensive lake systems, vast forests, and the legacy of the last ice age. It is one of the world's northernmost countries, with a significant portion of its territory lying above the Arctic Circle.

4.1. Topography and Landscapes

Lying approximately between latitudes 60° and 70° N, and longitudes 20° and 32° E, Finland's landscape is predominantly flat with low hills. The highest point, Halti, at 4.3 K ft (1.32 K m), is located in the far north of Lapland on the border with Norway. The highest mountain peak entirely within Finland is Ridnitšohkka at 4.3 K ft (1.32 K m), adjacent to Halti.

Much of Finland's topography is a result of the Ice Age. Glacial erosion smoothed the terrain and created numerous depressions that subsequently filled with water, forming an extensive network of lakes. Finland has approximately 168,000 lakes (larger than 5382 ft2 (500 m2)) and 179,000 islands. The Finnish Lakeland in the southeast is the country's largest lake district and is home to Saimaa, Europe's fourth-largest lake.

The Finnish coastline is highly indented, particularly in the southwest, where the Archipelago Sea forms the world's largest archipelago by number of islands, with over 50,000 islands.

Retreating glaciers left behind morainic deposits, including prominent eskers (long ridges of sand and gravel) and the three Salpausselkä ridges that traverse southern Finland. Due to post-glacial rebound, the land is still rising, especially around the Gulf of Bothnia (about 0.4 in (1 cm) per year), causing the country's land area to expand by approximately 2.7 mile2 (7 km2) annually.

Forests cover about 78% of Finland's land area, primarily coniferous taiga forests consisting of pine, spruce, and birch. Fens and bogs are also common. Granite is a ubiquitous rock type, visible wherever soil cover is absent. The most common soil type is moraine or till, often covered by a thin layer of humus. Podzol soils are typical in forests, while gleysols and peat characterize poorly drained areas.

4.2. Climate

Finland's climate is significantly influenced by its northern latitude, yet moderated by the North Atlantic Drift (an extension of the Gulf Stream) and the Baltic Sea. It varies from a humid continental climate in the south to a boreal climate (or subarctic climate) in the north.

Winters in southern Finland typically last about 100 days, with mean daily temperatures below 32 °F (0 °C). Snow cover usually lasts from late November to April in inland areas, and from late December to late March in coastal areas like Helsinki. Winter temperatures can drop to -22 °F (-30 °C) on the coldest nights, though such extremes are rarer on the coast.

Summers in southern Finland, with mean daily temperatures above 50 °F (10 °C), last from late May to mid-September. July can see temperatures exceeding 95 °F (35 °C) during warm spells. The southernmost coastal regions are sometimes classified as hemiboreal.

Northern Finland, particularly Lapland, experiences long, cold winters (around 200 days) with permanent snow cover from mid-October to early May. Temperatures can fall to -49 °F (-45 °C). Summers are short (two to three months) but can still have days above 77 °F (25 °C). While no part of Finland has true Arctic tundra, alpine tundra exists on the fells of Lapland.

A quarter of Finland's territory lies within the Arctic Circle. This results in the midnight sun in summer, where the sun does not set for up to 73 consecutive days at the northernmost point. Conversely, the polar night (kaamos) occurs in winter, when the sun does not rise for 51 days in the far north.

The climate supports cereal farming mainly in the southern regions, while northern regions are more suited to animal husbandry. Finland ranked 4th in the Environmental Performance Index for 2024, scoring well in climate change mitigation, waste management, and air quality.

4.3. Biodiversity

Phytogeographically, Finland is part of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. The WWF identifies three main ecoregions in Finland: the Scandinavian and Russian taiga (covering most of the country), Sarmatic mixed forests (in the southwest), and Scandinavian Montane Birch forest and grasslands (in the far north). Finland's Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score was 5.08/10 in 2018.

Finland hosts a diverse range of fauna. There are at least sixty native mammalian species, 248 breeding bird species, over 70 fish species, and 11 reptile and amphibian species. Prominent wildlife mammals include the brown bear (national animal), grey wolf, wolverine, and elk (moose).

Notable bird species include the whooper swan (national bird), the Western capercaillie, and the Eurasian eagle-owl, the latter being an indicator of old-growth forest connectivity. Common breeding birds are the willow warbler, common chaffinch, and redwing. Finland is also home to around 24,000 species of insects.

Freshwater fish such as northern pike and perch are abundant. Atlantic salmon is a prized game fish.

A unique and endangered species is the Saimaa ringed seal, one of only three lake seal species in the world. It exists exclusively in the Saimaa lake system in southeastern Finland, with a population of only around 390 individuals. It has become an emblem of Finnish nature conservation.

About one-third of Finland's land area originally consisted of moorland, roughly half of which has been drained for cultivation over the centuries. Conservation efforts focus on protecting vulnerable species and habitats, including its extensive network of national parks.

4.4. Regions and Administrative Divisions

Finland is divided into 19 regions (maakuntamaakunta (Finnish)Finnish; landskaplandskap (Swedish)Swedish). These regions are governed by regional councils, which serve as forums for cooperation among the municipalities within each region. The primary responsibilities of the regional councils include regional planning, economic development, and education. Public health services are also often organized at the regional level. Members of the regional councils are typically elected by municipal councils, with representation proportional to each municipality's population.

In addition to inter-municipal cooperation, each region has a state-run Centre for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment (ELY Centre), responsible for local administration of labor, agriculture, fisheries, forestry, and entrepreneurial affairs. Historically, the current regions are divisions of historical provinces of Finland, which more closely represent local dialects and cultural identities.

The fundamental administrative units are the municipalities (kuntakunta (Finnish)Finnish; kommunkommun (Swedish)Swedish), of which there were 309 as of 2021. Municipalities, which may also call themselves towns or cities, account for about half of public spending, financed by municipal income tax, state subsidies, and other revenues. Most municipalities have fewer than 6,000 residents.

Municipalities cooperate in seventy sub-regions (seutukuntaseutukunta (Finnish)Finnish; ekonomisk regionekonomisk region (Swedish)Swedish). The Åland Islands form an autonomous, demilitarized, and unilingually Swedish-speaking region with its own democratically elected regional council that handles many powers otherwise belonging to the mainland regions. The Sami people have a semi-autonomous Sami native region in Lapland, with rights concerning their language and culture.

For the organization of health, social, and emergency services, Finland is divided into 21 wellbeing services counties. These are largely based on the regional structure. County councils, elected every four years, are responsible for the operation, administration, and finances of these services. Wellbeing services counties are self-governing but are funded by the central government, not through local taxation.

The region of Eastern Uusimaa was merged with Uusimaa on January 1, 2011.

The 19 regions of Finland are:

| English name | Finnish name | Swedish name | Capital | Regional state administrative agency (historical) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lapland | LappiLappi (Finnish)Finnish | LapplandLappland (Swedish)Swedish | Rovaniemi | Lapland |

| North Ostrobothnia | Pohjois-PohjanmaaPohjois-Pohjanmaa (Finnish)Finnish | Norra ÖsterbottenNorra Österbotten (Swedish)Swedish | Oulu | Northern Finland |

| Kainuu | KainuuKainuu (Finnish)Finnish | KajanalandKajanaland (Swedish)Swedish | Kajaani | Northern Finland |

| North Karelia | Pohjois-KarjalaPohjois-Karjala (Finnish)Finnish | Norra KarelenNorra Karelen (Swedish)Swedish | Joensuu | Eastern Finland |

| North Savo | Pohjois-SavoPohjois-Savo (Finnish)Finnish | Norra SavolaxNorra Savolax (Swedish)Swedish | Kuopio | Eastern Finland |

| South Savo | Etelä-SavoEtelä-Savo (Finnish)Finnish | Södra SavolaxSödra Savolax (Swedish)Swedish | Mikkeli | Eastern Finland |

| South Ostrobothnia | Etelä-PohjanmaaEtelä-Pohjanmaa (Finnish)Finnish | Södra ÖsterbottenSödra Österbotten (Swedish)Swedish | Seinäjoki | Western and Central Finland |

| Central Ostrobothnia | Keski-PohjanmaaKeski-Pohjanmaa (Finnish)Finnish | Mellersta ÖsterbottenMellersta Österbotten (Swedish)Swedish | Kokkola | Western and Central Finland |

| Ostrobothnia | PohjanmaaPohjanmaa (Finnish)Finnish | ÖsterbottenÖsterbotten (Swedish)Swedish | Vaasa | Western and Central Finland |

| Pirkanmaa | PirkanmaaPirkanmaa (Finnish)Finnish | BirkalandBirkaland (Swedish)Swedish | Tampere | Western and Central Finland |

| Central Finland | Keski-SuomiKeski-Suomi (Finnish)Finnish | Mellersta FinlandMellersta Finland (Swedish)Swedish | Jyväskylä | Western and Central Finland |

| Satakunta | SatakuntaSatakunta (Finnish)Finnish | SatakuntaSatakunta (Swedish)Swedish | Pori | South-Western Finland |

| Southwest Finland | Varsinais-SuomiVarsinais-Suomi (Finnish)Finnish | Egentliga FinlandEgentliga Finland (Swedish)Swedish | Turku | South-Western Finland |

| South Karelia | Etelä-KarjalaEtelä-Karjala (Finnish)Finnish | Södra KarelenSödra Karelen (Swedish)Swedish | Lappeenranta | Southern Finland |

| Päijät-Häme | Päijät-HämePäijät-Häme (Finnish)Finnish | Päijänne-TavastlandPäijänne-Tavastland (Swedish)Swedish | Lahti | Southern Finland |

| Kanta-Häme | Kanta-HämeKanta-Häme (Finnish)Finnish | Egentliga TavastlandEgentliga Tavastland (Swedish)Swedish | Hämeenlinna | Southern Finland |

| Uusimaa | UusimaaUusimaa (Finnish)Finnish | NylandNyland (Swedish)Swedish | Helsinki | Southern Finland |

| Kymenlaakso | KymenlaaksoKymenlaakso (Finnish)Finnish | KymmenedalenKymmenedalen (Swedish)Swedish | Kotka and Kouvola | Southern Finland |

| Åland | AhvenanmaaAhvenanmaa (Finnish)Finnish | ÅlandÅland (Swedish)Swedish | Mariehamn | Åland |

4.4.1. Major Cities

Finland's population is largely concentrated in its southern regions. The major urban centers are hubs of economic activity, culture, and education.

- Helsinki: The capital and largest city, located on the shore of the Gulf of Finland. Helsinki is Finland's major political, educational, financial, cultural, and research center. It forms a metropolitan area with Espoo, Vantaa, and Kauniainen, housing over 1.4 million people.

- Espoo: The second-largest city, part of the Helsinki metropolitan area. Espoo is known for its strong technology sector, including the headquarters of companies like Nokia (historically) and the Aalto University campus in Otaniemi.

- Tampere: The third-largest city and the largest inland city in the Nordic countries, situated between two lakes, Näsijärvi and Pyhäjärvi. Tampere is a major industrial and technological hub, also known for its vibrant cultural life.

- Vantaa: The fourth-largest city, also part of the Helsinki metropolitan area. It is home to Helsinki Airport, Finland's main international airport.

- Oulu: A significant city in northern Finland, located at the mouth of the Oulujoki river on the Gulf of Bothnia. Oulu is a technology center, particularly strong in information technology and wellness technology, and hosts the University of Oulu.

- Turku: Finland's oldest city and former capital, located on the southwest coast at the mouth of the Aura River. Turku has a rich history and remains an important center for culture, education (with two universities), and maritime industries.

5. Government and Politics

Finland operates as a parliamentary republic within a framework of representative democracy. The political system is defined by its constitution, with power distributed among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The Prime Minister is considered the country's most powerful political figure in daily governance.

5.1. Constitution

The current Constitution of Finland was enacted on March 1, 2000, and has been amended since, notably in 2012. It defines Finland as a sovereign republic and lays down the fundamental principles of state governance and the fundamental rights of individuals. Key tenets include the rule of law, separation of powers, and parliamentary democracy. The constitution guarantees human rights and basic freedoms, such as freedom of speech, assembly, and religion. It also outlines the functions and powers of the highest state organs: the Parliament, the President of the Republic, and the Government (Cabinet). The constitutionality of new laws is assessed by the Parliament's Constitutional Law Committee, as Finland does not have a separate constitutional court.

5.2. President

The President of the Republic is the head of state. Historically, Finland had a semi-presidential system with a strong president, but constitutional reforms, particularly the 2000 constitution, have shifted more power to the Parliament and the Cabinet, making the presidency a primarily ceremonial office with specific responsibilities in foreign policy and national defense.

The President is elected directly by popular vote using a two-round system for a six-year term and can serve a maximum of two consecutive terms. The President's formal duties include appointing the Prime Minister as elected by Parliament, appointing and dismissing other ministers upon the Prime Minister's recommendation, opening parliamentary sessions, and conferring state honors.

In foreign policy, the President leads in cooperation with the Government, excluding matters related to the European Union, which are primarily handled by the Government. The President is the Commander-in-chief of the Finnish Defence Forces. While required to consult the Government on foreign and defense matters, the Government's advice is not binding in these areas. The President also holds certain domestic reserve powers, including the authority to veto legislation (which can be overridden by Parliament), grant pardons, and appoint some senior public officials. The President must dismiss individual ministers or the entire Government if they lose a parliamentary vote of no confidence.

Historical presidents include Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg (1919-1925), Lauri Kristian Relander (1925-1931), Pehr Evind Svinhufvud (1931-1937), Kyösti Kallio (1937-1940), Risto Ryti (1940-1944), Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim (1944-1946), Juho Kusti Paasikivi (1946-1956), Urho Kekkonen (1956-1982), Mauno Koivisto (1982-1994), Martti Ahtisaari (1994-2000), Tarja Halonen (2000-2012), and Sauli Niinistö (2012-2024). The current president is Alexander Stubb, who took office on March 1, 2024.

5.3. Parliament (Eduskunta)

The Parliament of Finland (EduskuntaEduskunta (Finnish)Finnish; RiksdagenRiksdagen (Swedish)Swedish) is the unicameral legislature exercising supreme legislative authority. It consists of 200 members elected for a four-year term using the D'Hondt method of proportional representation in multi-seat constituencies via an open list system.

The Parliament's key functions include enacting legislation, approving the state budget, ratifying international treaties, and overseeing the Government. It has the power to amend the constitution, dismiss the Cabinet through a vote of no confidence, and override presidential vetoes. The acts of Parliament are not subject to judicial review by courts; instead, the constitutionality of new laws is assessed by the Parliament's own Constitutional Law Committee before final passage. Various parliamentary committees play a crucial role in preparing legislation, holding hearings with experts and stakeholders.

5.4. Cabinet (Government)

The Finnish Cabinet (ValtioneuvostoValtioneuvosto (Finnish)Finnish; StatsrådetStatsrådet (Swedish)Swedish) exercises most executive powers and is responsible for the day-to-day governance of the country. After parliamentary elections, political parties negotiate to form a new Cabinet, which must be approved by a simple majority in Parliament. The Cabinet can be dismissed by a parliamentary vote of no confidence, though this is rare as coalition governments typically command a majority.

The Cabinet is headed by the Prime Minister and includes other ministers responsible for specific portfolios or ministries, as well as the Chancellor of Justice who ensures the legality of government actions. The Prime Minister is usually the leader of the largest party in the governing coalition, and the Minister of Finance is often the leader of the second-largest coalition party. The Cabinet originates most legislative bills, which are then debated and voted upon by Parliament.

As no single party typically wins an outright majority, Finnish Cabinets are usually multi-party coalitions. The current government is the Orpo Cabinet, which took office on June 20, 2023. It is led by Prime Minister Petteri Orpo of the National Coalition Party and is a coalition of the National Coalition Party, the Finns Party, the Swedish People's Party, and the Christian Democrats.

5.5. Law and Judiciary

Finland's legal system is a civil law system, primarily based on Swedish law and, more broadly, Roman law traditions. Finnish law is codified, meaning that laws are systematically collected into legal codes.

The judicial system is divided into two main branches:

1. Regular Courts: These courts handle civil and criminal cases. The system consists of:

- Local courts (käräjäoikeudetkäräjäoikeudet (Finnish)Finnish): Courts of first instance for most civil and criminal matters.

- Regional appellate courts (hovioikeudethovioikeudet (Finnish)Finnish): Hear appeals from local courts.

- The Supreme Court of Finland (Korkein oikeusKorkein oikeus (Finnish)Finnish): The highest appellate court for civil and criminal cases, which also oversees the administration of justice in its jurisdiction.

2. Administrative Courts: These courts handle litigation between individuals or corporations and public administrative bodies. The system includes:

- Regional administrative courts (hallinto-oikeudethallinto-oikeudet (Finnish)Finnish).

- The Supreme Administrative Court of Finland (Korkein hallinto-oikeusKorkein hallinto-oikeus (Finnish)Finnish): The highest appellate court for administrative cases.

In addition to these, there are a few special courts for specific branches of administration, and a High Court of Impeachment for criminal charges against certain high-ranking officeholders, including the President and members of the Cabinet.

The principles of the rule of law are strongly upheld. Finland has a low level of corruption; Transparency International consistently ranks it among the least corrupt countries. The overall crime rate is not high in the EU context, although certain types, like homicide, are somewhat higher than the Western European average. Finland uses a day-fine system, where fines for offenses like speeding are proportionate to the offender's income. Public confidence in Finland's security and judicial institutions is generally high.

5.6. Political Parties

Finland has a multi-party system, where several political parties compete for power, and coalition governments are the norm. No single party has held an absolute majority in Parliament in modern times. The major political parties represent a range of ideologies from left to right, as well as specific interest groups.

Key political parties include:

- The National Coalition Party (Kansallinen KokoomusKansallinen Kokoomus (Finnish)Finnish, Kok): A centre-right, liberal conservative party, generally pro-European and pro-business.

- The Social Democratic Party of Finland (Suomen Sosialidemokraattinen PuolueSuomen Sosialidemokraattinen Puolue (Finnish)Finnish, SDP): A centre-left party, one of Finland's oldest, traditionally representing the labor movement and advocating for the welfare state.

- The Finns Party (PerussuomalaisetPerussuomalaiset (Finnish)Finnish, PS): A nationalist and populist right-wing party, known for its euroscepticism and focus on immigration issues.

- The Centre Party (Suomen KeskustaSuomen Keskusta (Finnish)Finnish, Kesk): Historically an agrarian party, now a centrist party with strong support in rural areas, emphasizing decentralization and regional development.

- The Green League (Vihreä liittoVihreä liitto (Finnish)Finnish, Vihr): A green, social liberal party focusing on environmental issues, social justice, and human rights.

- The Left Alliance (VasemmistoliittoVasemmistoliitto (Finnish)Finnish, Vas): A democratic socialist and eco-socialist party, positioned to the left of the Social Democrats.

- The Swedish People's Party of Finland (Svenska folkpartiet i FinlandSvenska folkpartiet i Finland (Swedish)Swedish, SFP; Suomen ruotsalainen kansanpuolueSuomen ruotsalainen kansanpuolue (Finnish)Finnish, RKP): Represents the interests of the Swedish-speaking minority and generally holds liberal or centre-right positions.

- The Christian Democrats (Suomen KristillisdemokraatitSuomen Kristillisdemokraatit (Finnish)Finnish, KD): A Christian democratic party with socially conservative stances.

These parties, along with smaller ones, contribute to a dynamic political landscape where government formation often involves complex negotiations to build stable coalitions.

5.7. Human Rights

Finland has a strong record on human rights and is consistently ranked highly in global indices for civil liberties, democracy, and press freedom. The Constitution of Finland guarantees fundamental rights and freedoms for all individuals, including freedom of speech, assembly, religion, and protection from discrimination.

Civil Liberties: Finland upholds robust civil liberties. Freedom of the press is particularly notable, with Finland often ranking among the top countries in the world. Access to information and transparency in government are also key principles.

Gender Equality: Finland has a long history of promoting gender equality. It was the first country in Europe to grant women full suffrage (the right to vote and stand for office) in 1906. Women participate actively in all spheres of life, including politics and the workforce, though challenges such as gender pay gaps and underrepresentation in top corporate positions persist.

LGBTQ+ Rights: Finland has made significant progress in LGBTQ+ rights. Same-sex marriage was legalized in 2017. Anti-discrimination laws cover sexual orientation and gender identity. In 2023, ILGA-Europe ranked Finland sixth in Europe for LGBTQ+ rights. However, debates continue, particularly regarding reforms to transgender rights legislation.

Rights of Minorities:

- Sami People: As an indigenous people, the Sami have constitutionally protected rights to maintain and develop their own language and culture within the Sami Homeland in northern Finland. The Sami Parliament in Finland works to advance these rights. Challenges remain concerning land rights and effective participation in decision-making processes affecting them.

- Romani People: The Romani are a traditional minority in Finland. Despite legal protections, they continue to face societal discrimination and socio-economic disadvantages. Efforts are ongoing to improve their inclusion and address discrimination.

- Other minorities, such as the Swedish-speaking Finns, have strong linguistic and cultural rights. Recent immigrant groups also form part of Finland's multicultural landscape, with ongoing discussions about integration and equality.

Ongoing Challenges and Debates: Amnesty International and other human rights organizations have occasionally raised concerns. These have included the treatment of conscientious objectors to military service, conditions in some detention facilities, and persistent societal discrimination against Romani people and other minority groups. The rights of asylum seekers and refugees are also a subject of ongoing public and political debate, reflecting a concern for vulnerable groups. Finland generally demonstrates a commitment to upholding human rights through its legal framework and participation in international human rights conventions.

6. Foreign Relations

Finland's foreign policy is characterized by its membership in the European Union, its recent accession to NATO, strong Nordic cooperation, and a historically pragmatic relationship with its large eastern neighbor, Russia. The President leads foreign policy in cooperation with the government, except for EU affairs, which are primarily managed by the government.

6.1. General Foreign Policy

Historically, Finnish foreign policy was marked by a doctrine of neutrality, particularly during the Cold War era. This policy, often termed "Finlandization," involved maintaining good relations with the Soviet Union while preserving its sovereignty and democratic system. The YYA Treaty was a cornerstone of this era.

Since the end of the Cold War, Finland has increasingly integrated with Western structures. It joined the European Union in 1995. Key tenets of its contemporary foreign policy include:

- Active participation in the EU and shaping EU policies.

- Commitment to international law, multilateralism, and human rights.

- Strong Nordic cooperation through the Nordic Council and other forums.

- Participation in international crisis management and peacekeeping operations.

- Emphasis on free trade and global economic cooperation.

The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine marked a fundamental turning point, leading Finland to abandon its long-standing policy of military non-alignment.

6.2. NATO Membership

The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine caused a rapid and dramatic shift in Finnish public and political opinion regarding NATO. Previously, a majority of Finns opposed NATO membership, but the invasion led to overwhelming support for joining the alliance.

- Background**: Finland had maintained a close partnership with NATO for decades, participating in the Partnership for Peace program and NATO-led operations, but had refrained from seeking full membership to avoid antagonizing Russia.

- Accession Process**: In May 2022, Finland, alongside Sweden, formally applied for NATO membership. Following a swift ratification process by existing member states, Finland officially became the 31st member of NATO on April 4, 2023.

- Implications**: NATO membership represents the most significant change in Finnish security policy in decades. It provides Finland with collective defense guarantees under Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty. It has also led to increased defense spending and closer military integration with NATO allies. This move has been seen as strengthening regional security in Northern Europe but has also altered its relationship with Russia.

6.3. Relations with Key Countries

- Russia: Historically complex, the relationship with Russia deteriorated sharply after the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Finland shares a long border with Russia, and managing this relationship has always been a central element of its foreign policy. Post-2022, Finland has supported EU sanctions against Russia, restricted travel for Russian citizens, and significantly increased its own defense preparedness.

- Sweden: Finland and Sweden share a very close historical, cultural, and political relationship. They are key partners in Nordic cooperation and applied for NATO membership concurrently. Bilateral defense cooperation is extensive.

- Estonia: Relations with Estonia are strong, based on close linguistic and cultural ties, as well as shared interests within the EU and the Baltic Sea region.

- European Union: As an active EU member, Finland participates in shaping common foreign and security policy. The EU is Finland's most important economic and political framework.

- United States: Relations with the U.S. have strengthened significantly, particularly in security and defense cooperation, culminating in a Defense Cooperation Agreement (DCA) signed in December 2023. The U.S. was a strong supporter of Finland's NATO accession.

Finland's diplomatic efforts focus on promoting stability, security, and cooperation in its neighborhood and globally. Former President Martti Ahtisaari was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2008 for his work in international peace mediation, reflecting Finland's commitment to conflict resolution.

7. Military

The Finnish Defence Forces (PuolustusvoimatPuolustusvoimat (Finnish)Finnish; FörsvarsmaktenFörsvarsmakten (Swedish)Swedish) are responsible for the territorial defense of Finland. The structure and policy of the Finnish military have been significantly influenced by its history, geopolitical location, and, most recently, its membership in NATO.

The Finnish Defence Forces consist of a cadre of professional soldiers (mainly officers and technical personnel), currently serving conscripts, and a large, well-trained reserve. The standard readiness strength is approximately 34,700 personnel in uniform, of whom about 25% are professional soldiers. The wartime strength can be expanded to around 280,000 troops, drawing from its extensive reserve.

A key feature of the Finnish military is the system of universal male conscription. All male Finnish citizens are liable for military or civilian service upon reaching the age of 18. Military service typically lasts for 6 to 12 months, depending on the role and training. After completing conscript service, individuals become part of the reserve until the age of 50 or 60. Civilian service (siviilipalvelussiviilipalvelus (Finnish)Finnish) is an alternative for those who have conscientious objections to armed service and lasts 12 months. Women can volunteer for military service in all branches and combat arms; in 2022, 1,211 women entered voluntary military service.

The Finnish defense policy is based on the concept of "total defense," which involves the entire society in safeguarding the country's independence and security. The military strategy emphasizes a credible territorial defense capability, utilizing Finland's challenging terrain (forests, lakes) and harsh climate to its advantage.

The branches of the Finnish Defence Forces are:

- The Finnish Army (MaavoimatMaavoimat (Finnish)Finnish)

- The Finnish Navy (MerivoimatMerivoimat (Finnish)Finnish)

- The Finnish Air Force (IlmavoimatIlmavoimat (Finnish)Finnish)

The Finnish Border Guard (RajavartiolaitosRajavartiolaitos (Finnish)Finnish) is under the Ministry of the Interior in peacetime but can be incorporated into the Defence Forces during a crisis or war.

Finland's defense expenditure per capita is among the highest in the European Union. Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine and its decision to join NATO, Finland has further increased its defense budget and accelerated military procurement programs, including the acquisition of new fighter jets (F-35) and naval vessels.

Before becoming a NATO member on April 4, 2023, Finland had a long history of close cooperation with the alliance through the Partnership for Peace program and participation in NATO-led operations (e.g., in Afghanistan and Kosovo). Finland is also a member of the UK-led Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF) since 2017 and contributes to EU Battlegroups. In December 2023, Finland signed a bilateral Defense Cooperation Agreement (DCA) with the United States, further strengthening its security ties. NATO membership provides Finland with collective defense guarantees under Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty.

8. Economy

Finland possesses a highly industrialized, free-market economy with a per capita output comparable to other Western European economies like Sweden, Germany, and France. The country is known for its high standard of living, extensive welfare state, and strong emphasis on technology and innovation. As of 2022, Finland ranked 16th globally in nominal GDP per capita according to the IMF.

8.1. Economic Overview and Structure

The Finnish economy is highly integrated into the global economy, with international trade accounting for a significant portion of its GDP. The service sector is the largest component of the economy, contributing approximately 66% of GDP. Manufacturing and refining account for about 31%, while primary production (agriculture, forestry, fishing) makes up around 2.9%.

Historically, Finland's economy was reliant on forestry. After World War II, it rapidly industrialized. In the late 20th century, a shift towards high-technology occurred, famously exemplified by the rise of Nokia in the mobile phone industry. The recession of the early 1990s, caused by a combination of factors including the collapse of the Soviet Union (a key trading partner) and a domestic banking crisis, was severe but was followed by a period of strong, export-led growth.

Finland joined the European Union in 1995 and adopted the Euro in 1999. The country ranks highly in global innovation indices; it was 7th in the Global Innovation Index in both 2023 and 2024.

8.2. Major Industries

- Technology and Electronics: Historically dominated by Nokia, the electronics sector remains important. Finland has a vibrant startup scene and strengths in software development, gaming (Rovio Entertainment, Supercell), and health technology.

- Machinery and Engineered Metal Products: This sector includes the production of machinery for various industries, vehicles, and specialized metal products. Shipbuilding is also a notable sub-sector, with Finnish shipyards known for building large cruise ships (e.g., Oasis of the Seas built at Perno shipyard) and icebreakers.

- Forestry and Paper: Leveraging its vast forest resources (73% of land area), Finland is a major global producer of pulp, paper, and timber products. Companies like UPM, Stora Enso, and Metsä Group are significant players.

- Chemicals: The chemical industry produces a wide range of products, from industrial chemicals to specialty chemicals for various applications.

- Mining and Basic Metals: Finland has mineral resources including iron, chromium, copper, nickel, and gold. The Kittilä Gold Mine is the largest primary gold producer in Europe. Gold production in 2015 was 9 metric tons.

Private services represent the largest employer. In rural areas, forestry, paper mills, and agriculture remain important. The Helsinki metropolitan region generates roughly one-third of Finland's GDP.

8.3. Energy

Finland participates in the free and largely privately owned Nordic energy markets. In 2021, the energy market was around 87 terawatt-hours, with peak demand around 14 gigawatts in winter. Industry and construction consumed 43.5% of total energy, reflecting Finland's industrial base.

Finland's domestic hydrocarbon resources are limited to peat and wood. Renewable energy sources accounted for 43% of final energy consumption in 2021 (EU average 22%), primarily from hydropower and various forms of wood energy. About 20% of electricity is imported, mainly from Sweden. Finland maintains strategic petroleum reserves.

Nuclear power is a significant energy source, with five privately owned reactors producing about 40% of the country's electricity. The Olkiluoto Nuclear Power Plant is home to the Onkalo spent nuclear fuel repository, the world's first deep geological repository for spent nuclear fuel, currently under construction by Posiva.

8.4. Transport

Finland's extensive road network handles most internal cargo and passenger traffic. Major highways include the Turku Highway (E18), Tampere Highway (E12), and Lahti Highway (E75), along with ring roads around Helsinki and Tampere. Annual state expenditure on the road network is funded by vehicle and fuel taxes.

The primary international passenger gateway is Helsinki Airport, which handled about 15.3 million passengers in 2023. There are 26 other airports with scheduled passenger services. Finnair is the flag carrier, with other airlines like Nordic Regional Airlines and Norwegian Air Shuttle also operating.

The state-owned VR Group operates the 3.6 K mile (5.87 K km) railway network, connecting all major cities. Finland's first railway opened in 1862. The Helsinki Metro, opened in 1982, is the world's northernmost metro system.

International cargo is predominantly handled at ports. Vuosaari Harbour in Helsinki is the largest container port. Other major ports include Kotka, Hamina, Hanko, Pori, Rauma, and Oulu. Passenger ferry services connect Helsinki and Turku with Tallinn, Mariehamn, Stockholm, and Travemünde. The Helsinki-Tallinn sea route is one of the busiest in the world. Icebreakers are crucial for keeping ports open during winter.

8.5. Tourism

Tourism is a significant and growing industry in Finland. In 2017, tourism grossed approximately €15.0 billion, with €4.6 billion (30%) from foreign tourists. The sector contributed roughly 2.7% to Finland's GDP and supported a substantial number of jobs.

Finnish Lapland is a major tourist draw, especially in winter. Attractions include the Arctic Circle, the aurora borealis (Northern Lights), ski resorts like Levi, Ruka, and Ylläs, and the Santa Claus Village and Santa Park in Rovaniemi, which is promoted as the home of Santa Claus. Activities like reindeer and husky sleigh rides are popular. The midnight sun in summer is another natural attraction in Lapland.

Other key tourist attractions include:

- The Finnish Lakeland: With its thousands of lakes, it's ideal for cottage holidays, boating, fishing, and kayaking.

- National Parks: Finland has 40 national parks, such as Koli National Park, offering hiking and nature experiences.

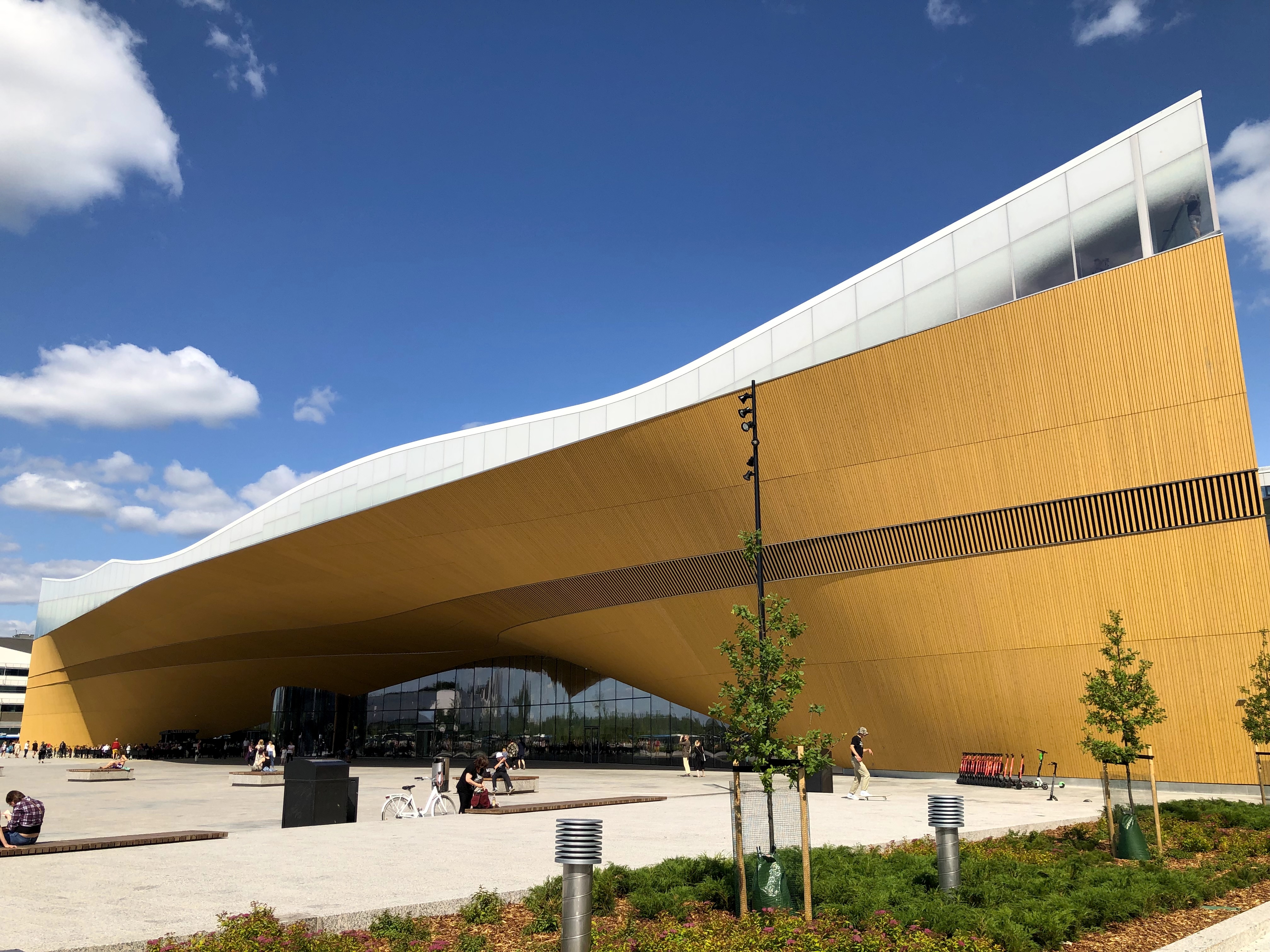

- Cities: Helsinki (with attractions like Helsinki Cathedral and the Suomenlinna sea fortress), the medieval environments of Turku, Rauma, and Porvoo.

- Cultural Events: The Savonlinna Opera Festival, held at St. Olaf's Castle, is internationally renowned. Amusement parks like Linnanmäki in Helsinki and Särkänniemi in Tampere are popular domestic attractions.

Commercial cruises between major coastal cities in the Baltic region also play a significant role.

8.6. Labor Market and Public Policy

Finland's labor market and public policy are characteristic of the Nordic model, emphasizing a strong welfare state, high levels of social equity, extensive social security, and the importance of collective bargaining and trade unions.

The labor market features a high rate of unionization (around 70%), especially in the middle class. Collective labor agreements are generally universally valid, meaning they apply to non-unionized workers as well if more than 50% of employees in a sector are union members. These agreements, typically negotiated every few years, cover wages, working hours, and other employment conditions for each profession and seniority level.

The employment rate for women is high, though gender segregation persists in certain professions. The proportion of part-time workers is relatively low compared to other OECD countries.

Public policy supports a comprehensive welfare system that includes free education (from primary to tertiary levels), universal healthcare, unemployment benefits, family support (including generous parental leave), and old-age pensions. These services are largely funded through taxation. The Social Insurance Institution of Finland (Kela) is the primary agency responsible for administering these benefits.

Finland is known for its relatively low levels of income inequality and high levels of social trust. The country has consistently ranked high in economic freedom and ease of doing business. It is also rated as one of the least corrupt countries in the world by the Corruption Perceptions Index.

As of 2022, the unemployment rate was 6.8%. In 2008, the average income level, adjusted for purchasing power, was comparable to that of Italy, Sweden, Germany, and France. In 2006, 62% of the labor force was employed by firms with fewer than 250 workers. The largest private sector employers in 2013 included Itella (now Posti Group), Nokia, OP-Pohjola, ISS, VR, Kesko, UPM-Kymmene, YIT, Metso, and Nordea.

Finland has the highest concentration of cooperatives relative to its population. The largest retailer (S-Group) and the largest bank (OP Group) are both cooperatives.

9. Demographics and Society

Finland's demographic and societal landscape is shaped by its northern location, historical development, and its status as a Nordic welfare state. The society emphasizes equality, education, and a high quality of life.

9.1. Population

As of 2023, the population of Finland is approximately 5.6 million. It has one of the lowest population densities in Europe, averaging 18 inhabitants per square kilometer. The population is concentrated in the southern parts of the country, particularly in urban areas. Three of the four largest cities-Helsinki, Espoo, and Vantaa-are located in the Helsinki metropolitan area. The vast majority of the population is of Finnish origin. As of 2023, approximately 10.2% of the population had a foreign background; this figure includes individuals with origins from other European countries (constituting 5.1% of the total Finnish population), Asia (3.3%), Africa (1.3%), and other continents (0.5%).

Demographic trends include:

- Aging Population: Finland has one of the oldest populations in the world, with a median age of 42.6 years. Approximately half of voters are estimated to be over 50.

- Low Fertility Rate: The birth rate is 7.8 per 1,000 residents, with a total fertility rate of 1.26 children born per woman (2023), significantly below the replacement rate of 2.1. This rate has been below replacement level since 1969. The mean age of women at first live birth was 28.6 in 2014.

- Life expectancy: In 2017, life expectancy was 79 years for men and 84 years for women.

- Household Structure: As of 2022, 46% of households consisted of a single person, 32% of two persons, and 22% of three or more persons. The average residential space is 431 ft2 (40 m2) per person.

9.2. Languages

Finland has two official languages:

- Finnish: Spoken as the native language by 84.9% of the population (2023). It is a Finnic language belonging to the Uralic language family, related to Estonian and Karelian, but not to Indo-European languages like Swedish or English.

- Swedish: Spoken as the native language by 5.1% of the population (2023), primarily the Swedish-speaking Finns. Swedish is mainly spoken in coastal areas in the west and south, and in the autonomous region of Åland, which is unilingually Swedish-speaking. Swedish is a compulsory school subject for Finnish speakers, and many non-native speakers have a good general knowledge of it. Similarly, most Swedish-speaking Finns (outside Åland) can speak Finnish.

Minority languages with recognized status include:

- Sámi languages: These have official status in parts of Lapland, the Sami Homeland. There are over 10,000 Sami people in Finland, about a quarter of whom speak a Sami language (davvisámegiellaNorthern SamiNorthern Sami, anarâškielâInari SamiInari Sami, or sääʹmǩiõllSkolt SamiSkolt Sami) as their mother tongue.

- Romani (Finnish Kalo): Spoken by some 5,000-6,000 Romani people out of a total Romani population of 13,000-14,000.

- Finnish Sign Language: Used natively by 4,000-5,000 people. Finland-Swedish Sign Language is used by about 150 people.

- Karelian: Recognized in parts of Finland.

- Tatar: Spoken by a small community of about 800 Finnish Tatars.

The most common foreign languages spoken as mother tongues (2023) are Russian (1.8%), Estonian (0.9%), Arabic (0.7%), English (0.6%), and Ukrainian (0.5%). English is widely studied as a compulsory subject from a young age, and proficiency is high. Other foreign languages like German, French, Spanish, and Russian are also taught.

9.3. Religion

The largest religious body is the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland, to which 63.6% of Finns belonged at the end of 2023. This church, along with the Finnish Orthodox Church (1.1% of the population), has a special status as a national church, recognized in law, with the right to levy a church tax on its members, collected by the state.

However, membership in the Evangelical Lutheran Church has been declining annually due to resignations and falling baptism rates. In 2016, 69.3% of Finnish children were baptized, and in 2012, 82.3% were confirmed at age 15.

The second-largest group consists of those with no religious affiliation, accounting for 33.6% of the population in 2023.

Other religious groups are much smaller. These include other Protestant denominations, the Roman Catholic Church, Muslim communities, Jewish communities, and others, collectively making up about 0.9% (Other Christian) and 0.8% (Other religions) of the population in 2023, based on registered affiliations.

Finland has freedom of religion, established by the constitution of 1919 and a specific law in 1922. While the main Lutheran and Orthodox churches have special roles (e.g., in state ceremonies and religious education in schools), most Finns attend church services infrequently, mainly for special occasions like Christmas, weddings, and funerals. The Lutheran Church estimates that about 1.8% of its members attend weekly services.

A 2010 Eurobarometer poll indicated that 33% of Finnish citizens "believe there is a God," 42% "believe there is some sort of spirit or life force," and 22% "do not believe there is any sort of spirit, God, or life force." An ISSP survey in 2008 found 8% considered themselves "highly religious," 31% "moderately religious," 28% "agnostic," and 29% "non-religious."

9.4. Education

Finland's education system is highly regarded internationally, known for its equity, high academic performance, and free tuition from pre-primary to tertiary levels.

- Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC): Provided for children before compulsory education begins.

- Comprehensive School: Compulsory education starts at age 7 and lasts for nine years (grades 1-9). Municipalities are responsible for arranging this. About 3% of students attend private schools, mostly specialist language or international schools. The curriculum is set by the National Agency for Education (formerly Finnish National Board of Education) under the Ministry of Education and Culture. Education is free, including school meals.

- Upper Secondary Education: After comprehensive school (around age 16), graduates can choose between:

- General upper secondary school (lukiolukio (Finnish)Finnish; gymnasium), which is academically oriented, prepares students for the matriculation examination (ylioppilastutkintoylioppilastutkinto (Finnish)Finnish; Abitur), and typically takes three years.

- Vocational upper secondary education and training (ammatillinen koulutusammatillinen koulutus (Finnish)Finnish), which provides job-specific skills. Approximately 40% of an age group chooses this path.

Graduation from either path formally qualifies students for tertiary education. Compulsory education was extended in 2021 to the age of 18 or until the completion of an upper secondary qualification.

- Tertiary Education: This comprises two sectors:

- Universities (yliopistoyliopisto (Finnish)Finnish): Focus on scientific research and provide education based on it. There are 15 universities in Finland.

- Universities of Applied Sciences (UAS) (ammattikorkeakouluammattikorkeakoulu (Finnish)Finnish, AMK): Offer professionally oriented higher education and focus on applied research and development. There are 24 UAS institutions.

Education at public tertiary institutions is free for students from EU/EEA countries. Living expenses are largely financed by the government through student benefits.

Finland's education system has consistently performed well in international assessments like PISA. Around 33% of residents have a tertiary degree. Notable universities include the University of Helsinki (ranked 75th in the Top University Ranking of 2010), Aalto University, University of Turku, Åbo Akademi University, Tampere University, University of Jyväskylä, University of Oulu, LUT University, and the University of Eastern Finland.

Finland is highly productive in scientific research, with strong fields in forest improvement, materials research, environmental sciences, low-temperature physics, biotechnology, and communications technology.

9.5. Health and Welfare

Finland has a universal healthcare system and a comprehensive social security system (Kela), which are cornerstones of the Nordic model of welfare. These systems aim to provide universal access to services and social support for all residents.

- Healthcare System: Public healthcare is funded primarily through taxation (77% in one estimate) and is managed by municipalities, which are now organized into larger wellbeing services counties for health and social services. Primary healthcare is provided by municipal health centers, and specialized medical care is available through a network of hospitals. Private healthcare services also exist and are used by some, often supplemented by private health insurance or employer-provided care. There are about 307 residents per doctor. About 19% of healthcare is funded directly by households.

- Health Indicators: Life expectancy in 2017 was 79 years for men and 84 years for women. The under-five mortality rate (2.3 per 1,000 live births in 2017) is among the lowest in the world. A 2011 Lancet study found Finland had the lowest stillbirth rate out of 193 countries.

- Health Challenges: Lifestyle-related diseases are on the rise. Over half a million Finns suffer from diabetes, with type 1 diabetes being globally most common in Finland. Type 2 diabetes is also increasing in children. Musculoskeletal diseases and cancer rates are increasing, though cancer prognosis has improved. Allergies and dementia are growing concerns. Mental health disorders, particularly depression, are a common reason for work disability. Suicide rates, while having decreased, remain relatively high among developed countries in the OECD.

- Social Security (Kela): Kela (Kansaneläkelaitos - The Social Insurance Institution) administers a wide range of social benefits, including family benefits (child benefit, maternity/paternity/parental allowances), unemployment benefits, sickness allowance, disability benefits, student financial aid, and basic pensions. These benefits aim to provide a safety net and ensure a basic standard of living.

Finland has been consistently ranked as one of the happiest countries in the world in the World Happiness Report since 2012, and has held the top spot since 2018. This reflects high levels of social support, freedom to make life choices, generosity, and low corruption, alongside good health and income.

9.6. Immigration and Minorities

Finland is increasingly a country of immigration, although its immigrant population is still smaller than in many other Western European countries.