1. Overview

Iceland is a Nordic island country located in the North Atlantic Ocean, characterized by its unique geography shaped by volcanic activity and glaciers. This document explores Iceland's history from its Norse and Gaelic settlement through periods of foreign rule to the establishment of a modern republic, highlighting its democratic development, such as the early Althing. It examines Iceland's political system, emphasizing its parliamentary democracy, commitment to social justice, advancements in women's rights, and robust human rights protections. The economy section delves into its traditional reliance on fisheries, the growth of renewable energy sectors like geothermal and hydropower, the significant impact of the 2008 financial crisis, and subsequent recovery efforts, alongside a focus on sustainable practices and social equality. Icelandic society is discussed through its demographics, unique language and naming customs, education and healthcare systems, and strong social welfare policies. The rich cultural heritage, including its famed Sagas, Eddas, contemporary arts, music, and distinctive cuisine, is also covered. This overview reflects a center-left/social liberal perspective, emphasizing social justice, human rights, democratic development, and sustainable practices throughout the detailed exploration of Iceland.

2. Etymology

The name 'Iceland' (ÍslandEE-slandIcelandic) literally means "Land of Ice." According to the Sagas of Icelanders, particularly the LandnámabókLand-naam-a-bokIcelandic (Book of Settlements), the island received its current name from a Viking named Flóki Vilgerðarson. Before Flóki, other Norse explorers had reached the island. Naddodd (or Naddador), a Norwegian, is said to be the first Norseman to reach Iceland in the ninth century. He reportedly named it SnælandSnigh-landIcelandic or "Snowland" because it was snowing at the time of his arrival.

Following Naddodd, the Swede Garðar Svavarsson circumnavigated the island, confirming it was an island. He wintered there and built a house in Húsavík. The island was then called GarðarshólmurGarth-ars-hoalm-urIcelandic, meaning "Garðar's Isle."

Flóki Vilgerðarson, another Viking, arrived later. The sagas recount that Flóki, despondent after his livestock starved and his daughter drowned en route, climbed a mountain and saw a fjord (ArnarfjörðurArnar-fyerth-urIcelandic) filled with icebergs. This sight led him to give the island its present name, Ísland. There is a popular myth that the Viking settlers chose this somewhat forbidding name to discourage others from settling their verdant island, but this is likely not true. The name simply reflected Flóki's experience with the ice in the fjord.

3. History

Iceland's history is a narrative of settlement by Norse and Gaelic peoples, the development of a unique commonwealth, centuries of foreign rule, a determined struggle for independence, and its emergence as a modern republic navigating economic prosperity and challenges. Key themes include the evolution of its democratic institutions, the resilience of its people in a harsh environment, and its engagement with the wider world.

3.1. Early settlement and Icelandic Commonwealth (874-1262)

The settlement of Iceland, according to both the LandnámabókLand-naam-a-bokIcelandic and ÍslendingabókEES-lending-ga-bokIcelandic, traditionally began in 874 AD with the arrival of the Norwegian chieftain Ingólfr Arnarson, who became the island's first permanent Scandinavian settler, establishing his homestead in what is now Reykjavík. However, archaeological evidence suggests earlier human presence. Ruins of a cabin in Hafnir on the Reykjanes Peninsula have been carbon-dated to between 770 and 880 AD. Additionally, a longhouse discovered in Stöðvarfjörður may date as early as 800 AD. Some historical accounts also mention the Papar, Irish or Hiberno-Scottish monks, living in Iceland before the Norse arrival.

Swedish Viking explorer Garðar Svavarsson was the first to circumnavigate Iceland around 870 AD, confirming it was an island. He wintered in Húsavík. One of his men, Náttfari, along with two slaves, stayed behind and became the first documented permanent residents.

Over the following centuries, Norsemen, primarily from Norway, and to a lesser extent other Scandinavians, emigrated to Iceland. They brought with them thralls, who were slaves or serfs, many of whom were of Gaelic (Irish or Scottish) origin. Genetic studies indicate a significant Norse patrilineal and Gaelic matrilineal contribution to the founding population. By 930, most arable land had been claimed.

This period saw the establishment of the Icelandic Commonwealth (ÞjóðveldiðThiodh-vel-dithIcelandic), a unique political structure without a king or central executive power. Instead, governance was managed through a system of chieftains (goðargoth-arIcelandic) and local assemblies. The most important institution was the Althing (AlþingiAl-thing-giIcelandic), a national assembly founded in 930 AD at Þingvellir. The Althing served as both a legislative and judicial body, making it one of the world's oldest functioning parliaments. It was here that laws were made, and disputes settled by a Lawspeaker (lögsögumaðurlerg-serg-u-math-urIcelandic) who recited one-third of the laws from memory each year at the Law Rock (LögbergLerg-bergIcelandic).

Early Icelandic society was characterized by farming and fishing. The Medieval Warm Period coincided with the initial settlement, offering relatively favorable conditions. However, the settlers significantly impacted the environment. Extensive deforestation occurred as forests, which covered about 25% of the island upon settlement, were cleared for timber, fuel, and grazing land for imported livestock like sheep. This, combined with Iceland's volcanic soil and harsh climate, led to severe soil erosion, a problem that persists to this day.

Christianity was formally adopted by consensus at the Althing around 999-1000 AD to avoid religious civil war, although Norse paganism persisted among parts of the population for some time. The lack of arable land eventually spurred further exploration and the settlement of Greenland beginning in 986.

3.2. Middle Ages and foreign rule

The Icelandic Commonwealth, despite its innovative political structure, eventually succumbed to internal strife. The 13th century was marked by the Age of the Sturlungs (SturlungaöldStur-lung-ga-erldIcelandic), a period of intense conflict and power struggles among a few dominant chieftains and their families. This internal instability weakened the Commonwealth, making it vulnerable to external pressures.

In 1262, facing civil war and pressure from the Norwegian crown, Icelandic chieftains signed the Old Covenant (Gamli sáttmáliGam-li saut-mau-liIcelandic), effectively ending the Commonwealth and bringing Iceland under the rule of the King of Norway. This marked a significant shift from independent self-governance to foreign suzerainty. Under Norwegian rule, Icelanders were required to pay taxes to the Norwegian king, and Norwegian laws began to supersede local ones, though the Althing continued to function, albeit with reduced authority.

In 1397, when Norway entered into the Kalmar Union with Denmark and Sweden, Iceland's allegiance shifted along with Norway's. After the Kalmar Union dissolved in 1523, Iceland remained a Norwegian dependency, which effectively meant it came under Danish rule as part of Denmark-Norway. Danish influence grew steadily stronger over the centuries.

Life in Iceland during this period was harsh. Infertile soil, frequent volcanic eruptions, deforestation, and a challenging climate made subsistence agriculture difficult. Society relied heavily on farming and fishing. The Black Death ravaged Iceland twice, first in 1402-1404, killing 50-60% of the population, and again in 1494-1495, killing another 30-50%. These demographic catastrophes had profound impacts on Icelandic society and economy.

The Protestant Reformation reached Iceland in the mid-16th century. King Christian III of Denmark imposed Lutheranism on all his subjects. This was met with resistance, notably from Jón Arason, the last Catholic bishop of Hólar. Jón Arason was beheaded in 1550 along with two of his sons, and Lutheranism subsequently became the dominant religion, officially established as the state church. Church properties were confiscated by the crown, further consolidating Danish control.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, Denmark imposed even harsher trade restrictions, establishing the Danish-Icelandic Trade Monopoly (1602-1786). This monopoly severely limited Iceland's economic development, forcing Icelanders to trade exclusively with Danish merchants at unfavorable terms. Natural disasters continued to plague the island. In 1627, Barbary pirates conducted raids known as the Turkish Abductions (TyrkjarániðTirk-ya-rau-nithIcelandic), enslaving hundreds of Icelanders. The smallpox epidemic of 1707-1708 killed a significant portion of the population. The eruption of the Laki volcano in 1783-1784 had devastating consequences, leading to the Mist Hardships (MóðuharðindinMoth-u-harth-in-dinIcelandic), a period of famine that killed over half of the livestock and about a quarter of the human population due to poisoned pastures and atmospheric changes. These events significantly reduced the population and deepened Iceland's economic hardship.

3.3. Independence movement and Kingdom of Iceland (1814-1918)

The 19th century saw the rise of the Icelandic independence movement, deeply influenced by romantic and nationalist ideas spreading across Europe following the French Revolution. After the Napoleonic Wars, the Treaty of Kiel in 1814 dissolved Denmark-Norway, but Iceland remained a Danish dependency. The difficult living conditions, exacerbated by a cooling climate, led to significant emigration, particularly to New Iceland in Gimli, Manitoba, Canada, with about 15,000 out of a population of 70,000 leaving the island.

A renewed sense of national consciousness emerged, spearheaded by Icelandic intellectuals educated in Denmark, such as the Fjölnismenn (members of the Fjölnir group). The central figure in the political struggle for independence was Jón Sigurðsson, a scholar and statesman. His efforts focused on restoring Icelandic autonomy and modernizing its governance.

The Danish crown began to make concessions. In 1799, the Althing had been suspended, but it was re-established in 1845 as a consultative assembly. In 1874, on the millennial anniversary of the settlement of Iceland, Denmark granted Iceland a constitution and limited home rule. This was a significant step, recognizing Iceland's distinct political identity. Home rule was further expanded in 1904, and Hannes Hafstein became the first Icelander to serve as Minister for Iceland within the Danish cabinet, effectively giving Iceland its first domestic government responsible to the Althing.

The push for greater sovereignty continued, culminating in the Danish-Icelandic Act of Union on December 1, 1918. This act recognized Iceland as a fully sovereign and independent state, the Kingdom of Iceland. It was linked to Denmark through a personal union, meaning both kingdoms shared the same monarch, King Christian X of Denmark. Under this act, Iceland gained control over most of its affairs, although Denmark continued to handle Iceland's foreign policy and defense, subject to consultation with the Althing. Icelandic embassies were not established, but Danish embassies displayed both Danish and Icelandic coats of arms and flags. This arrangement, valid for 25 years, marked a major milestone on Iceland's path to full independence, giving it a status comparable to dominions within the British Commonwealth at the time.

3.4. Independence and establishment of the Republic (1918-present)

The establishment of the Kingdom of Iceland in 1918 marked a period of increased autonomy. During World War II, Iceland's strategic location in the North Atlantic became critical. When Nazi Germany occupied Denmark on April 9, 1940, the formal ties between Iceland and Denmark were effectively severed. The Althing declared that the Icelandic government would assume control of its own defense and foreign affairs, and appointed a regent, Sveinn Björnsson, to represent the monarch.

Concerned that Germany might seize Iceland, Britain launched Operation Fork, an invasion and occupation of the country on May 10, 1940, violating Icelandic neutrality. There was no military resistance, and the occupation was largely peaceful. In 1941, the Icelandic government, now friendly to Britain, invited the then-neutral United States to take over Iceland's defense. This allowed British troops to be deployed elsewhere. American forces remained in Iceland for the duration of the war.

The Danish-Icelandic Act of Union was due to expire at the end of 1943. With Denmark still under German occupation, Icelanders saw an opportunity to achieve full independence. A referendum was held from May 20-23, 1944, on whether to terminate the personal union with Denmark and establish a republic. The results were overwhelmingly in favor: 97% voted to end the union, and 95% supported a new republican constitution. Iceland formally became a republic on June 17, 1944, a date chosen as it was Jón Sigurðsson's birthday. Sveinn Björnsson became the first President of Iceland.

After World War II, Iceland experienced substantial economic growth, driven by the industrialization of the fishing industry and significant aid from the Marshall Plan. Iceland received the most aid per capita of any European country under this program. The country formally joined NATO on March 30, 1949, amid domestic controversy and anti-NATO riots. In 1951, a defense agreement was signed with the United States, leading to the establishment of the Iceland Defense Force (IDF), an American military presence that remained throughout the Cold War until the last US forces withdrew on September 30, 2006.

The post-war era also saw the Cod Wars, a series of disputes with the United Kingdom over Iceland's successive extensions of its fishing limits. These "wars" involved confrontations between the Icelandic Coast Guard and British trawlers and naval vessels but resulted in Iceland successfully expanding its exclusive economic zone to 200 nmi.

In 1980, Vigdís Finnbogadóttir was elected president, becoming the world's first democratically elected female head of state. Her presidency, lasting until 1996, was a significant moment for gender equality globally. In 1986, Reykjavík hosted the historic Reykjavík Summit between U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev, a key step towards ending the Cold War. Iceland was also the first country to recognize the independence of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania in 1991 as they broke away from the Soviet Union. Throughout the 1990s, Iceland expanded its international role, contributing to NATO-led peacekeeping efforts in places like Bosnia and Kosovo.

In 1994, Iceland joined the European Economic Area (EEA), which further diversified and liberalized its economy. Sectors like finance, biotechnology, and manufacturing grew.

3.4.1. Economic boom and crisis

In the early 2000s, particularly from 2003-2007, Iceland experienced a rapid economic expansion. Following the privatization of state-owned banks under the government of Davíð Oddsson, the financial sector grew enormously, with Icelandic banks taking on substantial international investments and external debt. The country quickly became one of the most prosperous in the world, with a significant increase in gross national income. This period was characterized by easy credit, a booming stock market, and large-scale construction projects.

However, this rapid growth, heavily reliant on a burgeoning and highly leveraged banking sector, proved unsustainable. In October 2008, as the global financial crisis intensified, Iceland's three major commercial banks-Landsbanki, Kaupthing, and Glitnir-collapsed within days of each other. Their combined debt far exceeded the country's GDP. The Icelandic króna plummeted in value, the stock market crashed, and the country faced a severe national economic crisis. The government was forced to take over the banks, impose capital controls, and seek emergency loans from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and other Nordic countries.

The crisis led to widespread public anger and protests, known as the "Pots and Pans Revolution" (BúsáhaldabyltinginBoo-saau-halda-bil-ting-ginIcelandic), which ultimately resulted in the resignation of Prime Minister Geir Haarde's government in January 2009. The crisis also triggered significant emigration, the largest since 1887, as Icelanders sought opportunities abroad. The aftermath involved painful austerity measures, legal proceedings against some banking executives, and a national debate about the causes of the collapse and the future direction of the economy. There was also a significant social impact, challenging the perception of Iceland as a uniquely stable and egalitarian society.

3.4.2. Trends since 2012

Following the acute phase of the financial crisis, Iceland embarked on a path of economic stabilization and recovery. The government led by Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir (2009-2013), the world's first openly LGBT head of government, implemented austerity measures and worked with the IMF. The economy began to grow again, albeit slowly, by 2012. Capital controls, imposed during the crisis to prevent capital flight, remained in place for several years, gradually being lifted.

The political landscape saw shifts. The 2013 election brought a centre-right coalition of the Independence Party and the Progressive Party to power. However, political stability remained elusive. The Panama Papers scandal in 2016 implicated then-Prime Minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, leading to his resignation and early elections. Subsequent elections in 2016 and 2017 resulted in further coalition governments, often with narrow majorities. Katrín Jakobsdóttir of the Left-Green Movement became Prime Minister in 2017, leading a broad coalition that included the Independence Party and the Progressive Party, an unusual left-right combination aimed at providing stability. This coalition continued after the 2021 election. In April 2024, Bjarni Benediktsson of the Independence Party succeeded Katrín Jakobsdóttir as Prime Minister. Following a snap election in November 2024, the centre-left Social Democratic Alliance became the largest party, with Kristrún Frostadóttir becoming the next Prime Minister.

A major economic development since the crisis has been the explosive growth of the tourism industry. Attracted by Iceland's unique natural landscapes, the aurora borealis, and cultural offerings, the number of visitors increased dramatically, providing a significant boost to foreign exchange earnings and employment. This boom, however, also brought challenges, including pressure on infrastructure, environmental concerns, and debates about overtourism in certain areas.

Social challenges persist, including debates on income inequality, housing affordability in Reykjavík, and the integration of a growing immigrant population. Iceland continues to rank highly in global measures of gender equality, human rights, and quality of life. The process of drafting a new constitution, initiated after the financial crisis through a popularly elected constitutional assembly, stalled due to political disagreements, remaining an unresolved issue.

4. Geography

Iceland is an island nation situated at the confluence of the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. Its main island lies entirely south of the Arctic Circle, although the small Icelandic island of Grímsey, off the northern coast, does cross this line. The country is positioned between latitudes 63° and 68°N, and longitudes 25° and 13°W. While geographically closer to Greenland (about 180 mile (290 km) away), an island of North America, Iceland is culturally, historically, and politically considered part of Europe. Its nearest European neighbors are the Faroe Islands (about 261 mile (420 km) away) and Scotland (about 466 mile (750 km) away).

The main island of Iceland is the world's 18th-largest island and Europe's second-largest after Great Britain. It covers an area of 39 K mile2 (101.83 K km2), while the total area of the country, including its smaller islands, is 40 K mile2 (103.00 K km2). A significant portion of Iceland, 62.7%, is tundra. Lakes and glaciers cover 14.3% of its surface; only 23% is vegetated. The largest lakes are the Þórisvatn reservoir (32 mile2 (83 km2)) and Þingvallavatn (32 mile2 (82 km2)); other important lakes include Lagarfljót and Mývatn. Jökulsárlón is the deepest lake, at 814 ft (248 m). The coastline, deeply indented by numerous fjords, stretches for about 3.1 K mile (4.97 K km). Most settlements are located along the coast, particularly in the southwest. The interior, known as the Highlands of Iceland, is a cold and largely uninhabitable plateau of sand, mountains, and lava fields. Iceland has three national parks: Vatnajökull National Park (one of Europe's largest), Snæfellsjökull National Park, and Þingvellir National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Iceland is considered a strong performer in environmental protection.

4.1. Topography and Geology

Iceland is a geologically young landmass, primarily formed by volcanic activity over the last 16 to 18 million years. It is situated directly on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the divergent boundary between the Eurasian Plate and the North American Plate. Furthermore, it sits atop the Iceland hotspot, a mantle plume, which contributes to its high volcanic activity and the fact that it rises above sea level, unlike most of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. This unique geological setting makes Iceland one of the most volcanically active regions on Earth, with numerous active volcanoes (such as Hekla, Katla, Eldgjá, Herðubreið, Eldfell, and Eyjafjallajökull), geysers (including the famous Geysir, from which the English word is derived, and Strokkur, which erupts every 8-10 minutes), hot springs, and extensive lava fields. The island is largely composed of basalt, a volcanic rock, but also features more evolved lavas like rhyolite and andesite. There are approximately 30 active volcanic systems in the country, each with volcano-tectonic fissure systems, and many also have at least one central volcano. The 1783-1784 eruption of Laki caused a devastating famine.

The landscape is rugged and mountainous, with extensive glaciers covering about 11% of the land area. Vatnajökull is the largest glacier in Europe. These glaciers feed numerous glacial rivers that carve through the landscape, creating impressive waterfalls like Gullfoss and Dettifoss. The coastline is characterized by numerous fjords, especially in the west, north, and east, which were formed by glacial erosion. The Highlands of Iceland, the interior plateau, are largely barren and uninhabited. Iceland's geological activity also means it experiences frequent, though usually minor, earthquakes. The island of Surtsey, one of the youngest islands in the world, was formed by volcanic eruptions between 1963 and 1968 off the southern coast. Only scientists researching the growth of new life are allowed to visit Surtsey.

4.2. Climate

Iceland has a subarctic climate (Köppen: Cfc) along the coast and a tundra climate (ET) in the interior highlands. Despite its high latitude just south of the Arctic Circle, the climate is moderated by the warm North Atlantic Current, a continuation of the Gulf Stream. This current ensures that Icelandic coasts remain largely ice-free even in winter, and temperatures are generally milder than in other locations at similar latitudes, such as the Aleutian Islands, the Alaska Peninsula, and Tierra del Fuego. Ice incursions are rare, with the last major one on the north coast in 1969.

The climate varies across the island. The south coast tends to be warmer, wetter, and windier than the north coast. The Central Highlands are the coldest part of the country. Low-lying inland areas in the north are the driest. Snowfall is more common in the north during winter.

Average summer temperatures in Reykjavík are around 50 °F (10 °C), with occasional warmer days. Winter temperatures average around 32 °F (0 °C), but can drop lower, especially with wind chill. The highest recorded temperature was 86.9 °F (30.5 °C) at Teigarhorn on the southeastern coast on June 22, 1939, and the lowest was -36.400000000000006 °F (-38 °C) at Grímsstaðir and Möðrudalur in the northeastern hinterland on January 22, 1918. Reykjavík's records are 79.16 °F (26.2 °C) (July 30, 2008) and -12.100000000000001 °F (-24.5 °C) (January 21, 1918).

Iceland experiences unique daylight patterns due to its latitude. In summer, particularly around the summer solstice, there is near-continuous daylight (the midnight sun). Conversely, winters have very short daylight hours. The aurora borealis (Northern Lights) is a common sight during the dark winter months, from September to April, when solar activity is high and skies are clear.

Climate change is having a noticeable impact on Iceland. Glaciers are retreating at an accelerated rate, which has implications for hydrology, potential sea level rise of about a centimeter from Icelandic glacier melt alone, and landscape stability. The melting of Okjökull glacier led to it being officially declared "lost" in 2014. Changes in vegetation patterns and marine ecosystems are also being observed. Iceland is committed to policies aimed at mitigating climate change and adapting to its effects, leveraging its abundant renewable energy resources.

4.3. Biodiversity

Iceland's biodiversity is relatively low compared to mainland Europe due to its isolation, young geological age, and harsh climate. The entire country is considered part of the Iceland boreal birch forests and alpine tundra ecoregion. Some areas are covered by glaciers.

4.3.1. Plants

Phytogeographically, Iceland belongs to the Arctic province of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. When Norse settlers arrived around the 9th century, an estimated 25-40% of Iceland was covered by downy birch (Betula pubescens) woodlands, along with aspens (Populus tremula), rowans (Sorbus aucuparia), common junipers (Juniperus communis), and other smaller trees, mainly willows. Ari the Wise described it in the ÍslendingabókEES-lending-ga-bokIcelandic as "forested from mountain to sea shore".

Extensive deforestation for fuel, timber, and grazing land, combined with volcanic activity and a cooling climate (particularly during the Little Ice Age), and overgrazing by imported sheep led to a dramatic reduction in forest cover, to less than 1% by the early 20th century. This resulted in severe soil erosion, a significant environmental challenge; three-quarters of Iceland's 39 K mile2 (100.00 K km2) is affected by soil erosion, with 6.9 K mile2 (18.00 K km2) so seriously affected as to be useless. Current reforestation efforts by the Icelandic Forest Service and other forestry groups have increased forest cover to around 2% (a six-fold increase since the 1990s), with ongoing projects aiming to expand this further. Planted forests often include native birch as well as introduced species like Sitka spruce and lodgepole pine. The tallest tree in Iceland is a Sitka spruce planted in 1949 in Kirkjubæjarklaustur, measured at 83 ft (25.2 m) in 2013. The majority of Iceland's vegetation consists of grasslands, mosses, lichens, and low-growing shrubs adapted to the subarctic conditions. Algae such as Chondrus crispus, Phyllophora truncata and Phyllophora crispa have been recorded from Iceland.

4.3.2. Animals

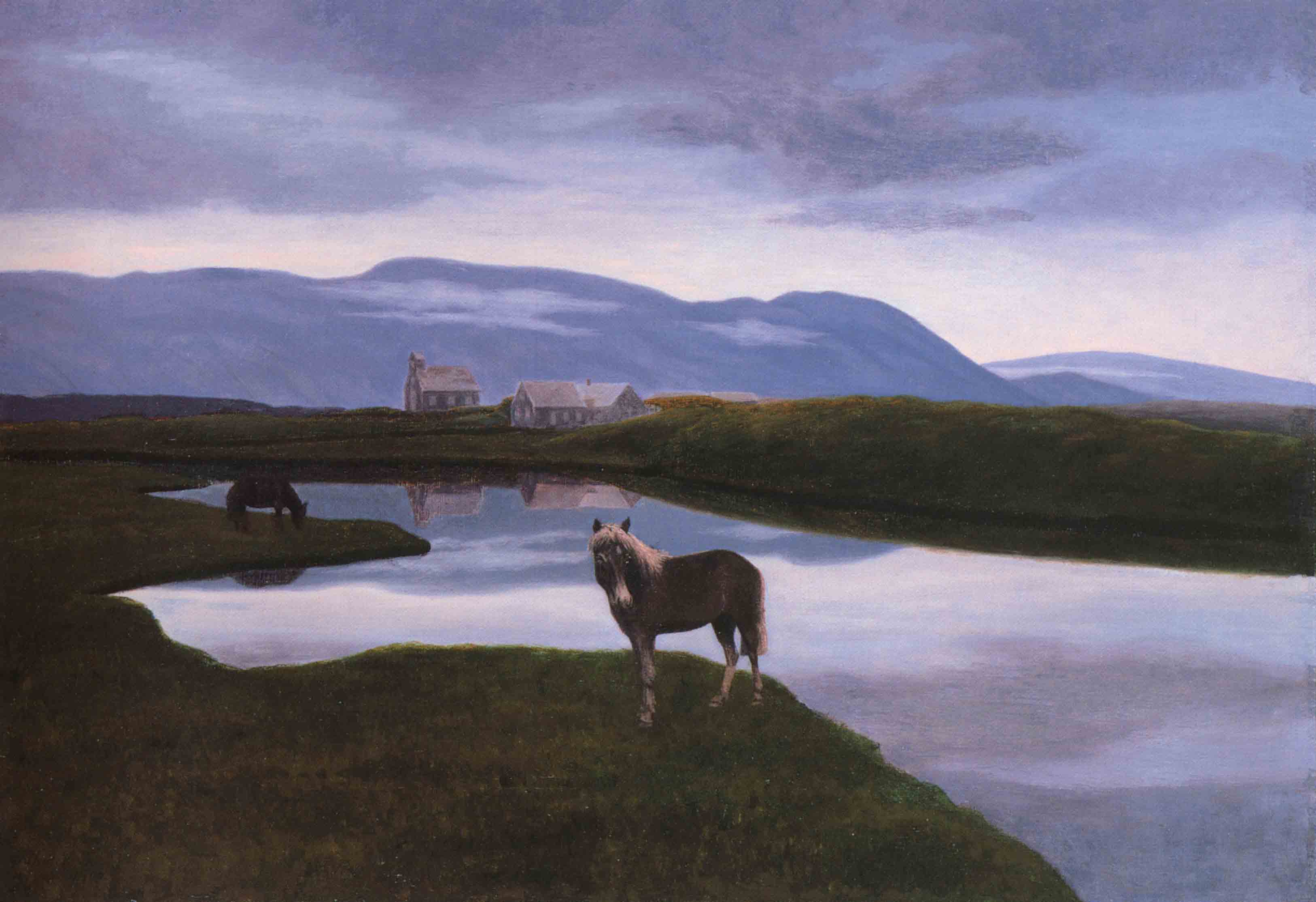

The only native land mammal present when humans arrived was the Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus), which likely crossed over sea ice during the last ice age. All other land mammals were introduced by humans, including the Icelandic horse, Icelandic sheep, cattle, chickens, goats, dogs, and inadvertently, mice and rats. Reindeer were introduced in the 18th century and now live wild in eastern Iceland. Mink, escaped from fur farms, have also established a wild population. Polar bears occasionally reach Iceland from Greenland on ice floes, but they do not form a permanent population; in June 2008, two arrived in the same month. On rare occasions, bats have been carried to the island with the winds, but they are not able to breed there.

Iceland boasts a rich birdlife, especially seabirds. Cliffs around the coast are home to massive colonies of birds like the Atlantic puffin (a national icon), northern fulmar, black-legged kittiwake, murres, and razorbill. Various species of skuas, gulls, and terns are also common. Freshwater birds include numerous duck species, geese (like the pink-footed goose), and the whooper swan. The gyrfalcon and the white-tailed eagle (sea eagle) are notable birds of prey.

The waters around Iceland are rich in marine life, supporting a vital fishing industry. Common fish species include cod, haddock, saithe, herring, and capelin. Marine mammals include various species of whale (such as minke whale, humpback whale, orca, and blue whale), dolphins (like the white-beaked dolphin), and seals (primarily harbour seal (Phoca vitulina) and grey seal (Halichoerus grypus)). Whale watching has become a significant tourist activity since 1997. Commercial whaling is practised intermittently, alongside scientific whale hunts.

There are no native reptiles or amphibians in Iceland. Around 1,300 species of insects are known in Iceland, which is low compared to other countries. Iceland is essentially free of mosquitoes.

5. Politics

Iceland operates as a parliamentary representative democratic republic. The political system is characterized by a multi-party system, a strong tradition of consensus-building, and high levels of civic participation and transparency. The country consistently ranks high in global indices for democracy, civil liberties, and gender equality. Following the 2021 parliamentary elections, the largest parties were the centre-right Independence Party (SjálfstæðisflokkurinnSyaulst-stie-this-flokkur-innIcelandic), the Progressive Party (FramsóknarflokkurinnFram-soak-nar-flokkur-innIcelandic), and the Left-Green Movement (Vinstrihreyfingin - grænt framboðVinstri-hrai-fing-in - grahnt fram-bothIcelandic), which formed a ruling coalition led by Katrín Jakobsdóttir. Other parties with seats include the Social Democratic Alliance (SamfylkinginSam-fil-king-inIcelandic), the People's Party (Flokkur fólksinsFlokkur folk-sinsIcelandic), Pirates (PíratarPee-ra-tarIcelandic), Reform Party (ViðreisnVith-raisnIcelandic), and the Centre Party (MiðflokkurinnMith-flokkur-innIcelandic). Iceland was ranked second in the strength of its democratic institutions in 2016 and 13th in government transparency. Voter turnout is high, at 81.4% in recent elections, and trust in legal institutions (police, parliament, judiciary) was around 73% in 2018. Many political parties remain opposed to EU membership, primarily due to concerns about losing control over natural resources, particularly fisheries.

5.1. Government structure

The Constitution of Iceland, adopted in 1944, outlines the structure of the government, which is divided into legislative, executive, and judicial branches.

The President of Iceland is the head of state. The president is elected by popular vote for a four-year term with no term limit, and has largely ceremonial duties. However, the president does have the power to veto legislation passed by the Althing, in which case the legislation must be put to a national referendum. The president also formally appoints ministers and plays a role in government formation after elections. The current president is Halla Tómasdóttir, in office since August 1, 2024.

The Prime Minister of Iceland is the head of government and leads the Cabinet (government). The prime minister is typically the leader of the largest party in the governing coalition in the Althing and is responsible for the day-to-day administration of the country. The Cabinet is responsible to the Althing.

The Althing (AlþingiAl-thing-giIcelandic) is the unicameral parliament of Iceland and holds legislative power. Founded in 930 AD as an assembly in the Commonwealth period, the modern parliament was re-established in 1845 as an advisory body and is arguably the world's oldest parliamentary democracy. It consists of 63 members elected for a maximum four-year term through a system of proportional representation by constituencies. The Althing enacts laws, approves the state budget, and oversees the executive branch.

The judiciary is independent. The court system includes district courts, a Court of Appeal (Landsréttur), and the Supreme Court of Iceland (Hæstiréttur ÍslandsHigh-stih-ryet-tur EES-landsIcelandic) as the highest judicial authority.

Elections for the president, the Althing, and local municipal councils are all held separately every four years. The cabinet is typically appointed by the president after a general election, usually negotiated by party leaders to form a majority coalition. If leaders cannot agree, the president may appoint the cabinet, though this has not happened since 1944. Icelandic governments have always been coalitions.

5.2. Major political parties

Iceland has a multi-party system, and coalition governments are the norm, as no single party usually wins an absolute majority in the Althing. Major political parties span the political spectrum:

- Independence Party (SjálfstæðisflokkurinnSyaulst-stie-this-flokkur-innIcelandic): A centre-right, conservative party, historically one of the largest parties in Iceland. It generally supports free-market policies and NATO membership but is traditionally Eurosceptic.

- Left-Green Movement (Vinstrihreyfingin - grænt framboðVinstri-hrai-fing-in - grahnt fram-bothIcelandic): A left-wing party emphasizing democratic socialism, environmentalism, feminism, and pacifism. It has been a significant force in recent coalition governments.

- Progressive Party (FramsóknarflokkurinnFram-soak-nar-flokkur-innIcelandic): A centrist, agrarian party, often playing a kingmaker role in coalition formations. It focuses on regional development and national interests.

- Social Democratic Alliance (SamfylkinginSam-fil-king-inIcelandic): A centre-left, social democratic party, generally pro-European Union.

- Pirate Party (PíratarPee-ra-tarIcelandic): Focuses on civil rights, direct democracy, government transparency, and copyright reform. It gained significant popularity, especially among younger voters, following the financial crisis.

- Reform Party (ViðreisnVith-raisnIcelandic): A liberal, pro-European party that split from the Independence Party, advocating for EU membership and market-liberal policies.

- People's Party (Flokkur fólksinsFlokkur folk-sinsIcelandic): A populist party focusing on the rights of the poor, elderly, and disabled.

- Centre Party (MiðflokkurinnMith-flokkur-innIcelandic): A populist, Eurosceptic party founded by former Prime Minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson after he left the Progressive Party.

The political landscape is dynamic, with new parties emerging and coalition formations often requiring negotiation across ideological lines.

5.3. Women's rights

Iceland has a strong record on women's rights and is consistently ranked among the top countries in the world for gender equality. Women gained restricted suffrage in 1915 for municipal elections and parliamentary elections for women over 40, with full suffrage for women aged 25 and older achieved in 1920.

A significant milestone was the women's "day off" (KvennafrídagurinnKvenna-free-dag-ur-innIcelandic}) in 1975, when 90% of Icelandic women went on strike to demonstrate their indispensable role in society and demand equal rights. This event had a profound impact. In 1980, Vigdís Finnbogadóttir was elected President, becoming the first democratically elected female head of state in the world. In 1983, the Women's List (KvennalistinnKvenna-list-innIcelandic), an all-female political party, was founded and gained seats in the Althing, advocating for women's issues. It left a lasting influence, with every major party subsequently adopting a 40% quota for female candidates. In the 2021 elections, 48% of members of parliament were female.

Iceland has robust legislation promoting gender equality, including laws on equal pay (the Icelandic Equal Pay Standard requires companies to prove they pay men and women equally for work of equal value), gender quotas on company boards, and extensive parental leave policies designed to encourage shared parenting. Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir became the world's first openly LGBT head of government in 2009. Despite these achievements, challenges remain, including addressing the gender pay gap in practice and combating gender-based violence. The commitment to advancing women's rights remains a strong feature of Icelandic society and politics.

5.4. Human Rights

Human rights are generally well-respected in Iceland, which has a strong constitutional and legal framework for their protection. The country is a signatory to major international human rights treaties and is often lauded for its commitment to civil liberties and democratic principles.

Key aspects include:

- Civil Liberties: Freedom of speech, assembly, association, and religion are constitutionally guaranteed and actively upheld. Iceland consistently ranks high in press freedom indices.

- LGBTQ+ Rights: Iceland is considered one of the most LGBTQ+-friendly countries in the world. Same-sex partnerships were legalized in 1996, and same-sex marriage was legalized in 2010. Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir became the world's first openly gay head of government in 2009. Anti-discrimination laws protect LGBTQ+ individuals, and there is broad societal acceptance.

- Rights of Minorities and Vulnerable Groups: Efforts are made to protect the rights of ethnic minorities, immigrants, and people with disabilities. However, challenges related to the integration of immigrants and asylum seekers have been noted.

- Democratic Development: Iceland has a strong democratic tradition, with high voter turnout and civic engagement. The aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis saw calls for greater democratic accountability and participatory processes, leading to an attempt to draft a new constitution through a popularly elected assembly, though its implementation has faced political hurdles.

- Justice System: The justice system is considered fair, though issues such as pre-trial detention lengths have occasionally drawn scrutiny.

Icelandic society generally reflects a strong commitment to social justice and equality. Non-governmental organizations play an active role in monitoring and advocating for human rights.

6. Administrative divisions

Iceland's administrative divisions consist of several tiers, primarily for statistical, electoral, and local governance purposes.

The main administrative units are:

1. **Regions** (landsvæðilands-vie-theeIcelandic): There are eight regions, which are primarily statistical divisions used for data collection and regional planning. They do not have administrative autonomy in the same way as regions in some other countries. The regions are:

- Capital Region (HöfuðborgarsvæðiðHurf-uth-borg-ar-svie-thithIcelandic)

- Southern Peninsula (SuðurnesSuth-ur-nesIcelandic)

- Western Region (VesturlandVest-ur-landIcelandic)

- Westfjords (VestfirðirVest-firth-irIcelandic)

- Northwestern Region (Norðurland vestraNorth-ur-land vest-raIcelandic)

- Northeastern Region (Norðurland eystraNorth-ur-land eist-raIcelandic)

- Eastern Region (AusturlandAust-ur-landIcelandic)

- Southern Region (SuðurlandSuth-ur-landIcelandic)

2. **Constituencies** (kjördæmikyeurd-die-miIcelandic): For parliamentary elections, Iceland is divided into six constituencies. This system was established in 2003 to better balance the weight of votes across different parts of the country, addressing previous disparities where rural votes had more weight than urban ones. The constituencies are:

- Reykjavík North

- Reykjavík South

- Southwest (four non-contiguous suburban areas around Reykjavík)

- Northwest

- Northeast

- South

3. **Municipalities** (sveitarfélögsvei-tar-fyer-lergIcelandic): These are the primary units of local government and the actual second-level administrative subdivisions. As of recent counts, there are around 69 municipalities. Municipalities are responsible for a wide range of local services, including schools (primary and lower secondary), public transport (in some areas), zoning, waste management, social services, and local infrastructure. They are governed by elected councils. Reykjavík is by far the most populous municipality. The number of municipalities has decreased over time due to amalgamations aimed at improving efficiency.

Historically, Iceland was also divided into **counties** (sýslursees-lurIcelandic) and independent towns (kaupstaðirkaup-stath-irIcelandic), but these divisions have largely been superseded by the modern municipal system for administrative purposes, though they may still be used in some historical or judicial contexts. District court jurisdictions also use an older version of the regional division.

7. Foreign relations

Iceland maintains an active foreign policy characterized by its commitment to international law, human rights, peace, and multilateral cooperation. Historically neutral until joining NATO, its foreign relations are shaped by its geographical location, economic interests (particularly fisheries and trade), and Nordic identity.

Key aspects of Iceland's foreign relations include:

- Nordic Cooperation**: Iceland has very close ties with the other Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden) through the Nordic Council and various other cooperative frameworks. This cooperation spans political, economic, cultural, and social spheres.

- NATO Membership**: Iceland has been a member of NATO since 1949. It is unique within NATO as it does not have a standing army. Its contribution to collective defense includes providing facilities for NATO allies (historically the Keflavík Naval Air Station used by the US), participating in air policing missions over its territory conducted by allies, and contributing civilian personnel to peacekeeping operations. Membership has been a cornerstone of its security policy, though it has sometimes faced domestic debate.

- Relations with the United States**: The US has historically been a key security partner, particularly during the Cold War. The defense agreement of 1951 provided for US military presence, which ended in 2006, but bilateral security cooperation continues.

- European Union (EU)**: Iceland is not a member of the EU but has a close relationship through its membership in the European Economic Area (EEA) since 1994. The EEA agreement grants Iceland access to the EU's single market. Iceland applied for EU membership in 2009 following the financial crisis, but negotiations were put on hold in 2013, and the application was later withdrawn by the government in 2015. The issue of EU membership remains a divisive topic in Icelandic politics, primarily due to concerns about fisheries policy and national sovereignty.

- International Organizations**: Iceland is an active member of the United Nations and its various agencies, the Council of Europe, the OECD, the WTO, and the EFTA. It champions issues such as gender equality, environmental protection, and disarmament on the international stage.

- Arctic Affairs**: As an Arctic nation, Iceland plays an active role in the Arctic Council and emphasizes sustainable development and environmental protection in the Arctic region.

- Cod Wars**: Historically, significant international disputes involved fisheries, most notably the Cod Wars with the United Kingdom in the mid-20th century. These disputes, centered on Iceland's unilateral extensions of its fishing limits, were eventually resolved in Iceland's favor, establishing its control over rich fishing grounds. This experience has had a lasting impact on Iceland's approach to maritime resources and sovereignty, but also caused hardship for British fishing communities that lost access to Icelandic waters.

- Development Cooperation**: Iceland contributes to international development aid, focusing on areas such as sustainable fisheries, geothermal energy, and gender equality in partner countries.

Iceland's foreign policy aims to balance its national interests with a commitment to global cooperation, often taking principled stances on human rights and international conflicts. Its relationships with Asian countries are expanding, reflecting growing trade and cultural exchange.

7.1. Relations with the European Union

Iceland's relationship with the European Union (EU) is primarily defined by its membership in the European Economic Area (EEA), which it joined in 1994 along with Norway and Liechtenstein. The EEA agreement grants Iceland full access to the EU's single market, meaning free movement of goods, services, capital, and people. This has had a significant impact on Iceland's economy, facilitating trade and investment. Iceland implements relevant EU legislation related to the single market into its national law.

However, Iceland is not a member of the EU. The question of full EU membership has been a recurring and often contentious issue in Icelandic politics.

- EU Membership Application (2009-2015)**: Following the severe financial crisis of 2008, the then-Social Democratic Alliance-led government applied for EU membership in July 2009, hoping that joining the EU and potentially the Eurozone would provide economic stability. Accession negotiations were formally opened in July 2010. Several chapters of the acquis communautaire (EU law) were opened and some provisionally closed.

- Suspension and Withdrawal of Application**: Public opinion on EU membership shifted, and concerns, particularly regarding the EU's Common Fisheries Policy and its potential impact on Iceland's vital fishing industry, remained strong. The 2013 election brought a new centre-right government (Progressive Party and Independence Party) to power, which was more skeptical of EU membership. In May 2013, the new government put the accession negotiations on hold. In March 2015, the Icelandic government, under Foreign Minister Gunnar Bragi Sveinsson, formally notified the EU that it was no longer seeking membership, effectively withdrawing its application, though it did so without a referendum that had been previously discussed.

- Current Status and Debates**: Iceland continues its participation in the EEA. The debate over EU membership resurfaces periodically in Icelandic politics. Proponents argue for the economic benefits of full membership, greater influence in European decision-making, and potential currency stability through Euro adoption. Opponents emphasize concerns about sovereignty, control over fisheries (Iceland's most important natural resource), and agricultural policy. Parties like the Reform Party (Viðreisn) are generally pro-EU, while others like the Independence Party and the Left-Green Movement have traditionally been more skeptical or opposed. A referendum on restarting accession talks or on full membership has been a recurring political demand, but no consensus has been reached to hold one. Subsequent calls for a referendum on the issue have been made.

Iceland also participates in other European cooperation frameworks, such as the Schengen Area, which allows for passport-free travel between member states.

8. Military

Iceland is unique among NATO member states in that it does not maintain a standing army, navy, or air force. Its defense capabilities and contributions are structured differently from most other countries.

- Icelandic Coast Guard** (Landhelgisgæsla ÍslandsLand-helgis-giesla EES-landsIcelandic): This is the primary force responsible for Iceland's maritime security, surveillance, search and rescue operations, law enforcement at sea, and explosive ordnance disposal. The Coast Guard operates patrol vessels (such as the ICGV Þór, launched in 2009) and aircraft. It plays a crucial role in protecting Iceland's vast exclusive economic zone (EEZ), particularly its valuable fishing grounds. It also maintains the Iceland Air Defence System, which includes radar stations.

- NATO Membership and Collective Defense**: Iceland has been a member of NATO since its founding in 1949. Its strategic location in the North Atlantic (the GIUK gap) has been considered important for transatlantic security. Iceland contributes to NATO by providing facilities for allied forces and participating in civilian peacekeeping and crisis response missions. Under NATO's collective defense principle (Article 5), an attack on Iceland would be considered an attack on all NATO members.

- Defense Agreements**: Iceland has a bilateral defense agreement with the United States, which historically involved the stationing of US forces at the Keflavík Naval Air Station (the Iceland Defense Force, IDF). The IDF, created at NATO's request, consisted of US military personnel, civilian Icelanders, and military members of other NATO nations. While US forces, including Air Force interceptor aircraft, withdrew in 2006 after the Cold War, the agreement remains, and the US and other NATO allies conduct periodic deployments and exercises in Iceland, including air policing missions to monitor Icelandic airspace since May 2008.

- Iceland Crisis Response Unit** (ICRU) (Íslenska friðargæslanEES-lenska frith-ar-gieslanIcelandic): This is a small, civilian-staffed organization that deploys personnel to international peacekeeping and crisis management operations led by organizations like NATO, the UN, and the OSCE. Participants are typically specialists like police officers, legal experts, and medical personnel. Iceland deployed a Coast Guard EOD team to Iraq during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, later replaced by ICRU members. It also participated in the conflict in Afghanistan and the 1999 NATO bombing of Yugoslavia.

- No Conscription**: Iceland has no military conscription.

Iceland's approach to defense reflects its small population, historical traditions, and reliance on collective security arrangements through NATO and bilateral agreements. Its emphasis is on maritime surveillance, resource protection, and contributions to international peace and security through civilian means. The country hosted the historic 1986 Reykjavík Summit between Reagan and Gorbachev. According to the 2024 Global Peace Index, Iceland is the most peaceful country in the world and is listed in Guinness World Records as the "country ranked most at peace" and for having the "lowest military spending per capita".

9. Economy

Iceland possesses a developed mixed economy characterized by high levels of free trade and government intervention. Historically reliant on fisheries, the economy has diversified, though it remains sensitive to global market fluctuations. Key features include abundant renewable energy, a high standard of living, and a strong social welfare system. The economy experienced a dramatic boom and subsequent severe crisis in 2008, from which it has since recovered, leading to structural reforms and a renewed focus on sustainable growth. Social aspects like labor rights, income equality, and environmental sustainability are important considerations in economic policy. In 2022, Iceland was the eighth-most productive country in the world per capita (78.84 K USD), and the thirteenth-most productive by GDP at purchasing power parity (69.83 K USD). It maintains one of the lowest rates of income inequality globally, based on the Gini coefficient.

9.1. Major industries

Iceland's economy, while small, is diverse and increasingly sophisticated. Key industries include:

- Fisheries**: Historically the backbone of the Icelandic economy, the fishing industry remains a vital sector, accounting for approximately 20% of export earnings (down from 90% in the 1960s) and employing 7% of the workforce. Cod, haddock, capelin, and herring are among the main catches. Iceland has a highly advanced fishing fleet and processing industry, emphasizing sustainable fishing practices. Whaling in Iceland has been historically significant.

- Tourism**: This sector has experienced explosive growth since around 2010, becoming a leading source of foreign exchange and a major driver of economic growth. Iceland's unique natural attractions, such as glaciers, volcanoes, geysers, waterfalls, and the Northern Lights, draw millions of visitors annually (around 1.1 million annually on average, increasing to 1.7 million in 2016, three times the number in 2010). This has spurred development in hospitality, transport, and related services but also raised concerns about infrastructure capacity and environmental impact.

- Energy (Renewable)**: Iceland is a world leader in renewable energy, with nearly 100% of its electricity generated from geothermal and hydropower sources. This abundance of clean energy supports energy-intensive industries and provides low-cost heating for homes and businesses.

- Aluminum Smelting**: The availability of inexpensive, renewable electricity has attracted significant foreign investment in aluminum smelters. Aluminum products and ferrosilicon are major exports.

- Geothermal Energy**: Beyond electricity generation, geothermal energy is used directly for district heating (heating most buildings in the country), swimming pools, greenhouses (enabling domestic agriculture), and fish farming.

- Manufacturing and Technology**: While dominated by aluminum, other manufacturing sectors exist, including food processing, machinery, and equipment for the fishing industry. The technology sector, including software production, biotechnology, and gaming (e.g., CCP Games, creators of EVE Online), is a growing area of innovation and export. The financial centre is Borgartún in Reykjavík. Iceland's stock market, the Iceland Stock Exchange (ISE), was established in 1985.

- Services**: The service sector is the largest part of the Icelandic economy (close to 70% of GDP), encompassing finance, retail, transportation, IT services, and public services. Industry accounts for about a quarter of economic activity.

- Agriculture**: Accounting for 5.4% of GDP, agriculture is limited by climate and terrain. It primarily focuses on livestock (sheep for mutton, cattle for dairy) and greenhouse cultivation of potatoes and green vegetables using geothermal heat.

The government actively promotes economic diversification, innovation, and sustainable use of natural resources. Iceland is ranked 22nd in the 2024 Global Innovation Index. The country has a flat tax system for personal income (around 22.75% plus municipal taxes, totaling no more than 35.7% after deductions) and a flat corporate tax rate of 18%. Employment regulations are relatively flexible. Despite low tax rates, agricultural assistance is high among OECD countries.

9.2. Financial crisis and recovery

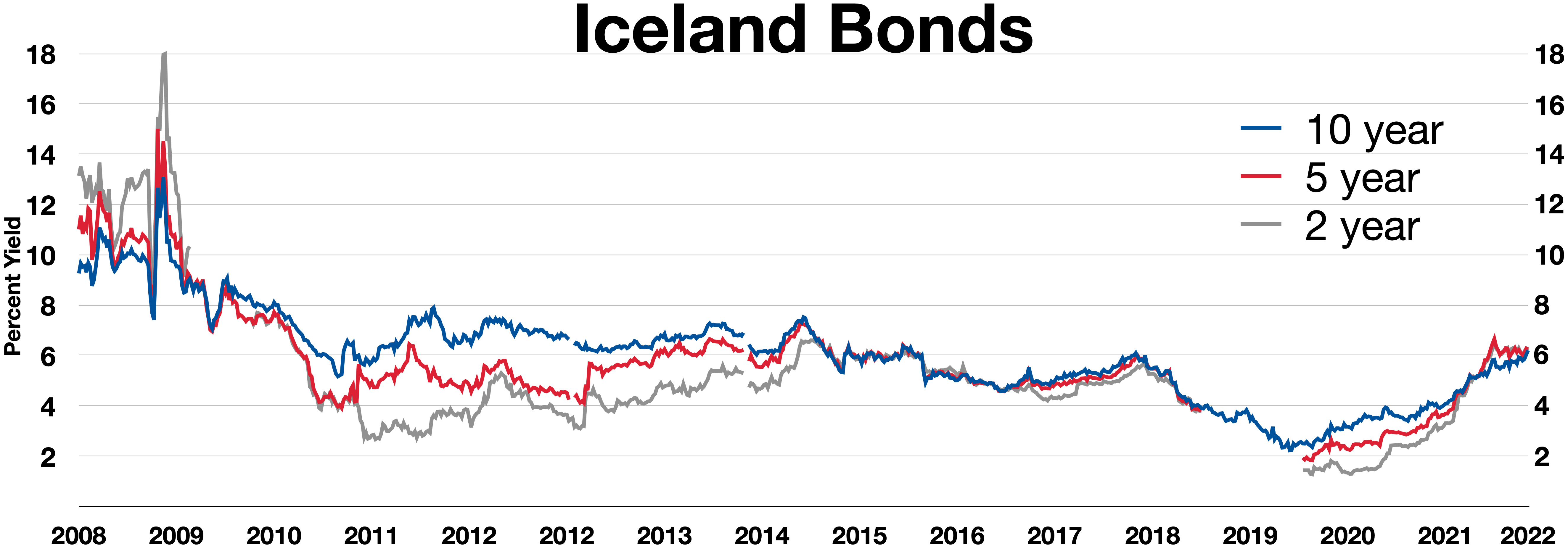

The 2008-2011 Icelandic financial crisis was a severe economic and political upheaval that had profound impacts on the nation.

Causes and Progression:

In the early 2000s, Iceland's banking sector was privatized and rapidly expanded, fueled by deregulation and access to international capital markets. The three main commercial banks - Landsbanki, Kaupthing, and Glitnir - grew to a size where their combined debt exceeded approximately six times the nation's GDP of 14.00 B EUR. This created an economic boom, but also an unsustainable financial bubble.

When the global financial crisis hit in September 2008, Iceland's oversized banking system found itself unable to refinance its short-term debts. Within days in early October 2008, all three major banks defaulted and were taken over by the government. The Icelandic króna (ISK) collapsed, the stock market plummeted by over 90%, and capital controls were imposed to prevent capital flight. Iceland faced national bankruptcy. The government raised interest rates to 18% in October 2008 as part of an IMF loan agreement.

Impact on Economy and Society:

The crisis led to a sharp recession, high unemployment (a new phenomenon for Iceland), soaring inflation, and a significant decline in living standards. Many Icelanders lost their savings, and businesses struggled. The social fabric was strained, leading to large-scale public protests (the "Pots and Pans Revolution"), which resulted in the resignation of the government in early 2009. There was a widespread sense of anger and betrayal, directed at bankers, politicians, and regulatory authorities. Thousands of Icelanders left the country, many moving to Norway. The crisis also triggered a debate about Iceland's economic model and national identity.

Recovery Efforts:

The recovery was guided by an IMF-led stabilization program, which included loans (e.g., 2.50 B USD from Nordic countries in November 2008), fiscal austerity, and restructuring of the financial sector. Key elements of the recovery included:

- Devaluation of the Króna**: While painful in the short term (increasing import costs and inflation), the weaker króna made Iceland's exports (especially fish) and tourism more competitive.

- Capital Controls**: These remained in place for several years to stabilize the currency and prevent disruptive capital outflows, though they also hindered foreign investment. They were gradually lifted, with the process largely completed by 2017.

- Focus on Exports and Tourism**: The fishing industry benefited from the weaker currency, and the tourism sector experienced a massive boom, becoming a key engine of recovery.

- Accountability**: A Special Investigation Commission published its findings in April 2010, revealing the extent of control fraud. Some banking executives were prosecuted and convicted. Central Bank governor Davíð Oddsson was removed in February 2009.

- Debt Repayment**: By June 2012, Landsbanki had repaid about half of the Icesave debt.

- Social Resilience**: Iceland's strong social safety net, high levels of education, and social cohesion helped mitigate some of the worst social impacts.

By the mid-2010s, Iceland's economy had returned to growth, unemployment had fallen (to around 2% by 2014), and fiscal health had improved. The crisis, however, left lasting scars, including a legacy of public and private debt (public debt was 31st highest globally by GDP proportion in 2015), and prompted ongoing discussions about economic diversification, sustainable development, and the role of finance in society. OECD assessments in 2008 and 2011 highlighted challenges in currency, macroeconomic policy, and the efficiency of the fishing industry, but also noted progress in fiscal sustainability and financial sector health.

9.3. Energy

Iceland is a global leader in renewable energy production and utilization, primarily from geothermal and hydropower sources. This abundance of clean energy is a cornerstone of its economy and environmental policy.

- Primary Energy Supply**: Around 85% of Iceland's total primary energy consumption comes from domestically produced renewable sources.

- Electricity Generation**: Virtually 100% of Iceland's electricity is generated from renewable resources. Hydropower accounts for roughly 70-75%, and geothermal power for about 25-30%. This makes Iceland the world's largest electricity producer per capita. Major power plants include the Kárahnjúkar Hydropower Plant (hydro, the country's largest hydroelectric station) and the Hellisheiði and Nesjavellir power stations (geothermal). When Kárahnjúkavirkjun started operating, Iceland became the world's largest electricity producer per capita.

- Direct Use of Geothermal Energy**: Beyond electricity, geothermal energy is extensively used for direct heating. About 90% of all buildings in Iceland are heated by geothermal district heating systems. It's also used for snow melting on sidewalks and roads, heating greenhouses for agriculture, fish farming, and recreational purposes (e.g., swimming pools like the Blue Lagoon).

- Energy Self-Sufficiency**: Thanks to its renewable resources, Iceland is largely self-sufficient in electricity and heating. Imported oil products are primarily used for transportation (vehicles and the fishing fleet).

- National Energy Policy**: Icelandic energy policy focuses on the sustainable utilization of its renewable resources, energy security, and promoting environmentally friendly energy technologies. In 2023, battery electric vehicles constituted 50.1% of new registrations, and around 18% of the country's vehicle fleet was electrified by 2024. Iceland has filling stations dispensing hydrogen fuel for fuel cell cars. There is ongoing research and development in areas like carbon capture and storage (e.g., the CarbFix project, which injects CO2 into basaltic rock where it mineralizes), and enhanced geothermal systems.

- Environmental Considerations**: While renewable energy significantly reduces greenhouse gas emissions from power generation, Icelanders emitted 16.9 t of CO2 per capita in 2016, the highest among EFTA and EU members, mainly resulting from transport and aluminium smelting. Nevertheless, Iceland has been recognized for its environmental efforts, named "the Greenest Country" by Guinness World Records in 2010 based on the Environmental Sustainability Index. The official governmental goal is to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by 2030 and reach carbon neutrality by 2040.

- Hydrocarbon Exploration**: In January 2009, Iceland announced its first round of offshore licenses for hydrocarbon exploration in the Dreki area, northeast of Iceland. Three exploration licenses were awarded but subsequently relinquished.

Iceland's expertise in geothermal energy technology is also an export, with Icelandic companies providing consultancy and services worldwide.

10. Transport

Iceland's transport infrastructure and systems are shaped by its sparse population, rugged terrain, and often challenging weather conditions. The country relies heavily on road and air transport, with no public railways.

10.1. Road

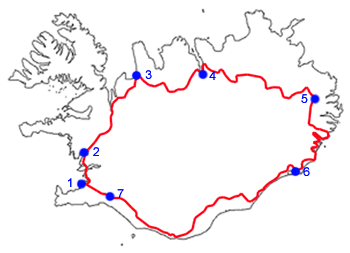

Iceland has a high level of car ownership per capita (a car for every 1.5 inhabitants), and it is the main form of transport. The country has approximately 8.1 K mile (13.03 K km) of administered roads, of which 2.9 K mile (4.62 K km) are paved and 5.2 K mile (8.34 K km) are not.

Route 1, or the Ring Road (Þjóðvegur 1Thiodh-vegur einnIcelandic or HringvegurHring-veg-urIcelandic), completed in 1974, is the main road that runs around Iceland, connecting most inhabited parts of the island. The interior of the island is mostly uninhabitable. The road is mostly paved and is 0.8 K mile (1.33 K km) long with one lane in each direction, except between and within larger towns where it has more lanes. There are still some 30 single-lane bridges on Route 1, particularly in the southeast.

A great number of interior roads, known as F-roads (mountain roads), remain unpaved and are mostly little-used rural roads, often requiring 4x4 vehicles and only open during summer. Road speed limits are typically 19 mph (30 km/h) and 31 mph (50 km/h) in towns, 50 mph (80 km/h) on gravel country roads, and 56 mph (90 km/h) on hard-surfaced roads.

10.2. Public transport

Public transport is primarily bus-based. Strætó bs operates city buses in Reykjavík and the surrounding Capital Region, as well as long-distance public bus services throughout the country. Smaller towns such as Akureyri, Reykjanesbær, and Selfoss also provide local bus services. Public and private bus services are available to and from Keflavík International Airport.

Iceland has never had passenger railways; historically, only temporary freight railways have operated.

10.3. Air travel

Keflavík International Airport (KEF) is the largest airport and the main aviation hub for international passenger transport. It is located in the southwest of the country, 30 mile (49 km) from the Reykjavík city centre.

Reykjavík Airport (RKV), located just 0.9 mile (1.5 km) from the capital's centre, is the second-largest airport. It serves daily regular domestic flights within Iceland, general aviation, private aviation, and medevac traffic.

Akureyri Airport (AEY) and Egilsstaðir Airport (EGS) are two other airports with domestic service and limited international service. Akureyri Airport opened an expanded international terminal in 2024. There are a total of 103 registered airports and airfields in Iceland, most of them unpaved and located in rural areas.

10.4. Sea

Several ferry services provide regular access to various island communities or shorten travel distances. The Smyril Line operates the ship Norröna, providing an international ferry service from Seyðisfjörður to the Faroe Islands and Denmark.

Several companies, including Eimskip and Samskip, provide maritime transport services to Iceland. Iceland's largest ports are managed by Faxaflóahafnir.

11. Society

Icelandic society is characterized by its small, relatively homogeneous population, a strong sense of national identity rooted in its unique language and history, a high standard of living, and comprehensive social welfare systems. It is known for its progressive social policies, particularly in areas like gender equality and LGBTQ+ rights.

11.1. Demographics

As of early 2024, the population of Iceland is approximately 380,000 people (around 332,529 in 2016, 357,050 in 2019), making it one of the most sparsely populated countries in Europe. The population density is low, concentrated mainly along the coast, particularly in the southwest.

- Population Growth**: Iceland has experienced steady population growth, supported by both natural increase and immigration. The fertility rate in 2008 was 2.1, one of the few European countries with a birth rate sufficient for long-term population growth, though it has declined in recent years.

- Age Structure**: The population is relatively young for a developed country, with one out of five people being 14 years old or younger in 2008, though it is aging.

- Ethnic Composition**: The original Icelandic population is largely of Norse (Scandinavian) and Gaelic (Irish/Scottish) descent, reflecting the original settlers. Genetic studies confirm this mixed heritage, indicating a majority of male settlers were of Nordic origin while the majority of women were of Gaelic origin. In recent decades, Iceland has become more ethnically diverse due to immigration. In December 2007, 33,678 people (13.5% of the total population) living in Iceland had been born abroad. Around 19,000 people (6% of the population) held foreign citizenship. The largest immigrant groups come from Poland (around 8,000 in 2008), Lithuania, and other European countries, as well as from Asia (e.g., Philippines, China, Thailand) and North America.

- Life Expectancy**: Iceland has one of the highest life expectancies in the world (average 81.8 years, 6th globally as of 2006).

- Migration**: Historically, Iceland experienced periods of emigration due to harsh conditions (e.g., 1870s to North America). In recent times, it has become a net immigration country. The 2008 financial crisis led to a temporary increase in emigration (net emigration of 5,000 in 2009), but immigration has since resumed.

The original population is believed to have varied from 40,000 to 60,000 from settlement until the mid-19th century. Cold winters, volcanic ash fall, and bubonic plagues adversely affected the population. There were 37 famine years between 1500 and 1804. The first census in 1703 revealed a population of 50,358. After the Laki volcanic eruptions (1783-1784), the population reached a low of about 40,000. Improving living conditions led to rapid population increase since the mid-19th century, from about 60,000 in 1850 to 320,000 in 2008. Extensive genealogical records date back to the late 17th century, with fragmentary records to the Age of Settlement. The biopharmaceutical company deCODE genetics has funded a genealogy database, Íslendingabók (genealogical database)EES-lending-ga-bokIcelandic, intended to cover all known inhabitants for genetic disease research.

11.1.1. Urbanisation

Iceland is a highly urbanized country. The vast majority of the population lives in urban areas, with a significant concentration in the Capital Region (HöfuðborgarsvæðiðHurf-uth-borg-ar-svie-thithIcelandic), which includes Reykjavík and its surrounding municipalities such as Kópavogur, Hafnarfjörður, and Garðabær. Approximately two-thirds (over 70% in the southwest corner including the Southern Peninsula) of Iceland's total population resides in this southwestern corner of the country, which covers less than two percent of Iceland's land area.

- Reykjavík**: As the capital and largest city (population 128,793 in 2019), Reykjavík is the political, economic, cultural, and educational center of Iceland.

- Other Urban Centers**: Outside the Capital Region, the largest town is Akureyri in northern Iceland (population 18,925 in 2019). Other notable towns include Reykjanesbær (population 18,920 in 2019, which includes Keflavík and its international airport), Selfoss in the south (part of Árborg municipality, pop. 9,485 in 2019), and Egilsstaðir in the east (part of Fjarðabyggð municipality, pop. 5,070 in 2019). Many coastal towns historically developed around the fishing industry.

The interior highlands of Iceland are virtually uninhabited. The trend towards urbanization has continued, with people moving from rural areas to towns and cities, particularly to the Capital Region, for education and employment opportunities. This concentration presents both opportunities for economic development and challenges related to housing, infrastructure, and regional disparities.

| Rank | Name | Icelandic Name | Region | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reykjavík | Reykjavík | Capital Region | 128,793 |

| 2 | Kópavogur | Kópavogur | Capital Region | 36,975 |

| 3 | Hafnarfjörður | Hafnarfjörður | Capital Region | 29,799 |

| 4 | Reykjanesbær | Reykjanesbær | Southern Peninsula | 18,920 |

| 5 | Akureyri | Akureyri | Northeastern Region | 18,925 |

| 6 | Garðabær | Garðabær | Capital Region | 16,299 |

| 7 | Mosfellsbær | Mosfellsbær | Capital Region | 11,463 |

| 8 | Árborg | Árborg | Southern Region | 9,485 |

| 9 | Akranes | Akranes | Western Region | 7,411 |

| 10 | Fjarðabyggð | Fjarðabyggð | Eastern Region | 5,070 |

11.2. Language

The official language of Iceland is Icelandic (íslenskaEE-slenskaIcelandic). It is a North Germanic language, descended from Old Norse, the language spoken by the Scandinavian settlers in the Viking Age.

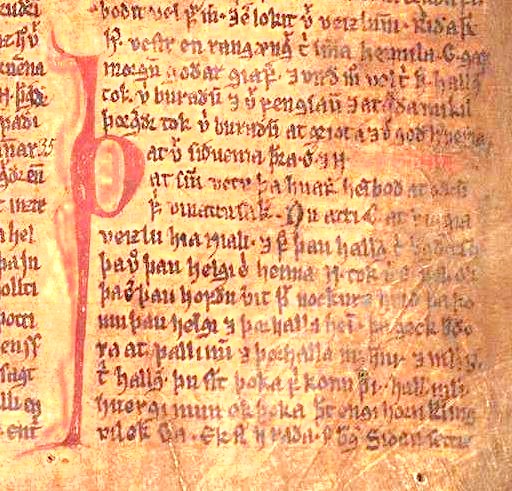

- Linguistic Conservatism**: Icelandic is remarkable for its linguistic conservatism. Due to centuries of relative isolation and conscious language preservation efforts, modern Icelandic has changed less from Old Norse than other Scandinavian languages (Danish, Norwegian, Swedish). As a result, modern Icelanders can, with some difficulty, read the ancient Sagas and Eddas in their original form. It has retained complex grammatical features like noun declensions and verb conjugations that have been largely simplified in other Germanic languages. Icelandic is the only living language to retain the use of the runic letter Þ (þorn) in its Latin alphabet. The closest living relative of the Icelandic language is Faroese.

- Language Purity and Preservation**: There is a strong tradition of linguistic purism in Iceland. New vocabulary is often created by coining new words from native Icelandic roots rather than borrowing directly from other languages. The Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies plays a key role in language research and preservation.

- Foreign Languages**: English and Danish are compulsory subjects in Icelandic schools. English is widely spoken and understood by a large majority of the population, especially younger generations. Danish, due to historical ties, is also understood by many, particularly older Icelanders; it is often referred to as skandinavískaskan-di-na-VEES-kaIcelandic (i.e., Scandinavian) in Iceland. Proficiency in other Nordic languages and German is also common. Polish is mostly spoken by the local Polish community, the largest minority.

- Icelandic Sign Language**: Recognized as an official minority language in 2011, its use for Iceland's deaf community is regulated by the National Curriculum Guide.

The Icelandic language is a crucial part of Icelandic national identity and cultural heritage.

11.2.1. Icelandic names

Iceland has a traditional patronymic (or occasionally matronymic) naming system, rather than the fixed family surnames common in most Western countries.

- How it works**:

- A person's last name indicates the first name of their father (patronymic) or, less commonly, their mother (matronymic).

- For a son, the suffix -son (meaning "son") is added to the genitive case of the parent's name. For example, if a man named Jón has a son named Ólafur, the son's full name would be Ólafur Jónsson (Ólafur, Jón's son).

- For a daughter, the suffix -dóttir (meaning "daughter") is added. If Jón also had a daughter named Katrín, her full name would be Katrín Jónsdóttir (Katrín, Jón's daughter). Example: Elísabet JónsdóttirElisabet YONS-doh-tirIcelandic ("Elísabet, Jón's daughter") or Ólafur KatrínarsonOH-la-vur KAT-reen-ar-sonIcelandic ("Ólafur, Katrín's son").

- Usage**: Icelanders are primarily addressed and referred to by their given name, even in formal situations. For example, Prime Minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir would be referred to as Katrín. Telephone directories and other listings are alphabetized by given name.

- No Shared Family Name**: This system means that members of the same immediate family will typically have different last names. For example, Jón Stefánsson's son might be Gunnar Jónsson, and his daughter Katrín Jónsdóttir. His wife would retain her own patronymic or matronymic name from her birth.

- Matronymics**: While less common, matronymic names (derived from the mother's given name) are used. This might be chosen for personal reasons, such as if the father is unknown or not involved, or as a statement of maternal connection.

- Family Surnames**: A small number of Icelanders do have inherited family surnames. These often originated before the patronymic system became legally dominant or belong to families of foreign origin who became Icelandic citizens. However, the adoption of new family surnames was effectively banned in 1925 to preserve the traditional system.

- Icelandic Naming Committee**: New given names not previously used in Iceland must be approved by the Icelandic Naming Committee (MannanafnanefndMan-na-nav-na-nemdIcelandic) to ensure they are compatible with Icelandic grammar and tradition.

This naming system is a distinctive cultural feature and reflects a strong connection to heritage.

11.3. Religion

Icelanders have freedom of religion, which is guaranteed by the Constitution. However, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Iceland (often simply called the Church of Iceland) holds the status of the established state church. Article 62 of the Constitution states: "The Evangelical Lutheran Church shall be the State Church in Iceland and, as such, it shall be supported and protected by the State."

Approximately 80% of Icelanders legally affiliate with a religious denomination, a process that can happen automatically at birth or by choice, and from which they can opt out. They also pay a church tax (sóknargjaldsoak-nar-gyaldIcelandic), which the government directs to support their registered religion or, if unaffiliated, to the University of Iceland.

The religious landscape in Iceland (based on 2017-2018 data) is as follows:

- Church of Iceland**: Around 67.22% of the population are members.

- Other Christian Denominations**: Around 11.56% belong to other Christian groups. This includes:

- Other Lutheran churches (e.g., Free Lutheran Churches of Reykjavík and Hafnarfjörður): 5.70%

- Roman Catholic Church: 3.85% (the largest Christian minority)

- Eastern Orthodox Church: 0.29%

- Other Christian denominations: 1.72%

- Germanic Heathenism (Ásatrú)**: ÁsatrúarfélagiðAU-sa-troo-ar-FYEL-a-githIcelandic, an organization reviving pre-Christian Norse pagan beliefs, is a recognized religious organization and has seen a growth in membership, accounting for 1.19% of the population (with 99% of these belonging to Ásatrúarfélagið).

- Other Religions and Life Stances**:

- Humanist association (Siðmennt): 0.67%

- Zuism: 0.55%

- Buddhism: 0.42%

- Islam: 0.30%

- Baháʼí Faith: 0.10%

- Unaffiliated/Other and Not Specified**: About 6.69% are unaffiliated, and 11.29% are categorized as 'Other and not specified'. Some studies indicate a higher percentage of atheists or agnostics (e.g., a 2001 study found 23% were atheist or agnostic, and a 2012 Gallup poll found 10% defined as "convinced atheists").

On March 8, 2021, Iceland formally recognized Judaism as a religion, allowing Jewish marriage, baby-naming, and funeral ceremonies to be civilly recognized.

While the Church of Iceland has historical and cultural significance, contemporary Icelandic society is largely secular in practice, with diverse beliefs and a high degree of religious tolerance. Church attendance is relatively low, similar to other Nordic countries.

| Affiliation | % of population |

|---|---|

| Christianity | 78.78% |

| Church of Iceland | 67.22% |

| Other Lutheran churches | 5.70% |

| Roman Catholic Church | 3.85% |

| Eastern Orthodox Church | 0.29% |

| Other Christian denominations | 1.72% |

| Other religion or association | 14.52% |

| Germanic Heathenism | 1.19% |

| Humanist association | 0.67% |

| Zuism | 0.55% |

| Buddhism | 0.42% |

| Islam | 0.30% |

| Baháʼí Faith | 0.10% |

| Other and not specified | 11.29% |

| Unaffiliated | 6.69% |

11.4. Education and Science