1. Overview

Zambia, officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country situated at the crossroads of Central, Southern, and East Africa. It is bordered by the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the north, Tanzania to the northeast, Malawi to the east, Mozambique to the southeast, Zimbabwe and Botswana to the south, Namibia to the southwest, and Angola to the west. The capital city, Lusaka, is located in the south-central part of the country. Zambia's geography is characterized by high plateaus, hills, mountains, and significant river valleys, notably the Zambezi, Kafue, and Luangwa rivers. The nation possesses abundant natural resources, including minerals like copper and cobalt, diverse wildlife, extensive forests, freshwater, and arable land.

Historically, the region was inhabited by Khoisan and Batwa peoples before the Bantu expansion in the 13th century. Various pre-colonial kingdoms, such as the Luba-Lunda states and the Maravi Confederacy, flourished before European colonization. The British South Africa Company administered the territory, which was later consolidated as Northern Rhodesia, a British protectorate. Zambia gained independence on October 24, 1964, with Kenneth Kaunda as its first president. The post-independence era saw periods of one-party rule under Kaunda's United National Independence Party (UNIP), significant economic challenges linked to copper dependency, and a transition to multi-party democracy in the early 1990s.

Zambia's political system is a presidential republic with a multi-party democratic framework. The government structure includes an executive branch led by the President, a unicameral National Assembly, and an independent judiciary. The country is divided into ten provinces for administrative purposes. Zambia's foreign policy has historically supported regional liberation movements and it is an active member of various international organizations, including the African Union and the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

The Zambian economy has traditionally relied heavily on copper mining. Efforts towards economic diversification are ongoing, focusing on agriculture, tourism, and other sectors. Despite periods of economic growth, poverty and social inequality remain significant challenges, with a large portion of the population affected by multidimensional poverty. The government and civil society organizations are working towards poverty reduction, improved social services, and sustainable development.

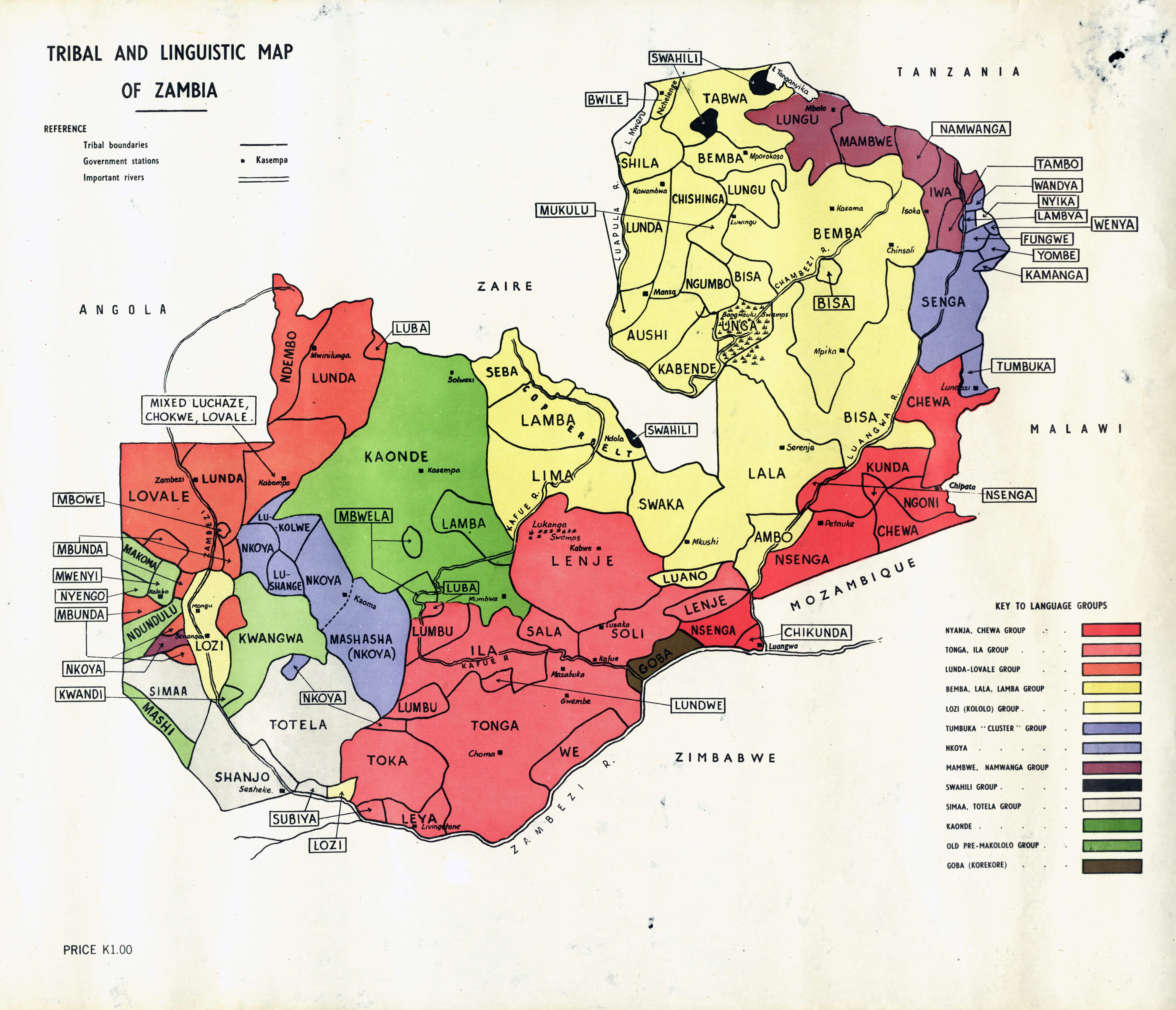

Zambian society is ethnically diverse, with over 70 distinct ethnic groups. English is the official language, though numerous indigenous Bantu languages are widely spoken. Christianity is the official religion, but freedom of religion is constitutionally protected, and various faiths are practiced. Education and healthcare systems face challenges, particularly in ensuring equitable access and quality, especially for vulnerable populations.

Culturally, Zambia boasts a rich heritage of traditional customs, arts, music, and dance, reflecting the diversity of its ethnic groups. The country is known for its wildlife and national parks, including the iconic Mosi-oa-Tunya / Victoria Falls, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

This article examines Zambia's multifaceted aspects from a perspective that emphasizes social justice, human rights, democratic development, and the welfare of minorities and vulnerable groups, critically analyzing historical and contemporary issues to provide a comprehensive understanding of the nation.

2. Etymology

The territory that is now Zambia was known as Northern Rhodesia from 1911 until 1964, reflecting its colonial administration under British rule and its geographical position relative to Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). The name "Rhodesia" itself was derived from Cecil Rhodes, a key figure in British colonial expansion in Southern Africa.

Upon achieving independence on October 24, 1964, the country was renamed Zambia. This name is derived from the Zambezi River, the fourth-longest river in Africa, which flows through the western part of the country and forms its southern border. The name "Zambezi" is believed by some to mean "grand river" or "great river" in one of the local languages, highlighting its significance to the region's geography and history. The adoption of the name Zambia marked a symbolic break from the colonial past and an assertion of national identity rooted in the African landscape.

3. History

The history of Zambia encompasses a vast timeline from early human presence to its contemporary status as a republic. This section details the major historical events and developmental phases from prehistoric times, through the rise and fall of pre-colonial kingdoms, the imposition and impact of colonial rule, the struggle for self-determination, and the nation's journey since independence, examining the profound social, economic, and political transformations that have shaped the country and its people.

3.1. Prehistoric Era and Early Inhabitants

Archaeological evidence indicates a long history of human habitation in the region now known as Zambia. Excavation work in the Zambezi Valley and at Kalambo Falls has revealed a succession of human cultures. Ancient campsite tools discovered near Kalambo Falls have been radiocarbon-dated to more than 36,000 years ago.

A significant discovery is the fossil skull remains of Homo rhodesiensis, also known as Kabwe Man or Broken Hill Man, found in Kabwe District. These remains, dated to between 300,000 and 125,000 years BC, provide crucial evidence of early hominin presence in the area.

The earliest identifiable modern human inhabitants of Zambia were the Khoisan peoples and the Batwa peoples (often referred to as Pygmies). The Khoisan are believed to have originated in East Africa and spread southwards around 150,000 years ago. The Twa people in Zambia were primarily divided into two groups: the Kafwe Twa, who lived around the Kafue Flats, and the Lukanga Twa, who inhabited the area around the Lukanga Swamp. These groups were hunter-gatherers, and numerous examples of ancient rock art found in Zambia, such as the Mwela Rock Paintings, Mumbwa Caves, and Nachikufu Cave, are attributed to them. With the arrival of Bantu-speaking agriculturalists, the Khoisan and Batwa populations were gradually displaced or absorbed, though some formed patron-client relationships with the newcomers. Their ancient lifestyles were profoundly impacted by these migrations and the subsequent socio-economic changes in the region.

3.2. Bantu Migrations and Pre-colonial Kingdoms

The period around AD 300 marked the beginning of significant migrations of Bantu-speaking groups into the Zambian region, an event part of the larger Bantu expansion across Africa. These migrations, originating from West and Central Africa (around present-day Cameroon and Nigeria), occurred over centuries and involved various routes, primarily a western one via the Congo Basin and an eastern one via the African Great Lakes. The Bantu migrants brought with them knowledge of agriculture, iron-working technology, and new social structures, which gradually transformed the existing hunter-gatherer societies.

The first Bantu groups to arrive in Zambia, likely via the eastern route around the first millennium CE, included the ancestors of the Tonga people (Ba-Tonga), the Ba-Ila, and the Namwanga, among others. They settled primarily in Southern Zambia near present-day Zimbabwe. Oral traditions of the Ba-Tonga suggest an origin from the east, near a "big sea." These early Bantu communities typically lived in villages without a highly centralized chiefly system, often relying on communal labor for agriculture. They practiced slash-and-burn cultivation and kept cattle. They also participated in regional trade networks, exemplified by the site of Ingombe Ilede in Southern Zambia, which connected them with Kalanga/Shona traders from Great Zimbabwe and Swahili traders from the East African coast. Goods traded included fabrics, beads, gold, and bangles, sourced locally and from as far as India and China. The decline of Great Zimbabwe led to the waning of Ingombe Ilede's importance.

A second major wave of Bantu settlement involved groups migrating from the Congo Basin, primarily associated with the Luba and Lunda states. These groups are ancestral to a majority of modern Zambians.

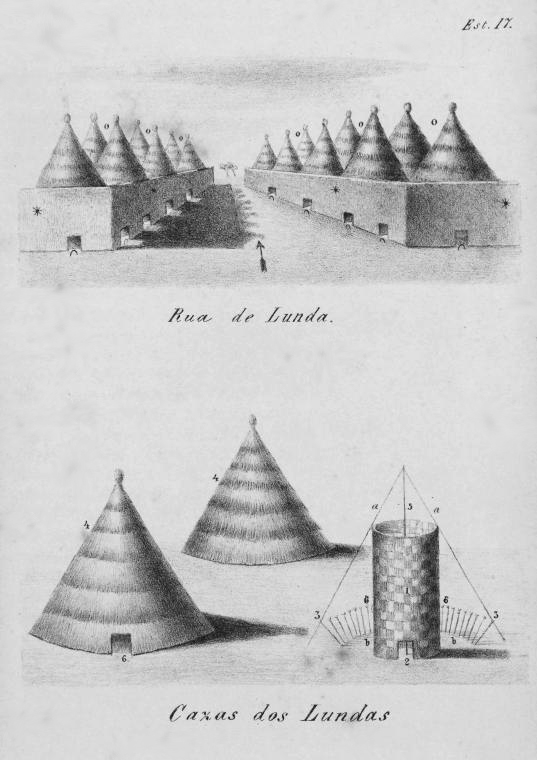

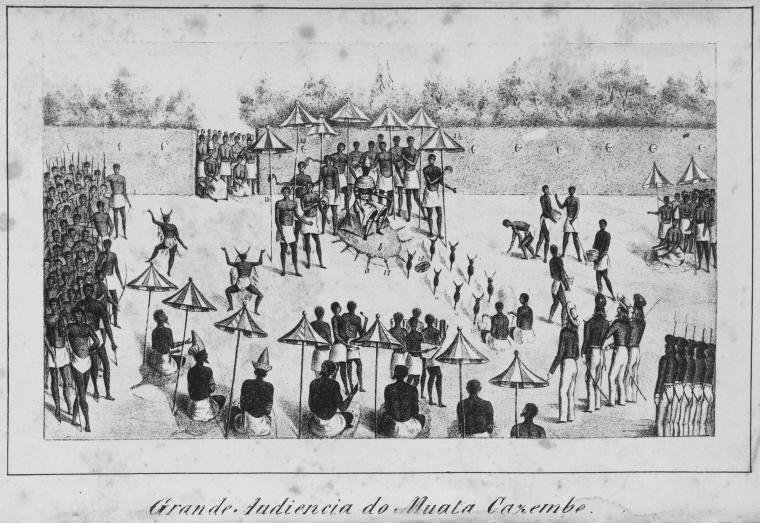

The Luba-Lunda states emerged in the Upemba Depression region of the Democratic Republic of Congo. The Kingdom of Luba, which arose in the 14th century, was characterized by a centralized government, extensive trading networks (linking the Congo forests, the Copperbelt region, and both Atlantic and Indian Ocean coasts), and a high regard for arts and oral literature. Peoples like the Bemba, Lamba, Bisa, Senga, Kaonde, Swaka, Nkoya, and Soli have historical links to the Luba Kingdom. The Lunda Empire developed as a satellite of Luba, adopting many Luba cultural and governance models. According to tradition, a Luba hunter, Chibinda Ilunga, married a Lunda princess, Lueji, around 1600, leading to the establishment of Lunda statecraft. The Lunda actively expanded their influence, engaging in trade, including copper and, unfortunately, slaves, with both European and East African traders. Internal conflicts and the pressures of the slave trade eventually led to the decline and dispersal of the Luba-Lunda states, contributing significantly to the peopling of Zambia.

The Maravi Confederacy (or Empire) was formed by Bantu migrants from the Congo Basin who settled around Lake Malawi by the 1400s. The Chewa people (AChewa) were prominent among them. Founded around 1480 by a Kalonga (paramount chief) of the Phiri clan, the Maravi Empire extended its influence from the Indian Ocean through Mozambique to parts of Zambia and Malawi. Its political structure resembled that of the Luba. The Maravi engaged in trade, primarily exporting ivory. They fiercely resisted Portuguese attempts to monopolize their trade in the late 16th century, with their WaZimba warriors sacking Portuguese towns. The Maravi are also associated with the Nyau secret society and its masked ritual dances, a significant cultural and religious tradition in the region. Succession disputes, attacks by the Ngoni, and slave raids by the Yao contributed to the Maravi's decline.

The Mutapa Empire was established by Nyatsimba Mutota, a prince from the declining Great Zimbabwe, in the 14th century. It ruled territory between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers, encompassing parts of present-day Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique. The Mutapa Empire was a key player in the Indian Ocean trade, exporting gold and ivory in exchange for silk and ceramics from Asia. Like the Maravi, they faced pressure from Portuguese traders who sought to control resources and convert the population. Portuguese military intervention, however, was largely unsuccessful due to disease. Internal strife and civil wars weakened Mutapa in the 1600s, eventually leading to its conquest by the Portuguese and rival Shona states.

The Mfecane (meaning "the crushing" or "the scattering") of the early 19th century, a period of widespread warfare and displacement in Southern Africa largely triggered by the rise of the Zulu Kingdom under Shaka, also profoundly impacted the Zambian region. Ngoni groups, led by figures like Zwangendaba, fled northwards, crossing the Zambezi River. These militarized Nguni groups caused significant disruption, contributing to the decline of existing states like the Maravi Empire. Many Ngoni eventually settled in parts of Zambia, Malawi, Mozambique, and Tanzania, often assimilating with local populations.

In western Zambia, the Kololo, a Sotho-Tswana group displaced by the Mfecane, conquered the Luyana (or Aluyi) people, who had earlier established the Barotse Kingdom on the Zambezi floodplains after migrating from Katanga. The Kololo imposed their language, but the Luyana eventually revolted and overthrew Kololo rule. By this time, the original Luyana language had largely been replaced by SiLozi, a hybrid language, and the Luyana became known as the Lozi. The Mbunda also migrated to Barotseland during this period and were valued for their fighting abilities.

By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the complex interplay of migrations, state formation, trade, and conflict had largely established the diverse ethnic and political landscape of the region that would eventually become Zambia.

3.3. Colonial Period

The colonial period in Zambia marked a transformative era, beginning with European exploration and culminating in direct British rule, which profoundly reshaped indigenous societies, economies, and political structures. This period witnessed the exploitation of mineral resources, the imposition of foreign governance, and the stirring of African nationalism.

3.3.1. European Exploration and BSAC Rule

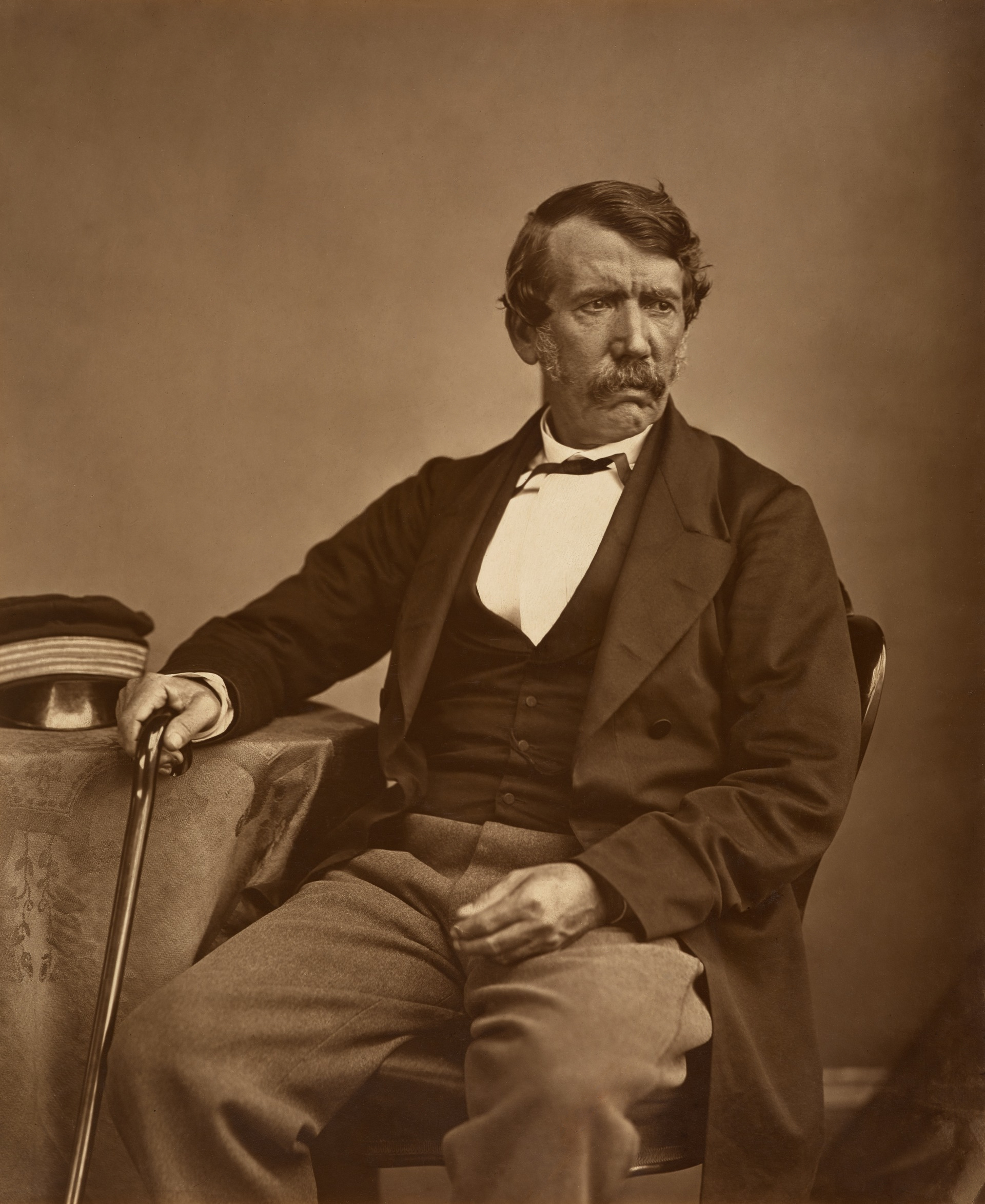

While Portuguese explorers like Francisco de Lacerda reached parts of present-day Zambia in the late 18th century, it was the expeditions of 19th-century European explorers, most notably the Scottish missionary David Livingstone, that brought the region to wider European attention. Livingstone, driven by a vision to end the slave trade through "Christianity, Commerce, and Civilisation," explored extensively between 1853 and 1873. In 1855, he was the first European to see the mighty waterfalls on the Zambezi River, which he named Victoria Falls after Queen Victoria. His widely publicized journeys and anti-slavery advocacy spurred further European missionary and commercial interest in the region following his death.

The late 19th century saw the intensification of the "Scramble for Africa" by European powers. Cecil Rhodes, a British mining magnate and imperialist, played a pivotal role in extending British influence north of the Limpopo River. In 1888, his British South Africa Company (BSAC) obtained controversial mineral rights concessions from Lewanika, the Paramount Chief of the Lozi in Barotseland. Rhodes aimed to create a contiguous British territory from the Cape to Cairo and to exploit the region's mineral wealth. The BSAC, chartered by the British government in 1889, was granted administrative powers over vast territories.

Through a series of treaties, often of dubious legitimacy and understanding by local chiefs, and sometimes through force, the BSAC extended its control. For instance, in December 1897, an Angoni rebellion under Tsinco, son of King Mpezeni, was suppressed. Frederick Russell Burnham, an American scout employed by Rhodes, discovered major copper deposits along the Kafue River in 1895, further fueling British interest. The company established two separate administrative entities: Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia and North-Eastern Rhodesia. These were amalgamated in 1911 to form Northern Rhodesia. The BSAC's rule was primarily focused on resource extraction and securing the territory for British interests, with limited investment in the welfare or development of the African population. Indigenous political structures were undermined, and land alienation began, setting the stage for future conflicts and grievances.

3.3.2. British Colonisation and Northern Rhodesia

The administration of Northern Rhodesia by the British South Africa Company (BSAC) continued until 1923. After the British government decided not to renew the company's charter to govern the territory, and following negotiations, direct British colonial rule was established. On April 1, 1924, Northern Rhodesia officially became a British protectorate, administered by the British Colonial Office through a Governor. This marked a shift from company rule to direct imperial governance, though the economic interests established by the BSAC, particularly in mining, continued to dominate.

A pivotal development during this period was the discovery and exploitation of vast copper deposits in the region that became known as the Copperbelt. Beginning in the late 1920s, large-scale mining operations were initiated by companies like the Anglo American Corporation and the Rhodesian Selection Trust. The Copperbelt quickly became the economic heartland of the protectorate, attracting significant foreign investment and a large migrant labor force, both from within Northern Rhodesia and neighboring territories. Towns like Ndola, Kitwe, and Mufulira grew rapidly around the mines.

The colonial administration implemented policies that prioritized European settler interests and the profitability of the mining industry. A dual system of governance and justice often disadvantaged the African population. Africans were largely confined to "native reserves," often on less fertile land, while better lands were reserved for European settlement and farming. Access to education and healthcare for Africans was limited and of inferior quality compared to that available to Europeans. The color bar, a system of racial discrimination, restricted Africans from skilled jobs in the mines and other sectors of the economy, ensuring a cheap labor supply for European enterprises. Taxes, such as the hut tax, were imposed on Africans, compelling them to seek wage labor in mines and on European farms to earn cash. These policies led to social disruption, economic hardship, and growing resentment among the African population, laying the groundwork for the rise of African nationalism.

3.3.3. Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland

In 1953, despite significant opposition from the African majority in all three territories, the British government established the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, also known as the Central African Federation. This political entity amalgamated the protectorates of Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) and Nyasaland (now Malawi) with the self-governing colony of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). The stated objectives of the Federation included economic development through shared resources and infrastructure, and the creation of a multi-racial partnership. However, in practice, the Federation was largely dominated by the interests of the European settler minority in Southern Rhodesia.

The federal capital was established in Salisbury (now Harare) in Southern Rhodesia, and political power was disproportionately held by white politicians from that territory. While Northern Rhodesia's copper revenues were a crucial economic pillar for the Federation, many Africans felt that these resources were being diverted to benefit Southern Rhodesia and European interests, with insufficient investment in African development in the northern territories.

African nationalists in Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland vehemently opposed the Federation from its inception. They viewed it as an entrenchment of white minority rule and a barrier to their aspirations for self-government and independence. Political leaders like Harry Nkumbula of the African National Congress (ANC) and later Kenneth Kaunda of the United National Independence Party (UNIP) in Northern Rhodesia, along with Hastings Banda in Nyasaland, spearheaded campaigns against the Federation. These campaigns involved protests, boycotts, and civil disobedience.

The growing African opposition, coupled with increasing international pressure against colonialism, rendered the Federation unsustainable. The British government eventually acknowledged the depth of African resistance. The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland was officially dissolved on December 31, 1963. This dissolution was a critical step on Zambia's path to independence, as it removed a major obstacle to majority rule. Nyasaland became independent as Malawi in July 1964, and Northern Rhodesia followed suit as Zambia in October 1964. Southern Rhodesia, under white minority rule, unilaterally declared independence in 1965, leading to a protracted liberation struggle. The Federation's legacy included heightened political consciousness among Africans and a strengthened resolve to achieve full sovereignty, but also economic and infrastructural ties that would continue to influence regional dynamics.

3.4. Struggle for Independence

The struggle for Zambia's independence was driven by a burgeoning African nationalist movement that sought an end to colonial rule and the establishment of a self-governing, majority-ruled nation. This movement gained momentum throughout the mid-20th century, particularly in opposition to the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

The rise of African nationalism in Northern Rhodesia was fueled by various grievances: economic exploitation, particularly in the Copperbelt where African miners faced poor working conditions and discriminatory wages; land alienation for European settlement; limited access to education and political participation; and the imposition of the Federation against the wishes of the African majority.

Early nationalist activities were often channeled through welfare associations and trade unions. The Zambian African National Congress (ANC), initially led by Godwin Mbikusita Lewanika and later by Harry Nkumbula, was a key early political organization. However, by the late 1950s, some younger, more radical nationalists grew impatient with the ANC's leadership and approach.

In 1958, a group of these more militant members, including Kenneth Kaunda, Simon Kapwepwe, and Mainza Chona, broke away from the ANC to form the Zambia African National Congress (ZANC). ZANC was quickly banned by the colonial authorities in 1959, and its leaders, including Kaunda, were imprisoned. Upon his release in 1960, Kaunda became the leader of the newly formed United National Independence Party (UNIP). UNIP rapidly grew into the dominant nationalist force, mobilizing mass support across the territory through its powerful organization and Kaunda's charismatic leadership.

UNIP's campaign for independence involved a combination of political agitation, civil disobedience (such as the "Cha-Cha-Cha" campaign of civil unrest in 1961), and international lobbying. They demanded "one man, one vote" and the dissolution of the Federation. The party successfully organized boycotts and protests, highlighting the injustices of colonial rule and the widespread desire for self-determination.

The British government, facing sustained pressure and recognizing the growing tide of decolonization across Africa, began to concede to nationalist demands. A two-stage election held in October and December 1962 resulted in an African majority in the legislative council and an uneasy coalition government formed by UNIP and the ANC. This government passed resolutions calling for Northern Rhodesia's secession from the Federation and demanding full internal self-government under a new constitution with a broader, more democratic franchise.

Following the dissolution of the Federation on December 31, 1963, Northern Rhodesia achieved internal self-government. In January 1964, elections were held, which UNIP won decisively. Kenneth Kaunda became the first Prime Minister of Northern Rhodesia. The path was now clear for full independence, which was granted on October 24, 1964. Northern Rhodesia became the Republic of Zambia, with Kenneth Kaunda as its inaugural president. The struggle for independence was a testament to the resilience and determination of the Zambian people and their leaders to achieve sovereignty and control over their own destiny, though the new nation faced significant challenges related to economic dependence, limited skilled human resources, and the need to forge national unity among diverse ethnic groups.

3.5. Post-Independence Era

Zambia's journey as a sovereign nation since its independence on October 24, 1964, has been marked by significant political, economic, and social developments. This era includes the long presidency of Kenneth Kaunda, economic challenges tied to its copper-dependent economy, a transition to multi-party democracy, and ongoing efforts to address contemporary issues of governance, development, and human rights.

3.5.1. Kaunda Era (1964-1991)

Upon independence, Kenneth Kaunda became Zambia's first president, and his United National Independence Party (UNIP) became the ruling party. The early years were characterized by nation-building efforts under the philosophies of "Zambian Humanism" and "One Zambia, One Nation." These ideologies aimed to foster national unity in a country with diverse ethnic groups and to create a socialist-inspired egalitarian society, emphasizing traditional African values of community and cooperation alongside Christian principles.

A major policy initiative was the nationalization of key industries, most notably the economically vital copper mines, through reforms like the Mulungushi Reforms (1968) and Matero Reforms (1969). The government acquired a majority stake in these enterprises, aiming to give Zambians greater control over their resources and to use the revenue for national development, including expanding education and healthcare services. Initially, high copper prices provided resources for these social programs.

In foreign policy, Kaunda's Zambia played a prominent role in supporting liberation struggles against colonial rule and apartheid in Southern Africa. Lusaka became a haven for nationalist movements from Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), South Africa (the African National Congress, ANC), Namibia (SWAPO), Angola, and Mozambique. This stance, while principled, brought considerable economic and security challenges, including border closures with Rhodesia in 1973, military incursions from neighboring white-minority regimes, and the burden of hosting large refugee populations. Zambia was a key member of the Frontline States, actively working towards the end of apartheid and minority rule in the region. Kaunda also engaged in regional diplomacy, often cooperating with international powers, including the United States, to find solutions to regional conflicts.

Domestically, political opposition was gradually marginalized. In 1972, Zambia officially became a one-party state under UNIP, with the Choma Commission paving the way for this constitutional change. While proponents argued this was necessary for national unity and development, it curtailed political freedoms and dissent. Kaunda's leadership, though initially popular, faced growing challenges as economic conditions deteriorated. The first internal conflict Kaunda faced as leader was the Lumpa Uprising in 1964, led by Alice Lenshina, which was suppressed by government forces.

3.5.2. Economic Challenges and Structural Adjustments

Zambia's post-independence economy was heavily reliant on copper, which accounted for the vast majority of its export earnings. This dependency made the nation vulnerable to fluctuations in global copper prices. In the mid-1970s, a severe decline in international copper prices, coupled with rising oil prices and disruptions to trade routes due to regional conflicts (particularly the closure of the Rhodesian border and instability in Angola), plunged Zambia into a prolonged economic crisis.

The cost of transporting copper to international markets was an additional burden for the landlocked country. Attempts to diversify the economy had limited success. The nationalization of mines, while aimed at increasing state control, sometimes led to inefficiencies and reduced investment. The government borrowed heavily from international lenders to finance development projects and cover budget deficits, leading to a mounting national debt.

By the 1980s, Zambia faced severe economic difficulties, including high inflation, shortages of essential goods, declining living standards, and an inability to service its foreign debt. The government sought assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, which prescribed Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs). These programs typically involved currency devaluation, privatization of state-owned enterprises, removal of subsidies (e.g., on maize meal, a staple food), trade liberalization, and cuts in public spending, including on social services like health and education.

The implementation of SAPs was often met with popular resistance due to their harsh social consequences. While intended to stabilize the economy and promote market-oriented reforms, they often led to job losses, increased poverty, and reduced access to essential services for the most vulnerable segments of the population. The impact on social welfare was significant, with declines in health and education indicators. Despite some debt relief initiatives, Zambia's per capita foreign debt remained among the highest in the world by the mid-1990s. These economic hardships contributed to growing public discontent with Kaunda's one-party rule and fueled demands for political and economic change.

3.5.3. Transition to Multi-Party Democracy

By the late 1980s, mounting economic hardships, coupled with a global wave of democratic movements and internal pressure, led to increasing calls for an end to one-party rule in Zambia. The perceived lack of political accountability and the desire for greater economic and political freedoms fueled a growing opposition movement.

Trade unions, particularly the powerful Zambia Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU) led by Frederick Chiluba, played a crucial role in advocating for political reform. Civil society organizations, students, and intellectuals also joined the clamor for change. In June 1990, riots erupted in Lusaka and other urban centers in protest against increases in the price of maize meal, a consequence of structural adjustment policies. These protests, though initially economic, quickly took on a political dimension, with demonstrators demanding multi-party democracy. The government's response, which included a crackdown and some fatalities, further galvanized the opposition.

In July 1990, the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD) was formed as a broad coalition of opposition groups, with Frederick Chiluba as its leader. The MMD campaigned vigorously for the re-introduction of multi-party politics. President Kaunda, facing unprecedented domestic and international pressure, including an attempted coup in 1990, eventually conceded to these demands. In December 1990, the constitution was amended to allow for multiple political parties.

Presidential and parliamentary elections were held in October 1991. These elections, generally considered free and fair, resulted in a landslide victory for the MMD. Frederick Chiluba defeated Kenneth Kaunda in the presidential race, and the MMD secured a large majority in the National Assembly. This marked a peaceful transfer of power and the end of 27 years of UNIP rule.

The transition to multi-party democracy was hailed as a significant step forward for Zambia. The new MMD government embarked on a program of further economic liberalization, including the privatization of remaining state-owned enterprises and efforts to attract foreign investment. However, the consolidation of democracy faced challenges, including navigating the complex socio-economic legacy of the previous era, managing political competition, strengthening democratic institutions, and addressing issues of governance and corruption that emerged under the new dispensation. Despite these challenges, the 1991 transition laid the foundation for a more pluralistic political system in Zambia.

3.5.4. Contemporary Zambia

Following the transition to multi-party democracy in 1991, Zambia has continued to navigate a complex political and socio-economic landscape. Frederick Chiluba's presidency (1991-2001) saw significant economic liberalization, including the privatization of many state-owned enterprises, most notably the copper mines. While these reforms aimed to revitalize the economy, they also led to job losses and social hardships for some. Governance under Chiluba was marred by allegations of widespread corruption and attempts to amend the constitution to allow him a third term, which were ultimately unsuccessful due to public and civil society pressure.

Levy Mwanawasa succeeded Chiluba in 2002, also from the MMD. Mwanawasa's presidency was notable for its strong anti-corruption drive, which targeted several high-profile figures from the previous administration. He also oversaw a period of economic growth, partly fueled by rising copper prices and increased foreign investment. Mwanawasa died in office in 2008. His vice-president, Rupiah Banda, became acting president and subsequently won the 2008 presidential election.

The 2011 general election saw a significant political shift, with Michael Sata of the Patriotic Front (PF) defeating Rupiah Banda. Sata's presidency focused on infrastructure development, often funded by Chinese loans, but also faced criticism regarding governance and shrinking democratic space. Sata also died in office, in October 2014. His vice-president, Guy Scott, a Zambian of Scottish descent, served as acting president, becoming the first white head of state in mainland Africa since F.W. de Klerk.

Edgar Lungu of the PF won the January 2015 presidential by-election and was re-elected in a tightly contested August 2016 general election, which was challenged by the opposition United Party for National Development (UPND) led by Hakainde Hichilema, citing allegations of fraud. Lungu's tenure was characterized by concerns over increasing authoritarian tendencies, restrictions on media freedom and opposition activities, and a growing national debt, partly due to large-scale infrastructure projects and borrowing. Economic challenges, including fluctuating copper prices and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, intensified. In November 2020, Zambia became the first African country to default on its sovereign debt during the pandemic era.

The 2021 general elections resulted in a decisive victory for Hakainde Hichilema and the UPND, with a high voter turnout. Hichilema, a long-time opposition leader, campaigned on a platform of economic reform, anti-corruption, and strengthening democratic institutions. Edgar Lungu conceded defeat, and Hichilema was sworn in as president in August 2021, marking another peaceful transfer of power. His administration has focused on debt restructuring, fiscal consolidation, attracting investment, and addressing governance and human rights issues.

Contemporary Zambia continues to grapple with challenges such as poverty, inequality, youth unemployment, and the need for sustainable and inclusive economic diversification. Ensuring the health of its democratic institutions, upholding human rights, and managing its natural resources for the benefit of all its citizens remain key priorities.

4. Geography

Zambia's geography is characterized by its landlocked position in Southern Africa, its generally high plateau landscape, diverse river systems, and tropical climate moderated by altitude. This section provides an overview of its topography, climate, and rich biodiversity.

4.1. Topography and River Systems

Zambia is a vast landlocked country in southern Africa, covering an area of approximately 291 K mile2 (752.61 K km2). Most of the country consists of a high plateau, with altitudes generally ranging from 3.3 K ft (1.00 K m) to 5.2 K ft (1.60 K m) above sea level. This plateau is interspersed with some hills and mountains and is dissected by numerous river valleys.

The country is drained by two major river basins: the Zambezi River basin and the Congo River basin.

The Zambezi basin covers about three-quarters of the country, primarily in the centre, west, and south. The Zambezi River itself is the most significant, flowing through western Zambia and then forming its southern border with Namibia, Botswana, and Zimbabwe. Its source is in Zambia, though it meanders into Angola before re-entering Zambia. Major tributaries of the Zambezi within or bordering Zambia include the Kabompo River, Lungwebungu River, Kafue River, and Luangwa River. The Kafue and Luangwa are the Zambezi's longest and largest tributaries flowing mainly within Zambia. The Zambezi is famous for the spectacular Victoria Falls (known locally as Mosi-oa-TunyaThundering SmokeLozi), located in the southwest corner of the country on the border with Zimbabwe. The falls drop about 328 ft (100 m) over a width of 1.0 mile (1.6 km). Downstream from the falls, the Zambezi flows into Lake Kariba, one of the world's largest artificial lakes, also shared with Zimbabwe. The Zambezi valley along the southern border is notably deep and wide.

The Congo basin drains the northern part of Zambia, covering about one-quarter of the country. The southernmost headstream of the Congo River rises in Zambia as the Chambeshi River. After passing through the extensive Bangweulu Swamps, it becomes the Luapula River, which forms part of Zambia's border with the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Luapula flows into Lake Mweru, another large lake shared with the DRC. The Luvua River drains Lake Mweru, eventually joining the Lualaba River (Upper Congo). Lake Tanganyika, one of the African Great Lakes, forms part of Zambia's northeastern border with Tanzania. The Kalambo River, which flows into Lake Tanganyika, features Kalambo Falls, Africa's second-highest uninterrupted waterfall.

The north of Zambia is generally flat with broad plains. The Barotse Floodplain in Western Province, on the Zambezi River, is a notable feature, flooding seasonally from December to June. This flooding profoundly influences the local ecology, society, and culture. In Eastern Zambia, the plateau between the Zambezi and Lake Tanganyika valleys tilts upwards to the north, rising from about 2953 ft (900 m) to 5.9 K ft (1.80 K m) near Mbala. The Mafinga Hills, an extension of the Nyika Plateau on the Malawi border, contain Zambia's highest point, Mafinga Central, at 7.7 K ft (2.34 K m). The Muchinga Mountains form a watershed between the Zambezi and Congo drainage basins and run parallel to the Luangwa Valley.

4.2. Climate

Zambia experiences a tropical climate, significantly modified by its generally high altitude. The average elevation of around 3.9 K ft (1.20 K m) gives the country a more moderate climate than its latitude might suggest. According to the Köppen climate classification, most of Zambia is classified as humid subtropical (Cwa) or tropical wet and dry (Aw). There are also small stretches of semi-arid steppe climate (BSh) in the extreme southwest and along parts of the Zambezi Valley.

There are two main seasons:

1. The Rainy Season: This season typically runs from November to April and corresponds to summer. It is characterized by warm to hot temperatures and significant rainfall, often in the form of afternoon thunderstorms. The intensity and duration of rainfall can vary regionally and from year to year.

2. The Dry Season: This season lasts from May/June to October/November and corresponds to winter and spring. It is further subdivided into:

- The Cool Dry Season (May/June to August): Temperatures are cooler, especially at night and in the early mornings. Frost can occasionally occur in some higher-altitude areas. Days are generally sunny and pleasant.

- The Hot Dry Season (September to October/November): Temperatures rise considerably during this period, leading up to the onset of the rains. It can be very hot and dry.

Average monthly temperatures remain above 68 °F (20 °C) over most of the country for eight or more months of the year. However, the high altitude provides relief from oppressive tropical heat, particularly during the cool dry season. Rainfall is highest in the north (around 0.0 K in (1.25 K mm) annually) and decreases southwards (around 28 in (700 mm) in Lusaka, and 20 in (500 mm) or less in the far south). The Zambezi Valley tends to be hotter and drier than the plateau areas.

4.3. Biodiversity and Conservation

Zambia boasts a rich and diverse array of flora and fauna, supported by its varied ecosystems, which include miombo woodlands (the dominant vegetation type), grasslands, wetlands (dambos), and various forest and thicket types. The country is home to an estimated 3,543 species of wild flowering plants, with the Northern and North-Western provinces exhibiting the highest plant diversity. Approximately 53% of these flowering plant species are considered rare.

The mammalian fauna is also diverse, with around 242 recorded species. Well-known African megafauna such as elephants, lions, leopards, buffalo, hippopotami, and various antelope species are found within its protected areas. Notable subspecies endemic or near-endemic to Zambia include the Thornicroft's giraffe (Rhodesian giraffe) and the Kafue lechwe, an antelope adapted to floodplain environments.

Zambia is a prime destination for birdwatching, with an estimated 757 bird species recorded. Of these, around 600 are resident or Afrotropical migrants, and approximately 470 species breed within the country. The Zambian barbet is a species endemic to Zambia. The country's extensive river systems and lakes support a rich fish fauna, with roughly 490 known fish species from 24 families. Lake Tanganyika is particularly noted for its high number of endemic fish species, especially cichlids.

Wildlife conservation is a significant focus in Zambia. The country has established a network of 20 National Parks and 34 Game Management Areas (GMAs), which together cover a substantial portion of its land area. Prominent national parks include South Luangwa National Park, Kafue National Park (one of Africa's largest), Lower Zambezi National Park, and North Luangwa National Park. These areas are crucial for protecting biodiversity and supporting the tourism industry, which is an important source of revenue.

Despite these efforts, Zambia faces environmental challenges, including deforestation (due to agriculture, charcoal production, and logging), poaching for ivory and bushmeat, habitat loss, and human-wildlife conflict. Climate change also poses a threat to its ecosystems and agricultural sector. Governmental bodies like the Zambia Wildlife Authority (ZAWA), now part of the Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW), along with various non-governmental organizations and community-based conservation initiatives, work towards sustainable resource management and the protection of Zambia's natural heritage. Ensuring that local communities benefit from conservation efforts is increasingly recognized as vital for long-term success and for promoting social equity in resource use.

5. Politics

Zambia's political system operates within the framework of a presidential republic and a multi-party democracy. This section details the structure of its government, administrative divisions, foreign policy, military, and the human rights situation, with a focus on democratic development and accountability.

5.1. Government Structure

Zambia is a presidential representative democratic republic. The President of Zambia is both the head of state and head of government. The President is elected by popular vote for a five-year term and is eligible for a second term. The executive branch also includes the Vice-President and the Cabinet, whose ministers are appointed by the President, typically from among the members of the National Assembly. The government exercises executive power.

Legislative power is vested in the unicameral National Assembly. It consists of 156 members elected by popular vote from single-member constituencies for five-year terms, plus up to eight members nominated by the President, and the Speaker. The National Assembly is responsible for enacting laws, overseeing government expenditure, and holding the executive accountable.

The judiciary is, in principle, independent of the executive and legislative branches. The highest court of appeal is the Supreme Court of Zambia. Other courts include the High Court, subordinate courts (magistrate courts), and local courts that handle customary law matters. A separate Constitutional Court was established in 2016 to deal with matters related to the interpretation of the constitution.

Elections in Zambia are managed by the Electoral Commission of Zambia (ECZ). Since the re-introduction of multi-party politics in 1991, Zambia has held several presidential and parliamentary elections, which have seen peaceful transfers of power between different political parties, including the United National Independence Party (UNIP), the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD), the Patriotic Front (PF), and the United Party for National Development (UPND). While generally peaceful, some elections have been marred by disputes over results and allegations of irregularities, highlighting ongoing challenges in consolidating democratic processes and ensuring electoral integrity.

5.2. Administrative Divisions

Zambia is administratively divided into ten provinces. Each province is headed by a Provincial Minister, appointed by the President. The provinces are further subdivided into districts; as of recent administrative changes, there are 117 districts. Each district is administered by a District Commissioner, also appointed by the President.

The ten provinces are:

# Central Province

# Copperbelt Province

# Eastern Province

# Luapula Province

# Lusaka Province

# Muchinga Province

# North-Western Province

# Northern Province

# Southern Province

# Western Province

Local governance is carried out through city, municipal, and district councils. Councilors are elected, and mayors or council chairpersons are elected by the councilors. The system of local government aims to promote citizen participation in development and governance at the local level, but it often faces challenges related to funding, capacity, and the degree of autonomy from the central government. Efforts towards decentralization have been ongoing, with the aim of devolving more power and resources to local authorities to improve service delivery and local development, thereby promoting social justice and more equitable resource distribution.

5.3. Foreign Relations

Zambia's foreign policy since independence has been characterized by its commitment to Pan-Africanism, support for decolonization and liberation movements in Southern Africa, and adherence to principles of non-alignment during the Cold War. Under President Kenneth Kaunda, Zambia played a pivotal role as a Frontline State, actively opposing white minority rule in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), apartheid in South Africa, and Portuguese colonialism in Angola and Mozambique. Lusaka hosted the headquarters of several liberation movements, including the African National Congress (ANC) of South Africa. This stance, while earning Zambia respect across Africa and internationally, also brought significant economic and security costs due to reprisals from neighboring minority-ruled regimes.

Zambia is an active member of numerous international and regional organizations, including the United Nations (UN), the African Union (AU), the Commonwealth of Nations, the Southern African Development Community (SADC), and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), whose headquarters are in Lusaka. Zambia has contributed to UN peacekeeping missions and has often played a mediatory role in regional conflicts.

Contemporary Zambian foreign policy continues to prioritize regional cooperation and integration, peace and security in Southern Africa, and economic development through international partnerships. The country maintains diplomatic relations with a wide range of nations globally. In its international dealings, Zambia often advocates for fair trade practices, debt relief for developing countries, and increased development assistance. Issues of human rights and good governance are increasingly important in its relationships with international partners and donor countries. Zambia seeks to attract foreign investment and promote trade to support its economic diversification efforts, while also aiming to ensure that international partnerships are equitable and contribute to sustainable development and the welfare of its citizens. The country has also engaged with emerging global powers, such as China, which has become a significant economic partner, particularly in infrastructure development and mining, though this relationship has also raised discussions regarding debt sustainability and labor practices.

5.4. Military

The Zambian Defence Force (ZDF) is the military organization responsible for the territorial defence of Zambia. It consists of three main branches: the Zambia Army (ZA), the Zambia Air Force (ZAF), and the Zambia National Service (ZNS). The President of Zambia is the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces. The ZDF's primary mandate is to defend the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Zambia against external aggression, although it can also be deployed for internal security operations if required.

The Zambia Army is the land component of the ZDF, responsible for ground operations.

The Zambia Air Force provides air support and defence capabilities. Its inventory has historically included aircraft sourced from various countries, including China and Russia.

The Zambia National Service (ZNS) is a paramilitary wing involved in national development projects, agricultural production, and skills training for youths, in addition to its defence roles.

Zambia's military has been involved in regional peacekeeping operations under the auspices of the United Nations and the African Union. Zambian troops have served in missions in countries such as the Central African Republic (MINUSCA). This participation reflects Zambia's commitment to regional peace and stability.

As a landlocked country, Zambia does not have a navy, but the Zambia Army maintains a small maritime patrol unit for operations on its inland waters, such as lakes and large rivers. Military expenditure as a percentage of GDP has varied over the years, influenced by the country's economic situation and perceived security threats.

In terms of international treaties, Zambia signed the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in 2019, underscoring its commitment to nuclear disarmament. The ZDF's development and modernization efforts often involve partnerships with other countries for training and equipment. The military also plays a role during national emergencies and disaster relief operations. The principles of civil-military relations in Zambia aim to ensure that the armed forces remain subordinate to civilian democratic control.

5.5. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Zambia presents a mixed picture, with constitutional guarantees often challenged by practical realities. While Zambia has made strides in democratic development since its transition to multi-party politics in 1991, concerns persist regarding the full enjoyment of civil and political liberties, as well as socio-economic rights, particularly for vulnerable and marginalized groups.

- Freedom of Expression, Assembly, and the Press:** The Zambian constitution protects freedom of expression and assembly. However, these rights have faced restrictions. The government has, at times, been sensitive to criticism, and legal instruments such as defamation laws have been used in ways that can stifle free speech and independent media. State-owned media outlets have often been perceived as biased towards the ruling party, while private media have faced pressures, including regulatory challenges and occasional harassment. Peaceful assembly and protests are generally permitted but have sometimes been met with restrictions or heavy-handed responses from authorities.

- Rights of Minorities, Women, and Vulnerable Groups:** Zambia is ethnically diverse, and inter-ethnic relations are generally peaceful. However, ensuring equitable representation and addressing potential discrimination against minority ethnic groups remain important. Women in Zambia face challenges related to gender inequality, including disparities in education, economic opportunities, and political representation, as well as issues of gender-based violence. The rights of children, persons with disabilities, and the elderly also require ongoing attention to ensure their protection and inclusion.

- LGBT Rights:** Same-sex sexual activity is illegal in Zambia for both males and females under colonial-era laws, and individuals face significant social stigmatization. There is limited public or political support for LGBT rights, and advocacy for these rights is challenging. In 2019, remarks by the then-US Ambassador Daniel Lewis Foote criticizing the sentencing of a same-sex couple to 15 years in prison led to a diplomatic row, with the Zambian government declaring him persona non grata, highlighting the sensitivity of this issue.

- Conditions in Detention:** Overcrowding, poor sanitation, and inadequate medical care are persistent problems in Zambian prisons and detention centers, falling short of international human rights standards. Efforts to reform the penal system and improve conditions are ongoing but face resource constraints.

- Access to Justice:** While the judiciary is constitutionally independent, access to justice can be challenging for many Zambians, particularly those in rural areas or from low-income backgrounds, due to costs, distance to courts, and a backlog of cases.

- Role of Human Rights Institutions and Civil Society:** The Zambian Human Rights Commission is a state institution mandated to promote and protect human rights. Numerous non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society groups actively work on human rights advocacy, monitoring, legal aid, and public education. These organizations play a crucial role in holding the government accountable and advocating for reforms.

Successive governments have expressed commitment to upholding human rights, but consistent implementation and the strengthening of democratic institutions are vital to ensure these commitments translate into tangible improvements for all Zambians, reflecting a genuine concern for democratic values and the welfare of all citizens.

6. Economy

Zambia's economy, classified as a lower-middle-income country, has traditionally been dominated by copper mining. The nation faces ongoing challenges in diversifying its economic base, reducing poverty, and ensuring sustainable and inclusive growth for its population. This section analyzes its economic structure, performance, key sectors, and development hurdles, emphasizing the need for policies that promote social equity and sustainable practices.

6.1. Overview and Structure

Zambia's economy has experienced periods of growth, particularly when global copper prices are high, but also significant downturns. As of recent years, its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has been subject to fluctuations based on copper markets, agricultural output, and global economic conditions. Key economic indicators include GDP growth rate, inflation, employment levels, and balance of trade. In 2022, Zambia's exports were estimated to be between 7.50 B USD and 8.00 B USD annually, reaching 9.10 B USD in 2018.

The mining sector, particularly copper and cobalt, remains a cornerstone of the economy, contributing significantly to export revenues and GDP. However, this reliance makes Zambia vulnerable to commodity price volatility. Recognizing this, successive governments have emphasized economic diversification. Key areas targeted for growth include agriculture, manufacturing, tourism, and energy.

Challenges include a high national debt burden, which led to a sovereign default in 2020, the first African country to do so during the COVID-19 pandemic. Efforts are underway for debt restructuring and fiscal consolidation. Inflation has been a persistent concern, impacting the cost of living. Unemployment and underemployment, especially among the youth, are significant social and economic issues.

The Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) is headquartered in Lusaka, highlighting Zambia's role in regional economic integration. The government is actively seeking foreign direct investment and promoting private sector development to spur growth and create jobs. Policies are also aimed at improving the business environment, though challenges related to bureaucracy and corruption persist. Zambia was ranked 116th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.

6.2. Poverty and Social Equity

Despite its natural resource wealth, Zambia faces significant challenges with poverty and inequality. According to 2015 data, about 54.4% of the population lived below the national poverty line, an improvement from 60.5% in 2010. However, poverty remains widespread, particularly in rural areas, where the rate was about 76.6%, compared to 23.4% in urban areas. The national poverty line in 2015 was ZMK 214 (approximately 12.85 USD at the time) per month. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) estimated in 2018 that 47.9% of the population was affected by multidimensional poverty, which considers various deprivations in health, education, and living standards.

Income inequality is also a major concern, with a significant gap between the rich and the poor. Access to essential social services such as quality healthcare, education, clean water, and sanitation is often limited, especially for marginalized communities, including those in remote rural areas, female-headed households, and persons with disabilities.

Government policies and initiatives aimed at poverty reduction and enhancing social equity include social cash transfer programs designed to support the most vulnerable households, investments in education and healthcare, and programs to promote agricultural productivity among small-scale farmers. Civil society organizations play a crucial role in advocating for the rights of the poor and marginalized, providing services, and monitoring the impact of government policies.

Addressing poverty and social equity requires sustained efforts in promoting inclusive economic growth that creates decent employment opportunities, strengthening social protection systems, improving governance and reducing corruption, and ensuring equitable access to resources and opportunities. The focus on vulnerable groups is critical for achieving social justice and sustainable development goals.

6.3. Mining

The mining sector, particularly copper and cobalt production, is a dominant feature of the Zambian economy, historically serving as its primary engine of growth and main source of export revenue. In 2019, mining and quarrying accounted for approximately 13.2% of Zambia's GDP, and copper exports constituted about 69% of the total value of Zambian goods exported. Zambia is one of the world's largest copper producers, typically ranking as the second-largest in Africa and among the top ten globally, accounting for around 4% of global production. In 2023, Zambia produced 698,000 metric tons of copper.

The Copperbelt Province in northern Zambia is the heart of the country's mining industry and accounts for a significant portion of the national GDP and nearly all copper production. Major mining towns include Kitwe, Ndola, Mufulira, and Chingola. The industry was nationalized in 1973 under Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines (ZCCM), but production declined under state control. Following privatization between 1996 and 2000, there was a resurgence in investment, production, and employment in the sector, driven by foreign mining companies. The state-owned ZCCM Investments Holdings (ZCCM-IH) retains minority stakes in several mining operations and is involved in partnerships, such as with Mopani Copper Mines (majority-owned by International Holding Company of the UAE) and operations by Vedanta Resources and First Quantum Minerals.

Besides copper and cobalt, Zambia also mines other minerals, including gold (e.g., at Kansanshi mine), manganese (e.g., Serenje mine), and nickel (e.g., Munali mine). The country is also a producer of gemstones, notably high-quality emeralds, amethyst, beryl, and tourmaline.

While mining is crucial for revenue and employment, it also presents significant social and environmental challenges. These include concerns about labor rights and working conditions (highlighted by past issues at Chinese-operated mines like the Collum Coal Mine), the equitable sharing of benefits with local communities, environmental degradation (such as water pollution and land disturbance), and the "resource curse" phenomenon where over-reliance on a single commodity can hinder broader economic development. Government policies aim to maximize revenue from the sector through taxation and royalties, promote local content and value addition, and enforce environmental and social safeguards. The fluctuating nature of global copper prices also poses a significant risk to Zambia's economic stability, reinforcing the need for economic diversification.

6.4. Agriculture

Agriculture is a vital sector in Zambia's economy, providing livelihoods for a majority of the population, especially in rural areas, and contributing significantly to employment, more so than the mining industry. The sector comprises a mix of small-scale subsistence farmers, who form the majority, and larger commercial farms.

Major food crops include maize (the primary staple food), cassava, sorghum, millet, sweet potatoes, and groundnuts. Cash crops include tobacco, cotton, sugarcane, soybeans, coffee, and horticultural products like flowers and vegetables, some of which are exported. The livestock sub-sector includes cattle, poultry, pigs, and goats. Fisheries, both from natural water bodies and aquaculture, are also important for food security and income.

Food security remains a key challenge, influenced by factors such as rainfall patterns (with increasing vulnerability to climate change-induced droughts and floods), access to inputs (seeds, fertilizers), credit, extension services, and markets for smallholder farmers. Land tenure issues can also be complex, with traditional land ownership systems coexisting with state leasehold systems.

Government policies have aimed to boost agricultural productivity and sustainability. These include input subsidy programs (like the Farmer Input Support Programme - FISP), investment in irrigation, research and development, and efforts to improve market access. There has been a notable increase in agricultural output in recent decades. For example, following land reforms and the influx of experienced commercial farmers (including some white Zimbabwean farmers invited to Zambia in the early 2000s), Zambia significantly increased its maize production, becoming a net exporter of corn in some years.

Diversification within the agricultural sector is encouraged, moving beyond maize dependency to other crops and livestock to enhance resilience and income opportunities. Promoting agribusiness and value addition to agricultural products are also seen as crucial for economic development and job creation. Sustainable farming practices that conserve soil and water resources are increasingly important in the face of environmental challenges. Ensuring that agricultural development benefits small-scale farmers and contributes to poverty reduction and improved nutrition for vulnerable populations are key objectives from a social equity perspective. In December 2019, the Zambian government legalized cannabis cultivation for medicinal and export purposes, aiming to tap into a new agricultural market.

6.5. Tourism

Tourism is a significant and growing sector in Zambia's economy, with the potential to contribute further to economic diversification, employment creation, and foreign exchange earnings. The country offers a diverse range of attractions, primarily centered around its abundant wildlife, pristine national parks, and natural wonders like the Victoria Falls. In 2021, tourism accounted for 5.8% of Zambia's GDP, with a record high of 9.8% in 2019 before the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key attractions include:

- Victoria Falls (Mosi-oa-Tunya - "The Smoke that Thunders"): One of the Seven Natural Wonders of the World, these spectacular falls on the Zambezi River are shared with Zimbabwe. The town of Livingstone serves as Zambia's main tourist hub for the falls, offering a variety of adventure activities such as white-water rafting, bungee jumping, and wildlife viewing.

- National Parks: Zambia has 20 national parks and 34 game management areas (GMAs) that are home to a rich array of wildlife.

- South Luangwa National Park: Famous for its walking safaris and high concentrations of leopards, elephants, hippos, and diverse birdlife.

- Kafue National Park: One of Africa's largest parks, offering vast wilderness and diverse habitats, home to cheetahs, wild dogs, and numerous antelope species.

- Lower Zambezi National Park: Known for its stunning riverine scenery, canoeing safaris, and opportunities to see elephants, buffalo, and predators along the Zambezi River.

- North Luangwa National Park: A more remote and wild park, also renowned for walking safaris.

- Liuwa Plain National Park: Famous for Africa's second-largest wildebeest migration and its unique, vast landscapes.

- Cultural Tourism: Opportunities exist to experience Zambia's diverse cultures through traditional ceremonies (like the Kuomboka ceremony of the Lozi people), village visits, and local arts and crafts.

The Zambian government has identified tourism as a priority sector for development. Strategies focus on promoting sustainable tourism practices that conserve the natural and cultural heritage while ensuring that local communities benefit from tourism revenues. This includes community-based tourism initiatives and efforts to improve infrastructure, such as airports, roads, and accommodation facilities. Challenges include the need for greater investment, marketing, skills development, and ensuring that tourism development is environmentally and socially responsible. The sector's growth aims to provide alternative livelihoods, reduce poverty in rural areas, and support conservation efforts through revenue generation.

6.6. Energy

Zambia's energy sector is predominantly reliant on hydroelectricity, which has historically provided the bulk of its electricity supply. The country has significant hydropower potential due to its numerous rivers and favorable topography. However, this reliance also makes the energy supply vulnerable to hydrological variations, particularly droughts, which can impact water levels in dams.

Key aspects of Zambia's energy sector include:

- Hydropower:** Major hydropower stations include the Kariba Dam (North Bank, shared with Zimbabwe on the Zambezi River), Kafue Gorge Dam, and Itezhi-Tezhi Dam. In 2009, Zambia generated 10.3 TWh of electricity, with hydropower being a major component.

- Energy Infrastructure:** The state-owned utility, ZESCO (Zambia Electricity Supply Corporation Limited), is responsible for most of the generation, transmission, and distribution of electricity. The national grid serves urban areas and industrial consumers, particularly the mining sector, which is a large consumer of electricity.

- Access to Electricity:** Access to electricity remains a challenge, especially in rural areas. While urban electrification rates are higher, many rural communities lack access to the national grid, relying on traditional biomass (firewood, charcoal) for energy needs, which contributes to deforestation and health issues.

- Challenges in Energy Supply:** Zambia has experienced periods of energy shortages (loadshedding), particularly when poor rainfall affects hydropower generation, as was the case in the mid-2010s. This impacts households, businesses, and industrial output, including mining. The need for investment in maintaining and expanding generation, transmission, and distribution infrastructure is ongoing.

- Renewable Energy Development:** Recognizing the vulnerabilities of over-reliance on hydropower and the need for energy security and environmental sustainability, Zambia is increasingly focusing on developing other renewable energy sources. Solar power has significant potential due to high solar irradiation levels across the country. Several solar projects have been initiated, including utility-scale solar farms and off-grid solutions. Wind power potential is also being explored. In September 2019, African Green Resources (AGR) announced a 150.00 M USD investment in a 50 MW solar farm.

- Petroleum:** Zambia is dependent on imported petroleum products (petrol, diesel, kerosene), which are transported via the Tazama Pipeline from Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, or by road and rail. Fluctuations in global oil prices significantly impact the domestic cost of fuel.

- Biomass:** Traditional biomass (firewood and charcoal) remains the primary source of energy for a large portion of the population, particularly for cooking and heating in rural and low-income urban households. This reliance contributes to deforestation and indoor air pollution.

Government policies aim to diversify the energy mix, improve energy efficiency, expand access to modern energy services, attract private sector investment in the energy sector, and ensure a reliable and affordable energy supply to support economic and social development.

7. Demographics

Zambia's population is characterized by its youthfulness, ethnic diversity, and significant urbanization. This section covers population trends, ethnic composition, languages, religion, education, and health, with a focus on social equity and the well-being of its diverse communities.

7.1. Population Trends and Urbanization

As of the 2022 Zambian census, Zambia's population was 19,610,769, a significant increase from 13,092,666 recorded in the 2010 census. The country has a high population growth rate, largely due to a high fertility rate, which was 6.2 children per woman as of 2007, though this has been gradually declining. The population is predominantly young, with a large proportion of children under the age of 15. This youthful age structure presents both opportunities (a large future workforce) and challenges (the need for sufficient education, healthcare, and employment opportunities).

Population density varies across the country, with rural areas being sparsely populated compared to urban centers. Zambia is one of the most urbanized countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Approximately 44% of the population lives in urban areas, primarily concentrated along the main transport corridors, especially in the capital city, Lusaka, and the Copperbelt Province cities such as Ndola, Kitwe, and Chingola. This urbanization trend began with the development of copper mining in the late 1920s and continued post-independence. While rapid urbanization offers economic opportunities, it also places strain on urban infrastructure and services, leading to challenges such as informal settlements, unemployment, and pressure on housing, water, and sanitation.

Historically, during the colonial period (1911-1963), Zambia attracted immigrants from Europe and the Indian subcontinent. While many Europeans left after independence, a significant Asian community, primarily of Indian and, more recently, Chinese descent, remains and plays an active role in the economy.

7.2. Ethnic Groups

Zambia is a culturally diverse nation, home to approximately 73 distinct ethnic groups, the vast majority of whom are Bantu-speaking. Despite this diversity, inter-ethnic relations are generally peaceful, often attributed to the national motto "One Zambia, One Nation," promoted since independence to foster unity.

The main ethnic groups, based on linguistic affiliation and population estimates (which can vary), include:

- Bemba**: Predominantly found in the Northern, Luapula, Muchinga, and Copperbelt provinces. They are one of the largest ethnic groups. (Approx. 21-33% of the population, depending on classification)

- Nyanja** (also closely related to or including Chewa): Predominant in the Eastern and Lusaka provinces. (Approx. 14-18%)

- Tonga**: Primarily inhabit the Southern and parts of Central and Western provinces. (Approx. 13-17%)

- Lozi** (or Barotse): Concentrated in the Western Province, with a distinct historical kingdom and cultural traditions like the Kuomboka ceremony. (Approx. 5-7%)

- North-Western Peoples**: This category includes groups like the Lunda, Luvale, and Kaonde, who inhabit the North-Western Province. (Collectively approx. 10%)

- Tumbuka**: Found mainly in the Eastern Province, near the border with Malawi. (Approx. 4-5%)

- Nsenga**: Primarily in the Eastern Province. (Approx. 5%)

- Ngoni**: Descendants of 19th-century migrants from Southern Africa, found in the Eastern Province. (Approx. 4%)

- Lamba**: Found in the Copperbelt and Central provinces.

Smaller communities and other groups make up the remainder of the population. Tribal identities, often linked to family allegiance and traditional leadership structures, remain relevant within these broader linguistic classifications.

In addition to indigenous African groups, Zambia has a small but economically significant population of citizens and residents of Asian descent (primarily Indian and Chinese), and a smaller number of Europeans. There is also a minority of people of mixed heritage. Zambia has also hosted refugees from neighboring countries, contributing to its demographic makeup. The emphasis on inclusivity aims to ensure that all ethnic groups contribute to and benefit from national development.

7.3. Languages

Zambia has a rich linguistic landscape, with numerous indigenous languages spoken alongside the official language. While often cited as having around 73 languages and/or dialects, the number of distinct languages based on mutual intelligibility is likely closer to 20 or 30.

- Official Language**: English is the official language of Zambia. It is used in government administration, the legal system, business, education (as the medium of instruction), and the media. Proficiency in English is generally higher in urban areas and among those with formal education.

- Indigenous Languages**: The vast majority of Zambians speak one or more indigenous Bantu languages. Seven of these are officially recognized as regional languages for purposes such as primary education and media broadcasts by the Zambia National Broadcasting Corporation (ZNBC). These are:

- Bemba: Widely spoken, especially in the Northern, Luapula, Muchinga, and Copperbelt provinces. It is a lingua franca in many urban areas of the Copperbelt.

- Nyanja (also known as Chewa or ChiNyanja): Predominant in Lusaka and the Eastern Province. It serves as a major lingua franca in the capital and other parts of the country.

- Tonga (ChiTonga): Spoken primarily in the Southern and parts of Central and Western provinces.

- Lozi (SiLozi): Spoken mainly in the Western Province.

- Lunda (ChiLunda): Spoken in the North-Western Province.

- Luvale: Also spoken in the North-Western Province.

- Kaonde: Spoken in parts of North-Western and Central provinces.

Other significant indigenous languages include Tumbuka, Nsenga, and Lamba. Most Zambians are multilingual, typically speaking their local ethnic language, a regional lingua franca, and English. Urbanization has led to the evolution of urban dialects and slang, incorporating words from various languages.

Due to historical and regional connections, Portuguese has been introduced as an optional foreign language in some schools, partly due to the presence of a significant Angolan community. French and German are also taught in some educational institutions. The use of local languages in education, media, and public life is important for cultural preservation and effective communication, especially in promoting access to information for all citizens.

7.4. Religion

Zambia is officially declared a "Christian nation" in the preamble of its 1996 constitution, yet it also guarantees freedom of religion for all its citizens. Christianity is the dominant religion, practiced by a large majority of the population.

According to estimates from the Zambia Statistics Agency (based on the 2010 census and subsequent data), approximately 95.5% of Zambians identify as Christian. This Christian population is diverse:

- Protestant**: Comprising about 75.3% of the population, this includes a wide array of denominations such as Anglican, Evangelical, Pentecostal, Seventh-day Adventist, New Apostolic Church, Lutheran, Baptist, and various independent churches. Pentecostal and Evangelical churches, in particular, have seen significant growth in recent decades. Zambia has one of the largest Seventh-day Adventist communities per capita in the world.

- Roman Catholic**: Accounting for about 20.2% of the population. The Catholic Church has a significant presence with dioceses across the country.

Many Zambian Christians incorporate elements of indigenous religious beliefs and practices into their Christian faith, a phenomenon known as syncretism.

Other religions and belief systems present in Zambia include:

- Islam**: Practiced by approximately 0.5% to 2.7% of the population (estimates vary). Muslims are primarily Sunni, with smaller Ismaili and Twelver Shia communities. The Muslim population includes Zambians of Asian descent, immigrants from other African countries, and local converts. They are mostly concentrated in urban areas.

- Hinduism**: Practiced by a small community, primarily Zambians of South Asian ancestry, numbering around 10,000.

- Baháʼí Faith**: Zambia has a notable Baháʼí community, one of the larger ones in Africa relative to its population.

- Traditional Beliefs**: While many adhere to Christianity or Islam, traditional spiritual beliefs and practices related to ancestors, spirits, and communal rituals continue to influence the worldview and daily lives of many Zambians, often coexisting with Abrahamic faiths. About 2.5% may primarily identify with traditional beliefs.

- Other Faiths**: Small numbers of Buddhists, Sikhs, and individuals adhering to other faiths, or no religion (around 1.8% atheist/agnostic), are also present.

- Judaism**: A very small Jewish community, historically mostly of Ashkenazi origin, exists, primarily in Lusaka.

Religious communities generally coexist peacefully in Zambia. Religious institutions often play a significant role in social service provision, including education and healthcare, contributing to the welfare of communities across the country.

7.5. Education