1. Overview

Italy, officially the Italian Republic (Repubblica Italianareˈpubblika itaˈljaːnaItalian), is a country located in Southern Europe, with a portion also considered part of Western Europe. It consists of a peninsula extending into the Mediterranean Sea, the major islands of Sicily and Sardinia, and numerous smaller islands. Italy shares its northern alpine boundary with France, Switzerland, Austria, and Slovenia, and encompasses the enclaved microstates of Vatican City and San Marino. With a rich history that includes the rise and fall of the Roman Empire, the flourishing of the Italian Renaissance, and the complexities of unification and modern conflicts, Italy has profoundly shaped Western civilization. Its geography is diverse, ranging from the Alpine peaks to extensive coastlines and volcanic regions. Italy operates as a unitary parliamentary republic, and its political system has evolved significantly, particularly in the post-World War II era, marked by democratic development and European integration. The Italian economy is a major global and European force, known for its industrial strength, particularly in manufacturing and design, though it faces challenges such as regional disparities and public debt. Italian society is characterized by a rich cultural heritage, a complex demographic profile including an aging population and significant immigration, and a strong emphasis on family, regional identity, and traditions. The nation's cultural contributions in art, architecture, literature, music, fashion, and cuisine are globally renowned, reflecting a deep historical legacy and ongoing innovation, which this article explores from a center-left perspective, emphasizing social equity, democratic values, and human rights.

2. Name

The etymology of the name "Italia" is subject to various hypotheses and has evolved over millennia. One prominent theory suggests that the name Italia derives from the Oscan term Víteliú, meaning "land of young cattle" or "calf-land" (cognate with Latin vitulus for "calf" and Umbrian vitlo for "calf"). This term was supposedly adopted by Greek settlers who encountered Italic tribes, possibly the Italói, in the southern part of the peninsula, a region now known as Calabria. The bull or calf was a symbolic animal for these southern Italic tribes and was sometimes depicted goring the Roman wolf, symbolizing defiance during events like the Social War.

Ancient authors like Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Aristotle, and Thucydides also mentioned that the land was named after a legendary king named Italus. Initially, the Greek term for Italy referred only to the southern tip of the Bruttium peninsula (modern Calabria) and parts of what are now the provinces of Catanzaro and Vibo Valentia. The concept of "Italy" gradually expanded northward. The term Oenotria (land of wine) also became synonymous with this early Italia, and the name soon applied to most of Lucania as well.

Before the Roman Republic's expansion, Greek writers used "Italia" to denote the land between the Strait of Messina and the line connecting the Gulf of Salerno and the Gulf of Taranto, roughly corresponding to present-day Calabria. As Roman influence grew, the geographical scope of "Italia" expanded. In addition to the "Greek Italy" in the south, some historians suggest the notion of an "Etruscan Italy" encompassing areas of central Italy under Etruscan influence.

The borders of Roman Italy, or Italia, became more clearly defined over time. Cato's Origines described Italy as the entire peninsula south of the Alps. By 264 BC, Roman Italy extended from the Arno and Rubicon rivers in the north-central region to the entire south. The northern area of Cisalpine Gaul, though geographically part of the Italian landmass and occupied by Rome in the 220s BC, was initially politically separate. It was legally incorporated into the administrative unit of Italy in 42 BC by Octavian (later Emperor Augustus). Diocletian further expanded the administrative definition of Italia in 292 AD to include the islands of Sardinia, Corsica, Sicily, and Malta, making late-ancient Italy largely coterminous with the modern Italian geographical region.

The Latin term Italicus was used to describe "a man of Italy," distinguishing him from a provincialis (an inhabitant of a Roman province). The adjective italianus, from which the English "Italian" is derived, originated in Medieval Latin and was used interchangeably with Italicus during the early modern period. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy was established. Following the Lombard invasions, "Italia" was retained as the name for their kingdom and its successor, the Kingdom of Italy within the Holy Roman Empire. This historical continuity of the name "Italia" reflects the peninsula's enduring identity, even through periods of political fragmentation, eventually culminating in the modern unified state.

3. History

The history of the Italian peninsula is a long and complex narrative, stretching from early human settlements through the rise and fall of major civilizations, periods of fragmentation and foreign influence, the cultural brilliance of the Renaissance, the struggles for unification, and the challenges and transformations of the modern era. This historical arc includes the development of ancient Italic peoples, the dominance of Rome, the societal shifts of the Middle Ages, the artistic and intellectual rebirth of the Renaissance, the turbulent path to national unity, the dark chapter of Fascism and World War II, and the subsequent establishment and evolution of the Italian Republic, with an emphasis on democratic progress and social justice.

3.1. Prehistory and antiquity

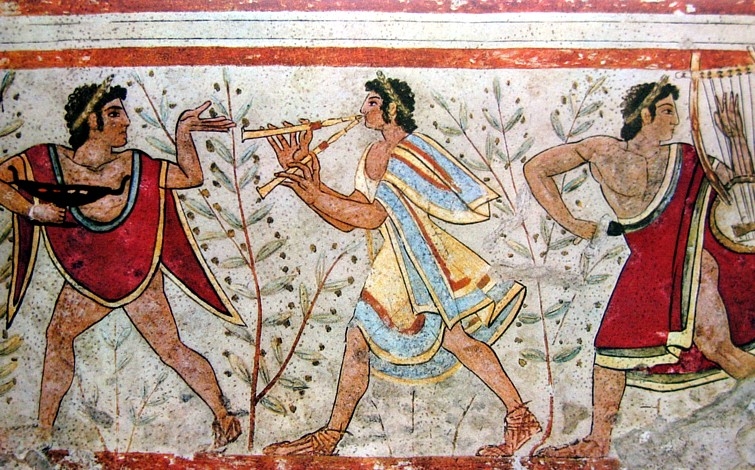

This section details the earliest inhabitants of the Italian peninsula, including Lower Paleolithic settlements, the emergence of various Italic peoples, the influential Etruscan civilization, the significant impact of Greek colonisation in Magna Graecia, and other pre-Roman cultures that laid the groundwork for later developments.

The Italian peninsula has been inhabited since prehistoric times. Lower Paleolithic artifacts, dating back as far as 850,000 years, have been discovered at sites like Monte Poggiolo. Evidence of Neanderthal presence during the Middle Paleolithic period, around 200,000 years ago, has been found throughout Italy. Modern humans (Homo sapiens) are believed to have appeared in the region approximately 40,000 years ago, with significant remains found at Riparo Mochi.

The ancient peoples of pre-Roman Italy were diverse. Many were Indo-European, particularly the Italic peoples such as the Latins, Oscans, Umbrians, and Samnites. However, there were also significant populations with possible non-Indo-European or pre-Indo-European origins. Among these were the Etruscans in Tuscany, whose civilization flourished from the 8th to the 1st century BC, leaving a rich legacy in art, engineering, and societal organization. In Sicily, the Elymians and Sicani were early inhabitants. The prehistoric Sardinians developed the unique Nuragic civilisation, characterized by its distinctive stone towers (nuraghi). Other ancient groups included the Rhaetian people in the Alpine regions and the Camunni, known for their extensive rock art in Valcamonica, a UNESCO World Heritage site. The discovery of Ötzi, a well-preserved natural mummy from the Copper Age (dated between 3400 and 3100 BC), in the Similaun glacier in the Alps in 1991, provided invaluable insights into early European life.

Starting in the 8th century BC, Phoenicians established trading posts and emporia along the coasts of Sicily and Sardinia. Some of these settlements evolved into small urban centers, developing alongside the Greek colonies. Around the same time, from the 8th to the 7th centuries BC, Greeks began a significant wave of colonization, establishing numerous city-states primarily in Southern Italy and Sicily. This area became known as Magna Graecia ("Great Greece") and included powerful cities like Syracuse, Tarentum (Taranto), Neapolis (Naples), and Rhegium (Reggio Calabria). Ionians, Doric colonists, Syracusans, and Achaeans were among the groups founding these cities. This Greek colonization had a profound impact, bringing the Italic peoples into direct contact with advanced forms of democratic government, sophisticated artistic traditions, and rich cultural expressions, deeply influencing the subsequent development of the peninsula.

3.2. Ancient Rome

This section traces the trajectory of Rome, from its mythical founding and early monarchical period, through the expansionist Roman Republic, the establishment and apogee of the Roman Empire, its vast influence over the Mediterranean world and beyond, and its eventual decline, division, and the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

Ancient Rome, traditionally founded in 753 BC as a small settlement on the banks of the River Tiber in central Italy, was initially ruled by a monarchical system for 244 years. In 509 BC, according to tradition, the Romans expelled their last king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, and established an oligarchic republic, a government of the Senate and the People (SPQR).

The Italian Peninsula, then referred to as Italia, was gradually consolidated under Roman control through a series of conflicts and alliances. This Roman expansion often came at the expense of other Italic tribes (such as in the Samnite Wars), the Etruscans, Celts in the north, and the Greek city-states of Magna Graecia in the south. Rome formed a permanent association with most local tribes and cities, creating a federation that served as the foundation for its further conquests. Rome then embarked on a period of expansion that saw it conquer Western Europe, North Africa, and parts of the Middle East.

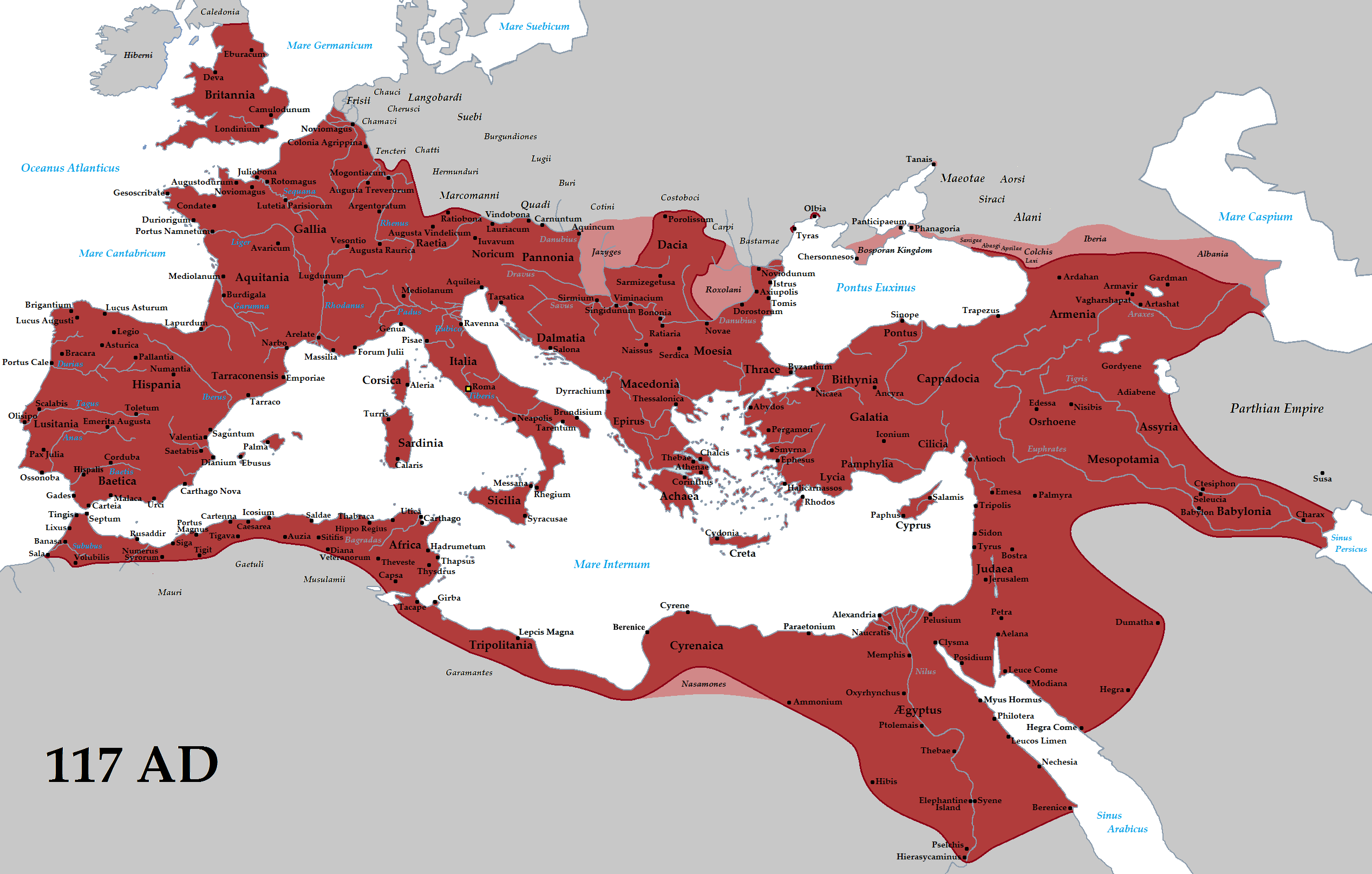

The assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BC marked a turning point, leading to civil wars and the eventual transformation of the Republic into the Roman Empire under Augustus, its first emperor. Augustus's long reign initiated the Pax Romana, an era of relative peace and prosperity that lasted for over two centuries. During this period, the Roman Empire reached its greatest extent, stretching from Britain in the northwest to Mesopotamia in the east, and encompassing the entire Mediterranean basin. Roman Italy remained the metropole of the empire, the homeland of the Romans and the territory of the capital, Rome.

The Roman Empire was one of the largest and most powerful empires in history, wielding immense economic, cultural, political, and military influence. Its legacy has profoundly shaped Western civilization and the modern world. The widespread use of Romance languages derived from Latin, the Roman numeral system, the modern Western alphabet, the Julian and later Gregorian calendars, and the emergence of Christianity as a major world religion are among the many enduring legacies of Roman dominance. Roman law, engineering (aqueducts, roads, public buildings like the Colosseum), and principles of governance also left an indelible mark.

However, by the 3rd century AD, the Empire began to face internal strife, economic difficulties, and external pressures. Emperor Diocletian attempted to manage its vastness by instituting the Tetrarchy, effectively dividing rule. Later, Emperor Constantine the Great moved the imperial capital to Constantinople (modern Istanbul) in 330 AD. In 395 AD, the Empire was formally divided into the Western Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire). The Western Roman Empire, beset by barbarian invasions and internal decay, gradually declined. The traditional date for the fall of the Western Roman Empire is 476 AD, when the last Western Roman Emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed by the Germanic chieftain Odoacer. The Eastern Roman Empire, however, would continue for another thousand years.

3.3. Middle Ages

This period encompasses the centuries following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, a time of significant transformation for the Italian peninsula. It includes the rule of the Ostrogoths and Lombards, continued Byzantine influence in parts of Italy, the rise of powerful Italian city-states and maritime republics like Venice and Genoa, the consolidation of the Papal States, and the Norman conquest of Southern Italy, all contributing to a complex political and social landscape.

Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD, Italy entered a period of profound political fragmentation and societal change. The Germanic chieftain Odoacer deposed the last Western emperor and ruled as king under the nominal authority of the Eastern Roman Emperor in Constantinople. However, his rule was short-lived, as the Ostrogoths, led by Theodoric the Great, invaded and established the Ostrogothic Kingdom in Italy by 493 AD. Theodoric sought to blend Roman and Gothic traditions, but his kingdom eventually fell to a renewed Byzantine (Eastern Roman) reconquest effort under Emperor Justinian I during the Gothic War (535-554).

Byzantine rule over the entire peninsula was brief. In 568 AD, another Germanic tribe, the Lombards, invaded Italy, conquering large parts of the north and center. This invasion shattered the political unity of the peninsula for centuries. Byzantine control was reduced to areas like the Exarchate of Ravenna, Rome, parts of Southern Italy, and Sicily. The Lombard Kingdom, with its capital at Pavia, coexisted with Byzantine territories and the increasingly autonomous Duchy of Rome, which evolved into the Papal States under the growing temporal power of the Popes.

In the late 8th century, the Lombard Kingdom was conquered by Charlemagne, king of the Franks, who was crowned Emperor by Pope Leo III in Rome in 800 AD. This event marked the beginning of the Holy Roman Empire and established a complex, often contentious, relationship between the Papacy and the imperial power based north of the Alps. The former Lombard kingdom became the Kingdom of Italy, nominally part of the Holy Roman Empire.

Throughout the High Middle Ages (roughly 1000-1300 AD), Italian politics was characterized by the struggle between the Holy Roman Emperors and the Papacy, known as the Investiture Controversy, and the related conflict between their supporters, the Ghibellines (pro-Emperor) and Guelphs (pro-Pope). This power vacuum allowed for the rise of independent Italian city-states, particularly in northern and central Italy. Cities like Milan, Florence, Siena, Pisa, Genoa, and Venice grew wealthy through trade, manufacturing (especially textiles), and finance, developing sophisticated forms of republican government and laying early groundwork for modern capitalism. In 1176, the Lombard League, an alliance of northern Italian city-states, famously defeated Emperor Frederick Barbarossa at the Battle of Legnano, securing significant autonomy.

The maritime republics of Venice, Genoa, Pisa, and Amalfi became dominant naval and commercial powers in the Mediterranean. They established extensive trade networks, connecting Europe with the Levant, North Africa, and the Black Sea. Venice and Genoa, in particular, built vast colonial empires and played crucial roles in the Crusades, often profiting from transporting crusaders and supplies. These republics, though typically oligarchic, fostered environments of relative political freedom that were conducive to artistic and academic advancement. Marco Polo, a Venetian merchant, famously traveled to the East in the late 13th century, his accounts expanding European geographical knowledge.

In Southern Italy, the situation was different. Sicily had been conquered by Arabs in the 9th century, becoming the Emirate of Sicily. This Islamic emirate thrived culturally and economically until the Norman conquest in the late 11th century. Norman adventurers, notably Robert Guiscard and Roger I of Sicily, also conquered Lombard and Byzantine territories in mainland Southern Italy, consolidating these lands into the County and later Kingdom of Sicily by 1130 under Roger II of Sicily. This kingdom, encompassing Sicily and Southern Italy (the Mezzogiorno), became a multicultural center, blending Norman, Byzantine, Arab, and Lombard traditions. It later passed through various dynasties, including the Hohenstaufens (under figures like Frederick II), Angevins (French), and Aragonese (Spanish).

The Late Middle Ages saw continued flourishing of city-states in the north, the rise of universities (like Bologna, one of the oldest in the world), and significant cultural figures like Dante Alighieri, Petrarch, and Giovanni Boccaccio in literature, and Giotto in art, heralding the Italian Renaissance. However, the period was also marked by internal conflicts, social unrest (like the Ciompi Revolt in Florence), and the devastating impact of the Black Death in the mid-14th century, which killed an estimated one-third of Italy's population. Despite these challenges, the wealth and dynamism of the Italian city-states laid the foundation for the cultural explosion of the Renaissance.

3.4. Early modern period

This era covers the Italian Renaissance, a period of unparalleled cultural, artistic, and intellectual achievement centered in Italy and spreading throughout Europe. It also includes the Italian Wars, which saw the peninsula become a battleground for foreign powers, leading to centuries of foreign domination in various regions. The Baroque era and the influence of the Enlightenment in Italy also mark this period, setting the stage for later nationalistic movements.

The Italian Renaissance, spanning roughly from the 14th to the 16th centuries, was a period of extraordinary cultural rebirth that began in Italy and profoundly influenced the rest of Europe. Fostered by the wealth accumulated by merchant cities like Florence, Venice, and Milan, and the patronage of powerful families such as the Medici in Florence, the Sforza in Milan, and the Popes in Rome, the Renaissance saw a resurgence of interest in classical antiquity, humanism, and artistic innovation. Italian polities, often regional states ruled by princes or oligarchies, became vibrant centers of arts and sciences. Figures like Lorenzo de' Medici ("the Magnificent") were pivotal patrons.

Artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, Botticelli, Titian, and Donatello produced masterpieces that remain iconic. Architects like Filippo Brunelleschi (famous for the dome of Florence Cathedral), Leon Battista Alberti, and Andrea Palladio revolutionized building design. Thinkers like Niccolò Machiavelli (in political philosophy with The Prince) and Pico della Mirandola (with his Oration on the Dignity of Man) explored new intellectual frontiers. The invention of the printing press, while not Italian, greatly facilitated the spread of Renaissance ideas.

Italian explorers and navigators, often sponsored by other European monarchies, played a key role in the Age of Discovery. Christopher Columbus (for Spain) reached the Americas in 1492, John Cabot (for England) explored North America, and Amerigo Vespucci (for Portugal and Spain) lent his name to the newly "discovered" continents.

However, this cultural flourishing occurred amidst political instability. A defensive alliance, the Italic League (1454), aimed to maintain peace among the major Italian powers (Venice, Naples, Florence, Milan, and the Papal States) but collapsed by the end of the 15th century. In 1494, King Charles VIII of France invaded Italy, initiating the Italian Wars (1494-1559). These wars involved France, Spain (later the Habsburgs), the Holy Roman Empire, and various Italian states, turning the peninsula into a major European battleground. While culturally vibrant, with Popes like Julius II and Leo X being significant patrons of the High Renaissance, Italy became increasingly subject to foreign influence and domination.

The Protestant Reformation in the early 16th century, though having less direct impact within Italy compared to Northern Europe, prompted the Catholic Church to launch the Counter-Reformation. The Council of Trent (1545-1563) was a key event, reaffirming Catholic doctrine and initiating reforms within the Church. New religious orders like the Jesuits became influential.

By the end of the Italian Wars with the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis (1559), much of Italy fell under the direct or indirect control of Habsburg Spain. The Kingdom of Naples, Sicily, Sardinia, and the Duchy of Milan were Spanish possessions. While some states like Venice, the Papal States, Tuscany (under the Medici Grand Dukes), and Savoy remained nominally independent, their autonomy was often constrained by larger European powers.

The 17th century, the Baroque era, saw continued artistic and architectural brilliance (e.g., Bernini, Caravaggio), but also economic decline for many parts of Italy as Atlantic trade routes superseded Mediterranean ones. Plagues also continued to affect the population. In the early 18th century, the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) led to a shift in power, with Austrian Habsburgs replacing Spanish Habsburgs as the dominant foreign influence in much of Italy, particularly in Milan and Naples. The House of Savoy, rulers of Piedmont, gained Sicily (later exchanged for Sardinia, becoming the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont), emerging as a significant Italian power.

The Enlightenment (Illuminismo) also had an impact in Italy during the 18th century, with reformers like Cesare Beccaria (on criminal justice) and thinkers like Giambattista Vico (in philosophy of history). Some Italian rulers implemented enlightened reforms.

The late 18th century was dramatically altered by the French Revolution and the subsequent Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon Bonaparte's campaigns in Italy (from 1796) led to the overthrow of existing regimes and the establishment of French-style "sister republics" (e.g., Cisalpine, Ligurian, Roman, Parthenopean). These were later consolidated into larger entities like the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy (in the north and center, with Napoleon as king) and the Napoleonic Kingdom of Naples (ruled by Napoleon's relatives). While bringing war and exploitation, the Napoleonic era also introduced modern legal codes, administrative reforms, and fostered early Italian nationalist sentiments. The first adoption of the Italian tricolour by an Italian state, the Cispadane Republic, occurred during this period, reflecting revolutionary ideals of national self-determination. This event is commemorated by Tricolour Day. The Congress of Vienna (1814-1815) largely restored the pre-Napoleonic order, but the seeds of nationalism and liberalism had been sown, setting the stage for the Risorgimento.

3.5. Unification and Kingdom of Italy

This section describes the Risorgimento, the 19th-century movement for Italian unification, highlighting the roles of key figures like Mazzini, Garibaldi, and Cavour. It covers the wars of independence, the establishment of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861 under the House of Savoy, the subsequent Liberal period, early industrialization, colonial expansion into Africa, and Italy's complex involvement and significant human cost in World War I.

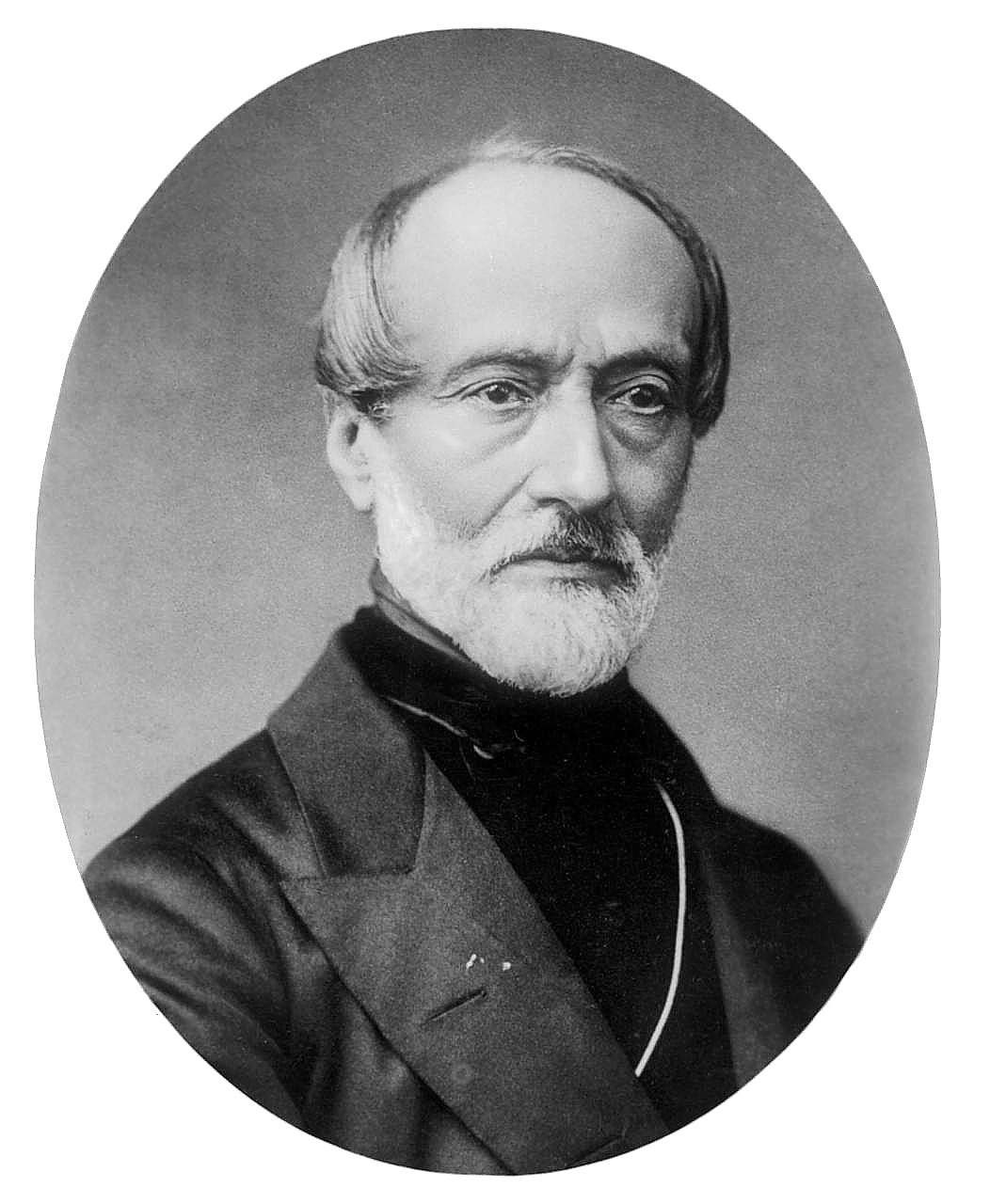

The unification of Italy, known as the Risorgimento (Resurgence), was a complex political and social process that consolidated different states of the Italian peninsula into a single nation, the Kingdom of Italy. Following the Congress of Vienna in 1815, which largely restored Austrian dominance in northern Italy and maintained political fragmentation, Italian nationalist sentiment grew. Early revolutionary movements, like the Carbonari, were often suppressed.

Giuseppe Mazzini, a key ideological figure, founded the Young Italy (Giovine Italia) movement in the 1830s, advocating for a united, republican Italy achieved through popular uprising. His ideas inspired many, though his direct revolutionary attempts were unsuccessful. In 1847, "Il Canto degli Italiani" (The Song of the Italians), which later became the Italian national anthem, was first publicly performed, reflecting the growing patriotic fervor.

The Revolutions of 1848 saw widespread uprisings across Italy. King Charles Albert of Sardinia-Piedmont declared the First Italian War of Independence against Austria, but was defeated. Despite the failures of 1848, Sardinia-Piedmont, under King Victor Emmanuel II and his skilled Prime Minister Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, emerged as the leading state for unification. Cavour pursued a pragmatic policy of modernization, economic development, and strategic alliances. In 1855, Sardinia-Piedmont joined Britain and France in the Crimean War, gaining international standing.

In 1859, Cavour, with the crucial military support of Napoleon III's France, provoked the Second Italian War of Independence against Austria. The Franco-Piedmontese victory led to the annexation of Lombardy by Sardinia-Piedmont. In exchange for French aid, Sardinia ceded Savoy and Nice to France, an event that caused the Niçard exodus of Italians from those regions. Uprisings in central Italian duchies (Tuscany, Parma, Modena) and the Papal Legations led to their subsequent annexation by Sardinia-Piedmont through plebiscites in 1860.

Meanwhile, Giuseppe Garibaldi, a charismatic revolutionary and military leader, launched his Expedition of the Thousand (Spedizione dei Mille) in May 1860. His volunteer force landed in Sicily and, with popular support, overthrew Bourbon rule there and then in mainland Naples. Garibaldi's rapid success in the south presented a challenge to Cavour's monarchist vision, but Garibaldi, in a pivotal meeting at Teano, famously handed over his conquests to Victor Emmanuel II, hailing him as King of Italy, thus prioritizing national unity over republican ideals.

On 17 March 1861, the Kingdom of Italy was officially proclaimed, with Victor Emmanuel II as its first king and Turin as its capital. The new kingdom initially excluded Venetia (still under Austrian rule) and Rome (still under Papal control and protected by French troops). The capital was moved to Florence in 1865. In 1866, Italy allied with Prussia in the Austro-Prussian War. Despite poor Italian military performance in this Third Italian War of Independence, Prussia's victory led to Austria ceding Venetia to Italy.

Finally, in 1870, during the Franco-Prussian War, French troops withdrew from Rome. Italian forces entered the city, effectively ending the temporal power of the Papacy and completing the territorial unification of the peninsula (except for Trentino and Trieste, which remained "unredeemed"). Rome became the capital of Italy in 1871. The Pope, Pius IX, declared himself a "Prisoner in the Vatican", leading to a long-standing conflict between the Italian state and the Catholic Church (the "Roman Question"), resolved only in 1929 with the Lateran Treaty.

The early Kingdom of Italy (the Liberal Period) faced significant challenges: integrating diverse regions with different laws and traditions, widespread poverty and illiteracy (especially in the South), brigandage in the South, and a limited electorate. The Sardinian Statuto Albertino was extended as the constitution for the whole kingdom. Politics was dominated by liberal factions, often divided into the "Historic Right" and "Historic Left." The period saw gradual industrialization, primarily in the North (the "industrial triangle" of Milan-Turin-Genoa), while the South remained largely agrarian and impoverished, fueling mass emigration to the Americas and other parts of Europe. The Italian Socialist Party grew in strength, challenging the established order.

From the late 19th century, Italy also pursued colonial expansion, acquiring territories in Africa, including Eritrea, Somaliland, and later, Libya (after the Italo-Turkish War of 1911-12). In 1913, universal male suffrage was introduced. The pre-World War I era was largely dominated by Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti, who sought to integrate the Socialists and Catholics into the political system and oversaw significant social and economic reforms, though the North-South divide persisted.

Italy initially remained neutral in World War I (1914). However, under pressure from nationalists and promises of territorial gains from the Entente powers (articulated in the secret Treaty of London), Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary in May 1915, and later on Germany. The war on the Italian front, primarily fought in the mountainous terrain of the Alps and the Isonzo River valley, was brutal and resulted in enormous casualties (over 650,000 Italian soldiers died). Key battles included the twelve Battles of the Isonzo and the disastrous Battle of Caporetto (1917), followed by a recovery and the final victory at the Battle of Vittorio Veneto (1918), which contributed to the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Italy's contribution earned it a place among the "Big Four" victorious powers.

The post-war treaties (Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye and Treaty of Rapallo) granted Italy Trentino-Alto Adige, the Julian March, Istria, and the city of Zara (Zadar). The later Treaty of Rome (1924) led to the annexation of Fiume (Rijeka). However, Italy did not receive all territories promised in the Treaty of London (particularly in Dalmatia), leading to the nationalist myth of a "mutilated victory" (vittoria mutilata), which was exploited by rising extremist movements like Fascism.

3.6. Fascist regime and World War II

This period covers the rise of Benito Mussolini and the Fascist Party, the establishment of a totalitarian dictatorship suppressing democratic freedoms, Italy's aggressive foreign policy including the invasion of Ethiopia and Albania, its alliance with Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan as an Axis power in World War II, its subsequent military defeats, the fall of Mussolini, the Italian Social Republic (a Nazi puppet state), the brutal civil war, and the Italian resistance against German occupation and Fascist collaborators. This section emphasizes the regime's anti-democratic nature and the human cost of its actions.

The aftermath of World War I left Italy in a state of economic crisis, social unrest, and political instability. The "Biennio Rosso" (Two Red Years, 1919-1920) saw widespread socialist agitations, factory occupations, and strikes, inspired by the Russian Revolution. Fear of a communist revolution among the liberal establishment, industrialists, and landowners led them to increasingly support the National Fascist Party, led by Benito Mussolini. Mussolini, a former socialist, had become a fervent nationalist.

In October 1922, Mussolini's Fascist Blackshirts organized the "March on Rome". While the march itself was not a decisive military event, King Victor Emmanuel III, fearing civil war and underestimating Mussolini, refused to authorize martial law and instead appointed Mussolini as Prime Minister on October 30, 1922, effectively transferring power to the Fascists without a major armed conflict.

Over the next few years, Mussolini consolidated his power, gradually dismantling democratic institutions. He suppressed political opposition, curtailed personal liberties, controlled the press, and established a one-party totalitarian state. The assassination of socialist leader Giacomo Matteotti in 1924 by Fascist thugs marked a key moment in this consolidation. Mussolini adopted the title of Duce (Leader). The Fascist regime was based on Italian nationalism, imperialism, and the idea of a corporatist state, seeking to restore Italy to the perceived glory of the Roman Empire and expand its possessions through irredentist claims and colonial conquest.

Fascist Italy pursued an aggressive foreign policy. In 1935, Italy invaded Ethiopia (Abyssinia), using brutal tactics including chemical weapons, and founded Italian East Africa. This action led to international condemnation and sanctions from the League of Nations, from which Italy subsequently withdrew. Italy then forged closer ties with Nazi Germany, forming the Rome-Berlin Axis in 1936 and later the Pact of Steel in 1939. Italy also actively supported Francisco Franco's Nationalist forces in the Spanish Civil War. In April 1939, Italy invaded and annexed Albania. The regime also implemented racial laws in 1938, primarily targeting Italian Jews, stripping them of citizenship and rights.

Italy entered World War II on June 10, 1940, on the side of the Axis powers, believing the war would be short and victorious. Mussolini hoped to gain territories in the Mediterranean and Africa. Italian forces engaged in campaigns in British Somaliland, Egypt, the Balkans (Greece, Yugoslavia), and the Eastern Front against the Soviet Union. However, the Italian military was often poorly equipped, inadequately led, and suffered significant defeats in North Africa (North African campaign), East Africa (East African campaign), and Greece. Italian war crimes, including mass killings and ethnic cleansing by deportation to Italian concentration camps, occurred in occupied territories, particularly in Yugoslavia. Yugoslav Partisans also perpetrated crimes against the ethnic Italian population, such as the Foibe massacres, during and after the war.

The tide turned decisively against Italy with the Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943. This led to the collapse of the Fascist regime. On July 25, 1943, Mussolini was deposed by the Grand Council of Fascism and arrested by order of King Victor Emmanuel III. The King appointed Marshal Pietro Badoglio as the new Prime Minister. On September 8, 1943, the Badoglio government signed the Armistice of Cassibile with the Allies, ending Italy's war against them.

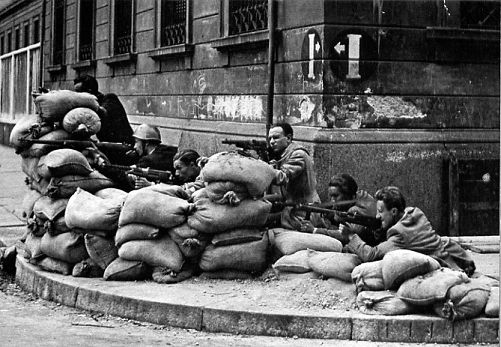

Immediately following the armistice, German forces swiftly occupied northern and central Italy. Mussolini was rescued by German paratroopers and installed as the leader of the Italian Social Republic (RSI), a Nazi puppet state and collaborationist regime based in Salò on Lake Garda. This effectively divided the country, leading to the Italian Civil War (1943-1945). Southern Italy, liberated by the Allies, became the "Kingdom of the South," with the King and Badoglio's government co-belligerent with the Allies. What remained of the Italian military was reorganized into the Italian Co-belligerent Army, Air Force, and Navy, fighting alongside the Allies. Other Italian forces remained loyal to Mussolini and fought with the Germans in the RSI's National Republican Army.

The period of German occupation and the RSI was marked by extreme brutality. German troops, often with RSI collaboration, committed numerous massacres of civilians (e.g., Ardeatine massacre, Marzabotto massacre, Sant'Anna di Stazzema massacre) and deported thousands of Italian Jews to Nazi death camps as part of the Holocaust. The post-armistice period also saw the emergence of a powerful and diverse Italian resistance movement (Resistenza), composed of partisans from various political backgrounds (communists, socialists, Christian Democrats, liberals, monarchists) united against the German occupiers and Italian Fascists. The Resistance fought a bitter guerrilla war, suffering and inflicting heavy casualties, and playing a significant role in the liberation of Italy.

In April 1945, as Allied forces advanced and the German front collapsed, the Resistance launched a general insurrection in northern Italy. Mussolini attempted to flee to Switzerland but was captured and summarily executed by partisans near Lake Como on April 28, 1945. Hostilities in Italy officially ended on April 29, 1945, with the surrender of German forces in Italy.

The war left Italy devastated. Nearly half a million Italians died, its economy was shattered, and society was deeply divided. The monarchy's endorsement of the Fascist regime led to widespread anger and a resurgence of Italian republicanism, setting the stage for the end of the monarchy and the birth of the Italian Republic.

3.7. Republican era

This section details Italy's history from the establishment of the Republic in 1946. It covers post-war reconstruction aided by the Marshall Plan, the "Economic Miracle" of rapid industrialization, significant socio-political upheavals like the "Years of Lead" (terrorism and social conflict), Italy's role as a founding member of the European Communities (later EU) and NATO, and contemporary challenges such as political instability, economic stagnation, organized crime, and migration. The narrative emphasizes the development of democratic institutions, efforts towards social equity, and Italy's integration into Europe.

Following the devastation of World War II and the collapse of the Fascist regime, Italy embarked on a new chapter. A referendum on June 2, 1946, abolished the monarchy, which was widely blamed for its complicity with Fascism, and established the Italian Republic. This date is now celebrated as Festa della Repubblica (Republic Day). It was also the first time Italian women voted nationally. King Umberto II, who had briefly reigned after his father Victor Emmanuel III's abdication, went into exile. A Constituent Assembly was elected to draft a new constitution, which came into effect on January 1, 1948, establishing a parliamentary republic with strong democratic safeguards.

The early years of the Republic were dominated by the Christian Democracy party (Democrazia Cristiana, DC), led by figures like Alcide De Gasperi. The 1948 general election was a crucial contest, with the DC and its allies defeating the Communist-Socialist popular front amidst Cold War tensions and fears of a Communist takeover, a concern strongly influenced by the United States and the Catholic Church. Italy became a staunch Western ally, joining NATO in 1949. The Marshall Plan provided significant aid for post-war reconstruction, fueling the Italian economic miracle (miracolo economico italiano) from the late 1950s to the late 1960s. This period saw rapid industrialization, particularly in the North, and a dramatic rise in living standards, though the North-South economic divide persisted. In the 1950s, Italy was a founding member of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) and the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1957, precursors to the European Union.

The late 1960s to the early 1980s were marked by the "Years of Lead" (Anni di piombo), a period of intense social and political turmoil. It was characterized by widespread student and worker protests, significant social reforms (e.g., legalization of divorce in 1970, abortion in 1978), and political violence from both far-left (e.g., Red Brigades) and far-right extremist groups, including bombings, kidnappings, and assassinations. The kidnapping and murder of former Prime Minister Aldo Moro by the Red Brigades in 1978 was a traumatic event. The economy also faced challenges, especially after the 1973 oil crisis.

Despite these difficulties, the Italian economy recovered, and Italy became the world's fifth-largest industrial nation, gaining entry into the G7 in the 1970s. However, this period also saw a significant rise in public debt. The fight against organized crime, particularly the Sicilian Mafia, Camorra, and 'Ndrangheta, became a major national concern, marked by violent campaigns by criminal organizations and state responses, including the work of courageous magistrates like Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, who were assassinated by the Mafia in 1992. Between 1992 and 1993, Italy faced terror attacks perpetrated by the Sicilian Mafia as a consequence of new anti-mafia measures by the government.

The early 1990s brought a major political upheaval known as Mani pulite (Clean Hands), a nationwide judicial investigation into political corruption that dismantled the long-dominant party system, often referred to as the "First Republic." The Christian Democrats, Socialists, and other traditional parties collapsed or were radically transformed. This led to a period of political restructuring, sometimes called the "Second Republic," characterized by new political formations and electoral reforms. The 1990s and 2000s saw alternating centre-right coalitions, often led by media magnate Silvio Berlusconi, and centre-left coalitions, led by figures like Romano Prodi. Italy adopted the Euro in 1999.

The 21st century brought new challenges. The Great Recession starting in 2008 hit Italy hard. In 2011, amidst the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis, Berlusconi resigned and was replaced by a technocratic government led by economist Mario Monti, which implemented austerity measures. Subsequent governments, including those led by Enrico Letta (2013-2014) and Matteo Renzi (2014-2016), attempted further reforms. Renzi's proposed constitutional reforms were rejected in a referendum in 2016, leading to his resignation and the appointment of Paolo Gentiloni as Prime Minister.

The European migrant crisis of the 2010s significantly impacted Italy, which became a primary entry point for migrants and asylum seekers, mainly from Africa and the Middle East. Between 2013 and 2018, Italy took in over 700,000 migrants, straining public resources and leading to a surge in support for populist, anti-immigration, and Eurosceptic parties. The 2018 general election saw the rise of the Five Star Movement and the League (formerly Northern League), leading to a populist coalition government headed by Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte.

The COVID-19 pandemic struck Italy with particular severity in early 2020, making it one of the worst-affected countries globally, with a high death toll and severe economic repercussions. The Conte government implemented strict lockdown measures. In February 2021, following a government crisis, Conte resigned. Mario Draghi, former president of the European Central Bank, formed a national unity government supported by most major parties, tasked with managing the pandemic recovery and implementing the EU-funded National Recovery and Resilience Plan. Draghi resigned in July 2022 after losing support from key coalition partners.

The 2022 general election resulted in a victory for a right-wing coalition led by Giorgia Meloni's Brothers of Italy party. On October 22, 2022, Meloni was sworn in as Italy's first female Prime Minister, leading a government that included the League and Forza Italia. Modern Italy continues to navigate complex economic, social, and political issues while maintaining its significant role in European and global affairs, and upholding its democratic traditions and commitment to social equity.

4. Geography

Italy is a country in Southern Europe, also considered part of Western Europe, located primarily on the Italian Peninsula. Its territory also includes the two largest islands in the Mediterranean Sea, Sicily and Sardinia, and numerous smaller islands. It shares land borders with France to the northwest, Switzerland and Austria to the north, and Slovenia to the northeast. The independent states of San Marino and Vatican City are enclaves within Italian territory. Italy's geographical position in the heart of the Mediterranean has historically made it a crucial crossroads of cultures and civilizations. The country's diverse geography encompasses Alpine mountain ranges, extensive coastlines, fertile plains, and volcanic regions.

4.1. Topography

Italy's topography is remarkably diverse, dominated by mountain ranges and a long coastline. Over 35% of Italian territory is mountainous. The Alps form a natural barrier in the north, arching from west to east and separating Italy from the rest of continental Europe. Italy's highest point is located on the summit of Mont Blanc (Monte Bianco) at 16 K ft (4.81 K m), shared with France. Other iconic Alpine peaks include the Matterhorn (Monte Cervino), shared with Switzerland, and the majestic Dolomites in the northeastern Alps, a UNESCO World Heritage Site known for its unique geological formations.

Running down the length of the Italian peninsula like a spine are the Apennine Mountains. This range extends for about 0.7 K mile (1.20 K km) from Liguria in the northwest to Calabria in the southwest, and continues into Sicily. The Apennines are generally lower than the Alps but are geologically younger and more seismically active.

The largest plain in Italy is the Po Valley (Pianura Padana), located in the north, between the Alps and the Apennines. This vast and fertile alluvial plain, covering approximately 18 K mile2 (46.00 K km2), is drained by the Po River, Italy's longest river (405 mile (652 km)). The Po River flows from the Cottian Alps eastward to the Adriatic Sea, forming a large delta. The Po Valley is Italy's primary agricultural and industrial heartland. Other significant plains are found along the coasts, such as the Maremma in Tuscany and the Tavoliere delle Puglie in Apulia.

Volcanic activity is a significant feature of Italian topography, due to its location at the convergence of the Eurasian and African tectonic plates. Italy is home to several active and dormant volcanoes. The most famous active volcanoes include:

- Mount Etna on Sicily: Europe's largest and most active volcano, with frequent eruptions.

- Vesuvius near Naples: Mainland Europe's only active volcano, infamous for the destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum in 79 AD.

- Stromboli and Vulcano: Two active volcanic islands in the Aeolian Islands archipelago north of Sicily.

Other volcanic areas include the Phlegraean Fields (Campi Flegrei), a large caldera west of Naples, and numerous extinct volcanoes that have shaped the landscape, particularly in central and southern Italy.

Italy has numerous rivers, with the Po being the most important. Other significant rivers include the Adige and Brenta (flowing from the Alps into the Adriatic), the Arno (flowing through Florence and Pisa into the Ligurian Sea), and the Tiber River (flowing through Rome into the Tyrrhenian Sea).

The country also boasts several large and scenic lakes, particularly in the Alpine foothills. The largest is Lake Garda (Lago di Garda), followed by Lake Maggiore (Lago Maggiore, shared with Switzerland), and Lake Como (Lago di Como). Central Italy has lakes of volcanic origin, such as Lake Bolsena and Lake Bracciano.

Italy's extensive coastline, approximately 4.7 K mile (7.60 K km) long, borders the Ligurian Sea and Tyrrhenian Sea to the west, the Ionian Sea to the south, and the Adriatic Sea to the east. The coastline varies from sandy beaches to rocky cliffs, with numerous bays, gulfs, and headlands. The major islands of Sicily and Sardinia, along with smaller archipelagos like the Tuscan Archipelago, Aeolian Islands, and Egadi Islands, contribute significantly to Italy's maritime character and diverse topography.

4.2. Climate

Italy's climate is highly diverse, primarily influenced by its considerable length from north to south, its mountainous interior, and the surrounding Mediterranean Sea, which acts as a reservoir of heat and humidity. While generally falling within the southern temperate zone, regional variations are significant.

The coastal areas of Liguria, Tuscany, and most of Southern Italy (including Sicily and Sardinia) generally fit the classic Mediterranean climate stereotype (Köppen classification: Csa). This means mild, wet winters and hot, dry summers. Temperatures along the coasts rarely drop below freezing in winter, and summer temperatures can often exceed 86 °F (30 °C).

In contrast, the northern inland regions, particularly the Po Valley, experience a climate that ranges from humid subtropical (Cfa) to humid continental. Winters here can be cold, foggy, and sometimes snowy, with average temperatures near freezing. Summers are hot and humid, often with thunderstorms, especially in the afternoons.

The Alpine regions in the far north have an Alpine climate (ET or EFH). Winters are long and severe with heavy snowfall, while summers are short and cool. The Apennine Mountains, running down the peninsula, also create localized climate variations, with higher altitudes experiencing colder temperatures and more precipitation, often as snow in winter, compared to adjacent lowlands.

Seasonal variations are distinct:

- Spring (March-May):** Generally mild and pleasant, though weather can be unpredictable with alternating sunny days and rainy periods. Temperatures gradually increase.

- Summer (June-August):** Hot and sunny, especially in the south and inland plains. Coastal areas benefit from sea breezes. Drought can be an issue in some southern regions.

- Autumn (September-November):** Often mild and sunny initially, becoming cooler and wetter as the season progresses. This is a harvest season for many crops.

- Winter (December-February):** Varies greatly. Cold with frost and snow in the Alps and northern plains. Milder, but often rainy, in central and southern coastal areas. Sicily and Sardinia typically have the mildest winters.

Precipitation patterns also vary. The Alps and parts of the Apennines receive the highest rainfall, often exceeding 0.1 K in (2.00 K mm) annually. The Po Valley and western coastal regions receive moderate rainfall, typically between 24 in (600 mm) and 0.0 K in (1.00 K mm) per year, often concentrated in spring and autumn. Southern regions and Sardinia tend tobe drier, particularly during the summer months.

Extreme weather events such as heatwaves, droughts (especially in the south), and occasional floods (due to heavy rainfall in mountainous areas) can occur. The Sirocco, a hot, humid wind from North Africa, can affect southern Italy, bringing oppressive heat and sometimes dust. The Mistral, a cold, dry wind from southern France, can impact the Ligurian coast and Sardinia.

4.3. Biodiversity

Italy boasts a remarkable level of biodiversity, considered among the highest in Europe. This richness is due to its varied geography, which includes the Alps, the Apennine Mountains, extensive coastlines, central Italian woodlands, and southern Italian garrigue and maquis shrublands, creating a wide array of habitats. Its central position in the Mediterranean, acting as a corridor between Central Europe and North Africa, has facilitated the presence of species from the Balkans, Eurasia, and the Middle East. Italy is home to over 57,000 recorded animal species, representing more than a third of all European fauna, and possesses the highest level of biodiversity of animal and plant species within the European Union.

The fauna of Italy includes approximately 119 mammal species, around 550 bird species, 69 reptile species, 39 amphibian species, 623 fish species, and an estimated 56,213 invertebrate species, of which 37,303 are insect species. Among the endemic or notable animal species are the Italian wolf (the national animal), Marsican brown bear (a critically endangered subspecies of the brown bear found in the Apennines), Sardinian long-eared bat, Sardinian red deer, Apennine shrew, spectacled salamander, brown cave salamander, Italian newt, Italian frog, Apennine yellow-bellied toad, Italian wall lizard, and the Sicilian pond turtle. Marine biodiversity is also significant, with the surrounding seas hosting diverse ecosystems and species, including dolphins, whales, and various fish and invertebrates.

The flora of Italy is equally diverse. Traditionally estimated to comprise about 5,500 vascular plant species, a 2005 databank recorded 6,759 species. Italy has 1,371 endemic plant species and subspecies. Notable endemic plants include the Sicilian fir, Barbaricina columbine, Sea marigold (Calendula maritima), lavender cotton species, and the Ucriana violet. The national tree of Italy is the strawberry tree (corbezzolo), chosen because its green leaves, white flowers, and red berries represent the colors of the Italian flag. The national flower is also considered to be the flower of the strawberry tree. The varied climate and topography support diverse vegetation types, from Alpine coniferous forests and meadows to Mediterranean maquis, evergreen forests (like holm oak and cork oak), and deciduous forests in the Apennines.

Italy is a signatory to the Berne Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats and the EU's Habitats Directive, which form the basis for its national conservation efforts. The country has established numerous protected areas, including 25 national parks (such as Gran Paradiso National Park, Stelvio National Park, and Abruzzo National Park), many regional parks, nature reserves, and marine protected areas. These protected areas cover approximately 11% of Italy's land territory and 12% of its coastline, aiming to conserve vulnerable species, habitats, and important ecosystems. Despite these efforts, biodiversity faces threats from habitat loss due to urbanization and agriculture, pollution, climate change, and invasive species. Conservation programs focus on protecting flagship species like the wolf, bear, and various bird species, as well as restoring degraded habitats. Italy also has a long tradition of botanical gardens and historic gardens, which contribute to ex-situ conservation and public awareness of plant diversity.

4.4. Environment

Italy faces a range of environmental challenges, stemming from its history of rapid industrial growth, high population density in certain areas, and unique geographical characteristics. While the country has made progress in addressing some issues, others remain significant concerns requiring ongoing attention and policy intervention, often with considerable social impact.

Air pollution is a major problem, particularly in the industrialized Po Valley and large urban centers. Emissions from traffic, industry, and domestic heating contribute to high levels of particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, and ozone, leading to respiratory problems and other health issues. Italy has been a significant producer of carbon dioxide, ranking as the twelfth-largest in some historical measures. Efforts to reduce smog levels have seen some success since the 1970s and 1980s, with decreases in sulphur dioxide, but urban air quality remains a concern.

Water pollution affects many rivers and coastal areas, resulting from agricultural runoff (pesticides and fertilizers), industrial discharges, and inadequately treated sewage. This pollution impacts aquatic ecosystems and can affect the quality of water used for drinking and recreation.

Land degradation, including soil erosion, deforestation (though forest cover has increased in recent decades in some areas), and illegal construction (abusivismo edilizio), is prevalent, especially in mountainous and coastal regions. Poor land-management policies and uncontrolled development have exacerbated these problems, leading to increased risks of landslides, floods, and coastal erosion. Italy's hydrogeological instability has resulted in several ecological disasters, such as the 1963 Vajont Dam disaster, the 1998 Sarno mudslide, and the 2009 Messina floods and mudslides.

Waste management is another critical issue, with challenges in collection, recycling, and disposal. Landfills are often overused, and illegal waste dumping, sometimes linked to organized crime (eco-mafia), poses serious environmental and health risks, particularly in regions like Campania. Efforts to increase recycling rates and promote a circular economy are underway but vary in effectiveness across regions.

Natural hazards are a constant concern. Italy is seismically active, prone to earthquakes, especially along the Apennine chain and in Sicily. Volcanic eruptions from Etna, Vesuvius, and Stromboli also pose risks. Climate change is expected to exacerbate existing environmental problems, leading to more frequent heatwaves, droughts (particularly in the south), extreme precipitation events, and rising sea levels, which threaten coastal cities like Venice.

In response to these challenges, Italy has implemented various environmental policies, often driven by EU directives. The country has invested significantly in renewable energy, becoming a leading producer of solar energy and having substantial wind power and geothermal power capacity. Renewable sources accounted for approximately 37% of Italy's energy consumption in 2020. Italy phased out nuclear power following a referendum in 1987 after the Chernobyl disaster, and a subsequent attempt to reintroduce it was rejected by another referendum in 2011 after the Fukushima accident.

Conservation efforts include the establishment of numerous protected areas. The total area protected by national parks, regional parks, and nature reserves covers about 11% of Italian territory, and 12% of Italy's coastline is protected as marine protected areas. These aim to preserve biodiversity and promote sustainable development. However, enforcement of environmental regulations and the integration of environmental considerations into economic development remain ongoing challenges, with social equity implications as environmental degradation often disproportionately affects more vulnerable communities.

5. Politics

Italy operates as a unitary parliamentary republic since the abolition of the monarchy in 1946. The country's political framework is defined by the Constitution of Italy, which came into effect on January 1, 1948. The constitution establishes a democratic system with a separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The Italian political landscape is characterized by a multi-party system, which has historically led to coalition governments and periods of political instability, though democratic institutions have remained resilient.

5.1. Government

The Government of Italy is structured as a parliamentary republic. The President of Italy is the head of state, currently Sergio Mattarella (since 2015). The President is elected for a seven-year term by an electoral college composed of both houses of Parliament and 58 regional representatives. The President's role is largely ceremonial but includes important powers such as appointing the Prime Minister, dissolving Parliament, and serving as a guarantor of the Constitution.

Executive power is exercised by the Council of Ministers (Cabinet), which is led by the Prime Minister (officially President of the Council of Ministers). The Prime Minister is the head of government. The President appoints the Prime Minister, usually the leader of the party or coalition that can command a majority in Parliament. The Prime Minister then proposes the other ministers, who are formally appointed by the President. The government must obtain and maintain the confidence of both houses of Parliament. The Prime Minister directs general government policy and is responsible for its implementation, coordinates the activities of ministers, and represents Italy in international relations. A peculiarity of the Italian system is that the Prime Minister has exclusive authority over intelligence policies, financial resources for intelligence, cybersecurity, state secrets, and authorizing covert operations.

Italy has a history of frequent government changes, reflecting the fragmented nature of its party system and the complexities of coalition politics. Major political parties currently include the Brothers of Italy (Fratelli d'Italia), the Democratic Party (Partito Democratico), the Five Star Movement (Movimento 5 Stelle), the League (Lega), and Forza Italia. Political discourse often revolves around economic policy, social issues, European integration, and, increasingly, immigration.

5.2. Legislature

The Italian Parliament (Parlamento Italiano) is the national legislature and is perfectly bicameral, meaning its two houses have equal powers. Legislation can be initiated in either house and must be approved in the exact same text by both to become law.

The two houses are:

1. The **Chamber of Deputies** (Camera dei Deputati): It meets in Palazzo Montecitorio. It currently consists of 400 members (following a constitutional referendum in 2020 that reduced the number of parliamentarians).

2. The **Senate of the Republic** (Senato della Repubblica): It meets in Palazzo Madama. It currently consists of 200 elected members, plus a small number of senators for life. Senators for life include former Presidents of the Republic (ex officio) and up to five citizens appointed by the President for outstanding patriotic merits in social, scientific, artistic, or literary fields.

Both houses are elected for a maximum term of five years through a mixed voting system that combines proportional representation with majoritarian elements. A unique feature of the Italian Parliament is the representation given to Italian citizens living abroad, who elect a number of deputies and senators in dedicated overseas constituencies.

The legislative process involves bills being debated, amended, and voted upon in committees and then by the full assembly of each house. The equal power of the two houses can sometimes lead to lengthy legislative processes or political deadlock if a government does not have a stable majority in both. Major political parties represented in the current parliament, following the 2022 general election, include Giorgia Meloni's Brothers of Italy, Matteo Salvini's League, Silvio Berlusconi's Forza Italia, and Maurizio Lupi's Us Moderates forming the centre-right coalition. Opposition forces include the Democratic Party, the Greens and Left Alliance, Aosta Valley, More Europe, Civic Commitment, the Five Star Movement, Action - Italia Viva, South Tyrolean People's Party, South calls North, and the Associative Movement of Italians Abroad.

5.3. Law and criminal justice

The Italian legal system is a civil law system, primarily based on Roman law, modified by the Napoleonic Code, and later statutes and constitutional principles. The Constitution of Italy (1948) is the supreme law of the land, and the Constitutional Court of Italy (Corte Costituzionale) rules on the conformity of laws with the constitution. The judiciary is independent of the executive and legislative branches.

The court system is hierarchical:

- Justices of the Peace** (Giudici di Pace): Handle minor civil and criminal cases.

- Tribunals** (Tribunali): Courts of first instance for most civil and criminal matters.

- Courts of Appeal** (Corti d'Appello): Hear appeals from the Tribunals.

- Supreme Court of Cassation** (Corte Suprema di Cassazione): Located in Rome, it is the highest court of appeal. It does not re-examine the facts of a case but ensures the correct application of law by lower courts.

Criminal justice is administered through an adversarial system, which replaced an earlier inquisitorial system. Law enforcement is carried out by multiple police forces. The principal national agencies include:

- Polizia di Stato** (State Police): A civilian force under the Ministry of the Interior, responsible for general policing, public order, and security.

- Carabinieri**: A gendarmerie force with both military and civilian police duties, under the Ministry of Defence for military tasks and the Ministry of the Interior for public order.

- Guardia di Finanza** (Financial Guard): A military corps under the Ministry of Economy and Finance, responsible for combating financial crime, tax evasion, smuggling, and customs enforcement.

- Polizia Penitenziaria** (Prison Police): Manages the prison system.

Additionally, there are provincial and municipal police forces (Polizia Provinciale and Polizia Municipale/Locale) with local responsibilities.

A significant challenge for the Italian criminal justice system has been organized crime, particularly the Sicilian Mafia, Calabrian 'Ndrangheta, Neapolitan Camorra, and Apulian Sacra Corona Unita. These organizations have historically infiltrated social and economic life, especially in Southern Italy, and have expanded their operations internationally. The state has waged a long and difficult struggle against organized crime, achieving notable successes but facing persistent threats. Mafia receipts have been estimated to constitute a significant percentage of Italy's GDP in the past, though precise figures are hard to ascertain.

Regarding human rights, Italy is a signatory to major international conventions. However, areas of concern have included prison overcrowding, the length of judicial proceedings, and the treatment of migrants and minorities. LGBT rights have seen some progress, with the legalization of civil unions in 2016, but Italy lags behind some other Western European nations in this area. A specific law criminalizing torture was introduced relatively late (2017) and has faced some criticism for not fully aligning with international standards. The country's murder rate and rape statistics are relatively low compared to many developed countries.

5.4. Foreign relations

Italy's foreign relations are characterized by its strong commitment to multilateralism, European integration, and transatlantic partnerships. As a founding member of the European Economic Community (EEC), now the European Union (EU), and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), Italy plays a significant role in European and international affairs. Italy was admitted to the United Nations in 1955 and is an active participant in numerous international organizations, including the OECD, the GATT/World Trade Organization (WTO), the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the Council of Europe, and the Central European Initiative.

Italy has held rotating presidencies of various international bodies, including the OSCE (2018), the G7 (most recently in 2017 and 2024), and the Council of the EU (most recently in the second half of 2014). It is a recurrent non-permanent member of the UN Security Council, reflecting its engagement in global peace and security issues.

Key pillars of Italian foreign policy include:

- European Integration:** Italy is a strong advocate for deeper European integration and has been a proponent of strengthening EU institutions and common policies. It actively participates in EU decision-making processes and contributes to EU foreign policy initiatives.

- Transatlantic Relations:** Membership in NATO is a cornerstone of Italian security policy. Italy hosts significant NATO and U.S. military facilities and participates in NATO missions and operations. The relationship with the United States is a key strategic alliance.

- Mediterranean Focus:** Given its geographical position, Italy places particular emphasis on the Mediterranean region, addressing issues such as migration, security, and economic cooperation with countries in North Africa and the Middle East. It is a member of the Union for the Mediterranean.

- Multilateralism and Peacekeeping:** Italy strongly supports the United Nations and its role in maintaining international peace and security. The country has a long history of contributing troops to UN peacekeeping missions and other international security operations. In 2013, Italy had over 5,000 troops deployed in 33 UN and NATO missions across 25 countries, including in Somalia, Mozambique, East Timor, Bosnia, Kosovo, Albania, and Afghanistan. Italy has also been a significant contributor to the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL).

- Development Cooperation and Human Rights:** Italy is involved in international development aid and promotes human rights and democratic values globally. It has been a notable financial contributor to the Palestinian Authority.

Italy's foreign policy aims to promote stability, security, and prosperity, both in its immediate neighborhood and on the global stage, often working through international institutions and alliances to achieve these goals. It navigates complex international issues reflecting its stance on international human rights and the promotion of democratic values.

5.5. Military

The Italian Armed Forces (Forze Armate Italiane) consist of four main branches: the Italian Army (Esercito Italiano), the Italian Navy (Marina Militare), the Italian Air Force (Aeronautica Militare), and the Carabinieri. The Carabinieri function as both a military police force and a gendarmerie with civilian policing duties. The President of the Republic is the commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces, with political and operational control exercised through the High Council of Defence and the government, particularly the Minister of Defence. According to Article 78 of the Constitution, the Italian Parliament has the authority to declare a state of war and grant the necessary war-making powers to the government.

Since 2005, military service has been voluntary. In 2010, the Italian military had approximately 293,202 active personnel, of which around 114,778 were Carabinieri. Italy's defense policy is anchored in its NATO membership and its commitment to collective defense and international security operations. As part of NATO's nuclear sharing strategy, Italy hosts U.S. B61 nuclear bombs at the Ghedi and Aviano air bases.

- The **Italian Army** is the national ground defense force. Formed in its modern iteration in 1946 from the remnants of the Royal Italian Army, it is equipped with a range of modern combat vehicles, including the Dardo infantry fighting vehicle, the Centauro tank destroyer, and the Ariete main battle tank. Its aviation component includes the Mangusta attack helicopter, which has been deployed in EU, NATO, and UN missions. The Army also operates older platforms like Leopard 1 tanks and M113 armored personnel carriers.

- The **Italian Navy** is a blue-water navy with significant capabilities, also formed in 1946 from the Regia Marina (Royal Navy). It operates a diverse fleet including aircraft carriers (like the Cavour), destroyers, frigates, submarines, and amphibious assault ships. The Navy is actively involved in international maritime security operations, anti-piracy missions, and humanitarian assistance. In 2014, the Navy had 154 vessels in service, including auxiliary vessels.

- The **Italian Air Force** was founded as an independent service arm in 1923 (as the Regia Aeronautica). In 2021, it operated approximately 219 combat jets, including modern aircraft like the Eurofighter Typhoon. Its transport capabilities are provided by aircraft such as the C-130J and C-27J Spartan. The Air Force's aerobatic display team is the renowned Frecce Tricolori (Tricolour Arrows).

- The **Carabinieri** are an autonomous corps of the military, serving as both the gendarmerie and military police of Italy. They police military personnel and also have wide-ranging civilian law enforcement responsibilities, operating alongside other police forces. While different branches report to various ministries for specific functions, the corps reports to the Ministry of Internal Affairs for public order and security tasks.

The Guardia di Finanza (Financial Guard), though not a branch of the Armed Forces, is a military corps with responsibilities in financial crime, customs, and border control, operating a significant fleet of ships and aircraft. Italy is a major contributor to international peacekeeping missions under the aegis of the UN, NATO, and the EU, reflecting its commitment to global stability. The military history of Italy is extensive, covering periods from ancient Rome to modern multinational operations.

6. Administrative divisions

Italy is a unitary state with a system of decentralized regional and local government. The country is divided into 20 **regions** (regioni). Five of these regions have a special autonomous status, granting them broader legislative and administrative powers on additional matters due to their specific cultural, linguistic, or geographical characteristics. These autonomous regions are:

- Aosta Valley (Valle d'Aosta)

- Friuli-Venezia Giulia

- Sardinia (Sardegna)

- Sicily (Sicilia)

- Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol (Trentino-South Tyrol)

The other 15 ordinary regions are:

- Abruzzo

- Apulia (Puglia)

- Basilicata

- Calabria

- Campania

- Emilia-Romagna

- Lazio

- Liguria

- Lombardy (Lombardia)

- Marche

- Molise

- Piedmont (Piemonte)

- Tuscany (Toscana)

- Umbria

- Veneto

Each region is further subdivided into **provinces** (province) or **metropolitan cities** (città metropolitane). As of recent administrative reforms, there are 107 such entities (a mix of provinces and metropolitan cities). Metropolitan cities, such as Rome, Milan, Naples, and Turin, have replaced provinces in major urban areas, aiming to provide more integrated governance for large conurbations.

The lowest tier of local government consists of **comunes** (municipalities, singular: comune). There are 7,904 comunes in Italy. Comunes are responsible for a wide range of local services, including registry offices, local roads, public transport, waste collection, and local planning. Each comune is headed by a mayor (sindaco) and a municipal council (consiglio comunale).

Regions have their own elected regional councils (Consiglio Regionale) and regional governments (Giunta Regionale) headed by a regional president (Presidente della Regione). They have legislative powers in areas specified by the Constitution, such as healthcare, local transport, and territorial planning. The degree of autonomy varies between ordinary and special statute regions. The system aims to balance national unity with local self-governance, though debates about the appropriate level of decentralization and regional powers continue.

7. Economy

The Italian economy is a highly developed mixed economy, ranking as the third-largest national economy in the Eurozone and the ninth-largest in the world by nominal GDP. It is a founding member of the G7, the Eurozone, and the OECD. Italy is characterized by its advanced industrial sector, particularly in manufacturing, a significant global trade presence, and a rich tradition of craftsmanship and design. However, it also faces structural challenges, including regional disparities, high public debt, and periods of economic stagnation.

7.1. Economic history and current situation

Italy's economic trajectory since World War II has been remarkable. Post-war reconstruction, aided by the Marshall Plan, led to the "Italian economic miracle" (miracolo economico) from the late 1950s to the late 1960s. This period saw rapid industrialization, primarily in the northern regions, transforming Italy from a predominantly agricultural nation into a major industrial power. Living standards rose dramatically, and Italy became a key player in the newly formed European Economic Community.

By the 1970s and 1980s, Italy had solidified its status as one of the world's leading economies, joining the G7. Key sectors driving this growth included automotive manufacturing, machinery, chemicals, textiles, and fashion. However, this period also saw rising inflation, increased public spending, and the accumulation of significant public debt. The "Years of Lead" also brought social and political instability that impacted the economy.

The 1990s were marked by efforts to control public finances in preparation for joining the Euro, which Italy adopted in 1999. Privatizations of state-owned enterprises were undertaken. However, economic growth began to slow compared to other European economies. The 2000s saw periods of stagnation, and the Great Recession of 2008 hit Italy hard, exacerbating structural weaknesses. These include:

- High Public Debt:** Italy's public debt-to-GDP ratio is one of the highest in the Eurozone, posing a persistent challenge to fiscal stability and economic policy. Much of this debt is domestically held.

- North-South Divide (Questione Meridionale):** A significant economic and social gap persists between the more industrialized and prosperous northern regions and the less developed, more agrarian southern regions (the Mezzogiorno). The South typically experiences higher unemployment, lower incomes, and greater reliance on public sector employment and transfers. This divide has deep historical roots and impacts social equity.

- Low Productivity Growth:** Italy has struggled with low productivity growth for several decades, hindering its competitiveness.

- Bureaucracy and Structural Rigidities:** Complex bureaucracy, a slow judicial system, and rigidities in the labor market are often cited as obstacles to investment and growth.

- Demographic Challenges:** An aging population and low birth rates put pressure on the pension system and healthcare, and affect labor supply.

Despite these challenges, Italy remains a major economic power. It has the second-largest manufacturing industry in Europe (after Germany). The economy is characterized by a strong backbone of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), often family-owned and clustered in specialized industrial districts, excelling in producing high-quality, niche products. Italy is a world leader in sectors like luxury goods, fashion, automotive design, machinery, and food products. It also has a significant tourism industry and a productive, albeit regionally specialized, agricultural sector. Recent efforts have focused on structural reforms, boosting investment, and managing public finances within the EU framework, with ongoing implications for social equity and regional development.

7.2. Main industries

Italy's industrial sector is diverse and highly developed, forming a cornerstone of its economy. It is particularly known for high-quality manufacturing and design. Key industrial sectors include:

- Manufacturing:** This is the heart of Italian industry.

- Automobiles:** Italy has a rich automotive heritage, home to iconic brands like Fiat (part of Stellantis), Ferrari, Lamborghini, Maserati, and Alfa Romeo. While mass-market production has faced challenges, Italy remains a leader in luxury and sports car manufacturing, as well as automotive components. The Italian automotive industry employed almost 485,000 people in 2015 and contributed significantly to GDP.

- Machinery and Equipment:** Italy is a major global exporter of industrial machinery, including machine tools, agricultural machinery, packaging machinery, and robotics. This sector is characterized by highly specialized SMEs.

- Metalworking and Fabricated Metal Products:** This includes steel production, metal components, and various fabricated metal goods.

- Fashion and Design (Textiles, Apparel, Leather Goods):** Italy is a global leader in fashion and luxury goods. Cities like Milan are world-renowned fashion capitals. Iconic brands such as Gucci, Prada, Armani, Versace, and Valentino are Italian. The "Made in Italy" label in this sector signifies high quality, craftsmanship, and design excellence. This industry heavily influences regional development, particularly in areas with specialized textile and leather districts. Labor practices and supply chain sustainability are increasingly important considerations.