1. Overview

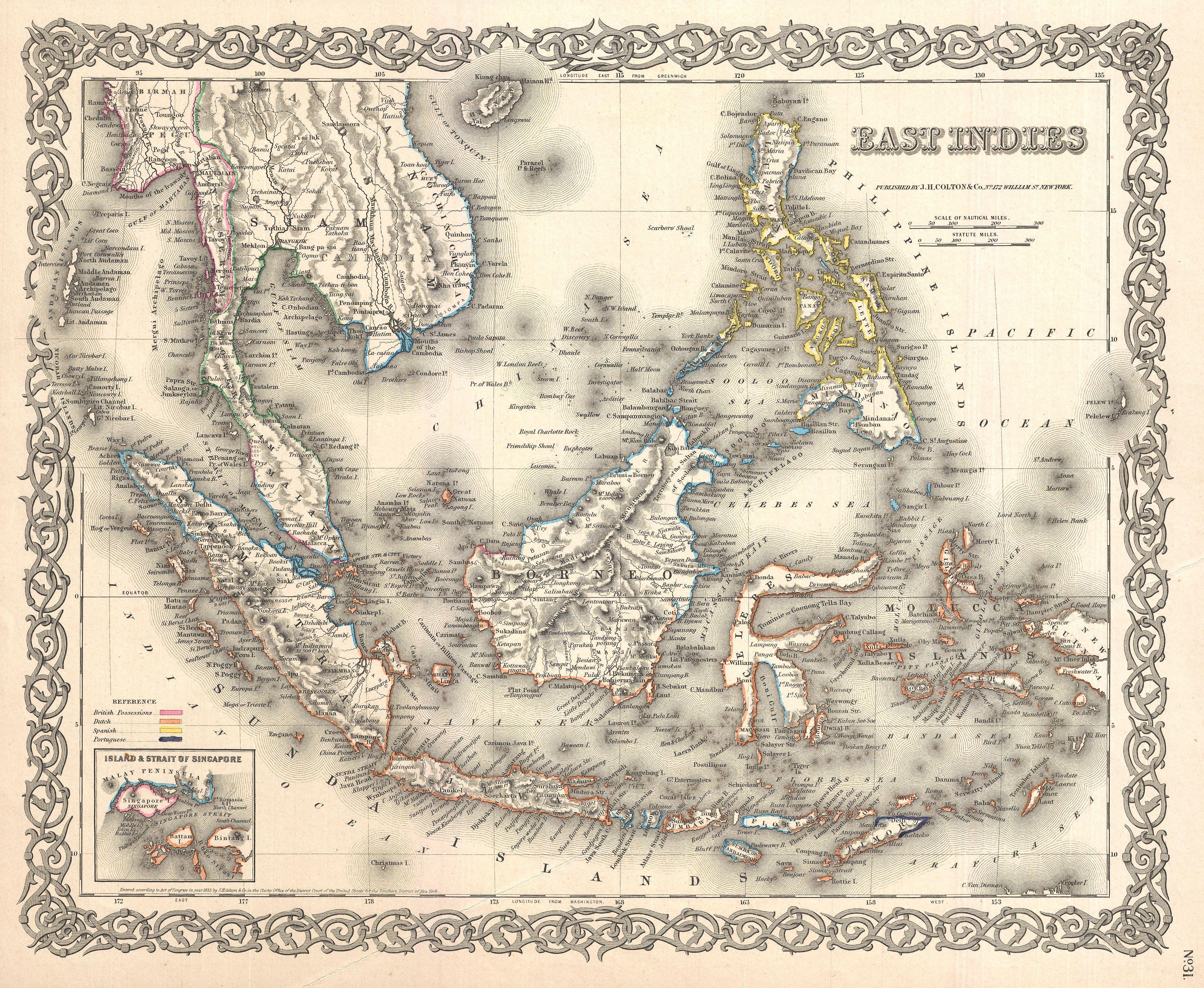

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia (Republik IndonesiaRe-poob-lik In-do-ne-si-aIndonesian), is a vast archipelagic state located in Southeast Asia and Oceania, strategically positioned between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. Comprising over 17,000 islands, including major landmasses such as Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guinea, it is the world's largest island country. With a population exceeding 280 million, Indonesia ranks as the fourth-most populous nation globally and is home to the world's largest Muslim-majority population. Java, the world's most populous island, accommodates over half of the country's inhabitants. Indonesia is a presidential republic with an elected legislature and is divided into 38 provinces, nine of which hold special autonomous status. The current capital, Jakarta, is one of the world's most populous urban areas; however, plans are underway to relocate the capital to Nusantara in East Kalimantan to address environmental and demographic pressures on Jakarta and promote more equitable development.

The history of Indonesia is a complex narrative of indigenous kingdoms, foreign trade and cultural influences, centuries of Dutch colonialism, a difficult struggle for independence, and subsequent nation-building. Early Hindu-Buddhist empires like Srivijaya and Majapahit flourished through maritime trade, leaving significant cultural and architectural legacies. The gradual arrival and spread of Islam reshaped the religious landscape, becoming the dominant faith while often integrating with local traditions. European powers, primarily the Dutch, exerted control for over three centuries, marked by economic exploitation and resistance from the Indonesian people. The Japanese occupation during World War II weakened colonial rule and inadvertently fueled the independence movement, leading to the proclamation of independence in 1945. A challenging period of national revolution followed, culminating in international recognition of sovereignty in 1949.

Post-independence, Indonesia navigated turbulent political transitions, including Sukarno's "Guided Democracy" and Suharto's authoritarian "New Order." The Suharto era, while achieving periods of economic development, was characterized by widespread human rights abuses, suppression of dissent, and systemic corruption, including the controversial occupation of East Timor. The fall of Suharto in 1998 ushered in the "Reformasi" period, a dynamic era of democratization, decentralization, and efforts to address past injustices and promote social equity. However, contemporary Indonesia continues to grapple with challenges such as corruption, regional separatism (particularly in Papua), environmental degradation including deforestation and climate change impacts, and the ongoing struggle to ensure human rights, religious freedom, and social justice for all its diverse communities, including ethnic and religious minorities and LGBTQ+ individuals.

Geographically, Indonesia is defined by its volcanic activity as part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, and its immense biodiversity, making it a megadiverse country. Its tropical climate supports vast rainforests, crucial for global ecology but under threat. The Indonesian economy is the largest in Southeast Asia, driven by services, industry, and agriculture. The nation plays a significant role in regional and international affairs, adhering to a "free and active" foreign policy and as a key member of ASEAN, the G20, and other multilateral organizations. Indonesia's cultural landscape is extraordinarily diverse, reflecting centuries of interaction between indigenous traditions and external influences in arts, music, cuisine, and social customs, all bound by the national motto, "Bhinneka Tunggal Ika" (Unity in Diversity).

2. Etymology

The name Indonesia is derived from two Ancient Greek words: ἸνδόςIndosGreek, Ancient, meaning "Indian," and νῆσοςnesosGreek, Ancient, meaning "island." Thus, Indonesia translates to "Indian islands," referring to the archipelago's location in the Indian cultural sphere. The name dates to the 19th century, long before the formation of an independent Indonesian state.

In 1850, George Windsor Earl, an English ethnologist, proposed the terms Indunesians and, his preference, Malayunesians for the inhabitants of the "Indian Archipelago or Malay Archipelago." In the same publication, one of Earl's students, James Richardson Logan, used Indonesia as a synonym for Indian Archipelago. However, Dutch academics writing in publications of the Dutch East Indies were hesitant to use the name Indonesia. They preferred terms such as Malay Archipelago (Maleische ArchipelMalay ArchipelagoDutch), the Netherlands East Indies (Nederlandsch Oost IndiëNetherlands East IndiesDutch), popularly known as IndiëIndië (Hindia)Dutch, the East (de Oostthe EastDutch), or InsulindeInsulindeDutch. The term Insulinde was introduced in the 1860 novel Max Havelaar by Multatuli (Eduard Douwes Dekker), which criticized Dutch colonialism.

After 1900, the name Indonesia became more common in academic circles outside the Netherlands. Native nationalist groups adopted it for political expression. Adolf Bastian of the University of Berlin popularized the name through his book Indonesien oder die Inseln des Malayischen Archipels, 1884-1894Indonesia or the Islands of the Malay Archipelago, 1884-1894German. The first native scholar to use the name was Ki Hadjar Dewantara (Suwardi Suryaningrat) when, in 1913, he established a press bureau in the Netherlands called the Indonesisch Pers-bureauIndonesian Press BureauDutch. The alternative name for the Indonesian archipelago, Nusantara, is also commonly used.

3. History

The history of Indonesia spans from prehistoric human inhabitation to the modern republic, encompassing ancient kingdoms, colonial rule, a struggle for independence, and contemporary developments. This historical narrative is significantly shaped by its archipelagic geography, which facilitated trade and cultural exchange but also posed challenges to unification and governance, as well as by the enduring impacts of colonialism and the ongoing pursuit of social justice and democratic ideals.

3.1. Prehistory

The Indonesian archipelago has been inhabited since the era of Homo erectus, also known as "Java Man," with fossils dating back between 2 million and 500,000 BCE. Fossils of Homo floresiensis, discovered on the island of Flores, date from around 700,000 to 60,000 BCE. Homo sapiens are believed to have arrived in the archipelago around 43,000 BCE. The islands of Sulawesi and Borneo are home to some of the world's oldest known cave paintings, with figurative art dating back 40,000 to 60,000 years, such as the bull depiction in the Lubang Jeriji Saléh cave. Megalithic sites such as Gunung Padang in western Java, Lore Lindu in Sulawesi, as well as sites in Nias and Sumba in Sumatra, reflect early human settlements and ceremonial practices. These findings indicate sophisticated early cultures long before recorded history.

The formation of the Indonesian archipelago itself involved complex tectonic activities starting from the early Cenozoic era (around 66 million years ago), reaching its current form during the Pleistocene epoch (around 2.58 million years ago). During the Pleistocene, global sea levels were significantly lower, leading to the emergence of Sundaland (connecting Sumatra, Java, Kalimantan with mainland Asia) and the Sahul continent (connecting New Guinea and Australia), with the Wallacea island group in between. The massive eruption of Mount Toba around 74,000 BCE, a VEI-8 supervolcanic event, is thought to have caused a global volcanic winter, potentially impacting human evolution and migration patterns. As the last glacial period ended around 12,000 years ago, rising sea levels submerged lower-lying lands, forming the present-day island configuration.

Around 2,000 BCE (or 3,500-1,500 BCE according to some sources), Austronesian peoples migrated from what is now Taiwan into Southeast Asia, gradually spreading through the Indonesian archipelago. They displaced or assimilated earlier Melanesian populations, pushing them towards the eastern parts of the archipelago. These Austronesian migrants became the ancestors of the majority of Indonesia's modern population. Favorable agricultural conditions, including the development of wet-field rice cultivation by the 8th century BCE, allowed for the growth of villages and, eventually, kingdoms by the first century CE. The archipelago's strategic maritime location fostered extensive inter-island and international trade with civilizations from the Indian subcontinent and mainland China, which profoundly influenced Indonesian history and culture.

3.2. Early Kingdoms

The early historical period of Indonesia was characterized by the rise and fall of influential kingdoms that shaped the political, cultural, and religious landscape of the archipelago. These kingdoms were heavily influenced by foreign cultures, primarily from India, through trade and religious exchange, leading to the flourishing of Hindu-Buddhist traditions, followed by the gradual spread of Islam. The arrival of European powers in the 16th century marked the beginning of a new era of foreign intervention and eventual colonization.

3.2.1. Hindu-Buddhist Kingdoms

The earliest historically verifiable kingdoms in the Indonesian archipelago, such as Kutai Martadipura in East Kalimantan and Tarumanagara in West Java, emerged around the 4th century CE. These kingdoms adopted Hinduism and Buddhism, indicating the early spread of these Indic religions.

By the 7th century CE, the Srivijaya naval kingdom, a Buddhist thalassocracy centered in Palembang, Sumatra, rose to prominence. It thrived on controlling maritime trade routes, particularly the Strait of Malacca, and its influence extended across Sumatra, the Malay Peninsula, parts of Java, Kalimantan, and even into what is now Thailand and Cambodia. Srivijaya became a major center for Buddhist learning and culture.

Between the 8th and 10th centuries CE, Central Java saw the rise of the Buddhist Shailendra dynasty and the Hindu Mataram Kingdom (also known as Medang Kingdom). The Shailendra dynasty was responsible for constructing monumental religious structures, most notably the Borobudur temple, the world's largest Buddhist monument. The Mataram Kingdom, contemporaneous with the Shailendra, built the equally impressive Prambanan temple complex, dedicated to the Hindu trinity. In the 10th century, the center of power in Medang shifted to East Java, ruled by the Isyana dynasty. Medang eventually collapsed in 1016 due to internal rebellion. It was revived as the Kahuripan kingdom by Airlangga in 1019, which later split into Kadiri and Janggala. Kadiri eventually absorbed Janggala.

In 1222, Ken Arok of the Rajasa dynasty overthrew Kadiri and established the Singhasari kingdom in East Java. Singhasari expanded its influence but was weakened by internal strife and external threats, eventually falling in 1292.

Following the collapse of Singhasari, Raden Wijaya, also of the Rajasa dynasty, founded the Majapahit kingdom in eastern Java in 1293. Majapahit grew into a vast maritime empire, often considered one of the greatest in Southeast Asian history. Under the leadership of its famed prime minister Gajah Mada during the reign of King Hayam Wuruk (14th century), Majapahit's influence is said to have extended over much of the Indonesian archipelago, the Malay Peninsula, and parts of mainland Southeast Asia. This period is often referred to as a "Golden Age" in Indonesian history. Majapahit was primarily a Hindu-Buddhist kingdom, practicing a syncretic form of Shiva-Buddhism. The empire's wealth was based on agriculture and extensive maritime trade. However, by the late 15th and early 16th centuries, Majapahit began to decline due to internal succession disputes, rising regional powers, and the growing influence of Islam, eventually falling to the Demak Sultanate in 1527.

Even as Islamic sultanates rose, some Hindu-Buddhist polities persisted, such as the Blambangan Kingdom in East Java and various kingdoms in Bali like Gelgel and its successors (Klungkung, Buleleng, Karangasem, etc.), which maintained their Hindu traditions.

3.2.2. Islamic Sultanates

Islam was introduced to the Indonesian archipelago gradually, beginning as early as the 7th or 8th century CE, primarily through Sunni Muslim traders and Sufi scholars from Gujarat (India), Persia, and southern Arabia. The Aceh region in northern Sumatra became one of the earliest centers for Islamic learning and dissemination. The Jeumpa Kingdom, established in the 7th century in what is now Bireuen Regency, is considered by some to be the first Islamic state in the archipelago, though evidence is debated.

By the 13th century, Islam had gained a significant foothold in northern Sumatra with the rise of sultanates like Samudera Pasai. The spread of Islam in Indonesia accelerated in the 15th and 16th centuries, particularly after the decline of Majapahit. Islam often blended with existing local customs and spiritual beliefs, resulting in a syncretic form of Islamic practice, especially in Java, where the Wali Sanga (Nine Saints) played a crucial role in its propagation through peaceful means.

Several powerful Islamic sultanates emerged across the archipelago. In Java, the Demak Sultanate and the Cirebon Sultanate, both established in the 15th century, were among the earliest and most influential. Demak played a key role in the final downfall of Majapahit. The Mataram Sultanate (distinct from the earlier Hindu-Buddhist Mataram Kingdom), founded in 1586 by the Mataram dynasty (Islamic), became a dominant power in central and eastern Java. It reached its peak under Sultan Agung in the early 17th century but later fragmented due to internal conflicts and Dutch intervention, leading to the Treaty of Giyanti.

In Sumatra, the Aceh Sultanate, founded in 1496, grew into a major regional power, especially under Iskandar Muda (1607-1636). It controlled important trade routes and fiercely resisted European colonial encroachment for centuries.

In Kalimantan, the Bruneian Empire reached its zenith in the 15th century, controlling coastal areas. The Banjarmasin Sultanate, established in 1520, became a significant power in southern Kalimantan before its decline and eventual abolition by the Dutch in 1905.

In Sulawesi, Islam spread from the 16th century. The Gowa and Tallo kingdoms formed an alliance, often referred to as the Makassar Sultanate, which became a major maritime and trading power, its influence extending to eastern Indonesia and even parts of Australia.

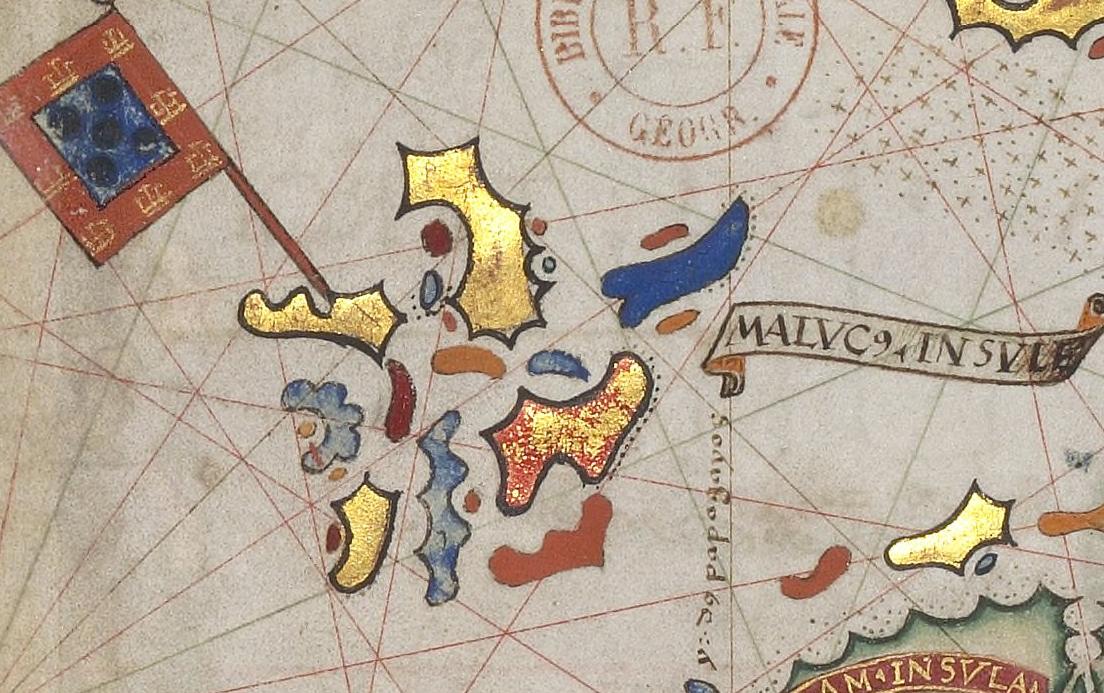

In the Maluku Islands (Spice Islands), the Sultanate of Ternate and the Sultanate of Tidore were dominant. Their wealth was derived from the lucrative spice trade, particularly cloves and nutmeg. These sultanates initially welcomed European traders but later came into conflict with them as European powers sought to monopolize the trade. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) eventually subdued them through manipulation and military force.

The rise of these Islamic sultanates marked a significant transformation in the political, religious, and socio-cultural fabric of the archipelago. While Islam became the dominant religion, it often coexisted and interacted with pre-existing Hindu-Buddhist and indigenous animist beliefs, creating a unique Indonesian Islamic identity. The arrival of European colonial powers in the 16th and 17th centuries began to challenge the sovereignty of these sultanates, leading to a long period of resistance and eventual subjugation.

A few Christian kingdoms also emerged, primarily due to missionary activities accompanying European colonial powers. These included kingdoms like Larantuka and Sikka (Catholic) in Flores, and Siau and Manganitu (Protestant) in North Sulawesi.

3.2.3. European Arrival and Early Colonial Activities

European involvement in the Indonesian archipelago began in the early 16th century, driven by the lucrative spice trade. Portugal was the first European power to establish a significant presence. In 1511, an expedition led by Afonso de Albuquerque conquered Malacca, a key trading port on the Malay Peninsula. Following this, in 1512, Portuguese traders under Francisco Serrão reached the Maluku Islands (Spice Islands), the primary source of cloves and nutmeg. They sought to monopolize this valuable trade. Sultan Bayanullah of Ternate allowed the Portuguese to build a fort (Benteng Kastela) and establish a trade monopoly in Ternate in exchange for military assistance against the rival Sultanate of Tidore.

Spain, also seeking a route to the Spice Islands, arrived in Maluku in 1521 when Juan Sebastián Elcano's expedition reached the islands after Ferdinand Magellan's death in the Philippines. The Spanish allied with Tidore, leading to conflict with the Ternate-Portuguese alliance. This rivalry ended with the Treaty of Zaragoza in 1529, which effectively demarcated Spanish and Portuguese spheres of influence, leaving Maluku largely to Portugal. The Portuguese also attempted to establish control over the Sunda Strait by making an alliance with the Sunda Kingdom in 1522, but this effort was thwarted by local resistance and storms.

Dutch and English traders soon followed the Portuguese. The Dutch, in particular, proved to be formidable competitors. In 1602, the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, VOC) was established, a powerful trading company granted quasi-governmental powers, including the authority to wage war, build forts, and establish colonies. The VOC systematically outcompeted and displaced the Portuguese and English from most of the archipelago. They established their headquarters in Batavia (present-day Jakarta) in 1619 after conquering Jayakarta.

The VOC focused on monopolizing the spice trade, employing often brutal tactics against local populations and rival European powers. The Amboyna massacre in 1623, where English traders were executed by the Dutch, effectively ended significant English competition in the Spice Islands for a period. Over the 17th and 18th centuries, the VOC expanded its control over key trading posts and production centers, often through treaties with local rulers, political manipulation (divide and rule tactics), and military force. While their primary interest was trade, their activities laid the foundation for direct Dutch colonial rule that would follow the VOC's dissolution.

3.3. Dutch Colonial Era

The Dutch colonial era in Indonesia spanned several centuries, evolving from the commercial dominance of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) to direct rule by the Dutch government. This period was characterized by economic exploitation, administrative control, significant social changes, and persistent Indonesian resistance, which eventually culminated in the national awakening and the movement for independence.

3.3.1. Dutch East India Company (VOC) Rule

The Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, VOC), chartered in 1602, was the primary instrument of Dutch commercial and political power in the Indonesian archipelago for nearly two centuries. Granted extensive powers by the Dutch government, including the right to wage war, make treaties, coin money, and establish colonies, the VOC aimed to monopolize the lucrative spice trade.

The VOC established its headquarters in Batavia (present-day Jakarta) in 1619 after conquering Jayakarta. Under governors-general like Jan Pieterszoon Coen, the company aggressively expanded its control over key spice-producing areas, particularly in the Maluku Islands (Spice Islands), and important trading ports throughout the archipelago. They systematically pushed out rival European traders, such as the Portuguese and English, often through military force and strategic alliances with local rulers.

The VOC's methods were often brutal. They imposed harsh trade monopolies, forced local populations to cultivate specific cash crops (like cloves and nutmeg), and ruthlessly suppressed any resistance. The company intervened frequently in the internal affairs of local sultanates and kingdoms, employing "divide and rule" tactics to weaken indigenous powers and secure favorable trade agreements. For example, VOC intervention in the Mataram Sultanate's succession disputes ultimately led to the kingdom's fragmentation through agreements like the Treaty of Giyanti (1755).

Economically, the VOC was immensely profitable for a considerable period, becoming one of the wealthiest corporations in the world by the mid-17th century. It controlled strategic areas like Java, parts of Sumatra (e.g., Painan), Makassar, Manado, and islands in Maluku. However, by the late 18th century, corruption within the company, high administrative costs, changing market demands, and ongoing conflicts in both Europe and the archipelago led to its financial decline. Wars such as the Geger Pacinan (Chinese massacre in Batavia and subsequent Java War of 1741-1743) and the Bayu War in Blambangan (1771-1772) drained its resources. Following the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War (1780-1784), the VOC was in severe financial crisis. The Dutch government (then the Batavian Republic) took over the company's assets and territories in 1796, and the VOC was formally dissolved on December 31, 1799. Its possessions became the Dutch East Indies, a nationalized colony under direct Dutch rule. The VOC's legacy was a system of economic exploitation and political subjugation that profoundly shaped the future of Indonesia.

3.3.2. Dutch Direct Rule and Colonial Expansion

Following the dissolution of the VOC in 1799, its territories in the Indonesian archipelago came under the direct administration of the Dutch government, first under the Batavian Republic and later the Kingdom of Holland (a French puppet state under Napoleon) and then the Kingdom of the Netherlands after 1815. This period marked a shift from company rule to formal colonial governance, characterized by efforts to centralize administration, intensify economic exploitation, and expand Dutch control over the entire archipelago.

Under Herman Willem Daendels (Governor-General 1808-1811, under French control), harsh measures were implemented, including the construction of the Great Post Road (Jalan Raya Pos) across Java, built with forced labor (Heerendiensten), causing immense suffering. A brief British interregnum (1811-1816) under Thomas Stamford Raffles saw some reforms, including the introduction of a land-rent system, but Dutch rule was restored after the Napoleonic Wars.

The 19th century was marked by the intensification of economic exploitation. Governor-General Johannes van den Bosch introduced the Cultivation System (Cultuurstelsel) in 1830. This system forced Javanese peasants to dedicate a portion of their land (typically one-fifth) or labor to cultivate export crops (such as coffee, sugar, and indigo) for the Dutch government. While it brought enormous profits to the Netherlands and helped pay off its national debt, the Cultuurstelsel led to widespread hardship, famines, and increased poverty for the Indonesian population. This system faced criticism and was gradually dismantled from the 1870s onwards, replaced by a more liberal economic policy that encouraged private European investment in plantations and mining.

Throughout the 19th century, the Dutch engaged in numerous military campaigns to consolidate and expand their control over islands beyond Java. This policy, often termed Pax Neerlandica, aimed to bring the entire archipelago under Dutch rule. Significant conflicts included:

- The Padri War (1803-1838) in West Sumatra, where the Dutch intervened in a conflict between traditional adat leaders and Islamic reformists (Padris), eventually subduing the region.

- The Java War (1825-1830), led by Prince Diponegoro, was a major Javanese uprising against Dutch rule. It was a costly war for the Dutch but ultimately resulted in the defeat of Diponegoro and the consolidation of Dutch power in Java.

- Numerous expeditions and wars in other islands, such as the Nias expeditions, conflicts in Bangka and Palembang, Banjarmasin War in South Kalimantan, and interventions in Bali (e.g., 1846, 1848, 1849, 1906, 1908), often culminating in puputan (mass ritual suicide) by Balinese royals and their followers.

- The long and brutal Aceh War (1873-1914) in northern Sumatra, where the Acehnese, under leaders like Teuku Umar and Cut Nyak Dhien, fiercely resisted Dutch colonization. Aceh was only nominally subdued in the early 20th century.

- Campaigns in Batak lands (North Sumatra) against leaders like Sisingamangaraja XII (1878-1907) and interventions in Lombok (1894).

By the early 20th century, the Dutch had established control over the territory that largely corresponds to modern-day Indonesia, including western New Guinea. Dutch colonial administration implemented policies that segregated society, maintained a hierarchical structure with Europeans at the top, and limited opportunities for Indonesians in governance and education, though the Dutch Ethical Policy (from 1901) aimed to improve welfare and provide some education, inadvertently contributing to the rise of Indonesian nationalism.

3.3.3. National Awakening and Rise of Independence Movements

The early 20th century witnessed the emergence of the Indonesian National Awakening (Kebangkitan Nasional Indonesia), a period marked by the rise of nationalist consciousness and organized movements aimed at achieving independence from Dutch colonial rule. Several factors contributed to this awakening, including the oppressive nature of Dutch colonialism, increased access to Western education for a small elite (partly due to the Dutch Ethical Policy initiated in 1901), the influence of nationalist movements in other Asian countries (like Japan's victory over Russia in 1905 and movements in India and the Philippines), and the unifying impact of the spread of the Malay language (which became Bahasa Indonesia) as a lingua franca.

Budi Utomo (Noble Endeavor), founded on May 20, 1908, by Javanese intellectuals and students from the STOVIA medical school, is often considered the first modern Indonesian nationalist organization. Initially focused on cultural and educational advancement for Javanese, it signaled a new phase of organized indigenous activity. May 20th is now commemorated as National Awakening Day in Indonesia.

Sarekat Islam (Islamic Union), founded in 1912 (originating from Sarekat Dagang Islam, an Islamic traders' association formed in 1909 by figures like Tirto Adhi Soerjo), quickly grew into a mass movement. Led by figures like Oemar Said Tjokroaminoto, it initially focused on economic empowerment for Indonesian Muslims but soon adopted a more political and anti-colonial stance, demanding self-governance. Its broad appeal made it one of the largest and most influential early nationalist organizations. However, internal divisions, including the influence of communist ideas, led to splits within the movement in the 1920s.

Other significant organizations emerged, reflecting diverse ideological currents:

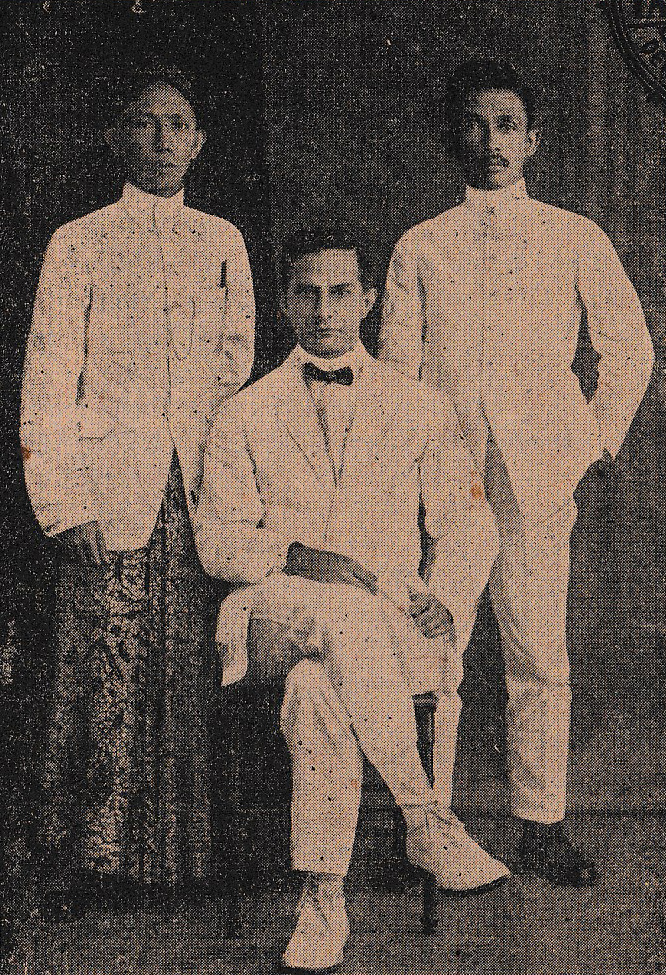

- The Indische Partij (Indies Party), founded in 1912 by the "Tiga Serangkai" (Three Serangkai) - Ernest Douwes Dekker (an Indo-European), Tjipto Mangoenkoesoemo, and Suwardi Suryaningrat (later known as Ki Hadjar Dewantara) - was more radical, openly advocating for independence and equality for all inhabitants of the Indies, regardless of race. It was quickly banned by the Dutch authorities.

- The Indonesian Communist Party (PKI, Partai Komunis Indonesia), formed in 1920 from the Indische Sociaal-Democratische Vereeniging (ISDV, founded 1914 by Henk Sneevliet), became a major force in the labor movement and organized uprisings against Dutch rule in 1926-1927, which were harshly suppressed, leading to the party's banishment.

- Educational movements also played a vital role. Ki Hadjar Dewantara founded Taman Siswa in 1922, an influential network of nationalist schools that emphasized Indonesian culture and self-reliance, challenging the colonial education system. Figures like Kartini and Dewi Sartika championed women's education and emancipation.

Indonesian students studying in the Netherlands formed organizations like Perhimpoenan Indonesia (Indonesian Association, originally Indische Vereeniging founded in 1908), which became a crucial hub for nationalist thought and international advocacy for independence. Figures like Mohammad Hatta and Sutan Sjahrir were active in this group.

A pivotal moment in the unification of the independence movement was the Youth Pledge (Sumpah Pemuda), declared during the Second Indonesian Youth Congress in Batavia (Jakarta) on October 28, 1928. Youth representatives from various regional organizations pledged to uphold "one motherland, Indonesia; one nation, the Indonesian nation; and one language of unity, the Indonesian language." This declaration was a powerful symbol of emerging national identity and unity, transcending ethnic and regional differences. The song "Indonesia Raya," composed by Wage Rudolf Supratman, was also introduced at this congress and later became the national anthem.

In 1927, Sukarno, along with figures like Tjipto Mangoenkoesoemo, founded the Indonesian National Party (PNI, Partai Nasional Indonesia), which advocated for full independence through non-cooperation with the Dutch. Sukarno's charismatic leadership and the PNI's growing popularity led to his arrest and imprisonment by the colonial authorities in 1929. The PNI later fragmented, but Sukarno remained a central figure in the nationalist struggle.

Despite Dutch suppression, including arrests, exile of leaders, and banning of organizations, the nationalist movement continued to grow, laying the groundwork for the eventual proclamation of independence after World War II. The shared experience of colonial oppression and the vision of a unified, independent Indonesia fueled these movements, which, despite their ideological diversity, contributed to a collective national consciousness.

3.4. Japanese Occupation

The Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies during World War II (1942-1945) was a pivotal period that profoundly impacted Indonesian society and significantly altered the course of its struggle for independence. The Dutch colonial administration, weakened by the German occupation of the Netherlands in 1940, collapsed swiftly in the face of the Japanese invasion, which began in January 1942. By March 1942, the Dutch forces surrendered, and Japan took control of the archipelago.

Initially, many Indonesians welcomed the Japanese as liberators from Dutch colonial rule, influenced by Japanese propaganda promoting the "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere" and slogans like the "3A Movement" (Japan, the Light of Asia; Japan, the Protector of Asia; Japan, the Leader of Asia). Japan released nationalist leaders like Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta from Dutch imprisonment and sought their cooperation to mobilize popular support for the Japanese war effort. Sukarno, while cautious, saw an opportunity to advance the cause of Indonesian independence.

However, the occupation soon proved to be harsh and exploitative. Japan's primary goal was to secure resources for its war machine, particularly oil, rubber, and other raw materials. This led to severe economic hardship for the Indonesian population. Food shortages became common as agricultural production was diverted to support Japanese troops. The most brutal aspect of the occupation was the system of forced labor known as romusha. Millions of Indonesian men were conscripted as romusha and sent to work on Japanese military construction projects across Southeast Asia under brutal conditions, resulting in hundreds of thousands of deaths from overwork, malnutrition, and disease. Additionally, many Indonesian women were forced into sexual slavery as "comfort women" (jugun ianfu) for the Japanese military, a profound violation of human rights.

Despite the initial welcome, Japanese rule quickly fostered resentment and resistance. Several local uprisings occurred, such as in Cirebon, Sukamanah (Tasikmalaya), and Aceh, as well as the Mandor Affair and the Dayak Desa War in Kalimantan, though these were swiftly and brutally suppressed by the Japanese military.

Politically, the Japanese occupation had a dual impact. On one hand, it dismantled the Dutch colonial state and, to some extent, allowed Indonesian nationalist leaders greater visibility and opportunities for political organization, albeit under Japanese supervision. The Japanese established various Indonesian auxiliary organizations, such as Putera (Pusat Tenaga Rakyat - Center of People's Power) and later Jawa Hokokai (Java Service Association), to mobilize the population. They also created Indonesian volunteer armies, most notably PETA (Pembela Tanah Air - Defenders of the Homeland) in Java and Sumatra, and Heiho (auxiliary soldiers). These organizations provided military training and organizational experience to many young Indonesians who would later form the backbone of the Indonesian armed forces during the National Revolution.

As the war turned against Japan in 1944, the Japanese began to make concessions towards Indonesian independence to secure continued support. In September 1944, Prime Minister Kuniaki Koiso promised future independence for Indonesia. In March 1945, the Investigating Committee for Preparatory Work for Independence (BPUPK, Badan Penyelidik Usaha-usaha Persiapan Kemerdekaan) was established, chaired by Radjiman Wedyodiningrat, with Sukarno and Hatta playing key roles. This committee drafted the basis for the Indonesian constitution, including Sukarno's formulation of Pancasila (the five principles of the Indonesian state).

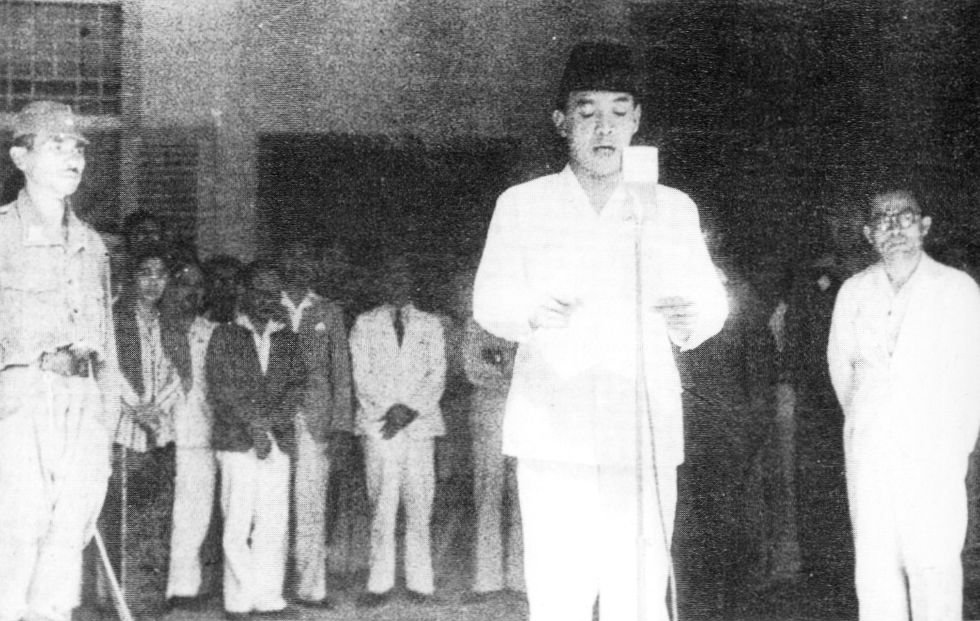

The Japanese surrender on August 15, 1945, following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, created a power vacuum. Indonesian nationalist leaders, particularly younger activists (pemuda), urged Sukarno and Hatta to declare independence immediately, fearing that the returning Dutch would try to re-establish colonial rule.

The Japanese occupation, despite its brutality and hardship, significantly weakened Dutch colonial power by dismantling its administrative and military structures. It also provided a platform for nationalist leaders, fostered a sense of national unity (albeit complexly), and equipped a generation of Indonesians with military and organizational skills that proved crucial in the subsequent fight for independence.

3.5. Indonesian National Revolution

The Indonesian National Revolution (1945-1949) was a period of intense armed conflict and diplomatic struggle between the newly proclaimed Republic of Indonesia and the Netherlands, which sought to re-establish its colonial rule after the Japanese surrender in World War II. This era was marked by widespread popular resistance, internal political divisions within Indonesia, and increasing international pressure on the Netherlands, ultimately leading to Indonesia's internationally recognized sovereignty.

3.5.1. Proclamation of Independence and Revolution

Two days after Japan's surrender to the Allies on August 15, 1945, Indonesian nationalist leaders Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta, under pressure from youth groups (pemuda), proclaimed Indonesian independence on August 17, 1945, in Jakarta. Sukarno became the first President and Hatta the first Vice President. The following day, the Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence (PPKI, Panitia Persiapan Kemerdekaan Indonesia) adopted a constitution (the 1945 Constitution) and formally established the new republic.

The news of independence spread, igniting revolutionary fervor across the archipelago. Indonesians, particularly the youth, formed militias and revolutionary groups, often armed with weapons seized from surrendering Japanese forces or homemade implements. They began to take over government buildings and infrastructure, challenging the remnants of Japanese authority and any attempts by the Dutch to return.

The Netherlands, with Allied support (primarily British initially), was determined to restore its colonial empire. British troops landed in Java and Sumatra in September 1945, ostensibly to disarm Japanese forces and repatriate Allied prisoners of war and civilian internees. However, their presence was often seen as paving the way for the return of Dutch colonial administration (NICA). This led to fierce clashes between Indonesian republicans and Allied (and later Dutch) forces.

Key events during this period of revolutionary war included:

- The Battle of Surabaya (October-November 1945): One of the most intense and bloody battles of the revolution. Indonesian militias and civilians fiercely resisted British attempts to disarm them in Surabaya, East Java. Although the British eventually took the city, the heavy casualties and the determination of the Indonesian resistance drew international attention and galvanized support for the republican cause. November 10th is commemorated as Heroes' Day in Indonesia.

- Other major battles and conflicts occurred across Java and Sumatra, including the Battle of Ambarawa, Battle of Medan, and the Bandung Sea of Fire.

- The Bersiap period: A violent and chaotic phase, particularly in late 1945 and early 1946, characterized by attacks by Indonesian groups against Dutch civilians, Eurasians, and others perceived as pro-colonial, highlighting the human cost from the perspective of victims of this revolutionary violence.

The Indonesian republic faced immense challenges, including internal political divisions between diplomatic and more militant factions, economic hardship, and the task of building a new state amidst warfare. Sutan Sjahrir served as the first Prime Minister, leading efforts for diplomatic recognition. The capital was temporarily moved from Jakarta (which was under Allied/Dutch control) to Yogyakarta in January 1946.

Diplomatic efforts ran parallel to the armed struggle. The Linggadjati Agreement (negotiated in late 1946, ratified March 1947) resulted in de facto Dutch recognition of republican control over Java, Sumatra, and Madura, with plans for a federal United States of Indonesia (RIS) linked to the Netherlands. However, differing interpretations and mutual distrust led to its breakdown.

In July 1947, the Dutch launched a major military offensive known as Operatie Product (Operation Product) or the First Police Action (Agresi Militer Belanda I), seizing large areas of republican-held territory in Java and Sumatra. This action drew international condemnation, particularly from the United Nations, which called for a ceasefire.

The Renville Agreement (January 1948), brokered by the UN aboard the USS Renville, established a ceasefire line (the "Van Mook Line") but was highly unfavorable to the Republic, significantly reducing its territory. Internal strife within the Republic intensified, including the Madiun Affair (September 1948), an abortive communist-led uprising that was suppressed by republican forces.

In December 1948, the Dutch launched a second major military offensive, Operatie Kraai (Operation Crow) or the Second Police Action (Agresi Militer Belanda II). They captured Yogyakarta, arrested Sukarno, Hatta, and other republican leaders, and declared the Republic dissolved. However, Indonesian republican forces, led by General Sudirman, waged a widespread guerrilla war. An emergency republican government (PDRI) was established in Sumatra under Sjafruddin Prawiranegara.

The Dutch military actions and the continued Indonesian resistance, including the General Offensive on Yogyakarta on March 1, 1949, further eroded international support for the Dutch position. The United States, fearing the conflict could push Indonesia towards communism, began to exert significant pressure on the Netherlands to negotiate a transfer of sovereignty.

The Roem-Van Roijen Agreement (May 1949) paved the way for the release of republican leaders and the restoration of the republican government in Yogyakarta. This was followed by the Dutch-Indonesian Round Table Conference held in The Hague from August to November 1949. On December 27, 1949, the Netherlands formally transferred sovereignty to the United States of Indonesia (RIS), a federal state with Sukarno as President. The issue of Western New Guinea remained unresolved and was to be negotiated later.

The Indonesian National Revolution was a transformative period that, despite immense human cost and internal complexities, successfully defended Indonesia's proclaimed independence and established it as a sovereign nation on the world stage. It demonstrated the strength of popular nationalism and the limits of colonial power in the post-World War II era.

3.5.2. Early Republic (United States of Indonesia)

Following the Dutch-Indonesian Round Table Conference and the formal transfer of sovereignty from the Netherlands on December 27, 1949, the United States of Indonesia (RIS, Republik Indonesia Serikat) was established. The RIS was a federal republic, a compromise structure agreed upon during the negotiations with the Dutch. It consisted of sixteen entities: the Republic of Indonesia (which itself comprised territories in Java and Sumatra, with Yogyakarta as its capital) and fifteen other states and autonomous regions largely created by the Dutch during the preceding conflict, such as the State of East Indonesia, State of East Sumatra, and others. Sukarno became the President of the RIS, and Mohammad Hatta its Prime Minister. The RIS Constitution of 1949 provided for a parliamentary system of government.

However, the federal structure was widely unpopular among many Indonesians, who viewed it as a Dutch colonial ploy to divide and weaken the newly independent nation and to maintain Dutch influence through the federal states. There was strong popular sentiment for a unitary state, reflecting the nationalist ideal of "One Nation, One Country, One Language" embodied in the Youth Pledge.

Almost immediately after its formation, movements arose within the federal states to dissolve themselves and merge into the Republic of Indonesia (the original Yogyakarta-based republic). This process occurred rapidly throughout the first half of 1950, often driven by popular demand and political pressure from republican nationalists. Several regional uprisings and disturbances also occurred during this period, reflecting dissatisfaction with the federal arrangement and ongoing political instability. Notable incidents included the APRA (Legion of Ratu Adil) rebellion led by Raymond Westerling in Bandung and Jakarta in January 1950, and uprisings in Makassar.

By August 1950, all constituent states of the RIS, except for the Republic of Indonesia itself, had voted to dissolve and merge into a unitary state. Consequently, on August 17, 1950, the fifth anniversary of the proclamation of independence, the United States of Indonesia was formally dissolved and replaced by the unitary Republic of Indonesia. A new provisional constitution, the Provisional Constitution of 1950, was adopted, which established a parliamentary system of government. Sukarno remained President, but real executive power lay with the Prime Minister and the cabinet, who were responsible to the parliament.

The brief period of the United States of Indonesia thus served as a transitional phase. The strong desire for national unity and the suspicion of federalism as a colonial legacy led to its swift demise and the re-establishment of Indonesia as a unitary republic, a form it has maintained ever since (with variations in its system of government). This transition, however, also set the stage for future challenges related to regional autonomy and central government authority.

3.6. Post-Independence Modern History

The post-independence modern history of Indonesia, following the establishment of the unitary republic in 1950, has been characterized by significant political, economic, and social transformations. This era includes periods of charismatic leadership, authoritarian rule, democratic transitions, economic crises and growth, and ongoing efforts to address social inequalities and human rights issues. The nation's journey has been marked by a continuous struggle to define its identity, unify its diverse population, and assert its place on the global stage, often amidst internal conflicts and external pressures.

3.6.1. Sukarno Era (Guided Democracy)

After the brief period of the United States of Indonesia (1949-1950) and the subsequent liberal democracy era (1950-1959), which was marked by political instability due to a multi-party parliamentary system and frequent cabinet changes, President Sukarno introduced Guided Democracy (Demokrasi Terpimpin) in 1959. Citing the failure of Western-style democracy to provide stability and progress, Sukarno reinstated the 1945 Constitution by presidential decree, which granted significantly more power to the presidency.

Under Guided Democracy, Sukarno sought to create a uniquely Indonesian political system that he believed would better suit the nation's character. Key features of this era included:

- Concentration of Presidential Power:** Sukarno's authority increased substantially. Political parties were weakened, and parliament's role was diminished, leading to concerns about authoritarianism.

- Nasakom Ideology:** Sukarno promoted the concept of "Nasakom" - an acronym for Nasionalisme (Nationalism), Agama (Religion), and Komunisme (Communism) - as the three pillars of Indonesian society and government. This was an attempt to balance the main political forces: the nationalists, Islamic groups, and the increasingly influential Indonesian Communist Party (PKI).

- Foreign Policy:** Indonesia pursued a highly assertive and anti-imperialist foreign policy. Sukarno became a prominent figure in the Non-Aligned Movement, co-hosting the Bandung Conference in 1955 which brought together leaders from Asian and African nations. Relations with Western powers deteriorated, particularly with the Netherlands over the dispute over West Irian (Western New Guinea) and with Malaysia, leading to the Konfrontasi (Confrontation) from 1963 to 1966. Indonesia also withdrew from the United Nations in 1965.

- Economic Policies:** The economy suffered during this period due to political instability, nationalization of foreign assets, and costly prestige projects. Inflation soared, and living standards declined for many, impacting the general populace.

- West Irian Campaign:** A major focus was the campaign to incorporate Dutch-controlled West Irian into Indonesia. This was achieved in 1963 through diplomacy and military pressure, with the territory coming under Indonesian administration (formally integrated in 1969 after the controversial "Act of Free Choice", an event criticized for its lack of genuine self-determination for Papuans).

The Guided Democracy period was characterized by strong nationalist rhetoric and Sukarno's charismatic but increasingly autocratic leadership. While it aimed to create national unity and stability, it also led to the suppression of political dissent and a decline in democratic institutions. Human rights concerns arose due to the curtailment of civil liberties and the imprisonment of political opponents.

Tensions between the military and the PKI, the two most powerful groups supporting Sukarno, escalated throughout the early 1960s. The PKI grew rapidly, becoming one of the largest communist parties outside the Soviet Union and China, which alarmed the staunchly anti-communist military leadership and conservative elements in society.

The era culminated in the 30 September Movement (Gerakan 30 September, or G30S) in 1965, an alleged coup attempt in which six high-ranking army generals were abducted and murdered. The army, under Major General Suharto, blamed the PKI for the coup attempt and launched a brutal and systematic anti-communist purge. Hundreds of thousands to over a million alleged communists and sympathizers were killed, and many more were imprisoned without trial in one of the 20th century's worst massacres, representing a grave human rights catastrophe. This violent episode effectively destroyed the PKI and severely weakened Sukarno's position.

Suharto gradually consolidated power, and in March 1966, Sukarno was pressured into signing the Supersemar (Order of March Eleventh), which transferred significant authority to Suharto. This marked the effective end of Guided Democracy and Sukarno's rule, paving the way for Suharto's "New Order" regime.

Assessments of the Sukarno era are complex. He is revered by many as Indonesia's founding father and a champion of national independence and anti-colonialism, embodying the aspirations of a new nation. However, his leadership during Guided Democracy is also heavily criticized for its authoritarian tendencies, economic mismanagement, and the suppression of democratic processes and human rights, which ultimately contributed to the violent and tragic transition of power.

3.6.2. Suharto Era (New Order)

Following the tumultuous events of the 30 September Movement in 1965 and the subsequent anti-communist purges that resulted in immense loss of life and a climate of fear, General Suharto gradually consolidated power, effectively sidelining President Sukarno. In March 1967, Suharto was appointed acting president, and in March 1968, he was formally elected president, ushering in the "New Order" (Orde Baru) era, which lasted for over three decades until his resignation in 1998.

The New Order regime prioritized political stability and economic development, often at the expense of democratic principles and human rights. Key characteristics and developments of this era include:

- Political Authoritarianism and Stability:** Suharto established a highly centralized and authoritarian government. Political opposition was severely suppressed, and civil liberties, including freedom of speech and assembly, were heavily curtailed. The military (then known as ABRI, later TNI) played a dominant role in politics through the Dwifungsi (dual function) doctrine, which granted it a socio-political role in addition to its defense responsibilities. Golkar, a state-backed political organization, became the dominant political vehicle, consistently winning elections that were tightly controlled and lacked genuine competition or fairness.

- Economic Development:** The New Order, with the guidance of Western-trained economists (often dubbed the "Berkeley Mafia"), implemented policies focused on attracting foreign investment, promoting export-oriented industries, and agricultural development (especially rice self-sufficiency through the "Green Revolution"). Indonesia experienced significant economic growth for much of this period, leading to improvements in infrastructure, education, and healthcare, and a reduction in absolute poverty. However, this development was often uneven, benefiting urban centers and well-connected elites more than rural populations or marginalized groups, and frequently came with significant social and environmental costs.

- Social Policies and Pancasila:** The state ideology of Pancasila was heavily promoted as the sole basis for all social and political organizations, aimed at fostering national unity and suppressing ideological challenges, particularly from Islamism and communism. Religious and ethnic expressions were often controlled to maintain social harmony, sometimes at the cost of minority rights and cultural freedoms.

- Corruption, Collusion, and Nepotism (KKN):** A major criticism of the New Order was the pervasive corruption, collusion, and nepotism that enriched Suharto's family and close associates. This crony capitalism created significant economic distortions and widespread public resentment.

- Human Rights Record:** The New Order regime was responsible for egregious and systematic human rights abuses. Besides the mass killings of 1965-66 at its inception, there was systematic suppression of dissent, restrictions on freedom of speech and assembly, torture, enforced disappearances, and extrajudicial killings of activists, students, and perceived political opponents.

- East Timor:** A particularly brutal chapter was the invasion of East Timor in 1975, following Portugal's decolonization. The subsequent 24-year occupation was marked by widespread human rights violations, including mass killings, torture, starvation as a weapon, and forced displacement, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 East Timorese, a significant portion of its population. This drew extensive international condemnation but was often met with indifference or support from Western powers prioritizing Cold War alliances.

- Papua:** Similar concerns about severe human rights abuses, military repression, suppression of local aspirations for self-determination, and exploitation of natural resources were prevalent in Papua (then Irian Jaya).

- Foreign Policy:** Suharto reversed Sukarno's confrontational foreign policy, rejoining the UN, normalizing relations with Malaysia, and becoming a founding member of ASEAN. The New Order aligned Indonesia closely with the West, particularly the United States, during the Cold War, often overlooking its human rights record in favor of geopolitical stability and anti-communist stances.

The 1997 Asian financial crisis severely impacted Indonesia's economy, exposing the vulnerabilities of its crony capitalist system. The crisis led to soaring inflation, widespread unemployment, and a sharp decline in living standards. This economic collapse fueled massive student-led protests and social unrest. Faced with mounting pressure and loss of support from key allies, including the military, Suharto resigned from the presidency on May 21, 1998.

The Suharto era left a profoundly complex and painful legacy. While credited with achieving economic development and political stability for a period, this came at an immense cost to democratic institutions, fundamental human rights, social equity, and justice. The pervasive corruption and authoritarian practices, underpinned by violence and repression, ultimately undermined its legitimacy and led to its downfall. The transition from the New Order marked the beginning of Indonesia's "Reformasi" period, with hopes for democracy and accountability for past atrocities.

3.6.3. Post-Suharto Era (Reformasi)

The period following President Suharto's resignation on May 21, 1998, is known as the Reformasi (Reformation) era in Indonesia. This era has been characterized by a significant transition towards democracy, decentralization of power, economic recovery efforts, and ongoing challenges related to human rights, social justice, and governance.

Key developments and features of the Reformasi era include:

- Democratic Transition and Constitutional Reforms:** Suharto was succeeded by his vice president, B. J. Habibie, who initiated crucial democratic reforms. These included the release of political prisoners, lifting restrictions on freedom of speech and the press, and allowing the formation of new political parties. The 1945 Constitution underwent four series of amendments between 1999 and 2002, which limited presidential power, strengthened the legislature (DPR), established a Constitutional Court, and introduced direct presidential elections. The military's formal role in politics (Dwifungsi) was gradually dismantled.

- Free and Fair Elections:** Indonesia held its first genuinely free and fair legislative elections in 1999, followed by the first direct presidential election in 2004, won by Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY). Subsequent elections have further consolidated democratic processes, although issues like money politics and low party institutionalization remain. Joko Widodo (Jokowi) became the first president from outside the traditional political or military elite, elected in 2014 and re-elected in 2019.

- Decentralization:** A major reform was the implementation of significant decentralization, transferring substantial administrative and fiscal powers from the central government to regional (provincial, regency, and city) governments. This aimed to address regional grievances and promote local democracy, though it also brought challenges related to capacity, corruption at the local level, and inter-regional disparities. Special autonomy status was granted or enhanced for regions like Aceh and Papua to address separatist sentiments, though implementation and effectiveness remain subjects of debate and concern, especially regarding genuine empowerment of local populations.

- Economic Recovery and Challenges:** The Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-1998 had devastated Indonesia's economy. Subsequent governments focused on macroeconomic stabilization, banking sector reform, and attracting foreign investment. The economy gradually recovered, showing resilience during the 2008 global financial crisis. However, challenges such as poverty, inequality, infrastructure deficits, and reliance on commodity exports persist. Corruption remains a significant impediment to sustainable and equitable development, undermining public trust and economic progress.

- Addressing Past Human Rights Abuses:** There have been efforts to address past human rights violations, including those committed during the Suharto era (e.g., the 1965-66 killings, abuses in Aceh, Papua, and East Timor). Truth and reconciliation initiatives have been discussed, and some ad hoc human rights courts established, but accountability for many past abuses remains severely limited, which is a major point of concern for human rights advocates and victims' groups who continue to call for justice and an end to impunity.

- Social Conflicts and Terrorism:** The early Reformasi period saw outbreaks of communal and sectarian violence in several regions (e.g., Maluku, Central Kalimantan, Poso). Indonesia also faced a significant threat from Islamist terrorism, notably the 2002 Bali bombings. The government has taken steps to counter terrorism and address radicalism, with mixed success and occasional concerns about human rights in counter-terrorism operations.

- Human Rights and Civil Liberties:** While freedom of expression and assembly has significantly improved compared to the New Order, challenges remain. Defamation laws and the Electronic Information and Transactions (ITE) Law have been criticized for their use in stifling criticism and targeting activists, journalists, and ordinary citizens. Issues related to religious freedom, minority rights (including LGBTQ+ individuals, Ahmadiyya Muslims, Shia Muslims, and followers of indigenous beliefs), and the rights of indigenous communities continue to be areas of serious concern. The situation in Papua remains particularly sensitive, with ongoing reports of human rights abuses by security forces, restrictions on access for journalists and international observers, and a failure to address underlying grievances.

- Democratic Consolidation and Challenges to Democracy:** Indonesia is often cited as a successful example of democratic transition in a large, diverse, Muslim-majority country. However, democratic institutions are still evolving, and there are persistent concerns about democratic backsliding, the influence of oligarchs in politics, weakening of anti-corruption efforts, rising intolerance, and the use of identity politics that threaten pluralism and democratic values.

The Reformasi era represents Indonesia's ongoing journey to build a more democratic, just, and prosperous society. It has achieved significant progress in establishing democratic institutions and processes, but it continues to face complex challenges in strengthening good governance, upholding fundamental human rights for all, ensuring social equity, achieving accountability for past atrocities, and managing its diverse cultural and political landscape in an inclusive manner.

4. Geography

Indonesia is an archipelagic state located in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. It is the world's largest island country, stretching approximately 3.2 K mile (5.12 K km) from east to west and 1.1 K mile (1.76 K km) from north to south. The country lies between latitudes 11°S and 6°N, and longitudes 95°E and 141°E. Indonesia comprises over 17,000 islands (with estimates ranging from 13,000 to over 17,504), of which about 6,000 are inhabited. Around 16,056 islands have been officially named.

The five main islands are Sumatra, Java, Borneo (known as Kalimantan in Indonesia and shared with Malaysia and Brunei), Sulawesi, and New Guinea (shared with Papua New Guinea). Indonesia shares land borders with Malaysia on Borneo and Sebatik, Papua New Guinea on the island of New Guinea, and Timor-Leste on the island of Timor. Maritime borders are shared with Singapore, Vietnam, the Philippines, Palau, and India (Andaman and Nicobar Islands) to the north, and Australia to the south. The total land area is approximately 0.7 M mile2 (1.90 M km2), making it the 14th-largest country by land area. Its extensive coastline measures around 67 K mile (108.00 K km). Indonesia also claims an Exclusive Economic Zone of 200 nautical miles. Despite its large population and densely populated regions, Indonesia has vast areas of wilderness that support one of the world's highest levels of biodiversity.

4.1. Topography and Geology

Indonesia's topography is highly varied, featuring towering volcanic mountains, extensive plains, dense rainforests, and vast coastal areas. The country is located on the Pacific Ring of Fire, at the confluence of several major tectonic plates, including the Eurasian Plate, the Indo-Australian Plate, and the Pacific Plate. This geological setting results in frequent earthquakes and significant volcanic activity. There are around 400 volcanoes in Indonesia, of which approximately 130 are considered active. A volcanic arc stretches from Sumatra, through Java, Bali, and the Lesser Sunda Islands, then curves through the Banda Islands of Maluku to northeastern Sulawesi.

The highest peak in Indonesia is Puncak Jaya in Papua, reaching 16 K ft (4.88 K m) above sea level. Lake Toba in Sumatra, the result of a massive supervolcanic eruption around 74,000 BCE, is the largest volcanic lake in the world, covering an area of approximately 0.4 K mile2 (1.15 K km2). This prehistoric eruption is believed to have caused a global volcanic winter. Other historically significant and devastating volcanic eruptions include Mount Tambora in 1815, which led to the "Year Without a Summer" in the Northern Hemisphere and caused around 92,000 deaths, and Mount Krakatoa in 1883, whose explosion was one of the loudest sounds in recorded history and resulted in about 36,000 fatalities from the eruption and subsequent tsunamis. Recent major disasters due to seismic activity include the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, which devastated Aceh and surrounding regions, and the 2006 Yogyakarta earthquake.

Volcanic ash, while sometimes making agriculture unpredictable, has also contributed to the formation of exceptionally fertile soils, particularly in Java and Bali, historically supporting high population densities. Major rivers, primarily found in Kalimantan and New Guinea, such as the Kapuas, Barito, Mamberamo, Sepik, and Mahakam, serve as vital transportation and communication routes for many inland and riverine communities.

4.2. Climate

Indonesia has a predominantly tropical climate, characterized by high temperatures and humidity throughout the year. Its equatorial position ensures relatively stable climatic conditions, with no extreme seasonal variations like summer or winter found in temperate zones. The climate is largely influenced by monsoon winds.

There are two main seasons:

- The wet season (musim hujan), typically occurring from November to April, is brought by the west monsoon originating from Asia and passing over Indonesia towards Australia. This season brings heavy rainfall, especially to the western parts of the country.

- The dry season (musim kemarau), generally from May to October, is influenced by the east monsoon, which carries drier air from Australia.

Rainfall patterns vary across the archipelago. Western Sumatra, Java, and the interiors of Kalimantan and Papua generally receive higher precipitation. In contrast, regions closer to Australia, such as the Nusa Tenggara islands, tend to be drier. Average annual rainfall in lowland areas ranges from 0.1 K in (1.78 K mm) to 0.1 K in (3.18 K mm), while mountainous regions can receive up to 0.2 K in (6.10 K mm).

Temperatures are consistently warm, with coastal areas averaging around 82.4 °F (28 °C), inland and lower mountain areas around 78.8 °F (26 °C), and higher mountain regions around 73.4 °F (23 °C). Humidity levels are typically high, ranging from 70% to 90%. The vast warm waters surrounding Indonesia's islands play a crucial role in moderating land temperatures.

While Indonesia is not typically affected by major typhoons, strong currents in straits like the Lombok Strait and Sape Strait can pose navigational hazards. The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) influences local weather patterns, and phenomena like El Niño can significantly impact rainfall, sometimes leading to prolonged droughts and increased risk of forest fires.

4.2.1. Climate Change Impact

Indonesia is considered highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Several studies project significant risks, which disproportionately affect impoverished communities and those reliant on climate-sensitive sectors:

- Temperature Rise:** An average temperature increase of around 2.7 °F (1.5 °C) by 2050 is anticipated if greenhouse gas emissions are not substantially reduced. This warming could exacerbate droughts, disrupt rainfall patterns critical for agriculture, and increase heat stress.

- Sea level rise**: Rising sea levels pose a severe threat to Indonesia's extensive and densely populated coastal regions, potentially leading to inundation, coastal erosion, displacement of communities, and loss of critical infrastructure. Cities like Jakarta are already experiencing significant land subsidence, compounding this threat.

- Increased Frequency and Intensity of Natural Disasters:** Climate change is expected to lead to more frequent and intense extreme weather events, such as floods, landslides, and droughts, further straining resources, impacting livelihoods, and increasing human vulnerability.

- Impacts on Agriculture and Food Security:** Changes in rainfall and temperature can disrupt agricultural cycles, leading to reduced crop yields and potential food shortages, particularly affecting vulnerable rural populations and jeopardizing national food security.

- Health Impacts:** Increased temperatures and changes in precipitation can expand the range of vector-borne diseases like malaria and dengue fever, and exacerbate other health issues related to heat and water scarcity.

- Ecosystem Degradation:** Coral reefs, mangrove forests, and rainforests, which are vital for biodiversity, coastal protection, and livelihoods, are highly susceptible to climate change impacts such as ocean acidification, rising sea temperatures, and altered weather patterns, leading to irreversible ecological damage.

Indonesia has committed to national adaptation and mitigation efforts, including targets for emissions reduction and investment in renewable energy. However, the nation faces significant challenges in implementing these plans effectively across its vast and diverse archipelago, particularly in ensuring a just transition that protects its most vulnerable communities and ecosystems from the escalating climate crisis and upholds principles of climate justice.

4.3. Biodiversity

Indonesia is recognized by Conservation International as one of the world's 17 megadiverse countries, possessing an exceptionally high level of biodiversity. This richness is attributed to its vast archipelago geography spanning two major biogeographical realms, its tropical climate, and varied ecosystems ranging from rainforests and peatlands to mangroves and coral reefs.

The country's flora and fauna represent a unique mixture of Asian (Indomalayan) and Australasian species, demarcated by the Wallace Line. This imaginary line, first described by naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, runs between Borneo and Sulawesi, and between Bali and Lombok. West of the line, species are predominantly Asian in origin, while to the east, they increasingly resemble Australasian forms. The transitional zone between the Wallace Line and Lydekker's Line (which separates the Australasian region from Wallacea more definitively) is known as Wallacea (comprising Sulawesi, the Lesser Sunda Islands, and Maluku) and is characterized by a high degree of endemism.

4.3.1. Flora and Fauna

Indonesia is home to an astonishing variety of plant and animal life. It hosts approximately 10% of the world's flowering plant species (around 25,000 species, with 55% endemic to Indonesia), 12% of the world's mammal species (around 515 species), 16% of its reptile and amphibian species, and 17% of its bird species (around 1,592 species).

Iconic and endemic fauna include:

- Mammals: Sumatran tiger, Javan rhinoceros, Sumatran rhinoceros (all critically endangered), Orangutan (Bornean and Sumatran species, both critically endangered), Proboscis monkey, Anoa, Babirusa, and various species of gibbons and tarsiers.

- Birds: Bali myna (critically endangered), Javan hawk-eagle (national bird), various species of Bird-of-paradise (especially in Papua), and numerous parrot and hornbill species.

- Reptiles: Komodo dragon (the world's largest lizard, found only on a few Indonesian islands), various crocodiles, snakes, and turtles.

- Fish: Indonesia lies within the Coral Triangle, an area with the world's highest marine biodiversity, hosting over 1,650 species of coral reef fish in its eastern waters alone.

Notable flora includes the Rafflesia arnoldii, which produces the world's largest individual flower, various species of pitcher plants (Nepenthes), numerous orchid species, and valuable timber trees like teak and meranti. The country's rainforests, particularly in Sumatra, Kalimantan (Borneo), and Papua, are among the most extensive in the world, although they are under severe threat. These forests, comprising a significant portion of Southeast Asia's old-growth forest, are crucial for regional ecological balance, global carbon storage, and the livelihoods of indigenous communities.

4.3.2. Environmental Issues and Conservation

Despite its rich biodiversity, Indonesia faces severe environmental challenges that have drawn international concern and impact vulnerable populations. Widespread deforestation and peatland destruction, driven primarily by logging, the expansion of palm oil plantations, agriculture, and mining since the 1970s, have led to significant habitat loss and made Indonesia one of the world's largest emitters of greenhouse gases from land-use change. Forest cover declined from an estimated 87% in 1950 to around 48-49.7% in recent years (data varies by source and year). This degradation has resulted in recurrent transboundary haze pollution affecting neighboring countries and public health, and threatens numerous endemic species. Many species are listed as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), such as the Bali myna, Sumatran orangutan, and Javan rhinoceros. Other significant issues include marine plastic pollution (Indonesia being a major contributor), overfishing, coral reef degradation, and water pollution from industrial and domestic waste. These environmental problems are often exacerbated by weak governance, under-resourced enforcement agencies, corruption, land conflicts affecting indigenous communities, and the prioritization of short-term economic development over environmental protection and social equity, particularly given high poverty levels in some regions. Some academics and activists have labeled activities leading to severe environmental degradation in Indonesia as forms of ecocide.

Conservation efforts are underway, although their effectiveness and commitment are often debated. As of 2023, Indonesia has designated approximately 21.3% of its land area as protected areas and aims to align its strategy with the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. There are 55 national parks, covering about 9% of the country's surface, including nine that are predominantly marine parks like Bunaken National Park and Komodo National Park. Six of these sites are recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, seven are part of the World Network of Biosphere reserves, and five wetlands are designated as Ramsar sites of international importance.

Marine conservation is also a priority, with over 100 marine protected areas (MPAs) established. Indonesia aims to increase its MPA coverage to 30% of its maritime area by 2045. However, studies indicate that many existing marine reserves are poorly managed and funded, lacking effective enforcement and community involvement. The government is also exploring the recognition of Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures (OECMs) to supplement the MPA network. Key challenges in conservation include balancing development needs with environmental protection, ensuring effective and equitable management and enforcement of protected areas, combating illegal logging and wildlife trade, respecting and involving indigenous and local communities in conservation efforts, and addressing the impacts of climate change.

5. Politics and Government

Indonesia is a republic with a presidential system. Following the fall of the New Order regime in 1998, the country underwent significant political reforms, including sweeping amendments to the 1945 Constitution. These reforms restructured the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, strengthening democratic institutions and decentralizing power to regional entities while maintaining its unitary state framework. The state ideology of Pancasila serves as the philosophical foundation of the Indonesian state, intended to unify its diverse population.

5.1. Governmental Structure and System

The Indonesian government operates under a system of separation of powers.

- Executive Branch:** The President is both the head of state and head of government, as well as the commander-in-chief of the Indonesian National Armed Forces (TNI). The President and Vice President are directly elected for a five-year term and can serve a maximum of two consecutive terms. The President appoints a cabinet of ministers. As of 2024, the current president is Prabowo Subianto, and the vice president is Gibran Rakabuming Raka.

- Legislative Branch:** The highest representative body is the People's Consultative Assembly (MPR, Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat). The MPR is a bicameral legislature consisting of:

- The People's Representative Council (DPR, Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat): With 575 members elected through a multi-member district proportional representation system, the DPR is the main legislative body responsible for law-making, budgeting, and executive oversight.

- The Regional Representative Council (DPD, Dewan Perwakilan Daerah): With 136 members (four from each province, regardless of population), the DPD focuses on regional matters, proposing bills related to regional autonomy, central-local government relations, and resource management, and providing input on these issues to the DPR.

The MPR's primary functions include amending the constitution, inaugurating or impeaching the president, and formalizing broad state policies.

- Judicial Branch:** The judicial system includes several key institutions:

- The Supreme Court (Mahkamah Agung): This is the highest judicial authority, handling final appeals (cassation) and conducting case reviews.

- The Constitutional Court (Mahkamah Konstitusi): Established after the constitutional reforms, its main functions are to review the constitutionality of laws, adjudicate disputes between state institutions, rule on the dissolution of political parties, and decide on electoral disputes. It also has the authority to rule on presidential impeachment proceedings initiated by the DPR.

- The Religious Courts (Pengadilan Agama): These courts handle cases related to Islamic personal law, such as marriage, divorce, inheritance, and endowments (waqf) for Muslim citizens.

- The Judicial Commission (Komisi Yudisial): This body is responsible for nominating candidates for Supreme Court justices and for monitoring the conduct and performance of judges to uphold their honor and dignity.

Pancasila, the state ideology, comprises five principles: Belief in the One and Only God; Just and Civilized Humanity; The Unity of Indonesia; Democracy Guided by the Inner Wisdom in the Unanimity Arising Out of Deliberations Amongst Representatives; and Social Justice for all the People of Indonesia. It is intended to be an inclusive ideology that underpins the diverse nation, though its interpretation and application have varied throughout Indonesia's history.

5.2. Political Parties and Elections

Indonesia operates under a multi-party system. Since the end of the New Order in 1998, numerous political parties have emerged, and no single party has consistently won an outright majority in legislative elections, necessitating coalition governments. Major political parties are often categorized as secular-nationalist or Islamic-based, though ideological lines can be fluid, with pragmatism and personality politics playing significant roles.

Some prominent political parties include:

- Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P, Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan): A secular-nationalist party associated with Sukarno's legacy.

- Golkar Party (Partai Golongan Karya): Formerly the state party under Suharto, now a major secular-nationalist party.

- Great Indonesia Movement Party (Gerindra, Partai Gerakan Indonesia Raya): A nationalist party led by Prabowo Subianto.

- Nasdem Party (Partai NasDem): A nationalist party.

- National Awakening Party (PKB, Partai Kebangkitan Bangsa): An Islamic party with strong ties to Nahdlatul Ulama, Indonesia's largest Muslim organization.

- Prosperous Justice Party (PKS, Partai Keadilan Sejahtera): An Islamic party with a more conservative platform.

- National Mandate Party (PAN, Partai Amanat Nasional): An Islamic-leaning reformist party.