1. Overview

Russia (РоссияRossiya, pronounced rɐˈsʲijəRussian), or the Russian Federation (Российская ФедерацияRossiyskaya Federatsiya, pronounced rɐˈsʲijskəjə fʲɪdʲɪˈratsɨjəRussian), is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the largest country in the world by land area, covering over 6.6 M mile2 (17.10 M km2) and encompassing eleven time zones. With a population of approximately 146 million people, Russia is the ninth-most populous country globally and the most populous in Europe. Moscow serves as its capital and largest city, while Saint Petersburg is its second-largest city and cultural center.

The history of Russia begins with the East Slavs, who emerged as a distinct group in Europe between the 3rd and 8th centuries CE. The first major East Slavic state, Kievan Rus', was founded in the 9th century and adopted Orthodox Christianity from the Byzantine Empire in 988, profoundly shaping Russian culture. Following the fragmentation of Kievan Rus' and the Mongol invasions, the Grand Duchy of Moscow gradually rose to prominence, unifying Russian lands and eventually proclaiming the Tsardom of Russia in 1547. By the 18th century, under rulers like Peter the Great and Catherine the Great, Russia had transformed into the vast Russian Empire, a major European power. The 19th century saw significant reforms, including the emancipation of serfs, and the beginnings of industrialization, but also growing social and political tensions.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 led to the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the Russian SFSR, the world's first constitutionally socialist state. After a devastating Russian Civil War, the Russian SFSR, along with other Soviet republics, formed the Soviet Union (USSR) in 1922. Under Joseph Stalin, the USSR underwent rapid industrialization and forced collectivization, policies that, while transforming the nation into an industrial powerhouse, came at an immense human cost, including widespread repression and famines. The Soviet Union played a critical role in the Allied victory in World War II but suffered enormous casualties. The post-war era was dominated by the Cold War, a global ideological and geopolitical struggle between the USSR and the United States. The Soviet period also witnessed significant scientific and technological achievements, including the launch of the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, and the first human spaceflight by Yuri Gagarin.

Economic stagnation and political challenges in the 1980s led to Mikhail Gorbachev's reforms of Perestroika and Glasnost, which ultimately resulted in the dissolution of the USSR in 1991. The Russian Federation emerged as its primary successor state. The 1990s were marked by a turbulent transition to a market economy, political instability, and social hardship. Since the early 2000s, under the leadership of Vladimir Putin, Russia has experienced economic recovery, largely driven by energy exports, but also increased political centralization, democratic backsliding, and growing concerns over human rights. Russia's foreign policy has become more assertive, leading to conflicts such as the war with Georgia in 2008 and the war with Ukraine, which escalated with the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, resulting in international condemnation, sanctions, and a severe humanitarian crisis.

Russia possesses a vast and diverse geography, ranging from tundra and taiga to steppes and mountains. It is rich in natural resources, particularly oil and natural gas, which form the backbone of its economy. The country's political system is a federal semi-presidential republic. Russia is a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council and participates in numerous international organizations. Russian culture has made profound contributions to global arts, literature, music, and science. However, contemporary Russia faces significant challenges related to democratic development, social inequality, corruption, and its international relations, particularly with Western countries.

2. Etymology

The name "Russia" in English, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, first appeared in the 14th century. It was borrowed from Medieval Latin Russia, a term used in the 11th century and frequently found in 12th-century British sources. This Latin term, in turn, was derived from Russi, meaning "the Russians," combined with the suffix -ia.

In the Russian language, several terms translate to "Russians" in English. The noun and adjective русскийrusskiyRussian refers to ethnic Russians. The adjective российскийrossiyskiyRussian denotes Russian citizens regardless of their ethnicity. Similarly, the more recently coined noun россиянинrossiyaninRussian refers to a citizen of the Russian state.

The oldest endonyms (names used by the people themselves) were Rus{{'}} (РусьRus'Russian) and the "Russian land" (Русская земляRusskaya zemlyaRussian). According to the Primary Chronicle, the term Rus{{'}} is derived from the Rus' people, who were a Swedish Varangian tribe from which the founding members of the Rurik dynasty originated. The Finnish word for Swedes, ruotsiRuotsiFinnish, shares the same origin. In modern historiography, the early medieval East Slavic state is commonly referred to as Kievan Rus', named after its capital city, Kiev. Another Medieval Latin name for Rus{{'}} was Ruthenia.

The current Russian name for the country, РоссияRossiya, pronounced rɐˈsʲijəRussian, comes from the Byzantine Greek name ΡωσίαRosíaGreek, Ancient. The form РосияRosiyaRussian was first attested in Russian sources in 1387. The name РоссияRossiyaRussian began to appear in Russian sources in the 15th century and started to replace the vernacular Rus{{'}} as Moscow rose as the center of a unified Russian state. However, until the end of the 17th century, the country was more often referred to by its inhabitants as Rus{{'}}, the "Russian land" (Русская земляRusskaya zemlyaRussian), or the "Muscovite state" (Московское государствоMoskovskoye gosudarstvoRussian), among other variations.

In 1721, Peter the Great proclaimed the Russian Empire (Российская империяRossiyskaya imperiyaRussian). The name Rossiya became the common designation for the multinational Russian Empire and subsequently for the modern Russian state. Rossiya is distinguished from the ethnonym russkiy, as Rossiya refers to a supranational identity that includes ethnic Russians among others. After the Russian Revolution and the proclamation of the Russian SFSR in 1918, the "Russian" in the state's title was Rossiyskaya rather than Russkaya. This choice was made because Rossiyskaya denoted a multinational state, whereas Russkaya carried ethnic dimensions. In modern Russian, the name Rus{{'}} is still used in poetry or prose to refer to either older Russia or an imagined essence of Russia.

The etymology of "Rus'" itself has been a subject of debate among scholars. The "Normanist theory" suggests that "Rus'" originates from Old Norse, specifically from words like Rōþr or the Finnish Ruotsi, meaning "rowers" or "seamen." This theory posits that Varangians, Norse traders and warriors, played a crucial role in the formation of the early Russian state. Evidence includes Scandinavian names in early treaties and accounts from Byzantine and Islamic sources distinguishing Rus' from Slavs. Conversely, the "Anti-Normanist theory" argues for a native Slavic origin, possibly linked to the Ros River, a tributary of the Dnieper, suggesting that Slavic tribes in the area had developed societies before significant Norse influence. Contemporary historians often view the formation of Rus' as a complex process involving interactions between Norse and Slavic elements, with the Norse contributing to state structures and trade networks, while the Slavic population formed the cultural and linguistic base.

3. History

The history of Russia is a vast narrative stretching from ancient settlements and the emergence of the East Slavs to the formation of Kievan Rus', its subsequent fragmentation, the Mongol invasions, the rise of Moscow, the Tsardom, the Russian Empire, the Soviet era, and finally the contemporary Russian Federation. This long history is marked by significant territorial expansion, profound societal transformations, pivotal political shifts, and a complex interplay of cultural influences, all of which have shaped the modern Russian state and its people.

3.1. Early History

Human settlement on the territory of modern Russia dates back to the Oldowan period in the early Lower Paleolithic. About 2 million years ago, representatives of Homo erectus migrated to the Taman Peninsula in southern Russia. Flint tools, approximately 1.5 million years old, have been discovered in the North Caucasus. Radiocarbon dated specimens from Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains estimate the oldest Denisovan specimen lived 195,000-122,700 years ago. Fossils of Denny, an archaic human hybrid that was half Neanderthal and half Denisovan and lived some 90,000 years ago, were also found within this cave. Russia was home to some of the last surviving Neanderthals, from about 45,000 years ago, found in Mezmaiskaya cave.

The first trace of an early modern human in Russia dates back 45,000 years, in Western Siberia. High concentrations of cultural remains of anatomically modern humans, from at least 40,000 years ago, were found at Kostyonki-Borshchyovo and at Sungir, dating back to 34,600 years ago-both in western Russia. Humans reached Arctic Russia at least 40,000 years ago, in Mamontovaya Kurya. Ancient North Eurasian populations from Siberia, genetically similar to the Mal'ta-Buret' culture and Afontova Gora, were an important genetic contributor to Ancient Native Americans and Eastern Hunter-Gatherers.

The Kurgan hypothesis places the Volga-Dnieper region of southern Russia and Ukraine as the urheimat (original homeland) of the Proto-Indo-Europeans. Early Indo-European migrations from the Pontic-Caspian steppe of Ukraine and Russia spread Yamnaya ancestry and Indo-European languages across large parts of Eurasia. Nomadic pastoralism developed in the Pontic-Caspian steppe beginning in the Chalcolithic. Remnants of these steppe civilizations were discovered in places such as Ipatovo, Sintashta, Arkaim, and Pazyryk, which bear the earliest known traces of horses in warfare. The genetic makeup of speakers of the Uralic language family in northern Europe was shaped by migration from Siberia that began at least 3,500 years ago.

In classical antiquity, the Pontic Steppe was known as Scythia. In the 3rd to 4th centuries CE, the Gothic kingdom of Oium existed in southern Russia but was later overrun by Huns. Between the 3rd and 6th centuries CE, the Bosporan Kingdom, a Hellenistic polity that succeeded the Greek colonies, was also overwhelmed by nomadic invasions led by warlike tribes such as the Huns and Eurasian Avars. The Khazars, who were of Turkic origin, ruled the steppes between the Caucasus in the south, to the east past the Volga river basin, and west as far as Kyiv on the Dnieper river until the 10th century. After them came the Pechenegs, who created a large confederacy which was subsequently taken over by the Cumans and the Kipchaks.

The ancestors of Russians are among the Slavic tribes that separated from the Proto-Indo-Europeans, appearing in the northeastern part of Europe approximately 1,500 years ago. The East Slavs gradually settled western Russia (approximately between modern Moscow and Saint Petersburg) in two waves: one moving from Kiev towards present-day Suzdal and Murom, and another from Polotsk towards Novgorod and Rostov. Prior to Slavic migration, this territory was populated by Finno-Ugric peoples. From the 7th century onwards, the incoming East Slavs slowly assimilated the native Finno-Ugrians.

3.2. Kievan Rus'

The establishment of the first East Slavic states in the 9th century coincided with the arrival of Varangians, the Vikings who ventured along the waterways extending from the eastern Baltic to the Black and Caspian Seas. According to the Primary Chronicle, a Varangian from the Rus' people, named Rurik, was elected ruler of Novgorod in 862. In 882, his successor Oleg ventured south and conquered Kiev, which had been previously paying tribute to the Khazars. Rurik's son Igor and Igor's son Sviatoslav subsequently subdued all local East Slavic tribes to Kievan rule, destroyed the Khazar Khaganate, and launched several military expeditions to Bulgaria, Byzantium and Persia.

In the 10th to 11th centuries, Kievan Rus' became one of the largest and most prosperous states in Europe. The reigns of Vladimir the Great (980-1015) and his son Yaroslav the Wise (1019-1054) constitute the Golden Age of Kiev, which saw the acceptance of Orthodox Christianity from Byzantium, and the creation of the first East Slavic written legal code, the Russkaya Pravda. The adoption of Orthodox Christianity was a pivotal moment, deeply influencing the cultural, spiritual, and political development of the Russian lands. It connected Rus' to the broader Byzantine world, bringing literacy, art, architecture, and a new legal framework.

The age of feudalism and decentralization followed, marked by constant in-fighting between members of the Rurik dynasty who ruled Kievan Rus' collectively. Kiev's dominance waned, to the benefit of Vladimir-Suzdal in the north-east, the Novgorod Republic in the north, and Galicia-Volhynia in the south-west. By the 12th century, Kiev lost its pre-eminence, and Kievan Rus' had fragmented into different principalities. Prince Andrey Bogolyubsky sacked Kiev in 1169 and made Vladimir his base, leading to a shift of political power to the north-east.

Led by Prince Alexander Nevsky, Novgorodians repelled the invading Swedes in the Battle of the Neva in 1240, as well as the Germanic crusaders in the Battle on the Ice in 1242. These victories were significant in preserving the independence and Orthodox faith of the northern Rus' lands against Western expansion.

Kievan Rus' ultimately disintegrated under the strain of internal conflicts and the Mongol invasion of 1237-1240. This invasion resulted in the sacking of Kiev and other major cities, widespread destruction, and the death of a significant portion of the population. The invaders, later known as Tatars, formed the state of the Golden Horde, which established suzerainty over the Russian principalities for the next two centuries. This period, often called the "Tatar Yoke," had profound consequences, isolating Russia from Western Europe and influencing its political and social structures. Only the Novgorod Republic largely escaped direct foreign occupation by agreeing to pay tribute to the Mongols. Galicia-Volhynia was later absorbed by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland. In the northeast, the Byzantine-Slavic traditions of Kievan Rus' were adapted, eventually forming the basis of the Russian autocratic state centered around Moscow.

3.3. Grand Duchy of Moscow

The destruction of Kievan Rus' paved the way for the rise of the Grand Duchy of Moscow, initially a part of Vladimir-Suzdal. While still under the dominion of the Mongol-Tatars and often with their connivance, Moscow began to assert its influence in the region in the early 14th century, gradually becoming the leading force in the "gathering of the Russian lands." The strategic location of Moscow, its capable rulers, and the support of the Russian Orthodox Church contributed to its ascendancy. When the seat of the Metropolitan of the Russian Orthodox Church moved to Moscow in 1325, the city's prestige and influence increased significantly. Moscow's last major rival, the Novgorod Republic, prospered as the chief fur trade center and the easternmost port of the Hanseatic League but was eventually subjugated by Moscow.

Led by Prince Dmitry Donskoy of Moscow, the united army of Russian principalities inflicted a milestone defeat on the Mongol-Tatars in the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380. Although this victory did not immediately end Tatar rule, it was a crucial psychological and military turning point, boosting Moscow's authority and demonstrating the possibility of resisting the Horde. Moscow gradually absorbed its parent duchy and surrounding principalities, including formerly strong rivals such as the Tver and Novgorod.

Ivan III ("the Great"), ruling from 1462 to 1505, is considered a key figure in the unification of Russian lands. He effectively threw off the control of the Golden Horde (symbolized by the stand on the Ugra river in 1480) and consolidated the whole of northern Rus' under Moscow's dominion. Ivan III was the first Russian ruler to take the title "Grand Duke of all Rus'." After the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, Moscow began to claim succession to the legacy of the Eastern Roman Empire. Ivan III married Sophia Palaiologina, the niece of the last Byzantine emperor Constantine XI, and adopted the Byzantine double-headed eagle as his own, and eventually Russia's, coat-of-arms. His son, Vasili III, continued the policy of unification, annexing the last few independent Russian states in the early 16th century, thus laying the groundwork for a centralized Russian state.

3.4. Tsardom of Russia

In development of the Third Rome ideas, the Grand Duke Ivan IV ("the Terrible") was officially crowned the first Tsar of All Rus' in 1547. This act signified a new level of sovereign power and imperial ambition. As Tsar, Ivan IV promulgated a new code of laws (the Sudebnik of 1550), established the first Russian feudal representative body (the Zemsky Sobor), revamped the military (creating the Streltsy), curbed the influence of the clergy to some extent, and reorganized local government.

During his long and tumultuous reign, Ivan IV nearly doubled the already large Russian territory by annexing the three Tatar khanates: the Khanate of Kazan and the Khanate of Astrakhan along the Volga, and the Khanate of Sibir in southwestern Siberia. This expansion opened up vast new lands for Russian settlement and control, particularly east of the Ural Mountains. However, the Tsardom was weakened by the long and ultimately unsuccessful Livonian War (1558-1583) against a coalition of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (later the united Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth), the Kingdom of Sweden, and Denmark-Norway. The war was fought for access to the Baltic coast and sea trade but drained Russian resources. In 1572, an invading army of Crimean Tatars was thoroughly defeated in the crucial Battle of Molodi, securing Moscow from a major southern threat. Ivan's reign was also marked by the Oprichnina, a period of brutal purges and state terror directed against the boyar aristocracy, which, while consolidating tsarist power, caused immense suffering and instability.

The death of Ivan's sons marked the end of the ancient Rurik dynasty in 1598. This, combined with the disastrous famine of 1601-1603, led to a period of profound crisis known as the Time of Troubles (1598-1613). This era was characterized by civil war, the rule of pretenders (such as the False Dmitriys), and foreign intervention. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, taking advantage of Russia's weakness, occupied parts of Russia, including the capital Moscow.

In 1612, the Poles were forced to retreat from Moscow by a Russian volunteer corps, famously led by the merchant Kuzma Minin and Prince Dmitry Pozharsky. This event is celebrated as a national holiday in modern Russia. The Romanov dynasty acceded to the throne in 1613 by the decision of the Zemsky Sobor, with Michael Romanov as the first Tsar of this new dynasty. The country then began its gradual recovery from the crisis.

Russia continued its territorial growth through the 17th century, which was also the age of the Cossacks. In 1654, the Ukrainian Cossack leader Bohdan Khmelnytsky, seeking protection from Polish rule, offered to place Ukraine under the protection of the Russian Tsar, Alexis. Alexis's acceptance of this offer led to another Russo-Polish War. Ultimately, Ukraine was split along the Dnieper, with the eastern part, (Left-bank Ukraine and Kiev), coming under Russian rule. In the east, the rapid Russian exploration and colonization of the vast territories of Siberia continued, driven by the hunt for valuable furs and ivory. Russian explorers pushed eastward primarily along the Siberian River Routes, and by the mid-17th century, there were Russian settlements in eastern Siberia, on the Chukchi Peninsula, along the Amur River, and on the coast of the Pacific Ocean. In 1648, Semyon Dezhnyov became the first European to navigate through the Bering Strait.

3.5. Russian Empire

The Russian Empire period, from its proclamation by Peter the Great in 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917, marked Russia's transformation into a major global power. This era was characterized by significant modernization efforts, vast territorial expansion across Eurasia and into North America, major societal upheavals including the emancipation of the serfs, the rise of capitalism, and ultimately the immense political and social pressures that culminated in the First World War and the empire's collapse.

3.5.1. Foundation and Early Expansion (Peter I to Alexander I)

Under Peter the Great, Russia was proclaimed an empire in 1721 and established itself as one of the European great powers. Ruling from 1682 to 1725, Peter implemented sweeping reforms aimed at modernizing Russia along Western European lines. He defeated Sweden in the Great Northern War (1700-1721), securing Russia's access to the Baltic Sea and vital sea trade routes. In 1703, on the Baltic Sea, Peter founded Saint Petersburg as Russia's new capital, a "window to Europe." Throughout his rule, his reforms brought significant Western European cultural influences to Russia, transformed the military and administration, and laid the foundations for a modern, centralized state.

Peter was succeeded by Catherine I (1725-1727), followed by Peter II (1727-1730), and Anna Ioannovna (1730-1740). The reign of Peter I's daughter, Elizabeth Petrovna (1741-1762), saw Russia's participation in the Seven Years' War (1756-1763). During this conflict, Russian troops overran East Prussia and even reached Berlin. However, upon Elizabeth's death, all these conquests were returned to the Kingdom of Prussia by her successor, the pro-Prussian Peter III.

Catherine II ("the Great"), who ruled from 1762 to 1796, presided over the Russian Age of Enlightenment. She extended Russian political control over the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth through the Partitions of Poland, annexing most of its territories into Russia and making Russia the most populous country in Europe. In the south, after successful Russo-Turkish Wars against the Ottoman Empire, Catherine advanced Russia's boundary to the Black Sea by dissolving the Crimean Khanate and annexing Crimea. As a result of victories over Qajar Iran through the Russo-Persian Wars, by the first half of the 19th century, Russia also conquered the Caucasus. Catherine's successor, her son Paul I, had a short and erratic reign, focusing predominantly on domestic issues. Following his rule, Catherine's expansionist strategy was continued by Alexander I (1801-1825), who wrested Finland from the weakened Kingdom of Sweden in 1809 and Bessarabia from the Ottomans in 1812. In North America, the Russians became the first Europeans to reach and colonize Alaska. In 1803-1806, the first Russian circumnavigation of the globe was made. In 1820, a Russian expedition discovered the continent of Antarctica.

3.5.2. Imperial Expansion and Societal Development

During the Napoleonic Wars, Russia joined alliances with various European powers and fought against France. The French invasion of Russia in 1812, at the height of Napoleon's power, reached Moscow. However, it ultimately failed due to obstinate Russian resistance, the scorched earth policy, and the bitterly cold Russian winter. This led to a disastrous defeat for the invaders, in which the pan-European Grande Armée faced utter destruction. Led by Mikhail Kutuzov and Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly, the Imperial Russian Army ousted Napoleon and drove throughout Europe in the War of the Sixth Coalition, ultimately entering Paris. Alexander I played a significant role at the Congress of Vienna, which redefined the map of post-Napoleonic Europe.

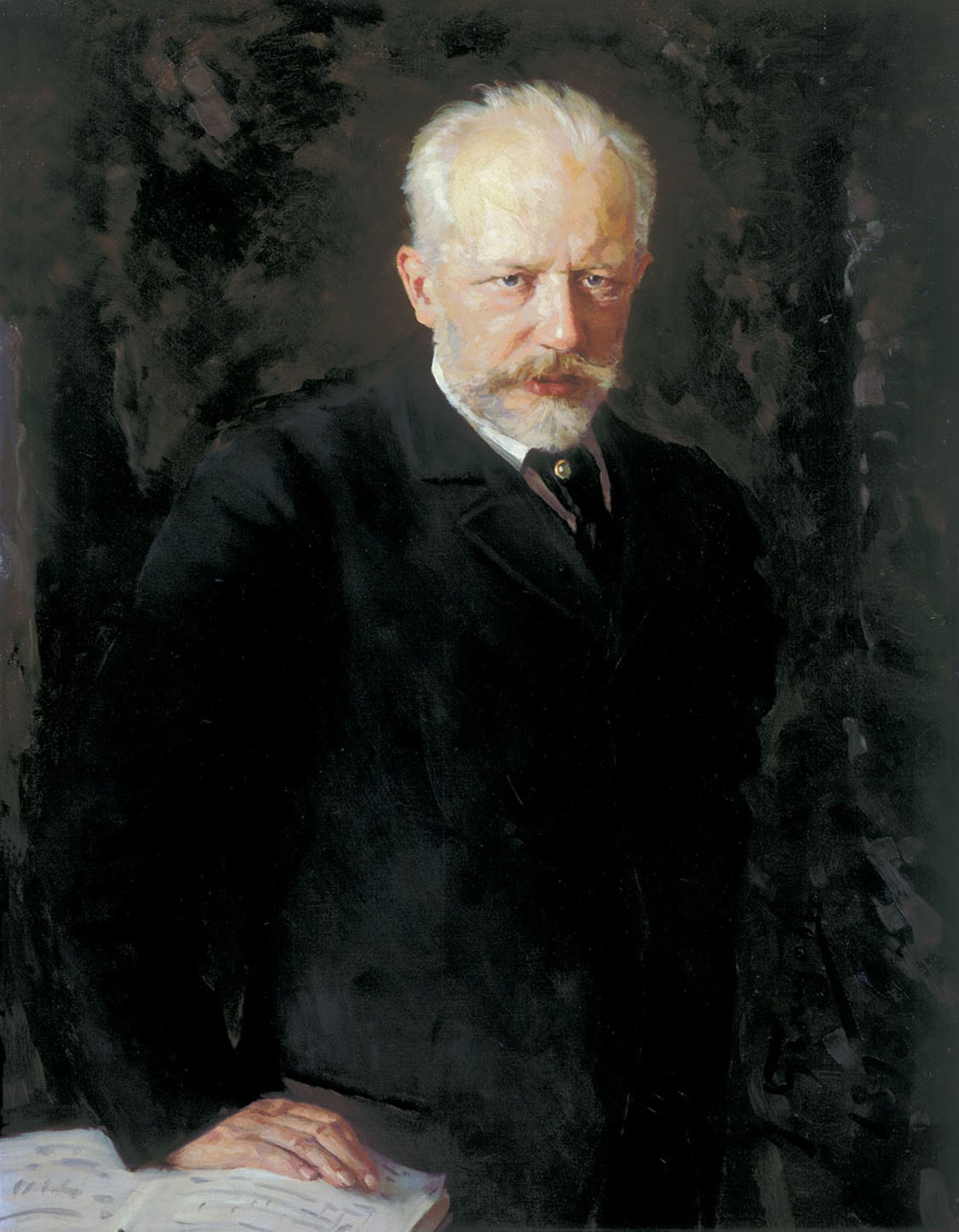

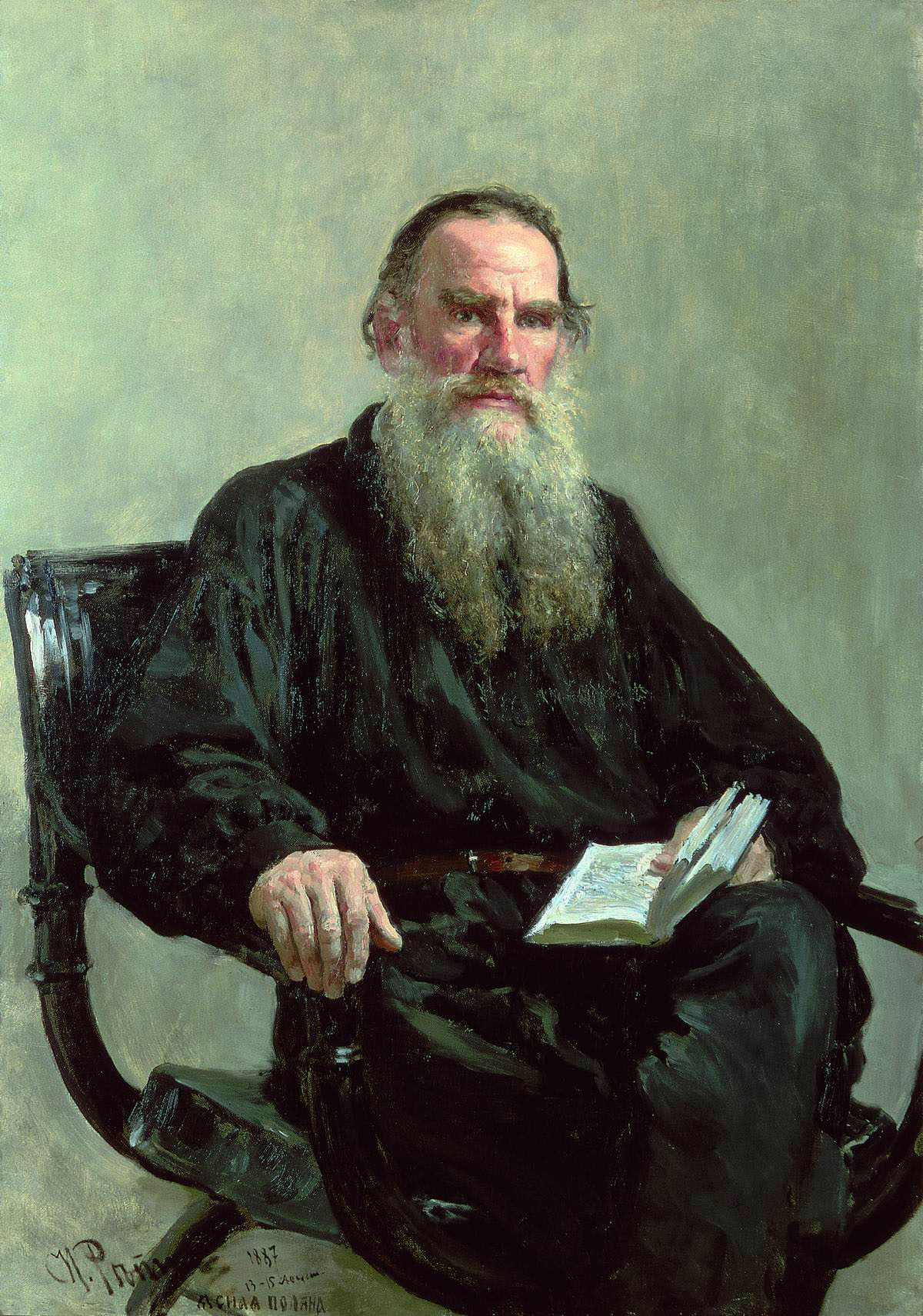

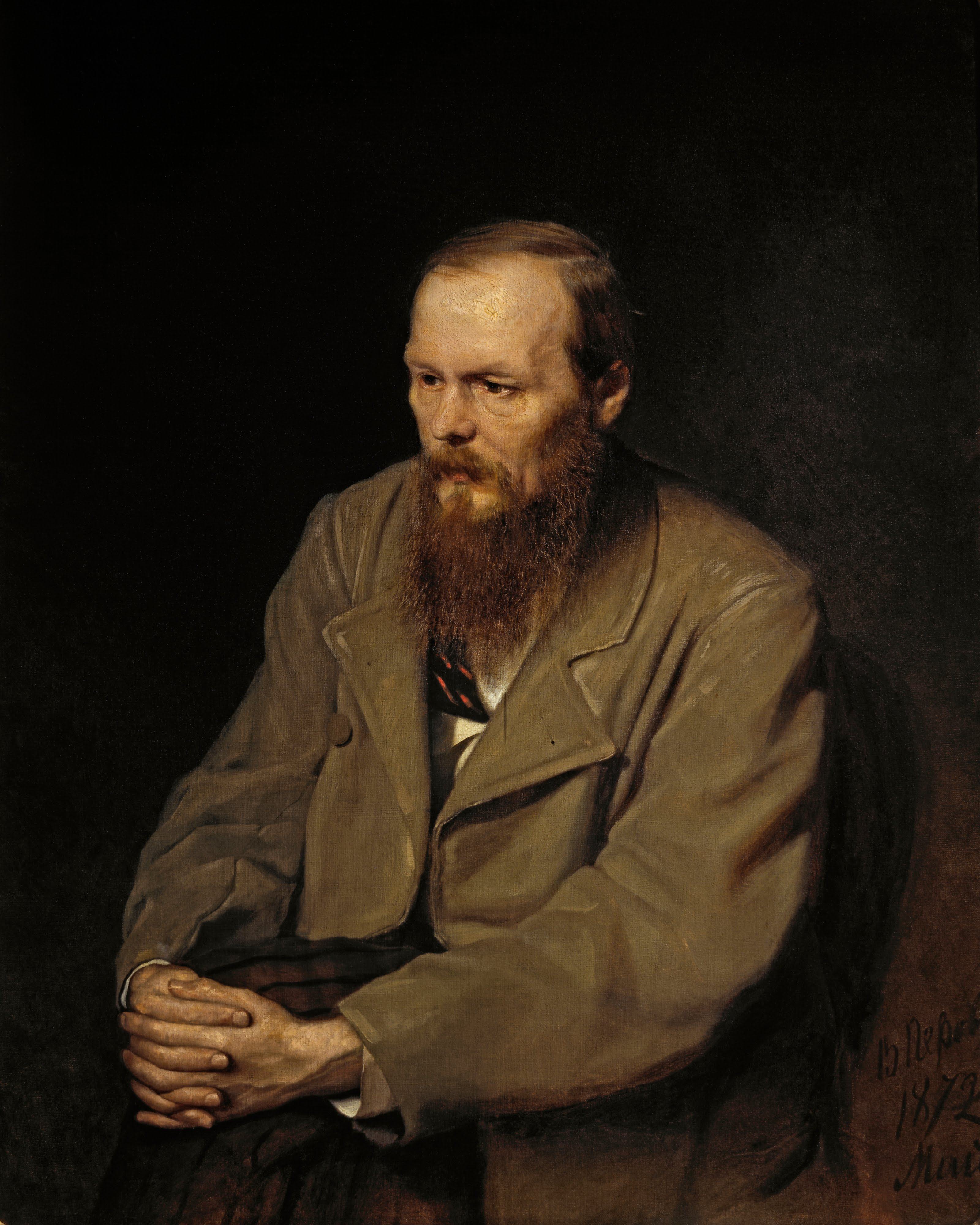

The 19th century was a period of significant territorial growth for the Russian Empire, expanding into Central Asia, the Far East, and further solidifying its control over the Caucasus. This expansion brought diverse populations under Russian rule, leading to complex interactions and often resistance from local peoples. The impact on these populations varied, with some experiencing Russification policies and economic exploitation, while others saw some benefits from integration into a larger empire. Russian society itself underwent development in arts, sciences, and literature, producing world-renowned figures. The empire emerged as a major European and global power, but internally, the autocratic system and the persistence of serfdom (until 1861) created deep social divisions and unrest.

The officers who pursued Napoleon into Western Europe brought ideas of liberalism back to Russia, contributing to the abortive Decembrist revolt of 1825, an attempt to curtail the tsar's powers. The conservative reign of Nicholas I (1825-1855) saw a zenith of Russia's power and influence in Europe, but this was disrupted by defeat in the Crimean War (1853-1856), which exposed Russia's military and technological backwardness compared to Western powers.

3.5.3. Reforms and Rise of Capitalism

Nicholas's successor, Alexander II (1855-1881), enacted significant changes throughout the country, most notably the emancipation reform of 1861, which freed the serfs. This was part of a broader series of "Great Reforms" that included judicial, local government, and military reforms. These reforms spurred industrialization and the beginnings of capitalism in Russia, although the process was often slow and uneven. The social consequences included the growth of an urban working class, changes in the peasantry, and the emergence of a new bourgeoisie. However, the reforms also created new tensions and did not satisfy radical elements, leading to Alexander II's assassination in 1881 by revolutionary terrorists.

The development of capitalism led to the construction of railways, the growth of factories, and an increase in foreign investment. However, working conditions were often harsh, and the peasantry faced land shortages and economic hardship, contributing to social unrest. The late 19th century saw the rise of various socialist movements and increasing revolutionary activity. The reign of Alexander II's son, Alexander III (1881-1894), was marked by political reaction and a reversal of some liberal reforms, but also by relative peace and continued industrial growth.

During most of the 19th and early 20th century, Russia and the British Empire engaged in a geopolitical rivalry over Afghanistan and its neighboring territories in Central Asia and South Asia, known as the Great Game.

3.5.4. Constitutional Monarchy and World War I

Under the last Russian emperor, Nicholas II (1894-1917), Russia experienced significant social and political turmoil. The Revolution of 1905, triggered by the humiliating failure of the Russo-Japanese War and the Bloody Sunday massacre, forced the Tsar to concede major reforms. The October Manifesto promised civil liberties and the creation of an elected legislative body, the State Duma. This marked a shift towards a constitutional monarchy, though the Tsar retained significant powers and often clashed with the Duma. Attempts at further political reform, such as those by Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin, were met with mixed success and ultimately cut short by his assassination.

In 1914, Russia entered World War I in response to Austria-Hungary's declaration of war on Russia's ally Serbia. Russia fought across multiple fronts as part of the Triple Entente but suffered immense casualties and economic strain. The war exposed the weaknesses of the Tsarist regime, leading to widespread discontent among the population and the military. In 1916, the Brusilov Offensive of the Imperial Russian Army almost completely destroyed the Austro-Hungarian Army, but it was a costly victory. The already-existing public distrust of the regime was deepened by the rising costs of war, high casualties, and rumors of corruption and treason. All this formed the climate for the Russian Revolution of 1917.

3.6. Revolution and Civil War

The accumulated social, economic, and political pressures, exacerbated by the devastation of World War I, culminated in the Russian Revolution of 1917, which unfolded in two major phases. The February Revolution (March 1917 by the Gregorian calendar) began with strikes and demonstrations in Petrograd (Saint Petersburg). The army's refusal to fire on protestors and widespread mutinies led to the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II. The monarchy was replaced by a Provisional Government, a shaky coalition of liberal and moderate socialist political parties.

However, the Provisional Government struggled to address the country's deep-seated problems, including the war, land reform, and food shortages. An alternative socialist establishment, the Petrograd Soviet (council of workers' and soldiers' deputies), wielded considerable power and often challenged the Provisional Government's authority. This period of "dual power" created instability.

The October Revolution (November 1917 by the Gregorian calendar), led by Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin, overthrew the Provisional Government. The Bolsheviks, advocating "Peace, Land, and Bread" and "All Power to the Soviets," seized control and established the world's first socialist state, the Russian SFSR. On {{OldStyleDateNY|19 January|6 January}}, 1918, the Russian Constituent Assembly, which had been elected with a non-Bolshevik majority, declared Russia a democratic federal republic but was dissolved by the Bolsheviks the next day.

The Bolshevik seizure of power was followed by the brutal Russian Civil War (1917-1922) between the Bolshevik Red Army and the anti-communist White movement, which was a loose alliance of monarchists, liberals, and other anti-Bolshevik socialists. The Civil War was marked by extreme violence, widespread atrocities (including the Red Terror and White Terror), and devastating famines that claimed millions of lives. Foreign powers, including the Allied powers, launched an unsuccessful military intervention in support of the White forces. The Bolsheviks signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918, ceding vast western territories to the Central Powers to exit World War I, a move that caused internal dissent but allowed them to focus on the Civil War.

By the end of the Civil War, Russia's economy and infrastructure were heavily damaged. As many as 10 million people perished during the war, mostly civilians. Millions became White émigrés, fleeing the country. The Bolsheviks emerged victorious, consolidating their power and laying the foundation for the Soviet Union. Nicholas II and his family were executed by the Bolsheviks in Yekaterinburg in July 1918.

3.7. Soviet Union

The Soviet Union (USSR) period fundamentally reshaped Russia and its place in the world. It encompassed the establishment of a socialist state, rapid industrialization, immense social upheaval, victory in World War II, the Cold War rivalry, and eventual dissolution. This era left a complex legacy of achievements and profound human suffering.

3.7.1. Establishment and Early Years

On 30 December 1922, Vladimir Lenin and his aides formed the Soviet Union (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, USSR), by joining the Russian SFSR into a single state with the Byelorussian, Transcaucasian, and Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republics. Eventually, internal border changes and annexations during World War II created a union of 15 constituent republics. The Russian SFSR was the largest in size and population and dominated the union politically, culturally, and economically.

Following Lenin's death in 1924, a power struggle ensued within the Communist Party. Joseph Stalin, the General Secretary, gradually suppressed all opposition factions and consolidated power, becoming the country's dictator by the 1930s. Leon Trotsky, a key figure in the revolution and proponent of world revolution, was exiled in 1929 and later assassinated. Stalin's doctrine of Socialism in One Country became the official line, focusing on building socialism within the USSR rather than immediate global revolution. The initial years also saw the implementation of the New Economic Policy (NEP), a period of limited market-oriented reforms designed to revive the war-torn economy. However, the NEP was later abandoned in favor of centralized planning.

3.7.2. Stalinism, Industrialization, and Collectivization

Under Stalin's leadership, the Soviet government launched a command economy, rapid industrialization of the largely rural country, and forced collectivization of its agriculture. This period, often referred to as Stalinism, was characterized by ambitious Five-Year Plans aimed at transforming the USSR into an industrial superpower. While industrial output increased dramatically, these policies came at an enormous human cost.

Forced collectivization met with widespread resistance from the peasantry and resulted in catastrophic famines, most notably the Holodomor in Ukraine and the Soviet famine of 1930-1933 in other regions, including parts of the Russian SFSR, which killed millions. Millions of people were sent to Gulag (penal labor camps), including many political prisoners suspected or accused of opposing Stalin's rule. Millions more were deported and exiled to remote areas of the Soviet Union. The Great Purge (or Great Terror) of the late 1930s saw mass arrests, show trials, and executions of party officials, military leaders, intellectuals, and ordinary citizens. The social and human costs of Stalin's policies were profound, leaving deep scars on Soviet society. Despite the brutality, the Soviet Union did achieve a costly transformation from a largely agrarian economy to a major industrial powerhouse in a short span of time, a factor that would prove critical in the upcoming world war.

3.7.3. World War II and the United Nations

The Soviet Union entered World War II on 17 September 1939 with its invasion of Poland, in accordance with a secret protocol within the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany. This pact effectively divided Eastern Europe into German and Soviet spheres of influence. The Soviet Union subsequently invaded Finland, and occupied and annexed the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania), as well as parts of Romania.

On 22 June 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union, opening the Eastern Front, the largest and bloodiest theater of World War II. The period of 1941-1945 is known in Russia as the Great Patriotic War. Despite initial rapid advances by the Wehrmacht, the Soviet Red Army halted the German attack in the Battle of Moscow. Key turning points included the Soviet victory at the Battle of Stalingrad (winter 1942-1943) and the Battle of Kursk (summer 1943). The Siege of Leningrad (1941-1944) by German and Finnish forces resulted in over a million civilian deaths from starvation and bombardment, but the city never surrendered. Soviet forces eventually pushed the Germans back, liberating Eastern and Central Europe, and captured Berlin in May 1945. In August 1945, the Red Army invaded Japanese-occupied Manchuria, contributing to the Allied victory over Japan.

The Soviet Union played a critical role in the Allied victory, but at an immense cost. Soviet civilian and military deaths are estimated at around 26-27 million, accounting for about half of all World War II casualties. German occupation policies, including the "Hunger Plan" and Generalplan Ost, led to the deliberate starvation and murder of millions of Soviet POWs and civilians. The Soviet economy and infrastructure suffered massive devastation, leading to the Soviet famine of 1946-1947. Despite the immense sacrifices, the Soviet Union emerged from the war as a global superpower and a founding member of the United Nations, holding a permanent seat on the Security Council.

3.7.4. Cold War and Superpower Rivalry

After World War II, the Red Army occupied parts of Eastern and Central Europe, including East Germany. Dependent communist governments were installed in the Eastern Bloc satellite states, solidifying Soviet influence in the region. The emergence of the Soviet Union as the world's second nuclear power in 1949 intensified the burgeoning Cold War with the United States and its NATO allies. This period was characterized by ideological conflict, an arms race (particularly in nuclear weapons), a space race, proxy wars, and geopolitical competition for global influence. The Soviet Union established the Warsaw Pact in 1955 as a military alliance of Eastern Bloc countries to counter NATO. The world was largely divided into two opposing camps, with a constant threat of nuclear annihilation.

3.7.5. Khrushchev Thaw and Economic Reforms

After Stalin's death in 1953 and a short period of collective rule, Nikita Khrushchev emerged as the new Soviet leader. In a secret speech at the 20th Party Congress in 1956, Khrushchev denounced Stalin's cult of personality and its consequences, initiating a period of de-Stalinization. Many political prisoners were released from the Gulag labor camps and rehabilitated. This era, known as the Khrushchev Thaw, saw a relative liberalization in Soviet society, arts, and culture, with greater openness to new ideas and some relaxation of censorship.

Khrushchev also attempted economic reforms aimed at decentralization and improving agricultural output, though with mixed success. Foreign policy during this time included efforts at "peaceful coexistence" with the West, but also major crises such as the suppression of the Hungarian Uprising in 1956 and the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, which brought the world to the brink of nuclear war after the U.S. deployed Jupiter missiles in Turkey and the Soviets deployed missiles in Cuba. The Soviet Union achieved significant technological breakthroughs, launching the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, in 1957, and sending the first human, Yuri Gagarin, into space aboard Vostok 1 on 12 April 1961.

3.7.6. Era of Stagnation

Following Khrushchev's ousting in 1964, another period of collective rule ensued until Leonid Brezhnev consolidated his position as the leader. The era of the 1970s and early 1980s under Brezhnev is often referred to as the Era of Stagnation (Период застояPeriod zastoyaRussian). While it was a time of political stability and some improvements in living standards for ordinary citizens (often termed "developed socialism"), it was also characterized by economic stagnation, declining growth rates, increasing technological gaps with the West, and social conservatism. The 1965 Kosygin reform aimed for partial decentralization of the Soviet economy but was largely stifled by bureaucratic resistance and a return to centralized control. Military expenditure remained high, particularly due to the ongoing arms race and Soviet involvement in conflicts like the Soviet-Afghan War (1979-1989). The war in Afghanistan became a costly and unpopular quagmire, often compared to the United States' experience in Vietnam. Dissidence within the Soviet Union was suppressed, though it continued to simmer beneath the surface.

3.7.7. Perestroika, Glasnost, and Dissolution

From 1985 onwards, the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, initiated sweeping reforms known as Perestroika (restructuring) and Glasnost (openness). Perestroika aimed to revitalize the stagnant Soviet economy through decentralization, introduction of market mechanisms, and increased enterprise autonomy. Glasnost sought to increase transparency in government and society, allowing for greater freedom of speech, press, and criticism of the past. Gorbachev also pursued democratization, introducing multi-candidate elections and reducing the Communist Party's monopoly on power.

These reforms, however, unleashed forces that Gorbachev could not control. Glasnost led to the open discussion of historical grievances and current problems, fueling nationalist movements in the various Soviet republics. Economic reforms were often piecemeal and poorly implemented, leading to further economic disruption and shortages. By 1991, the Soviet economy was in a deep crisis. The Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) declared their independence, and other republics followed suit.

A referendum in March 1991 saw a majority vote in favor of preserving the USSR as a "renewed federation," but the momentum for dissolution was strong. In June 1991, Boris Yeltsin was elected President of the Russian SFSR in Russia's first direct presidential election. An attempted coup in August 1991 by hardline Communist Party members against Gorbachev, aimed at halting the reforms and preserving the Union, failed due to popular resistance led by Yeltsin. This event fatally weakened Gorbachev's authority and accelerated the Soviet Union's collapse. On 25 December 1991, Gorbachev resigned, and the Soviet Union officially ceased to exist. Along with contemporary Russia, fourteen other post-Soviet states emerged as independent nations.

3.8. Russian Federation

The establishment of the independent Russian Federation in December 1991 marked a tumultuous new chapter in Russian history. The country embarked on a difficult transition from a communist, centrally planned system to a market-oriented democracy, facing profound economic, political, and social challenges.

3.8.1. Transition to Market Economy and Political Crises (1990s)

The economic and political collapse of the Soviet Union plunged Russia into a deep and prolonged depression. Under President Boris Yeltsin, wide-ranging reforms, including privatization of state-owned enterprises and market and trade liberalization, were undertaken. These reforms, often described as "shock therapy," aimed to rapidly transform the economy but led to severe social hardships. Hyperinflation wiped out savings, industrial production plummeted, and unemployment soared.

The privatization process was often corrupt and poorly managed, leading to the concentration of vast wealth and economic power in the hands of a few well-connected individuals, who became known as the Russian oligarchs. This period saw enormous capital flight as many of the newly rich moved billions in cash and assets out of the country. The collapse of social services was stark: the birth rate plummeted while the death rate skyrocketed, and millions were plunged into poverty. Extreme corruption became rampant, and organized crime flourished.

The political landscape was also highly unstable. Tensions between President Yeltsin and the Russian parliament (the Supreme Soviet and later the State Duma) culminated in the 1993 constitutional crisis. This crisis ended violently with the military shelling the parliament building on Yeltsin's orders. Over 100 people were killed. Yeltsin was backed by Western governments during this confrontation.

3.8.2. Constitutional Order and Economic Stabilization (Late 1990s - Early 2000s)

In December 1993, a referendum approved a new constitution, which established a strong presidential system, granting the president enormous powers. The 1990s were also plagued by armed conflicts in the North Caucasus, including local ethnic skirmishes and separatist Islamist insurrections. From the time Chechen separatists declared independence in the early 1990s, an intermittent and brutal guerrilla war was fought between rebel groups and Russian forces. Terrorist attacks against civilians were carried out by Chechen separatists, claiming thousands of Russian lives, including notorious incidents like the Budyonnovsk hospital hostage crisis and the Russian apartment bombings.

Russia assumed responsibility for settling the Soviet Union's external debts. In 1992, most consumer price controls were eliminated, causing extreme inflation and significantly devaluing the ruble. High budget deficits, coupled with increasing capital flight and an inability to pay back debts, caused the 1998 financial crisis. This crisis led to a sharp devaluation of the ruble and a further decline in GDP but also paved the way for some economic stabilization as it forced a more realistic exchange rate and curbed imports. Efforts towards international integration included joining the Council of Europe and seeking closer ties with Western economic institutions.

3.8.3. Political Centralization and Democratic Backsliding (2000s - Present)

On 31 December 1999, President Yeltsin unexpectedly resigned, handing the post to the recently appointed prime minister and his chosen successor, Vladimir Putin. Putin won the 2000 presidential election and quickly moved to consolidate power. He launched the Second Chechen War, which largely defeated the Chechen insurgency, though a low-level conflict and human rights abuses continued.

Under Putin's leadership (as president from 2000-2008 and 2012-present, and as prime minister from 2008-2012), Russia experienced significant economic recovery, driven largely by high oil prices and increased foreign investment, leading to improved living standards for many. However, this period was also characterized by increased political centralization. Putin reasserted federal control over the regions, curtailed the power of the oligarchs (selectively, often targeting those who challenged him politically), and brought major media outlets, particularly television, under state control or influence.

Concerns grew both domestically and internationally regarding democratic backsliding and the erosion of political freedoms and human rights. Elections were often criticized as unfair, opposition parties faced harassment, and restrictions were placed on freedom of speech, assembly, and the activities of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), particularly those receiving foreign funding (labeled as "foreign agents"). Russia has been described by many observers as transforming into an authoritarian dictatorship or a "managed democracy." The social and political impacts of these trends included a decline in political pluralism, increased state propaganda, and a chilling effect on dissent. Putin won a second presidential term in 2004. Due to constitutional term limits, he stepped down in 2008, and his close ally Dmitry Medvedev was elected President, with Putin becoming Prime Minister. This "tandemocracy" saw Putin retain significant influence. Putin returned to the presidency in 2012 after constitutional changes extended presidential terms to six years.

3.8.4. Invasion of Ukraine

In early 2014, following the pro-Western Euromaidan revolution in neighboring Ukraine which ousted the pro-Russian president Viktor Yanukovych, Russia responded by annexing the Crimean Peninsula. This followed a disputed referendum on the status of Crimea, staged under Russian military occupation. The annexation was widely condemned internationally and was not recognized by most countries.

Subsequently, a conflict erupted in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine, where Russian-backed separatists proclaimed the Donetsk People's Republic and Luhansk People's Republic. Russia provided significant military, financial, and political support to these separatists, leading to an undeclared war against Ukraine. Despite fostering anti-government and pro-Russian protests in the region, most residents had opposed secession from Ukraine. The conflict resulted in thousands of deaths and widespread displacement.

On 24 February 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, marking a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War that had been ongoing since 2014. This invasion, the largest conventional war in Europe since World War II, was met with widespread international condemnation. Numerous countries, including the United States, the European Union, and their allies, imposed severe sanctions on Russia, targeting its economy, financial institutions, and key individuals. Russia was expelled from the Council of Europe in March 2022 and suspended from the United Nations Human Rights Council in April 2022.

The invasion led to a massive humanitarian crisis, with millions of Ukrainians displaced or becoming refugees. There have been numerous accusations of war crimes committed by Russian forces. In September 2022, following successful Ukrainian counteroffensives, Putin announced a "partial mobilization", Russia's first mobilization since World War II. At the end of September 2022, Putin proclaimed the annexation of four partially-occupied Ukrainian regions (Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia), the largest annexation in Europe since World War II. These annexations, based on referendums widely denounced as illegal, are not recognized internationally. The war has resulted in hundreds of thousands of estimated casualties and has further exacerbated Russia's demographic crisis.

In June 2023, the Wagner Group, a Russian private military company heavily involved in the Ukraine war, launched a short-lived rebellion against the Russian Ministry of Defence, capturing Rostov-on-Don before halting its march on Moscow after negotiations. The leader of the rebellion, Yevgeny Prigozhin, was later killed in a plane crash in August 2023, the circumstances of which remain controversial. The ongoing war continues to have profound military, political, economic, and social consequences for Russia, Ukraine, and the wider world.

4. Geography

Russia's vast landmass stretches over the easternmost part of Europe and the northernmost part of Asia, making it a transcontinental country. It is the largest country in the world by total area, covering 6.6 M mile2 (17.10 M km2). Russia spans the northernmost edge of Eurasia and has the world's fourth-longest coastline, measuring over 23 K mile (37.65 K km). An additional 528 mile (850 km) of coastline is along the Caspian Sea, the world's largest inland body of water, which is variously classified as a sea or a lake. Russia lies between latitudes 41° and 82° N, and longitudes 19° E and 169° W, extending some 5.6 K mile (9.00 K km) from east to west, and 1.6 K mile (2.50 K km) to 2.5 K mile (4.00 K km) from north to south. By landmass, Russia is larger than three continents (Australia, Antarctica, and Europe, though it covers a large part of the latter) and has a surface area comparable to that of the dwarf planet Pluto.

Russia borders three oceans: the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Pacific Ocean to the east, and the Atlantic Ocean (via the Baltic Sea, Black Sea, and Sea of Azov) to the west and southwest. It shares land borders with fourteen countries: Norway and Finland to the northwest; Estonia, Latvia, Belarus, and Ukraine to the west (as well as Lithuania and Poland via the Kaliningrad exclave); Georgia and Azerbaijan to the southwest; Kazakhstan and Mongolia to the south; and China and North Korea to the southeast. Russia also shares maritime boundaries with Japan (across the Sea of Okhotsk and La Pérouse Strait) and the United States (across the Bering Strait). Additionally, Russia shares borders with the partially recognized breakaway states of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, whose territory it occupies within Georgia.

Its major islands and archipelagos include Novaya Zemlya, Franz Josef Land, Severnaya Zemlya, the New Siberian Islands, Wrangel Island, the Kuril Islands (four of which are disputed with Japan), and Sakhalin. The Diomede Islands, administered by Russia (Big Diomede) and the United States (Little Diomede), are just 2.4 mile (3.8 km) apart. Kunashir Island of the Kuril Islands is merely 12 mile (20 km) from Hokkaido, Japan.

4.1. Topography

Russia's topography is highly diverse. The country is broadly divided into several major regions. The vast East European Plain (also known as the Russian Plain) covers most of European Russia. This plain is predominantly flat or gently rolling, with highlands such as the Valdai Hills (source of the Volga River) and the Central Russian Upland. To the east, the Ural Mountains, a relatively low and ancient mountain range, traditionally form the boundary between Europe and Asia. They run north to south and are rich in mineral resources.

East of the Urals lies the immense West Siberian Plain, one of the largest flatland areas in the world. It is characterized by extensive wetlands and is drained by major river systems like the Ob and Irtysh. Further east is the Central Siberian Plateau, an elevated region of ancient rock.

Southern and eastern Russia are characterized by more mountainous terrain. The Caucasus Mountains stretch along the southwestern border, containing Mount Elbrus (19 K ft (5.64 K m)), the highest peak in both Russia and Europe. In southern Siberia, the Altai and Sayan Mountains form part of the border with Mongolia and China. The East Siberian Mountains and the Kamchatka Peninsula in the Russian Far East are characterized by rugged mountains and active volcanism, including Klyuchevskaya Sopka (16 K ft (4.75 K m)), the highest active volcano in Eurasia. The lowest point in Russia and Europe is situated at the head of the Caspian Sea, where the Caspian Depression reaches some 95 ft (29 m) below sea level.

Russia is home to over 100,000 rivers and has one of the world's largest surface water resources. Its lakes contain approximately one-quarter of the world's liquid fresh water. Lake Baikal, located in southern Siberia, is the world's deepest, purest, oldest, and most voluminous freshwater lake, containing over one-fifth of the world's fresh surface water. Ladoga and Onega in northwestern Russia are two of the largest lakes in Europe. Russia is second only to Brazil in total renewable water resources. The Volga in western Russia, widely regarded as Russia's national river, is the longest river in Europe and forms the Volga Delta, the largest river delta on the continent. The Siberian rivers of Ob, Yenisey, Lena, and Amur are among the world's longest rivers.

4.2. Climate

The vast size of Russia and the remoteness of many of its areas from the sea result in the dominance of the humid continental climate throughout most of the country, except for the tundra and the extreme southwest. Mountain ranges in the south and east obstruct the flow of warm air masses from the Indian Ocean and Pacific oceans, while the European Plain spanning its west and north opens it to influence from the Atlantic and Arctic oceans.

Most of northwest Russia and Siberia have a subarctic climate (Köppen Dfc, Dwc, Dfd, Dwd), with extremely severe winters in the inner regions of northeast Siberia (mostly Sakha Republic, where the Northern Pole of Cold is located with record low temperatures such as -96.16000000000003 °F (-71.2 °C) in Oymyakon), and more moderate winters elsewhere. Russia's vast coastline along the Arctic Ocean and the Russian Arctic islands have a polar climate (Köppen ET).

The coastal part of Krasnodar Krai on the Black Sea, most notably Sochi, and some coastal and interior strips of the North Caucasus possess a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa) with mild and wet winters. In many regions of East Siberia and the Russian Far East, winter is dry compared to summer (Köppen Dwa, Dwb, Dwc, Dwd); while other parts of the country experience more even precipitation across seasons. Winter precipitation in most parts of the country usually falls as snow. The westernmost parts of Kaliningrad Oblast and some parts in the south of Krasnodar Krai and the North Caucasus have an oceanic climate (Köppen Cfb). The region along the Lower Volga and Caspian Sea coast, as well as some southernmost slivers of Siberia, possess a semi-arid climate (Köppen BSk).

Throughout much of the territory, there are only two distinct seasons, winter and summer, as spring and autumn are usually brief periods of change between extremely low and extremely high temperatures. The coldest month is January (February on the coastline); the warmest is usually July. Great ranges of temperature are typical. In winter, temperatures get colder both from south to north and from west to east. Summers can be quite hot, even in Siberia. Climate change in Russia is causing more frequent wildfires and thawing the country's large expanse of permafrost.

4.3. Biodiversity

Russia, owing to its immense size and diverse geography, exhibits a wide range of ecosystems and a rich biodiversity. These ecosystems include polar deserts in the high Arctic, vast expanses of tundra across the northern regions, forest tundra (a transition zone between tundra and taiga), the extensive taiga (boreal coniferous forest) which is the largest forest biome on Earth, mixed and broadleaf forests further south in European Russia and parts of the Far East, forest steppe (a transition zone between forest and grassland), steppe (grasslands), semi-desert in some southern areas, and even subtropics along the Black Sea coast.

About half of Russia's territory is forested, and it possesses the world's largest forest area. These forests play a crucial role in global carbon sequestration. Russian biodiversity includes approximately 12,500 species of vascular plants, 2,200 species of bryophytes, about 3,000 species of lichens, 7,000-9,000 species of algae, and 20,000-25,000 species of fungi. The country's fauna is equally diverse, comprising about 320 species of mammals, over 732 species of birds, 75 species of reptiles, about 30 species of amphibians, 343 species of freshwater fish (with high endemism), approximately 1,500 species of saltwater fishes, 9 species of cyclostomata, and an estimated 100,000-150,000 invertebrates (also with high endemism). Approximately 1,100 rare and endangered plant and animal species are included in the Russian Red Data Book.

Russia has made efforts to conserve its natural ecosystems through a network of nearly 15,000 specially protected natural territories of various statuses, occupying more than 10% of the country's total area. These include 45 biosphere reserves, 64 national parks, and 101 strict nature reserves (zapovedniks). Despite these efforts, environmental challenges such as pollution, illegal logging, poaching, and the impacts of climate change (including permafrost thaw and increased wildfires) pose significant threats to Russia's biodiversity. Russia had a Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 9.02 in 2019, ranking it 10th globally out of 172 countries and first among major nations, indicating large areas of intact forest, mainly in the northern taiga and subarctic tundra of Siberia.

5. Government and Politics

The Russian Federation is constitutionally a symmetric federal republic with a semi-presidential system. The President is the head of state, and the Prime Minister is the head of government. The government is structured as a multi-party representative democracy, with the federal government composed of three branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. However, in practice, the political system has been characterized by strong presidential power and, particularly under Vladimir Putin, has experienced democratic backsliding, leading to its description by many observers as an authoritarian regime or a dictatorship.

5.1. Political System

The core of Russia's political system is defined by the Constitution of Russia, adopted by national referendum on 12 December 1993.

- Legislative Branch: The bicameral Federal Assembly of Russia consists of the State Duma (the lower house, 450 members) and the Federation Council (the upper house, currently 178 members representing the federal subjects). The State Duma is the primary legislative body, responsible for adopting federal law, declaring war, approving treaties, holding the power of the purse, and possessing the power of impeachment against the president. Members of the State Duma are elected for five-year terms. The Federation Council approves laws passed by the Duma, declares presidential elections, and approves presidential decrees on martial law or states of emergency.

- Executive Branch: The President is the commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces. The president is elected by popular vote for a six-year term (following constitutional amendments in 2008; originally four years) and may be elected for no more than two consecutive terms, though constitutional amendments in 2020 reset the term counts for incumbent and previous presidents, potentially allowing Vladimir Putin to remain in office until 2036. The president appoints the Government (Cabinet), including the Prime Minister (subject to Duma approval) and other ministers, who administer and enforce federal laws and policies. The president can issue decrees of unlimited scope, as long as they do not contradict the constitution or federal law.

- Judicial Branch: The judiciary includes the Constitutional Court, the Supreme Court, and lower federal courts. Judges of these courts are appointed by the Federation Council upon the recommendation of the president. The judiciary is tasked with interpreting laws and can overturn laws they deem unconstitutional.

United Russia is the dominant political party in Russia and has been described as a "big tent" party and the "party of power." While other parties exist and participate in elections, the political landscape is largely controlled by United Russia and parties loyal to the Kremlin. Under Vladimir Putin's administrations, Russia has seen increased political centralization, restrictions on media freedom and civil society, and elections that have been criticized by international observers for lacking fairness and competitiveness. Policies under Putin are often referred to as Putinism.

5.2. Political Divisions

Russia is a federation composed of 89 federal subjects. This number includes entities on territory internationally recognized as part of Ukraine but annexed by Russia: the Republic of Crimea and the federal city of Sevastopol (annexed in 2014), and four other Ukrainian oblasts whose annexation Russia declared in 2022. These annexations are not recognized by most of the international community. These subjects have equal representation in the Federation Council (two delegates each) but differ in the degree of autonomy they enjoy. The types of federal subjects are:

- 48 Oblasts (provinces): The most common type, with a governor (often appointed or heavily influenced by the federal center) and a locally elected legislature.

- 22 Republics: Nominally autonomous, often home to a specific ethnic minority, with their own constitution, official language (alongside Russian), president, and parliament. However, they are represented by the federal government in international affairs, and their autonomy has been significantly curtailed under federal centralization policies.

- 9 Krais (territories): Legally similar to oblasts; the title "krai" (frontier or territory) is historic.

- 4 Autonomous Okrugs (autonomous districts): Typically associated with substantial ethnic minorities, these were originally parts of krais or oblasts but some gained direct federal subject status. Most remain administratively subordinate to a larger federal subject.

- 3 Federal Cities: Major cities that function as separate regions (Moscow, Saint Petersburg, and Sevastopol - the latter's status is internationally disputed).

- 1 Autonomous Oblast: The Jewish Autonomous Oblast.

Map legend:

* Light Yellow: Oblasts

* Green: Republics

* Orange: Krais

* Dark Blue: Autonomous Okrugs

* Red: Federal Cities

* Purple: Autonomous Oblast

To facilitate central government control, President Putin established federal districts in 2000. There are currently eight federal districts, each headed by a presidential envoy appointed by the President of Russia. These districts are an additional administrative layer and not constituent entities of the Federation.

5.3. Foreign Relations

Russia maintains diplomatic relations with 187 United Nations member states, two partially-recognized states (Abkhazia and South Ossetia), and two United Nations observer states. It has the world's sixth-largest diplomatic network, with 143 embassies. Russia is one of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council (P5), granting it veto power.

Russia is generally considered a great power and a regional power, although its status has been debated, particularly following its performance in the invasion of Ukraine. It is a successor state to the Soviet Union, a former superpower. Russia is a member of the G20, the OSCE, and the APEC. It plays a leading role in post-Soviet organizations such as the CIS, the EAEU, and the CSTO. Russia is also a key member of the SCO and BRICS.

Russia maintains close relations with Belarus as part of the Union State, a supranational confederation. Serbia has been a historically close ally. India is a major customer of Russian military equipment and shares a long-standing strategic relationship. Russia wields significant political influence in the South Caucasus and Central Asia, often considered its traditional sphere of influence or "backyard."

In the 21st century, relations between Russia and China have strengthened significantly, driven by shared political and economic interests, often in opposition to perceived Western dominance. Relations with Turkey are complex, involving strategic cooperation in some areas (like energy) and rivalry in others. Russia maintains cordial relations with Iran, viewing it as a strategic and economic ally. Russia has also sought to expand its influence in the Arctic, Asia-Pacific, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America. Many countries in the Global South have remained neutral or maintained ties with Russia despite Western pressure.

However, Russia's relations with neighboring Ukraine and the Western world-especially the United States, the European Union, and NATO countries-have severely deteriorated, particularly since the 2014 annexation of Crimea and the 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine. These events led to widespread international condemnation, extensive sanctions against Russia, and Russia's increased international isolation from the West.

Russia's foreign policy in the 21st century has been characterized by assertiveness, aiming to restore its regional dominance and international influence, often to bolster domestic support for the government. This has included military interventions in post-Soviet states (Georgia in 2008, Ukraine since 2014) and involvement in conflicts further afield, such as the Syrian civil war. Russia has also been accused of cyberwarfare, airspace violations, and electoral interference in other countries.

5.3.1. Relations with Major Powers and Regions

Russia's relationships with major global powers and regions are multifaceted and often fraught with tension, particularly in the wake of the Ukraine invasion.

United States: Relations with the United States have been highly adversarial, especially since 2014. Areas of contention include NATO expansion, U.S. missile defense systems, Russia's actions in Ukraine and Syria, alleged interference in U.S. elections, and human rights issues. Despite this, some channels of communication remain, particularly on strategic stability and arms control, though these have been severely strained.

European Union: Relations with the European Union, once termed a "strategic partnership," have collapsed following the Ukraine crisis. The EU has imposed extensive sanctions on Russia. Energy dependence (Europe's reliance on Russian gas and oil) was a key feature of the relationship, but the EU is now actively seeking to reduce this dependency. Disagreements also exist over values, human rights, and Russia's influence in Eastern Europe.

China: Russia has cultivated a close strategic partnership with China, often described as a "no limits" friendship. This is driven by a shared desire to counterbalance U.S. influence, economic ties (Russia as an energy supplier, China as a market and source of investment), and cooperation in international forums like the SCO and BRICS. However, the relationship is also seen as asymmetrical, with Russia increasingly the junior partner.

CIS Countries: Russia views the CIS region (former Soviet republics, excluding the Baltics and Georgia, which left) as its primary sphere of influence. It maintains close political, economic, and military ties with many CIS states through organizations like the EAEU and CSTO. However, Russia's dominance is sometimes challenged, and its actions in Ukraine have caused apprehension among some CIS members. Relations with Ukraine and Georgia are overtly hostile due to territorial disputes and Russian military interventions.

Middle East: Russia has significantly increased its influence in the Middle East, notably through its military intervention in Syria supporting the Assad regime. It maintains relations with a wide range of regional actors, including Iran, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey, often playing a complex diplomatic game. Energy politics and arms sales are key components of its Middle Eastern policy.

India: India and Russia have a long-standing strategic partnership dating back to the Soviet era, characterized by strong defense cooperation (India is a major buyer of Russian arms) and diplomatic understanding. India has maintained a relatively neutral stance on the Ukraine war, abstaining from UN votes condemning Russia and continuing trade, including increased oil purchases.

These relationships are dynamic and subject to shifts based on geopolitical developments, economic interests, and internal political changes within Russia and the other involved countries. The prevailing perspective is that Russia seeks to assert itself as a major independent pole in a multipolar world, often challenging the U.S.-led international order, while facing significant economic and diplomatic pressure from Western nations.

5.3.2. International Disputes and Interventions

Russia has been involved in several significant international disputes and military interventions, particularly in the post-Soviet space and more recently in the Middle East. These actions have often been aimed at asserting Russian influence, protecting perceived security interests, or supporting allied regimes, but have frequently led to international condemnation and humanitarian concerns.

War in Georgia (2008): In August 2008, a brief but intense war erupted between Russia and Georgia over the breakaway regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Following Georgian attempts to reassert control over South Ossetia, Russian forces intervened, pushing deep into Georgian territory. The conflict resulted in Russia recognizing the independence of South Ossetia and Abkhazia (a move recognized by only a handful of other countries) and stationing troops in these regions, which Georgia and most of the international community consider occupied territories. The war led to civilian casualties, displacement, and a significant deterioration in Russia-West relations. Humanitarian impacts included the displacement of ethnic Georgians from South Ossetia.

War in Ukraine (2014-Present): This is the most significant and ongoing conflict involving Russia.

- Annexation of Crimea (2014): Following the 2014 Ukrainian Revolution of Dignity, Russia occupied and subsequently annexed the Crimean Peninsula after a disputed referendum. This act was widely condemned as a violation of international law and Ukrainian sovereignty, leading to the first wave of significant Western sanctions against Russia.

- War in Donbas (2014-2022): Russia supported and armed separatist forces in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine, leading to a protracted conflict that killed over 14,000 people before 2022. Russia denied direct military involvement but provided substantial backing to the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People's Republics.

- Full-Scale Invasion of Ukraine (2022-Present): On February 24, 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, aiming to overthrow the government and demilitarize the country. The invasion has resulted in tens of thousands of deaths, millions of refugees and internally displaced persons, widespread destruction of Ukrainian infrastructure, and accusations of numerous war crimes by Russian forces. International response has included massive military and financial aid to Ukraine, unprecedented sanctions against Russia, and condemnation by international bodies. The humanitarian impact has been catastrophic, with ongoing concerns about civilian suffering, food security, and the long-term consequences for regional and global stability. Russia later annexed four more Ukrainian oblasts (Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson, Zaporizhzhia) in September 2022, which are also not internationally recognized.

Intervention in Syria (2015-Present): In September 2015, Russia launched a military intervention in the Syrian civil war in support of President Bashar al-Assad's government. Russia's involvement, primarily through airstrikes and military advisors, was crucial in turning the tide of the war in Assad's favor and significantly altering the geopolitical landscape of the Middle East. While Russia stated its aim was to combat terrorist groups like ISIS and Al-Nusra Front, Western governments and human rights organizations accused Russia of targeting moderate opposition groups and causing significant civilian casualties. The intervention has solidified Russia's presence in the region but has also drawn criticism for its humanitarian impact and support for a regime accused of widespread human rights violations.

These interventions reflect Russia's willingness to use military force to achieve its foreign policy objectives, often in defiance of international norms. They have had profound impacts on the countries involved, international relations, and humanitarian conditions, with ongoing debates about their legality, motivations, and consequences.

5.4. Military

The Russian Armed Forces are the military forces of the Russian Federation. They are divided into the Ground Forces, the Navy, and the Aerospace Forces. There are also two independent arms of service: the Strategic Missile Troops (responsible for land-based nuclear missiles) and the Airborne Troops. The President of Russia is the Supreme Commander-in-Chief.

As of 2021, before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Russian military had around one million active-duty personnel, making it the world's fifth-largest. It also has a substantial reserve force, estimated at 2-20 million personnel, though the actual combat-readiness of these reserves varies. Conscription is mandatory for all male citizens aged 18-27 for a term of one year, though there are exemptions and deferrals.

Russia is one of the five recognized nuclear-weapon states under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and possesses the world's largest stockpile of nuclear weapons. Its nuclear arsenal includes intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and strategic bombers, forming a nuclear triad. Russia possesses the second-largest fleet of ballistic missile submarines and is one of only three countries (along with the US and China) operating strategic bombers.

Russia maintains the world's third-highest military expenditure, spending an estimated $109 billion in 2023, corresponding to around 5.9% of its GDP. The country has a large and largely indigenous defense industry, producing most of its own military equipment, and was the world's second-largest arms exporter in 2021, though its export share has declined since the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Since the early 2000s, Russia has undertaken significant military modernization efforts, aiming to create a more professional, mobile, and technologically advanced force. This has included the development of new weapons systems, such as hypersonic missiles, advanced fighter jets (like the Su-57), and modern tanks (like the T-14 Armata, though its widespread deployment has been slow). However, the performance of the Russian military in the 2022 invasion of Ukraine has exposed significant shortcomings in logistics, command and control, training, and equipment, despite years of modernization. The conflict has led to heavy losses in personnel and materiel for the Russian Armed Forces.

Russia's strategic doctrine emphasizes the importance of its nuclear deterrent, a strong conventional military capable of operating in its near abroad, and an assertive foreign policy to protect its perceived national interests.

5.5. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Russia has been a subject of significant concern and criticism from domestic activists and international organizations for many years, with a notable deterioration observed particularly since Vladimir Putin's return to the presidency in 2012 and a further sharp decline following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Freedom of speech and press has been severely curtailed. State control over major television networks is almost complete, and independent media outlets face increasing pressure, including restrictive laws, financial burdens, blocking of websites, and harassment of journalists. The "foreign agent" law and the law on "undesirable organizations" have been used to stigmatize and obstruct the work of independent media, NGOs, and human rights defenders. Following the 2022 invasion, new laws criminalizing the dissemination of "fake news" about the military and "discrediting" the armed forces have led to numerous prosecutions and effectively silenced much anti-war dissent.

Freedom of assembly is heavily restricted. Unauthorized protests are routinely dispersed, often with force, and participants face arrest, fines, and imprisonment. The legal framework for holding public gatherings is cumbersome and often used to deny permission for opposition rallies.

Political freedoms have also eroded. Opposition politicians and activists face harassment, politically motivated prosecutions, and exclusion from participating in elections. The assassination of opposition figure Boris Nemtsov in 2015 and the poisoning and imprisonment of Alexei Navalny are prominent examples of the risks faced by those who challenge the Kremlin. Elections are often criticized for lacking genuine competition and fairness.