1. Overview

The Republic of Lithuania (Lietuvos RespublikaLietuvós RespúblikaLithuanian) is a country situated in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is one of the three Baltic states, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, Poland to the south, and the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad Oblast to the southwest, with a coastline on the Baltic Sea to the west. Its capital and largest city is Vilnius. Lithuania covers an area of 25 K mile2 (65.30 K km2) and has a population of approximately 2.8 million people.

Lithuania boasts a long and significant history, with the first Lithuanian state emerging in the 13th century under Mindaugas. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania later became the largest state in Europe during the 14th century. Through the Union of Lublin in 1569, Lithuania formed the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a major political and cultural power in Europe for over two centuries. However, following partitions in the late 18th century, most of Lithuania's territory was annexed by the Russian Empire. Lithuania re-established its independence in 1918 after World War I, but this period of sovereignty was interrupted by World War II, during which it suffered occupations by the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. After the war, Lithuania was forcibly re-incorporated into the Soviet Union as the Lithuanian SSR.

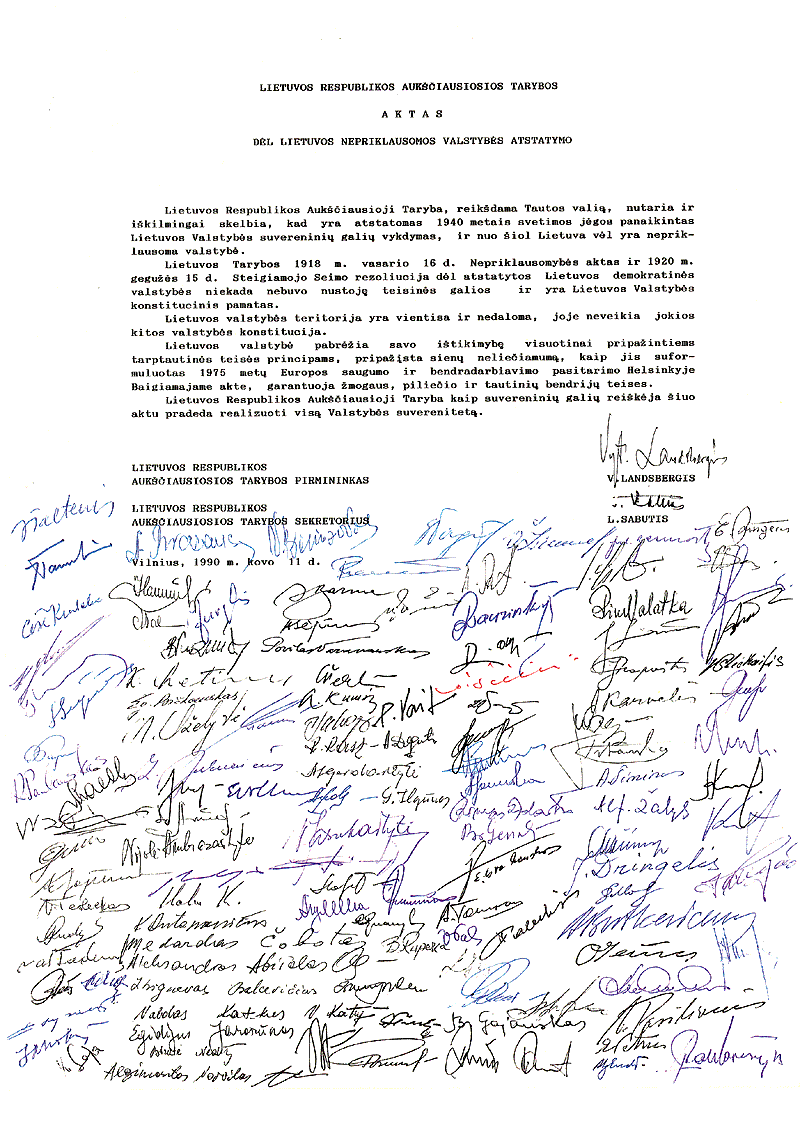

Driven by the Sąjūdis reform movement and the Singing Revolution, Lithuania was the first Soviet republic to declare the restoration of its independence on March 11, 1990. Since then, Lithuania has developed into a democratic republic with a strong commitment to human rights, social justice, and the rule of law. It has successfully integrated into Western political and economic structures, becoming a member of the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 2004, joining the Eurozone in 2015, and the OECD in 2018. Lithuania is recognized as a developed country with a high-income economy and a high standard of living, actively participating in international affairs and championing democratic values globally. The nation's culture is rich and diverse, with unique traditions in language, literature, music, and arts, reflecting its complex history and resilient national identity.

2. Etymology

The English spelling Lithuania is a later adaptation of the original Latinate form Lituania, which appeared around 1800 as a type of hyperforeignism, influenced by Greek loanwords incorporating the letter theta. Ultimately, the name derives from the Lithuanian word LietuvaLietuváLithuanian.

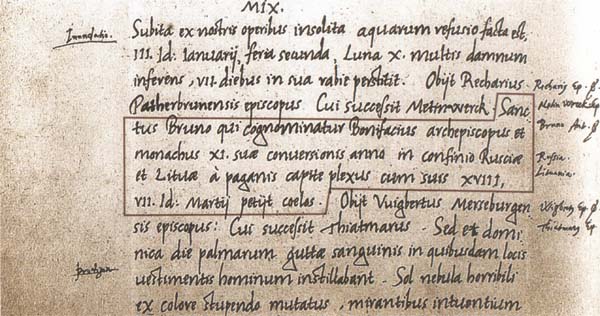

The first known written record of the name Lietuva appears in the Quedlinburg Chronicle in a story about Saint Bruno dated March 9, 1009 (though some scholars suggest February 14, 1009, is more accurate). The Chronicle recorded a Latinized form of Lietuva as LituaLítuaLatin (pronounced "litua"). Due to a lack of definitive evidence, the true meaning of the name Lietuva remains unknown, and scholars continue to debate its origins. Several plausible theories exist.

One commonly cited theory suggests the name originates from the LietavaLietavàLithuanian river, a small tributary of the Neris not far from Kernavė. Kernavė was a core area of the early Lithuanian state and a possible first capital of the eventual Grand Duchy of Lithuania. However, the Lietava is a very small river, leading some to find it improbable that such a minor local feature could have lent its name to an entire nation. Nevertheless, such naming practices are not without precedent in world history.

Another hypothesis, proposed by historian Artūras Dubonis, suggests that Lietuva is related to the word leičiai (plural of leitis). From the mid-13th century, the leičiai were a distinct warrior social group within Lithuanian society, subordinate to the Lithuanian ruler or the state itself. The term leičiai is used in historical sources from the 14th to 16th centuries as an ethnonym for Lithuanians (though not for Samogitians) and is still used, often poetically or in historical contexts, in the Latvian language, which is closely related to Lithuanian.

3. History

The history of Lithuania spans millennia, from ancient Baltic tribes to its medieval kingdom and expansive Grand Duchy, through periods of union with Poland, Russian imperial rule, 20th-century occupations, and its eventual restoration of independence and integration into modern Europe. This historical journey has shaped Lithuania's resilient national identity and its commitment to democratic values.

3.1. Early History and Baltic Tribes

The history of human settlement in the territory of present-day Lithuania dates back approximately 10,000 to 13,000 years, following the Last Glacial Period. The earliest inhabitants belonged to the Paleolithic Sviderian and Baltic Magdalenian cultures. Later, Mesolithic populations of the Kunda culture and Neman culture emerged. These early peoples were primarily nomadic hunters and gatherers. Around the 8th millennium BC, the climate grew warmer, leading to the expansion of forests and a shift towards more localized hunting, fishing, and gathering.

Agriculture reached the region in the 3rd millennium BC. The arrival of Indo-European peoples between the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC led to intermingling with the local populations, eventually forming various Baltic tribes. During the Neolithic period, the Pomeranian culture, part of the broader Corded Ware culture horizon, spread in the area and is considered to be associated with the Balts. By the first centuries AD, distinct Baltic tribal confederations, including the Samogitians and Aukštaitians (Lithuanians proper), were distinguishable.

The Baltic tribes did not maintain close political or cultural contacts with the Roman Empire, but they engaged in trade, notably through the Amber Road, which transported valuable Baltic amber from the region to Rome. The Roman historian Tacitus, in his work Germania (circa 98 AD), described the Aesti people, who lived on the southeastern shores of the Baltic Sea and are generally associated with the Western Balts. Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD was aware of the Galindians and Yotvingians.

From the 9th to the 11th centuries, coastal Balts faced raids by Vikings. The territory of Lithuania was broadly divided into culturally distinct regions: Samogitia in the west, known for its early medieval skeletal burials, and Aukštaitija (or Lithuania proper) further east, known for its early medieval cremation burials. This region was relatively remote and less attractive to outsiders, including traders, which contributed to its distinct linguistic, cultural, and religious identity, delaying its integration into broader European patterns. Traditional Lithuanian pagan customs and mythology, rich with archaic elements, were preserved for a long time. The bodies of rulers, such as Grand Dukes Algirdas and Kęstutis, were cremated until the eventual conversion to Christianity; descriptions of their cremation ceremonies have survived.

3.2. Kingdom of Lithuania and Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The first written record of the name Lithuania dates to 1009 AD. In the face of threats from the German crusading orders, Mindaugas united a large part of the Baltic tribes in the mid-13th century and founded the State of Lithuania. On July 6, 1253, he was crowned as the Catholic King of Lithuania, establishing the Kingdom of Lithuania. Taking advantage of the weakened state of the former Kievan Rus' due to the Mongol invasion of Kievan Rus', Mindaugas also incorporated Black Ruthenia into Lithuania. After Mindaugas's assassination in 1263, pagan Lithuania once again became a target of the Christian crusades conducted by the Teutonic Knights and the Livonian Order. Grand Duke Traidenis (reigned 1269-1282) reunified Lithuanian lands and achieved military successes against the Crusaders, often fighting alongside other Baltic tribes. His main residence was in Kernavė.

From the late 13th century, the Gediminids dynasty began its rule over Lithuania. They consolidated a hereditary monarchy, established Vilnius as the permanent capital city (as evidenced by the Letters of Gediminas), and eventually led the Christianization of Lithuania. By incorporating East Slavic territories (such as the principalities of Minsk, Kiev, Polotsk, Vitebsk, and Smolensk), the Grand Duchy of Lithuania significantly expanded its territory, reaching approximately 251 K mile2 (650.00 K km2) in the first half of the 14th century. By the end of the 14th century, Lithuania was the largest country in Europe.

In 1385, through the Union of Krewo, Lithuania entered a dynastic union with the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland when Grand Duke Jogaila (later Władysław II Jagiełło of Poland) married Queen Jadwiga. During the late 14th and 15th centuries, patrilineal members of the Lithuanian Gediminids dynasty, known as the Jagiellonians, ruled not only Lithuania and Poland but also the Kingdom of Hungary, Croatia, the Kingdom of Bohemia, and Moldavia. The German attacks on Lithuania effectively ceased after the decisive Polish-Lithuanian victory in the Battle of Grunwald in 1410 and the subsequent Treaty of Melno in 1422. Grand Duke Vytautas, Jogaila's cousin, ruled Lithuania during this period of great expansion and consolidation.

3.3. Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

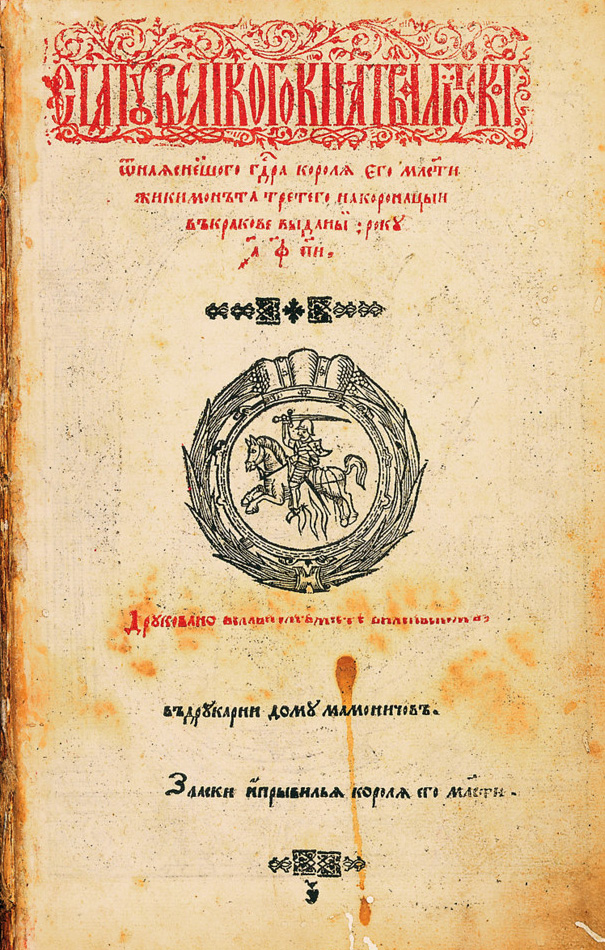

In the 15th century, the strengthened Grand Duchy of Moscow renewed the Muscovite-Lithuanian Wars to gain control over the Lithuanian-held Eastern Orthodox territories. Facing an unsuccessful start to the Livonian War, territorial losses to the Tsardom of Russia, and pressure from monarch Sigismund II Augustus who supported a closer Polish-Lithuanian union, the Lithuanian nobility agreed to the Union of Lublin in 1569. This union created the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a federative state with a joint monarch holding the titles of King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania. However, Lithuania remained a distinct state from Poland, retaining its own territory (approximately 116 K mile2 (300.00 K km2)), coat of arms, administrative apparatus, laws (the Statutes of Lithuania), courts, seal, army, and treasury.

Following the real union, Lithuania and Poland achieved joint military successes in the Livonian War, the Polish-Lithuanian occupation of Moscow (1610), wars with Sweden (e.g., the Polish-Swedish War of 1600-1611), and the Smolensk War with Russia (1632-1634). In 1588, King Sigismund III Vasa personally confirmed the Third Statute of Lithuania, which affirmed the equal rights of Lithuania and Poland within the Commonwealth and ensured the separation of powers. Despite these safeguards, the real union significantly intensified the Polonization of Lithuanian society, particularly among the nobility.

The mid-17th century was marked by disastrous military losses for Lithuania. During the Deluge, most of Lithuania's territory was annexed by the Tsardom of Russia, and its capital, Vilnius, was captured and ravaged by a foreign army for the first time in its history. In 1655, Lithuania unilaterally seceded from Poland under the Union of Kėdainiai, declaring King Charles X Gustav of Sweden as the Grand Duke of Lithuania and placing itself under the protection of the Swedish Empire. However, by 1657, following a Lithuanian revolt against the Swedes, Lithuania was once again part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Vilnius was recaptured from the Russians in 1661.

The Commonwealth experienced periods of prosperity but also significant internal strife and external pressures. In the second half of the 18th century, the weakened Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was subjected to three partitions by its neighboring powers: the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Austria. These partitions, occurring in 1772, 1793, and 1795, completely dissolved both independent Lithuania and Poland from the political map. The Kościuszko Uprising in 1794, which saw a short-lived recapture of Vilnius during the Vilnius uprising, ultimately failed to prevent the final partition. Most of Lithuania's territory was annexed by the Russian Empire, while the region of Suvalkija (Užnemunė) was annexed by Prussia.

3.4. Russian Empire and National Revival

Following its annexation into the Russian Empire, Lithuanian territories became part of a new administrative region known as the Northwestern Krai. The Russian Tsarist authorities implemented policies of Russification aimed at suppressing Lithuanian culture and identity. In 1812, during the French invasion of Russia, Napoleon established the puppet Lithuanian Provisional Governing Commission to support his war efforts; however, after Napoleon's defeat, Russian rule was firmly reinstated.

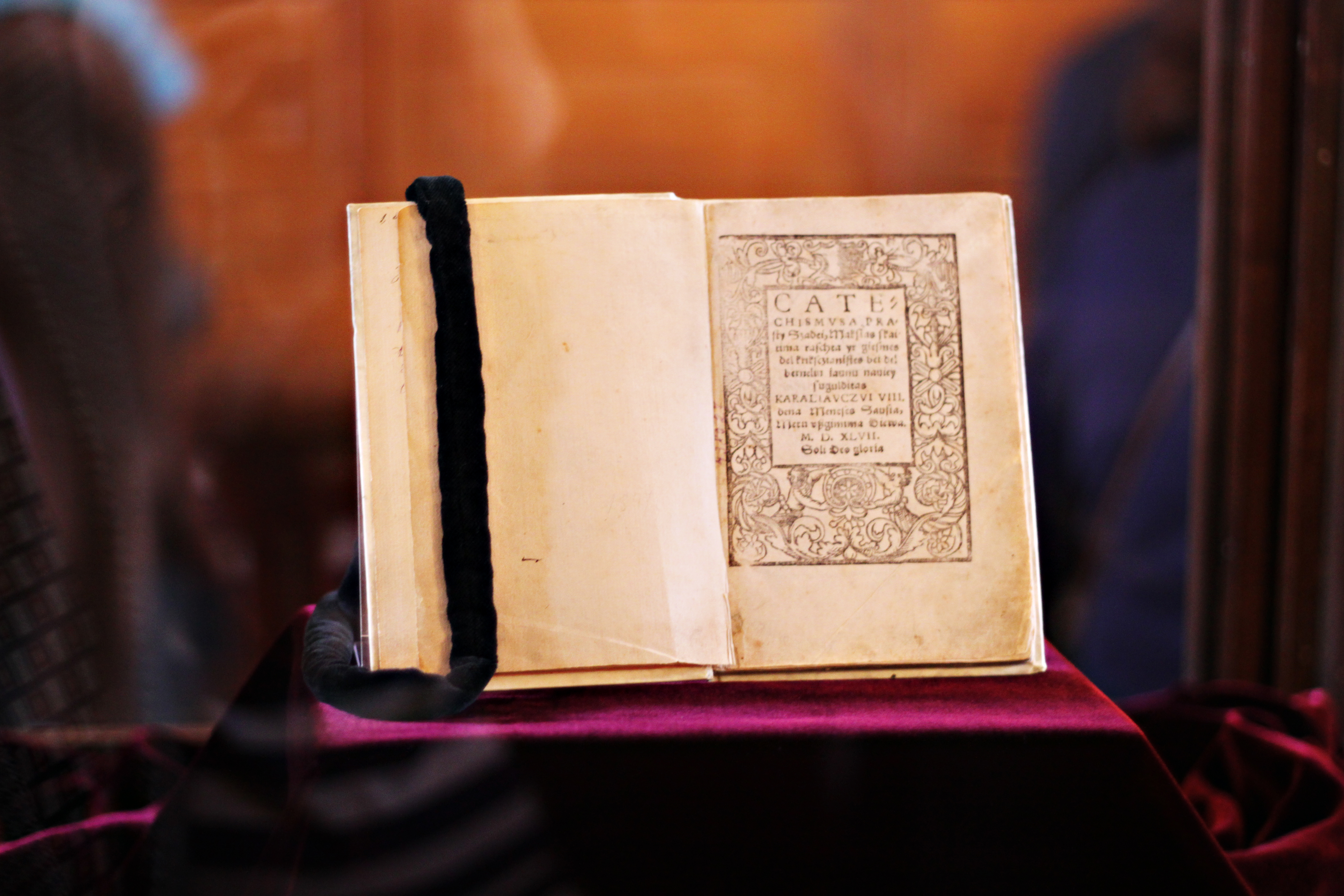

Throughout the 19th century, Lithuanians and Poles jointly attempted to restore their statehood. The November Uprising (1830-1831) was one such effort, but its defeat by Russian forces led to stricter Russification measures. The Russian language was introduced in all government institutions, Vilnius University was closed in 1832, and theories promoting the idea that Lithuania had historically been a "Western Russian" state were propagated. Subsequently, Lithuanians participated in the January Uprising (1863-1864), another attempt to regain independence. Its failure resulted in even stronger Russification policies, including the Lithuanian press ban (1864-1904), which prohibited printing in the Lithuanian language using the Latin alphabet, increased pressure on the Catholic Church in Lithuania, and severe repressions under Governor General Mikhail Muravyov.

Despite these oppressive measures, a Lithuanian National Revival (Lietuvių tautinis atgimimasLietuvių tautinis atgimimasLithuanian) emerged. This movement was inspired by Lithuanian history, language, and culture, aiming to preserve national identity and strive for self-determination. Figures like Simonas Daukantas promoted a return to Lithuania's pre-Commonwealth traditions, which he depicted as a Golden Age, emphasizing the renewal of native culture based on the Lithuanian language and customs. He wrote a history of Lithuania in Lithuanian, Darbai senųjų lietuvių ir žemaičių (The Deeds of Ancient Lithuanians and Samogitians), as early as 1822, though it was not published at the time. Teodor Narbutt, a contemporary of Daukantas, wrote a voluminous Ancient History of the Lithuanian Nation (1835-1841) in Polish, similarly expounding on the concept of historic Lithuania and pointing out the relationship between the Lithuanian and Sanskrit languages.

Lithuanians resisted Russification through an extensive network of knygnešiai (book smugglers) who secretly distributed Lithuanian-language publications printed abroad (mostly in Lithuania Minor, then part of East Prussia) and through secret Lithuanian homeschooling. This grassroots resistance was crucial for preserving the language and fostering national consciousness. The National Revival laid the intellectual and cultural foundations for the eventual re-establishment of an independent Lithuanian state. In 1905, the Great Seimas of Vilnius convened, and its participants adopted resolutions demanding wide political autonomy for Lithuania within the Russian Empire.

3.5. Republic of Lithuania (1918-1940)

During World War I, Lithuanian territories were occupied by the German Empire and administered as part of Ober Ost. In 1917, the Lithuanians organized the Vilnius Conference, which adopted a resolution expressing the aspiration for the restoration of Lithuania's sovereignty and elected the Council of Lithuania (Lietuvos TarybaLietuvos TarybaLithuanian). Initially, in 1918, a short-lived Kingdom of Lithuania was proclaimed with a German duke as king, but this plan was quickly abandoned. On February 16, 1918, the Council of Lithuania adopted the Act of Independence of Lithuania, declaring the restoration of Lithuania as a democratic republic with its capital in Vilnius, and severing all state relations that had previously existed with other nations.

The newly restored state had to defend its independence in the Lithuanian Wars of Independence (1918-1920) against Bolshevik Russia, the Bermontians (a German-Russian mercenary force), and Poland. Lithuania's aspirations clashed with Józef Piłsudski's vision of a Polish-led federation, Intermarium, encompassing territories of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Lithuanian authorities successfully thwarted a Polish-backed coup attempt in 1919. However, in October 1920, during Żeligowski's Mutiny, Polish forces under General Lucjan Żeligowski seized the Vilnius Region, establishing the puppet state of the Republic of Central Lithuania, which was subsequently incorporated into Poland in 1922.

Consequently, Kaunas became the temporary capital and the center of Lithuanian political life until 1940. The Constituent Assembly of Lithuania (Steigiamasis SeimasSteigiamasis SeimasLithuanian) convened in Kaunas and adopted a democratic constitution. In 1923, Lithuania organized the Klaipėda Revolt, successfully unifying the Klaipėda Region (Memel Territory), previously administered by the Allies, with Lithuania. The interwar Republic saw significant social and economic development, but also political instability. The 1926 Lithuanian coup d'état overthrew the democratically elected government and President Kazys Grinius, establishing an authoritarian regime led by Antanas Smetona, which lasted until 1940. This marked a significant setback for democratic development in Lithuania.

3.6. World War II and Occupations

The late 1930s brought immense pressure on Lithuania. In March 1938, Lithuania accepted a Polish ultimatum demanding the establishment of diplomatic relations, effectively a Lithuanian acknowledgment of Polish control over Vilnius. In March 1939, following a German ultimatum, Lithuania was forced to cede the Klaipėda Region to Nazi Germany. After the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, Lithuania initially declared neutrality. However, under the secret protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, Lithuania was initially assigned to the German sphere of influence, but later transferred to the Soviet sphere. In October 1939, Lithuania was compelled to sign the Soviet-Lithuanian Mutual Assistance Treaty, which allowed the Soviet Union to establish military bases on Lithuanian territory in exchange for the return of a part of the Vilnius Region (including the city of Vilnius) which the Soviets had taken from Poland.

In June 1940, the Soviet Union issued an ultimatum to Lithuania, demanding the formation of a pro-Soviet government and the stationing of unlimited numbers of Red Army troops. Faced with overwhelming force and lack of international support, Lithuania accepted the ultimatum. This led to the Soviet occupation of Lithuania on June 15, 1940. A puppet "People's Government" was installed, which subsequently declared Lithuania a Soviet Socialist Republic and requested its admission into the USSR, a process completed in August 1940. This period was marked by Sovietization, including nationalization of property and mass deportations of Lithuanian citizens, targeting political figures, intellectuals, and business owners, which constituted severe human rights violations.

When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the June Uprising broke out, with Lithuanians hoping to restore independence. A Provisional Government of Lithuania was formed, and the Red Army was briefly expelled from parts of the country. However, the Nazi German forces quickly occupied Lithuania, dissolved the Provisional Government, and incorporated Lithuania into the Reichskommissariat Ostland. The German occupation (1941-1944) was brutal. The Holocaust in Lithuania resulted in the systematic murder of approximately 91-95% of Lithuania's Jewish population, one of the highest extermination rates in Europe. About 190,000-195,000 Lithuanian Jews were killed, often with the collaboration of some local Lithuanian auxiliary police units. Lithuanian resistance movements, both anti-Nazi and later anti-Soviet, operated during this period. The war and occupations had a devastating impact on Lithuania's population, societal structures, and its sovereignty.

3.7. Soviet Era (1944-1990)

In mid-1944, as the tide of World War II turned against Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union re-occupied Lithuania. This marked the beginning of the second Soviet occupation, which lasted nearly five decades. The re-establishment of Soviet rule brought renewed political repressions, including mass deportations to Siberia and other remote parts of the USSR, which continued until Stalin's death in 1953. These deportations primarily targeted those perceived as enemies of the Soviet regime, including farmers resisting collectivization, intellectuals, and former members of the interwar Lithuanian state.

A large-scale armed resistance movement, often referred to as the "Forest Brothers" (miško broliaimiško broliaiLithuanian), fought against Soviet rule from 1944 until the early 1950s. Thousands of partisans and their supporters attempted to militarily restore independent Lithuania, but their struggle was eventually suppressed by the superior forces of the Soviet NKVD and MGB, with the assistance of local collaborators known as stribai. Leaders of the resistance, such as Jonas Žemaitis (posthumously recognized as President of Lithuania) and Adolfas Ramanauskas, were captured and executed.

Under Soviet rule, Lithuania underwent forced collectivization and rapid industrialization. Policies of Russification were implemented, although Lithuanian language and culture managed to survive, partly due to a strong sense of national identity and the efforts of dissidents. National symbols were prohibited, and the Communist Party maintained tight control over all aspects of life, imposing its ideology and promoting atheism. Freedom of speech, assembly, and press were severely curtailed, and any opposition was harshly repressed. The Soviet era had a profound negative impact on Lithuania's democratic development and human rights.

Despite the repression, dissident movements and underground cultural activities persisted. From the late 1980s, with the advent of Gorbachev's policies of Glasnost and Perestroika, the Sąjūdis reform movement emerged. Initially advocating for greater autonomy and cultural rights, Sąjūdis rapidly evolved into a force for full independence. In 1989, the Baltic Way, a human chain connecting Vilnius, Riga, and Tallinn, demonstrated the Baltic peoples' unified desire for freedom and drew international attention to their cause.

3.8. Restoration of Independence (1990-Present)

On March 11, 1990, the Supreme Council of the Republic of Lithuania, led by Vytautas Landsbergis, declared the restoration of Lithuania's independence. Lithuania thus became the first Soviet republic to break away from the USSR. The Soviet Union initially responded with an economic blockade, ceasing deliveries of raw materials from April 1990, but Lithuania did not renounce its declaration of independence.

Tensions escalated in January 1991 when Soviet forces attempted to stage a coup. Pro-Soviet groups, supported by the Soviet Army, MVD Internal Troops, and KGB, sought to overthrow the democratically elected government. However, tens of thousands of unarmed Lithuanian civilians converged on Vilnius to defend the Supreme Council building (Seimas Palace), the Vilnius TV Tower, and other key installations. During these January Events, Soviet troops attacked the TV Tower and other sites, killing 14 civilians and injuring hundreds. This violent crackdown was widely condemned internationally and further galvanized Lithuanian resolve. On July 31, 1991, Soviet paramilitaries killed seven Lithuanian border guards at the Medininkai border post on the Belarusian border.

Despite Soviet pressure, Lithuania's independence gained international recognition, particularly after the failed August Coup in Moscow. Iceland was the first Western nation to recognize Lithuanian independence in February 1991, followed by others. On September 17, 1991, Lithuania was admitted to the United Nations. The last units of the former Soviet Army (by then Russian Army) left Lithuania on August 31, 1993.

A new constitution was adopted by referendum on October 25, 1992, establishing a democratic, semi-presidential republic. Algirdas Brazauskas became the first directly elected president after the restoration of independence in February 1993. Since then, Lithuania has pursued a policy of integration into Western political and economic structures. It joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) on May 31, 2001. In March 2004, Lithuania became a member of NATO, and on May 1, 2004, it joined the European Union. Lithuania became part of the Schengen Area in December 2007 and adopted the Euro as its currency on January 1, 2015. On July 4, 2018, Lithuania officially joined the OECD.

Dalia Grybauskaitė served as President from 2009 to 2019, becoming the first female president and the first to be re-elected for a second consecutive term. Contemporary Lithuania faces challenges common to many democratic nations, but remains a strong advocate for democratic values and human rights in the region. In response to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Lithuania declared a state of emergency and, along with other NATO members, invoked Article 4 of the North Atlantic Treaty for consultations on security. On July 11-12, 2023, Vilnius hosted the 2023 NATO summit, underscoring its role in regional and international security.

4. Geography

Lithuania is located in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. The United Nations classifies Lithuania as a Northern European country, though other classifications may place it in Central or Eastern Europe due to historical and cultural ties. The country covers an area of 25 K mile2 (65.30 K km2). It lies between latitudes 53° and 57° N, and mostly between longitudes 21° and 27° E (a part of the Curonian Spit lies west of 21°). Lithuania has approximately 62 mile (99 km) of sandy coastline, of which only about 24 mile (38 km) face the open Baltic Sea, less than the other two Baltic states. The remainder of the coast is sheltered by the Curonian sand peninsula. Lithuania's major warm-water port, Klaipėda, is situated at the narrow mouth of the Curonian Lagoon (Kuršių mariosKuršių mariosLithuanian), a shallow lagoon that extends south to Kaliningrad. The country's main and largest river, the Nemunas, and some of its tributaries are used for international shipping. The geographical center of Europe, as determined by the French National Geographic Institute in 1989 by calculating the center of gravity of the geometrical figure of Europe, is located in Lithuania, at Purnuškės, 26 kilometers (16 mile (26 km)) north of Vilnius, at coordinates 54°54′N 25°19′E.

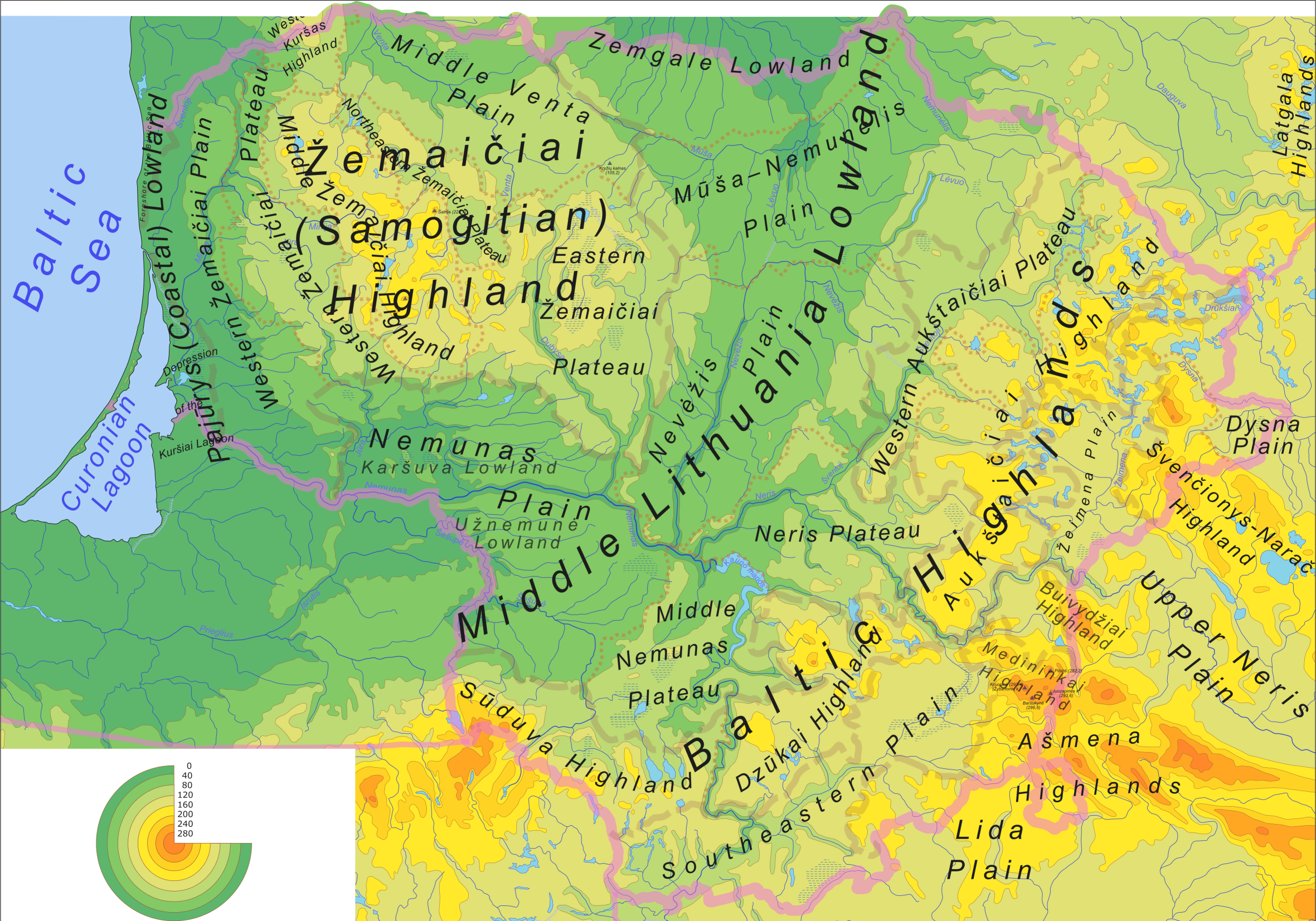

4.1. Topography and Landscape

Lithuania lies at the edge of the North European Plain. Its landscape was largely shaped by the glaciers of the last ice age, resulting in a terrain of moderate lowlands and highlands. The country lacks high mountains; its highest point is Aukštojas Hill at 965 ft (294 m) in the eastern part of the country. The landscape is characterized by numerous lakes (such as Lake Vištytis), wetlands, and morainic hills. A mixed forest zone covers over 33% of the country. Lake Drūkšiai is the largest lake, Lake Tauragnas is the deepest, and Lake Asveja is the longest lake in Lithuania. The typical Lithuanian landscape features flatlands interspersed with lakes, swamps, and forests. The sand dunes of the Curonian Spit near Nida are the highest drifting sand dunes in Europe and are recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

4.2. Climate

Lithuania has a temperate climate that transitions between maritime and continental influences. Under the Köppen climate classification, it is generally defined as humid continental climate (Dfb), although a narrow coastal zone exhibits characteristics closer to an oceanic climate.

Average temperatures on the coast are around 27.5 °F (-2.5 °C) in January and 60.8 °F (16 °C) in July. In the capital, Vilnius, located further inland, average temperatures are approximately 21.2 °F (-6 °C) in January and 62.6 °F (17 °C) in July. Summer daytime temperatures commonly reach 68 °F (20 °C), with nighttime lows around 57.2 °F (14 °C); temperatures have occasionally reached as high as 86 °F (30 °C) or 95 °F (35 °C). Winters can be very cold, with temperatures dropping to -4 °F (-20 °C) almost every year. Extreme winter temperatures can fall to -29.200000000000003 °F (-34 °C) in coastal areas and as low as -45.400000000000006 °F (-43 °C) in the eastern part of Lithuania.

The average annual precipitation is 31 in (800 mm) on the coast, 35 in (900 mm) in the Samogitian highlands, and 24 in (600 mm) in the eastern part of the country. Snowfall occurs annually, typically from October to April, though sleet can occasionally fall in September or May. The growing season lasts about 202 days in the western part of the country and 169 days in the eastern part. Severe storms are rare in eastern Lithuania but more common in coastal areas.

Historical temperature records for the Baltic area, covering about 250 years, indicate warm periods during the latter half of the 18th century, followed by a relatively cool 19th century. A warming trend in the early 20th century peaked in the 1930s, succeeded by a minor cooling period that lasted until the 1960s. A general warming trend has persisted since then. Lithuania experienced a drought in 2002, which led to forest and peat bog fires.

4.3. Biodiversity and Environment

Lithuanian ecosystems include natural and semi-natural environments such as forests, bogs, wetlands, and meadows, as well as anthropogenic ecosystems like agricultural and urban areas. Forests are a particularly important natural resource, covering approximately 33% of the country's territory. Wetlands, including raised bogs, fens, and transitional mires, cover about 7.9% of Lithuania. However, about 70% of wetlands were lost between 1960 and 1980 due to drainage and peat extraction. These changes have led to the replacement of moss and grass communities by trees and shrubs, and fens not directly affected by land reclamation have become drier due to a drop in the water table. Lithuania has 29,000 rivers with a total length of 40 K mile (64.00 K km), and the Nemunas River basin occupies 74% of the country's territory. The construction of dams has resulted in the loss of approximately 70% of spawning sites for catadromous fish species. Some river and lake ecosystems continue to be impacted by anthropogenic eutrophication.

After the restoration of Lithuania's independence in 1990, the Aplinkos apsaugos įstatymas (Environmental Protection Act) was adopted in 1992. This law provided the foundation for regulating social relations in environmental protection and established the basic rights and obligations for preserving Lithuania's biodiversity, ecological systems, and landscapes. As part of the European Union, Lithuania agreed to cut carbon emissions by at least 20% of 1990 levels by 2020 and by at least 40% by 2030. Additionally, by 2020, at least 20% (and 27% by 2030) of the country's total energy consumption was targeted to come from renewable energy sources. In 2016, Lithuania introduced an effective container deposit legislation, which resulted in the collection of 92% of all packaging in 2017. These policies reflect a growing concern for environmental sustainability, which has direct social impacts on public health and quality of life.

Lithuania is home to two terrestrial ecoregions: Central European mixed forests and Sarmatic mixed forests. The country has five national parks, 30 regional parks, 402 nature reserves, and 668 state-protected natural heritage objects. The landscape, though not mountainous, is marked by blooming meadows, dense forests, fertile fields, and numerous hillforts, ancient sites of pagan worship.

Agricultural land comprises 54% of Lithuania's territory, with roughly 70% of that being arable land and 30% meadows and pastures. Approximately 988 K acre (400.00 K ha) of agricultural land is not farmed, serving as an ecological niche for weeds and invasive plant species. Habitat deterioration is a concern in regions with highly productive land as crop areas expand. Currently, 18.9% of all plant species, including 1.87% of known fungi species and 31% of known lichen species, are listed in the Lithuanian Red Data Book. The list also includes 8% of all fish species.

Wildlife populations have rebounded as hunting has become more restricted and urbanization has allowed for forest replanting; forests have tripled in size since their historical lows. Lithuania currently has approximately 250,000 larger wild animals. The most prolific large wild animal is the roe deer (around 120,000), followed by wild boars (around 55,000). Other ungulates include red deer (c. 22,000), fallow deer (c. 21,000), and moose (c. 7,000). Among predators, foxes are the most common (c. 27,000), while wolves (around 800) and lynxes (around 200) are rarer but culturally significant.

5. Government and Politics

Lithuania is a semi-presidential democratic republic with a multi-party system. Since declaring the restoration of its independence on March 11, 1990, Lithuania has maintained strong democratic traditions, enshrined in its Constitution adopted on October 25, 1992. The political system is based on the separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches.

5.1. Governance Structure

President since 2019

The President is the head of state, directly elected for a five-year term, serving a maximum of two consecutive terms. The President oversees foreign affairs and national security, is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and appoints the Prime Minister (subject to parliamentary approval), the rest of the Cabinet (on the Prime Minister's nomination), a number of other top civil servants, and judges for most courts. The current President is Gitanas Nausėda, first elected in 2019 and re-elected in 2024.

Prime Minister since 2024

The Prime Minister is the head of government and is responsible for the day-to-day administration of the country. The Cabinet (Government) consists of the Prime Minister and ministers heading various government departments. The current Prime Minister is Gintautas Paluckas, who took office in December 2024.

Speaker of the Seimas since 2024

The Speaker of the Seimas leads the parliament.

5.2. Parliament (Seimas)

The Seimas is the unicameral parliament of Lithuania. It consists of 141 members elected for a four-year term through a mixed electoral system: 71 members are elected in single-member constituencies, and the remaining 70 are elected through nationwide proportional representation. A political party must receive at least 5% of the national vote (7% for coalitions) to be eligible for any of the 70 national seats. The Seimas is the primary legislative body, responsible for enacting laws, approving the state budget, overseeing the government, and ratifying international treaties. Its role is central to Lithuania's democratic governance and the protection of citizens' rights.

5.3. Political Parties and Elections

Lithuania has a fragmented multi-party system, where coalition governments are common due to no single party usually winning an outright majority. Major political parties include the Homeland Union - Lithuanian Christian Democrats (TS-LKD), the Social Democratic Party of Lithuania (LSDP), the Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union (LVŽS), the Liberal Movement (LS), and the Labour Party (DP), among others. The political landscape reflects a spectrum of ideologies from conservative and liberal to social democratic and agrarian.

Lithuania was one of the first countries in the world to grant women's suffrage, with women gaining the right to vote under the 1918 Constitution and exercising it for the first time in 1919. This early adoption of universal suffrage underscores a historical inclination towards democratic participation.

Elections are held regularly for the Seimas (parliamentary), President (presidential), municipal councils (local), and the European Parliament. To be eligible for election to the Seimas, candidates must be at least 21 years old, not under allegiance to a foreign state, and permanently reside in Lithuania. The 2024 Lithuanian parliamentary election resulted in the Social Democratic Party of Lithuania winning the most seats, leading to the formation of a coalition government headed by Gintautas Paluckas. Presidential elections determine the head of state, with the most recent held in 2024, won by Gitanas Nausėda. Local elections for municipal councils and mayors empower local self-government and democratic participation at the grassroots level. European Parliament elections allow Lithuanian citizens to participate in the EU's legislative process.

5.4. Law and Law Enforcement

The Lithuanian legal system is based on civil law, influenced by Roman law traditions. Its historical foundations include the Casimir's Code (1468) and the three editions of the Statutes of Lithuania (1529, 1566, 1588), which were sophisticated legal codes for their time. The Constitution of 3 May 1791 of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was Europe's first modern codified national constitution. The current Constitution of Lithuania was adopted by referendum on October 25, 1992, establishing the framework for a democratic state governed by the rule of law. Key legal codes, such as the Civil Code (2001) and Criminal Code (2003), have been updated to align with modern European standards. European Union law has been an integral part of the Lithuanian legal system since its accession in 2004.

Law enforcement is primarily the responsibility of the Lietuvos policija (Lithuanian Police), which operates through local commissariats. Specialized units include the Lietuvos policijos antiteroristinių operacijų rinktinė Aras (Anti-Terrorist Operations Team "Aras"), the Lietuvos kriminalinės policijos biuras (Lithuanian Criminal Police Bureau), and others. While Lithuania faced significant crime challenges after regaining independence, law enforcement agencies have worked to improve public safety. Crime rates have generally been declining.

Corruption remains a concern, with a 2013 Eurobarometer survey indicating that a significant portion of the population perceived it as widespread, though levels have reportedly been decreasing. Capital punishment was suspended in 1996 and abolished in 1998, reflecting a commitment to human rights standards. Lithuania has had a high number of prison inmates per capita compared to other EU countries, a situation attributed by some experts more to a punitive legal culture than to exceptionally high criminality.

5.5. Human Rights

The Constitution of Lithuania guarantees fundamental human rights and civil liberties, including freedom of speech, press, assembly, and religion. Lithuania is a party to major international human rights treaties and, as a member of the European Union and the Council of Europe, adheres to the European Convention on Human Rights. Overall, human rights are generally respected, but challenges remain in certain areas.

Areas of concern highlighted by human rights organizations and international bodies include the rights of LGBT individuals, where societal acceptance and legal protections have been slower to advance compared to some other EU countries. Protections for ethnic minorities, such as the Polish and Russian communities, are generally in place, including rights to education in minority languages, but issues related to language use in public life and representation have occasionally arisen. The state has taken steps to combat human trafficking and domestic violence.

Freedom of the press is largely upheld, though concerns about media ownership concentration and political influence on media have been noted. The legal framework provides for gender equality, but disparities in pay and representation in leadership positions persist. Efforts to improve prison conditions and reduce overcrowding are ongoing. The government has also focused on protecting the rights of children and persons with disabilities. Lithuania's commitment to democratic values inherently includes a focus on upholding and improving human rights for all its citizens and residents, aligning with social liberal principles of equality and justice.

6. Administrative Divisions

The current system of administrative division in Lithuania was established in 1994 and modified in 2000 to meet European Union requirements. The country is divided into counties, municipalities, and elderships, with distinct cultural regions also recognized.

6.1. Counties

Lithuania is divided into 10 counties (apskritisapskritìsLithuanian, plural: apskritysapskritýsLithuanian). These are:

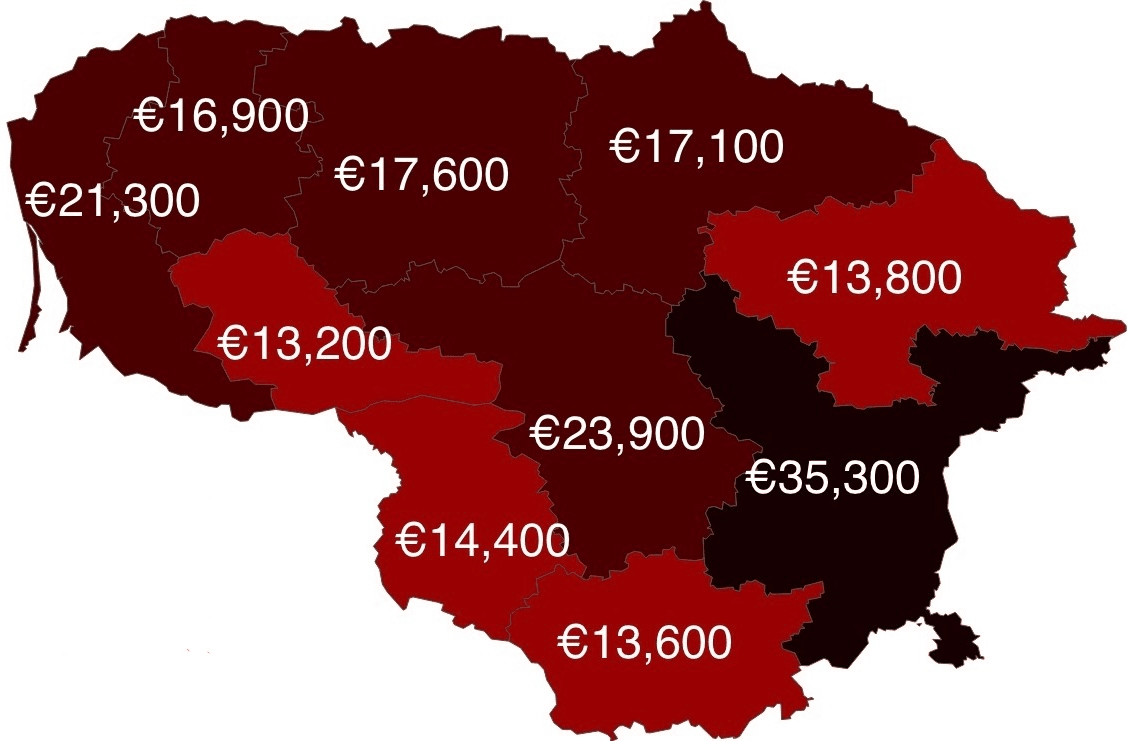

| County | Area (km2) | Population (2023) | GDP (billion EUR, 2022) | GDP per capita (EUR, 2022) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alytus County | 2.1 K mile2 (5.42 K km2) | 135,367 | 1.80 B EUR | 13.60 K EUR |

| Kaunas County | 3.1 K mile2 (8.09 K km2) | 580,333 | 13.70 B EUR | 23.90 K EUR |

| Klaipėda County | 2.0 K mile2 (5.21 K km2) | 336,104 | 7.00 B EUR | 21.30 K EUR |

| Marijampolė County | 1.7 K mile2 (4.46 K km2) | 135,891 | 2.00 B EUR | 14.40 K EUR |

| Panevėžys County | 3.0 K mile2 (7.88 K km2) | 211,652 | 3.60 B EUR | 17.10 K EUR |

| Šiauliai County | 3.3 K mile2 (8.54 K km2) | 261,764 | 4.60 B EUR | 17.60 K EUR |

| Tauragė County | 1.7 K mile2 (4.41 K km2) | 90,652 | 1.20 B EUR | 13.20 K EUR |

| Telšiai County | 1.7 K mile2 (4.35 K km2) | 131,431 | 2.20 B EUR | 16.90 K EUR |

| Utena County | 2.8 K mile2 (7.20 K km2) | 125,462 | 1.70 B EUR | 13.80 K EUR |

| Vilnius County | 3.8 K mile2 (9.73 K km2) | 851,346 | 29.40 B EUR | 35.30 K EUR |

| Lithuania Total | 25 K mile2 (65.30 K km2) | 2,860,002 | 67.40 B EUR | 23.80 K EUR |

County governors (apskrities viršininkasapskrities viršininkasLithuanian) used to be appointed by the central government, but the county governorships were abolished in 2010. Their primary role was to ensure that municipalities adhered to national laws. Currently, counties serve primarily as territorial units for state governance and statistical purposes.

6.2. Municipalities

The 10 counties are subdivided into 60 municipalities (savivaldybėsavivaldýbėLithuanian, plural: savivaldybėssavivaldýbėsLithuanian). These are the primary units of local self-government. There are several types of municipalities:

- 7 city municipalities (miesto savivaldybėmiesto savivaldybėLithuanian)

- 43 district municipalities (rajono savivaldybėrajono savivaldybėLithuanian)

- 10 municipalities (simply savivaldybėsavivaldybėLithuanian), established after 1994 under unique circumstances.

Each municipality has its own directly elected council and, since 2015, a directly elected mayor. Municipal councils are responsible for local services, infrastructure, education, healthcare, and social welfare within their jurisdictions.

6.3. Elderships

Municipalities are further divided into over 500 elderships (seniūnijaseniūnijàLithuanian, plural: seniūnijosseniūnijosLithuanian). Elderships are the smallest administrative units and are responsible for providing local public services, such as registering births and deaths in rural areas, and play a significant role in the social sector by identifying and assisting needy individuals and families, distributing welfare, and organizing local community initiatives. The head of an eldership is the elder (seniūnasseniūnasLithuanian), appointed by the municipal council.

6.4. Cultural Regions

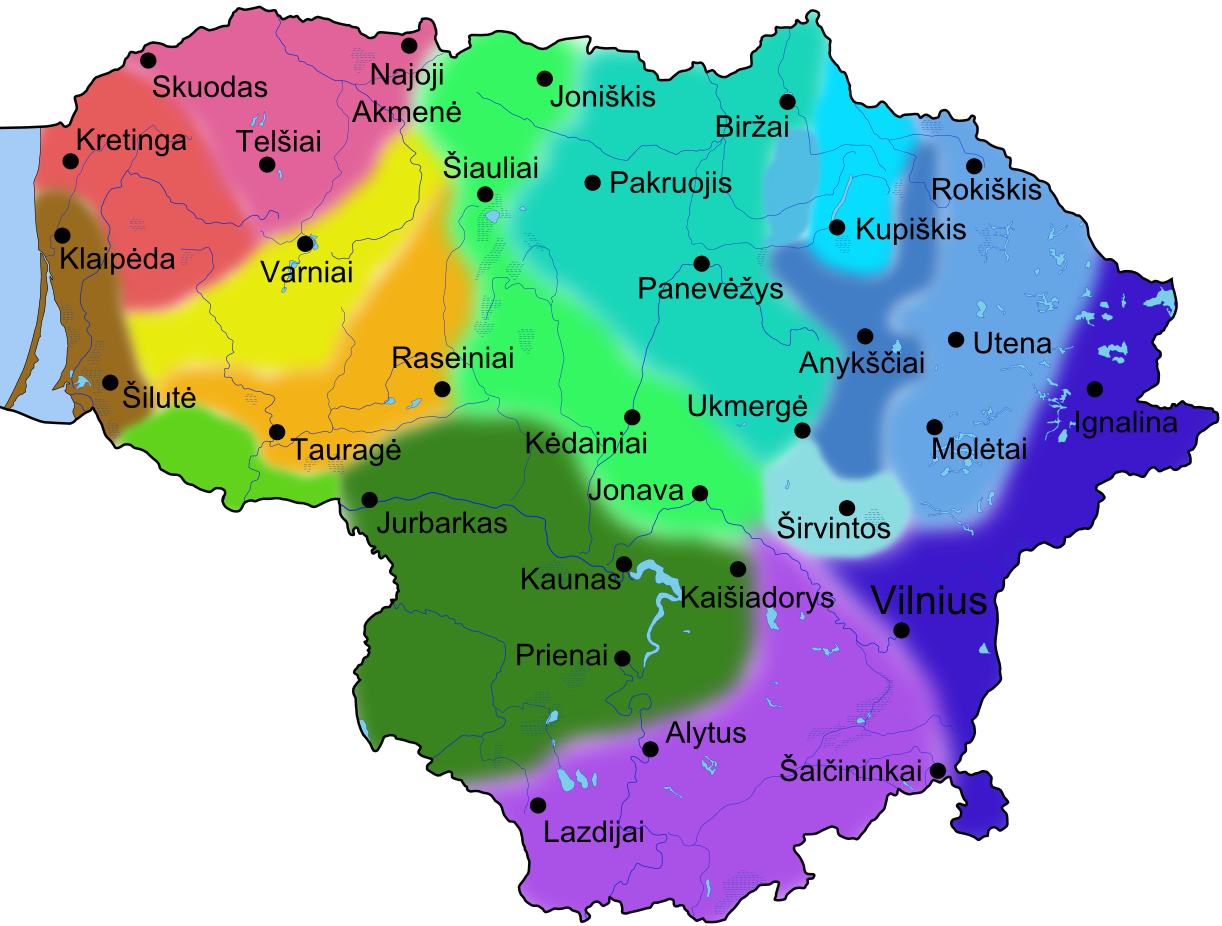

- Light yellow: Lithuania Minor (Mažoji Lietuva)

- Light green: Samogitia (Žemaitija)

- Pink: Aukštaitija (Aukštaitija)

- Light blue: Dzūkija (Dzūkija)

- Light orange: Suvalkija (Suvalkija)

In addition to formal administrative divisions, Lithuania is also characterized by five traditional ethnographic (or cultural) regions (etnografiniai regionaietnografiniai regionaiLithuanian). These regions are not administrative units but are recognized for their distinct cultural, historical, linguistic (dialectal), and traditional characteristics:

- Aukštaitija (Highlands): Located in northeastern Lithuania, it is the largest ethnographic region and considered the cradle of the Lithuanian state.

- Samogitia (ŽemaitijaŽemaitijaLithuanian, Lowlands): Situated in western Lithuania, known for its distinct dialect and strong regional identity.

- Dzūkija (also Dainava): Located in southeastern Lithuania, characterized by extensive forests and sandy soils, with unique cultural traditions and dialects.

- Suvalkija (also Sudovia or Užnemunė): Found in southwestern Lithuania, known for its fertile agricultural lands and distinct cultural heritage.

- Lithuania Minor (Mažoji LietuvaMažoji LietuvaLithuanian): A coastal region in southwestern Lithuania, historically influenced by Prussian and German culture. Only a small part of historical Lithuania Minor is within present-day Lithuania (mainly the Klaipėda Region).

These cultural regions play an important role in preserving Lithuania's diverse heritage and local identities.

7. Foreign Relations

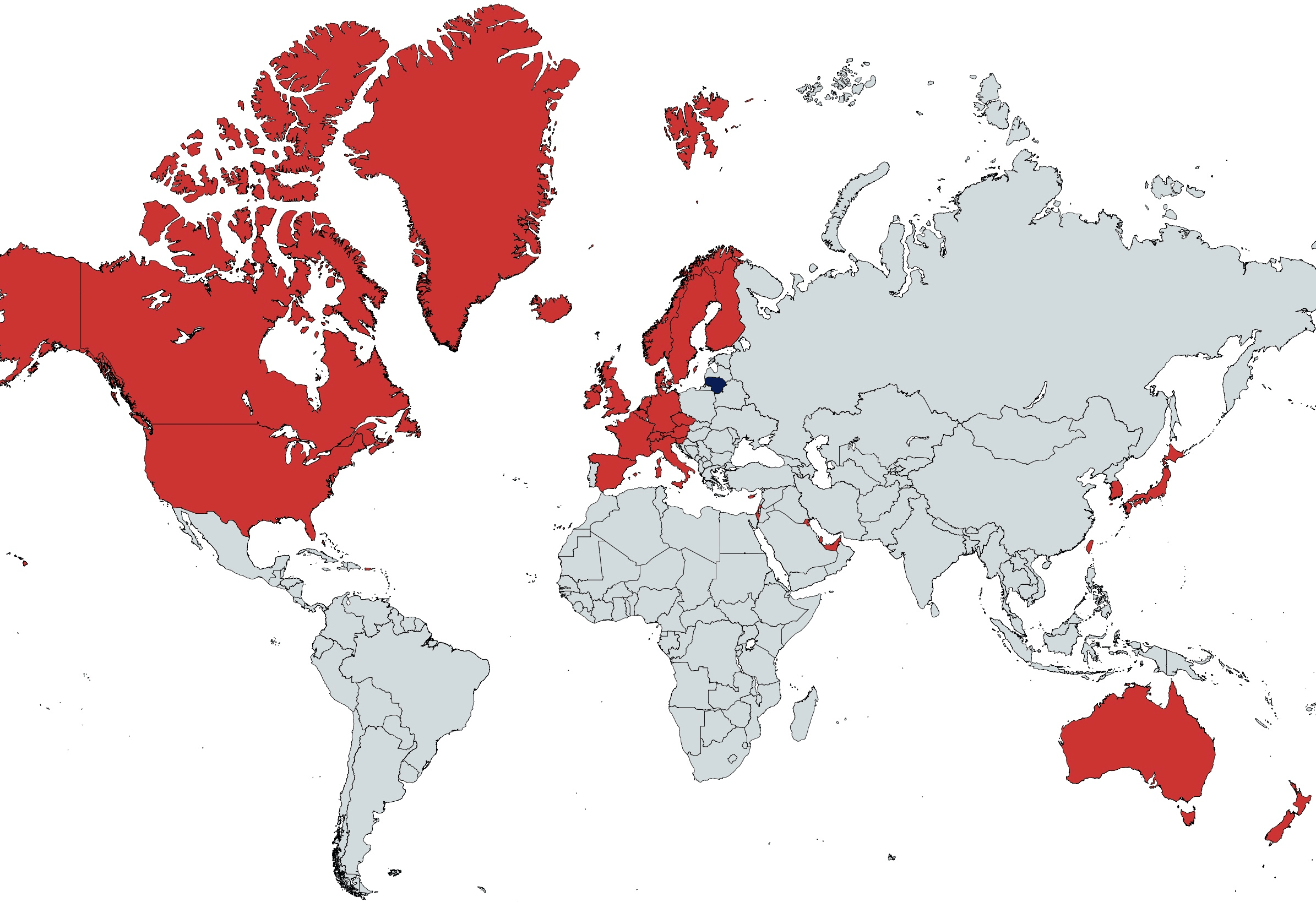

Lithuania pursues an active foreign policy focused on strengthening its sovereignty, ensuring national security, promoting democratic values and human rights, and fostering economic prosperity through international cooperation. Lithuania became a member of the United Nations (UN) on September 18, 1991. It is a signatory to numerous UN organizations and other international agreements. Key memberships include the European Union (EU) since May 1, 2004, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) since March 29, 2004. Lithuania also belongs to the Council of Europe, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the World Trade Organization (WTO) (since May 31, 2001), and the OECD (since July 5, 2018). Lithuania has established diplomatic relations with 149 countries.

Lithuania plays an active role in regional cooperation formats, such as the Nordic-Baltic Eight (NB8), the Baltic Assembly, the Baltic Council of Ministers, and the Council of the Baltic Sea States (CBSS). It also cooperates with Nordic countries through the Nordic Investment Bank (NIB) and the NORDPLUS educational program. In 2011, Lithuania hosted the OSCE Ministerial Council Meeting, and during the second half of 2013, it held the Presidency of the Council of the European Union.

A cornerstone of Lithuanian foreign policy is its commitment to democratic values and human rights. Lithuania has been a vocal supporter of democratic movements in neighboring countries and has advocated for stronger EU engagement with its Eastern partners. It has strongly supported Georgia's and Ukraine's Euro-Atlantic aspirations. During the Russo-Georgian War in 2008, then-President Valdas Adamkus, along with Polish and Ukrainian leaders, visited Tbilisi to show solidarity. Lithuania has also been a staunch supporter of Ukraine following the Russian aggression, providing humanitarian, financial, and military aid, and advocating for strong international sanctions against Russia. Lithuania was a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council for the 2014-2015 term, during which it actively condemned Russia's actions in Ukraine. In 2022, Lithuania declared a state of emergency in response to the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine and invoked NATO Article 4 for consultations.

Relations with Poland are generally close and strategically important, though historically complex, with periods of tension, particularly concerning the rights of the Polish minority in Lithuania. Former Polish President Lech Wałęsa had criticized Lithuania over these issues. However, cooperation on security, energy, and regional development remains strong.

Lithuania's relationship with the People's Republic of China became strained following Lithuania's decision to allow Taiwan (Republic of China) to open a representative office in Vilnius using the name "Taiwanese" in 2021. This led to diplomatic and economic pressure from Beijing, which downgraded its diplomatic relations with Lithuania. Lithuania, supported by some EU partners and the United States, has sought to diversify its economic relations in response.

The hosting of the 2023 NATO summit in Vilnius underscored Lithuania's role as a committed NATO ally on the Eastern Flank and its importance in regional security architecture. Lithuania consistently advocates for a strong transatlantic bond and robust collective defense.

8. Military

The Lithuanian Armed Forces (Lietuvos ginkluotosios pajėgosLietuvos ginkluotosios pajėgosLithuanian) are responsible for the defense of Lithuania's independence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity. The military operates under the democratic control of the civilian government, with the President as the commander-in-chief. The Ministry of National Defence oversees the armed forces.

The Lithuanian Armed Forces consist of several branches:

- Lithuanian Land Force (Sausumos pajėgosSausumos pajėgosLithuanian)

- Lithuanian Air Force (Karinės oro pajėgosKarinės oro pajėgosLithuanian)

- Lithuanian Naval Force (Karinės jūros pajėgosKarinės jūros pajėgosLithuanian)

- Lithuanian Special Operations Force (Specialiųjų operacijų pajėgosSpecialiųjų operacijų pajėgosLithuanian)

Other units include the Logistics Command, Training and Doctrine Command, Headquarters Battalion, and Military Police. The Lithuanian National Defence Volunteer Forces (Krašto apsaugos savanorių pajėgosKrašto apsaugos savanorių pajėgosLithuanian, KASP) serve as a reserve force and play a role in territorial defense and supporting civilian authorities. The paramilitary Lithuanian Riflemen's Union also acts as a civilian self-defense institution.

As of 2019, the Lithuanian Armed Forces consisted of approximately 20,000 active personnel. Compulsory conscription was ended in 2008 but was reintroduced in 2015 due to the changing geopolitical security situation in the region, particularly following Russia's aggression against Ukraine.

Lithuania has been a full member of NATO since March 2004. This membership is a cornerstone of its national security policy. NATO's Baltic Air Policing mission, where fighter jets from member states are deployed to Šiauliai Air Base, ensures the security of Baltic airspace. Lithuania actively participates in international military operations and missions led by NATO, the European Union, and the United Nations. Lithuanian forces have been deployed in Kosovo, Iraq, Afghanistan (as part of the ISAF, where Lithuania led a Provincial Reconstruction Team in Ghor Province), the Central African Republic, and other regions. Since joining international operations in 1994, Lithuania has lost two soldiers in service abroad.

The Lithuanian National Defence Policy aims to guarantee the preservation of the state's independence and sovereignty, the integrity of its land, territorial waters, and airspace, and its constitutional order. Key strategic goals include defending the country's interests and maintaining and expanding the capabilities of its armed forces to contribute to NATO and EU missions. In response to increased regional threats, Lithuania has significantly increased its defense spending, exceeding the NATO guideline of 2% of GDP in 2019 and allocating 2.13% in 2020. Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Lithuanian leaders have called for an increased NATO troop presence in Lithuania and on Europe's eastern flank.

The State Border Guard Service, with around 5,000 personnel, falls under the supervision of the Ministry of the Interior and is responsible for border protection, passport and customs duties, and works with the navy on interdicting smuggling and drug trafficking. The National Cyber Security Centre of Lithuania was established in 2015 to address threats in cyberspace.

9. Economy

Lithuania has an open and mixed economy that is classified as a high-income economy by the World Bank. Since regaining independence and transitioning from a planned economy to a market-based system, Lithuania has undergone significant economic reforms and integration into global and European markets. It joined NATO in 2004, the European Union (EU) in 2004, the Schengen Area in 2007, adopted the Euro on January 1, 2015, and became a member of the OECD in 2018.

As of 2017, the three largest sectors of the Lithuanian economy were services (accounting for 67% of GDP), industry (29%), and agriculture (3%). Key industrial sectors include chemical products, machinery and appliances, food processing, wood products and furniture, and mineral products. Major export categories include agricultural products and food (18.3% of exports in 2016), chemical products and plastics (17.8%), machinery and appliances (15.8%), mineral products (14.7%), and wood and furniture (12.5%). In 2016, more than half of Lithuania's exports went to seven countries: Russia (14%), Latvia (9.9%), Poland (9.1%), Germany (7.7%), Estonia (5.3%), Sweden (4.8%), and the United Kingdom (4.3%). Exports equaled 81.3% of GDP in 2017.

Lithuania experienced very high real GDP growth rates for the decade leading up to 2009, peaking at 11.1% in 2007, earning it the moniker of a "Baltic Tiger." However, the global financial crisis of 2008-2009 severely impacted the economy, causing GDP to contract by 14.8% in 2009 and the unemployment rate to reach 17.8% in 2010. The economy has since recovered, though growth has been more moderate. According to the IMF, financial conditions have been conducive to growth, and financial soundness indicators remain strong. The public debt ratio in 2016 was 39.9% of GDP, compared to 15% in 2008. The average monthly gross salary in Lithuania as of the second quarter of 2023 was 2.00 K EUR.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) primarily comes from EU countries, with Sweden historically being the largest investor. In 2017, FDI into Lithuania spiked, reaching its highest ever recorded number of greenfield investment projects. The United States was the leading source country for FDI projects in 2017.

Despite economic growth, emigration has been a significant demographic trend, with one out of five Lithuanians emigrating between 2004 and 2016, primarily due to income disparities compared to Western European countries and for educational opportunities. This long-term emigration, combined with economic growth, has led to labor shortages in some sectors and contributed to wage growth. The unemployment rate in 2017 was 7.1%.

Lithuania has a relatively flat tax system. As of 2023, the personal income tax is generally 20% (with a higher rate for income exceeding a certain threshold), and the corporate tax rate is 15% (with a reduced rate of 5% for small businesses). The country has several free economic zones offering tax incentives to attract investment.

The information technology (IT) sector is growing, with IT production reaching 1.90 B EUR in 2016. Lithuania has actively promoted itself as a FinTech hub, simplifying procedures for licensing. This has attracted numerous FinTech companies, including Google, which set up a payment company in Lithuania in 2018. Europe's first international Blockchain Centre launched in Vilnius in 2018. Lithuania has also issued hundreds of licenses for cryptocurrency exchange and storage operations. Issues of social equity, such as income inequality and regional disparities, alongside ensuring sustainable development, remain important considerations in Lithuania's economic policy.

9.1. Agriculture

Agriculture in Lithuania dates back to the Neolithic period, around 3,000 to 1,000 BC, and has been a cornerstone of the Lithuanian economy and way of life for many centuries. The country's climate and fertile soils are well-suited for various agricultural activities. Lithuania's accession to the European Union in 2004 brought significant changes to the sector, including access to the EU's Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and adherence to high standards of food safety and purity. The Seimas (parliament) adopted a Law on Product Safety in 1999 and a Law on Food in 2000, guiding the reform of the agricultural market.

In 2016, Lithuania's agricultural production was valued at 2.29 B EUR. Cereal crops constituted the largest share of production, with 5,709,500 tons harvested. Other significant crops included sugar beets (933,900 tons), rapeseed (392,500 tons), and potatoes (340,200 tons). Livestock farming, particularly dairy and meat production, also plays an important role.

Agricultural and food products are significant contributors to Lithuania's exports. In 2016, these products accounted for 18.8% of all goods exported, with a total value of 4.38 B EUR, of which products of Lithuanian origin amounted to 3.17 B EUR.

Organic farming is gaining popularity in Lithuania. The public body Ekoagros is responsible for certifying organic growers and producers. In 2016, there were 2,539 certified organic farms, cultivating an area of 225,541.9 hectares. Of this area, cereals occupied 43.1%, perennial grasses 31.2%, leguminous crops 13.5%, and other crops 12.2%. This trend reflects a growing emphasis on sustainable agricultural practices and healthier food production, aligning with broader social concerns for environmental protection and consumer well-being.

9.2. Science and Technology

Lithuania has a growing science and technology sector, with historical roots in academic pursuits and innovation. The establishment of Vilnius University in 1579 was a major catalyst for scientific and academic development. Over the centuries, notable figures with Lithuanian connections have contributed to various scientific fields. The 17th-century artillery expert Kazimieras Simonavičius is considered a pioneer of rocketry for his work Artis Magnae Artilleriae, which discussed multistage rockets and rocket batteries. Botanist Jurgis Pabrėža (1771-1849) created the first systematic guide to Lithuanian flora. German scientist Theodor Grotthuss (1785-1822), who proposed the Grotthuss mechanism in electrochemistry, lived and worked in Lithuania.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, Lithuanian scientists have made significant contributions both domestically and internationally. These include mathematician Jonas Kubilius, known for the Kubilius model in probabilistic number theory; archaeologist Marija Gimbutas, famous for her Kurgan hypothesis and studies of Old European cultures; primatologist Birutė Galdikas, a leading authority on orangutans; and biochemist Virginijus Šikšnys, one of the pioneers of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology, for which he received the Kavli Prize. Lithuanian-American engineer Arvydas Kliorė was instrumental in NASA's deep space communications.

Laser technology and biotechnology are flagship fields in contemporary Lithuanian science and high-tech industry. Lithuanian laser companies, such as Šviesos konversija (Light Conversion) and Ekspla, are global leaders in the production of femtosecond lasers and other advanced laser systems, used in research, medicine, and industry. The Vilnius University Laser Research Center is a prominent research institution. Lithuania has also launched three satellites into space: LitSat-1 and Lituanica SAT-1 in 2014, and LituanicaSAT-2 in 2017. The country is a cooperating state with the European Space Agency (ESA) and became an Associate Member State of CERN in 2018.

The Lithuanian government has actively promoted research and development (R&D) and innovation. Initiatives include the establishment of "Valleys" (integrated science, studies, and business centers) like Santara Valley (biotechnology, innovative medicine), Saulėtekis Valley (physics, technology, lasers), and Santaka Valley (sustainable chemistry, mechatronics). The Life Sciences Center at Vilnius University and the Center for Physical Sciences and Technology are leading research hubs. In 2016, the biotech and life science sector in Lithuania reported a yearly growth of 22% over the previous five years. The social and ethical implications of these technological advancements, particularly in biotechnology and artificial intelligence, are increasingly part of public and policy discussions. Lithuania was ranked 35th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.

9.3. Tourism

Tourism in Lithuania is a growing sector of the economy, offering a diverse range of attractions that appeal to both international and domestic visitors. In 2023, Lithuania received 1.4 million international tourists who stayed at least one night. The largest numbers of visitors came from neighboring countries like Poland (173,500), Latvia (144,300), and Belarus (141,900), as well as from Germany (127,400), the United Kingdom (74,200), the United States (69,700), Ukraine (67,000), and Estonia (61,300). Domestic tourism has also been on the rise.

Major tourist destinations include the capital city, Vilnius, with its UNESCO-listed Old Town, rich in Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, and Neoclassical architecture. Kaunas, the second-largest city, is known for its interwar modernist architecture and vibrant cultural scene. Klaipėda, the country's main seaport, serves as a gateway to the Curonian Spit, another UNESCO World Heritage site famous for its unique sand dunes and natural beauty. Coastal resorts like Palanga and Nida are popular for summer holidays.

Spa towns such as Druskininkai and Birštonas are renowned for their mineral water springs, sanatoriums, and wellness facilities, attracting visitors seeking health and relaxation treatments. Lithuania offers around 1,000 places of attraction, including numerous castles, manors, ethnographic villages, and natural parks.

Activities like hot air ballooning are particularly popular, especially over Vilnius and Trakai with its iconic island castle. Cycle tourism is growing, with well-developed routes like the Lithuanian Seaside Cycle Route. EuroVelo routes EV10 (Baltic Sea Cycle Route), EV11 (East Europe Route), and EV13 (Iron Curtain Trail) pass through Lithuania, with a total of 2.3 K mile (3.77 K km) of bicycle tracks in the country (1.2 K mile (1.99 K km) of which are asphalt-paved). Nature tourism is also prominent, with areas like Nemunas Delta Regional Park and Žuvintas Biosphere Reserve known for birdwatching.

The total contribution of tourism to Lithuania's GDP was 1.70 B EUR (2.3% of GDP) in 2023, and the sector is recovering and growing following the COVID-19 pandemic. The recent inclusion of Lithuanian restaurants in the Michelin Guide in 2024 is expected to further boost culinary tourism.

10. Infrastructure

Lithuania has been actively developing its infrastructure since regaining independence, focusing on modernizing its communication, transport, and energy networks to support economic growth and enhance connectivity with Europe and the world.

10.1. Communication and Information Technology

Lithuania possesses a well-developed communications infrastructure. The country, with approximately 2.8 million citizens, had around 5 million active SIM cards, indicating high mobile phone penetration. The largest LTE (4G) mobile network covers about 97% of Lithuania's territory, providing widespread high-speed mobile internet access. The use of fixed-line telephones has been rapidly declining due to the expansion of mobile-cellular services.

In 2017, Lithuania ranked among the top 30 countries globally for average mobile broadband speeds and in the top 20 for average fixed broadband speeds. It was also among the top 7 countries in the world for 4G LTE penetration in 2017. The country has made significant strides in e-government services, ranking 17th in the United Nations' e-participation index in 2016. Lithuania hosts four TIER III certified datacenters, supporting its growing digital economy.

The RAIN (Development of Rural Areas Broadband Network) project, running from 2005 to 2013 and funded by the EU and the Lithuanian government, aimed to provide fiber-optic broadband access to residents, state and municipal authorities, and businesses in rural areas. This infrastructure allows numerous communication operators to offer network services to their clients, bridging the digital divide. While in 2017, household internet access was around 72% (among the EU's lower rates at the time), it was projected to increase. Smartphone penetration was nearly 50% in 2016 and expected to grow. Lithuania boasts the highest Fiber to the home (FTTH) penetration rate in Europe (36.8% as of September 2016), according to the FTTH Council Europe.

10.2. Transport

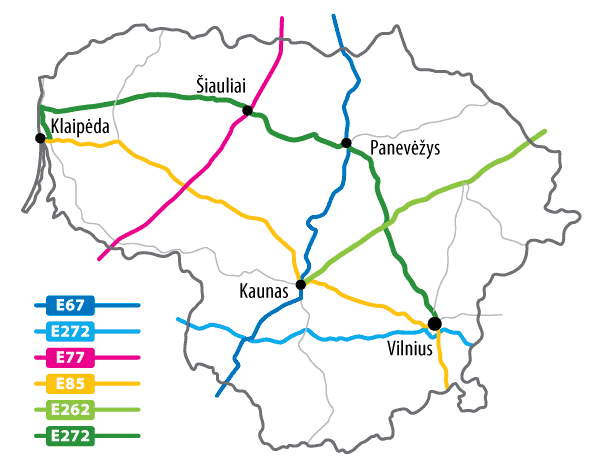

Transportation is a significant sector in the Lithuanian economy. The country's first railway connection was established in the mid-19th century with the construction of the Warsaw - Saint Petersburg Railway. Currently, Lithuania's railway network consists of 1.1 K mile (1.76 K km) of 0.1 K in (1.52 K mm) Russian gauge railway, of which 76 mile (122 km) are electrified. This network is largely incompatible with the European standard gauge, requiring train switching for cross-border traffic with Poland. However, Lithuania also has 71 mile (115 km) of standard gauge lines. The strategically important Rail Baltica project, a Trans-European standard gauge railway linking Helsinki-Tallinn-Riga-Kaunas-Warsaw and continuing to Berlin, is under construction and aims to integrate the Baltic states into the European rail network. Lietuvos geležinkeliai (Lithuanian Railways) operates most railway lines.

Lithuania has an extensive network of motorways and national roads. The World Economic Forum (WEF) has generally rated Lithuanian road quality reasonably well. The road haulage industry is highly developed, with Lithuanian transport companies being major players in the European market. Almost 90% of commercial truck traffic in Lithuania is international transport, the highest proportion in the EU.

The Port of Klaipėda is Lithuania's only commercial cargo port and is an important ice-free harbor on the Baltic Sea. In 2011, it handled 45.5 million tons of cargo (including figures from the Būtingė oil terminal). While not among the EU's top 20 largest ports by overall volume, it is a significant port in the Baltic Sea region and has ongoing expansion plans. The Lithuanian Inland Waterways Authority (Vidaus vandens kelių direkcija) is working to revive cargo shipping on the Nemunas River, aiming to connect Kaunas with Klaipėda via electric ships, which is projected to reduce truck traffic and emissions.

Vilnius Airport is the largest airport in Lithuania, handling 3.8 million passengers in 2016. Other international airports include Kaunas Airport, Palanga International Airport, and Šiauliai International Airport. Kaunas Airport also functions as a small commercial cargo hub. An inland river cargo port in Marvelė, connecting Kaunas and Klaipėda, received its first cargo in 2019.

10.3. Energy

Lithuania's key energy strategy revolves around the systematic diversification of energy imports and resources, aiming for greater energy independence and security. This was outlined in the National Energy Independence Strategy adopted by the Seimas in 2012.

Following the decommissioning of the Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant (Unit 1 closed in 2004, Unit 2 in 2009 as a condition for EU entry), Lithuania transitioned from an electricity exporter to an importer. Proposals for a new nuclear power plant, the Visaginas Nuclear Power Plant, were clouded by a non-binding referendum in 2012 where 63% of voters opposed the project. The country's main domestic source of electrical power is the Elektrėnai Power Plant, a thermal power station. Other important facilities include the Kruonis Pumped Storage Plant (the only one of its kind in the Baltic states, crucial for grid regulation) and the Kaunas Hydroelectric Power Plant. As of 2015, 66% of Lithuania's electricity was imported.

To enhance energy security and connect with European markets, Lithuania has developed significant interconnections. The NordBalt submarine electricity interconnection with Sweden and the LitPol Link electricity interconnection with Poland were launched at the end of 2015. In 2018, the process of synchronizing the Baltic states' electricity grid with the Continental European Network (CEN) began, aiming to reduce dependence on the Russian-controlled IPS/UPS grid.

Renewable energy is an increasing focus. In 2016, 20.8% of electricity consumed in Lithuania came from renewable sources. The first geothermal heating plant in the Baltic Sea region, the Klaipėda Geothermal Demonstration Plant, was built in 2004. Environmental and social considerations, such as reducing carbon emissions and ensuring affordable energy, are key drivers in energy policy.

To break Gazprom's monopoly in the natural gas market, Lithuania constructed the Klaipėda LNG terminal, the first large-scale LNG import terminal in the Baltic region, which became operational in 2014. The floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU) is named Independence. Norwegian company Equinor has been a key supplier. The terminal can meet Lithuania's entire demand and a significant portion of Latvia's and Estonia's demand. The Gas Interconnection Poland-Lithuania (GIPL), a natural gas pipeline between Lithuania and Poland, became operational in 2022, further enhancing regional energy security and market integration.

11. Demographics

Lithuania's population has remained relatively homogenous since the Neolithic period, with a high probability that current inhabitants share a similar genetic composition to their ancestors. Genetic studies indicate Lithuanians are closely related to Latvians and Estonians, as well as to Slavic and Finno-Ugric speaking populations of Northern and Eastern Europe. The population appears relatively homogeneous without significant genetic differences among ethnic subgroups.

As of 2021, the population of Lithuania was approximately 2.8 million. The age structure was: 0-14 years: 14.86%; 15-64 years: 65.19%; 65 years and over: 19.95%. The median age in 2022 was 44 years (male: 41, female: 47). Lithuania has a sub-replacement fertility rate; the total fertility rate (TFR) was 1.34 children born per woman in 2021. The mean age of women at childbirth was 30.3 years, and the mean age at first childbirth was 28.2 years. In 2021, 25.6% of births were to unmarried women. The mean age at first marriage in 2021 was 28.3 years for women and 30.5 years for men. Like many European countries, Lithuania faces challenges related to an aging population and emigration.

11.1. Ethnic Groups and Minorities

Lithuania has the most ethnically homogeneous population among the Baltic States. According to the 2024 data, Lithuanians make up approximately 82.6% of the country's 2.81 million residents. They speak Lithuanian, which is the official language.

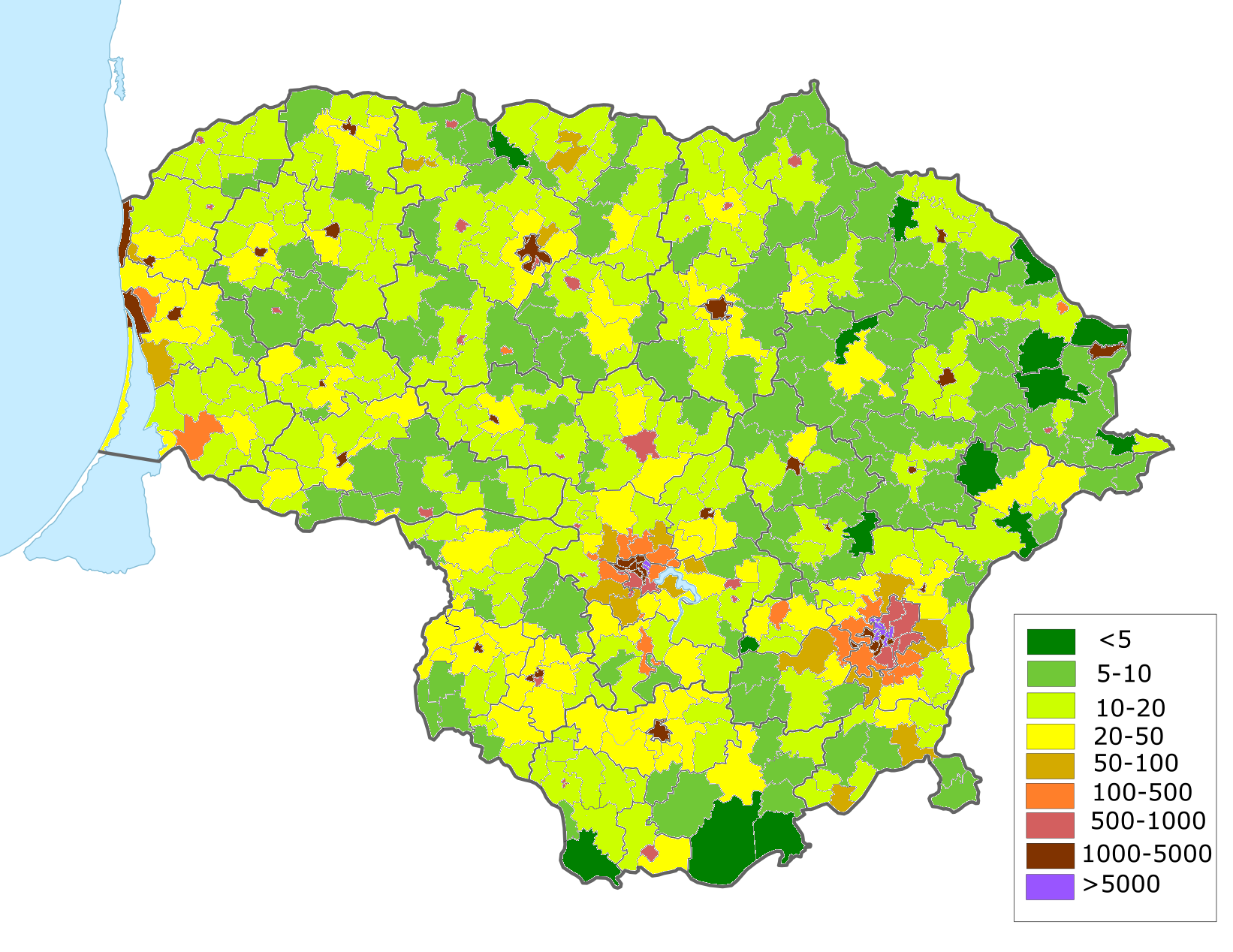

Several significant minorities exist:

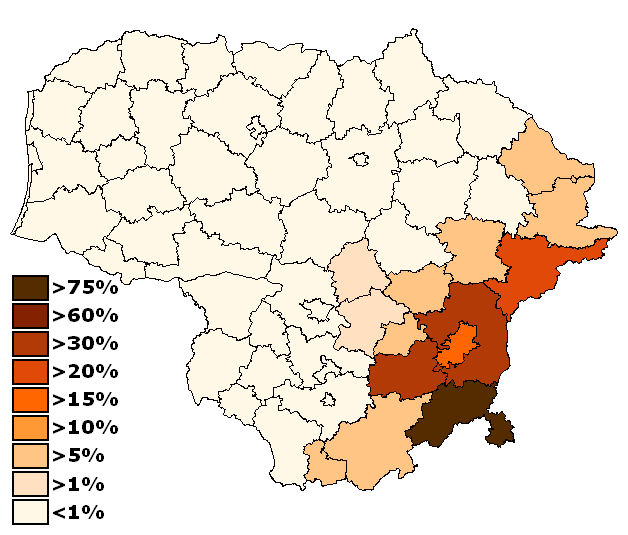

- Poles are the largest minority group, constituting about 6.3% of the population. They are primarily concentrated in southeastern Lithuania, particularly in the Vilnius Region, forming a majority in Šalčininkai District Municipality (76.3%) and a large minority in Vilnius District Municipality (46.8%).

- Russians are the second-largest minority, making up about 5.0%. They are concentrated mainly in cities like Visaginas (47.4% Russian), Klaipėda (16.0%), and the Zarasai District Municipality (17.2%).

- Belarusians account for about 2.1% of the population.

- Ukrainians constitute about 1.7%.

- Other smaller minority groups include about 2,250 Roma, mostly living in Vilnius, Kaunas, and Panevėžys. Historic communities of Lipka Tatars (around 2,150 registered in 2021) and Karaites (around 196 registered in 2021) have lived in Lithuania for centuries.

Lithuania's policies generally aim to protect the rights of ethnic minorities, including the right to education in their native languages. This commitment to multiculturalism is an important aspect of Lithuania's social fabric, though challenges related to social integration and representation sometimes arise.

11.2. Languages

The official language of Lithuania is Lithuanian (lietuvių kalbalietuvių kalbaLithuanian), which is also one of the official languages of the European Union. It is spoken as a native language by about 85.33% of the population (2021 census). Lithuanian is one of two living Baltic languages, the other being Latvian; while related, they are not mutually intelligible. Lithuanian is renowned among linguists for being one of the most conservative living Indo-European languages, retaining many archaic features of Proto-Indo-European. This makes the study of Lithuanian important for comparative linguistics. It is written using an adapted version of the Latin alphabet.

Minority languages spoken in Lithuania include Polish (native to 5.1% of the population), Russian (native to 6.8%), Belarusian, and Ukrainian. These languages are most prevalent in areas with significant minority populations, such as the Vilnius region (Polish) and cities like Visaginas and Klaipėda (Russian). Yiddish was historically spoken by the large Jewish community but is now used by only a very small number of people. The Lithuanian state guarantees education in minority languages, and there are numerous publicly funded schools where Polish or Russian is the language of instruction.

Knowledge of foreign languages is widespread. According to the 2021 census, 60.6% of residents reported speaking Russian as a foreign language, 31.1% English, 10.5% Lithuanian (among non-native speakers), 8% German, 7.9% Polish (among non-native speakers), and 1.9% French. English is taught as the first foreign language in most Lithuanian schools, with German, French, or Russian also offered. Around 80% of young Lithuanians are reported to know English.

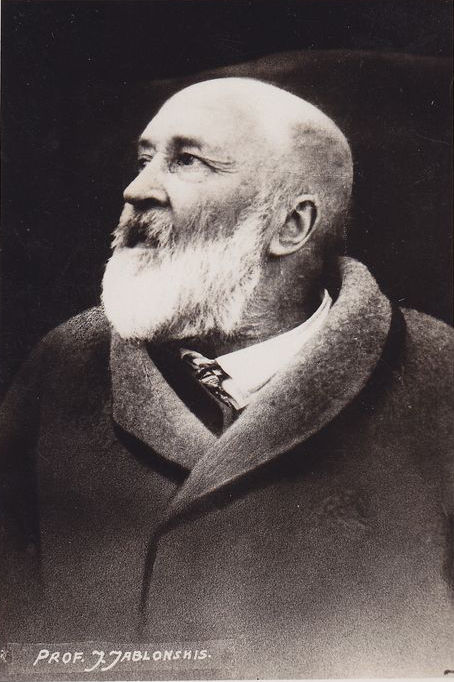

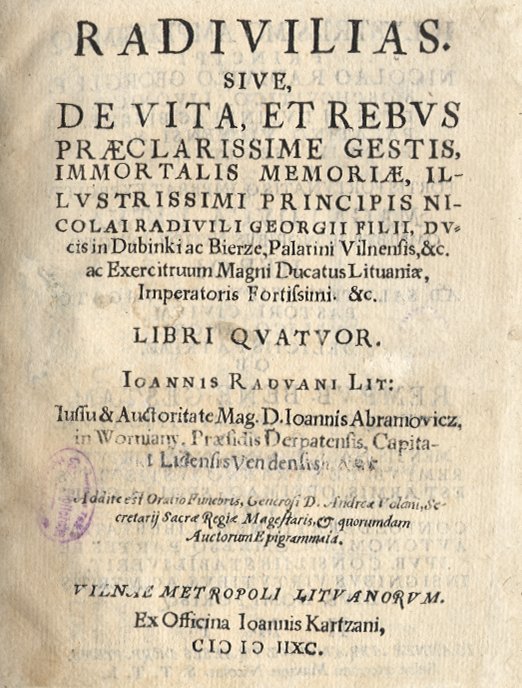

The development of written Lithuanian was significantly advanced in the 16th and 17th centuries by scholars such as Mikalojus Daukša, Martynas Mažvydas, and Konstantinas Sirvydas. Jonas Jablonskis played a crucial role in standardizing the modern Lithuanian language in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

11.2.1. Dialects

The Lithuanian language has two main dialect groups:

- Aukštaitian dialect (Aukštaičių tarmėAukštaičių tarmėLithuanian, High Lithuanian): Spoken in the central, southern, and eastern parts of Lithuania. Standard Lithuanian is primarily based on the Western Aukštaitian sub-dialects.

- Samogitian dialect (Žemaičių tarmėŽemaičių tarmėLithuanian, Low Lithuanian): Spoken in the western part of Lithuania, known as Samogitia. Samogitian is considerably different from Standard Lithuanian and is sometimes considered a separate language by some linguists and its speakers due to distinct phonology, morphology, and vocabulary.

These main dialect groups are further subdivided into sub-dialects and local varieties (šnektosšnektosLithuanian). The primary distinguishing phonetic feature between the two main dialects is the pronunciation of certain diphthongs, particularly the Proto-Baltic long *ō and *ē, which correspond to Lithuanian uo and ie respectively. Aukštaitian generally preserves these, while Samogitian has different reflexes. For example, Standard Lithuanian duona (bread) is douna in many Samogitian varieties, and pienas (milk) is pīns.

The preservation and study of these dialects are important for Lithuanian cultural heritage.

11.3. Urbanization and Major Cities

Lithuania has experienced a steady trend of urbanization since the 1990s, with a significant movement of the population from rural areas to cities. This has been partly encouraged by the planning of regional centers like Alytus, Marijampolė, Utena, Plungė, and Mažeikiai. By the early 21st century, approximately two-thirds of the total population lived in urban areas. As of 2021, 68.19% of the population resided in urban areas.

Lithuania's major functional urban areas (metropolitan areas) are centered around its largest cities:

- Vilnius (population of functional urban area: 708,203)

- Kaunas (population of functional urban area: 391,153)

- Panevėžys (population of functional urban area: 124,526)

Vilnius, the capital, is the largest city and the main political, economic, cultural, and educational center. It has received high rankings for economic potential and business friendliness in various international surveys. For example, fDi Intelligence (a service from the Financial Times) ranked Vilnius fourth among mid-sized European cities in its 2018-19 "Cities and Regions of the Future" report, second in the 2022-23 ranking, and second again in the 2023 ranking. Vilnius County also performed well in regional categories.

The largest cities in Lithuania by population (as of 2024/2025) are:

| Rank | City | County | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vilnius | Vilnius County | 607,404 |

| 2 | Kaunas | Kaunas County | 303,978 |

| 3 | Klaipėda | Klaipėda County | 160,885 |

| 4 | Šiauliai | Šiauliai County | 111,971 |

| 5 | Panevėžys | Panevėžys County | 85,774 |

| 6 | Alytus | Alytus County | 50,741 |

| 7 | Marijampolė | Marijampolė County | 36,240 |

| 8 | Mažeikiai | Telšiai County | 33,303 |

| 9 | Jonava | Kaunas County | 26,680 |

| 10 | Utena | Utena County | 25,587 |

Urban development trends focus on modernizing infrastructure, improving housing, and promoting sustainable urban environments, while also addressing challenges such as aging populations in smaller towns and regional economic disparities.

11.4. Religion

Roman Catholicism is the predominant religion in Lithuania. According to the 2021 census, 74.2% of residents identified as Catholic. Catholicism has been the main religion since the official Christianisation of Lithuania in 1387. The Catholic Church played a significant role in preserving Lithuanian national identity and culture, particularly during periods of foreign rule. It was persecuted by the Russian Empire as part of Russification policies and by the Soviet Union during its anti-religious campaigns. During the Soviet era, some priests actively led the resistance against the Communist regime, symbolized by sites like the Hill of Crosses and clandestine publications such as The Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania. Lithuania is considered the northernmost predominantly Catholic country in the cultural sphere of Europe.

Other Christian denominations include:

- Eastern Orthodoxy: Practiced by 3.7% of the population, mainly among the Russian minority.

- Old Believers: Comprising 0.6% of the population, this community dates back to the 17th century when they sought refuge from persecution in Russia.