1. Overview

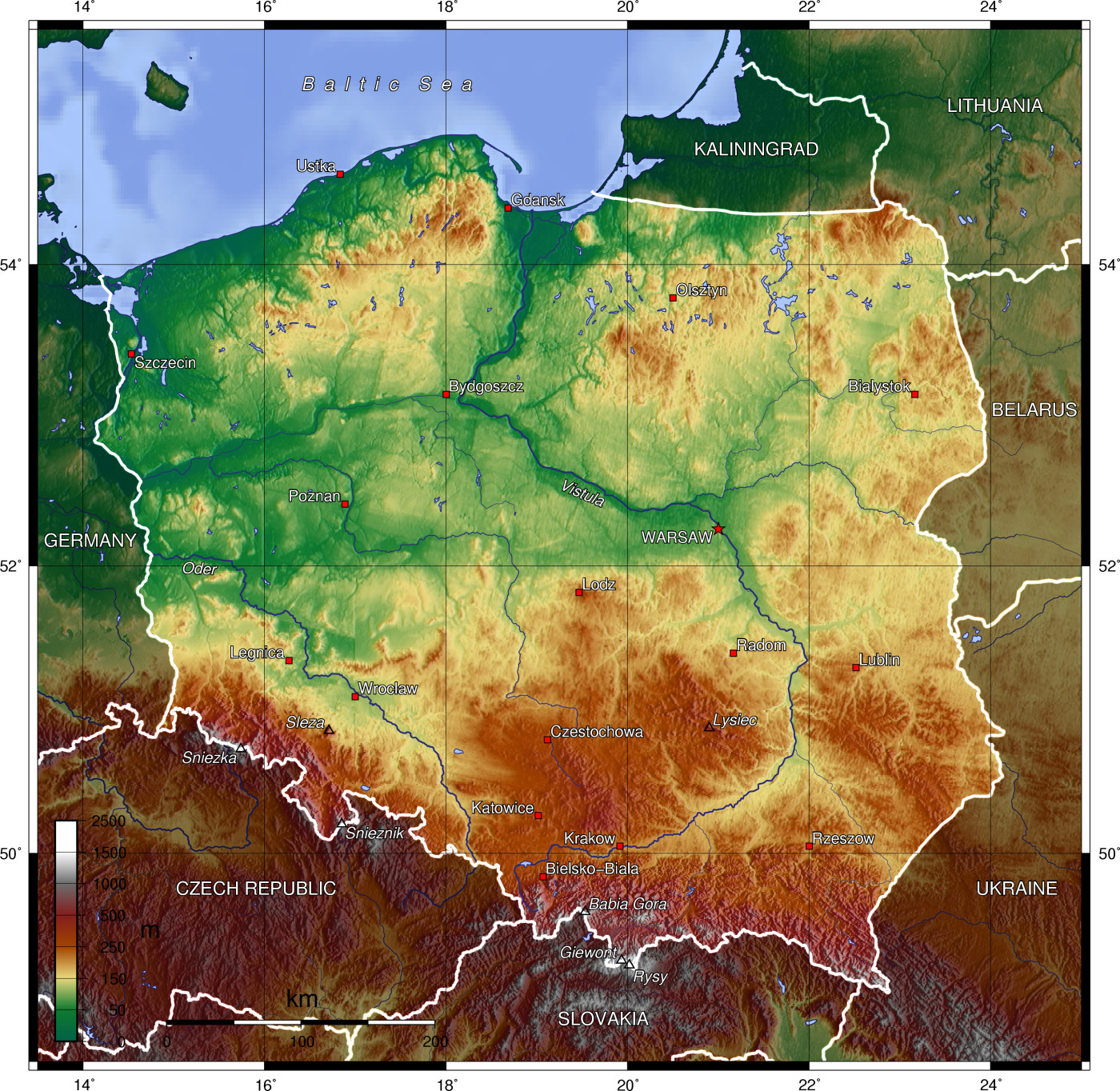

Poland (PolskaPOHL-skahPolish), officially the Republic of Poland (Rzeczpospolita Polskazhech-pos-POH-lee-tah POHL-skahPolish), is a country located in Central Europe. It is bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine and Belarus to the east; and the Baltic Sea, Lithuania, and Russia (via the Kaliningrad Oblast exclave) to the north. The country's territory covers 121 K mile2 (312.70 K km2), making it the ninth-largest in Europe. Poland has a population of over 38 million people, making it the fifth most populous member state of the European Union. The capital and largest metropolis is Warsaw.

Geographically, Poland features a diverse landscape, from the sandy beaches of the Baltic Sea coast in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south. The country is traversed by the Central European Plain and possesses a temperate transitional climate. Its major rivers include the Vistula and the Oder.

The history of human activity on Polish lands spans millennia. The formation of the Polish state is traditionally associated with Mieszko I's adoption of Christianity in 966 CE. The Kingdom of Poland emerged in 1025 and later, in 1569, formed a long-standing union with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, establishing the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. This entity was a major European power characterized by a unique aristocratic democracy and, in 1791, adopted Europe's first modern codified constitution. However, by the late 18th century, the Commonwealth was partitioned by neighboring empires, leading to 123 years of foreign rule. Poland regained independence as the Second Polish Republic in 1918 after World War I. The Second World War began with the invasion of Poland in 1939 by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, resulting in immense human suffering, including the Holocaust. Following the war, Poland became the Polish People's Republic, a satellite state within the Soviet-led Eastern Bloc. The rise of the Solidarity movement in the 1980s played a crucial role in the peaceful transition to a democratic government in 1989.

The modern Polish state is a unitary semi-presidential republic and a representative democracy. It has a developed market economy and is considered a high-income country, with a very high standard of living, social welfare provisions including free university education and universal healthcare. Poland is a member of the United Nations, NATO, the European Union, the Schengen Area, the OECD, and the Visegrád Group.

2. Etymology

The native Polish name for Poland is PolskaPOHL-skahPolish. This name originates from the Polans, a West Slavic tribe that inhabited the Warta River basin, part of the present-day Greater Poland region, during the 6th to 8th centuries CE. The tribe's name itself is derived from the Proto-Slavic noun pole, meaning "field" or "open country," which in turn comes from the Proto-Indo-European root *pleh₂-, indicating "flatland." This etymology reflects the predominantly flat topography of the Greater Poland region where the Polans settled.

During the Middle Ages, the Latin form Polonia was widely used throughout Europe to refer to Poland. The English name Poland was formed in the 1560s, derived from the German term Pole(n) (referring to the Polans) and the suffix -land, indicating a country or nation.

An alternative archaic name for Poland is Lechia. The root syllable of this name remains in official use in several languages, including Hungarian (Lengyelország), Lithuanian (Lenkija), and Persian (لهستانLahestânPersian). This exonym is thought to derive either from Lech, the legendary founder and ruler of the Lechites (a broader group of West Slavic tribes including the Polans), or from the Lendians, another West Slavic tribe that lived on the southeastern edge of Lesser Poland. The name "Lendians" itself comes from the Old Polish word lęda, meaning "plain" or "uncultivated field." In medieval chronicles, both names, Lechia and Polonia, were sometimes used interchangeably when referring to Poland.

3. History

The history of Poland spans from early human settlements to its current status as a modern republic, marked by periods of formation, golden ages, decline, partitions, and rebirth, with significant impacts on its society and democratic development.

3.1. Prehistory and protohistory

The earliest traces of human activity in what is now Poland date back approximately 500,000 years, with Homo erectus species being present. However, due to harsh climatic conditions, permanent settlements were scarce. Anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) arrived in the region after the Last Glacial Period, around 10,000 BC, when Poland became more habitable.

The Neolithic period saw significant developments. Evidence from Kuyavia indicates that cheesemaking was practiced in the area as early as 5500 BC, making it one of the earliest sites for such activity in Europe. The Bronocice pot, dating to around 3400 BC, features one of the oldest known depictions of a wheeled vehicle.

The Bronze Age (c. 2400 BC) and Early Iron Age in Poland, lasting from approximately 1300 BC to 500 BC, were characterized by the expansion of the Lusatian culture. This period saw an increase in population density and the establishment of fortified settlements known as gords. A prominent example is the settlement at Biskupin, dating to the 8th century BC.

During antiquity (c. 400 BC - 500 AD), the territory of present-day Poland was inhabited by various peoples, including Celts, Scythians, Germanic peoples, Sarmatians, Balts, and Slavic tribes. Archaeological findings also confirm the presence of Roman legions in the region, likely to protect the lucrative Amber Road trade routes. The Przeworsk culture (associated with the Lugii or Vandals) and the Zarubintsy culture (associated with early Slavs) were significant in this era.

The West Slavic tribes that would eventually form the Polish nation, including the Polans, Vistulans, Silesians, and Pomeranians, emerged more distinctly following the Migration Period around the 6th century AD. These tribes may have assimilated remnants of earlier populations. By the early 10th century, the Polans, centered in the Greater Poland region, began to dominate other Lechitic tribes, initially forming a tribal federation and later a centralized monarchical state that would give Poland its name.

3.2. Kingdom of Poland

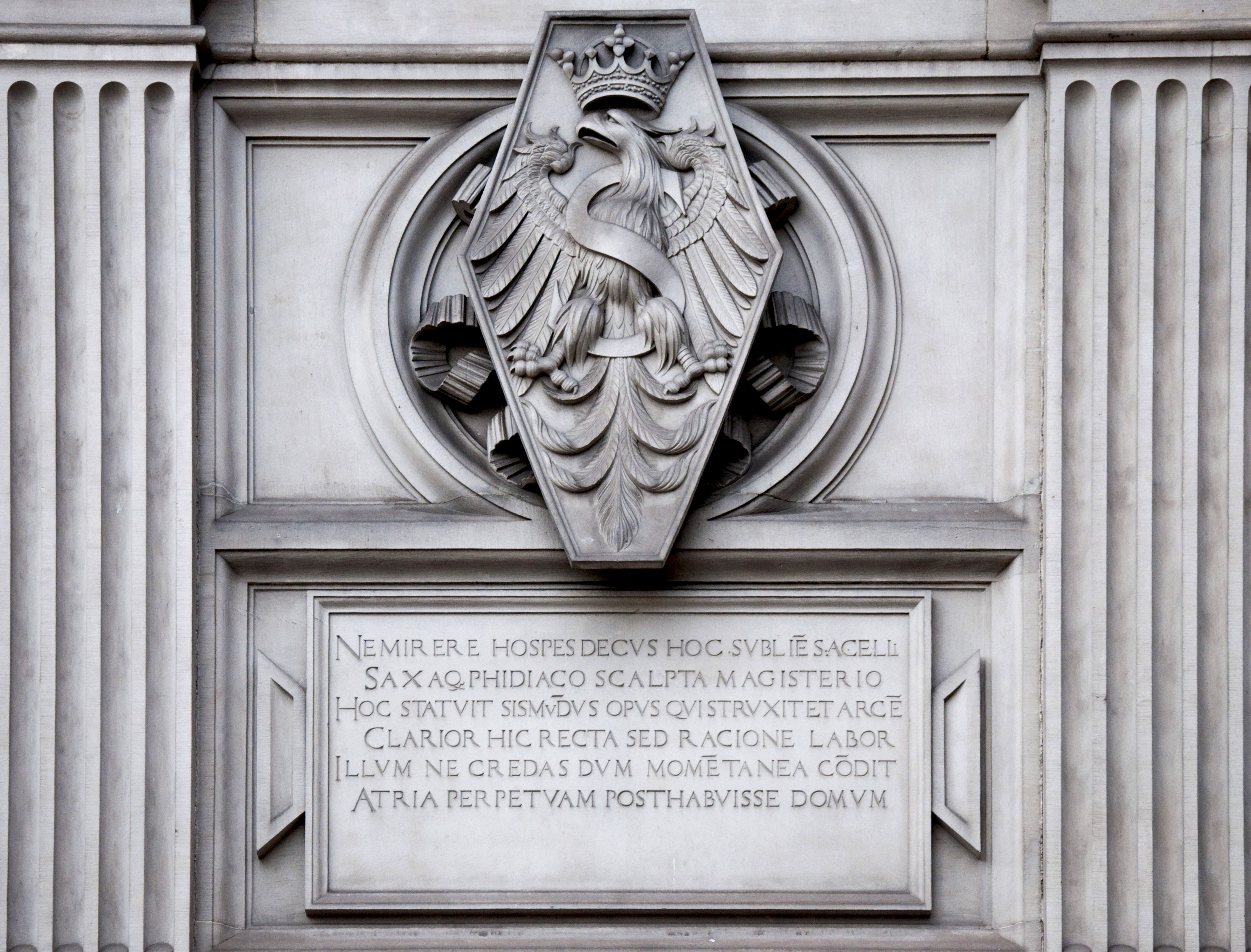

The formation of a recognizable Polish state began in the mid-10th century under the Piast dynasty. In 966, Mieszko I, the ruler of the Polans, adopted Christianity under the auspices of the Roman Catholic Church, an event known as the Baptism of Poland. This decision was pivotal, integrating Poland into Western Christendom and laying the groundwork for a unified state. A missionary bishopric was established in Poznań in 968. The earliest document defining Poland's approximate geographical boundaries, the Dagome iudex (c. 991), placed its capital in Gniezno and affirmed its monarchy was under the protection of the Apostolic See. The oldest Polish chronicle, the Gesta principum Polonorum by Gallus Anonymus, described these early origins. A significant event was the martyrdom of Adalbert of Prague in 997 by Prussian pagans; his relics were bought back by Mieszko's successor, Bolesław I the Brave.

In 1000, at the Congress of Gniezno, Bolesław I obtained the right of investiture from Holy Roman Emperor Otto III, who also consented to the creation of an archdiocese in Gniezno and new bishoprics in Kraków, Kołobrzeg, and Wrocław. Around 1025, Bolesław I was crowned the first King of Poland with the permission of Pope John XIX, establishing the Kingdom of Poland. He significantly expanded the realm, conquering parts of German Lusatia, Czech Moravia, Upper Hungary, and southwestern regions of Kievan Rus'.

The transition from paganism was not smooth, leading to a pagan reaction in the 1030s. Mieszko II Lambert lost the title of king in 1031 and fled. The ensuing unrest led Casimir I the Restorer to move the capital to Kraków in 1038. In 1076, Bolesław II the Generous reinstated the royal title but was banished in 1079 for the murder of Bishop Stanislaus.

A critical period of fragmentation began in 1138 when Bolesław III Wrymouth, in his testament, divided Poland among his sons into five principalities: Lesser Poland, Greater Poland, Silesia, Masovia, and Sandomierz, with Kraków as the seniorate province. This led to nearly two centuries of internal division. In 1226, Konrad I of Masovia invited the Teutonic Knights to help combat the Baltic Prussians, a decision that would lead to centuries of conflict with the Order.

The Mongol invasions in the 13th century, particularly the devastating Battle of Legnica in 1241 where Duke Henry II the Pious was killed, further hindered unification efforts and led to significant depopulation. This, in turn, spurred the migration of German and Flemish settlers, encouraged by Polish dukes to repopulate and develop the lands. This period also saw the establishment of important legal frameworks for minorities. In 1264, the Statute of Kalisz, issued by Duke Bolesław the Pious, granted unprecedented rights and protections to the Jewish population, who were fleeing persecution elsewhere in Europe. This statute became a cornerstone for Jewish life in Poland for centuries, fostering a significant Jewish diaspora that contributed to Poland's cultural and economic life.

Reunification efforts culminated in 1320 when Władysław I the Elbow-high was crowned King of a reunified Poland, the first to be crowned at Wawel Cathedral in Kraków. His son, Casimir III the Great (reigned 1333-1370), is considered one of Poland's greatest rulers. He reformed the Polish army and legal code, built numerous castles (the Eagle's Nests castles), and expanded Polish territory, notably incorporating Red Ruthenia. He also founded the University of Kraków (Academia Cracoviensis) in 1364, one of Europe's oldest universities. Casimir III's reign saw Poland avoid the worst of the Black Death due to his quarantine measures and transformed the country into a significant European power. With his death in 1370 without a male heir, the Piast dynasty ended. He was succeeded by his nephew, Louis of Anjou, King of Hungary, which led to a personal union between Poland and Hungary. Louis's younger daughter, Jadwiga, became Poland's first female monarch in 1384.

3.3. The Golden Age

The marriage of Queen Jadwiga to Władysław II Jagiełło, Grand Duke of Lithuania, in 1386, marked the beginning of the Jagiellonian dynasty and the Polish-Lithuanian union. This personal union brought the vast, multi-ethnic territories of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania into Poland's sphere of influence, creating one of Europe's largest political entities. The Jagiellonian era, particularly the 15th and 16th centuries, is often referred to as Poland's "Golden Age" due to its political power, economic prosperity, and cultural flourishing.

A major challenge during this period was the ongoing conflict with the Teutonic Knights. The decisive Battle of Grunwald (Tannenberg) in 1410, where a combined Polish-Lithuanian army defeated the Knights, significantly weakened the Order. The Thirteen Years' War concluded with the Peace of Thorn in 1466, under which Royal Prussia (including Gdańsk/Danzig) was incorporated into Poland, and the Teutonic State became a Polish fief. The Jagiellonian dynasty also extended its influence, with its members ruling Bohemia and Hungary at various times. Poland also faced challenges from the Ottoman Empire and the Crimean Khanate in the south, and Muscovy in the east.

Internally, Poland developed as a feudal state with a powerful szlachta (nobility). In 1493, the Sejm (parliament) was formally established as a bicameral legislature. The Nihil novi act of 1505 significantly increased the power of the Sejm by requiring the king to obtain noble consent for new laws, marking the formal beginning of "Golden Liberty" (Złota WolnośćZWOH-tah VOHL-noshchPolish). This system granted extensive rights and privileges to the nobility, creating a unique form of aristocratic democracy.

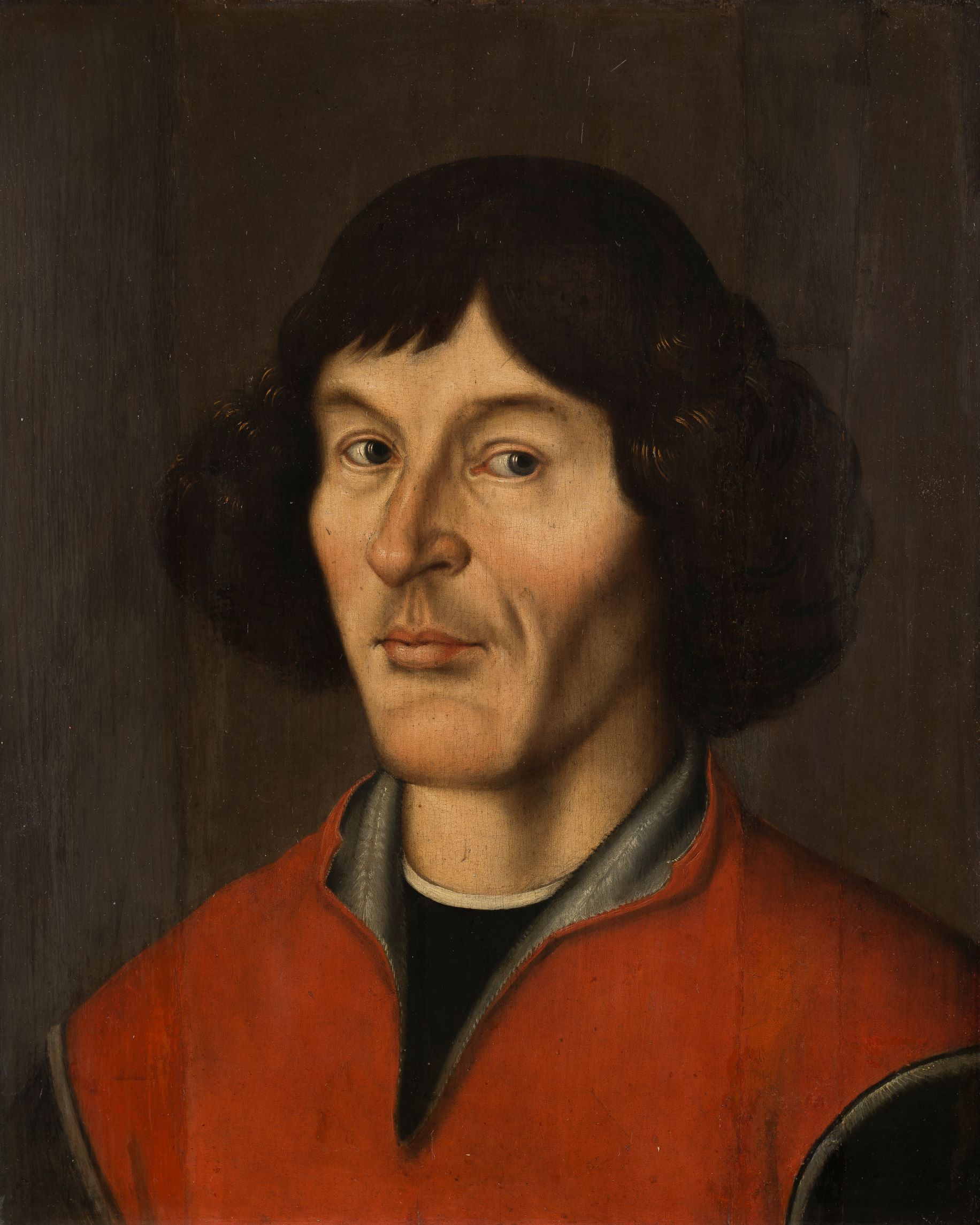

The 16th century was also a period of significant cultural and intellectual development, with the Polish Renaissance reaching its peak under Kings Sigismund I the Old and Sigismund II Augustus. Italian influences were strong, partly due to Sigismund I's Italian wife, Bona Sforza, who contributed to architectural styles, cuisine, and court customs. Nicolaus Copernicus published his revolutionary heliocentric theory in 1543.

Crucially, this era was characterized by remarkable religious tolerance. While much of Europe was torn by religious wars, Poland, through acts like the Warsaw Confederation of 1573, guaranteed freedom of religion to all its inhabitants. This allowed various Protestant denominations, including Lutheranism, Calvinism, and the anti-Trinitarian Polish Brethren, to flourish alongside the dominant Catholicism, as well as Orthodox Christianity and Judaism. This tolerance contributed to Poland becoming a haven for religious minorities and a vibrant multicultural society, though this ideal would be challenged in later centuries.

3.4. Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Union of Lublin in 1569 formally established the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita Obojga Narodówzhech-pos-POH-lee-tah oh-BOY-gah nah-ROH-doofPolish), transforming the personal union into a real union with a single monarch, parliament (Sejm), and foreign policy, though Poland and Lithuania retained separate armies, treasuries, and legal systems. The Commonwealth was an elective monarchy, where the king was elected by the entire nobility (szlachta). At its zenith in the early 17th century, the Commonwealth covered nearly 0.4 M mile2 (1.00 M km2) and was one of Europe's largest and most populous countries. It was a major European power, known for its unique political system of "Golden Liberty" which, while providing extensive rights to the nobility, often led to governmental inefficiency due to mechanisms like the liberum veto.

The Warsaw Confederation of 1573, passed during the first interregnum, formally established religious freedom, making the Commonwealth a relatively safe haven for religious minorities. The first elected king, Henry de Valois (later Henry III of France), was compelled to accept the Henrician Articles and Pacta conventa, which further limited royal power and enshrined the nobles' privileges. Subsequent elected kings, such as Stephen Báthory (reigned 1576-1586), a skilled military leader who waged successful campaigns in the Livonian War, and Sigismund III Vasa (reigned 1587-1632), who briefly held a personal union with Sweden, navigated complex internal and external politics. During Sigismund III's reign, Poland-Lithuania intervened in Russia's Time of Troubles, occupying Moscow for a period (1610-1612). The Commonwealth also fought numerous wars against the Ottoman Empire (e.g., Battle of Cecora and Khotyn), Muscovy, and Sweden.

The 17th century, however, saw the beginning of the Commonwealth's decline. The Khmelnytsky Uprising in Ukraine (1648) led to devastating wars and the loss of significant eastern territories to Russia. This was followed by the "Deluge"-a series of Swedish and Russian invasions in the mid-17th century that ravaged the country, leading to immense population loss and economic destruction. While King John III Sobieski achieved a famous victory against the Ottomans at the Battle of Vienna in 1683, temporarily bolstering the Commonwealth's prestige, the internal political system remained dysfunctional. The reigns of the Saxon kings, Augustus II the Strong and Augustus III of Poland, in the early 18th century were marked by further decline, increased foreign interference (particularly from Russia, Prussia, and Austria), and internal strife, including the Great Northern War and the War of the Polish Succession.

During this period, Polonization policies in the eastern territories, particularly affecting the Ruthenian (Ukrainian and Belarusian) populations, led to social and religious tensions. While the Commonwealth was officially tolerant, the Counter-Reformation gained strength, and the status of non-Catholic, non-Polish speaking minorities became more precarious, contributing to internal weaknesses that neighboring powers would later exploit. The social impact of these policies on minorities was significant, often leading to resentment and contributing to uprisings.

3.5. Partitions and Era of Insurrections

The 18th century witnessed the gradual decline of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, culminating in its complete annihilation by neighboring powers. The reign of the last king, Stanisław August Poniatowski (elected in 1764 with Russian backing), was marked by attempts at reform inspired by the Enlightenment. However, these efforts were often thwarted by internal opposition from conservative nobles (like the Bar Confederation, 1768-1772, which opposed Russian influence and the King's reforms) and increasing pressure from Russia, Prussia, and the Habsburg Monarchy (Austria).

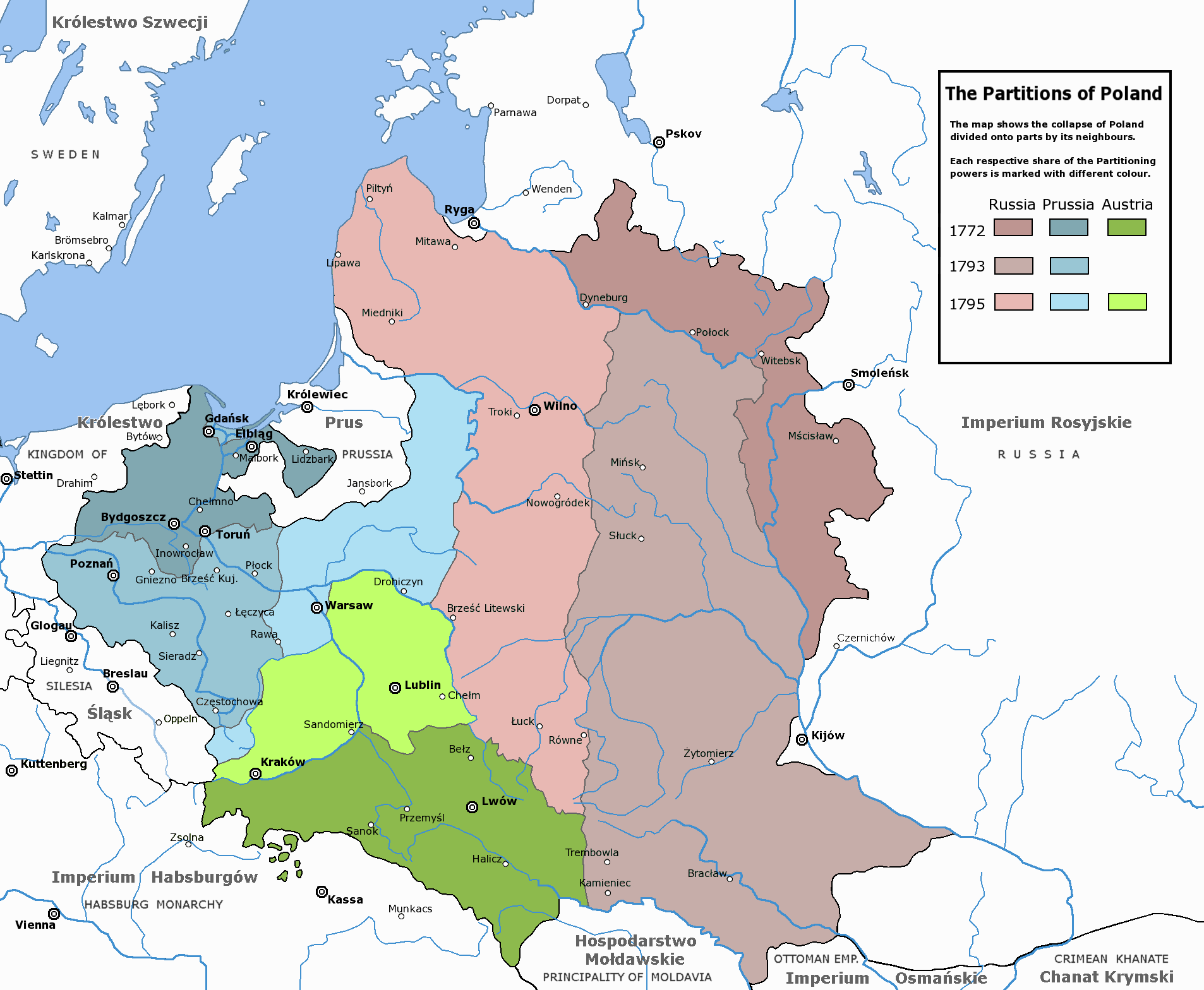

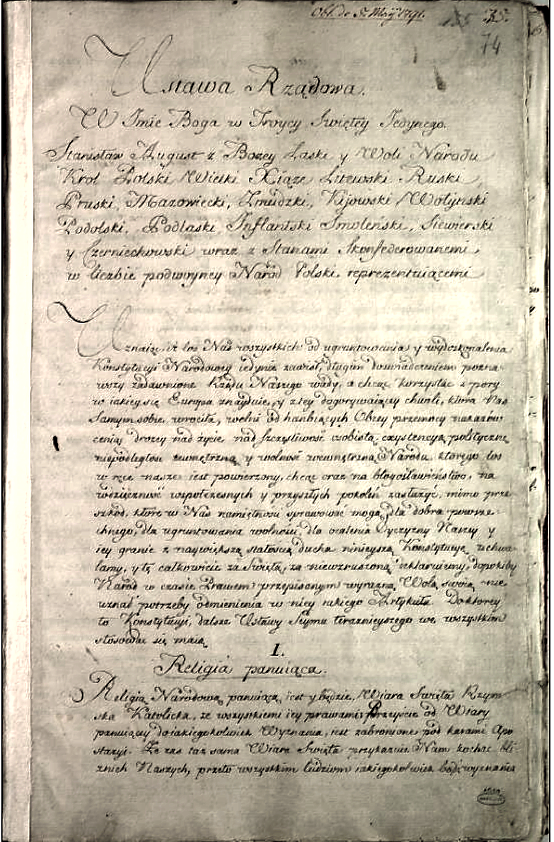

In 1772, these three powers carried out the First Partition of Poland, seizing significant territories. Despite this loss, reformers in Poland pushed forward, establishing the Commission of National Education in 1773, Europe's first ministry of education. The Great Sejm (1788-1792) adopted the landmark May 3rd Constitution in 1791. This progressive document, Europe's first modern codified constitution, aimed to create a constitutional monarchy, strengthen the central government, and grant more rights to townspeople, though it largely maintained the privileges of the nobility and did little to alleviate the plight of serfs.

The constitution provoked a hostile reaction from Russia and a confederation of Polish magnates known as the Targowica Confederation, who saw it as a threat to their traditional "Golden Liberties" and Russian influence. This led to the Polish-Russian War of 1792. Defeated, Poland was subjected to the Second Partition in 1793, with Russia and Prussia taking further lands, leaving a rump state.

In response to the ongoing dismemberment, the Kościuszko Uprising, led by Tadeusz Kościuszko (a hero of the American Revolutionary War), erupted in 1794.

Despite initial successes, the uprising was brutally suppressed. This paved the way for the Third Partition in 1795, by which Russia, Prussia, and Austria divided the remaining Polish territories among themselves, completely erasing Poland from the map of Europe for 123 years. King Stanisław August Poniatowski abdicated, and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth ceased to exist.

The "Era of Insurrections" followed, as Poles repeatedly attempted to regain independence throughout the 19th century. During the Napoleonic Wars, Poles fought alongside Napoleon, hoping for the restoration of their state. In 1807, Napoleon created the Duchy of Warsaw, a small Polish client state. After Napoleon's defeat, the Congress of Vienna in 1815 re-partitioned Polish lands, creating the Russian-controlled Congress Kingdom of Poland (with a theoretically autonomous status), the Prussian Grand Duchy of Posen, and the Free City of Kraków (later annexed by Austria in 1846), while Austria retained Galicia.

Major uprisings against foreign rule included the November Uprising (1830-1831) in Congress Poland against Russia, and the January Uprising (1863-1864), also primarily in the Russian partition. Both were defeated, leading to severe reprisals, including increased Russification and Germanisation policies, suppression of Polish culture and language, executions, and deportations to Siberia. Despite the oppression, Poles maintained their national identity through clandestine education, cultural activities, and "organic work" (economic and social self-improvement). The social and cultural impact of foreign rule was profound, fostering a strong sense of national martyrdom and a persistent desire for independence, which significantly shaped Polish identity and democratic aspirations.

3.6. Second Polish Republic

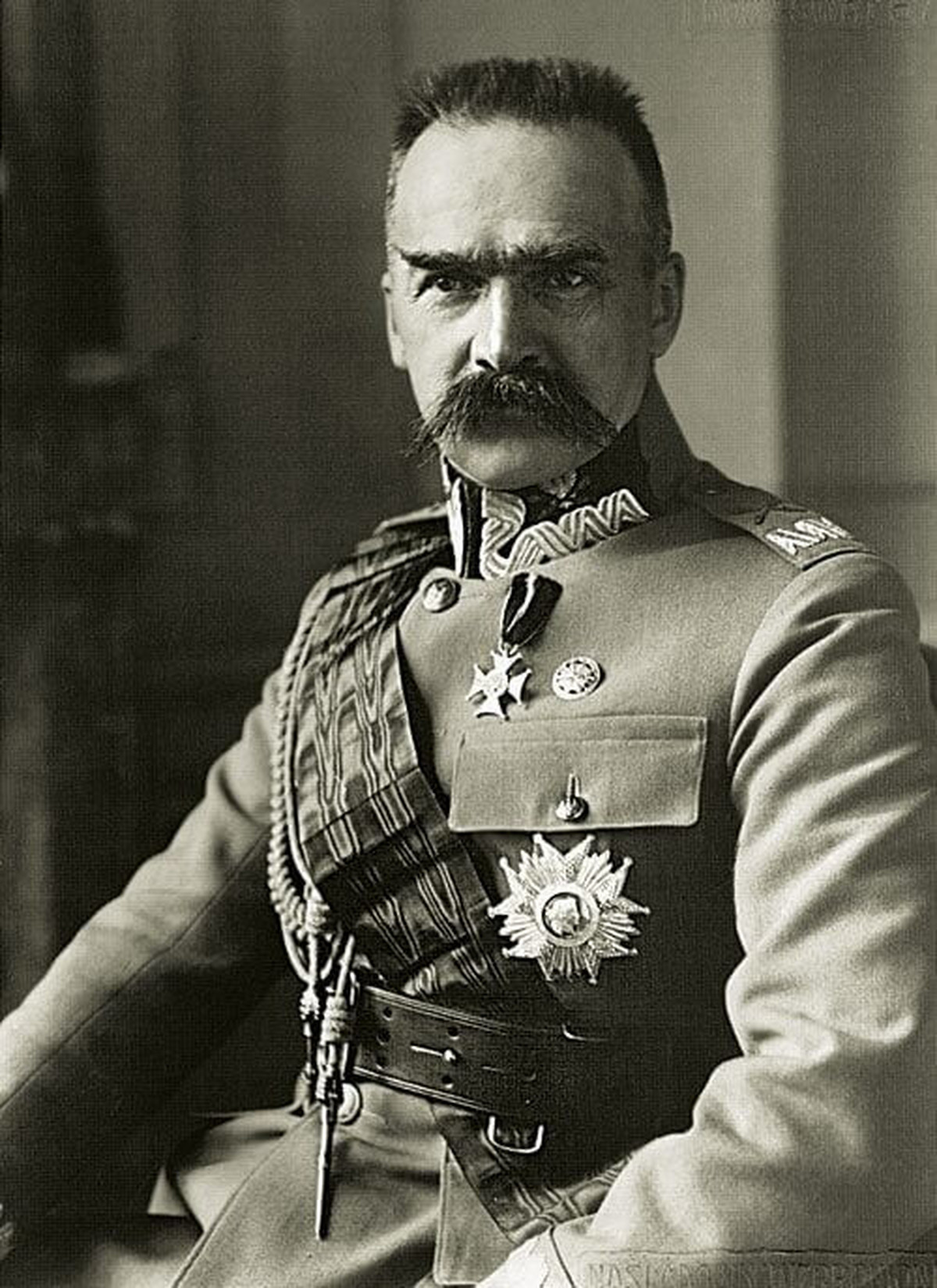

Poland regained its independence on November 11, 1918, at the end of World War I, following the collapse of the partitioning empires (Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Germany). The Second Polish Republic (II RzeczpospolitaDROO-gah zhech-pos-POH-lee-tahPolish) was established, with Józef Piłsudski emerging as a key national leader. The early years were marked by efforts to define its borders, leading to several conflicts. The most significant was the Polish-Soviet War (1919-1921), where Polish forces, against considerable odds, halted the westward advance of the Soviet Red Army at the Battle of Warsaw in 1920, an event often called the "Miracle on the Vistula." The Peace of Riga in 1921 established Poland's eastern borders, incorporating significant Ukrainian and Belarusian minorities. Other border conflicts occurred with Germany (Silesian Uprisings), Czechoslovakia (over Teschen Silesia), and Lithuania (over Vilnius).

The interwar period was characterized by significant political, social, and economic challenges. A democratic constitution was adopted in March 1921, establishing a parliamentary republic. However, the political scene was fragmented and unstable, with frequent changes in government. In 1922, Poland's first elected president, Gabriel Narutowicz, was assassinated by a right-wing nationalist, highlighting the deep political divisions.

Economic difficulties, including hyperinflation in the early 1920s and the impact of the Great Depression, hampered development. Despite these challenges, progress was made in industrialization (e.g., the port of Gdynia and the Central Industrial Region), education, and cultural life.

In May 1926, Marshal Piłsudski, disillusioned with the parliamentary system's instability, staged a coup d'état. While he declined the presidency, he remained the dominant political figure, leading the "Sanacja" (Sanation, meaning "healing") regime. This government aimed to restore political stability and national strength, but it became increasingly authoritarian, restricting democratic freedoms and suppressing political opposition, particularly from the left and ethnic minority groups. Piłsudski's death in 1935 led to a period of collective leadership by his successors, often referred to as the "colonels' regime," which continued the Sanacja policies.

The Second Polish Republic faced complex ethnic relations. Significant minorities, including Ukrainians, Jews, Belarusians, and Germans, constituted about a third of the population. While the constitution guaranteed minority rights, discrimination and assimilationist pressures were common, leading to tensions, particularly with the Ukrainian population. The Jewish community, one of the largest in Europe, faced growing antisemitism in the 1930s.

As the 1930s progressed, Poland found itself precariously situated between an increasingly aggressive Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler and the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin. Despite attempts to maintain a policy of equilibrium between these two powers, Poland's refusal to cede territory to Germany or allow Soviet troops on its soil led to the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in August 1939, which secretly provided for the division of Poland between Germany and the USSR, setting the stage for the outbreak of World War II.

3.7. World War II

World War II began on September 1, 1939, with the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany. On September 17, 1939, the Soviet Union, in accordance with the secret protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, also invaded Poland from the east. Despite fierce resistance, Polish forces were overwhelmed, and Warsaw fell on September 28. Poland was partitioned between Germany and the Soviet Union.

The German occupation was exceptionally brutal. Western Poland was directly annexed to the Reich, while the central part became the General Government. The Nazis implemented policies of terror, mass murder, and economic exploitation. Their racial ideology targeted Poles for enslavement and eventual extermination under plans like Generalplan Ost. Polish intelligentsia, clergy, and political leaders were systematically eliminated in operations like Intelligenzaktion and AB-Aktion. Polish culture and education were suppressed. Millions of Poles were subjected to forced labor, expulsions, and resettlement.

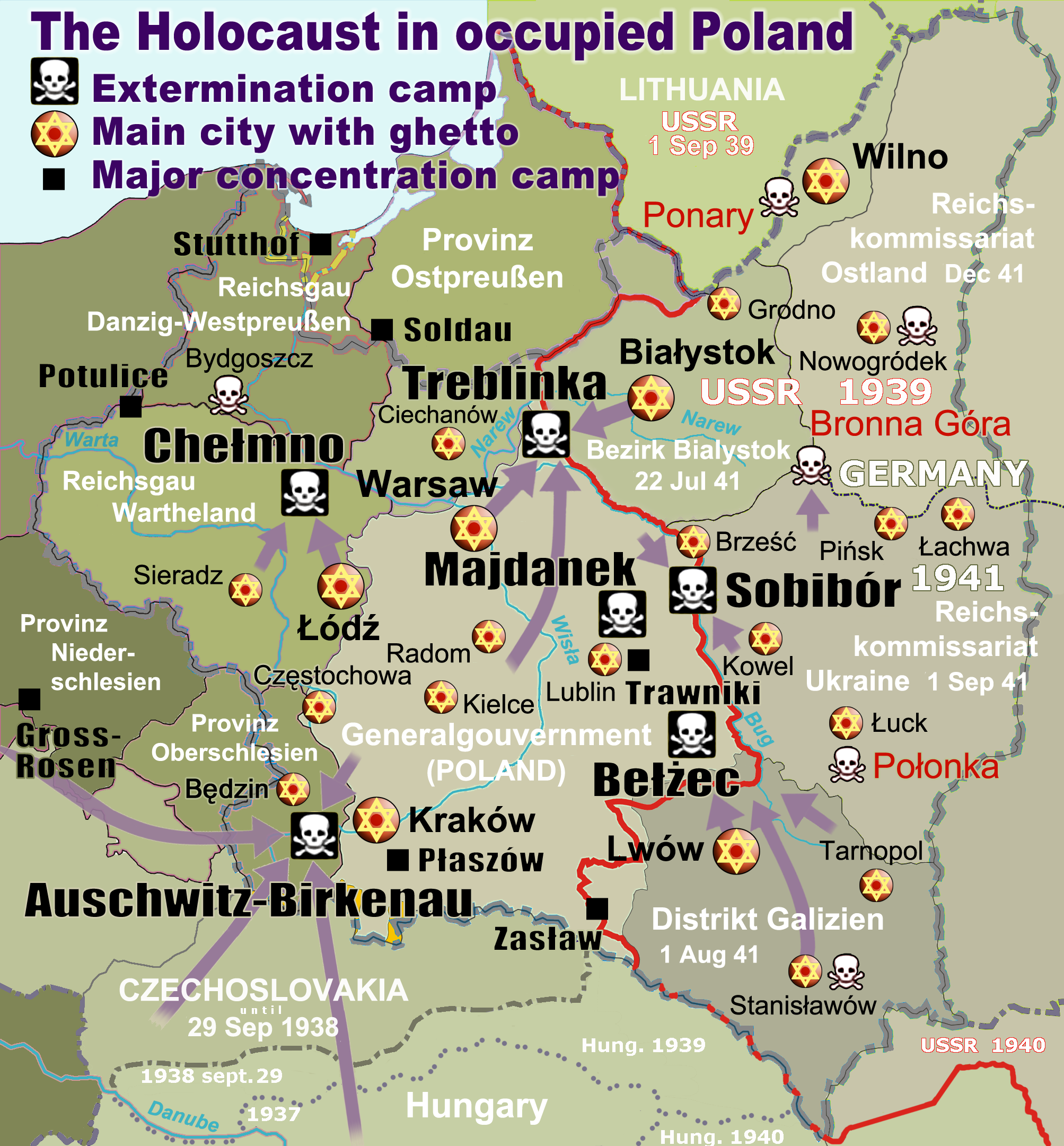

The Holocaust in Poland saw the systematic extermination of nearly all of Poland's 3 million Jews, who constituted about 90% of Poland's pre-war Jewish population. The Germans established ghettos in cities like Warsaw and Łódź and built major extermination camps on Polish soil, including Auschwitz-Birkenau, Treblinka, Bełżec, Sobibór, Chełmno, and Majdanek, where Jews from Poland and other occupied European countries were murdered. Ethnic Poles also suffered immense casualties, with estimates ranging from 1.8 to 2.8 million killed through direct Nazi actions. Massacres like the Wola massacre and Ochota massacre during the Warsaw Uprising resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of civilians.

The Soviet occupation of eastern Poland (1939-1941) was also marked by repression. Hundreds of thousands of Poles were deported to Siberia and other remote parts of the USSR. The Soviet NKVD executed thousands of Polish prisoners of war, most notably in the Katyn massacre of 1940. After Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941 (Operation Barbarossa), the entirety of pre-war Poland came under German occupation. Later in the war, between 1943 and 1944, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) committed massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia, resulting in an estimated 100,000 Polish civilian deaths.

Despite the occupation, a Polish government-in-exile was established in London, and a sophisticated Polish Underground State (Polskie Państwo PodziemnePOHL-skyeh PAHNST-voh pod-ZHYEM-nyehPolish) operated within Poland, organizing resistance, clandestine education, and social welfare. The main armed resistance force was the Home Army (Armia KrajowaAR-myah kra-YOH-vahPolish), one ofthe largest underground armies in occupied Europe. The Home Army launched Operation Tempest in 1944, a series of uprisings aimed at liberating Polish territory ahead of the advancing Soviet Red Army. The largest of these was the Warsaw Uprising (August 1 - October 2, 1944). Despite initial successes, the uprising was brutally crushed by the Germans after 63 days, while Soviet forces halted their advance on the outskirts of the city, a decision that remains controversial and has been interpreted by many Poles as a deliberate Soviet betrayal to weaken non-communist Polish resistance.

Polish armed forces fought alongside the Allies on all major fronts. The Polish Army in the West made significant contributions in the North Africa, the Italian Campaign (notably the Battle of Monte Cassino), and the Western Front (including the Battle of Normandy and the Battle of Arnhem). Polish pilots played a crucial role in the Battle of Britain, and Polish intelligence, including the cracking of the Enigma machine code, provided vital information to the Allies. The Soviet-organized Polish People's Army fought alongside the Red Army in the final stages of the war, participating in the liberation of Warsaw and the Battle of Berlin.

World War II resulted in the deaths of approximately 6 million Polish citizens, over one-sixth of the pre-war population, the highest proportion of any nation involved. About 90% of these deaths were non-military. The country suffered immense material destruction, with Warsaw and many other cities largely destroyed.

At the end of the war, Poland's borders were radically shifted westward by the Allied powers at the Yalta Conference and Potsdam Conference. Poland lost its eastern territories (Kresy) to the Soviet Union but gained former German territories in the west (the Recovered Territories), including parts of Silesia, Pomerania, and East Prussia. This resulted in massive population transfers, with millions of Poles expelled from the east and Germans expelled from the newly acquired western territories. This profound demographic and territorial shift fundamentally altered the character of the Polish state.

3.8. Post-war communism

Following World War II, Poland fell under Soviet influence, becoming part of the Eastern Bloc. The Yalta Conference decisions, largely dictated by Joseph Stalin, sanctioned the formation of a new provisional pro-Communist government in Moscow, which effectively sidelined the Polish government-in-exile based in London. This was seen by many Poles as a betrayal by the Western Allies. Despite Stalin's assurances of Polish sovereignty and democratic elections, the post-war elections were heavily manipulated by Soviet authorities to legitimize a communist regime. The Polish People's Republic (Polska Rzeczpospolita LudowaPOHL-skah zhech-pos-POH-lee-tah loo-DOH-vahPolish, PRL) was officially proclaimed with the adoption of a new constitution in 1952, though a pro-Soviet government had been in control since the adoption of the Small Constitution in 1947.

The imposition of communism was met with armed resistance (the "cursed soldiers") that continued into the 1950s. The new government accepted the Soviet annexation of pre-war eastern Polish territories and agreed to the permanent stationing of Red Army units on Polish soil. Poland became a founding member of the Warsaw Pact, aligning its military and foreign policy with the Soviet Union throughout the Cold War.

The early post-war period under Bolesław Bierut was characterized by Stalinist repression, nationalization of industry, and attempts at forced collectivization of agriculture (which largely failed in Poland compared to other Eastern Bloc countries). After Stalin's death and Bierut's death in 1956, Władysław Gomułka came to power during the "Polish October" (Polish Thaw). His regime initially brought a period of liberalization, including the release of many political prisoners and some expansion of personal freedoms. However, Gomułka's rule later became more rigid and intolerant of dissent.

The 1970s under Edward Gierek saw attempts at economic modernization financed by Western loans, leading to a temporary rise in living standards but ultimately resulting in a massive foreign debt crisis. Throughout the communist era, the Polish United Workers' Party (Polska Zjednoczona Partia RobotniczaPOHL-skah zyed-no-CHOH-nah PAR-tyah ro-bot-NEE-chahPolish, PZPR) maintained a monopoly on power, though Poland was generally considered one of the less oppressive states within the Soviet bloc, with a relatively vibrant cultural life and a strong, independent Catholic Church that often served as a focal point for opposition.

Social unrest and protests were recurrent. Major worker protests occurred in Poznań in 1956 (1956 Poznań protests), during the March 1968 events (student protests and an antisemitic campaign), in December 1970 on the Baltic coast (Polish 1970 protests against food price increases, leading to Gomułka's ousting), and in Radom and Ursus in 1976.

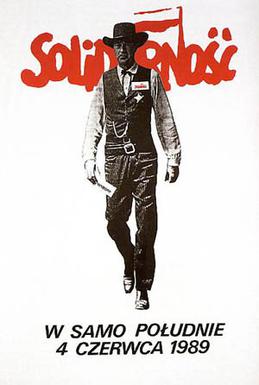

The election of Polish Cardinal Karol Wojtyła as Pope John Paul II in 1978 had a profound impact, inspiring a renewed sense of national and religious identity and galvanizing opposition to the communist regime. Labor turmoil in 1980, particularly strikes in the Gdańsk Shipyard, led to the formation of the independent trade union Solidarity (Solidarnośćso-lee-DAR-noshchPolish), led by Lech Wałęsa. Solidarity quickly grew into a mass social movement with millions of members, demanding not only workers' rights but also broader political and civil liberties.

The government, under General Wojciech Jaruzelski, responded by imposing martial law on December 13, 1981. Solidarity was outlawed, its leaders imprisoned, and civil liberties severely curtailed. However, the movement continued its activities underground. Despite the repression, Solidarity eroded the dominance of the PZPR. By the late 1980s, a combination of economic crisis, continued social pressure, and changes in the Soviet Union under Mikhail Gorbachev forced the communist government to negotiate with the opposition.

The Polish Round Table Talks in early 1989 between the government and Solidarity led to the re-legalization of Solidarity and an agreement for semi-free parliamentary elections. In the elections held in June 1989, Solidarity-backed candidates won a landslide victory in all contested seats. Tadeusz Mazowiecki, a Solidarity activist, became the first non-communist prime minister in the Eastern Bloc since the 1940s. Lech Wałęsa was elected president in the 1990 presidential election. The events in Poland triggered a wave of revolutions across Central and Eastern Europe, leading to the collapse of communist regimes and the end of the Cold War. This period marked a critical turning point for Poland, with a strong emphasis on restoring democratic institutions and human rights.

3.9. Third Polish Republic

Following the end of communist rule in 1989, Poland embarked on a transition to a liberal democracy and a market economy, establishing the Third Polish Republic. A key element of the economic transition was the "shock therapy" program, initiated by Finance Minister Leszek Balcerowicz in the early 1990s. This involved rapid price liberalization, privatization of state-owned enterprises, and stabilization of the currency. While these reforms led to temporary social and economic hardship, including high unemployment and declines in living standards for some, Poland became the first post-communist country to reach its pre-1989 GDP levels by 1995.

Poland actively pursued integration with Western institutions. It became a member of the Visegrád Group in 1991, joined NATO in 1999, and after a successful referendum in 2003, became a full member of the European Union on May 1, 2004. Poland joined the Schengen Area in 2007, allowing for border-free travel with most other EU member states.

The political landscape of the Third Republic has been characterized by a multi-party system and several changes in government. On April 10, 2010, a national tragedy occurred when President Lech Kaczyński, his wife, and numerous high-ranking Polish officials, military leaders, and clergy died in a plane crash near Smolensk, Russia, while en route to commemorate the Katyn massacre.

The Civic Platform (PO), a center-right liberal-conservative party, won the parliamentary elections in 2007 and 2011. Donald Tusk, leader of PO, served as Prime Minister and was later chosen as President of the European Council in 2014.

In 2015, the national-conservative Law and Justice party (PiS), led by Jarosław Kaczyński (twin brother of the late President Lech Kaczyński), won both the presidential and parliamentary elections. PiS secured a second term in the 2019 elections. Andrzej Duda (PiS-backed) was elected president in 2015 and re-elected in the 2020 election. The PiS government pursued policies that led to increased Euroscepticism and significant friction with the European Union, particularly concerning judicial reforms that critics argued undermined the rule of law and judicial independence, leading to a Polish constitutional crisis. Issues related to LGBT rights and restrictive abortion laws also became prominent, sparking large-scale protests and drawing international attention to human rights concerns.

In 2017, Mateusz Morawiecki (PiS) became Prime Minister, succeeding Beata Szydło. Poland faced a significant humanitarian challenge with the Ukrainian refugee crisis following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022; by November 2023, approximately 17 million Ukrainian refugees had crossed into Poland, with around 0.9 million remaining in the country.

The parliamentary election in October 2023 saw PiS win the largest share of the vote but lose its parliamentary majority. In December 2023, Donald Tusk returned as Prime Minister, leading a coalition government formed by the Civic Coalition, Third Way, and The Left, with PiS becoming the main opposition party. This change in government signaled a potential shift in Poland's domestic policies and its relations with the European Union, with a renewed focus on democratic development, human rights, and social equity.

4. Geography

Poland is a country in Central Europe with an administrative area of 121 K mile2 (312.72 K km2), making it the ninth-largest country in Europe. Approximately 120 K mile2 (311.89 K km2) of this area is land, while 0.8 K mile2 (2.04 K km2) consists of internal waters, and 3.4 K mile2 (8.78 K km2) is territorial sea. Poland shares land borders with Germany to the west, the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south, Ukraine and Belarus to the east, and Lithuania and the Kaliningrad Oblast of Russia to the northeast. Its northern border is formed by the Baltic Sea coastline. The country's location at the crossroads of European trade and migration routes has significantly shaped its history and cultural diversity.

4.1. Topography and Hydrology

Poland's topography is diverse. The northern and central regions lie within the Central European Plain and are predominantly flat or gently undulating. The average elevation of Poland is 568 ft (173 m) above sea level. The Baltic Sea coastline, stretching for 478 mile (770 km), features sandy beaches, dunes, spits (such as the Hel Peninsula), and lagoons (like the Vistula Lagoon, shared with Russia). The largest Polish island in the Baltic Sea is Wolin, part of Wolin National Park. Poland also shares the Szczecin Lagoon and Usedom island with Germany.

The southern part of the country is more mountainous. The Sudetes mountains lie in the southwest, with Śnieżka (5.2 K ft (1.60 K m)) as their highest peak, shared with the Czech Republic. The Carpathian Mountains stretch along the southern border in the southeast. The highest part of the Polish Carpathians is the Tatra Mountains, a popular area for hiking and skiing, where Poland's highest point, Rysy, is located at 8.2 K ft (2.50 K m). The lowest point in Poland, at 5.9 ft (1.8 m) below sea level, is near Raczki Elbląskie in the Vistula Delta.

Poland is rich in water resources. Its longest rivers are the Vistula (WisłaVEES-wahPolish), which flows through the heart of the country including Warsaw and Kraków, and the Oder (OdraOH-drahPolish), which forms a significant part of the western border with Germany. Other major rivers include the Warta and the Bug. Poland also boasts one of the highest densities of lakes in the world, with nearly ten thousand lakes, predominantly concentrated in the northeastern Masurian Lake District (Mazurymah-ZOO-riPolish). The largest lakes are Śniardwy and Mamry, and the deepest is Hańcza.

4.2. Climate

Poland has a temperate transitional climate, with characteristics of both oceanic climate (in the west and north) and continental climate (in the east and southeast). The mountainous southern regions experience an alpine climate.

Summers are generally warm, with average July temperatures around 68 °F (20 °C). Winters are moderately cold, with average December/January temperatures around 30.2 °F (-1 °C). However, temperatures can vary significantly, with summer heatwaves and severe winter frosts. The warmest region is typically Lower Silesia in the southwest, while the coldest is the northeast corner around Suwałki in Podlaskie Voivodeship, which is influenced by cold fronts from Scandinavia and Siberia.

Precipitation is fairly evenly distributed throughout the year, though it is generally higher in the summer months, particularly from June to September. Mountainous areas receive the highest rainfall. Snowfall is common in winter, especially in the mountains and eastern regions.

The weather in Poland can be quite variable, with significant fluctuations from day to day and year to year. The arrival of seasons can also differ annually. Climate change has contributed to rising average annual temperatures. For instance, the average annual air temperature between 2011 and 2020 was 48.794 °F (9.33 °C), approximately 2.0 °F (1.11 °C) higher than in the 2001-2010 period. Winters are also becoming drier, with less mixed precipitation and snowfall. The impacts of climate change, such as more frequent extreme weather events, pose challenges for Poland's environment and economy.

4.3. Biodiversity

Phytogeographically, Poland belongs to the Central European province of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. The country is home to four Palearctic ecoregions: the Central European mixed forests, Northern European mixed forests, Western European broadleaf forests, and the Carpathian montane conifer forests.

Forests cover approximately 31% of Poland's land area, with the Lower Silesian Wilderness being the largest continuous forest. The most common deciduous trees include oak, maple, and beech, while pine, spruce, and fir are the most common conifers. An estimated 69% of Polish forests are coniferous.

Poland's fauna is characteristic of Continental Europe. The wisent (żubrZHOO-brPolish), Europe's heaviest land animal, and the white stork (bocian białyBOCH-ahn BYAH-wiPolish) are considered national animals. The white-tailed eagle (bielikBYEH-leekPolish) is also a prominent symbol, featured on Poland's coat of arms. The red common poppy (mak polnyMAHK POHL-niPolish) is an unofficial floral emblem.

Among the most protected species are the wisent, the Eurasian beaver, the Eurasian lynx, the gray wolf, and the Tatra chamois. Poland was also the last refuge of the aurochs, with the final individual dying in the Jaktorów Forest in 1627. Game animals such as red deer, roe deer, and wild boar are common in many woodlands. Poland is a significant breeding ground for migratory birds, hosting about a quarter of the global population of white storks.

Conservation efforts are significant. Poland has 23 national parks, which protect around 779 K acre (315.10 K ha), or about 1% of the country's territory. Two of these, Białowieża National Park (a UNESCO World Heritage Site shared with Belarus, home to a large population of wisent and primeval forest) and Bieszczady National Park (part of the East Carpathian Biosphere Reserve), are internationally recognized. Additionally, there are 123 landscape parks (parki krajobrazowePAR-kee kra-yo-bra-ZOH-vehPolish), numerous nature reserves, and other protected areas under the Natura 2000 network. Environmental challenges include air pollution (particularly from coal burning), water pollution, and habitat loss, which are subjects of ongoing policy and public debate.

5. Government and politics

Poland is a unitary semi-presidential republic and a representative democracy. The country operates under a multi-party system. Its main governmental institutions reflect a commitment to democratic principles, though recent years have seen challenges regarding the rule of law and human rights. The current Constitution of Poland was adopted on April 2, 1997.

5.1. Government Structure

The executive branch consists of the President and the Council of Ministers (government).

The President is the head of state, elected by popular vote for a five-year term and can serve a maximum of two terms. The President is the supreme representative of Poland in international affairs, commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces in peacetime, and has the power to veto legislation (which can be overridden by a three-fifths majority in the Sejm), grant pardons, and call parliamentary elections under certain circumstances. The current president is Andrzej Duda.

The Prime Minister is the head of government and chairs the Council of Ministers. The Prime Minister is usually the leader of the majority party or coalition in the Sejm. The President nominates the Prime Minister, who then proposes the members of the Council of Ministers. The government must receive a vote of confidence from the Sejm. The Prime Minister and the Council of Ministers are responsible for implementing laws and managing the day-to-day affairs of the state. The current Prime Minister is Donald Tusk.

5.2. Parliament

The legislature is a bicameral National Assembly (Zgromadzenie Narodowezgro-mah-DZEN-yeh na-ro-DOH-vehPolish), composed of the Sejm (lower house) and the Senate (upper house). Both houses are elected for a four-year term.

The Sejm has 460 members (deputies), elected through proportional representation using the D'Hondt method in multi-seat constituencies. A 5% electoral threshold for political parties (8% for coalitions) is generally required to gain seats, though this threshold does not apply to parties representing national minorities. The Sejm is the primary legislative body; it passes laws, approves the state budget, appoints and dismisses government members (through votes of confidence or no confidence), and oversees the government's activities. The Marshal of the Sejm presides over its sessions.

The Senate has 100 members (senators), elected through a first-past-the-post system in single-member constituencies. The Senate's primary role is to review and amend legislation passed by the Sejm. It can propose amendments or reject a bill outright, but the Sejm can override the Senate's decisions by an absolute majority vote.

Major political parties include Law and Justice (PiS), Civic Platform (PO), Poland 2050, Polish People's Party (PSL), and The Left (Lewicaleh-VEE-tsahPolish). The political system has seen periods of robust democratic debate and participation, as well as controversies regarding political influence over state institutions.

5.3. Law

The Polish legal system is based on civil law (continental law), derived from Roman law. The Constitution of Poland, adopted in 1997, is the supreme law of the land. It guarantees fundamental human rights and freedoms, including freedom of speech, assembly, and religion, and prohibits discrimination.

The judiciary is independent. Key judicial institutions include:

- The Supreme Court (Sąd NajwyższySąd NajwyższyPolish): The highest court of appeal for civil and criminal cases.

- The Supreme Administrative Court (Naczelny Sąd AdministracyjnyNaczelny Sąd AdministracyjnyPolish): Reviews administrative decisions.

- Common courts: District courts (sądy rejonowesądy rejonowePolish), regional courts (sądy okręgowesądy okręgowePolish), and appellate courts (sądy apelacyjnesądy apelacyjnePolish) handle the majority of cases.

- The Constitutional Tribunal (Trybunał KonstytucyjnyTrybunał KonstytucyjnyPolish): Rules on the constitutionality of laws. Its independence and composition have been a subject of significant political controversy and concern regarding the rule of law in recent years, particularly under the Law and Justice (PiS) government.

- The State Tribunal (Trybunał StanuTrybunał StanuPolish): Adjudicates cases of constitutional responsibility against persons holding the highest state offices.

Judges are appointed by the President upon the recommendation of the National Council of the Judiciary (KRS), whose own composition and appointment process have also been controversial.

The Ombudsman (Rzecznik Praw ObywatelskichRzecznik Praw ObywatelskichPolish) is an independent office responsible for safeguarding human and civil rights and freedoms.

Significant legal acts and controversies in recent Polish history include debates and changes to abortion law, which is among the strictest in Europe. After a 2020 Constitutional Tribunal ruling, abortion is permitted only in cases of rape, incest, or when the woman's life is in danger; fetal defects are no longer a legal ground. This ruling sparked widespread protests. Issues surrounding the rule of law, judicial independence, and media freedom have been central to Poland's relationship with the European Union, leading to legal challenges and debates about democratic backsliding.

5.4. Security, law enforcement and emergency services

Internal security and law enforcement in Poland are handled by several agencies, primarily under the Ministry of Interior and Administration.

The Policja (State Police) is the main national police force responsible for preventing and investigating crimes, maintaining public order, and ensuring public safety. It has a hierarchical structure with national, voivodeship (provincial), and local levels.

The Border Guard (Straż GranicznaStraż GranicznaPolish) is responsible for protecting Poland's state borders, which include significant portions of the European Union's external frontier. It controls border traffic and combats illegal immigration and cross-border crime.

The Internal Security Agency (Agencja Bezpieczeństwa WewnętrznegoAgencja Bezpieczeństwa WewnętrznegoPolish, ABW) is Poland's domestic intelligence and counter-espionage agency, tasked with protecting the state's internal security and constitutional order from threats such as terrorism, espionage, and organized crime. The Foreign Intelligence Agency (Agencja WywiaduAgencja WywiaduPolish, AW) handles intelligence gathering abroad.

The Central Anticorruption Bureau (Centralne Biuro AntykorupcyjneCentralne Biuro AntykorupcyjnePolish, CBA) is a specialized service responsible for combating corruption in public and private sectors.

The State Fire Service (Państwowa Straż PożarnaPaństwowa Straż PożarnaPolish) is the national firefighting and rescue service, responding to fires, natural disasters, and other emergencies.

Emergency medical services (Państwowe Ratownictwo MedycznePaństwowe Ratownictwo MedycznePolish) are generally organized at the regional level but operate under a national framework, providing pre-hospital emergency care.

Crime rates in Poland are generally comparable to other European countries. While Poland has a low homicide rate, issues such as property crime and, more recently, cybercrime are areas of focus for law enforcement. Private security firms are also common, providing services for businesses and individuals. The organization and oversight of these agencies aim to uphold the rule of law and ensure the safety of citizens, though, like in many countries, public trust and the effectiveness of these services are subjects of ongoing public and political discussion.

6. Administrative divisions

Poland is a unitary state divided into three levels of administrative division. The primary level consists of 16 voivodeships (województwavoy-eh-VOOTST-vahPolish, singular: województwovoy-eh-VOOTST-vohPolish), which are broadly equivalent to provinces or states. These voivodeships are largely based on historical regions of Poland.

The voivodeships are:

| Voivodeship | Capital city(ies) | Area (km2) | Population (2021) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| in English | in Polish | |||

| Greater Poland | Wielkopolskie | Poznań | 12 K mile2 (29.83 K km2) | 3,496,450 |

| Kuyavian-Pomeranian | Kujawsko-Pomorskie | Bydgoszcz & Toruń | 6.9 K mile2 (17.97 K km2) | 2,061,942 |

| Lesser Poland | Małopolskie | Kraków | 5.9 K mile2 (15.18 K km2) | 3,410,441 |

| Łódź | Łódzkie | Łódź | 7.0 K mile2 (18.22 K km2) | 2,437,970 |

| Lower Silesian | Dolnośląskie | Wrocław | 7.7 K mile2 (19.95 K km2) | 2,891,321 |

| Lublin | Lubelskie | Lublin | 9.7 K mile2 (25.12 K km2) | 2,095,258 |

| Lubusz | Lubuskie | Gorzów Wielkopolski & Zielona Góra | 5.4 K mile2 (13.99 K km2) | 1,007,145 |

| Masovian | Mazowieckie | Warsaw | 14 K mile2 (35.56 K km2) | 5,425,028 |

| Opole | Opolskie | Opole | 3.6 K mile2 (9.41 K km2) | 976,774 |

| Podlaskie | Podlaskie | Białystok | 7.8 K mile2 (20.19 K km2) | 1,173,286 |

| Pomeranian | Pomorskie | Gdańsk | 7.1 K mile2 (18.32 K km2) | 2,346,671 |

| Silesian | Śląskie | Katowice | 4.8 K mile2 (12.33 K km2) | 4,492,330 |

| Subcarpathian | Podkarpackie | Rzeszów | 6.9 K mile2 (17.85 K km2) | 2,121,229 |

| Holy Cross | Świętokrzyskie | Kielce | 4.5 K mile2 (11.71 K km2) | 1,224,626 |

| Warmian-Masurian | Warmińsko-Mazurskie | Olsztyn | 9.3 K mile2 (24.17 K km2) | 1,416,495 |

| West Pomeranian | Zachodniopomorskie | Szczecin | 8.8 K mile2 (22.91 K km2) | 1,688,047 |

Each voivodeship is governed by a voivode (governor) appointed by the central government, and a popularly elected regional assembly (sejmik województwaSEY-mik voy-eh-VOOTST-fahPolish), which in turn elects an executive board headed by a voivodeship marshal.

The second level of administration consists of powiats (counties). As of 2022, there are 380 powiats, including 314 rural powiats and 66 cities with powiat status (miasta na prawach powiatumiasta na pravach powiatuPolish). Rural powiats are governed by an elected council (rada powiaturada powiatuPolish) which elects a starosta to head the executive board. Cities with powiat status combine the functions of a powiat and a gmina.

The third and lowest level of administration is the gmina (municipality or commune). As of 2022, there are 2,477 gminas. These are the basic units of local self-government. Gminas can be urban (consisting of a town), urban-rural (a town and its surrounding villages), or rural (consisting of villages). They are governed by an elected council (rada gminyrada gminyPolish) and a directly elected head: a mayor (burmistrzBURSH-mistshPolish) in urban and urban-rural gminas, or a wójtVOO-eetPolish in rural gminas. Large cities have a president (prezydent miastaprezydent miastaPolish) as their directly elected head.

This system of administrative division was established in 1999 as part of a major local government reform aimed at decentralization and strengthening local democracy.

6.1. Major cities

Poland has numerous urban centers, with Warsaw being the capital and largest city. Other major cities are significant economic, cultural, and educational hubs.

- Warsaw (Warszawavar-SHAH-vahPolish), located in the Masovian Voivodeship, is the capital and largest city of Poland, with a population of approximately 1.86 million within the city limits and over 3.1 million in its metropolitan area. It is the political, economic, and cultural heart of the country, home to numerous historical sites (many reconstructed after World War II, including the Old Town, a UNESCO World Heritage site), museums, theaters, and institutions of higher education like the University of Warsaw.

- Kraków, in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship, is Poland's former royal capital and one of its oldest cities, with a population of around 807,000. It is renowned for its well-preserved medieval Old Town (a UNESCO World Heritage site), Wawel Castle, and the Jagiellonian University. Kraków is a major center for tourism, culture, and academia.

- Wrocław, in the Lower Silesian Voivodeship, has a population of about 673,000. Known for its picturesque Old Town, numerous bridges and islands on the Oder River, and a vibrant cultural scene, it was a European Capital of Culture in 2016. It is also a significant industrial and technological center.

- Łódź, in the Łódź Voivodeship, with a population of around 648,000, was historically a major center of the textile industry. Today, it is known for its revitalized industrial architecture, the Łódź Film School, and a growing creative sector.

- Poznań, in the Greater Poland Voivodeship, has a population of about 536,000. It is an important historical city, a major trade and business center (known for its international trade fairs), and home to Adam Mickiewicz University.

- Gdańsk, in the Pomeranian Voivodeship, with a population of around 487,000, is a historic port city on the Baltic coast. It played a crucial role in European trade as part of the Hanseatic League and was the birthplace of the Solidarity movement. Its Old Town, rich in maritime history, is a major attraction. Together with Gdynia and Sopot, it forms the Tricity metropolitan area.

- Szczecin, in the West Pomeranian Voivodeship, near the German border, is a major seaport with a population of about 387,000.

- Lublin, in the Lublin Voivodeship, with a population of approximately 328,000, is an important historical and cultural center in eastern Poland.

- Bydgoszcz, in the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, has a population of around 324,000 and is a significant industrial and cultural city.

- Katowice, in the Silesian Voivodeship, with a population of about 278,000, is the heart of the Upper Silesian Industrial Region, historically a center for coal mining and heavy industry, now undergoing economic transformation.

7. Foreign relations

Poland's foreign policy is shaped by its geographical location in Central Europe, its historical experiences, and its membership in key international organizations. As a middle power transitioning into a regional power, Poland plays an active role in European and transatlantic affairs.

Key pillars of Polish foreign policy include:

- European Union (EU) Membership**: Poland joined the EU in 2004 and is an active member, participating in EU decision-making processes. It has 53 representatives in the European Parliament (as of 2024). Warsaw hosts Frontex, the EU's border and coast guard agency. Poland's relationship with EU institutions has sometimes been strained, particularly concerning rule of law issues, but cooperation on economic matters, security, and support for Ukraine remains strong.

- NATO Membership**: Poland joined NATO in 1999. Transatlantic security cooperation, particularly with the United States, is a cornerstone of its defense policy. Poland hosts NATO forces and infrastructure and is a significant contributor to the alliance's collective defense, especially on its eastern flank.

- United Nations (UN)**: Poland is a founding member of the UN and participates in its various agencies and peacekeeping missions.

- Regional Cooperation**: Poland is a key member of the Visegrád Group (with the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia), which promotes cooperation on regional and European issues. It also participates in the Three Seas Initiative, aimed at fostering infrastructure, energy, and digital connectivity in Central and Eastern Europe. Other regional forums include the Weimar Triangle (with Germany and France) and the Council of the Baltic Sea States.

- Eastern Policy**: Poland has a strong interest in the stability and democratic development of its eastern neighbors, particularly Ukraine. It has been a staunch supporter of Ukraine's sovereignty and territorial integrity, especially following the Russian invasion in 2022, providing significant humanitarian, financial, and military aid, and hosting a large number of Ukrainian refugees. Relations with Belarus are strained due to the political situation there.

- Relations with Russia**: Historically complex and often tense, relations with Russia deteriorated significantly after Russia's actions in Ukraine. Poland views Russia as a major security threat and advocates for strong collective defense measures within NATO and the EU.

- Relations with Germany**: Germany is Poland's largest trading partner and a key EU ally. While relations are generally close, historical issues, particularly concerning World War II reparations, have occasionally caused friction.

- International Human Rights and Democratic Promotion**: Poland has, at various times, sought to promote human rights and democracy abroad, drawing on its own experiences with authoritarianism and democratic transition. However, its own record on certain human rights issues (e.g., LGBT rights, abortion access, media freedom) has faced criticism from international organizations and EU partners.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Warsaw directs Poland's diplomatic efforts. Poland maintains an extensive network of embassies and consulates worldwide. It is also home to the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE).

8. Military

The Polish Armed Forces (Siły Zbrojne Rzeczypospolitej PolskiejSiły Zbrojne Rzeczypospolitej PolskiejPolish) are responsible for the national defense of Poland. They consist of five branches:

- Land Forces (Wojska LądoweWojska LądowePolish)

- Navy (Marynarka WojennaMarynarka WojennaPolish)

- Air Force (Siły PowietrzneSiły PowietrznePolish)

- Special Forces (Wojska SpecjalneWojska SpecjalnePolish)

- Territorial Defence Force (Wojska Obrony TerytorialnejWojska Obrony TerytorialnejPolish), a reserve component established in 2017.

The military is subordinate to the Ministry of National Defence. The President of Poland is the commander-in-chief in peacetime, nominating officers, the Minister for National Defence, and the Chief of the General Staff. Armed Forces Day is celebrated annually on August 15th.

As of July 2024, the Polish Armed Forces had a combined strength of approximately 216,100 active soldiers, making it one of the largest standing armies in the European Union and among the larger forces in NATO. Poland has been significantly increasing its defense capabilities and personnel numbers, with plans to expand the active military to 250,000 enlisted personnel and officers, plus 50,000 in the Territorial Defence Force.

Poland's defense budget has seen substantial growth. In 2024, the country allocated an estimated 4.12% of its GDP to military spending, equivalent to approximately 35.00 B USD, placing it among the highest NATO members in terms of GDP percentage dedicated to defense. This increase is part of a major modernization program initiated in response to the evolving security situation in Eastern Europe, particularly following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. This program involves acquiring advanced military equipment from American, South Korean, and domestic Polish defense manufacturers.

Poland ranks 14th globally in military expenditure. The country is also an exporter of arms and armaments, with exports valued at €487 million in 2020 according to SIPRI.

Compulsory military service for men was discontinued in 2008; the Polish Armed Forces are now fully professional. Polish military doctrine is aligned with that of its NATO partners, emphasizing collective defense. Poland actively hosts NATO military exercises and contributes to NATO's enhanced forward presence on the eastern flank.

Since 1953, Poland has been a significant contributor to various UN peacekeeping missions. Currently, it maintains military deployments in the Middle East, Africa, the Baltic states, and southeastern Europe as part of NATO, EU, and UN operations.

9. Economy

Poland has a developed social market economy, which is the sixth-largest in the European Union by nominal GDP and the fifth-largest by PPP-adjusted GDP. It is recognized as a high-income economy by the World Bank and achieved developed market status in 2018. The Polish economy has been one of the fastest-growing in Europe, notably being the only EU economy to avoid recession during the 2008-2009 financial crisis. The discussion of Poland's economy considers social aspects such as labor rights, environmental issues, and social equity alongside economic development.

| GDP (PPP) | 1.99 T USD (2025 est.) |

|---|---|

| Nominal GDP | 915.00 B USD (2025 est.) |

| Real GDP growth | 5.3% (2022) |

| CPI inflation | 2.5% (May 2024) |

| Employment-to-population | 57% (2022) |

| Unemployment | 2.8% (2023) |

| Total public debt | 340.00 B USD (2022) |

The country's currency is the Polish złoty (PLN); Poland has not adopted the Euro. The National Bank of Poland (NBP) is the central bank, responsible for monetary policy. Poland has a robust banking sector, the largest in Central Europe.

Key economic policies since 1989 have focused on liberalization, privatization, and integration into the global and European markets. Labor rights are protected by law, and trade unions, such as Solidarity, have historically played a significant role. Social equity and welfare remain important considerations in economic policy, though debates continue regarding income inequality and the adequacy of social safety nets. Since 2019, workers under the age of 26 are exempt from income tax.

9.1. Economic structure and indicators

Poland's economy is highly diversified. As of 2023, the service sector accounts for approximately 62% of employment, industry and manufacturing for 29%, and agriculture for 8%. The unemployment rate stood at 2.8% in 2023, one of the lowest in the EU.

GDP growth has been strong for much of the post-communist era, though it has faced fluctuations due to global economic conditions. Inflation has generally been managed, though recent global trends have posed challenges. Poland is a significant recipient of EU structural and investment funds, which have contributed to infrastructure development and economic modernization.

The Warsaw Stock Exchange (WSE) is the largest in Central and Eastern Europe. Major Polish companies are listed on indices such as the WIG20 and WIG30. Poland is also a notable destination for foreign direct investment (FDI) in the region.

9.2. Major industries

Poland has a strong industrial base. Key manufacturing sectors include:

- Automotive**: Production of passenger cars, commercial vehicles, and automotive parts is a major industry, with numerous international manufacturers having plants in Poland. Poland is a leading European exporter of buses.

- Electronics and Home Appliances**: Poland is a significant European producer of televisions, white goods (refrigerators, washing machines, etc.), and other electronic equipment.

- Machinery and Equipment**: Production of various types of machinery for industrial and agricultural use.

- Furniture**: Poland is one of the world's largest furniture exporters.

- Food Processing**: Leveraging its agricultural output, Poland has a large food processing industry.

- Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals**: A growing sector with both domestic and international companies.

Mining has historically been important, particularly for coal (hard coal and lignite) and copper. Poland is one of the world's largest producers of silver. However, the coal industry faces significant challenges related to environmental concerns, EU climate policies, and the need for economic restructuring in coal-dependent regions like Silesia. The social impact of transitioning away from coal, including effects on employment and regional economies, is a major policy concern. Environmental regulations and the push for a greener economy are influencing industrial practices across sectors.

Emerging high-tech industries, including IT, software development, and video games (e.g., CD Projekt Red, developer of The Witcher series and Cyberpunk 2077), are becoming increasingly important.

9.3. Energy

Poland's energy sector is heavily reliant on coal, which is the primary source for electricity generation and a significant source of employment. This reliance poses challenges for meeting EU climate targets and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The three largest Polish coal mining firms (Węglokoks, Kompania Węglowa, and JSW) extract substantial amounts of coal annually.

The government's "Energy Policy of Poland until 2040" (EPP2040) aims to diversify the energy mix, reduce coal's share in electricity generation (though it will remain significant for some time), increase energy efficiency, and develop renewable energy sources (primarily wind and solar). There are also plans for the development of nuclear power, with the first nuclear plants intended to be operational in the 2030s.

Poland is also a significant importer of natural gas and oil, historically relying heavily on Russia for these supplies. However, efforts have been made to diversify import sources, including the development of LNG terminals (e.g., Świnoujście LNG terminal) and new pipeline connections (e.g., the Baltic Pipe from Norway). The transition to a lower-carbon energy system while ensuring energy security and managing the social and economic impacts on coal regions is a major strategic challenge for Poland.

9.4. Science and technology

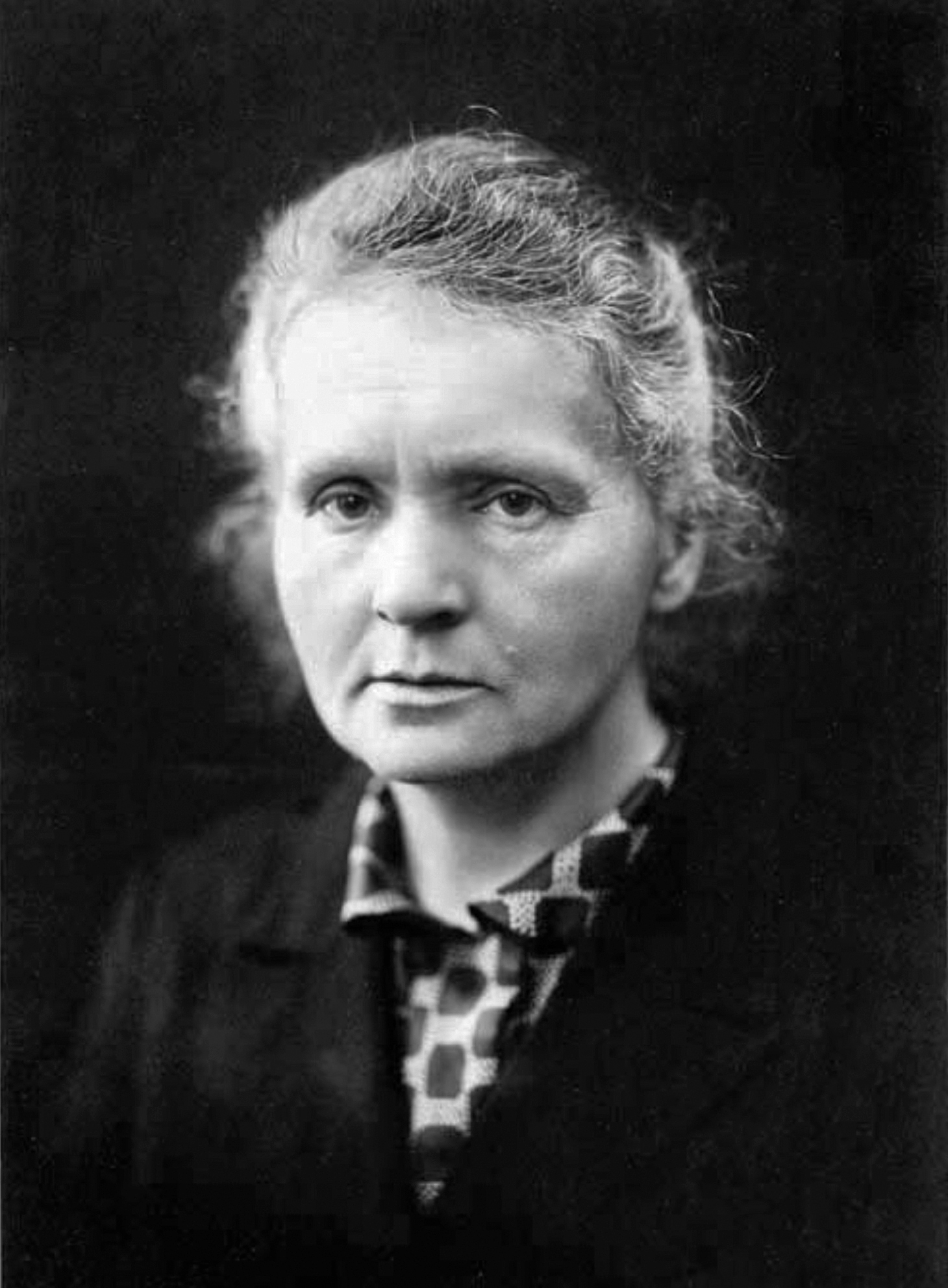

Poland has a rich history of contributions to science and technology. Nicolaus Copernicus (Mikołaj KopernikMikołaj KopernikPolish), the 16th-century astronomer, revolutionized science with his heliocentric model of the universe. Marie Skłodowska-Curie, a two-time Nobel Prize laureate (in Physics and Chemistry), conducted pioneering research on radioactivity and was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize. Other notable historical figures include Jan Heweliusz (astronomer), Ignacy Łukasiewicz (pharmacist, pioneer of the oil industry, inventor of the modern kerosene lamp), and Kazimierz Funk (biochemist, credited with formulating the concept of vitamins).

In mathematics, the Lwów School of Mathematics (with figures like Stefan Banach and Stanisław Ulam) and the Warsaw School of Mathematics (with Alfred Tarski, Kazimierz Kuratowski, and Wacław Sierpiński) made significant contributions in the first half of the 20th century. Polish cryptologists, including Marian Rejewski, played a crucial role in breaking the German Enigma cipher before and during World War II.

Contemporary Poland has numerous universities and research institutions conducting R&D activities. The Polish Academy of Sciences (Polska Akademia NaukPolska Akademia NaukPolish, PAN) is a leading scientific institution. There is a growing focus on innovation and technology, with sectors like IT, software development, biotechnology, and video game development gaining prominence. Poland was ranked 40th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.

Government and EU funding support R&D, but challenges remain in translating research into commercial applications and increasing private sector investment in innovation. Efforts are underway to foster a more dynamic innovation ecosystem, encourage startups, and enhance collaboration between academia and industry. Notable Polish scientists and inventors continue to contribute to various fields globally.

9.5. Transport

Poland's transportation infrastructure has undergone significant modernization, especially since its accession to the European Union in 2004, benefiting from EU funding.

- Roads**: Poland has an extensive network of roads, including motorways (autostradyautostradyPolish) and expressways (drogi ekspresowedrogi ekspresowePolish). As of August 2023, there were over 3.1 K mile (5.00 K km) of highways in use. Major European routes like the E40 and E30 pass through Poland.

- Railways**: Rail transport is well-developed. In 2022, Poland had 12 K mile (19.39 K km) of railway track, the third-longest network in the EU. The Polish State Railways (Polskie Koleje PaństwowePolskie Koleje PaństwowePolish, PKP Group) is the main railway operator, providing passenger (PKP Intercity) and freight services. Regional and commuter rail services are also operated by voivodeship-owned companies and private operators. High-speed rail development is underway, with some lines allowing speeds of up to 124 mph (200 km/h).

- Airports**: Poland has several international airports. The largest is Warsaw Chopin Airport (WAW), which serves as the primary hub for LOT Polish Airlines, the country's flag carrier. Other major airports include Kraków (KRK), Gdańsk (GDN), and Katowice (KTW). There is ongoing development of a new central hub airport, the Central Communication Port (CPK).

- Seaports**: Major seaports on the Baltic coast include Gdańsk, Gdynia, Szczecin, and Świnoujście. These ports handle significant freight traffic and offer ferry connections to Scandinavia. The Port of Gdańsk is the largest in Poland and one of the busiest in the Baltic Sea.

- Public Transport**: Urban public transport is well-developed in major cities, typically consisting of buses, trams, and, in Warsaw, a metro system.

Poland's strategic location in Central Europe makes it an important transit country for both east-west and north-south transport corridors.

9.6. Tourism

Tourism is a significant and growing sector of the Polish economy, contributing approximately 4.5% to the GDP in 2020. Poland attracted nearly 200,000 people employed in the hospitality sector in 2020 and ranked as the 12th most visited country globally by international arrivals in 2021.

Poland offers a diverse range of attractions:

- Historical Cities**: Kraków, with its medieval Old Town, Wawel Castle, and Kazimierz (former Jewish quarter), is a prime destination. Warsaw's Old Town, meticulously reconstructed after World War II, is also a UNESCO site. Other historic cities include Gdańsk, Wrocław (known for its dwarf statues and Market Square), Poznań, Toruń (birthplace of Copernicus), and Zamość (a Renaissance ideal city).

- UNESCO World Heritage Sites**: Poland boasts 17 UNESCO sites, including the Auschwitz-Birkenau German Nazi Concentration and Extermination Camp (1940-1945), the Wieliczka and Bochnia Royal Salt Mines, Malbork Castle (the world's largest brick castle), and the primeval Białowieża Forest.

- Natural Landscapes**: The Masurian Lake District offers thousands of lakes for sailing and water sports. The Tatra Mountains (Poland's highest range) provide opportunities for hiking, climbing, and skiing. Other mountainous regions include the Pieniny (known for the Dunajec River Gorge rafting), Bieszczady, and Karkonosze. The Baltic coast has sandy beaches and resort towns like Sopot.

- Castles and Palaces**: Poland has over 100 castles, with many located in Lower Silesian Voivodeship and along the Trail of the Eagles' Nests.

- Cultural Tourism**: Numerous museums, art galleries, music festivals (e.g., the International Chopin Piano Competition), and folk traditions attract visitors.

- Dark tourism**: Sites like Auschwitz-Birkenau and the Skull Chapel in Kudowa-Zdrój draw visitors interested in specific historical events.

The tourism industry benefits from Poland's improving infrastructure, diverse cultural heritage, and natural beauty.

10. Demographics

Poland's population was approximately 38.2 million as of 2021, making it the ninth-most populous country in Europe and the fifth-most populous member state of the European Union. The population density is about 122 /km2.

The total fertility rate (TFR) in Poland was estimated at 1.33 children per woman in 2021, which is below the replacement level and among the lowest in the world. Consequently, Poland's population is aging significantly, with a median age of 42.2 years. These demographic trends present challenges for social security systems and the labor market.

Approximately 60% of the population lives in urban areas, while 40% resides in rural zones. The most populous voivodeship is Masovian Voivodeship (which includes Warsaw). The capital city, Warsaw, has about 1.8 million inhabitants, with its metropolitan area housing 2 to 3 million people. The Katowice metropolitan area (also known as the Upper Silesian conurbation) is the largest urban conurbation, with a population ranging from 2.7 million to 5.3 million residents depending on the definition. Population density is generally higher in the south of Poland.

| Rank | City | Voivodeship | Population | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Warsaw | Masovian | 1,862,402 |  |

| 2 | Kraków | Lesser Poland | 807,644 |  |

| 3 | Wrocław | Lower Silesian | 673,531 |  |

| 4 | Łódź | Łódź | 648,711 |  |

| 5 | Poznań | Greater Poland | 536,818 | |

| 6 | Gdańsk | Pomeranian | 487,834 | |

| 7 | Szczecin | West Pomeranian | 387,700 |  |

| 8 | Lublin | Lublin | 328,868 |  |

| 9 | Bydgoszcz | Kuyavian-Pomeranian | 324,984 |  |

| 10 | Białystok | Podlaskie | 290,907 |  |

| 11 | Katowice | Silesian | 278,090 |  |

| 12 | Gdynia | Pomeranian | 240,554 |  |

| 13 | Częstochowa | Silesian | 204,703 |  |

| 14 | Rzeszów | Subcarpathian | 197,706 |  |

| 15 | Radom | Masovian | 194,916 | |

| 16 | Toruń | Kuyavian-Pomeranian | 194,273 |  |

| 17 | Sosnowiec | Silesian | 185,930 | |

| 18 | Kielce | Świętokrzyskie | 181,211 |  |

| 19 | Gliwice | Silesian | 169,259 |  |

| 20 | Olsztyn | Warmian-Masurian | 166,697 |  |

10.1. Ethnicity

Poles constitute the vast majority of the population. According to the 2011 census, 96.88% of the population identified as Polish. The largest officially recognized ethnic minorities include Silesians (846,719 declared Silesian identity, often alongside Polish), Germans (147,814), Ukrainians (around 51,000 declared in 2011, though this number increased significantly due to refugees after 2022), Belarusians (around 47,000), and Kashubians (232,547 declared Kashubian identity). Other smaller recognized minorities include Romani, Lithuanians, Russians, Lemkos, Slovaks, Czechs, Jews, and Tatars (Lipka Tatars). Some individuals declare multiple ethnic identities. The situation of minorities is protected by law, and their rights include the use of minority languages in certain contexts and representation in public life. However, challenges related to discrimination and social integration persist for some groups. Poland has also become a country of immigration in recent years, with a significant number of workers and refugees, particularly from Ukraine.

The ethnic structure of Poland by voivodeship, based on the censuses of 2002, 2011, and 2021, shows regional variations in minority populations, with Opole and Podlaskie Voivodeships having notable German and Belarusian minorities, respectively, and Silesian Voivodeship having a large number of people declaring Silesian identity.

| Census year | 2002 census | 2011 census | 2021 census | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voivodeship | Polish ethnicity | Non-Polish ethnicity | Not reported or no ethnicity | Polish ethnicity (including mixed) | Only non-Polish ethnicity | Not reported or no ethnicity | Polish ethnicity (including mixed) | Only non-Polish ethnicity | Not reported or no ethnicity |

| Lower Silesian | 98.02% | 0.42% | 1.56% | 97.87% | 0.38% | 1.75% | 99.25% | 0.72% | 0.03% |

| Kuyavian-Pomeranian | 98.74% | 0.13% | 1.13% | 98.73% | 0.12% | 1.15% | 99.63% | 0.34% | 0.03% |

| Lublin | 98.74% | 0.13% | 1.12% | 98.66% | 0.14% | 1.20% | 99.64% | 0.33% | 0.03% |

| Lubusz | 97.72% | 0.33% | 1.95% | 98.26% | 0.31% | 1.43% | 99.43% | 0.54% | 0.03% |

| Łódź | 98.06% | 0.15% | 1.78% | 98.86% | 0.16% | 0.98% | 99.61% | 0.37% | 0.02% |

| Lesser Poland | 98.72% | 0.26% | 1.02% | 98.22% | 0.24% | 1.54% | 99.50% | 0.47% | 0.03% |

| Masovian | 96.55% | 0.26% | 3.19% | 98.61% | 0.37% | 1.02% | 99.29% | 0.68% | 0.03% |

| Opole | 81.62% | 12.52% | 5.86% | 88.14% | 9.72% | 2.14% | 95.58% | 4.33% | 0.09% |