1. Overview

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe, recognized as the second-largest country in Europe by area, after Russia. It borders Russia to the east and northeast, Belarus to the north, Poland and Slovakia to the west, and Hungary, Romania, and Moldova to the southwest, with coastlines along the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov to the south. Kyiv serves as the nation's capital and largest city. Ukraine operates as a unitary state with a semi-presidential republic system, emphasizing the separation of powers among its executive, legislative, and judicial branches within a multi-party democracy.

Historically, the territory of modern Ukraine has been inhabited since 32,000 BC. It became a crucial center of East Slavic culture under the state of Kievan Rus', which emerged in the 9th century and flourished as a powerful realm in the 10th and 11th centuries. However, the region endured centuries of foreign domination and internal struggles, including devastating Mongol invasions, partitions among various empires, and periods of Russification. The 20th century saw brief periods of independence, followed by its incorporation into the Soviet Union as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, during which it suffered immensely from the Holodomor famine and the atrocities of World War II.

Ukraine regained its independence in 1991 following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, embarking on a path toward democracy and a free-market economy. This transition has been marked by significant challenges, including widespread corruption and political crises, such as the Orange Revolution in 2004 and the Euromaidan protests in 2013-2014, which led to the Revolution of Dignity. Since 2014, Ukraine has faced an ongoing conflict with Russia, beginning with the illegal annexation of Crimea and the war in the Donbas, escalating into a full-scale invasion in 2022. This conflict has profoundly impacted Ukrainian society, its sovereignty, and human security, while also accelerating its aspirations for integration with the European Union and NATO, symbolizing its commitment to democratic values and human rights. Despite the ongoing war, Ukraine remains a significant global exporter of grain due to its fertile land and continues to pursue reforms aimed at sustainable development and combating corruption.

2. Etymology

The name "Ukraine" (УкраїнаUkrainaUkrainian) has several historical interpretations regarding its origin. The most widespread and older hypothesis suggests it derives from an Old Slavic term for 'borderland' or 'frontier region,' similar to the word krajina. This interpretation stems from its geographical position as a border area between various historical empires and cultures.

However, more recent linguistic studies propose a different meaning, interpreting "Ukraine" as "homeland," "region," or "country." This view emphasizes that the term refers to an integral territory rather than merely a periphery. The word krai (крайUkrainian), a root word in Ukrainian, can mean "region," "edge," "border," or "end," but also implies "homeland" or "native land." The prefix u- (у-Ukrainian) or v- (в-Ukrainian) in Ukrainian signifies "in" or "within," suggesting "within the land" or "our land," which reinforces the "homeland" interpretation.

In the English-speaking world, for most of the 20th century, Ukraine was commonly referred to as "the Ukraine." This usage was analogous to other country names like "the Netherlands," where the definite article precedes a name derived from a common noun (e.g., "low lands"). However, since Ukraine's Declaration of Independence in 1991, the use of "the Ukraine" has become a politically sensitive issue. Ukrainian authorities and many international style guides now advise against it, asserting that its use implies a geographical region rather than a sovereign state, thus disregarding Ukrainian sovereignty. The official Ukrainian position is that "the Ukraine" is grammatically and politically incorrect, emphasizing the nation's independent statehood.

3. History

Ukraine's history is a complex tapestry woven from diverse cultures, periods of self-rule, and centuries of foreign domination. From prehistoric human habitation to its modern struggles for independence and sovereignty, its journey reflects deep-seated desires for self-determination and cultural preservation.

3.1. Early history

Human presence in the territory of modern Ukraine dates back to prehistoric times. Stone tools found in Korolevo, western Ukraine, dating back 1.4 million years ago, provide the earliest securely dated evidence of hominin presence in Europe. Settlement by modern humans is evidenced from 32,000 BC, with archaeological finds of the Gravettian culture in the Crimean Mountains. By 4,500 BC, the Neolithic Cucuteni-Trypillia culture flourished across wide areas of modern Ukraine, including Trypillia and the entire Dnieper-Dniester region, characterized by advanced agricultural practices and large settlements. Ukraine is also considered a probable location for the first domestication of the horse. The Kurgan hypothesis places the Volga-Dnieper region, encompassing parts of modern Ukraine and southern Russia, as the linguistic homeland of the Proto-Indo-Europeans, with early migrations from these Pontic steppes in the 3rd millennium BC spreading pastoralist ancestry and Indo-European languages across Europe.

During the Iron Age, the land was inhabited by various Iranian-speaking groups, including the Cimmerians, Scythians, and Sarmatians. Between 700 BC and 200 BC, the region was part of the Scythian kingdom. From the 6th century BC, ancient Greek, Roman, and Byzantine colonies, such as Tyras, Olbia, and Chersonesus, were established on the north-eastern shore of the Black Sea, thriving until the 6th century AD. The Goths also settled in the area but came under the sway of the Huns from the 370s. In the 7th century, the territory now known as eastern Ukraine was the center of Old Great Bulgaria. By the end of that century, most Bulgar tribes migrated in different directions, and the Khazars took over much of the land.

In the 5th and 6th centuries, the Antes, considered by some to be an early Slavic people, inhabited Ukraine. Their migrations from the territories of present-day Ukraine established many South Slavic nations in the Balkans. Northern migrations, reaching almost to Lake Ilmen, led to the emergence of the Ilmen Slavs and Krivichs. After an Avar raid in 602 and the collapse of the Antes Union, most of these peoples survived as separate tribes until the beginning of the second millennium.

3.2. Golden Age of Kyiv

The foundation of Kievan Rus' is complex and debated among historians. This powerful medieval state, which emerged in the 9th century, encompassed much of present-day Ukraine, Belarus, and western parts of European Russia. According to the Primary Chronicle, the early Rus' people were Varangians from Scandinavia, but the Varangian elite, including the ruling Rurik dynasty, later assimilated into the Slavic population. Kyivan Rus' consisted of several principalities ruled by interrelated Rurikid kniazes (princes) who frequently vied for control of Kyiv.

During the 10th and 11th centuries, Kyivan Rus' reached the zenith of its power and cultural development, a period often referred to as its Golden Age. This era began with the reign of Vladimir the Great (980-1015), who introduced Christianity as the state religion in 988 AD, profoundly shaping Ukrainian identity and culture. His son, Yaroslav the Wise (1019-1054), further solidified the state's standing, overseeing its cultural flourishing and military strength. However, the state eventually fragmented into separate principalities after the death of Yaroslav's son, Mstislav I of Kiev (1125-1132), as the relative importance of regional powers reasserted itself, though possession of Kyiv continued to carry great prestige. The frequent invasions by nomadic Turkic-speaking groups like the Cumans and Kipchaks in the 11th and 12th centuries also contributed to population movements within Rus'.

The Mongol invasions in the mid-13th century proved catastrophic for Kyivan Rus'. Following the devastating Siege of Kyiv in 1240, the city was largely destroyed. In the western territories, the principalities of Halych and Volhynia had already emerged and were later merged to form the Kingdom of Galicia-Volhynia. Daniel of Galicia, son of Roman the Great, successfully reunified much of southwestern Rus', including Volhynia, Galicia, and Kyiv. He was crowned by a papal envoy as the first King of Ruthenia (also known as the Kingdom of Galicia-Volhynia) in 1253, seeking Western support against Mongol dominance, although he ultimately had to submit to the Golden Horde. The legacy of Kyivan Rus' remains foundational for the national identities of Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus.

3.3. Foreign domination

Following the fragmentation of Kyivan Rus' and the devastating Mongol invasions, the lands of Ukraine entered a prolonged period of foreign domination. In 1349, in the aftermath of the Galicia-Volhynia Wars, the region was partitioned between the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. From the mid-13th century to the late 1400s, the Republic of Genoa established numerous colonies on the northern Black Sea coast, transforming them into significant commercial centers.

In 1430, the region of Podolia was incorporated into Poland, and Polish settlement in the lands of modern-day Ukraine increased. In 1441, the Genghisid prince Haci I Giray founded the Crimean Khanate on the Crimean Peninsula and the surrounding steppes. Over the next three centuries, the Khanate, along with Tatar raids, conducted extensive slave raids, enslaving an estimated two million people in the region. The Crimean Khanate remained a dominant power in Eastern Europe until the 18th century, even capturing and destroying Moscow in 1571.

In 1569, the Union of Lublin established the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and a significant portion of Ukrainian lands were transferred from Lithuania to the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, becoming de jure Polish territory. Under the pressures of Polonisation, many Ruthenian landed gentry converted to Catholicism and assimilated into the Polish nobility. Others joined the newly created Ruthenian Uniate Church. This period also saw the emergence of the Zaporozhian Cossacks as a distinct military and social force, offering protection to Ruthenian peasants and townspeople who felt alienated by Polish rule and the suppression of the Orthodox Church.

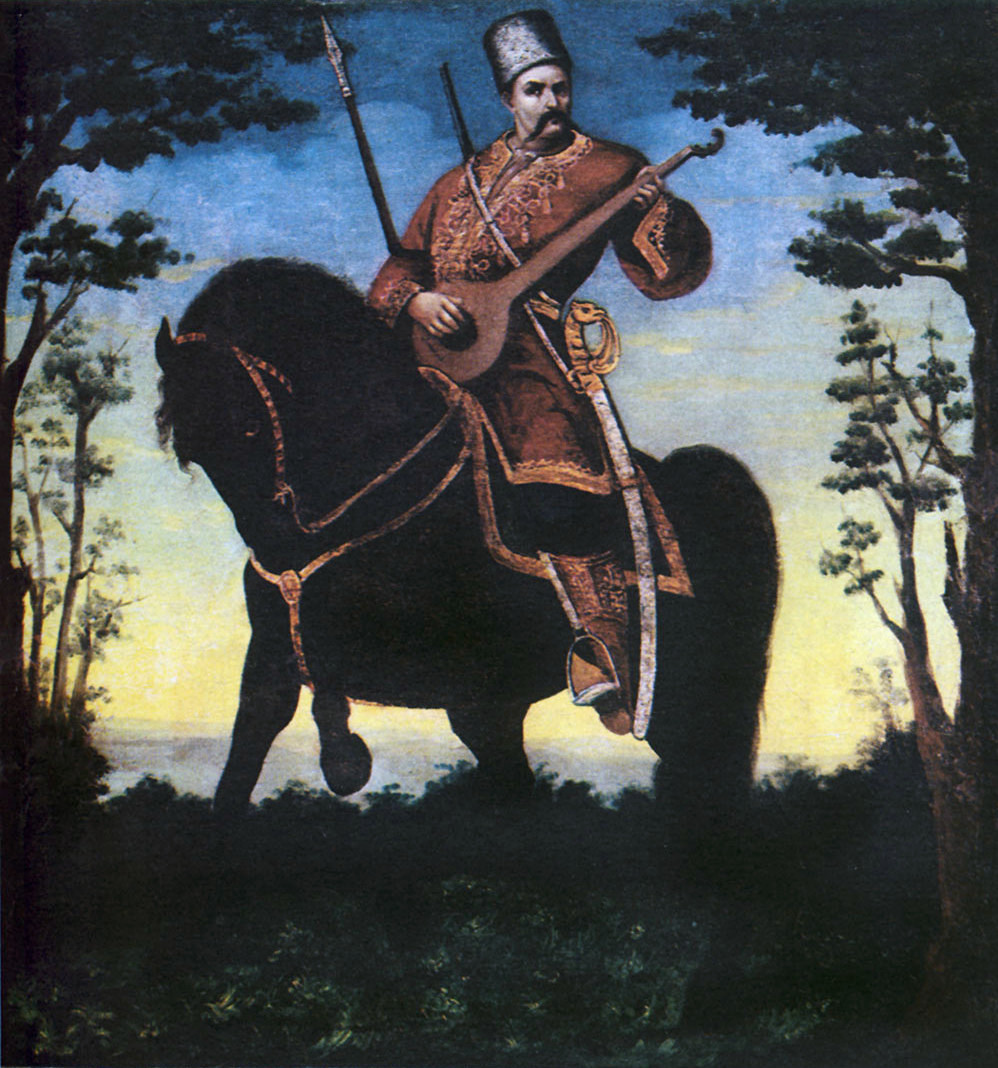

3.4. Cossack Hetmanate

The Zaporozhian Cossacks emerged as a powerful force in central Ukraine from the 15th century, driven by Ruthenian peasants fleeing Polish serfdom and by the absence of local protectors among the Ruthenian nobility. By the mid-17th century, they formed a military quasi-state, the Zaporozhian Host. While Poland initially found the Cossacks useful allies against the Turks and Tatars, the continued harsh enserfment of Ruthenian peasantry and the suppression of the Orthodox Church by the Polish szlachta (nobility) increasingly alienated the Cossacks. They actively resisted perceived enemies and occupiers, including local Catholic Church representatives.

In 1648, Bohdan Khmelnytsky led the largest of the Cossack uprisings against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which garnered widespread support from the local population. This rebellion led to the establishment of the Cossack Hetmanate, an independent Cossack state. Facing overwhelming Polish forces, Khmelnytsky sought assistance from the Russian tsar. In 1654, he signed the Pereiaslav Agreement, forming a military and political alliance with Russia that acknowledged loyalty to the Russian monarch.

After Khmelnytsky's death, the Hetmanate entered a devastating 30-year period of conflict known as "The Ruin" (1657-1686). This era saw a complex struggle for control involving Russia, Poland, the Crimean Khanate, the Ottoman Empire, and various Cossack factions. The Treaty of Perpetual Peace (1686) between Russia and Poland formally divided the Cossack Hetmanate, reducing the portion over which Poland claimed sovereignty to Ukraine west of the Dnieper River. In 1686, the Metropolitanate of Kyiv was annexed by the Moscow Patriarchate, shifting its ecclesiastical authority.

An attempt to reverse the Hetmanate's decline was made by Cossack Hetman Ivan Mazepa (1639-1709), who allied with the Swedes during the Great Northern War (1700-1721) to shake off Russian dependence. However, his capital city Baturyn was sacked in 1708, and his forces were crushed in the Battle of Poltava in 1709. Following this defeat, the Hetmanate's autonomy was severely restricted. Between 1764 and 1781, Catherine the Great incorporated much of central Ukraine into the Russian Empire, abolishing the Cossack Hetmanate and the Zaporozhian Sich. She was also responsible for suppressing the last major Cossack uprising, the Koliivshchyna. After the annexation of Crimea by Russia in 1783, the newly acquired lands, now called Novorossiya, were opened to settlement by Russians, further solidifying imperial control over Ukrainian territories.

3.5. Under the Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires

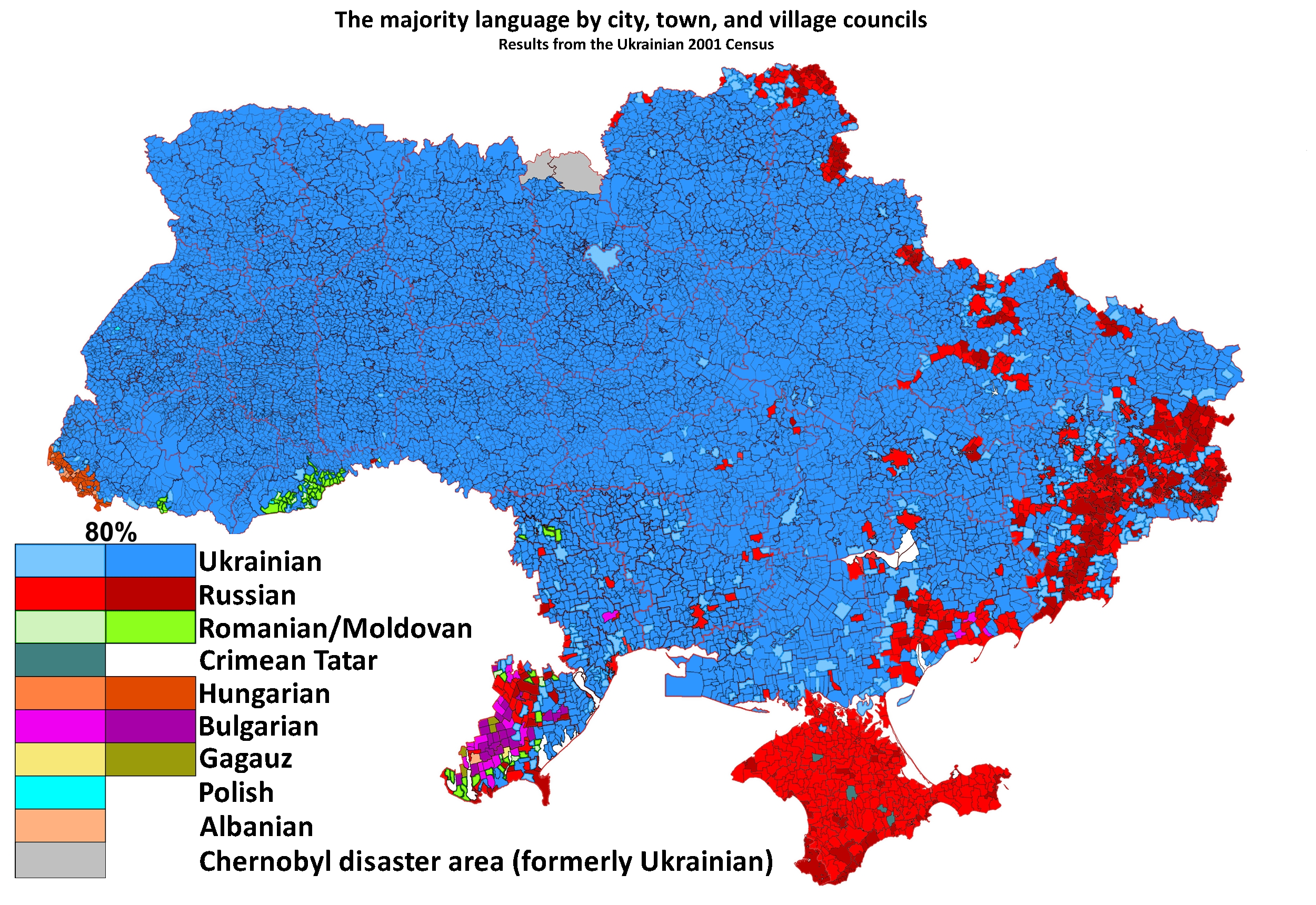

Following the Partitions of Poland in the late 18th century, Ukraine was divided between the Russian Empire and the Austrian Empire (later Austro-Hungarian Empire). The larger central and eastern parts of Ukraine came under Russian rule, while the western region of Galicia and Bukovina fell under Austrian control, and Zakarpattia under Hungary. This division had a profound impact on Ukrainian society, culture, and national development.

Under tsarist rule, policies of Russification were aggressively pursued, aiming to suppress Ukrainian national identity and the Ukrainian language. The Valuev Circular of 1863 and the Ems Ukaz of 1876 severely restricted or banned the publication and use of Ukrainian in print, forcing Ukrainian authors to publish in Russian or abroad. This suppression aimed to assimilate Ukrainians into the broader Russian identity, often referring to their lands as "Little Russia" or "South Russia."

Despite these repressive measures, the 19th century witnessed a significant rise of Ukrainian nationalism and a cultural revival. Intellectuals committed to national rebirth and social justice emerged, advocating for the recognition and development of Ukrainian culture. Key figures such as the serf-turned-national-poet Taras Shevchenko (1814-1861) and political theorist Mykhailo Drahomanov (1841-1895) led the growing nationalist movement. Shevchenko's literary works, written in modern Ukrainian, became foundational for the national identity.

In contrast, conditions for Ukrainian national development in Austrian Galicia under the Habsburgs were relatively more lenient. While industrialization, especially near the newly discovered coal fields of the Donbas, and in cities like Odesa and Kyiv, occurred, Ukraine largely remained an agricultural and resource extraction economy. The Austrian part of Ukraine, particularly Galicia, remained economically disadvantaged, leading hundreds of thousands of peasants to emigrate and form a significant Ukrainian diaspora in countries such as Canada, the United States, and Brazil. Some also settled in the Russian Far East, creating an area known as Green Ukraine.

This period of imperial rule fostered different experiences of national awakening and social justice movements across Ukrainian lands, setting the stage for future struggles for independence.

3.6. 19th and early 20th century

The early 20th century saw the culmination of Ukrainian national aspirations that had been fermenting under imperial rule. With the outbreak of World War I, Ukraine became a key battlefield on the Eastern Front, caught between the Central Powers (Germany and Austro-Hungary) and the Russian Empire. The vast majority of Ukrainians served in the Imperial Russian Army, though many also fought for Austro-Hungary.

As the Russian Empire collapsed following the Russian Revolution in 1917, Ukrainian national movements seized the opportunity to establish an independent state. On 23 June 1917, the left-leaning Ukrainian People's Republic (UNR) was declared under the leadership of Mykhailo Hrushevsky. However, the period was plagued by an extremely unstable political and military environment, leading to the complex Ukrainian War of Independence. Various factions, including the Bolshevik Red Army, the tsarist White Army, the anarchist Black Army, and local Green armies, as well as Polish, Hungarian, and German forces, vied for control over Ukrainian territory.

The UNR faced multiple challenges; it was briefly deposed by a coup led by Pavlo Skoropadskyi, which established the Ukrainian State under German protection. Attempts to restore the UNR under the Directorate ultimately failed. Other short-lived independent entities, such as the West Ukrainian People's Republic in Galicia and the Hutsul Republic in Transcarpathia, also emerged but were unable to consolidate their independence or unite with the rest of Ukraine.

The conflict resulted in a partial victory for the Second Polish Republic, which annexed western Ukrainian provinces, and a larger victory for the pro-Soviet forces. The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (Soviet Ukraine) was eventually established, though modern-day Bukovina was occupied by Romania and Carpathian Ruthenia was integrated into Czechoslovakia as an autonomous region. The widespread fighting and the subsequent famine of 1921 devastated the former Russian Empire's territory, including eastern and central Ukraine, leaving over 1.5 million people dead and hundreds of thousands displaced. The period highlighted the fervent desire for self-governance but also the immense challenges in achieving it amid geopolitical turmoil.

3.7. Inter-war period

The inter-war period saw Ukrainian lands divided among the Soviet Union, Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia, each implementing distinct policies that shaped Ukrainian identity and aspirations.

3.7.1. Ukrainization and repression

In Soviet Ukraine, the 1920s brought a period of "Ukrainization," an early Soviet policy aimed at promoting Ukrainian culture and language as part of a broader "Korenisation" (indigenization) effort. Led by figures like Mykola Skrypnyk, this policy encouraged a national renaissance, restoring the Ukrainian language in administration and education. This period also saw some prominent former UNR figures, including Hrushevsky, return to Soviet Ukraine, contributing to Ukrainian science and culture.

However, this cultural flourishing was abruptly reversed with the rise of Joseph Stalin. Beginning in the late 1920s and intensifying into the 1930s, Stalin's regime implemented severe repressions against Ukrainian intellectuals, cultural figures, and peasants. The "Ukrainization" policy was denounced as a "nationalist deviation," leading to widespread arrests, deportations, and executions. This era witnessed a profound loss of a generation of Ukrainian intelligentsia, now known as the "Executed Renaissance," as Stalin sought to consolidate central control and eliminate any potential for Ukrainian independence or national aspirations. This was coupled with the enforcement of Russification, which intensified political and cultural suppression.

3.7.2. Holodomor

A catastrophic event during this period was the 1932-1933 Holodomor, a man-made famine that devastated Soviet Ukraine. Stalin's policies, particularly the forced collectivization of agriculture and the ruthless confiscation of grain quotas, even when unrealistic, directly caused the famine. These measures were enforced by regular troops and the secret police (Cheka), leading to widespread starvation among the peasantry. Millions of Ukrainians perished, with estimates ranging from 4 million people to 10 million people or more.

The Holodomor is considered a deliberate act of mass murder, and while some countries recognize it as an act of genocide perpetrated by Joseph Stalin and other Soviet officials, it is more broadly acknowledged as a crime against humanity. The famine's political and economic causes, its devastating course, and its catastrophic consequences left an indelible mark on the Ukrainian population, contributing to a deep-seated distrust of Soviet rule and a stronger sense of national victimhood.

3.8. World War II

World War II brought immense devastation and complex allegiances to Ukraine. Following the Invasion of Poland in September 1939, German and Soviet troops divided Poland, and Eastern Galicia and Volhynia, with their Ukrainian populations, became part of the Ukrainian SSR. This marked the first time in history that a significant portion of Ukrainian ethnic lands were politically united. Further territorial gains occurred in 1940 when the Ukrainian SSR incorporated northern and southern districts of Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina, and the Hertsa region from Romania, territories later recognized by the Paris Peace Treaties, 1947.

On 22 June 1941, German armies launched Operation Barbarossa, invading the Soviet Union. Ukraine became a primary battleground on the Eastern Front. The Battle of Kyiv saw fierce Soviet resistance, earning the city the title of a "Hero City," but resulted in over 600,000 Soviet soldiers killed or captured, many suffering severe mistreatment. After its conquest, most of the Ukrainian SSR was organized within the Reichskommissariat Ukraine, with the intention of exploiting its resources and preparing for German settlement.

While some western Ukrainians initially welcomed the Germans as liberators from Soviet rule, Nazi policies quickly turned hostile. The Nazis preserved the collective-farm system, implemented genocidal policies against Jews (resulting in an estimated 1.5 million Jews killed), deported millions to work in Germany as OST-Arbeiter, and planned a depopulation program. They also blockaded food transport on the Dnieper River.

Although the majority of Ukrainians fought in or alongside the Red Army and Soviet resistance, a complex situation unfolded in Western Ukraine. The Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), formed in 1942 as the armed wing of the underground Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), sought an independent Ukrainian state. While initially clashing with Nazi Germany, elements of the OUN sometimes allied with Nazi forces. From mid-1943 until the war's end, the UPA carried out massacres of ethnic Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia, killing around 100,000 Polish civilians, which led to reprisals. These massacres were part of an OUN effort to create an ethnically homogeneous Ukrainian state. Another nationalist movement, the Ukrainian Liberation Army, also fought alongside the Nazis. The UPA continued its fight against the USSR until the 1950s.

The total human losses inflicted upon the Ukrainian population during the war are estimated at 6 million people, including civilians and military personnel. The vast majority of the fighting occurred on the Eastern Front, where 1.4 million ethnic Ukrainians were among the estimated 8.6 million Soviet troop losses. World War II remains a deeply traumatic and complex period in Ukrainian history, marked by immense suffering, moral ambiguities, and the struggle for survival and national identity.

3.9. Post-war Soviet Ukraine

After the devastation of World War II, the Ukrainian SSR faced immense challenges in rebuilding. Over 700 cities and towns and 28,000 villages were destroyed. A severe famine in 1946-1947, caused by drought and wartime destruction, resulted in the deaths of at least tens of thousands of people. Despite the hardships, Ukraine made significant strides in recovery. In 1945, the Ukrainian SSR became one of the founding members of the United Nations, a unique arrangement alongside Belarus that granted them voting rights in the UN even though they were not independent states.

Post-war, Ukraine's borders expanded further with the annexation of Zakarpattia, and the population became more homogeneous due to forced population transfers, including the deportation of Germans and Crimean Tatars. By 1953, Ukrainians comprised 20% of all adult "special deportees" in the Soviet Union.

Following Stalin's death in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev became the new leader of the USSR, initiating policies of de-Stalinization and the Khrushchev Thaw. During his leadership, Crimea was transferred from the Russian SFSR to the Ukrainian SSR in 1954, formally as a friendship gift and for economic reasons. This transfer established the final extent of Ukrainian territory, forming the basis for its internationally recognized borders today.

By 1950, the republic had surpassed pre-war levels of industrial production, rapidly becoming a European leader in industrial output and an important center for the Soviet arms industry and high-tech research. Many top positions in the Soviet Union were occupied by Ukrainians, most notably Leonid Brezhnev, who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 to 1982. However, Brezhnev and his appointee in Ukraine, Volodymyr Shcherbytsky, oversaw extensive Russification policies and suppressed a new generation of Ukrainian intellectuals known as the "Sixtiers."

3.9.1. Chernobyl disaster

A defining event of this period was the Chernobyl disaster on 26 April 1986. A reactor at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant exploded, causing the worst nuclear reactor accident in history. The accident released vast amounts of radioactive material, contaminating large areas of Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia. The Soviet government's initial handling of the crisis, marked by secrecy and delay in evacuation, drew international criticism. The disaster had severe immediate and long-term health and environmental consequences, impacting millions of people and causing widespread ecological damage. It also highlighted critical issues of transparency, accountability, and safety in Soviet technological programs, profoundly affecting public trust and contributing to growing discontent with the Soviet system.

3.10. Independence

Ukraine's path to independence was a culmination of historical aspirations and the rapidly changing political landscape of the late Soviet Union.

3.10.1. Path to independence and early state-building

Under Mikhail Gorbachev's policies of perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (openness), a limited liberalization of public life occurred, which, while failing to reform the stagnating Soviet economy, fueled nationalist and separatist tendencies among ethnic minorities, including Ukrainians. The national movement, spearheaded by organizations like the People's Movement for Perestroika (Rukh), gained significant momentum. On 16 July 1990, the newly elected Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic adopted the Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine, asserting the primacy of Ukrainian laws over Soviet ones.

Following a failed coup by conservative Communist hardliners in Moscow in August 1991, Ukraine formally proclaimed outright independence on 24 August 1991. This declaration was overwhelmingly approved by 92% of the Ukrainian electorate in a referendum on 1 December. Leonid Kravchuk, then Chairman of the Supreme Soviet, was elected the first President of Ukraine. He subsequently signed the Belavezha Accords on 8 December 1991 with the leaders of Russia and Belarus, effectively dissolving the Soviet Union and forming the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), though Ukraine never ratified the agreement to become a full member of the latter.

Ukraine was initially viewed as having favorable economic conditions among the former Soviet republics. However, its transition to a market economy was arduous. The country experienced a deep economic downturn, losing 60% of its GDP between 1991 and 1999, exacerbated by hyperinflation that peaked at 10,000% in 1993. This period also saw the rise of powerful and wealthy individuals known as "oligarchs" through the mass privatization of state property. The economy stabilized somewhat after the introduction of the new currency, the hryvnia, in 1996, but corruption and mismanagement became endemic issues, leading to widespread public discontent, protests, and organized strikes.

A new constitution was adopted in 1996, establishing Ukraine as a semi-presidential republic. Despite initial aspirations for neutrality, Ukraine began to balance its foreign policy between Russia and the West.

3.10.2. Orange Revolution

The 2004 Orange Revolution marked a pivotal moment for Ukrainian democracy and civil society. The revolution erupted in response to widespread electoral fraud in the 2004 presidential election, which initially declared pro-Russian candidate Viktor Yanukovych as the winner. Mass protests, characterized by their peaceful nature and the prominent use of orange symbols, engulfed Kyiv's Independence Square and other cities.

The protests, driven by a broad coalition of civil society groups, opposition politicians led by Viktor Yushchenko and Yulia Tymoshenko, and a strong popular demand for free and fair elections, successfully pressured the authorities. The Supreme Court of Ukraine annulled the fraudulent results, leading to a rerun of the election. In the repeat vote, Viktor Yushchenko was elected president, ushering in a period of increased democratic freedoms and an intensified focus on Euro-Atlantic integration. The Orange Revolution highlighted the power of civic engagement and set a precedent for popular uprisings against perceived injustice, fundamentally shaping Ukraine's political trajectory and demonstrating the public's commitment to democratic principles, despite the subsequent political infighting and economic challenges.

3.10.3. Euromaidan and Revolution of Dignity

The 2013-2014 Euromaidan protests and the subsequent Revolution of Dignity represented another critical turning point in Ukraine's post-Soviet history, deepening its pro-Western orientation and triggering profound domestic and international repercussions. The protests began in November 2013 when then-President Viktor Yanukovych abruptly refused to sign an Association Agreement with the European Union, opting instead for closer ties with Russia. This decision sparked widespread outrage, especially among pro-European Ukrainians, leading to large-scale demonstrations in Kyiv's Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) and across the country.

The protests, initially peaceful, grew in size and intensity, evolving into a broader movement against government corruption and authoritarianism. The government's violent crackdowns, particularly in January and February 2014, including the use of riot police and snipers against unarmed protesters, escalated the conflict. Over 100 protesters, known as the "Heavenly Hundred," were killed. These brutal actions galvanized public support for the opposition and further discredited Yanukovych's government.

By 21 February 2014, amidst escalating violence and widespread defection within his party, Yanukovych fled Ukraine. The parliament subsequently removed him from power, establishing an interim pro-Western government. This event, often referred to as the Revolution of Dignity, fundamentally reshaped Ukraine's political landscape, solidifying its commitment to European integration and democratic values.

However, Russia refused to recognize the new government, denouncing the events as an illegitimate "coup d'état" orchestrated by the United States. This narrative became a key justification for Russia's subsequent aggressive actions against Ukraine, setting the stage for the ongoing conflict.

3.10.4. Russo-Ukrainian War (2014-present)

The Russo-Ukrainian War, which began in 2014, represents the most severe challenge to Ukraine's sovereignty and territorial integrity since its independence. It started despite the Budapest Memorandum of 1994, in which Ukraine agreed to hand over its nuclear weapons in exchange for security assurances from Russia, the United States, and the United Kingdom.

4. Geography

Ukraine is the second-largest European country by area, after Russia, and the largest country located entirely within Europe, covering an area of 233 K mile2 (603.55 K km2). It lies between latitudes 44° N and 53° N, and longitudes 22° E and 41° E, predominantly within the East European Plain. Its coastline stretches for 1.7 K mile (2.78 K km) along the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov.

4.1. Topography and hydrography

The landscape of Ukraine primarily consists of fertile steppes (plains with few trees) and plateaus, traversed by major rivers flowing south into the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. Significant rivers include the Dnieper, Seversky Donets, Dniester, and Southern Bug. In the southwest, the Danube Delta forms part of the border with Romania.

While Ukraine is mostly flat, its regions possess diverse geographical features. The country's only mountain ranges are the Carpathian Mountains in the west, with Hoverla as the highest peak at 6.8 K ft (2.06 K m), and the Crimean Mountains in the extreme south along the coast. Other notable highland regions include the Volhynian-Podolian Upland in the west and the Near-Dnipro Upland on the Dnieper's right bank. The southwestern spurs of the Central Russian Upland extend into eastern Ukraine, forming part of the border with Russia. Near the Sea of Azov, the Donets Ridge and the Near Azov Upland are prominent. Snowmelt from the mountains feeds the rivers, creating waterfalls and contributing to the country's hydrography.

Ukraine is rich in natural resources, including significant reserves of lithium, natural gas, kaolin, and timber, alongside an abundance of highly fertile arable land, particularly the black-colored chernozem soil, which makes Ukraine a major agricultural producer often called the "breadbasket of Europe."

However, Ukraine faces numerous environmental challenges. Some regions suffer from inadequate supplies of potable water, and air and water pollution are widespread. Deforestation is an ongoing concern, and the northeastern regions continue to grapple with radiation contamination from the 1986 Chernobyl disaster. The ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War has caused severe environmental damage, described by some as an ecocide. The destruction of the Kakhovka Dam alone is estimated to cost over 50.00 B USD to repair, and the war has resulted in widespread pollution and millions of tons of contaminated debris, adding to the country's environmental burden.

4.2. Climate

Ukraine generally experiences a continental climate, situated in the mid-latitudes, except for its southern coasts which exhibit cold semi-arid and humid subtropical climates. Average annual temperatures range from 41.9 °F (5.5 °C) to 44.6 °F (7 °C) in the north, and 51.8 °F (11 °C) to 55.4 °F (13 °C) in the south.

Precipitation is unevenly distributed across the country, with higher levels in the west and north and lower amounts in the east and southeast. Western Ukraine, particularly in the Carpathian Mountains, receives around 47 in (120 cm) of precipitation annually, while Crimea and the coastal areas of the Black Sea receive approximately 16 in (40 cm).

Water availability from major river basins is projected to decrease due to climate change, especially during summer months, posing risks to the agricultural sector. While the negative impacts of climate change on agriculture are mostly felt in the country's southern steppe regions, some northern crops might benefit from longer growing seasons. The World Bank has identified Ukraine as highly vulnerable to climate change.

4.3. Biodiversity

Ukraine is rich in biodiversity, supporting a wide range of ecosystems and species. The country contains six terrestrial ecoregions: Central European mixed forests, Crimean Submediterranean forest complex, East European forest steppe, Pannonian mixed forests, Carpathian montane conifer forests, and Pontic steppe. While mixed forests are present, there is a slightly greater proportion of coniferous forests compared to deciduous forests. The most densely forested area is Polisia in the northwest, featuring pine, oak, and birch.

Ukraine is home to approximately 45,000 species of animals, predominantly invertebrates. Around 385 endangered species are listed in the Red Data Book of Ukraine. Internationally important wetlands, covering over 2.7 K mile2 (7.00 K km2), are crucial for conservation, with the Danube Delta being particularly significant.

4.4. Urban areas

Ukraine is a heavily urbanized country, with about 67% of its total population residing in urban areas. As of 2022, Ukraine has 457 cities. Of these, 176 are designated as oblast-class cities, 279 as smaller raion-class cities, and two cities hold special legal status. In addition, there are 886 urban-type settlements and 28,552 villages.

The two cities with special status are Kyiv, the capital and largest city, and Sevastopol. These cities have a higher degree of self-rule. Other major cities include Kharkiv, Odesa, and Dnipro. Their significance is determined by factors such as population size, socio-economic importance, historical relevance, and infrastructure.

| City | Region | Population (2022) |

|---|---|---|

| Kyiv | Kyiv (city) | 2,952,301 |

| Kharkiv | Kharkiv Oblast | 1,421,125 |

| Odesa | Odesa Oblast | 1,010,537 |

| Dnipro | Dnipropetrovsk Oblast | 968,502 |

| Donetsk | Donetsk Oblast | 901,645 |

| Lviv | Lviv Oblast | 717,273 |

| Zaporizhzhia | Zaporizhzhia Oblast | 710,052 |

| Kryvyi Rih | Dnipropetrovsk Oblast | 603,904 |

| Sevastopol | Sevastopol (city) | 479,394 |

| Mykolaiv | Mykolaiv Oblast | 470,011 |

5. Politics

Ukraine operates as a republic under a semi-presidential system, featuring a clear separation of powers among its legislative, executive, and judicial branches. The political landscape has historically been shaped by a division between pro-Western and pro-Russian sentiments, alongside a traditional left-right political spectrum, although recent events have seen a strong shift towards the West.

5.1. Constitution

The Constitution of Ukraine was adopted and ratified by the Verkhovna Rada, Ukraine's parliament, on 28 June 1996. All other laws and normative legal acts in Ukraine must conform to this foundational document. The power to amend the constitution rests solely with the parliament through a special legislative procedure. The Constitutional Court of Ukraine is the only body authorized to interpret the constitution and determine the legality of legislation. Constitution Day is celebrated annually on 28 June as a public holiday. A significant amendment was made on 7 February 2019, when the Verkhovna Rada voted to enshrine Ukraine's strategic objectives of joining the European Union and NATO into the constitution, reflecting the nation's Euro-Atlantic integration aspirations.

5.2. Government

Ukraine's government structure is based on a semi-presidential republic, dividing authority among its legislative, executive, and judicial branches.

5.2.1. President and executive branch

The President of Ukraine serves as the formal head of state and is elected by popular vote for a five-year term. The president holds significant powers, including the authority to nominate the ministers of foreign affairs and defense for parliamentary approval. The president also appoints the prosecutor general and the head of the Security Service. The Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, headed by the Prime Minister of Ukraine, forms the core of the executive branch and is primarily responsible for government administration and policy implementation, subject to parliamentary oversight and presidential influence.

5.2.2. Legislature (Verkhovna Rada)

Ukraine's legislative branch is the Verkhovna Rada, a unicameral parliament composed of 450 seats. The Verkhovna Rada is central to the country's political system, responsible for enacting laws, ratifying international agreements, approving the state budget, and forming the Cabinet of Ministers. Members of parliament are primarily responsible for the legislative process and representing the interests of their constituencies. The electoral system has evolved over time, with various mixes of proportional representation and single-mandate constituencies determining how members are elected.

5.2.3. Judiciary

Ukraine's judicial system operates independently, upholding the rule of law and interpreting legislation. The system includes various levels of courts, culminating in the Constitutional Court of Ukraine and the Supreme Court of Ukraine. The Constitutional Court is responsible for ensuring that laws and government acts comply with the constitution, while the Supreme Court serves as the highest court in the system of general jurisdiction, overseeing the application of law across different legal branches.

5.3. Courts and law enforcement

The Ukrainian judicial system is designed to uphold justice, with courts enjoying legal, financial, and constitutional freedom guaranteed by Ukrainian law since 2002. Judges are largely protected from dismissal, except in cases of gross misconduct. Court justices are appointed by presidential decree for an initial five-year period, after which the Supreme Council confirms their positions for life. While the system has improved significantly since Ukraine's independence in 1991, challenges persist. Martial law was declared in Ukraine following the 2022 Russian invasion and remains in effect, impacting civil liberties.

The World Justice Project ranked Ukraine 66th out of 99 countries surveyed in its annual Rule of Law Index. Prosecutors in Ukraine traditionally possess more powers than in most European countries, leading to concerns from the European Commission for Democracy through Law that their role and functions do not fully align with Council of Europe standards. Historically, conviction rates have been notably high, often exceeding 99%, similar to the Soviet era, with suspects sometimes incarcerated for long periods before trial. Efforts have been made to address these issues, with President Yanukovych in 2010 forming an expert group to reform the court system, acknowledging the need to improve the country's legal standing.

Regarding language in court proceedings, since 2010, Russian can be used by mutual consent of the parties, and citizens unable to speak Ukrainian or Russian may use their native language or a translator. Prior to this, all court proceedings were required to be held in Ukrainian.

Law enforcement agencies are overseen by the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine. They primarily consist of the National Police of Ukraine and specialized units like the State Border Guard and the Coast Guard. Law enforcement agencies, particularly the police, faced criticism for their handling of the 2004 Orange Revolution, where large numbers of officers were deployed, armed, and stationed in the capital to deter protesters.

5.4. Foreign relations

Ukraine's foreign policy objectives have consistently revolved around Euro-Atlantic integration, although historical ties with Russia previously necessitated a balancing act. Since the 2014 conflict and especially following the 2022 full-scale invasion, Ukraine has decisively pivoted towards the West, strengthening alliances and actively seeking membership in the European Union and NATO.

Ukraine has been a founding member of the United Nations since 1945, a unique status granted through a special agreement at the Yalta Conference. It has consistently supported peaceful, negotiated settlements to disputes and has contributed significantly to UN peacekeeping operations since 1992, participating in missions in Kosovo, Iraq, and off the coast of Somalia. It is also a member of the Council of Europe and the OSCE.

5.4.1. Relations with the European Union

Ukraine considers integration with the European Union a primary foreign policy objective. The Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) between Ukraine and the EU came into force in 1998, laying the groundwork for closer ties. The Ukraine-European Union Association Agreement, a more comprehensive agreement, was signed in 2014, and its Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) component entered into force in January 2016, formally integrating Ukraine into the European Single Market and the European Economic Area. This agreement led to significant cooperation in various areas, including trade and economic reforms. Ukrainian citizens were granted visa-free travel to the European Union in 2017. In June 2022, amid the full-scale Russian invasion, Ukraine was granted candidate status for EU membership, a significant step in its long-standing aspiration. Support for Ukraine's EU accession is also evident from the Visegrád Group through the International Visegrád Fund. In 2021, Ukraine, along with Georgia and Moldova, formed the Association Trio, a tripartite format aimed at enhanced cooperation and dialogue on European integration, reinforcing their commitment to EU membership prospects.

5.4.2. Relations with NATO

Ukraine's partnership with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) has been close and evolving, with the country expressing a strong interest in eventual membership. Ukraine has been the most active member of the Partnership for Peace (PfP) program. The NATO-Ukraine Action Plan, signed in 2002, aimed at deeper cooperation. While the question of joining NATO was initially slated for a future national referendum, the 2008 Bucharest summit declared that Ukraine would eventually become a NATO member once it met the necessary criteria. However, during his presidency, Viktor Yanukovych opposed Ukraine's NATO membership, considering the existing level of cooperation sufficient. The Russo-Ukrainian War, however, has profoundly influenced Ukraine's security policy, pushing it towards full integration with NATO.

5.4.3. Relations with Russia

Ukraine's relationship with Russia is historically complex and has become acutely antagonistic, particularly since 2014. While Ukraine sought to balance its ties with Russia and the West after independence, Russian interference and aggression have led to a decisive break. Key conflict points include:

- Annexation of Crimea (2014):** Russia's illegal annexation of Crimea in March 2014, following the Revolution of Dignity, fundamentally altered the relationship.

- War in Donbas (2014-2022):** Russia's support for separatists in eastern Ukraine ignited a protracted conflict in the Donbas region.

- Energy Dependence and Disputes:** Historical reliance on Russian energy, along with recurring payment disputes, has been a constant source of tension.

- Orthodox Church Independence (2019):** The recognition of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine as independent from Moscow in 2019 further eroded Russia's religious and cultural influence in Ukraine.

- Full-scale Invasion (2022):** The relationship deteriorated completely with Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, leading to the severance of diplomatic ties and an ongoing war.

Russia's actions, viewed by Ukraine and much of the international community as a gross violation of international law and Ukraine's sovereignty, have resulted in widespread international condemnation and sanctions against Russia. Ukraine's foreign policy has since been firmly reoriented towards the West, seeking greater security cooperation and integration with European and Euro-Atlantic structures.

5.5. Military

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Ukraine inherited a substantial military force of 780,000 personnel, equipped with the world's third-largest nuclear weapons arsenal. In 1992, Ukraine signed the Lisbon Protocol, agreeing to transfer all its nuclear weapons to Russia for disposal and to join the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty as a non-nuclear weapon state. By 1996, Ukraine had become nuclear-weapon-free.

Ukraine subsequently took consistent steps towards reducing conventional weapons, signing the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe. The country's military strength in 2022 stood at 196,600 active personnel and around 900,000 reservists. Ukraine has also gained recognition for operating one of the world's largest and most diverse drone fleets.

Historically, Ukraine declared itself a neutral state following independence and maintained a limited military partnership with Russia and other CIS countries while also engaging in a partnership with NATO since 1994. The NATO-Ukraine Action Plan, signed in 2002, aimed for deeper cooperation, with the question of NATO membership to be decided by a national referendum. However, former President Viktor Yanukovych was against Ukraine joining NATO.

Since the start of the Russo-Ukrainian War in 2014, Ukraine has undergone significant military modernization. Junior officers have been empowered to take more initiative, and a territorial defense force of volunteers was established. Many countries have supplied defensive weapons, including drones. While initially vulnerable to shelling and high-level bombing, the Ukrainian military effectively used shoulder-mounted weapons against tanks, armored vehicles, and low-flying aircraft during the 2022 Russian invasion. As of August 2023, estimates of Ukrainian military casualties during the Russian invasion included up to 70,000 soldiers killed and 100,000 to 120,000 soldiers wounded.

Ukraine has also played an increasing role in peacekeeping operations, contributing troops to missions in Kosovo (as part of a Ukrainian-Polish Battalion), Lebanon (as part of the UN Interim Force), and Iraq (under Polish command in 2003-2005). Military units from other nations regularly participated in multinational exercises with Ukrainian forces in Ukraine, including U.S. military forces.

5.6. Administrative divisions

Ukraine's administrative division system reflects its status as a unitary state, ensuring unified legal and administrative regimes for each unit, as stipulated in the country's constitution.

The country consists of 27 regions, including 24 oblasts (provinces), one autonomous republic (Autonomous Republic of Crimea, currently under Russian occupation since 2014), and two cities with special status-Kyiv, the capital, and Sevastopol (also under Russian occupation since 2014). The 24 oblasts and Crimea are further subdivided into 136 raions (districts) and city municipalities of regional significance, serving as second-level administrative units.

Populated places in Ukraine are categorized as either urban or rural. Urban areas are further classified into cities and urban-type settlements (a Soviet administrative invention), while rural areas comprise villages and other settlements. All cities possess a certain degree of self-rule, with the level of significance varying from national (Kyiv and Sevastopol) to regional (within each oblast or autonomous republic) or district. A city's significance is determined by factors such as population size, socio-economic and historical importance, and infrastructure.

| Oblasts | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|- | Autonomous republic | Cities with special status | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| style="vertical-align:top;"|

|} | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Date | Name | Local Name |

|---|---|---|

| January 1 | New Year's Day | Новий рікUkrainian |

| March 8 | International Women's Day | Міжнародний жіночий ДеньUkrainian |

| May 1 | Labour Day | День міжнародної солідарності трудящихUkrainian |

| (moveable) | Easter | ВеликденьUkrainian |

| May 8 | Day of Remembrance and Victory over Nazism in World War II | День пам'яті та перемоги над нацизмом у Другій світовій війніUkrainian |

| (moveable) | Trinity Sunday | ТрійцяUkrainian |

| June 28 | Constitution Day | День КонституціїUkrainian |

| August 24 | Independence Day | День НезалежностіUkrainian |

| December 25 | Christmas Day | РіздвоUkrainian |