1. Overview

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (د افغانستان اسلامي امارتDə Afġānistān Islāmī ImāratPushto; امارت اسلامی افغانستانEmārat-e Eslāmi-ye AfghānestānPersian), is a landlocked country situated at the crossroads of Central and South Asia. Its history is marked by its strategic location, which has made it a focal point for numerous empires, trade routes like the Silk Road, and unfortunately, prolonged conflicts. From ancient civilizations through periods of Buddhist and Hindu influence, Islamic caliphates, Mongol and Timurid rule, to the emergence of the modern Afghan state under the Hotak and Durrani dynasties, Afghanistan has a rich and complex past. The 19th and early 20th centuries saw the country navigate the "Great Game" between British and Russian imperial interests, eventually achieving full independence. However, the latter half of the 20th century and the early 21st century have been characterized by significant political instability, including coups, the Soviet invasion, devastating civil wars, the rise and fall and resurgence of the Taliban, and a US-led intervention.

This article examines Afghanistan's journey, emphasizing the profound social and humanitarian impacts of its history, particularly the ongoing struggles for social justice, human rights, and democratic development. It details the country's diverse geography, from the towering Hindu Kush mountains to its arid plains, and the environmental challenges it faces, including climate change. The political landscape, especially under the current de facto Taliban administration, is analyzed with a focus on governance structures, international relations, and the severe human rights situation, with particular attention to the drastic curtailment of women's rights and the persecution of minorities. The economy, while possessing significant untapped mineral wealth, grapples with poverty, reliance on aid, and the legacies of conflict. The nation's diverse demographics, rich cultural heritage encompassing traditions, literature, music, art, and cuisine, are also explored, alongside the challenges faced by its education and healthcare systems, and the state of its media under evolving political conditions. The overarching narrative seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of Afghanistan, highlighting its resilience while critically examining the obstacles to achieving a just, equitable, and democratic society.

2. Etymology

The name "Afghanistan" translates to "Land of the Afghans." The term "Afghan" has historically been used to refer to the Pashtun people, the largest ethnic group in the country. Some scholars suggest that the root name Afghān is derived from the Sanskrit word Aśvakan, which was a name used for ancient inhabitants of the Hindu Kush region. Aśvakan literally means "horsemen," "horse breeders," or "cavalrymen," from aśva, the Sanskrit and Avestan word for "horse." Greek historians like Arrian referred to these people as the Assakenoi. This connection implies that the region was known for its skilled horsemen and superior breeds of horses in ancient times.

The Arabic and Persian form of the name, Afġān, was first attested in the 10th-century geography book Hudud al-'Alam. The suffix "-stan" is a Persian suffix meaning "place of" or "land of." Therefore, "Afghanistan" means "Land of the Afghans" or, in a historical sense, "Land of the Pashtuns."

According to the Encyclopaedia of Islam, the name Afghanistan (Afghānistān) can be traced to the early 14th century (8th century Hijri), when it designated the easternmost part of the Kartid realm. This name was later used for certain regions in the Ṣafavid and Mughal empires inhabited by Afghans. While the Sadūzāʾī Durrānī polity that emerged in 1747 was based on an elite of Abdālī/Durrānī Afghans, it was not called Afghanistan in its own day. The name became a state designation only during the colonial intervention of the 19th century. The term "Afghanistan" was officially used in 1855 when the British recognized Dost Mohammad Khan as king of the Emirate of Afghanistan.

3. History

Afghanistan's history is a long and complex tapestry stretching from prehistoric human settlements to the tumultuous events of the 21st century. Its strategic location at the crossroads of major civilizations has made it a coveted territory for empires and a vital link in trade and cultural exchange, but also a frequent battleground. The nation's story encompasses ancient empires, the spread of major religions, Islamic dynasties, Mongol and Timurid rule, the rise of Afghan-led empires, colonial-era power struggles, periods of modernization and monarchy, republican experiments, socialist revolutions, foreign interventions, devastating civil wars, and the recurring dominance of the Taliban. Throughout these eras, the Afghan people have faced profound challenges to their social fabric, human rights, and aspirations for democratic development.

3.1. Prehistory and antiquity

Human habitation in the region now known as Afghanistan dates back to at least 50,000 years ago, during the Middle Paleolithic era. Archaeological excavations have revealed that farming communities in this area were among the earliest in the world, with evidence of peasant farming villages appearing around 7,000 years ago. Many believe that Afghanistan's archaeological sites rival those of Egypt in historical value. Artifacts from the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Bronze, and Iron Ages have been discovered across the country.

Urban civilization is thought to have begun as early as 3000 BCE. The ancient city of Mundigak, near Kandahar, was a significant center of the Helmand culture. More recent findings indicate that the Indus Valley Civilization extended its influence into modern-day Afghanistan, with an Indus Valley site found at Shortugai on the Oxus River (Amu Darya) in northern Afghanistan.

After 2000 BCE, successive waves of semi-nomadic peoples from Central Asia, many of whom were Indo-European-speaking Indo-Iranians, began migrating south into Afghanistan. These tribes later moved further into South Asia, Western Asia, and towards Europe. The region during this period was often referred to as Ariana.

By the mid-6th century BCE, the Achaemenid Empire of Persia, under rulers like Darius the Great, overthrew the Medes and incorporated regions such as Arachosia, Aria, and Bactria into its eastern territories. An inscription on Darius I's tomb lists the Kabul Valley as one of the 29 countries he had conquered. The region of Arachosia, around present-day Kandahar, was a significant center of Zoroastrianism and is considered by some scholars to have played a key role in the transmission of the Avesta (Zoroastrian holy texts) to Persia, sometimes being referred to as the "second homeland of Zoroastrianism."

In 330 BCE, Alexander the Great and his Macedonian forces arrived in Afghanistan after defeating Darius III of Persia at the Battle of Gaugamela. Alexander's conquest was brief, and following his death, the Seleucid Empire controlled the region. Around 305 BCE, the Seleucids ceded much of this territory to the Maurya Empire of India as part of an alliance treaty. The Mauryans, under emperors like Ashoka, introduced and promoted Buddhism in the areas south of the Hindu Kush. Their rule lasted until about 185 BCE, when their decline led to a Hellenistic reconquest by the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. Much of the region soon broke away to form the Indo-Greek Kingdom. These Hellenistic rulers were eventually defeated and expelled by the Indo-Scythians in the late 2nd century BCE.

The Silk Road emerged during the 1st century BCE, and Afghanistan, situated at its heart, flourished with trade. Routes connected China, India, Persia, and cities to the north like Bukhara, Samarkand, and Khiva (in present-day Uzbekistan). This facilitated the exchange of goods such as Chinese silk, Persian silver, and Roman gold, as well as ideas. Afghanistan itself was a source of prized lapis lazuli, mined extensively in the Badakhshan region.

During the 1st century BCE, the Parthian Empire subjugated the region but subsequently lost it to their Indo-Parthian vassals. By the mid-to-late 1st century CE, the vast Kushan Empire, centered in Afghanistan, became great patrons of Buddhist culture, leading to a flourishing of Buddhism throughout the region. The Kushans were overthrown by the Sasanids of Persia in the 3rd century CE, though the Indo-Sasanids continued to rule parts of the region. They were followed by the Kidarites, who in turn were replaced by the Hephthalites (White Huns). In the 7th century, the Turk Shahi dynasty ruled parts of the area. The Buddhist Turk Shahis of Kabul were eventually replaced by a Hindu dynasty, the Hindu Shahis, before the Saffarids conquered the area in 870 CE. Despite these dynastic changes, Buddhist culture remained dominant in much of the northeastern and southern areas of the country.

3.2. Medieval period

In 642 CE, Arab Muslims introduced Islam to Herat and Zaranj in western Afghanistan and began its eastward spread. While some native inhabitants accepted the new faith, others resisted. Before the advent of Islam, the region was a melting pot of various beliefs, including Zoroastrianism, Buddhism (often in its Greco-Buddhist form), ancient Iranian religions, Hinduism, Nestorian Christianity, and Judaism. Syncretism was common, with people often patronizing Buddhism while still worshipping local Iranian deities like Ahura Mazda, Lady Nana, Anahita, or Mihr (Mithra), and sometimes portraying Greek gods as protectors of Buddha.

The Zunbils and Kabul Shahis, who resisted Arab expansion for a considerable time, were eventually conquered in 870 CE by the Saffarid Muslims based in Zaranj. Subsequently, the Samanids, another Persianate dynasty, extended their Islamic influence south of the Hindu Kush. The Ghaznavids, of Turkic origin, rose to power in the 10th century, with Ghazni as their capital.

By the 11th century, Mahmud of Ghazni, the most prominent Ghaznavid ruler, had defeated the remaining Hindu rulers and effectively completed the Islamization of the wider region, with the notable exception of Kafiristan (present-day Nuristan), which retained its indigenous beliefs until the late 19th century. Mahmud transformed Ghazni into a major cultural and political center, patronizing intellectuals such as the historian Al-Biruni and the poet Ferdowsi, who composed the epic Shahnameh at his court.

The Ghaznavid dynasty was overthrown by the Ghurids in 1186. The Ghurids, originating from the Ghor region of central Afghanistan, were also patrons of Islamic art and architecture, with the remote Minaret of Jam being one of their most famous achievements. However, Ghurid control over Afghanistan lasted less than a century before they were conquered by the Khwarazmian dynasty in 1215.

3.3. Mongol and Timurid eras

In 1219 CE, Genghis Khan and his Mongol armies overran the region, marking a period of significant devastation. Mongol troops are said to have annihilated the Khwarazmian cities of Herat and Balkh, as well as Bamyan. The destruction caused by the Mongols forced many local populations to revert to an agrarian, rural society, disrupting established urban centers and trade networks.

Mongol rule continued under the Ilkhanate in the northwestern parts of Afghanistan. Meanwhile, the Khalji dynasty, of Turkic origin with Afghan affiliations, administered tribal areas south of the Hindu Kush. This period was relatively short-lived before the rise of Timur (also known as Tamerlane), a Turco-Mongol conqueror who established the Timurid Empire in 1370.

Under Timurid rule, particularly during the reign of Shah Rukh (Timur's son), the city of Herat became a focal point of the Timurid Renaissance. This era witnessed a remarkable cultural and artistic flourishing, with Herat's intellectual and artistic achievements rivaling those of Florence during the Italian Renaissance. The Timurids patronized arts, literature, science, and architecture, leaving a lasting impact on the region's cultural heritage.

In the early 16th century, Babur, a descendant of Timur, arrived from Ferghana (in present-day Uzbekistan) and captured Kabul from the Arghun dynasty. Babur used Kabul as a base to launch his conquest of the Indian subcontinent, eventually defeating the Afghan Lodi dynasty at the First Battle of Panipat in 1526 and establishing the Mughal Empire in India.

Between the 16th and 18th centuries, parts of Afghan territory were ruled by various external powers. The Uzbek Khanate of Bukhara controlled areas in the north, the Iranian Safavids held sway in the west (including Herat), and the Indian Mughals controlled regions in the east, including Kabul. During this medieval period and up to the 19th century, the northwestern area of Afghanistan was commonly referred to by the regional name Khorasan by its native inhabitants.

3.4. Hotak dynasty and Durrani Empire

In 1709, Mirwais Hotak, a prominent leader of the Ghilzai Pashtun tribe from Kandahar, successfully rebelled against the Safavid Persian rule. He defeated Gurgin Khan, the Georgian governor of Kandahar under the Safavids, and established an independent Pashtun kingdom in the region, known as the Hotak dynasty. Mirwais died in 1715 and was succeeded by his brother, Abdul Aziz. However, Abdul Aziz was soon killed by Mirwais's son, Mahmud, reportedly for planning to make peace with the Safavids.

In 1722, Mahmud Hotak led the Afghan army to the Persian capital of Isfahan. After the decisive Battle of Gulnabad, he captured the city and proclaimed himself King of Persia. This marked a period of Afghan control over Persia. However, the Afghan dynasty was eventually ousted from Persia by Nader Shah, the founder of the Afsharid dynasty, after the Battle of Damghan in 1729.

In 1738, Nader Shah and his Afsharid forces captured Kandahar in the siege of Kandahar, which was the last Hotak stronghold, from Shah Hussain Hotak. Soon after, Nader Shah, accompanied by his young Pashtun commander Ahmad Shah Durrani (then Ahmad Khan Abdali), launched an invasion of India. Nader Shah's forces plundered Delhi. Nader Shah was assassinated in 1747.

Following Nader Shah's death, Ahmad Shah Durrani returned to Kandahar with a contingent of 4,000 Pashtuns. The Abdali Pashtun tribes unanimously accepted Ahmad Shah as their new leader. In October 1747, a loya jirga (grand assembly) near Kandahar chose Ahmad Shah as king, marking the founding of the Durrani Empire. This event is widely considered the beginning of the modern state of Afghanistan. Ahmad Shah Durrani adopted the title "Durr-i-Durran" (Pearl of Pearls).

Ahmad Shah Durrani launched multiple military campaigns, expanding his empire significantly. He campaigned against the declining Mughal Empire in India, the Maratha Empire, and the weakening Afsharid Empire in Persia. He captured Kabul and Peshawar from the Mughal-appointed governor. Herat was conquered in 1750, and Kashmir was captured in 1752. Ahmad Shah also led two major campaigns into Khorasan (1750-1751 and 1754-1755). His forces besieged Mashhad and Nishapur, eventually securing Afghan sovereignty over parts of Khorasan.

Ahmad Shah invaded India eight times during his reign. His most significant victory was at the Third Battle of Panipat in 1761, where he decisively defeated the Maratha Confederacy. This battle created a power vacuum in northern India and temporarily halted Maratha expansion.

Ahmad Shah Durrani died in October 1772. His death was followed by a civil war over succession. His designated successor, Timur Shah Durrani, eventually secured the throne after defeating his brother, Suleiman Mirza. Timur Shah moved the capital of the Durrani Empire from Kandahar to Kabul, a more central location. His reign focused on consolidating the empire and quelling rebellions. He also campaigned in Punjab against the Sikhs, achieving some successes, including the recapture of Multan. However, Timur Shah had over 24 sons, which led to further succession crises and civil wars after his death in May 1793, weakening the Durrani Empire.

Zaman Shah Durrani succeeded his father, Timur Shah, but faced immediate revolts from his brothers, Mahmud Shah Durrani and Humayun Mirza. Zaman Shah defeated Humayun and initially secured Mahmud Shah's loyalty. He launched campaigns into Punjab but was forced to withdraw due to threats of a Qajar Persian invasion. Zaman Shah was eventually overthrown by Mahmud Shah Durrani. Mahmud Shah's first reign was short-lived; he was deposed by his brother Shah Shuja Durrani in 1803. Shah Shuja attempted to consolidate the empire but was himself overthrown by Mahmud Shah at the Battle of Nimla in 1809, marking Mahmud Shah's second reign. These internal conflicts significantly eroded the power and extent of the Durrani Empire.

3.5. Barakzai dynasty and British influence

By the early 19th century, the Durrani Empire was severely weakened by internal strife and external pressures from the Qajar dynasty of Persia to the west and the Sikh Empire under Ranjit Singh to the east. Fateh Khan, leader of the powerful Barakzai tribe and vizier to Mahmud Shah Durrani, had installed many of his brothers in positions of power. After Fateh Khan was brutally murdered in 1818 by Mahmud Shah, the Barakzai brothers rebelled, leading to a prolonged civil war. Afghanistan fractured into several smaller states, including the Principality of Qandahar, the Emirate of Herat, the Khanate of Kunduz, and the Maimana Khanate. The most prominent of these was the Emirate of Kabul, ruled by Dost Mohammad Khan, one of Fateh Khan's brothers.

With the collapse of Durrani authority, Punjab and Kashmir were lost to Ranjit Singh. The Sikhs captured Peshawar in March 1823 after the Battle of Nowshera. In 1834, Dost Mohammad Khan defeated an attempt by the former Durrani ruler Shah Shuja Durrani (supported by the British) to reclaim Kabul in the Expedition of Shuja ul-Mulk. In 1837, Dost Mohammad Khan's forces, led by his son Wazir Akbar Khan, fought the Sikhs at the Battle of Jamrud near the Khyber Pass. Although the Afghans failed to capture the Jamrud Fort, they killed the renowned Sikh commander Hari Singh Nalwa, effectively ending the Afghan-Sikh Wars.

By this time, the British Empire, advancing from India, and the Russian Empire, expanding from Central Asia, were vying for influence in the region, a period known as "The Great Game". Afghanistan became a critical buffer state. The British, fearing Russian encroachment towards India, launched the First Anglo-Afghan War (1839-1842). A British expeditionary force invaded, captured Kandahar, and seized Kabul in August 1839, reinstalling Shah Shuja Durrani as a puppet ruler. Dost Mohammad Khan, after initial successes, surrendered but was later allowed to return. An uprising against British occupation led to the assassination of Shah Shuja and the disastrous 1842 retreat from Kabul, where Elphinstone's army was annihilated. A punitive British expedition later sacked Kabul but ultimately withdrew, allowing Dost Mohammad Khan to return as ruler.

Dost Mohammad Khan then focused on reunifying much of Afghanistan, conquering Balkh, Kunduz, and Kandahar. His final campaign was against Herat, which he captured in 1863, shortly before his death. Despite the First Anglo-Afghan War, he maintained relatively friendly relations with the British, signing the Second Anglo-Afghan treaty in 1857 and resisted pressure from Bukhara and internal religious leaders to invade India during the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

Dost Mohammad's death in 1863 led to another civil war among his sons, primarily Mohammad Afzal Khan, Mohammad Azam Khan, and Sher Ali Khan. Sher Ali Khan emerged victorious in the Afghan Civil War (1863-1869). British concerns about Russian influence resurfaced, leading to the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878-1880). Sher Ali retreated north but died soon after. His son, Mohammad Yaqub Khan, became Amir and signed the Treaty of Gandamak in 1879, which ceded control of Afghanistan's foreign relations to Britain, making it an official British Protected State. An uprising in Kabul restarted the conflict, leading to Yaqub Khan's deposition. Abdur Rahman Khan, a grandson of Dost Mohammad Khan, seized power with British recognition. Ayub Khan, another claimant, defeated British forces at the Battle of Maiwand but was subsequently defeated at the Battle of Kandahar, securing Abdur Rahman's rule and ending the war.

Abdur Rahman Khan, known as the "Iron Amir" for his ruthlessness, consolidated power and centralized the state. In 1893, he signed an agreement with British India establishing the Durand Line as the border between Afghanistan and British India. This line divided Pashtun and Baloch territories, leading to long-standing tensions with Pakistan. He also conquered the Shia-dominated Hazarajat and pagan Kafiristan (renamed Nuristan) between 1891 and 1896, bringing these regions under central Afghan control. He died in 1901 and was succeeded by his son, Habibullah Khan.

Habibullah Khan maintained Afghanistan's neutrality during World War I, despite efforts by the Central Powers (the Niedermayer-Hentig Expedition) to persuade him to join them and attack British India. This neutrality caused some internal discontent. Habibullah was assassinated in February 1919, and his son Amanullah Khan eventually assumed power. Amanullah Khan, a supporter of full independence, invaded British India, initiating the Third Anglo-Afghan War.

3.6. Independence and Kingdom era

Following the Third Anglo-Afghan War and the signing of the Treaty of Rawalpindi on August 19, 1919, Emir Amanullah Khan declared the Emirate of Afghanistan a sovereign and fully independent state. He moved to end Afghanistan's traditional isolation by establishing diplomatic relations with the international community, particularly with the newly formed Soviet Union and the Weimar Republic of Germany. On June 9, 1926, he proclaimed himself King of Afghanistan, establishing the Kingdom of Afghanistan.

King Amanullah Khan initiated a series of ambitious reforms aimed at modernizing the nation. A key figure behind these reforms was Mahmud Tarzi, his father-in-law and foreign minister, who was an ardent supporter of education, particularly for women. Tarzi championed Article 68 of Afghanistan's 1923 constitution, which made elementary education compulsory. Slavery was officially abolished in 1923. King Amanullah's wife, Queen Soraya, played a significant role during this period, advocating for women's education and opposing their oppression.

Some of Amanullah's reforms, such as the abolition of the traditional burqa for women and the opening of co-educational schools, alienated many tribal and religious leaders. This opposition, coupled with social and economic grievances, led to the Afghan Civil War (1928-1929). Facing widespread rebellion, King Amanullah abdicated in January 1929. Kabul soon fell to Saqqawist forces led by Habibullah Kalakani, a Tajik leader.

Mohammed Nadir Shah, Amanullah's cousin, eventually defeated and executed Kalakani in October 1929, and was declared King Nadir Shah. He abandoned many of Amanullah's rapid reforms in favor of a more gradual approach to modernization. However, Nadir Shah was assassinated in 1933 by Abdul Khaliq, a Hazara student.

Mohammed Zahir Shah, Nadir Shah's 19-year-old son, succeeded to the throne and reigned as king from 1933 to 1973. His long rule was marked by relative stability, though challenged by the tribal revolts of 1944-1947, led by figures such as Mazrak Zadran and Mirzali Khan, many of whom were loyal to Amanullah. Afghanistan joined the League of Nations in 1934. The 1930s saw the development of roads, infrastructure, the founding of a national bank, and increased access to education. Road links in the north contributed to a growing cotton and textile industry. The country built close relationships with the Axis powers, with Nazi Germany playing a significant role in Afghan development at the time.

Until 1946, King Zahir Shah ruled with the assistance of his uncles, who held the post of Prime Minister of Afghanistan and continued Nadir Shah's policies. From 1946 to 1953, another uncle, Shah Mahmud Khan, served as prime minister and experimented with greater political freedom. In 1953, he was replaced by Mohammed Daoud Khan, the king's cousin and brother-in-law. Daoud Khan, a Pashtun nationalist, pursued the creation of a "Pashtunistan" (a state for all Pashtuns), leading to highly tense relations with Pakistan. He also pressed for social modernization reforms and sought a closer relationship with the Soviet Union. During his "Decade of Daoud" (1953-1963), Afghanistan received significant Soviet development aid. Following Daoud Khan's dismissal by the King, the 1964 constitution was promulgated, introducing a period of constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy, and the first non-royal prime minister was sworn in.

Throughout his reign, Zahir Shah, like his father, aimed to maintain national independence while pursuing gradual modernization and fostering nationalist sentiment. Afghanistan remained neutral during World War II and was not aligned with either power bloc in the Cold War. However, it benefited from the Cold War rivalry as both the Soviet Union and the United States vied for influence by funding major infrastructure projects like highways and airports.

3.7. Republic and Saur Revolution

In 1973, while King Zahir Shah was in Italy for medical treatment, his cousin and former Prime Minister, Mohammed Daoud Khan, launched a bloodless coup d'état. Daoud Khan abolished the monarchy and declared himself the first President of Afghanistan, establishing the Republic of Afghanistan. He initially enjoyed support from various factions, including some leftist elements. However, Daoud Khan's rule became increasingly autocratic, and he suppressed political opposition, including the nascent communist People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). His attempts to reduce Soviet influence and improve relations with Western and Islamic countries, alongside internal power struggles and economic difficulties, created an environment of discontent.

On April 27, 1978, the PDPA, with support from elements within the Afghan military, staged a violent coup known as the Saur Revolution. President Daoud Khan and most of his family were killed. The PDPA seized power and declared the establishment of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, a socialist state. Nur Muhammad Taraki, General Secretary of the PDPA, became the head of state (Chairman of the Revolutionary Council) and Prime Minister. The PDPA government immediately embarked on a radical program of socio-economic reforms, including land redistribution, secularization of marriage laws, and campaigns against illiteracy. These reforms, often implemented forcefully and without regard for traditional customs or religious sensitivities, provoked widespread opposition, particularly in rural areas. This opposition quickly coalesced into armed resistance by various groups collectively known as the Mujahideen. The PDPA itself was deeply divided between two main factions: the more radical Khalq (People) faction, led by Taraki and Hafizullah Amin, and the more moderate Parcham (Banner) faction, led by Babrak Karmal. Internal power struggles within the PDPA, particularly between Taraki and Amin, further destabilized the regime.

3.8. Soviet-Afghan War

The Soviet-Afghan War (1979-1989) was a devastating conflict that followed the Soviet Union's military intervention in Afghanistan to support the struggling communist government of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) against a growing insurgency by the Mujahideen.

The background to the war lay in the aftermath of the 1978 Saur Revolution, which brought the PDPA to power. The PDPA's radical reforms and brutal suppression of dissent led to widespread rebellion. Internal factionalism within the PDPA, particularly between the Khalq and Parcham factions, further weakened the regime. In September 1979, Hafizullah Amin overthrew and killed Nur Muhammad Taraki. Amin's increasingly erratic and brutal rule, coupled with the regime's inability to quell the Mujahideen insurgency, alarmed the Soviet leadership. Fearing the collapse of a friendly socialist state on its southern border and the potential spread of Islamic fundamentalism into Soviet Central Asia, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan on December 24, 1979. Soviet forces quickly occupied Kabul, killed Amin, and installed Babrak Karmal, leader of the Parcham faction, as the new head of state.

The Soviet intervention transformed the internal conflict into a major Cold War proxy war. The Mujahideen, a diverse coalition of Islamist groups, received substantial support from the United States (through Operation Cyclone), Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, China, and other countries. Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) played a crucial role in training and channeling aid to the Mujahideen. The resistance fighters waged a protracted guerrilla war against the technologically superior Soviet and Afghan government forces. Key Mujahideen commanders included Ahmad Shah Massoud, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, and Ismail Khan.

The war had a profound humanitarian impact. Estimates of Afghan deaths range from 562,000 to over 2 million civilians and combatants. Around 6 million Afghans became refugees, fleeing primarily to Pakistan and Iran, creating one of the largest refugee crises of the 20th century. Millions more were internally displaced. The conflict devastated Afghanistan's infrastructure, economy, and social fabric. Heavy Soviet air bombardment destroyed numerous villages, and millions of landmines were planted, causing long-term civilian casualties. Cities like Herat and Kandahar also suffered significant damage.

The Soviet military, despite its superior firepower, struggled to defeat the Mujahideen in the rugged Afghan terrain. The war became a costly quagmire for the Soviet Union, often referred to as its "Vietnam." Growing domestic opposition to the war, mounting casualties, and the economic burden led Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev to seek a withdrawal. The Geneva Accords were signed in April 1988, and the Soviet withdrawal was completed on February 15, 1989.

The Soviet-Afghan War left a legacy of destruction and instability. It fueled the rise of radical Islamist groups, contributed to the militarization of Afghan society, and exacerbated ethnic and tribal divisions. The war's geopolitical consequences were also significant, contributing to the weakening of the Soviet Union and altering regional power dynamics. The departure of Soviet troops did not bring peace, as the PDPA government, now led by Mohammad Najibullah, continued to fight the Mujahideen in the ensuing civil war.

3.9. Civil war and First Taliban regime

Following the Soviet withdrawal in 1989, the communist government of President Mohammad Najibullah continued to fight the Mujahideen in the Afghan Civil War (1989-1992). However, with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the cessation of Soviet aid, Najibullah's regime weakened significantly and fell in April 1992.

The Mujahideen factions, despite their common enemy, were deeply divided along ethnic, tribal, and ideological lines. The Peshawar Accords led to the formation of the Islamic State of Afghanistan, a coalition government. However, infighting quickly broke out among the various factions, most notably between forces loyal to President Burhanuddin Rabbani and Ahmad Shah Massoud (predominantly Tajik Jamiat-e Islami) and those of Prime Minister Gulbuddin Hekmatyar (Pashtun Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin). Other factions, such as Abdul Rashid Dostum's Uzbek Junbish-i Milli and various Hazara Shia groups, also played significant roles, often shifting alliances. The ensuing civil war (1992-1996) devastated Kabul and other parts of the country, leading to widespread civilian casualties, displacement, and human rights abuses.

Amidst this chaos, the Taliban emerged in southern Afghanistan in 1994. Composed largely of Pashtun religious students (talib) from madrassas in Pakistan and Afghanistan, and led by Mohammed Omar, the Taliban promised to restore order and implement a strict interpretation of Islamic law (Sharia). They received significant support from Pakistan and, to some extent, Saudi Arabia.

The Taliban quickly gained territory, capturing Kandahar in late 1994 and Herat in 1995. In September 1996, they captured Kabul, ousting the Rabbani government, which retreated to northern Afghanistan. The Taliban declared the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. Their rule (1996-2001) was characterized by the severe enforcement of their interpretation of Sharia law. This included public executions and amputations, a ban on music, television, and most forms of recreation, and strict dress codes.

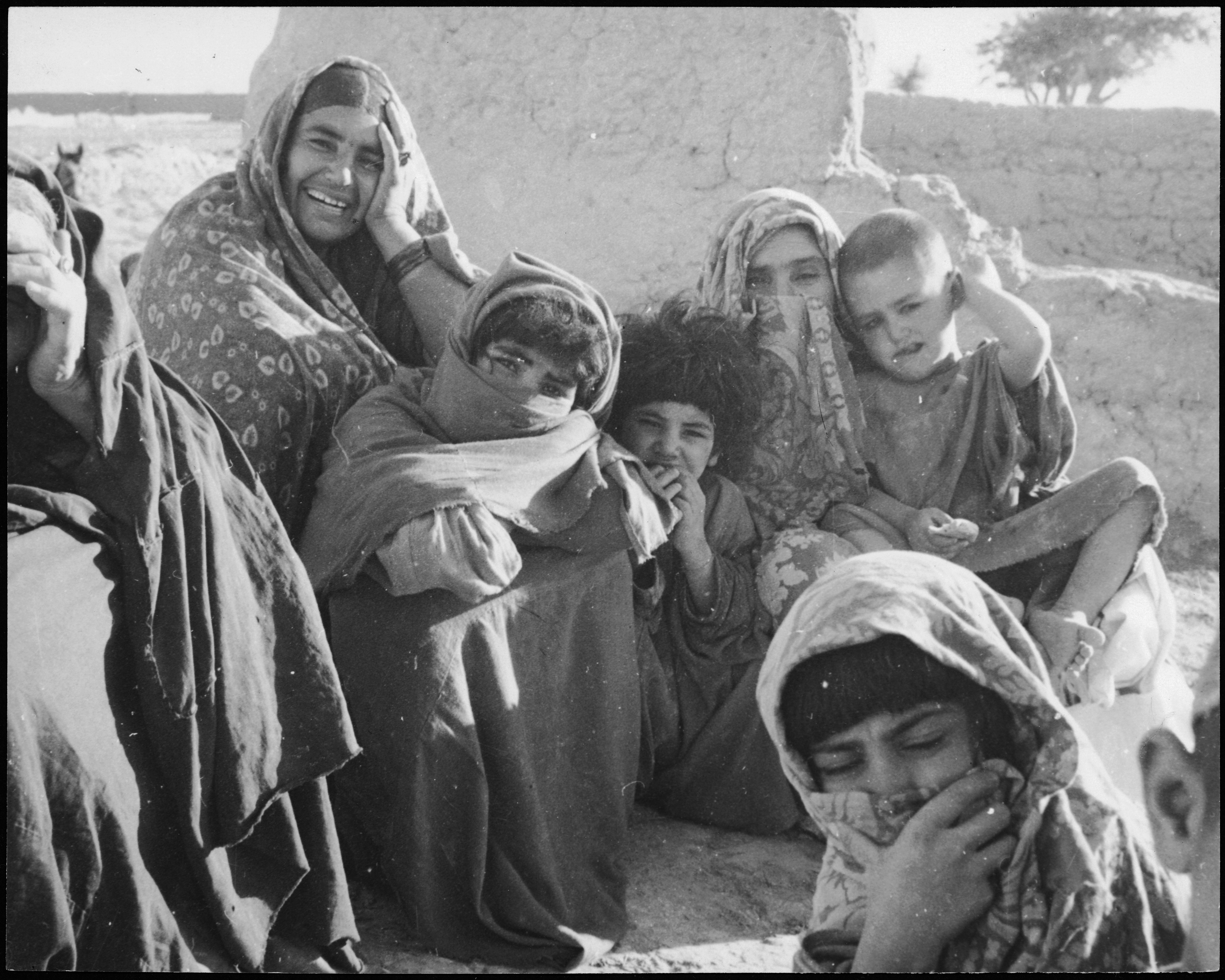

The Taliban's policies had a particularly devastating impact on women's rights. Women were largely barred from education and employment, required to wear the burqa in public, and severely restricted in their freedom of movement. Violations were met with harsh punishments by the Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice. Ethnic minorities, particularly the Hazaras, also faced persecution and massacres. The Taliban regime was internationally isolated, recognized only by Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. They provided sanctuary to Osama bin Laden and his al-Qaeda network, which established training camps in Afghanistan.

The remaining anti-Taliban forces, primarily composed of Massoud's Jamiat-e Islami, Dostum's Junbish-i Milli, and Hazara factions, formed the Northern Alliance (officially the United Islamic Front for the Salvation of Afghanistan). They continued to resist Taliban rule, controlling a small portion of northeastern Afghanistan. On September 9, 2001, just two days before the September 11 attacks, Ahmad Shah Massoud was assassinated by al-Qaeda operatives posing as journalists.

3.10. US-led intervention and Islamic Republic

Following the September 11 attacks in 2001, the United States identified Osama bin Laden and his al-Qaeda network, hosted by the Taliban in Afghanistan, as responsible. The US demanded that the Taliban hand over bin Laden. When the Taliban refused, the US, with support from allies including the United Kingdom, launched Operation Enduring Freedom on October 7, 2001, initiating the US-led invasion of Afghanistan. The invasion involved airstrikes against Taliban and al-Qaeda targets, coupled with support for the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance. By December 2001, the Taliban regime had collapsed, and many of its leaders, along with al-Qaeda members, fled to Pakistan or remote areas of Afghanistan.

In December 2001, the Bonn Agreement established the Afghan Interim Administration headed by Hamid Karzai. The International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) was created by the UN Security Council to provide security and assist the new Afghan government. The country faced immense challenges: a shattered infrastructure, a devastated economy, widespread poverty, high infant and child mortality rates, and millions of refugees and internally displaced persons. International donors pledged significant aid for reconstruction.

A loya jirga in 2002 appointed Karzai as President of the Afghan Transitional Administration. A new constitution was adopted in January 2004, establishing the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. Presidential elections were held in October 2004, which Karzai won. Parliamentary elections followed in 2005.

Despite these efforts, the Taliban regrouped and launched an insurgency against the new Afghan government and ISAF forces. The conflict escalated over the years, with the Taliban employing guerrilla tactics, suicide bombings, and improvised explosive devices (IEDs). Pakistan was repeatedly accused of providing sanctuary and support to the Taliban, a charge it denied. The war caused significant civilian casualties and hampered reconstruction efforts.

The international military presence peaked at around 140,000 troops in 2011, with the US contributing the largest contingent. Efforts were made to train and equip the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) to eventually take over security responsibilities. However, challenges such as corruption, weak governance, and the persistent insurgency undermined progress.

Hamid Karzai served two terms as president. The 2014 presidential election was marked by allegations of fraud and resulted in a power-sharing agreement, with Ashraf Ghani becoming president and Abdullah Abdullah becoming Chief Executive.

In December 2014, NATO formally ended ISAF combat operations, transitioning to a new, smaller mission called Operation Resolute Support, focused on training, advising, and assisting Afghan security forces. However, the security situation remained fragile, with the Taliban and other insurgent groups, including a branch of the Islamic State (ISIL-KP), continuing their attacks.

The war in Afghanistan (2001-2021) had a devastating human cost. Estimates suggest that over 176,000 people were killed in the conflict, including tens of thousands of civilians. Peace talks between the US and the Taliban gained momentum in the late 2010s, leading to the Doha Agreement in February 2020. This agreement stipulated the withdrawal of US and NATO forces in exchange for Taliban counter-terrorism guarantees and a commitment to intra-Afghan peace negotiations.

3.10.1. Taliban insurgency and international response

During the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (2004-2021), the Taliban insurgency remained a persistent and escalating threat. After being ousted from power in late 2001, Taliban forces regrouped, primarily in the border regions of Pakistan, and began launching attacks against the newly established Afghan government, the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF), and international ISAF/Resolute Support Mission troops.

The insurgency was characterized by guerrilla warfare, suicide attacks, improvised explosive device (IED) attacks, and targeted assassinations. The Taliban aimed to destabilize the Afghan government, expel foreign forces, and re-establish their Islamic Emirate. They gradually expanded their influence, particularly in rural areas of the south and east, establishing shadow governments and challenging state authority. Factors contributing to the insurgency's resilience included support from external actors (notably elements within Pakistan), exploitation of local grievances, corruption within the Afghan government, and the difficulties faced by ANSF and international forces in the rugged Afghan terrain and complex socio-political environment.

The international response was multifaceted, involving military, political, and developmental efforts.

Military Response:

ISAF, and later the Resolute Support Mission, led by NATO, conducted counter-insurgency operations, trained and equipped the ANSF, and provided air support. The United States maintained the largest military presence and played a leading role in combat operations. Strategies evolved over time, from a focus on direct combat to an emphasis on population-centric counter-insurgency and, eventually, a transition to an advisory and support role for ANSF. Despite significant military efforts and resources, completely defeating the insurgency proved elusive.

Political Response:

Efforts were made to support the Afghan government in strengthening its institutions, improving governance, and promoting national reconciliation. International partners facilitated elections and supported constitutional processes. However, political progress was often hampered by internal divisions, corruption, and the challenges of state-building in a conflict environment. Towards the later years of the Islamic Republic, direct peace negotiations between the United States and the Taliban gained prominence, culminating in the Doha Agreement in February 2020. This agreement, which excluded the Afghan government, outlined a timeline for US troop withdrawal in exchange for Taliban counter-terrorism commitments and a pledge to enter intra-Afghan peace talks. These intra-Afghan talks, however, made little progress.

Developmental Response:

Significant international aid was directed towards Afghanistan for reconstruction, infrastructure development, education, healthcare, and economic development. The aim was to address the root causes of instability and build a more prosperous and stable Afghanistan. While some progress was made in areas like education and healthcare access, development efforts were often undermined by insecurity, corruption, and a lack of sustainable capacity within Afghan institutions.

The Taliban insurgency and the international response during this period had a profound impact on Afghan society, leading to immense human suffering, displacement, and a protracted state of conflict that ultimately saw the Taliban return to power in 2021.

3.11. Second Taliban regime

The withdrawal of US and NATO troops from Afghanistan, initiated under the Doha Agreement of February 2020 and accelerated by the Biden administration in 2021, set the stage for the Taliban's rapid return to power. As international forces departed, the Taliban launched a major offensive across the country starting in May 2021. The Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF), despite years of international training and billions of dollars in support, proved unable to withstand the Taliban advance, collapsing quickly in many areas. Contributing factors to the ANSF's collapse included a lack of US air support following the Doha deal, corruption, poor leadership, logistical failures, and low morale.

By early August 2021, the Taliban had captured numerous provincial capitals. On August 15, 2021, Taliban forces entered Kabul, and President Ashraf Ghani fled the country, leading to the collapse of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. The Taliban declared victory and the re-establishment of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. The rapid takeover led to chaotic scenes at Kabul's Hamid Karzai International Airport as thousands of Afghans and foreign nationals attempted to evacuate. The US and its allies conducted a massive airlift operation, which ended with the departure of the last US troops on August 30, 2021, formally concluding the 20-year war.

On September 7, 2021, the Taliban announced an interim government, led by Hasan Akhund as Acting Prime Minister and with Hibatullah Akhundzada as the Supreme Leader. The cabinet was composed almost entirely of Taliban loyalists, predominantly Pashtuns, with no women included, drawing international criticism for its lack of inclusivity.

The Taliban government remains internationally unrecognized by any country As of November 2024. The international community has expressed grave concerns over the human rights situation, particularly the severe restrictions imposed on women and girls, including bans on secondary and higher education for girls, exclusion from most forms of employment, and strict dress codes. Freedom of speech, assembly, and the media have also been significantly curtailed. Ethnic and religious minorities, such as the Hazaras, have reported increased persecution.

Afghanistan plunged into a severe humanitarian crisis following the Taliban takeover. The freezing of Afghan central bank assets held abroad (primarily by the US) and the suspension of most international aid led to an economic collapse, widespread poverty, and food insecurity. While the Taliban have claimed some success in tackling corruption and improving security in some areas, armed conflict persists, primarily from the Islamic State - Khorasan Province (ISIL-KP) and an anti-Taliban republican insurgency, notably the National Resistance Front (NRF) based in the Panjshir Valley, although Taliban forces largely suppressed organized resistance there by mid-September 2021.

In October 2023, the Pakistani government ordered the expulsion of undocumented Afghans, leading to a further humanitarian challenge for the Taliban authorities. Iran also deported Afghan nationals. The Taliban condemned these deportations. The country continues to face immense challenges related to governance, economic recovery, human rights, and international relations. In a notable development, Taliban representatives attended the 2024 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP29) in November 2024, marking their first participation in such a UN summit since returning to power, emphasizing climate change as a humanitarian rather than political issue.

4. Geography

Afghanistan is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central and South Asia. It shares borders with Pakistan to the east and south (along the Durand Line), Iran to the west, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan to the north, and China to the northeast and east via the narrow Wakhan Corridor. Occupying an area of approximately 252 K mile2 (652.86 K km2), Afghanistan is the world's 41st largest country. Its geography is predominantly mountainous, dominated by the formidable Hindu Kush mountain range, an extension of the Himalayas. These mountains separate the northern plains from the southwestern plateau, influencing climate, culture, and lines of communication. The country's highest point is Noshaq, at 25 K ft (7.49 K m). The capital and largest city is Kabul. Afghanistan is rich in natural resources, including significant deposits of lithium, iron, zinc, copper, and natural gas, though many remain largely untapped due to decades of conflict and lack of infrastructure.

4.1. Topography

Afghanistan's topography is largely characterized by rugged mountains and high plateaus, with the Hindu Kush range being its most dominant feature. This vast mountain system runs from the northeast, where it connects with the Pamir and Karakoram ranges, southwestwards across much of the country, effectively dividing it. Many of the highest peaks, including Noshaq (25 K ft (7.49 K m)), are located in the eastern Hindu Kush and the Wakhan Corridor. These mountainous regions contain fertile valleys that have historically supported agriculture and settlement.

North of the central Hindu Kush highlands lies the Turkestan Plains (or Northern Plains), an area of rolling grasslands and semi-deserts that gradually slope towards the Amu Darya (Oxus River), which forms part of Afghanistan's northern border with Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. This region is agriculturally important, particularly along river valleys.

To the southwest of the Hindu Kush, the terrain transitions into arid plateaus and desert basins. The Sistan Basin, located in the southwest bordering Iran, is an endorheic basin and one of the driest regions in the world. It is fed by several rivers, most notably the Helmand River, Afghanistan's longest river, which originates in the Hindu Kush and flows southwestward into the Hamun wetlands in the Sistan Basin. Other significant rivers include the Kabul River, which flows east to join the Indus River in Pakistan, and the Hari Rud (Harirud River), which flows west from the central highlands towards Herat and then north along the Iranian border before dissipating in Turkmenistan.

The country also features distinct geographical areas like the Hazarajat in the central highlands, primarily inhabited by the Hazara people, and regions like Nuristan in the east, known for its forests and rugged valleys.

4.2. Climate

Afghanistan predominantly features a continental climate characterized by significant temperature variations between seasons and even between day and night. Winters are generally harsh, especially in the central highlands (Hazarajat), the glaciated northeast (around Nuristan and the Wakhan Corridor), where average January temperatures can fall below 5 °F (-15 °C) and reach as low as -14.799999999999997 °F (-26 °C). Summers, in contrast, are hot and dry, particularly in the low-lying areas such as the Sistan Basin in the southwest, the Jalalabad basin in the east, and the Turkestan plains along the Amu River in the north, where average July temperatures exceed 95 °F (35 °C) and can surpass 109.4 °F (43 °C).

Precipitation is generally low across most of the country and primarily occurs during the winter and spring months (December to April), often as snowfall in the mountains. The lower-lying areas of northern and western Afghanistan are the driest. The eastern parts of the country, particularly the Nuristan region, can receive some summer monsoon rains due to their proximity to the Indian subcontinent, although most of Afghanistan lies outside the main monsoon zone.

Climate change is a significant and growing concern for Afghanistan. Despite contributing minimally to global greenhouse gas emissions, it is one of the countries most vulnerable to climate change impacts. These impacts include more frequent and severe droughts, leading to desertification, reduced water availability, and threats to food security. Rising temperatures are also causing glacier melt in the Hindu Kush, which can initially increase water flow but poses long-term risks of water scarcity and glacial lake outburst floods. Extreme rainfall events, when they occur, can lead to flash floods and landslides, particularly in mountainous regions. These climatic changes exacerbate existing vulnerabilities and pose serious challenges to agriculture, livelihoods, and human well-being, potentially leading to increased internal displacement. On November 10, 2024, Afghanistan's Foreign Ministry confirmed that Taliban representatives would attend the 2024 United Nations Climate Change Conference, marking the first time the country participated since the Taliban's return to power in 2021, with officials stressing climate change as a humanitarian, not political, issue.

4.3. Biodiversity

Afghanistan's diverse geography supports a varied range of flora and fauna, although decades of conflict and environmental degradation have posed significant threats to its biodiversity. The country is home to several distinct ecoregions, from alpine tundra to desert plains.

Fauna: Notable mammal species include the elusive snow leopard (Panthera uncia), which inhabits the high-altitude alpine regions of the Hindu Kush and Pamir Mountains and is considered the national animal. The Marco Polo sheep (Ovis ammon polii), known for its long, spiraling horns, is found exclusively in the Wakhan Corridor. Other mountain dwellers include the ibex and marmots. Forested areas in the east, such as Nuristan, provide habitat for species like brown bears, wolves, lynx, and various deer. The semi-desert northern plains are home to hedgehogs, gophers, jackals, and hyenas. Gazelles and wild boars can be found in the steppe plains of the south and west, while mongooses and cheetahs (though extremely rare) have been reported in the southern semi-deserts. The native Afghan hound is a distinctive dog breed known for its speed and long hair.

Endemic fauna includes the Afghan flying squirrel, Afghan snowfinch, the Paghman mountain salamander (Paradactylodon), the Afghan leopard gecko (Eublepharis macularius afghanicus), and several insect species like Stigmella kasyi and Vulcaniella kabulensis. Afghanistan has a rich avifauna, with an estimated 460 bird species, of which around 235 breed within the country.

Flora: The forest regions of Afghanistan, primarily in the east and some central areas, feature vegetation such as pine trees, spruce trees, fir trees, and larches. The East Afghan montane conifer forests ecoregion is particularly noteworthy. Steppe and grassland regions are characterized by broadleaf trees (often in riverine areas), short grasses, perennial plants, and shrublands. The colder, high-elevation areas are dominated by hardy grasses and small flowering plants. Pistachio woodlands are also a significant feature in some areas. Endemic flora includes species like Iris afghanica. Forest cover is limited, estimated at around 2% of the total land area.

Conservation: Afghanistan has several protected areas, including three national parks: Band-e Amir National Park, renowned for its series of brilliant blue travertine lakes; Wakhan National Park in the remote northeast, home to snow leopards and Marco Polo sheep; and Nuristan National Park, encompassing rugged forested mountains. Conservation efforts face numerous challenges, including ongoing insecurity, poverty (leading to unsustainable resource use like deforestation and overgrazing), illegal wildlife trade, and the impacts of climate change. The country had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 8.85/10, ranking it 15th globally out of 172 countries, indicating relatively intact forest landscapes in some areas, though overall forest cover is low.

5. Government and politics

Afghanistan's political system has undergone profound transformations throughout its history, particularly in recent decades. Following the collapse of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan in August 2021, the Taliban declared the country an Islamic Emirate. This section outlines the governance structure under the de facto Taliban administration, administrative divisions, foreign relations, military, and the critical human rights situation, reflecting a center-left/social liberalism perspective that emphasizes social justice, democratic principles, and human rights.

5.1. Governance under the Taliban

Since regaining power in August 2021, the Taliban have established a de facto government known as the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. The supreme authority rests with the Supreme Leader (Amir al-Mu'minin), currently Hibatullah Akhundzada, who holds ultimate decision-making power on all major state affairs, typically based in Kandahar.

A caretaker cabinet, announced in September 2021, manages the day-to-day administration of the country. This cabinet is led by an Acting Prime Minister, currently Hasan Akhund, and includes various ministers overseeing different government departments. Key positions are predominantly held by Taliban figures, many of whom were part of the previous Taliban regime (1996-2001) or are influential in the current movement, including members of the Haqqani network. The cabinet notably lacks representation from women and most ethnic minority groups, drawing significant international criticism for its lack of inclusivity.

The legal framework under the Taliban is based on their interpretation of Islamic Sharia law. The 2004 constitution of the Islamic Republic has been suspended or largely disregarded. While the Taliban have stated they would govern according to Sharia, specifics of the legal system, including the roles of formal courts and judicial processes, remain opaque and have been subject to ad hoc decrees. Traditional consultative mechanisms like the loya jirga (grand assembly), historically used for major national decisions, have not been formally convened by the Taliban in a manner consistent with past inclusive practices, though some large gatherings of clerics and tribal elders have been held.

The governance structure is highly centralized, with key decisions emanating from the Supreme Leader and the Taliban leadership council (Rahbari Shura). There is a Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, which enforces the Taliban's social and religious edicts. As of June 2024, no country has formally recognized the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan as the de jure government of Afghanistan, reflecting widespread international concerns about human rights, inclusivity, and governance.

5.2. Administrative divisions

Afghanistan is administratively divided into 34 provinces (wilayat). Each province is headed by a governor, who is appointed by the central government. Provincial governors are responsible for local administration, security coordination, and implementation of national policies at the provincial level.

The provinces are further subdivided into numerous districts (wuleswali). There are nearly 400 districts in total. Each district is typically headed by a district governor, also appointed by the central or provincial authorities. Districts usually encompass a city or a collection of villages and represent a key level of local governance and service delivery, although capacity and resources at this level have historically been limited and vary significantly across the country.

Major cities like Kabul, Kandahar, Herat, and Mazar-i-Sharif serve as provincial capitals and are important economic, political, and cultural centers. Municipal governance in these cities involves mayors, who under previous systems were sometimes elected but are currently appointed by the Taliban administration.

The system of administrative divisions has remained largely consistent through various political changes in Afghanistan, though the control and influence of the central government over provinces and districts have fluctuated depending on the prevailing security and political situation. Under the current Taliban administration, appointments to provincial and district leadership positions are made by the Taliban leadership.

The 34 provinces, in alphabetical order, are:

- Badakhshan

- Badghis

- Baghlan

- Balkh

- Bamyan

- Daykundi

- Farah

- Faryab

- Ghazni

- Ghor

- Helmand

- Herat

- Jowzjan

- Kabul

- Kandahar

- Kapisa

- Khost

- Kunar

- Kunduz

- Laghman

- Logar

- Nangarhar

- Nimruz

- Nuristan

- Oruzgan

- Paktia

- Paktika

- Panjshir

- Parwan

- Samangan

- Sar-e Pol

- Takhar

- Wardak

- Zabul

5.3. Foreign relations

Afghanistan's foreign relations under the de facto Taliban administration are complex and largely defined by its lack of formal international recognition. Since the Taliban's return to power in August 2021, no country has officially recognized their government. Most Western nations and international organizations suspended diplomatic relations and development aid, citing concerns over human rights, particularly women's rights, the lack of an inclusive government, and counter-terrorism assurances. Afghanistan's seat at the United Nations continues to be held by representatives of the former Islamic Republic.

Historically, Afghanistan pursued a policy of neutrality during the Cold War, though it received aid from both blocs. It has been a member of the United Nations since 1946. Under the Islamic Republic (2004-2021), Afghanistan developed close ties with NATO countries, particularly the United States, which designated it a major non-NATO ally (a status later rescinded in 2022). It also maintained relations with regional powers like India and Turkey.

Currently, the Taliban regime engages with regional countries primarily on issues of trade, security, and humanitarian aid. Countries like China, Pakistan, Russia, Iran, and some Central Asian states have maintained diplomatic missions in Kabul or engaged with Taliban officials, though stopping short of formal recognition. Qatar has played a significant role as an intermediary, hosting a Taliban political office.

Foreign policy challenges for the Taliban include gaining international legitimacy, accessing frozen Afghan central bank assets, addressing international sanctions, ensuring continued humanitarian assistance to prevent a worsening crisis, and managing border issues and security concerns with neighboring countries. The international community largely conditions any future normalization of relations on the Taliban's adherence to international human rights norms, inclusive governance, and verifiable counter-terrorism measures.

5.3.1. Relations with neighboring countries

Afghanistan's relations with its neighboring countries are critical due to shared borders, ethnic and cultural ties, economic interdependence, and security concerns.

- Pakistan: Relations have historically been complex and often fraught with tension, primarily over the disputed Durand Line border and allegations of Pakistani support for insurgent groups in Afghanistan, including the Taliban. Pakistan hosts a large Afghan refugee population and is a key trade partner. Border security, cross-border militant movements, and trade facilitation are ongoing issues. In October 2023, Pakistan ordered the expulsion of undocumented Afghans, creating a significant humanitarian challenge.

- Iran: Iran shares a long border and significant cultural and linguistic ties with Afghanistan, particularly with Dari-speaking populations. Iran also hosts a large Afghan refugee population and is an important trade partner. Water rights concerning the Helmand River have been a source of tension. Iran has engaged with the Taliban on security and economic matters but has also expressed concerns about the rights of Shia minorities, particularly Hazaras, in Afghanistan.

- China: China shares a short border with Afghanistan via the Wakhan Corridor. Its interests in Afghanistan are primarily driven by security concerns (preventing Afghanistan from becoming a haven for Uyghur militants), economic opportunities (access to mineral resources), and its broader Belt and Road Initiative. China has maintained pragmatic engagement with the Taliban, urging stability and counter-terrorism efforts.

- Central Asian States (Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan): These countries share borders and ethnic ties (Tajik, Uzbek, Turkmen minorities in Afghanistan). Their primary concerns are border security, preventing the spillover of instability and extremism, and managing drug trafficking. They also have economic interests, including energy transit projects (like the TAPI pipeline) and trade. Tajikistan has been particularly critical of the Taliban's human rights record and has provided some support to anti-Taliban figures. Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan have maintained more pragmatic engagement focused on trade and security.

Refugee movements, cross-border trade (both formal and informal), and the activities of transnational militant groups continue to shape Afghanistan's relationships with its immediate neighbors.

5.3.2. Relations with major powers

Afghanistan's relations with major global powers have been significantly reshaped since the Taliban's return to power in August 2021.

- United States: Following two decades of military intervention and substantial financial support for the Islamic Republic, the US withdrew its forces in 2021. The US does not recognize the Taliban government and has led international efforts to freeze Afghan central bank assets held abroad. Engagement is largely limited to humanitarian issues and counter-terrorism concerns. The US has emphasized that any normalization of relations depends on the Taliban's actions regarding human rights, inclusive governance, and preventing Afghanistan from becoming a safe haven for terrorists.

- Russia: Russia, which has its own history of military involvement in Afghanistan during the Soviet era, has adopted a pragmatic approach to the Taliban. While not formally recognizing the Taliban government, Russia has maintained diplomatic contacts, hosted Taliban delegations, and emphasized the need for stability and counter-terrorism. Moscow is concerned about the potential spillover of instability and drug trafficking into Central Asia, its traditional sphere of influence.

- European Union: The EU, like the US, does not recognize the Taliban government and has suspended development aid, linking any future engagement to improvements in human rights, particularly for women and girls, and the formation of an inclusive government. The EU provides significant humanitarian assistance to Afghanistan through international organizations. Individual EU member states have varying degrees of informal contact with the Taliban, primarily on humanitarian and consular matters.

International sanctions, the Taliban's pursuit of international legitimacy, and the ongoing humanitarian crisis are key factors shaping Afghanistan's interactions with these major powers. The focus of these powers largely remains on preventing Afghanistan from becoming a source of regional or global instability, addressing humanitarian needs, and pressing the Taliban on human rights and counter-terrorism commitments.

5.4. Military

Following the Taliban's takeover in August 2021 and the collapse of the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, the de facto armed forces of the country are those controlled by the Taliban, often referred to as the Islamic Emirate Army or the Armed Forces of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.

The Taliban's forces largely consist of fighters who were part of their insurgency. Upon taking power, they captured a vast arsenal of weapons, vehicles, aircraft, and equipment previously supplied to the ANSF by the United States and other NATO allies. This captured equipment significantly bolstered their military capabilities. Estimates of the total value of this equipment run into many billions of US dollars.

The structure of the Taliban's military is evolving. It includes former insurgent units, and there have been efforts to create a more conventional army structure, incorporating some former ANSF personnel, though this has been limited. Key Taliban military leaders now occupy positions such as the Minister of Defense. The Taliban have announced plans to build a regular army, including potentially reactivating some of the captured aircraft and heavy weaponry.

The primary focus of the Taliban's military is currently on internal security, consolidating control over the country, countering remaining pockets of resistance (such as the National Resistance Front and the Islamic State - Khorasan Province (ISKP)), and border security. Their policies regarding recruitment, training, and military doctrine are largely based on their ideological interpretations and past insurgent experiences. The long-term capabilities, professionalism, and adherence to international norms of the Taliban's armed forces remain key concerns for the international community.

5.5. Human rights

The human rights situation in Afghanistan has deteriorated significantly since the Taliban's return to power in August 2021, drawing widespread international condemnation and raising grave concerns for the well-being and fundamental freedoms of the Afghan population. This section focuses on the impact of the Taliban regime on citizens' rights, reflecting a perspective centered on social justice and universal human rights principles.

Key areas of concern include:

- Freedom of Speech and Assembly: Freedoms of expression and assembly have been severely curtailed. Media outlets face restrictions, journalists have been detained and intimidated, and critical reporting is suppressed. Peaceful protests, particularly those led by women, have often been met with force.

- Freedom of Religion: While the Taliban adhere to a strict interpretation of Sunni Islam, the rights of religious minorities, including Shia Muslims (particularly Hazaras), Sikhs, and Hindus, are under threat. There have been reports of discrimination, attacks on places of worship, and pressure to conform to Taliban's religious edicts. The small Christian community practices in secret due to fear of persecution.

- Justice System and Due Process: The formal justice system of the previous republic has been largely dismantled or sidelined. Taliban courts, often applying their interpretation of Sharia law, have been established. Concerns exist regarding the lack of due process, fair trial standards, the independence of the judiciary, and the imposition of harsh punishments, including public floggings and executions. Extrajudicial killings and forced disappearances have also been reported.

- Restrictions on Civil Society: Independent civil society organizations, including human rights groups, face immense pressure and restrictions on their activities, severely limiting their ability to monitor and report on human rights violations.

- Torture and Ill-Treatment: Reports persist of torture and ill-treatment of detainees by Taliban forces, particularly those accused of affiliation with the former government or resistance groups.

- Targeting of Former Officials and Security Forces: Despite a declared general amnesty, there have been numerous credible reports of reprisal killings, detentions, and disappearances of individuals associated with the former Afghan government and its security forces.

The Taliban's governance has led to a systematic erosion of human rights protections that had been established over the previous two decades. The international community has consistently called on the Taliban to respect their international human rights obligations, ensure accountability for violations, and establish an inclusive government that protects the rights of all Afghans. The human rights situation remains a major obstacle to international recognition and engagement with the Taliban regime. In January 2025, the International Criminal Court issued two warrants against the Supreme Leader Hibatullah Akhundzada and Chief Justice Abdul Hakim Haqqani for crimes against humanity related to the oppression of Afghan women and girls.

5.5.1. Women's rights

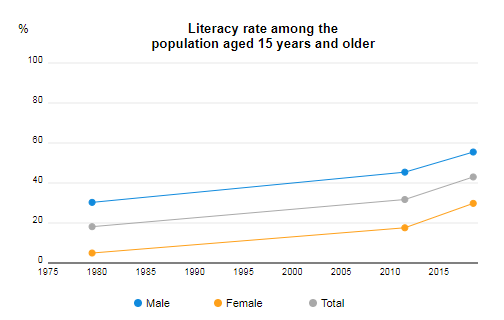

The status of women's rights in Afghanistan has seen a catastrophic decline since the Taliban's return to power in August 2021, reversing two decades of progress and drawing widespread international condemnation. The Taliban have implemented a series of decrees and policies that severely restrict women's and girls' fundamental freedoms and their participation in public life.

Key restrictions and impacts include:

- Education: The Taliban have banned girls from attending secondary school (beyond the sixth grade) and universities. This effectively denies an entire generation of Afghan girls the right to education, limiting their future opportunities and societal contributions. While some primary schools for girls remain open, the curriculum and environment are often subject to Taliban control. Some informal or secret schools attempt to operate, but face significant risks.

- Employment: Women have been largely excluded from the workforce. Most female government employees have been told to stay home, and women are barred from many professions. Exceptions exist in some sectors like healthcare and primary education, but opportunities are severely limited and often come with strict conditions. This has had a devastating economic impact on families, especially those headed by women.

- Freedom of Movement and Dress Code: Women are required to adhere to a strict dress code, including covering their faces in public (often interpreted as requiring the burqa or a niqab with an abaya). Their freedom of movement is curtailed; they are often required to be accompanied by a mahram (male guardian) for long-distance travel and, in some cases, even for leaving their homes. Women are restricted from accessing public spaces like parks, gyms, and public baths.

- Participation in Public Life: Women have been entirely excluded from political decision-making and senior government roles. The Ministry of Women's Affairs was abolished and replaced by the Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, which enforces many of the restrictions on women.

- Access to Justice and Healthcare: Women face increased barriers in accessing justice and healthcare, particularly specialized services. The dismantling of support systems for victims of gender-based violence has left many vulnerable.

- Increased Domestic Violence and Forced Marriage: Reports indicate a rise in domestic violence and forced marriages, including child marriage, as economic hardship and restrictive social norms intensify.

These policies represent a systematic effort to erase women from public life and deny them their basic human rights. Afghan women have bravely protested these restrictions, often facing violent suppression from Taliban forces. The international community has consistently condemned the Taliban's policies towards women and girls, making the restoration of their rights a key condition for any future international engagement or recognition of the Taliban regime. The severe regression in women's rights has profound social, economic, and psychological consequences for Afghan women and for the future of Afghan society as a whole. Reports indicate a rise in suicides among women since the Taliban takeover.

5.5.2. Rights of minorities and vulnerable groups

The rights of ethnic and religious minorities, as well as other vulnerable groups in Afghanistan, have faced increased threats and violations since the Taliban's return to power in August 2021. The Taliban's governance, based on a strict interpretation of Sunni Islam and a predominantly Pashtun leadership, has exacerbated existing vulnerabilities and created new challenges for these communities.

- Hazaras: The Hazara community, who are predominantly Shia Muslims, have historically faced discrimination and persecution in Afghanistan. Under the Taliban, there have been credible reports of targeted killings, forced displacement, and attacks on Hazara civilians and cultural sites. Their representation in governance is minimal, and concerns persist about their security and access to justice and resources. The Islamic State - Khorasan Province (ISKP), a rival militant group, has also frequently targeted Hazaras in deadly attacks on mosques, schools, and public places.

- Shia Muslims: Beyond the Hazaras, other Shia Muslim communities also face concerns about religious freedom and security. The Taliban's emphasis on Sunni jurisprudence raises questions about the legal and social status of Shia practices and personal status laws.

- Sikhs and Hindus: These small religious minorities have faced long-standing discrimination and declining numbers due to conflict and persecution. Many have fled the country. Those who remain face challenges in practicing their faith freely, maintaining their cultural heritage, and ensuring their security. Attacks on their places of worship (gurdwaras and mandirs) have occurred.

- LGBTQ+ Individuals: Homosexuality is criminalized under Taliban rule, based on their interpretation of Sharia law, and can be punishable by death. LGBTQ+ individuals face extreme danger, persecution, and are forced to live in hiding, with no legal recognition or protection of their rights.

- Other Ethnic Minorities (e.g., Uzbeks, Turkmens, Balochis): While some representation exists for larger groups like Uzbeks at lower levels, concerns remain about equitable access to power, resources, and cultural rights for all non-Pashtun ethnic groups. Historical ethnic tensions can be exacerbated by political and economic marginalization.

- Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) and Returnees: Decades of conflict and recent political upheaval have resulted in large numbers of IDPs. These populations, along with Afghans returning from neighboring countries (often involuntarily), face significant challenges in accessing shelter, food, healthcare, and livelihoods.

- Persons with Disabilities: Afghanistan has a high number of persons with disabilities, many due to conflict-related injuries. They face significant barriers to accessing services, education, employment, and participating in society.

- Christians and other unrecognised minorities: Small, often hidden, communities like Christians face extreme risks of persecution. There are no public churches, and practicing their faith openly is impossible.

The Taliban's commitment to an inclusive government that respects the rights of all Afghans, regardless of ethnicity, religion, or other status, remains a key demand of the international community. The lack of such inclusivity and protection for minorities and vulnerable groups contributes to Afghanistan's ongoing humanitarian crisis and international isolation.

6. Economy

Afghanistan's economy has been severely impacted by decades of conflict, political instability, and a heavy reliance on foreign aid. Since the Taliban's return to power in August 2021, the economic situation has deteriorated into a humanitarian crisis, exacerbated by the freezing of Afghan central bank assets held abroad and the suspension of most international development assistance. Key challenges include widespread poverty, high unemployment, a collapsing banking sector, and the impact of international sanctions. The country's nominal GDP was estimated at $20.1 billion in 2020, with a GDP per capita among the lowest in the world. Agriculture remains a significant sector, though poppy cultivation for opium production has historically been a major, albeit illicit, part of the economy. Afghanistan possesses substantial untapped mineral resources, but their development is hindered by insecurity and lack of infrastructure.

6.1. Agriculture

Agriculture is a cornerstone of the Afghan economy, traditionally employing a large portion of the workforce (around 40% as of 2018) and contributing significantly to the GDP. The country is known for producing a variety of fruits and nuts, including pomegranates, grapes, apricots, melons, and almonds, which are important exports. Staple crops include wheat, maize, and barley. Irrigation is crucial for agriculture due to the arid and semi-arid climate, with systems ranging from traditional canals (karez) to modern water pumps.

A significant and problematic aspect of Afghan agriculture has been the cultivation of opium poppies. Afghanistan has historically been the world's largest producer of opium, the raw material for heroin. This illicit trade provided livelihoods for many rural families but also fueled corruption, conflict, and addiction. Since their return to power in 2021, the Taliban have issued decrees banning poppy cultivation and trade. Reports in 2023 indicated a significant reduction in poppy cultivation, particularly in southern provinces like Helmand, though the long-term sustainability of this ban and its economic impact on farmers remain critical concerns. Efforts to promote alternative livelihoods, such as the cultivation of high-value crops like saffron, have been ongoing but face challenges in scale and market access.

Saffron has emerged as a promising alternative crop, particularly in provinces like Herat. Afghan saffron has gained international recognition for its quality. Other agricultural products include cotton and various vegetables.