1. Overview

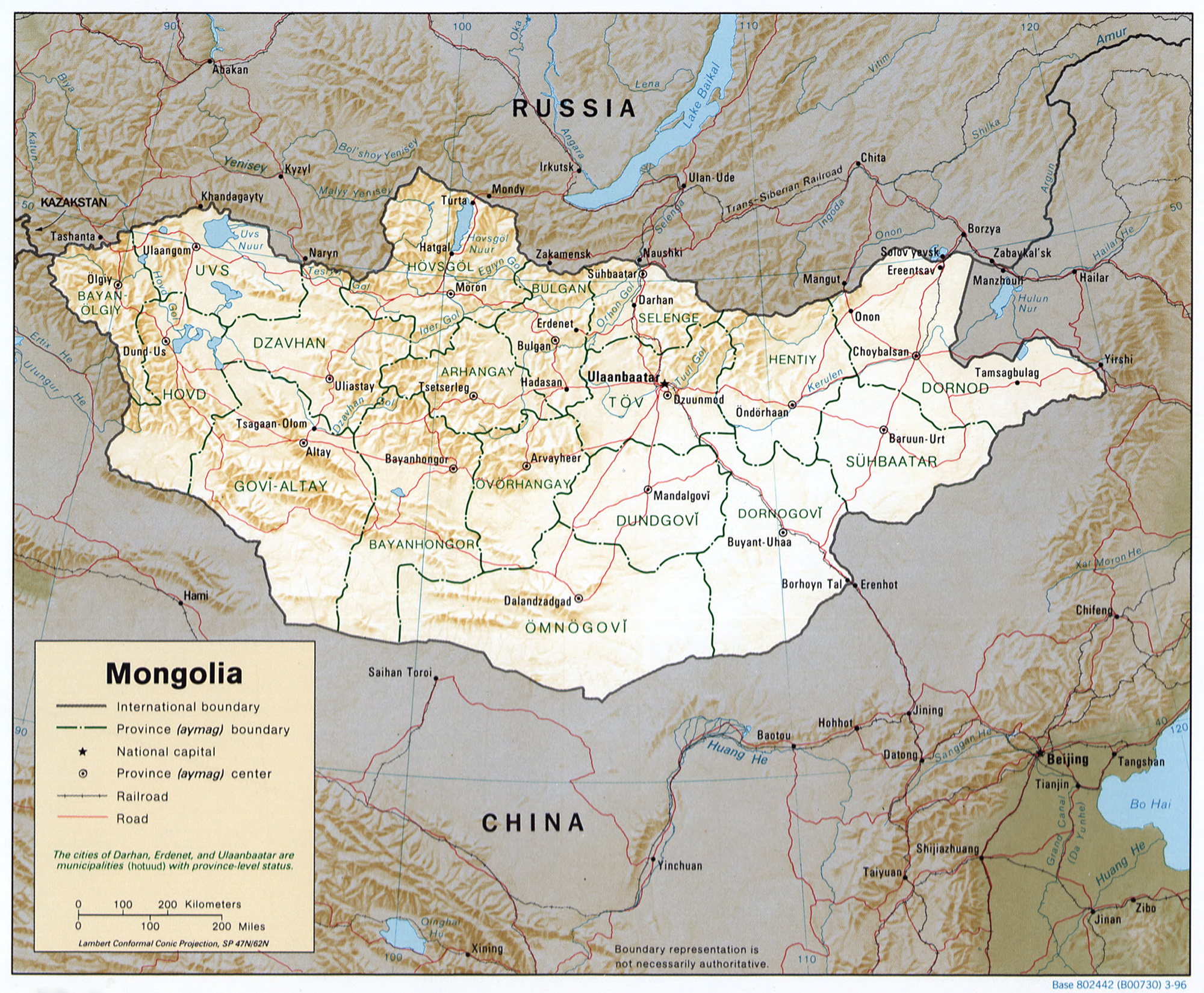

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, situated between Russia to the north and China to the south. It is the world's second-largest landlocked country and the most sparsely populated sovereign state, characterized by vast grassy steppes, mountains in the north and west, and the Gobi Desert in the south. Ulaanbaatar, the capital, is home to nearly half of its approximately 3.5 million people. Historically, the region was the heart of various nomadic empires, culminating in the Mongol Empire under Genghis Khan in the 13th century, the largest contiguous land empire in history. After the fall of the Yuan dynasty, established by Genghis Khan's grandson Kublai Khan in China, the Mongols retreated to their homeland. Tibetan Buddhism became prominent in the 16th century, and by the 17th century, Mongolia was absorbed into the Qing dynasty.

Following the Qing's collapse in 1911, Mongolia declared independence, eventually establishing the Mongolian People's Republic in 1924 with significant Soviet influence. This era saw socio-economic transformations but also severe political repression, particularly under Khorloogiin Choibalsan, with widespread human rights abuses targeting Buddhist clergy and intellectuals. The peaceful Democratic Revolution of 1990 led to a multi-party system, a new constitution in 1992, and a transition to a market economy. Contemporary Mongolia focuses on consolidating its democratic institutions, promoting social equity, protecting human rights, and ensuring the welfare of its diverse population, including ethnic minorities. The nation's economy is heavily reliant on mining and agriculture, with ongoing efforts to diversify and address social and environmental challenges. Mongolia pursues a "third neighbor" foreign policy, balancing its relationships with Russia and China while fostering ties with other nations to support its sovereignty and development. Culturally, Mongolia retains strong nomadic traditions, with a rich heritage in music, arts, and festivals like Naadam. This article explores Mongolia's multifaceted identity, examining its historical path, geographical context, political and economic systems, societal fabric, and cultural expressions from a perspective that prioritizes social justice, democratic progress, and human dignity.

2. Etymology

The name Mongolia means the "Land of the Mongols" in Latin. The Mongolian word МонголMongolMongolian itself is of uncertain etymology. Various theories exist regarding its origin. One proposal by Sükhbataar (1992) and de la Vaissière (2021) suggests it derives from Mugulü, the 4th-century founder of the Rouran Khaganate. This name was first attested as "Mungu" (蒙兀MěngwùChinese, Middle Chinese: Muwngu), a branch of the Shiwei mentioned in an 8th-century Tang dynasty list of northern tribes. This is presumably related to the Liao-era term "Mungku" (蒙古MěnggǔChinese, Middle Chinese: MuwngkuX).

After the fall of the Liao dynasty in 1125, the Khamag Mongols became a leading tribe on the Mongolian Plateau. However, their wars with the Jurchen-ruled Jin dynasty and the Tatar confederation had weakened them. The last head of this tribe was Yesügei, whose son Temüjin (later Genghis Khan) eventually united all the Shiwei tribes, forming the Mongol Empire (Ехэ Монгол УлсYekhe Mongol UlusMongolian, meaning "Great Mongol Nation"). In the thirteenth century, the word "Mongol" evolved into an umbrella term for a large group of Mongolic-speaking tribes united under the rule of Genghis Khan.

Since the adoption of the new Constitution of Mongolia on February 13, 1992, the official name of the state is "Mongolia" (Монгол УлсMongol UlsMongolian). In Mongolian, Uls means "country" or "nation."

3. History

The history of Mongolia spans millennia, from prehistoric human inhabitation to the rise and fall of great nomadic empires, its incorporation into larger political entities, and its journey towards modern statehood and democratic governance. Key periods include the formation of early states like the Xiongnu and Turkic Khaganates, the zenith of the Mongol Empire under Genghis Khan and his successors, subsequent periods of fragmentation and foreign rule, and the 20th-century struggles for independence, followed by socialist development and a peaceful transition to democracy.

3.1. Prehistory and Ancient States

Archaeological findings in Mongolia provide evidence of human presence dating back to the Lower Paleolithic period. The Khoit Tsenkher Cave in Khovd Province features vivid pink, brown, and red ochre paintings of mammoths, lynx, bactrian camels, and ostriches, dated to around 20,000 years ago, earning it the nickname "the Lascaux of Mongolia." The Venus figurines of Mal'ta (c. 21,000 years ago), found in an area now part of Russia but culturally linked to northern Mongolia, testify to the advanced Upper Paleolithic art in the region.

Neolithic agricultural settlements, such as those at Norovlin, Tamsagbulag, Bayanzag, and Rashaan Khad (c. 5500-3500 BC), predated the introduction of horse-riding nomadism, which became the dominant culture and a pivotal event in Mongolian history. The ethnogenesis of Mongolic peoples is largely linked with the expansion of Ancient Northeast Asians. The Mongolian pastoralist lifestyle may in part be derived from the Western Steppe Herders, but without much genetic flow between these two groups, suggesting cultural transmission.

Horse-riding nomadism is documented by archaeological evidence in Mongolia during the Copper and Bronze Age Afanasevo culture (3500-2500 BC). This Indo-European culture was active up to the Khangai Mountains in Central Mongolia. Wheeled vehicles found in Afanasevan burials have been dated to before 2200 BC. Pastoral nomadism and metalworking became more developed with the later Okunev culture (2nd millennium BC), Andronovo culture (2300-1000 BC), and Karasuk culture (1500-300 BC). Monuments of the pre-Xiongnu Bronze Age include deer stones, keregsur kurgans, square slab tombs, and rock paintings. Although crop cultivation continued since the Neolithic, agriculture always remained small in scale compared to pastoral nomadism. The population during the Copper Age has been described as Mongoloid in eastern Mongolia and Europoid in the west. Tocharians (Yuezhi) and Scythians inhabited western Mongolia during the Bronze Age. A mummy of a Scythian warrior, believed to be about 2,500 years old with blond hair, was found in the Altai Mountains of Mongolia. As equine nomadism was introduced, the political center of the Eurasian Steppe shifted to Mongolia, where it remained until the 18th century. Intrusions of northern pastoralists (e.g., Guifang, Shanrong, and Donghu) into China during the Shang dynasty (1600-1046 BC) and Zhou dynasty (1046-256 BC) presaged the age of nomadic empires.

From time to time, these nomadic groups formed great confederations that rose to power. Common institutions included the office of the Khan, the Kurultai (Supreme Council), left and right wings, an imperial army (Keshig), and a decimal military system. The first of these empires, the Xiongnu, were brought together by Modu Shanyu to form a confederation in 209 BC. They soon emerged as the greatest threat to the Qin dynasty of China, forcing the latter to construct the Great Wall of China. The Xiongnu empire (209 BC-93 AD) was followed by the Mongolic Xianbei empire (93-234 AD). The Mongolic Rouran Khaganate (330-555), of Xianbei origin, was the first to use "Khagan" as an imperial title. It ruled a massive empire before being defeated by the Göktürks (also known as Turkic Khaganate, 555-745), an even larger empire which expanded its territory to the Korean Peninsula and China.

The Göktürks laid siege to Panticapaeum (present-day Kerch) in 576. They were succeeded by the Uyghur Khaganate (745-840), who were in turn defeated by the Kyrgyz. The Mongolic Khitans, descendants of the Xianbei, ruled Mongolia during the Liao dynasty (907-1125), after which the Khamag Mongol confederation (1125-1206) rose to prominence.

Lines 3-5 of the memorial inscription of Bilge Khagan (684-737) in central Mongolia summarize this era, stating: "In battles they subdued the nations of all four sides of the world and suppressed them. They made those who had heads bow their heads, and who had knees genuflect them. In the east up to the Kadyrkhan common people, in the west up to the Iron Gate they conquered... These Khagans were wise. These Khagans were great. Their servants were wise and great too. Officials were honest and direct with people. They ruled the nation this way. This way they held sway over them. When they died ambassadors from Bokuli Cholug (Baekje Korea), Tabgach (Tang China), Tibet (Tibetan Empire), Avar (Avar Khaganate), Rome (Byzantine Empire), Kirgiz, Uch-Kurykan, Otuz-Tatars, Khitans, Tatabis came to the funerals. So many people came to mourn over the great Khagans. They were famous Khagans."

3.2. Mongol Empire

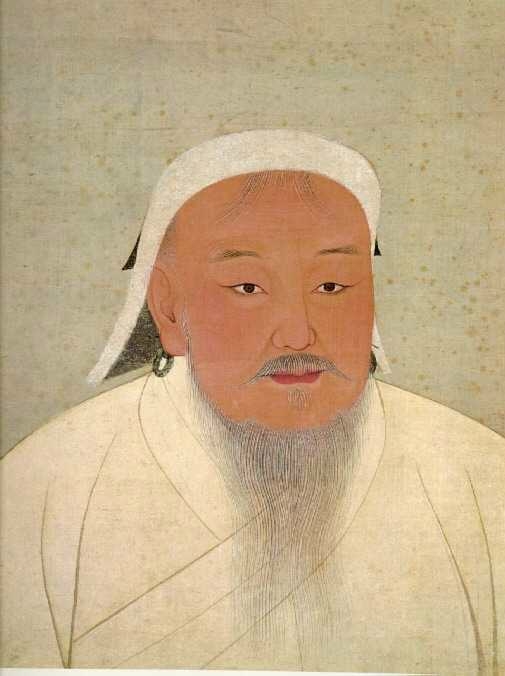

In the chaos of the late 12th century, a chieftain named Temüjin succeeded in uniting the Mongol tribes between Manchuria and the Altai Mountains. In 1206, he took the title Genghis Khan and waged a series of military campaigns, renowned for their brutality and ferocity, sweeping through much of Asia and forming the Mongol Empire, the largest contiguous land empire in world history. Under his successors, it stretched from present-day Poland in the west to Korea in the east, and from parts of Siberia in the north to the Gulf of Oman and Vietnam in the south. This vast empire covered some 13 M mile2 (33.00 M km2), (22% of Earth's total land area) and had a population of over 100 million people (about a quarter of Earth's total population at the time). The emergence of the Pax Mongolica significantly eased trade and commerce across Asia during its height.

After Genghis Khan's death, the empire was subdivided into four kingdoms or Khanates. These eventually became quasi-independent after the Toluid Civil War (1260-1264), which broke out following Möngke Khan's death in 1259. One of the khanates, the "Great Khanate," consisting of the Mongol homeland and most of modern-day China, became known as the Yuan dynasty under Kublai Khan, Genghis Khan's grandson. He established his capital in present-day Beijing. After more than a century of power, the Yuan dynasty was overthrown by the Ming dynasty in 1368, and the Yuan court fled north, thus becoming the Northern Yuan dynasty. As the Ming armies pursued the Mongols into their homeland, they successfully sacked and destroyed the Mongol capital Karakorum and other cities. Some of these attacks were repelled by the Mongols under Ayushridar and his general Köke Temür. The societal structure of the Mongol Empire was complex, with a hierarchical system based on tribal allegiances and military organization. While promoting trade and cultural exchange through the Pax Mongolica, the empire's expansion often involved immense destruction and loss of life, impacting the democratic development and human rights of conquered populations.

3.3. Northern Yuan Dynasty

After the expulsion of the Yuan rulers from China proper, the Mongols continued to rule their homeland, a period known in historiography as the Northern Yuan Dynasty. This era was also referred to among the Mongols as "The Forty and the Four" (Döčin dörben), reflecting a division of Mongol tribes. The subsequent centuries were marked by violent power struggles among various factions, notably the Genghisids (descendants of Genghis Khan) and the non-Genghisid Oirats (Western Mongols). The period also saw several Ming invasions, such as the five expeditions led by the Yongle Emperor.

In the early 16th century, Dayan Khan and his khatun (queen) Mandukhai reunited all Mongol groups under Genghisid rule. In the mid-16th century, Altan Khan of the Tümed, a grandson of Dayan Khan but not a hereditary or legitimate Khan, became powerful. He founded the city of Hohhot in 1557. A pivotal event during Altan Khan's rule was his meeting with the Dalai Lama Sonam Gyatso in 1578, after which he ordered the reintroduction of Tibetan Buddhism to Mongolia (this was the second introduction, the first having occurred during the Yuan dynasty). Abtai Sain Khan of the Khalkha also converted to Buddhism and founded the Erdene Zuu Monastery in 1585. His grandson, Zanabazar, became the first Jebtsundamba Khutuktu (spiritual head of Tibetan Buddhism in Mongolia) in 1640. Following these leaders, the entire Mongolian population gradually embraced Buddhism. Each family kept scriptures and Buddha statues on an altar at the north side of their ger. Mongolian nobles donated land, money, and herders to the monasteries. As was typical in states with established religions, the top religious institutions, the monasteries, wielded significant temporal power in addition to spiritual power. This religious revival had a profound impact on Mongolian society and culture, but also, in later centuries, contributed to a social structure where a large portion of the male population became monks, affecting economic productivity and military strength. The last Khagan of the Mongols was Ligden Khan in the early 17th century. He came into conflict with the Manchus over the looting of Chinese cities and also alienated most Mongol tribes. He died in 1634.

3.4. Mongolia under Qing Rule

By 1636, most of the Inner Mongolian tribes had submitted to the Manchus, who founded the Qing dynasty in China. The Khalkha of Outer Mongolia eventually submitted to Qing rule in 1691, bringing all of today's Mongolia under Manchu control. The Qing consolidated their rule after several Dzungar-Qing Wars, which led to the virtual annihilation of the Dzungars (Western Mongols or Oirats) during the Qing conquest of Dzungaria in 1757 and 1758. Some scholars estimate that about 80% of the 600,000 or more Dzungars were killed by a combination of disease and warfare.

Outer Mongolia was administered as a distinct entity within the Qing Empire, divided into four leagues (aimags) governed by hereditary Genghisid khanates: Tusheet Khan, Setsen Khan, Zasagt Khan, and Sain Noyon Khan. The Jebtsundamba Khutuktu of Mongolia, based in Urga (present-day Ulaanbaatar), held immense de facto authority. The Qing dynasty implemented policies to maintain control, including forbidding mass Chinese immigration into Outer Mongolia, which allowed the Mongols to preserve their culture to a certain extent. However, Qing rule also involved stationing Manchu officials (Amban) in key locations like Khüree (Urga), Uliastai, and Khovd. The country was divided into numerous feudal and ecclesiastical fiefdoms, often placing individuals loyal to the Qing in positions of power.

Over the course of the 19th century, the feudal lords (noyons) increasingly focused on representation and extraction of resources, while neglecting their responsibilities towards their subjects. The behavior of Mongolia's nobility, coupled with usurious practices by Chinese traders and the collection of imperial taxes in silver instead of animals, resulted in widespread poverty among the nomadic population. By 1911, there were 700 large and small monasteries in Outer Mongolia, with their 115,000 monks constituting 21% of the population. Apart from the Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, there were 13 other reincarnating high lamas, called 'seal-holding saints' (tamgatai khutuktu), in Outer Mongolia. Instances of Mongolian resistance to Qing rule occurred, though they were generally localized. The socio-economic changes during this period, including increased debt and hardship for common herders, laid groundwork for future nationalist movements.

3.5. Early 20th Century and Independence

The early 20th century was a period of immense upheaval for Mongolia, leading to its declaration of independence from the collapsing Qing dynasty. The Xinhai Revolution in China in 1911 provided the opportunity for Mongol nobles and high lamas in Outer Mongolia to assert their autonomy. On December 1, 1911, Outer Mongolia declared independence from Qing rule, and the 8th Jebtsundamba Khutuktu was proclaimed Bogd Khan (Great Khan, or Emperor) of Mongolia, establishing the Bogd Khanate. This new state sought to unite all Mongol-inhabited lands, including Inner Mongolia, but faced significant external pressures.

The newly established Republic of China considered Mongolia part of its territory and refused to recognize its independence. Yuan Shikai, the President of the Republic of China, viewed the new republic as the successor to the Qing. The Bogd Khan argued that both Mongolia and China had been administered by the Manchus during the Qing, and with the fall of the dynasty, Mongolia's submission to the Manchus was void. Russia, while supporting Mongolian autonomy, was reluctant to endorse full independence due to its own geopolitical interests and agreements with China. The 1915 Treaty of Kyakhta, a tripartite agreement between Russia, China, and Mongolia, recognized Mongolia's autonomy under Chinese suzerainty, effectively limiting its sovereignty.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 weakened Russia's influence, and China seized the opportunity to reassert control. In 1919, Chinese troops led by warlord Xu Shuzheng occupied Urga (Niislel Khüree, now Ulaanbaatar) and forced the Bogd Khanate to renounce its autonomy. This occupation was short-lived. In late 1920, White Russian forces under Baron Roman Ungern von Sternberg, fleeing the Russian Civil War, invaded Mongolia. With Mongol support, Ungern defeated the Chinese forces in Urga in early February 1921 and restored the Bogd Khan as a monarch, though Ungern himself held the real power, instituting a brutal regime.

To counter Ungern's threat and further their own revolutionary aims, Bolshevik Russia supported Mongolian revolutionaries. Figures like Damdin Sükhbaatar and Khorloogiin Choibalsan formed the Mongolian People's Party (MPP). With Soviet military assistance, the MPP forces, along with Red Army units, defeated Ungern's troops. The Mongolian army took the Mongolian part of Kyakhta from Chinese forces on March 18, 1921, and on July 6, Russian and Mongolian troops arrived in Khüree. Mongolia declared its independence again on July 11, 1921, this time as a constitutional monarchy with the Bogd Khan as a limited head of state. This event, known as the 1921 Revolution, marked a crucial step towards full, albeit Soviet-influenced, independence. The period was characterized by struggles for national self-determination amidst competing regional powers, laying the groundwork for the socialist state that would follow.

3.6. Mongolian People's Republic

Following the 1921 Revolution and the death of the Bogd Khan in 1924 (due to laryngeal cancer, though some sources claim at the hands of Russian spies), the Mongolian People's Republic (MPR) was proclaimed on November 26, 1924, establishing a socialist state. This marked the beginning of nearly seven decades of close alignment with the Soviet Union. The MPR became the world's second communist state. The early leaders of the MPR (1921-1952) included many with Pan-Mongolist ideals, but changing global politics and increased Soviet pressure led to the decline of these aspirations. The period was characterized by profound socio-economic transformations, including efforts to modernize the country, introduce literacy, and develop industry and agriculture, but also by significant political control and repression directed from Moscow.

3.6.1. Political Developments and Repression (Choibalsan Era)

Khorloogiin Choibalsan rose to power in the late 1920s and consolidated his rule by the 1930s, becoming the dominant political figure until his death in 1952. His era was marked by the wholesale adoption of Stalinist ideology and practices, leading to severe political repression and widespread human rights violations. Choibalsan instituted collectivization of livestock, which disrupted traditional nomadic life and often met with resistance.

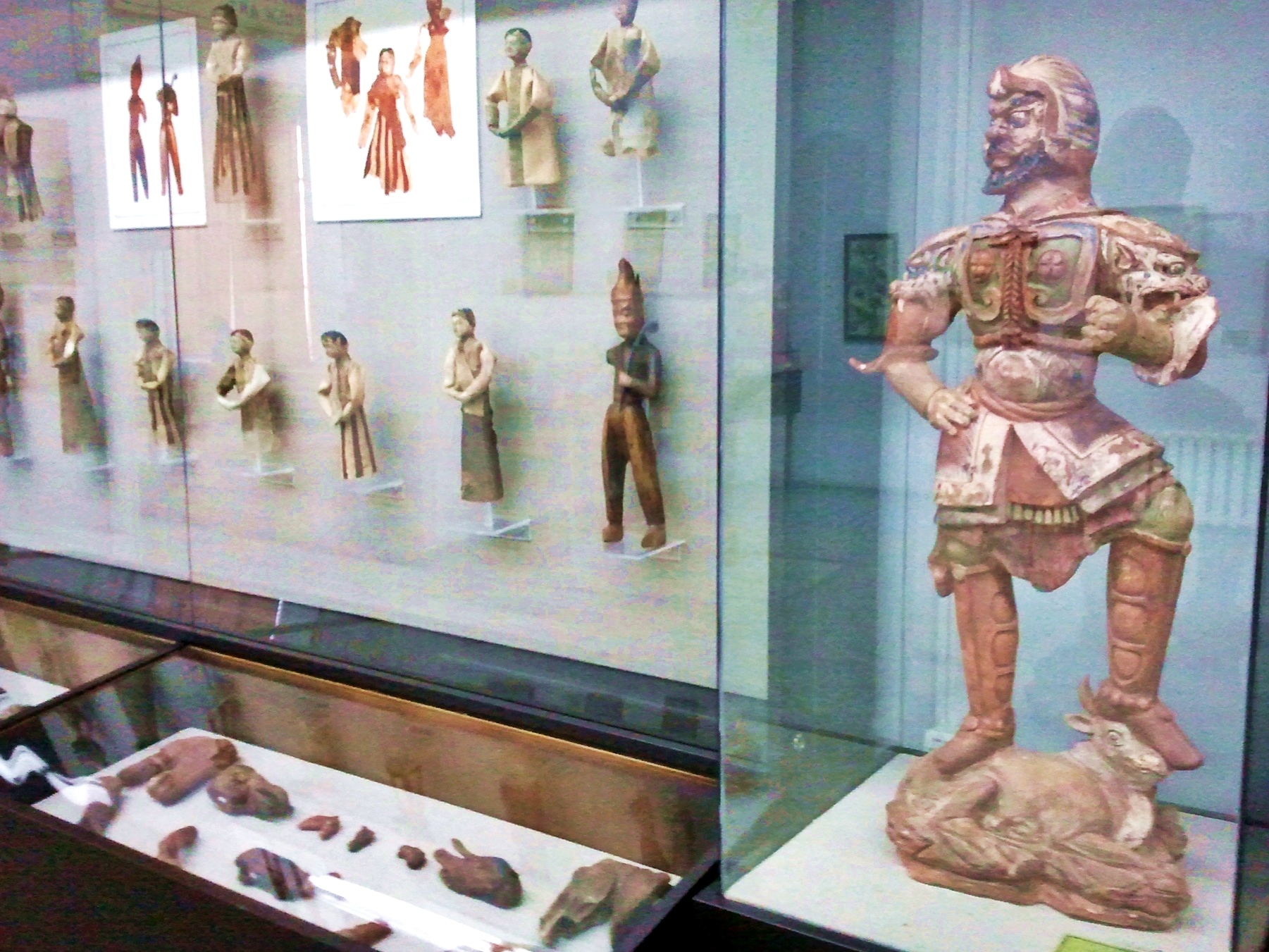

A key feature of this period was the brutal suppression of Buddhism, which had been deeply entrenched in Mongolian society and culture. The regime targeted the Buddhist clergy (lamas) and monastic institutions, viewing them as feudal remnants and obstacles to socialist progress. In the late 1930s, during the Great Purge in Mongolia (Ih Helsegdlèl), almost all of Mongolia's over 700 Buddhist monasteries were closed, looted, or razed. An estimated 17,000 to 30,000 monks were executed, and many others were imprisoned, laicized, or forced into labor. Intellectuals, former aristocrats, and anyone perceived as opposing the regime or having nationalist sentiments were also targeted. In Mongolia during the 1920s, approximately one-third of the male population were monks. By the beginning of the 20th century, 750 monasteries were functioning; by the end of the 1930s, almost all had been destroyed.

In 1930, the Soviet Union stopped Buryat migration to the MPR to prevent Mongolian reunification. Mongolian leaders who did not fully comply with Stalin's demands for implementing Red Terror against Mongolians, such as Peljidiin Genden and Anandyn Amar, were executed. Choibalsan's dictatorship, heavily influenced and supported by Stalin, organized these purges, leading to the deaths of tens of thousands of people. This period represents a dark chapter in Mongolian history, characterized by the severe curtailment of freedoms, the destruction of cultural heritage, and immense human suffering, deeply impacting the nation's social fabric and democratic development for decades to come. Choibalsan died suspiciously in the Soviet Union in 1952.

3.6.2. Cold War and the Tsedenbal Era

During the Cold War, Mongolia remained firmly aligned with the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc. Yumjaagiin Tsedenbal succeeded Choibalsan and became the paramount leader of Mongolia from 1952 until his ousting in 1984. His rule, spanning over three decades, was characterized by continued close ties with Moscow, significant Soviet economic aid, and efforts towards economic modernization and social development within a single-party socialist system.

Mongolia's foreign policy was largely dictated by its relationship with the Soviet Union. The country joined the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon) in 1962. After the Japanese invasion of neighboring Manchuria in 1931, Mongolia was threatened on this front. During the Soviet-Japanese Border War of 1939, the Soviet Union successfully defended Mongolia against Japanese expansionism. Mongolia fought against Japan during these battles and during the Soviet-Japanese War in August 1945 to liberate Inner Mongolia from Japan and Mengjiang.

The Yalta Conference in February 1945 provided for the Soviet Union's participation in the Pacific War. One of the Soviet conditions was that after the war, Outer Mongolia would retain its "status quo" (independence). A referendum on independence took place on October 20, 1945, with official numbers showing 100% of the electorate voting for independence. After the establishment of the People's Republic of China, both countries confirmed their mutual recognition on October 6, 1949. However, the Republic of China (Taiwan) used its Security Council veto in 1955 to stop the admission of the MPR to the United Nations, on the grounds it recognized all of Mongolia as part of China. Mongolia eventually joined the UN in 1961.

Under Tsedenbal, Mongolia experienced some industrialization and urbanization, particularly in Ulaanbaatar. Efforts were made to improve education and healthcare. However, the economy remained heavily dependent on Soviet aid, and political life was tightly controlled by the Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party (MPRP). Dissent was not tolerated, and while the overt brutality of the Choibalsan era lessened, a repressive political atmosphere persisted. Social conditions were characterized by limited personal freedoms and adherence to socialist ideology. Tsedenbal's long rule ended in August 1984 when, while he was visiting Moscow, his severe illness prompted the parliament to announce his retirement and replace him with Jambyn Batmönkh. This change occurred against the backdrop of emerging reforms in the Soviet Union under Mikhail Gorbachev, which would soon have a profound impact on Mongolia.

3.7. Democratic Revolution and Contemporary Mongolia

The late 1980s and early 1990s brought profound changes to Mongolia, mirroring the transformations occurring in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 strongly influenced Mongolian politics and its youth. Inspired by Perestroika and Glasnost, a peaceful Democratic Revolution unfolded in early 1990. This movement, driven by young activists and intellectuals, called for political reform, an end to the one-party rule of the Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party (MPRP), and a transition to democracy and a market economy. Key demands included freedom of speech, assembly, and the press, as well as respect for human rights.

The revolution led to the resignation of the MPRP Politburo in March 1990 and the legalization of opposition parties. The first multi-party elections were held in July 1990. A new constitution was adopted on January 13, 1992, which came into effect on February 12, 1992. This constitution enshrined democratic principles, a multi-party system, separation of powers, and protections for human rights. The term "People's Republic" was dropped from the country's name, officially becoming "Mongolia."

The transition to a market economy was often challenging. During the early 1990s, the country faced high inflation, food shortages, and economic hardship as Soviet aid, which had propped up the economy for decades, abruptly ended. However, Mongolia persevered with its democratic and economic reforms. The first election victories for non-communist parties came in 1993 (presidential elections) and 1996 (parliamentary elections). The former Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party transformed into the current social democratic Mongolian People's Party, adapting to the new political landscape.

Contemporary Mongolia continues to navigate the complexities of democratic consolidation and economic development. Challenges include combating corruption, reducing poverty and income inequality, ensuring environmental sustainability (particularly in the face of a booming mining sector), and strengthening the rule of law. Achievements include a vibrant civil society, a relatively free press, and regular, competitive elections. Mongolia has actively pursued a "Third Neighbor" foreign policy, seeking to balance its relations with Russia and China by cultivating ties with other countries like the United States, Japan, South Korea, and European Union members, aiming to bolster its sovereignty and support its democratic development. Efforts towards social justice, including addressing the rights of minorities and vulnerable groups, remain ongoing priorities as Mongolia charts its course in the 21st century.

4. Geography

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, situated between Russia to the north and China to the south. With an area of 0.6 M mile2 (1.56 M km2), it is the world's 18th-largest country. It mostly lies between latitudes 41° and 52°N (a small area is north of 52°), and longitudes 87° and 120°E. Although Mongolia does not share a border with Kazakhstan, its westernmost point is only 23 mile (36.76 km) from Kazakhstan. The country's geography is varied, featuring the vast Gobi Desert to the south, cold and mountainous regions to the north and west, and extensive grassy steppes.

4.1. Topography

Mongolia's topography is characterized by significant mountain ranges, vast steppes, and desert regions. The Altai Mountains dominate the west and southwest, with Khüiten Peak in the Tavan Bogd massif being the highest point in the country at 14 K ft (4.37 K m). The Khangai Mountains are located in central and northern Mongolia, and the Khentii Mountains are near Ulaanbaatar and to the northeast, extending towards the Russian border.

Much of Mongolia consists of the Mongolian-Manchurian steppe, an ecoregion characterized by extensive grasslands. Forested areas, primarily taiga (boreal forest), account for about 11.2% of the total land area and are concentrated in the northern, more mountainous regions. The southern part of the country is dominated by the Gobi Desert, a large, cold desert known for its arid plains, rocky outcrops, and sand dunes. The basin of the Uvs Lake, shared with the Tuva Republic in Russia, is a natural World Heritage Site. The whole of Mongolia is considered to be part of the Mongolian Plateau. Major rivers include the Selenga River and Orkhon River, which flow northwards into Russia and eventually into Lake Baikal, and the Kherlen River, which flows eastwards into China.

4.2. Climate

Mongolia experiences an extreme continental climate with long, cold winters and short, hot summers. The country is known as the "Land of the Eternal Blue Sky" or "Country of Blue Sky" (Мөнх хөх тэнгэрийн оронMönkh khökh tengeriin oronMongolian) because it has over 250 sunny days a year.

Most of the country is hot in the summer and extremely cold in the winter, with January averages dropping as low as -22 °F (-30 °C). A vast front of cold, heavy, shallow air comes in from Siberia in winter and collects in river valleys and low basins, causing very cold temperatures, while slopes of mountains are much warmer due to the effects of temperature inversion. In winter, the whole of Mongolia comes under the influence of the Siberian Anticyclone. The localities most severely affected by this cold weather are Uvs province (Ulaangom), western Khövsgöl (Rinchinlkhümbe), eastern Zavkhan (Tosontsengel), northern Bulgan (Hutag), and eastern Dornod province (Khalkhiin Gol). Ulaanbaatar is strongly, but less severely, affected. The annual average temperature in Ulaanbaatar is 29.66 °F (-1.3 °C), making it the world's coldest capital city.

Precipitation is generally low, highest in the north (average of 7.9 in (200 mm) to 14 in (350 mm) per year) and lowest in the south, which receives 3.9 in (100 mm) to 7.9 in (200 mm) annually. The Gobi Desert receives very little rainfall. The country is subject to occasional harsh climatic conditions known as zud. A zud is a winter disaster in which large numbers of livestock die due to starvation or freezing temperatures, often after a summer drought has reduced fodder availability. Zuds can have devastating impacts on the livelihoods of nomadic herders and the national economy, highlighting the vulnerability of Mongolia's traditional pastoral economy to climate extremes and variability. Climate change is expected to exacerbate these conditions, increasing the frequency and intensity of zuds and posing significant challenges to social equity and the welfare of rural communities.

4.3. Environment and Wildlife

Mongolia boasts diverse ecosystems, ranging from forests and steppes to deserts, supporting a variety of flora and fauna. The northern regions feature taiga forests with species like Siberian larch, pine, and birch, while the vast steppes are home to numerous grasses and wildflowers. The Gobi Desert, despite its aridity, supports unique desert vegetation and wildlife adapted to harsh conditions.

Notable wildlife includes the Przewalski's horse (takhi), the only truly wild horse species, which has been successfully reintroduced to several national parks. Other significant species include the snow leopard, Gobi bear (mazaalai), Bactrian camel, wild ass (khulan), ibex, argali sheep, and various species of gazelle and marmot. The eastern part of Mongolia, including the Onon and Kherlen rivers and Lake Buir, forms part of the Amur River basin and hosts unique aquatic species like the Eastern brook lamprey and Daurian crayfish. Mongolia has established several national parks and protected areas to conserve its biodiversity, such as Gorkhi-Terelj National Park, Khustain Nuruu National Park (home to Przewalski's horses), and Lake Khövsgöl National Park.

However, Mongolia faces significant environmental challenges. Desertification is a major concern, affecting a large percentage of the country's land, driven by overgrazing, climate change, and unsustainable land management practices. Deforestation is another issue, particularly in the northern regions. The impacts of climate change are evident in rising temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, and increased frequency of extreme weather events like zuds. The rapidly expanding mining industry, while crucial for the economy, poses threats to the environment through habitat destruction, water pollution, and soil degradation. These environmental issues have profound impacts on natural resources, biodiversity, and the livelihoods of local communities, particularly nomadic herders, raising concerns about social equity and sustainable development. There is a growing awareness and effort within Mongolia to address these environmental problems, but balancing economic growth with environmental protection and social welfare remains a critical challenge.

5. Government and Politics

Mongolia is a semi-presidential representative democratic republic. The political system is based on the Constitution of Mongolia adopted in 1992, which established a multi-party system and guarantees fundamental human rights and freedoms. The government structure includes an executive branch led by the President and Prime Minister, a unicameral legislature, and an independent judiciary. The nation's political landscape has been shaped by its transition from a single-party socialist state to a pluralistic democracy, with ongoing efforts to strengthen democratic institutions, ensure good governance, and uphold the rule of law.

5.1. Government Structure

The President of Mongolia is the head of state, commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and a symbol of national unity. The President is directly elected by popular vote for a single six-year term (following a 2019 constitutional amendment; previously it was a four-year term, renewable once). The President has powers to veto legislation (which can be overridden by a two-thirds parliamentary majority), propose a candidate for Prime Minister to the parliament, and appoint judges.

The Prime Minister of Mongolia is the head of government and leads the Cabinet. The Prime Minister is typically the leader of the party or coalition holding the majority in the parliament and is appointed by the President upon nomination by the State Great Khural. The Cabinet, consisting of ministers proposed by the Prime Minister and approved by the President and State Great Khural, is responsible for the day-to-day administration of the country.

The State Great Khural (Ulsyn Ikh Khural) is the unicameral parliament and the highest organ of state power. As of a 2023 constitutional amendment, it comprises 126 members (increased from 76) elected for four-year terms through a mixed electoral system involving both majoritarian and proportional representation. The State Great Khural enacts laws, approves the budget, ratifies international treaties, and oversees the government.

5.2. Political Parties

Mongolia has a multi-party system, though two parties have historically dominated the political scene: the Mongolian People's Party (MPP) and the Democratic Party (DP).

The Mongolian People's Party (MPP), formerly the Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party (MPRP), was the ruling party during the socialist era (1921-1990). Since the democratic revolution, it has transformed into a social democratic party and has been a major force in Mongolian politics, frequently forming governments. Its ideology generally emphasizes social welfare, state involvement in the economy, and maintaining strong ties with traditional partners.

The Democratic Party (DP) emerged from the pro-democracy movements of the late 1980s and early 1990s. It generally advocates for market-oriented reforms, privatization, and closer ties with Western countries and other "third neighbors." The DP has also formed governments at various times since 1992.

Besides these two major parties, several smaller parties exist and occasionally win seats in the State Great Khural, sometimes playing a role in coalition governments. The political landscape is dynamic, with parties often forming coalitions and undergoing internal realignments. The influence of these parties is central to shaping Mongolia's domestic and foreign policies, and their competition is a hallmark of its democratic system.

5.3. Judicial System and Human Rights

The judicial system of Mongolia is based on a three-tiered court structure: first instance courts (district and inter-soum courts), appellate courts (aimag and capital city courts), and the Supreme Court as the highest court of appeal for non-constitutional matters. The Constitutional Court (Tsets) is a separate body responsible for interpreting the constitution and reviewing the constitutionality of laws. Judges are nominated by a Judicial General Council, confirmed by the State Great Khural, and appointed by the President. The legal system is based on civil law traditions, influenced by Roman-Germanic law and, historically, socialist law.

Since its democratic transition in 1990, Mongolia has made significant progress in establishing a framework for human rights. The 1992 Constitution guarantees fundamental rights and freedoms, including freedom of speech, assembly, religion, and the press. However, challenges remain. Civil liberties, while generally respected, sometimes face pressure. Issues such as corruption, police brutality, and lengthy pre-trial detentions are areas of concern. The rights of minorities, including ethnic groups like Kazakhs and Tuvans, as well as other vulnerable groups such as women, children, and LGBT individuals, are subjects of ongoing attention from human rights organizations and civil society.

The government has made efforts to combat corruption and ensure the rule of law, including establishing an Independent Authority Against Corruption. However, effective implementation and enforcement of laws remain critical. Ensuring access to justice, particularly for marginalized communities, and strengthening judicial independence are key aspects of Mongolia's ongoing democratic development and commitment to human rights. The role of a vibrant civil society and a relatively free media is crucial in advocating for and monitoring human rights in the country.

6. Foreign Relations

Mongolia's foreign policy is shaped by its unique geopolitical position, landlocked between Russia and China. Since its democratic transition, it has pursued a multi-pillared approach, emphasizing balanced relations with its two powerful neighbors while actively developing ties with "third neighbors" - other influential countries and international organizations - to bolster its sovereignty, security, and economic development.

6.1. Overview of Foreign Policy

Mongolia's foreign policy is primarily guided by its National Security Concept, which identifies maintaining independence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity as paramount. A key tenet is the "Third Neighbor Policy," which aims to cultivate strong political, economic, and cultural relationships with countries beyond Russia and China. This policy is designed to provide a strategic balance, reduce over-dependence on its immediate neighbors, and integrate Mongolia into the wider international community. Mongolia officially declared itself a nuclear-weapon-free zone, a status recognized by the United Nations. It is committed to peaceful diplomacy, non-interference in the internal affairs of other states, and contributing to international peace and security. While maintaining neutrality on many global issues, Mongolia has actively participated in UN peacekeeping operations.

6.2. Relations with Russia

Russia has historically been a key partner for Mongolia. During the Soviet era, Mongolia was a close ally and received substantial economic and military assistance from the USSR. This historical relationship continues to influence contemporary ties. Political relations remain strong, with regular high-level visits and consultations. Economic cooperation includes trade, energy (Mongolia relies heavily on Russian fuel and electricity), and infrastructure projects, such as the Trans-Mongolian Railway. Security cooperation, including joint military exercises and arms sales, is also an important aspect of the relationship. Russia is seen as a crucial partner in maintaining a balance in Mongolia's foreign relations.

6.3. Relations with China

China is Mongolia's southern neighbor and its largest trading partner and source of foreign investment. The relationship with China is multifaceted, characterized by deep economic interdependence but also a degree of historical caution on the Mongolian side. Economic ties are dominated by Mongolian exports of mineral resources (coal, copper, etc.) to China and Chinese investment in Mongolia's mining sector and infrastructure. Border cooperation, trade facilitation, and people-to-people exchanges are also significant. Mongolia views China as essential for its economic development but also seeks to ensure that this economic relationship does not compromise its political sovereignty or lead to undue influence.

6.4. "Third Neighbor" Policy

The "Third Neighbor" policy is a cornerstone of Mongolia's foreign relations, aimed at diversifying its international partnerships. Key "third neighbors" include the United States, Japan, South Korea, India, Canada, Australia, and members of the European Union (particularly Germany).

- United States**: Relations focus on promoting democracy, security cooperation (including peacekeeping training and support for Mongolia's military modernization), and economic ties. The US has been a strong supporter of Mongolia's democratic development.

- Japan**: Japan is a major aid donor and investor in Mongolia. Cooperation spans economic development, infrastructure projects, cultural exchange, and support for Mongolia's democratic institutions.

- South Korea**: Relations are strong, driven by significant labor migration from Mongolia to South Korea, growing trade and investment, and cultural affinity.

- India**: Viewed as a "spiritual neighbor" due to shared Buddhist heritage, relations with India focus on cultural, educational, and increasingly, strategic and economic cooperation.

- European Union**: The EU and its member states are important partners in trade, investment, development aid, and support for good governance and human rights.

This policy aims to enhance Mongolia's international standing, attract diverse sources of investment and technology, and provide diplomatic and political support for its independence and democratic path.

6.5. Participation in International Organizations

Mongolia is an active member of the United Nations (UN) and its specialized agencies. It has contributed significantly to UN peacekeeping operations in various conflict zones around the world, earning a reputation as a reliable contributor to international peace and security. Mongolia is also a member of other international and regional organizations, including the World Trade Organization (WTO), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) as a partner for co-operation, and the Asia Cooperation Dialogue (ACD). It holds observer status in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). Through its participation in these organizations, Mongolia seeks to promote its national interests, contribute to global governance, and further integrate itself into the international community.

7. Military

The Mongolian Armed Forces (MAF; Монгол Улсын Зэвсэгт ХүчинMongol Ulsyn Zevsegt HüchinMongolian) are responsible for the national defense of Mongolia and consist of three main branches: the General Purpose Force (ground forces), the Air Force, and the Cyber Security Troops. Historically, during the Soviet era, the Mongolian military was closely modeled on and equipped by the Soviet Union. Since the democratic transition, Mongolia has undertaken efforts to reform and modernize its armed forces, focusing on creating a smaller, more mobile, and professional military.

The personnel strength is relatively modest, reflecting the country's small population. Mongolia maintains a conscription system, where male citizens are required to serve for one year, though alternatives such as monetary payment or equivalent service exist. The defense policy emphasizes self-defense, border security, and contributing to international peace and stability. Equipment is a mix of older Soviet-era hardware and more modern acquisitions from various countries, including Russia, China, and Western nations.

A significant aspect of Mongolia's contemporary military activity is its participation in international peacekeeping operations. Mongolian troops have served in numerous UN-mandated missions in conflict zones across Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, including Iraq, Afghanistan, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, and Chad. This participation is a key component of Mongolia's "Third Neighbor" foreign policy and its commitment to being a responsible member of the international community. Mongolia also engages in bilateral and multilateral military exercises with various partners, including Russia, China, the United States, and other "third neighbor" countries, to enhance interoperability and share expertise. The military also plays a role in disaster relief and internal security.

8. Administrative Divisions

Mongolia is divided into 21 aimags (provinces) and the capital city, Ulaanbaatar, which is administered as an independent municipality with provincial status. Each aimag is further subdivided into sums (districts), and sums are further divided into bags (sub-districts or brigades), which are the smallest administrative units, often corresponding to nomadic pastoral communities or small settlements. As of recent data, there are 330 sums in Mongolia. This administrative structure has roots in historical divisions but has been adapted for modern governance. Provincial and local governments have elected councils (Khurals) and appointed governors.

The 21 aimags are:

- Arkhangai

- Bayan-Ölgii

- Bayankhongor

- Bulgan

- Darkhan-Uul

- Dornod

- Dornogovi

- Dundgovi

- Govi-Altai

- Govisümber

- Khentii

- Khovd

- Khövsgöl

- Ömnögovi

- Orkhon

- Övörkhangai

- Selenge

- Sükhbaatar

- Töv

- Uvs

- Zavkhan

8.1. Major Cities

While Mongolia is one of the world's most sparsely populated countries with a significant portion of its population maintaining a nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyle, it also has several urban centers.

- Ulaanbaatar: The capital and by far the largest city, Ulaanbaatar is the political, economic, cultural, and educational hub of Mongolia. Located in the Tuul River valley, it is home to roughly half of the country's population. Originally a nomadic monastic center, it has grown into a bustling modern city with a mix of Soviet-era architecture, modern high-rises, and traditional ger districts on its outskirts. It hosts the main government institutions, universities, museums, and theaters.

- Erdenet: Located in Orkhon Aimag in northern Mongolia, Erdenet is the second-largest city. Its development is primarily linked to the Erdenet Mining Corporation, one of the largest copper mines in Asia. The city was built in the 1970s with Soviet assistance and serves as an important industrial center.

- Darkhan: Situated in Darkhan-Uul Aimag, also in northern Mongolia, Darkhan is the third-largest city. It was founded in 1961 as an industrial center with Soviet and Eastern European aid. It has industries related to construction materials, food processing, and light manufacturing. Darkhan is also an educational center with several university branches.

- Choibalsan: The administrative center of Dornod Aimag in eastern Mongolia, Choibalsan is the fourth-largest city. It is an important regional hub for trade and transportation, particularly with its proximity to China and Russia.

Other significant aimag centers include Mörön (Khövsgöl), Khovd (Khovd), and Ölgii (Bayan-Ölgii). These cities, while smaller than Ulaanbaatar, Erdenet, and Darkhan, serve as crucial administrative, commercial, and cultural centers for their respective regions, reflecting the ongoing process of urbanization in Mongolia alongside its enduring nomadic traditions. The concentration of population and economic activity in Ulaanbaatar, however, presents challenges related to infrastructure, housing, pollution, and equitable development across the vast country.

| Rank | City | Province | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ulaanbaatar | Ulaanbaatar | 1,426,645 |

| 2 | Erdenet | Orkhon | 101,421 |

| 3 | Darkhan | Darkhan-Uul | 83,213 |

| 4 | Choibalsan | Dornod | 46,683 |

| 5 | Mörön | Khövsgöl | 41,586 |

| 6 | Nalaikh | Ulaanbaatar (district) | 38,690 |

| 7 | Ölgii | Bayan-Ölgii | 38,310 |

| 8 | Arvaikheer | Övörkhangai | 33,743 |

| 9 | Bayankhongor | Bayankhongor | 31,948 |

| 10 | Khovd | Khovd | 31,081 |

9. Economy

Mongolia's economy has undergone a significant transformation from a centrally planned system under Soviet influence to a market-based economy since the early 1990s. It is rich in mineral resources and has a strong tradition of pastoral agriculture. The country faces challenges related to its landlocked geography, dependence on commodity prices, and the need for sustainable and equitable development.

9.1. Economic Overview

The transition to a market economy in the 1990s was initially difficult, marked by high inflation, economic contraction, and the loss of Soviet subsidies. Since the 2000s, Mongolia has experienced periods of rapid GDP growth, largely driven by the mining sector and high global commodity prices, particularly for copper and coal. However, this reliance on mining also makes the economy vulnerable to price fluctuations and external demand, primarily from China.

Key economic indicators such as inflation, unemployment, and trade balance vary with global economic conditions and domestic policies. Poverty and income inequality remain significant challenges, particularly between urban and rural areas, and among different social groups. The social impact of economic policies, especially those related to the mining boom, is a subject of ongoing debate, with concerns about resource distribution, environmental degradation, and impacts on traditional livelihoods. The government has implemented various social welfare programs, but ensuring equitable benefits from economic growth and protecting vulnerable populations are critical for sustainable development. The informal economy is also estimated to be substantial. As of 2022, 78% of Mongolia's exports went to China, and China supplied 36% of Mongolia's imports, with Russia supplying another 29%.

Mongolia's real GDP grew by 7% in 2023, driven by record-high coal production due to strong demand from China. Inflation in early 2024 dropped to 7% due to lower global food and fuel prices. Despite a robust increase in import volumes, Mongolia recorded a current account surplus due to the sharp increase in coal exports. Mining sector growth is expected to continue driving GDP growth, although the International Monetary Fund predicts the current account balance will revert to a sizable deficit due to declining coal prices. The World Bank notes promising development prospects due to mining expansion and public investment but highlights risks from inflation, weaker Chinese demand, and fiscal issues. According to the Asian Development Bank, 27.1% of Mongolia's population lived below the national poverty line in 2022. In the same year, GDP per capita (PPP) was estimated at $12,100.

The Mongolian Stock Exchange, established in 1991 in Ulaanbaatar, is one of the world's smallest stock exchanges by market capitalization. As of 2024, it listed 180 companies with a total market capitalization of 3.20 B USD.

9.2. Major Industries

Mongolia's economy is driven by several key sectors, with mining and agriculture being the most prominent.

9.2.1. Mining

Mining is the backbone of the Mongolian economy, accounting for a significant portion of its GDP and export revenues. The country possesses vast reserves of copper, coal, gold, molybdenum, tin, tungsten, uranium, and rare earth elements. Major mining projects include the Oyu Tolgoi copper and gold mine (one of the largest in the world) and the Tavan Tolgoi coal deposit. Minerals represent more than 80% of Mongolia's exports. Fiscal revenues from mining represented 21% of government income in 2010 and rose to 24% in 2018.

While the mining sector drives economic growth, it also presents significant environmental, social, and governance (ESG) challenges. Environmental concerns include water scarcity (especially in the Gobi region), land degradation, pollution, and impacts on biodiversity. Social challenges involve displacement of local communities, disputes over land use, impacts on traditional nomadic lifestyles, and ensuring that local populations benefit from resource extraction. Labor rights in the mining sector, including safety and fair wages, are also important issues. Governance challenges include transparency in licensing and revenue management, combating corruption, and ensuring that mining wealth contributes to sustainable national development and social equity. There are ongoing efforts and public debate regarding how to manage these challenges and ensure that the benefits of mining are shared equitably while minimizing negative impacts on communities and the environment. In September 2022, Mongolia launched a 145 mile (233 km) direct rail link to China for coal transport from Tavan Tolgoi.

9.2.2. Agriculture and Pastoralism

Agriculture, particularly nomadic pastoralism, has been a traditional mainstay of the Mongolian economy and way of life for centuries. Livestock herding remains central, with large populations of sheep, goats (the source of cashmere, a major export), cattle, horses, and Bactrian camels. These animals provide meat, dairy products, wool, cashmere, and transportation for a significant portion of the rural population. The traditional nomadic lifestyle, adapted to Mongolia's vast steppes and harsh climate, faces challenges from climate change, desertification, and market pressures.

Crop production is limited by the short growing season and arid climate but is important for domestic food supply. Wheat, potatoes, and vegetables are the main crops, primarily cultivated in the northern and central regions. Ensuring food security and supporting the livelihoods of herders while promoting sustainable land management are key policy objectives for the agricultural sector. Mongolia produces one-fifth of the world's raw cashmere.

9.2.3. Tourism

Tourism is a developing sector with significant potential, driven by Mongolia's unique natural landscapes, nomadic culture, and historical heritage. Attractions include the Gobi Desert, Lake Khövsgöl, national parks, ancient archaeological sites, and cultural experiences like staying in a traditional ger, horseback riding, and attending the Naadam festival. The tourism industry contributes to economic diversification and provides employment opportunities. Challenges include seasonal limitations, infrastructure development (particularly in remote areas), and the need to ensure sustainable tourism practices that respect the environment and local cultures while providing benefits to local communities.

10. Infrastructure

Mongolia's infrastructure, including transportation, energy, and communications networks, has been undergoing development to support economic growth and improve connectivity across its vast territory.

10.1. Transportation

The Trans-Mongolian Railway is the main rail link, connecting Russia and China via Ulaanbaatar. It is crucial for both passenger and freight transport, especially for mining exports. Branch lines connect to industrial centers like Erdenet and Baganuur. In 2022, a new 145 mile (233 km) cargo rail link from the Tavan Tolgoi coal mine to the Chinese border was launched.

The road network is being upgraded, with paved roads connecting Ulaanbaatar to major aimag centers and border points. The "Millennium Road" project aims to create an east-west highway across the country. However, many rural roads remain unpaved, posing challenges for transportation, particularly in harsh weather. Mongolia has 3.0 K mile (4.80 K km) of paved roads, with 1.1 K mile (1.80 K km) completed in 2013 alone.

Air transport is vital due to the country's size and limited road/rail infrastructure. Chinggis Khaan International Airport, south of Ulaanbaatar, is the main international gateway, with flights connecting to major cities in Asia and Europe. MIAT Mongolian Airlines is the national carrier, and several private airlines operate domestic and some international routes. Domestic airports serve aimag centers.

10.2. Energy

Mongolia's energy sector is heavily reliant on coal, which is the primary source for electricity generation and heating. Most electricity is produced by aging coal-fired thermal power plants, with Thermal Power Plant No. 4 in Ulaanbaatar being the largest. The country imports petroleum products and some electricity. Energy security is a key concern, with efforts underway to upgrade existing power plants, explore domestic oil resources (with the country's first oil refinery under construction), and reduce reliance on imports.

There is growing interest in developing renewable energy resources, particularly solar and wind power, for which Mongolia has significant potential. Several wind farms are operational, and solar projects are being developed. These initiatives aim to diversify the energy mix, reduce carbon emissions, and improve energy access, especially in remote rural areas not connected to the central grid. However, challenges remain in terms of investment, grid integration, and balancing renewable development with the dominant coal-based system.

10.3. Communications

The telecommunications sector in Mongolia has seen rapid development, particularly in mobile and internet services. Mobile phone penetration is high, even in rural areas. Several mobile operators compete in the market, offering voice and data services. Internet access has expanded significantly, with increasing broadband penetration in urban areas and growing mobile internet use across the country. Fiber-optic networks are being laid to improve connectivity. Mongol Post is the state-owned postal service provider, operating alongside other licensed operators. The development of communications infrastructure is crucial for economic growth, education, and connecting Mongolia's dispersed population.

11. Society

Mongolian society is a blend of ancient nomadic traditions and modern influences, shaped by its unique history, geography, and recent socio-economic transformations. Key aspects include its demographic profile, ethnic composition, languages, religions, and systems of education and healthcare, all of which are evolving as the country navigates the 21st century.

11.1. Demographics

Mongolia's population was estimated at around 3.5 million people as of early 2024. It is one of the most sparsely populated countries in the world, with a population density of just over 2 people per square kilometer. A significant demographic trend is urbanization, with approximately 47.6% of the population residing in the capital city, Ulaanbaatar (as of 2020). Another 21.4% lived in aimag centers and other permanent settlements, while 31.0% remained in rural areas, often maintaining nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyles.

The population is relatively young, with about 59% under the age of 30, though this proportion is gradually aging. The total fertility rate has declined significantly since the socialist era (from over 7 children per woman in the 1970s to around 2.5-2.6 in recent years) but remains above replacement level. Life expectancy has been increasing. Migration patterns include rural-to-urban migration, primarily towards Ulaanbaatar, driven by economic opportunities and access to services. There is also some international labor migration, particularly to South Korea. These demographic shifts present challenges for urban planning, infrastructure development, employment, and the provision of social services, as well as for the preservation of traditional rural lifestyles.

11.2. Ethnic Groups

Mongolia is ethnically quite homogeneous. The vast majority (around 95%) of the population are Mongols. Within this group, the Khalkha are the largest subgroup, making up about 86% of the ethnic Mongol population and forming the demographic and cultural core of the nation. Other Mongolic groups include Buryats, Oirats (including subgroups like Dörbet, Bayid, Zakhchin, Torguud, Myangad, Altai Uriankhai), Dariganga, Khotogoid, Khotons (a Mongolicized Turkic group), Üzemchin, Barga, and others. These groups are distinguished primarily by dialects of the Mongol language and some cultural variations.

The largest non-Mongol minority group is the Kazakhs, who constitute about 3-4.5% of the total population. They are predominantly concentrated in Bayan-Ölgii Province in western Mongolia, where they form the majority. Kazakhs maintain their distinct Turkic language, Islamic faith, and cultural traditions, including eagle hunting. Other smaller ethnic minorities include Tuvans (another Turkic group, mainly in Khövsgöl Province), Russians, and Chinese.

The 1992 Constitution guarantees equal rights for all citizens regardless of ethnicity. The government has policies aimed at preserving the cultural heritage of minority groups. While inter-ethnic relations are generally harmonious, ensuring the social integration, cultural preservation, and representation of minority groups, particularly in education, employment, and political life, remains an important aspect of social equity and democratic development in Mongolia.

11.3. Languages

The official and national language of Mongolia is Mongolian, spoken by about 95% of the population. The standard dialect is Khalkha Mongol, which belongs to the Mongolic languages family. Various other Mongolic dialects, largely mutually intelligible with Khalkha, are spoken by different subgroups, such as Oirat, Buryat, and Khamnigan. Many dialects have been gradually aligning more with the central Khalkha dialect.

Historically, Mongolian was written using the traditional Mongolian script (Mongol bichig), a unique vertical script. However, during the socialist era, the Cyrillic alphabet was introduced in the 1940s under Soviet influence and became the dominant script for official and everyday use. Since the 1990 democratic revolution, there has been a revival of interest in the traditional Mongolian script. It is taught in schools from the sixth grade onwards and has been officially declared the "national script." As of 2025, Mongolia began using both Cyrillic and traditional Mongolian scripts for legal papers and official documents, though Cyrillic remains the primary script in daily life for most practical purposes.

Among minority languages, Kazakh, a Turkic language, is widely spoken in Bayan-Ölgii, where it is also used in education and local media. Tuvan, another Turkic language, is spoken by the Tuvan minority in Khövsgöl. Mongolian Sign Language is used by the deaf community.

Regarding foreign languages, Russian was historically the most important foreign language due to close ties with the Soviet Union. However, since the 1990s, English has rapidly gained prominence and is now the most popular foreign language, taught in schools from the third grade and widely used in business and international communication. Other foreign languages studied include Chinese, Japanese, and Korean, with Korean being particularly popular due to labor migration to South Korea.

11.4. Religion

| Religion | Population (2010) | Share (2010) | Share (2020) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buddhism | 1,009,357 | 53.0% | 51.7% |

| Non-religious | 735,283 | 38.6% | 40.6% |

| Islam | 57,702 | 3.0% | 3.2% |

| Shamanism (Tengrism) | 55,174 | 2.9% | 2.5% |

| Christianity | 41,117 | 2.2% | 1.3% |

| Other religions | 6,933 | 0.4% | 0.7% |

| Total (aged 15+) | 1,905,566 | 100.0% | 100.0% |

The predominant religion in Mongolia is Tibetan Buddhism (Vajrayana school). According to the 2010 national census, among Mongolians aged 15 and above, 53% identified as Buddhist. This figure was 51.7% in the 2020 census. A significant portion of the population, 38.6% in 2010 and 40.6% in 2020, identified as non-religious or atheist.

Mongolian shamanism (Tengrism), the indigenous belief system, has been practiced throughout Mongolian history and continues to be a living tradition for some, with 2.9% adherents in 2010 (2.5% in 2020). It has influenced Buddhist practices and cultural identity.

Islam is primarily practiced by the ethnic Kazakh minority in western Mongolia, accounting for 3.0% of the population aged 15+ in 2010 (3.2% in 2020).

Christianity has a small but growing presence, with 2.2% adherents in 2010 (1.3% in 2020). This includes various Protestant denominations and a small Catholic community. The number of Christians grew after religious restrictions were lifted in 1991. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) and Seventh-day Adventists also report memberships in the country.

During the socialist era (1924-1990), religious practices were severely repressed by the communist government. The Buddhist clergy and monastic institutions were particularly targeted; almost all of Mongolia's over 700 Buddhist monasteries were closed, and tens of thousands of monks were executed or imprisoned in the late 1930s. The fall of communism in 1991 restored freedom of religion. Tibetan Buddhism has since experienced a significant revival. The search for the 10th Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, the spiritual head of Mongolian Buddhism, has been a subject of attention, complicated by China's desire to assert control over Tibetan Buddhist affairs. The state of religious freedom is generally respected, but the legacy of past repression and the dynamics of religious revival present ongoing societal considerations.

11.5. Education

Education was an area of significant development during the socialist period, transforming a society with literacy rates below one percent into one with virtually universal literacy by the 1950s, partly through seasonal boarding schools for children of nomadic families. Since the democratic transition in 1990, the education system has undergone further reforms.

The structure of the education system typically includes pre-primary (kindergarten), primary, lower secondary, and upper secondary education, followed by tertiary (higher) education. The duration of general education has shifted; formerly ten years, it was expanded to eleven, and a 12-year system began to be implemented for new first-graders from the 2008-2009 school year, with a full transition expected by the 2019-2020 school year.

Literacy rates remain high. English is widely taught as a foreign language in secondary schools, having largely supplanted Russian as the dominant foreign language, especially in urban areas. It is taught from the fourth grade, and in 2023 was declared the "first foreign language" to be taught from the third grade.

Higher education is provided by public and private universities and colleges. The National University of Mongolia and the Mongolian University of Science and Technology are the largest public universities. There has been a significant increase in university enrollment since the 1990s.

Challenges in the education sector include ensuring equitable access and quality, particularly for children in remote rural areas and from herder families. Disparities in educational resources and outcomes between urban and rural areas persist. Efforts are ongoing to modernize curricula, improve teacher training, and align the education system with the needs of a market economy and democratic society. Providing adequate funding for education, especially for rural boarding schools which saw cuts in the 1990s (contributing to a slight increase in illiteracy at the time), is crucial for social equity.

11.6. Health

Mongolia's healthcare system has seen improvements since the democratic transition, though challenges remain, particularly in providing equitable access to services across its vast and sparsely populated territory. During the socialist era, a state-funded healthcare system was established, which significantly improved public health indicators.

Key public health indicators such as life expectancy (around 67-68 years in recent estimates) and maternal and child mortality rates have generally improved since 1990. However, Mongolia faces a "double burden" of disease, with both communicable diseases and a rising prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and diabetes, often linked to lifestyle factors like diet, smoking, and alcohol consumption. Other health challenges include high rates of accidents and injuries, and issues related to environmental health, such as air pollution in Ulaanbaatar, particularly during winter.

The healthcare system comprises a network of state-run hospitals and clinics at national, aimag (provincial), and sum (district) levels, as well as a growing private sector. Access to medical services can be difficult for nomadic populations and those in remote rural areas due to distance, transportation challenges, and a shortage of healthcare professionals in these regions. Ensuring adequate funding, improving the quality of care, strengthening primary healthcare, and addressing health disparities between urban and rural areas are ongoing priorities. Efforts are also focused on public health campaigns, disease prevention, and promoting healthy lifestyles. Maternal and child health remains a focus, with programs aimed at reducing mortality and improving access to prenatal and postnatal care.

12. Culture

Mongolian culture is rich and distinctive, deeply rooted in its nomadic pastoral heritage and shaped by centuries of history, including the influence of the Mongol Empire and Tibetan Buddhism. Despite modernization and urbanization, many traditional aspects of life and cultural expression remain vibrant. The Soyombo symbol, a national emblem found on the flag, incorporates various elements representing Buddhist and cosmological themes.

12.1. Traditional Lifestyle

The nomadic way of life has been central to Mongolian identity for millennia. The ger (also known as a yurt in Russian) is the traditional dwelling - a portable, round tent made of a wooden frame covered with felt. It is well-suited to the nomadic lifestyle and harsh climate. Traditional Mongolian clothing, the deel, is a long, loose robe-like garment made of cotton, silk, or brocade, tied at the waist with a sash. Styles vary by region and occasion. Horsemanship is integral to Mongolian culture; horses are essential for transportation, herding, and are symbols of freedom and strength. Traditional customs related to hospitality, respect for elders, and family ties are highly valued. The traditional Mongolian script, a vertical alphabet, is a unique cultural heritage and is being revived.

12.2. Arts

Mongolian traditional music is characterized by unique instruments and vocal styles. The morin khuur (horsehead fiddle) is the most iconic Mongolian musical instrument. Khoomei (throat singing) is a remarkable vocal technique where a singer produces multiple pitches simultaneously. Urtyn duu ("long song") are lyrical, flowing folk songs often about nature, love, and horses. Traditional dance, such as the biyelgee, is often performed in gers and reflects daily nomadic life.

Visual arts include traditional Mongol zurag painting, a style characterized by detailed depictions of nomadic life, historical events, and Buddhist themes, often with a unique perspective and vibrant colors. Before the 20th century, most fine arts had a religious function, heavily influenced by Buddhist texts, including thangkas (painted or appliquéd scrolls) and bronze sculptures of deities attributed to artists like Zanabazar. In the late 19th century, painters like "Marzan" Sharav turned to more realistic styles. During the People's Republic, socialist realism was dominant, though Mongol zurag also continued. Modernism emerged in the 1960s, and all art forms flourished after the democratic reforms of the late 1980s. Otgonbayar Ershuu is a well-known contemporary Mongolian artist.

Performing arts also include theater and circus traditions. Contemporary artistic trends are emerging in Ulaanbaatar, blending traditional motifs with modern expressions.

12.3. Literature

Mongolian literature has a rich history, beginning with strong oral traditions, including heroic epics like the Epic of Jangar and the Geser Khan. The most famous historical chronicle is The Secret History of the Mongols, written in the 13th century, detailing the life of Genghis Khan and the rise of the Mongol Empire. Other historical chronicles and Buddhist texts also form part of the literary heritage. Modern Mongolian literature developed in the 20th century, influenced by socialist realism during the MPR era, and has diversified since the democratic transition, with contemporary writers exploring a wider range of themes and styles.

12.4. Cuisine

Mongolian cuisine is traditionally based on meat (primarily mutton and beef, but also goat, horse, and camel) and dairy products, reflecting the pastoral nomadic lifestyle. Vegetables and spices were historically less common but are now more widely used.

Staple dishes include:

- Buuz: Steamed dumplings filled with meat.

- Khuushuur: Deep-fried meat pastries.

- Tsuivan: Fried noodles with meat and vegetables.

- Boodog and Khorkhog: Traditional methods of cooking meat (often goat or marmot) using hot stones, either inside the animal's carcass (boodog) or in a sealed container (khorkhog).

- Dairy products (tsagaan idee, "white foods") are diverse, including aaruul (dried curds), urum (clotted cream), yogurt, cheese, and airag (kumis), which is fermented mare's milk, a popular traditional beverage.

Tea (suutei tsai), often milky and salty, is a ubiquitous drink.

12.5. Festivals and Sports

The most important national festival is Naadam (Eriin Gurvan Naadam - "the three manly games"), held annually in July, primarily from the 11th to the 13th, to celebrate the anniversaries of the National Democratic Revolution and the foundation of the Great Mongol State. The festival features three traditional sports:

- Mongolian wrestling (Bökh): The most popular sport, with hundreds of wrestlers competing.

- Horse racing: Long-distance races across the steppe, with child jockeys.

- Archery: Both men and women participate.

Other significant cultural celebrations include Tsagaan Sar ("White Moon"), the Mongolian Lunar New Year, which is a major family holiday involving feasting, gift-giving, and traditional rituals. The Golden Eagle Festival, held by Kazakh eagle hunters in Bayan-Ölgii, showcases the ancient tradition of hunting with golden eagles. The Ice Festival on Lake Khövsgöl and the Thousand Camel Festival in the Gobi are other notable traditional events.

Traditional sports like Shagaa (flicking sheep ankle bones) are popular. Modern sports such as basketball, football (soccer), boxing, judo, freestyle wrestling, weightlifting, and shooting have gained popularity. Mongolian athletes have achieved international success, particularly in combat sports like judo, boxing, and sumo wrestling (where Mongolians have dominated in Japan). Bandy is another sport where Mongolia has had success in Asian competitions.

12.6. Media

The media landscape in Mongolia has transformed significantly since the democratic revolution of 1990. During the socialist era, media was strictly controlled by the state and the ruling Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party, with newspapers like Unen ("Truth") serving as official organs.

Since the adoption of a new constitution and press freedom laws in the 1990s, a pluralistic media environment has emerged. There are numerous print (newspapers, magazines), broadcast (television, radio), and online media outlets, both public and private. The Mongolian National Broadcaster (MNB) is the public service broadcaster.

Press freedom is generally respected, and Mongolia often ranks favorably in regional press freedom indices. However, challenges remain, including issues related to media ownership concentration, political influence on media outlets, self-censorship, and the safety of journalists. Defamation laws have sometimes been used to pressure journalists. Access to diverse sources of information has increased significantly with the growth of the internet and social media. According to a 2014 Asian Development Bank survey, 80% of Mongolians cited television as their main source of information. The media plays a crucial role in public discourse, political debate, and holding power accountable, contributing to Mongolia's democratic development. Ensuring a truly independent, professional, and economically viable media sector is an ongoing objective.